|

|

The Ueda Engines

The above factors have combined to make this one of today's less commonly encountered Japanese model engine ranges from the “late classic” era. In the past, examples have shown up surprisingly rarely on eBay and elsewhere. Even so, until relatively recently they have tended to sell for comparatively low prices, in part because their reputation has preceded them but also because there has hitherto been very little readily-available information about them. No-one’s going to invest much in an undocumented range of engines with a less-than-stellar reputation, deserved or otherwise!

Fortunately, I can do something about the documentation side. Over the years I’ve taken a close interest in the history of the more obscure Japanese model engine ranges, while tales of the David and Goliath type have always intrigued me. Accordingly, a Japanese model engine range that briefly appeared from nowhere in the mid 1960’s to challenge the well-established might of O.S., Enya and Fuji, however unsuccessfully, holds a certain fascination for me. For this reason, I’ve paid a bit of attention to the Ueda engines over the years despite their reputation.

Quite apart from this, it’s readily possible to see in the full glare of hindsight that the worldwide model engine market was already well into decline as of 1964. After peaking in the early to mid 1950’s, the market had remained static for some years before entering the steady decline which has continued to this day, taking with it most of the more prominent manufacturers from the “classic” era. Consequently, the Ueda range was competing against well-entrenched competition for a share of a shrinking market. The rising profile of R/C flying with its attendant entry-limiting increase in the cost and complexity of participation had much to do with this, as did the ever-decreasing number of people both willing and able to build their own models. Basically, the accelerating metamorphosis of aeromodelling from a low-cost hands-on hobby to a ready-made “bought-in-a-box” leisure activity requiring a significant cash investment spelled the death knell of many once-famous model engine ranges. The former pool of impecunious school-age fliers from whom future life-long aeromodellers evolved were in effect economically excluded from participation, thus changing the status of aeromodelling from the relatively inexpensive mass-participation handicraft-oriented hobby that it once was to a leisure activity open only to those with the means to pay for their fun rather than create it for themselves. It's hard to think of another formerly mainstream hobby that killed off its own entry level so successfully. The attendant reduction in entry-level participation has bedevilled aeromodelling ever since ……….......

Reading between the lines, it's readily apparent that the introduction of this range could not have been motivated by any rational expectations of large profits. Moreover, as we shall see, the manufacturers had been successfully established in a completely different line of business well prior to becoming involved with model engine manufacture. There appears to have been no overriding business case to support the company’s entry into a completely different market area. These observations combine to support the view that the involvement of the Ueda company with model engines must surely have stemmed from a genuine interest in such engines on the part of someone in a position of influence within the Ueda company. Many if not most of the world’s model engine ranges had their origins in just such a personal interest, and it appears that the Ueda range was no exception. Peter Chinn recalled being told by the then-president of the company, M. Ueda, that the firm’s entry into the model engine market arose primarily because of his son’s personal interest in model engines.

That said, it’s my personal view that the sorry reputation of the Ueda engines is by no means as comprehensively warranted as a lot of people seem to think. Many of them ran perfectly well and gave good service, albeit without matching most of their contemporary competition. Moreover, a good proportion of them were actually quite well made - it was manufacturing consistency rather than capability coupled with a seemingly inadequate quality control program that let them down. There’s no denying the existence of the design anomalies noted earlier, while some examples undoubtedly did fall short in terms of quality. However, the better examples were certainly able to give good service at very reasonable cost to an owner having realistic expectations in terms of performance. The trick was seemingly to get a “good ‘un” and then use it appropriately! Production and Marketing History The registered name of the parent company responsible for the Ueda range was the Ueda Seisakusho Company Ltd. However, throughout the relatively brief period during which they were produced, the Ueda model aero engines were traded under the name Ueda Mfg. Co. Ltd. of Tokyo, Japan. The company name is correctly pronounced as OO-EH-DAH rather than YOU-EH-DAH as many Anglophones render it. In addition to the engines, the company manufactured both glow-plugs and fuel. Information extracted from Google Japan confirms that the Ueda company was founded as a family-owned enterprise in October 1946 at a location at Omori in the Ota-ku (Ota Ward) district of Tokyo. Its business from the outset was the manufacture of automotive accessories. The company appears to have been successful from the start in establishing itself as a sub-contractor to the burgeoning post-war Japanese automobile industry. By 1963, when it first turned its attention to the manufacture of model engines, it was very well established, having been in business very successfully for some 17 years. Clearly, this was no case of a new manufacturer commencing operation from the ground up - the Ueda company already had a long history of successful participation in the automotive manufacturing sector. In adding model engine manufacture to an ongoing business portfolio connected with the automotive industry, the Ueda company was following in the footsteps of several previous model engine manufacturers such as AMCO and Nordec. As events were to prove, the period covered by the Ueda company’s dual portfolio was actually to exceed those of the other two named companies by several years. However, they too eventually followed the same path as their English predecessors by abandoning model engines in favour of a return to their automotive roots. The Ueda company remained very much in business at my original time of writing (2014), trading as Ueda Manufacturing Ltd. from the same location in the Ota-ku district of Tokyo where it was founded almost 70 years previously. Its only significant expansive move came in 1970, when it acquired an adjoining industrial site to add to its existing premises at the Ota-ku location. The company remains in the hands of the Ueda family today, the President at my original time of writing (2014) being Daisuke Ueda. Its main product line continued to be a range of precision mechanical and electrical components for automotive applications. It’s extremely interesting to note that the manufacture of model engines does not feature as a facet of the company’s past activities as recorded in their own summary of their corporate history! It would appear that their relative failure to make any impression upon that particular market may have left a somewhat sour taste in their mouths, hence being seen as an episode that they would rather forget! Either that, or the manufacture of model engines was so much of a sideline that it failed to make any lasting impression upon the corporate consciousness of the company management. It was all more than half a lifetime ago, after all ………………

The above-mentioned January 1965 “Aeromodeller” article included the statement that the company then had a production capacity of up to 1000 engines per month. This is a remarkably low figure by then-current Japanese standards - indeed, it is extremely low even by world standards when we consider that firms such as E.D. are known to have routinely manufactured well over 2000 examples of some individual models in a month at a time when half-a-dozen or more such models were in simultaneous production. This seems to confirm that model engines were very much a sideline for the Ueda company. There is in fact considerable evidence to suggest that model engine manufacture at Ueda never advanced beyond sideline status and that the engines were produced intermittently in small batches as and when pressures of other work allowed this. Certainly, the serial numbers which appear on the majority of these units tend to be on the low side, indicating that production figures remained very small indeed by contemporary Japanese standards. In years of looking, I’ve never seen a 5-digit Ueda serial number or anything close, even on the more popular-displacement models like the 15. This adds credibility to the suggestion that the manufacture of model engines may have been justified to company management more as a way of utilizing the company’s excess production capacity than anything else. Their main business interests and expertise almost certainly remained focused all along on their established automotive accessory production activities which continue today. This reinforces the probability mentioned earlier that the manufacture of model engines did not represent a significant shift in the company’s business focus, being added to the company’s portfolio purely as a sideline as a result of a personal interest in the subject on the part of one or more of the Directors, in this case the then-company President. There are a number of precedents for this.

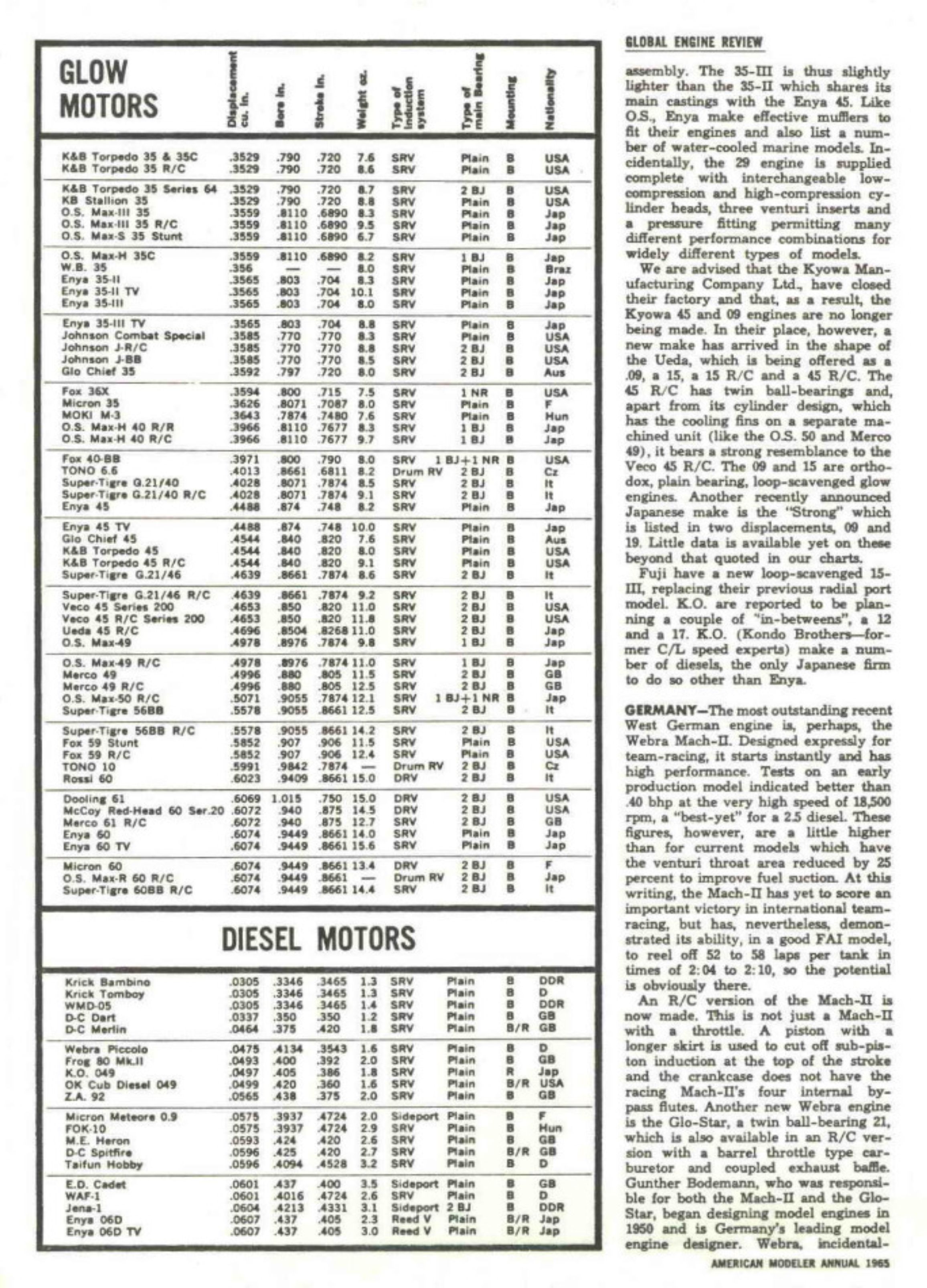

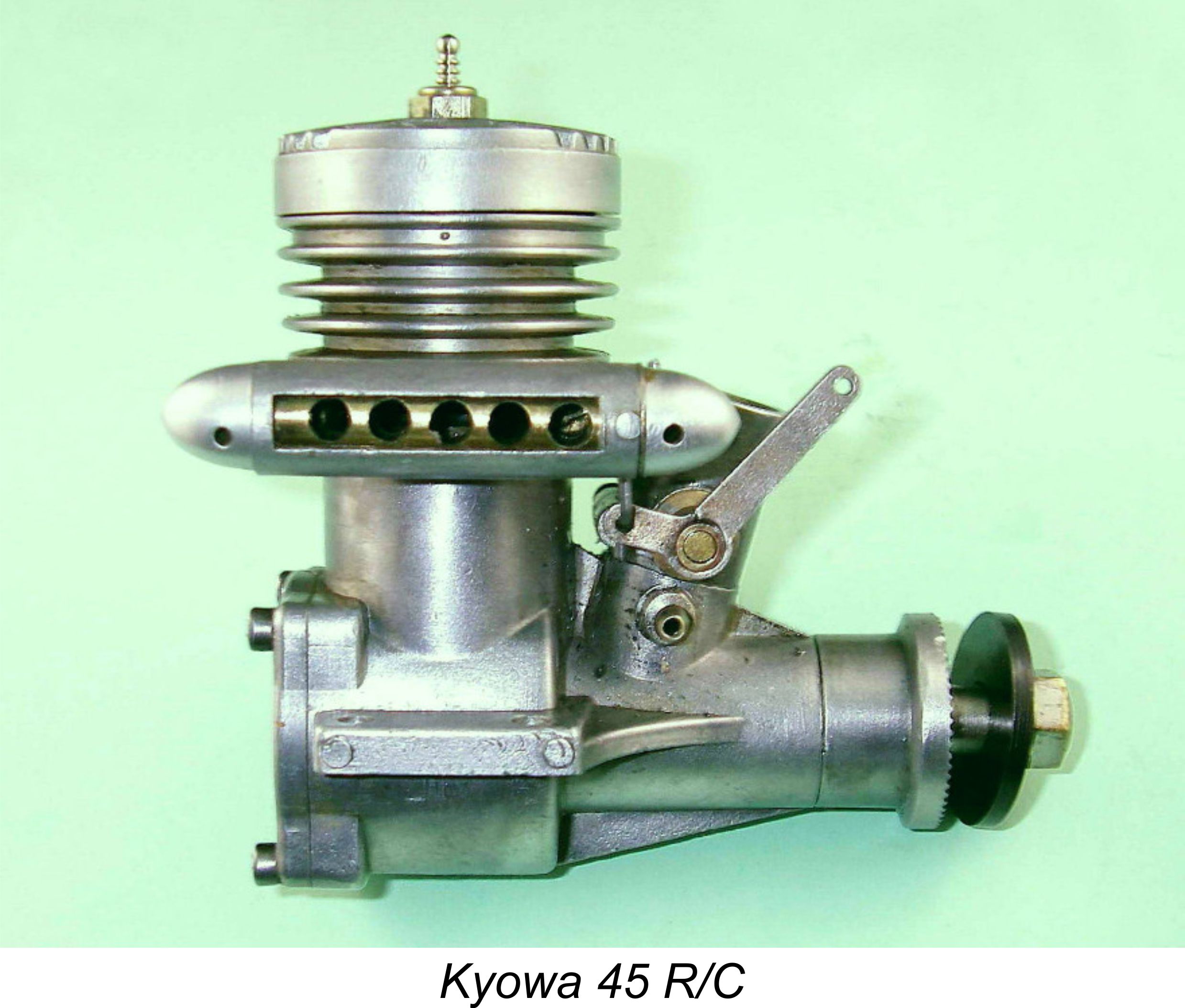

The Ueda engines appear to have reached the market in production guise later in 1964. This event was noted in the late 1964 edition of the Global Engine Review (“American Modeller”, 1965 Annual). The Ueda range was cited as a “replacement” range for the then recently-discontinued Kyowa line. This characterization was somewhat misleading since the appearance of the Ueda range certainly did not represent a take-over of the Kyowa plant by new owners. After all, the Kyowa factory was located in Osaka while the Ueda engines were made in Tokyo. I've written up the Kyowa story in a separate article to be found on this site. The initial Ueda model engine line-up consisted of glow-plug models in the .09, .15 and .45 cuin. displacement ranges. The .15 model was offered in both R/C and C/L guises, while the .09 initially appeared only as a un-throttled C/L or F/F engine and the .45 was sold only as an R/C unit, albeit in both air- Although they ran very steadily and were easy to start and adjust, the Ueda engines generally suffered from low performance by comparison with most of their competitors, mainly due to poorly thought-out porting arrangements as well as a number of seemingly mis-matched design features. They were reasonably well fitted for the most part and gave the impression of being fairly sturdy, although there have been a significant number of user reports to the effect that the crankshafts in certain models were flawed, sometimes failing in service without warning. More of this below….. Overall, it must be said that the Ueda engines exhibited unmistakeable symptoms of ill-considered design and inconsistent manufacturing standards. Although the engines did improve over time, implying that their manufacturers evidently learned from their initial mistakes, they never quite caught up to the manufacturing and performance standards set by the best of their competition, both domestic and overseas. These observations fly very much in the face of the fact that by the time in question both quality and performance were more or less taken for granted where Japanese manufacturers were concerned. During the latter half of the 1960’s the Ueda range was imported into the USA by Associated Hobby Manufacturers (AHM) of Philadelphia, who made a sincere effort to promote them. However, despite their very low selling prices the range failed to generate much market interest since the engines really offered Consequently, AHM’s efforts to promote the range in the USA met with very limited success. The engines were imported into the UK by a firm called Modelradio, who also didn’t have much luck with them. The overall result was that the export market which was crucial to the long-term survival of the Ueda marque never developed. This led to the manufacture of the range being terminated in around 1970 after only some 6 years or so. It would appear that the company recognized the inevitable and returned to their automotive roots. The fact that they undertook a major expansion of their premises in 1970 more or less concurrently with the cessation of model engine production confirms that their failure as model engine manufacturers had little or no effect upon either the financial health of the company or its business prospects in other fields.

Quite apart from the less-than-impressive sales figures achieved and consequent low production figures, many of the Ueda engines that did find buyers seem to have fallen short of expectations in one way or another, presumably being discarded since no-one was interested in buying them even second-hand in those far-off pre-collector days of almost 50 years ago. In addition, the fact that they were so inexpensive probably positioned them in peoples' minds as "disposable" engines rather than tradeable or saleable assets. This view of the engines as sub-standard, cheap and hence disposable units probably has much to do with the comparative present-day rarity of examples in good condition - a lot of them evidently went out with the rubbish. Times change, however! We saw earlier that the relative scarcity of surviving Ueda motors coupled with their curiosity value, attractive appearance and comparative affordability has made them something of a target for a small but steadily growing number of present-day collectors. As of the original appearance of this article in 2015, I was noticing a steady increase in the level of bidder interest in such examples as were appearing on eBay and elsewhere. In addition, I had been receiving a growing number of inquiries from people seeking information. This being the case, it seemed well worthwhile documenting the range to the extent possible. Accordingly, here’s a summary of the various models offered by Ueda. For convenience, I’ll describe the various models in order of ascending displacement categories. The Ueda .09

