|

|

Twin-Valve Trickery - the Later Atwood Champions

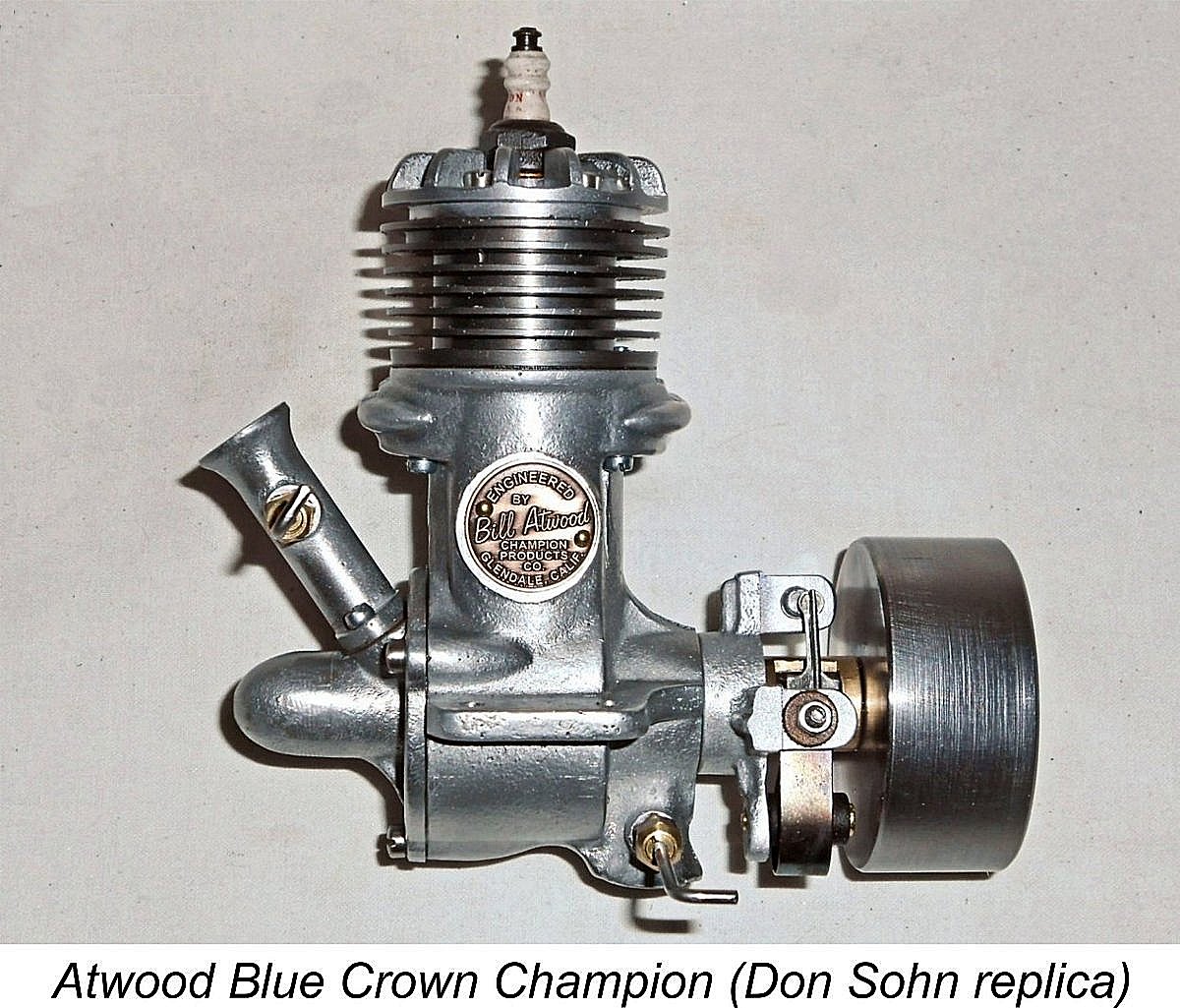

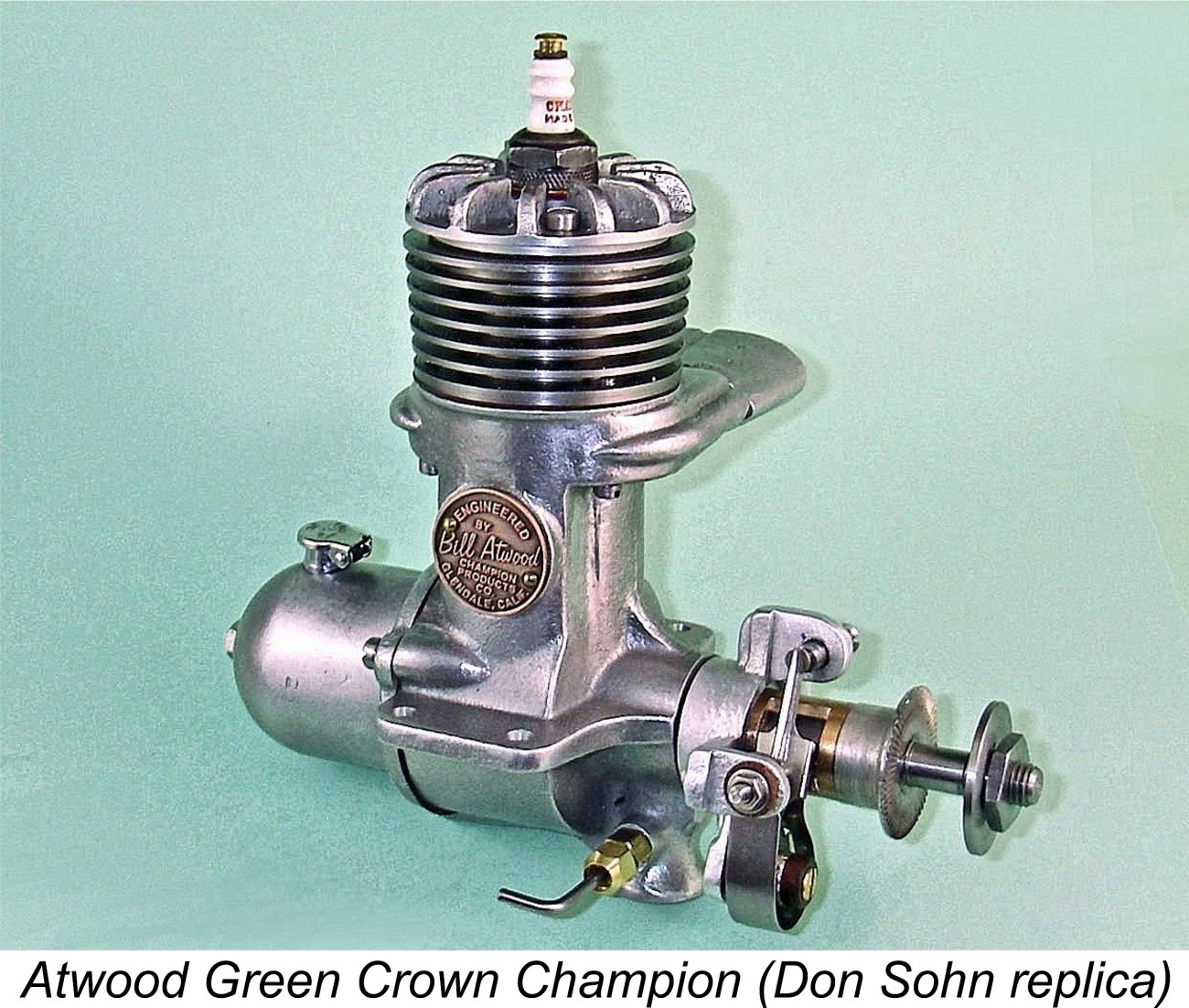

In an earlier article on this website, I recounted the story of the various Crown Champion model engines produced in relatively small numbers by Bill Atwood using the trade-name Champion Products Co. and apparently working from his own home machine shop on his own time while employed full-time by others. Busy man!! In this article, I'll cover the succession of twin-valve Champion models which followed the Crown Champion series. In my earlier article, I began by covering the remarkable 15 cc Silver Crown Champion hydroplane engine of 1938 which introduced the twin rotary valve arrangement that was to become an Atwood Champion signature, as we shall see. This was followed in 1940 by the 10 cc twin-valve Blue Crown Champion tether car engine, the simplified 10 cc single-valve Red Crown Champion car powerplant, the single-valve Green Crown Champion aero model and finally the 10 cc twin-valve Purple Crown Champion which was intended for hydroplane applications. The majority of these units were sold as casting kits, although Bill Atwood did complete a few examples for sale.

To judge by the very small number of surviving original examples, the manufacture of the Crown Champion engines and casting kits does not appear to have been pursued with any great vigor, doubtless due to the competing demands on Bill Atwood’s time from his concurrent employers. It appears that Champion Products Co. was simply Bill Atwood working on his own in his “spare” time (what spare time?!?) producing the engines and kits in very limited numbers at his home workshop in Glendale, California. However, there seems to be little doubt that the Crown Champion effort was seen by Bill as preparing the ground for an eventual stepping-out on his own - he certainly promoted them out of all proportion to the number sold.

