|

|

The BUGL and BG Engines - A Reality Check Editor's note - The BUGL engines which were designed and produced by the noted Austrian-born enthusiast Paul Bugl (1930 - 1978) are among that select group of model engines which have acquired a mystique and associated monetary value in a league of their own. Genuine examples of these masterpieces command extremely high prices on the collector market, particularly if unmodifiied.

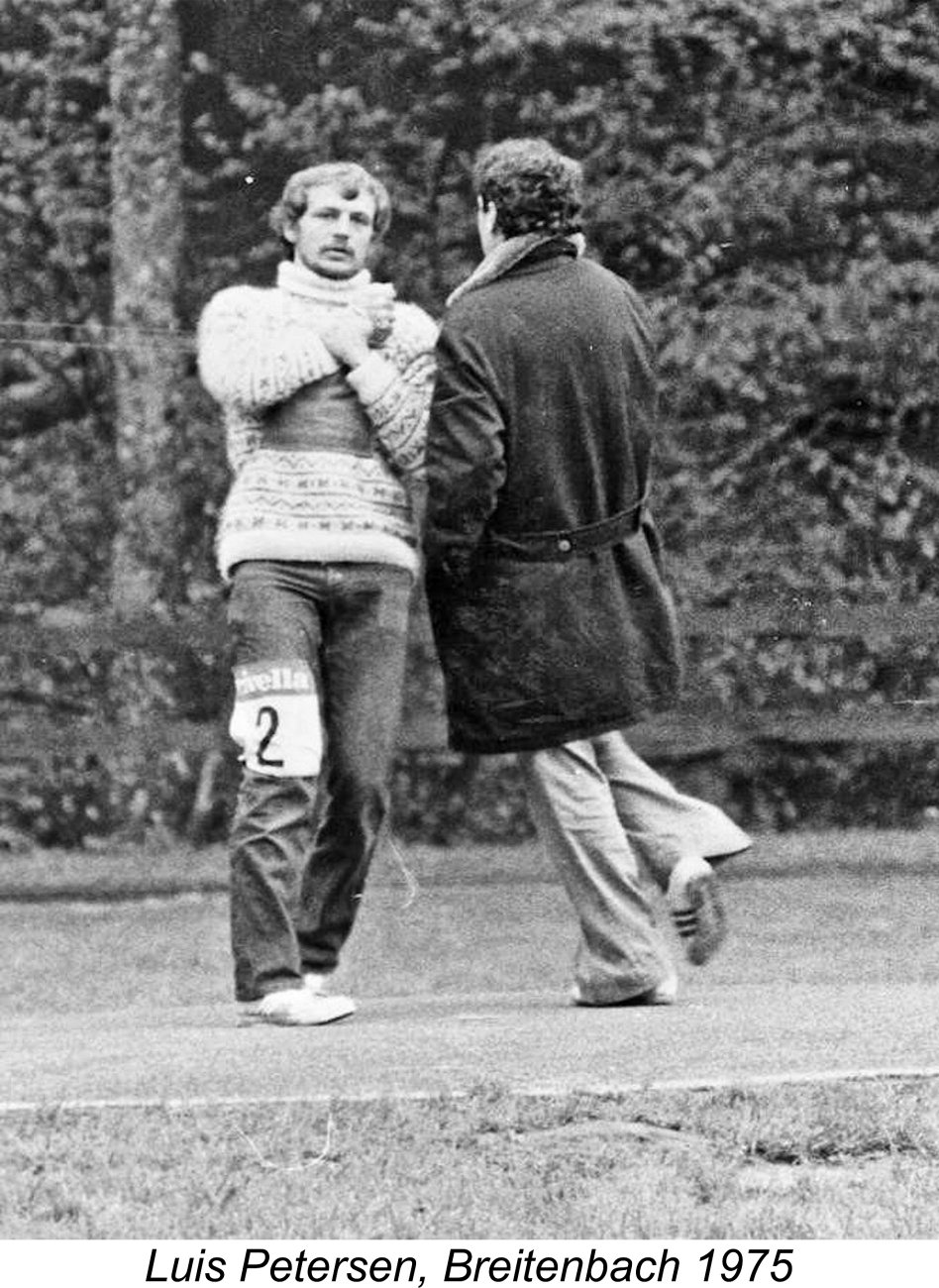

I had occasion to mention this problem in my February 2017 Editorial in connection with the then-recent sale of a Profi replica which was offered as a genuine Bugl. Unfortunately, the problem has not gone away - offerings of "BUGL" engines which never saw Paul Bugl's workshop continue to appear periodically, resulting in enthusiasts paying way over the odds for what they mistakenly believe to be a genuine Bugl product. My valued Danish friend and colleague Luis Petersen and I are in complete agreement that the best way to respond to such attempts is to make authoritative information widely available regarding the genuine article. There could be no-one better placed than Luis to accomplish this task, since he worked directly with Paul Bugl during the mid 1970's and remains today in possession of all the original Bugl records, including serial numbers, sales figures and drawings as well as some original components. If in doubt about the provenance of a particular Bugl offering, just ask Luis! With that as a preamble, it's time to turn the pen over to Luis for the full story of his personal involvement with Paul Bugl and the remarkable engines that he designed and produced. I hope that you enjoy it as much as I did!! BUGL/BG Team Race Diesel Development By Luis Petersen The following is my personal story and recollections of the relationship that I enjoyed with the famous Austrian model engine designer/manufacturer Paul Bugl. I also have full access to the files/drawings from Paul's estate.

Paul Bugl (1930 - 1978) was an early International competitor both in control-line Team Race and Speed. He first began appearing in Team Race in 1960 with his own engine design, which was somewhat similar to an Oliver Tiger. I first met Paul in 1966 at the World Championship meeting held at Swinderby, England. At the time, he had recently developed the HP15D diesel for the Austrian HP company, who were then new to model engine manufacture. I got a good look at the Türk/Günter Hohenberg HP15D, which gave them a second-place finish. That year, Stockton/Jehlik of the USA won with a much modified ETA 15D. Paul himself competed in the Speed category at that meeting, finishing a rather disappointing 30th with an un-piped HP15 glow-plug motor which was also of his own design. Of course, it was at this meeting that Bill Wisniewski and Roger Theobald of the USA unveiled their piped TWA (Theobald/Wisniewski Association) engines which instantly re-defined international performance standards in Speed. The accompanying photo at the right shows Paul at that meeting holding his HP15 glow-plug speed motor mounted in its alloy pan. At the 1967 European Championship meeting, Stockton/Jehlik won the Team Race event again, this time with an HP15D. The Danish Hasling brothers came second. The Danish team won the F2C team prize, all using Super Tigre engines. At the 1968 World Championship event in Helsinki, Stockton/Jehlik won yet again with the HP15D. In fact, there were 4 HP15D’s in the first 10 placings. At the 1969 European Championship, there were 3 HP15D’s among the first 10. The Hasling brothers had the fastest heat time of the meeting with an HP15D at 4:26, but ended up finishing fourth. (Editor's note: beginning in 1960, the officially-designated World Championships were held during even-numbered years, thus taking place every two years. The major International meeting in each of the intervening odd-numbered years was designated as that year's European Championship, although it was in effect a World Championship regardless. For those interested, a fascinating history of International team racing up to 1972 written by Pete Soule may be found here.)

