|

|

Everyman’s Workhorse – the Ohlsson 23 By Maris Dislers

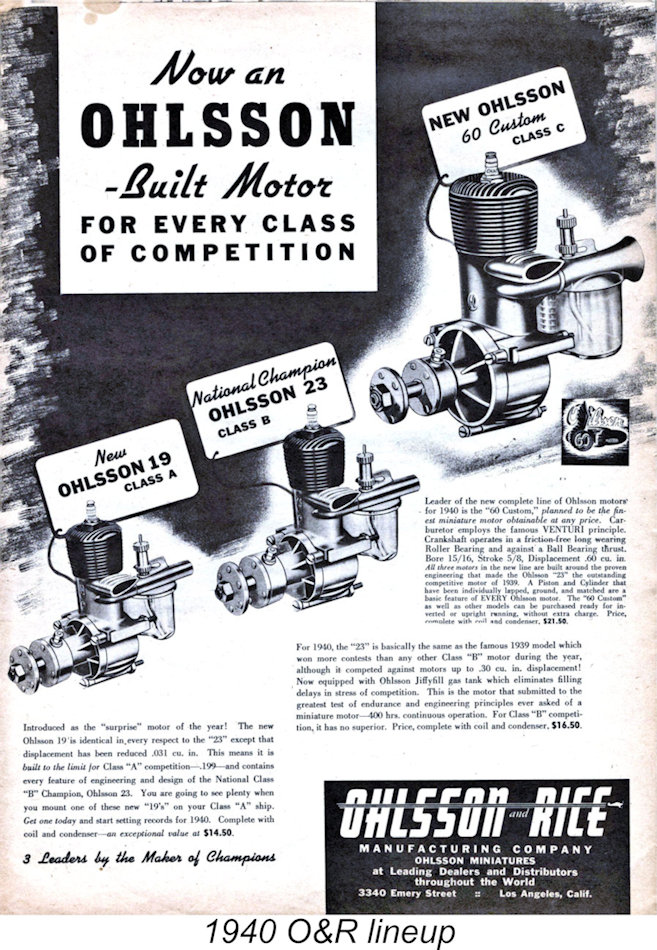

I’ll begin with some historical context. Irwin Ohlsson (always known as “Irv”) was born in 1913. Following high school graduation, he went to work for Douglas Aircraft but soon decided to branch out on his own, establishing the “Ohlsson Miniatures” hobby shop at 650 N. Alvarado Street in Los Angeles. In 1934 at the age of 21, Ohlsson built his first engines, a pair of 0.12 cuin. units which he constructed with the help of his friend Roland Barney. They apparently performed very well, encouraging Ohlsson to continue. It didn’t take Ohlsson long to develop a design for a 0.56 cuin. unit which he wished to see enter production. In late 1936 the 23-year-old Ohlsson entered into a partnership with Frank Bertelli. Each partner raised $1,300 to enable their machinist colleague Harry Rice to commence production of Irv’s .56 cuin. “Ohlsson Miniature” engine design. This morphed into the well-respected improved “Gold Seal” model in 1938. The engines were well received from the outset - Ohlsson was in the model engine manufacturing business! By 1938 there was an expanding market for engines suiting smaller, cheaper and more easily transported models. Guessing that the rule-makers would eventually introduce a separate competition class for models Soon thereafter, the National Aeronautics Association (N.A.A.) established three official competition classes based on engine displacement. Ohlsson’s 23 fell into the lower end of the intermediate Class B category (.201 - .30 cuin.). Regardless, the established Ohlsson reputation along with the 23’s rugged build, ease of operation and excellent power output created For Class A competition, a companion Ohlsson 19 became available in 1940. Essentially a reworked 23 with adjustments for its reduced stroke, it was the only real competition for the excellent disc-induction Bantam 19. The similar Ohlsson 60 Custom completed the 1940 model line. Frank Bertelli departed at around this time, leaving Harry Rice as the new partner in the Ohlsson and Rice Mfg. Co. (O&R) of 3340 Emery Street, Los Angeles California.

Begining in late 1944, post-war resumption of US model engine production was initially slow until old well-worn equipment had been replaced and augmented as part of the big plans for large volume production to meet the anticipated post-war boom in demand. Sales quickly soared to new heights. Prices for the O&R 19 or 23 dropped to $9.95 as a way of countering the cheap and nasty slag engines, rising slightly to $10.95 or $11.95 with later versions. In 1948 the company expanded into tether cars and updated engine designs, including front induction versions (also in glow-plug form). Side-port versions were phased out when Deluxe front induction versions with a roller crankshaft bearing were introduced. For 1950, larger 29 and 33 engines were added along with car and marine 29 versions.

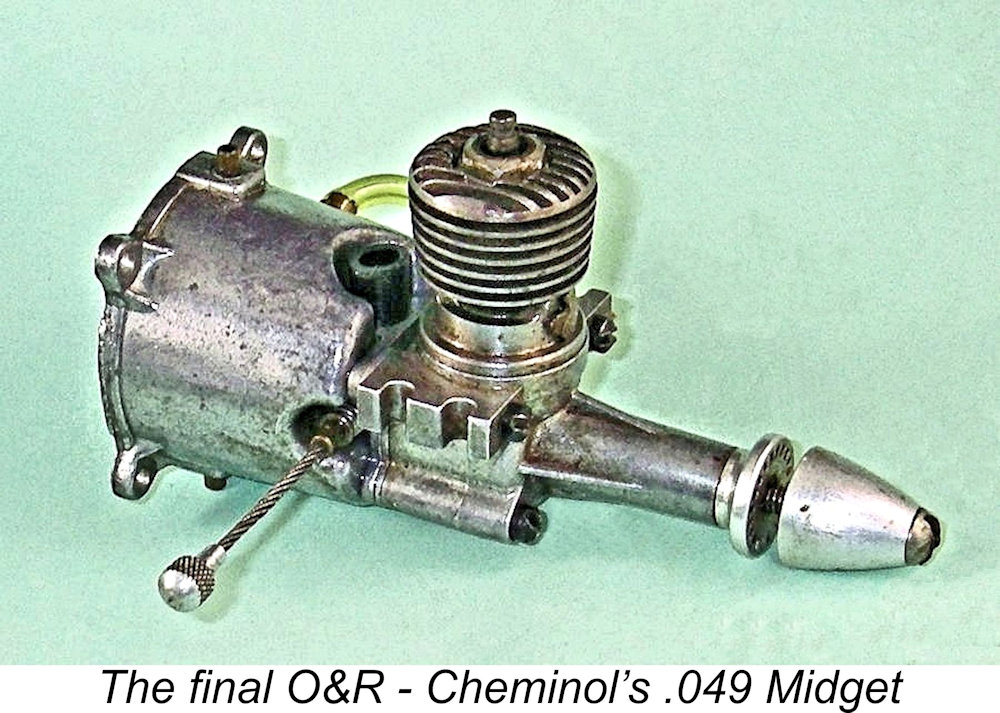

The engine manufacturing was reorganized under the company name Cheminol, whose O&R .049 Midget engine launched in 1955 was their last new model engine design. Going by America’s Hobby Center (AHC) adverts in “Model Airplane News” (MAN), the model engine range slowly diminished through the later 1950's into the early 1960's. Somewhat remarkably, the O&R 23 Deluxe spark ignition model was actually among the last to disappear from AHC’s stock. The company continued to make small Ohlsson & Rice utility engines up to 1 HP through to the 1970's. These found application in many products – chainsaws and other portable power tools, generators, etc. Construction

