|

|

Classic “Whodunnit” - the Keil K6

As I’ve noted in other articles about early post-WW2 British engines, the model engine manufacturing business in that country had taken an enforced 5½ year break while the outcome of WW2 was being decided. Other nations which were not directly involved in the conflict as battlegrounds for one reason or another had made considerable progress during the war years, particularly in the emerging field of model diesel design. The Brits came out of the war with a lot of catching up to do! Naturally, this catching up couldn’t take place overnight. During the first year or so following the conclusion of the conflict, British designers and manufacturers returned to what they already knew - turning out spark ignition motors having a distinctly late 1930’s style. In effect, they picked things up from where they’d left them in September 1939. It took a year or more for their focus to switch to the compression ignition (“diesel”) technology which had been developed in Europe before and during the war. The Keil K6 sparker was a typical product of the initial post-WW2 period. It was marketed by Keil Kraft, who were a wholesale-only business at the time in question. Let’s have a look at this engine. Description

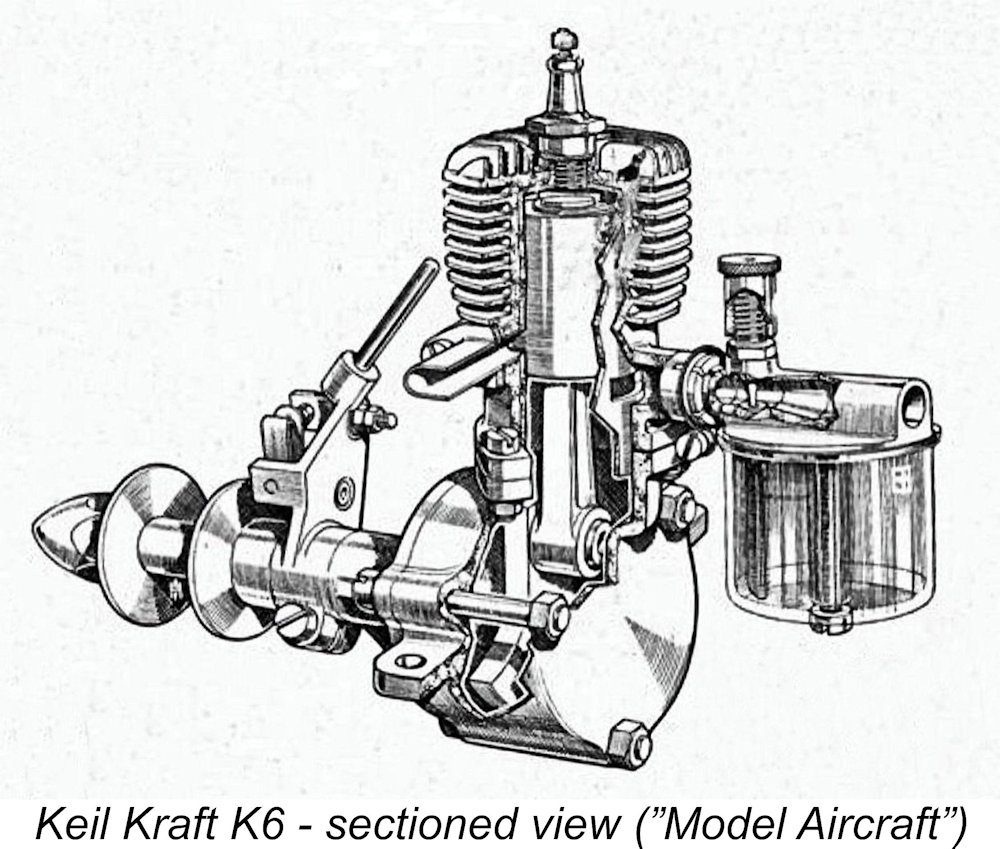

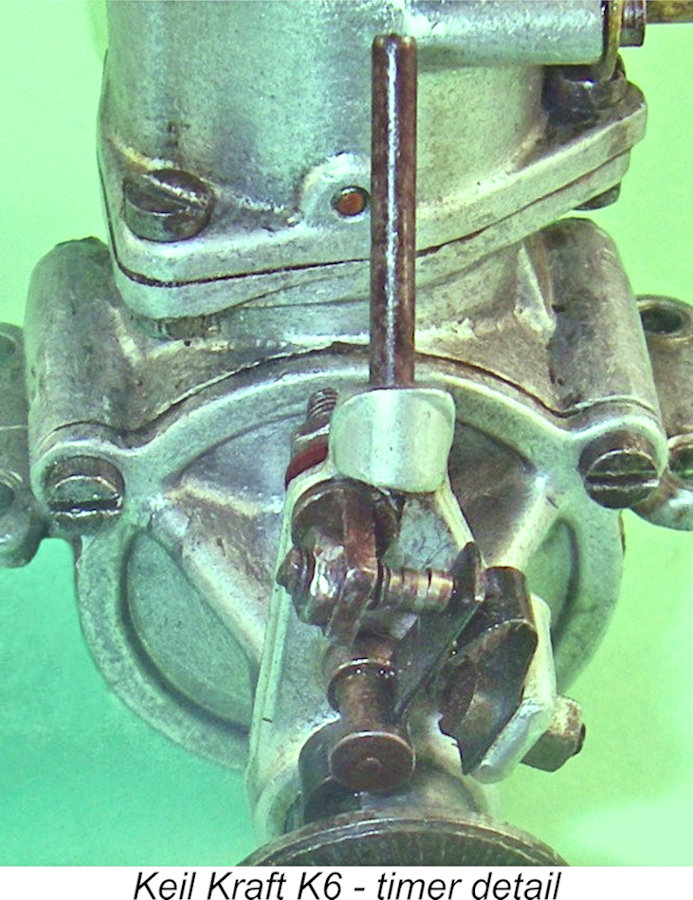

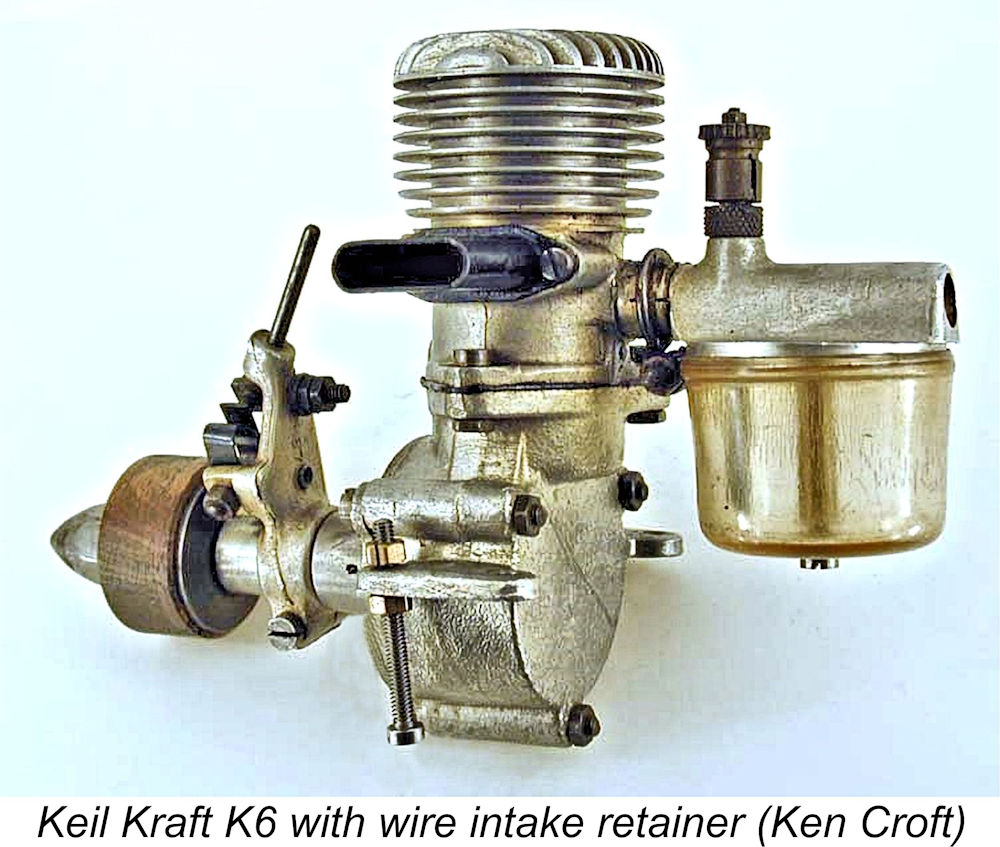

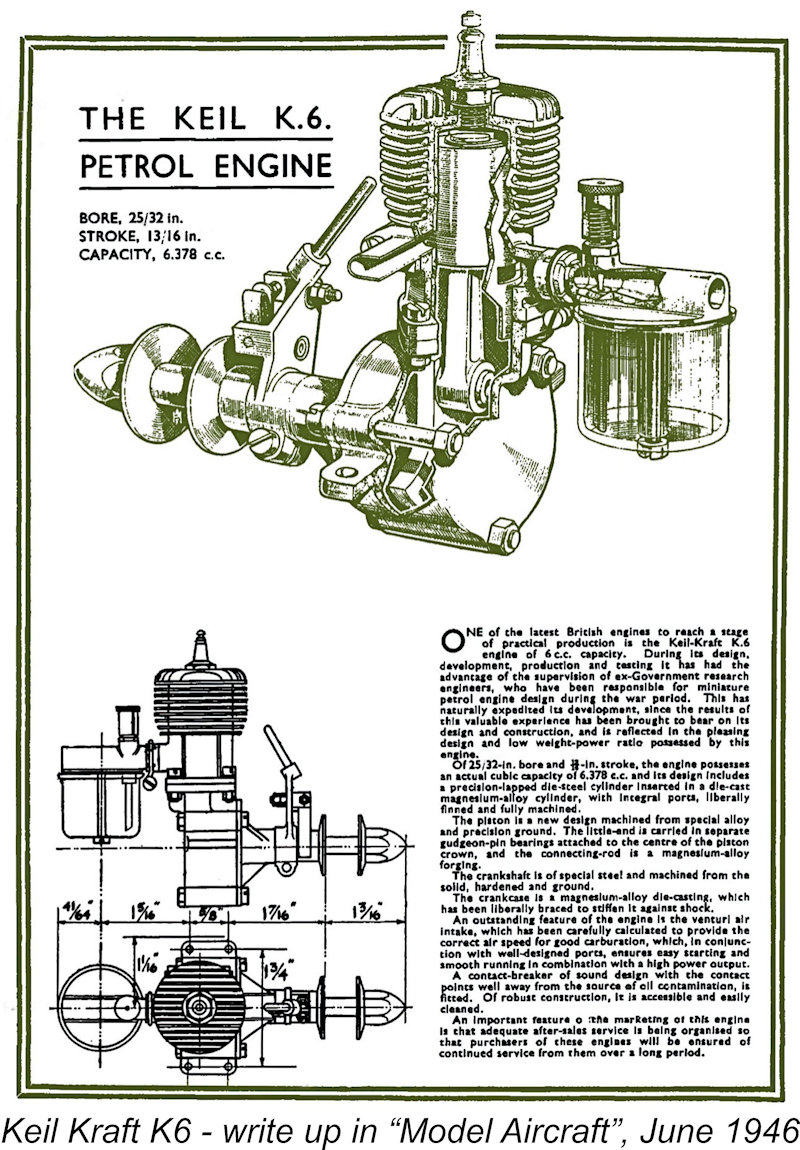

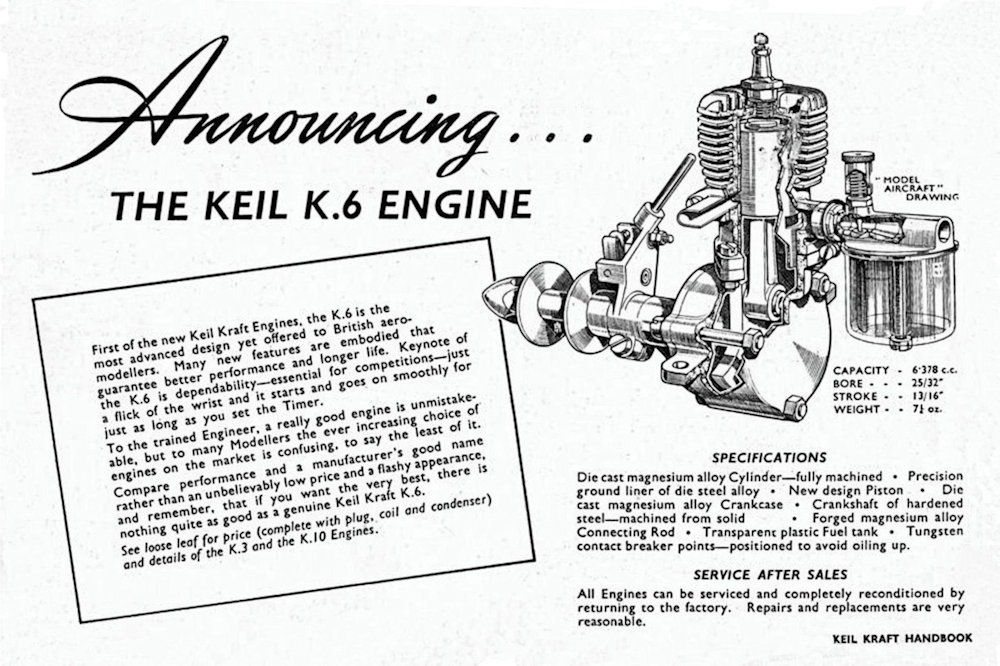

I acquired this example from Fred shortly before his death in 2011, and am thus only its third owner! It has clearly seen a considerable amount of use in a model at some point, but remains in generally excellent condition apart from some issues with the timer (see below) as well as a certain "softness" in the compression seal. Fred thought that he had almost certainly used it or at least run it himself, but could not recall the details after the passage of 65 years. Although it first appeared in early 1946, the K6 was basically a typical late 1930’s design featuring spark ignition, sideport induction, an open-frame timer, long-stroke internal geometry and relatively light construction. This was a period during which British precision engineers stubbornly maintained their long-established preference for working in fractional inch nominal dimensions. Despite this, British model engine designers of the day invariably expressed engine displacements in cubic centimetres (cc) - go figure!! Nominal bore and stroke As can be seen from the accompanying images, the K6 was a basically conventional sideport spark ignition engine of a type which had become more or less standard by the late 1930’s. It used separate upper and lower cylinder/crankcase castings which were secured to each other using three nut-and-bolt sets passing through matching lugs in both components. The use of nuts and bolts avoided reliance upon threads formed directly in the casting material - a good feature given the relatively thin lugs employed. The accompanying sectioned view from "Model Aircraft" shows