|

|

An Untold Story - Brazilian Model Aero Engines

With population figures of that magnitude, it would seem to be a logical assumption that the continent must have been home to a significant number of power modelling enthusiasts over the years. This in turn might reasonably be expected to create a viable domestic market for model engines, at least in some of the larger South American countries and population centres. And indeed, the existence of a number of model engine marques from several such countries has long been authoritatively attested, although details have been sadly lacking in most cases, as are examples of the engines in question. Overall, the amount of information on South American engines which has hitherto been available to the English-speaking model engine enthusiast is remarkably sparse. The country of Brazil (officially the Federative Republic of Brazil) is a case in point - search as I may, I can find very little English-language information on model engines originating in that country. Doubtless language barriers have played a significant role in giving rise to this situation. In a separate article on this website, I've presented information on the manufacture of model engines in Argentina. Time now to attempt to provide the same level of coverage of Brazilian model engine production!

Ferenc’s summary was originally compiled in 2014, but the subsequent receipt of additional information necessitated the preparation of a 2nd edition in 2020. The document was made freely available to all on the Brazilian VCC Online Forum, which is the most comprehensive communication channel for Brazilian modellers involved in the very popular Vintage Control Line (VCC - Vôo Circular Controlado) movement in their country. My gratitude to Ferenc for making this information freely available cannot be overstated. Big thanks also to my mate Peter Valicek for bringing it to my attention. The use of current translation technology soon had this invaluable reference translated into English. While extremely comprehensive in its scope, the document is organized more as a reference resource than as a narrative. It is also quite understandably written for a Brazilian audience, including references which only Brazilians would understand. This being the case, I’ve elected to prepare my own article using Ferenc’s work as my major information source rather than simply publishing an English translation of his work. I must re-emphasize the fact that I could not have so much as considered starting this article without having access to that material. This article is as much Ferenc’s work as mine – I’m merely the holder of the Editorial pen! It's also a pleasure to acknowledge the assistance rendered to me by the prominent Brazilian collector Alexandre Tapxure, who was always ready to provide answers to the many questions which Ferenc's article left unresolved. As if this wasn't enough, Alexandre also did me a very great favor by presenting me with an nice example of the Brazilian WB 2.5 cc plain bearing diesel for testing in support of this article. Without his unstinting assistance, the authoritativeness of the following text would be significantly diminished - I'm very much in his debt. It's quite impossible to provide a meaningful review of any model engine from any country without first placing it in the context of its time and place. Accordingly, before embarking on my review of the various model engines produced in Brazil, it seems to me to be essential to provide the reader with a picture of the political and economic background against which these activities took place. Those having no interest in this background are cordially invite to skip ahead to the subsequent sections of this article. Brazil - A Capsule History

The land area now known as Brazil was inhabited by various indigenous peoples prior to the landing of Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500, after which it was claimed and settled by Portugal. It remained a Portuguese colony until 1815, when it was elevated to the rank of a kingdom upon the formation of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves following the short-lived transfer of the Portuguese court to Rio de Janeiro. Thereafter, Prince Pedro of Braganza declared the country’s independence in 1822, establishing the Empire of Brazil, a unitary state governed under a parliamentary constitutional monarchy.

In World War I (1914–1918), Brazil initially declared neutrality but late joined the war on the Allied side in October 1917 in response to repeated German submarine sinkings of Brazilian merchant ships. Its military role during the remainder of the war was largely confined to Brazilian Navy patrols of various areas of the Atlantic Ocean.

During World War II, Brazil remained neutral until August 1942, when the country suffered retaliation by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in a strategic dispute over the South Atlantic. In response, Brazil entered the war on the Allied side. In addition to its Navy’s participation in the battle of the Atlantic, Brazil also sent an expeditionary force to fight in the Italian campaign. With the Allied victory in 1945 and the downfall of the fascist regimes in Europe, Vargas's position became unsustainable, and he was swiftly overthrown in yet another military coup, with democracy ironically "reinstated" by the same army that had ended it 15 years earlier. Several brief interim governments followed Vargas's suicide. Finally, Juscelino Kubitschek became president in 1956, assuming a conciliatory posture towards the political opposition that allowed him to govern for five years without major crises. The economic and industrial sectors grew remarkably during this period, but perhaps Kubitschek’s greatest achievement was the construction of the new capital city of Brasília, which was inaugurated in 1960. It was during this relatively stable period that commercial model engine manufacture in Brazil first got off the ground. However, Kubitschek’s success had not been without cost. During his tenure there was a significant increase in external debt, inflation, wealth concentration and wage erosion. Kubitschek's successor, Jânio Quadros, failed to resolve these issues, resigning in 1961 less than a year after taking office. His vice-president, João Goulart, assumed the presidency but aroused strong political opposition and was deposed in April 1964 by another coup that resulted in the establishment of yet another military dictatorship. The new regime was intended initially to be transitory but gradually became entrenched, finally becoming a full dictatorship with the promulgation of the Fifth Institutional Act in 1968. The military regime adopted extremely brutal and repressive tactics, attacking institutional opponents, artists, journalists and other members of civil society inside and outside the country who were perceived as antagonists. Despite these measures, the Brazilian economy boomed in what became known as the “economic miracle”. Consequently, the military regime reached a peak of popularity in the early 1970’s. However, the regime’s inability to deal with newly emerging economic crises as well as popular reaction against the ongoing repression eventually made a more open policy inevitable. With the enactment of the Amnesty Law in 1979, Brazil began a slow return to democracy, which was completed during the 1980’s. These were the “golden years” of model engine production and aeromodelling participation in Brazil.

Throughout the 45-year period from the end of WW2 up to the election of Collor, imports from other countries were severely restricted. This naturally included model engines, imported examples of which consequently remained in very short supply, also being prohibitively expensive even when the odd example did become available through some channel or other. This situation had been a major factor in encouraging the development of the domestically-manufactured model engines which we’ll discuss in due course. However, among Collor’s immediate actions upon his election was the lifting of almost all import restrictions. He also took steps to greatly restrict the circulation of cash among the Brazilian population. Referred to collectively as the Collor Plan, these measures exposed domestic model engine manufacturers for the first time to overseas competition from established high-volume “name” producers while at the same time eroding people’s discretionary spending capabilities. As a result, the commercial manufacture of engines in Brazil became economically unjustified overnight, grinding to a halt quite rapidly. Collor resigned in December 1992, just ahead of being impeached for political corruption. He was succeeded by his vice-president Itamar Franco, who appointed Fernando Henrique Cardoso as Minister of Finance. In 1994, Cardoso produced the highly successful Plano Real. After decades of failed attempts by previous governments to curb hyperinflation, this Plan finally stabilized the Brazilian economy. Cardoso won the 1994 election, and again in 1998. For his part, Collor went on to become involved in further instances of political corruption, ending in his 2023 conviction for accepting bribes which earned him a prison sentence of almost 9 years. Despite a series of crises based predominantly upon further issues relating to political corruption, Brazil has since continued to make progress. Today the country is recognized as an emerging upper-middle income economy and newly-industrialized country having one of the 10 largest economies in the world. It has the largest economy in Latin America and indeed in the Southern Hemisphere, and the largest share of wealth in South America. With a complex and highly diversified economy, Brazil is one of the world's major exporters of a variety of agricultural products, mineral resources and manufactured goods. It will have become clear from the preceding account that the commercial producers of model engines in Brazil from the 1950’s onwards were working for much of the time against a background of political instability and repression. However, until the actions taken by Fernando Collor in the early 1990’s pursuant to the failed Collor Plan, they were protected from having to compete with imported products from well-established volume manufacturers in other countries. The elimination of that protection spelled the end of commercial Brazilian model engine production. Now, having set the scene, it’s time to begin our survey of model engine manufacture in Brazil. Since many of the products of different manufacturers were on offer concurrently, I’ve chosen to group the products of the various manufacturers in the order in which I believe that those manufacturers first entered the model engine manufacturing business. The dates applicable to many of the engines to be listed here are far from certain, but I’ve done my best to list them in what I believe to be the most appropriate chronological sequence. If any reader can produce evidence to prove me wrong, I'll be happy to amend the article accordingly! Before we embark on this journey, I must admit quite openly that many of the images with which this article is illustrated leave much to be desired both in terms of composition and resolution. I've done my best to refine them to the extent possible, but many of them are still very far from perfect. I can only plead that such illustrations are in very short supply, forcing me to use whatever I can find. And surely any illustration is better than none at all! In almost all cases I have no information regarding the identity of the photographer - my apologies to anyone who recognizes one of his own images! OK, on with the show……………….!! The First Brazilian Model Engines – the WB Series

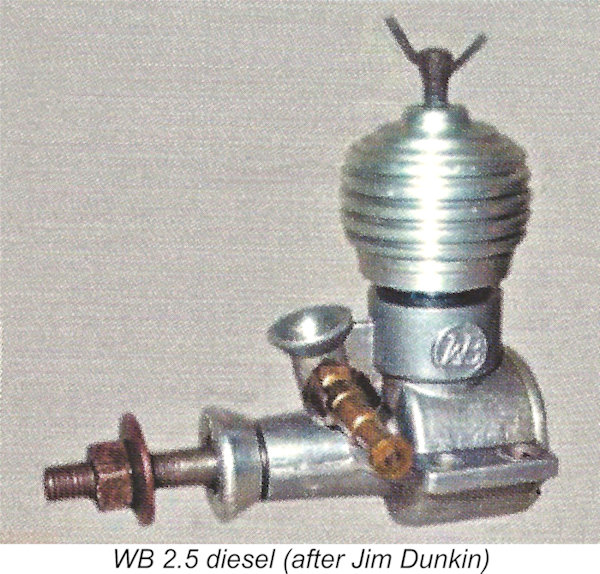

The range was apparently an initiative on the part of of two Germans named Wesolek and Baumer who immigrated to Brazil in the 1950’s. Presumably being aeromodelling enthusiasts themselves, and noting the virtual non-availability of model engines to Brazilian modellers, they saw a market opportunity, hence deciding to develop a range of diesels based to a significant extent upon the German Webra range with which they were familiar. Their company traded as Motores WB Ltda. The firm operated from premises at Rua Doutor José F. Domingues Alexandre 150 in Apucarana, Paraná, Brazil. The WB trade-name was formed from the initials of the company founders. Note the cute cast-on trademark which neatly combines the two initials. According to Alexandre Tapxure, the WB manufacturers possessed somewhat "basic" machine tooling, hence having great difficulty in maintaining consistent standards of quality and precision. A good one was very good, but some others left the factory so poorly finished and fitted that they were unble to start and run properly. It appears that purchasers simply paid their money and took their chances!

Those diesels which were undoubtedly produced all followed a very similar general arrangement, also bearing an unmistakable design imprint inherited from the Webra plain-bearing models, although they were not as well finished. The crankcases were gravity-cast from permanent molds. The quality of these castings was somewhat variable. The second 2.5 cc plain bearing variant appeared in around 1965 in the form of the WB 25 S diesel. It was apparently a very good engine. The Brazilian enthusiast Luis Eduardo Mei considered it to be the best WB engine of them all. He used one of these engines extensively between 1966 and 1969, with very good results.

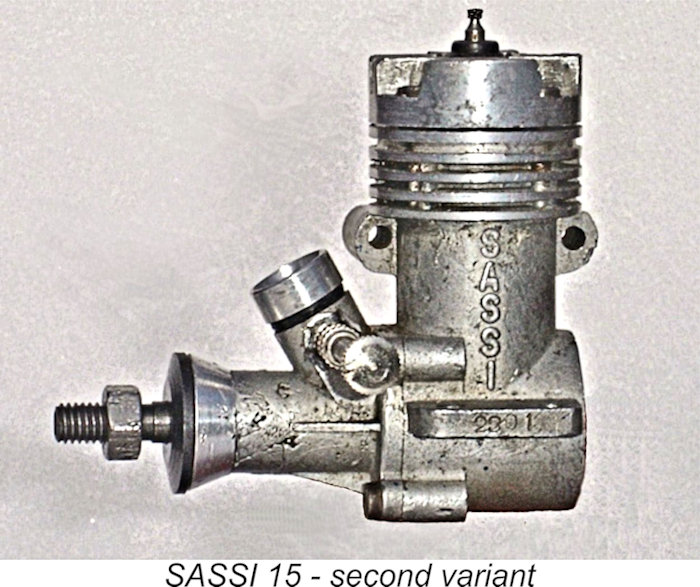

After the abandonment of the WB venture, the residue of the project was eventually acquired by the Sassi family, along with what remained of the WB factory. The first examples of the SASSI 15 glow-plug motor (the so-called 1st version) were manufactured in 1976 using the crankcase of the WB 2.5 S diesel as a basis. Some enthusiasts refer to this first SASSI 15 unofficially as the SASSI 15 S. Much more of the SASSI engines below in their place.