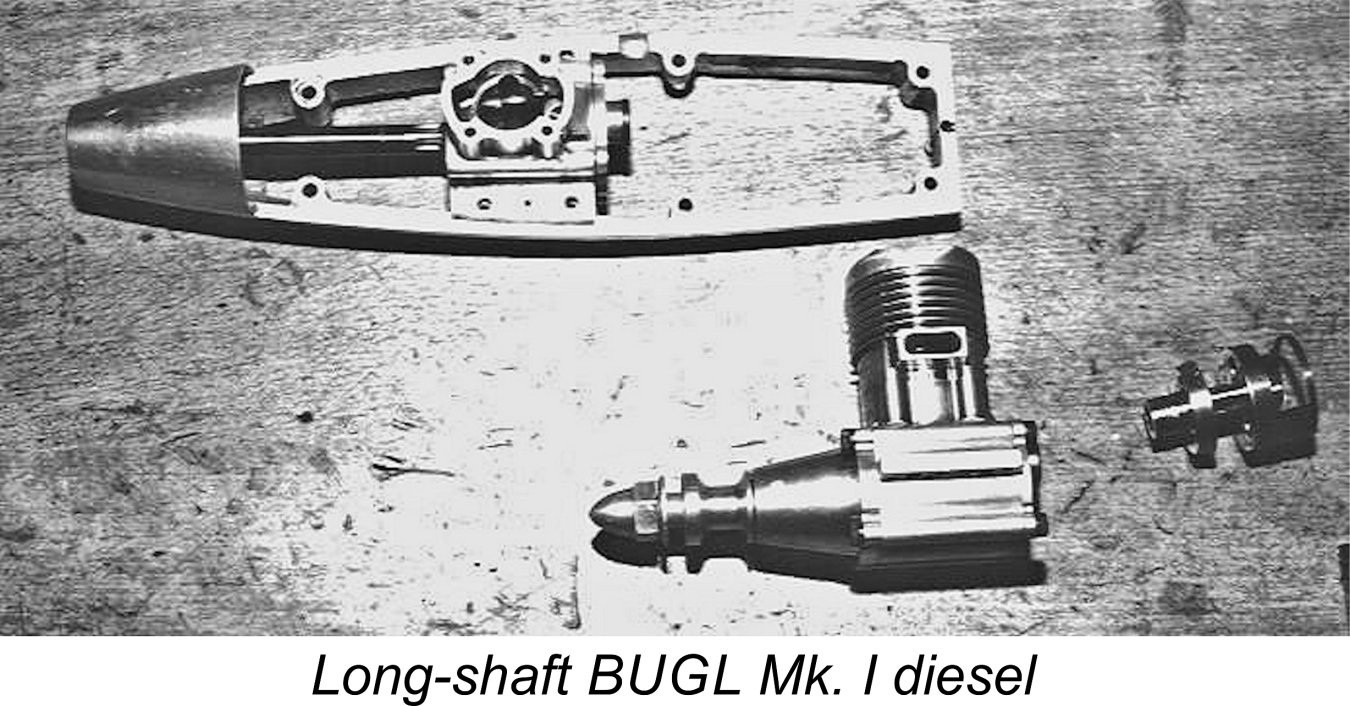

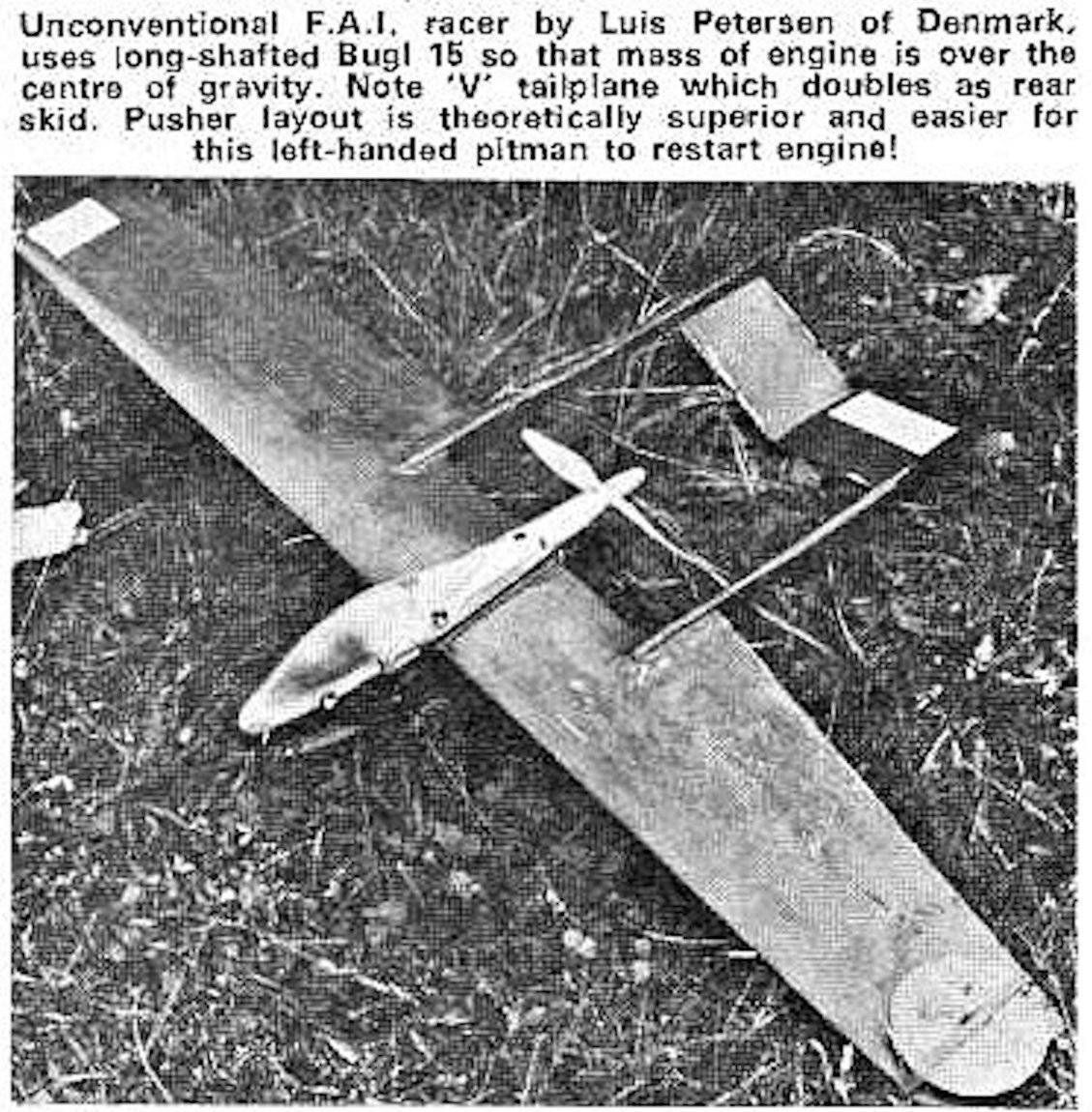

The “genuine” BUGL’s finally arrived in 1971. At that year’s European Championship meeting, the first long-shaft BUGL’s were seen in the Austrian models. Subsequently, two Danish At the British Nationals in 1973, Paul flew my pusher team racer with my own DILU engine, not a BUGL as previously stated by others. Great fun! This model is seen at the right, complete with mis-identified engine!

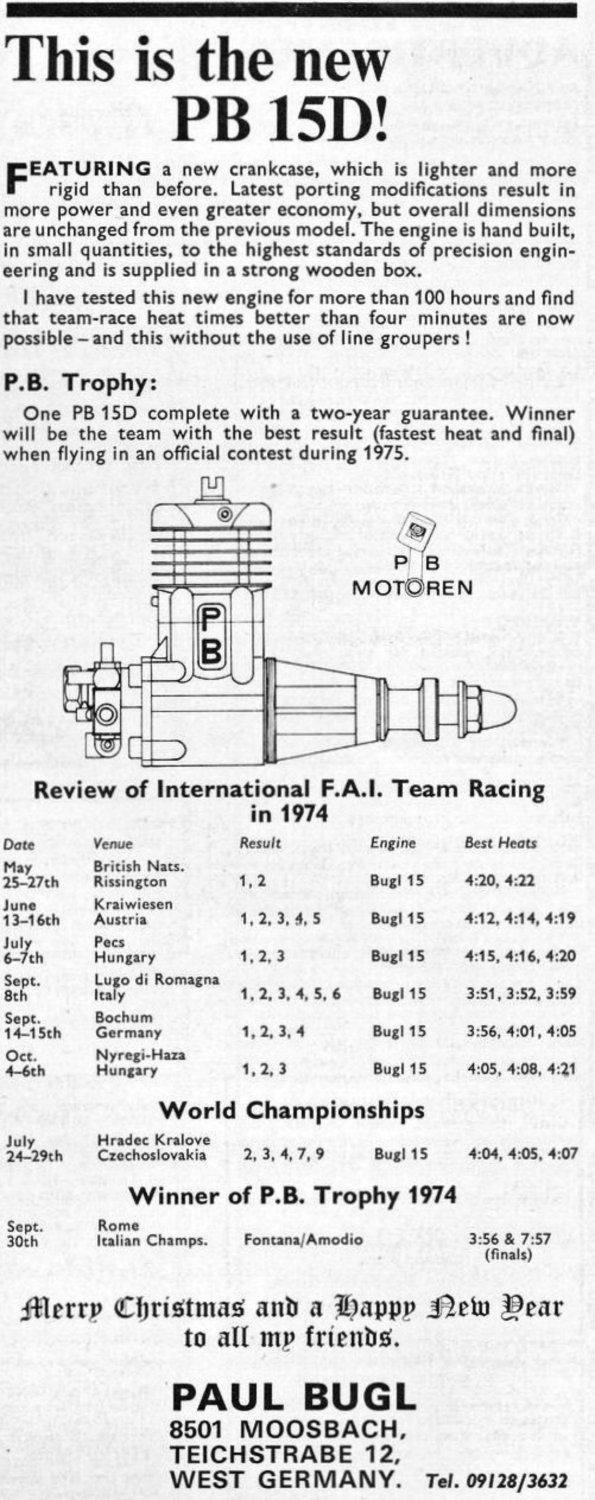

During 1974 Paul began the development of a Mk. II version of the BUGL engine, which he called the PB 15D. Paul began promoting this model prior to Christmas 1974, as witness the accompanying advertisement at the left. In that same advertisement, Paul also mentioned the P.B. Trophy award program, under which he would present a new PB 15D engine complete with two-year guarantee to the team posting the best result (fastest heat and final) at an official contest during a given year. He noted that the Italian team of Fontana/Amodio had been the 1974 winners for their performance in the Italian Championship meeting at Rome on September 30th, 1974. Jens and I later won that prize in 1976.

That year we beat both Paul and Fontana/Amodio in the final at Breitenbach in May 1975. All of us were using BUGL power. Our model, "AluKlotz", was based on Paul's aluminium crutch for his Moskito models. In 1976 I finished my engineering degree, majoring in model engine design and lubrication. Paul Bugl was very busy, and I went down to join him in Nürnberg, where I worked with him for a month making engines. Every morning, he got up around 5-6 o'clock to After finishing work for the day, it was time for relaxation with a beer or two and some of Paul’s favourite Lionel Hampton music, looking out on the pasture from his veranda. I tested 30 Bugl engines at that time and they were all within 300 rpm of each other on an 8x4 Blue Kavan prop. Contrary to some earlier comments, nobody got special engines. It was only a matter of how you used/modified them.

