|

|

An Aussie Classic - the Glo Chief 45 By Maris Dislers

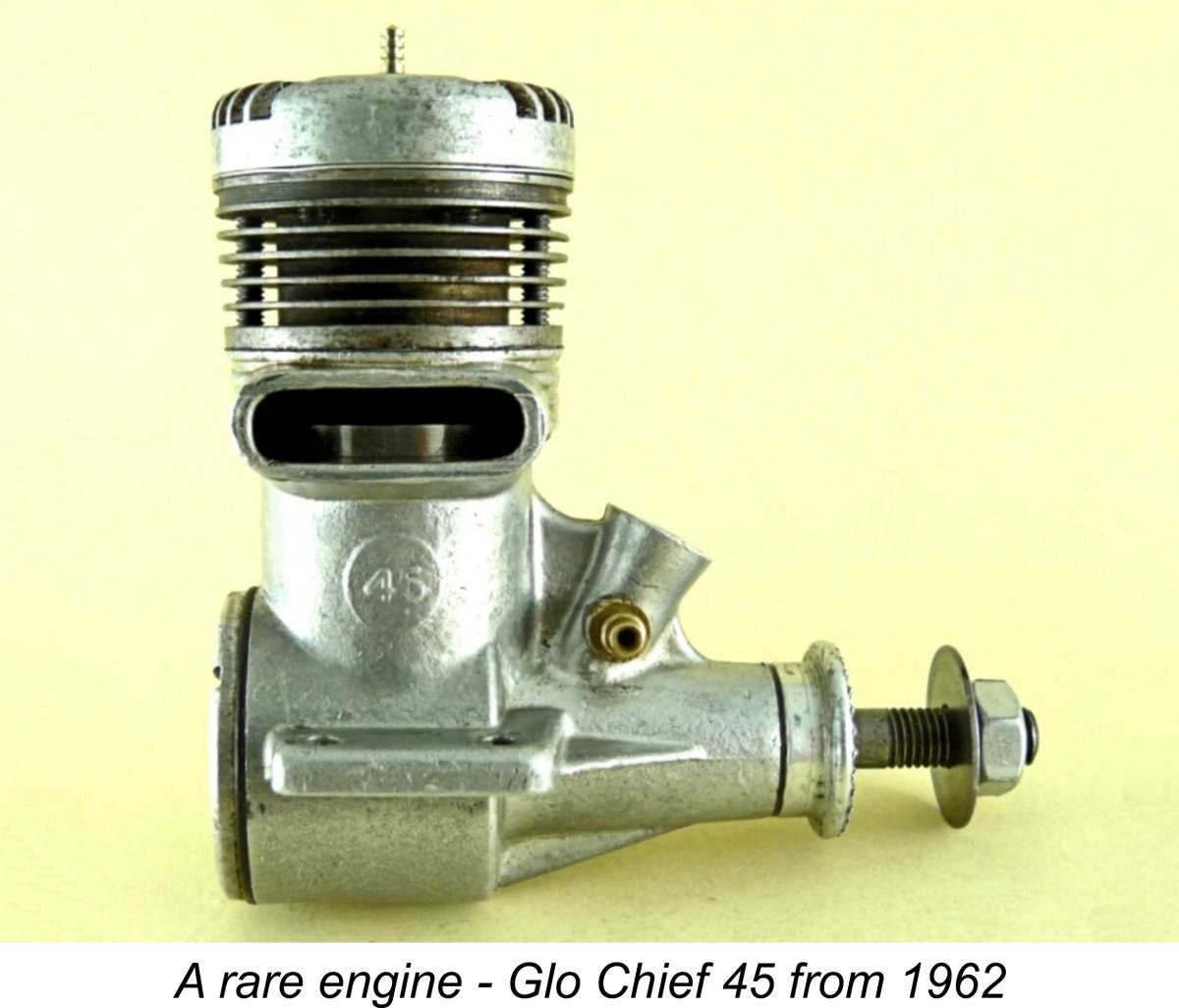

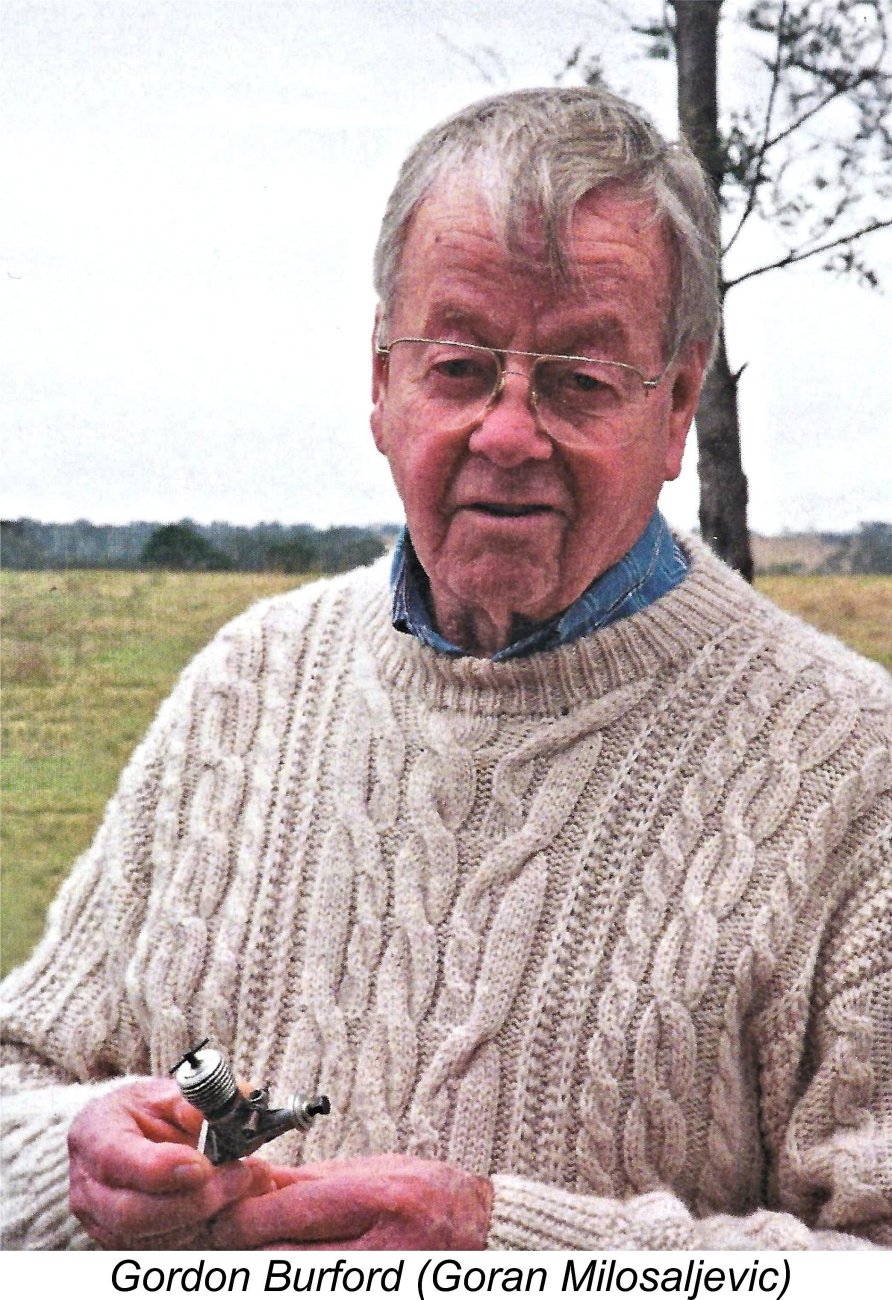

Now it’s common enough to have multi-size engines based upon a common design, perhaps to straddle two competition classes (such as the Cox TD .049 and .051 duo) or to broaden the sales potential of a given basic design at minimal extra cost in tooling, like the many 29 and 35 pairings. But after a little thought, we began to wonder just how one does shoe-horn a 45 into a 29’s crankcase? And like Peter Chinn, who examined an example (“Model Aircraft”, December 1961), we wondered if the probable extra vibration and heat had been adequately dealt with. Reason enough then to peer back through the curtains of time. For those unfamiliar with the brand, Glo Chiefs were the larger glowplug engines produced by Gordon Burford and Co. in During that era, multi-reed radio equipment was gaining traction thanks to the emergence of power transistors in the circuits. These systems allowed full control of aerobatic R/C models, which could then be flown faster and through a wider range of manoeuvres. That in turn fuelled the demand for more powerful engines than the top of the line 35’s which had been used up to that time. Veco’s 45 was an early and very successful answer to this need, as were the Kyowa 45, the Merco 49, the Enya 45 and the O.S. 49. Perhaps it was hoped that the Glo Chief 45 could fulfil a similar role. Alternatively, Gordon Burford may have had control-line aerobatics more in mind. Australian stunt ace Brian Horrocks had done a splendid public relations job in winning the prestigious Gold Trophy at the British National Championships in 1959 and 