|

|

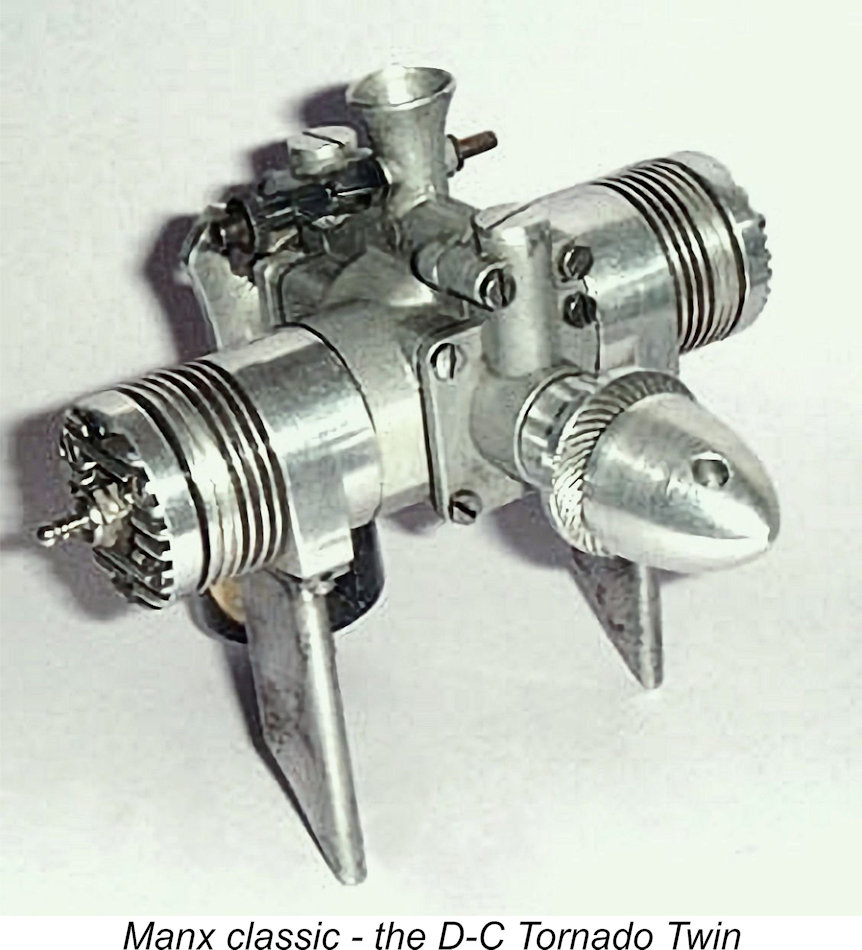

Double Trouble – the D-C Tornado Twin

My initial attempt to tell this story appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s fabulous “Model Engine News” (MEN) website in October 2007. It was actually only the third article on MEN for which I was primarily responsible! My purpose in presenting this extensively revised edition on my own website is threefold. Firstly, I’ve subsequently learned a great deal more about the circumstances surrounding the production and demise of the Tornado. My relative ignorance back in 2007 led to the inclusion of a number of serious errors in my original text. These urgently required correction. Secondly, my research, editorial and photographic skills have developed considerably over the intervening years - practise makes perfect! I believe that I’m now able to present a far more readable and informative text, also being in a position to greatly improve the quality of the illustrations. I’ve been assisted in this regard by my ever-helpful Aussie mate Gordon Beeby, whose documentary research activities have been invaluable. Last but by no means least, my mate Ron left us in early 2014 without sharing the access codes for his heavily-encrypted site. Because no maintenance has since been possible, the MEN site is slowly but perceptibly deteriorating as the various links fail progressively - an inexorable process which can have only one ending in the long run. I thought that it would be a shame to risk the potential loss of reader access to the information on the Tornado, hence the article’s re-publication here. OK, time to get on with this review! I’ll begin by providing a little background which may be helpful in placing the Tornado Twin in context. Background

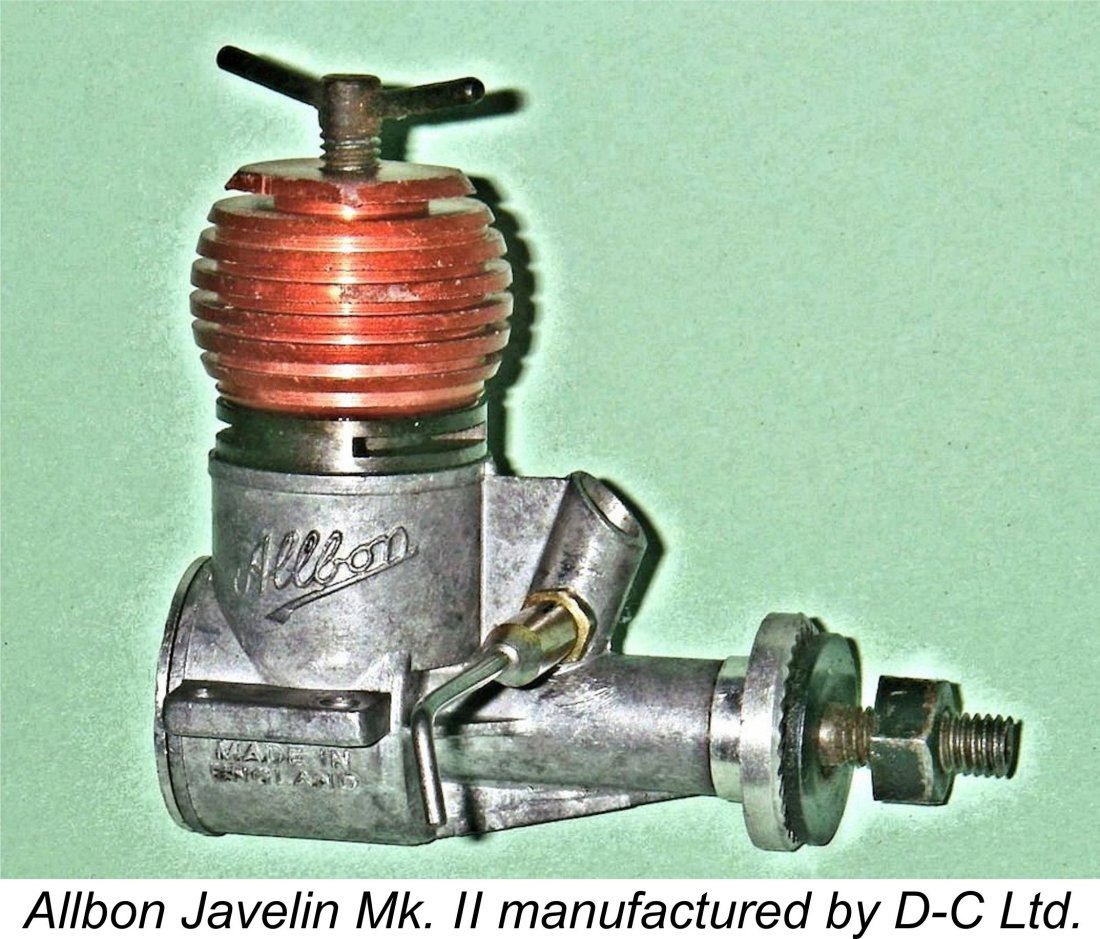

During the early 1950’s the company diversified and became increasingly involved with defence-related sub-contract work for Rolls Royce and others arising from Britain's involvement in the Korean War. This work took up an increasing amount of Hefin Davies’ time, diverting his attention from the model engines which undoubtedly remained his first love. This situation eventually prompted a change in early 1952, when Davies-Charlton joined forces with Alan Allbon, who had been making his own rather more diverse engine line since 1948 at a plant located at 51A Thames Street, Sunbury-on-Thames, just to the west of London on the north bank of the River Thames.

The merger with Davies allowed Allbon to resume and expand the production of his excellent engine designs while also freeing Davies to continue to lead the doubtless-lucrative defence-related work. Allbon assumed primary responsibility for the model engine development and production program, also occupying the position of Works Manager. Production of the Allbon engines by that name now took place at Davies-Charlton’s Barnoldswick plant in Lancashire along with that of the continuing Davies-Charlton models. In early 1955 a move to the Isle of Man (IOM) was put in hand, evidently for tax and business incentive reasons. Subsequent Davies-Charlton products were manufactured at the thoroughly modernized Davies-Charlton factory at Hills Meadow, Douglas, Isle of Man.