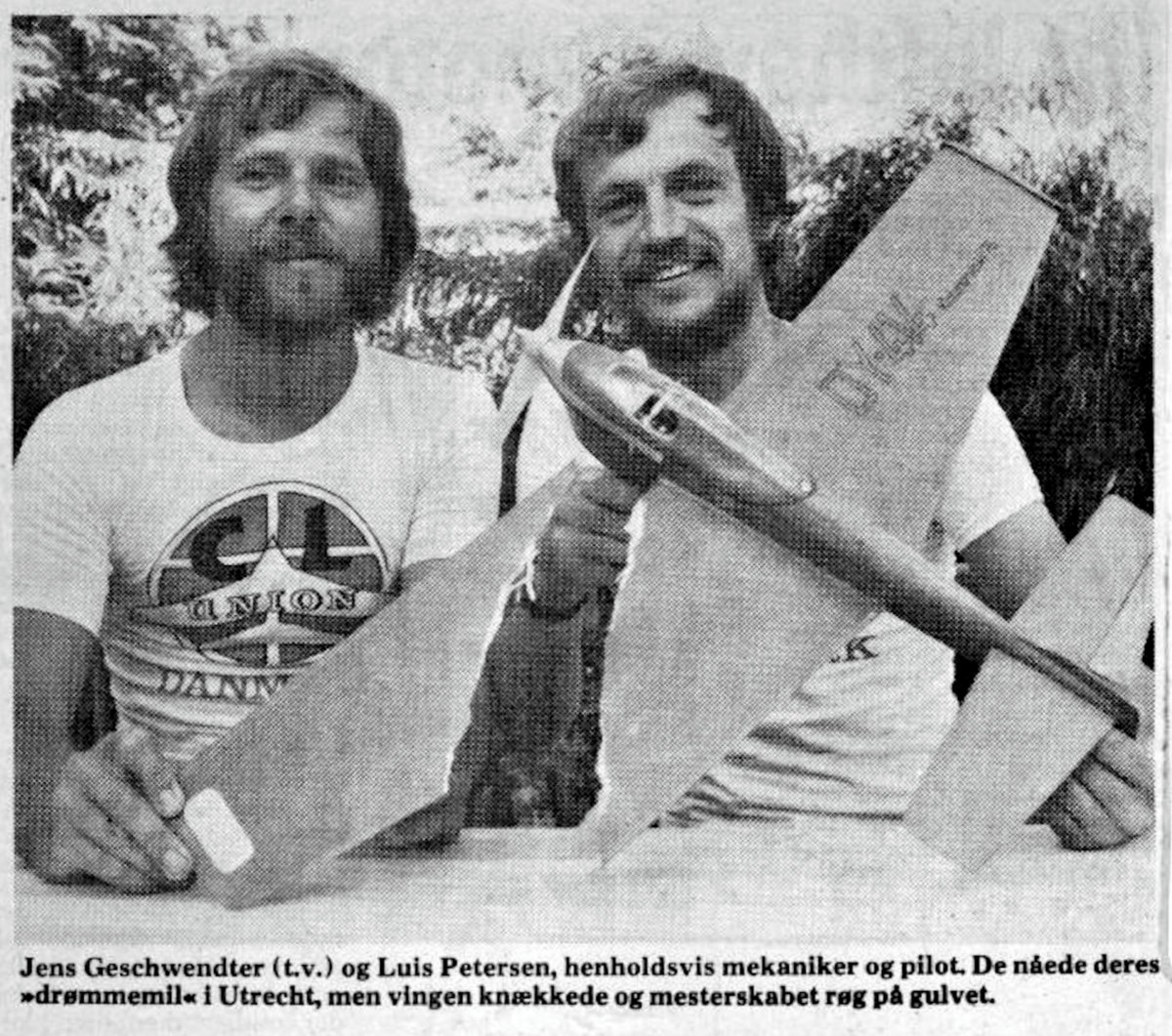

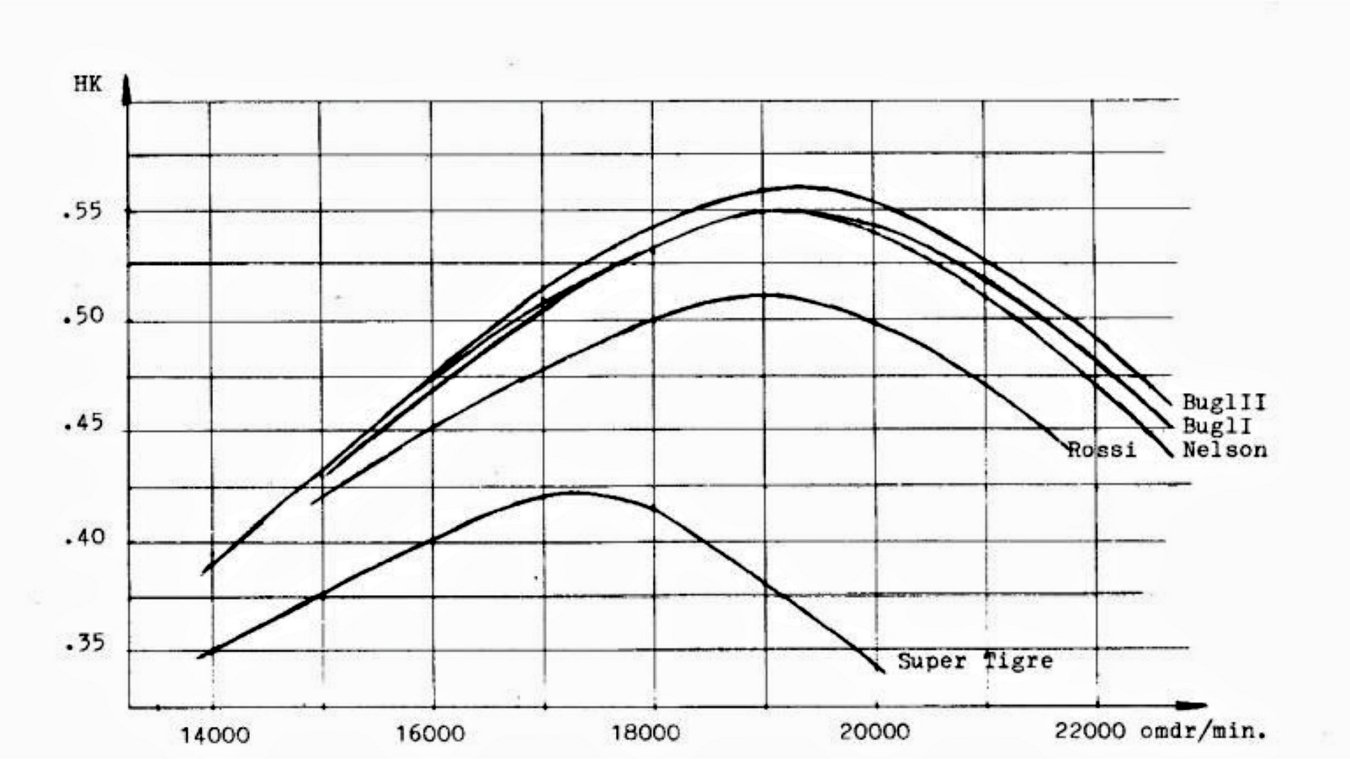

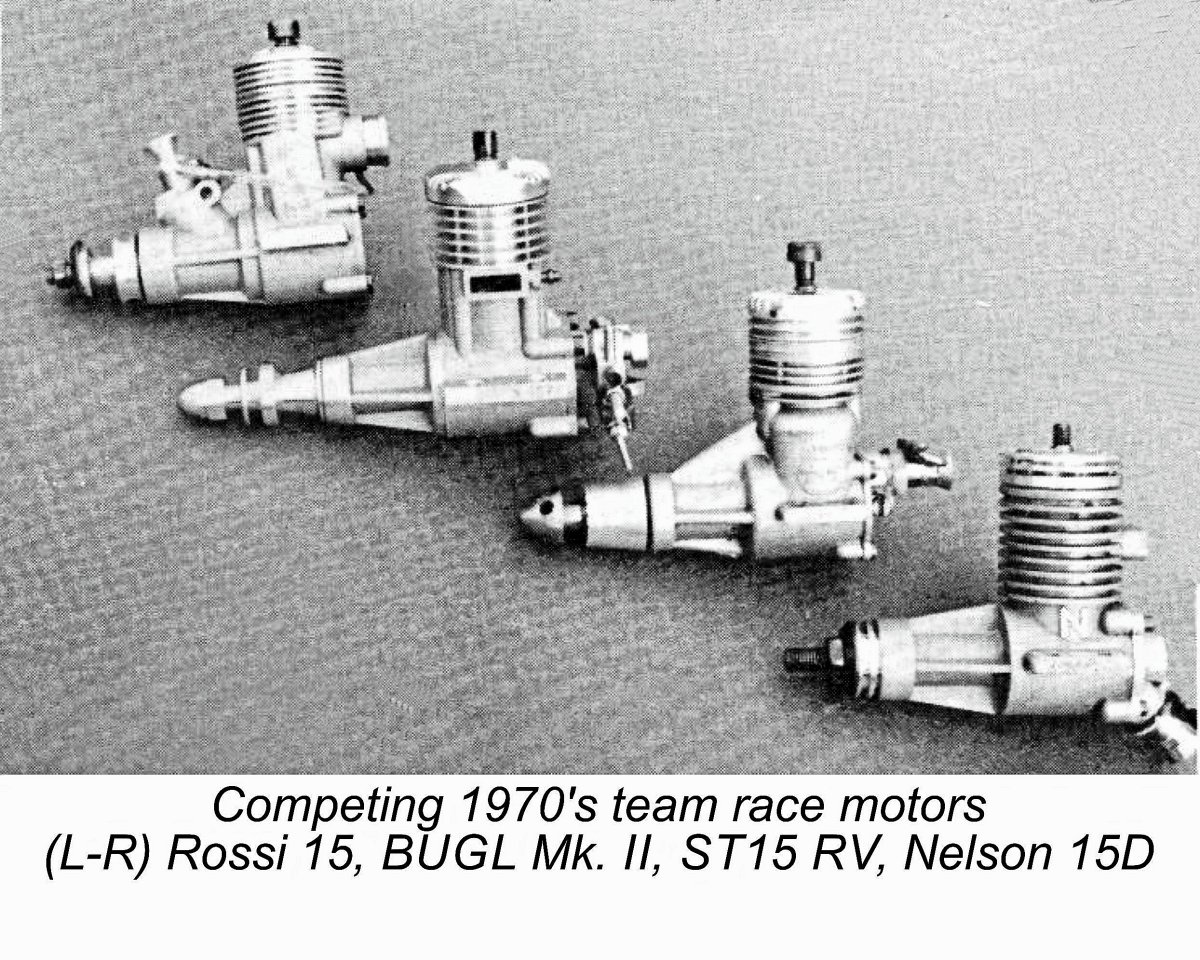

Our results that year were impressive, winning most of the contests entered with heat times below 4 minutes. Our top result was a World Record heat time of 3:56 flying against the former Russian World Champion plus the fastest Russian team at the Utrech event. Unfortunately, a Thereafter I became the official repair man for Paul. I got spares from him and repaired engines for owners worldwide. This continued until Paul’s untimely death in 1978. The BUGL Mk. 2 price list is shown at the left. The second price column to the right is in Danish krone (DDK) - the official Danish currency. Two problems that we encountered with the Mk. II's were a relatively loose main bearing fitting and the fact that the crankweb effectively sealed off the main bearing, thus preventing enough oil from reaching that bearing set. Paul carried these design features over to the Mk. III. We always took the shrunk-on ring off the crankweb and ground the flanges down to allow oil to reach the bearings. The Mk. II engine was also very heavy, so I did a lot of lightening. It was Paul who christened my modified Mk. II engine the “Emmenthaler”! It was difficult to persuade Paul to lower the oil content in the fuel and not to use steel bolts for the head. You had to show him on his own model from 1976! At this time I conducted a comparative engine test which appeared in Modelflyvenyt 1977-5. 8x4 Kavan 7x3½ Cox GF Super Tigre RV 14,700 20,100 Rossi FRV 15,500 21,900 Nelson Steel 16,000 22,200 BUGL Mk. II No. 6 WC engine 15,600 22,200 BUGL "Emmenthaler" 16,000 22,500

