Early Diesel Development

Editor’s note - The origins of the model diesel engine and the international dissemination of its technology are among the least well-understood aspects of model engine history. The model diesel has typically been thought of as essentially a post-WW2 development, largely due to the fact that commercially-produced diesels did not begin to appear in the major English-speaking markets of Britain and the USA until after the conclusion of that conflict.

While it’s true that the pace of international diesel development picked up very rapidly from 1945 onwards, the fact is that the development of diesels had been well underway in a number of European countries during WW2 and indeed considerably earlier. My good mate Maris Dislers has undertaken the daunting task of documenting the spread of diesel technology within a number of European countries in the years preceding 1945.

My sincere thanks to Maris for tackling this challenging subject. Enjoy!! ACD.

The Spread of Diesels During WW2

By Maris Dislers

The power-to-weight ratio of aircraft propulsion systems has always been important. Aeromodellers in the 1930’s no doubt rued the “parasitic weight” of the electrical system for spark ignition, hence seeking alternatives.

The power-to-weight ratio of aircraft propulsion systems has always been important. Aeromodellers in the 1930’s no doubt rued the “parasitic weight” of the electrical system for spark ignition, hence seeking alternatives.

Indeed, the search for alternatives went way back in time. Just before WW1, German modellers could buy the Zanker 2-stroke engine which used the “ancient” hot tube ignition system. A slender tube screwed into the cylinder head was heated to dull red-orange by a small external flame, creating an ignition source. The flame was fed by an off-take from the fuel tank pressurized by crankcase compression.

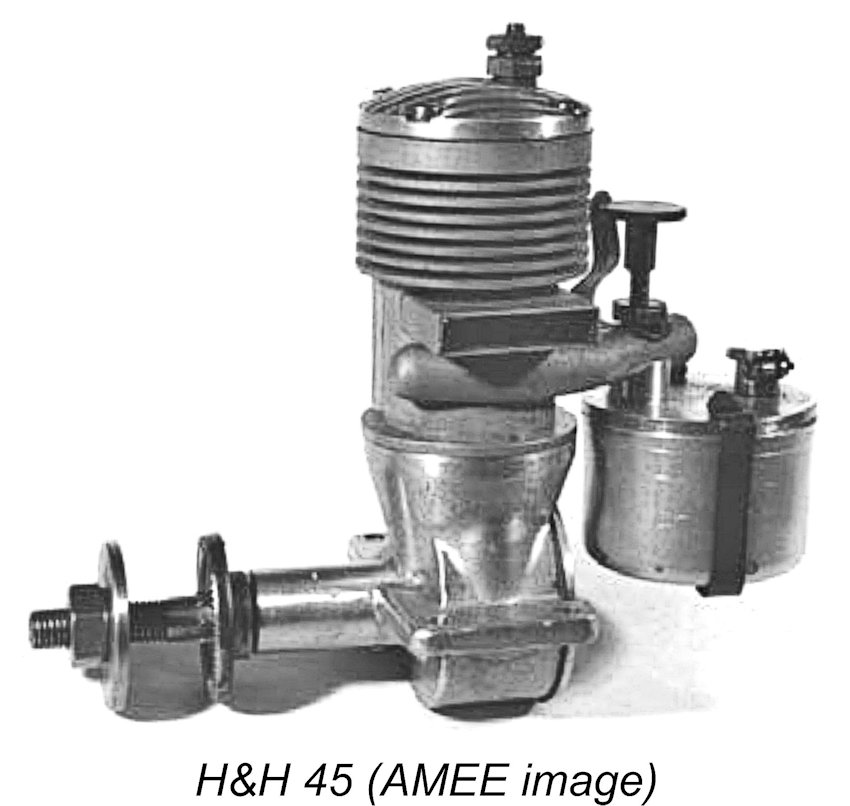

Kenneth Howie waited too long to put his 1937 patented platinum-coil-in-head engine into production in the form of the H&H 45 of 1947. Italian Elios Vantini had limited success with a platinum wire coil in a spark plug body, reporting his results in 1942. But his arrangement suffered frequent element breakage, while he was ignorant of methanol for fuel.

Kenneth Howie waited too long to put his 1937 patented platinum-coil-in-head engine into production in the form of the H&H 45 of 1947. Italian Elios Vantini had limited success with a platinum wire coil in a spark plug body, reporting his results in 1942. But his arrangement suffered frequent element breakage, while he was ignorant of methanol for fuel.

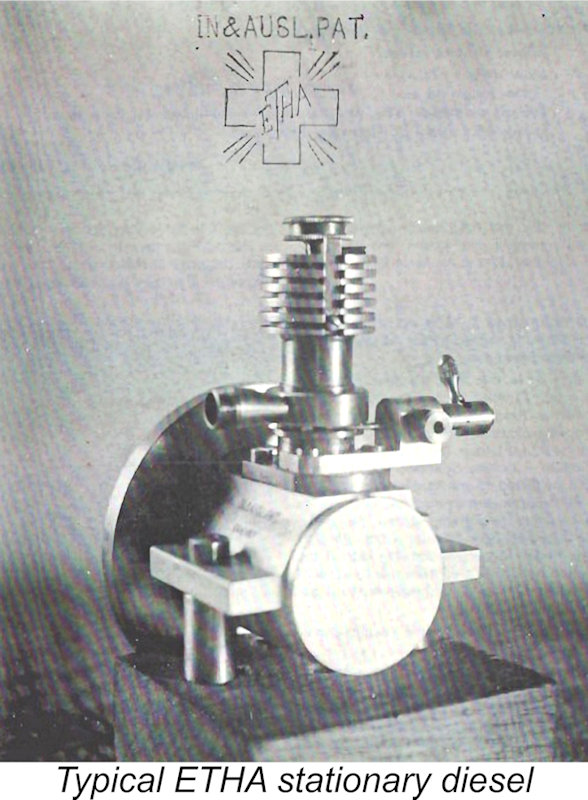

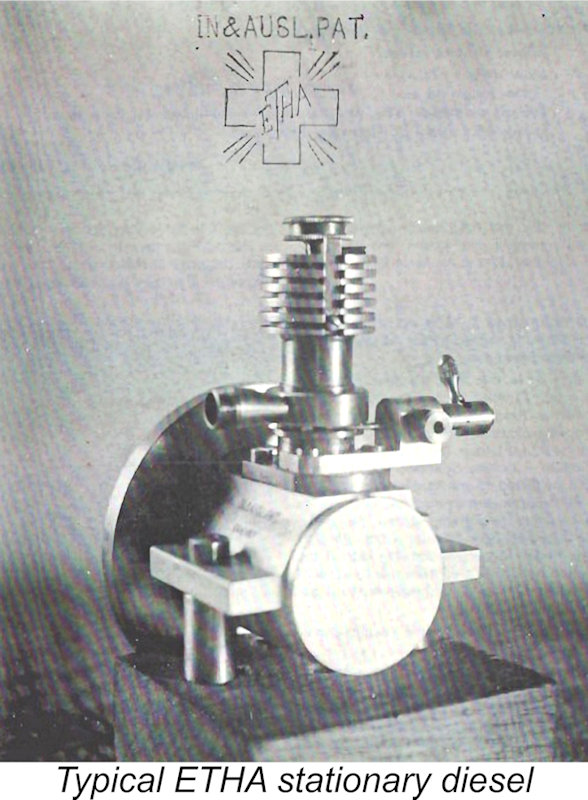

The diesel revolution began with the Patent taken out by Ernst Thalheim of Switzerland in 1928. This Patent covered the use of both compression ignition and variable compression using a contra-piston. Thalheim’s patented “ETHA” miniature stationary engines were distributed by the O. Hoppeller firm in Zürich from 1930 to 1938. These units featured the  revolutionary compression ignition principle and were extremely robust, as they had to be to withstand the high compression ratios required for the self-ignition of kerosene or light oil fuels, perhaps with naphtha as the igniter. But they did incorporate the important feature of adjustable compression for starting at a high setting and then backing off once warmed up.

revolutionary compression ignition principle and were extremely robust, as they had to be to withstand the high compression ratios required for the self-ignition of kerosene or light oil fuels, perhaps with naphtha as the igniter. But they did incorporate the important feature of adjustable compression for starting at a high setting and then backing off once warmed up.

In 1938 the Swiss aviation journal reported on compression ignition engines for model aircraft. At around this time, Swiss modellers were becoming proficient at flying models with internal combustion engines but had their share of spark ignition troubles. The originator of the use of ether in the fuel  mix for compression ignition engines is not recorded, but that breakthrough allowed for lower compression ratios and dramatically lighter and smaller engines potentially suitable for model aircraft applications.

mix for compression ignition engines is not recorded, but that breakthrough allowed for lower compression ratios and dramatically lighter and smaller engines potentially suitable for model aircraft applications.

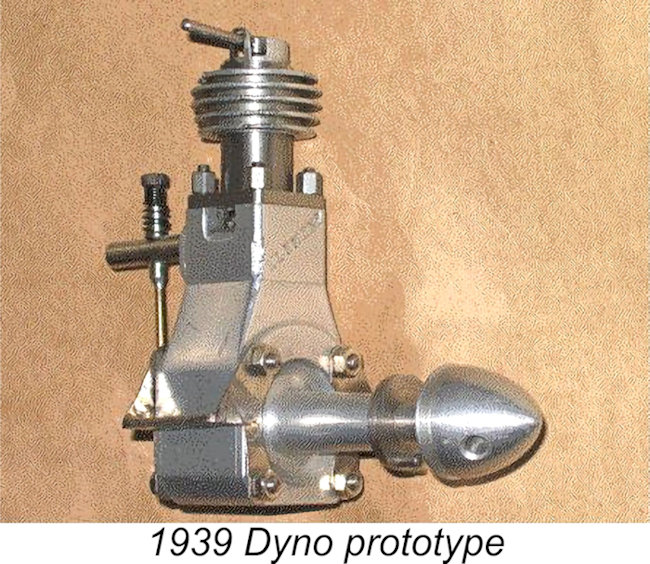

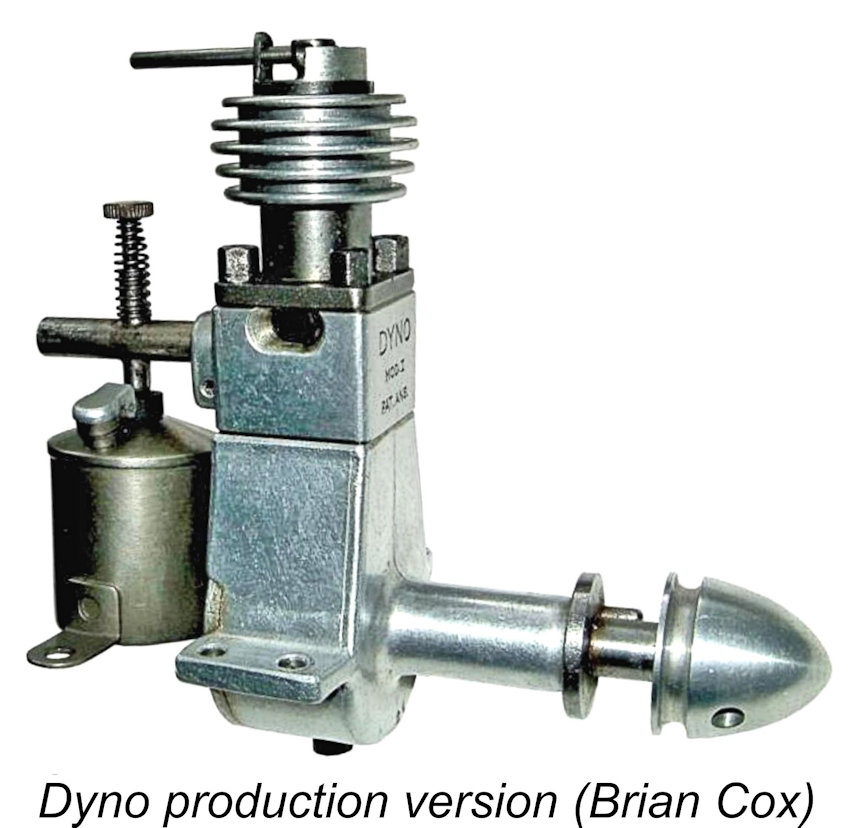

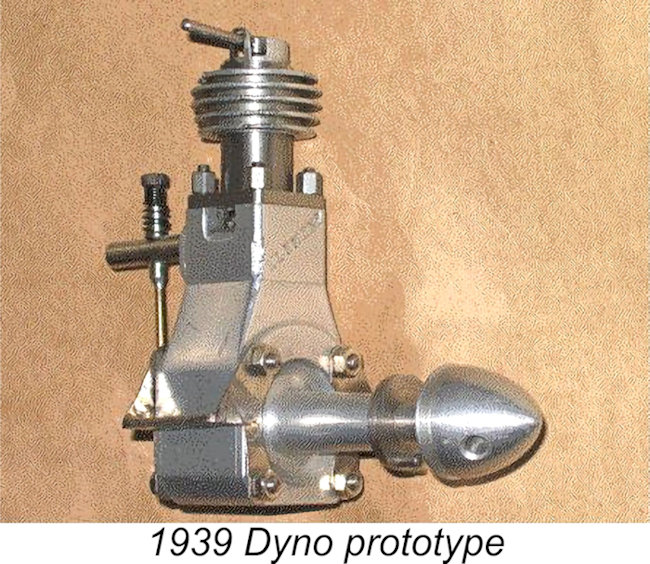

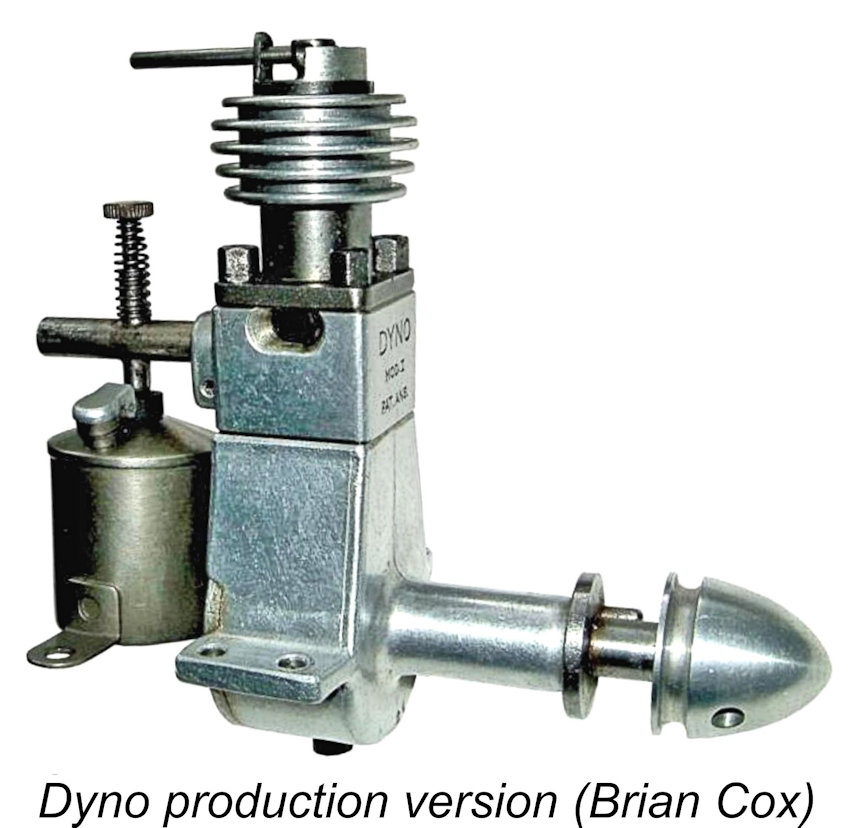

Encouraged by Thalheim (and in parallel with his own developments towards compression ignition engines for model aircraft), a collaboration between machinist/designer X.M. Wuest, model aircraft enthusiast Alwin Kuhn and manufacturer Johannes Klemenz-Schenk led to the development of a practical design in 1939. This was developed further by Klemenz-Schenk and put into quantity production at his factory, which was primarily in the business of making dynamo lighting units for bicycles, hence the engine’s Dyno name. Commercial sales of the 2 cc Dyno 1 commenced in mid-1941.

The Dyno’s important features were the “long” stroke-to-bore ratio that enhanced the vital compression of fuel/air mixture to achieve self-ignition temperature, given the prevailing production machining tolerances. The variable compression feature was taken from Thalheim’s earlier work. The

The Dyno’s important features were the “long” stroke-to-bore ratio that enhanced the vital compression of fuel/air mixture to achieve self-ignition temperature, given the prevailing production machining tolerances. The variable compression feature was taken from Thalheim’s earlier work. The  engine used Wuest’s T-scavenging cylinder porting arrangement (single front transfer at a right angle to the two exhausts in plan view) that eliminated the need for a piston baffle and allowed reasonably smooth running.

engine used Wuest’s T-scavenging cylinder porting arrangement (single front transfer at a right angle to the two exhausts in plan view) that eliminated the need for a piston baffle and allowed reasonably smooth running.

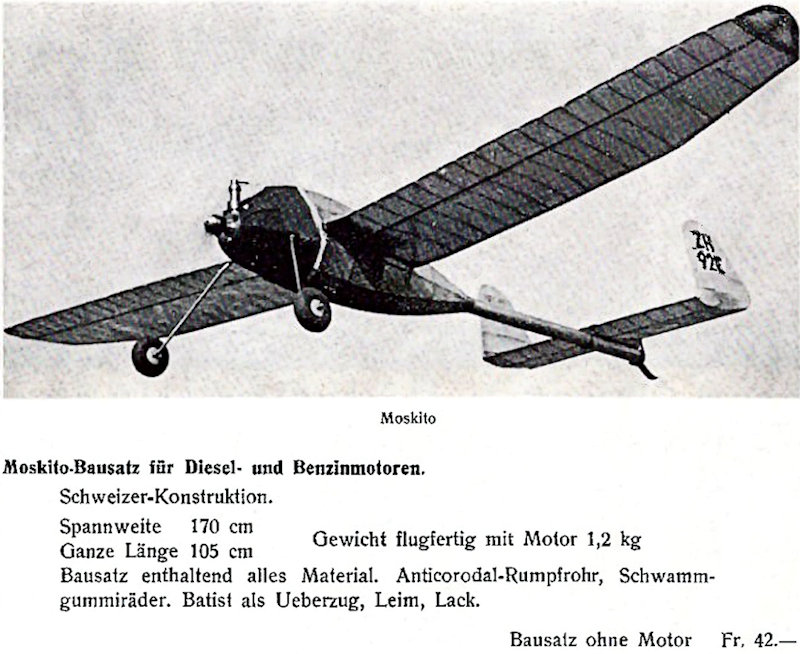

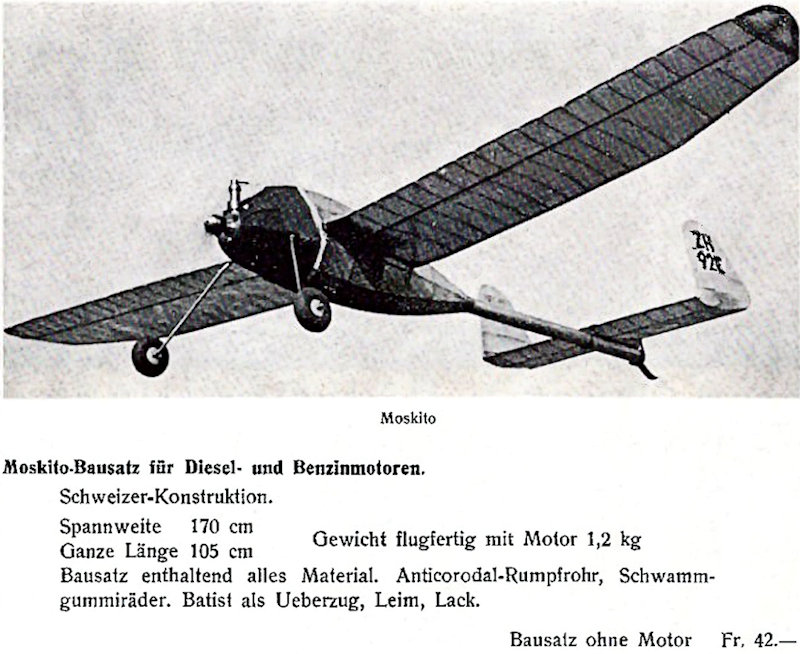

Thalheim’s own developments bore fruit in two new designs, the 2.5 cc ETHA 1 and 6 cc ETHA 2 diesels. The “Moskito” kit (showing an ETHA 1 engine) in Hoppeller’s 1942 catalogue was perhaps a world first for diesel engines in being the first commercial kit model to feature a diesel as its standard powerplant.

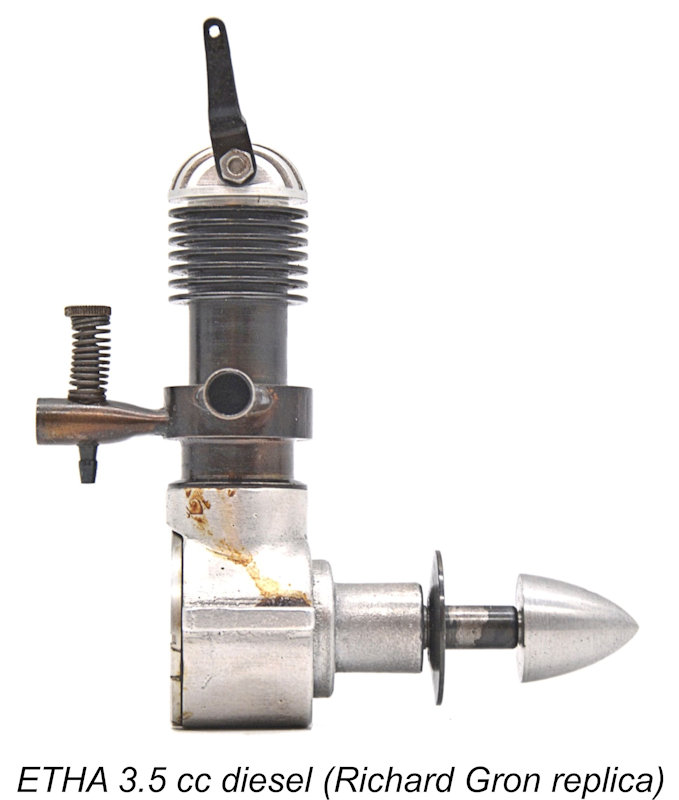

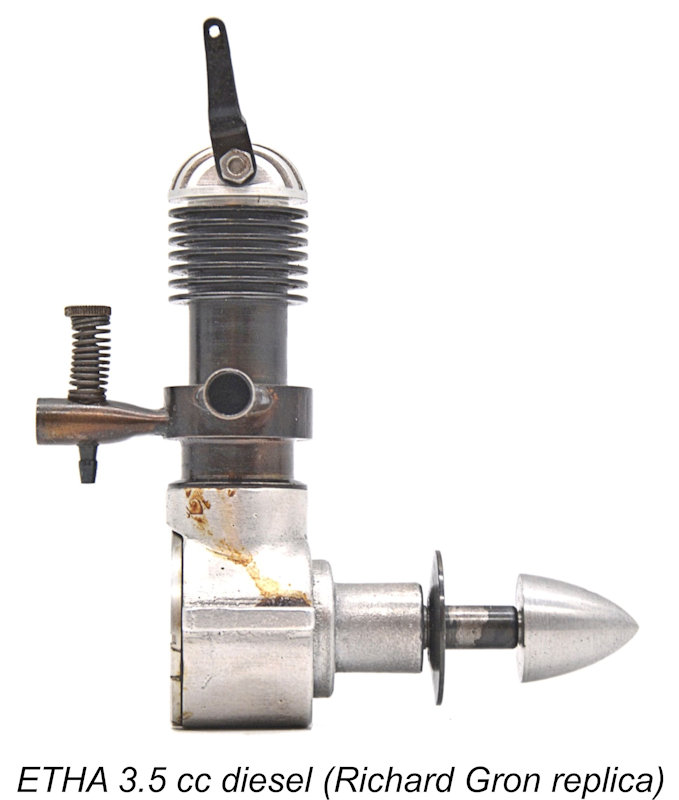

At the 1941 Swiss National Championships, around half the power models used diesels - 11 Dynos and 5 ETHA’s. The Dynos performed well, and Thalheim’s ETHA units were no match for them. He made some effort to compete with improved derivatives, such as the 3.5 cc type circa 1942. This featured a novel lever-and-cam compression  adjustment system as well as an additional rotary counterweight driven by the crankpin. However, the ETHA engines soon faded from the scene. We explored a possible reason in our test of the ETHA 1, which may be found elsewhere on this website.

adjustment system as well as an additional rotary counterweight driven by the crankpin. However, the ETHA engines soon faded from the scene. We explored a possible reason in our test of the ETHA 1, which may be found elsewhere on this website.