1961 (second in 1960) with his uncommonly large and slow-flying models powered by a Glo Chief 49 engine. He was in fact a very early exponent of what was to become the norm in this field. Despite these successes, the Glo Chief 49 was discontinued after 1961 for some unknown reason. It seems not unlikely that the 45 which appeared in 1962 was intended to take its place. Contemporary accounts, such as the report on the Australian attempt at the F.A.I. R/C distance record (“Aeromodeller”, November 1962) suggest that the 45 was a vibrator. This was of course a common enough problem for non-competition engines of this size with iron pistons. Despite any such problems, the 45 lingered on in the Burford engine range until 1965 before being lost in the stampede of newer competitors. It is now remembered only for having been the lightest engine in its class at 7.6 oz (215 g). Construction

The stretching of a basic .29 cuin. design to .45 cuin. (a displacement increase of 55%) might be expected to impose a number of compromises upon the designer. And indeed that's exactly what we encounter when we take a really close look at the Glo Chief 45.

Naturally, the 45 needs a reasonable ratio between piston diameter and skirt height to maintain piston stability. That means an adequately long conrod and a reduced back plate inner diameter to clear the piston skirt at bottom dead centre. The exhaust port in the 1962 Glo Chief trio’s cylinders seems too high for the crankcase outlet, which could have been positioned around 1.5mm higher. While it does not look good, performance is probably not unduly affected.