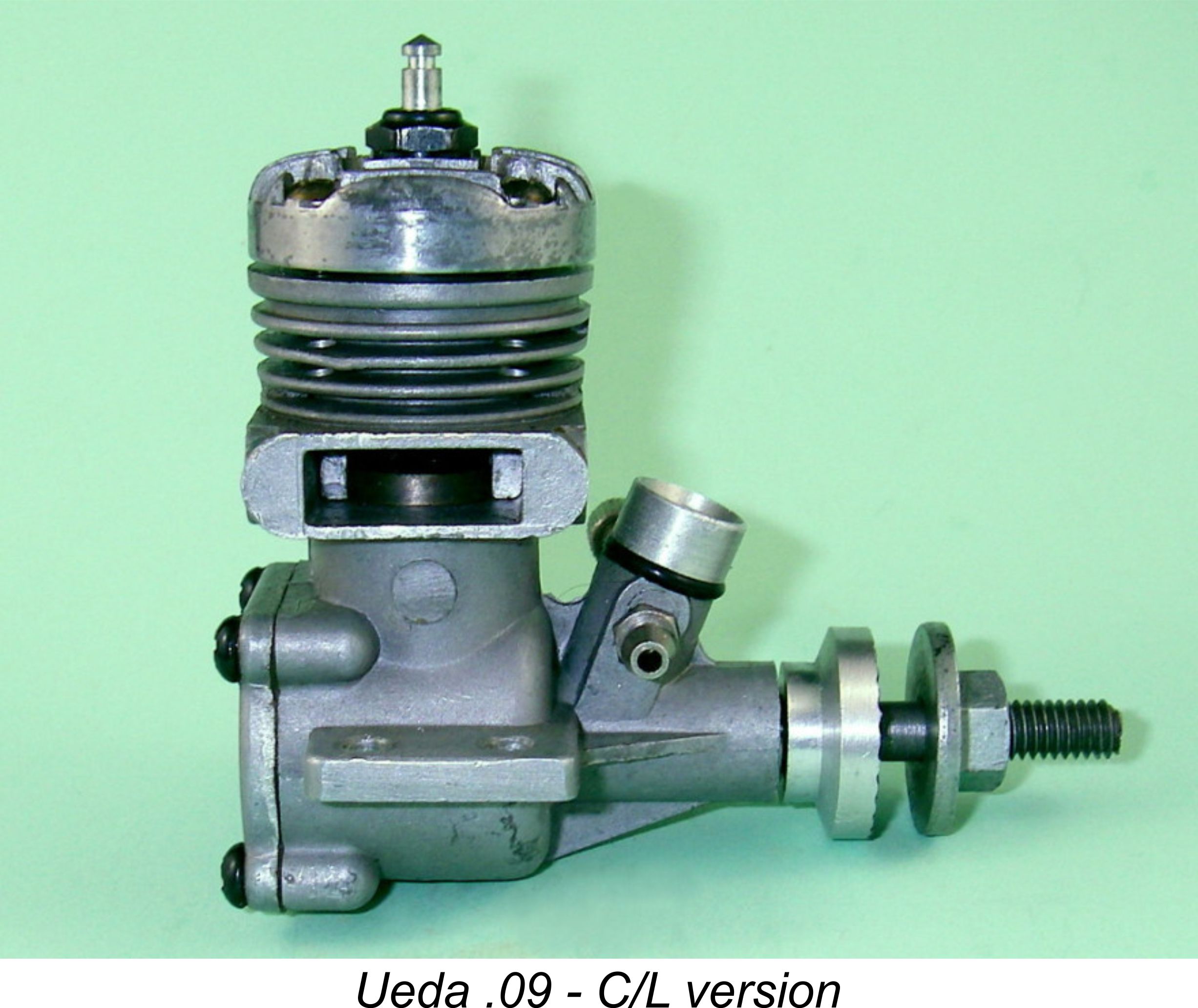

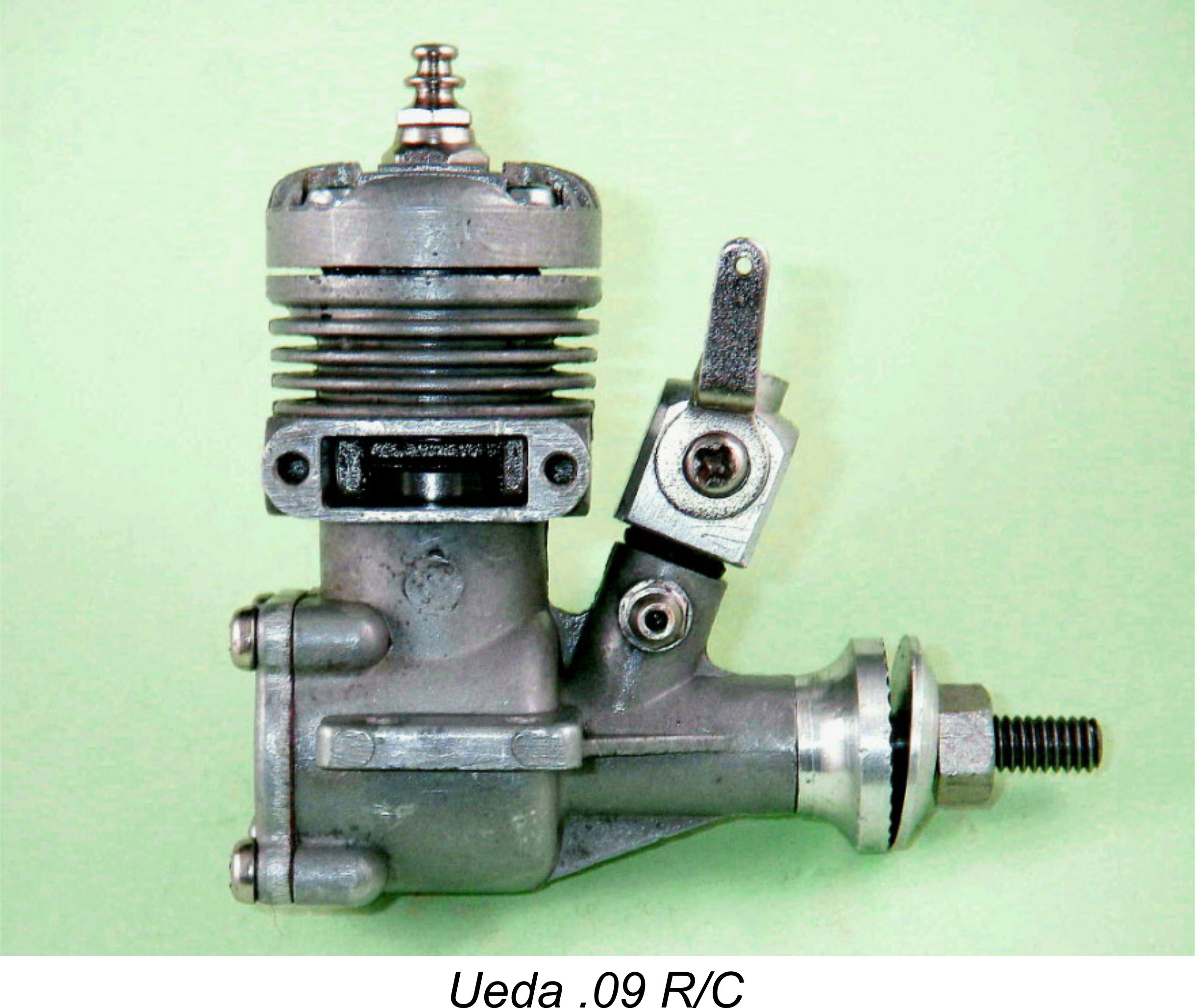

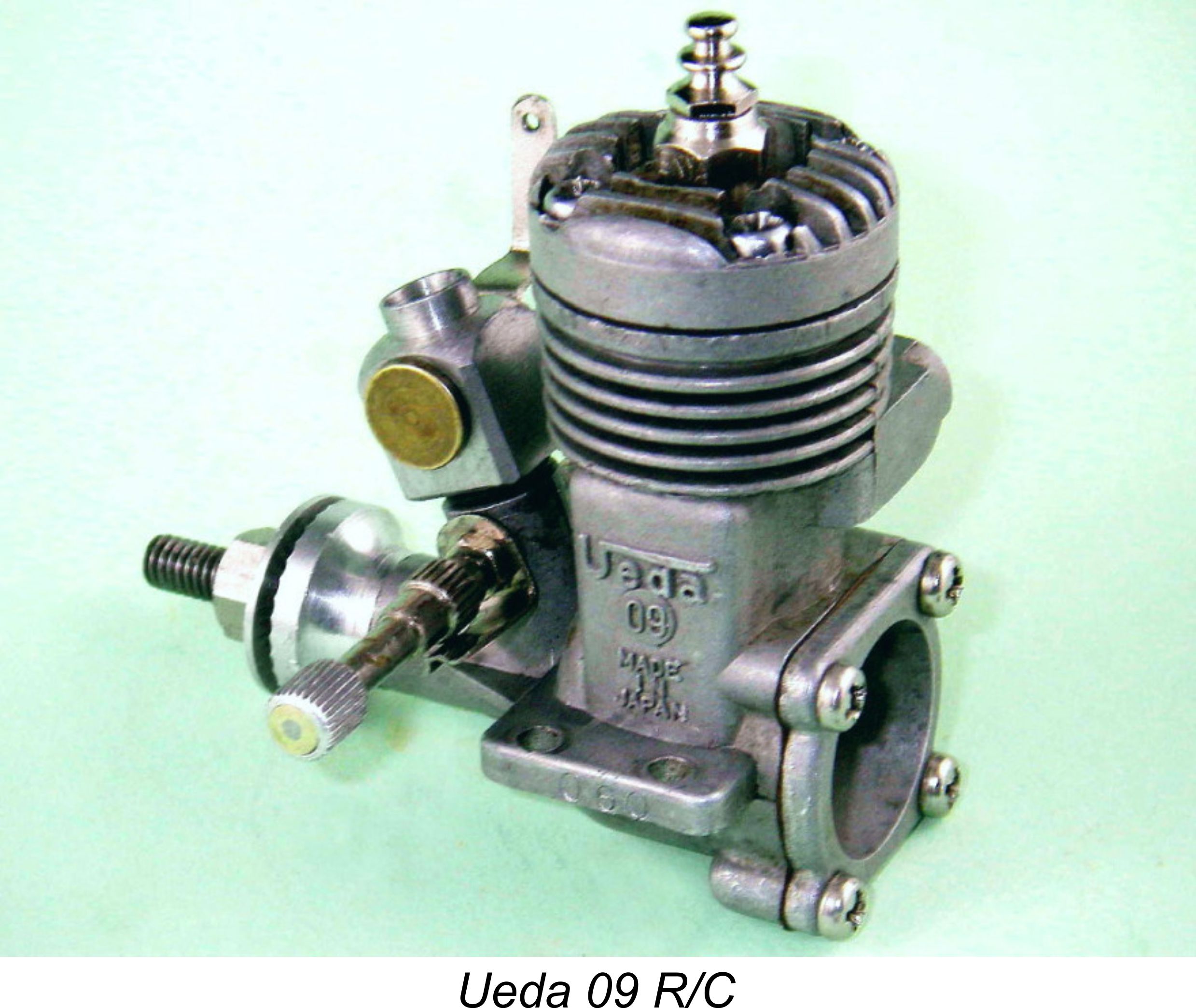

The illustrations will confirm that this unit was a completely conventional loop-scavenged glow-plug motor somewhat retroactively designed along mid 1950’s lines, with a cast-iron baffle piston and a plain bearing crankshaft featuring FRV induction. The bronze-bushed main bearing was cast in unit with the crankcase. Bore and stroke were 12.80 mm and 12.50 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.61 cc (0.098 cuin.). Stated compression ratio was a relatively low (and I would say somewhat marginal) 7 to 1. Direct volumetric measurements confirm that this was a geometric figure, as usually quoted by model engine manufacturers. The original control-line version weighed in at 100 gm (3.53 ounces), while the somewhat later R/C variant was of course a little heavier at 109 gm (3.83 ounces). Cylinder porting was completely conventional, with a single rectangular transfer port on the bypass side of the drop-in liner and a single exhaust port of similar shape directly opposite. The transfer port was fed by a conventional bypass “bulge” cast into the crankcase on the transfer side. Port timing was quite conservative, with both exhaust and transfer ports opening rather later than in most engines of this type. By contrast, the crankshaft rotary valve gave an unusually long induction The crankshaft of the original models had a checked main journal diameter of a nominal 7.5 mm and an internal gas passage diameter of 5.5 mm. This left a wall thickness of only 1 mm (0.039 inch), which seems very marginal, even for a low-compression sports .099 cuin. glow motor. However, as we shall see, thin-walled crankshafts were something of an unfortunate Ueda design trait. The milled rectangular induction port was cut with sharply squared-off edges, which gives very efficient operation but might be expected to create stress concentration points at the corners. Coupling the above features with the fact that the shafts were extremely hard and therefore potentially brittle, we might expect to hear of shaft reliability issues with this engine. However, shaft breakages do not appear to have been the chronic problem with the .09 model that they were with several of the larger designs to be discussed below - I have so far encountered no user reports regarding problems of this nature with the .09.

The prop driver on the original small-shaft C/L model was keyed to the shaft using a flat machined onto a boss in front of the shaft journal which matched a corresponding flat in the prop driver mounting hole. On the later models with the slightly larger shafts, this arrangement was supplanted by a conventional self-releasing taper system which was unquestionably far more dependable. The original version of this engine featured an integrally-cast intake venturi which incorporated the venturi throat, no insert being used. When the decision was subsequently taken to produce an R/C version of this model, the same casting remained in use but the cast venturi body was machined out to accommodate either a separate throttle or a C/L insert. The C/L version of this variant used a conventional 5 mm internal diameter venturi insert in concert with a 3 mm spraybar which was waisted to a central diameter of 2.5 mm.

The early engines did not feature any tapped holes in the exhaust stacks for mounting a muffler. However, the later versions did feature such holes. A muffler was available for this model, as it was for all the other Ueda models during the later half of the 1960’s. The C/L examples in my possession do not bear serial numbers. However, my illustrated later R/C example does have such a number (060), stamped in the usual Ueda location on the outer end of the left-hand mounting lug.

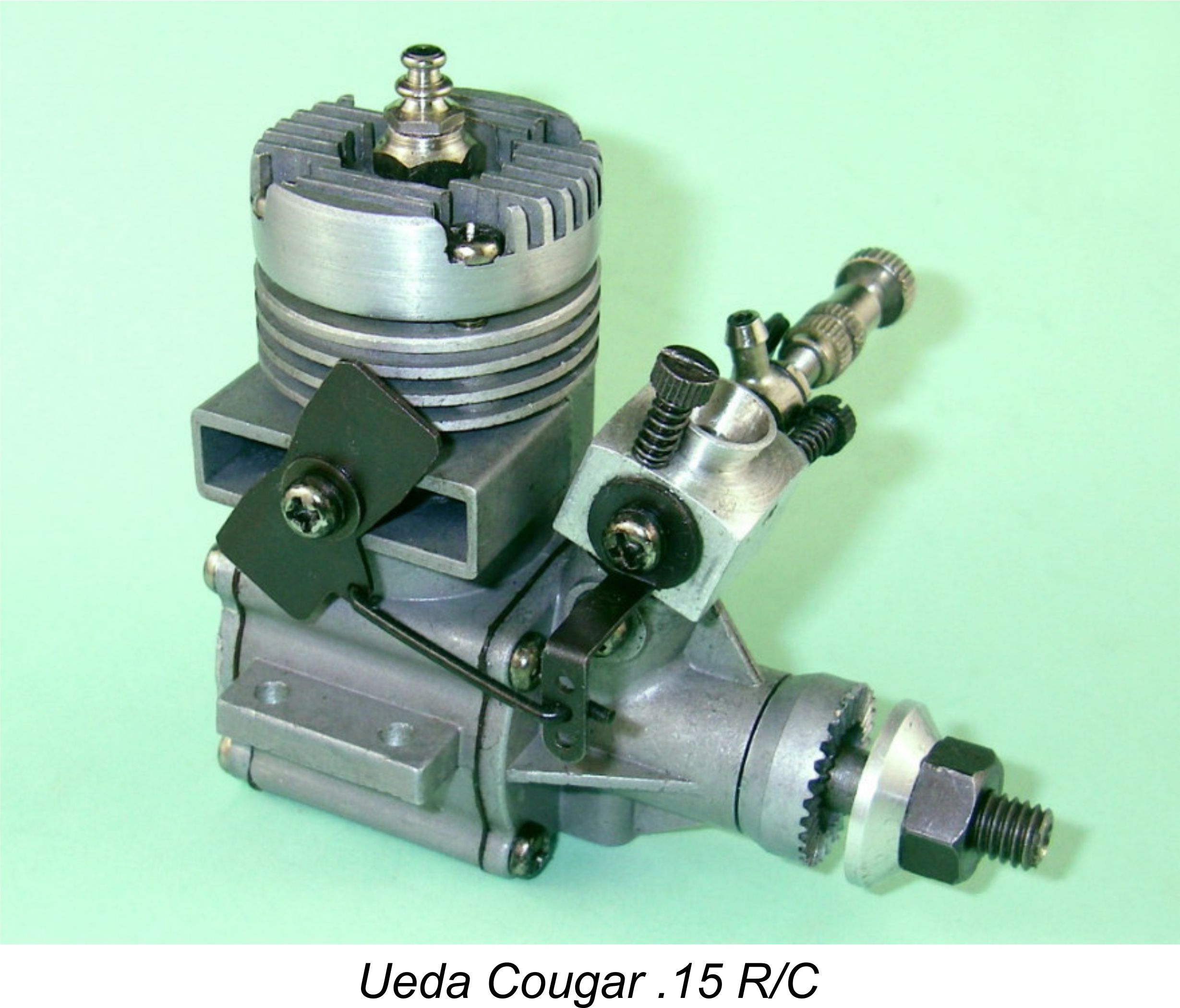

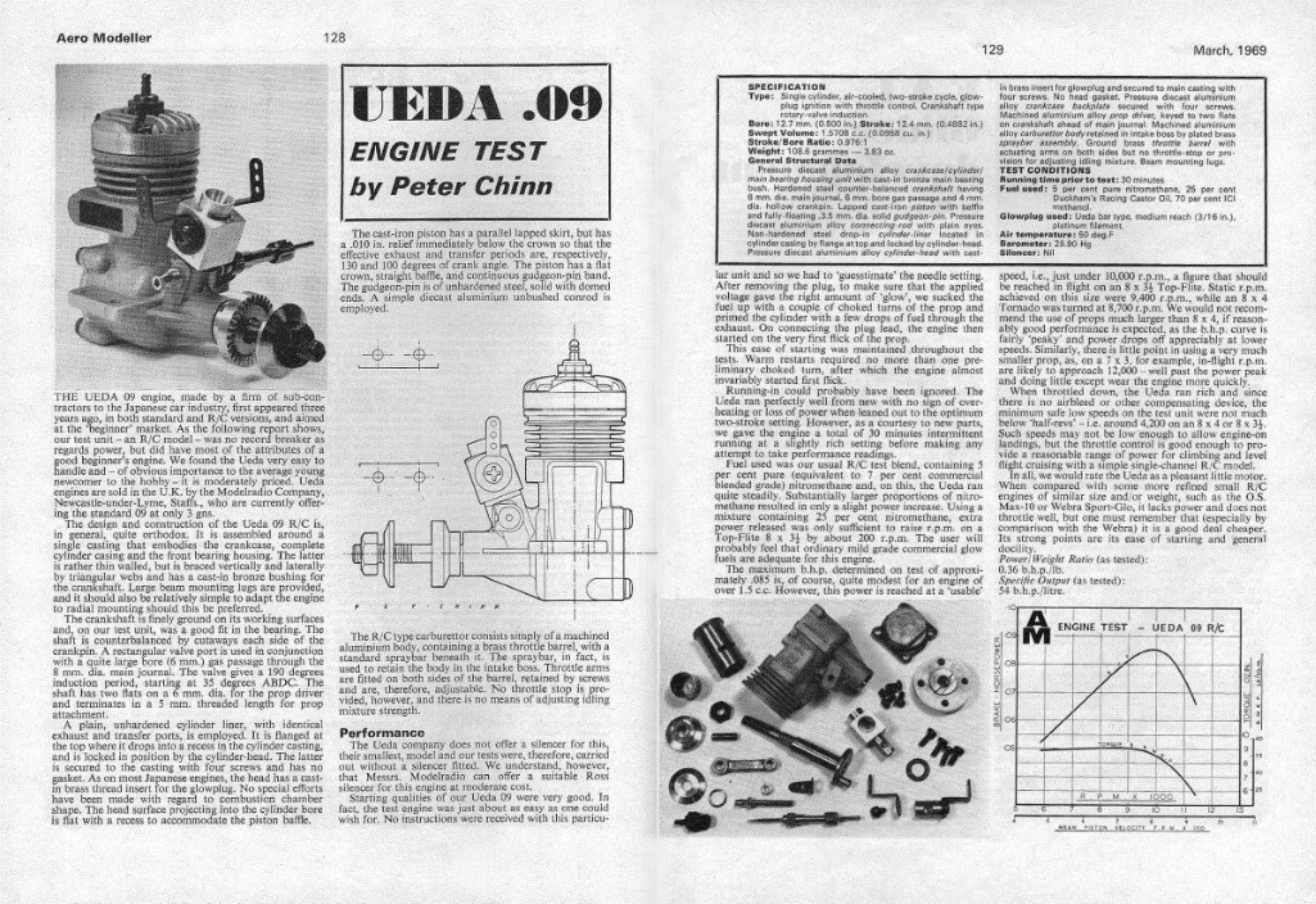

During the later stages of its production life, the Ueda 09 was marketed as the Cougar 09 in both R/C and standard versions. The R/C version of the Cougar .09 was the subject of a test by Peter Chinn which appeared in the April 1967 issue of “Model Airplane News”. A further Peter Chinn test of the R/C version of the Ueda .09 appeared in the March 1969 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Chinn summarized his view of the engine by stating that the engine “was no record breaker as regards power, but did have most of the attributes of a good beginner’s engine”. He found the engine to be extremely easy to start, hot or cold, and reported that it ran “perfectly well from new with no sign of over-heating or loss of power when leaned out to the optimum two-stroke setting”.

As noted earlier, the very basic throttle functioned simply by restricting the air supply and thus enriching the mixture, forcing the engine into four-stroke mode and hence reducing speed. As we might expect, Chinn found that this severely limited the extent to which the engine could be dependably throttled down. Using the 8x3½ or 8x4 props which the engine’s performance seemed to dictate, the throttle could only reduce speeds to something under half the wide-open figure. i.e., around 4,200 rpm. The throttle’s application was thus effectively limited to control of climb and maintenance of altitude - landings under power would be rather fraught! Chinn concluded his report by characterizing the Ueda .09 R/C as “a pleasant little motor” which, although it ”lacks power and does not throttle well” compared with its competitors, was a good deal less expensive. Apart from the cost factor, Chinn cited the engine’s strong points as “its ease of starting and general docility”. Definitely a case of praising with faint damns!! The Ueda 15

