|

|

The Dennymite Variants

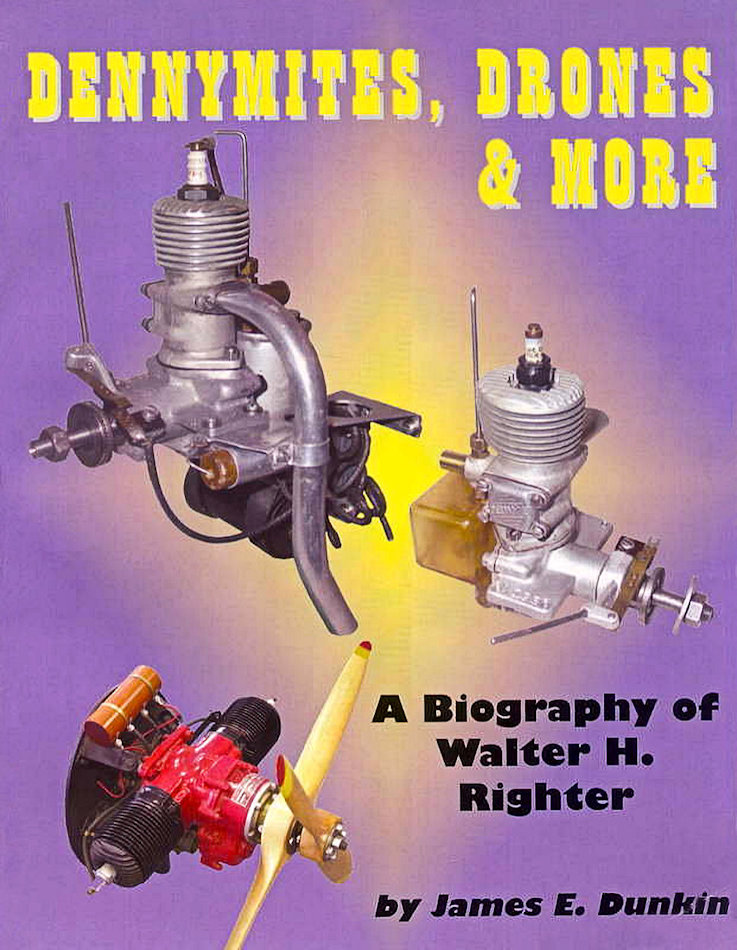

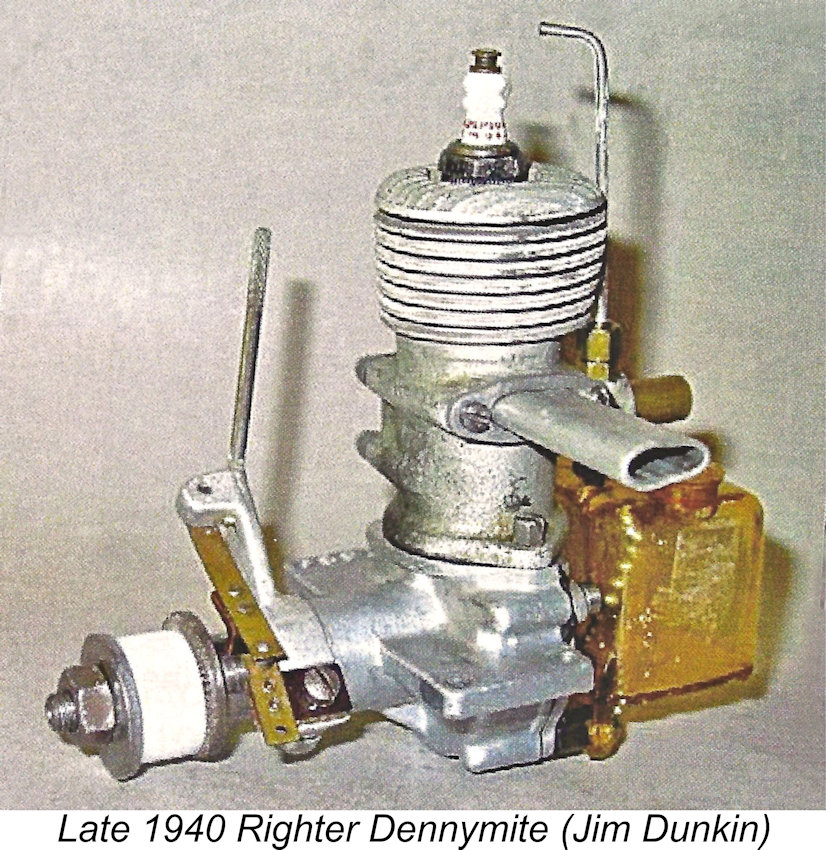

In undertaking this project, I’m straying into ground which has been hallowed by my late and much-missed friend and colleague Jim Dunkin. Jim’s lavishly-illustrated and very detailed biography of Dennymite manufacturer Walter H. Righter entitled “Dennymites, Drones & More” represents the definitive source of information on this famous series of model engines. I’ve used a number of Jim’s illustrations in the preparation of this article, something which So what’s my purpose in writing this article? What’s left to say about the Dennymites that hasn’t already been said by my late mate Jim? Well for one thing, Jim’s work isn’t available online – you have to find a copy of his book to read his very detailed account (and I strongly recommend that you do so!). In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the one thing that you won’t find in Jim’s book is a comparative bench test of a few of the various Dennymite variants. That’s the one thing that I can contribute to the telling of the Dennymite story, apart from making the bones of the tale accessible online. This being the case, I may as well come clean by saying up front that I will not be repeating most of the information so ably gathered and presented by Jim in full consultation with Dennymite manufacturer Walter Righter. Readers wanting the full story are advised to track down a copy of Jim’s book. All that I will do is present a condensed outline of the Dennymite story, during the course of which I’ll report some bench test impressions gained through experience with my own examples. I’ll begin this article with a summary of the Dennymite saga up to 1940, when the first of my test engines made its appearance. The Early Dennymites

