|

|

Taipan 40 - The Story of the Last Production Taipan Model Engine by Maris Dislers

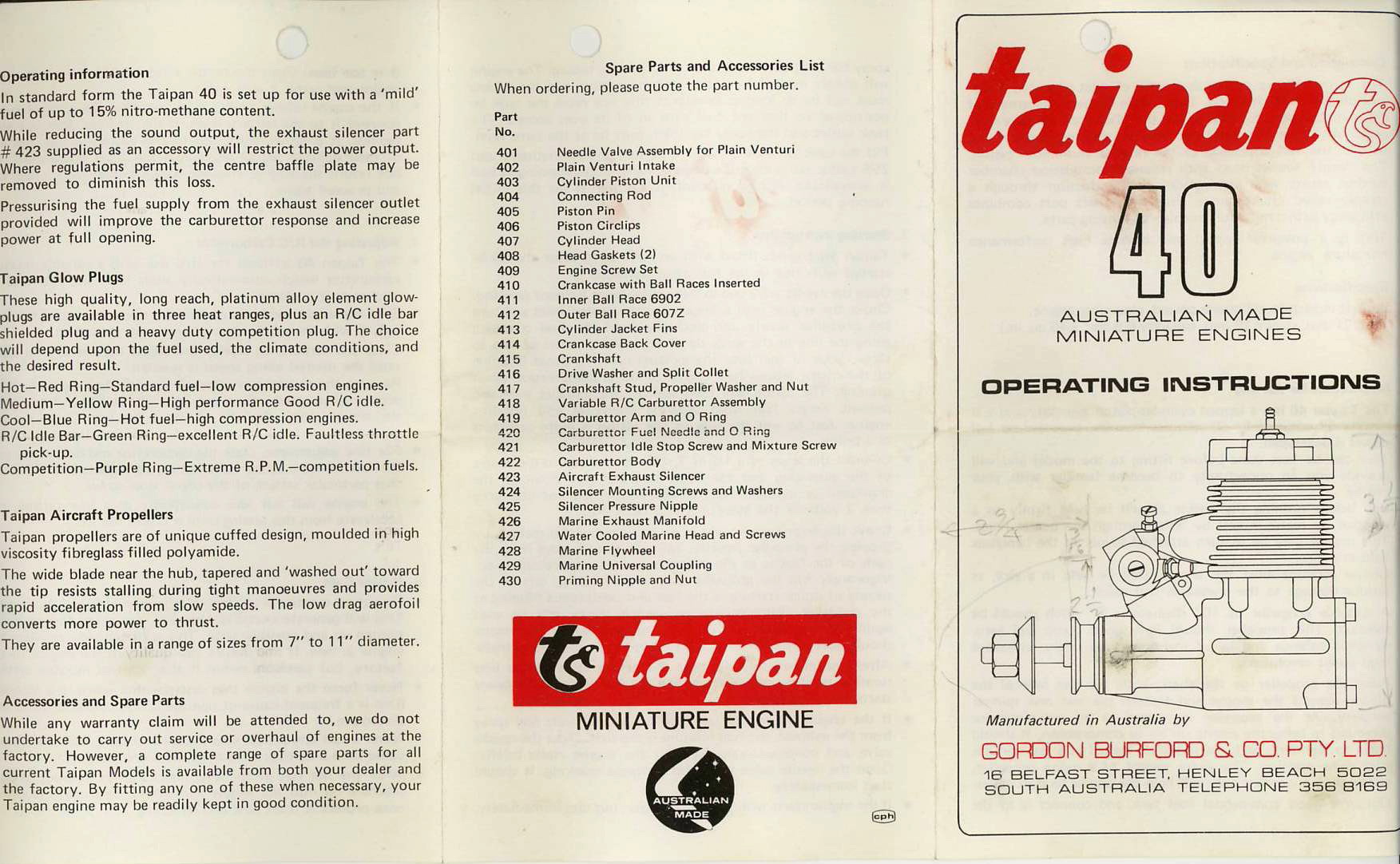

By my count, 54 basic Burford engine types were manufactured between 1946 and 1976 (based on unique crankcases). Of course, many of those cases were used in different displacement categories (e.g. 29 and 35), went through various model changes and/or were offered in several model specifications (e.g. R/C or marine) in addition to the standard models. Hence the total number of different Burford models offered for sale is much higher, depending on what degree of rigor one wants to apply to the criteria. In 1968, you’d have thought that Gordon’s revamped Taipan range (the epitome of then well-established design principles) would see the company right for quite a while. The models on offer at that time ranged from a 1cc diesel through 1.5cc and 2.5cc diesel and glow-plug models, the .19 cuin. By the time in question, proportional multi-function radio control units had become both reliable and cheap enough to divert ever-increasing numbers of existing model flyers and novices away from their former modelling activities. This caused some traditional market segments to shrink, a trend which progressed quite rapidly to the point where the most popular engines in the 1970-1980 period were those in the “forty” R/C category – 0.40 cuin. (6.5cc) displacement R/C glow-plug engines. They were good for medium sized R/C aerobatic and scale models as well as becoming increasingly popular with “Sunday flyers”, who were well supplied with basic but capable models such as Phil Kraft’s epochal “Das Ugly Stik” using four functions (rudder, elevator, ailerons, throttle), a box fuselage, tricycle undercarriage and “barn-door” wing. At the other end of the scale, K&B and some others were producing really hot Schnuerle ported 40’s for the very popular Pylon Racing competition category. The dramatic developments in racing and speed engines soon began filtering down to general purpose types. Gordon Burford & Co had no engine of this size, but had gained a design edge by introducing their .21 cuin. (3.5cc) and .15 cuin. (2.5cc) Schnuerle ported engines in the early 1970’s ahead of the pack. Peter Burford (Gordon’s son) assumed control of the factory in 1974 as Gordon moved into a well-earned retirement. Peter’s vision was to produce a new 40 engine in large quantities for the upper end of the worldwide “sport” R/C engine market. It would feature the accepted front induction/side exhaust layout for general-purpose use, but incorporate a “60 sized” crankshaft for less restricted induction together with Schnuerle porting and ABC piston/cylinder metallurgy as used in the best classes of racing engines. It was hoped that this combination would give it a sales edge. The Taipan 40 inside and out

