|

|

An Obscure Argentinian Diesel - the DALOR 4.5 cc Model

With population figures of that magnitude, it would seem to be a logical assumption that the continent must have been home to a significant number of power modelling enthusiasts over the years. This in turn might reasonably be expected to create a viable domestic market for model engines in at least some of the larger South American countries. And indeed, the existence of a number of model engine marques from several such countries has been authoritatively attested, although details are sadly lacking in most cases, as are examples of the engines in question. Overall, the amount of information on South American engines which is available to the English-speaking model engine enthusiast is remarkably sparse. The country of Argentina (more correctly, the Argentinian Republic) is a case in point - search as I may, I can find very little information on model engines originating in that country. Doubtless language barriers played a significant role in giving rise to this situation.

This being the case, the present article will necessarily be confined very largely to a physical description of the DALOR 4.5 cc diesel, followed by a bench test. It’s my very sincere hope that the article may be read by someone who has some well-founded knowledge regarding this interesting design and is willing to share that knowledge with the rest of us. One such individual with whom I was put in contact following the initial appearance of this article was Sr. Daniel Iele of Hurlingham, a city in the Province of Buenos Aires. As a former long-time President of the Federacion Argentina de Aeromodelismo (1996-2006, 2009-2011), Daniel had enjoyed a long and close connection with the aeromodelling scene in his native country. Remarkably, he lived (and indeed still lives) only a few blocks from the location of the workshop that made the DALOR engines! He was immensely helpful in filling me in on a number of matters about which I had little or no knowledge. Daniel's input has added greatly to the authoritativeness of this article - he has my very sincere thanks! It's quite impossible to provide a meaningful review of any model engine from any country without first placing it in the context of its time and place. Accordingly, before embarking on my review of the DALOR, it seems to me to be essential to provide the reader with a picture of the aeromodelling scene in Argentina leading up to the appearance of the first domestically-produced model engines from that country, of which the DALOR appears to be one. Here goes ............... The Early Post-WW2 Aeromodelling Scene in Argentina

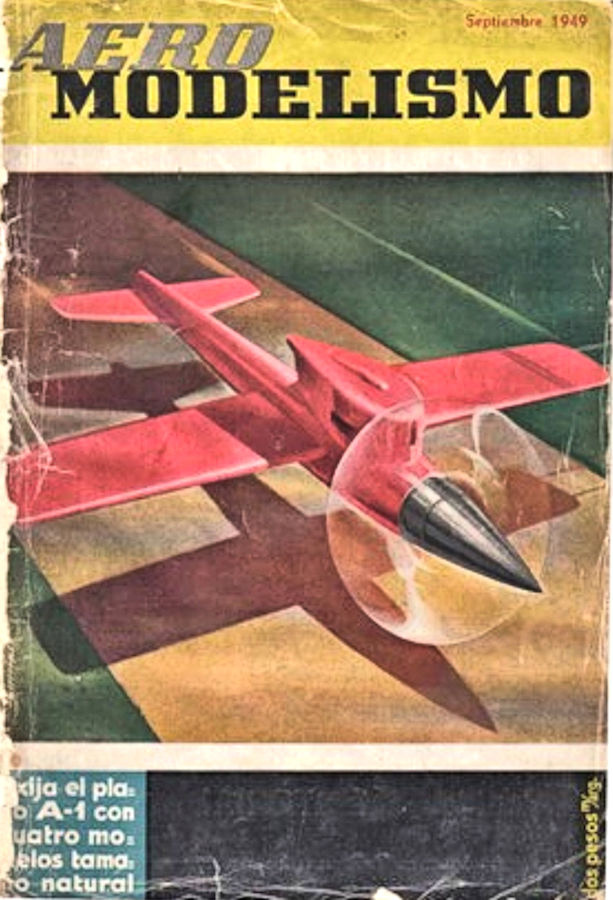

Under these conditions, it comes as no surprise to learn that post-WW2 Argentinians felt themselves to be able to pursue hobby interests, aeromodelling being very much among them. Although it was essentially invisible to the rest of the world due to language and other barriers, it's abundantly clear that a thriving aeromodelling scene developed very quickly in Argentina during the early post-WW2 years. The level of interest was sufficient to support the publication of at least one periodical devoted to the hobby, namely "Aeromodelismo" ("Model Aircraft") magazine. A number of issues of this Spanish-language magazine are accessible today in the pages to be found on the invaluable RC Bookcase website. These issues come from the period September 1949 (the magazine's first issue) to January 1953. I do not know whether or not publication continued beyond this date. My sincere thanks to my valued Aussie friend and colleague Gordon Beeby for drawing my attention to this invaluable resource.

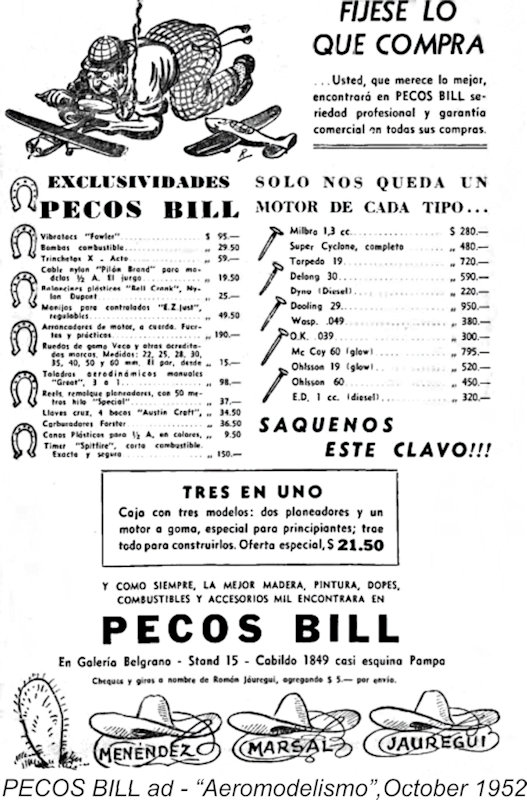

In support of this officially-encouraged interest in aeromodelling, a number of firms emerged which were engaged in the supply of modelling goods to the public. At the outset, there was little or no domestic manufacturing capability - the bulk of the material on sale was necessarily imported. This very much included model engines - the available advertising record confirms that the imported brands included such well-known names as Mills (referred to as Milbro), E.D., FROG, Ohlsson, Forster, McCoy, Arden, Atwood, Anderson, OK and others. Even the odd Dooling seems to have made its way down there! The problem was that these imported engines were extremely expensive, mainly due to the very high import tariffs imposed upon them by protectionist Government policies, which were directed towards the encouragement of domestic industry to the maximum extent possible. As a result, power modelling could only be pursued by the better-heeled members of society - the rest had to content themselves with gliders and rubber-powered models. Even with this restriction, it's clear that aeromodelling was developing into a very popular hobby. As time went on, the number of companies supplying modelling goods steadily increased. By late 1949, the aeromodelling community in Argentina had grown to the point where the establishment of a periodical publication devoted to the hobby was seen as being economically viable. The resulting magazine, the previously-mentioned "Aeromodelismo", published its first issue in September 1949, as seen at the right. The "Aeromodelismo" magazines carried a mix of information, including some articles devoted to model cars. Both free flight and control line models were covered. Much of the material consisted of articles copied and translated from "Aeromodeller" and various US publications. Indeed, there's an appearance of a strong American influence on aeromodelling in Argentina - most of the advertised engines and featured model designs were of US origin, as were most of the published engine reviews, although a few British designs and engines were included.

This company's advertising in "Aeromodelismo" was plentifully illustrated with horseshoes, horseshoe nails, cacti, lassos and ten-gallon hats, very much in keeping with the image of the legendary fictional character of Texas folklore after whom the business was named! It would seem that old Bill had a substantial following in Argentina, whose gaucho culture closely mirrored the cowboy culture of the American West. Unfortunately, the economy began to decline from 1950 onwards due in part to excessive levels of Government expenditure but also as a result of its protectionist economic policies. Moreover, Perón's pursuit of a policy of political suppression involving the dismissal or arrest of anyone viewed as a political dissident did nothing to improve the stability of the nation or enhance its intellectual resources. Although he won re-election in 1951, the economy continued to tank, resulting in Perón's 1955 overthrow which forced him into exile in Spain. He was to make a brief return to power in 1973 but died of a heart attack in June 1974 at the age of 78. It was likely the aforementioned economic decline which brought about the cessation of publication of "Aeromodelismo" magazine, seemingly in early 1953. There can be little doubt that the Government's protectionist policies were the cause of the very high prices of imported modelling goods. It was inevitable that someone would respond to the latter issue by taking steps to establish domestic manufacture of model engines in Argentina. As the record confirms, the initial manifestation of such an initiative came in late 1952. Model Engine Manufacturing in Argentina It appears that the initial thrust to establish model engine manufacture in Argentina came from the previously-mentioned Aeromodelling Department of the Ministry of Aviation. They somehow managed to induce a company called FIAMMA to undertake the development of Argentina's first domestically-produced model engine. The company name FIAMMA stood for Fabrica Italo Argentina de Micromotores y Afines (Italian/Argentinian Manufacturer of Model Engines and Acccessories). The implication is that this was an Italian company which had established a separate satellite manufacturing operation in Argentina. The company always referred to its dual Italian and Argentinian roots in its advertising. The technical director of its Argentinian operation was Dr. Pablo Salani.

