|

|

Iron Curtain Classics - the Alag Range

Under these circumstances, such luxuries as new model engines were generally well beyond my means. I started out in the late ‘50’s using beat-up but still serviceable fourth-hand examples of the Allbon Merlin and the Frog 80. My first new model engine was a Series 2 E.D. Bee which I received from my parents for my 12th birthday in October 1959. But apart from that, I was pretty much on my own, since my parents elected to support my musical interests rather than my modelling ones (which they wrongly assumed that I would soon outgrow!). During the first half of the 1960’s, this situation resulted in my being constantly on the lookout for bargain-priced used engines, which were far more plentifully and cheaply available in those golden pre-collector years than they later became. At that time, I was not a collector in any sense – in fact, the very concept of engine collecting had yet to present itself. I was simply an active but impecunious teenage flyer who needed serviceable and affordable second-hand engines. Many of those which came along are regarded as prized collector’s items today …………….. and packrat that I am, I still have the majority of them!

I had first become aware of these engines from reading about them in the modelling press. I knew that they had been imported into Britain in relatively small quantities during the late 1950’s and had been the subject of two quite favourable reviews by Ron Warring which had appeared in “Aeromodeller” magazine, to which I was then a subscriber (another ongoing birthday gift from my parents). As a result, a number of Alag engines had found their way into the hands of British modellers, including those of several active flyers in my area. This latter fact had provided me with the opportunity of seeing a few examples in actual use, and the owners of these engines were continuing to use them without apparent problems. Now it should be clear from the above that I had no reason at the time to question the basic serviceability of the Alag diesels. It was only many years later that I became aware that by the early 1960’s (when I purchased my two used engines), the Alags had already acquired a thoroughly evil reputation in certain parts of the world, being widely considered to be so poorly made as to be basically un-useable. Whether for this or some other reason, their importation to Britain had ceased as of 1960 and many of them appeared to have gone out with the rubbish! This could explain their relative scarcity today .............

For the benefit of potential present-day users, it’s probably worth recalling one flaw that we did notice. This was the fact that the fitting of the prop driver taper on some examples was set so that there was excessive end-float on the shaft when the engine was assembled. The result was that the crankpin and rod big end were free to bear directly on the backplate when the shaft was moved towards the rear. Not a serious problem in normal use, but the fact that the backplate of the X-03 was moulded in thermoset plastic meant that it would not do well in a pusher installation or in a crash in which the shaft was knocked back - excessive wear or an outright fracture of the backplate would be the almost inevitable result. The cure that we adopted was the fitting of a steel shim behind the prop driver so that the shaft could not move back to the point where the crankpin made contact with the backplate. I’d recommend this modification to any present-day user of an Alag of any displacement which displays this characteristic. A more elegant alternative for those having the equipment is to re-cut the 22 degree included angle taper inside the prop driver to adjust the clearance to around 10 thou end float when assembled. This latter approach has the added benefit of increasing the available length of prop mounting thread, which is undeniably a bit marginal on these engines. Another matter that quickly forced itself upon our consciousness was the fact that the integral hub on the prop driver had a monumental diameter of 10 mm (0.394 inches). This required a major boring-out of the prop hub to a dimension which did not conform to any standard British drill diameter. I blush now to admit that most of us who had access to a lathe turned the prop driver hub down to 3/8 (0.375) inch so that a standard 3/8 inch drill could be used to bore out the prop hub. Please don't follow our sorry example today - conservation of these engines in as original condition as possible is important! After a period of about two years, I was able to obtain several similar-displacement British engines of higher performance, hence being quite happy to sell my still-serviceable Alags as a pair to another impecunious modeller who needed some cheap ‘n cheerful engines for basic sport flying. He carried on using them successfully for some time thereafter, and was still doing so when I left England for Canada in 1966. I don’t know what became of them thereafter.

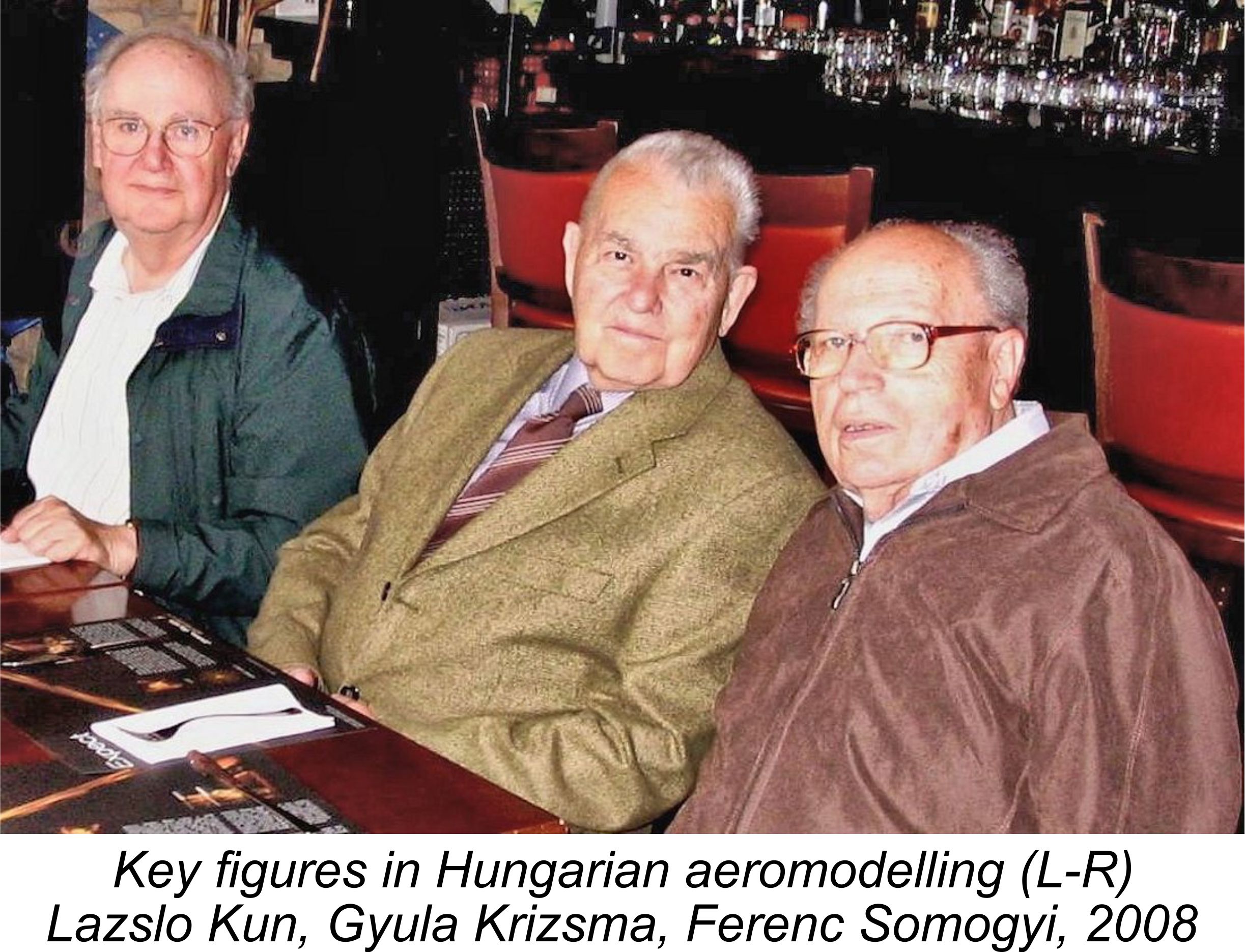

Since my latter-day “flier” Alag followed the example set by its predecessors by performing very well indeed, I remained in complete ignorance of the contempt in which these engines were apparently held by a number of individuals! It was only when word got around that I had begun to write up my original article about the Alag engines that negative reports from other previous users began to emerge. Although I fully accept the sincerity with which these views have been expressed, I could only write about these engines at first hand on the basis of my own encounters with them. In the case of the Alag range, my own positive experiences (and those of my club-mates) were evidently not shared by a number of others, and this must be recognized at the outset. The initial result of my renewed interest in the Alag range was the 2011 publication of an article on the late Ron Chernich's now-frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) web-site. My greatest reward for the considerable effort involved in the preparation of such articles is the receipt of additional information from readers following their initial publication. In the present instance, my late friend and colleague Ron Chernich and I were delighted to hear from our good mate Maris Dislers, who was able not only to provide us with additional documentation but also to point out several avenues for further research. Our indebtedness to Maris cannot be overstated. The text of the original article was amended in accordance with the new information resulting from this contact, with the revised article appearing here on MEN web-site in May 2011. So far so good – job done, or so we thought! However, there was much more to come! Maris would be the first to agree that even his contribution paled beside that of Hungarian resident Ferenc Somogyi (in Hungarian naming order, Somogyi Ferenc), an 89 year old retired mechanical engineer (in 2018) who is generally addressed by his English-speaking colleagues as Francis (an English rendering of Ferenc) but is known to his family and Hungarian friends by his nickname of "Somi". At his request, I’ve referred to him as Somi throughout this updated article. After reading the article in its revised form with Maris’s suggestions incorporated, Somi was kind enough to contact me directly to provide a wealth of additional data and photographs as well as correct a number of errors, some of them highly significant. The scope of the new information provided by Somi was such that a complete re-write of the article was unmistakeably necessary. The result was the text which follows. The original intention had been to replace the article on MEN with the revised text, but the tragic passing of Ron Chernich in early 2014 and the subsequent freezing of the MEN site has precluded this. Hence I have been obliged to publish the substantially revised article here. It would be impossible to overstate our indebtedness to Somi, since he was actively involved in the Hungarian model engine manufacturing industry at the time in question, thus having intimate first-hand knowledge of the designs and personalities involved. Regular readers of this site will doubtless recall his excellent article on the history of the MOKI engines which first appeared on this web-site in February 2015. A full summary of Somi’s modelling career will be found in that article. In his professional career, Somi was the chief of the diesel engine department at the Ganz MÁVAG Wagon and Locomotive Factory. Accordingly, his primary focus was the development of full-sized railway diesel engines. However, from 1944 onwards he had become increasingly involved with the Hungarian modelling movement, initially as a competitor and member of the Hungarian Association of Modellers but later serving at various times as a model club president, competition jury member, event organizer, model engine designer and ultimately Team Manager of various Hungarian teams competing in National, European and World Championship C/L speed events, including World Championship meetings held in Sweden, England and the USA. This is the kind of contact that model engine historians like me dream about - there could be few individuals in a better position to comment upon our present subject. Many thanks indeed, my friend!! Now, with these acknowledgements openly and gratefully recorded, we’ll begin with a summary of the early years of the Hungarian model engine manufacturing industry. This section of the article will contain quite a lot of material which has appeared previously in the companion article about the MOKI range. This material is repeated here purely to relieve the new reader of the necessity to search other articles for background information. Readers who are already familiar with this background material are invited to skip to the following section of this article. For the rest of you, read on .......... In the Beginning - an Overview

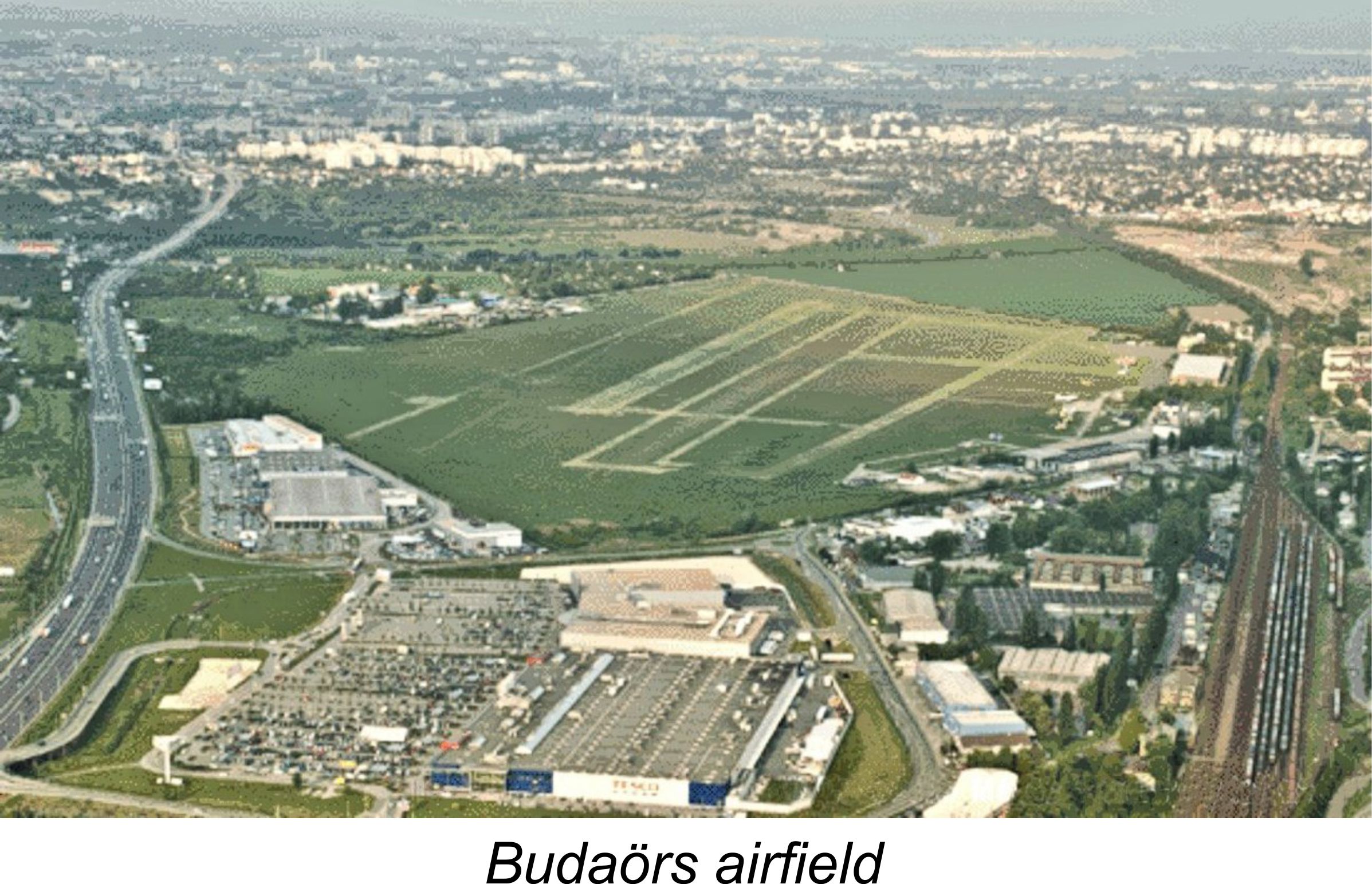

Here we clearly see the origin of the engine’s name. Armed with this information courtesy of Maris, it was a simple matter to seek out further information on the Web. This generated a wealth of detail which did much to clarify the origins of the Alag range. Our sincere thanks to Maris for drawing our attention to this fruitful line of inquiry! The subsequent intervention of my good friend Somi added greatly to the information derived from my initial research. It turns out that the facility at which the Alag engines were designed and initially constructed actually had its origins in the field of full-size sport-flying aircraft. Sport flying using both gliders and powered aircraft had apparently been quite popular in Hungary prior to WW2, with a number of very active aero clubs. At that time, the Kingdom of Hungary (as the country was then known) was very much allied with the Axis powers in Europe, relying increasingly upon trade with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to pull itself out of the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Although reluctant to actually involve itself in all-out war, Hungary was inexorably drawn into the conflict of WW2, becoming directly involved on the Axis side in the 1941 invasions of both Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. However, as time went on the Hungarians became increasingly disenchanted with the direction that the war was taking, accordingly attempting to negotiate secretly on their own account with However, the imposition of this change in government did not proceed smoothly - it took until August 1949 for the country to finally become stabilized as the Hungarian People’s Republic (Magyar Népköztársaság), a Communist state which was administered by the Socialist Workers’ Party, still under dominating Soviet influence. The Hungarian People’s Republic was destined to survive until October 23rd, 1989, at which point the collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with the completion of an orderly transition to a Western-style democracy designated the Republic of Hungary. However, all of the engines to be covered in this article were produced during the Communist era. Returning now to the early post-war period, the events of WW2 and its aftermath had of course left the country’s sport-flying resources in a shambles. Some measure of the importance attached to this activity may be gauged from the fact that steps were taken as rapidly as possible after the war to start rebuilding the sport-flying movement in Hungary. The role of this activity in producing potential military fliers doubtless influenced this decision. Until June 1947, the Control Commission of the Allied powers imposed a complete ban on all sport-flying in Hungary. However, immediately upon the lifting of that ban, the Hungarians moved vigorously to re-establish sport-flying on an organized basis. In early 1948 a new organization called the National Hungarian Flying Association (Országos Magyar Repülö Egyesület - OMRE) was created to administer all sport-flying activity in Hungary. All existing aero clubs along with all their assets were incorporated into this new organization, and all sport airfields were managed and financed by OMRE in addition. A number of aircraft suitable for sport-flying, both gliders and powered designs, had survived the ravages of war, but repairs and upgrades to these were urgently needed. In addition, a number of partially- To deal with the required restoration, maintenance and repair work, new workshops were founded, among them the OMRE Central Aircraft Repair Plant, Budaörs (OMRE Központi Repülögépjavító Üzem, Budaörs) at Budaörs airfield near Budapest in June, 1948. The airfield at Budaörs immediately became the central sport-flying airfield for OMRE. Of course, new designs were also required, and a central design office was also established at Budaörs to develop such designs along with all the necessary documentation, restoration and repair programs required in addition. It's worth noting in passing that the airfield at Budaörs later became the scene of several Control-Line World Championship meetings, most notably in 1960 and 1964. OMRE was quite successful in meeting its goals, to the point that government attention was soon drawn to its further potential. This led to the assets and mandate of OMRE being taken over by a new group called the Hungarian Aeronautical Association (Magyar Repülö Szövetség - MRSz) having a somewhat broader overall mandate. Part of the plant at Budaörs, which was then engaged in building new aircraft, was moved to Mátyásföld airport in 1951. The other part of the plant was taken over by the Hungarian military.

