|

|

½A Rarity—the ROC .049

According to no less an authority than Peter Chinn, the ROC .049 was the first Japanese .049 cuin. engine to reach the market. Since there is ample evidence to suggest that the rival Fuji .049 appeared in late 1950, this would place the advent of the ROC .049 in early to mid 1950, within a year or so of the class really getting started in the USA where it originated. Given this fact, the ROC is actually one of the earlier engines of this displacement regardless of its country of origin. If the ROC .049 gained any advantage from appearing first on the Japanese market, it would appear that any such advantage was extremely short-lived. The engine's marketplace tenure appears to have been unusually short - by 1954, when Japanese model engine developments first began to receive attention from the English-language modelling media, the ROC .049 was already long gone, as were its manufacturers to all appearances. It seems not unlikely that the competition from Fuji proved to be too much for the ROC company to resist. As a result of its seemingly short production life, the ROC .049 is extremely rare today, at least outside Japan - in fact, it must surely have a claim to being one of the greatest challenges for anyone having an interest in expanding their ½A collection. In 40 or more years of looking, the illustrated example is the only one that I've ever encountered in the metal. Despite its obvious flaws, including the fact that it was missing both its tank and its needle, I snapped it up when it appeared on eBay, figuring that I might never get another chance. It is only thanks to this that I am able to present the information in this article. Before starting, I'd like to record my indebtedness to the late Tim Dannels, who most generously shared information in his files relating to this engine. Tim did more than anyone I know to preserve the history of these wonderful little pieces of precision machinery, and we all owe him a great debt. Now, having characterized our subject, let's review some background. Background

It's important to recognize at this point that the emergence of the ½A class for 0.049 cuin. engines was very much a "made in America" development. A full account of this development in America has been prepared by my good mate Maris Dislers. It may be read elsewhere on this website.

