|

|

The Tempest Racing Engine and its Australian Competitors

Anyone beginning to read this article in the expectation of detailed technical descriptions and tests of a sequence of racing engines is doomed to disappointment! As much as anything else, this is a story, and one which is greatly enriched by the personalities involved as well as anecdotes of their activities. The engines are always at the core of this tale, but they are by no means the sole participants! As much as anything else, this is the story of the talented and colourful individuals involved in early post-WW2 power modelling in Australia. I've also inserted a few personal anecdotes from my own time in Australia, where I was bon in 1947 in Adelaide, South Australia. In fact, the Tempest and I were born in the same year in the same country! Before getting started, a few acknowledgements are very much in order. First and foremost, I must acknowledge the amazing generosity of my valued German friend Peter Rathke. Peter was kind enough to present me with the boxed example of the Mk. II Tempest racing engine which is central to this article. He did so purely as an act of friendship, stating that it was an expression of his appreciation for my ongoing efforts on this website. He would not hear of any payment. All I can say is - thanks, mate, and I hope that my ongoing scribblings are ample recompense for your generosity. Second, I must recognize the immense contribution to this article which has been made by my great Aussie mate Maris Dislers of Glandore, South Australia (a suburb of Adelaide which is not that far from our old family residence at 58 Thomas Street). No writer living in Canada as I do could hope to present any authoritative information on long-ago events in far-away Australia without some help “on the ground”. Upon learning of my desire to write this story, Maris was indefatigable in digging out information and documentation on the subject. Without his help, I couldn’t have so much as begun the writing of this article. Although I held the pen and therefore accept full responsibility for any errors or omissions, this article is as much Maris's work as mine. An invaluable source of information on the Tempest is the article by Mal Ward which appeared in the September 1992 issue (no. 102) of the late Tim Dannels' ever-informative "Engine Collector's Journal" (ECJ). Mal's efforts preserved a great deal of background to the story of this engine. We are all in his debt. I must also recognize the contribution of Kenneth J. Burke, whose fascinating self-published 2009 book “Politics & Personalities in Australian Aeromodelling” has preserved so much of the early history of aeromodelling in Australia. All of us latter-day researchers stand on the shoulders of our predecessors, and this is very much a case in point. I’m greatly indebted to Kenneth for his efforts. As you go through this article, you’ll notice that the quality of many of the images leaves much to be desired. I make no apologies for this - many of these images are scans of low-resolution prints of 70-plus year old photos. I’ve included them regardless both because they’re all that’s available and because any image is surely better than none! With the above acknowledgements and admissions having been duly recorded, it’s now time to get on with the story! For context, we’ll go back to the pre-war pioneering era of power modelling in Australia and pick up the tale from there. Early Power Modelling in Australia

From this point onwards, power modelling began a steady rise in popularity in Australia. Most of the engines used were imported from America despite their very high cost delivered to Australia. This latter factor led to the appearance of a few home-grown designs in small numbers, including the Winner 10 cc, Whirlwind .52 and Austral Tornado units from Melbourne and the Walther from Sydney. The Winner was essentially a clone of the Brown Junior while the Walther was a close Naturally, the onset of WW2 in September 1939 put a very serious dent in the progress of Australian power modelling. Supplies of all kinds from the USA and England dried up, leaving any modellers who remained active despite the war using what they already had on hand. By war’s end, the aeromodelling scene had changed dramatically. A major factor was the emergence of control line flying, which had originated in the USA during the war years. This form of flying arrived in Australia more or less coincidentally with the end of the war. A second factor of relevance to our story was the arrival of tether car racing. This had originated in the USA during the late 1930’s and had stimulated the development of the first all-out all-out racing engines such as the Hornet, Hassad, Batzloff and McCoy .60 cuin. models, to name just a few. It didn’t take too long for aeromodellers to work out that if all-out speed competitions were now possible using tether cars which could safely run at elevated speeds under full restraint, why not tethered model aircraft? Thus was born the control line speed category which is at the heart of our present story. Early Post-WW2 Developments in Australia Naturally, word of the new forms of tethered model racing quickly filtered back to Australia. This created a surge of interest in participation among many Australian modellers. The problem was that a strict import embargo was imposed following the war in an effort to prevent precious currency from leaving the country. As a result, engines from America and elsewhere were virtually unobtainable during the early post-WW2 period.

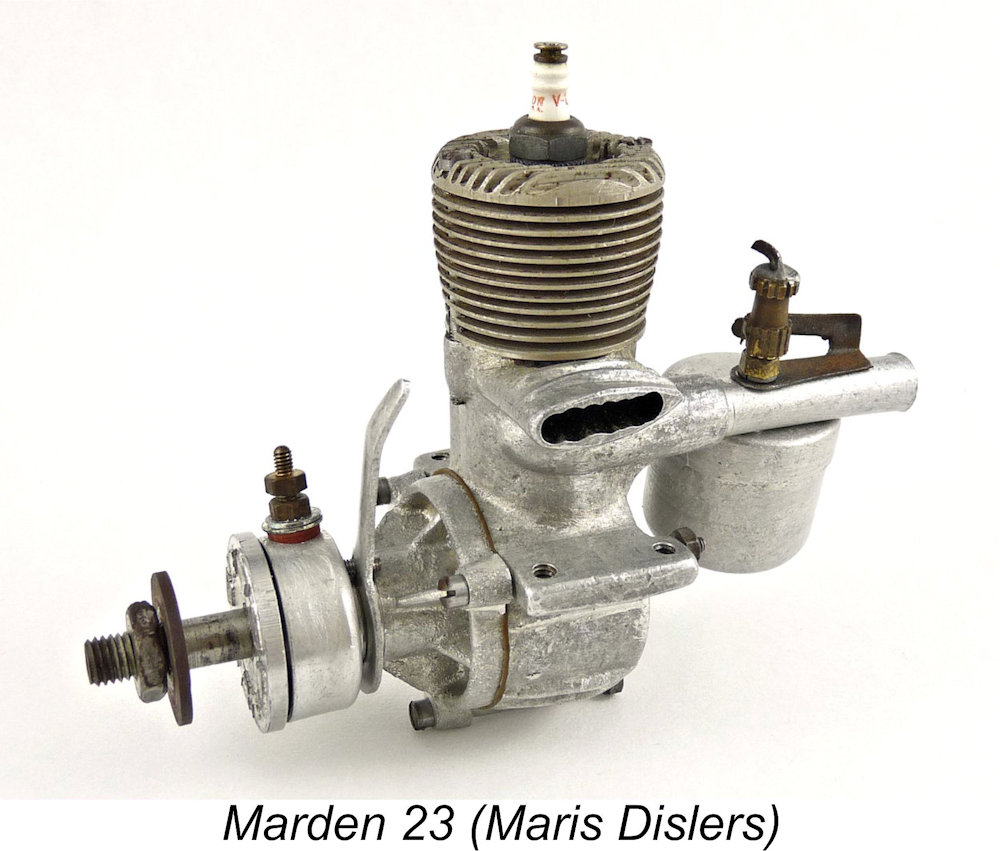

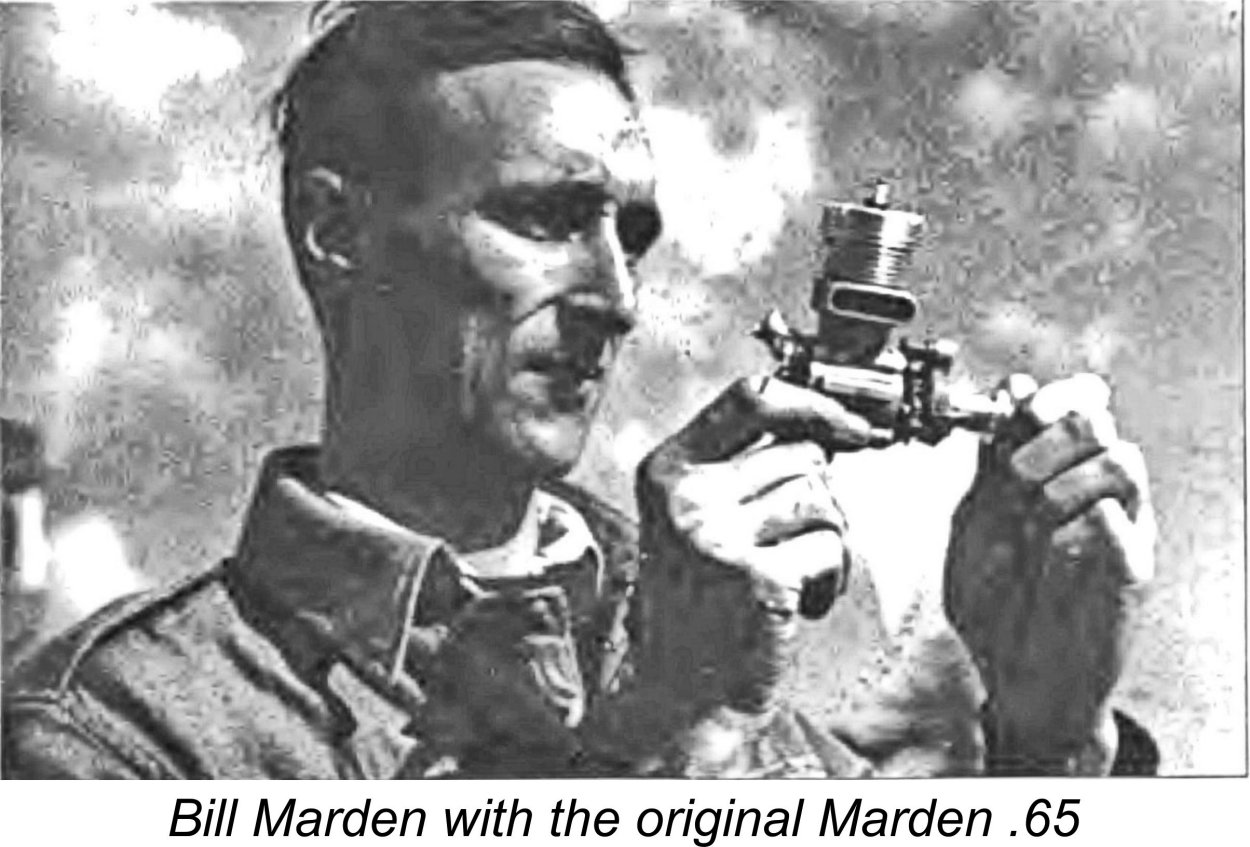

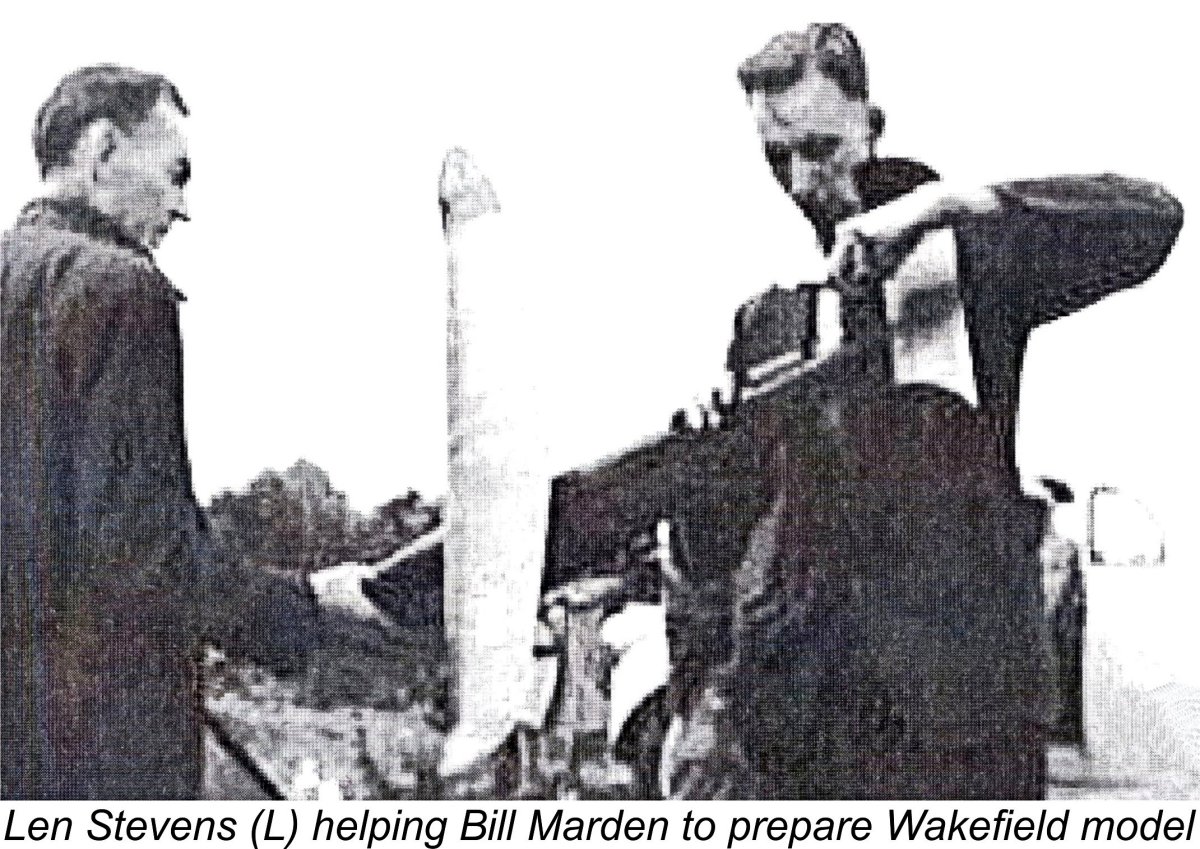

Among these individuals was Bill Marden. Born near Dover, England on March 23rd, 1918, Bill relocated with his family to Tamworth, NSW in 1929. While attending Tamworth High School he began his lifelong involvement with model aircraft by building a series of rubber-powered models. He left Tamworth in 1934 at age 16 to board in Sydney while undergoing training as a toolmaker with a firm called Sonnerdales. During this period his involvement with modelling was temporarily put on hold. In 1937 the Australian modelling scene had a remarkable stroke of luck when Bill broke his leg in a crash while testing a motorcycle for an endurance race. During his lengthy rehabilitation period his love of aeromodelling was rekindled, lasting until his untimely death in October 1984. During that time, he made an immense contribution to Australian aeromodelling.