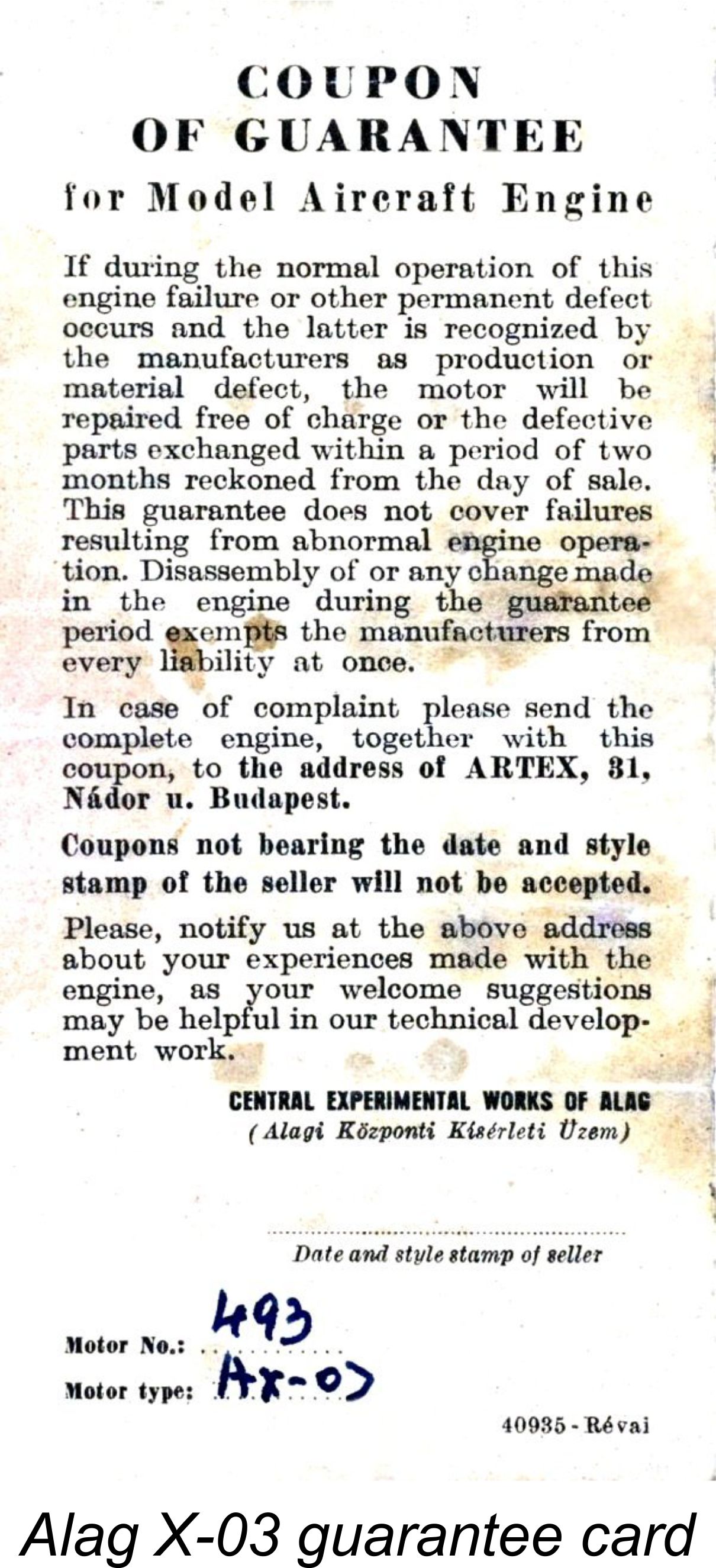

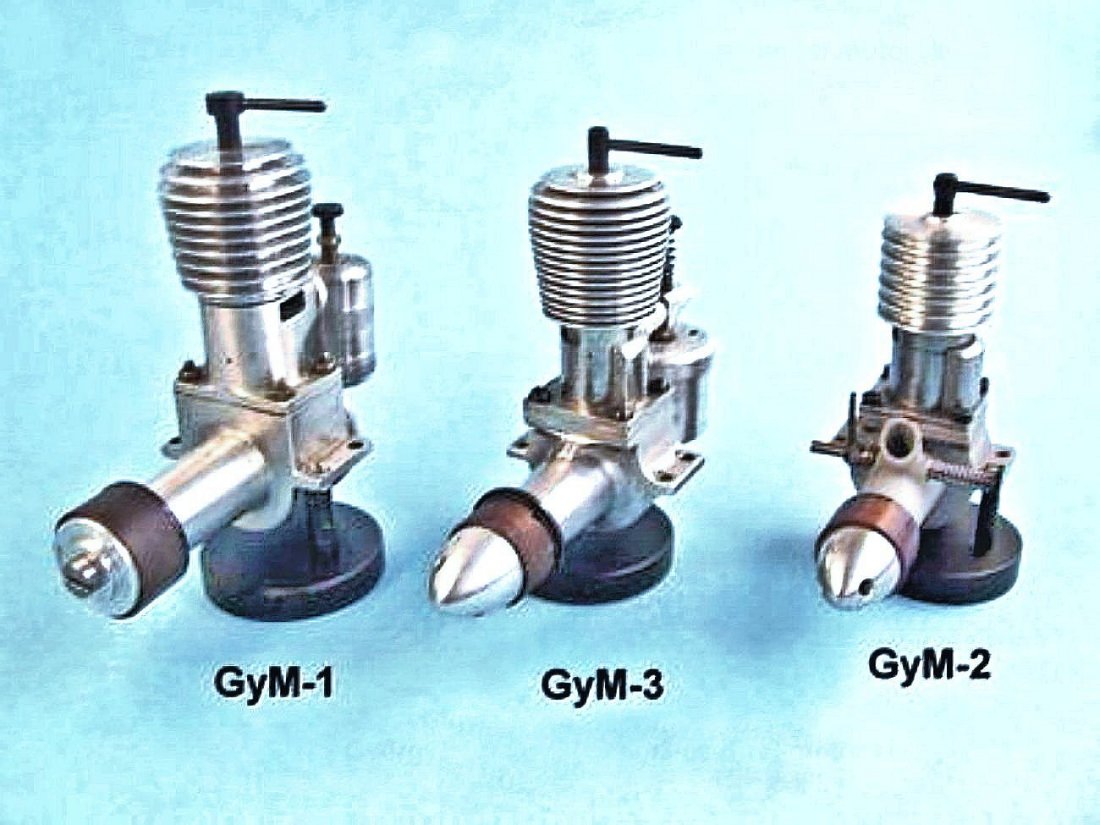

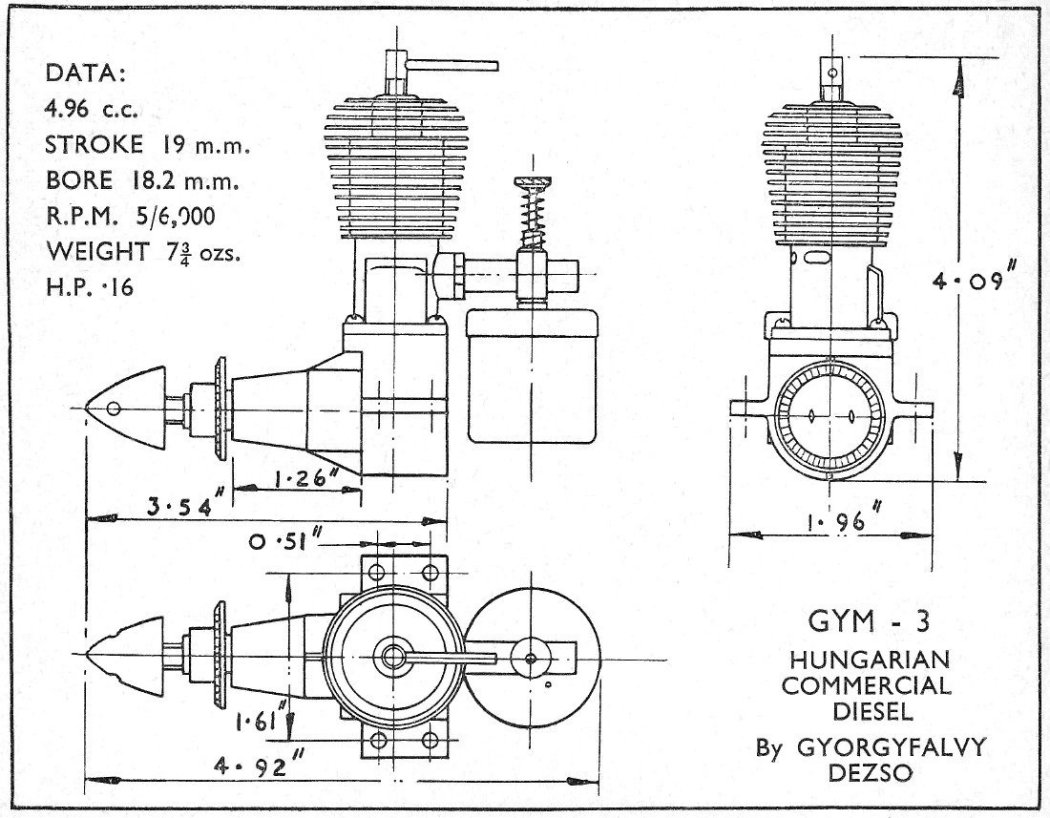

The relocated MRSz plant and associated design office was very successful in developing and manufacturing a series of gliders as well as undertaking modifications to powered aircraft to make them suitable for glider towing and flight training purposes. In 1954 the full-sized aircraft side of MRSz was absorbed into the Hungarian Voluntary National Defence Association (MÖHOSz). At the same time, portions of the operation were taken over by the Ministry of Metallurgical and Mechanical Industry (Kohó és Gépipari Miniszterium). This latter take-over occurred in March 1955, and the resulting government-run precision engineering facility was designated the Alag Central Experimental Plant (Alagi Központi Kisérleti Üzem - AKKÜ). This of course is the facility identified on the Alag X-03 guarantee card referenced earlier. We have thus reached the point at which the evolution of the Hungarian sport-flying movement finally intersected with the production of model engines in Hungary. Having done so, let’s approach the same intersection point from a different angle by returning to the history of the parallel growth of the aeromodelling movement in Hungary. The Beginnings of Hungarian Model Engine Manufacture While all of the activity outlined above had been going on in the context of full-scale aviation in Hungary, the sport of aeromodelling had also quickly gained ground following the end of WW2. It appears that the fostering of interest in aviation through participation in modelling was understandably seen in Government circles as having value in terms of producing both future fliers and aircraft designers/technicians. The early post-war head of the Hungarian Modelling Department was the supremely well-qualified György Benedek (1921- 2004), who was internationally known for his very successful “B” aerofoil design for free-flight models. However, Mr. Benedek was forced out of his post for political reasons when the Communists finally It’s worth noting in passing that after the Hungarian revolution of October-November 1956 this situation changed very much for the better. Rezső Beck (1928-2002) then became the chief of what had now become the Hungarian Association of Modellers. Mr. Beck was a well-known early post-war competitor in various categories of aeromodelling, subsequently becoming a very successful control-line speed flier in the 1950’s. Thanks to his wide-ranging professional knowledge and considerable political influence, he was well able to guide the further development of Hungarian aeromodelling, also serving as the Hungarian representative on the FAI Aeromodelling Commission (CIAM). Returning now to the early 1950’s, Somi tells us that contemporary Hungarian modellers faced a serious problem – a chronic lack of suitable model powerplants. A few Czechoslovakian and Soviet engines were evidently in Somi tells us that the first model engine to enter series production in Hungary, albeit on a very small scale, was the GyM 1 diesel of 5 cc displacement, which first appeared in 1950. This engine was designed by the late Györgyfalvy Dezső (d. 2010) and made in a very small series by a single Another pioneering Hungarian manufacturer was the Szegedi Vas és Fémipari Szövetkezet (Szeged Iron and Metallurgical Co-operative), which began to manufacture model engines in 1953

According to Somi, who knew them both personally, the Vella brothers were talented machinists who had a small workshop on Csepel, a large island in the Danube in the Budapest area. They had no modern machine tools, but they were well-trained and highly experienced toolmakers and craftsmen who knew how to use what they had to the best advantage. They had assistants both in the design and manufacture of the VT engines.

In May of 1955, production of the Alag engines also commenced at the AKKÜ facility at Dunakeszi. The almost simultaneous advent of the VT and Alag ranges represented a major expansion of model engine production in Hungary, with both ranges subsequently becoming quite widely known beyond the Iron Curtain. This came about entirely as a result of a parallel initiative by the Hungarians to develop an export market for the growing number of Hungarian-made model engines which were then appearing. The national export drive which was underway at this time was driven by a chronic shortage of foreign currency in Hungary at the time and the consequent need to generate such currency through export sales. The seriousness with which this goal was pursued is underscored by the fact that the marketing of Hungarian model engines was now added to the portfolio of ARTEX, a trading organization which had been established some time previously for the express purpose of developing export markets for a range of Hungarian products. That range was now expanded to include model engines.