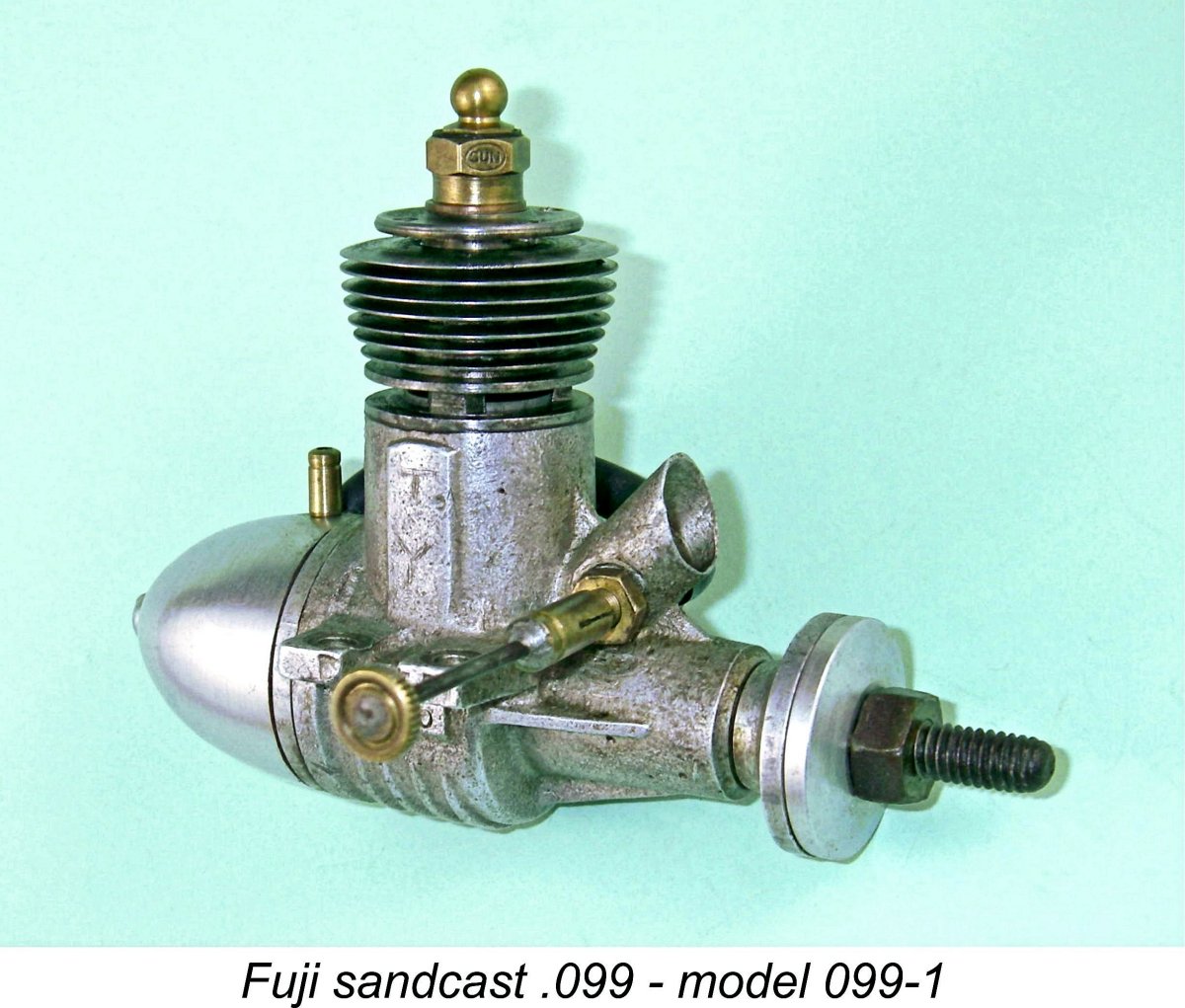

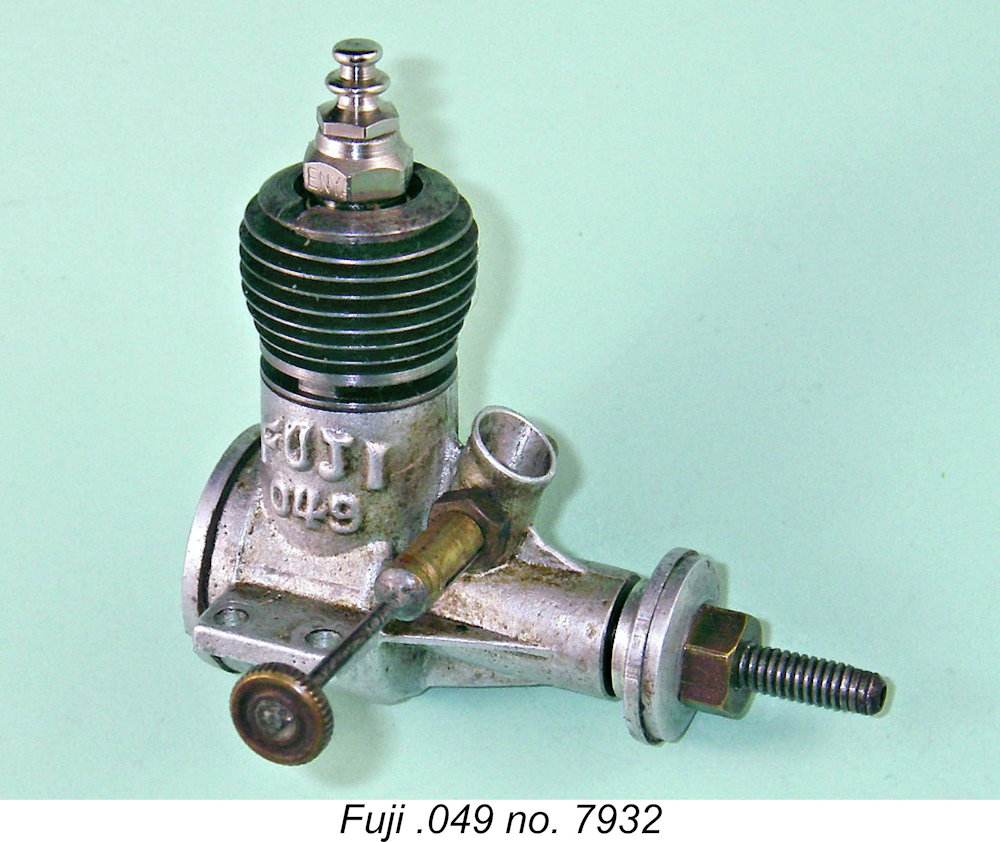

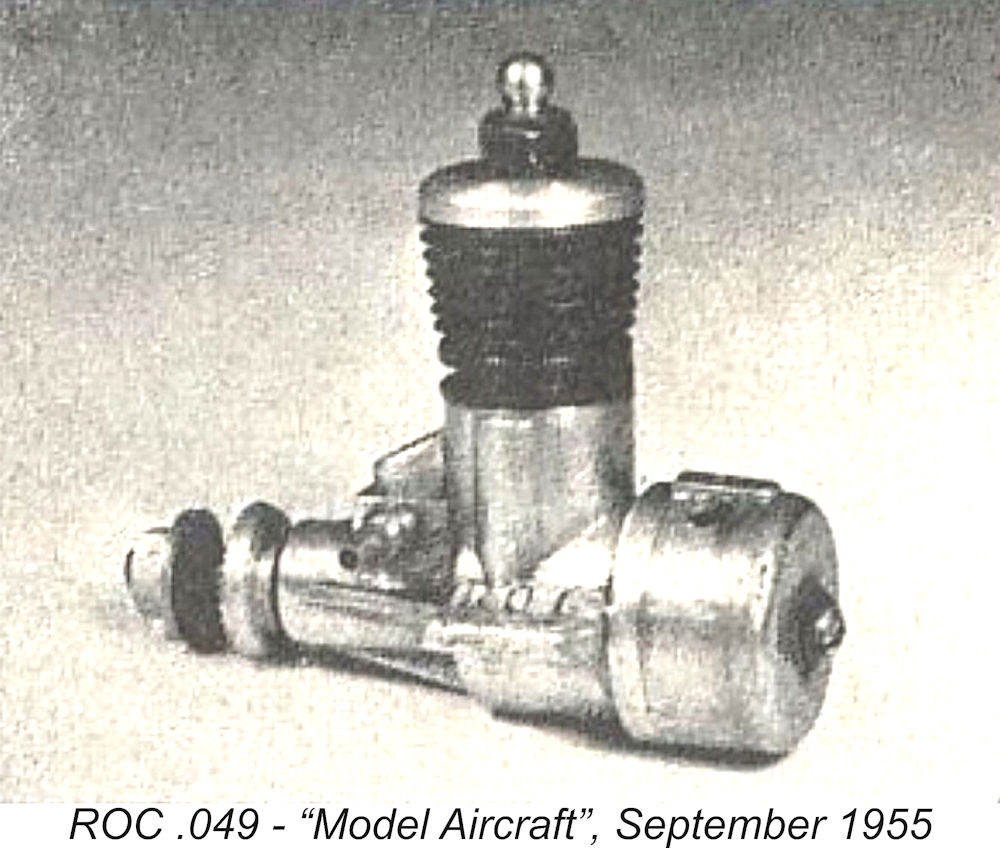

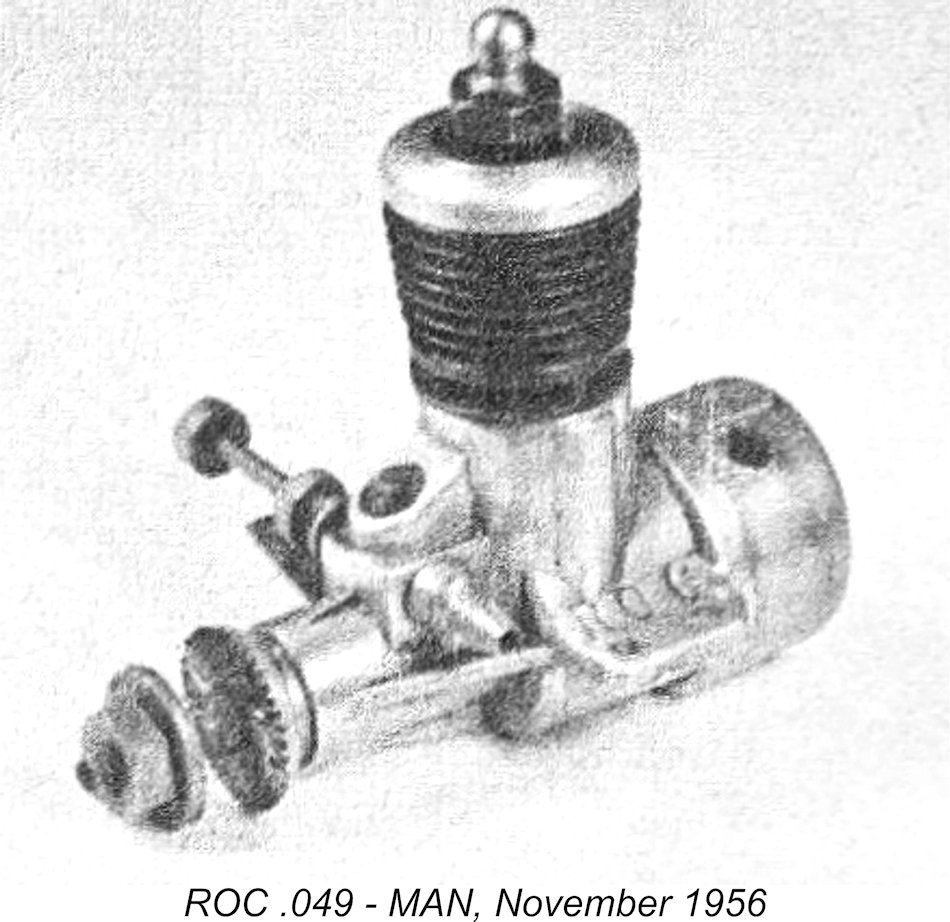

By contrast, the .049 cuin. category was largely neglected by Japanese makers. In fact, This focus on the 1.5 cc displacement category was in fact mirrored in Britain, where the displacement limit for the S.M.A.E. ½A class (originally Class 1) was established at 1.5 cc (0.091 cuin.). This naturally drew considerable consumer attention to that displacement category, the result being that all of the major British manufacturers other than Mills Brothers produced popular 1.5 cc models. Although domestically-manufactured engines of around .049 cuin. displacement did become increasingly available in Britain as the 1950's drew on, opportunities for their use in competition were minimal. Although a few engines of similar or even smaller displacement had appeared in America prior to 1949, the ½A .049 cuin. boom only really This was a period during which Japanese manufacturers were soaking up influences from American makers, whose products were then appearing regularly in Japan in the hands of American service personnel stationed there following the conclusion of WW2. No doubt a number of the new American ½A engines quickly showed up in Japan in the hands of these individuals. It seems almost certain that the makers of the ROC and Fuji .049 engines got the idea of entering this market through exposure to American .049 models in the hands of US service personnel. Given the introductory dates of the more trend-setting American .049 models, such exposure could not have commenced prior to mid 1949 or thereabouts. This completely explains the fact that both ROC and Fuji appear to have entered this market in 1950 following a period of appraisal of what they were seeing. Since the "popular" domestic market seems to have been centred upon the .099 category, the primary target market for the Japanese .049's was most likely the aforementioned US service personnel. This was a time when the more forward-thinking Japanese companies in many areas of endeavour were very much open to making anything that might find acceptance among the very sizeable and well-funded "imported" American service population, thus potentially opening the door to export activity down the road. At this stage, they did not have to reach out to the American market - that market had come to them! As one might expect given the implied date of the engine's introduction, contemporary references to the ROC .049 in the English-language modelling media appear to be non-existent. This is no surprise, since the activities of the Japanese model engine industry were not subject to international scrutiny at this time. The only two authoritative English-language references to the ROC that I've been able to find were a pair of far later articles by Peter Chinn which appeared in the September 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” and the November 1956 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN). These articles both referred to the engine in retrospective terms. An image of the engine accompanied each article.

It seems clear that the ROC .049 was out of production as of 1954 since it was not included with other Japanese products in Chinn's listing of glow-plug engines for 1954/55 which appeared in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. This actually underscores the sincerity of Chinn's belief that the ROC was the first such engine to appear in Japan, since Chinn clearly remembered it primarily for that reason. However, it would be nice to have some hard evidence to clarify these statements. Alas, none appears to be available. However, even assuming that Chinn's understanding was correct, there's little doubt that Fuji were not far behind.

