|

|

Macclesfield Masterpieces - the Early P.A.W. Engines

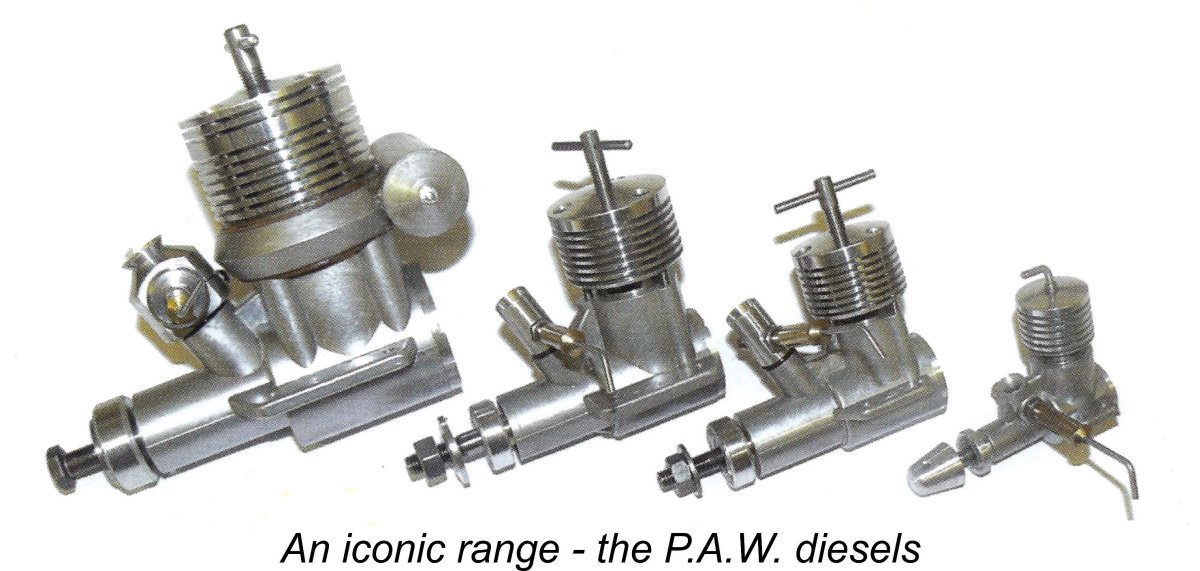

A significantly more powerful motivation is the technical originality displayed in a particular design. I’ve always been attracted to engines which demonstrate some innovative thinking on the part of their designers. The central subjects of this article, the classic P.A.W. engines from Macclesfield in England, scarcely fall into that category. Although both very capably designed and constructed to extremely high standards, they really exhibited no radical technological departures from conventional model diesel design practise as it stood when they first appeared in commercial form. Nor have they changed greatly since! However, there’s another extremely powerful driving force behind my selection of subjects! This is the degree to which my valued readers have expressed a desire to see me cover a given model engine range. Many of them evidently share my previously-expressed view that it's far more relevant and hence important for me to cover the more common ranges, examples of which may very well end up in the hands of my fellow enthusiasts. People want to learn about what they have or may reasonably aspire to have, not what they will likely never have!

My long-standing failure to cover the P.A.W. engines has absolutely nothing to do with any negative perceptions of the range on my part. On the contrary, I’ve been a completely satisfied P.A.W. owner and user for over 60 years now - more of my models have been powered by P.A.W. engines than any other brand. My previous omission of any coverage of the engines was based solely on my perhaps unwarranted perception that this iconic range is so widely used and so familiar to model diesel engine enthusiasts that I wouldn’t be able to find anything to say that would engage the interest of most of my readers! However, several readers have commented recently that the P.A.W. range is the only British model engine marque of note that I've yet to cover. They point out that while I’m old enough to have “been there” when the range first came to prominence and to have been an enthusiastic user of the P.A.W. engines almost right from their commercial introduction, others were not so favoured. To them, the early years of the range are just as obscure as the start-up periods of most other classic model engine marques, hence in their view fully meriting documentation along with the rest. OK, fair comment - it's a wise Editor who listens to his readers! In my defence, I must point out that the early years of the P.A.W. venture were previously covered in considerable detail by Andrew Nahum, whose very informative series of articles on the history of the P.A.W. range appeared during 1994 in the pages of John Goodall's long-defunct “Model Engine World” (MEW) magazine. The problem with this 28 year old reference is that it’s only accessible to those who retain (or have access to) copies of that magazine. Printed media has the great advantage of being permanent if securely stored, but it suffers from strict limitations when it comes to general accessibility. A website like mine is only as long-lasting as the cyber-platform upon which it’s built, but at least it has the advantage of general accessibility while it’s active. It also has the considerable advantage of being easily updated on the fly if new information becomes available, while printed media is frozen once published. This being the case, I’ll proceed to summarize the early history of the P.A.W. range in order to create an on-line reference for the benefit of those interested. However, I’ll qualify the following content by saying that I plan to restrict my coverage to the early years of the P.A.W. model engine venture. My intention is to present the story up to the mid 1960’s, by which time the three models which established the range as one of England’s finest - the 149, 249 and 19-D models - had all made their appearance and commenced the long process of detail refinement which has continued to this day. I’ll leave it to others to cover the many later models which have subsequently appeared. In summarizing this story, I freely acknowledge that I’ll be presenting nothing new. The commercial P.A.W. range was well documented in the contemporary British modelling media, including both published tests and regular advertisements. Moreover, a number of earlier writers, most of them far more knowledgeable than I am, have generously shared their knowledge of the P.A.W. range - Andrew Nahum’s previously-cited efforts are a prime example. All that I hope to accomplish is to consolidate the available information and to present a reasonably complete and coherent on-line account of the early years of the immensely successful P.A.W. venture for the convenience of my valued readers who may not have access to those earlier references. Model engines don’t just happen - they’re designed, created and used by people! It’s only those factors that give them life - otherwise, they’re just dead hunks of metal. Accordingly, when setting out to write about any model engine range, one of my first priorities is always to attempt to share what I can about the human interest side of the story. I’ll begin by doing just that. “Gig” Eifflaender - the Man Behind the Motors

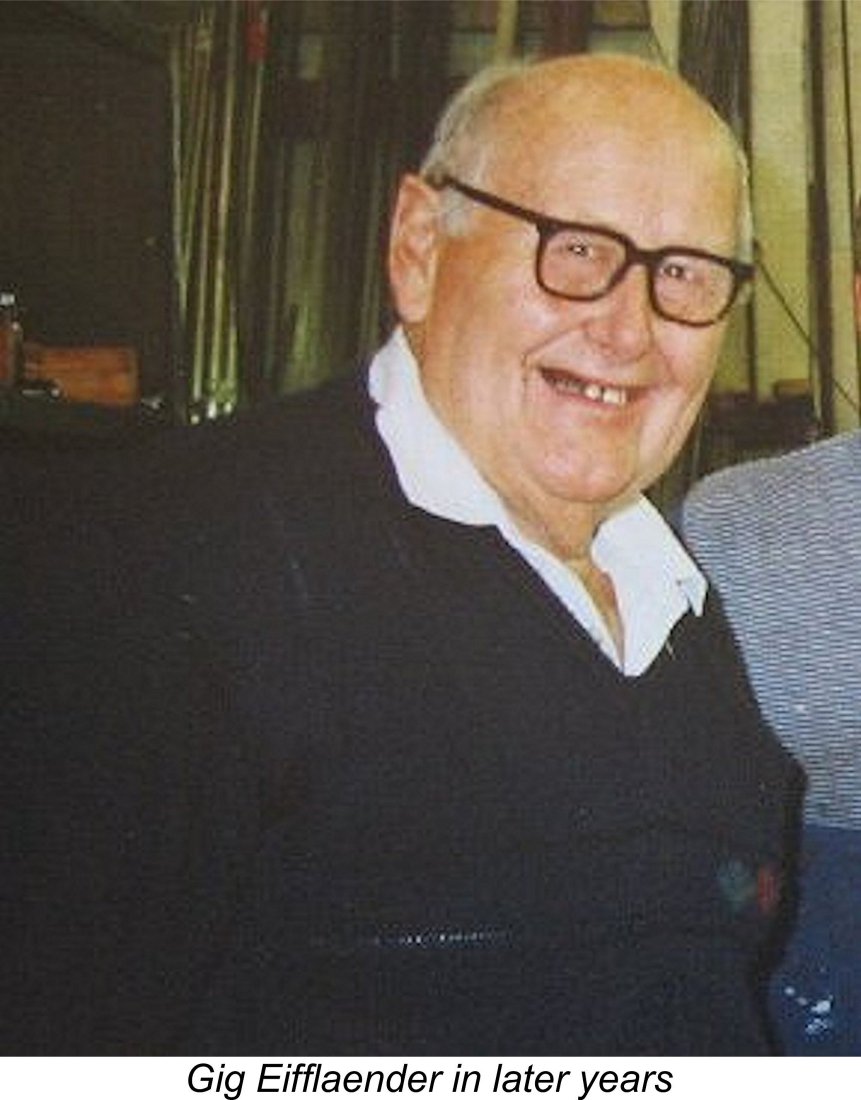

Joachim Gunter (“Gig”) Eifflaender was born on July 5th, 1922 in Krefeld, Germany to Charles and Gertrude Eifflaender. Krefeld was a major centre of the German silk and velvet industries, in which his father worked. In 1932, when Gig was only ten years old, Charles Eifflaender obtained a position as the manager of a silk mill located at Macclesfield in eastern Cheshire, England on the banks of the River Bolin some 16 miles south of Manchester (centre of accompanying map). This obviously necessitated a family move from Germany to Macclesfield. The silk industry was a major element of the Macclesfield economy at this time. Indeed, the town was the centre of the British silk Up to this point in time, young Gig had naturally done all of his communicating in his native German. He was thus faced with the immediate challenge of learning a new language, a challenge which he met in very short order. He continued to enjoy a normal family upbringing, polishing his English-language skills (complete with East Cheshire accent!) and attending the local grammar schools. During this period he became a dyed-in-the-wool aeromodelling enthusiast, flying rubber-powered models whenever and wherever he could find someone to hold the model while he wound! At school, Gig proved to be an outstanding pupil, excelling in particular at physics, mathematics and drawing. His scholastic prowess gained him early admission to Manchester University, where he studied engineering while working part-time in a University-sanctioned work-experience position at the well-known heavy electrical engineering firm of Metropolitan Vickers in Manchester. He eventually earned an intermediate B.Sc in engineering.

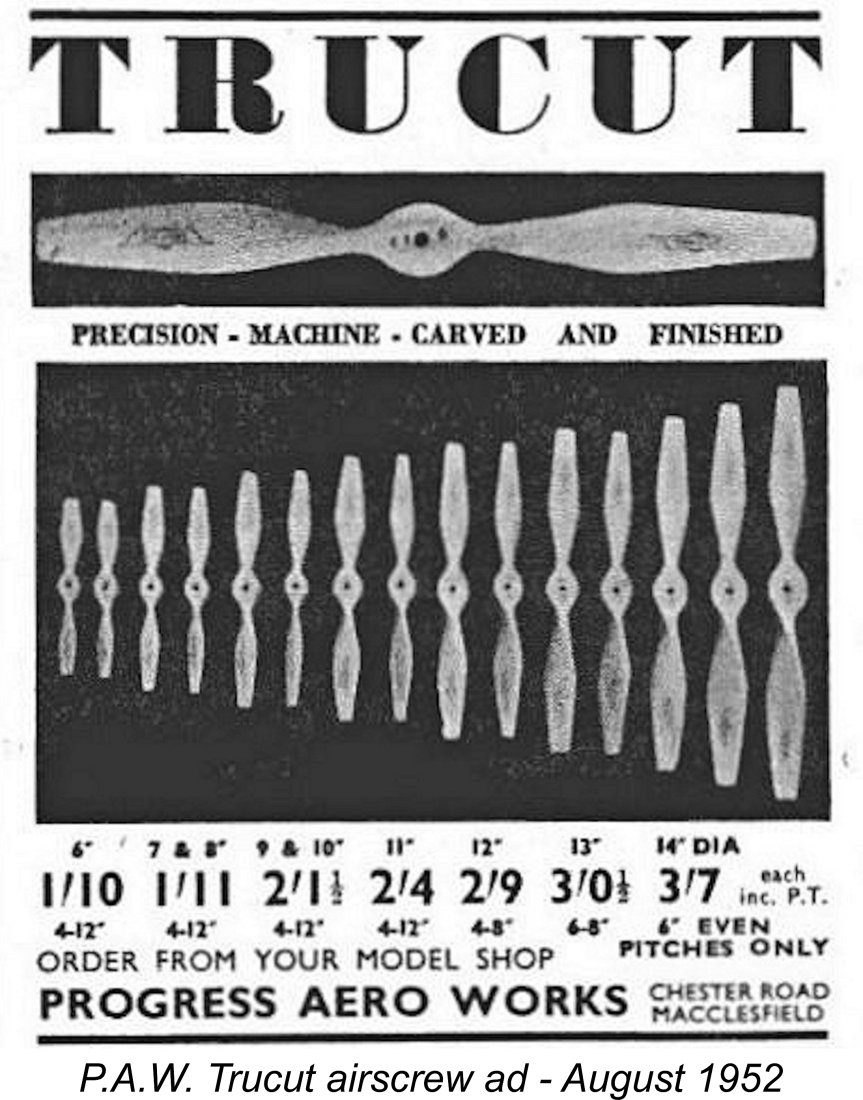

Having emigrated from Germany to England only seven years prior to the outbreak of war, the Eifflaenders became viewed as “enemy aliens” whose involvement in wartime work potentially relating to Britain’s national defence was considered undesirable. Consequently, Gig’s employment at Metropolitan Vickers was ended by the outbreak of hostilities. Even more problematically from a family standpoint, his father Charles also lost his position in the silk industry, which was now heavily involved in the production of parachute material for military use. The priority for the family now became simple economic survival. Gig contributed by finding work at a local garage. To supplement the family income, he also started a “cottage industry” at home in the evenings, making hand-carved propellers, wheels and other accessories for model aircraft, selling them through such outlets as Model Aircraft (Bournemouth), later to become Veron, and Halifax Models. Gig’s success in this line of work quickly grew to the point where expanded premises were required. He somehow gained the use of a disused tennis pavilion associated with a large house on Chester Road called Field Bank, converting it by enclosing the verandah. In the former verandah space he installed a set of copy mills of his own creation which were used to produce his increasingly popular Trucut beechwood airscrews in commercial quantities. This marked the beginning of Progress Aero Works. The former tennis pavilion soon became a small factory. A basic metalworking machine shop was installed in the main room, although this part of the operation suffered from the ingress of beechwood sawdust from the prop-making activities in the former verandah space. Apparently this dust combined with the cutting oil used in the machine shop to form “sawdust stalactites”!

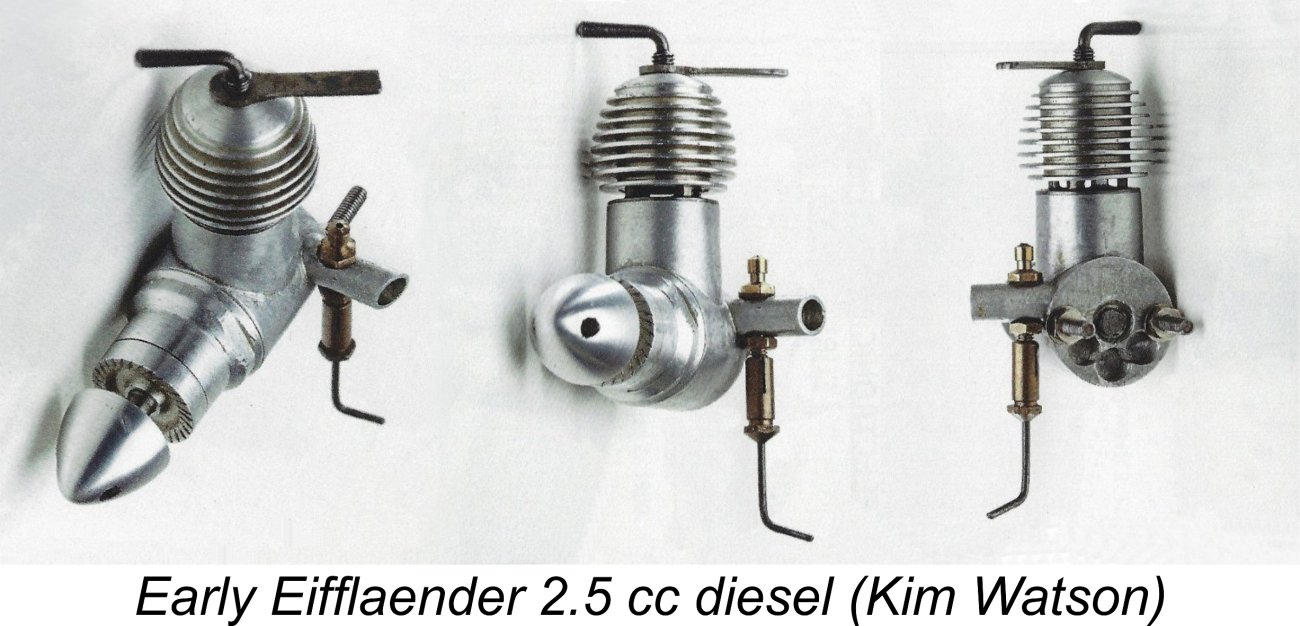

Gig made his first I/C engine in 1945 at the age of 23. Naturally, this was a spark ignition unit, but in 1947 Gig saw his first diesel engine and was suitably impressed, promptly deciding to have a go himself. His first diesel was a 2.2 cc sideport design, but he soon switched to a 2.5 cc rear induction rotary valve model. Some seven or eight of these were made for Gig’s own use and that of his friends. The illustrated disc valve engine with its unique side intake may well be one of these motors.

