|

|

The Short-lived King Range – the 1.5 cc Kingcat and Glo-Cat Models

The best prior source of information on these engines that I’ve been able to find takes the form of an article written way back in 2004 by my late and much-missed mate Ron Chernich. This article can still be found on Ron’s frozen and slowly deteriorating “Model Engine News” (MEN) website which is kept available through the greatly-appreciated efforts of Maris Dislers. Ron’s article didn’t have much to say about the Glo-Cat, but did provide some very useful information on the Kingcat diesel models. The information gathered by Ron definitely merits preservation, hence the appearance of this revised and expanded article here. Without further ado, let’s get right into the story! The Kingshire Engines - Marketing History

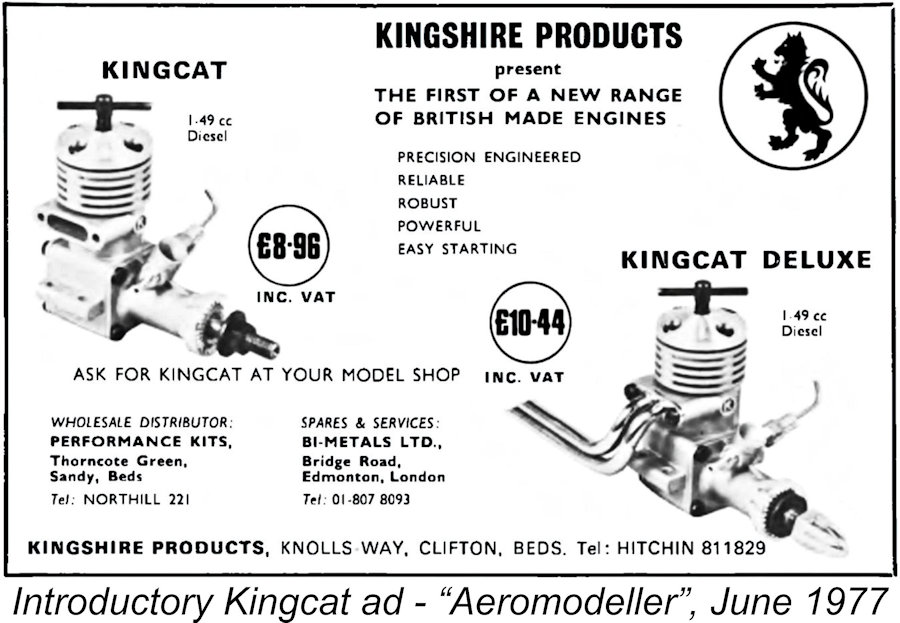

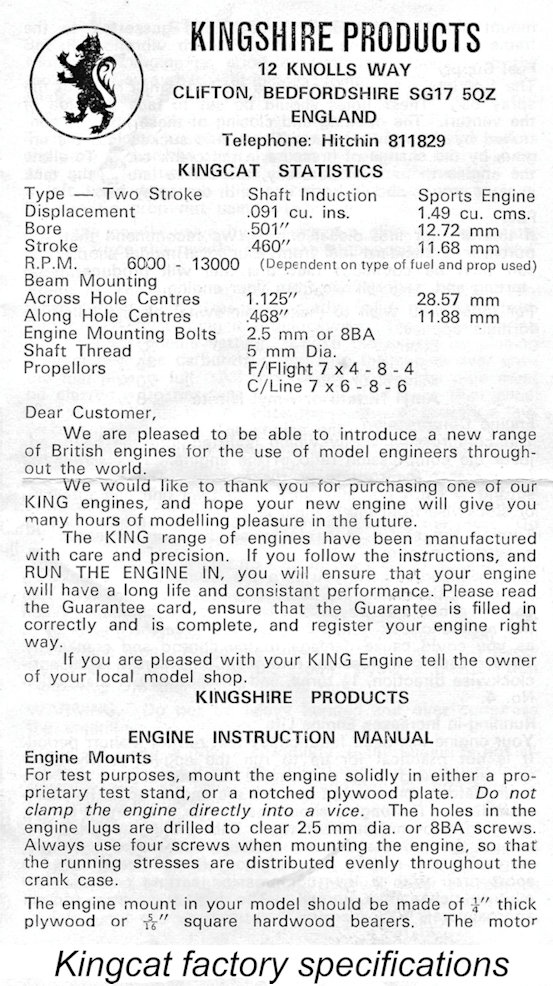

In the instruction leaflets which were supplied with the engines, the manufacturers specifically referred to the series as the King range, although the engines seldom seem to be identified by that name among today's engine collectors. I've taken my lead from the manufacturers by referring to the range as they did. The company logo was certainly a heraldic-style “rampant lion” image, in keeping with the “Royal” connotation!

Former Allen-Mercury (A-M) employee Mick Clarke reported that the Edmonton (North London) premises in which the Allen-Mercury and Merco engines were manufactured were later used in the manufacture of the King range. Inquiries regarding spares and service were directed to a firm called Bi-Metals Ltd. of Bridge Road in Edmonton. Rather oddly, although the engines were apparently manufactured and serviced in Edmonton, the company gave its address as somewhat distant Clifton in Bedfordshire. Marcus Tidmarsh undertook some valuable research into the history of the Bi-Metals company. The firm's full name was BI-METALS (BRITINOL) Ltd. Established in 1949, the company was a family-run business operated by the Heyer family, being located in premises called St. Mary’s Works at 1A Balfour Mews, Bridge Road, Edmonton, London. The building was a new build in about 1949, possibly a re-development following bomb damage to the original Mews buildings during WW2.

This arrangement continued through to mid-1961, when the MERCO business and its assets were sold to Dennis Allen’s D. J. Allen Engineering company which was located nearby at 28 Angel Factory Colony, still in Edmonton. It appears that the manufacture of the MERCO engines by Bi-Metals may well have continued despite this sale, because they continued to be cited as the spares and service providers for the MERCO engines. Indeed, they may have had a hand in the ongoing production of the Allen-Mercury range.

The Bi-Metals company continued in business until 1992, when it was dissolved. Their building at 1A Balfour still existed in 2023, having functioned latterly as a carpet warehouse.