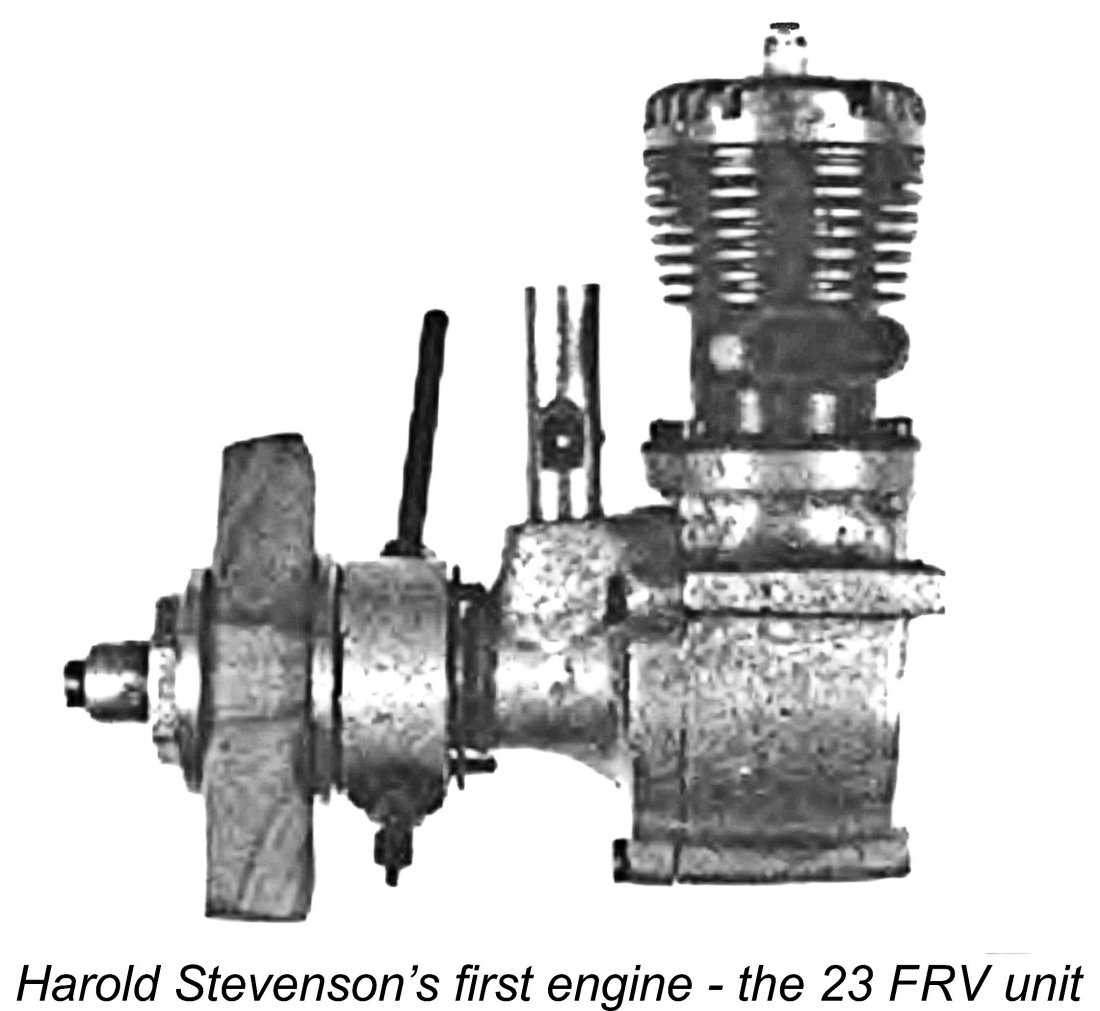

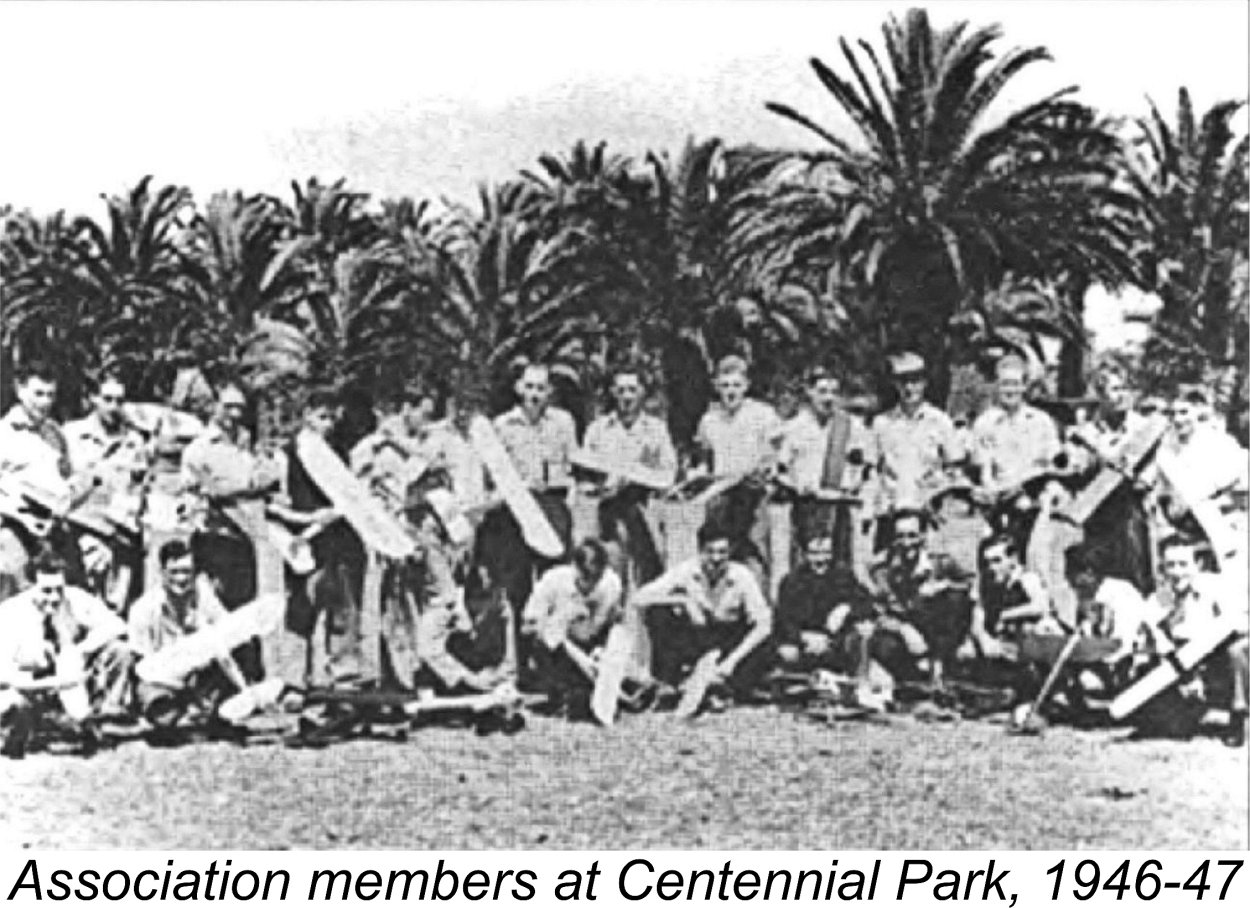

The success of this engine was such that Bill arranged for castings to be produced by K-Dee of Bathurst Street in Sydney, subsequently producing some 50 examples of his engine using a 3½ in. Myford lathe which he then owned. He also offered casting kits for home construction by others. These engines did much to keep Australian power modellers aloft during the war years when nothing else was available. Bill also produced a few .15 cuin. units as well In 1945 Bill met a 23 year old fellow enthusiast named Harold Stevenson. This was a fateful meeting in the context of our story! Born in 1922, Stevenson too had begun his involvement with aeromodelling during the pre-war years. He was a few years younger than Bill but shared his enthusiasm for model engine construction. He acquired a set of castings and materials for Bill’s Ohlsson 23 copy and proceeded to construct his own example, which was not perfect but ran reasonably well. Harold took the engine back to show Bill, who was very pleased because this was the first complete operating example built by another constructor which he had seen. This marked the beginning of a close friendship which was to last until Bill’s untimely death in 1984. Harold Stevenson didn’t stop with his rendition of the Marden 23 - in fact, he was just getting started! Before 1945 was out he had bought his own lathe and had begun to design and construct his own engines. His first effort was a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) .23 cuin. spark ignition engine. The crankcase of this unit was cast from material obtained by melting down a few saucepans! An improved version of this engine was soon developed. Harold built four of these improved models, which reportedly ran very well. Control-line Competitions Commence As far as the record shows, the first control-line contest in NSW, and possibly in all of Australia, was held at some point in 1946 at Centennial Park in Sydney. This was a very significant event as things turned out. Jack Finneran, whom we met earlier in connection with that inaugural powered flight in 1936, built a speed model into which Bill Marden installed one of his .23 cuin. Ohlsson copies, winning the contest. Clearly Australian racing engine development had some way to go at this point in time! Finneran was to go on to become one of the leading lights in Australian speed flying over the next several decades.

