|

|

The Ira Hassad Story

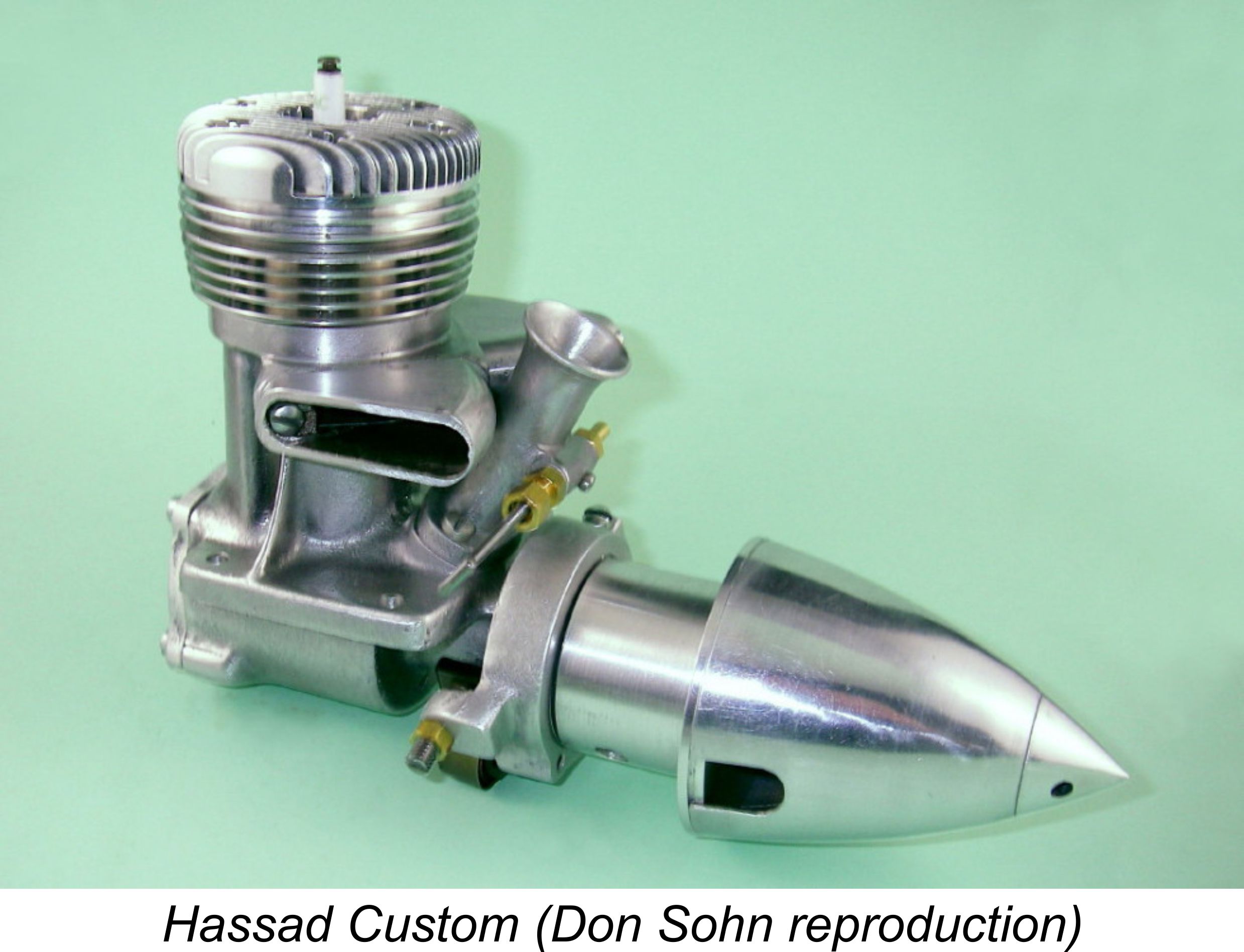

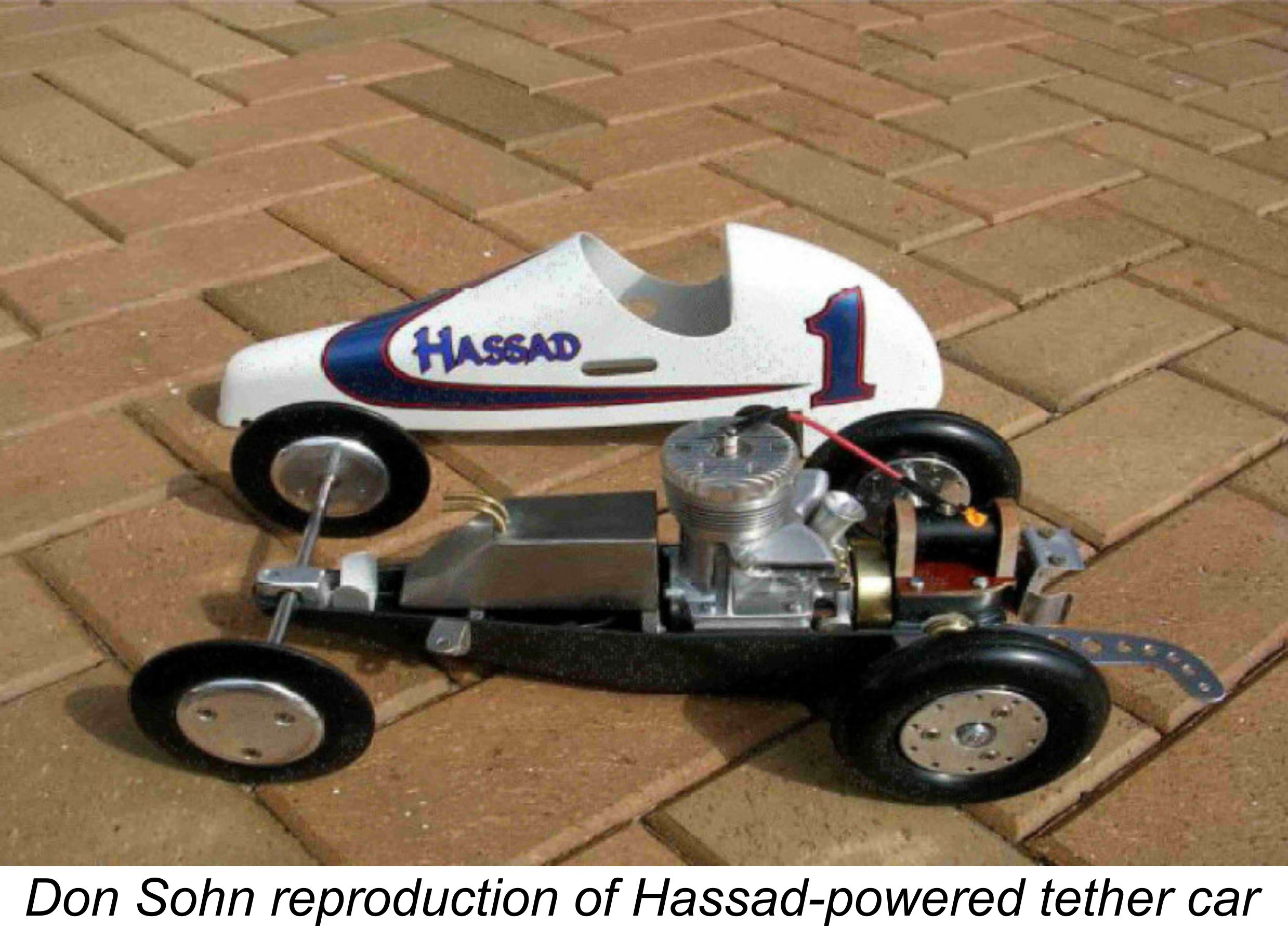

Before getting started on this story, it’s both my duty and my very sincere pleasure to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement which I received from my valued friend and colleague Don Sohn of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA. Don is a highly skilled model engineer who is one of America’s most respected constructors of classic racing engine and tether car reproductions. He is also a very sincere Hassad enthusiast, having reproduced a number of Ira Hassad’s most famous model engine designs as well as a few of his prototype models, all to the very highest standards.

Another individual to whom tribute must be paid is the late William “Bill” Thompson. Much of what is known about Ira Hassad’s model engine career was recorded by Bill in 1973, when Ira himself was still available for consultation. Bill’s two-part article on Ira Hassad appeared in 1973 in the pages of the sadly now-discontinued "Engine Collector's Journal" ECJ nos. 46 and 47. We are all immensely indebted both to Bill and to former ECJ publisher and editor Tim Dannels for the preservation of this information, upon which I freely and gratefully acknowledge having drawn extensively in what follows. I should also mention that Tim Dannels’ outstanding “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE) is a required reference for anyone interested in classic American model engines. If you don't have a copy, do yourself a favour by tracking one down! Finally, I must record my debt of gratitude to Ira's son Jim Hassad, who read this article in its originally-published form and was kind enough to contact me in the latter part of 2018 to provide further information. Jim was very complimentary about the original article, in which he found no significant errors, but he was able to add to the human interest of the story as well as clear up a few points of uncertainty. Thanks, Jim!! Now, in order to fully grasp just how individualistic Ira Hassad’s approach to model racing engine design really was, it’s necessary to go back to the very beginning and trace the history of model racing engine development from its earliest years. Let’s commence by doing just that…………… Background

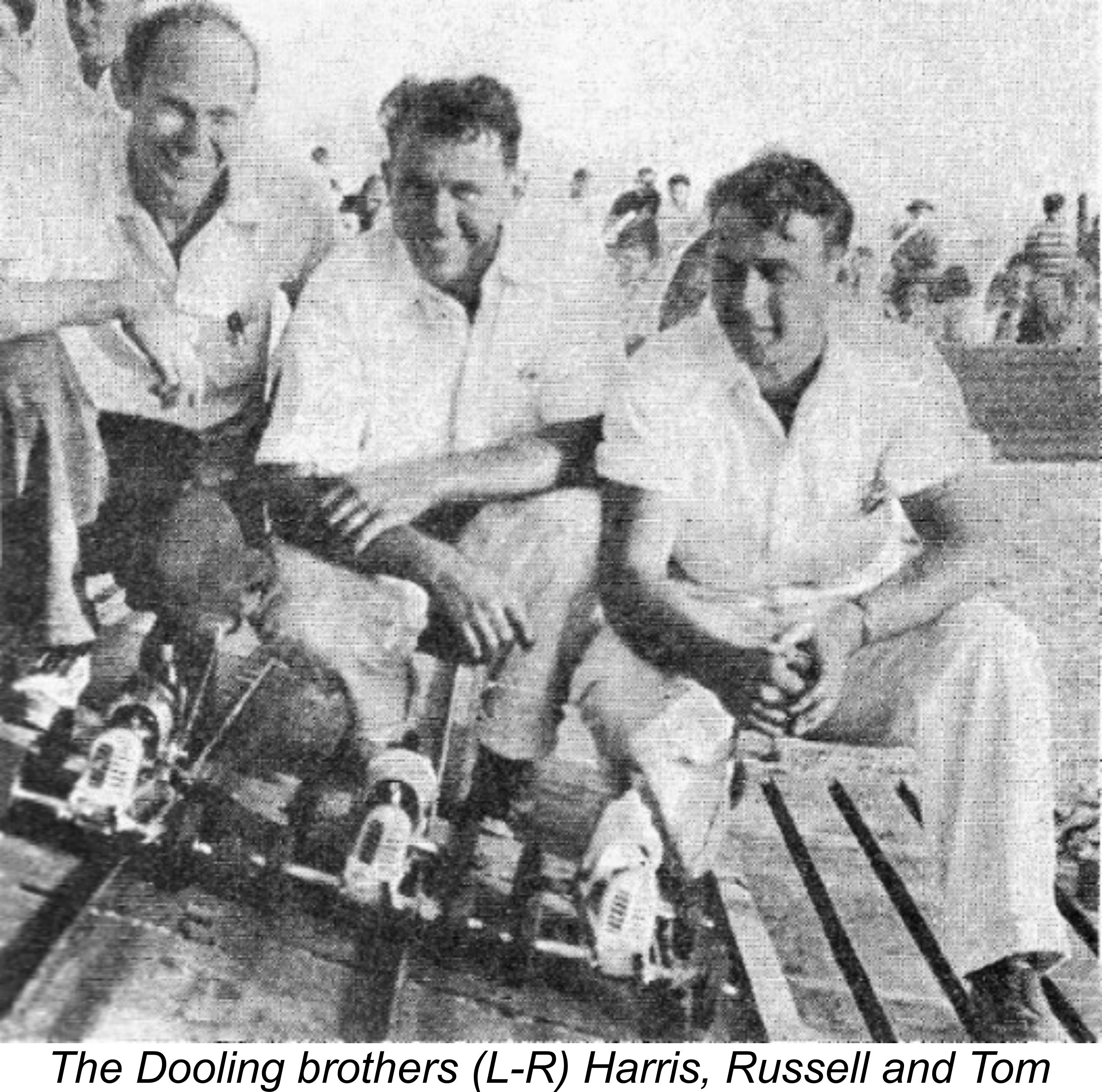

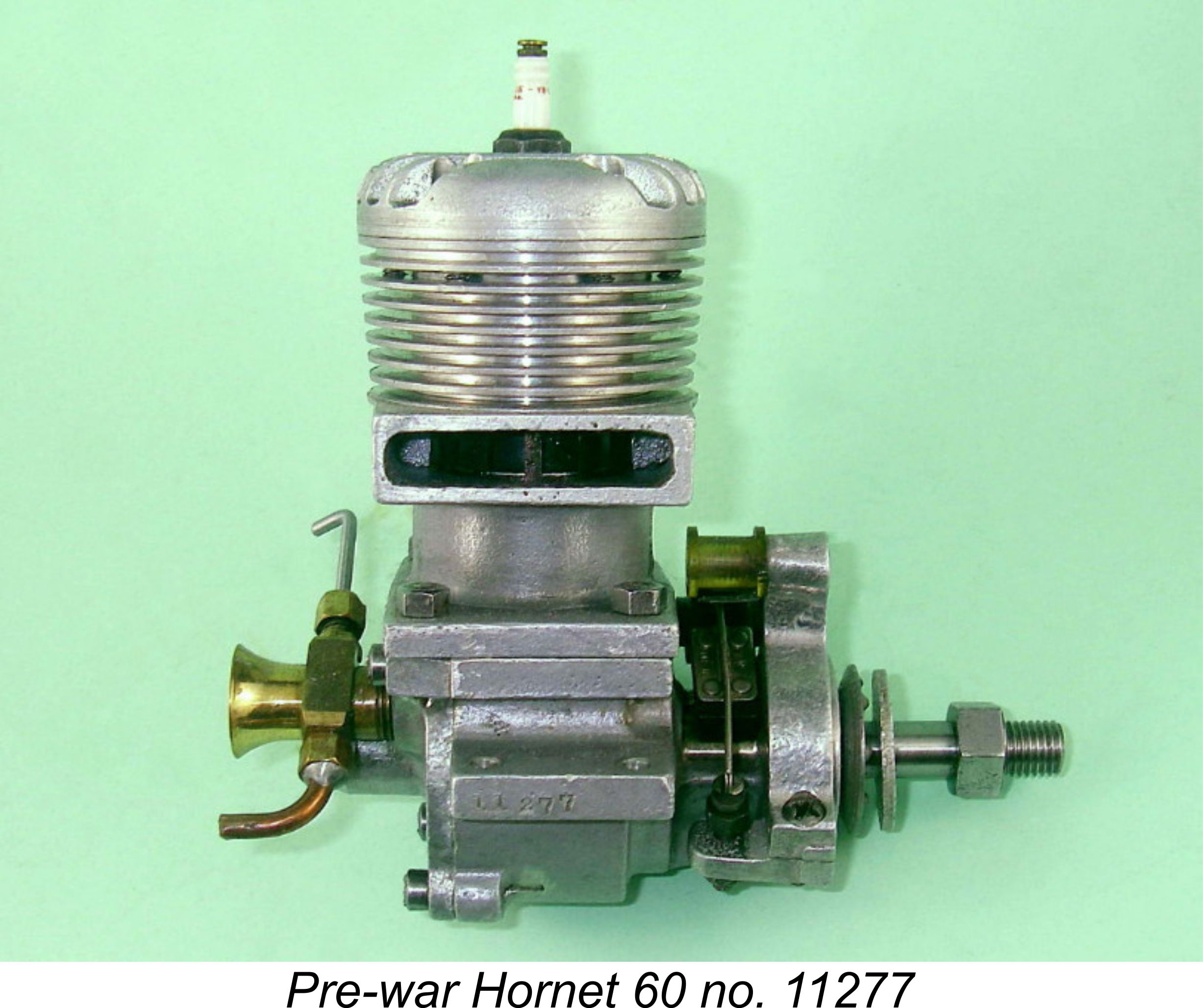

Although tethered hydroplane racing was taking place during this period, the scarcity of suitable venues meant that it attracted a relatively small following - too small to make model racing engine development appear to be an economically-attractive proposition. As a result, its most consistently successful practitioners tended to make their own specialized powerplants in order to out-perform the standard aero units which were the only alternative. There was thus little stimulus for the commercial development of all-out model racing engines at this stage. This all changed in early 1937, when a group of Los Angeles model aircraft fliers who were looking for a new challenge decided to try using their model aero engines to power model race cars which could be run at high speeds on a tether or rail track, thus keeping them under restraint at all times. The leading lights in this movement were the three Dooling brothers, who The Dooling brothers were soon joined by others, including the legendary Dick McCoy and Bill Atwood as well as Ray Snow of Hornet fame. The rapid nationwide increase in the popularity of this new branch of the hobby soon created market conditions in which the commercial development of suitable racing engines at last became a viable proposition. The resulting powerplants evolved along lines which were quite distinct from those of their aero predecessors. Weight was far less of an issue - instead, all-out performance and durability were now the primary concerns of the various competing racing engine designers. The origin of the “classic” model racing engine may be traced back to 1938, when the A. C. Special was manufactured in very small numbers by Charlie Anderson and Walt Cave in Oakland, California. This ground-breaking design and its direct successor, the Hornet 60 from Fresno, California, established the basic pattern for model racing engine design over the following 25 years or so. The design of the iconic McCoy 60 was very much influenced by that of these two pioneering models. The history of the Hornet and its relatives has been recorded elsewhere on this website.

However, even at the outset there were those who felt that the above layout could be improved upon. One notable and very influential designer who sincerely believed that crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction offered greater potential than the RRV system for racing engines was our main subject, California resident Ira J. Hassad (1915 - 1981). Hassad was one of the true pioneers of model racing engine development, with a decided preference for drawing upon his own insights in design terms rather than merely trying to improve upon what had been done before. His conviction that FRV induction offered a viable alternative to the RRV system for racing engines was to sustain a 10-year struggle for supremacy between the two systems. Ira Hassad and the 1940’s FRV Racing Engine Movement Ira James Hassad was born on October 18th, 1915 in Los Angeles, California. He attended Polytechnic High School, which was then located at the intersection of Washington Boulevard and Flower Street in what is today downtown Los Angeles. An expert machinist and a keen aeromodeller from an early age, Ira started making model engines for his own use in the early 1930’s while still in his teens. Some of these ran better than others……… One of his contemporary friends and fellow modellers was none other than Irwin Ohlsson, with whom Ira was to maintain a lifelong friendship.