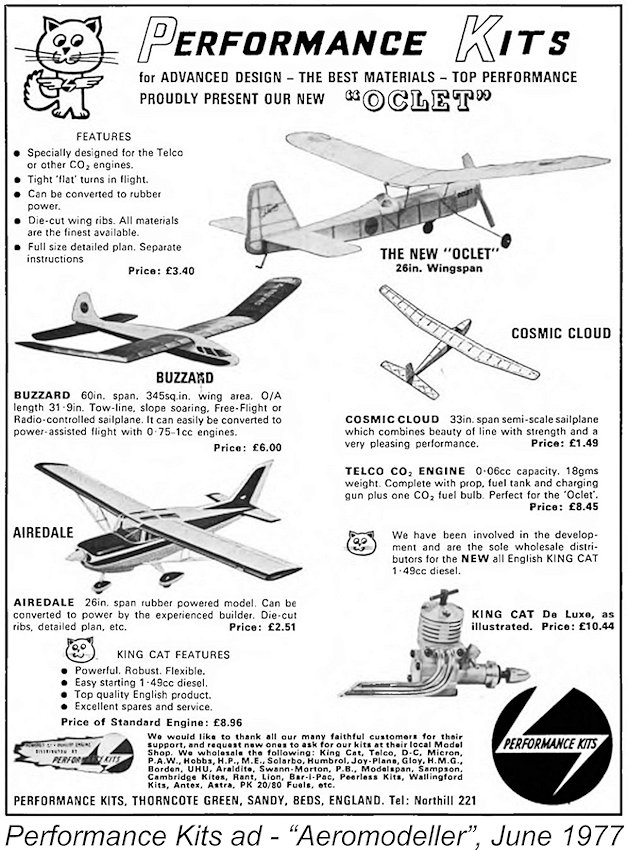

Performance Kits of Thorncote Green, Sandy, Bedfordshire (only 12 km from Clifton) were named as the distributors of the engines, although this arrangement was seemingly short-lived. The Performance Kits advertisement in the same June 1977 issue of the magazine as reproduced below included the Kingcat along with the claim that Performance Kits had been "involved in the development" of the engine. The nature and extent of any such involvement are unknown.

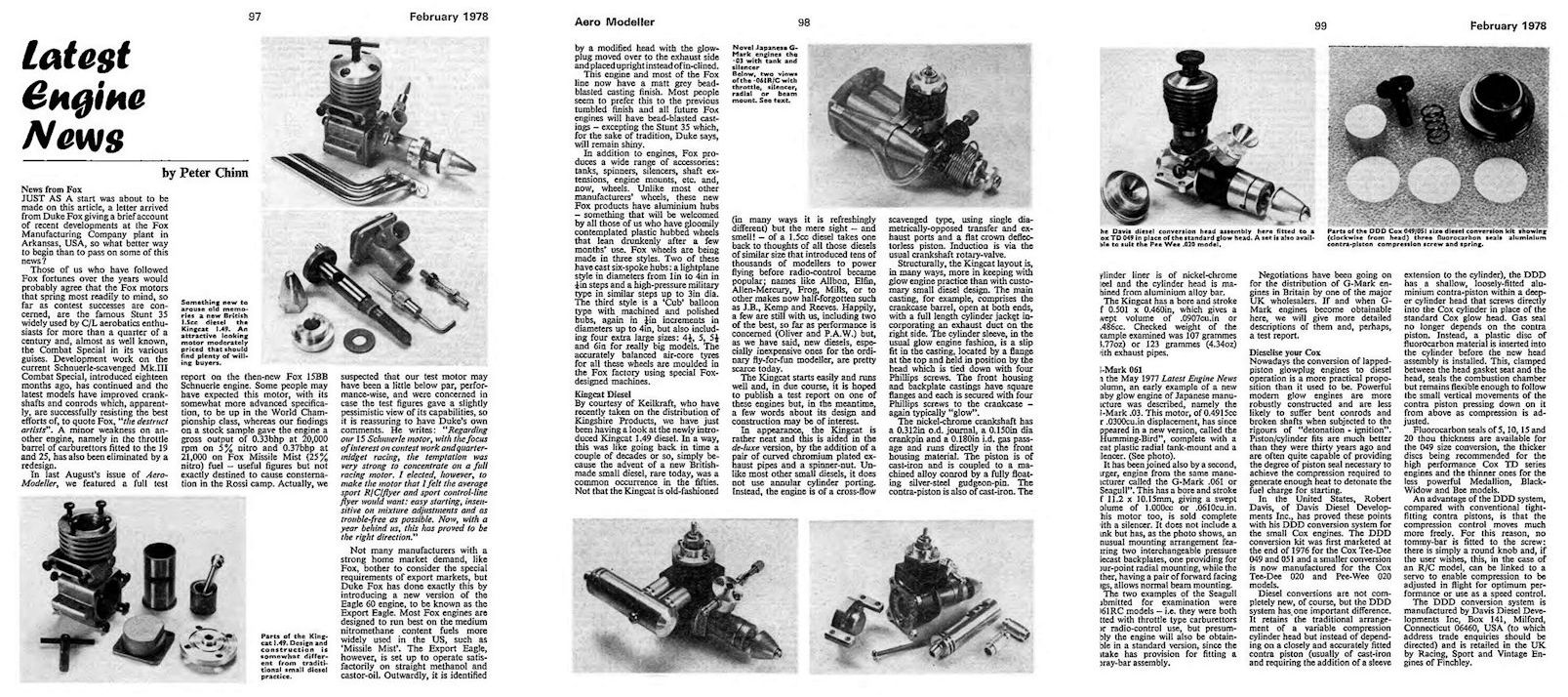

The Glo-Cat evidently appeared in July 1978. It was announced by the manufacturers in September 1978 and was first listed by both Maple Models and Michael's Models in October 1978. Michael's Models listed the Glo-Cat along with the Kingcat for the rest of the range's appearances in their advertising down to February 1981. At some point a further change was made in the distribution arrangements for the Kingshire engines, with the distributor's role being assumed by Ripmax. The first Ripmax advertisement of which I'm aware appeared in the January 1980 issue of "Aeromodeller", the last being placed in the September 1980 issue. Ripmax's tenure evidently didn't last long, apparently being ended by the withdrawal of the range from production in late 1980. My sincere thanks to my good mate Gordon Beeby for his asistance in tracking the range's advertising record. The King Engines in the Modelling Media Peter Chinn included a mini-review of the Kingcat diesel in the February 1978 issue of “Aeromodeller” as reproduced below.

Chinn noted that the engine provided for review had been supplied by KeilKraft, who had "……....recently taken on the distribution of Kingshire Products……….". Evidently the tenure of Performance Kits as Kingshire distributors had been short-lived. Chinn characterized the engine's general design features as "in many ways .....refreshingly different". He reported that the engine started easily and ran well, but no performance figures were provided. He hoped to publish a full test report later.

It's an interesting reflection of the aeromodelling culture into which the Kingcat engines were launched that Chinn felt motivated to comment that examining the Kingcat was "like going back in time a couple of decades or so, simply because the advent of a new British-made small diesel, rare today, was a common occurrence in the fifties". He went on to comment that "the mere sight - and smell! - of a 1.5 cc diesel takes one back to thoughts of all those diesels of similar size that introduced tens of thousands of modellers to power flying before radio control became popular". A sad commentary upon the declining status of diesels within the aeromodelling community even 45 years ago ..................... Chinn was back in the September 1978 issue of “Aeromodeller” with a similar review of the new "Glo-Cat" from Kingshire Products, as reproduced here at the right. This engine shared the castings of the diesel version, although Chinn noted that the crankshaft was larger in diameter, with a square rather than round inlet port and a larger diameter gas passage. It also featured a heavily counter-balanced crankweb as opposed to the plain disc used in the diesel. It was another very attractive engine with its red head and matt grey case. Interestingly, the muffler provided with the Glo-Cat was a conventional expansion chamber type as opposed to the twin-pipe accessory supplied with the earlier Deluxe diesel models. As far as I can discover, the two articles mentioned above were the only commentaries on these engines ever to appear in the contemporary modelling media. No test reports on either model ever materialized. Description

