|

|

The T.Y.C. 2.5 cc Diesel

Various possible identities were bandied about, including the possibilities that the engine was an Alag from Hungary or perhaps an Elgin from East Germany. A potential Chinese origin was also considered based on the engine's general similarity to the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow series from Shanghai, China. However, there were also a sufficient number of differences to make a direct connection with the Shanghai series appear rather unlikely. There the matter rested until the late .15 cuin. engine maestro Jim Dunkin weighed in on the subject. Jim reported that the engine (of which he had a boxed example) was a T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel made in Chongqing, China, a location very distant from Shanghai! The engine appeared to have something to do with the Three Leaves Company of Shen Zhen City, China, since a certificate issued by that company was included with Jim's engine. Jim was unable to provide any further information. In keeping with its obscure subject, this will be a rather atypical article for a web-site devoted to model engine history, since it is extremely short on historical detail! This is because the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel appears to be completely undocumented, in the English-language modelling media at least. Consequently I know almost nothing about these mega-obscure engines! Indeed, I'll openly admit that until I first read Ron's previously-cited "Watzit" article and then stumbled across a nice boxed example of the engine, I had not even been aware of the existence of the T.Y.C. marque………. A subsequent check of the late Jim Dunkin's incredibly comprehensive catalogue of 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.) engines turned up his entry for the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc model. Frankly, I'd have been amazed if it hadn't! This monumental piece of work is entitled "Reference Book of International .15 ci / 2.5 cc Model Airplane Engines". A total of 1646 different models from all over the world are included in its expanded second edition. That said, even Jim was evidently unable to uncover any additional detail regarding the origins of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc model. Accordingly, what follows will be mainly confined to a description and test of this seemingly rare engine, of which mine is the only example that I've ever personally encountered in the metal. My main purpose in publishing this article is to hopefully encourage some reader who knows something about this range to share that knowledge with the rest of us. Any information received will be added to this article with full acknowledgement along with my grateful thanks! Now let's look at a little background........... Background Much of this historical background material has already appeared on this site in my earlier article on the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow range from Shanghai, China. However, I’ll repeat it here for the convenience of new readers. Those already familiar with this material are invited to proceed directly to the following section. Others, please read on ……….. The early history of aeromodelling and model engine manufacturing in China is perhaps more obscure than that of almost any other major engine-producing nation. This is due both to the language barrier and to the fact that at the time in question the nation and its Command Economy remained under the tight control of the hard-line Communist regime, which kept all such activities completely invisible behind the Bamboo Curtain. My English informant Alan Strutt has done a fair bit of very useful research into the making of model aero engines in China during the classic era. This activity appears to have started in the 1950’s at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and to have been further pursued at the Northwestern Polytechnical University at Xi'an from the late 1950’s onwards. Xi'an is the capital city of Shaanxi Province in central China, very distant from Shanghai but not all that far from Chongqing where the T.Y.C. engines were to be manufactured (see below). There may be a connection ………….. Jim Dunkin also did some valuable research on this topic. As far as he was able to discover, it seems that in 1953 a facility called the Chang Jiang factory was built in the town of Ju Cio in central China, with technical assistance from a number of Russian specialists. The primary purpose of this factory was to manufacture full-size piston engines for aircraft. A year or two after the establishment of this factory, it was assigned the additional task of producing limited numbers of model aero engines for the use of young Chinese having an interest in aviation, an interest which the authorities wished to encourage. These engines were essentially copies of then-current Russian MK series diesels. They ranged in size from 1.5 cc up to 10 cc. Production at the Chang Jiang factory was confined to the years 1954-58, after which the factory returned its full attention to full-sized aero engines, not to resume any involvement with model engines until 1978, when the previously-mentioned Three Leaves range was launched. Following the withdrawal of the Chang Jiang factory in 1958, the construction of model engines seems to have been continued by students at the Northwestern Polytechnical University, who were tasked with the design and construction of model engines for their own use and that of other Chinese modellers. The objective of these activities was apparently to maintain the availability of engines to Chinese competitors who would represent China’s interests at the various modelling meetings involving entrants from other communist countries. From the accounts that Alan Strutt had read, there doesn’t seem to have been any initial intention to sell the products on the open (Western) market. However, things began to change in the early 1960's when a desire to acquire foreign currency prompted the Chinese government to relax foreign trade restrictions somewhat. This allowed Chinese manufacturers to begin looking beyond the political boundaries of China to find fresh marketing opportunities. In pursuit of such opportunities, a factory for commercial-scale model engine manufacture was soon established in Shanghai. This was the Teh Ming Sports Goods Factory, which manufactured the Yin Yan (later Silver Swallow) engines beginning in 1962. I’ve covered that series of engines in a separate article to be found on this website.