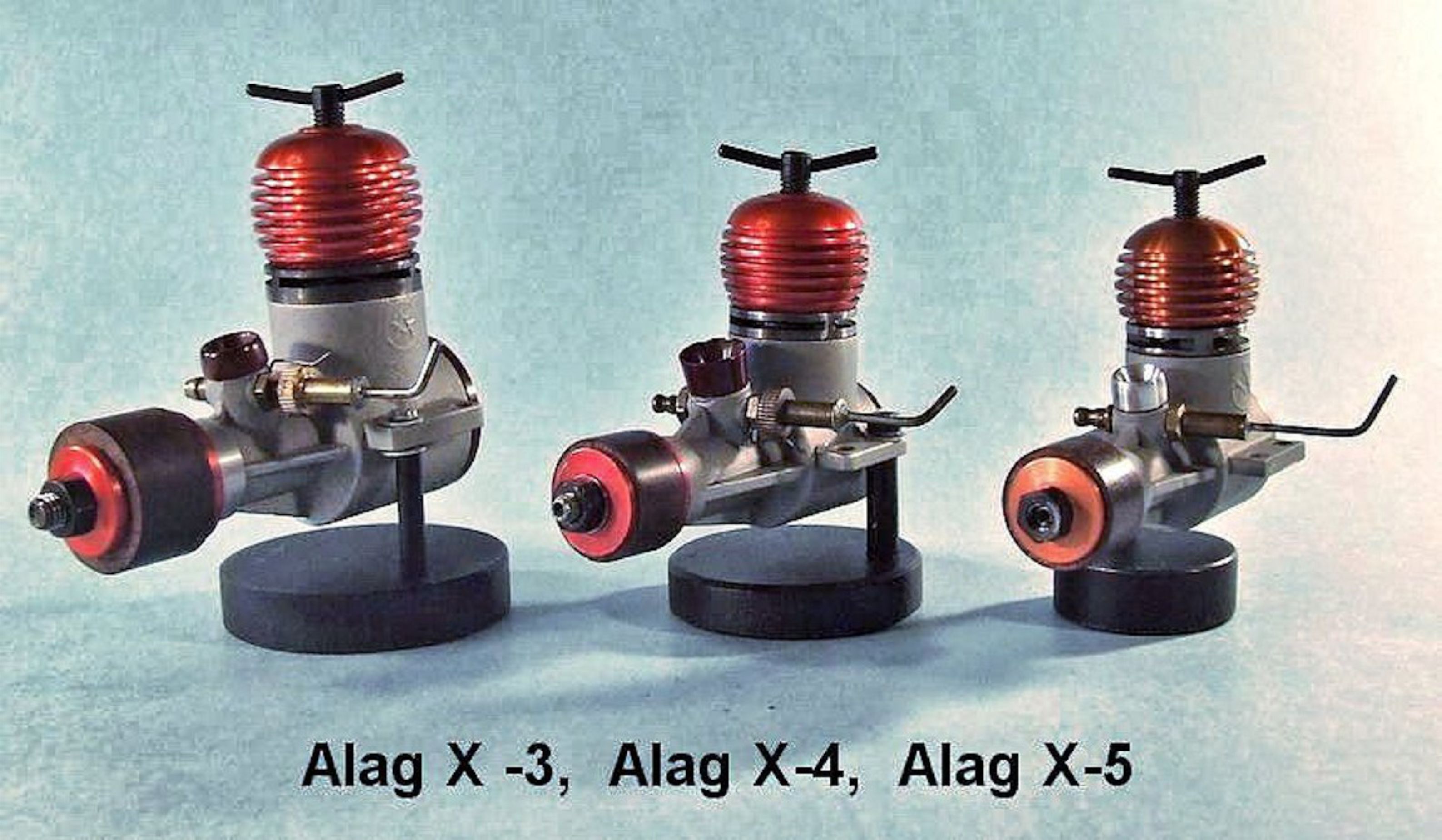

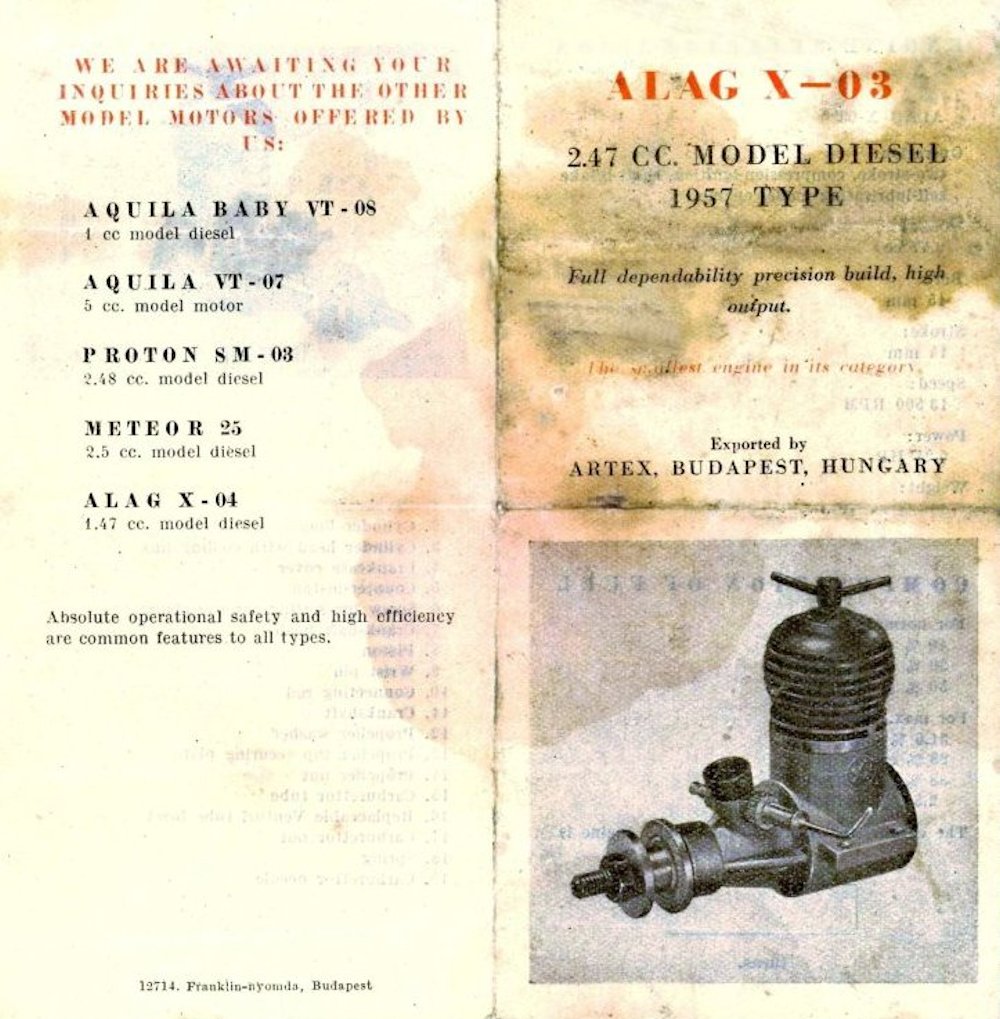

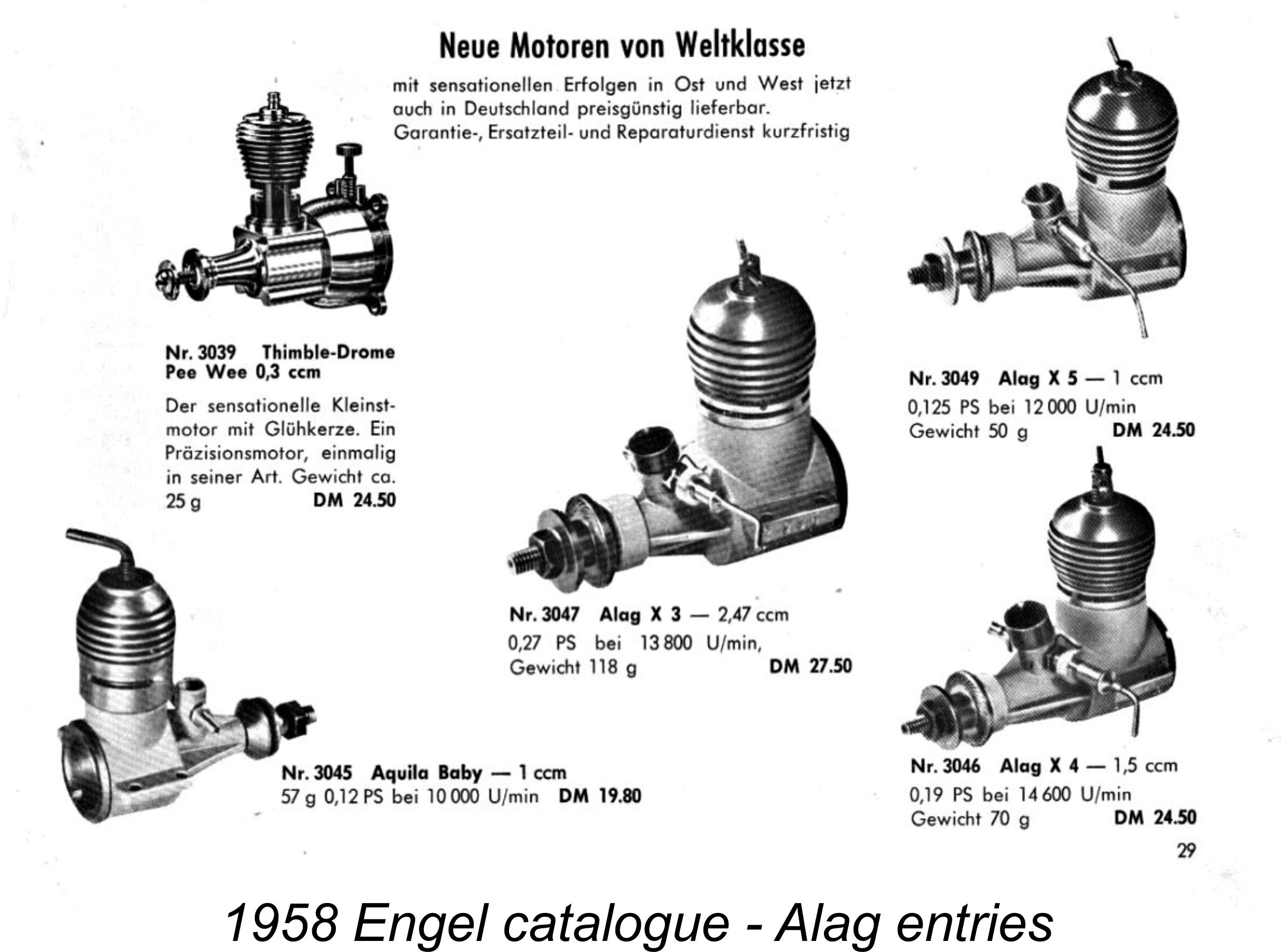

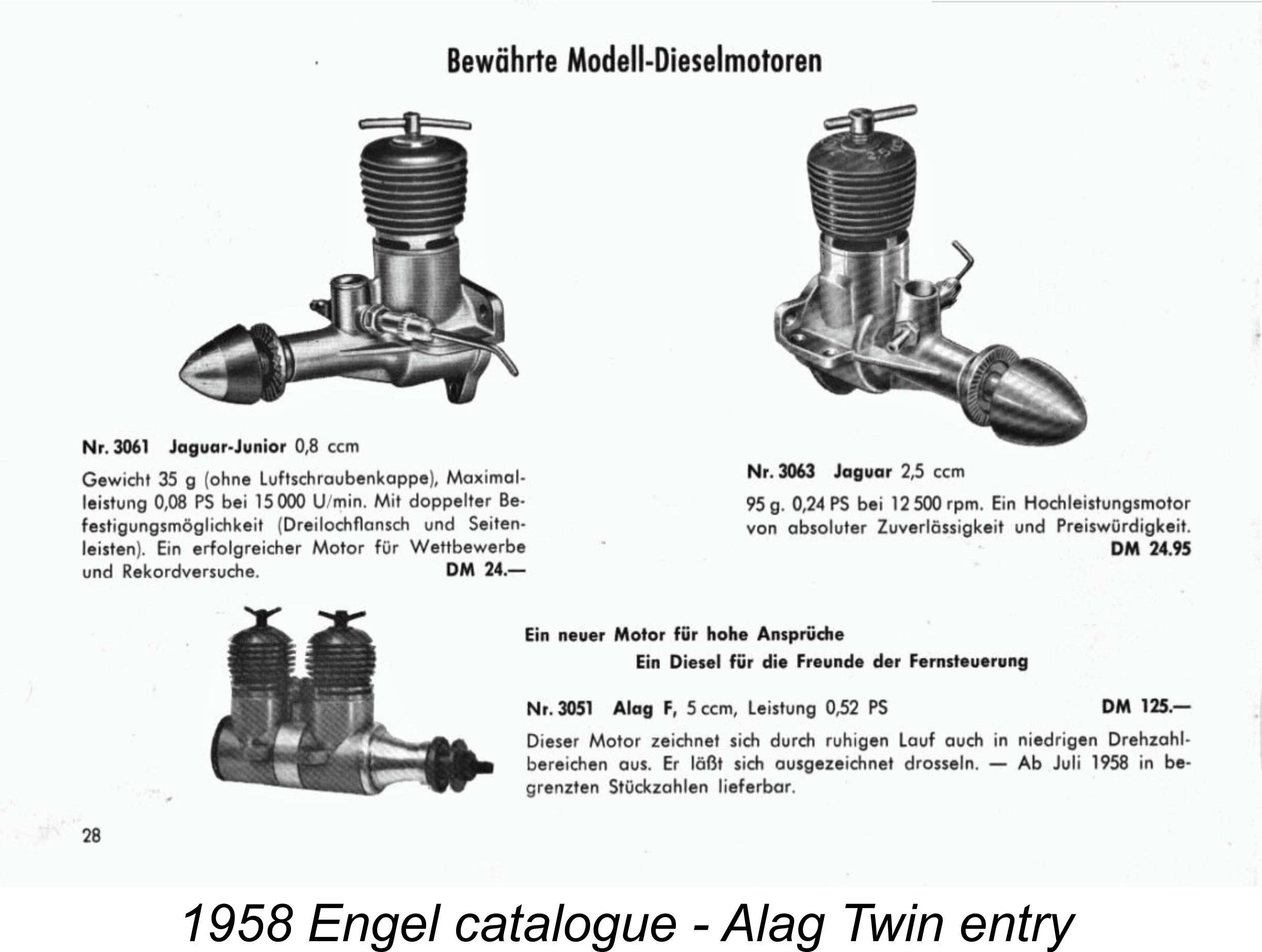

By 1957 the list of Hungarian model engines offered by ARTEX as summarized in the previously-noted instruction leaflet with Maris Dislers’ 1957 Alag X-03 had grown to impressive proportions. Apart from the Alag X-03 itself, ARTEX was also offering the 1.5 cc Alag X-04 diesel, the Proton SM-03 diesel of 2.5 cc displacement, the previously-mentioned VT-08 1 cc diesel, the Meteor 25 2.5 cc diesel and the VT-07 5 cc racing glow-plug motor. Some of these offerings never made any real impression on the International market, but others became quite widely known. Chief among the latter were the Alag X-series of model diesels which form our main subject as well as the VT-08 "Aquila Baby" model. The series of engines manufactured by the Vella Brothers over the years was most impressive, ranging from simple sport diesels suitable for beginners all the way up to highly sophisticated racing glow-plug engines. The scope of this series was such that the VT engines richly merit an article all to themselves, which will be found elsewhere on this web-site. Now, having set the stage upon which the Alag story was played out, let's begin our detailed examination of that range. Alag Production Commences

As events were to prove, Kun’s involvement didn’t last long – in the aftermath of the 1956 revolution, he somehow managed to escape to the West, eventually settling in the USA. At that point, Gyula Krizsma took over responsibility for the design of the Alag engines, switching the focus to glow-plug models, as we shall see. There were doubtless several reasons for the addition of model engine manufacture to the government-sponsored work program of AKKÜ. Firstly, we have already noted that at the time in question foreign currency was in very short supply in Hungary. For this reason, the importation of specialized goods such as model engines from Western countries was impossible. This situation rendered it inevitable that efforts would It’s also likely that the initiative had much to do with the previously-noted desire on the part of government to advance interest in aviation among young people through involvement with aeromodelling. Someone within the Ministry doubtless realized that future sport-fliers, military pilots and aircraft designers may well develop from keen aero-modellers, whose activities therefore warranted encouragement. The Soviet Union certainly pursued such a policy using existing aircraft-related facilities, as discussed in the companion article on this web-site about the MD-5 Kometa racing engine.

Before we dive into our detailed examination of the Alag range, we may as well deal with one of the more confusing aspects of the Alag story. This is the fact that their model identification systems bore no relation whatsoever to their displacements. The Alag diesel engines were designated by the letter X followed by a two-digit number indicating the particular model. The later glow-plug engines were designated by the letter Y followed by a two-digit model number. In both series, the model number was unrelated to the engine’s displacement. Moreover, the application of serial numbers to these engines appears to have been a bit haphazard – most have numbers, but certain others do not. At this point, some readers may be wondering about the correctness of my assertion that the engines bore two-digit model identification numbers. Previous commentators have almost invariably used only the last numerical digit, since (unlike the far more extensive VT range), the Alag range never progressed beyond the 05 numerator, making the 0 effectively redundant. Indeed, the engines themselves did not display the 0, confining themslves to the final digit alone. However, in all of their literature, both ARTEX and the manufacturers invariably included both digits (including the seemingly-redundant 0). I have chosen to follow their lead in referring to these engines. Having dealt with this issue, let's take a close look at the initial product of the Alag venture. The Alag X-03

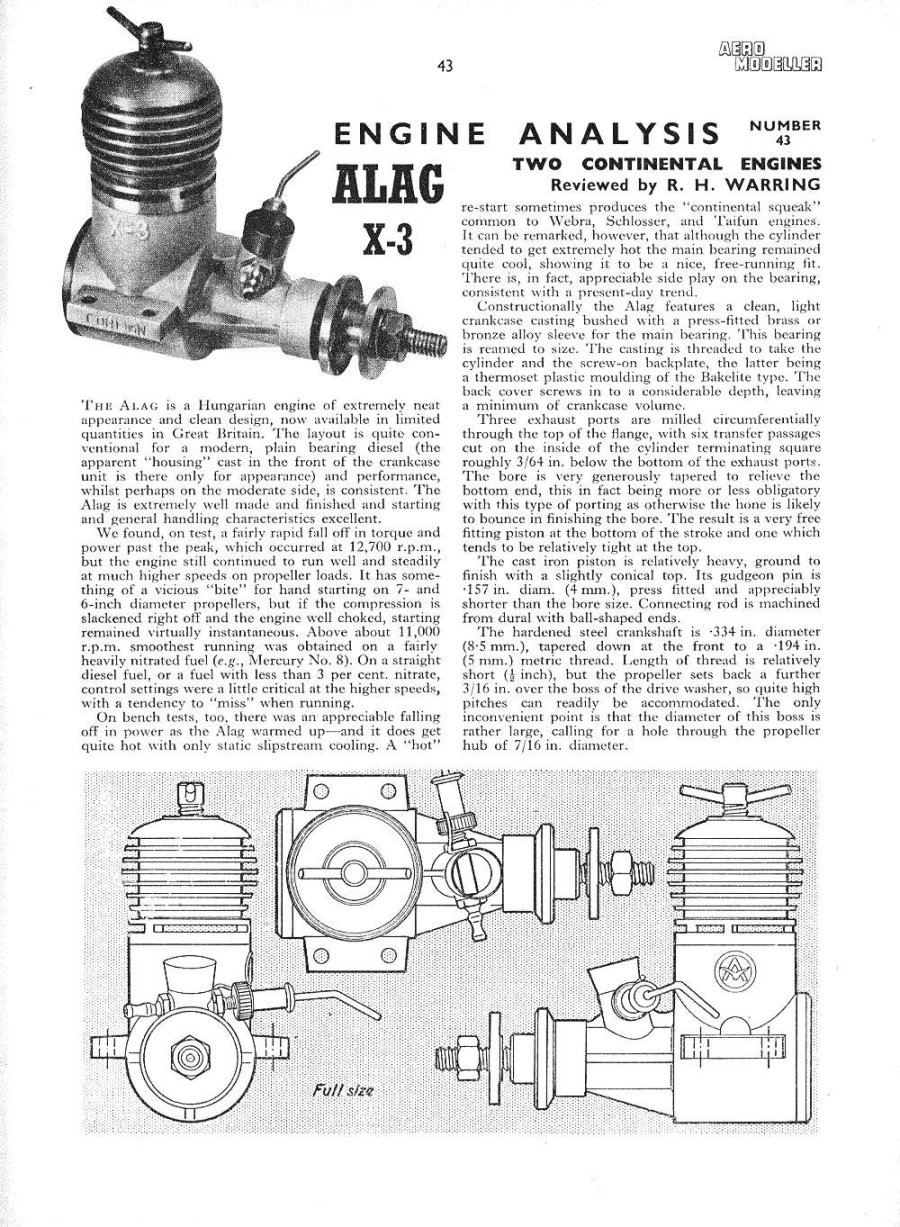

Design-wise, the X-03 had little to teach the Western model engine industry. It was a totally conventional crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) design with circumferential porting and a bronze-bushed main bearing. Both the piston and contra-piston were of cast iron, operating in a hardened steel cylinder. Bore and stroke were 15 mm and 13.9 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.46 cc (.1499 cu. in.). The engine thus met both the International rules and the US Class A rules. It weighed 119 gm (4.2 ounces) - a comparatively low figure for a 2.5 cc diesel. The engine was also unusually compact for its displacement. Indeed, the manufacturer's literature characterized it as "the smallest engine in its category". This was probably a valid claim. In common with many of its Continental counterparts at the time, the X-03 featured a relatively heavy piston while also lacking any form of counterbalance on the crank web. These features together with the engine's very low weight combined to make it a bit of a “vibration producer” at certain speeds. Another feature which the X-03 shared with several of its contemporaries (notably the Webra range) was the transfer system, which consisted of six generously-proportioned internal flute-style transfer passages formed in the inner cylinder wall. These took up the majority of the circumference of the lower cylinder wall, leaving relatively thin vertical “bands” of cylinder wall to support the piston near bottom dead centre. The transfer passages terminated in square ends just below the lower edges of the three sawn exhaust ports - it is not possible to provide any overlap between exhaust and transfer ports with this design arrangement. Although the available transfer period was necessarily somewhat limited, the combined area of the six ports was such that transfer efficiency must have been quite adequate – the famous Webra Mach I had an identical set-up, and there was nothing wrong with its top-end performance! It’s clear that with this style of porting, a relatively short transfer period can be tolerated without adverse effect upon performance. In addition, piston cooling and lubrication with this system are unusually effective.