A further compromise along the same lines is evident in the The oval "race-track" form of the shaft induction port is a very good approach to the often contradictory requirements of providing efficient induction valve action along with adequate strength. The absence of any stress-raising sharp corners makes this a very effective arrangement in terms of strength, while rapid opening and closing of the valve can still be assured. One area in which the designer did not compromise was the thickness of the lower cylinder wall, which was made The cylinder head is of essentially conventional design for a baffle-piston glow-plug motor of this era. The form is basically flat apart from the necessary groove to accommodate the baffle at TDC - there is no provision for the creation of swirl in the combustion chamber during Port timing numbers are quite normal, with the exhaust and transfer durations being 140 degrees and 110 degrees respectively. The induction period of 170 degrees begins at 50 degrees ABDC and closes at 40 degrees ATDC. When fitted with the restrictor insert, the venturi has an effective choke area of 9.9 square mm, increasing to 20.1 square mm with the insert removed. The above description paints a picture of a successful conversion of the basic Glo Chief .29 cuin. design to a displacement of .45 cuin. - a 55% increase. However, I hope I've made it clear that this was not accomplished without a considerable degree of compromise. This might be expected to yield a less-than-proportionate increase in performance. One area in which no compromise was made is is in the engine's weight. The 45 actually ends up weighing only 2 gm (!!) more than its 29 and 35 companions in the Glo Chief range. The following table summarizes the principal specifications of the 1962 Glo Chief models.