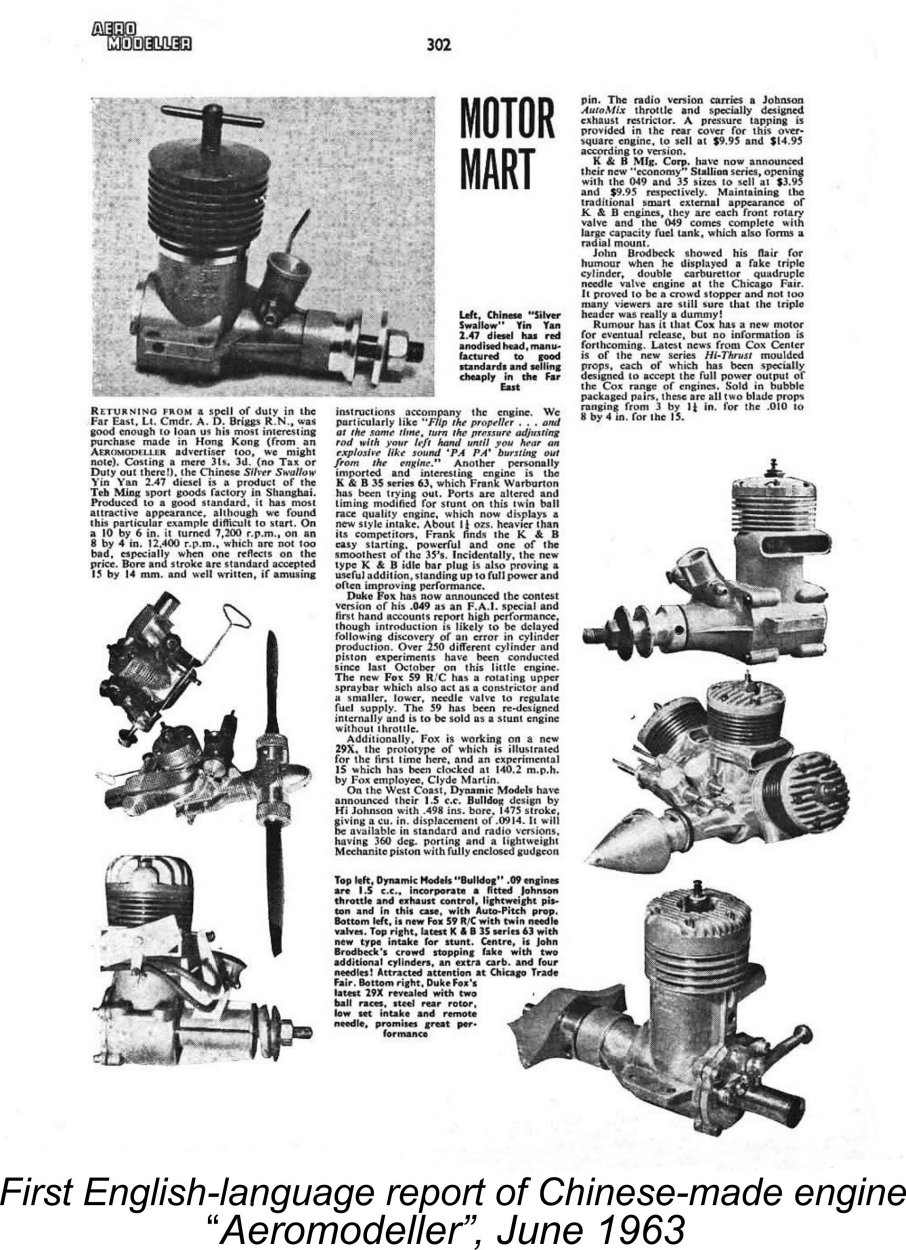

It was in 1963 that modellers in the world at large first became aware that commercial model engine manufacture was taking place in the People's Republic of China. In 1962, a number of good-quality Chinese-made model diesels had quietly made their appearance on the market in "open" ports like Hong Kong and Macau where they could readily be purchased by overseas visitors. These were the Yin Yan series of 2.47 cc model diesel engines, which were produced at the previously-mentioned factory in Shanghai. This was the first range of model diesels presently known to have been produced in the People's Republic of China on a commercial scale. It was certainly the first model engine marque to be exported from that country in commercial quantities. The engines were initially marketed under the Yin Yan label ("Yin Yan" actually means "Silver Swallow" in Chinese), but in 1966 this name was Anglicized to the more familiar Silver Swallow, presumably due to the growing importance of the export market by that time. At around the same time, a 1.49 cc model was added to the range. Both marine and aero variants were offered. The target market for these engines at the time of their introduction may not have been confined to the export arena. The technological revolution was just beginning to be a factor in the planning of China’s long-term economic future, and the Chinese may have wanted a supply of home-grown model engines to be utilized in the encouragement of aeronautical and technical awareness among young Chinese at the school level. This approach had been successfully pursued by the Russians since 1957, possibly prompting the idealogically-aligned Chinese to follow suit. In terms of sheer numbers, the potential market arising from this concept alone was vast, even if they never sold a single engine outside of China.

As mentioned earlier, sales outlets were quickly established in Asian open market centres such as Hong Kong, then still a British Colony. As a result, a number of these engines were purchased by British servicemen and civil servants stationed in Hong Kong as well as visiting businessmen and servicemen from many countries worldwide. Inevitably, some of these units eventually found their way back to Britain and elsewhere.

It was thus that the British modelling public first became aware of the then-startling fact that model diesel engines were being produced in China, and reportedly to a good standard at that. The engines first came to the general notice of modellers in the USA through being described in the January/February 1964 issue of “American Modeller” magazine. Now, during the era in question the term “Made in China” was almost universally seen in the developed nations as being synonymous with ultra-cheap crap quality merchandise. What a difference from today, when everything seems to be made there and people are very happy to buy Chinese-made high-tech goods! As a 15 year old “Aeromodeller” subscriber myself at the time, I clearly remember reading the article in question with a mixture of astonishment and skepticism. I recall my own feelings of extreme surprise upon learning that But the reality was that the engines were in fact far better than our pre-conditioned “colonial” attitudes would allow us to conceive at the time. Objectively speaking, the early Yin Yan models were made to more than acceptable standards by any measure, particularly with respect to their truly excellent piston/cylinder fits. Admittedly, quality did slide somewhat in later years during the Silver Swallow era which began in 1966, but this takes nothing away from the standard to which those early examples were made. A separate article on the long and convoluted history of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow series will be found elsewhere on this web-site. It's a far more interesting story than you might suppose! Enter T.Y.C. Naturally the early success of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow range in generating sales outside China drew attention to the fact that this was a market in which Chinese manufacturers could compete successfully. The manufacturers of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow engines remained in business in Shanghai for many years, being joined in 1978 by both the CS company (also located in Shanghai) and the previously-mentioned Chang Jiang factory of Ju Cio, which was involved in the introduction of the Three Leaves range. CS were in fact destined to perpetuate the Silver Swallow design for some years following the withdrawal of the original manufacturers. However, that's another story which has been recounted elsewhere........... Another manufacturer who joined in the fun at some indeterminate time (most likely but by no means definitely during the mid to late 1970's) was the unknown maker of our subject engine, the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel. I've turned the 'Web upside down and posted on my own blog site in my efforts to find out more about this manufacturer, with absolutely no success. The only substantive information that I've been able to find comes from the box and instruction leaflet which accompanied this example of the engine.

It’s interesting to note that this location is well removed from that of the other documented Chinese model engine manufacturers, which tended to congregate either in the Shanghai area or on Taiwan. However, it's not all that far from Xi'an, location of the Northwestern Polytechnical University where the design and construction of model engines had been pursued since the late 1950's. The T.Y.C. engines are the first of my personal acquaintance to have been manufactured in China at an inland location. The Yin Yan (subsequently Silver Swallow) engines and the later CS models originated on the central coast in Shanghai, as did the Jin Shi range. Although the initial manufacture of the Three Leaves engines was undertaken by the Chang Jiang factory in Ju Cio in central China, the manufacture of that range was soon transferred to a new factory in Shen Zhen City on the coast near Hong Kong. The Thunder Tiger Corporation is based offshore in the Republic of China on Taiwan, as was the Star Light Hou Industry Co. Ltd., makers of the SLH engines. It’s a sad sign of the times that none of these companies are still making model I/C engines today.