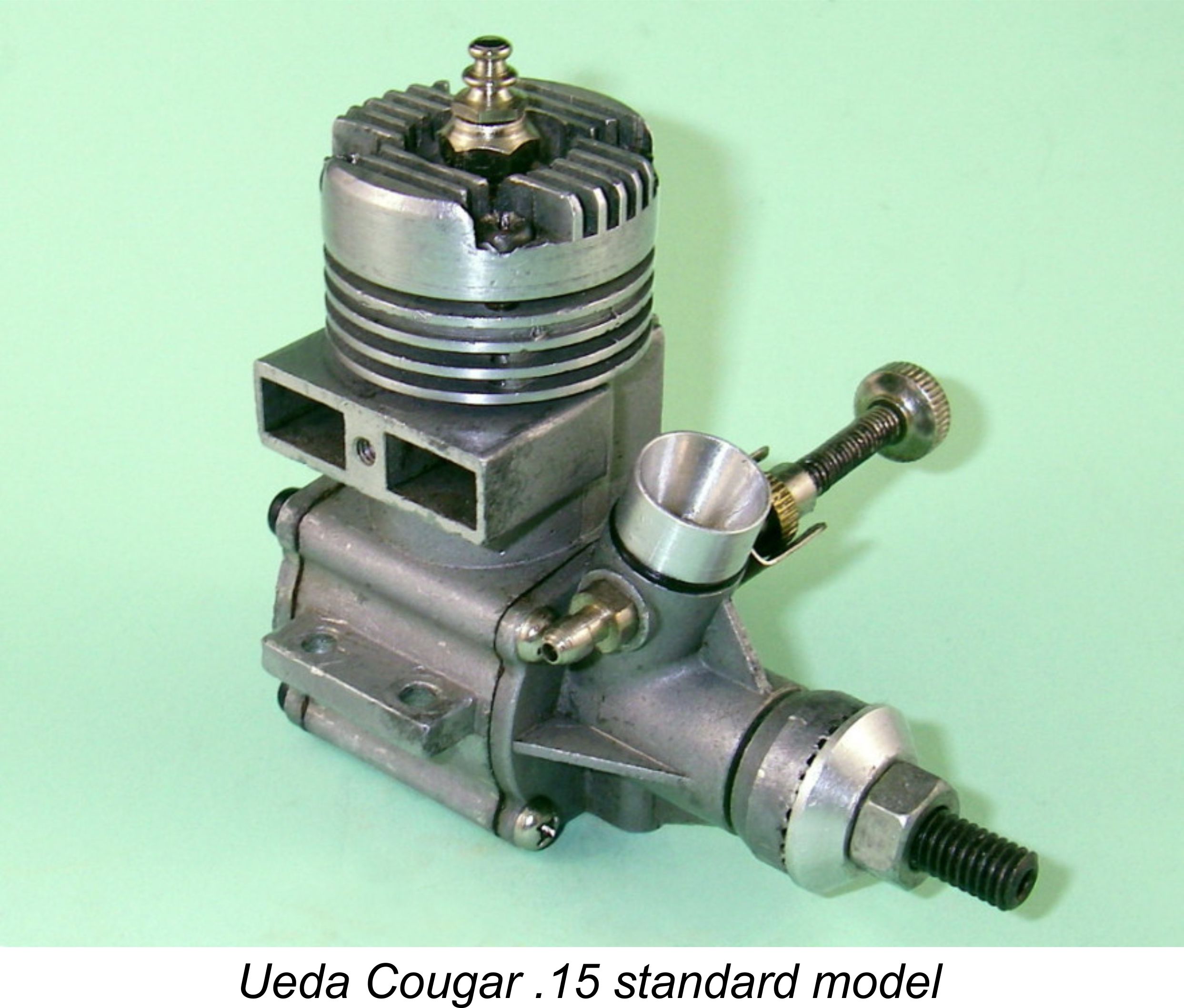

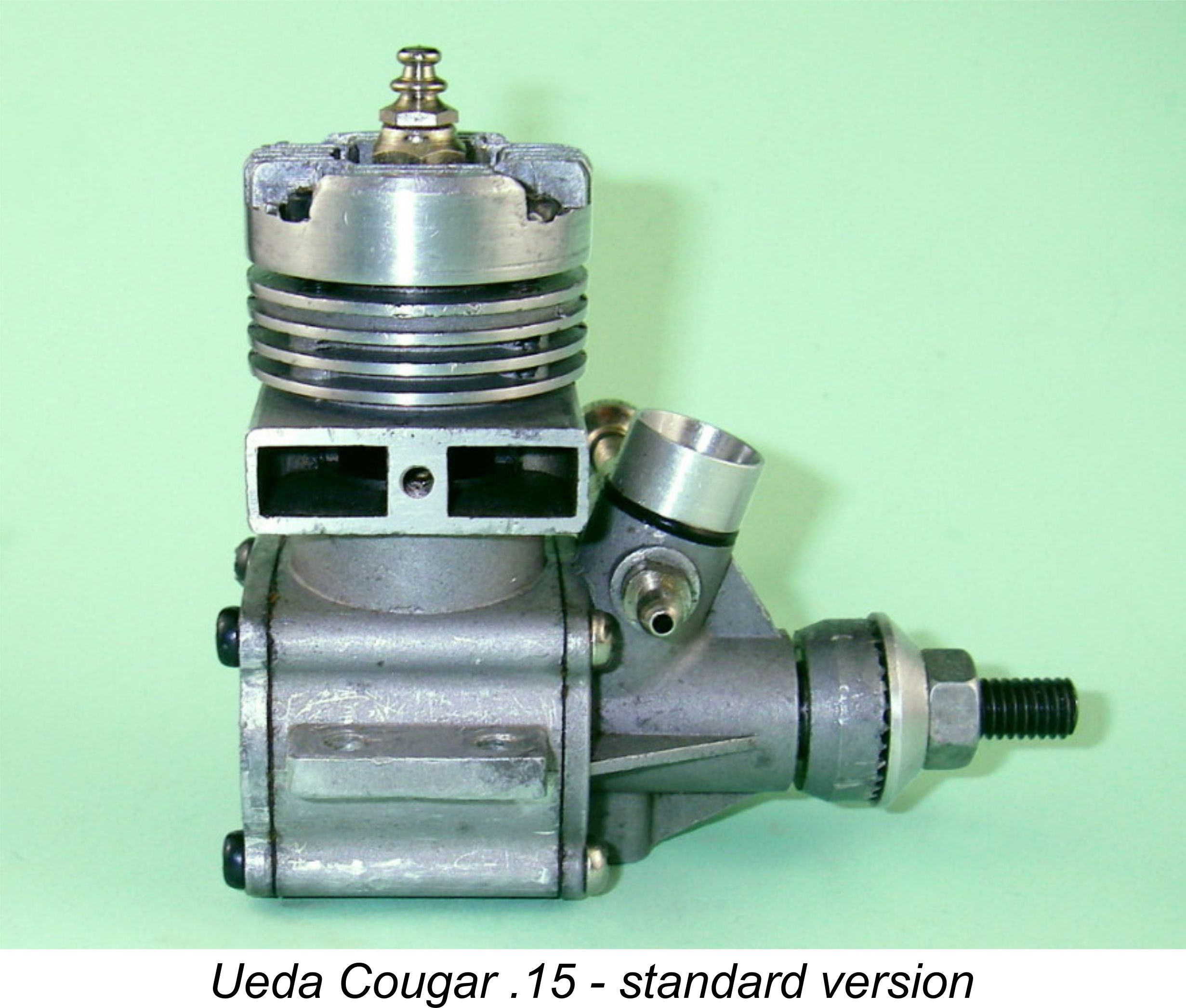

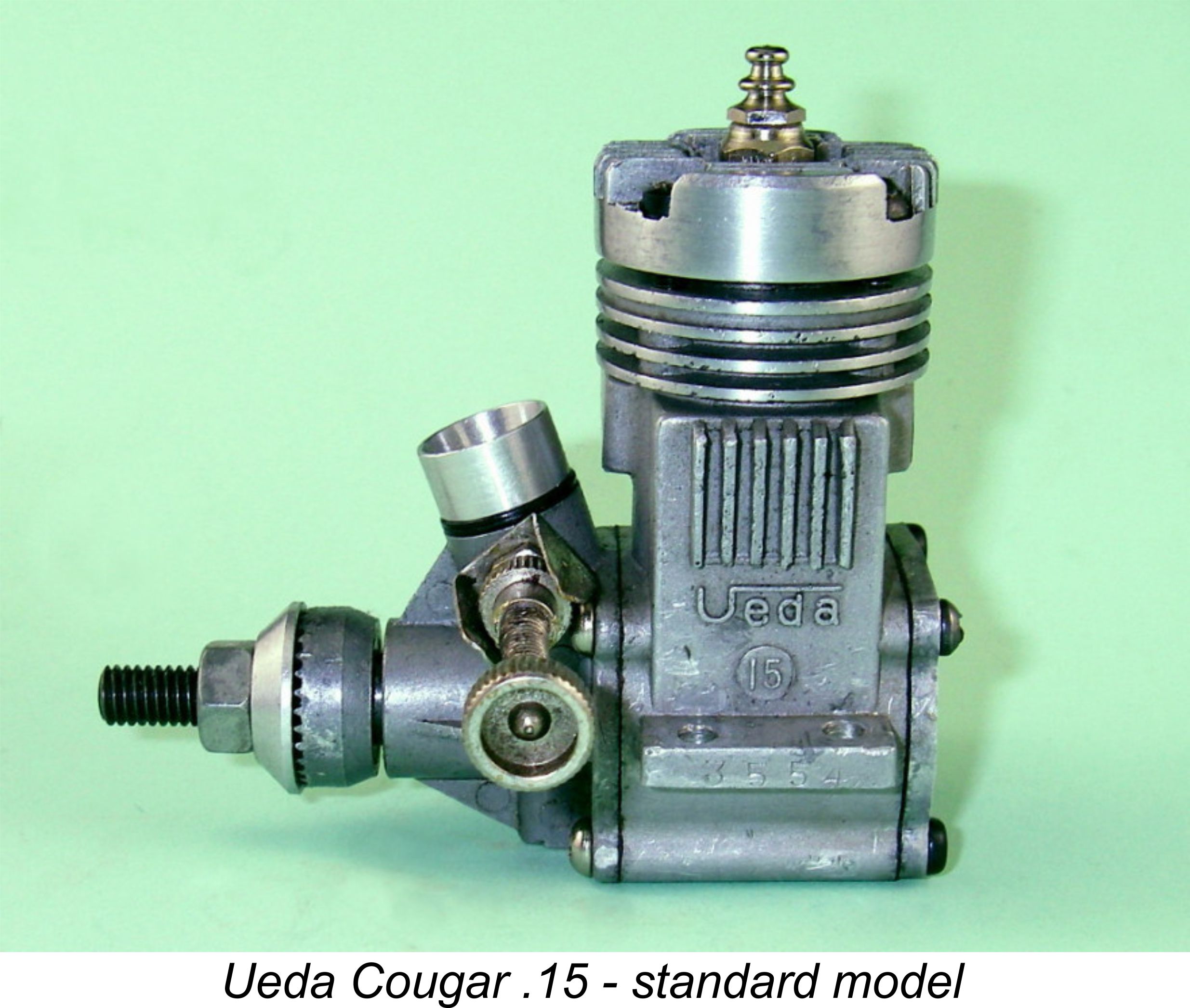

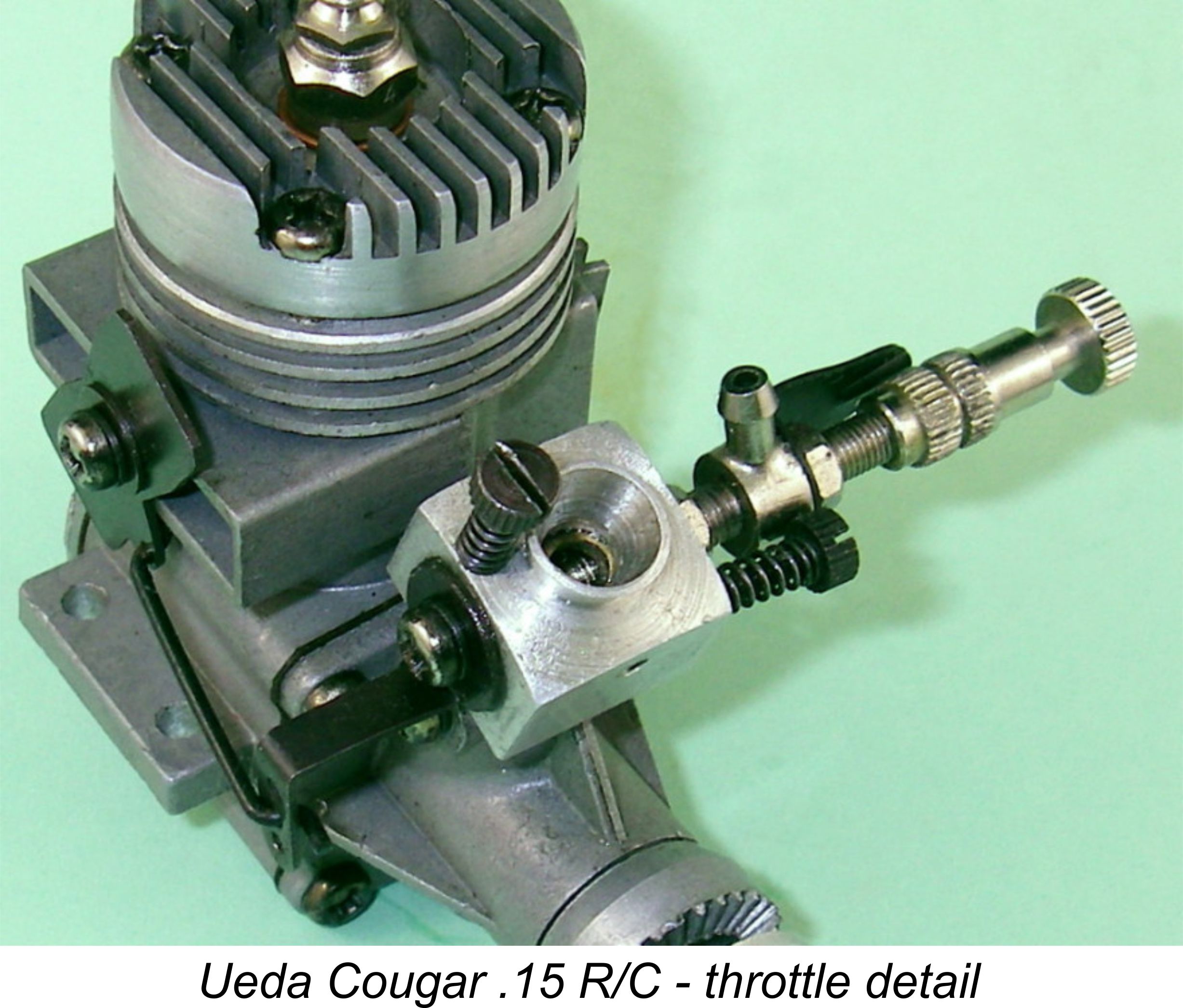

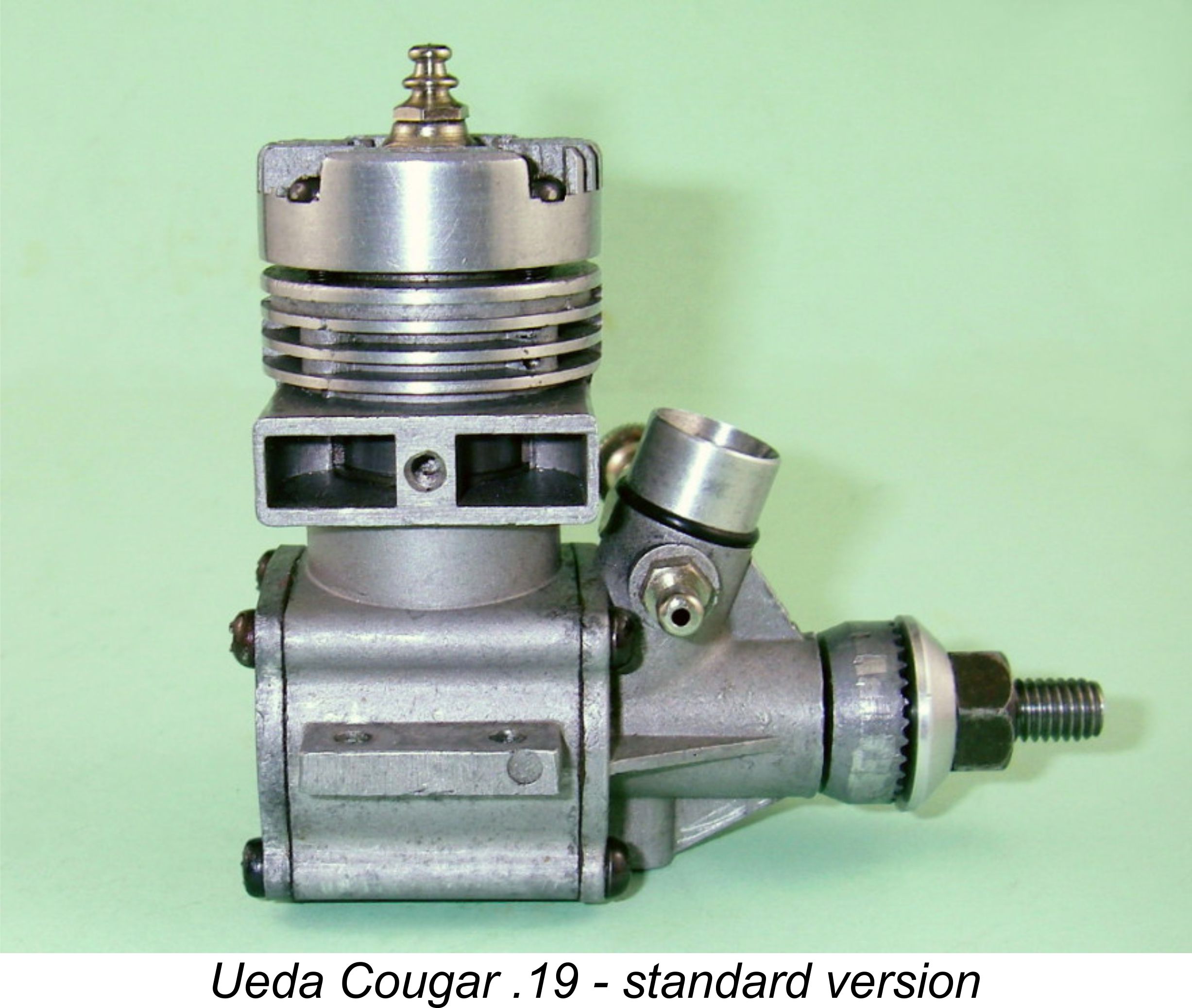

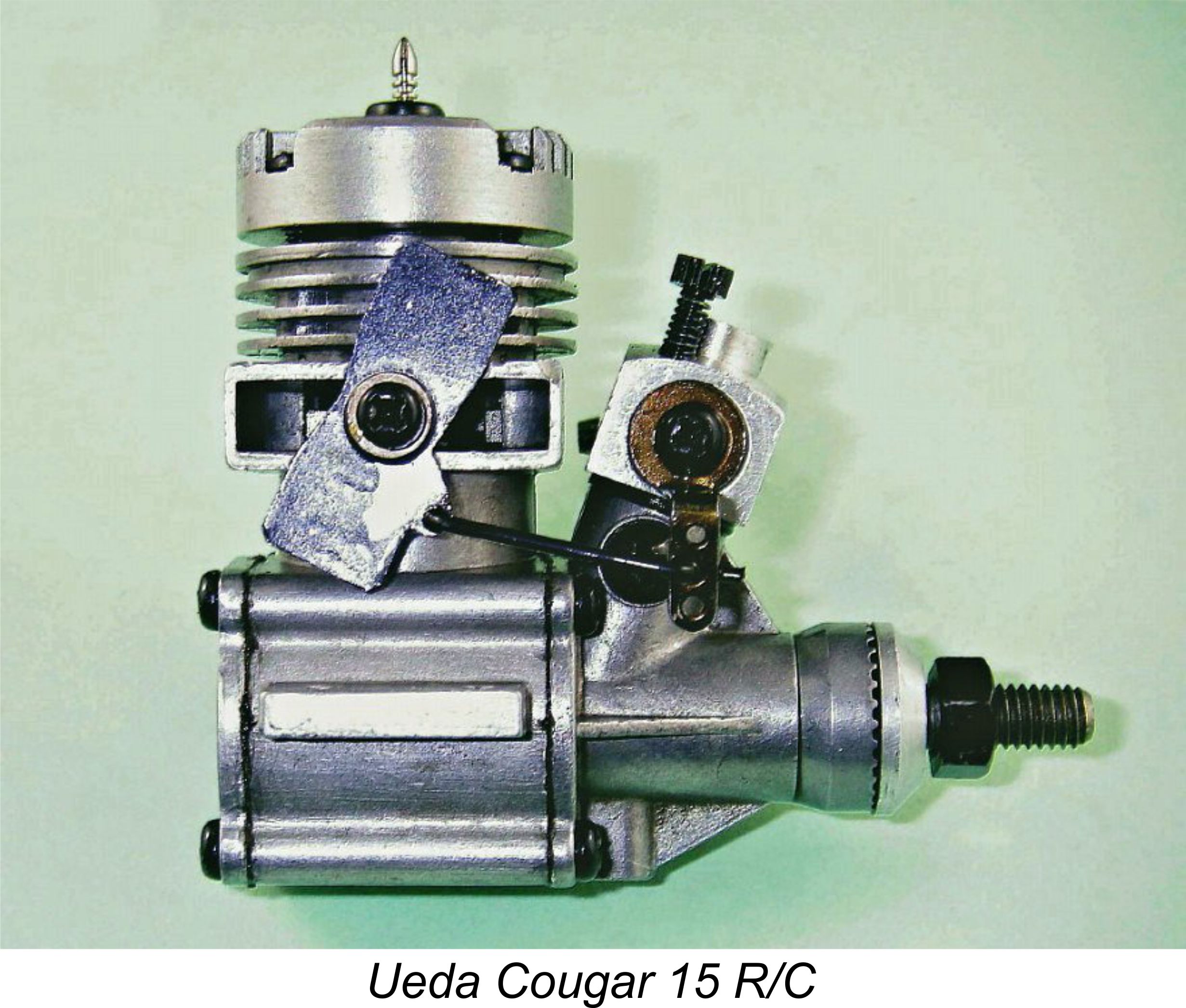

The engine was available in both C/L and R/C versions from the outset. However, the R/C version lacked the exhaust restrictor plate which was to be a feature of the later Cougar .15 R/C model. The throttle on this early version was essentially the same as that used on the .09 model discussed above. In 1966 this version of the Ueda 15 was replaced by a This revised model was marketed for much of its existence as the Cougar 15 in both C/L and R/C configurations. It measured up at 15.0 mm and 14.0 mm respectively for an unchanged displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The bulkier construction gave rise to a substantial increase in weight - the control-line version weighed in at a very hefty 5.38 ounces to go along with its relatively massive construction for an engine of its displacement. The R/C version was even porkier at a checked weight of 6.05 ounces. In functional terms, the engine pretty much followed the design format of its predecessor. The internal arrangements were little changed, although the styling The crankshaft ran as before in a bronze-bushed main bearing. A feature worthy of comment in this context was the provision of a narrow channel running axially along the lower surface of this bearing. This communicated with an annular channel near the front of the bearing. The intent of this feature was clearly to improve lubrication of the bearing at the front and on the loaded surface at the rear. The throttle on the revised R/C model was far more sophisticated than that used on the earlier version. It featured such refinements as an idle stop and an air bleed screw along with an inter-connected exhaust restrictor plate. This made it far more effective in use than its predecessor.

However, an equally likely culprit is the shaft design. The journal diameter is 9 mm - reasonable enough for a low-compression 2.5 cc sports glow-plug motor, but not when applied to a shaft having a 7 mm dia. internal gas passage! The resulting wall thickness of only 1 mm (0.039 inch) seems quite inadequate for the job. In addition, the rectangular induction port is far longer than it needs to be given the fact that it registers directly with the perfectly round base of the 6 mm diameter intake venturi. This excessive length has the effect of removing far more material from the shaft To compound this problem, the induction port opening was milled into the shaft using a sharp-edged tool which formed very sharp corners, creating potential stress concentration points. Moreover, the internal edges of the aperture were very roughly finished prior to hardening. This might be expected to create stress concentration points along the edges of the opening which could lead to failure. Almost all of the reported shaft failures have occurred in the region of the induction port. After examining this shaft, I’d recommend that anyone contemplating the use of one of these engines use a suitable Dremel grinding tool to round off the ends to eliminate the sharp corners at those locations. I’d also suggest cleaning up the side edges of the opening while leaving the timing unaltered. Following these modifications, I’d recommend normalizing and stress-relieving the shaft. This is achieved by placing the shaft in a cold domestic oven, heating the oven to 550 degrees Fahrenheit with the shaft inside, then leaving it at the set temperature for 2 hours. At the end of this period, one switches the oven off and allows it to cool slowly with the door remaining closed and the shaft still inside. Following this treatment, the shaft should have a distinct blue colouration. This process will not guarantee the integrity of the shaft, but it should make its failure considerably less likely. I treated my own illustrated “flying” example in this way, and it has so far stood up well, with some hours’ flight time under its belt in a sport-stunt control-line model (I like flying engines that are "different".........!).