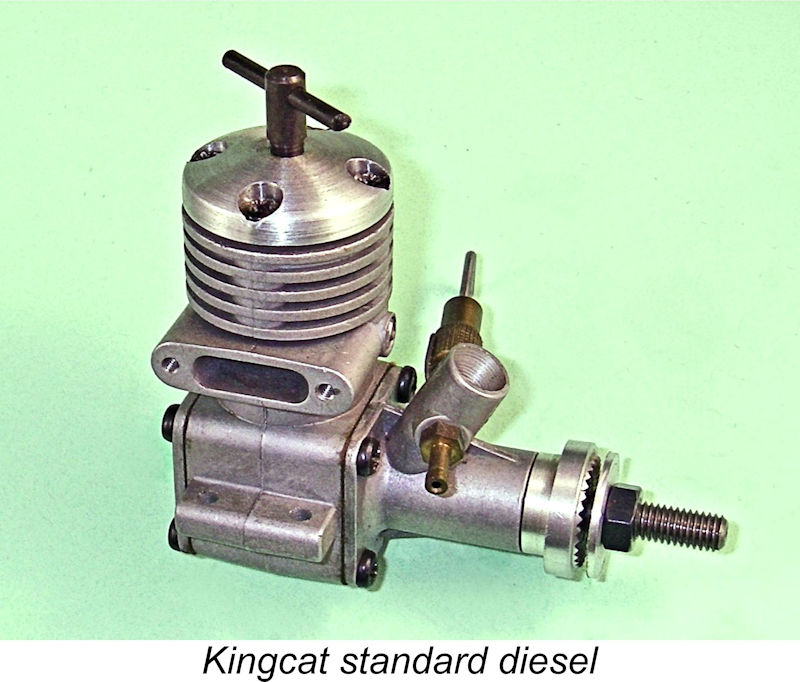

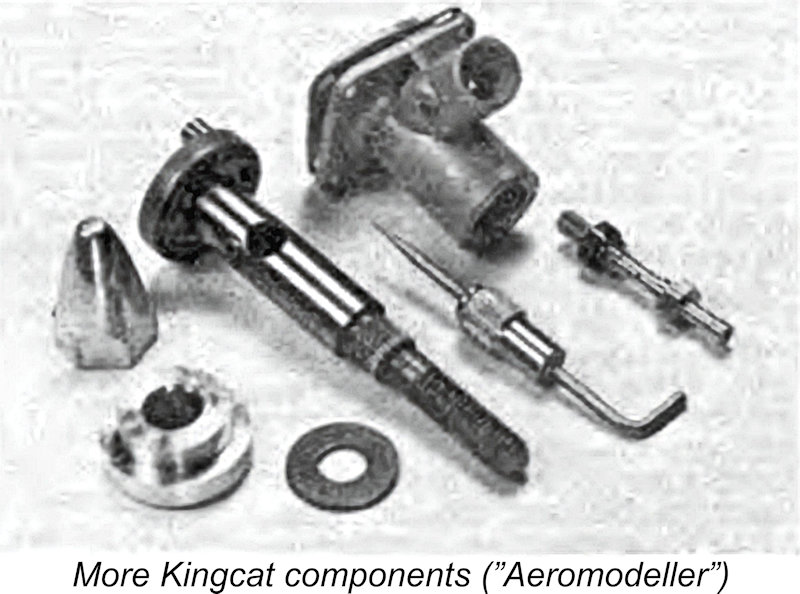

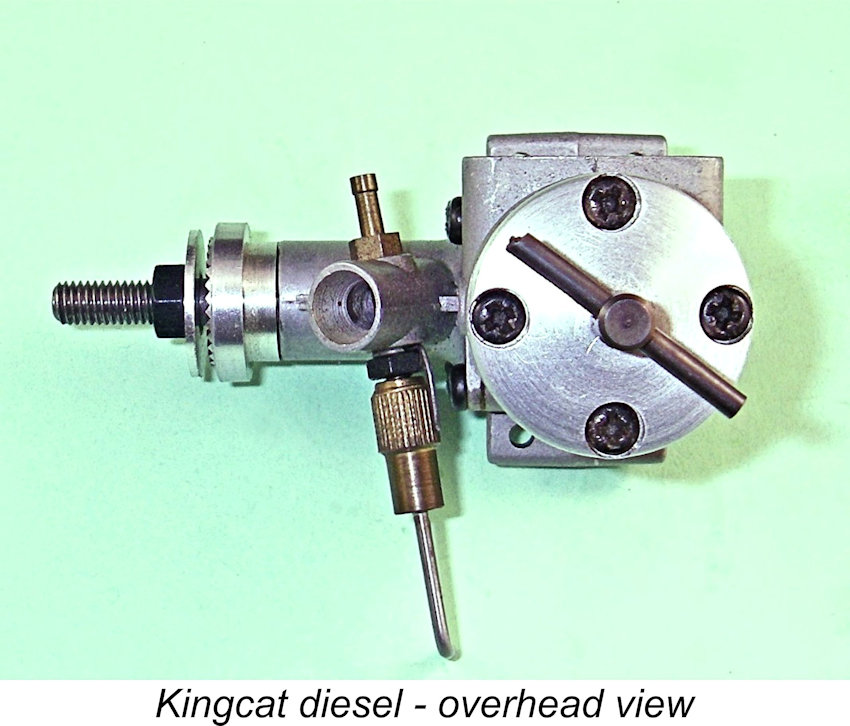

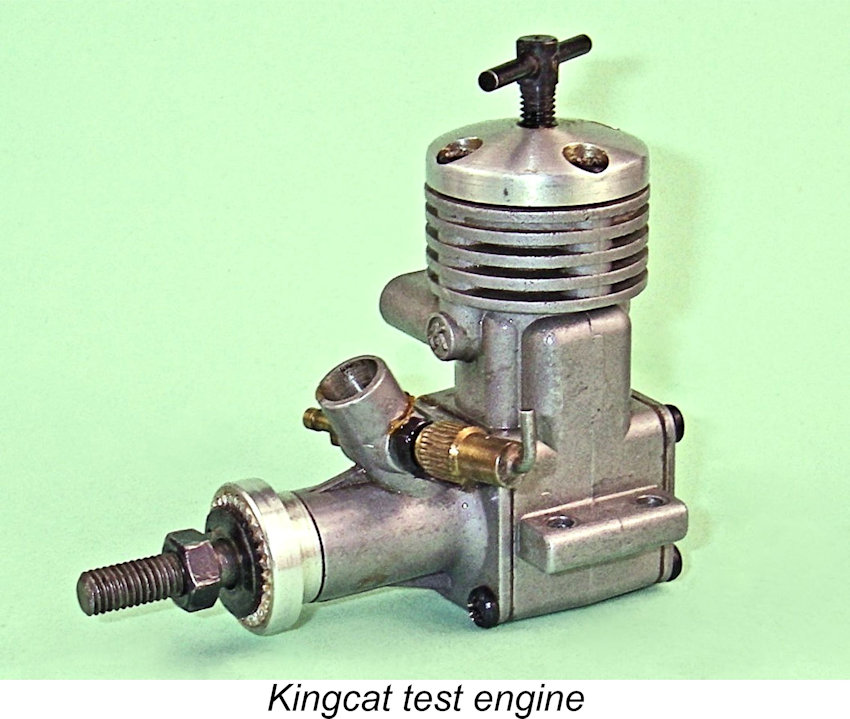

The accompanying “Aeromodeller” component views should help to clarify the engine’s construction. A straight drop-in steel liner was vertically located in the central casting by a top flange. The die-cast case incorporated a single bypass bulge, with both the rear cover and front shaft housing attaching by four screws each. The castings were given an attractive matte finish. The cast-iron piston was flat-topped in recognition of the difficulty of creating a contra-piston which accommodated an upstanding baffle. While The piston featured a crescent-shaped cut-out on the front lower edge of the skirt to clear the crank disk. This was made necessary by the compact, over-square design. The piston was unusual in featuring relatively thin walls which were supplemented by a cylindrical aluminium alloy insert. Presumably the idea was to reduce crankcase volume without having to use a heavy thick-walled cast iron piston.