The walls of the conical-topped piston were relatively shallow, resulting in a period of sub-piston induction at the top of the stroke - roughly 20 degrees each side of top dead centre for a total of some 40 degrees or so. The induction hole in the crankshaft was comparatively small for an engine of this size – only 5 mm in diameter in an 8.5 mm diameter shaft. However, this did have the effect of leaving plenty of metal to ensure adequate crankshaft strength, while the sub-piston induction would have helped to deal with any shortfall in the filling of the crankcase during the induction phase at higher speeds. The X-03 may be encountered with two different prop mounting set-ups. Early examples used a simple nut and washer, while later models employed a racing-style sleeve nut, evidently the same unit used on the companion Alag Y-Series glow-plug models (see below). This had the advantage of increasing the active length of thread and facilitating the use of props having thicker hubs. The majority of X-03’s seem to have featured red-anodized cooling jackets, prop drivers and prop washers. However, a number of the marginally-functional examples imported to Australia by Bill Evans (see below) featured green anodizing. The one area in which the X-03 did offer something novel was in the use of a thermo-set type of plastic for the screw-in backplate and the intake venturi. At the time, this was a relatively new application of plastics technology to model engine manufacture, although it later became commonplace using improved materials. The engine was supplied with two venturis having different bores. The smaller-bored venturi was generally fitted as delivered.

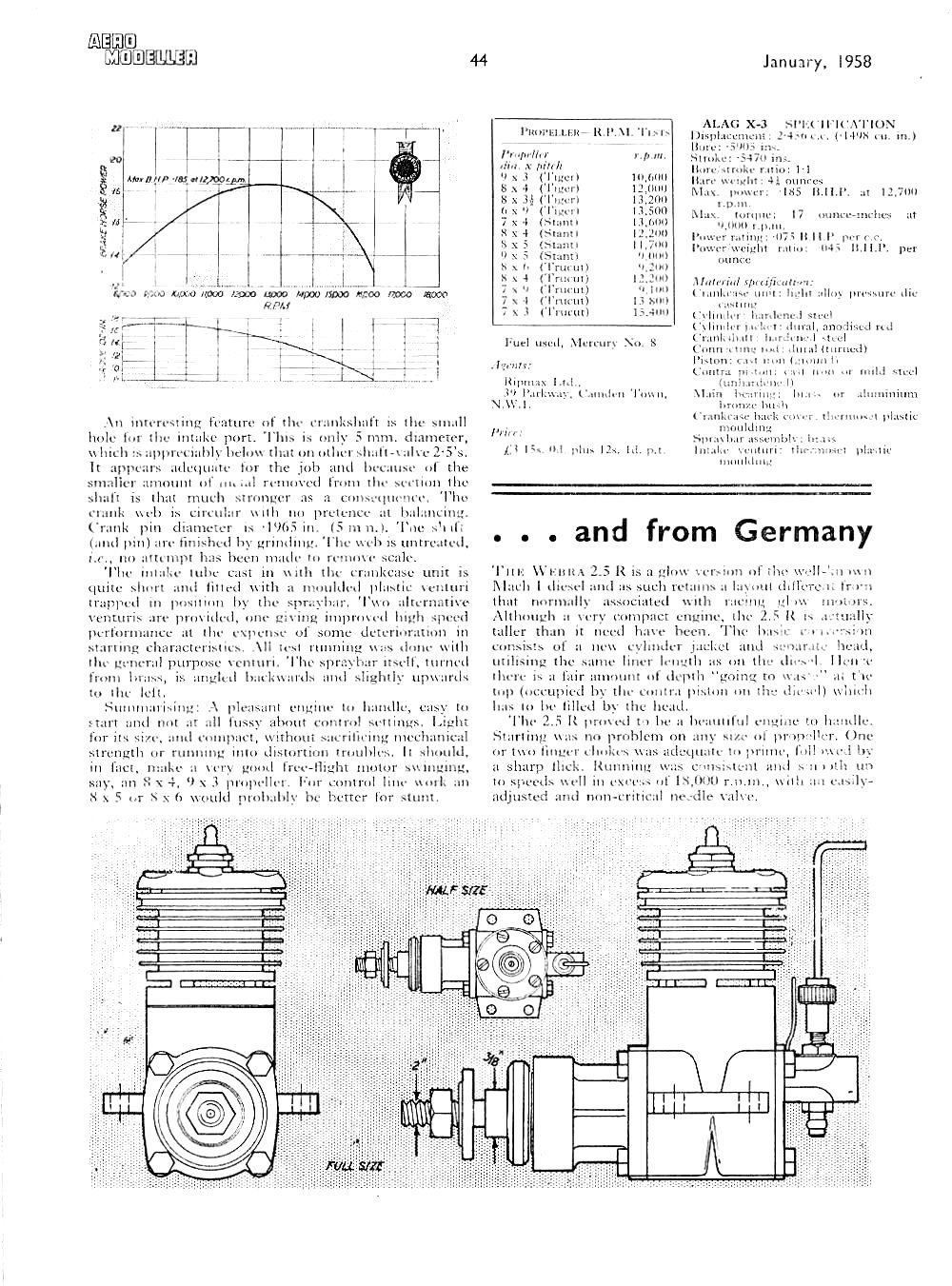

Maris Dislers has an Alag X-03 which is LNIB and bears the serial number 493 as well as another example bearing a serial number of 1555. The latter engine also has the word “Foreign” stamped on the outer edge of one lug, presumably indicating that it was earmarked for export. A similarly marked engine featuring the "Foreign" stamping and bearing the serial number 1398 appeared on eBay in 2018. Engine number 853 recently appeared on eBay as well, albeit in very incomplete condition. Reader Richard Jackson of Dorset, England has reported that he owns engine number 1582, which is apparently well-used but still feels like new and runs perfectly. Following the initial publication of this article, I acquired another Alag X-03 to add to my existing pair. This one bore the number 12354 with no accompanying extra number. This is the highest serial number of which I am currently aware. The numbers reported to date make it appear probable that the numbering sequence started from engine number 1 and that over 12,000 examples were made over a 41/2-year period up to late 1959, when production appears to have ended. However, no firm conclusions can be drawn from such a tiny sample, and I would be most grateful for any additional serial numbers which readers may be able to provide. The Alag X-03 on test The X-03 had the distinction of being the first Alag design to be the subject of a published test report in the Western modelling media. Ron Warring’s test of the engine appeared in the January 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. The engine had of course been available in limited quantities in Britain for some time prior to the publication of that test. At the time in question, RipMax were still the distributors for the engine.

In contrast to the latter-day opinions expressed by a number of individuals with respect to these engines, Warring’s report was very favourable. He described the engine as being of “extremely neat appearance and clean design” as well as being “light for its size”. Neither of these comments are open to dispute – the engine certainly merits this description on the basis of its purely physical attributes. However, Warring also commented that it was “extremely well-made” with “excellent” starting and handling characteristics. This characterization runs very much counter to the experiences of a number of previous owners, although my own experiences both past and present bear it out completely.

In addition, Warring stated very clearly that his test results were obtained using the smaller-bored of the two optional venturis that were supplied with the engine when new. Again, there’s little doubt that he would have obtained substantially better figures if the larger-bored component had been used. My own flying example of the engine is fitted with a larger-bored venturi of my own manufacture, and it performs very well in the air with no sign of suction issues. There appears to be no argument in practical terms for the use of a smaller-bored venturi. Nevertheless, the published figures are quite comparable with those achieved by a number of contemporary plain bearing “sport” (as opposed to contest) diesels of similar displacement. Moreover, the engine’s relatively light weight for its displacement of only a little over 4 ounces gave it a quite competitive power-to-weight ratio. It was also unusually compact for its displacement, thus being readily usable to supply some real zip to models designed for 1.5 cc engines. Notwithstanding the negative views that some others conveyed during the initial preparation of this article, honesty compels me to record the fact that my own experiences with the X-03 fully bear out Warring’s assessment. Handling of the engine that I used in the 1960’s was first-class and power output quite adequate in practical terms. My present examples appear to be just as good in all respects.

A 2007 test of my well-used example of the X-03 (number 10133) in company with a 1955 Mk. I Taifun Tornado (to provide a bench-mark) yielded the following results:

Both engines were in original and unmodified condition but had been well freed-up through an appreciable amount of previous use. In addition, the tested example of the Alag had a significantly larger-bored venturi fitted than the one used in Warring’s test. Both of these factors would lead us to expect a considerably higher performance than that measured by Warring. And that’s exactly what we get! My notes confirm that both engines were very easy starters indeed, performing extremely consistently. The above figures were obtained following a complete warm-up – they are the “steady state” figures. As can be seen, the Alag was a match for the far more sophisticated Taifun up to around 13,000 RPM after which it fell behind, but only a little. However, in the context of its times there’s nothing at all wrong with these figures for a simple plain-bearing sports diesel of such light weight! The implied power output is considerably in excess of that achieved by Warring. The above figures suggest an output in the region of 0.290 BHP @ 12,600 RPM - same peaking speed as Warring, but a lot more torque. No doubt the combination of a larger venturi area plus a well freed-up piston fit had much to do with this. A more recent spot check of prop-RPM figures for my latter-day acquisition, Alag X-03 number 12354 yeilded almost identical figures. This conforms that the results of the 2007 test were by no means a flash in the pan! Fellow Alag owner Maris Dislers reports that his Alag X-03 number 493 is just as willing a performer - it apparently started on the second flick following a basic clean-up after 20 years sitting on a shelf! He reckons that one bad rap requires ten positive testimonials to counter it, and wishes to align himself with the present writer as number two on the positive side! Somi also joins with us in strongly contradicting the unfavourable reputation which the X-03 somehow acquired in certain parts of the world - he states that the engine is well-remembered and respected in Hungary as “a very popular and successful sport engine”. There’s no doubt at all that if they had all been like the examples that I have experienced, the one tried by Maris and the one tested by Warring, there would have been nothing at all about which to complain! But it appears that some weren’t ...........a number of reliable reports from knowledgeable sources (mainly from My earlier X-03 from many years ago got a lot of air time and was accordingly very well freed-up by the time that it left my hands. I don’t recall it as being particularly tight even when I first received it – in fact, it appeared to me at the time to be quite well fitted, although it’s true that it had been run a fair bit before I got it. Overall, I found little reason to complain about that engine’s performance in the context of the non-contest uses to which it was put. It seemed to perform in the air at a very similar level to my well-used old tuned AM 25. The above test results on my present flying example are entirely consistent with this recollection, and a recent air test using engine number 12354 re-confirmed that the Alag performs just as well in the air. Everyone who saw it in action was impressed! Further independent confirmation of the X-03's qualities is to be found in the fact that the engine was considered to be worthy of inclusion in the 2.5 cc comparative test conducted by Ron Moulton for publication in the 1958 “Aeromodeller Annual”. Although unable to equal the performance of its more sophisticated rivals in this comparison, the X-03 came in for praise from Moulton, who described it as "a neat export from Hungary" which would "satisfy anyone who wants an engine that will last a long while, stand up to abuse and crashes, yet offering excellent handling characteristics". A very valid summation in my book! The Alag X-04 and X-05