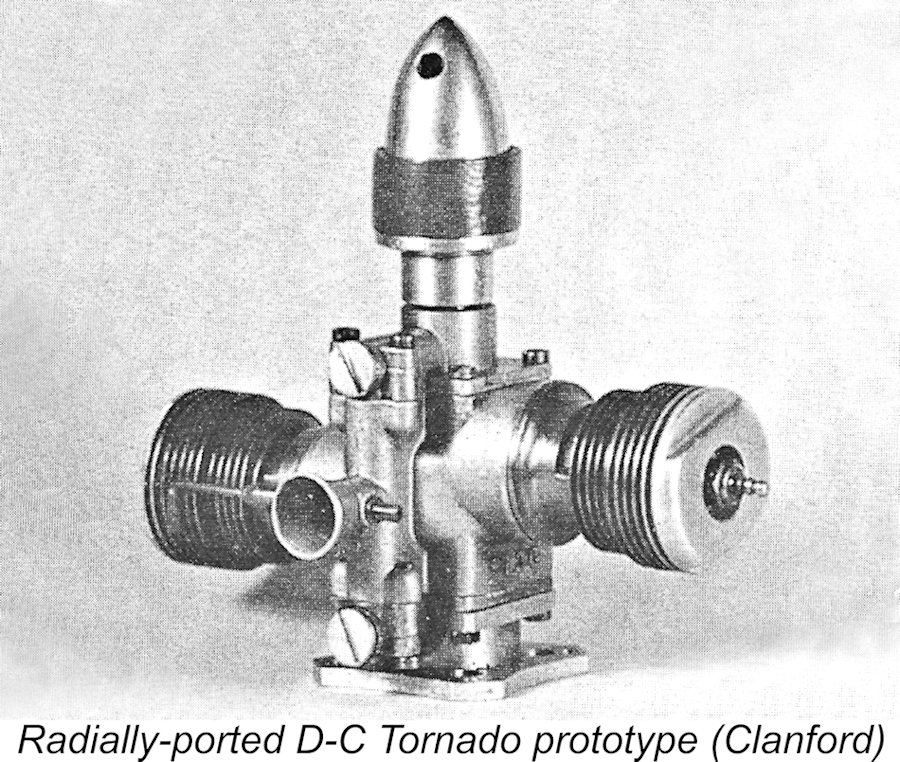

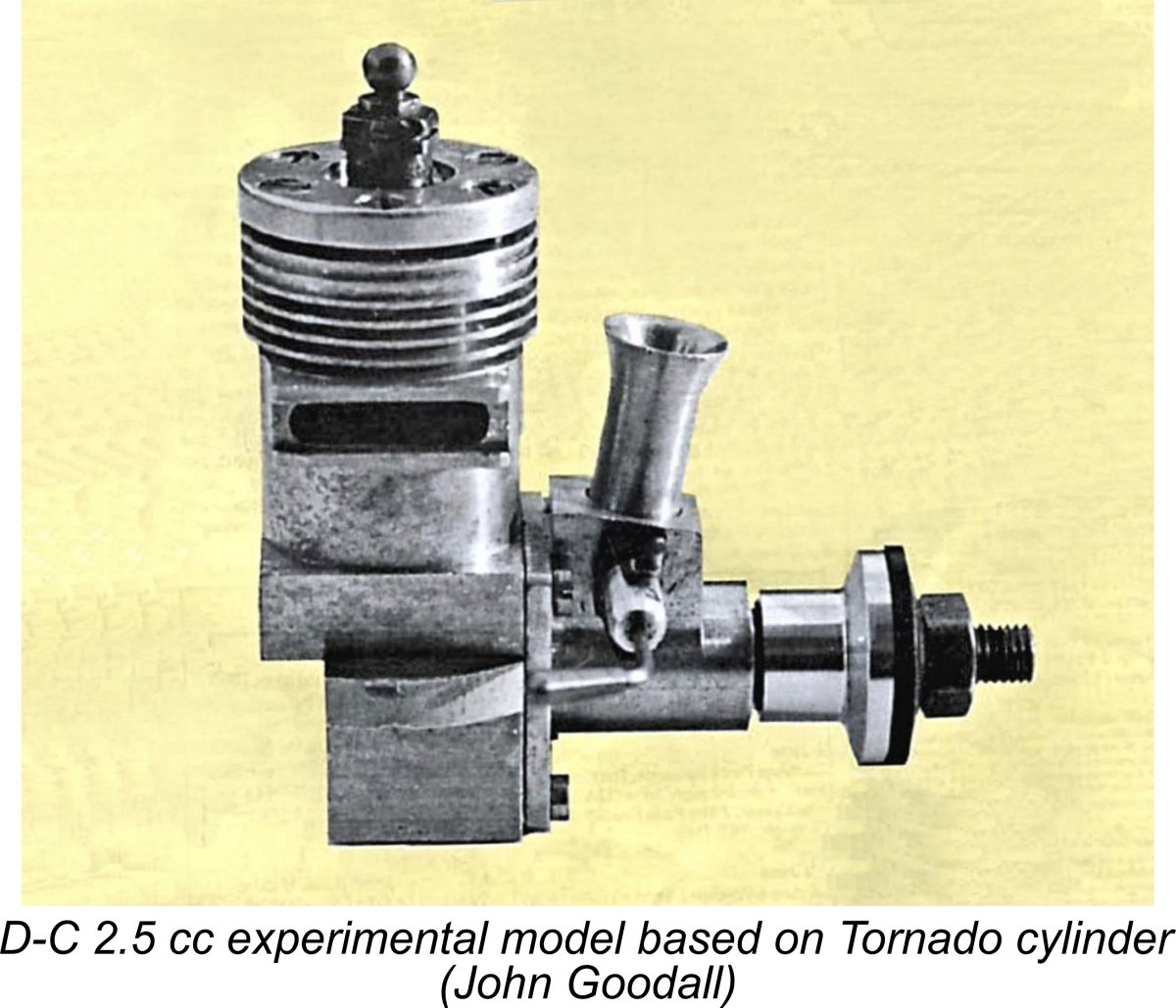

Alan Allbon’s place as Works Manager at D-C Ltd. was taken up in 1955 by Ted Saunders. In 1959, Allbon and Saunders joined forces, relocating to the English mainland to establish their own joint venture under the Allbon-Saunders (A-S) name. The new company produced the excellent little 0.55 cc A-S 55 diesel in the early 1960’s before abandoning the model engine field for more lucrative work. I’ve recounted the Allbon-Saunders story elsewhere. Alan Allbon had left Davies-Charlton long before the company embarked upon its most ambitious project of all - the simultaneous-firing opposed-twin 4.87 cc glow-plug motor to be known as the Tornado. Although this engine had been envisioned originally as a diesel, its subsequent development in glow-plug form was the result of an early 1958 decision by Hefin Davies that D-C Ltd. would re-enter the increasingly-popular glow-plug field. With this in mind, Davies undertook an extensive tour of the USA in mid-1958 to study American production methods. Since Davies-Charlton was not seen in America as a competitor, he was apparently welcomed by the manufacturers whom he visited. Ted Saunders doesn’t appear to have had any particular expertise in model engine design - he was basically a manager. Accordingly, it’s likely that Hefin Davies was the lead designer on this project, which commenced in 1958. As usual in such cases, development of the engine was pursued through the construction of a number of prototypes. Among these prototypes was a twin-cylinder unit which employed radially-ported screw-in cylinders. There was also a 2.5 cc loop-scavenged single-cylinder prototype. Both of these experimental powerplants survive to this day.

No commercial 2.5 cc single cylinder glow-plug model ever appeared from D-C Ltd, although there is evidence that such a release was contemplated for a time. The development process continued through the construction of a number of further twin-cylinder prototypes and pre-production models, several of which ended up during 1959 in the hands of selected reviewers for field testing. This process eventually resulted in the early 1960 appearance of the D-C Tornado Twin, which was Davies-Charlton’s finest achievement in the model engine field in my personal view. Praiseworthy though it may have been from a design and production standpoint, it’s clear from the evidence that the Tornado’s development, production and marketing histories were far from smooth. Let’s look at those aspects next. Development and Production History

The engine that was illustrated in that December 1958 advertisement was a prototype example lacking fins on the cylinder heads. The text of the advertisement took the form of a pre-production announcement stating that the Tornado would “be available early in 1959 when full details will be announced in our regular inside cover advertisement”.