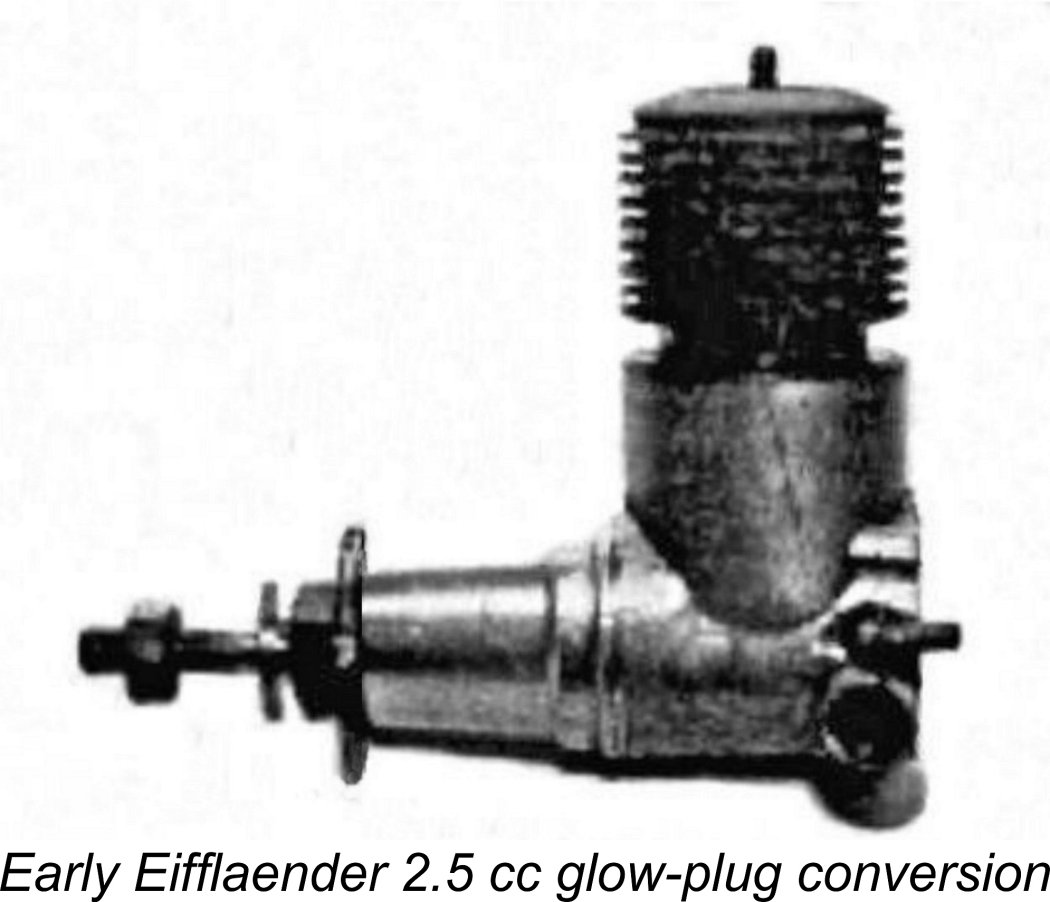

Meanwhile, the P.A.W. Trucut wooden airscrews were nationally advertised following the end of WW2, becoming widely used by British aeromodellers during that period. Recognizing a niche to be filled, Gig also established an engine reboring service which was greatly appreciated and widely used by British power modellers. I later became a repeat customer myself. By the late 1940’s Gig had become a very active contest flier, using 2.5 cc diesel engines of his own design and construction. He had some success in the free flight field, actually winning the Woodford Rally in 1949. However, his main focus was on control line. He competed in control line speed events, trying a glow-plug conversion of his previously-illustrated side intake disc valve diesel. Four examples of this conversion were reportedly made.

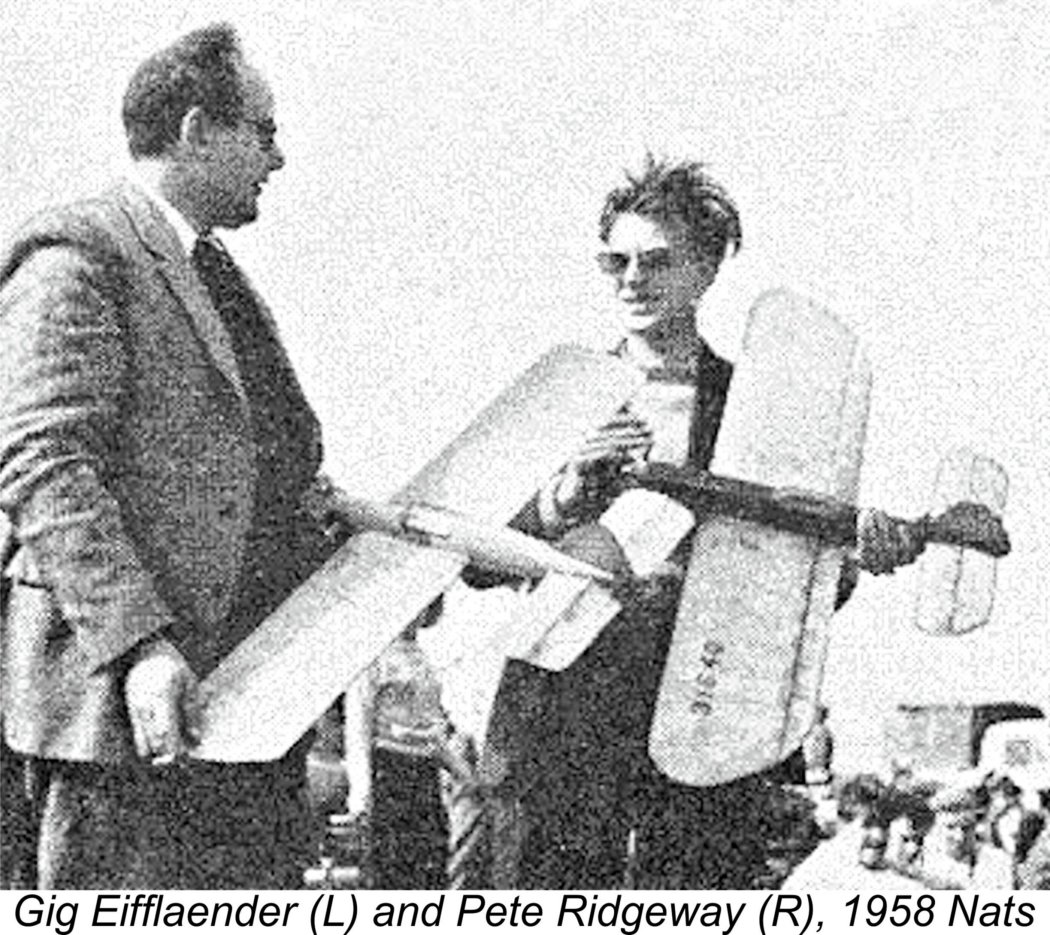

One of Gig’s best friends in Macclesfield was Pete Ridgeway, a textile machinery engineer who had his own premises in a former mill in Macclesfield. Pete helped Gig out from time to time by doing foundry work for him. At some point, the P.A.W. machine shop operation was moved into Pete Ridgeway’s premises, where it was to remain until Pete’s untimely death in 1991. At that point, the operation was relocated to premises on Union Street, where it remains today.

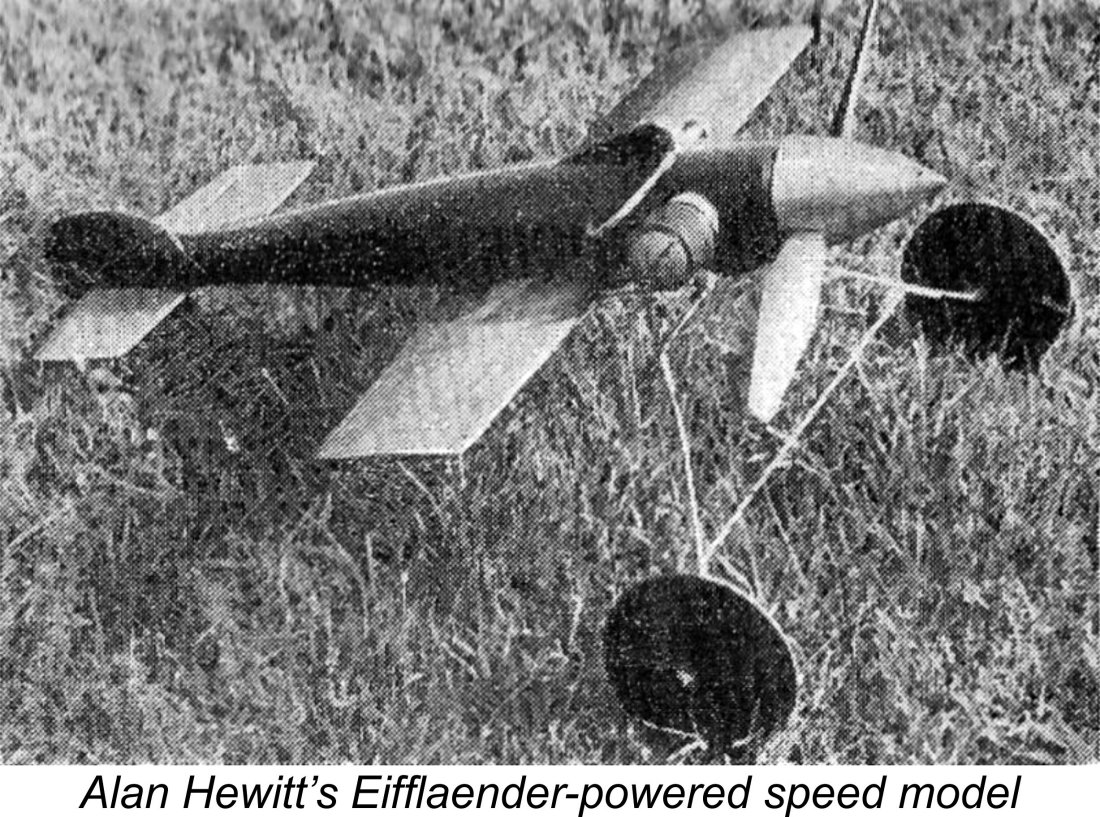

For me, one of the most impressive technical successes achieved by Gig during this period came in 1951. During that year he very generously removed the self-constructed 2.5 cc diesel engine from his personal free flight competition model and loaned it to Alan Hewitt, younger brother of 1949 and 1950 Gold Trophy winner Brian Hewitt. Alan installed this engine in a speed model which he took to Knokke in Belgium, where he won the 1951 European Stunt Championship which had been won by Gig himself during the previous year. The model used to achieve this success (and subsequently to win that year’s Gold Trophy) was Hewitt’s “Ambassador” design powered by an Elfin 2.49 PB diesel. Alan Hewitt also entered the 2.5 cc speed competition at Knokke. Gig's Eifflaender Special powerplant ran perfectly, powering Hewitt to first place with a speed of 151.075 km/hr (93.88 mph). Lest anyone feel inclined to sneer at this speed by present-day standards, let me point out that this was 1951 (73 years ago) and Hewitt’s speed was a new 2.5 cc World Looking at the accompanying photograph, the engine in Hewitt's model appears to be an example of Gig’s previously-illustrated rear induction model with side-oriented induction tube. Incidentally, note the asymmetrical positioning of the fuselage on the wing and tailplane - start of a trend?!? Gig’s good friend and colleague Pete Ridgeway had also been using the Eifflaender Special diesel to power his own stunt models. In 1952 he proved that the earlier successes achieved by both Gig and Alan Hewitt were no flukes by winning the 1952 European Stunt Championship, thus following in Gig’s footsteps using the same engine. For his own part, Gig continued his annual participation at the Gold Trophy, failing to achieve any wins but always putting in competitive performances. Until 1955 he continued to use the same model/motor combination, but in that year he suffered the misfortune of failing to pull out of a wing-over, destroying the 7 year old model. John O’Donnell upheld Eifflaender honour at this meeting by winning the free flight event using one of Gig’s engines.

The positive reception of this unit was the catalyst that convinced Gig to enter the field of commercial model engine production. A revised crankshaft front rotary valve model was destined to enter production in early 1957 (see below) as the first of the long line of commercial P.A.W. engines which continues to this day (2022). Up to 1957 stunt competitions in Britain had been flown to the relatively simple Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.) schedule. Many competitors felt that this schedule had become “too easy”, resulting in a dwindling level of commitment among serious fliers who were looking for a challenge. This prompted a 1957 decision by the S.M.A.E. to adopt the American AMA schedule, which emphasized “square” corners and added such complexities as cloverleaf and hourglass figures. This decision created a high level of controversy. Some felt that the increased complexity of the schedule might discourage new fliers from giving it a go - the event was seen as being in danger of becoming an “experts-only” affair. Moreover, it was immediately obvious that the new schedule would favour larger models which could turn more tightly and present a slower development of each more complex manoeuver for the judges. The competitive death knell of the smaller diesel-powered model was immediately recognized. The higher cost of the larger model/motor combinations which would now be required to win was seen as another potential deterrent to wider participation. Feelings ran high, to the point that at least one prominent competitor, Dave Chizlett, actually withdrew from further participation. Interestingly enough, although he was among the diesel-powered competitors whose participation would be greatly handicapped by the new schedule, Gig Eifflaender openly expressed his personal support for this decision. His comments were published in the February 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, as follows: “I like the introduction of a new schedule - this has been long overdue and will definitely stimulate stunt model design, albeit that all the sharp corners suggested will very likely bring forth a crop of ton-and-a-half wingtip-weighted 35-powered boxcars by way of acclimatisation. I would like to see more points awarded for realism and finish; less points for landing; and the removal from the proposed schedule of the design-detail-and-flight-pattern points. I feel that those particulars could only be judged by a very competent designer cum builder cum stunt-flier with any hope of achieving a fair decision. As it stands, the schedule proposed is in itself difficult indeed to judge from the flying aspect alone, especially when it is remembered that the old S.M.A.E. schedule was pruned because of difficulty in the judging of square loops, etc.”

However, that was to be the swan-song of the small diesel-powered model in major stunt competition. From 1959 onwards the event was ruled by large glow-plug powered models, exactly as Gig had foreseen. Gig was among those who chose not to continue participation using the new style of equipment - as his business grew, other priorities now claimed his attention. As far as I can tell, 1958 was Gig’s last appearance as a competitor in the Gold Trophy. I hope that the above account has given the reader some appreciation of the talented individual behind the P.A.W. motors. It’s now time to turn our attention to the engines themselves. At this point in my narrative, I think that it’s worthwhile summarizing what I’ve been able to learn about the progression of Gig’s earlier designs which finally led him to the FRV P.A.W. Special which was his first commercial model engine. I must apologise for the poor quality of some of the images, but they’re all that I could find. Surely even a poor image is better than none at all! The Early Eifflaender Designs

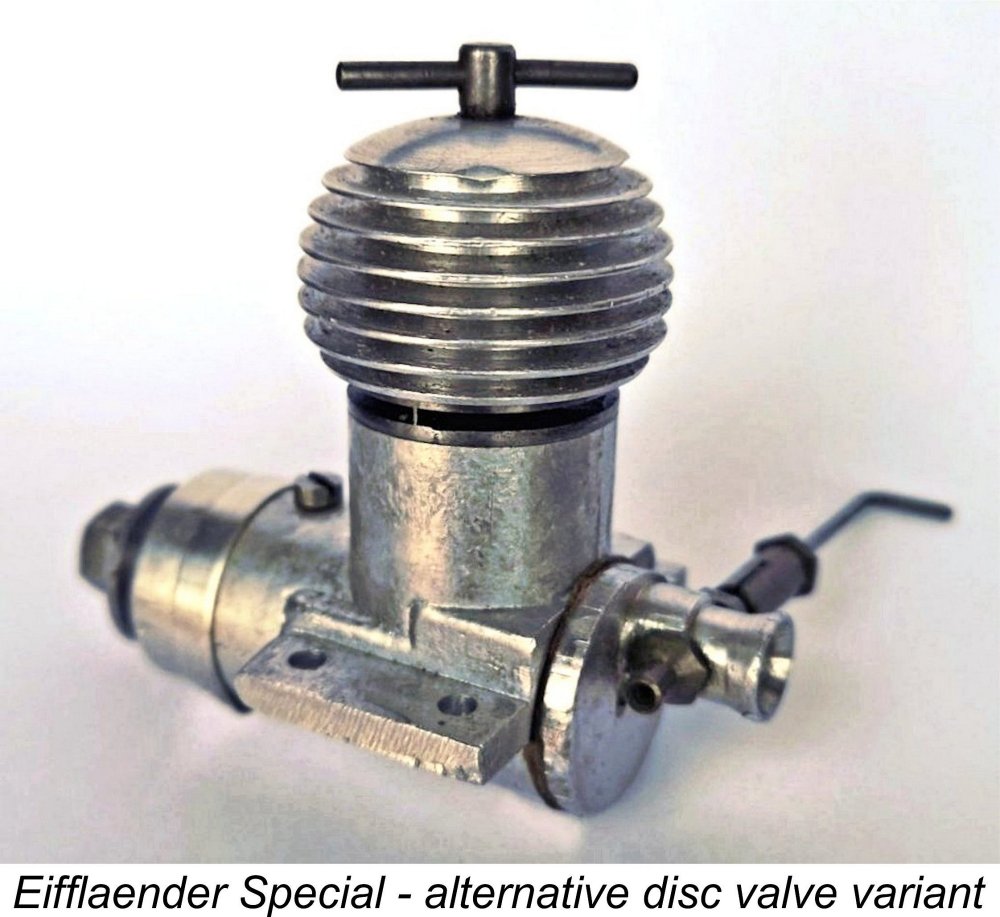

Gig soon became aware of the potential advantages of rotary valve induction. This led him to commence experiments with disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction, initially grafting such a system on to his earlier sideport model which had now been bored out to 2.5 cc. One of these units is illustrated here. Gig evidently still had something to learn about structural integrity - check out that main bearing housing! This induction arrangement was found to work very well indeed. The design was quickly finalised into a cleaner and more streamlined package which featured a twin ball-race shaft supported in a screw-in front housing along with an integrally-cast backplate and a very An early insight which was to greatly inform Gig’s future designs was his realisation that while a twin ball-race shaft offers considerable potential for performance enhancement, all of the potential benefits can be undone if the bearing alignment isn’t perfect. It was this realization that was to lead him to adopt the single rear ball race arrangement in his initial commercial designs. In later years he used to quip that a single rear ball-race engine might well be 10% more powerful than a plain bearing equivalent, but a twin ball-race version of the same engine could be up to 3% less powerful! When he finally began making commercial twin ball-race models in the 1980’s, he went to great lengths to ensure perfect alignment of the bearings, going so far as to create special tooling for this purpose. Even so, Gig’s earlier non-commercial competition models like that illustrated here used twin ball races. The need for perfect alignment explains why the front housing of his original disc-valve model was a screw-in component - this facilitated the set-up for the tricky process of boring the main journal and ball-race housings in perfect alignment.

The intake was now straight in from the rear as opposed to the sideways alignment used earlier. However, the engine also featured an integrally-cast main bearing housing! Given the fact that the backplate was not removable, how the heck was this unit assembled?? A moment’s thought should be enough to convince the reader that everything must have gone in from the front. The crankcase casting was clearly bored though from the front at full crankcase internal diameter, with the disc valve seat also being created at this time. The precisely-aligned bearings were housed in a separate cylindrical component which was an accurate push fit in the crankcase bore. The portion of that bore forward of the actual crankcase may have been machined to a slightly larger diameter to create a location shelf for the main bearing assembly.

