|

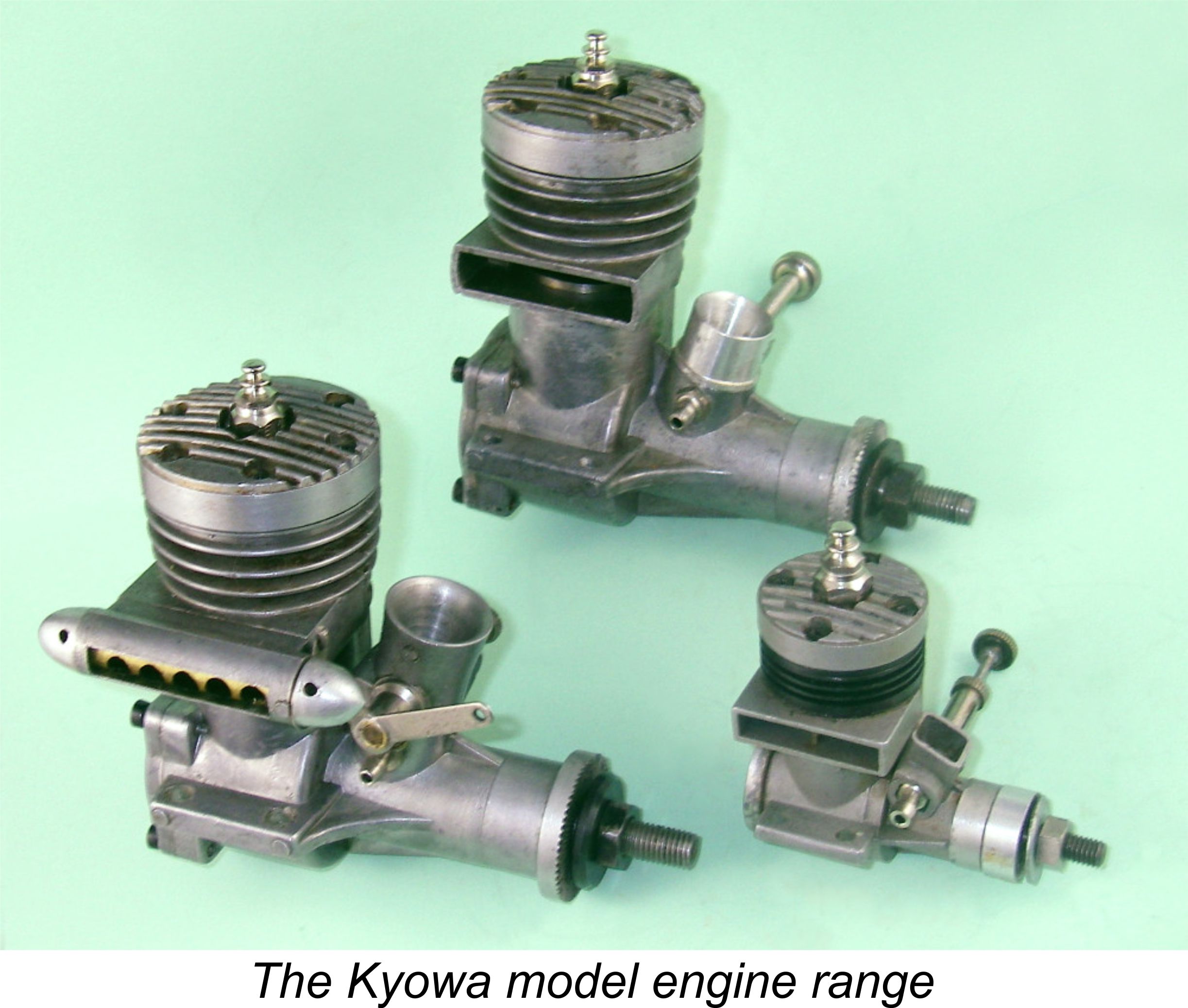

The Kyowa Engines

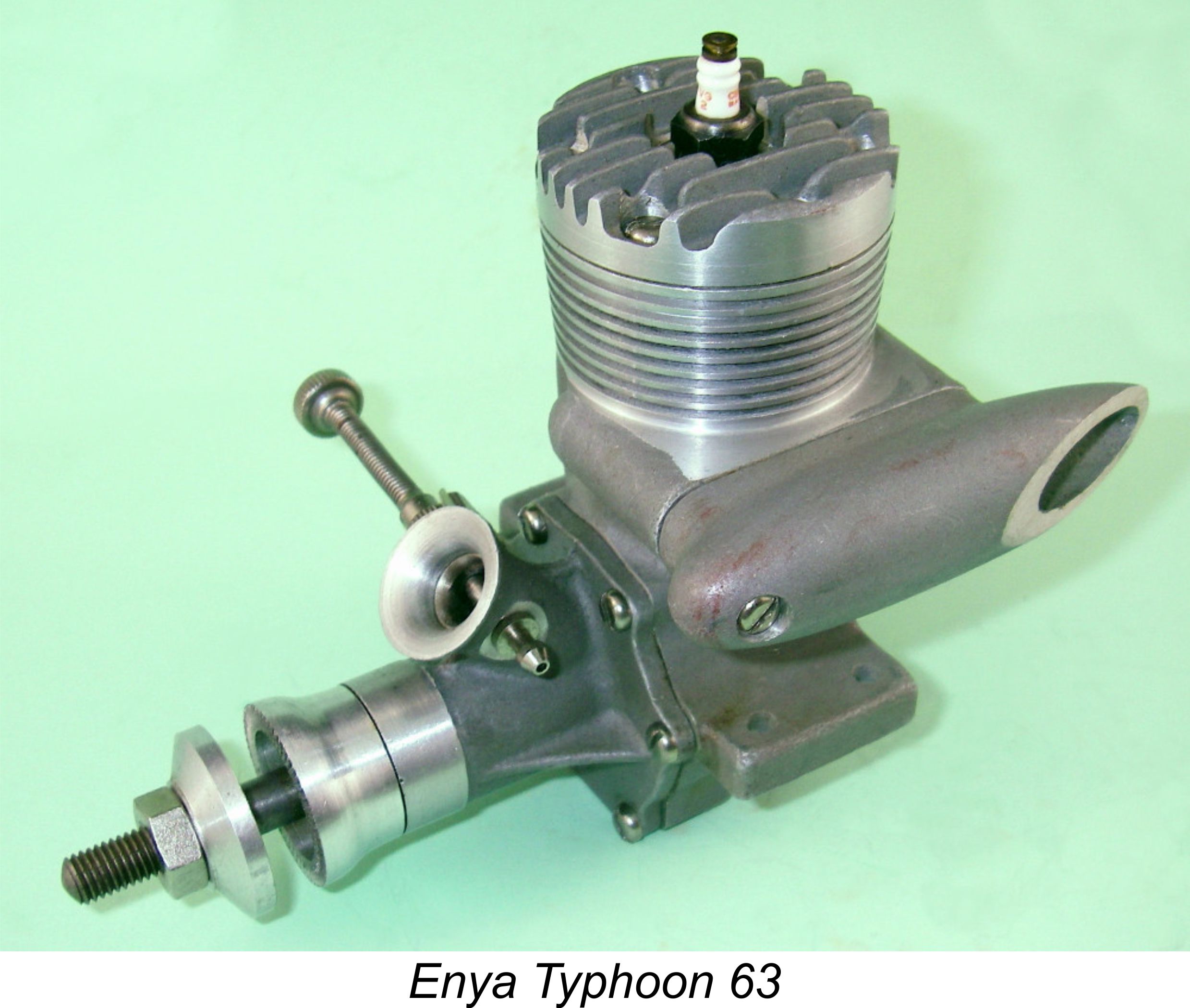

This is a pity, because the Kyowa 45 R/C glow-plug motor which launched the range and remained the flagship product throughout was a trend-setting engine having a significance which is in danger of being forgotten at this late date. The Kyowa was in the vanguard of the trend towards the development of larger model glow-plug motors built expressly for radio control use which began to find expression in the late 1950’s. Prior to that time, the majority of model glow-plug engines (as opposed to their spark-ignition forebears) had been restricted to displacements of .36 cuin. or less and had been designed for general purpose use, primarily in control-line and The only large general-purpose glow-plug engines on offer during the majority of the 1950’s were the Fox 59 and the Enya Typhoon 63 (which was first joined and then replaced by the almost identical Enya Typhoon 60 in the mid-1950’s). The 1950’s incarnations of all three of these designs were aimed primarily at the control-line market, although a few brave souls doubtless tried them in free flight applications and a number were fitted by their owners with somewhat rudimentary throttles for R/C use. This situation existed at the time mainly due to the relatively primitive nature of the radio control equipment which was then commercially available. Until the second half of the 1950’s, most of the Multi-channel radio gear began to appear in the mid 1950’s but remained both expensive and unreliable. Vic Smeed quoted an unattributed American magazine article from as late as 1957 which pronounced that multi-channel radio control equipment was “too expensive for the average modeller and likely to remain so”. This was a sadly prophetic statement - it’s easy to see in hindsight that the eventual dominance of radio control with the attendant massive increase in the cost and complexity of participation led directly to the elimination of the “average modeller” who had previously formed the backbone of the aeromodelling hobby. Such individuals had previously needed only a basic no-frills engine (often acquired cheaply at second-hand) or a few strands of rubber along with some bits of balsa to become involved - now they were called upon to make a serious investment just to get started. Consequently, the young entry-level modellers (typically teenagers) who had always represented the future of aeromodelling were dealt out of the game. In terms of participation, the hobby has been suffering ever since ………I can think of no other hobby which has killed off its own entry-level participation so effectively.