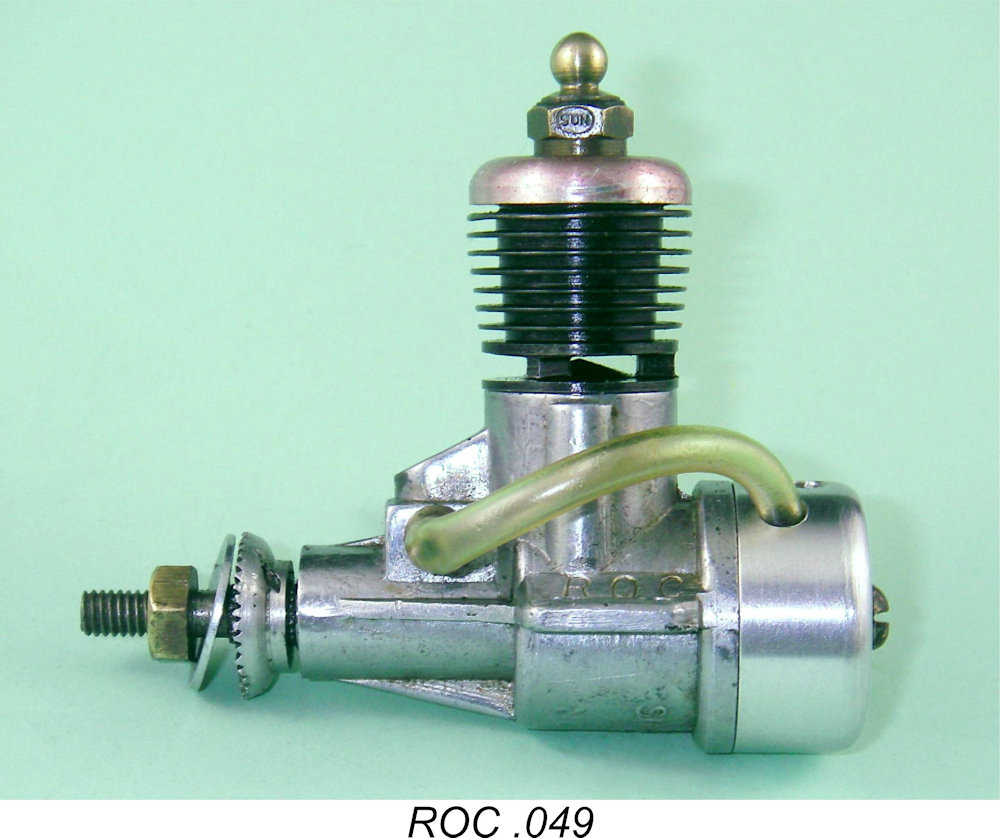

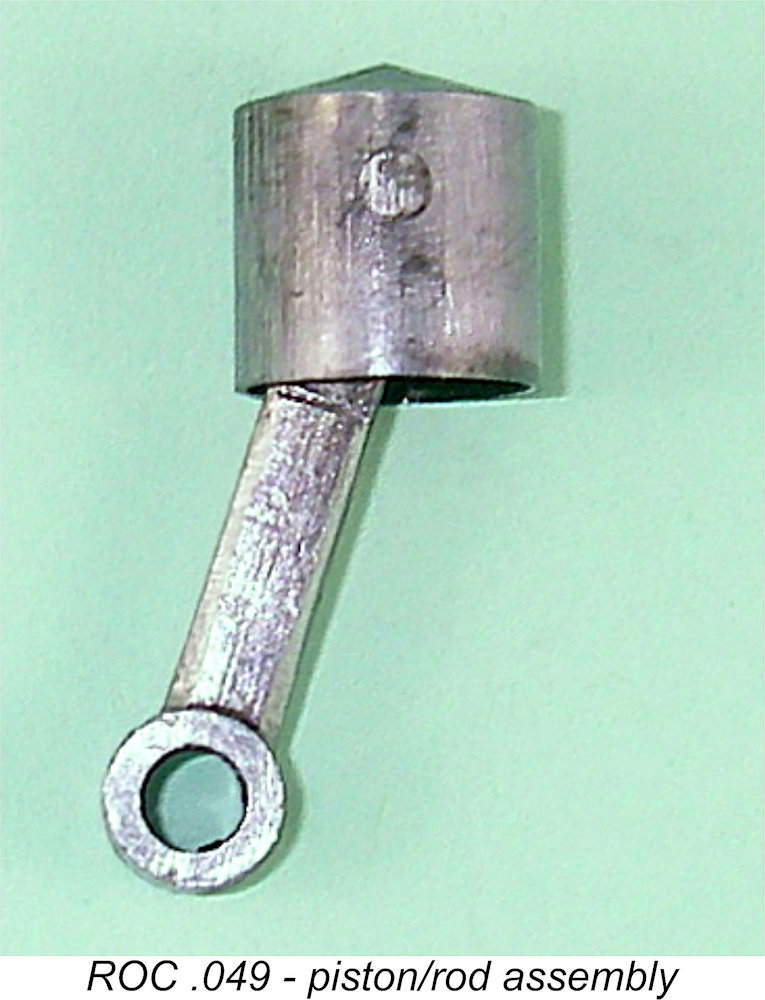

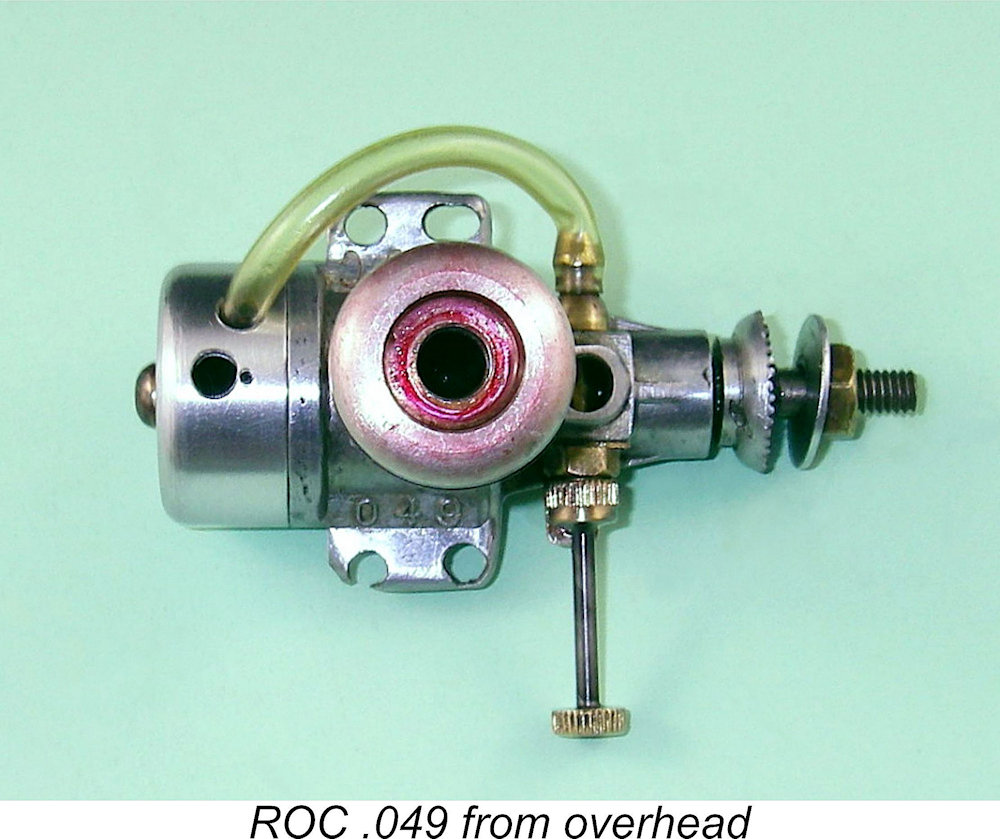

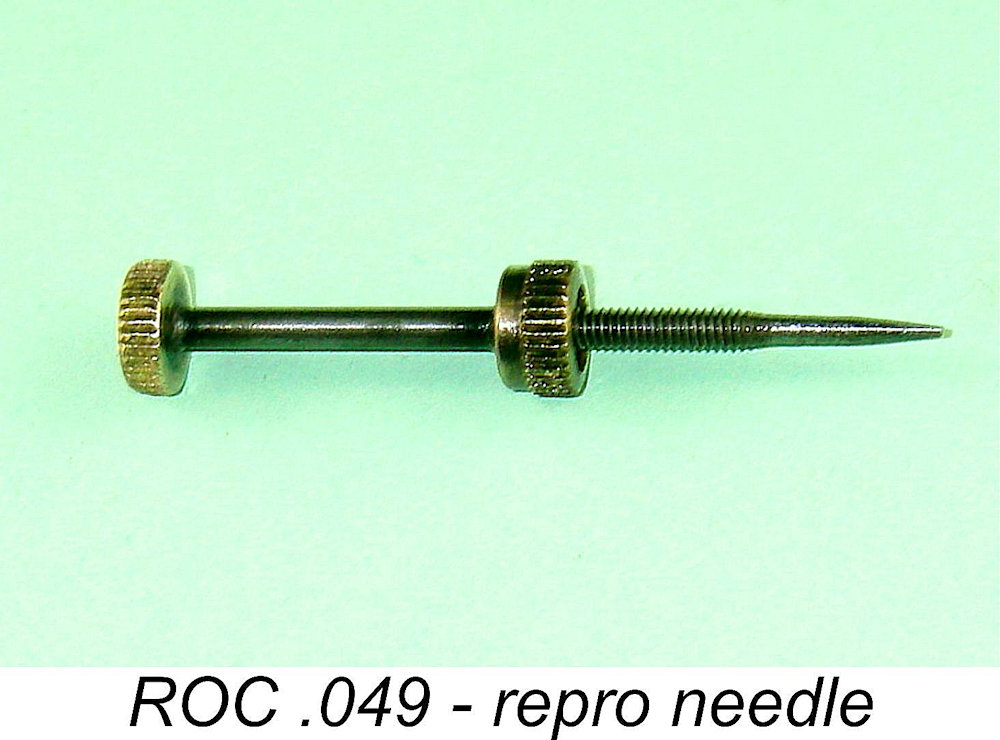

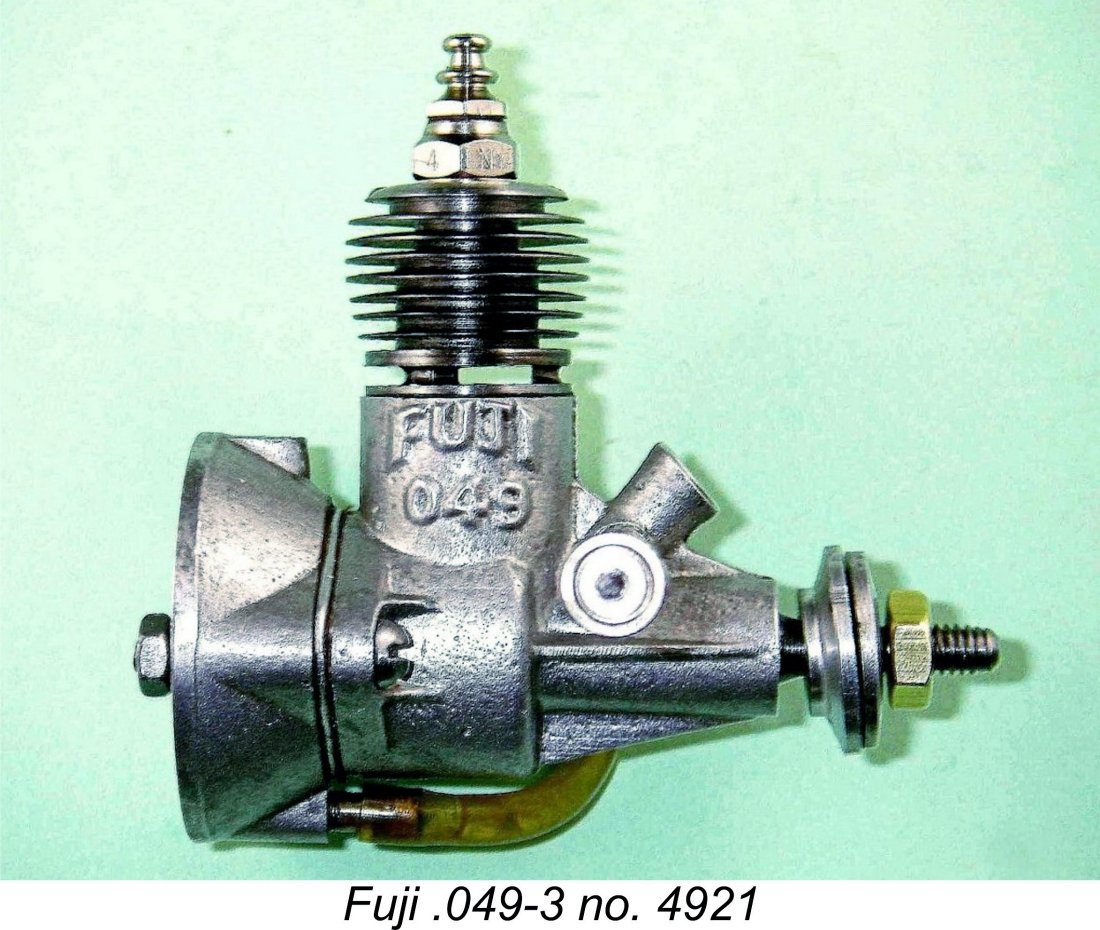

Whether or not the ROC company got there first, there is ample evidence to suggest that Fuji had entered the .049 category prior to the end of 1950. This seems to date the introduction of both models to that year. Regardless of which came first, the That said, the possibility actually exists that both the Fuji and ROC .049 models were preceded by the ultra-obscure and seemingly short-lived Haru .049 which is known to have been manufactured by Mr. N. Haruyama, later designer of the Sky Shark and Sky Queen engines which have been reviewed elsewhere. However, the very existence of the Haru range appears to have been a very well-kept secret outside Japan, while the Haru .049 itself probably sets the standard for present-day invisibility! Consequently, at present there is no way of knowing which of these designs really took precedence. There is also some evidence to suggest that the TOP range which I’ve covered separately may have included an even earlier .049 model. I’m aware of a relatively early Japanese spark ignition engine (missing its timer) which has been claimed by its owner as a TOP .049, although the engine carries no identification to this effect and I have yet to see any firm evidence to substantiate this claim. However, if this engine is indeed a TOP .049 as claimed, then it is almost certainly not only the true "first" Japanese ½A model but one of the first such engines produced anywhere in the world, dating in fact from before the term ½A came into use. Description The illustrated example of the ROC .049 arrived well gummed up and missing its tank and needle. The latter was in fact broken off, leaving the stump inside the internally-threaded spraybar. In addition, the holes in the beam mounting lugs were enlarged, to the point that one had actually broken through the edge of the lug. The engine did however still have an original and functional Japanese "Sun" glowplug, a near-clone of the contemporary Arden item. I was able to free up and clean the engine, after which I made a machined look-alike tank as well as a new look-alike needle to replace the missing items. I elected to leave the mounting lugs well alone - aluminium alloy repairs on such small cases carry an unacceptably high risk of making matters worse. Apart from that, the finished engine looks pretty much like those illustrated with the two previously-mentioned articles by Peter Chinn. In fact, I used those two images to scale off the dimensions for the replacement parts. The main flaw in my restoration is my enforced use of a machined aluminium alloy tank in place of what was clearly a die-cast item based on the original images.