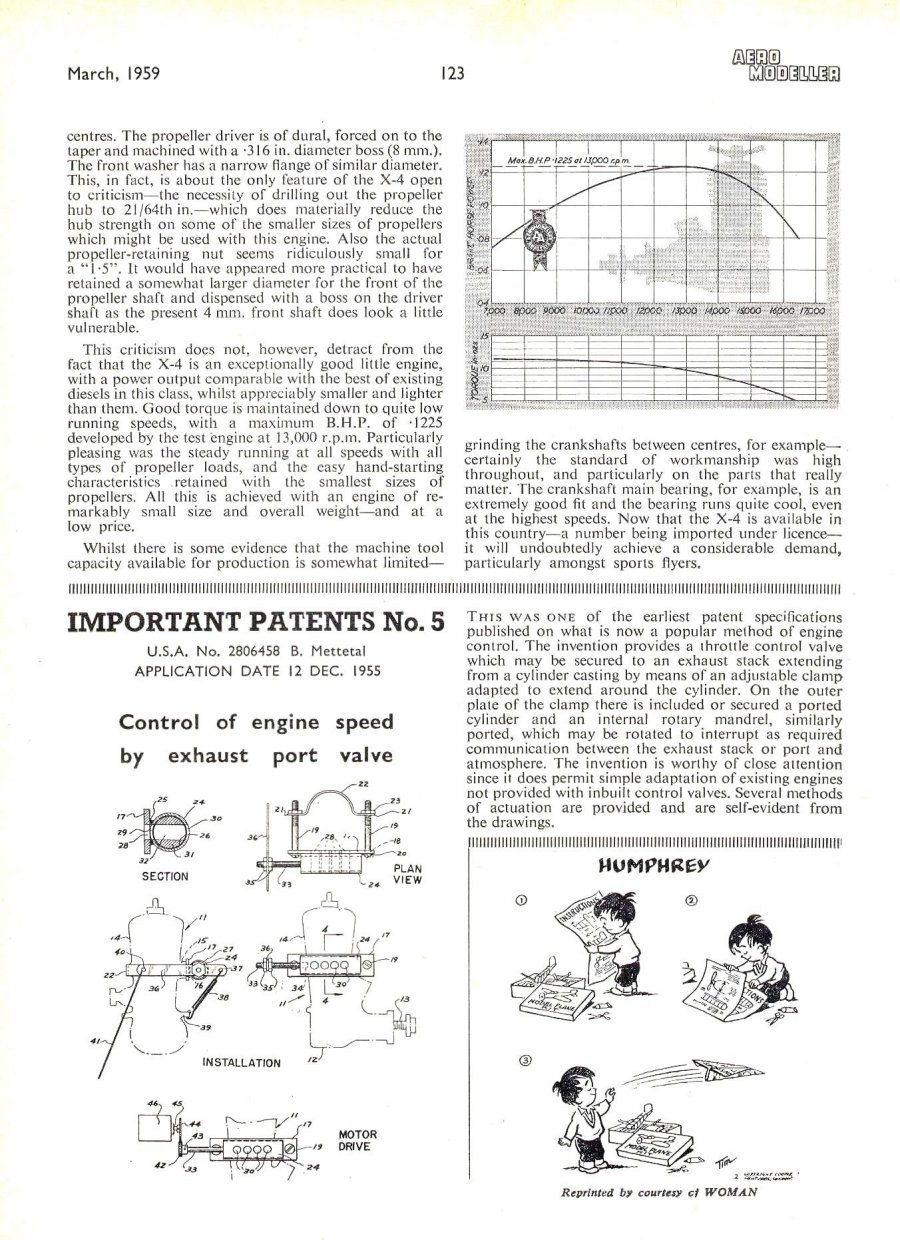

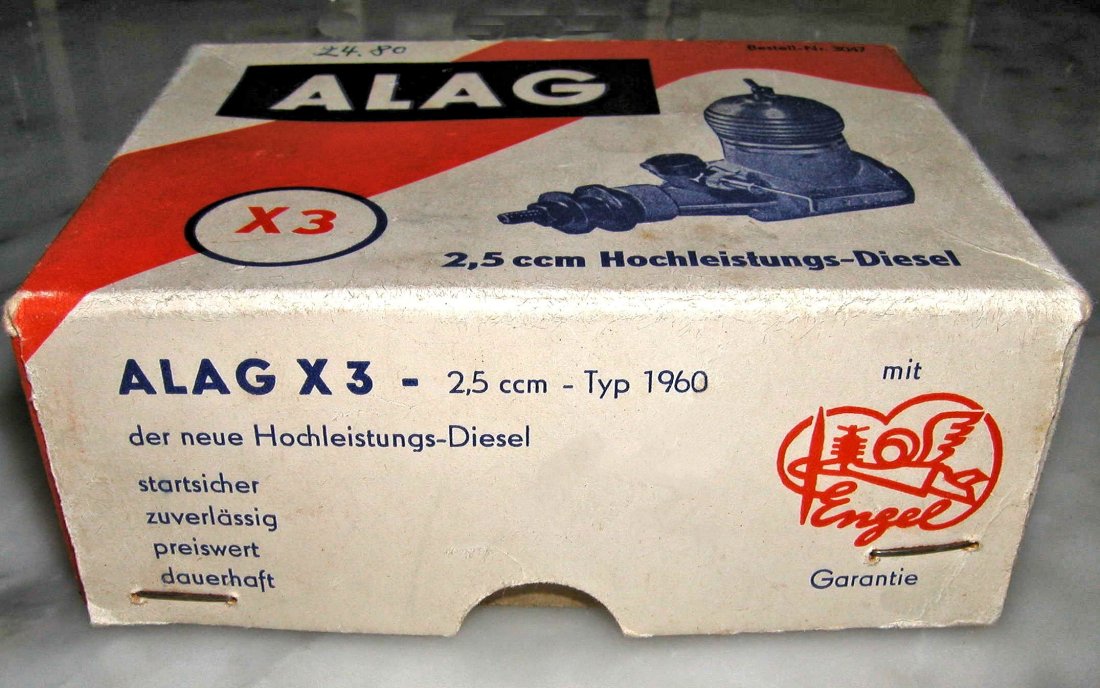

There was also a 1 cc version known as the Alag X-05, although this appears never to have hit the Western marketplace in significant numbers and is quite rare today outside Europe. The date of the introduction of the Alag X-05 is at present uncertain, but it appears to post-date the appearance of the X-04. For reasons which will doubtless remain forever obscure, the introduction of the smaller models to overseas markets lagged far behind that of the larger X-03. The X-04 was first announced in the Western media in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” feature in the January 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”, in which the engine was illustrated and briefly described. If Kalina is to be believed, this was some three years after the engine's original appearance in its native Hungary. By this time, the Alag X-03 had been available in Britain for the better part of two years and Relum Ltd. had taken over from RipMax as the Alag distributors in the UK (see below for details). Chinn mentioned in passing that Relum Ltd. were also importing the VT "Aquila Baby" 1.02 cc diesel mentioned earlier, confirming that this model remained in production concurrently with the Alag range.

By contrast, the 1.49 cc Alag X-04 did make it to the West in fairly substantial numbers. This engine was to all intents and purposes an exact scaled-down replica of the X-03 with its dimensions reduced in proportion to its smaller displacement. Like its larger relative, it was an extremely compact and lightweight engine for its displacement - the accompanying image of an X-04 with the smaller X-05 should make this clear. Bore and stroke respectively were 13 mm and 11.2 mm for a displacement of 1.49 cc. Weight was a commendably light 71 gm (2.5 ounces).

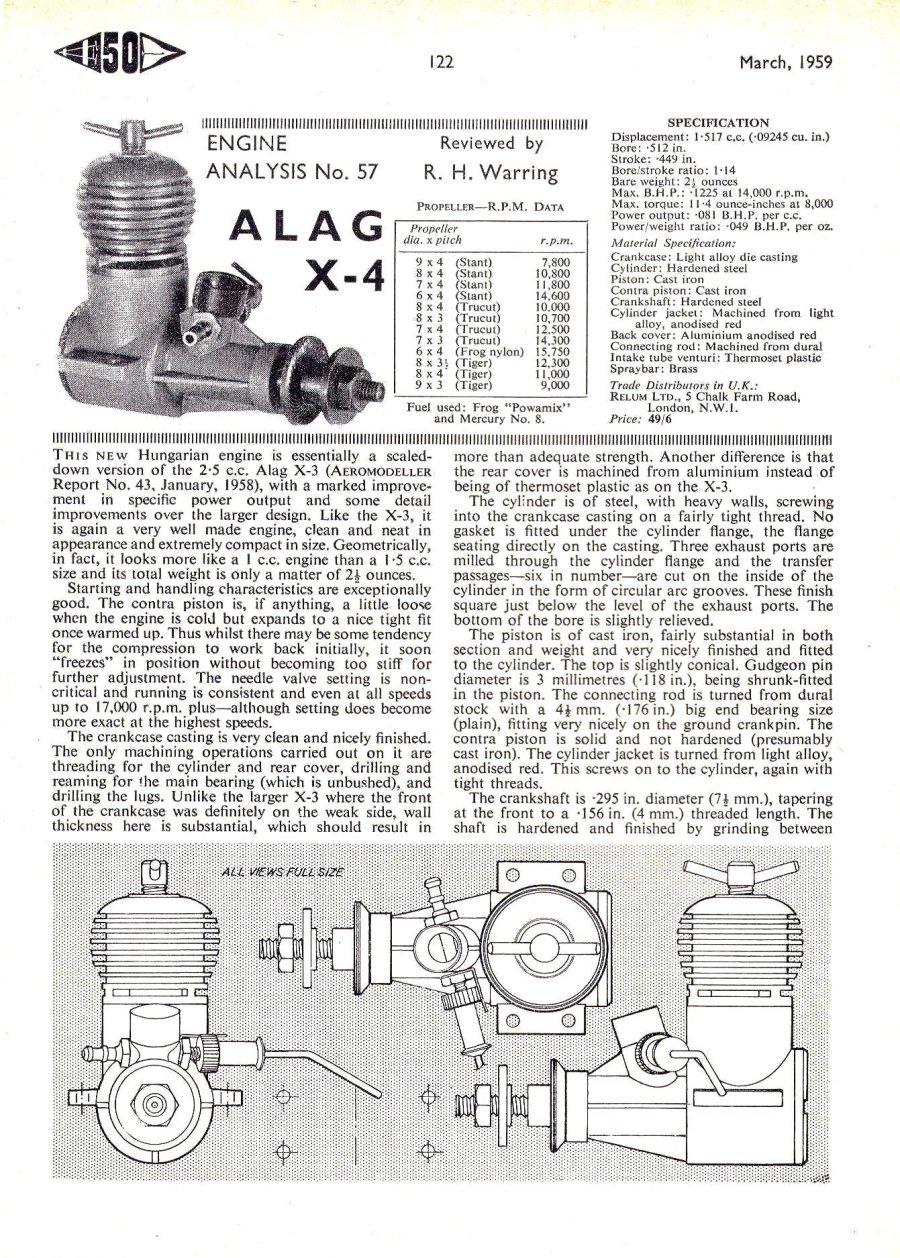

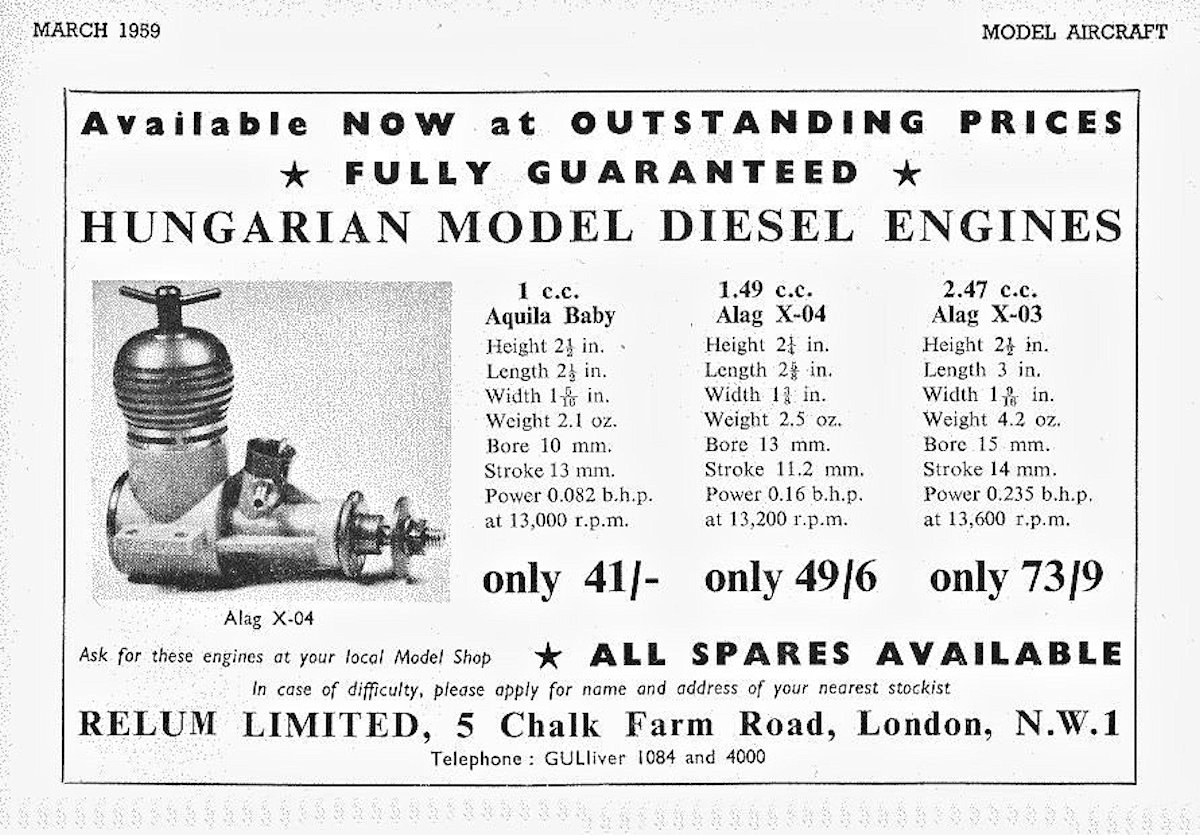

The Alag X-04 was subsequently featured as the subject of Ron Warring’s “Engine Analysis” published in the March 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. As in the earlier case of the Alag X-03, Warring’s test report on the X-04 was very favourable indeed, belying the legend regarding the basic un-serviceability of the Alag range. He described it as “a very well-made engine, clean and neat in appearance and extremely compact in size”.

Warring measured a quite lively performance (for the time) of 0.1225 BHP at 14,000 RPM, actually giving the X-04 a slightly higher specific reported power output than that of its larger companion. He characterized the starting and general handling characteristics of the X-04 as “exceptionally good” and noted that “the standard of workmanship was high throughout”. His overall conclusion was that the X-04 was “an exceptionally good little engine”. These comments strongly echoed those which Warring had previously made in connection with his review of the X-03.

As noted earlier, I had one of these engines myself at one time, and never had any cause to complain of its performance or quality. I used it for a few years in sport control-line service alongside my previous X-03 and then sold both engines on – this was in my pre-collector period! I have never had a subsequent opportunity to acquire a replacement, hence no longer owning an example of this motor. However, my own experience (and that of my two 1960’s acquaintances who also had them) certainly supports all of Warring’s conclusions set out in his test report. The validity of Warring’s test reports In light of the widespread subsequent condemnation of the two Alag models described above, it has been suggested to me that Ron Warring’s very positive published test reports may have been “coloured” by a reluctance to offend a major advertiser such as Ripmax. This may or may not be true, but I personally find the notion rather unconvincing - Warring undoubtedly did sometimes publish adverse test reports when he felt that this was warranted. However, it’s perhaps fair to say that the more openly adverse reports were generally confined to engines of overseas manufacture for which there were no British import plans – the MD-5 Kometa and the Rhythm 2.5 (both Russian products unavailable in Britain) come to mind. But even in cases where a British manufacturer or a major British importer were involved, the record shows that Warring did not shrink from recording any significant criticisms that he felt to be warranted. However, in such instances he appears to have stopped short of open condemnation, instead taking the approach of “damning with faint praise” combined with the presentation of excuses of one sort or another. His style in these cases was to focus on such positive features as he found while reporting on the negative qualities of the engine in question almost in passing, along with such excuses as he was able to conjure up. But that’s the point – he did report such failings! Among others, his tests on the E.D. Baby, the Elfin 249 BB, the JB Atom and the D-C Rapier come immediately to mind. This being the case, if Warring had actually found the Alags to be as bad as their subsequent reputation in certain quarters might suggest, it’s very hard for me to believe that he would have been as overtly and consistently complimentary about them. Based on his track record, I for one would have expected a review which was carefully crafted to focus on the engine’s good points while somewhat “apologetically” noting its flaws more or less in passing.

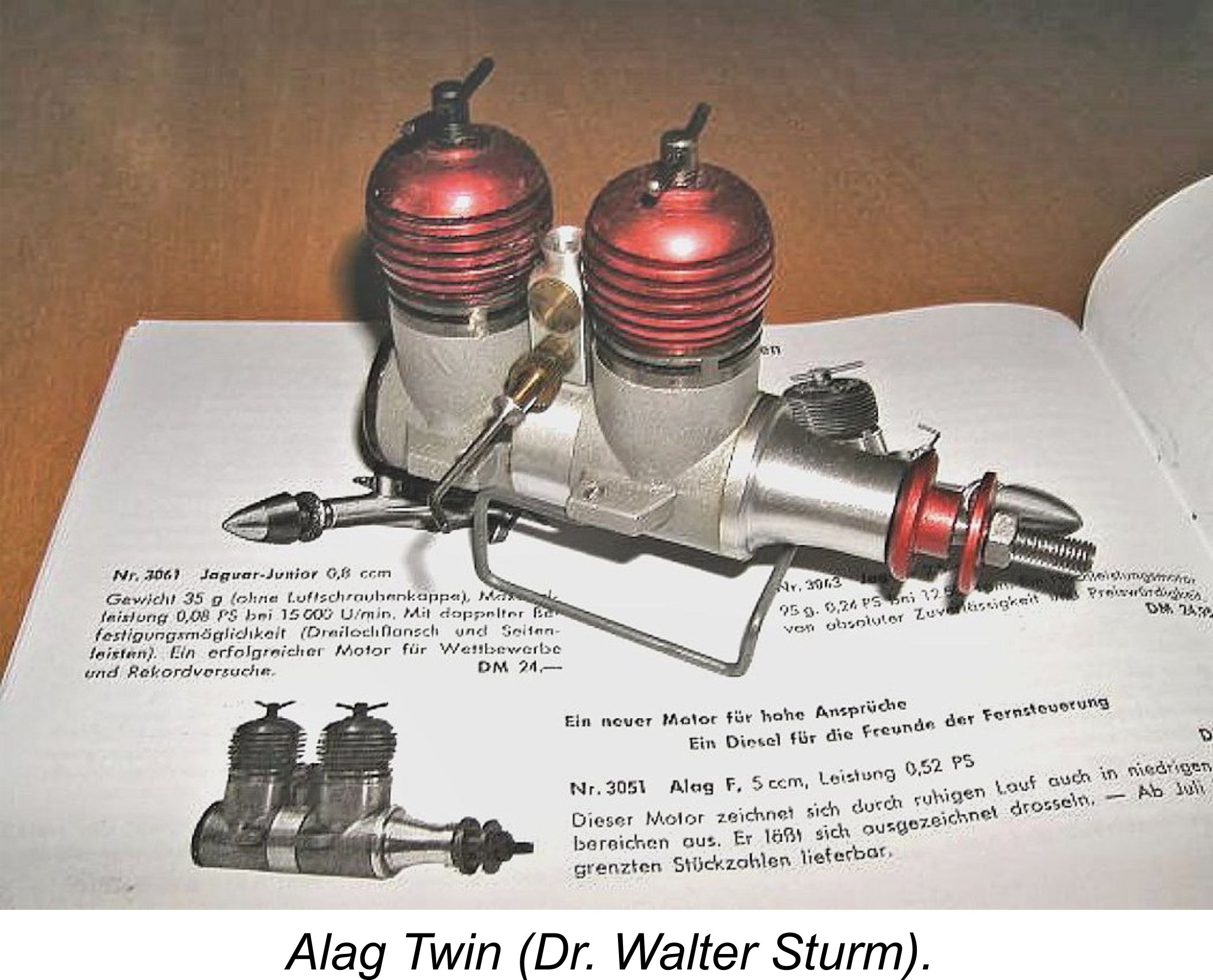

.........and I don't! It seems far more likely to me that the importers attempted to ensure by one means or another that the examples of the Alags which found their way into Warring’s hands for test were “good” examples of their type. From my own experiences as well as that of others, we know beyond doubt that many “good” examples did exist, notwithstanding the opinions of some others! Even if Warring’s practise was to buy his test motors over the counter, ways come to mind in which the distributor could have maximized the probability that he got a good ‘un! The other possibility is that the earlier engines were built to acceptable standards of quality but that quality control fell off its perch as time went by. What is unarguably clear is that the engines tested by Warring as well as those experienced by myself and my colleagues in South Yorkshire were (and still are) above average in terms of quality and performance in a sports context. The negative experiences reported by others, most notably in Australia, suggests that the quality of these engines was all over the shop – the best of them were actually very good indeed, while the worst of them wouldn’t so much as run! I guess my mates and I were just lucky ........... although I’m now fairly certain that the very bad batch of engines received by Bill Evans in Australia (see below) were the exceptions rather than the rule. A Change in Manufacturer Government support for the manufacture of the Alag X-series diesel engines continued until some point in 1957, at which time the resources of AKKÜ were diverted to other purposes. The more or less concurrent establishment of the MOKI Institute may well have had something to do with this, although this is of course mere speculation. Whatever the reason, the decision seems to have been taken that the Alag range was by then sufficiently well-established that it could stand on its own feet without direct government support. At this point in our story, it becomes necessary to correct another false impression which has been created in the past in the English-language modelling media and which was unfortunately reflected in the originally-published text of this article on MEN. The fact that the manufacture of the Alag engines by AKKÜ at Dunakeszi ceased at some point in 1957 seems clear enough. However, earlier commentators (including the normally-reliable Peter Chinn) have incorrectly credited the previously-mentioned Vella Brothers with taking over the manufacture of the Alag diesels at that point. Somi informs us that this was not in fact the case – to his certain first-hand knowledge, the Vella Brothers never at any time manufactured the Alag engines. The production of these engines by AKKÜ at Dunakeszi did indeed cease in 1957 when the facility was diverted to other activities, but production of the engines was then transferred to an entirely distinct entity called Preciziós KTSZ (Precision Co-operative) which had no connection whatsoever with the Vella brothers. This organization continued the production of the Alag X-series diesel models, also developing and manufacturing the 5 cc Alag Y-2 and 2.5 cc Alag Y-3 glow-plug engines, of which more below. ARTEX continued to promote the export of the engines produced by the new manufacturer. Since László Kun had defected to the West in 1957, his former assistant Gyula Krizsma stepped into the designer’s role for the two new Alag glow-plug models. Krizsma was a busy man at this time, since he was also closely involved with the production of the Krizsma Rekord K-8 and K-9 diesels at the Hungarian National Defence Association Accessory Supply Company (MHS Felszerelési és Ellátó Vállalat), continuing in this role until he moved over to MOKI in 1960, as related elsewhere. Let's look at the two Alag glow-plug models for which Krizsma was responsible. In doing so, we must remain mindlful of the fact that these were among the first glow-plug models designed by a man who not only designed the majority of the later MOKI racing engines but also collected a World Control Line Speed Championship along the way using a MOKI engine of his own design. As such, the Alag glow-plug models have a very special significance as far as I'm concerned. The Alag Y-02 and Y-03 Glow-plug Models

