|

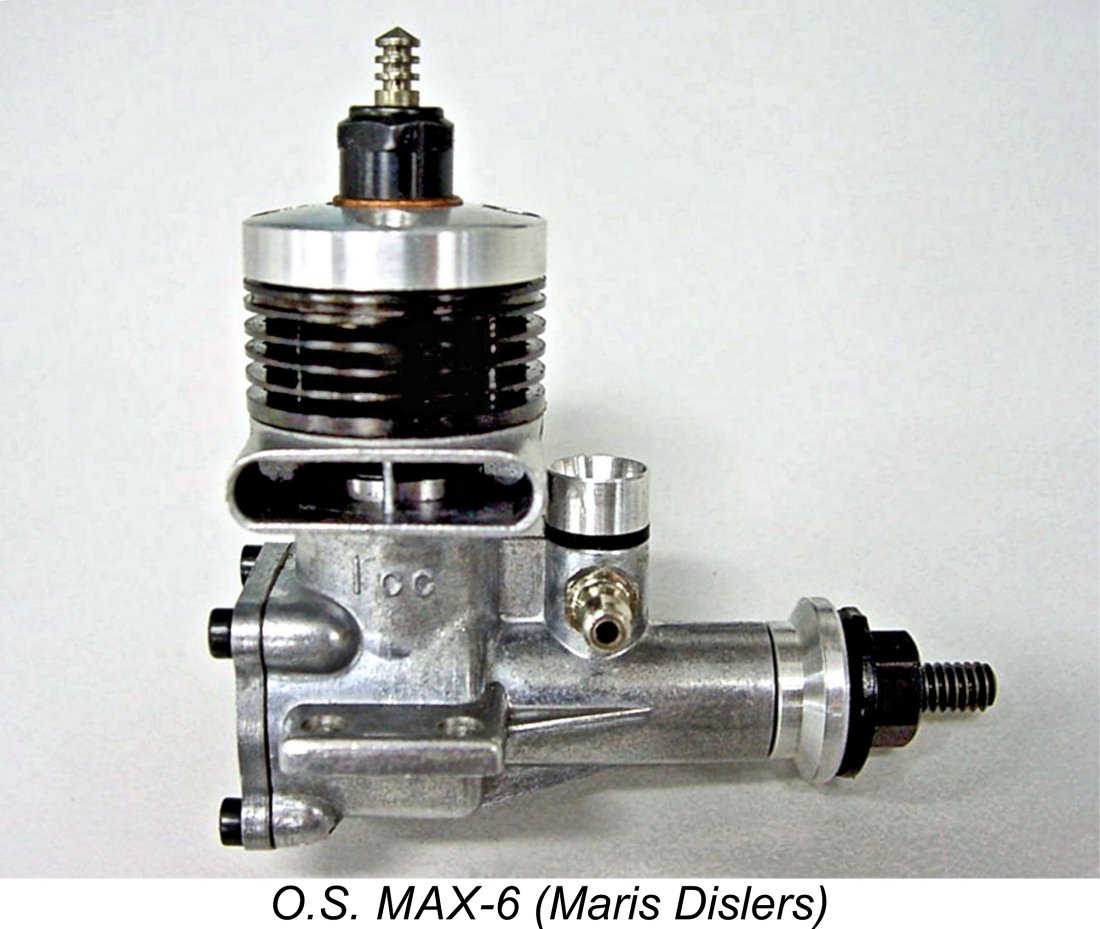

The 1 cc O.S. MAX-6 Glow-Plug MotorBy Maris Dislers

Those models were just entering the American market when along came K&B’s new 1951 Torpedo range. These motors represented a very significant improvement over that company's 1947 series – the new Torpedo 19 was particularly outstanding in terms of power output, without the complexities then expected as the price to be paid for high performance. The new Torpedos were simple designs, featuring crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction, plain crankshaft In response, O.S. released their first MAX-1 29 and 35 engines in 1954 along very similar lines. These were quickly followed by the smaller MAX-1 15, which gained world attention when the U.K.’s Ron Draper took the 1956 Free Flight (now F1C) World Championship crown with his model powered by one of these These O.S. MAX engines were progressively developed over the following years through second and third variants. Thanks to expanded production capacity, they were joined by the MAX-D .15 in3 (2.5 cc) diesel, the MAX-6 .06 in3 (1 cc) in 1961 and the MAX-19 .19 in3 (3.2 cc) in 1962 to broaden the range. This review looks at the smallest of these - the MAX-6 glow-plug model of 1961. As events were to prove, this was destined to be the smallest-displacement motor ever The accompanying instruction leaflet states: “Your O.S. MAX-6 engine is an O.S. quality small sister to the recognized MAX series engines…....MAX-6 engine is the first engine with loop scavenging (which is the best scavenging system for the miniature glow plug engine), in this size, engine on the market. Although this engine has been designed for contest use, handling is still easy and simple.” Which neatly summarizes its characteristics. Internally, the MAX-6 was much the same as the larger MAX engines, with high quality fits and finishes throughout. The vertical carburettor and un-finned head were the most obvious differences. The needle valve with flexible extension (unique to this model) was a nice touch. When engaged in the clip provided, this keeps the fingers well clear of the propeller. The accompanying photos do not convey this engine’s small size. The MAX-6 is significantly smaller and lighter than the little-known O.S. 1 cc Diesel from around a decade before. Its particulars are as follows:

The MAX-6 On the Bench

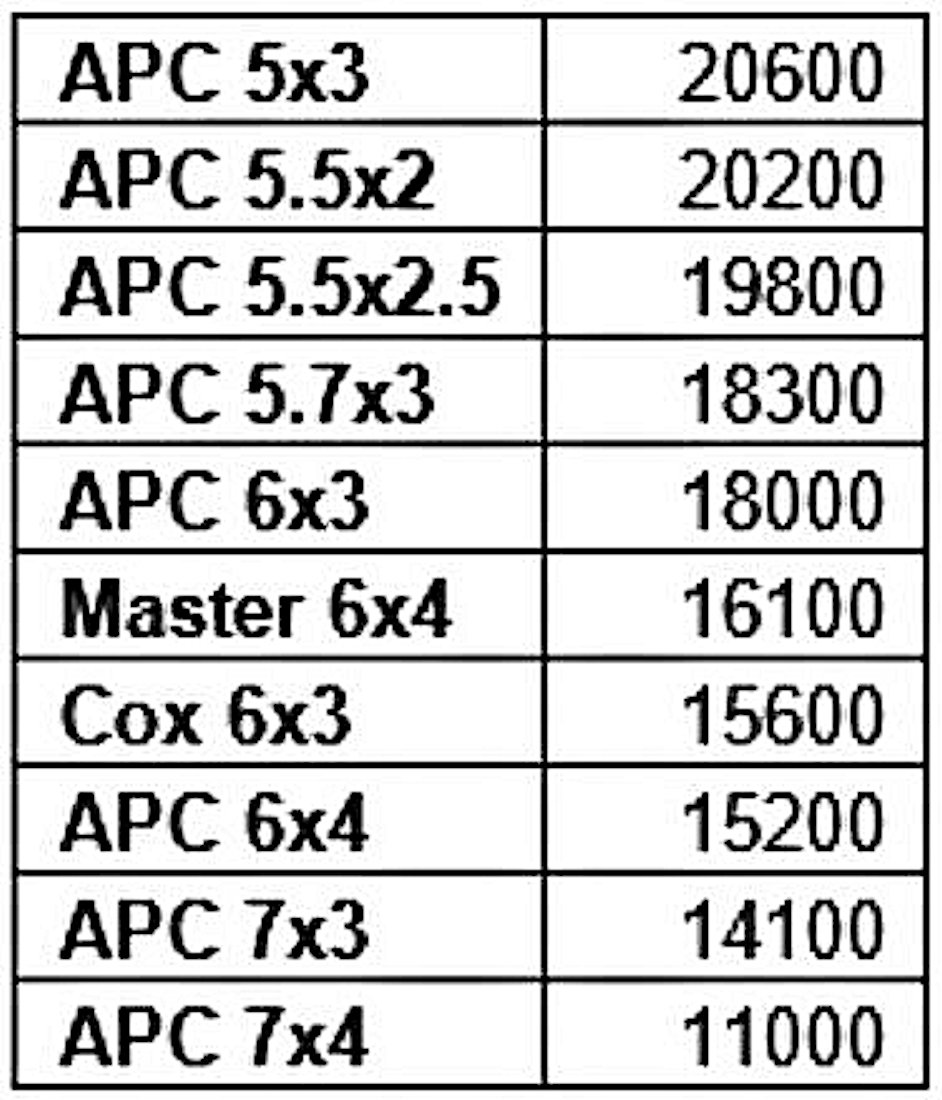

The engine proved to be well-mannered, without pre-ignition or other nastiness, even with small propeller loads. Unlike some small engines that essentially run either 4-cycle rich or flat out, we could adjust the MAX-6 progressively from rich 4-cycle to smooth 2-cycle mode and back, or leave it running anywhere between. The engine was not particularly fussy about mixture setting around peak RPM, with good leeway if set a little lean. We found the 7x4 propeller to be a bit much, but the MAX-6 was delightful when loaded for mid-range speeds. Vibration became quite evident at speeds over 18,000 RPM, suggesting that operation up to the suggested 24,000 RPM limit may be unwise. Performance analysis

Having demonstrated the engine’s general performance, we didn’t pursue absolute top power by increasing nitro content. An owner could drill and tap the backplate for a pressure nipple and remove the venturi insert for extra performance. As a point of reference, Peter Chinn’s tests of the contemporary OS MAX-III 15 gave .144 BHP per cc using (higher) 30% nitro methane fuel, rising to .168 BHP per cc with the venturi removed and using pressure feed. The MAX-6 is likely to give similar power increases under those conditions.

For the more numerous budget-minded novice or leisure fliers, who were happy to juggle power and engine weight/size priorities, there were plenty of alternatives costing US$6.95 or less. O.S.’s own Pet 099 II was really good value at US$5.98, versus the MAX-6 at US$8.98. The US$3.95 K&B Tornado .06 was another budget-priced alternative. Even the contemporary Enya .06, which was available in both glow-plug and diesel versions, represented stiff competition. Similar market complexities existed in Japan and elsewhere. Consequently, relatively few MAX-6 engines were produced and sales ended around 1965-66. That and being the smallest member of the O.S. model engine range makes surviving MAX-6’s quite collectible, fetching significantly more than similar engines from other makers. ___________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia First published February 2022