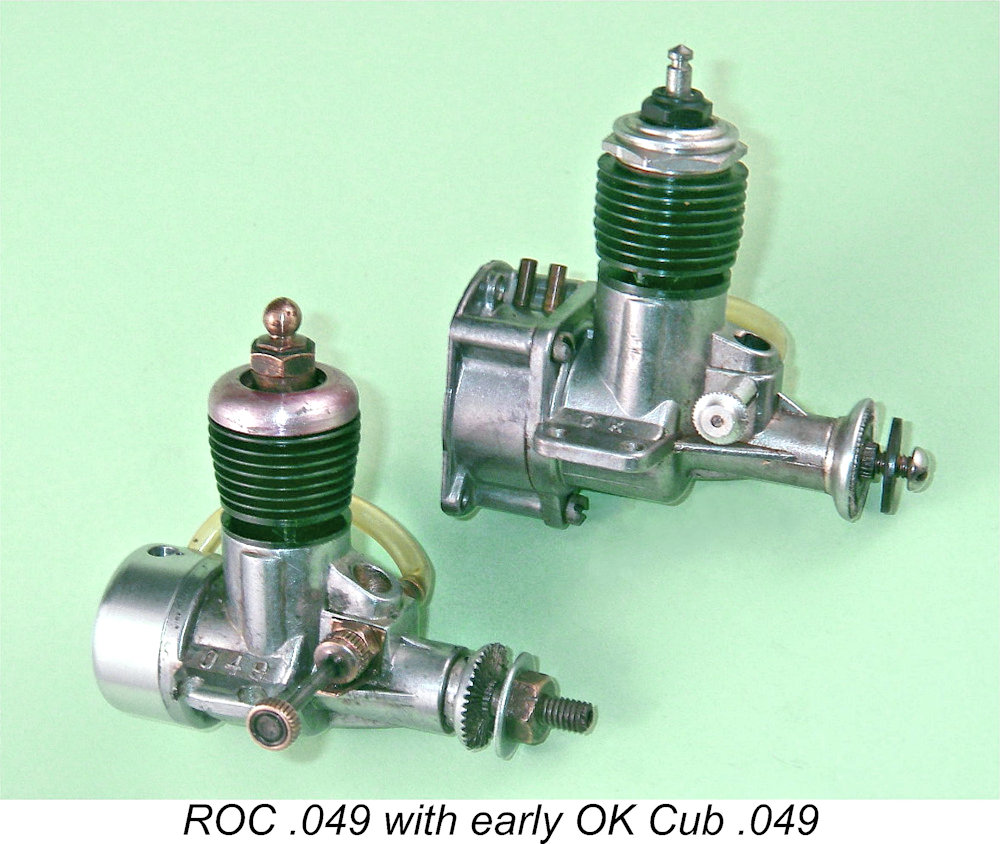

A side-by-side comparison between the ROC and Cub .049's is sufficient to highlight the close similarities between the two. These similarities are even more obvious when the somewhat differently-configured tanks of both engines are removed (the Cub acquired a bolt-on radial tank mount and lost its Arden glow plug later in 1949 when it appeared in "kit" form). Both are radially-ported plain-bearing FRV glow-plug engines having screw-in steel cylinders with integrally-formed cooling fins. Both have screw-in alloy heads which are tapped to accept a ¼-32 long-reach glow plug. Both use conventional gudgeon pins at the small end of the con-rod instead of the increasingly popular ball-and-socket arrangement. The design of the intake venturi on both models is more or less identical. Finally, both models have screw-in backplates and cast alloy back tanks. To determine the individual characteristics of the ROC, we have to take it apart. The first thing to do is measure up the bore and stroke. When we do so, we encounter a very interesting fact - the major working dimensions of the engine were established using Imperial units! Bore and stroke measure up very precisely at 13/32 in. (.4063 in./10.33 mm) and 3/8 in. (0.3750 in./ 9.52 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.798 cc (0.0487 cuin.). In addition, the crankshaft main journal diameter is 1/4 in. exactly (0.2500 in./ 6.35 mm). The fact that other dimensions depart from the Imperial standard shows that the use of Imperial units was confined to the engine's major working dimensions. With a single exception to be noted later, the rest of the engine appears to be dimensioned to metric standards throughout.

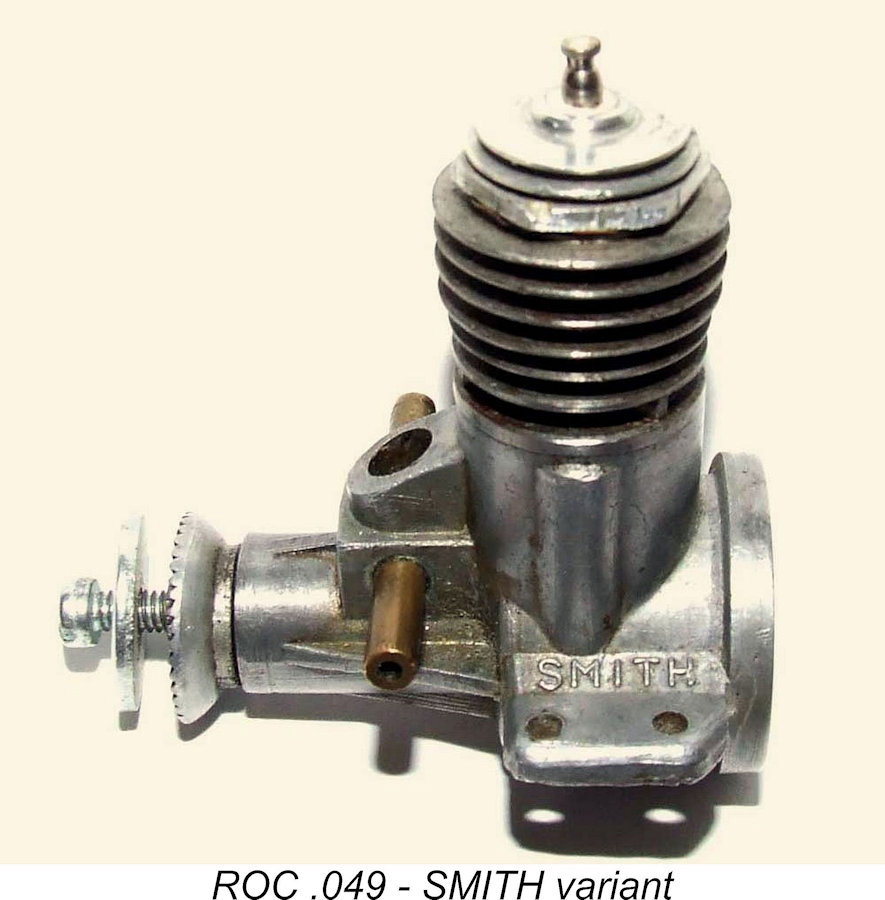

The engine is constructed around a cleanly pressure die-cast crankcase which incorporates both the main bearing and intake venturi as well as the necessary internally-threaded spigot for the screw-in cylinder. The engine's ROC identity is stamped onto a fillet above the left-hand mounting lug (looking forward in the direction of flight), while the numerals 049 are cast in relief onto the corresponding fillet above the right-hand lug. Unlike the case of the OK Cub .049 which allowed either beam or radial mounting, the ROC case is arranged strictly for beam mounting.