Many (but not all) of these engines carried serial numbers neatly stamped into the outer edge of the left engine bearer. The numbering sequence presumably started at engine number 1 (or perhaps 100), since I have encountered Ueda 15 R/C engine number 660, while the highest-numbered example of my present acquaintance is C/L engine number 3690. My present sample is admittedly fairly small - some 10 engines only - and it’s entirely likely that they may have gone considerably higher than that. However, it seems highly doubtful that the sequence ever approached five figures. That said, this would appear to be the Ueda model which was manufactured in the largest numbers. Oddly enough, neither of my own two R/C examples displays any serial number at all, although R/C engine number 2186 appeared on eBay in 2011. This makes it clear that at least some of the R/C examples were numbered, quite possibly within the main sequence. As far as I’m aware, neither variant of the Ueda 15 was ever the subject of a published test in any contemporary English-language modelling publication. In his test of the Ueda 19 R/C which appeared in the March 1968 issue of “Model Airplane News” (see below), Peter Chinn recalled testing two examples of the Ueda 15 R/C immediately following its release. However, he found a considerable variation in output between the two examples, added to which neither engine came up to the performance standards then expected of a .15 cuin. R/C motor. Moreover, the engines suffered from excessive vibration. Based on these findings, Chinn shelved his plan to publish a test of the engine, instead contenting himself with reporting his recommendations to the manufacturers. Although he never obtained confirmation that his recommendations were adopted, he did report that the later Ueda 19 R/C which he was then testing showed a number of improvements along with a significantly increased specific power output. It thus appears that Chinn's recommendations may have had some effect. Time constraints have not yet permitted me to conduct a full test of the Ueda Cougar 15 as I would have liked to do. I hope to remedy this at some point in the future. For now, all that I can say is that my own “flyer” example of the Cougar 15 starts and runs very consistently, albeit at a relatively modest level of performance by mid 1960’s standards. Vibration levels are on the high side, although not unmanageably so if a firm mounting is provided. The Ueda 19