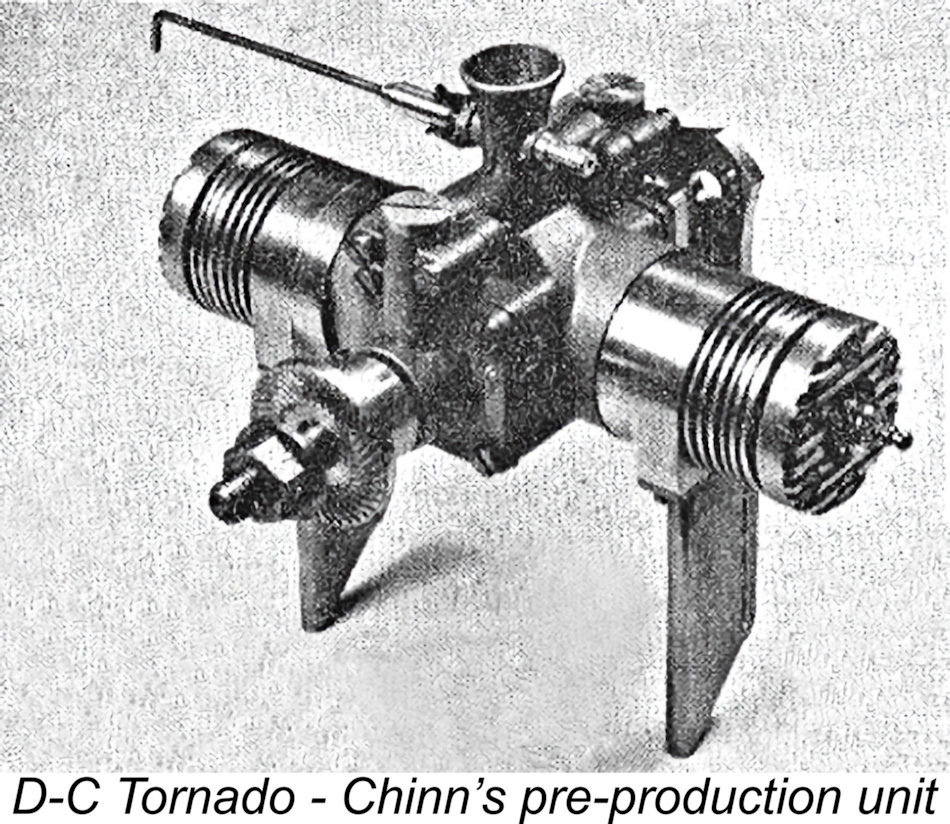

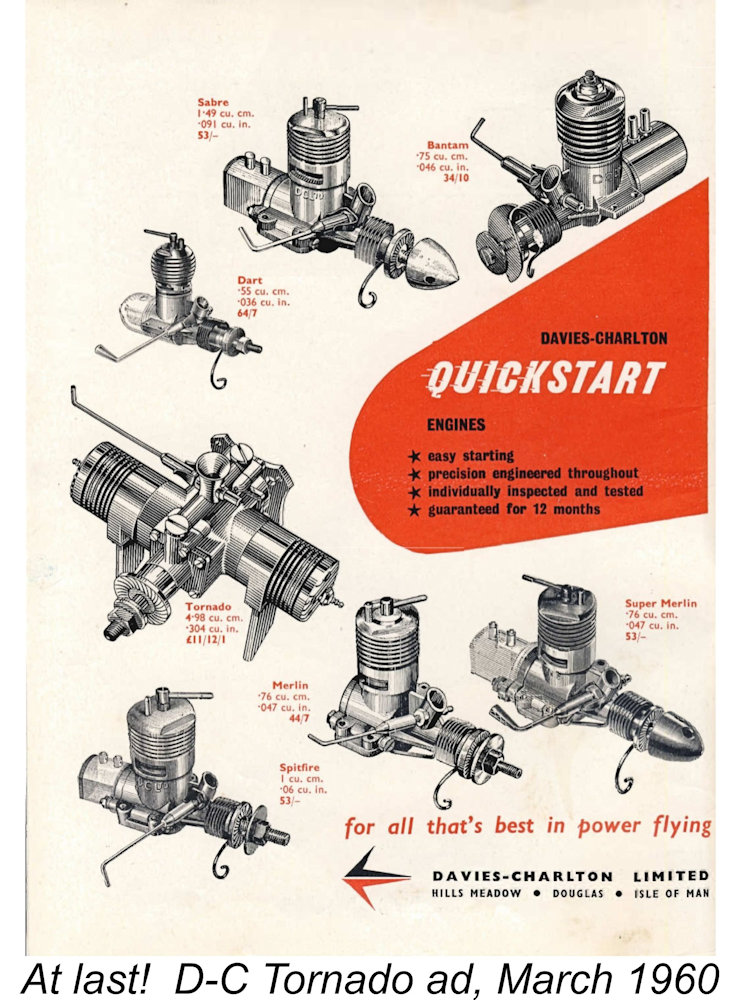

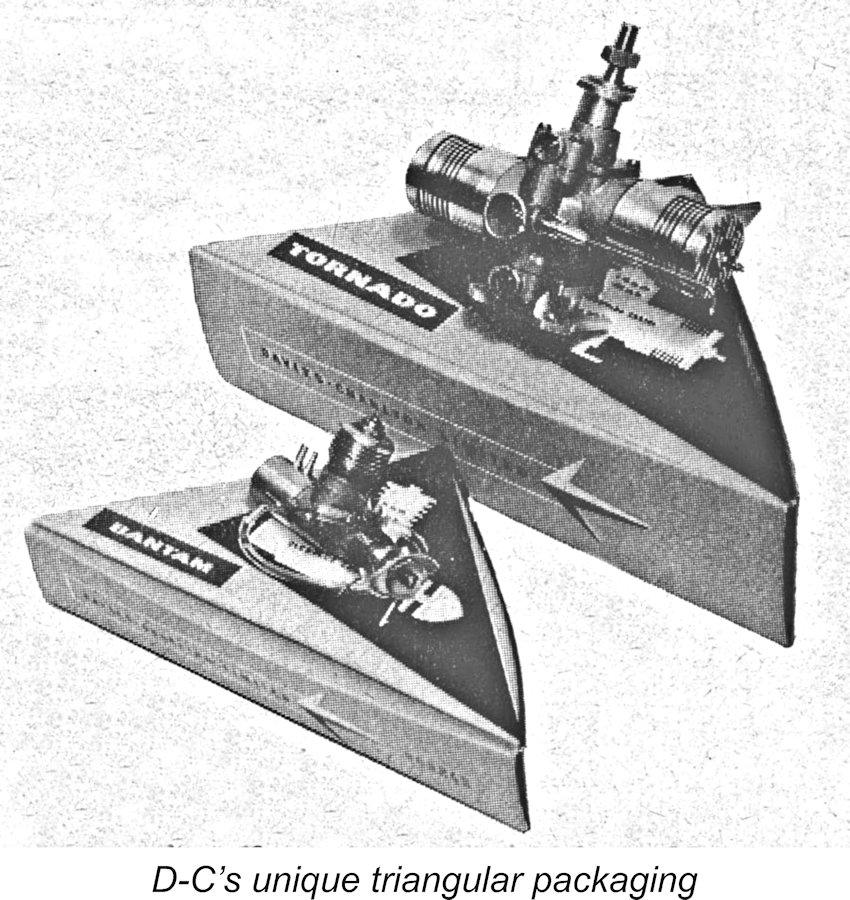

While the delay in the appearance of the engine in final production form may have been due to some significant unforeseen engineering or manufacturing difficulties, it's equally likely that it resulted from an early 1959 switch of company focus to the development of the 0.76 cc (.046 In my personal view, the Bantam represented a blatant scam on the British modelling public, since the pre-production examples supplied to reviewers (and tested by Ron Warring of "Aeromodeller") differed significantly from the final production version, hence having a far higher performance. Many contemporary young modellers (including myself) were grievously misled by this. I've covered this sorry episode in my separate article on the D-C Bantam. Returning to our main subject, the next mention of the Tornado in the modelling media came in an article entitled “Manx Glowings-On” which appeared in the January 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. This article took the form of a report on a staff visit to D-C Ltd.’s factory at Hills Meadow in the IOM. The text included the comment that “the promised D-C glow twin to be named Tornado is piling up Peter Chinn included a photograph of a pre-production example of the Tornado in his “Latest Engine News” feature in the February 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The caption included the information that “the production version will be available with a speed control fitting on the The Tornado finally made its appearance as a member of the D-C model engine range in the company’s full-page inside cover advertisement in the March 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The Tornado was attractively presented in a striking triangular box representing the three-legged emblem of the Isle of Man together with its associated motto: Whichever way you throw me, I stand. The advertised price was a rather shocking £11 12s 1d (£11.60) – this at a time when D-C Ltd. were also pushing their notably mediocre D-C Bantam 0.76 cc (.046 cuin.) glow-plug model at only £1 14s 0d (£1.70). Talk about opposite ends of the price spectrum!

