|

|

Prague Pioneer – the Půrok 2.0cc Diesel

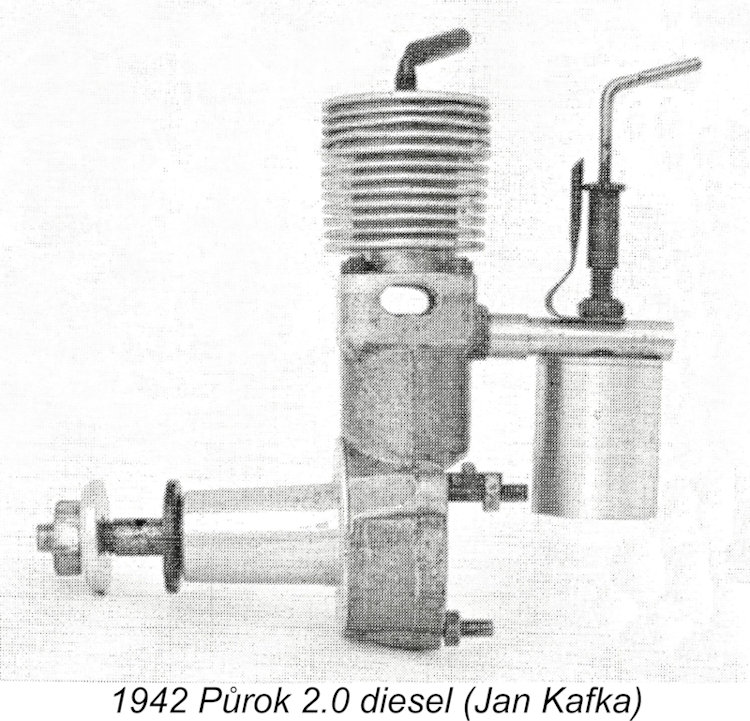

The illustrated engine came to me in 1981 as a sweetener in a broader trade with the late prominent English collector Jack Law. Neither Jack nor I knew what it was – merely that it was an unusual design with a distinctly Eastern European flavor along with a somewhat “home-made” feel. At the time when I first brought it to the attention of my late mate Ron Chernich in 2007, I still had no idea what it was! Neither did Ron, but he was sufficiently intrigued to take steps to find out. Accordingly, the engine was posted on Ron’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website in September 2007 as a “wotizit”. Almost immediately, we heard back from no less an authority than Jiří Linka, co-author of the extremely useful 2004 reference book "České Modelářské Motory" (Czech Model Engines) along with Jan Kafka. Jiří positively identified the engine seen in the accompanying illustrations as a possibly one-off variant of the Půrok 2.0 diesel first constructed in occupied Czechoslovakia (now Czechia) during the period late 1941 to early 1942. This makes it one of the very earliest two-stroke compression ignition (“diesel”) model airplane engines made outside of Switzerland, where the concept is generally accepted to have originated. For more information on that topic, see Maris Dislers’ excellent article on the origins and spread of model diesels in Europe.

The introduction to the previously-referenced book by Jiří Linka and Jan Kafka explains that even before World War II, model engines had been very difficult to obtain in Czechoslovakia. The extremely limited number that were available were all spark ignition models which were either self-constructed or produced in very small production runs for local distribution, generally by those with access to machinery normally applied to other purposes. Gustav Bušek of Prague was a notable early producer of such engines.

At this stage, Půrok specialized in the manufacture of propellers for rubber-powered models, preceding Bušek in this activity. He later became actively involved in full-sized slope-soaring (gliding), but was “grounded” following the German occupation which commenced in October 1938 with the annexation of the Sudetenland. His association with Gustav Bušek catalyzed an increasing interest in model engines at this time given his inability to continue full-sized flying. Following the commencement of the German occupation, Czechoslovakia became a major producer of military materiel for the Germans. For this reason, the German authorities initially adopted a relatively restrained attitude towards the population at large, whom they needed to keep working productively in the various fields of war production.

