|

|

Indonesian Interlude - the BOMA Story By Adrian Duncan with Sten Persson

In September 2021 Sten contacted me with regard to my article on the Russian MK-12S diesel as well as my related piece which appeared in the Free Flight Quarterly publication. He told me that for more than 60 years an MK-12S had been sitting in his engine collection, causing him to read my relevant articles with particular interest. Sten took particular note of the fact that in August 2021 I had been reminded of the existence of an Indonesian-made copy of the MK-12S which had appeared under the BOMA trade-name. I had added some limited information about that model to my article on the MK-12S. It turned out that Sten possessed a considerable amount of additional information on the BOMA model engine venture as a whole - indeed, he had played a not-inconsequential part in making the latter stages of that venture possible! Sten has now been kind enough to share his knowledge of these engines with the rest of us. The following account is based largely upon the information that he provided, with a few additional comments by myself. I’d like to extend my very sincere thanks to Sten for preserving and sharing an interesting and in many ways unique chapter of model engine history which would otherwise have been irretrievably lost. It is for this reason that his name appears with mine at the top of this article. With that essential acknowledgement having been made, let’s get on with the story! In the Beginning

A serious problem facing these enthusiasts was the fact that the importation of model engines into Indonesia was severely restricted by the government of the day. As a result, the acquisition of model engines by Indonesian modellers wishing to participate in power modelling was virtually impossible. In early 1960, the members of the Pasuruan model club decided to do what they could to alleviate this situation. A club spokesman sent a letter to the staff of “Aeromodeller” magazine describing the austere conditions and restrictions that prevented the club members from acquiring model engines. An appeal for donations of surplus secondhand engines was published in the magazine, eventually resulting in four such donations, as reported in “Aeromodeller” for November 1960. These were forwarded to the Pasuruan club by magazine staff.

