A Condensed History of American Half-A Engines

By Maris Dislers

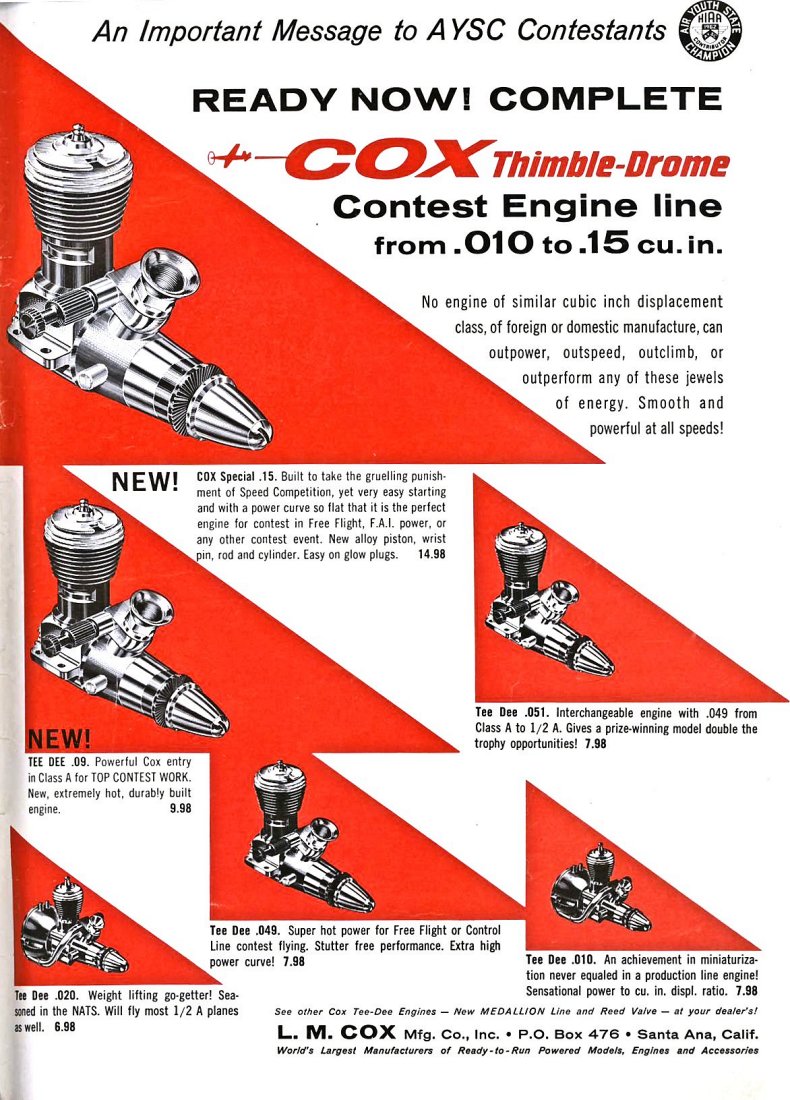

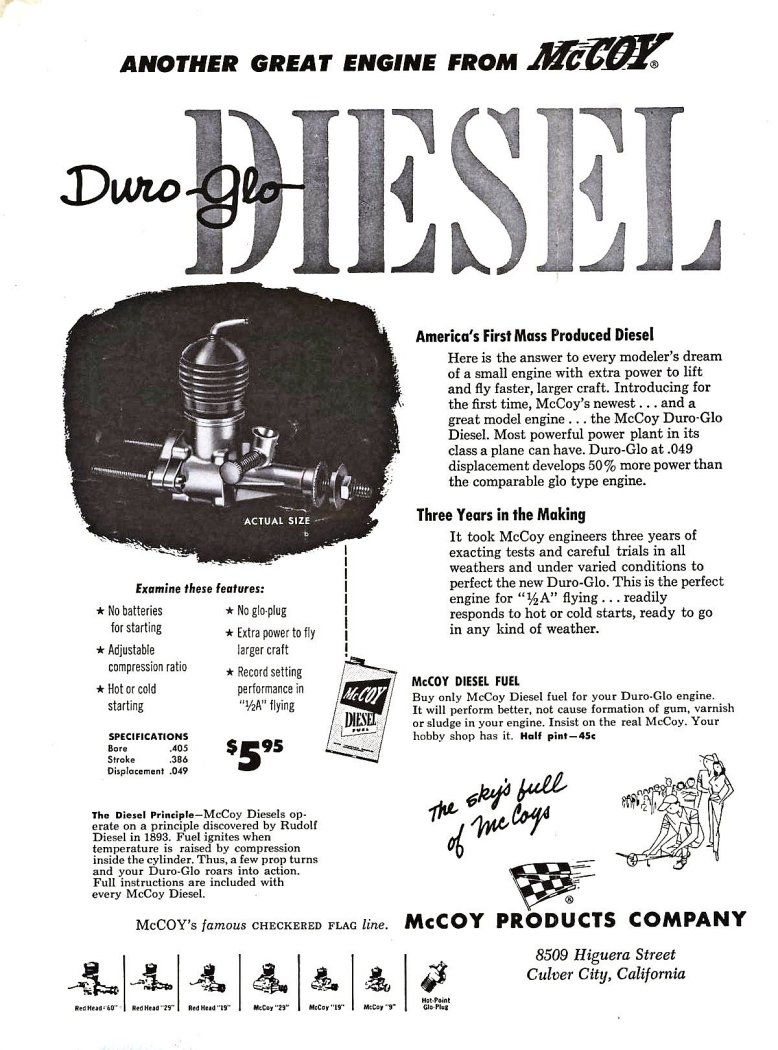

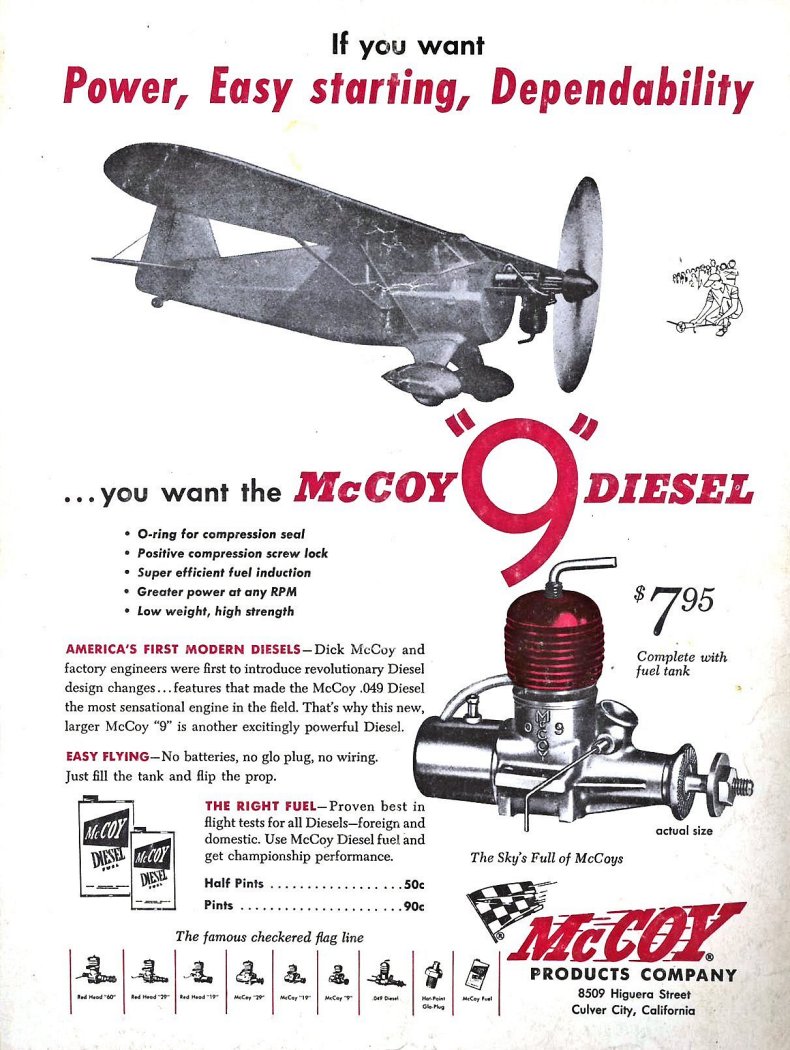

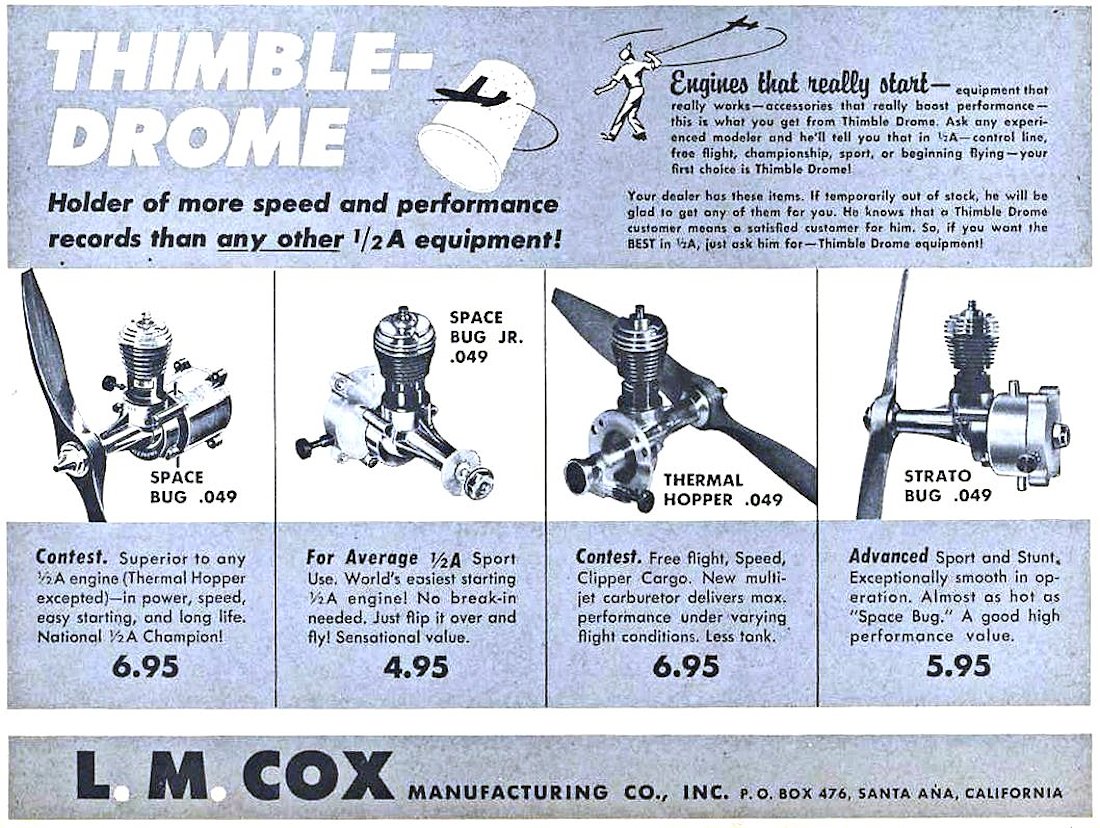

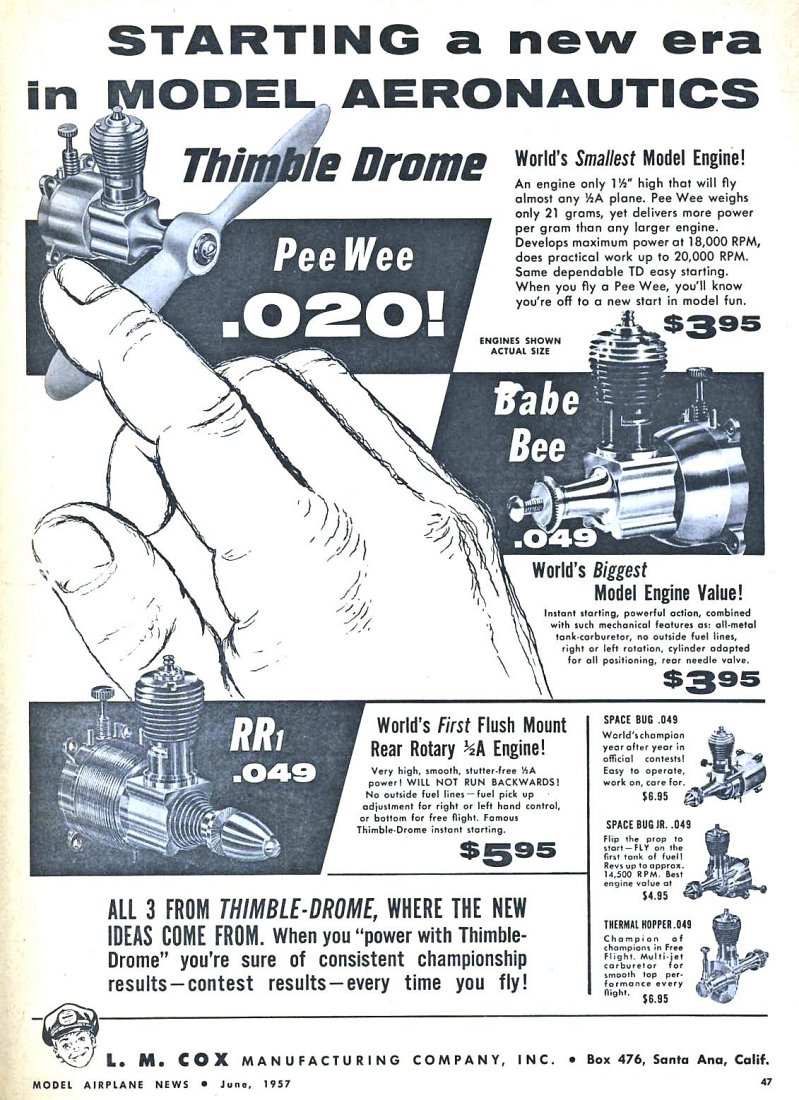

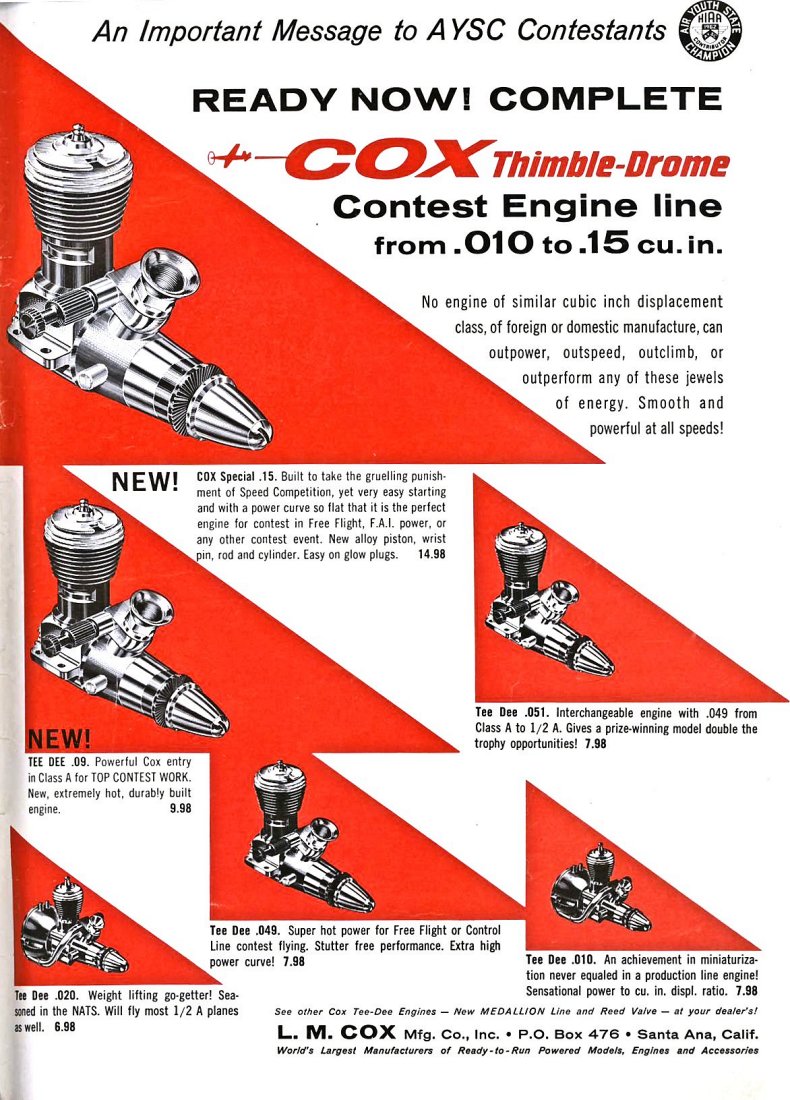

(Editor’s note - Due to the number of images required to illustrate this article, it has been necessary to present them in the text at relatively small sizes. To view them at full size, as many of them need to be, simply right-click on the image and select the “open image in new tab” option from the drop-down menu. I strongly suggest that you do this, because the ads in particular contain a wealth of relevant detail that is not included in Maris's text. My sincere thanks to Maris for rising to the considerable challenge of putting this story together! A.D.)

(Editor’s note - Due to the number of images required to illustrate this article, it has been necessary to present them in the text at relatively small sizes. To view them at full size, as many of them need to be, simply right-click on the image and select the “open image in new tab” option from the drop-down menu. I strongly suggest that you do this, because the ads in particular contain a wealth of relevant detail that is not included in Maris's text. My sincere thanks to Maris for rising to the considerable challenge of putting this story together! A.D.)

Among America’s enormous contributions to model engine development, the .049 cuin. Half-A sub-group is undoubtedly one of the most important. Cox .049s come easily to mind, being by far the most successful in terms of numbers and longevity in the market. But many others came and went, particularly in the 1950’s and into the 1960’s, resulting in a progression of design advances and commercial ups and downs in a business environment involving unprecedented sales volume and operating in a mini-universe of its own. This piece is intended to weave the individual threads into an overall tapestry, made richer by viewing it primarily through the lens of contemporary advertisements in “Model Airplane News” (MAN).

Pre-History

Before WW2, all engines under 0.200 cuin. displacement fell into the “A” class under the prevailing American displacement-based engine classification system. The obvious choices for competition use were those engines with displacements which were close to the maximum allowable in the chosen class. The most popular classes were Classes B (0.300 cuin.) and C (0.500 cuin.).

However, there was a growing interest in small gas-powered models suitable for non-contest sport flying in more confined spaces. This interest was tempered by the inescapable fact that the enforced use of spark ignition in the absence of alternatives created some obvious barriers to progress in that direction. After factoring in the weight of airborne ignition equipment (which was essentially fixed), the smallest practical engines with adequate power to fly a model were around half of the A limit. Dan Calkin’s Elf Single Model 10 and Ray Arden’s Mighty Atom were popular choices. Released in 1939 to popular acclaim, both had swept volumes of just under 0.100 cuin.

However, there was a growing interest in small gas-powered models suitable for non-contest sport flying in more confined spaces. This interest was tempered by the inescapable fact that the enforced use of spark ignition in the absence of alternatives created some obvious barriers to progress in that direction. After factoring in the weight of airborne ignition equipment (which was essentially fixed), the smallest practical engines with adequate power to fly a model were around half of the A limit. Dan Calkin’s Elf Single Model 10 and Ray Arden’s Mighty Atom were popular choices. Released in 1939 to popular acclaim, both had swept volumes of just under 0.100 cuin.

Wartime priorities imposed a temporary halt on model engine production, but did not prevent people from continuingto think about engine design. After considerable experimentation, Ray Arden returned in 1946 with a new Arden .099 model, followed in 1947 by a .19 design. These engines set new benchmarks for specific power output and power-to-weight ratios, especially when the spark ignition equipment was left “on the ground” after starting through the use of “Liquid Dynamite” fuel which could be ignited by the hot spark plug electrodes without an actual spark.

Wartime priorities imposed a temporary halt on model engine production, but did not prevent people from continuingto think about engine design. After considerable experimentation, Ray Arden returned in 1946 with a new Arden .099 model, followed in 1947 by a .19 design. These engines set new benchmarks for specific power output and power-to-weight ratios, especially when the spark ignition equipment was left “on the ground” after starting through the use of “Liquid Dynamite” fuel which could be ignited by the hot spark plug electrodes without an actual spark.

The truly great advance came with Arden’s introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug having an internal platinum element that could replace the sparking plug as a point source of ignition in any suitable engine. Since the glow-plug only required heating with a battery for starting when using a methanol-based fuel, airborne ignition gear was made redundant and power potential increased thanks to the qualities of the fuel. Released commercially in late 1947, the glow-plug’s impact was only slightly delayed by the need to develop better fuels. With the dead weight of the airborne ignition system now eliminated, the potential for significantly smaller engines became obvious.

The First Generation

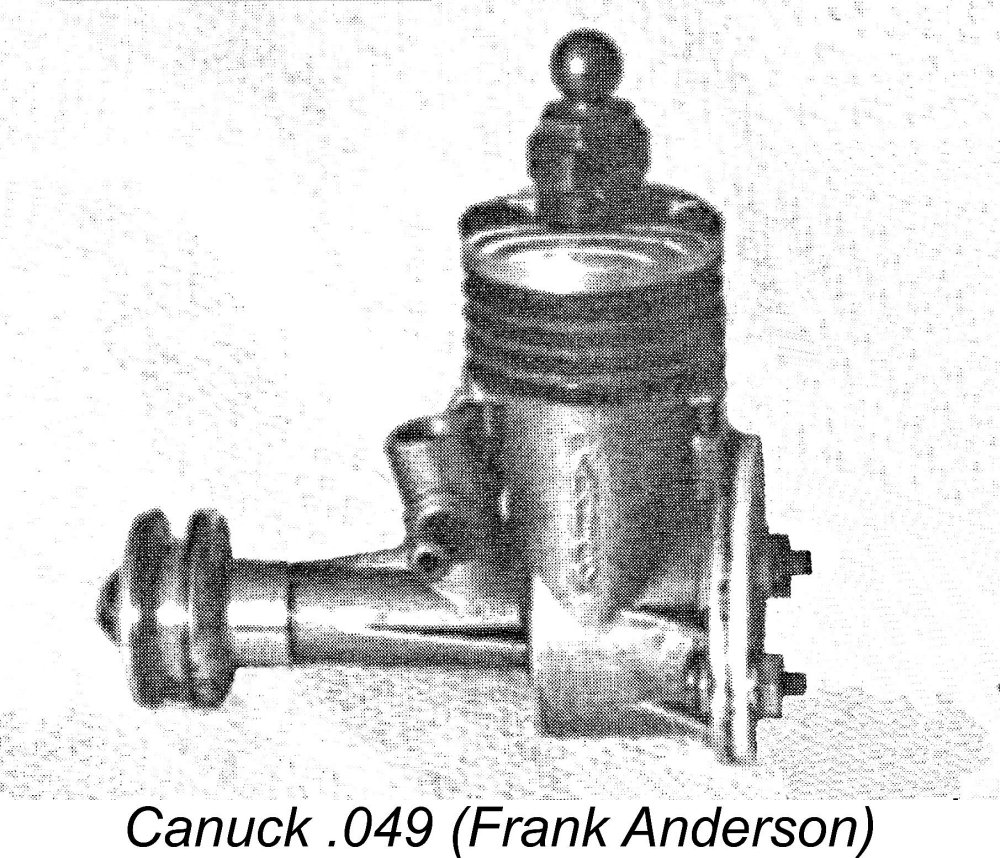

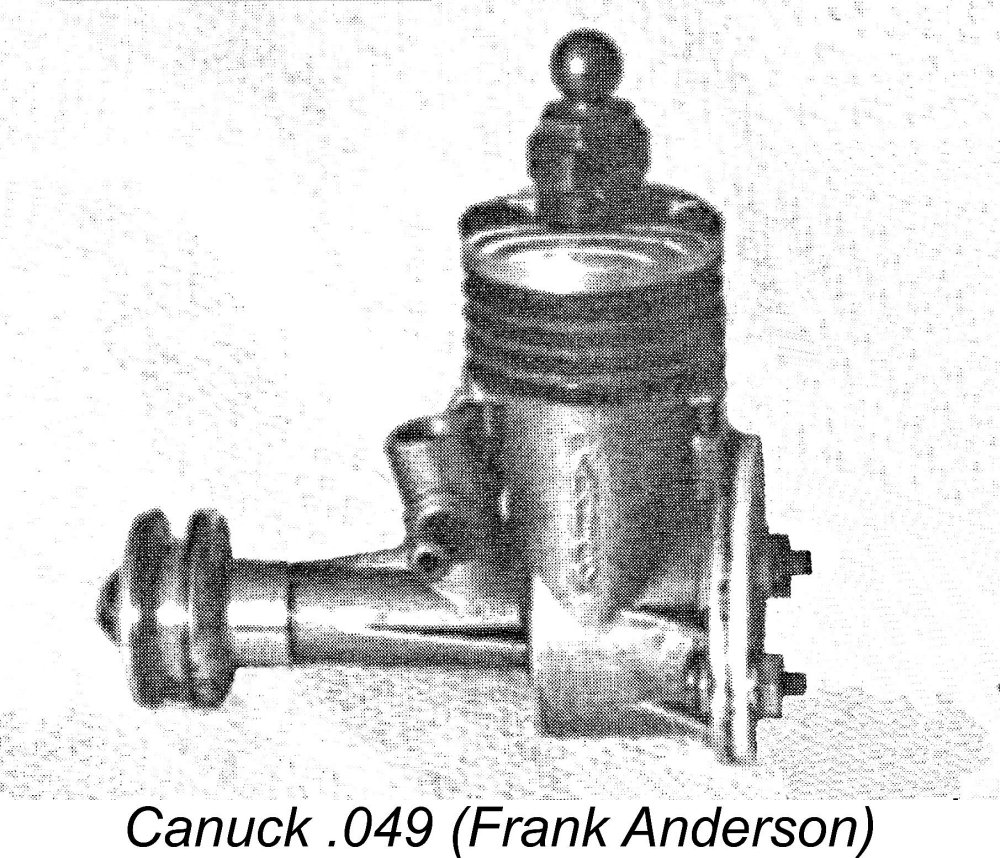

In his invaluable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE), Tim Dannels lists two miniature glowplug engines from 1948 havng nominal .05 cuin. displacements, neither of which was made in commercial quantities. Around a dozen Canuck .049s were made in a variety of slightly different configurations by Lionel Gay and Keith Wooley while working at the AVRO Canada plant in Malton, Ontario, Canada. The other was Elmer Larsen’s Larson Royal .05 from Seattle Washington - the “scale” version with extended crankshaft to facilitate cowling in a model. Both of these pioneers were quite similar, based on die-cast

In his invaluable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE), Tim Dannels lists two miniature glowplug engines from 1948 havng nominal .05 cuin. displacements, neither of which was made in commercial quantities. Around a dozen Canuck .049s were made in a variety of slightly different configurations by Lionel Gay and Keith Wooley while working at the AVRO Canada plant in Malton, Ontario, Canada. The other was Elmer Larsen’s Larson Royal .05 from Seattle Washington - the “scale” version with extended crankshaft to facilitate cowling in a model. Both of these pioneers were quite similar, based on die-cast  (permold) crankcases, front rotary valve (FRV) induction and cross-flow cylinder porting. Larson abandoned his plans for commercial production when Herkimer released a similar engine in 1949.

(permold) crankcases, front rotary valve (FRV) induction and cross-flow cylinder porting. Larson abandoned his plans for commercial production when Herkimer released a similar engine in 1949.

Another early venture was the 1948 Vivell Precision .035 diesel. This little unit was made to order in small numbers by Jack Keener and Jim Brown. Machined entirely from bar stock, it featured rear rotary valve (RRV) induction and radial mounting. A glow-plug version appeared briefly in 1949, with a couple of .013 cuin. derivatives being made in 1950. In this latter design, the glowplug screwed directly into the internally-threaded upper cylinder, thus forming the entire cylinder head and combusion chamber!

