|

|

The Classic Fuji .049/.061 Series

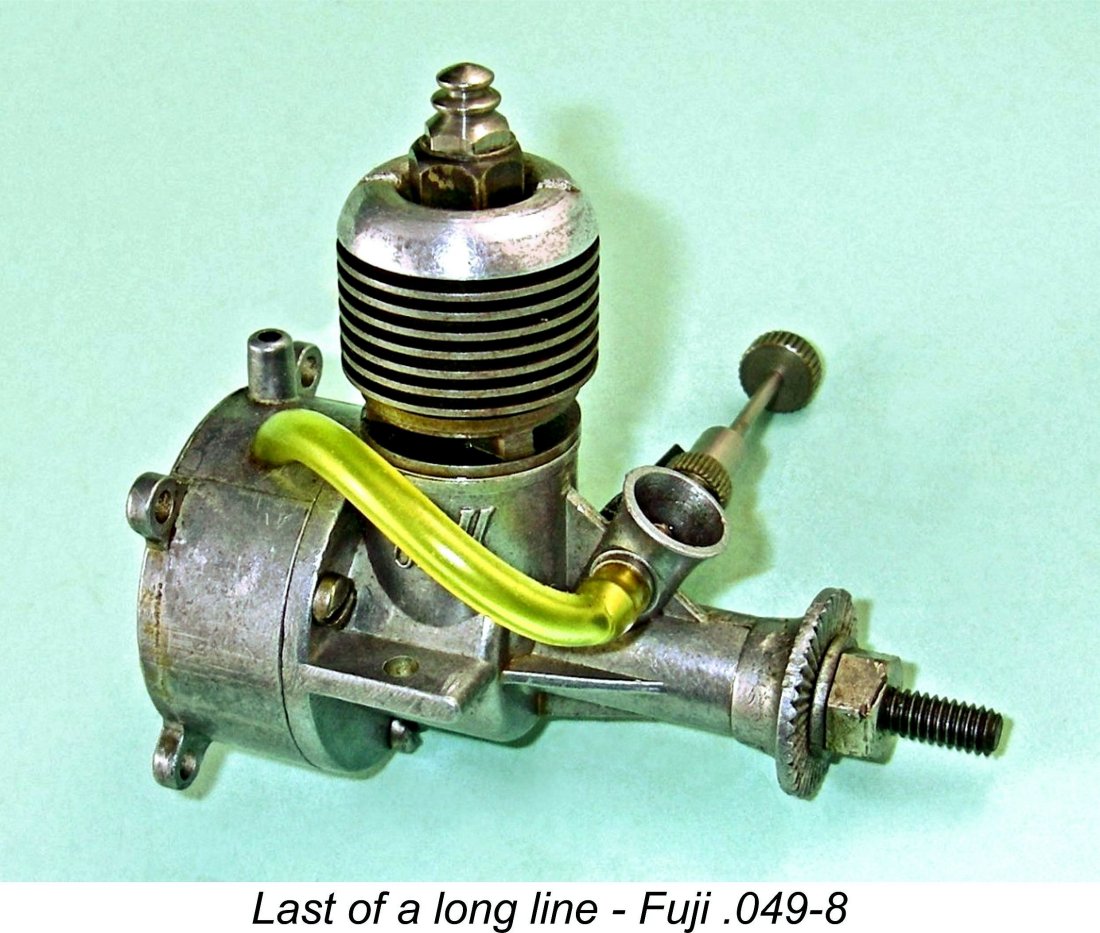

A subsequent article which appears on my own website contains a detailed review of the .29 and .35 cuin. models marketed by Fuji. In the present article, I’ll turn to the smallest engines manufactured by the Fuji enterprise during the “classic” era with which I’m mainly concerned. These were the .049 cuin. models and their closely-related .061 cuin. cousins which were sold over the years under the Fuji banner. These little engines were produced in an astonishing number of variants, the majority of which were never marketed with any intensity in the English-speaking world. As a result, most of the various designs have largely escaped the notice of enthusiasts outside Japan. Indeed, many people seem to be unaware of the existence of many of the variants which preceded the final model illustrated above. The latter model is quite well-known thanks to its having been the only Fuji .049 offering which did appear in North American and other non-Asian markets in sizeable numbers. The earlier variants remained in the shadows for the most part, hence being relatively rare today outside Japan and commanding surprisingly high prices when they do appear on eBay and elsewhere. If you’re going to consider paying that much for odd-ball little engines like these, you may as well know what you’re getting! Accordingly, I’ll attempt to sort out the various models which did appear and place them in their appropriate context and sequence.

Thus the 049-1 model is the first presently-documented Fuji .049 cuin. design, while the 049-6 model is the sixth such design variant, and so on. I must emphasize that these designations are mine alone and have nothing whatsoever to do with Fuji themselves. I also recognize that these designations may be subject to change if additional design variants are identified and dated. However, I hope that readers and collectors may find them useful, as McCoy aficionados have found the “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ) model numbering system established by Tim Dannels over the years. I must also emphasize the fact that given the paucity of printed material in the English language relating to these engines, what follows is based almost entirely upon my own observations of the limited number of examples to which I have access as well as my deductions based upon the very useful promotional material put out from time to time by Fuji themselves. I freely acknowledge that my present knowledge of these engines is almost certainly incomplete and that other variants may exist of which I’m presently unaware. I also caution readers that the given dates are best estimates only based on presently-available information. These dates could well be out by a year or more. It is my sincere hope that the publication of this article may stimulate the sharing of further information which could help to refine the information presented herein. All contributions gratefully and openly acknowledged! Finally, before embarking upon this journey I’d like to pay tribute to my friend, colleague and fellow Fuji enthusiast Mel Reid of England. Although we haven’t corresponded in some years now, I retain copious notes supplied by Mel with respect to the Fuji range with which he was closely familiar. These notes helped me greatly during the preparation of this article. Thanks, Mel!! Now, before I get down to the main task at hand, a little historical background is in order. Background

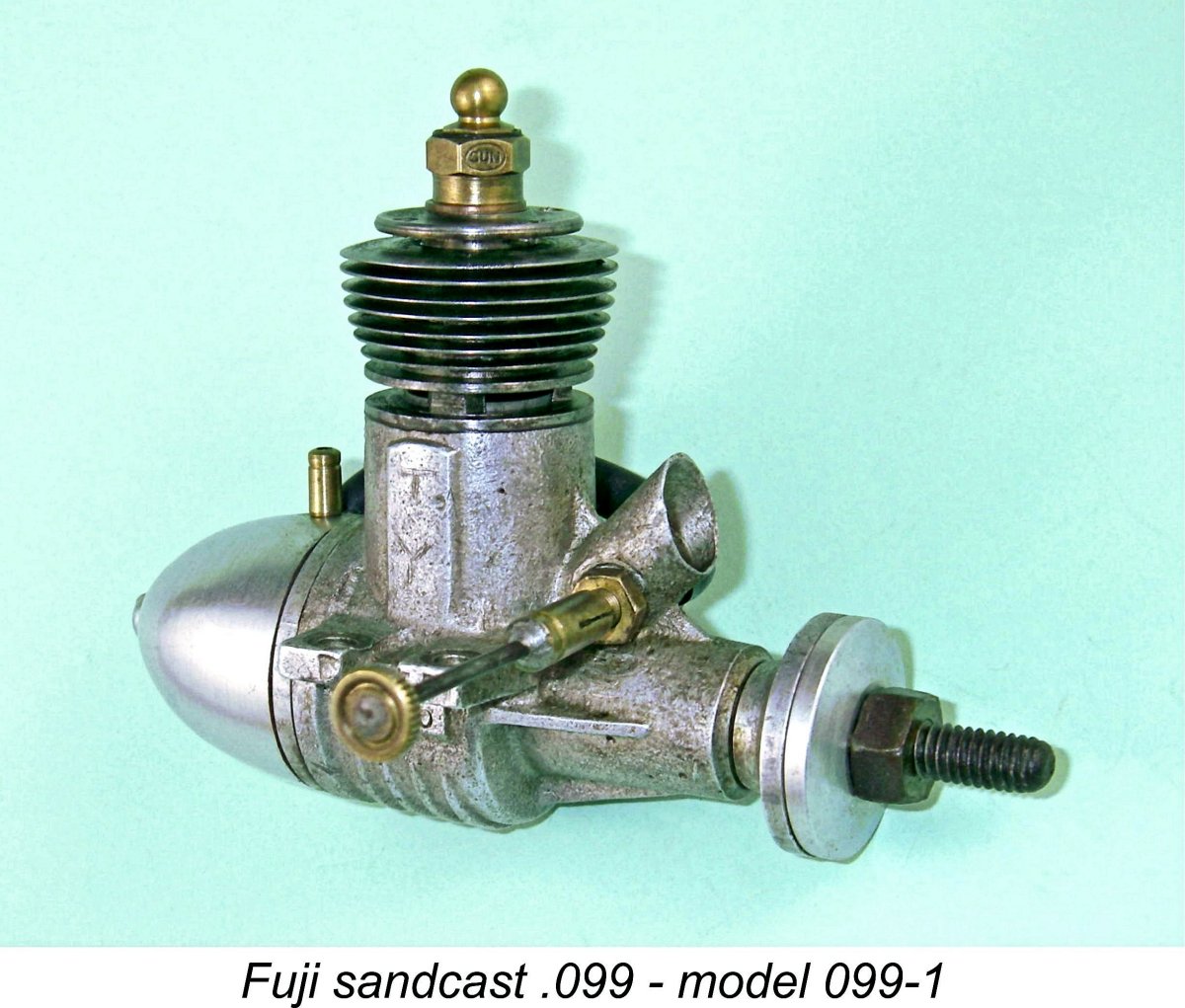

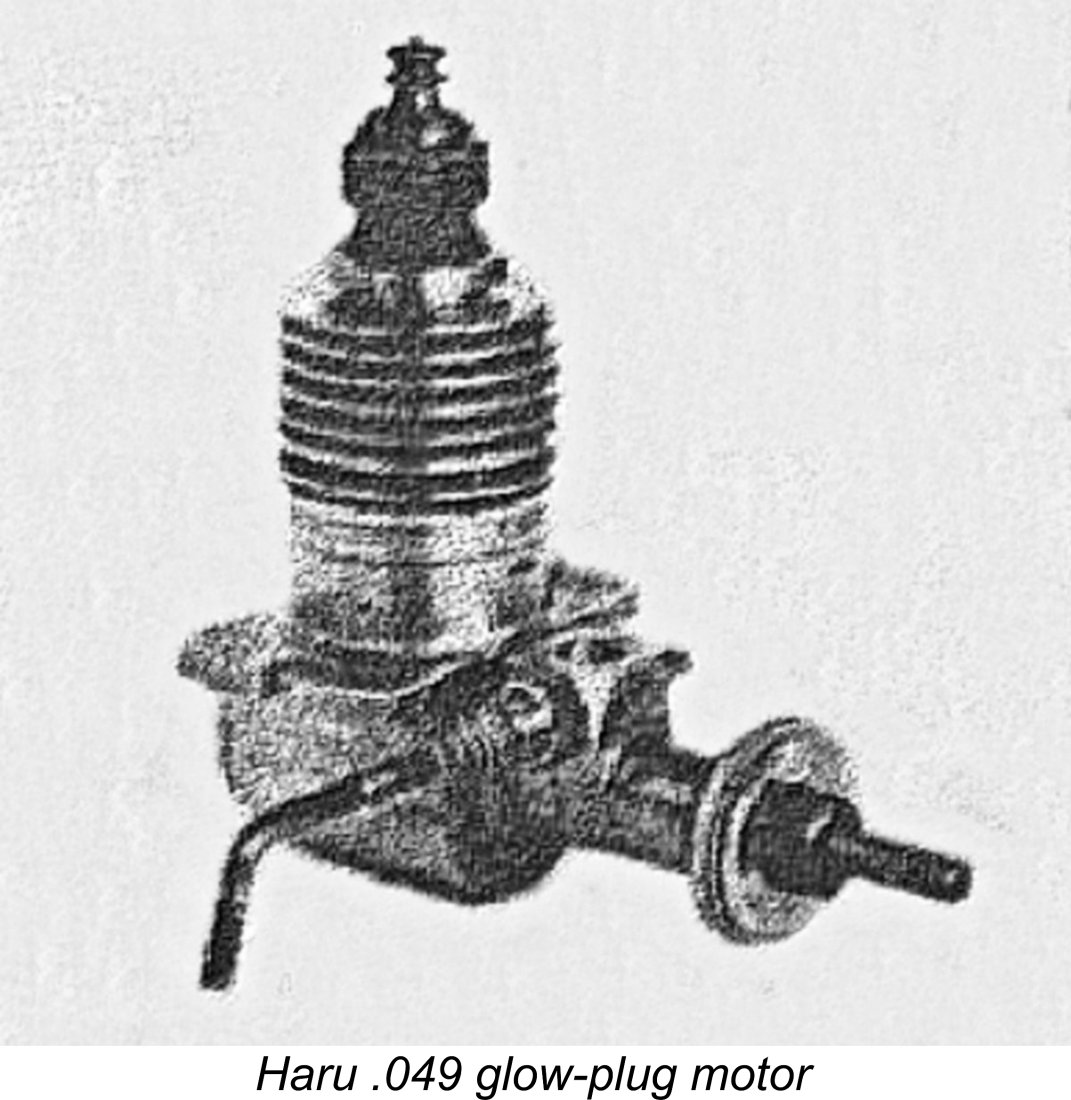

As a result, all of the major Japanese manufacturers (and even many of the minor players) became involved with the .099 classification from a fairly early stage in their respective careers. Fuji in particular focused on this displacement category almost from the outset, probably making more classic .099 cuin. engines than all of their other models combined! I covered that story in detail in the original article on the Fuji .099 series. By contrast, the .049 cuin. category was largely neglected by Japanese makers. In fact, only two Japanese manufacturers (Fuji and the ultra-obscure ROC company) became seriously involved with the volume manufacture of .049 models during the heyday of that category in the 1950’s. I’ve commented previouslythat one of the characteristics which set Fuji apart from other Japanese makers was their tendency to lead the charge into The very first Japanese .049 model seems to have been the ultra-obscure Haru .049 from the late 1940’s. However, that model does not appear to have been manufactured in sufficient numbers to qualify it as a mainstream commercial production. The honour of leading the way in that category seemingly belongs either to Fuji or to the manufacturers of the ROC .049. I’ve covered the story of the ROC .049 in a separate article to be elsewhere on this website. It’s an open question which came first - the ROC or the Fuji .049 model. Writing some years later, the always knowledgeable Peter Chinn, who was evidently unaware of the earlier Haru effort, stated that the ROC .049 had been the first Japanese engine of that displacement. Setting aside the strong claim to priority of the Haru, it is certainly possible that the ROC .049 preceded the first Fuji .049 offering, but if so it was not by very much. I say this with some confidence because the ½A .049 cuin. boom only really got underway in America in 1949 with trend-setting offerings from the likes of K&B, Holland, Anderson and OK, who were soon joined by many others. Maris Dislers has ably recounted this story in a separate article to be found on this website.

It seems likely that the makers of the Fuji and ROC .049 engines both got the idea of entering this market through exposure to American .049 models in the hands of US service personnel. Given the introductory dates of the more trend-setting American .049 models, such exposure could not have commenced prior to mid 1949 or thereabouts. This being the case, it seems almost certain that both ROC and Fuji entered this market in 1950 following a period of appraisal of what they were seeing. Since the “popular” domestic market seems to have been centred upon the .099 category, the primary target market for the Japanese .049’s was almost certainly the aforementioned US service personnel. This was a time when the more forward-thinking Japanese companies in many areas of endeavour were very much open to making anything that might find ready buyers among the very sizeable and well-funded “imported” American service population, thus opening the door to export activity down the road. The fact that the American market had in effect come to them represented an opportunity of which they were naturally keen to take full advantage.