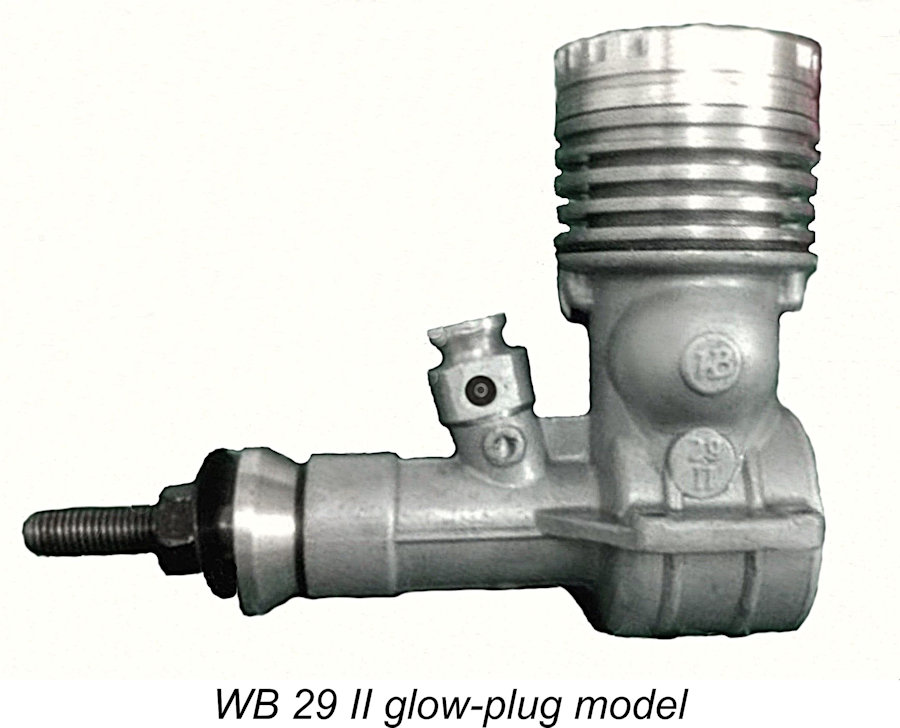

The first WB 29 glow was a basically conventional FRV glow-plug unit of its era featuring cross-flow loop scavenging and a detachable front main bearing housing secured by three machine screws. The WB 29 II model was a basically similar design which dispensed with the detachable front housing, also featuring a “bulge bypass” transfer system based upon the earlier Dooling 29 and Dooling 61 models. It was colloquially known as the “Barrigudinho” (Big Belly) model, presumably due to its bulge bypass configuration.

Dr. Franco also related an entertaining story which was going the rounds at the time concerning an incident involving one of the two manufacturing partners in the WB venture – he thought it was Mr. Wesolek, although his recollection was a little fuzzy. This individual apparently went to São Paulo to negotiate the marketing of the WB engines through Felício Cavalli’s well-known Mobral shop (see below). He was wearing a white linen suit and a panama hat. At one point, he excused himself to go to the bathroom. A little earlier, an employee engaged in mixing some fuel had evidently thrown some highly inflammable material into the toilet, where it floated on the surface and evaporated. Being a smoker, Mr. Wesolek lit a cigarette and threw the match into the toilet. After the resulting explosion, his hat and suit were no longer white! There’s a lesson there ……………… The dates applicable to the VB engines are a little fuzzy. All that I can say is that production of these engines appears to have ended during the late 1960's, creating a gaping void in the availability of engines to Brazillian power modellers. The WB Diesels on Test

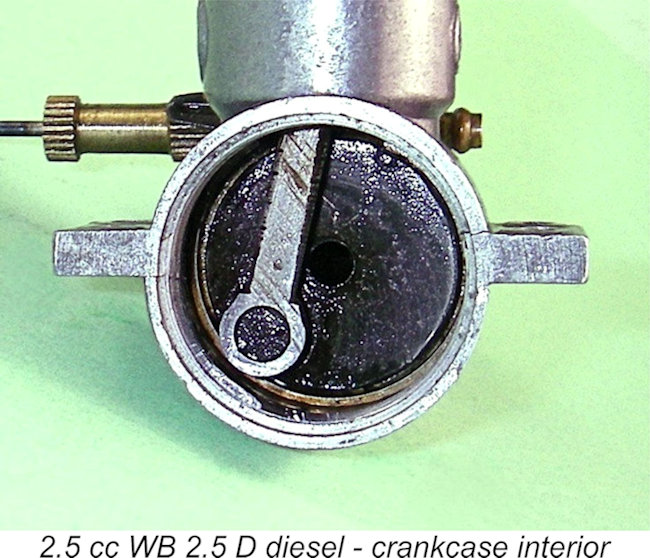

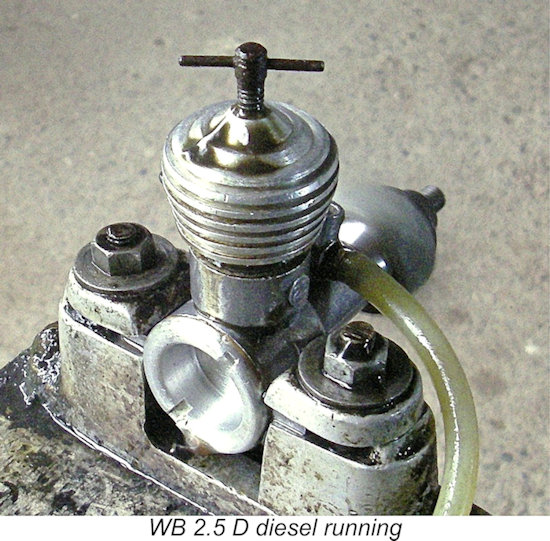

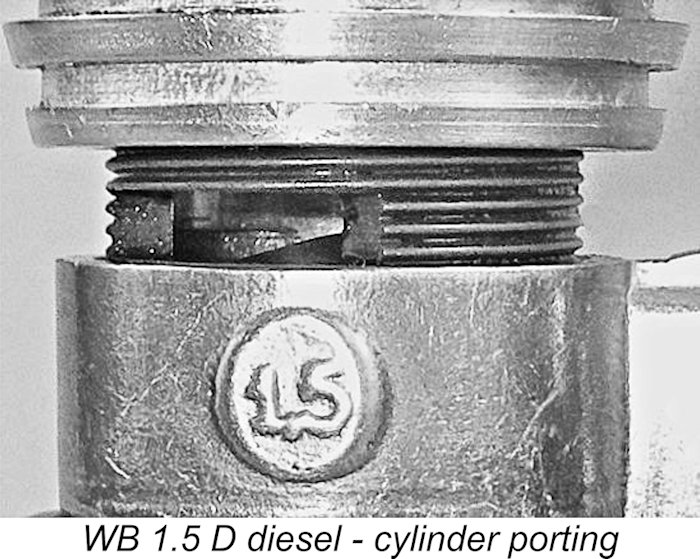

The WB 2.5 D displayed a few somewhat individualistic design features. It featured four sawn exhaust slits which were separated by unusually thin columns of metal which appear to be a little on the minimalist side in terms of strength. I’d recommend care when removing or tightening the cylinder. Bypass and transfer chores were handled by four internally-machined channels which terminated just below the exhaust separation columns. With this porting arrangement, no overlap could be provided between transfer and exhaust ports.

The most unusual feature was the very small diameter of the crankshaft’s internal gas passage. This was drilled to a diameter of only 4 mm (0.157 in.), a seemingly quite inadequate dimension for a 2.5 cc diesel, particularly when allied to the engine’s very conservative induction period of only 135º (60º ABDC to 15º ATDC). Things become a little clearer when one discovers that the engine is provided with a very healthy 50º sub-piston induction period around Top Dead Centre. The designer was clearly relying on this feature to ensure a full charge of mixture in the crankcase at the start of each primary compression cycle. The central role of the FRV induction system was obviously to contribute the fuel content to the mixture.

For this test, I used my standard test fuel consisting of a 35/35/30 blend of kerosene, ether and castor oil, with 1½% added ignition improver. Set up in the test stand with an APC 10x4 prop fitted, the engine felt pretty good when flicked over. I anticipated no trouble in getting it going, nor was I disappointed. Following a couple of choked flicks to fill the fuel line and get a little fuel into the crankcase, a small exhaust prime had the engine firing immediately. A few more flicks, and it was running - simple as that! This extremely easy starting was maintained throughout the test. Once running, the engine proved to be very easy to set. Both controls held their settings perfectly throughout. Since the piston fit in the upper cylinder felt a little tight to me, I elected to put 15 minutes of slightly rich under-compressed running on the engine, just to stay on the conservative side. At the end of this, the engine felt just fine, encouraging me to begin the process of obtaining a set of prop/RPM figures.

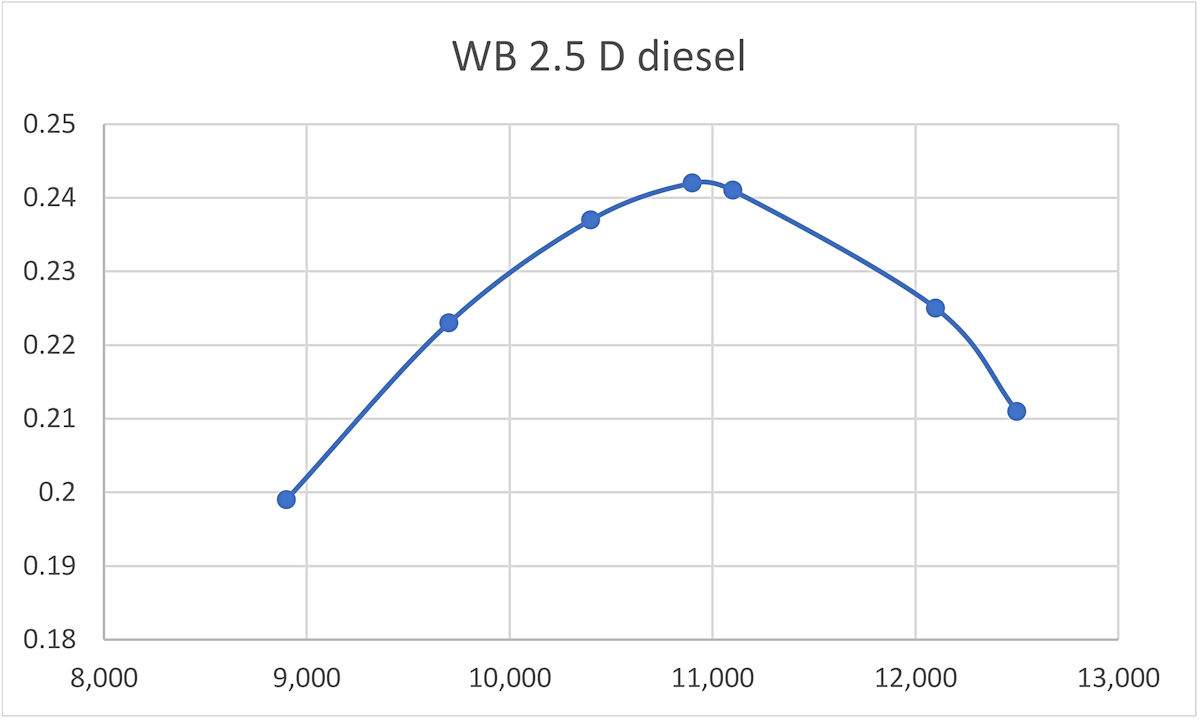

The one fly in the ointment was the development of an increasingly noticeable level of vibration as speeds climbed. By the time that the operating speed passed the 11,000 RPM mark, the vibration had begun to show signs of reaching into what I would view as an uncomfortable level. Vibration when running with the 8x4 prop (the lightest load tested) seemed to me to have reached a problematic state. The long stroke, seemingly heavy piston and unbalanced crankdisc doubtless combined to account for this behaviour. Fortunately, it became apparent that there would be no reason whatsoever to operate the engine in a model at speeds in excess of 11,000 RPM, since the WB 2.5 appeared to peak at around that figure. Alexandre Tapxure advised that Brazilian VCC users of these engines routinely keep their on-the-ground RPM below 10,000 RPM, which seems entirely appropriate. Alexandre also advised that he and his fellow enthusiasts always ensure that the fuel contains at least 25% castor oil. The following data were recorded on test:

The above data suggest a peak output of around 0.242 BHP @ 11,000 RPM. I must confess that this performance exceeded my expectations going in! Although the actual output is by no means earth-shaking in an early 1960's context, it is developed at a relatively moderate speed, meaning that the engine is well able to swing an airscrew of meaningful size, presumably due in large part to its long stroke. The manufacturer's recommended 9x6 or 8x8 airscrews would suit it well for control line, while a 9x5 or the maker's recommended 10x4 would appear to be very suitable props for free flight. Those props shift a reasonable amount of air even at these modest speeds. The WB 2.5 D may be a rather "basic" design with a few rough constructional edges, but from a design point of view it appears to be a perfectly sound powerplant having ample performance for the average sport flyer, with excellent handling as a bonus. I'd say that the needs of many 1960's-era would-be Brazillian power modellers were well catered for by such engines as this one. The trick was seemingly to get a good 'un!!