In 1935 the then 20-year old Hassad was hired by former WW1 fighter pilot and later Pulitzer Air Race winner Major Corliss C. Moseley, who had previously been closely involved with the foundation of Western Air Express (later to become Western Airlines). As of the mid 1930's, Moseley was managing Grand Central Terminal in Glendale, California, some 12 miles to the north of downtown Los Angeles, doing so on behalf of his employers, the Curtiss-Wright Airport Corporation. In addition to his managerial duties for Curtiss-Wright, Moseley ran a sideline business of his own called Aircraft Industries Corporation which was located at Grand Central Terminal. The main business of Moseley’s company was the provision of full-scale aircraft maintenance and repair services. However, Moseley was interested in model aviation and saw the potential of a .364 cuin. (5.96 cc) engine which had been designed by Bill Atwood and had achieved considerable competition success. In 1934 Moseley entered into negotiations with Atwood to purchase the design for manufacture by Aircraft Industries Corporation. After persuading Atwood to join him in producing what was to become famous as the Baby Cyclone, he also managed to bring Ira Hassad on board to help. Apart from Bill Atwood and Ira Hassad, another of Moseley’s employees in this venture included then 32 year old Mel Anderson, who had been brought in on Atwood’s recommendation to help sort out some residual issues with the Baby Cyclone. All three of these colleagues later became noted manufacturers in their own right - quite a team!

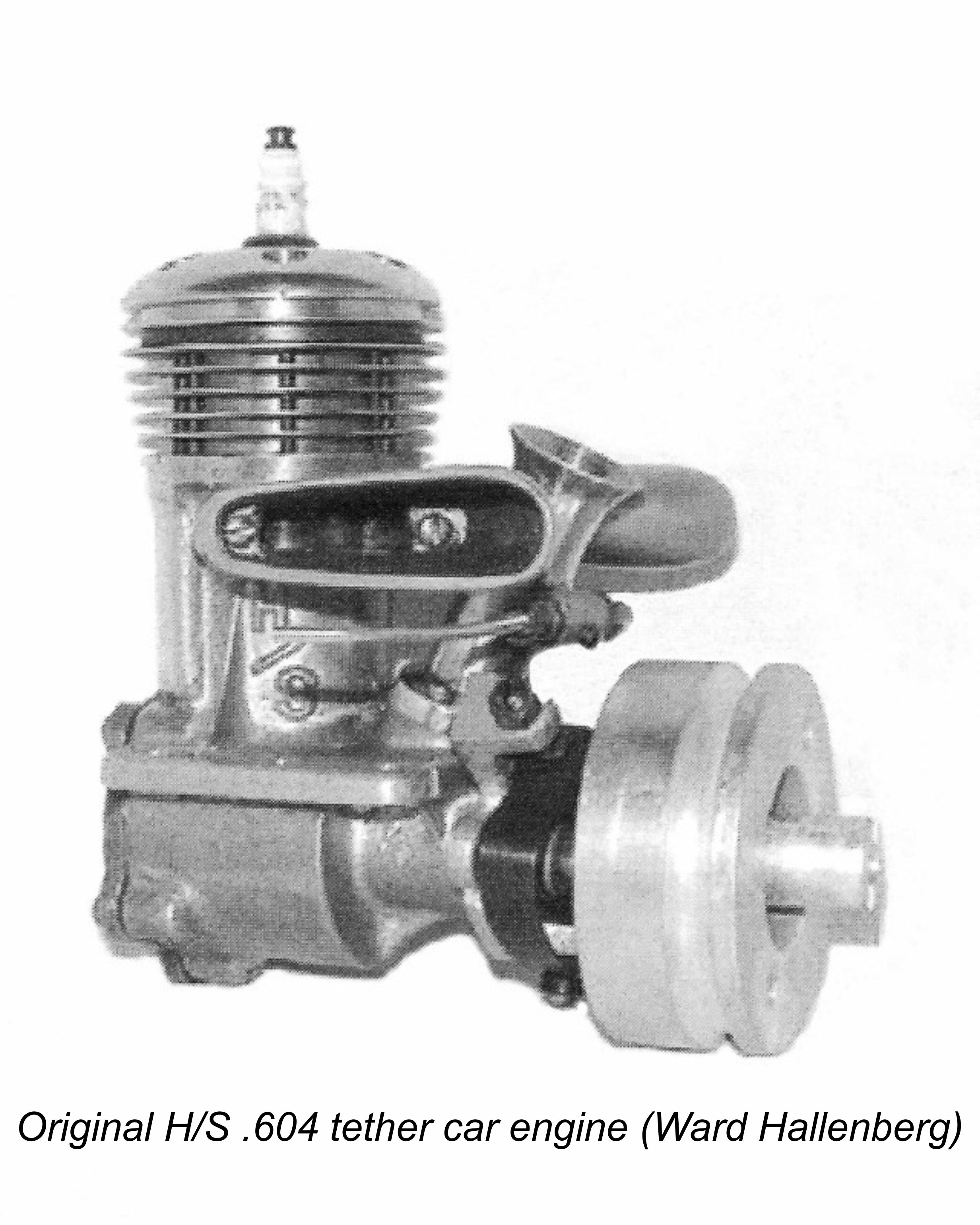

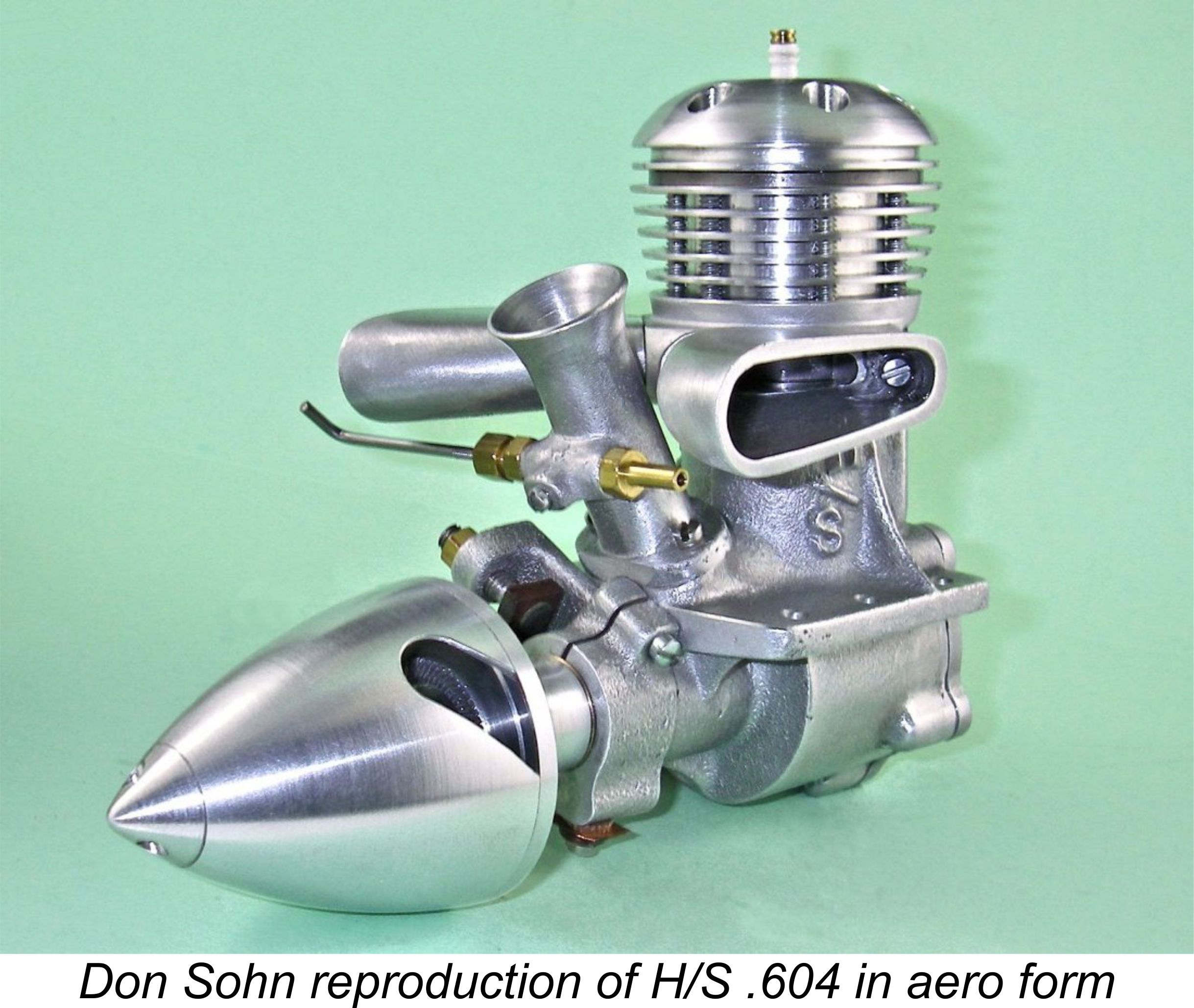

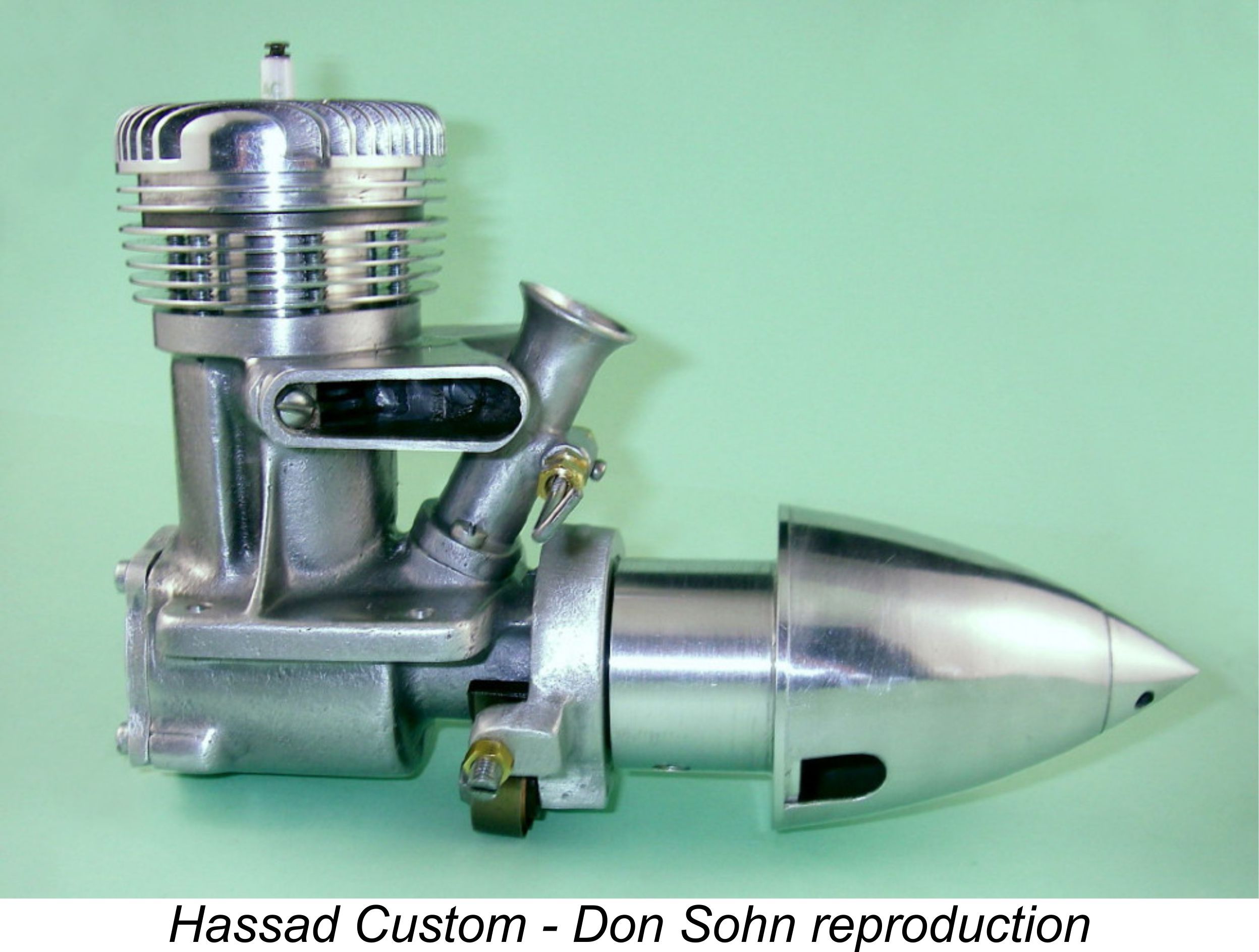

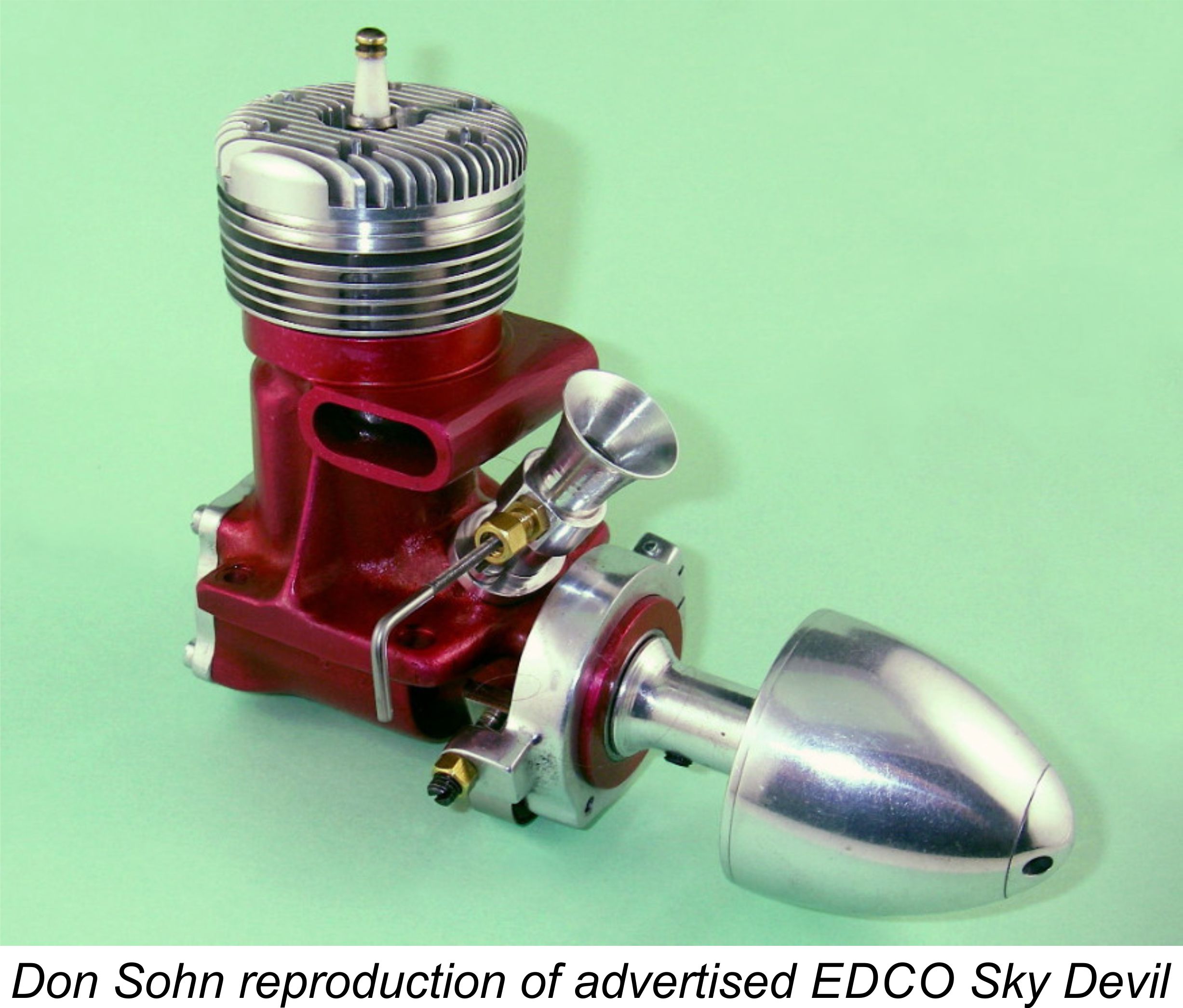

A number of Ira’s fellow employees were student pilots paying for their instruction by working for Moseley. Ira was later to recall that his main task was the lapping of the pistons and cylinders to the required fit. Surviving examples of the Baby Cyclone are a testament to his expertise in this area. At least 18,000 of these engines were reportedly manufactured in total - an impressive total for a pre-war product. During his time working for Moseley, Ira had full access to the machine shop at Grand Central Terminal. He made very good use of this privilege, spending many of his weekend days off working on the construction of engines for his own use, many of which were of his own design. These included a couple of 10 cc units of extremely light construction and painted orange on the crankcase with black on the bypass, cooling fins and head. Another engine made at this time which was not of Ira’s own design was a superb example of the Edgar Westbury 30 cc model, which Ira kept in his personal collection for the remainder of his life. Other days off were spent entering model flying contests all over California. The highlight of Ira’s model airplane contest career was perhaps an occasion on which he actually travelled all the way to Detroit, Michigan to enter a major contest there using a California Chief airplane powered by a Baby Cyclone. Hassad remained with Moseley until 1939, when he left to strike out on his own at age 24. Initially he went over to the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles, which had been making Baby Cyclone parts under contract to Moseley. There he joined former colleague Bill Atwood, who had also left Moseley and was getting independent production going on the Phantom, Torpedo and Bullet series at this time. However, Ira had now become interested in the emerging sport of model car racing, finding himself tempted by the challenge of developing his own all-conquering race car engine. In September 1939, using a $300 loan from close friend and Lockheed employee Louis Schock, Ira bought a lathe which he set up in the garage of his home in Maywood, California, a little to the south-east of Los Angeles. Here he commenced the manufacture of the H/S (Hassad/Schock) .604 cuin. race car engine, with part-time assistance from Schock. The castings for this engine were produced by the Rogers Pattern & Foundry company, who were to supply the castings for Hassad for many years to come. This engine featured the groundbreaking combination (for a racing engine) of a front exhaust with twin stacks, a plain bronze-bushed main bearing, a lapped piston, a five-bolt backplate and FRV induction. It also sported an early rendition of the remote needle valve system later to be employed by Cox, among many others. The selling price of this engine was $35, quite a chunk of change in those pre-war days when one could buy a house for $1000! Even so, the engine was a fine performer, for which people were The twin-stack front exhaust was to remain a Hassad trade-mark for most of the following decade. There is much to commend the layout when the engine is used in aircraft service, since it places the hottest side of the cylinder at the front where it receives maximum cooling airflow, thus contributing to more uniform cylinder temperatures. The internally-cooled bypass passage takes care of the rear of the cylinder which receives less external cooling airflow. The illustrated Don Sohn reproduction of the engine has been fitted out as an aero engine, an application to which it was very well suited. It's possible that a few examples were used in this form.

