|

|

The VEGA Four-Stroke Engines

Although I’m not one of the fortunate owners of a VEGA engine, I found the range sufficiently interesting that I saw considerable merit in Don’s suggestion. I therefore responded positively to Don, advising him to finalize his recollections and pass them along to me together with any relevant images that he retained. While awaiting receipt of Don’s input, I did a bit of Web searching on my own, finding that my late mate Ron Chernich had beaten me into the field by publishing a detailed review of the VEGA 30 in January 2008 on his fascinating but now frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. I quickly realized that I had a very good fit here! Ron’s technical comments combined perfectly with Don’s personal recollections to present as complete a picture of the VEGA story as we’re ever likely to get! Since Ron’s half of the article was drawn from the now-frozen and slowly deteriorating pages of MEN, I’ve categorized this compilation as an MEN transfer article. However, Don’s recollections add a further dimension which was not part of the MEN article, hence adding considerable value. Rather than mix the two accounts up, I’ve elected to present them in sequence. I’ll begin with Ron Chernich’s comments. Over to you, mate - how nice to be able to say that once more!! The VEGA 30 by Ron Chernich

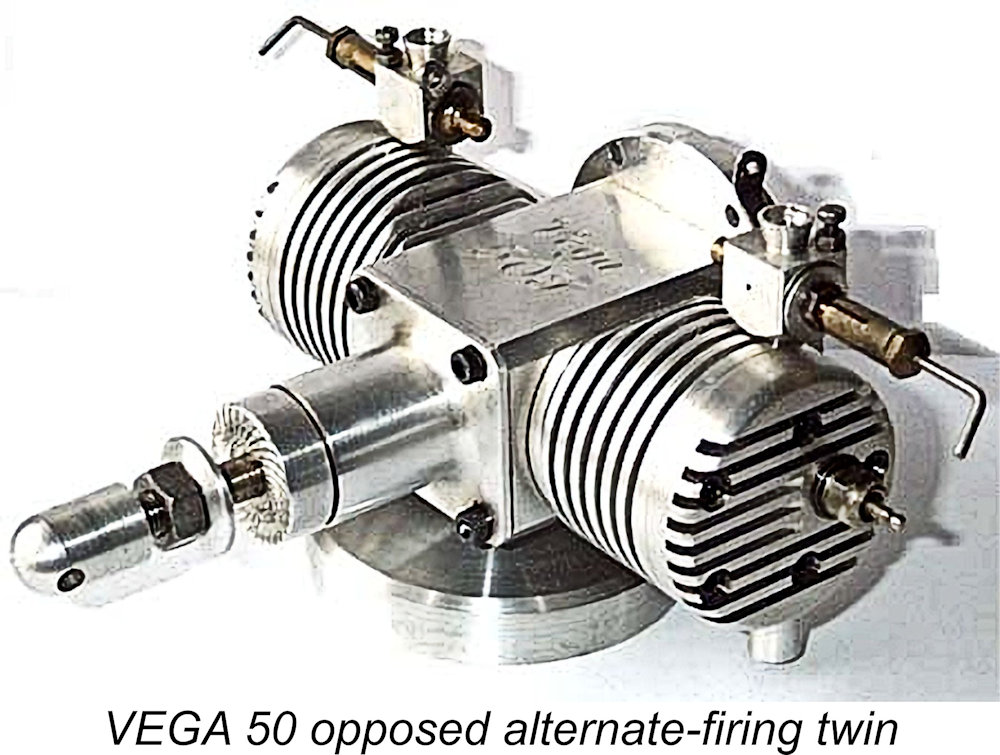

The initial models were all side-valve four-strokes typified by the .30 cuin. model reviewed in detail here. The range also included a .61, a .25 and a horizontally-opposed alternate firing twin using two .25 cylinders to give .50 cuin. total displacement. Towards the end, .61 and .91 cuin. displacement overhead valve (OHV) prototypes were constructed, although they did not reach production. There was also a massive 180 twin built around two .91 cylinders. All models are comparatively rare today, but they do appear occasionally as sought-after collectables. The following table summarizes the range as I understand it. The engines designated as T models are alternate-firing horizontally-opposed twins.