By mid-1950 things were looking good for Fuji, causing them to begin to think about expanding the range still further. Having presumably assessed the market prospects, they elected to do so by moving next into the .049 category. They could not have failed to notice that there was minimal domestic competition in that displacement class at the time. Hence they would not have to share the market with a host of competitors, at least initially. Regardless of whether or not the ROC company got there first, it appears to be beyond dispute that Fuji had entered the .049 category well prior to the end of 1950. With this clarified, let’s begin our examination of the various Fuji .049 models in the order in which they appeared. 1950 - The first Fuji .049 (Model 049-1)

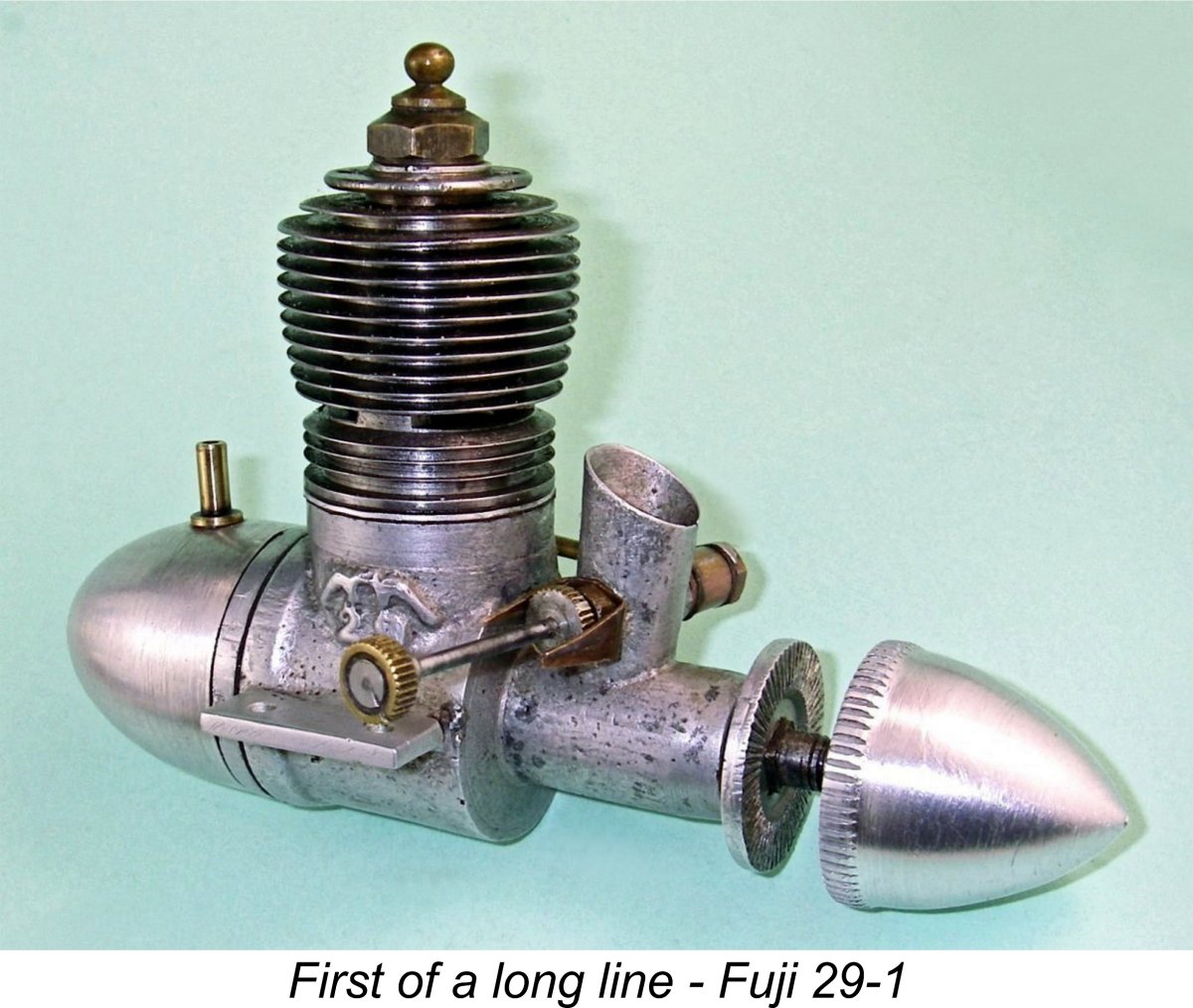

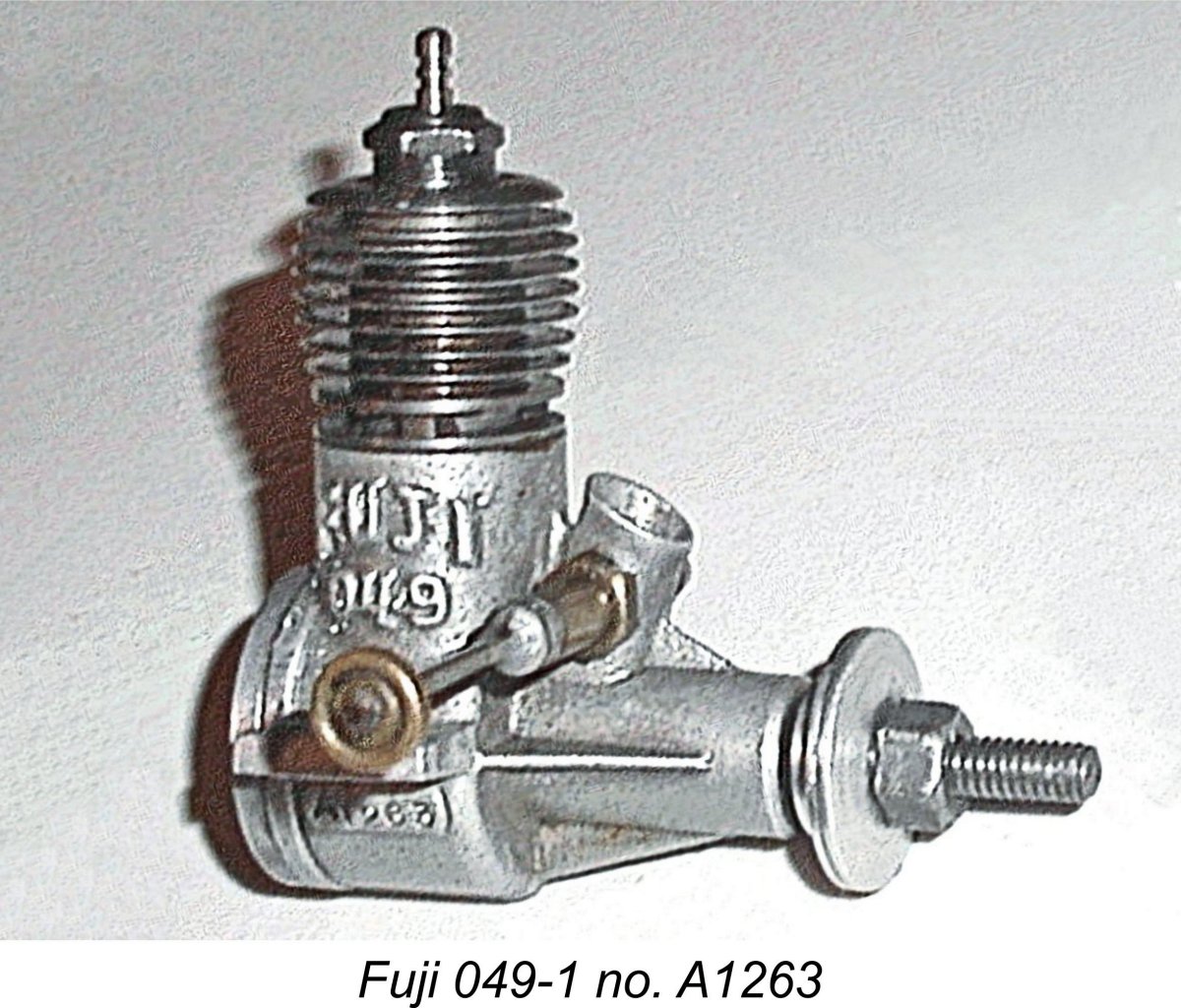

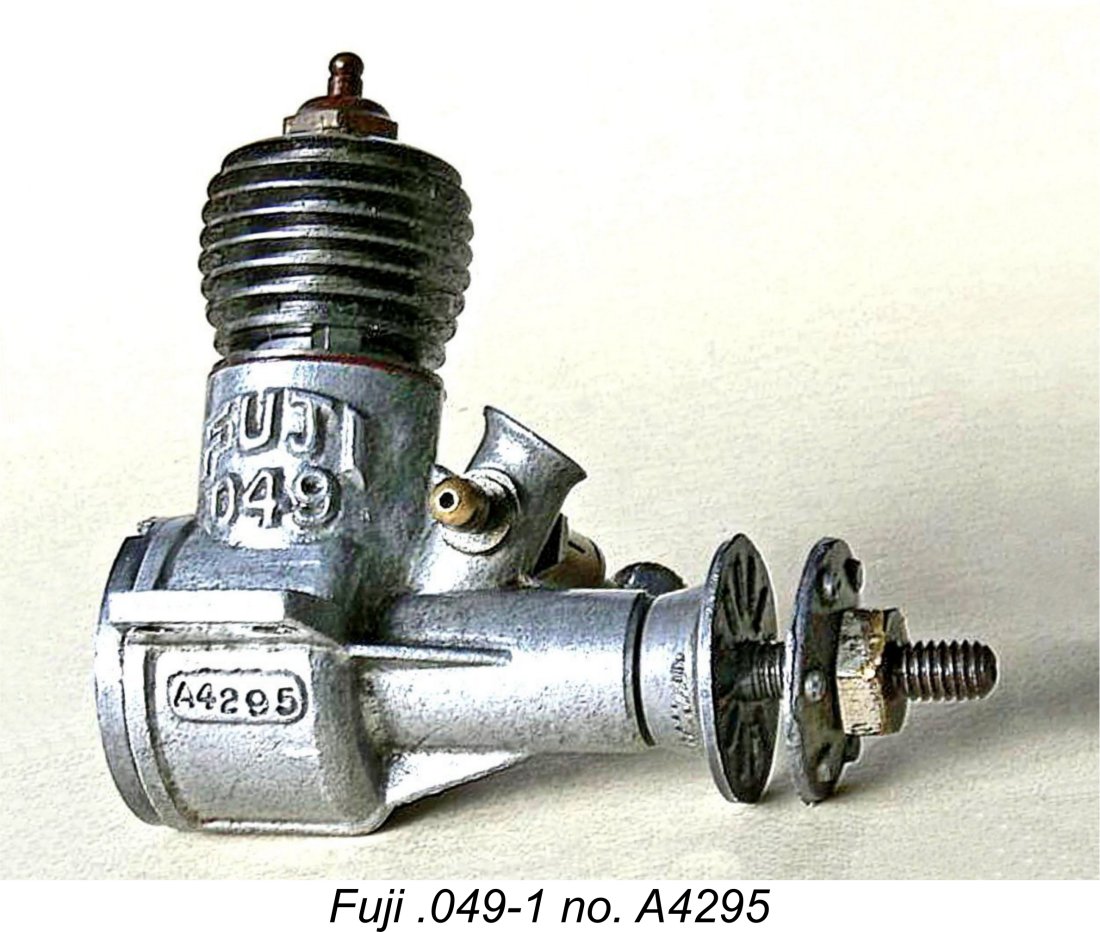

At the time when Fuji entered the .049 market, likely in the latter part of 1950, they were still producing all of their cast components through the sand-casting process. The initial version of the Fuji .049 was no exception, using a sand-cast crankcase in keeping with its larger relatives. The first Fuji .049 offering, which I have designated the 049-1 model, was a very simple beam-mounted radially-ported front rotary valve (FRV) induction unit. The engine weighed in at 45 gm (1.59 ounces). Bore and stroke were 10.2 mm and 10.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.817 cc (0.0499 cuin. - taking full advantage of the 0.050 cuin. American ½A class limit!). These dimensions were to be retained throughout the entire production life of the “classic” Fuji .049 sequence. The factory literature claimed a peak output of 0.079 BHP @ 8,000-9,000 rpm for this model. However, these figures are simply not credible. Based on rational considerations of design as well as first-hand impressions and later tests of subsequent models, the output actually achieved was significantly below this claim, albeit with peak power being reached at a considerably higher speed. Nonetheless, the engines do start and run very well. In addition to the use of a sand-cast crankcase, this model shared many other design features with its larger .099 and .29 cuin. siblings, including a radially-ported screw-in cast-iron cylinder having a blind bore with an integral cylinder head and thin integrally-machined cooling fins. The porting was very similar to that used on the .099 model, with three sawn exhaust ports cut through a thick flange at exhaust port level and three upwardly-angled drilled transfer ports aligned with the pillars between the exhaust ports. These ports did not quite overlap the exhaust, but the blow-down period was considerably shorter than would have been possible using sawn transfer slots.

In common with the larger engines in the range, a turned steel con-rod was used in combination with a steel gudgeon pin and a one-piece steel crankshaft having a counterbalanced full-disc crankweb. The shaft had a round induction hole which was fed by a forward-angled intake reminiscent of those used on the larger engines, albeit considerably less extreme in appearance. A standard Fuji .099 needle valve assembly was fitted, using a split thimble for tension and a brass control knob at the outer end. The push-through spraybar was retained by a nut in the usual manner. The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate. No provision was made for a tank on this initial model of the Fuji .049, nor was there any provision for radial mounting. The engines had a rather utilitarian external finish, no attempt being made to “pretty up” the casting or polish any external surfaces. However, they were very well made where it counted - all internal fits and finishes were first-class. Like all Fuji engines, these units bore serial numbers, which appeared in a raised panel cast onto the crankcase below the right-hand mounting lug (looking forward in the direction of flight). The initial series appears to have been numbered with an A prefix, similar to that being used concurrently on the companion .099 model. This letter appears to represent a production era rather than a particular model. The three examples of this model of which I have direct knowledge bear the numbers A1263, A4295 and A5668, indicating that at least 6000 examples were made. The true number may well be higher. This model of the Fuji .049 seems to have continued in production for perhaps the better part of a year. It’s clear from the serial numbers reported above that this variant was produced at a very substantial rate during that year or so. At some point in 1951, some minor design changes were introduced which led to the appearance of the next model to be discussed. 1951 - The Second Fuji .049 (Model 049-2)

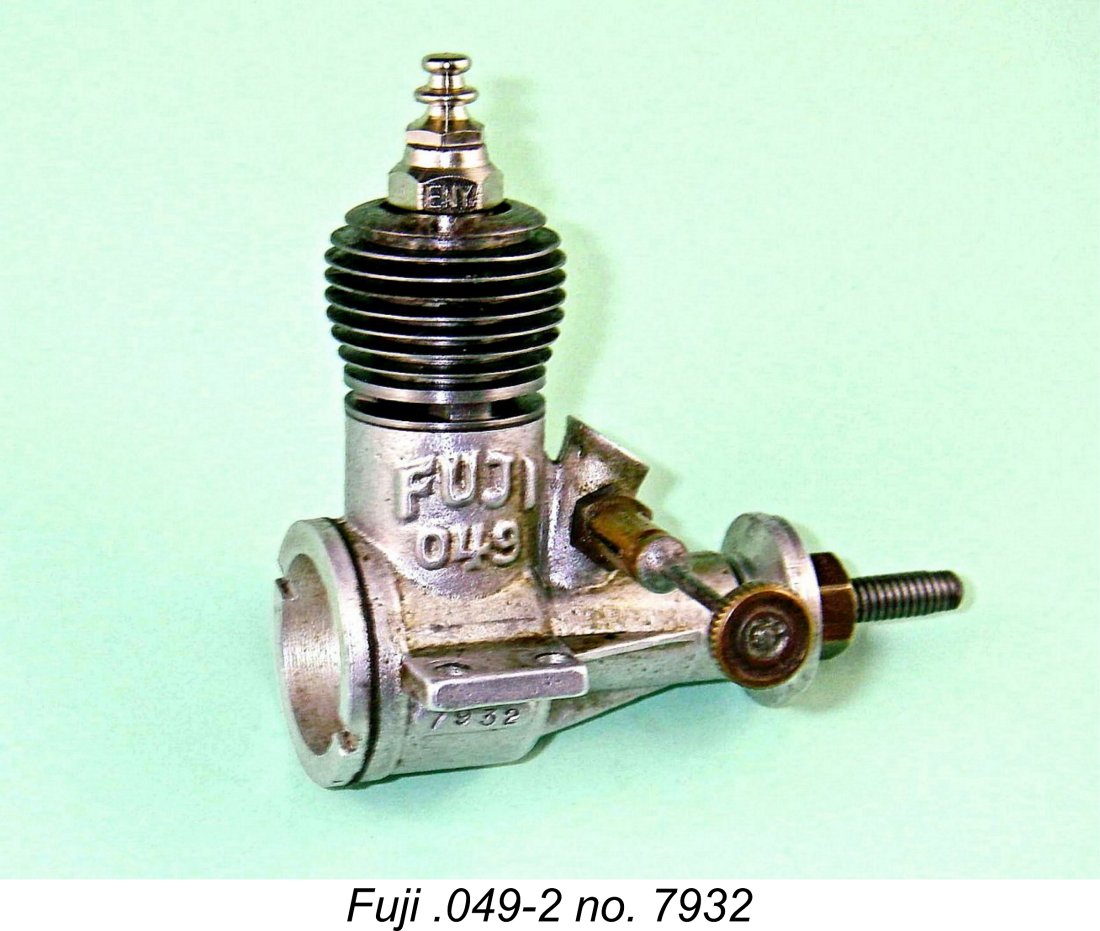

To respond to this situation, Fuji developed a revised design which allowed owners to mount the engine in either beam or radial configuration. It’s likely that this change dated to around mid-1951. The crankcase pattern was modified to incorporate a slightly more substantial “ring” of metal at the rear of the crankcase, evidently to provide extra thread length and a stiffer seating for the radial mounting system which was now made available as an owner’s option. It also appears that the beam mounting lugs were thickened slightly - perhaps experience had shown that the original thinner lugs were overly damage-prone. In other respects, the design was essentially unchanged from that of the previous model. The engines continued to carry a serial number stamped into a raised panel cast onto the crankcase below the right mounting lug. However, the introduction of the revised crankcase seems to have prompted Fuji to re-start the serial numbering sequence without the former A prefix - I’m aware of engine number 279 of this type. It seems clear that the engines were numbered in a straight numerical sequence starting at 1. On this basis alone, the use of a distinct identification code for this model appears amply justified. It's evident that the basic engine continued to be offered in beam mount form, with the radial mounting system being available as an option. I don’t have access to an example of the radially-mounted version, but beam-mounted versions of this model continued to appear in Fuji’s promotional literature into the latter part of 1953.

It’s important to note that the longer backplate and the radial mounting ring definitely went together as a set - if the ring is omitted, the longer backplate cannot be screwed home without fouling the rear of the crankpin. Conversely, a standard backplate lacks the length necessary to retain the radial mounting ring and fill the rear of the crankcase adequately. Nevertheless, the beauty of this arrangement was that the switch from beam to radial mounting required only a change to a different backplate and the addition of the radial mounting ring. The rest of the engine was common to both versions, resulting in clear production economies.