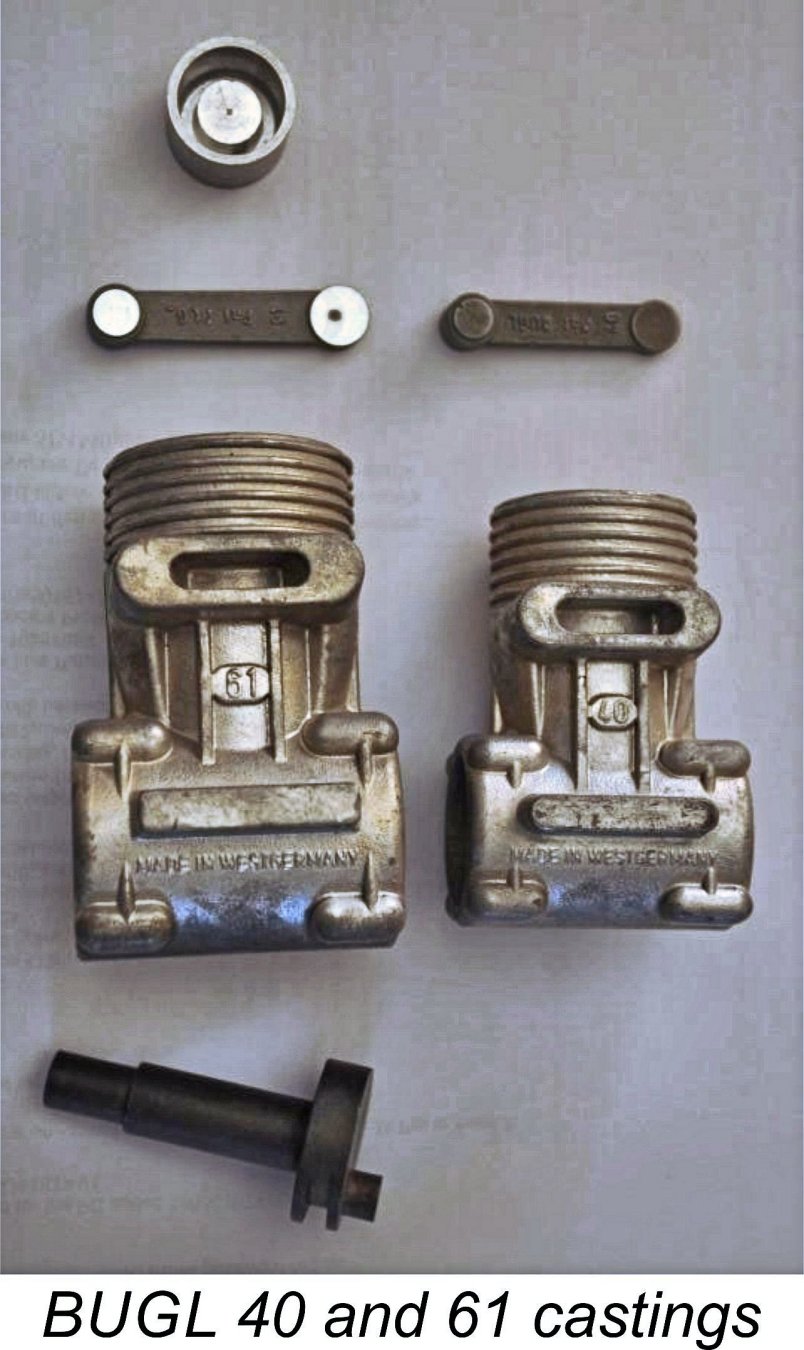

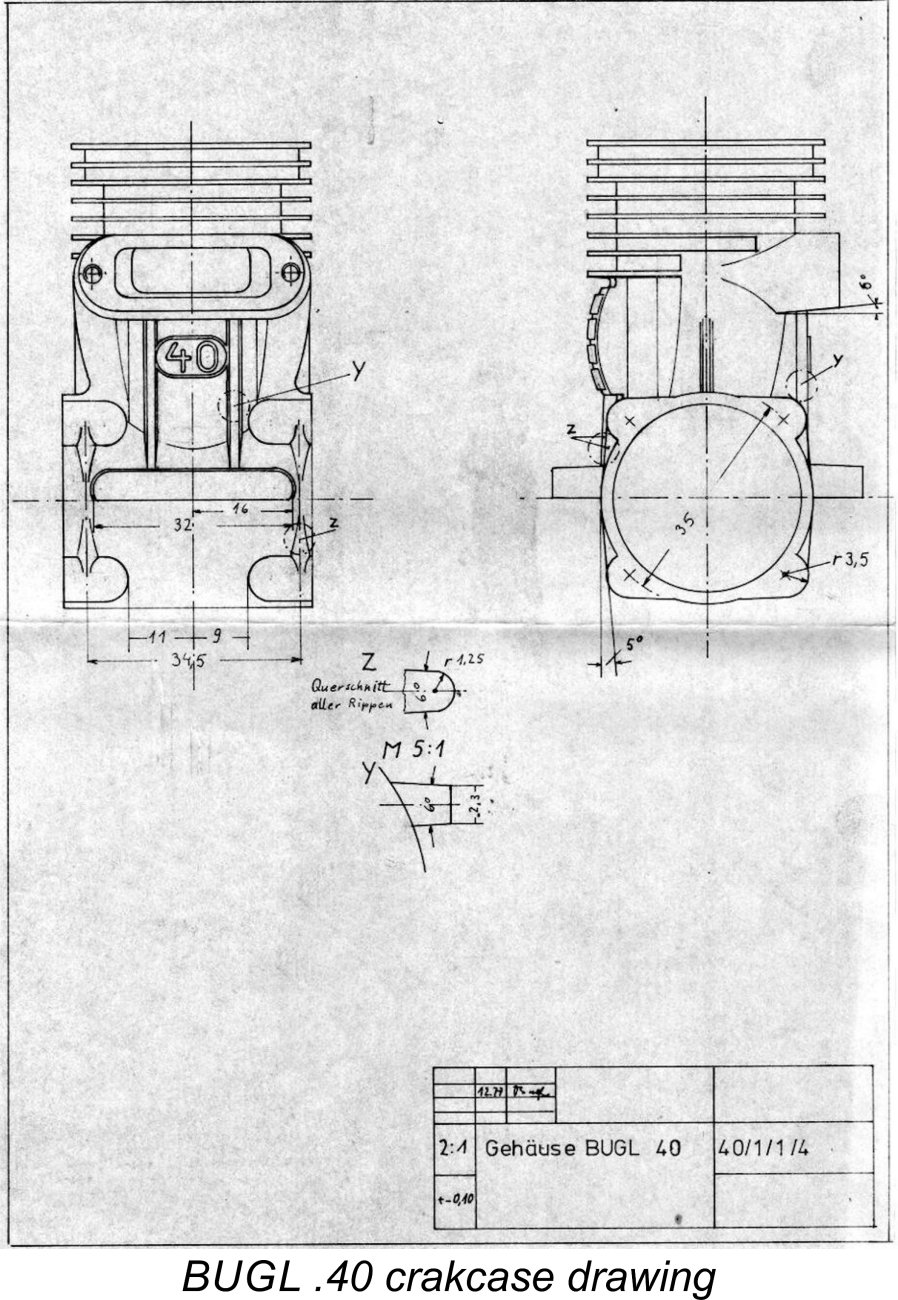

In 1976 Paul began to entertain ideas about expanding his range. He came up with the basic designs for a pair of larger glow-plug motors having displacements of .40 and .61 cuin However, he evidently decided that he needed more production capacity if these were to become a reality. Accordingly, a separate workshop, BUGL MODEL ENGINES GMBH, was set up in 1976 to produce BUGL engines and parts in partnership with Georg Müller of Nürnberg. Jens Geschwendtner visited Paul during

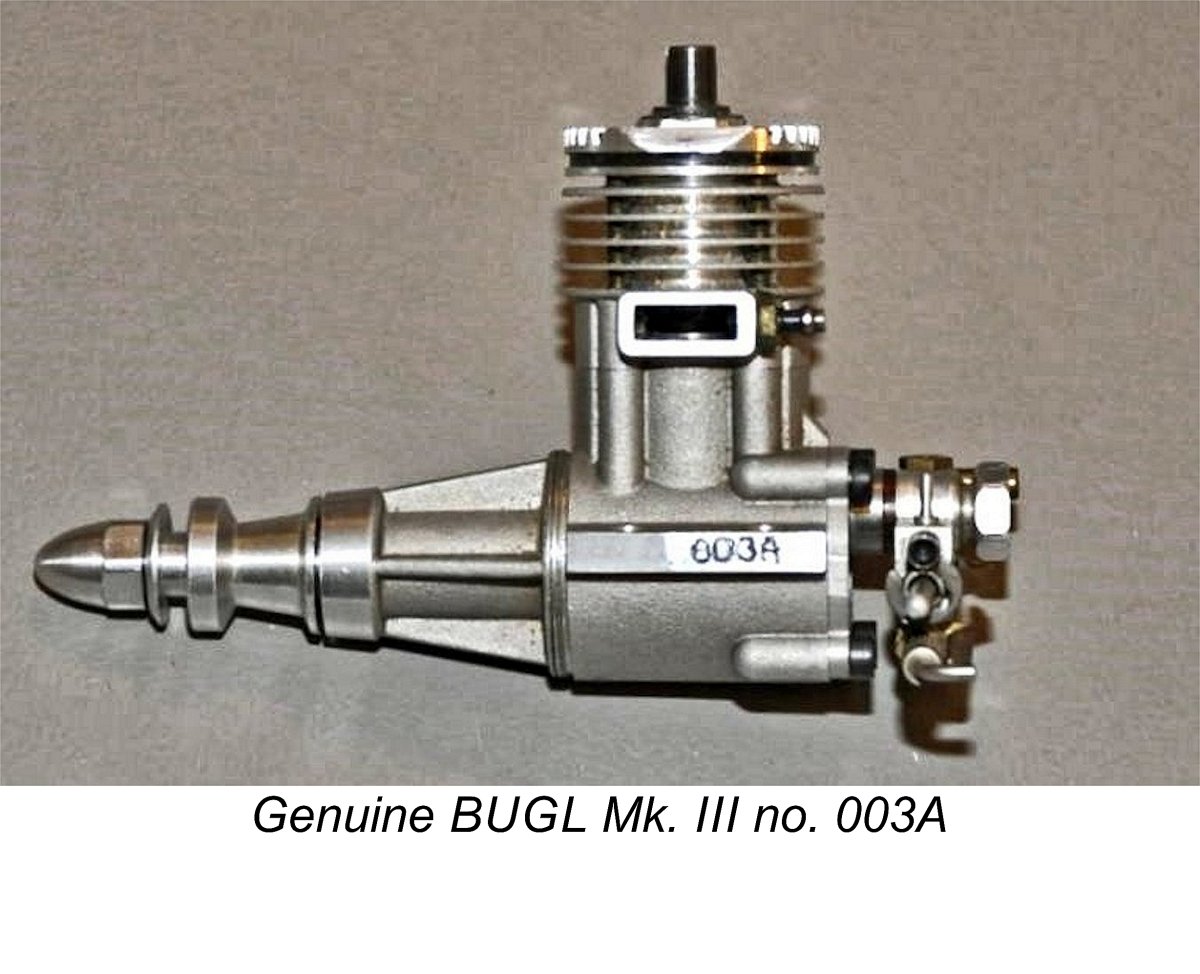

However, no engines were ever finished! I have seen some homemade engines from the original castings, but no originals were ever finished by Paul, who sadly died on June 29th, 1978. If someone is offering one of these engines for sale, it was not manufactured by Paul! During the same period, Paul had also made good progress in developing a Mk. III version of his now-famous 2.5 cc team race diesel. However, as late as the beginning of June 1978, no Mk. III engines had been finished due to the late delivery of castings and chroming. Paul complained about this at the time in a letter to me. Strangely enough, I have not encountered any drawings of the Mk. III, although some parts were definitely produced. I don't know for sure, but I have a suspicion that the production of a number of parts for the Mk. III and most of the work on the big engine moulds was undertaken in the new shop set up together with Georg Müller. This would explain why we did not find more evidence of the initial batch of Mk. III engines in Paul's own workshop and also why only a few of the 40 and 61 castings were recovered. Sadly, Paul Bugl died unexpectedly of a heart attack on June 29th, 1978 before making much real progress on finishing the first series of his Mk. III engines. Only six engines were finished and sent out. Today I'm not really sure who ended up with them! I do know that Jim Dunkin had No. 006. (ex. Hans Straniak). Pietro Fontana/Amodio possibly received two, the Austrian teams got two more examples, and Jens and I were Shortly after Paul’s death, but before the 1978 World Championships in Liverpool, England, I had a talk with his widow Margot, after which Jens Geschwendtner and I went down for a couple of days to finish the outstanding repair orders before the World Championships. At the same time I took the opportunity to finish the two BUGL Mk. III engines which we had been promised. These were numbers 003A (seen at the right) and 007. There were no more parts available at the time, so these were the last Mk. III BUGL engines to be produced. We tried out the Mk. III, but the performance was not as good as our own modified Mk. II “Emmenthaler” which had now been updated with an integral push/pull compression head. So we used that engine at the 1978 World Championship meeting at Liverpool, England. Another comparative test conducted in 1978 showed some interesting results. Once again, the "Emmenthaler" came out on top! 8x4 Blue Kavan 7x3½ Cox GF BUGL Mk. II Emmenthaler, Alu top 16,400 23,300 BUGL Mk. II no. 0153, standard 16,200 23,200 BUGL Mk. III no. 003A 16,000 23,000

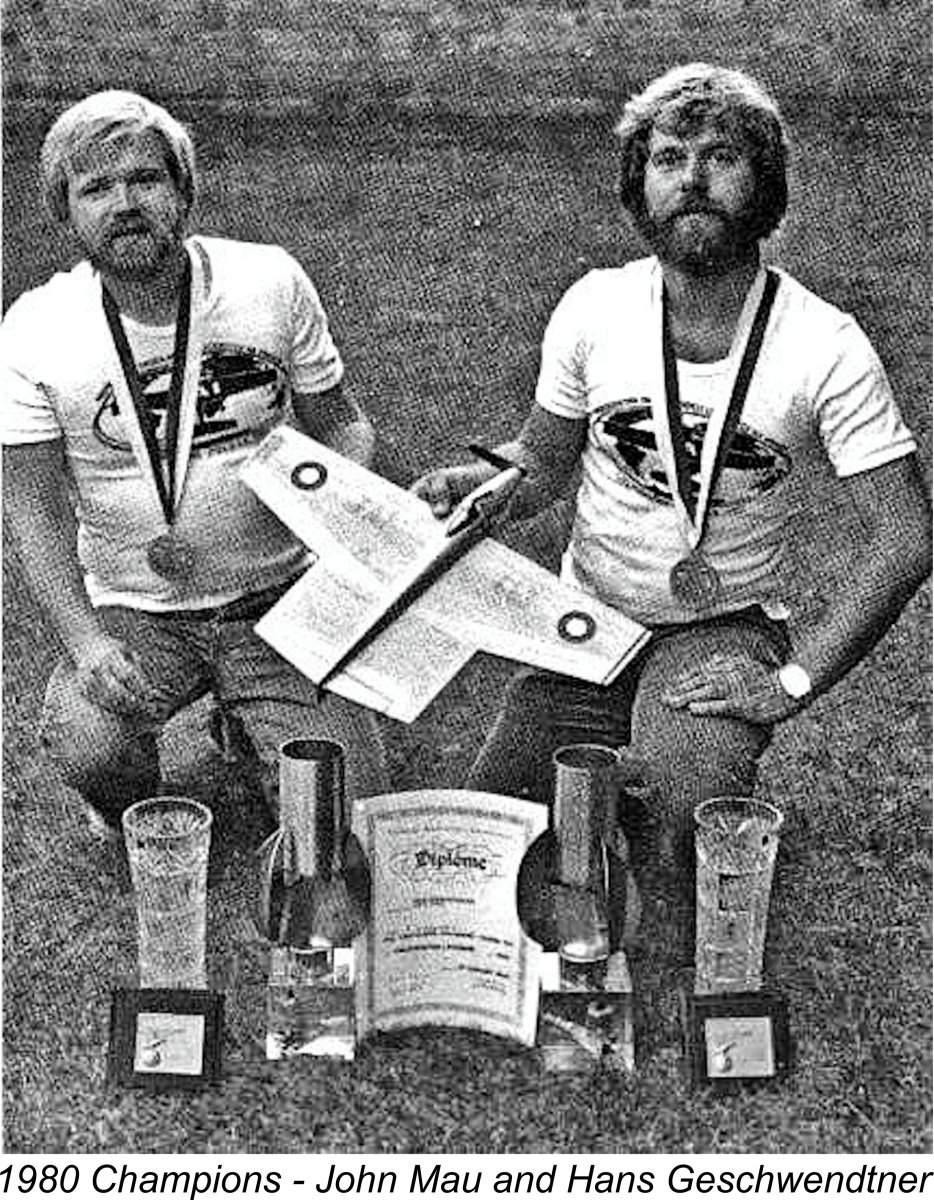

The trophies were supposed to be returned to each World Championship event (held in even years) to be competed for once again. Hans and John duly returned them to be available to the winners of the 1982 World Championship meeting in Sweden. At that meeting, the Russian team of Shapovalov/Onufrienko won the trophies, which have never been returned or even seen thereafter. Paul was very innovative and a brilliant machinist. His workshop was the cleanest that I ever worked in! Some of the lesser known Bugl tests/designs included a cooling duct opening which was regulated by the engine head temperature using a bi-metallic “spring”. Unfortunately, I don’t have a picture of this innovation.

First, a retractable undercarriage as flown by Baumgartner in 1976 and crashed at Kraiwiesen with Seen at the left is an extended compression screw with cooling fins and a lightened retracting undercarriage. This is Ronnie Tribe's BUGL Mk. II installation.