Despite its different geographic origin, the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc model bears the unmistakable imprint of the Chinese “house style” of the classic era. In terms of its general appearance and underlying design, it comes across very much as a restyled Yin Yan/Silver Swallow 2.5 cc model. It uses the same induction and cylinder porting arrangements as well as an identical assembly configuration. The seller of my example claimed that it was manufactured in around 1984, although the serial number of 1008-79 seems to suggest that it was actually made in 1979. In either case, we would have to conclude that its design was substantially influenced by that of the earlier engines from Shanghai. In the absence of any higher level of historical detail, we must now return to firmer ground by embarking upon a description of this seemingly elusive engine. Description

It’s always good to start off with a few basic numbers. Bore and stroke of this engine are the standard Continental 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). Speaking personally, I’ve always found it a bit puzzling that so many Continental manufacturers stuck religiously to these figures. Admittedly, they keep the engines within the FAI International class displacement limit of 2.5 cc, with a little headroom. However, they set the engine’s displacement at fractionally over the equivalent AMA displacement limit of 0.150 cuin., if you really want to split hairs. Based upon my own experience, this limit is not strictly enforced in North America, probably because no-one’s deriving any measurable advantage from an extra 0.001 cuin. anyway!! Be that as it may, the manufacturers of the T.Y.C. stuck to the established metric formula, as had the makers of the earlier Yin Yan and Silver Swallow models from Shangahi. The design of the T.Y.C. is in fact markedly derivative from that of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow series, to the extent that it seems appropriate to draw a few direct comparisons between the two designs as we go.

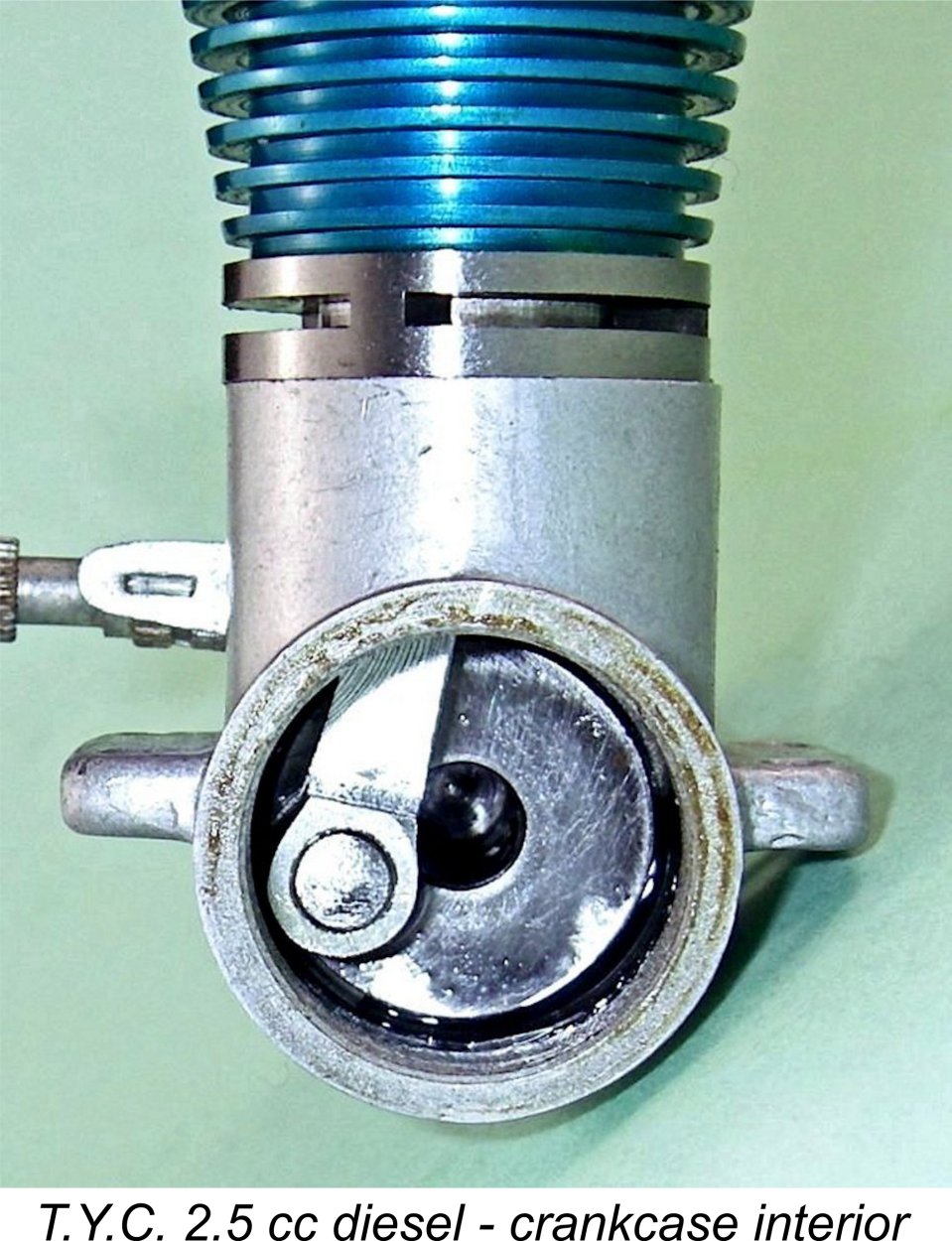

Returning to our description of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel, we have to start somewhere, so let’s begin with the crankcase. The engine is built around a cleanly die-cast vapour-blasted crankcase which incorporates the bronze-bushed main bearing in unit. The main bearing housing incorporates a stub socket to accept a separate venturi insert, thus mirroring the design of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow series. Perhaps most interestingly, the mounting hole spacing exactly matches that of the Shanghai models (and for that matter their Alag predecessors). Again like the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow models, provision is made for the accommodation of a screw-in cylinder and backplate.

The T.Y.C. weighs in at a not-unreasonable 143 gm (5.05 ounces). This is fractionally greater that the 138 gm (4.87 ounces) of the Yin Yan, although only marginally so. The T.Y.C.'s thicker cylinder probably accounts for much of the difference. Moving downwards, the steel cylinder is ported exactly like that of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow models and their Alag predecessors. There are three wide but shallow exhaust slots, with six internal bypass passages formed on the inner wall of the lower cylinder. In order to maintain the crankcase seal, these necessarily terminate at the top some distance below the bottom edge of the exhaust ports, giving rise to an unavoidably lengthy blow-down period.

In the case of the T.Y.C., the exhaust period is a quite reasonable 130 degrees (opening 115 degrees after top dead centre). However, the need to terminate the transfer ports well below the lower edge of the exhaust ports means that the blow-down period is a very substantial 20 degrees of crank angle, leaving a transfer period of only 90 degrees based upon the ports opening at 135 degrees after top dead centre. This might appear to be a rather crippling liability in performance terms, but in fact the extremely large transfer area and long crankcase compression period provided by this style of porting appear to make a lengthy transfer period unnecessary to achieve the engine's design operating speeds.

