|

|

The Ercolino 2 cc Diesel Text and Images By Maris Dislers

Allan Laycock had sent a box of various model engines for me to “play with” and the one for this report rather stood out in that company. It was large, of vintage type and only vaguely familiar. It was eventually identified as a 2 cc Ercolino – one of those enigmatic 1940’s Italian Dyno copies. One reference puts the Ercolino back to 1943, which is entirely possible.

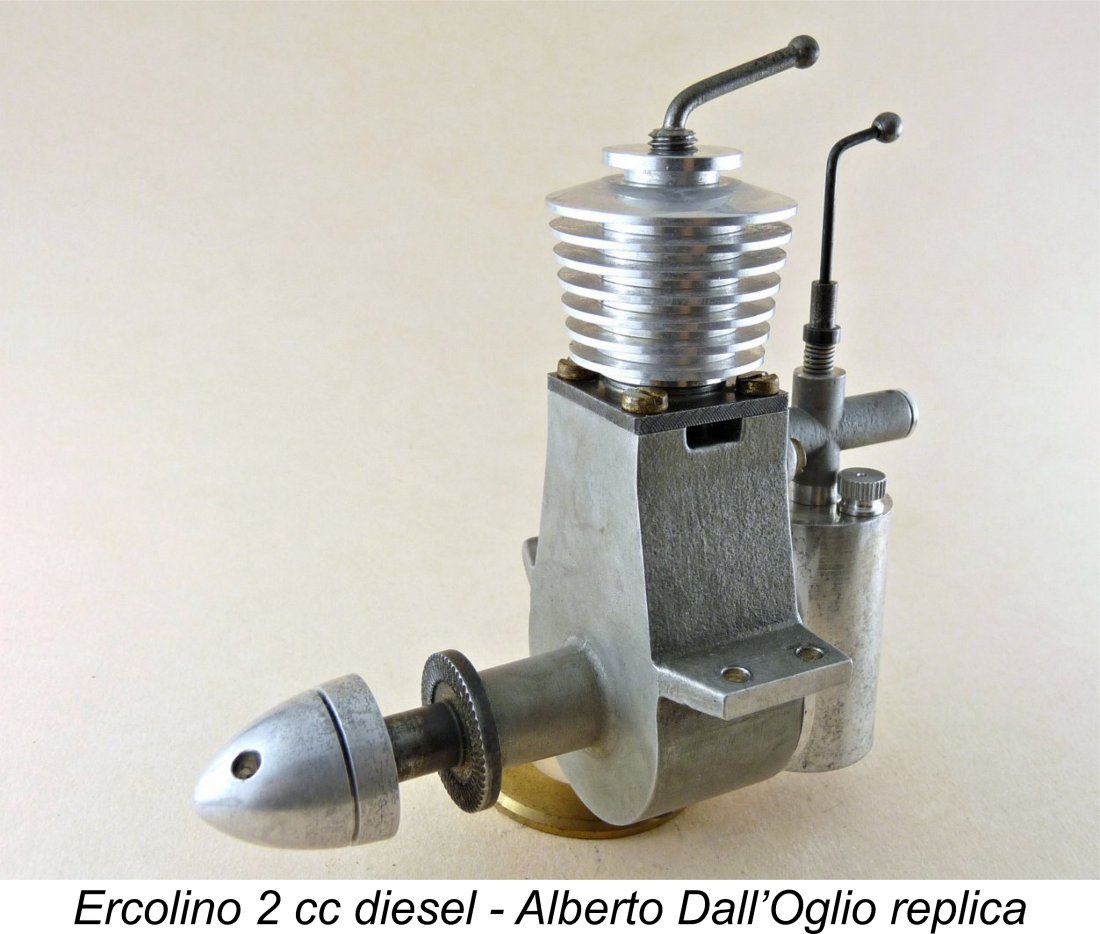

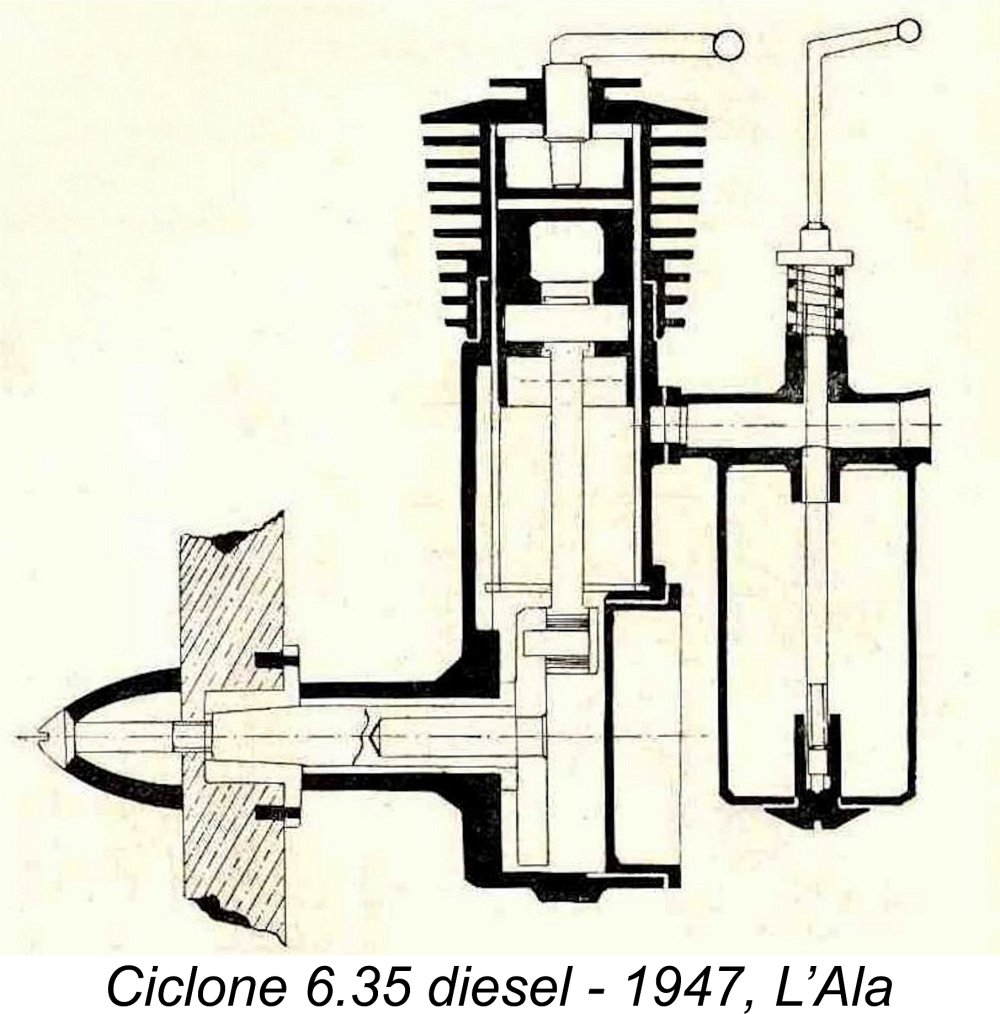

A little more research confirmed that Allan’s engine is a replica made in 1999 by engine maestro Alberto Dall’Oglio in Vicenza, north-eastern Italy. Alberto is better known for his superb AD 15 F1C and AD 06 F1J free flight competition engines. It seems that he gave up making those models, “retiring” to building small numbers of replicas of earlier prototype engines that took his fancy. Alberto’s replica Ercolino was p The Ercolino has as many differences as similarities when compared against the cutaway diagram of the larger Ciclone extracted from the 1947 L’Ala article. However, it is presumably based on a genuine original example. The quality of workmanship is outstanding. All fits are superb, especially the piston/cylinder which will hold compression without the aid of any oil but is not tight. The cylinder bore has a very low taper, so the piston skirt is “barrelled” (10 microns smaller in its upper and lower portions) both to reduce friction and to wedge oil into the sealing area when running. The design generally follows that of the Dyno, with nominal 12 mm bore and 18 mm stroke for a swept volume of a whisker over 2 cc. This of course explains its size and bulk. The engine weighs 170 grams (6 oz). It is built around a substantial monobloc aluminium crankcase with beam mounting lugs set well above the crankshaft axis. The crankcase drain screw at bottom of the casting is a real period feature.