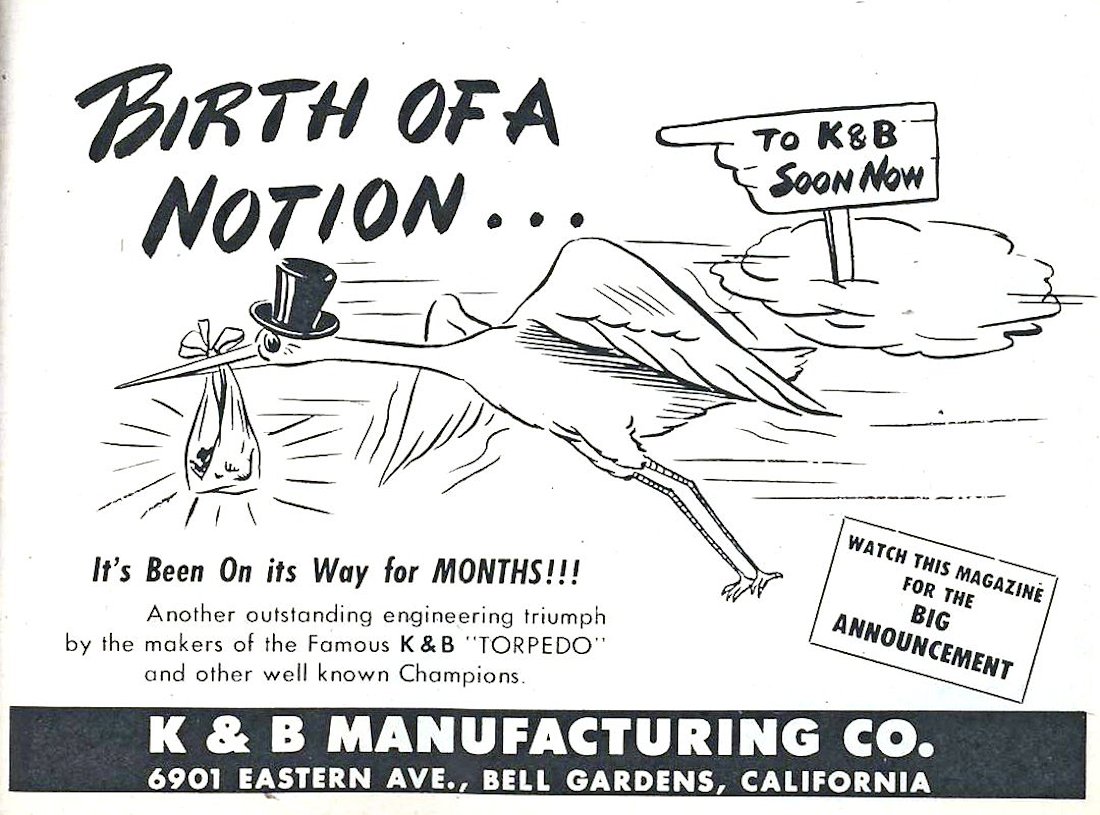

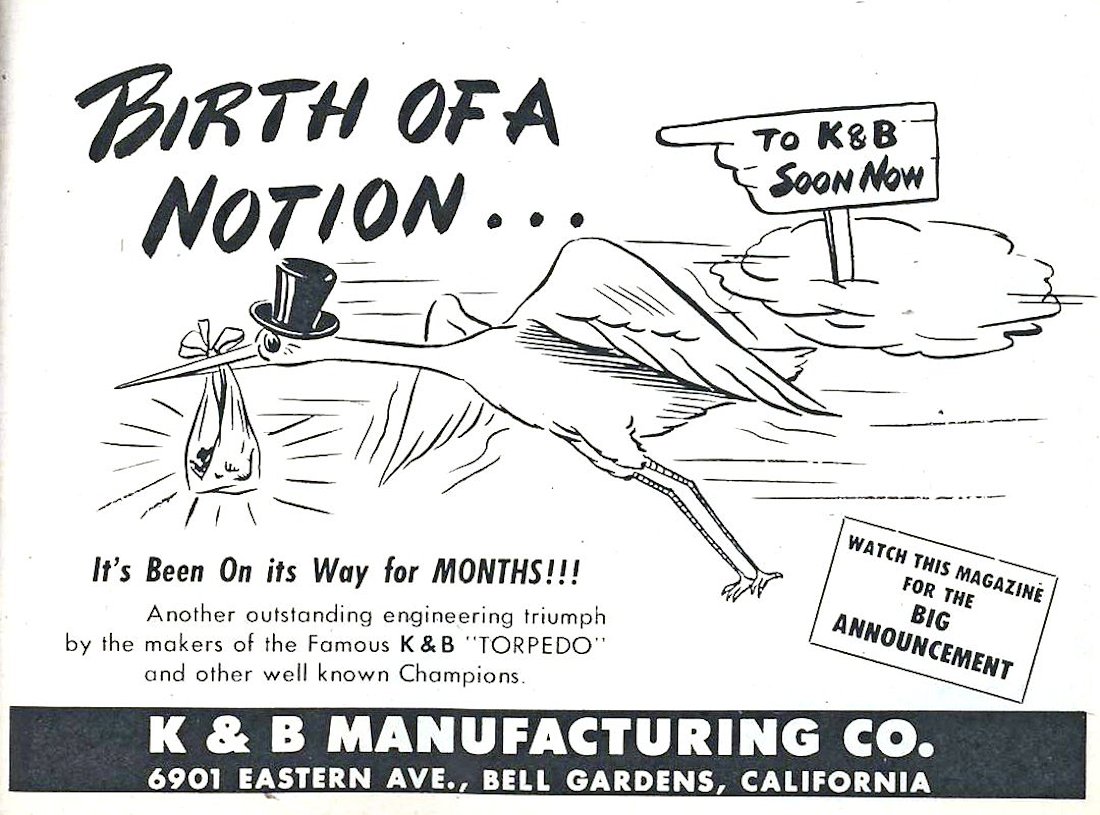

The first miniature glow-plug engine to be made in commercial quantities was K&B’s Infant .020, which began to reach the model shops just in time for the 1948 Christmas trade. Designed by Lud Kading (the K of K&B), this little unit showed some Arden .099 influence mixed with a few new innovations. Machined entirely from bar stock, its tiny .020 cuin. displacement necessitated a

The first miniature glow-plug engine to be made in commercial quantities was K&B’s Infant .020, which began to reach the model shops just in time for the 1948 Christmas trade. Designed by Lud Kading (the K of K&B), this little unit showed some Arden .099 influence mixed with a few new innovations. Machined entirely from bar stock, its tiny .020 cuin. displacement necessitated a  special glowplug design comprising the entire combustion chamber along with the heating element. This feature was subsequently found to increase glow-plug engine performance quite substantially, being widely used in later designs. Wildly successful, the Torpedo .020 led the way in opening up the prospect of truly small models.

special glowplug design comprising the entire combustion chamber along with the heating element. This feature was subsequently found to increase glow-plug engine performance quite substantially, being widely used in later designs. Wildly successful, the Torpedo .020 led the way in opening up the prospect of truly small models.

Scaled-up variants soon followed from K&B - the .035 cuin. Torpedo Jr. in mid-1950 and the Torpedo .049 in September 1950. All featured the same two-screw radial mounting dimensions. The .049 introduced the twin opposing transfers at 90 degrees to twin opposing exhaust ports which later became popularly associated with the Cox engines and was widely emulated.

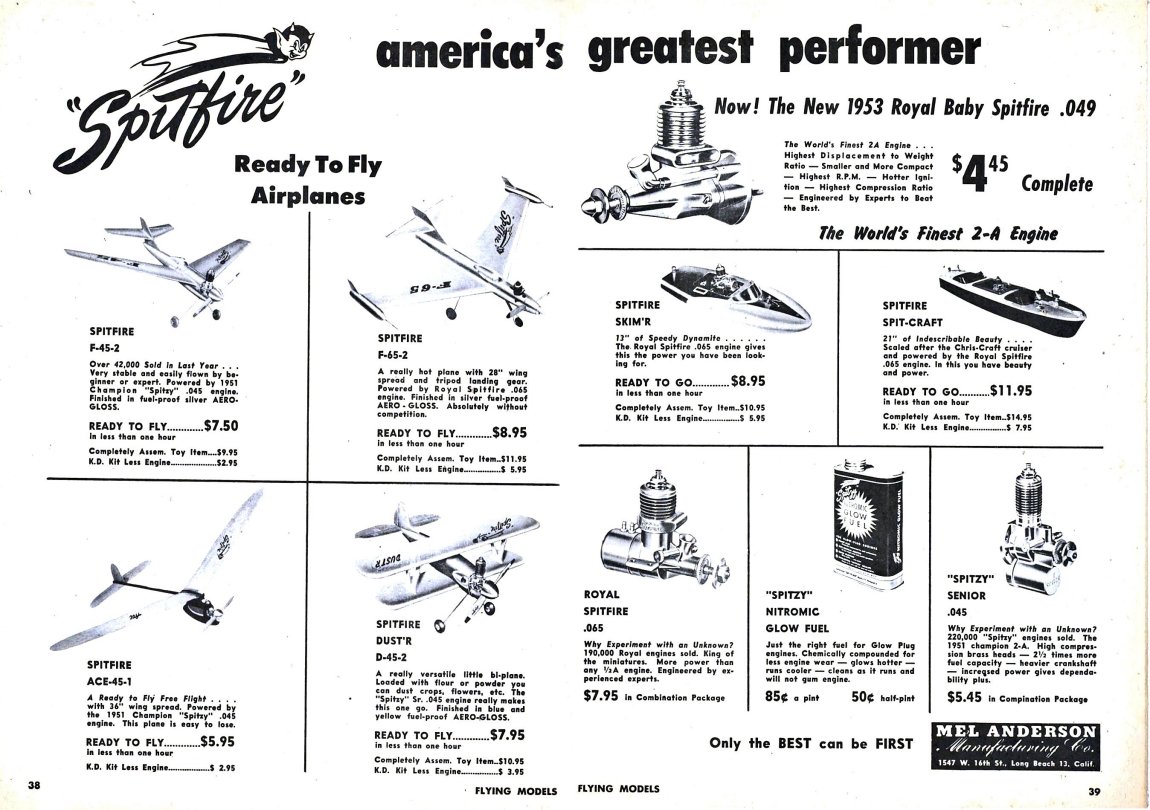

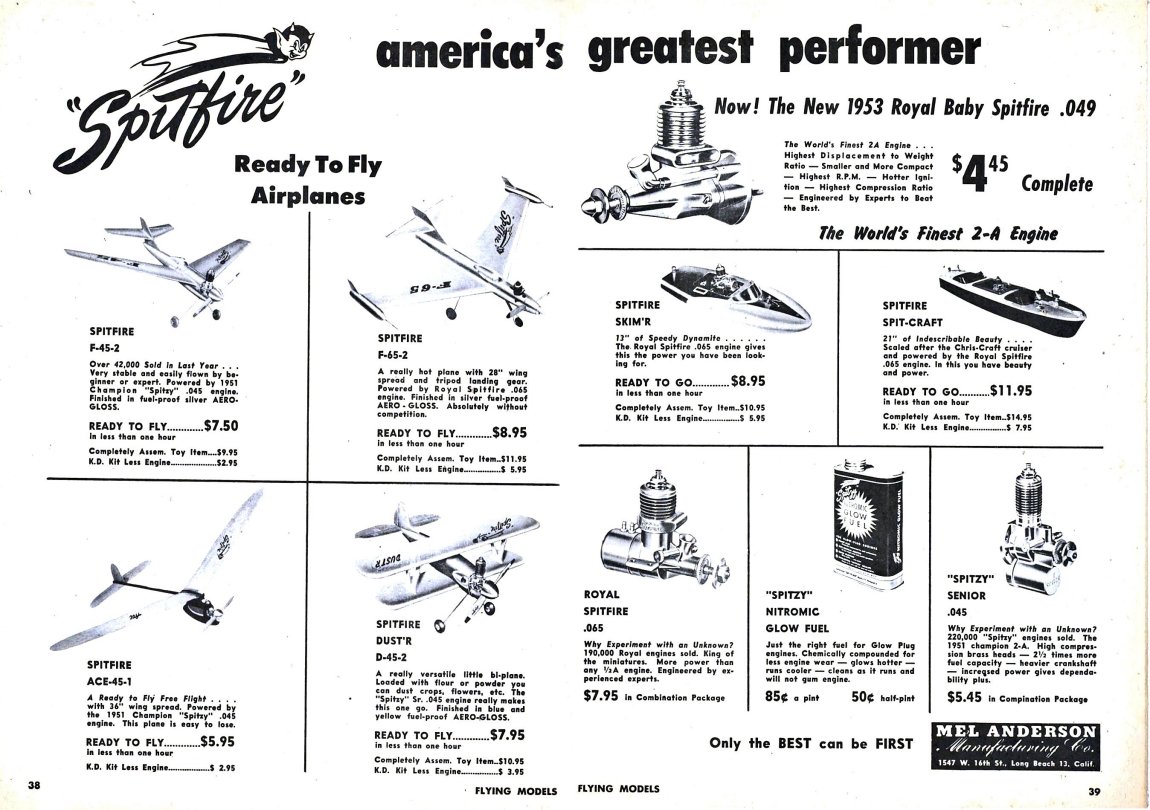

1949 was really the year when it all took off. Mel Anderson’s .045 cuin. Baby Spitfire, Herkimer’s OK Cub .049 and Cox’s O-Forty-Five car unit (which was based upon a Baby Spitfirepiston/cylinder) were released almost concurrently. The Baby Spitfire (left) had 360-degree cylinder porting with a screw-in cylinder clamping against a tubular aluminium bypass cover. The crankcase had four  radial mounting ears, with a pressed aluminium tank at the rear. The original stamped aluminium mounting bracket was not provided with later versions, making direct mounting in a model difficult. This model was replacedin 1950 by the Spitzy .045 (below right), which was essentially the same engine with a newcrankcase incorporating an integrally-cast

radial mounting ears, with a pressed aluminium tank at the rear. The original stamped aluminium mounting bracket was not provided with later versions, making direct mounting in a model difficult. This model was replacedin 1950 by the Spitzy .045 (below right), which was essentially the same engine with a newcrankcase incorporating an integrally-cast  underslung fuel tank. The 1951 Spitzy Senior had a larger tank volume which was better suited for control line work.

underslung fuel tank. The 1951 Spitzy Senior had a larger tank volume which was better suited for control line work.

Back in 1947, Charles Brebeck had taken maximum advantage of Herkimer Tool & Model Works production capacity by adding Ben Shereshaw’s Bantam .19 and Bill Brown’s .018 cuin. CO2 engine designs to the existing OK Super 60, OK Twin and OK B-29 models. Losing little time following the advent of glow-plug ignition, in 1949 he added the OK Cub .049 and .074 models. These featured FRV induction along with a crankcase arranged for either beam or radial mounting. The cylinders utilized Brebeck’s patented porting, with three upwardly inclined drilled transfer ports located between three sawn exhausts and supplied with mixture by an annular passage surrounding the cylinder at transfer port level. This was the first volume-produced ½A engine to feature transfer ports which overlapped the exhausts. An optional radial tank mount was also available.

Later that same year, these models were joined by the OK Cub .099. This was very similar overall, but its crankcase was arranged for beam mounting only, with the same mounting hole pattern as used on the .049 and .074.

Leroy Cox expanded his range of Thimble Drome tether cars in 1949, with the smallest being powered by his previously-mentioned O-Forty-Five. This was the first power unit made by the L.M. Cox Mfg. Co. It was a combination drive unit using a Baby Spitfire piston/cylinder assembly, reed valve induction, an on-board fuel tank, a muffler and two axle shafts. Exhaust gasses supplied lubrication to the 4:1 planetary gears on the drive axle.

Leroy Cox expanded his range of Thimble Drome tether cars in 1949, with the smallest being powered by his previously-mentioned O-Forty-Five. This was the first power unit made by the L.M. Cox Mfg. Co. It was a combination drive unit using a Baby Spitfire piston/cylinder assembly, reed valve induction, an on-board fuel tank, a muffler and two axle shafts. Exhaust gasses supplied lubrication to the 4:1 planetary gears on the drive axle.

During this period there was no clear distinction between the hobby and toy markets, but the new small, cheap, potent and easy-to-use glow-plug engines soon gained considerable market traction among boys between 10 and 16 years old. Ready-to-fly (RTF) control line (U-control) models offered a way to circumvent the traditional flier-built construction approach, instead providing instant flying fun in small vacant neighbourhood spaces. Big companies with big capital at their disposal quickly began to take an interest. Injection moulded plastic technology soon largely outpaced wood for RTF models.

Developing the Concept

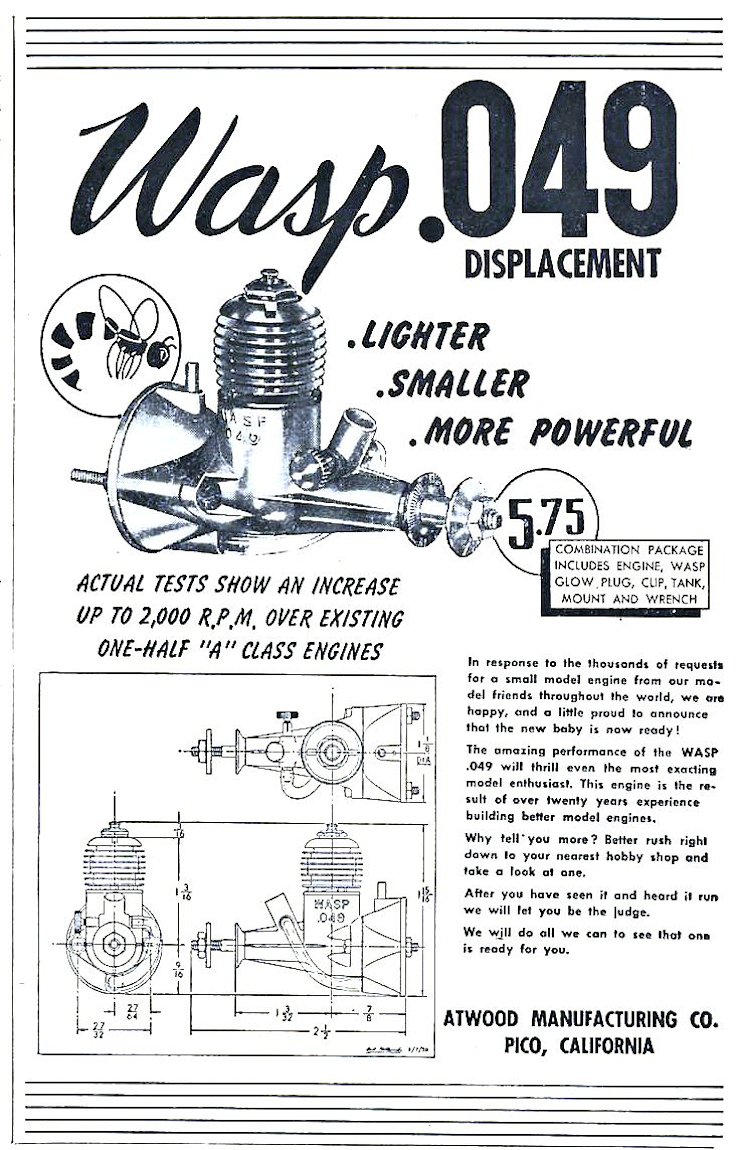

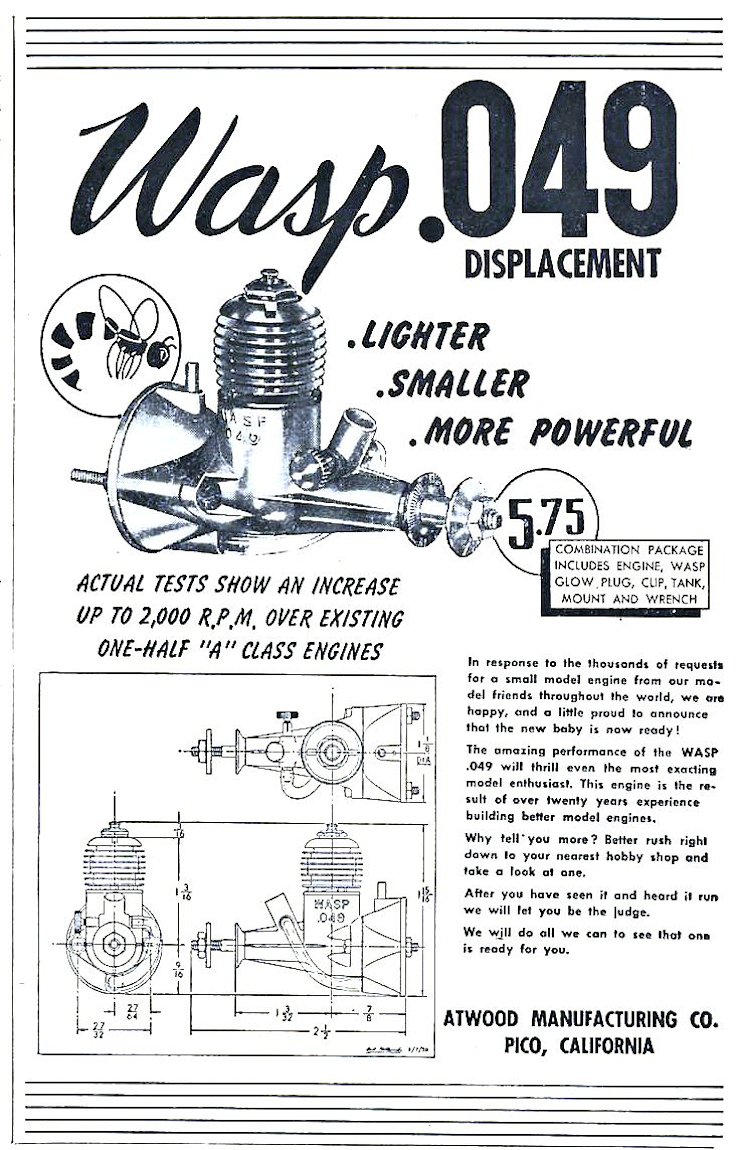

In 1950 a new California player, Atwood Mfg., entered the ½A field with their Wasp .049 (left). Designed by Bob Holland and engineered to the production stage by Bill Atwood, every feature was aimed at minimal weight/size along with maximum power. Checked weight with plug (no tank) was 1.12 oz versus the Baby Spitfire’s 1.25 oz. The 1.62 oz. OK Cub .049 (essentially a small-bore .074 variant) was a distant third place in the weight department.

In 1950 a new California player, Atwood Mfg., entered the ½A field with their Wasp .049 (left). Designed by Bob Holland and engineered to the production stage by Bill Atwood, every feature was aimed at minimal weight/size along with maximum power. Checked weight with plug (no tank) was 1.12 oz versus the Baby Spitfire’s 1.25 oz. The 1.62 oz. OK Cub .049 (essentially a small-bore .074 variant) was a distant third place in the weight department.

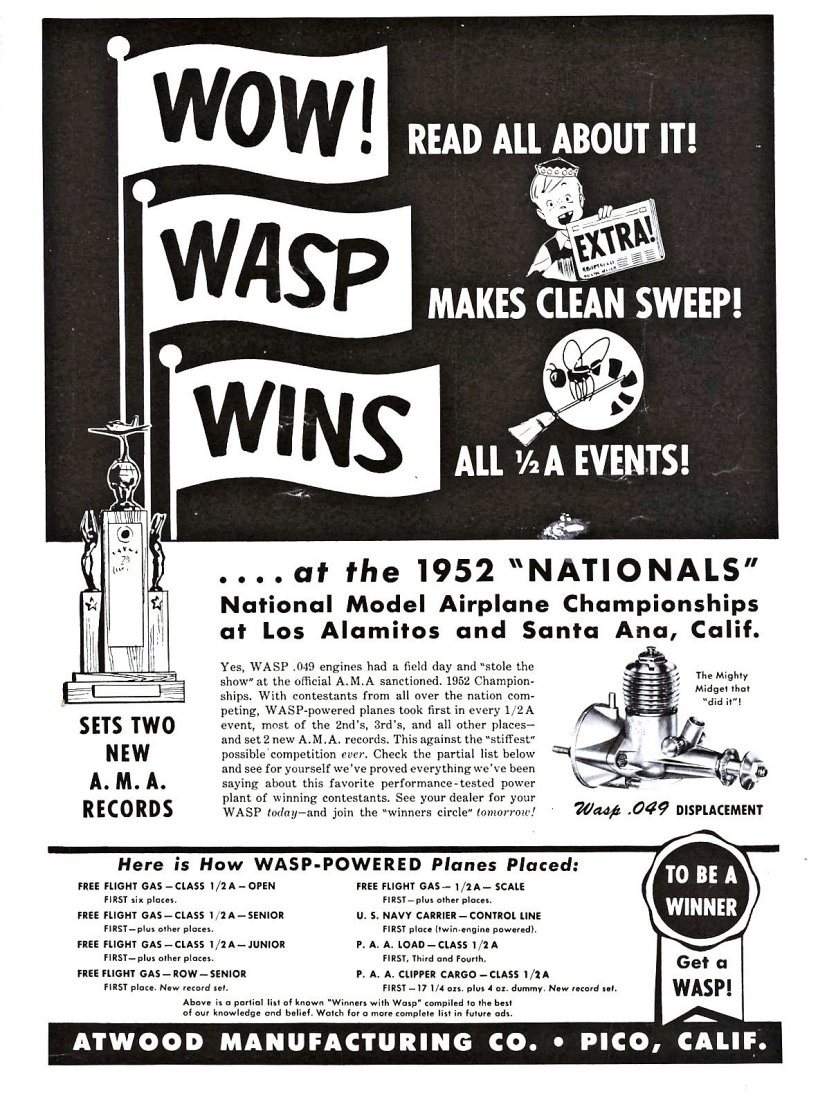

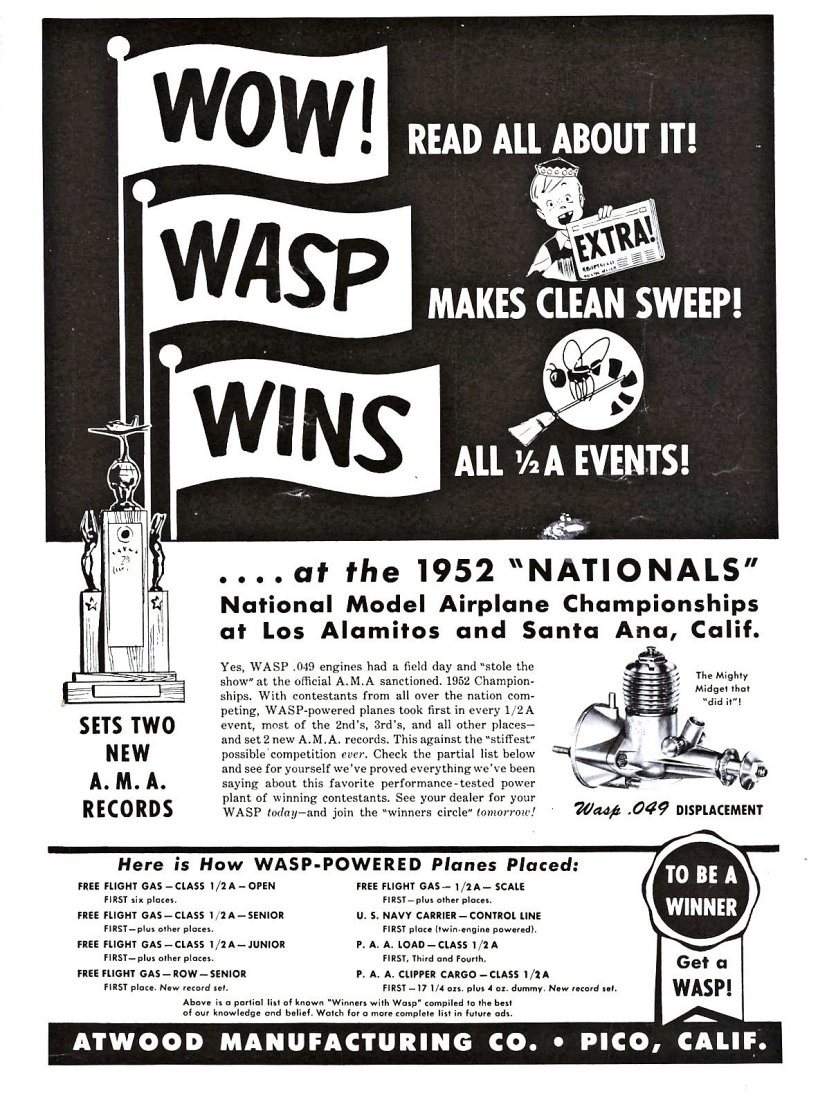

The Wasp featured simple two-screw radial mounting either direct to the firewall or through the use of an optional fuel tank mount which replaced the standard rear cover. A significantly over-square bore/stroke ratio and generous sawn exhausts above transfer porting aimed for high rpm. Peak power came in at around 15,000 rpm, substantially higher than the competition at the time. Contests for free flight duration with engines of this displacement quickly gained popularity. This prompted the AMA to define a new ½A Class based upon a maximum .05 cuin. displacement. The Wasp immediately became the go-to competition engine in this class (right).

The Wasp featured simple two-screw radial mounting either direct to the firewall or through the use of an optional fuel tank mount which replaced the standard rear cover. A significantly over-square bore/stroke ratio and generous sawn exhausts above transfer porting aimed for high rpm. Peak power came in at around 15,000 rpm, substantially higher than the competition at the time. Contests for free flight duration with engines of this displacement quickly gained popularity. This prompted the AMA to define a new ½A Class based upon a maximum .05 cuin. displacement. The Wasp immediately became the go-to competition engine in this class (right).

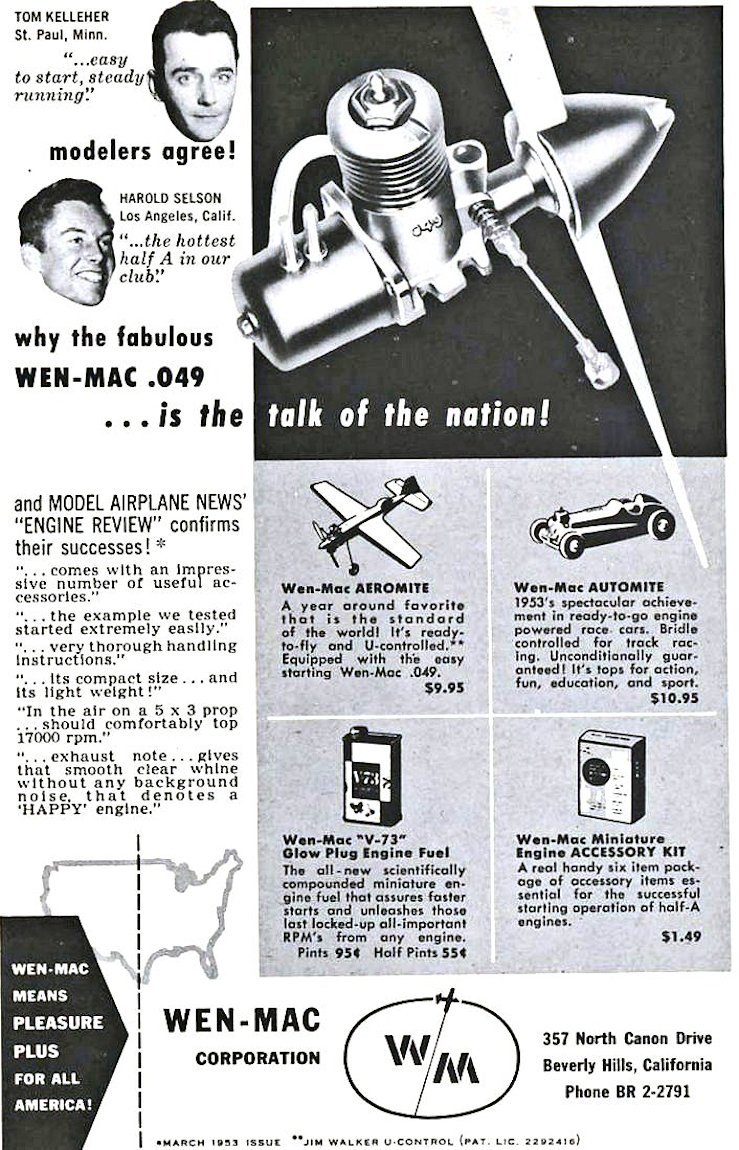

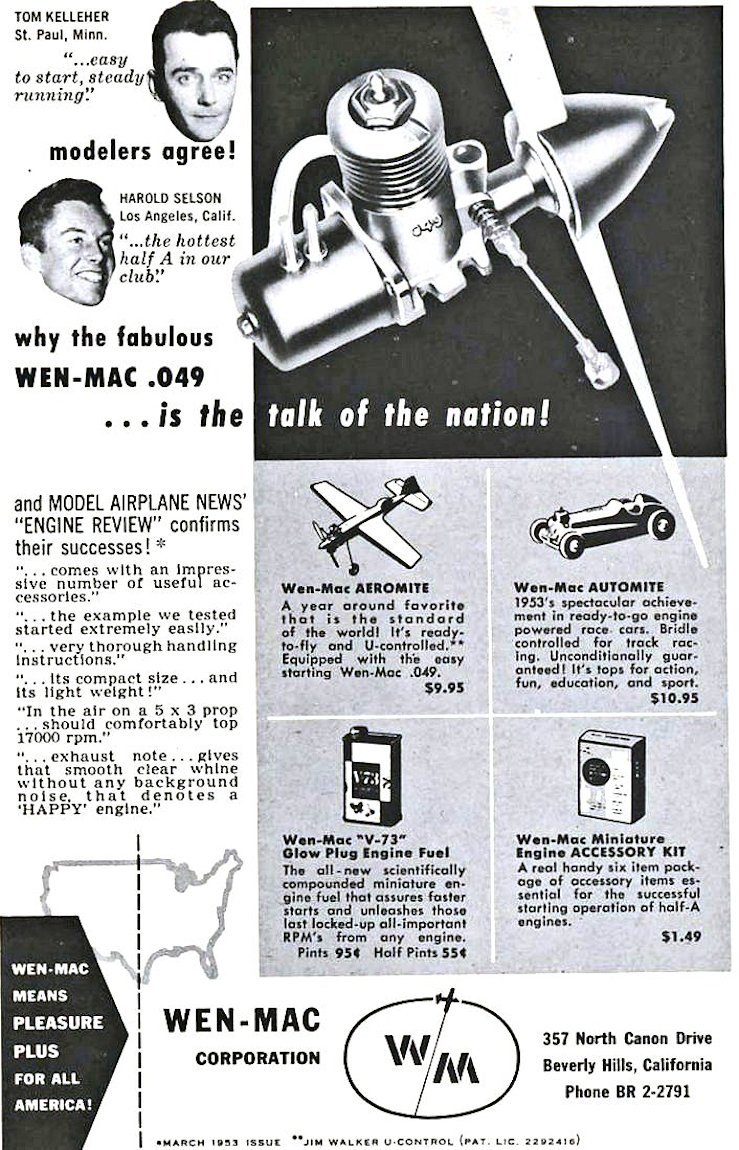

Beginning in 1950, the major RTF model producer Wen-Mac initially used Wasp and Baby Spitfire engines in its very successful Aeromite model, but  soon decided that it needed to manufacture its own .049 engines in-house to match its booming product sales. In 1952 Bill Atwood designed the Wen-Mac Mk. 1 .049 for them (left). Basically similar to the Wasp, this engine had a tapered fin profile along with a beam/radial mount crankcase.

soon decided that it needed to manufacture its own .049 engines in-house to match its booming product sales. In 1952 Bill Atwood designed the Wen-Mac Mk. 1 .049 for them (left). Basically similar to the Wasp, this engine had a tapered fin profile along with a beam/radial mount crankcase.