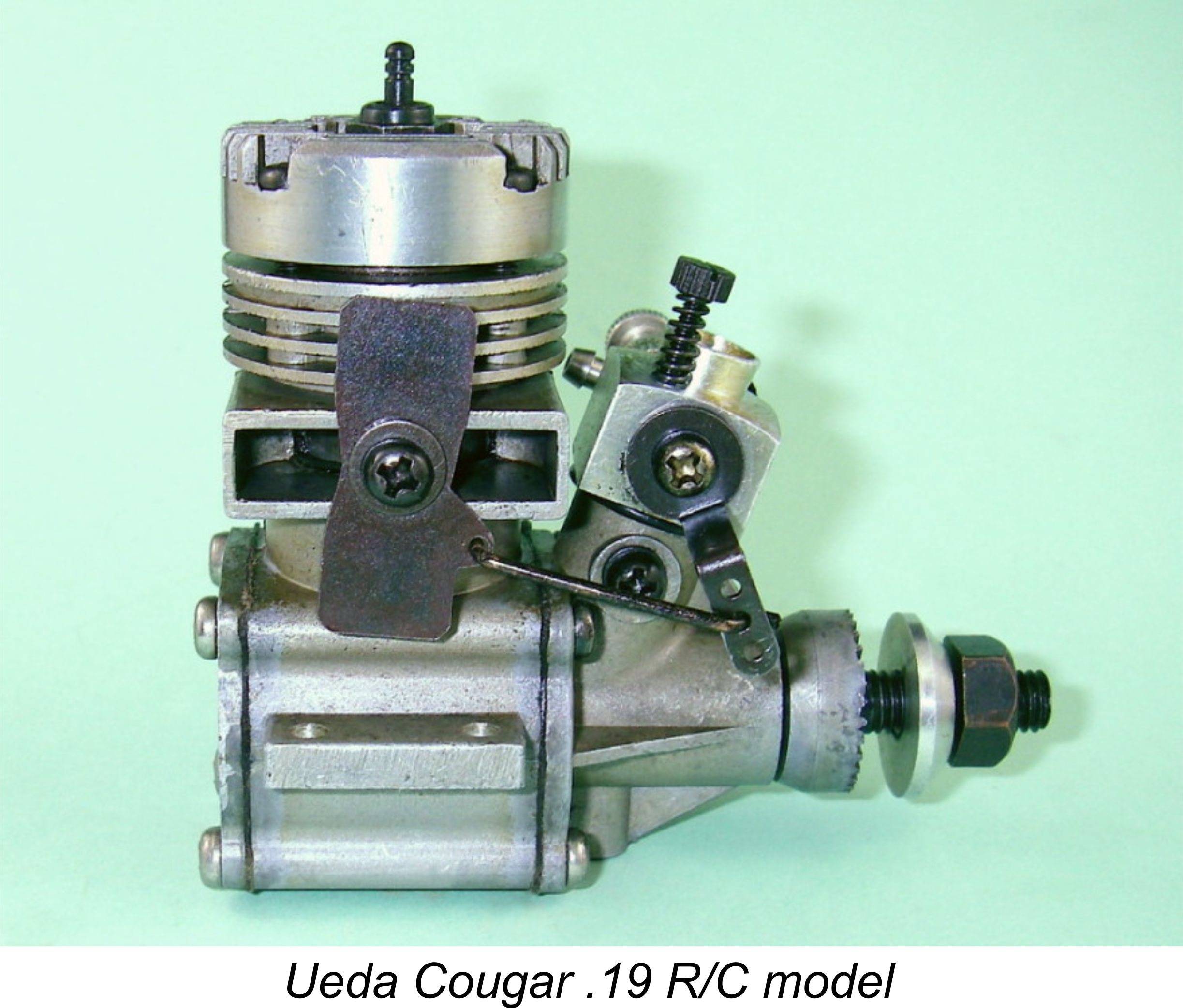

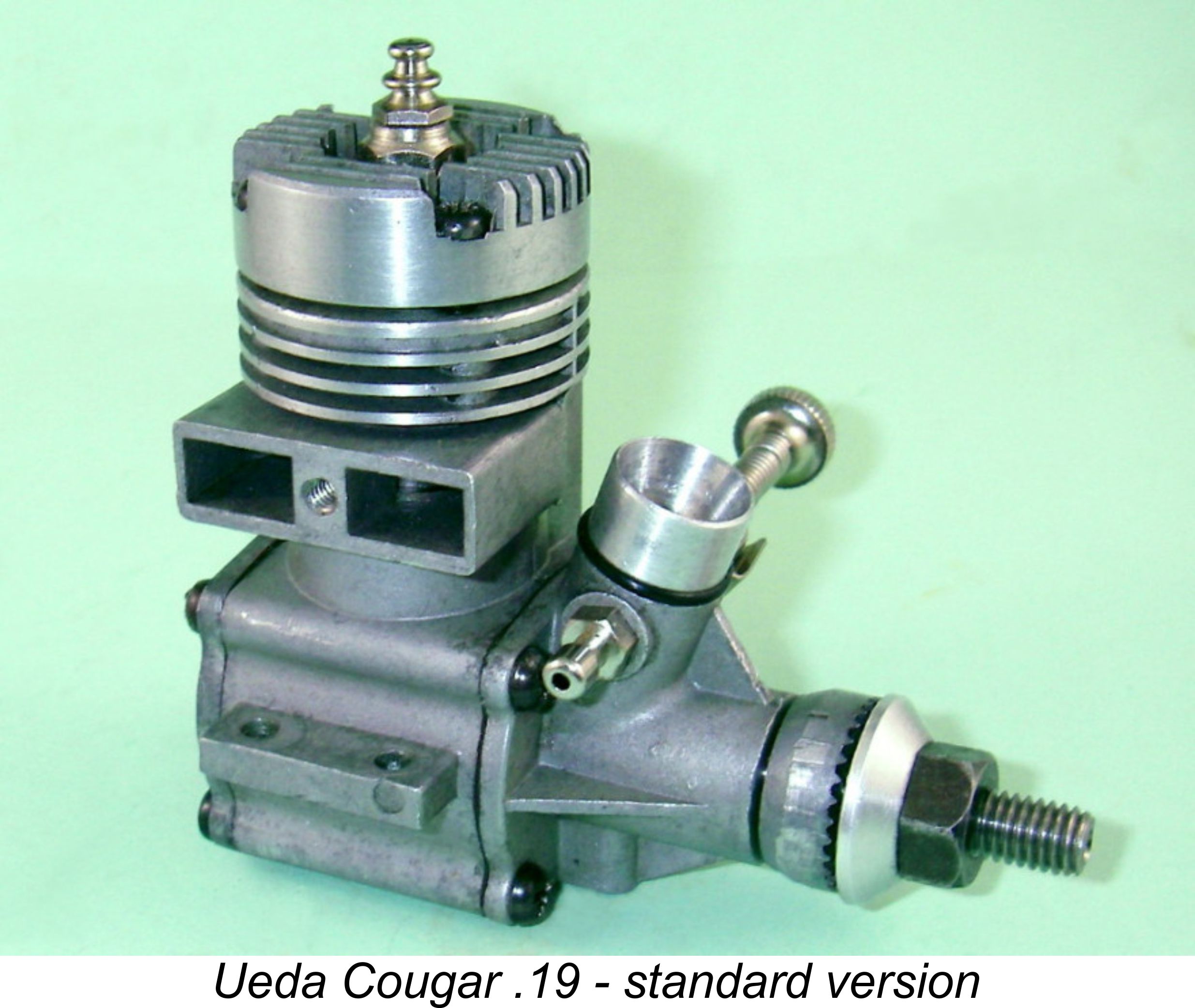

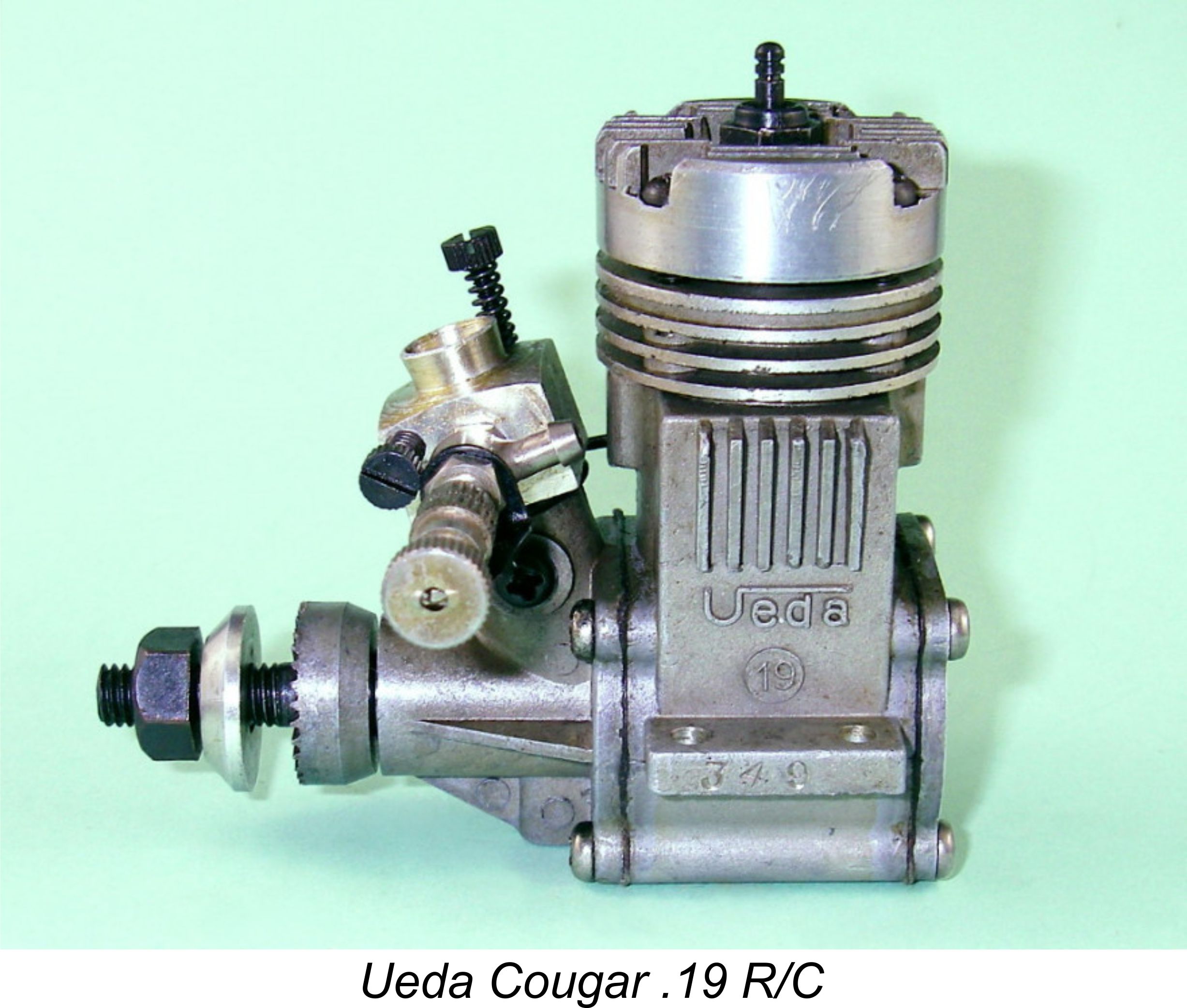

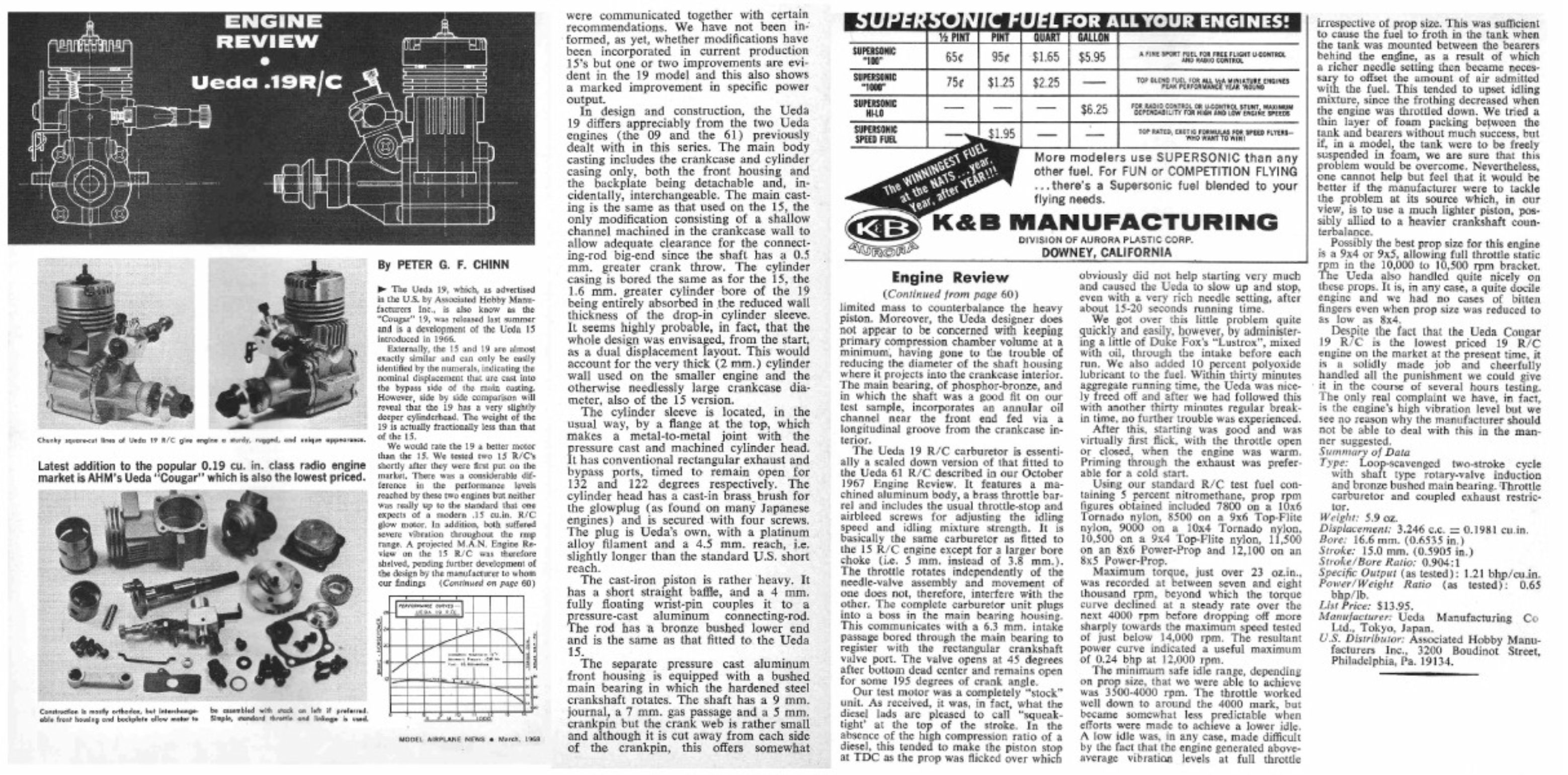

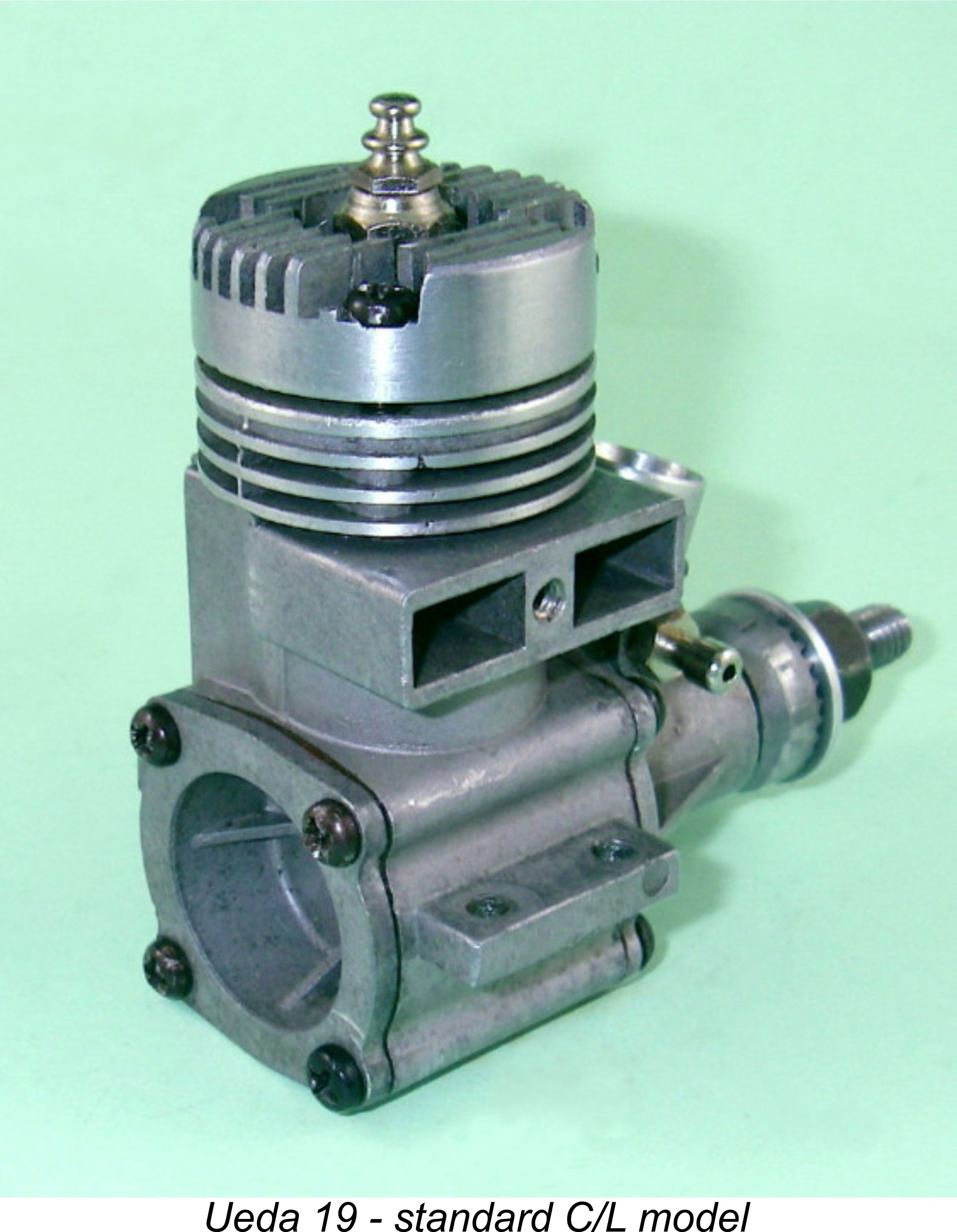

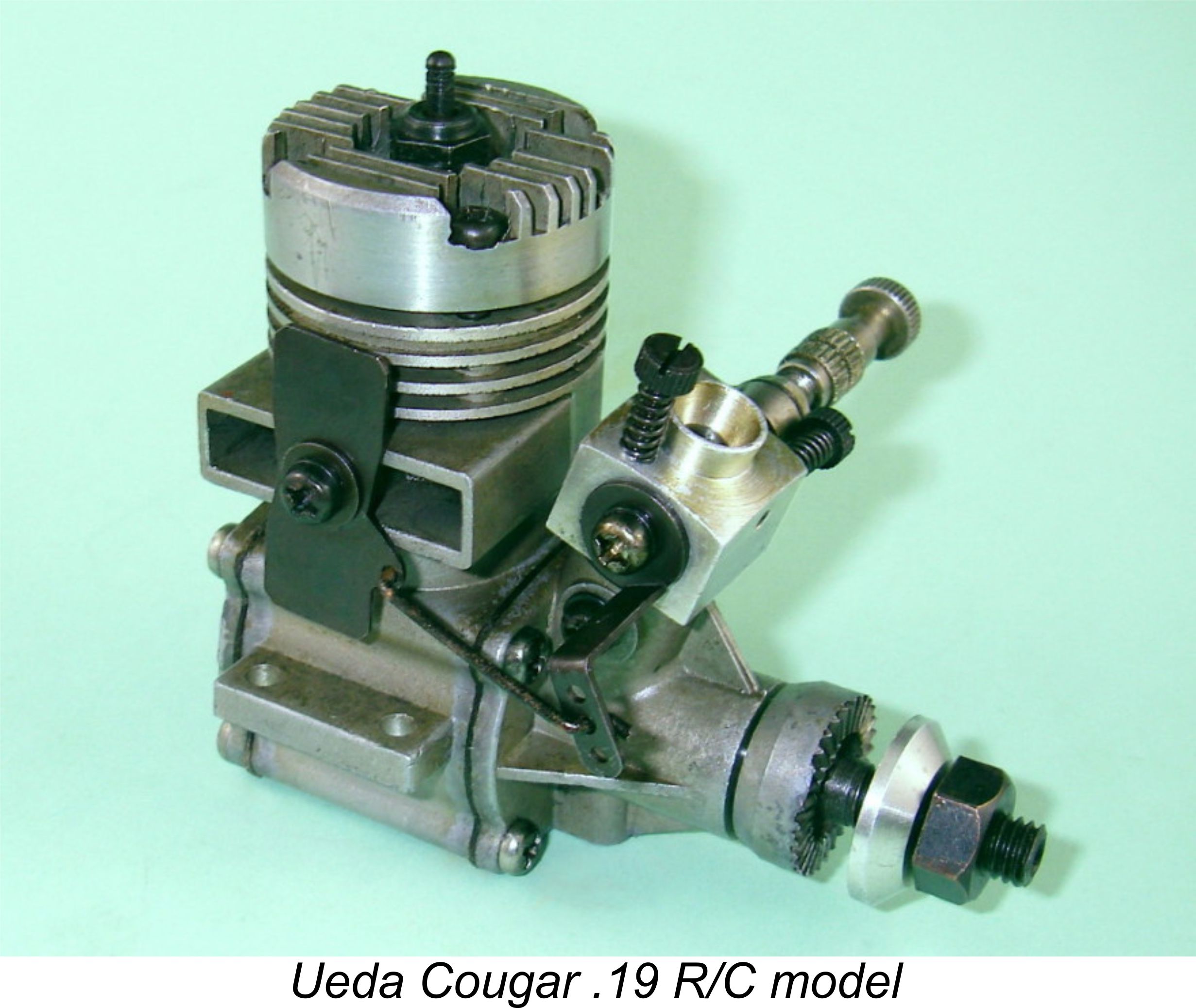

However, this was very far from being a simple case of boring out an existing 15 design. Both bore and stroke were different, the 19 having bore and stroke measurements of 16.6 mm and 15.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 3.25 cc (0.198 cuin.). The crankcase had an internally-machined annular channel to accommodate the additional space requirements of the con-rod big end arising from the increased stroke. As a result, relatively few components were interchangeable between the two models. The R/C version of this engine weighed in at 5.90 ounces, while the control-line model tipped the scales at 5.35 ounces. Interestingly, both these weights were slightly less than the checked figures for the equivalent 15 models! Presumably the thinner cylinder wall of the 19 accounted for much of this.

A probable explanation for the relative rarity of the 19 may be found in the crankshaft design, which featured the same 7 mm internal gas passage and elongated sharp-cornered induction port allied to a 9 mm journal diameter as its smaller relative. It was also left in a mega-hard state. Consequently, it suffered from the same crankshaft fragility issues as the 15 model, which were of course greatly exacerbated by the fact that it had to deal with the increased loads imposed by a larger bore and stroke. My “runner” C/L example of the engine arrived with a crank which had broken at the induction port, and I have heard of a number of others which suffered the same fate. This is actually one of the rarer Ueda Once again, the only available remedy (which may or may not cure the problem) is to round off the sharp corners of the induction port and normalize the crankshaft. In the case of my own C/L example number 983, the damage was already done, leaving me with no alternative other than to make a new crankshaft from scratch. In doing so, I reduced the diameter of the internal gas passage to 6 mm and also used a far less elongated induction port which was matched to the venturi base and had rounded corners. This shaft has so far proved completely reliable in service, and the engine runs well both on the bench and in the air. It is noticeably more powerful than its 15 relative, although its performance is by no means stellar when compared with that of its contemporary rivals. The R/C version of the Ueda Cougar .19 was the subject of a test by Peter Chinn which appeared in the March 1968 issue of “Model Airplane News”. Chinn commented on the differences between the 15 and the 19 models, noting that the basic design had probably been intended from the outset as a dual displacement production. In his view, this was the explanation for the seemingly excessive bulk and weight of the 15 model.

Chinn reported that the freed-up engine was extremely easy to start, usually needing only one flick. An exhaust prime was found to enhance cold starting. The engine apparently ran well once started, the main problem being the continued generation of excessive levels of vibration. Chinn put this down to the use of an excessively heavy piston coupled with a crankweb counterbalance of inadequate weight. He saw both of these issues as matters which could readily be dealt with by the manufacturer through an appropriate re-design. The vibration levels were reportedly such that fuel in a tank mounted directly on the engine bearers behind the unit would froth to the point of introducing air bubbles into the fuel line. This required the use of a richer needle setting to compensate for the air in the fuel supply. Fair enough, but when the engine was throttled down, the vibration naturally decreased and the bubbles subsided. This left the needle at a setting that was Using 5% nitro fuel, Chinn reported an output of 0.24 BHP @ 12,000 rpm for the Ueda .19 R/C. If typical trends were in force, the U/C version would doubtless have done a little better than this - the U/C venturi would be inherently less restrictive than the R/C carburettor. Nevertheless, this seemingly modest output was actually within the ballpark for R/C glow-plug motors of the day - Chinn’s January 1969 “Aeromodeller” test of the competing Enya 19-IV TV model reported a very comparable output of 0.24 BHP @ 11,600 rpm, admittedly with a muffler fitted. Removal of the muffler raised output by some 12% to around 0.27 BHP. Even so, the Ueda was not completely outclassed by the Enya in terms of peak performance. What let it down was a seemingly inadequate quality control program coupled with an inherent excess of vibration. That said, my own example number 983 with the home-made shaft is a fine runner both on the bench and in the air. The Ueda 45 For unknown reasons, Ueda never released any models in the popular .29 and .35 cuin. categories. We have to go to the .45 cuin. displacement classification to find the next engine in our survey.

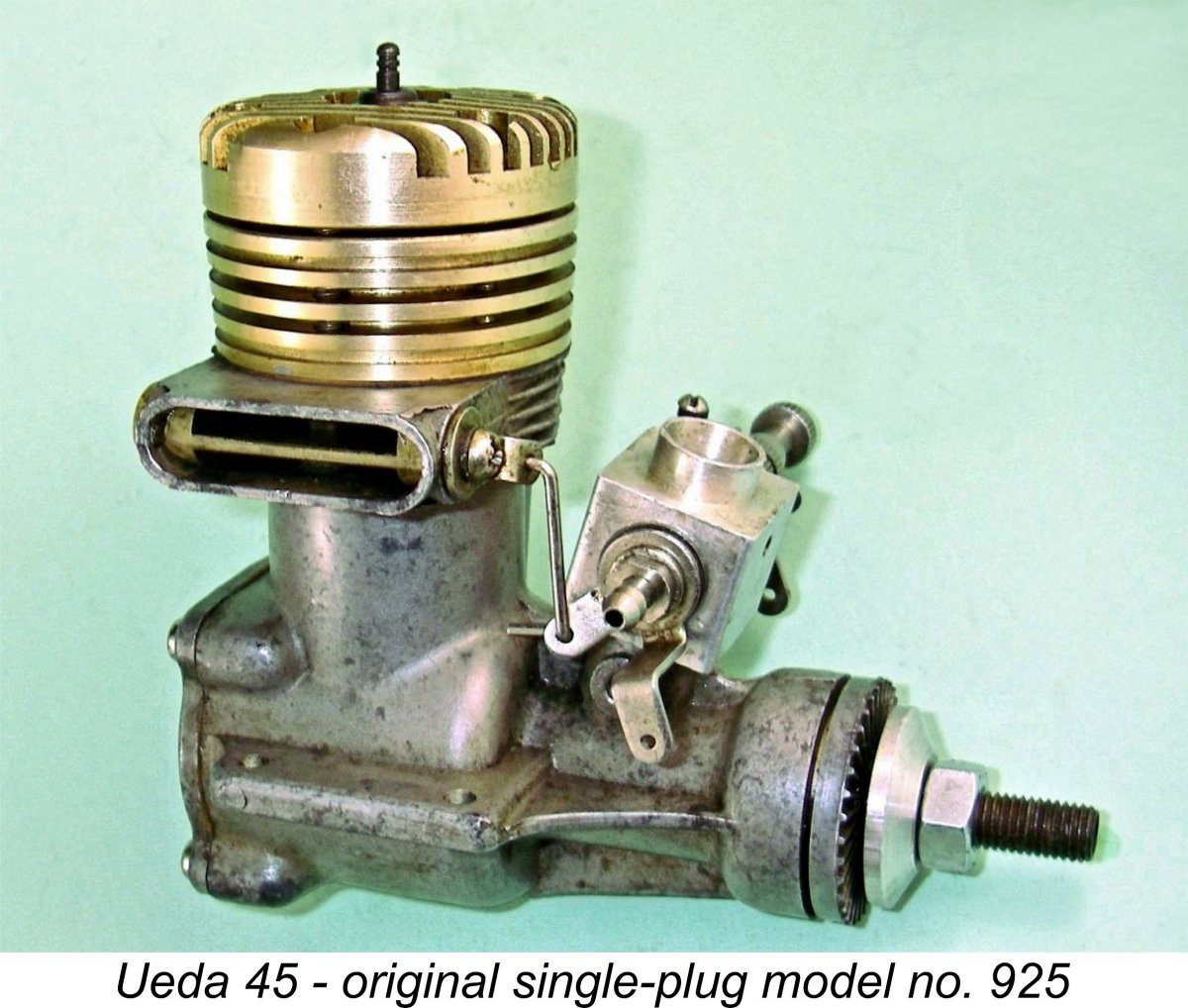

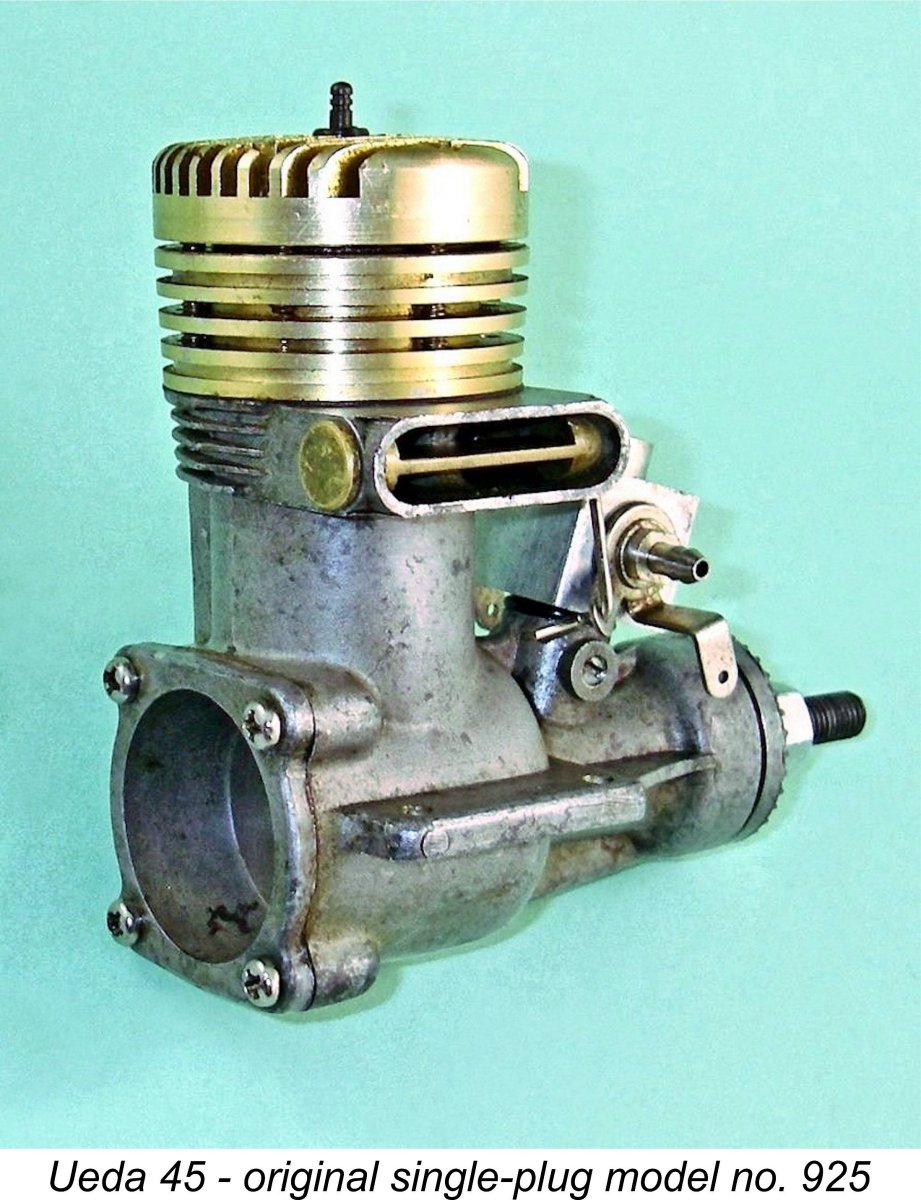

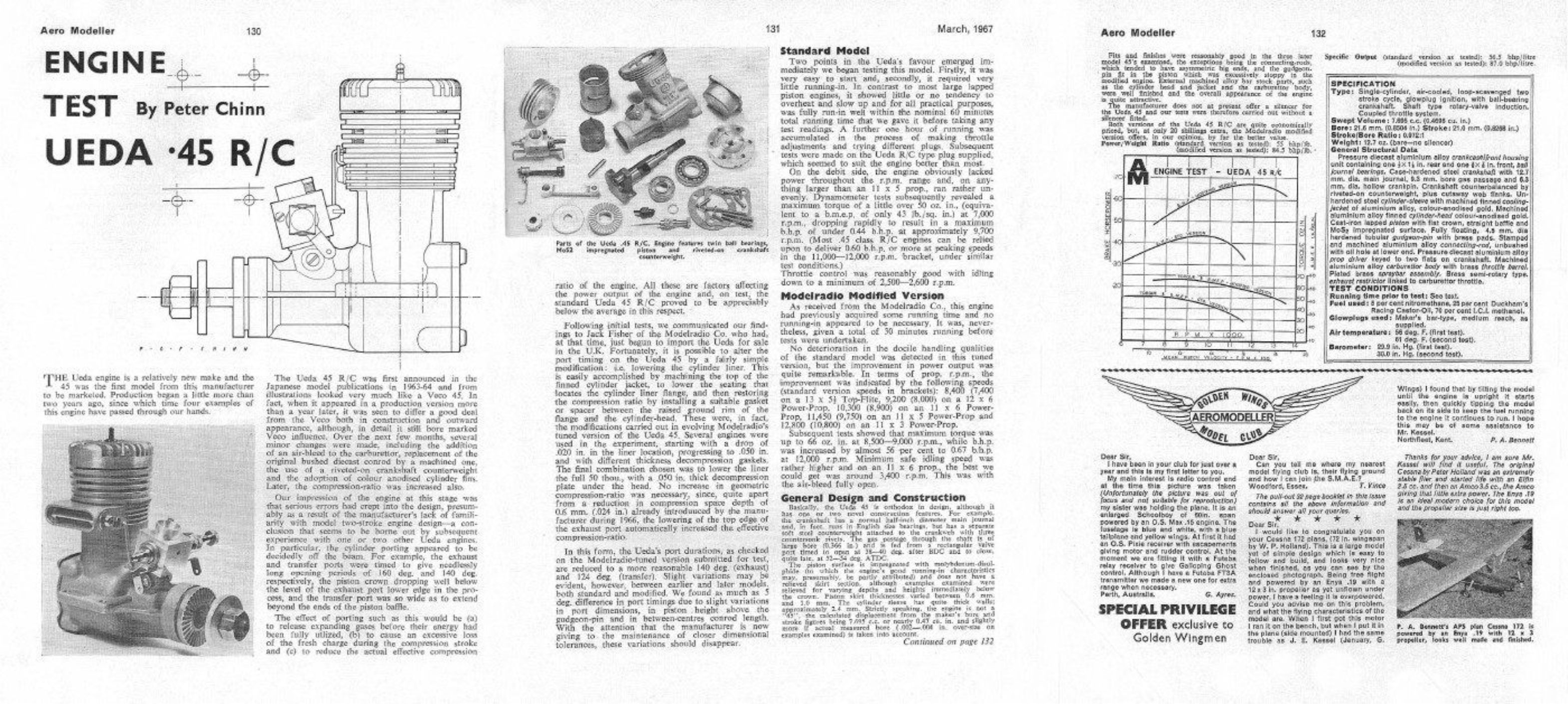

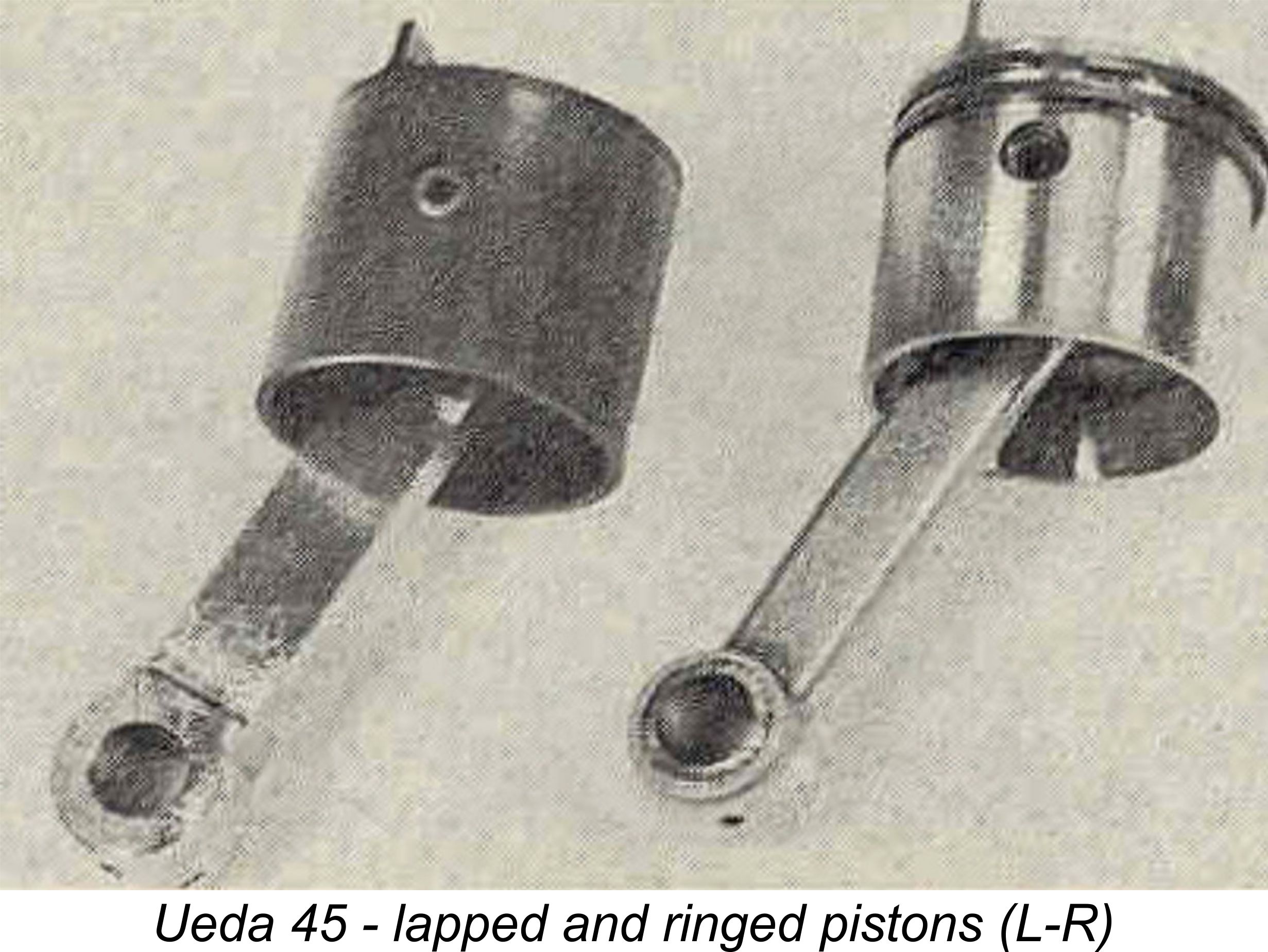

The manufacturers claimed a weight of 9.5 ounces for the original single-plug version of the engine, although I have been unable to confirm this figure. The weight reported by Peter Chinn in his later test (see below) was considerably in excess of this claim. Chinn quoted a weight of 12.7 ounces, a number which is confirmed by a measurement taken from my own illustrated example. The general design of the engine indicated a significant degree of Veco influence. The crankshaft was supported in two ball races. The initial version had a It would appear that a good prototype example of this version of the engine must have been a quite competitive performer by the standards of the day. The previously-mentioned “Motor Mart” article from the January 1965 issue of “Aeromodeller” reported that examples of this engine had placed first and second in the high-profile All-Japan/America Goodwill R/C contest in 1964 - no mean feat considering the quality of the competition at the time. It is of course very likely that the engines in question were factory prototypes which were specially prepared for the event. Be that as it may, the “Aeromodeller” article cited speeds of 11,000 rpm and 12,000 rpm for 11x6 and 12x4 airscrews respectively - not too shabby at all by then-current standards. In fairness, it must be stated that the source of these figures was not clarified, nor were the fuel or the brand of the airscrews specified. A further development of the single-plug variant of the Ueda 45 was the subject of a test by Peter Chinn which appeared in the March 1967 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Chinn reported that the engine had appeared “a little more than two years ago”, which was clearly in error as of the date of publication of this test. It seems likely that the test had been conducted and written up well prior to its publication date.