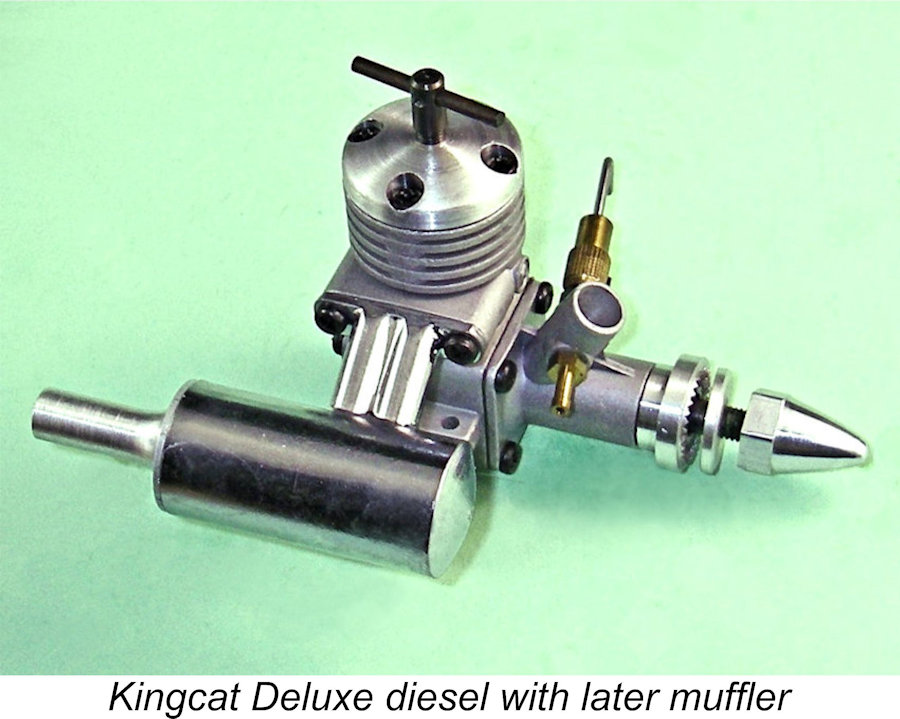

The crankweb was a plain disc with no counterbalancing. The one-piece front-rotary valve (FRV) induction shaft had a main journal diameter of 0.312 in. (7.92 One slightly niggly feature was the fact that the conventional needle valve and spray bar were mounted into the venturi with a slight backwards slant, in this instance to the left. This relatively common design feature inspires mixed feelings. The slant does give some added finger clearance to the prop. Moreover, when the engine is mounted in sidewinder mode as commonly applied to an engine intended primarily for control line use, the needle is placed in a very convenient From the outset, the Kingcat diesel came in two variants - the "Standard" and "Deluxe" models. The only difference was the inclusion with the “Deluxe” model of a set of very sporty-looking chrome-plated “boy racer” twin exhaust pipes and an aluminium spinner nut for an extra £1.48. As far as I can tell, the engines themselves were functionally identical. A more conventional muffler was

Overall, the Kingcat was an extremely attractive and well-made unit. The quality of construction displayed in the Kingshire engines was uniformly high. All of the examples that either Ron Chernich or I ever handled had excellent fits all round, with outstanding compression. Although Peter Chinn reviewed the engines in general terms as summarized above, no actual performance figures were ever released in the contemporary modelling media. As a former user, all that I can say on that score is that the engines were easy starters and very steady performers as At first glance, the Glo-Cat variant of mid 1978 appears to be in essence a simple glow-plug conversion of the original diesel model which preceded it. However, appearances can be deceiving - in reality it is a completely different design, with very few components being interchangeable between the two models. The Glo-Cat has the same bore and stroke as the diesel, also being based upon the same castings. However, the piston is very different, incorporating an upstanding baffle. The deeply-spigoted red-anodized cylinder head is machined internally to provide baffle clearance. The volumetrically-measured compression ratio is around 7 to 1. The manufacturers recommended a mild fuel containing 5% nitromethane.

Although the same casting is used for the front end, the larger journal diameter obviously requires a matching increase in the main bearing diameter. Consequently, the front ends of the glow-plug and diesel models are not interchangeable. Nor for that matter are the cylinders. Quite apart from the absence of a contra-piston, the Glo-Cat cylinder features enlarged cylinder ports which are both wider and slightly deeper.

Overall, the design changes detailed above were clearly intended to improve the breathing ability of the Glo-Cat, perhaps reflecting an opinion on the part of the designer that it might be expected to operate best at higher speeds. The upper limit on successful operation was cited in the instruction leaflet as 15,000 RPM - a considerable increase over the 13,000 RPM maximum speed claimed for the Kingcat diesel. At the very least, the changes seem to confirm the designer’s understanding that a simple conversion from diesel to glow-plug ignition seldom results in the best performer – other changes are required to get the best out of such a switch. That lesson had been well taught in the past, but surprisingly few British designers had taken it to heart. It's nice to encounter one designer who had clearly done so! As a final comment on the Glo-Cat, it's worth observing that as far as the record shows, Kingshire Products never developed a throttle-equipped R/C version of the engine. This seems really strange given the ever-increasing predominance of the R/C field and the evident suitability of the Glo-Cat for such service. It appears to be highly likely that such a variant would have emerged in due course if other circumstances had not put a premature end to all production of the range in late 1980. The Kingcat Diesel on Test Neither the Kingcat nor the Glo-Cat were ever the subject of published test reports. This is rather odd, since the arrival of an all-new British engine was becoming a bit of an "event" by this time. Such engines generally received prompt attention from “Aeromodeller” tester Peter Chinn, particularly if they presented some unusual design features as in this case. There’s probably a story there, but it seems destined to remain untold! I found a comment relating to a YouTube video of a Kingcat Deluxe diesel running (pipes and all!) in which one of the viewers stated that he had a standard Kingcat diesel which he had found to be "gutless", only managing 7,000 RPM on a 7x6 prop. Although this figure sounds a little pessimistic to me, I can confirm on the basis of personal experience that the Kingcat diesel was a rather lacklustre performer as supplied. It's actually entirely possible that this relative lack of performance explains why Peter Chinn never published a test - he may not have wanted to embarrass the manufacturer. It was characteristic of Chinn, especially when reviewing a new British product, that if he envisioned having to make unfavourable comments, he generally chose to say nothing at all.