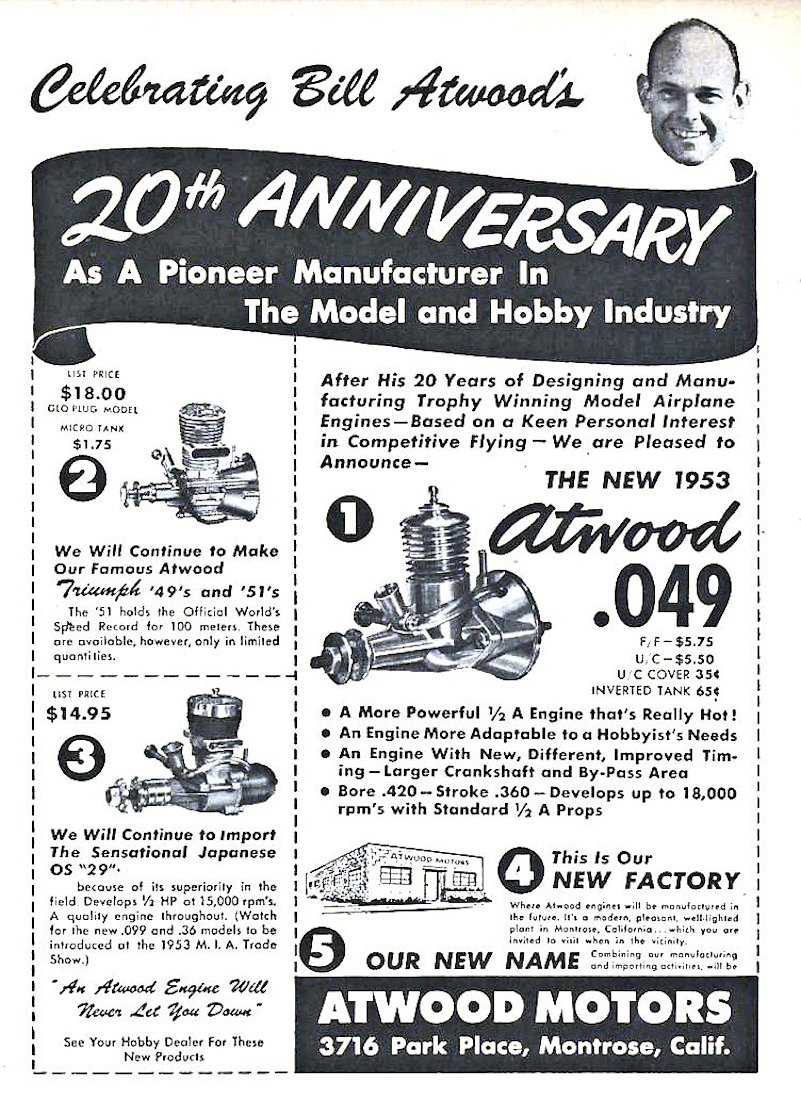

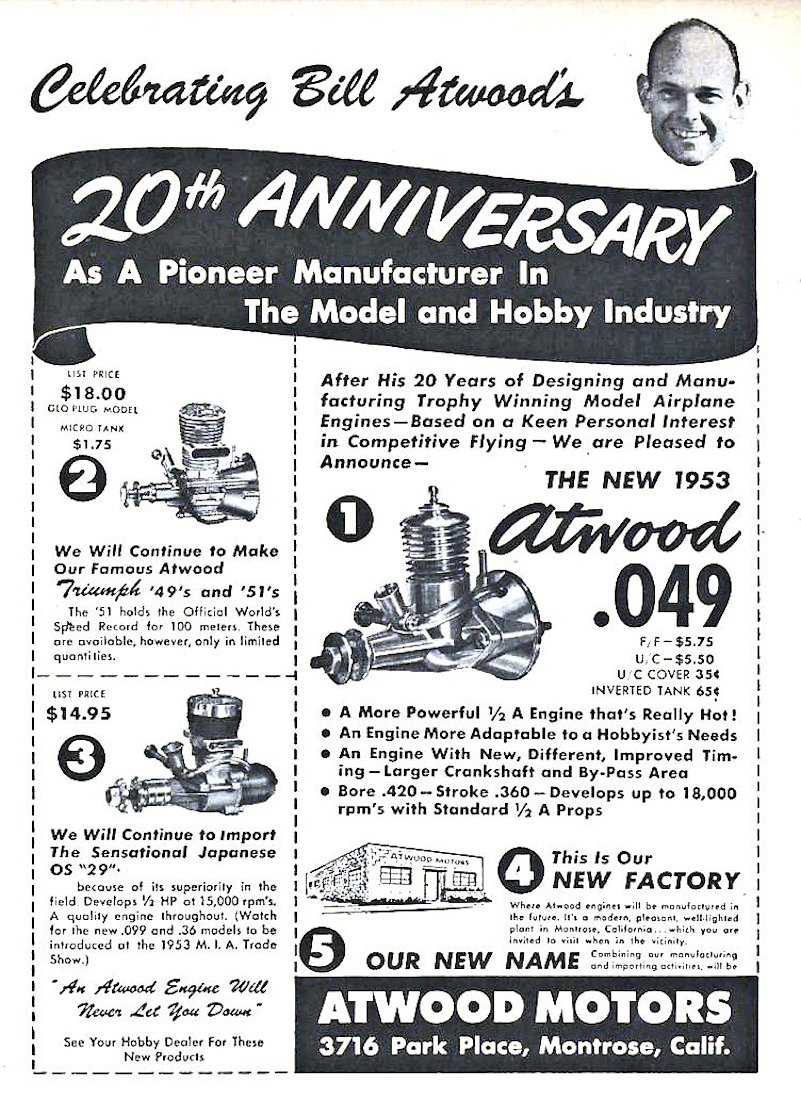

Atwood’s cooperation with Wen-Mac in facilitating their introduction of what amounted to a re-badged Wasp caused a rift between him and Bob Holland, soon leading to an outright split. Holland retained the production of the Wasp, while Atwood released a very similar Atwood .049 and .051 pairing in 1953 (right).

Atwood’s cooperation with Wen-Mac in facilitating their introduction of what amounted to a re-badged Wasp caused a rift between him and Bob Holland, soon leading to an outright split. Holland retained the production of the Wasp, while Atwood released a very similar Atwood .049 and .051 pairing in 1953 (right).

In 1951 Duro-Matic had entered the market with the McCoy Baby Mac .049. This featured 360-degree porting along with over-square bore/stroke measurements. The crankcase style echoed the larger McCoy racing engines, including a side exhaust stack despite the 360 degree cylinder porting. Anderson followed a similar path with the .065 cuin. Royal Spitfire engine in 1951, intended mainly for a forthcoming product line in conjunction with the Royal Product Corporation (below left). A smaller Royal Baby Spitfire .049 followed in 1952.

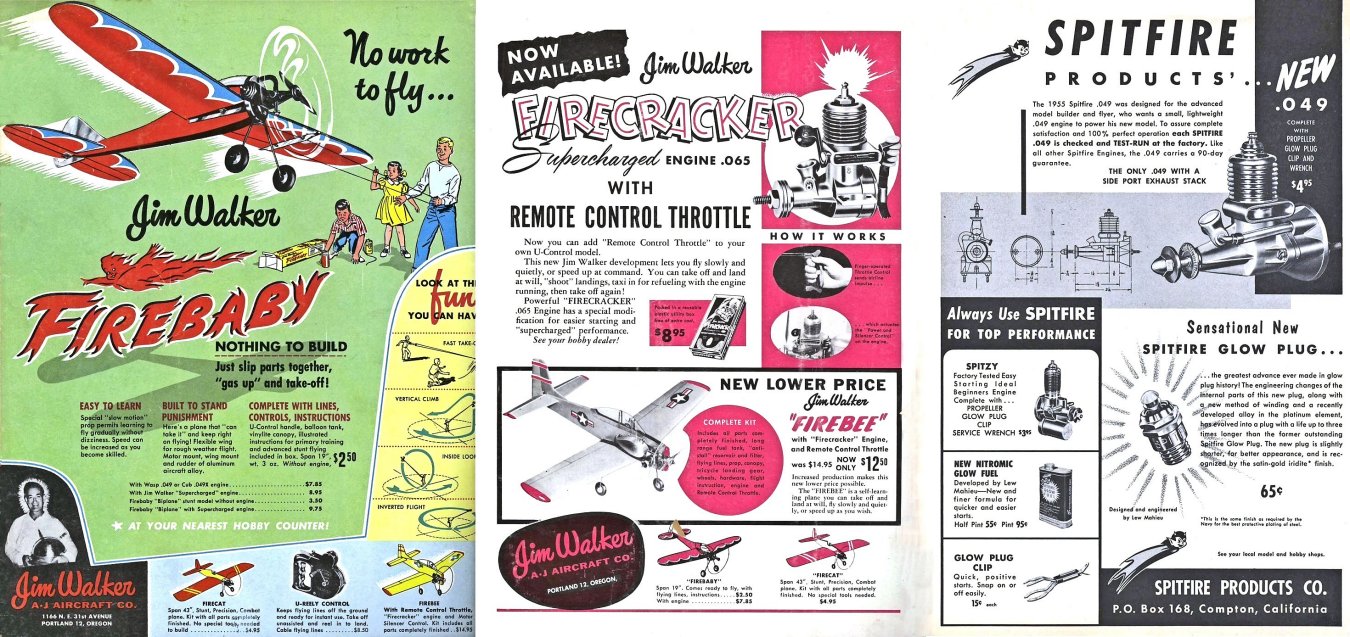

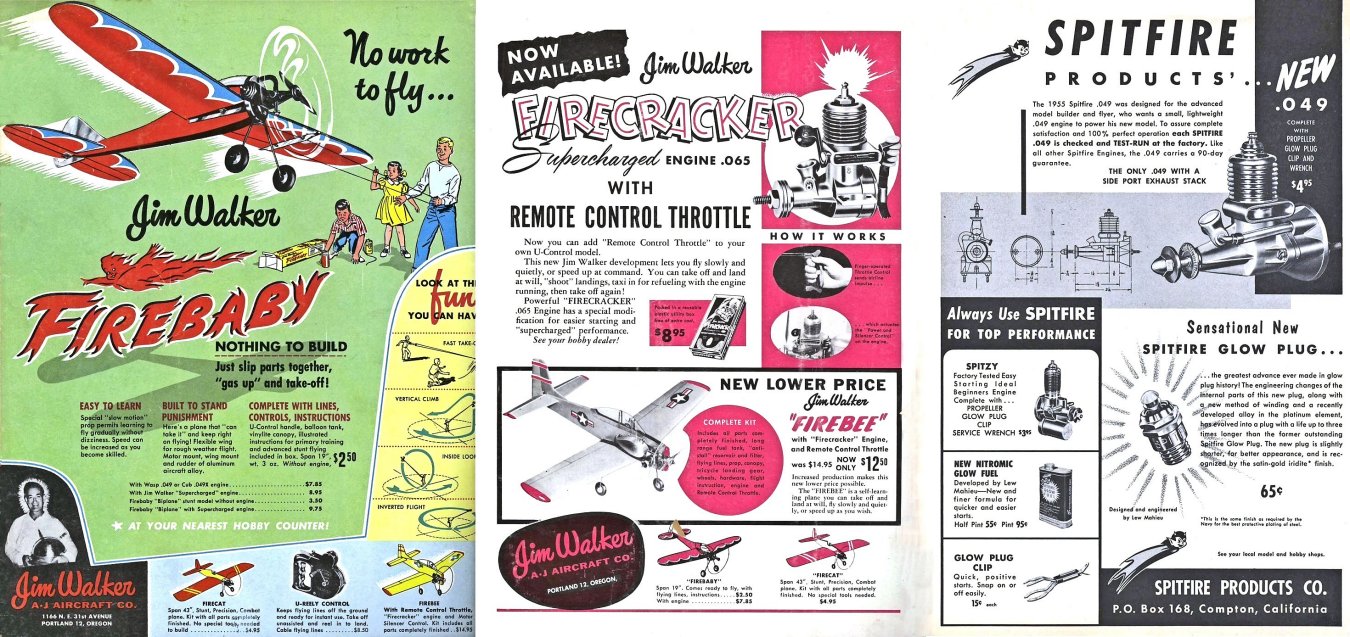

Lew Mahieu took over the production of the Spitzy .065, now called the Jim Walker “Supercharged” .065. This was intended for use in Walker’s AJ

Lew Mahieu took over the production of the Spitzy .065, now called the Jim Walker “Supercharged” .065. This was intended for use in Walker’s AJ  Firebaby and Firebaby Bipe RTF models. A “Firecracker” variant with a pneumatically controlled throttle appeared in 1955 for use in the Fire Bee model. A slightly revised Spitfire .049 was released in 1955 (right).

Firebaby and Firebaby Bipe RTF models. A “Firecracker” variant with a pneumatically controlled throttle appeared in 1955 for use in the Fire Bee model. A slightly revised Spitfire .049 was released in 1955 (right).

Seeking a slice of K&B’s market share, Herkimer had released a smaller Wasp-like OK Cub .039 in 1950. In 1952, Herkimer also tried to catch up in the contest arena with a lighter, more powerful short-stroke Wasp-inspired OK Cub .049X. This was aimed at competition flyers. The engine was also used to power the Jim Walker Firebaby RTF model.

Raising the Bar

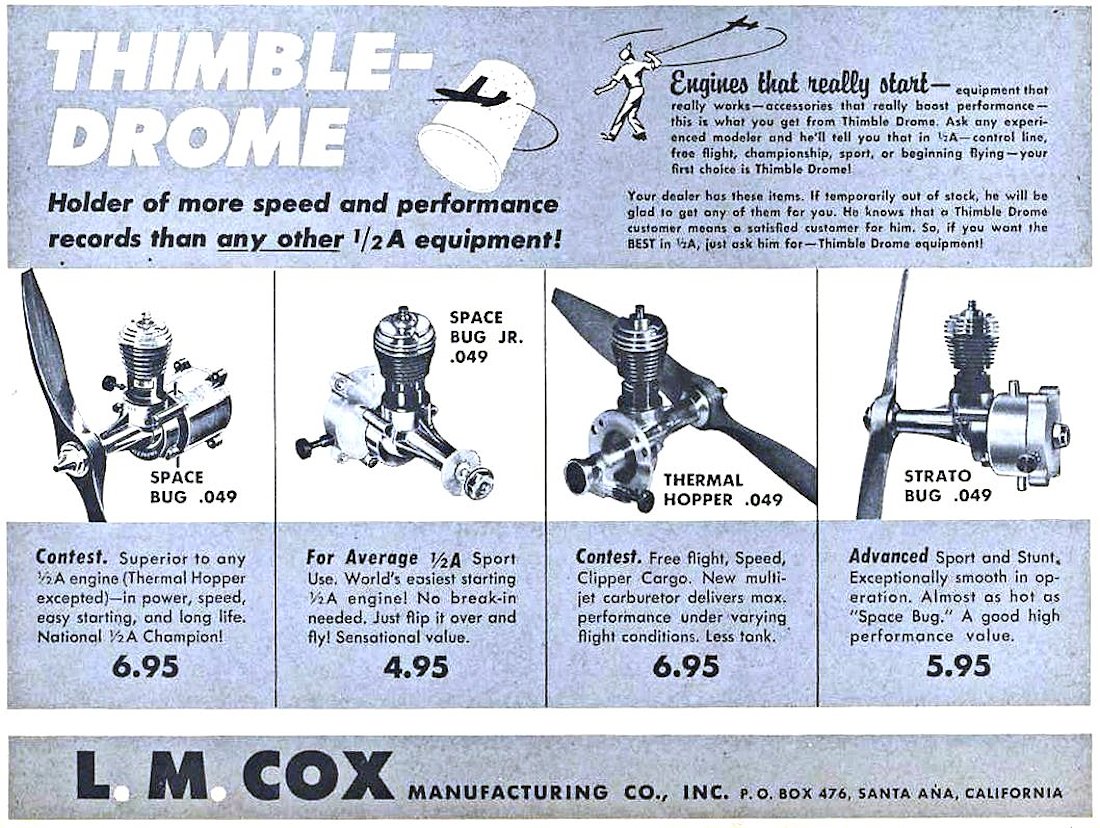

Cox entered the ½A model aero engine field in their own right with their first design that was fully manufactured in-house, the Thimble-Drome Space Bug .049 (left). One source cites a 1950 introduction, but this is contradicted by the fact that the engine was first advertised in 1952.

Cox entered the ½A model aero engine field in their own right with their first design that was fully manufactured in-house, the Thimble-Drome Space Bug .049 (left). One source cites a 1950 introduction, but this is contradicted by the fact that the engine was first advertised in 1952.

The Space Bug established the basic design parameters that would be carried over to subsequent Cox derivatives. It featured a large rear-mounted fuel tank with reed valve induction drawing mixture through a central carburettor intake. The tank was vented for stunt flying.

The engine was built up around a compact die-cast crankcase, with the cylinder featuring twin opposed transfers and opposed exhausts with considerable overlap as well as a glow-head with integral element. The engine immediately set new standards for quality and easy starting. Its already superior power output  could be further enhanced with an optional hop-up kit which included a tank with larger carburettor choke area as well as a high compression head. This kit yielded up to 1,500 extra rpm with light propeller loads. Peak power was delivered at around 19,000 rpm.

could be further enhanced with an optional hop-up kit which included a tank with larger carburettor choke area as well as a high compression head. This kit yielded up to 1,500 extra rpm with light propeller loads. Peak power was delivered at around 19,000 rpm.

The Cox range expanded in 1953 with the iconic Thermal Hopper .049 (right). This was in effect a tankless version of the hopped-up Space Bug. The absence of a tank allowed the use of a peripheral jet carburettor. The  engine was primarily intended for competition F/F use. There was also the general-purpose Space Bug Junior (left). which had a small moulded nylon tank and a cylinder featuring only a single transfer port.

engine was primarily intended for competition F/F use. There was also the general-purpose Space Bug Junior (left). which had a small moulded nylon tank and a cylinder featuring only a single transfer port.

The first Cox RTF model was the TD-1 (Space Bug) released in 1953, with the smaller TD-3  (Space Bug Jr.) appearing in 1954. Both models had wings formed in thick stunt sections from aluminium sheet.

(Space Bug Jr.) appearing in 1954. Both models had wings formed in thick stunt sections from aluminium sheet.

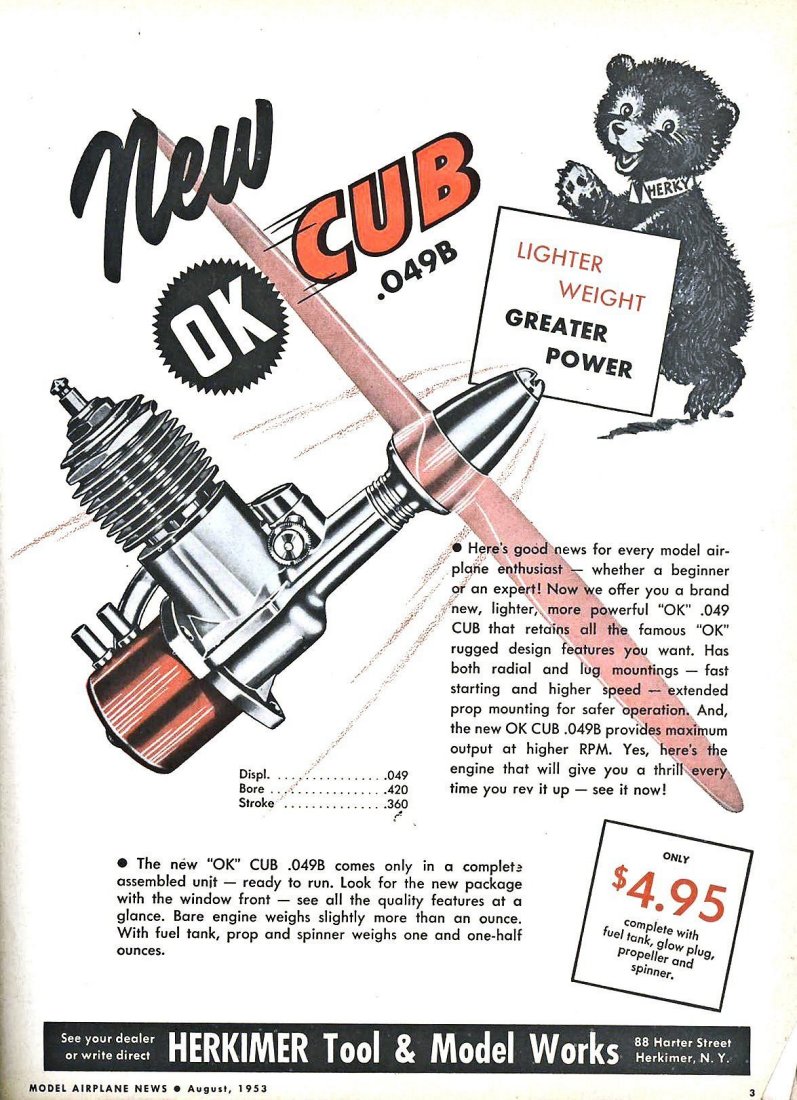

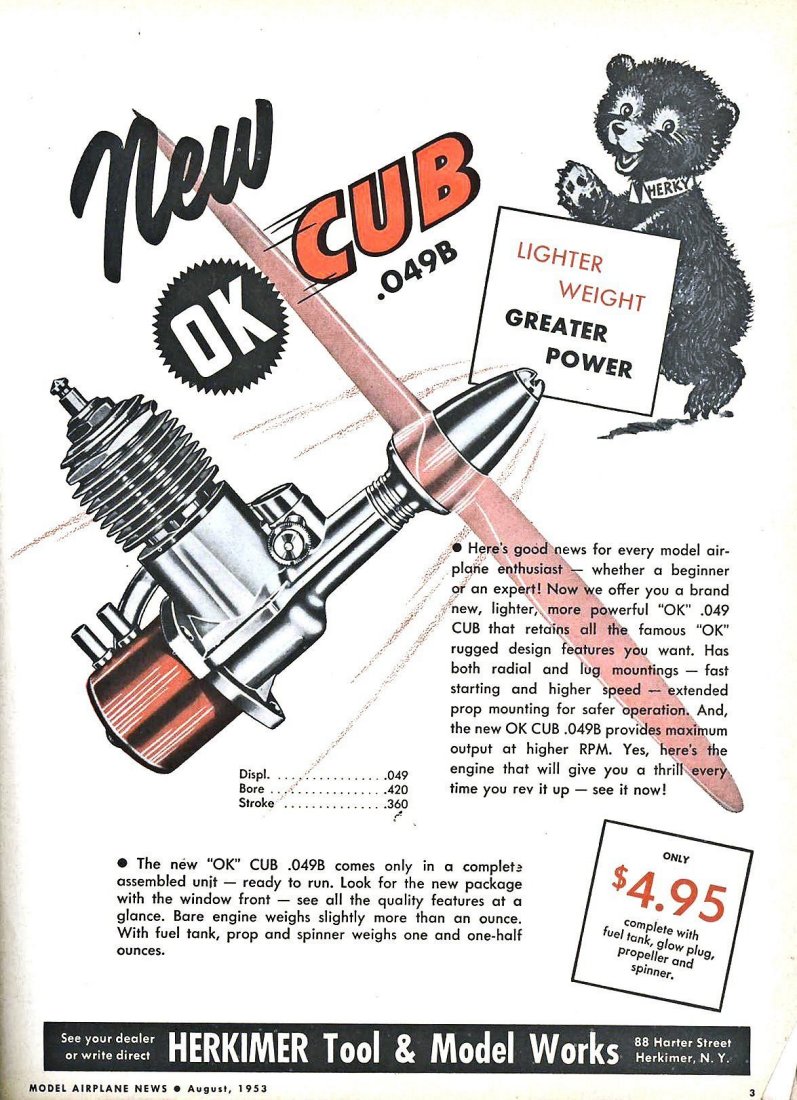

Meanwhile, Herkimer carried over their short-stroke OK Cub .049X design to their new 1953 .049B model (right) with beam/radial mount crankcase and a stamped aluminium tank attached with a central screw to the backplate. This design yielded a useful power increase along with some weight reduction over the original OK Cub .049.

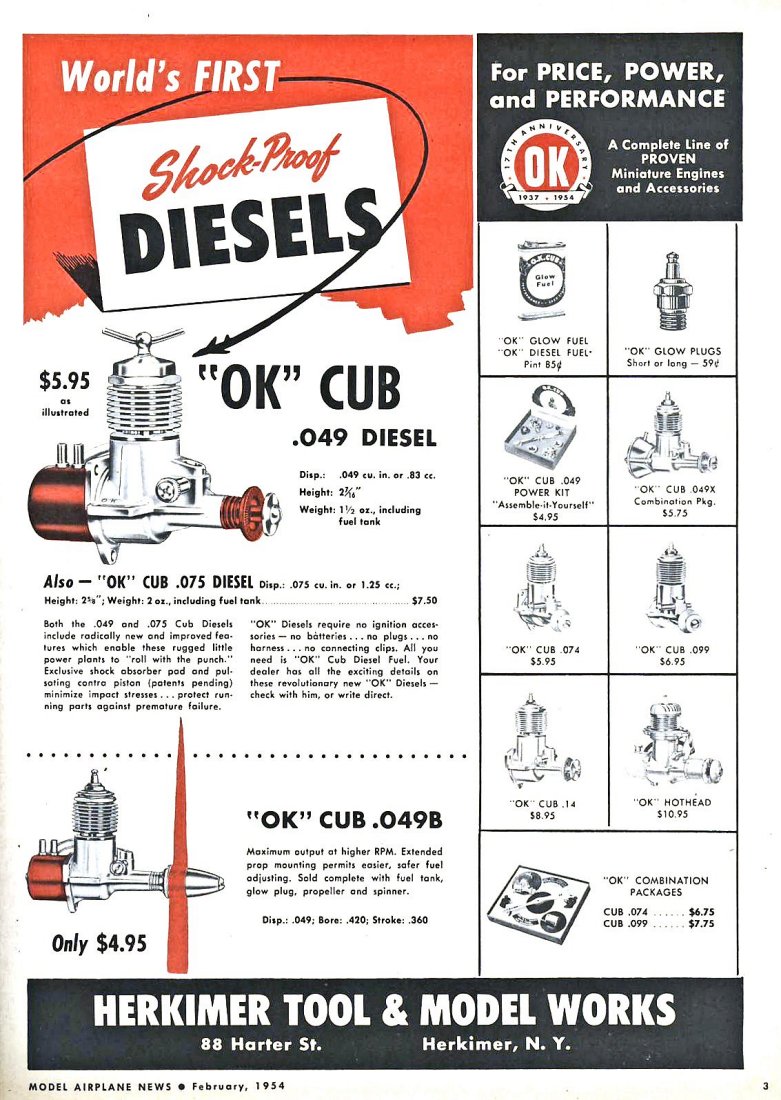

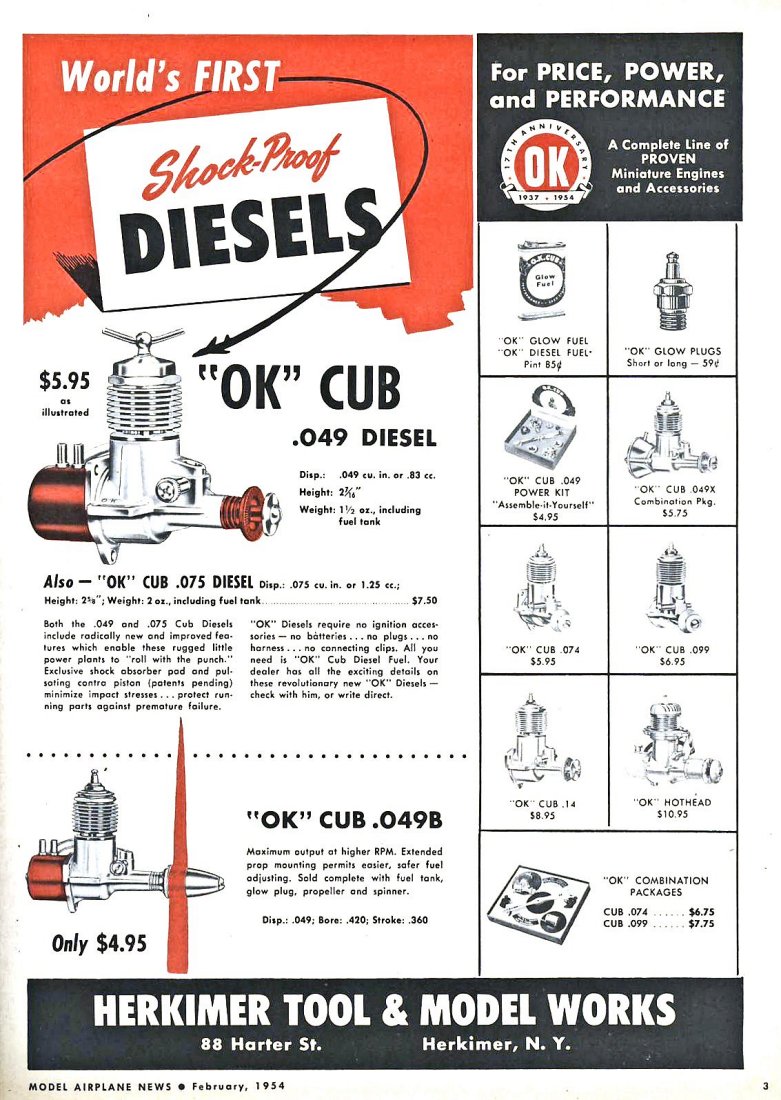

At the same time, Herkimer began experiments with compression ignition,  producing small batches of approximately 500 OK Cub 06 diesels (based on the old .049 crankcase and new .049 bore size) and OK Cub 15 diesels (based on glow OK Cub .14 components). The contra pistons in these units were housed in extended cylinders, with a screw-on head.

producing small batches of approximately 500 OK Cub 06 diesels (based on the old .049 crankcase and new .049 bore size) and OK Cub 15 diesels (based on glow OK Cub .14 components). The contra pistons in these units were housed in extended cylinders, with a screw-on head.