Cylinder port timing is less conservative than the Dyno’s 100 degrees intake and transfer, 130 degrees exhaust. We measured 125 degrees intake, 120 degrees transfer and 130 degrees exhaust. Also notable is the 8 mm2 effective choke area – very generous for a slow-revving engine of this displacement.

Performance testing was done using a traditional equal parts ether/kerosene/castor oil fuel with no ignition improver. The engine evidently liked this brew. Starting was so easy that you’d wonder why they invented electric starters, but suction was poor, giving false starts despite a wide-open needle setting. We resorted to part-choking with a finger to speed up air flow past the jet and provide a richer mixture as required, while the needle spun uselessly around the place – the little coil spring was much too short to keep it still when wide open. This had to be maintained until the engine was running at high speed, where control became only just OK.

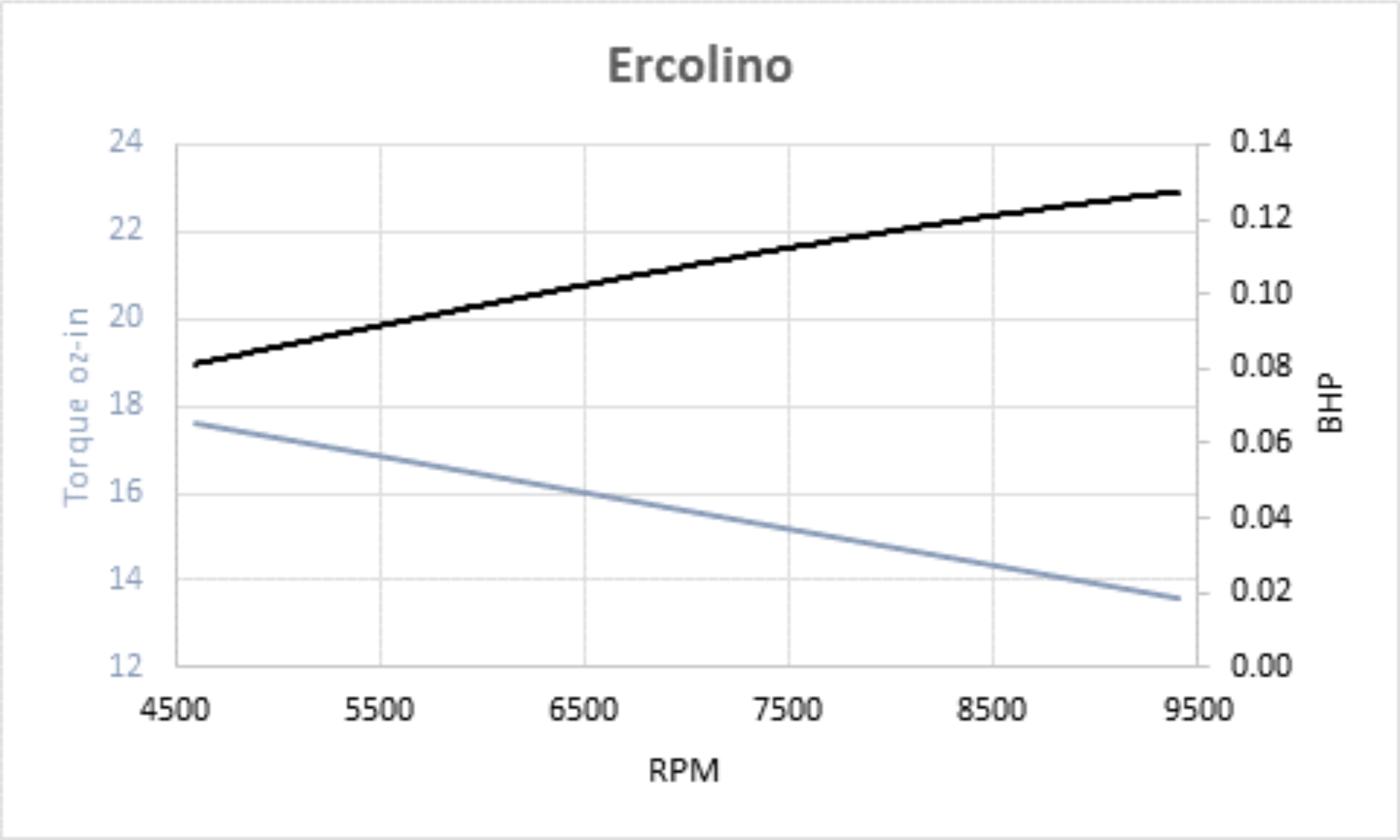

With this small modification, the engine was a real pleasure to operate. Balancing compression and mixture controls permitted any desired speed to be dialled in, down to tick-over just above 2,000 RPM. Much like a Mills 1.3, which is a better-known example of the same design approach. The ball ends on the needle and compression screw really do feel nice in operation. Vibration is kept in check reasonably well, yet there was enough with some propellers to explain the absent screw-in tank filler cap. I made a replica, which does need to be nipped up tight. It’s a bit fiddly to remove and reinstall – a screwdriver slot would be an improvement. First generation diesels of this displacement were typically expected to give maximum flight performance when loaded to around 6,000 rpm. A contemporary German performance curve for the Dyno shows its power peaking at around that speed for a little over 0.1 BHP. That might be a reasonable starting point for the Ercolino, but its real merits showed with lighter loads right up to 9,000+ rpm, at which point it hinted at needing ignition improver for smooth higher-speed running. Using a doped fuel and a light propeller load would very likely show its full potential, with that generous choke area allowing full design potential. Something for another day when Allan’s engine is fully run in. For the record, we measured a little over 0.12 BHP between 8,500 and 9,300 RPM on straight fuel, with a likely rapid drop-off thereafter. Maximum torque of 17.5 oz-in was indicated by our 12x6 propeller at 4,600 rpm. Torque and power trends were virtually linear, so that propeller choice in the usable speed range depends on the desired torque and power balance for the intended model, unlike many of its general type that need just the right propeller to shine.

We hope that you’ve enjoyed this look at a fine replica of a pioneering Italian classic! ___________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia First published December 2021 |

|

| |