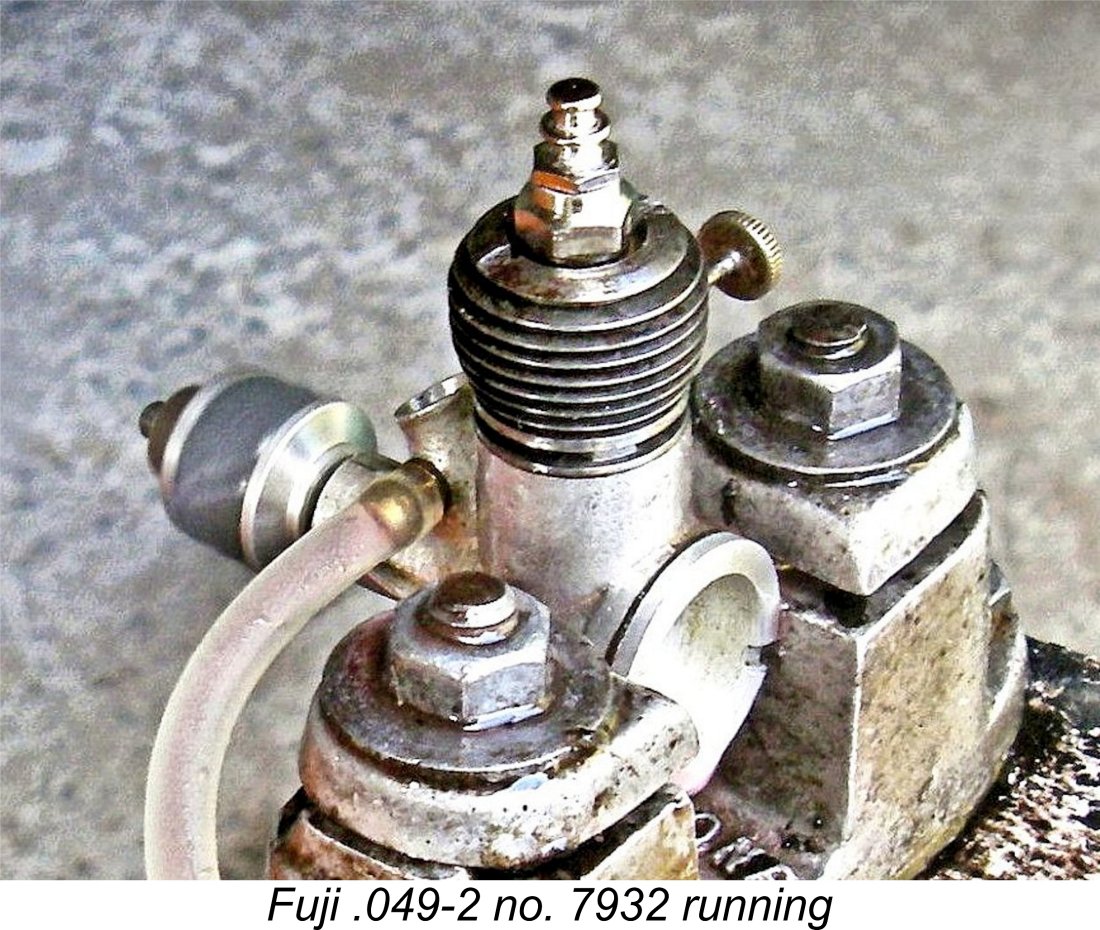

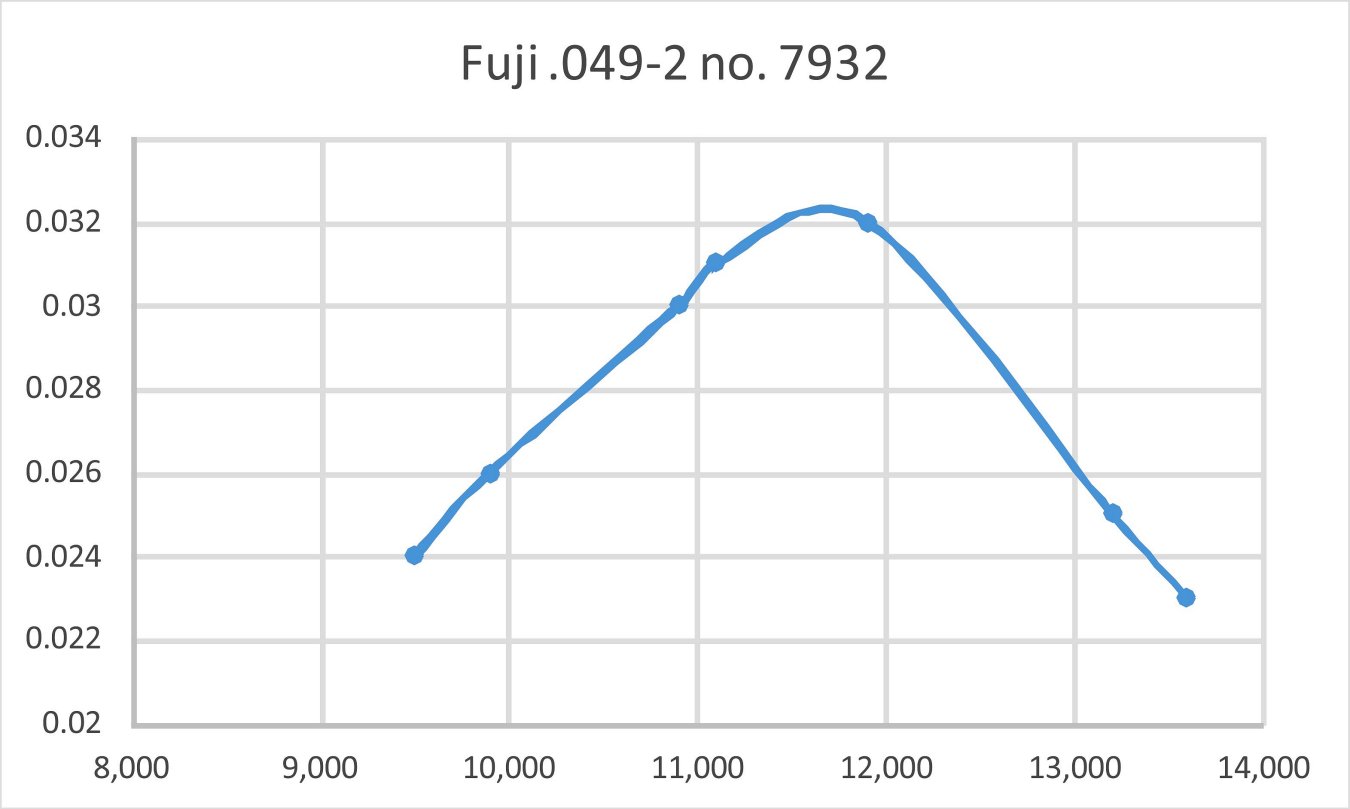

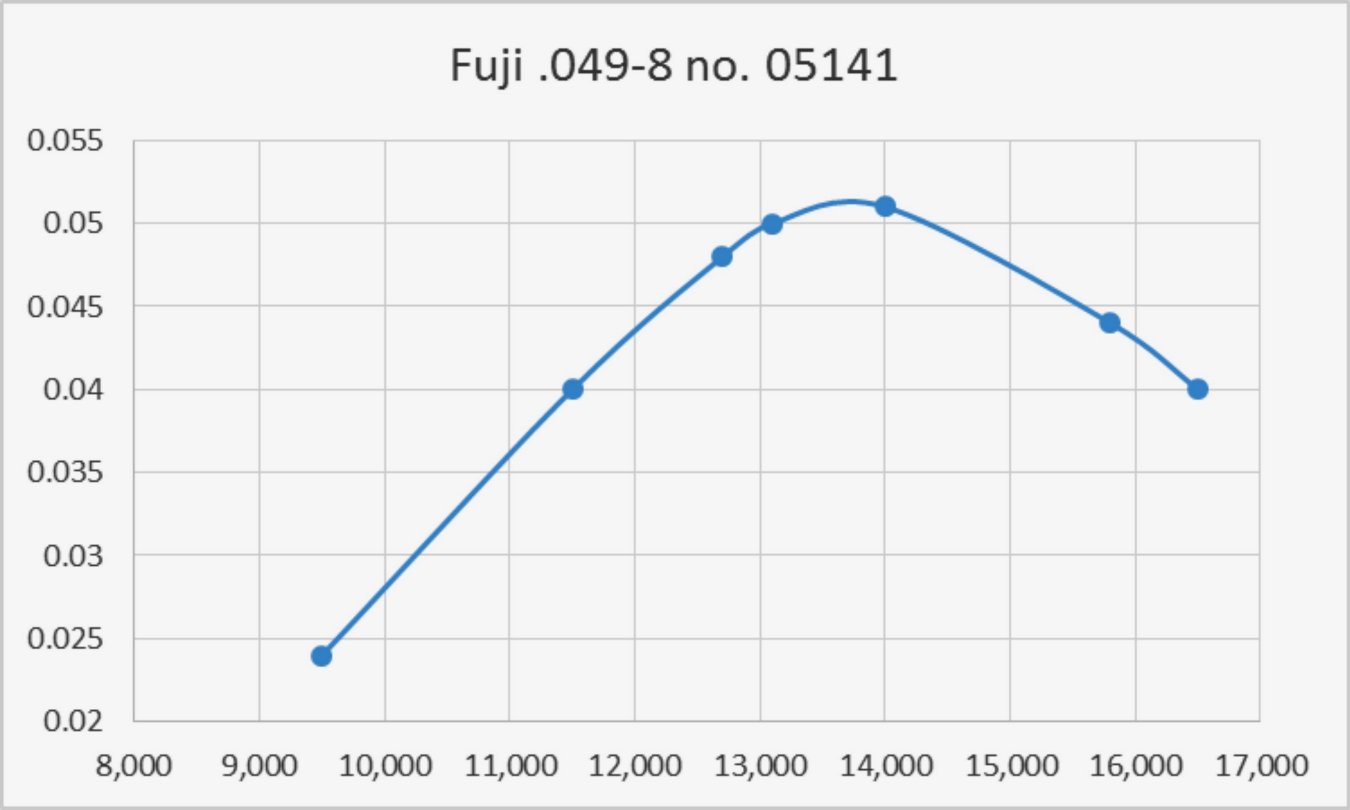

Just for fun, I ran a test on illustrated 049-2 no. 7932. At the time I hadn’t been able to replenish my fuel stocks during the COVID lockdown period, hence being forced to use a fuel containing only 5% nitro. Given the very low compression ratio which was readily apparent merely by turning the engine over, this was clearly an inadequate proportion of nitro. The testing bore out this impression completely. The engine proved to be a breeze to start following a prime, but even with a “hot” plug fitted, a persistent misfire crept in at around 11,000 rpm which could not be cured with the needle - a classic symptom of a compression ratio that is too low for the fuel and plug being used. Further confirmation of this was the very rapid drop-off in output past the measured peak. This is a typical symptom of a glow-plug engine that has run past its built-in ignition timing limitations - analogous to a diesel running under-compressed. The following data bear out these comments completely.

The engine seems to develop around 0.0325 BHP @ 11,800 rpm using this fuel. I have absolutely no doubt at all that it would do considerably better than this using a fuel containing 15-20% nitro. Moreover, the test confirmed that it handles beautifully and seems to be sturdy enough to serve well over the long haul. The beam and radially-mounted versions were evidently not numbered in separate sequences but were simply numbered in sequence as they came off the line, regardless of the mounting option featured. This raises the strong possibility that the engines were all sold as basic beam mount models and that the radial mount conversion was offered separately as an after-market accessory. The fact that we have yet to see an image of the radially-mounted variant in any Fuji promotional literature may be a further point supporting this possibility. Nonetheless, the engine may be encountered today in either form. The possibility also exists that the engines were sold with both backplates plus the radial mounting ring, so that the purchaser had the choice of mounting arrangements right out of the box. At present I have no way of determining the truth or otherwise of this. 1952 - American influence to the fore - the third Fuji .049 (Model 049-3)

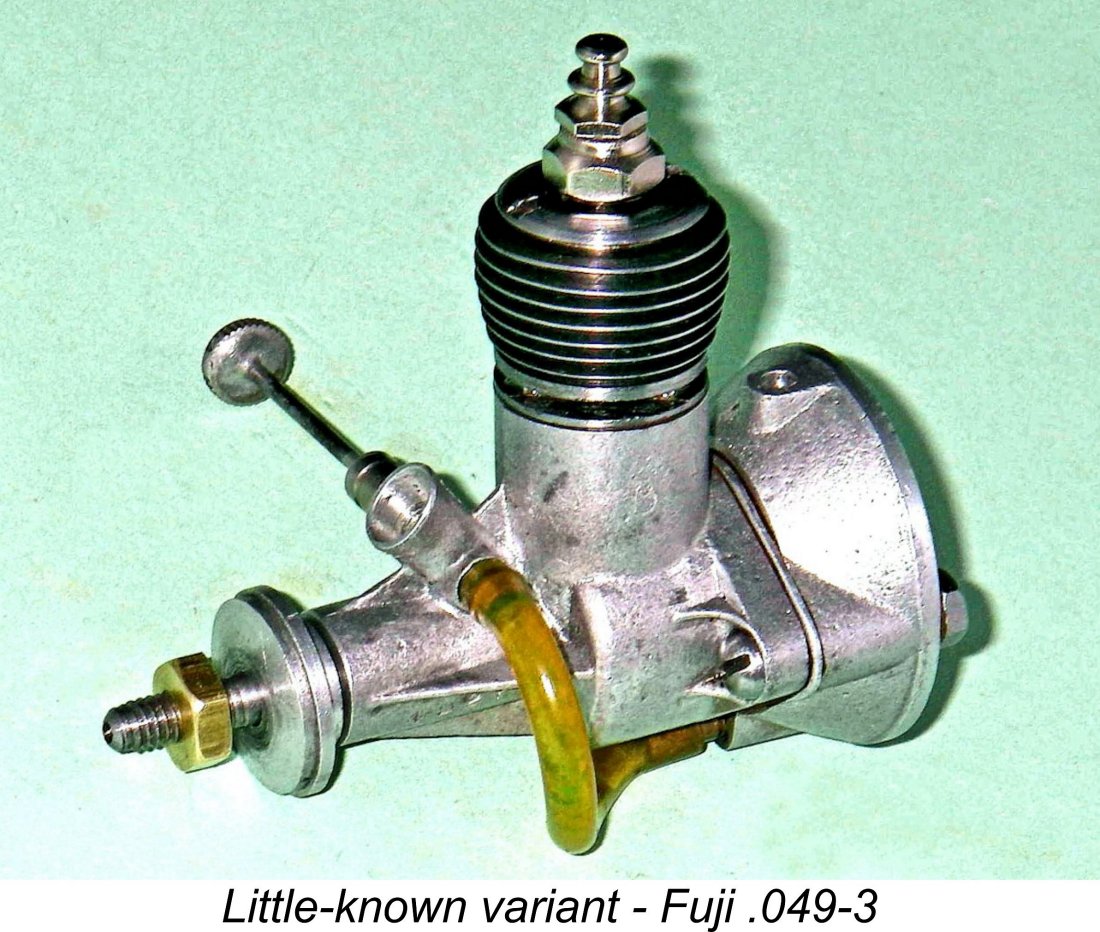

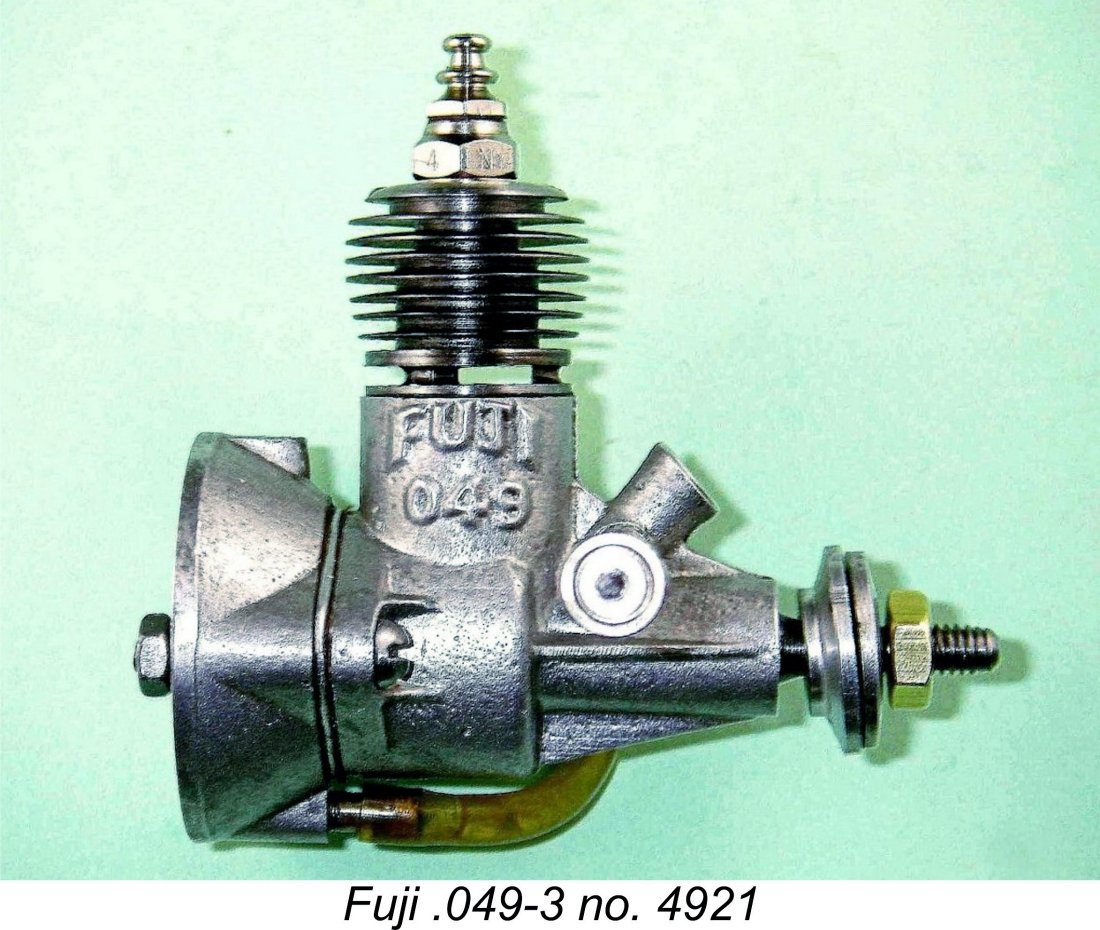

In 1950, Bill Atwood and Bob Holland had introduced their very popular Wasp .049 design. This model was arranged exclusively for radial mounting, and the majority of them featured a conical tank mount which offered a very stable mounting surface as well as accommodating an adequate fuel supply for free flight purposes. An optional version of this tank mount incorporated a cut-out for free flight use. It’s clear that the Fuji design team soon became aware of the Wasp. Certainly, it didn’t take them long to come up with a completely revised version of their sand-cast .049 model which bore irrefutable testimony to its strong Atwood influence. If I had to hazard a guess as to the date of this model’s appearance, I’d probably hedge my bets by saying that it likely materialized during late 1951 or early 1952 following a period of appraisal of the 1950 Holland/Atwood design. I can’t be any more definite than that, and I could very well be wrong. Whatever its date, it seems quite likely that this variant was produced concurrently with the 049-2 model described above, perhps with the idea of supplanting the radial mount conversion applied to that model. As far as I'm presently aware, it never appeared in any Fuji promotional literature.