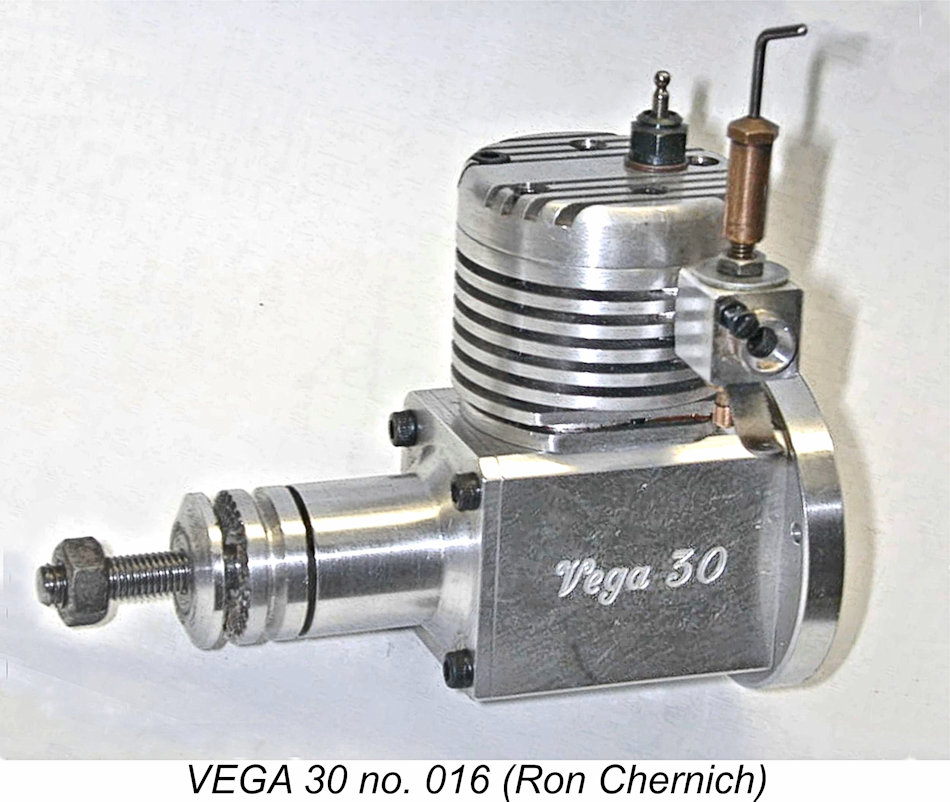

Each model was offered in two versions at the buyer’s option. On Type "A", the carburettor and exhaust were oriented to the rear of the engine, while Type "B" placed them on the side of the head. The illustrated 30 is a Type "B" model. Harbone’s promotional material stressed the enclosed valve gear, freedom from tappet adjustment, the compact size, "solid" (bar-stock) construction, quiet running and ability to idle for long periods with instant throttle response. The VEGA 30 - Construction

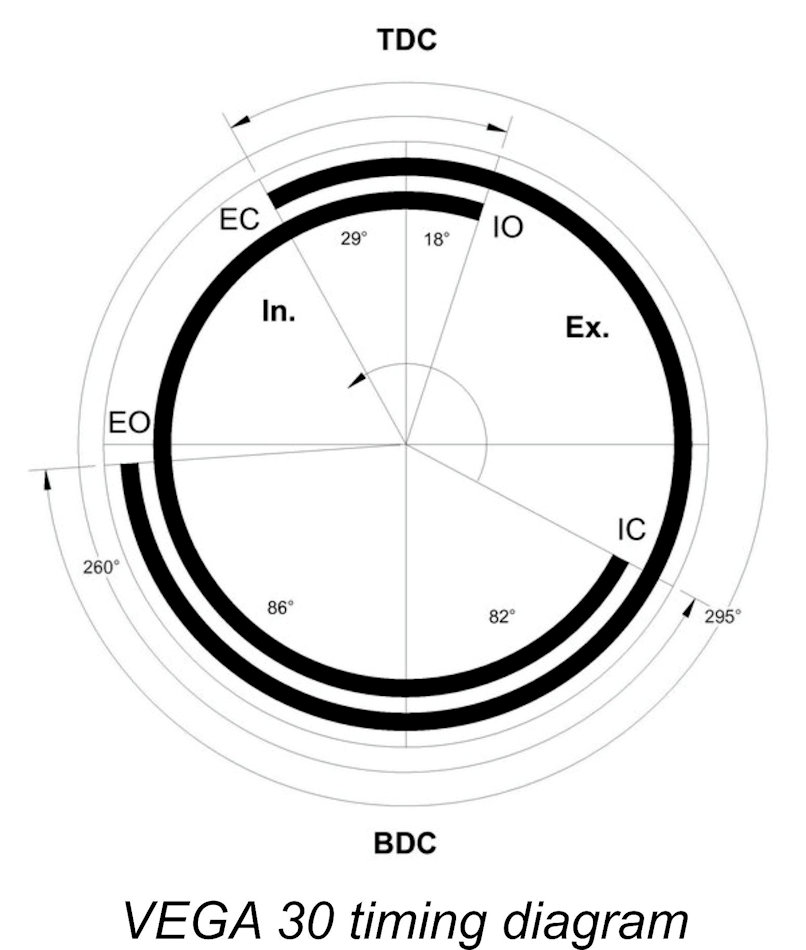

As is normal in small four-strokes, the valves seat directly onto the aluminum cylinder jacket - there are no cages. The exhaust and inlet stubs are secured by grub screws, located according to customer request in “A” or “B” configurations as mentioned earlier. The head has a Ricardo-style chamber. In a departure from convention, the glow-plug is located midway between inlet and exhaust. Normal side-valve practice would place it at the coolest point, over the inlet valve. The head and cylinder assembly are secured to the crankcase by five long cap-head screws. In place of a gasket, the VEGA uses what The valve event timing of the sample (serial number 016) was checked using a degree wheel and a plunger-type dial indicator. Rendered in the Westbury-style timing diagram seen here, the results As a final comment on the valve train, it’s worth recalling that the gear teeth are cut directly into the three shafts. They are 48DP (Diametrical Pitch) with 12 teeth on the crankshaft follower and 24 on the camshafts. This means that the smallest incremental timing shift that can be made by slipping a tooth one way or the other is 15°. This is a big change timing wise, so there is really only one way that the parts can be assembled for sane valve timing. More significant, the teeth have to be cut very precisely in relation to the cam lobes, adding yet more effort and expense to manufacture. Conclusion

