|

|

Clone Wars - the Classic Enya 15 Copies Revisited

It’s an inescapable marketplace truism that success breeds imitation. There's a great deal of truth in the old saying that imitation is the most sincere form of flattery - it's the good products that get copied! This has led to the appearance over the years of numerous low-priced clones and near-clones of successful model engines. It's important to understand that these engines can in no way be viewed as replicas or reproductions. Engines in those two categories generally represent the re-creation of models which are long out of production. When we speak of "clones", we're talking about copies or near-copies of engines which remain in concurrent production. These clones are generally (but not always) offered for sale in the same markets in which the original engines on which they are based remain on offer. Accordingly, unlike most replicas or reproductions the clones compete directly with the originals for sales. Purely on the basis of price considerations, these copies and near-copies have found many buyers, doubtless to the detriment of the sales figures for the (usually) higher quality but also higher-priced originals. Although not by any means solely responsible for the decline and disappearance of so many once-great model engine manufacturing concerns, the low-cost clone syndrome undoubtedly contributed to the acceleration of that process. Perhaps more significantly, these engines also siphoned off a sizeable proportion of the financial returns due to the designers of the original models on which they were based - the cloning companies did not pay design royalties. This kind of thing is very much on the radar of today’s media companies, who bring considerable resources to bear on the fight against media piracy. As they never tire of telling us quite rightly, “piracy is not a victimless crime”. Morally speaking, this is just as true for the wholesale copying of model engine designs as it is for movies and the like. However, model engines are not subject to copyright laws, hence being wide open to direct imitation. The actual design drawings of a given model are doubtless registered against their designer’s name, but that’s not quite the same thing in a legal sense if no patentable technology is involved. In any case, it’s almost impossible to find a model engine which doesn’t embody some degree of imitation of earlier designs by others. The cloning process merely takes this all the way. Unless carried to extremes, no actual crime is involved - it’s more of an ethical issue in which both the clone manufacturer and the customer are caught up. Since its establishment in 1949, the Japanese Enya model engine manufacturing company has always been known for producing high-quality model engines in a range of displacements and types. Accordingly, it comes as no surprise to find that certain classic Enya products have been subjected to the cloning treatment by a number of manufacturers. The question has always been - how did these clones stack up against the contemporary Enya originals? What did buyers get for their money, and what (if anything) did they give up? By buying these clones instead of an original, they certainly hastened the decline of Enya sales - was it worth it? In this article I’ll present the results of some comparative testing of a couple of original classic Enya 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) models and the clones from other manufacturers which they inspired. We may as well begin with a brief comment upon the first original Enya design with which we are concerned here. This is the Enya 15-II Model 3302 which first appeared in late 1960. The Enya 15-II

Nominal bore and stroke of the new model remained unchanged at 15.00 and 14.00 mm respectively. There was a slight weight penalty associated with the revised cylinder design - weight had crept up from 4.2 ounces to a still not unreasonable 4.7 ounces (133 gm). The earlier conventionally-ported 15-IB model had been tested by Peter Chinn (“Model Aircraft”, October 1957) and found to develop around 0.28 BHP @ 15,100 RPM on 25% nitromethane. By 1957 standards, this was an excellent performance for a lightweight plain-bearing crankshaft-induction 2.5 cc glow-plug motor. The Enya company had claimed an output of 0.30 BHP at some undisclosed speed below 17,000 RPM for the 15-IB. Chinn’s figures came very close to substantiating this claim. He actually commented in his test report that two previous tests of other Enya models had more than substantiated the factory performance claims, suggesting that Enya were unusually honest in publicizing performance data for their products. It appears that unpublished tests by Chinn himself may have been the source of some of these claims - we know of at least two unpublished tests of Enya models undertaken by Chinn which were most likely commissioned by Enya themselves, and there may have been others.

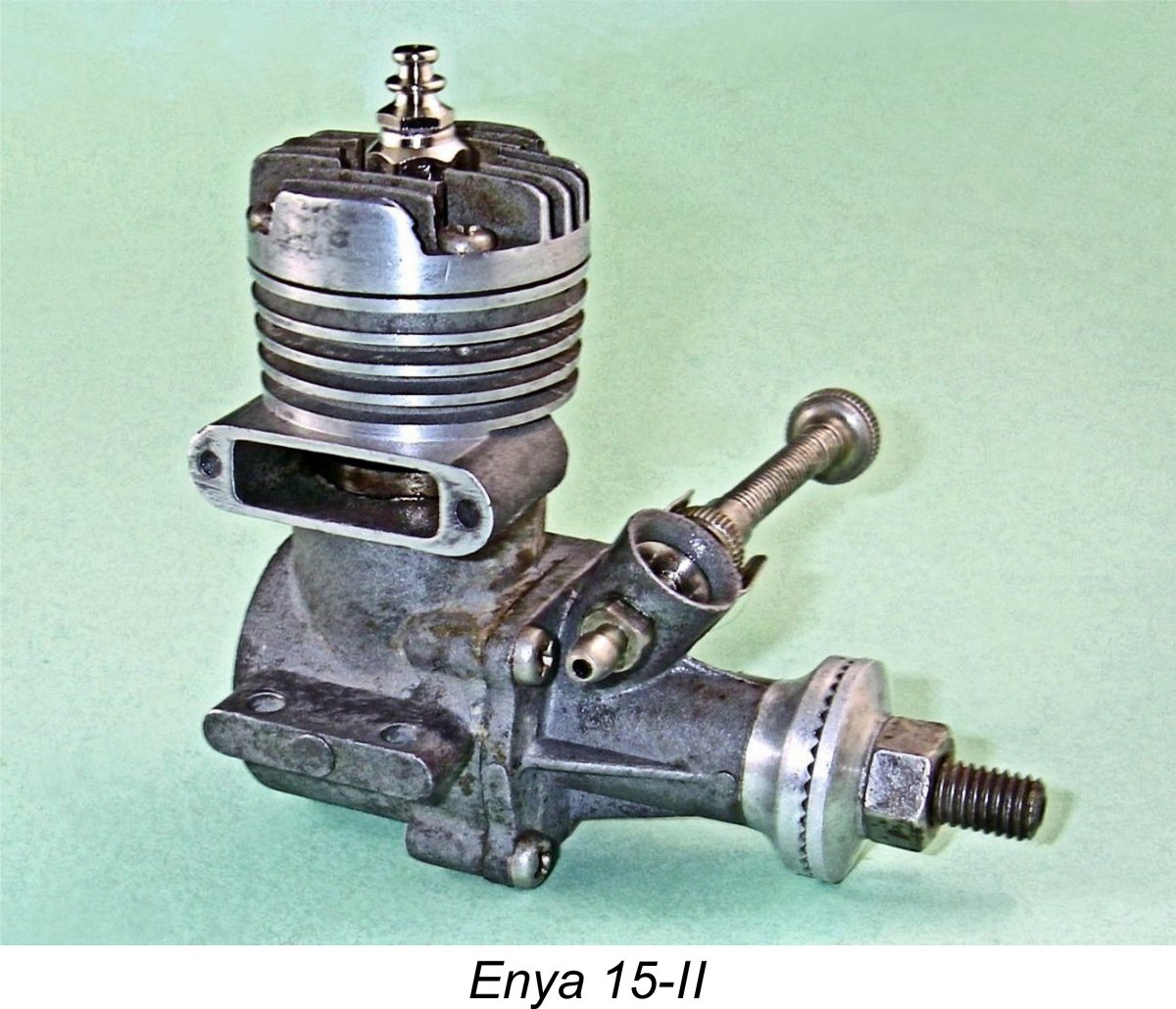

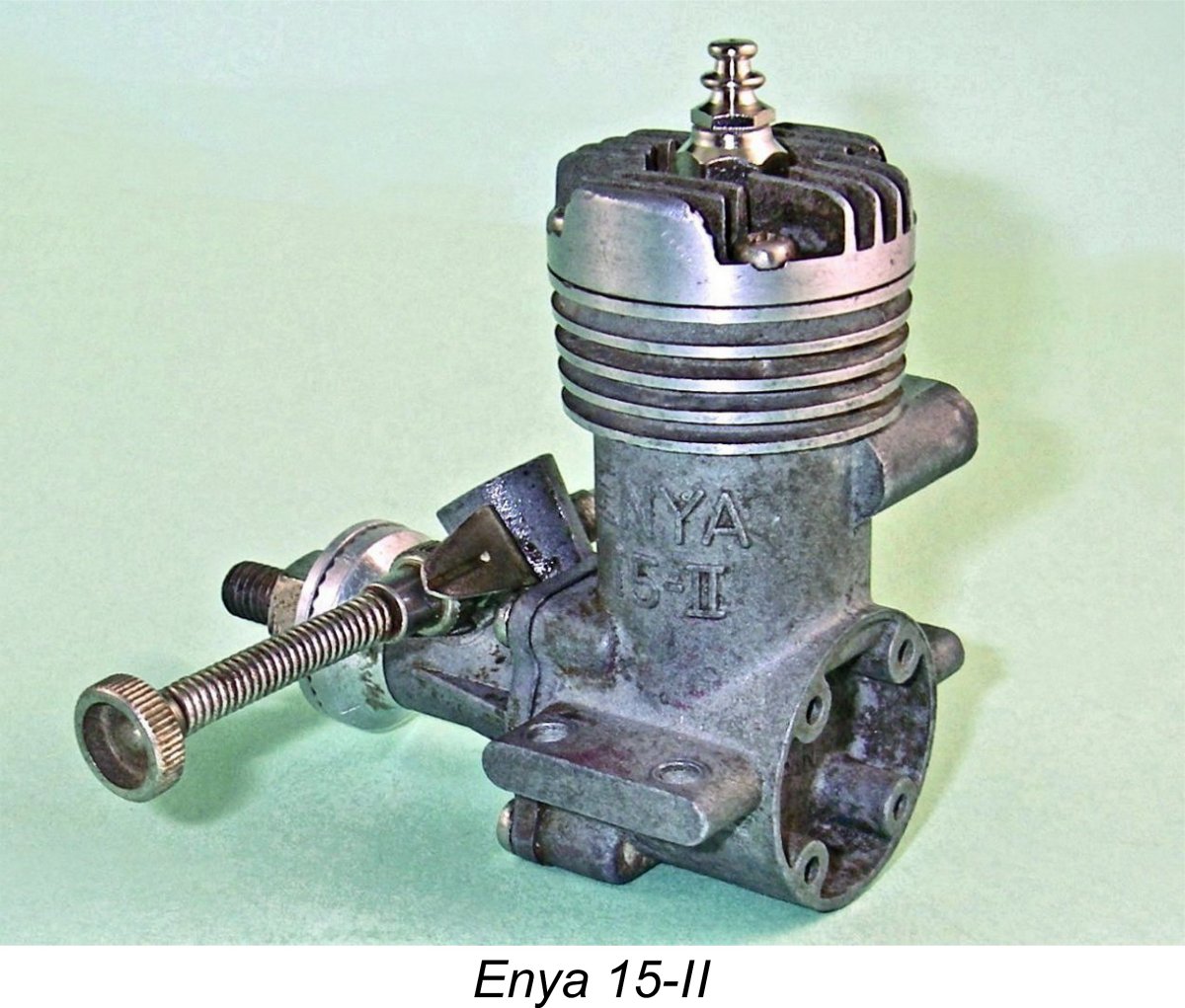

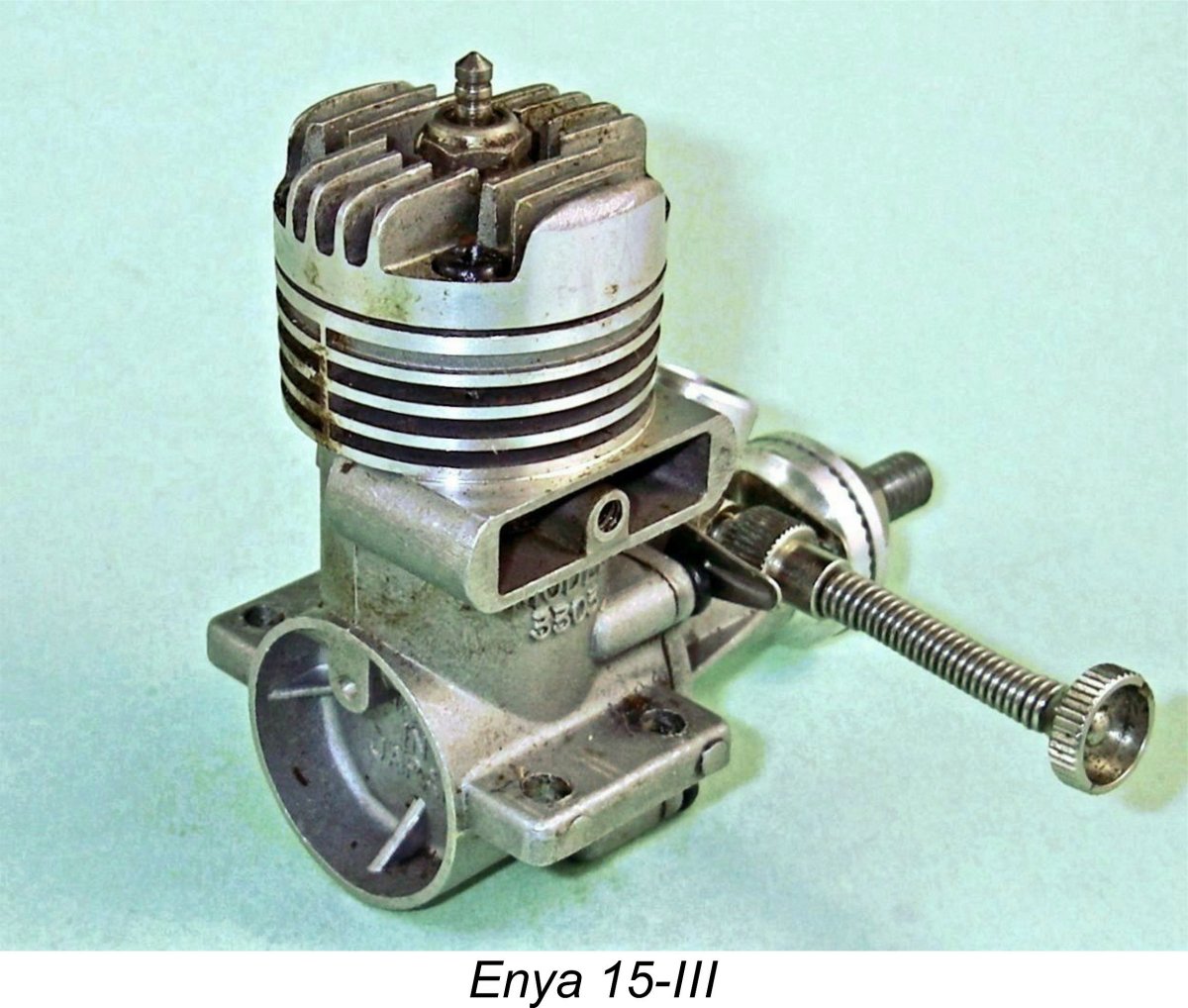

Which leaves it down to me!! My sole example of this model is the somewhat abused but nonetheless complete and original unit which appears in the accompanying illustrations. It has seen considerable use in the past, also displaying clear signs of improper storage at some stage. Nevertheless, it remains in very good mechnical condition, turning over smoothly with more than adequate compression seal and bearing fits. Old Enyas never die - you have to kill them with a sledgehammer! This being the case, I was quite comfortable with the notion of putting this example into the test stand to obtain a few representative prop/RPM figures.

