|

|

Diamond from Down Under – the Owen T2.5 Diesel Here we examine a recent model engine production from the workshop of a master craftsman from Australia. We’ll be evaluating the Owen T2.5 diesel, a modern product with a classic pedigree if ever there was one!

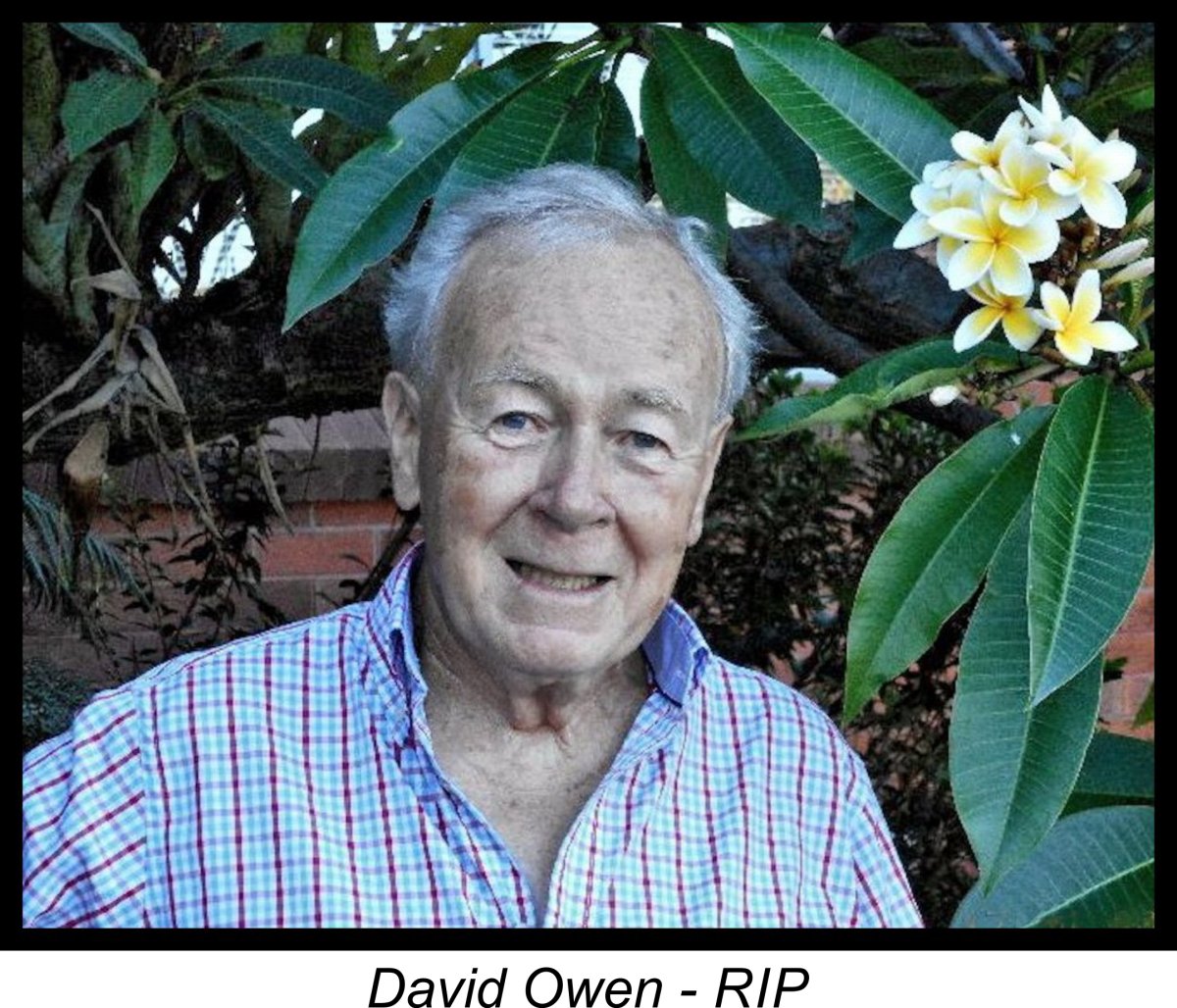

I never met David in the flesh (my loss), but I was in constant touch with him over the years. I always found him to be a friendly and ever-forthcoming colleague in the research which always precedes these historical articles of mine. The images, serial numbers and insights which he so willingly provided did much to add credibility to my scribblings, while his constant encouragement was a great source of inspiration to keep me going. I will miss him immensely. Although it feels very strange to be presenting this article only a few weeks after David's demise, a few days' reflection convinced me that David himself would have seen it as entirely appropriate. He would have wanted us to remember him for his achievements rather than indulge in unrequitable regrets at his departure. He himself remained positive right to the end, encouraging me every step of the way during the writing of this report and responding to my many questions until only two weeks or so prior to his death (of which in his characteristic unassuming way he gave me absolutely no warning). He was greatly looking forward to reading the finished article. I will always regret having failed to publish it in time for him to do so. However, I was able to keep him abreast of my very positive findings, which pleased him greatly.