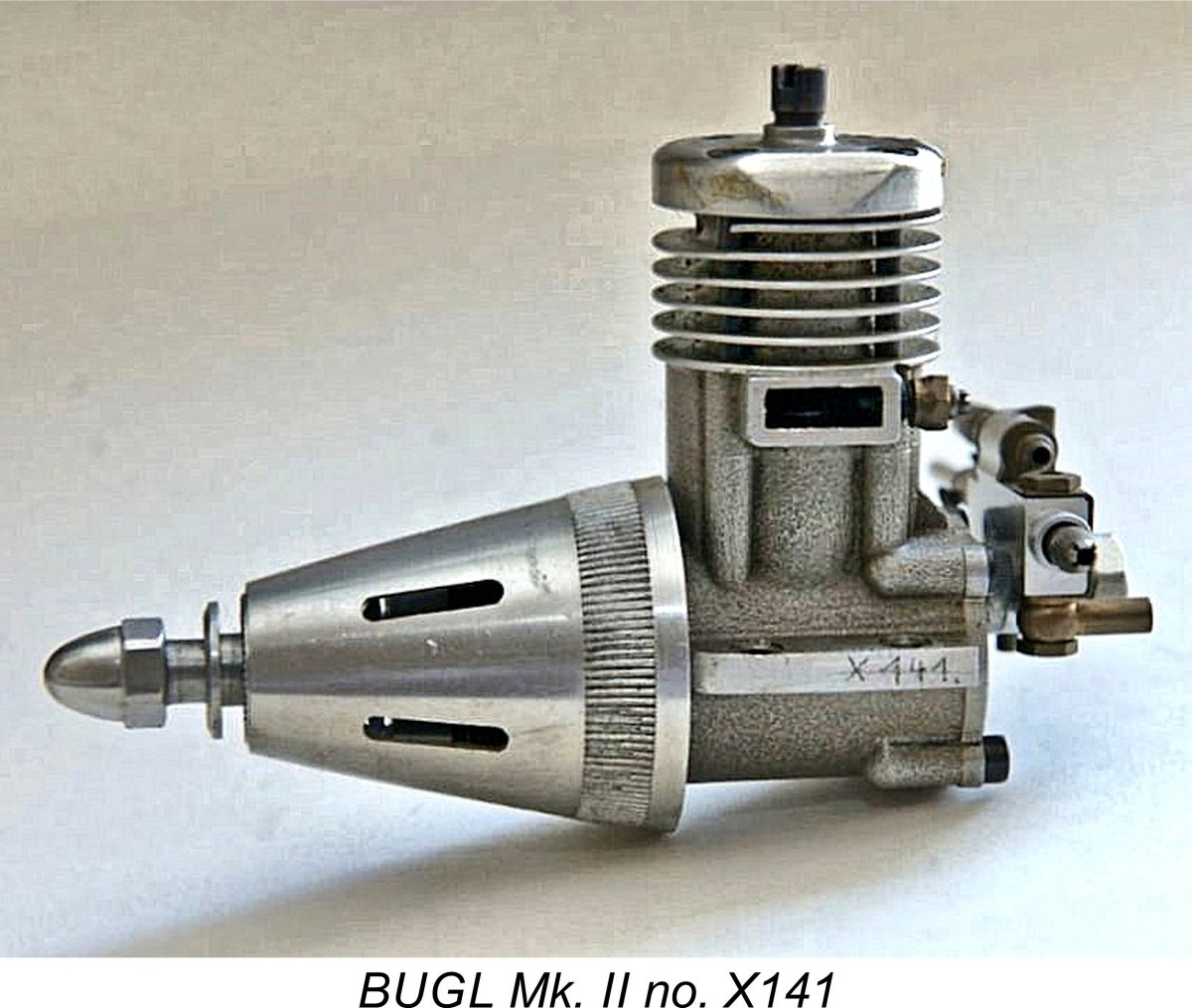

Now we get to the matter of the number of genuine BUGL engines produced. Going through Paul's papers, I found sales lists with engine numbers and buyers. Those numbers indicate that a total of 460 numbered BUGL engines were sold – around 290 Mk. I and some 170 Mk. II units.