What finally triggered the full-blown onset of the radio control revolution was the introduction beginning in around 1958 of the first commercial multi-channel proportional-control radio gear. This allowed a previously unattainable degree of multi-function control which, when coupled with the ever-increasing reliability of the new equipment as well as the far greater value received for one’s investment, made competitive R/C aerobatic flying an attractive proposition for a considerably wider group of modellers than had hitherto been the case, always provided they had the financial means. Hence competition R/C aerobatic flying and multi-channel R/C scale modelling now began to attract increasing numbers of competitors, thus assuming a far greater degree of importance in the marketplace. Modellers taking up R/C flying using the new equipment, particularly those interested in R/C aerobatics, soon found that a larger airframe was highly desirable both in performance terms and to carry the still-bulky multi-channel R/C gear of the day. This of course further exacerbated the cost factor, since larger models cost more to build and operate, also being more challenging to transport. Nonetheless, those having the means to do so took an ever-increasing interest in larger models, as a result of which a demand quickly began to develop for efficiently-throttled engines which produced more power than the majority of the general-purpose units then available. Given the relatively static development phase through which model engine technology was then going, this meant larger engines along with improved throttling arrangements.

The securing of a firm foothold in the marketplace against the established competition has always been a great challenge for any new model engine manufacturer. To attract sales attention away from existing well-established lines, a new manufacturer must either offer something special by way of quality or performance or must enter the market with a product that fills a vacant sales niche not then being served by the established manufacturers. The second of these two alternatives has the great merit of giving the new and previously unknown manufacturer a fair opportunity to attract attention and demonstrate his skills with a product which faces minimal direct competition at the outset. The Kyowa 45 was clearly targeted at just such a market niche which existed at the time. The steadily-growing number of R/C pattern flyers were beginning to demand larger and more powerful throttled engines, presenting a market opportunity to which the majority of the established engine manufacturers had been unaccountably slow to react.