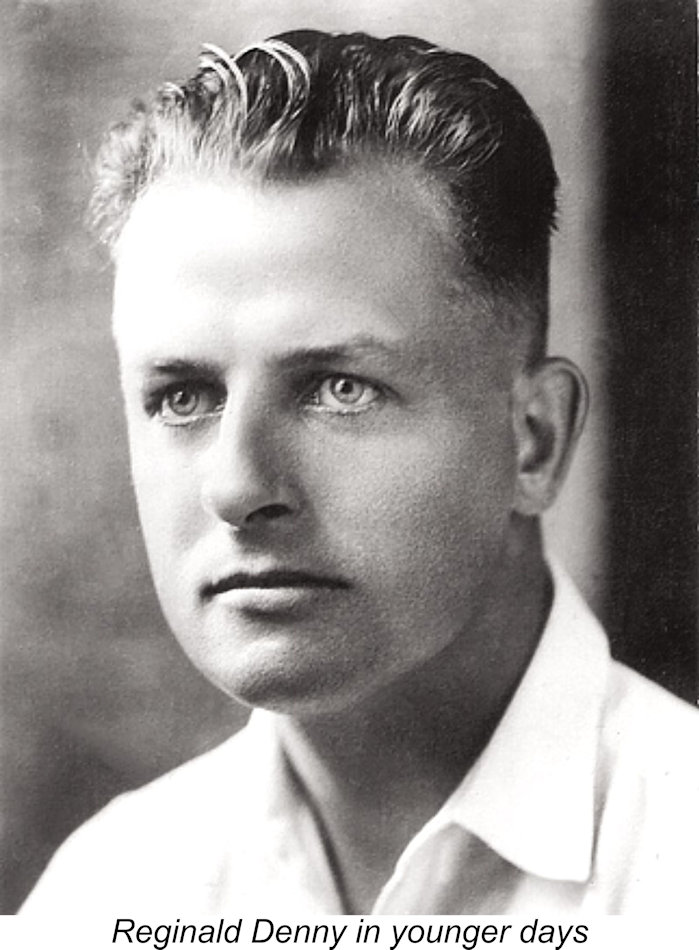

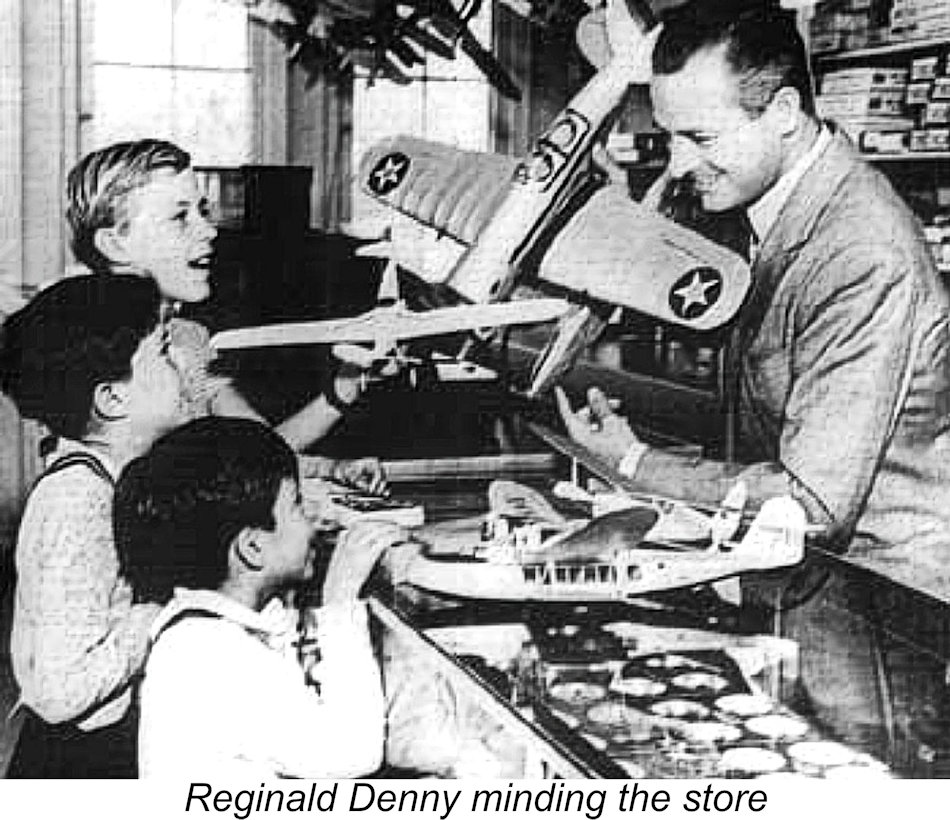

Reginald Denny (always known as just plain “Reg”) was an interesting and multi-faceted character. Born into a thespian family as Reginald Leigh Dugmore in November 1891 in Richmond, Surrey, England, he began acting as a child performer at the age of 8 years. He was enrolled at St. Francis Xavier College in Mayfield, Sussex, from which he ran away at age 16 to train as a boxer under Sir Harry Preston at the National Sporting Club in London. Denny first visited the USA in 1911 to appear in a Broadway production with his father W. H. Denny, a well-known actor and opera singer in his own right. At this time he changed his name legally to Reginald Denny, thus formalizing the Denny name which had long been used by his father as a stage name. Reginald Denny had a fine baritone singing voice, which enabled him to go on an extended international tour with the Bandmann Opera Company starting in 1911. During a 1913 tour of India with that company he married one of his fellow performers, Irene Hilda Haismann, with whom he had a daughter named Barbara Denny who was born in 1916. Denny returned to the USA in 1915, gaining his first US silent movie role in that year. However, after the USA entered WW1 as a combatant in April 1917, Denny travelled to England to join the British Army, enlisting on October 8th, 1917 as Reginald Leigh Denny with the service number 767282. It’s unclear whether he volunteered or was called up – as a British citizen, he was eligible for call-up despite his US residency. Denny enlisted as a member of a Rifle Brigade and was immediately assigned to an O.T.C. unit for officer training. However, he must have volunteered quite early on for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which was still a part of the Army at this stage. On April 1st, 1918 the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) were amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). Accordingly, after a medical Board evaluation on May 31st, 1918, Denny was transferred from the Army to the RAF with a new service number 318727. He was immediately assigned to RAF No. I Officer’s Technical Training Wing stationed at Hastings. Over the following months Denny underwent training in aerial observation and gunnery at various RAF locations in England. During this period he also put his pre-war boxing training to good use, becoming his Brigade's heavyweight boxing champion. He was later to showcase his boxing skills when playing the lead role in the 1922 Universal Pictures action series "The Leather Pushers".

On February 28th, 1919, Denny was granted a Temporary Commission as a Flight Lieutenant in the RAF Reserve and re-assigned to Canada, presumably an administrative ploy to facilitate his formal discharge there in due course. Although his plan was to return to New York, as a British subject and a member of the British armed forces he couldn’t be discharged in the USA. On March 15th, 1919 Denny boarded a ship at Barry Docks in South Wales to return to New York. His formal discharge from the RAF Reserve took effect on May 16th, 1919, presumably in Canada. This ended his military service. The fact that Denny was granted what amounted to an honorary commission as Flight Lieutenant right at the end of his service confirms that he was one of the many thousands of flying officer trainee cadets who at war's end had either not commenced or not completed any pilot training, hence not becoming certified as pilots during their RAF service. Such commissions were routinely granted as a courtesy to officer trainees who finished the war in this category. Following Denny's post-war return to New York, the acting career which had begun in England when he was only 8 years old blossomed, first in New York and later in Hollywood. Denny became a very prominent lead actor in silent films during the 1920's. His wartime experiences must have instilled a great love of flying, because he clearly completed training as a pilot following his 1919 return to New York. He even went so far as to purchase his own WW1-vintage Sopwith Snipe biplane, maintaining his aviation activities during the 1920’s by performing periodically as a stunt pilot in between movie roles, flying as a member of the 13 Flying Black Cats. He loaned his own Sopwith Snipe to Howard Hughes for use in Hughes' 1927 movie epic "Hell's Angels". In 1929 Denny made a successful transition into talkies, a step which eluded some other stars of the silent screen. Although his very “British” accent kept him out of major Hollywood lead roles in sound films, he established himself as a frequently-employed A-level supporting actor, often in character roles. He ended up appearing in almost 100 sound films, also becoming well-known during the 1950’s for his many TV appearances.

In late 1935 Denny and a number of his employees at Reginald Denny Industries developed a model airplane design called the Dennyplane which Denny intended to market as a kit. This design used basswood instead of balsa for the most part, also featuring a number of metal components. Consequently, it was a little on the heavy side. This led to the development of a lighter model called the Dennyplane Junior. Marketing of these designs in kit form commenced in 1936. They were subsequently joined by the Denny Bullet as well as a series of rubber-powered endurance models.

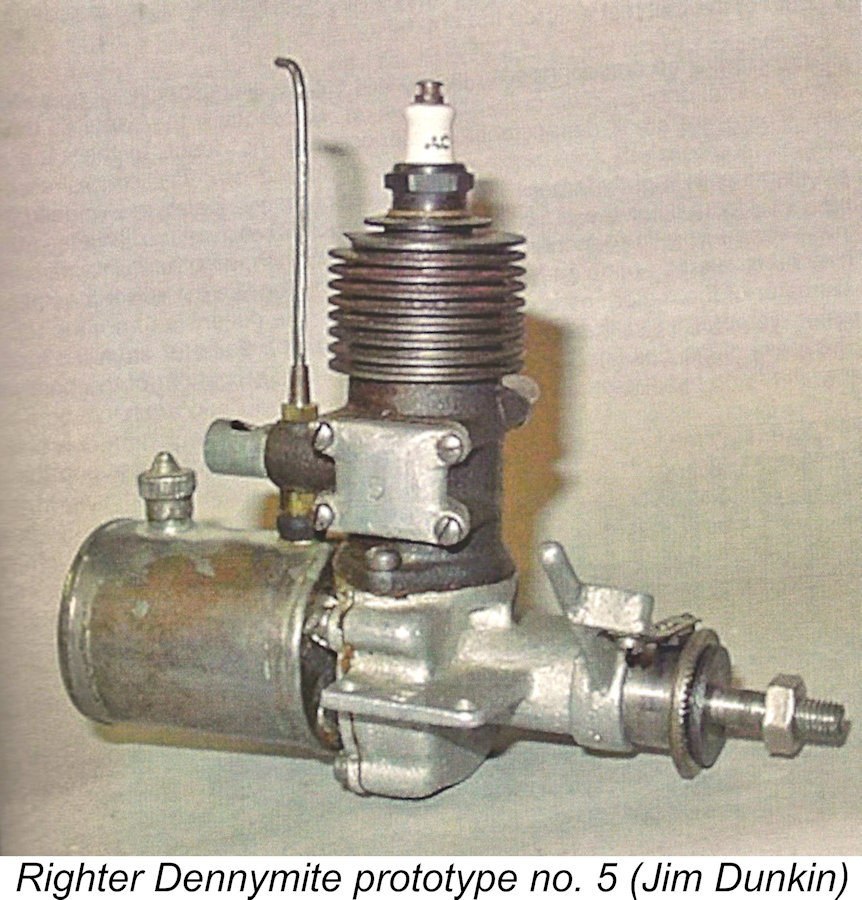

Following a successful fifty-hour running test, the Denny Sky Charger was put into small-scale production in Denny’s own shop. Reg Denny personally used one of these engines in his Dennyplane Junior model to make an N.A.A. certified flight of one hour and forty-seven minutes duration, a feat of which much was made in his advertising. However, Denny became convinced that a larger and more powerful motor than the Sky Charger was required. In late 1936 he met the talented engineer Walter Righter of Glendale, California, who expressed interest in designing and producing such an engine. It was agreed that if Righter could produce a batch of ten engines which stood up to the fifty-hour endurance test (the same standard applied to full-sized aero engines seeking certification), Denny would enter into a production and marketing agreement with him. The engines would bear the Dennymite name.

The prospect of putting the Dennymite into commercial-scale series production forced Walter Righter to recognize the fact that he would need a larger production facility. Accordingly, in August 1937 he established a larger machine shop at a different location, albeit still in Glendale. Using this facility, he began producing the original Dennymite engines in commercial quantities for Reginald Denny Industries in December 1937. This model was quickly followed in early 1938 by a “Special I” version featuring minor modifications, and then later in 1938 by a further modified model called the “Special II”.