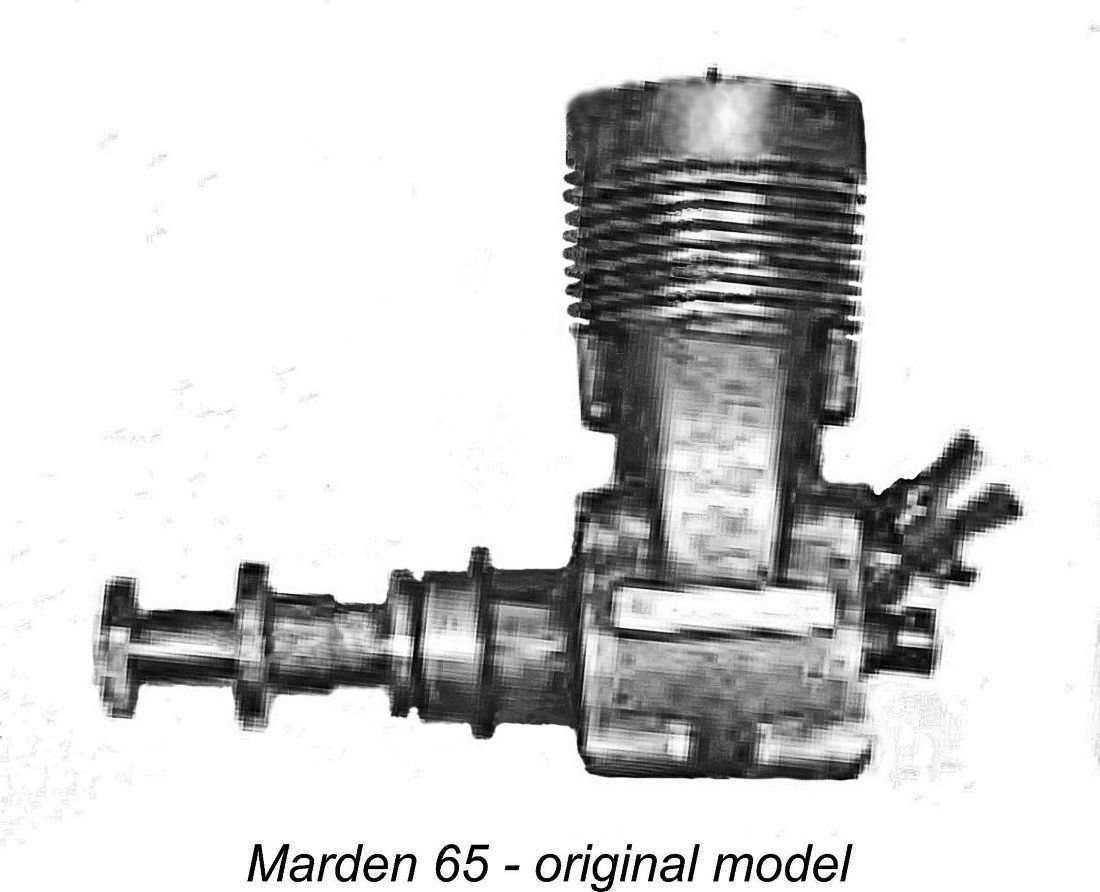

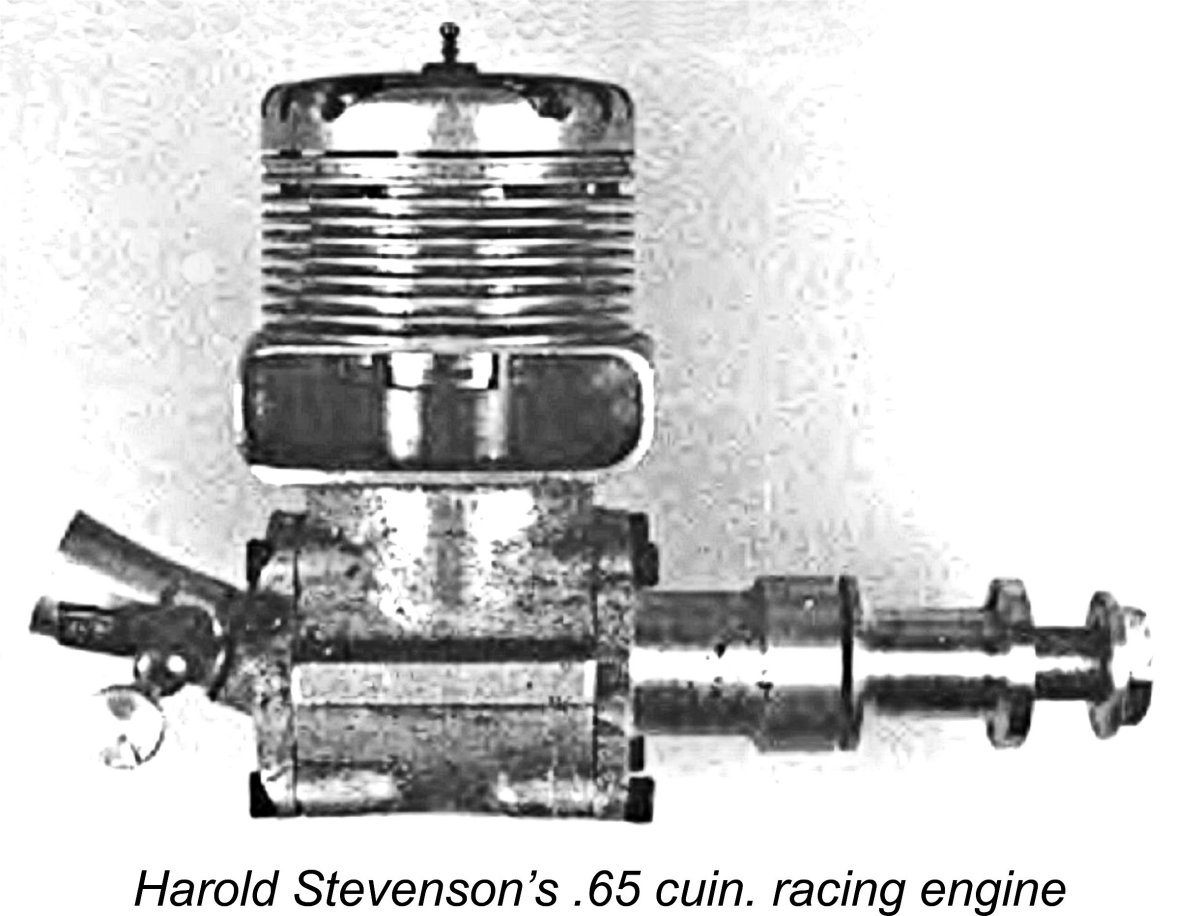

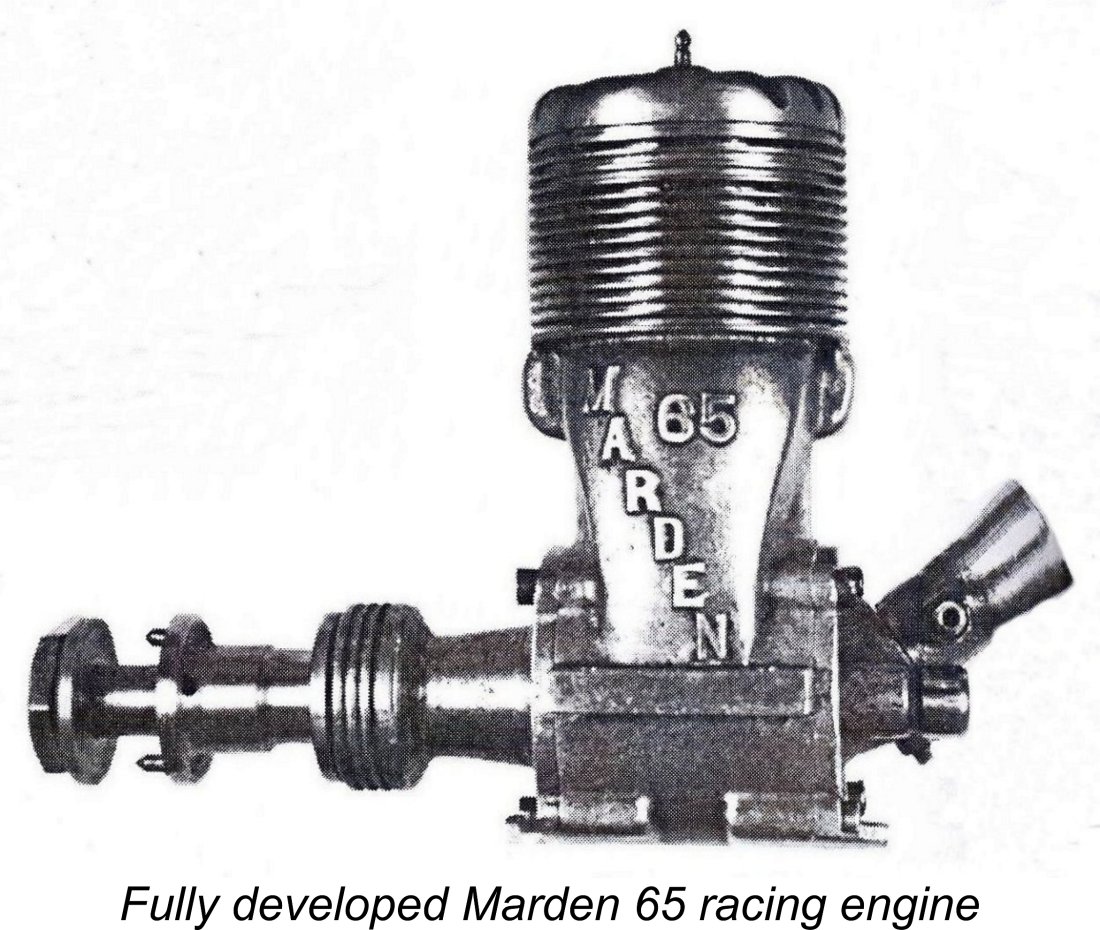

Model engines continued to be in short supply at this time. Despite the import embargo, the odd motor did somehow slip into the country from overseas, but at a high price tag. According to Mal Ward, if you were lucky enough to be able to obtain a McCoy 60 or Hornet 60 at all, it would cost the equivalent of around two week's wages for the average Australian. How about that for a strain on marital relationships - half your monthly take-home for a model engine! Tough sell .........! The consequence was that by and large Australian modellers had to make do with whatever was already on hand in the country. It was inevitable that sooner or later someone would take steps to redress this situation. The first post-war Australian production motor seems to have been Jack Black's Jay Bee 60 from Over in NSW, the focus was very much on control line speed at this time. Consequently, the attention of model engine constructors like Bill Marden and Harold Stevenson was mainly directed towards the development of racing engines suitable for use in that category. Bill Marden was soon at work developing a .65 cuin. disc rear rotary valve (RRV) twin ball-race racing engine called the Marden 65. Beginning in 1946 he constructed two examples of this design with a longer-term view towards putting the engine into series production. His friend Harold Stevenson bought a set of castings in 1947 and constructed his own rendition of this unit.

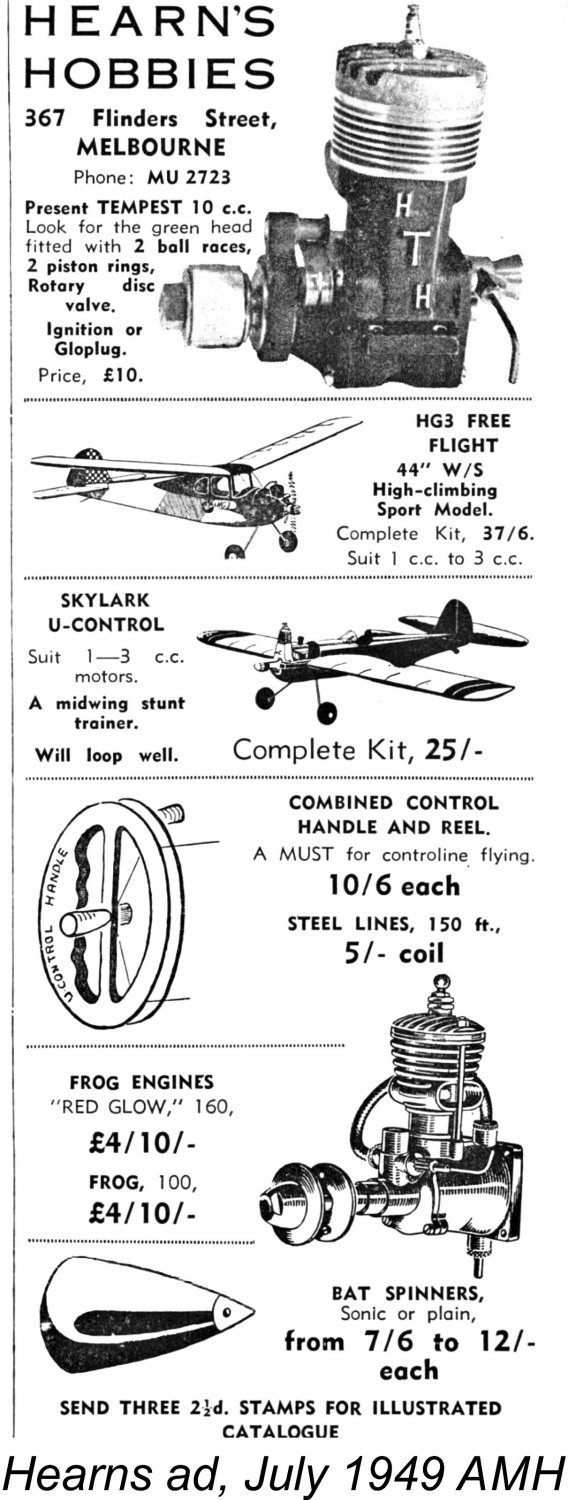

In 1946 or 1947 the three brothers decided to attempt to earn their livings through their modelling interests. To this end, they established a hobby shop known as Hearns Hobbies (sometimes rendered as Hearn's Hobbies) at 367 Flinders Street in Melbourne. On a personal note, I must have gone past that shop many times during my childhood stay in Melbourne in 1952 while my Dad was away in England on a one-year academic junket – Mum locked up the Thomas Street house in Adelaide for the year and took me and my brother and sister to live in Melbourne with my aunt and uncle. I was always dragging Uncle Jack or Grandma Booth down to Flinders Street railway station to watch trains. At that time my interest in models had yet to be kindled - steam locos were the thing!