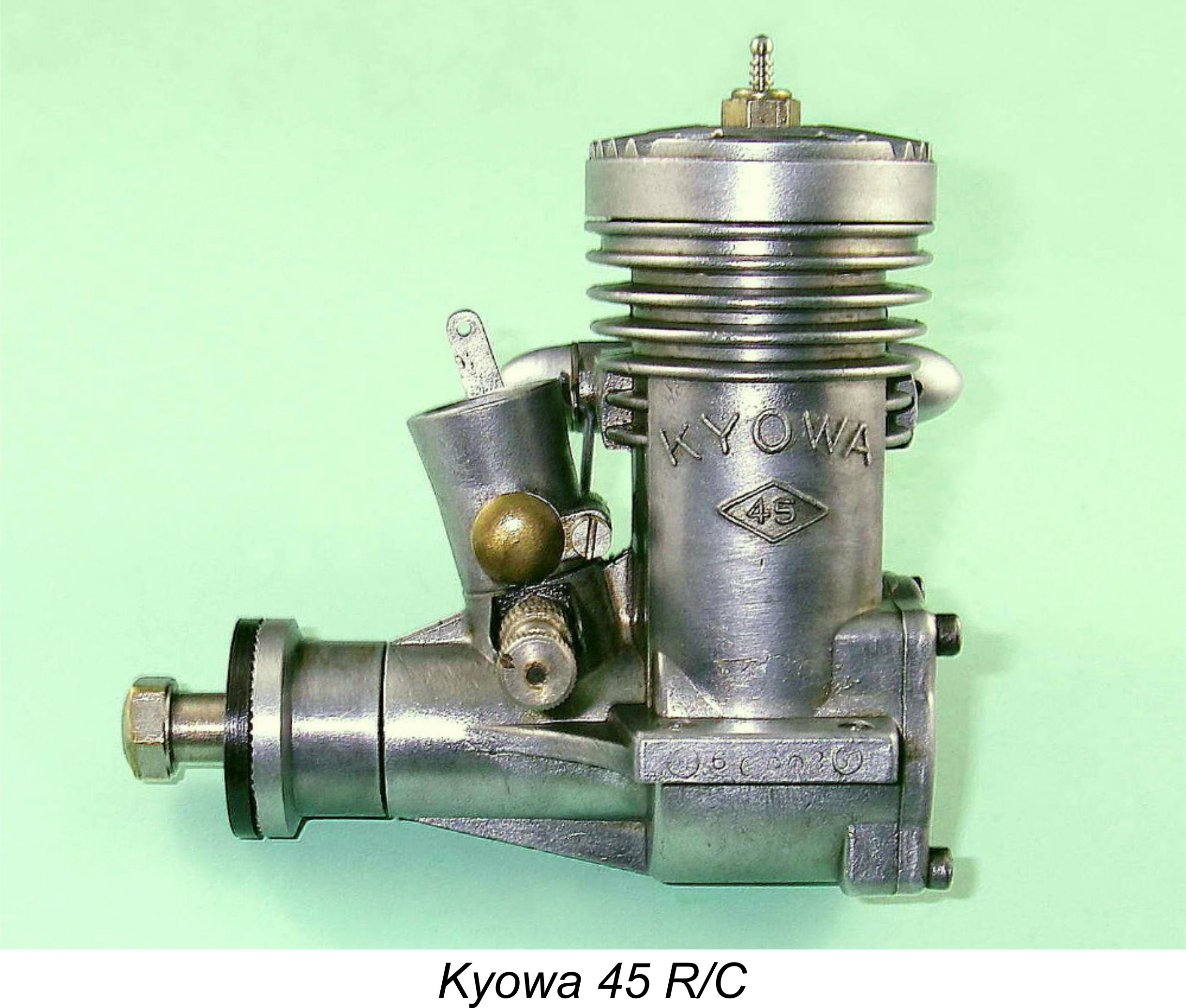

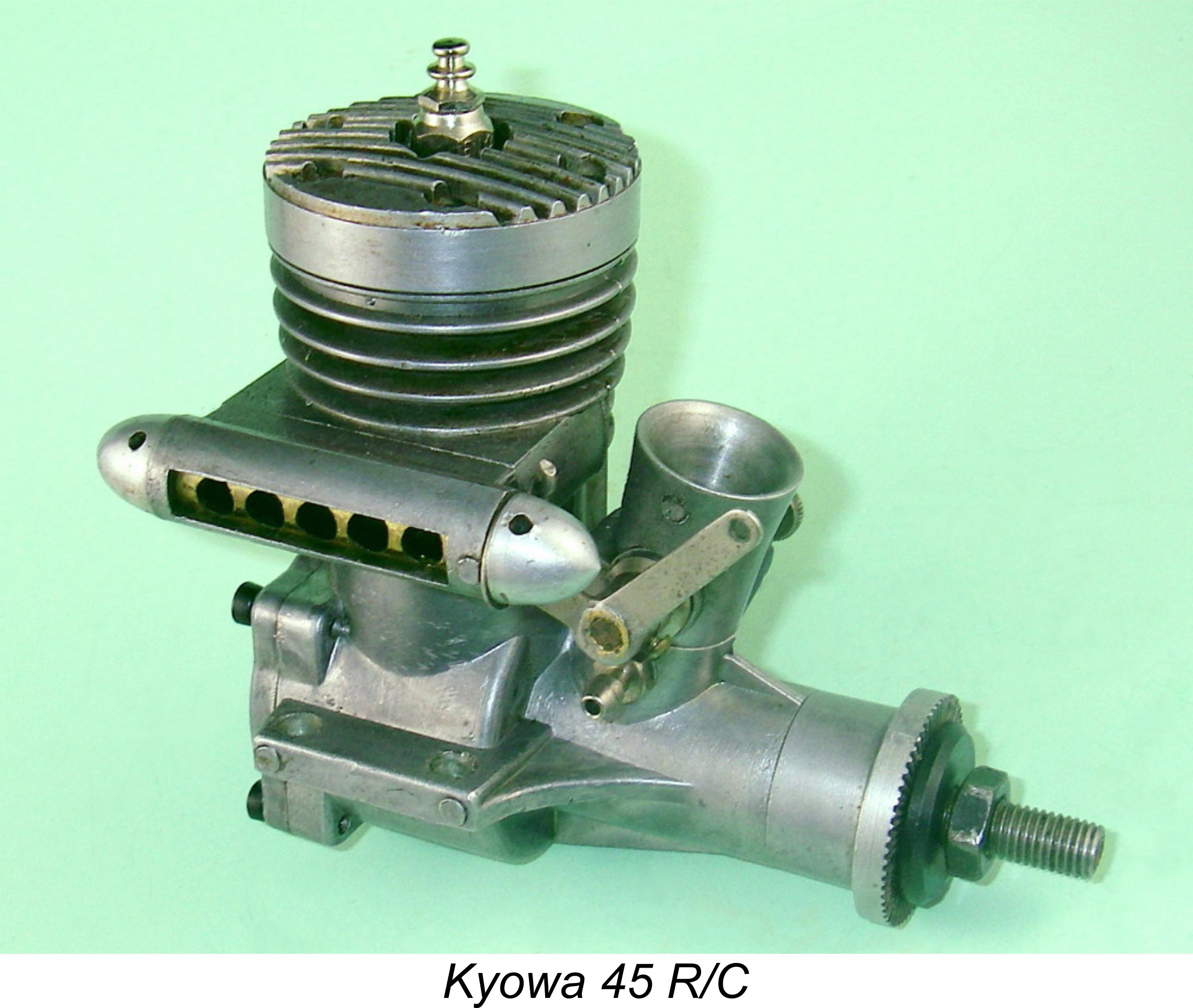

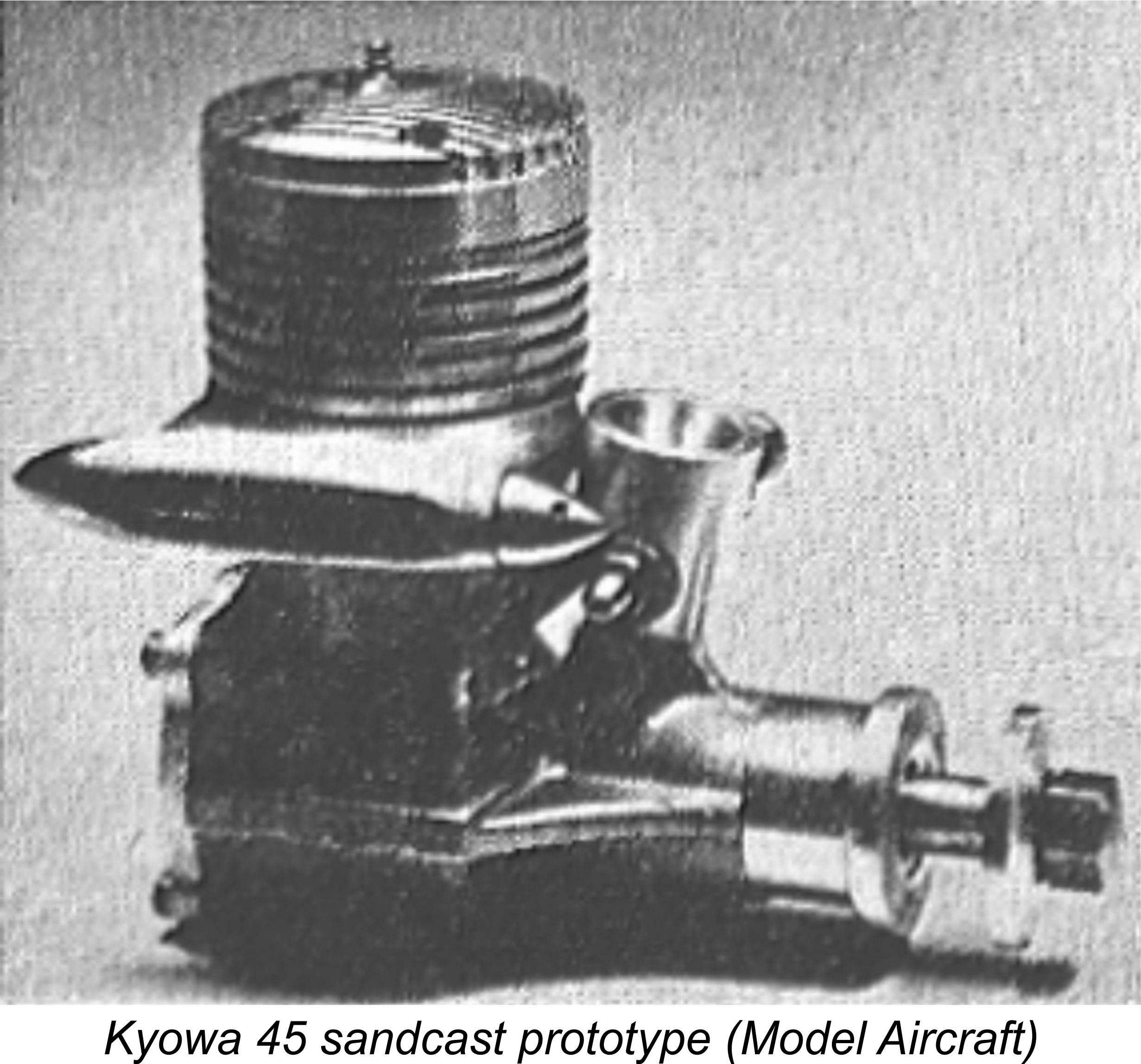

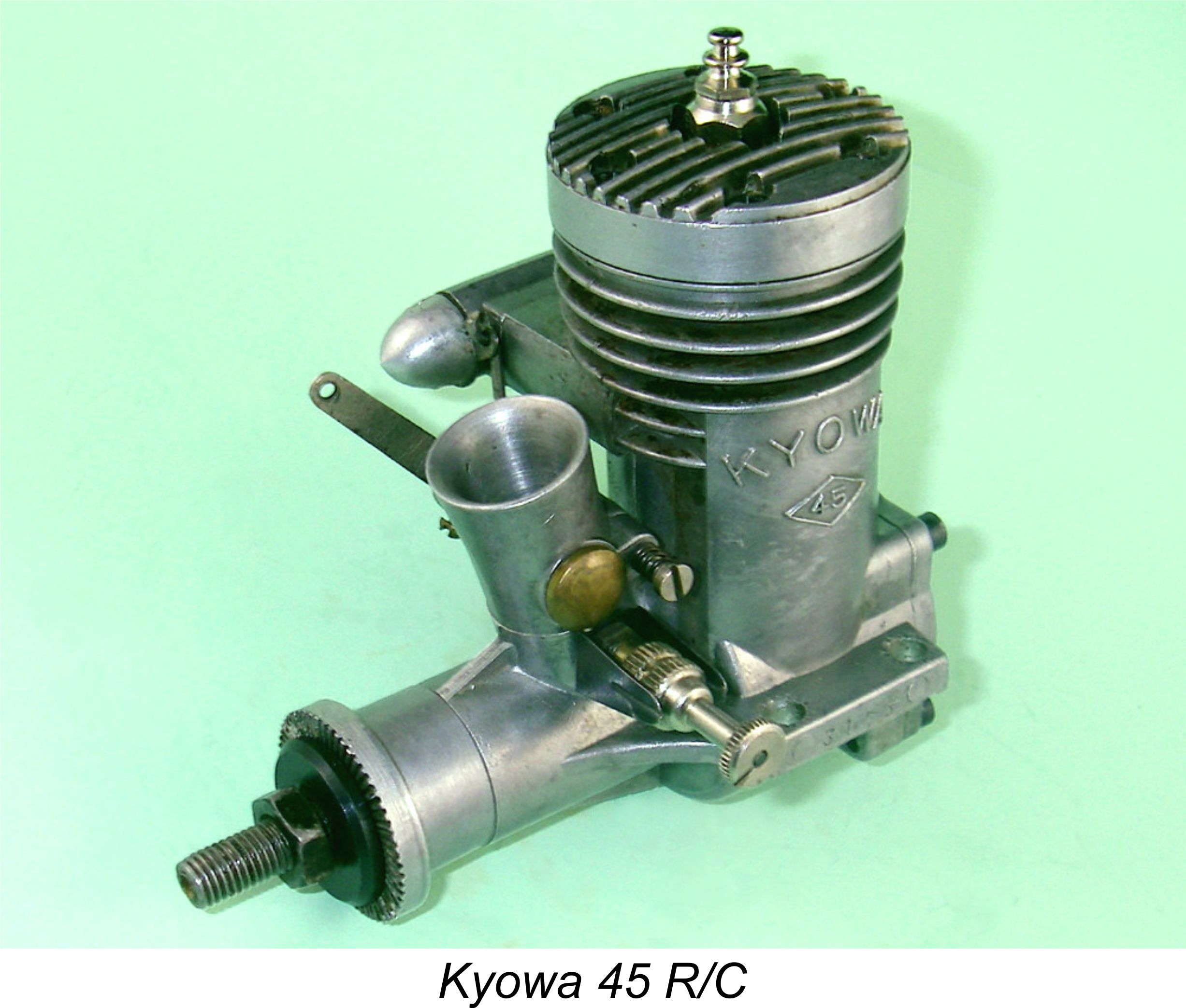

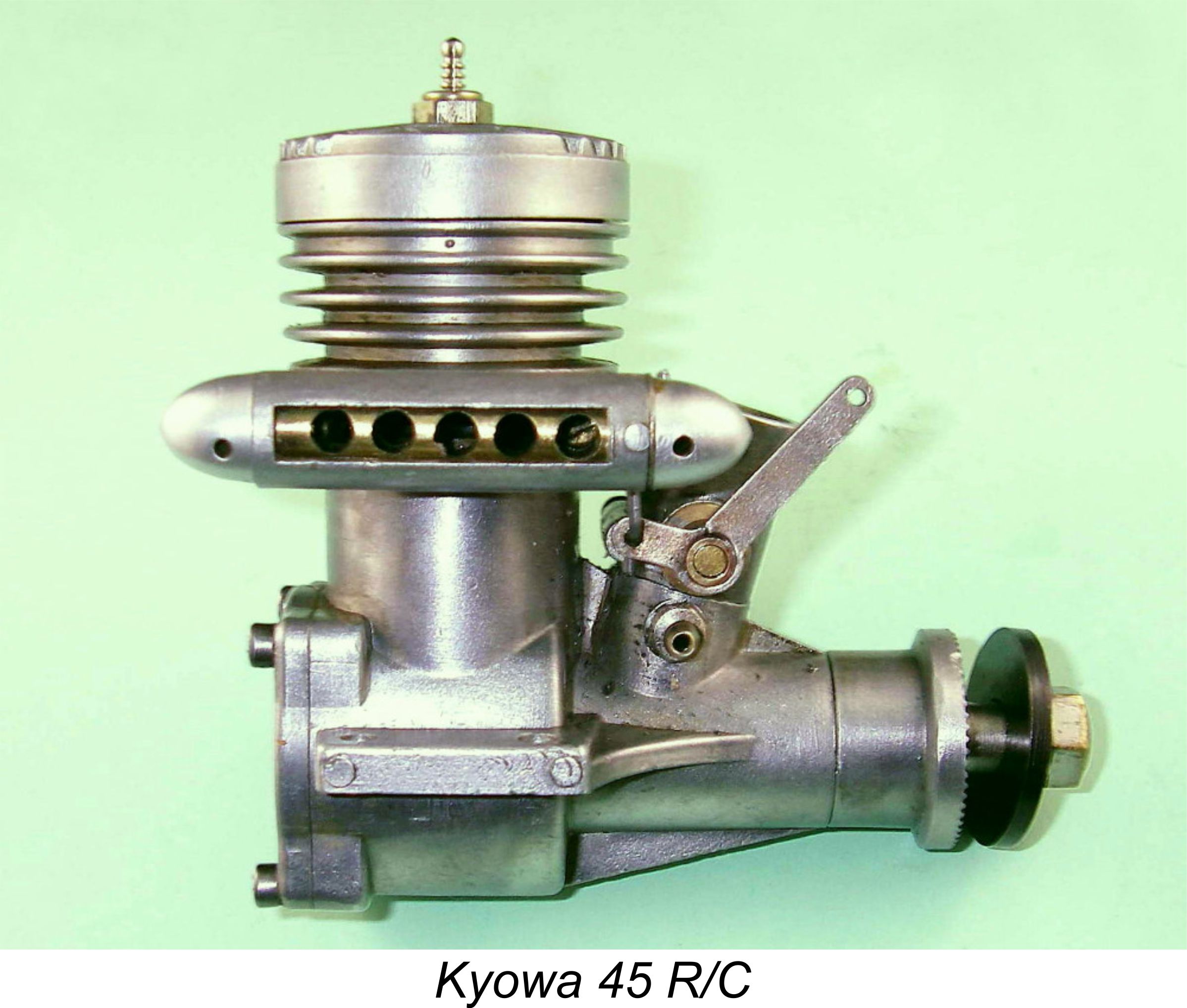

The design of the Kyowa 45 originated in 1959, when sandcast prototypes were first tested. Following a successful conclusion to these tests, the production model with die-cast crankcase appeared in the spring of 1960. The introduction of the Kyowa 45 was noted by Peter Chinn in his “Latest Engine News” column in the May 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