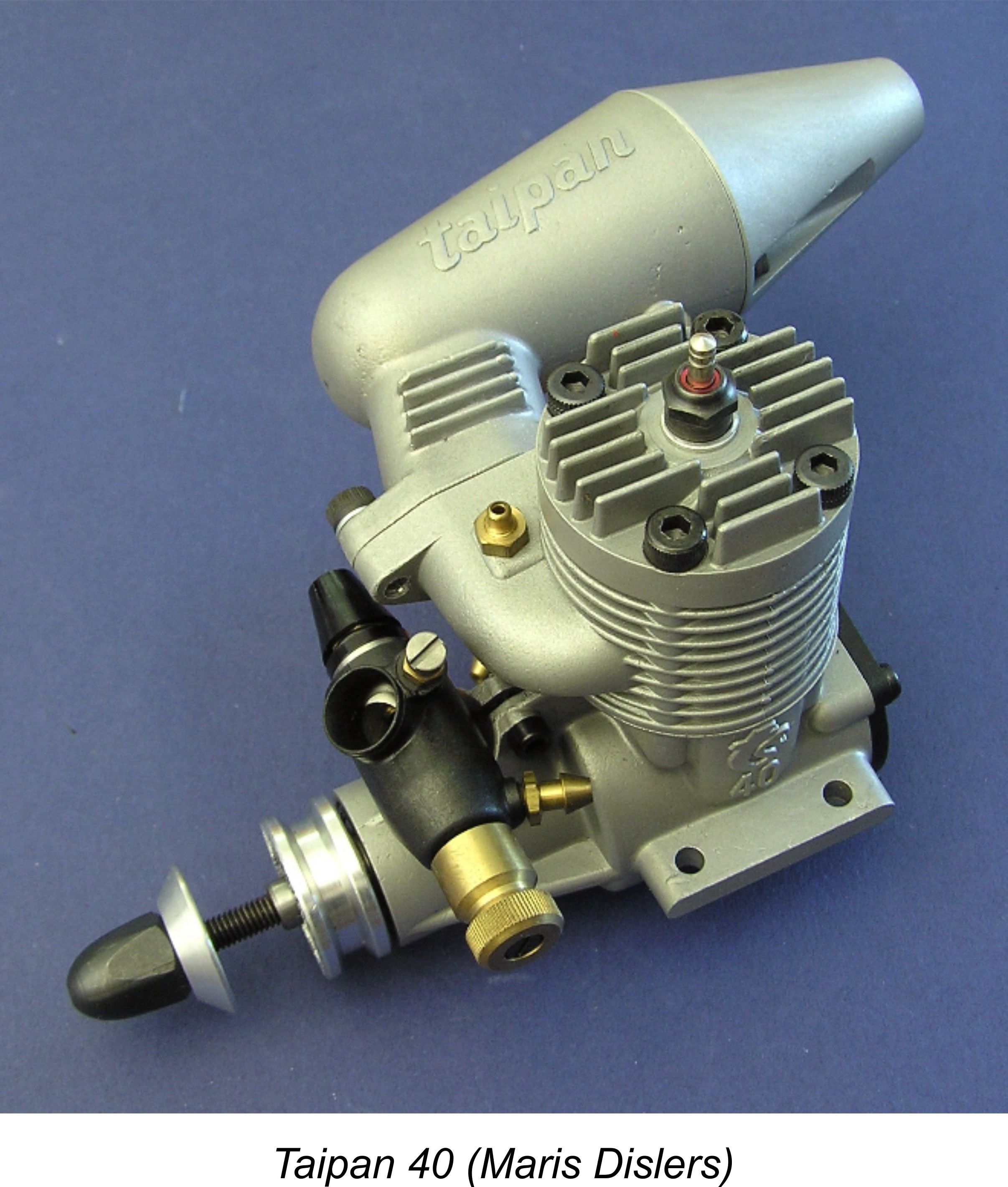

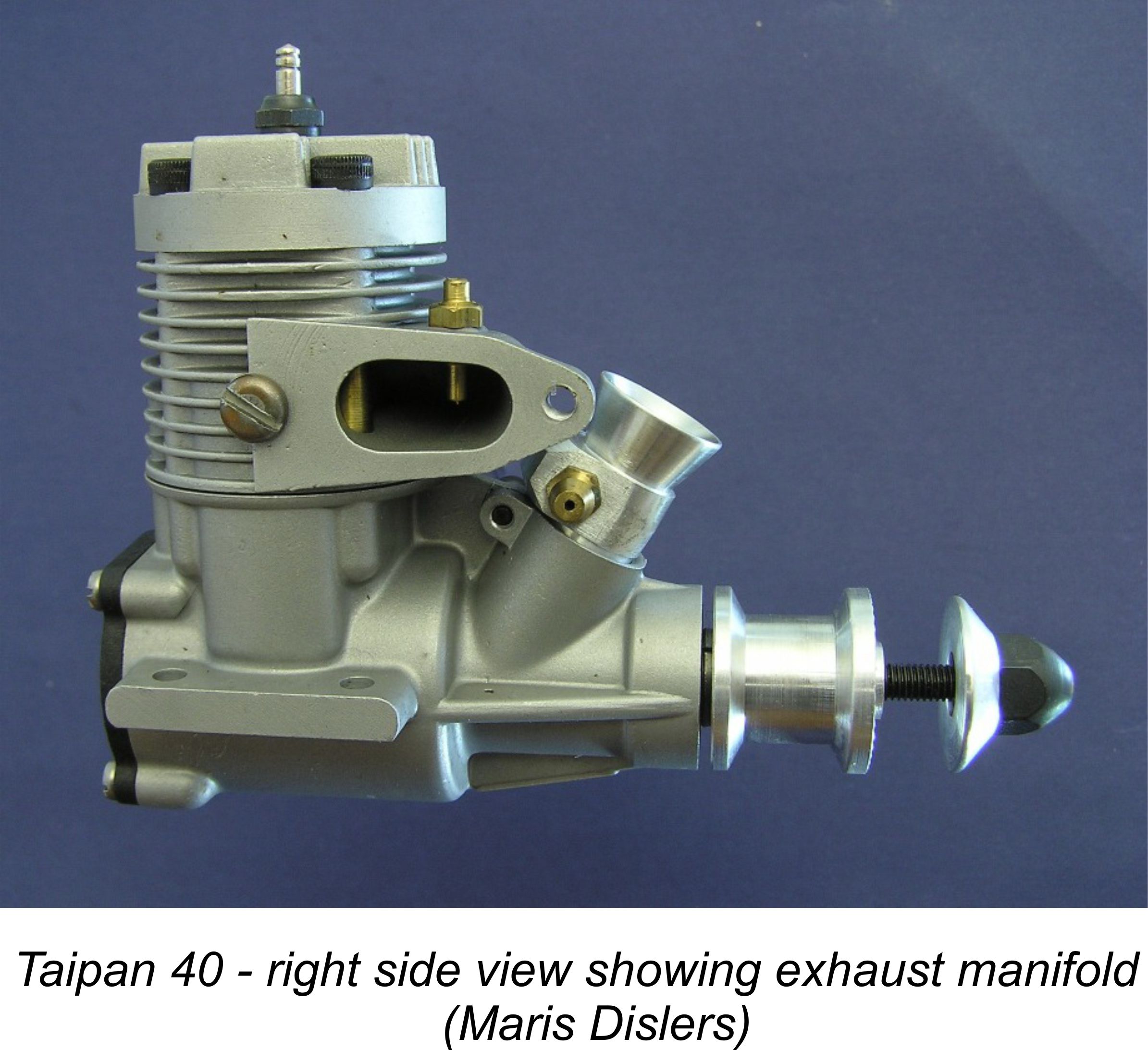

The Taipan 40 retains some of the established Taipan design elements, such as a two-part crankcase split below the exhaust area. However, the really unique feature is the forward-facing exhaust port. The upper crankcase incorporates a neatly formed exhaust manifold terminating at a flat face on the right hand side, so that the muffler can be mounted in the traditional location. The rear muffler mounting hole intersects one of the transfer passages, so the engine cannot be run without the muffler (or a short blanking screw) in place. Four long M4 socket-head screws retain the upper cylinder block and cylinder head with its cast cooling fins and squish combustion chamber incorporating a deep bowl. Crankcase, head and muffler components are pressure die cast in CB401 aluminium alloy.

The unhardened steel crankshaft (made from free cutting steel similar to S1214, but stronger) has a rectangular induction window of generous proportions and a 10mm diameter gas passage. Crankpin is a 7/32 in. (5.6mm) diameter INA bearing roller, pressed into the generously counterbalanced crankweb. The crankshaft rides in a 15x28x7mm rear bearing and a shielded 7x19x6mm front bearing, while a 3/16 in UNFstud and dome-nut retain the propeller. A brass cylinder liner with 1.5mm wall thickness has the usual three-port Schnuerle loop scavenging arrangement, with the two side transfer port windows extending well down the cylinder. The liner was internally ground, after which its bore was hard- Backplate and carburettor body are moulded from fibreglass-reinforced plastic. The carburettor is of the twin needle automatic mixture adjusting type with an