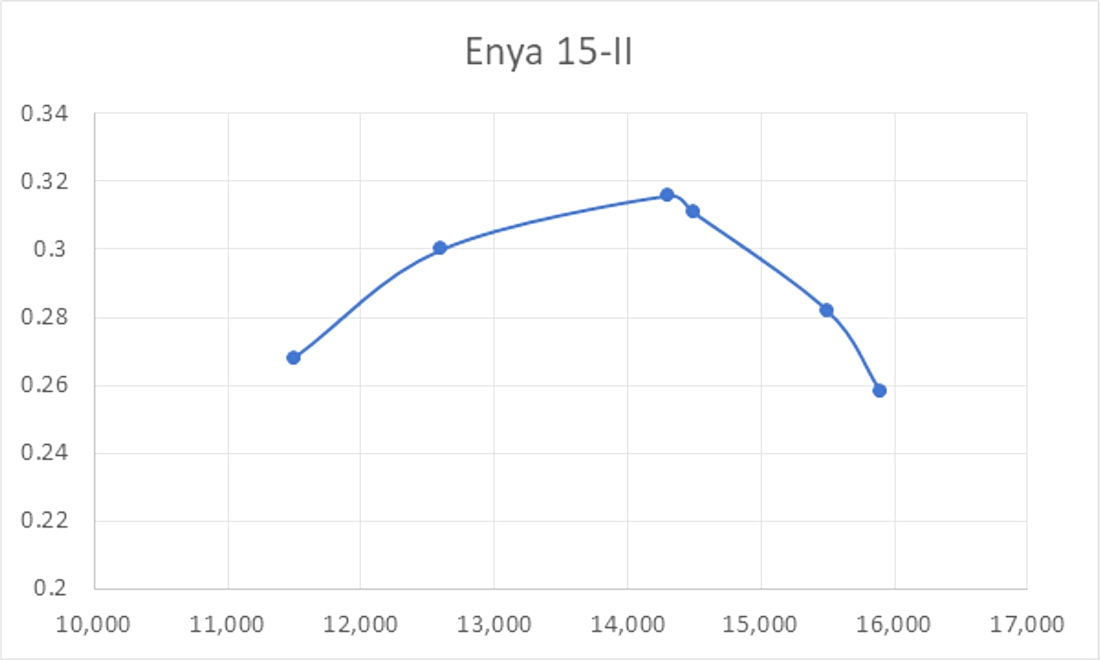

Since the Enya 15 was the design inspiration for all of the others, it followed that it should go first. So into the test stand it went! The extensive previous use to which my example of the engine had clearly been put meant that no preliminary break-in was required - I started right in with the 8x6 APC prop, using an Enya no. 3 (hot) glow-plug with the 15% nitro test fuel. Every time I run an Enya engine, I'm reminded once more of just how excellent a series of model engines emanated from the Enya factory! The 15-II was a genuine pleasure to test, starting first or second flick every time following an exhaust prime. Once running, response to the needle was exemplary, making the establishment of optimum running settings for each prop an extremely simple matter. Running once leaned out was absolutely smooth and mis-free, with no tendency to sag. Vibration levels were minimal. You simply couldn't ask for more - what a user-friendly engine! The following data were recorded during this test:

A very spirited performance on 15% nitro! I was clearly missing a few props to fill the gaps between 11,500 RPM and 14,300 RPM, but these figures nonetheless imply a peak output of around 0.320 BHP @ 14,000 RPM on the 15% nitro test fuel. Coupled with the engine's exemplary quality and fine handling, it set a really high bar for the clones to attempt to clear! The Enya 15-II was produced with both matte finish and shiny castings, being offered in both U/C and R/C variants. It was a great success and a thoroughly satisfying engine to use - by all accounts, one of the best-ever Enya 15 models. Its long-wearing qualities were legendary - it could easily outlast a series of owners. It remained in production for 6 years until September 1966, when it was replaced by a new model, the Enya 15-III Model 3303. More of that offering below in its place. The Fuji 15-III

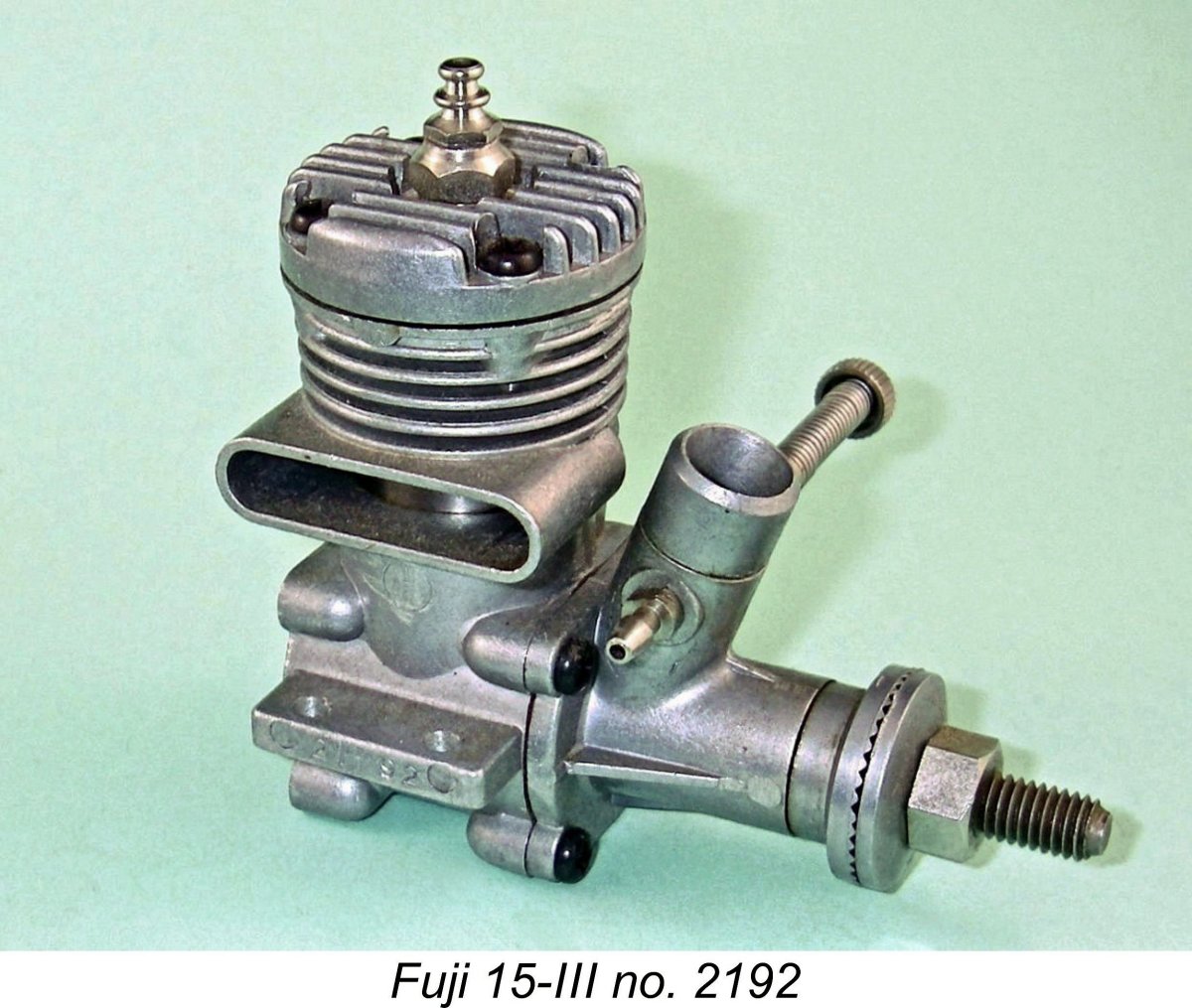

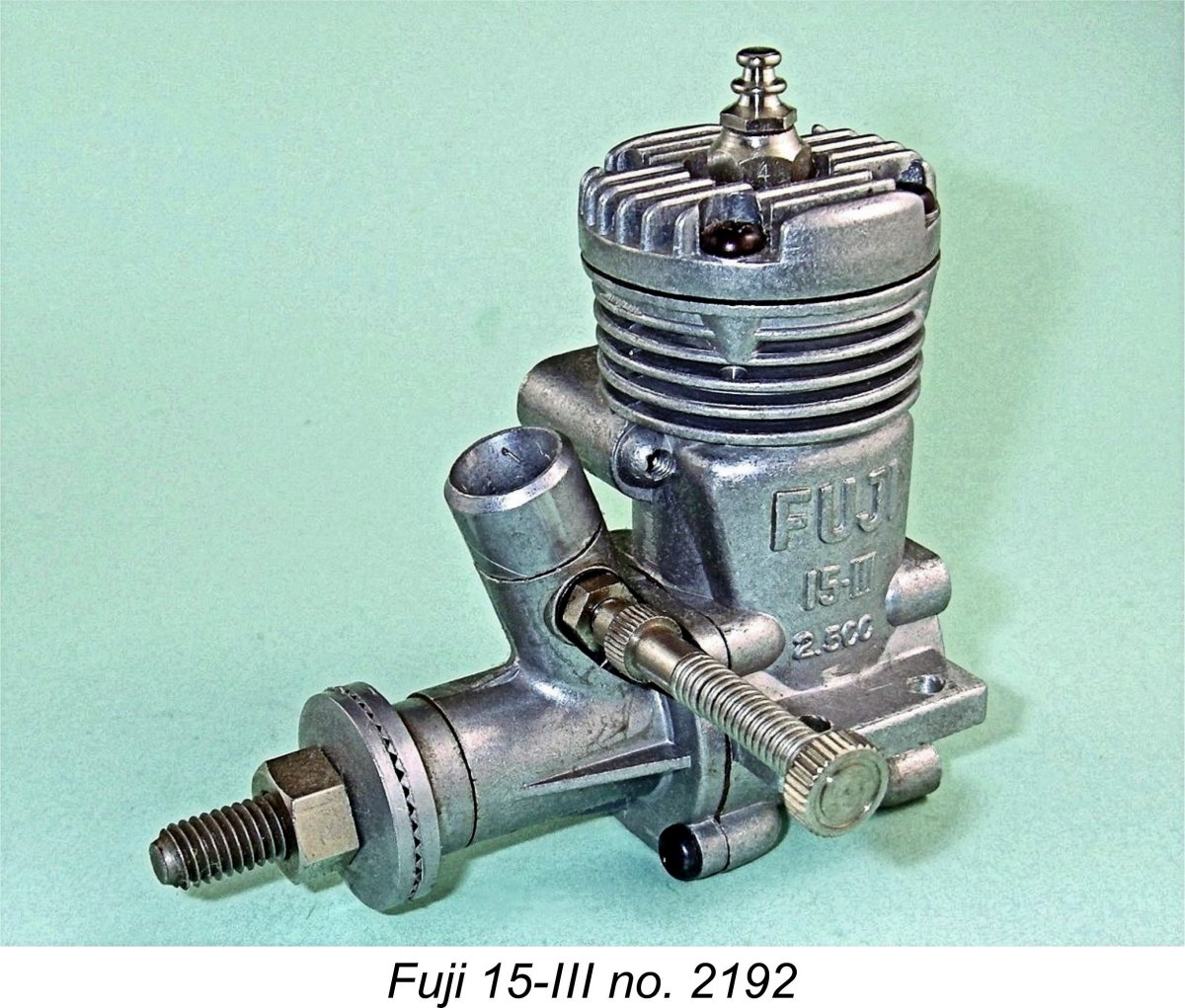

The only real difference was the use of a restyled main crankcase casting and cylinder head. Otherwise, the Fuji followed the established Enya pattern in featuring the same bore and stroke along with a main casting which incorporated the cooling jacket, the exhaust stack, the main crankcase and the backplate in a single casting. The bronze-bushed main bearing was carried in a separate housing which was attached to the front of the crankcase by four screws. The new model duplicated the massive lower cylinder with twin internal-flute bypass/transfer passages which had been pioneered by Enya in their outstanding 09-II model 3002 of 1959 and subsequently applied to their 15-II model 3302 of 1960. It also retained the baffle piston. Indeed, apart from the previously-mentioned cosmetic differences, the Fuji 15-III actually followed the design pattern of the Enya 15-II almost exactly. The prominent "bypass bulge" visible on the left-hand side of the case was a solid dummy, playing no functional role whatsoever. The spacing of the beam mounting holes was identical to that of the Enya, allowing the Fuji to be switched with an Enya in the same model. Fuji may have been hoping for a few converts ......... Like the Enya 15-II, the Fuji 15-III featured a finned cast alloy cylinder head which was retained by four screws and accommodated a centrally-located glow-plug. The checked compression ratio of around 6½ to 1 in my example was unusually low, being slightly lower than the Enya's checked 7 to 1 figure. One apparent difference was the use of an intake venturi which was a separate component. This was inserted into a cylindrically-bored intake housing and retained there by the spraybar. The needle valve was of straight Enya pattern, having the familiar flexible stem popularized by that company. The arrangement was clearly intended to facilitate the fitting of an R/C throttle, and an R/C version was quickly placed on the market.