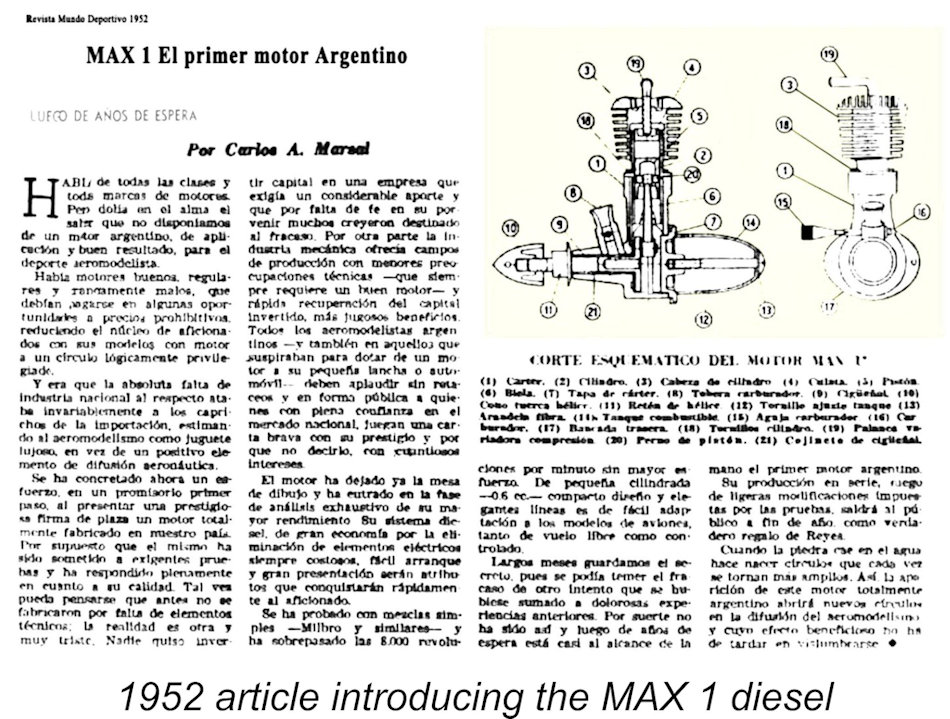

During my research, I was fortunate enough to stumble upon a 1952 article (in Spanish, naturally) by the previously-mentioned Carlos A. Marsal, former Head of the Aeromodelling Department of the Ministry of Aviation and part-owner of the PECOS BILL distribution concern. In addition to his other activities, Marsal evidently wrote about models and model engines for the Argentinian magazine “Mundo Deportivo” (Sporting World) on a regular basis. The article announced the impending arrival of what was reportedly the first-ever model engine to enter series production in Argentina. This dates it in all probability to mid-1952. The writer lamented the fact that Argentinian modellers had had to wait so long for the first commercially-available home-grown model engine to appear. He noted that prior to this point, model engines all had to be imported. Some were good and others were not so good, but all of them came with near-prohibitive price tags due in large part to the high importation tariffs applied to model engines by the Government. Marsal commented that this situation had restricted the pursuit of power modelling to a very small privileged circle.

The writer went on to state that the engine had performed very well in its pre-production testing phase. Using a standard diesel fuel mix - Mills fuel was actually mentioned - the engine was apparently found to exceed 8,000 rpm without any signs of undue stress. Starting was said to be very easy. Deliveries of the engine were expected to commence before the end of 1952. The writer predicted a high level of modeller acceptance of the new home-grown product. In this article, he stopped short of actually naming the manufacturers, stating simply that they were a “prestigious company”.

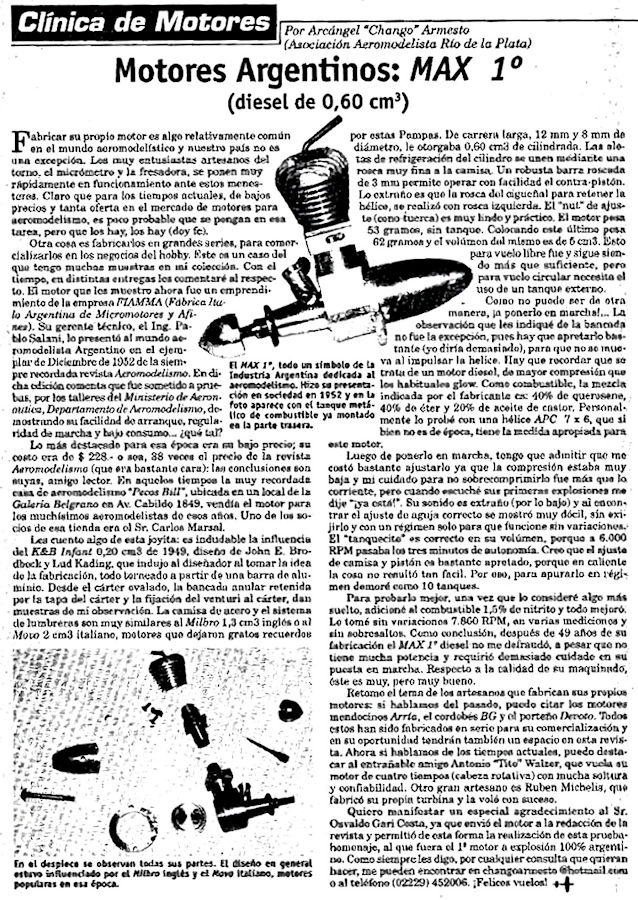

The December 1952 issue of "Aeromodelismo" carried an introductory two-page promotional spread for the MAX 1 which referred to the engine as the "FIAMMA MAX 1 0.6 cc diesel" and specifically named the manufacturer as the FIAMMA company. Both Dr. Salani of FIAMMA and Carlos Marsal of PECOS Following the initial publication of this article, my good mate Maris Dislers sent along several excellent photographs of an example of the MAX 1 along with a latter-day review of a surviving example by the late well-known Argentinian collector Arcángel “Chango” Armesto. For the benefit of my Spanish-speaking readers, this article is reproduced here at the left. Although Maris did not know either the name of the publication or the date, the text stated that the test was performed 49 years after the introduction of the engine. Since that event took place in 1952, this dates the article pretty reliably to 2001.

The test engine was a new and previously unrun example which was loaned to the magazine by Osvaldo Cesta to allow this retrospective test to take place. Following a 30-minute break-in, Armesto recorded a steady speed of 7,800 RPM on an APC 7x6 airscrew, implying an output of around 0.048 BHP at that speed, with torque being of the order of 6 oz-in. For a diesel engine of this type and displacement, those are pretty good figures! Moreover, Armesto praised the engine's quality very highly. Both Marsal's previously-cited article and Armesto's published review leave no room for doubt that this late 1952 product was the first model engine to enter series production in Argentina, making the country rather a late-comer as a model engine-producing nation. However, it was by no means the last such product to I base this opinion in large part upon a recollection shared by reader Adam Bruckner, who contacted me to say that as a boy he lived with his family in Buenos Aires, Argentina for some years spanning the late 1940's to the mid 1950's. Adam developed a keen interest in models during this period, spending considerable time drooling over the engines (mainly American and European) on display in the local hobby shop where he purchased his basic model supplies. Adam retained a very clear recollection of being particularly intrigued by a diesel engine of medium size which appeared in the shop during 1954. This engine proclaimed on the case that it was made in Argentina. He never noted the name at the time, but his description pretty much confirmed that this was a DALOR diesel. This would date the DALOR to 1954 or perhaps a little earlier. The engine’s design characteristics and general style of production are both completely consistent with this dating. Much more of this model below in its place.