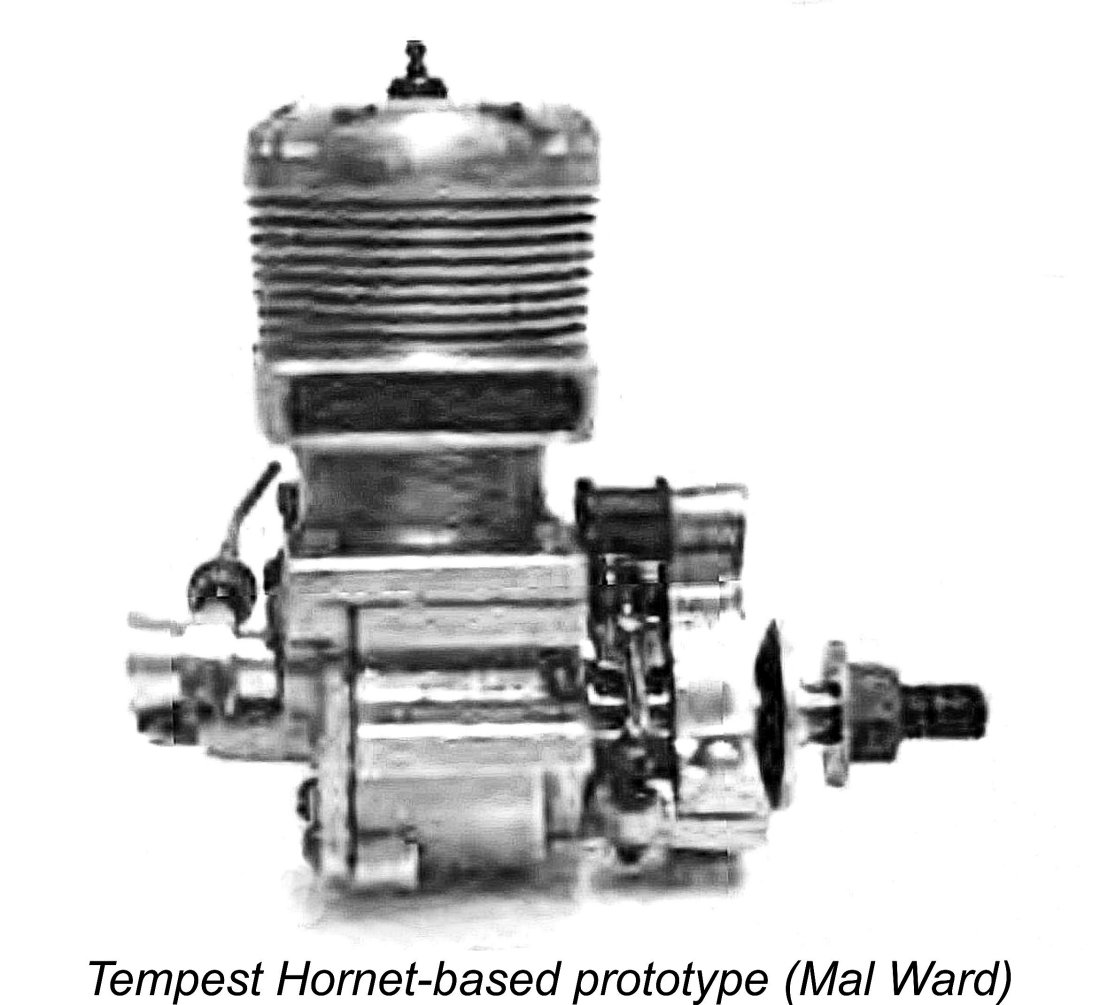

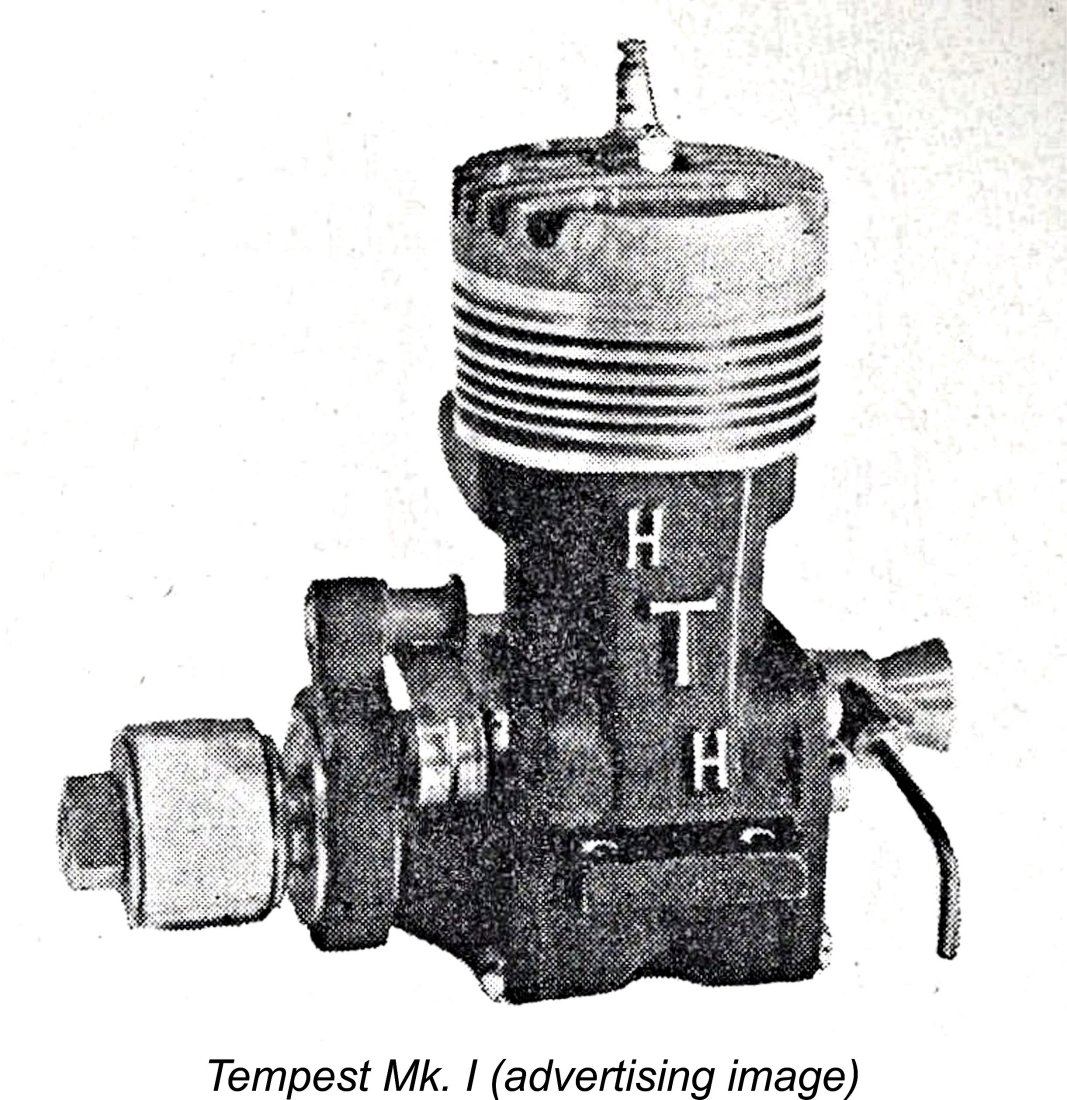

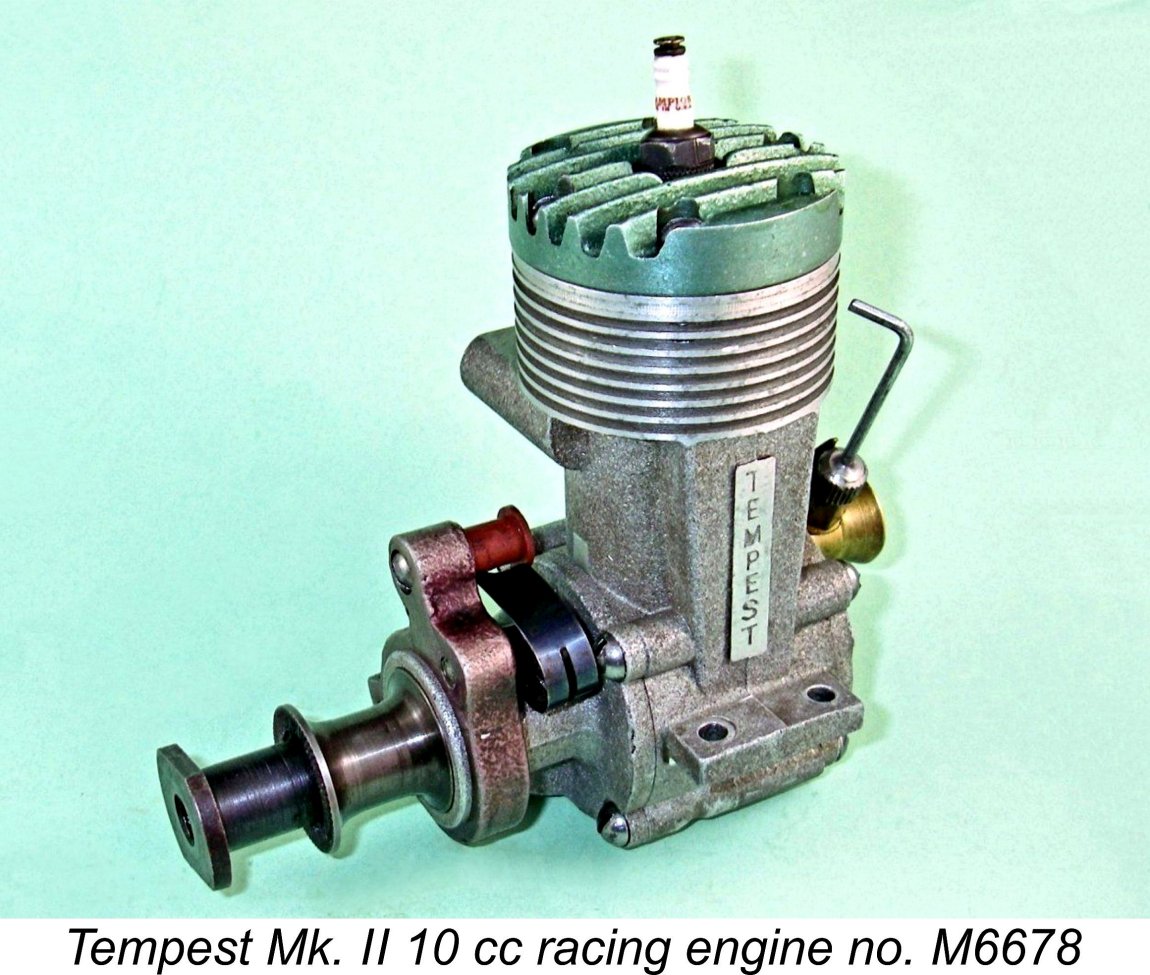

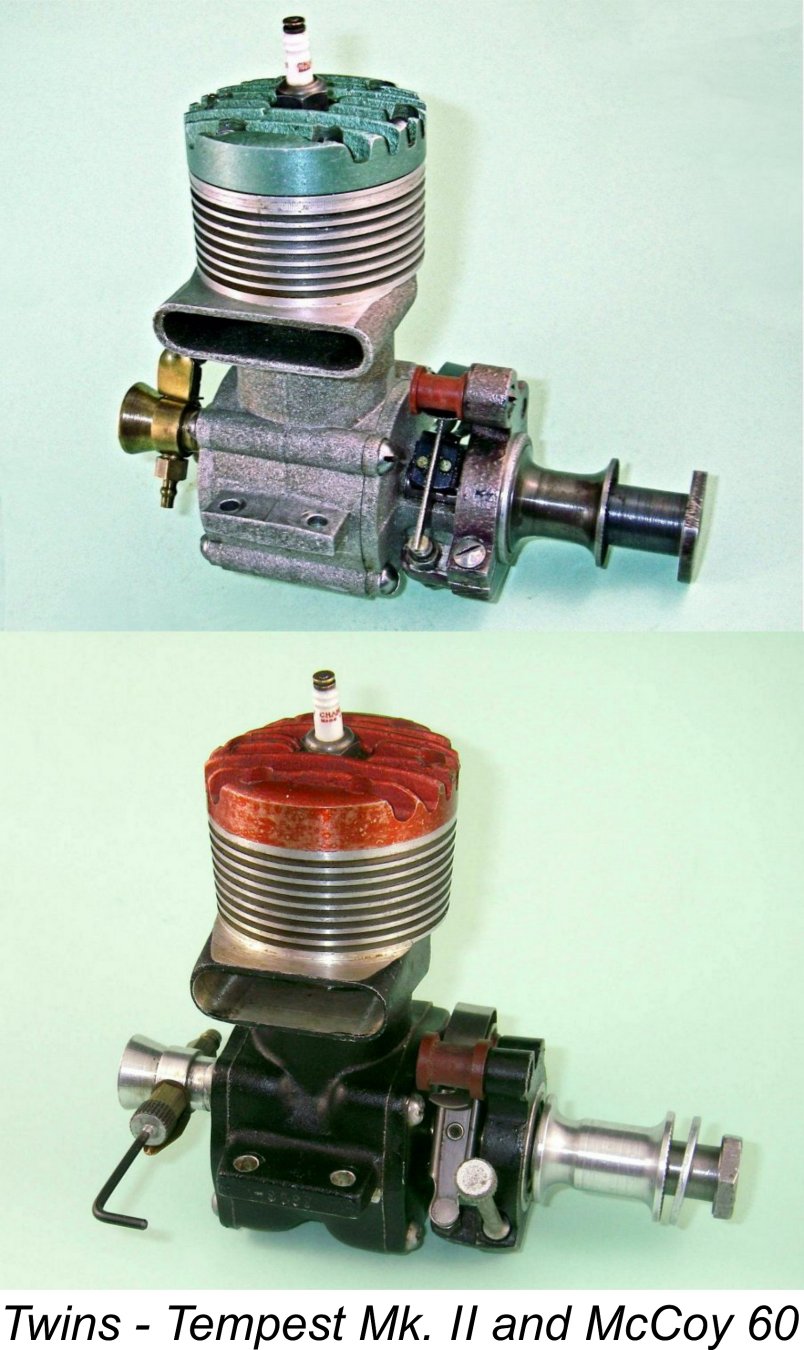

Having the green light from his brothers, Keith Hearn approached an acquaintance named Graham Baker (as likely as not a fellow modeller) who owned a small precision engneering company called Lynella Engineering Works at 32 Harold Street in Melbourne. Baker agreed to act as consulting engineer for the project, also taking on the production role. Through his connections with the Australian speed scene, Keith was able to borrow a Hornet 60 from Cec White and a McCoy 60 from Jack Hadaway. Both of these individuals had been turning good speeds in Class D competition. The relative merits of both the Hornet and McCoy were discussed and a couple of prototypes were constructed. One was basically a Hornet copy, while the other followed the 1946 McCoy 60 design very closely. The Hornet copy was distinguished from the original After initial testing and some further discussion, Graham Baker recommended the adoption of the McCoy-based layout, noting that among other things it would be easier and hence less costly to produce. It was agreed that a finalized version of this prototype would be put into production as the Hearns Hobbies Tempest Mk. I. From the outset, the engine was very closely identified with the Hearns Hobbies business, even to the extent of having the initials “H T H” cast in relief onto the bypass (combining the initials of Hearns Hobbies and Tempest). Many examples also feature the initials “L.E.W.” stamped onto the left mounting lug to recognize the actual manufacturer. The Tempest initially sold quite well at a price tag of £10, considerably less than the cost of a McCoy or Hornet at that time. Those who bought them reportedly found them to be very dependable in service. The engines were fitted with a Lodge spark plug as supplied. When glow-plug versions began to be offered some time later, they were supplied with KLG Miniglow "brass knob" plugs. Thus as 1948 rolled around there were two significant Australian-built 10 cc racing engines in the control line speed field - the Marden 65 and the Mk. I Tempest. Let’s have a quick look at these two home-grown contenders. The Marden and Tempest Mk. I Racing Engines

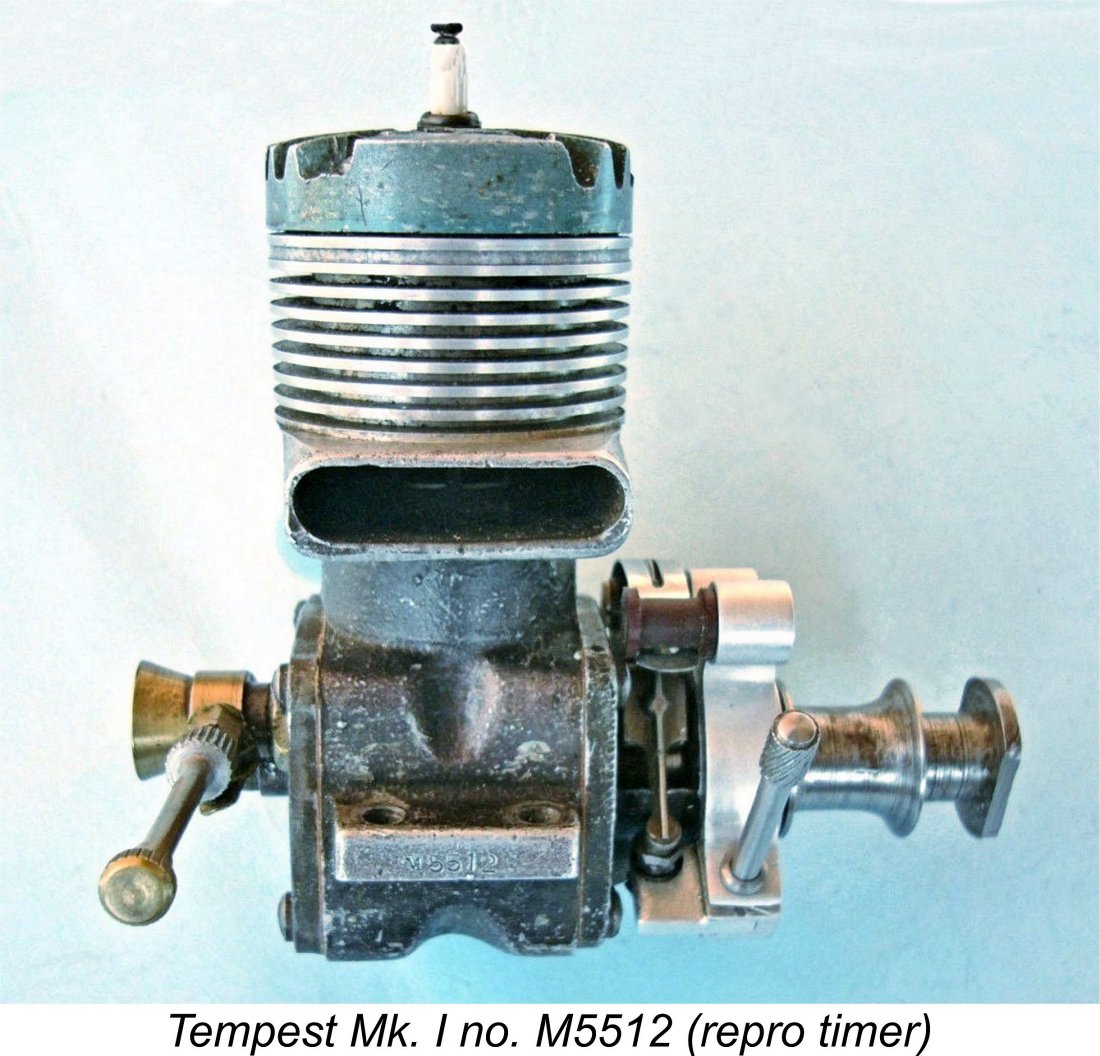

The Marden 65 departed from the McCoy in one respect - it used a downdraft rear intake of the type that would appear on the Dooling a little later. The Tempest Mk. I used a straight brass intake of the type seen on the Hornet 60. The Australian Class D category for which these engines were intended was open to engines of up to .65 The Tempest was a pretty close copy of the 1946 black-case McCoy 60 Red Head, even down to the black sand-case case. It was mainly distinguished by its green-anodized cylinder head. The McCoy's bore and stroke figures were adopted unchanged in the Mk. I Tempest, being set at 0.940 in. and 0.875 in. respectively for a displacement of 0.607 cuin (9.95 cc). Direct measurements taken from my own example confirm that these figures were carried over to the Mk. II Tempest. It’s clear from the surviving photographs that the original Marden 65 was equipped with a timer for spark ignition but lost the timer at some point following the 1948 appearance of glow-plug ignition. The Mk. I Tempest was similarly equipped. Of course, once the glow-plug arrived in Australia during 1948, owners would have been free to discard the timers in favour of the new form of ignition. Many of them evidently did so. These then were the Australian-made contenders in Class D control line speed as 1948 rolled around. Their opportunity to square off against one another would come at the 1948 Bankstown Nationals. The 1948 Bankstown Nationals. The major National meeting held at Bankstown Airport near Sydney, NSW in November 1948 was billed as the second Australian National Championship event. This was the first National Championship meeting to cater to the various control line categories.

Returning to the aeromodelling theme, Class D Speed was reportedly viewed as the premier control-line event at the 1948 Bankstown event, attracting a large entry. Contestants were mostly using American engines which had somehow side-slipped their way through the import embargo to reach Australia. These included such unlikely speed engines as Anderson Spitfires and Ohlsson 60’s, although at least one Dooling 61 seems to have magically appeared. By this time (late 1948), most of the entrants would likely have been using glow-plug ignition. This would explain the missing timers on the previously illustrated Marden 65 and Tempest Mk. I. During his invaluable research in support of this article, Maris Dislers spoke with Mal Sharpe, who flew in the Free Flight category at the 1948 Bankstown Nationals. The conversation got around to the issue of American engines somehow making it into Australia despite the import embargo. In Mal's recollection, US Navy ships were still docking regularly in Melbourne (and doubtless in other Australian ports) during the early post-war years. The trick was to establish contact with US sailors who were willing to help out. Model engines and other stuff were exchanged for high quality Aussie woolen garments. This was how Monty Tyrrell got his Atwoods for stunt and the racing crowd obtained their Doolings, McCoys and the like.