the K6's main structural features. The upper casting incorporated the cylinder head in unit and The engine employed cross-flow loop scavenging with a baffle piston. The gudgeon pin was installed inside the piston in a separate alloy carrier which had a quite broad spigot protruding through a central hole in the piston crown, being secured to the piston by swaging. The volumetrically measured compression ratio of my example is a quite healthy 8 to 1. The exhaust stack was a separate component made from a flattened brass tube which was brazed to the sheet brass installation The description of the engine which appeared in the 1946 Keil Kraft Handbook (see below) informs us that the engine used a substantial-looking forged alloy conrod driving a one-piece steel crankshaft. The crankweb was heavily counterbalanced. The same description states that all castings as well as the conrod were made of magnesium alloy. This may have been true of the original examples, but my engine and that owned by Ken Croft both feature aluminium alloy die-castings. I would guess that the conrod was of the same material as the case in all instances. The backplate was cast in unit with the crankcase, the front housing being of the removable type which was secured with three long bolts and matching nuts. Again, the designer avoided any reliance upon threads The timer cam was machined directly into the front of the crankshaft’s main journal. The engine was equipped with an open-frame timer of quite complex design. It was fully adjustable in terms of both point gap and rotational tension. The measured dwell period provided on my example (angle of crankshaft rotation during which the points are closed and the coil is charging) is around 50 degrees, implying an expectation that running speeds would be relatively modest. The one comment that can be made here is that the transversely-oriented timer looks extremely vulnerable to crash damage. On most examples, the prop was secured by a small-diameter hexagonal spinner nut and washer. My engine has a conventional spinner with a cross-hole for tightening which is well matched to the prop driver, hence very likely being original. Former owner Fred Johnson claimed that this spinner Another change is to be found at the rear. The delivery end of the intake tube plugs into a split spigot at the rear of the cylinder casting. The earlier models like that illustrated in the 1946 KeilKraft Handbook used a wire circlip to tighten the split. Ken Croft's illustrated example displays this feature. This circlip was tensioned with a screw and nut combination. However, my example has a seemingly far more sophisticated split collar machined from a light alloy casting. I suspect that both this feature and the spinner indicate a later example of the engine. The fuel supply arrangements were completely conventional. The needle valve was a surface jet assembly typical of those still in widespread use at the time. A split thimble was used for tensioning. The tank top was cast integrally with the intake venturi, while the tank was made of translucent plastic. Earlier engines had a typical hinged cover for the filler hole, but my seemingly later example has a screw-in plug with a vent hole to admit air as the fuel level is drawn down.