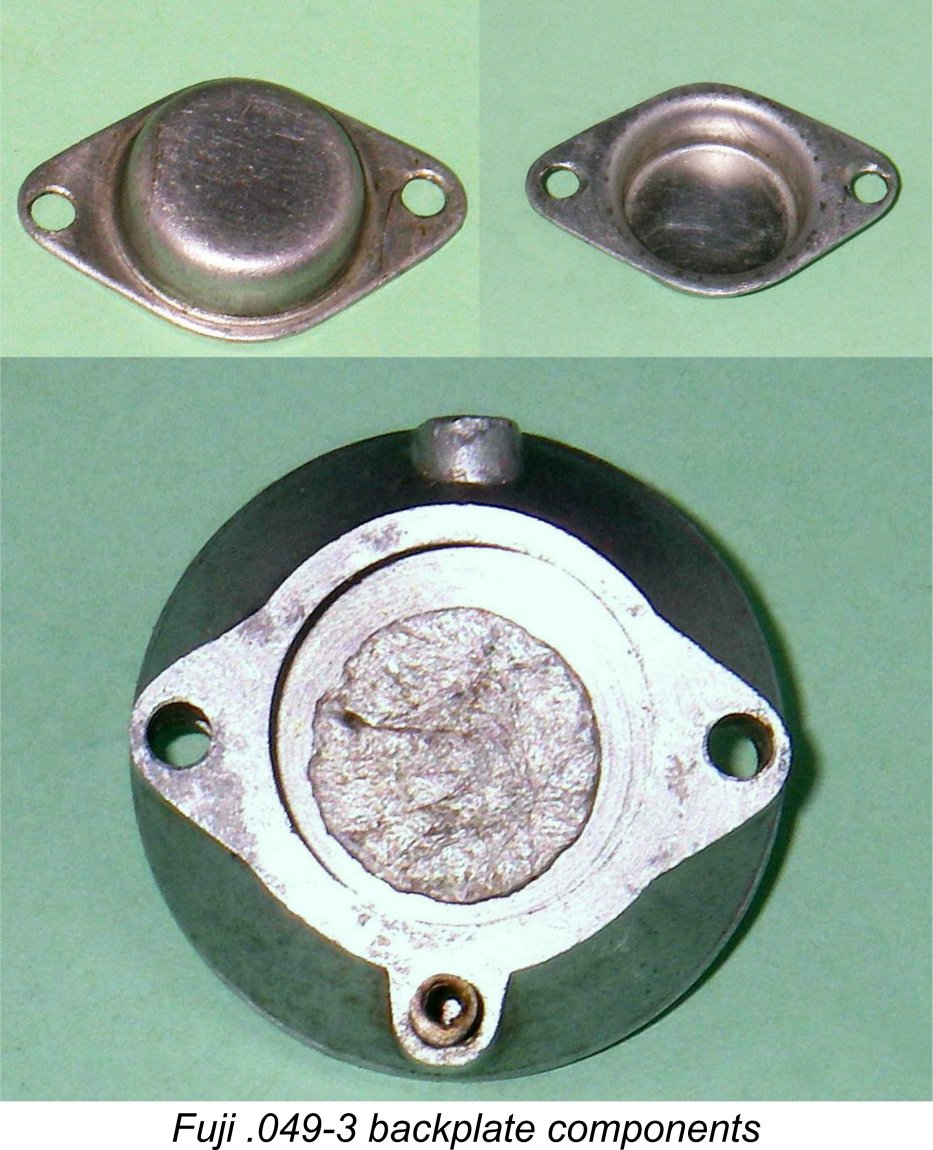

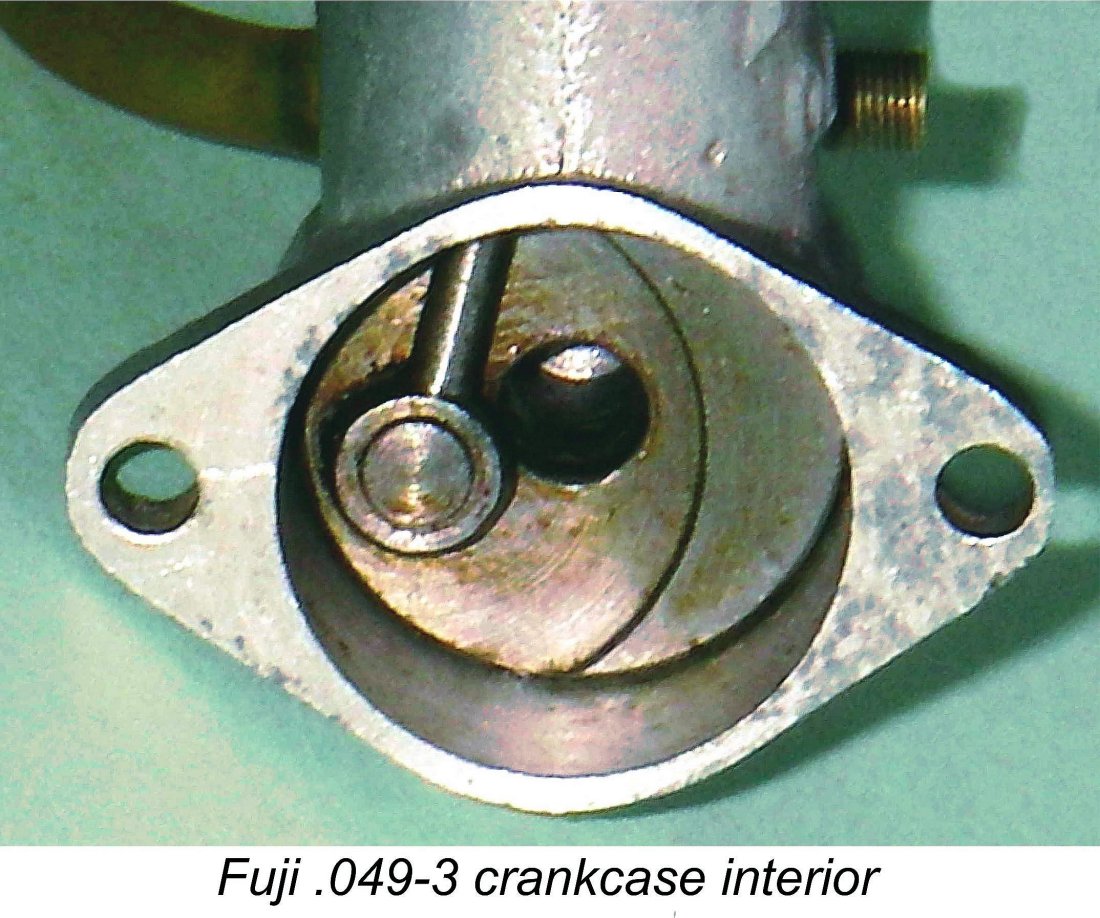

The screw-in backplate was abandoned, there being no female thread cut into the rear of the crankcase. This was the sole Fuji .049 variant not to feature such a thread. Instead, a backplate made of stamped aluminium sheet was simply pushed into the open end of the crankcase, sealing against a gasket around the rim. This backplate was in turn held in place by the front rim of a conoidal tank mount externally very similar in style to that used by Atwood. The Fuji tank mount may have looked a lot like the Atwood design, but in fact it was a very different component in many respects. For one thing, it was a For another thing, it was open at the front rather than at the rear. This of course required the use of a second gasket between the rim of the stamped backplate and the front rim of the tank mount to ensure a seal. However, the design eliminated the use of the somewhat problematic large gasket used with the Atwood tank to create a seal around the rim of the separate rear face of that component. It also allowed the cavity at the rear of the backplate to form part of the fuel tank, increasing its capacity. The entire engine/backplate/tank assembly was secured by the two 3mm screws with which the engine was mounted against the firewall in the model. Two nuts were used to hold things together when the engine was not in the model. The assembly was a flexible one in that the engine could easily be mounted without the conoidal tank mount in place, in which form it would closely resemble the 049-2 model fitted with the optional radial mount components. The Atwood influence was further apparent in the fact that the spraybar of the new model was pressed into the venturi rather than being secured with a nut as on all other Fuji models of my acquaintance. The reason for this change is a bit obscure - the nut mounting system is far better, especially when it comes to replacing this rather vulnerable component. The impression given is that the intent was simply to make this model as Atwood-like as possible!

This model is extremely rare today - illustrated example no. 4921 is the sole example with which I'm presently familiar. The serial number is stamped onto the left underside of the main bearing since the former cast panel for this purpose was omitted from the revised casting. It seems extremely doubtful that anything like 5,000 examples were made if present-day survival rates are any indication. It appears to be more likely than not that these engines were made in batches along with the beam mount 049-2 models and that they were simply numbered sequentially with the others as they came off the line. Certainly, this example's serial number falls well within the established range for the 049-2 variant. It’s actually quite possible that this was a short-lived “experimental” model built in small numbers during the production period for the 049-2 variant simply to test the reaction of the many American modellers then stationed in Japan to a product built along somewhat more familiar lines. If so, it does not appear to have been a success - both the fact that I’ve never seen this variant in any of Fuji’s promotional literature and the scarcity of surviving examples combine to provide eloquent testimony supporting this conclusion. 1954 - American Influence Continues - the Fourth Fuji .049 (Model 049-4)

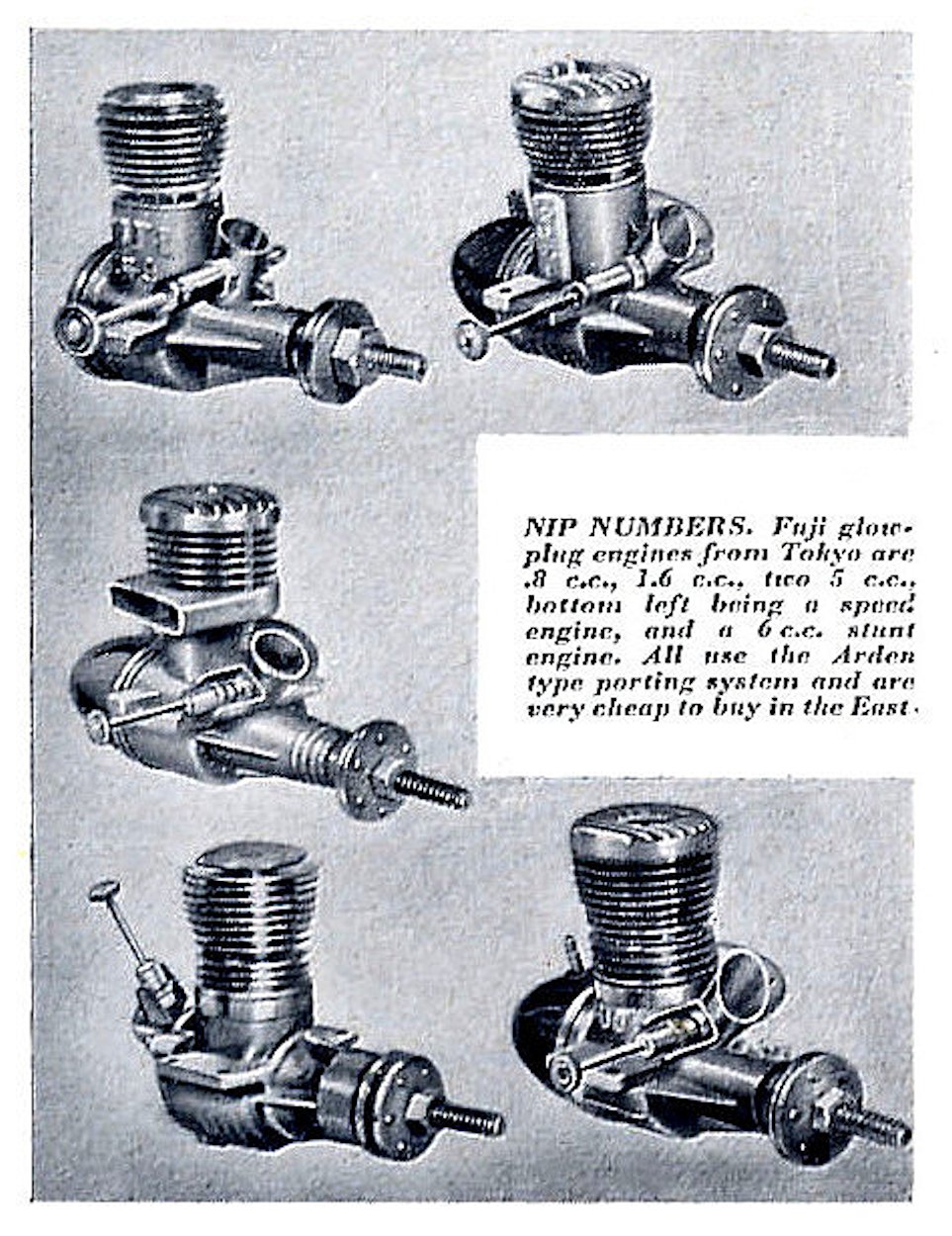

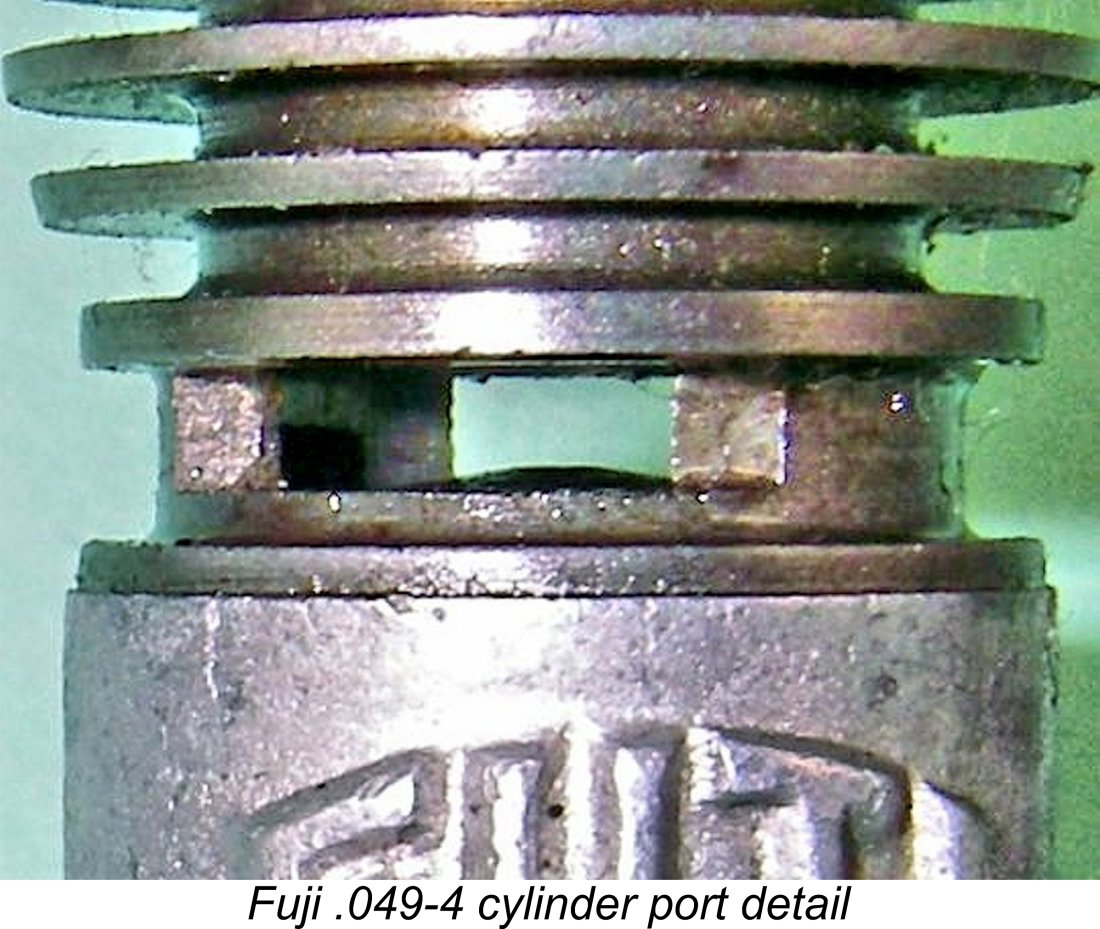

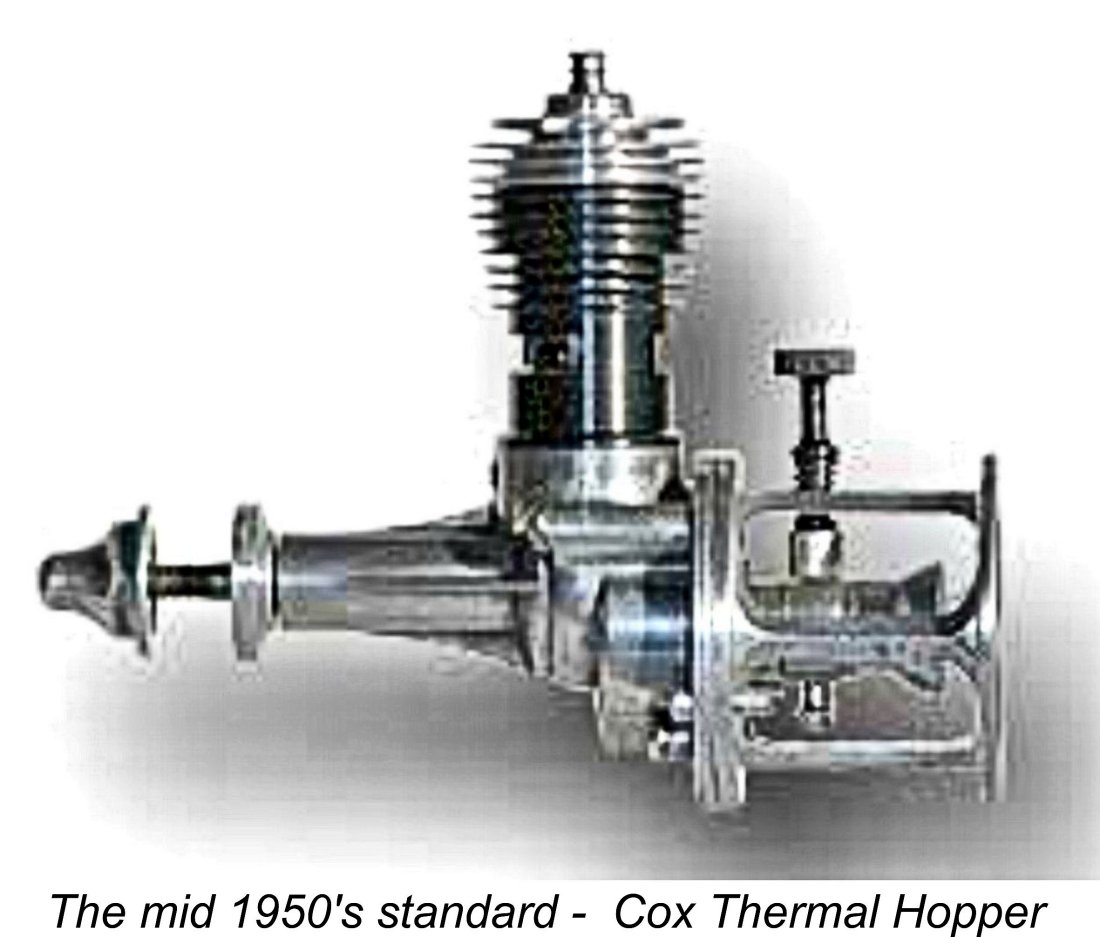

The beam-mount version of the previously-described 049-2 version of the Fuji .049 appears on what is clearly a Fuji promotional image of their range dating from late 1952 or early 1953. This image, which is reproduced below, appeared in the February 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. However, it undoubtedly shows the Moreover, this variant of the Fuji .049 is still in evidence in a Fuji promotional leaflet which undoubtedly dates from late 1953, since the 29 RV has now gone and the 099-4 model has made its appearance. It thus appears highly likely that it was in early 1954 that the next version of the Fuji .049 made its debut. Once again, we have to look to America to find what appears to have been the primary influence on this engine’s design. This was the cylinder porting system which had been made internationally famous beginning in 1952 by the L. M. Cox company with their renowned Space Bug and Thermal Hopper .049 designs. This system involved the use of twin opposed exhaust ports with twin overlapping internally-cut bypass/transfer flutes between them. The performance of the Thermal Hopper in particular provided ample proof of the system’s effectiveness in an .049 context. This demonstration clearly convinced Fuji, since their next move was to give this system a try themselves.