It might be asked why Hassad saw FRV induction as a more promising arrangement than the RRV system which had already been very convincingly

Production of this engine was apparently suspended rather abruptly after a well-heeled friend of Ira Hassad’s called on Lockridge and threatened him with legal action over what he saw as an unauthorized Hassad “rip-off”!! In reality, there was enough original thinking in the design to give Lockridge a strong case for defending any such challenge - Hornet designer Ray Snow would have had a far better case for taking action against the likes of Dick McCoy or Talisman/Atomic manufacturer Bill Cubitt! Evidently Lockridge either lacked the resources to mount a defence or (perhaps more likely) considered the financial stakes to be too small to warrant taking such an action.

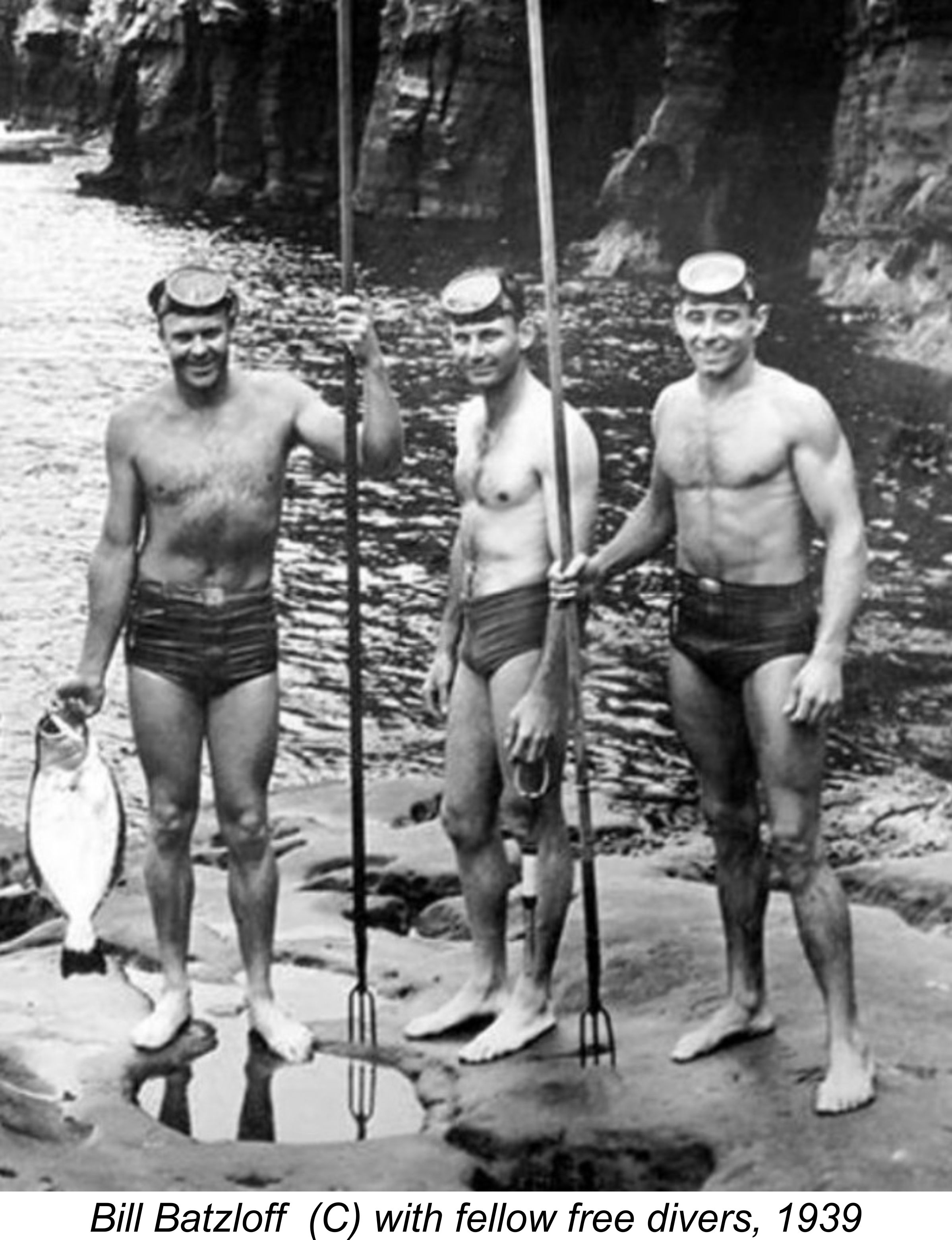

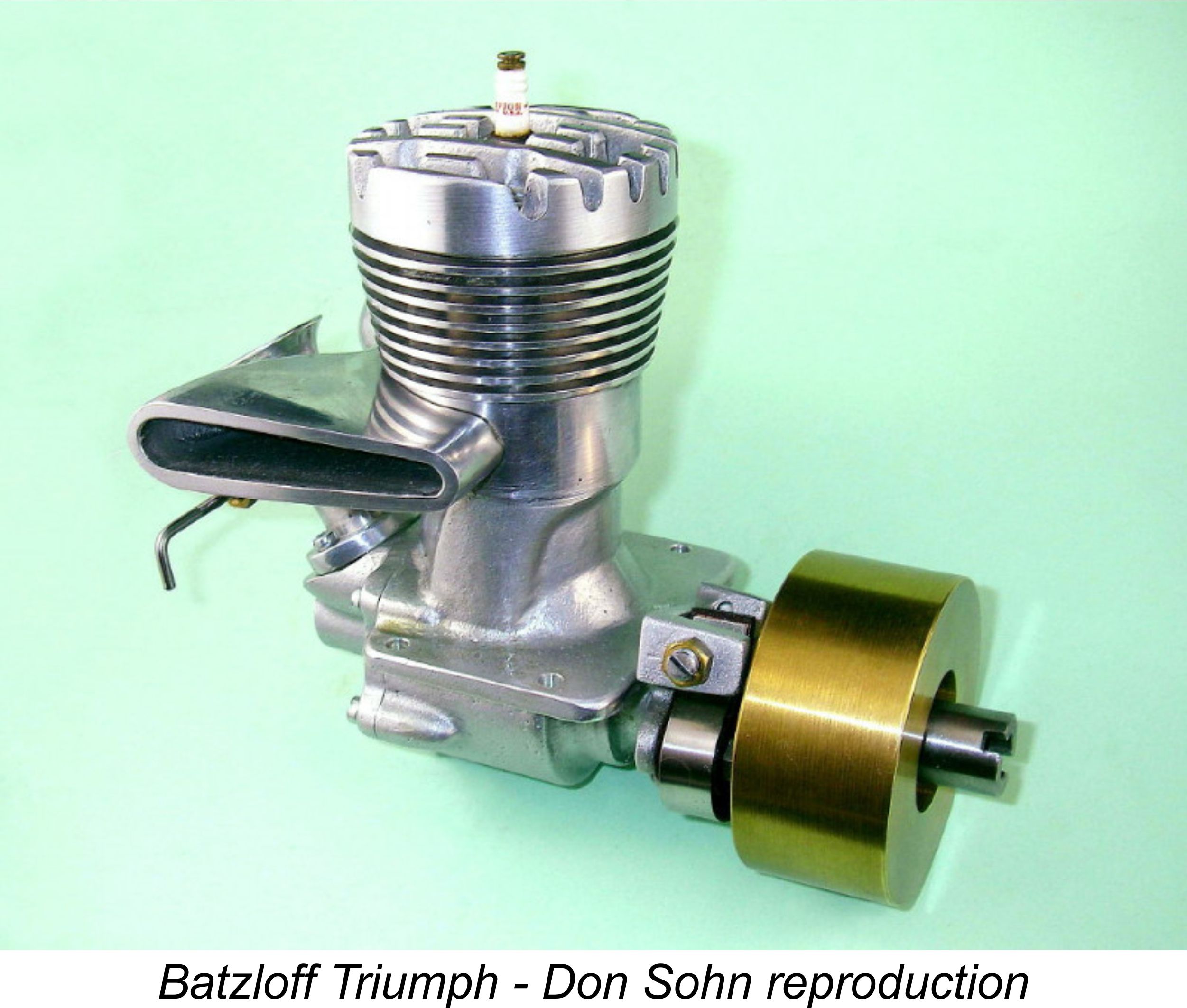

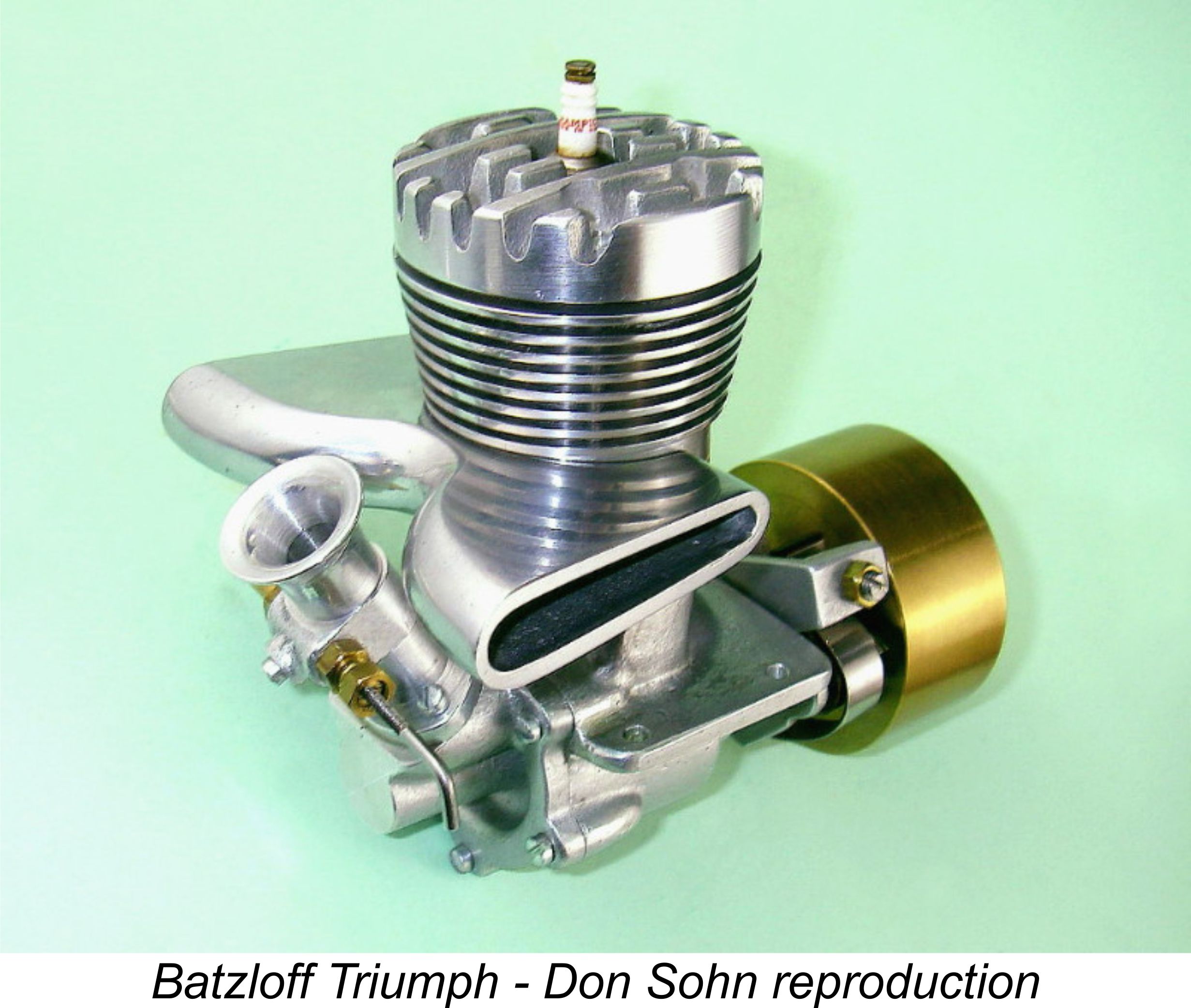

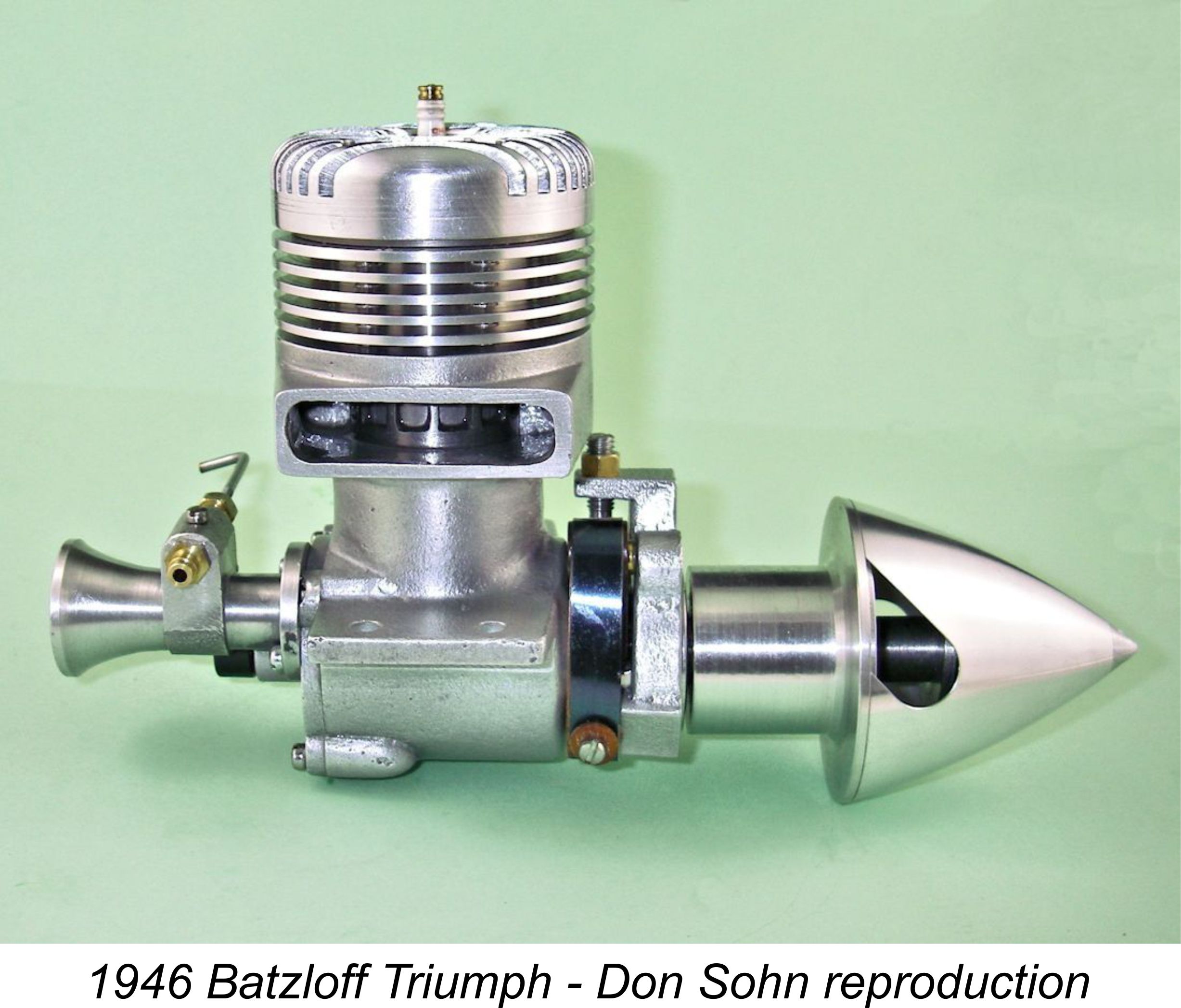

The very clear Hassad influence arose from the fact that Bill Batzloff and Ira Hassad were close friends and racing buddies who together pioneered the sport of I/C model car racing in the San Diego area. Batzloff actually used one of Hassad’s engines at the 1941 US National model car race championships in Chicago, a meeting at which Ira himself finished second, competing against the best in the country using his own engine. In fact, it was only an ignition problem caused by a high tension wire which broke while Ira's car was leading the final race that prevented Ira from winning this event outright. After his second place finish, he "borrowed" the track the next day to try his car with the ignition problem corrected. His speed on that test run would not only have given him first place on the previous day but would also have established a new National record! Returning to Bill Batzloff, the Triumph was made by Batzloff in very small numbers, production being quickly curtailed by the onset of WW2 (as far as the USA was concerned) in December 1941. Seemingly no more than a dozen complete engines were supplied to custom order, although an unknown number of additional examples were reportedly sold to fellow enthusiasts as casting kits for home construction. The illustrated example is one of five superb examples constructed from castings by Don Sohn, whose invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article has already been acknowledged.

This arrangement allowed the designer to take far greater liberties in terms of induction port size and associated timing without introducing any undue structural weakness. In fact, it allowed the drum valve unit to be machined from light alloy, thus saving some weight. The alloy drum rotated in a bronze bushing at the rear. The Triumph retained the spectacular twin exhaust stacks of the contemporary Hassad model, but these were placed at the rear of the cylinder instead of at the front, thus keeping them in the same orientation relative to the induction system as in the Hassad designs. This arrangement placed the “hot” side of the cylinder facing into the slipstream when the engine was mounted in the usual orientation in car or hydroplane service with the flywheel towards the rear of the vehicle. This should promote more uniform cylinder temperatures. Although the Triumph appeared at first glance to be in effect a "back to front" version of the Hassad model, it was in fact a completely distinct design in a number of ways. It incorporated a single ball race at the rear end of the crankshaft in place of the Hassad's bronze bushing. Furthermore, instead of the Hassad's single bypass bulge at the rear, the Triumph used twin bypass passages, one on each side, to supply a pair of transfer ports at the front of the cylinder. This change was of course forced upon the designer by the fact that the crankweb and ball race now occupied the former bypass entry. One rather odd feature of the 1941 Batzloff was the fact that it was timed for “reverse” rotation. Don Sohn copied this feature exactly when constructing his fine reproductions, so there’s no doubt at all regarding this fact. The drum valve is timed so that the engine runs in a clockwise direction when viewed from the flywheel end. The idea behind this feature was most likely to utilize the engine’s torque to create a tendency for the car (or hydroplane) to turn to the left. This would reduce the vehicle’s resistance to turning in what would be the normal direction for tethered or rail racing. Power not required to overcome turning resistance would then be available to generate speed - a very logical concept. A detailed article about Bill Batzloff and his engines appears elsewhere on this website.