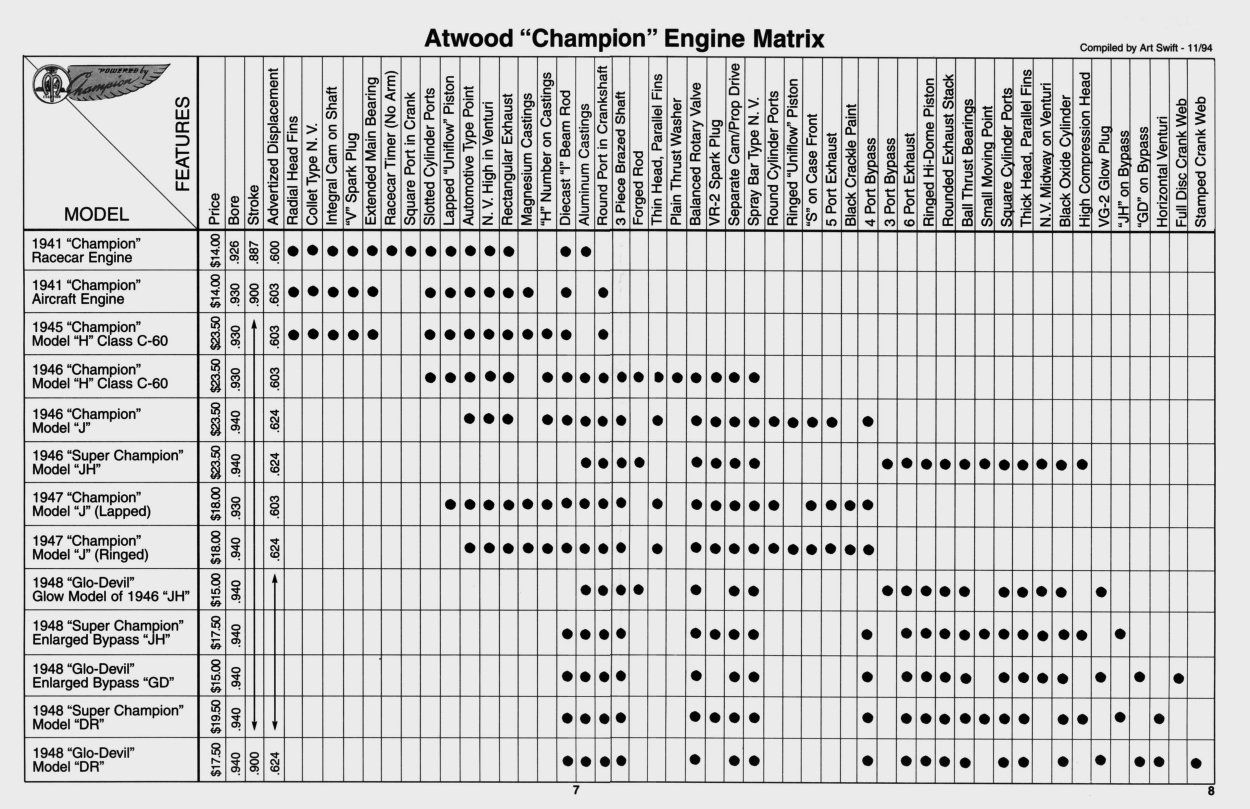

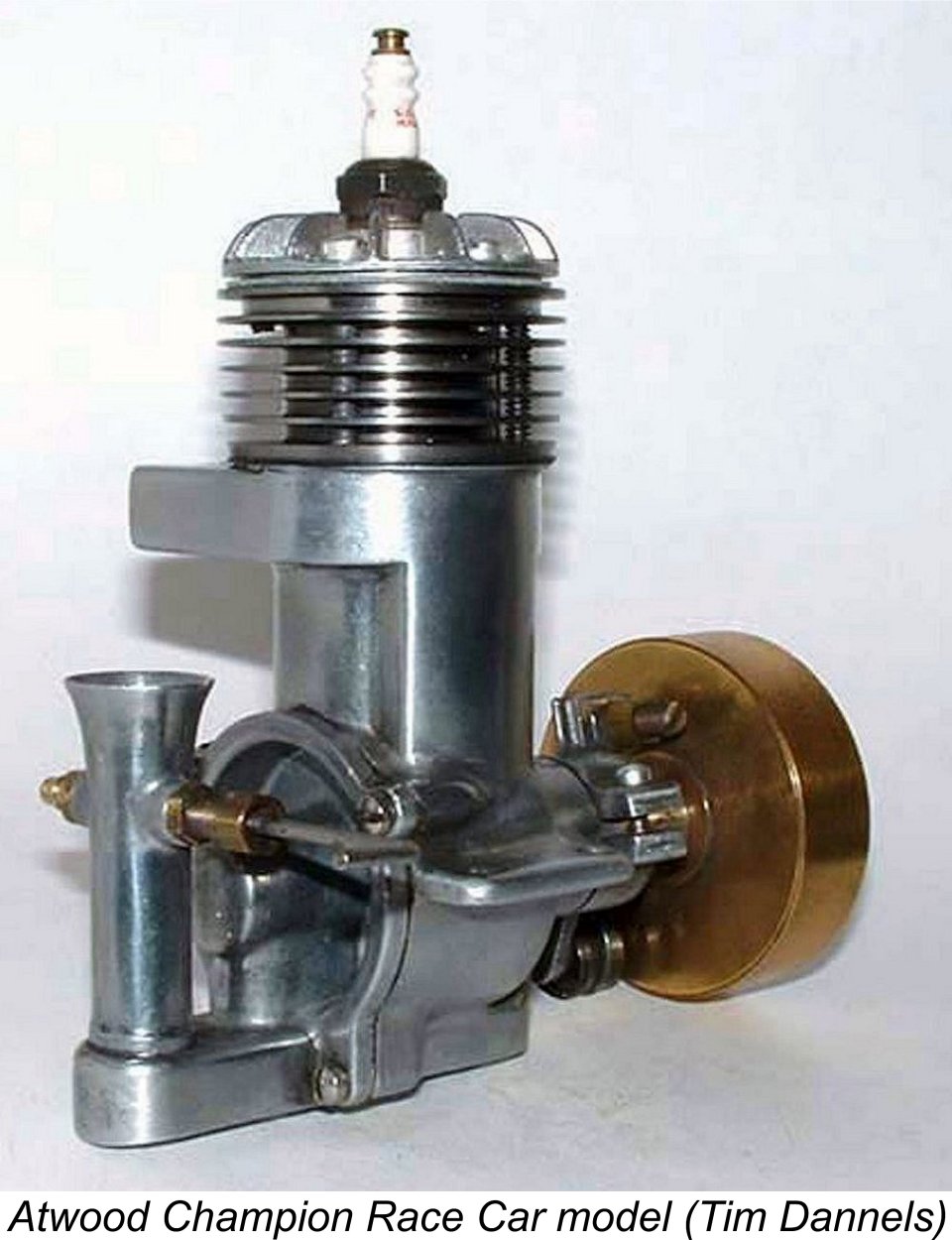

While all of the development and production work on the Crown Champion series had been ongoing, Atwood had retained a close connection with the Phantom Motors company, a subsidiary of the Automatic Screw Machine Company of Los Angeles. He designed the Hi-Speed Bullet, Phantom Bullet and Phantom Torpedo models for them. This had not prevented his ever-fertile mind from identifying potential improvements to his own parallel Crown Champion series. It appears that Phantom Motors were not interested in becoming involved with the further development and production of the Crown Champion line. Despite this, as 1940 drew on Atwood evidently became increasingly convinced of the merits of his twin rotary valve induction system. He had recognised the fact that the main obstacle to the commercial success of these models was their relatively high cost of manufacture. In addition, the need to synchronize two needle valves posed operating problems which might appear somewhat daunting to prospective purchasers. In the present article, I’ll be examining the Before proceeding further with this article, I wish to pay homage to the late Charlie Bruce, who wrote a detailed article describing the Atwood Champions in considerable detail. This article appeared in December 2000 in issue no. 143 of the late Tim Dannels’ outstanding “Engine Collectors’ Journal” (ECJ). I freely acknowledge having consulted this article freely during the preparation of the following text. I also wish to pay tribute to the efforts of Art Swift, who went to immense trouble to prepare the accompanying matrix of features seen on the various Champion models. Readers may find it very useful to consult this matrix when reading the following text or when researching the fine details of examples in their possession. All Champion fanciers are indebted to Art for his invaluable efforts. The Atwood Champion Race Car Model It appears that the manufacture of the Crown Champion engines was confined to around an 8-month period during 1940. No wonder the number produced was small! Before the end of 1940 Atwood had designed a revised twin-valve car engine called the Champion Race Car model – no mention of any Crown coloration!

In terms of its functional design, the new model also addressed one of the obvious shortcomings of the earlier Blue Crown model, namely the difficulty of establishing a good mixture setting using the dual needle valves of that model. The Champion Race Car unit retained the dual rotary valves of its twin-valve predecessors, but there was only a single intake and needle valve at the rear supplying both rotary valves. The rear intake was a vertical “smokestack” structure which supplied mixture to both a rear drum valve and a front crankshaft rotary valve through a conduit or plenum cavity which ran fore and aft beneath the main crankcase, feeding both rotary valves. A single needle valve was used, eliminating the former mixture synchronisation problems completely. The needle valve was a collet-type assembly with an externally-threaded needle, typical of racing engines of the period. The head continued the Crown Champion pattern of featuring radially-oriented cooling fins. This has led to the component often being referred to as the "Spoke Head". The plug used in these early models was a centrally-located 3/8-24 component. A lapped cast iron piston continued to be used in this model along with a die-cast I-beam section rod. Nominal bore and stroke of this model were 0.926 in. (23.52 mm) and 0.887 in. (22.52 mm) respectively for an advertised displacement of 0.597 cuin. (9.79 cc). Since this model was intended for race car use, the timer did not include a timing adjustment arm. The timer was activated by a cam formed integrally with the crankshaft. The use of a flywheel instead of a prop driver eliminated the need for flats on the front of the shaft to lock the driver to the shaft. These engines did not bear any serial numbers - indeed, this was true of the entire Atwood Champion series. As a result, accurate production figures for the various models are almost impossible to estimate. The Atwood Champion Aircraft Model