My valued Czech informant Libor Janouch shared a recollection that the making of model engines was illegal during the German occupation, since it involved the use of light alloys which were required for the higher-priority activity of military equipment manufacture. Anyone making such engines risked imprisonment, particularly since the Germans maintained a security presence at facilities engaged in military production, primarily to discourage acts of industrial sabotage but also to prevent the unauthorized "diversion" of materials. Despite this, a few brave souls continued to produce such engines in very small numbers. Antonín Půrok became one such individual.

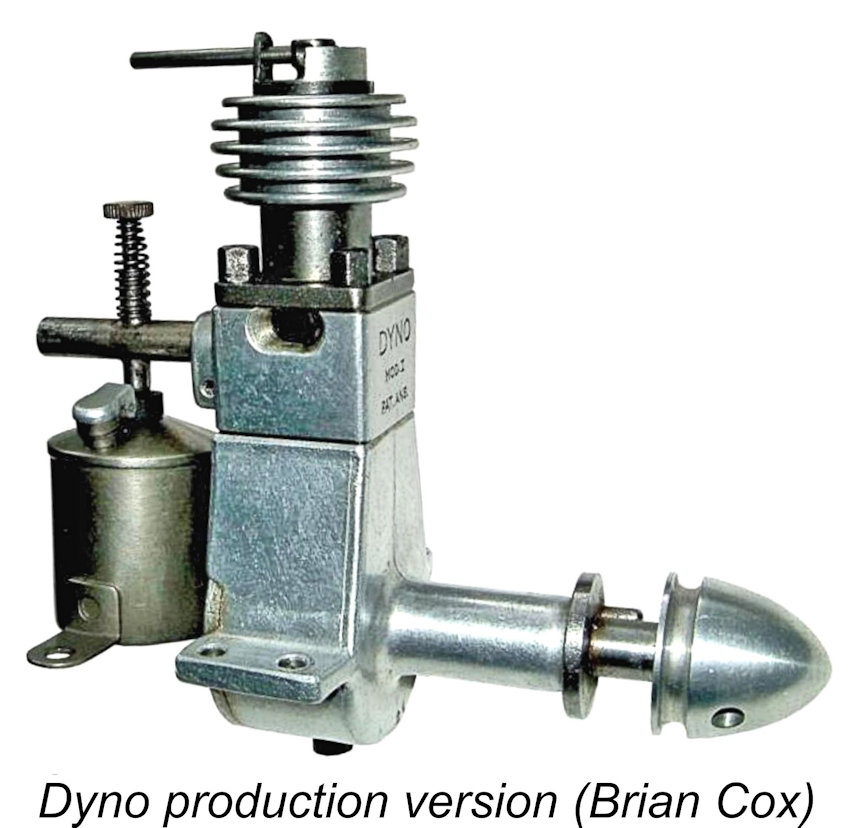

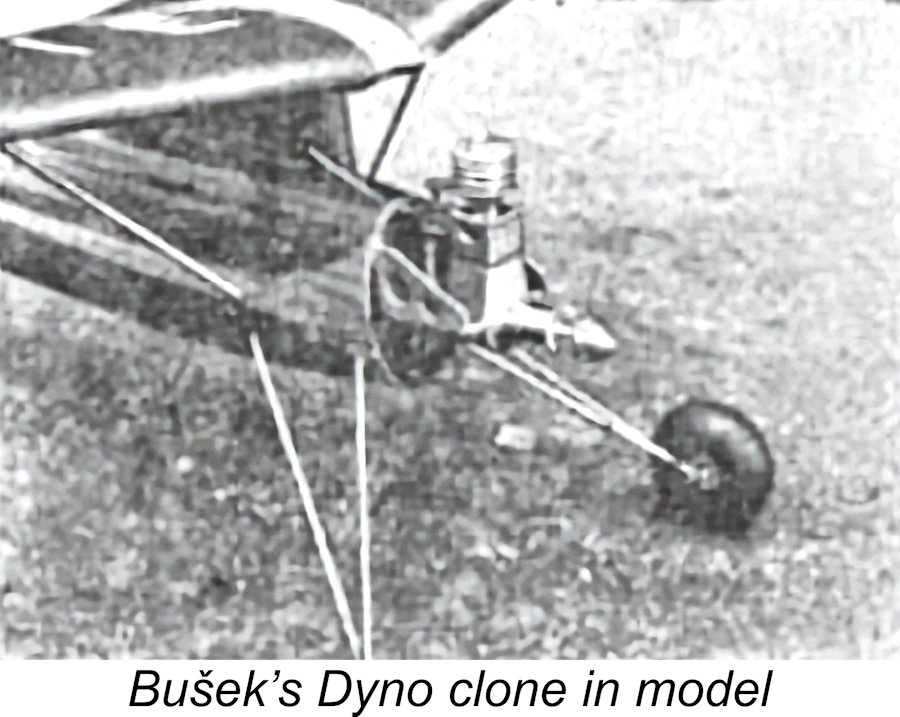

Given the prevailing circumstances, Půrok’s activity must have been very much an under-the-table venture. Although the hand-filing and fitting could have been done at home, some use must surely have been made of machine tools at Půrok’s workplace, with management evidently turning a blind eye. According to Jiří Kalina (writing in 1986), Půrok’s first effort was not a success. However, in the meantime his associate and fellow engine-builder Gustav Bušek had somehow managed to acquire an actual example of the Dyno. After studying this unit in the metal, Půrok made a few changes to his design which resolved the engine’s previous problems, notably the addition of a second exhaust port. Incidentally, this sequence of events is consistent with Kalina’s stated contention that Půrok’s diesel development efforts preceded those of Bušek.

