|

|

The E.D. Story

Before getting started, it’s both a duty and a pleasure to acknowledge the fact that it would be quite impossible to write with any authority on the subject of E.D. and their products without drawing upon the wealth of knowledge and experience of this marque held by my good mate Kevin Richards. Since there’s no question at all that Kevin is the world authority on E.D., I freely admit that I wouldn’t have even begun to write up this summary without being assured in advance of his willingness to advise and assist at many points along the way when I found myself stumbling! True to his word, Kevin invariably responded to my many and varied requests for guidance and clarification - thanks, mate!! Kevin has been working for years now on a book covering the E.D. story in full detail. I have no doubt at all that his book will represent the last word on the subject of the E.D. enterprise. I can't wait to read it myself! However, in the meantime this basic summary will have to do..........

Even after my update of the Ron Reeves article on MEN, there was still more to come! Following the appearance of my updated article, I was delighted to hear from the late Gordon Cornell, former E.D. chief engineer, who was able both to provide further clarification and correction on a number of important matters and to supply a number of key images. Such input from one who was “there” is quite invaluable. I also heard from Mike Noakes of Launceston in Cornwall, England, who had done a lot of research on the early stages of the establishment of the E.D. enterprise. More recently, my friend and colleague Marcus Tidmarsh conducted some detailed in-depth research which has done much to clarify the circumstances surrounding the establishment and early operations of the E.D. enterprise. It is only assistance of this sort whch enables me to maintain my efforts to keep these articles as complete and authoritative as possible. Marcus has my very sincere thanks! Taking all of this into account, there was no doubt in my mind that a further update had become urgently required in order to bring the story up to a higher level of authority by correcting a certain amount of inaccurate or incomplete information which still appears in the revised MEN article. Since the opportunity to do so on MEN was lost with the tragic passing of my mate Ron Chernich in early 2014, I have elected to publish the updated article here, with the above acknowledgements very much in mind. Now, time to get started on this task! As a preliminary, before we consider the range of products emanating from E.D. it’s necessary first to delve a little into the origin and background of the enterprise. Background The registered name of the original company which manufactured the E.D. range was Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. This company appeared on the scene in 1946 shortly after the end of WW2, having been formed by a group of individuals who for the most part had worked during the war years for Nash & Thompson and Hawker-Siddeley, both of Kingston-upon-Thames.

During the war, Nash & Thompson had been engaged in making the Frazer-Nash gun turrets used in the RAF’s Wellington, Manchester, Stirling and Lancaster bombers. However, Ministry contracts were naturally terminated following the cessation of hostilities, the immediate result being that large numbers of former Nash & Thompson employees were facing redundancy. This somewhat ruthless process of downsizing allowed the Parnall company to survive the early post-war retrenchment by moving into a completely different line of business. They subsequently become renowned for their washing machines and their Jackson range of cookers. Another group of wartime workers facing redundancy were many employees of the Hawker Siddeley group (makers of the famous Hurricane fighter), who were headquartered on Canbury Park Road in Kingston-upon-Thames. The looming redundancies left these individuals in a very precarious position when facing the need to continue to make a living in the war-ravaged British economy. Times were hard ……………. This makes it all the more impressive to learn that a number of the individuals facing unemployment elected to participate in what amounted to a collective leap of faith. Under the managing directorship of former Hawkey-Siddeley employee Jack E. Ballard (1904 - 1990), some 65 ex-Nash & Thompson and Hawker-Siddeley employees each contributed £50 to finance the start-up of the new Electronic Developments (E.D.) enterprise. This provided the new company with a start-up capital fund of £3250 - not all that far short of a quarter-million pounds in today's currency. The £50 individual investment represented a very sizeable commitment for a soon-to-be unemployed working man in 1946, when a person earning £8 per week before taxes was considered to be well-off. Each individual stake in the business was roughly equivalent to around three thousand dollars in today’s money. The company was thus established very much along the lines of a worker’s co-operative - all of the employees had a financial stake in the company, in effect becoming working shareholders. In addition, the fact that many employees already had a history of working together as a team at Nash & Thompson or Hawker Siddeley must have paid dividends during the early years in terms of the camaraderie and team spirit which likely existed from the outset. It appears that Jack Ballard took the initial steps on behalf of the group in late 1945 or early 1946 by registering a company called Electronic Developments Ltd. This reflects the somewhat surprising fact that when the E.D. company was formed, its original purpose had nothing whatsoever to do with models! The intention at the outset was to produce electronic hearing aids for the many servicemen who had returned from WW2 with damaged hearing, war being the noisy business that it is. The name of the company confirms that the electronic side of the business was viewed at the outset as the primary activity - no mention of models or engines there! The address of this company appeared in the 1946 London telephone directory as 227 Hammersmith Road, London W6. This location was very distant from Kingston on the other side of the River Thames - evidently the premises on Villiers Road in Kingston-upon-Thames had yet to be secured. Marcus Tidmarsh confirmed that this was actually Jack Ballard's residential address, at which he had been living for many years. At some later point in 1946 the new company established its workshops in premises located in the south-west area of Greater London at 18 Villiers Road in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey. At the same time, the company changed its registered name to Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. Since the Villiers Road location was only some three road-miles from the Nash & Thompson plant on Oakcroft Road, also being close to the Canbury Park Road headquarters of Hawker-Siddeley, the shareholder/workers were not faced with any need to relocate. According to later reports, the floor area of the new premises was around 4,500 square feet.