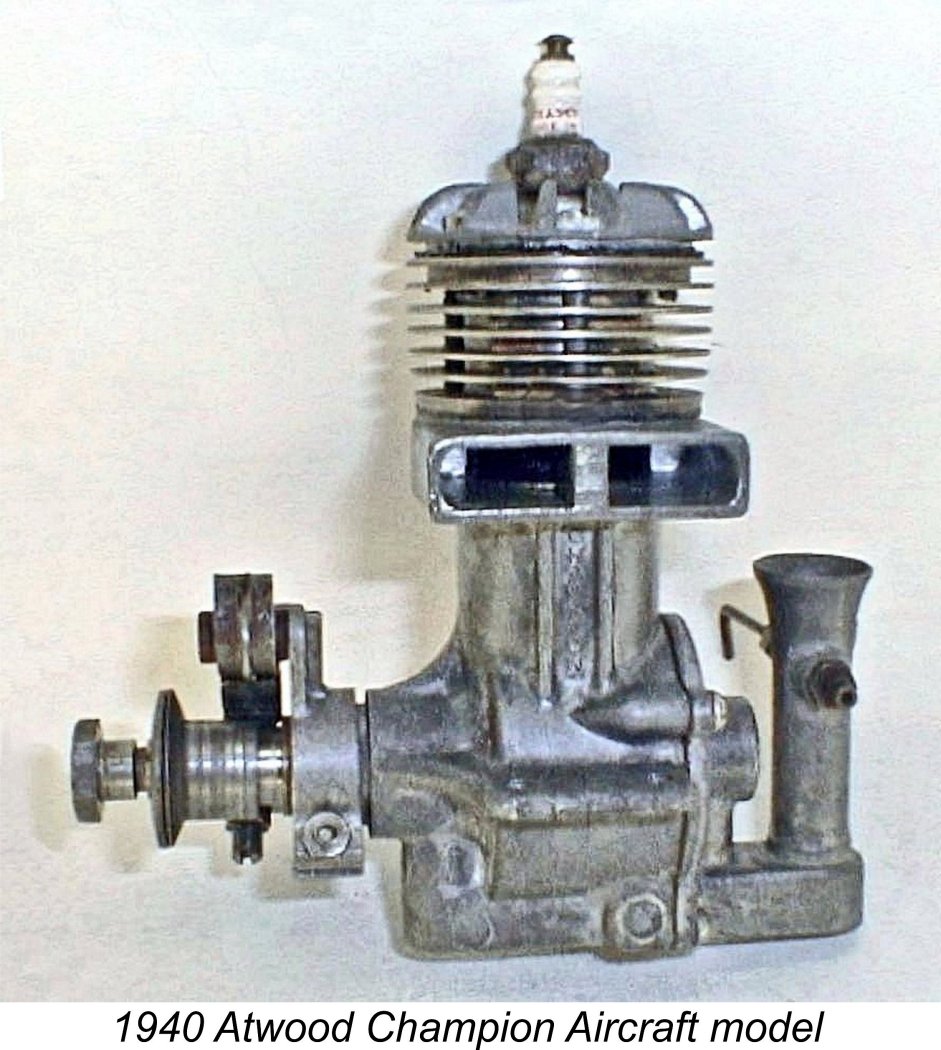

For one thing, weight was now a more pertinent issue. To assist in addressing this factor, the castings for the Champion Aircraft model were die-cast in magnesium alloy and were left in their as-cast finish. Another required change was the fitting of a prop driver, which in turn required the provision of two flats at the front of the shaft to lock it to the shaft. The timer now featured an integrally-cast control arm to allow adjustment of the timing on the run following hand starting. The induction ports in the shaft and drum were changed from rectangular to round. The bypass continued to display no lettering. The name ATWOOD appeared in vertical letters between two stiffening ribs under the left-hand exhaust. Those members of the Champion series that found early buyers seem to have impressed those who saw them perform. This was particularly true of the car models. As a result of their evident success, a couple of individuals named Shaw and Kaw (sounds like a comedy team!) persuaded Bill Atwood to finally leave Phantom Motors (and Champion Products) in early 1941 to join them in manufacturing and further promoting the latest Champion engines. Bill did so, at the same time retaining all rights to the Phantom Torpedo and Bullet designs. The later Phantom P-30, postwar Bullet 100, and Miniature Motors Torpedo Special were not Atwood designs.

This resulted in a definite shift of the American industrial economy towards war-related production. The Lend-Lease program was being expanded, while military aircraft production was being ramped up in anticipation. Supplies of magnesium were diverted almost wholesale into the manufacture of aircraft and the production of munitions such as incendiary bombs. Consequently, magnesium alloys were no longer available for such non-military purposes as model engine manufacture. This doubtless had significant implications for the ongoing production of the Champion Aircraft model. The association with Messrs. Shaw and Kaw proved to be a very brief one, for reasons which are now lost. Thereafter, Bill joined forces with Wetzel Motors of 420 S. Manhattan Place, Los Angeles, California, with whom he continued to manufacture his revised Champion designs. However, the December 1941 entry of America into WW2 signalled a major change for Bill, since his talents were now needed for the war effort. After working for a time in war-related production as a toolmaker while maintaining a “hobby” connection with the Champion engines, he became a full-time glider pilot instructor for the US Army Air Corps. Wetzel kept the Champion dies and parts inventory, assembling a few engines during the war years from pre-war parts stock. The Post-War Atwood Champions

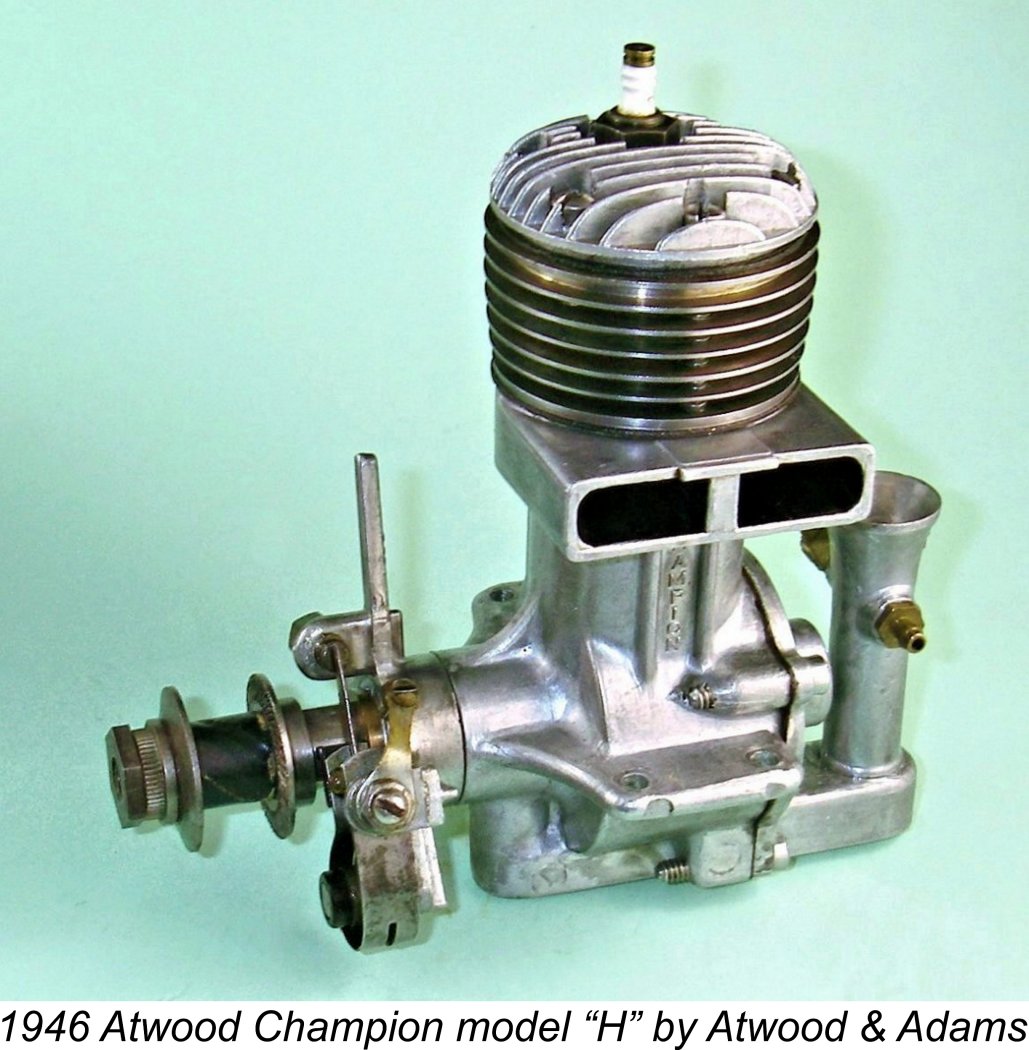

The first post-war version of the Champion to appear after the war was the Atwood Champion model “H”. Allowing for editorial lead time, the attached advertisement from the January 1945 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN) proves quite conclusively that this model had already made its post-war appearance in limited quantities by December 1944 - quick work by the partners following that September 1944 relaxation of restrictions! The engine on offer was basically identical to the pre-war Champion Aircraft model, including the use of magnesium alloy castings. The one observable change was an amendment to the die to produce the letter “H” cast onto the bypass. This letter also appeared on various internal components. For reasons which are lost in the mists of time, the Wetzel and Atwood partnership did not long survive the end of WW2. At the time of the split, there appears to have been a difference of opinion over who owned what - each partner evidently thought that he owned the rights to earlier Atwood designs. During the war, The concurrent transfer of the Torpedo naming rights to two distinct entities resulted in a three-cornered lawsuit, the full details of which have since been very effectively swept under the rug as evidently being best forgotten. History records that Brodbeck came out on top in that particular contest, although Miniature Motors used the name for a while with their Torpedo Special, seemingly without challenge. In mid-1945, having split with Wetzel, Bill Atwood relocated to the Ace Model Shop in Pasadena, where he carried on producing magnesium-casting model "H" Champions under the trade-name of Atwood Motors. The engine continued to feature both a lapped Meehanite piston running in a cast iron cylinder and a radially-finned "spoke" cylinder head with a centrally-located 3/8-24 plug. At some point in 1945, Bill decided that he would no longer compete in power competitions against his own engine customers, accordingly turning his attention back to indoor flying, in which he had first competed way back in the 1920’s. He was just as successful in this field as he had been in others, winning four consecutive indoor titles at the US National Championship meetings from 1945 through 1948 inclusive. He was to win again at the 1952 US Nationals at Los Alamitos.