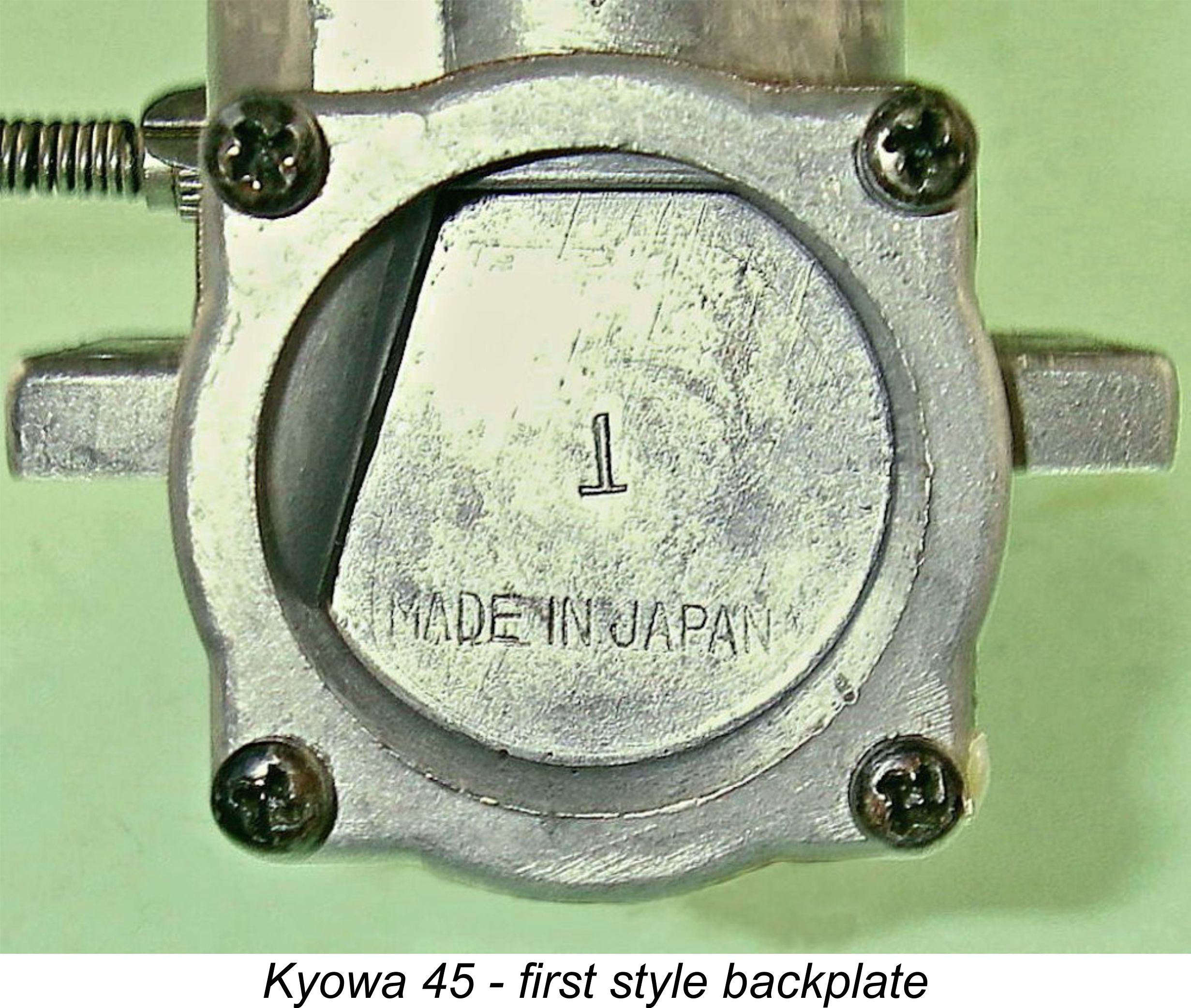

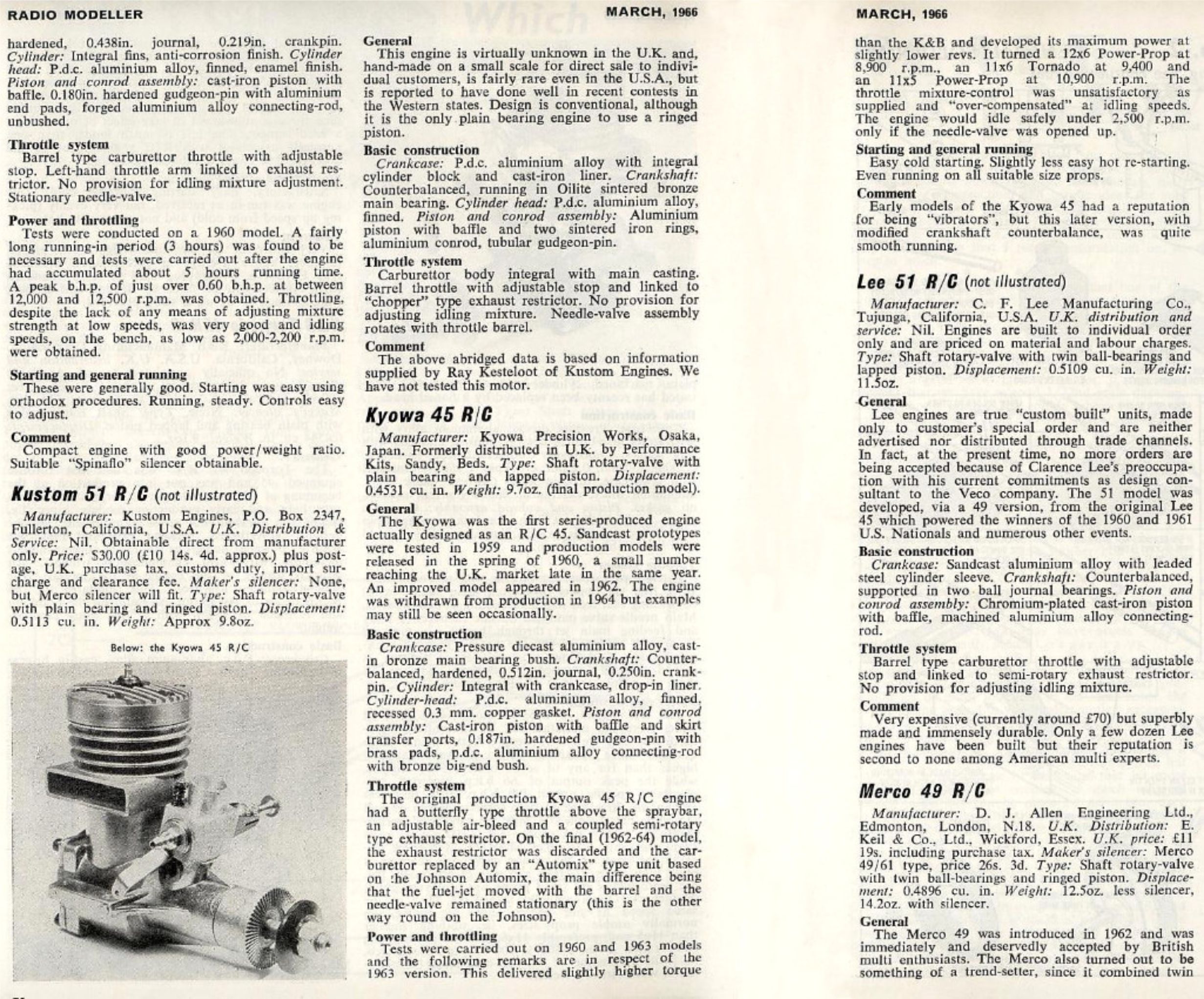

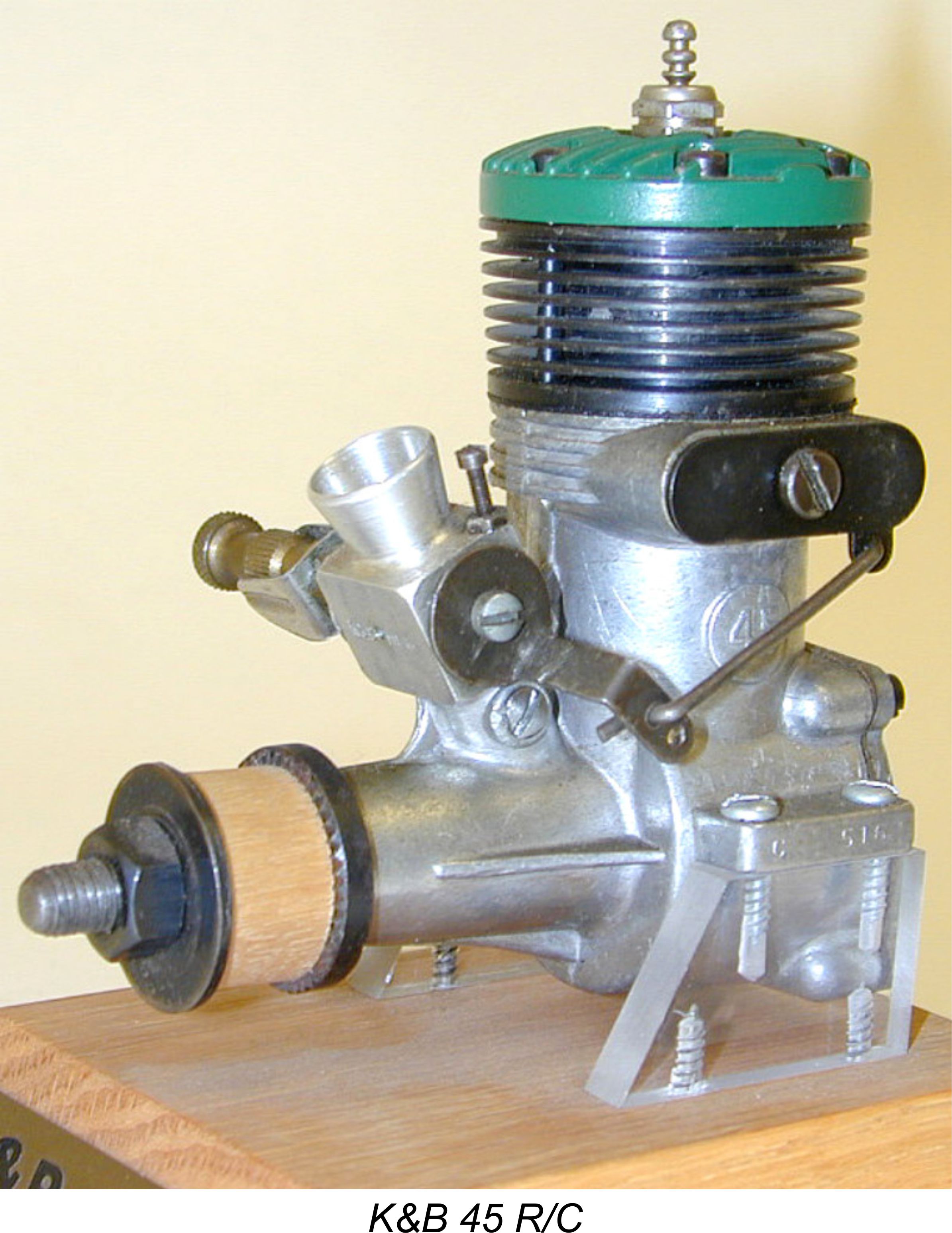

The lapped cast iron piston was extremely well fitted to the steel cylinder liner. The piston featured a conventional upstanding baffle as well as a pair of skirt ports which aligned at bottom dead centre with matching ports in the cylinder wall, presumably to improve bypass efficiency as well as promote improved piston cooling by facilitating gas flow though the piston interior. The nicely squared-off induction port in the crankshaft and the matching semi-rectangular intake base were also aids to good breathing. Apart from the Kyowa 45 identification cast onto the bypass, the engines were identified by having “MADE IN JAPAN” stamped in block capitals into the During its brief four-year existence, the Kyowa line did not achieve great prominence in Western modelling circles, hence escaping the notice of the world’s English-language modelling media for the most part. The only substantive English-language references that I’ve been able to find sofar are the published test by Peter Chinn of the later version of the Kyowa 45 R/C which appeared in the July The 1966 “Radio Modeller” article (most probably written by Peter Chinn) informs us that the Kyowa 45 enjoyed the distinction of having been the first series-produced engine of its displacement to be specifically designed from the outset as an R/C powerplant. This assessment might legitimately be challenged by aficionados of the American K&B and C. F. Lee lines - K&B had introduced a .45 cuin model in April 1959 which was available from the outset in an R/C version as well as the standard control-line model. Clarence Lee had also introduced a limited-edition R/C 45 model in the same year.

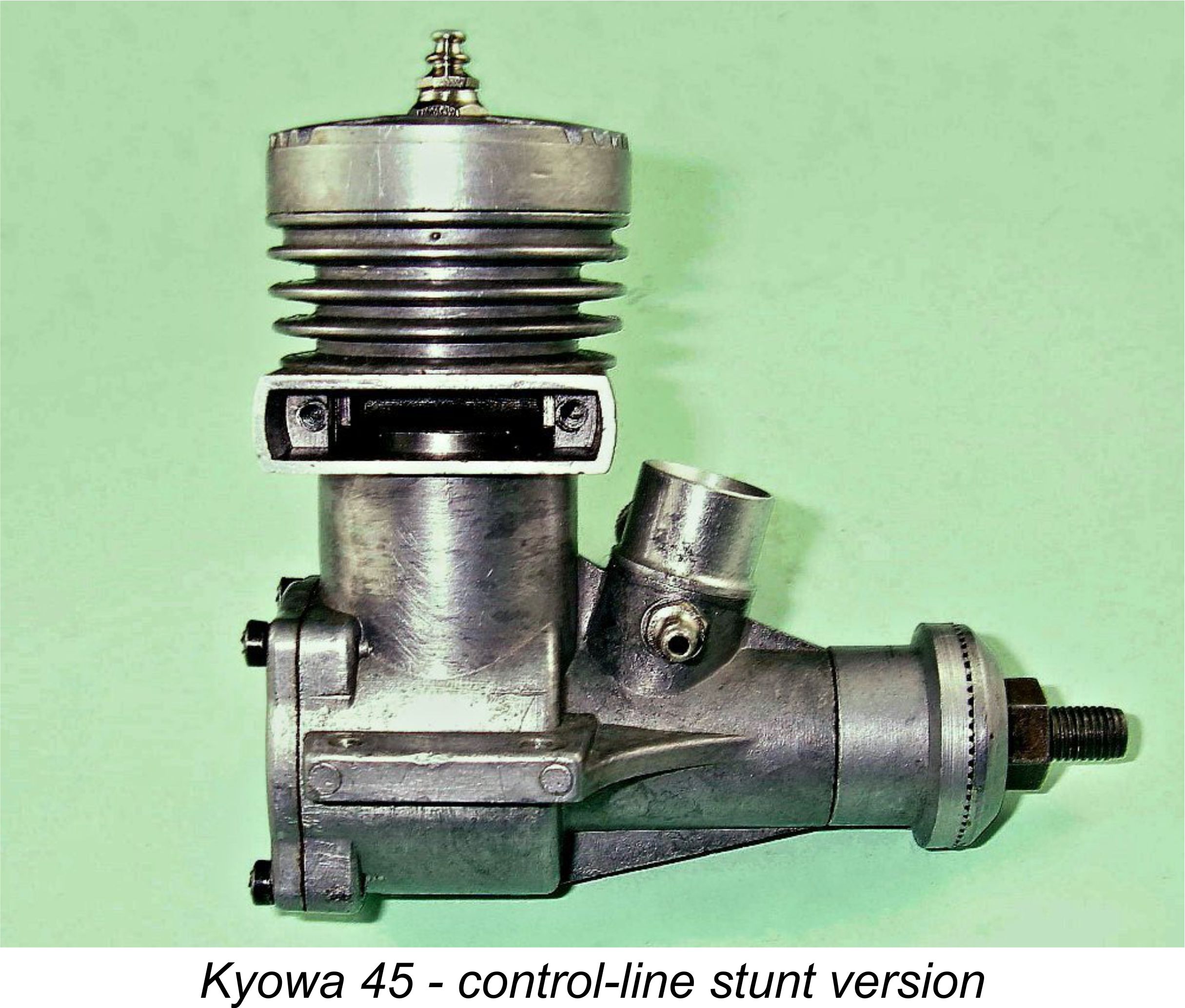

By contrast, the Kyowa was a series-production model which was clearly aimed specifically at the R/C market and was designed with that objective in mind throughout. As such, the qualified claim made on its behalf by “Radio Modeller” does have some validity. The original Kyowa 45 R/C had bore and stroke measurements of 21.9 mm and 19.7 mm respectively for a displacement of 7.42 cc (0.453 cuin). The engine tipped the scales at 9.9 ounces. It was fitted with an O.S.-influenced throttle set-up (again consistent with the notion expressed earlier regarding a possible O.S.-Kyowa connection) which basically consisted of a simple butterfly intake restrictor with air bleed adjustment A control-line stunt version of the Kyowa was also offered, but this seems to have been something of an afterthought, essentially being a retro-conversion of the R/C model (reversing the previous trend) rather than a purpose-built stunt engine. It was identical in all respects to the R/C model apart from the fact that the rotary exhaust restrictor was omitted and the R/C carburettor was replaced by a simple turned venturi tube. In this form, the engine weighed in at 9.2 ounces. The control-line version attracted little customer attention, with original examples consequently being very rare today. When un-throttled examples appear at all, they usually turn out to be owner conversions of an R/C model. I myself have an example (s/n 2285) of such a conversion - it still has its butterfly throttle to prove its R/C ancestry, I never actually flew either of my C/L Kyowa’s, but perhaps I should have done so! While researching this article, I came across a most informative comment posted on a popular modelling forum by US stunt expert Bob Jones. Bob stated that he acquired one of these engines back in the early 1960's. A friend of his bought an R/C version with the intention of using it in its intended R/C application. However, it seems that his choice of engine was derided by his colleagues to the point that he went out and bought a Merco 49 instead! He gave his NIB Kyowa to Bob Jones, who converted it for stunt use.