In addition, the three lugs which accommodate the cylinder hold-down bolts are very much on the skimpy side - a hard blow to the cylinder might very well break or at least crack one or more of these lugs. It is likely for the above reasons that very few examples of this engine ever see actual airborne service today. That having been said, a few of these engines evidently did see airborne service. My friend Allan Brown wrote in to tell be that he recently acquired a near-perfect example of this engine from Tony Overton after Tony's retirement from active aeromodelling. Tony had been using this engine successfully in a KK Junior 60 with R/C elevator/rudder controls. Allan tells me that the engine is a strong runner, althhough he has never flown it himself. Many examples bear serial numbers which are engraved onto the bottom of one of the mounting lugs - engine number 1016 of this type appeared a while back on eBay. My example bears the number 1275 engraved beneath the right-hand lug. My mate Peter Scott reports owning engine nos. 1373 and 1610. The implication is that the sequence started at 1001 and that over 600 examples were constructed - possibly more. I have encountered another example which does not bear a serial number of any kind. The example reported by Allan Brown also lacks a serial number. Could these be "spare parts" cases fitted to replace broken originals?!? Wouldn't surprise me! Recommended airscrews for the K6 were 12x6 for free flight and 10x8 for control line. I’d have to say that the engine’s rather flimsy structure and extremely vulnerable timer would argue strongly against its use in control line service, where occasional hard contacts with the ground are pretty much guaranteed. Anyone planning to use the engine in such an application would have done well to use the radial mounting option. But that still leaves the highly vulnerable timer ................ So much for the description of the K6. I’ll now summarize what is known or can be deduced about its development and marketing history. Origins

Despite the fact that the Kemp K4 and the Keil K6 display absolutely no design relationship, the identical naming protocol has been taken to suggest that both engines were the work of Harold Kemp and that the K4 diesel followed the K6 sparkie, with the respective numbers being loosely based upon the engines' displacements. In addition, it's known that there was undoubtedly a close association between Harold Kemp and Eddie Keil, since from the outset Keil acted as one of the main distributors of the Kemp engines. A further straw in the wind has been gleaned from a fairly detailed write-up on the K6 which appeared in the June 1946 issue of “Model Aircraft”. In that text (which actually reads like a manufacturer’s statement), the writer included the following comment:

It’s definitely known that Harold Kemp spent the war years working at Rochester, Kent for the famous aircraft manufacturer Short Brothers, who produced such iconic aircraft as the Sunderland flying boat and the Stirling bomber at their factory located at Rochester Airport. It’s less well known that in 1934 Shorts had purchased the co-located Pobjoy Airmotors company, who developed and manufactured small petrol engines for such applications as reduced-scale prototype aircraft and airborne generators, working closely with Short Brothers in doing so. The reference to the involvement of wartime small-engine designers could well refer to members of the engineering staff at Pobjoy, and Harold Kemp could undoubtedly have been one of those individuals. That said, it must be admitted that the design layout and construction style of the K6 bear no resemblance whatsoever to Harold Kemp’s later work. If Kemp was involved at all, he was almost certainly not the lead designer. Even so, the notion that Pobjoy Airmotors were involved in the design and manufacture of the Keil K6, with some level of involvement from Harold Kemp, seems to me to constitute the most compelling theory presented to date. It is certainly consistent with the information set out in the "Model Aircraft" write-up. In a brief article about the engine which appeared on Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website, K6 owner Ken Croft had this to say about the engine: “The Keil K6 is in a different league. I cannot imagine Harry Kemp turning out anything quite so complex and nice and nobbly as the fragile K6. I think it is a lovely thing, but rarely flown these days due to the three very weak cylinder hold-down lugs, and the equally thin beam mounting lugs. In good condition with the exhaust stack and all the bits, they are quite difficult to find these days. They usually have a cracked casting somewhere, missing or broken fins, a melted tank, sometimes a complete repro tank/carb top, and almost always no exhaust stack. I am lucky as I found a good complete one some years ago. Still no idea who made them. There was no British engine I can recall that was so nicely made at the time”. Another straw in the wind that has surfaced comes from my friend and colleague Kevin Richards, who recalls someone (he can’t remember who) telling him years ago that the K6 was manufactured for Eddie Keil by Bassett-Lowke. This is certainly possible, but there’s absolutely no supporting evidence of which either Kevin or I are aware.

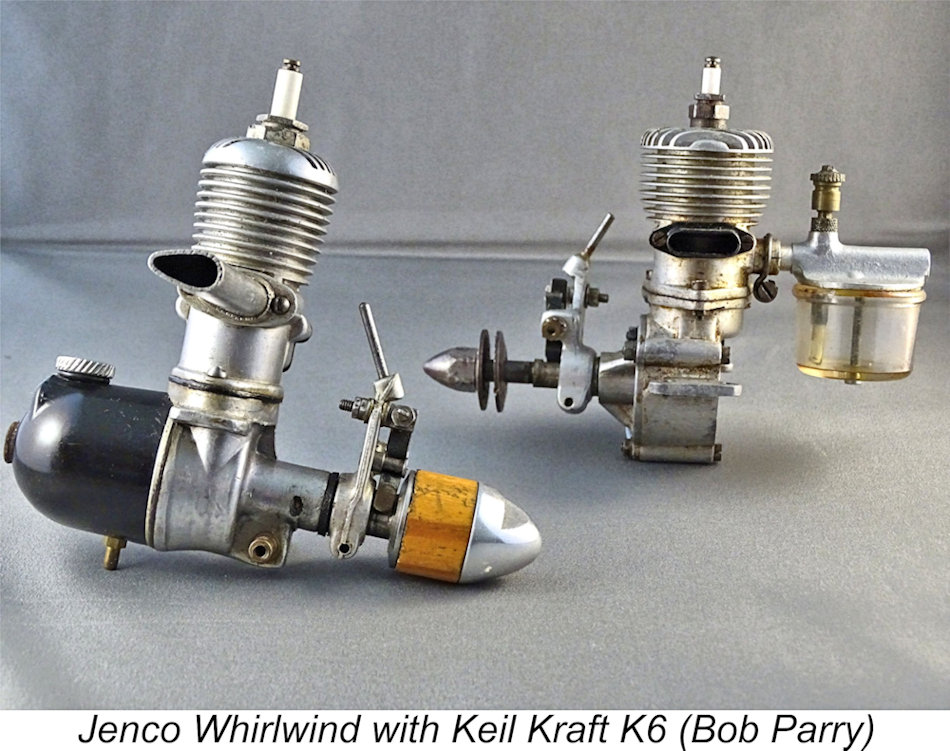

What set Bob to thinking was the fact that his new acquisition sports a timer which is a clone of that used on the Keil Kraft K6. There is no sign of the engine having been dismantled at any time so that any required machining of the front housing could be carried out. In any case, why would an owner discard a perfectly functional Jenco timer in favour of the finicky and rather vulnerable K6 set-up?? And where would he get such a timer in any case?

Bob's interpretation was that Jenco may well have been the manufacturers of the K6 and that when making the final examples of their own 6.2 cc FRV model they simply used up some left-over K6 timers. They were certainly in business during the appropriate period, also undoubtedly possessing the necessary capabilities. But then ........why would they go into production for themselves in competition with an engine of similar displacement which they were then manufacturing for others? It's equally likely that a previous owner had fiitted the K6 timer to Bob's engine to replace a missing or broken Jenco original. This is all fascinating food for thought, but the sad fact is that it’s no more amenable to being proved than any of the other suggestions. It’s extremely doubtful that we’ll ever know the truth of this matter, although the Pobjoy Airmotors theory appears to me to be the most credible one offered so far. Regardless, my thanks to Bob for making us aware of this alternative possibility! Marketing History