By 1939, although his hobby shop remained very much in business at this time, Denny’s personal interest had become focused on the development of radio-controlled target drones for military anti-aircraft training purposes. To this end, he established a separate business entity called the Radioplane Company which would focus on drone development. This new company did not supersede Reginald Denny Industries, which continued in operation as a parallel entity involved in the model field. The Radioplane Company quickly produced prototype drones designated the RP-2, RP-3 and RP-4 with the ongoing involvement of Walter Righter on the design and technical side. While working on the drone engines for Radioplane, Righter continued to produce and develop the Dennymite for Reginal Denny Industries. A revised variant based upon permanent mold castings appeared in 1940.

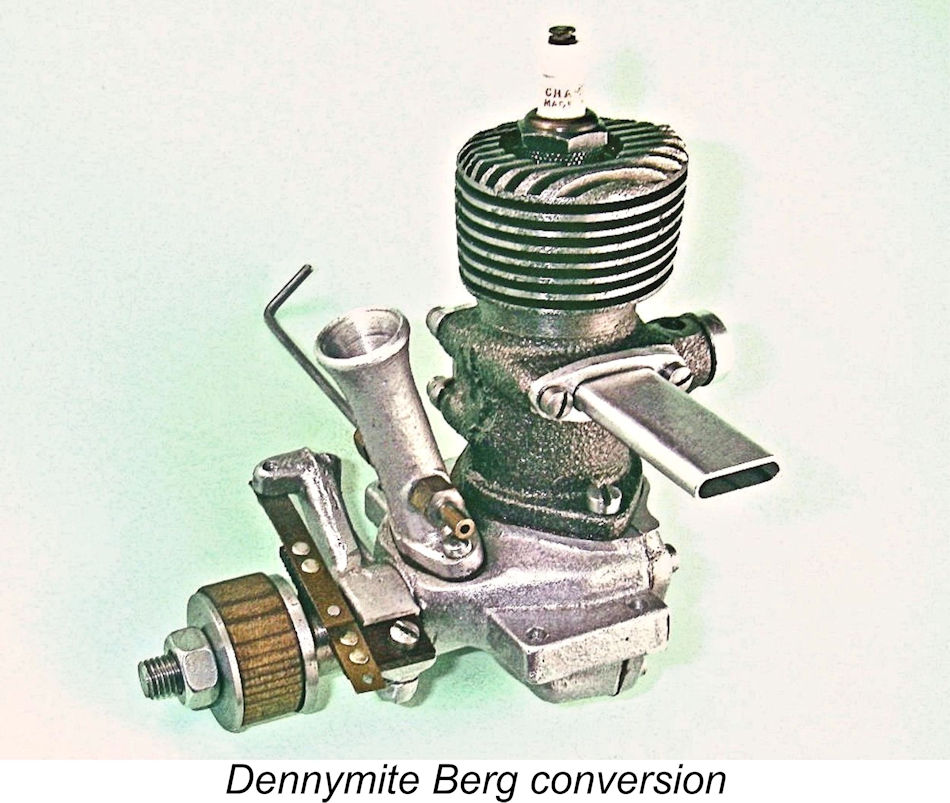

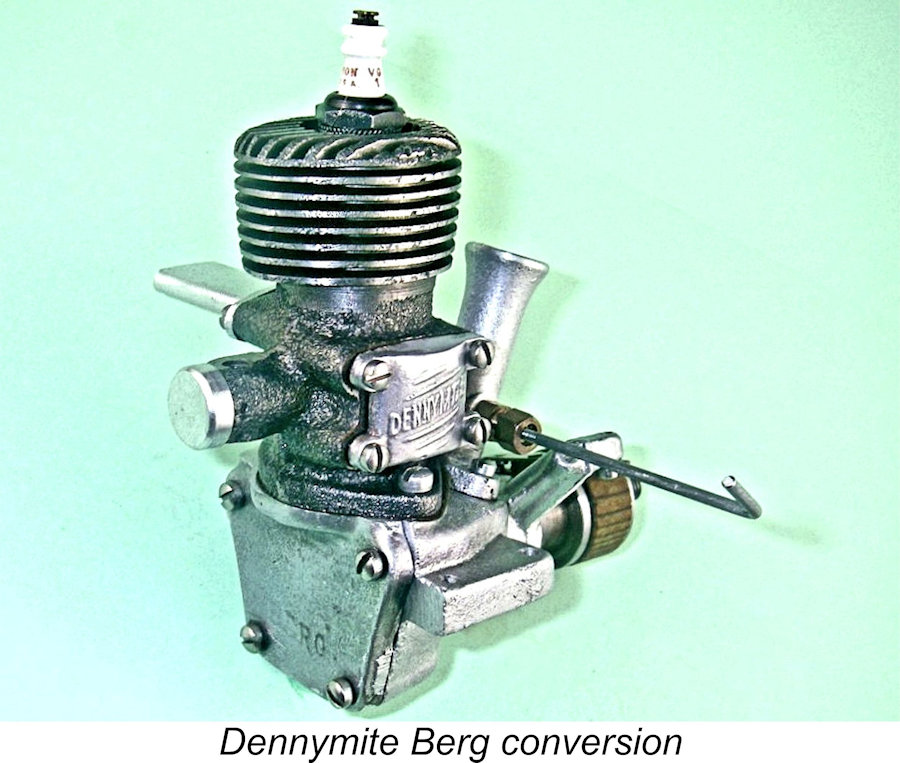

This partnership was successful to the point that the Dooling brothers were soon able to establish themselves in expanded manufacturing facilities at 3433 West 59th Street, Los Angeles, California. They designed and produced a series of car designs for distribution by Denny. Naturally, many of these early Dooling cars were Dennymite-powered. The advertisement reproduced here appeared in the December 1939 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN). The widespread use of the Dennymite in car service at this time naturally led a number of individuals to explore ways and means of improving its performance. Foremost among these was the concept of converting the engine to rotary valve induction. One individual who went so far as to market such a conversion was John Berg of Los Angeles. It is one of Berg’s conversions that is the first Dennymite variant to be analyzed here. The Dennymite Rotary Valve Conversions

It was of course necessary to use a modified crankshaft having the required holes drilled to allow the FRV induction system to function. Owners had the option of drilling these holes themselves or purchasing a shaft from Berg with the drilling already done. The complete kit featuring the revised crankcase with matching backplate, bolt-on venturi and modified shaft was offered for $8.65. If one was comfortable with doing the necessary drilling on the original Dennymite shaft, the crankcase and venturi alone could be purchased for $4.95. A separate company called Matthews Racing Accessories also developed a more sophisticated timer and an improved bypass cover for the Dennymite. These accessories were often fitted to Berg conversions. However, my example of the Berg conversion retains the standard Dennymite components apart from the use of Berg’s revised backplate with the name “BERG” stamped onto its surface.

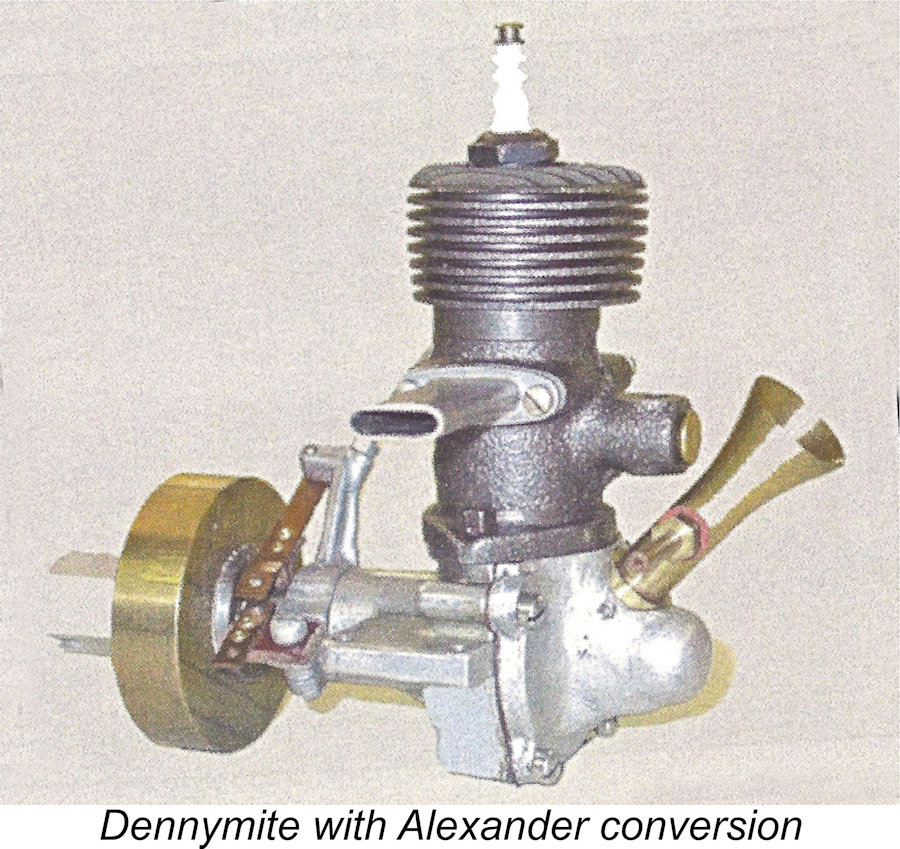

A third company called Alexander Automotive Engineering marketed several different rotary valve conversions for the Dennymite, including one that featured twin rotary valves (one each front and rear) and another that utilized a disc rear rotary valve. Alexander did not offer their components as after-market accessories, apparently assembling their modified Dennymites as complete engines to special order only.