It seems clear that Chinn had been working closely with the manufacturer on the further development of the Ueda 45. Chinn stated that prior to the completion of his test report, no fewer than four examples of the Ueda 45 had passed through his hands. The first example actually tested by Chinn (in 1966 by his own account) proved to be an excellent starter with a reasonably good idle, but was well down on expectations in the power department, recording only 0.43 BHP @ 9,700 rpm - nowhere for an engine of this displacement at a time when such engines were expected to develop well over 0.6 BHP in R/C configuration. An investigation into the reasons for this revealed that, in Chinn’s words, “serious errors had crept into the design, presumably as a result of the manufacturer’s lack of familiarity with model two-stroke engine design”. In particular, the cylinder porting design appeared to be “decidedly off the beam”. Exhaust and Although Chinn did not make these facts public at the time of his initial tests, he does seem to have communicated them both to the newly-appointed British importers, Messrs. Modelradio, and to the factory, along with his recommendations. Changes were made as a result of Chinn’s initial findings, soon allowing the importers to offer a modified version in which the crankcase was machined so as to lower the cylinder and delay the opening of both exhaust and transfer ports by some 10 degrees, thus reducing both periods by around 20 degrees in total and also raising the compression ratio. In this modified form, the engine showed a 56% increase in power output to the order of 0.67 BHP at 12,000 rpm, putting the Ueda well up among the top level performers in this class at the time.

Chinn reported that the improvement in performance resulting from the revisions to the Ueda 45’s cylinder port timing was achieved without any loss of handling or running qualities, which remained excellent. However, he found that the minimum safe idling speed was of the order of 3,400 rpm - a little higher than ideal, although within acceptable limits.

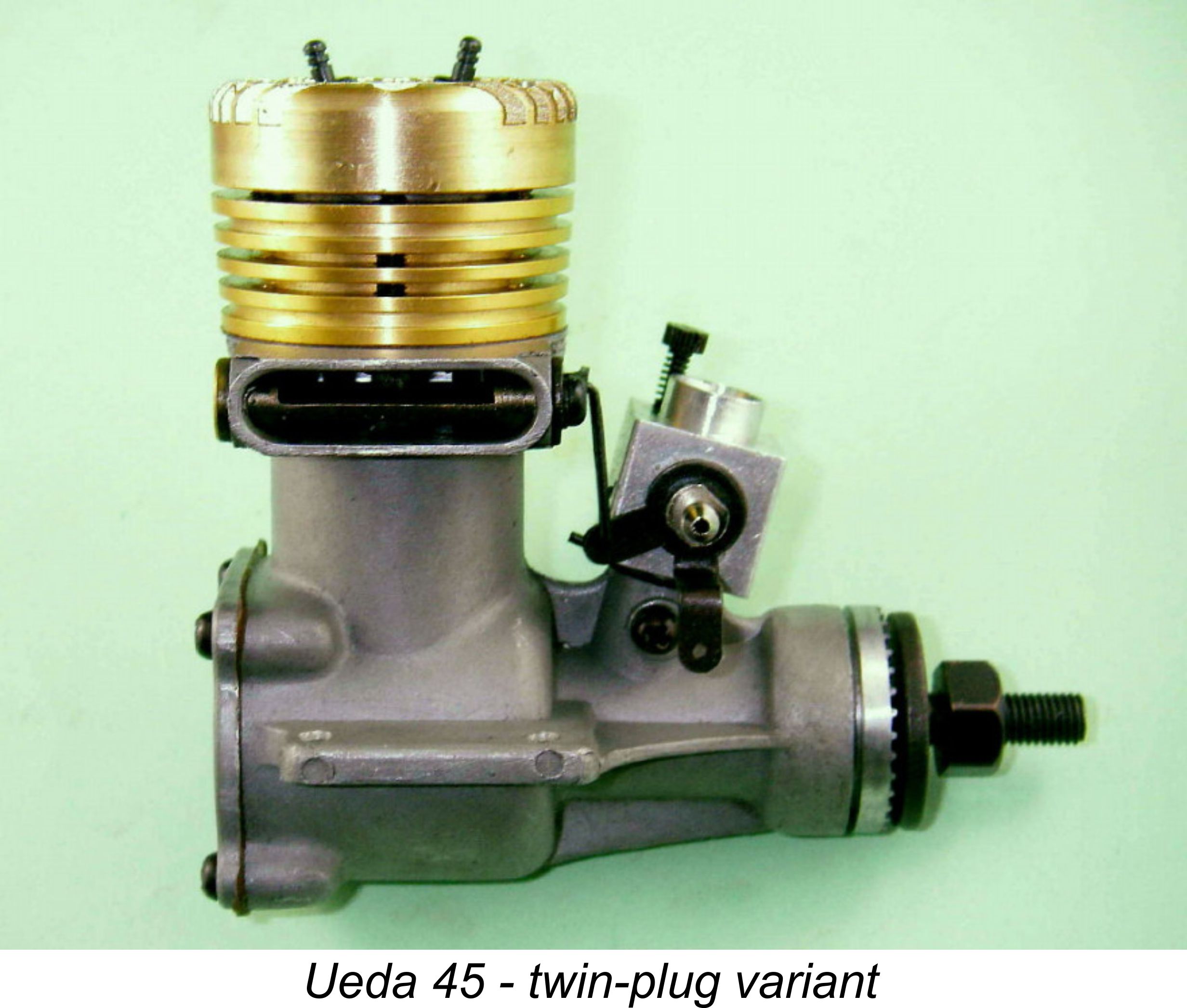

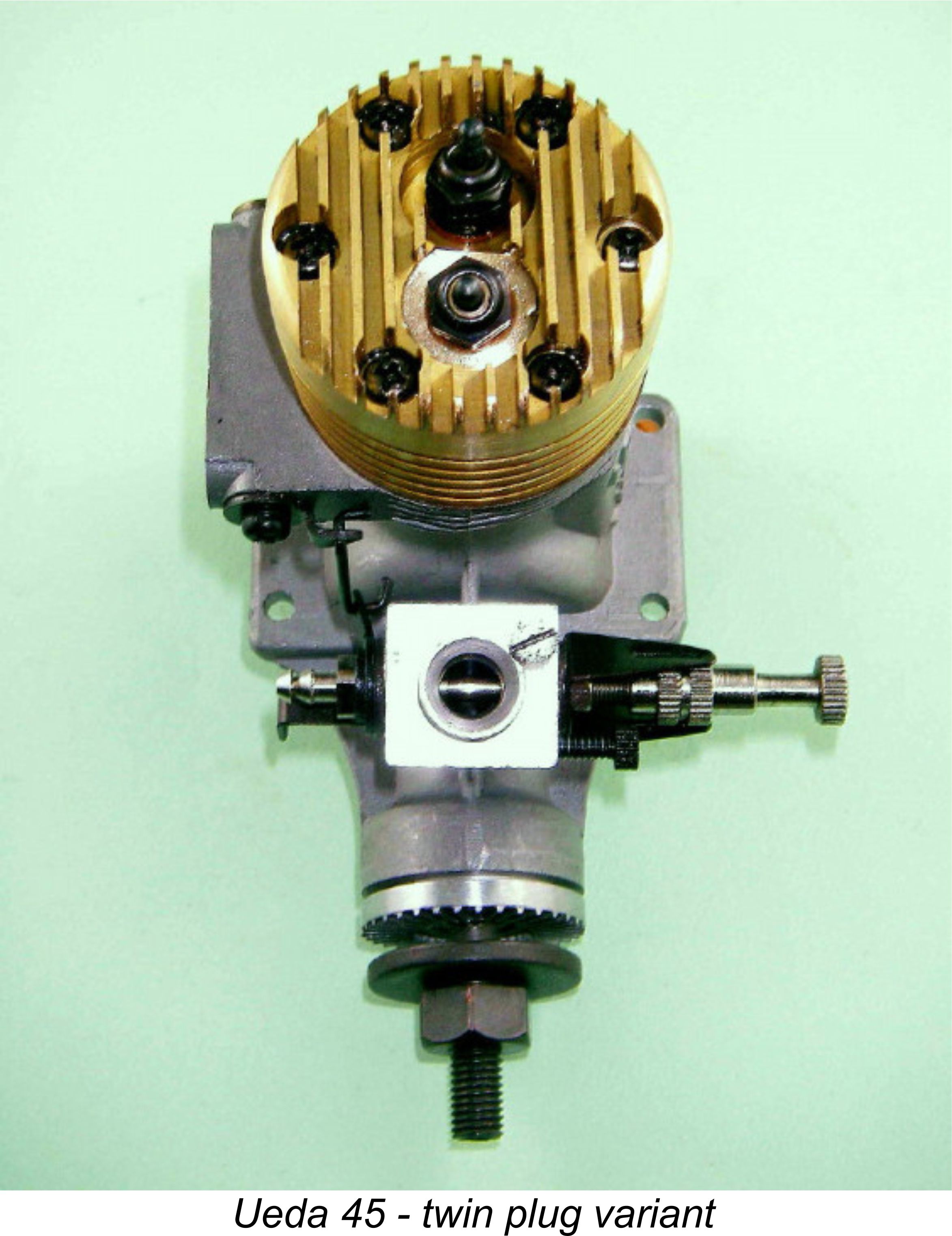

Despite arriving in a sorry state of neglect as far as its external appearance went, the engine was found to be in excellent condition internally thanks to the presence of a coating of castor oil gum. Following a full clean-up as described in my other article, it still retained clear external evidence of improper long-term storage in the past, but proved to be an excellent starter and runner which throttled very well. Timing measurements confirm that it's one of the later improved examples mentioned in Chinn's test report, a finding which is consistent with the serial number. As far as the engine’s quality of construction went, Chinn reported some evidence of variation between different examples, with such factors as con-rod working length and port timings showing slight At some later point in 1967 the variant described above was replaced by a revised model having a twin-plug head of the type first popularized by Merco beginning in 1965. The piston design was also changed, the new model featuring a twin-ringed alloy piston as well as a forged con-rod with a bronze-bushed big end. The geometric compression ratio of this latter variant was 8 to 1. Weight was unchanged, with the new model weighing a checked 12.7 ounces. It was a very handsome engine with its gold anodized cylinder jacket and head. Prospective users take warning - this anodizing fades very rapidly from repeated heat cycles………

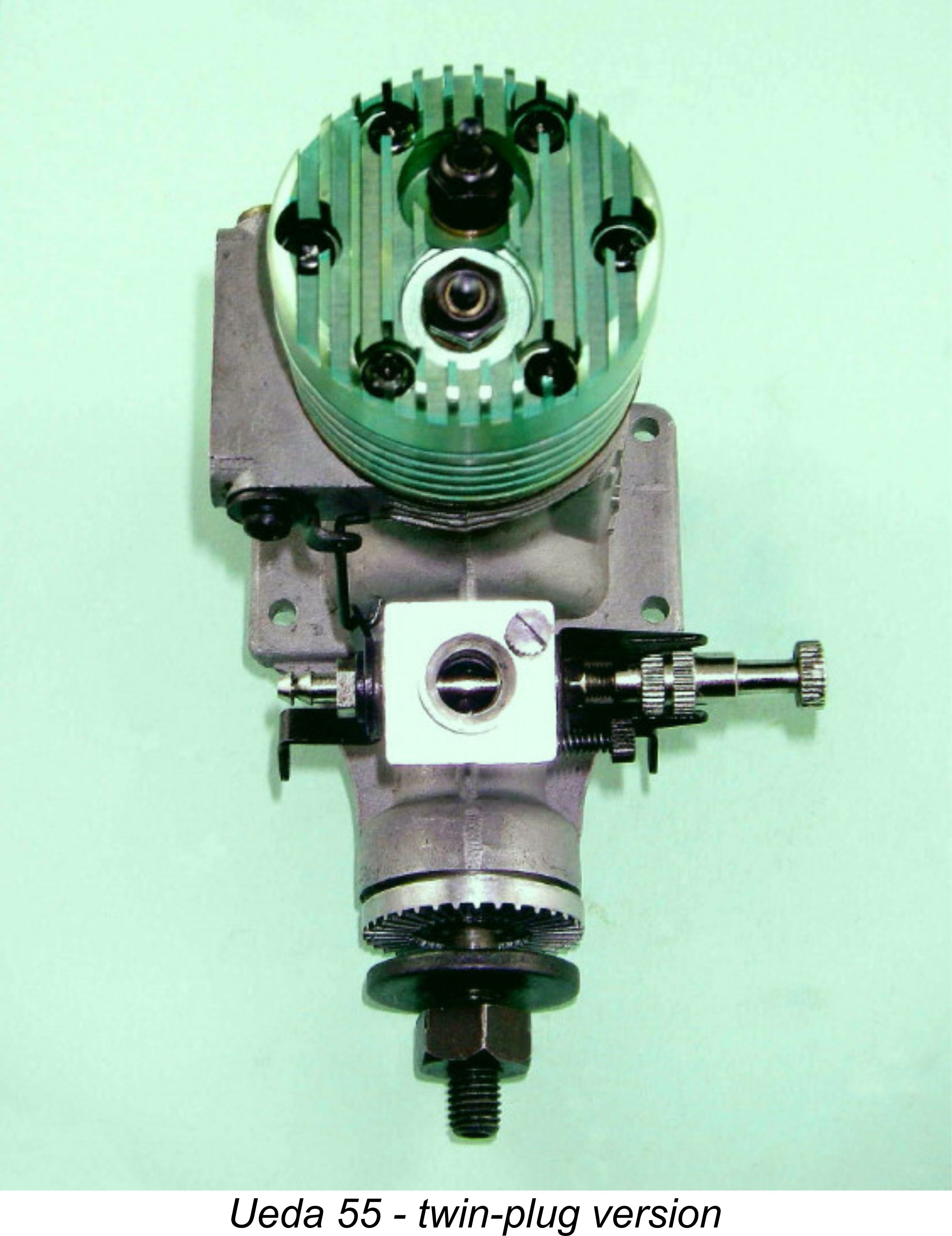

Once again, the engines carried serial numbers - I have yet to encounter an un-numbered example of this model. At present, the highest serial number for a twin-plug Ueda 45 of which I’m aware is engine number 1658. I’m convinced that there must surely have been more than this! The attached images of a later twin-plug model are of my own new and un-run example, engine number 1612. It seems to be extremely well made with a clean finish, tight bearings and an outstandingly good compression seal despite the fact that the rings have not been bedded in The main effect of the use of twin plugs appears to be to improve both the dependability of the engine’s idle and its response to a snap opening of the throttle following an extended period of idling. It’s also logical to assume that it may help power output in a big-bore engine by reducing the maximum flame propagation pathway within the combustion chamber, although in terms of peak output there seems to be little measurable difference. An interesting operational point which seems to apply to all twin-plug engines, not just the Uedas, is the fact that it’s necessary to “light” both plugs to get them both working. To me, this is a very surprising finding - one would think that starting on one plug would be sufficient, with the other plug lighting up as a result of the heat generated through the combustion process. However, several persuasive tests have been conducted that indicate the contrary - it is in fact necessary to electrically light up both plugs to get them both working. The engine can be started on one plug, but the other plug then has to be briefly stimulated to get it working as well. A number of people have reported a small but measurable fall-off in performance for a twin-plug engine when only one plug is lit instead of both, but the cited difference is only in the order of a few hundred rpm. Any such difference is likely due to the second ignition point reducing the flame propagation time required for the full involvement of the charge of mixture in the combustion process. For a more detailed discussion of the intriguing issue of twin plug operation, see my separate article on this web-site. The Ueda 55

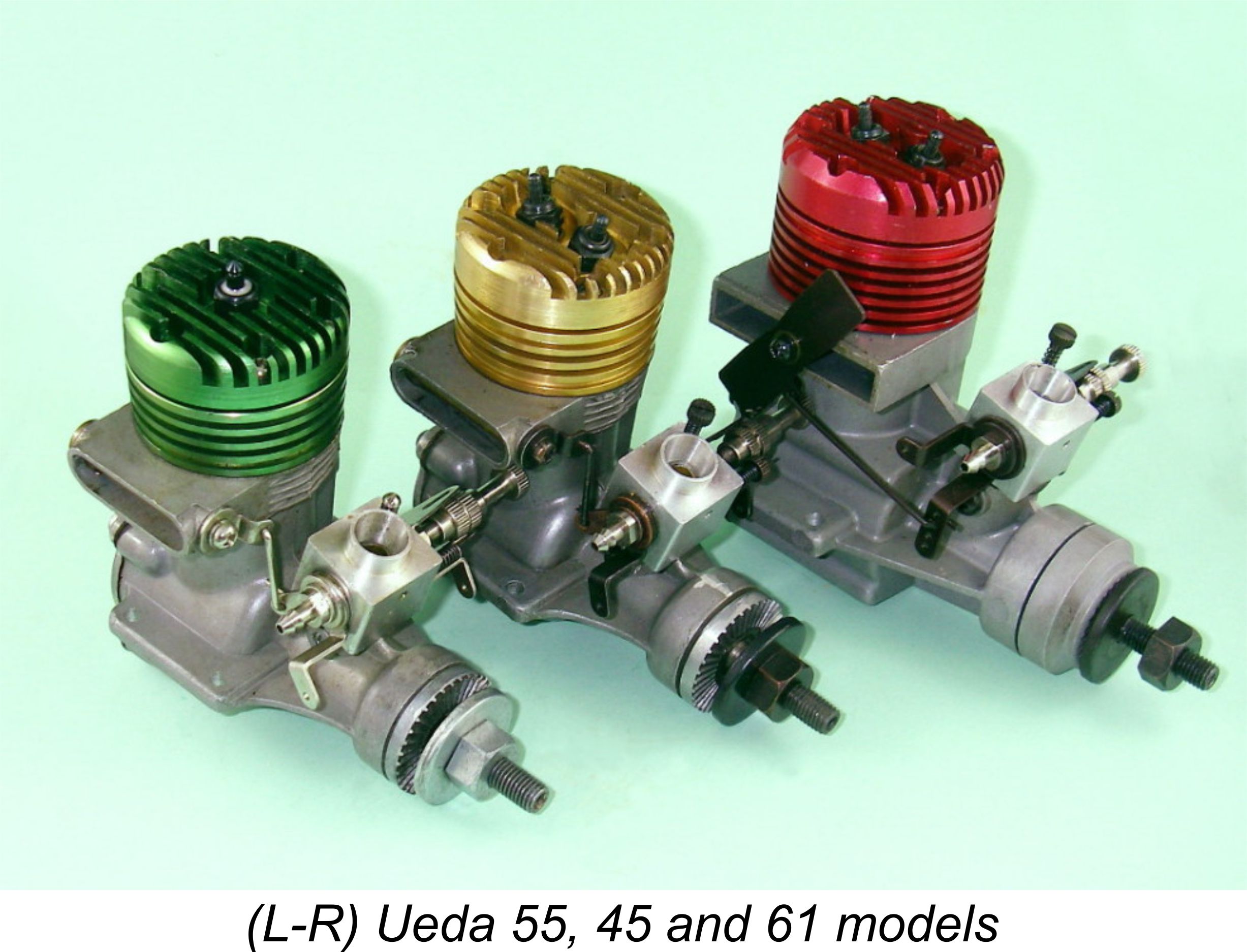

Bore and stroke checked out at 23.5 mm and 21.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 9.11 cc (0.556 cuin.). As in the case of the companion .45 cuin. model described earlier, the original version of the Ueda 55 featured a lapped cast iron baffled piston and a conventional single-plug head The design progression of the Ueda 55 followed that of the companion 45 exactly, going from the original configuration to a twin-plug head with ringed alloy piston and forged bushed rod. This change evidently occurred during 1967. Compression ratio of the revised variant was 8 to 1. Claimed output was 0.90 BHP with a cited operating speed range of 1,500 to 12,000 rpm. The illustrated example of the later twin-plug model bears the serial number 1256. It tips the scales at a checked 12.2 ounces (346 gm - understandably, a fraction less than the earlier lapped piston model but oddly enough also some 0.5 ounce less than the contemporary 45 Like their .45 cuin. companions discussed earlier, the illustrated new examples of the Ueda 55 are extremely well finished and fitted, with outstanding compression despite never having been run in. I also have a used example of the twin-plug ringed-piston variant (number 977) which remains just as well fitted despite the running time that it has received. I’ve never flown it, but it starts and runs very well on the bench. In fairness to the manufacturers, I have to say that none of the larger Ueda models in my own possession display any obvious manufacturing deficiencies. As far as I am aware, the Ueda 55 was never the subject of a published test in the contemporary English-language modelling media. So once again, the manufacturer’s performance claims remain unsubstantiated. However, based on the output found by Chinn for the updated 45 model, the claim does have a certain stamp of credibility. If time ever permits, I may get around to testing my "runner" example, just to see............. The Ueda 61