The Tempest was also very much in evidence. Using what he was promoting, Keith Hearn had a model powered by a Mk. I Tempest running on glow-plug ignition, while Norm Bell also entered using an identical powerplant. There were thus no fewer than 5 home-grown powerplants to uphold Australian honour. The report of this meeting which is included in Kenneth Burke’s previously-cited book makes such interesting reading that I though it worthwhile to include it in full. It’s an evocative account of the way in which things were done in those long-ago years when aeromodelling was a hands-on activity practised by real craftsmen! “Class D Speed was the premier event and it attracted a large entry. Prior to this competition, rumours were rife. Bill Marden was said to have been secretly timed during the week at 128 mph. Marden’s model was powered by a motor that he had designed and built himself (the Marden 65). Whether it would be good enough to match the Doolings, Anderson Spitfires, Ohlssons and the many other hot American motors that had slipped into Australia despite the import embargo, only time would tell. There was little to differentiate the models: all but one followed the conventional tractor layout with the motor upright and shrouded in a streamlined fairing. Ron Sharp’s model differed in that it had no wing on one side of the fuselage and no horizontal stabilizer on the other. All the models used a dolly undercarriage designed to fall away as the model left the ground. Bill Marden ran into trouble on his first attempt when the dolly refused to release. His repeated attempts to dislodge it by bouncing the model on the tarmac only resulted in bursting a tyre. Still, with the dolly attached he recorded 81 mph. Len Stevens, using a Marden 65 motor loaned to him by Bill Marden, had crashed and badly damaged the airframe of the model on the first flight. There seemed little chance that he could repair the model in time to record an official flight. The Tempest motor powering Norm Bell’s model was not considered a match for the Marden 65 or the potent American motors, but it had already propelled Bell’s speedster to a shade over 80 mph despite running extremely rich. Keith Hearn, using a similar engine, had recorded 106.4 mph. Towards the end of the round, Bill Marden managed to record a speed, sans dolly, of 109.4 mph and went into the lead. Len Stevens had worked furiously all day to repair his model, and just before the end of the final session he recorded 110.9 mph. The first four places were thus filled by motors designed and built in Australia. The final result was - first, Len Stevens (NSW - Marden 65); second, Bill Marden (NSW - Marden 65); third, Keith Hearn (Victoria - Tempest)”

Bill Marden was a busy man at this meeting! In addition to competing so successfully in Class D Speed, he also flew his rubber-powered duration model in the Wakefield event, finishing in another second place. Another notable participant was Bill Evans of Glenelg, South Australia, who won the free flight power category with his “Super Hatchet” model powered by an Arden .199 glow-plug engine. We shall be hearing much more of Bill Evans below……… Harold Stevenson was also a multi-event man at this meeting. He entered the Class B Speed event using a model powered by one of the four examples of his .23 cuin. FRV unit that he had built, running it on glow-plug ignition. His effort was good enough to earn him a win in that class.

During his previously-mentioned conversations with Maris Dislers, Mal Sharpe recalled that after seeing the Tempest in action at the 1948 Bankstown Nationals, he ordered an engine from the Hearn brothers. The Marden 65 was not in series production, so the Tempest was the only option if you wanted an Australian-made 10 cc racing engine. 12 months after placing the order, Mal still hadn't received his Tempest, only finally taking delivery by visiting the Hearns Hobbies shop in person during a work-related visit to Melbourne. Mal reckoned that the local Victoria fliers got priority and were probably supplied reasonably promptly, but modellers from elsewhere weren't so lucky. As far as Mal was aware, his was the only Mk. I Tempest to surface in South Australia at the time. He judged the engine to be very well made and ran it a few times. However, he was not all that impressed with its performance and ended up swapping it for an Austin 7 racer! Mal's experience seems to support the notion that the number of engines produced was quite low and that there were reasons for this............. An important occurrence in 1948 was the establishment of Australia’s first National aeromodelling control organization, the Model Aeronautical Association of Australia (M.A.A.A.). From 1950 onwards this body took over the organization of the annual National Championship events. Enter Bill Evans At this point a new actor steps onto our stage - Bill Evans, or William Wilton-Evans to give him his full name. Bill Evans was born in around 1923 and grew up in Glenelg, a beachfront suburb of Adelaide, South Australia (my own birthplace). During the 1930’s, a thriving model aero club existed in Glenelg. One of its leading lights was a gentleman named Alex (Bill) Barter, who flew spark ignition free flight models in the West Beach area of Adelaide, which is now the location of the present-day Adelaide Airport. One of Alex’s primary activities in support of the club was helping the many younger modellers who joined the club at that time. Benefiting greatly from his tutelage, these youngsters became known as Bill's Boys. In 1937 a lad of about fourteen years of age named Bill Evans joined the Glenelg Club. He was taught by "Bill" Barter to build and fly rubber powered models, thus becoming one of Bill's Boys. In 1941 Bill Evans reached the military age of 18 and joined the Australian army. Finding the Army to be not to his liking, Bill wangled a transfer to the Royal Australian Air Force. Since his ambition was to become a pilot, he was transferred to Canada (my own latter-day adopted country) where he was to complete his pilot training on Tiger Moths. However a head-on collision with another Tiger Moth ended his chance to become a pilot. Still in Canada, he began training to be a navigator but got lost in the Canadian wilderness on his first mission and had to be rescued! Since Bill had impressed his superiors with his ability to mess things up, they decided to turn him into a bomb aimer - at least any damage that he caused would theoretically be done to the other side! This worked out OK, and Bill completed his wartime service flying from bases in England as a bomb aimer in Lancasters.

Returning to Australia after demobilization, Bill first opened a restaurant beside the famous and historic Glenelg Town Hall (a noted local heritage landmark) which he called “The Rendezvous”. However, he was at heart first and foremost a modeller, and in 1948 he established a company called Model Aircraft Industries, which was originally located in a rented shed on High Street, Glenelg. He also became extremely active in organizing and promoting aeromodelling events in his area.

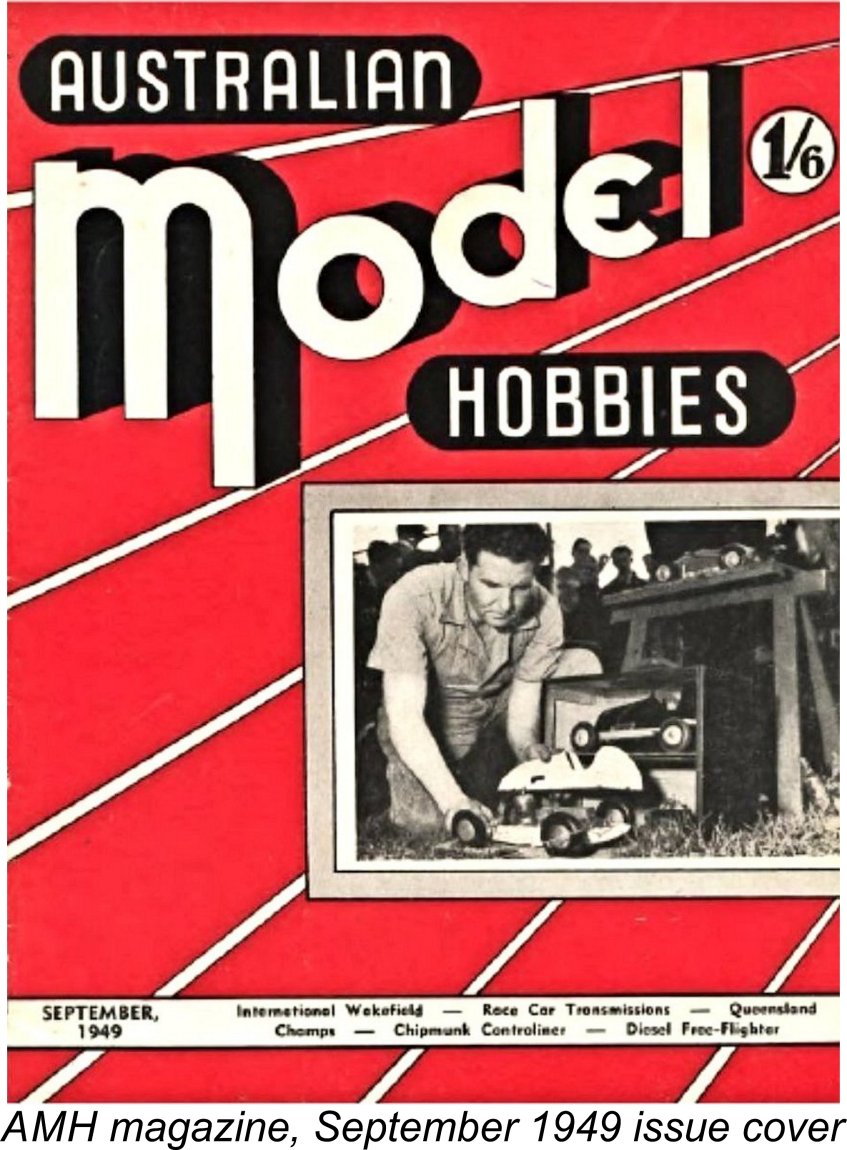

The magazine was produced on a somewhat irregular basis as time and content permitted. It did not survive for very long since Bill Evans found out the hard way that he was spread too thin to allow time for its continuing publication. Three issues a year were produced in 1949, 1950 and 1951, but the Spring 1952 issue turned out to be the last. Still, the publication covered our main period of interest very nicely. The Tempest racing engine was the headline feature in the Hearn's Hobbies advertisement which appeared in the inaugural July 1949 issue of AHM. The advertisement featured an image of the Mk. I version of the engine with its black case and “HTH” identification. The engine was priced at £10 with no distinction being made between spark and glow-plug ignition. This implies that all engines were supplied as sparkers, with glow-plug operation being at the buyer’s discretion. More Major Competitions Perhaps the contest highlight of 1949 was the so-called Australian Championship meeting held in October 1948 at Glenelg, South Australia. This was a two-day event, with free flight taking place on Sunday October 9th and control line being scheduled for Monday October 10th. Needless to say, Bill Evans was the primary organizer of this hometown event. Although it was touted as having Australian Championship status, this meeting was not conducted under the auspices of the recently-formed Model Aeronautics Association of Australia (M.A.A.A.). It was promoted by Bill Evans as a tune-up for the upcoming 3rd Australian Nationals to be held with M.A.A.A. sanction the following Easter in Victoria.

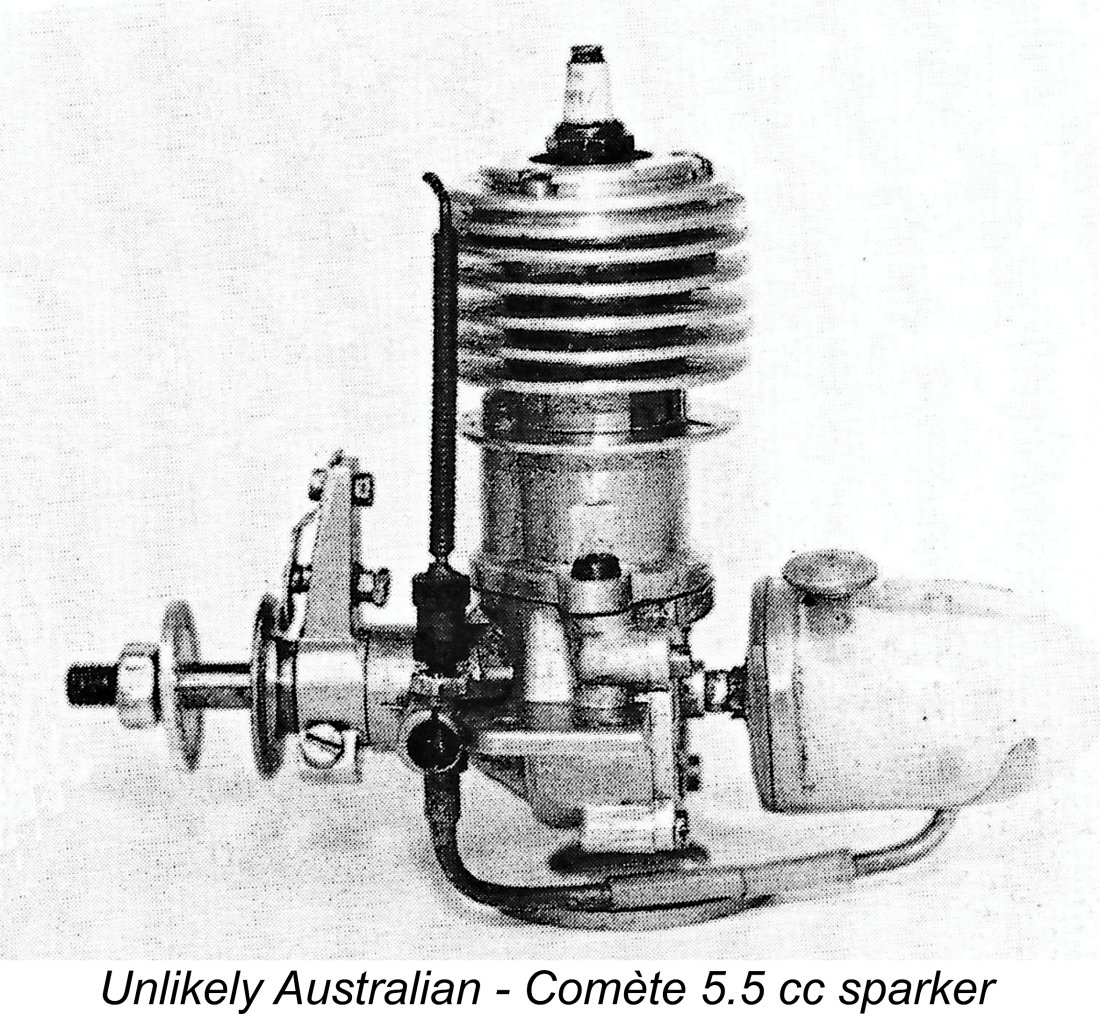

The winner in Free Flight Power was the aforementioned Jack Black flying a modified “Toreador” design powered most improbably by a 5.5 cc Comète engine all the way from France. This was presumably the spark ignition version running on glow-plug. Bill Evans came in second flying his own-design powered by an AMCO 3.5 cc diesel, while Wally Reeves finished third with a low-wing own design model powered by a Bantam .199. Clearly Australian modellers were still using whatever they could get at any given time! On Monday the control line events were held at the Glenelg Oval. The stunt winner was Jack Black once again, this time flying a model powered by his own Jay Bee 60 running on glow-plug. Second was Gordon Burford flying a DeBolt “Stunt Wagon” with a GB 5 cc diesel, and third was Rex Myers. Great excitement resulted from Keith Hearn’s very noisy demonstration of a Dynajet-powered speed model during the day. The November-December 1949 issue of AMH included two references to Tempest-powered models entered in Class D Speed at this meeting. The issue included photos of Jim Leighton of Sydney and Jim Connell of Victoria, both with Tempest-powered speed models. Bill Marden and Harold Stevenson were both still active with their own engines described earlier, but it's not known if they were in attendance at this meeting. Currently we have no information on the results of this event. The M&S 29 Racing Engine

What deflected Harold away from the series production of his Sport 29 was a decision taken in the latter part of 1949 that he would join forces with his good friend Bill Marden to produce a .29 cuin. racing engine which would be suitable for Open Power free flight models, Class B control line speed models and Class B team racing, then just getting started. There appeared to be good market prospects for such an engine. The result of their joint efforts was the M&S .29 racing engine. Two prototype examples were constructed in 1949, after which the engine entered small-scale series production in early 1950. 40 more examples The engine was an excellent performer - Harold Stevenson was using one to turn speeds of over 120 mph in Class B speed during 1951. Plans were put in hand to commence the production of a second batch in that year, but this fell through in part due to difficulties in obtaining sufficient supplies of the necessary materials and also due to Bill Marden’s increasing focus on the gunsmithing business which was his main source of income. The 42 engines produced prior to the end of 1950 were thus the only examples of the M&S 29 ever made. Harold Stevenson went into the glow-plug manufacturing business on a commercial scale. He made and sold some 15,000 examples of his H.S.S. “Micro Glow” glow-plugs over the years. He also manufactured the H.S.S. Micro-Screen filter and the Micro Tac rev counter. Unfortunately, all of his stock and tooling was destroyed in a fire in 1971, putting an end to his involvement with model manufacturing. Further National Championship Events The big event of the year 1950 was the third Australian National Championship meeting held over Easter 1950 at Reservoir, Victoria (a suburb of Melbourne). This was actually the first Nationals to be held under the auspices of the Model Aircraft Association of Australia (M.A.A.A.) - the 1949 Glenelg "Australian Championship" meeting had not enjoyed official National Championship status.