In the meantime, all-out speed model competitions were confined to tethered car and hydroplane racing. This being the case, the various Dennymite rotary valve conversions were used primarily in car service. It's a testament to the growing popularity of this branch of the hobby and the widespread use of the Dennymite in such applications that no fewer than three accessory manufacturers (Berg, J.L. and Alexander) believed that they could make money selling such conversions. However, none of the various rotary valve conversions of the Dennymite survived WW2. By the time that peace returned, engines such as the Hornet 60, McCoy 60, Hassad Custom 61 and numerous others had extended model engine performance standards far beyond what even a converted Dennymite could achieve. During the preparation of this article, I had an opportunity to sample an FRV Dennymite by testing an example of the basic 1940 Berg FRV conversion of an otherwise-standard Dennymite. Let’s get right to it!! The Berg FRV Dennymite Conversion on Test

This being the case, I decided that a little additional running-in prior to the actual test would not come amiss. I set the engine up in the test stand with a Top Flite 14x4 wood prop fitted, since this prop had worked well with other sparkies of similar vintage and displacement. The fuel was my usual 75/25 blend of white gas (Coleman Camp Fuel) and S.A.E. 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120). The sparks were supplied by one of my ultra-dependable Larry Davidson SSIGNCO units.

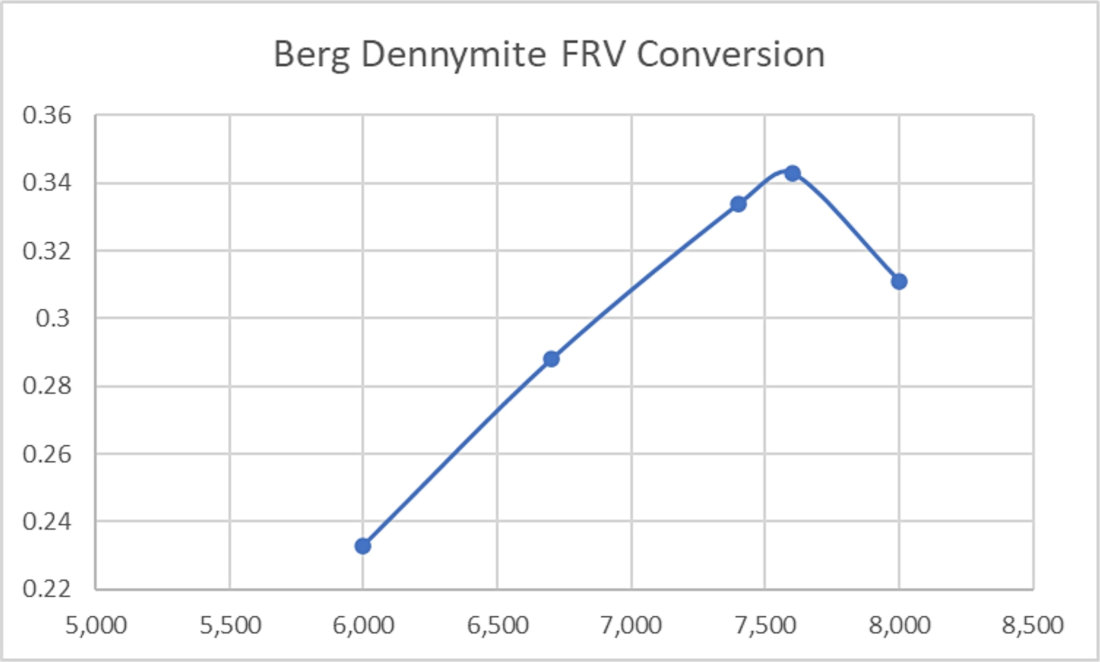

Leaning the engine out and optimizing the timing, I found that the Berg-Denny would turn the 14x4 prop at a smooth 'n steady 6,700 RPM. This was pretty good by 1940 standards, but there was a downside - vibration levels were relatively high. Wishing to find out which side of the peak I was on, I next tried an APC 13x7 prop, which has a slightly higher torque absorption coefficient. The engine turned this at a considerably lower 6,000 RPM, implying that the power curve was still climbing on the 14x4. I therefore tried a series of lower loads, ending up with a Top Flite 10x8 wood prop, which the engine turned at 8,000 RPM. At this point, vibration was becoming somewhat problematic, besides which the engine appeared to be past its peak at this speed in any case. I therefore concluded the testing at this point - no point in thrashing these old classic survivors unduly! The data collected during the test were as follows:

The minimal number of data points renders the power curve approximate at best, but the data are at least mutually consistent. The implied peak output is of the order of 0.343 BHP @ 7,600 RPM, considerably more lively than a standard side-port Dennymite, as we shall see in due course. The main downside of the Berg FRV Dennymite, which it shares with other variants, is the high level of vibration. It's likely that this would be less of an issue in car service, but an aero user would certainly notice this characteristic! There would be a strong temptation to operate the engine at speeds some distance below its peaking speed, thereby sacrificing some of the benefit gained by the use of this conversion. Even so, the performance enhancement resulting from the use of an FRV conversion was clearly considerable. A little work on the balance factor would make one of these conversions into an excellent performer by the standards of its day. The War Years and Beyond As WW2 cast its ever-lengthening shadow over the immediate future of the USA, Reginald Denny became increasingly keen to pursue his military target drone project through his Radioplane company. Naturally, the development of these units required money. Up to this point Denny had financed the drone project from his own resources, but his hobby shop was no longer generating much revenue, while his acting in mainly supporting roles did not command superstar fees. Moreover, his Radioplane company had yet to generate any revenue despite showing considerable promise. Given these circumstances, Denny now decided that he needed help. Consequently, he approached his major financial backers, the Whittier Oil Company, only to learn that they were not interested in participating in the drone project. As events were to prove, this was a very poor business decision ............... In mid-1940 Denny's cash-flow problems forced him to sell both Reginald Denny Industries and the hobby shop to Mr. Pete Vier. A domino effect resulted from this sale, because Mr. Vier ended the purchase of Dennymite engines from Walter Righter at this point. The final advertisement for Reginald Denny Industries appeared in the August 1940 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN).