This makes it absolutely clear that the only reason for anyone to buy a Tornado was a novelty-inspired desire to own a twin. There cannot have been many British modellers who were willing to pay the £5 plus premium for such a novelty – you could buy two ETA or MERCO 29’s for the price of a Tornado! This being the case, it should come as no surprise to learn that the engine appears to have been an instant marketing failure. The Tornado’s inclusion in that March 1960 advertisement proved to be its sole appearance in a D-C Ltd. advertising placement. The implication is that production ended very soon after it had been initiated. My late and greatly-missed friend Tim Dannels stated on his now-deactivated Model Engine Collecting web site that “it is believed that fewer than 100 of these engines were made”. I would personally be a little surprised if this were true - there were a few of them kicking about at the time, and I recall seeing one or two actually being used in the early 1960’s. In his article on the Tornado which formed part of his well-known series of model engine profiles in the newsletter of the Denver chapter of SAM, the late David R. Janson claimed that the number of examples of the engine which ended up being produced was "estimated at less than 500", a figure which I personally consider to be nearer the mark. That said, I don’t doubt that the figure quoted by Tim Dannels could be true – the engine was certainly manufactured in far smaller numbers than any other D-C Ltd. product. Even so, a number of examples were evidently shipped out to dealers. Gordon Beeby’s research has revealed that the Tornado began appearing in model shop advertising placements as of June 1960. Advertisers included such well-known outlets as Roland Scott (Bolton), BMW (Wimbledon), The Model Shop (Canterbury), The Model Shop (Manchester), Reading Model Supplies and Howes Model Shop (Oxford). Some of these were only one-time offerings, but the suggestion of relatively wide distribution is unmistakable. The most consistent advertiser was Arthur Mullett (Brighton), most of whose advertisements between August 1960 and December 1961 included the Tornado. Mullett’s December 1961 advertisement represented the Tornado’s final promotional appearance.

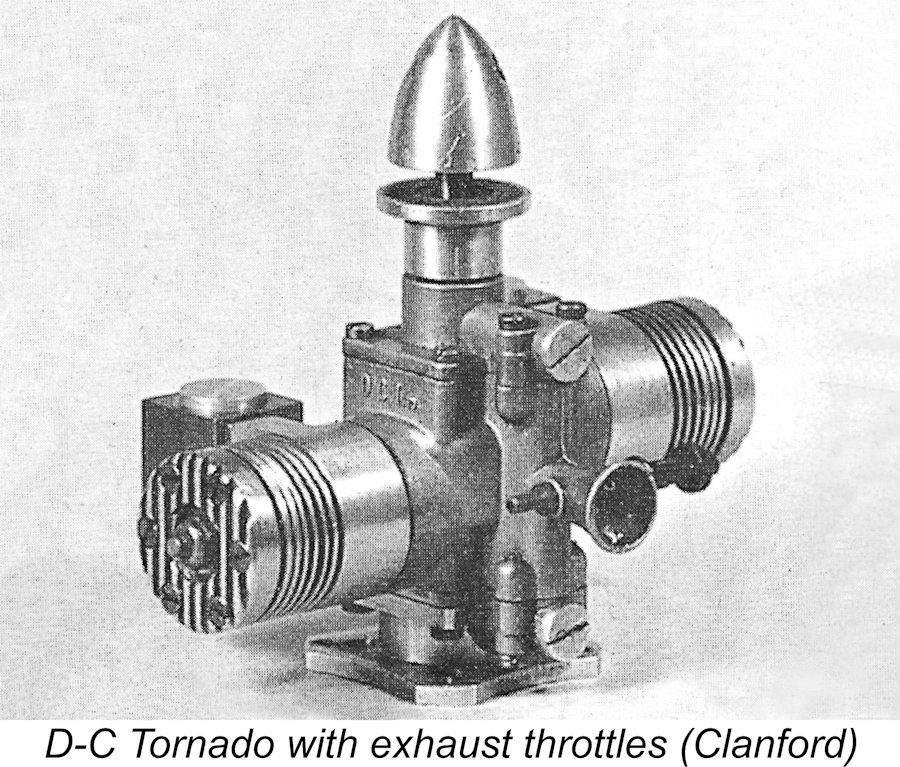

The standard production model lacked any kind of throttle control, the inclusion of which would have greatly enhanced the Tornado’s appeal to the R/C crowd. D-C Ltd. did undoubtedly develop a pair of rather bulky exhaust restrictors to provide a measure of speed control for the Tornado, but in the event these never appear to have been advertised. The example illustrated by Mike Clanford in his well-known but often unreliable "A-Z" book is almost certainly a pre-production experimental unit. The intake throttle mentioned in February 1960 by Peter Chinn never materialized. For other purposes, the prospective customer had cheaper, lighter and more powerful alternatives. Unfortunately, D-C Ltd.’s failure to adequately address the speed control issue has had a very negative effect upon the survival of good unmodified examples of the Tornado. Tim Dannels noted that it’s unusual to find an example of the engine that has not had the venturi cut back, presumably for the fitting of an R/C throttle. Given the engine’s obvious suitability for R/C service, it was inevitable that owners would attempt to implement such conversions in the inexplicable absence of appropriate provisions on the part of the manufacturers. In the end, all that the Tornado really had going for it was its novelty appeal. The number of people willing to pay such a premium price solely on this basis could never have been large. Once those few individuals had bought their examples, the residual market would have dried up, a situation which must have become immediately apparent to the engine’s manufacturers. That said, my mate Gordon Beeby has pointed out that production or at least availability of the Tornado may have continued for some time "below the radar". The engine continued to be mentioned in the "Global Engine Review" features in the issues of "Air Trails Annual" for the years 1963 through 1968. The author of these summaries (almost certainly Peter Chinn) stated in the preamble to the 1963 edition that some engines not in then-current production were included nonetheless if components and finished engines were known to be warehoused or if a resumption of production was considered possible. The Tornado appears to have been one such engine. Despite the complete absence of advertising either by the manufacturers or by dealers after December 1961, it was listed in the 1963 review (written in mid 1962) as being available, with no indication that production had ceased. It continued to be listed in the 1964 edition, with the comment that Mark II and R/C versions were expected to be available from late 1964. The Mk. II Tornado was tabulated in the 1965 edition but was not mentioned in the text. The text which was included in the 1966 edition stated that the Tornado was "temporarily out of production", but still included both the Mark 2 and Mark 2 R/C in the tables. There was no "Air Trails Annual" for 1967, but the 1968 "Global Engine Review" stated that production of the Tornado had ceased and wouild not be resumed. To further confuse the issue, Peter Chinn's "Latest Engine News" column for the July 1967 issue of "Aeromodeller" included a brief history of D-C engines. The statement was made that the Tornado had been out of production for 3 years at Chinn's time of writing (mid 1967). If this statement was true, all production had ceased as of mid 1964. This is actually not completely inconsistent with the comments in the various "Global Engine Review" compilations - the manufacturers seem to have ended production in 1964 but did not foreclose on the possibility of resumed production until 1967. All of this makes it appear that the Tornado may have remained available at some level into 1964, albeit well under the radar and possibly to special order only. This activity may have been confined to the creation of a few more examples using previously-manufactured components already on hand. The Tornado may best be characterized as a noteworthy technological success that turned out to be a commercial failure. It’s highly doubtful that D-C-Ltd. even came close to recovering their very considerable investment in the development of this innovative engine. The Tornado Twin – Description and Performance

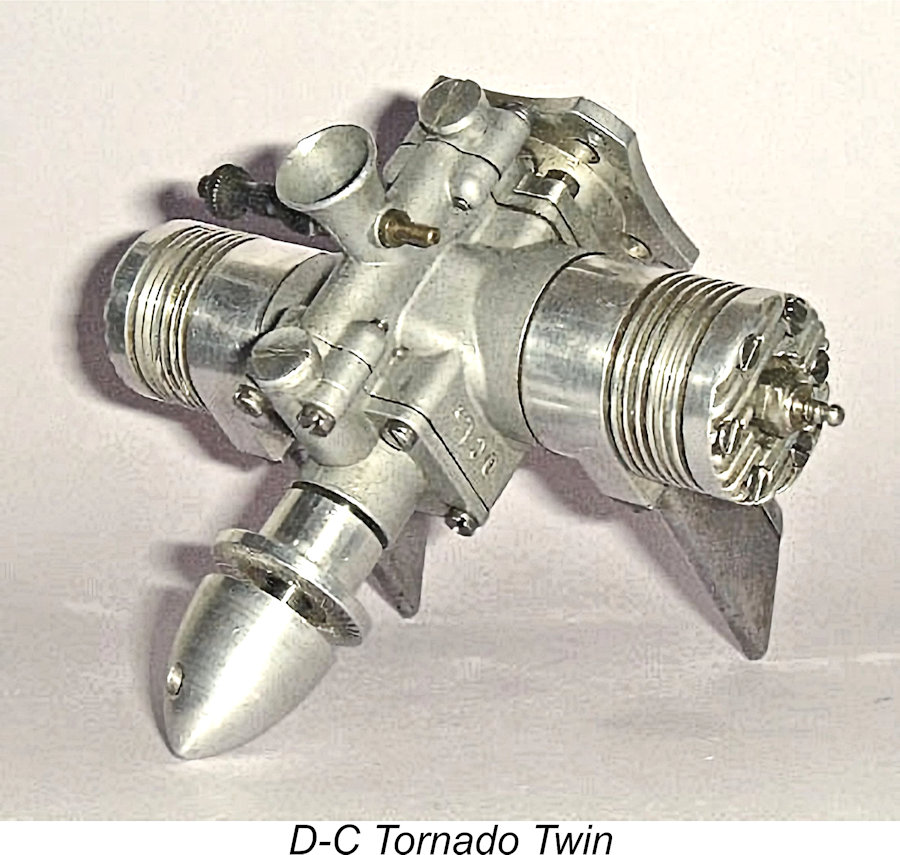

The Tornado was very slightly under-square, with each cylinder having bore and stroke measurements of 0.570 in. x 0.582 in. (14.48 mm x 14.78 mm) respectively for a combined displacement of 4.867 cc. (0.297 cuin.). The weight of the unit minus the optional exhaust stacks was 10 ounces exactly (284 gm). A bit heavy for a 5 cc glow-plug engine, but not excessively so considering the design challenges involved.