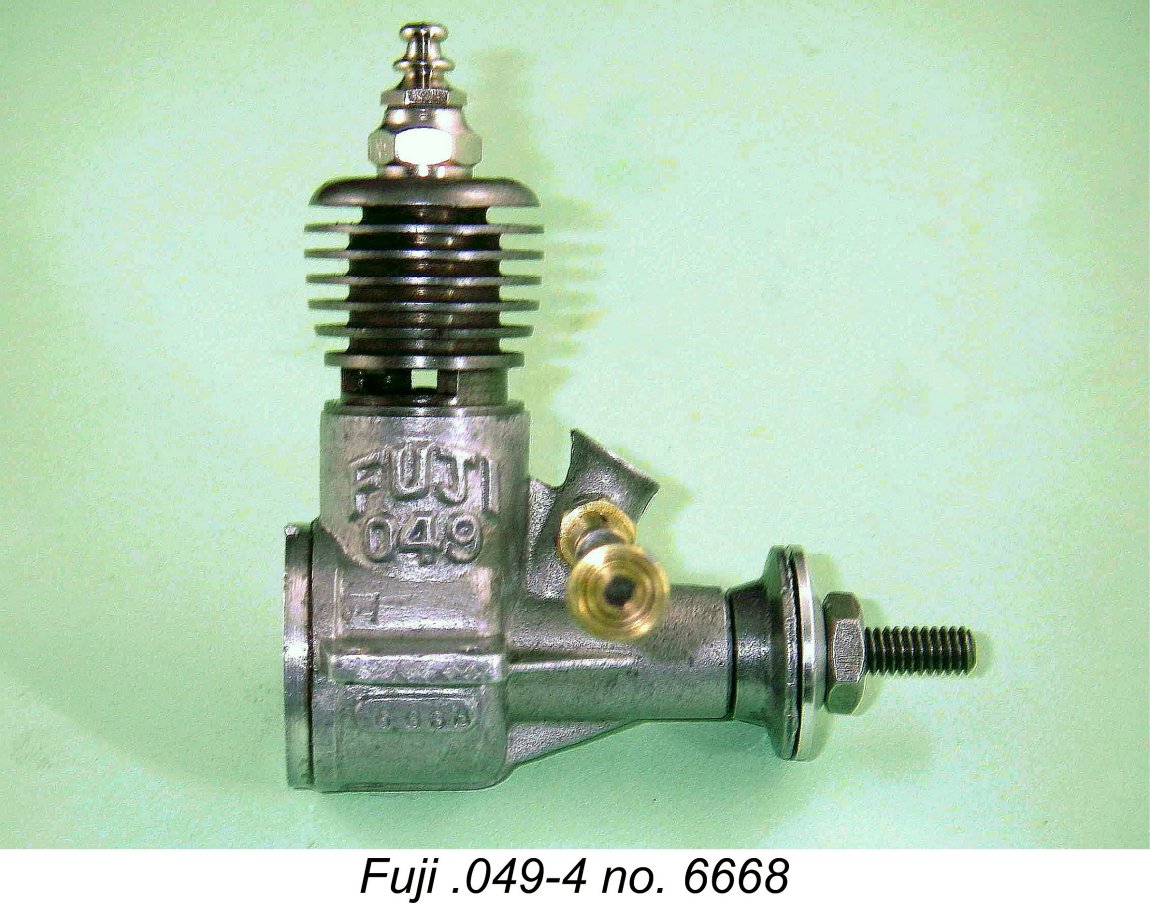

The new Fuji .049 was no exception to this rule. Although the crankcase casting was closely related to its sand-cast predecessor in design terms, it was now produced by the die-casting process at which Fuji were well on the way to becoming virtuosos. The venturi intake was given a more pronounced bell-mouth and the stiffening webs on the main bearing ended further back from the front of the bearing. The protruding rim at the rear of the crankcase reverted to the thinner section of the 049-1 model described earlier. Otherwise, the case was little changed apart from the method of production. A screw-in backplate continued to be employed, as it had been on all previous models apart from the Atwood-influenced 049-3 model described above. However, there was no provision for a tank - Fuji had evidently decided that their customers mostly preferred to make their own fuel supply arrangements rather than be constrained by the configuration of their engine.

The exhaust ports were significantly deeper than those on the earlier models, and this introduced a new feature for Fuji .049’s - sub-piston induction. The revised design incorporated a sub-piston induction period of some 40 degrees equally disposed around top dead centre. The established bore and stroke of 10.2 mm and 10.0 mm respectively were retained, but the more massive cylinder caused the weight to rise slightly to 49 gm (1.73 ounces). The result was a very neat little engine having a significantly enhanced performance potential over its predecessors. My sole example of this model bears the serial number 6668, which is stamped onto the raised panel beneath the right mounting lug which continued to appear on this variant. Since this number is less than the highest reported serial number for the earlier sand-cast 049-2 variant, it would seem logical to assume that the serial numbering sequence was restarted at 1 and that at least 7,000 or so examples were made. But if so, one wonders where they all are now .............

The point to be made here is that even in their heyday these engines were clearly produced at a rate which was in no way comparable with those achieved in the USA by makers such as Cox, Wen-Mac and Atwood. This being the case, it’s likely that domestic sales to Japanese and Asian modellers probably absorbed all of the production. This is entirely consistent with the fact that the models discussed so far do not appear to have been the subject of any concerted effort to market them internationally. This picture changed considerably as of April 28th, 1952, when the occupation of Japan officially ended, removing the formerly-significant Japanese-based American servicemen’s market from the equation. From that point onwards, Japanese manufacturers had to make it or break it on the basis of their success or otherwise in the domestic and Asian markets as well as the degree to which they were able to penetrate the mainstream international marketplace. At this stage of their existence, Fuji appear to have been making very minimal efforts in the latter direction, although that was soon to change. The fifth Fuji .049 (Model 049-5) The next model to be described may or may not be placed here in its proper sequence. In reality, it was almost certainly released in early 1954 more or less simultaneously with the previous model, since it is nothing more than a radial-mount version of the same engine. However, we’ll stick with our present identification codes - there’s no basis for saying that one or the other variant has priority in the sequence. The important thing is to differentiate between them for identification purposes.

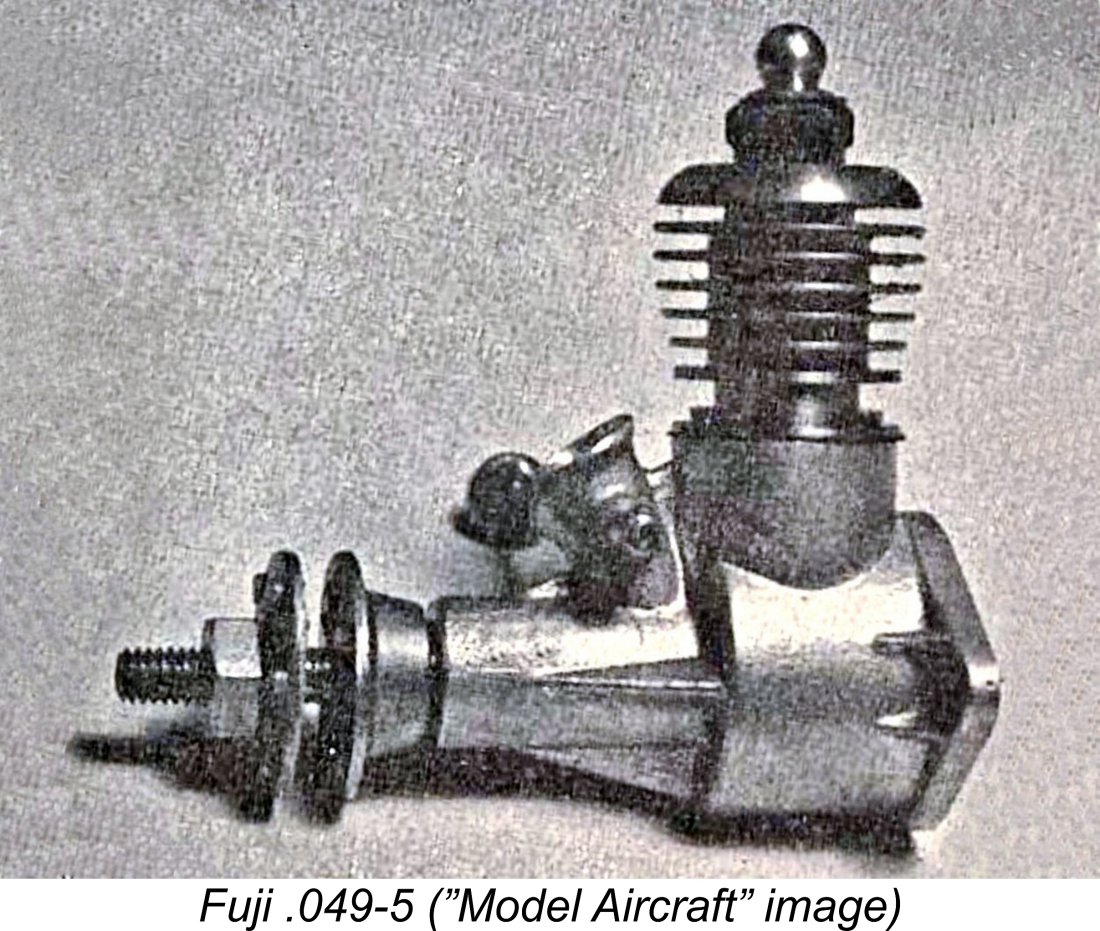

This is the first model of the Fuji .049 which drew considerable attention from the English-speaking modelling media. As far as I’m able to determine, it first appeared as an illustration in an article by Peter Chinn which was published in the September 1954 issue of “Model Aircraft”. This illustration is reproduced at the left. Allowing for editorial lead-time, this indicates that Chinn must have come into possession of his example by July of 1954 at the latest. This is consistent with my previous assertion that the two twin-port models were both released in early 1954. The fact that Chinn was somehow provided with an example of this engine so soon after its release date may be an indication that Fuji were now beginning to think in terms of stepping up their efforts to market their products world-wide. Chinn was perhaps the most respected model engine writer of his day, and it would be entirely logical for Fuji to seek his reaction to their products in order to gauge their probable reception in overseas markets.

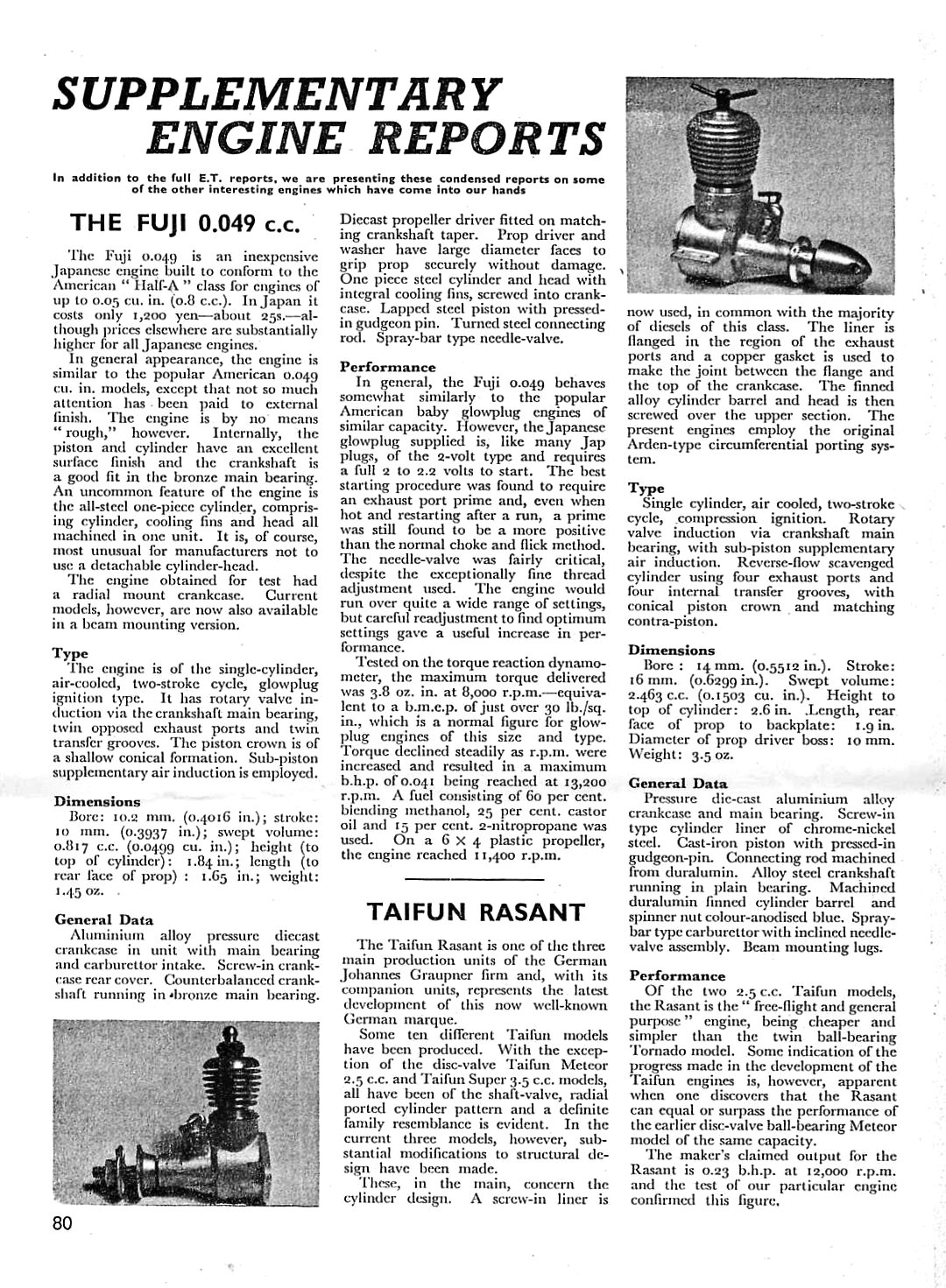

A published test of this model of the Fuji .049 finally appeared in the February 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. This test formed part of a series of condensed reports which were then being published in addition to the regular monthly detailed tests, simply in order to keep pace with the rate at which new designs were being received for test at this time (how times change!). The report was unattributed, but was almost certainly authored by Peter Chinn using the same example of the engine which had appeared in the September 1954 and May 1955 issues of the magazine. It is unclear exactly when the test was actually carried out - it could have been at any time between mid 1954 and late 1955. Chinn commented that the engine was better finished internally than it was externally, stating that it was by no means the rather rough effort that its no-frills appearance might lead one to expect. He found the little Fuji to be quite a useful performer, although he could not get near the figures claimed by Fuji themselves for the earlier 049-2 model. Using a fuel containing 15% nitromethane, he found a peak output of 0.041 BHP @ 13,000 rpm - rather better than my own previously-reported results for 049-2 no. 7932. The extra 10% nitro used by Chinn clearly had its effect, as presumably did the sub-piston induction.