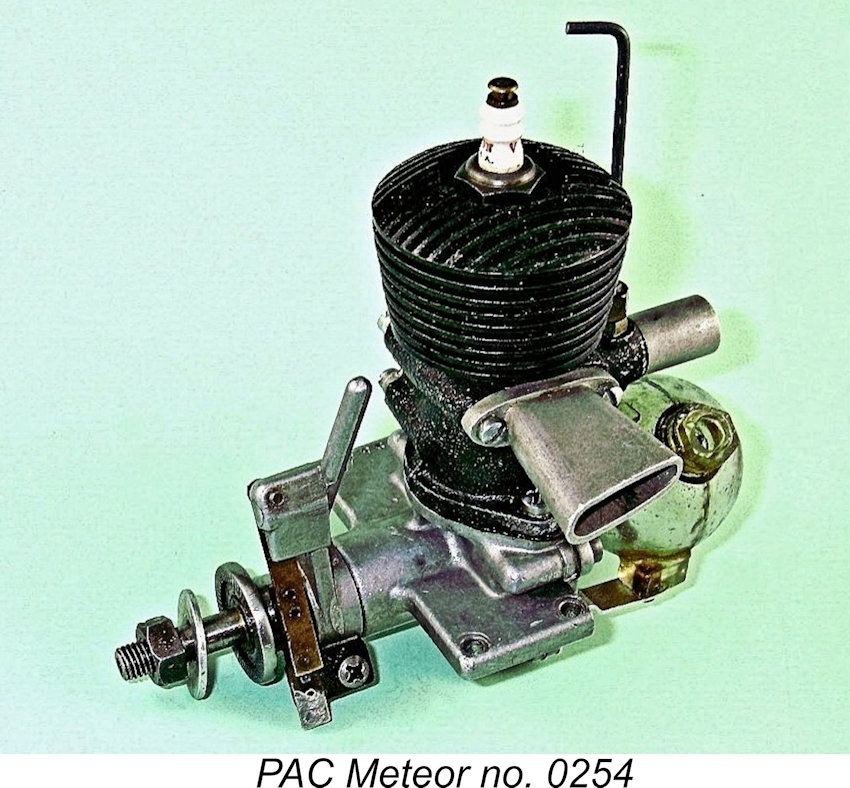

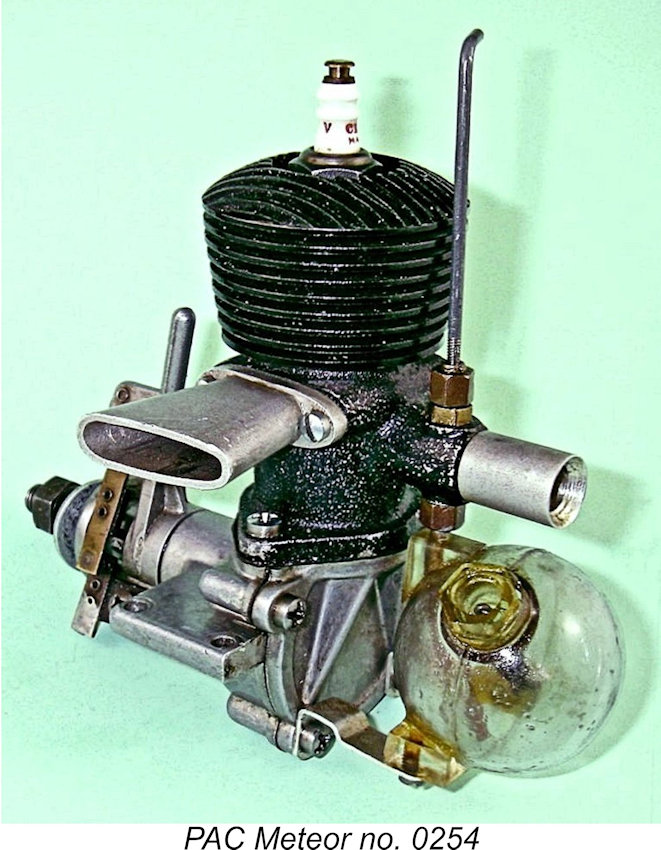

However, as of late 1940 the US military build-up in anticipation of the seemingly-inevitable American entry into the war was already having its effect upon material supply. As an example, the availability of the cadmium used to plate the Dennymite cylinders dried up, forcing Righter to substitute an application of heat-resistant silver paint. The demands of America’s war effort stopped all Dennymite production in late 1941. Righter diverted his efforts into the design and production of target drone engines, on which he had actually been working for some time previously in support of Reg Denny’s drone initiative. Denny’s RP-4 drone had first flown in These small unmanned R/C aircraft were powered by a compact opposed twin-cylinder two-stroke engine designed by Walter Righter. They were manufactured in a facility located at Van Nuys Airport in Los Angeles. One of the employees was a young lady The Radioplane company went on to manufacture over 15,000 target drones during WW2, fully justifying Reg Denny's unswerving faith in the Radioplane concept. The highly successful business carried on after the war, eventually being sold to Northrop Aviation in 1952. Denny himself continued his acting career, eventually passing away in 1967 from a stroke at the age of 75. His final screen role was an appearance in the 1966 film “Batman” as Commodore Schmidlapp. As the end of the war drew near, Walter Righter had every intention of resuming Dennymite production. In 1944 he drew up an improved design and offered it to the owner of Reginal Denny Industries, the aforementioned Mr. Pete Vier. However, Vier lacked both the desire and the resources to expand into the model engine business. Looking things over, Righter concluded that he didn’t have the financial clout to continue the Dennymite project on his own. He decided to relinquish the project and go instead into business as an engineering consultant. Righter’s interest in his Righter Manufacturing Company was sold to Radioplane on May 23rd, 1945. Naturally, this purchase related strictly to the Drone engines. The Dennymite project soon followed, being sold to the Pacific Automotive Company on June 12th, 1945 along with the Dennymite naming rights. The Pacific Automotive Company (PAC) had been formed in late 1943 to manufacture aircraft servicing equipment under military contract. At war’s end it was looking for new projects to keep its production lines busy. The Dennymite project met this requirement very well. The initial PAC Dennymites were made using existing parts inventory obtained in the deal with Walter Righter, but the company soon had its own production lines working. Their first national advertisement appeared in the December 1945 issue of MAN. The original PAC Dennymites were very similar to the pre-war Righter models, albeit with a few detail modifications, including a larger die-cast exhaust stack and a revised bypass cover. However, the company was not content to let matters rest there – they wanted an engine that looked sufficiently different from the standard Dennymite that it would be identified with their company rather than with Reginald Denny or Walter Righter. The result of their thinking was the PAC Meteor. The PAC Meteor

The cylinder was visually far more massive than the Dennymite Airstream component. It had a round planform as opposed to the Airstream “teardrop” shape of the earlier Dennymites. It had a considerably larger external diameter as well as an additional cooling fin, thus providing a substantially greater air-cooling surface. This was a logical response to the characteristic tendency of the Dennymite Airstream model to run relatively hot. The fins presented an attractive tapered side profile. The cylinder was given a durable black finish which was created by copper-plating the surface and then dipping it in an acid bath.

The number of these engines produced by Pacific Automotive seems to have been rather small - they decided to suspend production fairly soon after it had begun (see below). The engines were never distributed to dealers. In fact, many of the examples that exist today are thought to have been assembled by employees from salvaged parts on hand after the decision was made by Pacific Automotive to abandon the project. Since relatively few spherical tanks were produced, many surviving PAC Meteors have the standard "cube" Dennymite tanks. A complete and seemingly unrun spherical-tanked example of the PAC Meteor bearing the serial number 0254 was the second of the various Dennymite derivatives on hand for testing during the preparation of this article. As far as I can discover, the Meteor was never the subject of a published media review. Accordingly, I was on my own here! I decided to try the engine once more with the Top Flite 14x4 wood prop fitted. As previously noted, this prop has proved itself to be a very suitable load for larger WW2-era sparkies in general. Both fuel and ignition system were the same as used for the previous test of the Dennymite Berg conversion.

I put about 20 minutes of running time on the engine in short rich runs, after which things had improved somewhat. Even so, there was still a considerable degree of excessive residual tightness which would take quite a bit more running time to work out, although the engine would now at least run the tank out with minimal sagging provided the needle was kept rich. I judged that it would take a lot more running time than I was prepared to give the engine to get it all the way up to speed, although it was clearly heading in the right direction. Since the engine still wouldn't sustain sag-free two-stroke operation long enough to allow meaningful prop-RPM figures to be measured, I abandoned the testing at this point, contenting myself with having proved that the engine started just fine and had the potential to perform at a fully satisfactory level once freed up. I'm certain that it would at least equal the performance of a standard Dennymite Airstream model. The O&R/WBC Dennymites

O&R were not interested in manufacturing any engines other than their own established lines – their sole interest in the Dennymite venture was simply to recover their investment and make a profit by selling off completed Dennymite units. This being the case, O&R entered into a joint financing agreement of some kind with an outfit called WBC set up a production line and began making engines using the parts and castings obtained from Pacific Automotive. The WBC Dennymites were basically re-creations of the earlier Airstream models, with a few minor detail changes. Many of them were sent to O&R for sale through their network, although some engines were apparently sold directly by WBC. It isn’t known when WBC ended production, but it couldn’t have been long after the appearance of the commercial miniature glow-plug in late 1947 – that event had signaled the impending eclipse of the spark ignition engine in unmistakable terms. O&R Dennymites provided by WBC continued to be advertised through most of 1948, stressing that they were “special deals”. The last such advertisement appears to have been placed in the December 1948 issue of MAN by the Crescent Model Shop of Los Angeles, California.