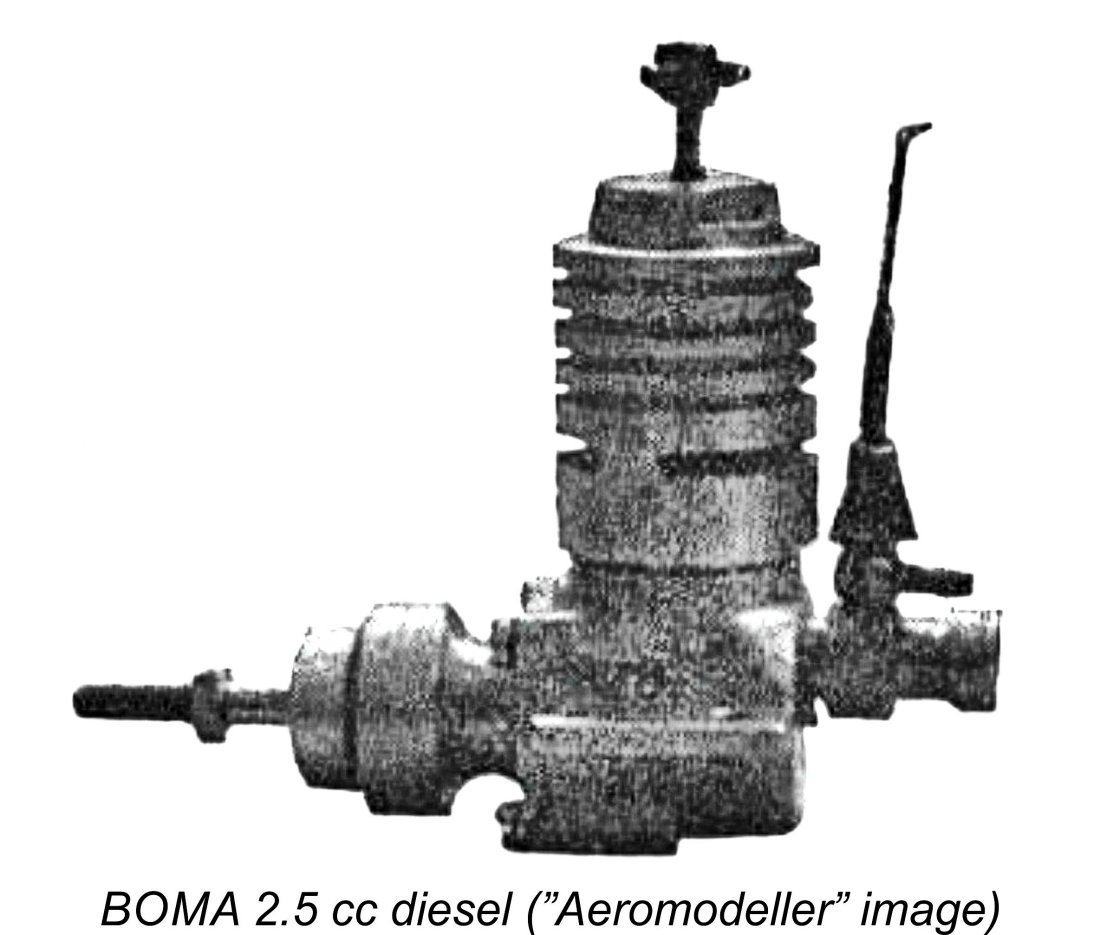

Unfortunately, practically nothing is known about this engine beyond its existence, its appearance and its source. In particular, it’s unclear whether this was an all-new Indonesian production or whether it utilized any original Russian-made MK-12S components somehow obtained from Russia. In recognition of his employer’s cooperation in allowing him to use their facilities on an after-hours basis, this engine was designated as a BOMA model, probably (but not definitely) the BOMA 250. It’s unclear how many examples of this unit were produced, but the number can’t have been large. Nevertheless, it represented a praiseworthy first attempt by Mr. Tjong to alleviate the model engine supply situation in his area. The BOMA 150 Diesel This effort appears to have been sufficiently well received that Mr. Tjong was encouraged to pursue the development of a 1.5 cc diesel engine of his own design. His employers once again granted him access to the facilities of the BOMA works to produce this engine in his spare time. In appreciation for this favor, he named it the BOMA 150.