A noteworthy feature was O&R’s unique cylinder retention method, where the blind-bored cylinder slips into the crankcase, seating on its lowest fin against a soft gasket. This assembly was clamped in a jig, after which steel slugs were inserted through crankcase apertures at front and rear and spot welded. The apertures were then sealed with aluminium “bullseye” plugs.

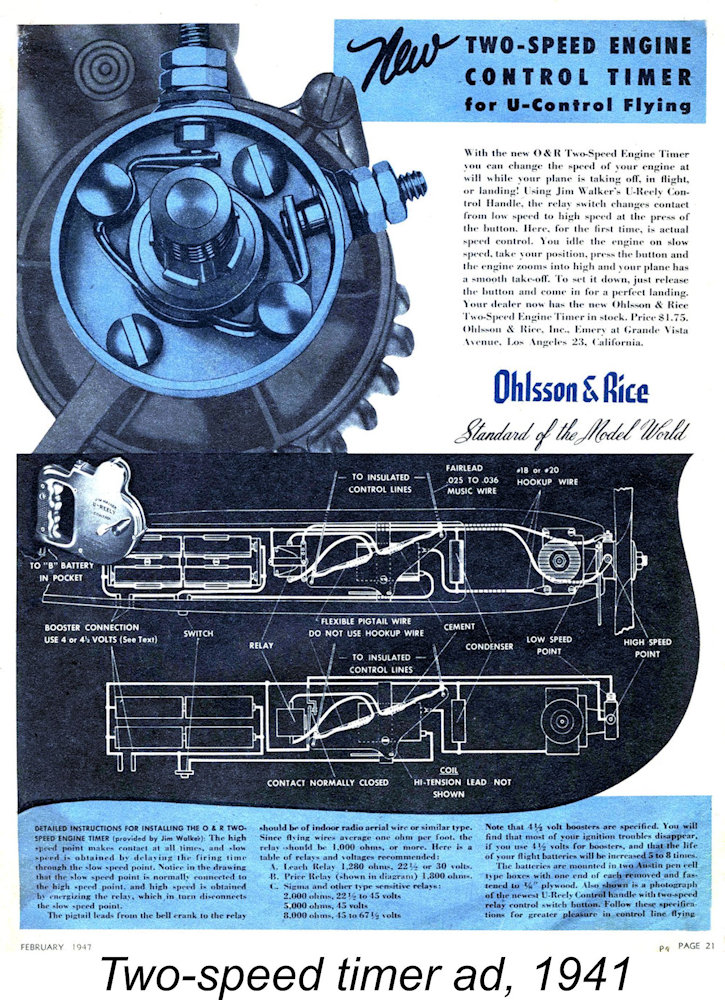

Some variations exist, perhaps material differences owing to wartime restrictions or minor improvements. Typical weight with a Champion V-2 ¼-32 spark plug was 5.6 ounces (160g). The bore of .687 in. (17.45 mm) and stroke of .625 (15.88 mm) yielded a swept volume of .232 cuin. (3.8 cc). O&R offered a 2-speed timer accessory from 1940/41. The most famous user was Jim Walker – the father of U-Control, which really took off post-war. Jim used it in his special A-J Fireball models, performing his signature “Sabre Dance” manoeuvre or when flying three Fireballs at once during his promotional demonstrations. Post-War 23’s

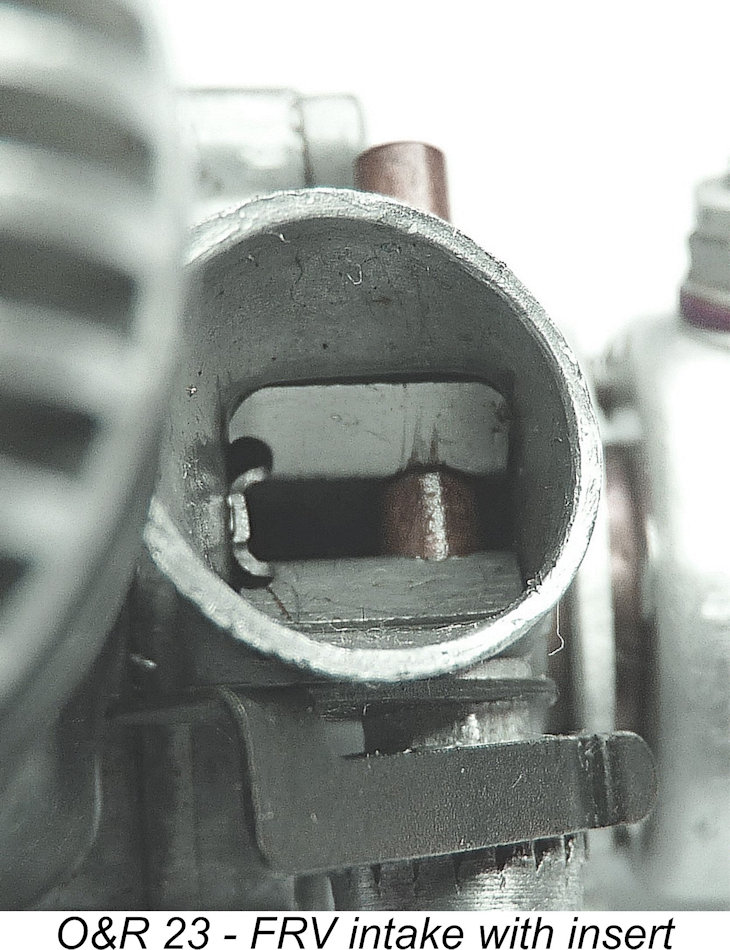

A further new front casting appeared which was arranged for front rotary valve (FRV) induction. This casting featured a large intake blending into an almost square induction aperture. To provide adequate suction, a stamped and folded steel insert (retained by the transverse needle valve assembly) created a narrow slot venturi for an effective choke area of 11.3 mm2. The crankshaft had a rectangular intake port cut with a Woodruff key-seat cutter. O&R offered front induction conversion kits for existing engines at a price of $5.