Bore and stroke remained unchanged from earlier Fuji models at 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. The claimed weight of 135 gm (4.76 ounces) was somewhat higher than that of the discontinued twin-stack Fuji 15-II, no doubt due to the rather massive lower cylinder liner as well as the solid dummy bypass bulge. This weight claim is not confirmed by direct measurement - my examples all weigh in at around 143 gm (5.04 ounces) with plug, a little heavier than the competing Enya 15-II. Perhaps the manufacturer's claimed weight was measured without a plug........ As usual with Fuji, the makers published a seemingly rather extravagant performance claim of 0.30 BHP at some unspecified speed below 15,000 RPM. This claim is rather difficult to accept on the basis of actual running experience with these low-compression engines. Presumably they wished to create the impression that the 15-III was a match for Enya’s 15-II. Having said this, there’s no doubt that this is a well-made, fine-running and very dependable engine which does itself great credit in a classic control-line sport-stunt model where peak performance is not an over-riding issue. I know this from personal experience. The Fuji 15-III proved to be very popular, with known serial numbers implying that over 30,000 examples were manufactured and sold worldwide.

So how did the Fuji actually stack up against the Enya? Well to begin with, it can't be denied that it's almost equally well made. This should perhaps come as no surprise given that the Fuji marque had originated in 1949, the same year as the Enya range, and had survived the intervening years in direct head-to-head competition with Enya and O.S., successfully carving its own niche in the world model engine marketplace. It could not have done so without maintaining a good standard of quality and dependability. To evaluate the engine's relative performance, I put one of my own examples, Fuji 15-III no. 2192, into the stand to test it using the same props and fuel with which I had run the previous test on the Enya 15-II. This example of the Fuji had received some earlier running time in my hands, hence being ready for testing right away.

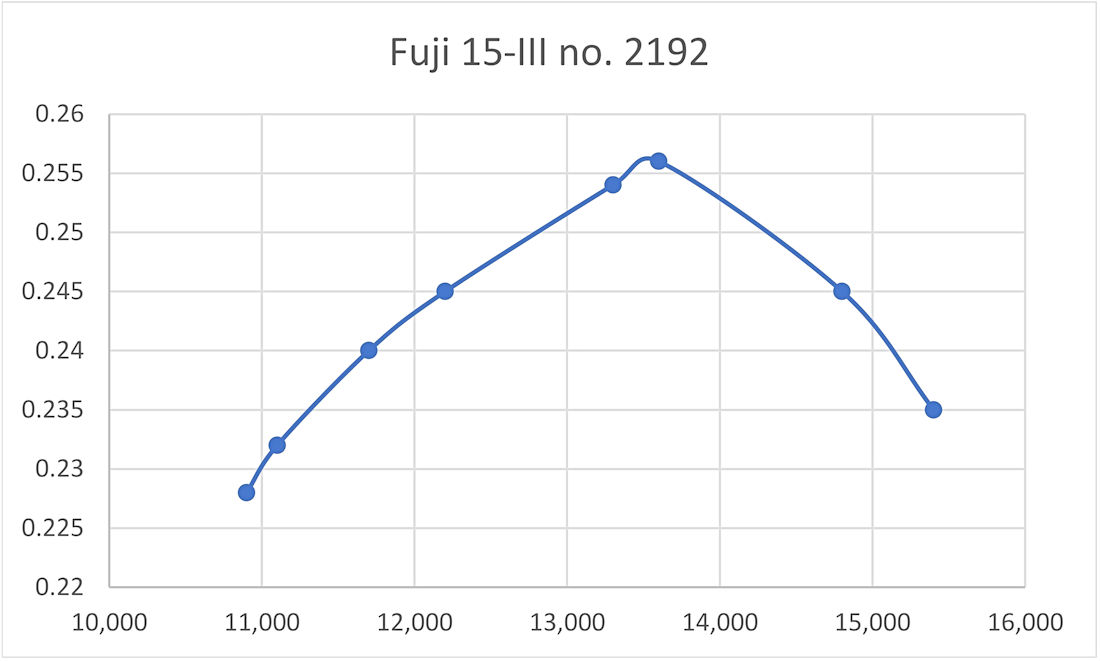

I commented earlier on the engine's relatively low compression ratio of only 6½ to 1. Even with a "hot" Enya no. 3 glow-plug fitted, the Fuji's performance showed clear evidence of this. Once started, it would keep running with the plug driver removed, but slowed down noticeably. When leaned out all the way on the faster props, it picked up speed progressively as the components reached full working temperature. Finally, when running at over 14,000 RPM on the APC 7x5 and 7x4 airscrews, a persistent misfire crept in which couldn't be eliminated with the needle valve. All of these characteristics point to a compression ratio somewhat lower than ideal. I have little doubt that the Fuji 15-III's performance would be enhanced considerably by a modest increase in the compression ratio. In testing the Fuji 15-III, I added two previously-calibrated wide-blade cut-down props to the mix in an attempt to fill the obvious gaps in my original test suite as applied to the Enya 15-II. The 7x6 WB is a cut-down APC 9x6, while the 7½x4 WB is a cut-down APC 9x4. Using this expanded suite of test props, the following data were recorded on test.

An acceptable sports performance for an unpretentious low-cost powerplant like this one, but some way short of confirming the manufacturer's performance claims, just as I had expected. My engine developed a peak output of around 0.256 BHP @ 13,600 RPM - about what I'd expect. In particular, the Fuji clearly poses no threat to Enya performance supremacy. Here we may see a clue as to why the Enya brothers never took action against Fuji for appropriating the core features of their design - quite apart from its distinct cosmetic styling, the Fuji 15-III was an also-ran in the performance department. In my personal view, this was largely down to the unreasonably low compression ratio. Nonetheless, the Fuji 15-III was undeniably a well-made and very user-friendly engine which would serve its owners well provided that performance expectations were kept in check. I certainly enjoyed flying simple lightweight sport control-line models powered with this engine! The Enya 15-III