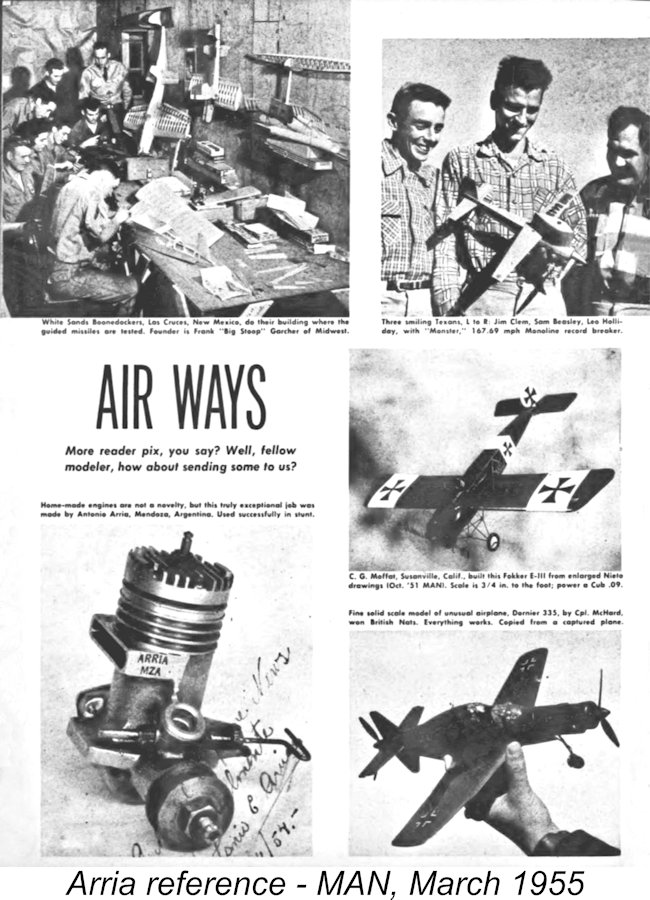

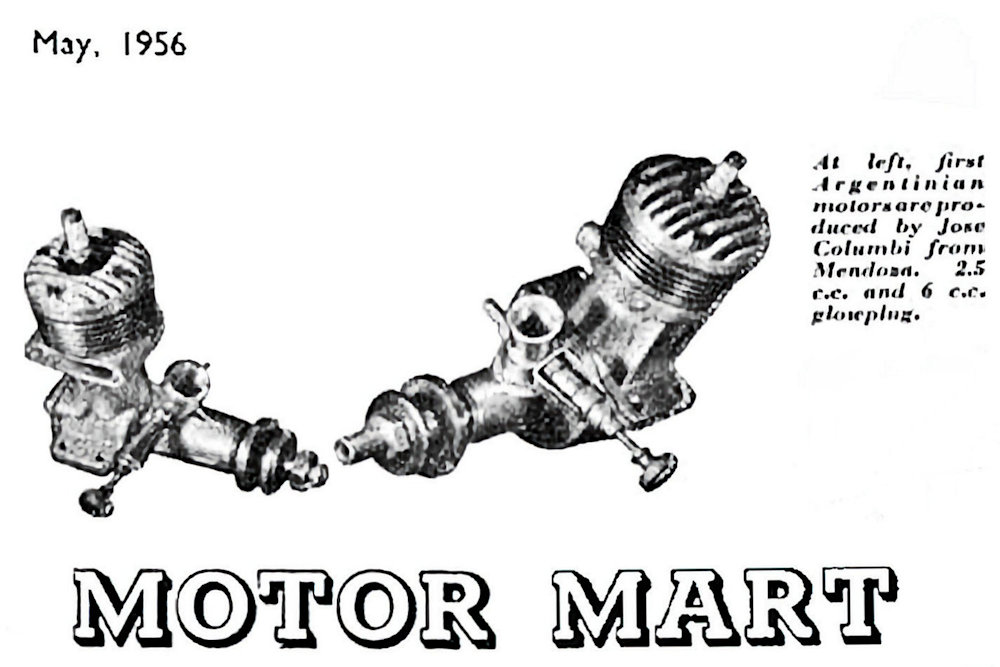

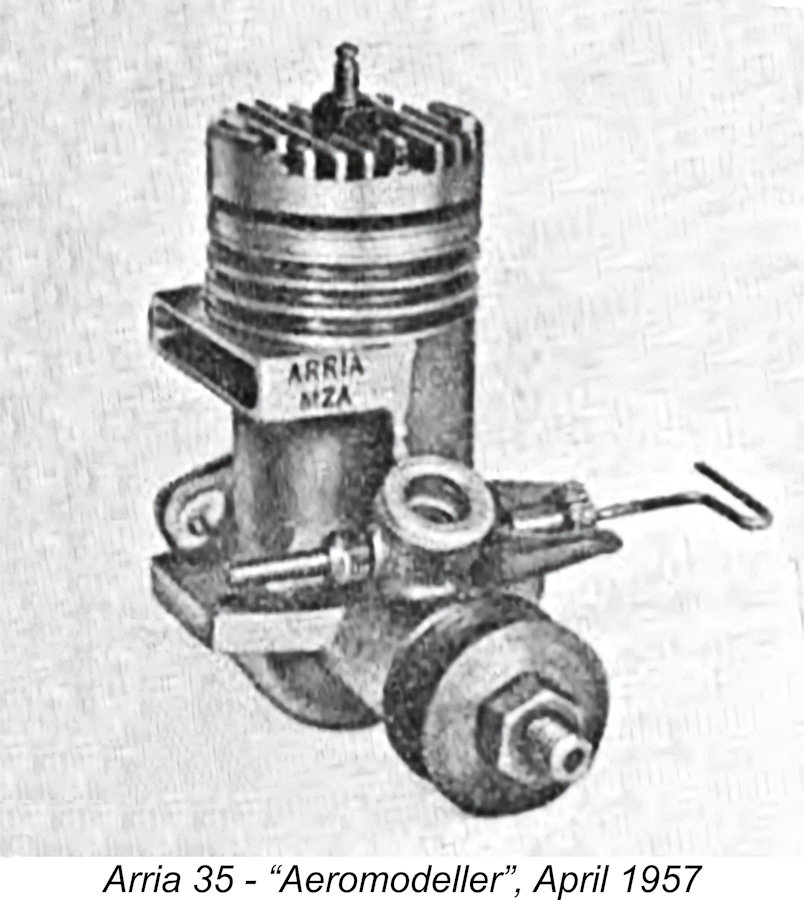

The first of the references found by Gordon took the form of a single image which was included in the “Air Ways" feature of the March 1955 issue of MAN, in which readers' photos were presented. This showed a supposedly home-made engine made by Antonio Arria of Mendoza, a city located in west-central Argentina in the foothills of the Andes. Antonio Arria was a prominent competitor who had rated the occasional mention in “Aeromodelismo” prior to 1953. The image confirmed that the engine was a virtual clone of the early Fox 29/35 design. It had reportedly been used successfully for control line stunt. The MZA characters beneath the Arria name may be a short-hand rendition of Mendoza.

During a sponsored demonstration tour of Argentina in 1961, which was reported in the 1962 "American Modeller" Annual, Bob Palmer and Dale Nutter were presented with examples of the Colombi 35, which was evidently still in production, selling at the time for 1,300 pesos. Although the engines had an attractive appearance, their quality did not come up to American standards.

In his previously-cited review of the MAX 1, Arcángel Armesto mentioned several commercial model engine marques which had originated in Argentina over the years. Among these was the Arria range, the series production of which was confirmed by Armesto. The accompanying image extracted from the “Aeromodeller” article appears to be the same one that had appeared in the March 1955 issue of MAN. It confirms once again that these engines were virtual clones of the earlier Fox 29 and 35 models. The 1957 "Aeromodeller" article stated that the Arria engines had “already distinguished themselves in team racing and stunt events”. The claim was made that the 35 version would turn a 10x6 prop at 11,800 RPM, a pretty fair performance if true. Bob Palmer and Dale Nutter encountered Antonio Arria during their previously-mentioned 1961 tour. By that time Arria was involved with R/C flying, with no mention being made of his engines. Presumably their manufacture had ended by that time.

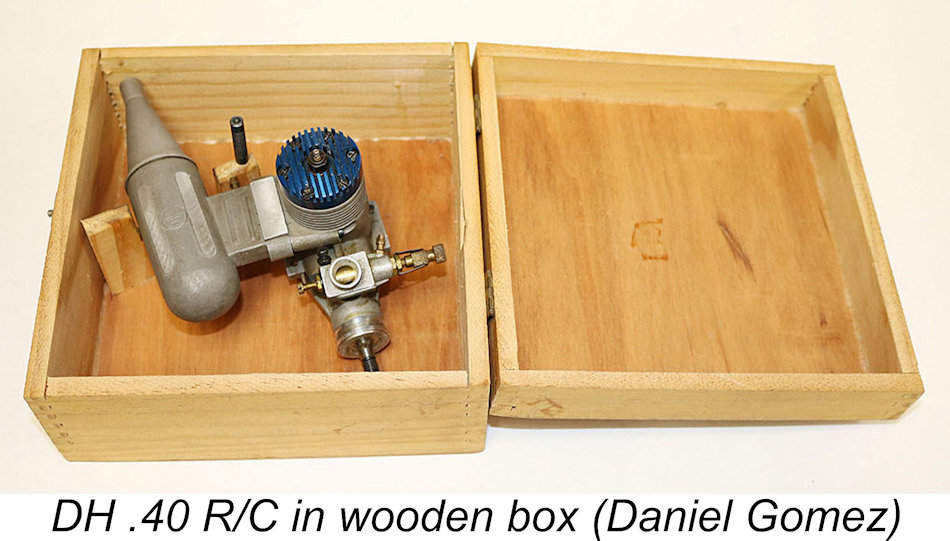

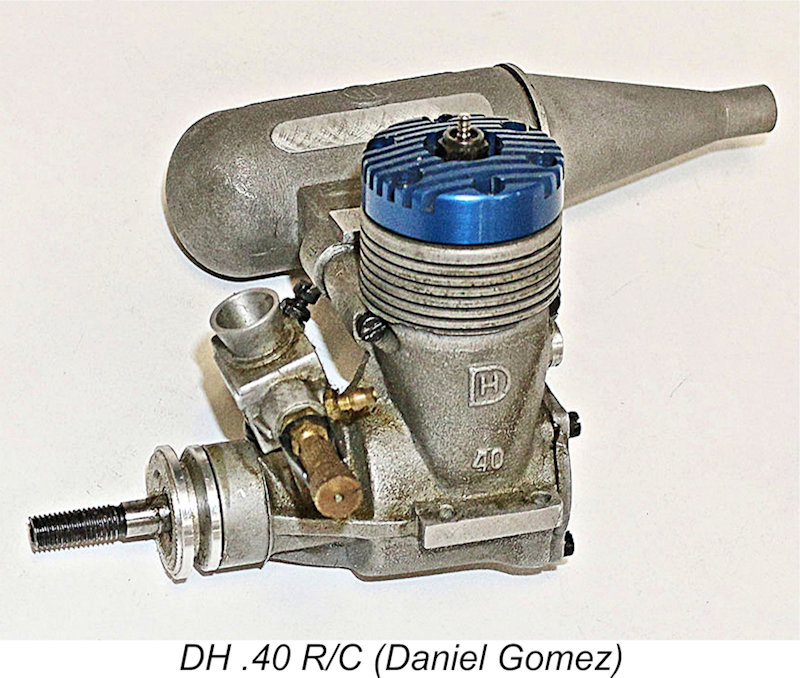

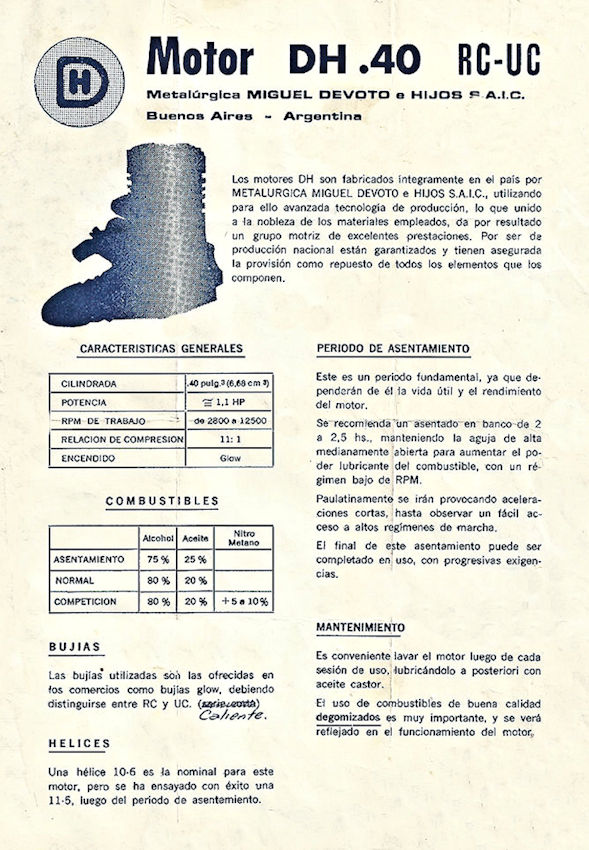

An Argentinian model engine about which a little can be shared is the DH .40 RC-UC from Buenos Aries. Our modest knowledge of this model arises from the fact that the owner of a boxed as-new R/C example, Daniel Gomez, shared a few details on the Craftsmanship Museum website.

The illustrated example is new in the original wooden box - Daniel Gomez stated that he purchased it new but never ran it. A really classy (and expensive) approach to packaging, suggesting somewhat limited production! The "RC-UC" designation indicates that the engines were designed to be used in both Radio Control and U-control applications.