O-ring seal on the main mixture needle. Maximum barrel aperture is 7mm diameter. Accounting for the idle needle and main jet nipple, effective choke area is a fairly generous 28 square mm. Other particulars are; bore 20.84mm (0.820 in.), stroke 19.05mm (0.750 in.), swept volume 6.298 cc (0.397 cu in), bare weight 328 g (11.6 oz), weight with muffler 416g (14.7 oz). Checked port durations on our test example are; exhaust 148 degrees, transfers 128 degrees, boost 126 degrees, Intake 198 degrees – opens quite early at 27 deg. ABDC & closes 45 deg. ATDC. Summing up, fits and finish of components are generally very good, although all castings have some porosity or minor external casting flaws. Also, our engine showed a patch of brass cylinder material just above the exhaust port where the hard chrome plating had been honed away. This is unlikely to have a noticeable effect on the performance of this particular engine, but we’ve seen one other Taipan 40 cylinder showing brass in a more critical position near top dead centre. It seems that the thickness of the chrome plating was not up to specification. Bare and total weights are 15-20% higher than other established cross-flow ported 40’s of that time, but similar to the Schnuerle ported engines of the era. On the test bench Since we are not aware of any published performance tests of the Taipan 40, we set about conducting our own tests on a lightly used example. An electric starter grips the prop nut and tapered prop washer neatly, providing the small hole of the rubber insert is used. Starts were of course a doddle, providing the throttle was set around half way open. The engine ran smoothly throughout the useable speed range and particularly so at higher speeds.