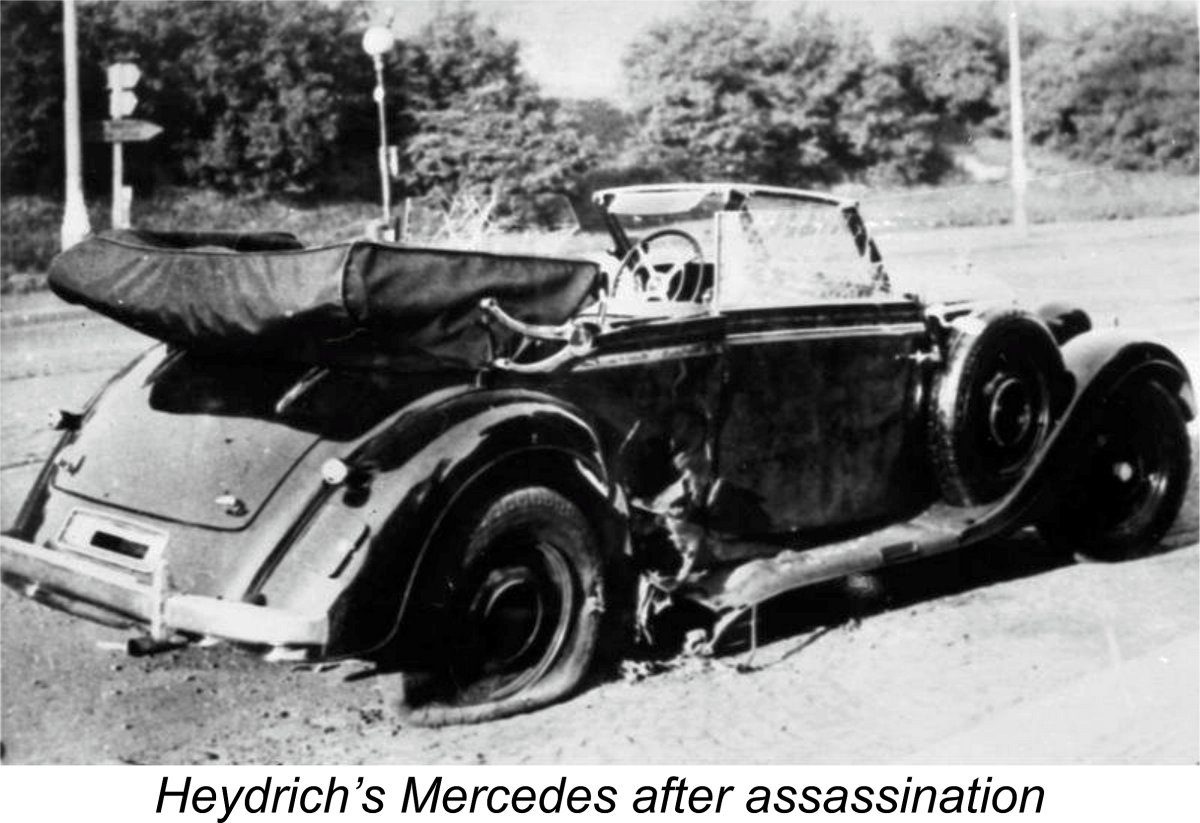

The clandestine illegal manufacture of model engines in a plant which was undoubtedly engaged primarily in producing materiel for the Nazi war effort was a bold move. A certain level of tolerance on the part of plant management is clearly implied – it’s otherwise hard to see how Půrok could have got away with it for as long as he did. However, it appears that in May 1942 he was finally caught, subsequently spending six months or so in a German prison. As matters turned out, being thrown into jail at this time may have been a lucky break for Půrok! In September 1941, the country had come under the control of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, aka the “Butcher of Prague”, the "Blond Beast" or "Hangman Heydrich", who had previously founded the dreaded German Sicherheitsdienst (SD - Security Service), and later organized the November 1938 Kristallnacht anti-Semitic demonstrations. Having decided that the “soft” approach to the Czech population was not working, in September 1941 Hitler appointed Heydrich to the post of Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia in the former Czechoslovakia, with a brief to apply a considerably firmer hand.

On May 27th, 1942, a small group of Czech partisans trained in Scotland and parachuted into Czechoslovakia mounted an assassination attempt as Heydrich drove an established route in an open-top car to his Prague offices. Heydrich was wounded and died on June 4th from blood poisoning brought on by fragments of auto upholstery, steel and his own uniform that had lodged in his spleen. Retaliation was swift, extreme and too violent to bear detailed repetition here. Suffice it to say that as many as 5,000 innocent Czechs were murdered indiscriminately in reprisal, while over 13,000 others were arrested and imprisoned arbitrarily. Many of them did not survive the war. Tolerance of side-lines like Půrok's enginemaking would seem to have been another casualty. Although Půrok was released from jail in November 1942 and returned to working at the Pragovka factory, he made no more engines at that time, presumably being a marked man. Instead, he wisely kept a low profile until after the war, when he returned to full-size soaring. Meanwhile, Gustav Bušek had evidently found his original Dyno to be a

According to Jiří Kalina, these engines were manufactured by Půrok himself. However, Půrok then abandoned modelling completely, returning to his former full-sized gliding activities, in which he achieved considerable success. Since he was evidently not concerned with having his name attached to these engines, they seem to have been sold for the most part as “Uran” (Uranium) engines. Moučka subsequently marketed a revised barstock model which was sold under his own name.