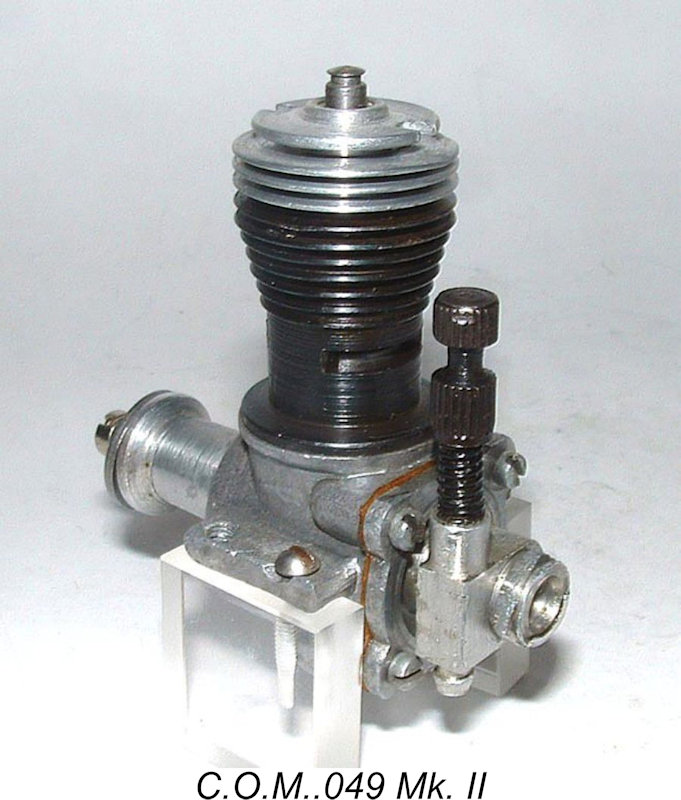

Miguel Devoto & Sons continued to produce model engines into the 1990's. Their later products were thoroughly up-to-date designs featuring Schürle porting and ABC piston/cylinder sets. An Argentinian engine about which we know quite a bit more was the C.O.M. 049 of 1971-1974. I'm greatly indebted to the late Tim Dannels for information regarding this very obscure engine. Much of Tim's information came originally from the late previously-mentioned Argentinian engine aficionado Arcángel Armesto, who interviewed the maker of the C.O.M. 049, one Oscar Nocera. The accompanying images of the engines were supplied by Tim, with my sincere thanks. It appears that Nocera had begun designing and constructing .049 glow and diesel engines for his own use in the 1960's. However, in the early 1970's a market niche became apparent to him, leading him to commence the small-scale commercial The C.O.M. 049 was manufactured in two distinct series, both using a Cox-style piston/cylinder set-up. The Series 1 model pictured at the right used a bar-stock crankcase and a screw-in reed valve carburettor set-up very reminiscent of the earlier Cox Space Hopper design. The Series 2, however, used a cast crankcase and a bolt-on At first glance, the resemblance of the Series 2 model to the Cobra is quite striking, the main immediately observable difference being the mounting of the needle valve. However, there is no evidence that Nocera was in any way influenced by the "British Cox". It's quite likely that he didn't even know of its prior existence. The C.O.M. project was initially quite successful, with over 1,500 engines reportedly being manufactured and sold domestically. Nocera clearly had plans to expand his range, because Daniel Iele reported that Nocera commenced the development of a .49 cuin. model, subsequently selling the license for its manufacture to Carlos Minoli. Unfortunately, the 1974 death of restored President Juan Perón triggered a period of political instability which resulted in an economic collapse, forcing the premature cessation of model engine production. Manufacture was never resumed subsequently. Both Oscar Nocera and Carlos Minoli are now deceased.

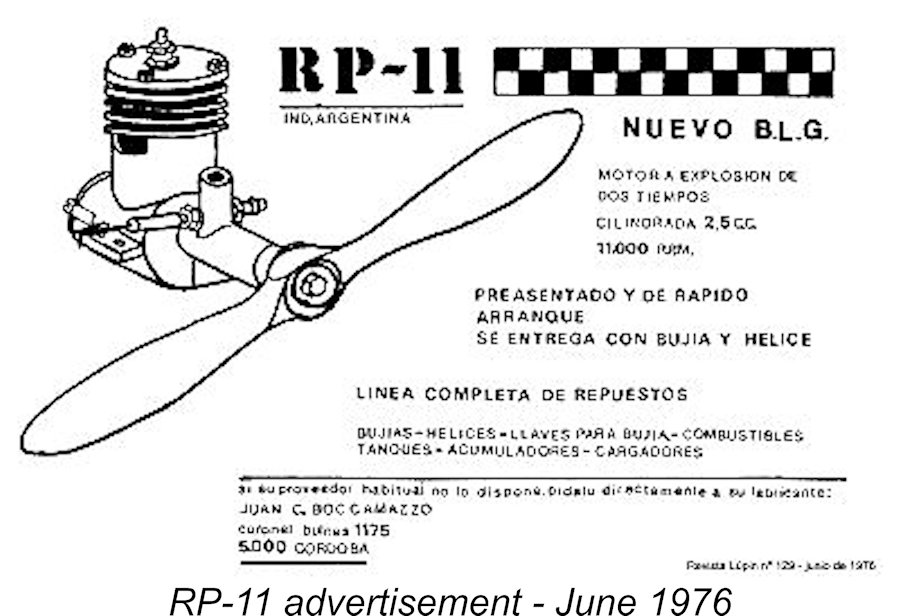

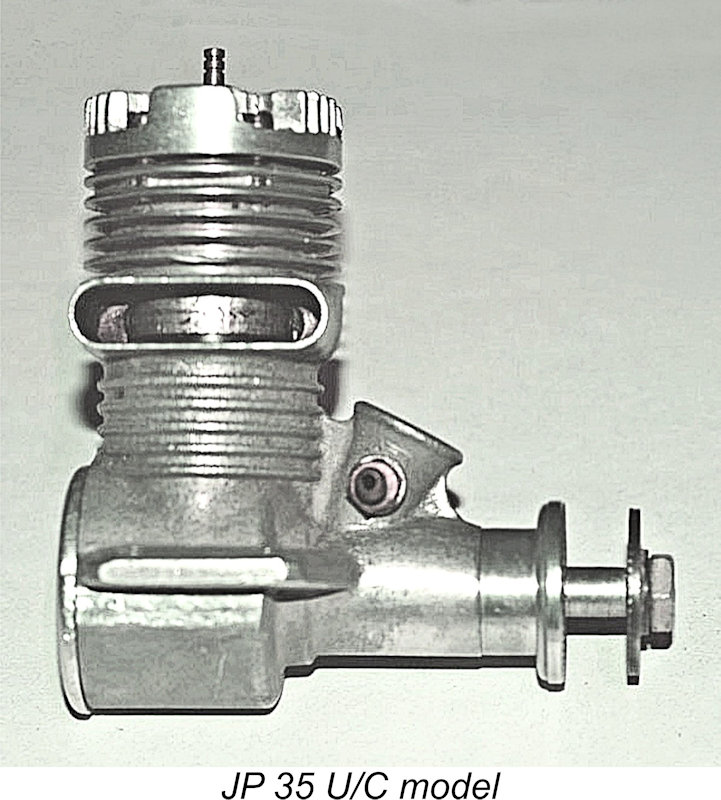

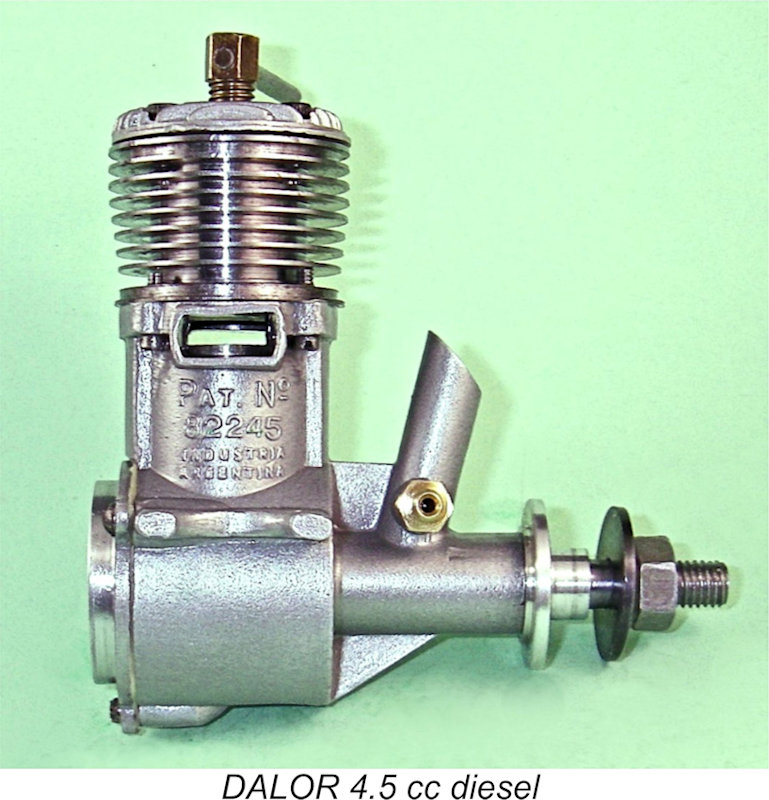

Boccamazzo produced a series of engines under the general marque identification of BG (not to be confused with the far later BG team race diesels manufactured in Denmark by Luis Petersen and Jens Geschwendtner). The RP-11 was one of a number of models produced by Boccamazzo. The available advertising image shows that the RP-11 was a plain bearing FRV glow-plug motor, seemingly of relatively unpretentious design. The reproduced advertisement is a little indistinct, but appears to be dated June 1976. The claimed operating speed appears to be a slightly truncated 21,000 RPM – a bit hard to accept given the style of the engine! Perhaps it was intended to read 11,000 RPM ...........or perhaps the image in the advertisement is a form of trade-mark rather than a representation of the actual engine. Boccamazzo appears to have been a rather consequential member of the Argentinian modelling community. He went into tuned pipe technology, publishing a quite detailed article setting out the principles of this technology, which had its origins in the mid 1960’s with Bill Another Argentinian model engine marque of which I’ve become aware was the JP series. This was a small range of glow-plug motors built to a common design in two different displacements. The cited compression ratio for all models was 10:1. There were units having displacements of .36 and .40 cuin. (5.82 cc and 6.55 cc). Both sizes were offered in U/C and R/C versions. Claimed outputs Daniel Iele confirmed that there was one final attempt to market a range of Argentinian model engines. This took the form of the Snorer units, which were produced during the first decade of the present millenium. They were thoroughly up-to-date glow-plug designs featuring ABC piston-cylinder combinations allied to Schnürle porting - The above summary includes all commercially-produced Argentinian model engines of which I’ve become aware to date. The fact that this many commercial manufacturers felt able to go into series production at different times certainly confirms that interest in power modelling must have been quite high in Argentina during the years leading up to the 1980's and probably beyond. However, the problem facing any Argentinian model engine manufacturer trying to compete with the imports on the domestic market was the relatively small size of the overall market for such products. In the absence of any realistic opportunity to export these engines, manufacturers were confined to a scale of production which kept unit costs relatively high, thus offsetting any commercial advantage which a domestic range might have over the imports. For that reason, prices were generally quite comparable with those of the competing imports despite the import duties and taxes to which the latter were subject. Modellers tended to be attracted to the internationally-recognized name-brand powerplants which could be obtained for very comparable prices. This undoubtedly explains the relatively short production lives of the various Argentinian model engine ranges. If any reader knows more about the Argentinian model engine manufacturing scene, please get in touch! Any additional information which may be received will be added to this article with full acknowledgement. Meanwhile, having sampled a few of the model engines presently known to have been manufactured in Argentina, it’s now time to commence our in-depth examination of a specific product of that country - the DALOR 4.5 cc diesel. The DALOR 4.5 cc Diesel Described The DALOR engines were produced in a manufacturing facility located on San Juan Street in Hurlingham, a city which forms part of Greater Buenos Aires in its western sector. I mentioned earlier that the home of my valued informant Daniel Iele was (and still is) located only a few blocks from the location of the DALOR workshop. Daniel recalled that for some years he passed the DALOR facility daily on his way to and from school.