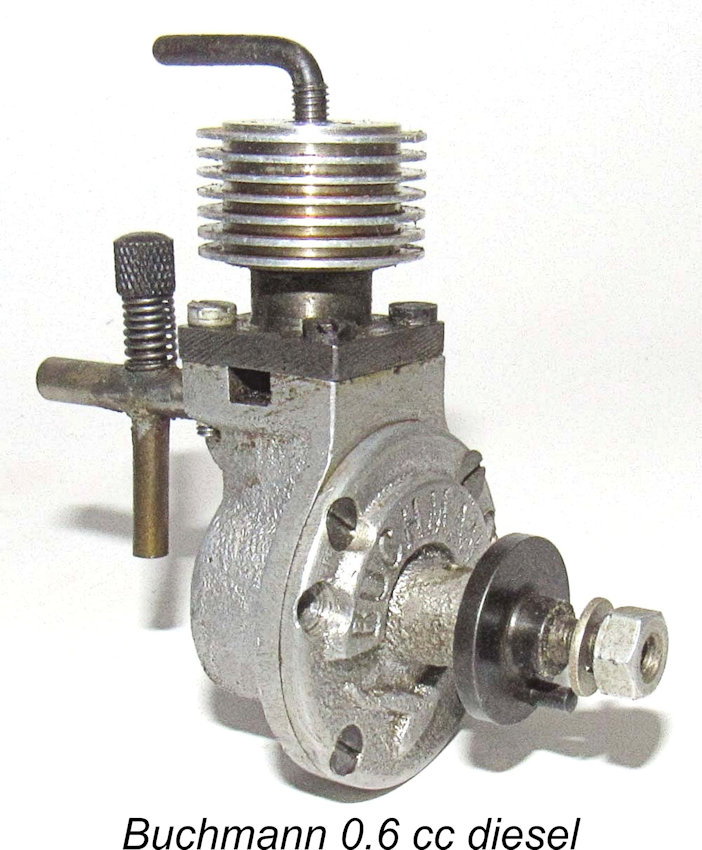

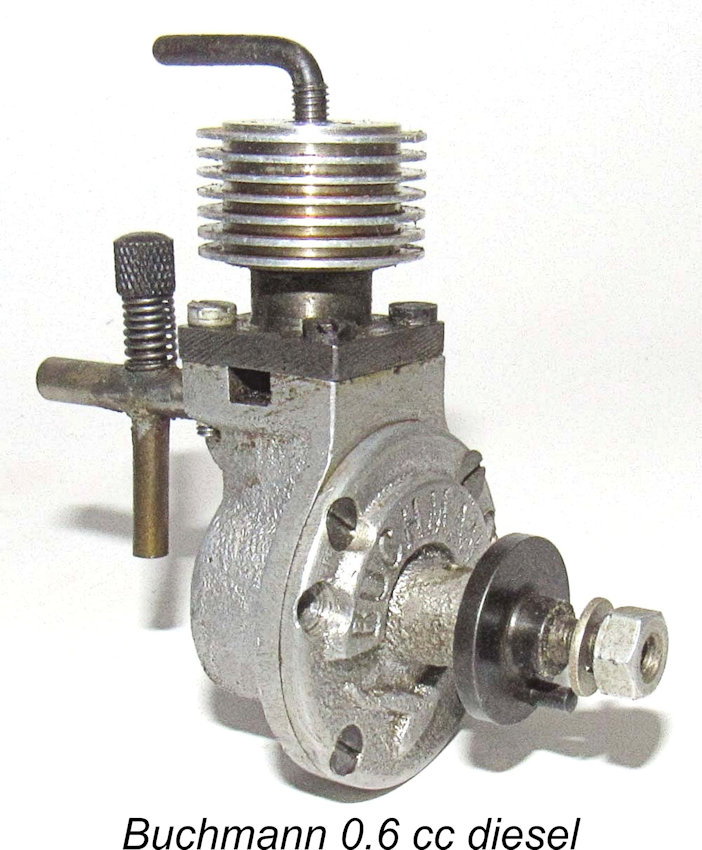

The subsequent 0.6 cc Buchmann diesel was the other pioneering Swiss model diesel engine. Heralding the mini-diesel revolution to come, it was probably inspired by Wuest’s earlier engine of around the same very small swept volume. It seemingly combined the ETHA’s radial crankcase mounting design with the Dyno’s cylinder porting. Its most unusual feature was the absence of a crank-disc, which allowed its height to be considerably reduced, presumably at the expense of elevated levels of vibration. Its design exerted a strong influence over that of the far later British E.P.C Moth of 1950.

The subsequent 0.6 cc Buchmann diesel was the other pioneering Swiss model diesel engine. Heralding the mini-diesel revolution to come, it was probably inspired by Wuest’s earlier engine of around the same very small swept volume. It seemingly combined the ETHA’s radial crankcase mounting design with the Dyno’s cylinder porting. Its most unusual feature was the absence of a crank-disc, which allowed its height to be considerably reduced, presumably at the expense of elevated levels of vibration. Its design exerted a strong influence over that of the far later British E.P.C Moth of 1950.

Under normal circumstances, the Dyno would have been a sensational commercial success, even if it could only be obtained through the Swiss Aero Club for a princely 80 Swiss Francs. But at that time neutral Switzerland was completely surrounded by countries under Axis control, which restricted trade and information flow. No word of diesels got beyond that boundary and no news of recent American advances with spark ignition engines came the other way.

Even so, enterprising individuals within the Axis control zone found ways of obtaining a Dyno via “channels”. Once those engines had been studied and appraised, model diesels began to be constructed and marketed in countries other than Switzerland. Let’s share a look at these early wartime developments.

FRANCE

Pierre Meunier demonstrates his Dyno 1 in the summer of 1942 (presumably in Paris). Inspired by this demonstration, Maurice Delbrel constructs a 1 cc engine, the first successful French diesel. After some experimentation, André Gladieux concludes that fixed compression is practical with larger engines. His Micron 10AA and 5AA engines are concurrently released commercially in July 1943, “AA” standing for Auto Allumage (French for “auto ignition”). The 10 cc model is brutish, but the 5 cc variant is a fine performer. It develops 0.18 BHP at 4,500 RPM, easily flying models intended for

Pierre Meunier demonstrates his Dyno 1 in the summer of 1942 (presumably in Paris). Inspired by this demonstration, Maurice Delbrel constructs a 1 cc engine, the first successful French diesel. After some experimentation, André Gladieux concludes that fixed compression is practical with larger engines. His Micron 10AA and 5AA engines are concurrently released commercially in July 1943, “AA” standing for Auto Allumage (French for “auto ignition”). The 10 cc model is brutish, but the 5 cc variant is a fine performer. It develops 0.18 BHP at 4,500 RPM, easily flying models intended for  10 cc spark ignition engines and achieving good contest results. Production volume is modest until after the war, when it remains popular.

10 cc spark ignition engines and achieving good contest results. Production volume is modest until after the war, when it remains popular.

Prosper Allouchéry produces his first “Éclair” 5.7 cc spark ignition engine in November 1943. His “Allouchéry” 1.25 cc diesel introduced towards the end of 1944 is much more successful. It is clearly Dyno-inspired, including the horizontal cylindrical fuel tank as per early Dyno sales literature. It features a monobloc crankcase and four long screws retaining the cylinder and fins. This engine appers to have exerted a strong design influence over the 1946 British Mills 1.3 diesel.

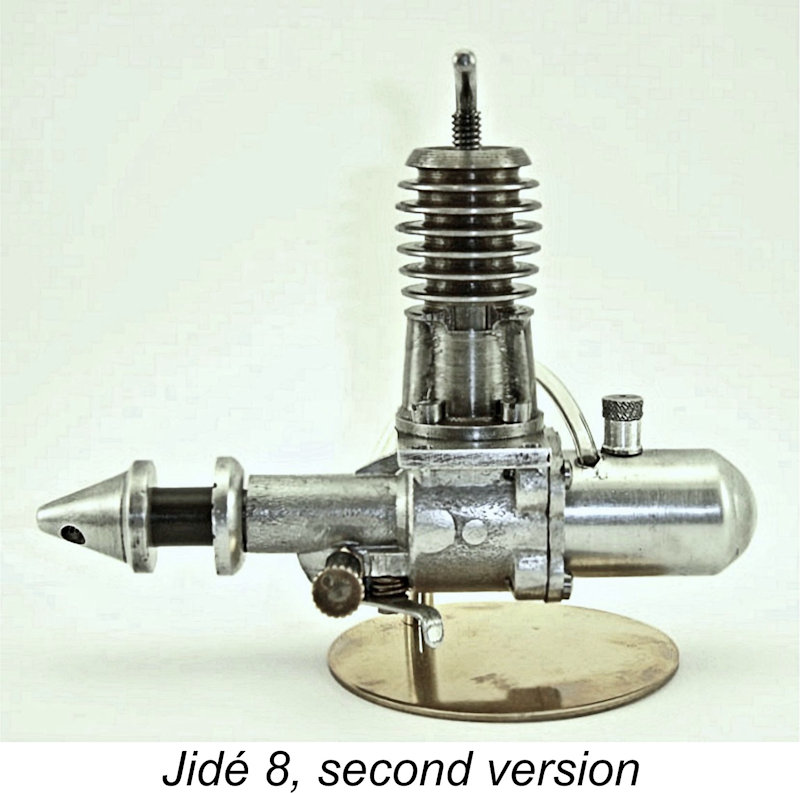

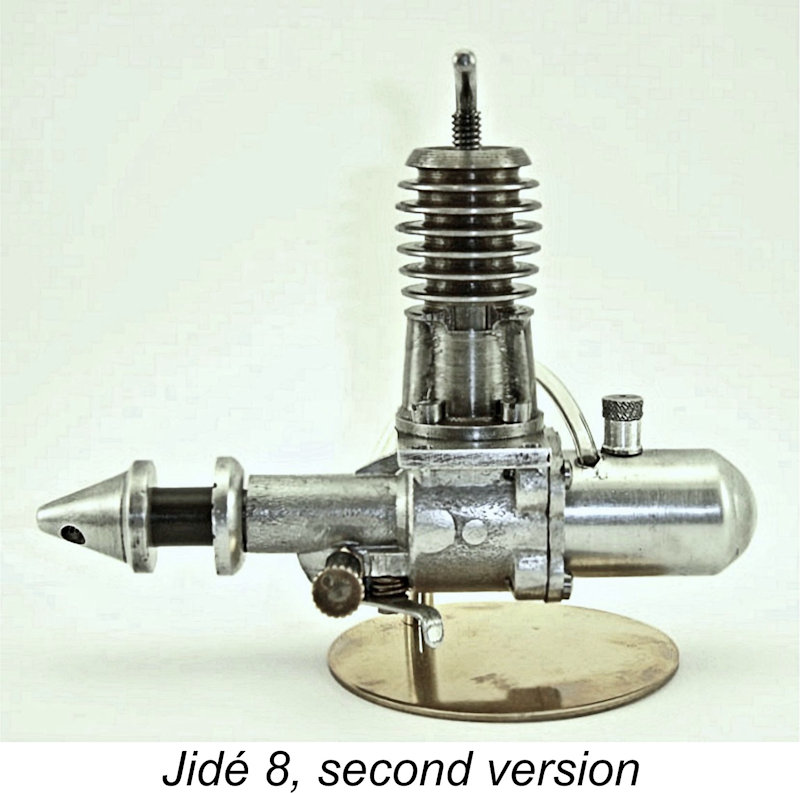

Moteurs Jidé produce “Jidé 8” 1.7 cc and “Jidé 9” 10 cc diesels in 1944. These feature crankshaft rotary valve induction, fixed compression, fore/aft transfer ports and left-right exhausts (the + scavenging system). The Jidé 8 is notable as the smallest fixed compression engine. That feature proves to be not so successful, resulting in the later 1944 appearance of a more practical second version with variable compression.

Moteurs Jidé produce “Jidé 8” 1.7 cc and “Jidé 9” 10 cc diesels in 1944. These feature crankshaft rotary valve induction, fixed compression, fore/aft transfer ports and left-right exhausts (the + scavenging system). The Jidé 8 is notable as the smallest fixed compression engine. That feature proves to be not so successful, resulting in the later 1944 appearance of a more practical second version with variable compression.

Other French diesels are introduced from 1945 onwards, perhaps delayed by the turmoil surrounding the Allied invasion. These include designs by DELMO, Airplan, Bosmorin, Ouragan, Bonnier and Comete as part of a remarkably fertile decade of French model engine production. Maurice Delbrel’s 2.65 cc DELMO design of early 1945 is particularly noteworthy for its unusual compression adjustment method of raising/lowering the position of its blind-bored cylinder liner within the crankcase.

Other French diesels are introduced from 1945 onwards, perhaps delayed by the turmoil surrounding the Allied invasion. These include designs by DELMO, Airplan, Bosmorin, Ouragan, Bonnier and Comete as part of a remarkably fertile decade of French model engine production. Maurice Delbrel’s 2.65 cc DELMO design of early 1945 is particularly noteworthy for its unusual compression adjustment method of raising/lowering the position of its blind-bored cylinder liner within the crankcase.

Faced with this rising tide of diesel engine development, the Parisian company STAB adopts a strategy of overcoming the additional stresses arising from compression ignition by reducing the cylinder bore of their spark ignition models for lower swept volume. Tested during the summer of 1945, diesel conversion plans or kits (consisting of a complete piston/cylinder assembly and a steel reinforcing ring for the crankcase nose) are offered in October. The 2.27 cc spark ignition model converts to a 1.25 cc diesel, while the 7.6 cc sparker converts to 3.52 cc. Ready-to-run STAB diesels follow in early 1946. Claims placing these diesels closer to the 1941 and 1942 introduction of their original spark ignition foundation designs are unfounded.

POLAND

During 1942, a local modeller in Poznań, Poland pays the German owner a lot of money to part with his Dyno 1 engine. This is a revelation when it is demonstrated in great secrecy to other local modellers. Inspired, 17-year-old Felicjan Gadomski resolves to make his own copy, using the lathe in his father’s small basement workshop.

During 1942, a local modeller in Poznań, Poland pays the German owner a lot of money to part with his Dyno 1 engine. This is a revelation when it is demonstrated in great secrecy to other local modellers. Inspired, 17-year-old Felicjan Gadomski resolves to make his own copy, using the lathe in his father’s small basement workshop.

On August 30th, 1942 after overcoming numerous technical difficulties, Gadomski demonstrates his engine to trusted friends and builds a model for it by the end of the year. It flies, but he is not satisfied with the low power output. More spare-time development leads to the creation of four variants by the end of the war. Limited production of 200 “GADO-2” and “F.G.3” engines by November 1946 goes to the Department of Civil Aviation’s Model Training Centre or to private buyers. Also, Gadomski’s one-off 0.23 cc “Lilliput” diesel (bore 6 mm, stroke 8 mm) successfully flies a 29 cm wing-span FF model. It is rated at 0.003 BHP!

On August 30th, 1942 after overcoming numerous technical difficulties, Gadomski demonstrates his engine to trusted friends and builds a model for it by the end of the year. It flies, but he is not satisfied with the low power output. More spare-time development leads to the creation of four variants by the end of the war. Limited production of 200 “GADO-2” and “F.G.3” engines by November 1946 goes to the Department of Civil Aviation’s Model Training Centre or to private buyers. Also, Gadomski’s one-off 0.23 cc “Lilliput” diesel (bore 6 mm, stroke 8 mm) successfully flies a 29 cm wing-span FF model. It is rated at 0.003 BHP!

Plans for the GADO-3 design are published for DIY construction. This 3.87 cc model (bore 15 mm, stroke 20 mm) is rated at 0.2 HP @ 6,000 RPM. It runs on 40% ether, 40% diesel oil and 20% olive oil.

ITALY

At this time, Italian model engine production is in small series on a cottage industry basis, mainly for local distribution. Broader marketing of the majority of “first generation” Italian diesels commences soon after the war ends. Although the Dyno engine strongly influences the basic designs, Italian constructors show notable flair in developing overall shapes and details.

At this time, Italian model engine production is in small series on a cottage industry basis, mainly for local distribution. Broader marketing of the majority of “first generation” Italian diesels commences soon after the war ends. Although the Dyno engine strongly influences the basic designs, Italian constructors show notable flair in developing overall shapes and details.

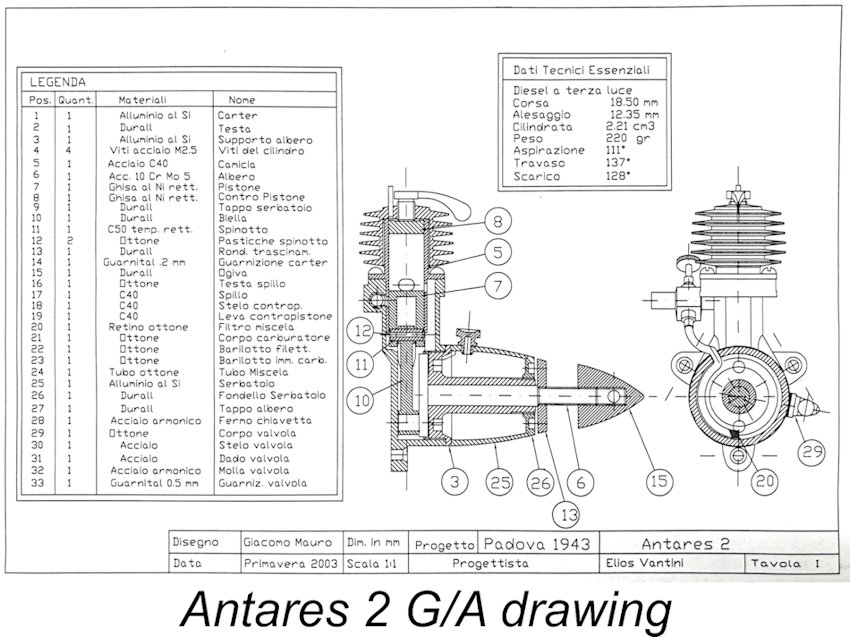

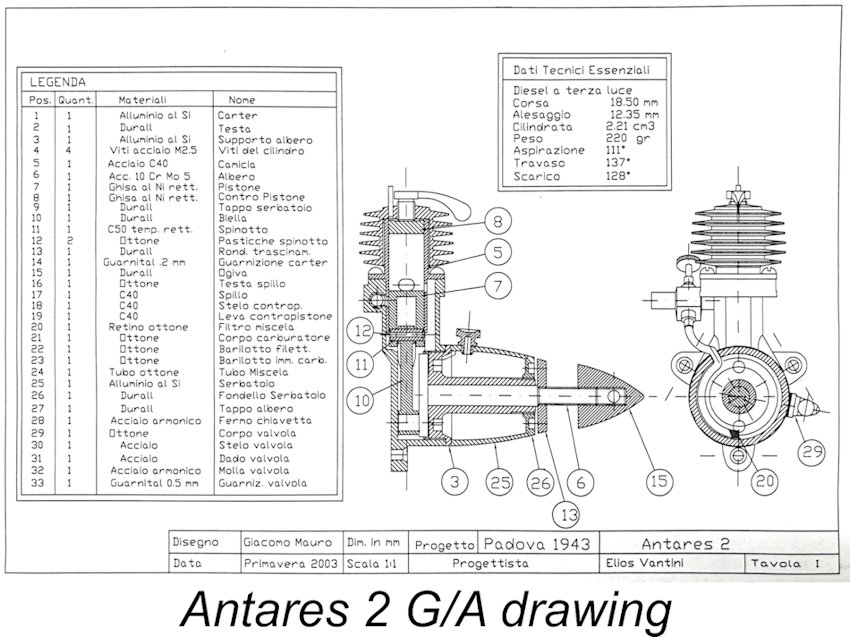

Although experiments by a few individuals had been underway for some time, the average Italian modeller is probably first informed about model diesel engines in "L’Aquilone" magazine, 20-27 June 1943. The  general principle is explained before the writer reviews the Antares 4 engine produced in Padua by Elios Vantini. This was a side-line to Vantini’s “real” business of manufacturing glass syringes. The engine follows earlier work with a 2 to 3 cc type that was also made in a very small series. Vantini is shown with his model at the then-recent National championships, featuring one of his engines.

general principle is explained before the writer reviews the Antares 4 engine produced in Padua by Elios Vantini. This was a side-line to Vantini’s “real” business of manufacturing glass syringes. The engine follows earlier work with a 2 to 3 cc type that was also made in a very small series. Vantini is shown with his model at the then-recent National championships, featuring one of his engines.

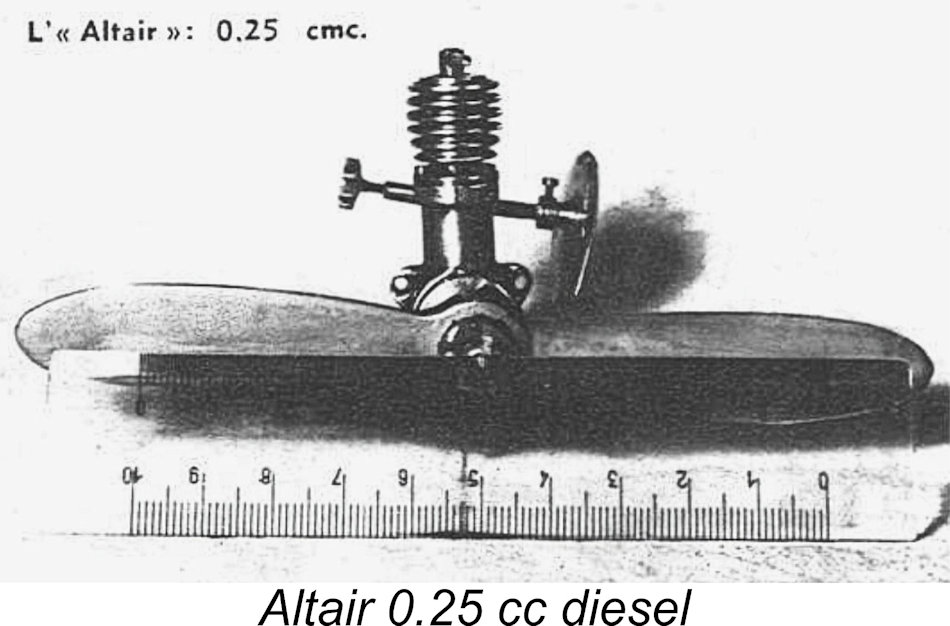

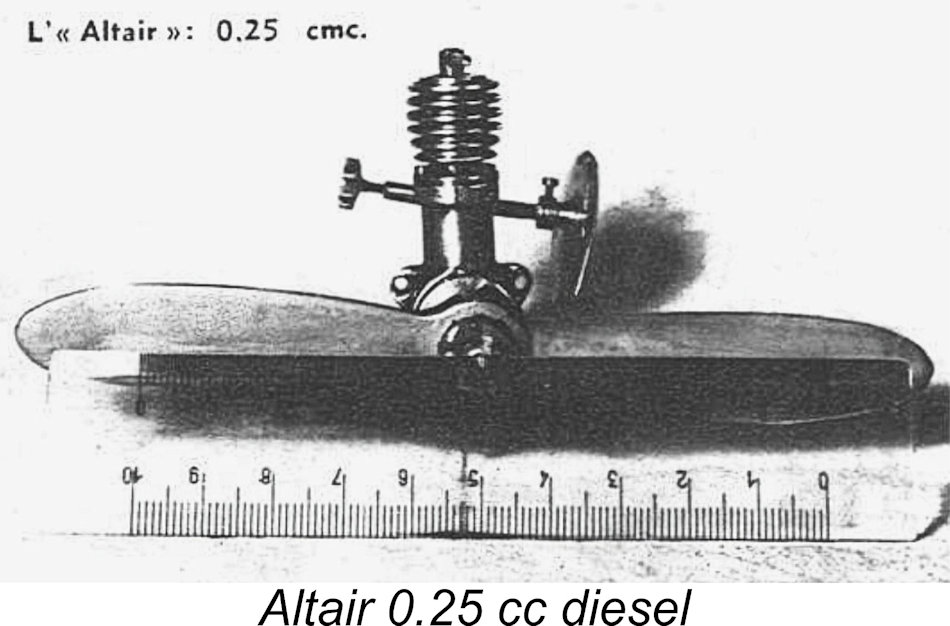

The Antares 4 is at heart a Dyno type, but has 3-point radial mounting, a side-facing intake and an innovative fuel tank shrouding the crankshaft area. Overall, the design offers superior streamlining in a model. The weight is 300 gm with propeller. The engine develops 1/5 BHP at 5,000  RPM with a 300 mm x 200 mm prop. Approximately 200 examples are produced. Vantini also makes a one-off “Altair” 0.25 cc diesel engine. Although too demanding in construction terms to make in quantity, it proves practical and flies Vanni Pedrina’s 60 cm wing-span model, probably in the summer of 1945.