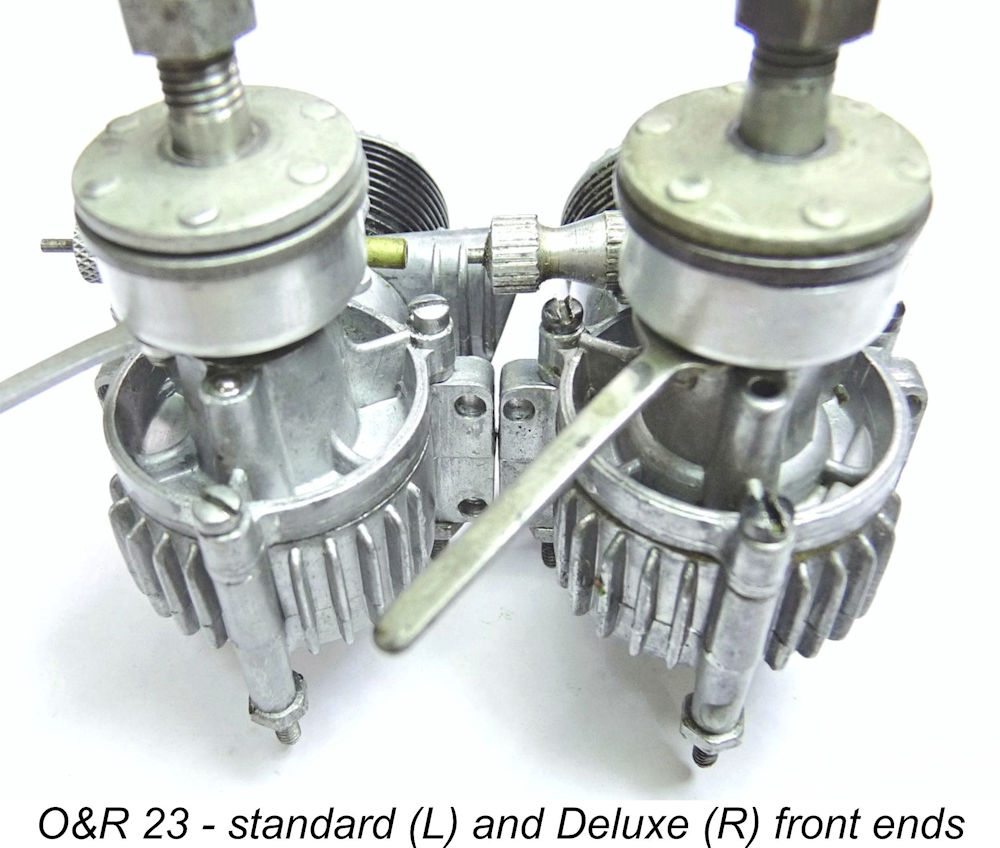

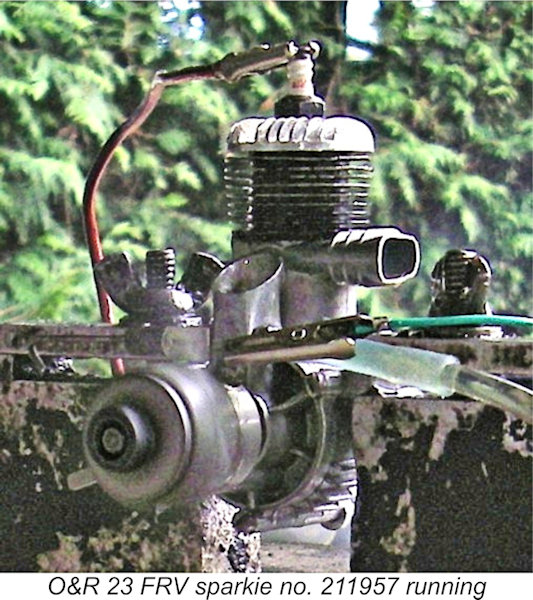

From 1948 onwards, the engines had beam mounting lugs (with holes, not slots), a larger exhaust stack and other cosmetic changes. A finned The O&R 23 front rotary valve (FRV) version was introduced in June 1948. The glow-plug front induction version had a cadmium plated cover over the timer slot. The side-port version remained spark ignition only and was progressively phased out. "Deluxe" front induction models from mid-1949 onwards had a roller bearing at the rear of the shaft instead of the former ball thrust bearing. The revised crankshaft with stroke increased from .625 to .660 inch was shared with the new larger-bore 29 model. This change yielded an increased swept volume of .244 cuin. (4.0 cc), while the compression ratio was also slightly higher. A new “Adjustomatic timer” was developed for the spark ignition version. External steel parts were black “ebonized” against corrosion, while the crankcases were polished. From 1951 onwards a nickel-plated rear fuel tank was fitted. Preparing to Test the Ohlsson 23 This review isn’t the simple “test one engine and report the results” kind, but a thorough study across all versions and modes. Accordingly, there’s much ground to cover! Thanks to the cooperation of Allan Laycock and Bill Britcher, we had the luxury of nine O&R 23’s to choose from – side-port, FRV, FRV Deluxe and glow-plug. Some of our specimens were like new, The best piston/cylinder fit was exhibited by Allan’s circa 1946 side-port model. That became the core test engine, on which Bill’s best FRV and FRV Deluxe front end assemblies could be swapped in after blocking the rear intake. This approach eliminated other variables while also high-grading the available components. The post-1947 crankcases had no internal changes to aid performance, and our workaround mimicked folk making the switch with O&R’s optional FRV conversion kit. Back in the day, reviewers quoted 30 minutes to 10 hours break-in time. The average probably lay somewhere between those extremes and was not unusual for engines with “lapped” piston fits at that time. Judging the fit by turning over by hand to gauge compression seal was found to be inconclusive. All the pistons in our available engines had some degree of ovality and adverse taper - around 10 microns (.0004 inch), which was four times O&R’s claimed production tolerance. Typically, the pistons were narrower in line with the wrist pin holes and a little larger at the bottom than the top. The inaccuracies were perhaps inevitable given the entire piston production sequence.