Italian modellers were clearly impressed by the two Dyno compression ignition “diesel” engines which showed up at the 1942 National Championships held that year at the town of Asiago in northern Italy. This was their first sight of this new technology from Switzerland. Despite the vicissitudes of wartime, Dyno-inspired engines were soon popping up in various Italian locations. Surviving examples of these early Italian diesels are now much prized, leading to a number of replicas being produced for current cognoscenti.

Italian modellers were clearly impressed by the two Dyno compression ignition “diesel” engines which showed up at the 1942 National Championships held that year at the town of Asiago in northern Italy. This was their first sight of this new technology from Switzerland. Despite the vicissitudes of wartime, Dyno-inspired engines were soon popping up in various Italian locations. Surviving examples of these early Italian diesels are now much prized, leading to a number of replicas being produced for current cognoscenti.

A Dyno-style porting arrangement is featured, with front transfer, opposed side exhausts and piston-controlled induction port at the rear. The steel cylinder is a sliding fit into the crankcase, being retained by four screws through the location flange located above exhaust height. The aluminium alloy cooling jacket screws over the externally-threaded upper cylinder. The engine features a composite piston consisting of a hardened cast iron shell threading over an

A Dyno-style porting arrangement is featured, with front transfer, opposed side exhausts and piston-controlled induction port at the rear. The steel cylinder is a sliding fit into the crankcase, being retained by four screws through the location flange located above exhaust height. The aluminium alloy cooling jacket screws over the externally-threaded upper cylinder. The engine features a composite piston consisting of a hardened cast iron shell threading over an

The unusually deep suspended fuel tank has a fuel capacity of around 11 ml. This provides a very generous run time for a free flight model, with no facility for cut-off. The unusually deep tank requires that the engine develop decent suction to avoid excessive mixture strength variation as the fuel level goes down.

The unusually deep suspended fuel tank has a fuel capacity of around 11 ml. This provides a very generous run time for a free flight model, with no facility for cut-off. The unusually deep tank requires that the engine develop decent suction to avoid excessive mixture strength variation as the fuel level goes down. I machined an insert with a 2.5 mm central hole terminating a little before the needle and jet position. This component can be seen in the underside view presented earlier as well as in the image at the left. By my calculation, the resulting 4.9 mm

I machined an insert with a 2.5 mm central hole terminating a little before the needle and jet position. This component can be seen in the underside view presented earlier as well as in the image at the left. By my calculation, the resulting 4.9 mm