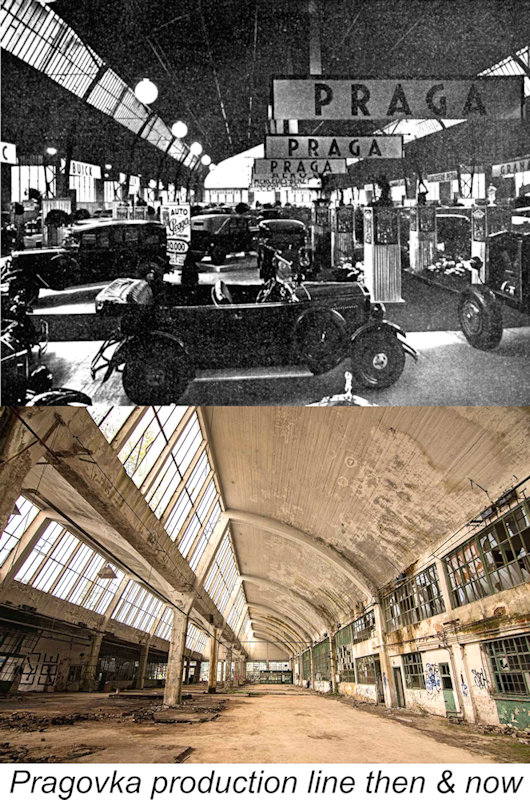

The Pragovka car factory at which Půrok had worked remained in operation after WW2, even surviving the January 1993 partitioning of Czechoslovakia into the independent Czech and Slovak Republics. However, changing business conditions forced the closure of the facility in 2003. The Praga company remains very much in business today (2024), albeit utilizing updated production facilities located elsewhere. For many years the sprawling Pragovka facility stood derelict and abandoned on the outskirts of Prague. However, it became recognized as a heritage site, and recent years have seen efforts aimed at revitalizing the site through the establishment of an arts district on the property along with facilities for film screenings, concerts and exhibitions. There's even a retro-themed restaurant! Further site re-development is planned.

My European informants believed that this engine may be a modification by Bušek of the basic Půrok design - the location of the joint between the crankcase and upper cylinder is characteristic of Bušek's early work. Regardless, the identification of the original designer is beyond question and the engine, unique in Jiří Linka’s extensive experience, is a historically priceless artefact with a more-than-usually interesting history. ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First edition written and published by Ron Chernich on MEN January 2008 This extensively revised edition by Adrian C. Duncan published here May 2024 |

| |

This article won’t take long to write, because there’s not that much to tell! This account is far more of a human-interest story than a model engine review. Its chief value is the light which it throws upon the challenges facing model aircraft enthusiasts in wartime Czechoslovakia (as Czechia was then) and the remarkable courage and determination of those enthusiasts in persevering in the face of these challenges.

This article won’t take long to write, because there’s not that much to tell! This account is far more of a human-interest story than a model engine review. Its chief value is the light which it throws upon the challenges facing model aircraft enthusiasts in wartime Czechoslovakia (as Czechia was then) and the remarkable courage and determination of those enthusiasts in persevering in the face of these challenges. Ron’s

Ron’s  In the accompanying article published

In the accompanying article published  At this time Antonín Půrok was apparently employed at the automobile plant of a major Czech heavy engineering company called

At this time Antonín Půrok was apparently employed at the automobile plant of a major Czech heavy engineering company called

Perhaps as a compensatory activity given the ban on his slope soaring activities, Půrok had maintained an active interest in aeromodelling. Word of the mid-1941 appearance of the Dyno 1 diesel in neutral Switzerland filtered through rather quickly to the Czech aeromodelling community, and Jiří Kalina stated that Půrok managed somehow to obtain a copy of a brochure describing the engine. Using the illustrations in that brochure as his sole guide, he constructed his own diesel engine of 2 cc displacement beginning in late 1941. He was doubtless encouraged to try this by the impossibility of obtaining supplies of suitable rubber at the time, making the flying of rubber-powered models impracticable. Engine-powered models were the only option apart from gliders.