RPM with a 300 mm x 200 mm prop. Approximately 200 examples are produced. Vantini also makes a one-off “Altair” 0.25 cc diesel engine. Although too demanding in construction terms to make in quantity, it proves practical and flies Vanni Pedrina’s 60 cm wing-span model, probably in the summer of 1945.

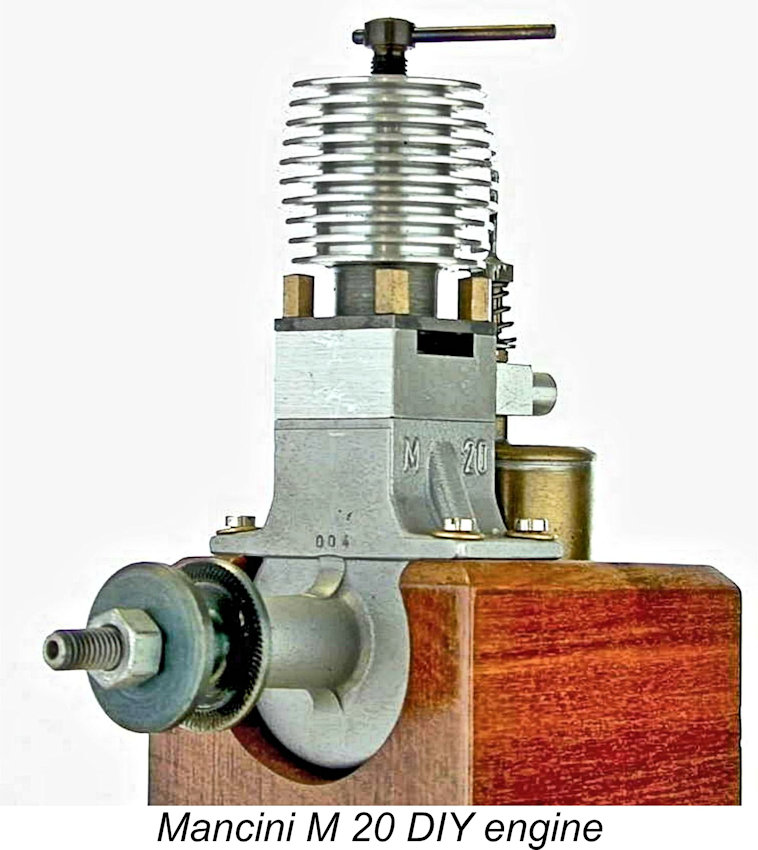

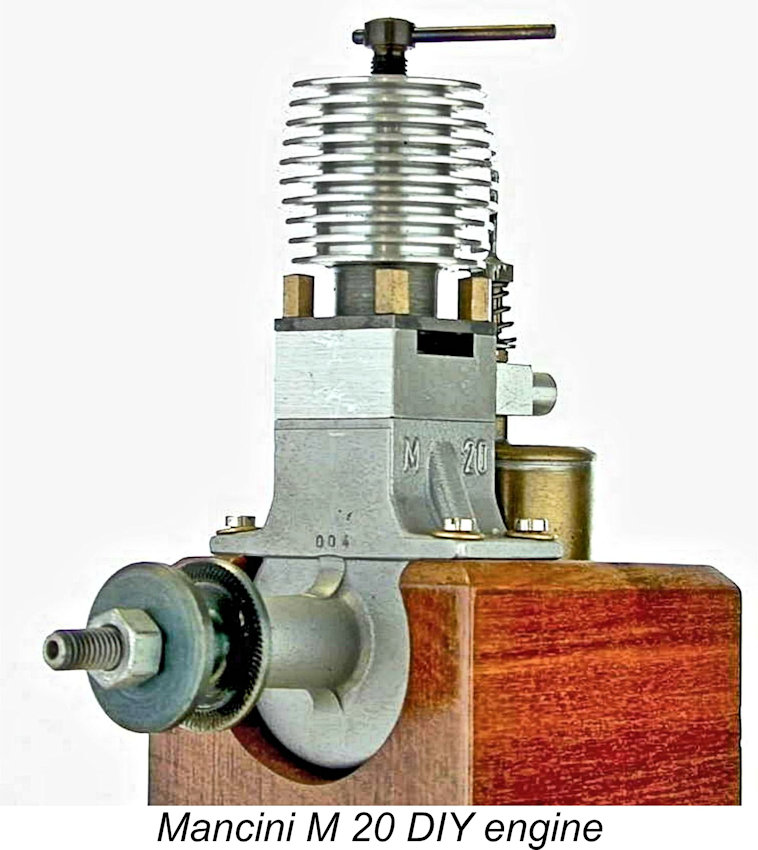

Budding engine designer Enzo Mancini of Florence has his first diesel engine design, the Mancini M 20, published in the August 1943 issue of “L’Aquilone” as a DIY project. The 3.7 cc Dyno-derived design becomes well known when the article is translated to German and republished in “Der Sportflieger” of February 1944 and then into French for “Le Modele Reduit D'Avion” of May 1944. In subsequent years, Mancini designs and constructs the Alfa, Uranio 4 and Meteor 47 diesels.

Budding engine designer Enzo Mancini of Florence has his first diesel engine design, the Mancini M 20, published in the August 1943 issue of “L’Aquilone” as a DIY project. The 3.7 cc Dyno-derived design becomes well known when the article is translated to German and republished in “Der Sportflieger” of February 1944 and then into French for “Le Modele Reduit D'Avion” of May 1944. In subsequent years, Mancini designs and constructs the Alfa, Uranio 4 and Meteor 47 diesels.

Ferricio Cassola of Pisa might have the distinction of being the first Italian to produce a model diesel engine (circa 1943) with compression adjusted via eccentric crankshaft bushing. His one-off 6 cc engine is successfully flown, but not in competitions.

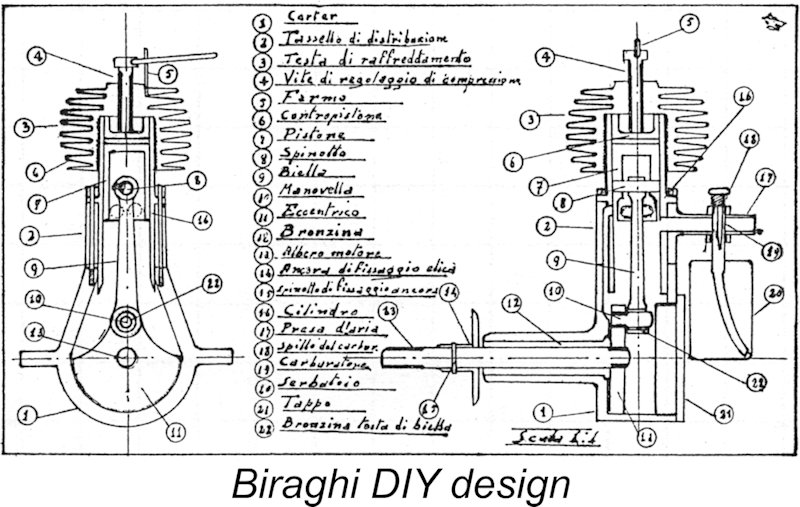

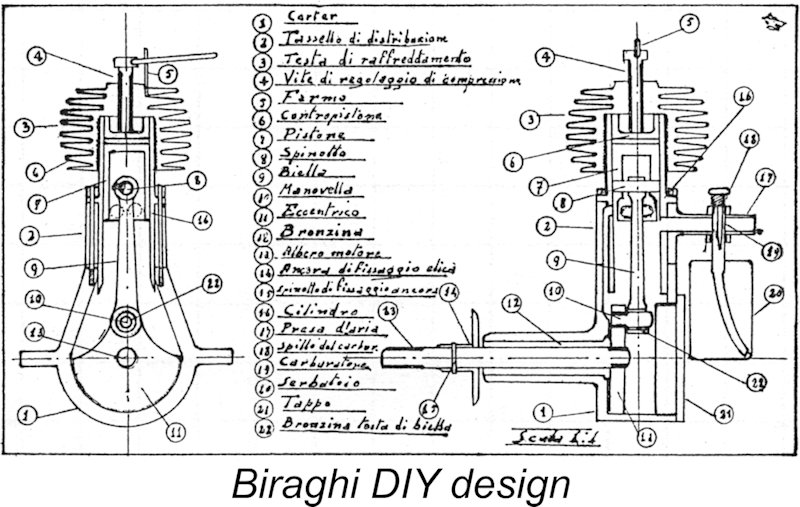

Living close to Switzerland, Emilio Biraghi of Milan uses a sporting prize to buy a Dyno engine, beginning his engine-making career in 1944 with a series of diesels, each showing improvement. His 4.2 cc “Jupiter Junior” and 2.2 cc “Mirius Senior” and “Mirius Junior” are Dyno-derived engines, made in small series. Plans for his DIY engine are published in “L’Aquilone” in 1944. He is best remembered for the 0.7 cc “Micro” diesel made in 1000 pieces from 1946.

Living close to Switzerland, Emilio Biraghi of Milan uses a sporting prize to buy a Dyno engine, beginning his engine-making career in 1944 with a series of diesels, each showing improvement. His 4.2 cc “Jupiter Junior” and 2.2 cc “Mirius Senior” and “Mirius Junior” are Dyno-derived engines, made in small series. Plans for his DIY engine are published in “L’Aquilone” in 1944. He is best remembered for the 0.7 cc “Micro” diesel made in 1000 pieces from 1946.

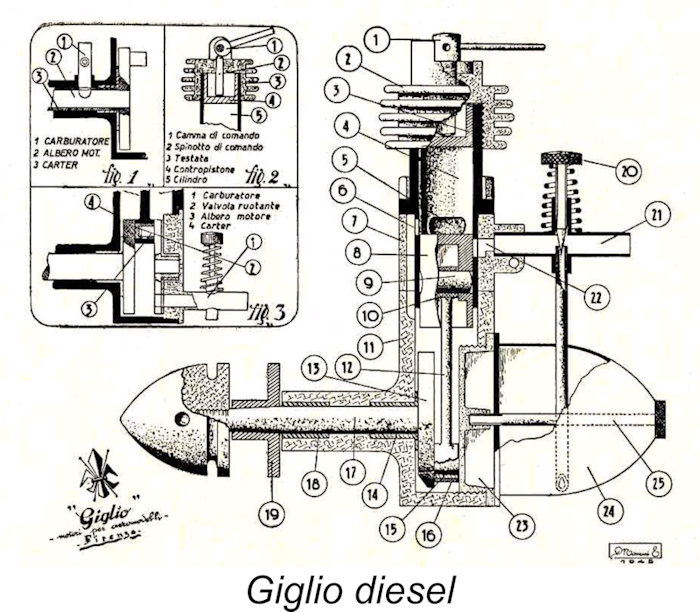

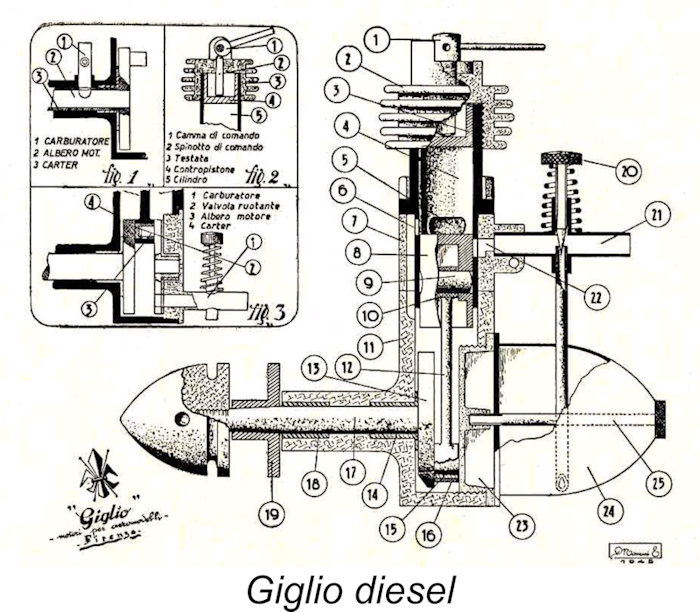

Bruno Grazzini, already respected for a range of “Giglio” spark ignition engines, produces the “Giglio” diesel, which was one of the first Italian series production diesels, circa 1945. It closely follows the Dyno design, but with a streamlined fuel tank mounted on the backplate. A subsequent magazine review shows front crankshaft rotary or rear disc induction and cam-operated compression adjustment, which are probably not production variants. Production ceases quite soon when Grazzini closes the business and moves to France to work for Renault.

Bruno Grazzini, already respected for a range of “Giglio” spark ignition engines, produces the “Giglio” diesel, which was one of the first Italian series production diesels, circa 1945. It closely follows the Dyno design, but with a streamlined fuel tank mounted on the backplate. A subsequent magazine review shows front crankshaft rotary or rear disc induction and cam-operated compression adjustment, which are probably not production variants. Production ceases quite soon when Grazzini closes the business and moves to France to work for Renault.

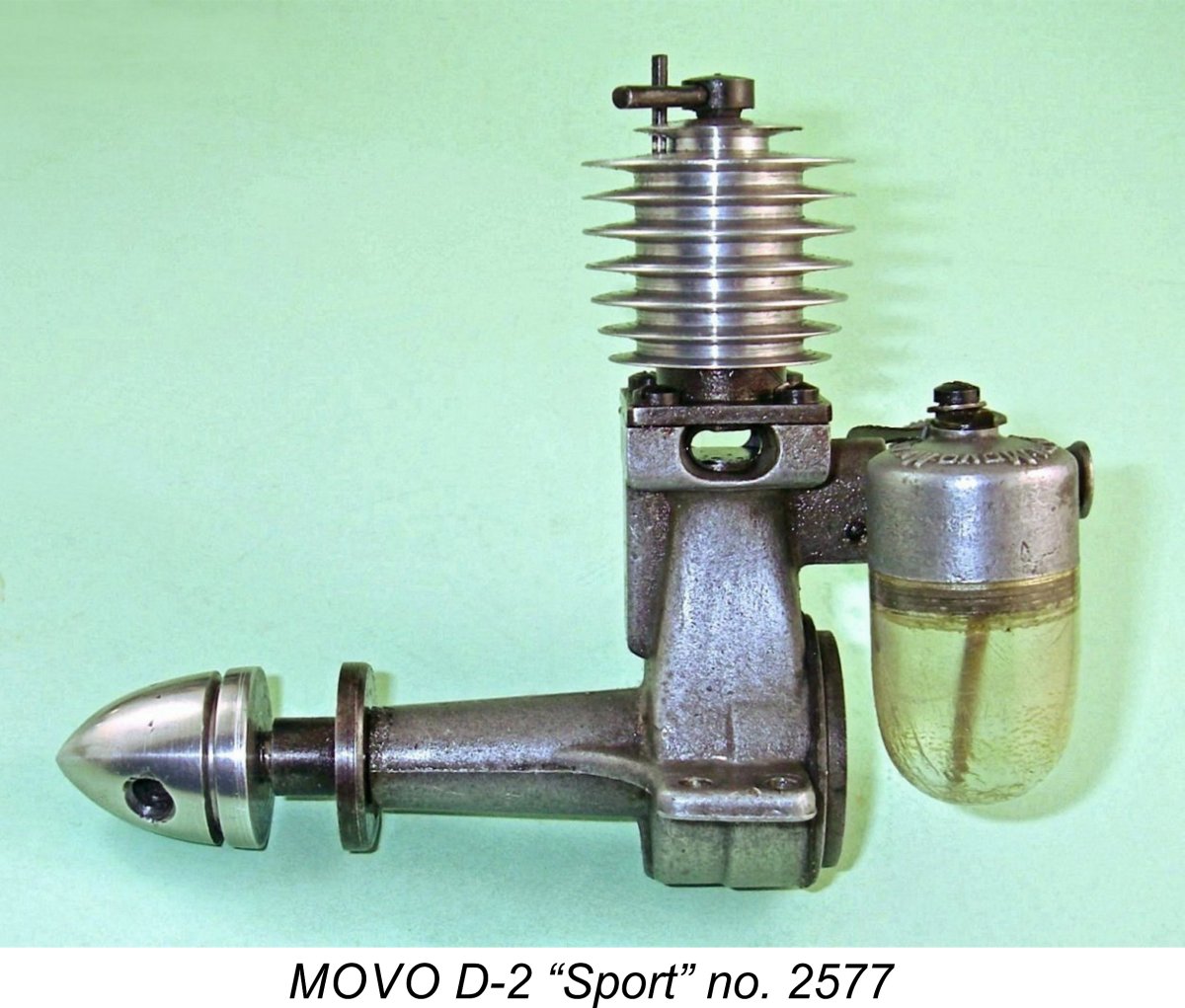

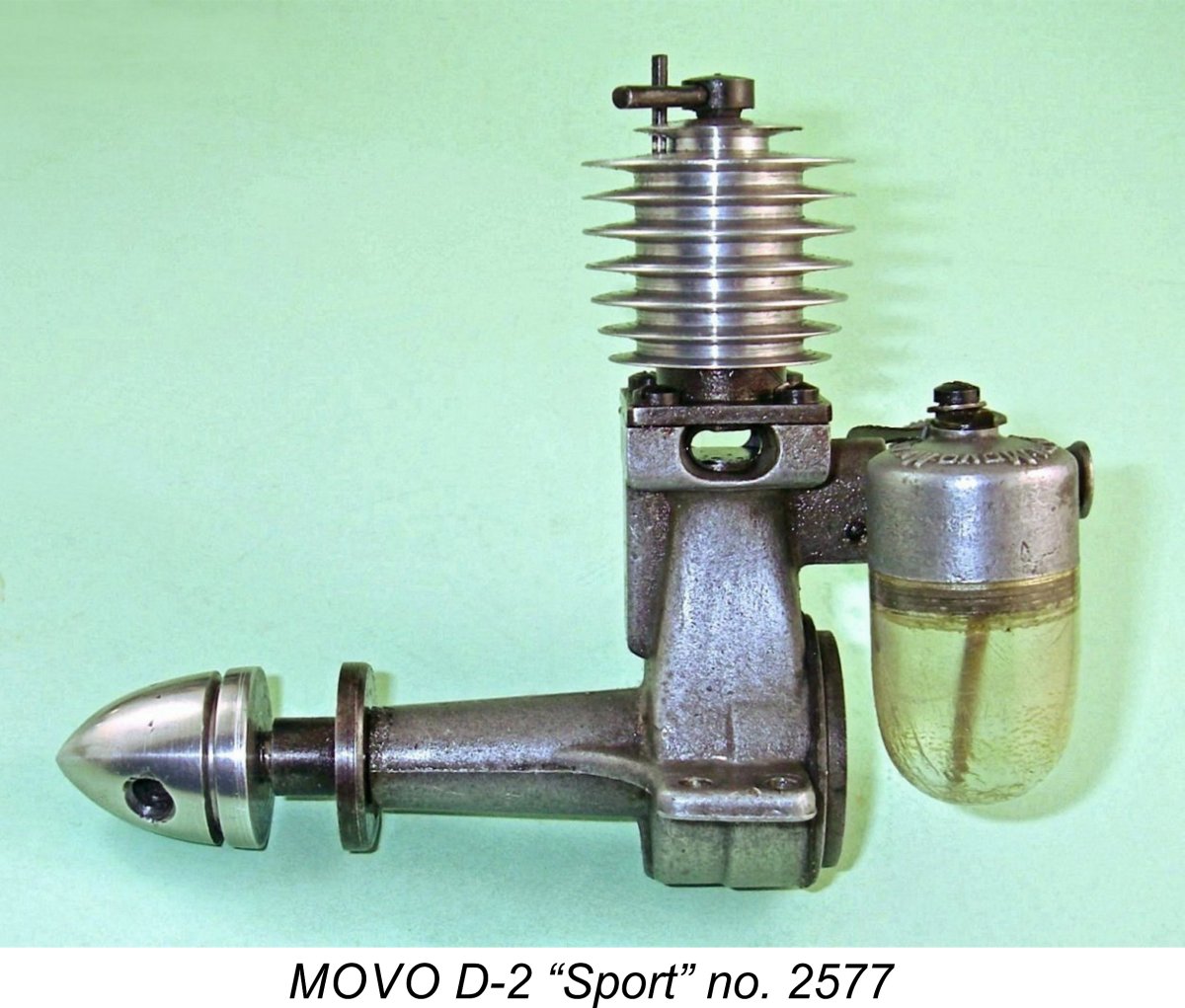

The MOVO company of Milan is well placed to produce model engines with high quality equipment and is already known for its “GIL 10” and “DP 23” spark ignition engines. Prototypes of a 2 cc Dyno-derived engine are successfully tested in 1944 and examples of the stylish “MOVO D-2” are available for sale early in 1945. The engine is offered in two versions - “Normal” with streamlined tank mounted on the backplate, and “Sport” with smaller tank suspended from one side of the rear induction carburettor. It enjoys great sales success and is exported to U.S.A., Argentina, Mexico, Switzerland and Belgium.

The MOVO company of Milan is well placed to produce model engines with high quality equipment and is already known for its “GIL 10” and “DP 23” spark ignition engines. Prototypes of a 2 cc Dyno-derived engine are successfully tested in 1944 and examples of the stylish “MOVO D-2” are available for sale early in 1945. The engine is offered in two versions - “Normal” with streamlined tank mounted on the backplate, and “Sport” with smaller tank suspended from one side of the rear induction carburettor. It enjoys great sales success and is exported to U.S.A., Argentina, Mexico, Switzerland and Belgium.