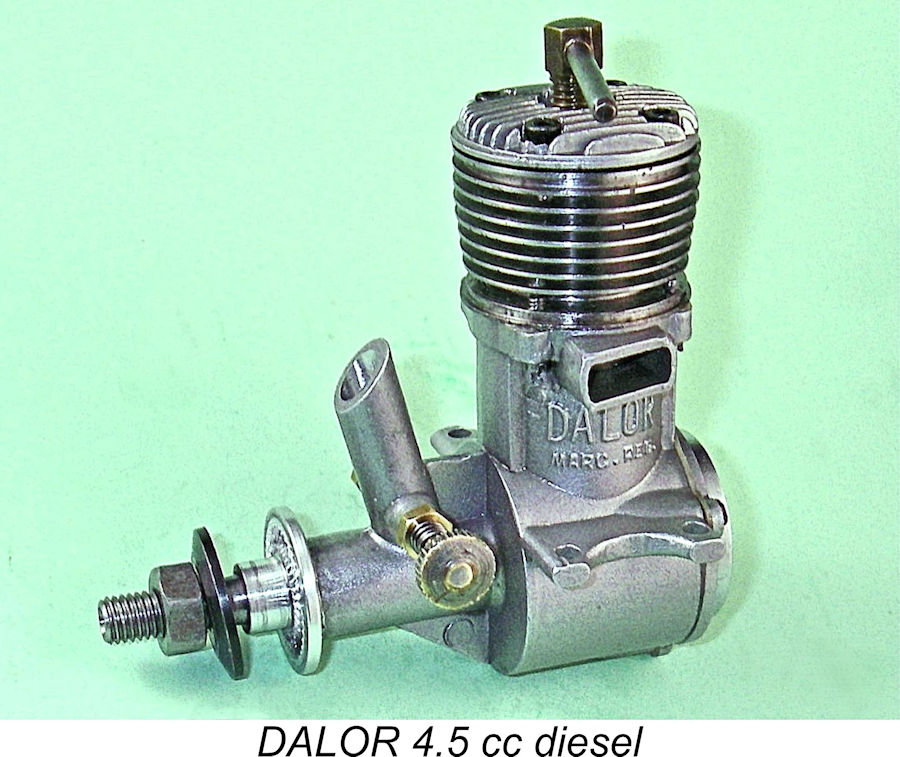

The fine example of the DALOR 4.5 cc diesel which I’m fortunate enough to have available for inspection and testing was acquired from master engine builder Dean Clarke of New Zealand. The engine had come to Dean in an estate sale a few years earlier. He hadn't done anything with the engine prior to my expressing an interest in acquiring it for review and test. As many readers will know, Dean produces a number of outstanding engines through his Cre8tionworx company. He also undertakes restorations of interesting and unusual engines. The illustrated example of the DALOR turned out to have a significant number of issues requiring correction, but Dean’s amazing skills were well up to the task. Having had the opportunity to examine the engine in detail during its rebuild, Dean felt obliged to make the comment that the DALOR was perhaps the worst-designed commercially-produced model diesel of his long experience! The piston, rod, transfer ports and crankshaft all drew their fair share of well-founded criticism. It appears that whoever designed the DALOR had a lot to learn about the structural integrity and operational efficiency issues relating to model diesel design. This in turn seems to confirm a relatively early date for this engine's introduction, in line with my earlier comments.

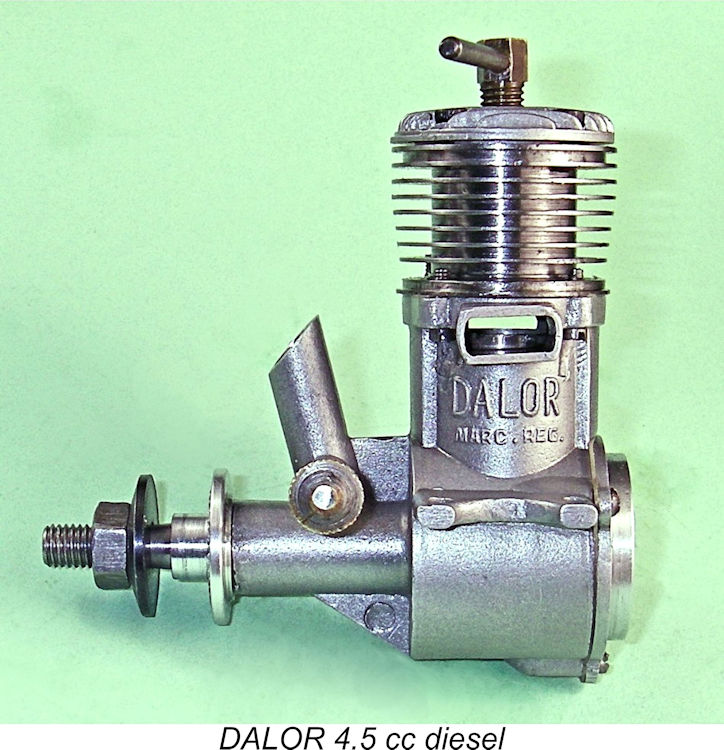

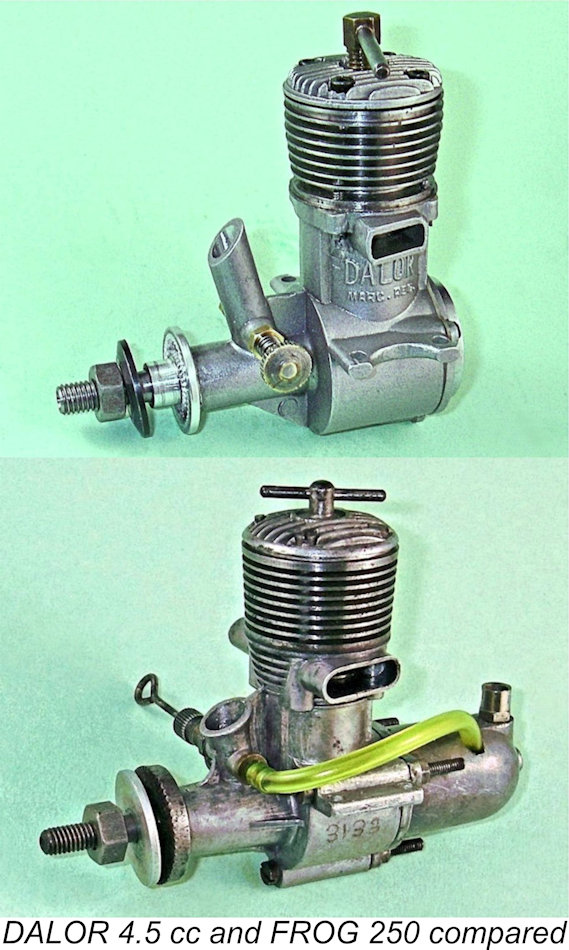

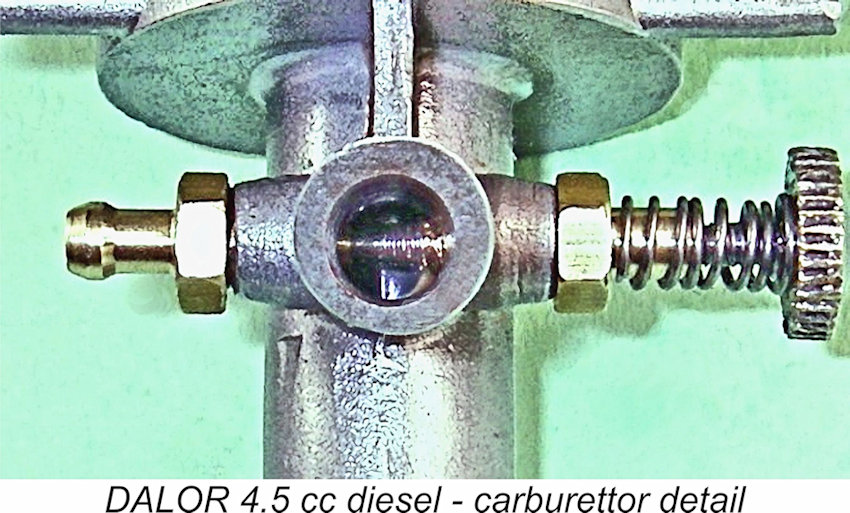

A complete description of Dean's restoration work may be found on the Cre8tionworx website. It's a bit difficult to comment on the original standard of workmanship because so much of the engine's present outstanding quality is down to Dean's restoration. The quality of workmanship visible in the remaining original components (which are still with the engine) appears to be generally adequate, although certain design details leave something to be desired, as we shall see. The DALOR 4.5 cc diesel is a long-stroke plain bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) unit of somewhat utilitarian appearance. Bore and stroke are 17.3 mm and 19 mm respectively for a true displacement of 4.47 cc. The engine weighs in at 171 gm (6.03 ounces) - a relatively low figure for a 4.5 cc diesel. Looking at the engine from an overall standpoint, the general design seems to have been quite strongly influenced by that of the FROG 250 which was introduced in England in mid-1950. A review of the scanned copies of "Aeromodelismo" to be found on the RC Bookcase website confirms that English model engines, including the FROG designs, were definitely being imported into Argentina in limited quantities during the early 1950's. It's thus quite likely that examples of the FROG 250 were available for study. This observation is completely consistent with the assumed dating of the DALOR to the first half of the 1950's.