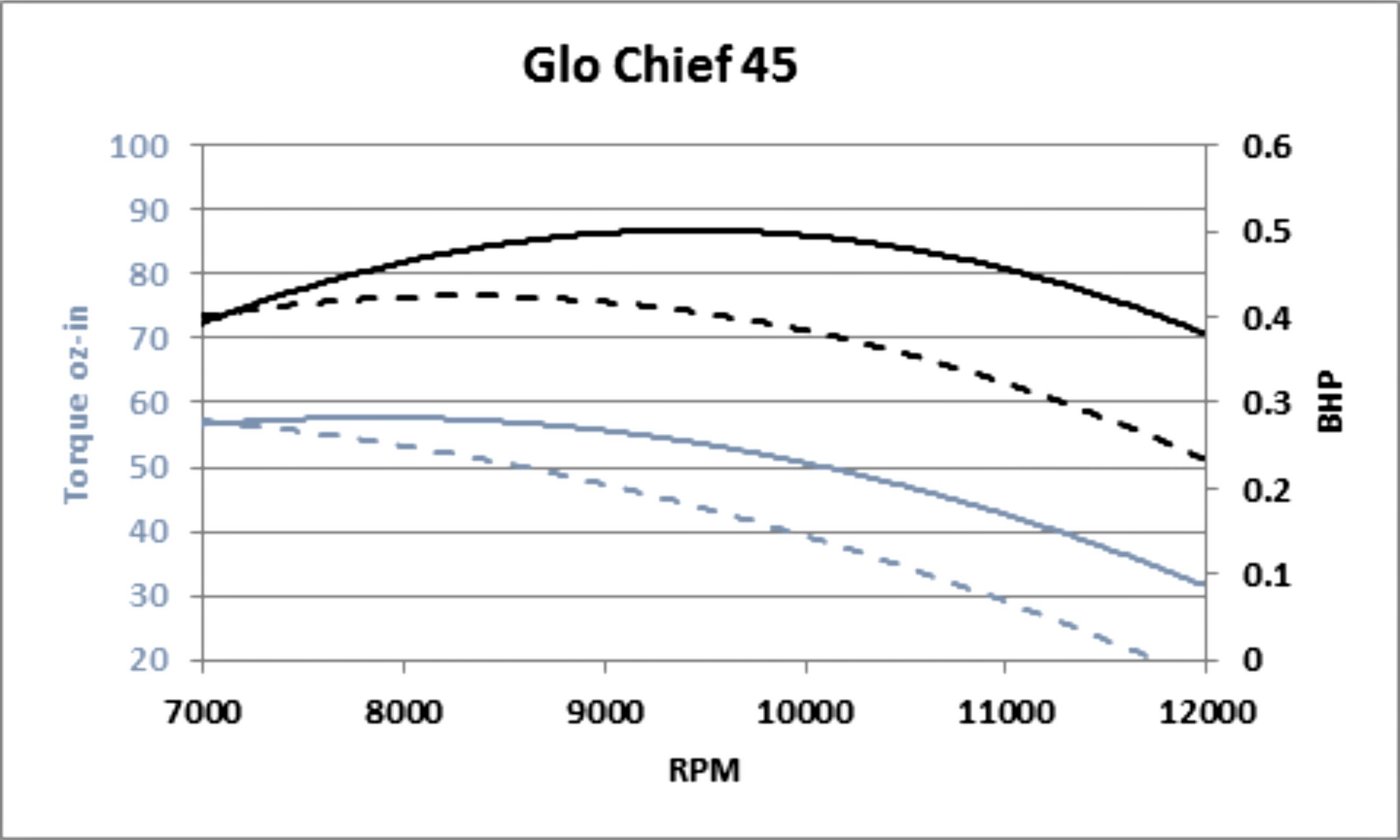

Since all three models were interchangeable in the same model, the user could take his choice! The only issues were those relating to power output and other performance characteristics. The Glo Chief 45 on Test David had assembled this example of the Glo Chief 45 from several donor engines so as to end up with one in good running condition. To do this, the piston had to be “cherry bombed” as described earlier to restore an acceptable fit in the cylinder. In the present instance, this process was applied successfully, with the resulting compression seal feeling good despite signs of the engine having eaten dirt in a former life. For the test, we used fuel containing 5% nitromethane and 28% castor oil along with 66% methanol. Few owners in 1962 would have used any nitromethane at all, as it was then a very expensive option. Initial tests were conducted with the venturi insert in place. Starting proved to be quite easy, but the Fireball medium heat plug was clearly too cool for anything but flat-out running. Switching to the Fireball idle bar plug allowed broad mixture adjustment across the usable range. For the sake of our ears, we’d fitted an Enya muffler originally intended for the cross-flow loop scavenged Enya engines of around this size. The Glo Chief seemed happy enough with this and we doubt that it reduced performance markedly, nor would it account for the Glo Chief’s unwillingness to cut loose at high RPM. This latter characteristic certainly prevented the engine from overheating. Removing the venturi restrictor yielded a significant performance boost without upsetting the engine’s generally easy-going nature. As for the expected bad vibration, we rated it as acceptable - no worse than many 29/35 engines of its time. This happy state was not a reflection of any magic (although the piston is about as light as could be safely achieved), but was rather due to the engine’s modest operating speeds. The following figures were measured on test, using the above-mentioned fuel and with the Enya muffler fitted:

Performance appraisal On paper, the effective choke area with the restrictor fitted would be ideal for the Glo Chief 29 in control line aerobatics, giving very steady runs at around 10,000 RPM. However, with the larger 45 this choke area would have a significant throttling effect at anything much over 7,000 RPM. This is clearly seen in our 45’s rather sad decline in power output at “normal” operating speeds, as reflected in the accompanying power curves derived from the above prop-RPM figures.

That would make the R/C Glo Chief 29 quite OK, but the 45 R/C would be a real slouch for any application other than lugging a really heavy model at low speed. It would undoubtedly fulfil the latter function thanks to its good torque development of 53 oz-in at the rather modest peak power point of 0.43 BHP at a little over 8,000 RPM. Maybe just the thing for that distance record model which barely snuck in below the F.A.I.’s 11 pound (5 kg) limit. Removing the restrictor alleviated this limitation sufficiently to gain around 1,000 RPM at higher speeds and improve the power peak to the region of 0.50 BHP at about 9,500 RPM. You might sneak that figure up a little by removing the muffler, but it’s hardly the stuff to set the adrenal glands pumping! Any attempt to coax the engine past 12,000 RPM was futile. We figure that the restricted bypass passage represents the principal limitation here, although the smaller-than-usual crankshaft induction passage may also play a role. Our results certainly illustrate why these engines are now so rarely encountered. Anyone expecting a decent power output by comparison with established standards for engines of this displacement would have been very disappointed. This would have been especially true of the R/C version. Word of this probably spread quickly, and the 45’s staying power in the range was probably more a reflection of how long it took to move the sole production batch than it was of any real popularity.

However, it is possible to look at the 45 from a different angle. Disregarding the displacement, its power to weight ratio is actually not all that bad. Moreover, peak power is achieved at a speed not so very far removed from that at which the maximum torque of 76 oz-in. is developed. This torque level is handsomely above that which could be expected from its 29 or 35 stable mates, or any of the more famous contemporary 35’s for which 60 oz-in. would have been considered truly excellent at the time. Quite enough to fly an overweight Nobler or Thunderbird-sized control line aerobatic model with authority using a nice large slow-revving propeller. In addition, its self-imposed RPM limit should reduce wind-up in windy conditions. Perhaps this engine deserves a little more credit than it received in its day? _________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Adelaide, Australia First published February 2017

|

|||

| |

David Burke of Adelaide Aeromotive recently dropped a 1962 Glo Chief 45 in my lap, asking for it to be run through some tests. First question - why bother testing an almost forgotten and technically unremarkable engine from another era? Well, Gordon Burford created this engine by somehow stuffing a set of .45 cuin. working components into a basically 29-size crankcase. One is forced to wonder how this was done, and how effective it was ……….

David Burke of Adelaide Aeromotive recently dropped a 1962 Glo Chief 45 in my lap, asking for it to be run through some tests. First question - why bother testing an almost forgotten and technically unremarkable engine from another era? Well, Gordon Burford created this engine by somehow stuffing a set of .45 cuin. working components into a basically 29-size crankcase. One is forced to wonder how this was done, and how effective it was ………. Australia for a decade or so until the mid 1960’s. Companions to Burford’s Taipan range which covered the smaller sizes, they were general-purpose engines with a reputation for decent performance and reasonable price, backed by the local manufacturer’s excellent after-sales service. A good market share in Australia, but tiny by world standards.