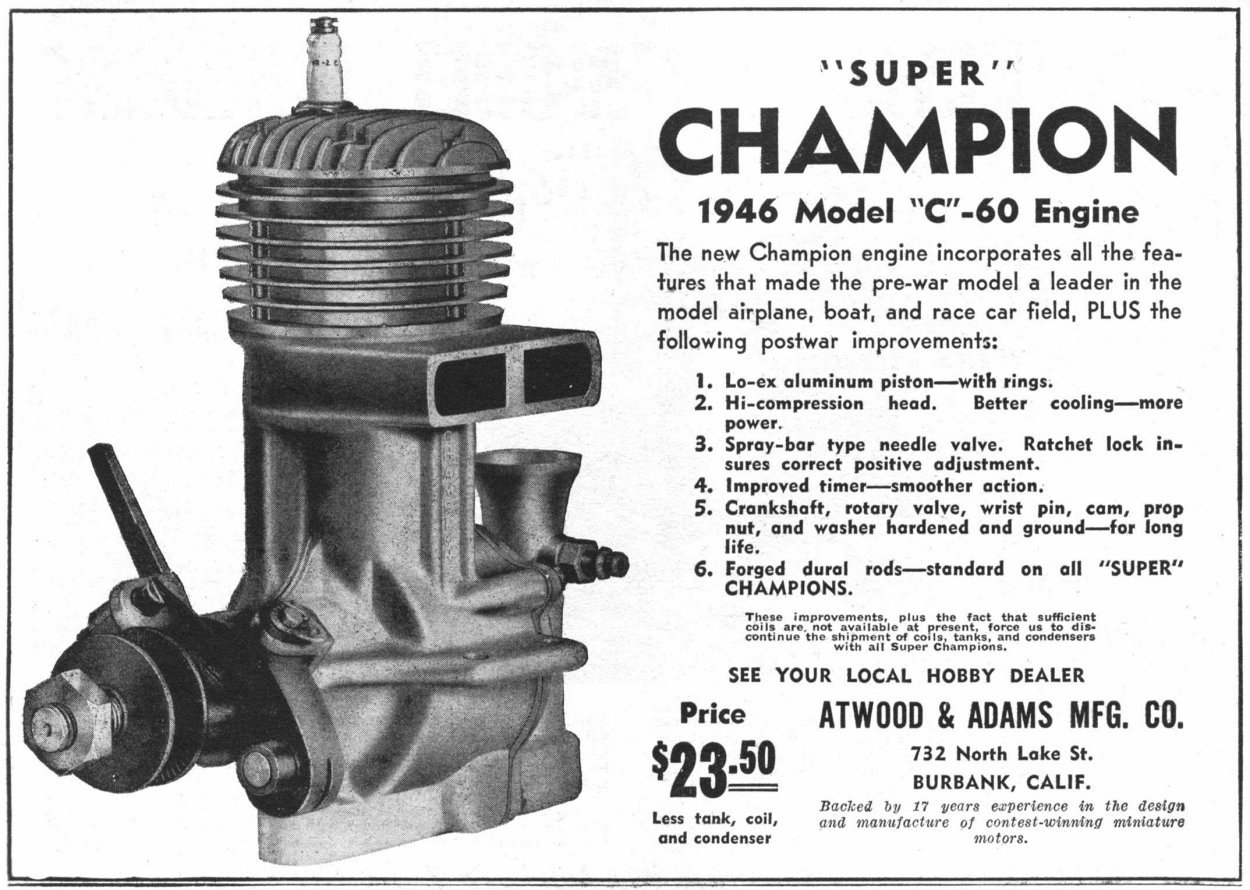

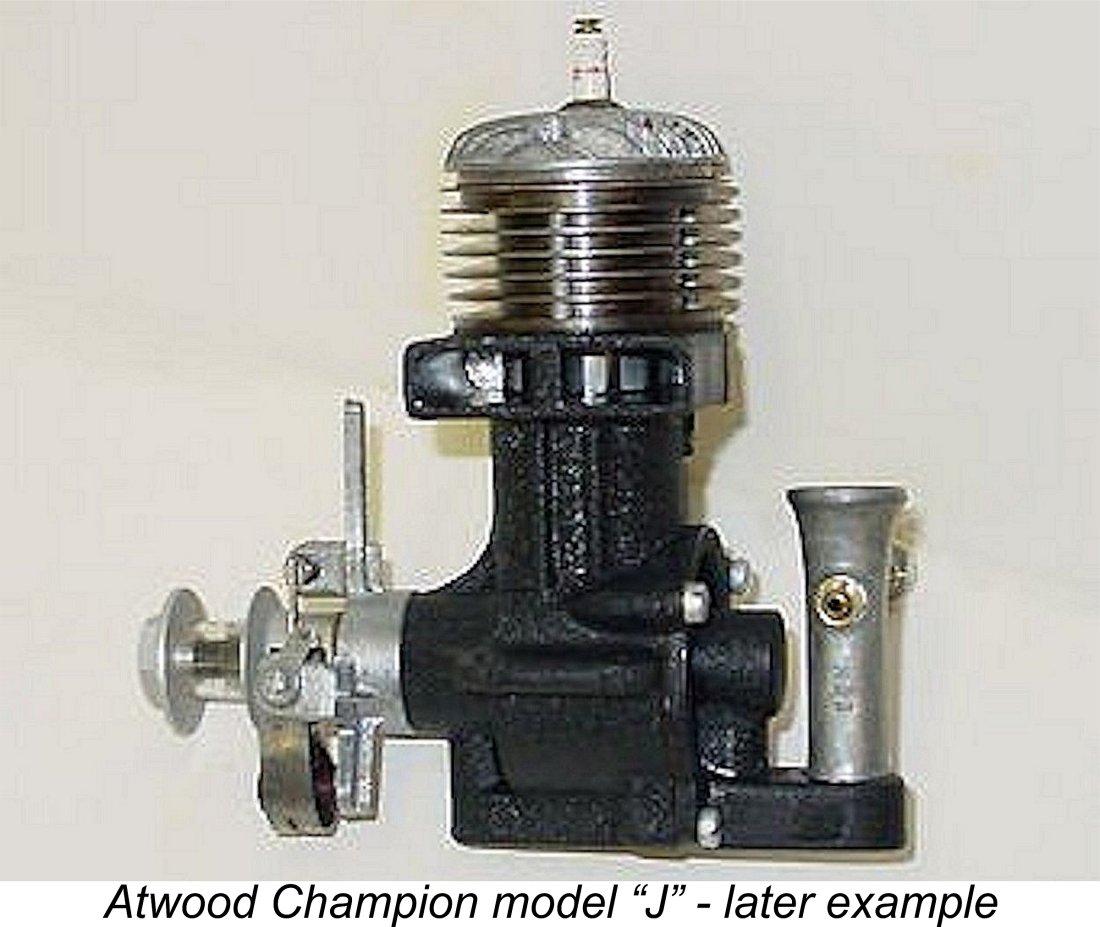

The model “H” Atwood Champion continued in production under the Atwood & Adams banner, being referred to somewhat confusingly in the company's advertisements as the Model “C”-60, presumably reflecting the fact that it was a Class C engine. However, it displayed a number of quite significant changes from the earlier renditions. The castings were now in aluminium alloy, while the cylinder material was changed from the former cast iron to heat-treated steel, with a lapped cast-iron baffle piston - a far superior wearing combination. The former radially-finned "spoke" head was replaced by a thinner component having parallel fore-and-aft fins and accommodating a 1/4-32 V-2 spark plug which was offset well to the bypass side. The cam was no longer formed in unit with the shaft - instead, the timer was activated by a cam formed integrally The designation “H23” now appeared cast vertically onto the surface of the bypass in very small characters, while the characters "H32" were cast onto the right-hand side of the "smokestack" intake. The backplate recess displayed the letters "H27". These figures presumably referred to part numbers. The bore continued to be 0.930 in. (23.62 mm) with a stroke of 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) for a displacement of 0.611 cuin. (10.02 cc). It would appear that primary reliance was placed upon the rear drum valve to perform the induction function. The induction port in the drum valve was a large rectangular opening, while that in the crankshaft was a far smaller round aperture. The manufacturer actually referred to the front induction portion of the system as the “intake bypass”. This model was soon joined by an engine designated the model “J” which displayed only a few minor cosmetic differences from its companion. The major change which produced this model was its use of a ringed light alloy piston in place of the lapped component used in the model “H”. It was the first Champion model to feature such a piston. Charlie Bruce pointed out in his previously-cited article that this reflected a fairly common marketing strategy employed by Bill Atwood - make minimal changes to an existing design and advertise it as a new model to encourage sales to established Atwood users. The cylinder porting consisted of rows of circular drilled holes instead of the more usual series of square openings. The stroke was unchanged, but the bore was increased slightly to 0.940 in. (23.88 mm), raising the displacement to 0.625 cuin. (10.24 cc). It seems not unlikely that this change was made to match the bore of the ringed-piston Champion model to that of the McCoy and Hornet 60 designs, thus allowing the use of the same proprietary piston rings. A few examples of the model "H" were apparently also supplied with this ringed piston - such a variant was actually advertised by Atwood & Adams in the July 1946 issue of "Air Trails". The letter “S” appeared on the front of the model “J” cases, apparently to indicate the starting position for the timing control arm.

A switch was also made to a high-domed McCoy-style ringed alloy piston as opposed to the "uniflow" piston used in the ringed model "J", operating in a bore of 0.940 in. (23.88 mm) and resulting in a displacement of 0.625 cuin. (10.24 cc). The compression ratio was raised from 6.5 to 1 to 8 to 1, while the bypass passage and exhaust port area were both enlarged. This was accomplished in part by using more conventional cylinder openings of basically square section in place of the drilled round openings used in the model "J". A forged con-rod was used to deal with the increased loads resulting from the higher compression ratio. A thicker head was now featured, still with parallel fins. From early 1947 onwards, a straight-in rear intake carburetor as opposed to the standard downdraft “smokestack” was made available as an option, chiefly intended to facilitate inverted operation. The crankshaft was now fitted with a ball-bearing thrust race. One-time user Charlie Bruce recalled this model as having been the finest control-line stunt engine of its day. His engine (which he still had in 2000) invariably started on the first or second flick and ran the tank out smoothly and consistently. The lightweight ringed piston allowed the Champion to run with far less vibration than the competing lapped piston Super Cyclone or Orwick models which were the main competition. In stunt service, it reportedly turned a 13x8 prop with great authority. The "J"-model Champions continued in production at this time, presumably to use up the remaining left-hand exhaust castings. A number of the 1947 examples of the “J” models used magnesium castings, presumably in order to offer a lightweight option and perhaps also to use up some left-over magnesium castings.

It appears that the dies for the model “J” became quite worn-out over time, resulting in the castings becoming progressively rougher. This led to the main crankcase and backplate castings of later examples of this model being given a black wrinkle paint finish to hide the casting imperfections. The Atwood & Adams partnership didn’t last long either. In fact, this highlights a recurring situation in Bill Atwood’s career which the attentive reader may have noticed by now - none of his various partnerships seem to have lasted long. The reasons for this remain unclear. This pattern was to continue through the 1950’s up to the point in 1960 when Bill finally settled down to work for Cox right up until his somewhat untimely death in 1978 at the age of 67.