The cylinder is topped by a cleanly pressure-diecast light alloy cylinder head with integrally-cast cooling fins. This is secured to the cylinder by four short machine screws which engage with threads formed in the top flange of the cylinder itself. The original screws and threads were well and truly graunched, leading Dean to drill and re-tap the cylinder holes to accept M2.5 high-tensile cap screws. The cylinder is quite nicely machined from a steel billet, with the fins being formed integrally. This is a good design in that there are no joints to act as potential heat dams, thus affecting cooling. Peter Chinn commented favorably on this arrangement in his February 1951 test of the FROG 250, stating that it rendered that engine remarkably free from any tendency to sag as it became hot. Presumably the same benefit would have been conferred upon the DALOR.

The crankcase is another cleanly-formed pressure diecasting. It incorporates both the main bearing and the intake venturi in a single casting. The left-hand side of the case bears the ciphers "DALOR MARC. REG." cast in relief, while the right-hand side displays the inscription "PAT. NO 82245 INDUSTRIA ARGENTINA" in similar ciphers. It's hard to work out what the patentable technology embodied in this engine may have been as of c. 1954! Perhaps the cited Patent only applied in Argentina?!? At thjis point you're probably wondering: "This all sounds pretty good! Where are the design shortomings that the guy hinted at?" Well, here they come!! For starters, the beam mounting lugs appear rather under-nourished for an engine of this displacement. Their "mouse-ear" configuration does nothing to dispell this impression. During the course of his rebuild, Dean noted some evidence of a crankcase weld repair which had been quite competently carried out. This seems to confirm that the case may indeed have been a little inadequate in terms of its crash resistance.

The situation is not improved by the conrod, which is a light alloy diecasting of somewhat minimal dimensions. A diesel engine of this displacement really needs a more substantial rod, especially with a piston this heavy. The small end bearing is drilled well off centre. As received by Dean, both rod bearings were completely shot. In the course of his rebuild project, Dean took advantage of the opportunity to make the new piston a little lighter than the original, which would undoubtedly confer some operational benefits. He also made a new high-strength rod, which should comfortably outlast the original. A further design issue is to be found in the transfer arrangements. The cylinder is provided with four small-diameter drilled holes arranged in two pairs to serve as transfer ports. These are arranged with one pair associated with each of the two bypass passages fore and aft. This arrangement follows that used in the FROG 250 except for the fact that the DALOR holes are drilled straight through the liner wall at right angles to the bore axis, while those in the FROG are drilled at an upward 45 degree angle to impart some upward direction to the incoming transfer gas. The FROG system would be expected to provide superior scavenging.

Cylinder port timing is actually quite reasonable. The exhaust period is around 140 degrees, while the transfer period is approximately 126 degrees, with a blow-down period of only some 7 degrees. There is no sub-piston induction as such, but the outer corners of the two piston skirt cutaways mentioned earlier do intersect with the exhaust ports near Top Dead Centre, allowing a little sub-piston induction to occur at that point. The original one-piece steel crankshaft seen at the left probably embodies the most serious design errors in this engine. It has a nominal main journal diameter of only 8 mm - pretty marginal for a diesel engine of this displacement. Even worse, the diameter of the central gas passage associated with the FRV induction system is 5.8 mm, leaving a wall thickness of only 1.1 mm. The somewhat excessive 5.8 mm diameter of the crankshaft induction port aperture doesn't help - the shaft looks extremely weak at that always-vulnerable point. Frankly, I would anticipate a high probability of crankshaft failure with any example of this engine that was run hard for any length of time. Once again, Dean took advantage of the need to make a new shaft by slightly resizing the bronze main bearing bushing and fractionally enlarging the crankshaft journal diameter to match. In addition, he reduced the diameter of the crankshaft induction port in order to increase the component's strength at that point. The induction register window in the case was also amended to restore appropriate induction timing. The revised shaft should be somewhat stronger than the original. The resulting induction timing is quite reasonable for an engine of this vintage and specification. The induction period is around 152 degrees, extending from 50 degrees after Bottom Dead Centre to 22 degrees after Top Dead Centre. These figures are probably quite appropriate for an engine like this one which may be expected to operate at somewhat lower than average speeds.

Finally, the prop driver is mated to a shallow self-locking taper formed at the front of the shaft. It features a hub diameter of 9 mm, requiring that any prop used with this engine have its hub drilled to this diameter. The prop is conventionally secured using a simple nut and washer.

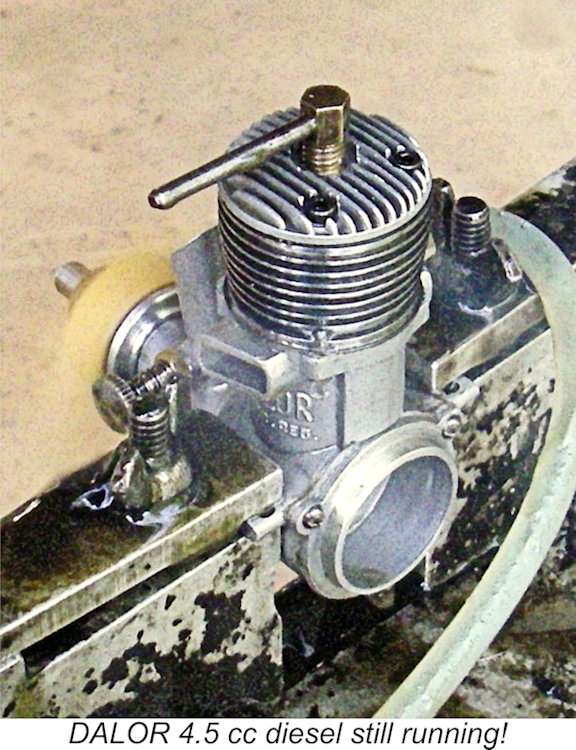

In the complete absence of any meaningful documentary information, it's impossible to estimate either the production life of the engine or the number of examples produced. The engines seem to have borne serial numbers which were stamped onto the underside of the crankcase near the front. The illustrated example bears the number 181, seemingly indicating that at least that many units were manufactured. At present, that's all that I know. The DALOR 5 cc Diesel on Test Given the structural deficiencies documented above, I was a bit nervous about putting this engine through its paces on the test bench. However, both the shaft and the rod were replacements made by Dean as part of his restoration of the engine, although the original shaft remained intact - just a bit worn. Indeed, the fact that the engine had done enough running to make these repairs necessary suggests that it had been a perfectly useable engine when new - it's the good 'uns that get the running time! Its survival (more or less!) implied that its structural integrity as delivered was perhaps better than might have been suggested by this example prior to restoration. Moreover, Dean had run the engine himself after completing his remedial work. His own assessment was that the restored engine with its beefed-up shaft and rod should certainly be good for a few runs. Thus encouraged, I decided that I would give the engine the said "few runs" just to experience its handling and running qualities while remaining very conservative with my use of the compression screw. I felt that a 10x6 or an 11x4 airscrew would probably suit this unit very well. I also decided that my usual test fuel mix of 35/35/30 kerosene/ether/castor oil plus 1½% ignition improver should be quite suitable. So into the test stand went the old DALOR! For the first runs, I fitted a Zinger 11x4 wood prop. I opened the needle 3 turns - purely a guess based on the speed with which fuel was drawn through the fuel line when the engine was choked. I left the compression where it had been set during Dean's test run.

It turned out that I had opened the needle too far - the engine was slobbering rich at my three-turn setting. Suction actually appeared to be considerably better than I had anticipated. Closing the needle down by over a turn got things to a far happier place, with the engine running slightly rich on a reduced compression setting - a perfect break-in condition. In this condition, the 11x4 prop was being spun at around 7,500 RPM. Here I was in a bit of a quandary! The DALOR was clearly in need of a full break-in following Dean's careful rebuild. However, I didn't want to put too much running time on the engine given the uncertainties regarding the shaft's structural integrity. Accordingly, I decided to put 15 minutes on it in 5 minute rich and under-compressed runs, leaning out briefly at the very end to ensure that the piston was subject to the full-range heat cycles which are so essential to a good break-in of an iron-and-steel piston/cylinder combination. To the same end, I allowed complete cooling between runs. At the end of the third run, I measured the leaned-out speed briefly achieved on the 11x4 prop, optimizing the compression setting while doing so. The DALOR got the prop up to 8,400 RPM under that condition. I decided that I would continue to test the engine on different props using the same technique, running the engine rich for 2 minutes and then leaning out briefly to get the speed, thus also putting the piston through another full-range heat cycle. In this way, the break-in process would continue in 2 minute bursts instead of 5. The testing of the other 5 props that I tried thus added about 12 minutes to the engine's break-in time in my hands for a total of around 27 minutes plus whatever time Dean had put on the engine during its post-rebuild shake-down runs in his hands.

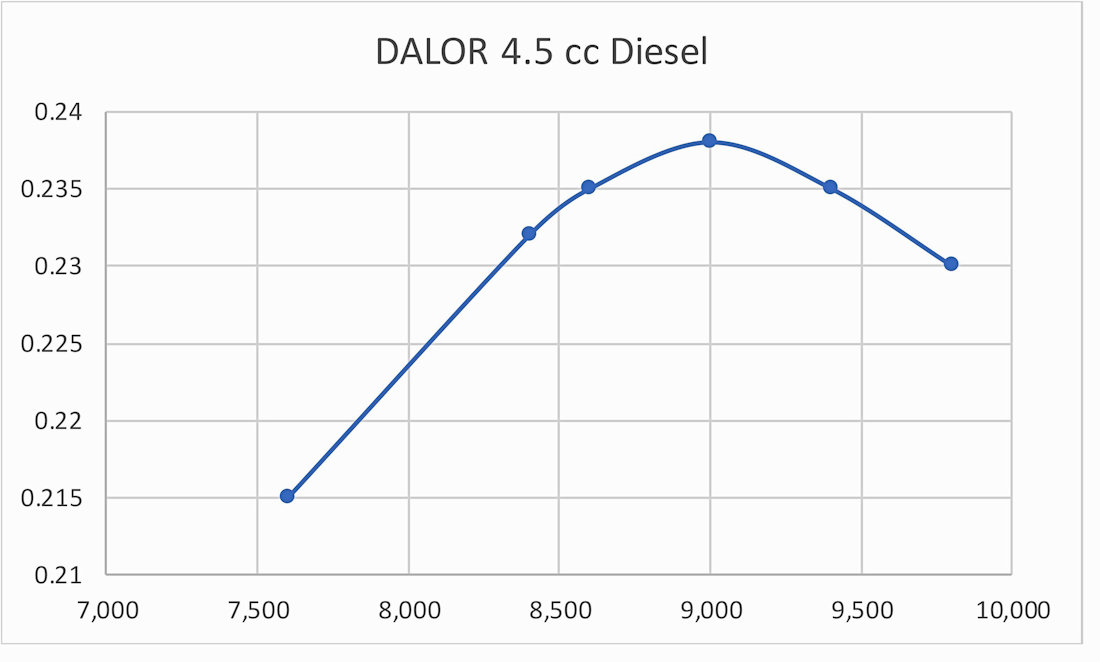

Objectively speaking, I would actually rate the DALOR as an extremely easy starter, particularly for a larger diesel. Once running, response to the controls was outstanding - very responsive but by no means overly sensitive. Both controls held their settings very securely. I took a bit of extra care in establishing the leaned-out settings for the two fastest props tried near the end. This demonstrated the fact that the leaned-out engine ran completely smoothly without missing a beat. It also displayed no tendency to sag at any time. The only fly in the ointment was the development of a noticeable level of vibration at the higher speeds, just as I had expected. A very firm mounting in the model would definitely have been indicated. With the heavier original piston fitted, this characteristic would have been appreciably worse. The engine delivered a perfectly acceptable performance for a 4.5 cc long-stroke diesel of its probable vintage. I'm sure that it would do a little better given a completed break-in period, but even so the figures recorded weren't dismal by any means! The test data are summarized below.