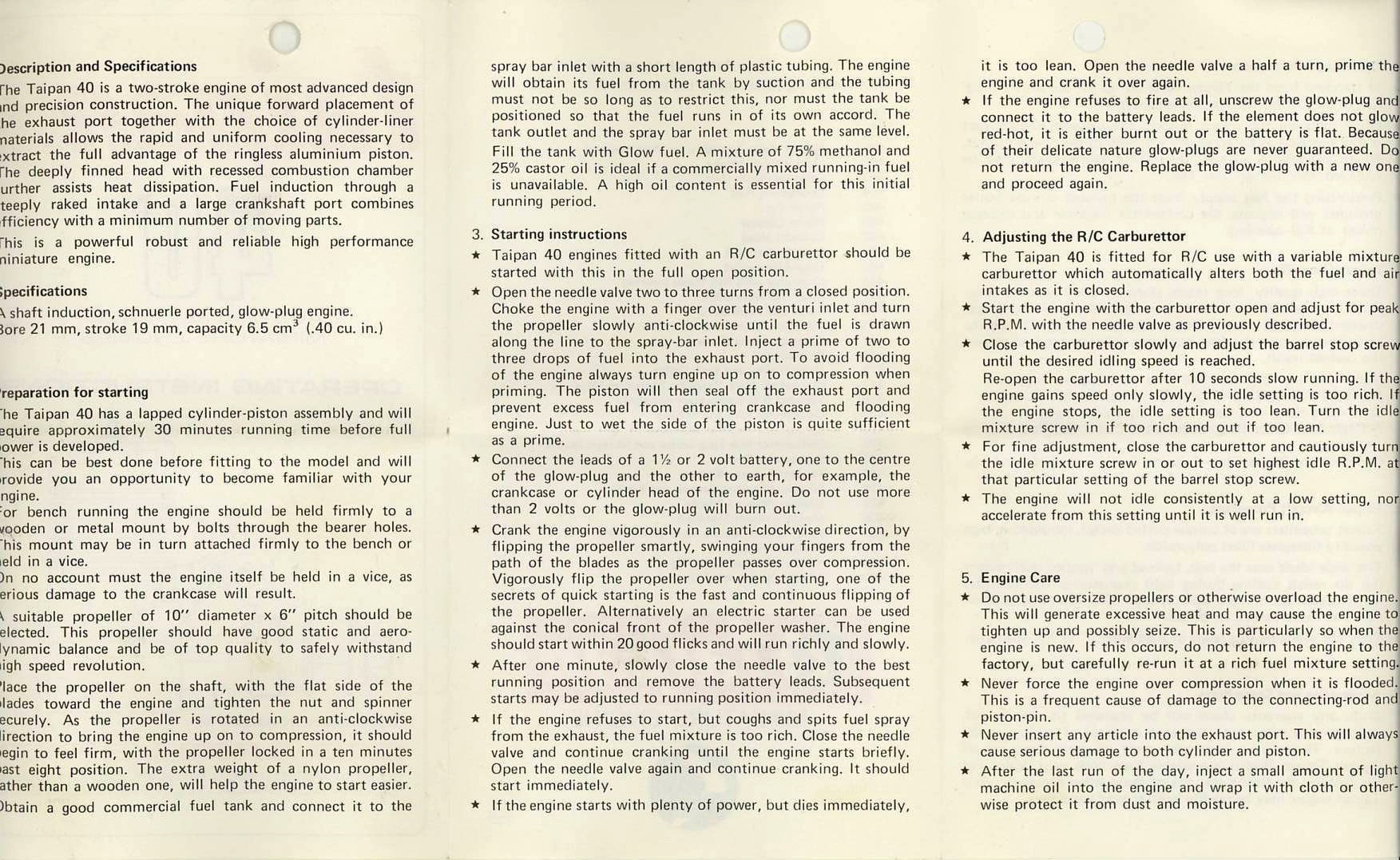

The Taipan 40 is intended for mild fuels with up to 15% nitro methane content. We used fuel containing 5% nitro methane, 20% castor oil and 75% methanol, allowing for direct comparison with published tests of other engines conducted with this mixture. We had difficulty obtaining smooth running on the largest propellers using suction alone, so switched to muffler pressure for all test results. Mixture adjustment for peak running was fairly insensitive, but with a little care one could find a nice boost in RPM when loaded to run in the 13,000-16,000 range. In that range, the engine was seemingly in harmony with the muffler, which purportedly had some design input from engineers at Adelaide University. The performance curves show peak power of almost 0.75 BHP developed around 15,700 RPM, dropping fairly sharply at higher speeds. The torque curve demonstrates a marked reduction in the rate of decline at speeds consistent with the observed happy engine/muffler relationship. Maximum torque of over 60 oz-in occurs well down the scale, perhaps at 8,000-9,000 RPM. While power output at those speeds would be reasonable at around 0.5 BHP, the Taipan 40 was not very happy when loaded down. In fact, it showed a marked preference for the lower pitch/lighter test propellers – not surprising given the general design emphasis towards higher running speeds. There was considerable scatter in the individual test results around our “best fit” trend lines. Users might well find an ideal propeller for their Taipan 40 that appreciably lifts performance in their specific application. Maximum RPM checks on typical propellers from the 1970’s that might suit the engine were as follows;