The illustrated example features several options which were then available. One is a two-speed timer which offered a limited degree of speed control for R/C applications. The other is the optional straight-in induction conduit which had been available for the Super Champion model "JH" since early 1947. In November 1947 an event took place that was to change the power modelling scene forever - Ray Arden introduced his commercial miniature glow-plugs to the world. Both model engine manufacturers and their customers immediately saw that this put the writing on the wall in very large letters for the spark ignition motor. Bill Atwood was quick to recognise the implications of this event. He found that his high-compression Super Champion twin-valve design of 1947 performed very well on glow-plug ignition using a methanol fuel and was undoubtedly sufficiently sturdy to withstand the additional operating stresses. Consequently, all that was necessary was to eliminate the timer to create a “purpose-built” glow-plug model. Such an engine duly appeared in the early part of 1948 as the Atwood Glo-Devil model. The initial variant of this model was identical to the 1947 spark ignition Atwood Super Champion apart from the omission of the timer. It retained the narrow bypass, ringed piston and 0.625 cuin. displacement of its sparkie progenitor. It also retained the spark ignition prop driver/cam component, making its conversion back to spark ignition a very simple matter - indeed, the Glo-Devil instructions included a paragraph describing this very process.

Indeed, as of 1948 there remained a segment of the power modelling community which continued to favour spark ignition operation, especially with larger displacements for which the incremental additional weight of the ignition support system was a relatively minor issue. The principal advantage was seen as the ability to adjust the ignition timing very precisely to suit any desired operating speed. There’s a great deal of logic behind this view - even today it remains one of the great advantages of spark ignition operation. The use of white gas for fuel also reduced fuel costs considerably - another advantage of the use of spark ignition in large thirsty engines. It was likely this lingering demand which prompted the release of a spark ignition version of the big-bypass “GD” glow-plug model in mid 1948. This was essentially identical to the glow-plug variant apart from the addition of a timer. However, it was seemingly only available with the straight-in rear induction tube (as opposed to the vertical ”smokestack” intake) which had previously been only an option. In addition, the letters “DR” appeared on the bypass in place of the “GD” designation.

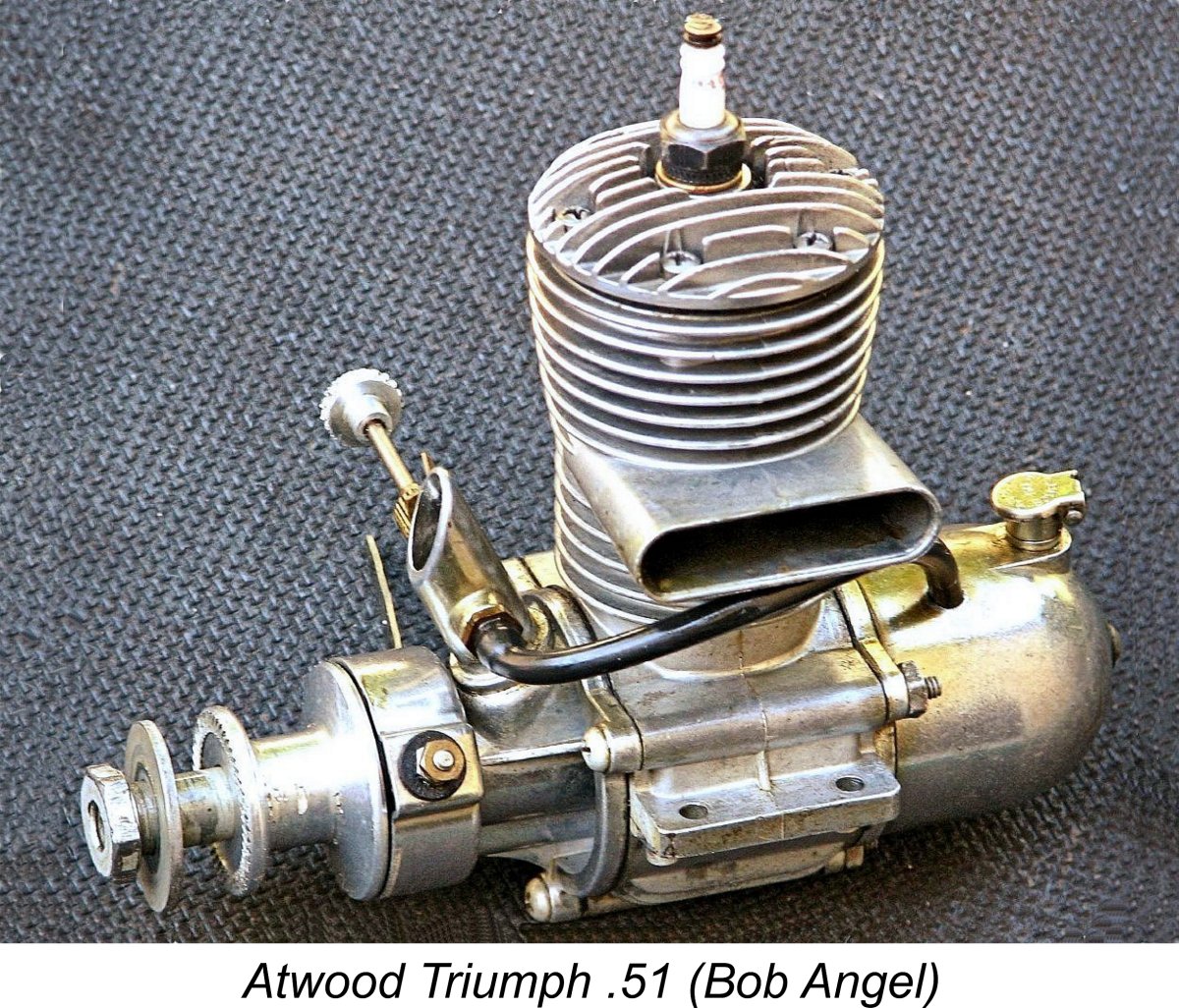

However, it was later in that same year that Bill Atwood finally abandoned the twin rotary valve arrangement to which he had remained faithful for 10 years. He had evidently decided that there was no point in trying to compete with the new generation of high-performance 10 cc powerplants like the McCoy 60 and the Dooling 61. Accordingly, he abandoned that displacement category, instead bringing out the Triumph line of high performance single-valve FRV engines in .49 and .51 cuin. displacements. These displacement options allowed Triumph-powered models to compete in both the .499 and .649 cuin. displacement classes which then existed, depending on which motor was installed. Both spark and glow-plug ignition versions were offered. This design was used by Gene Stiles to bring the first Free Flight speed record (81.587 mph) to the U.S. with his June 1949 flights. His airplane was subsequently placed in the Smithsonian Institute. This put an end to the very successful series of twin-valve engines which had been associated with Bill Atwood for the previous 10 years. It had been a great run for these highly individualistic and very powerful engines. Let’s now turn our attention to the question of just how powerful they were! The Atwood Twin-Valve Models on Test