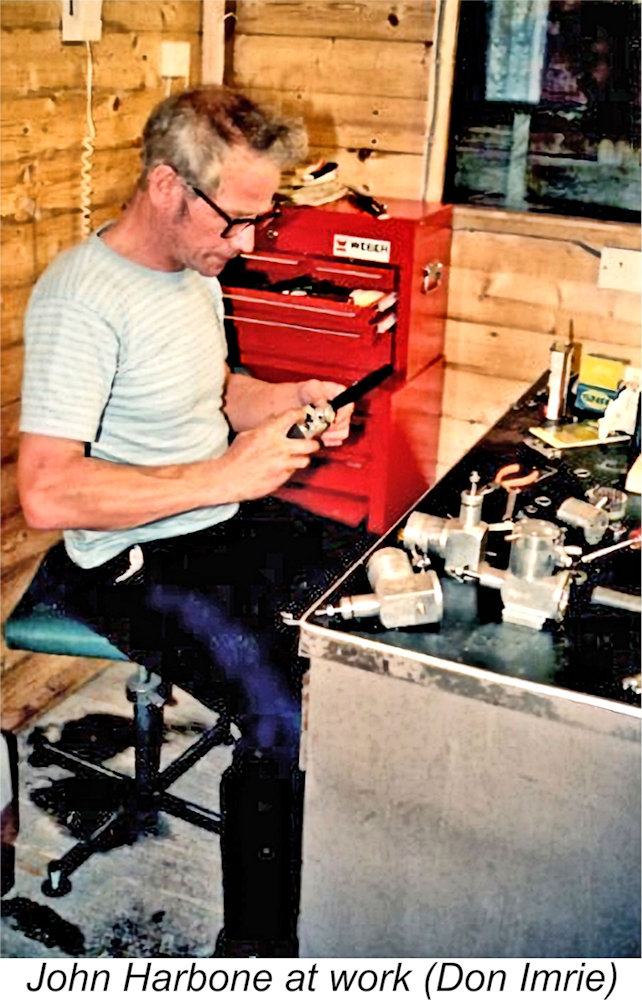

An article by John Goodall which appeared in the pages of the now-defunct “Model Engine World” (MEW) magazine stated that the VEGA series were made using CNC equipment. This is certainly true of the later examples made by others, but Don Imrie’s workshop visits (see below) and other sources identify John’s own equipment as Colchester capstan and Myford centre lathes plus a small milling machine and several grinders. If anything, this makes the number produced, relatively small as it is, all the more remarkable. John Goodall was presumably speaking about the later examples which were constructed by others after John Harbone sold the designs in the mid 1990’s.

A search through all the British model magazines spanning five years from 1988 onwards found only a single reference to the VEGA engines, and even that was peripheral, showing a magneto attached to one by a third party. Although John Harbone did not advertise the range widely, he did run a booth at the 1989 British Nationals where he distributed flyers and demonstrated the VEGA’s. As the engines were essentially hand-made by him working alone, this limited promotion plus word of mouth apparently provided all the business that he could handle.

To really appreciate the VEGA, it needs to be pulled apart and viewed with an engineer's eye. This reveals a well thought-out and very well-made engine. That it would be no power-house is inevitable; no side-valve engine could be. But high performance was not the designer's objective, so the VEGA’s relatively low power output should not be viewed as any basis for criticism. It is unfortunate that the designer chose, or was forced by circumstances, to sell the design rights. This is an engine that could be built easily in a modest home shop and would be a delight to the builder. And even if it is no power-house, the skin on the rice pudding would probably come out second-best! _____________________ This concludes Ron’s technical review of the VEGA 30. Time now to turn the pen over to Don Imrie for his personal experiences with the VEGA range. Personal Experiences with the VEGA Engines By Don Imrie

As of 1989, although resident in my native Scotland, I was working for a company based in Bristol, having to attend monthly meetings there. Getting to and from these meetings involved driving past Birmingham both coming and going, so it was fairly easy for me to visit John in his workshop at 41 Frances Road, Cotteridge, Birmingham. I took full advantage of these opportunities, benefiting from Lyn's hospitality, which was second to none - I enjoyed a few fine meals there en route between Bristol and Scotland! Lyn was always completely supportive of John's work.

I used the term “unique” because although there were many different four-stroke designs on the market by the mid-1980’s, only John’s VEGA units featured the side-valve layout. Although less powerful in terms of sheer power/speed, these engines would turn a very large prop economically and would have been ideal for scale applications. John had designed a very clever engine test rig which had a water-filled silencer. This allowed him to run engines at any time, unheard by the neighbours - a clever idea since John and Lyn lived in a built-up area. Being manufactured in Britain, of course, John’s side-valve designs suffered from that old British malady of technological short-sightedness, generally expressed by the knee-jerk verdict "It will never work". Other very clever British engineers such as Dr. Barnes Wallis, Sir Stanley Hooper, R. J. Mitchell, Sir Frank Whittle and many others laboured under the same handicap, taking ages to persuade others that they had a very good and eminently workable idea!

A notable characteristic of John’s engines was their remarkably low noise levels. I well remember once whilst flying my VEGA-powered model having to ask a couple of nearby clubmates to stop talking for a moment so I could hear if the airborne VEGA was still running – it was that quiet, and this was without any silencer at all!

John used different carburettors, mainly based upon availability as I understood it – O.S., Meteor and then P.A.W. types. My late .61 sports a Super Tigre carburettor, but I'm not sure if this was standard on the later engines. John continued to offer these engines into the mid-1990’s. I understand that the design rights were subsequently sold, but if so I have no knowledge of the buyer’s identity, nor do I know how many if any were produced following the sale, and by whom. I read somewhere that John produced 100 of each size before selling the rights on, but this seems too clinical a number to be credible in the real world. If any reader knows more, please get in touch with Adrian!