The crankshaft fit in its bearing is sufficiently free for adequate lubricant flow. Some oil escapes at the front but does not foul the points, which are well out of the way at the top. With the cam at the side, the vertical slop seems not to affect the timing function. This is fine for the side-port version, but the rotary valve model has only around 3/32 inch (2.3 mm) of bearing between the thrust race and intake window to seal crankcase compression. The generous .0035 inch (.09 mm) radial clearance when new only gets larger with wear. The free-floating ball thrust race does not support the shaft vertically, so that the crank web etc. is cantilevered out a full 1/8 inch (3.1 mm) from the plain bearing. Eventually, crankcase compression can begin to leak appreciably when hand cranking, making starts more difficult. You can hear the “squelch” (much like walking in soaked shoes) as this occurs. The Deluxe version with a good supportive roller bearing came out one year later, solving this problem. We had one “Standard” 1949 engine - with a bronze plug instead of a roller bearing - that refused to run at all. Excessive clearance in the plug’s bore, misalignment and 2-thou relief in the crankshaft journal’s valve port area (a feature intended to reduce friction) scuttled any chance of sealing crankcase compression with gas/mineral oil fuel. The 70+ year old cylinder base gaskets can leak at their narrowest portions on the bypass side. No-one now offers specialist cylinder removal/replacement for O&R engines. They still run that way, seemingly OK but perhaps not at their best. The inability of an owner to replace these gaskets is undeniably a limitation. The O&R 23 on Test – Spark Ignition

With the priming routine sorted, cold starts would take half a dozen flips for a pop, then a few more and it would burst into life. A few false starts perhaps, depending on the needle setting. Restarting when warm was very easy – needle opened a quarter turn, one choked turn and a few flips.

At a rich 4-cycle setting the Ohlsson is quite at ease, accepting a wide range of needle settings before approaching 2-cycle mode. Then it becomes more exacting. The front rotary versions were particularly keen to jump into 2-cycle mode with one more click leaner when lightly loaded, and then stay there. However, optimum mixture when at full temperature was a click or two richer. Again, evidently necessary to resist overheating. Data tables circa 1940 list recommended propellers of 10-12 inch diameter and 6-7 inch pitch, revised later to 10x6. Then 8x9 or 10x5 for the 1949 FRV version, which should turn at 7,000+ RPM. Peak BHP was said to be developed at 9,400 RPM. Spot tests with a genuine O&R 10x4 wood propeller were a few hundred RPM less than our modern APC 10x5.

The remarkably light piston (5.5 grams, 0.19 oz) and generous crankshaft counterbalance combined to keep vibration at normal speeds perfectly acceptable. The Deluxe version was smoother still, as the roller bearing eliminated rattle coming from the easy plain bearing to crankshaft fit. The O&R timer gave consistent sparks up to peak BHP speeds, but did show some tendency to misfire at the highest test speeds. We liked all the Ohlsson 23 sparkie versions. The side-port versions benefitted from the easily-reached needle valve and jiffy-fill feature. Even without a tachometer, the rotary valve version was clearly a stronger runner. The Deluxe was better still, the roller bearing making it our pick for the nicest version to operate. Good power without fuss or special attention. O&R 23 Test on Methanol Fuel

On spark ignition, the change to methanol required a wider-open needle setting and significantly retarded ignition timing – to around the point where we’d set it for initial starts on gasoline. There was no need to retard the timer further when restarting, while adjustment from that position had very little effect, regardless of load. Starts were much the same as with gasoline - a light choke or dropwise intake prime and flip. Hot restarts after changing propellers were also very easy. Response to mixture adjustments was much broader than with gasoline and the engine was obviously less prone to signs of overheating. Running at higher speeds was affected by inconsistent timer function, more so than when burning gasoline. Possibly our Stitt spark plug? In glow-plug mode, the Enya No. 5 (Medium) plug seemed ideal for the job. Running was much like ignition mode, but exhibited a more gradual transition from 4-cycle to 2-cycle running. With lighter loads, allowing the cylinder temperature to fully equilibrate gained a few extra RPM. Switching to 10% nitro fuel certainly perked the 23 up with lighter loads, giving impressive results. This is not surprising, given its measured 6.4:1 compression ratio. However, there were signs of strain when lugging large propellers. Performance Analysis A great piston/cylinder fit is sine qua non for top performance. I’d say that was the true Goldilocks ingredient in our test engine. Spot tests with others showed differently. Tired units were around 500 RPM down and tight ones were not yet able to show their best. With FRV front ends also in top shape, our results likely represent a “good” one. If you get lost among the table of RPM numbers, refer to the performance curves, which give a better picture.