The Taipan 40’s power and torque compare well with the better cross-flow ported sport 40’s of its time, such as the OS Max 40-H, Enya model 6002, Webra 40, etc. Upping nitro to 15% (or removing the muffler baffle, as suggested in the instruction sheet) would boost performance. Open exhaust running with 15% nitro would likely reach 0.9 BHP. At the time, the muffler was sold separately as an accessory. The engine was a tight fit in the regular box used by the smaller Taipan engines, so the muffler came in another of these boxes, which by clever design folds into its final shape without the need for staples. Reliable idling speed down to 2,700 RPM was achieved using a Tornado nylon 10x6 propeller and Taipan green idle-bar plug. When pushed lower, the idle mixture had to be set richer than was desirable for quick response when the throttle barrel was rapidly opened. Consistency at all intermediate speed settings was excellent and general throttle response was smooth and progressive. Tough times in a changing market During the mid to late 1970’s, rising costs fueled by rapid inflation together with unfavorable exchange rates progressively eroded profitability. The very high cost of retooling the factory for more efficient production, along with delays arising from problems with the new pressure die casting process, proved to be beyond the financial capability of the company, forcing it into liquidation soon after the first Taipan 40’s went on sale in mid 1976. As a result, total production of this model was only about 1,500 units.

Our tests show that the Taipan 40 was a credible performer for its time in the context of its intended purpose. Somewhat unusually, it was not the result of a long development phase of prototypes. Rather, it went more or less straight from the drawing board into production with a blend of proven design features taken from the smaller Taipan engines together with a good measure of innovation. Had the Taipan 40 become available a year earlier, it might have established a reasonable market niche for itself before the “big guns” brought out their new models. As events transpired, mid-1976 also saw the introduction of the OS Max F-SR 40 and Webra Speed 40 schnuerle ported engines, which along with the HP40F established a new performance level in the crowded “sport 40” market segment. Because of this, the Taipan 40 was effectively left at the starting gate. Realistically speaking, it could only sell in a lower price bracket along with the remaining “old school” 40’s of comparable performance. Even if Gordon Burford and Co. had remained solvent long enough for the Taipan 40 to become established, the resulting revenue might not have been enough to sustain the company in the long run. ____________________________________ Editor’s note – I only ever saw one of these engines in a local hobby shop in British Columbia, Canada. This was prior to my final acceptance of the fact that I was more of a model engine nut than I was a model flier! So being heavily into control line at the time (still am!), I foolishly let it get away. I have been kicking myself ever since. My sincere thanks to Maris for reminding us all just what a nice engine the Taipan 40 really was! All images are as attributed apart from the exploded view of the engine, which was extracted from: http://grabcad.com/library/taipan-40-rc-aircraft-model-engine-1 Article © Maris Dislers, first published December 2014 |