This left the Class D field wide open for the Tempest entries, flying on their home turf. However, they signally failed to distinguish themselves at this meeting. Jim Connell of Victoria showed up with his Tempest-powered model to win, albeit with a notably lacklustre speed of 93.7 mph. He was followed by H. From the standpoint of Hearns Hobbies and their flagship Tempest racing engine, this was not a positive result. By this time the Tempest had morphed into its Mk. II version with a gravity die-cast crankcase which was now steel grit shot-blasted instead of being blackened. The name “TEMPEST” was now engraved onto a polished panel on the bypass passage The engine looked even more like the 1946 McCoy 60 Red Head than its Mk. I predecessor, being mainly distinguished by its green anodized cylinder head. The new model weighed a checked 478 gm (16.86 ounces). The production quality remained outstanding. Hearns Hobbies made the best of a bad job. They advertised the engine one more time in the August 1950 issue of AMH, citing it correctly as having won the Class D speed event at the 1950 Nationals and having been the fastest Australian engine. They naturally failed to cite the actual speeds achiever or mention the fact that the Tempest was the ONLY Australian engine in the Class D competition! This being the case, how could it not be the fastest?!? Unlike its Mk. I predecessor, the Mk. II version of the Tempest was available in both spark ignition and glow-plug configuration. The only difference was that the glow-plug model lacked both a timer and the access window in the main The engines were supplied in sturdy cardboard boxes with a multi-colour label on the lid. Evidently the The August 1950 advertising placement in AMH was the final Hearns Hobbies advertisement to feature the Tempest. Indications both from this fact and from available serial numbers imply that production most likely did not continue past the end of 1950.

Once the application of serial numbers commenced, the Mk. I Tempests were evidently numbered in an M55xx sequence, although we have only two confirmed numbers at present. Previously-illustrated Mk. I engine no. M5512 has a latter-day replica timer fitted, but is otherwise in pretty good used condition. In addition to his un-numbered example, Douglas Rochlin also reported owning Mk. I engine number M5517 which appeared to be complete and original. His two examples provide convincing evidence that both the black crankcase finish and the green head anodizing tended to fade with use. All seven examples of the Mk. II Tempest of which I’m presently aware bear serial numbers in an M66xx sequence. The basis for the M55 and M66 portions of these numbers is quite obscure, but it's clear that they designate either a Mk. I or Mk. II example. The xx figures evidently represent the engine's position in the production sequence. Douglas Rochlin reported owning glow-plug Mk. II engine number M669 which lacked both a timer and an opening for the cam follower. This unit is important in that it seems to confirm that the numbering sequence started from M661. Presumably the same argument applied to the M55 numbering system applied to the Mk. I units once that sequence was started. Mk. II engines nos. M6624, M6647 and M6658 are also glow-plug models having no provision for a timer. Engines nos. M6637 and M6678 (my own example) are spark ignition variants, as is engine number 6651 owned by Scott Clydesdale. In terms of overall production figures, Mal Ward stated that the number of engines of all types produced over the Tempest's three-year production life was at least 400 units. Of these, some 250 were reportedly sold as glow-plug units, most of which were of the Mk. II variety. Unfortunately, the serial numbers so far reported do not provide any support for these figures - in fact, they appear to contradict them. Pending the provision of more serial numbers which extend the known sequence, we'll have to leave it there for now. The fate of the Tempest racing engine appears to have been very similar in many ways to that of the equally elusive Rowell 60 in Britain. Like the Rowell 60, the Mk. I Tempest was rendered obsolete more or less as soon as it was released thanks to the mid 1947 introduction of the Dooling 61 and the 1948 appearance of the vastly improved McCoy 60 Series 20. The Mk. II model was basically just the same engine dressed up a little. Once supplies of those potent American engines or credible copies thereof became available, who would want to buy a Tempest? It was just an obsolete engine which carried a high price tag ……..

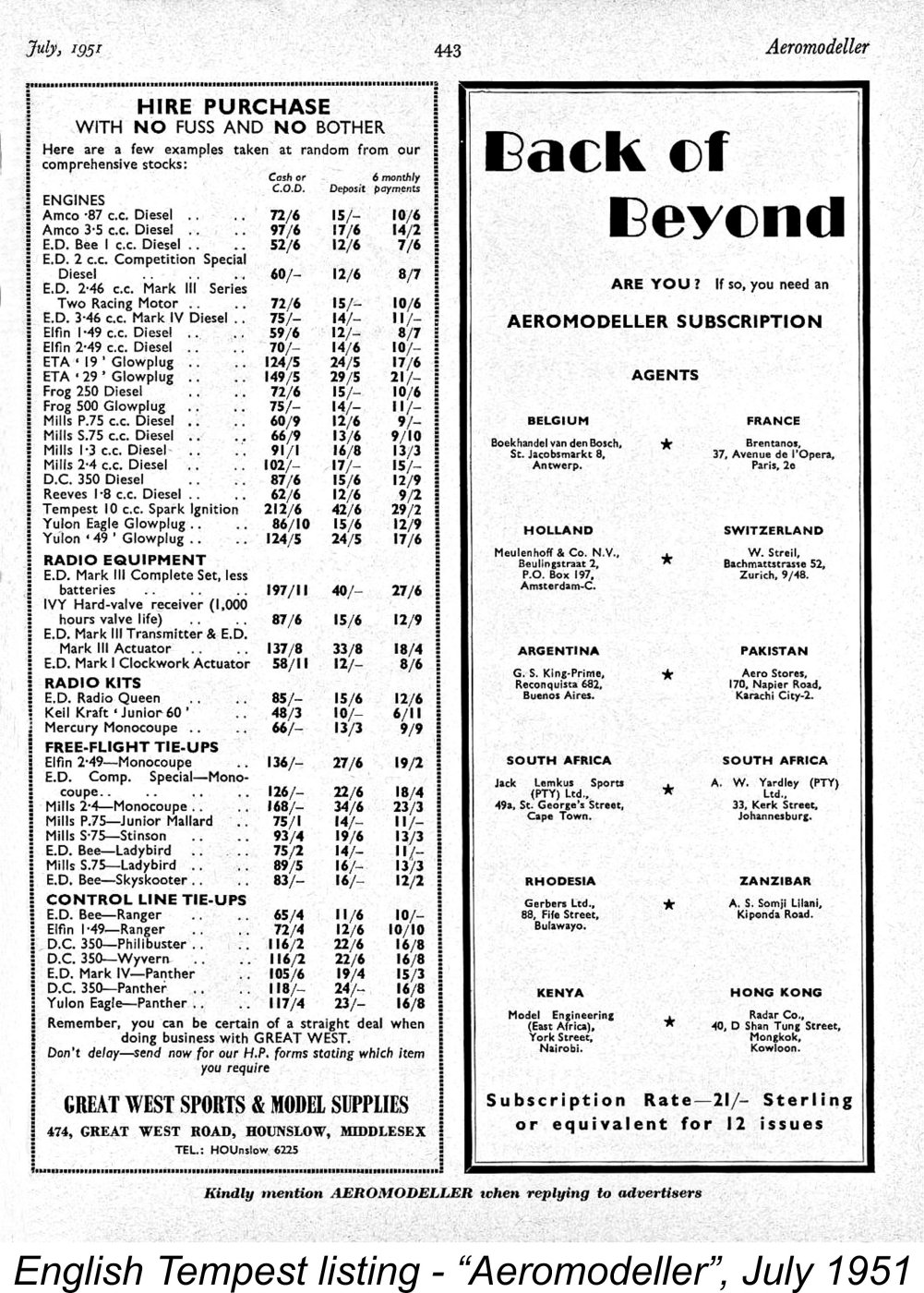

One extremely interesting fact unearthered by Maris Dislers was the very surprising discovery that the Tempest managed to make it all the way back to Blighty as a commercial offering! Maris found an advertisement placed in the July 1951 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine by a company called Great West Sports & Model Supplies of 474 Great West Road in Hounslow, Middlesex. The engines listed in this advertisement included the 10 cc Tempest at £10 12s 6d (£10.63). Interestingly enough, only the spark ignition version was on offer. This may be a case of the Hearns taking advantage of family or ex-military connections in England to sell off remaining stocks of spark ignition Tempests, for which demand must have dried up in Australia by this time. It's unclear how many examples (if any) were sold in England. Returning to Australia, in mid 1950 Bill Evans abandoned the rented shed on High Street, Glenelg which had housed his Evans Model Aircraft Industries venture since 1948, opening a new business called the Australian Hobby Centre at 132 Franklin Street, Adelaide. At this time he was acting as the distributor for both Gordon Burford's GB engines from nearby Grange and the K engines from Gravesend in Kent, England. The accompanying illustration below at the right shows Bill in 1950 holding the K Kestrel-powered stunter of his mate Brian Horrocks, a future Gold Trophy winner. Horrocks went on to work for Bill starting in 1951. Bill's next major initiative was the organization of the fourth Australian National Championship meeting held over the New Year weekend of 1950 - 1951. This event The meeting was a huge promotional success - the 5-day event was attended by over 22,000 paying spectators. It would seem almost impossible not to make money on such an event, but Bill Evans somehow managed to do so! He was a great organiser and a natural promoter but was not such a good businessman. In the June 1951 issue of AMH, he admitted that the event had actually managed to lose money! "All of those arrangements and trophies cost a great deal of money, but the final deficit of the SAAA was about £250 which, when what was achieved is taken into consideration, was not a very high figure. It is hoped this will be made up during the year by various displays." As a matter of record, this was the first National Championship event at which there was a category for R/C models. Our old friend Jack Hearn from Melbourne flew a “Rudderbug” to win the inaugural event. The Hearns Hobbies Tempest also enjoyed a final moment in the limelight when G. Cash of Victoria used a 10 cc Tempest mounted in an 8 foot span pylon model to win the Class C Open Power free flight duration competition. However, by this time the Tempest was evidently history in market terms, and we hear no more of it. Even so, the Australian Class D racing engine was not quite dead yet! Over in Melbourne, another such model had been taking shape. The Vampire 61 By 1950 the go-to powerplant among serious big-bore racing enthusiasts was the Dooling 61 from America. Factory-built examples remained hard to get and very expensive if they could be brought in somehow. It was inevitable that this iconic design would attract the attention of yet another Australian racing engine producer.

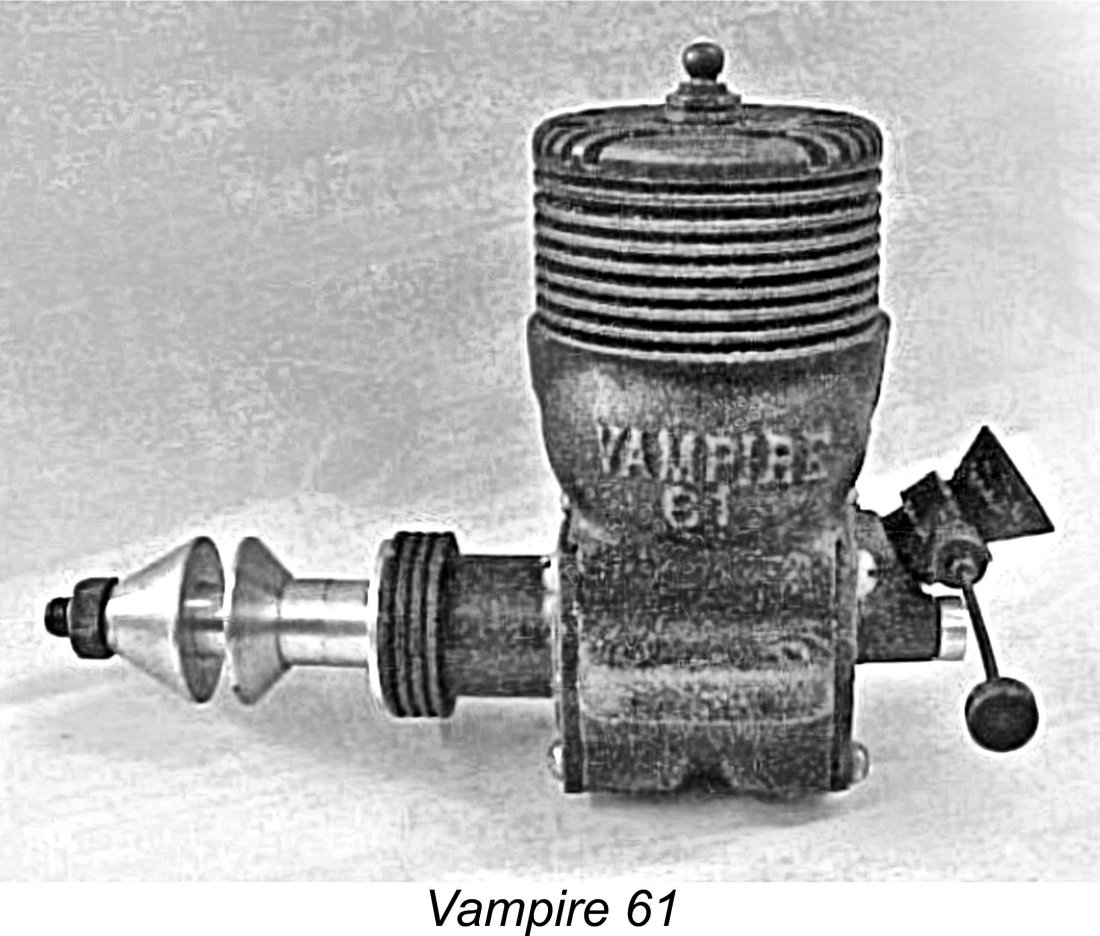

Between 1950 and 1953, Wright produced very limited numbers of his Vampire 61 racing engine, which was closely based upon the Dooling 61. The name was doubtless suggested by that of the de Havilland Vampire fighter with which CAC had a connection through its licensed production of the Rolls-Royce Nene jet engines used in the F.30 and FB.31 Vampires built by de Havilland Australia at their Bankstown plant. The Vampire 61 featured magnesium castings which were chromate-blackened. Bore and stroke were 1.050 in. (a little larger than the Dooling's 1.015 in. bore) and 0.750 in. respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.649 cuin., thus contradicting the Vampire's 61 designation. But who was checking?!? It was still legal for Class D! The engines sold by word of mouth only, never being advertised at any time. Despite the princely selling price of £18, some 25 examples were sold, all of them glows. It’s clear that this was a very competitive engine by the standards of its day. Max Wright reportedly achieved an unofficial speed of 142 mph using one of these units. However, I am presently unaware of any documented competition success which this fine engine may have enjoyed. Other Large Australian Racing Engines