At first glance, the WB 1.5 D appears to be basically a down-scaled version of the 2.5 cc model described above - its construction seems to follow identical lines. However, appearances can be deceptive! In reality, the variant of the WB 1.5 in my possession is a quite different and somewhat more advanced design. It may be a development of an earlier model. Bore and stroke are 12 mm and 13 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.47 cc. The engine weighs in at 113 gm (3.98 ounces) - somewhat on the hefty side for a simple plain-bearing 1.5 cc diesel. As in the case of its big brother, its construction is a little rough in spots, but the critical working fits and finishes in this particular example all appear to be well within acceptable limits.

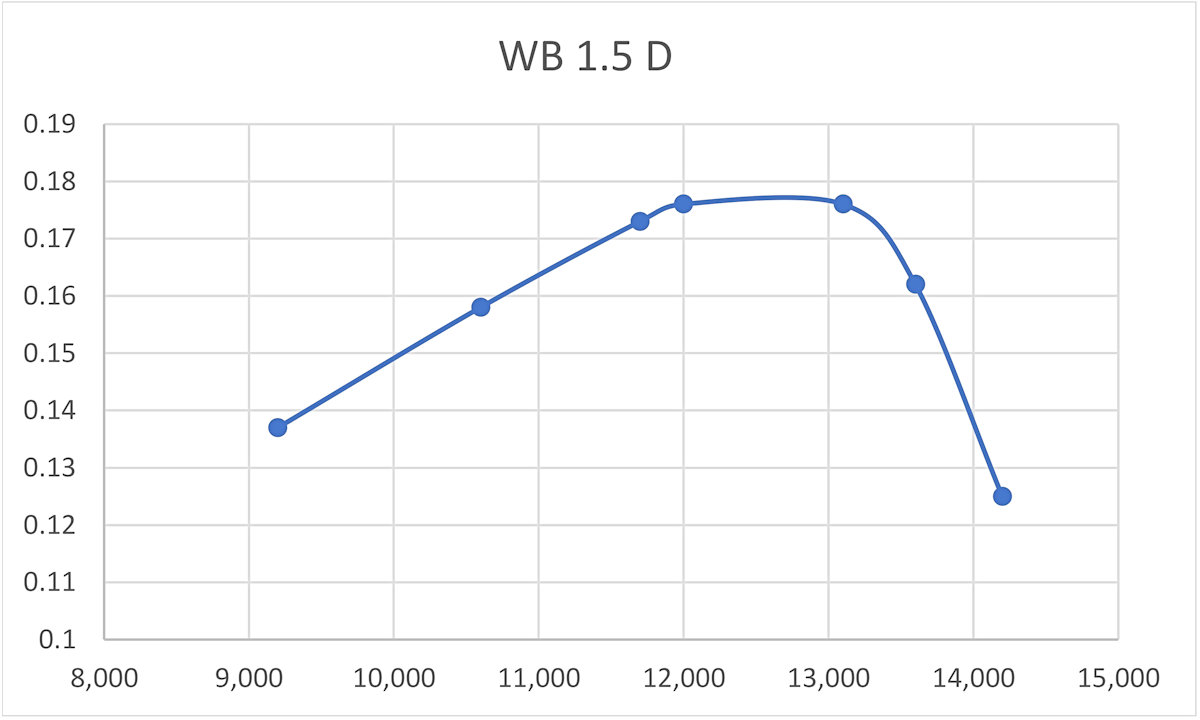

The induction timing of the WB 1.5 is approximately the same as that for the 2.5 cc model, complete with sub-piston induction. Despite the smaller displacement, the central gas passage in the shaft is the same 4 mm diameter used in the These impressions were amply confirmed by the test of the engine which I undertook. This example has clearly been used, but all of its working fits remain well within acceptable limits for easy starting and efficient operation. The engine proved to be a very easy starter following a "dry" prime (exhaust ports closed) on a full fuel line, its one idiosyncracy being that it like to have the needle opened a turn for cold starting - fuel line pick-up at starting wasn't brilliant. Once running, however, the engine responded very well to both controls, making the establishment of optimum settings a very straightforward matter. Operating suction appeared to be perfectly adequate. The engine proved to be a very smooth runner, with no tendency to sag or misfire on any prop tried. Both controls held their settings perfectly at all times, while the compression remained readily adjustable right up to maximum temperature. Some vibration was undoubtedly present, but in this case it never reached what I would consider to be problematic levels, even at the highest speeds tested. The following data were obtained on test:

I accept the comments received from my Brazilian informants to the effect that the quality and performance of the WB diesels was highly variable, ranging from very good all the way down to virtually unuseable. I seem to been fortunate enough to have acquired particularly good examples of both the 1.5 cc and 2.5 cc models. This being the case, I can only say that my testing has shown that good examples of these engines undoubtedly did exist and that a good example was actually a very useable sports diesel by the standards of its day. I would have been happy to use either of them myself for sport-flying back in the early to mid-1960's! Now having sampled a couple of representative examples of the first commercial diesels to appear in Brazil, it's time to consider the country's "other" diesel model of note - the VIMO/MPG 2.5 cc diesel. The VIMO/MPG Diesel

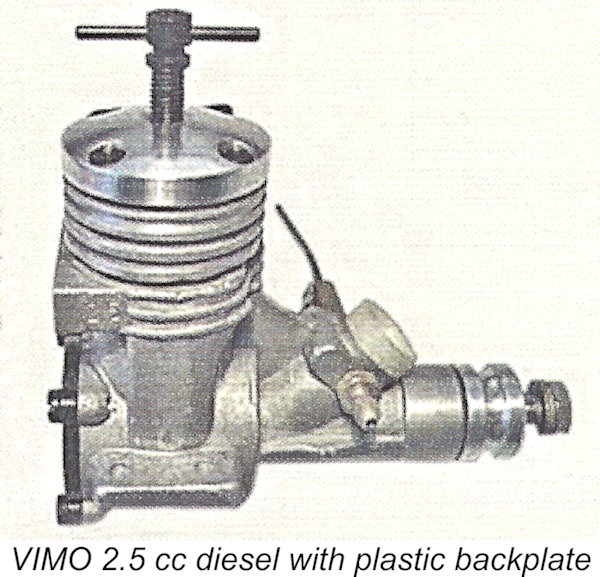

The idea of manufacturing a quality Brazilian competition engine was inspired by the lack of such engines following the cessation of the WB operation described above. A strong impetus for this plan came from Vladimir Vik in 1973 when he imported a Czechoslovakian MVVS 2.5 RLS diesel, which was probably the first engine designed for F2C (control line team racing) with a rear exhaust. Both Garuli and Vik were practitioners of F2A (control line speed), but were quite impressed with the MVVS, deciding in effect to clone it. They opted to produce it as a diesel since it would be more affordable, eliminating the need for glow-plugs and batteries. The hope was that this would extend its appeal to a wider spectrum of Brazillian aeromodellers. Like those of their WB predecessors, the crankcases were gravity-cast from a permanent mold. A source of Meehanite cast iron for the pistons was located, and limited production commenced. The initial small series featured conventional screw-in backplates. They were sold through the previously-mentioned Mobral store. Eolo Carlini, a Brazilian F1C free flight power competitor who represented Brazil in many World Championships and other international competitions, tested the engine in an F1C model. It wasn't a Rossi, but it was at least competitive. Ferenc Zamolyi entered an F2A (control line speed) contest using one of these engines, securing 2nd place among 11 competitors, some of whom were using such engines as Super Tigre, Rossi and K&B 15R glows.

The store on Rua Major Sertório remained a major marketing participant in plastic modelling and aeromodelling for almost 80 years, inspiring generations of Brazilian model enthusiasts. Sadly, in the first half of 2020 rumors of incipient closure began to emerge, which came to fruition in the second half of 2021. The store was finally closed in December 2021. A sad but all too familiar reflection of the changing stature of the modelling hobby. Returning now to happier times, conversations between Vitor Garuti and Soji Ueno revealed that he was quite impressed with the engine, stating his willingness to purchase 400 engines per month for distribution through Casa Aero Brás. Naturally, Garuli and Vik were keen to take advantage of this opportunity! They made a few changes to the design, including a switch to a bolt-on backplate which was made of injection-molded reinforced plastic. They arranged for the crankshafts to be made at the Technical Research Institute (IPT) in São Paulo using the microfusion investment casting process and subjected to X-ray and magnaflux tests to confirm their ability to withstand diesel operation. Forged aluminum connecting rods were used.

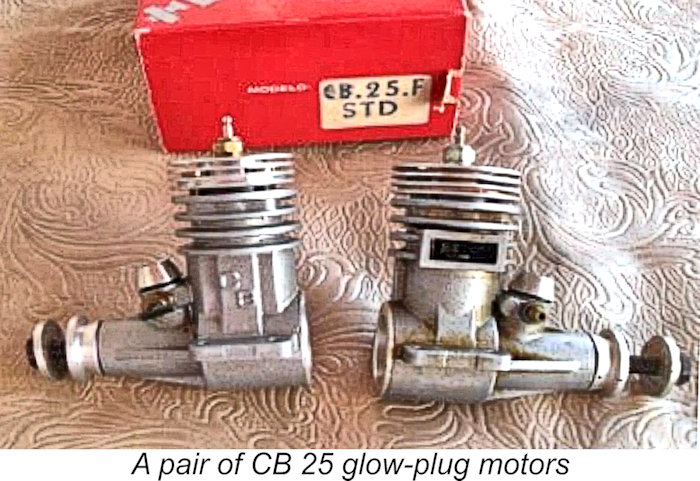

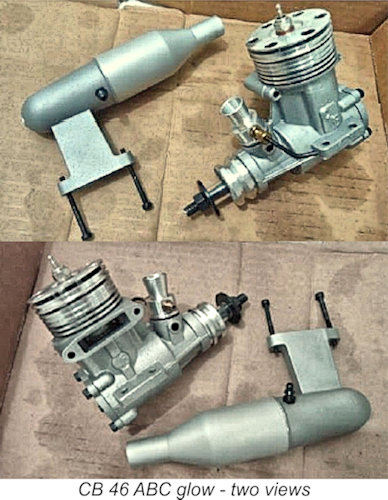

Despite these problems, the partners did manage to produce around 400 engines, all of them diesels. These motors were sold through Casa Aero Brás, many of them under the MPG trade-name for reasons which remain unclear. They were very strong performers, capable of reaching rotational speeds of up to 28,000 RPM. However, it had become clear that the makers were unable to achieve consistent standards of production at an acceptable cost. Accordingly, they decided to abandon the project. Vitor Garuli recalled that a very few examples of a glow-plug version of this engine were produced, although these were never sold to the public, the above advertisement notwithstanding. They were evidently very strong performers. One of them was used successfully by Eolo Carlini in F1C free flight power competitions. Another was used by Vitor himself to secure a 2nd place finish in a national F2A competition. The CB Engines These engines were manufactured by Daniel Torneiro of the Micromecanica CB Ltda. company of São Paulo. It's not presently clear to me when this range first appeared, but they were reportedly the last domestically-produced model engines to remain on the Brazilian market, finally disappearing in the mid-1990's.