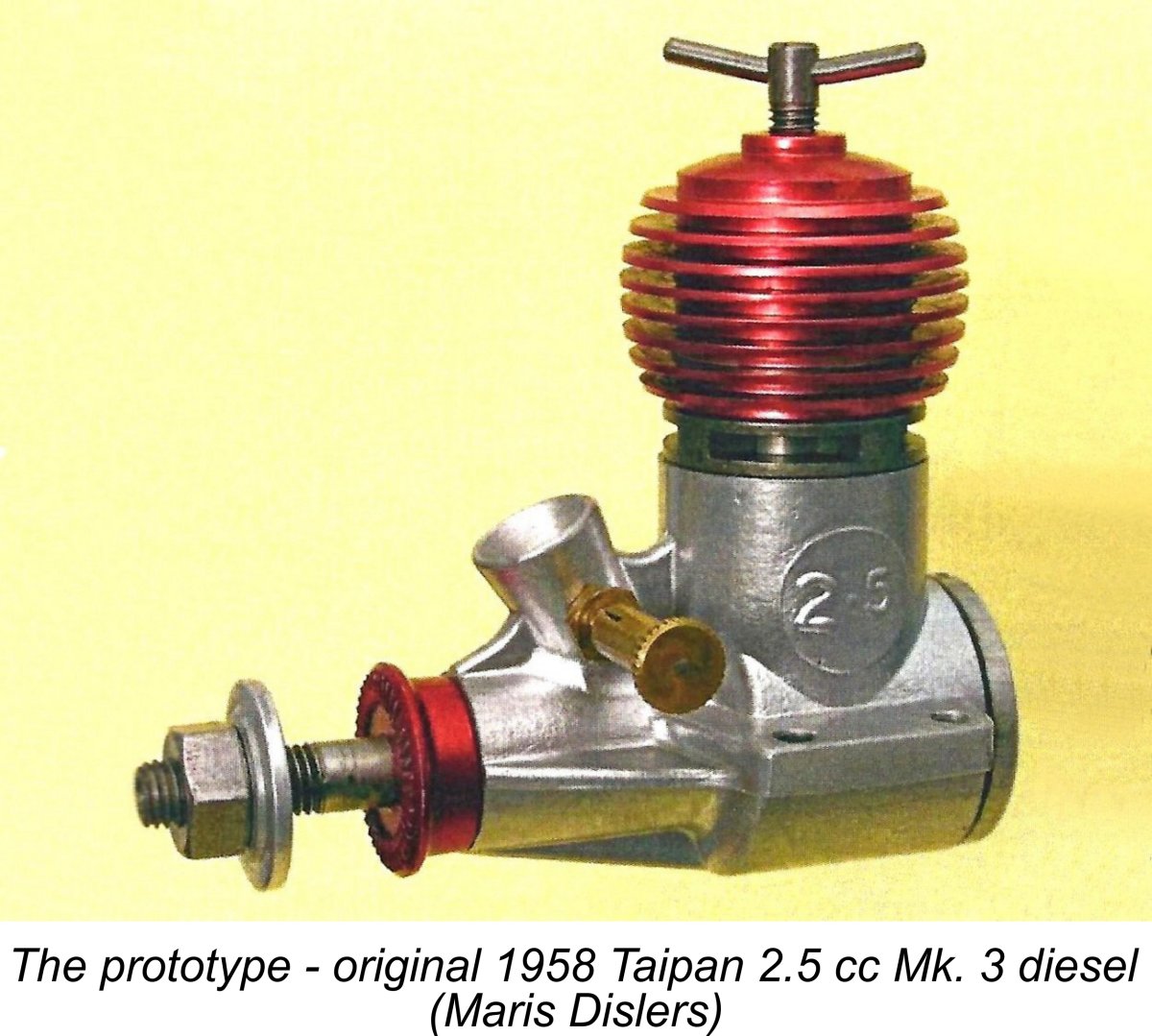

The Owen T2.5 is based very closely on the 1958 version of the Mk. 3 Taipan 2.5 cc plain-bearing diesel which was manufactured in Australia by the legendary Gordon Burford between 1957 and 1959 with a few variations. The Mk. 3 was Gordon’s personal favourite plain-bearing diesel and arguably the most powerful such model that he produced between 1957 and 1967. The engine is very fondly remembered by all its past users. One’s first question might be why David went to all the trouble of re-creating (and improving) a model engine design from 1957! The answer is that there is an event in Australia called GB R/C Assist Old Timer which requires (among other things) the use of a diesel engine of between 1 cc and 2.5 cc displacement which was manufactured or at least designed by Australia's premier model engine producer Gordon Burford. The relatively low production figures achieved by Gordon have combined with the disappearance of many Taipan engines into collections to create a present-day shortage of engines which remain available for use in these events. The T2.5 represents David’s attempt to create an updated powerplant for the use of present-day competitors.

This particular engine spent quite a few years in the development stage, going back to 2008. In that year, noting the growing shortage of engines suitable for the GB R/C Assist event in Australia and worried that support for the event might dwindle in consequence, Gordon suggested to David that he contemplate doing a reproduction of the Taipan Mk. 3 diesel specifically for that event. Liking the idea, David immediately began considering the form that such a reproduction might take. Thankfully, he was able to finalize the new model's main design features (which included a few changes from the original) in time for Gordon to approve them prior to his untimely death in 2010. Hence this model may legitimately be viewed as the final design to which Gordon attached his seal of approval. Indeed, for the most part it remains a Gordon Burford design with just a few approved modifications. David subsequently built three prototypes featuring the agreed changes. Following testing by my good mate Maris Dislers, these units had been in service for over three years as of my original time of writing (2016), thus proving the basic durability of the design. One of the most critical objectives of the T2.5 project was realised in 2013, when the engine was officially homologated by the Model Aeronautical Association of Australia (MAAA) as being eligible for use in their