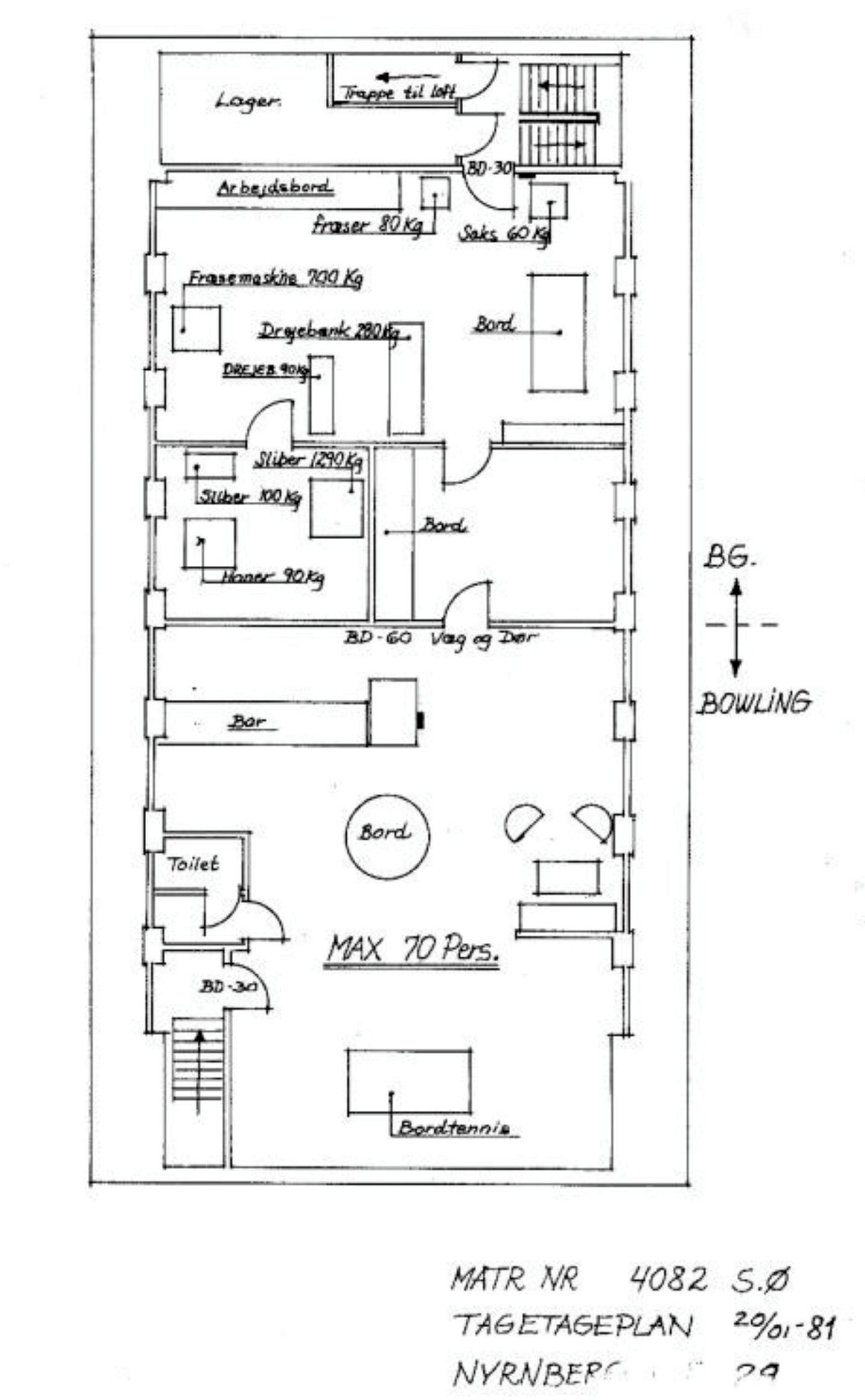

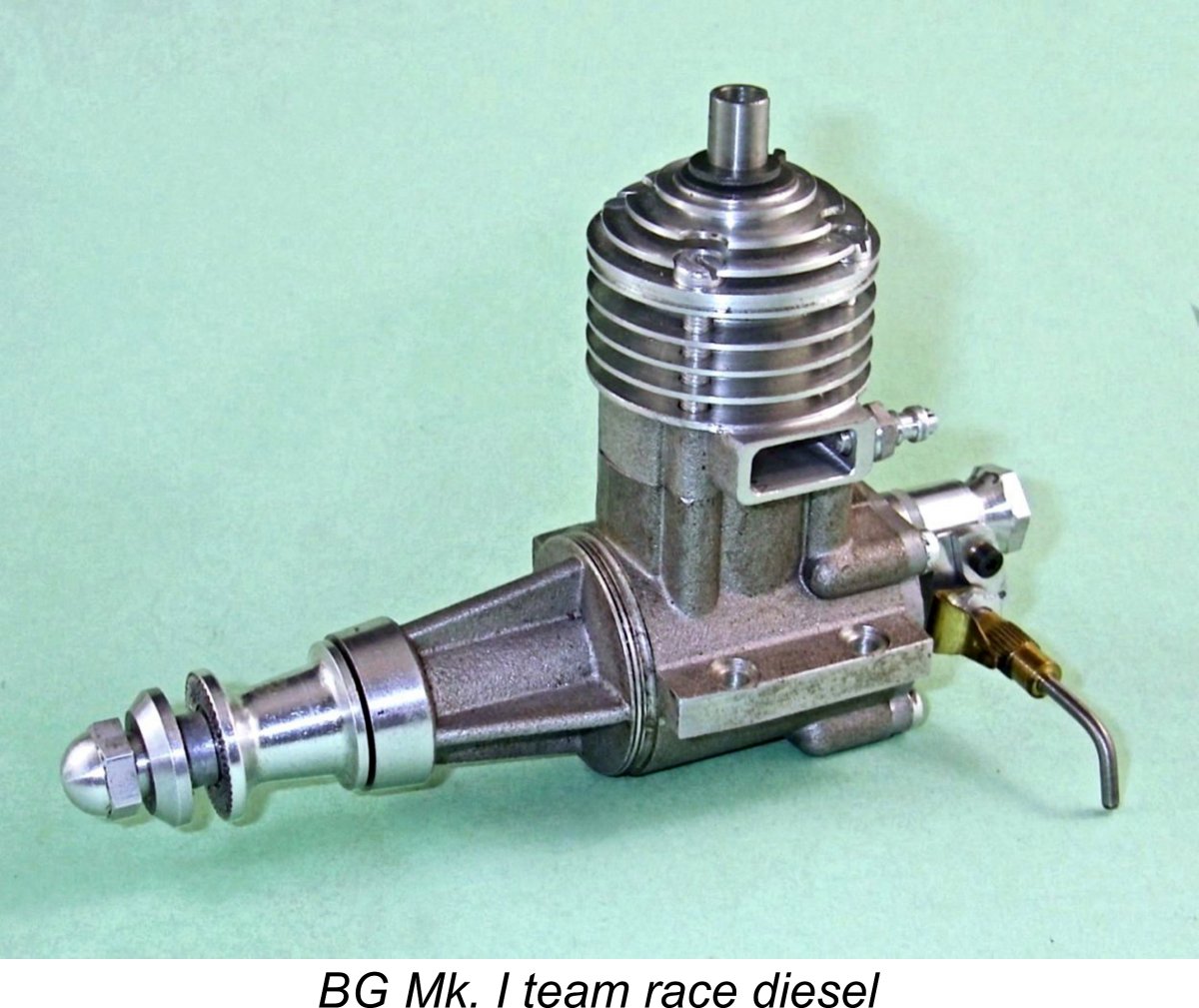

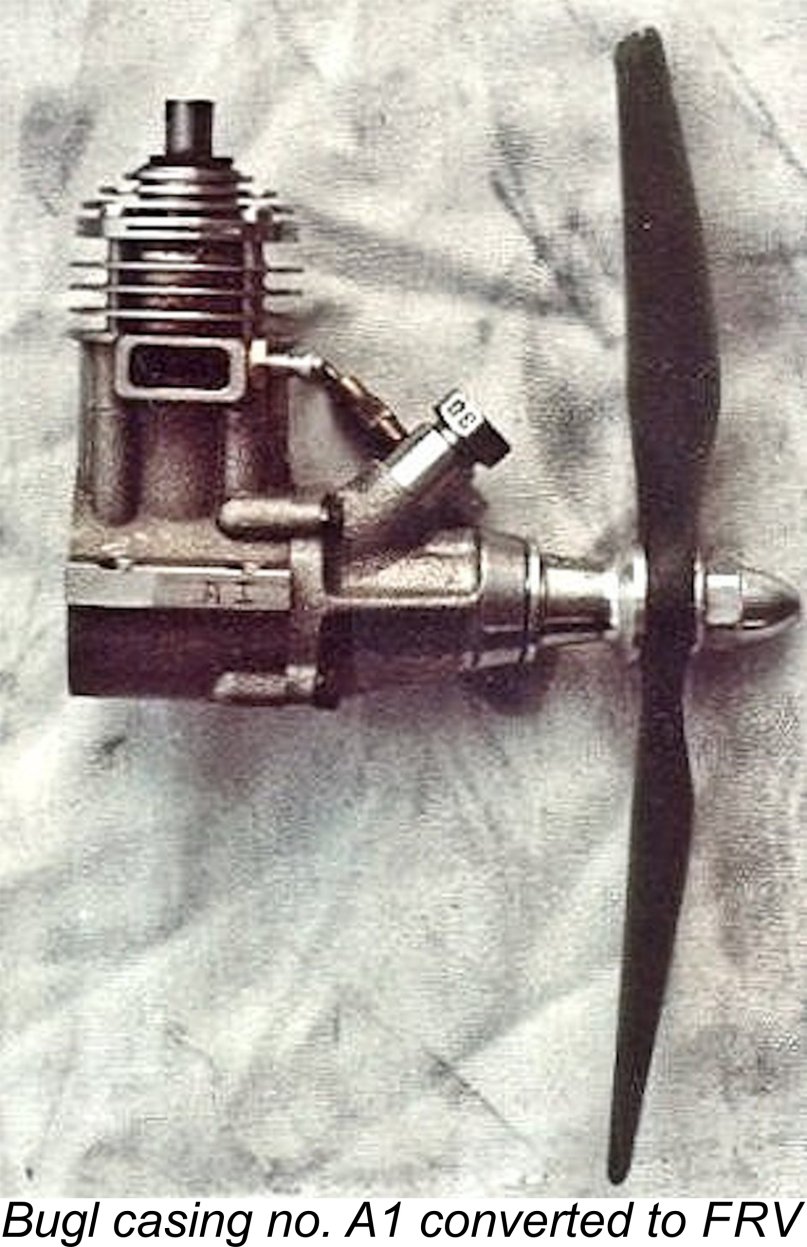

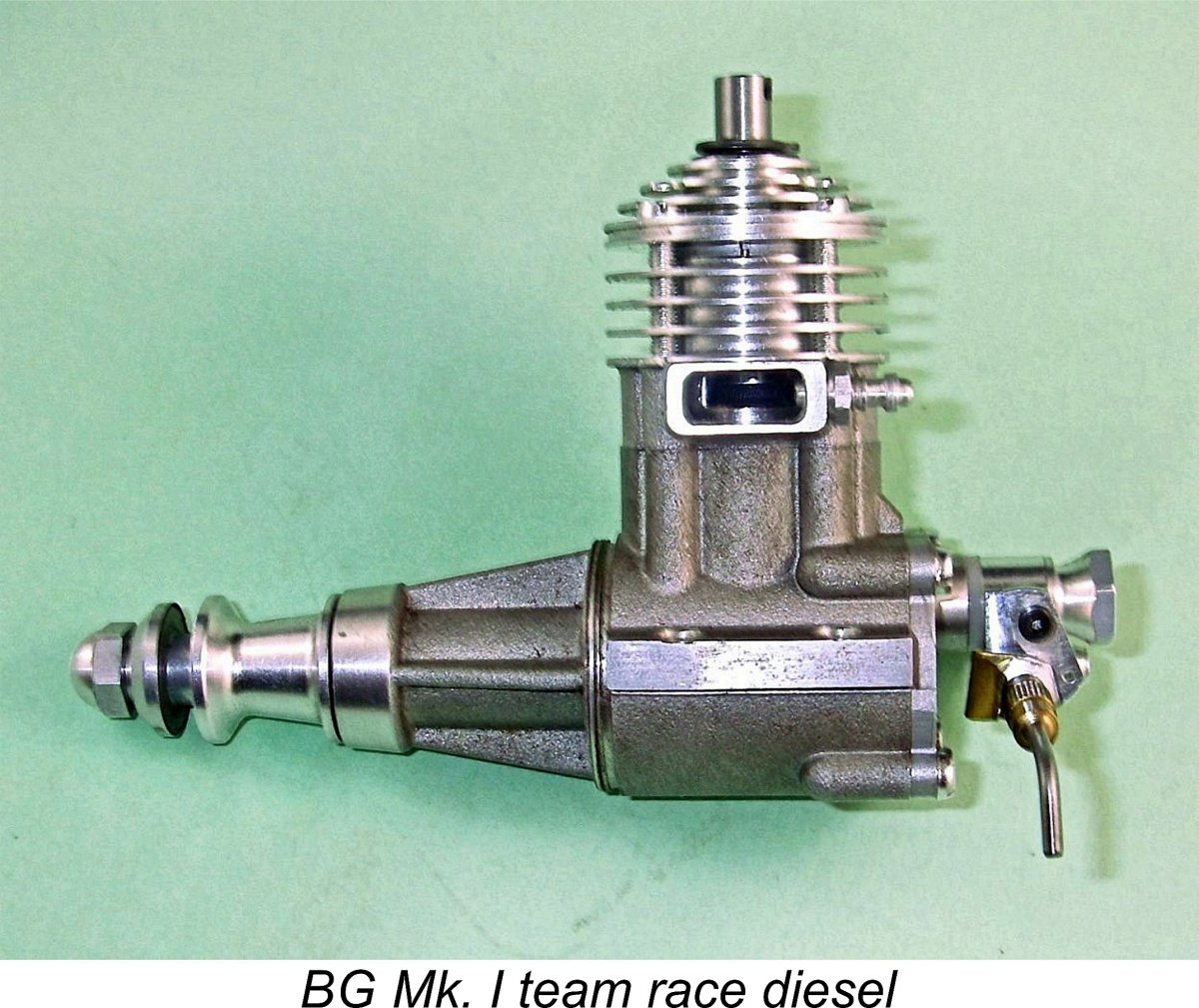

Numbers more or less went straight through the Mk. I series, with the alphabetical letter indicating batches, not the year manufactured. F indicates a front rotary valve (FRV) engine. Presently 5 genuine BUGL FRV engines are known. Their numbers fit into the voids in the Mk. I A series. But it is very uncertain how many FRV engines were actually made. Johnny Dubell of Germany, is known to have flown a couple in F2D Control Line Combat. For the BUGL Mk. II, the numbering sequence was started all over again. Both A and X numbers are recorded, indicating different batches. For the BUGL Mk. II, the highest number I have yet seen mentioned For the Mk. III, only 8 examples ended up being made. The highest recorded number is 007, which is my own engine. I have made an Excel spread-sheet with numbers/buyers, etc. But it is by no means complete and needs further input from BUGL owners. The image at the right as well as that reproduced earlier both show what a genuine BUGL Mk. III looks like. Square exhaust corners, round compression head, 5 cooling fins. The castings are quite distinctive. The image below at the left shows a variety of cylinder castings, some of which are genuine BUGL items while others are from the later BG engines made by the Geschwendtner brothers and myself. From left to right they are; BG If anyone is in doubt about the origin or version of a given engine which is claimed to be a genuine BUGL, please ask me at lup@image.dk. Jens and I have a list of production numbers. But I would welcome additional numbers from buyers/owners to update the files. Following Paul’s death in 1978, Hans and Jens Geschwendtner bought the shop and the exclusive rights to produce BUGL engines from his widow Margot. We started producing the much improved BG Mk. I engines in Copenhagen during early 1979. I did all the drawings for the BG The engine illustrated at the right is a BG Mk. I, not a BUGL Mk. III as sometimes claimed, although it is based largely on the Bugl design and does bear the BUGL name on the boost port bypass. However, it was never touched by the hands of Paul Bugl and shows a number of readily-identifiable departures from the original Bugl design. The story of the BG engines is completely distinct from that of the original Bugl products. In fact, it didn't even begin until after Paul's untimely death. We made a total of around 150 examples of the BG Mk. I through 1981, subsequently constructing eight BG Mk. II engines in 1982. I also made a front rotary induction BG for Goodyear. The full story of the BG engines is set out in the following section of this article. Meanwhile, any comments and additional information on the BUGL engines are welcome. Contact me directly at lup@image.dk The BG Story - 1978-1987 After the 1978 World Championship meeting at Liverpool, England, we contacted Paul Bugl's widow Margot once more. An agreement was soon reached whereby Jens and Hans Geschwendtner bought the workshop, tools, drawings, parts and patents from Margot. This enabled us to continue production of the basic Bugl design, albeit now under the BG name and with a number of our own modifications. The workshop machinery that was collected from Paul's shop was all moved on a lorry (truck), which had to work hard to get it over the hills at Kassel! The equipment was set up in Copenhagen in a new workshop on Nürnberggade on the top floor. A plan of this workshop is reproduced at the left. It was in operation by December 1978. Bjørn Hansen, modeller and master craftsman, was employed to do the machining. Ole Hasling, a well-known Team Race mechanic, was used as a sub-supplier for various items which involved repetitive kinds of work. Hans Geschwendtner was appointed book-keeper, while Jens and I both did development, testing and machining work, etc. My previous BUGL repair business was transferred to the BG workshop, but remained my responsibility.

Major changes made from the Bugl Mk. II design to create the BG Mk. I included:

A batch of 25 engines was completed in the spring of 1979, of which 10 performed well at once. The rest showed small problems with tolerances etc. Some of Paul’s stock parts were used (wrist pin, rings, conrods, etc.). The main problem was actually that the bearings were now too tight. So special high clearance bearings were ordered from GRW Bearings in Germany.

The first real test of the new BG Mk. I team race engines came at Breitenbach in May 1979. Although the finals were marred by heavy rain which resulted in about 20 mm of standing water on the circle and missed catches, etc., the 3 fastest heats were achieved with BG engines, resulting in a new Danish record. Similar results were obtained in other competitions around Europe, resulting in further new Danish records. However, as a result of the higher performance and associated mechanical loadings now being achieved, the piston/conrod connection wore out faster than expected. The GG20 material was perfect for the piston/liner setup, but much too soft for the unique BUGL connection We had a second batch of crankshafts giving problems, as the hardening was too soft. So we started chrome-plating the crankpin. This solved the problem, but it also pointed to a marginal lubrication condition due to the Bugl drum valve blocking/hindering lubrication and cooling of the engine’s bottom end. After the World Championships, we put a titanium nitride coating on a few to try it out. At 4800 Vickers hardness, this change resolved that issue. However, it introduced another problem - the coating was so hard that you needed a diamond wheel to grind it. One fix leads to another problem ..........!

Trying to improve the model performance using these engines, two BG Mk. 1 units (named “Polen”) were lightened as much as possible. At that time in early 1980, Jens and I were testing the engines at around 98 gm (3.46 ounces). However, it was soon found that the low mass was insufficient to dampen the vibration generated by the ferrous piston movement. Doing around 19 sec/10 laps, they had a habit of getting into resonance, losing both speed and canopy elements. Bolts came loose and the models more or less came apart in the air! We ended up with a minimum engine weight of 125 gr. to solve the problem, with the same models totaling around 300 gm ready to fly.