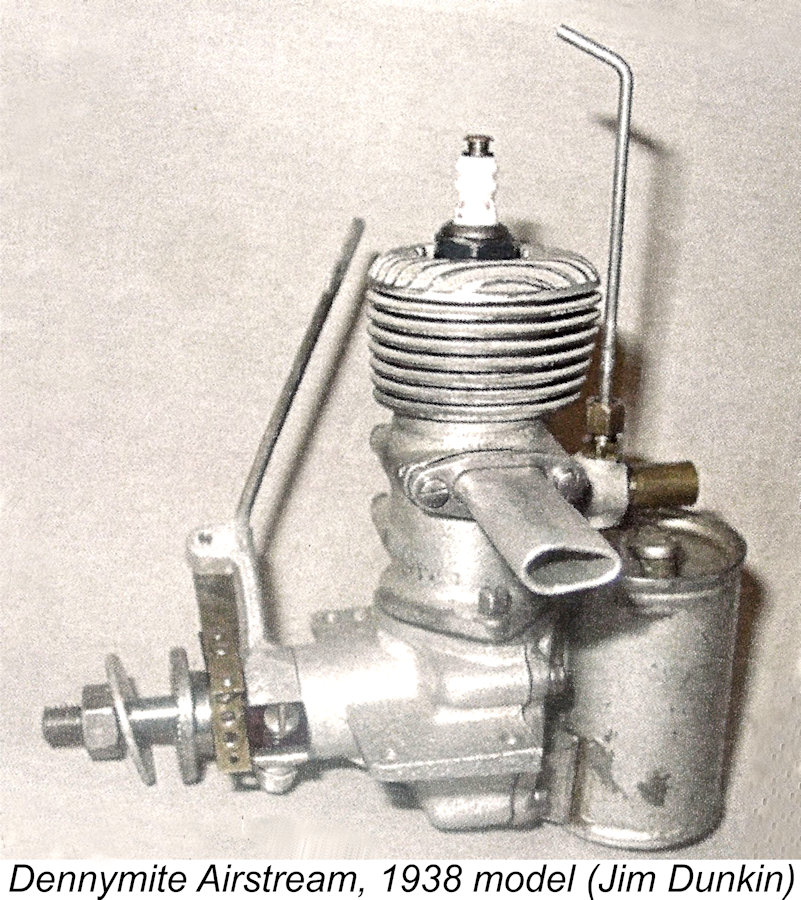

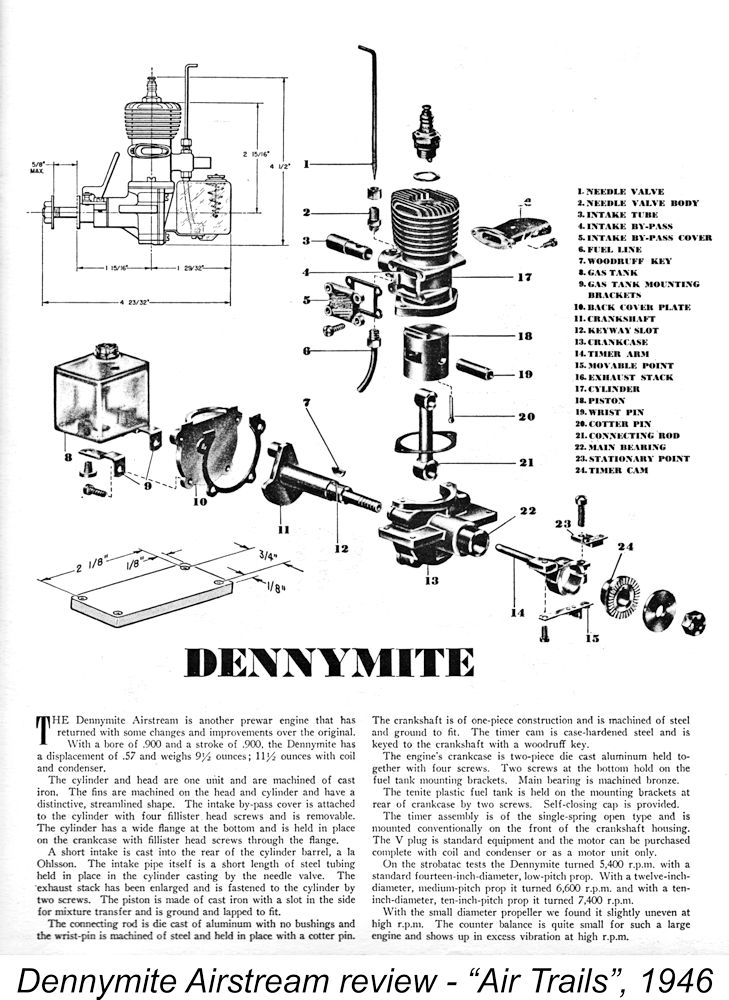

The only published review of the Dennymite Airstream that I've been able to find was that published in "Air Trails" in 1946. This clearly related to the PAC Airstream mentioned earlier - the enlarged exhaust stack was specifically mentioned, as was the fact that this was a post-war re-release. As usual with the tests which appeared in "Air Trails" during this period, this report was rather sketchy as regards performance data. The only figures provided were 5,400 RPM with a "standard 14 inch diameter low-pitch prop" (whatever that meant!); 6,600 with a "12 inch diameter medium-pitch prop" (ditto!); and 7,400 RPM on a 10x10 airscrew. The comment was made that at the higher speeds tested, running became "slightly uneven" with "excess vibration". The relatively lightly-counterbalanced crankweb was cited as the culprit here. Personally speaking, I would be looking at the very heavy piston as well!

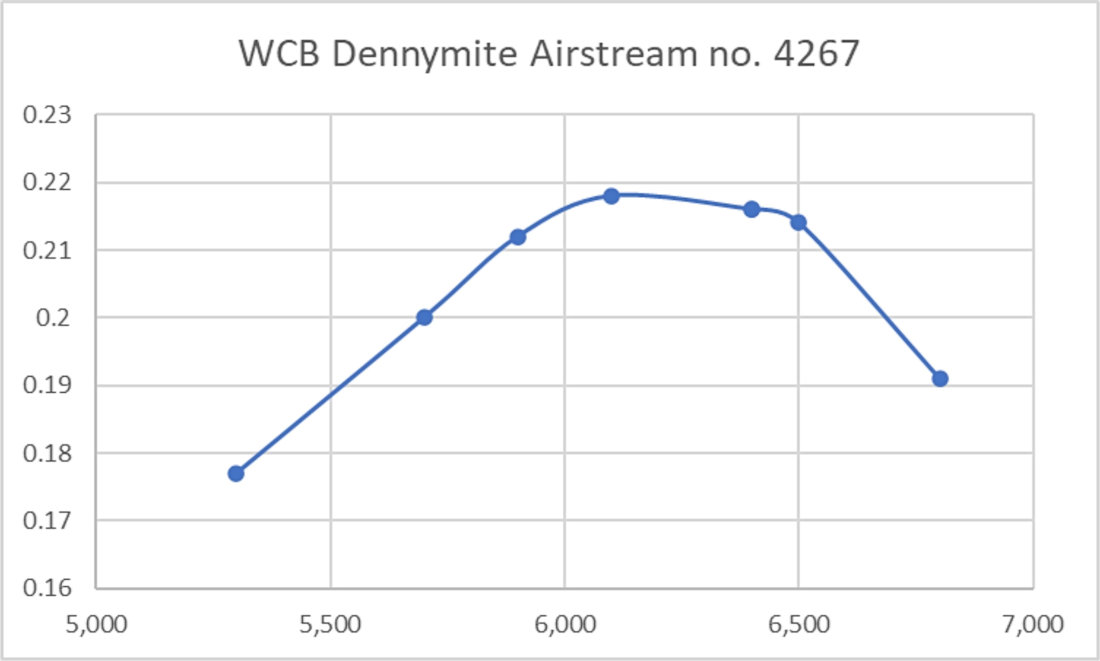

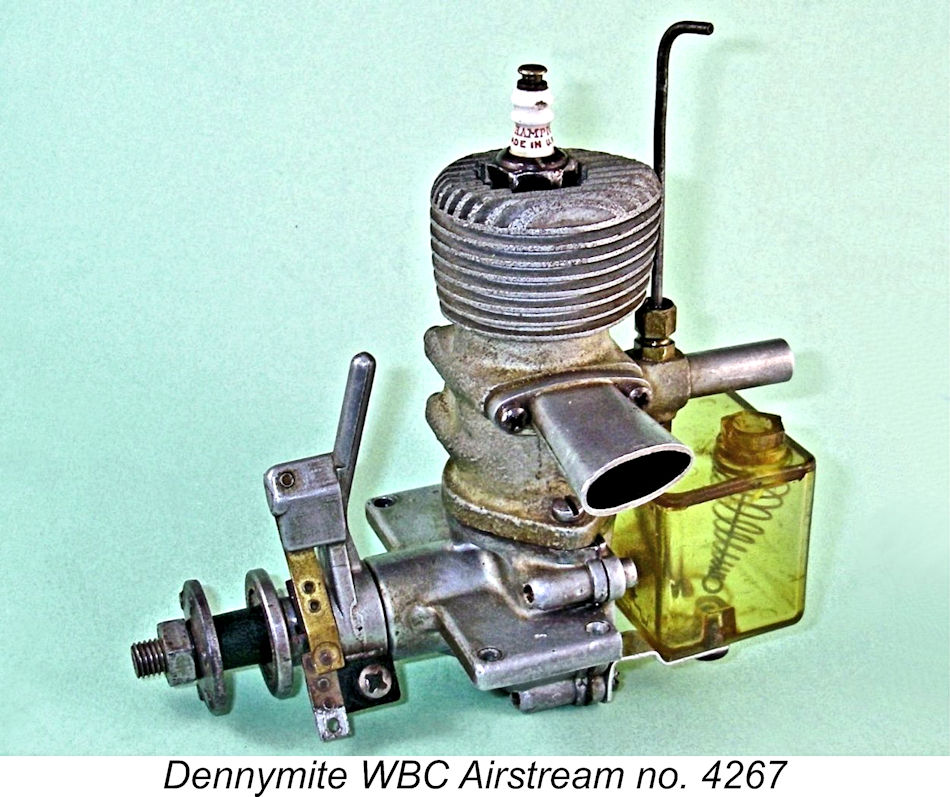

The WBC Dennymite proved to be a very easy starter. Like the two previously-tested variants, it liked a light exhaust prime, but started very readily thereafter. It showed itself to be very responsive to the controls, making the establishment of optimum settings extremely straightforward. Running was smooth and steady on all props tested. The engine displayed none of the sagging issues that had bedeviled the PAC Meteor, allowing me to obtain very stable maximum speed readings for each prop tested. Once again, vibration became a limiting factor at the higher speeds. The following data were recorded on test:

I appear to have missed the actual peak, which evidently fell "between props". However, the general trend of the data suggests a peak output of around 0.220 BHP @ 6,300 RPM. While nothing spectacular, this is a perfectly useful sports performance by the standards of the mid 1940's. All in all, I really liked the WBC Dennymite. Although it's no ball of fire in the performance department, it's a well-made engine that handles very nicely indeed and would probably last for a very long time in service. Pity about that vibration! Conclusion It's readily apparent from the above account that Walter Righter created a model engine of real value by the standards of its day. In its over-the-counter form, it presented its owners with a well-made, easy-handling and smooth-running model powerplant which would have given very good service over the long haul. It could certainly have been improved through more attention being paid to the dynamic balance factor, but even so it would have served perfectly well as supplied in a sport flying context. If one needed more pep, the available rotary valve conversions were available to provide it. So hats off to Walter Righter, and kudos to Reginald Denny for supporting Righter's efforts! Between them, these two notable enthusiasts left a model engine legacy of which they could be proud! _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2023

|

||

| |

Here I’ll be taking a comparative look at several variants of the famous Dennymite 0.57 cuin. (9.38 cc) sparkie which had its origins in pre-WW2 America but returned following the war and survived in production right to the end of the spark ignition era.

Here I’ll be taking a comparative look at several variants of the famous Dennymite 0.57 cuin. (9.38 cc) sparkie which had its origins in pre-WW2 America but returned following the war and survived in production right to the end of the spark ignition era.