GB R/C Assist event described above. David subsequently completed the main production run of almost 200 examples, all of which were quickly spoken for (including my own example!). Many of these engines will doubtless end up being used in their intended Australian event, where they will certainly do very well indeed! It's obvious that there will be no more, but David had no intention of making any further batches in any case. Now, having established the background to this fine model diesel, let’s have a closer look at it! Description

David Owen’s latter-day realization of this fine model engine is visually extremely faithful to the original. It does however incorporate a few detail changes, all of which were approved by Gordon Burford himself prior to his death in 2010. Several of the most important changes were directed towards reducing the engine’s level of operating vibration, which was the main criticism which could legitimately be directed at the original 1957 design. The Owen T2.5 features a crankshaft having an improved balance factor, together with a lighter piston. The con-rod and gudgeon pin were also re-designed to improve strength and durability. The performance aspects of the original design also came in for some attention. The T2.5’s porting is slightly modified from that of the original Taipan Mk. 3 to optimize both timing and breathing. The four exhaust ports are a compromise 2.7 mm deep, while the four externally-formed transfer flutes are of rectangular cross-section instead of being round. This of course gives them slightly greater cross-sectional area. As in the originals, they feed drilled upwardly-angled transfer ports which overlap the exhaust to a considerable degree.

The instruction leaflet supplied with the T2.5 notes that each engine has been hand-started and test-run for approximately ten minutes prior to packing and despatch. This will have initiated the running-in process, but David recommended that at least a further 30 minutes be added to this total prior to putting the engine into normal service. David stated that the engine should deliver its best performance in the 11,000 to 14,000 rpm speed range. Recommended airscrews range from 7x6 through to 10x3.5, depending upon the intended purpose. A particular point was made of the need to carefully balance all props prior to use, and this very wise advice should be followed. The use of straight synthetic lubricant is strongly discouraged, the only recommended oil other than pure castor oil being Klotz Benol blended castor lubricant – my own personal favourite.