However, in tethered cable car racing where the runs were not interrupted by changes in track radius and associated friction, the higher peak horsepower of Ray Snow's RRV Hornet 60 gave it a commanding edge. It was thus a bit of a stand-off between the FRV and RRV induction systems at this stage.

The high standard of workmanship and design expertise which the Hassad engines exemplified inevitably led to Ira’s being consulted by others with respect to their ideas for improved racing engine designs. One such individual who approached Ira during the years immediately prior to America’s entry into WW2 was a gentleman named Adam Cappell, a resident of far-off Dayton, Ohio. Speaking to Bill Eventually all of this talk led Ira (perhaps in self-defence!) to design and construct an actual prototype along the lines suggested by Cappell. This more or less unique .61 cuin. design was designated the H.R.E. Special (standing for Hassad Racing Engines). It featured exhausts at front and rear of the cylinder as opposed to Hassad’s normal arrangement of two openings at the front. Twin bypass passages, one on each side, fed transfer ports located between the exhausts, very much along the lines of the system later employed by Cox and others. A twin-plug head was featured. The engine utilized disc valve induction, with the timer being driven rather unusually by the disc valve spindle. The crankshaft was carried in two ball races. The engine’s highly individualistic appearance resulted in large part from the pair of spectacular megaphone Speaking many years later to Bill Thompson, Ira recalled that Cappell paid him $200 for the prototype of this model - a lot of money in those far-off days! Ira subsequently made a second example for himself, which he kept until his death. These were the only two examples made by Ira. A number of additional examples have been made since by others.

The entry of the USA into WW2 in December 1941 put an end to Ira Hassad’s experiments with FRV racing engines, since his engineering talents were required for the war effort. He was relocated to San Diego, where he spent the war years working for the US Navy as a machinist at their “Sound Lab”, located at Fort Rosecrans Naval Base at Point Loma. He later told his son Jim that he was primarily engaged in making prototype parts for sonar systems, which of course at that time was a top secret technology. In undertaking this work, Ira had in fact become a colleague of his friend Bill Batzloff, who was working at the same time on the same development program though his employment at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, later to be closely associated with the University of California's San Diego campus when it opened in 1960. The situation doubtless facilitated the further cementing of the friendship between the two men. Jim Hassad recalls his father speaking "kindly" of Bill Batzloff in later years. Interestingly enough, Jim tells us that his father's interest in miniature engines pretty much evaporated during the war. He became very interested in Germany’s prewar race car development, spending his personal time during this period reading extensively and taking classes on related subjects such as internal combustion engine supercharging. This was to stand him in good stead later on when he switched his full attention to high-performance full-sized automobiles. More of that below in due course. Jim still has Ira's notebook recording the concepts derived from his studies of thermodynamics and I/C engine design.

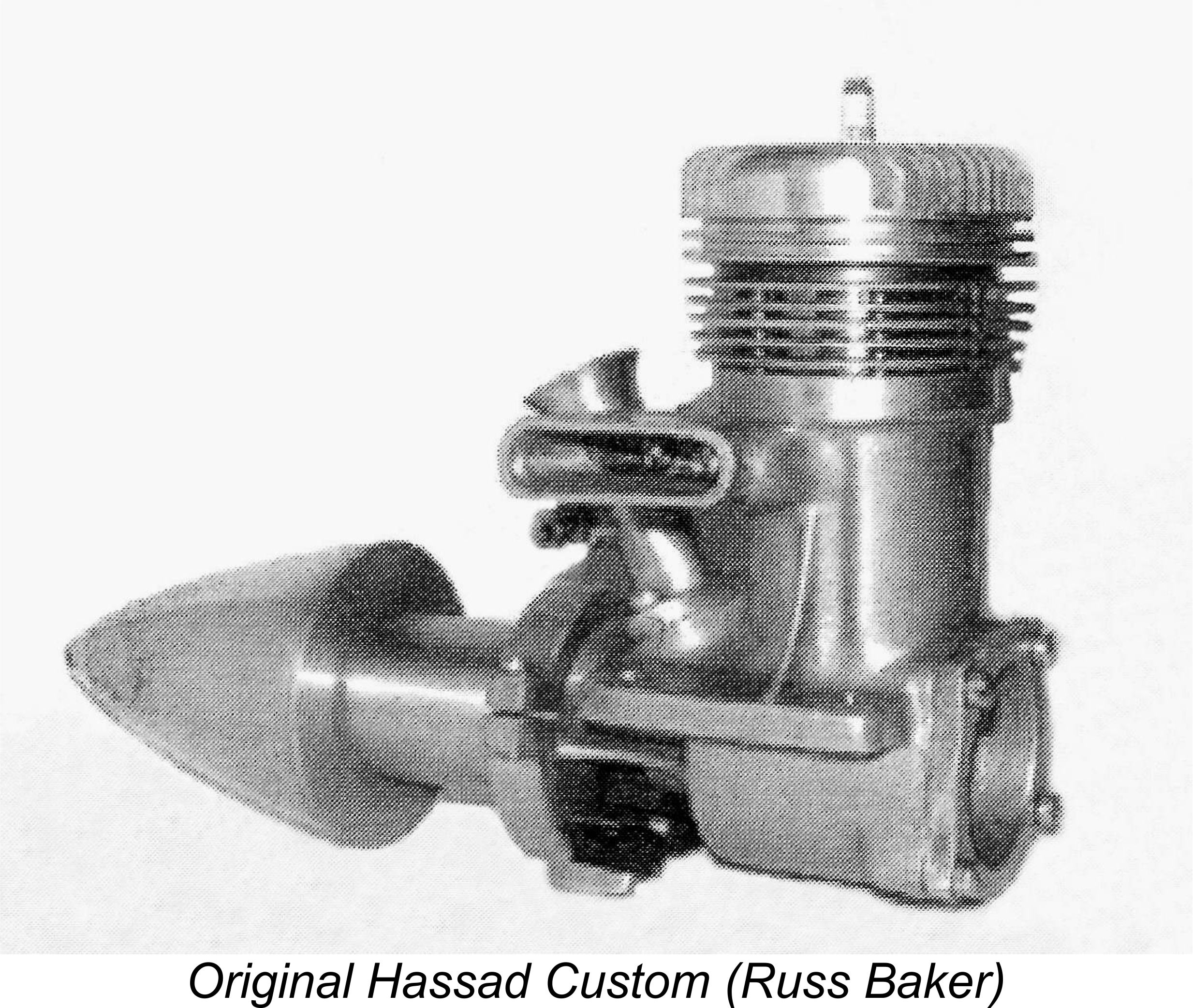

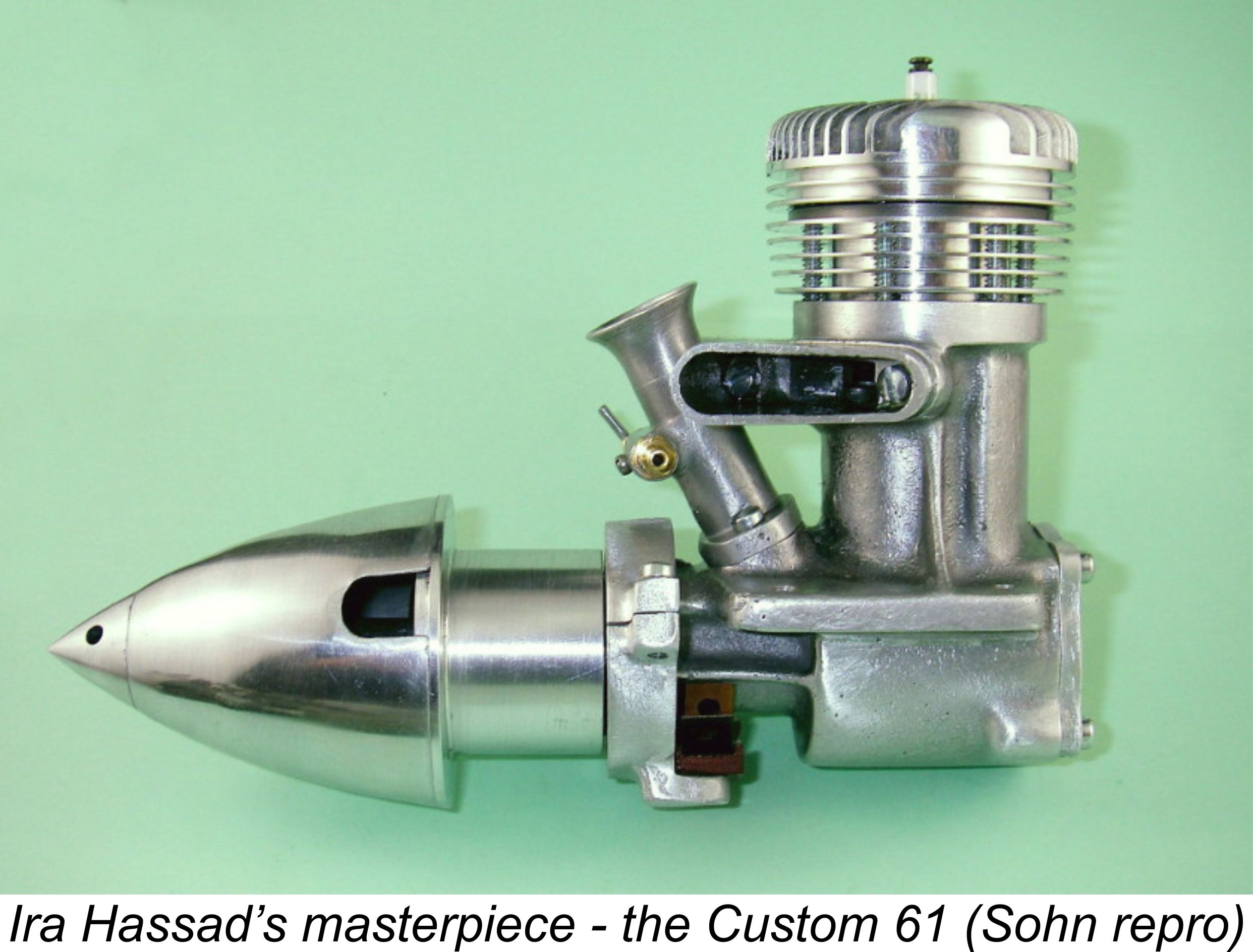

According to Clarence Lee, who knew Ira Hassad personally, the Custom was actually designed by Bill Batzloff, although it was manufactured by Hassad as the name suggests. This division of responsibilities is almost certainly an indication of Ira's fading interest in model engines, although their manufacture remained quite a lucrative venture for Ira since his reputation allowed him to charge top dollar for his products. In keeping with Ira’s pre-war models, the castings for the Custom were produced by the Rogers Pattern & Foundry company which was still in operation. It would appear that Bill Batzloff was less convinced than Ira of the inherent superiority of FRV induction, although he had incorporated this system into the design of the Custom in deference to Ira's own perceptions. After helping Ira to finalize the design of the Custom .61, Batzloff went his own way, developing a completely different design which closely followed the configuration established by the Hornet and early McCoy 60 models. In 1946 he ended up producing very limited numbers of a completely revised custom- The illustrated example is one of a small number of outstanding reproductions built by Don Sohn. It is in aero configuration, reflecting the increasing importance of that market area at the time as a result of the rapidly rising profile of control-line speed competition during the early post-war era. A more complete review of this engine appears elsewhere on this website. Hassad was left alone to pursue his further activities along the lines established during the pre-war years, remaining true to his FRV leanings. The illustrated example of the Hassad Custom is one of a run of some 50 or more superb reproductions of this engine made by Don Sohn. The number of examples built by Ira Hassad himself is somewhat clouded. Bill Thompson, who discussed these engines directly with Ira, reported Ira's own recollection that between 100 and 125 engines were manufactured in total - a perfectly believable figure for a one-man operation over a single year. However, this seems to run counter to the fact that Don Sohn has personally encountered serial numbers for unquestionably original examples of this model which lie in the mid 300 range. To further confuse matters, Bob Christ had an original example with the number H199. Just to throw even more sand in the works, a few seemingly orginal examples have surfaced bearing no serial numbers at all!

One possibility that comes to mind is the notion that the serial numbers' starting digit could indicate a particular variant of the engine in its development sequence. This idea is circumstantially consistent with the fact that we know of three-digit serial numbers starting with 1, 2 and 3 but no two-digit numbers and no numbers starting with any other figures. In this scenario, the two-digit numbers following the starting digit which indicated the variant need not have gone all the way up to 99 in any particular case, thus opening up the possibility of reconciliation with Ira's stated production figure. Whatever the true number of these engines produced, it cannot have been large - original unmodified examples of the Hassad Custom .61 are very rare today. The Hassad Custom was reviewed in some detail in the article by Edward G. Ingram entitled “Latest Model Motors” which appeared in the April 1947 issue of “Model Airplane News”. Since this appears to be the sole contemporary review of a Hassad engine, it seems worth reproducing the text in full. “Described as a competition engine designed with one object, that of optimum performance, the Hassad, which has a displacement of .605 cu. in., is claimed to develop the remarkably high output of 1 1/8 BHP at 19,900 rpm. Designed by Ira J. Hassad, it is stated to incorporate what is termed “resonic” timing, a feature said to have been developed through laboratory research work, exhaustive trials and the cooperation of physicists. It is hoped some information about this timing principle and the claimed advantages can be presented in a future article. It also is stated all the technicians who are building the engine were formerly with the University of California, Division of War Research. The engine is intended for model racing cars, boats and planes, a propeller adaptor being supplied for the latter use. Since the compression ratio of the Hassad is 13.80 to 1, highest of those ratios listed in the tables, the operator is warned against using straight methyl alcohol (methanol) fuel because of detonation, which may cause a dangerous rise in temperature. It is noted that the main purpose of using methyl alcohol is lower the temperature of the intake tract and thus allow a greater charge to enter the cylinder; but unless the fuel is chemically treated it cannot be with a compression ratio much higher than 9 to 1. A particular brand of racing fuel is recommended for the Hassad. When tuned for racing it is stated a condition called “splattering” should be noted when the ignition is shut off. This is caused by the heated spark plug firing the engine for a couple of second, and denotes optimum fuel efficiency, as the engine should be at a high temperature for best performance. The spark plug porcelain should become a light tan colour, as a gray-white denotes too lean a mixture and a dirty brown or black too rich a mixture. The cylinder, which incorporates twin exhaust stacks, is machined from aluminum bar stock, and the fins of the detachable cylinder head are milled on to minimize distortion. Through-bolts attach the head and cylinder to the sand-cast aluminum alloy crankcase. Meehanite iron is used for the cylinder liner and piston. The dural connecting rod has a bronze bushing at the lower end. Two ball bearings having diameters of 5/8 in. and ½ in. support the chrome-moly steel crankshaft. A shaft-type rotary valve is used. The engine speed of 17,000 rpm with a 9 in. diameter, 12 in. pitch propeller is stated to have been certified by the U.S. Bureau of Standards. The weight of 18 ounces is somewhat higher than most engines of this displacement”. If accurate, the performance figures cited in this report would have placed the Hassad Custom in the front rank of big-bore racing engines as of 1946-47 - the Dooling 61 and McCoy 60 Series 20 had yet to appear. It's hard not to be a little amused by the talk of the "resonic" timing, a typical example of promotional hyperbole during an era when "gee whiz" manufacturer claims were the order of the day! Certainly, no more was ever heard of this feature. Although the Custom was very much a typical expression of Hassad’s staunch commitment to the further development of FRV racing engines, there is ample evidence that his preference for this layout did not by any means represent a blind or unquestioning allegiance. Apart from the pre-war H.R.E. Special mentioned earlier, the existence of a barstock RRV racing 60 which Ira made towards the end of his model engine designing career in the late 1940's demonstrates very clearly that he was open to experimentation with other configurations. Oddly enough, Ira never mentioned this latter engine during his 1973 conversations with Bill Thompson. Perhaps he didn’t consider it to have been a success …………or perhaps he viewed it as irrelevant since it evidently led nowhere in commercial terms.

Jim was able to confirm that the Hassad barstock special was made by his father in the late 1940's. In fact, it appears to have represented his swan-song as a model engine designer. The barstock special goes even further than the H.R.E. Special had done in exploring the “classic” Hornet/McCoy layout, since it features not only RRV induction and a twin ball-race shaft but also a conventional side-stack exhaust with a ringed piston. It also exhibits a strong Dooling influence, which is of course consistent with what we now know about the date of its construction. To all appearances, it would have been a very stout performer indeed by the standards of the late 1940's. Jim tells us that his father went so far as to mount the barstock special in a car chassis, but as far as Jim is aware the engine was never run. In 2017, Don Sohn completed a few examples of a fine re-creation of this engine based on dimensions carefully scaled from the photographs. A full report on this superb re-creation may be found elsewhere on this website. Returning to our discussion of the 1946 Hassad Custom 61, the “standard” formula was now beginning to make inroads into the design of the Hassad engines. For one thing, the engine featured a twin ball-race shaft. Moreover, although the lapped piston seems to have been retained in the majority of examples, a few engines have been reported with ringed aluminium pistons - according to page 110 of Volume 1 of Tim Dannel’s indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia”, Russ Baker’s example illustrated on that page was so equipped. Moreover, Bill Thompson reported his understanding from his 1973 discussions with Ira that at least some examples of the Custom 61 had ringed pistons.