|

| |

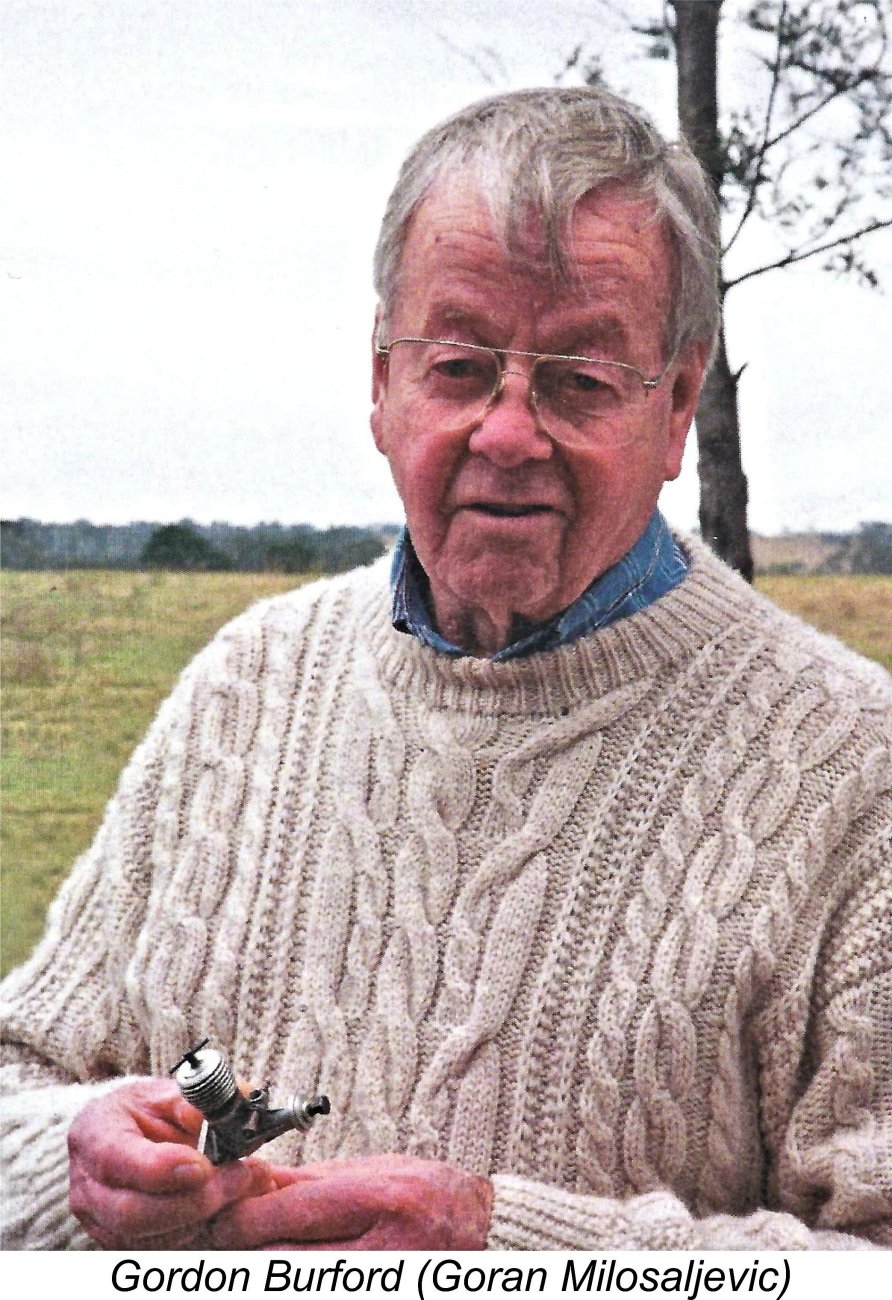

Gordon Burford and his fine Australian-made model engines are no longer as well-known as they were in their time. By way of introduction for folk not familiar with them, Gordon Burford had a lot in common with Duke Fox. Both began manufacturing model aircraft engines in the late 1940’s, producing wide ranges of engines in subsequent decades from family-run businesses. Like Fox engines in the USA, almost every Australian modeller from those years used a GB, Sabre, Glo Chief or Taipan engine from Gordon Burford and Co. at one time or another. They were always keenly priced, well made, dependable engines for the beginner and general “Sunday flyer”.

Gordon Burford and his fine Australian-made model engines are no longer as well-known as they were in their time. By way of introduction for folk not familiar with them, Gordon Burford had a lot in common with Duke Fox. Both began manufacturing model aircraft engines in the late 1940’s, producing wide ranges of engines in subsequent decades from family-run businesses. Like Fox engines in the USA, almost every Australian modeller from those years used a GB, Sabre, Glo Chief or Taipan engine from Gordon Burford and Co. at one time or another. They were always keenly priced, well made, dependable engines for the beginner and general “Sunday flyer”.  glow in plain bearing or ball race versions, marine versions of the diesels and the 19 right up to the flagship .61 cuin. R/C glow engines. However, the venture was destined not to survive in the longer term.

glow in plain bearing or ball race versions, marine versions of the diesels and the 19 right up to the flagship .61 cuin. R/C glow engines. However, the venture was destined not to survive in the longer term.