The other issue that became apparent in a few cases was a loose backplate. David said that he had recently changed to a new (and untried) 0.4 mm gasket material which appeared to compress after it sucked up a little fuel. Hence it should be re-tightened after a few runs. This should hopefully cure the problem. But please use the correct tool for tightening this component – we need to conserve these engines to the extent possible. David’s overall comment was that these issues demonstrated the need to test every little detail to exhaustion. Having had three test engines out in the field for over three years, David thought he had it all nailed down! Just emphasises how complex a task building quality model engines really is!

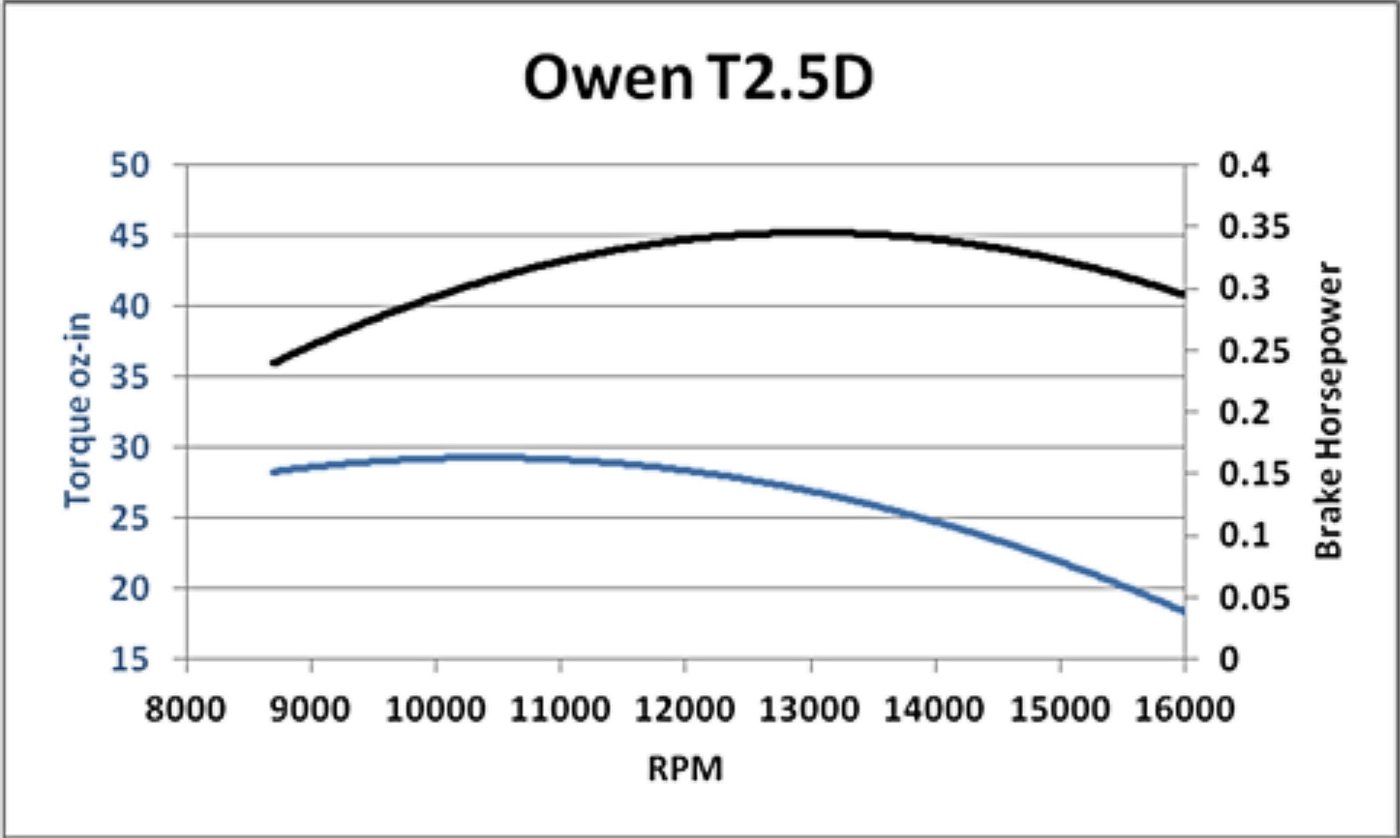

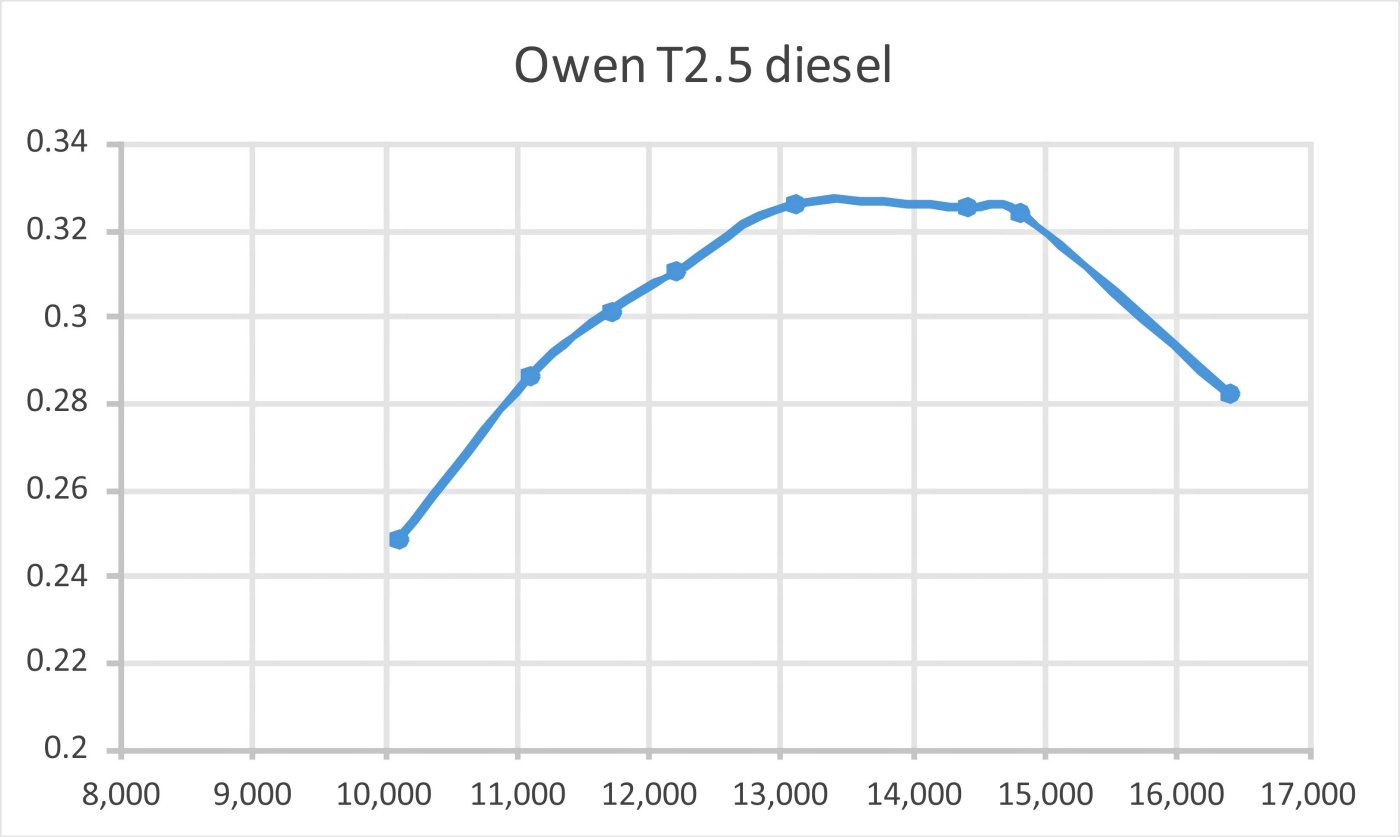