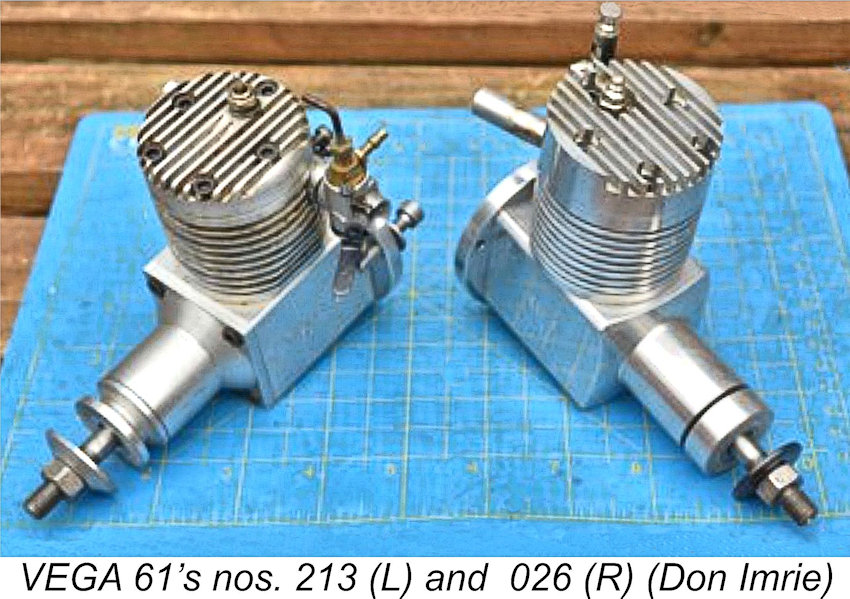

Another regret was in letting some of my VEGA's go, but hey - I still have a few left, and I am about to put a .61 into a sport model which will provoke many questions when I turn up at the club field with it! The engines in the accompanying photographs are doubtless as rare as hen's teeth by now. This is a great pity, but at least those of us lucky enough to have a VEGA or two will be enjoying these lovely pieces of fine model engineering for some time to come. Some very original and, I'm proud to say, British thinking went into these engines, along with a great measure of hands-on model engineering talent. John Harbone deserves his place alongside the likes of John Oliver, Ken Bedford, Gerry Jackman, Neil Tidey and the rest. We owe them all a great deal of gratitude for all their hard work, and will always be in their debt. Footnote Some of Don’s questions can be answered at this point. It was apparently ill-health that forced John Harbone to cease work on the VEGA range in around 1994 and relocate to a new residence. The rights, tooling and designs were sold to Phil Ramsey of Ramsey Engineering, the idea being to continue the manufacture of VEGA’s using CNC technology. However, this arrangement was quickly terminated due to severe quality issues and un-approved modifications, but not before examples of the .61 and .91, now known as "Andy" engines, were distributed. All of these have serial numbers greater than 100 (the Harbone engines have sequential serial numbers starting at 001, and he never reached 100). Some of the latter-day engines were OK, but others performed so badly that they had to be replaced free of charge with "genuine" VEGA’s. According to John Harbone's long-time friend and colleague Ken Humphries, John was still on deck as of 2005 and remained in good spirits despite having then recently suffered two heart attacks. At that time, Phil Ramsey still owned the VEGA project but had no intention of attempting a resurrection at that time. However, an individual named Luke Daniels of 2D Engineering was then attempting to reach an agreement with Ramsey which would have allowed the resumption of VEGA production by 2D Engineering. Doug Campbell was privy to some of the relevant discussions, and he advised that nothing ever came of them. Apart from the serial numbers, the CNC engines can be instantly identified by the curved inlet and exhaust pipes. Collectors should take note and be aware that these engines are of lesser value in comparison to the individually hand-crafted engines made by John Harbone personally. ___________________________ This compilation © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada Individual contributing authors' rights reserved First published July 2023

|

||||

| |

In March 2023 I was approached by my good friend and colleague Don Imrie of Scotland, who wished to share his personal recollections of a little-known but nonetheless noteworthy model engine range from England – the VEGA four-stroke units from Birmingham. As some of you may know, Don is a notable figure in Scottish aeromodelling, having been prominent in the movement for many years and having served for a time as Chairman of the

In March 2023 I was approached by my good friend and colleague Don Imrie of Scotland, who wished to share his personal recollections of a little-known but nonetheless noteworthy model engine range from England – the VEGA four-stroke units from Birmingham. As some of you may know, Don is a notable figure in Scottish aeromodelling, having been prominent in the movement for many years and having served for a time as Chairman of the  The VEGA range was designed and built from the late 1980's through to the mid 1990's by John Harbone of Birmingham, England. His intent was to provide a range of engines for sport or scale flying that would be both quiet and reliable. The VEGA engines that he produced were manufactured in small quantities from bar-stock until ill-health forced an end to the venture. The rights to all the designs were sold on with the intention that they would continue in production, but sadly this did not eventuate.