As can be seen, the DALOR 4.5 cc diesel delivered around 0.238 BHP @ 9,000 RPM on this showing. These figures are very comparable to those measured earlier for the "K" Vulture 5 cc diesel, as reported elsewhere. I could easily envision the DALOR doing a little better than this following some additional break-in running. It might be expected to reach 0.250 BHP @ 9,500 RPM. Even as it stands, it certainly has more than enough power to fly a sizeable model, besides which it handles superbly. Assuming that the shaft held together, it would have been a highly satisfactory powerplant for most sport-flying applications. As I had anticipated, a 10x6 prop appears to be the ideal load. Overall, I'd have to say that its fine handling and running qualities made the DALOR a real pleasure to test. It came through the test completely unscathed and seemingly ready for more. In particular, the shaft held up just fine. Perhaps it's less of an issue than I had feared ........... certainly, Dean's improved shaft seems to be up to the task! Summary and Conclusion

The DALOR supports the indications from the published comments on the pioneering MAX 1 that the early model engine productions originating in Argentina would have served their owners well, hence constituting persuasive ambassadors for the country's then-emerging domestic model engine production. Later products of the Argentinian industry seem to have been brought well up to date with their competitors from elsewhere - it was the ambassadorial roles played by the MAX 1 and the DALOR, among others, which paved the way for this to happen. Judging by the engine's rarity and lack of documentation, it appears that the DALOR didn't remain long in production, nor were that many examples produced in total. It's possible that some degree of structural weakness or manufacturing deficiency became apparent to prospective purchasers, but it's equally likely that the engine was simply sidelined in a technical sense - by 1954, when the DALOR seems to have appeared, it was already lagging well behind more advanced designs from elsewhere in both technical and performance terms. Still, a very worthy effort by the engine's unknown designer and manufacturer! I hope that you've enjoyed making its acquaintance as much as I have! Kudos to Dean Clarke for a great restoration! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2024 |

||

| |

Those readers who are up on their global geography will doubtless know that South America is the world’s fourth-largest continent by area, behind only Asia, Africa and North America in that order. South America also boasts the world’s fourth-largest continental population at almost 450 million people. As of 2023, 46 million of those individuals lived in Argentina, speaking Spanish as their primary language.

Those readers who are up on their global geography will doubtless know that South America is the world’s fourth-largest continent by area, behind only Asia, Africa and North America in that order. South America also boasts the world’s fourth-largest continental population at almost 450 million people. As of 2023, 46 million of those individuals lived in Argentina, speaking Spanish as their primary language. My recent acquisition of a fine example of a DALOR 4.5 cc diesel produced in Argentina brought this dearth of information very sharply into focus. Despite an intensive search, I’ve been unable to find any authoritative published information regarding this very rare engine. None of the standard reference works by authors such as

My recent acquisition of a fine example of a DALOR 4.5 cc diesel produced in Argentina brought this dearth of information very sharply into focus. Despite an intensive search, I’ve been unable to find any authoritative published information regarding this very rare engine. None of the standard reference works by authors such as  The rise to power of Juan Perón's Labour Party in 1946 brought great changes to Argentina. Perón nationalized strategic industries and services, improved wages and working conditions, paid off the country's external debt and claimed to have achieved almost full employment. He pushed Congress to enact womens' suffrage in 1947, also developing a system of social assistance for the more vulnerable members of society. After the previous years during which the fortunes of the country were dominated by self-serving and corrupt military power-mongers, these changes must have been very welcome to many Argentinian citizens.

The rise to power of Juan Perón's Labour Party in 1946 brought great changes to Argentina. Perón nationalized strategic industries and services, improved wages and working conditions, paid off the country's external debt and claimed to have achieved almost full employment. He pushed Congress to enact womens' suffrage in 1947, also developing a system of social assistance for the more vulnerable members of society. After the previous years during which the fortunes of the country were dominated by self-serving and corrupt military power-mongers, these changes must have been very welcome to many Argentinian citizens.

The names of the various supply companies which advertised in the magazine are equally suggestive. A surprising number of them had English-language names, including King-Prime (which promoted the Mills range indefatigably under the name "Milbro"), Aero Argentina, All-Hobbies, TELMAC Argentina - and my personal favorite, PECOS BILL! The latter company was owned in part by Carlos A. Marsal, who was a former Head of the Aeromodelling Department at the Ministry of Aviation.

The names of the various supply companies which advertised in the magazine are equally suggestive. A surprising number of them had English-language names, including King-Prime (which promoted the Mills range indefatigably under the name "Milbro"), Aero Argentina, All-Hobbies, TELMAC Argentina - and my personal favorite, PECOS BILL! The latter company was owned in part by Carlos A. Marsal, who was a former Head of the Aeromodelling Department at the Ministry of Aviation.

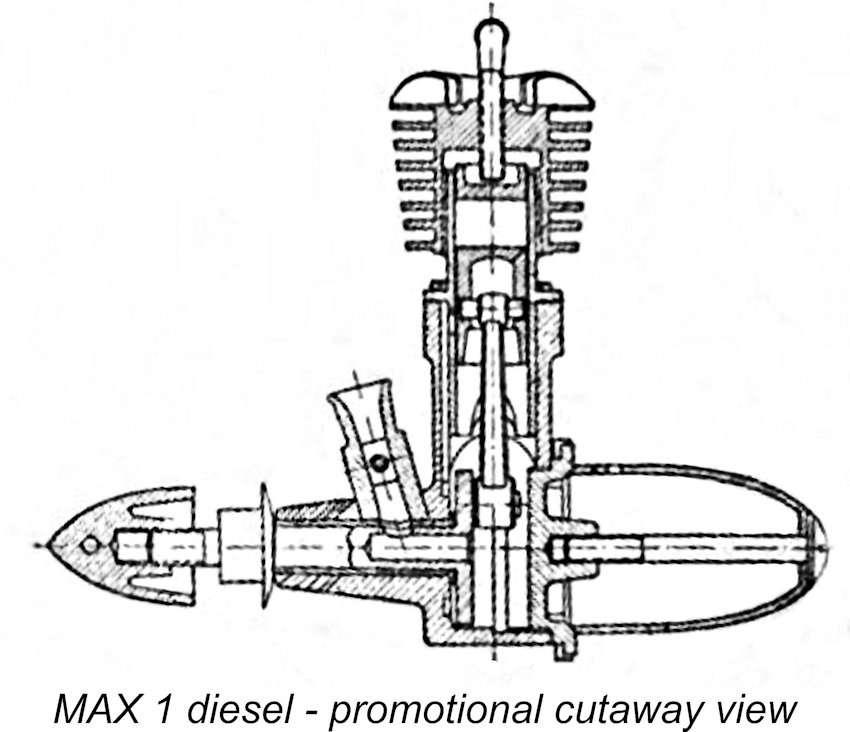

The engine which he announced was designated the MAX 1. It was a small plain bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) 0.6 cc diesel engine of somewhat retrospective design by 1952 standards prevailing elsewhere. For one thing, it was a very long-stroke design - bore and stroke were 8 mm and 12 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.603 cc. This geometry naturally resulted in a rather “tall” unit displaying unmistakeable early post-WW2 Italian influence. The unit reportedly weighed 53 gm (2.05 ounces) without tank and 62 gm (2.45 ounces) with the tank fitted.

The engine which he announced was designated the MAX 1. It was a small plain bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) 0.6 cc diesel engine of somewhat retrospective design by 1952 standards prevailing elsewhere. For one thing, it was a very long-stroke design - bore and stroke were 8 mm and 12 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.603 cc. This geometry naturally resulted in a rather “tall” unit displaying unmistakeable early post-WW2 Italian influence. The unit reportedly weighed 53 gm (2.05 ounces) without tank and 62 gm (2.45 ounces) with the tank fitted.  In the event, it appears that the goal of introduction in late 1952 was met. The initial advertisement for the MAX 1 appeared in the November 1952 issue of "Aeromodelismo". The ad was placed by FIAMMA but specifically named Marsal's PECOS BILL company as the exclusive distributors.

In the event, it appears that the goal of introduction in late 1952 was met. The initial advertisement for the MAX 1 appeared in the November 1952 issue of "Aeromodelismo". The ad was placed by FIAMMA but specifically named Marsal's PECOS BILL company as the exclusive distributors.

Apart from confirming the dimensions and weights reported above, the article clarified a few more points. The engine was constructed from barstock without the use of castings. Somewhat unusually by 1952, the neat aluminium alloy spinner nut was mounted on a left-hand thread. Armesto drew attention to a few features which suggested that the design of the K&B Infant had influenced that of the MAX 1 to a considerable extent.

Apart from confirming the dimensions and weights reported above, the article clarified a few more points. The engine was constructed from barstock without the use of castings. Somewhat unusually by 1952, the neat aluminium alloy spinner nut was mounted on a left-hand thread. Armesto drew attention to a few features which suggested that the design of the K&B Infant had influenced that of the MAX 1 to a considerable extent.

Unfortunately, the surviving back issues of "Aeromodelismo" only go up to early 1953, very soon after the introduction of the MAX 1 but prior to the appearance of the DALOR. A search of “Aeromodeller” and "Model Airplane News" (MAN) back issues for the 1950’s by my good mate Gordon Beeby turned up only three references to Argentinian model engines. There was no mention of the DALOR. I have seen a reference to the engine somewhere, but I can't remember where - memory can be a chancy resource!