My valued mate Miles Patience wrote in to provide some images of a distinct variant of this design which featured a slightly revised crankcase casting incorporating a separate screw-in backplate allied to the same front-loading crankshaft assembly. The angular orientation of the backplate when fully tightened was adjustable through the use of shims/gaskets of differing thicknesses. Perhaps this was an experimental unit intended to allow the designer to test different induction timing figures? In all other respects, this variant appears identical to the version having the integrally-cast backplate. To say that the front end assembly used in these RRV models is a rather “fiddly” arrangement is a bit of an understatement! Given Gig’s well-demonstrated commitment to practicality in his commercial designs, it’s At some point in the mid 1950’s Gig evidently came to the conclusion that a well-developed crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction arrangement could work just as well as the RRV design used up to that time. Accordingly, his next development involved a switch to FRV induction. The crankcase casting now featured a vertical intake on top of the main bearing housing. The twin ball races were retained, but the case, main bearing and ball-race housings were all bored from the rear, with a screw-in backplate now being featured. My thanks again to Miles Patience for providing a number of excellent images of this model. This seems to have been the final design evolution prior to the early 1957 appearance of the P.A.W. Eifflaender Special in commercial form. The only real changes from the earlier FRV prototype were a reduction in the external diameter of the main bearing housing and the elimination of the front ball race. I’m sure that there were other experimental engines of which I have no present knowledge. However, I hope that the above summary has provide a few interesting insights into Gig Eifflaender’s design journey towards his first commercial offering. Time now to turn attention to that model! The First Commercial P.A.W. Appears By the mid 1950’s, the use of wooden propellers was fast losing ground to the new plastic “unbreakable” propellers (which sometimes weren’t - I could break ‘em!). The increasing popularity of the rough-and-tumble field of control line flying had much to do with this trend, which naturally became apparent to Gig Eifflaender. It was evident that if P.A.W. was to survive, the company would have to develop a product line which went beyond the wooden propeller and reboring fields.

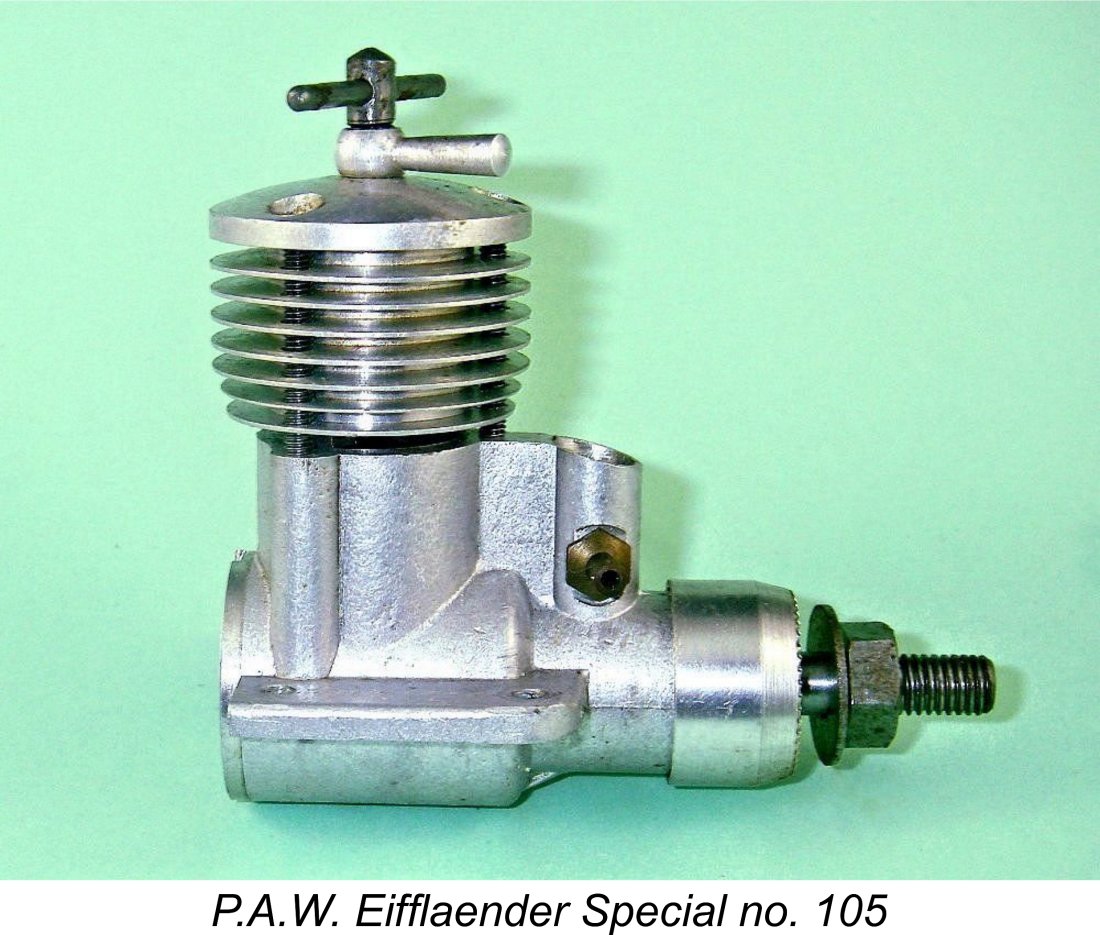

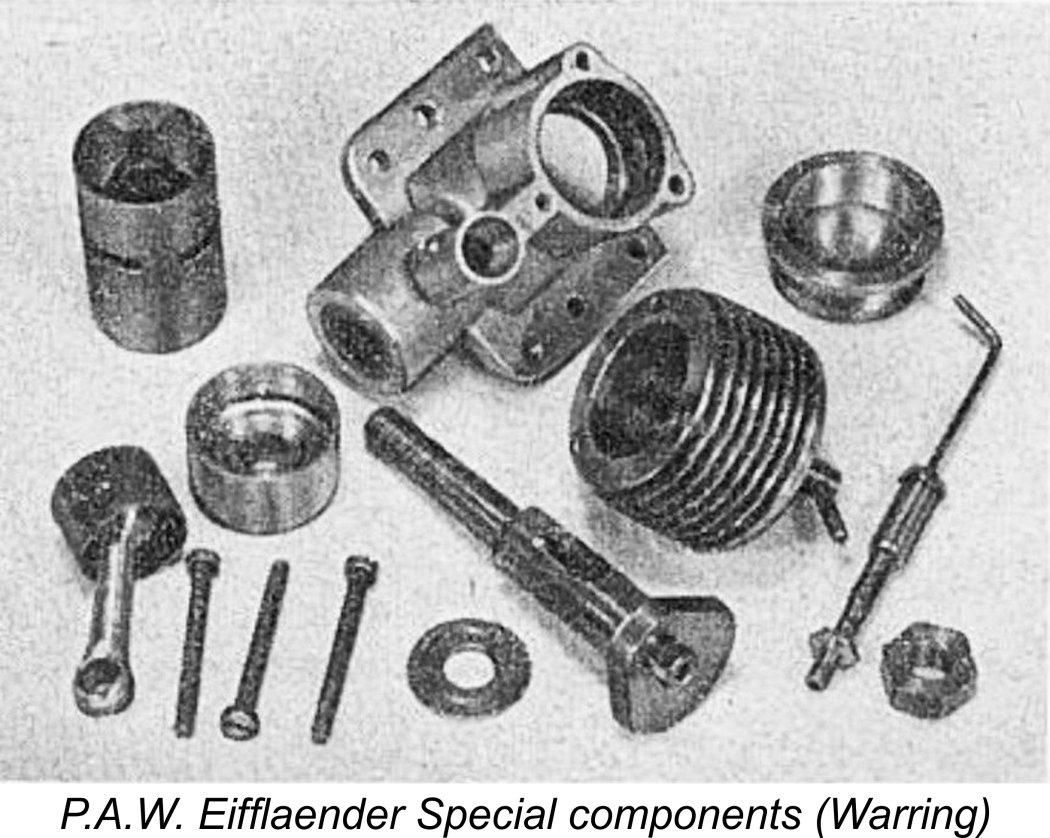

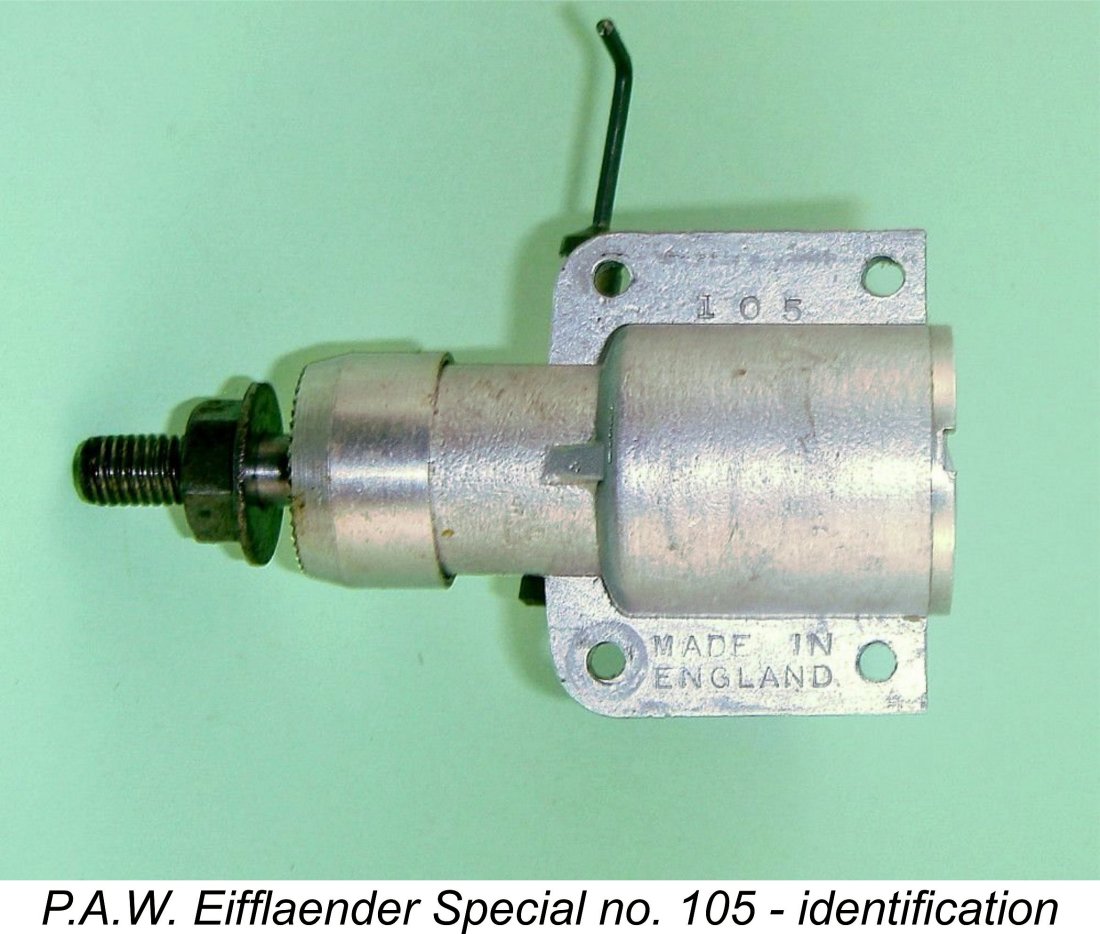

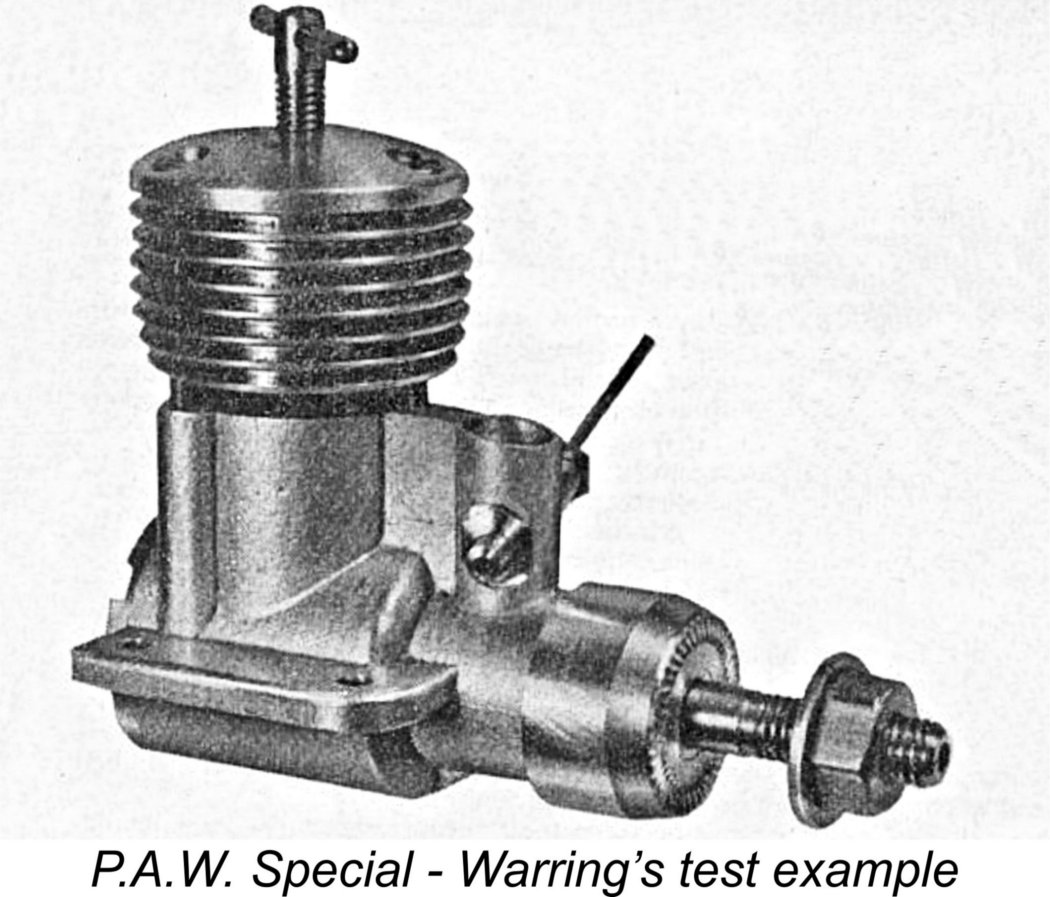

The result was the early 1957 release of the first-ever commercial P.A.W. powerplant - the 2.5 cc “Eifflaender Special” diesel. This was a slightly simplified version of Gig's first FRV design mentioned previously. In order to test the waters, Gig began by making a batch of 25 examples of this model. These were supplied to a model shop in nearby Manchester, where they quickly sold out. 50 more examples were ordered immediately, and P.A.W. was in the model engine manufacturing business in which they were to continue to participate for the next 65 years and counting! It’s worth spending some time describing this engine, since it exemplifies the basic P.A.W. design which was to remain in production right down to the time of writing (2022) and beyond. The reason for this design longevity is quite simple - Gig Eifflaender got it right first time! I think my good Aussie mate Bob Allan summed it up very well - if nobody had yet designed a compression ignition engine suitable for model aero applications, and if the brief was to come up with a design that was powerful, tough and reliable yet light in weight, easy to handle and infinitely long-lasting, you would probably end up with a drawing of a P.A.W.!

Some idea of the basic excellence of the original P.A.W. design can be gleaned from the fact that in 65 years of continuous production, the biggest single visual change has been the intake venturi being made removable instead of integrally cast! In fact, the only other major changes were the elimination of the cast iron bushing which helped to support the shafts of the earlier models and the use in some models of twin ball-races supporting the shaft. This remarkable design longevity has actually created a problem for would-be collectors of these engines. The different models in a given displacement category look so similar that unless they’re still in the box, it can be really difficult to sort them out. In fact, the only way to tell some of them apart is to take them apart! I agree wholeheartedly with Bob’s observations, as would thousands of satisfied users all over the globe. It was always Gig’s intention that his P.A.W. engines would provide above-average performance and quality to his fellow aeromodellers at a price that the average participant could afford. In this, he succeeded completely. My good friend Hugh Blowers of the fabulous Onthewire website very much shares Bob's opinions. He recalls that many years ago he was present at a particularly "enthusiastic" combat session in Richmond Park. At the conclusion of the event, one disgusted flier who hadn't fared too well threw the remains of his model into the rubbish bin, complete with P.A.W. engine! This was duly rescued a day later by an impecunious student (Hugh), who removed the perfectly functional P.A.W. from the wreckage, cleaned it up and used it very happily for years thereafter! Those P.A.W.'s were survivors!! Let’s have a closer look at the engine which established P.A.W. as a model engine marque to be reckoned with. The P.A.W. 249 “Eifflaender Special” - Description