The CB 25 catered to beginners as well as those involved in racing, speed, combat and aerobatics using engines in its displacement range (.25 cuin. – 4 cc). It could be optimized for any of these applications with suitable adjustments relating mainly to the fuel, compression ratio, venturi At the end of the ‘80’s, when it became available, this engine was used as the basic powerplant for the Brazilian national team racing category known as Formula Brazil, which was developed and established by veteran “racerista” Nelson Mary in an effort to spread and popularize team racing in Brazil. The availability of this engine also inspired another veteran, Eduardo Belmonte, to create the national Combate 25 category. The CB 25 was also made available in an auto version. This was basically the same engine specially adapted for use in model cars. Note that the muffler did not have a 90º elbow like those used in model airplanes. Few of these units were sold.

According to information supplied by collector Renato C. Marques, the VCC version of the CB 46 appeared in two variants. One was simply the R/C engine with a VCC-specific venturi/spraybar assembly replacing the original R/C carburetor. The other variant was specifically dedicated from the outset to VCC use, having a different head and muffler in addition to the venturi/spraybar assembly. The collector and expert Carlo A. Marceddu noted that there was also a difference in the combustion chambers, with the dedicated VCC version having its crankshaft/cylinder port timing optimized for that application All of the engines noted above were glow-plug models. However, the company did develop a single CB 25 diesel model intended for VCC applications. According to information provided by Giancarlo Bianchi, very few of these units were produced – certainly fewer than half a dozen – while this model was never offered to the public. As of 2014, veteran VCC practitioner Douglas Bykoff advised that one of these units was owned by Nelson Mary, another resided with Giancarlo Bianchi and a third was owned by Douglas himself. Douglas lived close to the Micromecanica CB factory in São Paulo and was in constant contact with the people there. The JJR Engines

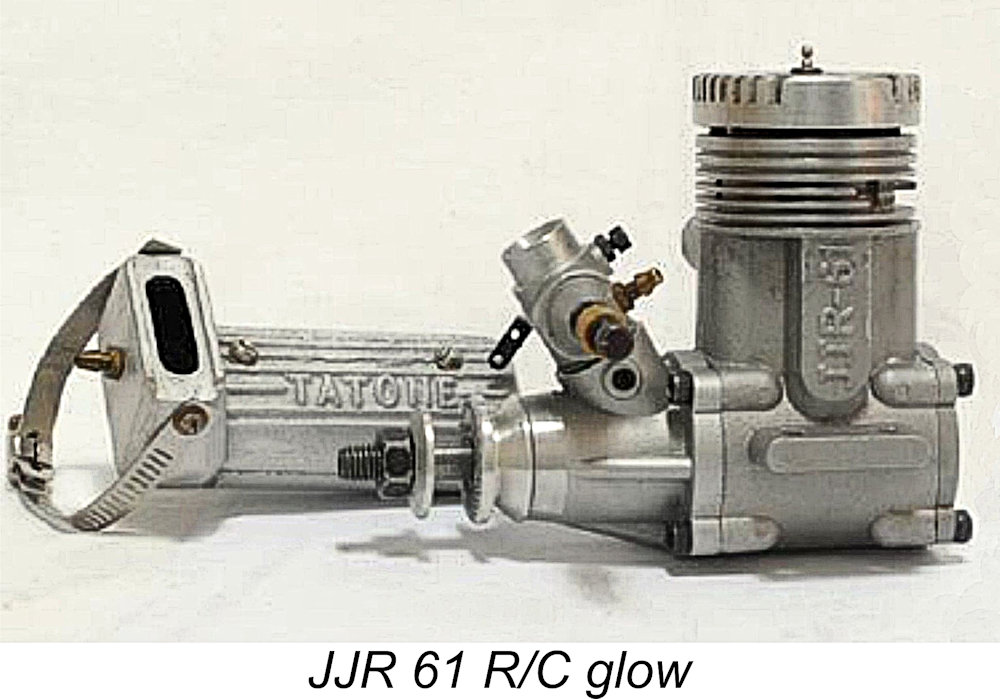

According to Alexandre Torres, a renowned Brazilian aeromodeller, the JJR 61 was “the best engine in the world”, possessing a winning combination of outstanding power, first-time starting and perfect carburetion. As of 2014, Torres still had two of these engines, both still alive and powerful 20 years or more after their manufacture. The MOBRAL Engines These engines were a “house brand” for the prominent Mobral Modelismo store in São Paulo which has been mentioned previously. This store was established in the early 1960’s by Mr. Felício Cavalli, later being taken over by Célio Pinho. Mobral manufactured and retailed kits, engines and material for modelling in general. It survived for over 30 years, finally closing its doors in 1993. It is still remembered as one of the all-time best model shops in Brazil along with Casa Aero Brás.

There were three attested MOBRAL models – the MOBRAL 40 Glow VCC (control line) Ring, the MOBRAL 40 ABC Glow R/C model and the MOBRAL 61 R/C. I have no further information to share regarding these engines. The TM ENGINES

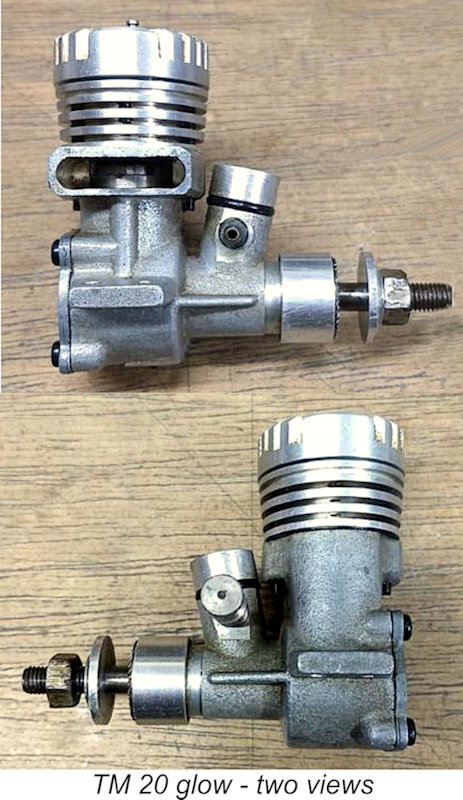

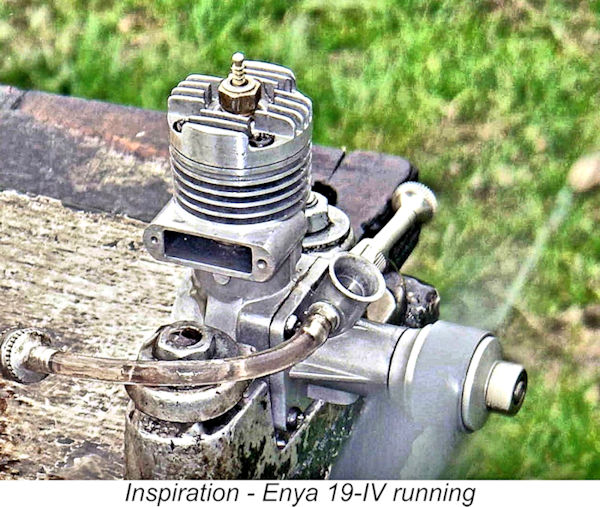

The TM factory was located on the shores of the Americana dam. Mr. Tomaz was the son of a German engineer at General Motors Brazil, also located in São Paulo. The person responsible for the actual manufacturing was Eduardo Napoli, who as of 2014 owned Orion ferries and was focused on manufacturing ultralights. Well-known model aircraft designer and collector Edson Zanini recalled that TM engines were characterized by the different colors of their heads. The TM 15 had a blue head, the TM 20 an aluminum head, the TM 35 a yellow gold head (although the first examples had plain heads) and the prototype TM 46 an aluminum head. The TM 46, which Zanini had seen at the development stage in the early 1990’s, was pretty much a copy of the Enya, with the same cylinder and piston configuration. According to André L. Costa's personal experience, the best TM model in terms of its power to weight ratio was the TM 20, which had a much better performance than the TM 15 and TM 46 in relative terms.

As stated earlier, the planned TM 46 was a copy of its Enya equivalent. It was still in the development phase in the early 1990's, when the factory ceased its activities. Consequently, very few units were produced. Prototypes were made in both R/C and VCC versions. One of the latter was acquired by Lupércio Brasil from Rio de Janeiro, who installed it in a Shark 45. He had no luck with the engine, ending up destroying the Shark due to engine failure. He was quite disappointed, having anticipated that Brazilian modellers would finally have access to a good quality Brazilian 46 engine. However, this model would evidently have required a lot more development. The AB ENGINES (AERO BRÁS)

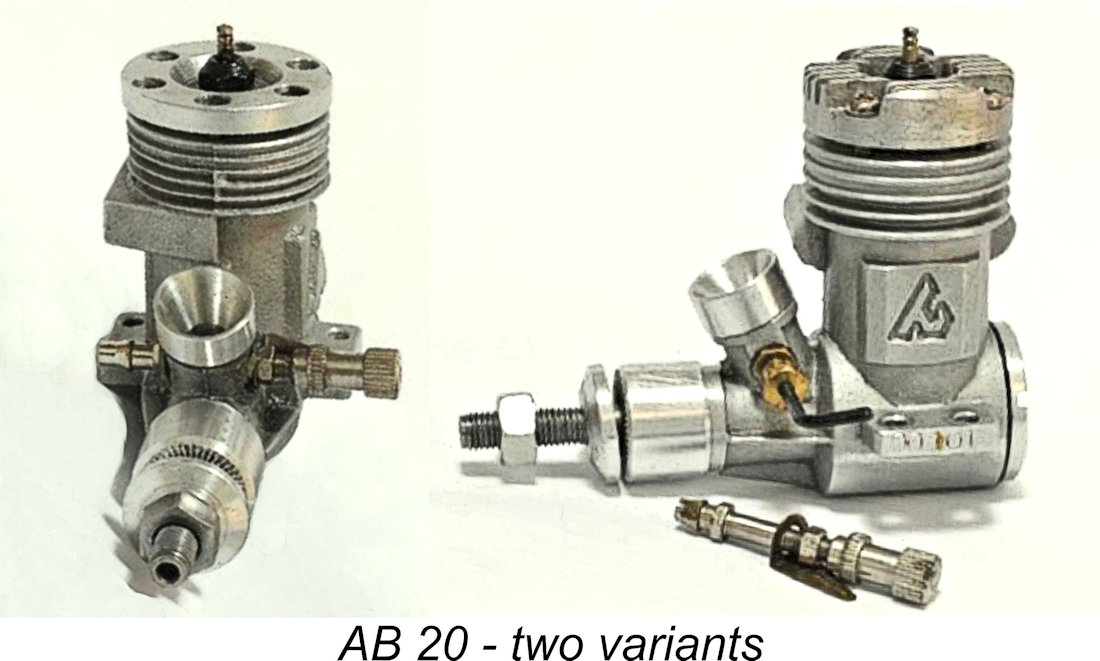

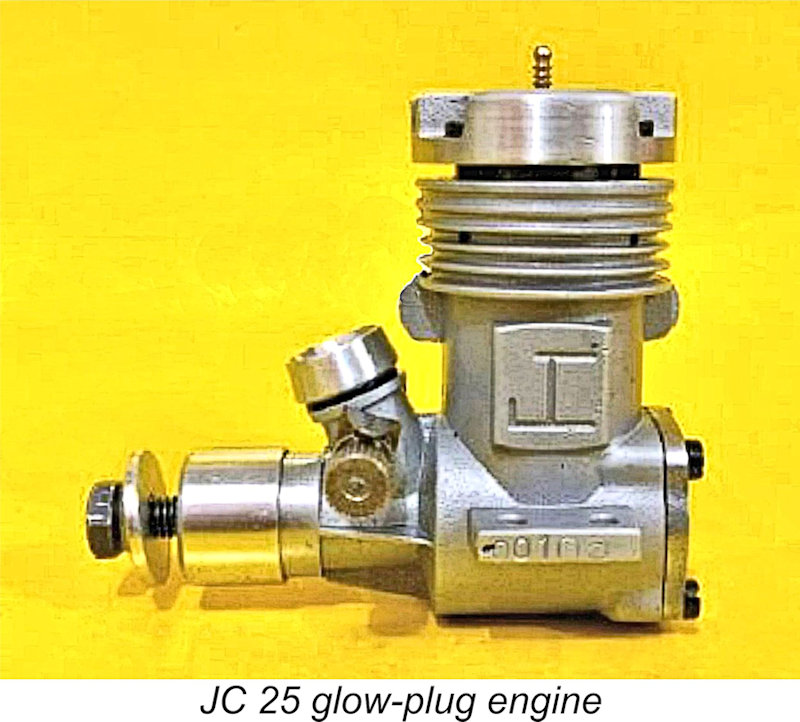

Luiz Eduardo Mei recalled that Tomaz Modelismo manufactured a few examples of an initial version of the AB 20 with a smooth head (left in the accompanying image), subsequently producing a batch of 300 engines having finned heads which were specially commissioned by Casa Aero Brás (right in the image) for marketing under the AB (Aero Brás) trade-name. These latter models came to be known as the AB 20-II, differing from version one only by the finned head. The JC ENGINES

The JC 25 was manufactured by Tomaz Modelismo, but it is unclear who commissioned the production of these engines under the JC trade-name. Note the clever manner in which the two letters of the engine's name have been combined to create its crankcase identification. Mr. Tomaz was well-known as the manufacturer of the TM engines as well as the AB 20 engines for Casa Aero Brás. Note that the designs of the offerings under all three trade-names (JC, AB and TM) are very similar to each other – seemingly a case of “badge engineering” to a large extent. The resemblance of the JC 25 to the previously-illustrated AB 20 is particularly striking. The HR ENGINES

Two models bearing the HR trade-name have been reported. These were the HR 35 VCC/R/C model and the HR 60 R/C offering. The HR 35 was a bushing motor, while the HR 60 R/C had twin ball bearings. There was an optional muffler, with a pressurization nipple. The HR 35 VCC came in two control line versions, one for aerobatics and one for combat. The differences were in the crankshaft timing, the intake venturis and the compression ratio. The R/C version of this model was identical to the one intended for control line combat, but with a specific R/C carburetor and a lower compression ratio.