Although a test of the beam-mount 049-4 version of this engine was never published, there is no reason to suppose that its performance would have been in any way different. As stated earlier, the two engines were functionally identical, the only difference being in the form of mounting employed. The engine made a final appearance in the September 1956 issue of “Model Airplane News”, when Chinn’s earlier comment was repeated to the effect that the engine was better finished internally than externally and that it performed more strongly than the finish might lead one to expect. However, it appears that by this time Fuji had already embarked upon the next stage of their involvement with the .049 cu. in. displacement category. 1956 - A Turning Point - the Sixth Fuji .049 (Model 049-6) By 1956, Fuji stood at something of a crossroads in terms of their participation in the .049 market. It’s evident that sales of the Fuji .049 were sufficiently steady that the model was making a worthwhile contribution to the company’s revenues. On that basis alone, the company's continued involvement with the .049 displacement category was clearly seen as justified. However, it must have been equally apparent to Fuji that their .049-4/5 design as it stood was never going to pose any kind of a performance threat to the best of the American competition. This left them with two alternatives - either continue to develop their existing design into a higher performance unit which could compete with the American opposition, or change direction and in effect sidestep any further performance-based competition with the Americans. The design progression of the larger models in their range provides unmistakable evidence to the effect that Fuji had already abandoned any thoughts of competing with the likes of Enya and O.S. in the larger-displacement performance sweepstakes. Instead, they had adopted a policy of catering to the sports fliers who far outnumbered their serious competition counterparts and merely wanted inexpensive and dependable engines which would get their models aloft and keep them there.

The above considerations led to a decision by Fuji to remain active in the .049 field, albeit with a very different focus. There would be no ongoing effort to keep pace with American standards of performance - instead, the company would direct its efforts towards meeting the needs of sport fliers in the domestic and Asian marketplace. The wisdom of this decision was amply demonstrated by the 1958 emergence of the Holland Hornet, which went toe to toe with Cox for ½A competition supremacy. Fuji wouldn’t have stood a chance ……….. The issue was how to proceed from where Fuji stood as of 1956. The recognition that they were no longer participating in the international ½A performance sweepstakes removed any imperative to continue to respond to design influences from the USA. This being the case, there was no reason for the company to continue its flirtation with the Cox-style porting that had been a feature of the previous two models. It was decided to return to the radial porting which the company knew so well and which provided ample levels of performance for the market in which they would now be competing. Indeed, they would have little competition in that market, since they remained the only Japanese volume manufacturer active in the ½A field. Looked at from this perspective, this was a very rational business decision. Along with the decision to change their market focus came the realization that it made little business sense to have to keep on producing two distinct versions of the same engine merely to accommodate the divergent mounting preferences of their customers. Low cost was now the overriding imperative, and this criterion would be best served if a single model could be designed which would accommodate all tastes. All of the above considerations led to the introduction of the next model in the Fuji .049 series - the 049-6, as I have designated it. This model appears at first glance to represent a retrograde step in design terms, since it reverts to the radial porting seen on the original 099-1 model way back in 1950. However, when evaluated in the context of Fuji’s new market focus, the design made perfect sense.

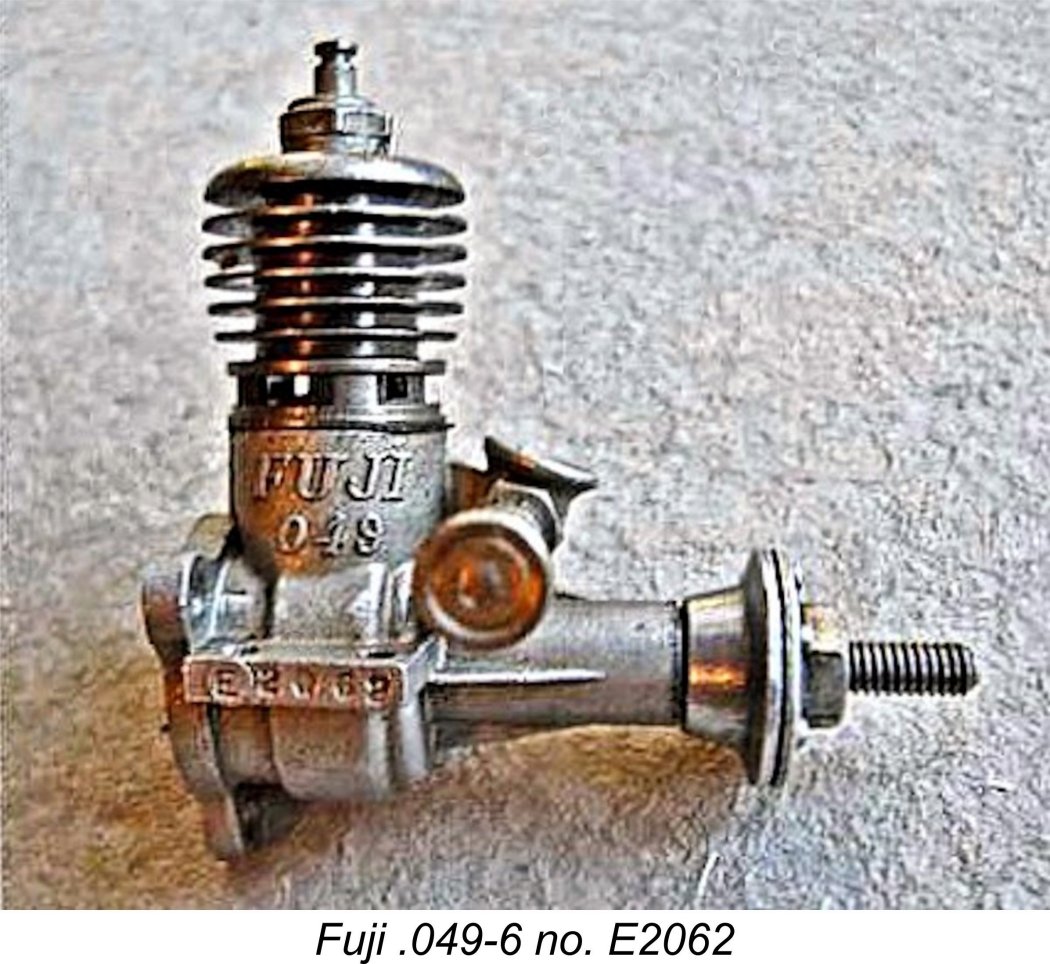

The new crankcase design was provided with both beam and radial mounting lugs which were cast in unit with the case. There were three "mouse ear" radial mounting lugs at the rear of the case, with a pair of conventional beam mounting lugs, one on each side. By adopting this crankcase design, Fuji relieved themselves of the costly requirement of making two distinct versions of the same engine - buyers of the new model had a free choice of mounting systems right out of the box. At first glance, the cylinder was very similar to that of the previous model in that it retained the blind bore and the 5 thick integrally-machined fins of its predecessor. However, it reverted to the use of three radially-disposed exhaust ports with drilled transfer ports between them. In effect, the cylinder was functionally identical to those seen on the first three variants of the Fuji .049. One consequence of this was the fact that the sub-piston induction which had been a feature of the two previous models was once more eliminated. The engine continued to use a screw-in backplate with no provision for a tank, while the major working components were also unchanged. Bore and stroke were unaltered, and the weight was back down to 45 gm (1.59 ounces). The needle valve too continued to be the standard Fuji pattern with the split thimble, just as it had been from the outset. The company maintained their claim to an output of 0.079 BHP @ 11,000-12,000 rpm - a highly improbable figure given the far more modest results obtained by Peter Chinn for the previous model! The serial numbers on these engines now appeared on the outer end of the right-hand mounting lug instead of on the main crankcase casting. It appears that when they commenced production of this variant, the company re-started the serial number sequence with the letter E added as a prefix. The only two confirmed numbers that I have for this variant are E2062 and E5451, indicating that production certainly ran well into the 5000 bracket and possibly higher. Most of these appear to have been sold in Japan and Asia, resulting in their relative rarity elsewhere today. I don’t have an example myself.

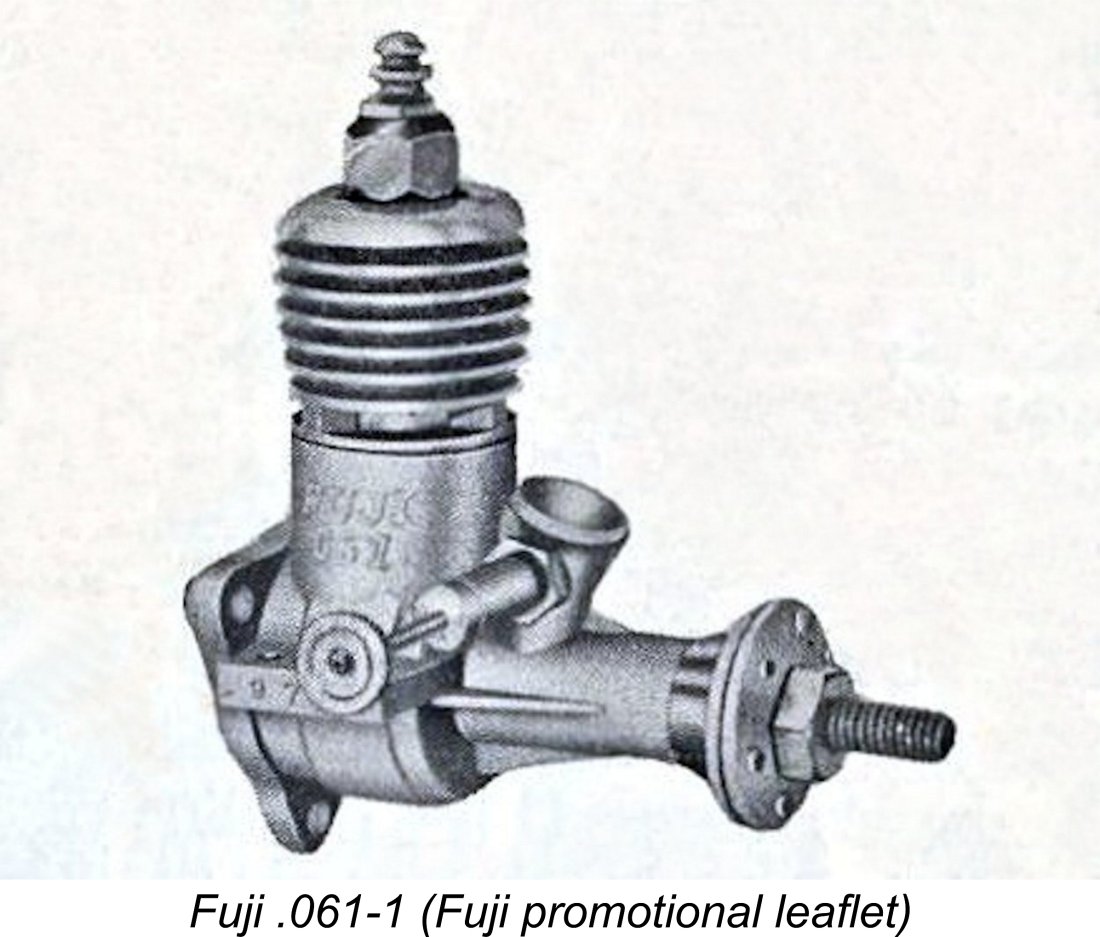

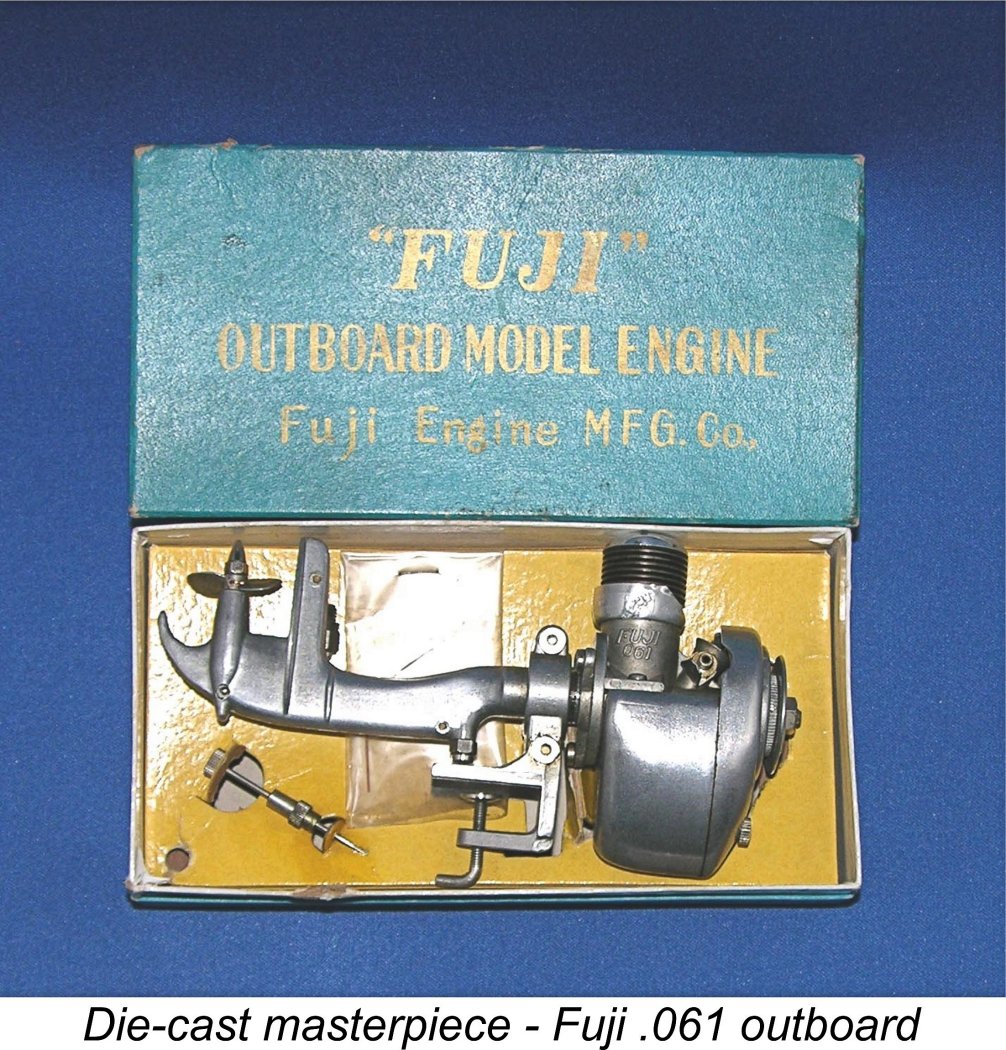

The production of perhaps 6,000 units over an approximately 3-year period suggests an ongoing annual production rate of around 2,000 pieces - somewhat lower than the figures evidently achieved with the earlier models. It appears from this that demand for engines of this size was now beginning to decline in the Japanese and Asian markets which were now the main focus. This of course mirrored the parallel trends elsewhere - the sun was past the zenith and just beginning to set on the ½A boom of the 1950's. A new twist - the first Fuji .061 (model 061-1) Despite the abandonment of their participation in the ½A performance game, Fuji could not fail to be aware that some of their customers might be interested in using engines of this class in applications requiring a higher level of performance. This realization notwithstanding, Fuji remained true to their decision to avoid any costly involvement in performance races. However, they very shrewdly realized that there’s more than one way to enhance performance! If a manufacturer is competing in performance terms in a given competition class which enforces an upper limit on displacement, then the only path to higher performance is through the further development of one’s design. However, once the decision is taken, as it had been by Fuji and presumably by their sport-flying customers, to abandon any pretence at participation in the competition arena, the displacement imperative is instantly removed. This realization led to Fuji’s next move in this particular game. They took a look at their existing .049 design and noted that if the bore were increased by only a matter of just over 1 mm, they could achieve a displacement increase of over 20% without changing anything else! A quick examination of the 049-6 model confirmed that this bore increase could be accommodated by making a revised cylinder which could still be mounted in the same basic crankcase casting with minor modifications. All of the other components of the .049-6 model could still be used, and the result would be an engine having exactly the same external dimensions and mounting requirements but having a 22% greater displacement and accordingly more torque and horsepower. Basically, an .049 on steroids!

The resulting model was the first Fuji .061 design, accordingly being designated under my classification system as model 061-1. Apart from the bore, it was based upon a revised crankcase die which produced a slight enlargement of the boss into which the cylinder screwed as well as the Fuji .061 identification instead of the former .049 figure. In all other respects, the .061 model was identical to its .049 companion, and there is no need to describe it further in this article. It seems likely that it was introduced in 1956 more or less concurrently with the companion 049-6 model and that it remained in production until 1959 or thereabouts. Since the .049 and .061 engines were completely interchangeable in the same model, purchasers of the Fuji .049 model now had a ready-made option if they wished to upgrade the performance of their existing models. All they had to do was buy and install a Fuji .061, and their goal was achieved! An overpowered model using the .061 could of course be tamed by making a move in the opposite direction. The .061 models too bore serial numbers, although in this instance the numbers were not accompanied by any letter prefix. The sole surviving example of the rather rare model which has come to my attention bears the number 600, located on the outer end of the right mounting lug. The illustrated example from the Fuji catalogue bears a number which begins with the digits 97, probably 97x if the placement is anything to go by. It is however likely that actual production was considerably higher than this. 1959 - the Seventh Fuji .049 (Model 049-7)