Unfortunately, the surviving back issues of "Aeromodelismo" only go up to early 1953, very soon after the introduction of the MAX 1 but prior to the appearance of the DALOR. A search of “Aeromodeller” and "Model Airplane News" (MAN) back issues for the 1950’s by my good mate Gordon Beeby turned up only three references to Argentinian model engines. There was no mention of the DALOR. I have seen a reference to the engine somewhere, but I can't remember where - memory can be a chancy resource!

On purely architectural grounds, the unit appears to fit into the early 1970’s period. It was manufactured by Metalurgica Miguel Devoto e Hijos S.A.I.C., who were located somewhat confusingly on Rio de Janeiro Street near the center of Buenos Aires, Argentina. This address has led some observers to conclude erronously that the DH engines originated in Brazil!

On purely architectural grounds, the unit appears to fit into the early 1970’s period. It was manufactured by Metalurgica Miguel Devoto e Hijos S.A.I.C., who were located somewhat confusingly on Rio de Janeiro Street near the center of Buenos Aires, Argentina. This address has led some observers to conclude erronously that the DH engines originated in Brazil! Daniel shared the contents of the original Spanish language instructions, as reproduced at the left. The fact sheet on the engine claimed an output of 1.1 BHP using an 11:1 compression ratio and running on a 75/25 or 80/20 methanol/castor oil mixture. For competition applications, 5-10% nitromethane was to be added. The cited speed range was 2,800 to 12,500 rpm.

Daniel shared the contents of the original Spanish language instructions, as reproduced at the left. The fact sheet on the engine claimed an output of 1.1 BHP using an 11:1 compression ratio and running on a 75/25 or 80/20 methanol/castor oil mixture. For competition applications, 5-10% nitromethane was to be added. The cited speed range was 2,800 to 12,500 rpm.

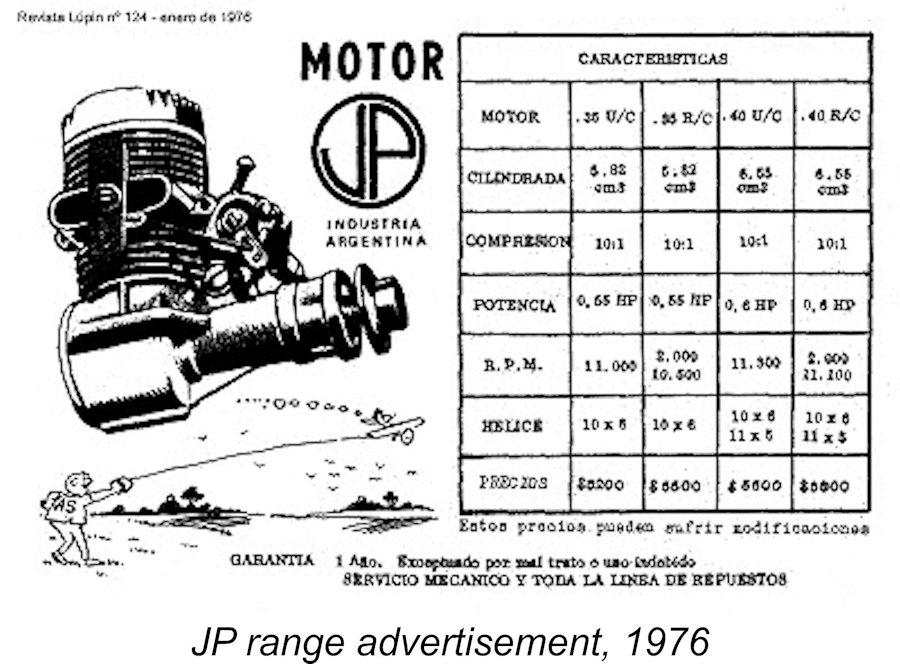

were 0.65 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for the .36 U/C, 0.55 BHP @ 10,500 rpm for the .36 R/C and 0.6 BHP @ 11,300 rpm for both versions of the .40 model. On architectural grounds, the JP engines seem to belong to the mid to late 1970’s period. The advertisement which is reproduced here appeared in 1976.

were 0.65 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for the .36 U/C, 0.55 BHP @ 10,500 rpm for the .36 R/C and 0.6 BHP @ 11,300 rpm for both versions of the .40 model. On architectural grounds, the JP engines seem to belong to the mid to late 1970’s period. The advertisement which is reproduced here appeared in 1976.

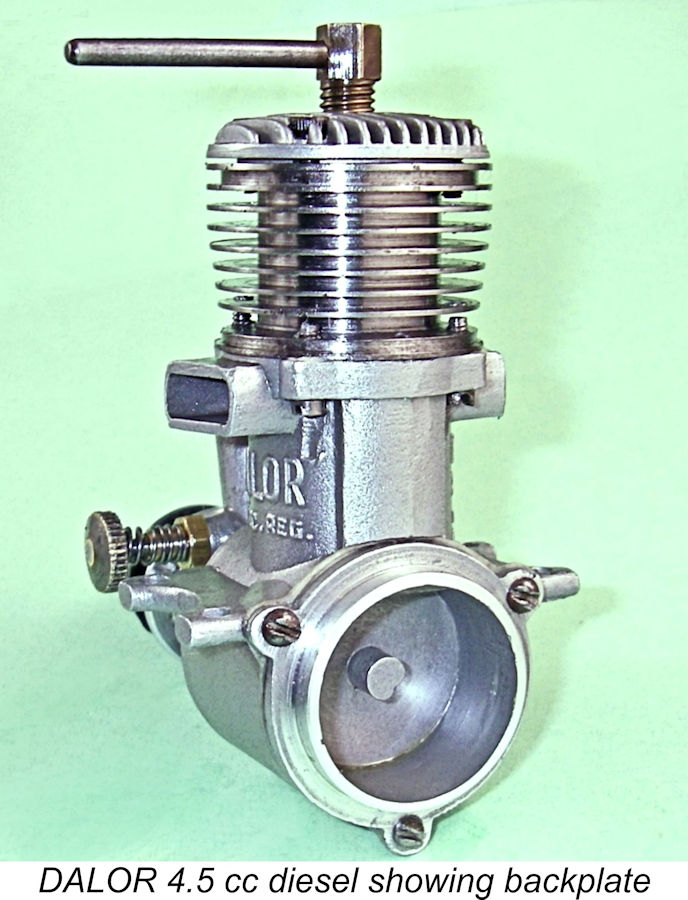

Apart from the relative displacements, one immediately obvious difference is that the FROG 250 was supplied with a tank, whereas the DALOR was not. However, even here we see some evidence of FROG influence - the backplate's undrilled and untapped central spigot as well as the peripheral annular shelf combine to suggest that the addition of a tank was on the radar of the DALOR designer. The backplate is machined from a pressure diecasting and is secured to the case with three short machine screws.

Apart from the relative displacements, one immediately obvious difference is that the FROG 250 was supplied with a tank, whereas the DALOR was not. However, even here we see some evidence of FROG influence - the backplate's undrilled and untapped central spigot as well as the peripheral annular shelf combine to suggest that the addition of a tank was on the radar of the DALOR designer. The backplate is machined from a pressure diecasting and is secured to the case with three short machine screws.  Somewhat unusually, the cylinder is secured to the crankcase by four machine screws which are inserted from below to engage with threads formed in the cylinder's lower location flange. This too is a good arrangement insofar as it eliminates any installation stresses from the cylinder walls, thus minimizing any possibility of distortion when the cylinder is tightened down. The same approach was used in the construction of the earlier

Somewhat unusually, the cylinder is secured to the crankcase by four machine screws which are inserted from below to engage with threads formed in the cylinder's lower location flange. This too is a good arrangement insofar as it eliminates any installation stresses from the cylinder walls, thus minimizing any possibility of distortion when the cylinder is tightened down. The same approach was used in the construction of the earlier

The twin exhaust ports are milled at the sides of the lower cylinder, with the two pairs of transfer ports placed fore and aft between them. They discharge into a pair of stubby integrally-cast exhaust stacks located at the sides of the crankcase opposite one another. The transfer ports overlap the exhaust ports to a very significant extent.

The twin exhaust ports are milled at the sides of the lower cylinder, with the two pairs of transfer ports placed fore and aft between them. They discharge into a pair of stubby integrally-cast exhaust stacks located at the sides of the crankcase opposite one another. The transfer ports overlap the exhaust ports to a very significant extent.

As stated earlier, the standard of workmanship displayed by the surviving original components is generally at least adequate, although the original fits may or may not have left something to be desired. The excellent quality of the die-cast components is particularly worthy of mention. If it wasn't for that skinny shaft and underfed rod, I would have said that a well-fitted example of this engine should have given excellent service to its owners provided that their performance expectations were held in check. The overweight piston might be expected to limit the engine's useable speed range due to vibration.

As stated earlier, the standard of workmanship displayed by the surviving original components is generally at least adequate, although the original fits may or may not have left something to be desired. The excellent quality of the die-cast components is particularly worthy of mention. If it wasn't for that skinny shaft and underfed rod, I would have said that a well-fitted example of this engine should have given excellent service to its owners provided that their performance expectations were held in check. The overweight piston might be expected to limit the engine's useable speed range due to vibration.  Initially I tried just a few finger chokes to see if this would suffice for starting. After flicking for a little while with no response even with a small compression increase, I administered a small exhaust prime. Presto!! An almost instant start in a couple of flicks!

Initially I tried just a few finger chokes to see if this would suffice for starting. After flicking for a little while with no response even with a small compression increase, I administered a small exhaust prime. Presto!! An almost instant start in a couple of flicks!  I realize that this process likely didn't allow the DALOR to reach its full potential - it probably needs at least a further half-hour to get to that point. However, I was able to get a pretty good handle on the engine's level of performance as well as its handling characteristics, which turned out to be extremely favourable. The DALOR would start using finger choking alone, although it generally took a few flicks to get the fuel up into the cylinder. A small exhaust port prime generally resulted in quicker starts, although the engine was a competely dependable starter using both techniques, never requiring that many flicks to get it going.

I realize that this process likely didn't allow the DALOR to reach its full potential - it probably needs at least a further half-hour to get to that point. However, I was able to get a pretty good handle on the engine's level of performance as well as its handling characteristics, which turned out to be extremely favourable. The DALOR would start using finger choking alone, although it generally took a few flicks to get the fuel up into the cylinder. A small exhaust port prime generally resulted in quicker starts, although the engine was a competely dependable starter using both techniques, never requiring that many flicks to get it going.