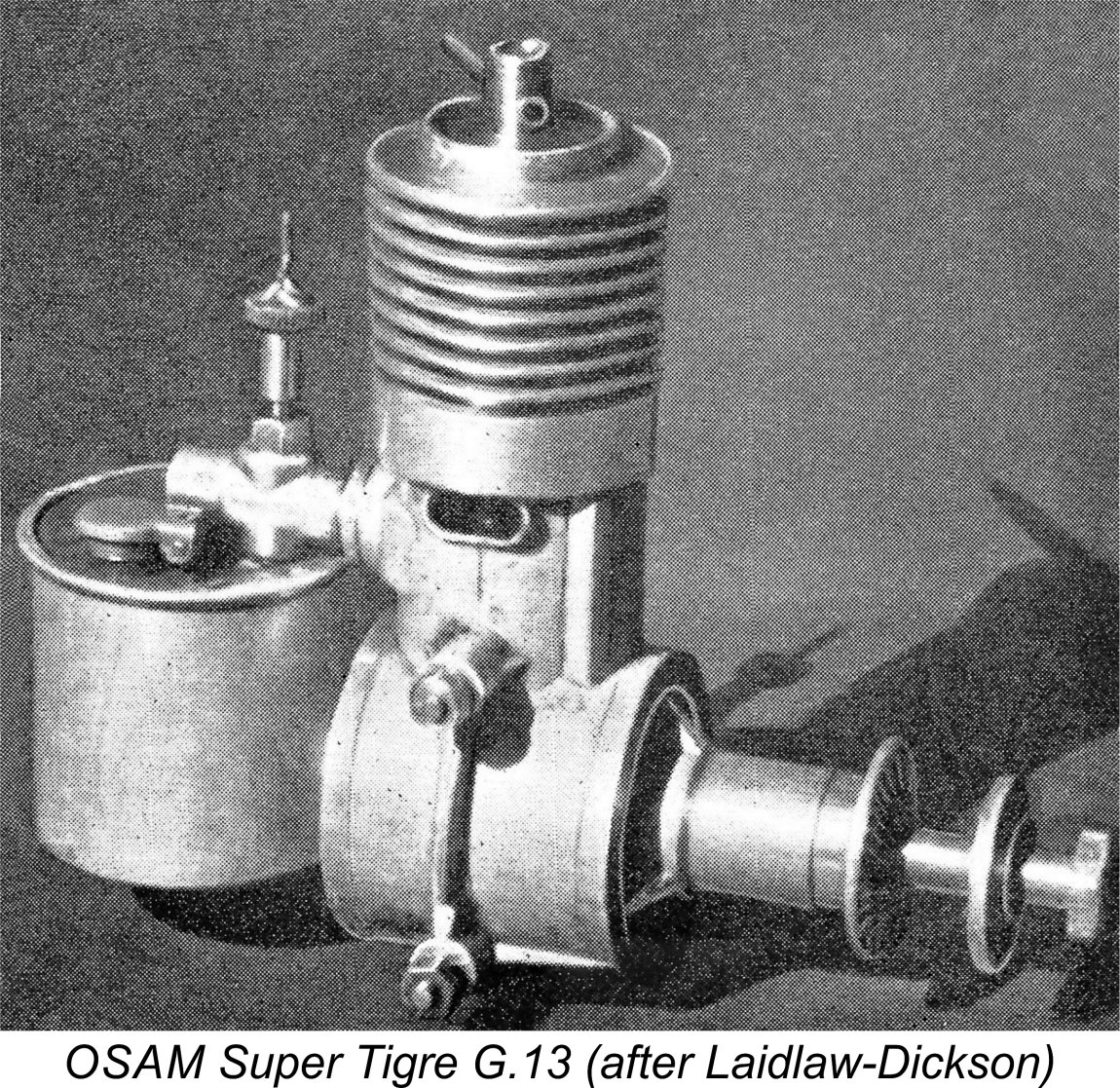

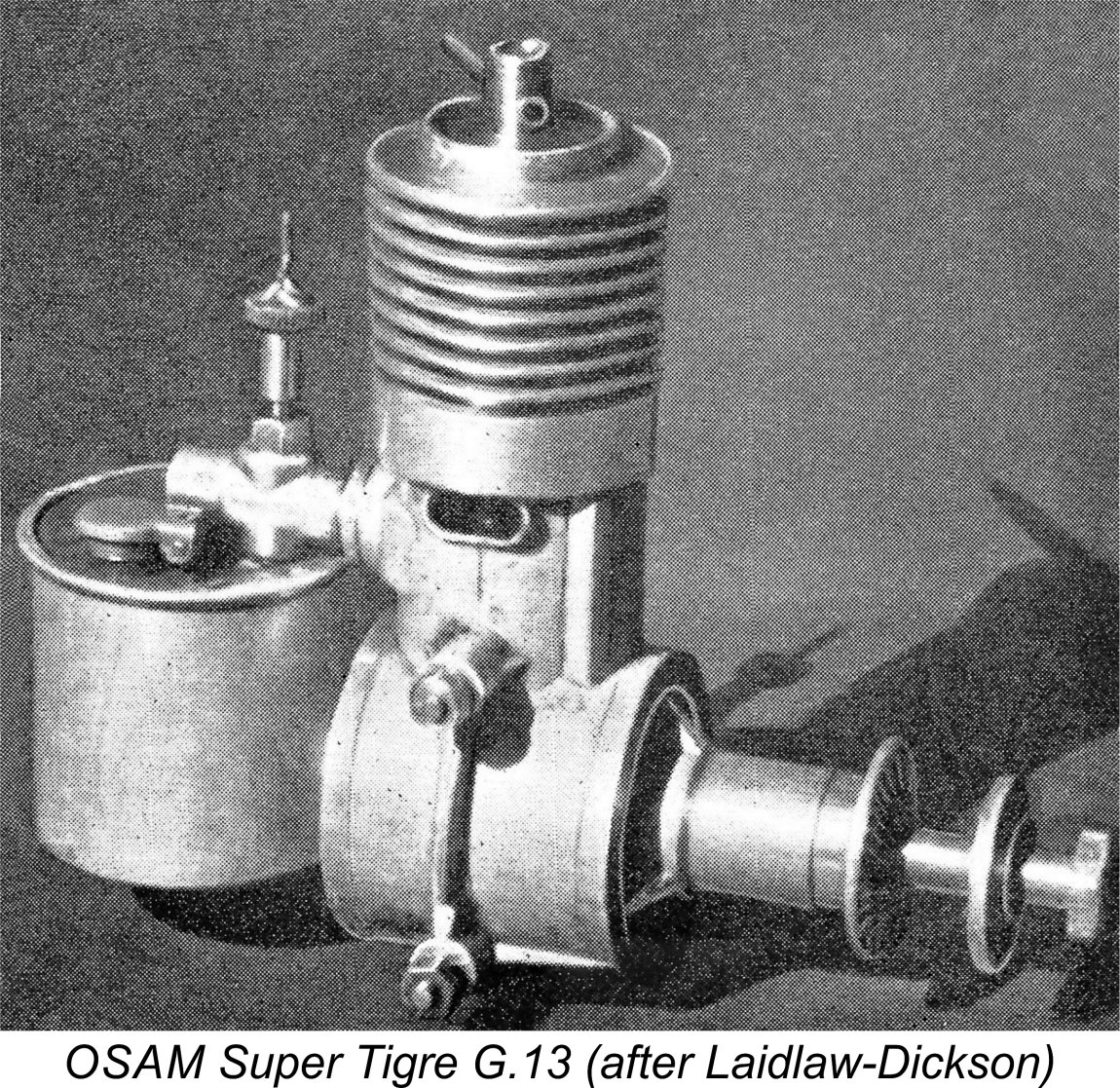

Becoming intrigued after seeing a Dyno, Jaures Garofali of Bologna designs his first diesel engine, the G-13, in 1943. His previous twelve designs had been spark ignition units, of which only a few went beyond the design phase to metal in a few pieces. Unable to make engines until late 1945, 24 O.S.A.M. G-13 “Super Tigre” 5.28 cc engines are sold via Aviomodelli in Cremona from mid-1946. These engines are of classic side port layout with T-scavenging. They feature an unusual mounting arrangement using vertically-placed pairs of screw attachment points on the sides of the case to facilitate the adjustment of engine downthrust in a model. Other similar designs with crankshaft or rotary disc induction follow, until Garofali parts from his business partner in 1949 to found Micromeccanica Saturno, with the soon to be famous “Super Tigre” trademark.

Becoming intrigued after seeing a Dyno, Jaures Garofali of Bologna designs his first diesel engine, the G-13, in 1943. His previous twelve designs had been spark ignition units, of which only a few went beyond the design phase to metal in a few pieces. Unable to make engines until late 1945, 24 O.S.A.M. G-13 “Super Tigre” 5.28 cc engines are sold via Aviomodelli in Cremona from mid-1946. These engines are of classic side port layout with T-scavenging. They feature an unusual mounting arrangement using vertically-placed pairs of screw attachment points on the sides of the case to facilitate the adjustment of engine downthrust in a model. Other similar designs with crankshaft or rotary disc induction follow, until Garofali parts from his business partner in 1949 to found Micromeccanica Saturno, with the soon to be famous “Super Tigre” trademark.

Other Italian diesels which enter production at some level prior to the end of WW2 include the Atomatic 1 cc and 4 cc models from Rome, developed by Uberto Travagli; the 2 cc P.O. 2 diesel from Bergamo; and the Folgore LN 2 of 1.99 cc displacement from Cremona. Several additional models originate in Turin in the form of the Elia 4.2 cc unit and the Helium B.6 and C.6 designs of 6 cc displacement. As can be seen, Italy is well placed to become a major diesel-producing nation by the end of the war.

GERMANY/AUSTRIA

Organised model aircraft flying in Germany is controlled under the auspices of the Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps (National Socialist Flyer Corps) and Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) as a means of promoting air-mindedness among young Germans and expanding their technical knowledge in the field. Models are divided into specific classes, with the focus on advancing the state of the art and striving for records, rather than “sport” flying.

“Der Deutscher Sportflieger”, November 1941 reports on the Dyno 1 as a practical model diesel engine that is commercially available (in Switzerland, at least).

“Der Deutscher Sportflieger”, November 1941 reports on the Dyno 1 as a practical model diesel engine that is commercially available (in Switzerland, at least).

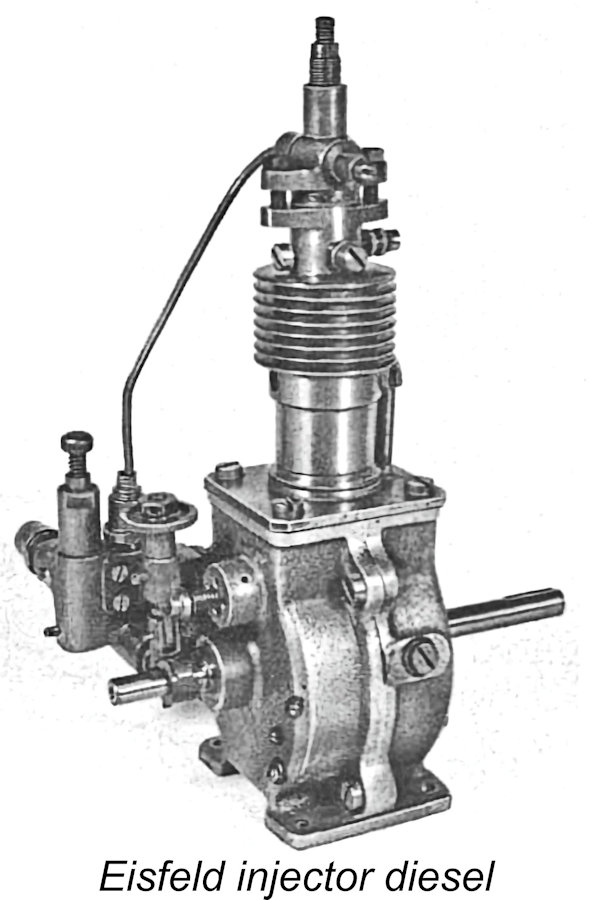

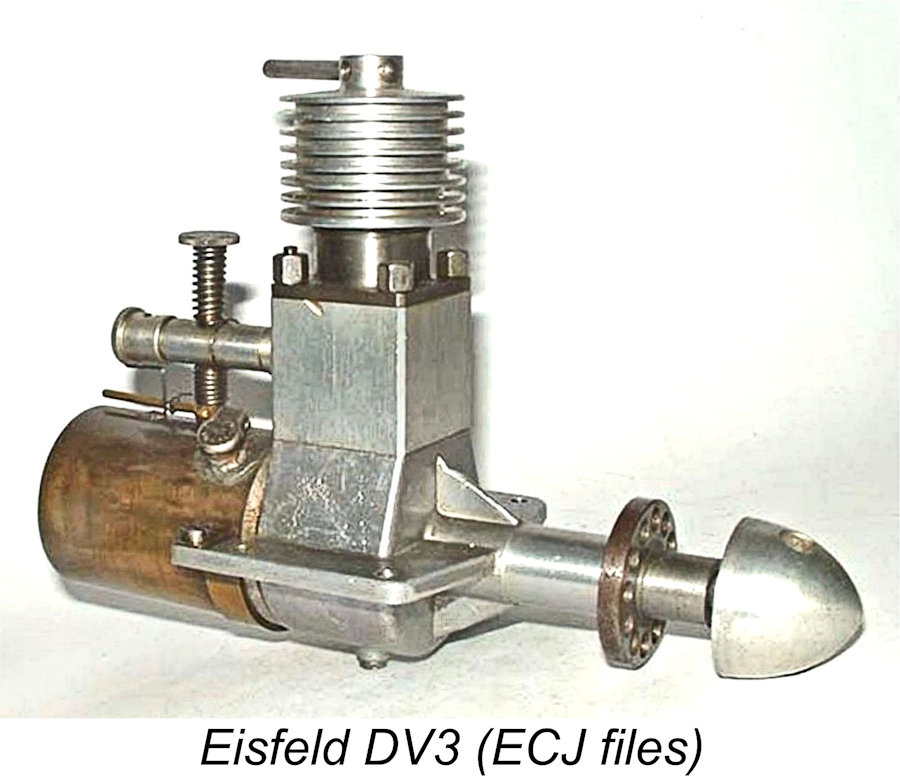

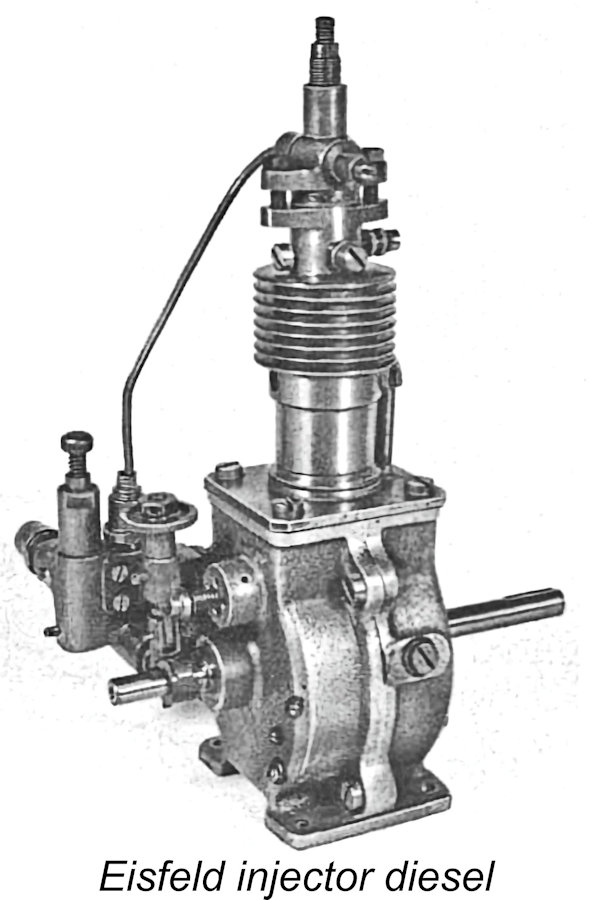

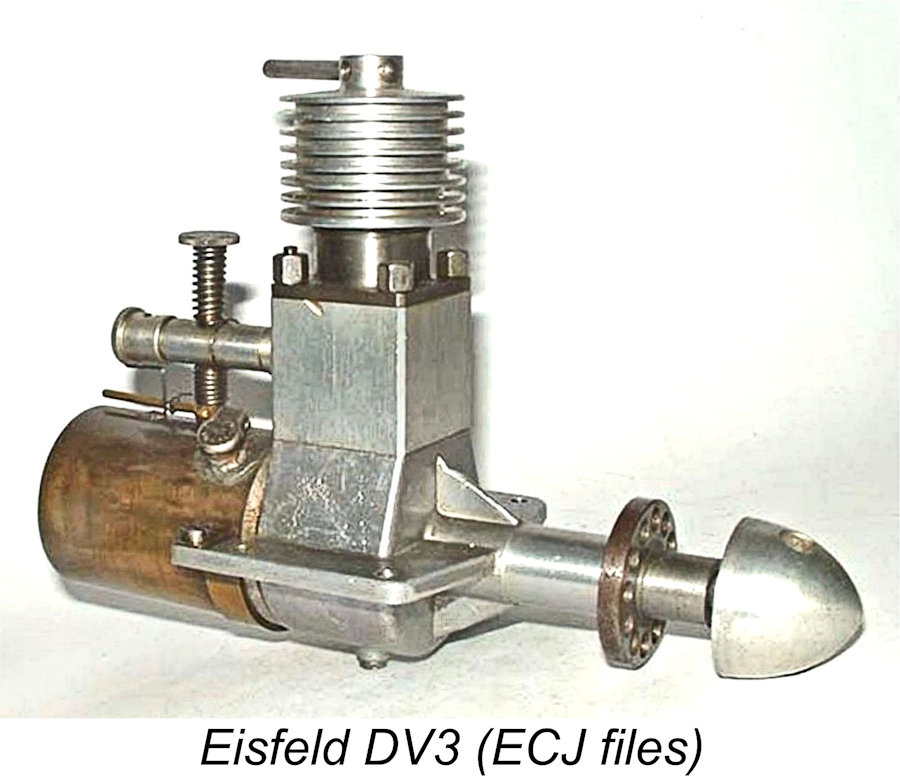

The November 1943 issue of “Modellflug” is largely devoted to model engines. The Editor’s foreword explains the principle of compression ignition engines and ponders the correct naming (lacking injectors, they are not “true” diesels). The first concrete exposure to diesels for the average German modeller likely comes when Gustav Eisfeld (Germany’s second most important manufacturer of spark ignition engines after Walter Kratsch) relates his earlier experiments with “true” direct injection model diesels and presents the results of recent developments relating to his new designs based upon the simpler 2-stroke carburettor type that had originated in Switzerland. These follow the Dyno’s general design but have a shorter stroke and only one exhaust port.

Eisfeld’s range of six engine sizes from 0.5 cc to 10 cc is presented together with thorough test results reflecting power output, fuel consumption, propeller sizes and power-to-weight data. Two Eisfeld diesels are produced commercially in small series – the “DV2” of 2.5 cc and “DV3” of 6 cc. Their introductory date of 1942 which has been cited by some could not be independently verified, but a DV3 fitted to a model is shown in a 1944 issue of the magazine.

Eisfeld’s range of six engine sizes from 0.5 cc to 10 cc is presented together with thorough test results reflecting power output, fuel consumption, propeller sizes and power-to-weight data. Two Eisfeld diesels are produced commercially in small series – the “DV2” of 2.5 cc and “DV3” of 6 cc. Their introductory date of 1942 which has been cited by some could not be independently verified, but a DV3 fitted to a model is shown in a 1944 issue of the magazine.

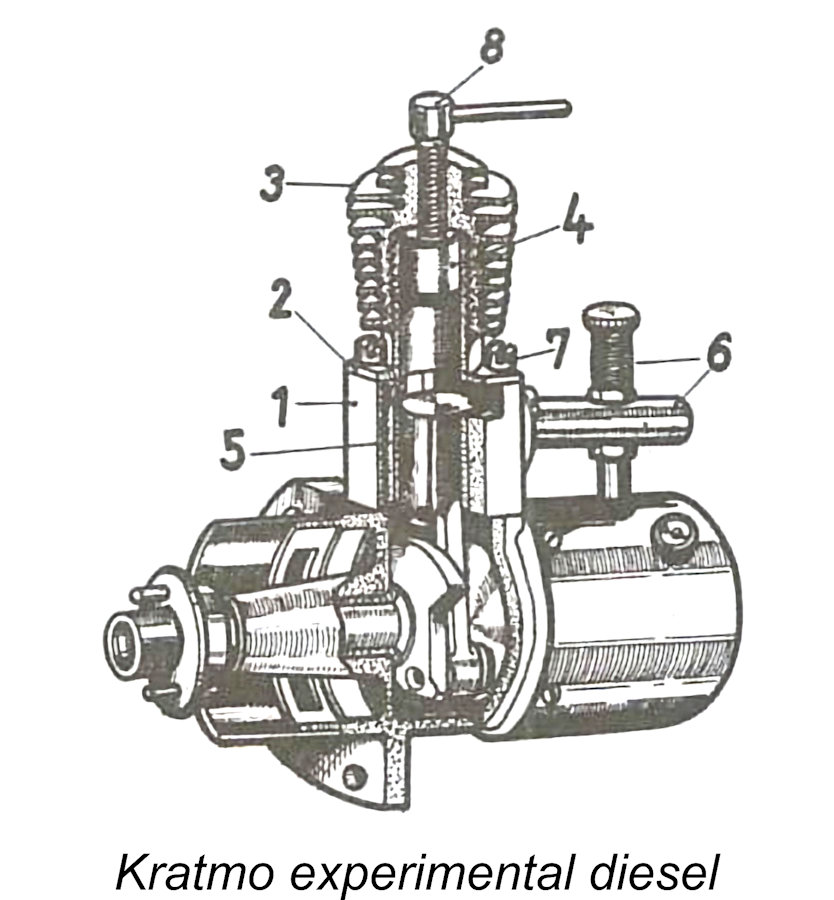

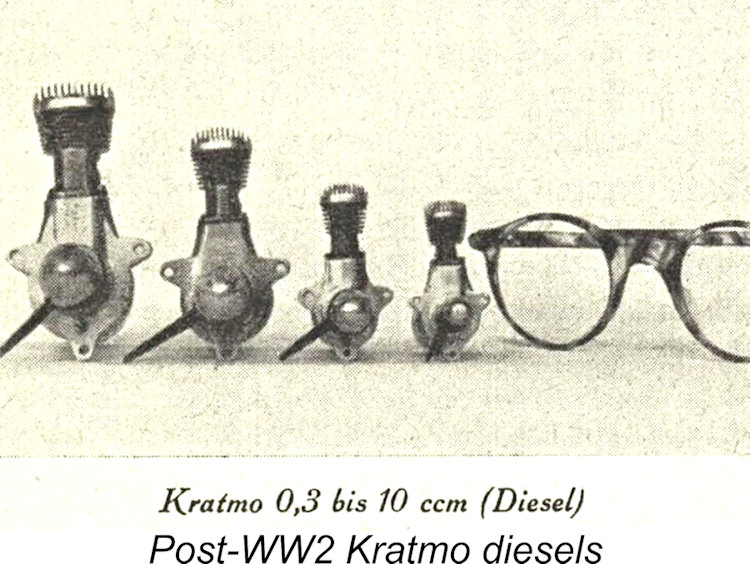

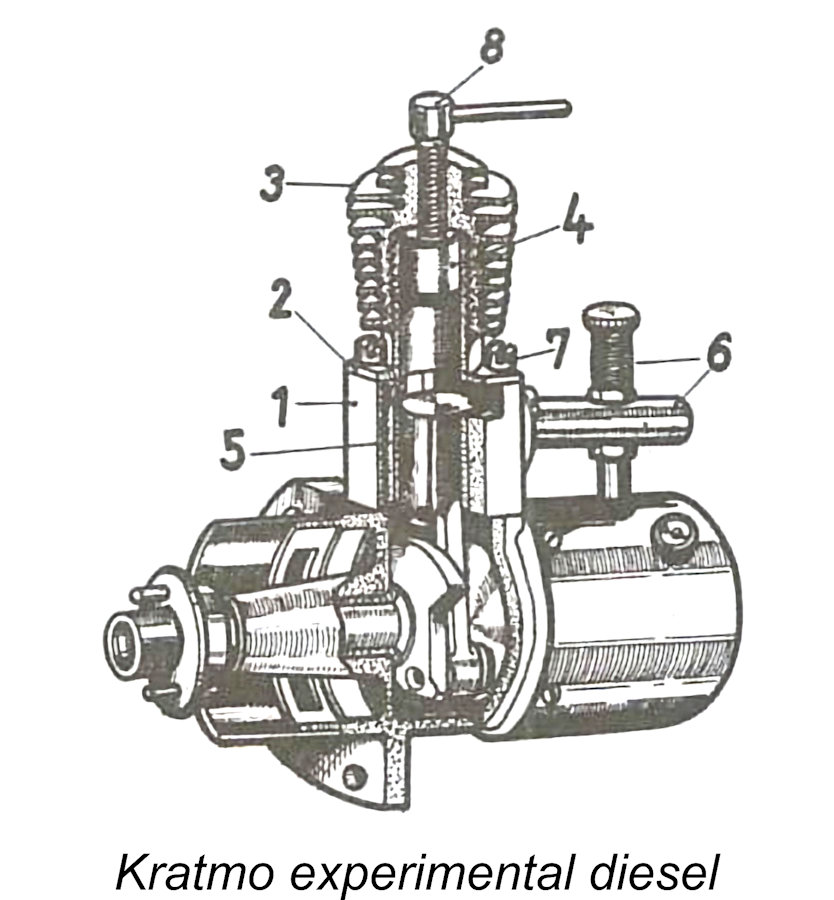

Although Walter Kratsch’s line of Kratmo spark ignition engines forms the subject of the magazine's lead article, there is no mention of his experiments with diesels. His first such effort is a conversion of the Kratmo 10 cc sparker using a smaller-bore cylinder assembly. Wishing to carry over the blind-bored cylinder, for which his company has special capability, he develops the eccentric crankshaft bushing method of variable compression adjustment, but is unable to patent it at that time.