Jim Walker’s wartime development of the control line system for model aircraft had now made all-out speed contests for model aircraft a practical proposition, since high-speed model aircraft could be flown safely under complete control at all times in a confined area. Accordingly, Ira’s engines were now appearing in aircraft service in addition to the tethered car and hydroplane racing applications for which they had been primarily intended at the outset. In common with a number of reported original examples, Don Sohn’s illustrated reproduction of the Hassad Custom is set up for aircraft use. From this point onwards, the model aircraft market became increasingly important to the designers and manufacturers of model racing engines, to the point where it eventually became dominant. In fact, it was probably the clear unsuitability of the pre-war H.R.E. Special for aircraft use that led Ira to drop any further experiments along that line after the war. The Hassad Custom 61 was by no means cheap. The car version with flywheel sold for $45, while the aircraft variant cost $43. One could also save a buck by ordering the engine bare at a cost of $42, although one is forced to wonder why anyone would do so……… These were premium prices by the standards of the early post-war racing engine market. However, Ira's reputation plus that of the engines that he produced was such that people would happily pay prices of this magnitude for them. The Hassad Custom .61 proved to be a formidable competitor, a fact which did not go un-noticed by others. In 1947, a certain Mr. Frank Howarth, owner of a company called Engineering Development Co. Inc. (EDCO), decided that a mass-produced version of this engine would enjoy good sales prospects, accordingly inviting Ira Hassad to come to work for him on the engine side. The company was established Hassad’s involvement with this company during 1947 resulted in perhaps his most recognizable design of them all, the EDCO Sky Devil. This was in effect a somewhat simplified production-line version of the Hassad Custom .61. It was another FRV twin-stack front exhaust unit with a twin ball-race shaft, but now featuring a ringed aluminium alloy baffle piston on all examples. The standard formula was continuing to make inroads ……. The original prototypes of the EDCO Sky Devil were based upon a very slight variation of the crankcase casting used in the Hassad Custom. The main change was in the exhaust stack configuration - the twin stacks were now cast in unit with the case rather than being separate bolt-on This appears to have led to some customer confusion! Don Sohn has recalled that a friend of his took note of the EDCO advertising and ordered an engine on the strength of it. When he received his EDCO, it was of course the standard production model as illustrated above rather than the somewhat more substantial variant illustrated in the advertisements, as shown at the right. Don’s friend actually tried to return the engine, saying that he wanted the engine illustrated in the advertisement. However, he was out of luck, because the company was not selling engines in that configuration. This apparently rankled somewhat with Don’s friend! Many years later, after Don was well embarked upon The Sky Devil was offered in both a .649 cuin. aircraft version (the regulations then in force for model aircraft allowed engines of up to .650 cuin.) and a .607 cuin. race car variant which was used in EDCO’s own race car offerings. The two models shared a common stroke, with the different displacements being achieved Complete original examples of the EDCO engines are relatively rare these days. This rarity coupled with the engine’s general desirability led to later efforts to produce commercial replicas of the Sky Devil both for collectors and for old-time flying. I've illustrated an example of one such effort here. This engine is one of some 250 fine .649 cuin. replicas produced in 1983 by Randy Linsalato of RJL (later combined with MECOA). These were made under contract for the late Terry Toupes. Unfortunately, they were sold without the spectacular extended spinner unit which was such a memorable feature of the originals.

Randy subsequently began work on a second series which was to be closer to the originals, but this project never reached completion due to a perception that demand was fading. My sincere thanks to Randy for personally sharing this information with me.

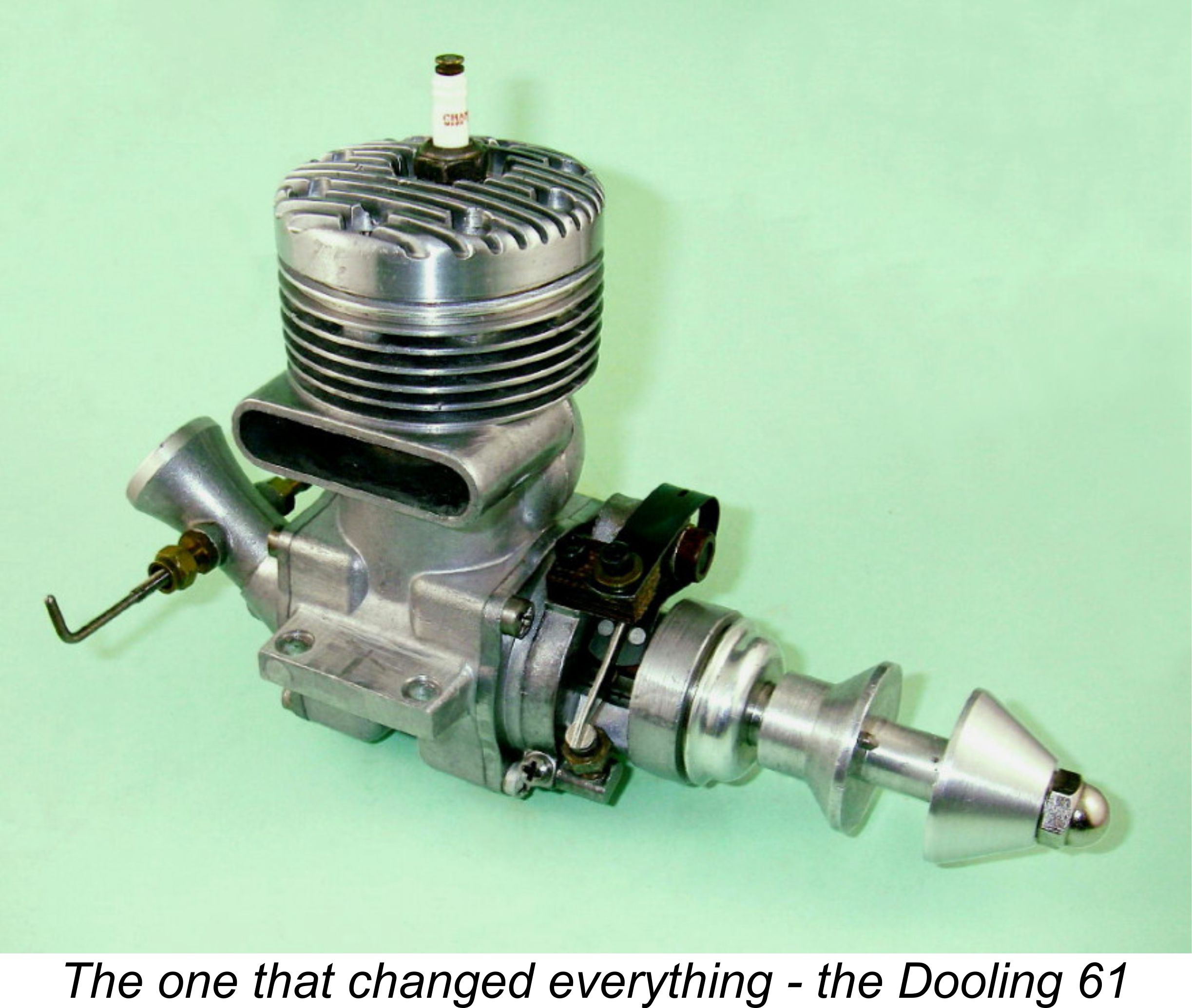

However, the big-bore racing engine market was becoming dominated by the McCoy 60, with the Hornet 60 also still very much in evidence as of 1947. The arrival of the Dooling 61 later in 1947 did nothing to help. Consequently, the Sky Devil did not meet sales expectations, with only some 1000 - 1500 examples being produced in total before financial difficulties forced the EDCO company into liquidation in 1948. As a result of the liquidation process, the bulk of the remaining Sky Devil parts and tooling ended up as the property of EDCO’s major creditors, the Tyce brothers, who owned a company called International Tool Corporation of Chula Vista, California, just to the south of San Diego. The established business of this company was the provision of full-sized aircraft engineering services, but they decided to see if anything could be salvaged from the remains of the EDCO venture. To that end, they hired Ira Hassad to come up with a new model engine design in which the former EDCO parts and tooling could be used to the maximum extent possible. The design brief this time was specifically for an aero engine for free flight and control-line applications - cars were no longer seen as the major market that they had once been. 1948 was a big year for Ira, because apart from the commission from the Tyce brothers to design a new engine for them, it was in that year that he married his first wife Charlene, with whom he had one son, James Charles Hassad, who was born on December 15th, 1949 at San Diego, California. In the event, this marriage did not last, freeing Ira to marry his second wife Lois, who was 12 years his junior.

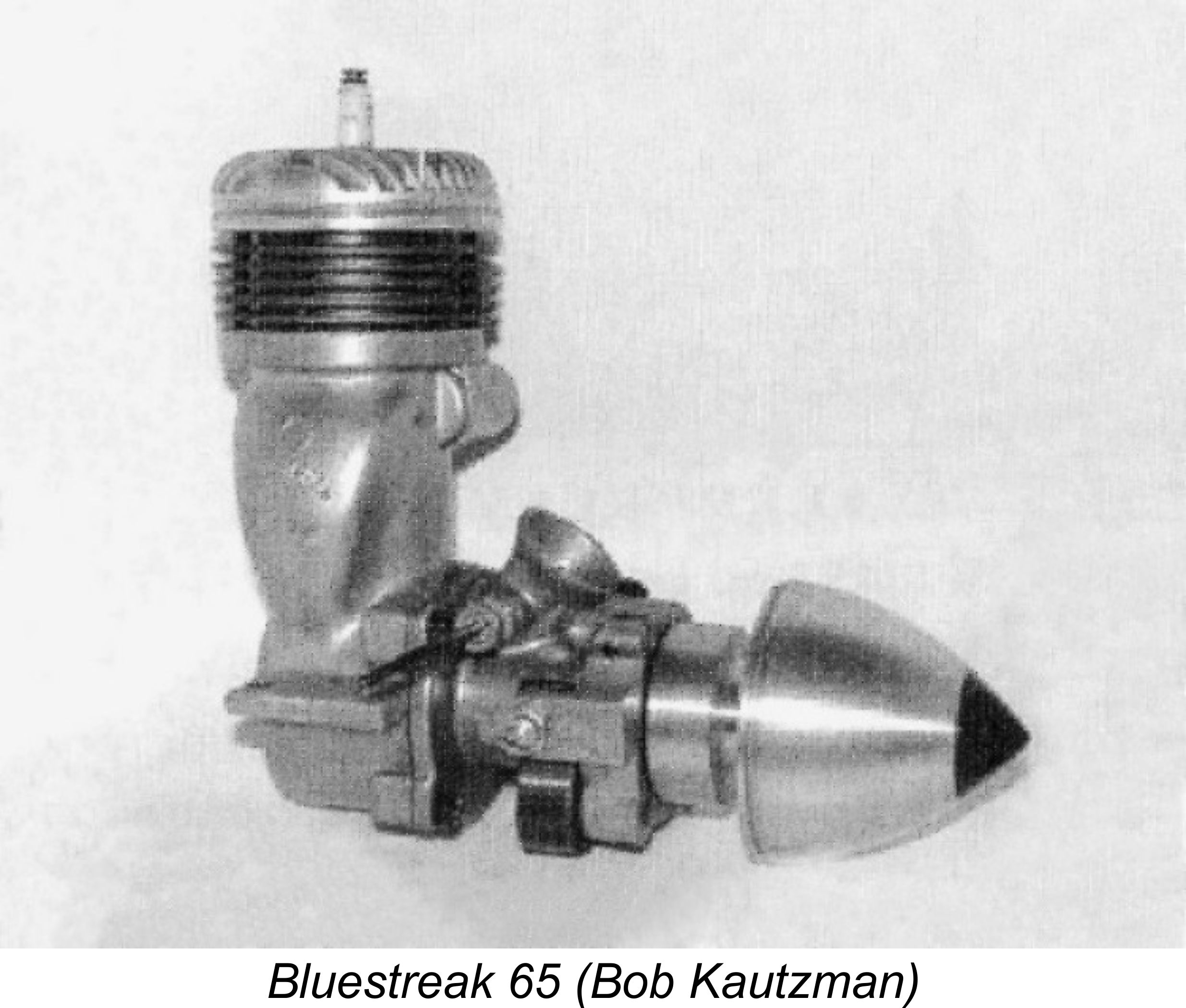

Reflecting its time and place, the Bluestreak was offered in both spark ignition and glow-plug versions. It was reportedly a fine engine for free flight and non-racing control line applications. However, in a racing context it could not hold its own with the then-current crop of big-bore racing engines from other manufacturers. Ira himself was quick to recognize this - Bill Thompson reported a relevant quote from Ira which seems worth reproducing here: “The Bluestreak was my last engine. I always felt bad that it did not become popular. It just didn’t have what was needed to pull U/C speed planes. Until this day (1973), I couldn’t tell you why!” The Bluestreak was covered in the article by Edward G. Ingram entitled “Present Day Motors” which appeared in the June 1949 issue of “Model Airplane News”. The relevant text read as follows: “The Bluestreak, designed by Ira J. Hassad, is a new racing engine with a displacement of .65 cuin. and a rated output of 1+ HP at 15,000 rpm. The cylinder is iron, centrifugally cast, and has a bore of .940 in. and a stroke of .934 in. Six screws attach the head and cylinder to the aluminum alloy crankcase, which is a permanent mold casting, as is the piston. The connecting rod is machined from 24S-T aluminum alloy bar stock. A hardened steel spinner is attached to the end of the chrome molybdenum crankshaft, which turns on twin ball bearings. A shaft type rotary valve is used. The cylinder compression ratio is 11 to 1. The preferred fuel is a methanol-castor mixture”. There’s no denying the fact that the claimed performance figures were some way below those being achieved by such competing products as the Dooling 61, McCoy 60 Series 20 and even the “bulge bypass” Hornet 60. It may well have been his feeling of disappointment regarding the Bluestreak 65's performance shortcomings that led Ira to construct the barstock special mentioned earlier, immediately prior to the switch of his main Despite the Bluestreak's inability to compete as a racing engine, all 2,000 or so examples which were manufactured did eventually find buyers, although it took a few years. Long before that happened, Ira Hassad had moved on into other engineering ventures, leaving model engines behind together with his own legend. He left the Tyce company in 1949 to set up on his own once again. Model engine manufacturing had been relatively lucrative since Ira was able to charge top dollar for his renowned engines. As a result of this, as well as his US Navy employment during the war years, he now found himself with the resources necessary to establish his own independent fully-equipped machine shop. It comes as something of a surprise to learn that despite his obvious talents, designing and building model engines had never been activities that Ira enjoyed all that much, by his own frank admission. His first love all along had been full-sized automotive technology, which we saw him earlier studying in detail during the WW2 years. It seems that he had only become involved with the model engine and model car fields because he lacked the resources to undertake full-scale automotive projects. This did not stop him from tackling various projects associated with full-sized high-performance automobile engines during his model engine manufacturing years. Cylinder head modifications or the manufacture of custom pistons were typical of the projects of this nature that Ira took on. However, prior to 1949 these activities had been relegated to sideline status. Now all that changed - with his own machine shop up and running on a commercial basis, Ira was finally poised to become fully involved in the world of high-performance custom automobiles, or “hot rods” as they were widely known. Although the primary business of his new machine shop was the provision of services to the aviation industry (in competition with his former employers, the Tyce brothers), Ira threw himself into the hot rod field with his usual energy and ability, becoming a leading light in the San Diego Roadster Club (SDRC). Founded in 1941, this prestigious group had quickly became one of the premier Land Speed Racing clubs in the world, a position which it continues to hold to this day. The SDRC “secret” motto WMBCSBWE (“We May Bitch, Cuss and Swear, But We Enter”) and associated jingle were reportedly originated by Ira Hassad many years ago. A few examples of Ira’s work in this field are worth mentioning. In 1953 Ira teamed up with an individual named Merrill Walton to prepare a car for that year’s Bonneville Speed Week meet. The March 31st, 1953 issue of the “Reading Eagle” newspaper in far-off Reading, Pennsylvania carried an article about the upcoming 1953 event for which a new salt-racing streamliner was said to have emerged from the workshop of Ira Hassad and Merrill Walton in San Diego, California. The builders were said to have utilized parts of a midget race car, adapting them to a long tubular frame. The engine was reportedly equipped with a pair of superchargers. Unfortunately, I have been unable to track down a photograph of this creation.