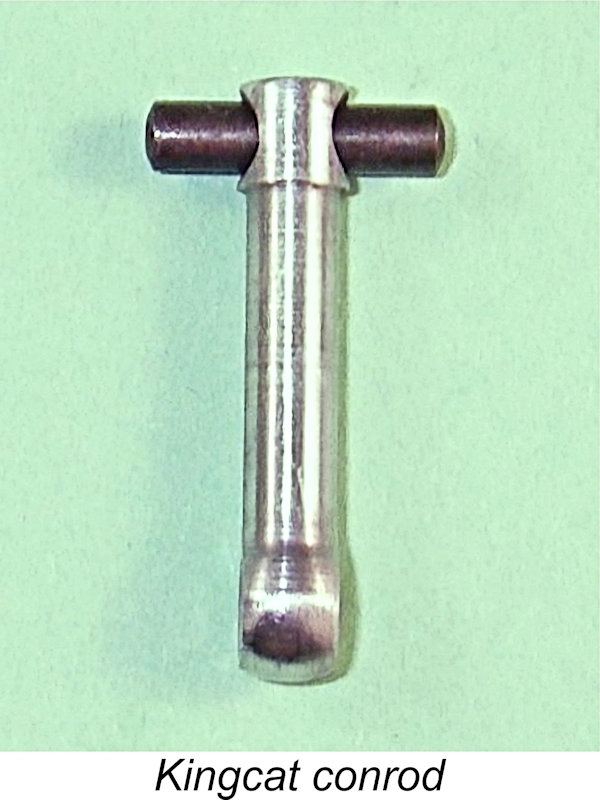

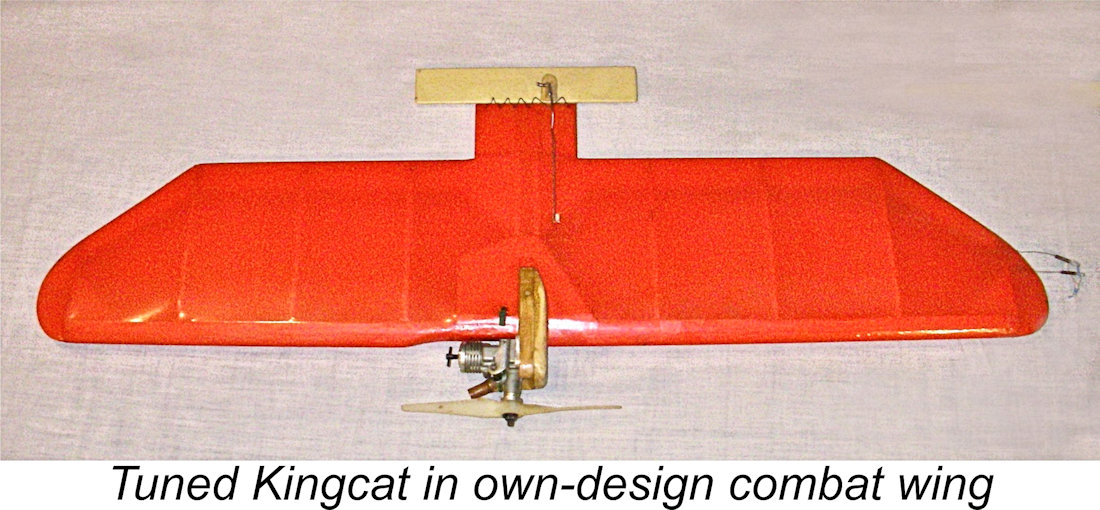

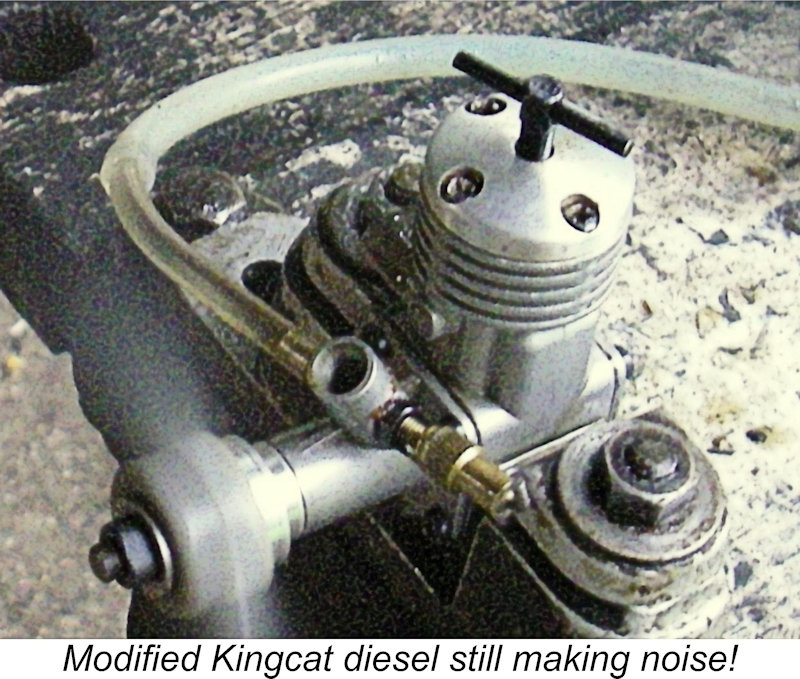

Finding that its performance as supplied wasn’t quite up to the task, I had modified it by smoothing out the bypass passage internally and chamfering the upper edge of the cylinder transfer port at an upward angle both to reduce the blow-down period and direct the incoming charge upwards towards the combustion chamber. I had also extended the crankshaft induction port fore and aft to create more rapid opening and closing, maintaining a round-ended "race track" shape to avoid the development of stress concentrations. I made a new piston having more substantial gudgeon pin bosses, also dispening with the aluminium insert. This component was internally milled to reduce weight to the extent possible. In addition, I made a far sturdier conrod with a small end bearing of more rational length. Finally, I added a little counterbalance by grinding wedges of metal off the crankdisc on the crankpin side.

The original needle valve was shortened to minimize its vulnerability, also being fitted with a sheet metal crash protector while mounted in a model. This precautionary measure explains its survival despite many encounters with the Big Green Thing! Happily the engine was never involved in a potentially engine-damaging mid-air collision. I had a New-in-Box unmodified example of the same model, but testing it would require a full break-in which I was reluctant to give it in view of its New condition. Therefore, the modified diesel would just have to do! If nothing else, it would at least allow me to document the Kingcat’s potential. Although it had seen a good deal of hard running in the air, the engine remained in excellent condition, with very secure compression and minimal play in the rod bearings. The manufacturers recommended 7x4 or 8x4 props for free flight use, with 7x6 or 8x6 props being suggested for control line applications. All of these prop sizes would clearly have to be included in the suite of test props used on this engine. Given this example's extensive previous use, it was obvious that no break-in would be required. I set it up in the stand with an 8x6 airscrew fitted, intending to give it a few shake-down runs after its long layoff and then commence testing beginning with the slowest prop.