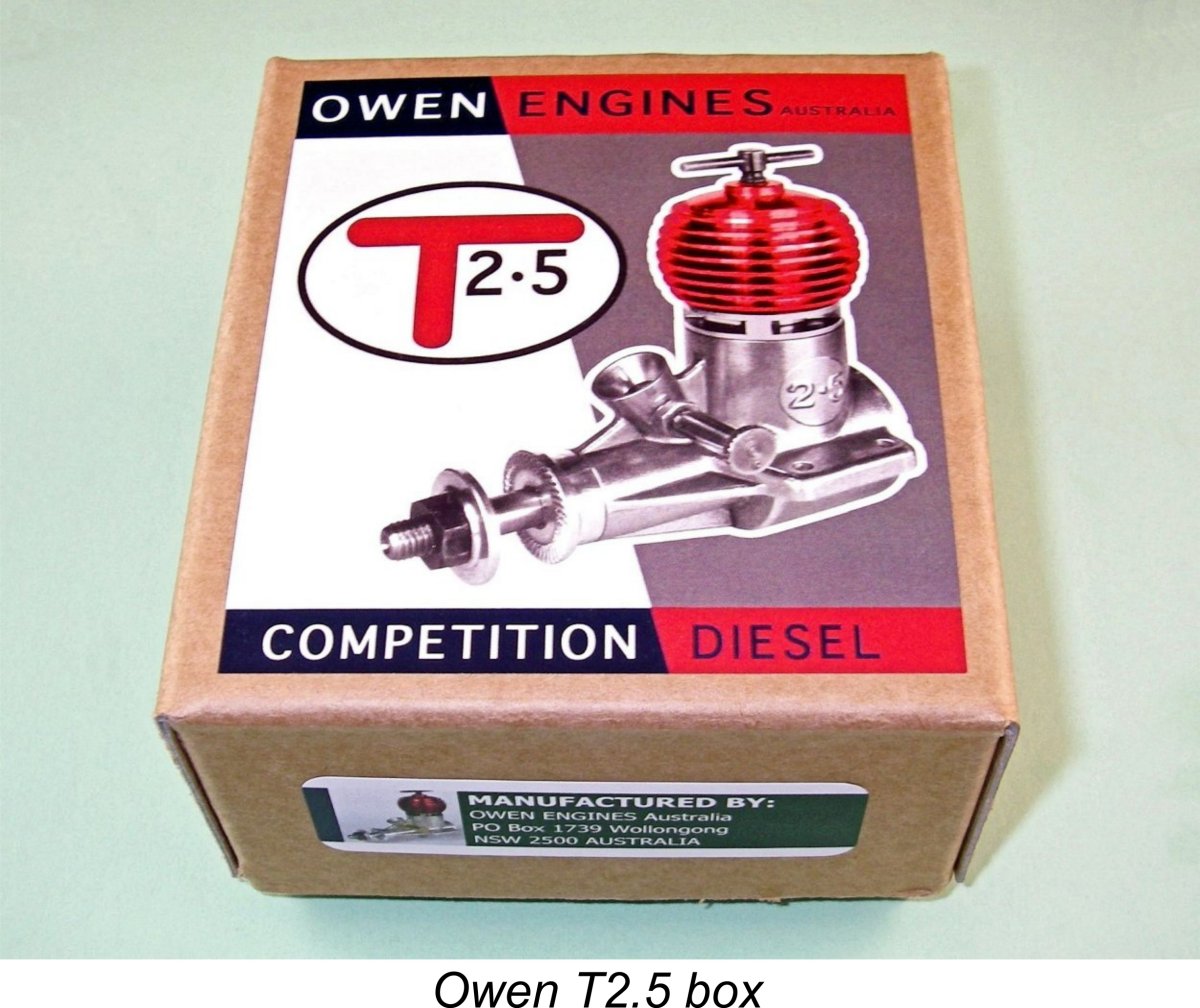

David then contacted Tom Ridley's box maker in Leicester, but the first thing they asked was – did David have a die?!? Well………in a word, no!! Thankfully, Tom very kindly loaned his Oliver box die, which was used to make the boxes for the T2.5. As far as the label went, David drew up a rough presentation based on the superb early artwork produced by the E.D. company during their Golden era, after which a local friend in Australia put David’s efforts into the finished form in which it appears on the boxes. The result is a package which bears comparison with any other when it comes to quality of presentation. Summing up, we have here a superbly-made all-Australian model diesel engine which fully reflects its classic Taipan heritage while improving upon the functional design of the original in a number of ways. It is also presented to a very high standard indeed. All good so far ………… now, how does it run? Only one way to find out – run it! The Owen T2.5 on Test As noted earlier, Maris Dislers’ test of an original Taipan 2.5 Mk. 3 found an output of 0.29 BHP @ 12,500 RPM. This is an excellent performance for a 1957 plain bearing diesel, but Maris also tested one of David Owen’s three prototype T2.5 units, finding an even more impressive output of 0.35 BHP @ 13,100 rpm. Quite a few far heavier and more bulky ball-race competition diesels of the late 1950’s and early 1960’s couldn’t match this figure! For reference, Maris very kindly provided me with the raw data obtained during his previously-unpublished test, with permission to use it as part of the documentation for this article. Here are the results of Maris’s testing:

Reviewing the above data, it will readily be appreciated that I approached my own independent test with quite high expectations. It’s fair to say that I was not disappointed, as we shall see. I began by running the engine in using the approach recommended by David Owen. When cold, the engine started most readily on a small prime administered with the ports closed. Once running, it was very responsive to the controls without being the least bit critical - optimum settings were very easily established. Running characteristics were all that could be desired - smooth and steady without a trace of a misfire and no tendency to sag. Both the comp screw and needle valve held their settings perfectly at all speeds. Vibration levels were very low. I put on six 5-minute runs using a 9x6 APC prop and running slightly rich and under-compressed on an “oily” castor-based fuel. At the end of each run, I followed my usual procedure by leaning out for around 20 seconds or so to get the piston and cylinder up to full operating temperature. I then stopped the engine by cutting off the fuel supply, after which I allowed complete cooling prior to the next re-start. For reasons which are fully explained in my companion article on breaking in a classic model diesel, the full-range heat cycles which result from this procedure are essential to a proper break-in for an iron-and-steel piston/cylinder combination. I then tried a shorter run with the engine set for peak performance throughout, as it would be in flight. There was no tendency to sag, and the engine ran absolutely steadily, holding a speed of 10,100 RPM throughout. The exhaust residues were notably clear, indicating good combustion characteristics plus an absence of any rubbing wear. I deduced from this that the break-in was effectively complete. Certainly, the engine felt absolutely superb at this stage. However, upon checking the backplate prior to commencing the actual test, I discovered that it was in the process of coming loose, just as David had warned that it might. I retightened it and was all set. Having got the engine ready to deliver its best performance and given it a pre-test check-up, I then ran a series of my usual calibrated test props. Given the fact that the engine clearly peaked at well above 10,000 rpm, I saw no reason to take measurements at speeds below that figure. The selected test props reflect this decision. The APC 8x4WB is a trimmed 9x4 which I made to fill a glaring gap in my range of calibrated test props.

I experienced no further trouble with the backplate coming loose, and the cooling jacket stayed put throughout. Most satisfactory! Hot restarts were instantaneous with just a few choked flicks. The power curve that I obtained had a very different shape to that extracted by Maris from his prototype test example. Maris's engine was more powerful overall, in particular delivering considerably more low-end torque. As a result of this, his curve was a great deal flatter. I suspect that there may have been some functional differences between the two engines, or perhaps his example had more prior running time. I obtained a fairly comparable peak, finding some 0.330 BHP at around 14,000 RPM, but there's no doubt that my example was somewhat down on Maris's engine overall. The big difference was torque - my engine peaked at a higher speed but managed less torque throughout the lower end of the range. That said, what's wrong with 0.330 BHP @ 14,000 RPM for a simple lightweight plain-bearing diesel of classic design?!? A lot of twin ball-race diesels from the late fifties and early sixties couldn't top those figures! In my book, this represents an outstanding achievement by David Owen and his good mate Gordon Burford! Well done, lads!! Conclusion We all have to go sometime, and I suspect that for most of us the best compensation would be to go out on a high note. With this remarkable engine, David Owen did exactly that. The Owen T2.5 will stand as a lasting testimonial to his manufacturing skills and to the mega-talented design team that put this project together. It's obvious that there will be no more of these engines now that David has left us. However, that's one thing that actually wasn't affected by David's untimely passing - he had made it very clear that he had no intention of turning out any further production runs. So those of us who were lucky (or smart) enough to get in on this project must count ourselves extremely fortunate to own such a sparkling piece of model engine history. Treasure these engines ...........they deserve it! ________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2016 |

||

| |

This finely-crafted limited-edition 2.47 cc (0.15 cuin.) model diesel was made by David Owen of Woolongong, New South Wales, Australia. Sadly, events have unfolded which will make this the final expression of David's immense talents in the model engineering field. He had been fighting cancer for some years and had seemingly achieved some success in keeping the beast at bay. However, things took a sudden turn for the worse at the beginning of 2016, just as David was winding up the distribution of the T2.5 engines and beginning to talk about his next project. As this article was being subjected to the final pre-publication checks, the news came through that David succumbed to his cancer on March 17