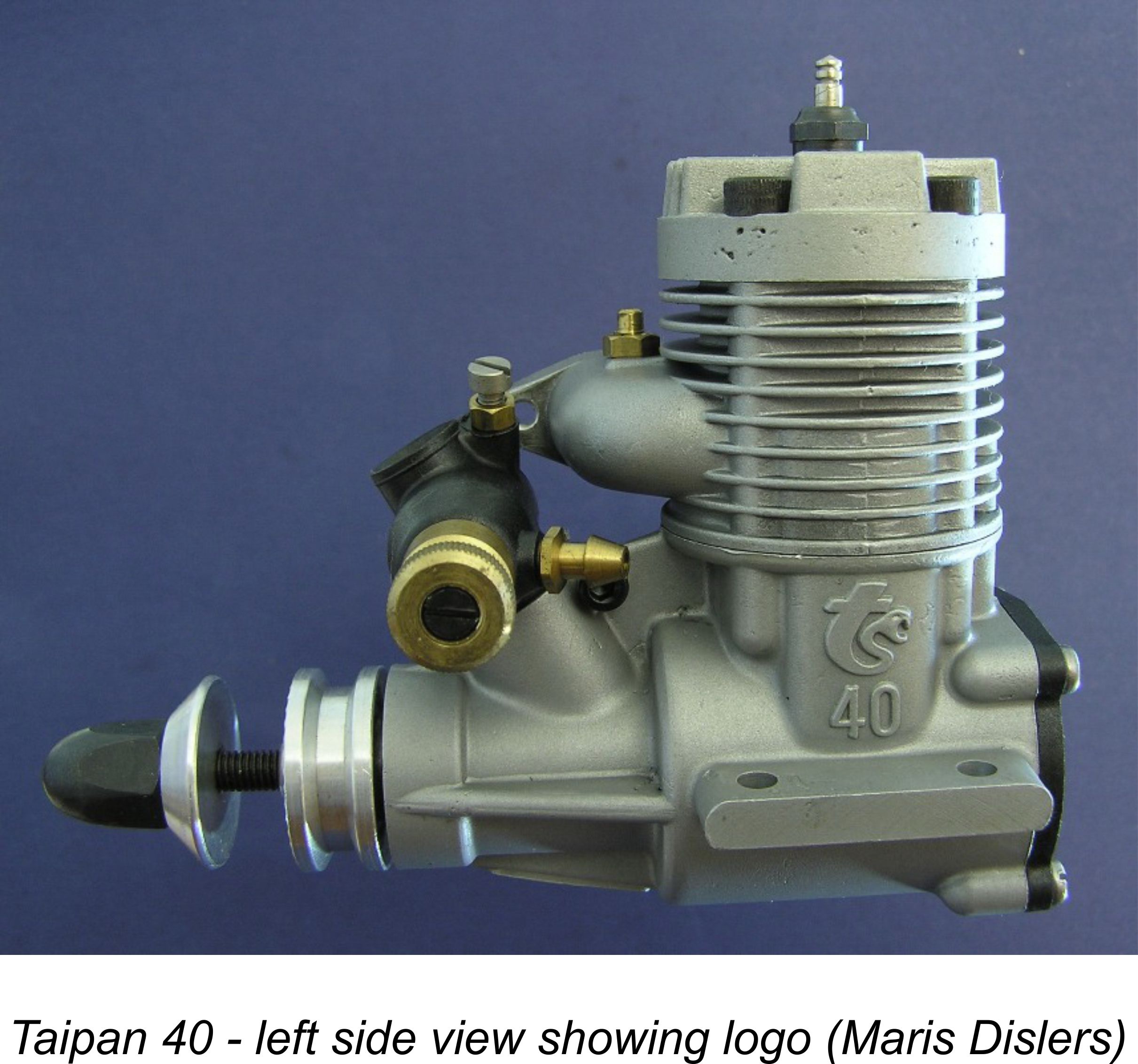

A new-style Taipan logo is cast in relief on the main crankcase body above its “40” designation. The carburettor boss is offset somewhat to the right of the crankshaft axis with a single screw clamping the carburettor in place. This arrangement works well enough, but the rigid crankcase boss has minimal capability of movement, while the thin-walled carburettor spigot is easily distorted. Over-tightening of the screw could break off the clamping portion of the crankcase boss – please be careful!

A new-style Taipan logo is cast in relief on the main crankcase body above its “40” designation. The carburettor boss is offset somewhat to the right of the crankshaft axis with a single screw clamping the carburettor in place. This arrangement works well enough, but the rigid crankcase boss has minimal capability of movement, while the thin-walled carburettor spigot is easily distorted. Over-tightening of the screw could break off the clamping portion of the crankcase boss – please be careful! chrome plated by an external contractor. It was then honed to final size. The aluminium piston (gravity cast from CP401 alloy with silicon addition to 18%) has pressed-in bronze bushes with grooves for the gudgeon pin retaining circlips. Its skirt has two windows aligning with the side transfer ports, allowing for a degree of mixture flow through the piston for cooling. The conrod is from 7075-T6 aluminium alloy, with a bronze bush at each end.

chrome plated by an external contractor. It was then honed to final size. The aluminium piston (gravity cast from CP401 alloy with silicon addition to 18%) has pressed-in bronze bushes with grooves for the gudgeon pin retaining circlips. Its skirt has two windows aligning with the side transfer ports, allowing for a degree of mixture flow through the piston for cooling. The conrod is from 7075-T6 aluminium alloy, with a bronze bush at each end.