Perhaps as a compensatory activity given the ban on his slope soaring activities, Půrok had maintained an active interest in aeromodelling. Word of the mid-1941 appearance of the Dyno 1 diesel in neutral Switzerland filtered through rather quickly to the Czech aeromodelling community, and Jiří Kalina stated that Půrok managed somehow to obtain a copy of a brochure describing the engine. Using the illustrations in that brochure as his sole guide, he constructed his own diesel engine of 2 cc displacement beginning in late 1941. He was doubtless encouraged to try this by the impossibility of obtaining supplies of suitable rubber at the time, making the flying of rubber-powered models impracticable. Engine-powered models were the only option apart from gliders. According to Jiří Linka, a few more examples of the engine were made during the first four or five months of 1942, presumably for the use of Půrok and his friends. Jiří believed that Gustav Bušek assisted Půrok in this activity. These engines featured bore and stroke dimensions of 12 mm and 17.6 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.99 cc. They weighed around 130 gm (4.58 ounces) with tank.

According to Jiří Linka, a few more examples of the engine were made during the first four or five months of 1942, presumably for the use of Půrok and his friends. Jiří believed that Gustav Bušek assisted Půrok in this activity. These engines featured bore and stroke dimensions of 12 mm and 17.6 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.99 cc. They weighed around 130 gm (4.58 ounces) with tank. Heydrich had immediately declared martial law, resulting in the subsequent arrest and summary execution of significant numbers of Czech nationals suspected of anti-German sentiments. Heydrich had also taken time out to organize and chair the

Heydrich had immediately declared martial law, resulting in the subsequent arrest and summary execution of significant numbers of Czech nationals suspected of anti-German sentiments. Heydrich had also taken time out to organize and chair the

At the end of the war, a short series of some 20 examples of the Půrok 2.0 diesel were produced with minor variations and sold through the M. K. Moučka model shop in Prague. The accompanying advertisement is noteworthy for its use of an image of a smiling youth sporting an unambiguous Hitler hairstyle! One would have thought that such an image would not be viewed positively at that time!

At the end of the war, a short series of some 20 examples of the Půrok 2.0 diesel were produced with minor variations and sold through the M. K. Moučka model shop in Prague. The accompanying advertisement is noteworthy for its use of an image of a smiling youth sporting an unambiguous Hitler hairstyle! One would have thought that such an image would not be viewed positively at that time!  Antonín Půrok remained at the pinnacle of his chosen sport of slope soaring for many years, never returning to model engine production. He died in 1986 at the age of 71. Gustav Bušek, on the other hand, went on to become one of the most prolific model engine manufacturers in Czechoslovakia. As the manufacturer of the Buš series of engines, Jiří Kalina rightly rated him as a "legendary" Czech engine designer.

Antonín Půrok remained at the pinnacle of his chosen sport of slope soaring for many years, never returning to model engine production. He died in 1986 at the age of 71. Gustav Bušek, on the other hand, went on to become one of the most prolific model engine manufacturers in Czechoslovakia. As the manufacturer of the Buš series of engines, Jiří Kalina rightly rated him as a "legendary" Czech engine designer. Returning for one final time to our subject engine, the design of the illustrated unit is very close to that of the examples seen in the images which accompany both the Moučka advertisement and the previously-cited 1986 article by Jirí Kalina. The tank is identical, as is the general layout, although there are differences in the location of the joint between the crankcase and cylinder jacket and the treatment of the exhaust apertures. The engine has been bench-tested and found to start and run very well despite its rather worn condition – it seems to have had plenty of use. A 9x6 prop seems to suit it nicely.

Returning for one final time to our subject engine, the design of the illustrated unit is very close to that of the examples seen in the images which accompany both the Moučka advertisement and the previously-cited 1986 article by Jirí Kalina. The tank is identical, as is the general layout, although there are differences in the location of the joint between the crankcase and cylinder jacket and the treatment of the exhaust apertures. The engine has been bench-tested and found to start and run very well despite its rather worn condition – it seems to have had plenty of use. A 9x6 prop seems to suit it nicely.