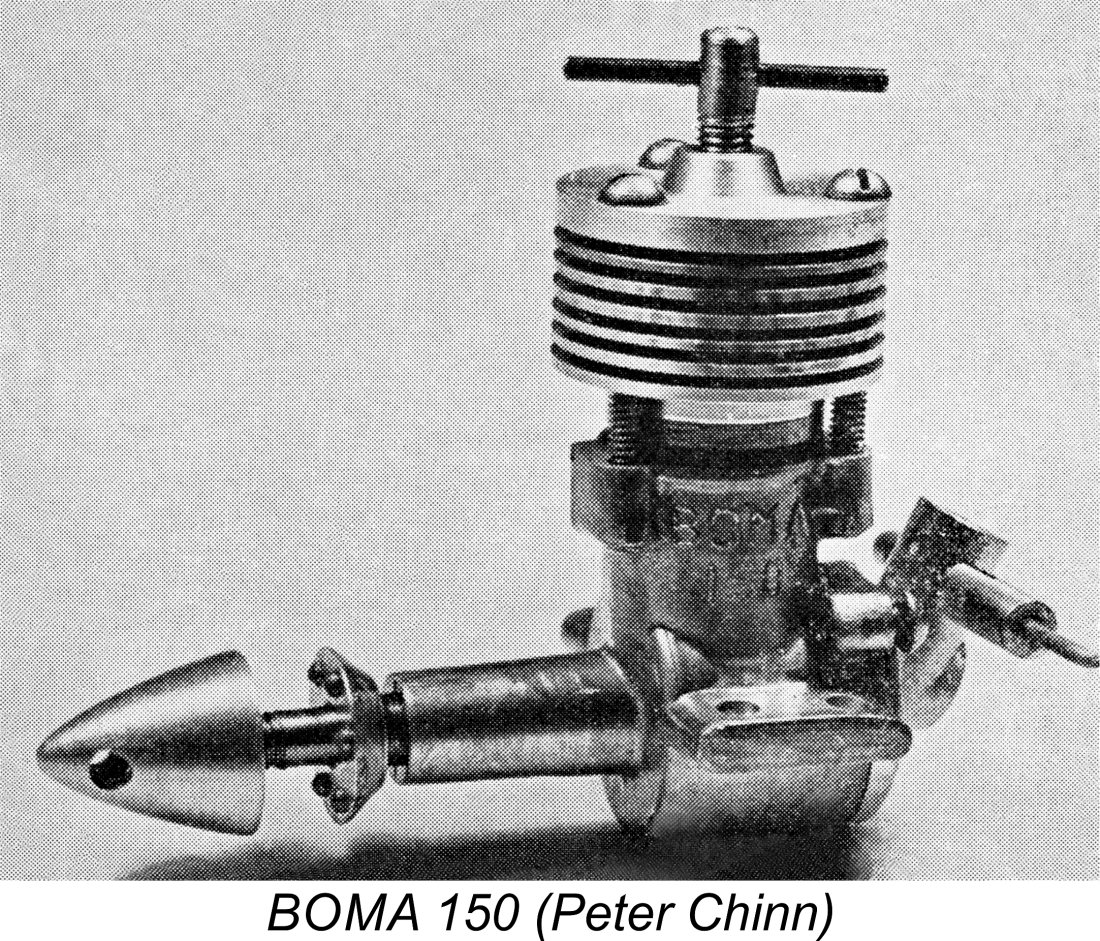

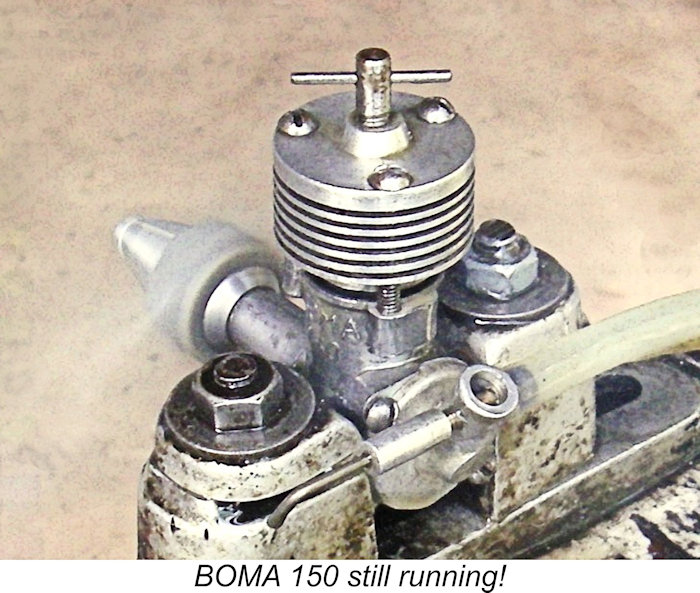

An example of this engine was sent to Peter Chinn, who was widely recognized as the world’s leading authority on model engines at the time. Chinn featured the engine in his “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the December 1964 issue of “Model Aircraft” magazine. The BOMA 150 turned out to be a well-made plain bearing 1.48 cc diesel with circumferential cylinder porting and rear reed valve induction through a down-draft intake. The latter feature was clearly intended to minimize the engine's overall length. Chinn reported the bore and stroke as 12.5 mm and 12.0 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 1.48 cc. Weight was given as a little over 3 ounces. Chinn made the comment that “the BOMA 150 may not be a rival for the Oliver Cub in performance or refinement, but it obviously represents a great step forward in the model movement in Indonesia.”

As a young student and an avid model builder at the time, Sten Persson was well and truly bitten by the engine collecting bug as of the 1960’s. At that time the size of his collection was very modest but his interest was already attracted towards what might be called “exotic” examples. He became an early member of the Model Engine Collectors Association (MECA - est. February 1960) and developed a good relationship with Peter Chinn – no email in those days, but they managed! It was Peter Chinn who helped Sten to get in touch with the Pasuruan club and, eventually, Mr. Tjong himself in 1965. Needless to say, Sten’s goal in making this contact was to acquire one of Mr. Tjong’s BOMA 150 diesels for himself. However, that was not to be, since production had ended by that time and no more examples were available. There had never been any plans to export these engines - they were produced purely to satisfy the immediate needs of Indonesian modellers for useable engines. Once that demand was met, at least for an engine of this displacement, there was no incentive to continue production of this particular model. Nonetheless, Sten stayed in touch with Mr. Tjong, consequently gaining a growing appreciation of the significant challenges which had to be overcome to enable the production of these engines. An Opportunity to Test the BOMA 150

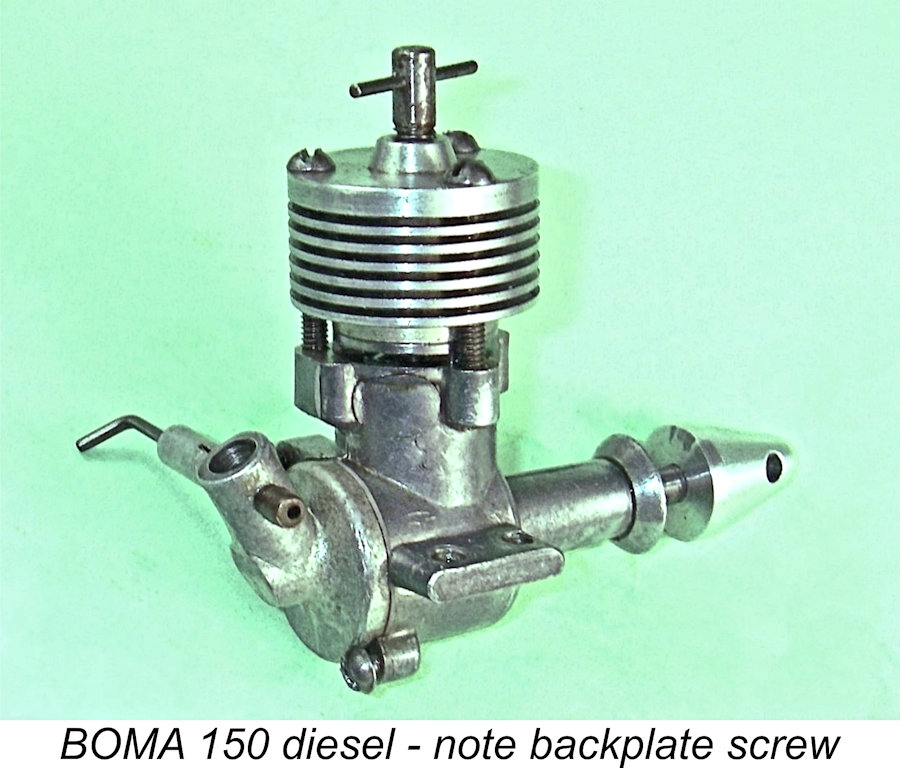

One feature that had previously escaped my notice was the method of securing the backplate. I had previously assumed that the backplate casting incorporated two "mouse-ear" eyes to accommodate the two retaining screws. However, I found that no such eyes were present, nor had they ever After much thought, I came up with what I believe to be a rational explanation for this unusual design approach. Since the BOMA 150 is a reed valve engine, the backplate can be installed in any desired orientation without in any way affecting the running. The "eyeless" approach to its retention allows it to be secured in any orientation that may suggest itself as being most convenient for a given model installation. If anyone has a better idea, I'd love to hear it! Although I wasn't prepared to dismantle the engine, I was certainly more than game to give it a few runs on the test bench! Dean had provided strong encouragement by sending me a short video of the engine undergoing its test run following his rebuild. I therefore knew that the engine was a runner!