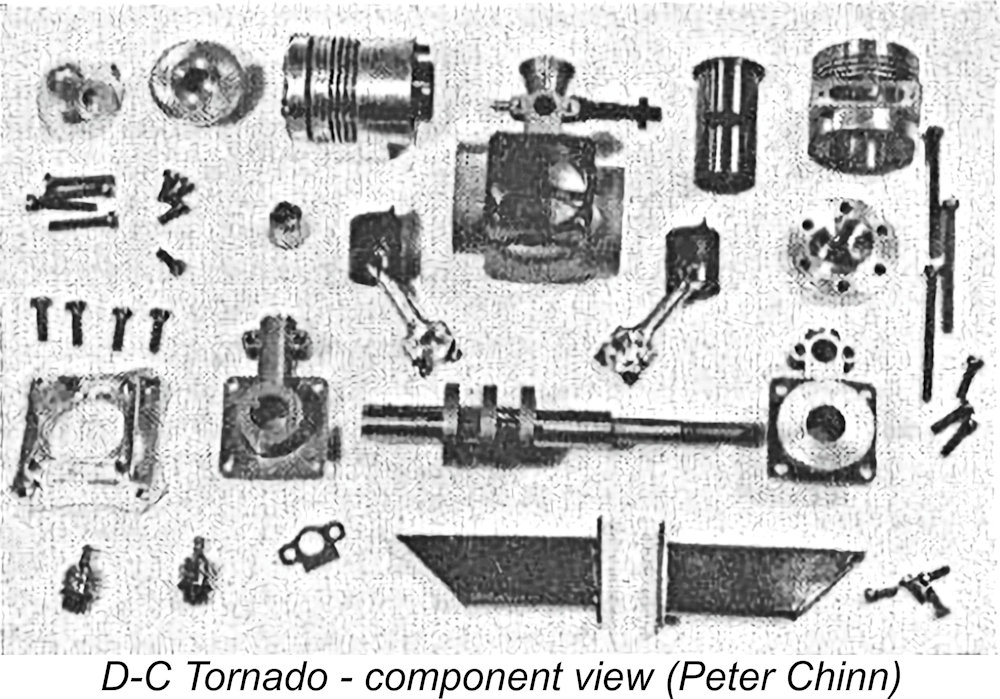

The shaft was necessarily supported at both ends, the finely-finished steel journals running in closely-fitted un-bushed bearings of quite generous length in the end cover casting material. I consider the un-bushed main bearings to be a potential weakness of this design. In an engine of this kind, there is no "give" in the shaft since it is made in one piece and has no "joints" or points of connection. Accordingly, the slightest mis-alignment of the bearings will be reflected in the generation of cyclic bending stresses in the crankpins - the classic fatigue situation. It is critical to avoid such stresses in the crankpins, since these stresses can become very substantial if the journals at each end are free to flex out of alignment to any degree. At only 0.1875 in. dia. (4.76 mm), the crankpins were somewhat undersized, as Peter Chinn pointed out in one of his commentaries. The slightest error in the structural alignment could have a very negative effect upon crankshaft life.

The most unusual feature of the engine was the fact that advantage was taken of both ends of the crankshaft to aid in the induction process. There were conventional crankshaft rotary valves at each end of the engine, although these were fed through a common longitudinal header passage which was in turn supplied by a single carburetor located centrally on top of the main case. The engine thus had two rotary valves feeding a common crankcase, but only one carburetor and hence only one needle valve. Clever!

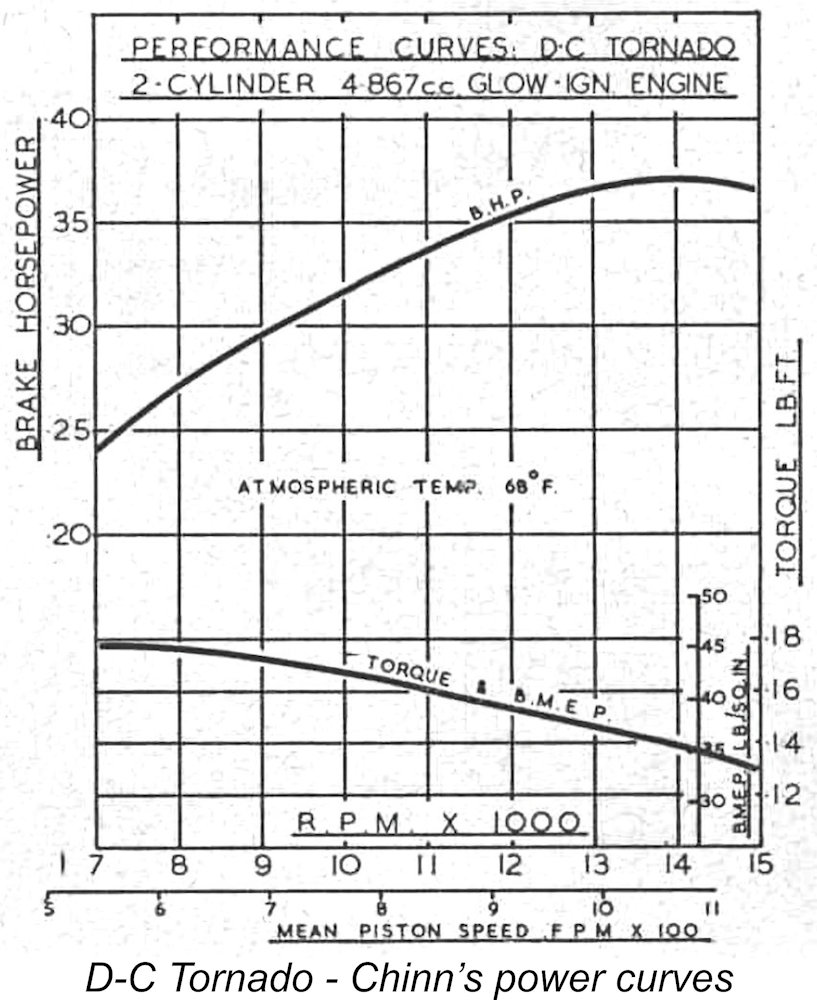

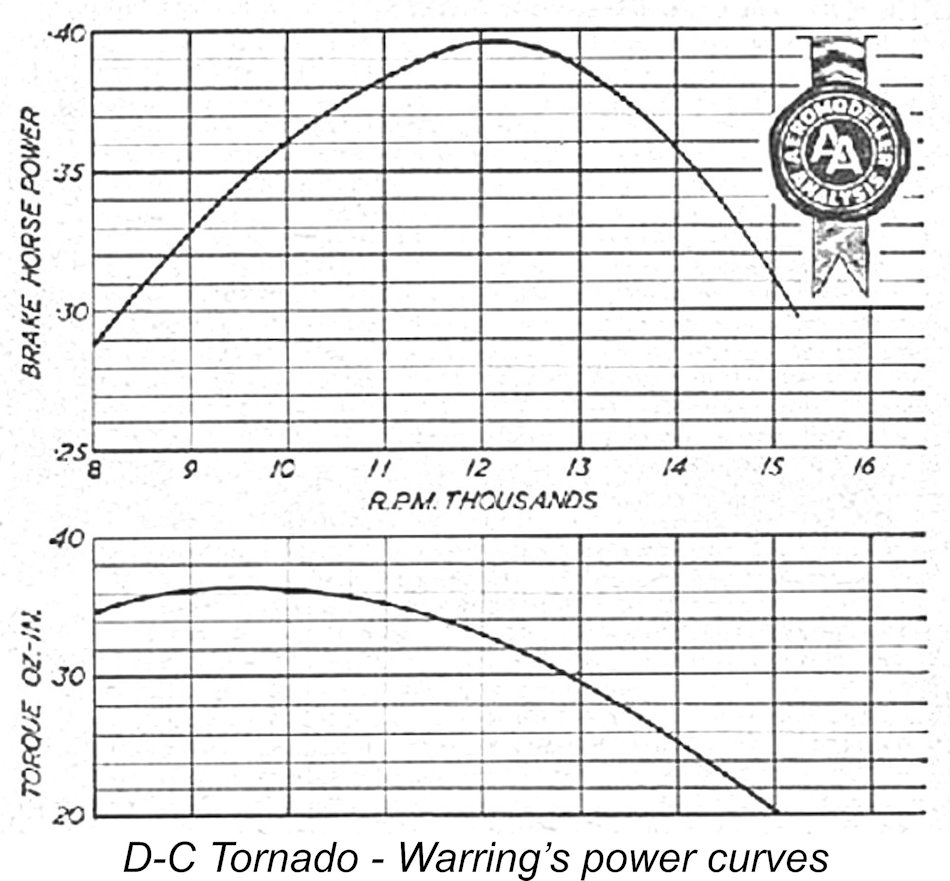

On test, Peter Chinn reported obtaining 0.37 BHP at 14,000 rpm running on low nitro fuel. These are both extremely good figures for a twin, and Chinn commented with some justification that the addition of some nitro would probably push output up over the 0.40 BHP mark. The engine was also tested by Ron Warring in the September 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, and a figure of 0.397 BHP was obtained, albeit at the somewhat lower speed of 12,200 rpm. However, this second test confirmed the validity of Peter Chinn’s comment regarding the engine’s power potential. Warring must have extracted considerably more torque than Chinn to have achieved this result!