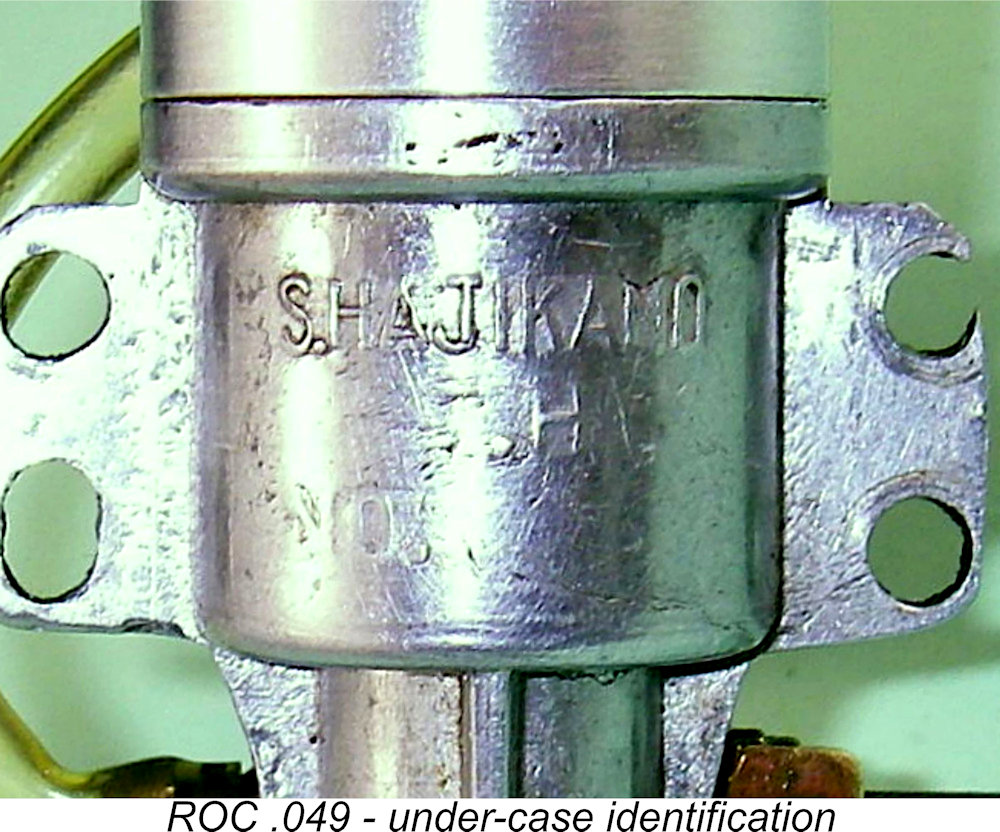

Alternatively, although perhaps less probably, this may refer to the company which produced the castings - there's no way of knowing for sure. The meaning of the letters T.H is presently obscure. The fact that the letters NO. are offset to the left of centre as read may well indicate an original intention to apply serial numbers to these engines, since the offset created the necessary space to do so. If this was the intention, the practise was evidently abandoned either at the outset or by the time this particular engine was manufactured.

There is clear evidence in the form of some residual coloration that this head was originally anodized a metallic maroon colour. However, the coloration did not survive the repeated operational heat cycles to which this well-used example has clearly been subjected. This was a not-uncommon failing of anodizing at the time with which we are concerned. As usual in these cases, the original coloration is best preserved beneath the plug seal where it is not exposed to the air during heat cycles. The porting of the ROC .049 again follows the OK Cub arrangements exactly. There are three sawn rectangular exhaust openings with three transfer ports drilled at an upward angle through the pillars of metal between the exhaust ports. These transfer ports overlap the exhaust ports to a large extent, giving a relatively short blow-down period. This is the only other case in which an Imperial dimension is encountered - the unusually small transfer ports have a diameter of 1/16 in. exactly. It is of course possible that this is merely a reflection of the tools which were available at the time of manufacture - during Japan's post-war industrial recovery phase, Japanese manufacturers simply used what they could get.

This arrangement is identical in all respects to that utilized in the OK Cub models. As such, it was theoretically covered by US Patent no. 2,179,683 which had been taken out by Charles Brebeck to protect his system. Like the OK Cub model, the ROC .049 used a conventional pressed-in steel gudgeon pin to link the piston to the rod small end. This pin appears to have been pressed in prior to the final sizing of the piston, since the exposed ends of the pin are flush with the outer ends of the piston bosses, being finished as part of the overall piston surface. The rod is a die-casting of quite sturdy dimensions for an engine of this size. The un-bushed big end bearing has a diameter of 3.50 mm (0.138 in.).

Although it is not identical, the ROC's integrally-cast intake venturi is very similar in design to that of the OK Cub. The ROC venturi's inside diameter of 4.50 mm (0.177 in.) is somewhat less than that of the crankshaft induction port. The combination of the two results in relatively rapid opening and closing of the induction system along with an unusually long induction period for an engine of this type, the relevant figures being 30 deg. after bottom dead centre to 30 deg. after top dead centre for a total opening period of 180 degrees.

The brass spraybar has a major external diameter of 4 mm, being externally threaded M4x0.75 for its brass retaining nut. The portion which corresponds with the actual venturi throat is however waisted to only 3 mm. A single jet hole communicates from the spraybar interior to the venturi. The arrangement of the needle valve assembly departs significantly from that of the OK Cub, being designed along typical Japanese lines. The spraybar is internally threaded M2x0.4 to accept the externally-threaded steel needle. Although the needle was broken off from the illustrated example as received, the stub remained in place and could be extracted to obtain the working dimensions of the taper. The image which was published with the November 1956 The needle in the illustrations is of my own manufacture based on the MAN image. Thanks to the fine 0.4 mm thread pitch, the diametrically-relieved section at the fuel jet location and the well-fitted tensioning spring, it provides very precise mixture control along with a high level of stability. Based on the available image as well as the surviving original stub, I reckon that my repro is pretty close to the original.

In terms of workmanship, I would objectively rate the standard of manufacture of this engine as being well up to that encountered in the majority of such commercial products from outside Japan. This example has clearly had a fair bit of use (and abuse!) but remains in fine running condition with adequate compression and excellent bearing fits. The external finish too is well up to the best contemporary standards. Most purchasers back in 1950 would have found little about which to complain. Anyway, there we have it - a full description of what may well have been the first Japanese .049 engine of them all! The design similarities between this engine and the original 1949 OK Cub .049 are simply too great to be coincidental, making it appear almost certain that the ROC was quite deliberately modelled very closely upon the American original in an attempt to attract sales from among the numerous American members of the Army of Occupation. However, appearance and styling are one thing - performance is quite another! How does it run by comparison with its American ancestor and its Japanese Fuji rival? Only one way to find out - let's put them all to work making some noise! The ROC, Fuji, and OK Cub .049's on the Bench

Although small glow-plug engines like these tend to respond very well to healthy doses of nitro, I elected to run this comparison using a fuel containing only around 5% nitro plus a bit of extra oil. This would be an accurate reflection of the fact that few modellers other than all-out competition types would have used high percentages of nitro in 1950.

I used the repro back tank for all runs with this engine, also installing a Fox glowplug to conserve the original Sun plug. The tank gave a leaned-out running time of around 1 min 45 seconds including warm-up - a bit long for free flight, but completely manageable by timing the run prior to launch or injecting a specific amount of fuel into the tank before starting.