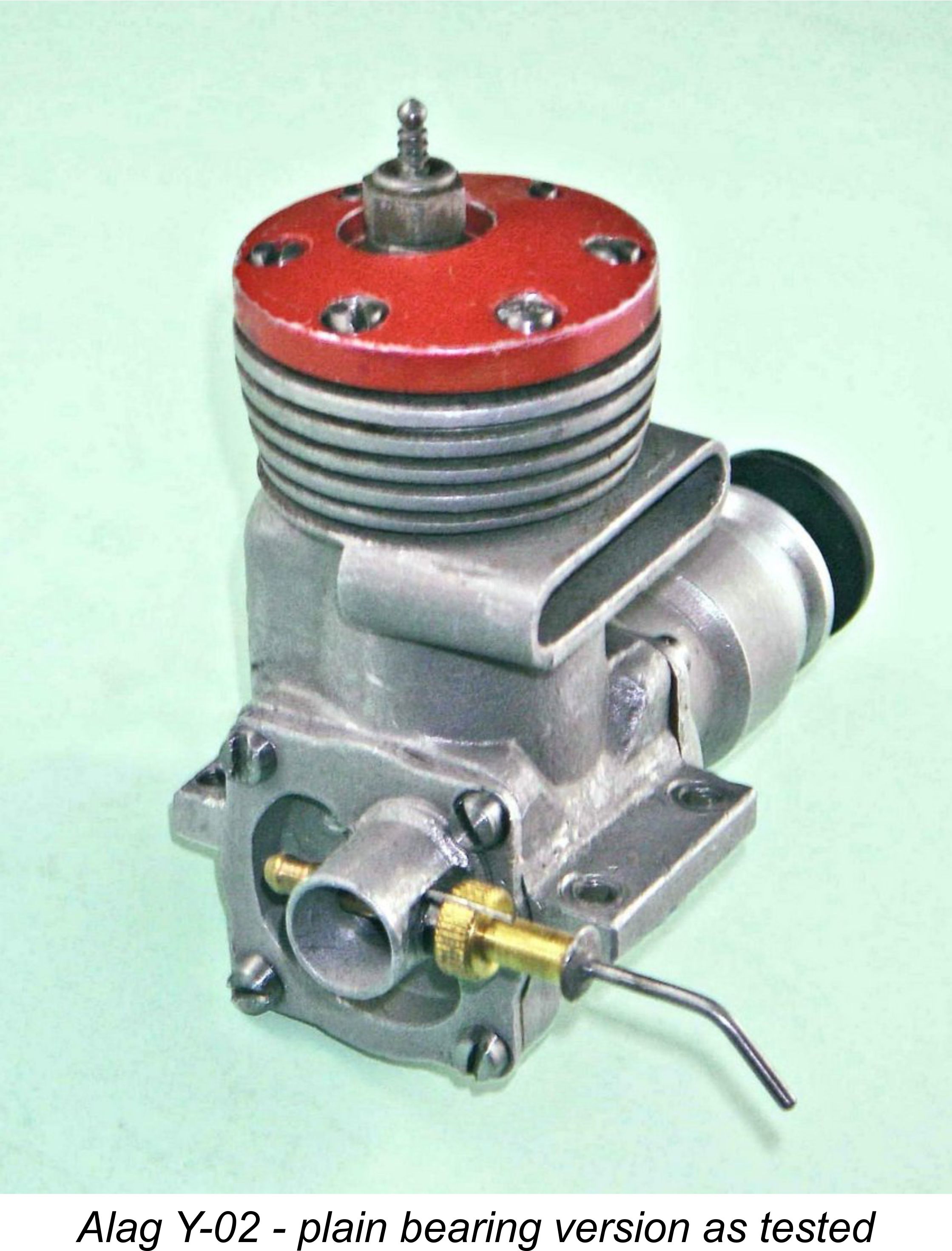

This may reflect the fact that until the early 1960’s the majority of British modellers remained committed to the use of diesels as opposed to glow-plug motors. Perhaps even more likely, they had a very competitive home-grown alternative in the shape of the very successful ETA 29 glow-plug model. Both 2.5 cc and 5 cc Alag Y-series glow-plug models were manufactured to a basically similar design. The sole model which appears to have come to the notice of the English-speaking modelling community was the Y-02 glow-plug engine of 5 cc displacement. This engine appeared in the “Motor Mart” feature published in the February 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. However, unlike the Alag diesel models, it appears never to have been imported into Britain. Accordingly, the above article may well represent the engine’s one appearance in the contemporary English-language modelling media. There were actually two versions of this engine – one with ball bearings and one without. The ball-race models appear to predominate - my own plain bearing example is the only one that I've ever encountered. My ball-race example bears the serial number 0154, while the plain bearing model is un-numbered. I have no way of knowing whether or not this was typical. I’m also unclear whether or not the plain-bearing and ball-bearing versions bore different designations as far as the manufacturer was concerned. Nor do I know whether or not the example examined by the “Aeromodeller” staff was a plain or ball bearing example – the article does not clarify this point.

The ball-bearing and plain bearing versions of the engine both used the same front housing. This housing was attached to the front of the crankcase with four screws in the conventional “classic racing engine” manner. The only difference was that the expansions in the casting for the two ball bearings were left un-machined in the case of the plain bearing version, and the steel shaft ran directly in the metal of the casting. The generous bearing length meant that the shaft remained very well supported. The one-piece steel shaft is counterbalanced to a modest degree. The standard of machining in both of my examples is high.

The piston skirt is quite short, resulting in the rather unusual feature (for this design layout at least) of a considerable period of sub-piston induction, some 45 degrees in total (22.5 degrees each side of top dead centre) being provided. The value of this feature in an engine of this layout appears questionable – at first sight, the sub-piston induction seems far more likely to draw spent exhaust gases into the crankcase than fresh air!! However, the same feature was successfully incorporated into the later versions of the ETA 29 as well as the Frog 349 diesel of similar porting arrangement. The original fit of the piston in the cylinder was stated in the “Aeromodeller” article to be quite tight, but the illustrated plain bearing example has been run quite extensively and is nicely freed-up. Compression seal is excellent, but there is very little friction when the engine is turned over with the plug removed. The un-finned red-painted cylinder head is only very minimally contoured to match the deflector on the piston crown – basically, it is flat with a shallow recess to provide clearance for the piston baffle. The plug is offset towards the transfer side.

That said, our friend Somi has once again set the record straight, at least as far as Hungary was concerned. It seems that ethanol was not used by Hungarian modellers, whatever the case may have been elsewhere. Hungarian model clubs were actually supplied with methanol free of charge by the Hungarian Association of Modellers. The real problem was nitromethane, which was both very expensive and extremely difficult to obtain. This in itself would have argued in favour of high compression ratios to deal with the straight fuel which had to be used for the most part. Regardless, my own testing of the plain bearing model (I've never run my as-new ball-race example) seems to suggest that the compression ratio was set rather higher than desirable even when running on methanol – even on low-nitro fuel and a relatively cold plug, the engine actually exhibited progressively-worsening symptoms of pre-ignition as it warmed up. For non-contest use, the engine would almost certainly benefit from a reduction in the compression ratio. As it is, a super-cold plug has to be used, and even then the pre-ignition problem persists to some degree. It seems possible that my example has had the compression ratio raised by a previous owner through a reduction in the shimming of the head. The rear induction tube is notably short, again displaying clear Dooling influence. The venturi on my ball-race example of the engine is considerably longer, implying perhaps that the component on my plain bearing model has been shortened by a previous owner. If so, it was done very neatly indeed ....... you can't tell from an examination. It may well be an original feature. The companion Y-03 was similarly equipped. Throat diameter is a relatively small 6.5 mm – almost down to typical 2.5 cc diesel size - and a conventional 3 mm diameter spraybar-type needle valve assembly is featured which further restricts the induction tube. This results in a throat area which appears totally inadequate for a high-performance 5 cc glow-plug engine, perhaps indicating that the plain bearing version of this engine was intended for applications such as control line stunt rather than any form of pure racing. The needle valve assembly actually appears to be identical to that used on the X-03 and X-04 diesels covered earlier in this discussion, and the venturi area provided is not that much bigger! Although a bit restrictive in terms of high-speed induction efficiency, the combination used certainly gives excellent suction for normal running purposes.

The 1959 “Aeromodeller” article stated on unspecified authority that the engine had a performance which was comparable with that of the earlier ETA and McCoy units which it closely resembled. The general specification of the engine would certainly suggest that this should be the case, apart from the rather restrictive induction set-up. When I tested my plain-bearing example some years ago now, I found that starting was extremely easy, but the running qualities were greatly impaired by the apparently excessive compression ratio and the consequent tendency towards pre-ignition when the mixture was leaned out.

Still, starting and running qualities were now extremely good, to the point that it’s rather hard to believe that the engine could have left the factory or successfully completed the running that it appears to have done using the ultra-high compression ratio with which it came into my hands. It seems that this example may have been the object of some misguided and rather heavy-handed “tuning” by a previous owner. It certainly appears to be far happier with the reduced compression ratio. However, even with the compression ratio sorted it’s clear that peak power of this example with its present restrictive carburettor set-up and seemingly-inefficient combustion chamber is well down on that of the Dooling, ETA and McCoy opposition. Even the addition of ball races would probably do little to bring this example of the Alag up to genuine “racing” performance. The opening-up of the intake would doubtless help a lot more, as would an improved combustion chamber design.

An interesting comment which appeared in the “Aeromodeller” article was the fact that their example of the Y-02 (and presumably others) arrived with its mounting holes un-drilled! The mounting lugs on both of my own illustrated examples were very neatly and accurately drilled as received, but I cannot say when or by whom this was done. The “Aeromodeller” article noted that there were no plans to import this model into Britain, and I myself cannot recall them ever being advertised commercially for sale. Nor was The companion 2.5 cc Y-03 model was basically nothing more than a scaled-down version of the larger Y-02. This being the case, the same general description applies to both models. Like its larger brother, this model too was available in both twin ball-race and plain bearing variants - I have one of each type, confirming this statement. The two external distinguishing features are that the plain bearing model is painted rather than anodized and the front bearing housing is not externally machined in the case of the plain bearing version. Watch for these points when considering the purchase of one of these units! My illustrated new and little-used ball-race example is a very neat and well-made unit indeed. It bears the serial number 1208. My equally pristine plain bearing example carries the serial number 0705. I would expect a useful if not necessarily world-beating performance from the ball-race unit, with considerable potential for further improvement through appropriate reworking. I plan to test these expectations in the future through the preparation of a detailed test report which will appear in due course on this website. In terms of this model's performance potential, it's only fair to point out that in the 1957 World Control Line Speed Championship which was reported in the October 1957 issues of both "Model Aircraft" and "Aeromodeller", Gyula Krizsma competed as a member of the Hungarian team using a modified Alag Y-03 prototype. Krizsma finished in fourth place at this event with a best speed of 205 km/hr (127.381 mph), a very impressive figure indeed. Even more impressively, Krizsma had previously set a 2.5 cc Hungarian national record using this same engine with a speed of 211 km/hr (131.11 mph), presiumably using thinner lines than those permitted in FAI competition. Clearly the Y-03 was an engine with plenty of potential by the standards of its era! However, it was soon to be supplanted as the leading Hungarian 2.5 cc speed engine by the MOKI S-1 unit which Krizsma was then just beginning to develop. Distribution of the Alag Range One of ARTEX's earliest export customers was RipMax Ltd. of Camden Town, London, England, who had become their British agents in 1956, featuring the Vella Brothers' VT-08 “Aquila Baby” 1 cc diesel. Since RipMax were naturally keen to increase the visibility of their new Hungarian model engine lines, one of their first promotional moves was to send samples to the most respected and widely-read model engine commentator in England at the time, Peter Chinn.

By May of 1957, RipMax had added the Alag range to their catalogue, which already included the VT-08. An advertisement of that month offered the X-03 at a price of £3 15s 0d (£3.75). However, a rather large fly soon appeared in the distribution ointment! Despite RipMax’s claim to being the “sole trade distributors”, as of November 1957 a certain L. E. Mayall of Builth Wells in South Wales had also somehow acquired a stock of engines and spares and was placing Alag ads in the classified advertisement section of “Model Aircraft” in competition with RipMax! Mayall was matching the advertised RipMax price and claimed to have full spares availability as well. It would appear from this that ARTEX had perhaps been a little less careful than they might have been in protecting the exclusive interests of their appointed UK agent. Although there’s no direct evidence for this, it seems not unlikely that this had something to do with RipMax dropping the Alag line in early 1958 - the final RipMax ad for the Alag engines that I can find appeared in the December 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”. There appears to have been something of a hiatus in the British distribution before the Alag range was taken up by a new distributor, Messrs. Relum Ltd. of Chalk Farm Road in London N.W. 1. By the latter part of 1958 both the Alag and VT-08 "Aquila Baby" engines were being advertised by the new distributor. The price of the 2.5 cc X-03 (incorrectly designated the X-5 in the ads) had dropped a little to £3 13s 9d (£3.69) and the 1 cc Aquila Baby was offered at a very competitive £2 1s 0d (£2.05). As of late 1958 the 1.5 cc Alag X-04 model had also been added to the range of products distributed by Relum Ltd. It seems likely that by this time the Alag engines had begun to acquire their somewhat unfair "grapevine" reputation for inconsistent quality, and it was probably this plus an innate mistrust of Iron Curtain products and their spare parts backup which resulted in the Alag X-series models eventually losing the struggle to make any real headway in the UK market despite the efforts of Relum Ltd. This failure notwithstanding, a number did find their way into the hands of British modellers (like myself) one way or another. If those that did so had all come up to the standard exhibited by my own examples and those tested by Ron Warring, they should certainly have provided very good service to any owner who persisted in using them. The fact that a number of them seemingly did not do so must reflect a far higher than usual degree of inconsistency in terms of quality control and may well explain their relatively early disappearance from the British market.