This freedom from vibration probably accounts for a characteristic which was noted both by Chinn and others, namely that the Tornado had the potential to pick up speed in the air to a greater extent than a conventional motor. This aspect of the engine’s performance came in for specific comment in an interesting article on twin-cylinder model aero engines which appeared in the 1959 “Aeromodeller Annual”. During tests of the prototype Tornado in a control-line stunt model, the engine’s pick-up in the air was found to be significantly greater than with other engines of similar displacement under the same load conditions. It can’t be denied that the Tornado was a noteworthy technical achievement on the part of Hefin Davies and the staff at D-C Ltd. However, notwithstanding the technical excellence of the engine and its outstanding performance in the context of its twin-cylinder layout, it never achieved a high level of sales success, remaining more of a technological ambassador for D-C Ltd. than anything else. The development of an R/C version might have improved the engine’s sales prospects considerably, but sadly this opportunity was never pursued by the company. The Tornado in Service

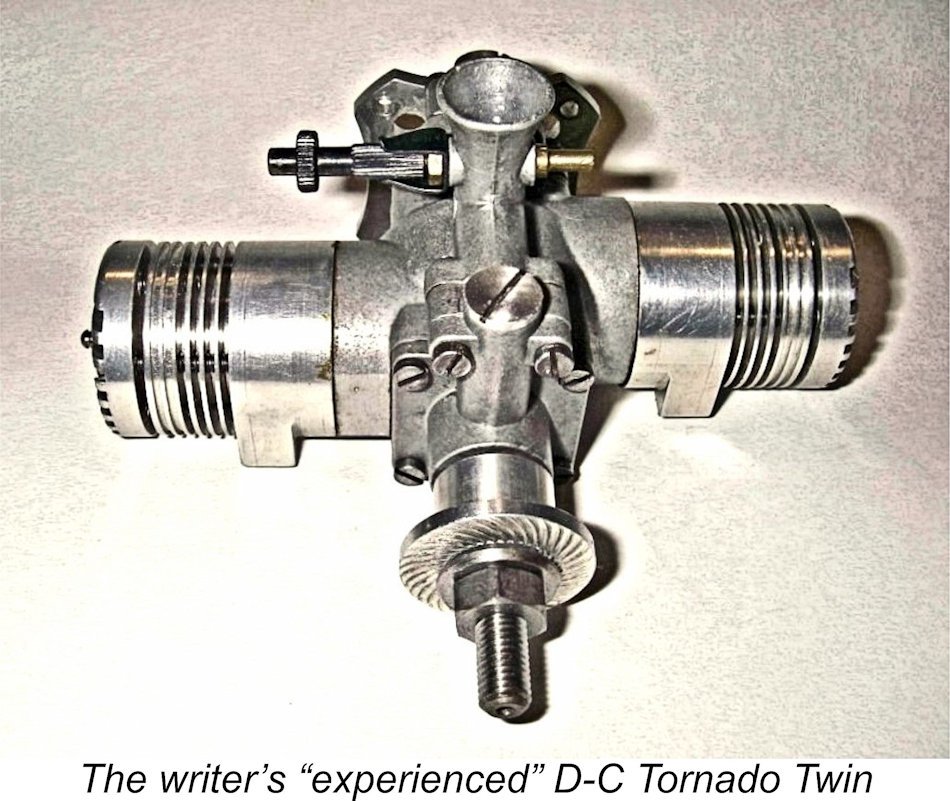

I had this example in an own-design profile sport-stunt job for a few years and used it a fair bit, not at that time seeing it as a rare collector’s item but rather as a neat and unusual engine with which to turn a few heads while having some fun! As time went on, it sure drew a crowd at the field!! I used to run it on a "fat" 9x6 prop, on which it pulled very well indeed and probably ran at or near the peak in the air. The freedom from vibration was almost uncanny, and it certainly did pick up well in the air.

Despite getting quite a bit of running, the engine remains in fine shape today. By always flying it very conservatively I managed not to put it into the ground or get it into lean runs, and I retired it from flying when I started to receive substantial offers for it and came to appreciate its value as a modelling artefact that should be conserved rather than as just another interesting engine to use. The piston/cylinder fits remain if anything a little on the tight side, and the shaft bearings remain free from detectable side-play. The only sign of wear is some very slight but detectable play in the conrod bearings - not sure which ends are involved, since I haven’t disturbed the motor at any time. But there’s hours of life left in the old beast, although I won’t be putting those hours on it any more apart from the odd demonstration run just for fun! This is a true classic and a fine example of what the British model engine industry could do if they really put their backs into it! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN October 2007 This revised edition published July 2024

|

| |

In a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve recounted the story of the

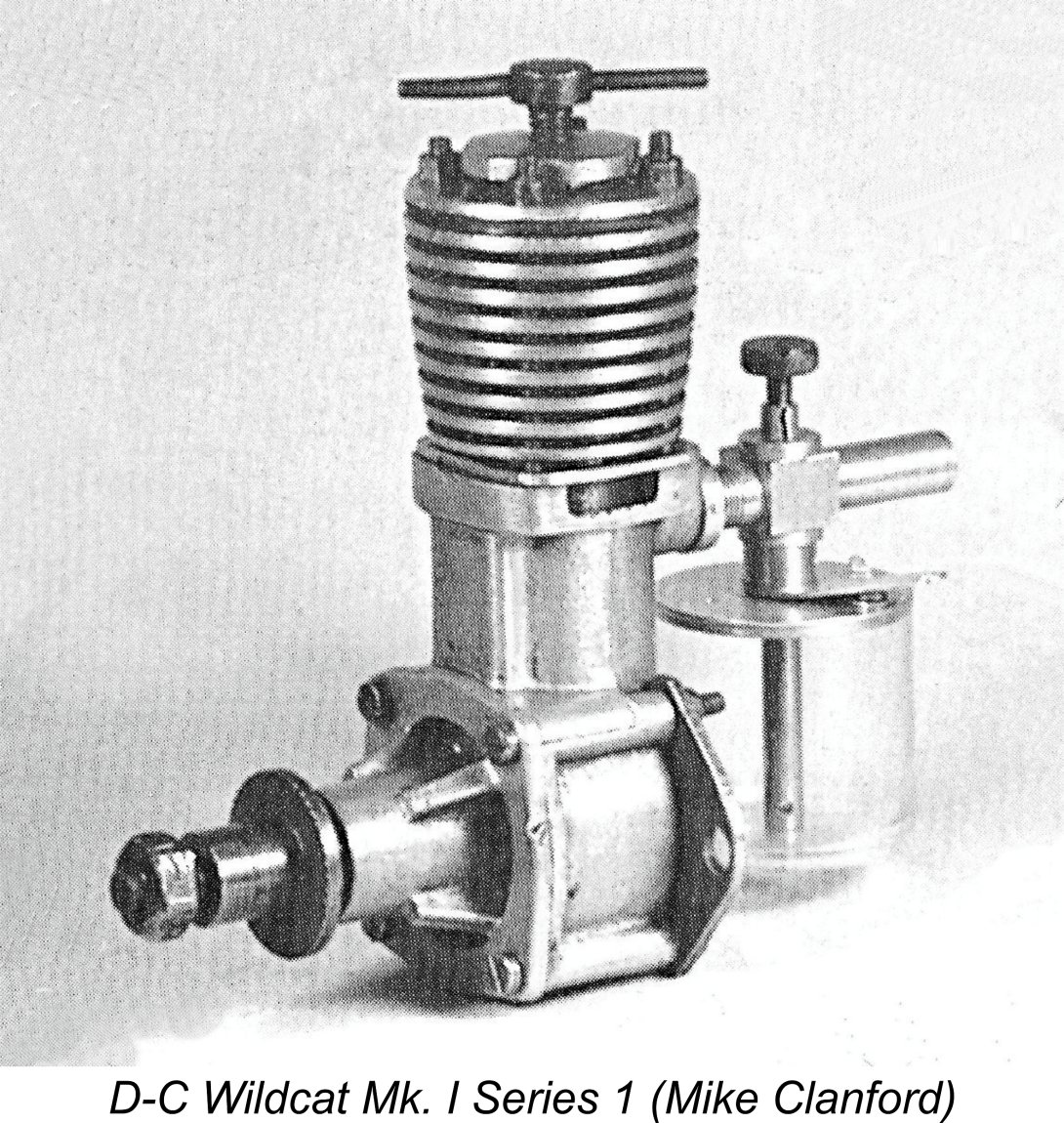

In a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve recounted the story of the  The Davies-Charlton company (D-C Ltd.) was established in 1947 by a former Rolls Royce toolmaker named Hefin Davies at a rather obscure location in Barnoldswick, Lancashire. Davies' initial offerings were the D-C Wildcat 5.3 cc diesel and then the 3.49 cc D-C 350 diesel and glow-plug models. These early products appear to have been designed primarily by Hefin Davies.