I'd have to say that the running qualities of the Fuji were not quite as good as those of the ROC. There was a very subtle but nonethelesspersistent misfire with the Fuji which couldn't be completelycleared using the needle. I'd say that either Finally, I fired up the OK Cub. This example has had a lot of use and is a little leaky as regards its piston seal. This did not prevent it from starting up very nicely on a prime and running superbly. As soon as it fired up, it was immediately clear that it was going to outperform the other two. The test figures obtained with the various props amply bore out this impression. The comparative figures obtained for all three engines were as follows, with implied horsepower figures for the ROC also included:

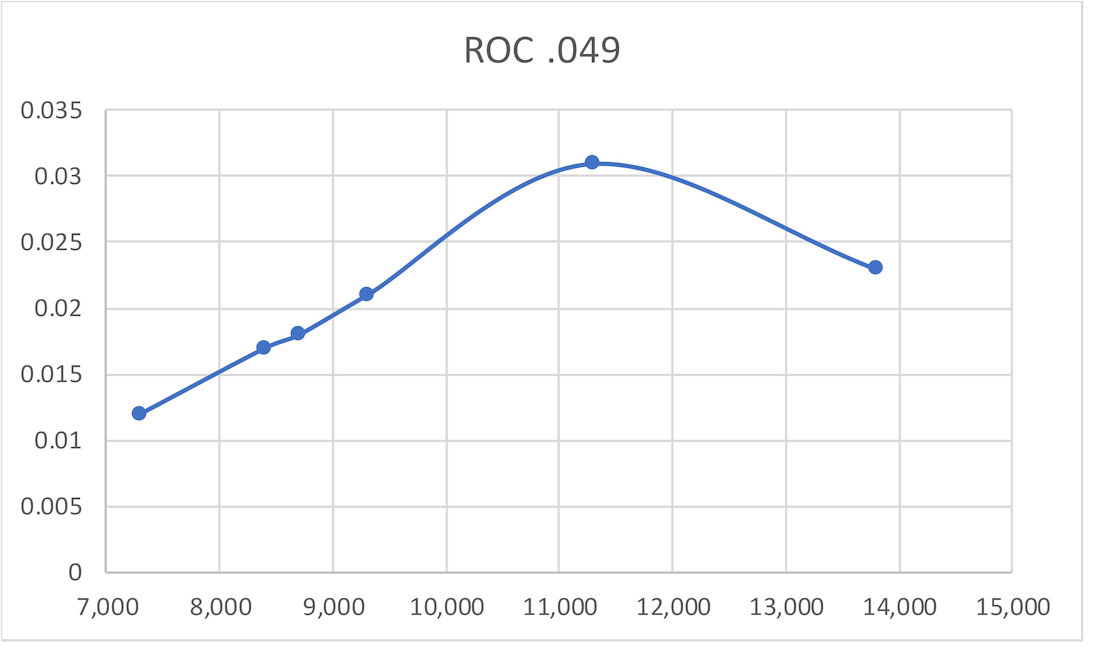

The comparative figures are most illuminating! Although I didn't bother including actual power curves for the Fuji and OK Cub given the fact that this article is not primarily about them, I did check the indicated power output figures. In terms of peak output, there's no doubt at all that the OK Cub wins hands down - the above RPM numbers imply a peak output of somewhere around 0.045 BHP @ 12,800 rpm. By contrast, the ROC could only muster somewhere around 0.033 BHP @ 12,000 or thereabouts. The power curve for the ROC looks something like this. Clearly I'm missing a few intermediate props from my "classic" .049 test set. As a result of this, the peak is poorly defined. I'll have to rectify this at some point.

It is of course necessary to keep these figures in perspective. Results obtained in 1959-1961 by Peter Chinn for the four British glow-plug .049's which appeared during that period included 0.052 BHP @ 14,300 rpm for the A-M .049 Wen-Mac "clone" (admittedly on 15% nitro), 0.049 BHP @ 14,600 rpm for the Cobra .049 (again on 15% nitro), 0.042 BHP @ 12,700 rpm for the FROG .049 and 0.035 BHP @ 12,600 rpm for the anaemic D-C Bantam. The latter two figures were obtained using low-nitro fuel similar to that used in my own tests. It would appear that none of the c. 1960 British .049's represented any major advance over the 1950 crop tested for this article, at least in performance terms! The SMITH and PIGEON enigmas

The sole example of an engine marked in this manner which has come to my attention had a screw-in glow head very like an OK item in place of the conventionally-tapped head featured on the ROC. I have no idea if this is original or if it represents an owner intervention. The engine also utilized a machine screw which engaged with a tapped hole at the front of the shaft to secure the prop.

It seems to be a completely unsubstantiated possibility that Even more obscurely, at least one existing example of the engine displays the name PIGEON cast in relief onto the left-hand side of the crankcase above the mounting lug. The other side bears the cast 049 inscription seen on the ROC examples. This engine also sports a different fuel tank. I have been unable to ferret out even the slightest trace of any indication of the significance of this name. All that can be said is that the manufacturers of the ROC .049 were clearly willing to produce engines which were marketed under other names. There's definitely a story there if one could somehow unravel it ...................but I'm not holding my breath! Conclusion

Such an image would not work in the favour of our unknown manufacturer. Fuji probably did well to plough their own furrow by giving their own .049 model a rather distinctive "Japanese" appearance which owed little (at this time It's certainly possible that despite the ROC having an apparent modest performance edge, the marketplace competition provided by the Fuji .049 proved to be more than the ROC .049 could withstand. However, it's equally possible that the manufacturer of the ROC .049 simply discovered that he could make more money by applying his obvious precision engineering talents to some form of commercial endeavour other than model engine manufacture. He wouldn't have been the first to do this, nor would he have been the last by any means. Whatever the reason, the ROC .049 clearly faded from the scene rather quickly, leaving Fuji in uncontested control of the Japanese ½A manufacturing category, a position which they were to maintain throughout the 1950's. There's no way of knowing how many examples of the ROC were made and sold - all that can be stated with certainty is that examples outside Japan are few and far between today. So look long and hard, all you ½A collectors out there - there must be other examples waiting to be found! If anyone can help to add to this story through the provision of additional images or design details, I will as always gladly add the new information to this article along with full acknowledgement of my sources! ________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN March 2013 This revised edition published here October 2023 |

||||

| |

Here we return to Japan for a look at a neat little engine which remains one of the least commonly encountered members of the ½A model engine family. We’ll be taking a close-up look at the very elusive ROC .049.

Here we return to Japan for a look at a neat little engine which remains one of the least commonly encountered members of the ½A model engine family. We’ll be taking a close-up look at the very elusive ROC .049. The specific goal of the ROC .049’s manufacturer was clearly to produce a new model which would tap into a market which was as yet unexploited by Japanese model engine manufacturers. This was the ½A class for engines of 0.049 cuin. (0.817 cc) displacement which was just beginning its rise to dominance of the North America market during much of the 1950's.

The specific goal of the ROC .049’s manufacturer was clearly to produce a new model which would tap into a market which was as yet unexploited by Japanese model engine manufacturers. This was the ½A class for engines of 0.049 cuin. (0.817 cc) displacement which was just beginning its rise to dominance of the North America market during much of the 1950's. In my study of the

In my study of the

In his 1955 article, Chinn referred to the ROC .049 as having been "among the very first" Japanese ½A engines to reach the market. The 1956 article went further - the engine was unequivocally described as having been "the first" Japanese ½A motor. At this distance in time, I consider it to be an open question which really came first - the ROC or the Fuji .049 model. Although at this late date we have no basis for questioning Chinn's statements regarding this issue, it must be recognized that he was writing even then about events which lay some years in the past and which were completely undocumented in the English language.

In his 1955 article, Chinn referred to the ROC .049 as having been "among the very first" Japanese ½A engines to reach the market. The 1956 article went further - the engine was unequivocally described as having been "the first" Japanese ½A motor. At this distance in time, I consider it to be an open question which really came first - the ROC or the Fuji .049 model. Although at this late date we have no basis for questioning Chinn's statements regarding this issue, it must be recognized that he was writing even then about events which lay some years in the past and which were completely undocumented in the English language. Although it provides no proof whatsoever, the order of appearance of the ROC and Fuji which was suggested by Chinn would at least be circumstantially consistent with the idea that the manufacturer of the ROC .049 may have broken away from Fuji to go on his own, perhaps following an unsuccessful earlier attempt to persuade Fuji to enter the .049 category. Rather than abandon the idea, he may then have gone off on his own to produce his own model. It would be completely logical for Fuji to react to this move by reconsidering their position and getting their own .049 onto the market to head off this threat to their market position. We'll probably never know for sure.

Although it provides no proof whatsoever, the order of appearance of the ROC and Fuji which was suggested by Chinn would at least be circumstantially consistent with the idea that the manufacturer of the ROC .049 may have broken away from Fuji to go on his own, perhaps following an unsuccessful earlier attempt to persuade Fuji to enter the .049 category. Rather than abandon the idea, he may then have gone off on his own to produce his own model. It would be completely logical for Fuji to react to this move by reconsidering their position and getting their own .049 onto the market to head off this threat to their market position. We'll probably never know for sure. decision by both manufacturers to enter the .049 field must have been greatly eased by the fact that there was a complete absence of domestic competition in that displacement class at the time. Hence they would not have to share the market with a host of competitors, at least initially.

decision by both manufacturers to enter the .049 field must have been greatly eased by the fact that there was a complete absence of domestic competition in that displacement class at the time. Hence they would not have to share the market with a host of competitors, at least initially. One look at the ROC .049 confirms that its design was indisputably based quite closely upon that of the original OK Cub .049 which had first appeared in 1949. No doubt its designer had encountered examples of the Cub in the hands of members of the predominantly US Army of Occupation and had decided rightly or wrongly that a Cub look-alike would fare well in the marketplace as it then existed.

One look at the ROC .049 confirms that its design was indisputably based quite closely upon that of the original OK Cub .049 which had first appeared in 1949. No doubt its designer had encountered examples of the Cub in the hands of members of the predominantly US Army of Occupation and had decided rightly or wrongly that a Cub look-alike would fare well in the marketplace as it then existed. The bore and stroke measurements cited above highlight one significant design difference between the ROC and OK Cub .049 models. The original 1949 Cub featured long-stroke geometry, having bore and stroke measurements of 0.390 in. (9.91 mm) and 0.415 in. (10.54 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.0496 cuin. (0.812 cc). By contrast, the ROC was a short-stroke design. Clearly the ROC designer was doing at least some original thinking and was not convinced that long-stroke geometry offered any advantage in a glow-plug engine of this size and type. OK themselves were eventually to come to the same conclusion, switching to a short-stroke .049 design in 1952 with their .049X model and subsequent variants.