Because of its large displacement together with the relative absence of direct competition, the Kyowa 45 attracted considerable interest among R/C flyers at the time of its introduction. The engines were exported by the Kosaka Corporation of Osaka, who were successful in securing distribution agreements in a number of the world’s major model engine market zones. Their agents in the UK were Performance Kits, while their Australian distribution was handled by The Model Dockyard Pty. Ltd. of Melbourne.

Although at the outset the Kyowa 45 enjoyed a relatively uncluttered market niche which resulted in fairly strong initial sales, its positive reception made it inevitable that further direct competition would be quick to appear. The K&B and Lee models had been there all along in the USA, with the custom-built Lee 45 winning both the 1960 and 1961 US National R/C aerobatic championships as well as numerous other contests. This naturally drew attention to the .45 - .50 cuin. R/C engine category, resulting in O.S. releasing their own .49 cuin. model in 1961.

To their credit, the Kyowa company did attempt to react to this highly competitive situation. In 1962 they revised the 45 in an attempt to keep it competitive with the newer designs from other makers which were now on the market or under development. The somewhat basic throttle design on the original model was changed to a more up-to-date unit resembling the then-fashionable Johnson Automix design. The exhaust restrictor was abandoned on this revised model, thus facilitating the increasingly-common use of a muffler. In addition, the counterbalance arrangements on the crankshaft were updated to reduce vibration levels, a factor which had given rise to some criticism of the original 1960 model. The heavy cast-iron piston was doubtless a major culprit here. If I was planning to fly one of my Kyowas, I'd probably strip it down and machine some metal out of the piston - I'd bet that this would improve the engine significantly. The previously-mentioned 1966 article in "Radio Modeller" referred to tests which had been carried out on the second (1962) model of the Kyowa. It’s almost certain that the test referred to was the previously-mentioned “Model Aircraft” report by Peter Chinn which appeared in July 1963. Using 5% nitro fuel, the Kyowa had been found to deliver slightly higher torque than its K&B rival, hence developing its peak power of 0.61 BHP at 11,700 rpm, slightly less than the peaking speed of the K&B and not at all a bad thing in the context of the intended purpose. It turned a 12x6 Power Prop at 8,900 rpm, an 11x6 Tornado at 9,400 rpm and an 11x5 Power Prop at 10,900 rpm. It’s worth noting at this point that Ron Warring’s double test of the Enya 45 R/C and O.S. Max 49 R/C published in the January 1963 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine reported performance figures of 0.55 BHP @ 12,400 rpm and 0.55 BHP @ 12,200 rpm respectively. Even allowing for the fact that Warring consistently tended to find slightly lower peak power figures than Chinn for the same engine (probably reflecting differences in engine management and testing techniques), it’s clear that the revised Kyowa was by no means lacking in performance by comparison with its rivals as of 1963. Cold starting of the Kyowa was found to be very easy, with hot re-starting a little less straightforward. Running qualities were generally considered excellent. However, the revised throttle was found to be sub-standard in terms of its idling performance, since an idle below 2,500 rpm could not be sustained without opening the needle slightly. Clearly a needle with a slightly revised taper was required, but this was not supplied with the test engine. This published finding cannot have helped the Kyowa cause despite its excellent performance figures.

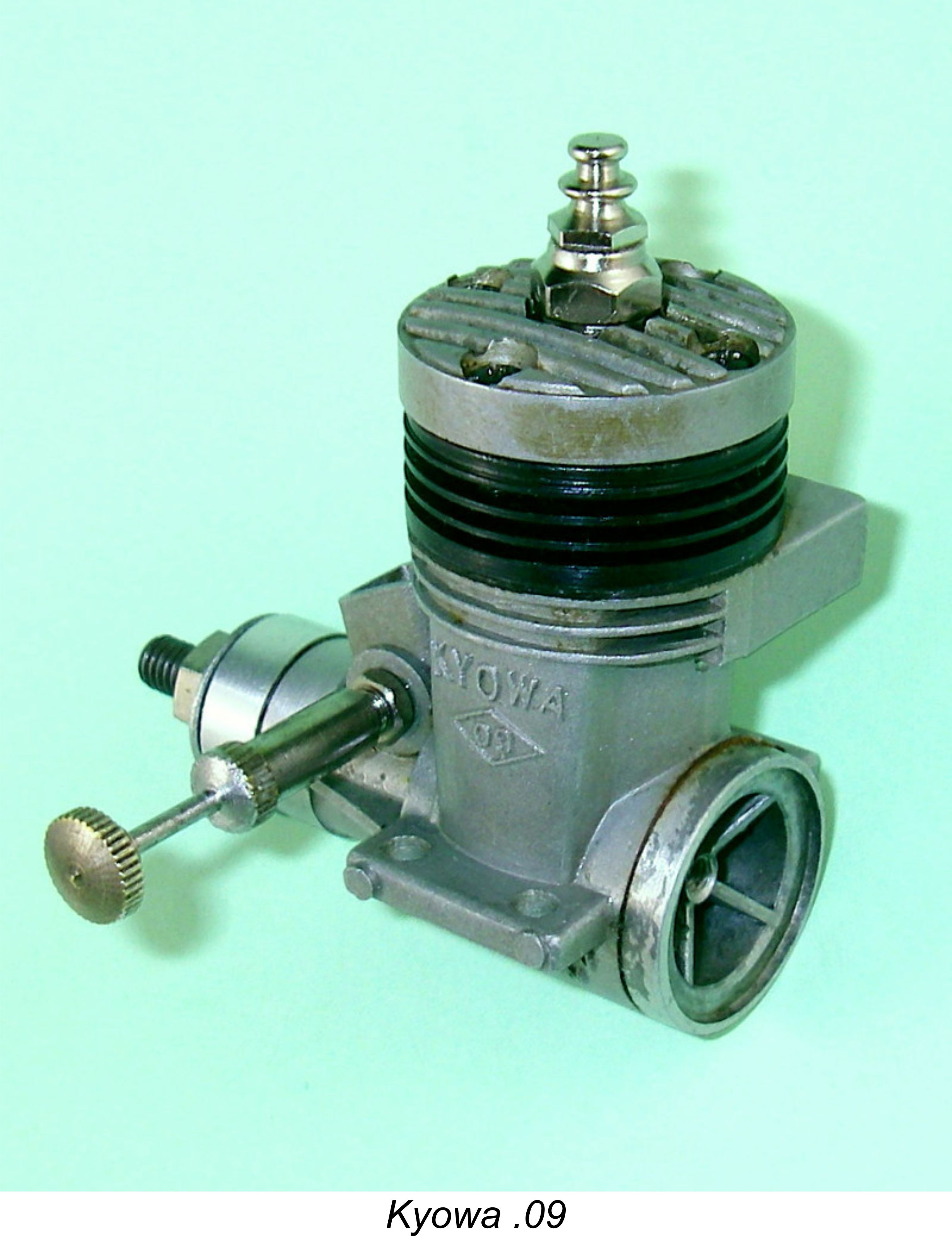

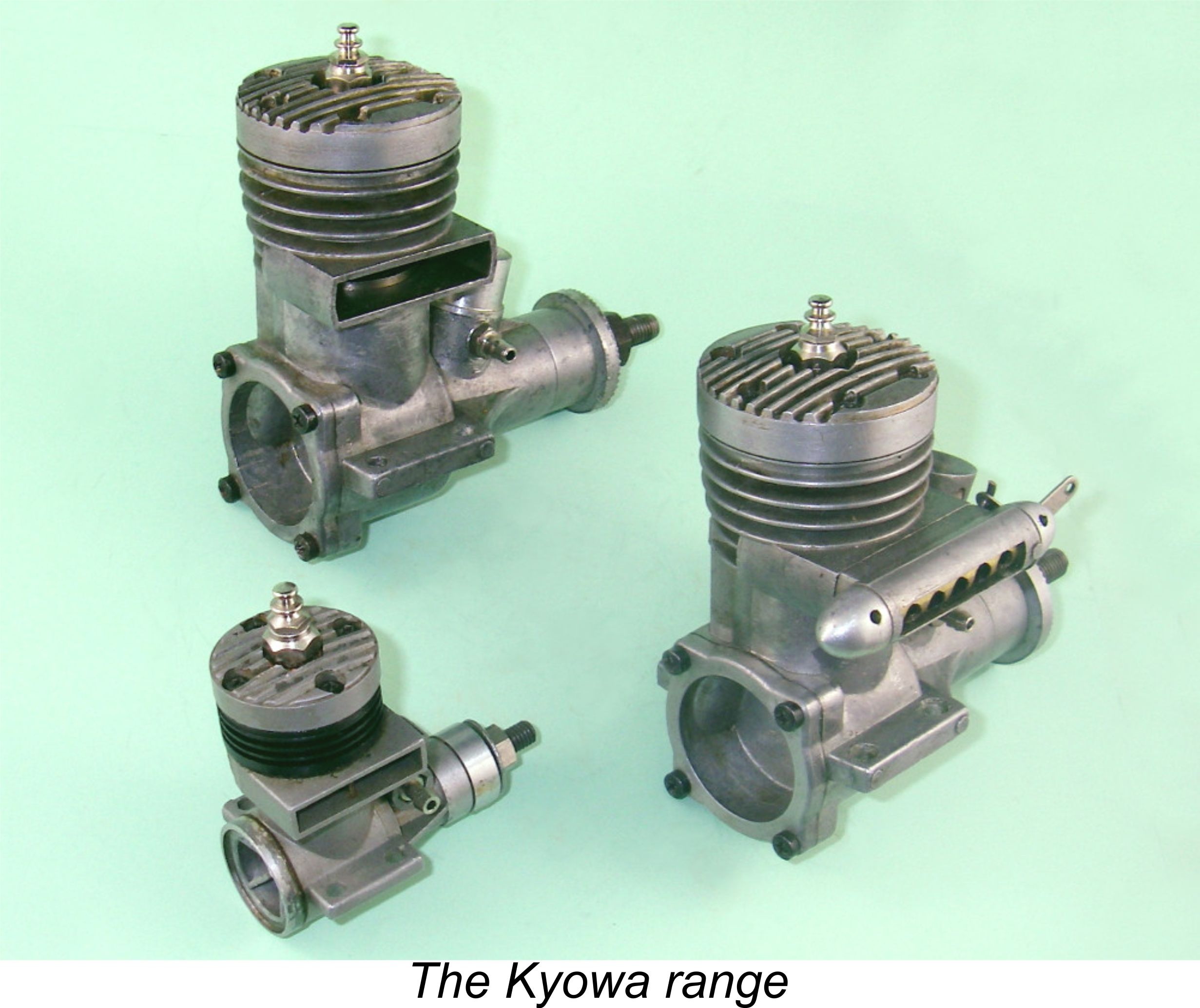

This model was a very neat and well-made little unit, albeit offering nothing new in terms of design features. In many ways it was reminiscent of the rival O.S. Pet. It featured bore and stroke measurements of 13.60 mm and 11.12 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.61 cc (.0985 cuin). The new model weighed a checked 83 gm (2.93 ounces) in standard un-throttled form. If the “Plans Handbook” entry is to be believed, it was only offered in this form.