Here we encounter the first of several functional changes from the design of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow. With the style of transfer porting used, coupled with the fact that the final alignment of the screw-in cylinder cannot be guaranteed, the strong possibility exists that the piston bosses may end up being aligned with one of the three opposing pairs of bypass channels. If the gudgeon (wrist) pin were to come out of its bosses, it could easily foul the top of the bypass passages and damage the bore. For this reason, it’s necessary to secure the gudgeon pin in the piston bosses by some means. In the Yin Yan (and later Silver Swallow) models, this requirement was met by the solid steel gudgeon pin being swaged into the piston bosses after assembly of the pin and con-rod into the piston. The conical dimples resulting from this process are easily seen through the exhaust ports of any example of those models. By contrast, the gudgeon pin of the T.Y.C. is a simple tubular steel component showing no evidence of having been swaged in place. Moreover, there is no visible evidence of the use of circlips to retain the pin. This being the case, it is presumably a press fit in the piston bosses.

The steel crankshaft of the T.Y.C. is basically very similar to that of its Shanghai predecessors. It has a plain unbalanced crankweb and is beautifully finished and fitted to a bronze bushing which is installed inside the main bearing housing. Main journal diameter is a very generous 10 mm, exactly as with the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow series. However, it appears that the T.Y.C. designer may have been paying attention to the tales of all-too-frequent shaft breakages with the Yin Yan /Silver Swallow models, since he reduced the diameter of the internal gas passage in the shaft from 6.8 mm down to only 6 mm, thus providing additional wall thickness in the hollow portion of the shaft. A wise move if experience with the Silver Swallow is anything to go by ……………for sport flying, I’ll settle for long-term dependability over a marginal increase in short-term performance any day! Besides, 6 mm (0.236 in.) is a more than adequate induction passage diameter for a 2.5 cc sports motor. The induction port in the shaft is a round hole – a good design in terms of structural integrity since it’s very easily formed and doesn’t create any sharp corners to give rise to stress concentrations in the shaft material during operation. However, it’s less efficient than the more complex rectangular or oval shape, which provides both larger area and more rapid opening and closing but adds a degree of manufacturing complexity and also has a greater potential to create stress concentration points in the shaft material. Ya pays yer money, etc. ……… it’s all about trade-offs! The induction port opens at 45 degrees after bottom dead centre and closes at 35 degrees after top dead centre for a quite adequate 170 degree total induction period. However, the fact that both the venturi base register and the crankshaft induction port are circular means that the system is fully open for a relatively short period of time. There is a very short sub-piston induction period of around ten degrees either side of top dead centre (20 degrees total), which doubtless helps a little at the higher speeds. This brings me to one of the two manufacturing flaws that I mentioned at the outset. The induction port in the shaft is placed a little forward of where it needed to be to exactly match the base (register) of the inlet tract in the main bearing top surface. As a result, there’s a “step” at the interface between the rear of the intake tract register and the crankshaft induction port. Moreover, the crankshaft induction port is slightly obscured at the front when fully open. I don’t see this as being enough to cause any significant reduction in performance in the sport context in which this engine would most likely be used, but it needs to be pointed out in an objective review of this nature.

This is not good, since it’s bound to result in scraped-off metal particles being circulated through the engine, to the detriment of its working surfaces. Since I was planning to run this engine fairly extensively for test purposes, I re-machined the taper in the prop driver to eliminate all but about five thou of end-float. The rearward movement of the shaft is now restrained by the rear face of the prop driver contacting the front of the bearing housing rather than by the crankpin contacting the backplate. If one didn’t have a lathe handy, the same result could be achieved by fitting a steel shim washer of appropriate thickness. I hasten to point out that both of the above faults (particularly the inadequate depth of the female prop driver taper) may be incidental to this one specific example. Moreover, neither of them were such as to prevent the engine from running. As I said before, in all other respects the quality of construction of this engine is superb.

The spraybar mounting holes are drilled at a slight rearward angle to the left. This is a highy convenient arrangement for sidewinder mounting in a control-line model (for example), but it does compromise the re-assembly of the needle valve in the opposite orientation on the right if that were desired.