The bore and stroke measurements cited above highlight one significant design difference between the ROC and OK Cub .049 models. The original 1949 Cub featured long-stroke geometry, having bore and stroke measurements of 0.390 in. (9.91 mm) and 0.415 in. (10.54 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.0496 cuin. (0.812 cc). By contrast, the ROC was a short-stroke design. Clearly the ROC designer was doing at least some original thinking and was not convinced that long-stroke geometry offered any advantage in a glow-plug engine of this size and type. OK themselves were eventually to come to the same conclusion, switching to a short-stroke .049 design in 1952 with their .049X model and subsequent variants. The crankcase offers the sole potential clue to the manufacturer's identity. The name S.HAJIKANO is cast in low relief onto the underside of the case, with the letters T.H and NO. also appearing as written on separate lines below. The name Hajikano is a not uncommon Japanese family name, strongly suggesting that the engine's manufacturer may have been a certain S. Hajikano.

The crankcase offers the sole potential clue to the manufacturer's identity. The name S.HAJIKANO is cast in low relief onto the underside of the case, with the letters T.H and NO. also appearing as written on separate lines below. The name Hajikano is a not uncommon Japanese family name, strongly suggesting that the engine's manufacturer may have been a certain S. Hajikano.  The ROC name most probably refers to the mythical bird of the

The ROC name most probably refers to the mythical bird of the  The ROC .049 employs a conical-topped hardened steel piston running in an unhardened steel cylinder having integrally-formed cooling fins. The head is a separate screw-in item made of light alloy. Both of these features mimic those of the OK Cub .049, as does the long-reach plug thread. The head of the ROC is of particular interest since it has what appears to be a narrow but still functional squish band running round its circumference with a fairly deep bowl-shaped combustion chamber at the centre. Surprisingly "modern" in design terms! The volumetrically checked compression ratio is of the order of 7:1.

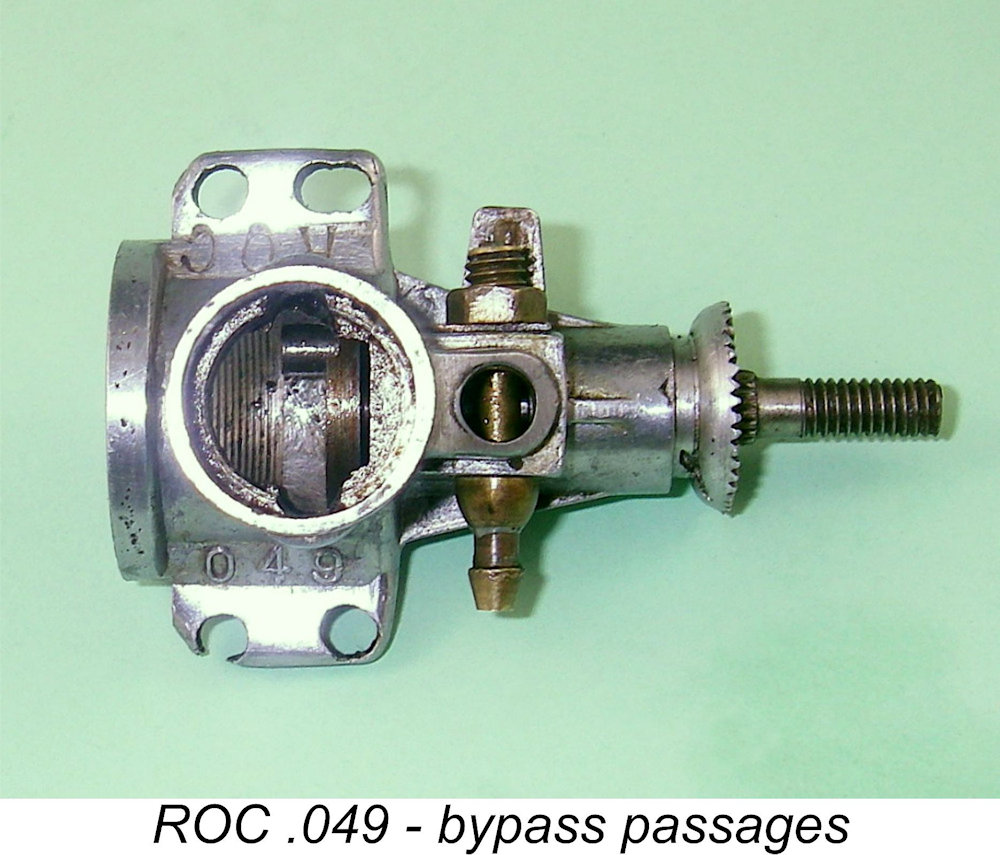

The ROC .049 employs a conical-topped hardened steel piston running in an unhardened steel cylinder having integrally-formed cooling fins. The head is a separate screw-in item made of light alloy. Both of these features mimic those of the OK Cub .049, as does the long-reach plug thread. The head of the ROC is of particular interest since it has what appears to be a narrow but still functional squish band running round its circumference with a fairly deep bowl-shaped combustion chamber at the centre. Surprisingly "modern" in design terms! The volumetrically checked compression ratio is of the order of 7:1. The transfer ports are supplied with mixture from the main crankcase by means of a pair of bypass passages formed one on each side of the interior of the cylinder installation spigot. These passages necessarily interrupt the female installation thread for the screw-in cylinder. Both the interior of the cylinder installation spigot and the exterior of the lower cylinder below the exhaust port belt are diametrically relieved in order to create an unthreaded 360 degree annular passage around the lower cylinder at the entry level of the transfer ports. Thus the functioning of the transfer system is theoretically unaffected by the orientation of the cylinder when fully tightened.

The transfer ports are supplied with mixture from the main crankcase by means of a pair of bypass passages formed one on each side of the interior of the cylinder installation spigot. These passages necessarily interrupt the female installation thread for the screw-in cylinder. Both the interior of the cylinder installation spigot and the exterior of the lower cylinder below the exhaust port belt are diametrically relieved in order to create an unthreaded 360 degree annular passage around the lower cylinder at the entry level of the transfer ports. Thus the functioning of the transfer system is theoretically unaffected by the orientation of the cylinder when fully tightened. Presumably it was felt that this patent did not extend to Japan, since Fuji were to use exactly the same system in their own early .049 models. It's also possible that the Japanese makers simply felt safe from any challenge by virtue of their relative commercial marginalization at the time.

Presumably it was felt that this patent did not extend to Japan, since Fuji were to use exactly the same system in their own early .049 models. It's also possible that the Japanese makers simply felt safe from any challenge by virtue of their relative commercial marginalization at the time. The crankshaft is a one-piece item of hardened steel. The full-disc crankweb has a conventional crescent-shaped counterbalance opposite the 3.5 mm dia. crankpin. The central gas passage has a fairly generous diameter of 4.10 mm (0.162 in.). while the main journal has a diameter of 6.35 mm (0.250 in.), leaving a seemingly-reasonable wall thickness of 1.12 mm (0.044 in.). The induction port in the crankshaft wall has what appears to be a somewhat excessive diameter of 4.95 mm (0.195 in.). This takes a larger bite out of the shaft than I would view as really advisable, but the fact that the opening is a simple round hole means that it does not create any sharp edges to act as stress concentration points. So the shaft is probably dependable enough in service.

The crankshaft is a one-piece item of hardened steel. The full-disc crankweb has a conventional crescent-shaped counterbalance opposite the 3.5 mm dia. crankpin. The central gas passage has a fairly generous diameter of 4.10 mm (0.162 in.). while the main journal has a diameter of 6.35 mm (0.250 in.), leaving a seemingly-reasonable wall thickness of 1.12 mm (0.044 in.). The induction port in the crankshaft wall has what appears to be a somewhat excessive diameter of 4.95 mm (0.195 in.). This takes a larger bite out of the shaft than I would view as really advisable, but the fact that the opening is a simple round hole means that it does not create any sharp edges to act as stress concentration points. So the shaft is probably dependable enough in service. At the front of the shaft, the prop mounting thread is M4x0.75. The prop driver is another pressure die-casting which is mounted on splines formed immediately in front of the main journal. In typical Japanese fashion for the time, a brass nut is used to secure the prop.

At the front of the shaft, the prop mounting thread is M4x0.75. The prop driver is another pressure die-casting which is mounted on splines formed immediately in front of the main journal. In typical Japanese fashion for the time, a brass nut is used to secure the prop. "Model Airplane News" (MAN) article shows that the needle had a serrated inner disc which engaged with a single-leaf tensioning spring, still in place together with the original spraybar on this example. The outer end of the needle featured a serrated control disc - a typical Japanese design of the period.

"Model Airplane News" (MAN) article shows that the needle had a serrated inner disc which engaged with a single-leaf tensioning spring, still in place together with the original spraybar on this example. The outer end of the needle featured a serrated control disc - a typical Japanese design of the period. At the rear of the crankcase, a screw-in backplate is utilized, again following the approach taken in the OK Cub. The item used in the ROC is yet another pressure die-casting, a technique with which the manufacturer was clearly very comfortable. The backplate seals to the case with a fibre gasket in the usual manner.