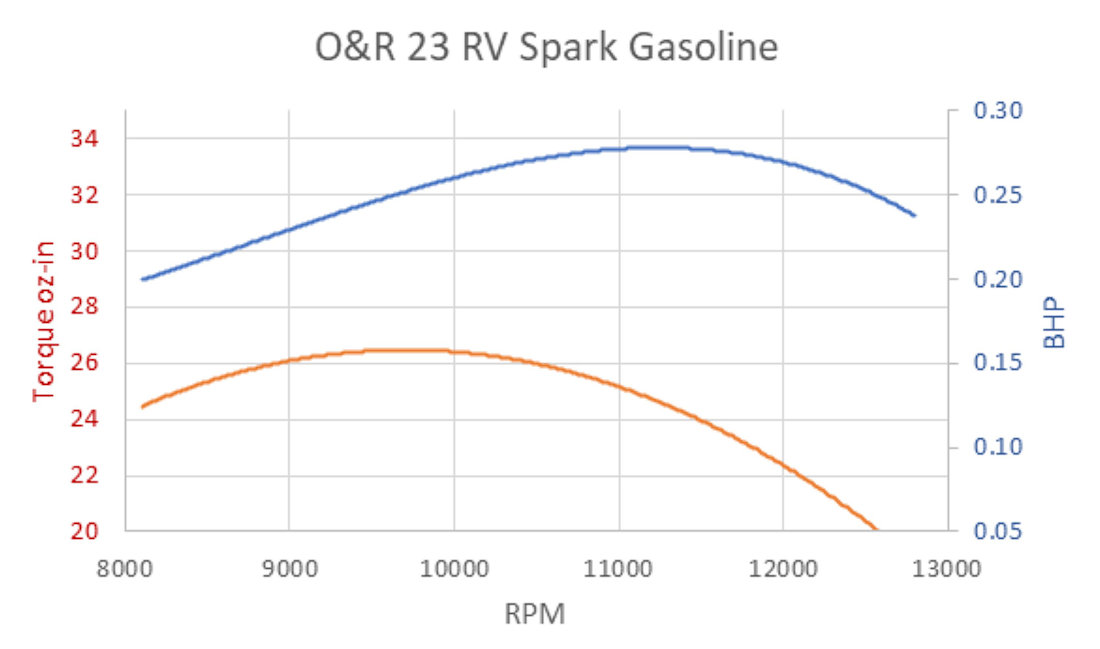

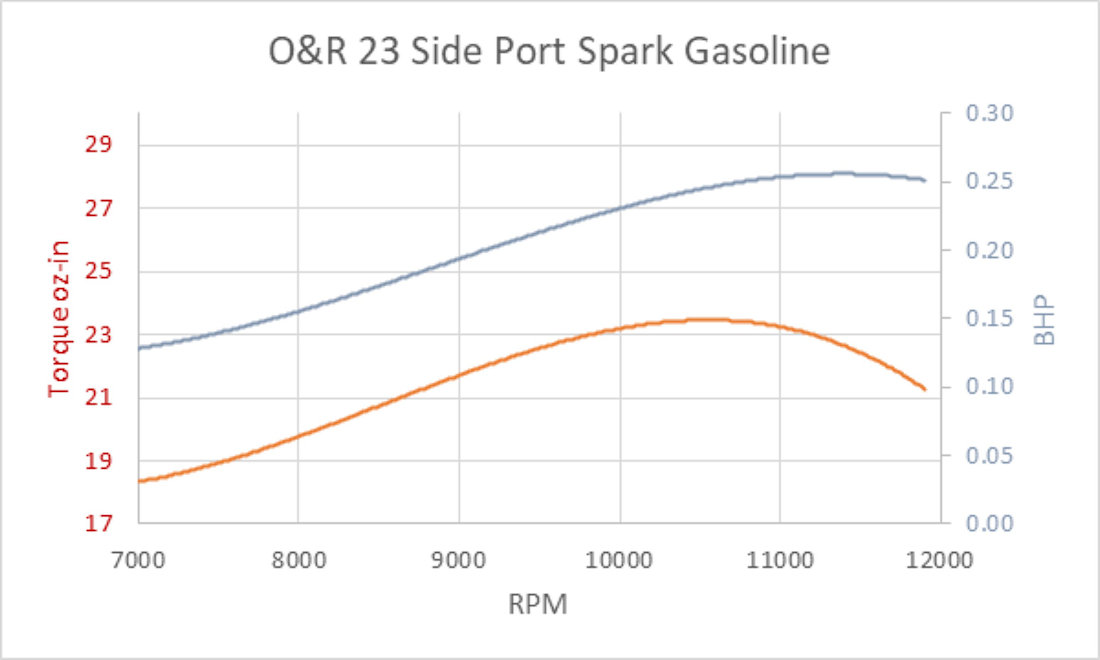

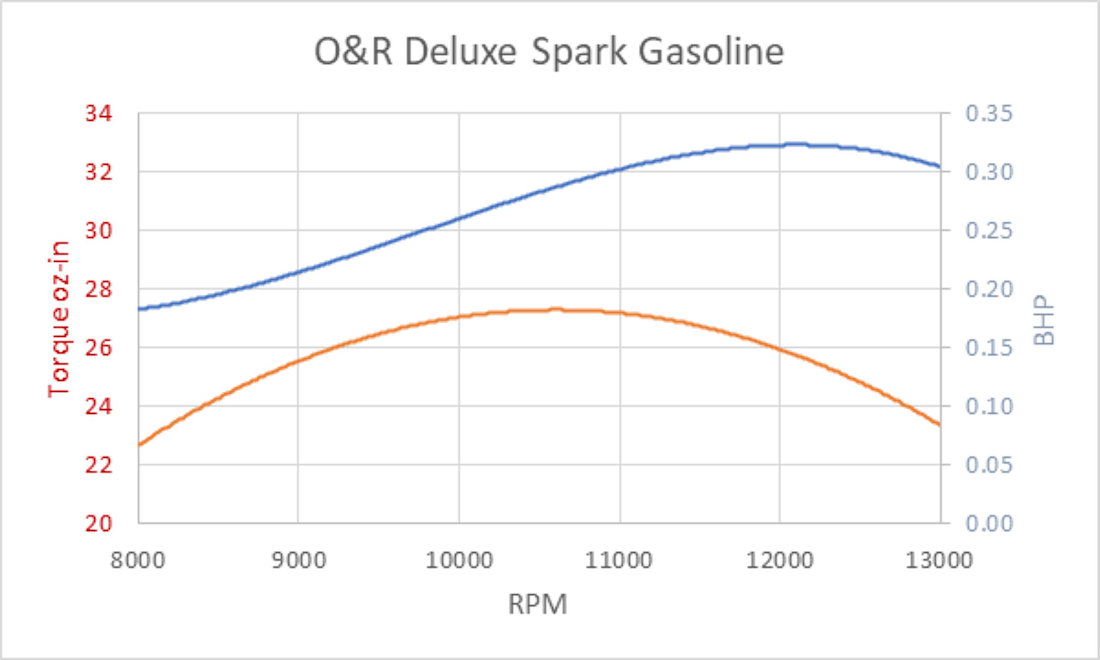

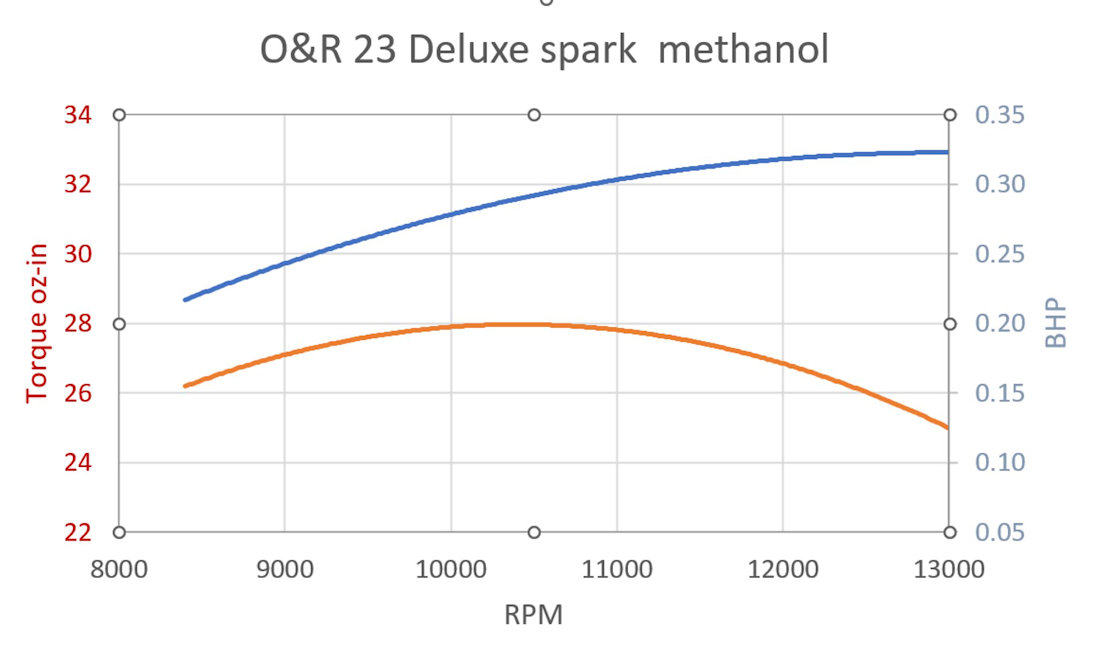

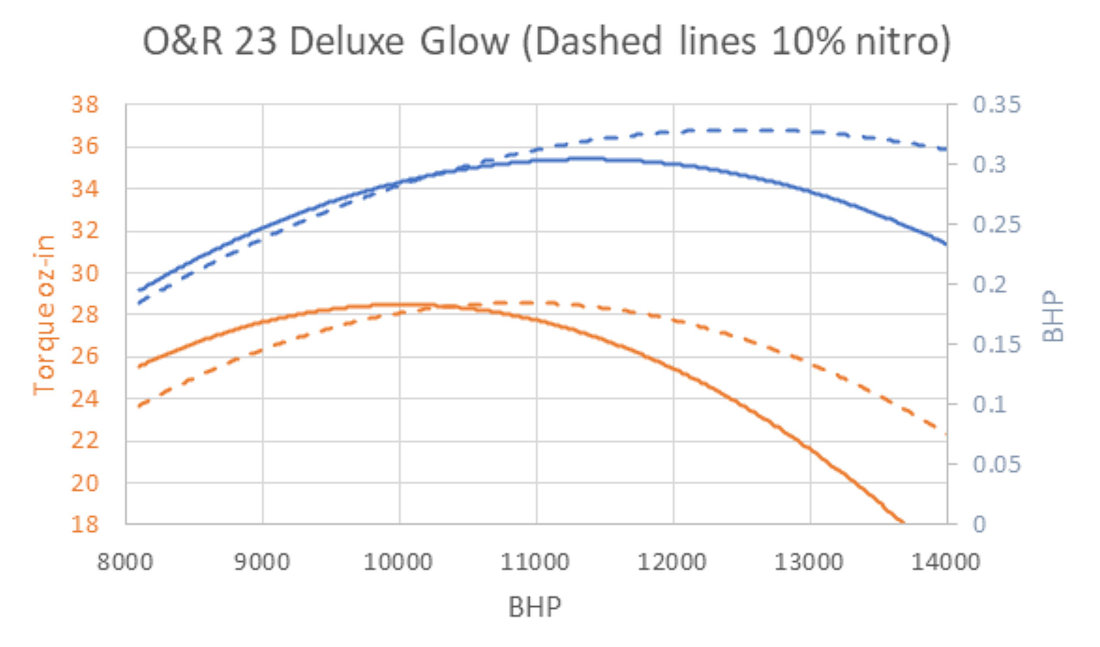

I’m guessing that back in the day, rated horsepower for model aircraft engines was based more on a rule of thumb formula calculation than on the results of extensive testing. The originally claimed 1/7 HP at 6,500 was not so different from the Ohlsson 23’s peers. This rose to a rating of 1/6 HP at 7,500 RPM by 1946 (perhaps to give the Ohlsson 19 the 1/7 HP slot) with the later rotary valve model peaking at a claimed 9,400 RPM for an undisclosed power rating. Our performance tests using calibrated propellers told a different story. Using the recommended propellers substantially under-sells a good Ohlsson 23. Our side-port 23 delivered the requisite 1/7 HP at 7,500 RPM, but seemed to be lugging it. Looking at the torque curve shows why. Maximum torque is achieved at around 10,500 RPM and peak power around 1000 RPM after that. A touch over 23 oz-in and .25 BHP must have been scary stuff for the opposition in 1938. The FRV version boosts torque to over 26 oz-in but at lower speeds, centred around 9,700 RPM. The .275 BHP peak is at a little more than 11,000 RPM, with the decline thereafter being less pronounced than with the side-port version. The Deluxe version raises the bar. Maximum torque is higher in the RPM range at a new maximum, topping 27 oz-in between 10,000 and 11,000 RPM. The ability to work at higher speeds sees peak power of .32 BHP, broadly around 12,000 RPM. It can legitimately be surmised that the