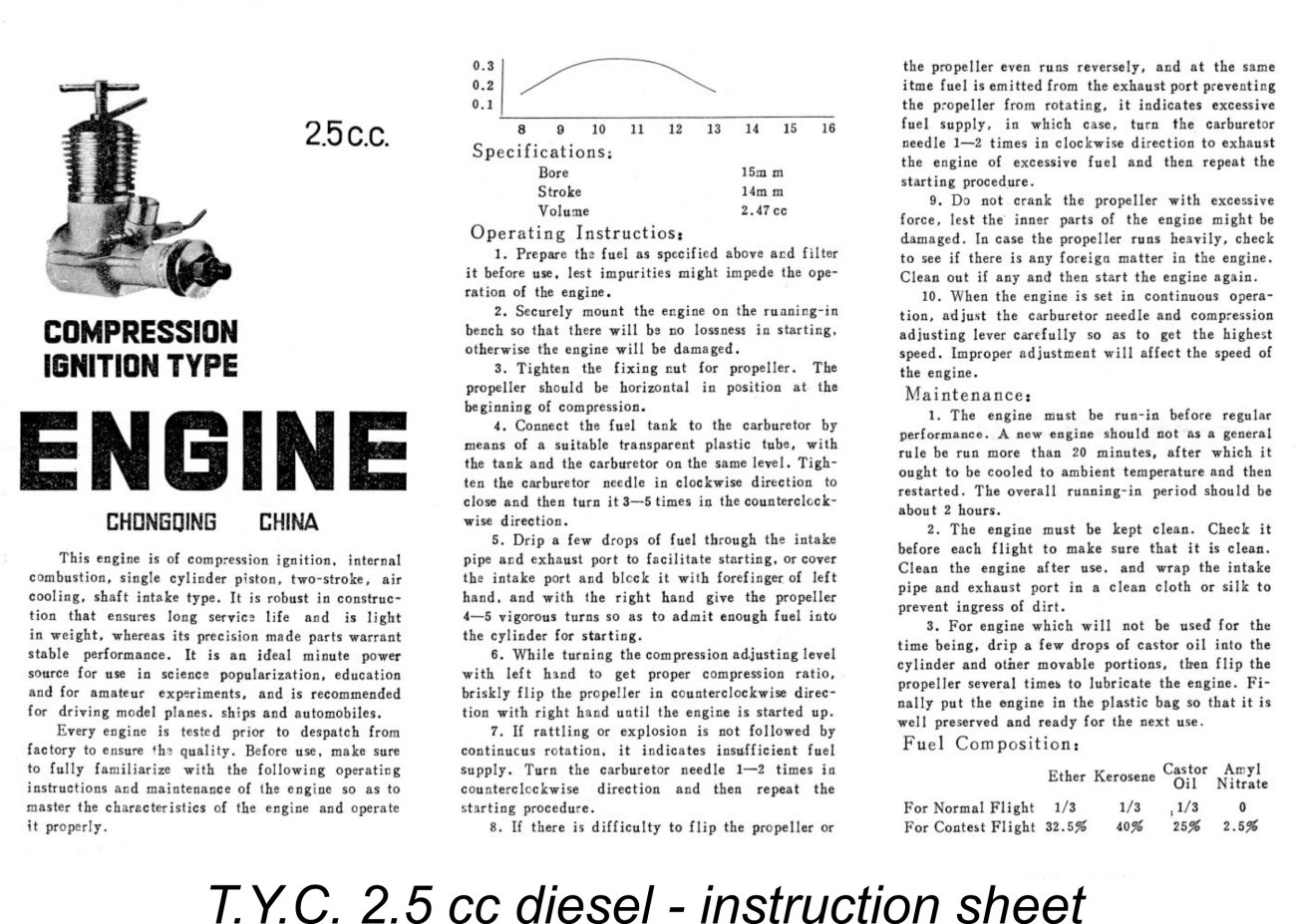

The engine is supplied in a nicely-decorated cardboard box, together with a well-written and informative instruction leaflet. The presentation of both box and instruction leaflet in both Chinese characters and English text proves conclusively that the manufacturer had ambitions to generate sales in the English-speaking world. The fact that relatively few of these engines seem to surface on eBay and elsewhere these days suggests that he was rather less than successful in achieving this goal. Too bad – this is actually a very worthy effort on his part. It certainly deserved more widespread notice than it appears to have achieved. My example has the number 1008 stamped under the left-hand lug, with the number 79 stamped under the right hand lug. Identical engine no. 1011 along with the number 79 appeared recently on eBay. Reader Michel Rosanoff reports owning engine no. 1040 with the same 79 stamping, while Richard Dalby's example bears the numbers 1043 and 79. Bert Streigler's example bore the numbers 1059 and 79. The example illustrated by Jim Dunkin is similarly marked with the numbers 1084 and 78. Derek Butler reported owning engine number 1071 and 79. To me, this looks like an engine made in 1978 and six engines made in 1979. However, this cannot be proved at the present time. All that can be said is that such a numbering system would almost exactly parallel that used by the makers of the Yin Yan and Silver Swallow engines, at least during the first decade or so. The dates are also consistent with the date of the establishment of the Three Leaves range. The one odd thing about the very small sample of serial numbers so far reported is the fact that all of the four-figure numbers lie within such a close range. It almost seems that the sequence may have started at no. 1000, but we currently have no way of confirming this. Alternatively, these engines may have all originally belonged to a couple of small specific batches that did somehow make their way out of China to be scattered around the world. More serial numbers are definitely required here!! OK, so here we have a very well-made sports diesel engine of completely conventional construction. Full marks to the unknown manufacturer for a job well done, despite the two flaws noted earlier. How does it run? Let’s find out! The T.Y.C. 2.5 cc Diesel on Test According to the manufacturer’s instruction leaflet, “every engine is tested prior to despatch from (the) factory to ensure the quality”. I can only report my own complete certainty that this example had never been run at any time prior to coming into my possession. For one thing, the spraybar was installed with the single fuel jet hole oriented vertically upwards! You could have flicked until Doomsday and never got the thing to start with the spraybar in that orientation! Needless to say, I corrected this assembly error right away. For another thing, there was absolutely no trace of any scuffing on the front face of the backplate where it presents itself to the crankpin and con-rod. Given the previously-noted excessive end-float in the crankshaft assembly as supplied, there is simply no way that a test run would not have left some evidence in the form of scuffing of the backplate surface. Another clue came later when I first tried to start the engine. The contra-piston proved to have been really tightly fitted - I had to work quite hard to unstick it using moderate heat as an aid. Moreover, it was set at least a turn too low for starting - it was only after I got it moving in the bore sufficiently to allow upward adjustment that I was able to get the compression up to where it needed to be. The bottom line is that there was no way that it would have run at the setting with which it was evidently supplied in a "semi-frozen" state. This strongly implies that it was never run at all. Finally, there wasn't the slightest trace of residual castor oil gum in or on the engine. In my experience, any engine that has been test-run and then stored for 35 years almost always exhibits a little residual stiffness or "stickiness" from this cause. Not so in this instance ............ For all of these reasons, I elected to treat this as a completely un-run example of the engine. The fact that it had never been run further underscored the excellence of the fits and finishes achieved during the manufacturing stage. If it hadn't been for the clear evidence set out above, I would objectively have assessed this engine as having been fully run in on the bench - the working fits and finishes were that good! The instruction leaflet recommends a two-hour break-in period for the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel, to be accumulated in runs of not more than 20 minutes, with complete cooling in between. In my view based on long experience, this particular example did not require anywhere near such a lengthy break-in period - it would have been a waste of both time and fuel. What the engine did require (like all cast iron/steel piston/cylinder assemblies) was some running time to bed in the various sliding bearings (piston, con-rod, crankshaft) as well as a series of complete heat cycles to stabilize the piston in the cylinder. The manufacturer’s recommendations would only provide 6 such cycles, which I consider to be inadequate. For a full discussion of this important issue, see my earlier article on breaking in a ferrous model engine.

I used a 10x6 Taipan prop for the break-in period. Starting on this prop proved to be extremely easy. A prime semed to be an essential prerequisite, but once that was given the engine fired up very promptly. Response to the needle was very good indeed, making it very simple to establish the desired mixture. The two-leaf spring clip held the needle settings very securely. The compression setting was more of a problem due to the extreme tightness of the initial contra piston fit - sometimes it failed to return when compression was reduced. However, I worked it up and down a little as I went along, which eased the fit to a noticeable extent. A few hours of use would doubtless work the contra-piston into a very good if still snug fit. As it was, the tight fit meant that the compression locking lever with which the engine is equipped was never required. The effectiveness of a break-in undertaken along these lines may be monitored as one goes along by spot-checking the speed obtained during the brief leaned-out period which ends each break-in run. The break-in may be considered complete when at least ten heat cycles have been applied and there is no measurable improvement in maximum peak speed between successive runs on the same prop. In the present instance, the engine turned the hefty Taipan prop at 8,200 RPM at the end of the first break-in run and had only improved to 8,300 RPM by the end of the final such run 40 minutes later. That was good enough for me!