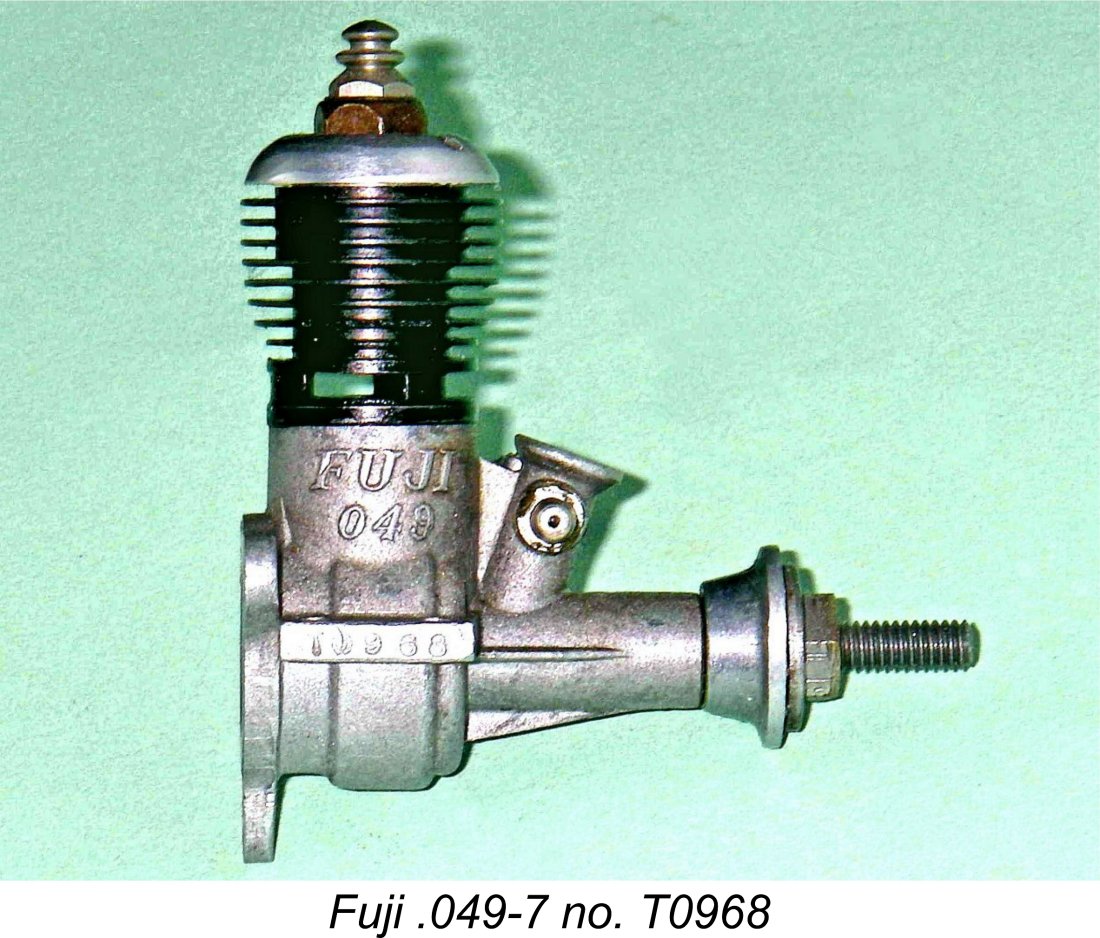

Apart from this change, the resulting engine was in fact little different from the preceding model. The main crankcase casting was identical, with the arrangements for alternative beam or radial mounting being continued unaltered. The moving parts were also unchanged. As before, a screw-in backplate was used with no provision being made for a tank. However, there were several changes which undoubtedly warrant the application of a different identification code to this model. The most obvious change was in the cylinder. The porting arrangements were essentially unaltered, with three sawn exhaust ports and three drilled transfer ports supplied in the same manner as before. However, the transfers now overlapped the exhausts to a significant extent, thus giving a longer transfer period. The really big news was that the blind bore had gone, to be replaced by a threaded recess at the open top of the cylinder. A turned aluminium alloy cylinder head screwed into this recess and sealed with a thin copper gasket on a locating shoulder at the base of the recess. This head was centrally tapped to accommodate a long-reach plug. The new head configuration naturally required that the cylinder be made somewhat taller to accommodate the threaded recess. The vertically-extended cylinder now had 8 somewhat thinner cooling fins instead of the 5 thicker fins seen on the previous .049 model.

The engines continued to bear serial numbers stamped onto the outer ends of the right-hand mounting lugs. The only two examples of this model of my present acquaintance bear the serial numbers T0968 and T1878, indicating that the serial number sequence had been re-started yet again, this time with a letter T to identify the series in question. This model is rarely encountered today outside Japan and does not appear in any Fuji promotional material presently in my possession. In all probability, only about 2,500 or so examples were produced, if that. If the previously-estimated production rate of some 2,000 units annually was being maintained, the implication is that this variant was in production for just over a year, beginning at some point during 1959. Indeed, it may legitimately be seen as a transition model linking the 049-6 variant with the next .049 model to be discussed - the iconic 049-8 variant. The Second Fuji .061 (model 061-2)

One point worth noting is that the die which produced the crankcase of the .061 outboard engine to which we refer was modified to produce the inscription “Fuji .061” on the right side of the case in place of the .049 designation of its smaller companion. It seems safe to assume that the aero versions would have been similarly identified. Presumably also the crankcase boss into which the cylinder screwed was also made larger to accommodate the increased cylinder diameter. On the basis of this outboard motor engine, it’s clear that the .061 version of the then-current Fuji .049 was once again identical to the .049 version, with a larger bore and the amended identification being the only major differences. These units appear to be extremely rare, at least outside Japan - I’ve never found one in years of looking! Still it’s necessary to recognize the existence of this model in an article in which I’m attempting to present a definitive summary of the Fuji .049/.061 models. 1960 - American Influence Returns - the Eighth Fuji .049 (Model 049-8)

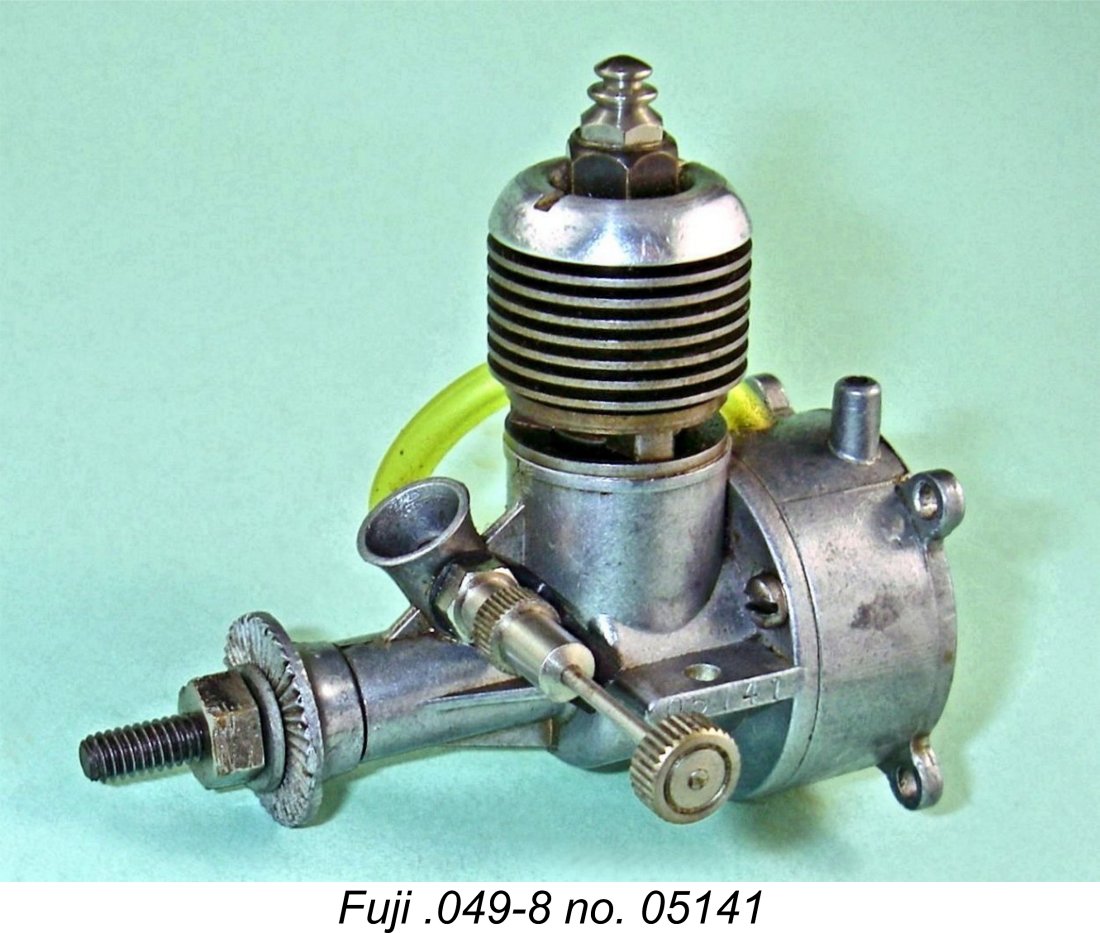

It’s very difficult to be certain regarding the date of this model’s introduction, but it was certainly well prior to 1964, based on its appearance on a Fuji promotional leaflet which undoubtedly pre-dates that year. It first appears on leaflets which also show the 099-9 model which apparently dates from around 1959-1960, and production figures for its predecessor suggest that it was probably introduced at some point in 1960 or perhaps early 1961. As I stated above, it's not possible to be certain about this pending the receipt of further evidence. This model represented an interesting combination of the old and the new. For the first time since the demise of the short-lived 049-3 model way back in 1952, it returned to the use of a radial tank mount, thus following the trend popularized by Cox with their Babe Bee and Golden Bee models of the late 1950’s and emulated by Herkimer with their radially-mounted Cub .049 models. It seems likely that this was a significant influence in the design of the new Fuji model - the timing is right. Yet again, the American influence was apparently in play!

The tank could be installed in any one of three orientations of the filler spigot relative to the cylinder. As supplied, the engine was set up for upright mounting. If one removed the tank and re-installed it rotated 120 degrees anticlockwise viewed from the rear, the filler spigot and fuel tubing hole ended up in a very good location for sidewinder mounting in a control line model. I once tried one of these engines experimentally in that orientation with complete success - you just need to route the fuel line appropriately. The crankcase retained the alternative beam and radial mounts, but the engine as supplied was definitely set up for radial mounting. It was perfectly possible to mount the unit radially without the tank, but to mount the engine on beams required that portions of the lower half of the tank mounting flange at the rear of the crankcase be filed away. Once this was done, the engine could no longer be radially mounted using the tank since the sealing perimeter was broken. The cylinder was basically similar to that used on the previous model, the screw-in alloy head being retained unaltered. Once again, the transfer ports overlapped the exhaust ports to a consideranble degree, greatly extending the transfer period. The cooling fins were somewhat thicker, the extra thickness being accommodated by the fact that there was one less fin - 7 instead of the former 8. The outer profile of these fins was now parallel instead of curved. The connecting rod was now of bronze alloy, but otherwise the engine was identical to its predecessor, including the extremely functional revised needle valve assembly with its spring clip for tension. Bore and stroke remained unchanged at 10.2 mm and 10.0 mm respectively, as they had throughout the life of the Fuji .049 series. The addition of the tank plus the somewhat heavier cylinder construction had sent the weight up to 67 gm (2.36 ounces) all inclusive - a fairly hefty figure for an .049 glow-plug motor.

For that reason, while finalizing the text of this article I actually dug out one of my examples of this engine (no. 05141) to run a latter-day test. This time I used a fuel containing 15% nitromethane, having replenished my fuel inventory. This was a typical ½A fuel in Britain back in the day. Most of us back then used KK Nitrex 15 in our small glow-plug motors - the boost in performance was considered to be well worth the extra cost. All of the contemporary British ½A units from 1959-1960 were tested at the time on such a fuel, so this seemed fair enough to me. There was no way that I could fit the engine into a test stand using the beam mounting lugs - the presence of the radial mounting flange and tank as well as the proximity of the needle valve saw to that. In fact, to use the beam mounts in a test stand you'd have to remove the tank mounting flange altogether. Rather than resort to such drastic measures, I made up a simple radial mount from a suitably drilled and tapped length of extruded T-section aluminium bar stock. I used the standard back tank throughout the test.

Starting proved to be very straightforward as long as one didn't get the crankcase too wet. If too much fuel got into the crankcase, the engine tended to drown the plug on a firing burst and stop. It was best just to choke to fill the fuel line. After that, a modest exhaust prime was all that was required to get the little Fuji running in very short order. The excellent suction allowed the engine to pick up immediately on the fuel line. Once running, response to the needle was excellent, with the optimum setting being very easy to establish. The one thing that I noticed was that the engine didn't appear too happy at speeds below 11,000 rpm - it tended to "hunt" a little rather than maintaining a constant speed. It was definitely unhappy turning the Cox 6x3 with which I started. Above 11,000 rpm, this issue became far less noticable, and by 12,000 rpm running became dead smooth and consistent, with no trace of a misfire. The only evidence of the engine's rather low compression ratio was a tendency to speed up a little when the needle was fully leaned out and the engine worked up to its peak operating temperature - it took a few seconds for the Fuji to come up to its full speed on that setting, after which a final adjustment could sometimes extract a few hundred extra rpm. However, the misfiring issue that had beset the engine's 049-2 predecessor on test (see above) never presented itself. Of course, I was using 10% more nitro this time than I had used for the earlier test, which probably explains the difference. The following data were recorded on test:

As can be seen, the engine developed a peak output of around 0.051 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, at which speed it ran superbly with never a missed beat. All in all, I would rate the little Fuji's performance on test as being well up to established standards for a 1960 non-competition .049 glow-plug motor. It certainly beats the One thing that can be stated with some certainty is that this was the most long-lived and widely-distributed Fuji .049 model of them all. The design seems to have remained in production for the better part of a decade, albeit at a significantly lower production rate than formerly. I’m familiar with engines bearing serial numbers which range from a low of 194 to a high of 5340. However, there’s a joker in this particular pack - it appears that at some point Fuji stopped putting serial numbers on these units, since I've confirmed the existence of two NIB examples bearing no numbers whatsoever. So the actual production figure is doubtless considerably higher than the serial numbers might suggest. These engines showed up in model shops in many parts of the world during the 1960’s. They were regularly carried by hobby shops here in Canada, presumably selling well enough to keep them on the shelves. As a result, there’s no question that this is by far the most commonly-encountered Fuji .049 model today, likely in large part because it was the company's sole such product that was so widely distributed. However, the ½A boom had already passed by this time - R/C with its demand for larger engines was very much in the ascendant and the market for ½A engines was now shrinking rapidly. In addition, the somewhat antiquated design specification (radial porting, radial tank mount, etc.) and less-than-stellar performance of the Fuji .049 placed it at a sales disadvantage compared with the more sophisticated models from Cox and others. As a result, many of them hung about in hobby shops for years, finally being sold off at fire-sale prices just to free up the shelf space! I myself bought two new bargain-priced boxed examples from local hobby shops in the mid 1970’s!

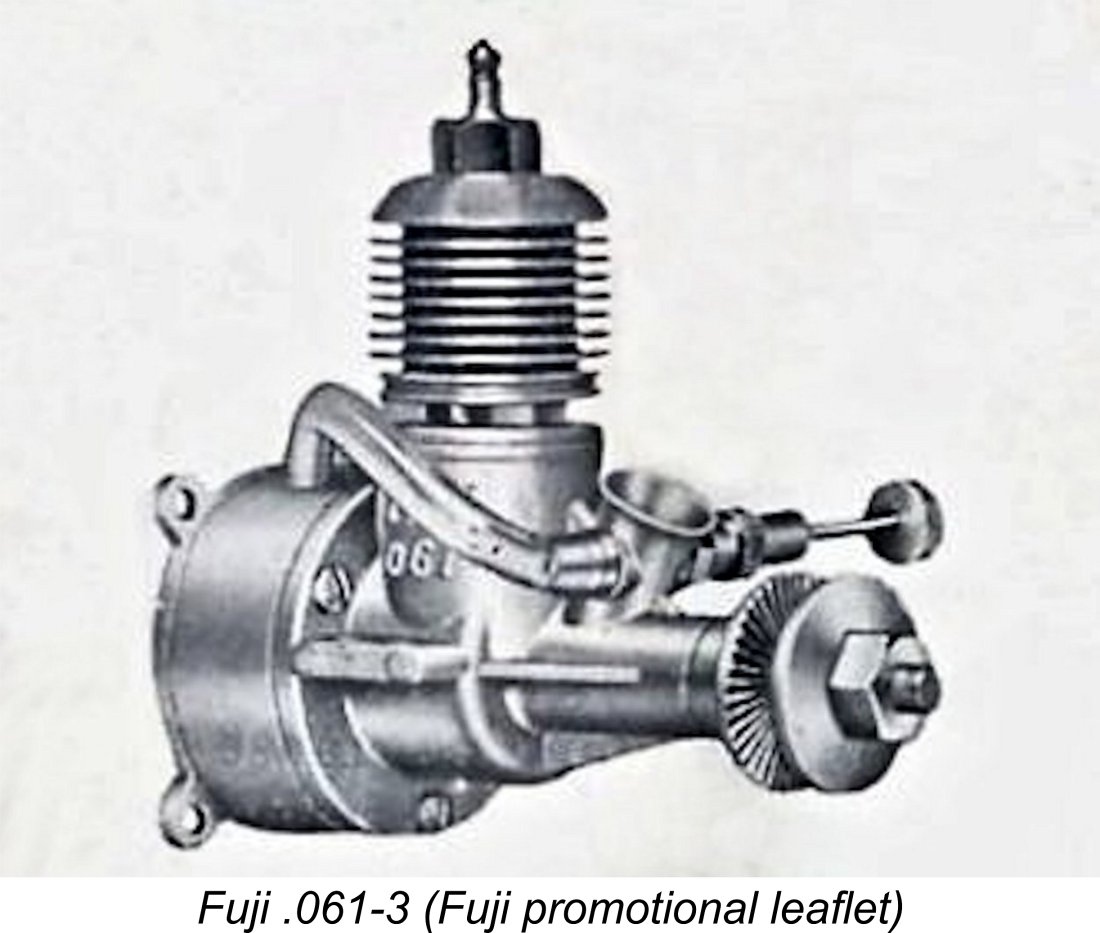

Even if production continued into, say, 1971, it’s very clear that production rates for this model were substantially lower than they had been for the earlier variants. We know of at least 5340 numbered examples as well as an indeterminate number of un-numbered ones. We might assume for discussion purposes that perhaps 10,000 of these engines were produced over a ten-year period, yielding an average annual production rate of some 1,000 units - well down on previous levels. Presumably this could have been higher at the beginning and tailed off as demand fell. Of course, it's also perfectly possible that far more than 10,000 examples were actually produced - there's no way of knowing. Whatever the circumstances, it appears certain that it was the sales performance (or evolving lack thereof) of this model that finally convinced Fuji to throw in the towel and bow out of the ½A displacement category, probably no later than 1971. As far as I’m presently aware, this was the final classic Fuji .049 model. The third Fuji .061 (model 061-3)

As had become usual with the .061 cuin. variants, the crankcase die on this version was slightly modified to accommodate the larger cylinder and to display the correct identification on the cases. The inscription “Fuji .061” was cast onto the right side in place of the .049 designation seen on the companion model. The figures “1.00 cc” appeared on the left side of the case, perhaps indicating that the European market was a primary target for this engine. In all other respects, the two models were identical, and there is no need to repeat the earlier description here. The sole example of this engine with which I’m directly familiar bears the serial number 4275. Presently I have no way of knowing whether these units were numbered in the same sequence as their smaller .049 relatives or whether they had their own serial numbering sequence starting at 1. Conclusion So ends our look at the classic Fuji .049 and .061 cuin. models. These engines were never produced in numbers anything like comparable to those of their American ½A contemporaries. Accordingly (with the exception of the final .049-8 model), they remain among the more difficult ½A units to track down and acquire today. Still, when you do find one, you learn that these were very competently designed and capably-executed little engines which were well able to give good service to their owners, regardless of their experience levels. As such, they doubtless served their intended purpose well. ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2021 |

||

| |

In a series of earlier articles, I’ve covered a number of the Japanese engines marketed during the “classic” era under the Fuji trade-name. I dealt first with the

In a series of earlier articles, I’ve covered a number of the Japanese engines marketed during the “classic” era under the Fuji trade-name. I dealt first with the  But before I get started, I’d like to remind readers of the classification system that I’ve chosen to apply to all of the various Fuji models. There are so many variants all designated by the same name (in this case, Fuji .049!) that it becomes necessary to establish some means of model identification beyond that which was used by Fuji themselves. My system is very simple - it consists of the numerals of the engine’s displacement, followed by a number signifying the chronological position of the variant in question within the overall design sequence for that displacement category.

