|

|

Operation of twin-plug model glow-plug engines

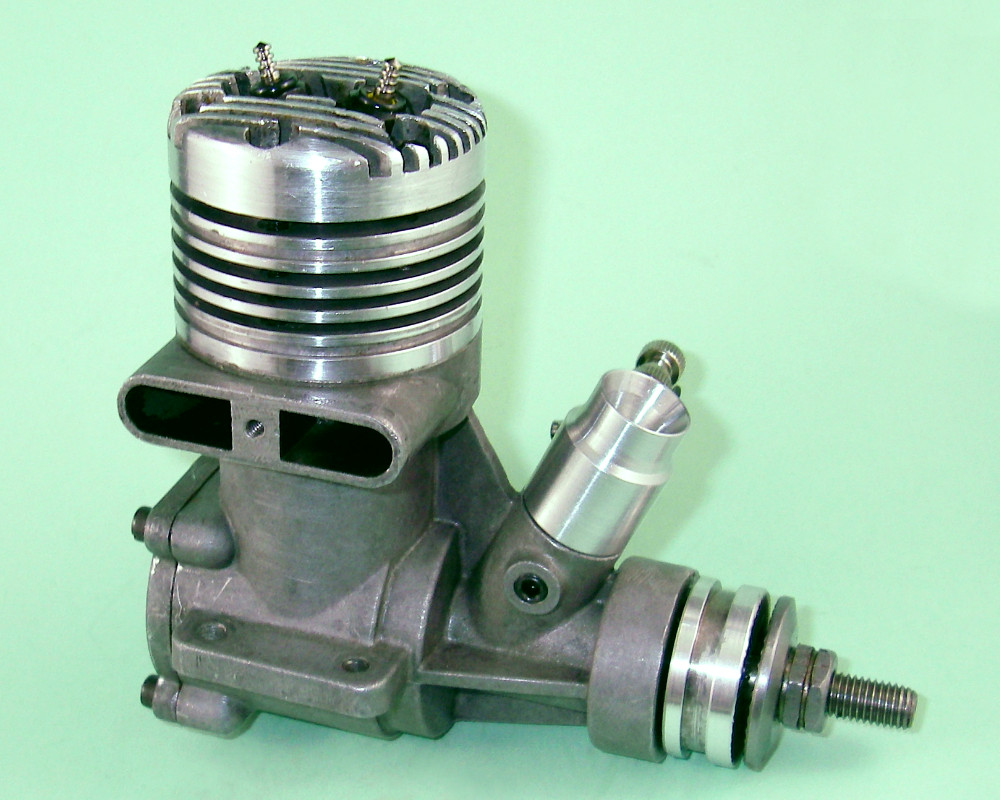

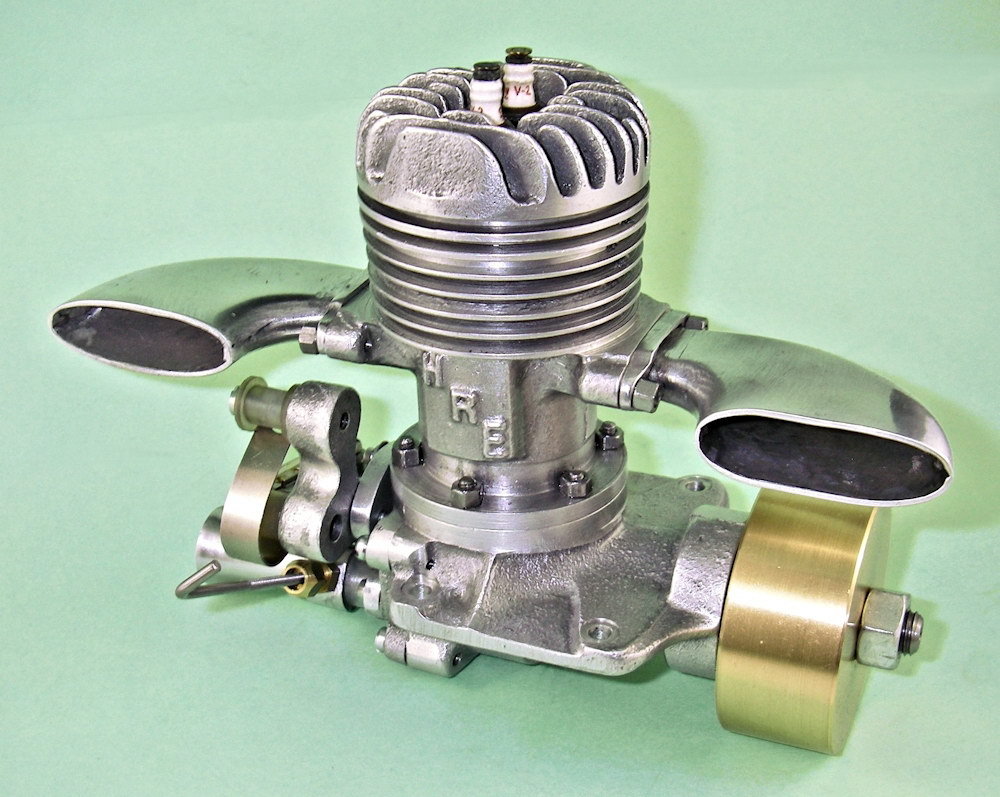

Most model engine aficionados will be aware of the various model glow-plug engines which have been produced over the years with twin-plug heads. Well-known examples include the larger-displacement Merco and Ueda engines of the 1960’s, and there are others. Even during the 1960’s, the twin-plug concept was not new, going back to the spark-ignition era of the 1940’s. The illustrated H.R.E. Special, an Ira Hassad design from 1941, is a case in point. The main objective of the use of twin plugs appears to be to improve the potential power output of a big-bore engine by reducing the maximum flame propagation pathway within the combustion chamber, that is, the maximum distance which the flame has to travel from the ignition source to involve the entire fuel charge once the combustion process has been initiated. Although measurable in micro-seconds, it nonetheless takes time for the flame to travel across the combustion chamber to involve the entire charge, thus maximizing the pressure in the combustion chamber at the start of the power stroke. This time represents a lag in the achievement of complete combustion. The greater the bore, the greater this potential lag. By reducing the time required to achieve complete combustion, more efficient engine operation may be achieved. The use of twin plugs in an R/C engine reportedly also has a tendency to enhance both the dependability of the engine’s idle and its response to a snap opening of the throttle following an extended period of idling. However any such effects are probably minimal, although they may exist. Not being an R/C flier myself, I am not in a position to comment on this aspect of the matter. Now we get to the main subject of this short article! An often-overlooked operational point which seems to apply to all tw The truth of the above observation may be tested by examining the reflected glow through the open exhaust port of an un-muffled engine (wearing hearing protection!) with the engine running at full chat under low-light conditions. After starting and adjusting on one plug, there is an observable ongoing increase in the intensity of the reflected glow when one briefly applies current to the second plug. I’ve observed this myself. A number of people have reported measuring a small but detectable fall-off in performance for a twin-plug engine when only one plug is lit instead of both. However, the cited difference is generally only in the order of a few hundred rpm. As discussed above, any such difference is likely due to the second ignition point reducing the maximum flame propagation time required for the full involvement of the charge of mixture in the combustion process. Objectively speaking, one would expect a modest improvement in performance to result from this, particularly at higher operating speeds.