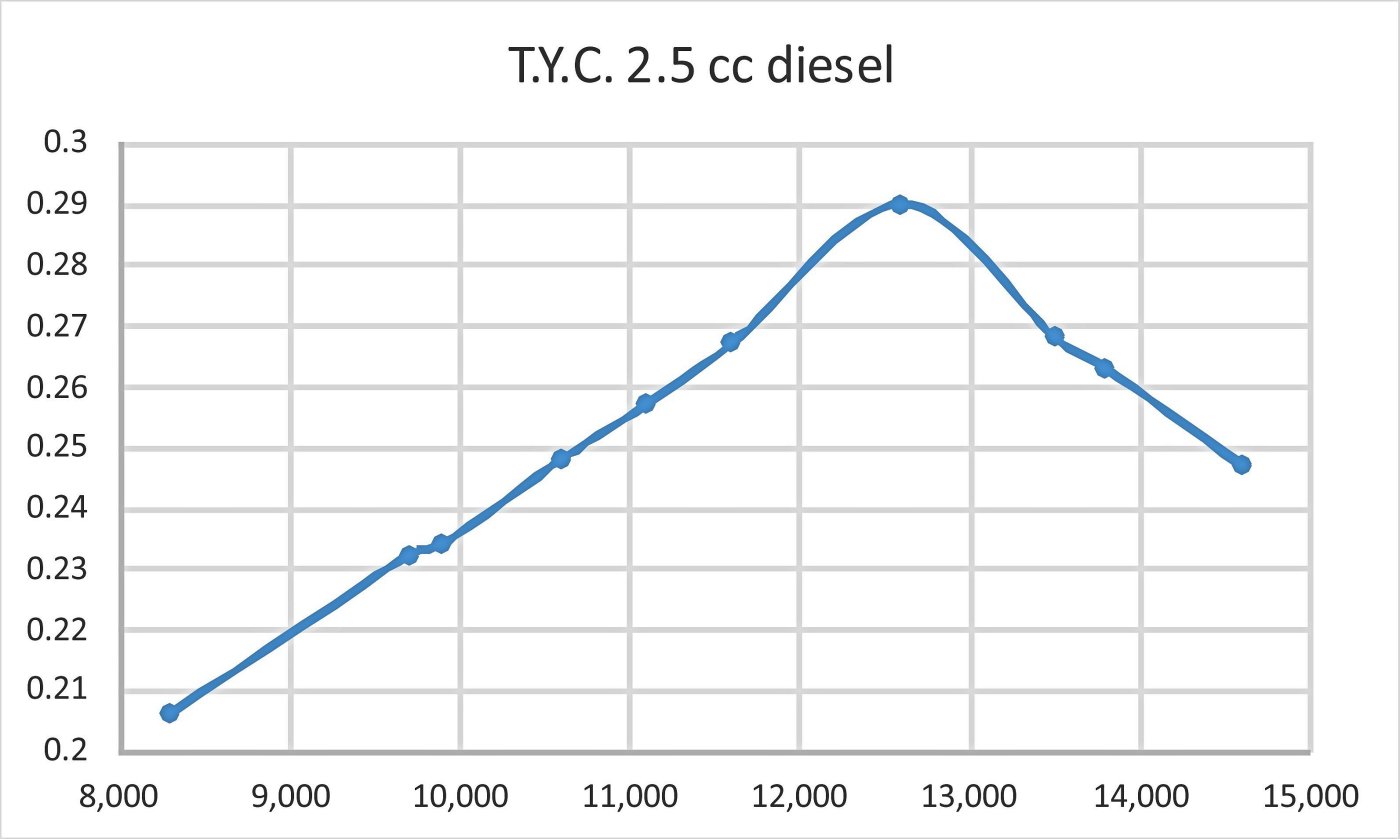

Starting continued to be very straightforward indeed throughout the tests. A choked turn to fill the fuel line followed by a small prime were the only prerequisites to a very prompt start. The engine would keep on running even when either the compression or the needle (or both!) were way off, allowing plenty of time to make adjustments. I have to say that the results achieved exceeded my expectations. The very vague "power curve" included in the previously-reproduced instruction leaflet implied a claimed output of around 0.30 BHP at some highly indeterminate speed. I approached this test harbouring considerable doubt that the engine would achieve such a performance. Just how wrong I proved to be is well reflected in the following figures:

The APC 8x4 WB (wide blade) is a cut-down APC 9x4 created to fill a gap in the range of power absorption coefficients represented by my standard calibrated APC test set. It actually proved to be the prop which ran at this particular engine's peak operating speed, thus fully justifying its inclusion. As can be seen, the figures obtained suggest a peak power output of around 0.290 BHP @ 12,600 RPM, more or less exactly as claimed by the manufacturers. Really an excellent performance for a simple lightweight plain-bearing sports diesel like this one! What's more, the peak is reasonably flat - the engine is beating 0.260 BHP at all speeds between 11,300 RPM and 13,900 RPM. Good flexibility there when it comes to prop selection! An 8x6 would work well for control line, while a 9x4 would probably be an excellent free-flight airscrew. The engine came through this test with flying colours. At the end of all the runnng undertaken it felt absolutely superb - in a blindfold test, you'd pick it as a far more expensive engine! No trance of any detectable play developed in the rod or shaft bearings, while the piston fit remained perfect - silky-smooth with a perfect seal. Well done, whoever made this fine little unit! The contra-piston remained somewhat more tightly fitted than ideal, but that would work itself out in time. In any case, better tight than loose! Conclusion I The existence of my own engine (bought from a seller in the USA) as well as those owned by both Jim Dunkin and Bert Streigler seems to prove that at least a few of these engines somehow found their way to North America. How they did so remains an open question at present. It's possible that they were bought in places like Hong Kong by North American visitors who then brought them back as personal importations. We may never know ...... Regardless, this is a better-than-average sports diesel which would serve any owner well and which does great credit to the Chinese model engine manufacturing industry. I just wish that we knew more about its origins! If anyone out there has more information on this rather obscure model engine manufacturer, please get in touch either directly or through my blog site. All contributions gratefully and openly acknowledged! ________________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2017 |

||

| |

Some years ago now, the late Ron Chernich published an article in the "Watzit" section of his wonderful "

Some years ago now, the late Ron Chernich published an article in the "Watzit" section of his wonderful "

That may or may not be so, but there can be no doubt that from the outset the Chinese envisioned these engines being distributed and used beyond the Bamboo Curtain! For one thing, the engines were clearly identified in English characters, complete with "Made in China" being proudly displayed along with the Yin Yan name. For another, an English (?!?) language translation of the instruction manual was quickly produced. This included such evocative gems as the starting direction to “Flip the propeller ....... and at the same time, turn the pressure adjusting rod with your left hand until you hear an explosive like sound “PA PA” bursting out from the engine”!! All such idiosyncacies aside, the intent of the instructions was clear enough, and they actually made a lot of sense. Their English was certainly far better than my Chinese!!