Although Walter Kratsch’s line of Kratmo spark ignition engines forms the subject of the magazine's lead article, there is no mention of his experiments with diesels. His first such effort is a conversion of the Kratmo 10 cc sparker using a smaller-bore cylinder assembly. Wishing to carry over the blind-bored cylinder, for which his company has special capability, he develops the eccentric crankshaft bushing method of variable compression adjustment, but is unable to patent it at that time.

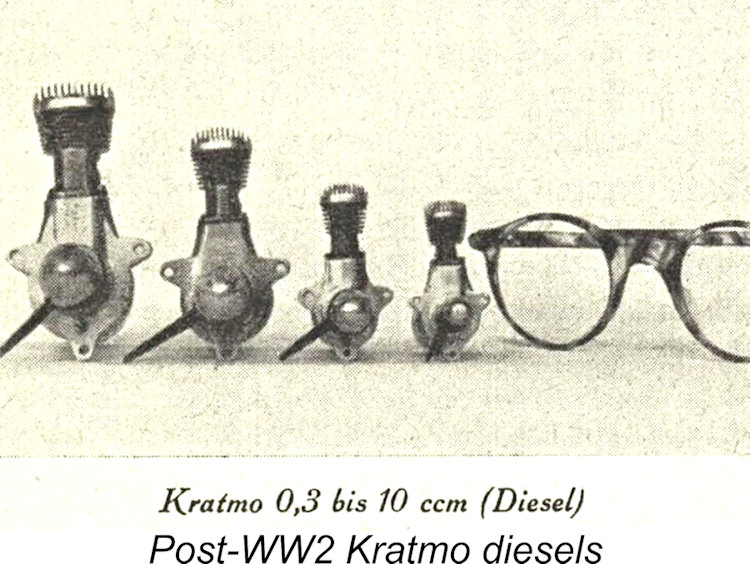

Wartime production of Kratmo diesels only reaches the prototype stage, but very limited postwar Kratmo engine production includes diesels in several sizes, with the unusual compression adjustment feature. This is soon halted by the government as representing a waste of scarce raw materials.

Wartime production of Kratmo diesels only reaches the prototype stage, but very limited postwar Kratmo engine production includes diesels in several sizes, with the unusual compression adjustment feature. This is soon halted by the government as representing a waste of scarce raw materials.

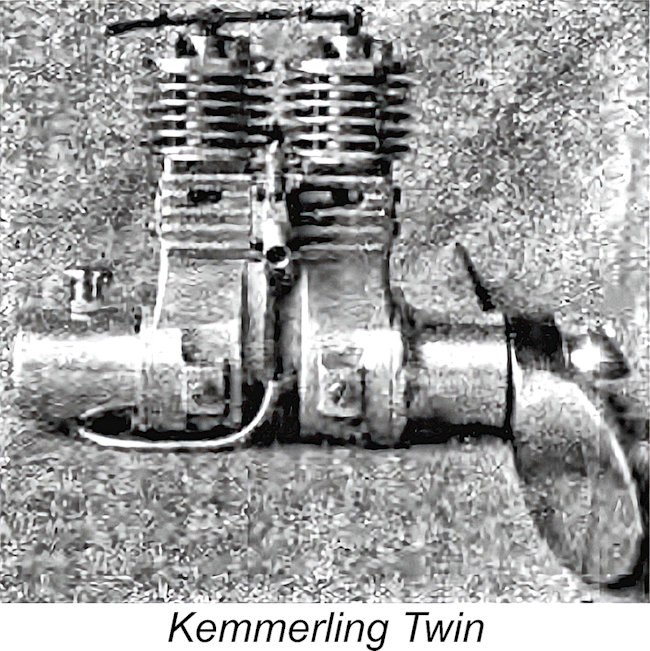

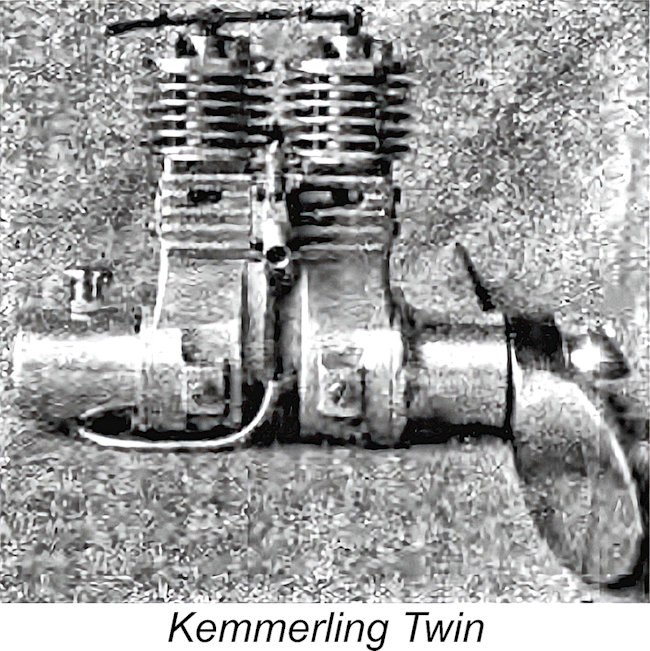

Also in that same issue of the magazine, Carl Kemmerling of Aachen describes his home-made diesels. His first is a close copy of the Dyno.  The second, a 9.6 cc in-line twin cylinder type, reportedly produces 0.45 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 400 mm x 240 mm propeller. Both engines use side-port induction and T-scavenging. His third model, a 9.0 cc single cylinder type with crankshaft rotary induction, develops 0.40 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 270 mm

The second, a 9.6 cc in-line twin cylinder type, reportedly produces 0.45 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 400 mm x 240 mm propeller. Both engines use side-port induction and T-scavenging. His third model, a 9.0 cc single cylinder type with crankshaft rotary induction, develops 0.40 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 270 mm  x 220 mm propeller. It weighs 380 gm. Kemmerling prefers a fuel mix of 75% kerosene, 20% ether and 5% motor oil.

x 220 mm propeller. It weighs 380 gm. Kemmerling prefers a fuel mix of 75% kerosene, 20% ether and 5% motor oil.

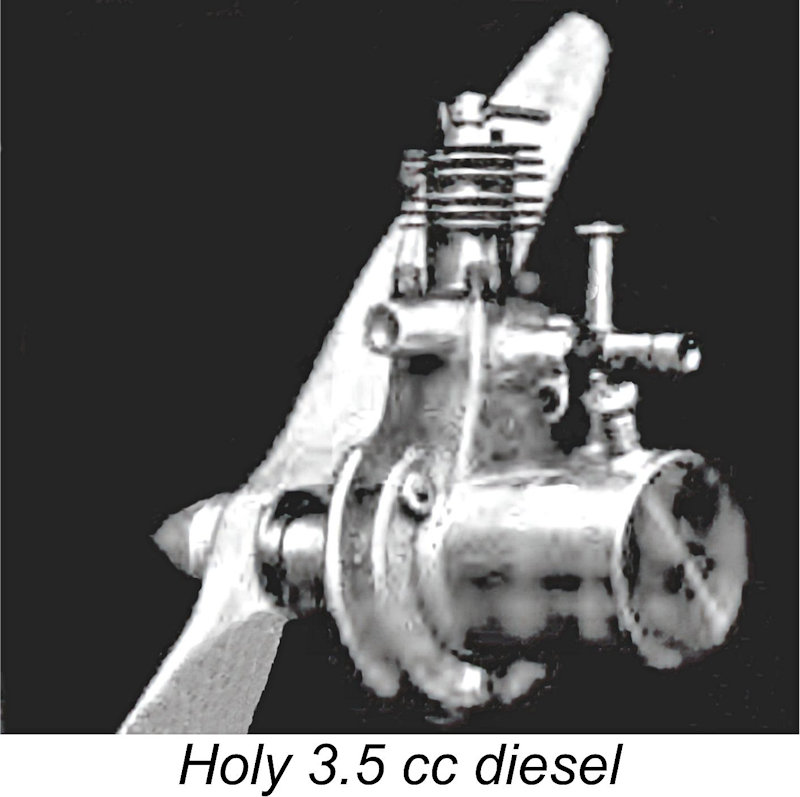

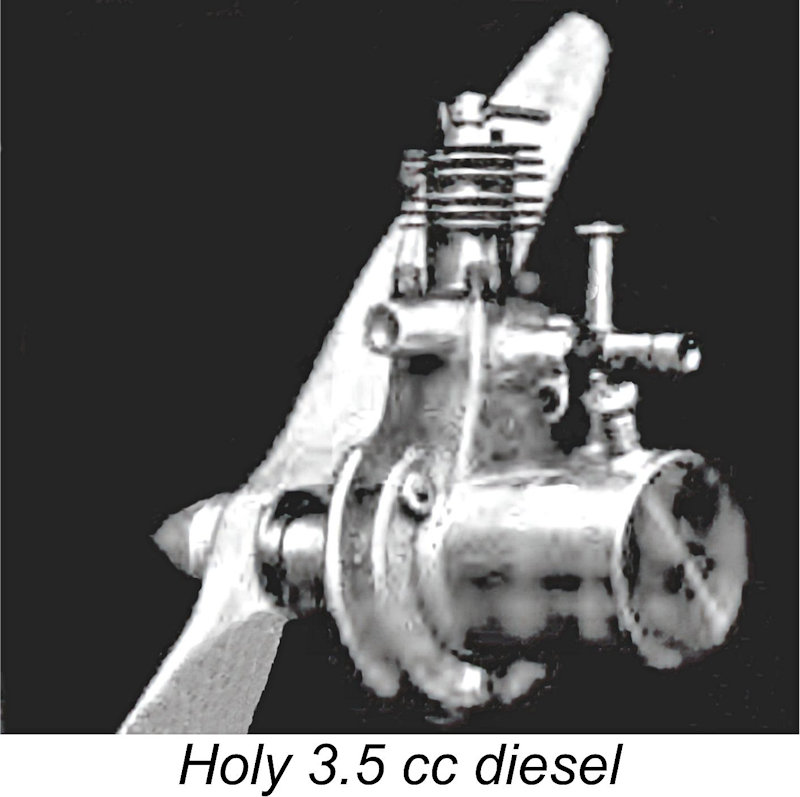

Another home-built engine, the “Holy-Diesel” by Austrian Karl Holy of Mistelbach, is described. This unit is Dyno-derived with 15 mm bore and 20 mm stroke for a 3.5 cc swept volume. Its most distinctive features are flexible metal exhaust tube extensions and the mounting method of two circular crankcase flanges slotting over a board of suitable thickness cut with a U-shaped aperture. It runs on 7 parts motor diesel, 2 parts motor oil and 2 parts ether.

NETHERLANDS

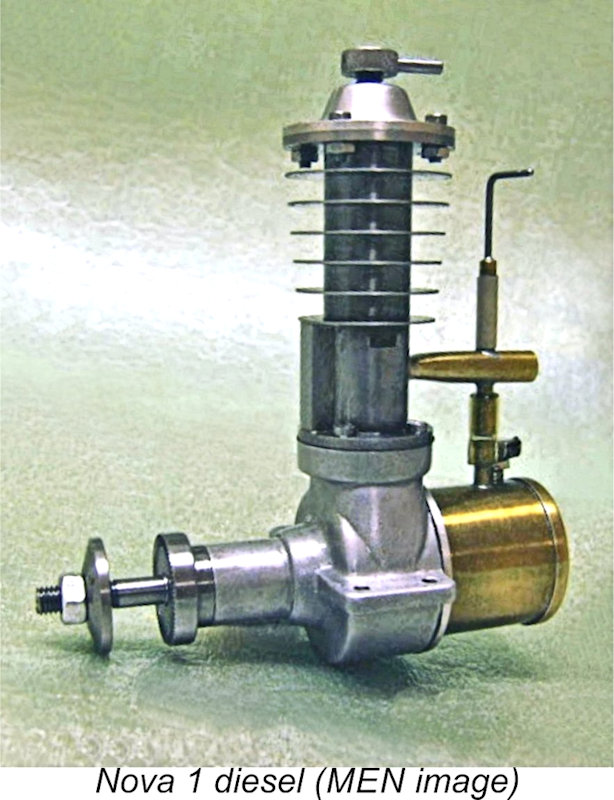

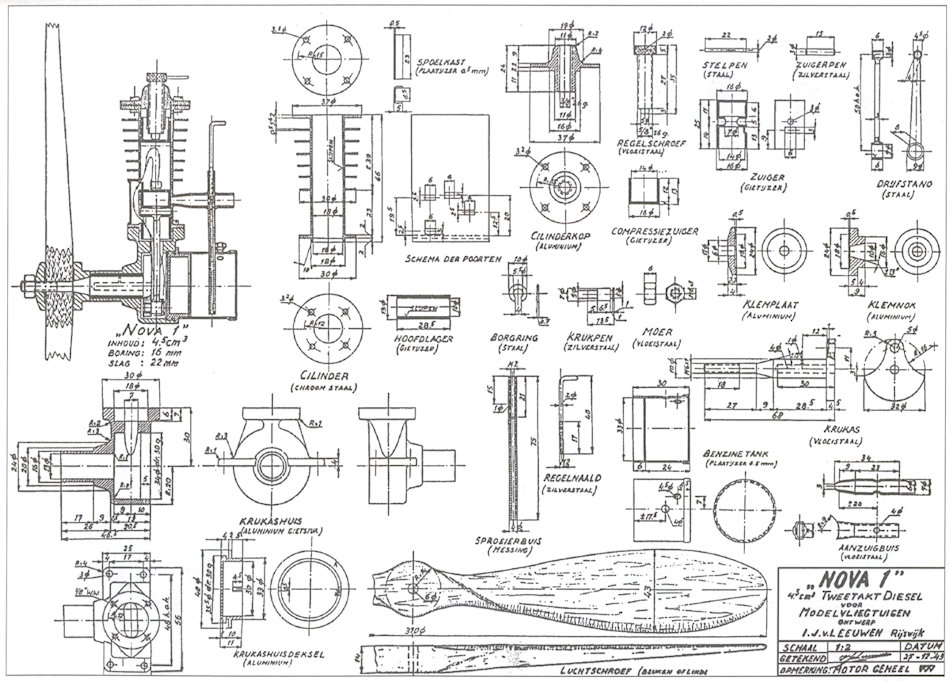

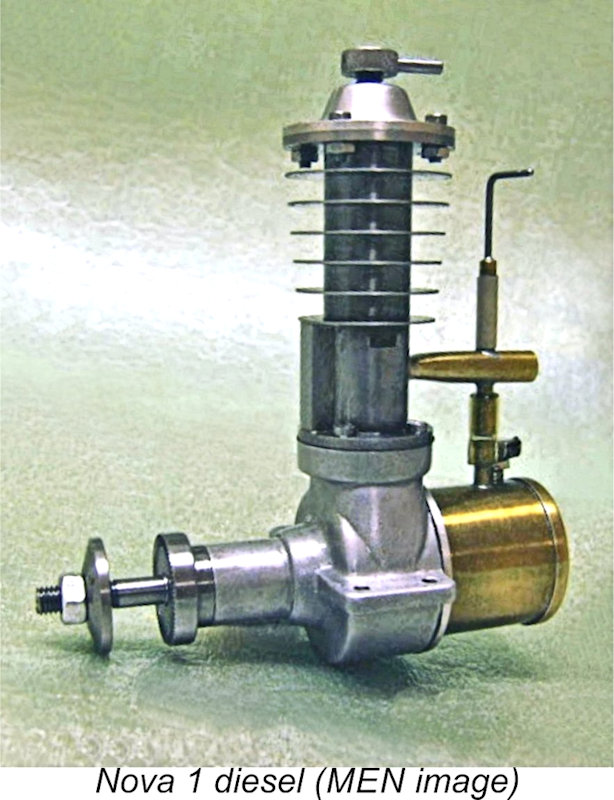

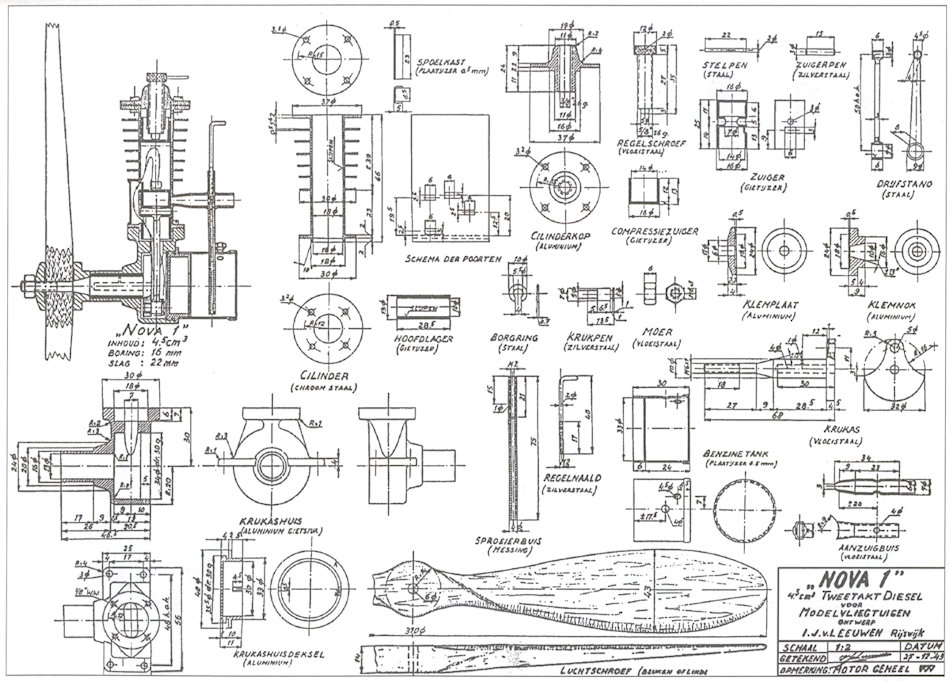

The Dutch magazine “De Modellbauer” publishes plans and a short history of I. J. v. Leeuen’s Nova 1 diesel engine of 1943. Of 4.5 cc displacement, it has classic side-port induction and a T-scavenging layout. The widely-spaced integral cooling fins on its tall steel cylinder lend a somewhat exaggerated appearance. The plan’s title block is dated December 1943 and is intended for “Modelvliegtuigen” in Antwerp, Belgium. It is not known if it was published there, but it subsequently appears in the May 1946 issue of the English “Model Aircraft” magazine.

The Dutch magazine “De Modellbauer” publishes plans and a short history of I. J. v. Leeuen’s Nova 1 diesel engine of 1943. Of 4.5 cc displacement, it has classic side-port induction and a T-scavenging layout. The widely-spaced integral cooling fins on its tall steel cylinder lend a somewhat exaggerated appearance. The plan’s title block is dated December 1943 and is intended for “Modelvliegtuigen” in Antwerp, Belgium. It is not known if it was published there, but it subsequently appears in the May 1946 issue of the English “Model Aircraft” magazine.

SCANDINAVIA

Although neutral, Sweden has significant trade links with Germany and maintains contact with other countries in a limited way, particularly neighbours Denmark and Norway, both of which are German-occupied.

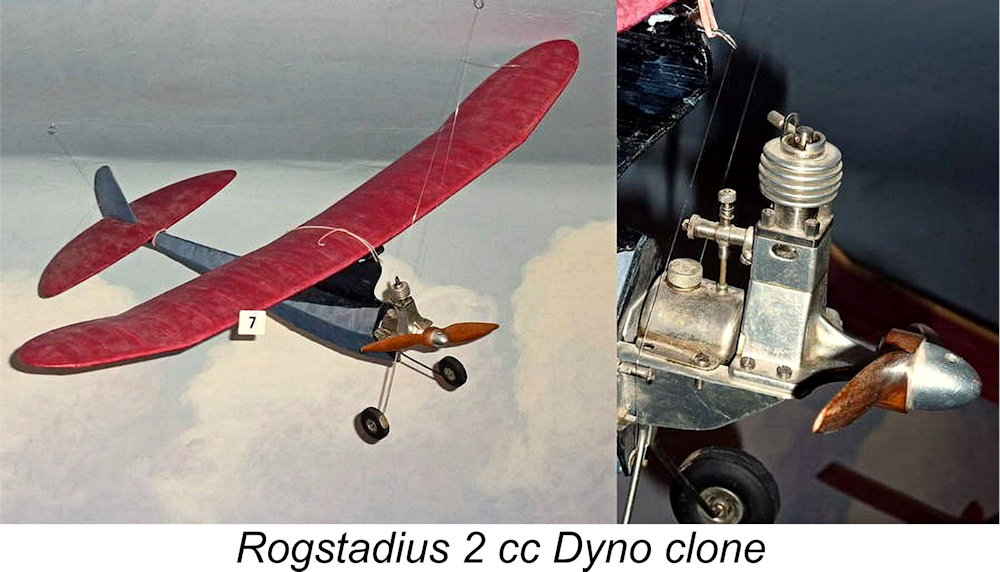

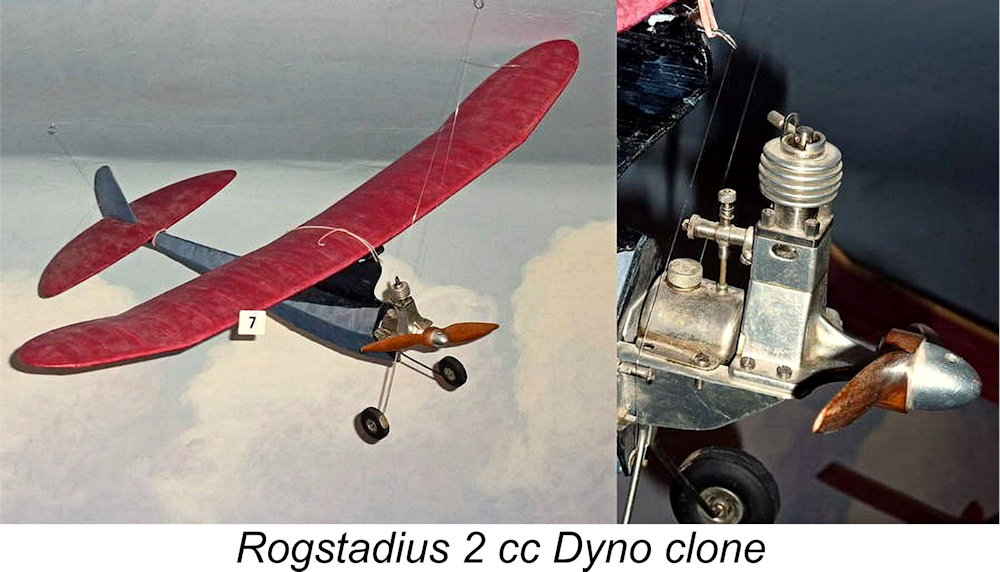

In 1942, the editor of the Swedish magazine “Teknik för Alla”, Gunnar Fahlnäs, somehow acquires a Dyno engine and has model engineer Ivan Rogstadius examine it with the intent of publishing a construction feature article in a future issue. Ivan constructs the prototype engine, with a successful flight test being reported in “Svensk Flygtidning” No. 7, July 1943. His drawings and construction articles for a Dyno clone appear in the December 1943 and January 1944 issues of “Teknik för Alla”. Minor differences are its crankcase nose strengthening webs and streamlined fuel tank attached to the back plate.

In 1942, the editor of the Swedish magazine “Teknik för Alla”, Gunnar Fahlnäs, somehow acquires a Dyno engine and has model engineer Ivan Rogstadius examine it with the intent of publishing a construction feature article in a future issue. Ivan constructs the prototype engine, with a successful flight test being reported in “Svensk Flygtidning” No. 7, July 1943. His drawings and construction articles for a Dyno clone appear in the December 1943 and January 1944 issues of “Teknik för Alla”. Minor differences are its crankcase nose strengthening webs and streamlined fuel tank attached to the back plate.