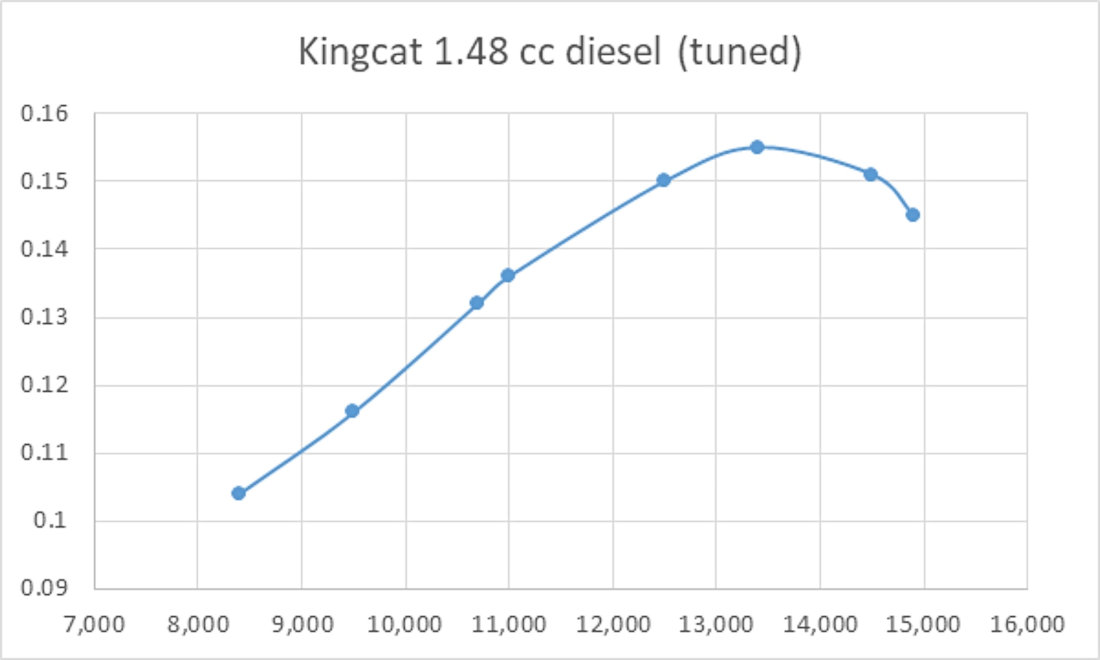

In my recollection, the engine was far less prone to this issue when mounted in a sidewinder orientation, since excess fuel tended to leave by way of the exhaust as oppposed to the bypass. My notes state that the engine was a very dependable starter when mounted in that fashion. As mounted in the test stand, the best approach was to choke only enough to fill the fuel line and then administer a modest "dry" port prime (exhaust port closed), after which flicking commenced immediately. The engine invariably responded to this treatment by starting up very promptly. Once running, response to the controls was found to be excellent - very positive but by no means overly sensitive. The optimal settings were thus very easy to establish with some precision. Once set, both controls held their settings perfectly. Running qualities were outstanding. The engine ran absolutely smoothly at all speeds tested, with no tendency to sag as the cylinder warmed up. Vibration levels were very modest, doubtless helped by the very light piston and counterbalanced crankweb. I never recorded any prop/RPM figures for the engine prior to its modification. All I can say is that I noted a substantial improvement in airborne performance following my ministrations. The modified unit certainly beat the rather woeful figure posted on YouTube, getting an APC 7x6 up to a seemingly effortless 11,000 RPM. Indeed, the engine managed quite acceptable "sports engine" figures for the full range of props tested, as the following data confirms.

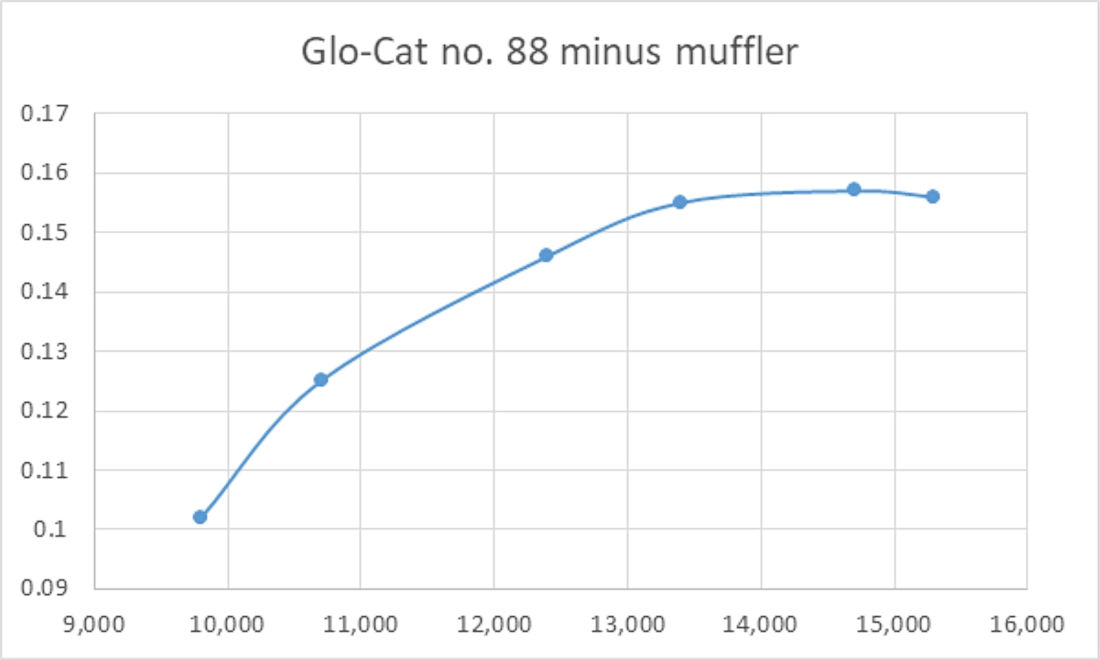

Looking at the above data, the engine's excellent performance in the model using a 7x6 prop is readily explained. With a "fast" 7x6 prop fitted, it would have been operating at close to its peaking speed in the air. It certainly served me well, giving me a lot of enjoyable flying hours back in the day. The performance of the Kingcat diesel left me very curious to know how the Glo-Cat version of the engine would compare. After some soul-searching, I decided to break down and test one of the two New-in-Box Glo-Cat models that I acquired new back in the day and never ran. The chosen example, engine no. 88 according to its papers, was unmodified and unrun since its acquisition in 1979. I felt that a little careful running on an oily fuel wouldn't do any harm, although a break-in of around 30 minutes would be required if the manufacturer's recomendations were to be respected. The manufacturer recommended 7x3 or 8x4 props for free flight use, with 7x4 or 7x6 props being suggested for control line applications. These sizes implied that the Glo-Cat was expected to produce its best results at somewhat higher speeds than the diesel. All of these prop sizes would clearly have to be included in the suite of test props used on this engine. The makers recommended a fuel containing only 5% nitromethane, but I elected to give the engine a helping hand by using an oily 15% blend since I had plenty of such a fuel on hand.