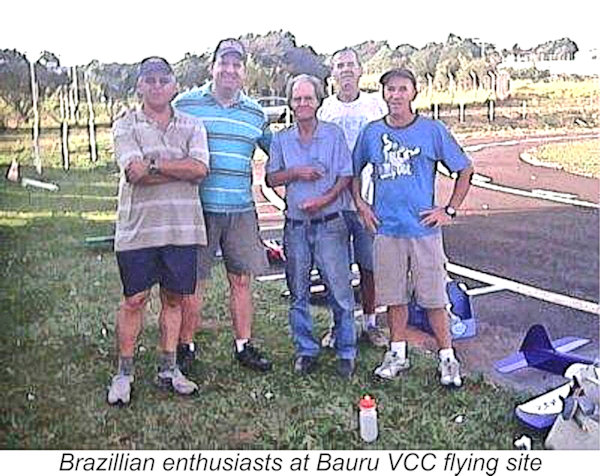

According to Paul Palhares of the Bauru VCC group, Mr. Hélio was a frequent visitor to the Bauru flying site for many years after abandoning the model engine manufacturing business. He is seen in Paul’s July 2014 image reproduced here – he is the shorter gentleman in the centre of the line-up of modellers. He was apparently always ready to chat, sharing photos and reminiscences quite freely. The ATF 20 Glow-Plug Model

Mei also recalled that this engine had a very attractive appearance, as well as an excellent performance by the standards of its day. Carlo A. Marceddu reported having once seen, in Gaspar, Santa Catarina, a Tamanco B model equipped with this engine. It powered the model so well that he thought it was an Enya 19 or O.S. 25. He was quite surprised to learn that it was a relatively little-known Brazilian engine! The engine was offered in VCC and R/C versions, each version having its specific carburetor. The SASSI Engines This is the Brazilian model engine range about which the most historical information is recorded. In large part, this is because one of the manufacturers, Mr. Wellington Sassi, created a written history of the marque which was published on the previously-cited VCC ONLINE website. The manufacturers traded under the company name Sassi Industria Mechanica Ltda.

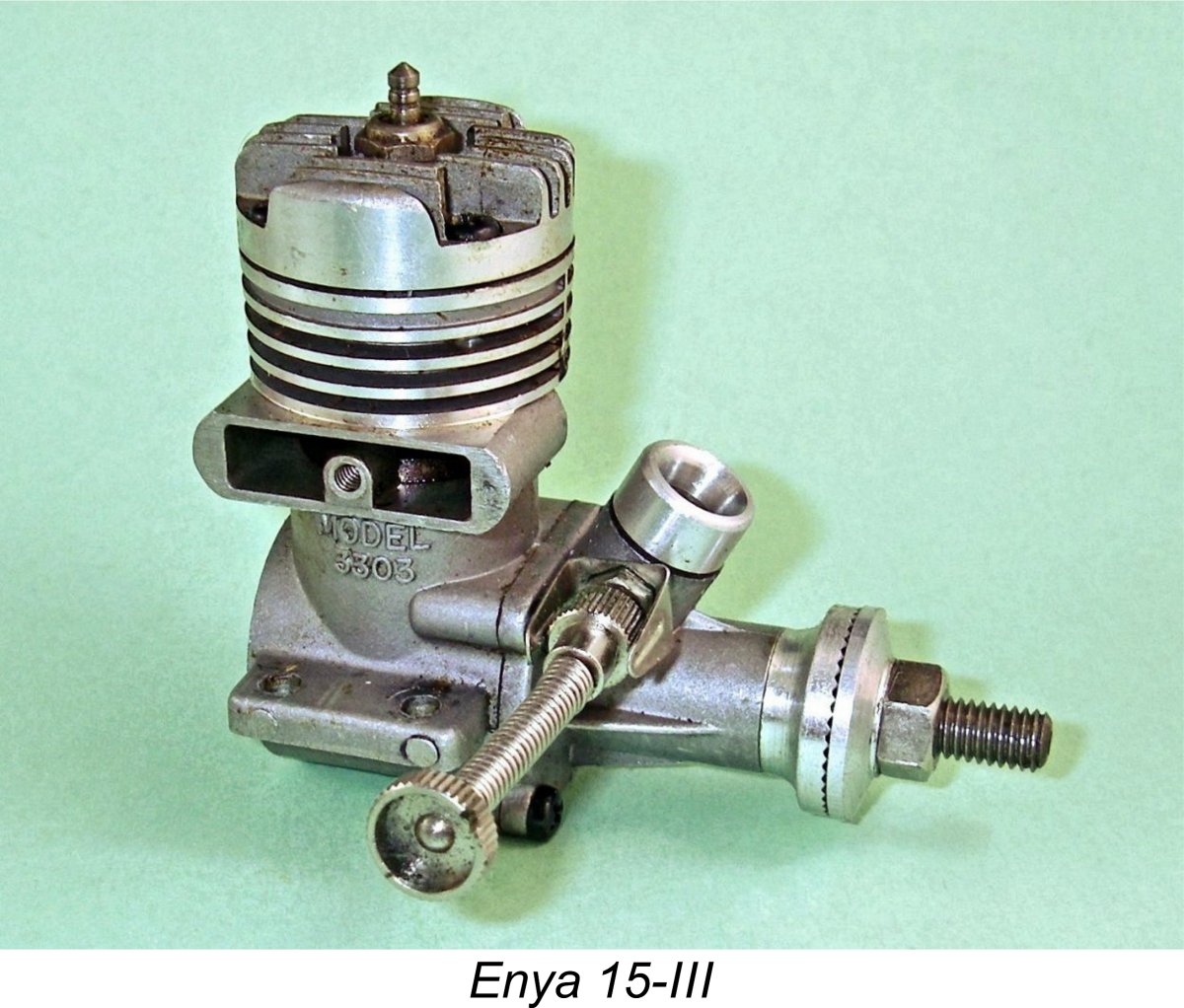

Going back to the beginning, it all started in Curitiba, Paraná where the Sassi family had a television antenna factory. As of the mid-1970’s they didn't Wellington Sassi mentioned this to his late father, Mr. Onofre Sassi, who promptly claimed that he could fix the engine by manufacturing a new piston and connecting rod. Although Sassi Sr. was working for a bank at the time, he had previously worked in the field of agricultural machinery maintenance, hence having well-developed mechanical skills. Over the following weekend, he manufactured replacement parts that kept the Enya going for a long time thereafter. It so happened that at that time the Sassi's were having serious problems sourcing raw materials to manufacture antennas (aluminum tubes). Consequently, they had begun to look for other market opportunities. The experience with the Enya repair led them to begin researching model aero engines as a potential manufacturing option. This initiative was pursued by Wellington Sassi in company with his brothers Onofre C. Sassi and Wilson Sergio Sassi The brothers soon learned about the earlier WB initiative. Elements of the former WB factory still existed, along with some residual pieces. The Sassi brothers bought the remains of the WB factory and tried to resume the manufacture of the WB diesel. However, this proved to be a dead end, since they lacked the machinery to produce the engine at the level of quality that WB had achieved.

Producing this engine was a challenge since the brothers lacked the equipment to maintain a high standard of repeatable dimensions and fits. Consequently, each engine was in some sense unique! However, they persevered. Initially they could only produce around 20 engines per month. These were distributed to the two major São Paulo stores, Mobral and Casa Aero Brás. Fortunately, the engine was very well received, since at the time there was nothing else available in Brazil. This provided strong encouragement for the Sassi family to continue their work.

The Sassi 15 glow went through several versions – at least four. The various versions are illustrated in the accompanying photo. All models were configured for both VCC and R/C, with specific carburetors for each mode. In the photo, the illustrated engines are: top left, 1st version, still featuring the WB 2.5 S crankcase; on the upper right, the 2nd version, with vertical logo and detachable front housing. Bottom left, the 3rd version (Silver Series), with natural brass needle and shiny crankcase; at the bottom right, the 4th version (the definitive and best-known variant) having a matte-finished crankcase with nickel-plated needle.

2nd Version – featuring a new Enya-inspired case, with the inscription “Sassi” cast vertically in relief. Serial numbers are low, indicating minimal production figures. Note details that demonstrate that this is an intermediate version between Version 1 (which used the WB 2.5 S crankcase) and the first model displaying the definitive layout – Version 3. The propeller thrust washer is identical to that of the WB 2.5 S and the casting quality of the crankcase is still not much improved.

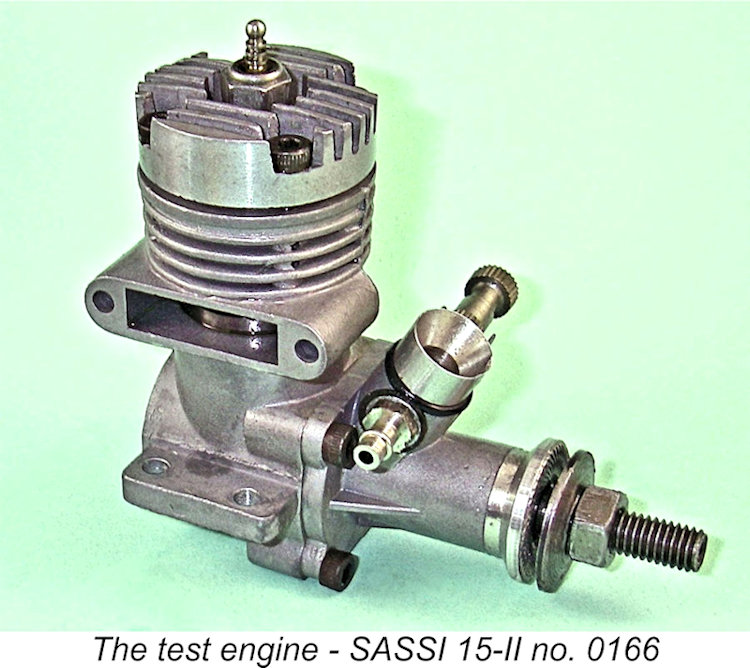

Although the SASSI 15-II was essentially an Enya 15-III clone, it embodied manufacturing technology and materials that were entirely Brazilian. Moreover, the engine performed at least on par with the imports. At this stage, production was up to some 400 engines per month. However, the manufacturers still had problems with standardization of the engines - the best of them managed over 13,000 RPM with an 8x6 nylon propeller, while others did not get above 11,500 RPM.

Despite this issue, once it was properly set up the SASSI 15-II performed very well, providing an excellent introduction to powered flight for many people. My own test of an example of this engine (see below) amply supported this view. It can't be denied that the quality of the SASSI 15-II fell some way short of that of the Japanese original, but it did provide Brazilian modellers with a perfectly useable powerplant which was readily available to them at reasonable cost.