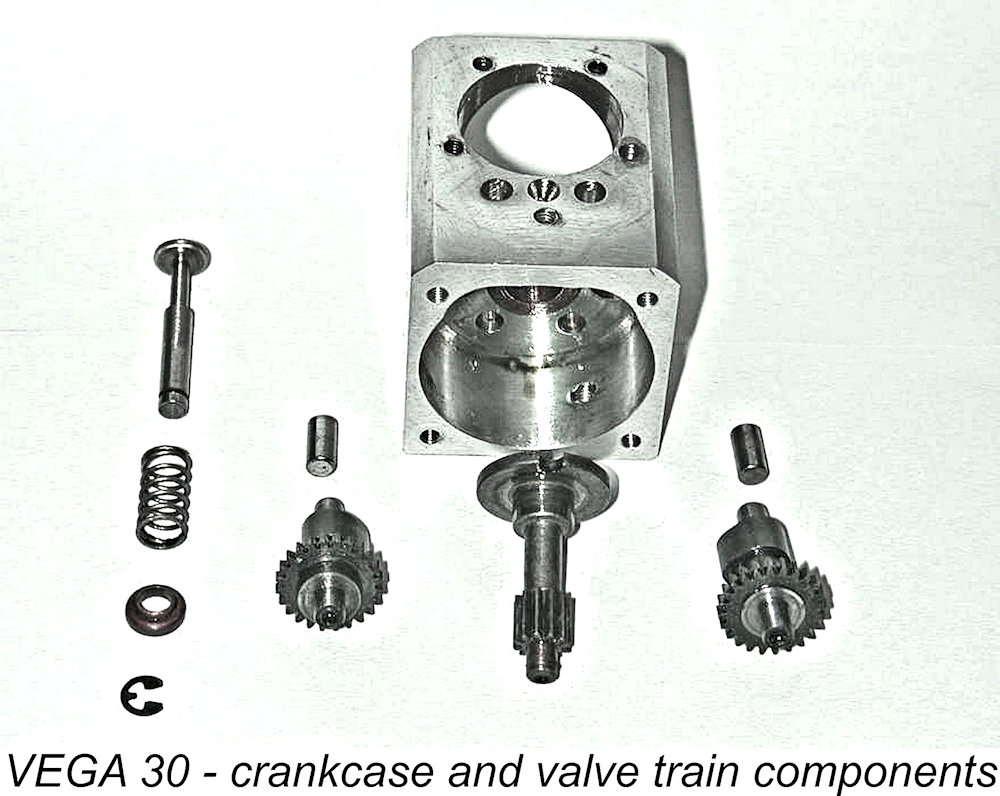

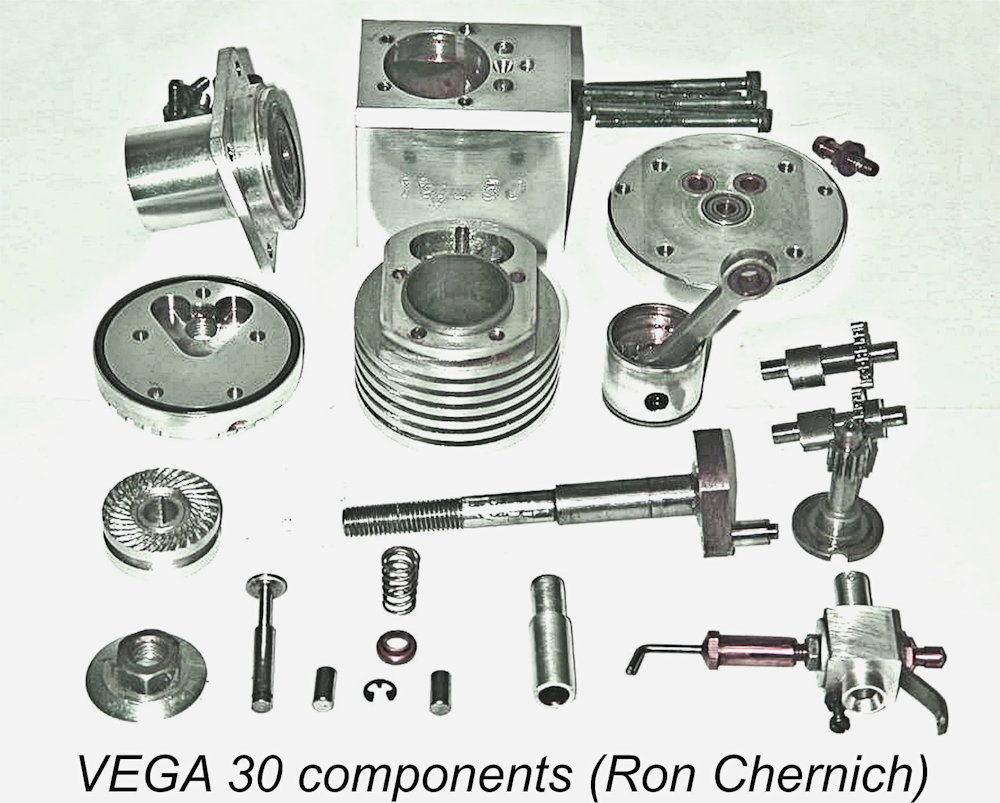

The VEGA range was designed and built from the late 1980's through to the mid 1990's by John Harbone of Birmingham, England. His intent was to provide a range of engines for sport or scale flying that would be both quiet and reliable. The VEGA engines that he produced were manufactured in small quantities from bar-stock until ill-health forced an end to the venture. The rights to all the designs were sold on with the intention that they would continue in production, but sadly this did not eventuate. The design is really quite elegant. A conventional overhung crankshaft rides in twin ball bearings housed in a turned nose piece. The nose piece is secured with four screws to a square section bar that has been blind-bored from both ends with the partition between the bores providing support for a follower shaft that engages with the crankpin, hence turning at engine speed. The follower shaft has a long spur gear to drive the cams with the requisite 2:1 reduction. It is supported in a ball-race fitted to the engine’s backplate that doubles as the bulkhead mounting flange.

The design is really quite elegant. A conventional overhung crankshaft rides in twin ball bearings housed in a turned nose piece. The nose piece is secured with four screws to a square section bar that has been blind-bored from both ends with the partition between the bores providing support for a follower shaft that engages with the crankpin, hence turning at engine speed. The follower shaft has a long spur gear to drive the cams with the requisite 2:1 reduction. It is supported in a ball-race fitted to the engine’s backplate that doubles as the bulkhead mounting flange. Twin camshafts are used, arranged so that the gears overlap (i.e., they are staggered fore and aft) which makes for lateral compactness at the expense of a little extra length. These shafts ride in oilite bushings pressed into the backplate, but run un-bushed in the central partition where they are most heavily loaded. The cams are positioned to sit side by side to actuate twin solid tappets, the latter being 4 mm x 8 mm solid steel rollers. The rear section of the case carries a screwed-in breather tube.