combination of front induction and roller bearing boosts efficiency and hence power output. The manufacturer claimed that the latter feature increased performance by 500 to 1,000 RPM over the standard model. We saw a 500 – 700 RPM gain at higher speeds.

Results with methanol were a little stronger across the entire speed range, but not dramatically so. The potential for working at higher speeds was clouded by timer-induced misfire. While the maximum power point was pushed towards 13,000 RPM, actual power was no better than with gasoline. One attempt with the 8x4 propeller showed promise. The numbers were all over the place, but 14,500 RPM were briefly seen. By that stage the scrunched-up facial tissue blocking the side-port intake had dropped out, so the number was not used. That happened a few times on a few other test runs, resulting in the rear intake giving a measure of sub-piston induction. The observed gain was maybe 300 RPM at higher speeds.

In this operating mode, ignition trouble was sidestepped. Yet the faster rate of torque decline beyond maximum resulted in slightly lower power output than on spark ignition. Adding nitromethane gave the required boost. Torque was now much better maintained and power back up to that achieved in spark ignition mode with straight methanol fuel. However, things were less positive when lugging oversize propellers. The engine was then obviously less happy – a reminder that glow-plug operation still requires matching of ignition timing to the desired engine speed range through appropriate fuel and plug choices. The following table and power curves summarize the results obtained.