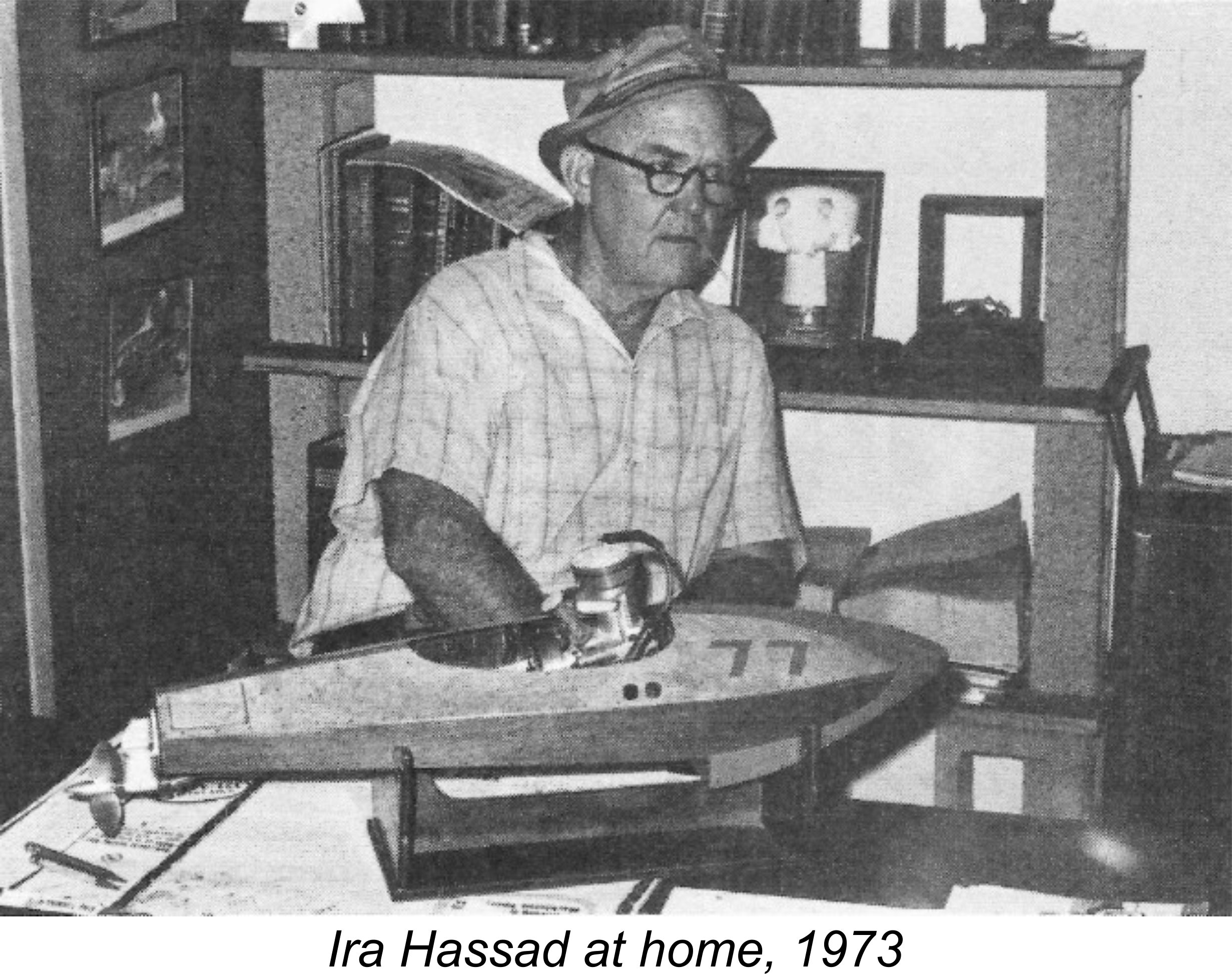

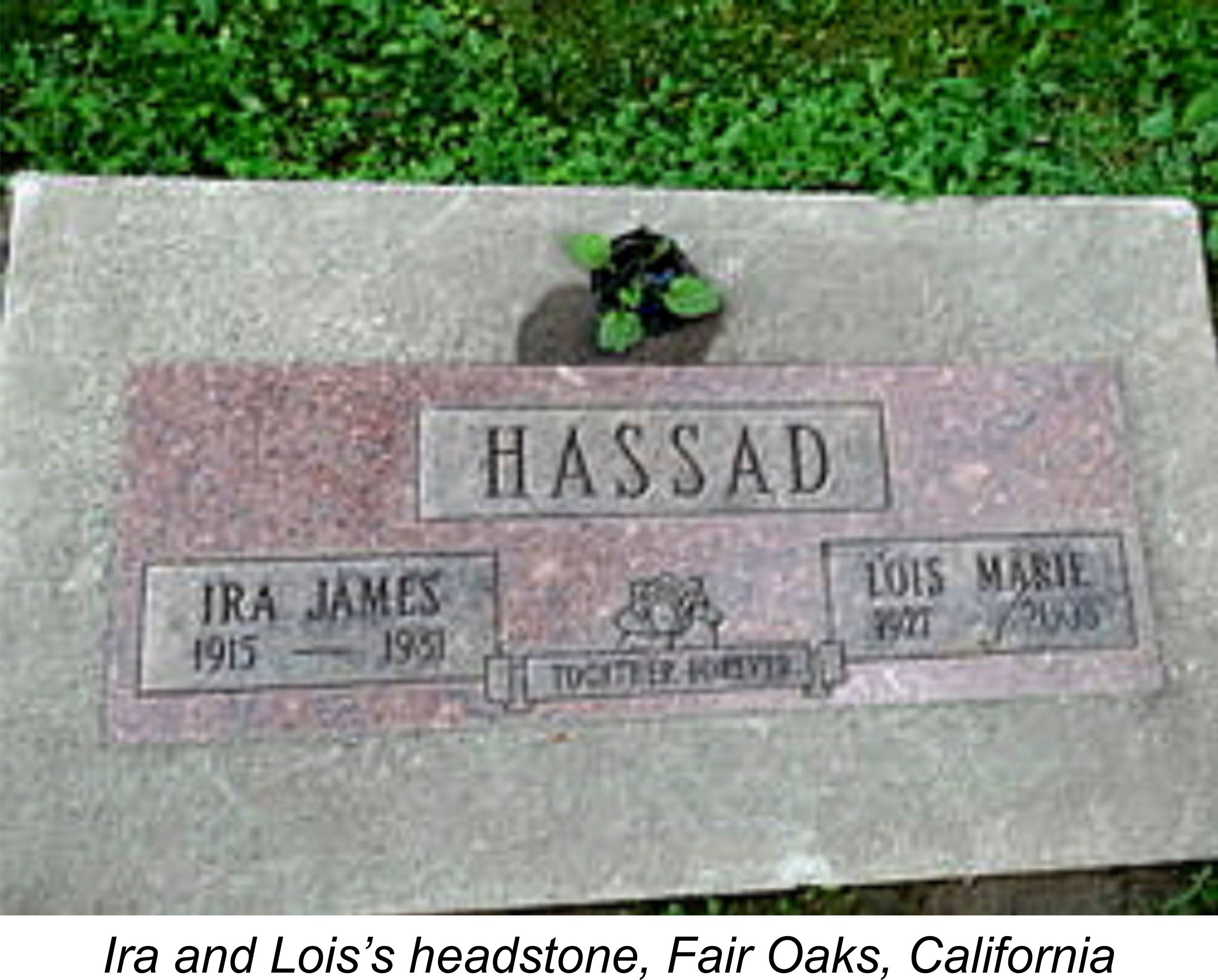

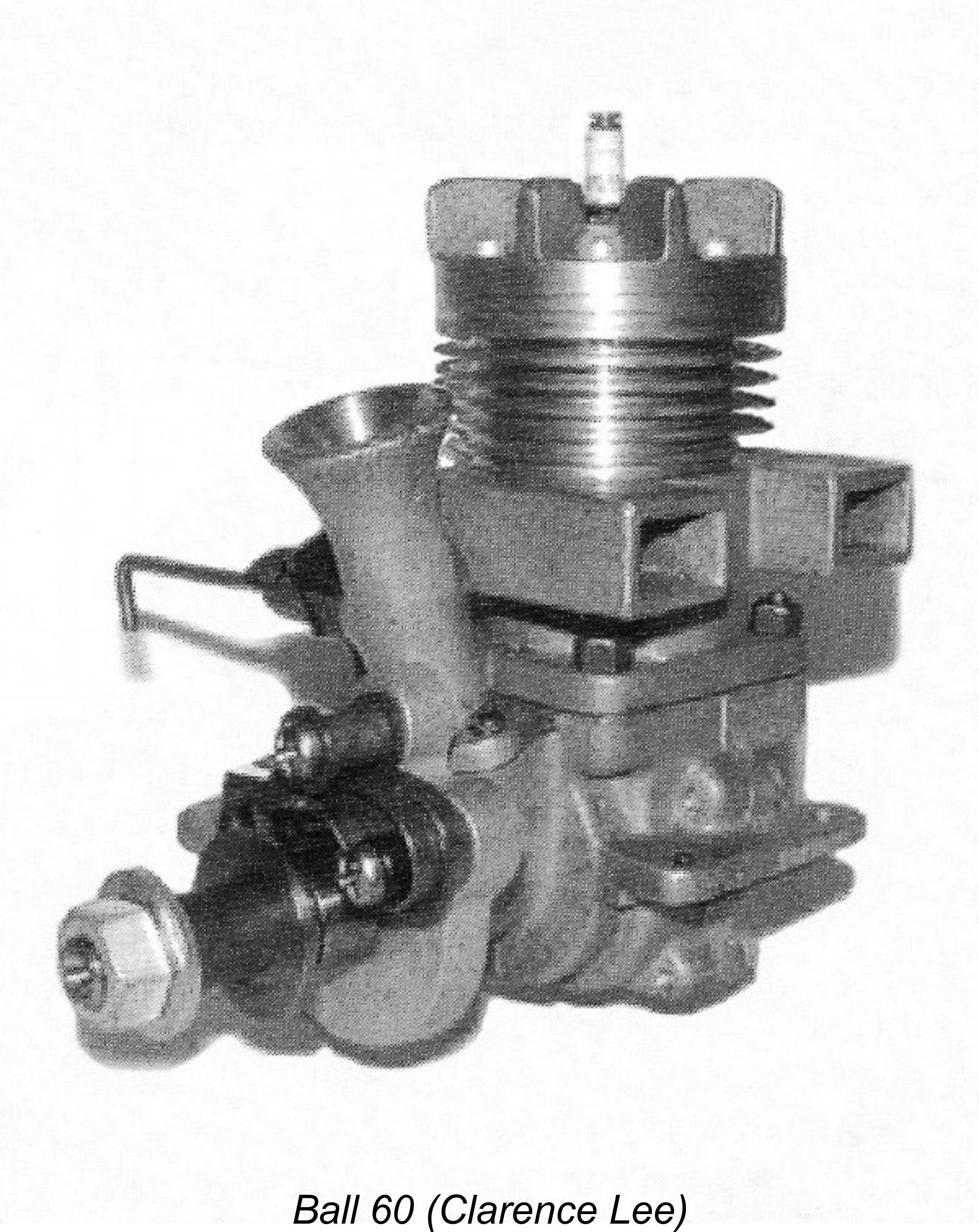

Although he never returned to the field of model engine design, Ira retained an active interest in modelling. At the instigation of his old-time colleague and good friend Bill Atwood, he got into indoor flying using micro-film models. A strange twist for the designer of some of the most powerful model racing engines of their day! As the attached photograph of Ira taken in 1973 shows, his home was well supplied with memorabilia of his time at the forefront of the model racing engine and hot rod fields. The hydroplane seen in the Ira also continued to attend model engine collectos on a semi-regular basis. A notable event was the October 14th, 1972 MECA collecto in Los Angeles, at which Ira Hassad, Dick McCoy and Irwin Ohlsson were the joint guests of honour. This was the first meeting between Ira and his old friend Irwin Ohlsson in over 25 years, presumably being an occasion which both men relished to the full. According to Bill Thompson, they spent most of the day together, including a shared lunch. At this time, Ira was still very active in the precision machining business, working from expanded premises in the community of El Cajon, a little to the east of San Diego. According to Ira’s business card at the time, this business primarily served the needs of the air transportation industry, although Ira was evidently prepared to tackle almost any kind of machining challenge that might come up from any source. Ira oversaw the ongoing activities in the machine shop, which now had a number of additional employees. His wife Lois Marie Hassad, who was the co-owner of the business, took care of the secretarial and book-keeping chores. The company name of LOMAR was of course derived directly from Ira’s wife’s name! Jim Hassad tells us that during the late 1970's, Ira embarked upon a project which is possibly unique among model engine designers. He spent a good deal of "spare" time in the years 1977 - 1978 completing one example of every model engine that he had ever designed, using original castings that he had saved down through the years. He subsequently designated this series of engines plus a few survivors from the old days to be a gift to his grandson (Jim Hassad's son Brett) by way of a legacy. This bequest included the barstock special, still mounted in its car chassis, as well as the previously-illustrated hydroplane with the 1941 car motor. Jim tells us that this "legacy" group of motors included re-creations of the two previously-mentioned 10 cc units that Ira had made for himself while working for Major Moseley in the 1930's. This design never entered commercial production, so these are the only two in existence. As stated earlier, they are of extremely light construction and are painted orange on the crankcase with black on the bypass, cooling fins and head. Since Brett was only one year old at the time of Ira's death, these “legacy” engines remained in Jim Hassad's care until Brett was settled enough to properly care for them. In accordance with Ira's wishes, Brett took possession of these engines, including the hydroplane with the 1941 championship car engine Ira retired in 1980 amid plans to relocate to a new home in Arizona, actually commencing work on his new residence there. Clarence Lee had retained a connection with Ira down through the years, getting together with him for lunch in early 1981. However, fate had other plans for Ira, who at the very premature age of 65 died quite unexpectedly in May 1981 at Carmichael in Sacramento County, California as the result of complications arising from an intestinal problem. He never got to live in his new home. Ira Hassad is buried in Fair Oaks Cemetery in the community of that name in Sacramento County. His second wife Lois survived until 2008, when she was reunited with Ira at Fair Oaks. Rest in peace ……….. Ira Hassad’s FRV Rivals Although he was the most prominent and persistent advocate of FRV racing engines during the period just covered, Ira Hassad was not the only such individual. Over in the small community of Drayton Plains, Michigan, a fellow named Henry "Hank" Ball had established a facility known as the B&D Racing Engine Laboratory. Here he developed and manufactured another FRV racing engine, the Ball 60. The initial model of this engine appeared in 1946, with limited production continuing into 1948.

It’s extremely interesting to note the design similarities between the Ball 60 and the H.R.E. Special described in the previous section of this article. Both share the same highly unusual cylinder porting arrangements, although the Ball reverts to the FRV induction system in place of the RRV set-up used in the H.R.E. Special. Both also employ two exhaust stacks discharging to the same side of the engine. One is forced to wonder whether one design influenced the other….......after all, Drayton Plain, Michigan is not actually all that geographically distant from Dayton, Ohio, home of the H.R.E.s instigator Adam Cappell. It seems entirely possible that Hank Ball was acquainted with Adam Cappell or at least had an opportunity to examine Cappell’s H.R.E., although we’ll probably never know for certain. I've covered the Ball 60 in detail in a separate article to be found on this website.

Speaking of influence, the advent of the Ball 60 seems to have influenced the thinking of another Michigan model engine designer, Wilfred Gibbs Orr of Lansing, Michigan. Orr had begun working on prototype engines before the onset of WW2, but did not release his first commercial offering until the early part of 1946, Prior to that, in 1945 Orr had made a few prototypes of a .604 cuin. FRV powerplant. Although apparently intended for series production, these never progressed beyond the prototype stage to reach the market in commercial numbers. This was apparently due to their failure to achieve the levels of performance that Orr considered necessary for commercial success. After perhaps some half-dozen examples had been made, Orr switched his focus to the .65 cuin. Tornado RRV racing model for which he is best remembered. A detailed article covering the Orr engines appears elsewhere on this website. The upshot of the above experiments with FRV induction was that as 1948 rolled around, only the Bluestreak and Ball .61 cuin. (10 cc) FRV racing engines remained available to competition modellers who wished to try something different. However, the 1947 introduction of the RRV Dooling 61 had raised the performance bar significantly, to the point where even such leading RRV models as the McCoy 60 and the Hornet 60 suddenly found themselves badly outclassed. This event prompted Dick McCoy to develop his famous Series 20 version of the McCoy 60 which was destined to outlast the Dooling and remain the world standard for 10 cc racing engines well into the 1960’s. Despite the speedy development of a bulge bypass performance enhancement kit, the once-dominant Hornet quickly fell by the wayside. It Under these circumstances, it may appear in some ways a little surprising that yet another FRV racing engine should appear in 1948. However, it was in that year that the Bungay “High Speed” 600 model made its all-too-brief appearance in far-off New York. I've covered the story of the Bungay in an earlier article which is still to be found on MEN. The Bungay 600 is today one of the rarest model racing engines of them all. I’ve never so much as seen an original in the metal, although I am in contact with several original examples owned by colleagues in other countries. The illustrated example is one of a series of 100 fine reproductions of this engine which were produced to a very high standard in Ukraine for the late Woody Bartelt. As events were to prove, the Bungay Hi-Speed 600 was to be the final commercial FRV product to challenge the might of the RRV designs in the big-bore racing category. However, another maker who was considering the introduction of an FRV .60 cuin. racing engine at this time was Al Salonen of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, who was the artisan manufacturer of the beautifully-made Queen Bee .24 and .29 powerplants (not to be confused with the far later 1987 There's incontrovertible evidence in the form of two surviving examples in my possession that Al Salonen produced at least two prototype examples of a superbly-made twin ball-race short-stroke ringed-piston FRV racing .60. These were built in both spark ignition and glow-plug forms. Furthermore, the survival of several unfinished additional components confirms that Salonen was in the process of constructing further examples when the whole Queen Bee venture ended at some point in 1950, leaving the .60 models frozen at the prototype stage. This had nothing to do with any shortcomings of the still-born .60 model - rather, it resulted from Salonen recognizing his inability to compete with the mass-produced and hence less expensive offerings from others such as K&B, OK and Ohlsson. The Queen Bee 60 prototypes were almost certainly constructed during 1949. They thus represented the very last attempt by a commercial manufacturer to create a competitive FRV .60 cuin. racing engine. From 1949 onwards the field was completely dominated by RRV models which adhered to the “classic” racing engine formula established by the Hornet and McCoy 60 designs. Don Sohn and the Hassad reproductions It will have become readily apparent from many of the preceding photos that if there’s one individual who deserves enormous credit for bringing Ira Hassad’s engines back to life for the enjoyment of present-day enthusiasts, it’s the very talented model engineer Don Sohn of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA, to whom acknowledgement was made in an earlier section of this article. This being the case, I felt that a little information on Don would be an appropriate inclusion in this article. Don Sohn was born in 1934. He has been building and flying models since he was ten years old, starting with control line stunt flying in company with his modelling father. Around the time when Don entered college in the mid 1950’s, father and son switched to radio control. They apparently ran the full gamut of radio control gear from the original single tube equipment all the way through to proportional. They evidently flew a lot - Don recalls that he and his father would buy a 50 gallon drum of glow fuel at the start of each season and burn it all up during the year!

Don started engine collecting relatively early on - his MECA number is 309. He took his first steps into the field of model engine restoration and replication by repairing Dennymites. These remain among his favourite engines today. In 1978 a situation arose which was to propel Don into the forefront of the custom model engine manufacturing community. Beginning in 1966, Ben Shereshaw’s Bronner Manufacturing Co. of Hanover, New Jersey, had been experimenting with an opposed twin cylinder glow-plug engine of .60 cuin. displacement which was designated the Bantam Twin. After building a number of prototypes, by 1978 they had a design which seemed to them to merit putting into production. Some 500 sets of castings were made, along with at least some of the required tooling. However, in one of those twists of fate which can so often intervene in the best-laid plans, Bronner received a far more lucrative contract at the very time when they were preparing to go into production with the Bantam Twin. They quickly realized that they couldn’t handle both the new contract and the Bantam Twin project simultaneously. Consequently, they looked for a buyer for the Bantam Twin project and found Don Sohn, who purchased the castings and much of the existing tooling from Bronner later in 1978.

By this time, Don had developed a particular interest in sand-cast racing .60 cuin. engines from the pioneering era, in particular those associated with Ira Hassad. He has remained active in this field ever since, having now replicated and sold an impressive array of different models, a number of which have been illustrated in this article. Engines reproduced by Don include the Hassad/Schock .604, the Hassad EDCO Prototype, the Hassad Custom 61, pre-war and postwar Batzloff models, standard and bulge bypass Atomic models, the Cave Cobra, the Atwood Crown Champion models, the Custom Crown (Don’s own version of the Atwood Silver Crown), the Talisman 60 and both prewar and post-war Orr models, as well as numerous twin cylinder original designs based on engines such as the Atwood Silver Crown, Blue Streak 65, EDCO Sky Devil and Hassad Custom. Don’s approach has always been to replicate these engines as faithfully as possible to the originals. His engines are thus more accurately described as reproductions than as replicas - he simply picks up the production from where the original manufacturer left off! His engines are sufficiently accurate that great care and considerable knowledge are needed in some cases to distinguish them from the originals. As far as quality goes, Don’s work is beyond reproach - as the fortunate owner of a representative number of examples, I’m in a good position to render judgment on this point! Don’s method has been to locate an original example to acquire or borrow, from which he would make his own engineering drawings. His mechanical engineering background was doubtless of great value here. In the case of certain mega-rare models, Don has had to reconstitute the design from an incomplete example, a small collection of parts or even a group of surviving photographs. These however have provided sufficient data to allow Don to re-create the engines to high standards of accuracy.

The majority of the engines reproduced by Don were primarily designed as tether car powerplants. In around 1997 Don built a tether car from a casting kit to provide himself with a vehicle into which he could put one of his engines for testing purposes. This got him off and running in the car construction business. He eventually assembled a collection of over thirty superbly-built cars which he had constructed from scratch. Not surprisingly, he spendt as much time building cars as engines! He formerly took on a fair amount of car repair work as well as making reproductions of rare parts to assist others in their own restorations, although at age 90 he is now trying to cut back a little! In 2010 Don purchased the residual assets of the Bruce Underwood Yellow Jacket (YJ) engine project from a Although now (2024) 90 years old and counting, Don remains open to serious inquires from people having an interest in acquiring any of his creations which he can still supply. His address is: Don Sohn 3091 Sawyer Creek Drive Oshkosh, Wisconsin 54904 USA Tel: 920-233-4307 Email: donsengines@aol.com Some readers may recognize Oshkosh, Wisconsin as the home of the Experimental Aircraft Association. Anyone visiting Oshkosh for the Association’s summer show is cordially invited to visit Don at his home. Looking at the quality and range of Don’s work, I’d say that such a visit would be very well worthwhile! Conclusion Although the big-bore FRV racing engine finally met its Waterloo in 1949, that takes nothing whatsoever away from the achievements of Ira Hassad, who for ten years had led a very spirited FRV challenge to the might of the evolving RRV models. A lesser man would likely have thrown in the towel far earlier.