The Davies-Charlton company (D-C Ltd.) was established in 1947 by a former Rolls Royce toolmaker named Hefin Davies at a rather obscure location in Barnoldswick, Lancashire. Davies' initial offerings were the D-C Wildcat 5.3 cc diesel and then the 3.49 cc D-C 350 diesel and glow-plug models. These early products appear to have been designed primarily by Hefin Davies.

Alan Allbon had already learned the hard way that he and Hefin Davies were incompatible personalities. Although he moved to the IOM in early 1955 along with the company, Allbon parted company with Davies-Charlton later in 1955, establishing his own precision engineering business on the IOM. The Allbon name was progressively dropped by D-C Ltd. following this move, seemingly disappearing entirely in 1957.

Alan Allbon had already learned the hard way that he and Hefin Davies were incompatible personalities. Although he moved to the IOM in early 1955 along with the company, Allbon parted company with Davies-Charlton later in 1955, establishing his own precision engineering business on the IOM. The Allbon name was progressively dropped by D-C Ltd. following this move, seemingly disappearing entirely in 1957. The fact that Davies took the time and spent the money to undertake this trip is an indication of the increasing importance of the company’s model engine manufacturing activities at this time as the defence-related sub-contract work wound down.

The fact that Davies took the time and spent the money to undertake this trip is an indication of the increasing importance of the company’s model engine manufacturing activities at this time as the defence-related sub-contract work wound down. The single cylinder unit would have represented an inexpensive means of testing different port timings for the loop-scavenged variant of the Twin which was eventually adopted for production. The surviving example of the 2.5 cc single clearly doesn't represent an actual production prototype since the vestigial mounting lugs are only sufficient to allow for mounting in a test stand. This adds credibility to the notion that it may have been a test-bed for the Tornado cylinder. According to the engine's owner following its re-discovery, it ran very well.

The single cylinder unit would have represented an inexpensive means of testing different port timings for the loop-scavenged variant of the Twin which was eventually adopted for production. The surviving example of the 2.5 cc single clearly doesn't represent an actual production prototype since the vestigial mounting lugs are only sufficient to allow for mounting in a test stand. This adds credibility to the notion that it may have been a test-bed for the Tornado cylinder. According to the engine's owner following its re-discovery, it ran very well.  The Tornado Twin was first unveiled to the modelling public through its appearance in a full-page advertisement in the December 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. The "Motor Mart" feature in the same issue of the magazine included a few interesting comments regarding the engine. It was stated that the Tornado had originally been envisioned as a diesel model pending a later decision to switch to glow-plug ignition. The article made much of the manufacturer's intention to utilize exhaust restriction as the means of speed control.

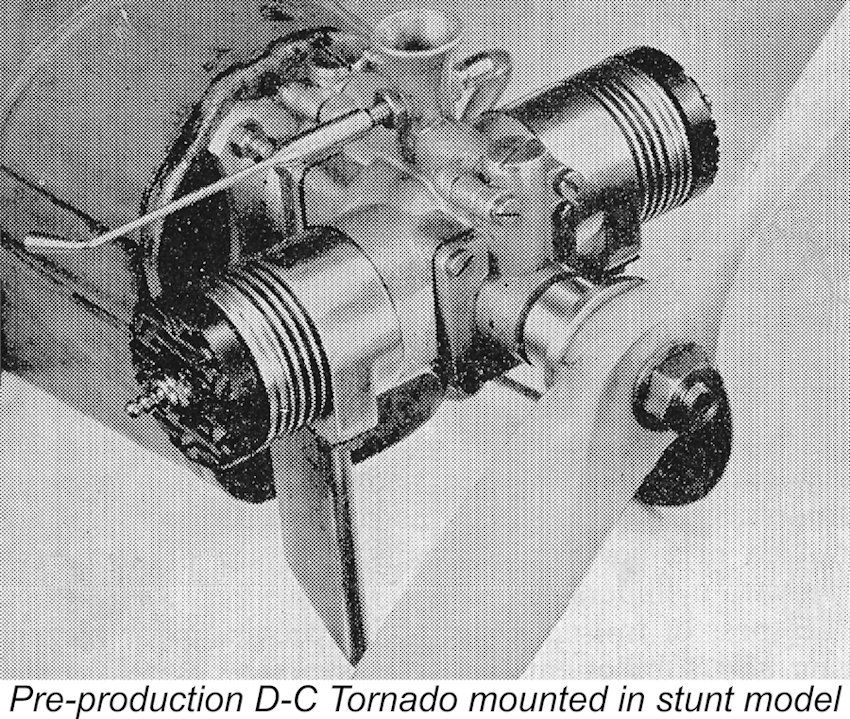

The Tornado Twin was first unveiled to the modelling public through its appearance in a full-page advertisement in the December 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. The "Motor Mart" feature in the same issue of the magazine included a few interesting comments regarding the engine. It was stated that the Tornado had originally been envisioned as a diesel model pending a later decision to switch to glow-plug ignition. The article made much of the manufacturer's intention to utilize exhaust restriction as the means of speed control. It's clear from the record that this announcement was premature by at least a full year, since the Tornado did not re-appear in D-C Ltd.’s advertising at any time during 1959. A photograph of a pre-production unit mounted in a control-line stunt model appeared in the September 1959 “Motor Mart” feature in “Aeromodeller”, showing that some progress had been made. However, the production version still failed to appear.

It's clear from the record that this announcement was premature by at least a full year, since the Tornado did not re-appear in D-C Ltd.’s advertising at any time during 1959. A photograph of a pre-production unit mounted in a control-line stunt model appeared in the September 1959 “Motor Mart” feature in “Aeromodeller”, showing that some progress had been made. However, the production version still failed to appear.  cuin.) D-C Bantam which had a far greater sales potential. The development of the Bantam may have been pushed in order to meet the challenges posed by .049 glow-plug motors known to be under development by competing manufacturers. Pre-release examples of the Bantam were provided to selected reviewers in August 1959, with the new model reaching the hobby shop shelves in late October 1959, just in time for Christmas.

cuin.) D-C Bantam which had a far greater sales potential. The development of the Bantam may have been pushed in order to meet the challenges posed by .049 glow-plug motors known to be under development by competing manufacturers. Pre-release examples of the Bantam were provided to selected reviewers in August 1959, with the new model reaching the hobby shop shelves in late October 1959, just in time for Christmas.  to its pre-release stock”. This implies that production of the Tornado was finally getting underway in late 1959, a full year after the initial announcement of the engine.

to its pre-release stock”. This implies that production of the Tornado was finally getting underway in late 1959, a full year after the initial announcement of the engine. intake manifold”. In the event, no such fitting ever materialized. The Tornado was also mentioned in the article entitled “At the National Model Exhibition” which was featured in the March 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

intake manifold”. In the event, no such fitting ever materialized. The Tornado was also mentioned in the article entitled “At the National Model Exhibition” which was featured in the March 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. It can’t be doubted that this selling price must have represented a significant sales deterrent. At this time, the British modeler wanting a 5 cc glow-plug motor had the choice between the

It can’t be doubted that this selling price must have represented a significant sales deterrent. At this time, the British modeler wanting a 5 cc glow-plug motor had the choice between the  Taking all of the above comments into consideration, it would appear that having developed their technologically-impressive glow-plug twin, D-C Ltd. were unable to resolve the problem of how to approach the marketing of the engine at a time when they were staking their future on the production of super-cheap smaller engines for the masses with their "Quickstart" range aimed at beginners. The question requiring an answer was – what was the target market for the Tornado?