The Glo-Cat turned out to share one characteristic with its diesel companion - it didn't like to be too wet for starting. This is a bit unusual for a glow-plug unit, but there it is - the engine appeared to be unusually susceptible to crankcase flooding if even a little too much fuel was introduced either through the intake or from a port prime. I found that the same starting technique applied to the Glo-Cat - choke to fill the fuel line, administer a "dry" exhaust port prime and get stuck in! Using this approach, starting was extremely easy - it never took more than a few flicks. I followed the maker's directions by putting on 30 minutes in 5 minute runs, keeping the needle a little rich but leaning out briefly right at the end before allowing complete cooling between runs. This ensured that the piston went through the series of full-range heat cycles which are so necessary for a successful break-in of an iron-and-steel piston/cylinder set. At the end of this process, the engine felt superb - clearly all ready for testing. I then proceeded to run the majority of the test props that I had used earlier on the Kingcat diesel. However, I omitted the 8x6 and 8x5 props in view of the glow-plug engine's limited leaned-out ignition timing range - such props might slow the engine down to the point where pre-ignition could become a damaging factor. Better safe than sorry! The engine continued to start very easily throughout the test. Response to the needle was gratifyingly progressive, with no tendency towards excessive sensitivity. Running was absolutely smooth at all speeds, with notably low levels of vibration - the crankshaft counterbalance measures were clearly very effective. It appears that the 15% nitro fuel suited the Glo-Cat very well! The following figures were measured on test.

The level of performance reflected in these results is considerably in excess of my expectations going in! Worthy of particular note is the fact that while the Glo-Cat lags a little behind the diesel at the lower speeds, it has caught up by 13,400 RPM on the 7x4 and is actually a little ahead above 14,000 RPM. It appears to develop a peak output of around 0.158 BHP @ 14,900 RPM, compared with the tuned I'm actually not completely taken aback by the comparative results presented here. I hope that I've made it clear that the Glo-Cat is very far from being a straight glow-plug conversion of the Kingcat diesel model - it is in fact a completely different design, with very few interchangeable components. All of the documented changes reflect a serious and apparently successful attempt to improve the breathing of the Glo-Cat by comparison with the diesel, while the presence of the upstanding piston baffle may be expected to keep more of the incoming mixture in the cylinder where it can be used. In addition, the Glo-Cat had the advantage of that 15% nitro ................... It all adds up to an extremely well-made and attractive 1.5 cc glow-plug motor having a sprightly performance by 1970's sports engine standards, and one which should give long and satisfactory service. For general-purpose use, I would rate it very highly! Conclusion I mentioned at the outset that the Kingshire Products enterprise was apparently a privately-owned concern having a single individual serving as owner/manager. The sudden seemingly premature demise of the range apparently resulted from the unexpected death of this individual in 1980. A great pity - this was a quality range with plenty of development potential. The Kingcat and Glo-Cat engines were in production for only some 3 years. A fair number must have been produced during that period - the serial numbers recorded above certainly seem to imply that the number manufactured must have run into the multiple thousands. However, oddly enough they show up relatively infrequently today on the collector market, although examples do go on offer from time to time. Any enthusiast acquiring one will be well satisfied with his acquisition! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN April 2004 This revised edition published here January 2024 |

||

| |

In this article I’ll share what I know about a somewhat ephemeral pair of British 1.5 cc engines which appeared in mid 1977 and were gone by late 1980. These are the Kingcat diesel and Glo-Cat glow-plug models from Edmonton in North London, England.

In this article I’ll share what I know about a somewhat ephemeral pair of British 1.5 cc engines which appeared in mid 1977 and were gone by late 1980. These are the Kingcat diesel and Glo-Cat glow-plug models from Edmonton in North London, England. The engines covered in this article were produced by a company called Kingshire Products. A search by my valued English friend and colleague Marcus Tidmarsh revealed that no company was ever formally registered under this name - it appears to have been nothing more than a trade-name used by some as-yet unidentified individual.

The engines covered in this article were produced by a company called Kingshire Products. A search by my valued English friend and colleague Marcus Tidmarsh revealed that no company was ever formally registered under this name - it appears to have been nothing more than a trade-name used by some as-yet unidentified individual.

The company’s original activity was the production of spirit blowlamps and other soldering equipment. The accompanying 1955 advertisement typifies their offerings in this line of business. In 1955 they expanded their activities to include the manufacture of a range of petrol-driven heavy-duty power tools. They first became involved with model engines in late 1958, when Bill Morley and Ron Checksfield arranged for production of the then-new MERCO 29 and 35 stunt glow-plug engines to take place at 1A Balfour Mews. Their venture's full name was Model Engine Research Co. Ltd., but the actual manufacturing was almost certainly undertaken using Bi-Metals premises and equipment.

The company’s original activity was the production of spirit blowlamps and other soldering equipment. The accompanying 1955 advertisement typifies their offerings in this line of business. In 1955 they expanded their activities to include the manufacture of a range of petrol-driven heavy-duty power tools. They first became involved with model engines in late 1958, when Bill Morley and Ron Checksfield arranged for production of the then-new MERCO 29 and 35 stunt glow-plug engines to take place at 1A Balfour Mews. Their venture's full name was Model Engine Research Co. Ltd., but the actual manufacturing was almost certainly undertaken using Bi-Metals premises and equipment.  Bi-Metals continued to occupy the premises at 1A Balfour Mews throughout the entire period under discussion here. They were still very much a going concern when they began to be cited as the spares and service agents for the Kingshire engines in mid-1977. This makes it appear very likely that they were the actually manufacturers of the Kingshire range. Such a view would make complete sense of Mick Clarke’s previously-recorded recollection that the same Edmonton premises were used by both D. J. Allen Engineering and the Kingcat manufacturers. It would also make sense of their being cited as the spares and service providers for the engines.

Bi-Metals continued to occupy the premises at 1A Balfour Mews throughout the entire period under discussion here. They were still very much a going concern when they began to be cited as the spares and service agents for the Kingshire engines in mid-1977. This makes it appear very likely that they were the actually manufacturers of the Kingshire range. Such a view would make complete sense of Mick Clarke’s previously-recorded recollection that the same Edmonton premises were used by both D. J. Allen Engineering and the Kingcat manufacturers. It would also make sense of their being cited as the spares and service providers for the engines.  Returning now to 1977, all of the engines in the King range which appeared during that year were 1.48 cc designs. The initial product, the Kingcat diesel, was launched in the June 1977 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine through the placement of the accompanying manufacturer's advertisement. The cited price of the basic engine was £8.96, with the Deluxe version selling for £10.44. The same advertisement appeared in the following two issues as well.