Twin camshafts are used, arranged so that the gears overlap (i.e., they are staggered fore and aft) which makes for lateral compactness at the expense of a little extra length. These shafts ride in oilite bushings pressed into the backplate, but run un-bushed in the central partition where they are most heavily loaded. The cams are positioned to sit side by side to actuate twin solid tappets, the latter being 4 mm x 8 mm solid steel rollers. The rear section of the case carries a screwed-in breather tube. The lubrication system is open to interpretation. The source of lubricant is clearly the oil in the fuel, some of which will blow by the piston ring as the engine runs. What looks like a countersunk hole between the tappets could allow oil leaking past the valve stems to drain into the gear-case. Generous holes connect the gear-case with the main crankcase cavity. On the other hand, lubricant blow-by from the ring could pass in the other direction. Doubtless, one or the other does the job, and no trapped pockets exist.

The lubrication system is open to interpretation. The source of lubricant is clearly the oil in the fuel, some of which will blow by the piston ring as the engine runs. What looks like a countersunk hole between the tappets could allow oil leaking past the valve stems to drain into the gear-case. Generous holes connect the gear-case with the main crankcase cavity. On the other hand, lubricant blow-by from the ring could pass in the other direction. Doubtless, one or the other does the job, and no trapped pockets exist. The crankshaft is counterbalanced in the usual way. It features a pressed-in crankpin made from a 5 mm roller which rides in an oilite bushing in the big end of the con-rod. The cams on the other hand are machined entirely from the solid, including the gears (48DP), as can be seen from the blanks in this photo of bits obtained from the "receiver" of the VEGA project by Eric Offen. The cams appear to have been formed using a polygon box tool. The camshaft journals are very well finished - possibly ground - then nitrided. Very high quality for what was essentially a hand-made engine.

The crankshaft is counterbalanced in the usual way. It features a pressed-in crankpin made from a 5 mm roller which rides in an oilite bushing in the big end of the con-rod. The cams on the other hand are machined entirely from the solid, including the gears (48DP), as can be seen from the blanks in this photo of bits obtained from the "receiver" of the VEGA project by Eric Offen. The cams appear to have been formed using a polygon box tool. The camshaft journals are very well finished - possibly ground - then nitrided. Very high quality for what was essentially a hand-made engine. The aluminium piston is turned from bar-stock and fitted with a single compression ring. It runs in a cast iron liner that is positioned off-center in a turned alloy cooling jacket, allowing the valves to be fully contained in the aft portion. The valve spring caps are retained by circlips. There is no provision for tappet clearance adjustment apart from the length of the tappets and the valve stems themselves, coupled with the deck and cylinder jacket heights. Given the highly compact

The aluminium piston is turned from bar-stock and fitted with a single compression ring. It runs in a cast iron liner that is positioned off-center in a turned alloy cooling jacket, allowing the valves to be fully contained in the aft portion. The valve spring caps are retained by circlips. There is no provision for tappet clearance adjustment apart from the length of the tappets and the valve stems themselves, coupled with the deck and cylinder jacket heights. Given the highly compact  assembly required by the design, I can see no practical alternative, although this would require very close attention to dimensions, further adding to the cost of manufacture. It also means that the tappets act against the bare ends of the valve stems, which is not exactly ideal.

assembly required by the design, I can see no practical alternative, although this would require very close attention to dimensions, further adding to the cost of manufacture. It also means that the tappets act against the bare ends of the valve stems, which is not exactly ideal.

show a rather early exhaust opening and a late-ish inlet close, but the figures are not awful. There is evidence that the tappets are too small in diameter for the cam profile as there is a distinct "click" as each cam passes the fully open position, caused by the tappet suddenly slapping down onto the cam flank - a clear indication that tangential contact is not being maintained. A purist would condemn this as limiting top speed due to slap-induced valve bounce. But being a side-valve design, I somehow doubt that this is going to be a great problem.