Summary Yes, there were differences between different variants, alternative fuels and alternative ignition types. However, all Ohlsson 23’s have notably similar performances in the sport-utility range, rather than in any outright racing category. A relatively narrow best working range between the torque and power peaks of around 1000 RPM - 2000 RPM at most is very much in keeping with competing engines of the period. The range was a little wider when using methanol. The side-port version was definitely less happy with large propellers. For best performance, smart people would choose a propeller to hit that best working range in flight. This would involve measuring approximately 1000 RPM slower on the ground before launch. The differences between spark ignition and glow-plug modes were not so great. I see merit in spark/gasoline for cleaner running and its greater kindness to simple doped finishes. The glow-plug mode is simplest to use and involves less weight, with no batteries to go flat or high-speed ignition niggles. We hear tales of O&R glow-plug engines blowing the cylinder out as the spot welds gave way. This problem must have been recognized by the manufacturers, since the newer 1948 crankcase type (when glow-plug versions were introduced) has larger weld slugs for greater security – the original 5/32 inch (4 mm) slugs were expanded to ¼ inch (6.3 mm) diameter. We didn’t push the test engine too far or pump in a hot fuel to explore its limits. It's easy to see why O&R 23’s were so popular. They were kind to the novice, offering good power outputs with a dependability that begged being used in a model. No wonder that SAM USA have special R/C competition classes for Ohlsson 23 engines. Serial Numbers Serial number information from Jim Alaback ("Model Builder", November 1994). 1938 – 1940 To approx. 8,800 1940 – 1946 To approx. 78,000 1947 Approx 97,000 – 109,000 1948 - Onward To approx. 506,000 (19 & 23 serial numbers merged) Factory rebuilt engines have “X” added to Serial Number Copies

It’s not surprising that the very successful O&R engines inspired others. As of 1940 in the UK, Bonds of Euston Road in London (former makers of the Simplex 4-stroke) were intending to produce 3.8 cc and 10 cc 2-strokes very much along the lines of the O&R 23 and 60 engines. Drawings of the Hurricane Minor and Hurricane Major dated 1940 are known, while some casting sets were advertised after the war. Actual engine production was most likely shelved in favour of more pressing or lucrative contract work for the rearmament programme. WW2 in the Pacific halted imports of good American model engines to Australia, inspiring enterprising Sydney gunsmith Bill Marden to produce his own copy of the much-admired O&R 23. Between 1940 and 1945, Marden used his 3½ inch Myford lathe to build 50 engines from his home in Punchbowl (a suburb of Sydney) to keep local modellers active. He used genuine O&R crankcase components as patterns for his sand-cast copies. Marden’s replicas were outwardly rough, but were superbly machined and fitted for fine Far more numerous, the Cameron 23 was introduced in 1946. It was the first offering from Cameron Precision Engineering of Chino, California. It may have been intended to cash in on the shortage of O&R 23’s, which it resembled closely. However, it had different bore/stroke dimensions, a separate head, a cast iron piston/cylinder retained by four screws and other unique features. A grey hammertone paint finish was applied to the zinc-aluminium alloy crankcase. The Camerons were very good performers. At the time of writing (2023), MECOA still sold brand new Cameron 23’s assembled from original factory parts, but with a stronger modern conrod. References https://www.modelaviation.com/venerable-ohlsson-23Engine Collectors’ Journal, Issues 78 (February 1985), 137 (Dec 1999)SAM Yearbook No 6 http://craftsmanshipmuseum.com/artisan/irwin-irv-ohlsson/http://sceptreflight.com/Model%20Engine%20Tests/O&R%2023.html

________________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia First published March 2023

|

||||||

| |

The seemingly ubiquitous Ohlsson 23 was so popular in its day that by my calculation there was one for every 300 citizens in the USA at one point in time! The engine boasted the highest-ever production volume of a model engine design prior to the deluge of cheap

The seemingly ubiquitous Ohlsson 23 was so popular in its day that by my calculation there was one for every 300 citizens in the USA at one point in time! The engine boasted the highest-ever production volume of a model engine design prior to the deluge of cheap  with smaller engines, Ohlsson edged their new small engine design down to what he considered to be a likely cut-off displacement. He did so by adding an extra 1/16 inch to the piston diameter of most competitors’ “5/8 in. bore” jobs for a .232 cuin. swept volume. Introduced at the Eastern States Meet in the fall of 1938, the Ohlsson 23 reportedly stole the show.

with smaller engines, Ohlsson edged their new small engine design down to what he considered to be a likely cut-off displacement. He did so by adding an extra 1/16 inch to the piston diameter of most competitors’ “5/8 in. bore” jobs for a .232 cuin. swept volume. Introduced at the Eastern States Meet in the fall of 1938, the Ohlsson 23 reportedly stole the show.  such a demand for the new model that production facilities had to be expanded. Even so, back orders were not cleared until production was resumed and scaled up even more following the interruption of WW2.

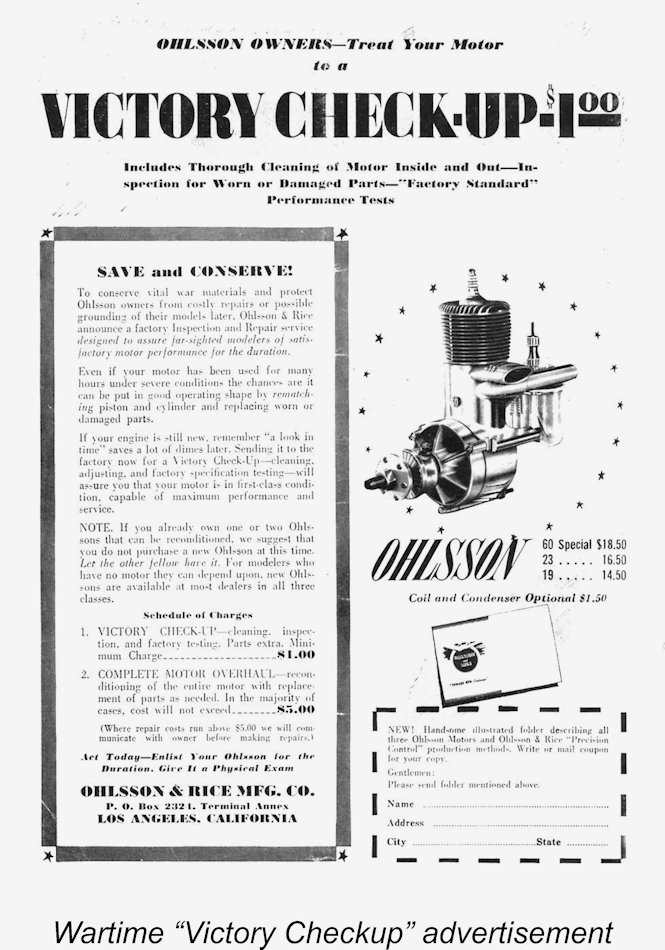

such a demand for the new model that production facilities had to be expanded. Even so, back orders were not cleared until production was resumed and scaled up even more following the interruption of WW2.  The December 1941 onset of the war with Japan caused O&R to suspend model engine production and switch to wartime production work. Throughout this period, Irv Ohlsson remained in very close touch with the aeromodelling community, serving as the fourth President of the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) from 1943 to 1946. The company did its best to keep existing customers flying, including a “Victory Check-up and overhaul” service to keep previously-sold units working so that the relatively scarce remaining new engines could go to new owners.