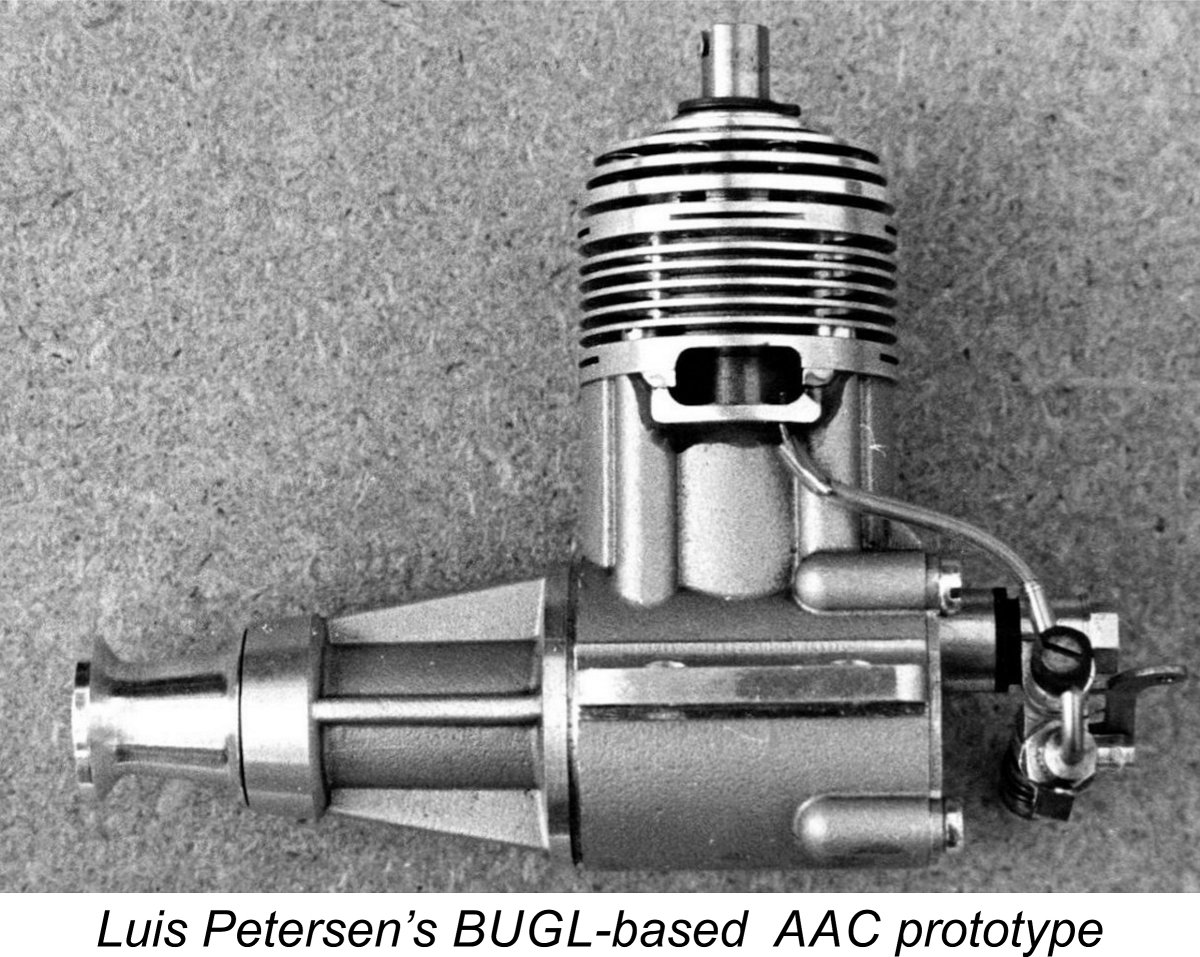

Jørgen Kjærgård, another Danish modeller, started making a more traditional Ryton injection-moulded drum valve/cut off for the BG. This solved the lubrication problems which Other manufacturers, notably Nelson, had started using AAC engines, and we also began experimenting with this technology. Paul had used ABC already on the BUGL Mk. I in 1971, so this was really nothing new. The biggest problem with AAC is getting the correct We also tried hard-anodizing liners and chroming the piston. This worked like a dream, enabling us to set a new Danish heat record at 3:38 in Utrecht. But the layer thickness was too difficult to reproduce consistently, so we stayed with AAC. We used a gas-heated soldering iron as seen at the left to warm up the tight AAC engines before races. After producing around 140 engines, the “production team” ran into personal/professional difficulties in finding the time to maintain production of a series of high performance competition engines while also sustaining other careers, families, etc. Moreover, whenever we came to a competition, half our time was taken up by people complaining that their BG engines were not performing properly. When we put their engines in our model together with our fuel/prop combination to assess the problem, they often turned out to be better than our own! Frustrating ........... I recollect that Paul had similar problems. So we more or less stopped actively selling the BG engines. Only when available time made it possible to finish a small batch did we sell them to serious and knowledgeable teams. On a personal level, my “day job” with F. L. Smidth now involved so much travel time that it was becoming difficult to attend all the competitions around Europe. Eventually, in 1981 we completely stopped A brief word of warning - if you ever acquire an example of the BG Mk. I engine, do not dismantle it. In particular, do not dismantle the drum from the crankshaft. You need a special tool to set it up properly during reassembly. Best to leave well alone. I did produce a prototype AAC integral liner engine in 1981 based on the Bugl casing. This recorded a heat time of 3:45 at Bochum while devouring half the piston skirt in the race! We still made the final. Pit stops were taking around 18 sec. each. Model speed was around 18.5 -18.8 sec/10 laps in the race. Our lightened BG Mk. I "Emmenthaler" from the 1980 World Championships in Poland was now further modified with a longer liner which supported the piston in the bottom position. It also featured a new compression head with 8 x 2 mm bolts, resulting in a very good engine.

The new engine had an AAC integral liner/piston set-up and used either the Kjærgård Ryton backplate/cut-off or a Nelson type. The traditional piston/conrod connection was also tried, together with different types of piston materials. Cylinder material was Mahle 124 and the piston Mahle 138. This variant of the BG carried the BG name on the boost port bypass, ending any possibility of its being claimed as a BUGL original. 8 BG Mk. II engines were finished at the time, all performing at the highest international levels. Three Danish teams used them for some years. However, interest in F2C Team Racing was now declining. Where before there would be 6-8 Danish teams at any international contest, now there would be 3-4 at the most.

In 1987 I actually made an integral hardchromed steel liner for the BG. This was the fastest engine ever on the test stand, turning an 8x4 blue Kavan prop at 17,400 rpm compared to the standard 17,000 rpm. But the engine proved to be very difficult to race because a stable airborne setting could not be achieved.

Since 1987, no new parts for the BG engines have been produced. There has only been some limited assembly of previously-produced components. The production machinery acquired from Bugl has been sold - only the special jigs, etc. remain. I still have all the machinery required to manufacture engines, but not for competition any more. The present-day situation in relation to competition engine production is very different! You create a design and send it to the specialists in Russia/Ukraine, pay them appropriately and you get a first class manufactured item back. In 1988 Jens Geschwendtner and I stopped flying at Internationals, except in Denmark. I became an FAI judge at F2C events, finally retiring from that role in 2005. For several years Hans Geschwendtner & John Mau kept on winning the Danish Nationals with the BG Mk. II. Jens has now started flying seriously again last year (2018). But with the ready availability of the Ukrainian/Russian engines, we’ve realized that making one's own engines to compete at the highest level no longer pays off.

The problem of people offering engines as genuine BUGL's has not gone away. The Profi replicas are quite convincing, with their wooden boxes and generally professional construction, although not up to genuine Bugl standards. However, if you know your BUGL's, they're easy to spot. For one thing, if the mounting lugs have rounded corners and an as-cast finish on their outer edges, it's a Profi! Likewise, if it has paper gaskets, it's a Profi. The serial numbers also tell the tale. I have recently seen a BG Mk. I sold on eBay for a very high price – no less than US$950!! It was falsely claimed to be a very rare BUGL Mk. III despite the fact that the seller was clearly told in advance of the sale what it really was. An original BUGL Mk. III would be worth that price at least, but as I’ve stated earlier, only 8 were made. So the chances of a given offering being a genuine BUGL Mk. III are very small indeed! A major reason for publishing this article is to try to prevent this kind of thing from happening in the future. I’ll close by repeating that if anyone is in doubt about the true origin of a claimed BUGL or BG engine, please contact me at lup@image.dk to seek confirmation. Luis Petersen ____________________ Article © Luis Petersen, Denmark First published February 2019

|

| |

Unfortunately, human nature being what it is, this has led to a distressing number of attempts to pass off replicas and spin-offs which were not made by Paul Bugl as the genuine items. There's the replica BUGL Mk. I Series 2 model which was manufactured in Ukraine during the 1990's by Alexander Osovitch of Profi Micro Engines - nice engines, but they're not BUGL's! Another series which has periodically been subject to similar chicanery is the Danish-made BG series of team race diesels which were closely based upon the Bugl design but were all manufactured by the Geschwendtner brothers and Luis Petersen in Denmark after Paul's death.

Unfortunately, human nature being what it is, this has led to a distressing number of attempts to pass off replicas and spin-offs which were not made by Paul Bugl as the genuine items. There's the replica BUGL Mk. I Series 2 model which was manufactured in Ukraine during the 1990's by Alexander Osovitch of Profi Micro Engines - nice engines, but they're not BUGL's! Another series which has periodically been subject to similar chicanery is the Danish-made BG series of team race diesels which were closely based upon the Bugl design but were all manufactured by the Geschwendtner brothers and Luis Petersen in Denmark after Paul's death.

The oldest dated drawings for the BUGL Mk. II that I have seen are the housing dated 25-9-1974. We ordered two Bugl Mk. II engines in September 1974, finally receiving them in February 1975 when my wife and I went down to meet Paul and collect them in person. By this time he had relocated from Austria to Moosbach, West Germany, perhaps for tax reasons.

The oldest dated drawings for the BUGL Mk. II that I have seen are the housing dated 25-9-1974. We ordered two Bugl Mk. II engines in September 1974, finally receiving them in February 1975 when my wife and I went down to meet Paul and collect them in person. By this time he had relocated from Austria to Moosbach, West Germany, perhaps for tax reasons.

We then went down together to the contest at Kraiwiesen, Austria, where Paul/Hans Straniak won and I tested/repaired BUGL engines. Naturally, I paid special attention to our own two engines, preparing them for the 1976 World Championship meeting to be held at Utrecht, Holland. Those engines were standard BUGL’s, but were set up to run on less oil and at a somewhat higher RPM compared to the “normal” BUGL configuration.

We then went down together to the contest at Kraiwiesen, Austria, where Paul/Hans Straniak won and I tested/repaired BUGL engines. Naturally, I paid special attention to our own two engines, preparing them for the 1976 World Championship meeting to be held at Utrecht, Holland. Those engines were standard BUGL’s, but were set up to run on less oil and at a somewhat higher RPM compared to the “normal” BUGL configuration.

The attached illustration at the left shows a group of

The attached illustration at the left shows a group of

Two more non-functioning BUGL Mk. III engines were later assembled by us and given to the Austrians. They cast them into a pair of acrylic cubes and presented them to the FAI as the Paul Bugl memorial awards for F2C team racing. They were to be presented for the first time at the 1980 World Championship meeting in Poland. Hans Geschwendtner (Jens Geschwendtner’s brother) and John M

Two more non-functioning BUGL Mk. III engines were later assembled by us and given to the Austrians. They cast them into a pair of acrylic cubes and presented them to the FAI as the Paul Bugl memorial awards for F2C team racing. They were to be presented for the first time at the 1980 World Championship meeting in Poland. Hans Geschwendtner (Jens Geschwendtner’s brother) and John M Here are some images of a few of Paul's other innovations. Right-click on the images to see them at a higher resolution.

Here are some images of a few of Paul's other innovations. Right-click on the images to see them at a higher resolution.

The Geschwendtner brothers made the journey to collect the various items and transfer them all to Copenhagen. They received none of the equipment that had previously been moved to Georg Müller's shop - they were not invited. I'm sure that quite a bit of Paul's stuff was "lost" in that way. For example, only a few castings for the 40 and 60 models were found.