Consequently, the small head start in the market that Kyowa had enjoyed with the 45 proved insufficient to allow the company to gain the kind of foothold necessary to compete successfully in the longer term. The outcome was sadly inevitable, and the late 1964 edition of the Global Engine Review (American Modeller, 1965 Annual) stated that manufacture of the Kyowa engines had ceased during 1964. As a result of their relative lack of sales success and consequently short production life, these fine engines are relatively uncommon today. It’s unclear how many were made, but the number can’t have been all that high by Japanese commercial standards. I have yet to encounter an example of the Kyowa 45 which did not bear a serial number, and the serial numbers of the majority of examples encountered today tend to be very much on the low side. Since I started keeping track of serial numbers for these engines prior to writing this article, I have logged seven examples having four-digit serial numbers ranging from a low of 2007 up to 3173. This is a surprisingly narrow range of numbers, even having regard to the relatively small sample involved.

The example which upsets this particular apple-cart is another of my own first model examples bearing the number 609083! This is another of the engines which were marketed in the USA as Aristo-Craft 45’s, since it has a backplate which is stamped in the usual manner for those engines. However, the serial number is way out in left field by comparison with the six other examples of my direct acquaintance! I simply cannot believe that Kyowa made over 600,000 of these engines - to allow for a production figure of this magnitude, the engines would have had to achieve far greater prominence than they did, and we’d see far more of them today. This being the case, the clear The true significance of the Kyowa 45 in the history of the model engine industry is best summarized by stating the fact that it was the very first series production model glow-plug engine to be designed from the outset strictly as an R/C model, the control-line version being relegated to the status of an afterthought which was simply a retro-conversion of t It may thus be legitimately argued that the Kyowa 45 marked a significant turning point both in the evolution of marketing philosophy among model engine manufacturers and in the future evolution of the hobby itself. If for no other reason, it deserves to be remembered with respect. ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2014

|

| |

Here I'll present a few details about another now-obscure model engine range from Japan - the Kyowa marque. The manufacturers of this short series of model engines (correctly pronounced Key-

Here I'll present a few details about another now-obscure model engine range from Japan - the Kyowa marque. The manufacturers of this short series of model engines (correctly pronounced Key-

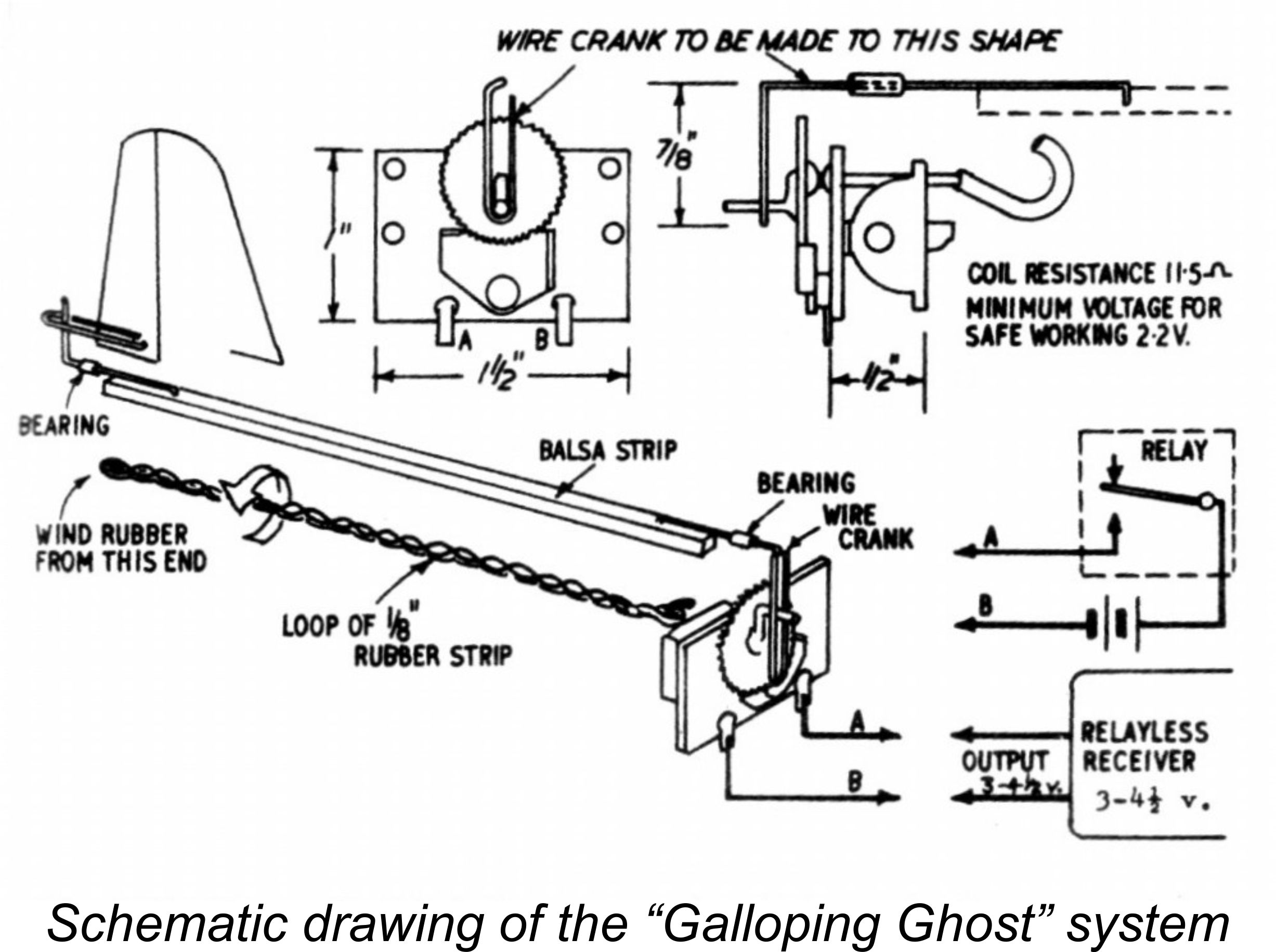

The first widely-followed steps towards proportional control were taken with the largely-forgotten “Galloping Ghost” setup. While extremely ingenious, this system was somewhat less than ideal, placing excessive reliance upon both electronic and mechanical jiggery-pokery to function. However, it did work quite well if properly set up and was far less expensive than the more sophisticated proportional setups, hence surviving well into the 1960’s. As many as three functions could be controlled using the system.

The first widely-followed steps towards proportional control were taken with the largely-forgotten “Galloping Ghost” setup. While extremely ingenious, this system was somewhat less than ideal, placing excessive reliance upon both electronic and mechanical jiggery-pokery to function. However, it did work quite well if properly set up and was far less expensive than the more sophisticated proportional setups, hence surviving well into the 1960’s. As many as three functions could be controlled using the system. The Kyowa 45 was introduced specifically to tap into this demand. It was manufactured by the Kyowa Precision Works of Osaka, Japan, just across town from the rival O.S. factory. The name “Kyowa” in Japanese means something along the lines of “Co-operative”. Reports from Japan indicate that the Kyowa company founder and designer (whose name is not now recalled by my informants) was an ex-employee of the O.S. company. The name certainly suggests the possibility that the Kyowa may have been manufactured by a co-operative formed by a breakaway group of former O.S. employees. It’s undeniably true that the O.S. and Kyowa engines displayed a number of common design and construction features, including the use of assembly screws having an unusual coarse metric thread, indicating perhaps a common inspiration and source. Owner recommendation - do

The Kyowa 45 was introduced specifically to tap into this demand. It was manufactured by the Kyowa Precision Works of Osaka, Japan, just across town from the rival O.S. factory. The name “Kyowa” in Japanese means something along the lines of “Co-operative”. Reports from Japan indicate that the Kyowa company founder and designer (whose name is not now recalled by my informants) was an ex-employee of the O.S. company. The name certainly suggests the possibility that the Kyowa may have been manufactured by a co-operative formed by a breakaway group of former O.S. employees. It’s undeniably true that the O.S. and Kyowa engines displayed a number of common design and construction features, including the use of assembly screws having an unusual coarse metric thread, indicating perhaps a common inspiration and source. Owner recommendation - do  This created a clear opportunity for a fledgling manufacturer to step up to the plate with a product which could enter the marketplace against relatively minimal opposition. It appears to have been this factor which led Kyowa to chose the .45 cuin. R/C category for their initial foray into the highly competitive world of model engine manufacture. They also took good care to ensure that their new product was well up to the best contemporary standards of quality - another imperative for any new manufacturer.