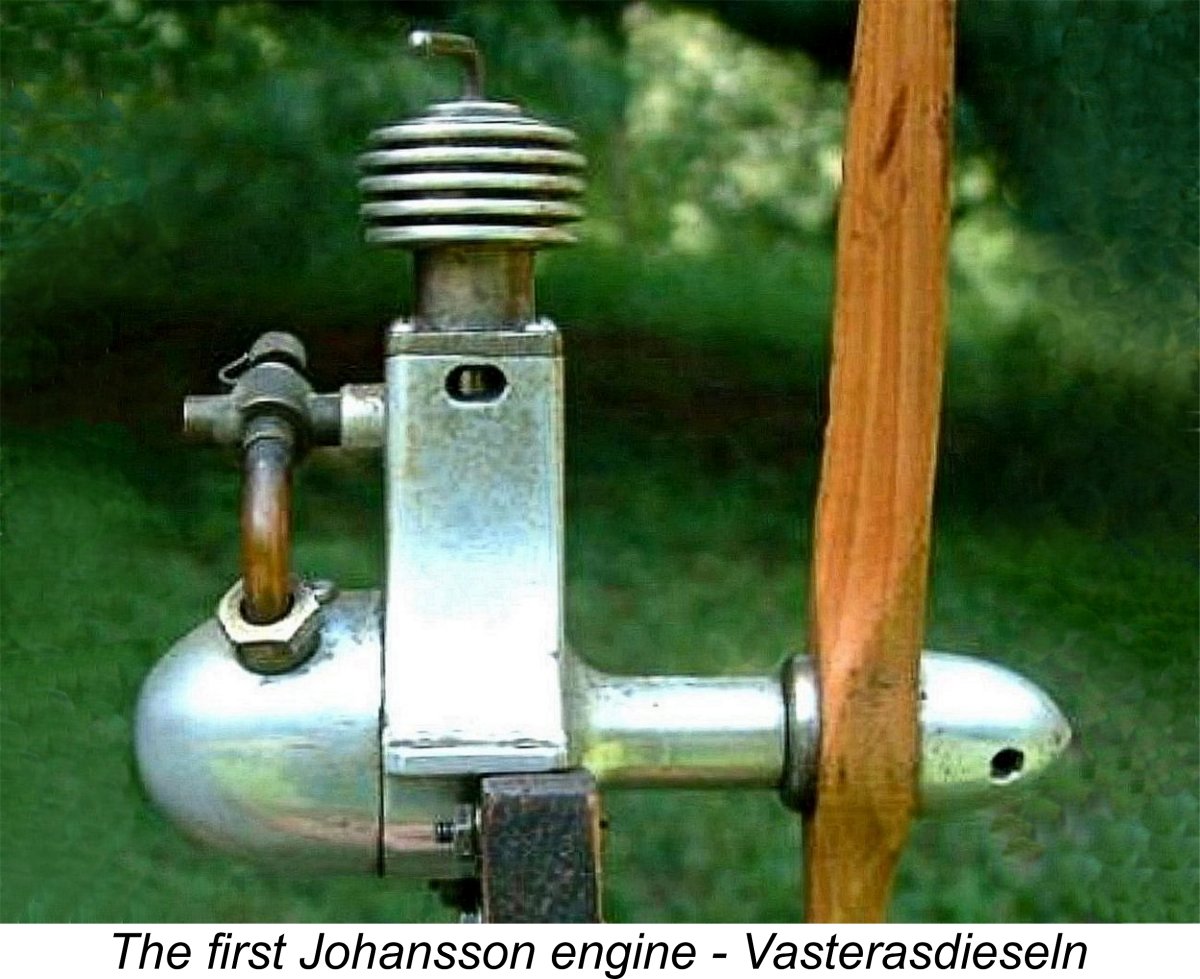

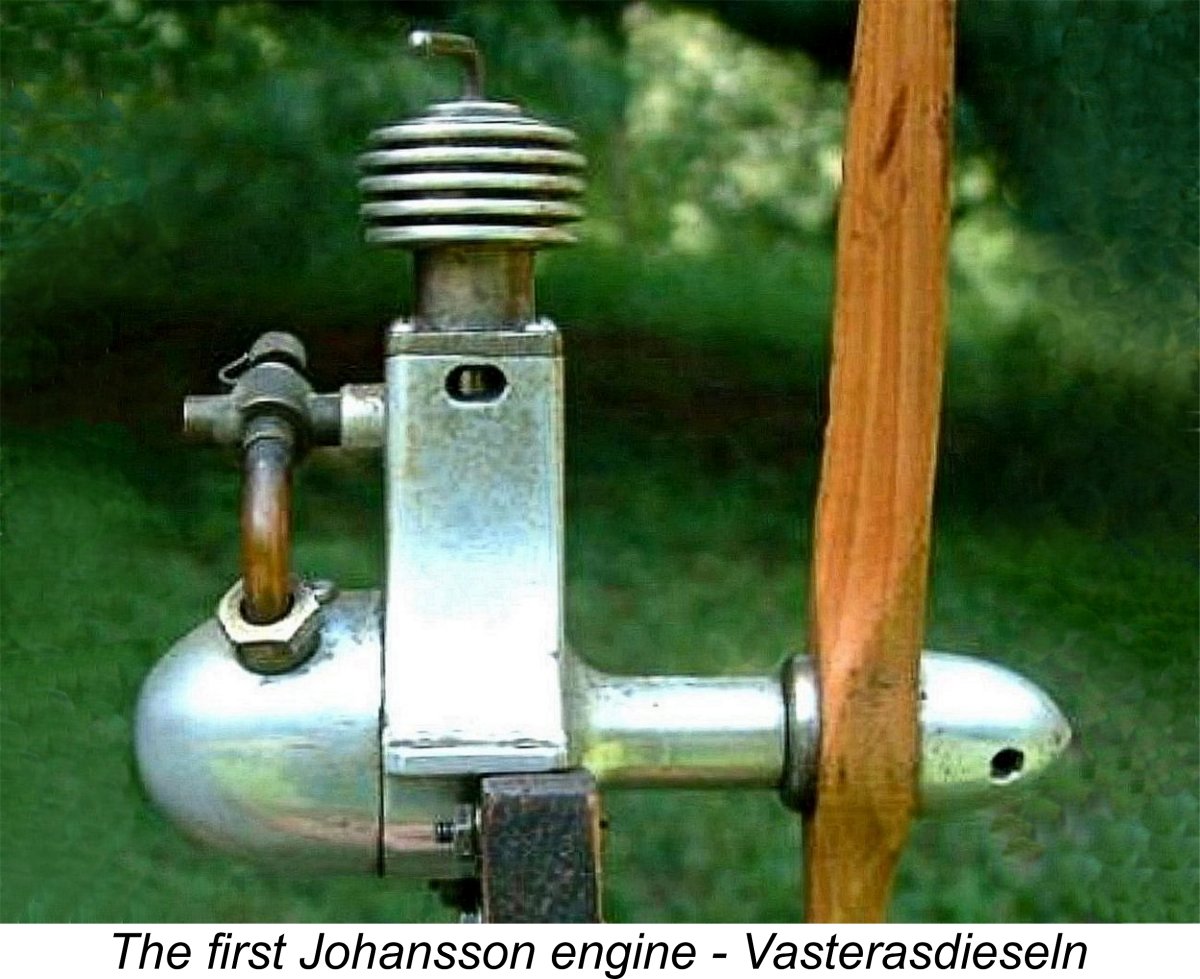

Rogstadius is not involved in the production of the subsequent commercial engines from different makers which closely follow his Dyno clone design. Some were made by engineer H. Vileén and advertised in 1944 for direct sale, later by several retailers. Closely following his later monobloc crankcase variation, H & B Johansson of Västerås release their first entry into model engine manufacture, the Västeråsdieseln, producing some 500 pieces. Under the Komet

Rogstadius is not involved in the production of the subsequent commercial engines from different makers which closely follow his Dyno clone design. Some were made by engineer H. Vileén and advertised in 1944 for direct sale, later by several retailers. Closely following his later monobloc crankcase variation, H & B Johansson of Västerås release their first entry into model engine manufacture, the Västeråsdieseln, producing some 500 pieces. Under the Komet  trade-name, the company becomes Sweden’s largest model engine manufacturing concern, continuing with a series of Komet diesel and glow-plug engines through the 1950’s.

trade-name, the company becomes Sweden’s largest model engine manufacturing concern, continuing with a series of Komet diesel and glow-plug engines through the 1950’s.

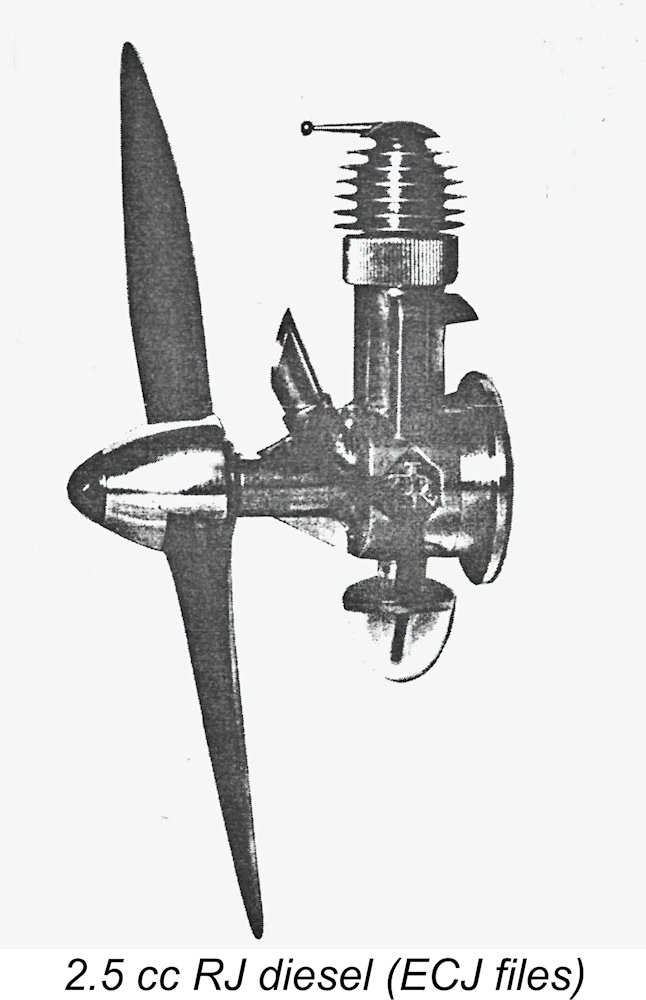

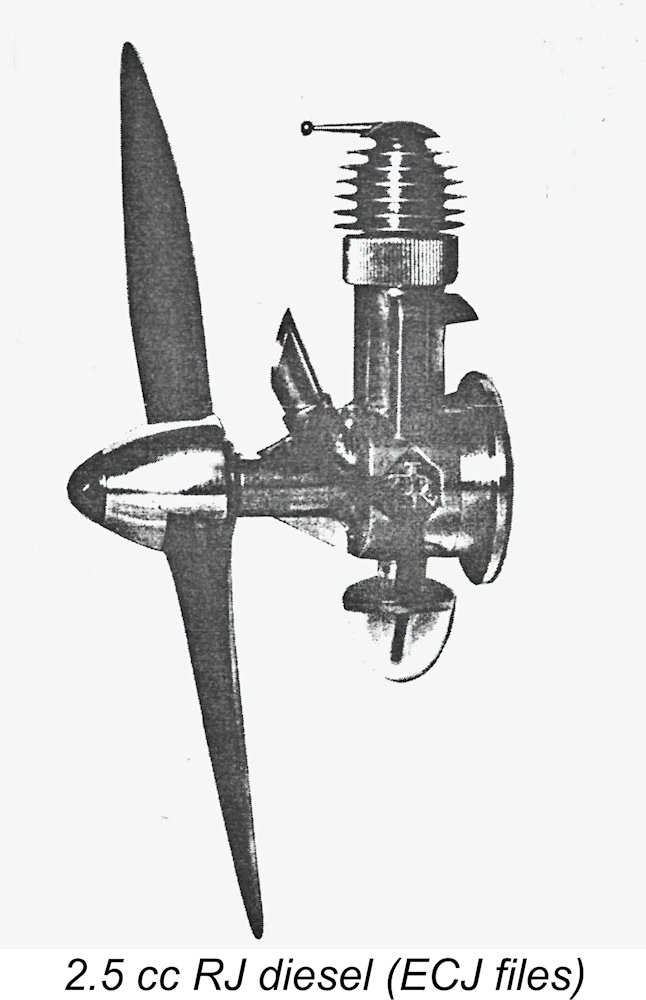

Independently, Rune Johansson produces a small series of fifteen 2.5 cc and five 3.2 cc "RJ" engines, from 1943 to 1946. These feature front rotary valve induction, radial mounting and a small underslung fuel tank.

Italian-born Swedish resident Giancarlo Pinotti produces the “GP” 1.5 cc diesel in 1944. Its most interesting feature is the elaborate method for setting thecompression adjustment range and then rotating the cooling jacket on its thread to vary compression within that range. Low production volume from this father and son venture.

Italian-born Swedish resident Giancarlo Pinotti produces the “GP” 1.5 cc diesel in 1944. Its most interesting feature is the elaborate method for setting thecompression adjustment range and then rotating the cooling jacket on its thread to vary compression within that range. Low production volume from this father and son venture.

In Denmark, Carl Rose (known for his pre-war “CEROS” spark ignition engines) experiments with model diesels and is reported to have made a successful engine in 1940, although this can't now be confirmed. He turns to glow plug ignition when production resumes in the later 1940s.

D enmark’s first commercial model diesel is the “Diesella” 2.4 cc, a collaboration between Eli Andersen and A Jeppesen. Released in November 1943, it is well received. It features a sturdy crankcase with streamlined profile accentuated by a matching rear-mounted fuel tank and spinner nut. It employs side-port induction with a

enmark’s first commercial model diesel is the “Diesella” 2.4 cc, a collaboration between Eli Andersen and A Jeppesen. Released in November 1943, it is well received. It features a sturdy crankcase with streamlined profile accentuated by a matching rear-mounted fuel tank and spinner nut. It employs side-port induction with a  single exhaust, as well as a crankshaft mounted on ball races. The cited output is 1/6 HP at 4,500 RPM.

single exhaust, as well as a crankshaft mounted on ball races. The cited output is 1/6 HP at 4,500 RPM.

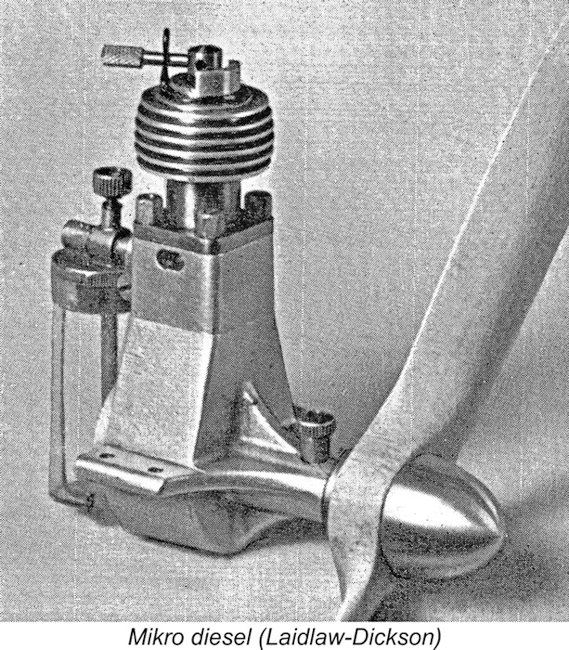

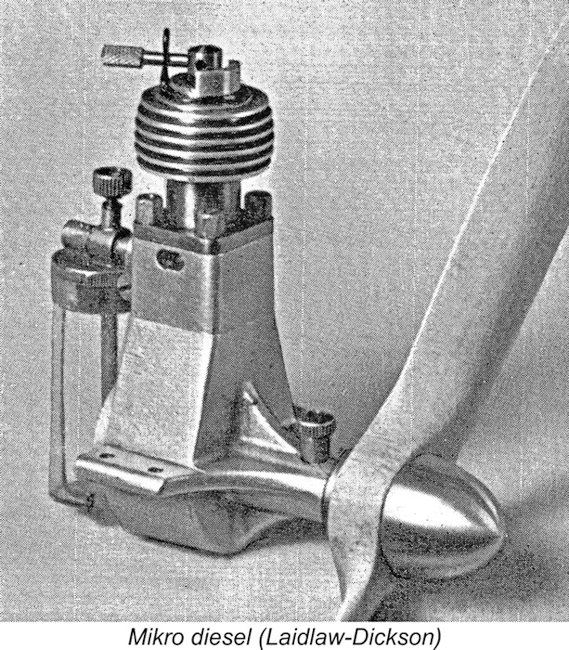

Kaj Neilsen’s “Mikro” 2 cc diesel follows in 1944. It is essentially a Dyno clone, strongly influenced by the Rogstadius adaptation.

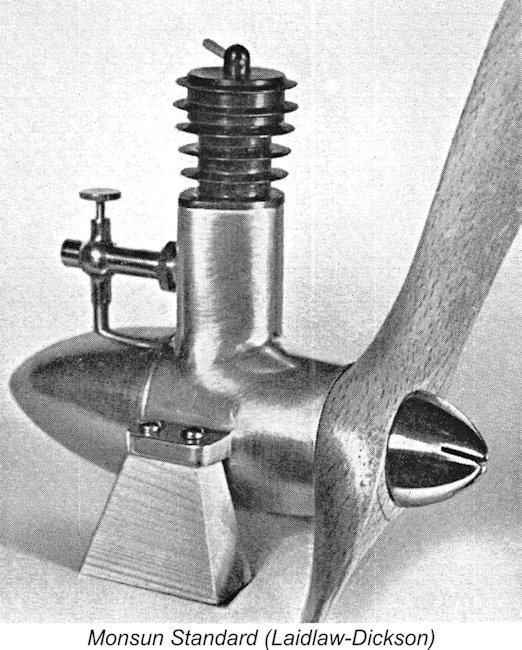

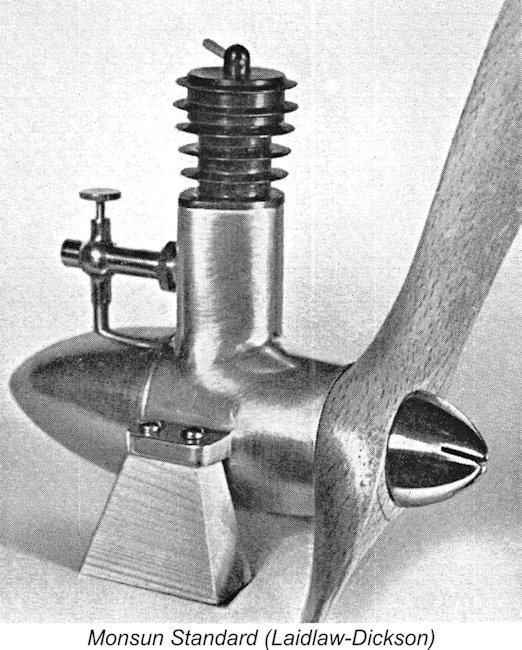

Although not produced until after the German occupation ends, the 2.4 cc “Monsun Standard” is developed from 1944 onwards and flight-tested by Jorgen Dommergard and Christian Petersen. Manufactured by Thorning Bensen of Helsingør, its key feature is the cylinder porting, inspired by the German DKW 2-stroke motorcycle  and car engines. It is the first model engine featuring basic Schnürle porting (transfers either side of the exhaust, all on one side of the cylinder to provide loop scavenging without a baffle).

and car engines. It is the first model engine featuring basic Schnürle porting (transfers either side of the exhaust, all on one side of the cylinder to provide loop scavenging without a baffle).

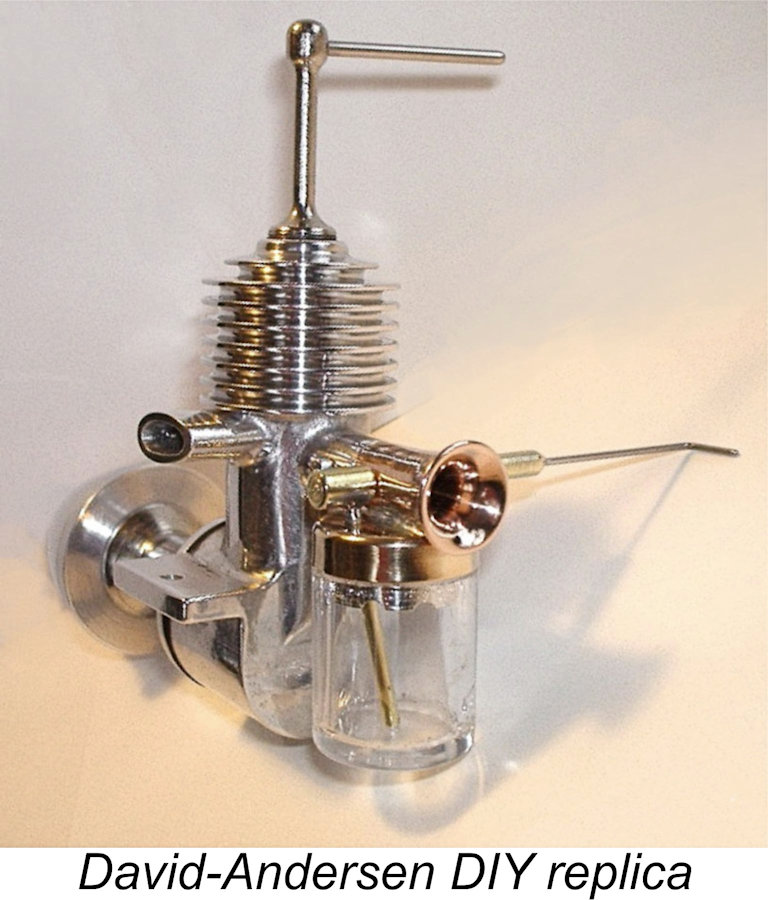

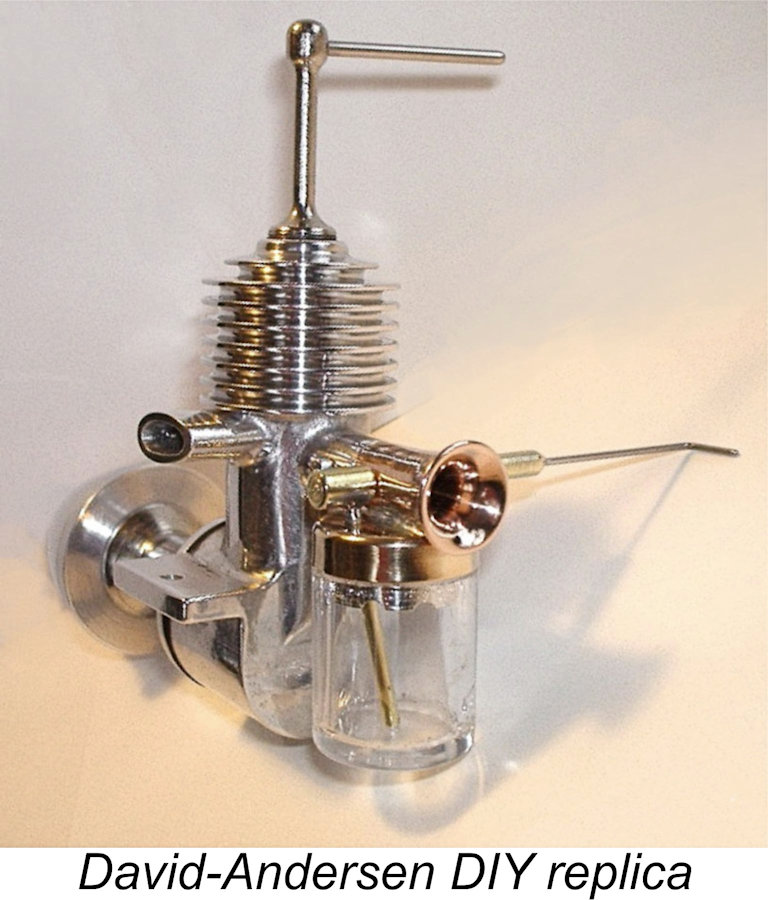

Remembered now as Norway’s premier post-war model engine producer, Jan David-Andersen reads about the compression ignition principle and constructs his first 3.5 cc model diesel in Oslo, Norway during the winter of 1943/1944. It breaks on test, owing to a faulty casting, but he perseveres, producing 10 examples of a successful refined version later that year. Following the accepted long stroke and 3-port formula, it uses no assembly screws. The front crankcase section and cylinder retaining jacket screw onto the cast crankcase.  David-Andersen refines the concept further, arriving at a 2.4 cc design which he presents in his DIY book "Diesel Motor for Modell-Fly, Båt og Bil" in January 1945. Its most interesting feature is a compression adjusting cap that registers on the outside of the cylinder, thus reducing overall height. Complete with tank and propeller, it weighs only 200 grams.