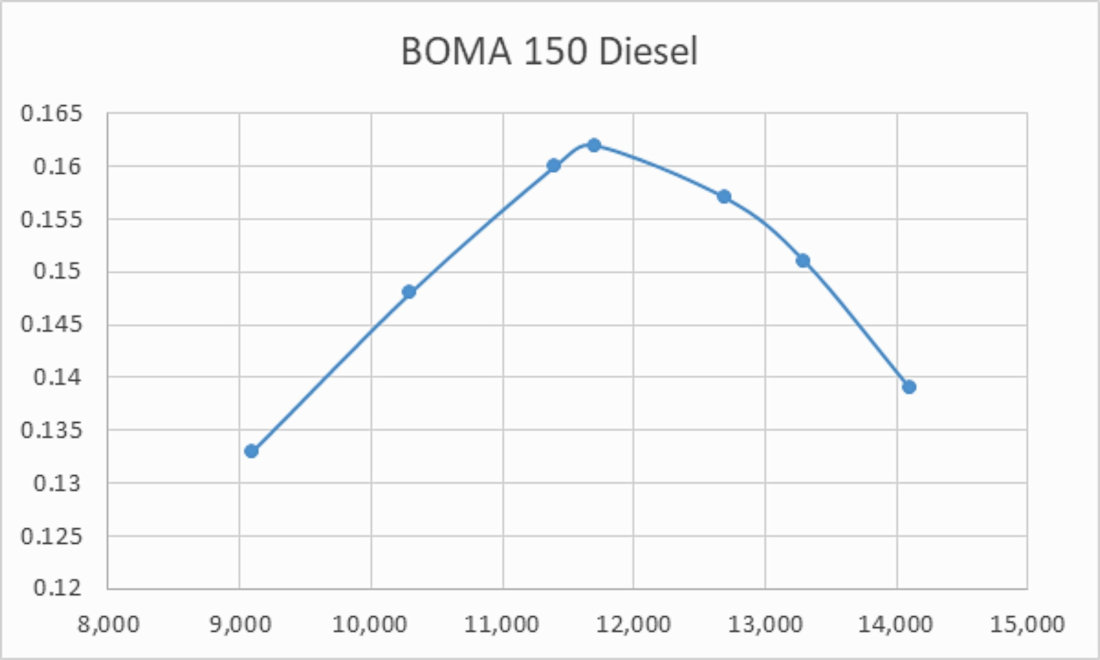

The BOMA proved to be a very easy starter provided that a small exhaust prime was administered as a preliminary. For some reason, choking alone didn't seem to have the desired effect - perhaps the reed valve played a part there. However, the engine was a more or less immediate starter following a prime - I would characterize its starting qualities as excellent. Once running, the BOMA exhibited the The reason for this behaviour is quite simple - with a reed valve, induction timing is variable, being controlled by the pressure variations in the crankcase during operation. The magnitude and timing of these variations will be significantly affected by engine speed. Unless you're very close to the optimum setting, a change in the needle setting almost invariably changes the engine speed and hence the induction timing. The engine requires a few seconds to stabilize at the new timing figures. Since the engine clearly required some running-in following Dean's rebuild, I put on 30 minutes in 5 minute rich under-compressed runs, leaning out briefly at the end to subject the piston to the series of full-range heat cycles which are so essential to a proper break-in of an iron-and-steel piston/cylinder combination. At the end of this period, the engine felt superb, clearly all ready for testing. I proceeded to obtain prop/RPM readings for a series of appropriate props, with results as follows.

In all honesty, these results exceeded my expectations by a considerable margin! Based on Chinn's comments, I had been expecting a relatively mediocre performance from this engine. What I got instead was an impressive ability to swing a relatively large prop at very useable speeds, with a peak output that was a match for most contemporary sports diesels of 1964. Because of the high torque in evidence, this output was released at a relatively low speed by then-current standards - the engine appeared to develop around 0.163 BHP @ 12,000 RPM. Needless to say, this would have constituted a more than acceptable performance for any Indonesian modeller who was lucky enough to acquire an example back in 1964. Mr. Tjong clearly succeeded completely in achieving his design objectives. I myself was thoroughly impressed with the engine! The T.S. 35 Diesel