|

|

| |

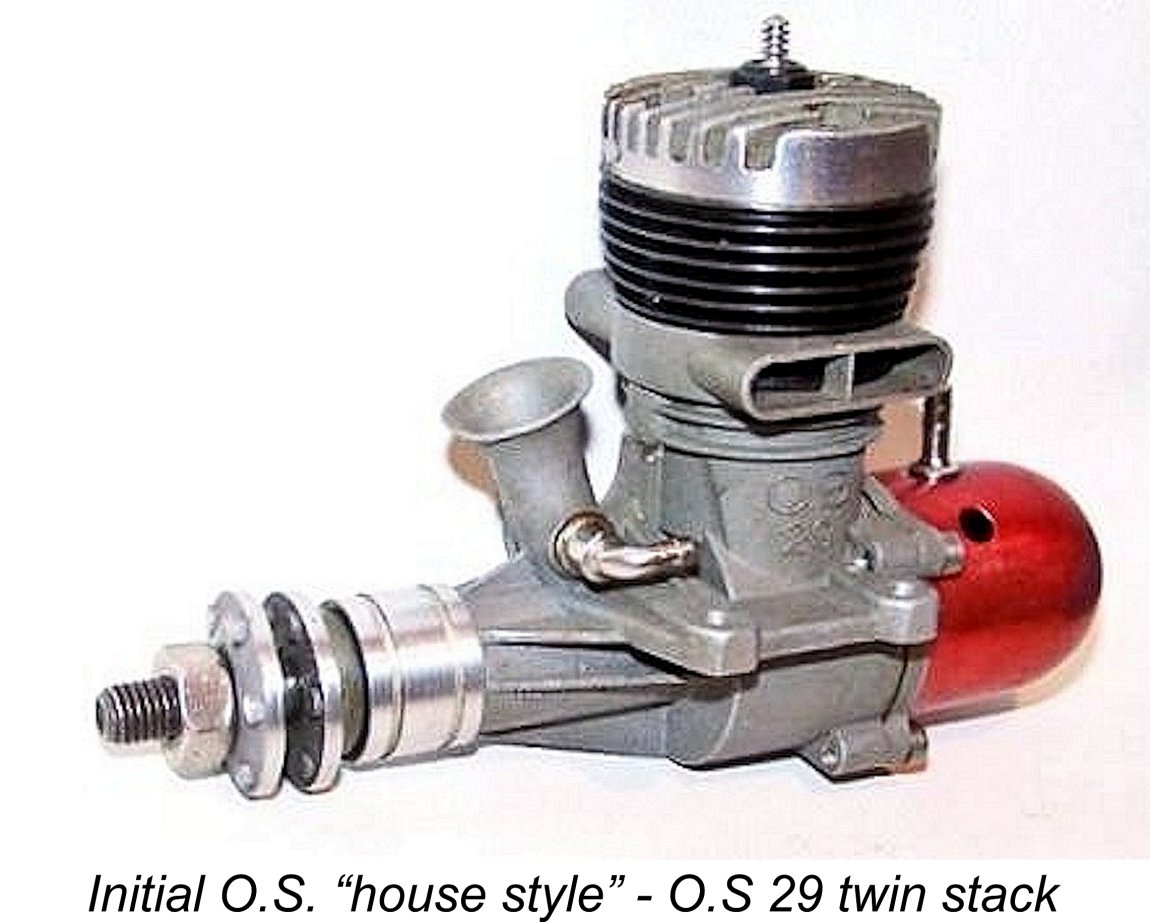

The Ogawa Model Manufacturing Company of Osaka, Japan, better known as O.S., took a decisive step forward in 1954 with their MAX series of engines. Their previous engine designs had been a mix of types during a period of very dynamic model engine technological progress. Their initial house style began to take shape with the

The Ogawa Model Manufacturing Company of Osaka, Japan, better known as O.S., took a decisive step forward in 1954 with their MAX series of engines. Their previous engine designs had been a mix of types during a period of very dynamic model engine technological progress. Their initial house style began to take shape with the

Japanese engines. Further success followed in the 1960 Championship when Larry Conover’s (U.S.A.) model, powered by an “internally cleaned up” O.S. MAX 15, was part of an extraordinary five-way tie for first place.

Japanese engines. Further success followed in the 1960 Championship when Larry Conover’s (U.S.A.) model, powered by an “internally cleaned up” O.S. MAX 15, was part of an extraordinary five-way tie for first place.