David-Andersen refines the concept further, arriving at a 2.4 cc design which he presents in his DIY book "Diesel Motor for Modell-Fly, Båt og Bil" in January 1945. Its most interesting feature is a compression adjusting cap that registers on the outside of the cylinder, thus reducing overall height. Complete with tank and propeller, it weighs only 200 grams.

Independently, Øivind Andersen (no relation) also finalizes his own model diesel engine design in 1944 and reportedly produces 150 examples, although none appear to exist today. His engine uses a wedge activated by a horizontal compression screw to vary the compression by raising or lowering the blind-bored cylinder. After the war, he makes various diesels in small series, ranging from 0.25 cc to 4.5 cc, incorporating a variety of novel design features.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

Organised model aircraft flying in Czechoslovakia (now Czechia) ends with the German occupation which begins in October 1938. Individuals still fly models, so activity continues in a reduced way. From 1942,  Anthony Grains organises annual competitions for trainees and workers of the SK AERO company on the outskirts of Prague. Contests are based on technical merit and flight duration and are divided into three classes – sheet wing gliders, built-up gliders and engine-powered models.

Anthony Grains organises annual competitions for trainees and workers of the SK AERO company on the outskirts of Prague. Contests are based on technical merit and flight duration and are divided into three classes – sheet wing gliders, built-up gliders and engine-powered models.

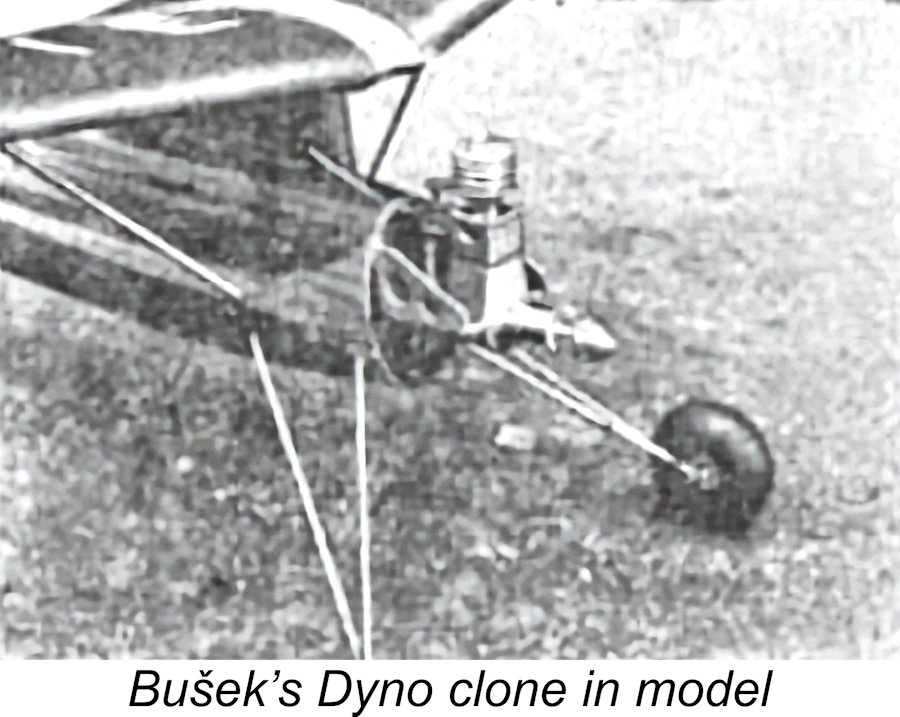

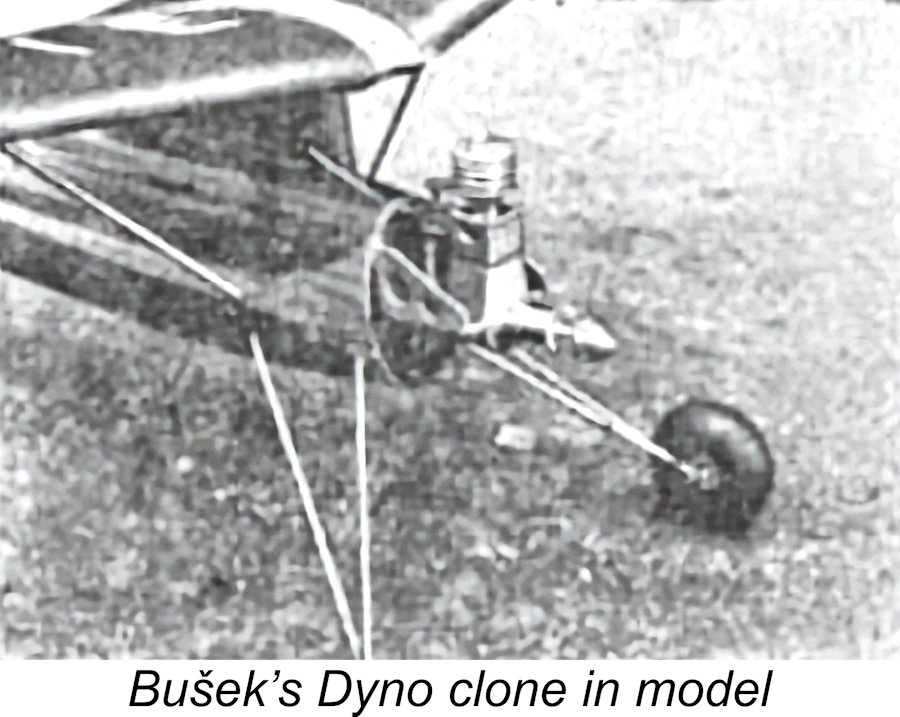

The 1943 competition includes a category specifically for models powered by diesels. Three models are entered, including one by a group of five boys wearing Hitler Youth uniforms. One model crashes, so that category is not contested, but successful flights by the others make a positive impression. Gustav Bušek, already established as the main local model engine producer, vows to make a diesel by the end of the year. Having previously obtained an example of the Dyno, he closely copies its design. His engine is shown mounted in a variant of the “Rejnok VB-602” model in “Mladý Konstruktér” magazine. This article covers the principle of compression ignition and describes the engine. Its performance is said to be equivalent to a 6 cc spark ignition unit.

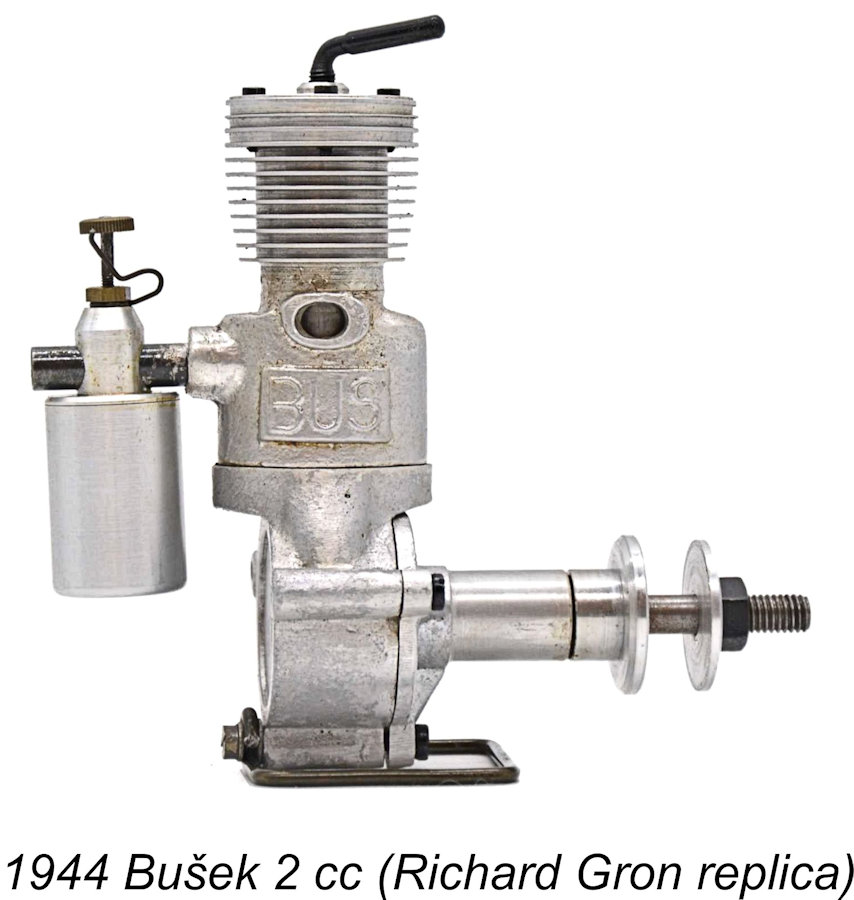

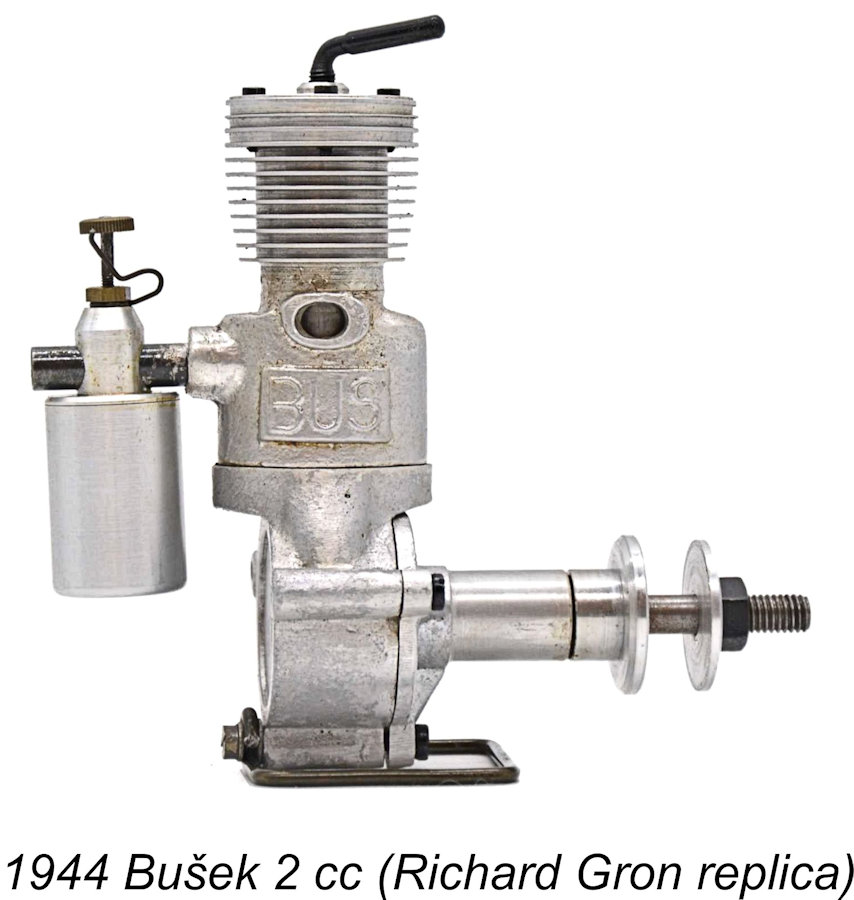

Bušek produces a small series of diesels for the 1944 flying season. These are of approximately 2 cc displacement, with side port induction and three-point radial mounting via threaded studs. Two exhaust tubes are featured. Compression is “factory set” via an external nut engaging the threaded extension of the contra piston. The engines are expensive at 1000 Protectorate Crowns (versus a little over 400 for a 6 cc “Letná” spark ignition engine complete with spark plug, coil and propeller). Jaroslav Prchal flies his example at the 1944 competition. Although not exactly matching Prchal’s description, known surviving Bušek side-port diesels probably represent the design concept.

Bušek produces a small series of diesels for the 1944 flying season. These are of approximately 2 cc displacement, with side port induction and three-point radial mounting via threaded studs. Two exhaust tubes are featured. Compression is “factory set” via an external nut engaging the threaded extension of the contra piston. The engines are expensive at 1000 Protectorate Crowns (versus a little over 400 for a 6 cc “Letná” spark ignition engine complete with spark plug, coil and propeller). Jaroslav Prchal flies his example at the 1944 competition. Although not exactly matching Prchal’s description, known surviving Bušek side-port diesels probably represent the design concept.

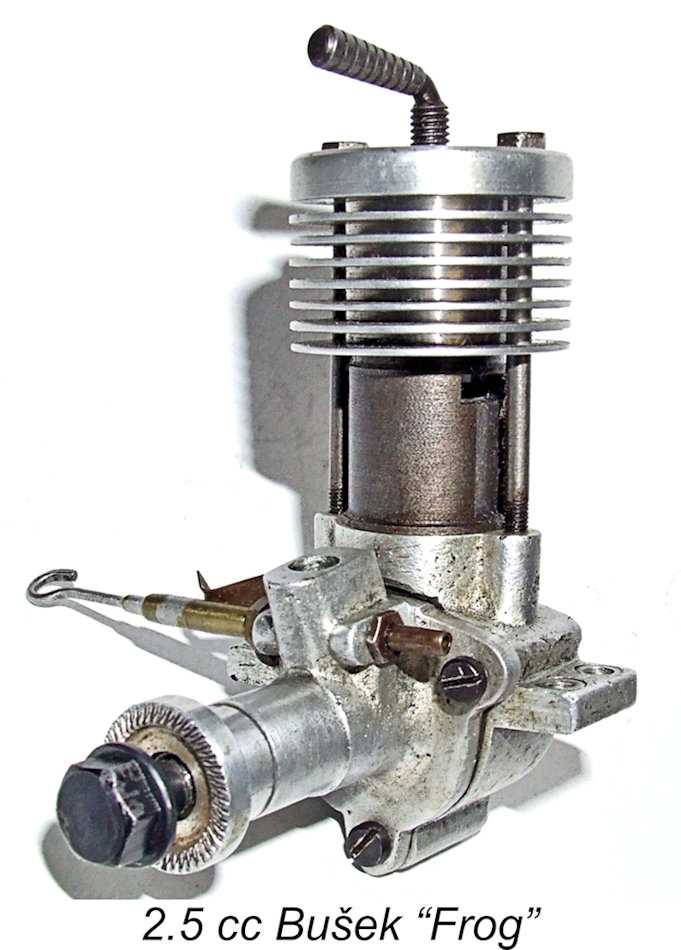

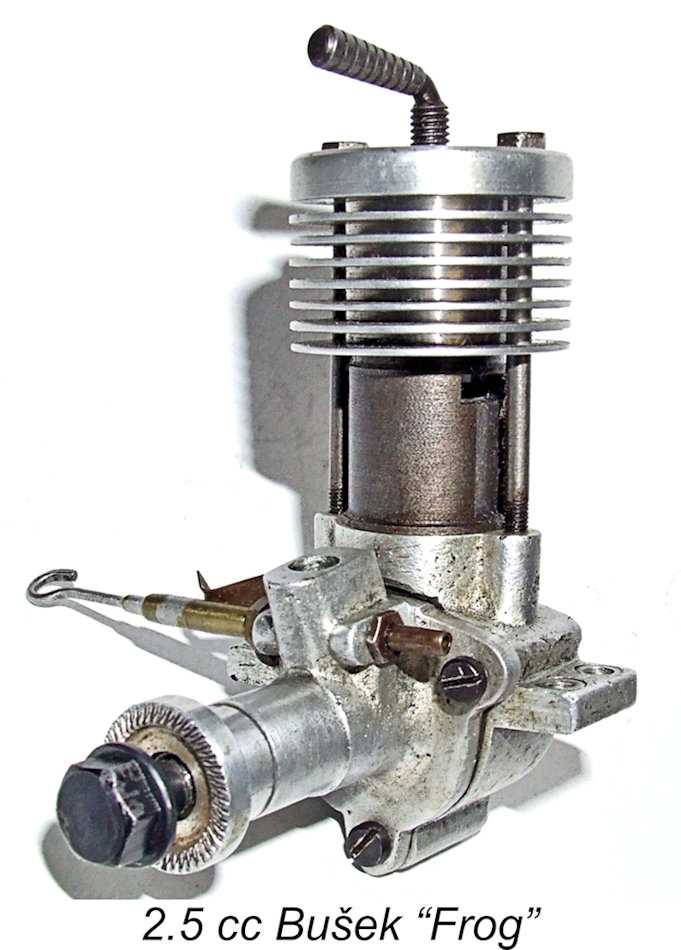

Towards the end of the war Bušek develops a new 2.5 cc design with front rotary valve induction, beam mounting and cylinder retention by two long screws. Porting is left-right exhausts and front-back internal transfer flutes - the + configuration. The engine is subsequently made in considerable numbers with variations and nicknamed “Frog”.

In issue 11/1986 of Modeláŕ magazine, Jiŕi Kalina credits Antonin Půrok with making his first model diesel engine of 2 cc capacity using information from the  Dyno sales brochure, not at that point having seen an actual example. It is not a success, but after seeing

Dyno sales brochure, not at that point having seen an actual example. It is not a success, but after seeing  Bušek’s actual Dyno engine, he realises that it needs a second exhaust port. With this added, the engine then starts and runs. Or perhaps the story could read that he did not fit the piston closely enough and a rebore produced the desired result.

Bušek’s actual Dyno engine, he realises that it needs a second exhaust port. With this added, the engine then starts and runs. Or perhaps the story could read that he did not fit the piston closely enough and a rebore produced the desired result.

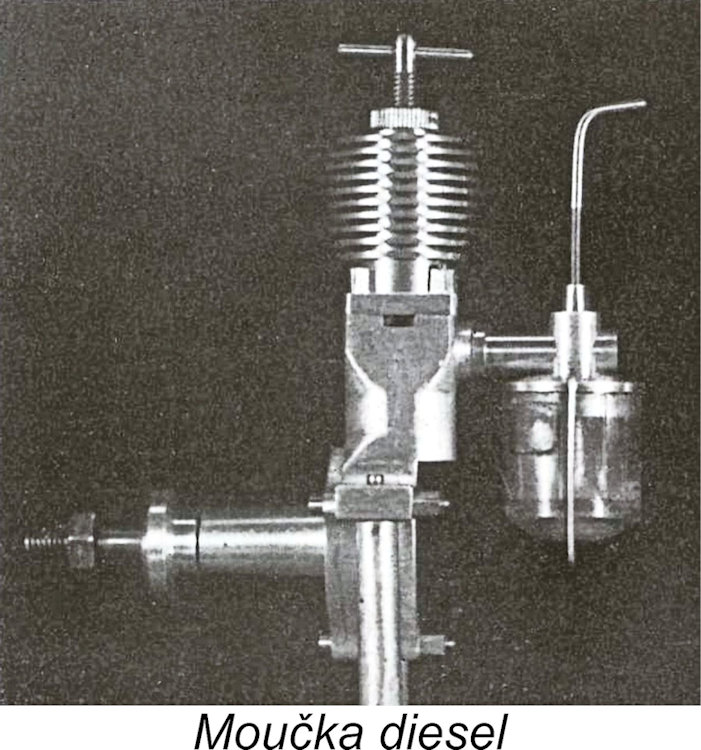

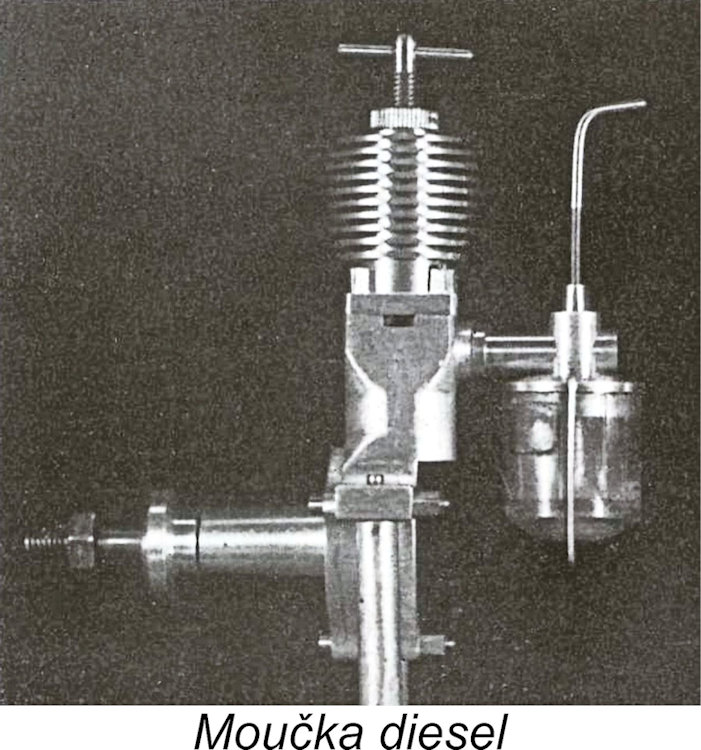

Approximately 20 Půrok engines with screw-in front crankcase section and three-point firewall mounting are made at the end of the war and sold by the M. K. Moučka shop in Prague, along with plans for a very similar type called “Uran” featuring push-pull contra piston adjustment. In his review of European diesels written in 1946, Jim Noonan describes an engine called “Moucka”. Handmade entirely from bar stock matching this design.

Various plans for Czech model engine designs, including commercially-made types, are  published or sold by model shops. Notable here is the Kubíček of nominal 1 cc displacement, which was designed by Vladimir Rauschgold in 1944, constructed in November 1945 and subsequently published as a DIY project in “Mladý Konstruktér”. Its

published or sold by model shops. Notable here is the Kubíček of nominal 1 cc displacement, which was designed by Vladimir Rauschgold in 1944, constructed in November 1945 and subsequently published as a DIY project in “Mladý Konstruktér”. Its  design shows similarities to Bušek’s early diesels.

design shows similarities to Bušek’s early diesels.

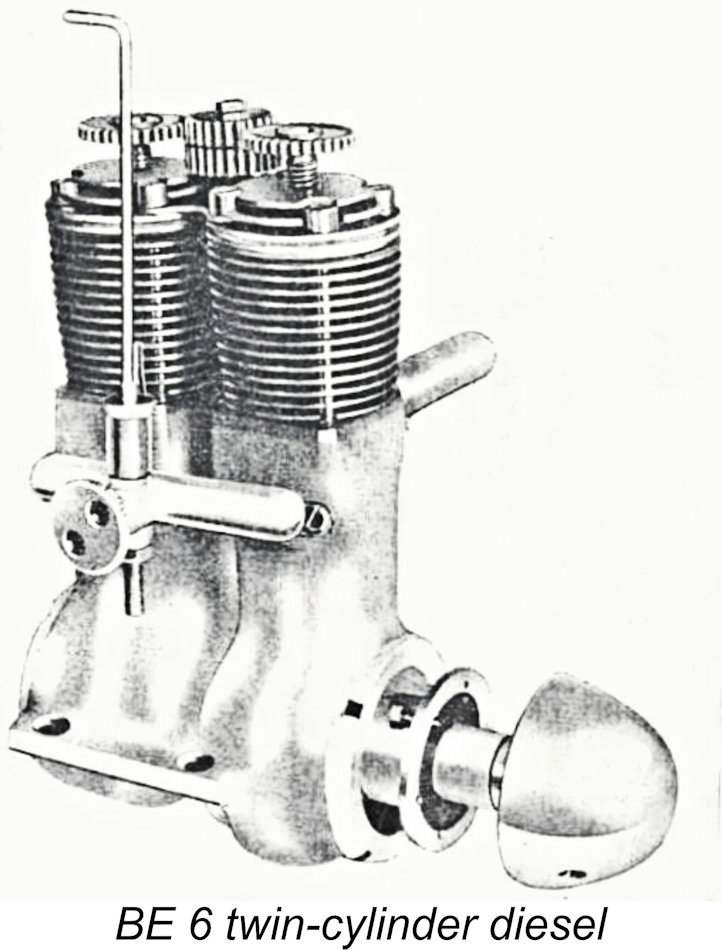

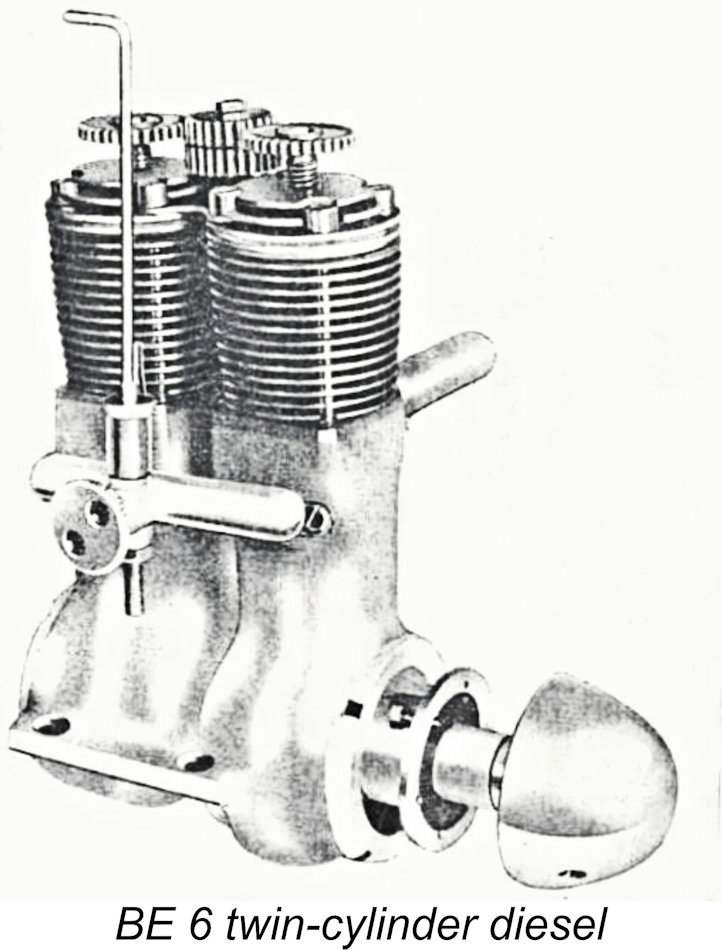

Post-war issues of that journal feature plans for engines by F. Kohout. His 1942 BE-4 of 4.4 cc displacement features opposed transfers and intake/exhaust on opposite sides - the + arrangement again. There is also his more ambitious 1943 BE-6 in-line twin cylinder diesel of 6.1 cc displacement. Following syncronization of the contra-pistons, compression is simultaneously adjusted via a central shaft linked to the adjusting screws by pinion gears.