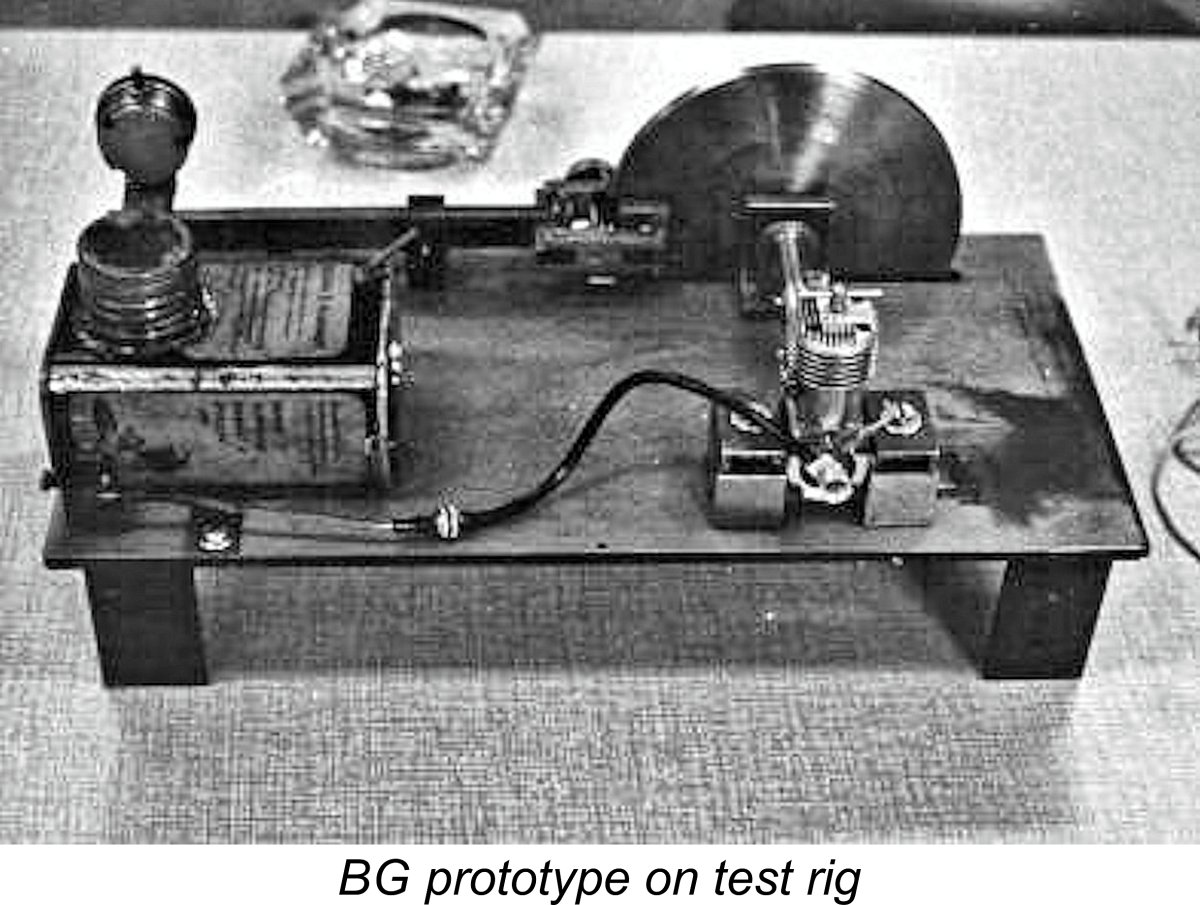

The Geschwendtner brothers made the journey to collect the various items and transfer them all to Copenhagen. They received none of the equipment that had previously been moved to Georg Müller's shop - they were not invited. I'm sure that quite a bit of Paul's stuff was "lost" in that way. For example, only a few castings for the 40 and 60 models were found.  A new engine to be called the BG Mk. I was quickly designed, based on the Bugl Mk. II drawings and the BUGL Mk. III castings which were available. Our own BUGL Mk. III No. 007 was modified into the BG Mk. I prototype and used as the workshop template. This first BG engine was ready to be tested in January. It later ended up as another much lightened “Emmenthaler” engine which was used to compete at the 1980 World Championship in Poland.

A new engine to be called the BG Mk. I was quickly designed, based on the Bugl Mk. II drawings and the BUGL Mk. III castings which were available. Our own BUGL Mk. III No. 007 was modified into the BG Mk. I prototype and used as the workshop template. This first BG engine was ready to be tested in January. It later ended up as another much lightened “Emmenthaler” engine which was used to compete at the 1980 World Championship in Poland.

During the Fall of 1979, Bjørn Hansen had to leave us in order to take over his father's machine shop. So another arrangement was initiated. Fortunately, several of our club members were experienced machinists, so for the club meetings the machines were set up for doing specific jobs. This enabled production of the BG Mk. I to continue, albeit at a slower pace.

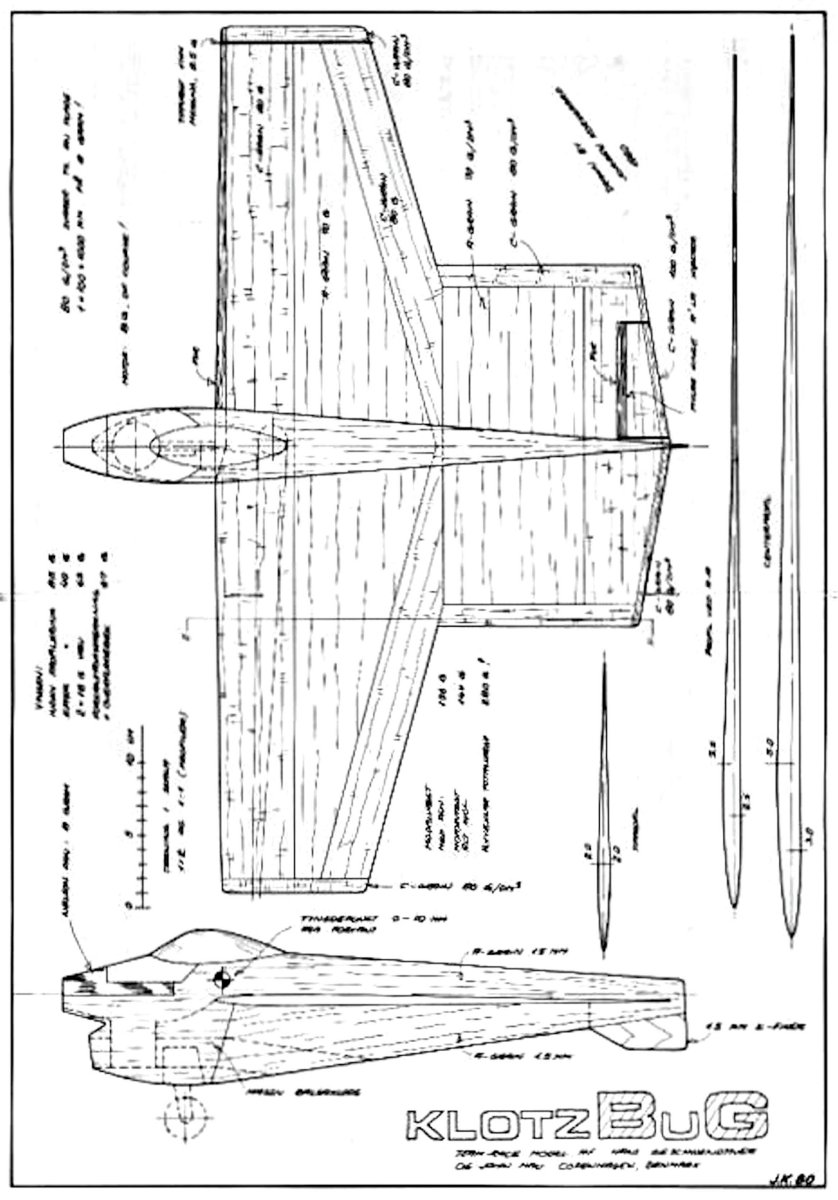

During the Fall of 1979, Bjørn Hansen had to leave us in order to take over his father's machine shop. So another arrangement was initiated. Fortunately, several of our club members were experienced machinists, so for the club meetings the machines were set up for doing specific jobs. This enabled production of the BG Mk. I to continue, albeit at a slower pace. We came to the 1980 World Championship in Poland with high hopes, but had some further problems with bluing pins. As previously stated, Hans Geschwendtner and John Mau ended up winning the Championship that year. The Danish BG team placed second in the team standing. The winning model was a typical Danish BG model named KlotzBuG. A plan of this model is seen at the right.

We came to the 1980 World Championship in Poland with high hopes, but had some further problems with bluing pins. As previously stated, Hans Geschwendtner and John Mau ended up winning the Championship that year. The Danish BG team placed second in the team standing. The winning model was a typical Danish BG model named KlotzBuG. A plan of this model is seen at the right.

we had been experiencing, as the fresh charge was led directly onto the big end, without the engine being any slower.

we had been experiencing, as the fresh charge was led directly onto the big end, without the engine being any slower. expansion rates and actually carrying out the chrome plating. Eventually I found a galvanic shop 500 meters from my home, who would do the plating and teach me how we could do it ourselves.

expansion rates and actually carrying out the chrome plating. Eventually I found a galvanic shop 500 meters from my home, who would do the plating and teach me how we could do it ourselves. producing BG engines for sale. At that point, 126 numbered examples had been sold. Probably another 30 have been finished during the years since. But these were intended only for collectors and were no longer competitive. (Editor's note: Thanks to the kindness of Jens Geschwendtner, I'm fortunate enough to own the previously-illustrated example of one of these latter engines).

producing BG engines for sale. At that point, 126 numbered examples had been sold. Probably another 30 have been finished during the years since. But these were intended only for collectors and were no longer competitive. (Editor's note: Thanks to the kindness of Jens Geschwendtner, I'm fortunate enough to own the previously-illustrated example of one of these latter engines).  Development of the BG engines did not stop after we ceased series production in 1981. In the winter of 1981 I came up with a new design for a BG Mk. II with integral liner and a much stronger lost wax crankcase casting weighing only 32 gr. Kjærgård made the moulds for the wax and 18 castings were produced at Thüssen Gieserie in Germany. The same company cast my designs for a massive grinding table in GGG40 weighing 110,000 kg!

Development of the BG engines did not stop after we ceased series production in 1981. In the winter of 1981 I came up with a new design for a BG Mk. II with integral liner and a much stronger lost wax crankcase casting weighing only 32 gr. Kjærgård made the moulds for the wax and 18 castings were produced at Thüssen Gieserie in Germany. The same company cast my designs for a massive grinding table in GGG40 weighing 110,000 kg! The shaft shown at the right with other components features forced lubrication for the connecting rod along with a tungsten-balanced crankweb. It forms part of a late BG Mk. II. The biggest problem encountered was the fact that the piston material quality was not consistent. This led to a large number of “fallouts” during manufacturing. We finally got some good piston material from Rob Metkemeijer, which solved the problem. The BG Mk. II engine was flown at the 1982 World Championships, doing around 18.2 sec/10 laps. Our best heat time with a BG Mk. II was 3:23.

The shaft shown at the right with other components features forced lubrication for the connecting rod along with a tungsten-balanced crankweb. It forms part of a late BG Mk. II. The biggest problem encountered was the fact that the piston material quality was not consistent. This led to a large number of “fallouts” during manufacturing. We finally got some good piston material from Rob Metkemeijer, which solved the problem. The BG Mk. II engine was flown at the 1982 World Championships, doing around 18.2 sec/10 laps. Our best heat time with a BG Mk. II was 3:23. We tested a number of different changes which did not yield any improvement. These included flywheel propdrivers, the addition of lead to the fuel (which blew off the top on the standard head!), a “loose” steel

We tested a number of different changes which did not yield any improvement. These included flywheel propdrivers, the addition of lead to the fuel (which blew off the top on the standard head!), a “loose” steel  mounting for the front bearing, insulating the integral liner from the housing, the production of a couple of castings to test the BG setup in a rear exhaust configuration, and packing the crankcase to improve volumetric pumping efficiency. None of these experiments resulted in any improvement. We also produced two more crankcases for a piped version, with a loose manifold, but this project was abandoned.

mounting for the front bearing, insulating the integral liner from the housing, the production of a couple of castings to test the BG setup in a rear exhaust configuration, and packing the crankcase to improve volumetric pumping efficiency. None of these experiments resulted in any improvement. We also produced two more crankcases for a piped version, with a loose manifold, but this project was abandoned.

Looking at the BG Mk. II design from 1982, I can only see minor differences from present-day designs. The major thing is piston material. I am certain that the Bugl piston design is still the best you can get, but it is very time-consuming to manufacture. His drum valve system is also very good, but with present day team race oil contents (5-10%) you need either a needle roller bearing at the big end or forced crankpin lubrication to make it work.

Looking at the BG Mk. II design from 1982, I can only see minor differences from present-day designs. The major thing is piston material. I am certain that the Bugl piston design is still the best you can get, but it is very time-consuming to manufacture. His drum valve system is also very good, but with present day team race oil contents (5-10%) you need either a needle roller bearing at the big end or forced crankpin lubrication to make it work.