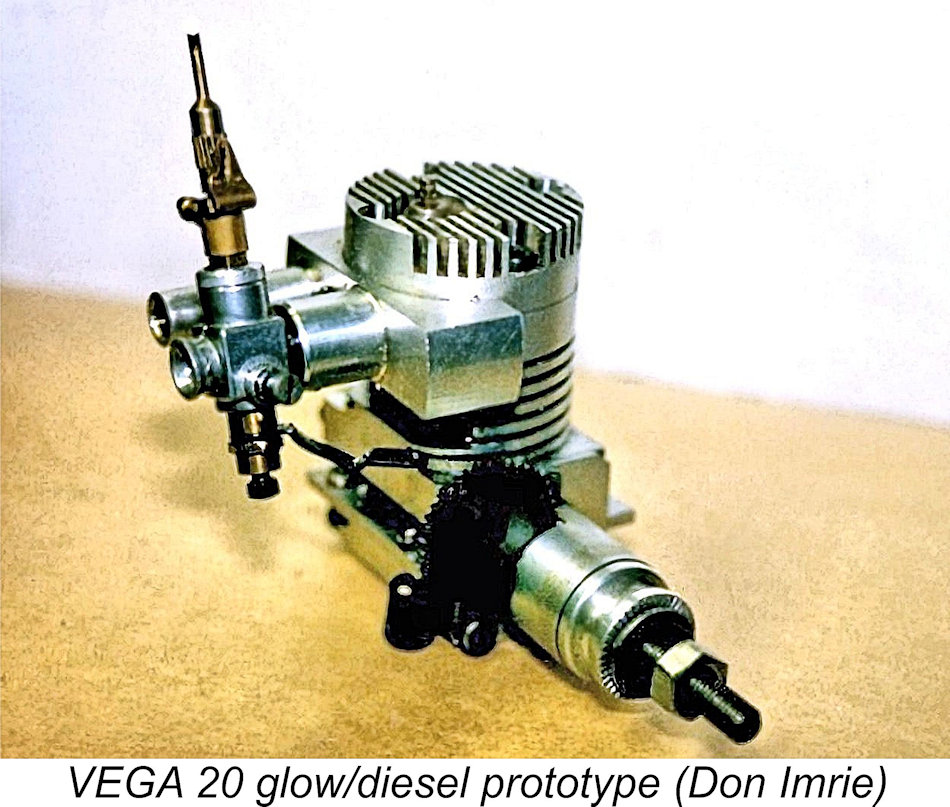

show a rather early exhaust opening and a late-ish inlet close, but the figures are not awful. There is evidence that the tappets are too small in diameter for the cam profile as there is a distinct "click" as each cam passes the fully open position, caused by the tappet suddenly slapping down onto the cam flank - a clear indication that tangential contact is not being maintained. A purist would condemn this as limiting top speed due to slap-induced valve bounce. But being a side-valve design, I somehow doubt that this is going to be a great problem. As well as the OHV prototypes already mentioned, John Harbone's experimental types included a .20 cuin. glow/diesel side-valve model (yes, on the same engine!), and timing belt-driven OHV single and four cylinder in-line engines. There was also a V-twin OHV prototype.

As well as the OHV prototypes already mentioned, John Harbone's experimental types included a .20 cuin. glow/diesel side-valve model (yes, on the same engine!), and timing belt-driven OHV single and four cylinder in-line engines. There was also a V-twin OHV prototype.  Goodall also stated correctly that although they were very quiet, the VEGA side-valve engines gained a reputation for not being very powerful - scarcely a surprising trait given their type. This would certainly be an appropriate characterization if the engines were compared with Neil Tidy’s

Goodall also stated correctly that although they were very quiet, the VEGA side-valve engines gained a reputation for not being very powerful - scarcely a surprising trait given their type. This would certainly be an appropriate characterization if the engines were compared with Neil Tidy’s  My rather subjective impression is that the VEGA engines have a distinctly "home-made" look due to their very simple outward appearance, coupled with their square section crankcase and bulkhead mounting disk. The Lasers on the other hand - unfair comparison though it may be - have conventional beam mounts and undeniably do look more "professional".

My rather subjective impression is that the VEGA engines have a distinctly "home-made" look due to their very simple outward appearance, coupled with their square section crankcase and bulkhead mounting disk. The Lasers on the other hand - unfair comparison though it may be - have conventional beam mounts and undeniably do look more "professional". The following is a brief resume of my personal involvement with a fascinating model engine design and with two of the most decent and really nice people whom I have ever met in many years of meeting folks through this great hobby of ours – Mr. John Harbone, designer and manufacturer of the VEGA four-stroke engines, and his lovely wife Lyn.

The following is a brief resume of my personal involvement with a fascinating model engine design and with two of the most decent and really nice people whom I have ever met in many years of meeting folks through this great hobby of ours – Mr. John Harbone, designer and manufacturer of the VEGA four-stroke engines, and his lovely wife Lyn.  John's workshop machinery would not be considered “state of the art” today. I seem to recall that he had both Colchester Student and Myford lathes; a small milling machine; a couple of grinders; and a paraffin wash. This equipment was quite adequate for the small-scale production of John’s range of very unique four-stroke engines which were marketed under the VEGA brand-name.

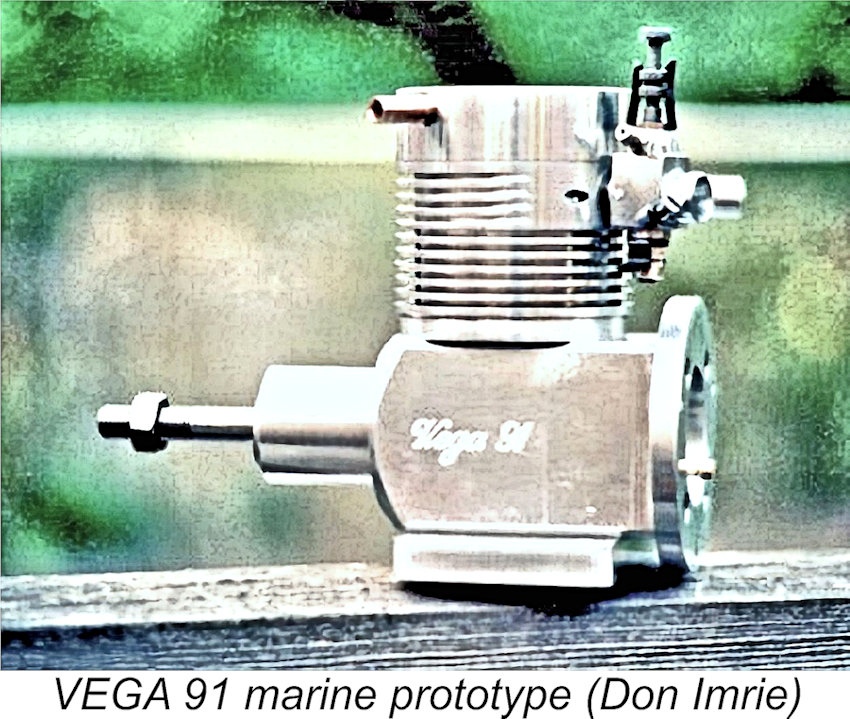

John's workshop machinery would not be considered “state of the art” today. I seem to recall that he had both Colchester Student and Myford lathes; a small milling machine; a couple of grinders; and a paraffin wash. This equipment was quite adequate for the small-scale production of John’s range of very unique four-stroke engines which were marketed under the VEGA brand-name.  John began by making a number of prototypes, including a .20 size side-valve four-stroke glow/diesel which would run on almost anything, including paraffin! This engine was illustrated earlier in this article. He also had a four-cylinder side-valve prototype as well as OHV twin cylinder and four-cylinder models. There was also a marine version of the .91, although I’m not sure if this was ever actually marketed.