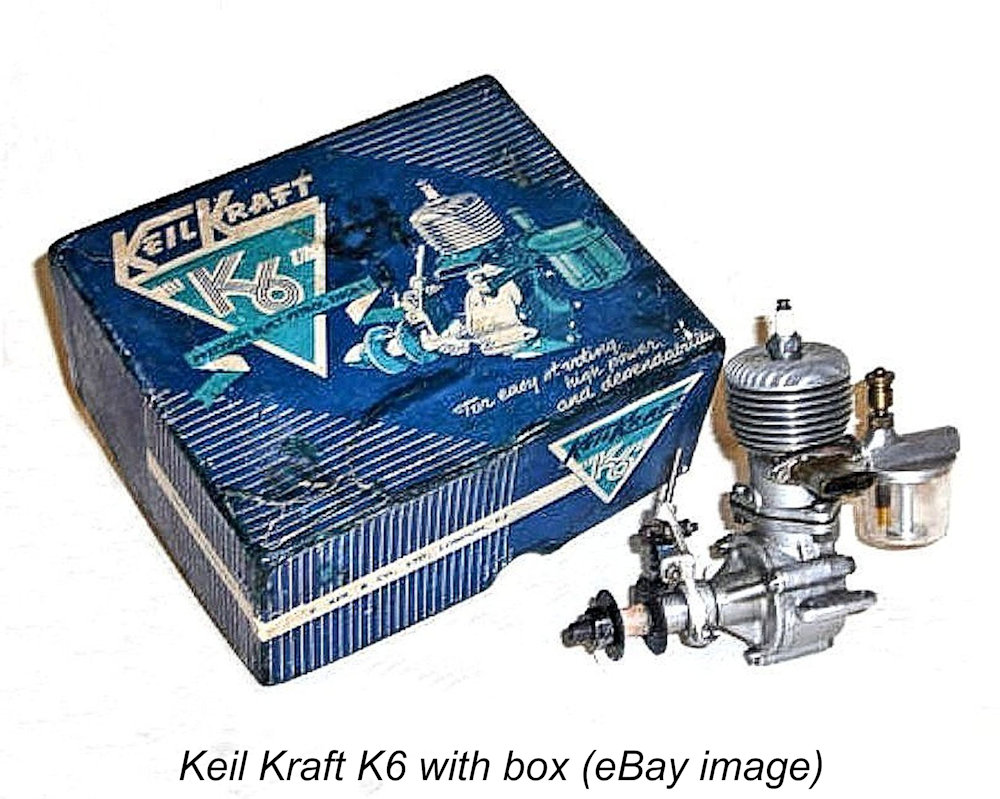

The major problem with the identification of the engine's manufacturer is the fact that from the outset it was promoted specifically as a Keil Kraft product despite the seeming improbability of Keil Kraft having had anything to do with its manufacture. They were woodworkers and marketing specialists, not precision engineers. Even so, whoever actually produced it, Keil Kraft were clearly determined to take the credit! In their own 1946 Handbook Keil Kraft characterised the K6 as being "the first of the new Keil Kraft engines", thereby The engines were sold in attractively-decorated cardboard boxes complete with coil and condenser. The box label extolled the engine’s virtues as being “easy starting, high power and dependability”. Keil Kraft gave their own company name as that of the manufacturer, once again bringing us no closer to discovering who really manufactured these engines. It bears repeating that it certainly wasn’t Keil Kraft, who were a woodworking operation concerned with balsa wood kit manufacture. The engine’s first “starring” appearance seems to have come in the previously-cited article from the June 1946 issue of “Model Aircraft”. In addition to the previously-quoted The K6 was also the subject of a full-page spread in the 1946 Keil Kraft Handbook as reproduced here. The cutaway drawing from “Model Aircraft” was used to illustrated the text in this publication, presumably with the magazine’s permission. The engine’s listing in the Handbook is interesting in that it refers to the K6 as “the first of the new Keil Kraft engines”. This somewhat enigmatic statement is clarified a little by the mention on the “Accessories” By September of 1946 the K6 was being more prominently featured in Keil Kraft’s advertising, The K6 continued to be listed until November 1946, after which its advertising appearances declined in prominence, also becoming very sporadic. The final Keil Kraft advertisement in which the engine was on offer was their placement of November 1947 which is reproduced at the left. The advertisement for the K6 included the advice to "get yours while supplies last". The unmistakable implication was that production had ended in mid 1947 at the latest. An extremely interesting observation is the fact that none of Keil Kraft’s advertisements included a selling price for the engine. In part, this may have been due to the fact that at the time Keil Kraft was a strictly wholesale business, inviting trade inquiries only. Reader Dave Causer has suggested that this was perhaps a parallel situation to that of Rolls Royce automobiles - if you had to ask about the price, you couldn't afford one!

The engine also continued to appear sporadically in KeilKraft advertisements through most of 1947. Its final appearance in one of these advertisements seems to have been in November of 1947, when it was included in Keil Kraft’s previously-cited full-page rear cover advertisement. Its very last appearance came in Keil Kraft’s May 1948 advertisement which focused upon the Slicker series of free flight power duration models. The K6 was listed as one of the engines suitable for the largest member of the clan, the Super Slicker 60. After that, the rest is silence…………….it would appear certain that actual production had ended by late 1947. The K6 remained on offer from a few dealers throughout the remainder of 1948, but these were undoubtedly New Old Stock. Both Bud Morgan and Laws Model Supplies offered the engine until at least November 1948. Oddly enough, the K6 was included in the listing of British engines which formed Appendix II of Ron Warring’s early 1949 book "Miniature Aero Motors". No structural details were provided, but the engine was not accompanied by the asterisk which would have indicated that it was no longer in production. It would appear that Warring was singularly ill-informed regarding this engine - one wonders why he bothered to list it at all! There’s no question that it was long out of production as of the date of Warring’s publication. The K6 on Test This phase of my review was considerably constrained by the fact that, as received, my otherwise very nice example had a non-functional timer. The moving point had broken, and a previous owner (Fred Johnson or a well-meaning friend trying to help?!?) had attempted to make an ultimately unsuccessful repair by brazing.

While considering an appropriate range of test props for the K6, I referred to my previous test of the contemporary Mechanair 5.9 cc model. It seemed reasonable to suppose that the K6 would have a fairly similar performance to that of the slightly lesser-displacement Mechanair. A Zinger 11x7 wood prop had suited the Mechanair very well, so I decided to begin with that prop and see where the results led me. The plastic tank would clearly not stand up to methanol fuel, so I used my standard classic sparkie brew of 75% Coleman Camp Fuel (white gas substitute) and 25% SAE 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120). Few British modellers would have used anything other than a petrol-based fuel in 1946-47. The sparks were supplied by one of my Larry Davidson SSIGNCO units, which have proved completely dependable in service. Once the engine was mounted in the test stand, a major problem soon asserted itself. It turned out that the "soft" compression seal mentioned earlier was far more of an issue than I had originally supposed. Once the thick storage oil was replaced by far less viscous fuel mixture, most of the compression went away, leaving too little to sustain operation of the engine. So my first attempt ended in failure. Things were looking bleak ........

Athough it lacked a tank assembly and an exhaust stack, this unit turned out to have excellent compression. By combining the components of Ken's example with those from my own unit, I was able to assemble a fully operable example of the engine. One point that should be mentioned here in passing is the fact that Ken's engine was equipped with a very neat tankless intake venturi presumably intended to facilitate control-line use. I can't say whether or not this was a factory accessory - all I can report is that it is extremely well made and suits the engine perfectly. It was clearly made specifically for this unit. That said, I'd be very reluctant to expose this very "fragile" engine to the rough-and-tumble of control-line flying .............. Anyway, with the engine now in excellent running order, I returned it to the test stand with the 11x7 Zinger prop fitted once more. It was immediately apparent that there was plenty of compression for starting. For the purposes of this test, I fitted a modern Rimfire plug, since these are more dependable than any vintage plug. I also fitted a conventional propnut and washer to conserve the aluminium alloy spinner nut. After checking the timer function one last time and filling the tank with my standard white gas fuel, I got stuck in.