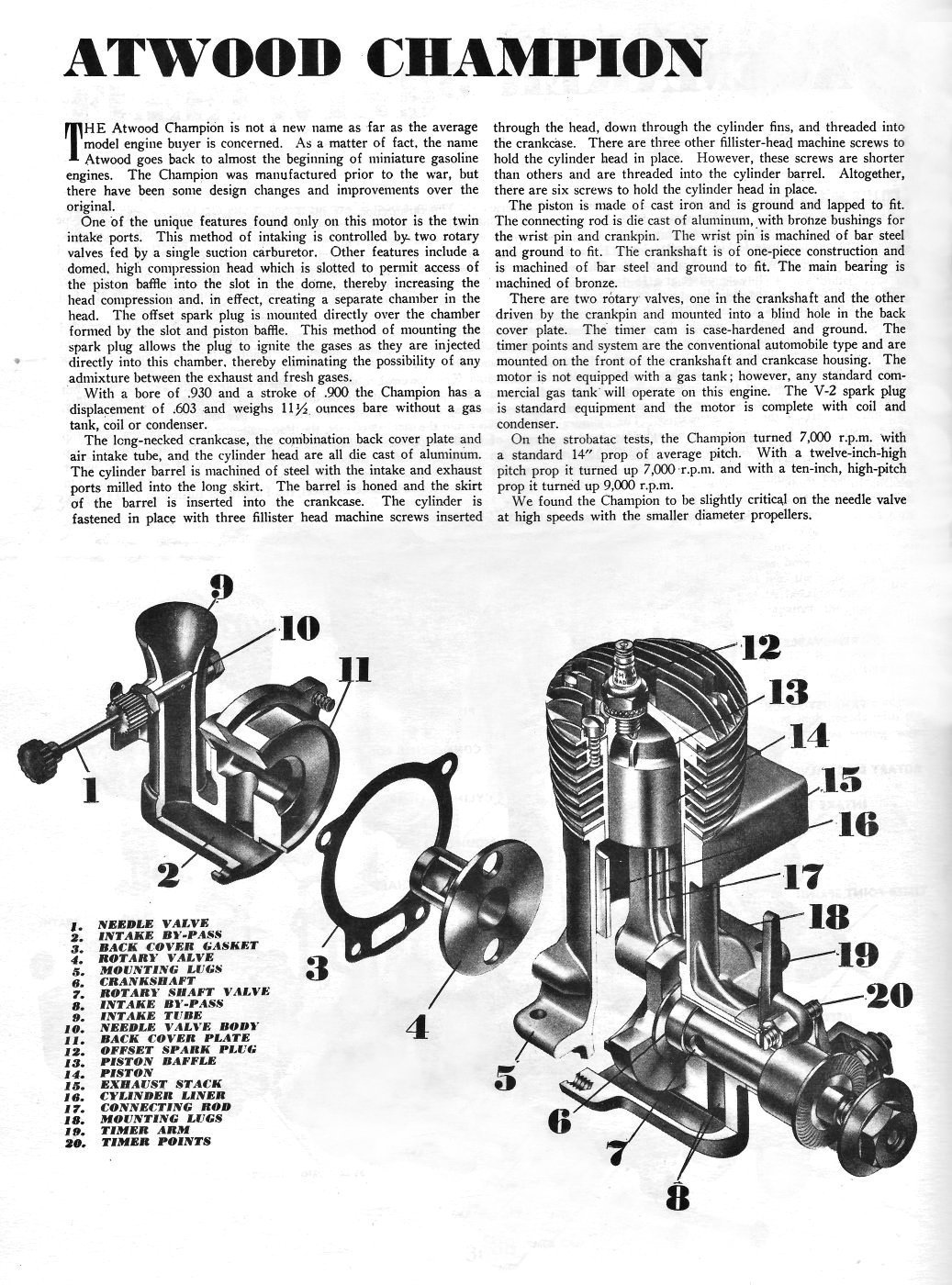

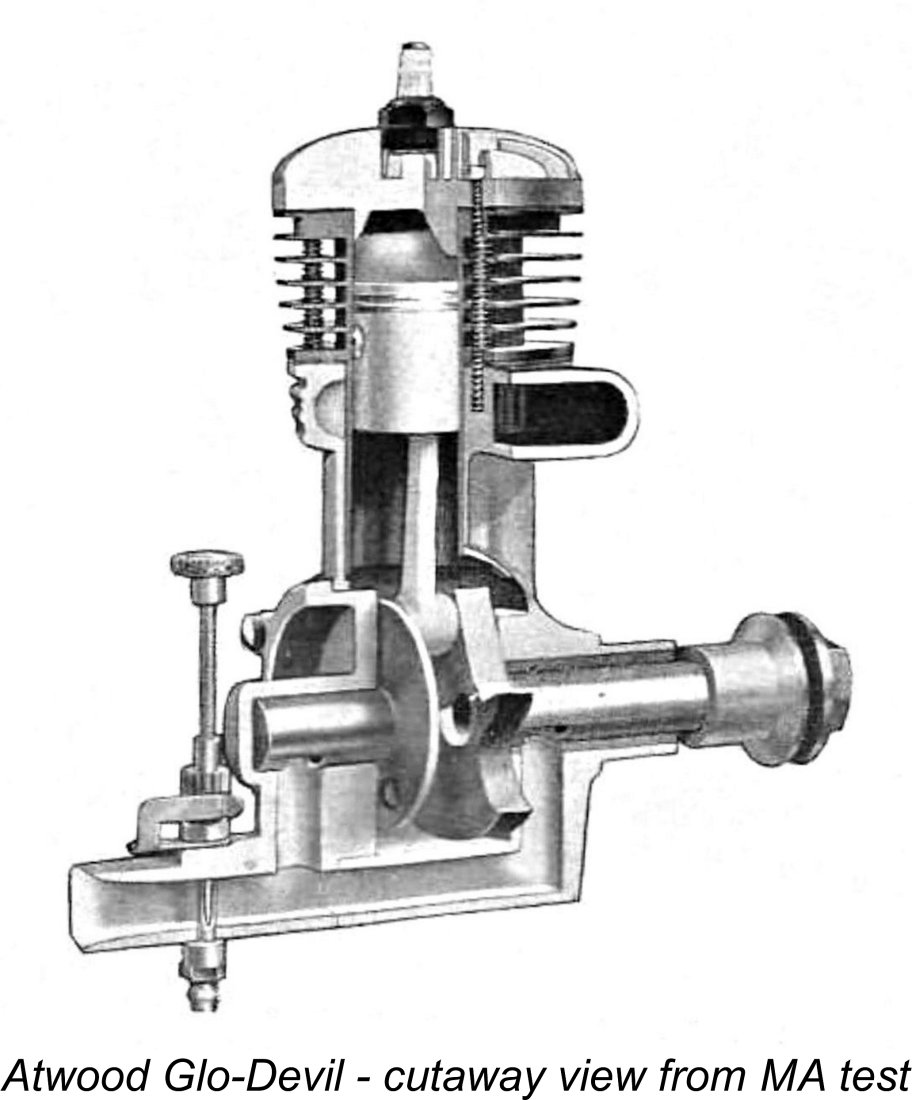

Although the specific model was not identified by the author, the text of the unattributed article makes it quite clear that this was one of the model “H” Atwood Champion "C"-60 engines produced in 1946 under the Atwood & Adams banner. The text states quite specifically that the tested model featured aluminium alloy castings with a left-hand exhaust stack. It had a steel cylinder along with a lapped cast iron baffle piston and a thin parallel-fin head. It also featured the downdraft “smokestack” intake. The bore was 0.930 in. with a stroke of 0.900 in. for a displacement of 0.611 cuin. (incorrectly stated in the article as 0.603 cuin. - the writer clearly never checked). Taken together, these features are persuasively indicative of the Atwood & Adams model “H” Champion of 1946. The test engine’s weight was given as 11½ ounces bare. My illustrated example of this model weighs in at 366 gm (12.90 ounces) with plug. I have no explanation for the discrepancy. The “Air Trails” article was particularly informative in that it included a fine cutaway drawing of the engine as seen at the left. This provided a high level of clarity regarding the engine’s construction. The article also confirmed that the engines were initially supplied with V-2 spark plug, coil and condenser, although the later advertising stated that supply problems had forced the eventual cessation of the provision of coils and condensers with each engine.

If we assume that the 14 in. prop might have been something like a 14x6, a quick calculation confirms that turning an APC airscrew of that size at 7,000 RPM requires the development of some 0.400 BHP at that speed. If we take “high pitch” to be something in the order of 10 in., my old calibrated 10x10 wood prop absorbs some 0.62 BHP when turning at 9,000 RPM. These actually appear to me to be not unreasonable figures - they are certainly mutually consistent, although since I have no knowledge of the actual props used, I can’t be definite. However, they do provide an interesting and perfectly valid comparison with the more or less contemporary figures reported in the same "Air Trails" test series for the competing Super Cyclone. The latter model was cited as tuning a 14x6 prop at 6,800 RPM, a 12x8 prop at 7,200 RPM and a 10x10 prop at 8,500 RPM. The implication is that the Atwood Champion was the slightly more powerful engine of the two. I suspect that the Champion's peak would lie at somewhat higher speeds than these. Although the reported figures are vague in the extreme, the indications are that the Atwood Champion model “H” was a pretty stout performer for a plain bearing non-racing engine of its era. I’d hazard a guess that it might produce something in the range of 0.700-0.800 BHP in the region of 11,000-12,000 RPM running on white gas.