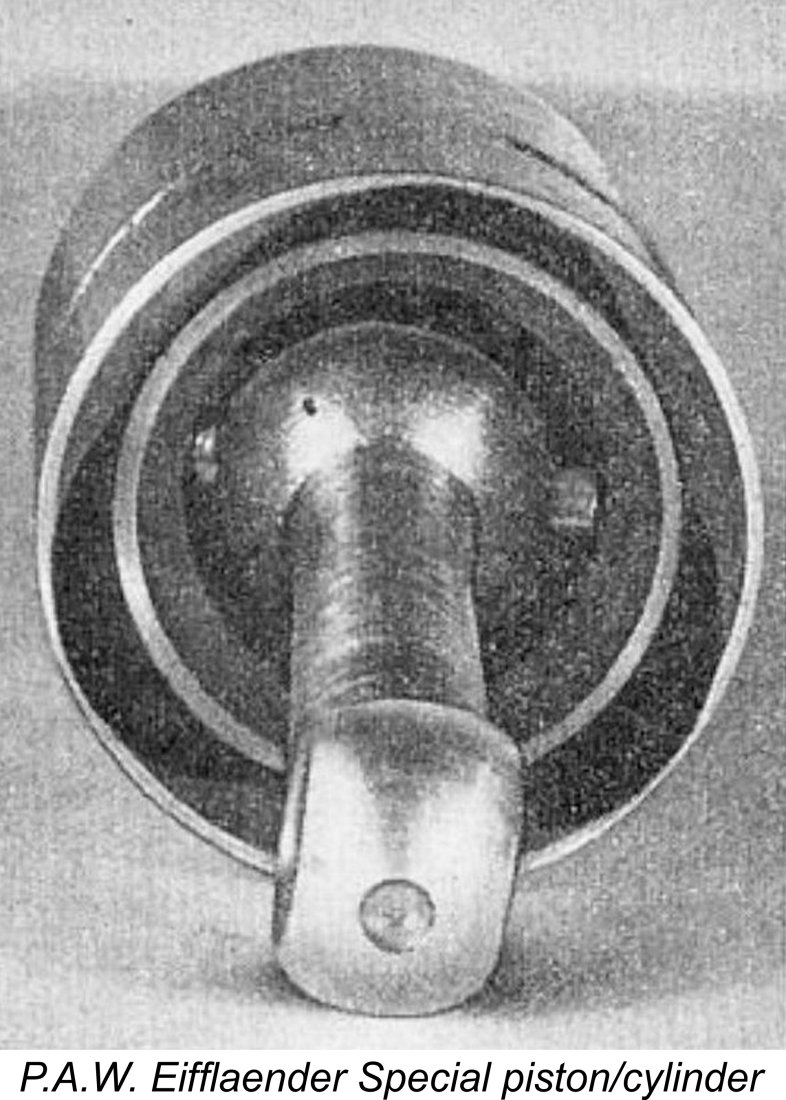

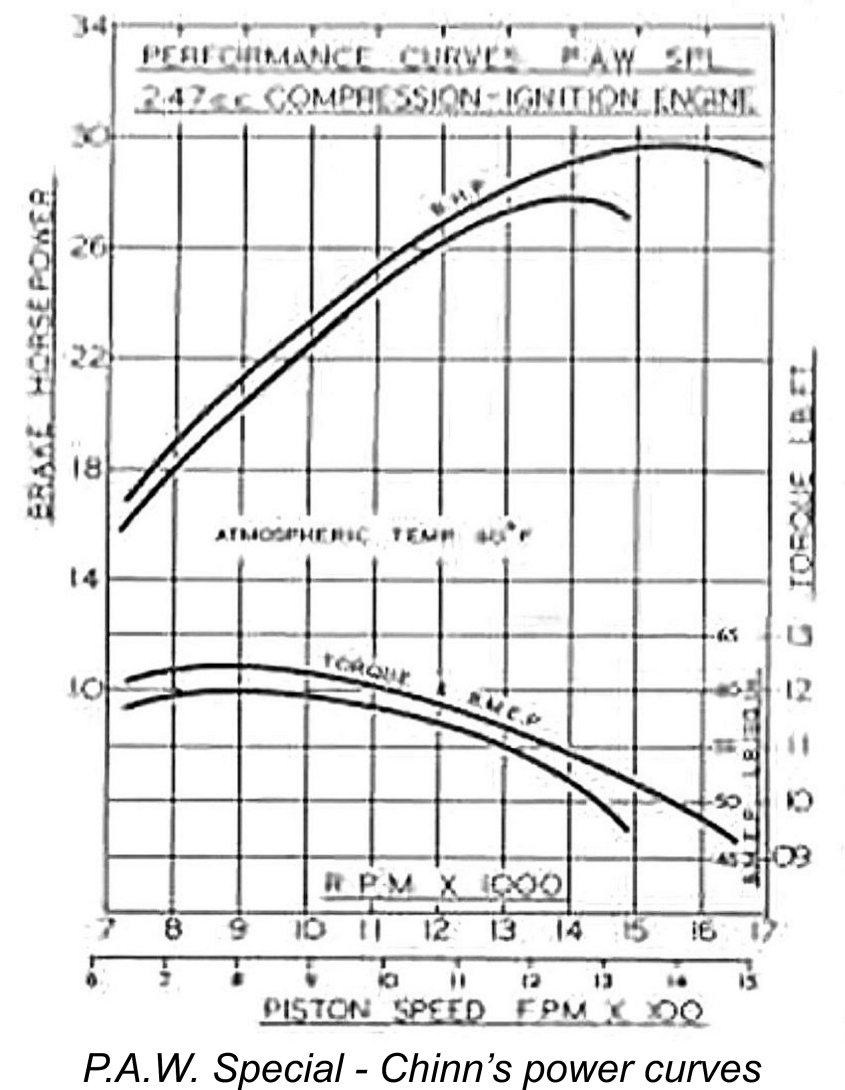

In this article, Chinn reported that he had been undertaking some earlier testing of the engine for the manufacturer. He had measured a peak output of 0.28 BHP @ 14,000 RPM for the original version, but stated that the design had since been amended through changes to the induction and transfer porting as well as the use of a somewhat lighter piston. He was hopeful that this might get the engine up to the then-magic mark of 0.30 BHP which was the expected standard for 2.5 cc competition diesels at the time. The new model was a basically conventional 2.5 cc radially-ported crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) diesel with a few interesting design features which lifted it out of the rut. Bore and stroke were 0.597 in. (15.16 mm) and 0.538 in. (13.67 mm) respectively for a displacement of 2.467 cc (0.1506 cuin.). These figures were to be retained throughout the long production life of the classic 2.5 cc P.A.W. diesels. The engine weighed a commendably light 5 ounces (141 gm) - a very modest figure for a high-performance ball-race 2.5 cc diesel.

The steel cylinder liner was perfectly cylindrical externally, being secured by three 6BA screws passing through suitably-placed holes in the slip-on light alloy cooling jacket to engage with tapped holes in the upper crankcase deck. The liner was vertically located at its base by a narrow shelf machined into the installation bore in the upper crankcase. Exhaust porting consisted of three rectangular apertures machined into the liner. The transfer porting was unusually well developed, consisting of three very large internal flutes which tapered towards the top and terminated just above the level of the exhaust ports’ lower edges. The exhaust period was of the order of 140 degrees.

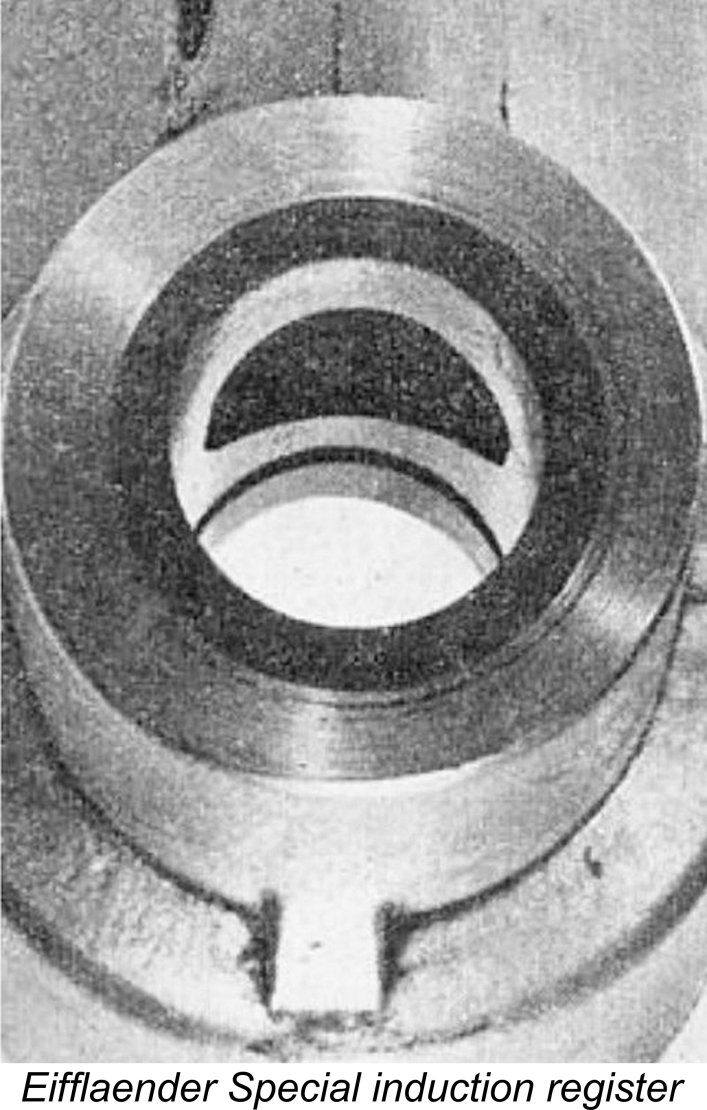

The induction port in the actual shaft had a relatively narrow elongated race-track shape which combined with the previously-mentioned cut-out to provide very rapid opening and closing of the induction system along with a lengthy full-open period. Induction timing was a generous 175 degrees (45 deg. ABDC to 40 deg. ATDC). This was supplemented by an equally generous 60 degree sub-piston induction period. The prop driver was mounted on a split collar. It was of the wrap-around type, enclosing the front of the main bearing housing. This is a very good design in that it minimizes the possibility of dirt getting into the bearing. The propeller was secured using a nut and washer which engaged with a threaded shaft extension of adequate length to accommodate any airscrew which might reasonably be used.

Unusually by later P.A.W. standards, at least some of these engines bore serial numbers. These may have been either very early examples or engines designated for export - there’s no way of knowing. The numbers were stamped under the left-hand mounting lug - my illustrated New-in-Box example bears the number 105. The statement “Made in England” was stamped under the other mounting lug. If any reader can supply additional serial numbers, please get in touch!

As one might expect, quality at this level didn’t come cheap - the engine was introduced at a price of £6 10s 0d (£6.50), pushing up towards Oliver territory and well over £2 more than most of the opposition. However, its performance and quality fully justified this price, and people lined up to buy it.

After describing the Special’s construction in uniformly positive terms and praising its starting and running qualities very highly, Chinn reported test figures for both the Mk. I and Mk. II versions of the engine. The original Mk. I variant was found to develop 0.28 BHP @ 14,000 RPM, while the improved Mk. II version managed 0.298 BHP @ 15,500 rpm, with an outstanding peak Brake Mean Effective Pressure (BMEP) figure of 62 PSI. This put the engine up among the most powerful 2.5 cc diesels of the period. Chinn characterized the engine as “probably the most important new British International 2.5 cc class motor to appear on the home market for the past three years”.

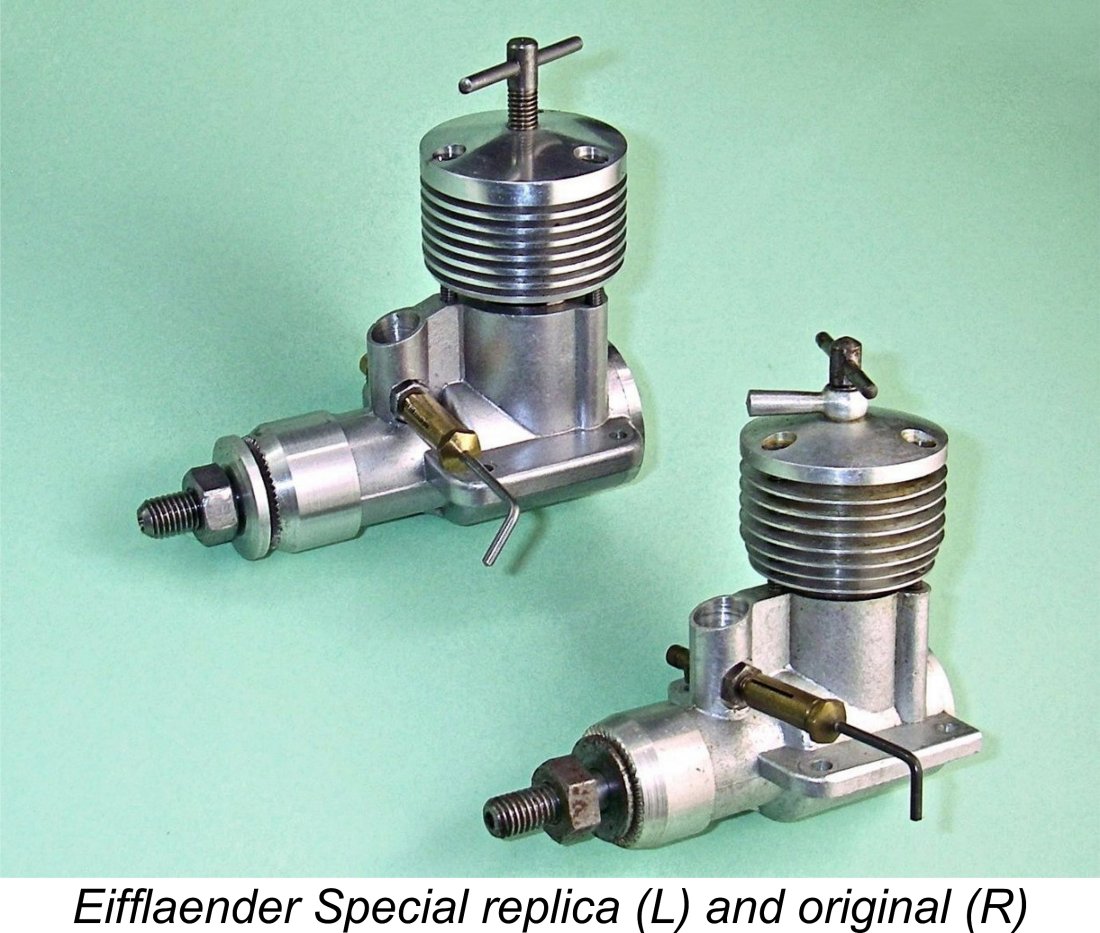

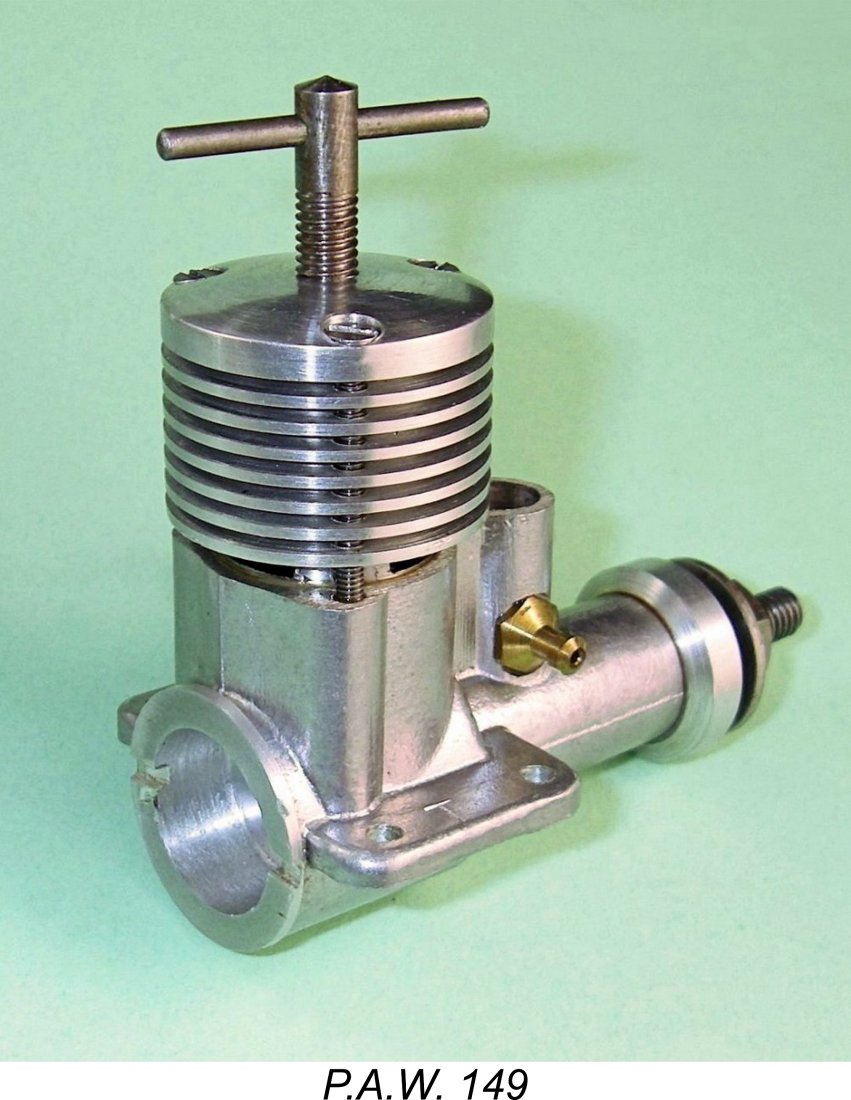

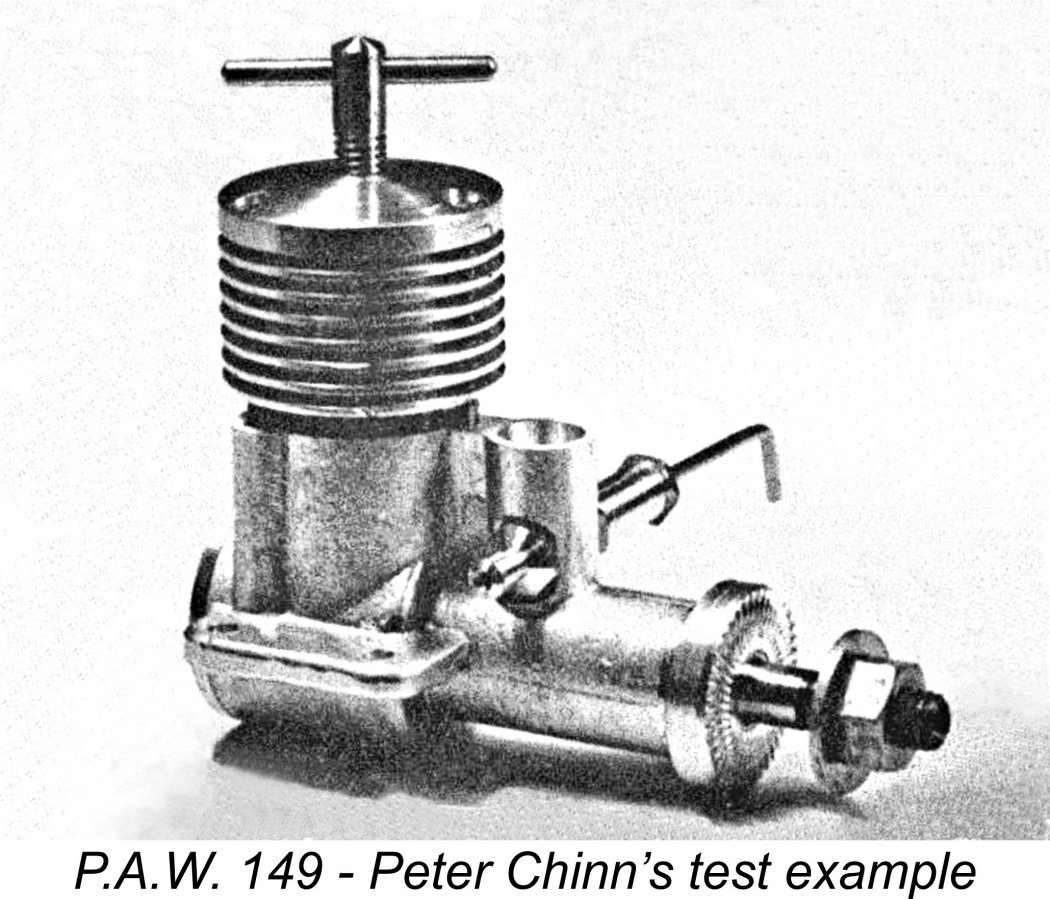

Before I move on, it’s worth noting for the record that during the 1990’s P.A.W. re-activated one of their earlier integral-intake molds to produce a limited number of examples of what they called a replica of the original Eifflaender Special. This was not a true replica - it was in essence a standard 1990's-specification 249 BR single ball-race model with an integrally-cast intake and a wrap-around prop driver. However, it did convey a reasonable impression of the original Eifflaender design. It remains one of the more collectible latter-day P.A.W. models. The Range Expands - the P.A.W. 149 As noted earlier, the P.A.W. 249 Eifflaender Special was very far from being the least expensive 2.5 cc diesel of its day. We previously noted Gig Eifflaenders’ desire to produce quality engines at prices which the average aeromodeller could afford. This led him to consider the development of a smaller model in a “popular” displacement category which would retain similar standards of quality and performance, but at a lower selling price which put it within reach of a far larger potential customer base.