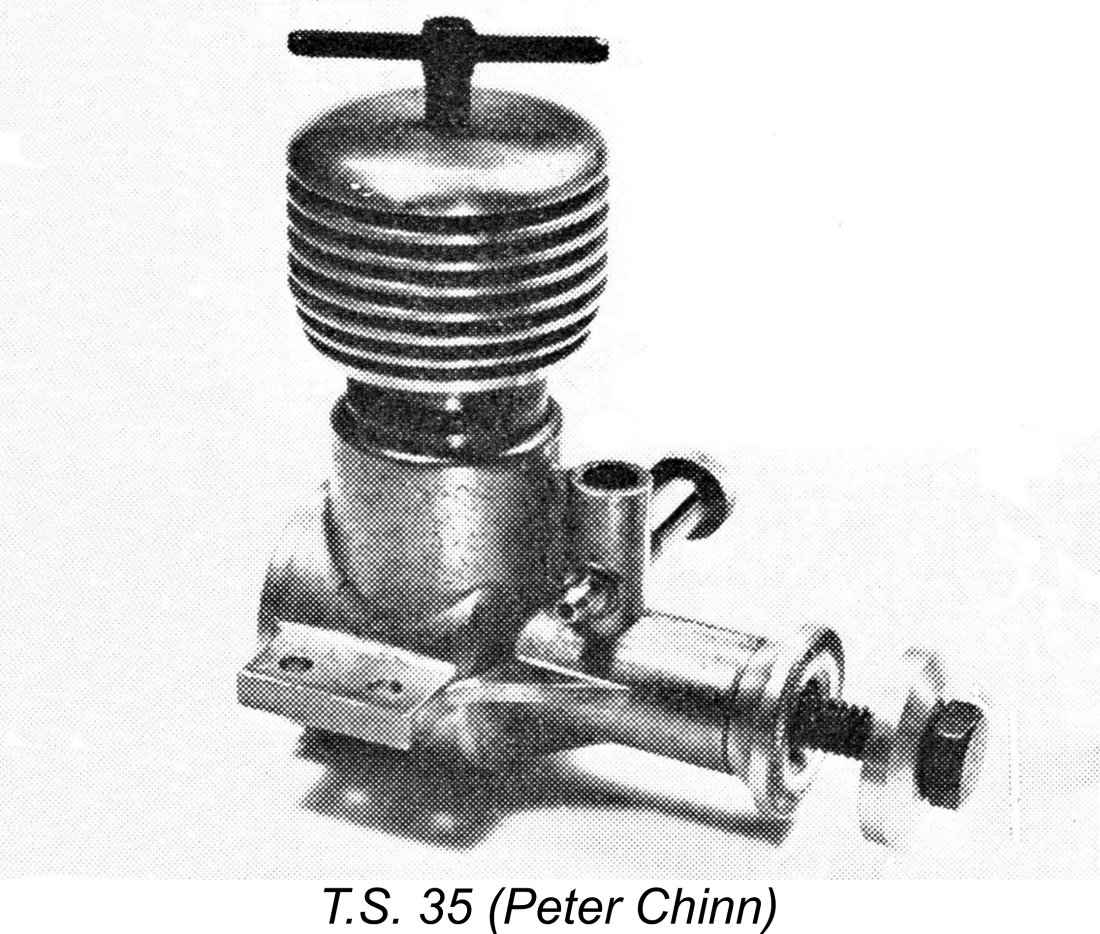

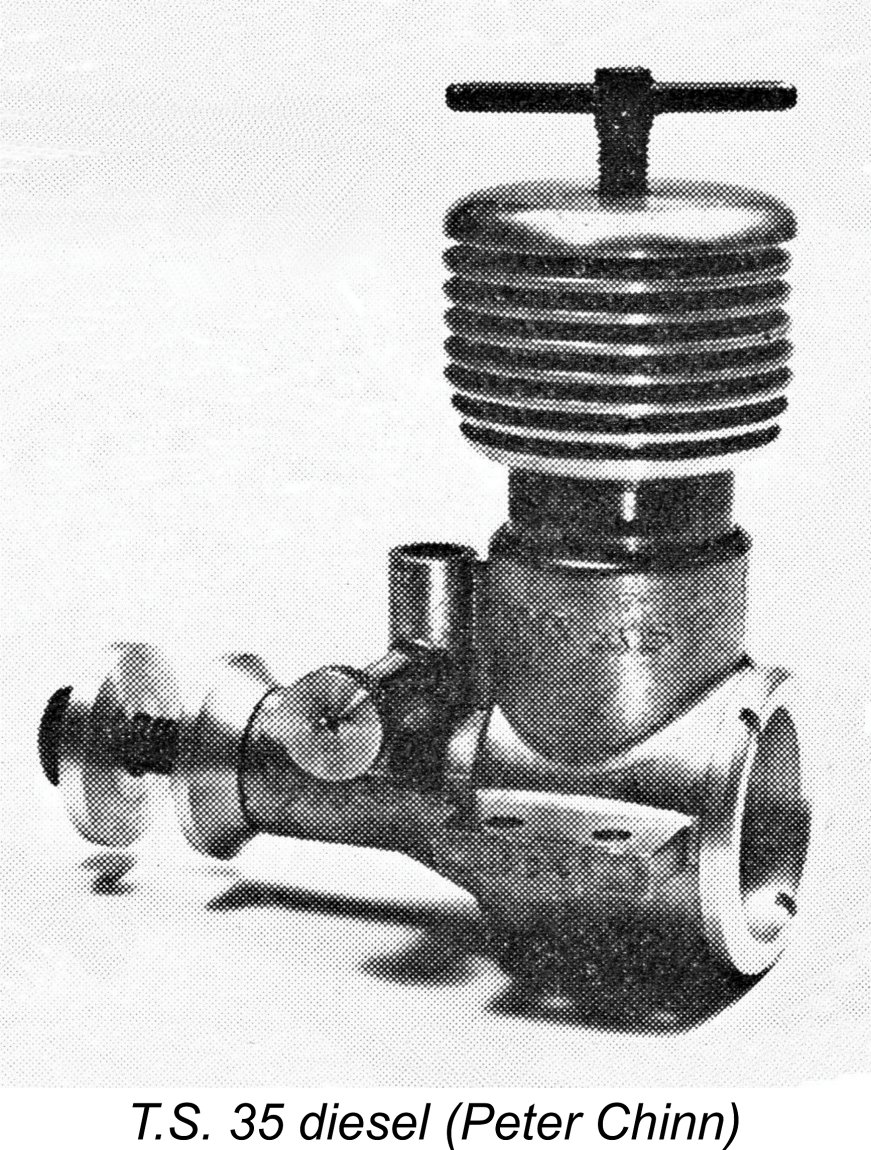

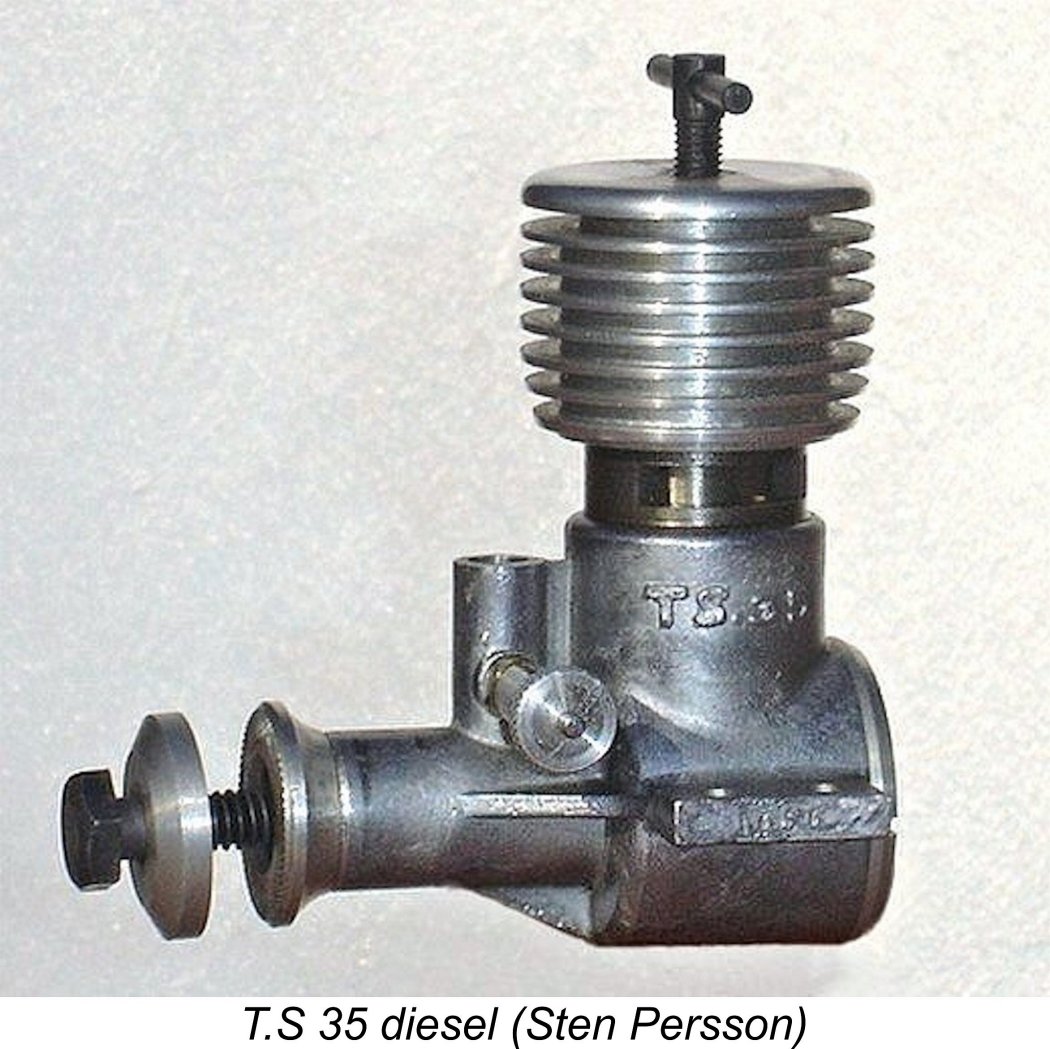

Miraculously, the tools actually reached the little town of Pasuruan, and sometime later a shipment of about half a dozen Indonesian model diesel engines reached Sten in faraway Sweden! Mr. Tjong’s new engine was called the Tiga Serangkai (Series Three) 35 model, shortened to T.S. 35. Presumably the BOMA 250 and 150 models were viewed as the The T.S. 35 turned out to be a hefty 3.2 cc plain bearing shaft-valve diesel engine of conventional layout which bore little design relationship to the two earlier BOMA models. Sten sent an example to Peter Chinn for evaluation, resulting in its being featured in the November 1969 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Chinn found that despite its nominal stated displacement of 3.5 cc, the T.S. 35 had square bore and stroke measurements of 16.0 mm x 16.0 mm, yielding an actual displacement of 3.216 cc (0.196 cuin.). The engine was quite bulky for its displacement, weighing in at 197 gm (6.95 ounces). The die-cast crankcase was threaded to accommodate the screw-in cylinder and backplate. The porting used was basically that popularized by Cox, with twin exhaust ports and twin bypass flutes between them. A flat-topped piston was employed. This time, Chinn reported that the T.S. 35 was manufactured in Surabaya, which was the actual location of the P. N. BOMA plant at which the earlier engines had been made. The absence of the BOMA name may suggest either that Mr. Tjong had established his own workshop or that his BOMA employers had withdrawn their official support for the venture. We’ll probably never know …………