BRITAIN

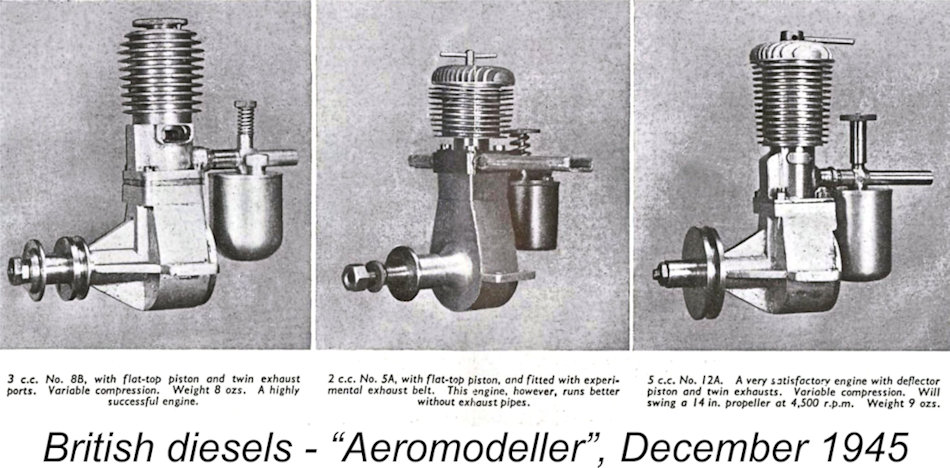

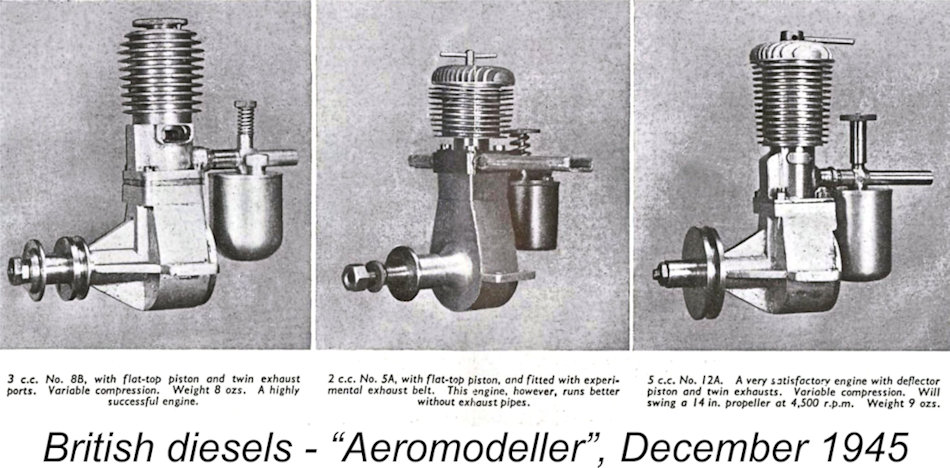

Britain is actually a Johnny-come-lately among the European nations involved with model diesel development. It is possible that “rumours” of model diesel engines precede Allied landings in Italy (September 1943) and France (June 1944). First-hand knowledge, then actual engines follow via returning servicemen, who include such influential figures as Peter Chinn. A seminal article entitled “The Gen on “Diesel” Engines” appears in the December 1945 issue of “Aeromodeller”, stating that L.H. Sparey and D.A. Russell had “successful model  diesel engines running a considerable time ago”. D.A. Russell had filed for a patent on June 4, 1945, relating particularly to the variable compression feature.

diesel engines running a considerable time ago”. D.A. Russell had filed for a patent on June 4, 1945, relating particularly to the variable compression feature.

The article describes the general principles and running characteristics of model diesels, also including photographs of several continental types. It also presents photos of four engines from the authors’ own development series of (presumably) 12 different types, in particular the 3 cc design that was later offered in kit form as the MASCO Buzzard as well as 5 cc and 0.7 cc (sic) types offered as DIY plans in subsequent “Aeromodeller” issues.

George Court, the designer of the early FROG engines, had evidently begun work on what would become the FROG 100 diesel in 1945, since he had demonstrated a prototype to his club-mates by the end of that year. However, that engine didn’t appear on the market in production form until 1947. The Leesil 2.4 cc, Mills 1.3 and Owat 5 cc were probably the first British commercial diesels to reach the market in mid-1946.

__________________________

My sincere thanks to Maris for stepping up to meet this rather daunting challenge! As will be apparent, the model diesel was already well embarked upon the commercialization road by the end of WW2. The designers who subsequently brought the model diesel to such a high pitch of perfection owe a great deal to the pioneers mentioned in Maris’s article - ACD.

___________________________

Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia

First published April 2024

The power-to-weight ratio of aircraft propulsion systems has always been important. Aeromodellers in the 1930’s no doubt rued the “parasitic weight” of the electrical system for spark ignition, hence seeking alternatives.

The power-to-weight ratio of aircraft propulsion systems has always been important. Aeromodellers in the 1930’s no doubt rued the “parasitic weight” of the electrical system for spark ignition, hence seeking alternatives. Kenneth Howie waited too long to put his 1937 patented platinum-coil-in-head engine into production in the form of the H&H 45 of 1947. Italian Elios Vantini had limited success with a platinum wire coil in a spark plug body, reporting his results in 1942. But his arrangement suffered frequent element breakage, while he was ignorant of methanol for fuel.

Kenneth Howie waited too long to put his 1937 patented platinum-coil-in-head engine into production in the form of the H&H 45 of 1947. Italian Elios Vantini had limited success with a platinum wire coil in a spark plug body, reporting his results in 1942. But his arrangement suffered frequent element breakage, while he was ignorant of methanol for fuel.

mix for compression ignition engines is not recorded, but that breakthrough allowed for lower compression ratios and dramatically lighter and smaller engines potentially suitable for model aircraft applications.

mix for compression ignition engines is not recorded, but that breakthrough allowed for lower compression ratios and dramatically lighter and smaller engines potentially suitable for model aircraft applications.  The Dyno’s important features were the “long” stroke-to-bore ratio that enhanced the vital compression of fuel/air mixture to achieve self-ignition temperature, given the prevailing production machining tolerances. The variable compression feature was taken from Thalheim’s earlier work. The

The Dyno’s important features were the “long” stroke-to-bore ratio that enhanced the vital compression of fuel/air mixture to achieve self-ignition temperature, given the prevailing production machining tolerances. The variable compression feature was taken from Thalheim’s earlier work. The

The subsequent 0.6 cc Buchmann diesel was the other pioneering Swiss model diesel engine. Heralding the

The subsequent 0.6 cc Buchmann diesel was the other pioneering Swiss model diesel engine. Heralding the  Pierre Meunier demonstrates his Dyno 1 in the summer of 1942 (presumably in Paris). Inspired by this demonstration, Maurice Delbrel constructs a 1 cc engine, the first successful French diesel. After some experimentation, André Gladieux concludes that fixed compression is practical with larger engines. His Micron 10AA and 5AA engines are concurrently released commercially in July 1943, “AA” standing for Auto Allumage (French for “auto ignition”). The 10 cc model is brutish, but the 5 cc variant is a fine performer. It develops 0.18 BHP at 4,500 RPM, easily flying models intended for

Pierre Meunier demonstrates his Dyno 1 in the summer of 1942 (presumably in Paris). Inspired by this demonstration, Maurice Delbrel constructs a 1 cc engine, the first successful French diesel. After some experimentation, André Gladieux concludes that fixed compression is practical with larger engines. His Micron 10AA and 5AA engines are concurrently released commercially in July 1943, “AA” standing for Auto Allumage (French for “auto ignition”). The 10 cc model is brutish, but the 5 cc variant is a fine performer. It develops 0.18 BHP at 4,500 RPM, easily flying models intended for  10 cc spark ignition engines and achieving good contest results. Production volume is modest until after the war, when it remains popular.

10 cc spark ignition engines and achieving good contest results. Production volume is modest until after the war, when it remains popular. Moteurs Jidé produce “Jidé 8” 1.7 cc and “Jidé 9” 10 cc diesels in 1944. These feature crankshaft rotary valve induction, fixed compression, fore/aft transfer ports and left-right exhausts (the

Moteurs Jidé produce “Jidé 8” 1.7 cc and “Jidé 9” 10 cc diesels in 1944. These feature crankshaft rotary valve induction, fixed compression, fore/aft transfer ports and left-right exhausts (the  Other French diesels are introduced from 1945 onwards, perhaps delayed by the turmoil surrounding the Allied invasion. These include designs by

Other French diesels are introduced from 1945 onwards, perhaps delayed by the turmoil surrounding the Allied invasion. These include designs by  During 1942, a local modeller in Poznań, Poland pays the German owner a lot of money to part with his Dyno 1 engine. This is a revelation when it is demonstrated in great secrecy to other local modellers. Inspired, 17-year-old Felicjan Gadomski resolves to make his own copy, using the lathe in his father’s small basement workshop.

During 1942, a local modeller in Poznań, Poland pays the German owner a lot of money to part with his Dyno 1 engine. This is a revelation when it is demonstrated in great secrecy to other local modellers. Inspired, 17-year-old Felicjan Gadomski resolves to make his own copy, using the lathe in his father’s small basement workshop. On August 30th, 1942 after overcoming numerous technical difficulties, Gadomski demonstrates his engine to trusted friends and builds a model for it by the end of the year. It flies, but he is not satisfied with the low power output. More spare-time development leads to the creation of four variants by the end of the war. Limited production of 200 “GADO-2” and “F.G.3” engines by November 1946 goes to the Department of Civil Aviation’s Model Training Centre or to private buyers. Also, Gadomski’s one-off 0.23 cc “Lilliput” diesel (bore 6 mm, stroke 8 mm) successfully flies a 29 cm wing-span FF model. It is rated at 0.003 BHP!

On August 30th, 1942 after overcoming numerous technical difficulties, Gadomski demonstrates his engine to trusted friends and builds a model for it by the end of the year. It flies, but he is not satisfied with the low power output. More spare-time development leads to the creation of four variants by the end of the war. Limited production of 200 “GADO-2” and “F.G.3” engines by November 1946 goes to the Department of Civil Aviation’s Model Training Centre or to private buyers. Also, Gadomski’s one-off 0.23 cc “Lilliput” diesel (bore 6 mm, stroke 8 mm) successfully flies a 29 cm wing-span FF model. It is rated at 0.003 BHP!  At this time, Italian model engine production is in small series on a cottage industry basis, mainly for local distribution. Broader marketing of the majority of “first generation” Italian diesels commences soon after the war ends. Although the Dyno engine strongly influences the basic designs, Italian constructors show notable flair in developing overall shapes and details.

At this time, Italian model engine production is in small series on a cottage industry basis, mainly for local distribution. Broader marketing of the majority of “first generation” Italian diesels commences soon after the war ends. Although the Dyno engine strongly influences the basic designs, Italian constructors show notable flair in developing overall shapes and details. general principle is explained before the writer reviews the Antares 4 engine produced in Padua by Elios Vantini. This was a side-line to Vantini’s “real” business of manufacturing glass syringes. The engine follows earlier work with a 2 to 3 cc type that was also made in a very small series. Vantini is shown with his model at the then-recent National championships, featuring one of his engines.

general principle is explained before the writer reviews the Antares 4 engine produced in Padua by Elios Vantini. This was a side-line to Vantini’s “real” business of manufacturing glass syringes. The engine follows earlier work with a 2 to 3 cc type that was also made in a very small series. Vantini is shown with his model at the then-recent National championships, featuring one of his engines.

Budding engine designer Enzo Mancini of Florence has his first diesel engine design, the Mancini M 20, published in the August 1943 issue of “L’Aquilone” as a DIY project. The 3.7 cc Dyno-derived design becomes well known when the article is translated to German and republished in “Der Sportflieger” of February 1944 and then into French for “Le Modele Reduit D'Avion” of May 1944. In subsequent years, Mancini designs and constructs the Alfa, Uranio 4 and Meteor 47 diesels.

Budding engine designer Enzo Mancini of Florence has his first diesel engine design, the Mancini M 20, published in the August 1943 issue of “L’Aquilone” as a DIY project. The 3.7 cc Dyno-derived design becomes well known when the article is translated to German and republished in “Der Sportflieger” of February 1944 and then into French for “Le Modele Reduit D'Avion” of May 1944. In subsequent years, Mancini designs and constructs the Alfa, Uranio 4 and Meteor 47 diesels. Living close to Switzerland, Emilio Biraghi of Milan uses a sporting prize to buy a Dyno engine, beginning his engine-making career in 1944 with a series of diesels, each showing improvement. His 4.2 cc “Jupiter Junior” and 2.2 cc “Mirius Senior” and “Mirius Junior” are Dyno-derived engines, made in small series. Plans for his DIY engine are published in “L’Aquilone” in 1944. He is best remembered for the 0.7 cc “Micro” diesel made in 1000 pieces from 1946.

Living close to Switzerland, Emilio Biraghi of Milan uses a sporting prize to buy a Dyno engine, beginning his engine-making career in 1944 with a series of diesels, each showing improvement. His 4.2 cc “Jupiter Junior” and 2.2 cc “Mirius Senior” and “Mirius Junior” are Dyno-derived engines, made in small series. Plans for his DIY engine are published in “L’Aquilone” in 1944. He is best remembered for the 0.7 cc “Micro” diesel made in 1000 pieces from 1946. Bruno Grazzini, already respected for a range of “Giglio” spark ignition engines, produces the “Giglio” diesel, which was one of the first Italian series production diesels, circa 1945. It closely follows the Dyno design, but with a streamlined fuel tank mounted on the backplate. A subsequent magazine review shows front crankshaft rotary or rear disc induction and cam-operated compression adjustment, which are probably not production variants. Production ceases quite soon when Grazzini closes the business and moves to France to work for Renault.

Bruno Grazzini, already respected for a range of “Giglio” spark ignition engines, produces the “Giglio” diesel, which was one of the first Italian series production diesels, circa 1945. It closely follows the Dyno design, but with a streamlined fuel tank mounted on the backplate. A subsequent magazine review shows front crankshaft rotary or rear disc induction and cam-operated compression adjustment, which are probably not production variants. Production ceases quite soon when Grazzini closes the business and moves to France to work for Renault. The MOVO company of Milan is well placed to produce model engines with high quality equipment and is already known for its “GIL 10” and “DP 23” spark ignition engines. Prototypes of a 2 cc Dyno-derived engine are successfully tested in 1944 and examples of the stylish

The MOVO company of Milan is well placed to produce model engines with high quality equipment and is already known for its “GIL 10” and “DP 23” spark ignition engines. Prototypes of a 2 cc Dyno-derived engine are successfully tested in 1944 and examples of the stylish  Becoming intrigued after seeing a Dyno, Jaures Garofali of Bologna designs his first diesel engine, the G-13, in 1943. His previous twelve designs had been spark ignition units, of which only a few went beyond the design phase to metal in a few pieces. Unable to make engines until late 1945, 24 O.S.A.M. G-13 “Super Tigre” 5.28 cc engines are sold via Aviomodelli in Cremona from mid-1946. These engines are of classic side port layout with T-scavenging. They feature an unusual mounting arrangement using vertically-placed pairs of screw attachment points on the sides of the case to facilitate the adjustment of engine downthrust in a model. Other similar designs with crankshaft or rotary disc induction follow, until Garofali parts from his business partner in 1949 to found Micromeccanica Saturno, with the soon to be famous

Becoming intrigued after seeing a Dyno, Jaures Garofali of Bologna designs his first diesel engine, the G-13, in 1943. His previous twelve designs had been spark ignition units, of which only a few went beyond the design phase to metal in a few pieces. Unable to make engines until late 1945, 24 O.S.A.M. G-13 “Super Tigre” 5.28 cc engines are sold via Aviomodelli in Cremona from mid-1946. These engines are of classic side port layout with T-scavenging. They feature an unusual mounting arrangement using vertically-placed pairs of screw attachment points on the sides of the case to facilitate the adjustment of engine downthrust in a model. Other similar designs with crankshaft or rotary disc induction follow, until Garofali parts from his business partner in 1949 to found Micromeccanica Saturno, with the soon to be famous

Eisfeld’s range of six engine sizes from 0.5 cc to 10 cc is presented together with thorough test results reflecting power output, fuel consumption, propeller sizes and power-to-weight data. Two Eisfeld diesels are produced commercially in small series – the “DV2” of 2.5 cc and “DV3” of 6 cc. Their introductory date of 1942 which has been cited by some could not be independently verified, but a DV3 fitted to a model is shown in a 1944 issue of the magazine.

Eisfeld’s range of six engine sizes from 0.5 cc to 10 cc is presented together with thorough test results reflecting power output, fuel consumption, propeller sizes and power-to-weight data. Two Eisfeld diesels are produced commercially in small series – the “DV2” of 2.5 cc and “DV3” of 6 cc. Their introductory date of 1942 which has been cited by some could not be independently verified, but a DV3 fitted to a model is shown in a 1944 issue of the magazine.

Wartime production of Kratmo diesels only reaches the prototype stage, but very limited postwar Kratmo engine production includes diesels in several sizes, with the unusual compression adjustment feature. This is soon halted by the government as representing a waste of scarce raw materials.

Wartime production of Kratmo diesels only reaches the prototype stage, but very limited postwar Kratmo engine production includes diesels in several sizes, with the unusual compression adjustment feature. This is soon halted by the government as representing a waste of scarce raw materials.  The second, a 9.6 cc in-line twin cylinder type, reportedly produces 0.45 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 400 mm x 240 mm propeller. Both engines use side-port induction and T-scavenging. His third model, a 9.0 cc single cylinder type with crankshaft rotary induction, develops 0.40 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 270 mm

The second, a 9.6 cc in-line twin cylinder type, reportedly produces 0.45 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 400 mm x 240 mm propeller. Both engines use side-port induction and T-scavenging. His third model, a 9.0 cc single cylinder type with crankshaft rotary induction, develops 0.40 BHP at 5,000 RPM with a 270 mm  x 220 mm propeller. It weighs 380 gm. Kemmerling prefers a fuel mix of 75% kerosene, 20% ether and 5% motor oil.

x 220 mm propeller. It weighs 380 gm. Kemmerling prefers a fuel mix of 75% kerosene, 20% ether and 5% motor oil.

The Dutch magazine “De Modellbauer” publishes plans and a short history of I. J. v. Leeuen’s Nova 1 diesel engine of 1943. Of 4.5 cc displacement, it has classic side-port induction and a T-scavenging layout. The widely-spaced integral cooling fins on its tall steel cylinder lend a somewhat exaggerated appearance. The plan’s title block is dated December 1943 and is intended for “Modelvliegtuigen” in Antwerp, Belgium. It is not known if it was published there, but it subsequently appears in the May 1946 issue of the English “Model Aircraft” magazine.

The Dutch magazine “De Modellbauer” publishes plans and a short history of I. J. v. Leeuen’s Nova 1 diesel engine of 1943. Of 4.5 cc displacement, it has classic side-port induction and a T-scavenging layout. The widely-spaced integral cooling fins on its tall steel cylinder lend a somewhat exaggerated appearance. The plan’s title block is dated December 1943 and is intended for “Modelvliegtuigen” in Antwerp, Belgium. It is not known if it was published there, but it subsequently appears in the May 1946 issue of the English “Model Aircraft” magazine.  In 1942, the editor of the Swedish magazine “Teknik för Alla”, Gunnar Fahlnäs, somehow acquires a Dyno engine and has model engineer

In 1942, the editor of the Swedish magazine “Teknik för Alla”, Gunnar Fahlnäs, somehow acquires a Dyno engine and has model engineer  Rogstadius is not involved in the production of the subsequent commercial engines from different makers which closely follow his Dyno clone design. Some were made by engineer H. Vileén and advertised in 1944 for direct sale, later by several retailers. Closely following his later monobloc crankcase variation, H & B Johansson of Västerås release their first entry into model engine manufacture, the Västeråsdieseln, producing some 500 pieces. Under the Komet

Rogstadius is not involved in the production of the subsequent commercial engines from different makers which closely follow his Dyno clone design. Some were made by engineer H. Vileén and advertised in 1944 for direct sale, later by several retailers. Closely following his later monobloc crankcase variation, H & B Johansson of Västerås release their first entry into model engine manufacture, the Västeråsdieseln, producing some 500 pieces. Under the Komet  trade-name, the company becomes Sweden’s largest model engine manufacturing concern, continuing with a series of Komet diesel and glow-plug engines through the 1950’s.

trade-name, the company becomes Sweden’s largest model engine manufacturing concern, continuing with a series of Komet diesel and glow-plug engines through the 1950’s.

enmark’s first commercial model diesel is the “Diesella” 2.4 cc, a collaboration between Eli Andersen and A Jeppesen. Released in November 1943, it is well received. It features a sturdy crankcase with streamlined profile accentuated by a matching rear-mounted fuel tank and spinner nut. It employs side-port induction with a

enmark’s first commercial model diesel is the “Diesella” 2.4 cc, a collaboration between Eli Andersen and A Jeppesen. Released in November 1943, it is well received. It features a sturdy crankcase with streamlined profile accentuated by a matching rear-mounted fuel tank and spinner nut. It employs side-port induction with a

and car engines. It is the first model engine featuring basic Schnürle porting (transfers either side of the exhaust, all on one side of the cylinder to provide loop scavenging without a baffle).

and car engines. It is the first model engine featuring basic Schnürle porting (transfers either side of the exhaust, all on one side of the cylinder to provide loop scavenging without a baffle).  David-Andersen refines the concept further, arriving at a 2.4 cc design which he presents in his DIY book "

David-Andersen refines the concept further, arriving at a 2.4 cc design which he presents in his DIY book "

Dyno sales brochure, not at that point having seen an actual example. It is not a success, but after seeing

Dyno sales brochure, not at that point having seen an actual example. It is not a success, but after seeing

design shows similarities to Bušek’s early diesels.

design shows similarities to Bušek’s early diesels.  diesel engines running a considerable time ago”. D.A. Russell had filed for a patent on June 4, 1945, relating particularly to the variable compression feature.

diesel engines running a considerable time ago”. D.A. Russell had filed for a patent on June 4, 1945, relating particularly to the variable compression feature.