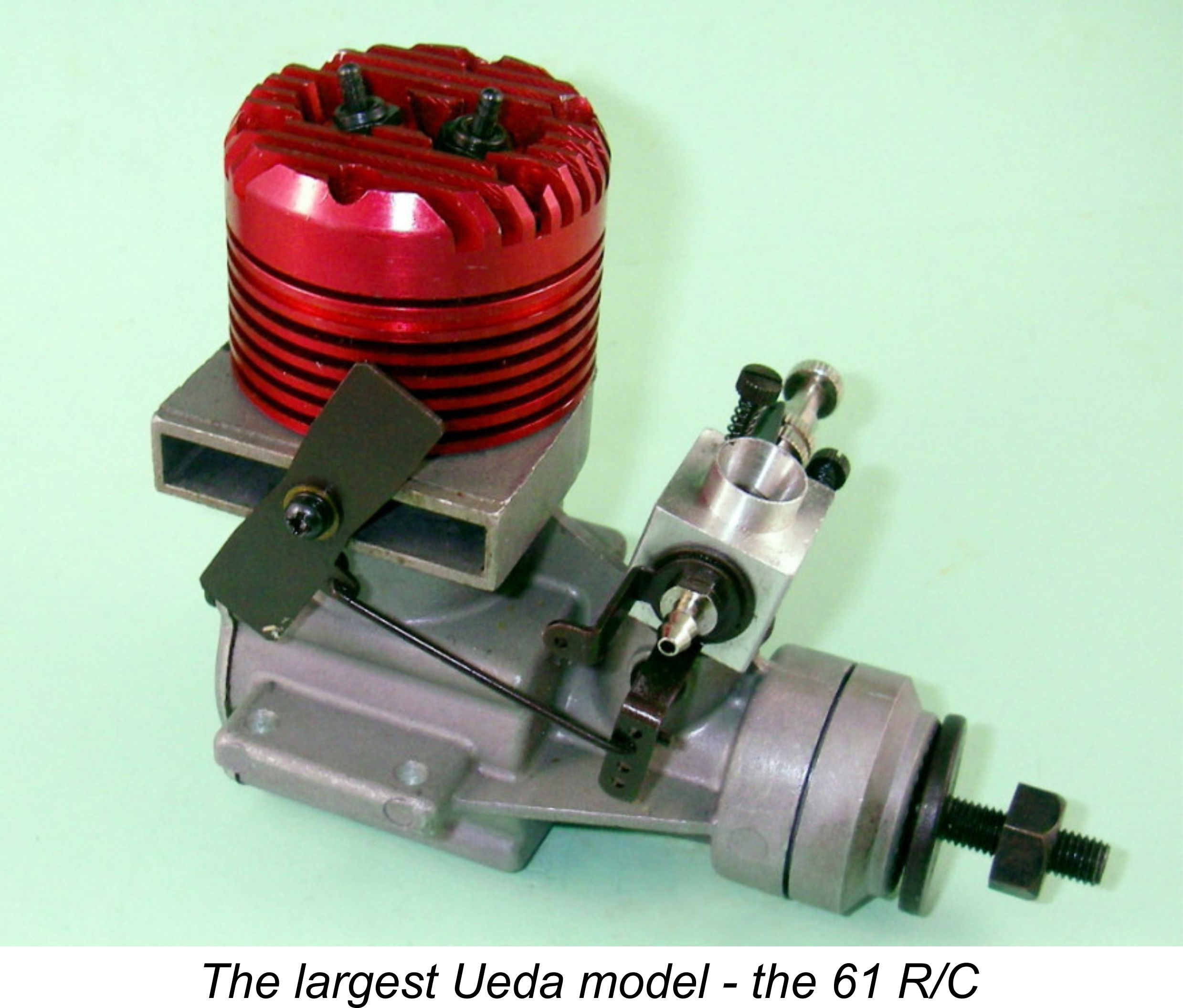

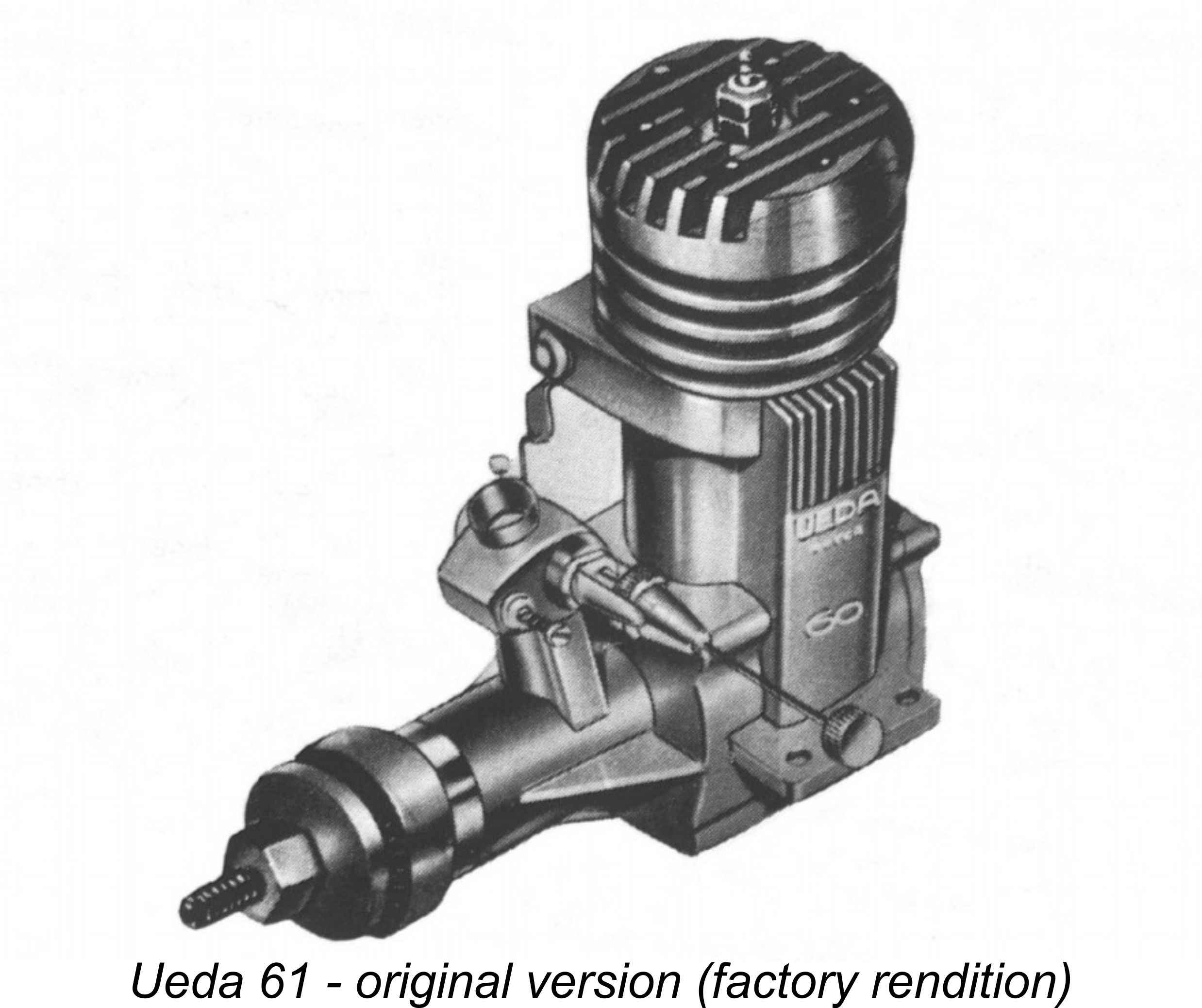

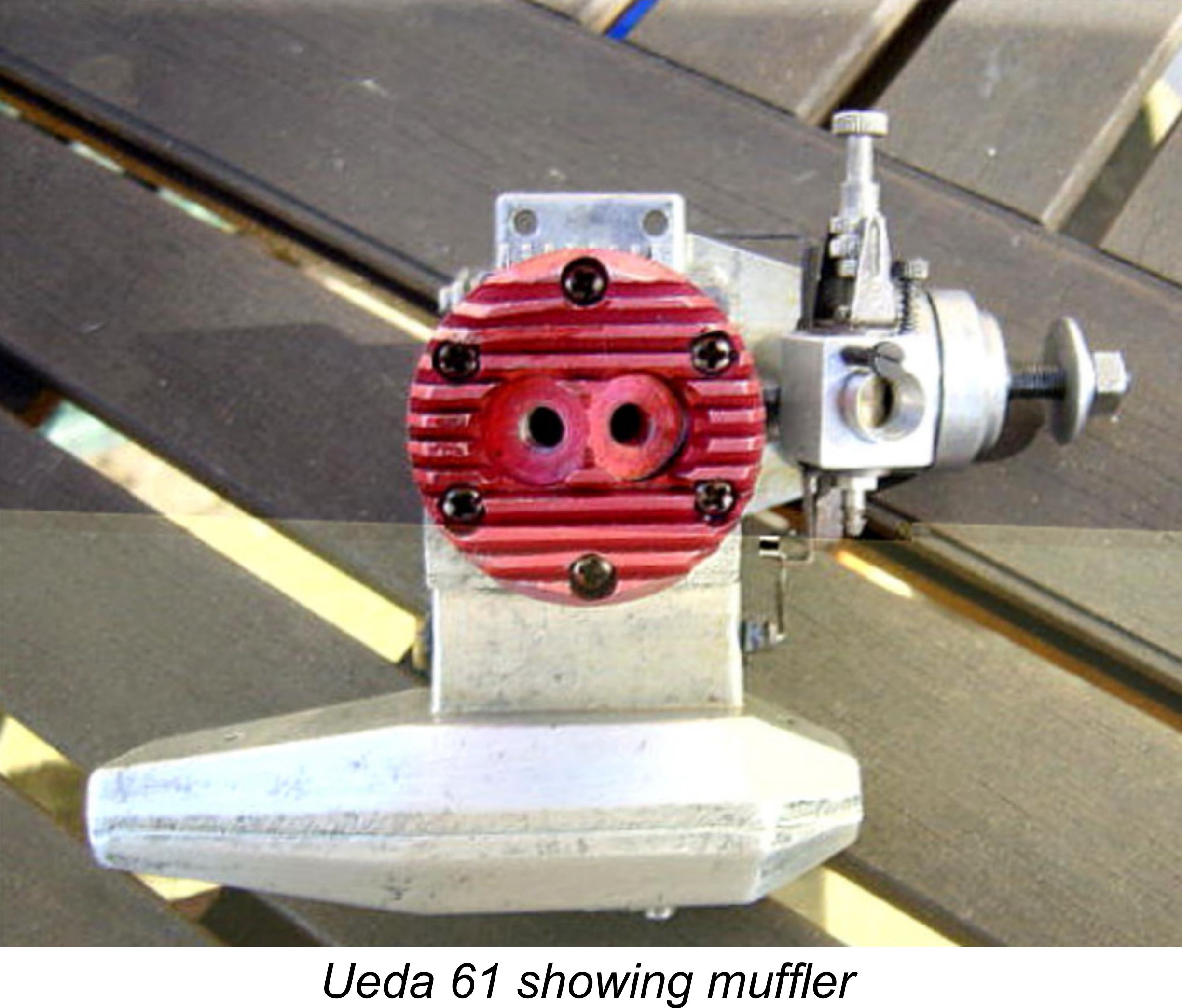

It would appear that the Ueda 55 had represented the maximum practicable displacement increase which could be accommodated by the original 45 crankcase casting. For the 60/61 models, a completely revised and far more massive casting was employed together with larger-diameter ball races. In addition, the basic twin-plug version like that illustrated below used a conventional butterfly exhaust restrictor as opposed to the rotary barrel restrictor used in the 45 and 55 models. The downside of this arrangement was of course that the butterfly could not be used in conjunction with a muffler. To deal with this issue, a bolt-on barrel restrictor fitting was made available as an alternative - note the extra hook-up point on the carburettor for the alternative restrictor in the attached images. The 61 was thus a completely distinct design as opposed to an over-bored 55, although it retained a general stylistic Both bore and stroke were increased over those of the 55 model described earlier. The 61 model measured up at 24 mm bore and 22 mm stroke for a displacement of 9.95 cc (0.607 cuin.). The illustrated twin plug version weighs a checked 458 gm (16.15 ounces) without a muffler - significantly more than the 55 unit. Without dismantling an example of each model, it’s not really possible to determine exactly where the additional 108 gm of weight came from compared with the 55, although the 61 is certainly a far more massively-constructed unit.

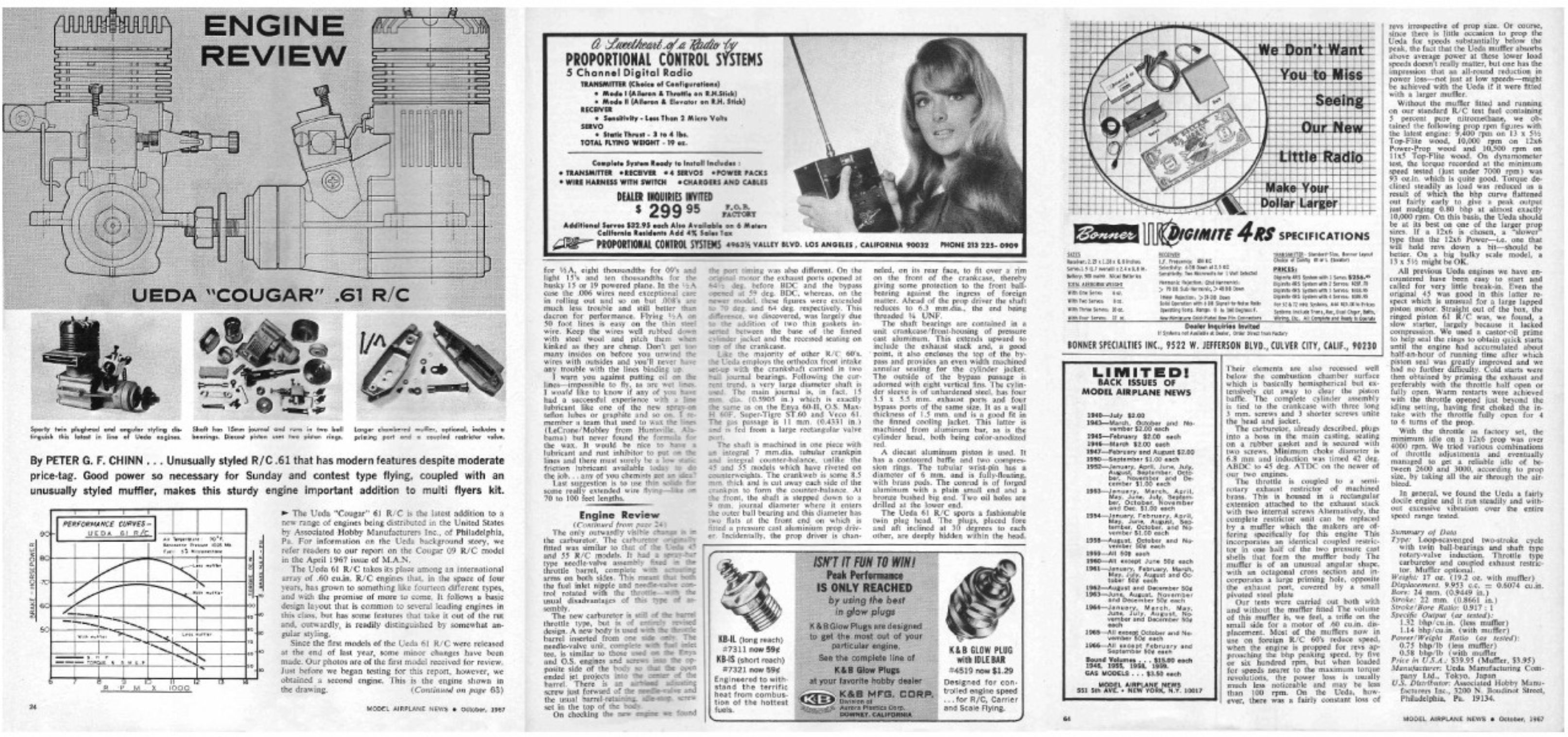

It seems likely that this model too was made in relatively small numbers by industry standards. The highest serial number of my acquaintance for one of the twin-plug variants is engine number 1124 which appeared a few years ago on eBay. I have no numbers at all for the original single-plug model. The Cougar .61 was the subject of a test by Peter Chinn which appeared in the October 1967 issue of “Model Airplane News”. Chinn began by noting the design changes which had been incorporated since the original release of the engine in the latter part of 1966. The balance of his report was largely confined to a detailed description of the engine, with little additional comment either pro or con. A strangely “neutral” report, in fact, with neither criticism nor praise! One gets the impression that while Chinn found the Ueda to be a perfectly acceptable product, he was unable to find any attributes which were sufficiently noteworthy to warrant being highlighted.

Chinn tested the Ueda both with and without the muffler which was made available as described earlier. He found that with the muffler fitted there was a more or less constant drop in prop speeds across the entire speed range. He noted that this was unusual in that muffler-induced speed loss usually decreased at the lower speeds. In Chinn’s opinion, the somewhat anomalous finding with the Ueda might be attributable to a muffler design having (in Chinn’s view) a smaller than ideal internal volume. Chinn characterized the engine as “fairly docile” with respect to its handling qualities. He reported that it ran “steadily and without excessive vibration over the entire speed range tested”. In terms of performance, Chinn found that the engine developed quite good torque at the lower speeds, a desirable attribute for a large R/C glow-plug motor. Peak output without the muffler and using a fuel containing 5% nitromethane was found to be 0.80 BHP @ 10,000 rpm, which is of course somewhat less than the manufacturer’s claim for the slightly smaller and considerably lighter 55 model. With the muffler fitted, this was reduced to 0.69 BHP @ 9,500 rpm. These figures are somewhat below those reported for several contemporary large R/C glow-plug motors, including the Merco .61. Still, the engine developed good power at relatively moderate rpm, a highly desirable characteristic for a non-competition R/C engine. It was also very competitively priced. Chinn felt that a “slow” 12x6 or perhaps a 13x5½ prop would suit the engine well for flying purposes. The Ueda Engines - User Opinions Opinions regarding these engines seem to vary widely. Some users evidently found them to be perfectly satisfactory in service provided one’s performance expectations were reasonably tempered, while others have gone so far as to characterize them as the “slag engines” of the 1960’s! With that range of opinions on offer, nothing that I present here will come as much of a surprise……......... My own flying experience of these engines has been confined to the modified 15 and 19 models mentioned earlier, which to date have performed in a fully satisfactory if unspectacular manner in sport control-line service. However, my 15 has had its shaft reworked for greater durability, while the shaft in the 19 is of my own manufacture. Hence my experiences cannot be cited as typical. In contrast to most of the more obscure pioneering ranges which I’ve tended to cover in these articles, the Ueda range is of sufficiently “recent” vintage (a mere half-century at the time of writing!) that a considerable number of older present-day model fliers still recall its existence, with some retaining clear memories of actually having used the engines. Moreover, the level of interest in these engines is now such that they come up fairly frequently as a topic for discussion. A recent search of the Internet threw up a number of discussion threads on various forums regarding the Ueda engines. Most of these were triggered by owners or prospective buyers looking for information on the range in general. The responses clearly showed that such information is in demand but is also in rather short supply, hence in part the motivation for the present article. However, opinions regarding specific models were plentifully provided! Here’s an edited sample:

Reviewing the above litany, it’s clear that individual views of the Ueda range depended very much on three things - one, which model one was talking about; two, whether or not the person in question got a “good” example; and three, the level of their expectations in terms of performance. It’s also clear that a good few users found these engines to be very acceptable sports performers, and it must be recalled that the sport-flying crowd have always far outnumbered their more competition-oriented colleagues. Viewed in this light, a fair number of buyers appear to have been pretty happy with the deal that they got! As noted by one of the commentators quoted above, one of the secrets to getting the best out of a Ueda engine, particularly those with lapped cast iron pistons, is to ensure that the engines are adequately lubricated. I’ve always run my 15 and 19 on fuel containing 25% castor oil while avoiding lean runs like the plague. So far, the wear rates in both these engines appear completely normal - neither shows any detectable wear after some hours each in C/L flying service. I suspect that the engines that “wore out faster than the importer could get them in” suffered the not-uncommon fate of being under-lubricated or run on non-castor lubricants. Conclusion

Despite these comments, it’s hard to see the Ueda engines as anything other than a range that should probably never have been introduced in the first place. They offered no technological edge over the competition and in fact underperformed by comparison with most of their competitors. They also fell short of the competition in the quality control department. Viewed in this light, their failure in the marketplace must be seen as inevitable, their low prices notwithstanding. Even so, there’s little doubt that a “good” Ueda represented an excellent deal for any modeller lucky enough to acquire one and smart enough to use it appropriately. The larger models in particular are very handsome engines that run well and will grace any collection of “classic” R/C glow-plug motors. This being the case, I have little doubt that the Ueda range will continue to draw interest from those attracted to something a little “different” who are able to accept them at their face value for what they are - good-looking but unpretentious sports motors with a few design quirks and pitfalls! __________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published January 2015

|

| |

Here I'll focus attention upon another largely forgotten Japanese model engine marque, albeit this time from the 1960’s. My subject is the Ueda range of engines which were produced in relatively small numbers in Tokyo, Japan between 1964 and 1970. During their relatively short production life, these engines acquired a reputation for being under-performers by comparison with most of their contemporaries, also exhibiting a number of design and manufacturing anomalies. As a result, they made little impression upon the contemporary market, only remaining in production for about 6 years.

Here I'll focus attention upon another largely forgotten Japanese model engine marque, albeit this time from the 1960’s. My subject is the Ueda range of engines which were produced in relatively small numbers in Tokyo, Japan between 1964 and 1970. During their relatively short production life, these engines acquired a reputation for being under-performers by comparison with most of their contemporaries, also exhibiting a number of design and manufacturing anomalies. As a result, they made little impression upon the contemporary market, only remaining in production for about 6 years.  However, this situation has begun to change in recent years. The relative rarity of the Ueda engines by comparison with many of their contemporaries has combined with their highly individualistic and in many respects unusually attractive appearance to create a steadily growing level of interest in them. As of the original time of writing in 2014, good boxed examples of the larger models were regularly selling for over $150, while even the smaller models were pushing up towards the $100 threshold. As recently as January 2024 a nice used and unboxed example of the single-plug Ueda 45 sold on eBay for US$160. The relatively limited supply seems likely to ensure that this interest will continue despite the absence of detailed documentation.