The engines that Ira created are true classics of their era, besides being superbly made. The originals are extremely rare today, but thanks to the work of Don Sohn and perhaps a few others it’s still possible to experience the Hassad magic now and hopefully for years into the future. I hope that you’ve enjoyed this summary of the life and work of one of America’s most innovative model engine designers from the pioneering era. No true model engine enthusiast can fail to be impressed by an examination of one of the highly original designs from this very creative individual! _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2014 Updated September 2018 Updated May 2019

|

| |

In this article we pay tribute to Ira J. Hassad, one of the most innovative designers from the pioneering era of model racing engine development. Ira Hassad was a true original, never being one to slavishly follow other established designs but rather preferring to plough his own furrow from the outset. The resulting engines were among the more individualistic racing designs to emerge from the intense competition of the pre-WW2 and early post-war eras in America.

In this article we pay tribute to Ira J. Hassad, one of the most innovative designers from the pioneering era of model racing engine development. Ira Hassad was a true original, never being one to slavishly follow other established designs but rather preferring to plough his own furrow from the outset. The resulting engines were among the more individualistic racing designs to emerge from the intense competition of the pre-WW2 and early post-war eras in America.

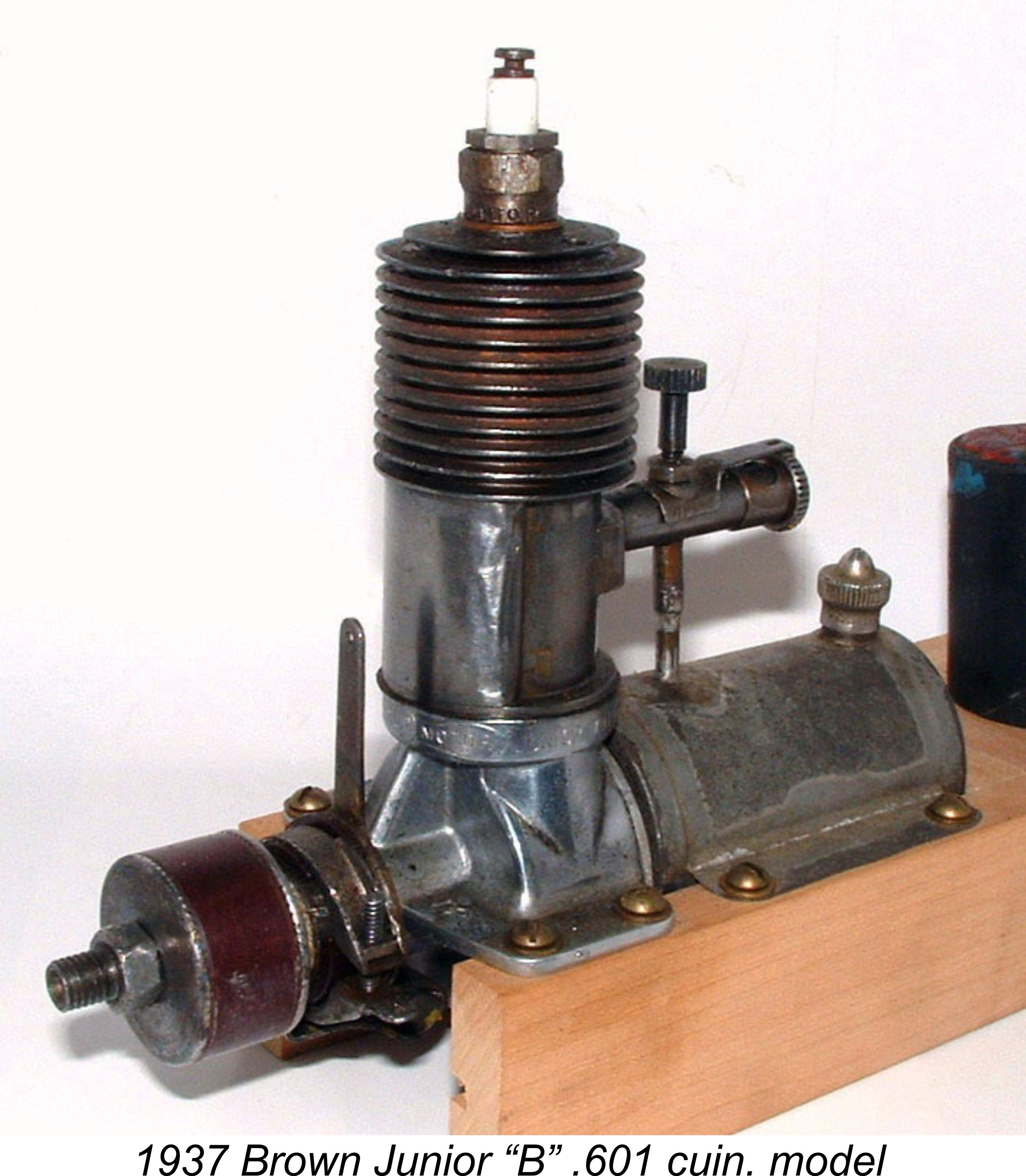

Prior to 1937, the majority of model engines were used to power large free flight model aircraft. Since these models were uncontrolled following launch, focused attempts to achieve high speeds would have been potentially hazardous, to say nothing of the difficulty of obtaining accurate speed measurements. Contests were therefore based upon flight duration for a given motor run rather than speed. Accordingly light weight, ease of handling and operational consistency were the primary goals of engine designers. All-out horsepower was a lesser consideration - if you needed more power to fly a given model, you just used a bigger engine! The illustrated Brown Junior "B" .601 cuin model is a typical example of the engines then in common use.

Prior to 1937, the majority of model engines were used to power large free flight model aircraft. Since these models were uncontrolled following launch, focused attempts to achieve high speeds would have been potentially hazardous, to say nothing of the difficulty of obtaining accurate speed measurements. Contests were therefore based upon flight duration for a given motor run rather than speed. Accordingly light weight, ease of handling and operational consistency were the primary goals of engine designers. All-out horsepower was a lesser consideration - if you needed more power to fly a given model, you just used a bigger engine! The illustrated Brown Junior "B" .601 cuin model is a typical example of the engines then in common use.  were to go on to develop some of the most famous model racing cars and engines of them all. The history of their efforts has been recorded in my

were to go on to develop some of the most famous model racing cars and engines of them all. The history of their efforts has been recorded in my  The “formula” established by these front-running early American racing engines was soon to become familiar to performance-oriented modellers worldwide, being widely emulated in many countries outside the USA. When we reflect upon the classic early post-WW2 10 cc (0.61 cuin.) racing engine, we tend to think of a design featuring spark ignition (the only available option prior to 1948); an automotive-style ignition timer; disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction; cross-flow loop scavenging with side-stack exhaust; a ringed aluminium piston having a high domed baffle crown; and a twin ball-race crankshaft. Apart from the general switch to glowplug ignition in the late 1940’s, this basic design package was to remain the standard for large racing engines well into the 1960’s.

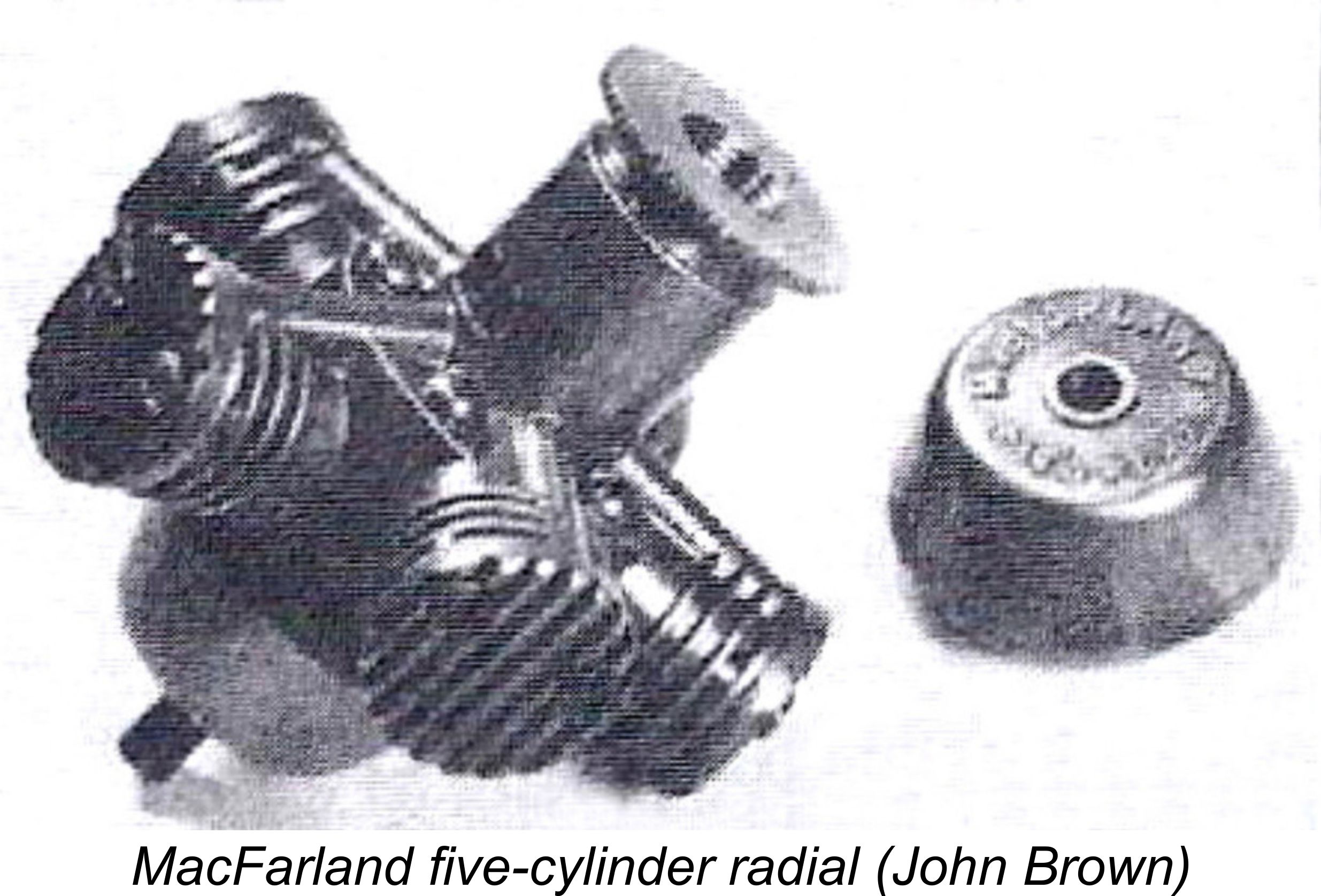

The “formula” established by these front-running early American racing engines was soon to become familiar to performance-oriented modellers worldwide, being widely emulated in many countries outside the USA. When we reflect upon the classic early post-WW2 10 cc (0.61 cuin.) racing engine, we tend to think of a design featuring spark ignition (the only available option prior to 1948); an automotive-style ignition timer; disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction; cross-flow loop scavenging with side-stack exhaust; a ringed aluminium piston having a high domed baffle crown; and a twin ball-race crankshaft. Apart from the general switch to glowplug ignition in the late 1940’s, this basic design package was to remain the standard for large racing engines well into the 1960’s. Ira graduated from Polytechnic High in 1934. His first job was with the MacFarland Motors company which made (among other things) a highly unusual .138 cuin. five-cylinder compressed gas motor for model use. This engine did not rely on the usual compressed gas propellant, instead utilizing the gasses given off by the burning of an oil-based solid fuel propellant in an enclosed container, very much in the manner of the far later Jetex solid fuel reaction units from the late 1940’s and 1950’s. It used steel pistons with brass rings. Around 20 prototypes were built, but the engine suffered from a chronic tendency to gum up from the fuel emissions and never entered series production. One of Ira’s fellow employees at MacFarland was none other than his buddy from his high-school days, Irwin Ohlsson.

Ira graduated from Polytechnic High in 1934. His first job was with the MacFarland Motors company which made (among other things) a highly unusual .138 cuin. five-cylinder compressed gas motor for model use. This engine did not rely on the usual compressed gas propellant, instead utilizing the gasses given off by the burning of an oil-based solid fuel propellant in an enclosed container, very much in the manner of the far later Jetex solid fuel reaction units from the late 1940’s and 1950’s. It used steel pistons with brass rings. Around 20 prototypes were built, but the engine suffered from a chronic tendency to gum up from the fuel emissions and never entered series production. One of Ira’s fellow employees at MacFarland was none other than his buddy from his high-school days, Irwin Ohlsson. The Baby Cyclone engines were ostensibly manufactured by Moseley's Aircraft Industries Corporation at Grand Central Terminal. In reality, much of the machining work was actually carried out under contract by the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles, although the fitting, assembly testing and packaging were carried out at Moseley’s facility along with some machining.

The Baby Cyclone engines were ostensibly manufactured by Moseley's Aircraft Industries Corporation at Grand Central Terminal. In reality, much of the machining work was actually carried out under contract by the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles, although the fitting, assembly testing and packaging were carried out at Moseley’s facility along with some machining.

prepared to pay a premium price. Some 200 examples of this model were reportedly made and sold, a figure which encouraged Ira to continue on his own after Louis Schock found it necessary to devote himself full-time to his regular job at Lockheed. A basically identical model was still in production in 1941, albeit by that time under Hassad’s own name.

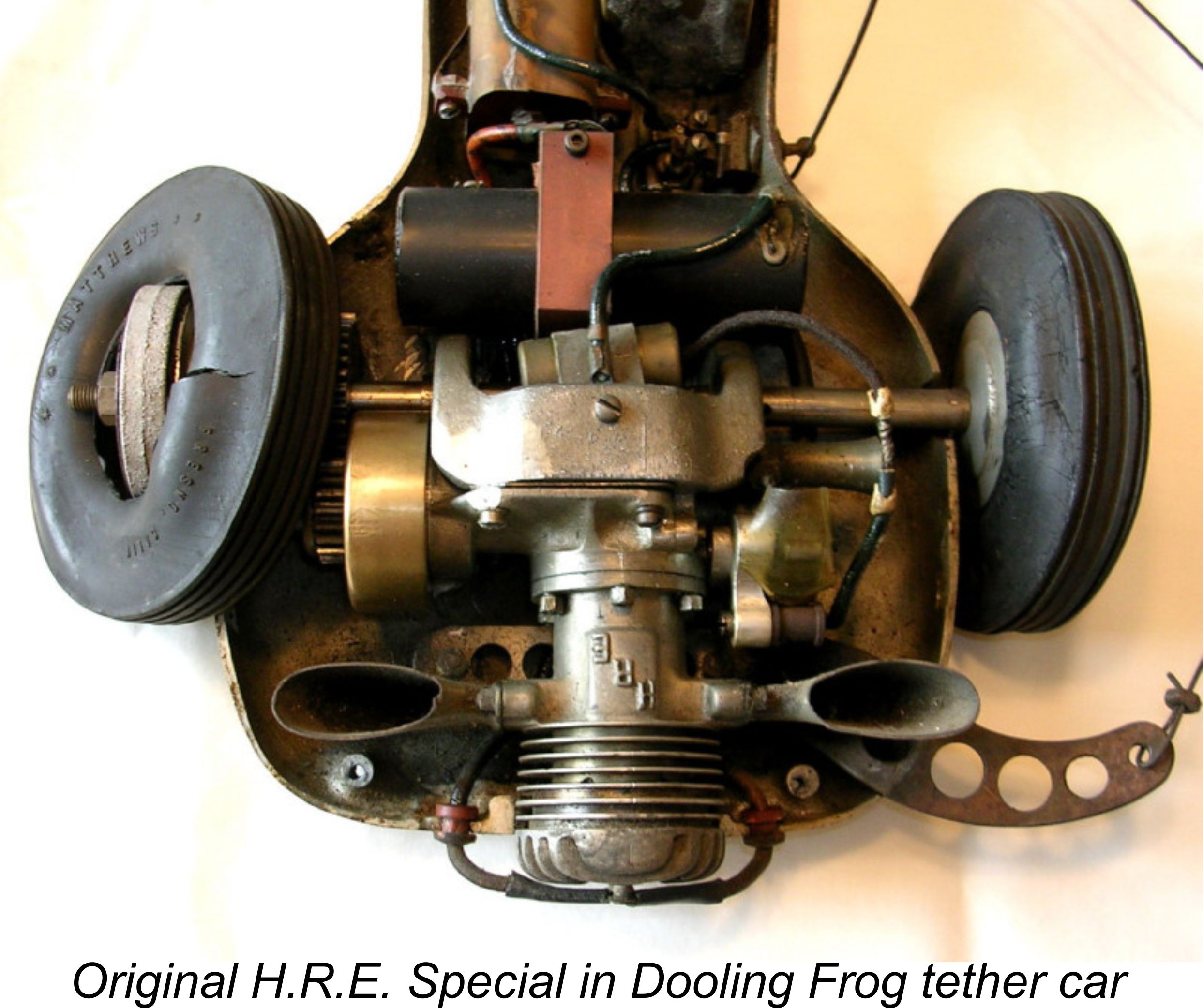

prepared to pay a premium price. Some 200 examples of this model were reportedly made and sold, a figure which encouraged Ira to continue on his own after Louis Schock found it necessary to devote himself full-time to his regular job at Lockheed. A basically identical model was still in production in 1941, albeit by that time under Hassad’s own name. However, most of the H/S engines were undoubtedly used for their intended purpose as tether car powerlants. From the standpoint of the engine’s use in a typical bevel-geared car featuring rear wheel drive (like that illustrated here) which was the contemporary standard, this arrangement allows for a very elegant twin exhaust configuration. However, any advantage in terms of operating temperatures is negated in such an installation, since the hotter exhaust side of the cylinder faces the rear of the vehicle away from the cooling slipstream. The same would apply to the engine’s use in tethered hydroplane service. This did not prevent the Hassad engines from being very successful in both applications.

However, most of the H/S engines were undoubtedly used for their intended purpose as tether car powerlants. From the standpoint of the engine’s use in a typical bevel-geared car featuring rear wheel drive (like that illustrated here) which was the contemporary standard, this arrangement allows for a very elegant twin exhaust configuration. However, any advantage in terms of operating temperatures is negated in such an installation, since the hotter exhaust side of the cylinder faces the rear of the vehicle away from the cooling slipstream. The same would apply to the engine’s use in tethered hydroplane service. This did not prevent the Hassad engines from being very successful in both applications.