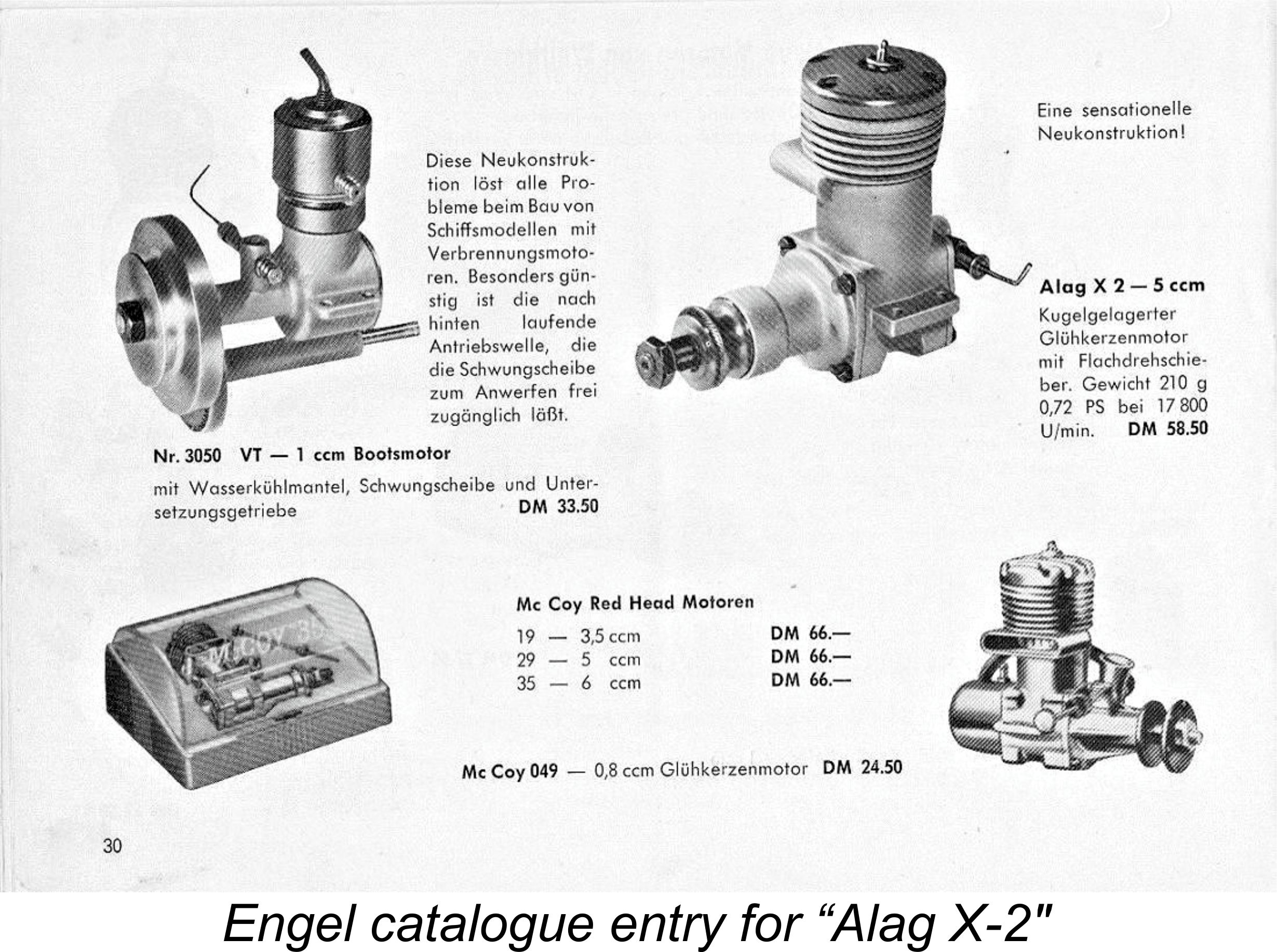

Walter has also confirmed that the ball-race version of the 5 cc Alag Y-02 glow-plug model was marketed in Germany by the Engel organization. However, for In Australia, the Alag distributor was Eden Distributors of Sydney. This company was run by Bill Evans, a well-known model flier of the time who may have imported them solely in an attempt to throw sand in the bearings of the domestic engine manufacturing activities of the late Gordon Burford, with whom he was at daggers drawn at the time. Evans had exclusively distributed Burford's Gee Bee range, but a dispute arose over ownership of the name, giving rise to Burf abandoning "Gee Bee" and adopting "Sabre" for his engine range (Burf did not have a good run on names as his use of Sabre also led to a dispute with another party, causing him to change to Taipan and Glo Chief for his engines). The story goes that Bill Evans showed Gordon a bag of Alag engines which were ".....going to put him out of business". Burf needn't have worried — Evans appears to have got a very bad batch, since few if any of the Alags imported to Australia by Evans were supplied in running condition, leading to their acquiring such a bad reputation Down-Under that it lasts to this day! As stated earlier, it seems that this batch was far from typical of the range as a whole, since examples used elsewhere gave excellent service (and still do in my case!). Finally, a limited number of examples of both the Y-02 and Y-03 glow-plug models appear to have been marketed in the Scandinavian countries. To this point, I have been unable to positively identify the distributor in those countries. However, it seems not unlikely that the engines were distributed by Bertil Beckman & Co. of Stockholm of Stockholm, who undoubtedly imported the VT engines for sale under their own BX brand-name. If any Swedish reader can clarify this point, please get in touch! The End of the Line ……or Perhaps Not! As of August 1962, when “American Modeller” magazine published their very interesting article entitled “Iron Curtain Engines – Da? Nyet?” (un-attributed, but almost certainly authored at some time well prior to that date by Peter Chinn), an incorrect statement was included to the effect that production of engines under the trade-names of Alag, Aquila and VT was then still continuing simultaneously at the Vella Brothers plant in Budapest. As we have seen, the Vella Brothers never had any involvement with the Alag range at any time. We also have authoritative evidence to the effect that Alag production actually ended in late 1959. Finally, we have incontrovertible evidence to confirm that all production by the Vella Brothers ended in mid 1961. In this regard, Chinn was clearly (and somewhat uncharacteristically) mis-informed. However, the story does not end at that point in time! One of the most fascinating aspects of researching model engine history is the recognition of connections and influences. It now appears that although production of the Alag diesels ended in their native Hungary in late 1959, this was by no means the end of the road for the basic design! In fact, it was merely the end of the beginning .............

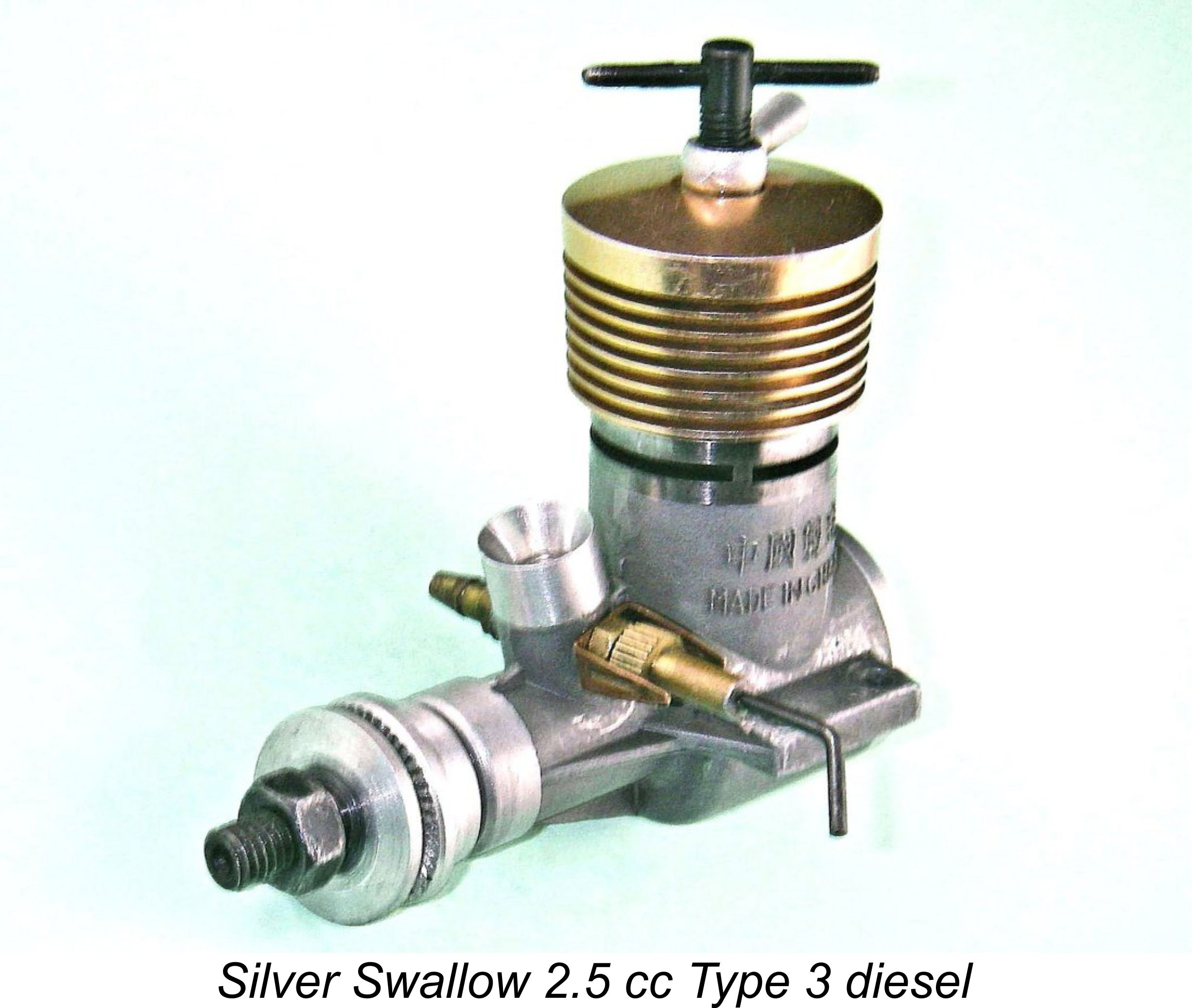

At the time, the engines were sold under the name “Yin Yan”, although this was later anglicized to “Silver Swallow”. The initial offering was a 2.47 cc model, with a 1.49 cc model appearing some time later. The standard of construction of the early products was unexpectedly high, and the engines ran well. It would appear that in entering the model engine market, the Chinese wished to begin from the basis of an established design given the fact that at the time in question they lacked experience in model engine design and manufacture. Since the production of the Alag engines in Hungary had ceased in late 1959, the Alag X-03 design was presumably available to the Hungarians’ Communist-bloc colleagues.

The Yin Yan cylinders are taller and the cooling jackets are shaped differently, but that’s mere window-dressing – the fact remains that the 2.5 cc Yin Yan engines are recognizably based on the Alag X-03 design, to the point that the resemblance appears to be too close to be entirely coincidental. The clincher appears to be the fact that the mounting holes on the 2.47 cc Yin Yan are identically spaced to those of the Alag X-03, making the engines directly interchangeable in the same model.

It thus appears that the Alag range soldiered on in slightly modified form and under a new name from a new manufacturing base in Communist China! It would be fascinating to know if the Chinese somehow got hold of the drawings, tooling and patterns from the defunct Alag production venture and used these as their starting point. It seems possible ...... both Hungary and China were in the Communist bloc at the time in question, and the timing’s right ........ But perhaps they It must be said that the early examples of the Yin Yan appear to have been rather better made than some examples of their Alag forebears! Later examples of the Chinese engines reverted to a rather more chequered level of quality control, but nonetheless carried on for decades in various forms. Examples remain plentiful today - indeed, the engine remained in intermittent production for much of the first decade of the 21st Century, albeit under a different name courtesy of the CS company of Shanghai, China. But how many people realise that in using one of these nice little engines they are actually participating in the continuance of the often-maligned Alag range?? A limited amount of information on the Silver Swallow engines may be found here on Ron Chernich's "Model Engine News" (MEN) web-site. However, Ron's article only tells a fraction of the full Yin Yan/Silver Swallow story. A full history of this interesting range appears elsewhere on this web site. Conclusion Well, there we have it!! On the above showing, I truly believe that the Alag engines were basically sound designs which had the potential to serve their owners well. In my view, the widespread condemnation of the Alag models which I encountered during the preparation of this article needs to be qualified. They were not bad designs by any means – rather, they were sound if generally rather uninspiring designs of which a certain number appear to have been poorly executed. The batch imported to Australia by Bill Evans seems to have been particularly bad, as a result of which much of the condemnation of the Alag engines has originated from that country. Users elsewhere appear for the most part to have found the engines to be perfectly satisfactory. I know I have!

However, the final word must surely relate to the Hungarian model engine manufacturing industry as a whole. We hope that we’ve demonstrated that if Hungary had produced no more than the engines mentioned in this article and in the companion MOKI article, the country would still deserve an honoured place in the history of commercial model engine design and production. ___________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada First published May 2015 Updated September 2018

|

||

| |

During my long-ago teenage years (more years ago in fact than anyone who still “plays with toy airplanes” should be prepared to admit!), I was forced to support my aeromodelling addiction on a somewhat less-than-optimal budget. My sources of disposable income at that time were limited to a few bob a week pocket money from my parents plus the odd bit of extra cash earned now and then by playing music in a local pop group and doing the “bob-a-job” routine for a few of the better-heeled or perhaps more sympathetic neighbours.

During my long-ago teenage years (more years ago in fact than anyone who still “plays with toy airplanes” should be prepared to admit!), I was forced to support my aeromodelling addiction on a somewhat less-than-optimal budget. My sources of disposable income at that time were limited to a few bob a week pocket money from my parents plus the odd bit of extra cash earned now and then by playing music in a local pop group and doing the “bob-a-job” routine for a few of the better-heeled or perhaps more sympathetic neighbours. Accordingly, when I had separate chances in quick succession to pick up a couple of used engines of Hungarian origin in pretty good condition at very reasonable prices, I seized the opportunities gratefully. These were a 2.5 cc Alag X-03 diesel and an example of its smaller relative, the Alag X-04 of 1.5 cc displacement. The fact that the engines originated from behind the then-mysterious and forbidding Iron Curtain added a certain allure to their acquisition - I've always enjoyed flying something “different”!

Accordingly, when I had separate chances in quick succession to pick up a couple of used engines of Hungarian origin in pretty good condition at very reasonable prices, I seized the opportunities gratefully. These were a 2.5 cc Alag X-03 diesel and an example of its smaller relative, the Alag X-04 of 1.5 cc displacement. The fact that the engines originated from behind the then-mysterious and forbidding Iron Curtain added a certain allure to their acquisition - I've always enjoyed flying something “different”! But none of our very small and somewhat isolated group of South Yorkshire-area Alag owners knew any of this – certainly, we were not aware that these engines were un-useable! Consequently, we just went ahead and used them, with completely satisfactory results. I’m sure that if we’d realised how bad they really were, we’d have followed the lead of modellers elsewhere and thrown them into the rubbish bin! But we didn’t – instead, we just enjoyed flying them in blissful ignorance of their many flaws!

But none of our very small and somewhat isolated group of South Yorkshire-area Alag owners knew any of this – certainly, we were not aware that these engines were un-useable! Consequently, we just went ahead and used them, with completely satisfactory results. I’m sure that if we’d realised how bad they really were, we’d have followed the lead of modellers elsewhere and thrown them into the rubbish bin! But we didn’t – instead, we just enjoyed flying them in blissful ignorance of their many flaws!  Many years later, when I was settled in Canada and had entered my “collector” period, I successively encountered a number of engines from the same manufacturing source, including several more examples of the X-03. Both of the latter models appear to be just as serviceable as my original example had been, and I test-ran and flew the more “experienced” of the two for old time’s sake while preserving the other in seemingly un-run “as new” condition. Mounted in a "Dominator" or similar combat model, the Alag's very light weight and (dare I say it?) very sprightly performance resulted in a fine-performing model which could out-turn almost anything!

Many years later, when I was settled in Canada and had entered my “collector” period, I successively encountered a number of engines from the same manufacturing source, including several more examples of the X-03. Both of the latter models appear to be just as serviceable as my original example had been, and I test-ran and flew the more “experienced” of the two for old time’s sake while preserving the other in seemingly un-run “as new” condition. Mounted in a "Dominator" or similar combat model, the Alag's very light weight and (dare I say it?) very sprightly performance resulted in a fine-performing model which could out-turn almost anything!  One of the documents supplied by Maris Dislers was a guarantee card from his NIB 1957 Alag X-03 (of which much more below). This card clearly gave the name of the group responsible for the Alag engines (in Hungarian, naturally) as the Alag Central Experimental Plant (Alagi Központi Kisérleti Üzem - AKKÜ).

One of the documents supplied by Maris Dislers was a guarantee card from his NIB 1957 Alag X-03 (of which much more below). This card clearly gave the name of the group responsible for the Alag engines (in Hungarian, naturally) as the Alag Central Experimental Plant (Alagi Központi Kisérleti Üzem - AKKÜ). Britain and the USA. The German discovery of these initiatives led to the country being occupied by the Nazis in March 1944. This occupation lasted until April of 1945, after which further negotiations between the Allied powers led to the February 1st, 1946 supplanting of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Second Republic of Hungary (Magyar Köztársaság) which was governed by the Hungarian Communist Party under close Russian supervision.

Britain and the USA. The German discovery of these initiatives led to the country being occupied by the Nazis in March 1944. This occupation lasted until April of 1945, after which further negotiations between the Allied powers led to the February 1st, 1946 supplanting of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Second Republic of Hungary (Magyar Köztársaság) which was governed by the Hungarian Communist Party under close Russian supervision. constructed aircraft were awaiting completion. On top of this, new aircraft were urgently required to meet the growing needs of the revitalized movement.