To all intents and purposes, the P.A.W. 149 was simply a scaled-down and slightly re-styled version of the 249 Eifflaender Special. However, the absence of a ball bearing at the rear of the shaft was symptomatic of the fact that every effort was being made to minimise costs while maintaining established P.A.W. standards of quality. A full length cast iron bushing was used to support the unusually substantial crankshaft, which had a heroic main journal diameter of 0.353 in. (8.73 mm).

A full description of this engine would be redundant since apart from the omission of the ball bearing; a switch to a standard prop driver in place of the wrap-around component; and a transverse needle valve instead of the swept-back orientation of the larger model, the main design and construction features were identical to those of the larger companion offering. The same system of cylinder porting was used, as was the arrangement of the induction ports with an elongated shaft port and a substantial cut-out through the main bearing bushing to create an accumulation chamber in addition to speeding up the opening and closing of the induction system. Induction timing was somewhat more conservative in this model than it had been for the 249 Special. The induction period was reduced to around 145 degrees (60 deg. ABDC to 25 deg. ATDC). The early closure was made possible by the fact that a generous 60 degree sub-piston induction period continued to be featured. The exhaust period of 140 degrees was retained, but the tops of the transfer flutes were raised considerably to overlap the exhaust to a large extent, thus minimising the blow-down period.

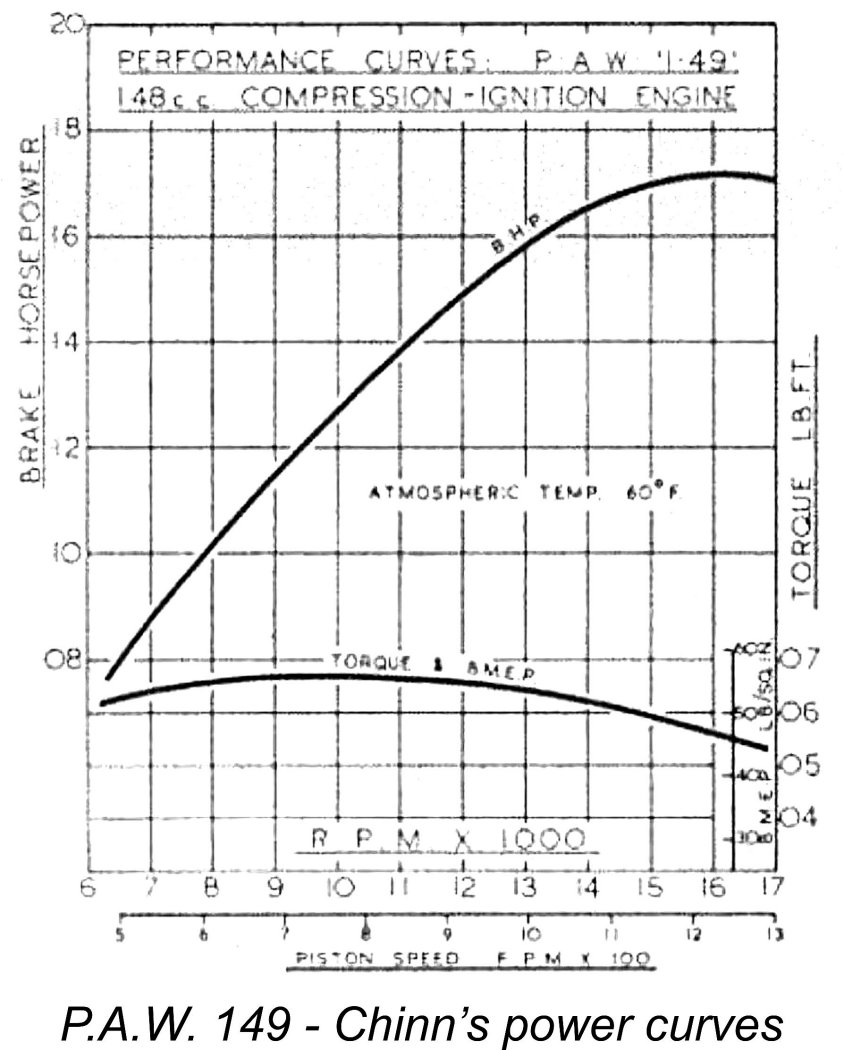

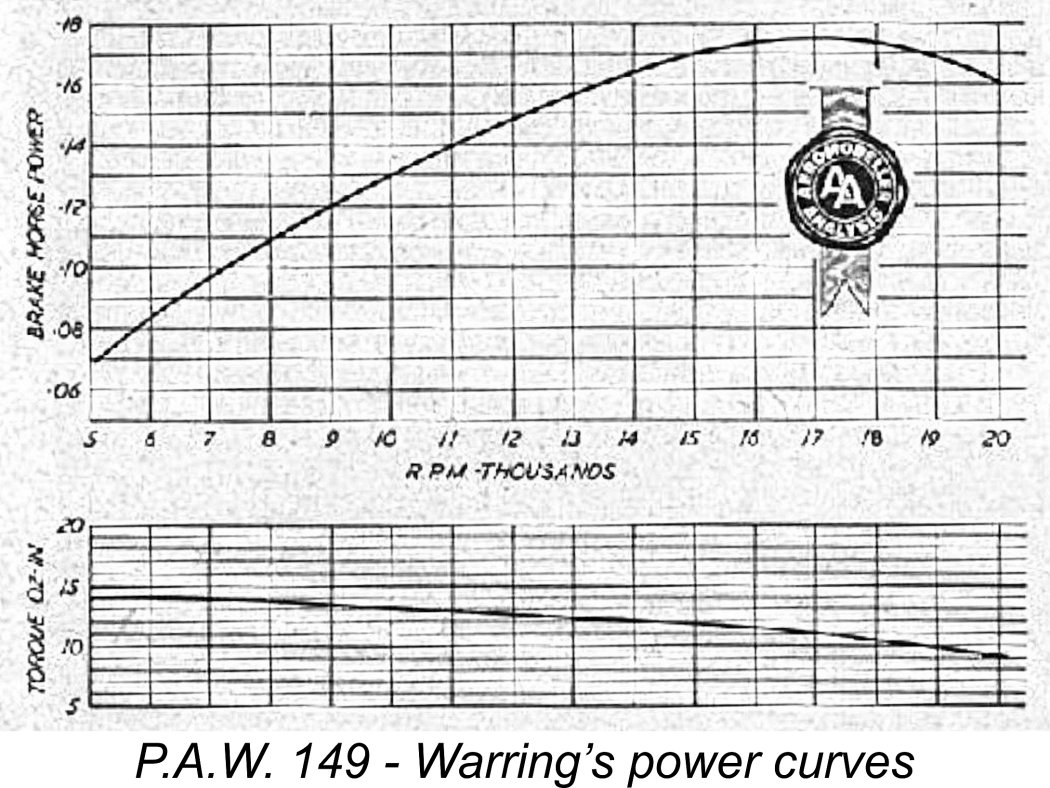

After praising the engine’s construction, Chinn turned his attention to its performance. He rated both starting and running qualities very highly. A peak output of 0.172 BHP @ 16,200 RPM was reported, which Chinn characterised as ”the best so far recorded for a 1.5 cc engine in this series”. He was particularly impressed with the flatness of the engine’s torque curve over a relatively wide range of speeds. A peak BMEP figure of 58 PSI @ 10,000 RPM was considered "most creditable" for an engine of this displacement.

Despite its higher-than-average price, the P.A.W. 149 was deservedly well-received by the aeromodelling community. Several of my own associates immediately bought them, and none were in any way disappointed. I couldn’t afford one myself, being an impecunious 12-year old schoolboy at the time, but I had plenty of opportunities to handle a number of examples when starting and launching for my better-heeled friends. I was just as impressed as they were! I reckon that it was my experience with this engine that cemented my lifelong respect for the P.A.W. range. Further development - the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III The success of the 249 Eifflaender Special and the companion 149 had enabled Gig Eifflaender to invest in some additional equipment which enhanced his production capabilities. Building upon this, he set his mind towards the development of a revised 2.5 cc model which could be sold at a lower price while retaining the positive qualities of the original design. Such an engine could reasonably be expected to sell in the larger numbers which were consistent with the enhanced production capacity now available.

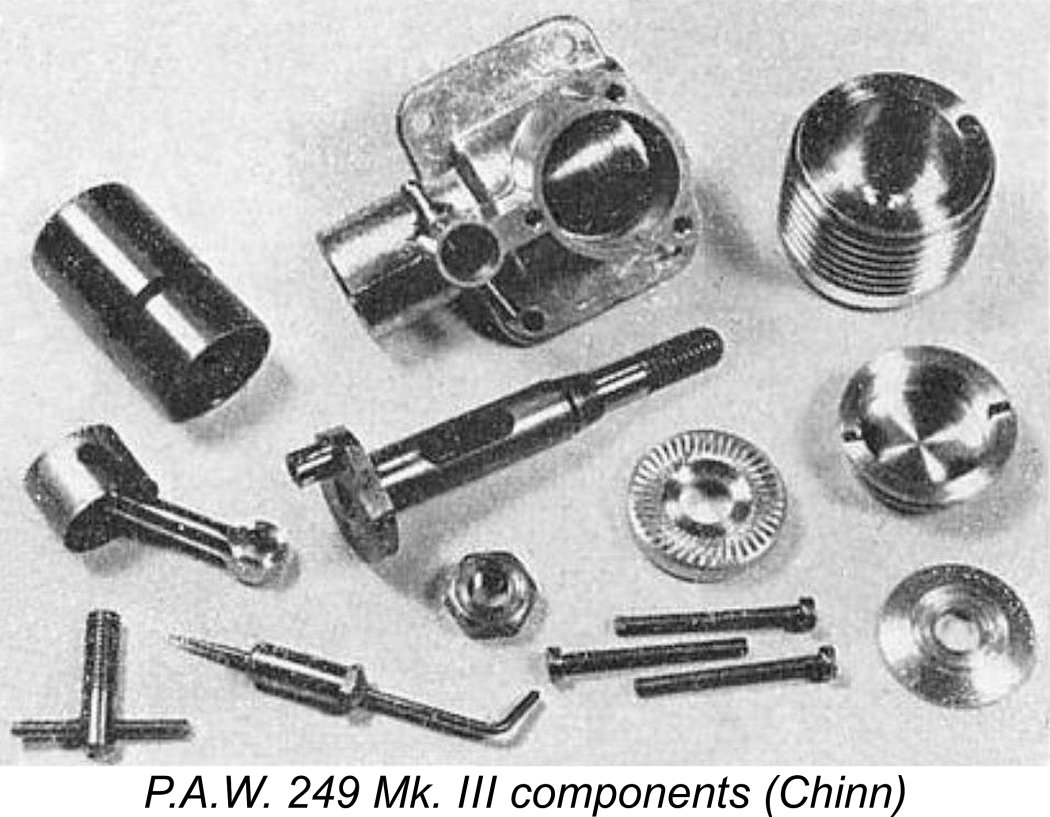

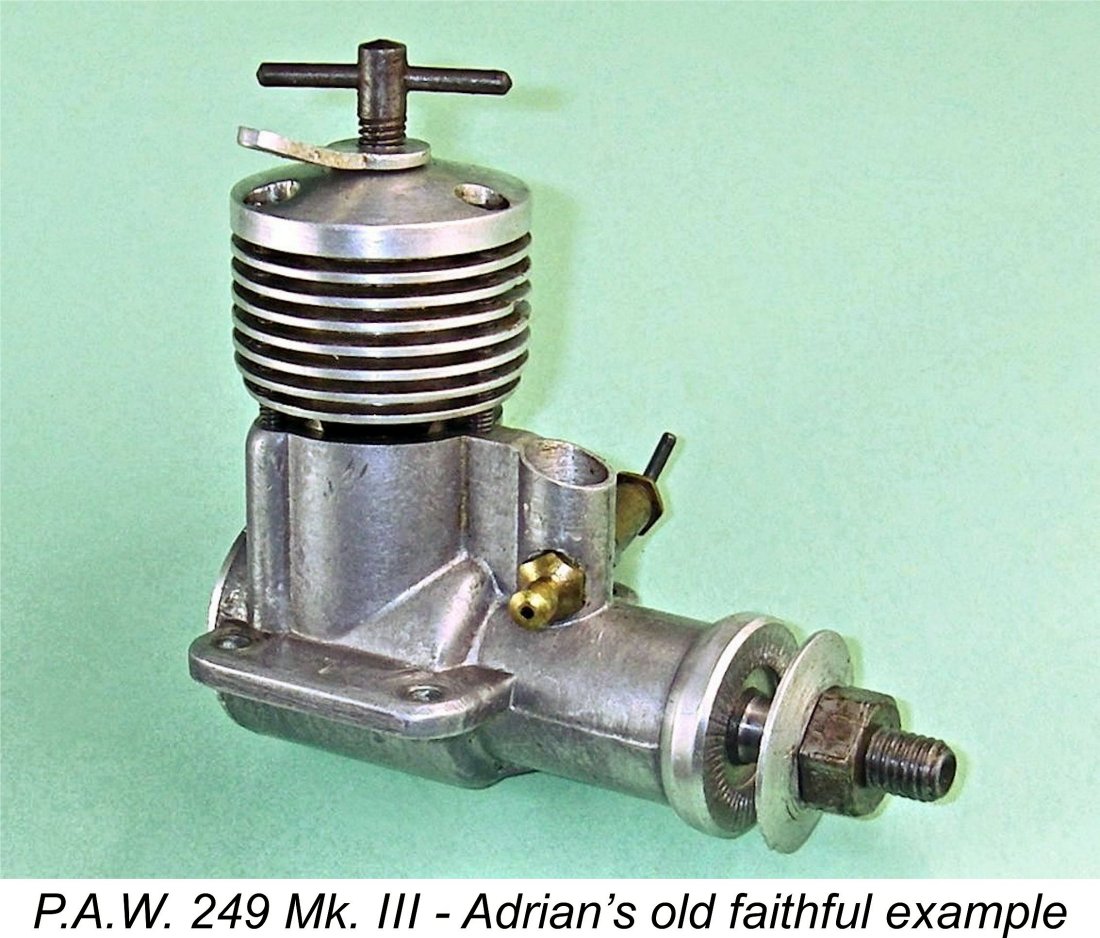

The price of the Mk. III was set at £4 18s 0d (£4.90), a significant reduction from the price of the Special which it replaced. Despite this reduction, Chinn commented that the high quality of the engine’s construction had been maintained, while the single rear ball-race and cast iron main bearing bushing continued to be featured. Visually speaking, the new model more closely resembled the companion 149 which continued in production, with visibly thicker cooling fins, a slightly longer main bearing and a conventional prop driver. The latter component was secured on a tapered expansion machined onto the shaft rather than by a tapered split collar as used on the Eifflaender Special.

Internally, the three transfer flutes were extended upwards to overlap the exhaust ports almost completely, resulting in a minimal blow-down period. To facilitate this change, the exhaust ports were now cut using a tool which produced an opening which was narrower at the bottom than at the top, thus creating more space between the exhausts to accommodate the tapered top portions of the extended upper transfer ports. This change can be seen very clearly in the above view of the engine. The cylinder material was also changed from silver steel to heat-treated high-tensile steel.