I set the engine up in the test stand to give it a few runs just to experience its qualities. All working fits turned out to be superb, with outstanding compression and I tried the T.S. 35 on an APC 10x6 airscrew, using which it seemed quite happy. Starting proved to be excellent, with only a very small prime required as a preliminary to a one or two flick start. Response to both controls was very positive, with both holding their settings very securely while remaining fully adjustable at all times. The engine seemed quite willing to turn the test prop with some authority, but unfortunately the tightness problem caused it to nip up and sag quite badly if any attempt was made to lean it out all the way. I therefore failed to get any meaningful performance data, but did confirm that the T.S. 35 was an extremely well-made engine which started very easily and would doubtless perform at a perfectly acceptable level once run in. The Aftermath

In his ongoing correspondence with Mr. Tjong, Sten had mentioned that he was going to be married in June 1970. Just a few days before the big event, a small parcel arrived, wrapped in brown paper and covered with Indonesian postage stamps. It was a wedding gift from Mr. Tjong - nothing less than his personal and last-produced BOMA 150! Sten doesn’t remember if his bride appreciated that particular wedding gift, but needless to say the groom was overwhelmed! So far, the story has been a tribute to the enthusiasm, dedication and ability of Mr. Tan Hien Tjong - clearly a talented individual and a modelling enthusiast whom I would have been proud to know. This being the case, it’s truly unfortunate to have to report that this story does not have a happy ending. Following the receipt of his “wedding gift” example of the BOMA 150, Sten never again heard from Mr. Tjong - his repeated letters went unanswered.

As far as Sten and I are aware, the BOMA 150 and T.S. 35 remain the only model engines ever to enter series production in Indonesia - we know too little about the original BOMA 250 to confirm its qualification for inclusion in that category. Naturally, Sten’s wedding gift BOMA 150 occupies a predominant place in his collection, as does the example of the T.S. 35 that he retains. All of the additional examples of the T.S. 35 found homes with others, so thanks to Sten’s contact with Mr. Tjong some 60 years ago, at least 5 or 6 T.S. 35’s should still be sitting in collections out there! An example appeared on eBay a few years ago, demonstrating that they do remain in circulation. And as noted above, another now resides with me ............ It’s presently unclear how many BOMA 150 diesels left Indonesia by various means. Sten recalls seeing unsubstantiated production numbers that if true would suggest that quite a number of BOMA 150’s should by rights have found their way into collections around the world. However, since 1970 when Mr. Tjong sent Sten his last example, Sten has never seen another BOMA 150 offered for sale or swap apart from my own recently-acquired example. It would be very interesting to learn how many more examples (if any) are still around. Conclusion For me, this necessarily brief account should stand as a testimonial to a talented and dedicated model enthusiast whose achievements under difficult circumstances are well worthy of our highest admiration. Mr. Tan Hien Tjong richly deserves to occupy an honoured place in the pantheon of designers and constructors of model engines worldwide. He certainly deserved a better fate than that which seemingly befell him. My very sincere thanks to Sten Persson for sharing this bitter-sweet story with us. If any reader can add to the information presented here, please get in touch! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2021 Updated November 2023 (additional variant of BOMA 150 plus test) |

||

| |

I must begin this article by making the very clear statement that I couldn’t have so much as put finger to keyboard on this topic without the immense help received from my valued Swedish friend Sten Persson. For many decades now, Sten has been one of Sweden’s best-known and most knowledgeable model engine enthusiasts. He has generously supplied valuable information in connection with a number of my earlier articles.

I must begin this article by making the very clear statement that I couldn’t have so much as put finger to keyboard on this topic without the immense help received from my valued Swedish friend Sten Persson. For many decades now, Sten has been one of Sweden’s best-known and most knowledgeable model engine enthusiasts. He has generously supplied valuable information in connection with a number of my earlier articles.  Indonesia is probably one of the last names that comes to mind when one thinks about countries with a history of active involvement in aeromodelling. Nonetheless, during the 1950’s a small but enthusiastic community of aeromodellers emerged in that country. Some of these enthusiasts organized themselves into clubs, one such club being located in the small coastal town of Pasuruan in the East Java region of the island of Java. The town appears near the centre of the accompanying map.