But before I get started, I’d like to remind readers of the classification system that I’ve chosen to apply to all of the various Fuji models. There are so many variants all designated by the same name (in this case, Fuji .049!) that it becomes necessary to establish some means of model identification beyond that which was used by Fuji themselves. My system is very simple - it consists of the numerals of the engine’s displacement, followed by a number signifying the chronological position of the variant in question within the overall design sequence for that displacement category.  In the previously-referenced article on the

In the previously-referenced article on the

In earlier articles I’ve recorded the fact that the Fuji company got its start in early 1949 making a series of simple and presumably competitively-priced sandcast

In earlier articles I’ve recorded the fact that the Fuji company got its start in early 1949 making a series of simple and presumably competitively-priced sandcast  Fuji were unique among Japanese manufacturers in doing all of their manufacturing work in-house without resorting to outside contracting. This self-sufficiency extended to the production of the necessary castings as well as the manufacture of glow-plugs.

Fuji were unique among Japanese manufacturers in doing all of their manufacturing work in-house without resorting to outside contracting. This self-sufficiency extended to the production of the necessary castings as well as the manufacture of glow-plugs.  The transfer ports were fed by three bypass passages formed through the machining of flats in the outer cylinder wall beneath the transfer ports. These flats interrupted the male cylinder assembly thread. Again, this arrangement precisely mirrored the design of the companion .099 model.

The transfer ports were fed by three bypass passages formed through the machining of flats in the outer cylinder wall beneath the transfer ports. These flats interrupted the male cylinder assembly thread. Again, this arrangement precisely mirrored the design of the companion .099 model.  We saw that the initial model of the Fuji .049 was offered (as far as I’m presently aware) in beam-mount form only. It can’t have taken Fuji long to recognize that many of the American model engine designs which then exerted such a powerful influence upon the ½A market were radially mounted. Indeed, many ½A model designs were appearing which were specifically tailored to that form of mounting.

We saw that the initial model of the Fuji .049 was offered (as far as I’m presently aware) in beam-mount form only. It can’t have taken Fuji long to recognize that many of the American model engine designs which then exerted such a powerful influence upon the ½A market were radially mounted. Indeed, many ½A model designs were appearing which were specifically tailored to that form of mounting.

We now come to the Fuji .049 variant which displays the greatest degree of American influence of them all. If there was any doubt that Fuji were observing trends in American model engine design very closely, this model alone would dispel them!

We now come to the Fuji .049 variant which displays the greatest degree of American influence of them all. If there was any doubt that Fuji were observing trends in American model engine design very closely, this model alone would dispel them!  This version of the Fuji .049 was based upon a completely revised sand-cast crankcase having no provisions for beam mounting. Instead, two thick and well-braced lugs were provided at the rear of the case, and these were drilled through fore and aft to accommodate the two 3mm mounting screws which held things in place. The intake venturi was angled forward more sharply, thus being more in keeping with the style of the larger Fuji models described elsewhere.

This version of the Fuji .049 was based upon a completely revised sand-cast crankcase having no provisions for beam mounting. Instead, two thick and well-braced lugs were provided at the rear of the case, and these were drilled through fore and aft to accommodate the two 3mm mounting screws which held things in place. The intake venturi was angled forward more sharply, thus being more in keeping with the style of the larger Fuji models described elsewhere.

The working components of the engine (cylinder, piston, rod, crankshaft) remained unchanged from those of the earlier models. Bore and stroke also remained unaltered (as they were to do throughout the existence of the Fuji .049 series), but the weight had crept up a little to 55 gm (1.94 ounces) as a result of the addition of the tank.

The working components of the engine (cylinder, piston, rod, crankshaft) remained unchanged from those of the earlier models. Bore and stroke also remained unaltered (as they were to do throughout the existence of the Fuji .049 series), but the weight had crept up a little to 55 gm (1.94 ounces) as a result of the addition of the tank.  The sand-cast Atwood-influenced Fuji .049-3 variant may not have taken the modelling world by storm, but Fuji were clearly far from discouraged. As 1953 drew on, it seems almost certain that the rival ROC .049 had fallen by the wayside - certainly, we hear no more about it in the modelling media thereafter apart from the occasional retrospective reference. Accordingly, Fuji now had no domestic competition in the .049 class. But at this stage, we do begin to hear about the Fuji .049 in the English-language media. We also find the engine appearing on a regular basis in Fuji’s promotional literature. At last, we are beginning to stand on somewhat firmer ground!

The sand-cast Atwood-influenced Fuji .049-3 variant may not have taken the modelling world by storm, but Fuji were clearly far from discouraged. As 1953 drew on, it seems almost certain that the rival ROC .049 had fallen by the wayside - certainly, we hear no more about it in the modelling media thereafter apart from the occasional retrospective reference. Accordingly, Fuji now had no domestic competition in the .049 class. But at this stage, we do begin to hear about the Fuji .049 in the English-language media. We also find the engine appearing on a regular basis in Fuji’s promotional literature. At last, we are beginning to stand on somewhat firmer ground!

However, it didn’t stop there. Fuji had begun to use die-casting in late 1952 with their then-new Silver Arrow 29 design (model 29-5) and had subsequently expanded the use of this technology in mid 1953 with their 099-4 model. It seems clear that by this time they had decided as a matter of policy that any new model would be produced by die-casting.

However, it didn’t stop there. Fuji had begun to use die-casting in late 1952 with their then-new Silver Arrow 29 design (model 29-5) and had subsequently expanded the use of this technology in mid 1953 with their 099-4 model. It seems clear that by this time they had decided as a matter of policy that any new model would be produced by die-casting.  The moving parts also continued to be more or less unchanged, but the same could not be said of the cast iron cylinder! This was a completely different design which abandoned the former radial porting in favour of a set-up which was clearly derived from the Cox .049 models. It used twin exhaust ports with a pair of internal-flute bypass/transfer passages overlapping the exhaust ports to a significant extent. The blind bore, integral cylinder head and integrally-machined cooling fins were retained, but there were now fewer fins, only 5 in number, which were made considerably thicker than before.

The moving parts also continued to be more or less unchanged, but the same could not be said of the cast iron cylinder! This was a completely different design which abandoned the former radial porting in favour of a set-up which was clearly derived from the Cox .049 models. It used twin exhaust ports with a pair of internal-flute bypass/transfer passages overlapping the exhaust ports to a significant extent. The blind bore, integral cylinder head and integrally-machined cooling fins were retained, but there were now fewer fins, only 5 in number, which were made considerably thicker than before.  Speaking of production figures, it’s worth noting at this point that the highest presently-known numbers for the original A-prefix series (5668), the subsequent un-prefixed 049-2 series (7932) and the 6668 figure for the 049-4 model now under discussion total over 20,000 units altogether. These are only the known numbers from a rather small sample - the true total was almost certainly considerably higher. Be that as it may, the implication is that production rates between mid 1950 and 1956 (6 years in total) had averaged at least 3300 units annually, and it may well have been significantly more than this at times. Figures derived from known serial numbers for later models suggest that this rate of production steadily declined from the mid 1950's onwards.

Speaking of production figures, it’s worth noting at this point that the highest presently-known numbers for the original A-prefix series (5668), the subsequent un-prefixed 049-2 series (7932) and the 6668 figure for the 049-4 model now under discussion total over 20,000 units altogether. These are only the known numbers from a rather small sample - the true total was almost certainly considerably higher. Be that as it may, the implication is that production rates between mid 1950 and 1956 (6 years in total) had averaged at least 3300 units annually, and it may well have been significantly more than this at times. Figures derived from known serial numbers for later models suggest that this rate of production steadily declined from the mid 1950's onwards.  The only difference between this model and that previously described was the crankcase casting. Like that of its sibling, this component was produced by die-casting. However it was in effect a die-cast version of the sand-cast case which had appeared on the former 049-3 radial tank-mount model. The use of die-casting allowed the use of somewhat thinner lugs at the rear of the case, and the venturi was identical to that which appeared on the companion 049-4 model described earlier. In fact, apart from the change in the mounting lug configuration, the case was identical to that used on its sibling. The use of the same working components meant that the two variants were functionally identical.

The only difference between this model and that previously described was the crankcase casting. Like that of its sibling, this component was produced by die-casting. However it was in effect a die-cast version of the sand-cast case which had appeared on the former 049-3 radial tank-mount model. The use of die-casting allowed the use of somewhat thinner lugs at the rear of the case, and the venturi was identical to that which appeared on the companion 049-4 model described earlier. In fact, apart from the change in the mounting lug configuration, the case was identical to that used on its sibling. The use of the same working components meant that the two variants were functionally identical.  Be that as it may, the engine’s next appearance was in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”, when an illustration of the engine was included in an article by Chinn which discussed the spectrum of glow-plug engines then available to the modelling public worldwide.

Be that as it may, the engine’s next appearance was in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”, when an illustration of the engine was included in an article by Chinn which discussed the spectrum of glow-plug engines then available to the modelling public worldwide.  This was actually a good average figure for a sports ½A glow-plug motor of the period. However, it came nowhere near the figure of 0.066 BHP @ 17,200 rpm which Chinn had measured for the standard-setting

This was actually a good average figure for a sports ½A glow-plug motor of the period. However, it came nowhere near the figure of 0.066 BHP @ 17,200 rpm which Chinn had measured for the standard-setting  Applying this philosophy to the Fuji .049, it must have been clear that even if its future impact was limited to helping a number of new modellers to get started in the hobby and convincing them to stay with Fuji when they moved on to larger engines, that in itself would be a worthwhile contribution. Given the realization that competing successfully in the performance-oriented American market would be both expensive and problematic, they clearly decided that their future efforts in the .049 field would be far better focused on the domestic and Asian sport-flying markets. It’s certainly true that the following few variants do not appear to have been promoted with any intensity in English-speaking markets.

Applying this philosophy to the Fuji .049, it must have been clear that even if its future impact was limited to helping a number of new modellers to get started in the hobby and convincing them to stay with Fuji when they moved on to larger engines, that in itself would be a worthwhile contribution. Given the realization that competing successfully in the performance-oriented American market would be both expensive and problematic, they clearly decided that their future efforts in the .049 field would be far better focused on the domestic and Asian sport-flying markets. It’s certainly true that the following few variants do not appear to have been promoted with any intensity in English-speaking markets.  The crankcase continued to be a die-cast item, although it was far more cleanly-cast than that of the preceding two models. It’s apparent that Fuji was now well on the way to acquiring the complete mastery of this technology that they were soon to display in products such as their classic range of outboard motors. In making this statement, it’s worth reminding ourselves once more that Fuji produced their own castings throughout their existence.

The crankcase continued to be a die-cast item, although it was far more cleanly-cast than that of the preceding two models. It’s apparent that Fuji was now well on the way to acquiring the complete mastery of this technology that they were soon to display in products such as their classic range of outboard motors. In making this statement, it’s worth reminding ourselves once more that Fuji produced their own castings throughout their existence.

So this was what Fuji did. They released an over-bored version of the 099-6 model described above which had a bore of 11.27 mm as opposed to the former 10.2 mm. The stroke remained the same at 10.0 mm, and the resulting model looked identical to the .049 version but had a displacement of 0.998 cc (0.0609 cu. in.). Weight was essentially unchanged at 45 gm (1.59 ounces). The output claimed by the factory had rise to 0.10 BHP @ 11,000 - 13,000 rpm, again a figure which we may well feel justified in viewing with some scepticism.

So this was what Fuji did. They released an over-bored version of the 099-6 model described above which had a bore of 11.27 mm as opposed to the former 10.2 mm. The stroke remained the same at 10.0 mm, and the resulting model looked identical to the .049 version but had a displacement of 0.998 cc (0.0609 cu. in.). Weight was essentially unchanged at 45 gm (1.59 ounces). The output claimed by the factory had rise to 0.10 BHP @ 11,000 - 13,000 rpm, again a figure which we may well feel justified in viewing with some scepticism.  The next stage in the Fuji .049 saga involved a significant change in the design of the upper cylinder. For the first time in the .049 category, Fuji abandoned the blind bore in favour of a separate screw-in cylinder head turned from alloy bar stock.

The next stage in the Fuji .049 saga involved a significant change in the design of the upper cylinder. For the first time in the .049 category, Fuji abandoned the blind bore in favour of a separate screw-in cylinder head turned from alloy bar stock.  A further change seen on this model was the abandonment of the old split thimble needle valve in favour of a far more sophisticated item using a knurled thimble which was tensioned by a single-leaf spring clip. This gave far more positive and stable needle valve control than the former system. At this time, Fuji was abandoning the split thimble on all of its remaining models which retained this feature - a wise move.

A further change seen on this model was the abandonment of the old split thimble needle valve in favour of a far more sophisticated item using a knurled thimble which was tensioned by a single-leaf spring clip. This gave far more positive and stable needle valve control than the former system. At this time, Fuji was abandoning the split thimble on all of its remaining models which retained this feature - a wise move.

We now come to the model by which Fuji’s participation in the ½A displacement category is most commonly recognized today. This is because this model of the Fuji .049 was the only one which seems to have been widely distributed around the world. It was also the variant which enjoyed by far the longest production period.

We now come to the model by which Fuji’s participation in the ½A displacement category is most commonly recognized today. This is because this model of the Fuji .049 was the only one which seems to have been widely distributed around the world. It was also the variant which enjoyed by far the longest production period.  The die-cast tank was closed at the back, just as on the earlier 099-3. It sealed at its front rim with the circular mounting flange which was cast in unit onto the crankcase and machined to accommodate the tank. Inside the tank, a screw-in backplate was employed.

The die-cast tank was closed at the back, just as on the earlier 099-3. It sealed at its front rim with the circular mounting flange which was cast in unit onto the crankcase and machined to accommodate the tank. Inside the tank, a screw-in backplate was employed.  The engine was (and is) a very easy starter with excellent running qualities, albeit showing nothing remarkable in the way of performance. The makers published a modestly reduced but still rather extravagant performance claim of 0.06 BHP @ 11,000-12,000 rpm - a little closer to reality than the former claim, but still somewhat inflated based on actual experience. Some years ago I made a note of an alternative claim of 0.042 BHP @ 13,300 rpm, which I find quite believable. However, I seem to have mislaid the source of that claim, hence being unable to vouch for its authenticity.

The engine was (and is) a very easy starter with excellent running qualities, albeit showing nothing remarkable in the way of performance. The makers published a modestly reduced but still rather extravagant performance claim of 0.06 BHP @ 11,000-12,000 rpm - a little closer to reality than the former claim, but still somewhat inflated based on actual experience. Some years ago I made a note of an alternative claim of 0.042 BHP @ 13,300 rpm, which I find quite believable. However, I seem to have mislaid the source of that claim, hence being unable to vouch for its authenticity.  The engine's rather low compression ratio was very obvious when flicking it over in the test stand - there simply wasn't much resistance! However, it felt really good - smooth as silk, and would hold what compression it had at top dead centre for a very long time. The quality of its construction left little to be desired.

The engine's rather low compression ratio was very obvious when flicking it over in the test stand - there simply wasn't much resistance! However, it felt really good - smooth as silk, and would hold what compression it had at top dead centre for a very long time. The quality of its construction left little to be desired.

competing British offerings from

competing British offerings from  It seems unlikely that production of these engines continued much if at all past 1970. The 049-8 was featured in a Fuji promotional leaflet dating from around 1965 (based on the appearance of the Fuji 099-11 on this leaflet), and a fair number of them were sold in the red, black and white checkerboard boxes which seem to have originated in around 1966. The design also appeared in a later leaflet which associated it with the Fuji 15-IV (model 15-5), the Fuji 099J-II (model 099-12) and the Fuji 099S-II (model 099-13), all of which seem to have appeared in around 1970. However, it’s likely that production ceased very soon thereafter, if it had not already done so in reality.

It seems unlikely that production of these engines continued much if at all past 1970. The 049-8 was featured in a Fuji promotional leaflet dating from around 1965 (based on the appearance of the Fuji 099-11 on this leaflet), and a fair number of them were sold in the red, black and white checkerboard boxes which seem to have originated in around 1966. The design also appeared in a later leaflet which associated it with the Fuji 15-IV (model 15-5), the Fuji 099J-II (model 099-12) and the Fuji 099S-II (model 099-13), all of which seem to have appeared in around 1970. However, it’s likely that production ceased very soon thereafter, if it had not already done so in reality.  I couldn’t call this article complete without a reference to what appears to have been the final Fuji .061 model. This was an over-bored version of the 049-8 model just described, evidently appearing concurrently with that model. Once again, it was more or less identical in all respects to its .049 cuin. relative with the exception of the bore, which was as usual increased to 11.27 mm to give the greater displacement.

I couldn’t call this article complete without a reference to what appears to have been the final Fuji .061 model. This was an over-bored version of the 049-8 model just described, evidently appearing concurrently with that model. Once again, it was more or less identical in all respects to its .049 cuin. relative with the exception of the bore, which was as usual increased to 11.27 mm to give the greater displacement.