Even then, my troubles weren't over. I had set the needle by guesswork at 2 turns open. This proved to be way too rich - the engine fired very sluggishly and immediately flooded itself to a halt, leaving another cylinder-full of excess fuel to be cleared. I ended up with the needle at only ½ a turn open, and even then the engine started up quite rich. But start it eventually did, and I was finally away! The K6 turned out to be unusually sensitive to the needle setting - only around a quarter-turn covered the range from super-rich to leaned-out. However, response was quite linear within this range, making the establishment of the desired setting perfectly straightforward. Response to the timer setting was very positive - the best position was easily established. Both controls held their settings perfectly. The engine ran with a throaty exhaust note that was music to my ears (but perhaps not to those of the neighbours!).

Re-starts proved to be completely straightforward, hot or cold - a few choked flicks, switch on the ignition and a few more flicks invariably had the K6 going once more. Being such a slow-speed unit, the engine could be started on running settings with no difficulty. I could see little point in putting this engine through a full test - I had proved to my own satisfaction that it was a fine-handling and smooth-running powerplant with a better-than-average performance for a spark ignition sports engine of its date. So after putting on 4 or 5 more runs just for fun, I terminated the testing with the engine still in perfect running order and clearly willing to do more if called upon to do so. That'll do me!! Summary and Conclusion The Keil K6 was among the very first model engines to appear on the British market following WW2 - quick work on someone’s part. The long-standing oral tradition that Harold Kemp was involved is very thinly supported by circumstantial evidence, but on architectural grounds it appears to be highly unlikely that he was the engine’s primary designer. If he was involved at all, it was most likely as part of a team. At this point, the engineering staff at Pobjoy Airmotors, of whom Harold Kemp may have been a member, remain the most likely suspects. The K6 evidently appeared in January 1946, since it was first mentioned in February 1946 in a Keil Kraft advertisement. It continued to be mentioned in those ads from time to time until November 1947, after which its only appearance was in a May 1948 list of powerplants suitable for the Super Slicker 60. It was advertised by Henry J. Nicholls until February 1948, after which it disappeared from his listings as well.

I confess to harbouring a strong suspicion that all examples of the K6 were manufactured in 1946 and early 1947. It would have made no sense at all to continue to manufacture and market a big, heavy sparker once the diesels took over, especially when no kit in the Keil Kraft range was large enough for the K6 at the time. This situation probably also killed off the planned K4 and K10 models. It’s actually quite surprising that the K6 remained on offer into early 1948, although by that time it was almost certainly New Old Stock that was being marketed. It’s even more surprising to note that the quoted selling price was never reduced - evidently the K6 was seen as something of a “Rolls Royce” among model spark ignition engines. Those who remained faithful to sparkies (and there were some) were evidently willing to pay for this one! My assessment is that they got value for money, although they would have had to be careful to keep the engine out of hard contact with the Big Green Thing! I hope that you’ve enjoyed this look at one of the more enigmatic and seldom-seen model engines of the early post-WW2 era in Britain. Despite its various design quirks, this engine does credit to its designers and manufacturers! I truly wish that we knew who they were ………. __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published July 2024 |

| |

Here I’ll be taking a look at a short-lived post-WW2 British spark ignition motor - the Keil K6 sideport unit of 6.38 cc displacement. This article will be somewhat different from my usual efforts in that it won’t contain a great deal of the history that is one of my main personal interests. That’s because we really don’t know a great deal about the history of this engine or the personalities involved, so there’s not much to tell! The main focus here will be a full description of the engine itself - much of the rest remains a mystery. If any reader can enlighten me further, please get in touch!

Here I’ll be taking a look at a short-lived post-WW2 British spark ignition motor - the Keil K6 sideport unit of 6.38 cc displacement. This article will be somewhat different from my usual efforts in that it won’t contain a great deal of the history that is one of my main personal interests. That’s because we really don’t know a great deal about the history of this engine or the personalities involved, so there’s not much to tell! The main focus here will be a full description of the engine itself - much of the rest remains a mystery. If any reader can enlighten me further, please get in touch! The Keil K6 is a relatively rare engine today, especially in complete and original condition. I obtained my own illustrated example from an elderly gentleman named Fred Johnson (now deceased) who claimed to be only its second owner! Fred knew Keil Kraft founder Eddie Keil personally, associating with him at numerous early post-WW2 aeromodelling events. By Fred’s own account, this example was given to him by Eddie Keil in person at a meeting at Fairlop in 1946. Reportedly such expressions of generosity towards friends were typical of Eddie Keil. Fred had kept the engine ever since as a memento of his mate Eddie.

The Keil K6 is a relatively rare engine today, especially in complete and original condition. I obtained my own illustrated example from an elderly gentleman named Fred Johnson (now deceased) who claimed to be only its second owner! Fred knew Keil Kraft founder Eddie Keil personally, associating with him at numerous early post-WW2 aeromodelling events. By Fred’s own account, this example was given to him by Eddie Keil in person at a meeting at Fairlop in 1946. Reportedly such expressions of generosity towards friends were typical of Eddie Keil. Fred had kept the engine ever since as a memento of his mate Eddie. of the K6 were 25/32 in. (0.7812 in. - 19.84 mm) and 13/16 in. (0.8125 in. - 20.64 mm) respectively for a nominal displacement of 6.38 cc (0.389 cuin.). The engine’s checked weight with plug, stack and tank but minus the ignition support system was 207 gm (7.3 ounces) – a very reasonable figure for an engine of this displacement complete with tank.

of the K6 were 25/32 in. (0.7812 in. - 19.84 mm) and 13/16 in. (0.8125 in. - 20.64 mm) respectively for a nominal displacement of 6.38 cc (0.389 cuin.). The engine’s checked weight with plug, stack and tank but minus the ignition support system was 207 gm (7.3 ounces) – a very reasonable figure for an engine of this displacement complete with tank. accommodated a blind-bored hardened steel cylinder liner. The plug installation spigot was machined integrally with the steel liner and protruded through the cylinder head casting to accommodate the plug. I have chosen not to disturb my well-sealed and “experienced” example, but the visible presence of a steel pin at the front (clearly visible in several of the accompanying images) suggests that the cylinder liner is retained in its correct annular alignment relative to the passages formed in the housing through the use of a hole in the liner which matches the pin location.