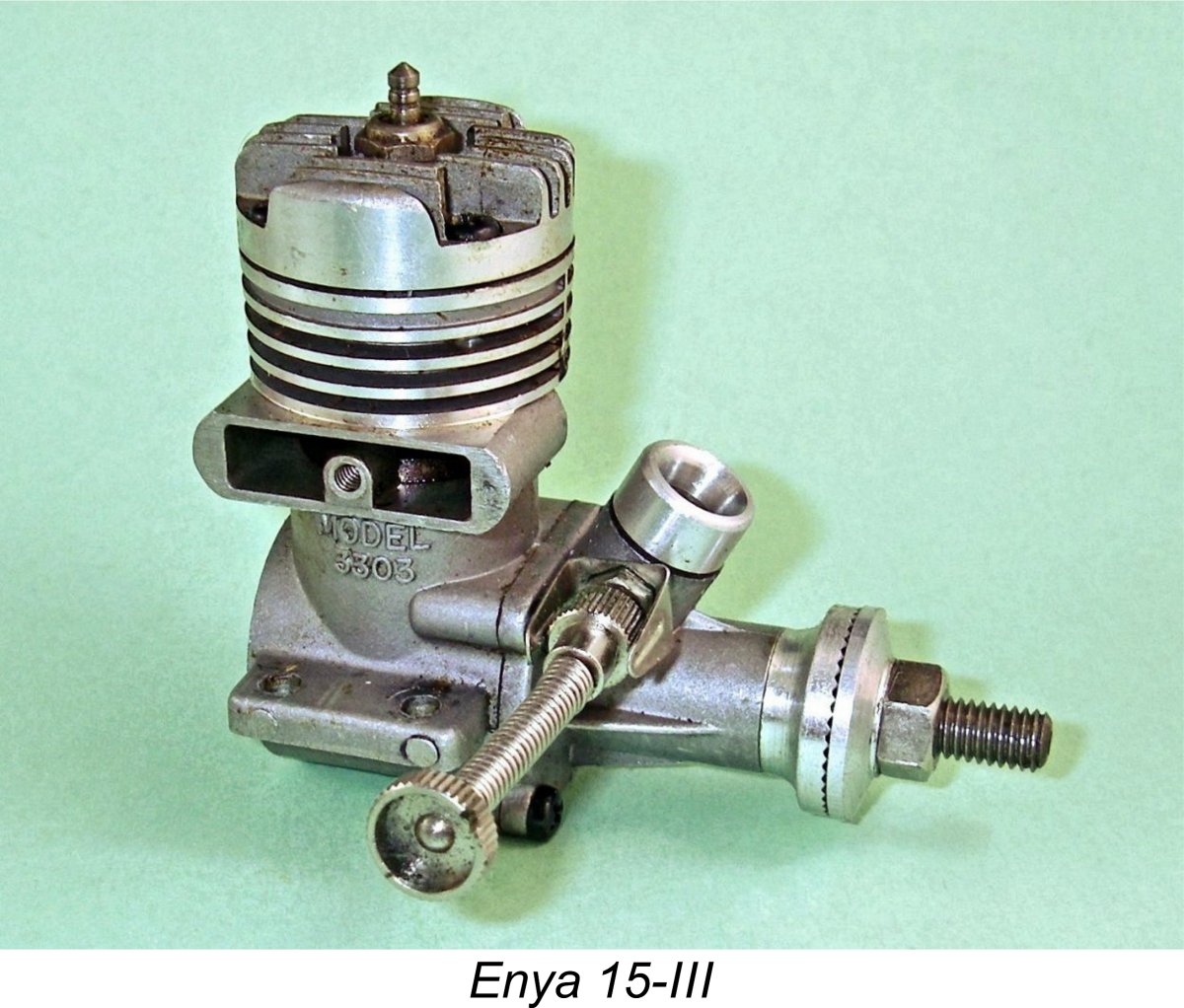

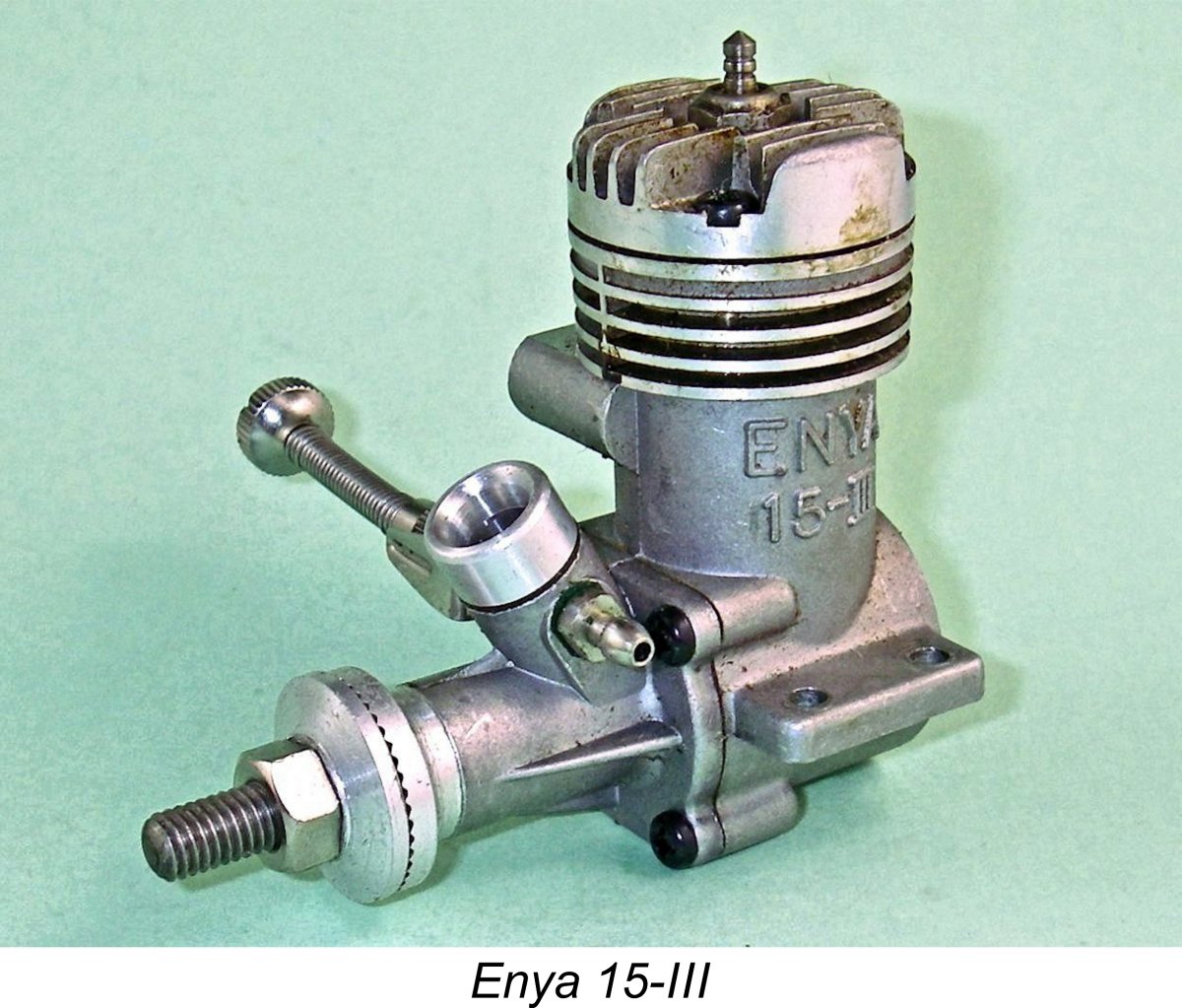

This change was driven by the unstoppable upsurge in the relative popularity of R/C flying due to the ever-increasing reliability of the radio gear coupled with the steadily-decreasing cost of that gear. As a consequence, the “classic” disciplines of control line and free flight were now in a steep decline from which neither they nor the modelling hobby were ever to recover. The overall result of the increased cost and complexity of participation resulting from the R/C "boom" was a steady decline in the number of hands-on participants in the hobby, particularly those of school age. It was the relatively low-cost fields of control line and free flight that had hitherto produced the younger hands-on practically-skilled modelling enthusiasts upon whom the long-term future of the hobby depended. Now their numbers were in free-fall............. aeromodelling is one of the few hobbies which has successfully killed off its own entry level. The result of this change of market focus was very evident in terms of both model engine sales figures and model engine design trends. The customer base for model engines was now shrinking, while the majority of those customers that remained were R/C exponents. Accordingly, the provision of a good general-purpose R/C engine had now become the primary concern. Gone were the days when an R/C engine was simply the U/C version with a throttle grafted on - now the reverse was true. The primary design aim was now to make a dependable and sufficiently powerful R/C motor with good throttling characteristics, and the U/C version (where such a version was even offered) was simply the R/C engine minus the throttle - a complete reversal of the former situation.

In keeping with this new focus, the designer's intent with the new model was aimed squarely at improving the engine's performance as an R/C powerplant. There was no thought of going for an improvement in peak power output - indeed, the need to create an engine which continued to work well at low throttled-down speeds was actually incompatible with the extraction of greater top-end performance. The designer was now prepared to sacrifice top end output for improved mid-range and low-speed performance, thus creating a design which would perform extremely well in general-purpose R/C service. In the case of the Enya 15-III, the changes required to accomplish this objective were actually relatively minor. The major functional modifications were a slight increase in the crankshaft journal diameter to accommodate a larger internal gas passage, along with a slight reduction in the internal crankcase volume to maintain the engine's base pumping efficiency. The configuration of the exhaust stack was also altered slightly to accommodate the rotary exhaust baffle which now formed an element of the engine's R/C throttling system. In place of the former two-screw muffler attachment, the accessory muffler was secured with a single centrally-located screw which engaged with the threaded hole for the exhaust baffle.

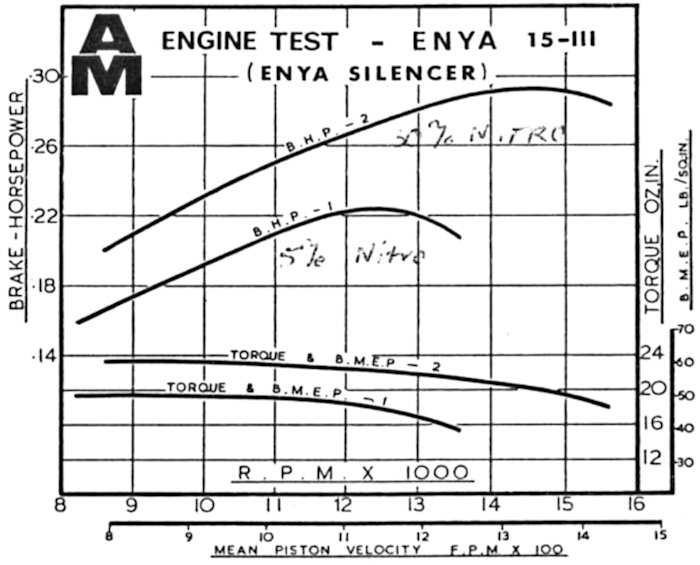

A further test of the Enya 15-III by Peter Chinn appeared in the September 1967 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN). This time, Chinn took the Enya 15-III R/C model as his test subject. He used a typical R/C fuel containing 5% nitro for this test. On this occasion, Chinn measured a peak output of 0.23 BHP @ 12,000 rpm with a muffler fitted in place of the exhaust baffle. Removing the muffler increased these figures to 0.25 BHP @ 12,700 rpm. Chinn praised both the engine's construction and its throttle performance very highly.

Both of my examples of the Enya 15-III are New-In-Box (NIB), hence requiring a full break-in prior to any testing being undertaken. Enyas take a lot of running in, and this seemed to me to be a waste of time and fuel given the fact that I have no plans to actually fly either of them and would prefer to maintain their NIB status. Accordingly, I'll refer to Peter Chinn's previously-cited test results when comparing the performance of the un-throttled Enya 15-III with that of the models to be discussed next. Using the same props and power coefficients applied to the other engines tested for this article, it's possible to determine how fast his test engine would have spun the same airscrews using his published power curves. Chinn's curve for the Enya 15-III running on 30% nitro fuel while fitted with the bigger-bore venturi and standard Enya muffler suggests that in that configuration his engine would have achieved approximately the following RPM figures with the same props:

These figures all lie on or very near to Chinn's published power curve reproduced above. Even so, they must necessarily be regarded as approximations, quite apart from being derived from a graph based on the use of 30% nitro. However, the muffler should even things up a little. Accordingly, these figures will serve as a potentially useful basis for a broad comparison. Enter Thunder Tiger

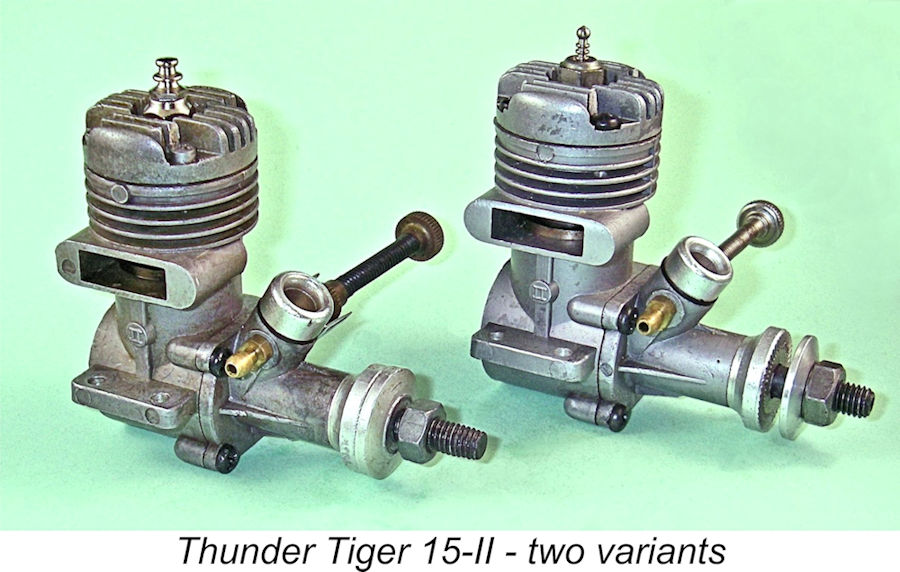

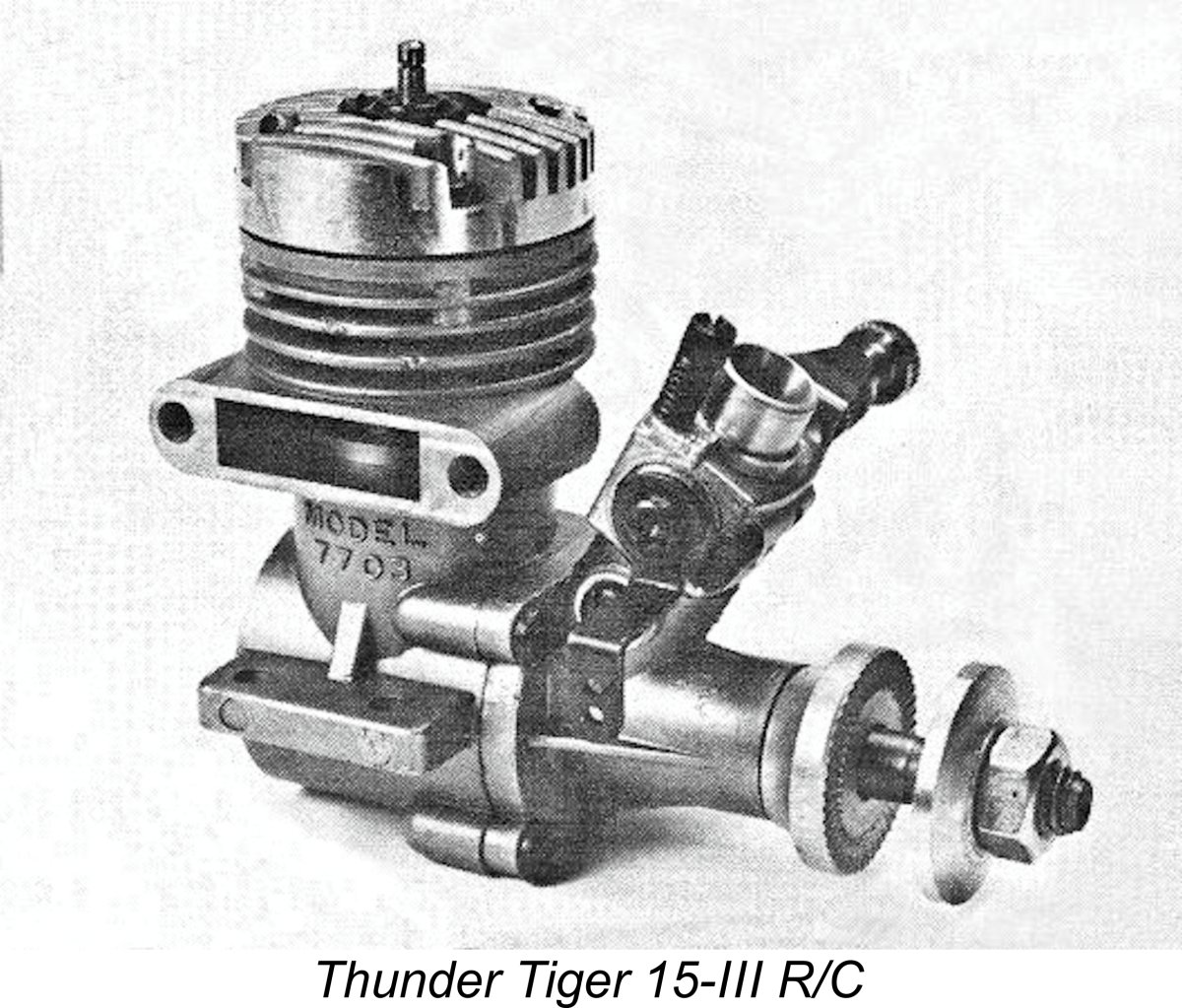

When considering their inaugural design, the company decided to speed things up and cut costs by sidestepping the normally expensive and time-consuming design and development process. They did so very simply by copying a well-established design more or less wholesale, choosing the very successful and highly-regarded Enya 15-III as their basic design template. This resulted in the appearance of the first version of the Thunder Tiger 15. Around 4,000 examples of this now-rare original model were produced in 1974, most of them being sold locally in Taiwan. This was of course at a time when the Enya 15-III was still in production by Enya in Tokyo. In taking a successful 7 year old sport-flying design as its starting point, Chung Yang was clearly signalling that they were going after the “budget” sport-flying market rather than seeking to establish any significant performance markers. The basic idea was to produce a sports motor Local user reaction to this engine was sufficiently encouraging that in 1975 the company decided to expand its sales horizons beyond the shores of Taiwan. They developed an improved and visually altered version of their Thunder Tiger 15, designating it in true Enya style as the Thunder Tiger 15-II. It is a couple of examples of this model that appear in the accompanying illustrations. It was probably this version that first drew Enya’s attention to the fact that their design was being copied!