This finely-crafted limited-edition 2.47 cc (0.15 cuin.) model diesel was made by David Owen of Woolongong, New South Wales, Australia. Sadly, events have unfolded which will make this the final expression of David's immense talents in the model engineering field. He had been fighting cancer for some years and had seemingly achieved some success in keeping the beast at bay. However, things took a sudden turn for the worse at the beginning of 2016, just as David was winding up the distribution of the T2.5 engines and beginning to talk about his next project. As this article was being subjected to the final pre-publication checks, the news came through that David succumbed to his cancer on March 17 Anyway, without further comment from me, here's my review of the final production from David Owen. I hope that everyone will read it as my tribute to a great modeller, a great model engineer, a true craftsman and a good mate.

Anyway, without further comment from me, here's my review of the final production from David Owen. I hope that everyone will read it as my tribute to a great modeller, a great model engineer, a true craftsman and a good mate.  There could have been no-one better qualified than David Owen to undertake this project. Apart from his long-term personal friendship with Gordon Burford, David was also one of Gordon’s most active technical collaborators in the production of a number of the limited-edition engines that Gordon made following the demise of the Taipan marque in 1976.

There could have been no-one better qualified than David Owen to undertake this project. Apart from his long-term personal friendship with Gordon Burford, David was also one of Gordon’s most active technical collaborators in the production of a number of the limited-edition engines that Gordon made following the demise of the Taipan marque in 1976. The original Taipan 2.5 cc Mk. 3 model has been comprehensively described by Maris Dislers in his indispensable book “

The original Taipan 2.5 cc Mk. 3 model has been comprehensively described by Maris Dislers in his indispensable book “ Bore and stroke of the T2.5 are 14.65 mm (0.577 in.) each for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.15 cuin.). The engine weighs in at a very compact 138 gm (4.90 ounces), a figure which is achieved at minimal cost in terms of sturdiness. As we would expect from David Owen, the quality of the engine’s construction is well up to the very highest model engineering standards.

Bore and stroke of the T2.5 are 14.65 mm (0.577 in.) each for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.15 cuin.). The engine weighs in at a very compact 138 gm (4.90 ounces), a figure which is achieved at minimal cost in terms of sturdiness. As we would expect from David Owen, the quality of the engine’s construction is well up to the very highest model engineering standards. David shared two possible issues which may arise during operation of this engine. The first is the familiar tendency of engines having screw-in cylinder components to unscrew during operation. A very few examples of the T2.5 have exhibited this tendency. David believed that this issue relates to the design of the contra-piston, which tends to lock firmly to the compression screw when the engine is running. During cold starting, any backing-off of the comp screw may loosen the cylinder somewhat, resulting in its unscrewing once the engine is running. David recommended that the cooling jacket be gripped firmly with one hand while unscrewing the comp screw with the other. If this is done, no further trouble should be experienced.

David shared two possible issues which may arise during operation of this engine. The first is the familiar tendency of engines having screw-in cylinder components to unscrew during operation. A very few examples of the T2.5 have exhibited this tendency. David believed that this issue relates to the design of the contra-piston, which tends to lock firmly to the compression screw when the engine is running. During cold starting, any backing-off of the comp screw may loosen the cylinder somewhat, resulting in its unscrewing once the engine is running. David recommended that the cooling jacket be gripped firmly with one hand while unscrewing the comp screw with the other. If this is done, no further trouble should be experienced. The T2.5 was supplied in a high-quality box made of extremely sturdy cardboard, with a handsome label affixed to the lid. This provides another excellent example of the kind of challenges faced by anyone wishing to offer a quality product. David wanted a “proper” box for this engine, but found it impossible to buy the required high-quality manila cardboard in Australia. Tony Eifflaender of

The T2.5 was supplied in a high-quality box made of extremely sturdy cardboard, with a handsome label affixed to the lid. This provides another excellent example of the kind of challenges faced by anyone wishing to offer a quality product. David wanted a “proper” box for this engine, but found it impossible to buy the required high-quality manila cardboard in Australia. Tony Eifflaender of