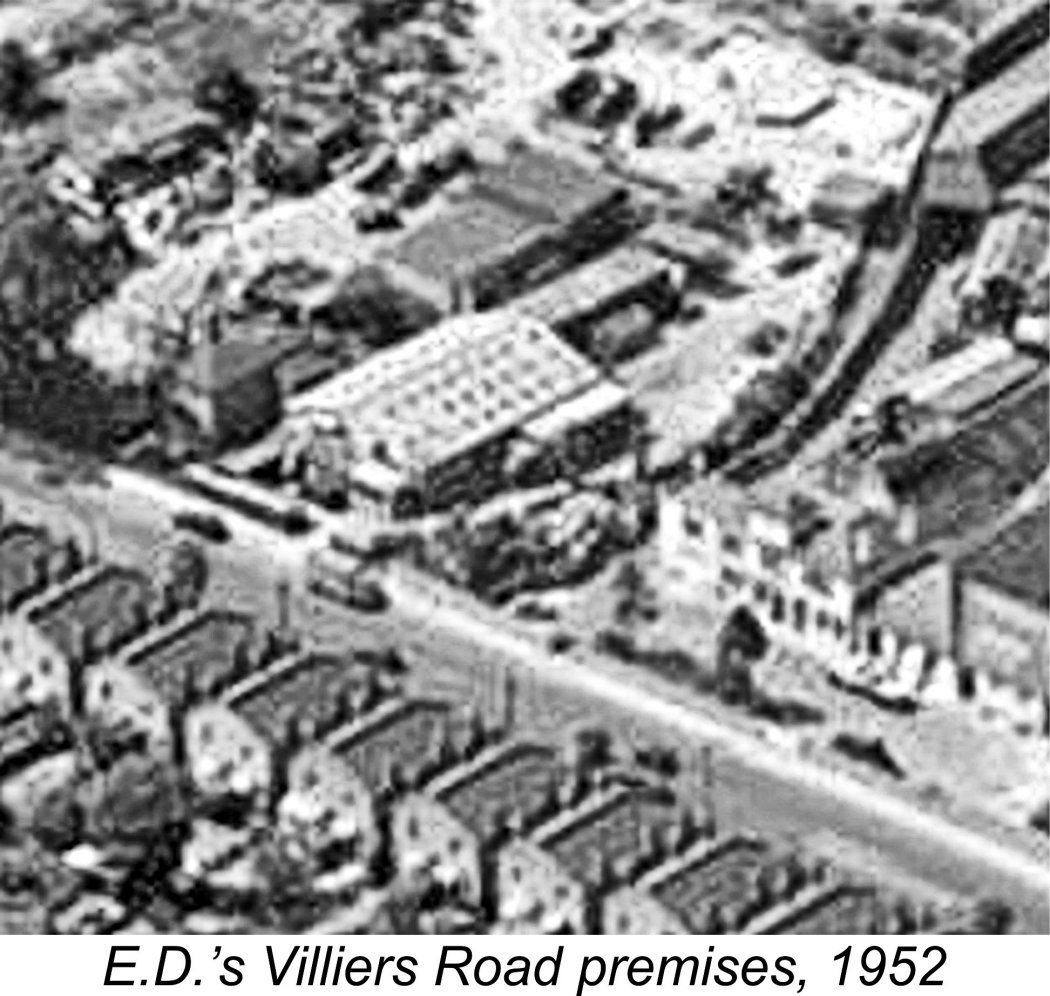

Mike didn't learn about the site's use in WW2, but he did find out that near the end of the war, planning permission was sought to re-develop the site for residential purposes. However, this was refused due to the site's designation for industrial use. At some indeterminate point in time, the name of the street was changed from Oil Mill Lane to Villiers Street, at which time the former laundry site was re-numbered from 16 to 18. E.D. appears to have commenced its occupation of that address in the latter part of 1946. Their occupancy was presumably on a rental or lease basis - their start-up capital fund of £3250 would not have sufficed to purchase and refit the property. E.D.'s new Villiers Road premises were located immediately adjacent to the very large Vine Products (VP) wine bottling and distribution plant. In the somewhat fuzzy air photo reproduced above at the right, the E.D. premises are the large white gable-roofed rectangular building with multiple skylights. The rather grand building to the right is the VP office complex. My sincere thanks to Mike Noakes for providing this information along with the attached 1952 air photo of the E.D factory. The location has been comprehensively redeveloped today for residential purposes - the late wartime re-development proposal has finally taken effect! We've seen that the original purpose of the new company had nothing whatsoever to do with models, focusing instead upon the development and production of specialized electronic equipment as the name suggests. However, for reasons which are now lost in the mists of time, the original plan was quickly abandoned. Instead, the new company quickly shifted its focus towards model-related production, presumably on the basis of a personal interest in this field on the part of some of the founding Directors. Model radio control equipment was then in its infancy and still highly experimental. E.D.’s early involvement with this field was doubtless a direct offshoot of their original interest in electronic equipment. It was only natural that this modelling focus would quickly lead to what was seen at the outset as a subsidiary interest in model engines. Jack Ballard’s management team included such then-famous names as George Honnest-Redlich, noted pioneering author on the subject of radio control for models. In addition to his duties as a Director, Honnest-Redlich was in charge of the technical side of the radio control development program. Bill Wedlock was workshop foreman, with Bert Day the expert on honing cylinders and radio assembly. Completing the executive team were Doug Fifield and Jim Donald, both with a strong model engineering background. The remaining staff served the company in various capacities as working shareholders.