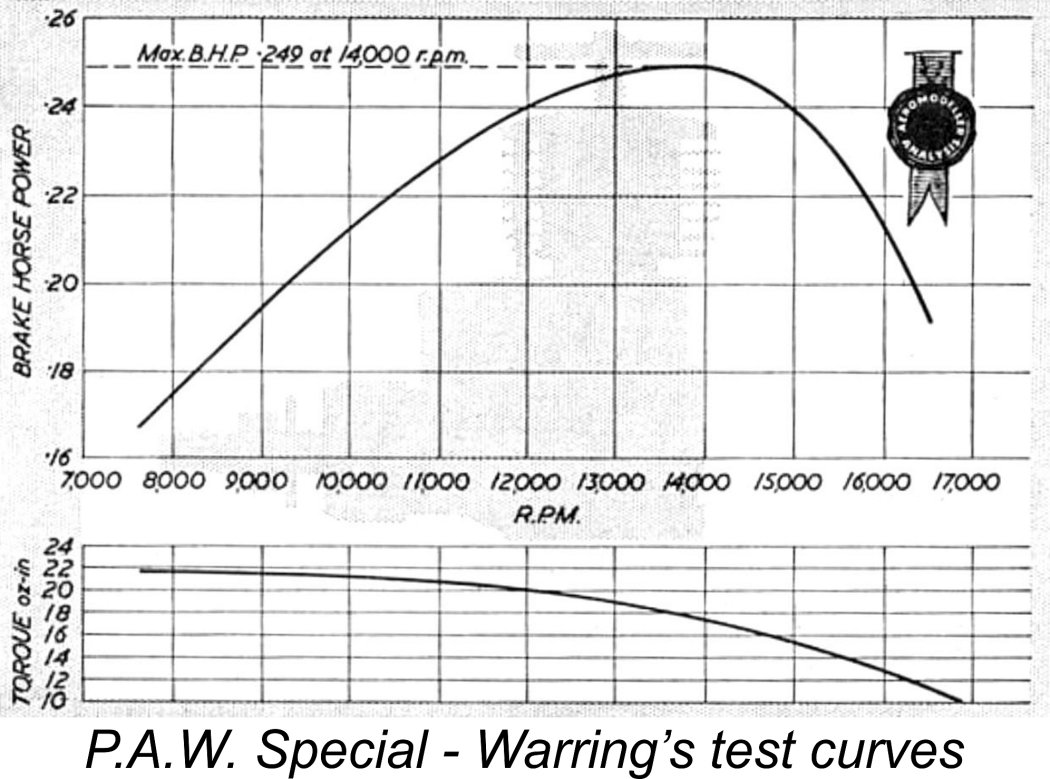

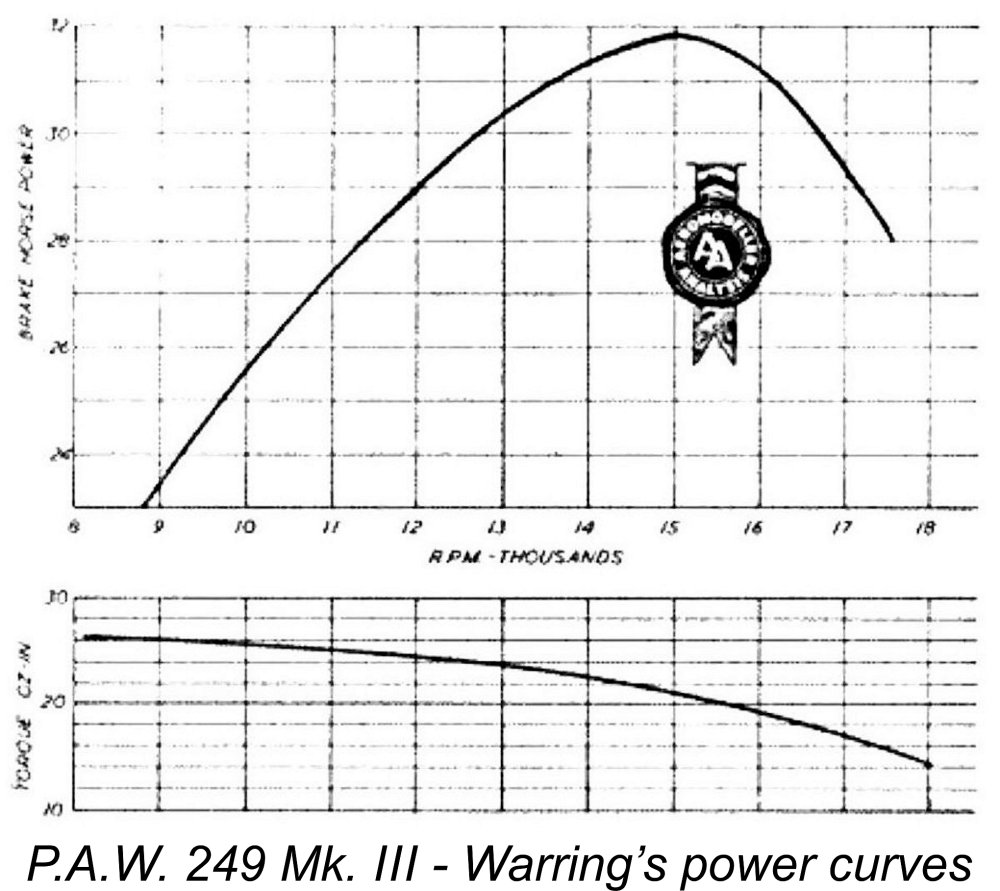

Warring’s comments on the engine were uniformly complimentary in terms of its quality, handling and performance. He found a peak output of 0.318 BHP @ 15,000 RPM, a significant improvement over the figures which he had reported earlier for the 249 Eifflaender Special. He felt that this performance would likely improve still further with more running time. Overall, he was clearly thoroughly impressed! Peter Chinn was behind Warring for once, only getting his report into print in the April 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Although people read Warring’s reports and were influenced by them, Chinn was generally recognized as Britain’s leading authority on model engines. His reports therefore tended to carry a bit more weight with the contemporary aeromodelling community.

Chinn summed up the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III as offering “excellent all-round performance and, as the most powerful 2.5 cc diesel currently available at less than £5 inclusive of purchase tax, is very good value”. Well, that was good enough for me! With my 14th birthday coming up in October 1961, I took pains to let it be known in certain quarters how much I really wanted a P.A.W. 249 Mk. III! Amazingly enough, I managed to get this message through to my rather workaholic Dad, who had no time for aeromodelling himself. Despite this, he actually took the trouble to find out from an aeromodelling colleague at work just what this engine was and where it could be purchased. Even more amazingly, he went out of his way during a work-related visit to Manchester from our hometown of Sheffield to present himself by pre-arrangement at the Chester Road workshop in Macclesfield to take delivery of a new example of the engine directly from Gig Eifflaender. I still recall the joy with which I received this fabulous gift - I couldn’t find the words to thank my parents for their generosity!

That engine went on to become one of my all-time favourites, powering many a model. I later sent it back to P.A.W. to have them tune it - a service which they began to offer in the mid 1960’s. After their ministrations, it went like smoke! Eventually, the engine had to go back again for a rebore, but returned even better than new! I still have the plain unlabelled box in which it was supplied originally, complete with my name hand-written on the lid by Gig Eifflaender himself when he set it aside for my Dad to collect by prior arrangement. I last used this engine in competition in the late 1990’s, when it powered several combat models in the low-cost 2.5 cc single ball-race vintage diesel class which we ran in the Pacific Northwest for a while. It could still give a very good account of itself against the predominantly P.A.W. 249 BR opposition! I retain it to this day as one of my most treasured possessions. It shows unmistakable evidence of its rough-and-tumble experience, but still runs superbly. OK, enough of my reminiscent ramblings! On to the next stage of the P.A.W. story............... The Next Step - the P.A.W. 19-D

However, this was a period during which control line combat was enjoying a very high level of popularity in Britain. Moreover, the S.M.A.E. displacement limit for combat was then set at 3.5 cc. The absence of mega-powerful 3.5 cc diesels at the time meant that most competitive fliers used well-tweaked 2.5 cc competition powerplants such as Copeman-tuned Oliver Tigers and works-tuned Rivers Silver Streaks. It didn’t take Gig Eifflaender long to recognise the market niche created by this situation. He took a look at his very successful basic design which had worked so well in 1.5 cc and 2.5 cc displacements, coming to the conclusion that the 2.5 cc design could be stretched out to over 3 cc without unduly stressing the components or increasing the weight. Such an engine would theoretically be ideal for combat applications. Better yet, it would face minimal competition from other manufacturers. As the icing on the cake, it would also undercut the high-performance 2.5 cc opposition very significantly in terms of price - a standard unmodified Oliver Tiger Mk. III sold at the time for £6 10s 0d (£6.50), while a works-tuned Rivers Silver Streak Mk. II would set you back £8 15s 8d (£8.78).

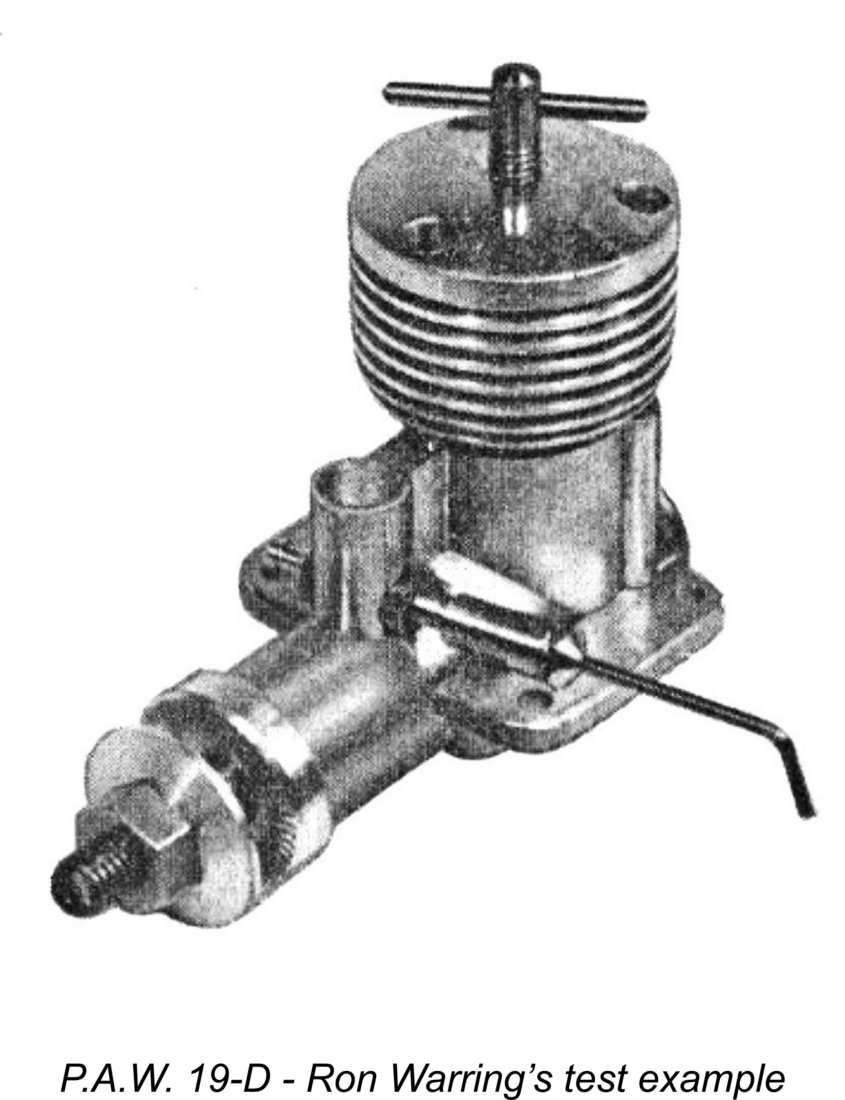

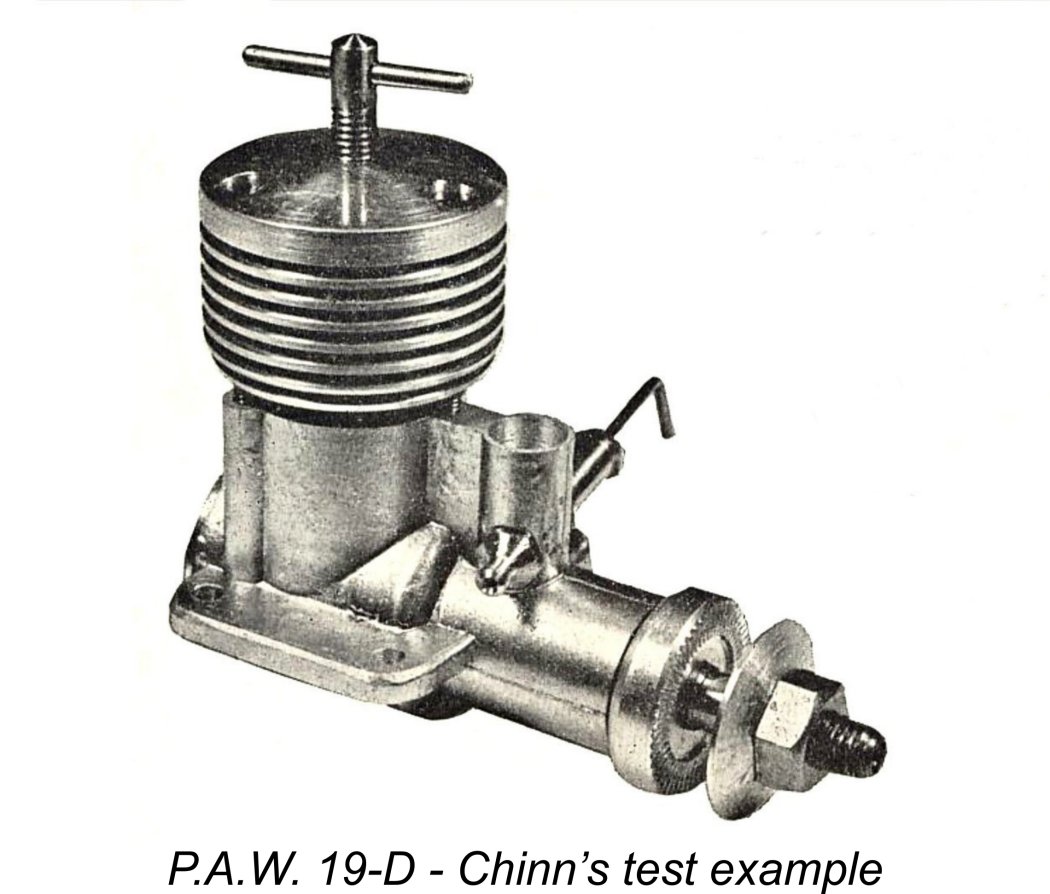

As we would expect, the new model followed the design of the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III almost exactly. Indeed, you had to look very closely to tell them apart! A positive selling point was the fact that the 19-D was based upon the same crankcase casting and mounting hole configuration as the 249 model, meaning that it could be used as a straight bolt-in replacement for the smaller engine in the same model. This might lead one to assume that the additional displacement was achieved solely through a bore increase. In fact, both bore and stroke were increased to 0.640 in. (16.25 mm) and 0.590 in. (14.99 mm) respectively, making the 19-D a very slightly longer-stroke motor than the 249. Displacement of the new model was 3.186 cc (0.1944 cuin.), while weight had crept up by only some 12 gm to 160 gm (5.6 ounces). Most ball-race 2.5 cc diesels weighed more than this, while the displacement fell well within the S.M.A.E. class limits for control line combat.

Returning to the original P.A.W. 19-D of 1961, the crankshaft continued to be supported by the same combination of a rear ball race and a cast iron bushing for the rest

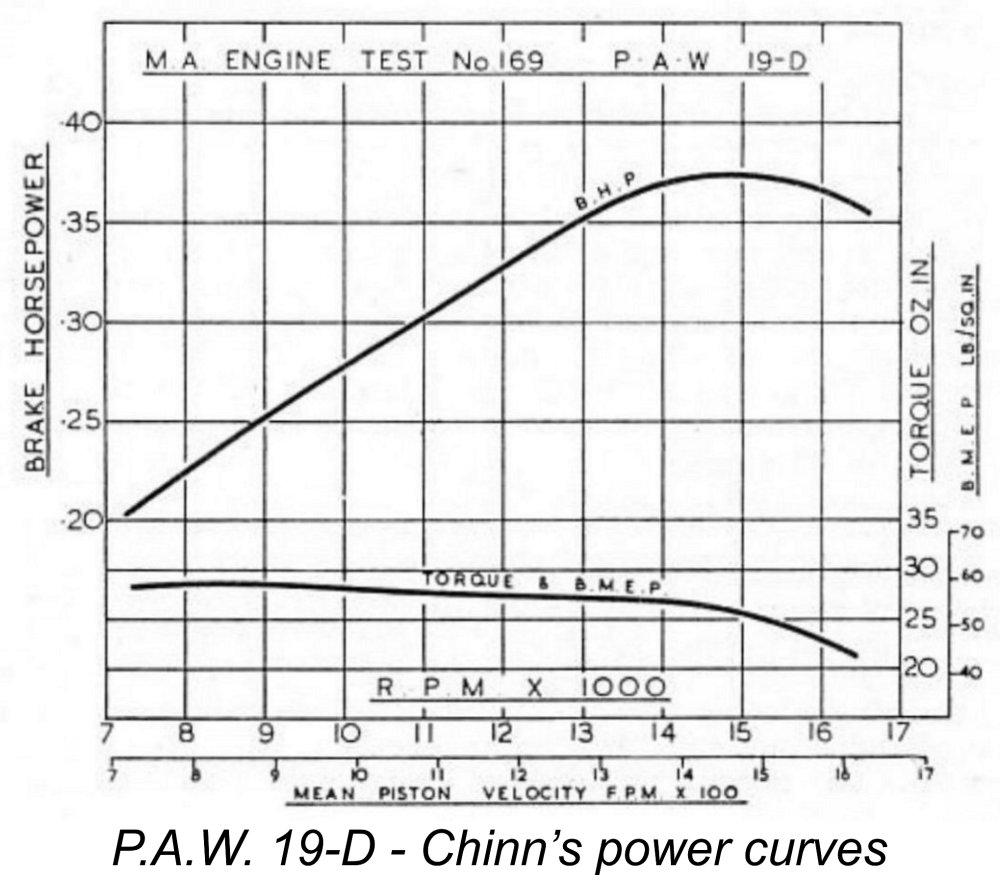

It was left to Peter Chinn to set the record straight, which he did in his test of the 19-D which appeared in the November 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Apart from the now-familiar litany of positive comments on the engine’s various qualities, Chinn was able to report a peak output of 0.375 BHP @ 15,000 RPM, thus matching the manufacturer’s claim almost exactly. Job done ……………or so it seemed! Further P.A.W. Developments The positive experiences of users of the 19-D as well as the laudatory media reviews ensured that the engine quickly became a very steady seller for Gig Eifflaender. The 19-D’s success was such that it became the catalyst for a somewhat controversial set of rule changes. The trigger seems to have been the engine’s performance at the 1962 British Nationals, where two contestants using 19-D’s somehow managed to tie for 1st place in the combat event. The success of this relatively inexpensive and readily available powerplant against the far more costly and exclusive tuned Olivers and the like in which some participants had made a considerable investment didn’t go down well in some quarters - people didn’t take kindly to their Ferraris being beaten by a Volkswagen! This seems to have led to pressure being applied to the S.M.A.E. to draw the teeth of the larger engines through changes to the rule book for the 1963 season and beyond. The first such change was the reduction of the maximum displacement for S.M.A.E. combat to 3.2 cc, recognising the existence of the P.A.W. 19-D but eliminating such engines as the Rivers Silver Arrow. This was probably not that big a deal, since few people were using that engine anyway due to its excessive weight in a combat context - indeed, the Silver Arrow was already in the process of being phased out, along with the rest of the Rivers range.