The resulting production OK Cub .075 diesel which appeared in 1953 was based on 074 glow components. It incorporated a patented “shock spring” insert between the compression adjusting screw and the contra piston. This was intended to reduce shock loadings on the working components during operation. The contra pistons were sealed in their  bores using synthetic rubber O-rings. A similar OK Cub .049 diesel (left) based on .049B glow parts followed in 1954. Both diesels developed substantially greater power than their equivalent glow-plug models.

bores using synthetic rubber O-rings. A similar OK Cub .049 diesel (left) based on .049B glow parts followed in 1954. Both diesels developed substantially greater power than their equivalent glow-plug models.

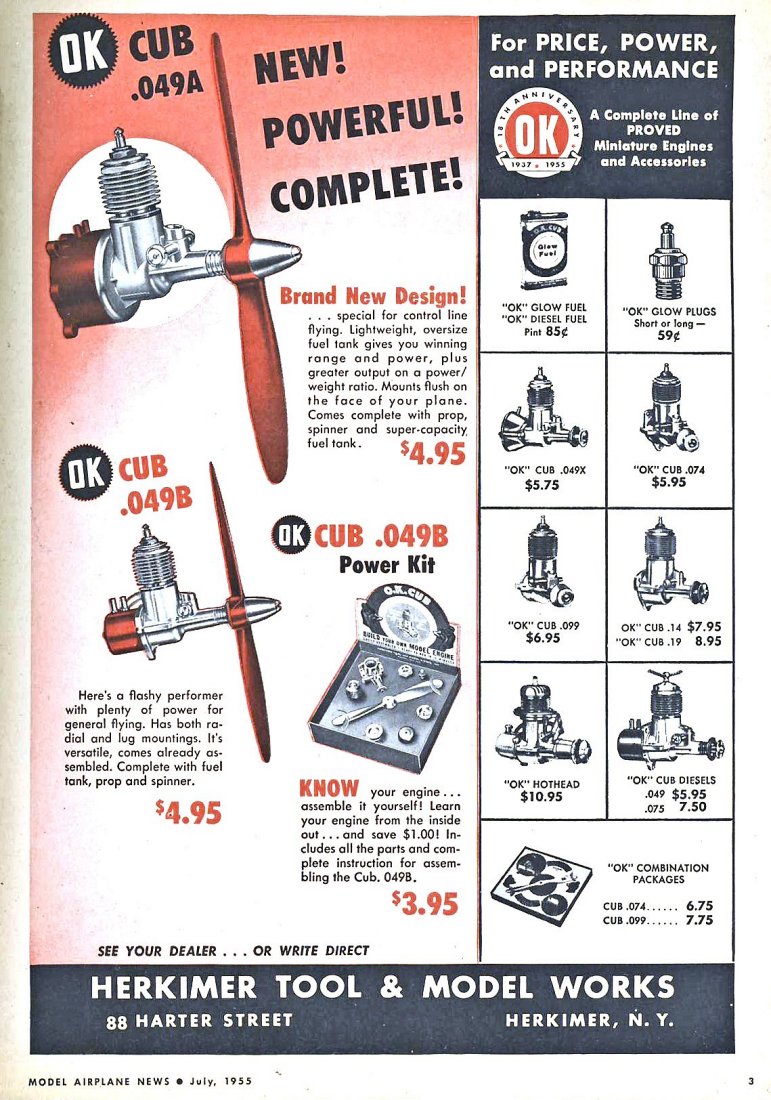

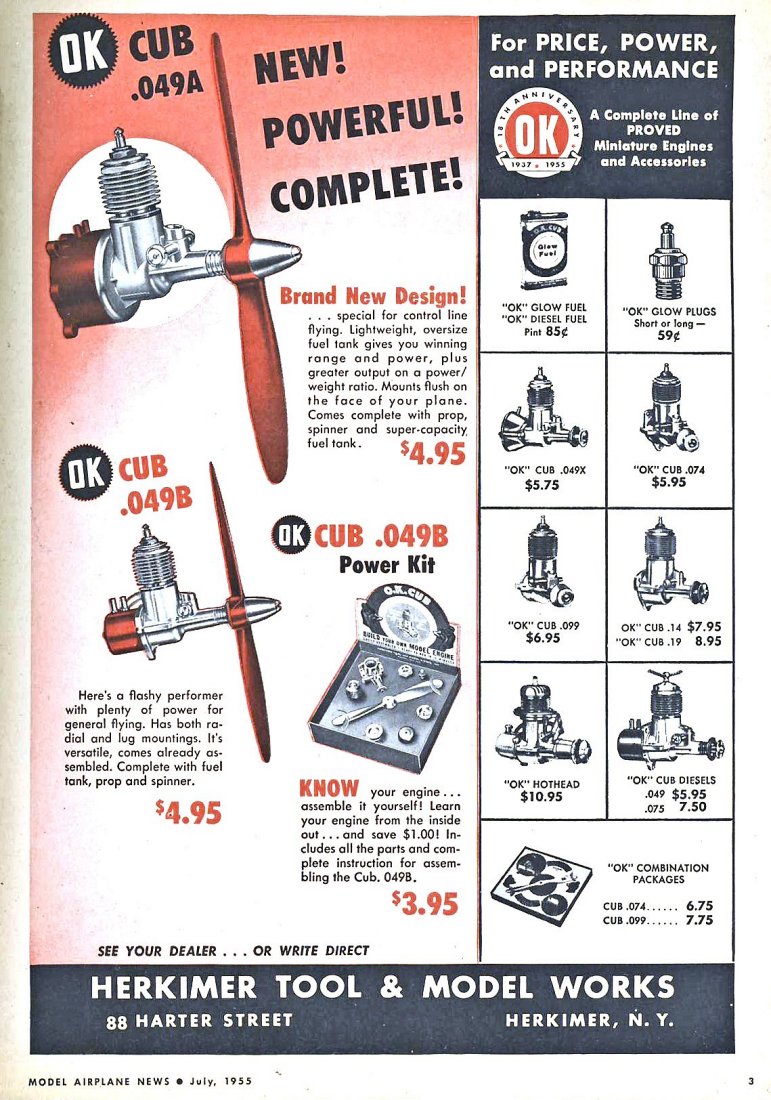

In 1954 the Cub .049B was used to power the first plastic RTF model from the long-established Comet company - the Sabre 44. Herkimer subsequently released the OK Cub .049A variant in 1955 (right), with a red nylon tank/radial mount. Both A and B OK Cub models were used extensively in Comet RTF planes and ready-to-run cars through to the late 1950’s.

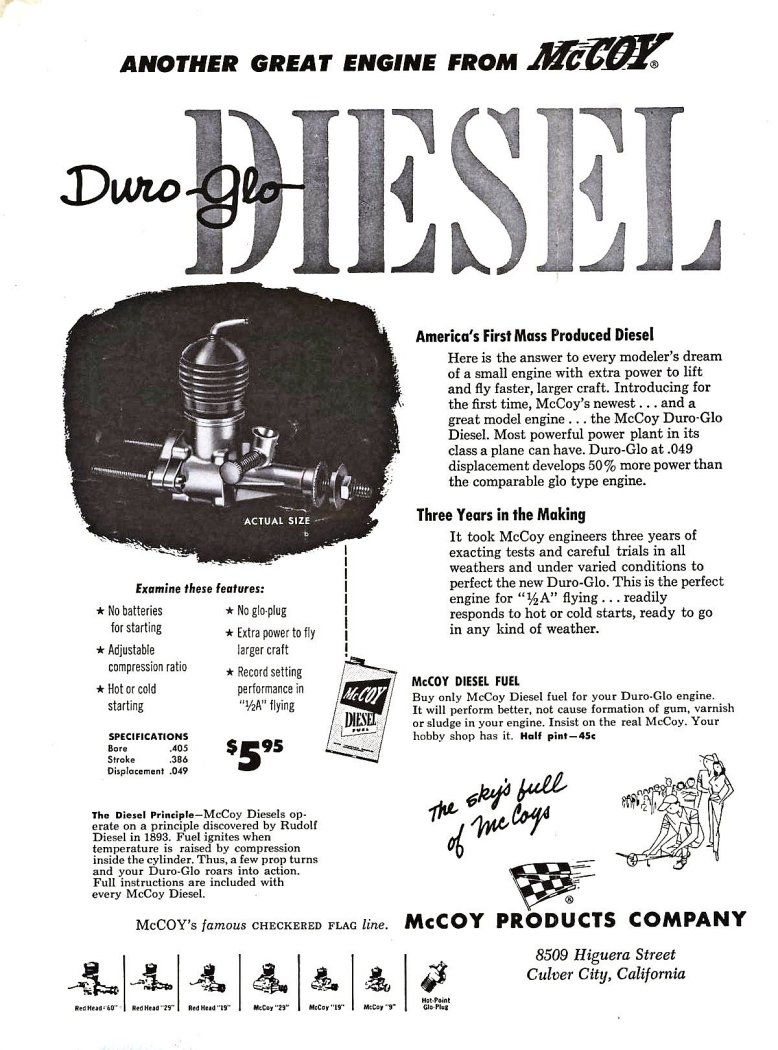

In 1953 McCoy had also joined the diesel parade with their oddly-named McCoy Dura-Glo .049 diesel, which also used an O-ring seal on the contra piston. It featured 360-degree porting and two-screw radial mounting. The red anodized head had a fibre insert to prevent the compression screw from wandering during operation. These engines influenced design trends in Germany, Denmark and Italy. The British International Model Aircraft (IMA) company tried the O-ring seal idea in its Mk. 1 FROG 80 diesel of January 1957, but later reverted to a normal precision-fitted contra piston.

In 1953 McCoy had also joined the diesel parade with their oddly-named McCoy Dura-Glo .049 diesel, which also used an O-ring seal on the contra piston. It featured 360-degree porting and two-screw radial mounting. The red anodized head had a fibre insert to prevent the compression screw from wandering during operation. These engines influenced design trends in Germany, Denmark and Italy. The British International Model Aircraft (IMA) company tried the O-ring seal idea in its Mk. 1 FROG 80 diesel of January 1957, but later reverted to a normal precision-fitted contra piston.

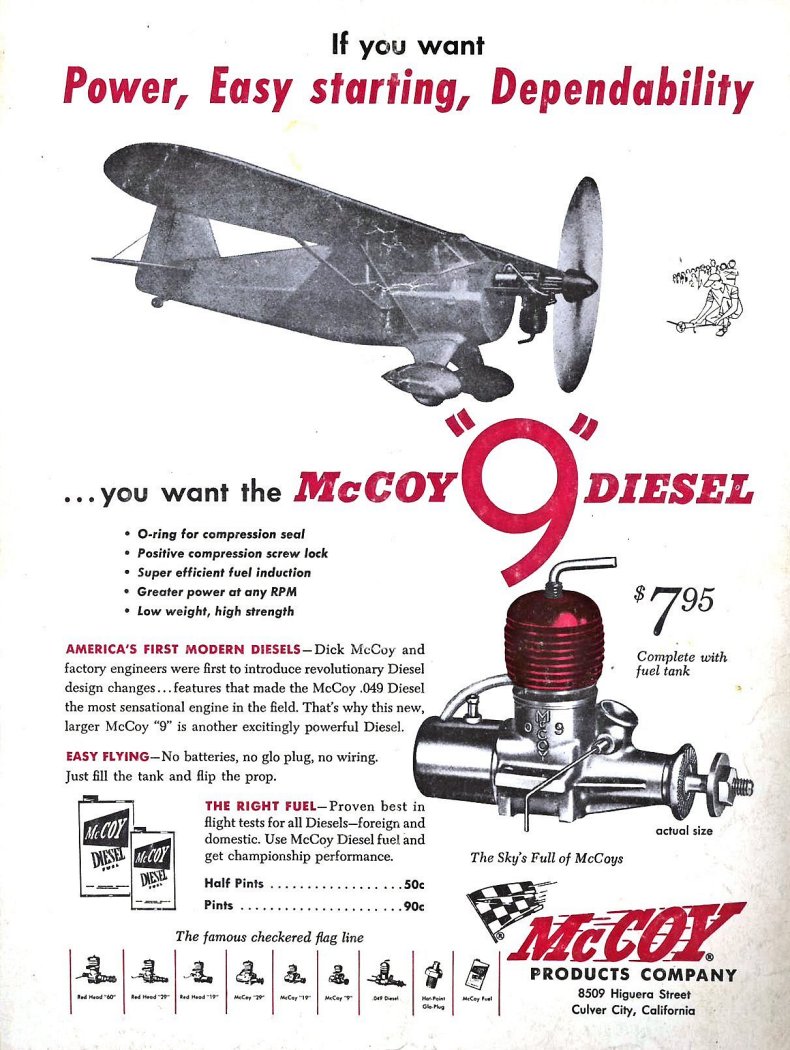

The McCoy .049 diesel gained considerable competition success in free flight PAA-load events, where its superior torque and consequent ability to swing large propellers helped it to lift more payload to win. A similar but considerably beefed-up 1954 model was provided with beam mounting lugs, later being fitted with a spring-loaded poppet valve in the venturi upstream of the spraybar. The makers claimed an improvement in starting and flexibility, but this was not evident - indeed, many owners (including the Editor!) have found superior performance without the valve. The larger McCoy “9” .099 cuin. diesel variant (right) did not have this valve and was a standout performer. (It is one of my personal favourite 1.5 cc diesels from the classic era - A.D.).

The McCoy .049 diesel gained considerable competition success in free flight PAA-load events, where its superior torque and consequent ability to swing large propellers helped it to lift more payload to win. A similar but considerably beefed-up 1954 model was provided with beam mounting lugs, later being fitted with a spring-loaded poppet valve in the venturi upstream of the spraybar. The makers claimed an improvement in starting and flexibility, but this was not evident - indeed, many owners (including the Editor!) have found superior performance without the valve. The larger McCoy “9” .099 cuin. diesel variant (right) did not have this valve and was a standout performer. (It is one of my personal favourite 1.5 cc diesels from the classic era - A.D.).

Once again, the diesel version of the McCoy .049 showed itself to be more powerful than the 1955 McCoy Baby Mac .049 glow-plug version, despite the latter model’s integral-element glow button head. The McCoy ½A glow-plug engines were to go on to partner with Testors by powering their plastic RTF models. Testors eventually acquired the McCoy line outright.

In 1954 Bill Atwood introduced several variations on his established .049 design, such as the cheaper “Cadet” .049 model and the high-performance “Signature” .049 (left). The latter models were hand-picked for superior performance, being identified by a green anodized head. In addition, Atwood offered inboard marine models (some with water cooled heads) and outboard 049/051 units. Atwood’s final effort came with the 1956 – 1958 “Shriek“ series. This was little changed, but now featured a redesigned cooling jacket having an integral glow element.

In 1954 Bill Atwood introduced several variations on his established .049 design, such as the cheaper “Cadet” .049 model and the high-performance “Signature” .049 (left). The latter models were hand-picked for superior performance, being identified by a green anodized head. In addition, Atwood offered inboard marine models (some with water cooled heads) and outboard 049/051 units. Atwood’s final effort came with the 1956 – 1958 “Shriek“ series. This was little changed, but now featured a redesigned cooling jacket having an integral glow element.

Following the demise of the O&R Manufacturing Co., a new company called Cheminol Corporation re-introduced some engines under the O&R label. Among these was the O&R Midjet .049, which appeared in 1955 (right). Designed by Harry Rice, this engine featured reed valve induction along with the now-familiar opposed pairs of cylinder transfer and exhaust ports.

Following the demise of the O&R Manufacturing Co., a new company called Cheminol Corporation re-introduced some engines under the O&R label. Among these was the O&R Midjet .049, which appeared in 1955 (right). Designed by Harry Rice, this engine featured reed valve induction along with the now-familiar opposed pairs of cylinder transfer and exhaust ports.

The Midget sported many unique features, including a blind-bored cylinder with integral cooling fins. This required the use of a special ultra-short reach glow plug developed expressly for this engine. A composite conrod was used, with a floating bronze big end bearing. The pressed-in little end pin swivelled in the piston  bosses rather than on the rod, being retained by a plate and snap ring inside the piston. The engine was fitted with a large die-cast stunt tank with radial mounting ears. The companion O&R Mite .049 was essentially a tankless version of the same engine – it used thick integrally-cast cast beam mounts.

bosses rather than on the rod, being retained by a plate and snap ring inside the piston. The engine was fitted with a large die-cast stunt tank with radial mounting ears. The companion O&R Mite .049 was essentially a tankless version of the same engine – it used thick integrally-cast cast beam mounts.

An inboard marine version called the Mariner (left), a race car model and a pull-start version all appeared soon afterwards. The power output of the Midget and its relatives was very good, but fell short of the standard-setting Cox Thermal Hopper. Moreover, the Cheminol engines were not cheap.

The Later 1950’s

Cox’s 1955 Strato Bug .049 was the last variation of the original Cox design, differentiated by its spun aluminium stunt tank and nylon rear mounting plate. Very few of these were made. William (Bill) Selzer re-engineered the basic design elements for cheaper production, while also adding a number of improvements.

Cox’s 1955 Strato Bug .049 was the last variation of the original Cox design, differentiated by its spun aluminium stunt tank and nylon rear mounting plate. Very few of these were made. William (Bill) Selzer re-engineered the basic design elements for cheaper production, while also adding a number of improvements.

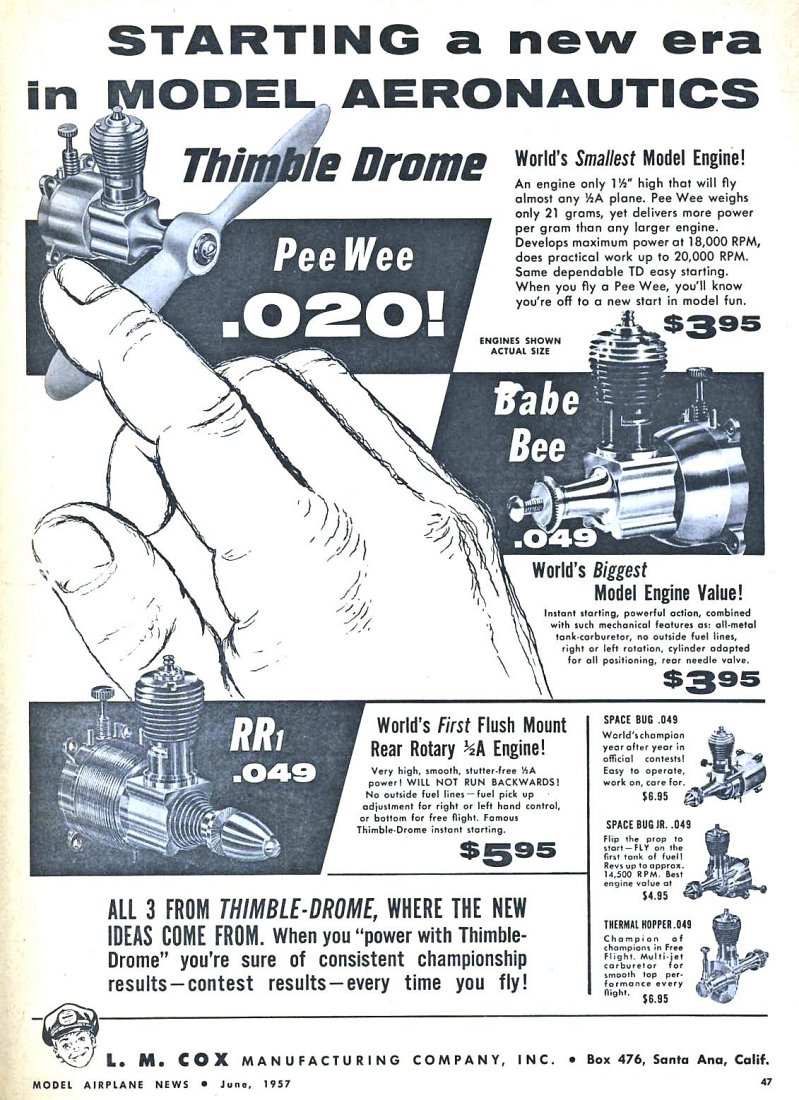

All second-generation Cox engines used crankcases machined from extruded aluminium bar stock. The Babe Bee .049 of 1956 was the first of Cox’s long-running Bee series. It had a shorter and stronger crankshaft along with a turned aluminium fuel tank/venturi. The reed valve was simplified, now using an X-shaped free-floating reed element. The tank’s rear cover/radial mount was now cast metal and incorporated a vertical needle valve assembly. The conrod/piston ball joint was considerably simplified. The single bypass cylinder was altered at the top to accommodate a revised head with a larger-diameter thread, seating on an internal shoulder formed above the bore.

All second-generation Cox engines used crankcases machined from extruded aluminium bar stock. The Babe Bee .049 of 1956 was the first of Cox’s long-running Bee series. It had a shorter and stronger crankshaft along with a turned aluminium fuel tank/venturi. The reed valve was simplified, now using an X-shaped free-floating reed element. The tank’s rear cover/radial mount was now cast metal and incorporated a vertical needle valve assembly. The conrod/piston ball joint was considerably simplified. The single bypass cylinder was altered at the top to accommodate a revised head with a larger-diameter thread, seating on an internal shoulder formed above the bore.

The companion RR-1 .049 of 1957 (right) had a larger blue-anodized tank with stunt venting. It incorporated a rotary drum induction valve - the first Cox design to feature rotary valve induction - also using a dual bypass cylinder. A second variant of the RR-1 sported a distinctive stepped crankcase nose and fuel tank profile. The RR-1 was a very strong performer, foreshadowing the FRV Tee Dee designs of the early 1960’s. As such, it represented a very significant step forward in Cox’s design thinking.

The companion RR-1 .049 of 1957 (right) had a larger blue-anodized tank with stunt venting. It incorporated a rotary drum induction valve - the first Cox design to feature rotary valve induction - also using a dual bypass cylinder. A second variant of the RR-1 sported a distinctive stepped crankcase nose and fuel tank profile. The RR-1 was a very strong performer, foreshadowing the FRV Tee Dee designs of the early 1960’s. As such, it represented a very significant step forward in Cox’s design thinking.

The prices of the various Cox models pretty much reflected their respective power outputs. The Golden Bee .049 of 1958 was a visually  near-equivalent but cheaper version of the RR-1, reverting to reed valve induction and a single bypass cylinder while retaining the large stunt-vented tank, which was now anodized gold. Cox engines did very well at the 1957 AMA nationals.

near-equivalent but cheaper version of the RR-1, reverting to reed valve induction and a single bypass cylinder while retaining the large stunt-vented tank, which was now anodized gold. Cox engines did very well at the 1957 AMA nationals.

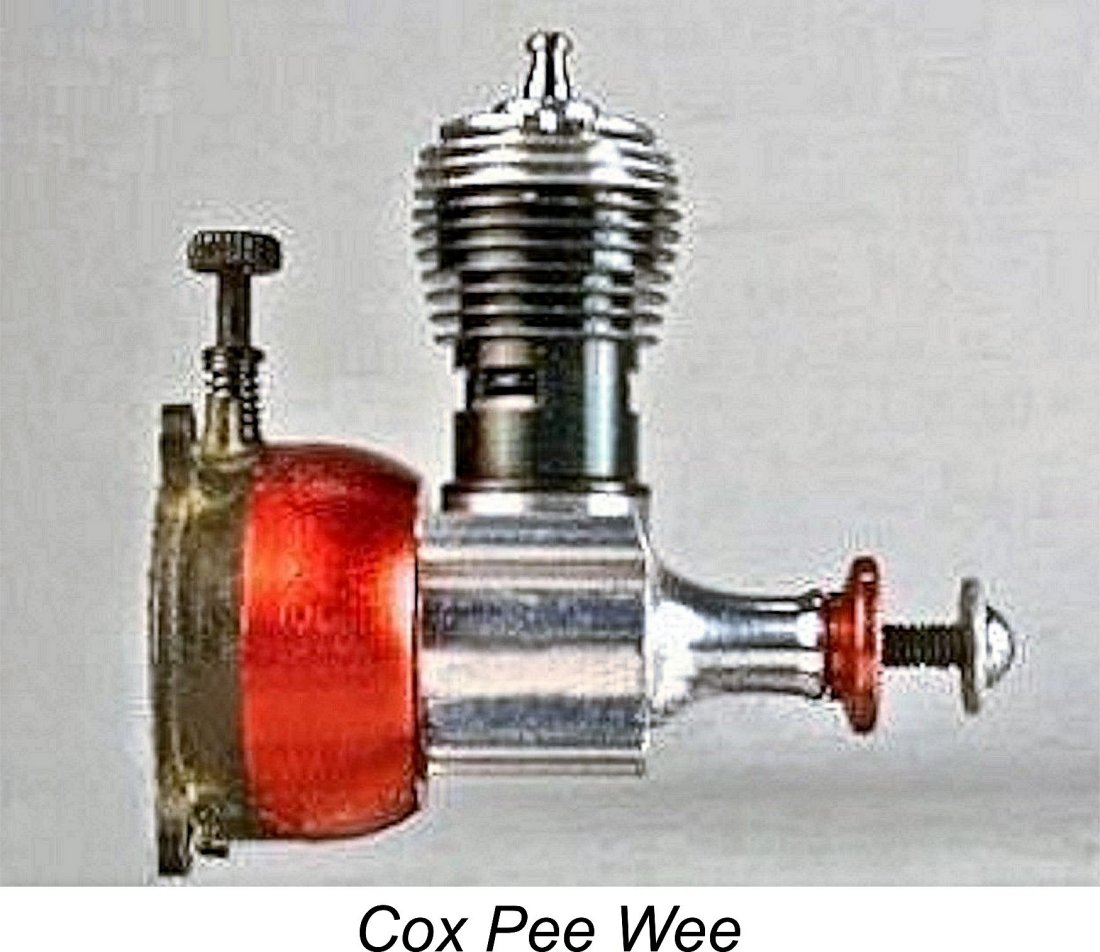

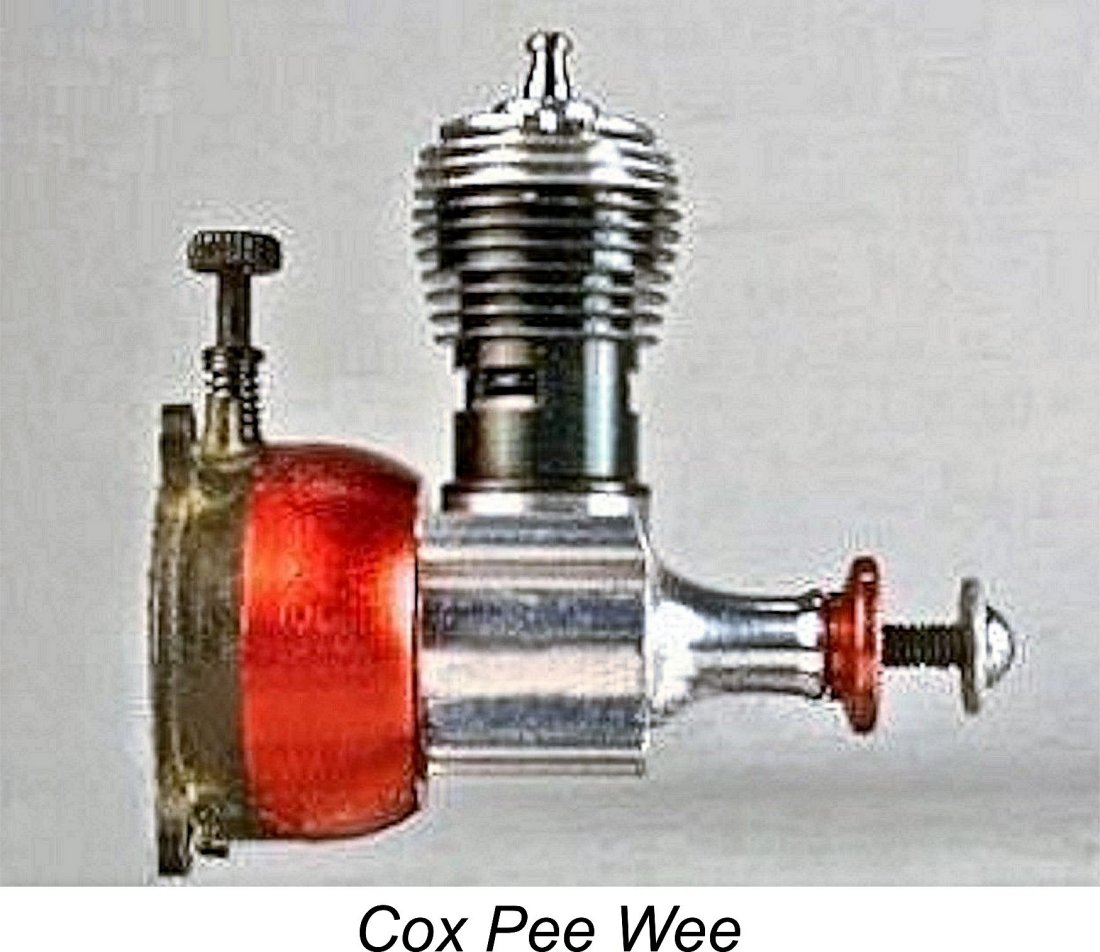

In 1958 Leroy Cox decided to introduce a smaller version of the Babe Bee. The .020 cuin. Pee Wee was just that apart from its use of a twin bypass cylinder. The over-the-counter hobby versions were fitted with red-anodized fuel tanks, while the examples used in Cox RTF models such as the Pitts Li’l Stinker had un-anodized tanks stamped THIMBLE-DROME. Performance and ease of operation of the Pee Wee  were exceptional. However, the manufacturer’s original claim that this was the world’s smallest production engine was simply not true. The Allbon Bambi diesel, made by Davies Charlton in the UK, was physically slightly shorter and had a far smaller .009 cuin. displacement.

were exceptional. However, the manufacturer’s original claim that this was the world’s smallest production engine was simply not true. The Allbon Bambi diesel, made by Davies Charlton in the UK, was physically slightly shorter and had a far smaller .009 cuin. displacement.