That may or may not be so, but there can be no doubt that from the outset the Chinese envisioned these engines being distributed and used beyond the Bamboo Curtain! For one thing, the engines were clearly identified in English characters, complete with "Made in China" being proudly displayed along with the Yin Yan name. For another, an English (?!?) language translation of the instruction manual was quickly produced. This included such evocative gems as the starting direction to “Flip the propeller ....... and at the same time, turn the pressure adjusting rod with your left hand until you hear an explosive like sound “PA PA” bursting out from the engine”!! All such idiosyncacies aside, the intent of the instructions was clear enough, and they actually made a lot of sense. Their English was certainly far better than my Chinese!!  One such purchaser was Lt. Cmdr. A. D. Briggs, R.N., who purchased his example of the Yin Yan 2.47 cc model in Hong Kong while on a tour of duty in the Far East. The price was a startlingly low 31s. 3d. (£1.56 in "modern" money), at least partially due to the absence of purchase tax and import duty in Hong Kong. Cmdr. Briggs was kind enough to send his purchase along to the offices of “Aeromodeller” magazine, resulting in the engine making an appearance in the regular “Motor Mart” feature in the June 1963 issue of that magazine.

One such purchaser was Lt. Cmdr. A. D. Briggs, R.N., who purchased his example of the Yin Yan 2.47 cc model in Hong Kong while on a tour of duty in the Far East. The price was a startlingly low 31s. 3d. (£1.56 in "modern" money), at least partially due to the absence of purchase tax and import duty in Hong Kong. Cmdr. Briggs was kind enough to send his purchase along to the offices of “Aeromodeller” magazine, resulting in the engine making an appearance in the regular “Motor Mart” feature in the June 1963 issue of that magazine.  model diesel engines were being produced in "Red China" as well as my pre-conditioned and admittedly very elitist opinion that even if they were, there was no way that they could be made to anything like the required precision!! I’m sure that many others must have experienced the same initial reactions.

model diesel engines were being produced in "Red China" as well as my pre-conditioned and admittedly very elitist opinion that even if they were, there was no way that they could be made to anything like the required precision!! I’m sure that many others must have experienced the same initial reactions.  According to these sources, the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel was made in Chongqing, China. Chongqing is a major city in south central China which serves as the economic centre for the upstream Yangtze River basin. Its history as a city goes all the way back to 1189, when it first received the name Chongqing to replace the earlier name of Yu Prefecture which had previously been applied to the general area. In 1997 it was reconstituted as one of China’s four major direct-controlled municipalities, the other three being Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin. It is the only one of these four located in inland China. It is a major manufacturing centre and transportation hub.

According to these sources, the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel was made in Chongqing, China. Chongqing is a major city in south central China which serves as the economic centre for the upstream Yangtze River basin. Its history as a city goes all the way back to 1189, when it first received the name Chongqing to replace the earlier name of Yu Prefecture which had previously been applied to the general area. In 1997 it was reconstituted as one of China’s four major direct-controlled municipalities, the other three being Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin. It is the only one of these four located in inland China. It is a major manufacturing centre and transportation hub. Jim Dunkin presented some evidence identifying the production of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel with the makers of the previously-mentioned Three Leaves range. His basis for making this connection was the fact that the boxed example which he used to illustrate his book was accompanied by a certificate issued by the Three Leaves factory. There may indeed be something in this - the timing seems right, although it would imply that the Three Leaves manufacturers divided their model engine manufacturing activities between several widely-spaced locations. This is entirely possible, since they are known to have manufactured full-sized aero engines as well as model units. They are also known to have operated from more than one location.

Jim Dunkin presented some evidence identifying the production of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel with the makers of the previously-mentioned Three Leaves range. His basis for making this connection was the fact that the boxed example which he used to illustrate his book was accompanied by a certificate issued by the Three Leaves factory. There may indeed be something in this - the timing seems right, although it would imply that the Three Leaves manufacturers divided their model engine manufacturing activities between several widely-spaced locations. This is entirely possible, since they are known to have manufactured full-sized aero engines as well as model units. They are also known to have operated from more than one location.  The T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel is a completely conventional plain-bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) design of the "classic" era. In fact, the only thing that really sets it apart is the quality of its construction, which is of the very highest order apart from a few relatively minor issues, of which more below. I have encountered many contemporary diesels of European origin which did not come up to the same standard of quality in terms of fits and finishes.

The T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel is a completely conventional plain-bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) design of the "classic" era. In fact, the only thing that really sets it apart is the quality of its construction, which is of the very highest order apart from a few relatively minor issues, of which more below. I have encountered many contemporary diesels of European origin which did not come up to the same standard of quality in terms of fits and finishes. The design of the 1962 Yin Yan 2.47 cc model (later marketed as the Silver Swallow) seems to have been derived more or less directly from that of the 1955

The design of the 1962 Yin Yan 2.47 cc model (later marketed as the Silver Swallow) seems to have been derived more or less directly from that of the 1955  At the top of the engine, the cooling jacket is a screw-on component which engages very precisely with an externally-formed thread on the upper cylinder liner. It is equipped with a two-handled compression screw and compression locking lever. It shares all of these features with the Yin Yan. However, here we begin to see some evidence of independent design thinking. The T.Y.C. cylinder has considerably thicker walls with a consequently larger-diameter cooling jacket installation thread. Hence the Yin Yan head cannot be installed onto the T.Y.C. cylinder, and vice versa.

At the top of the engine, the cooling jacket is a screw-on component which engages very precisely with an externally-formed thread on the upper cylinder liner. It is equipped with a two-handled compression screw and compression locking lever. It shares all of these features with the Yin Yan. However, here we begin to see some evidence of independent design thinking. The T.Y.C. cylinder has considerably thicker walls with a consequently larger-diameter cooling jacket installation thread. Hence the Yin Yan head cannot be installed onto the T.Y.C. cylinder, and vice versa. This style of porting came to prominence in the mid 1950’s through its use in the highly-regarded 2.5 cc Webra Mach 1 unit from West Germany (as it was then). The downside of this arrangement is the inevitably short transfer period created by the unavoidably long blow-down period noted above. Against that, the area of the bypass and transfer system created in this way is unusually large. The two issues appear in effect to cancel each other out, creating a very efficient transfer system. Certainly, this style of porting proved highly effective when applied to the Webra Mach 1 as well as a number of other successful models, including the aforementioned Alag X-03 from which the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow design appears to have been derived.

This style of porting came to prominence in the mid 1950’s through its use in the highly-regarded 2.5 cc Webra Mach 1 unit from West Germany (as it was then). The downside of this arrangement is the inevitably short transfer period created by the unavoidably long blow-down period noted above. Against that, the area of the bypass and transfer system created in this way is unusually large. The two issues appear in effect to cancel each other out, creating a very efficient transfer system. Certainly, this style of porting proved highly effective when applied to the Webra Mach 1 as well as a number of other successful models, including the aforementioned Alag X-03 from which the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow design appears to have been derived. The conical-topped cast iron piston is beautifully fitted to the finely-finished cylinder bore. I have actually encountered very few diesels of any era or source having a superior piston/cylinder fit out of the box. Compression seal is outstanding, with no trace of “stiction” at any point in the stroke – just the desirable slight tightening around top dead centre.