Of course, the rule-makers overlooked the fact that they were dealing with Gig Eifflaender! Gig’s response to this bureaucratic elimination of his engine from the competition in which it had been designed to compete was both simple and direct - he immediately came up with a plain bearing version of the same engine! This was released in early 1963 as the P.A.W. 19-D Mk. II, just in time for the 1963 season. To sweeten the pot, the elimination of the ball bearing allowed the selling price to be reduced to £4 8s 6d (£4.43). The 19-D Mk. II was basically the same engine as its predecessor, but without the rear ball race. To compensate for this, the crankshaft journal diameter was increased to a whopping 0.437 in. (11.1 mm), with a corresponding increase in the induction porting dimensions. Gig claimed an output of over 0.400 BHP @ 15,500 RPM for the revised model, a claim which experience in the field seemed to bear out. Although this model was never the subject of a published test, my own impressions as a former user bear out Gig’s claim completely. For an engine which weighed only 160 gm (5.64 ounces), this thing had some real grunt! It also handled superbly. My illustrated example of this model joins my previously-mentioned P.A.W. 249 Mk. III in being one of my most treasured possessions, but for very different reasons. This example was the first 19-D Mk. II to appear in the hands of any of my fellow control line enthusiasts in Sheffield, England. It was purchased new in early 1963 by one of my closest friends, Pete Cattell, a keen combat flier who was a class-mate of mine at school and who also played with me both in the school orchestra and in the rock ’n roll band which I had formed with a few of my friends at that time. He was also a fellow petrol-head, although his fancies ran to cars, while I favoured motorcycles. Close bonds ………… When I left England for Canada in 1966, Pete presented this engine to me as a memento of our many happy hours of shared aeromodelling activity. Sadly, Pete passed away in tragic circumstances some years later, but his 19-D Mk. II remains with me to this day, having made the trip back to Macclesfield in the Like most others, Pete’s old engine doesn’t bear a serial number. However, some examples did display such numbers. I have a second example of the 19-D Mk. II which bears the number 131 on one lug, along with a “Made in England” stamping under the lug. Although I can’t be certain, I assume that examples designated for export may have been stamped in this way. The reader may recall that my original 2.5 cc Eifflaender Special is similarly marked. The introduction of the 19-D Mk. II indicated that Gig Eifflaender wasn’t going to “go quietly”! The displacement issue was eventually resolved very simply by setting the maximum displacement for control line combat in Britain at 2.5 cc. Exit the 19-D, at least from “official” events!! This did admittedly have the merit of bringing British combat into line with the FAI displacement standard. In the face of these rule changes, a fair number of us just kept on flying our unsanctioned “fun” bouts at the club level using the oversized equipment - we couldn’t afford Ollies, but the use of the 19-D made our models perform to the same standard, more or less. More fun was had by all!! Perhaps somewhat perversely, I used my self-tuned FROG 349 motors in some of these non-sanctioned events, just to be different! They ran really well, but a good P.A.W. could still out-haul them. Despite the confining rule changes (at least in an S.M.A.E. combat context), a demand remained for an even more powerful rendition of the 19-D, even if it couldn’t be used in combat events run to strict S.M.A.E. rules. This ongoing demand led to the late 1964 re-introduction of the 19-D in single ball-race form, just as it had been released originally. The larger shaft of the 19-D Mk. II was retained, necessitating the development by Ransome & Marles of a custom ball bearing specifically designed to match. The new model was called the P.A.W. 19 BR. This was the first of many BR models to be offered by the company over the years.

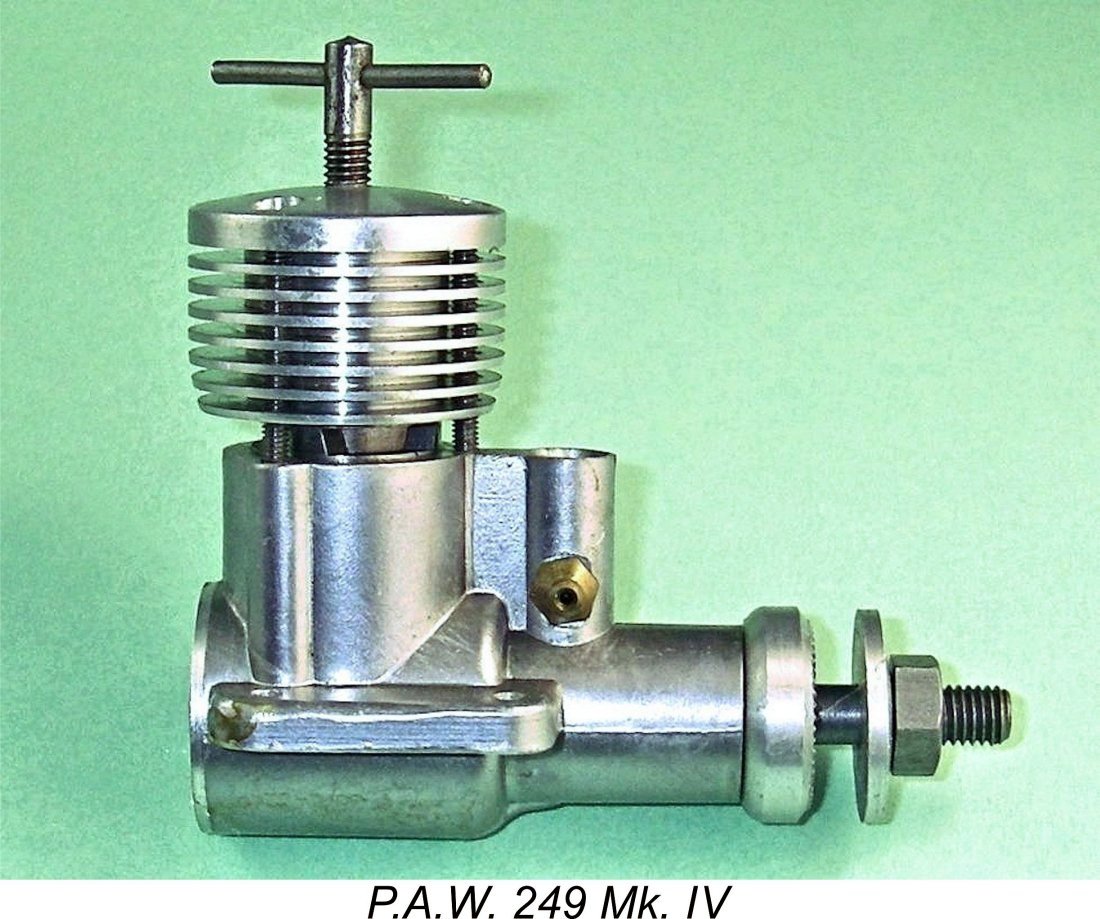

This feature finally appeared in mid 1966 in the shape of the P.A.W. 249 Mk. IV. In addition to the flat-topped piston and squish head, this model incorporated a few other changes which pointed the way ahead. For one thing, the sub-piston induction was eliminated in order to enhance performance with a silencer fitted - an unmistakable sign of the times. This is a sure-fire way of distinguishing between a Mk. III and a Mk. IV, as is the flat topped piston. To restore power output, a revised shaft was used which had a massive main journal diameter of 0.437 in. (11.1 mm) with correspondingly enlarged gas passages. This diameter matched that of the 19 BR - indeed, it came close to equalling the all-time 2.5 cc classic diesel record-holder, the Enya 15D-II with its 11.5 mm diameter shaft. The special ball-race developed earlier by Ransome & Marles for the 19 BR was also used in the 249 Mk. IV. Somewhat surprisingly, the crankdisc in this model did not incorporate any counterbalance. Gig Eifflaender himself characterised this model as "the sweetest-handling P.A.W. of them all". He made the quite credible claim that the Mk. IV developed 0.340 BHP @ 15,000 RPM in standard unsilenced form, with even more power available if the engine was works tuned. I see absolutely no reason to doubt this claim. In design terms, the range was now finalised apart from a later switch to a removable intake venturi to facilitate the installation of an R/C throttle. Squish head variants of the 149 and 19 quickly appeared, being identified by the DS suffix, as were later renditions of the 249 model. New models in other displacement categories soon followed as well. I’ve now completed my self-appointed task of recording the history of P.A.W. up to the mid 1960’s. In the interests of providing some context, I’ll finish up by setting down a few observations relating to the following decades. The More Recent Years

Consequently, the P.A.W. range went from strength to strength, proving to be by far the most durable British model diesel range of them all. Further models were added as the years went by. The majority of these engines remained true to the well-establish design configuration developed by Gig Eifflaender way back in the 1950's, although there were a few experiments with Schnuerle porting. A number of models were also offered in twin ball-race (TBR) configuration. P.A.W. eventually covered the displacement range all the way from 0.55 cc up to 10 cc. A noteworthy event took place in 1985, when Gig’s son Tony won the Gold Trophy using a P.A.W. 35 diesel (5.83 cc). Tony thus emulated his father’s earlier successes using a diesel engine of his own construction. His 1985 Gold Trophy win was the first diesel-powered win in that annual contest since Pete Ridgeway had accomplished the feat 27 years previously in 1958, also using a P.A.W. diesel! A remarkable continuity of competition success - Gig must have been proud of his son! Tony was to go on to win the Gold Trophy six more times, using P.A.W. diesel power on each occasion.

Unfortunately, while these engines started easily and ran well enough, they proved to be dismal under-performers by comparison with their diesel equivalents. My own testing of the illustrated example (which was kindly donated by my good Danish friend Luis Petersen) bears this out completely. Tony put this down to the fact that the Eifflaenders had no experience with glow-plug engines. All they really did was prove yet again that a simple conversion from diesel to glow-plug ignition seldom or never produces worthwhile results - IMA (FROG), Allbon, AMCO, D-C Ltd. and E.D. had all demonstrated this many years previously. That said, in the late 1990's curiosity led Tony to construct more carefully-considered .09, .06 and .049 conversions of P.A.W. diesel models using Nelson glow heads among other tweaks. These units comfortably out-performed their diesel equivalents - the .09 was found to develop over 0.30 BHP, and this without a pipe. However, Gig Eifflaender put his foot down and told Tony that after the debacle of the 1980's they weren't going there again! As a result, only the three prototypes were ever constructed. The original glow-plug models from the 1980's are relatively rare collectibles these days.

Until 1997 I had never heard of the Sharma engines. However, in that year curiousity led me to acquire a 2.5 cc plain bearing example from Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine Imports in Phoenix, Arizona. When the engine arrived, it proved to be extremely well made, performing at a level which was entirely consistent with that of its P.A.W. progenitor.

The visit was one of the highlights of my aeromodelling life! I was privileged to meet Gig Eifflaender himself, taking the opportunity to thank him for all the pleasure that his engines had been giving me for 36 years and counting. I also met his sons Tony and Paul, who had largely taken over the company’s operations by this time. Upon my producing the Sharma diesel for their examination, the Eifflaenders instantly recognized its design inspiration! Tony’s immediate comment was “Blimey, we never made this! Where’s me royalties?!?” The engine was The boys were quite impressed………... they agreed completely with my assessment of the Sharma's quality and performance. To their great credit, they took the appearance of the Sharma engines as the very sincere compliment that it undoubtedly was. A really memorable visit! To add spice to the occasion, I took delivery of the previously-illustrated P.A.W. 249 TBR Schnuerle engine directly from Gig. It has since served me well in a number of models. Gig Eifflaender retired (or semi-retired, if you believe Tony!) in 2000, passing away on December 1st, 2005 at the age of 83, only 8 years after my visit. I’m immensely glad that I had the opportunity to meet the great man himself and to thank him personally for his efforts on behalf of myself and my fellow aeromodellers worldwide. His contribution to both sport and competition aeromodelling in the UK and elsewhere cannot be overstated in my opinion. I was grateful for the opportunity to tell him so directly. Paul Eifflaender retired in 2012, but the P.A.W. company remains in operation today (2022) in the capable hands of Tony, his wife Cathy and his son Chris. As the model engine market has retreated, the company has moved into other areas of precision engineering, including work relating to the fields of aerospace, medical equipment, textiles and full-size automotive engineering. However, they continue to supply P.A.W. engines to those wishing to experience a truly fine example of the model diesel constructor’s art, just as the firm has been doing for the past 65 years and counting. Long may this continue!! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2022 Revised July 2023 (P.A.W. glow-plug models added) |

| |

As all of my regular readers should know by now, my motivations for researching and writing these articles vary considerably. It may seem surprising to some of you to learn that the rarity of a given engine is not among the major criteria upon which my selections are based. Some of my subjects are indeed rare, but that’s not the primary reason for their appearance in these pages. In fact, I see extreme rarity more as an argument against making the considerable investment of time required to cover a given engine or range, because very few people will ever be able to experience such engines for themselves, making commentaries on them far less practically relevant.

As all of my regular readers should know by now, my motivations for researching and writing these articles vary considerably. It may seem surprising to some of you to learn that the rarity of a given engine is not among the major criteria upon which my selections are based. Some of my subjects are indeed rare, but that’s not the primary reason for their appearance in these pages. In fact, I see extreme rarity more as an argument against making the considerable investment of time required to cover a given engine or range, because very few people will ever be able to experience such engines for themselves, making commentaries on them far less practically relevant. The P.A.W. engines fall squarely into this category - there can be few long-time aficionados of model diesels who have not used one of these outstanding engines at some point in their aeromodelling lives! At the time of writing (2022), the range is still going strong after some 65 years (and counting) in continuous production!

The P.A.W. engines fall squarely into this category - there can be few long-time aficionados of model diesels who have not used one of these outstanding engines at some point in their aeromodelling lives! At the time of writing (2022), the range is still going strong after some 65 years (and counting) in continuous production! It’s well-known that the initials P.A.W. stand for “Progress Aero Works”. This very successful business was established during the WW2 years by one of the more iconic and perhaps under-appreciated figures in British model engine history - J. G. “Gig” Eifflaender.

It’s well-known that the initials P.A.W. stand for “Progress Aero Works”. This very successful business was established during the WW2 years by one of the more iconic and perhaps under-appreciated figures in British model engine history - J. G. “Gig” Eifflaender.

Undaunted, Gig built a new model and continued to compete. By now he had developed a new rear disc valve twin ball-race 2.5 cc diesel design which was also called the “Eifflaender Special”. Apart from the disc valve, this was very clearly influenced by the

Undaunted, Gig built a new model and continued to compete. By now he had developed a new rear disc valve twin ball-race 2.5 cc diesel design which was also called the “Eifflaender Special”. Apart from the disc valve, this was very clearly influenced by the  Gig’s open acceptance of the revised schedule despite his recognition of the handicap under which it placed him and other users of smaller diesel-powered models didn’t end his ongoing participation, at least not immediately. Indeed, his Macclesfield compatriot Pete Ridgeway actually won the 1958 Gold Trophy (the first run to the new schedule) flying a flapped model powered by one of the new commercial P.A.W. “Eifflaender Special” diesels (see below). To emphasize this achievement, Gig himself finished fourth at the same contest using similar equipment but without the flaps.

Gig’s open acceptance of the revised schedule despite his recognition of the handicap under which it placed him and other users of smaller diesel-powered models didn’t end his ongoing participation, at least not immediately. Indeed, his Macclesfield compatriot Pete Ridgeway actually won the 1958 Gold Trophy (the first run to the new schedule) flying a flapped model powered by one of the new commercial P.A.W. “Eifflaender Special” diesels (see below). To emphasize this achievement, Gig himself finished fourth at the same contest using similar equipment but without the flaps. As mentioned previously, Gig started out in 1945 by making a spark ignition engine. In 1947 he became aware of the compression ignition (“diesel”) principle as applied to model engines and began his diesel-building career by making a handful of 2.2 cc sideport units. I have been unable to locate reproducible images of any of these creations.

As mentioned previously, Gig started out in 1945 by making a spark ignition engine. In 1947 he became aware of the compression ignition (“diesel”) principle as applied to model engines and began his diesel-building career by making a handful of 2.2 cc sideport units. I have been unable to locate reproducible images of any of these creations.

An illustration of how far Gig was prepared to go in this regard is provided by the arrangement of his next design. This was another twin ball-race disc valve model having an integrally-cast backplate. The influence of the contemporary Elfin ball-race models was very obvious.

An illustration of how far Gig was prepared to go in this regard is provided by the arrangement of his next design. This was another twin ball-race disc valve model having an integrally-cast backplate. The influence of the contemporary Elfin ball-race models was very obvious.  The disc valve would obviously be inserted first, after which the complete cylindrical shaft assembly would be installed from the front. As this was being done, the conrod would have to be assembled onto the crankpin from above just before the crankpin was located in the disc valve, more or less in a single operation. The entire shaft assembly was then secured in position by the set screw which is visible on top of the main bearing housing.

The disc valve would obviously be inserted first, after which the complete cylindrical shaft assembly would be installed from the front. As this was being done, the conrod would have to be assembled onto the crankpin from above just before the crankpin was located in the disc valve, more or less in a single operation. The entire shaft assembly was then secured in position by the set screw which is visible on top of the main bearing housing.

During 1956, Gig had developed the previously-mentioned revised 2.5 cc diesel design featuring crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. Both he and fellow Macclesfield resident Pete Ridgeway used this engine to very good effect in their initial competitive outings following its development. This convinced Gig that the engine was well worthy of commercial-scale series production.

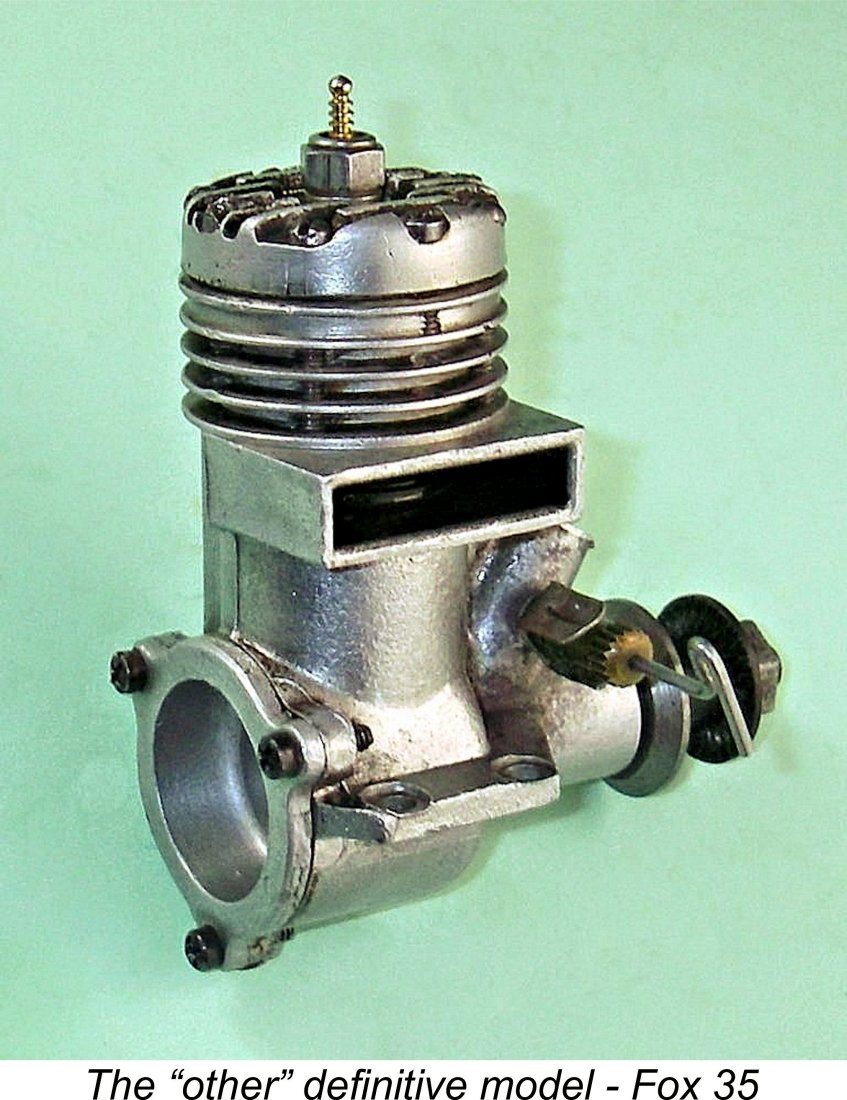

During 1956, Gig had developed the previously-mentioned revised 2.5 cc diesel design featuring crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. Both he and fellow Macclesfield resident Pete Ridgeway used this engine to very good effect in their initial competitive outings following its development. This convinced Gig that the engine was well worthy of commercial-scale series production.  Bob went further, stating his opinion that the P.A.W. comes closer than any other engine to earning the tag of "the definitive classic model diesel engine". Probably only one other model engine in history can compare with the P.A.W. for design longevity, and that’s the Fox 35 Stunt of 1949. Both designs were nigh on perfect for their intended applications right from the very beginning, and throughout their long production lives both remained very close to the original concept, receiving only minor improvements over the years.