In 1959 the Space Hopper .049 replaced the Thermal Hopper. It featured beam mounts for more convenient installation, particularly in a ½A speed model pan. Cox price and quality continued to lead in the RTF model field.

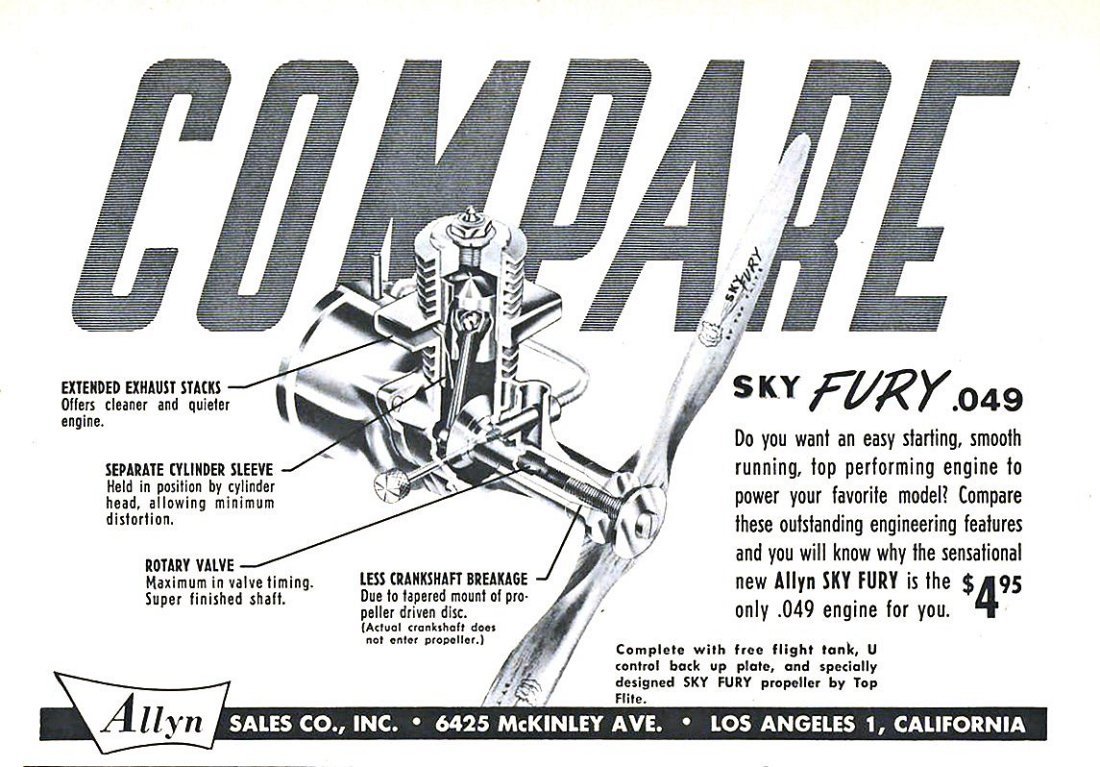

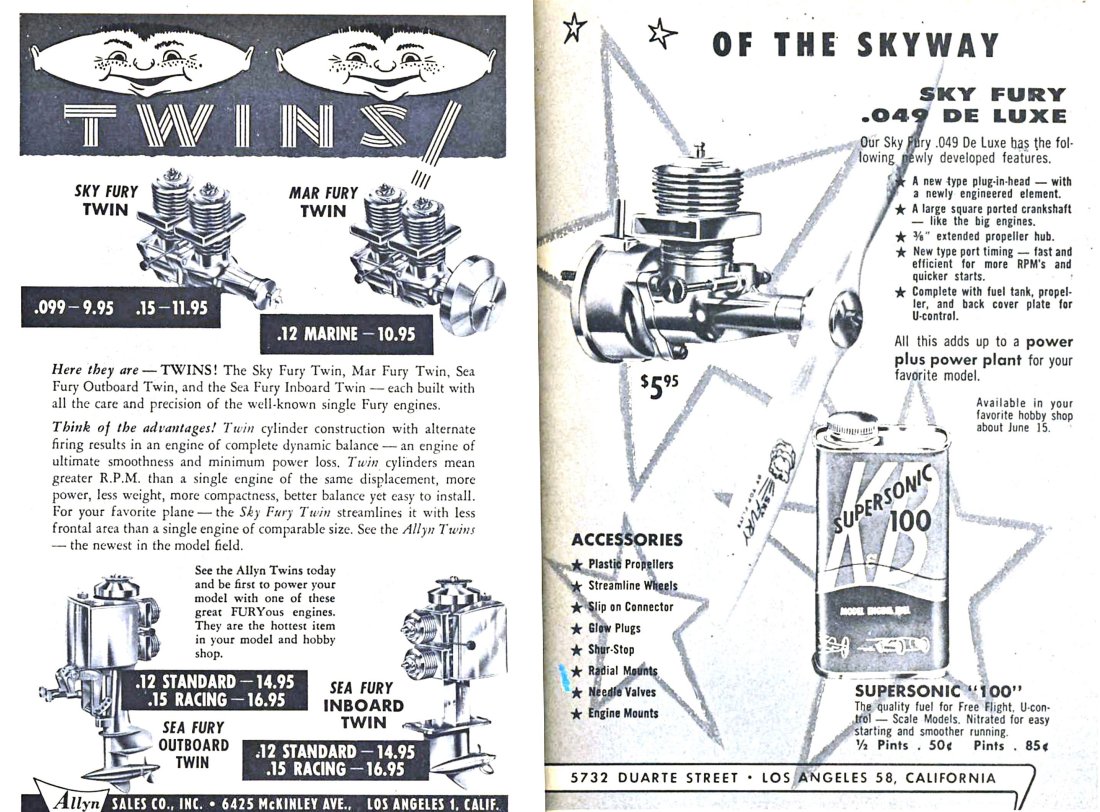

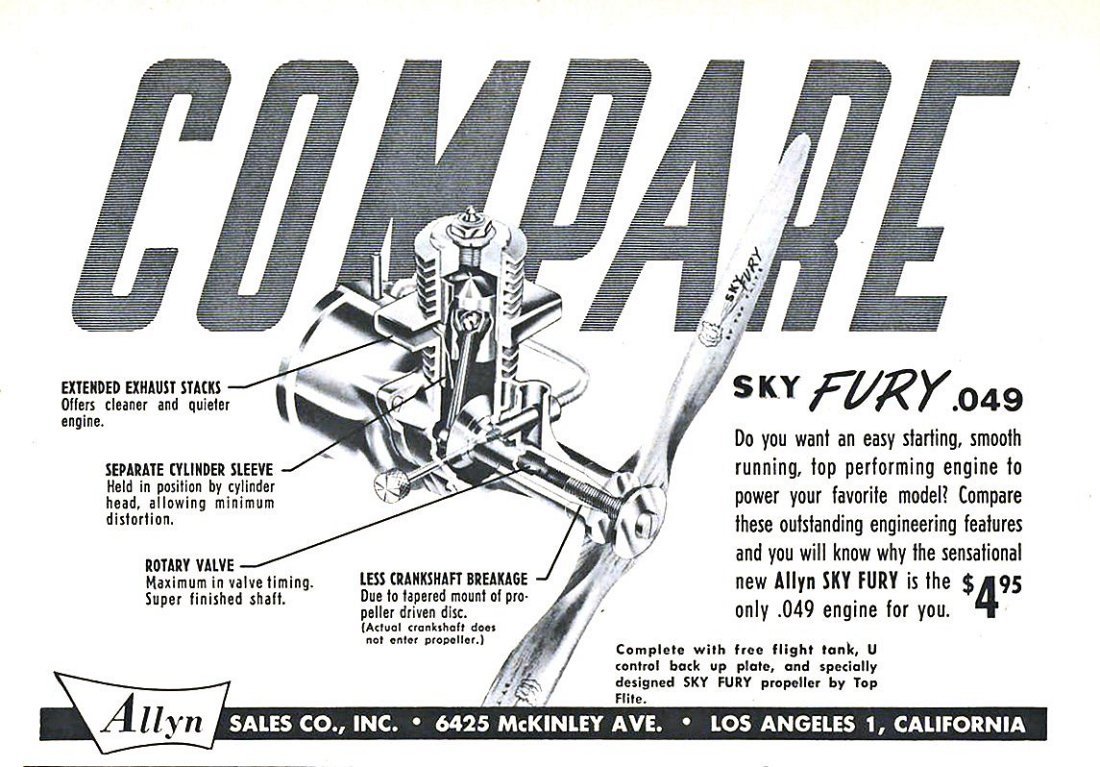

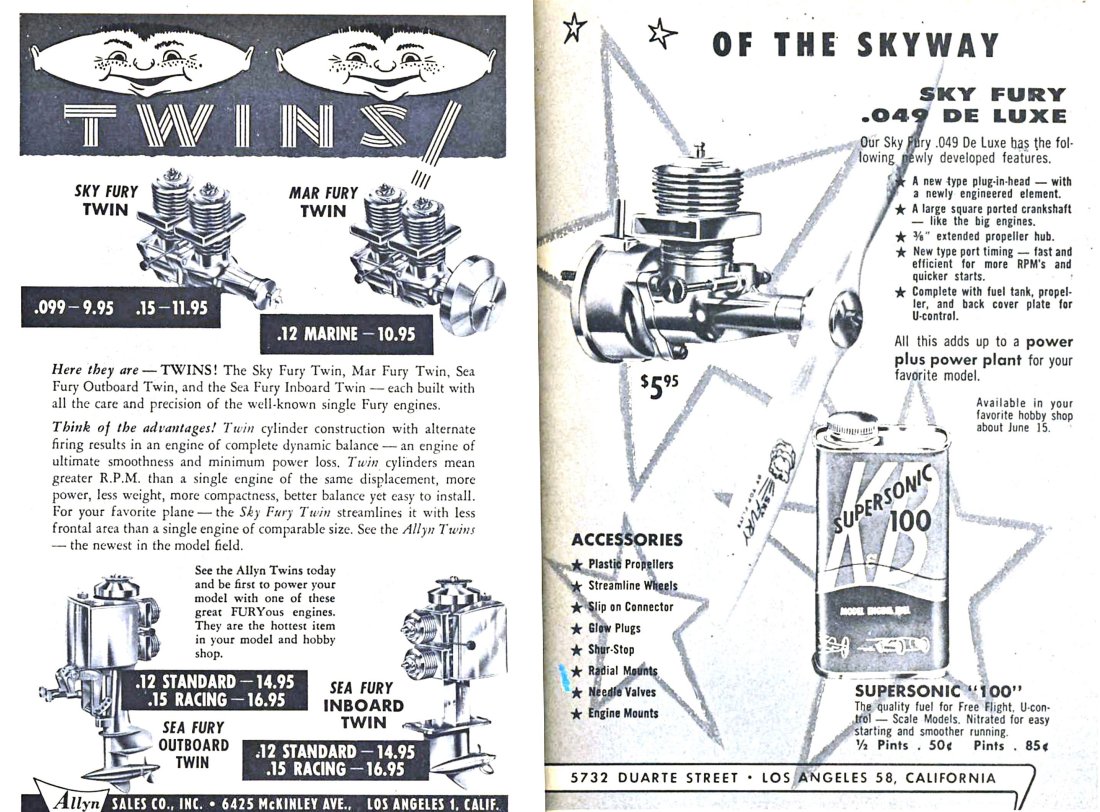

Returning now to the first half of the 1950’s, the Allyn Sales Co. had entered the ½A market in late 1953 with their Sky Fury .049 (left). Designed by Perin Culver, it had twin opposed exhaust stacks and a drop-in cylinder sleeve retained by a threaded head disc, which was tapped to accept a standard glow plug. Companion inboard and outboard marine engines followed in 1954/55.

Returning now to the first half of the 1950’s, the Allyn Sales Co. had entered the ½A market in late 1953 with their Sky Fury .049 (left). Designed by Perin Culver, it had twin opposed exhaust stacks and a drop-in cylinder sleeve retained by a threaded head disc, which was tapped to accept a standard glow plug. Companion inboard and outboard marine engines followed in 1954/55.

The Allyn company merged with K&B in 1955 to form K&B/Allyn, resulting in the 1955 appearance of the inline Sky Fury .098 and .15 Twins, together with companion inboard/outboard twins for model  boat use. The revised 1955 Sky Fury Deluxe aero unit had an integral glow element plus other improvements for more power. That model won Open ½A Speed at the 1956 AMA Nationals, also setting a new AMA ½A Open Free Flight record of 39 minutes 29 seconds in 1957.

boat use. The revised 1955 Sky Fury Deluxe aero unit had an integral glow element plus other improvements for more power. That model won Open ½A Speed at the 1956 AMA Nationals, also setting a new AMA ½A Open Free Flight record of 39 minutes 29 seconds in 1957.

An over-bored Sky Fury .074 made its appearance in 1957. K&B then bought Allyn out of  the business altogether. At the time, K&B was in turn owned by Nabisco, who subsequently sold K&B to the Aurora Plastics Corporation in 1959.

the business altogether. At the time, K&B was in turn owned by Nabisco, who subsequently sold K&B to the Aurora Plastics Corporation in 1959.

This led K&B to develop and produce the Aurora Tornado .049 (left) for use in Aurora’s RTF models. This engine sported some unusual features, including a white Delrin plastic fuel tank and a unique ”flex-o-valve” diaphragm induction design - a highly original form of reed valve. The same engine was marketed to the hobby trade beginning in 1960 under the K&B .049 name. It survived until 1963.

Meanwhile, the long-established Comet company had been expanding its plastic RTF range in 1958-59. Some models had engines with recoil pull-start starters. However, Herkimer’s OK Cub A and B models  were struggling to fly some of Comet’s new and heavier models to the required standard. This led Comet to seek alternatives.

were struggling to fly some of Comet’s new and heavier models to the required standard. This led Comet to seek alternatives.

Attempting to stem the tide, Charles Brebeck produced a new OK Cub .049 version for 1958. This featured a revised cylinder with an integral-element glow head as per the Cox Bee models. It also employed reed valve induction through a red nylon tank instead of the former FRV induction. The tell-tale bump on the crankcase casting nose indicates where a plug-in to the A model die eliminated the now-redundant FRV intake venturi. These engines were probably only used in action toys, including the OK Hot Rod tether car. Few if any seem to have appeared on the hobby market.

It appears that the power of this revised .049 model fell short of expectations. In an effort to deal with this problem, Herkimer quickly developed a companion OK Cub .06 model based on modified .049 A & B dies. This was basically the same engine with a ball conrod/piston joint and a longer stroke. All of these engines went to Comet – the .06 was never sold as a hobby engine. I’ve presented a detailed analysis of the OK reed valve models in a separate article to be found on this website.

It appears that the power of this revised .049 model fell short of expectations. In an effort to deal with this problem, Herkimer quickly developed a companion OK Cub .06 model based on modified .049 A & B dies. This was basically the same engine with a ball conrod/piston joint and a longer stroke. All of these engines went to Comet – the .06 was never sold as a hobby engine. I’ve presented a detailed analysis of the OK reed valve models in a separate article to be found on this website.

The 1960 OK Cub .024 (left) proved to be Herkimer’s last new engine. It too featured reed valve induction through a red nylon fuel tank/mount. I've presented a full analysis elsewhere on this website. The crankcase had twin exhaust stacks similar to OK’s earlier 29/35 engines. The .024 abandoned Brebeck’s patented porting for the now-standard twin opposed bypasses and exhausts. Charles Brebeck died in 1963, after which Herkimer closed down in 1965.

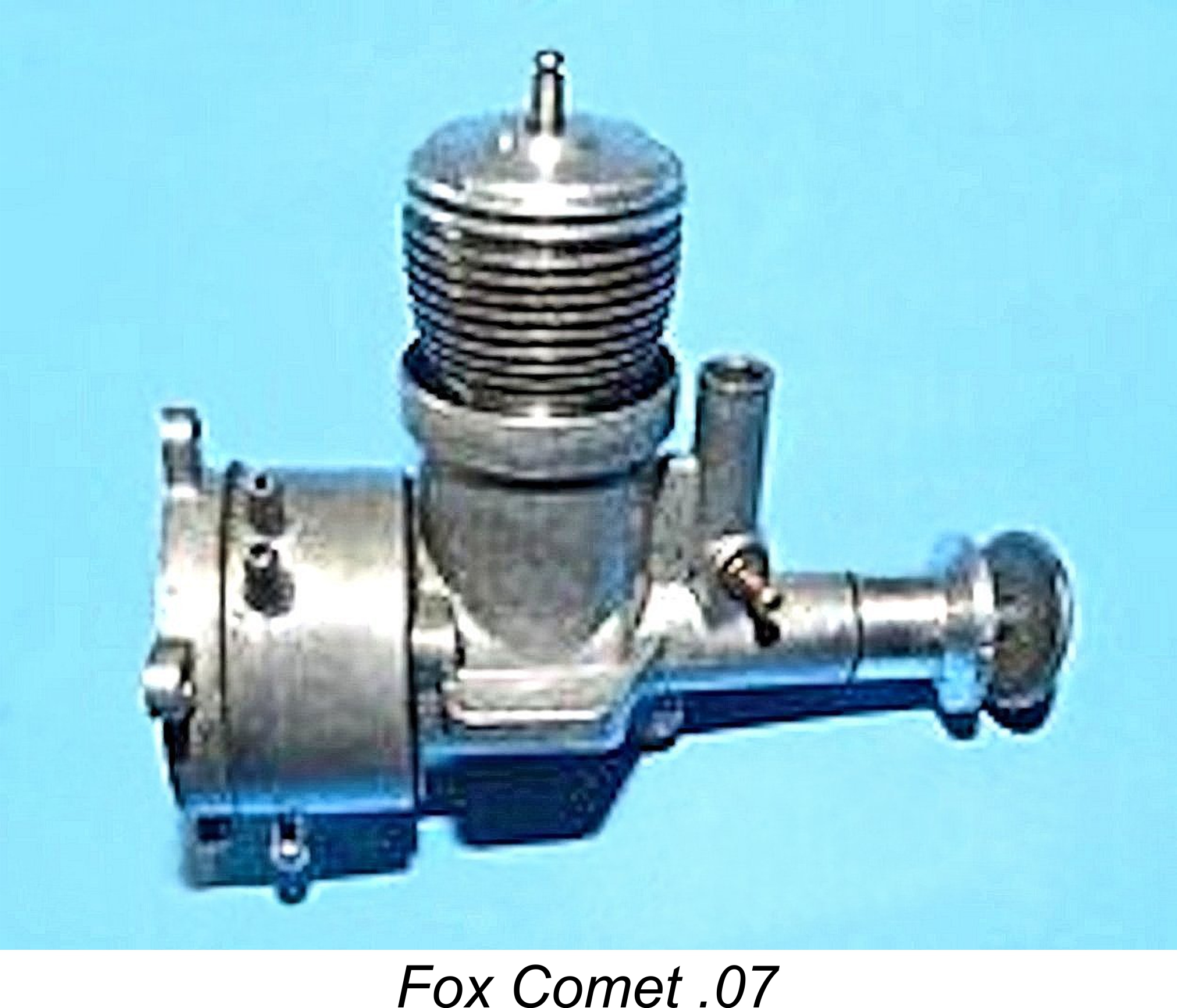

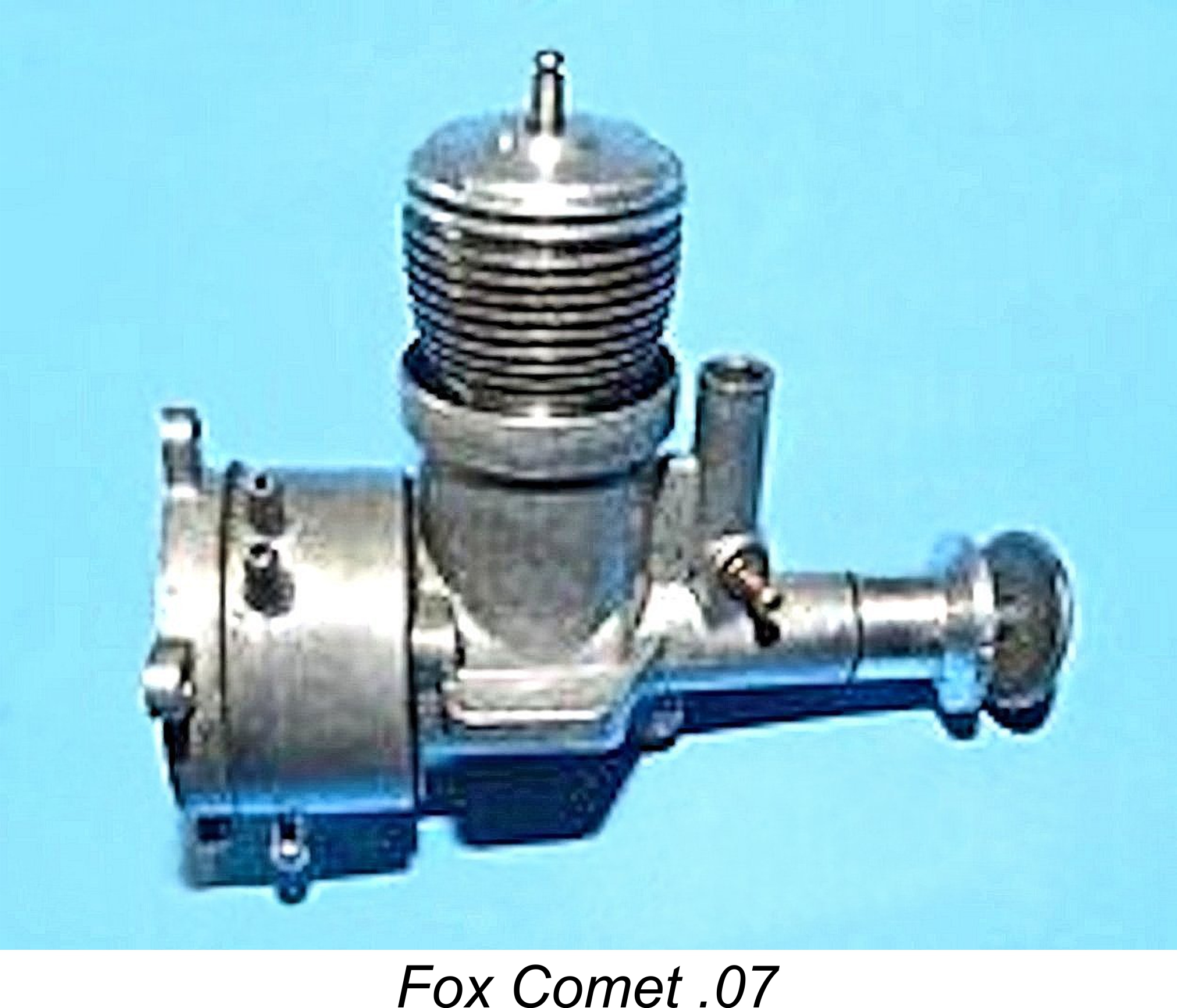

Duke Fox also responded to Comet with his Fox-Comet .07 of 1960 (right). This featured FRV induction and beam mounts, but used a radial-mount fuel tank/back cover. It had a typical ½A-style cylinder which accommodated an integral-element glow-head. In 1960 Comet was encouraged to advertise that its entire line of models had “powerful Comet engines”. This did not prevent its once-thriving RTF business from faltering and eventually collapsing, severely affecting both Herkimer and Fox. Once one of the big three along with Wen-Mac and Cox, Comet was forced to sell its plastics division to rival Aurora Plastics Corp. in 1963. Aurora were mainly interested in Comet’s static scale model kits, then very popular.

Duke Fox also responded to Comet with his Fox-Comet .07 of 1960 (right). This featured FRV induction and beam mounts, but used a radial-mount fuel tank/back cover. It had a typical ½A-style cylinder which accommodated an integral-element glow-head. In 1960 Comet was encouraged to advertise that its entire line of models had “powerful Comet engines”. This did not prevent its once-thriving RTF business from faltering and eventually collapsing, severely affecting both Herkimer and Fox. Once one of the big three along with Wen-Mac and Cox, Comet was forced to sell its plastics division to rival Aurora Plastics Corp. in 1963. Aurora were mainly interested in Comet’s static scale model kits, then very popular.

Meanwhile, Wen-Mac had been expanding its range, introducing its very ingenious but failure-prone Rotomatic starter in 1957. Starters of one type or another became more common on most ½A brands in the later 1950’s, K&B’s Tornado being a notable exception. The reality was that these engines were so easy to start by hand that the starter was quite unnecessary, being more of a sales gimmick than anything else.

Seeing the sales of Wasp .049’s waning, Bob Holland designed a far more powerful replacement, releasing the Holland Hornet .049 (left) and its companion .051 version in 1957. These units were distinguished by their distinctive chunky cast crankcases with almost full diameter front to back. The two-point radial mounting/tank option used in the Wasp was retained. Performance was enhanced by a large rectangular intake venturi and an unusually large crankshaft journal/gas passage. The cylinder displayed yet another variation of the now well-tested system of twin opposed exhausts separated by twin opposed transfers. The engines used glow heads with integral elements. The heads could be obtained with hemispherical or high compression conical combustion chambers.

Seeing the sales of Wasp .049’s waning, Bob Holland designed a far more powerful replacement, releasing the Holland Hornet .049 (left) and its companion .051 version in 1957. These units were distinguished by their distinctive chunky cast crankcases with almost full diameter front to back. The two-point radial mounting/tank option used in the Wasp was retained. Performance was enhanced by a large rectangular intake venturi and an unusually large crankshaft journal/gas passage. The cylinder displayed yet another variation of the now well-tested system of twin opposed exhausts separated by twin opposed transfers. The engines used glow heads with integral elements. The heads could be obtained with hemispherical or high compression conical combustion chambers.

Ted Martin (MAN) and Ron Warring (“AeroModeller”) both tested the original Holland Hornet, finding good but otherwise unremarkable levels of performance. In 1960, Bob sold his Holland Engineering business to Dynamic Models (Hi Johnson), continuing to work for the new owner to develop an essentially unchanged Mark 2 version and bring its production up to speed. It was at this time that tuned “factory special” engines were offered for $5 more than the regular $6.96 price. Whatever the differences, Peter Chinn (“Model Aircraft”) found a quite unprecedented power output for an engine of this displacement, with the modified engine peaking at a speed well above what the best reed valve engines could manage. These tuned Holland Hornets quickly overtook the previously-unmatched Cox engines in the trophy hunt. By mid-1961 they held 7 out of 9 AMA ½A records!

We’ve now brought the story up to 1960. Conveniently enough for our purposes, Larry Conover (“AeroModeller”, December 1960) summarised ½A engine performance progress up to that point in time. His data is not directly comparable since it was based upon runs with 10 - 15% nitro fuel and unspecified thin-bladed 6x3 or 5.5x4 props. In addition, his table appears to incorporate progress made by individual owner(s) in extracting maximum power from a given engine type. Still, it gives a good general indication of progress made up to 1960.

|

Year

|

Engine

|

RPM

|

|

1949

|

Torp .035

|

8,000

|

|

1949

|

Baby Spitfire

|

10,000

|

|

1950

|

Torp .049

|

12,000

|

|

1951

|

Cub .049

|

11,000

|

|

1952

|

Cox Spacebug

|

14,000

|

|

1952

|

McCoy .049

|

13,500

|

|

1953

|

Atwood .049

|

14,500

|

|

1954

|

Thermal Hopper

|

15,500

|

|

1955

|

Thermal Hopper

|

16,500

|

|

1956

|

Thermal Hopper

|

17,000

|

|

1957

|

Thermal Hopper

|

17,500

|

|

1958

|

Thermal Hopper

|

18,000

|

|

1959

|

Space Hopper

|

18,000 +

|

|

1959

|

Holland Hornet

|

18,500

|

|

1960

|

Hornet & Hopper

|

18,500 +

|

The 1960’s

In 1960 Bill Atwood went to work for Leroy Cox. The hiring of Atwood was motivated at least in part by a desire to have him work on a proposed tiny .010 cuin. engine. At this size, Cox’s preferred reed valve induction was clearly not practical. Atwood solved the problem by using FRV induction, probably after referring to the earlier RR1 model and experimenting with rotary drum valve induction to improve Cox’s 1959 international-class Olympic .15 (essentially an enlarged Space Hopper with reed valve induction and twin ball races).

The resulting Cox Tee Dee .010 of 1961 was acclaimed for its tiny size, quality, ease of operation and very high operating speed - 27,000 rpm with its specially developed matching airscrew. The little gem carried over many established Cox design elements, but used a front induction carburettor mounted in a plastic moulding secured to the crankcase. The slightly larger companion 1961 Cox Tee Dee .020 also had both plastic radial mount/back plate or fuel tank options.

The resulting Cox Tee Dee .010 of 1961 was acclaimed for its tiny size, quality, ease of operation and very high operating speed - 27,000 rpm with its specially developed matching airscrew. The little gem carried over many established Cox design elements, but used a front induction carburettor mounted in a plastic moulding secured to the crankcase. The slightly larger companion 1961 Cox Tee Dee .020 also had both plastic radial mount/back plate or fuel tank options.

Cox expanded its range of high-performance engines in 1961 with the beam-mount Tee Dee .049/.051 and Tee Dee .15. These were joined in 1962 by the Tee Dee .09. All of these models set new performance benchmarks in their respective Classes. The Tee Dee .049/.051 models were clear winners at the 1962, 1963 and 1964 AMA Nationals, dominating the ½A competition classes, a position which they were to maintain for decades.