However, this situation has begun to change in recent years. The relative rarity of the Ueda engines by comparison with many of their contemporaries has combined with their highly individualistic and in many respects unusually attractive appearance to create a steadily growing level of interest in them. As of the original time of writing in 2014, good boxed examples of the larger models were regularly selling for over $150, while even the smaller models were pushing up towards the $100 threshold. As recently as January 2024 a nice used and unboxed example of the single-plug Ueda 45 sold on eBay for US$160. The relatively limited supply seems likely to ensure that this interest will continue despite the absence of detailed documentation. The big question for me has always been - why were the Ueda engines introduced in the first place?? They really offered nothing in the way of a performance or technological incentive to encourage prospective buyers. Consequently, it should come as no surprise to learn that even their comparatively low selling prices failed to promote large sales.

The big question for me has always been - why were the Ueda engines introduced in the first place?? They really offered nothing in the way of a performance or technological incentive to encourage prospective buyers. Consequently, it should come as no surprise to learn that even their comparatively low selling prices failed to promote large sales.  Consequently, as of 1964 the model engine market was pretty well saturated, with an over-supply of excellent engines to suit any conceivable purpose in every displacement category. To stand any chance of success in the buyer’s market stemming from these conditions, a new range simply had to offer something special by way of performance or quality (or both). The Ueda engines manifestly did neither. Really, the wonder is not that the range disappeared so quickly but that it ever appeared at all!!

Consequently, as of 1964 the model engine market was pretty well saturated, with an over-supply of excellent engines to suit any conceivable purpose in every displacement category. To stand any chance of success in the buyer’s market stemming from these conditions, a new range simply had to offer something special by way of performance or quality (or both). The Ueda engines manifestly did neither. Really, the wonder is not that the range disappeared so quickly but that it ever appeared at all!!  Unfortunately, the interest in model engines on the part of Ueda Junior does not seem to have been matched by a comparable level of expertise in model engine design and manufacture - the engines certainly left something to be desired in basic design terms, also exhibiting a higher than usual variation in quality by 1960’s Japanese standards. They did improve over time, but never caught up with their competition.

Unfortunately, the interest in model engines on the part of Ueda Junior does not seem to have been matched by a comparable level of expertise in model engine design and manufacture - the engines certainly left something to be desired in basic design terms, also exhibiting a higher than usual variation in quality by 1960’s Japanese standards. They did improve over time, but never caught up with their competition.  The company’s automotive roots were noted in a report which formed part of the regular “Motor Mart” feature in the January 1965 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine in which the fledgling Ueda model engine range as it then existed was discussed. In one of his later published tests reports, Peter Chinn also mentioned the fact that the manufacturers were sub-contractors to the Japanese automobile industry.

The company’s automotive roots were noted in a report which formed part of the regular “Motor Mart” feature in the January 1965 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine in which the fledgling Ueda model engine range as it then existed was discussed. In one of his later published tests reports, Peter Chinn also mentioned the fact that the manufacturers were sub-contractors to the Japanese automobile industry.  The Ueda engines first appeared in Japan during 1963, albeit at that stage only in prototype form. The range made its European debut during February of 1964, when prototypes were displayed at the high-profile Nuremberg Trade Fair. The model highlighted at that event was the Ueda .45 R/C offering, then in its original single-plug lapped piston form, of which more below in its place. This event was recorded in the “Motor Mart” feature which appeared in the May 1964 issue of “Aeromodeller”. As far as I’m presently aware, this was the first reference to the Ueda range in the English-language modelling media.

The Ueda engines first appeared in Japan during 1963, albeit at that stage only in prototype form. The range made its European debut during February of 1964, when prototypes were displayed at the high-profile Nuremberg Trade Fair. The model highlighted at that event was the Ueda .45 R/C offering, then in its original single-plug lapped piston form, of which more below in its place. This event was recorded in the “Motor Mart” feature which appeared in the May 1964 issue of “Aeromodeller”. As far as I’m presently aware, this was the first reference to the Ueda range in the English-language modelling media. cooled and water-cooled versions. Other models were to appear fairly regularly during the lifetime of the range. By 1967 the R/C versions had become predominant in response to the rapidly-changing face of the model engine marketplace.

cooled and water-cooled versions. Other models were to appear fairly regularly during the lifetime of the range. By 1967 the R/C versions had become predominant in response to the rapidly-changing face of the model engine marketplace.  nothing to set them apart from their better-known competition other than their very low prices. Apart from their reputation for sub-standard performance and fragility, several models also exhibited a tendency towards “porkiness” - the C/L version of the “Cougar” .15 model, for instance, weighed in at a relatively hefty 5.38 ounces, which is a

nothing to set them apart from their better-known competition other than their very low prices. Apart from their reputation for sub-standard performance and fragility, several models also exhibited a tendency towards “porkiness” - the C/L version of the “Cougar” .15 model, for instance, weighed in at a relatively hefty 5.38 ounces, which is a  As of the early 1970’s, AHM was liquidating their remaining stocks at fire-sale prices directly from their Philadelphia warehouse. A number of smart modellers got some very good deals as a result of this, as we shall see in due course. AHM was subsequently taken over by International Hobby Corporation (IHC), also of Philadelphia, who switched their primary focus towards model railroading. They remained very much in business at the original time of writing (2014).

As of the early 1970’s, AHM was liquidating their remaining stocks at fire-sale prices directly from their Philadelphia warehouse. A number of smart modellers got some very good deals as a result of this, as we shall see in due course. AHM was subsequently taken over by International Hobby Corporation (IHC), also of Philadelphia, who switched their primary focus towards model railroading. They remained very much in business at the original time of writing (2014).  This was Ueda’s smallest-ever offering. It was one of the first models offered by Ueda beginning in 1964. The initial version of this engine was offered only in un-throttled form, but an R/C model was added in around 1966.

This was Ueda’s smallest-ever offering. It was one of the first models offered by Ueda beginning in 1964. The initial version of this engine was offered only in un-throttled form, but an R/C model was added in around 1966.

In part this may be due to a modification which seems to have been applied fairly early on. The journal diameter of the shaft was increased at some indeterminate point to 8 mm, with the internal gas passage also being enlarged to 6 mm diameter. Shaft wall thickness was unaffected by this measure, but the larger diameter should have increased strength a little. It’s unclear whether this was a response to a demonstrated weakness or whether it represented an attempt to improve power output. I personally suspect the latter ……………….

In part this may be due to a modification which seems to have been applied fairly early on. The journal diameter of the shaft was increased at some indeterminate point to 8 mm, with the internal gas passage also being enlarged to 6 mm diameter. Shaft wall thickness was unaffected by this measure, but the larger diameter should have increased strength a little. It’s unclear whether this was a response to a demonstrated weakness or whether it represented an attempt to improve power output. I personally suspect the latter ……………….  The throttle used on the R/C version was very basic, giving the impression that it was very much an afterthought which was grafted onto the C/L version of the engine simply to give the company an entry into the .09 cuin. R/C engine market. It lacked any refinements such as air bleed controls, idle stops and the like, being merely a simple barrel-type butterfly valve which restricted the air supply while leaving the fuel supply unaffected. Its main effect was simply to enrich the mixture, thus slowing the engine down. Unlike most other Ueda R/C designs, no exhaust baffle plate was employed in conjunction with this throttle.

The throttle used on the R/C version was very basic, giving the impression that it was very much an afterthought which was grafted onto the C/L version of the engine simply to give the company an entry into the .09 cuin. R/C engine market. It lacked any refinements such as air bleed controls, idle stops and the like, being merely a simple barrel-type butterfly valve which restricted the air supply while leaving the fuel supply unaffected. Its main effect was simply to enrich the mixture, thus slowing the engine down. Unlike most other Ueda R/C designs, no exhaust baffle plate was employed in conjunction with this throttle.

The output measured by Chinn was very much on the modest side - using a fuel containing 5% nitromethane, the maximum output was 0.085 BHP at around 9.900 rpm. Measured prop/rpm figures included 9,400 rpm on a Top Flite 8x3½ and 8,700 rpm on a Tornado 8x4. Substantial increases in the nitromethane content did not produce any marked improvement in these figures - about 200 rpm or so on a given prop. This implies that the engine was limited by its breathing capabilities together with excessivly retarded ignition timing. For me, the cylinder port timing combined with the very low compression ratio are the likely culprits here.

The output measured by Chinn was very much on the modest side - using a fuel containing 5% nitromethane, the maximum output was 0.085 BHP at around 9.900 rpm. Measured prop/rpm figures included 9,400 rpm on a Top Flite 8x3½ and 8,700 rpm on a Tornado 8x4. Substantial increases in the nitromethane content did not produce any marked improvement in these figures - about 200 rpm or so on a given prop. This implies that the engine was limited by its breathing capabilities together with excessivly retarded ignition timing. For me, the cylinder port timing combined with the very low compression ratio are the likely culprits here.  The Ueda 15 was another of the original offerings of the company beginning in 1964. I do not have access to an example of the original version of the engine, but it was reportedly styled very similarly to its smaller .09 cuin. companion described earlier, sharing essentially all of its design features. Bore and stroke were 15.0 mm and 14.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The control-line version reportedly weighed 4.5 ounces, although I have not been able to gain access to an actual example to check this figure.

The Ueda 15 was another of the original offerings of the company beginning in 1964. I do not have access to an example of the original version of the engine, but it was reportedly styled very similarly to its smaller .09 cuin. companion described earlier, sharing essentially all of its design features. Bore and stroke were 15.0 mm and 14.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The control-line version reportedly weighed 4.5 ounces, although I have not been able to gain access to an actual example to check this figure.  significantly revised model having a heavier and more angular crankcase casting and a bolt-on front housing among other changes. Here I’m able to comment from direct experience, since I own a few of these engines and have actually flown one of them.

significantly revised model having a heavier and more angular crankcase casting and a bolt-on front housing among other changes. Here I’m able to comment from direct experience, since I own a few of these engines and have actually flown one of them.  was different and the bypass was of far more heroic proportions. The same style of cast-iron baffle piston and cylinder porting were used. Geometric compression ratio was unchanged at a somewhat anaemic 7 to 1.

was different and the bypass was of far more heroic proportions. The same style of cast-iron baffle piston and cylinder porting were used. Geometric compression ratio was unchanged at a somewhat anaemic 7 to 1.  There have been a number of credible user reports of shaft failures with these engines, which led me to check out my own “flyer” example (number 3554) before using it. This revealed that the shaft design appears quite out of keeping with the modest performance pretensions of this engine. The central gas passage is a whopping 7 mm in diameter and the induction port has an exaggeratedly elongated rectangular shape for very rapid opening and closing - features more typical of high-performance engines. The shaft material is super-hard, leading one to suspect that part of the reported weakness of this shaft may be down to brittleness.

There have been a number of credible user reports of shaft failures with these engines, which led me to check out my own “flyer” example (number 3554) before using it. This revealed that the shaft design appears quite out of keeping with the modest performance pretensions of this engine. The central gas passage is a whopping 7 mm in diameter and the induction port has an exaggeratedly elongated rectangular shape for very rapid opening and closing - features more typical of high-performance engines. The shaft material is super-hard, leading one to suspect that part of the reported weakness of this shaft may be down to brittleness.  than necessary as well as reducing the available bearing surface in the highly-loaded region immediately aft of the port. Not at all a well thought-out design, in fact.

than necessary as well as reducing the available bearing surface in the highly-loaded region immediately aft of the port. Not at all a well thought-out design, in fact.  By the time of this model’s introduction, the box style had also changed to a far more sturdy cardboard item with a hinged lid and a styrofoam insert. The “hinge” is a rather flimsy piece of paper which is easily torn - be warned! The boxes of engines sold in North America carried a supplementary sticker which was applied by the North American distributors AHM.

By the time of this model’s introduction, the box style had also changed to a far more sturdy cardboard item with a hinged lid and a styrofoam insert. The “hinge” is a rather flimsy piece of paper which is easily torn - be warned! The boxes of engines sold in North America carried a supplementary sticker which was applied by the North American distributors AHM.  The Ueda 19 model was a later addition to the range, appearing in 1967 some time after the introduction of the second model of the Ueda 15. It was to all intents and purposes an enlarged version of the Cougar 15 model just described, sharing all of its design and architectural features. The same basic casting was used, albeit with the cast-on identification changed to reflect the enlarged displacement. Otherwise, the two models were externally indistinguishable. The mounting dimensions were identical, allowing the 15 and 19 to be used interchangeably in the same model.

The Ueda 19 model was a later addition to the range, appearing in 1967 some time after the introduction of the second model of the Ueda 15. It was to all intents and purposes an enlarged version of the Cougar 15 model just described, sharing all of its design and architectural features. The same basic casting was used, albeit with the cast-on identification changed to reflect the enlarged displacement. Otherwise, the two models were externally indistinguishable. The mounting dimensions were identical, allowing the 15 and 19 to be used interchangeably in the same model.  The engines normally bore serial numbers stamped into the outer edge of the left engine bearer, just as in the case of the Cougar 15 model. The seven confirmed serial numbers of which I’m presently aware are 19 R/C engine numbers 157, 308, 349, 450 and 973 plus my own C/L examples number 983 and 1458. However, they must surely have gone considerably higher than this. Even so, these engines seem to be far less common than most of the other Ueda models. Consequently, good examples tend to sell for significantly higher prices than the companion 15 model when they do go on offer.

The engines normally bore serial numbers stamped into the outer edge of the left engine bearer, just as in the case of the Cougar 15 model. The seven confirmed serial numbers of which I’m presently aware are 19 R/C engine numbers 157, 308, 349, 450 and 973 plus my own C/L examples number 983 and 1458. However, they must surely have gone considerably higher than this. Even so, these engines seem to be far less common than most of the other Ueda models. Consequently, good examples tend to sell for significantly higher prices than the companion 15 model when they do go on offer.

The example of the 19 R/C that Chinn tested proved to be “squeak-tight” at the top of the stroke as received, to the point that the engine would slow down and stop after fifteen to twenty seconds of running time, even when set rich. Chinn got around this by administering a dose of oil mixed with Fox Lustrox break-in compound before each run along with some additional polyoxide lubricant in the fuel. After thirty minutes of running under these conditions, the engine was nicely freed up, giving no further trouble of any kind.

The example of the 19 R/C that Chinn tested proved to be “squeak-tight” at the top of the stroke as received, to the point that the engine would slow down and stop after fifteen to twenty seconds of running time, even when set rich. Chinn got around this by administering a dose of oil mixed with Fox Lustrox break-in compound before each run along with some additional polyoxide lubricant in the fuel. After thirty minutes of running under these conditions, the engine was nicely freed up, giving no further trouble of any kind.

The Ueda 45 was one of the first models announced by the company in 1963, albeit only in prototype form at that stage. It was only ever marketed in R/C form, although home conversion for control-line use would have been a very straightforward matter if anyone had cared to try. Bore and stroke checked out at 21.6 mm and 21.0 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 7.70 cc (0.47 cuin.), oddly enough a little larger than the cited displacement.

The Ueda 45 was one of the first models announced by the company in 1963, albeit only in prototype form at that stage. It was only ever marketed in R/C form, although home conversion for control-line use would have been a very straightforward matter if anyone had cared to try. Bore and stroke checked out at 21.6 mm and 21.0 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 7.70 cc (0.47 cuin.), oddly enough a little larger than the cited displacement.

Interestingly, Chinn reported the weight of his tested examples as 12.7 ounces - well up on the 9.5 ounces cited during the engine’s introductory phase over two years previously. In the absence of any early example to check, I'm unable to comment upon this discrepancy. My own measurements taken from my own presumably later variant example bear out Chinn’s figure, leaving a great deal of uncertainty regarding the figure quoted in the 1965 article - even assuming that there had been design changes in the interim, it’s very difficult to see where that amount of additional weight could have come from.

Interestingly, Chinn reported the weight of his tested examples as 12.7 ounces - well up on the 9.5 ounces cited during the engine’s introductory phase over two years previously. In the absence of any early example to check, I'm unable to comment upon this discrepancy. My own measurements taken from my own presumably later variant example bear out Chinn’s figure, leaving a great deal of uncertainty regarding the figure quoted in the 1965 article - even assuming that there had been design changes in the interim, it’s very difficult to see where that amount of additional weight could have come from.  transfer periods were 160 degrees and 140 degrees respectively, both far longer than appropriate for a large engine intended for R/C use where good “slogging power” at moderate rpm was the most desirable attribute.

transfer periods were 160 degrees and 140 degrees respectively, both far longer than appropriate for a large engine intended for R/C use where good “slogging power” at moderate rpm was the most desirable attribute.

My illustrated example of the single-plug Ueda 45, engine no. 925, arrived in a deplorably abused and neglected state. It had apparently spent the previous 50 years stored in a bucket in the previous owner's carport! It was one of the subjects covered in my separate article on

My illustrated example of the single-plug Ueda 45, engine no. 925, arrived in a deplorably abused and neglected state. It had apparently spent the previous 50 years stored in a bucket in the previous owner's carport! It was one of the subjects covered in my separate article on

Claimed output of the twin-plug variant was 0.80 BHP with a cited speed range of 1,500 to 12,000 rpm. The peak performance claim is by no means out of line with Chinn’s test results for the modified single-plug version, especially when we consider that the manufacturers had undoubtedly been paying attention to the comments of Chinn and others, thus becoming far more aware of the importance of port timing and manufacturing tolerances. However, as far as I’m aware no test of the twin-plug Ueda 45 ever appeared in the English-language modelling media. Therefore, the manufacturer’s claim remains unsubstantiated.

Claimed output of the twin-plug variant was 0.80 BHP with a cited speed range of 1,500 to 12,000 rpm. The peak performance claim is by no means out of line with Chinn’s test results for the modified single-plug version, especially when we consider that the manufacturers had undoubtedly been paying attention to the comments of Chinn and others, thus becoming far more aware of the importance of port timing and manufacturing tolerances. However, as far as I’m aware no test of the twin-plug Ueda 45 ever appeared in the English-language modelling media. Therefore, the manufacturer’s claim remains unsubstantiated.

This model seems to have appeared in 1966. It was in effect an over-bored version of the 45 design, having a very similar appearance. It had the same stroke as the 45 model and was based upon the same main casting incorporating twin ball races for shaft support. It was only ever marketed in R/C form. The engines featured green-anodized cylinder components, giving them a most attractive appearance when new. However, the anodizing unfortunately faded rapidly in service due to heat - a few hot runs would do it. Be warned - if you have a new example and want to retain that lovely bright colour for display purposes, don’t run it!!

This model seems to have appeared in 1966. It was in effect an over-bored version of the 45 design, having a very similar appearance. It had the same stroke as the 45 model and was based upon the same main casting incorporating twin ball races for shaft support. It was only ever marketed in R/C form. The engines featured green-anodized cylinder components, giving them a most attractive appearance when new. However, the anodizing unfortunately faded rapidly in service due to heat - a few hot runs would do it. Be warned - if you have a new example and want to retain that lovely bright colour for display purposes, don’t run it!!

The .61 model was the largest model ever released by Ueda. It was introduced in single-plug form in 1966 as the Ueda 60 but was marketed as the Cougar 61 for much of its existence. It was offered exclusively in R/C form. Oddly enough, the manufacturers made no performance claim for this model, confining themselves to stating that it could be used over a speed range of 2,000 - 13,000 rpm.

The .61 model was the largest model ever released by Ueda. It was introduced in single-plug form in 1966 as the Ueda 60 but was marketed as the Cougar 61 for much of its existence. It was offered exclusively in R/C form. Oddly enough, the manufacturers made no performance claim for this model, confining themselves to stating that it could be used over a speed range of 2,000 - 13,000 rpm.  similarity to its smaller siblings. It followed the same design progression as the others, going from a single plug head to a twin plug component, with twin ball races being used to support the crankshaft in both variants. Apart from its far more massive construction, it was distinguished from its smaller relatives by the use of a red-anodized cooling jacket and head.

similarity to its smaller siblings. It followed the same design progression as the others, going from a single plug head to a twin plug component, with twin ball races being used to support the crankshaft in both variants. Apart from its far more massive construction, it was distinguished from its smaller relatives by the use of a red-anodized cooling jacket and head.  The muffler which was offered for use with this engine was another very substantial affair having a somewhat unusual “angular” shape which was actually reminiscent of a coffin in plan view! Since the butterfly exhaust restrictor could not of course be used with a muffler, the latter component incorporated the barrel-type exhaust restrictor mentioned earlier.

The muffler which was offered for use with this engine was another very substantial affair having a somewhat unusual “angular” shape which was actually reminiscent of a coffin in plan view! Since the butterfly exhaust restrictor could not of course be used with a muffler, the latter component incorporated the barrel-type exhaust restrictor mentioned earlier.

At age 14 I bought a Ueda 19 because the local hobby shop had them at a ridiculously low price, which was all that I could afford. An adult member of our club bought a Ueda 15 at the same time. I only bench-ran the 19 once. The other fellow mounted his 15 in a Veco kit. I remember that on the first and only flight he had the engine set quite rich, and half a lap into the flight the engine came to an abrupt halt, having snapped the crankshaft in two at the intake port.

At age 14 I bought a Ueda 19 because the local hobby shop had them at a ridiculously low price, which was all that I could afford. An adult member of our club bought a Ueda 15 at the same time. I only bench-ran the 19 once. The other fellow mounted his 15 in a Veco kit. I remember that on the first and only flight he had the engine set quite rich, and half a lap into the flight the engine came to an abrupt halt, having snapped the crankshaft in two at the intake port.

I had no luck at all with my Ueda 19 around 1970. Broke the crank while bench running it. The hobby shop replaced it. Broke the crank on the second one in the same way. The hobby shop replaced it with a McCoy. End of problem …………

I had no luck at all with my Ueda 19 around 1970. Broke the crank while bench running it. The hobby shop replaced it. Broke the crank on the second one in the same way. The hobby shop replaced it with a McCoy. End of problem …………