The Dennymite series had a somewhat unusual genesis, arising from a strong interest in model aircraft on the part of a well-known Hollywood movie star, British-born Reginald Denny. The name Dennymite obviously stemmed from Denny’s own name, although the fact that it was an alliterative cousin of the word “dynamite” doubtless played its part in the adoption of the name!

The Dennymite series had a somewhat unusual genesis, arising from a strong interest in model aircraft on the part of a well-known Hollywood movie star, British-born Reginald Denny. The name Dennymite obviously stemmed from Denny’s own name, although the fact that it was an alliterative cousin of the word “dynamite” doubtless played its part in the adoption of the name!

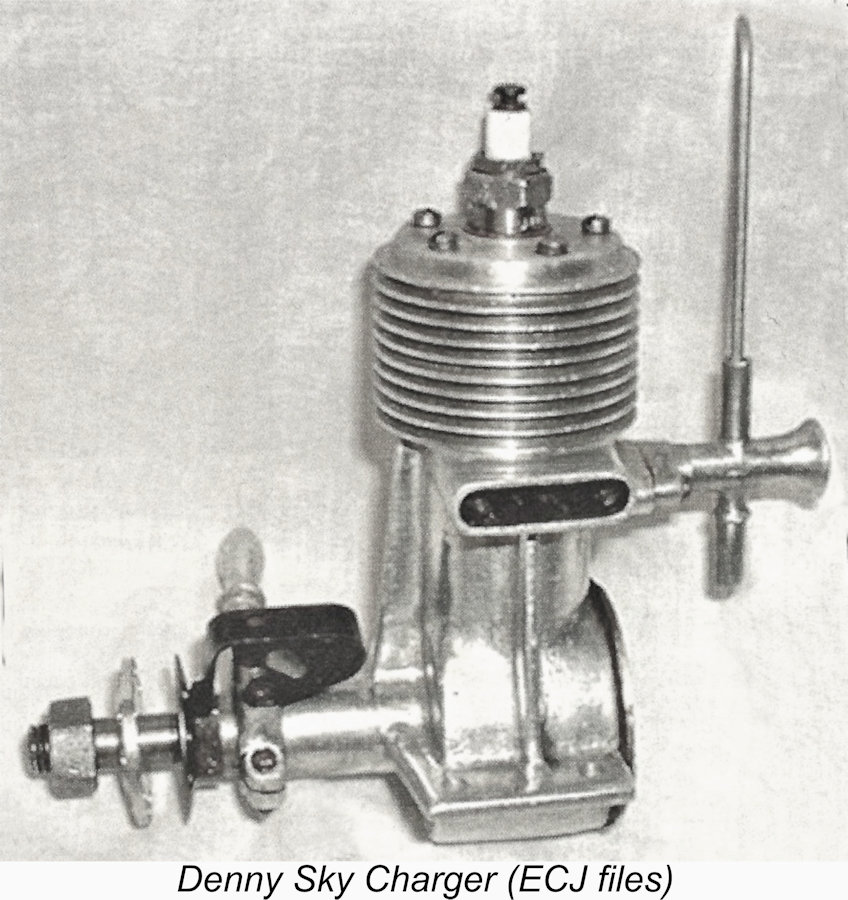

Naturally, Reg Denny was keen to market his own engine to power his new model designs. As it happened, an employee of Denny’s named Jack Rowe had designed a 0.36 cuin. engine called the Sky Charger back in 1931. He approached Denny with the suggestion that this engine be developed into a marketable form.

Naturally, Reg Denny was keen to market his own engine to power his new model designs. As it happened, an employee of Denny’s named Jack Rowe had designed a 0.36 cuin. engine called the Sky Charger back in 1931. He approached Denny with the suggestion that this engine be developed into a marketable form. Righter immediately established a company called the Righter Manufacturing Company. The ten-engine prototype series was duly completed and tested in Righter’s own workshop, which he set up adjacent to the garage of his Glendale home! Like all of the subsequent models, the original Dennymite prototypes had bore and stroke dimensions of 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) apiece for a displacement of 0.573 cuin. (9.38 cc). Righter assured Denny that he could produce his design at a lower cost than the Sky Charger, and the deal was done. It’s important to keep in mind that from the outset it was Walter Righter who actually designed and produced the engines which bore Denny’s name – apart from contributing that name, Denny’s role was confined to the marketing of the engines.

Righter immediately established a company called the Righter Manufacturing Company. The ten-engine prototype series was duly completed and tested in Righter’s own workshop, which he set up adjacent to the garage of his Glendale home! Like all of the subsequent models, the original Dennymite prototypes had bore and stroke dimensions of 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) apiece for a displacement of 0.573 cuin. (9.38 cc). Righter assured Denny that he could produce his design at a lower cost than the Sky Charger, and the deal was done. It’s important to keep in mind that from the outset it was Walter Righter who actually designed and produced the engines which bore Denny’s name – apart from contributing that name, Denny’s role was confined to the marketing of the engines. The more familiar Dennymite Airstream model with its “teardrop” fin planform made its debut in mid-1938. The initial rendition of this unit was designated the Dennymite “Airstream Standard”. It was followed in short order by the Dennymite “Airstream Deluxe” version which was supplied complete with motor mounts, coil and condenser, also having an extended timer arm to allow access with the engine mounted in the cowl of a Dennyplane model. A third variant was offered as the Dennymite “Airstream Unit”, which differed from the "Deluxe" model only in not being supplied with the mount, coil and condenser.

The more familiar Dennymite Airstream model with its “teardrop” fin planform made its debut in mid-1938. The initial rendition of this unit was designated the Dennymite “Airstream Standard”. It was followed in short order by the Dennymite “Airstream Deluxe” version which was supplied complete with motor mounts, coil and condenser, also having an extended timer arm to allow access with the engine mounted in the cowl of a Dennyplane model. A third variant was offered as the Dennymite “Airstream Unit”, which differed from the "Deluxe" model only in not being supplied with the mount, coil and condenser. During this period, Reg Denny’s interests were by no means confined to model airplanes. As early as 1937 he had constructed a model car powered by an I/C engine. This vehicle was seen in action by the Dooling brothers Russell, Harris and Tom, who believed that they could do better and set out to prove it! They worked to very good effect, establishing themselves in modest premises as Dooling Bros. Precision Machine Products. By late 1938 they had a model that they felt could be successfully offered to the public on a commercial basis. Reg Denny saw their design and agreed with their assessment. He made a commitment to market all that the brothers could make.

During this period, Reg Denny’s interests were by no means confined to model airplanes. As early as 1937 he had constructed a model car powered by an I/C engine. This vehicle was seen in action by the Dooling brothers Russell, Harris and Tom, who believed that they could do better and set out to prove it! They worked to very good effect, establishing themselves in modest premises as Dooling Bros. Precision Machine Products. By late 1938 they had a model that they felt could be successfully offered to the public on a commercial basis. Reg Denny saw their design and agreed with their assessment. He made a commitment to market all that the brothers could make. Berg’s conversion of the standard side-port Dennymite appeared in 1940. It involved the plugging of the side-port intake and the fitting of an entirely new sand-cast crankcase which incorporated provision for FRV induction through a long sand-cast downdraft intake venturi to be mounted on the main bearing housing using two machine screws for attachment. A revised backplate was also produced.