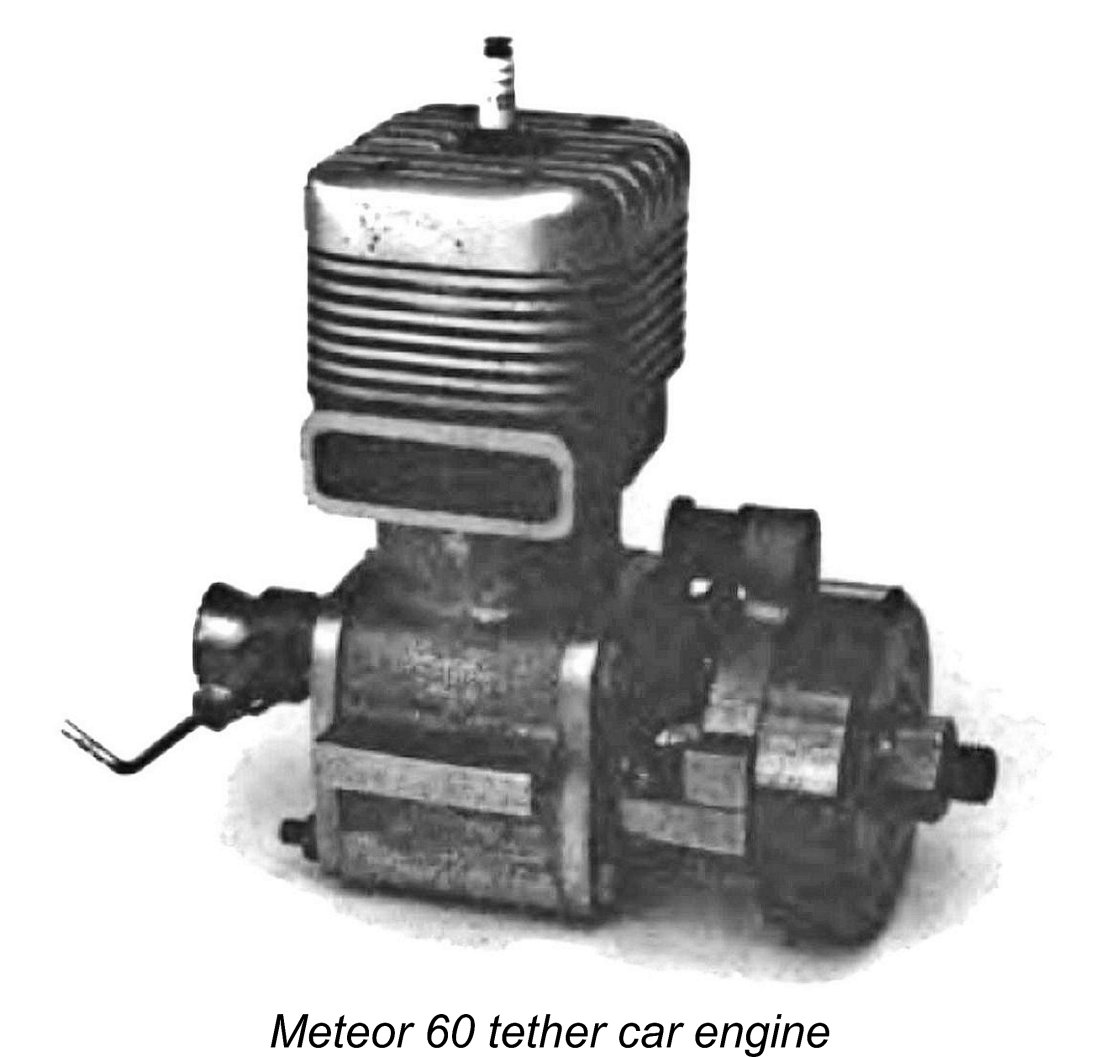

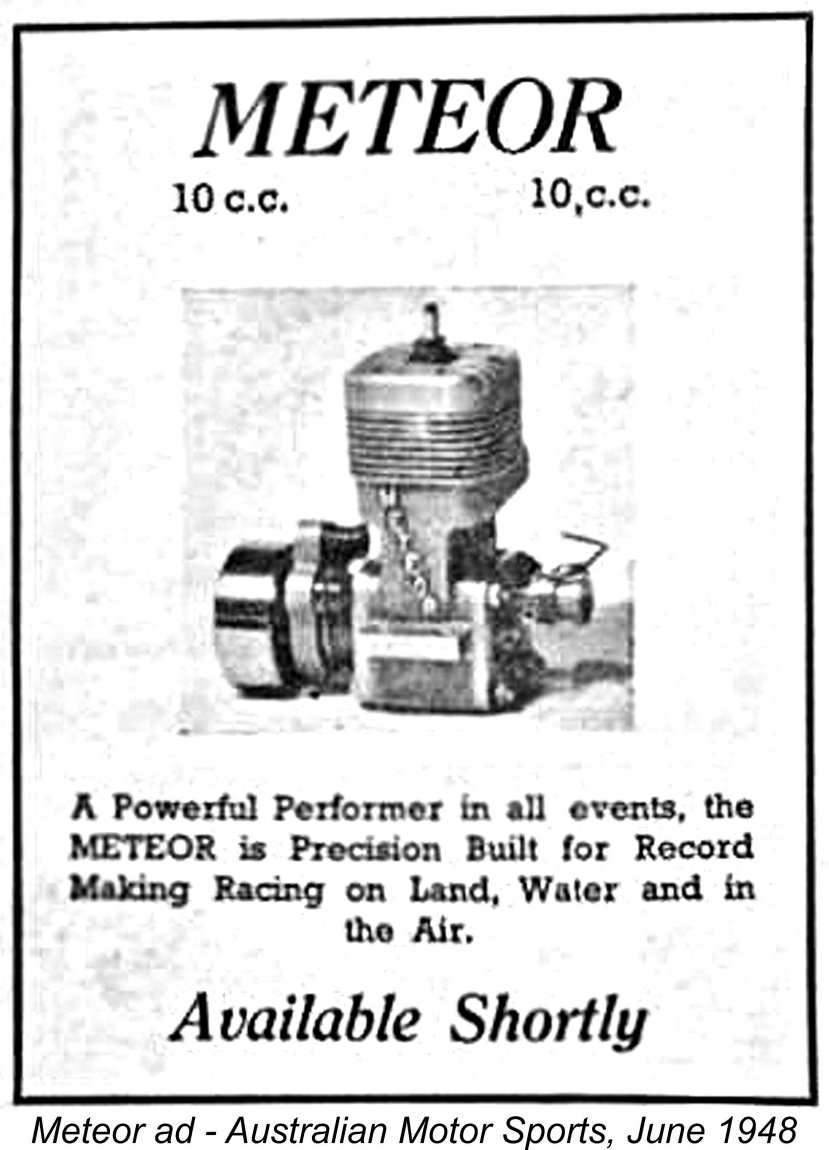

Maris Dislers did some digging with respect to these engines, contacting several individuals with past involvement in tether car racing or possessing knowledge regarding the early years of the sport in Australia. It was learned that both the Manx and the Meteor were the work of Peter Larson, a pioneering Aussie tether car racer from Victoria. This identification was confirmed by the late David Owen in a communication with Tim Dannels. As of the late 1940’s, Peter was the Vice-President of Victoria’s Riverside Miniature Car Club. The Meteor evidently dated from 1948. It appears that as of that year there were plans to put the engine into series production. An advertisement placed in the June 15th, 1948 issue of the Australian magazine "Australian Motor Sports" showed an image of the engine along with the statement that the Meteor would be One really odd thing about this advertisement is the fact that it included no contact information or any other details regarding the manufacturer. How interested parties were supposed in inquire about the engine is anyone's guess! The ad appears to have been more of a "teaser" than anything else. David Owen confirmed that Peter Larson made the drawings and produced the patterns for both the Meteor and Manx engines. Apparently the two engines were identical apart from their cooling fin profiles. Neither engine ever entered series production, although castings were offered by The Model Dockyard of Melbourne. it’s also possible that the odd completed engine was available from Peter Larson if he was satisfied that the prospective buyer would put it to good use. A number of examples were completed, and the engines became quite highly regarded as tether car powerplants. Based upon the number of present-day survivors, the number completed must have been quite small. Former World Record holder Tony Peacock knew Peter Larson personally and was able to provide further confirmation that Peter was responsible for both the Meteor and Manx 60's. Interestingly enough, at the time of writing in 2020 Tony still had an example of the Meteor in a car, which he ran as recently as July 2020. Using Tony’s own home-made magneto on spark ignition, it was good for a speed of 193 km/hr. However, most examples were operated as glow-plug units.

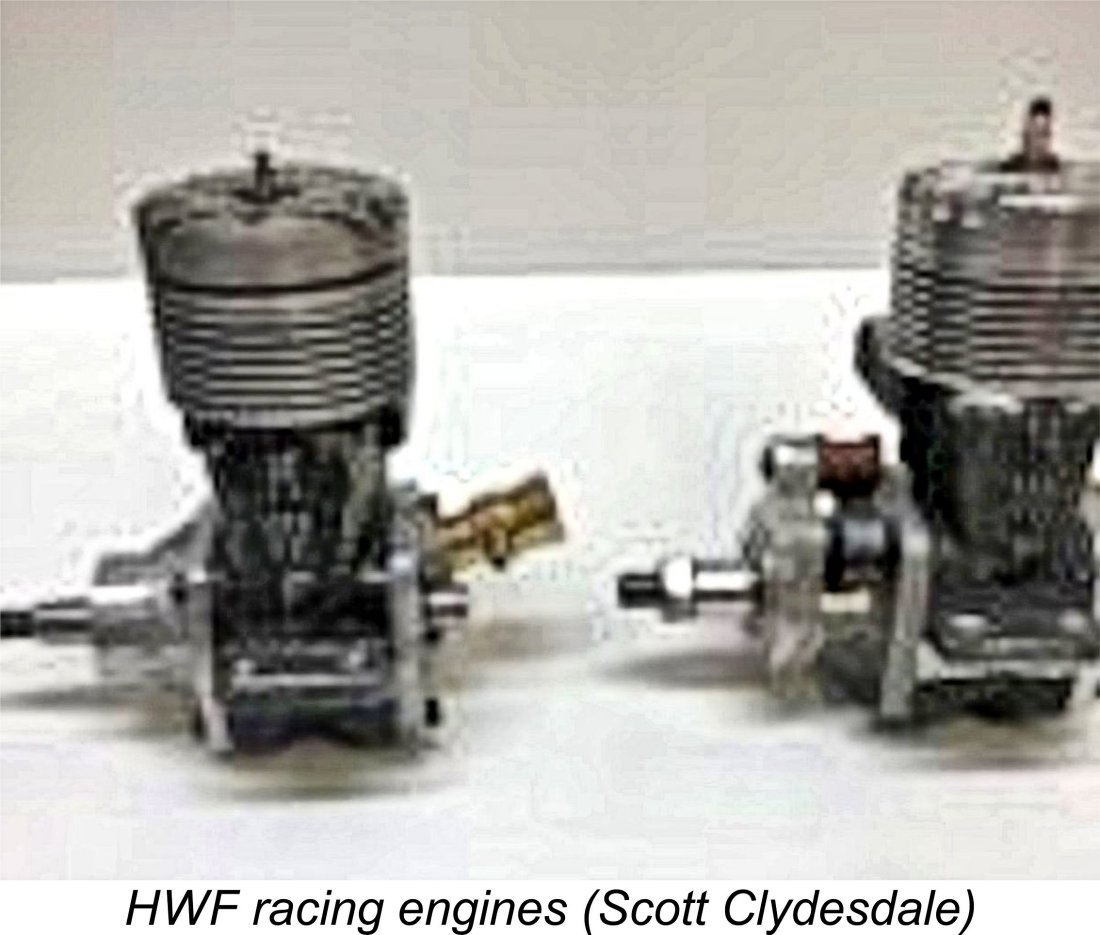

It thus seems most probable that the Meteor came first during the period 1948-49 and that the slightly re-styled Manx design followed that of the Meteor, likely in 1949-1950. The two engines appear to represent a last-ditch attempt by Larson to fend off the ever-growing challenge from the Dooling 61 and its derivatives. In his July 6th, 2005 message to Tim Dannels, David Owen provided an interesting postscript to the Manx/Meteor story. Peter Larson had apparently died some years prior to that date, but it seems that in the late 1990's a Sydney resident named Ron Bernhardt borrowed the patterns and drawings from the Larson family, ostensibly in order to make an engine for himself. However he subsequently produced and sold quite a number of casting sets and copies of Peter Following this unhappy incident, Bernhardt produced drawings and castings for his own retro racing engine, which he named the Bern .61. This model was very definitely based on the Dooling, with some apparent influence from Bruce Underwood's Dooling-based Yellow Jacket. A number of casting sets were sold prior to Bernhardt's death in 2002. However, the Bern .61 is a considerably more complicated engine to build than the Manx and Meteor models. Consequently, very few examples seem to have been completed. The mega-talented David Owen produced a small handful of these engines, one of which is illustrated here. The Meteor and Manx engines appear to have been just two of a number of Hornet and McCoy-style racing One such engine of which I was not previously aware was the HWF 60 produced in some quantity by the late Harry Ferguson of Sydney. This was basically another McCoy clone with a few detail modifications. Harry Ferguson was a Sydney garage owner who at one time employed future three-time World Formula One Champion Jack Brabham. In addition to producing the HWF engines, he was also responsible for the HWF Lightning tether cars which still circulate today in repro form among US tether car enthusiasts. He also produced a line of Old-Timer "Balloon" tyres which remain available today, still being produced from the original molds. Harry relocated to Brisbane around 1980 and passed away in 1992. My sincere thanks to Scott Clydesdale of Brisbane for sharing this information with us!