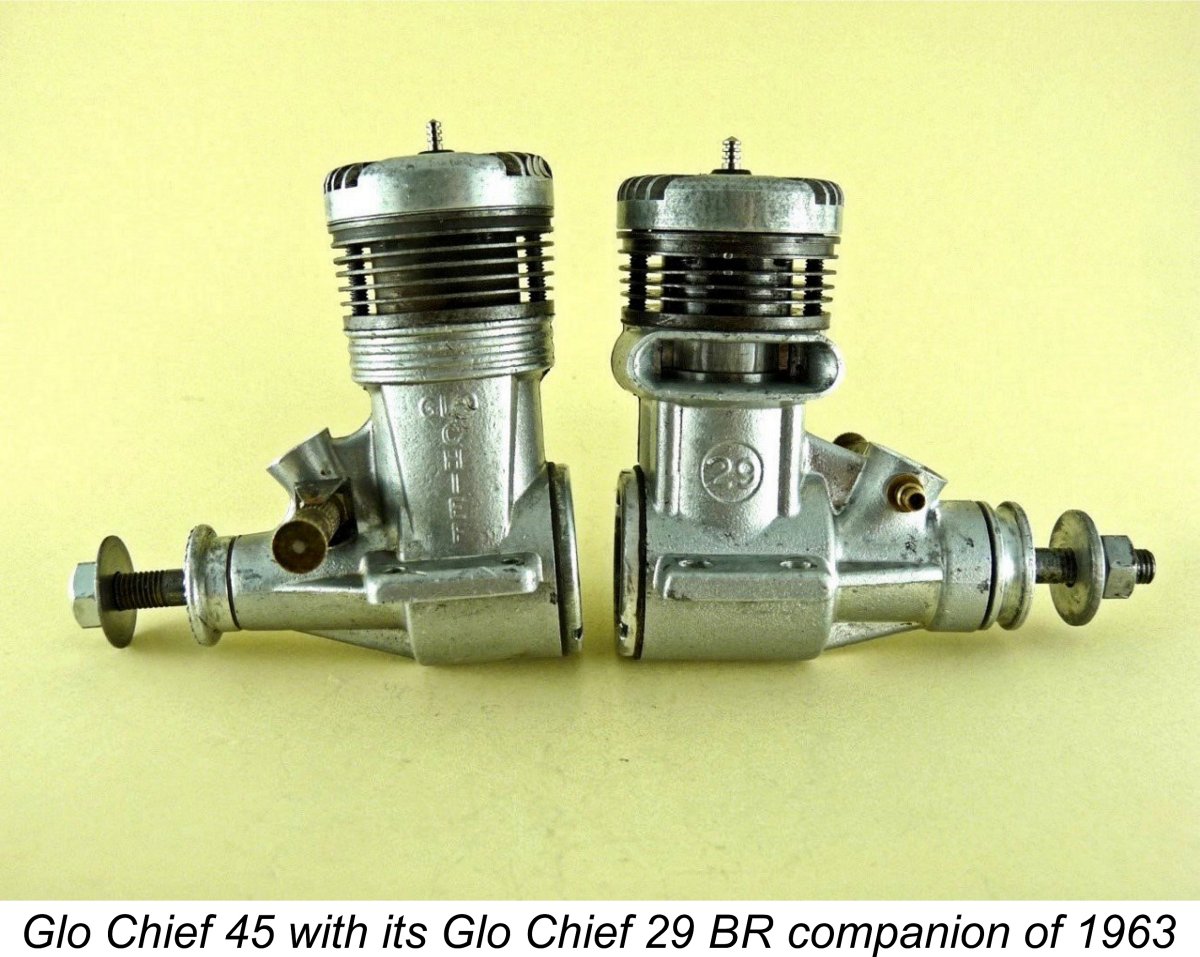

Australia for a decade or so until the mid 1960’s. Companions to Burford’s Taipan range which covered the smaller sizes, they were general-purpose engines with a reputation for decent performance and reasonable price, backed by the local manufacturer’s excellent after-sales service. A good market share in Australia, but tiny by world standards. The Glo Chief 29/35/45 trio for the 1962 season all appear very similar externally, with the size designator on the crankcase casting under the exhaust outlet being the most immediately obvious difference. Overall, the design follows orthodox lines, not differing greatly from the K&B Torpedo Green Head engines of the early 1950’s.