Returning now to 1977, all of the engines in the King range which appeared during that year were 1.48 cc designs. The initial product, the Kingcat diesel, was launched in the June 1977 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine through the placement of the accompanying manufacturer's advertisement. The cited price of the basic engine was £8.96, with the Deluxe version selling for £10.44. The same advertisement appeared in the following two issues as well.  The range appeared a couple more times with a small picture in the Performance Kits display ads down to February 1978. At that point, the distribution of the range was taken over by KeilKraft. The engines were offered for a few years by various retailers advertising in “Aeromodeller”, including Maple Models (Luton), Aero Nautical Models (Camden Town), Howes Model Shop (Oxford), M. A. Chapman (Nottingham), The Model Shop (Guernsey) and Michael's Models of Finchley. The latter company was the most persistent promoter, listing the Kingcat almost every month from August 1977 to February 1981 as well as the Glo-Cat from October 1978 onwards. I purchased my own examples new in 1978 – 79 by mail order from Michael’s Models. The Model Shop (Guernsey) was almost as consistent, listing the Kingcat almost every month between April 1978 to January 1981. Oddly enough, they never listed the Glo-Cat.

The range appeared a couple more times with a small picture in the Performance Kits display ads down to February 1978. At that point, the distribution of the range was taken over by KeilKraft. The engines were offered for a few years by various retailers advertising in “Aeromodeller”, including Maple Models (Luton), Aero Nautical Models (Camden Town), Howes Model Shop (Oxford), M. A. Chapman (Nottingham), The Model Shop (Guernsey) and Michael's Models of Finchley. The latter company was the most persistent promoter, listing the Kingcat almost every month from August 1977 to February 1981 as well as the Glo-Cat from October 1978 onwards. I purchased my own examples new in 1978 – 79 by mail order from Michael’s Models. The Model Shop (Guernsey) was almost as consistent, listing the Kingcat almost every month between April 1978 to January 1981. Oddly enough, they never listed the Glo-Cat.

The problem arising from this design approach was that the bosses in the cast iron portion of the piston to accommodate the gudgeon (wrist) pin were necessarily very short, with a considerable unsupported length of gudgeon pin in between. This would give rise to amplified cyclic bending stresses during operation. Another legitimate criticism of the design was the turned aluminium alloy conrod, which featured a small end bearing that was far too short to encourage good wearing qualities, also focusing loadings on the centre of the gudgeon pin rather than distributing them.

The problem arising from this design approach was that the bosses in the cast iron portion of the piston to accommodate the gudgeon (wrist) pin were necessarily very short, with a considerable unsupported length of gudgeon pin in between. This would give rise to amplified cyclic bending stresses during operation. Another legitimate criticism of the design was the turned aluminium alloy conrod, which featured a small end bearing that was far too short to encourage good wearing qualities, also focusing loadings on the centre of the gudgeon pin rather than distributing them.

The packaging for the Kingcat was quite conventional. The nicely-labelled box was made from rather thin card stock without any internal support. A small folded instruction leaflet provided adequate operational instructions for the beginner. A nice touch included with the papers was a note regarding the prop used to factory-test and set the compression screw for the particular engine, assuming that it had not been fiddled with by some ham-fisted shopper!

The packaging for the Kingcat was quite conventional. The nicely-labelled box was made from rather thin card stock without any internal support. A small folded instruction leaflet provided adequate operational instructions for the beginner. A nice touch included with the papers was a note regarding the prop used to factory-test and set the compression screw for the particular engine, assuming that it had not been fiddled with by some ham-fisted shopper!

The crankshaft too is very different, sporting a crankdisc which features a substantial crescent-shaped counterbalance and a longer crankpin. The main journal diameter is increased to 0.345 in. (8.76 mm), while the diameter of the internal gas passage is significantly increased to 0.250 in. (6.35 mm). The induction port is considerably enlarged, being rectangular rather than round and providing a considerably lengthened induction period together with more rapid opening and closing.

The crankshaft too is very different, sporting a crankdisc which features a substantial crescent-shaped counterbalance and a longer crankpin. The main journal diameter is increased to 0.345 in. (8.76 mm), while the diameter of the internal gas passage is significantly increased to 0.250 in. (6.35 mm). The induction port is considerably enlarged, being rectangular rather than round and providing a considerably lengthened induction period together with more rapid opening and closing.

Be that as it may, I felt that it was incumbent upon me to put an example through its paces on the test bench. Unfortunately, the candidate diesel unit which was available for testing could not by any means be viewed as a standard unmodified example. I had used the engine quite extensively in a series of ½A (British 1.5 cc class) combat models, a class that I and my club-mates flew strictly for low-key fun. It flew my own-design "Root Beer Special" very well indeed.

Be that as it may, I felt that it was incumbent upon me to put an example through its paces on the test bench. Unfortunately, the candidate diesel unit which was available for testing could not by any means be viewed as a standard unmodified example. I had used the engine quite extensively in a series of ½A (British 1.5 cc class) combat models, a class that I and my club-mates flew strictly for low-key fun. It flew my own-design "Root Beer Special" very well indeed.  This work had released a noticeably more lively performance. Thereafter, the engine served me well for a number of years in a series of models, showing itself to be a smooth and consistent runner in the air. It was by no means an all-out contest performer, but it did deliver an above-average sport-flying performance, also handling very well. No mechanical failures were experienced during its fairly extended period of use.

This work had released a noticeably more lively performance. Thereafter, the engine served me well for a number of years in a series of models, showing itself to be a smooth and consistent runner in the air. It was by no means an all-out contest performer, but it did deliver an above-average sport-flying performance, also handling very well. No mechanical failures were experienced during its fairly extended period of use.  Having quite extensive prior experience with this engine, I had both my memories and the notes in my log-book to provide some guidance. The engine didn't like to be too wet for starting - it was relatively easy to flood the crankcase. This was particularly true if an exhaust prime was given - the absence of a baffle tended to encourage the prime to shoot straight across the piston crown and head down the bypass into the crankcase.

Having quite extensive prior experience with this engine, I had both my memories and the notes in my log-book to provide some guidance. The engine didn't like to be too wet for starting - it was relatively easy to flood the crankcase. This was particularly true if an exhaust prime was given - the absence of a baffle tended to encourage the prime to shoot straight across the piston crown and head down the bypass into the crankcase.

The modified Kingcat seems to have managed a peak output of around 0.156 BHP @ 13,700 RPM. My read from these figures is that the standard Kingcat must have been a rather mediocre performer at best. I suspect that the main culprit was the absence of a piston baffle, which would have encouraged the short-circuiting of fuel mixture from the transfer to the exhaust without ever getting burned. With such a piston, it's necessary for the transfer port to exercise directional control over the incoming mixture without any help from a baffle, as in the

The modified Kingcat seems to have managed a peak output of around 0.156 BHP @ 13,700 RPM. My read from these figures is that the standard Kingcat must have been a rather mediocre performer at best. I suspect that the main culprit was the absence of a piston baffle, which would have encouraged the short-circuiting of fuel mixture from the transfer to the exhaust without ever getting burned. With such a piston, it's necessary for the transfer port to exercise directional control over the incoming mixture without any help from a baffle, as in the  For the break-in runs I fitted an 8x4 prop. The engine retains its original glow-plug, but for conservation reasons I elected to use a standard Fox plug for these tests.

For the break-in runs I fitted an 8x4 prop. The engine retains its original glow-plug, but for conservation reasons I elected to use a standard Fox plug for these tests.