The basically similar general purpose Medallion 049/09/15 range also had FRV induction, but used regular spraybars traversing the venturis along with detuned internals. All three sizes were offered in 1963 with coupled venturi/exhaust throttles. Lightweight transistorized radio control equipment was becoming ever more reliable and popular, opening up the market for smaller R/C powerplants.

The basically similar general purpose Medallion 049/09/15 range also had FRV induction, but used regular spraybars traversing the venturis along with detuned internals. All three sizes were offered in 1963 with coupled venturi/exhaust throttles. Lightweight transistorized radio control equipment was becoming ever more reliable and popular, opening up the market for smaller R/C powerplants.

On the RTF side, Cox made a number of detail changes to its established Bee platform, including adaptations to particular models such as its cars and other specific power requirements. The 1963 Cox 290 version of the basic .049 with a minimal back cover was developed for the Spook flying wing kit model. It was the first of a line of similar variants designed to  use an external fuel tank. The QZ 049 with silencer was another distinct variant. Cox also introduced ½A gas-powered outdoor slot cars at around this time.

use an external fuel tank. The QZ 049 with silencer was another distinct variant. Cox also introduced ½A gas-powered outdoor slot cars at around this time.

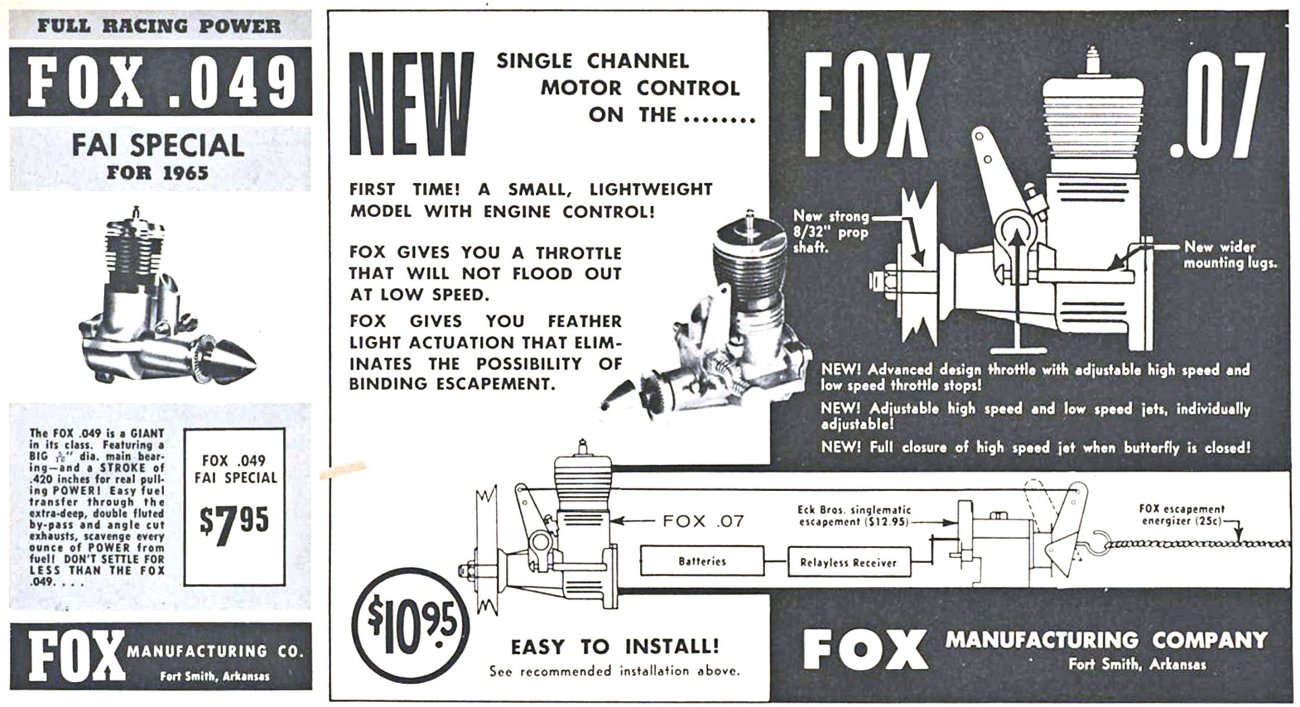

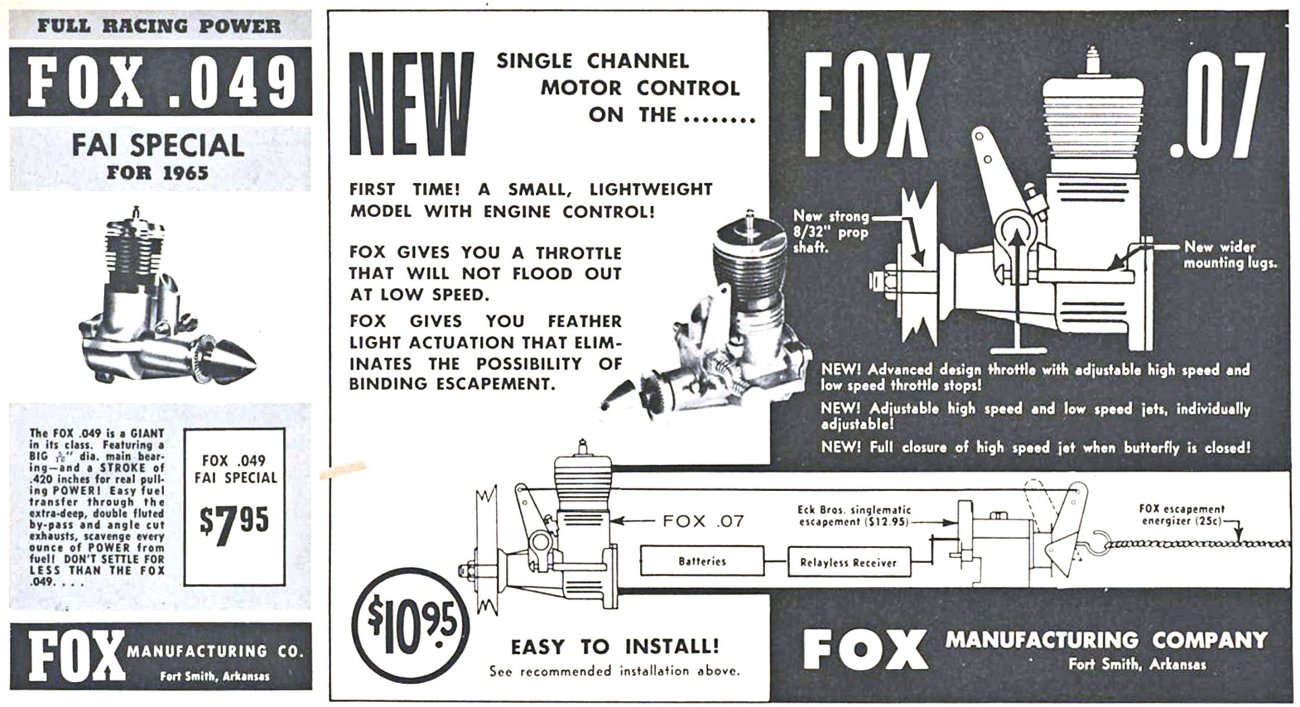

Duke Fox recovered quite quickly from his previously-mentioned foray into the RTF business. His Comet 07 (with the name removed) became the Fox “Compact Stunt Motor”. The 1962 Fox .049 (right) was a derivative using common parts, featuring FRV induction, a radial tank mount, an optional back cover for beam mounting and a typical ½A top end. This engine was facelifted in 1964 with fins and the name on the crankcase along with minor internal changes.

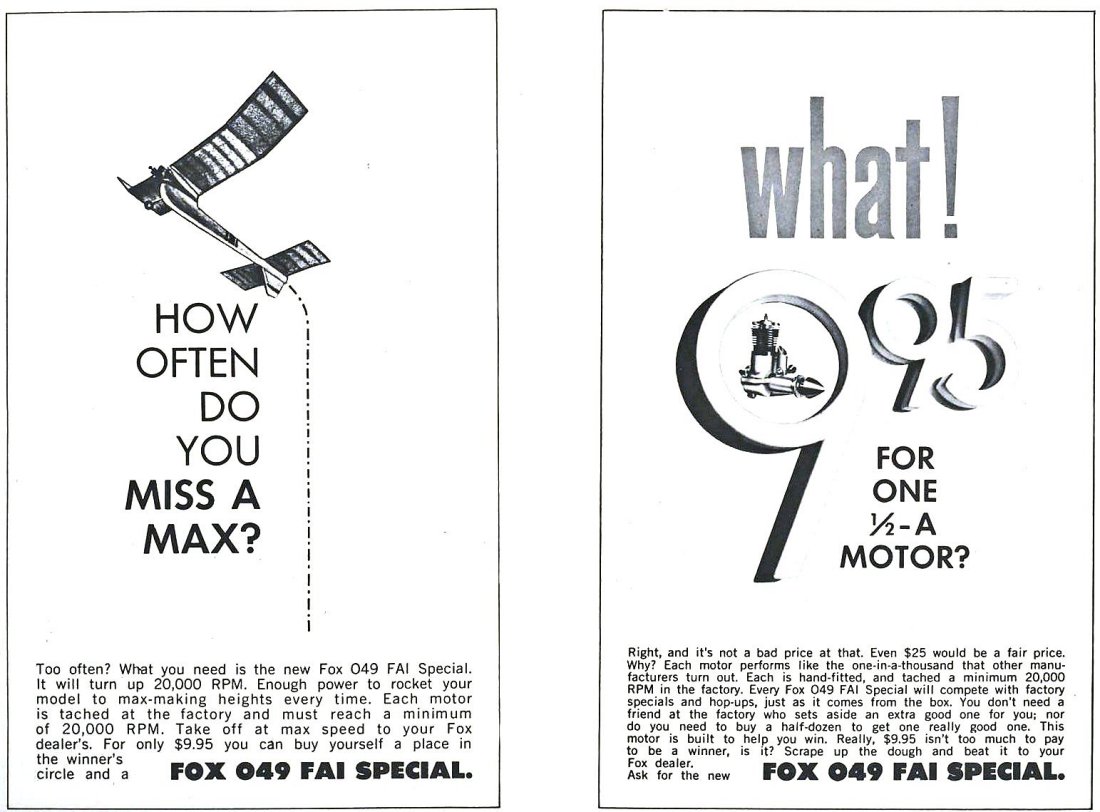

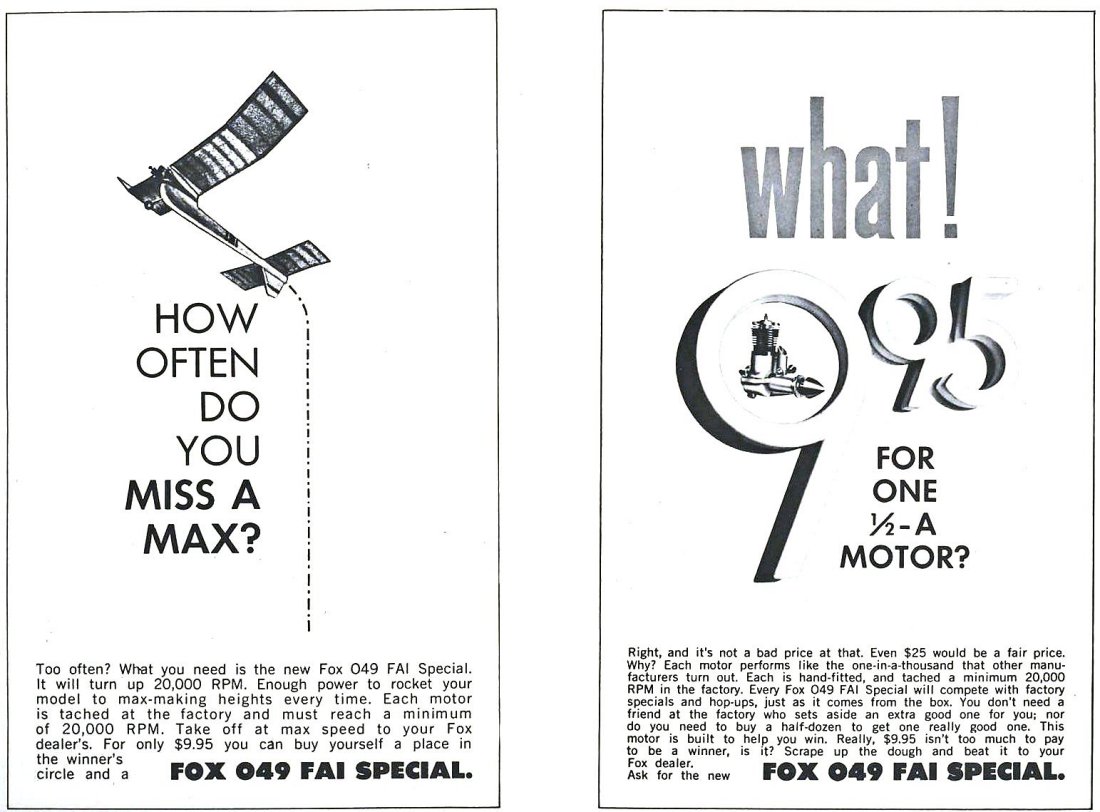

Always competition-minded, Fox had been working on upping his engines’ performances. He began advertising a Fox .049 FAI Special in 1963, but this model was not actually released until 1964. It had a new crankcase to accommodate a far larger crankshaft, along with significantly revised cylinder porting. Its power output was potentially sufficient to move it into the running for competition applications. The advertising claim that “each one tached at 20,000 RPM

Always competition-minded, Fox had been working on upping his engines’ performances. He began advertising a Fox .049 FAI Special in 1963, but this model was not actually released until 1964. It had a new crankcase to accommodate a far larger crankshaft, along with significantly revised cylinder porting. Its power output was potentially sufficient to move it into the running for competition applications. The advertising claim that “each one tached at 20,000 RPM  or more” suggests a certain level of quality variation, requiring individual factory testing to weed out so-so examples. In the event, the new Fox failed to threaten the dominance of the Cox Tee Dee .049, causing the price to drop to $7.95. The 1964 Fox .07 R/C proved to be Fox’s last small engine.

or more” suggests a certain level of quality variation, requiring individual factory testing to weed out so-so examples. In the event, the new Fox failed to threaten the dominance of the Cox Tee Dee .049, causing the price to drop to $7.95. The 1964 Fox .07 R/C proved to be Fox’s last small engine.

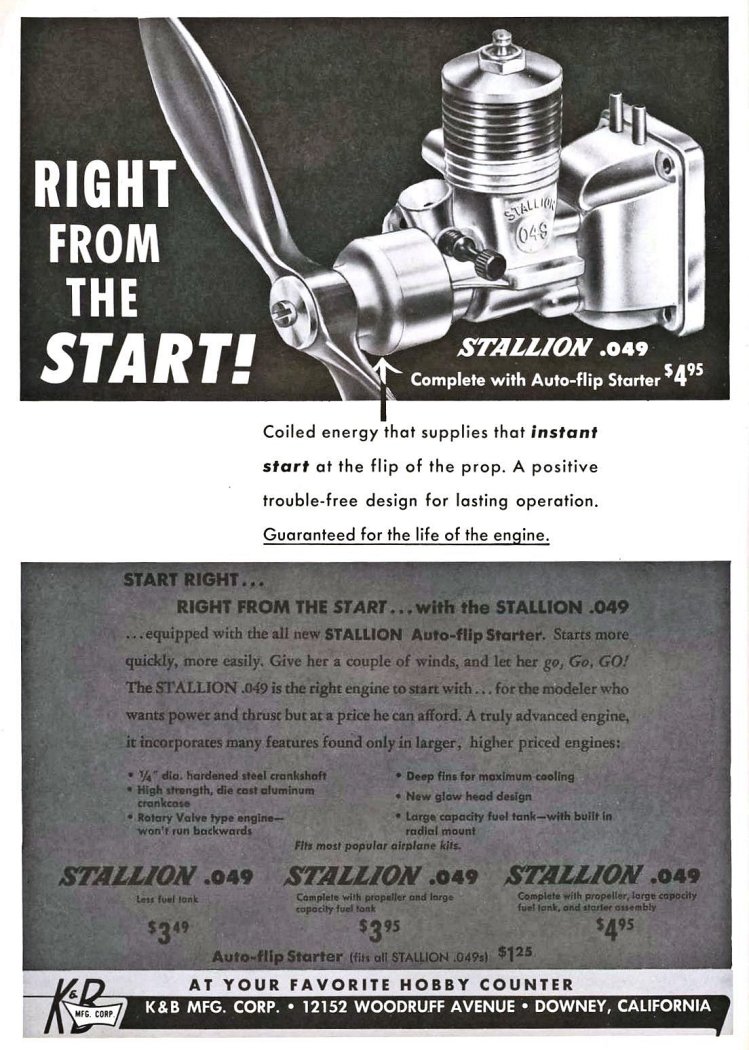

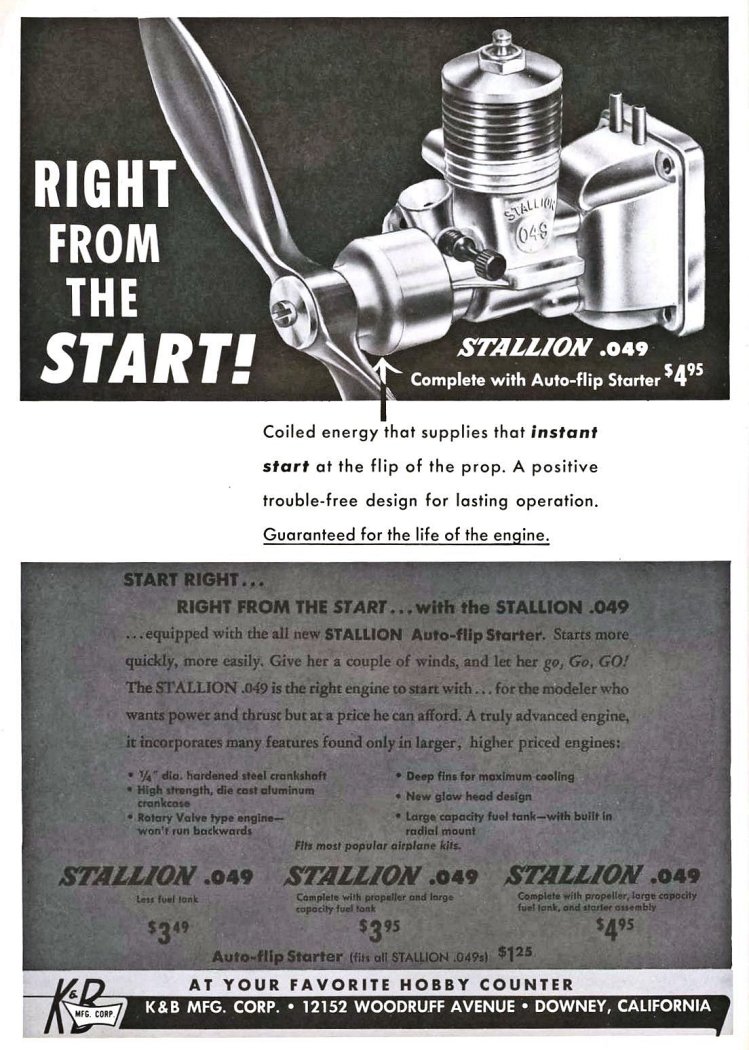

In 1963 K&B adverts were pushing its RTF models, powered by the K&B  Tornado .060 Gold head, which was based on the earlier Aurora .049 design. An all-new 1963 K&B Stallion .049 (left) was targeted more at the hobby market, although it did power the popular Comet Piper Tri-Pacer RTF model which was re-released under the K&B brand. It was K&B’s last engine of this displacement.

Tornado .060 Gold head, which was based on the earlier Aurora .049 design. An all-new 1963 K&B Stallion .049 (left) was targeted more at the hobby market, although it did power the popular Comet Piper Tri-Pacer RTF model which was re-released under the K&B brand. It was K&B’s last engine of this displacement.

The little Stallion had  a good general-purpose performance to go along with its $3.95 price tag, which included a matching nylon airscrew. It featured FRV induction, a single exhaust stack, a beam mount crankcase and an alternative radial tank mount. Despite the appearance imparted by the single stack, it actually used a screw-in twin exhaust/twin bypass cylinder. It was also available with an optional auto-flip starter (right).

a good general-purpose performance to go along with its $3.95 price tag, which included a matching nylon airscrew. It featured FRV induction, a single exhaust stack, a beam mount crankcase and an alternative radial tank mount. Despite the appearance imparted by the single stack, it actually used a screw-in twin exhaust/twin bypass cylinder. It was also available with an optional auto-flip starter (right).

In an era of significant acquisitions and mergers in the toy and leisure industries, Wen-Mac was absorbed by American Machine and Foundry (AMF, better known for their bowling equipment and bowling centres). The new 1963 Wen-Mac/AMF Hotshot .049 engine series (below left) looked similar to previous models, but had now fallen into line by switching to the preferred twin opposed exhausts and opposed transfers.An integral-element glow head and larger cooling fins were also featured. Power was very significantly higher than before. The derivative  Thunderbolt model with an exhaust throttle was released in 1965. The Testor Corporation bought Wen-Mac in 1968 and the basic engine design carried on between 1969 and 1972, now under the McCoy/Testors brand.

Thunderbolt model with an exhaust throttle was released in 1965. The Testor Corporation bought Wen-Mac in 1968 and the basic engine design carried on between 1969 and 1972, now under the McCoy/Testors brand.

The 1970’s

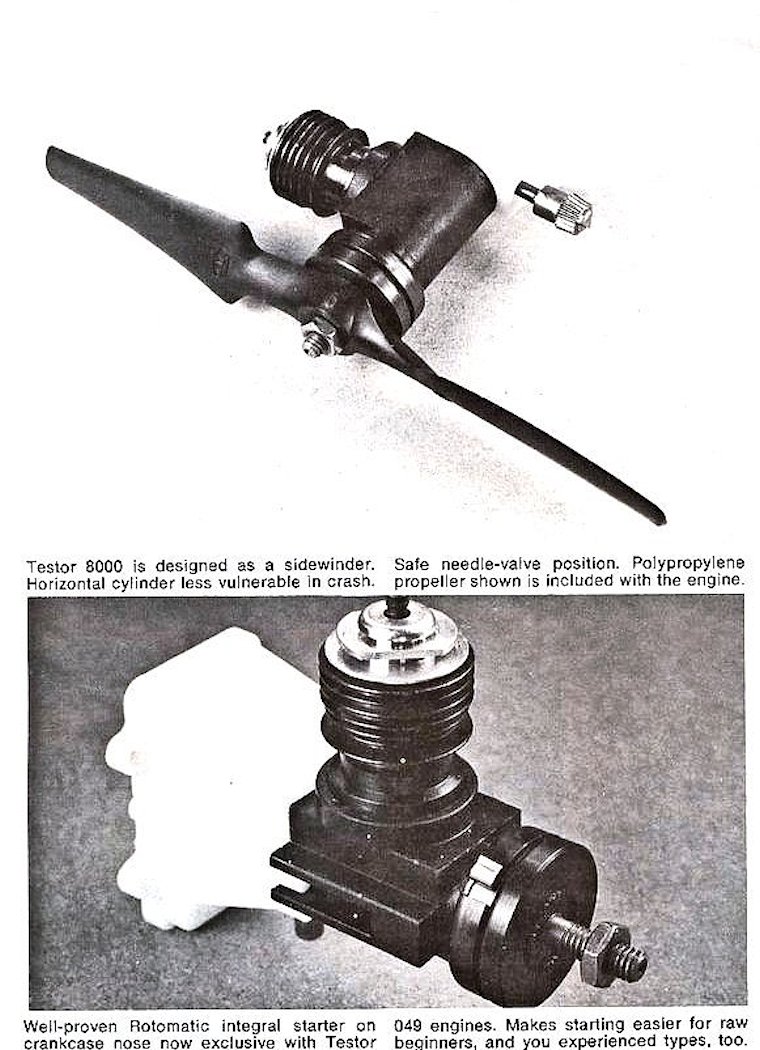

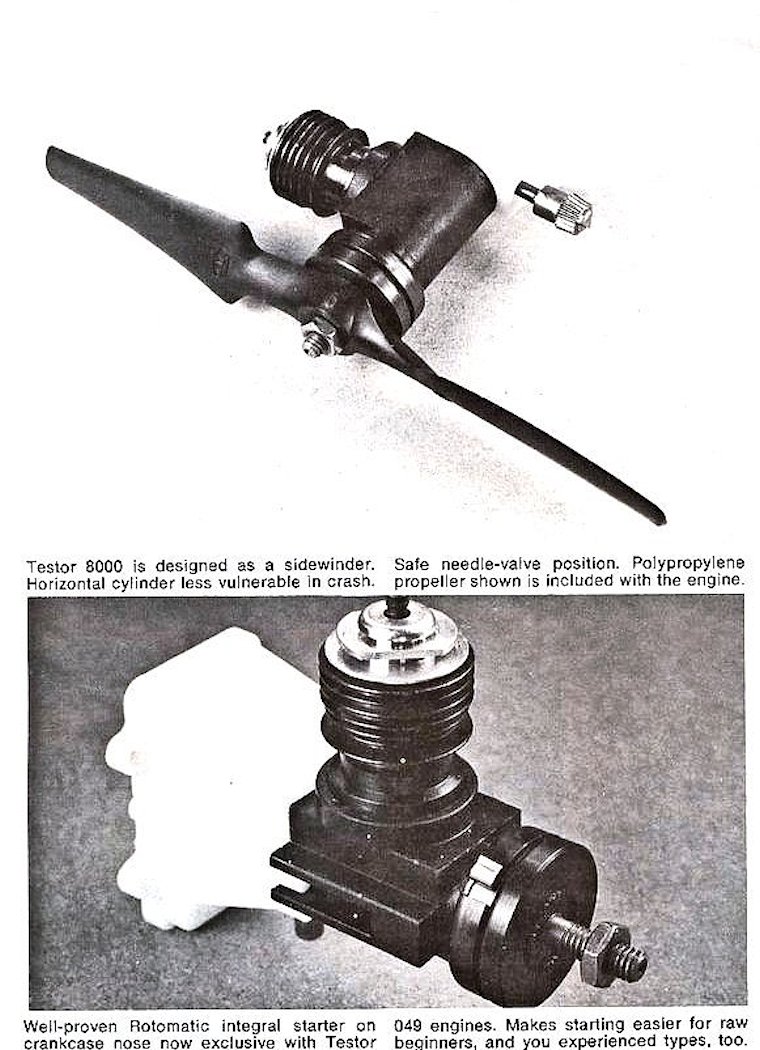

During the 1960’s, changing consumer tastes such as the mid-1960’s slot car craze and non-flying plastic model kits combined to further shrink the ½A  engine market. By the 1970’s, that market was only supporting two players - Cox and Testor. Both were still competing in the RTF model market, while Cox enjoyed a far stronger presence in the hobby trade, largely driven by their still-unrivalled Tee Dee .049. Testor focused on their RTF lines, developing innovative engines with features such as slot-in crankcases. Later versions had crankcases made from glass-filled nylon rather than aluminium. All the Testor engines from 1975 to 1982 used reed valve induction. The 1978 Testor 8000 model (right), intended for the hobby market, had a nylon crankcase, a radial mount fuel tank, a proprietary Rotomatic starter and a top end similar to the Hotshot. The engine had a quite respectable power output.

engine market. By the 1970’s, that market was only supporting two players - Cox and Testor. Both were still competing in the RTF model market, while Cox enjoyed a far stronger presence in the hobby trade, largely driven by their still-unrivalled Tee Dee .049. Testor focused on their RTF lines, developing innovative engines with features such as slot-in crankcases. Later versions had crankcases made from glass-filled nylon rather than aluminium. All the Testor engines from 1975 to 1982 used reed valve induction. The 1978 Testor 8000 model (right), intended for the hobby market, had a nylon crankcase, a radial mount fuel tank, a proprietary Rotomatic starter and a top end similar to the Hotshot. The engine had a quite respectable power output.

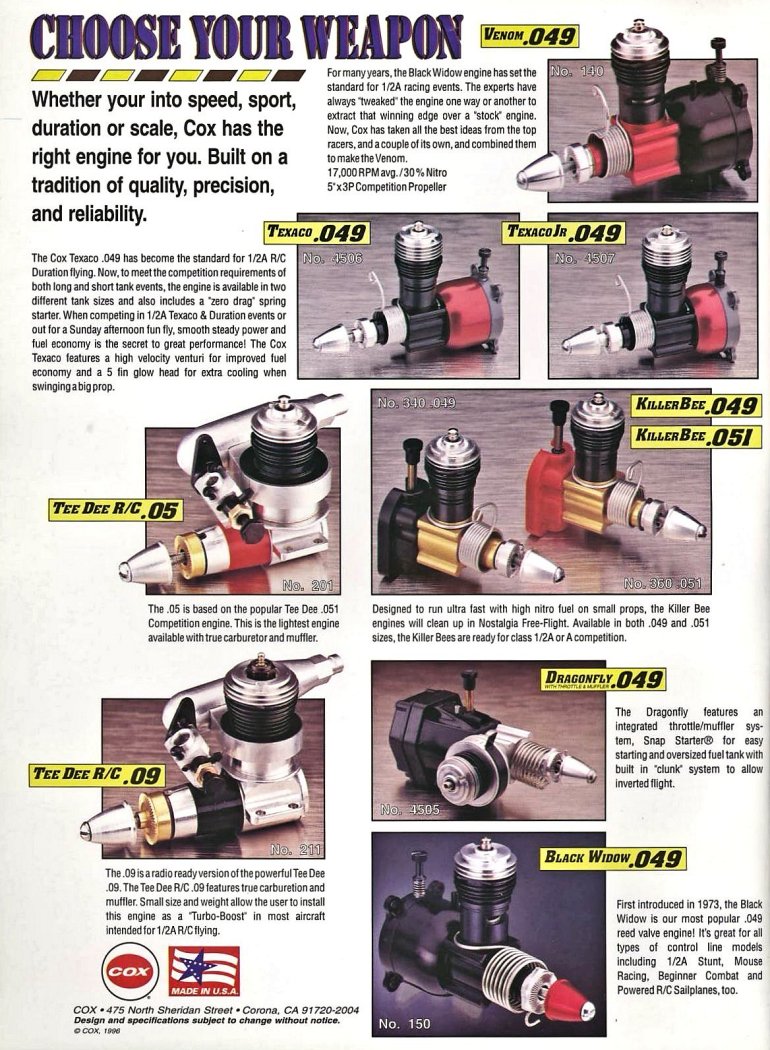

Cox was sold to Leisure Dynamics in 1969, subsequently going through various ownership changes. The brand continued to progress with the 1973 release of the Black Widow .049, which was primarily aimed at control line Mouse Racing. The Black Widow was essentially a reed-valve Bee engine with a Tee Dee twin-port piston/cylinder assembly, a larger choke area and a distinctive black crankcase.