The Glo Chief 29/35/45 trio for the 1962 season all appear very similar externally, with the size designator on the crankcase casting under the exhaust outlet being the most immediately obvious difference. Overall, the design follows orthodox lines, not differing greatly from the K&B Torpedo Green Head engines of the early 1950’s. To begin with, it must have been obvious from the outset that stretching the basic 29 design to 45 size would require more than simply increasing the cylinder bore. A longer stroke was also needed. This requirement is reflected in the fact that the 45’s crankpin is located right out at the very edge of the crankweb. There’s also a groove machined in the crankcase to clear the conrod big end as it moves through the greater stroke. This leaves the crankcase with a relatively minimal wall thickness at the groove location.

To begin with, it must have been obvious from the outset that stretching the basic 29 design to 45 size would require more than simply increasing the cylinder bore. A longer stroke was also needed. This requirement is reflected in the fact that the 45’s crankpin is located right out at the very edge of the crankweb. There’s also a groove machined in the crankcase to clear the conrod big end as it moves through the greater stroke. This leaves the crankcase with a relatively minimal wall thickness at the groove location.  The crankcase is of course bored vertically to accept the 45’s larger lower cylinder. The extra diameter required to accommodate the larger cylinder significantly reduces the cross section area of the bypass passage to about 27% less than that of the 29. Taking the 55% increase in swept volume into account, the effective bypass area is only 47% of the 29’s on an area per cc basis. In addition, the 45’s longer lower cylinder further limits transfer effectiveness.

The crankcase is of course bored vertically to accept the 45’s larger lower cylinder. The extra diameter required to accommodate the larger cylinder significantly reduces the cross section area of the bypass passage to about 27% less than that of the 29. Taking the 55% increase in swept volume into account, the effective bypass area is only 47% of the 29’s on an area per cc basis. In addition, the 45’s longer lower cylinder further limits transfer effectiveness. crankshaft design. While retaining the 29's main shaft journal diameter of 11.1mm (.437 in.), the 45’s gas passage is reduced for added strength to 7.68mm (.302 in) from the 29’s dimension of 8.06mm (.317 in). This was doubtless a prudent decision in view of the relatively small main journal diameter for an engine of this displacement (another compromise), but it does leave us with a significantly larger-displacement engine being supplied through a smaller crankshaft induction passage - yet another compromise which was forced upon the designer by strength considerations.

crankshaft design. While retaining the 29's main shaft journal diameter of 11.1mm (.437 in.), the 45’s gas passage is reduced for added strength to 7.68mm (.302 in) from the 29’s dimension of 8.06mm (.317 in). This was doubtless a prudent decision in view of the relatively small main journal diameter for an engine of this displacement (another compromise), but it does leave us with a significantly larger-displacement engine being supplied through a smaller crankshaft induction passage - yet another compromise which was forced upon the designer by strength considerations.

operation. We did not measure the compression ratio, but by “feel” it seemed to be about right, in the 7.5:1 or 8:1 region.

operation. We did not measure the compression ratio, but by “feel” it seemed to be about right, in the 7.5:1 or 8:1 region. This is pertinent, because the R/C version of this engine had a Bramco-style throttle assembly, probably shared by all members of the trio. The needle valve assembly passes through the rotating throttle barrel. We don’t have one handy, but would hazard a guess that the throat of the barrel in all three engine sizes matched the common ID of the tubular mounting spigot. If so, effective choke area in the fully open position is probably the same as when the restrictor is fitted in fixed-choke mode.

This is pertinent, because the R/C version of this engine had a Bramco-style throttle assembly, probably shared by all members of the trio. The needle valve assembly passes through the rotating throttle barrel. We don’t have one handy, but would hazard a guess that the throat of the barrel in all three engine sizes matched the common ID of the tubular mounting spigot. If so, effective choke area in the fully open position is probably the same as when the restrictor is fitted in fixed-choke mode.  As postulated earlier in this review, the many unavoidable compromises in the design of the Glo Chief 45 did undoubtedly result in a significantly less-than-proportional gain in performance over its smaller companions which were based upon the same main casting. As an example, the very ballsy Glo Chief 29 BR model which joined the range in 1963 developed 40% more power for only 20% more weight. Not much of a contest there!

As postulated earlier in this review, the many unavoidable compromises in the design of the Glo Chief 45 did undoubtedly result in a significantly less-than-proportional gain in performance over its smaller companions which were based upon the same main casting. As an example, the very ballsy Glo Chief 29 BR model which joined the range in 1963 developed 40% more power for only 20% more weight. Not much of a contest there!