In the stated opinion of Ferenc Zamolyi, this was the most beautiful and externally best-finished of all the Brazilian-made engines. It appears to have been an extremely good performer – Zamolyi had heard only glowing comments about it. The company’s facilities in Curitiba were small – an expansion was now urgently needed. However, Curitiba only permitted new industrial facilities to be located in the Industrial District, which was not where the existing Sassi factory was located. Needing to expand their facilities, the family decided to relocate to Presidente Prudente, São Paulo. The move to Presidente Prudente was completed in September 1982.

Still focused on expansion, the company now began the development of an even larger model, the SASSI 40. This represented a further step forward with its twin ball-race crankshaft, but unfortunately it failed to perform up to the standard which the makers felt was required for it to be competitive in the marketplace. The project was quickly abandoned in favour of the development of R/C versions of both the SASSI 15-II and SASSI 35. In 1986 the Sassi company moved to a new location in Presidente Prudente, installing modern automatic machines to accelerate production. They were the first company in Presidente Prudente to acquire a CNC lathe. They also built a new large aluminum injection molding machine and created new machining devices. Due to this developing technology, they became the subject of major reports in the national press. Now having an enhanced production capacity, the company began to produce parts for other large companies under contract. Among other things, they manufactured reducers for automated gates, complete motor grinders (including the electric motor), molds for plastic injection, etc............

In 1987 the Dutch group also bought Sandiz and sales increased even more, as they were now marketing the engines in other countries such as Argentina, Chile and Portugal. The Sassi factory started working two shifts to be able to meet the growing demand from Sears. By 1988 the entire factory had been computerized, with totally automated control of production. Steel parts were now produced using microfusion investment casting technology, which was an innovative technology in a Brazillian context. Using this technology, the SASSI crankshafts were formed ready to grind to size and cut the thread. The company also built a machining center for the major engine castings. It carried out all the machining operations on the main casting at one setting: drilling, threading and internal machining to accommodate the cylinder and crankshaft. Done the old way, this process took around 20 minutes, with major quality control challenges. With the machining center, a casting could be fully machined every 2 minutes to an excellent standard of consistent quality. By 1989 the company was delivering an average of 2000 motors per month. They had to terminate the production of gate reducers and end the provision of services for third parties – their business was now exclusively the manufacture of model engines. However, a yawning pitfall now lay across their path. More than 90% of their revenue now came from Sears, and the absence of mass marketing alternatives meant that they had no way of overcoming this economic dependency. Even so, sales demand was still outstripping production.

The opening up of imports by Collor caused a complete transformation of the Brazilian consumer market. Brazilians were like kids in a candy store, snapping up the now-cheap imports and ignoring Brazilian products. This forced an immediate cessation of all SASSI model engine production in 1991. They adapted the factory, producing woodworking machines, vehicle couplings and micro lathes. They also took on the Johnson outboard motor marketing franchise for Brazil. Unfortunately, the Collor Plan failed to resolve Brazil’s financial problems – its only effect was to severely restrict credit, creating a situation in which there was no currency in circulation. Eventually, in the early years of the present millenium, the Sassi family decided to terminate all manufacturing activities. Their 15-year involvement with model engines had been a great run, during which time Wellington Sassi estimated that the company had produced over 50,000 engines. A great contribution to Brazilian aeromodelling! The SASSI 15-II on Test

As stated earlier, the SASSI 15-II was perhaps the Brazilian engine that was produced and sold in the greatest numbers. The attentive reader will recall that this engine attracted criticism for its handling and flight performance shortcomings, which were cited as being mainly down to the manufacturers’ fitting of a venturi insert having an excessive internal diameter of 6 mm to go with the 3.4 mm diameter spraybar. Maris Dislers' invaluable choke area calculator tells us that this combination results in a choke area of 9.026 mm2 with a minimum stable operating speed of 13,155 RPM in typical sport C/L use. Clearly a reduction in the venturi diameter could undoubtedly benefit the engine's handling and flight performance. Despite this, I elected to begin proceedings with the standard 6 mm venturi fitted, along with the standard spraybar. Although seemingly having experienced little if any use, my example of the SASSI 15-II suffered from a relatively "soft" piston/cylinder fit which fell some way short of Enya standard - perhaps an indication of less-than-perfect quality control at the factory, although the sliding bearings all appeared to be very well fitted. I anticipated a certain level of challenge in getting this engine to perform..............

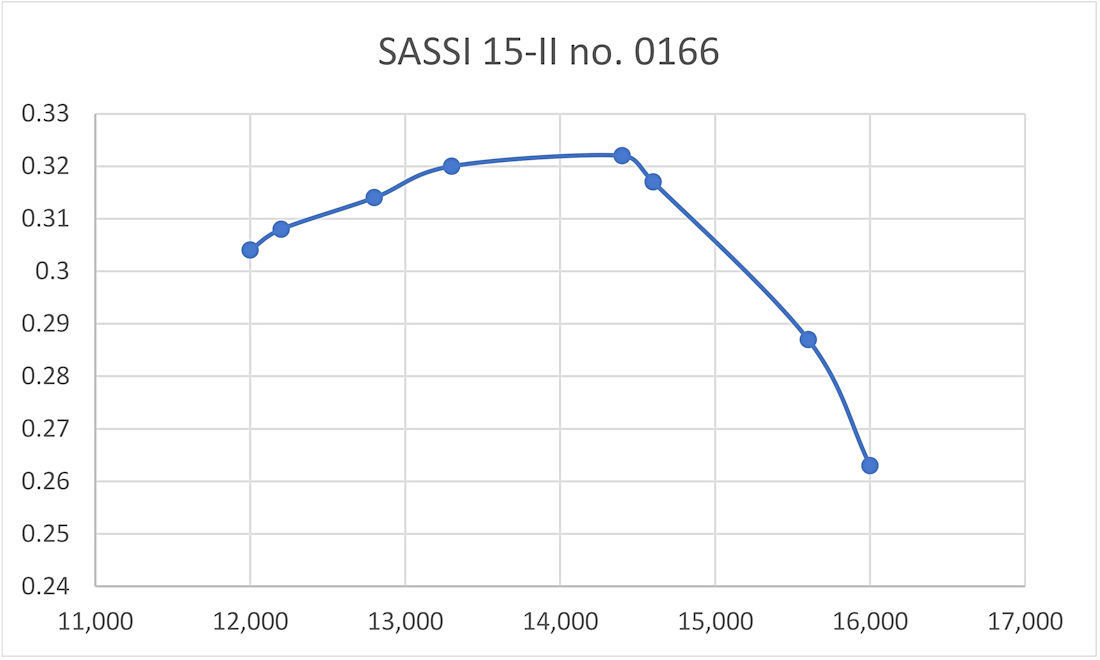

Even though the engine felt more as if it was on the way out than in need of a break-in, I elected to put 16 minutes of running on an 8x4 prop to settle down the sliding bearings. I did this in in four-minute rich runs, leaning it out briefly at the end of each run and then allowing complete cooling between runs. This procedure put the piston/cylinder components through a few of the full-range heat cycles which are necessary to achieve stability. It turned out that the SASSI didn't like being too wet for cold starting. In particular, it objected to having too much fuel in the crankcase. I found that the best approach was to choke to fill the fuel line, followed by a healthy "dry" exhaust prime (exhaust port closed). Using this approach, the SASSI was almost invariably a first flick Once running, the engine settled into a very smooth and smoky four-stroke operating mode, waiting for me to set the needle. Once I started performing the actual leaned-out prop speed tests in which the engine reached full operating temperature, I found that the SASSI was very responsive to the needle, with the optimal setting for each prop being very easily established. Once leaned out, running was absolutely smooth and mis-free. I discovered that the engine appreciated the needle being opened half a turn from the running setting for cold re-starts. One positive observation immediately following these leaned-out test runs was the fact that the compression seal became considerably better when hot. This is presumably a reflection of the metallurgy involved. It certainly explains why the engine showed no tendency to sag when fully leaned out. The following data were recorded during the test:

These data reflect a performance which is directly comparable with that of the Enya original. Using the 15% nitro fuel, the SASSI 15-II appeared to develop around 0.325 BHP @ 14,000 RPM. There's little doubt in my mind that the quality of the SASSI didn't match that of the Enya on which it was based, but it nonetheless constituted a perfectly acceptable substitute at a time when the Japanese originals were essentially both unavailable and unaffordable. It's worth reiterating the fact that I experienced no operational difficulties of any kind in conducting this test. I have to confess to being at a loss to account for the previously-noted criticisms of the engine's handling and running characteristics. SENAI Engines

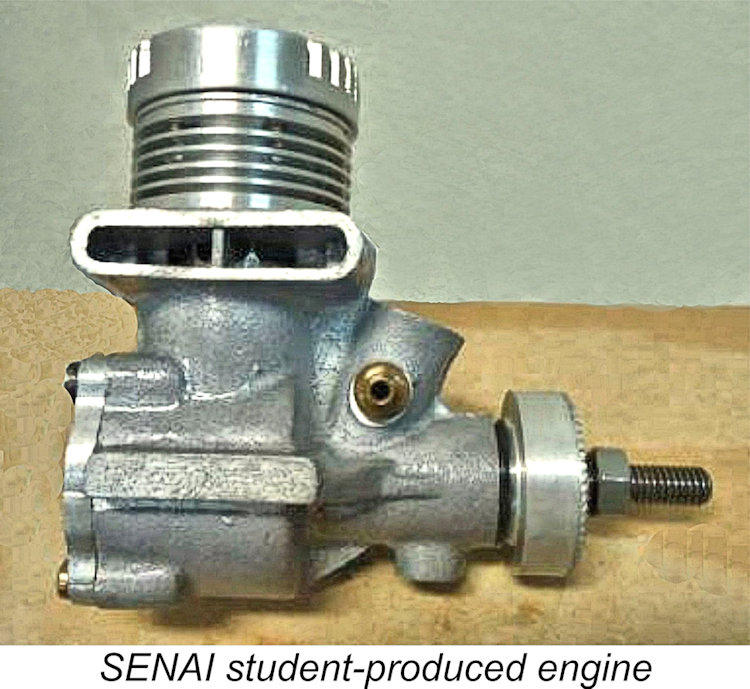

This generic design was apparently a .20 or .25 cuin. model. It was certainly not manufactured for commercial purposes, although a fair number of examples must have been made, doubtless to varying degrees of quality depending on the skill of the individual constructor. No doubt individual constructors also applied details of their own devising to the finished engine, leading to an expectation that many sub-variants may be enccountered. Thanks are due to the prominent Brazilian collector and engine expert Renato Cesar Marques for drawing attention to these engines. Brazilian Glow-Plugs

The first Brazilian-made glow-plugs to become available, the A.C. Corrêa products, were offered in short and long reach versions. There were no specific versions for VCC or R/C. The long reach plugs came in blue packaging and the short reach ones in red packaging.

At around the same time, there was the MOLINA plug, also offered in long and short reach versions. Ferenc Zamolyi had no experience with these plugs, since they weren’t commonly available in Rio de Janeiro at the time. He had no data regarding them. SASSI glow plugs appeared at the same time as the engines of the same name. Once again, Ferenc Zamolyi had no data on these, on types, quality, durability, etc. The last glow-plugs to be manufactured in Brazil, as well as the last engines, were from Micromecanica CB Ltda. They were great plugs - Ferenc Zamolyi used them a lot and still had some in stock as of 2014. Conclusion The story of the Brazilian model engine manufacturing industry is a testament to the determination of Brazilian aeromodellers to pursue their chosen hobby in the face of all obstacles, in this case the unavailability at reasonable prices of imported model engines from elsewhere. Undeterred, a number of them did their very best to provide the aeromodelling enthusiasts of their country with domestically-manufactured engines that were both useable and affordable. My own direct experience with a few representative Brazilian model engines has demonstrated that while the quality and performance of many Brazilian engines may have been somewhat below that of the imports and moreover may have been somewhat variable between different examples of the same model, an average example was a perfectly useable powerplant. And at least they were available, which is more than can be said of the products of other countries. Viewed in this light, the Brazilian model engine manufacturers listed above performed a great service for their fellow Brazilian aeromodelling enthusiasts! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published October 2025 |

||

| |

Those readers who are up on their global geography will doubtless know that South America is the world’s fourth-largest continent by area behind only Asia, Africa and North America in that order. South America also boasts the world’s fourth-largest continental population at almost 440 million people. As of 2023, 212 million of those individuals (triple the population of the British Isles and over 60% of the current US population) lived in Brazil, speaking Portuguese as their primary language.