Extensive tuning of the Cox Tee Dee .049, especially for ½A speed work, lifted its performance potential still further. Dale Kirn led the way with his Kirn-Kraft custom parts and engines. The most important modifications were his revised bypass ports, with additional channels widening and lifting both sides of the originals. More radical developments by individual users with blank cylinders machined for Schnuerle-like ports and tuned exhausts raised the records but did not change the design of the basic production engine.

Extensive tuning of the Cox Tee Dee .049, especially for ½A speed work, lifted its performance potential still further. Dale Kirn led the way with his Kirn-Kraft custom parts and engines. The most important modifications were his revised bypass ports, with additional channels widening and lifting both sides of the originals. More radical developments by individual users with blank cylinders machined for Schnuerle-like ports and tuned exhausts raised the records but did not change the design of the basic production engine.  Fusite (left) expanded its range of flat-coil element glow plugs with glow heads for Cox engines, promising an extra 1000 rpm with extended plug life.

Fusite (left) expanded its range of flat-coil element glow plugs with glow heads for Cox engines, promising an extra 1000 rpm with extended plug life.

In 1976, with the ever-expanding popularity of radio control, Cox introduced the QRC .049. This was a Bee with a cylinder modified to suit a silencer, also being provided with an 8 cc fuel tank. The substantially new 1979 R/C Bee .049 (right) had a cast crankcase, a large moulded plastic fuel tank with flexible “clunk” pickup, stunt venting, a snap starter spring and a combination sleeve-type exhaust throttle and muffler. Although initially advertised as having rear rotary induction it actually featured a revised mylar induction reed valve with a snap-on plastic retainer.

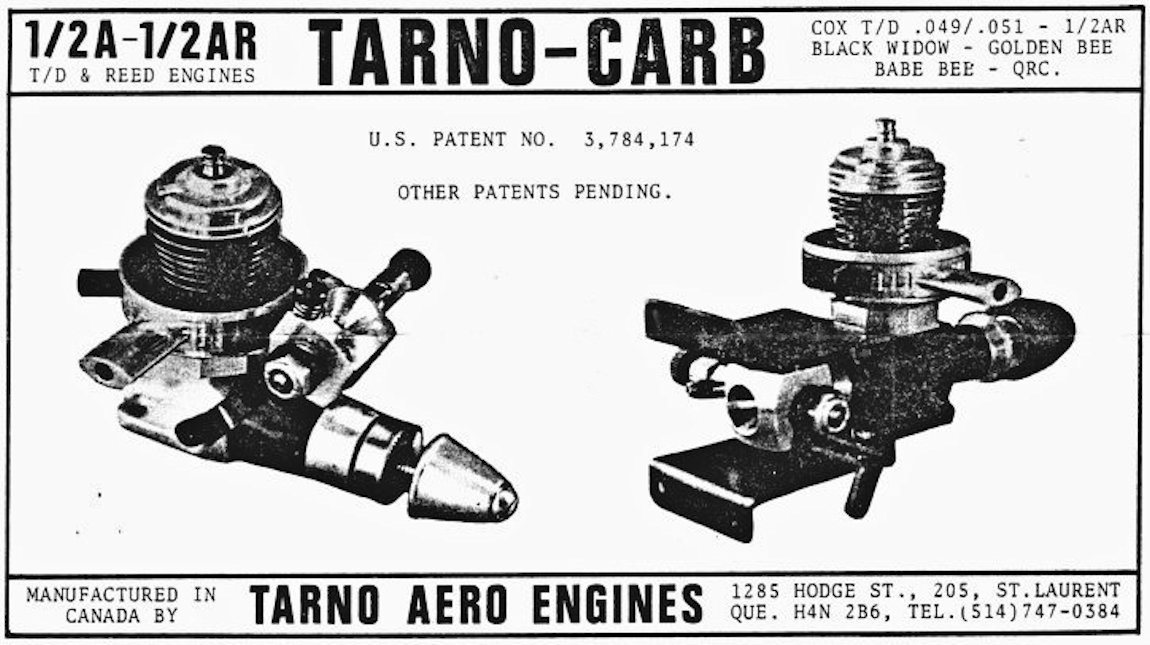

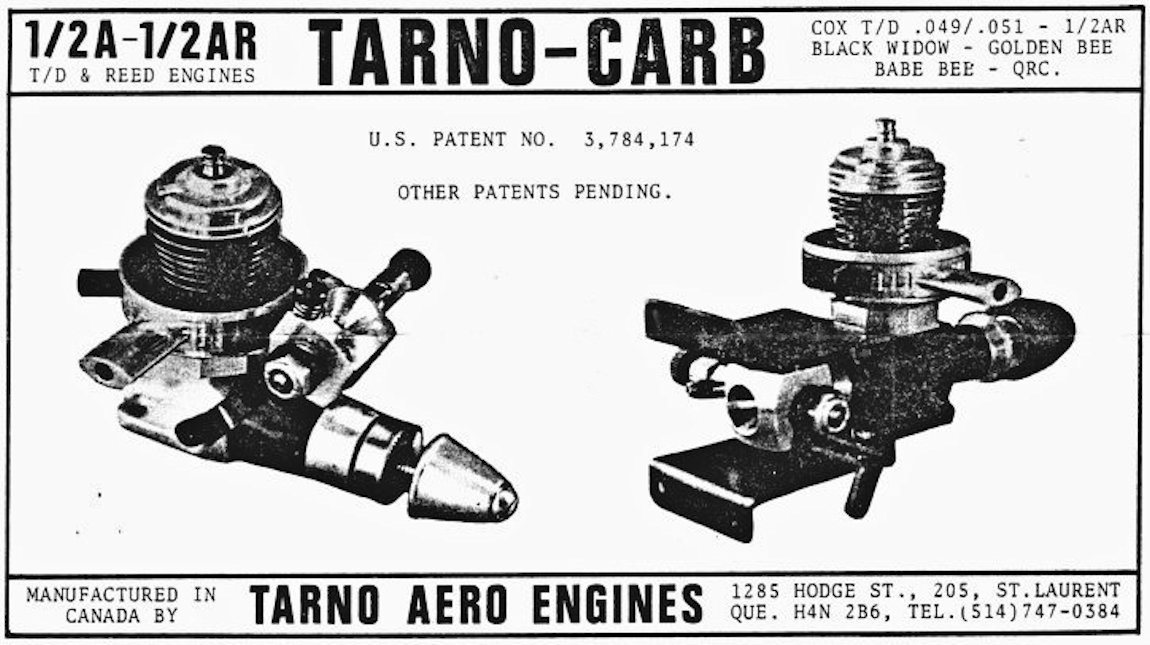

Third party supplier Tarno of Canada offered a neat R/C throttle (below left) for the Cox Tee Dee .049 for better control than that provided by Cox’s simple  rotating exhaust collar, which acted more like a two-speed device. A variant of that design was also offered for the Cox reed valve models.

rotating exhaust collar, which acted more like a two-speed device. A variant of that design was also offered for the Cox reed valve models.

Trading as Davis Diesel Developments, Robert Davis introduced a novel diesel conversion for Cox engines (right). It had a loose-fitting contra piston in the head with a thin fluorocarbon disc to seal against compression loss. Davis offered heads for 020/049/09 sizes. Not unexpectedly, the .049 size proved to be the most popular. Cox did not endorse diesel operation of its engines, partly because the crankshafts could break under the higher stresses imposed by diesel operation. To deal with this issue, Davis added a stronger crankshaft for Cox Bee .049 engines to his expanding range of products, which now included conversion heads for larger engines. These used O-ring seals set into their in-head contra pistons.

Trading as Davis Diesel Developments, Robert Davis introduced a novel diesel conversion for Cox engines (right). It had a loose-fitting contra piston in the head with a thin fluorocarbon disc to seal against compression loss. Davis offered heads for 020/049/09 sizes. Not unexpectedly, the .049 size proved to be the most popular. Cox did not endorse diesel operation of its engines, partly because the crankshafts could break under the higher stresses imposed by diesel operation. To deal with this issue, Davis added a stronger crankshaft for Cox Bee .049 engines to his expanding range of products, which now included conversion heads for larger engines. These used O-ring seals set into their in-head contra pistons.

In 1977 Dub Jett and Johnny Shannon made a small number of DJS .049s for ½A Speed competition. These featured Schnuerle porting, rear induction and ball race shafts. They were set up for tuned pipe operation.

Later Developments

Ted Brebeck, the grandson of Herkimer founder Charles Brebeck, had inherited a large inventory of original OK engine parts. In 1975 Brebeck set up the OK Engine Company. He offered spares and repair services, also undertaking limited production of new engines using original and fresh parts. His first such offering was the 1978 Anniversary Mohawk Cub. This was based on a Cub .049B crankcase, but with a blue-anodized tank and extended prop driver reminiscent of the 1948 Mohawk Chief .299 spark/glow engine.

Brebeck also undertook limited production of 500 OK Cub A and B .049’s between 1997 and 1999, with variations depending on original parts availability. These variations included a novel OK Cub .049 fixed compression diesel. This had a beryllium-copper fixed compression head with a blind hole for a glow plug, which was used to pre-heat the head before starting. Later releases included .049R and .06R reed valve engines as well as an .049BR reed induction engine styled after the never-manufactured “racing” version similar to the Cox Space Hopper. There were also the Mohawk CO2 with bar-stock crankcase and finally, the OK Cub .025 in 2014.

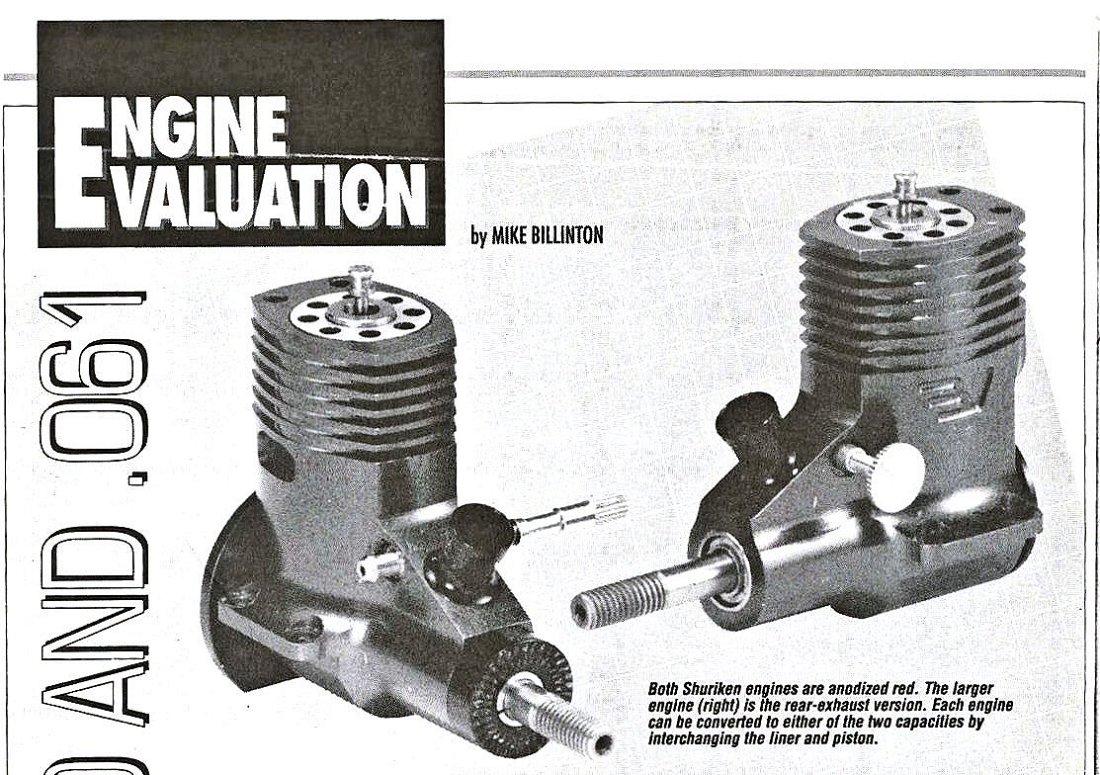

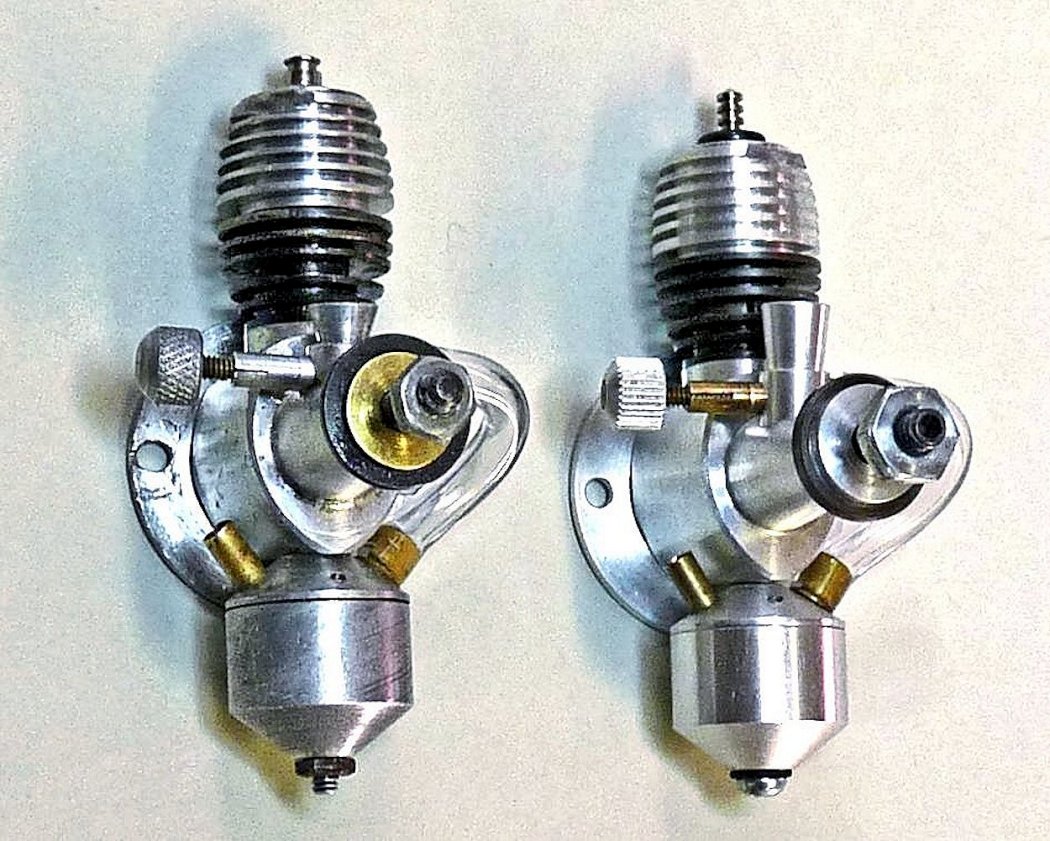

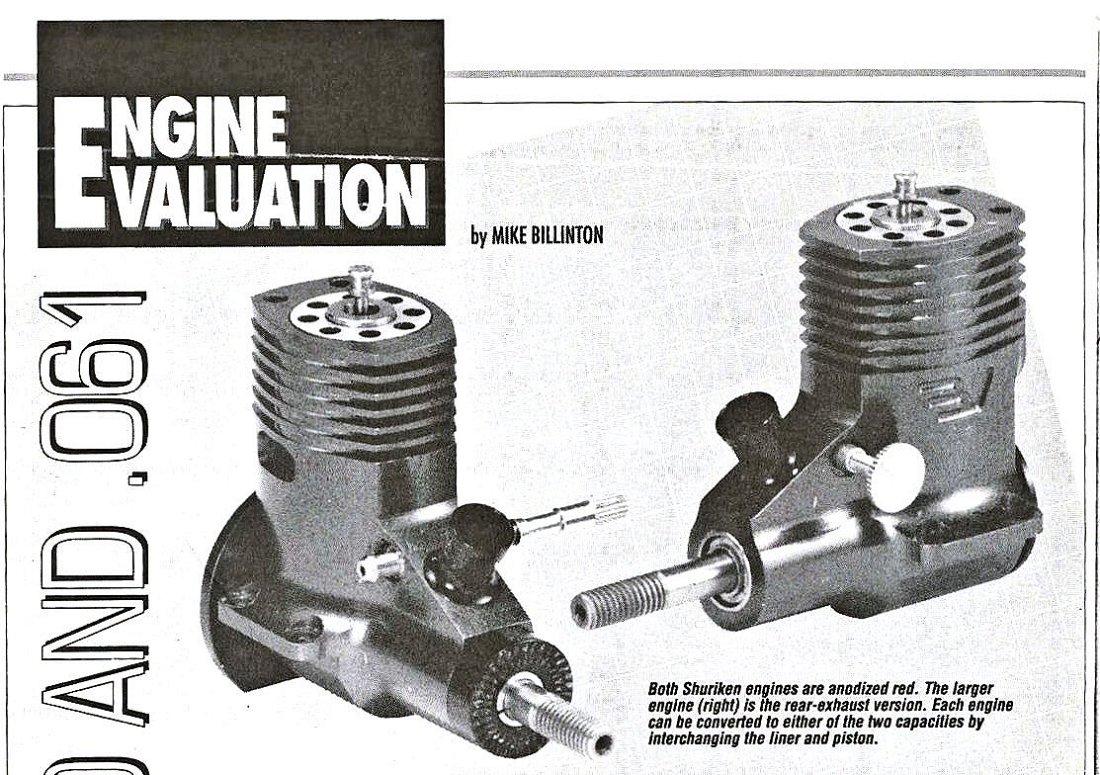

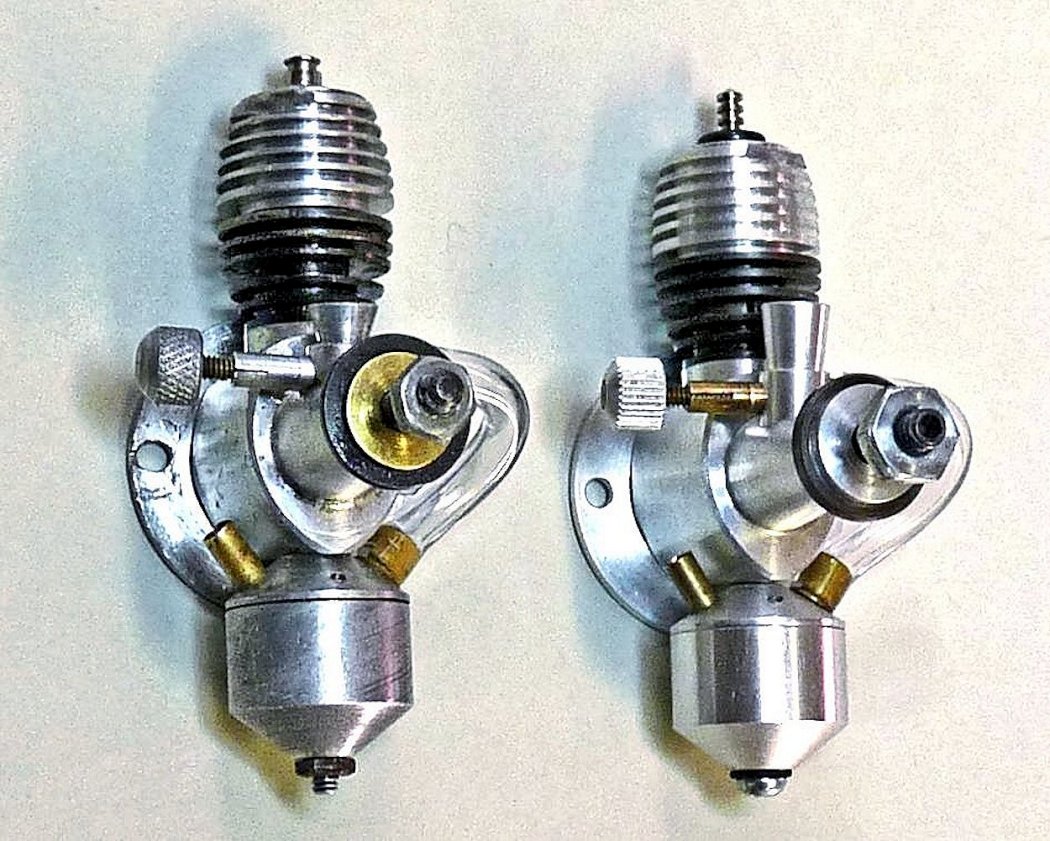

In 1990, Fred Baldwin and Jim Van Arsdall stepped aside from their usual Indycar parts supply work to form BV Competition Engines. They released their Shuriken units in 1990. These were photographed and tested by Mike Billinton, as seen at the left. They featured FRV induction, red-anodized CNC-machined crankcases, ABC piston/cylinders, Schnuerle porting and twin ball races. The .049 version developed around .27 BHP and the .061 some .35 BHP, both at 35,000 rpm. The tuned pipe versions ran at over 45,000 rpm. Although the partnership dissolved in 1992, a little further independent production took place - Baldwin’s (red case) and Van Ardsall’s (gold case). Total produced was only in the hundreds.

In 1990, Fred Baldwin and Jim Van Arsdall stepped aside from their usual Indycar parts supply work to form BV Competition Engines. They released their Shuriken units in 1990. These were photographed and tested by Mike Billinton, as seen at the left. They featured FRV induction, red-anodized CNC-machined crankcases, ABC piston/cylinders, Schnuerle porting and twin ball races. The .049 version developed around .27 BHP and the .061 some .35 BHP, both at 35,000 rpm. The tuned pipe versions ran at over 45,000 rpm. Although the partnership dissolved in 1992, a little further independent production took place - Baldwin’s (red case) and Van Ardsall’s (gold case). Total produced was only in the hundreds.

During the 1990’s, a combination of very low wages and new business opportunities in China and the former Soviet Union countries shifted the focus of US suppliers away from domestic manufacture towards commissions for overseas production and sales in the USA. Larry Hutson worked on special head and tuned pipe design details for the Chinese CS .049 Speed engine. Dan Rutherford initiated efforts by several individuals/groups in St Petersburg, Russia (with aerospace expertise and access to high-quality production technology) to make a modern Tee Dee .049 replacement.

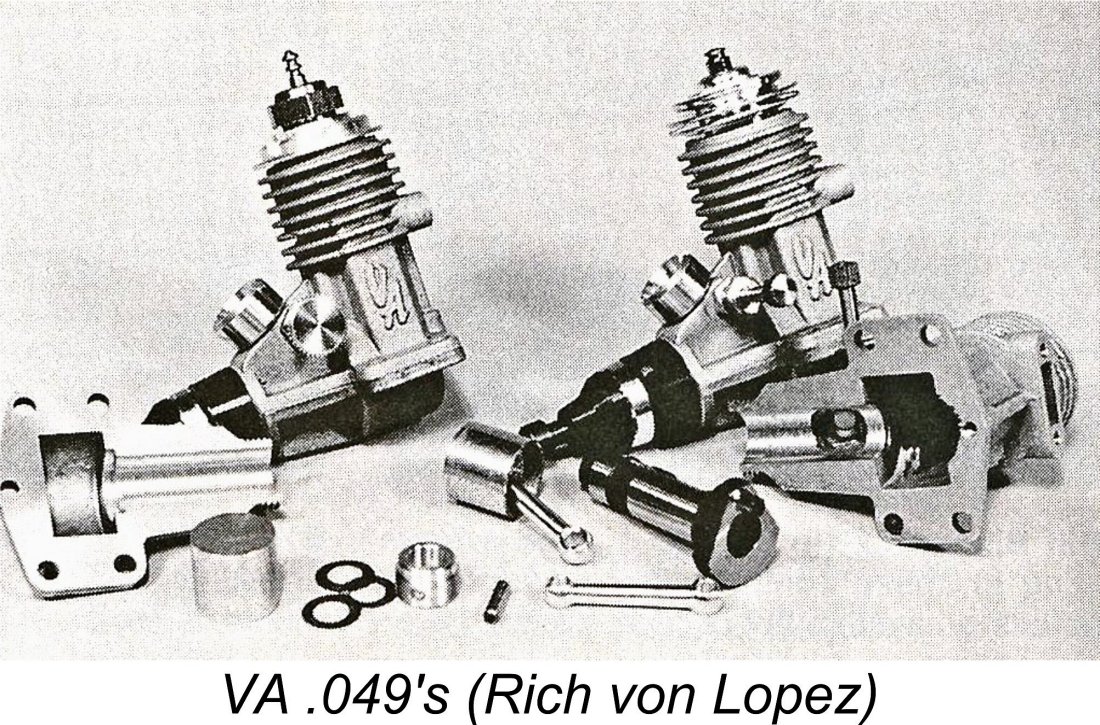

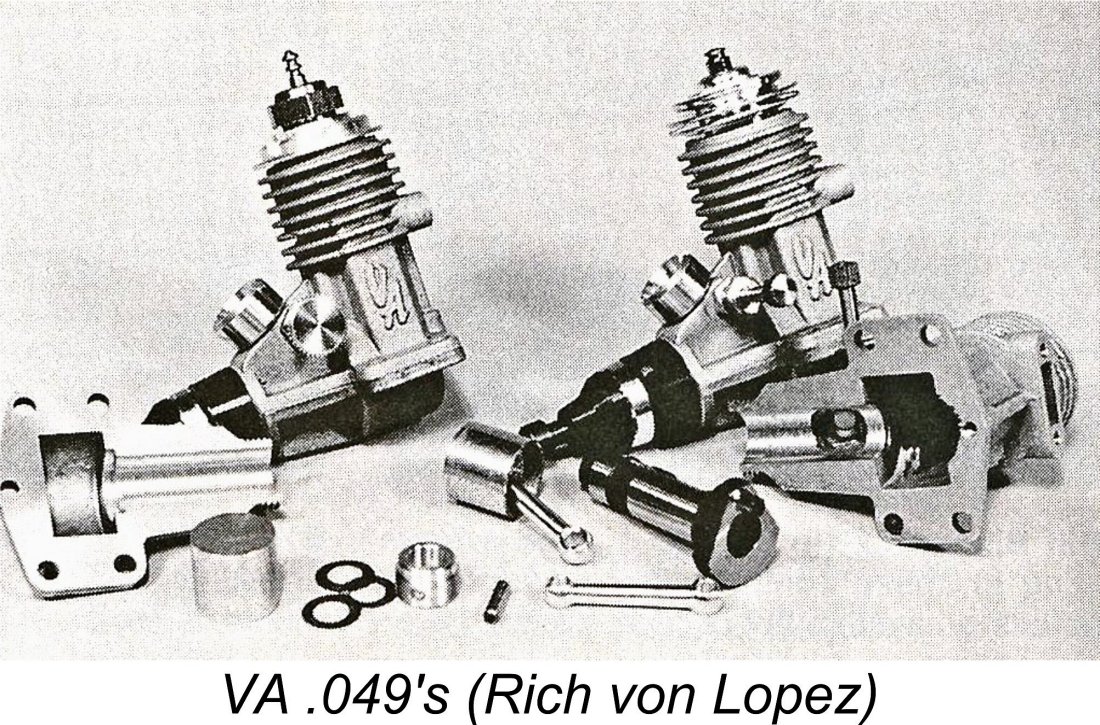

Various designs from the early 1990s by Stels (Alexander Gieviesky), VA (Valentin Aloshkin) and AME featured Schnuerle porting with ABC or AAC piston/cylinders. The VA .049 was the most original of these, with the crankcase split horizontally along the crankshaft axis; a hard nickel-plated cylinder bore integral with the crankcase; and a piston which screwed onto a threaded wrist pin yoke. Shims allowed fine adjustment of port timing. These engines were distributed in the USA by George Aldrich. A more conventional Mk. 2 version followed, including a small run of an R/C version. However, Aloshkin eventually shifted to different work, while Stels also ceased production.

Various designs from the early 1990s by Stels (Alexander Gieviesky), VA (Valentin Aloshkin) and AME featured Schnuerle porting with ABC or AAC piston/cylinders. The VA .049 was the most original of these, with the crankcase split horizontally along the crankshaft axis; a hard nickel-plated cylinder bore integral with the crankcase; and a piston which screwed onto a threaded wrist pin yoke. Shims allowed fine adjustment of port timing. These engines were distributed in the USA by George Aldrich. A more conventional Mk. 2 version followed, including a small run of an R/C version. However, Aloshkin eventually shifted to different work, while Stels also ceased production.

Like the others, the AME .049s offered a little more performance than the Cox Tee Dee .049, peaking at significantly higher rpm with light propeller loads. Commercial success came when Norvel began to distribute the engines in the USA and elsewhere from the mid-1990s onwards. The original design was refined, with a parallel general purpose Big Mig series being added. The range expanded with .06 and .074  versions along with larger 15/25/40 models. Features included R/C throttles, mufflers, plastic fuel tank/mounts and innovative Revlite AAO (aluminium piston, nickel plated aluminium cylinder, oxide ceramic coating) technology. These units set new standards for small engines heading into the 2000’s. The business faltered and finally stopped, but a limited supply of engines and spares resumed via internet order through NV Engines.

versions along with larger 15/25/40 models. Features included R/C throttles, mufflers, plastic fuel tank/mounts and innovative Revlite AAO (aluminium piston, nickel plated aluminium cylinder, oxide ceramic coating) technology. These units set new standards for small engines heading into the 2000’s. The business faltered and finally stopped, but a limited supply of engines and spares resumed via internet order through NV Engines.