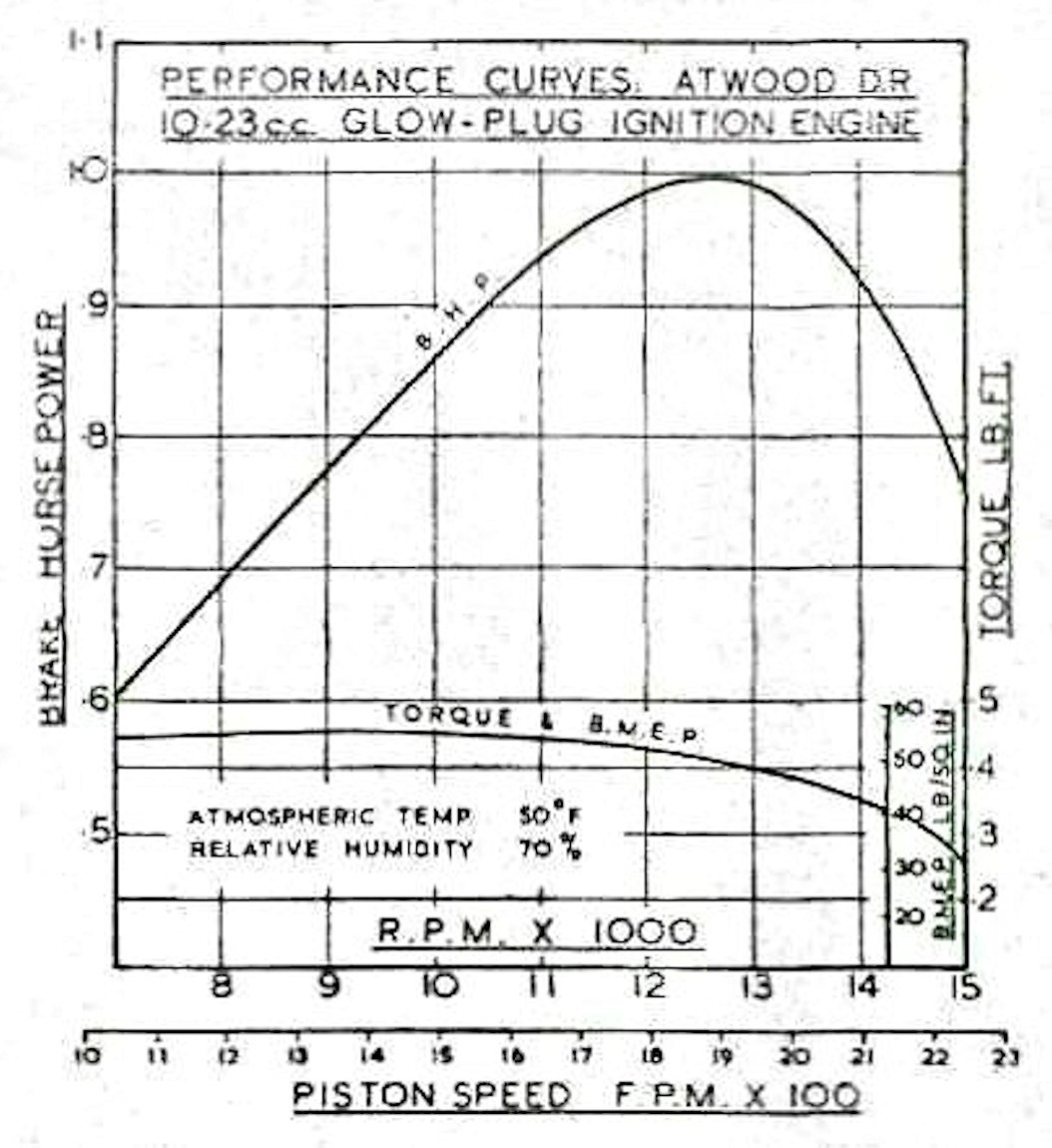

Regardless, Chinn was clearly extremely impressed with the Glo-Devil, stating that its performance compared very favourably with several British-made racing-type 10 cc engines which had recently passed through his hands at the After describing the engine’s construction and praising its quality, Chinn turned to a consideration of its performance. Following a suitable break-in period, he tested it up to 15,000 RPM. He found that an exhaust prime was an aid to cold starting, but hot re-starts required only a couple of choked flicks as a preliminary. He also found that little or no needle adjustment was required between starting and running - a good feature. The needle valve was found to be very positive in action without being at all critical. Chinn found that the Glo-Devil ran very smoothly with a “clear, crisp exhaust note, free from “crackle”, and maintains a steady output” at all speeds above 8,000-9,000 RPM. He also stated that “no vibratory period was evident over the range of speeds at which the engine was tested”. Maximum Brake Mean Effective Pressure was measured at a very good figure of 55 psi at around 9,000-10,000 RPM, while peak power output was found to be exactly 1.00 BHP @ 12,700 RPM. The For a relatively lightweight 10 cc engine lacking ball races and ported more for torque than high speeds, Chinn rightly characterized this as an “exceptional performance” - indeed, the reported output of the Glo-Devil came whisker-close to matching the figures which I have measured for my own examples of the Nordec and Rowell racing models. Chinn mentioned this very fact, also commenting that the Glo-Devil weighed considerably less than the racing units which it more or less matched in terms of output. He made a particular point of noting that the recorded power-to-weight ratio of over 1.4 BHP/lb was “the highest so far published in these tests”. So the Glo-Devil came through its test in the hands of one of the world’s ranking experts with flying colours. Even though Bill Atwood had moved on to other things by December 1950, he must have been pleased! This is the point at which I would normally insert my own test results to compare with the data presented above. However, the Covid-19 situation prevailing when I wrote this article made any testing at the flying field appear unwise, while the noise levels to be expected from these large engines precluded any thoughts of testing at home. So there we have to leave it ….. for now. If circumstances ever permit, I’ll run some tests and add the findings to this article. As a final note, it's worth recording the fact that the Atwood Champion was one of the engines featured in Peter Chinn's short-lived "Notable Model I.C. Engines" series which appeared in the pages of "Model Engineer" during the mid-1950's. Chinn's retrospective article on the Atwood Champion was published in the magazine's June 23rd, 1955 issue. Chinn's review was extremely positive - in fact, he concluded with the statement that "by our own experience, it (the Atwood Champion) was one of the finest factory-made model engines of all time". 'Nuff said I think ................! Conclusion I hope that I’ve convinced you that the twin-valve Atwood Champion series consisted of a succession of technically unusual and very successful model engines from one of the most talented designers of the era in question. To go along with their outstanding designs, they were also very well made, seemingly well able to give long service to their owners. I doubt very much that many purchasers (if any) were disappointed! Charlie Bruce's previously-cited article in ECJ makes a particular point of mentioning the high degree of interchangeability of the components used in the construction of these engines. Consequently, examples may well be encountered which don't precisely match the descriptions provided in the present article - I've seen a few myself. One has to examine each engine and fit it into the sequence as closely as possible. Anyway, if you like well-made model engines with both a pedigree and a healthy helping of design innovation, give one a try! Anyone who likes model engines is sure to enjoy an encounter with one of these beauties! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2025 |

| |

Few individuals who take a serious interest in classic model engines will not have some degree of familiarity with the name of Bill Atwood (1910 - 1978). For a full half-century Bill was one of the most prolific and inventive figures in the field of model engine design and manufacture. The listing of the engines with which he was involved in his own right occupies over 8 pages in Volume 1 of the late Tim Dannel’s indispensable “

Few individuals who take a serious interest in classic model engines will not have some degree of familiarity with the name of Bill Atwood (1910 - 1978). For a full half-century Bill was one of the most prolific and inventive figures in the field of model engine design and manufacture. The listing of the engines with which he was involved in his own right occupies over 8 pages in Volume 1 of the late Tim Dannel’s indispensable “ All of the Crown Champion models featured a lapped cast iron piston. The twin-valve models all featured both a crankshaft rotary valve and a drum valve which was driven by a crankpin extension. These designs all featured dual intakes, one each for the crankshaft and rear drum rotary valve systems. Each intake had its own independent needle valve, thus requiring synchronisation of settings. The two single-valve models both featured updraft crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) intakes. All of these models were covered in detail in my

All of the Crown Champion models featured a lapped cast iron piston. The twin-valve models all featured both a crankshaft rotary valve and a drum valve which was driven by a crankpin extension. These designs all featured dual intakes, one each for the crankshaft and rear drum rotary valve systems. Each intake had its own independent needle valve, thus requiring synchronisation of settings. The two single-valve models both featured updraft crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) intakes. All of these models were covered in detail in my  The model that seems to have been manufactured in the largest numbers during this period was the Blue Crown Champion car engine, and even that model is rarely encountered today. Very few original examples of the Red and Green Crown engines survive, and there are no reported original survivals of the Purple Crown model - just a few repros. It actually seems doubtful that any examples of that model were actually produced back in the day.

The model that seems to have been manufactured in the largest numbers during this period was the Blue Crown Champion car engine, and even that model is rarely encountered today. Very few original examples of the Red and Green Crown engines survive, and there are no reported original survivals of the Purple Crown model - just a few repros. It actually seems doubtful that any examples of that model were actually produced back in the day.

One of Atwood’s goals in developing this revised model was clearly to facilitate production. To this end, the formerly sand-cast components were now produced by die-casting using permanent molds. The aluminium alloy castings for this model did not feature any additional letters such as the letters “H” or “JH” which were cast onto the bypasses of later models. The castings were polished - perhaps even tumbled.

One of Atwood’s goals in developing this revised model was clearly to facilitate production. To this end, the formerly sand-cast components were now produced by die-casting using permanent molds. The aluminium alloy castings for this model did not feature any additional letters such as the letters “H” or “JH” which were cast onto the bypasses of later models. The castings were polished - perhaps even tumbled.  Naturally enough, Bill Atwood was quick to recognize the potential of this revised design for aircraft use. Accordingly, by the end of 1940 an aero version of the new unit designated the Champion Aircraft model had been developed. It was basically the same engine with the flywheel replaced by a prop driver, although the bore and stroke were now standardised at 0.930 in. (23.62 mm) and 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) respectively for a slightly increased displacement of 0.611 cuin. (10.02 cc). However, there were a few other changes to address the engine’s intended application to model aircraft instead of cars.

Naturally enough, Bill Atwood was quick to recognize the potential of this revised design for aircraft use. Accordingly, by the end of 1940 an aero version of the new unit designated the Champion Aircraft model had been developed. It was basically the same engine with the flywheel replaced by a prop driver, although the bore and stroke were now standardised at 0.930 in. (23.62 mm) and 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) respectively for a slightly increased displacement of 0.611 cuin. (10.02 cc). However, there were a few other changes to address the engine’s intended application to model aircraft instead of cars.  By mid-1941 the winds of change were blowing strongly in the American industrial sector. The war in Europe had heated up, while US/Japanese relations were becoming increasingly strained, placing the two countries on an unmistakable collision course. It had become obvious to most clear-thinking participants in the governance of the USA that the country’s entry into WW2 as a combatant in the fairly near future was inevitable.

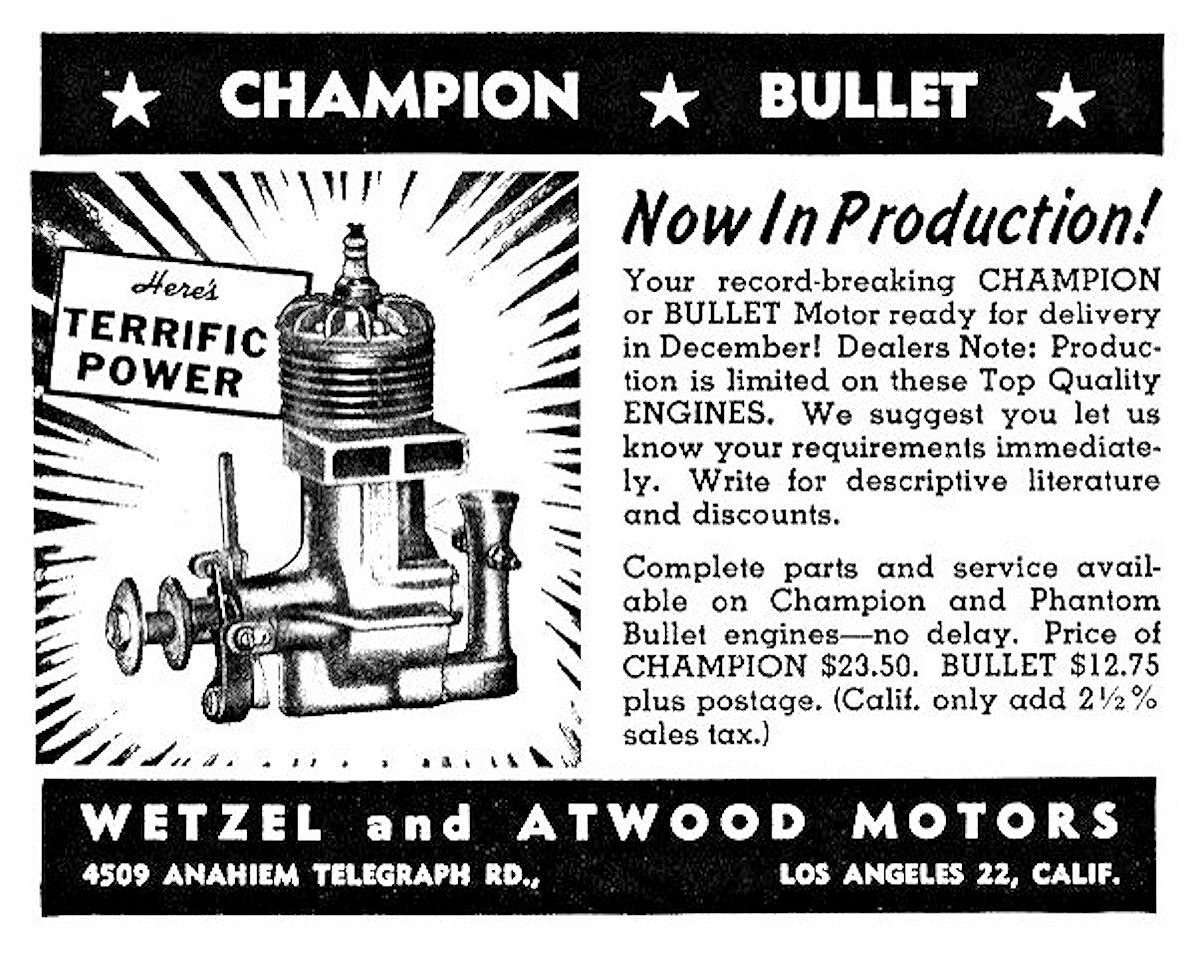

By mid-1941 the winds of change were blowing strongly in the American industrial sector. The war in Europe had heated up, while US/Japanese relations were becoming increasingly strained, placing the two countries on an unmistakable collision course. It had become obvious to most clear-thinking participants in the governance of the USA that the country’s entry into WW2 as a combatant in the fairly near future was inevitable. In September 1944 as war production requirements were ramping down, the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient quantities of the appropriate metals for non-military purposes to allow the limited resumption of model engine production in the USA. At this point, Atwood was quick to resume his association with Wetzel under the name Wetzel & Atwood Motors of 4509 Anaheim Telegraph Road, Los Angeles, resuming production of both the Atwood Champion and the pre-war Phantom Bullet.