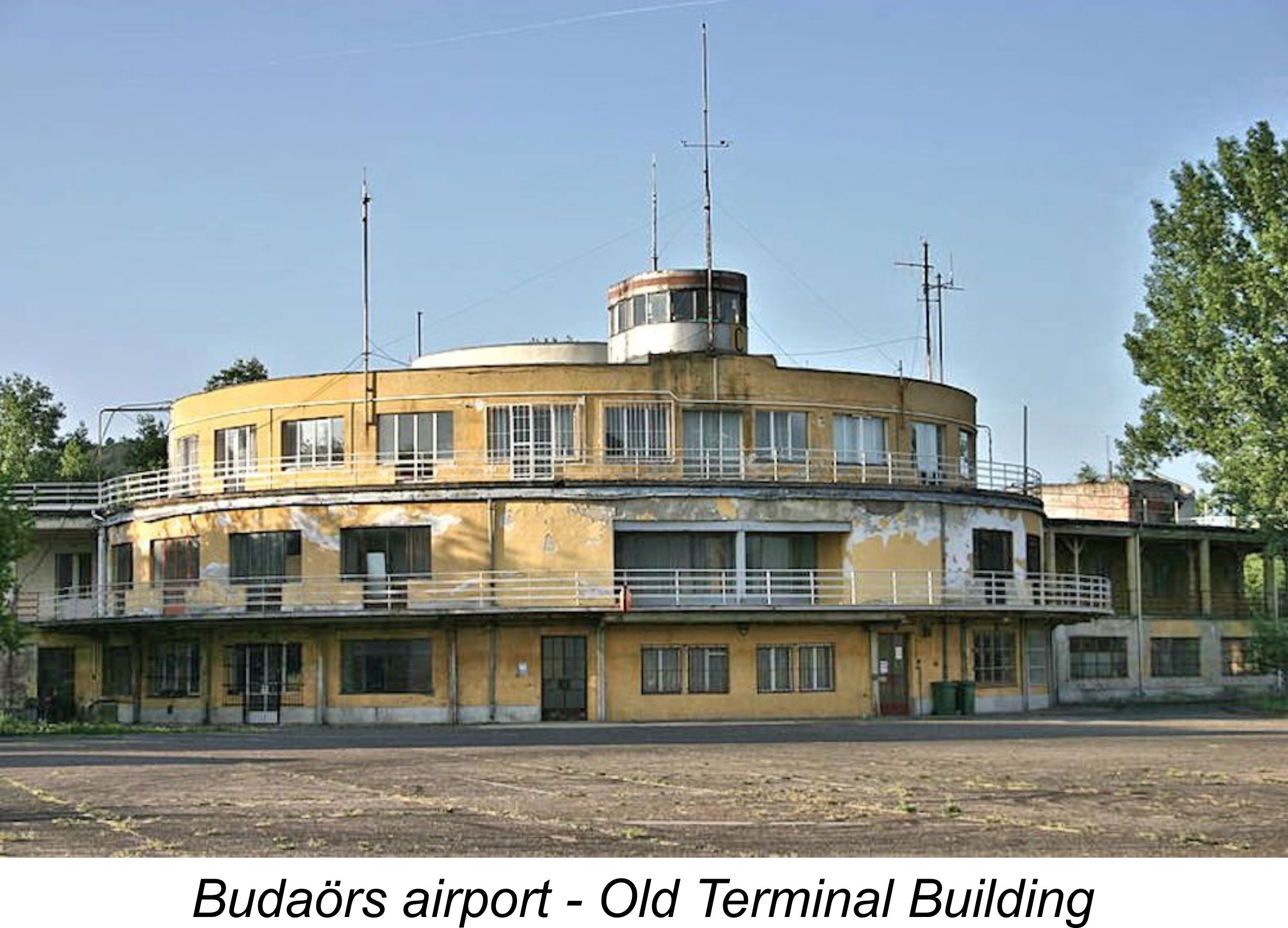

constructed aircraft were awaiting completion. On top of this, new aircraft were urgently required to meet the growing needs of the revitalized movement. The old terminal building at Budaörs appears in the background of many photographs taken at those meetings. It's rather sad to see its somewhat diminished and neglected state today. Many a World Title was won on the flat area in front of the building in the photograph at left. This photograph more or less provides a competitor's-eye-view of the building. A bit of nostalgia for you ...............

The old terminal building at Budaörs appears in the background of many photographs taken at those meetings. It's rather sad to see its somewhat diminished and neglected state today. Many a World Title was won on the flat area in front of the building in the photograph at left. This photograph more or less provides a competitor's-eye-view of the building. A bit of nostalgia for you ............... The remaining MRSz plant at Budaörs was relocated in 1952 to a newly-constructed sport-flying airfield at Dunakeszi, a town lying just to the north of Budapest but still within the Budapest metropolitan area. It is here that the Alag model engine story really had its beginnings.

The remaining MRSz plant at Budaörs was relocated in 1952 to a newly-constructed sport-flying airfield at Dunakeszi, a town lying just to the north of Budapest but still within the Budapest metropolitan area. It is here that the Alag model engine story really had its beginnings. established firm control of the country in 1949. His expert leadership was replaced by uninformed Communist political appointees, a move which did nothing to help the Hungarian modelling movement to improve its standards.

established firm control of the country in 1949. His expert leadership was replaced by uninformed Communist political appointees, a move which did nothing to help the Hungarian modelling movement to improve its standards.  circulation, but both the quality and performance of these engines were generally sub-standard at this time. It was consequently inevitable that efforts would be made to initiate the domestic development and manufacture of such engines.

circulation, but both the quality and performance of these engines were generally sub-standard at this time. It was consequently inevitable that efforts would be made to initiate the domestic development and manufacture of such engines. individual whose name is now lost, working in a tiny workshop with minimal machine tooling. Revised models soon followed in the shape of the GyM-2 and GyM-3 variants. The inclusion of a three-view drawing of the GyM-3 which appeared in the 1951 edition of “Aeromodeller Annual” and is reproduced at the left proves that these three models were all in existence by the latter part of 1951.

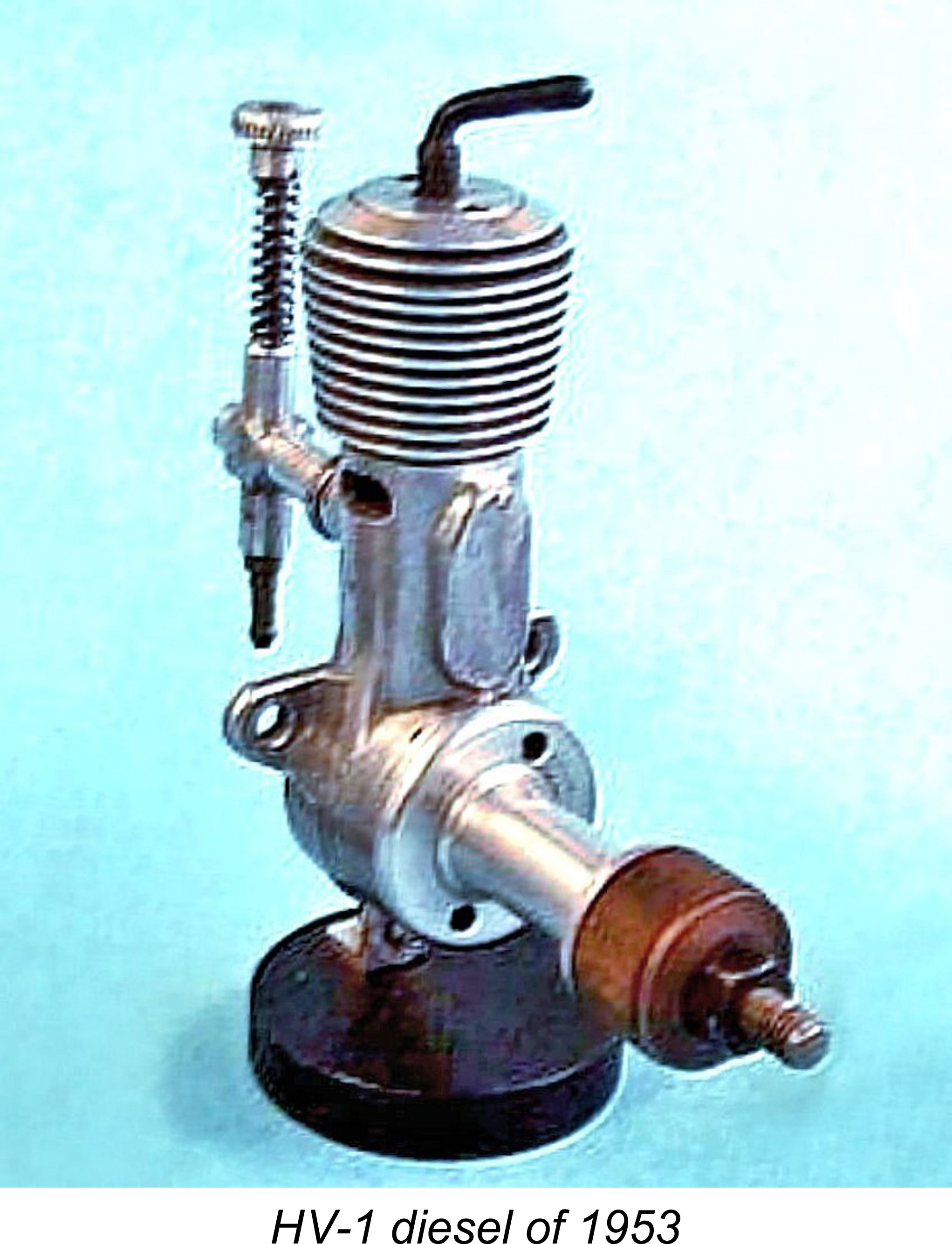

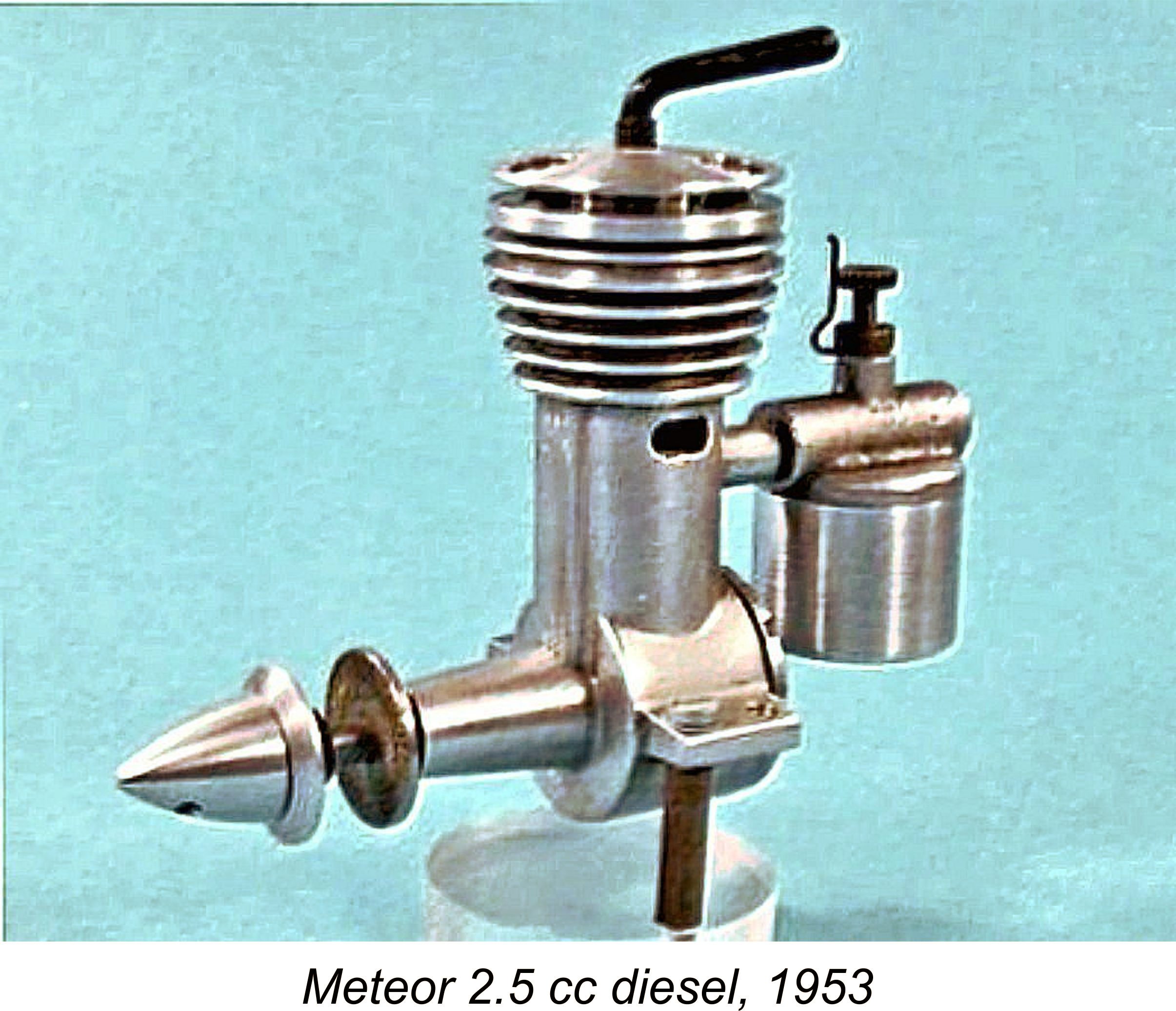

individual whose name is now lost, working in a tiny workshop with minimal machine tooling. Revised models soon followed in the shape of the GyM-2 and GyM-3 variants. The inclusion of a three-view drawing of the GyM-3 which appeared in the 1951 edition of “Aeromodeller Annual” and is reproduced at the left proves that these three models were all in existence by the latter part of 1951.  under the direction of the well-known Hungarian free-flight modeller László Hódi. Early products included the 2.3 cc HV-1 sideport diesel and the Meteor 2.5 cc sideport diesel. In 1954, the co-operative initiated production of the Darú 2.3 cc sideport diesel (a development of the HV-1) and the Proton series of rotary valve models. The designer of the Proton engines was none other than our esteemed Hungarian informant, Ferenc “Somi” Somogyi! This manufacturing venture was located in Szeged, a town situated in southern Hungary. The

under the direction of the well-known Hungarian free-flight modeller László Hódi. Early products included the 2.3 cc HV-1 sideport diesel and the Meteor 2.5 cc sideport diesel. In 1954, the co-operative initiated production of the Darú 2.3 cc sideport diesel (a development of the HV-1) and the Proton series of rotary valve models. The designer of the Proton engines was none other than our esteemed Hungarian informant, Ferenc “Somi” Somogyi! This manufacturing venture was located in Szeged, a town situated in southern Hungary. The  At around the same time, the Budapest-based Vella brothers András and Géza were also embarking upon the manufacture of engines under their own initials of VT (standing for Vella Testverek, or Vella Brothers), later adding both the Engel Rebell and the now-obscure BX lines to their list of products. A separate article on the history of the

At around the same time, the Budapest-based Vella brothers András and Géza were also embarking upon the manufacture of engines under their own initials of VT (standing for Vella Testverek, or Vella Brothers), later adding both the Engel Rebell and the now-obscure BX lines to their list of products. A separate article on the history of the  By 1955 the brothers were producing the 1 cc Aquila Baby diesel, which was somewhat confusingly identified on the case as the VT 8. This was the first Vella Brothers product, and indeed the first commercially-produced Hungarian model engine, to be brought to the attention of modellers outside the Iron Curtain.

By 1955 the brothers were producing the 1 cc Aquila Baby diesel, which was somewhat confusingly identified on the case as the VT 8. This was the first Vella Brothers product, and indeed the first commercially-produced Hungarian model engine, to be brought to the attention of modellers outside the Iron Curtain.  Although the Alag and VT engines were initially sold mainly on the domestic Hungarian market, ARTEX’s success in reaching export agreements soon grew to the extent that much of their production eventually ended up on the export market. We will look at ARTEX's distribution arrangements in a later section of this article.

Although the Alag and VT engines were initially sold mainly on the domestic Hungarian market, ARTEX’s success in reaching export agreements soon grew to the extent that much of their production eventually ended up on the export market. We will look at ARTEX's distribution arrangements in a later section of this article.  We saw ealier that the AKKÜ operation at Dunakeszi became involved with model engine production in the first half of 1955, very soon after its initial establishment. The head of AKKÜ’s model engine section was László Kun, who was the chief designer of all the Alag X-series diesel engines. His assistant and subsequent replacement was Gyula Krizsma, later the chief of the

We saw ealier that the AKKÜ operation at Dunakeszi became involved with model engine production in the first half of 1955, very soon after its initial establishment. The head of AKKÜ’s model engine section was László Kun, who was the chief designer of all the Alag X-series diesel engines. His assistant and subsequent replacement was Gyula Krizsma, later the chief of the  be made to increase the scale of domestic model engine production both to cater to the needs of Hungarian modellers and to allow for an increase in the scale of exports to the West to gain much-needed hard currency. The Alag engines represented just such an initiative on the part of the government of the day.

be made to increase the scale of domestic model engine production both to cater to the needs of Hungarian modellers and to allow for an increase in the scale of exports to the West to gain much-needed hard currency. The Alag engines represented just such an initiative on the part of the government of the day. Somi tells us that the first example of the initial Alag offering, the 2.5 cc Alag X-03 diesel, came off the production line in May 1955, only some two months after the establishment of the AKKÜ facility at Dunakeszi. It is an undeniable fact that the manufacture of model engines was an activity which was very far removed from the design and manufacture of gliders which had previously been the Dunakeszi facility’s main function. Model engine manufacture required completely different tooling as well as different employee skills. This being the case, it's greatly to the credit of those responsible that they were able to get the X-03 into production so soon after the formal establishment of AKKÜ. It actually seems highly likely that the design of the engine had been initiated prior to the March 1955 official opening of the AKKÜ facility.