Taking all of the above comments into consideration, it would appear that having developed their technologically-impressive glow-plug twin, D-C Ltd. were unable to resolve the problem of how to approach the marketing of the engine at a time when they were staking their future on the production of super-cheap smaller engines for the masses with their "Quickstart" range aimed at beginners. The question requiring an answer was – what was the target market for the Tornado?  An excellent description of this fine unit is to be found in

An excellent description of this fine unit is to be found in  The Tornado looked like a pretty conventional simultaneous-firing opposed twin with the usual staggered cylinders to accommodate the two-throw crankshaft. However, it did display some quite original thinking. For one thing, the crankshaft was a one-piece twin-throw unit rather than following the more common pattern of using composite construction. The use of a one-piece twin-throw crankshaft forced the makers to use split conrod big-end bearings exactly like those used in full-sized engines. These were secured with 8BA high-tensile bolts and lock-washers. Sounds a bit dodgy, but in fact this arrangement rarely if ever gave any trouble.

The Tornado looked like a pretty conventional simultaneous-firing opposed twin with the usual staggered cylinders to accommodate the two-throw crankshaft. However, it did display some quite original thinking. For one thing, the crankshaft was a one-piece twin-throw unit rather than following the more common pattern of using composite construction. The use of a one-piece twin-throw crankshaft forced the makers to use split conrod big-end bearings exactly like those used in full-sized engines. These were secured with 8BA high-tensile bolts and lock-washers. Sounds a bit dodgy, but in fact this arrangement rarely if ever gave any trouble. If it had been me, I would probably have used Meehanite bushings for the two bearings in order to permit an even closer initial fit to be achieved by lapping and to preserve that close fit over the working life of the engine. But cost was probably becoming a critical factor even without such refinements, as was weight. It’s true that the bearings are of fairly generous length and their fit and alignment as supplied seem to be beyond reproach. Top marks to Davies-Charlton in that regard! Indeed, the workmanship throughout was of a very high order, as indeed it had to be for the design to function effectively.

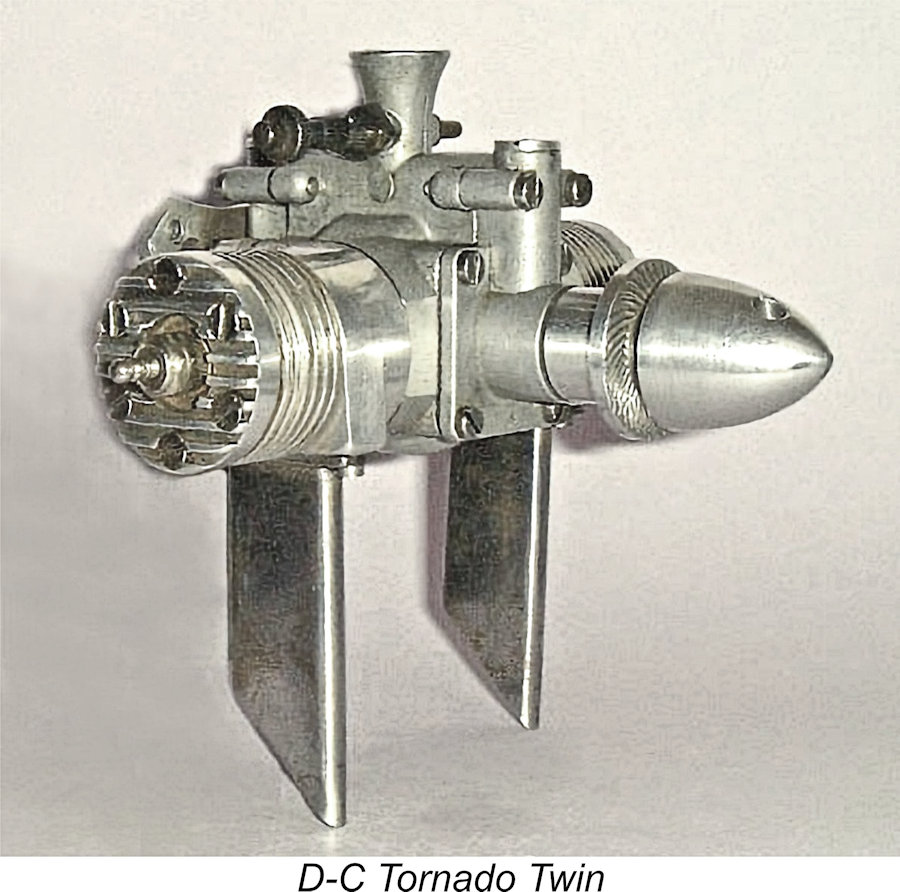

If it had been me, I would probably have used Meehanite bushings for the two bearings in order to permit an even closer initial fit to be achieved by lapping and to preserve that close fit over the working life of the engine. But cost was probably becoming a critical factor even without such refinements, as was weight. It’s true that the bearings are of fairly generous length and their fit and alignment as supplied seem to be beyond reproach. Top marks to Davies-Charlton in that regard! Indeed, the workmanship throughout was of a very high order, as indeed it had to be for the design to function effectively.  The opposed-twin layout naturally forced the use of radial mounting for the unit. The engine came with a pair of exhaust stacks which could be attached to get the exhaust clear of the model in a cowled mounting situation. Unfortunately, the stacks were no longer with my second-hand example when I acquired it, and neither was the original box. The spinner nut was also long gone. Pity!! That said, the factory promotional images reproduced earlier prove that not all examples featured this spinner nut. Ron Warring's test example also used a plain nut-and-washer combination.

The opposed-twin layout naturally forced the use of radial mounting for the unit. The engine came with a pair of exhaust stacks which could be attached to get the exhaust clear of the model in a cowled mounting situation. Unfortunately, the stacks were no longer with my second-hand example when I acquired it, and neither was the original box. The spinner nut was also long gone. Pity!! That said, the factory promotional images reproduced earlier prove that not all examples featured this spinner nut. Ron Warring's test example also used a plain nut-and-washer combination.  Chinn was most complimentary regarding the starting and general handing qualities of the unit, commenting particularly on the "negligible" vibration of the engine when running. This is of course to be expected from such a design, since the reciprocating components are essentially balanced apart from the small rocking couple arising from the unavoidable staggering of the cylinders. Chinn also noted that the manufacturers were contemplating the introduction of an R/C throttle-equipped version at that time – the low vibration levels would have been a positive asset in such a context. However, in the event this never materialized.

Chinn was most complimentary regarding the starting and general handing qualities of the unit, commenting particularly on the "negligible" vibration of the engine when running. This is of course to be expected from such a design, since the reciprocating components are essentially balanced apart from the small rocking couple arising from the unavoidable staggering of the cylinders. Chinn also noted that the manufacturers were contemplating the introduction of an R/C throttle-equipped version at that time – the low vibration levels would have been a positive asset in such a context. However, in the event this never materialized. I’m one of the relatively small (and ever-decreasing!) number of surviving modellers who have actual flying experience with the Tornado. I picked up my own illustrated example in the late 1960’s from a fellow control-line flyer who wanted more power and less weight. He had actually used the engine very little when he sold it to me - apparently, the novelty wore off quite quickly! It’s a sign of the way in which "collector-mania" subsequently affected things that there was little or no competition for the acquisition of this "overweight, underpowered" engine, and I got it at a very reasonable price!! I guess I’m fortunate that my example was never contemplated for R/C use, since it retains its original intake structure.

I’m one of the relatively small (and ever-decreasing!) number of surviving modellers who have actual flying experience with the Tornado. I picked up my own illustrated example in the late 1960’s from a fellow control-line flyer who wanted more power and less weight. He had actually used the engine very little when he sold it to me - apparently, the novelty wore off quite quickly! It’s a sign of the way in which "collector-mania" subsequently affected things that there was little or no competition for the acquisition of this "overweight, underpowered" engine, and I got it at a very reasonable price!! I guess I’m fortunate that my example was never contemplated for R/C use, since it retains its original intake structure.  The Tornado needled very responsively and would do the 2-stroke/4-stroke stunt thing very effectively when set right. Suction was excellent, and starting was a breeze - you had to light up both plugs to start, but two choked turns were all that was required to get enough fuel into the cylinders for starting. The engine was a one or two flick starter at all times. Even back then, I already knew enough about engines to be aware of the crankshaft stress issue, and I was always very careful to balance my props and keep the engine very clean, thus looking after the bearings and crankpins. I also avoided hard contact with the Big Green Thing!

The Tornado needled very responsively and would do the 2-stroke/4-stroke stunt thing very effectively when set right. Suction was excellent, and starting was a breeze - you had to light up both plugs to start, but two choked turns were all that was required to get enough fuel into the cylinders for starting. The engine was a one or two flick starter at all times. Even back then, I already knew enough about engines to be aware of the crankshaft stress issue, and I was always very careful to balance my props and keep the engine very clean, thus looking after the bearings and crankpins. I also avoided hard contact with the Big Green Thing!