Bob went further, stating his opinion that the P.A.W. comes closer than any other engine to earning the tag of "the definitive classic model diesel engine". Probably only one other model engine in history can compare with the P.A.W. for design longevity, and that’s the Fox 35 Stunt of 1949. Both designs were nigh on perfect for their intended applications right from the very beginning, and throughout their long production lives both remained very close to the original concept, receiving only minor improvements over the years.

The Special was built up around a well-produced gravity die-cast crankcase unit which incorporated the main bearing housing and vertical intake in a single unit. A noteworthy feature was the unusual length of the beam mounting lugs - an important aid to a really secure mounting.

The Special was built up around a well-produced gravity die-cast crankcase unit which incorporated the main bearing housing and vertical intake in a single unit. A noteworthy feature was the unusual length of the beam mounting lugs - an important aid to a really secure mounting. The cast iron piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a light alloy conrod of conventional British “dog bone” pattern, albeit having a far larger than usual upper ball end giving a small end bearing of adequate length with good lateral stability. The crankweb was counterbalanced through the removal of wedges of material on both sides of the crankpin. Main journal diameter was a generous 0.375 in. (9.52 mm). The internal gas passage diameter was 0.203 in. (5.16 mm), leaving adequate wall thickness for strength.

The cast iron piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a light alloy conrod of conventional British “dog bone” pattern, albeit having a far larger than usual upper ball end giving a small end bearing of adequate length with good lateral stability. The crankweb was counterbalanced through the removal of wedges of material on both sides of the crankpin. Main journal diameter was a generous 0.375 in. (9.52 mm). The internal gas passage diameter was 0.203 in. (5.16 mm), leaving adequate wall thickness for strength. The shaft ran in a composite bearing consisting of a Hoffman ball-race at the rear and a thick cast iron sleeve forward of the ball-race. The inclusion of this sleeve allowed the provision of a very large cut-out in the sleeve which communicated with the integrally-cast vertical intake and formed the induction register. This cut-out also served as a mixture accumulation chamber to pre-charge the system for the next induction cycle.

The shaft ran in a composite bearing consisting of a Hoffman ball-race at the rear and a thick cast iron sleeve forward of the ball-race. The inclusion of this sleeve allowed the provision of a very large cut-out in the sleeve which communicated with the integrally-cast vertical intake and formed the induction register. This cut-out also served as a mixture accumulation chamber to pre-charge the system for the next induction cycle. The needle valve was angled back to the left, providing easy access with the engine mounted either upright or sidewinder. A brass split thimble was used for tension. The P.A.W. needle valve assembly became recognized as an industry standard for dependability in use - I used to fit them regularly to engines from other manufacturers for flying purposes. The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate at the rear.

The needle valve was angled back to the left, providing easy access with the engine mounted either upright or sidewinder. A brass split thimble was used for tension. The P.A.W. needle valve assembly became recognized as an industry standard for dependability in use - I used to fit them regularly to engines from other manufacturers for flying purposes. The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate at the rear. The Eifflaender Special was very much a custom-produced engine at this stage, with a lot of individual work put into each engine. Gig Eifflaender stated that he had no plans to embark upon a major advertising campaign, relying on the engine’s quality and reputation to sell it as fast as he could make it!

The Eifflaender Special was very much a custom-produced engine at this stage, with a lot of individual work put into each engine. Gig Eifflaender stated that he had no plans to embark upon a major advertising campaign, relying on the engine’s quality and reputation to sell it as fast as he could make it! The Special was the subject of two published tests in the contemporary modelling media. First into the fray was Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” magazine, whose

The Special was the subject of two published tests in the contemporary modelling media. First into the fray was Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” magazine, whose  A

A  The Special made a further appearance in the 2.5 cc engine comparison prepared for the 1957 “Aeromodeller Annual” by Editor Ron Moulton using his own prop/RPM test figures. The engine appeared near the top of the performance listings for the diesel models tested, comparing quite favourably with even the industry-standard Oliver Tiger Mk. III.

The Special made a further appearance in the 2.5 cc engine comparison prepared for the 1957 “Aeromodeller Annual” by Editor Ron Moulton using his own prop/RPM test figures. The engine appeared near the top of the performance listings for the diesel models tested, comparing quite favourably with even the industry-standard Oliver Tiger Mk. III.

The result of his deliberations appeared in March 1959 in the shape of the 1.5 cc P.A.W. 149 model. The £4 6s 0d (£4.30) selling price of this engine was still well above average for a 1.5 cc diesel - the popular A-M 15 sold at the time for £2 19s 8d (£2.98) while the excellent FROG 150R was tagged at a bargain price of £2 13s 4d (£2.66). However, the P.A.W 149 was over £2 less expensive than the companion 249 Eifflaender Special which continued in production. People were prepared to pay such a premium for P.A.W. quality and performance.

The result of his deliberations appeared in March 1959 in the shape of the 1.5 cc P.A.W. 149 model. The £4 6s 0d (£4.30) selling price of this engine was still well above average for a 1.5 cc diesel - the popular A-M 15 sold at the time for £2 19s 8d (£2.98) while the excellent FROG 150R was tagged at a bargain price of £2 13s 4d (£2.66). However, the P.A.W 149 was over £2 less expensive than the companion 249 Eifflaender Special which continued in production. People were prepared to pay such a premium for P.A.W. quality and performance.

The P.A.W. 149 was announced by Peter Chinn in his “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the May 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Naturally, the appearance of the second member of the P.A.W. range attracted considerable attention, leading both “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” magazines to publish full test reports on the engine.

The P.A.W. 149 was announced by Peter Chinn in his “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the May 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Naturally, the appearance of the second member of the P.A.W. range attracted considerable attention, leading both “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” magazines to publish full test reports on the engine.  Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” was first into print with a

Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” was first into print with a

The result was the late 1960 release of the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III - the first and second versions of the Eifflaender Special were viewed as the 249 Mk. I and Mk. II models. The new design’s arrival on the market was announced in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the magazine’s February 1961 issue.

The result was the late 1960 release of the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III - the first and second versions of the Eifflaender Special were viewed as the 249 Mk. I and Mk. II models. The new design’s arrival on the market was announced in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the magazine’s February 1961 issue. Bore and stroke remained unchanged from the previous model at 0.597 in. (15.16 mm) and 0.538 in. (13.67 mm) respectively for a displacement of 2.467 cc (0.1506 cuin.). The same main journal diameter of 0.375 in. was also retained. The engine’s weight had crept up very slightly to 5.25 ounces (148 gm), still a very modest figure for a high-performance ball-race 2.5 cc diesel.

Bore and stroke remained unchanged from the previous model at 0.597 in. (15.16 mm) and 0.538 in. (13.67 mm) respectively for a displacement of 2.467 cc (0.1506 cuin.). The same main journal diameter of 0.375 in. was also retained. The engine’s weight had crept up very slightly to 5.25 ounces (148 gm), still a very modest figure for a high-performance ball-race 2.5 cc diesel.

The resident engine testers of the day were quick to get this model into their test stands. First up was “Aeromodeller” tester Ron Warring,

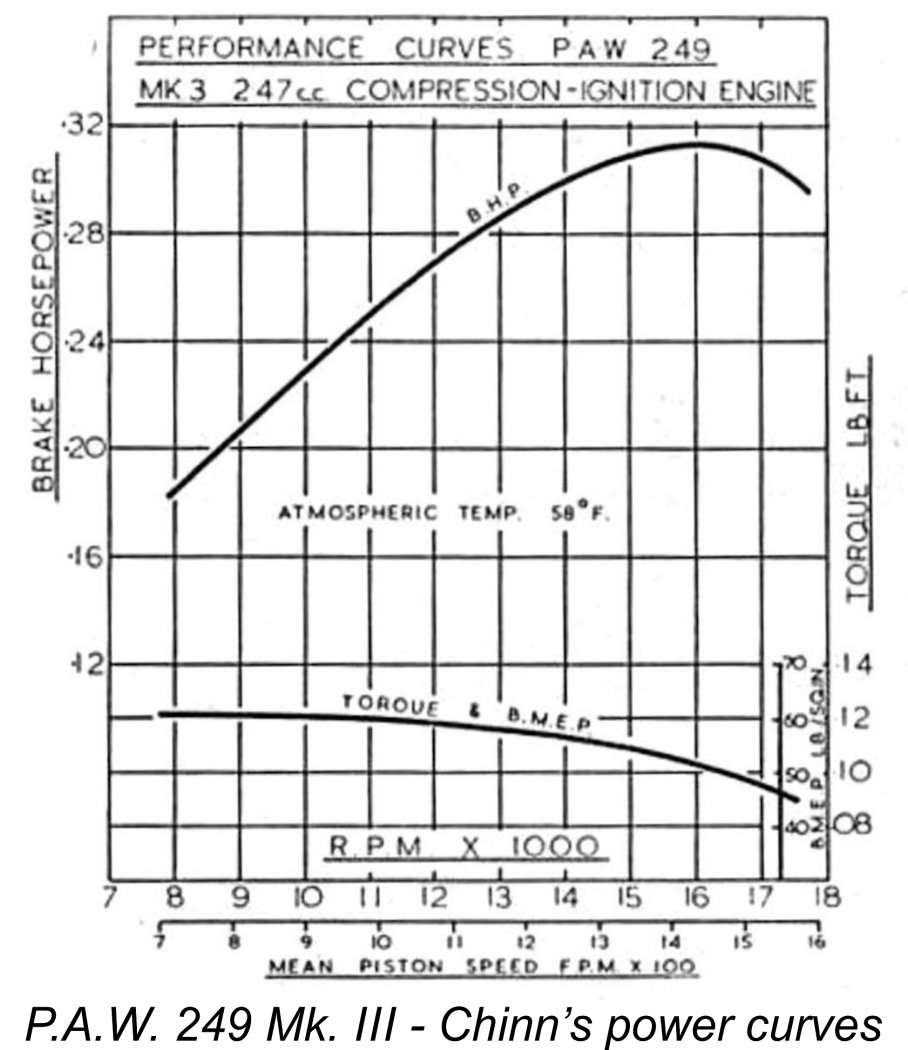

The resident engine testers of the day were quick to get this model into their test stands. First up was “Aeromodeller” tester Ron Warring,  In this instance, Chinn’s report more or less precisely endorsed Warring’s findings. He was equally complimentary regarding the engine’s construction, handling and running qualities, also finding a very similar level of performance. He reported a peak output of 0.314 BHP @ 16,000 RPM, which he rightly cited as putting the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III among the most powerful 2.5 cc diesels then available. The peak BMEP of 60 PSI @ 8,000 rpm was very slightly lower than that measured by Chinn for the earlier model, but the revised design sustained its torque better at higher RPM, accounting for the improvement in peak power output.

In this instance, Chinn’s report more or less precisely endorsed Warring’s findings. He was equally complimentary regarding the engine’s construction, handling and running qualities, also finding a very similar level of performance. He reported a peak output of 0.314 BHP @ 16,000 RPM, which he rightly cited as putting the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III among the most powerful 2.5 cc diesels then available. The peak BMEP of 60 PSI @ 8,000 rpm was very slightly lower than that measured by Chinn for the earlier model, but the revised design sustained its torque better at higher RPM, accounting for the improvement in peak power output.  Dad told me that he had quite a long chat with Gig Eifflaender (who was only 3 years younger than Dad), finding that, quite apart from their common engineering backgrounds, they shared previous involvements with both Manchester University (where Dad had been a Professor of Engineering) and Metropolitan Vickers (where Dad had worked for a time in the early 1950's). He recalled his visit as a very enjoyable experience. He was particularly impressed with the "artisan" character of the workshop.

Dad told me that he had quite a long chat with Gig Eifflaender (who was only 3 years younger than Dad), finding that, quite apart from their common engineering backgrounds, they shared previous involvements with both Manchester University (where Dad had been a Professor of Engineering) and Metropolitan Vickers (where Dad had worked for a time in the early 1950's). He recalled his visit as a very enjoyable experience. He was particularly impressed with the "artisan" character of the workshop.  With the advent of the 249 Mk. III, P.A.W. had a very capable performer in the 2.5 cc category. This dovetailed nicely with the displacement limits established by the FAI for free flight power events as well as control line team racing.

With the advent of the 249 Mk. III, P.A.W. had a very capable performer in the 2.5 cc category. This dovetailed nicely with the displacement limits established by the FAI for free flight power events as well as control line team racing. Accordingly, Gig went ahead and drew up the design for a new model to be called the P.A.W. 19-D Combat Special. This was put into production in April 1961, being announced by Peter Chinn in his “Latest Engine News” column which was published in the May 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The selling price was set at a very competitive £5 4s 6d (£5.23).

Accordingly, Gig went ahead and drew up the design for a new model to be called the P.A.W. 19-D Combat Special. This was put into production in April 1961, being announced by Peter Chinn in his “Latest Engine News” column which was published in the May 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The selling price was set at a very competitive £5 4s 6d (£5.23). At this point, it’s perhaps worth recording the fact that Gig Eifflaender later actually managed to squeeze a little more displacement out of the same basic design! During the 1990’s, the British vintage diesel combat event was open to plain bearing engines up to 3.5 cc displacement. The Eifflaenders came up with a built-to-order plain-bearing variant called the Combat Special CT3 (the CT standing for Combat Tuned), in which both bore and stroke were further stretched to 16.50 mm and 15.50 mm respectively for a displacement of 3.32 cc (0.202 cuin.). Amazingly, the same case was still used, albeit with the removable venturi which was in use by that time, although some additional internal machining was required to accommodate the extra stroke. I reckon that this was about as far as the basic 249 crankcase could be stretched! This variant weighed in at a still-reasonable 174 gm (6.14 ounces).

At this point, it’s perhaps worth recording the fact that Gig Eifflaender later actually managed to squeeze a little more displacement out of the same basic design! During the 1990’s, the British vintage diesel combat event was open to plain bearing engines up to 3.5 cc displacement. The Eifflaenders came up with a built-to-order plain-bearing variant called the Combat Special CT3 (the CT standing for Combat Tuned), in which both bore and stroke were further stretched to 16.50 mm and 15.50 mm respectively for a displacement of 3.32 cc (0.202 cuin.). Amazingly, the same case was still used, albeit with the removable venturi which was in use by that time, although some additional internal machining was required to accommodate the extra stroke. I reckon that this was about as far as the basic 249 crankcase could be stretched! This variant weighed in at a still-reasonable 174 gm (6.14 ounces).

The remaining threat to the elite 2.5 cc establishment was the P.A.W. 19-D. After its showing at the 1962 British Nationals, it was clearly felt that something had to be done to rein it in. This was accomplished very simply by adding a rule to the effect that engines over 2.5 cc used in the S.M.A.E. combat event had to be plain bearing designs! At one stroke of the rule-makers’ pen, the P.A.W. 19-D had been eliminated! If you can’t beat ‘em, toss ‘em!!

The remaining threat to the elite 2.5 cc establishment was the P.A.W. 19-D. After its showing at the 1962 British Nationals, it was clearly felt that something had to be done to rein it in. This was accomplished very simply by adding a rule to the effect that engines over 2.5 cc used in the S.M.A.E. combat event had to be plain bearing designs! At one stroke of the rule-makers’ pen, the P.A.W. 19-D had been eliminated! If you can’t beat ‘em, toss ‘em!! interim to be works-tuned. Like my old faithful 249 Mk. III, it has seen countless hours of service, but still runs as well as ever. Just holding it today brings back some very special memories of my mate Pete. I still miss him ………….

interim to be works-tuned. Like my old faithful 249 Mk. III, it has seen countless hours of service, but still runs as well as ever. Just holding it today brings back some very special memories of my mate Pete. I still miss him …………. The P.A.W. range was now well established in design terms. The only noteworthy feature of the more recent models which had yet to appear was the domed combustion chamber formed on the underside of the contra piston (commonly referred to as the squish head) in conjunction with a flat-topped piston.

The P.A.W. range was now well established in design terms. The only noteworthy feature of the more recent models which had yet to appear was the domed combustion chamber formed on the underside of the contra piston (commonly referred to as the squish head) in conjunction with a flat-topped piston.  If someone asked me to choose one word which sums up the P.A.W. model engine range, that word would be "practical". They weren't the most exotic of engine designs, but they delivered a level of service and value to their users which endeared them to every modeller who ever gave them a try. Their sturdiness, dependability, longevity and ease of handling became legendary.

If someone asked me to choose one word which sums up the P.A.W. model engine range, that word would be "practical". They weren't the most exotic of engine designs, but they delivered a level of service and value to their users which endeared them to every modeller who ever gave them a try. Their sturdiness, dependability, longevity and ease of handling became legendary.  A little-recalled phase in the activities of the P.A.W. venture (and perhaps one which Tony Eifflaender would prefer us to forget!) was their brief foray into the production of glow-plug models. In the early 1980's, in response to pressure from a number of their wholesalers, P.A.W. embarked upon the production of glow-plug versions of their 1.5 cc (.09 cuin.) and 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) models. These were based upon the company's plain-bearing Schuerle-ported "Contest" diesel models which had then recently been developed. Between 200 and 300 examples of each glow-plug variant were produced between 1982 and 1985 - a total of around 500 engines.

A little-recalled phase in the activities of the P.A.W. venture (and perhaps one which Tony Eifflaender would prefer us to forget!) was their brief foray into the production of glow-plug models. In the early 1980's, in response to pressure from a number of their wholesalers, P.A.W. embarked upon the production of glow-plug versions of their 1.5 cc (.09 cuin.) and 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) models. These were based upon the company's plain-bearing Schuerle-ported "Contest" diesel models which had then recently been developed. Between 200 and 300 examples of each glow-plug variant were produced between 1982 and 1985 - a total of around 500 engines.