Those readers who are up on their global geography will doubtless know that South America is the world’s fourth-largest continent by area behind only Asia, Africa and North America in that order. South America also boasts the world’s fourth-largest continental population at almost 440 million people. As of 2023, 212 million of those individuals (triple the population of the British Isles and over 60% of the current US population) lived in Brazil, speaking Portuguese as their primary language. My ability to shed some long-overdue light upon this facet of the worldwide model engine manufacturing scene was made possible entirely as a result of my valued friend Peter Valicek of the Netherlands coming into possession of a Portuguese-language document on the subject prepared by Brazilian enthusiast Ferenc I. L. Zamolyi. This document consists of a summary listing of all model engines produced over the years in Brazil, along with some comments and images provided by a number of makers and users of these engines. A treasure trove indeed!

My ability to shed some long-overdue light upon this facet of the worldwide model engine manufacturing scene was made possible entirely as a result of my valued friend Peter Valicek of the Netherlands coming into possession of a Portuguese-language document on the subject prepared by Brazilian enthusiast Ferenc I. L. Zamolyi. This document consists of a summary listing of all model engines produced over the years in Brazil, along with some comments and images provided by a number of makers and users of these engines. A treasure trove indeed!  Brazil (officially the Federative Republic of Brazil) is the largest and easternmost country in South America. It is the world's fifth-largest country by area and the seventh largest by population, with over 212 million people. The country is a federation composed of 27 states and a Federal District which hosts the national capital, Brasília. Its most populous city is São Paulo, followed by Rio de Janeiro. Brazil has the largest number of Portuguese speakers in the world and is the only country in the Americas where Portuguese is an official language.

Brazil (officially the Federative Republic of Brazil) is the largest and easternmost country in South America. It is the world's fifth-largest country by area and the seventh largest by population, with over 212 million people. The country is a federation composed of 27 states and a Federal District which hosts the national capital, Brasília. Its most populous city is São Paulo, followed by Rio de Janeiro. Brazil has the largest number of Portuguese speakers in the world and is the only country in the Americas where Portuguese is an official language. Brazil became a presidential republic following a military coup d'état on November 15

Brazil became a presidential republic following a military coup d'état on November 15 Between the wars, Brazil endured a series of insurrections, including a 1930 revolution which established a military dictatorship. This unsettled period culminated in the 1937 coup d'état under which the National Congress was abolished altogether, the 1938 election was cancelled and Getúlio Vargas was formally installed as Dictator, ruling by decree.

Between the wars, Brazil endured a series of insurrections, including a 1930 revolution which established a military dictatorship. This unsettled period culminated in the 1937 coup d'état under which the National Congress was abolished altogether, the 1938 election was cancelled and Getúlio Vargas was formally installed as Dictator, ruling by decree. Vargas returned to power by election in 1950 but subsequently committed suicide in August 1954 amid another political crisis.

Vargas returned to power by election in 1950 but subsequently committed suicide in August 1954 amid another political crisis. Civilian control was finally restored in 1985 when José Sarney assumed the presidency. He suffered from the handicap of inheriting an economic crisis from the military regime along with hyper-inflation, and his failure to deal effectively with these issues led eventually to the early 1990 election of Fernando Collor.

Civilian control was finally restored in 1985 when José Sarney assumed the presidency. He suffered from the handicap of inheriting an economic crisis from the military regime along with hyper-inflation, and his failure to deal effectively with these issues led eventually to the early 1990 election of Fernando Collor.  As far as I know, the WB engines were the first domestically-manufactured model engines to be sold commercially in Brazil, first appearing in around

As far as I know, the WB engines were the first domestically-manufactured model engines to be sold commercially in Brazil, first appearing in around

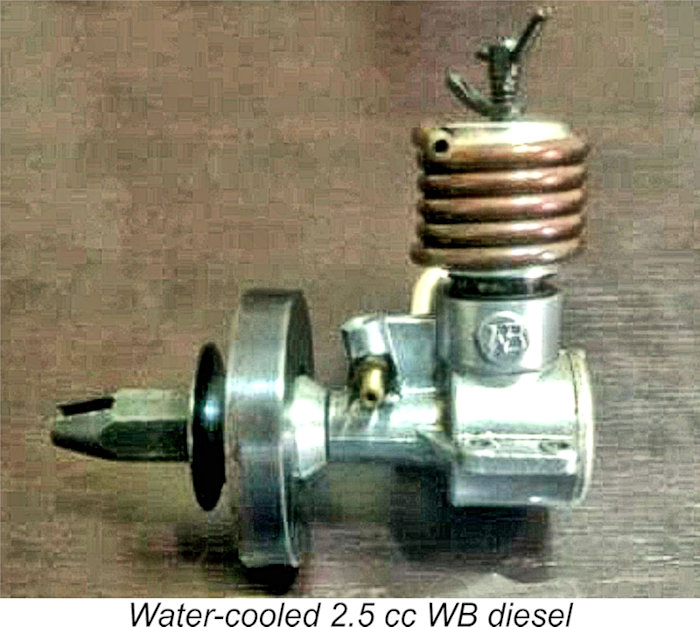

My valued informant Alexandre Tapxure contributed an image of a water-cooled marine version of the original WB 2.5 cc diesel. Unusually, the cooling jacket of this engine is a copper tubing wrap. No details are apparently available regarding this engine – it is not even known if it is a factory effort or an owner conversion. No other examples are evidently known to exist, suggesting the latter possibility.

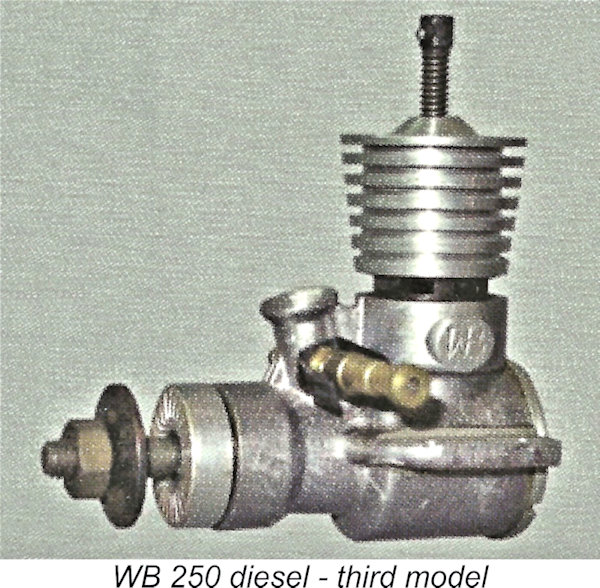

My valued informant Alexandre Tapxure contributed an image of a water-cooled marine version of the original WB 2.5 cc diesel. Unusually, the cooling jacket of this engine is a copper tubing wrap. No details are apparently available regarding this engine – it is not even known if it is a factory effort or an owner conversion. No other examples are evidently known to exist, suggesting the latter possibility.  The final WB diesel model was a twin ball-race version of the WB 2.5 S. This was marketed as the WB 250 model, which appeared in three successive sub-variants. These engines reportedly run very well. Of all the WB diesels, the 250 bears the least resemblance to any earlier Webra model – evidently some more original thinking was now entering the picture.

The final WB diesel model was a twin ball-race version of the WB 2.5 S. This was marketed as the WB 250 model, which appeared in three successive sub-variants. These engines reportedly run very well. Of all the WB diesels, the 250 bears the least resemblance to any earlier Webra model – evidently some more original thinking was now entering the picture. Although the WB trade-name is generally associated with diesels, there were also WB 29 and 35 glow engines. Alexandre Tapxure stated that these appeared in the mid-1960's. There were also a very few examples of a 1 cc glow, about which no details are available. Presumably it was a glow-plug conversion of the WB 1 cc diesel mentioned earlier.

Although the WB trade-name is generally associated with diesels, there were also WB 29 and 35 glow engines. Alexandre Tapxure stated that these appeared in the mid-1960's. There were also a very few examples of a 1 cc glow, about which no details are available. Presumably it was a glow-plug conversion of the WB 1 cc diesel mentioned earlier. Brazilian enthusiast Dr. Elizio Franco recalled that in his first competition in Londrina, Paraná during the 1960's, he won first place in aerobatics. In addition to the trophy, he also received an example of the then recently-released WB 29 II which was presented in person by Mr. Wesolek (the “W” of WB). It turned out to be an excellent engine which performed in the air pretty much like a Fox 35.

Brazilian enthusiast Dr. Elizio Franco recalled that in his first competition in Londrina, Paraná during the 1960's, he won first place in aerobatics. In addition to the trophy, he also received an example of the then recently-released WB 29 II which was presented in person by Mr. Wesolek (the “W” of WB). It turned out to be an excellent engine which performed in the air pretty much like a Fox 35. Thanks entirely to the great kindness extended to me by Brazilian enthusiast Alexandre Tapxure, I’m in possession of a nice example of the WB 2.5 D which was the first 2.5 cc diesel produced by Motores WB Ltda. This engine was a compact plain bearing 2.5 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) diesel which displayed clear Webra influence in its design. It was a long-stroke unit having bore and stroke dimensions of 14 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.46 cc. It weighed in at 141 gm (4.97 ounces).

Thanks entirely to the great kindness extended to me by Brazilian enthusiast Alexandre Tapxure, I’m in possession of a nice example of the WB 2.5 D which was the first 2.5 cc diesel produced by Motores WB Ltda. This engine was a compact plain bearing 2.5 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) diesel which displayed clear Webra influence in its design. It was a long-stroke unit having bore and stroke dimensions of 14 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.46 cc. It weighed in at 141 gm (4.97 ounces).  The conrod appeared to have been machined from a piece of flat aluminium alloy plate. It drove a one-piece steel crankshaft having a plain crank-disc with no counterbalance. Rod bearing fits in my example are very good at both ends.

The conrod appeared to have been machined from a piece of flat aluminium alloy plate. It drove a one-piece steel crankshaft having a plain crank-disc with no counterbalance. Rod bearing fits in my example are very good at both ends. The example so kindly presented to me by Alexandre Tapxure has had some use but remains in fine condition, with good fits all round. The main casting is a little rough, but that was apparently typical. The standard of machining exhibited by this example is generally good with a few rough edges. Most importantly, all of the important operating fits in this example appear to be well within acceptable limits. The needle valve on this particular engine is not original, but that should have a minimal effect upon performance. The unit thus constitutes a completely representative test subject.

The example so kindly presented to me by Alexandre Tapxure has had some use but remains in fine condition, with good fits all round. The main casting is a little rough, but that was apparently typical. The standard of machining exhibited by this example is generally good with a few rough edges. Most importantly, all of the important operating fits in this example appear to be well within acceptable limits. The needle valve on this particular engine is not original, but that should have a minimal effect upon performance. The unit thus constitutes a completely representative test subject.  When leaned out with the compression set at its optimum level, the WB ran extremely smoothly and steadily, with no apparent tendency to sag as things became hot. It also ran rather more strongly than I had expected! It was immediately clear that torque development at moderate speeds would be its strong suit.

When leaned out with the compression set at its optimum level, the WB ran extremely smoothly and steadily, with no apparent tendency to sag as things became hot. It also ran rather more strongly than I had expected! It was immediately clear that torque development at moderate speeds would be its strong suit.

As chance would have it, at around the same time that Alexandre Tapxure was sending the WB 2.5 D to me for testing, I bid on a seemingly nice example of the smaller WB 1.5 D which just happened to appear out of the blue on offer from an American seller - a very rare but timely occurrence! Happily, I was successful in winning the auction. This put me in a position to add a bench test of this model to this article to supplement the previously-reported test of its 2.5 cc relative.

As chance would have it, at around the same time that Alexandre Tapxure was sending the WB 2.5 D to me for testing, I bid on a seemingly nice example of the smaller WB 1.5 D which just happened to appear out of the blue on offer from an American seller - a very rare but timely occurrence! Happily, I was successful in winning the auction. This put me in a position to add a bench test of this model to this article to supplement the previously-reported test of its 2.5 cc relative.  The major differences between this engine and its bigger brother are to be found in the cylinder porting arrangements. Instead of the four exhaust slots and four internal non-overlapping bypass/transfer channels of the 2.5 cc model, the 1.5 cc unit has only two of each. This creates two far broader columns of material separating the exhaust ports, which in turn provides ample cylinder wall area to permit the extension of the two generously-dimensioned bypass/transfer channels further up the cylinder wall to overlap the exhausts to a significant extent. This overlap may be seen clearly in the attached image. In effect, the porting follows the familiar Cox 2x2 pattern precisely.