The Thunder Tiger 15-II appeared in two minor variants. These variants were produced using two distinct crankcase dies which produced a different set of characters on the surface of the dummy bypass, as seen in the image above at the left. One variant bore the Thunder Tiger name in Chinese characters set between two elongated letter "T's", while the other displayed the name Thunder Tiger rendered in Latin characters. In both cases the die produced the model designation II in a raised circle on the right-hand side of the case beneath the exhaust. The finish on the castings differed between these two variants. Those with the more complex TT insignia generally have a dark matte finish, while those bearing the less complex insignia seen at the right in the Although there's presently no evidence to establish which style came first, I suspect that the matte-finished case featuring the more complex insignia came before the satin-finished case with its less complex marking. This opinion is based on the absence of Latin characters on the matte-case variant, suggesting that it dated from the earlier period when Thunder Tiger was still testing the waters by challenging the Asian market primarily. Regardless, in either case the engine continued to be designated as the Thunder Tiger 15-II. The majority of these units were sold in offshore markets in direct competition with Enya. The Thunder Tiger 15-II performed quite well enough for sport-flying applications, while its checked weight of 4.97 ounces was very comparable with that of its more expensive Enya progenitor. On the test bench, my matte-case example of the Thunder Tiger 15-II was an instant starter following a prime, also being a very strong and smooth runner. It achieved the following figures using my eight test props with the same 15% nitro fuel:

Somewhat disheartened, I switched to the other example - the one with the satin-finished "Thunder Tiger" case. However, it soon became apparent that this example was going to fall short of the levels of performance displayed by its now-defunct colleague. It was 200 - 400 RPM down on every prop tested. The very impressive data for its now-defunct sibling must thus serve as the representative performance for this particular contestant. The success of the Thunder Tiger 15-II encouraged the company to develop a further-amended 15-III model which was produced in quite significant numbers beginning in 1977. It was exported to many countries including the US, the UK, France, Germany and Australia. Although it was somewhat re-styled externally, its internal arrangements continued to reflect the Enya design in almost every respect. In R/C configuration, it weighed in at 5.5 ounces minus muffler, a figure which was again very close to that of the Enya competition. Not unexpectedly, this Nationalist Chinese clone did not quite match the quality of the Japanese original, employing as it did ferrous bushes in the main bearing and con-rod big end instead of the more durable bronze. However, internal fits were perfectly acceptable as supplied, while the quality of the castings was quite good even if the exterior didn't quite match Enya's very high standard. The Thunder Tigers represented very stiff competition for Enya in the same markets since they offered the opportunity to acquire a very close Enya copy at a significantly lower cost. One might wonder why Enya didn’t go after the Chung Yang company for imitating their design. It’s admittedly possible that some kind of royalty agreement was in fact reached under the table, but I believe it to be far more likely that the Thunder Tiger engine was changed just sufficiently to dissuade Enya from any such action. After all, Fuji had got away with a significant degree of functional imitation with their earlier Fuji 15-III simply by changing the engine’s outward appearance. The Chung Yang company had merely followed suit. As with the Fuji model, the Thunder Tiger was cosmetically restyled to some extent, including the retention of a bypass bulge which was actually a non-functional dummy. However, in purely functional terms the engine was more or less identical to the Enya 15-III. I suppose that if challenged, the Chung Yang company could have claimed that they were actually copying the now-discontinued Fuji 15-III of ten years previously, against which Enya had taken no action.

No actual performance data were reported in this review - a somewhat odd omission. Instead, the writer contented himself with reporting a factory claim of 0.26 BHP at unspecified RPM and using unspecified fuel. This compared quite well with figures obtained for the Enya 15-III R/C during the previously-cited testing undertaken in 1967 by MAN. That test had yielded an output of 0.25 BHP @ 12,700 rpm using 5% nitro without a muffler. Following the release of the Thunder Tiger 15-III in 1977, a new corporate entity was split off from the parent company for the express purpose of manufacturing radio controlled models and related products including airplanes, helicopters, cars, boats and accessories as well as model engines. This new company was called the Thunder Tiger Corporation as distinct from the Chung Yang company from which it had sprung. It was established in 1979, with operations remaining in Taichung.

In 1997 the Thunder Tiger Corporation was involved in a takeover of the ACE R/C corporation of America. Its 1/8 scale EB4 car was honored as the 1999 Off-Road Champion of Europe. In 2004 it established a marketing center for Europe in Germany and was involved in a further takeover of Associated Electrics of America in 2005. It remains in business today (2025) as a world leader in the R/C model field, focusing on drones and robotics as well as producing state-of-the-art dental/medical equipment. However, it has long since embraced a world-wide trend by winding up its involvement in model I/C engine production. The SLH 15-A