The December 1941 onset of the war with Japan caused O&R to suspend model engine production and switch to wartime production work. Throughout this period, Irv Ohlsson remained in very close touch with the aeromodelling community, serving as the fourth President of the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) from 1943 to 1946. The company did its best to keep existing customers flying, including a “Victory Check-up and overhaul” service to keep previously-sold units working so that the relatively scarce remaining new engines could go to new owners.  Irwin Ohlsson left the partnership in 1953, going on to develop his own line of glow-plugs and model engine fuels. He also designed and manufactured special igniters for the aerospace industry. He remained active in the aeromodelling field until his death in April 1996 at the age of 83 years.

Irwin Ohlsson left the partnership in 1953, going on to develop his own line of glow-plugs and model engine fuels. He also designed and manufactured special igniters for the aerospace industry. He remained active in the aeromodelling field until his death in April 1996 at the age of 83 years.  Some design evolution is evident through the Gold Seal series, but the 23 represents a leap ahead from the pioneering model engine styles to “next generation” features. Importantly, it was simpler to manufacture en masse. The lightweight pressure die-cast crankcase extended above exhaust height, eliminating the familiar separate bolt-on bypass cover.

Some design evolution is evident through the Gold Seal series, but the 23 represents a leap ahead from the pioneering model engine styles to “next generation” features. Importantly, it was simpler to manufacture en masse. The lightweight pressure die-cast crankcase extended above exhaust height, eliminating the familiar separate bolt-on bypass cover.  The stamped steel piston with intricately formed crown and wrist pin bosses is hardened and precision-ground to size. Grooves for two wire snap rings to retain the large- diameter hollow wrist pin are featured just inside the piston bosses. The wrist pin connects with the substantial cast aluminium alloy connecting rod with bushed big end bearing. This assembly is fed up the bore via the crankcase opening, then turned 90 degrees and the front crankcase/crankshaft assembly attached with three long screws - an ingenious approach. Those screws could be used for firewall mounting, the option being beam mounting via fore/aft slots in the crankcase side lugs.

The stamped steel piston with intricately formed crown and wrist pin bosses is hardened and precision-ground to size. Grooves for two wire snap rings to retain the large- diameter hollow wrist pin are featured just inside the piston bosses. The wrist pin connects with the substantial cast aluminium alloy connecting rod with bushed big end bearing. This assembly is fed up the bore via the crankcase opening, then turned 90 degrees and the front crankcase/crankshaft assembly attached with three long screws - an ingenious approach. Those screws could be used for firewall mounting, the option being beam mounting via fore/aft slots in the crankcase side lugs.  Soon after the introduction of the O&R 23, a ball thrust bearing was added in front of the crankweb. Up front there was a neat enclosed timer assembly (widely copied by others) and a stamped steel prop driver which engaged with four crankshaft splines. A stamped concave prop washer with faux miniature prop retaining screw heads w

Soon after the introduction of the O&R 23, a ball thrust bearing was added in front of the crankweb. Up front there was a neat enclosed timer assembly (widely copied by others) and a stamped steel prop driver which engaged with four crankshaft splines. A stamped concave prop washer with faux miniature prop retaining screw heads w

The 1947 engines had a new front casting with shorter near-vertical webs. The lugless main crankcase was primarily intended for mounting to a cast aluminium fuel tank with beam and radial mounts. Stamped beam mounting plates could also be used.

The 1947 engines had a new front casting with shorter near-vertical webs. The lugless main crankcase was primarily intended for mounting to a cast aluminium fuel tank with beam and radial mounts. Stamped beam mounting plates could also be used.  The “Spraybar Control” feature mentioned in the May 1947 “Air Trails” advert was never produced. It would appear that the idea may have been to adjust the fuel mixture by rotating the spraybar using the attached arm, thus varying the jet hole exposure to the airstream.

The “Spraybar Control” feature mentioned in the May 1947 “Air Trails” advert was never produced. It would appear that the idea may have been to adjust the fuel mixture by rotating the spraybar using the attached arm, thus varying the jet hole exposure to the airstream.

The result was that you always get some compression leakage (except perhaps with castor oil when cold), but might nonetheless have significant tightness resulting from high spots. Those defects make full 2-cycle running impossible. Very late production examples had an additional small ground step to relieve the tendency of the sharp top edge of the piston wall to scrape oil off the cylinder wall if the fit got tight there when at running temperatures. This step is clearly visible in the accompanying image of a late piston/rod assembly.

The result was that you always get some compression leakage (except perhaps with castor oil when cold), but might nonetheless have significant tightness resulting from high spots. Those defects make full 2-cycle running impossible. Very late production examples had an additional small ground step to relieve the tendency of the sharp top edge of the piston wall to scrape oil off the cylinder wall if the fit got tight there when at running temperatures. This step is clearly visible in the accompanying image of a late piston/rod assembly. The following notes relate to all three spark ignition variants – side-port, rotary valve and rotary valve Deluxe. Some magazine tables list 2:1 gas/oil for the Ohlsson 23, others 3:1. Our test fuel was 3 parts Shellite (very similar to white gas) and one part AeroShell 100 (straight SAE 50 mineral oil). A single choked turn, perhaps two from cold, was sufficient for priming if the needle setting was right. Or four to six drops of fuel into the venturi. However, it was best not to go overboard. A good reminder of how very little is needed when burning gasoline.

The following notes relate to all three spark ignition variants – side-port, rotary valve and rotary valve Deluxe. Some magazine tables list 2:1 gas/oil for the Ohlsson 23, others 3:1. Our test fuel was 3 parts Shellite (very similar to white gas) and one part AeroShell 100 (straight SAE 50 mineral oil). A single choked turn, perhaps two from cold, was sufficient for priming if the needle setting was right. Or four to six drops of fuel into the venturi. However, it was best not to go overboard. A good reminder of how very little is needed when burning gasoline.

Magazine adverts showed O&R spark ignition models alongside glow-plug versions well into the mid-1950s. Indeed, the O&R 23 Deluxe spark ignition model was the last to drop off AHC’s offerings in our selection of old magazines. This could mean that those models were the hardest to shift, or maybe they had their own innate goodness. We tested our Deluxe FRV test engine with 3:1 methanol and castor oil fuel, first with spark ignition, then glow plug.

Magazine adverts showed O&R spark ignition models alongside glow-plug versions well into the mid-1950s. Indeed, the O&R 23 Deluxe spark ignition model was the last to drop off AHC’s offerings in our selection of old magazines. This could mean that those models were the hardest to shift, or maybe they had their own innate goodness. We tested our Deluxe FRV test engine with 3:1 methanol and castor oil fuel, first with spark ignition, then glow plug.