|

|

K Vulture and Falcon Series Replacement Piston & Conrod Assemblies By Dave Causer

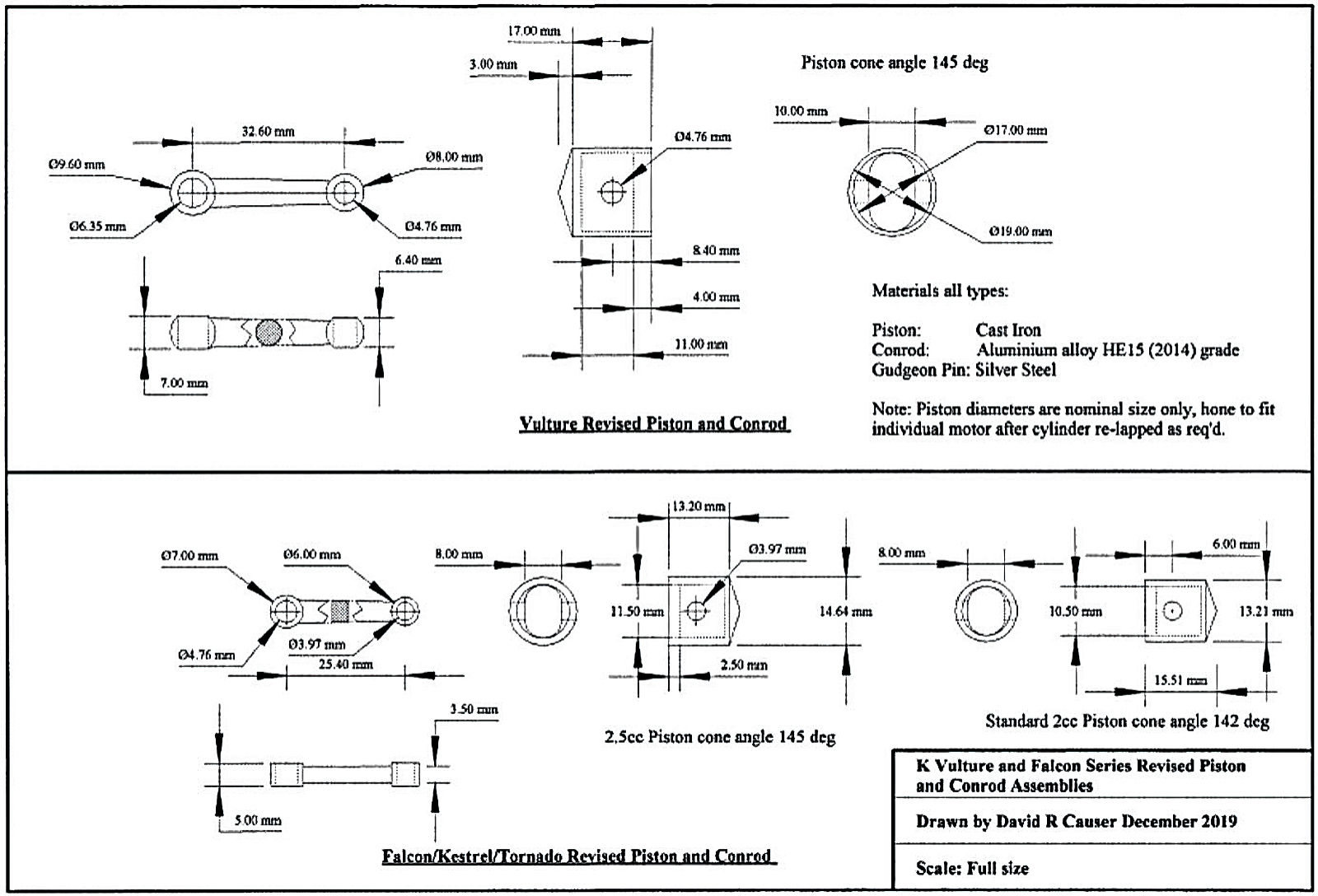

Unusually among diesels of their era, the K engines used a ball-and-socket small end connection between the hardened steel piston and steel conrod. The socket in the hardened piston and the ball little end on the conrod make an accurate reproduction by the home builder extremely difficult without specialist tooling. In this short article I will describe how I've re-bored a Vulture and a Falcon by reproducing conventional alloy conrod and gudgeon (wrist) pin items. The relevant drawings are reproduced below. Unlike the later Cox engines, where an unbroken piston wall surface is essential due to the large ports and the high risk of a floating gudgeon pin fouling them, the transfer grooves and annular gallery on the K engines are much smaller, so a reasonably-sized gudgeon pin creates no problems. There are six transfer grooves and four exhaust ports, so you will find that one pair of opposing lands between the grooves will coincide with an opposing pair of bridges between exhaust ports. If the cylinder liner is set up with that pair of exhaust port bridges fore and aft, then the gudgeon pin hole only traverses the transfer gallery, which even on the 5 cc Vulture is only a couple of mm wide, hence no fouling problems. The drawings are dimensioned in mm (as is my lathe), but it should be easy enough for a competent model engineer to convert the dimensions back to Imperial units. The only dimensions that absolutely have to be Imperial are the conrod big ends, since they have to fit the existing Imperially-dimensioned crankpins. These have diameters of 1/4" on the Vulture and 3/ 16" on the Falcon series.