accommodated a blind-bored hardened steel cylinder liner. The plug installation spigot was machined integrally with the steel liner and protruded through the cylinder head casting to accommodate the plug. I have chosen not to disturb my well-sealed and “experienced” example, but the visible presence of a steel pin at the front (clearly visible in several of the accompanying images) suggests that the cylinder liner is retained in its correct annular alignment relative to the passages formed in the housing through the use of a hole in the liner which matches the pin location. flange. It was secured to the engine with two screws. This stack is missing on many examples encountered today.

flange. It was secured to the engine with two screws. This stack is missing on many examples encountered today. cut directly into the crankcase material, making a stripped thread a far less serious issue than it would be otherwise. The arrangement also offered the possibility of mounting the engine radially, in which mode it would be far less subject to crash damage than with the rather skimpy beam mounts provided.

cut directly into the crankcase material, making a stripped thread a far less serious issue than it would be otherwise. The arrangement also offered the possibility of mounting the engine radially, in which mode it would be far less subject to crash damage than with the rather skimpy beam mounts provided.  was with the engine when he received it from Eddie Keil. It appears that a change may have been made at some point along the way to increase the engine’s eye appeal.

was with the engine when he received it from Eddie Keil. It appears that a change may have been made at some point along the way to increase the engine’s eye appeal.  A few comments are in order with respect to the engine’s structural integrity. I already mentioned the seeming vulnerability of the timer to crash damage. The split spigot which is used to mount the fuel supply system also appears highly susceptible to impact-related failure. Most glaringly, the mounting lugs are extremely ill-adapted to deal with impacts arising from unplanned contacts with terra firma, being unusually thin for an engine of this size and also having a relatively short attachment length on the crankcase. The logic of the design is really difficult to discern - even a modest crash impact would be almost guaranteed to break one or both lugs.

A few comments are in order with respect to the engine’s structural integrity. I already mentioned the seeming vulnerability of the timer to crash damage. The split spigot which is used to mount the fuel supply system also appears highly susceptible to impact-related failure. Most glaringly, the mounting lugs are extremely ill-adapted to deal with impacts arising from unplanned contacts with terra firma, being unusually thin for an engine of this size and also having a relatively short attachment length on the crankcase. The logic of the design is really difficult to discern - even a modest crash impact would be almost guaranteed to break one or both lugs.  There’s a long-standing but completely unsubstantiated oral association of the name of Harold Kemp of

There’s a long-standing but completely unsubstantiated oral association of the name of Harold Kemp of  “During its design, development, production and testing (the K6) has had the advantage of the supervision of ex-Government research engineers, who have been responsible for miniature petrol engine design during the war period. This has naturally expedited its development, since the results of this valuable experience have been brought to bear on its design and construction and are reflected in the pleasing design and low weight-power ratio possessed by this engine”.

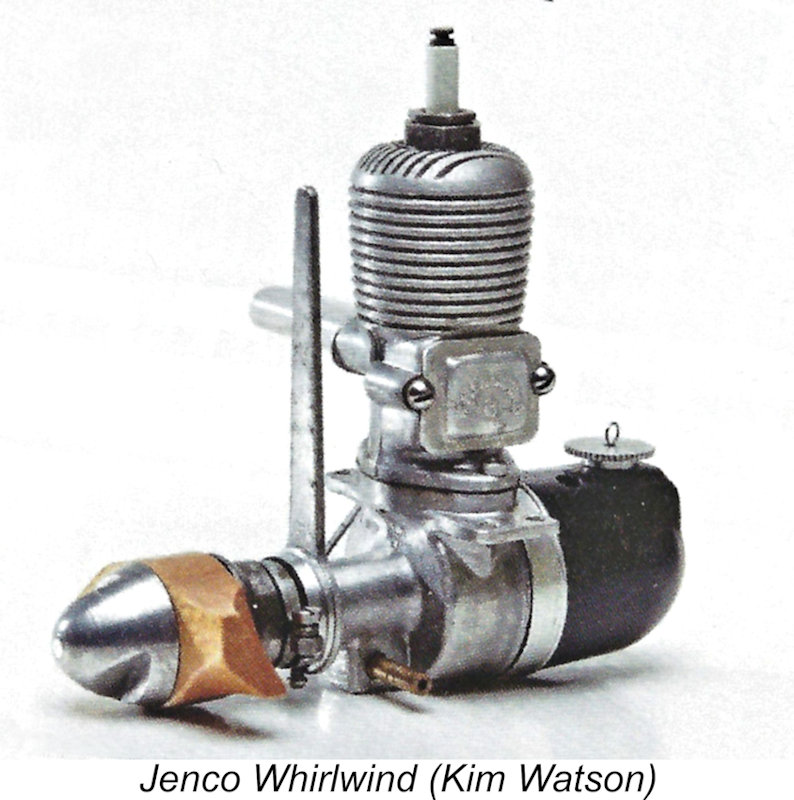

“During its design, development, production and testing (the K6) has had the advantage of the supervision of ex-Government research engineers, who have been responsible for miniature petrol engine design during the war period. This has naturally expedited its development, since the results of this valuable experience have been brought to bear on its design and construction and are reflected in the pleasing design and low weight-power ratio possessed by this engine”. Another credible theory comes from reader Bob Parry, who had acquired a seemingly unused example of the very rare Jenco Whirlwind 6.2 cc front rotary valve (FRV) spark ignition engine. These engines were manufactured in 1946-47 by Jenco Engineering Co. Ltd. of 43 Castle Street, Hinkley, Leicestershire. The company continued in small-scale production until 1948, producing both glow-plug and diesel variants along the way.

Another credible theory comes from reader Bob Parry, who had acquired a seemingly unused example of the very rare Jenco Whirlwind 6.2 cc front rotary valve (FRV) spark ignition engine. These engines were manufactured in 1946-47 by Jenco Engineering Co. Ltd. of 43 Castle Street, Hinkley, Leicestershire. The company continued in small-scale production until 1948, producing both glow-plug and diesel variants along the way. Bob’s impression was that the K6 timer was original equipment on this example of the Whirlwind. Against that, the example illustrated in Ted Sladden's book "

Bob’s impression was that the K6 timer was original equipment on this example of the Whirlwind. Against that, the example illustrated in Ted Sladden's book " Whatever the truth regarding the origins of the K6, it’s an undeniable fact that the engine appeared remarkably quickly following the conclusion of WW2. As far as I’m aware, the engine was first mentioned in the attached Keil Kraft advertisement which appeared in the February 1946 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Its inclusion was confined to a small-print footnote at the lower right in the advertisement under the heading "Petrol Engines", a position which it was to continue to occupy until at least August 1946. Nonetheless, its mention in this advertisement appears to date its market debut to January 1946 at the latest.