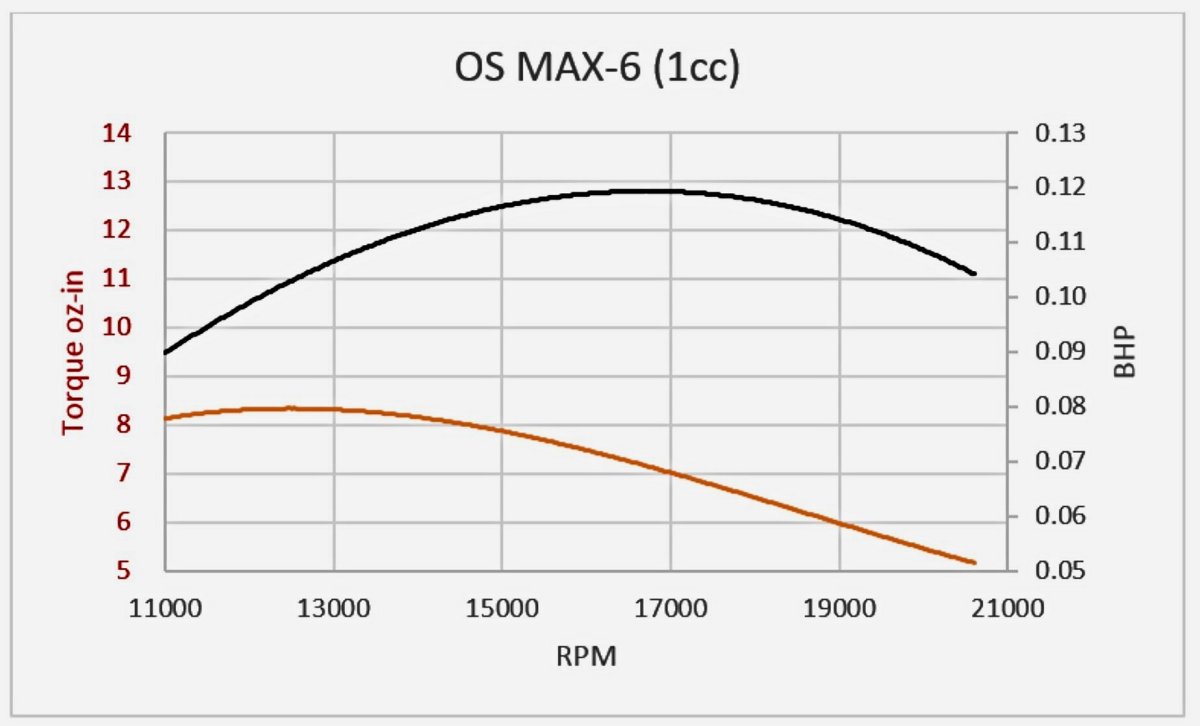

Our performance curves show maximum torque broadly around 12,000 RPM, corresponding with the lower end of the recommended practical range. Agreeing with the experience of other users, this one does not like to be loaded to slower speeds. Torque is sustained to around 14,000 RPM before dropping in essentially linear fashion. The resulting power curve indicates a maximum .12 BHP in the 16,000 – 17,000 RPM region. Individual data points are somewhat scattered, suggesting that experimenting with a range of propellers across the 14,000 – 19,000 RPM range can find particular “favourites”. On the other hand (with our particular test rig) there was an interesting soft spot in the 15,000 to 16,000 RPM area where performance with several different propellers having similar known load characteristics was up to 10% below the expected trend.

Our performance curves show maximum torque broadly around 12,000 RPM, corresponding with the lower end of the recommended practical range. Agreeing with the experience of other users, this one does not like to be loaded to slower speeds. Torque is sustained to around 14,000 RPM before dropping in essentially linear fashion. The resulting power curve indicates a maximum .12 BHP in the 16,000 – 17,000 RPM region. Individual data points are somewhat scattered, suggesting that experimenting with a range of propellers across the 14,000 – 19,000 RPM range can find particular “favourites”. On the other hand (with our particular test rig) there was an interesting soft spot in the 15,000 to 16,000 RPM area where performance with several different propellers having similar known load characteristics was up to 10% below the expected trend. Conclusion

Conclusion  Although it was an excellent little engine, the O.S. MAX-6 faced marketing challenges which are often unrecognized. By far the largest market for small engines was the American ½A class, with maximum .05 in

Although it was an excellent little engine, the O.S. MAX-6 faced marketing challenges which are often unrecognized. By far the largest market for small engines was the American ½A class, with maximum .05 in