Do make sure that you use the correct hard grade of alloy (HE I5/2014) for the conrods. The more readily-available HE 30 is too soft, and the first firing stroke will bend it! I made the Vulture rod in the classic "dog-bone" style as I didn't have any HE l5 flat stock thick enough at the time, enforcing the use of 3/8" diameter alloy stock. There would be no problem converting to a rectangular cross-section rod, like the Falcon component, as long as the working length was the same. The external dimensions of the big ends are rather smaller than I would have liked, but it has to be so for crankcase clearance. However, as the stresses on the conrod are predominantly compressive, no problems have arisen.

I didn't want to do any "recreational dismantling" of my 2 cc Kestrel in order to check the cone angle, as the fits are good and the engine runs nicely. The important dimension is, of course, the length of the piston skirt. I won't go into detail about how to re-lap cylinders and pistons, as those of you with the skills and equipment will have your own methods, and newcomers to this fascinating side of our hobby can find detailed articles both here on Adrian's site and on the Model Engine News site. Most of the K engines that one comes across have gouged knurling on the cylinder retaining "dog-collar" ring. This can easily be restored by turning up an alloy mandrel of suitable diameter and externally threading it 26 tpi. With this mandrel mounted in the lathe, the ring can be screwed onto it, after which the application of a diamond pattern knurling tool will restore the pattern nicely. By mounting the cylinder as well and then screwing on the cooling jacket, any gouges in the fins can be filed out and the fins polished using oil, fine emery cloth and metal polish. Just make sure that any polishing compound is washed off thoroughly. Also make sure that there is a gasket between the cylinder base and the top of the crankcase. If you feel the need to use pliers or "mole" grips (vice grips) to tighten the "dog-collar"', then please make sure that you use a strip of leather to protect your newly-restored knurls! While the K motors were never "hot" performers, they were very useful engines which generally start easily and run well. There are still quite a few of them around, to the point that they appear fairly regularly on eBay and elsewhere in various states of disrepair. I hope that this article will encourage prospective purchasers to go ahead, knowing that they can be restored to running condition despite their unusual design and construction. Should there be any questions or anything that I've got wrong, please feel free to contact me via the web site. David Causer December 2019 (Editor's note - the one K engine regarding which caution must be exercised is the Mk. I Vulture. Although it ran well, this early model suffered from a series of failures both of the conrod and crankshaft. Examples with bent rods and cracked shafts are by no means uncommon. Later variants featured thicker rod columns and stronger shafts, hence giving no trouble. However, the problems with the Mk. I Vulture did much to damage the company's reputation, eventually forcing it to cease trading - A.D.)

|

| |

The K Model Engineering Company of Gravesend, Kent only existed for a short time at the end of the 1940's, but they produced a number of designs of variable quality and performance. The production and design of model engines was still in its relative infancy, leading manufacturers and designers to attempt many different ways of producing their engines. The K method of transfer porting was unique to themselves, and Adrian has fully described their system

The K Model Engineering Company of Gravesend, Kent only existed for a short time at the end of the 1940's, but they produced a number of designs of variable quality and performance. The production and design of model engines was still in its relative infancy, leading manufacturers and designers to attempt many different ways of producing their engines. The K method of transfer porting was unique to themselves, and Adrian has fully described their system  Having a stock of mostly imperial sized silver steel, I used that for the gudgeon pins, but 5 mm instead of 3/16" on the Vulture and 4 mm instead of 5/32" on the Falcon would be perfectly acceptable, likewise the nearest Imperial equivalents for the milling out of the pistons. The other critical dimensions are the conrod length, location of the gudgeon pin hole and the external height of the piston walls. The dimensions shown on the drawing have worked just fine, bearing in mind the difficulty of accurately measuring the piston when the original conrod is still in place. I'm pretty sure that all the Vulture variants had dimensionally identical piston/conrod set-ups (although the later Vulture rods had substantially thicker columns) and similarly within the Falcon/ Kestrel/ Tornado variants, but it would be wise to double check your individual engine.

Having a stock of mostly imperial sized silver steel, I used that for the gudgeon pins, but 5 mm instead of 3/16" on the Vulture and 4 mm instead of 5/32" on the Falcon would be perfectly acceptable, likewise the nearest Imperial equivalents for the milling out of the pistons. The other critical dimensions are the conrod length, location of the gudgeon pin hole and the external height of the piston walls. The dimensions shown on the drawing have worked just fine, bearing in mind the difficulty of accurately measuring the piston when the original conrod is still in place. I'm pretty sure that all the Vulture variants had dimensionally identical piston/conrod set-ups (although the later Vulture rods had substantially thicker columns) and similarly within the Falcon/ Kestrel/ Tornado variants, but it would be wise to double check your individual engine.  When I came to re-bore my Falcon (no. 7006 or perhaps 7008), I found that it had been bored out to 14.64 mm to yield a displacement of 2.4 cc. The total piston height in this example gave a 145 deg. cone angle, same as the Vulture. Using the same piston height on the usual 2 cc variants with the standard 13.21 mm bore gives 142 deg. So if you're re-boring one of the usual 2 cc engines, please check the piston height and cone angle. Also be aware that other examples having anomalous bores may exist - always measure!

When I came to re-bore my Falcon (no. 7006 or perhaps 7008), I found that it had been bored out to 14.64 mm to yield a displacement of 2.4 cc. The total piston height in this example gave a 145 deg. cone angle, same as the Vulture. Using the same piston height on the usual 2 cc variants with the standard 13.21 mm bore gives 142 deg. So if you're re-boring one of the usual 2 cc engines, please check the piston height and cone angle. Also be aware that other examples having anomalous bores may exist - always measure!