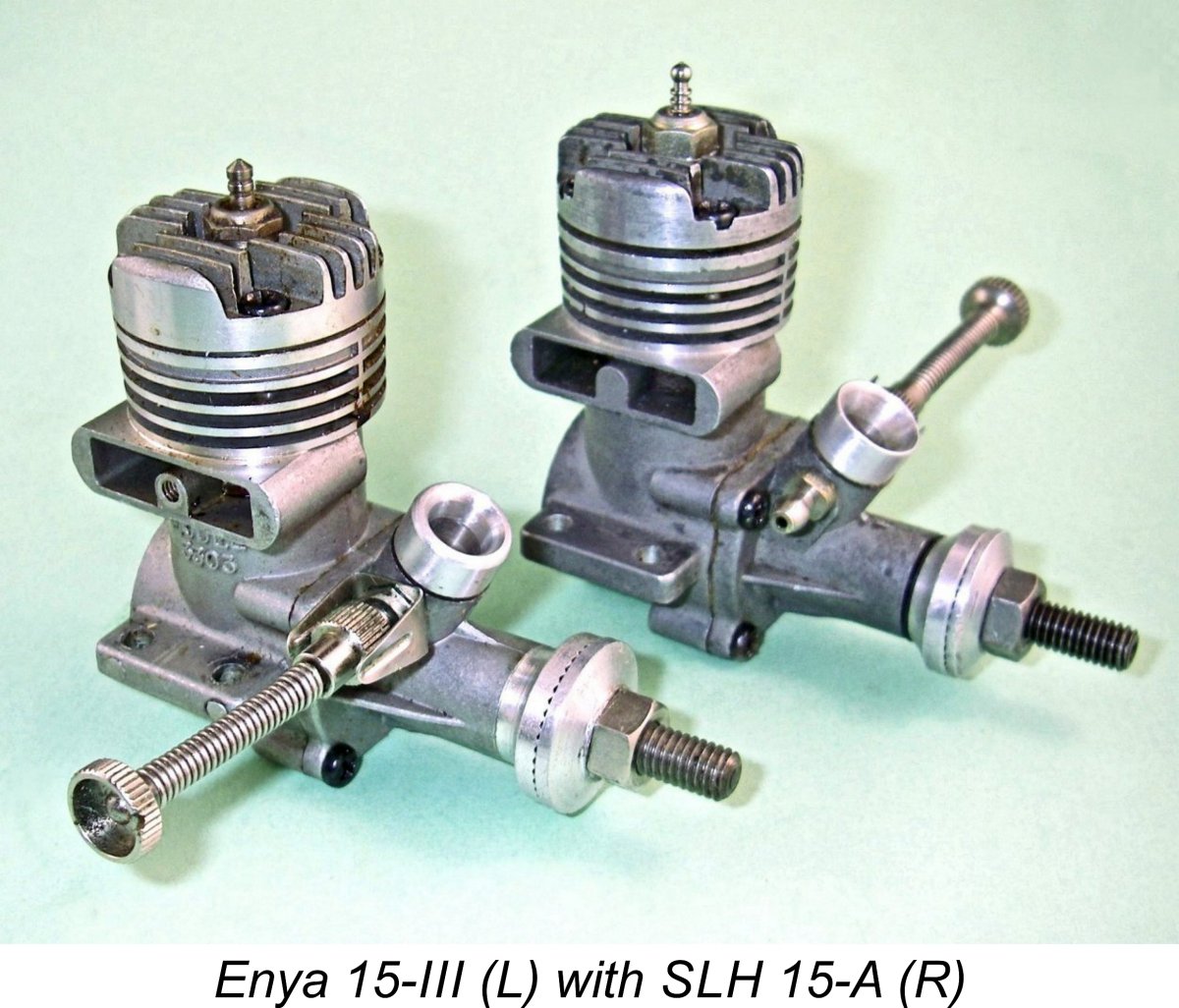

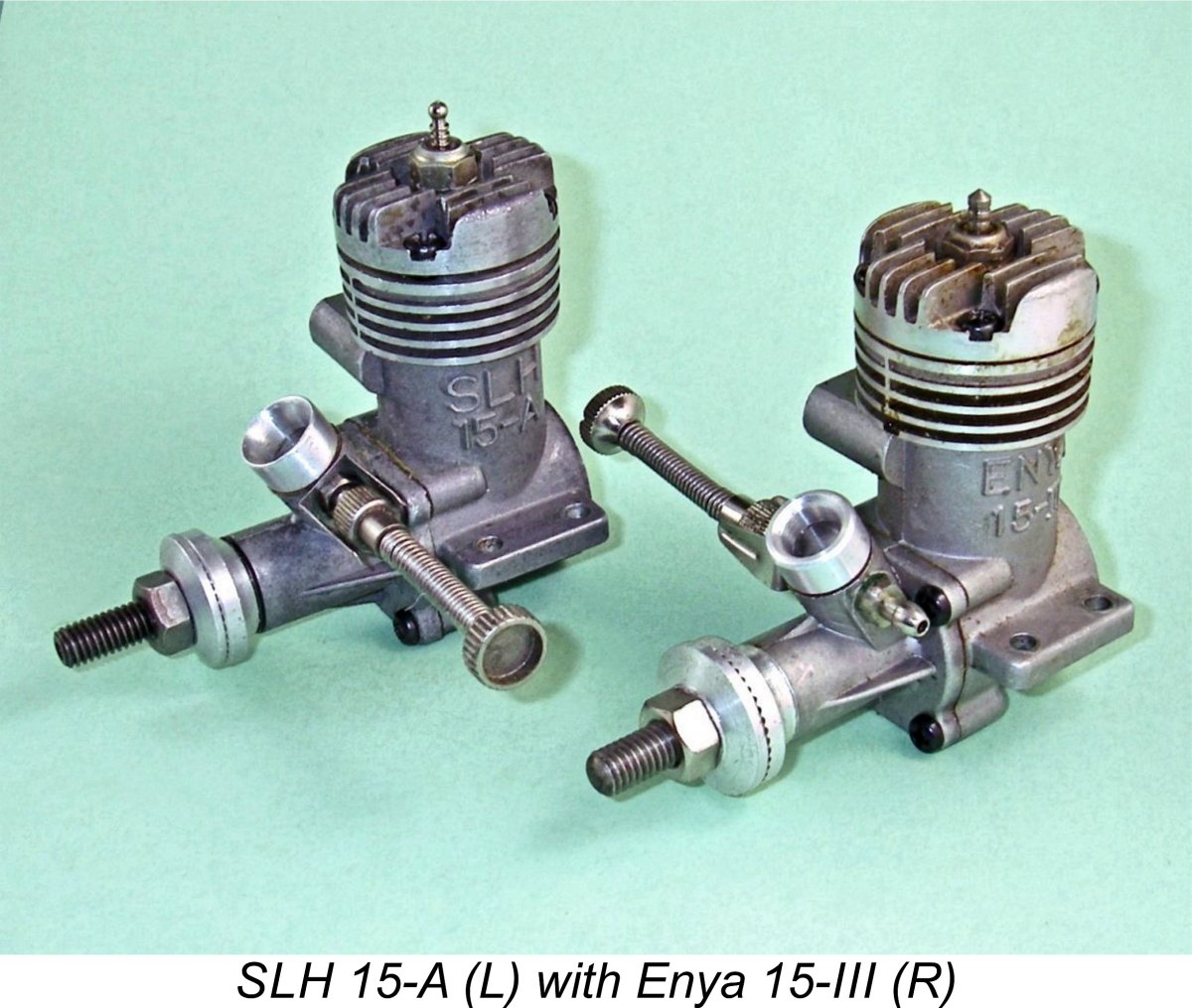

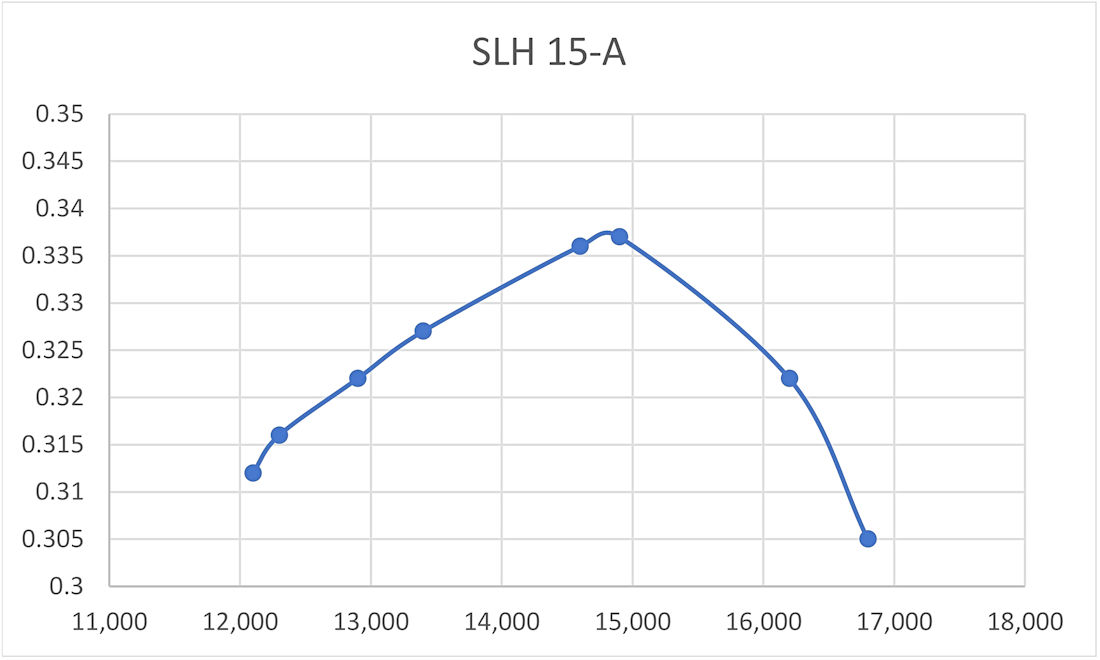

One of the units produced by this company was an unashamed exact copy of the Enya 15-III which was marketed as the SLH 15-A. This one made absolutely no pretence of being anything other than an Enya clone, dispensing with the dummy bypass bulge and pretty much duplicating the Enya 15-III in every interior and exterior detail. Even the mounting hole spacing was once again identical. Viewed from any distance at all, the two engines look identical - to see one is to see the other! You have to read the bypass-side lettering to distinguish between the two units. Internally, the two engines are essentially exact duplicates. Their respective weights are also very similar - the checked weight of the SLH 15-A is 4.94 ounces with plug. The engine was offered in both unthrottled and R/C variants. The wholesale manner in which this engine was copied from the Enya original was too much for Enya to tolerate. If ever there was a genuine clone, this was it! They took legal action against the Star Light Hou Industry Co. for design infringement, succeeding in The number of examples of the SLH 15-A manufactured during the engine’s one-year production life is unclear because the motors didn’t carry serial numbers. That said, I would not be at all surprised to learn that the number ran well into the multiple thousands despite the early cessation of production - the Taiwanese could turn out such engines at a prodigious rate. They manufactured several other SLH models in different displacements at the same time, including the SLH Flash 20 which was an unashamed clone of the contemporary O.S. Max 20. As in the case of the Thunder Tiger models, initial fits in these engines were generally quite good, as were the quality of the castings and general standard of The engine proved to be a very easy starter and a very fine runner. It handled more or less exactly like the other Enya 15 clones tested here, requiring only a small exhaust prime on a full fuel line as a preliminary to an almost instant start. Once running, it responded very well to the needle. From the outset, it was apparent that my example of the SLH 15-A was going to earn its place at or near the top of the performance table among these engines. On the test bench, the engine achieved the following figures on my eight test props using the same 15% nitro fuel used for the other test runs:

As can be seen, this example of the SLH 15-A seems to have out-performed its Enya progenitors, developing a peak output in the vicinity of 0.337 BHP @ 14,900 RPM - a very creditable performance indeed. This may well provide an insight into the motivation for Enya's legal challenge to the manufacturers of this engine - the Taiwanese were supplying a well-made powerplant that actually out-performed the Enya original. What's more, they were doing so at a significantly lower price. The SLH 15-A might not have worn as well as the Enya originals, but relatively few potential customers would have cared greatly about that. The MRC 15

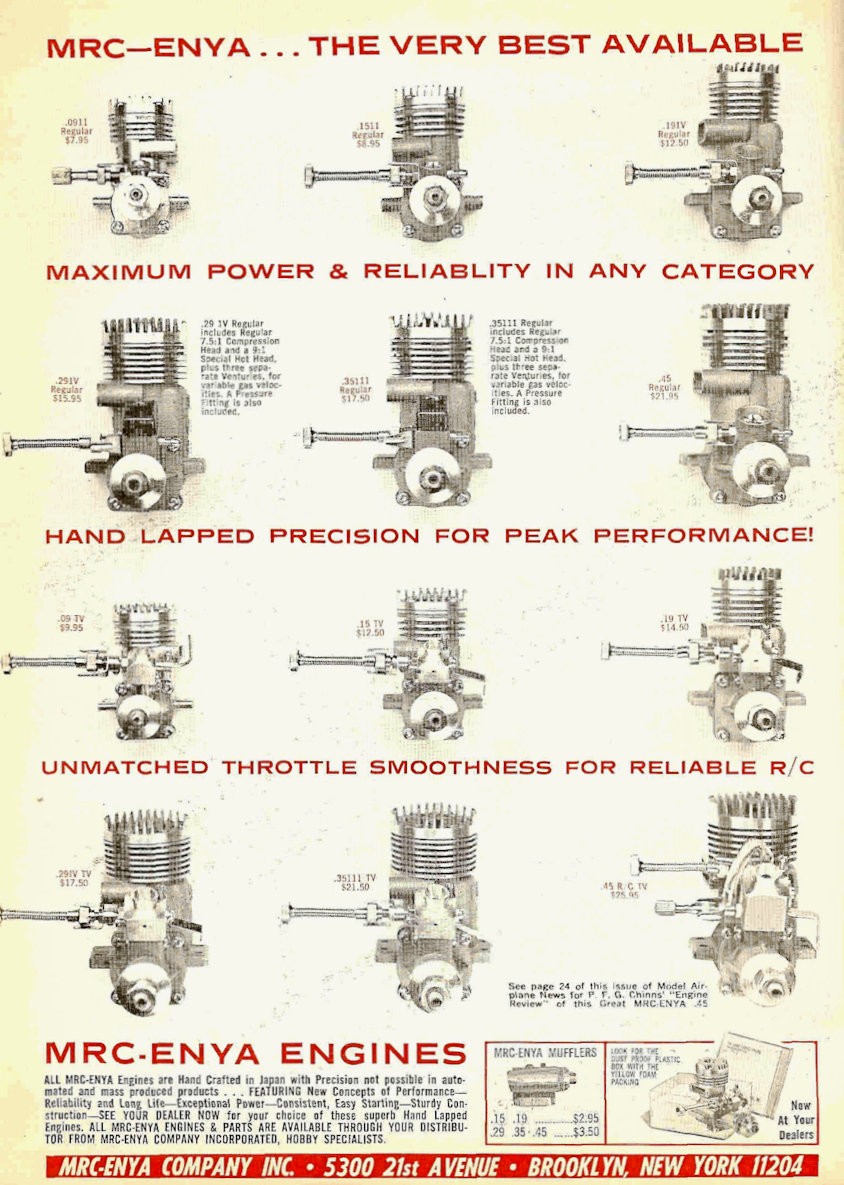

MRC had been established in 1947, initially focusing on the production of electrical components for model railroads and slot cars. Over its history, MRC pioneered realistic train controls and became a leading after-market manufacturer of AC, DC, and DCC model train controls and sound systems. The company was very successful, expanding into the distribution of various hobby products such as model kits, model engines, diecast models and radio-controlled aircraft. It was during this diversification phase that the MRC-Enya partnership was established. The new company promoted the Enya model engine range very energetically thereafter.

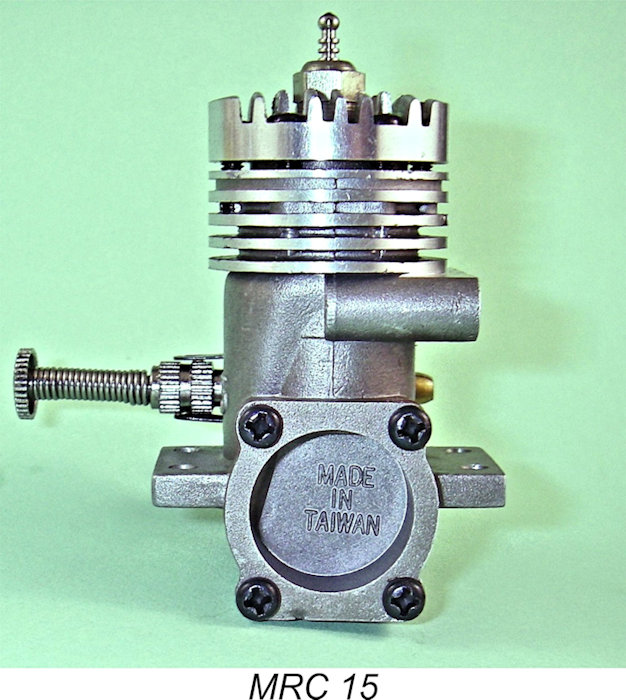

The introduction of this engine is extremely puzzling, since as far as I’m aware the MRC-Enya partnership was still in operation at this time. Why MRC would go off on a tangent to offer direct competition to the Enya range that they were promoting in partnership with Enya themselves is a question that defies any obvious response. The only possibility that I can suggest is that MRC’s agreement with Enya was perhaps confined to the Whatever the truth of that matter, the engine is far more than coincidentally similar to the Enya 15-III, also being manufactured to a very acceptable standard. It starts and runs just as well as any of the other engines tested for this article, hence offering additional competition to Enya at (presumably) a more advantageous price. I have no information regarding the duration of the engine’s production life, nor do I know how many were produced. All I can say is that this is one of the less commonly-encountered Enya 15 clones today. MRC continued to feature Enya engines right up to 2006, when their last stocks of the engines were finally sold. They had built up a sizeable inventory of spare parts, all of which were subsequently acquired by the Model Engine Corporation of America (MECOA) along with the US marketing rights to the Enya name. I haven’t been able to learn any more about the Taiwanese engines manufactured for MRC. If any reader can provide clarification, please get in touch! The SASSI 15-II

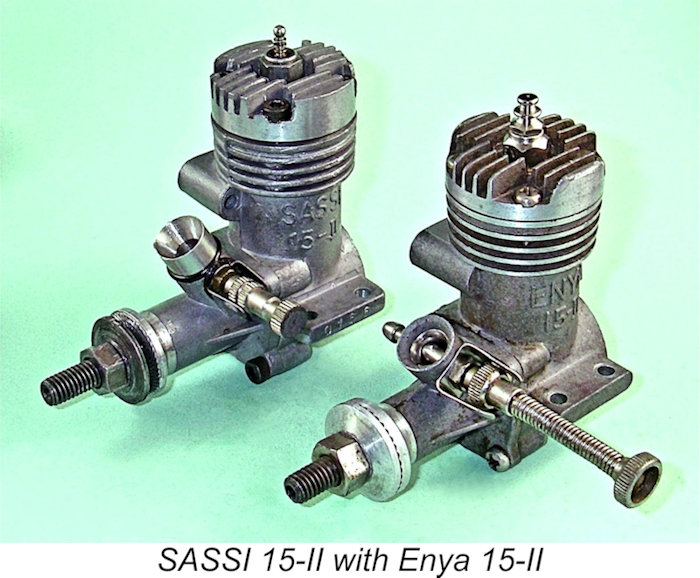

The SASSI 15 undoubtedly belongs in any discussion about Enya 15 clones. The SASSI 15 model appeared in four successive variants, the third and fourth of which were essentially Enya clones, both being The SASSI 15-II reportedly became the all-time best-selling engine in Brazil. It was apparently in production from 1975 through to 1990, during which time it was produced in significant numbers. The fact that Enya never seems to have taken any action against SASSI during the long period of production of the SASSI 15-II might imply either that they were unaware of the existence of the engine or that they didn’t care because then-current import restrictions precluded their involvement in the Brazilian market to any significant degree. Those restrictions minimized the availability of imported engines, also making them prohibitively expensive when they did appear. This situation lasted until 1991, when Brazilian import restrictions were finally lifted.

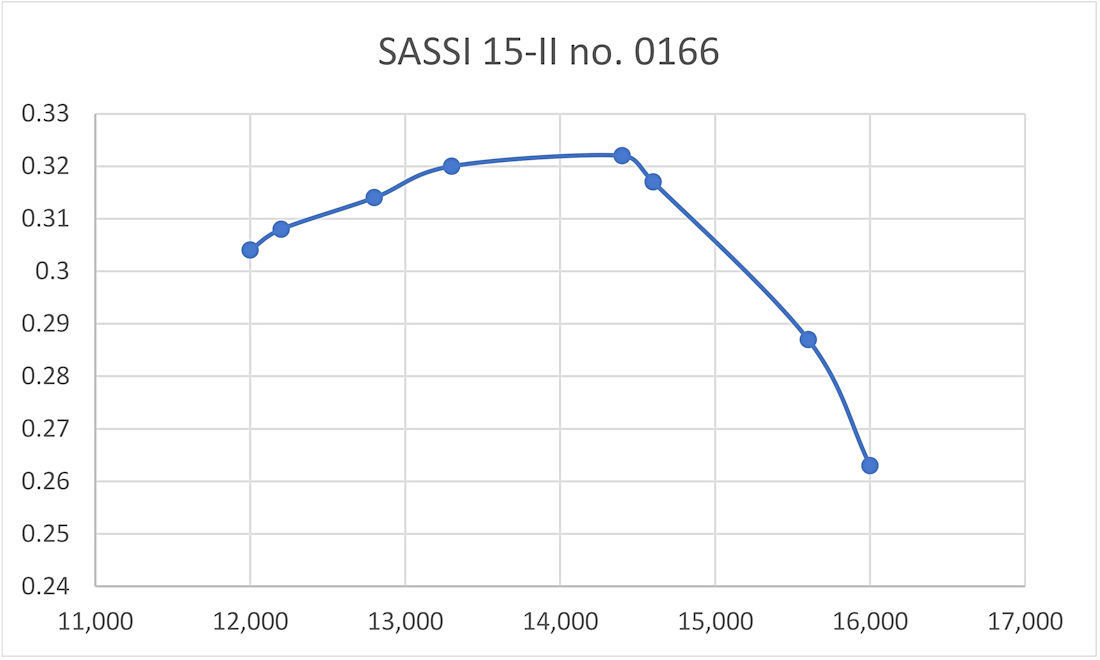

During the preparation of this article, I was able to obtain an example of the SASSI 15-II from the collection of the late Jim Dunkin. This is engine number 0166 - an early unit. It's not a perfect example - despite being apparently unused, its compression is a bit on the "soft" side, although all other fits appear to be OK. I'd objectively rate its quality as somewhat below that of the Enya original. On the test bench, my example of the SASSI 15-II proved to be an easy starter and a very smooth runner. It achieved the following figures on my eight test props using the same 15% nitro fuel as used for the other test runs:

As the above data confirm, the SASSI 15-II more or less duplicated the performance measured for the Enya 15-II as reported above. It seems to have developed a peak output of around 0.325 BHP @ 14,000 RPM runing on 15% nitro without a muffler. It would have served its Brazilian owners well at a time when the Japanese original was both unaffordable and essentially unavailable. Even so, its quality fell somewhat short of that of the original Enya if my example is any indication. It's very doubtful that it would have exhibited the same long-lasting qualities as those of its design inspiration. This concludes my survey of the Enya 15 clones of which I've so far become aware. The table below shows the comparative RPM figures measured for each of the competing models tested for this article.