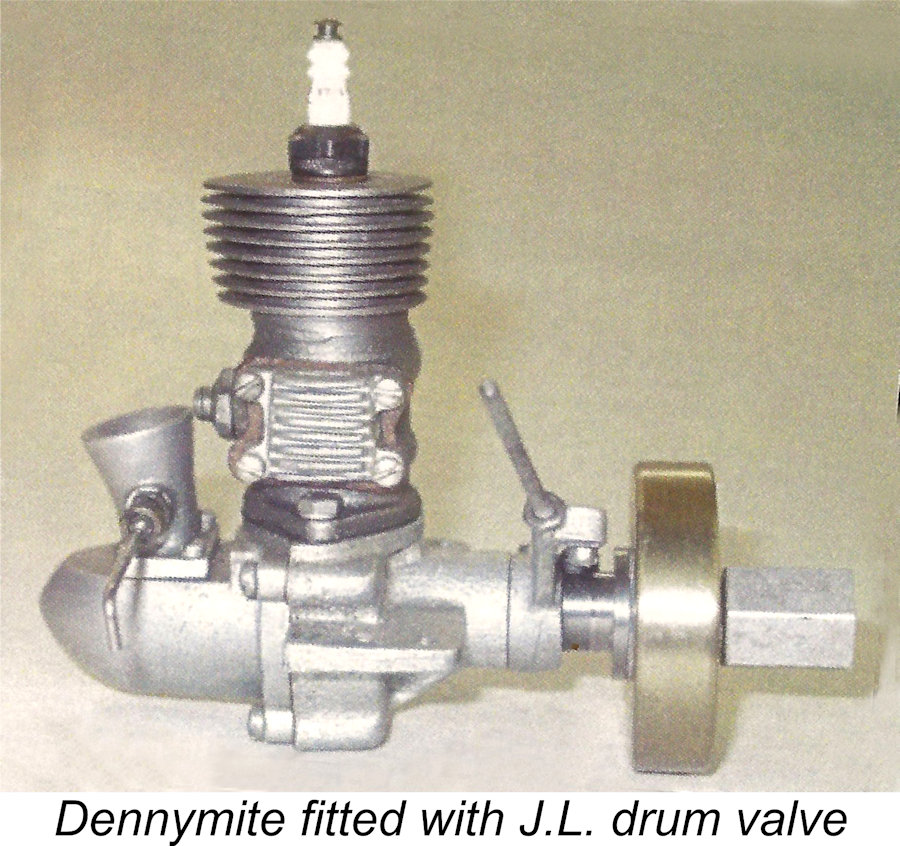

Berg’s conversion of the standard side-port Dennymite appeared in 1940. It involved the plugging of the side-port intake and the fitting of an entirely new sand-cast crankcase which incorporated provision for FRV induction through a long sand-cast downdraft intake venturi to be mounted on the main bearing housing using two machine screws for attachment. A revised backplate was also produced. A downside to the use of the Berg conversion was the inescapable fact that the required holes for induction weakened the crankshaft considerably. This does not appear to have been highlighted as a truly problematic issue in actual service, but it was undoubtedly a factor to be considered. Another company called J. L. Engineering of Santa Monica, California got around this issue by developing a rear drum valve which could be used to replace the standard Dennymite backplate, leaving the stock crankshaft undrilled. However, they hedged their bets by also offering a front rotary valve crankcase and modified shaft which were more or less identical to the Berg set-up, even going so far as to claim that both systems could be used together on the same engine with very good results.

A downside to the use of the Berg conversion was the inescapable fact that the required holes for induction weakened the crankshaft considerably. This does not appear to have been highlighted as a truly problematic issue in actual service, but it was undoubtedly a factor to be considered. Another company called J. L. Engineering of Santa Monica, California got around this issue by developing a rear drum valve which could be used to replace the standard Dennymite backplate, leaving the stock crankshaft undrilled. However, they hedged their bets by also offering a front rotary valve crankcase and modified shaft which were more or less identical to the Berg set-up, even going so far as to claim that both systems could be used together on the same engine with very good results.  It must be recalled for context that speed competitions for model aircraft were not yet practical, since there was no means of controlling them with sufficient precision to allow for accurate speed measurements and observer safety. That only came about with the adoption of control line in the early 1940's.

It must be recalled for context that speed competitions for model aircraft were not yet practical, since there was no means of controlling them with sufficient precision to allow for accurate speed measurements and observer safety. That only came about with the adoption of control line in the early 1940's.  The example of the Berg FRV Dennymite conversion that was available for testing features the replacement crankcase and backplate developed by Berg, together with the long downdraft intake venturi which was supplied with the case. Berg’s cases were evidently not stamped with serial numbers. The side-port intake was very effectively plugged with a light alloy insert. In all other respects, the engine is a standard Dennymite – even the standard needle valve assembly was used. This example appears to have seen little previous use, although it gave the impression as received of having done a little previous bench running.

The example of the Berg FRV Dennymite conversion that was available for testing features the replacement crankcase and backplate developed by Berg, together with the long downdraft intake venturi which was supplied with the case. Berg’s cases were evidently not stamped with serial numbers. The side-port intake was very effectively plugged with a light alloy insert. In all other respects, the engine is a standard Dennymite – even the standard needle valve assembly was used. This example appears to have seen little previous use, although it gave the impression as received of having done a little previous bench running.  The engine quickly earned my respect by proving itself to be a very easy starter. It appreciated a small exhaust prime, but picked up very well on the fuel line and showed very positive responses to both controls. I set it just on the four-stroke side of the 4-2 break and put on an extra 15 minutes in 3-minute runs, allowing complete cooling between runs. At the end of this, the engine felt superb, clearly all ready to go.

The engine quickly earned my respect by proving itself to be a very easy starter. It appreciated a small exhaust prime, but picked up very well on the fuel line and showed very positive responses to both controls. I set it just on the four-stroke side of the 4-2 break and put on an extra 15 minutes in 3-minute runs, allowing complete cooling between runs. At the end of this, the engine felt superb, clearly all ready to go.

This setback did not deter Walter Righter, who wished to continue manufacturing and selling the Dennymite engines. He did so under the name of his own company, the Righter Manufacturing Co. of Glendale, California. The first Dennymite advertisement in the name of Righter’s company appeared in the October 1940 issue of MAN. It would appear that Righter somehow retained the rights to the use of the Dennymite name.

This setback did not deter Walter Righter, who wished to continue manufacturing and selling the Dennymite engines. He did so under the name of his own company, the Righter Manufacturing Co. of Glendale, California. The first Dennymite advertisement in the name of Righter’s company appeared in the October 1940 issue of MAN. It would appear that Righter somehow retained the rights to the use of the Dennymite name.  1939, attracting immediate interest from the U.S. Army, which placed an order in 1940 for 53 of these aircraft, which they re-designated as the OQ-2 Radioplane (OQ being military code-letters for a sub-scale target). The receipt of this contract resolved Denny’s cash flow problems very nicely. A far larger order was soon placed following America’s December 1941 entry into WW2, along with a separate order from the U.S. Navy.

1939, attracting immediate interest from the U.S. Army, which placed an order in 1940 for 53 of these aircraft, which they re-designated as the OQ-2 Radioplane (OQ being military code-letters for a sub-scale target). The receipt of this contract resolved Denny’s cash flow problems very nicely. A far larger order was soon placed following America’s December 1941 entry into WW2, along with a separate order from the U.S. Navy. named Norma Jeane Dougherty, later far more famous as the film star Marilyn Monroe. She later stated that her time with Radioplane and Walter Righter represented the hardest work that she ever had to do!

named Norma Jeane Dougherty, later far more famous as the film star Marilyn Monroe. She later stated that her time with Radioplane and Walter Righter represented the hardest work that she ever had to do!  Despite their evident desire to plough their own furrow, the engine that Pacific Automotive Company came up with was still easily recognizable as a Dennymite derivative. This model appeared in mid-1946. The crankcase, internal components and timer bracket were all unchanged from those of the original PAC Dennymite model of 1945. The most obvious changes were the cylinder and tank.

Despite their evident desire to plough their own furrow, the engine that Pacific Automotive Company came up with was still easily recognizable as a Dennymite derivative. This model appeared in mid-1946. The crankcase, internal components and timer bracket were all unchanged from those of the original PAC Dennymite model of 1945. The most obvious changes were the cylinder and tank. The tank was a striking spherical component which nonetheless had its drawbacks, having a smaller capacity than the original Dennymite “cube” and also adding to the engine’s length, requiring that it be mounted further ahead of the firewall. Both the induction port and the exhaust stack were increased in size, while a new diecast bypass cover bearing the cast-on name “PAC METEOR” was fitted.

The tank was a striking spherical component which nonetheless had its drawbacks, having a smaller capacity than the original Dennymite “cube” and also adding to the engine’s length, requiring that it be mounted further ahead of the firewall. Both the induction port and the exhaust stack were increased in size, while a new diecast bypass cover bearing the cast-on name “PAC METEOR” was fitted. Unfortunately, my example of the PAC Meteor, engine no. 0254, turned out to have been assembled diabolically tight, to the point that it had trouble carrying over from one firing stroke to the next. I was able to get it going after a bit of a struggle (actually wishing for once in my life that I owned an electric starter!), but quickly found that its performance was greatly inhibited by the tightness. It actually had trouble running the tank out, forcing me to stop it prematurely as it began to sag, even when running rich. If left to its own devices, it might well have seized.

Unfortunately, my example of the PAC Meteor, engine no. 0254, turned out to have been assembled diabolically tight, to the point that it had trouble carrying over from one firing stroke to the next. I was able to get it going after a bit of a struggle (actually wishing for once in my life that I owned an electric starter!), but quickly found that its performance was greatly inhibited by the tightness. It actually had trouble running the tank out, forcing me to stop it prematurely as it began to sag, even when running rich. If left to its own devices, it might well have seized.  In late 1946 or early 1947, Pacific Automotive decided to go into a new line of business – refurbishing aircraft which had been manufactured during the war but were now surplus to requirements and selling them to smaller governments in South America and elsewhere as well as private interests. Since this would leave them with no time to continue with Dennymite production, they decided to sell the entire project. With this in mind, they approached the well-established manufacturer Ohlsson & Rice (O&R) with a proposal to sell them the entire Dennymite project – naming rights, finished engines (of which there were quite a few), tooling, dies, surplus components, etc.

In late 1946 or early 1947, Pacific Automotive decided to go into a new line of business – refurbishing aircraft which had been manufactured during the war but were now surplus to requirements and selling them to smaller governments in South America and elsewhere as well as private interests. Since this would leave them with no time to continue with Dennymite production, they decided to sell the entire project. With this in mind, they approached the well-established manufacturer Ohlsson & Rice (O&R) with a proposal to sell them the entire Dennymite project – naming rights, finished engines (of which there were quite a few), tooling, dies, surplus components, etc.

One of the WBC Dennymites bearing the serial number 4267 was available to me for testing. It seemed to me that since this was the last of the Dennymites, a test would form a fitting conclusion to this article. The engine in question had clearly had some previous use, but remained in fine completely original condition.

One of the WBC Dennymites bearing the serial number 4267 was available to me for testing. It seemed to me that since this was the last of the Dennymites, a test would form a fitting conclusion to this article. The engine in question had clearly had some previous use, but remained in fine completely original condition.