Whatever the truth regarding the origins of the K6, it’s an undeniable fact that the engine appeared remarkably quickly following the conclusion of WW2. As far as I’m aware, the engine was first mentioned in the attached Keil Kraft advertisement which appeared in the February 1946 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Its inclusion was confined to a small-print footnote at the lower right in the advertisement under the heading "Petrol Engines", a position which it was to continue to occupy until at least August 1946. Nonetheless, its mention in this advertisement appears to date its market debut to January 1946 at the latest.

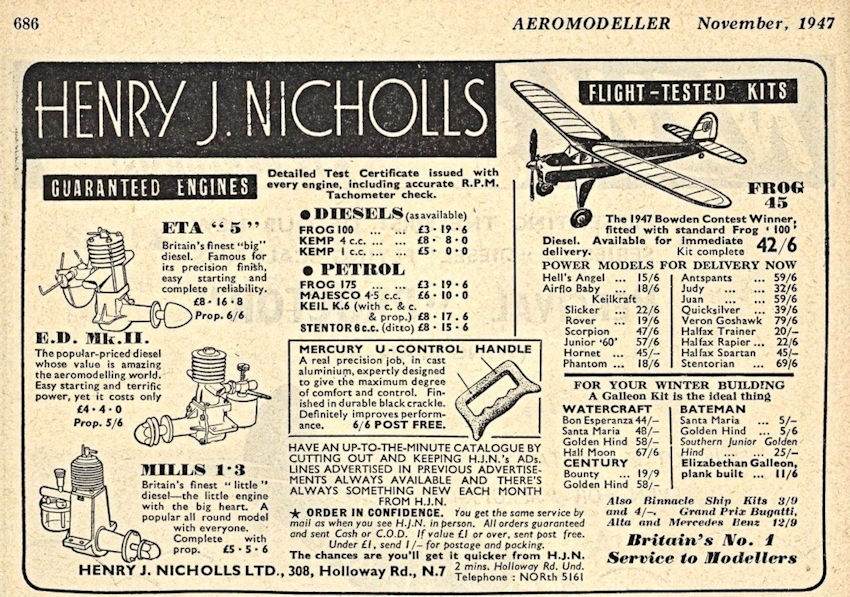

Our best guide to the selling price of the engine comes from the fact that at some point along the way the K6 was picked up by Henry J. Nicholls’ rapidly-expanding model supply business at 308 Holloway Road in London. From mid 1947 onwards for some time thereafter, the K6 was listed regularly as being among the engines supplied by HJN. The list price was a princely £8 17s 6d (£8.88) complete with coil, condenser and prop - over a week’s before-tax wages for a reasonably well-off individual in early post-WW2 Britain. The K6 continued to be listed in Nicholl’s advertisements through to February 1948, being offered at an unchanged price throughout. After February 1948 it quietly disappeared from Nicholls' advertising.

Our best guide to the selling price of the engine comes from the fact that at some point along the way the K6 was picked up by Henry J. Nicholls’ rapidly-expanding model supply business at 308 Holloway Road in London. From mid 1947 onwards for some time thereafter, the K6 was listed regularly as being among the engines supplied by HJN. The list price was a princely £8 17s 6d (£8.88) complete with coil, condenser and prop - over a week’s before-tax wages for a reasonably well-off individual in early post-WW2 Britain. The K6 continued to be listed in Nicholl’s advertisements through to February 1948, being offered at an unchanged price throughout. After February 1948 it quietly disappeared from Nicholls' advertising.  I’m blessed with many good friends in the model engine community, among whom is my valued English mate Miles Patience. Upon learning of my difficulty, Miles was kind enough to search out a complete original timer and send it my way. This timer functioned perfectly once installed, paving the way to a full test of this engine.

I’m blessed with many good friends in the model engine community, among whom is my valued English mate Miles Patience. Upon learning of my difficulty, Miles was kind enough to search out a complete original timer and send it my way. This timer functioned perfectly once installed, paving the way to a full test of this engine.  However, things have a way of working out somehow! A little later, I was lucky enough to establish contact with a fellow resident of British Columbia's Lower Mainland - Ken Campbell. Ken's collecting vice is classic British motorcycles, but he had then recently come into possession of his late brother Dave's extensive model engine collection. Among those items was an incomplete but functional example of the Keil K6!

However, things have a way of working out somehow! A little later, I was lucky enough to establish contact with a fellow resident of British Columbia's Lower Mainland - Ken Campbell. Ken's collecting vice is classic British motorcycles, but he had then recently come into possession of his late brother Dave's extensive model engine collection. Among those items was an incomplete but functional example of the Keil K6!  Unfortunately, I let myself in for a hard time by making one mistake - I administered an exhaust prime. Wrong!!! It turned out that the K6 simply hated being anything approaching "wet" - all that was really required were a few choked flicks. When really wet, it wouldn't even fire! As it was, I had to flick for ages to clear enough fuel out of the engine to get a few firing strokes.

Unfortunately, I let myself in for a hard time by making one mistake - I administered an exhaust prime. Wrong!!! It turned out that the K6 simply hated being anything approaching "wet" - all that was really required were a few choked flicks. When really wet, it wouldn't even fire! As it was, I had to flick for ages to clear enough fuel out of the engine to get a few firing strokes.  When adjusted correctly, the K6 proved to be quite a sturdy performer, turing the 11x7 Zinger prop at a dead smooth and sag-free 6,300 RPM - well up on the performance of the slightly lower-displacement Mechanair on the same prop. This implies an output at that speed of around 0.191 BHP - not at all bad by the standards of 1946 for a 6.4 cc engine running on white gas. There might be a little more power available at a higher speed, but I rather doubt it - I reckon that the engine was operating near its peak on that prop. There was some vibration at the tested speed, but it didn't appear to be excessive.

When adjusted correctly, the K6 proved to be quite a sturdy performer, turing the 11x7 Zinger prop at a dead smooth and sag-free 6,300 RPM - well up on the performance of the slightly lower-displacement Mechanair on the same prop. This implies an output at that speed of around 0.191 BHP - not at all bad by the standards of 1946 for a 6.4 cc engine running on white gas. There might be a little more power available at a higher speed, but I rather doubt it - I reckon that the engine was operating near its peak on that prop. There was some vibration at the tested speed, but it didn't appear to be excessive.  The implication is that the engine was probably only in production for a year or so at most - quite possibly less. The relatively small number of survivors suggests that production figures were not large. The K6 had the misfortune to be introduced only a few months prior to the appearance of early British diesels like the

The implication is that the engine was probably only in production for a year or so at most - quite possibly less. The relatively small number of survivors suggests that production figures were not large. The K6 had the misfortune to be introduced only a few months prior to the appearance of early British diesels like the