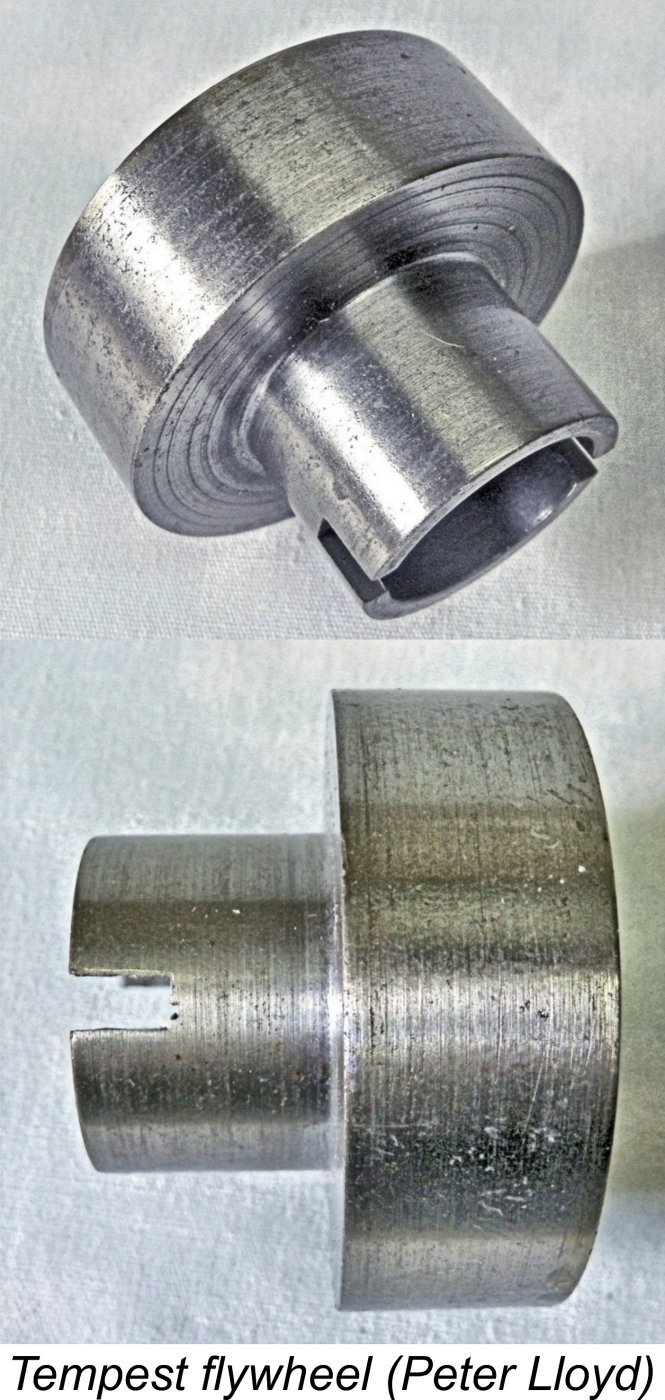

They then changed the engine's name to the Hurricane (after all, a form of tempest!), leaving the cast-on letter H in place in recognition of the fact that H stands for Hurricane as well as Hearn. The casting The Tempest itself was apparently also used in tether car service - Peter Lloyd has several engines, as well as a flywheel which he believes to be an original Tempest component. The case-hardened mild steel flywheel weighs in at 289 gm (10.28 ounces), with a diameter of 50.35 mm and a thickness of 17.64 mm. The integrally-machined 19.12 mm long drive extension has an external diameter of 27.64 mm. The internal hole has a diameter of 22.0 mm and a depth of 22.45 mm. The drive slots are 4 mm wide x 7.23 mm deep. The 7.85 mm diameter central shaft hole has a 1.64 mm x 1.64 mm Woodruff keyway cut into its surface. The flywheel is obviously intended specifically for tether car racing since it lacks the V-groove for a starting cord which would be required for use in hydroplane service.

In concluding this section of the article, it’s worth mentioning the fact that the late David Owen made a small number of Manx, Meteor and Bern replicas a few years prior to his untimely death in 2016. These were constructed to David’s usual impeccable standards. Any example encountered today is far more likely than not to be one of David’s replicas - the illustrated Manx unit is a case in point. David’s standards of adherence to the original with his replicas were very high. He must have had access to authoritative detailed information regarding the original Manx design, but any such information appears now to be lost to us. His magazines and reference books were donated to the NSW Free Flight Society and are held at West Wyalong, NSW. However, much of David’s information on the Manx would probably have been collected personally and stored on his computer, hence now being lost. Conclusion I hope that you’ve enjoyed this ramble down Memory Lane to recall the heady early post-war period during which modellers in Australia were coming to grips with the challenges of creating winning racing engines On a final personal note, I was amazed to learn that Hearns Hobbies was still going, 77 years on at the time of writing (2024)! The business had been relocated down the block to 295 Flinders Street, which is actually in today’s Flinders Street Station. The funny thing is that I didn’t notice it As it turns out, I may not have missed much! My Aussie mate John Peric wrote in to tell me that for about 60 years, Hearns had been his hobby Mecca, which he had visited and patronized on a number of earlier occasions when in Melbourne. On August 6th, 2025 John's wife took him on a visit to Melbourne for his birthday, and a pilgrimage to Hearns Hobbies was an essential feature of this visit. Sadly, this visit turned out to be disappointing in the extreme. It turned out that the Hearns family had sold the business over twenty years ago. Under the new ownership, the shop had met the same fate that has befallen so many of the old "classic" hobby shops by morphing into an out-of-the-box toys 'n games outlet. John found nothing in the store relating to the aeromodelling hobby. True, there was the odd example of boxed push-button self-gratification on the shelf, but John couldn't even buy a token Dubro fuel tank! Fuel?!? Wot's that?!? John noticed some Hearns T-shirts hanging from the ceiling. These were left-overs from the store's 75th Anniversary a few years back. In desperation, John said that he'd take a shirt as a souvenir. "Haven't got any" was the response, after which John skulked out of the shop, vowing never to return. Seems that I was lucky in overlooking a visit back in 2015! A sad symptom of a dying hobby - how long can it be until we observe the last rites?!? ___________________________ Article Ⓒ Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2020 Revisions to "Other Australian Racing Engines" added April 2021 |

| |

In this article, I’ll present a summary of the development of classic racing engines in my native country of Australia during the first post-WW2 decade. The focus will be on the Tempest 10 cc model from Melbourne, Victoria because that’s the only such model of which I own an example. It’s also the only one that was ever advertised commercially and was subjected to an earlier historical review, hence being far better documented than its competitors. However, those competitors will by no means be ignored!

In this article, I’ll present a summary of the development of classic racing engines in my native country of Australia during the first post-WW2 decade. The focus will be on the Tempest 10 cc model from Melbourne, Victoria because that’s the only such model of which I own an example. It’s also the only one that was ever advertised commercially and was subjected to an earlier historical review, hence being far better documented than its competitors. However, those competitors will by no means be ignored! In a

In a

This led a number of talented Australian model enthusiasts to pursue the option of creating their own engines. Several of the key individuals who will feature later in this story became involved in model engine construction at this early stage.

This led a number of talented Australian model enthusiasts to pursue the option of creating their own engines. Several of the key individuals who will feature later in this story became involved in model engine construction at this early stage. Being a trained toolmaker, Bill was naturally attracted to the challenge of building his own model engine. He made his first such unit in around 1941. It was in essence a copy of the

Being a trained toolmaker, Bill was naturally attracted to the challenge of building his own model engine. He made his first such unit in around 1941. It was in essence a copy of the

During the post-contest

During the post-contest

I don’t intend to spend a lot of time on this section of the article because neither of these engines appears to present any unusual features which will not be completely familiar to most of my readers. Both engines were evidently designed very much along the same lines as the McCoy 60 from America which was the rising star in the American racing scene at the time, challenging the previously-dominant

I don’t intend to spend a lot of time on this section of the article because neither of these engines appears to present any unusual features which will not be completely familiar to most of my readers. Both engines were evidently designed very much along the same lines as the McCoy 60 from America which was the rising star in the American racing scene at the time, challenging the previously-dominant

Bankstown Airport had served as a military field during WW2. I actually have a familiy connection with this phase of the airport's existence thanks to the fact that aircraft manufacturer

Bankstown Airport had served as a military field during WW2. I actually have a familiy connection with this phase of the airport's existence thanks to the fact that aircraft manufacturer  Australian home-grown engines were well represented at this contest. Bill Marden had his own Marden 65-powered model and had also lent his second engine to his friend Len Stevens. A third Marden 65 entry was powered by the example which had been constructed by Harold Stevenson from castings supplied by Bill Marden. In Harold’s later recollection, this engine ran very well during testing but failed in the actual competition.

Australian home-grown engines were well represented at this contest. Bill Marden had his own Marden 65-powered model and had also lent his second engine to his friend Len Stevens. A third Marden 65 entry was powered by the example which had been constructed by Harold Stevenson from castings supplied by Bill Marden. In Harold’s later recollection, this engine ran very well during testing but failed in the actual competition.

Although this was a public holiday weekend, it seems that Australians played or watched sport on Saturdays and flew model aircraft on Sundays back then. The free flight day on the Sunday was held at nearby West Beach. The weather was rather windy, and there were several crashes, including the Tempest-powered model of future International Wakefield Trophy winner Allan King, which was wrecked. The main significance of this unhappy occurrence is the confirmation that it provides that the Tempest did see some use as an Open Power free flight powerplant. We'll encounter it again in that capacity.

Although this was a public holiday weekend, it seems that Australians played or watched sport on Saturdays and flew model aircraft on Sundays back then. The free flight day on the Sunday was held at nearby West Beach. The weather was rather windy, and there were several crashes, including the Tempest-powered model of future International Wakefield Trophy winner Allan King, which was wrecked. The main significance of this unhappy occurrence is the confirmation that it provides that the Tempest did see some use as an Open Power free flight powerplant. We'll encounter it again in that capacity. At around this time, Bill Marden was still working on improvements to his Marden 65, now in glow-plug configuration with a significantly enlarged bypass passage. Harold Stevenson still had his own .65 cuin. model running well but was now focusing on the development of a .29 cuin. sport model which was envisioned for series production. He constructed at least one prototype of this Sport model, actually still using it himself in 1955 when he installed it in his first R/C model, a “Rudderbug”. He continued to fly this model regularly until around 1960.

At around this time, Bill Marden was still working on improvements to his Marden 65, now in glow-plug configuration with a significantly enlarged bypass passage. Harold Stevenson still had his own .65 cuin. model running well but was now focusing on the development of a .29 cuin. sport model which was envisioned for series production. He constructed at least one prototype of this Sport model, actually still using it himself in 1955 when he installed it in his first R/C model, a “Rudderbug”. He continued to fly this model regularly until around 1960. were produced during 1950, all but six of the 42 engine batch finding buyers prior to the end of 1951 at a selling price of ten guineas (£10.50). The remaining six were held back for personal use and as experimental subjects. The engines were fitted with M&S glow-plugs which were primarily manufactured by Harold Stevenson.

were produced during 1950, all but six of the 42 engine batch finding buyers prior to the end of 1951 at a selling price of ten guineas (£10.50). The remaining six were held back for personal use and as experimental subjects. The engines were fitted with M&S glow-plugs which were primarily manufactured by Harold Stevenson.

Munro, also of Victoria, with an even more dismal speed of 73.7 mph. Even Norm Bell with his rich-running Tempest Mk. I of 1948 would have beaten Munro! The top speeds in Class B exceeded those of Class D by a handsome margin.

Munro, also of Victoria, with an even more dismal speed of 73.7 mph. Even Norm Bell with his rich-running Tempest Mk. I of 1948 would have beaten Munro! The top speeds in Class B exceeded those of Class D by a handsome margin. bearing housing for the cam follower. The omission of these features allowed the glow-plug version to be sold at a price of £10 even while the spark ignition variant was priced at £10 19s 6d (£10.95). This price differential dates the switch from the Mk. I to the Mk. II variant to some point prior to July 1950.

bearing housing for the cam follower. The omission of these features allowed the glow-plug version to be sold at a price of £10 even while the spark ignition variant was priced at £10 19s 6d (£10.95). This price differential dates the switch from the Mk. I to the Mk. II variant to some point prior to July 1950.

The fact that the Mk. II spark ignition and glow plug numbers appear to be freely intermingled in the sequence implies that the engines were numbered sequentially as they came off the line, regardless of the type of ignition. A further implication is that overall production figures were quite small. No M55xxx or M66xxx numbers have been reported so far.

The fact that the Mk. II spark ignition and glow plug numbers appear to be freely intermingled in the sequence implies that the engines were numbered sequentially as they came off the line, regardless of the type of ignition. A further implication is that overall production figures were quite small. No M55xxx or M66xxx numbers have been reported so far.  It’s hard not to conclude that the promoters of the Tempest must have lost money on the engine, considering the outlay in tooling up, dies, etc. as well as the clear attention paid to maximizing the quality of the final product. Certainly no other in-house model engine designs were subsequently promoted by Hearns Hobbies.

It’s hard not to conclude that the promoters of the Tempest must have lost money on the engine, considering the outlay in tooling up, dies, etc. as well as the clear attention paid to maximizing the quality of the final product. Certainly no other in-house model engine designs were subsequently promoted by Hearns Hobbies.

For completeness, it remains to acknowledge the existence of several other big-bore Australian racing engines both from this period and from a later era. Among these are the Meteor 60 and the Manx 60 spark ignition models from the late 1940's. Both of these units appear to have been intended specifically for tether car racing - there’s no record of their use in aeromodelling. Both engines were very much based upon the design of the McCoy 60 Series 20.

For completeness, it remains to acknowledge the existence of several other big-bore Australian racing engines both from this period and from a later era. Among these are the Meteor 60 and the Manx 60 spark ignition models from the late 1940's. Both of these units appear to have been intended specifically for tether car racing - there’s no record of their use in aeromodelling. Both engines were very much based upon the design of the McCoy 60 Series 20.  "available shortly". My thanks to Douglas Rochlin for bringing this advertisement to my attention.

"available shortly". My thanks to Douglas Rochlin for bringing this advertisement to my attention.

Larson's original drawing. Buyers were mostly unaware of the somewhat questionable background to this unauthorized offering. Quite understandably, the Larson family were most unhappy about Bernhardt's unsanctioned commercial use of their material, accordingly asking him to return the patterns. Of course, the plans were "out there" and couldn't be recovered.

Larson's original drawing. Buyers were mostly unaware of the somewhat questionable background to this unauthorized offering. Quite understandably, the Larson family were most unhappy about Bernhardt's unsanctioned commercial use of their material, accordingly asking him to return the patterns. Of course, the plans were "out there" and couldn't be recovered.