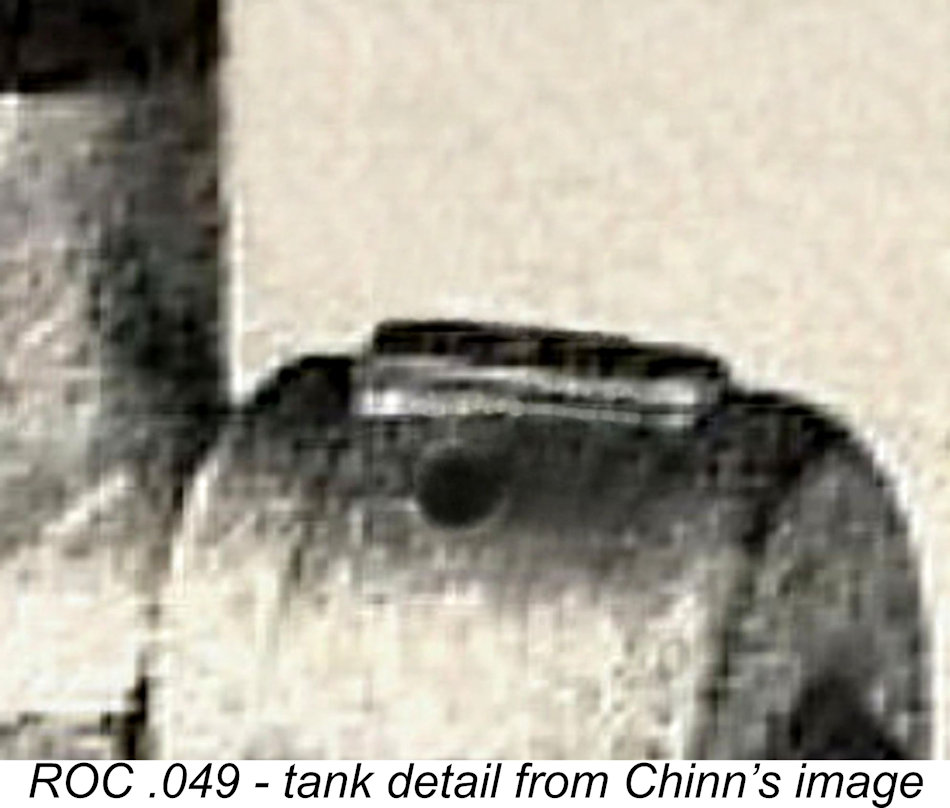

At the rear of the crankcase, a screw-in backplate is utilized, again following the approach taken in the OK Cub. The item used in the ROC is yet another pressure die-casting, a technique with which the manufacturer was clearly very comfortable. The backplate seals to the case with a fibre gasket in the usual manner. The two available images from Peter Chinn's previously-noted articles show that the engine originally had a relatively short die-cast back tank. This differed considerably from the die-cast tank used on the "kit" examples of the original OK Cub .049. The presence of a flat-surfaced extrusion at the top of the ROC tank for the filler hole proves that the tank must have been a casting. However, its internal design remains something of a mystery. When fully tightened, the screw-in backplate ends up flush with the rear face of the surrounding flange at the rear of the case, leaving no step to locate the tank. There is however a shallow double-segmented protrusion surrounding one of the two slots for tightening of the backplate. This is an original feature, not a casting or mis-handling flaw. It appears that this may have engaged with some kind of socket formed in the front surface of the tank to locate it correctly.

The two available images from Peter Chinn's previously-noted articles show that the engine originally had a relatively short die-cast back tank. This differed considerably from the die-cast tank used on the "kit" examples of the original OK Cub .049. The presence of a flat-surfaced extrusion at the top of the ROC tank for the filler hole proves that the tank must have been a casting. However, its internal design remains something of a mystery. When fully tightened, the screw-in backplate ends up flush with the rear face of the surrounding flange at the rear of the case, leaving no step to locate the tank. There is however a shallow double-segmented protrusion surrounding one of the two slots for tightening of the backplate. This is an original feature, not a casting or mis-handling flaw. It appears that this may have engaged with some kind of socket formed in the front surface of the tank to locate it correctly. In the absence of any certainty in this regard, I simply machined a standard bowl-type tank from aluminium bar stock, using the two images from Chinn's articles as my guide to its approximate length. This tank is located simply by the central 3 mm mounting screw and by pressure on the fibre gasket which I used to create a seal. Once tightened up, it remains firmly in place and seals with no problems. Although it is clearly by no means an accurate replica, it works well and restores the engine's original appearance pretty closely.

In the absence of any certainty in this regard, I simply machined a standard bowl-type tank from aluminium bar stock, using the two images from Chinn's articles as my guide to its approximate length. This tank is located simply by the central 3 mm mounting screw and by pressure on the fibre gasket which I used to create a seal. Once tightened up, it remains firmly in place and seals with no problems. Although it is clearly by no means an accurate replica, it works well and restores the engine's original appearance pretty closely. A rather annoying design feature, and one which the ROC shares with its OK Cub .049 progenitor, is the fact that the flange at the rear of the crankcase is of considerably larger diameter than the case exterior, thus extending well into the natural line of the inner beam mount face. Either the bearers have to be spaced to clear the flange or they have to be notched to accommodate it. In the case of the ROC, the bearers would actually have to be relieved for the whole length of the tank if that component was to be used. The mount holes are aligned such that the bearers can be spaced to clear both tank and flange, but this significantly reduces the contact area beneath the mounting lugs - not a desirable situation.

A rather annoying design feature, and one which the ROC shares with its OK Cub .049 progenitor, is the fact that the flange at the rear of the crankcase is of considerably larger diameter than the case exterior, thus extending well into the natural line of the inner beam mount face. Either the bearers have to be spaced to clear the flange or they have to be notched to accommodate it. In the case of the ROC, the bearers would actually have to be relieved for the whole length of the tank if that component was to be used. The mount holes are aligned such that the bearers can be spaced to clear both tank and flange, but this significantly reduces the contact area beneath the mounting lugs - not a desirable situation. It was clearly a matter of interest to learn how the ROC .049 compared in performance terms with the OK Cub .049 upon which it was clearly based. However, I thought that while I was at it, I might as well also compare its performance with that of the Fuji .049 which was its sole commercial Japanese ½A rival and which appears to have displaced it from the marketplace. Accordingly, I assembled a complete set of these engines for testing.

It was clearly a matter of interest to learn how the ROC .049 compared in performance terms with the OK Cub .049 upon which it was clearly based. However, I thought that while I was at it, I might as well also compare its performance with that of the Fuji .049 which was its sole commercial Japanese ½A rival and which appears to have displaced it from the marketplace. Accordingly, I assembled a complete set of these engines for testing. Having assembled a selection of typical ½A airscrews both ancient and modern, things soon became noisy beneath the sundeck at our house! First up was the ROC. The piston seal on this well-used example is not as secure as it doubtless once was - the engine appears to have ingested dirt at some point in its career. However, there was ample compression for starting. In fact, the engine proved to be a very prompt and dependable starter once a good prime was administered. Once running, the engine's response to the needle proved to be very positive without being in the least bit sensitive. This made it very easy to establish the optimum setting on any prop. Running was extremely smooth on all props tested and the needle held its settings extremely well.

Having assembled a selection of typical ½A airscrews both ancient and modern, things soon became noisy beneath the sundeck at our house! First up was the ROC. The piston seal on this well-used example is not as secure as it doubtless once was - the engine appears to have ingested dirt at some point in its career. However, there was ample compression for starting. In fact, the engine proved to be a very prompt and dependable starter once a good prime was administered. Once running, the engine's response to the needle proved to be very positive without being in the least bit sensitive. This made it very easy to establish the optimum setting on any prop. Running was extremely smooth on all props tested and the needle held its settings extremely well. Next up was the Fuji. This engine has had far less previous use than the ROC, consequently possessing a very good piston seal. This made it even easier to start, although it bears repeating that neither engine actually presented the least difficulty in that regard.

Next up was the Fuji. This engine has had far less previous use than the ROC, consequently possessing a very good piston seal. This made it even easier to start, although it bears repeating that neither engine actually presented the least difficulty in that regard.

One of the unresolved issues surrounding the largely untold ROC story is the fact that at some indeterminate point during its period of manufacture

One of the unresolved issues surrounding the largely untold ROC story is the fact that at some indeterminate point during its period of manufacture I've been unable to track down any information which might shed some light on this odd situation. All that I've been able to find is a couple of references to a "SMITH car" which apparently appeared at some point on the Japanese market. This is not to be confused with the latter-day car models marketed by Paul Smith - the SMITH car to which I'm

I've been unable to track down any information which might shed some light on this odd situation. All that I've been able to find is a couple of references to a "SMITH car" which apparently appeared at some point on the Japanese market. This is not to be confused with the latter-day car models marketed by Paul Smith - the SMITH car to which I'm

It should surely be clear from the foregoing that by 1950 standards the ROC .049 represented a sincere and generally successful attempt by its unknown Japanese manufacturer to create an up-to-date ½A glow-plug motor along American lines. However, the success of the manufacturer in this respect may in fact have worked against him - the appearance of an engine bearing such an overt similarity to an established American product may have backfired by giving the engine the appearance of a "cheap Japanese copy" of the original. This was at a time, remember, when the Japanese were not held in high regard by many and when Japanese precision engineering capabilities were vastly under-rated. Why buy a "second-rate" Japanese copy when you could easily get the American original?!?

It should surely be clear from the foregoing that by 1950 standards the ROC .049 represented a sincere and generally successful attempt by its unknown Japanese manufacturer to create an up-to-date ½A glow-plug motor along American lines. However, the success of the manufacturer in this respect may in fact have worked against him - the appearance of an engine bearing such an overt similarity to an established American product may have backfired by giving the engine the appearance of a "cheap Japanese copy" of the original. This was at a time, remember, when the Japanese were not held in high regard by many and when Japanese precision engineering capabilities were vastly under-rated. Why buy a "second-rate" Japanese copy when you could easily get the American original?!? anyway) to any American original. It is true that they later came out with a version of their .049 which was quite clearly patterned upon the contemporary Atwood .049 models, but by then they had become well established in the marketplace and had achieved a positive reputation for offering good value for money.

anyway) to any American original. It is true that they later came out with a version of their .049 which was quite clearly patterned upon the contemporary Atwood .049 models, but by then they had become well established in the marketplace and had achieved a positive reputation for offering good value for money.