The engine was repeatedly started on the dud plug and would continue running as long as the electrical current was maintained. However, when the current was removed the engine stopped immediately every time, confirming that the “good” plug had failed to light up on its own. By contrast, when started on the “good” plug the engine would keep running when the current was disconnected. This test appears pretty conclusive. It’s not widely appreciated that the functioning of a glow-plug is not primarily related to simple element temperature. Rather, it depends chiefly upon a self-sustaining catalytic reaction between the methanol in the fuel and the platinum-iridium wire of the plug element. It seems that it’s necessary to achieve a temperature well into the “red heat” range for this reaction to be initiated and to become self-sustaining. The bright glow produced by the application of electrical current to the plug is apparently the only way to ensure that this critical initiation temperature is reached. However, it also appears that once the catalytic reaction is initiated, it becomes self-sustaining regardless of ongoing glow-plug element temperature. This explains why operating an R/C engine at low throttle openings for extended periods, with the attendant major reduction in glow-plug element temperature, does not stop the engine or affect the plug’s ability to resume its normal bright glow when the throttle is opened once more. Another mystery ……..really, the wonder is not that glow-plug ignition works so well but that it works at all!! Anyone owning a twin-plug engine is invited to try his own experiments along the above lines. I’d be most interested to hear of any findings ………. _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, first published January 2015 |

| |

in-plug engines is the fact that it’s necessary to “light” both plugs to get them both working. To me, this is a very surprising finding - one would think that starting on one plug would be sufficient, with the other plug lighting up as a result of the heat generated through the combustion process. However, several persuasive tests have been conducted that indicate the contrary - it is in fact necessary to electrically light up both plugs to get them both working. The engine can be started on one plug, but the other plug then has to be briefly stimulated to get it working as well.

in-plug engines is the fact that it’s necessary to “light” both plugs to get them both working. To me, this is a very surprising finding - one would think that starting on one plug would be sufficient, with the other plug lighting up as a result of the heat generated through the combustion process. However, several persuasive tests have been conducted that indicate the contrary - it is in fact necessary to electrically light up both plugs to get them both working. The engine can be started on one plug, but the other plug then has to be briefly stimulated to get it working as well.