The major differences between this engine and its bigger brother are to be found in the cylinder porting arrangements. Instead of the four exhaust slots and four internal non-overlapping bypass/transfer channels of the 2.5 cc model, the 1.5 cc unit has only two of each. This creates two far broader columns of material separating the exhaust ports, which in turn provides ample cylinder wall area to permit the extension of the two generously-dimensioned bypass/transfer channels further up the cylinder wall to overlap the exhausts to a significant extent. This overlap may be seen clearly in the attached image. In effect, the porting follows the familiar Cox 2x2 pattern precisely.

I have to say that this engine really surprised me, performing at a far higher level than I had been expecting. It appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.180 BHP @ 12,700 RPM. The higher peaking speed by comparison with the WB 2.5 cc model was almost certainly due in large part to the more advanced cylinder porting arrangements.

I have to say that this engine really surprised me, performing at a far higher level than I had been expecting. It appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.180 BHP @ 12,700 RPM. The higher peaking speed by comparison with the WB 2.5 cc model was almost certainly due in large part to the more advanced cylinder porting arrangements.  This excellent 2.5 cc diesel made its appearance some years after the demise of the WB diesel series. It was manufactured during the mid-1970's by the well-known Brazilian model enthusiast Vitor Garuti in partnership with the Czech immigrant Vladmir Vik (nickname Vicky). Much of the following information came directly from Garuti himself in later communications with Ferenc Zamolyi.

This excellent 2.5 cc diesel made its appearance some years after the demise of the WB diesel series. It was manufactured during the mid-1970's by the well-known Brazilian model enthusiast Vitor Garuti in partnership with the Czech immigrant Vladmir Vik (nickname Vicky). Much of the following information came directly from Garuti himself in later communications with Ferenc Zamolyi. At this time, the Mobral store’s major competitor was Casa Aero Brás, another traditional model airplane manufacturer and store also located in the city of

At this time, the Mobral store’s major competitor was Casa Aero Brás, another traditional model airplane manufacturer and store also located in the city of  Production of the revised model then commenced. However, finishing and fitting the liner and piston became a problem, as they could not achieve repeatability in the dimensions and fits. This was in the mid-1970’s, at which time their equipment was extremely limited, preventing them from maintaining the desired production dimensional tolerances. Consequently, each engine had to be assembled and fitted individually.

Production of the revised model then commenced. However, finishing and fitting the liner and piston became a problem, as they could not achieve repeatability in the dimensions and fits. This was in the mid-1970’s, at which time their equipment was extremely limited, preventing them from maintaining the desired production dimensional tolerances. Consequently, each engine had to be assembled and fitted individually. The best-known of the CB engines was the CB 25 glow-plug model, which first became available in the late 1980’s. It was offered in both VCC (control line) and R/C versions. In the stated opinion of Ferenc Zamolyi, the CB 25 was the best general-purpose engine ever produced in significant quantities in Brazil. With this engine, he considered the national industry to have reached a standard that could potentially have placed Brazil on the international stage as an engine-manufacturing country had other factors not intervened.

The best-known of the CB engines was the CB 25 glow-plug model, which first became available in the late 1980’s. It was offered in both VCC (control line) and R/C versions. In the stated opinion of Ferenc Zamolyi, the CB 25 was the best general-purpose engine ever produced in significant quantities in Brazil. With this engine, he considered the national industry to have reached a standard that could potentially have placed Brazil on the international stage as an engine-manufacturing country had other factors not intervened.  diameter and airscrew. It had an excellent power/weight ratio. The engine was produced in an ABC version as well as a variant with steel liner and cast-iron piston, the latter being identified as the CB 25 F.

diameter and airscrew. It had an excellent power/weight ratio. The engine was produced in an ABC version as well as a variant with steel liner and cast-iron piston, the latter being identified as the CB 25 F.

The JJR engines were created by Zé Torneiro, the father of Daniel Torneiro from CB. They were marketed and advertised alongside the CB engines, presumably being manufactured in the same São Paulo factory. Three distinct models have been reported – the JJR 40 in VCC and R/C variants, the JJR 50 R/C model and the JJR 61 offering. All three were Schnuerle-ported glow-plug models. They were apparently produced during the 1980's and early 1990's.

The JJR engines were created by Zé Torneiro, the father of Daniel Torneiro from CB. They were marketed and advertised alongside the CB engines, presumably being manufactured in the same São Paulo factory. Three distinct models have been reported – the JJR 40 in VCC and R/C variants, the JJR 50 R/C model and the JJR 61 offering. All three were Schnuerle-ported glow-plug models. They were apparently produced during the 1980's and early 1990's.

These engines were manufactured by Mr. Tomaz of Tomaz Modelismo of

These engines were manufactured by Mr. Tomaz of Tomaz Modelismo of  Luis Eduardo Mei recalled that the TM 15 and 35 crankcases were sand-cast, a truly artisan process. Due to the resulting porosity, the minimum thickness of the casing wall was 3 mm, resulting in a heavy engine that required a lot of machining time, raising the production cost. The liners were machined from steel tubing, while the pistons were made of nodular cast iron. The liner/piston fits were established individually on the lathe, with only approximate “precision” rather than adhering to a pre-determined dimensional range within fixed tolerances. Consequently, each engine was unique, while the quality was somewhat variable.

Luis Eduardo Mei recalled that the TM 15 and 35 crankcases were sand-cast, a truly artisan process. Due to the resulting porosity, the minimum thickness of the casing wall was 3 mm, resulting in a heavy engine that required a lot of machining time, raising the production cost. The liners were machined from steel tubing, while the pistons were made of nodular cast iron. The liner/piston fits were established individually on the lathe, with only approximate “precision” rather than adhering to a pre-determined dimensional range within fixed tolerances. Consequently, each engine was unique, while the quality was somewhat variable. The AB engines were commissioned by Soji Ueno’s Casa Aero Brás store to be their “house brand” of model engines. They were actually manufactured by Mr. Tomaz of Tomaz Modelismo of Americana, São Paulo, whose TM range was covered in the previous section of this article.

The AB engines were commissioned by Soji Ueno’s Casa Aero Brás store to be their “house brand” of model engines. They were actually manufactured by Mr. Tomaz of Tomaz Modelismo of Americana, São Paulo, whose TM range was covered in the previous section of this article.  Only one model engine was apparently marketed under the JC trade-name. This was the JC 25, a conventional FRV glow-plug motor of .25 cuin. (4 cc) displacement. The illustrated example is configured for VCC use – I don’t know if an R/C version was ever offered.

Only one model engine was apparently marketed under the JC trade-name. This was the JC 25, a conventional FRV glow-plug motor of .25 cuin. (4 cc) displacement. The illustrated example is configured for VCC use – I don’t know if an R/C version was ever offered.

At the time, these differences were poorly understood, leading to some attempts to use the combat version in applications for which it was not designed. Ferenc Zamolyi recalled that the combat version of the HR 35 had a very large venturi throat, indicating that the objective was to obtain maximum RPM using a pressurized fuel supply. This was obviously appropriate for combat use when combined with appropriate port and ignition timing. However, many under-informed owners tried to use that same model for aerobatics. Understandably, this did not yield good results, leading many modellers to characterize the HR 35 unfairly as a bad engine. Reducing the diameter of the venturi partially solved the problem, although the high compression ratio and high-speed crankshaft timing remained unaltered. This was therefore a somewhat lame solution, but it did at least allow the engine’s use for aerobatics, albeit still imperfect.

At the time, these differences were poorly understood, leading to some attempts to use the combat version in applications for which it was not designed. Ferenc Zamolyi recalled that the combat version of the HR 35 had a very large venturi throat, indicating that the objective was to obtain maximum RPM using a pressurized fuel supply. This was obviously appropriate for combat use when combined with appropriate port and ignition timing. However, many under-informed owners tried to use that same model for aerobatics. Understandably, this did not yield good results, leading many modellers to characterize the HR 35 unfairly as a bad engine. Reducing the diameter of the venturi partially solved the problem, although the high compression ratio and high-speed crankshaft timing remained unaltered. This was therefore a somewhat lame solution, but it did at least allow the engine’s use for aerobatics, albeit still imperfect.  I have no information regarding when, where or by whom this engine was produced. It appears to have been essentially a copy of an Enya design. Luiz Eduardo Mei evidently believed that this engine had its origin in the 1980’s, but I have found no confirmation of this – I would actually have put it in the 1970’s on architectural grounds.

I have no information regarding when, where or by whom this engine was produced. It appears to have been essentially a copy of an Enya design. Luiz Eduardo Mei evidently believed that this engine had its origin in the 1980’s, but I have found no confirmation of this – I would actually have put it in the 1970’s on architectural grounds. In terms of quantity, unless I am mistaken, this company produced the all-time largest selling Brazilian-made engine, the SASSI 15-II. At the time when the original SASSI 15 was placed on the market (1976), the availability of imported engines was still very limited and the SASSI 15 became an accessible option for those Brazilian enthusiasts who wanted to become involved with power modelling.

In terms of quantity, unless I am mistaken, this company produced the all-time largest selling Brazilian-made engine, the SASSI 15-II. At the time when the original SASSI 15 was placed on the market (1976), the availability of imported engines was still very limited and the SASSI 15 became an accessible option for those Brazilian enthusiasts who wanted to become involved with power modelling.

At this point, they decided to re-think their objectives. Receiving strong encouragement from their friend Célio Pinho, now the owner of the Mobral store, they decided to focus their further efforts on glow-plug engines. Once again, Wellington Sassi’s father Mr. Onofre Sassi took the lead, producing the first SASSI 15 using the old WB 25 S crankcase with a steel liner and cast iron piston along with revised crankcase identification.

At this point, they decided to re-think their objectives. Receiving strong encouragement from their friend Célio Pinho, now the owner of the Mobral store, they decided to focus their further efforts on glow-plug engines. Once again, Wellington Sassi’s father Mr. Onofre Sassi took the lead, producing the first SASSI 15 using the old WB 25 S crankcase with a steel liner and cast iron piston along with revised crankcase identification. The business now evolved quickly, with machinery and equipment upgrades. A major innovation was a switch from gravity permanent mold casting to pressure die-casting. This technology was practically unknown in Brazil at the time, forcing the Sassi brothers to build their own injection molding machine, make the dies and produce the aluminum alloy for injection - no suitable raw casting alloy was available commercially.

The business now evolved quickly, with machinery and equipment upgrades. A major innovation was a switch from gravity permanent mold casting to pressure die-casting. This technology was practically unknown in Brazil at the time, forcing the Sassi brothers to build their own injection molding machine, make the dies and produce the aluminum alloy for injection - no suitable raw casting alloy was available commercially.  1st Version – The first version used the WB 2.5 S diesel crankcase, as can be seen in the original inscription left on the right side of the case. It appears that this Version I was actually an initial series (or pilot series), manufactured in small quantities purely to test market receptivity. They are quite rare nowadays.

1st Version – The first version used the WB 2.5 S diesel crankcase, as can be seen in the original inscription left on the right side of the case. It appears that this Version I was actually an initial series (or pilot series), manufactured in small quantities purely to test market receptivity. They are quite rare nowadays. 3rd and 4th Versions (both known as the Sassi 15-II). This design is based very closely on that of the Enya 15-III, although the crankcase bore a close resemblance to that of the Enya 15-II. These two variants were practically identical (they were, in reality, two sub-versions of the same engine) and are the best known SASSI models. They are also those that were sold in the most substantial numbers. In this definitive version, the brand inscription is horizontal. The first sub-version, here called the 3

3rd and 4th Versions (both known as the Sassi 15-II). This design is based very closely on that of the Enya 15-III, although the crankcase bore a close resemblance to that of the Enya 15-II. These two variants were practically identical (they were, in reality, two sub-versions of the same engine) and are the best known SASSI models. They are also those that were sold in the most substantial numbers. In this definitive version, the brand inscription is horizontal. The first sub-version, here called the 3 During the development of the SASSI 15-II, a metallurgical engineer at the Tupy foundry in Joinville, Santa Catarina assisted the Sassi family by developing suitable materials for the cylinder liner and piston. A great fan of model airplanes, he visited the Sassi factory to learn about their manufacturing process. Less than 30 days after his visit, he returned with some bars of the material along with instructions regarding their machining and heat treatment. This apparently worked out very well.