In September 1944 as war production requirements were ramping down, the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient quantities of the appropriate metals for non-military purposes to allow the limited resumption of model engine production in the USA. At this point, Atwood was quick to resume his association with Wetzel under the name Wetzel & Atwood Motors of 4509 Anaheim Telegraph Road, Los Angeles, resuming production of both the Atwood Champion and the pre-war Phantom Bullet.

with the steel prop driver. The racing-type collet needle valve assembly used formerly was now replaced by a conventional spring-tensioned spraybar system.

with the steel prop driver. The racing-type collet needle valve assembly used formerly was now replaced by a conventional spring-tensioned spraybar system.  Bill Atwood was never content to stand pat with the same models for long! In mid 1946, some further design revisions produced the Atwood Super Champion model “JH” which replaced the former model “H” (aka “C”-60). The most immediately obvious change here was the switch of the exhaust stack from the left hand side (looking forward in the direction of flight) to the right-hand side. The stack shape was also changed from its former rectangular section to a round-ended "race-track" profile. The revised die which these changes necessitated also eliminated the vertically-oriented ATWOOD name between the two stiffening ribs beneath the exhaust stack. The name now appeared in vertical characters on the bypass, with the letters “JH” in a circle above the ATWOOD identification.

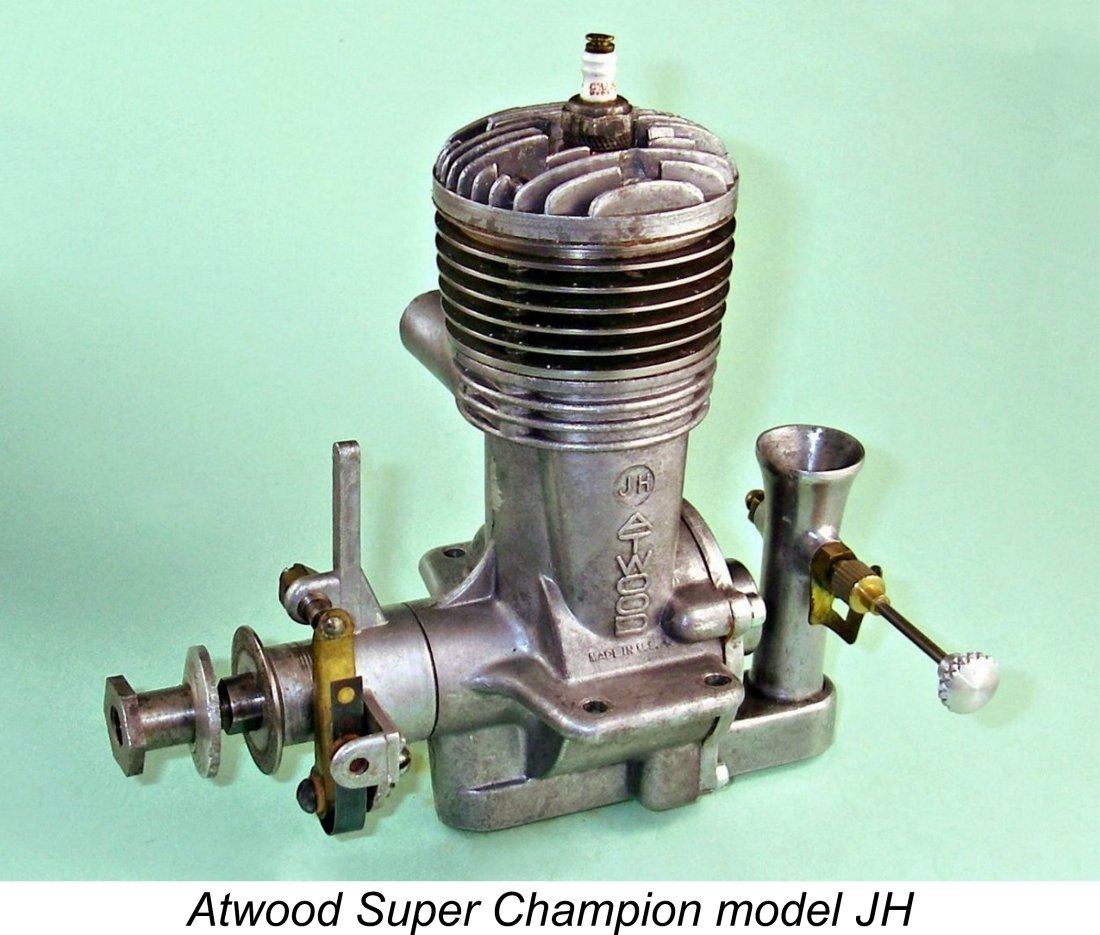

Bill Atwood was never content to stand pat with the same models for long! In mid 1946, some further design revisions produced the Atwood Super Champion model “JH” which replaced the former model “H” (aka “C”-60). The most immediately obvious change here was the switch of the exhaust stack from the left hand side (looking forward in the direction of flight) to the right-hand side. The stack shape was also changed from its former rectangular section to a round-ended "race-track" profile. The revised die which these changes necessitated also eliminated the vertically-oriented ATWOOD name between the two stiffening ribs beneath the exhaust stack. The name now appeared in vertical characters on the bypass, with the letters “JH” in a circle above the ATWOOD identification.

Regardless of the reason for the split with Adams, the result was the 1947 re-establishment of Atwood Motors at 734 North Lake Avenue in Burbank, right next door to the former Atwood & Adams premises at no. 732. The initial product of Atwood’s new company was a slightly revised version of the Super Champion model “JH”, albeit with a narrower bypass passage having the name “SUPER CHAMPION” now cast in relief onto its surface, the “SUPER” being cast horizontally. The “JH” letters were omitted from the bypass of this model. A ringed piston continued to be used in a 0.940 in. bore for a displacement of 0.625 cuin.

Regardless of the reason for the split with Adams, the result was the 1947 re-establishment of Atwood Motors at 734 North Lake Avenue in Burbank, right next door to the former Atwood & Adams premises at no. 732. The initial product of Atwood’s new company was a slightly revised version of the Super Champion model “JH”, albeit with a narrower bypass passage having the name “SUPER CHAMPION” now cast in relief onto its surface, the “SUPER” being cast horizontally. The “JH” letters were omitted from the bypass of this model. A ringed piston continued to be used in a 0.940 in. bore for a displacement of 0.625 cuin.  The Glo-Devil design was updated later in 1948 by the incorporation of a revised crankcase casting featuring an enlarged bypass passage as seen earlier on the original Super Champion model “JH” of 1946. The exhaust ports were widened, while an extra transfer port opening was added. The “JH” designation was replaced by the characters “GD” in a circle above the vertically-oriented ATWOOD name. A few of these models were sold with timers fitted for spark ignition operation - an example is illustrated here.

The Glo-Devil design was updated later in 1948 by the incorporation of a revised crankcase casting featuring an enlarged bypass passage as seen earlier on the original Super Champion model “JH” of 1946. The exhaust ports were widened, while an extra transfer port opening was added. The “JH” designation was replaced by the characters “GD” in a circle above the vertically-oriented ATWOOD name. A few of these models were sold with timers fitted for spark ignition operation - an example is illustrated here.  The Glo-Devil continued in production throughout most of 1948. The later examples of the Glo-Devil featured the straight-in rear induction tubes of the “DR” sparkie, although the “GD” lettering on the large bypass was maintained. These examples retained the 0.940 in. bore with a ringed alloy piston, giving an unchanged displacement of 0.625 cuin. (10.24 cc).

The Glo-Devil continued in production throughout most of 1948. The later examples of the Glo-Devil featured the straight-in rear induction tubes of the “DR” sparkie, although the “GD” lettering on the large bypass was maintained. These examples retained the 0.940 in. bore with a ringed alloy piston, giving an unchanged displacement of 0.625 cuin. (10.24 cc).  The pre-WW2 Atwood Champion models appear never to have been the subject of any published reviews, although they were mentioned in a number of articles about model engines in general. As far as I can discover, the first published test of an Atwood twin-valve Champion model appeared in the pages of “Air Trails” magazine at some indeterminate date in 1946.

The pre-WW2 Atwood Champion models appear never to have been the subject of any published reviews, although they were mentioned in a number of articles about model engines in general. As far as I can discover, the first published test of an Atwood twin-valve Champion model appeared in the pages of “Air Trails” magazine at some indeterminate date in 1946.  In performance terms, the tester reported finding that the needle valve setting became “slightly critical” at the higher speeds with smaller airscrews. However, he reported no starting difficulties. Unfortunately, like most of the “Air Trails” tests of the period, the text was woefully short on precise details of the airscrews tried. All that the writer reported was that the engine reached 7,000 RPM on a 14 in. dia. prop of “average” pitch, whatever that means! Using a 10 in. dia. prop of “high pitch”, it managed 9,000 RPM.

In performance terms, the tester reported finding that the needle valve setting became “slightly critical” at the higher speeds with smaller airscrews. However, he reported no starting difficulties. Unfortunately, like most of the “Air Trails” tests of the period, the text was woefully short on precise details of the airscrews tried. All that the writer reported was that the engine reached 7,000 RPM on a 14 in. dia. prop of “average” pitch, whatever that means! Using a 10 in. dia. prop of “high pitch”, it managed 9,000 RPM.  Thankfully, the other published test of a twin-valve Atwood model provided far more persuasive data! This was a December 1950

Thankfully, the other published test of a twin-valve Atwood model provided far more persuasive data! This was a December 1950  time. Presumably these were the

time. Presumably these were the