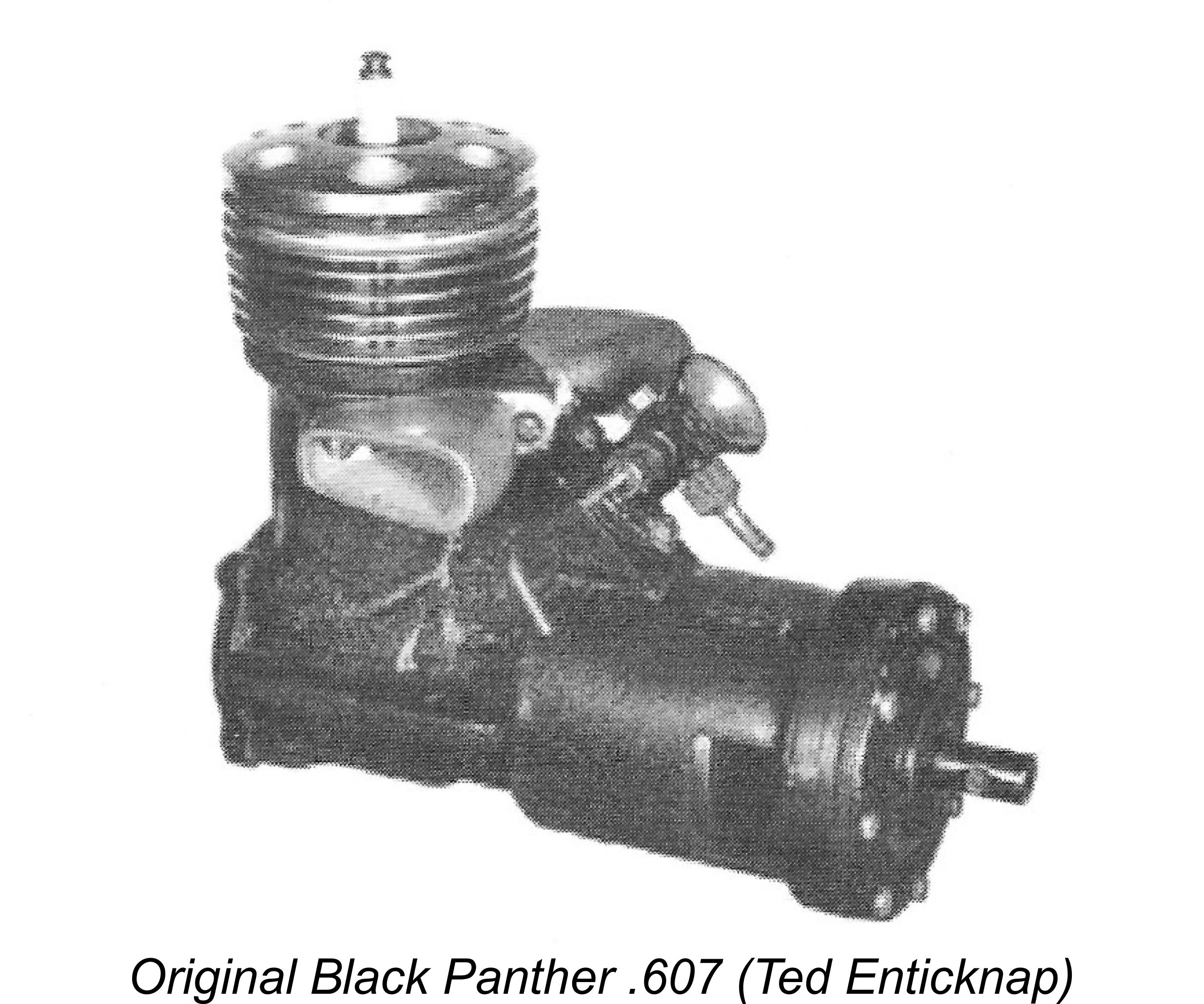

There’s no question that the Hassad engines were very successful in competition, a fact which did not go unnoticed by other California-based model engine designers. In 1941, Los Angeles resident Johnny Lockridge produced a very few examples of the Black Panther .607 cuin. car engine. While the Black Panther certainly incorporated a good deal of Lockridge’s own thinking, it displayed a very definite Hassad influence, featuring FRV induction to go along with a twin-stack front exhaust system. The flywheel and timer of this ultra-rare model were neatly enclosed in a forward extension of the main crankcase.

There’s no question that the Hassad engines were very successful in competition, a fact which did not go unnoticed by other California-based model engine designers. In 1941, Los Angeles resident Johnny Lockridge produced a very few examples of the Black Panther .607 cuin. car engine. While the Black Panther certainly incorporated a good deal of Lockridge’s own thinking, it displayed a very definite Hassad influence, featuring FRV induction to go along with a twin-stack front exhaust system. The flywheel and timer of this ultra-rare model were neatly enclosed in a forward extension of the main crankcase.  Another small-scale effort which applied a bit of a twist to the basic Hassad formula was the .604 cuin.

Another small-scale effort which applied a bit of a twist to the basic Hassad formula was the .604 cuin. The Triumph clearly embodied Batzloff’s views regarding potential improvements to the basic Hassad design. The engine reversed the usual Hassad arrangement by using a rear drum valve instead of FRV induction. The operating principle was of course identical, the difference being that the drum valve did not have to do double duty by transmitting the engine’s torque in addition to controlling the induction cycle.

The Triumph clearly embodied Batzloff’s views regarding potential improvements to the basic Hassad design. The engine reversed the usual Hassad arrangement by using a rear drum valve instead of FRV induction. The operating principle was of course identical, the difference being that the drum valve did not have to do double duty by transmitting the engine’s torque in addition to controlling the induction cycle.

During the period just described, Hassad engines dominated the rail-guided model car racing category at meets in Southern California. This was evidently due to their superior torque in the 12,000-13,000 rpm range, which helped them to accelerate out of the turns. Users of these engines included such rail car luminaries as Roy Richter and Clarence Felker in addition to Ira himself and his colleague Bill Batzloff. The accompanying photograph at the right shows Ira at the superb Mission Beach rail track in California standing behind a kneeling row of 10 competitors, all of whom were using his engines. The eleventh car in the photo must be Ira's own entry.

During the period just described, Hassad engines dominated the rail-guided model car racing category at meets in Southern California. This was evidently due to their superior torque in the 12,000-13,000 rpm range, which helped them to accelerate out of the turns. Users of these engines included such rail car luminaries as Roy Richter and Clarence Felker in addition to Ira himself and his colleague Bill Batzloff. The accompanying photograph at the right shows Ira at the superb Mission Beach rail track in California standing behind a kneeling row of 10 competitors, all of whom were using his engines. The eleventh car in the photo must be Ira's own entry. Photographs of Ira from this early period are in fairly short supply. The two images reproduced here were extracted from Art Bagnall's outstanding book "Roy Richter - Striving for Excellence", which includes a fascinating chapter on Roy's noteworthy achievements in the model rail car racing field using engines made by his close friend Ira Hassad. Jim Hassad tells us that his father always stood out in any group photograph due to his unusual height. The image at the left shows Ira standing (right) behind a group of happy racers in the winners' circle at the Goodwin Rail Track in Culver City, California. Roy Richter is kneeling at the far left of the front row in this photograph.

Photographs of Ira from this early period are in fairly short supply. The two images reproduced here were extracted from Art Bagnall's outstanding book "Roy Richter - Striving for Excellence", which includes a fascinating chapter on Roy's noteworthy achievements in the model rail car racing field using engines made by his close friend Ira Hassad. Jim Hassad tells us that his father always stood out in any group photograph due to his unusual height. The image at the left shows Ira standing (right) behind a group of happy racers in the winners' circle at the Goodwin Rail Track in Culver City, California. Roy Richter is kneeling at the far left of the front row in this photograph.

exhausts which directed the exhaust gasses from each exhaust port to the right-hand side of the engine (viewed from the disc valve end). These exhausts displayed a total mastery of the metalworking art. This engine would have been LOUD!! I should try running my example sometime to find out just how loud ................

exhausts which directed the exhaust gasses from each exhaust port to the right-hand side of the engine (viewed from the disc valve end). These exhausts displayed a total mastery of the metalworking art. This engine would have been LOUD!! I should try running my example sometime to find out just how loud ................ The unique exhaust stack arrangement seen on the H.R.E. Special implies pretty conclusively that it was designed quite specifically to match the revolutionary spur-geared

The unique exhaust stack arrangement seen on the H.R.E. Special implies pretty conclusively that it was designed quite specifically to match the revolutionary spur-geared  Ira himself ran into one of these engines years later at a collecto, the date and location of which are not now recalled. Ira’s presence at this event certainly confirms that he retained an interest in model engines despite having moved on to other activities, while the accompanying photo taken on that occasion amply reflects his surprise at running across a fine example of one of his own lesser-known designs! The source of the example of the H.R.E. in the photograph is unknown.

Ira himself ran into one of these engines years later at a collecto, the date and location of which are not now recalled. Ira’s presence at this event certainly confirms that he retained an interest in model engines despite having moved on to other activities, while the accompanying photo taken on that occasion amply reflects his surprise at running across a fine example of one of his own lesser-known designs! The source of the example of the H.R.E. in the photograph is unknown.

built version of the

built version of the  At first glance, the reconciliation of these numbers would seem to imply that the numbering sequence for these engines likely started at 100 and went up to the mid 300 range. This was a very common practise at the time in question - it gave prospective buyers the impression that the engine had sold in greater numbers than was actually the case. But if this was the case, and assuming that the numbering sequence was continuous, the production of at least 250 examples would then be clearly implied. Indeed, it would be 350 if the sequence actually started at 001. How do we reconcile this with Ira's own previously-noted recollection that he made betwen 100 and 125 examples of this engine?

At first glance, the reconciliation of these numbers would seem to imply that the numbering sequence for these engines likely started at 100 and went up to the mid 300 range. This was a very common practise at the time in question - it gave prospective buyers the impression that the engine had sold in greater numbers than was actually the case. But if this was the case, and assuming that the numbering sequence was continuous, the production of at least 250 examples would then be clearly implied. Indeed, it would be 350 if the sequence actually started at 001. How do we reconcile this with Ira's own previously-noted recollection that he made betwen 100 and 125 examples of this engine?  Until Jim Hassad made contact with me in late 2018, the existence of this engine had only been known through the fortuitous survival of a number of somewhat deteriorated photographs of the original unit. Moreover, there was no information regarding the date of its construction. Where and when the photos were taken, and by whom, remains unknown. The photos surfaced as part of an assembly of Hassad materials acquired by a collector from a close friend of Ira's after the latter's death in 1981.

Until Jim Hassad made contact with me in late 2018, the existence of this engine had only been known through the fortuitous survival of a number of somewhat deteriorated photographs of the original unit. Moreover, there was no information regarding the date of its construction. Where and when the photos were taken, and by whom, remains unknown. The photos surfaced as part of an assembly of Hassad materials acquired by a collector from a close friend of Ira's after the latter's death in 1981.  This being the case, it’s rather odd to have to report that Hassad enthusiast and replicator Don Sohn has never actually seen an example of the Custom with such a piston! Don’s superb reproductions therefore feature lapped pistons for the most part, although he did make a few with ringed pistons. Even so, the continued use of FRV induction together with the twin-stack front exhaust set the design well apart from other leading racing engines of the period while also stamping Ira Hassad’s trade-mark upon the design.

This being the case, it’s rather odd to have to report that Hassad enthusiast and replicator Don Sohn has never actually seen an example of the Custom with such a piston! Don’s superb reproductions therefore feature lapped pistons for the most part, although he did make a few with ringed pistons. Even so, the continued use of FRV induction together with the twin-stack front exhaust set the design well apart from other leading racing engines of the period while also stamping Ira Hassad’s trade-mark upon the design. in premises located at Del Mar Airport in the oceanside community of Del Mar, a little to the north of San Diego, where Hassad had been living since the beginning of WW2. The company’s range of advertised products encompassed engines, model airplane kits and model race cars.

in premises located at Del Mar Airport in the oceanside community of Del Mar, a little to the north of San Diego, where Hassad had been living since the beginning of WW2. The company’s range of advertised products encompassed engines, model airplane kits and model race cars. items. Interestingly enough, the promotional images for the engine were based upon a mock-up of this prototype configuration rather than on the further simplified variant which became the standard commercial offering.

items. Interestingly enough, the promotional images for the engine were based upon a mock-up of this prototype configuration rather than on the further simplified variant which became the standard commercial offering. his long and distinguished career of making replica powerplants to an amazingly high standard, his friend actually went to the trouble of making a pattern for the engine as shown in the advertisement, using the Hassad Custom case as his guide along with the advertising rendition of the engine. Don had castings made from this pattern and finished the engine, much to his friend’s satisfaction. Don subsequently made another five examples of the same variant, one of which I am privileged to own. This is the example which is illustrated here - another superb demonstration of Don’s talents.

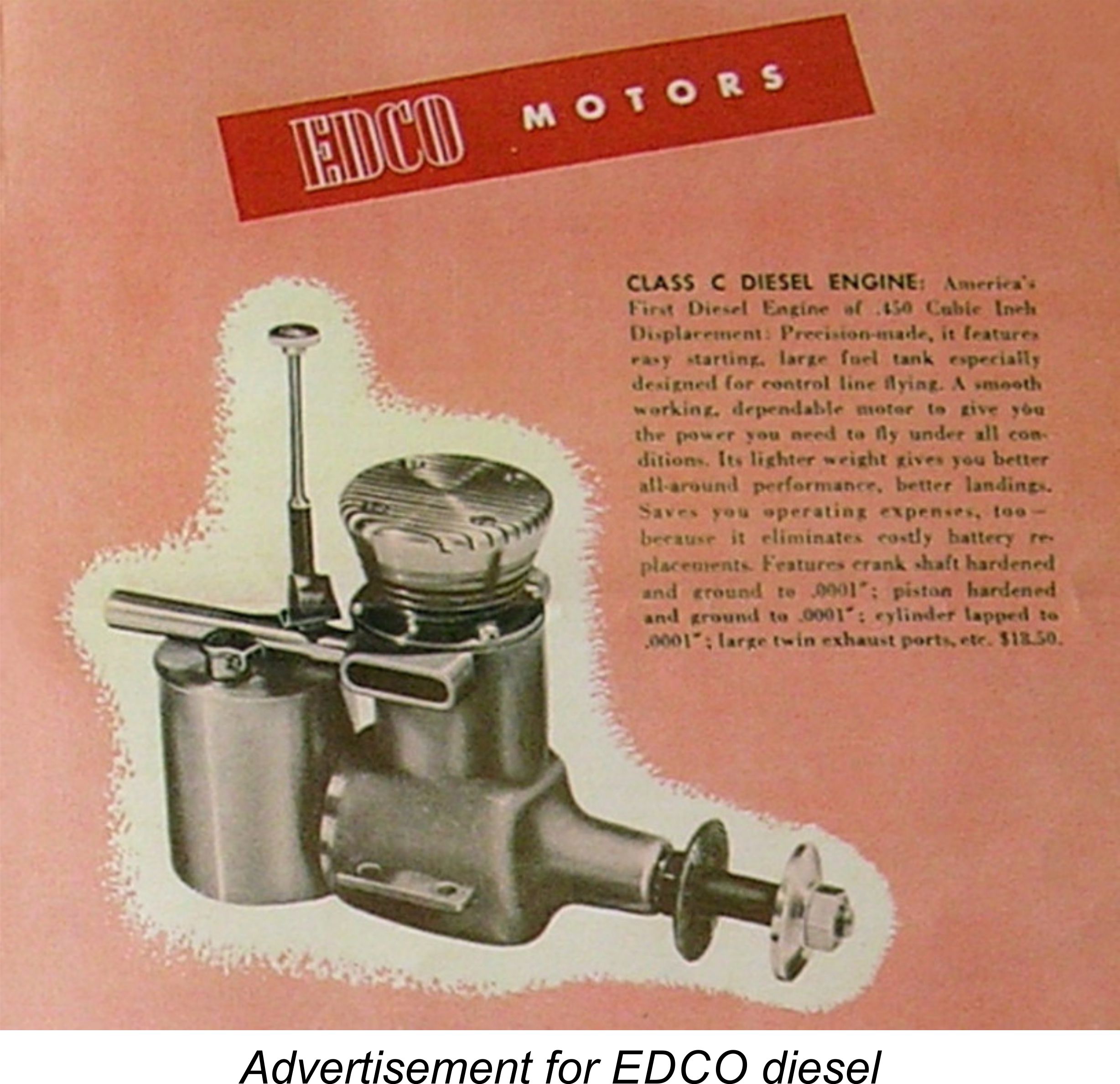

his long and distinguished career of making replica powerplants to an amazingly high standard, his friend actually went to the trouble of making a pattern for the engine as shown in the advertisement, using the Hassad Custom case as his guide along with the advertising rendition of the engine. Don had castings made from this pattern and finished the engine, much to his friend’s satisfaction. Don subsequently made another five examples of the same variant, one of which I am privileged to own. This is the example which is illustrated here - another superb demonstration of Don’s talents.  through variances in the bore dimensions. A sideport induction .45 cuin. fixed compression diesel was also planned by EDCO, but it never got past the prototype stage despite appearing in EDCO’s advertising and being mentioned in the contemporary modelling media. Ira Hassad later stated that he had nothing to do with the diesel design, although he did recall having test-run one of the prototypes at Del Mar.

through variances in the bore dimensions. A sideport induction .45 cuin. fixed compression diesel was also planned by EDCO, but it never got past the prototype stage despite appearing in EDCO’s advertising and being mentioned in the contemporary modelling media. Ira Hassad later stated that he had nothing to do with the diesel design, although he did recall having test-run one of the prototypes at Del Mar.  Internally, the RJL engines are not exact replicas, utilizing some readily-available parts from other engines to keep costs under control. However, in many ways their quality equals or even exceeds that of the originals, from which they may be readily distinguished by having the inner surfaces of their exhaust stacks anodized as opposed to the plain milled finish of the originals. They also carry serial numbers having a TDCxxx pattern. Check before you buy! These engines run very well indeed and are now fine collectibles in their own right. Far fewer of them were actually made than the originals, although the proportion of presently-surviving examples is of course considerably higher.

Internally, the RJL engines are not exact replicas, utilizing some readily-available parts from other engines to keep costs under control. However, in many ways their quality equals or even exceeds that of the originals, from which they may be readily distinguished by having the inner surfaces of their exhaust stacks anodized as opposed to the plain milled finish of the originals. They also carry serial numbers having a TDCxxx pattern. Check before you buy! These engines run very well indeed and are now fine collectibles in their own right. Far fewer of them were actually made than the originals, although the proportion of presently-surviving examples is of course considerably higher. Although it was a well-made and fine-running engine, the EDCO Sky Devil never matched the performance levels of the earlier Hassad Custom model. This was due in large part to the fact that it was not individually fitted and assembled as was its progenitor. For an extra charge of $15 over and above the standard engine’s selling price of $37.50, Ira Hassad would undertake to rework a Sky Devil to realize its full potential. A number of smart purchasers took advantage of this.