The conical-topped cast iron piston is beautifully fitted to the finely-finished cylinder bore. I have actually encountered very few diesels of any era or source having a superior piston/cylinder fit out of the box. Compression seal is outstanding, with no trace of “stiction” at any point in the stroke – just the desirable slight tightening around top dead centre. A further difference is the design of the con-rod itself. The Yin Yan/Silver Swallow engines use a standard turned British-style “dog bone” component. This is a less than optimal design, since it provides only a relatively short bearing length at the small end where it engages with the gudgeon pin, with a consequent reduction in the vertical stability of the rod, particularly as running wear develops. By contrast, the T.Y.C. uses a sturdy milled rod of basically rectangular section, with an extended bearing at the top end. It is a far more substantial and stable component than its Yin Yan/Silver Swallow equivalent.

A further difference is the design of the con-rod itself. The Yin Yan/Silver Swallow engines use a standard turned British-style “dog bone” component. This is a less than optimal design, since it provides only a relatively short bearing length at the small end where it engages with the gudgeon pin, with a consequent reduction in the vertical stability of the rod, particularly as running wear develops. By contrast, the T.Y.C. uses a sturdy milled rod of basically rectangular section, with an extended bearing at the top end. It is a far more substantial and stable component than its Yin Yan/Silver Swallow equivalent. The second manufacturing flaw is also related to the crankshaft assembly. On this example, the female 20 degree (40 degree included) taper in the rear of the prop driver was cut a little too shallow, leaving a considerable gap between the rear of the prop driver and the front of the main bearing when a prop was fitted and the shaft was in its normal running position under forward thrust from the prop. This gap may be clearly seen in the image at the right. The shaft was free to move back in its bearing to the point where the crankpin contacted the backplate. Such contact would almost inevitably occur during starting, and would be continuous in pusher operation.

The second manufacturing flaw is also related to the crankshaft assembly. On this example, the female 20 degree (40 degree included) taper in the rear of the prop driver was cut a little too shallow, leaving a considerable gap between the rear of the prop driver and the front of the main bearing when a prop was fitted and the shaft was in its normal running position under forward thrust from the prop. This gap may be clearly seen in the image at the right. The shaft was free to move back in its bearing to the point where the crankpin contacted the backplate. Such contact would almost inevitably occur during starting, and would be continuous in pusher operation. Looking now at the carburetion arrangements, the venturi with which this example of the engine was supplied has an internal diameter of 5 mm (0.197 in.) with a spraybar having a diameter at the crossing location of 3 mm (0.118 in.). These figures appear quite appropriate in the sport-flying context for which this engine seems to be designed. The example illustrated on the instruction sheet has an extended needle, but my example has a truncated component with no extension past the thimble. Looking at the unit closely, I'm certain that this is original. Moreover, the example illustrated in Jim Dunkin's book is similarly equipped, as are two other examples which have come to my attention since writing this article. In either case, needle tension is very effectively provided by a double leaf spring clip in the conventional manner.

Looking now at the carburetion arrangements, the venturi with which this example of the engine was supplied has an internal diameter of 5 mm (0.197 in.) with a spraybar having a diameter at the crossing location of 3 mm (0.118 in.). These figures appear quite appropriate in the sport-flying context for which this engine seems to be designed. The example illustrated on the instruction sheet has an extended needle, but my example has a truncated component with no extension past the thimble. Looking at the unit closely, I'm certain that this is original. Moreover, the example illustrated in Jim Dunkin's book is similarly equipped, as are two other examples which have come to my attention since writing this article. In either case, needle tension is very effectively provided by a double leaf spring clip in the conventional manner. The engine is completed by a conventional screw-in backplate which is matched to its installation thread with noteworthy precision. Beyond removing this component as well as the cooling jacket, I was unable to dismantle the engine further because the cylinder appeared to be screwed into the crankcase “for keeps” – I couldn‘t shift it by “fair” means, even using moderate heat. I suspect that some kind of thread-locker may have been used to guard against the common problem of a screw-in cylinder becoming loose in service ……………

The engine is completed by a conventional screw-in backplate which is matched to its installation thread with noteworthy precision. Beyond removing this component as well as the cooling jacket, I was unable to dismantle the engine further because the cylinder appeared to be screwed into the crankcase “for keeps” – I couldn‘t shift it by “fair” means, even using moderate heat. I suspect that some kind of thread-locker may have been used to guard against the common problem of a screw-in cylinder becoming loose in service …………… I elected instead to put some 40 minutes on the engine in four-minute runs on a slightly rich mixture with reduced compression, leaning out and optimizing compression for the final 20 seconds or so to bring the piston and cylinder up to somewhere near their normal working temperature. After that, the engine was allowed to cool completely before being re-started in its slightly rich and under-compressed state. In this way, the 40 minute break-in period provided ten full heat cycles, which I consider to be an appropriate minimum number.

I elected instead to put some 40 minutes on the engine in four-minute runs on a slightly rich mixture with reduced compression, leaning out and optimizing compression for the final 20 seconds or so to bring the piston and cylinder up to somewhere near their normal working temperature. After that, the engine was allowed to cool completely before being re-started in its slightly rich and under-compressed state. In this way, the 40 minute break-in period provided ten full heat cycles, which I consider to be an appropriate minimum number. I took more time than usual over this series of tests, since I elected to continue to allow complete cooling between runs on the different test props in order to add to the number of complete heat cycles to which the engine had been subjected. As usual, I went from the slowest props up to the fastest. At the end, I followed my usual practise of going back and re-checking one of the props in the middle of the tested range. If a significant increase in speed is noted on such a prop after the series of runs at the top end, it's an indication that the engine was still settling down. In such a case, the entire test must be repeated. Thankfully, this didn't happen in the present instance!

I took more time than usual over this series of tests, since I elected to continue to allow complete cooling between runs on the different test props in order to add to the number of complete heat cycles to which the engine had been subjected. As usual, I went from the slowest props up to the fastest. At the end, I followed my usual practise of going back and re-checking one of the props in the middle of the tested range. If a significant increase in speed is noted on such a prop after the series of runs at the top end, it's an indication that the engine was still settling down. In such a case, the entire test must be repeated. Thankfully, this didn't happen in the present instance!

t's clear from the English-language instructions that the makers of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel had ambitions to market the engine in English-speaking countries. Had they succeeded in doing so, there's little doubt that the engine would have been quite favourably received. As it is, I have so far been unable to turn up any evidence that the engine was seriously marketed either in North America or in Europe.

t's clear from the English-language instructions that the makers of the T.Y.C. 2.5 cc diesel had ambitions to market the engine in English-speaking countries. Had they succeeded in doing so, there's little doubt that the engine would have been quite favourably received. As it is, I have so far been unable to turn up any evidence that the engine was seriously marketed either in North America or in Europe.