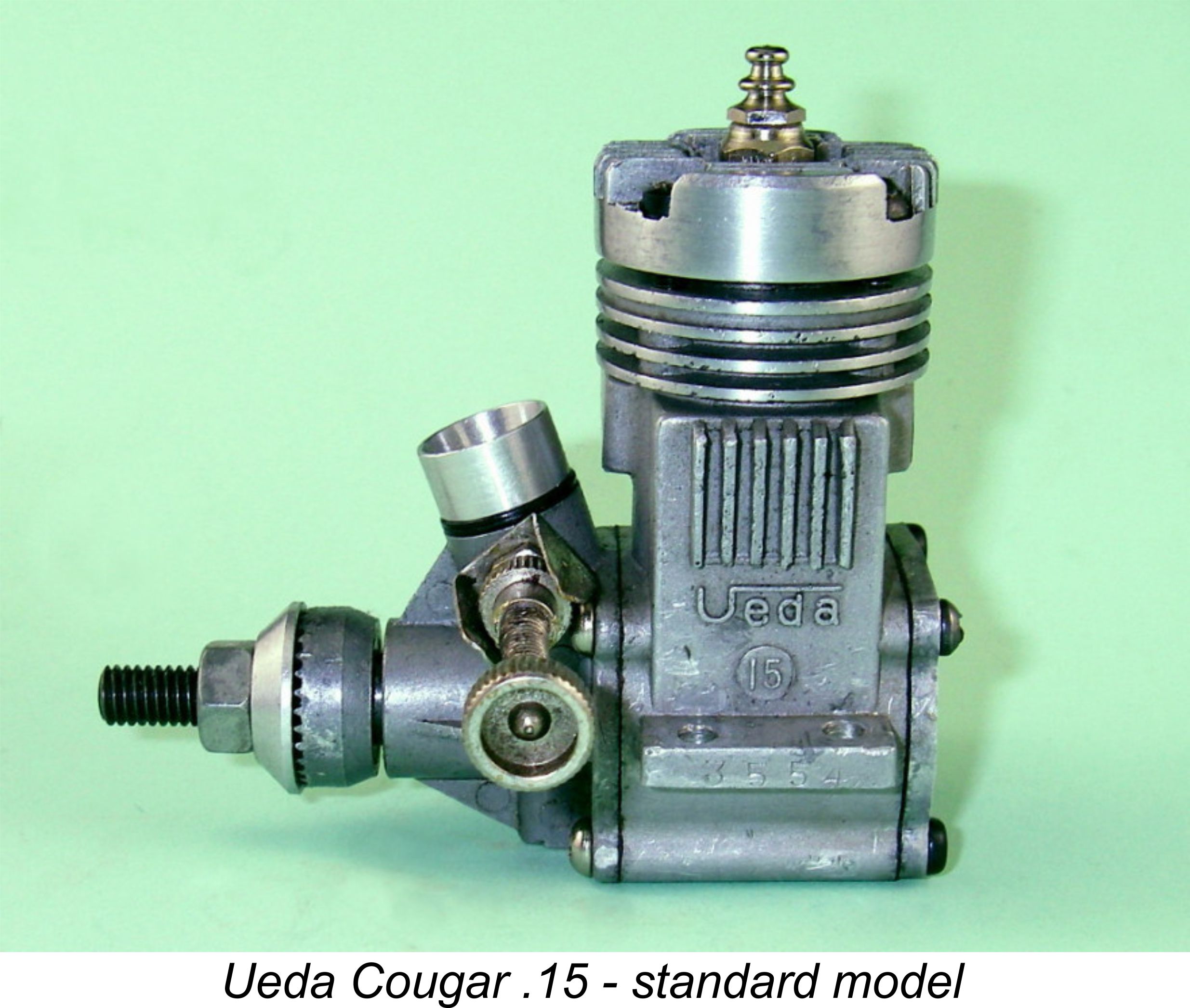

Some readers may be wondering why the Ueda 15 of 1964 was not included in this list. The reason is that the Ueda stayed with the time-honoured cross-flow loop-scavenging system involving a transfer port cut through the cylinder liner and fed by an external bypass passage. Coupled with its highly individualistic styling, this disqualifies it from consideration as a true Enya clone. That having been said, it’s quite likely that there were other Enya 15 clones of which I presently have no knowledge. If any reader can supply authoritative information on such products, please get in touch! The Impact of the Clones It has often been suggested that the appearance of these low-priced clones had much to do with steadily-declining sales of the generally superior originals. There may be some truth to this in the case of the Fuji 15-III, which may well have attracted potential customers away from the Enya competition at a time when model I/C engine sales figures remained relatively strong. However, it must be recalled that Fuji was a long-established major manufacturer in its own right, having commenced production in the same year as Enya (1949) and hence having its own well-established heritage and loyal following. Moreover, despite their somewhat lower prices, the quality of the Fuji engines during the 1960’s and 1970’s was generally more or less comparable with that of their Enya and O.S. rivals. Accordingly, Fuji’s sales may have been more a reflection of brand loyalty and a perception of genuine value for money than an expression of dismissal of the Enya model solely on the basis of price. Either way, the Fuji 15-III almost certainly drew sales away from the contemporary Enya 15-II and 15-III. However, the cosmetic changes applied to the Fuji were evidently sufficient to forestall any legal action on Enya’s part. The situation relating to the Thunder Tiger and SLH engines was very different. At the time of their release, neither manufacturer was exactly a household word among modellers worldwide. Consequently, no sense of brand loyalty was in play. They were targeting customers who were not necessarily looking for a "name brand" engine which embodied the latest technology or the highest level of precision but were attracted primarily by low prices under any name. For manufacturers wishing to serve this market, the cheapest and quickest way to proceed was to avoid the usual development costs by simply copying an established original from others.

As noted earlier, the situation with SASSI may have been different yet again. They may not have been competing with Enya, instead simply supplying a need which Enya were not able to meet through active involvement in the Brazilian market. If this was the case, they were providing a valuable service to Brazilian modellers, and were doing so on the basis of a very highly-regarded design without causing significant financial harm to the original manufacturers. Can’t hold that against them ………. Enya seemingly didn't do so! All this having been said, there’s no question at all that the worldwide decline in the manufacture of model engines by established "name" makers had far more to do with changing market conditions than with any diversion of sales to the clones. The transformation of aeromodelling from a creative hands-on craft-based hobby to a passive push-button activity based on ARF, drones and electric technology purchased over the counter was itself more than sufficient to consign model engines to the speciality niche market which they now occupy. This change would have occurred with or without the clones - they merely accelerated the process. Conclusion On the basis of the above comparison, I suppose that you’d have to concede that the various Enya 15 clones offered reasonably good value for money. They didn’t come up to the quality of the Enya originals, although the Fuji 15-III came close. Against that, for the most part they offered a level of performance which fell little if at all short of that of the original Enya products. A typical sport flier wouldn't have noticed the difference in a practical application. The other area in which they almost certainly fell short of their Enya counterparts was their longevity in service. Enya engines have an almost unrivalled reputation for outlasting a whole series of owners, which is why you almost never see a totally clapped-out example even today after the passage of 70 or more years. The Fujis also appear to wear pretty well, but still not quite up to Enya standard. By contrast, all of my Taiwanese clones apart from the seemingly unused MRC 15 show clear evidence of bearing wear despite the fact that none of them appear to have seen an unreasonable amount of service. But how much would that bother the average buyer-on-a-budget who just wanted a reasonably serviceable engine to use for a year or two pending the creation of a bigger, better model or a move out of aeromodelling into other interests? Probably not at all - the average sport flying engine would typically get nowhere near its full service life with its original owner. Long before it was worn out, its original owner would doubtless have moved on, quite possibly discarding the engine as he did so. So we can see that by providing these cut-priced clones, the manufacturers concerned were undoubtedly tapping into a market niche which was there for the taking. The key was low price, with brand loyalty, ultimate performance and longevity being secondary considerations. The average buyer of these engines would generally have neither known nor cared about any such shortfalls. We might decry the ethics of copying the designs of others so slavishly, but it’s hard to argue against the impression that the clones earned their place in the marketplace, for better or worse. _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published July 2025 Revised September 2025 - addition of MRC 15 |

||||||

| |

The concept of Clone Wars is by no means confined to the annals of the Star Wars series - model engine manufacturers have engaged in such conflicts from time to time! Here we take a look at a classic case in point.

The concept of Clone Wars is by no means confined to the annals of the Star Wars series - model engine manufacturers have engaged in such conflicts from time to time! Here we take a look at a classic case in point.  The Enya 15-II Model 3302 was a replacement for the Enya 15-IB Model 3101 which had appeared in January 1957 and remained in production for well over three years. The new 15-II model of 1960 followed the 1959 lead of its smaller Enya 09-II Model 3002 companion in the range by adopting a far thicker lower cylinder liner which accommodated a pair of internally-machined vertical bypass/transfer flutes, thus doing away with the former bypass bulge. The baffle piston was however retained.

The Enya 15-II Model 3302 was a replacement for the Enya 15-IB Model 3101 which had appeared in January 1957 and remained in production for well over three years. The new 15-II model of 1960 followed the 1959 lead of its smaller Enya 09-II Model 3002 companion in the range by adopting a far thicker lower cylinder liner which accommodated a pair of internally-machined vertical bypass/transfer flutes, thus doing away with the former bypass bulge. The baffle piston was however retained.  When it came to the Enya 15-II, the makers did not claim any significant performance improvement over the previous model - rather, the changes reportedly allowed the engine to be more competitively priced. It thus seems reasonable to assume that the revised 15-II model would have performed at a very similar level to the previously-cited figures measured by Chinn for the earlier 15-IB. However, as far as I can determine, the Enya 15-II was never the subject of a published test in aero configuration - a rather strange omission given the engine's popularity.

When it came to the Enya 15-II, the makers did not claim any significant performance improvement over the previous model - rather, the changes reportedly allowed the engine to be more competitively priced. It thus seems reasonable to assume that the revised 15-II model would have performed at a very similar level to the previously-cited figures measured by Chinn for the earlier 15-IB. However, as far as I can determine, the Enya 15-II was never the subject of a published test in aero configuration - a rather strange omission given the engine's popularity.  It was my intention to try each of the engines covered in this article using the same test props and the same fuel containing 15% nitromethane along with a proportion of castor oil. I settled on APC 8x6, 8x5, 8x4, 7x6, 7x5 and 7x4 airscrews, which represent the full range of props normally used with 2.5 cc sports glow-plug motors. I felt that this series should bracket the peak for these units quite comfortably. These props might not permit the development of a completely representative power curve on their own, but I was more interested in the comparative RPM figures for the various engines using the same props and fuel.

It was my intention to try each of the engines covered in this article using the same test props and the same fuel containing 15% nitromethane along with a proportion of castor oil. I settled on APC 8x6, 8x5, 8x4, 7x6, 7x5 and 7x4 airscrews, which represent the full range of props normally used with 2.5 cc sports glow-plug motors. I felt that this series should bracket the peak for these units quite comfortably. These props might not permit the development of a completely representative power curve on their own, but I was more interested in the comparative RPM figures for the various engines using the same props and fuel.

Now we get to the first of our clones! In 1964 the

Now we get to the first of our clones! In 1964 the  The use of silencers was then becoming more widespread as urban pressure on flying fields continued to increase. The fitting of a silencer to the Fuji 15-III was facilitated by the provision of tapped holes fore and aft in the rear wall of the exhaust stack. Once again, this reflected the design of the Enya 15-II. A neat matching silencer was quickly made available.

The use of silencers was then becoming more widespread as urban pressure on flying fields continued to increase. The fitting of a silencer to the Fuji 15-III was facilitated by the provision of tapped holes fore and aft in the rear wall of the exhaust stack. Once again, this reflected the design of the Enya 15-II. A neat matching silencer was quickly made available.  An article discussing the R/C version of this model appeared in the June 1966 issue of “Radio Modeller” magazine. The article provided details of the engine’s construction, also reporting that performance had been found to be “satisfactory” on 8x4 and 9x4 airscrews. Throttle response was said to be “quite good”, and handling was reported as “easy”. Unfortunately, no performance figures were presented.

An article discussing the R/C version of this model appeared in the June 1966 issue of “Radio Modeller” magazine. The article provided details of the engine’s construction, also reporting that performance had been found to be “satisfactory” on 8x4 and 9x4 airscrews. Throttle response was said to be “quite good”, and handling was reported as “easy”. Unfortunately, no performance figures were presented.  I found the Fuji to be every bit as user-friendly as its Enya progenitor. It needed a prime on a full fuel line, but once those conditions were met it was a one- or two-flick starter every time. Response to the needle was excellent, with the best setting for each prop being established very easily. Levels of vibration remained well within acceptable limits at all speeds tested.