This created a clear opportunity for a fledgling manufacturer to step up to the plate with a product which could enter the marketplace against relatively minimal opposition. It appears to have been this factor which led Kyowa to chose the .45 cuin. R/C category for their initial foray into the highly competitive world of model engine manufacture. They also took good care to ensure that their new product was well up to the best contemporary standards of quality - another imperative for any new manufacturer. The production version was a very neat, well-made and well-proportioned design, albeit quite conventional in its general arrangement. It featured a lapped cast iron piston along with a bronze-bushed plain bearing. All the major components were extremely sturdy - the shaft had a generous journal diameter of 13 mm, while the very substantial cast alloy con-rod was bronze bushed at the big end.

The production version was a very neat, well-made and well-proportioned design, albeit quite conventional in its general arrangement. It featured a lapped cast iron piston along with a bronze-bushed plain bearing. All the major components were extremely sturdy - the shaft had a generous journal diameter of 13 mm, while the very substantial cast alloy con-rod was bronze bushed at the big end.

However, it appears that the K&B 45 was intended all along as a general-purpose unit for both R/C and control-line use, with the R/C model following the established protocol of being in effect a conversion of the standard U/C version. The Lee model was undoubtedly a purpose-built R/C engine, but it was always a custom-manufactured unit rather than a production-line model.

However, it appears that the K&B 45 was intended all along as a general-purpose unit for both R/C and control-line use, with the R/C model following the established protocol of being in effect a conversion of the standard U/C version. The Lee model was undoubtedly a purpose-built R/C engine, but it was always a custom-manufactured unit rather than a production-line model.

Bob installed the converted engine in a Shark 45 that was then in the building stage, subsequently finding it to be a very good stunt engine indeed. He recalled that it ran with great authority, exhibiting a perfect 2-stroke/4-stroke break. He never parted with the engine - in fact, he liked it so much that he acquired a second example later at a swap meet. Another individual who posted in the same thread stated that he had seen Bob fly the model in question and was able to confirm that the engine performed very impressively in that application. Classic stunt fliers, take note …………….

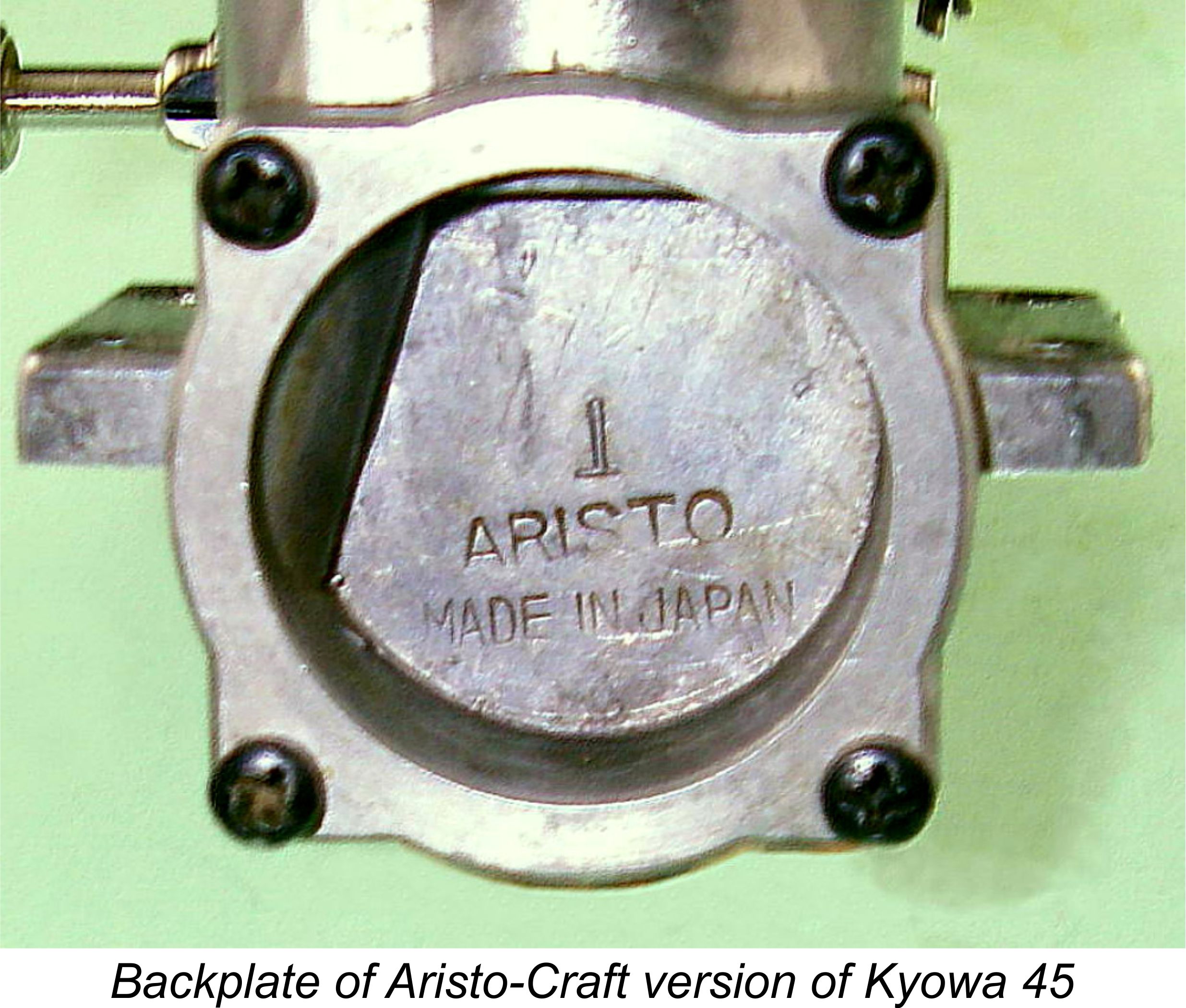

Bob installed the converted engine in a Shark 45 that was then in the building stage, subsequently finding it to be a very good stunt engine indeed. He recalled that it ran with great authority, exhibiting a perfect 2-stroke/4-stroke break. He never parted with the engine - in fact, he liked it so much that he acquired a second example later at a swap meet. Another individual who posted in the same thread stated that he had seen Bob fly the model in question and was able to confirm that the engine performed very impressively in that application. Classic stunt fliers, take note ……………. This variant of the engine was marketed in the USA by Aristo-Craft Distinctive Miniatures of Newark, New Jersey. Interestingly enough, under the terms of the deal the engine was actually marketed as the Aristo-Craft 45 R/C glow-plug engine, complete with Aristo-Craft box and Aristo-Craft instruction leaflet. The backplates were also stamped “ARISTO” along with the “MADE IN JAPAN” attribution.

This variant of the engine was marketed in the USA by Aristo-Craft Distinctive Miniatures of Newark, New Jersey. Interestingly enough, under the terms of the deal the engine was actually marketed as the Aristo-Craft 45 R/C glow-plug engine, complete with Aristo-Craft box and Aristo-Craft instruction leaflet. The backplates were also stamped “ARISTO” along with the “MADE IN JAPAN” attribution.  Despite this identity change, the Kyowa 45 identification continued to appear cast in relief onto the bypass - in fact, the engines were identical to those sold elsewhere as Kyowa products.

Despite this identity change, the Kyowa 45 identification continued to appear cast in relief onto the bypass - in fact, the engines were identical to those sold elsewhere as Kyowa products.

In any event, it must always have been quite clear that the company could not survive for long on the basis of a single rather specialized model, however good. Accordingly, in 1963 an .099 cuin. model of conventional design was introduced by Kyowa in an attempt to diversify their range by establishing a foothold in the “popular” engine field. This model is practically forgotten today - indeed, modellers outside Japan were only made aware of the Kyowa .09 through its inclusion in the listing of the world’s engines in the 1963 edition of the “Aeromodeller & Model Maker Plans Handbook”. Probably very few readers even noticed …………

In any event, it must always have been quite clear that the company could not survive for long on the basis of a single rather specialized model, however good. Accordingly, in 1963 an .099 cuin. model of conventional design was introduced by Kyowa in an attempt to diversify their range by establishing a foothold in the “popular” engine field. This model is practically forgotten today - indeed, modellers outside Japan were only made aware of the Kyowa .09 through its inclusion in the listing of the world’s engines in the 1963 edition of the “Aeromodeller & Model Maker Plans Handbook”. Probably very few readers even noticed ………… Sadly, the introduction of the .09 model proved insufficient to bring the company’s sales performance up to par with its established rivals. The major Japanese and American manufacturers already had well-developed .09 glow models on the market, also enjoying the advantage of well-entrenched brand recognition around the world. This meant that the new model faced an uphill battle right from the start in competing for market attention, both domestically and world-wide.

Sadly, the introduction of the .09 model proved insufficient to bring the company’s sales performance up to par with its established rivals. The major Japanese and American manufacturers already had well-developed .09 glow models on the market, also enjoying the advantage of well-entrenched brand recognition around the world. This meant that the new model faced an uphill battle right from the start in competing for market attention, both domestically and world-wide.  Engine number 3173 is a first model example which was originally sold in the USA as an Aristo-Craft 45, based on the ARISTO stamping on the backplate. It bears the highest four-digit serial number of which I’m currently aware.

Engine number 3173 is a first model example which was originally sold in the USA as an Aristo-Craft 45, based on the ARISTO stamping on the backplate. It bears the highest four-digit serial number of which I’m currently aware.

he R/C unit. This was a complete reversal of the situation which had prevailed up to that time, in which the control line version was the primary model with the R/C version being created by merely grafting a throttle onto the C/L version. As such, the Kyowa led the way towards the future, in which the R/C engine would come to dominate an ever-shrinking marketplace and control-line versions would be consigned to afterthought status when they existed at all.

he R/C unit. This was a complete reversal of the situation which had prevailed up to that time, in which the control line version was the primary model with the R/C version being created by merely grafting a throttle onto the C/L version. As such, the Kyowa led the way towards the future, in which the R/C engine would come to dominate an ever-shrinking marketplace and control-line versions would be consigned to afterthought status when they existed at all.