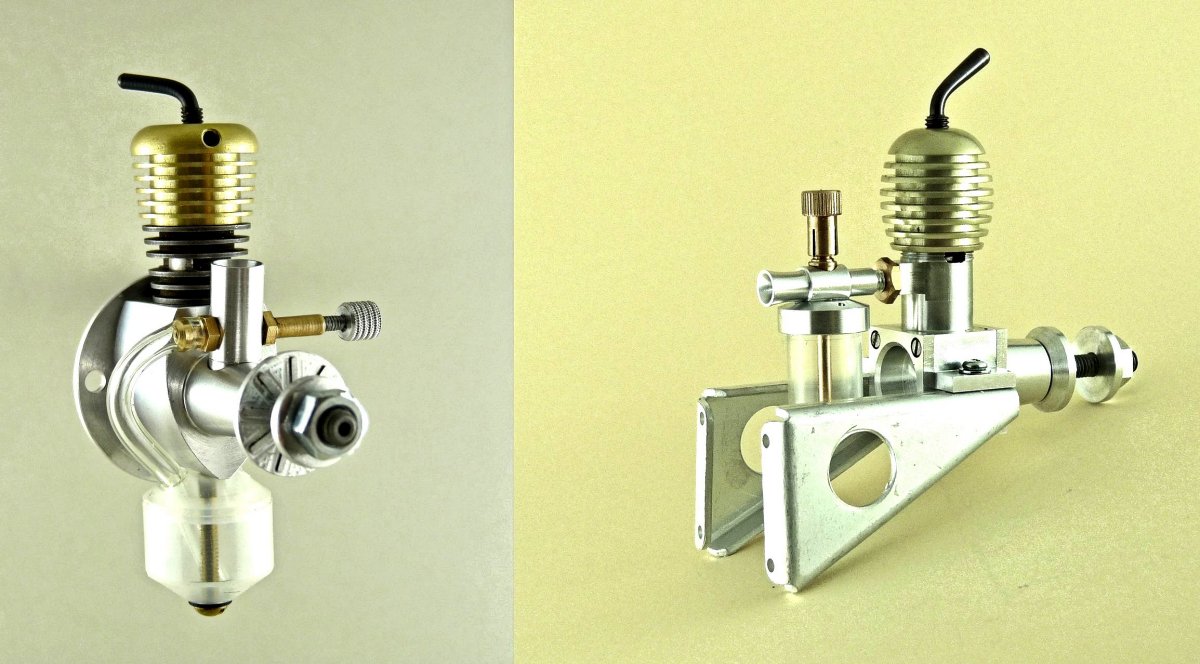

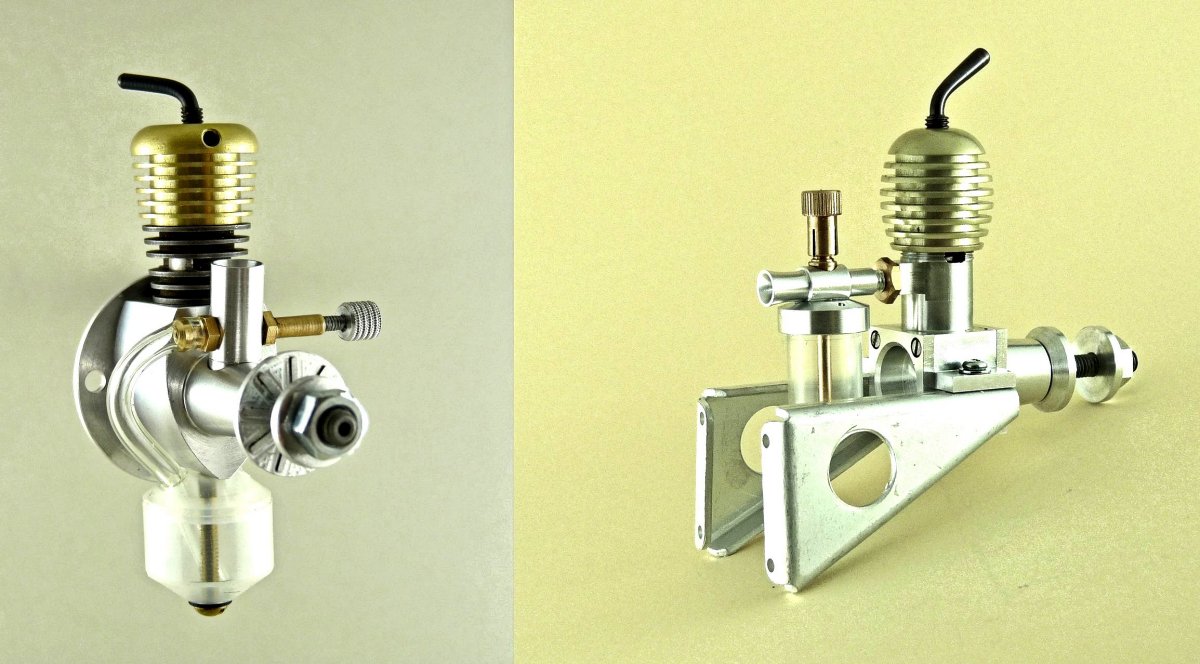

In 1998, P.A.L. Model Products (Neville Palmer, Dave Acton, Bob Langelius) commissioned Alexander Kalmykov to produce a 50th Anniversary run of replica K&B Infant .020s (on right in photo, original to the left). They followed this up with a short run of 100 replica McCoy Duro-Glo .049 diesels in 2003.

The 2015 Ukrainian-made PAL LOLA .020 diesel (based on the K&B Infant design - left in the photo) was supplied with an R/C throttle. The 0.44cc (.027 cuin.) traditional PAL Pesky side-port diesel (right in the photo) soon followed.

The 2015 Ukrainian-made PAL LOLA .020 diesel (based on the K&B Infant design - left in the photo) was supplied with an R/C throttle. The 0.44cc (.027 cuin.) traditional PAL Pesky side-port diesel (right in the photo) soon followed.

Less well known is the VA .020, commissioned by PAL as a Cox TD .020 beater. The Cox engine had been finding recent application in ¼A Nostalgia free flight competition. The VA 020 ended up not being sold at the time of its original production, as its performance turned out to be uncompetitive. The completed examples were sold off much later during the clearing of Neville Palmer’s estate.

Less well known is the VA .020, commissioned by PAL as a Cox TD .020 beater. The Cox engine had been finding recent application in ¼A Nostalgia free flight competition. The VA 020 ended up not being sold at the time of its original production, as its performance turned out to be uncompetitive. The completed examples were sold off much later during the clearing of Neville Palmer’s estate.

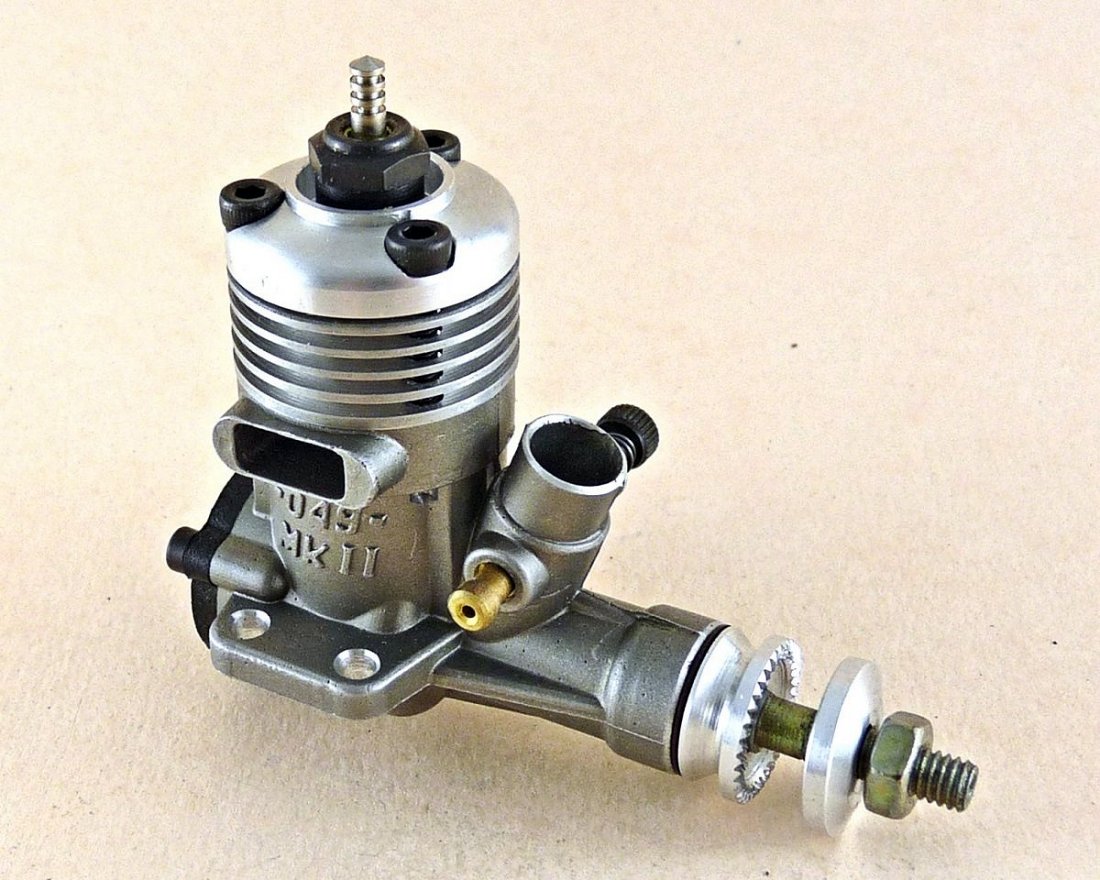

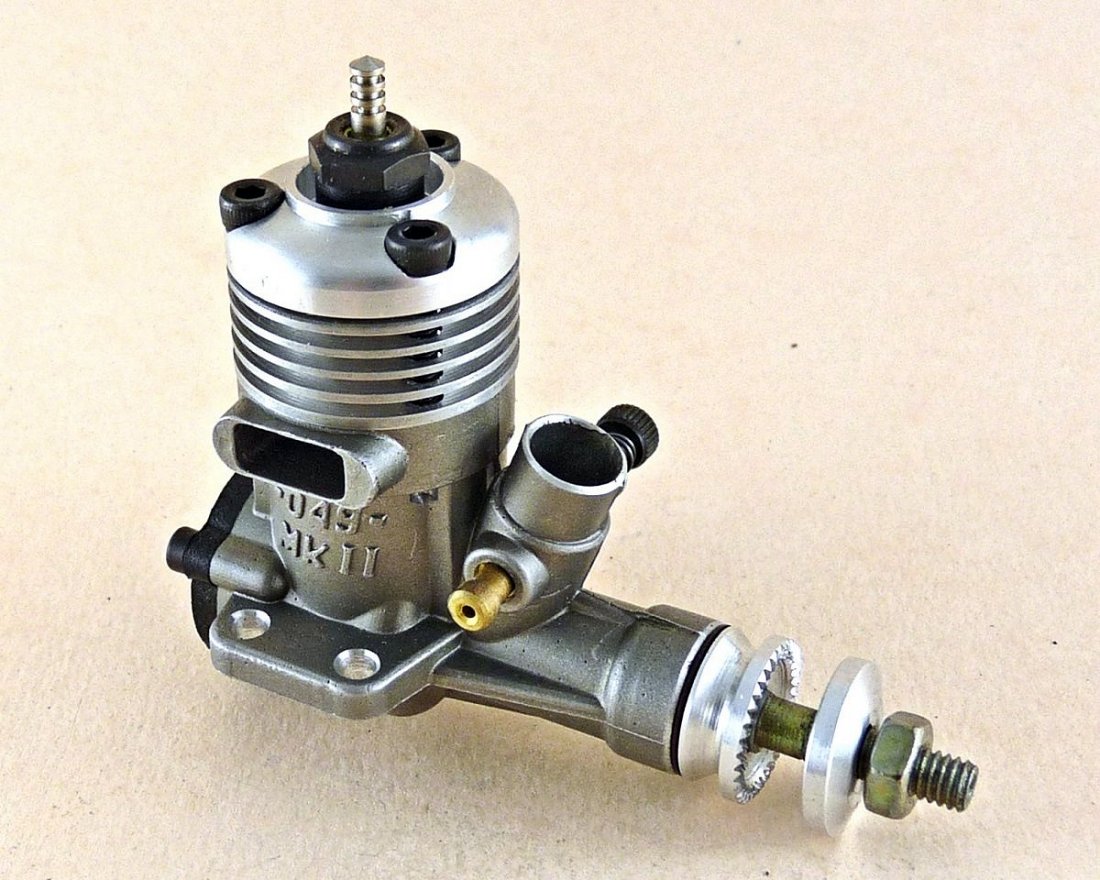

The Brodak Mk. 1 .049 and companion .06 was made by CS in China circa 2010. These engines were intended for sport C/L or R/C flying. They featured plain bearings, Schnuerle ports and a matching muffler. In common with some other latter-day CS products, they displayed a few quality control problems, although some examples performed well, particularly with an after-market head to suit a Nelson glow plug.

The Brodak Mk. 1 .049 and companion .06 was made by CS in China circa 2010. These engines were intended for sport C/L or R/C flying. They featured plain bearings, Schnuerle ports and a matching muffler. In common with some other latter-day CS products, they displayed a few quality control problems, although some examples performed well, particularly with an after-market head to suit a Nelson glow plug.

The Brodak Mk. 2 .049 was similar, being made in Moldova. It had a plain bearing, a side exhaust, simple drilled ports in a Schnuerle-like arrangement and an AAC piston/cylinder assembly. It took a regular glow plug.

The Brodak Mk. 2 .049 was similar, being made in Moldova. It had a plain bearing, a side exhaust, simple drilled ports in a Schnuerle-like arrangement and an AAC piston/cylinder assembly. It took a regular glow plug.

Returning now to the later fortunes of Cox, company owners Leisure Dynamics had filed for bankruptcy in 1980, taking Cox Hobbies with them. Former President Bill Selzer bought Cox and revived its fortunes. New engines and RTF products soon followed.

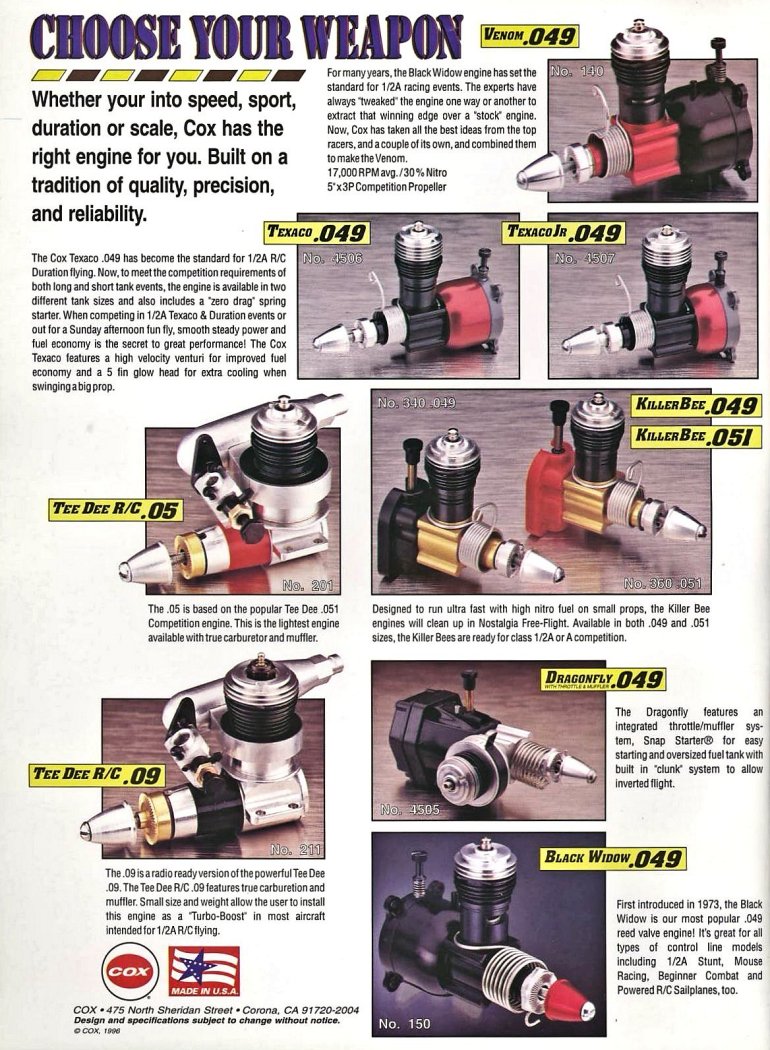

The Society of Antique Modellers (SAM) introduced ½A Texaco events for Cox .049’s beginning in around 1981. In essence this was a fuel economy event, being based on flight durations on a limited prescribed amount of fuel rather than on engine running time. Hence the event favoured slow engine speeds with large propellers to greatly extend running time and flight duration. The 1989 Cox Texaco .049 was  specifically designed for this event. It had a black-anodized crankcase, a red 8 cc fuel tank, a special five-fin glow head and a single bypass cylinder. The 1995 Texaco Junior had a smaller 5 cc tank in response to some competitors having trouble with models frequently flying out of sight on the larger tanks.

specifically designed for this event. It had a black-anodized crankcase, a red 8 cc fuel tank, a special five-fin glow head and a single bypass cylinder. The 1995 Texaco Junior had a smaller 5 cc tank in response to some competitors having trouble with models frequently flying out of sight on the larger tanks.

Selzer’s 1982 Cox Dragonfly .049 was essentially the same as the earlier R/C Bee, but had an extruded aluminium crankcase. The 1987 Cox Queen Bee .074 (seen at the right) had a rear-mounted R/C carburettor with reed valve induction  and muffler. Unusually for Cox, it took a regular glowplug. In 1994 the Tee Dee .05 and .09 were similarly reconfigured with muffler and R/C carburettor. The company also produced a limited run of the 1995/96 Cox Venom (fuel tank) and Killer Bee (plastic back plate for external tank) engines designed by Larry Renger. These had stronger crankshafts, tapered piston/cylinder bores (as per the Tee Dee) and additional bypass ports cut on one side only of the standard pair. These were the most powerful reed valve Cox .049’s ever produced.

and muffler. Unusually for Cox, it took a regular glowplug. In 1994 the Tee Dee .05 and .09 were similarly reconfigured with muffler and R/C carburettor. The company also produced a limited run of the 1995/96 Cox Venom (fuel tank) and Killer Bee (plastic back plate for external tank) engines designed by Larry Renger. These had stronger crankshafts, tapered piston/cylinder bores (as per the Tee Dee) and additional bypass ports cut on one side only of the standard pair. These were the most powerful reed valve Cox .049’s ever produced.

The Estes Corporation took control of Cox in 1996. The National Free Flight Society commissioned a special run of Cox Medallion .051’s for its Nostalgia Free Flight events. 258 numbered engines were delivered in December 1996. Production consistency had always been a Cox characteristic, but engine production now became less consistent as Estes sub-contracted the production of most components to others. Some unprofitable models were discontinued as parts ran out; others used a mix of available parts. The Surestart .049 with plastic “horseshoe” back plate and “stovepipe” intake extension (which allowed for finger-choking or carburettor priming before starting) was among the last variations in 2000. It powered the Cox Hyper Viper RTF aerobatic model.

The residual Cox inventory was finally sold to private buyers in 2009. Cox International and EX Engines have continued Cox engine sales/support, including new production parts and cosmetic variations. At the time of writing in 2021, EX Engines could also supply freshly assembled Fox FAI Special .049s.

Beginning in around 1980, rivals Leisure Electronics and Astro Flight had offered competing .05 engine-equivalent electric systems. Although expensive and weighing around 17 ounces, these units found favour particularly with R/C glider fliers, who liked the ability to switch power on and off at will. This was the beginning of a trend - advances in electric motors, batteries and associated electronics progressed dramatically, causing consumer tastes to change once again. ½A gas engine-powered flying shrank to niche level.

Picco (Italy) and Toki (Japan) produced potent ½A engines for the smaller R/C cars before electric alternatives took over. These engines were very robust, with ABC piston/cylinder sets, Schnuerle porting and twin ball-race mounted crankshafts. They developed high power at high rpm. A number of individuals in the USA modified Picco engines for competition flying. At the time of writing, MECOA still listed a Toki-based Fuji .05 aero engine (right).

Picco (Italy) and Toki (Japan) produced potent ½A engines for the smaller R/C cars before electric alternatives took over. These engines were very robust, with ABC piston/cylinder sets, Schnuerle porting and twin ball-race mounted crankshafts. They developed high power at high rpm. A number of individuals in the USA modified Picco engines for competition flying. At the time of writing, MECOA still listed a Toki-based Fuji .05 aero engine (right).

Other overseas developments focusing on 1 cc (.06 cuin.) high-performance engines for the international F1J free flight class have stagnated. Profi (Ukraine) continues to offer .049 competition engines for AMA ½A free flight and ½A C/L Combat, Speed and Racing classes.

Postscript

The Argentinian COM .049 was South America’s contribution to this history, if we choose to go south of the equator. Around 1500 examples were made by Oscar Nocera and Jorge Straseri in the early 1970’s. These engines were generally similar to the Cox Space Hopper with beam mounting, rear reed valve induction and Cox-style piston/cylinder design etc. The first version had a machined bar stock crankcase, while the second version utilized a cast crankcase.

The Argentinian COM .049 was South America’s contribution to this history, if we choose to go south of the equator. Around 1500 examples were made by Oscar Nocera and Jorge Straseri in the early 1970’s. These engines were generally similar to the Cox Space Hopper with beam mounting, rear reed valve induction and Cox-style piston/cylinder design etc. The first version had a machined bar stock crankcase, while the second version utilized a cast crankcase.

Cox engines or components thereof have found favour in various projects by others, such as the Schroeder Simple Single diesel and Twin, using Cox .049 cylinder assembly. Such an approach overcomes difficulty in achieving good compression seal for amateur constructors.

Various manufacturers have used Cox engine units or piston/cylinder assemblies for their multi-cylinder designs. The Werner 5-cylinder radial .24 (1960) using 049 parts and a monobloc crankcase was perhaps the first such effort. It was definitely advertised, but production figures are unknown. Swift Associates (1961) used Cox 15  assemblies for their .30 flat-twin and .596 flat-4 engines. Smaller 2 and 4 cylinder versions using .049 assemblies might also have been made. The Widecanyon Babe Bee and Black Widow 5-cylinder dummy radials (1997) used one working Cox .049 cylinder assembly along with four dummies.

assemblies for their .30 flat-twin and .596 flat-4 engines. Smaller 2 and 4 cylinder versions using .049 assemblies might also have been made. The Widecanyon Babe Bee and Black Widow 5-cylinder dummy radials (1997) used one working Cox .049 cylinder assembly along with four dummies.

Davis/Cox sold a CO2 conversion kit for the Cox .020 engine, circa 1985. The valve, tank and plumbing were made by Bill Brown. A similar Cox .049 conversion followed. The range expanded in 1991 with opposed twin .020 (two Cox .010 cylinder assemblies), twin .040 (Cox .020 assemblies) based on crankcases machined from bar stock.

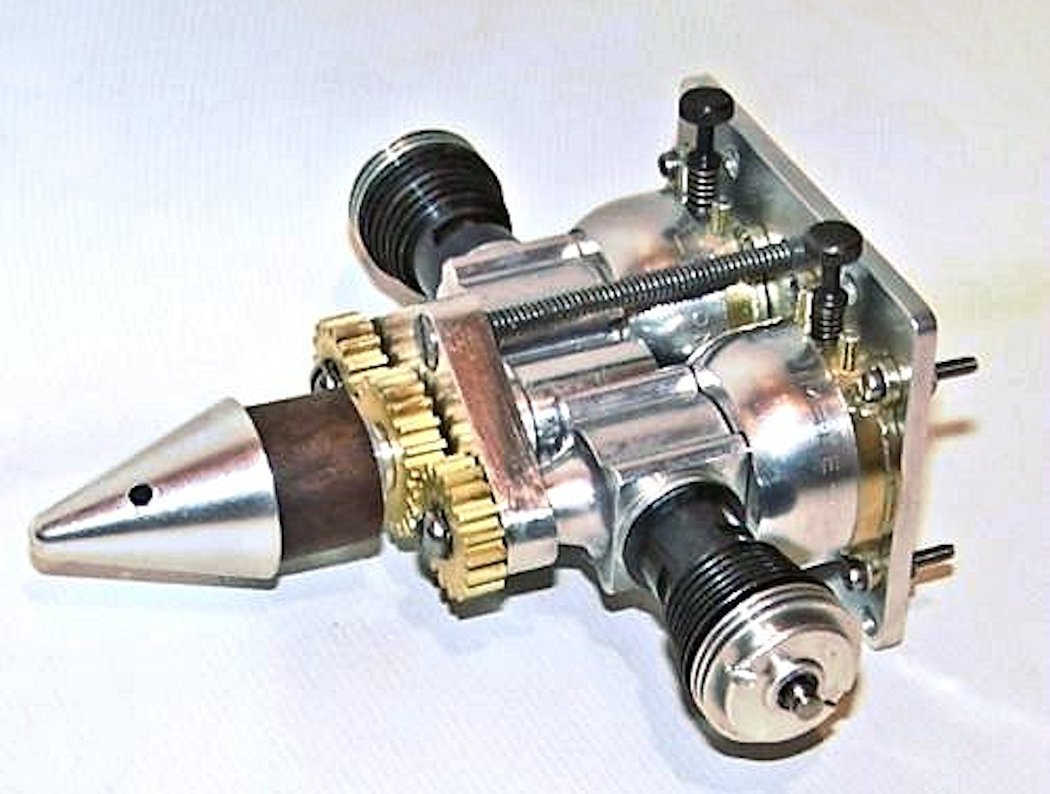

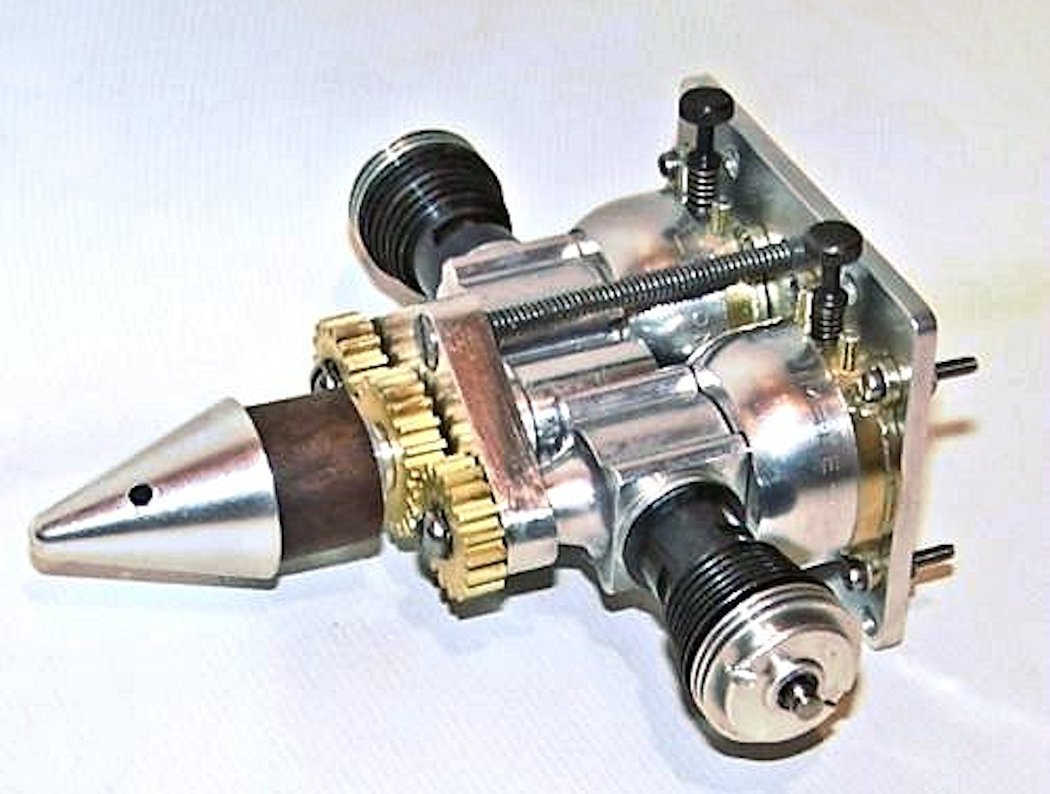

A simple but less elegant approach had multiple Cox .049 units driving the propeller shaft via spur gears. Flight Control Products’ Twin Bee .099 (1967 - seen at right) linked two Babe Bee .049s in this manner. The Brice Twin (1976) .098 twin and .196 Flat 4 are more refined versions of the concept. Other makes have existed, along with many home-built engines on a similar theme. Engineering Possibilities’ .345 cuin. 2R71 Radial (1990) 7-cylinder geared radial using Cox .049 parts is an example, but possibly not made in any quantity.

__________________________

Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia

First published March 2021

(Editor’s note - Due to the number of images required to illustrate this article, it has been necessary to present them in the text at relatively small sizes. To view them at full size, as many of them need to be, simply right-click on the image and select the “open image in new tab” option from the drop-down menu. I strongly suggest that you do this, because the ads in particular contain a wealth of relevant detail that is not included in Maris's text. My sincere thanks to Maris for rising to the considerable challenge of putting this story together! A.D.)

(Editor’s note - Due to the number of images required to illustrate this article, it has been necessary to present them in the text at relatively small sizes. To view them at full size, as many of them need to be, simply right-click on the image and select the “open image in new tab” option from the drop-down menu. I strongly suggest that you do this, because the ads in particular contain a wealth of relevant detail that is not included in Maris's text. My sincere thanks to Maris for rising to the considerable challenge of putting this story together! A.D.) However, there was a growing interest in small gas-powered models suitable for non-contest sport flying in more confined spaces. This interest was tempered by the inescapable fact that the enforced use of spark ignition in the absence of alternatives created some obvious barriers to progress in that direction. After factoring in the weight of airborne ignition equipment (which was essentially fixed), the smallest practical engines with adequate power to fly a model were around half of the A limit. Dan Calkin’s Elf Single Model 10 and Ray Arden’s

However, there was a growing interest in small gas-powered models suitable for non-contest sport flying in more confined spaces. This interest was tempered by the inescapable fact that the enforced use of spark ignition in the absence of alternatives created some obvious barriers to progress in that direction. After factoring in the weight of airborne ignition equipment (which was essentially fixed), the smallest practical engines with adequate power to fly a model were around half of the A limit. Dan Calkin’s Elf Single Model 10 and Ray Arden’s

In his invaluable “

In his invaluable “

The first miniature glow-plug engine to be made in commercial quantities was K&B’s Infant .020, which began to reach the model shops just in time for the 1948 Christmas trade. Designed by Lud Kading (the K of K&B), this little unit showed some Arden .099 influence mixed with a few new innovations. Machined entirely from bar stock, its tiny .020 cuin. displacement necessitated a

The first miniature glow-plug engine to be made in commercial quantities was K&B’s Infant .020, which began to reach the model shops just in time for the 1948 Christmas trade. Designed by Lud Kading (the K of K&B), this little unit showed some Arden .099 influence mixed with a few new innovations. Machined entirely from bar stock, its tiny .020 cuin. displacement necessitated a  special glowplug design comprising the entire combustion chamber along with the heating element. This feature was subsequently found to increase glow-plug engine performance quite substantially, being widely used in later designs. Wildly successful, the Torpedo .020 led the way in opening up the prospect of truly small models.