Indonesia is probably one of the last names that comes to mind when one thinks about countries with a history of active involvement in aeromodelling. Nonetheless, during the 1950’s a small but enthusiastic community of aeromodellers emerged in that country. Some of these enthusiasts organized themselves into clubs, one such club being located in the small coastal town of Pasuruan in the East Java region of the island of Java. The town appears near the centre of the accompanying map.  In the meantime, an example of the Russian

In the meantime, an example of the Russian

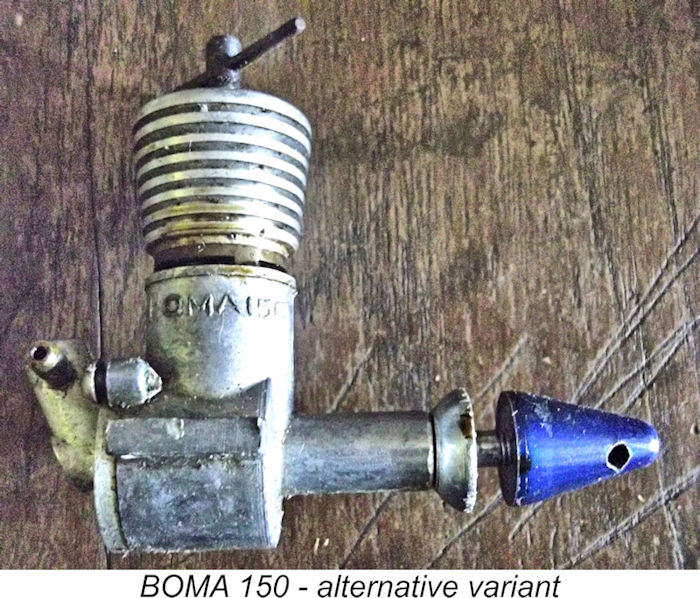

The model described above was not the only variant to appear. In 2013 my Aussie friend Bob Allan provided irrefutable photographic evidence that a distinct variant of the BOMA 150 having a screw-in cylinder also appeared at some point. Bob posted this information on the widely-read RC Groups forum (Vintage Glow Engines thread,

The model described above was not the only variant to appear. In 2013 my Aussie friend Bob Allan provided irrefutable photographic evidence that a distinct variant of the BOMA 150 having a screw-in cylinder also appeared at some point. Bob posted this information on the widely-read RC Groups forum (Vintage Glow Engines thread,  The cited reference is the only one that I've ever seen in relation to this model, and I've never encountered another example at either first or second hand. It thus appears to be vanishingly rare - perhaps a prototype? However, its undoubted existence deserves our notice. The fact that the illustrated box contained two engines confirms that more than one example was made.

The cited reference is the only one that I've ever seen in relation to this model, and I've never encountered another example at either first or second hand. It thus appears to be vanishingly rare - perhaps a prototype? However, its undoubted existence deserves our notice. The fact that the illustrated box contained two engines confirms that more than one example was made.  In 2023 I was fortunate enough to acquire my own example of the BOMA 150. This opportunity was provided by my good New Zealand mate Dean Clarke. As many readers will know, Dean produces a number of outstanding engines through his

In 2023 I was fortunate enough to acquire my own example of the BOMA 150. This opportunity was provided by my good New Zealand mate Dean Clarke. As many readers will know, Dean produces a number of outstanding engines through his  been. The backplate was retained solely by being "wedged" by the heads of the two screws. This discovery prompted me to go back and review all of the images of this engine that I had accumulated during the course of my research. Without exception, all of them exhibited the same odd feature! Check the images for yourself .......

been. The backplate was retained solely by being "wedged" by the heads of the two screws. This discovery prompted me to go back and review all of the images of this engine that I had accumulated during the course of my research. Without exception, all of them exhibited the same odd feature! Check the images for yourself .......

Subsequent to the original publication of this article, I was fortunate enough to acquire an example of the T.S. 35 in seemingly almost unrun condition. Interestingly enough, this bore the serial number 1663 stamped onto the outer end of the left-hand mounting lug. Taking a closer look at the available images of other examples, I confirmed that all of these engines appear to have borne a 4-digit serial number at that location. None of the other numbers was decipherable with any certainty, while Sten never recorded the numbers on the examples that passed through his hands. I'm therefore unable to draw any conclusions regarding the pattern of these numbers and the implied production figures.

Subsequent to the original publication of this article, I was fortunate enough to acquire an example of the T.S. 35 in seemingly almost unrun condition. Interestingly enough, this bore the serial number 1663 stamped onto the outer end of the left-hand mounting lug. Taking a closer look at the available images of other examples, I confirmed that all of these engines appear to have borne a 4-digit serial number at that location. None of the other numbers was decipherable with any certainty, while Sten never recorded the numbers on the examples that passed through his hands. I'm therefore unable to draw any conclusions regarding the pattern of these numbers and the implied production figures.

Naturally, Sten was very happy to have an Indonesian engine in his collection at last, as well as a group of very attractive swap objects! However, the sole such engine was the T.S. 35 - he had been too late to acquire an example of the BOMA 150 …….. or so it seemed!

Naturally, Sten was very happy to have an Indonesian engine in his collection at last, as well as a group of very attractive swap objects! However, the sole such engine was the T.S. 35 - he had been too late to acquire an example of the BOMA 150 …….. or so it seemed!  Much later, Sten learned that there had been widespread

Much later, Sten learned that there had been widespread