I found the Fuji to be every bit as user-friendly as its Enya progenitor. It needed a prime on a full fuel line, but once those conditions were met it was a one- or two-flick starter every time. Response to the needle was excellent, with the best setting for each prop being established very easily. Levels of vibration remained well within acceptable limits at all speeds tested.

In September 1966, Enya released a new 2.5 cc glow-plug motor designated as the 15-III Model 3303. The most immediately obvious externally-visible change from the previous model was that instead of the previous cast bell mouth venturi with internal metal insert, a shorter cylindrical intake stub was featured. This accommodated either of 2 differently-sized turned alloy inserts which were supplied with the engine. The primary intent of this arrangement was clearly to facilitate the fitting of an R/C throttle.

In September 1966, Enya released a new 2.5 cc glow-plug motor designated as the 15-III Model 3303. The most immediately obvious externally-visible change from the previous model was that instead of the previous cast bell mouth venturi with internal metal insert, a shorter cylindrical intake stub was featured. This accommodated either of 2 differently-sized turned alloy inserts which were supplied with the engine. The primary intent of this arrangement was clearly to facilitate the fitting of an R/C throttle. By this point in time, Enya had given up trying to compete with other manufacturers who were producing specialised ultra-high performance 15's for expert competition modellers, contenting themselves instead with providing a reliable, long lasting and versatile engine at reasonable cost for the average modeller. This made excellent sense economically speaking - there were always far more modellers who just wanted a dependable, easy-handling and affordable engine with an adequate performance than there were head-bangers who wanted the last fraction of horsepower regardless of cost.

By this point in time, Enya had given up trying to compete with other manufacturers who were producing specialised ultra-high performance 15's for expert competition modellers, contenting themselves instead with providing a reliable, long lasting and versatile engine at reasonable cost for the average modeller. This made excellent sense economically speaking - there were always far more modellers who just wanted a dependable, easy-handling and affordable engine with an adequate performance than there were head-bangers who wanted the last fraction of horsepower regardless of cost. The un-throttled version of the Enya 15-III was the subject of another

The un-throttled version of the Enya 15-III was the subject of another  Taken together, these results confirm the earlier comment that the designer's intention was clearly to produce a dependable R/C engine, with peak power being very much a secondary consideration. In this, he undoubtedly succeeded. The Enya 15-III was another very successful design, surviving for some ten years in the marketplace. It was known as a dependable and long-lasting unit with a more than adequate performance, while its R/C throttle was widely viewed as one of the best in the business. Even so, its sales figures were undoubtedly affected by the steady worldwide decline in demand for model engines which had begun in the late 1950's and has continued to the present day as the face of model airplane flying changes almost beyond recognition.

Taken together, these results confirm the earlier comment that the designer's intention was clearly to produce a dependable R/C engine, with peak power being very much a secondary consideration. In this, he undoubtedly succeeded. The Enya 15-III was another very successful design, surviving for some ten years in the marketplace. It was known as a dependable and long-lasting unit with a more than adequate performance, while its R/C throttle was widely viewed as one of the best in the business. Even so, its sales figures were undoubtedly affected by the steady worldwide decline in demand for model engines which had begun in the late 1950's and has continued to the present day as the face of model airplane flying changes almost beyond recognition.  The Enya 15-III clearly impressed other people, including the Chung Yang Industries Company Ltd. of Taichung, Taiwan, whose main activity up to the early 1970’s had been the manufacture of sewing machine components. In 1973 this company made the decision to enter the model engine manufacturing field. They did so under the brand-name of Thunder Tiger.

The Enya 15-III clearly impressed other people, including the Chung Yang Industries Company Ltd. of Taichung, Taiwan, whose main activity up to the early 1970’s had been the manufacture of sewing machine components. In 1973 this company made the decision to enter the model engine manufacturing field. They did so under the brand-name of Thunder Tiger.

This variant was quite successful. As with the Fuji 15-III, its mounting hole spacing was once again identical to that of the Enya, allowing instant interchangeability in the same model. Around 14,000 examples were produced over the following three years or so.

This variant was quite successful. As with the Fuji 15-III, its mounting hole spacing was once again identical to that of the Enya, allowing instant interchangeability in the same model. Around 14,000 examples were produced over the following three years or so.

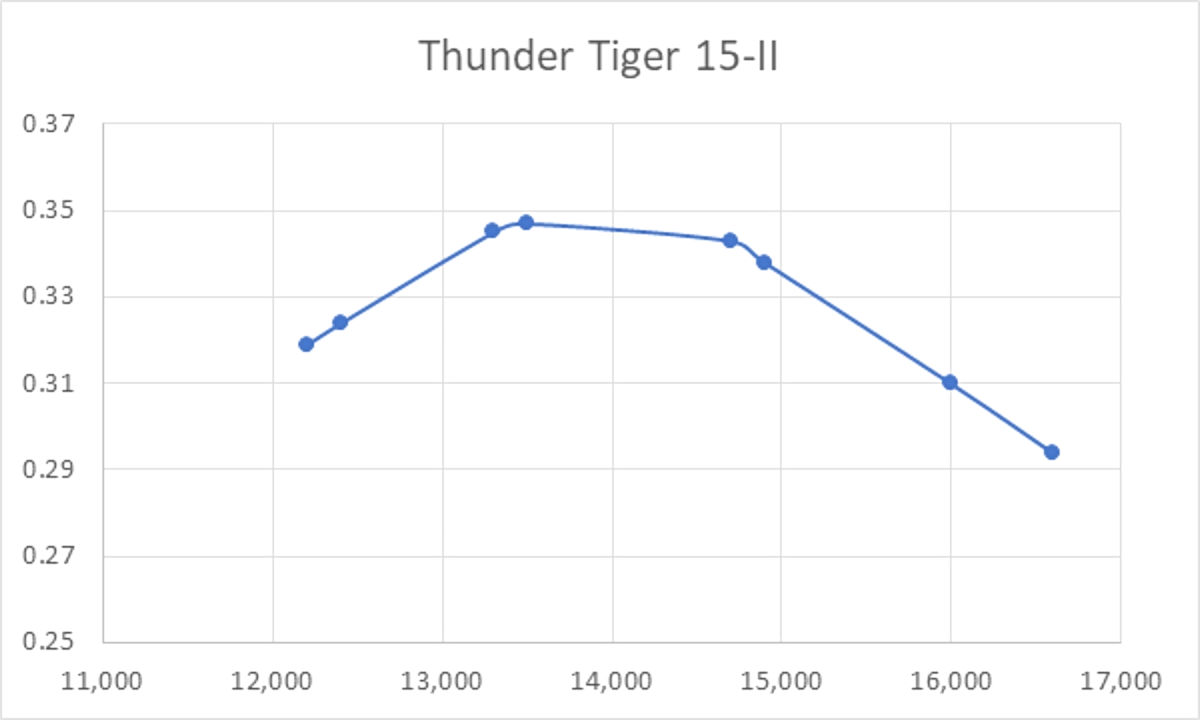

As can be seen, the Thunder Tiger 15-II did itself proud, managing a peak output of around 0.350 BHP @ 14,000 RPM. However, this test turned out to be the last hurrah for this particular example of the engine! As I was quite literally reaching for the fuel line to stop the engine in full cry on the 7x4 prop (the last one tested), the engine suddenly stopped dead with a sickening crunch! It turned out that the rod had let go and had taken the piston skirt out in doing so. Admittedly this happened with the engine running at

As can be seen, the Thunder Tiger 15-II did itself proud, managing a peak output of around 0.350 BHP @ 14,000 RPM. However, this test turned out to be the last hurrah for this particular example of the engine! As I was quite literally reaching for the fuel line to stop the engine in full cry on the 7x4 prop (the last one tested), the engine suddenly stopped dead with a sickening crunch! It turned out that the rod had let go and had taken the piston skirt out in doing so. Admittedly this happened with the engine running at  2,600 RPM above its peak, but even so I would expect a quality engine to survive such an overspeed. Regardless, a sad end to a very good motor - it's not worth repairing.

2,600 RPM above its peak, but even so I would expect a quality engine to survive such an overspeed. Regardless, a sad end to a very good motor - it's not worth repairing.  The R/C version of the

The R/C version of the

Now we get right down to it!! At some indeterminate point during the 1970’s, a new manufacturer briefly entered the Enya clone wars. This was the Star Light Hou Industry Co. Ltd., also of Taiwan. They produced clones of both Enya and O.S. designs, selling them at prices which substantially undercut the originals.

Now we get right down to it!! At some indeterminate point during the 1970’s, a new manufacturer briefly entered the Enya clone wars. This was the Star Light Hou Industry Co. Ltd., also of Taiwan. They produced clones of both Enya and O.S. designs, selling them at prices which substantially undercut the originals.

At some point in the early 1960’s, Enya moved to solidify its presence in the vast US market by establishing a new US-based company in partnership with the long-established Model Rectifier Corporation (MRC). The new company was called the MRC-Enya Co. Inc., with headquarters at 5300 21

At some point in the early 1960’s, Enya moved to solidify its presence in the vast US market by establishing a new US-based company in partnership with the long-established Model Rectifier Corporation (MRC). The new company was called the MRC-Enya Co. Inc., with headquarters at 5300 21 At some point during the mid to late 1970’s the MRC company arranged to have a series of engines manufactured in Taiwan to be marketed under their own name. One of these offerings was a .15 cuin. glow-plug model which at first glance was almost identical in appearance and design to the Enya 15-III apart from displaying no markings of any sort which would identify it as an Enya product. The sole markings took the form of the ciphers “.15” cast as written onto the bypass side of the crankcase and the statement “Made in Taiwan” cast onto the backplate - no mention of either MRC or Enya.

At some point during the mid to late 1970’s the MRC company arranged to have a series of engines manufactured in Taiwan to be marketed under their own name. One of these offerings was a .15 cuin. glow-plug model which at first glance was almost identical in appearance and design to the Enya 15-III apart from displaying no markings of any sort which would identify it as an Enya product. The sole markings took the form of the ciphers “.15” cast as written onto the bypass side of the crankcase and the statement “Made in Taiwan” cast onto the backplate - no mention of either MRC or Enya.  Closer examination reveals that there were actually a few rather minor changes. The bypass side of the upper crankcase now featured a Fuji-style dummy bypass “bulge”, while the exhaust stack was configured slightly differently internally. In addition, the form of the intake venturi mounting was slightly amended. However, these changes didn’t alter the inescapable impression that this was yet another Enya 15 clone - internally, it was more or less identical. It was offered in both R/C and U/C configurations.

Closer examination reveals that there were actually a few rather minor changes. The bypass side of the upper crankcase now featured a Fuji-style dummy bypass “bulge”, while the exhaust stack was configured slightly differently internally. In addition, the form of the intake venturi mounting was slightly amended. However, these changes didn’t alter the inescapable impression that this was yet another Enya 15 clone - internally, it was more or less identical. It was offered in both R/C and U/C configurations.  North American market. MRC may have wished to participate in the international market with their own products. Alternatively, they may have taken note of the burgeoning challenge of the Taiwanese clones and wanted to get a foot in that particular door themselves. Either way, this would certainly have strained relations with Enya!

North American market. MRC may have wished to participate in the international market with their own products. Alternatively, they may have taken note of the burgeoning challenge of the Taiwanese clones and wanted to get a foot in that particular door themselves. Either way, this would certainly have strained relations with Enya!  The Asian countries were not alone in imitating the design of the Enya 15. Another very close copy of the Enya 15-III (with elements of the Enya 15-II) appeared in Brazil under the name SASSI 15-II. The SASSI engines were produced by SASSI Industria Mecanica Ltda. of Presidente Prudente, São Paulo. Engines were produced in .15 cuin., .25 cuin. and .35 cuin. displacements. The SASSI 25 was a virtual clone of the O.S. 25 FP. My thanks to Pat King for first making me aware of these engines. A full discussion of Brazilian model engines will appear in due course elsewhere on this website.

The Asian countries were not alone in imitating the design of the Enya 15. Another very close copy of the Enya 15-III (with elements of the Enya 15-II) appeared in Brazil under the name SASSI 15-II. The SASSI engines were produced by SASSI Industria Mecanica Ltda. of Presidente Prudente, São Paulo. Engines were produced in .15 cuin., .25 cuin. and .35 cuin. displacements. The SASSI 25 was a virtual clone of the O.S. 25 FP. My thanks to Pat King for first making me aware of these engines. A full discussion of Brazilian model engines will appear in due course elsewhere on this website.

, they could hardly be seen as competing with Enya for global sales. This sets them apart from the Taiwanese clone manufacturers.

, they could hardly be seen as competing with Enya for global sales. This sets them apart from the Taiwanese clone manufacturers.

This direct comparison places the two Taiwanese clones (Thunder Tiger and SLH) at the top of the performance scale, with the Fuji bringing up the rear as Tail End Charlie. The differences are not all that great - the average sport flier would scarcely notice the difference, except perhaps in the case of the Fuji 15-III. But the fact remains that most of the clones could give the original Enya a very good run for its money in performance terms.

This direct comparison places the two Taiwanese clones (Thunder Tiger and SLH) at the top of the performance scale, with the Fuji bringing up the rear as Tail End Charlie. The differences are not all that great - the average sport flier would scarcely notice the difference, except perhaps in the case of the Fuji 15-III. But the fact remains that most of the clones could give the original Enya a very good run for its money in performance terms.  While the purchase of a model engine purely on the basis of low price is of course false economy (as many British buyers of the post-1950's

While the purchase of a model engine purely on the basis of low price is of course false economy (as many British buyers of the post-1950's