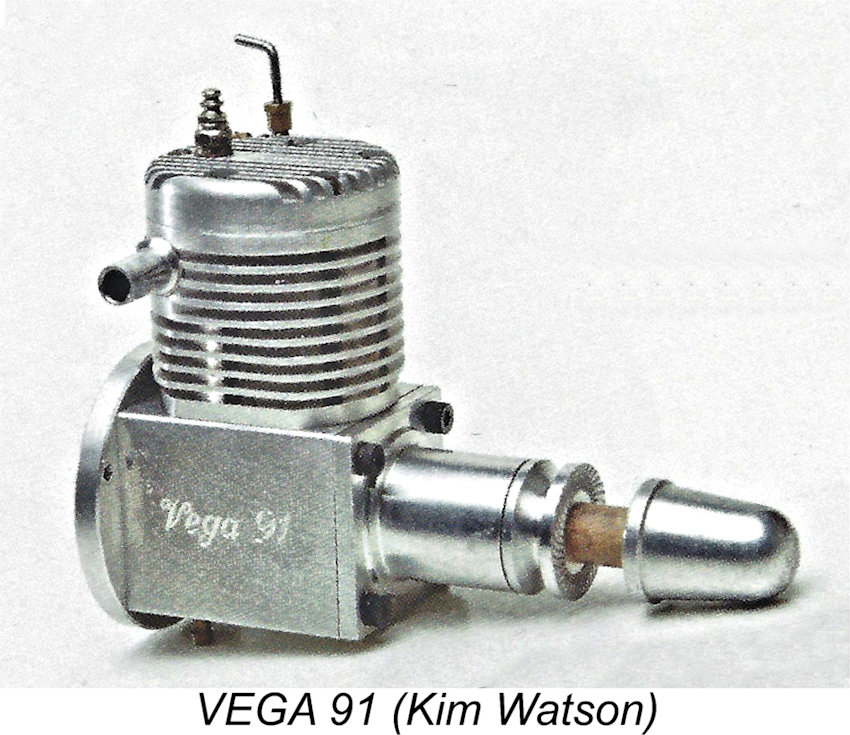

John began by making a number of prototypes, including a .20 size side-valve four-stroke glow/diesel which would run on almost anything, including paraffin! This engine was illustrated earlier in this article. He also had a four-cylinder side-valve prototype as well as OHV twin cylinder and four-cylinder models. There was also a marine version of the .91, although I’m not sure if this was ever actually marketed.  My .91 was the first .91 which John made (serial no. 001). It took a bit of persuasion to get him to release this engine to me, as he hadn't quite sorted it out. For one thing, the carburettor became quite hot, causing a few operating problems. John characteristically viewed this as “just another problem to solve”. After reminding me that I had pushed him for the engine, he set about curing it. He was successful, and all subsequent .91's were lovely well-behaved engines. The .91 was about the same height as an average .61 two-stroke engine.

My .91 was the first .91 which John made (serial no. 001). It took a bit of persuasion to get him to release this engine to me, as he hadn't quite sorted it out. For one thing, the carburettor became quite hot, causing a few operating problems. John characteristically viewed this as “just another problem to solve”. After reminding me that I had pushed him for the engine, he set about curing it. He was successful, and all subsequent .91's were lovely well-behaved engines. The .91 was about the same height as an average .61 two-stroke engine.  John’s .25 prototype powered one of my Autopilots for ages and was so frugal that my fuel was in constant danger of “going off!” It came to me without a carburettor, but as I happened to have one from an HP21VT which fitted perfectly, the problem was quickly solved. The prototype was .20 sized, but became the VEGA .25 when put into production. John then put two of these back to back as it were, to produce the lovely little VEGA .50 alternate firing twin which was illustrated earlier. They were all so quiet and very economical - unlike my old Ford 100E with its side-valve four-stroke 1172cc engine which struggled to reach 25 miles to the gallon on a good day!

John’s .25 prototype powered one of my Autopilots for ages and was so frugal that my fuel was in constant danger of “going off!” It came to me without a carburettor, but as I happened to have one from an HP21VT which fitted perfectly, the problem was quickly solved. The prototype was .20 sized, but became the VEGA .25 when put into production. John then put two of these back to back as it were, to produce the lovely little VEGA .50 alternate firing twin which was illustrated earlier. They were all so quiet and very economical - unlike my old Ford 100E with its side-valve four-stroke 1172cc engine which struggled to reach 25 miles to the gallon on a good day!  My main regret is the fact that I subsequently lost touch with John and Lyn. I know that we are all guilty of this far too often, and I did try to find them. However, I was told that they had moved and there was no forwarding address. It’s my hope, even at this late stage, that some reader may be able to add to this story, and perhaps I can be put in touch with this lovely couple once more if they are still around.

My main regret is the fact that I subsequently lost touch with John and Lyn. I know that we are all guilty of this far too often, and I did try to find them. However, I was told that they had moved and there was no forwarding address. It’s my hope, even at this late stage, that some reader may be able to add to this story, and perhaps I can be put in touch with this lovely couple once more if they are still around.