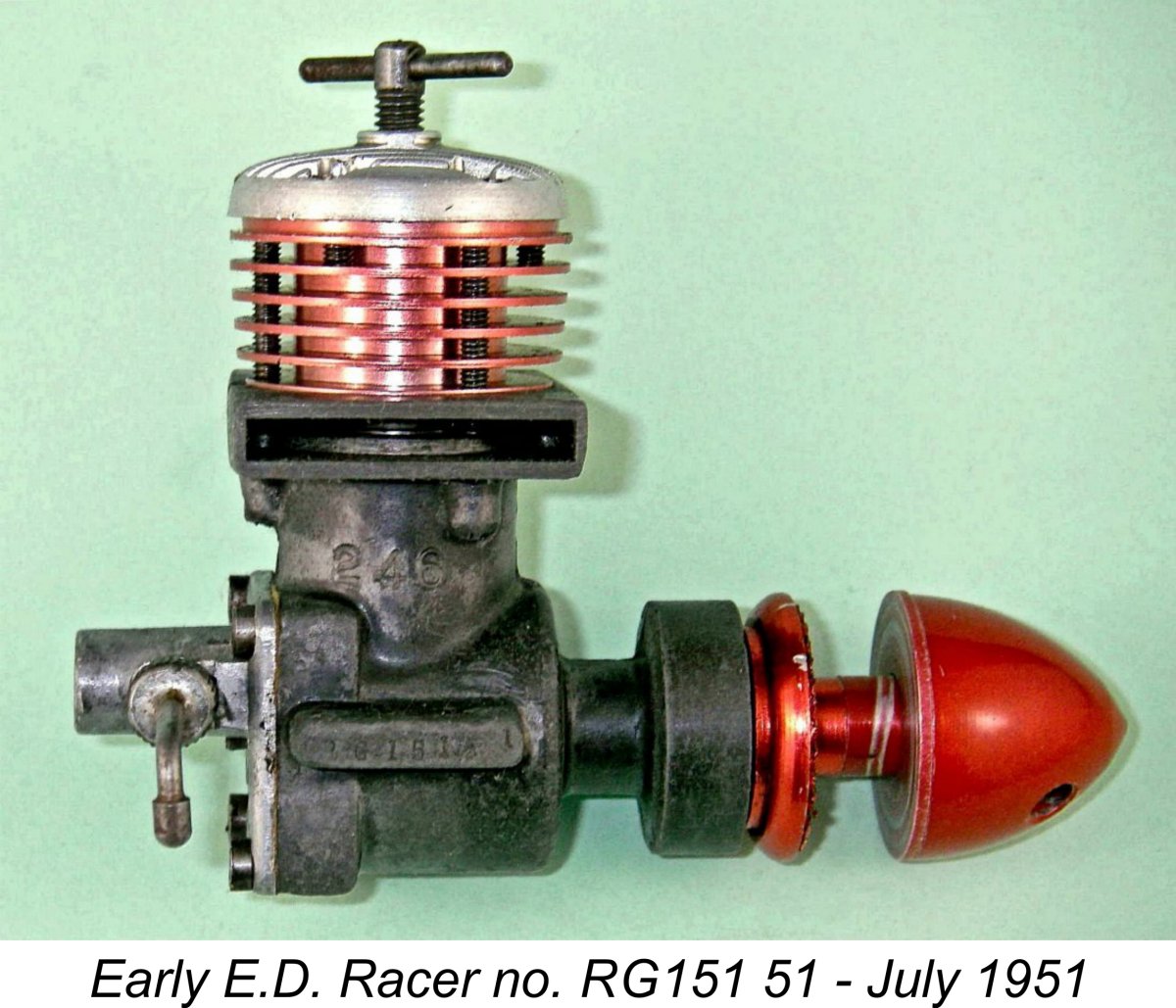

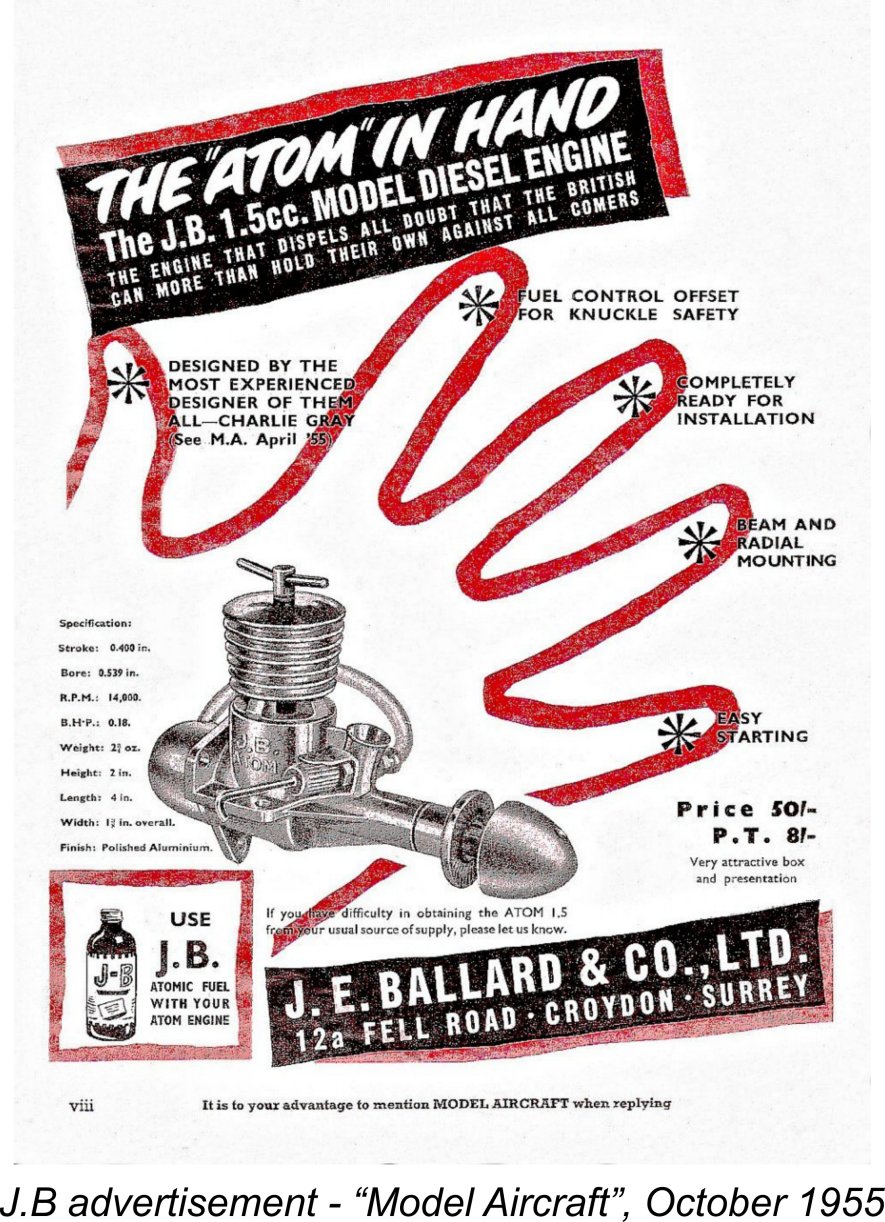

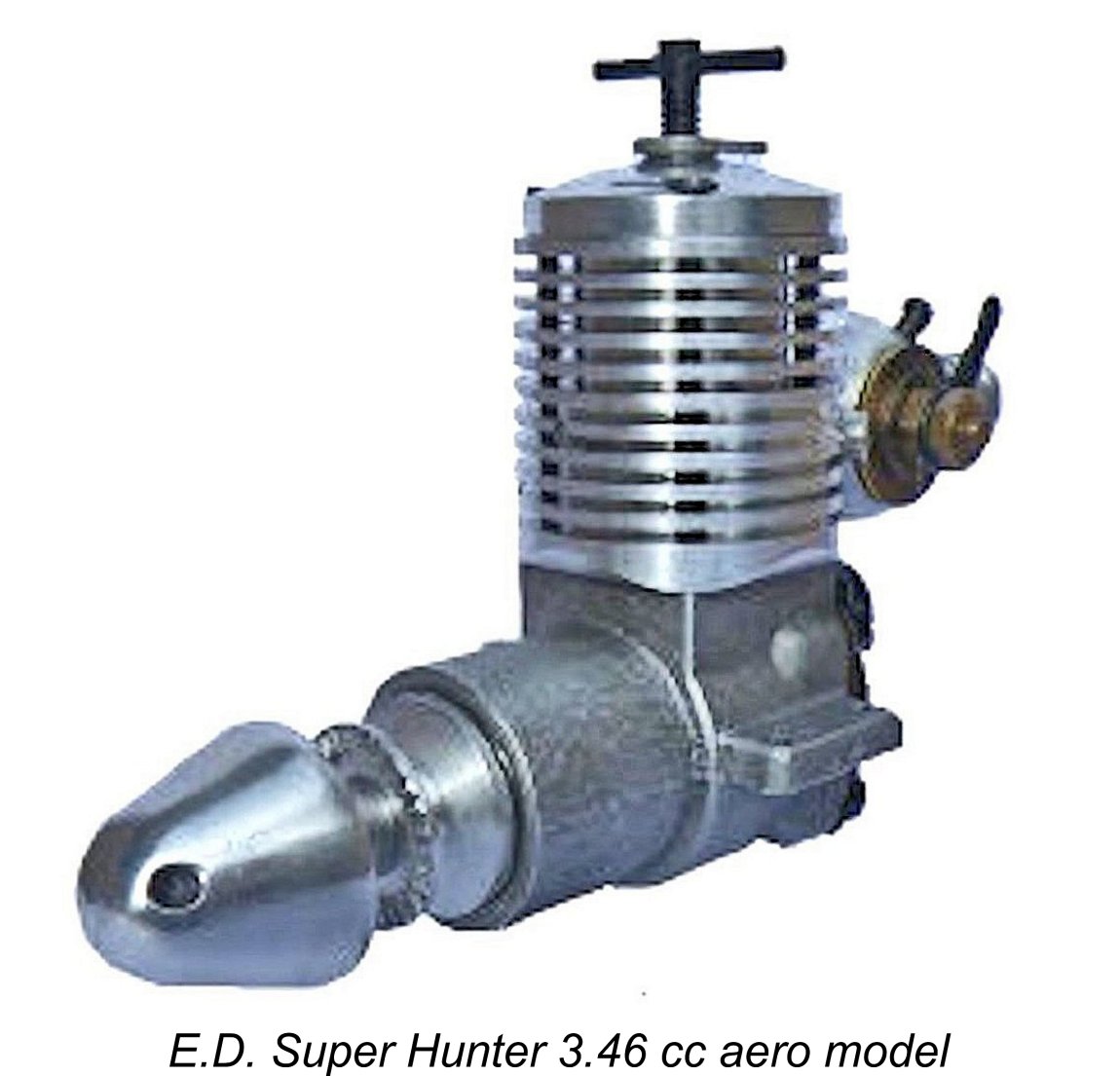

This makes it appear probable that Miles actually became directly associated with E.D. considerably later than many people have hitherto believed, although he may well have exerted some influence on the company's entry into model engine manufacture. The first E.D. product with which Miles’ name was openly associated by the company was the 2.46 cc E.D. Mk. III Racer introduced in March 1951, although it does appear very likely that he played a significant role in the 1949 design of the 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV, with which he is pictured in the attached illustration. Certainly, Miles was later to claim the Hunter design as his own. The idea that Basil Miles was not directly involved at the outset is strongly supported by the observation that the design of the early E.D. "stovepipe" engines represented a significant step backwards from the far more sophisticated designs which had been produced by Miles prior to and immediately following WW2. Hence it has always seemed somewhat improbable that Miles had a major design influence on the development of the early E.D. model engine designs. He seems highly unlikely to have missed a few of the very obvious and easily-implemented design modifications which would have improved these engines considerably. If we can believe the later evidence of E.D.'s founding Managing Director Jack Ballard, the early E.D. engines were actually designed by a fellow named Charlie Cray. This fits well with the fact that Basil Miles and Charlie Cray were fellow members of the Malden model hydroplane racing club, doubtless facilitating Miles' input to model engine developments at E.D. and ultimately leading to his central role in the design of later models.

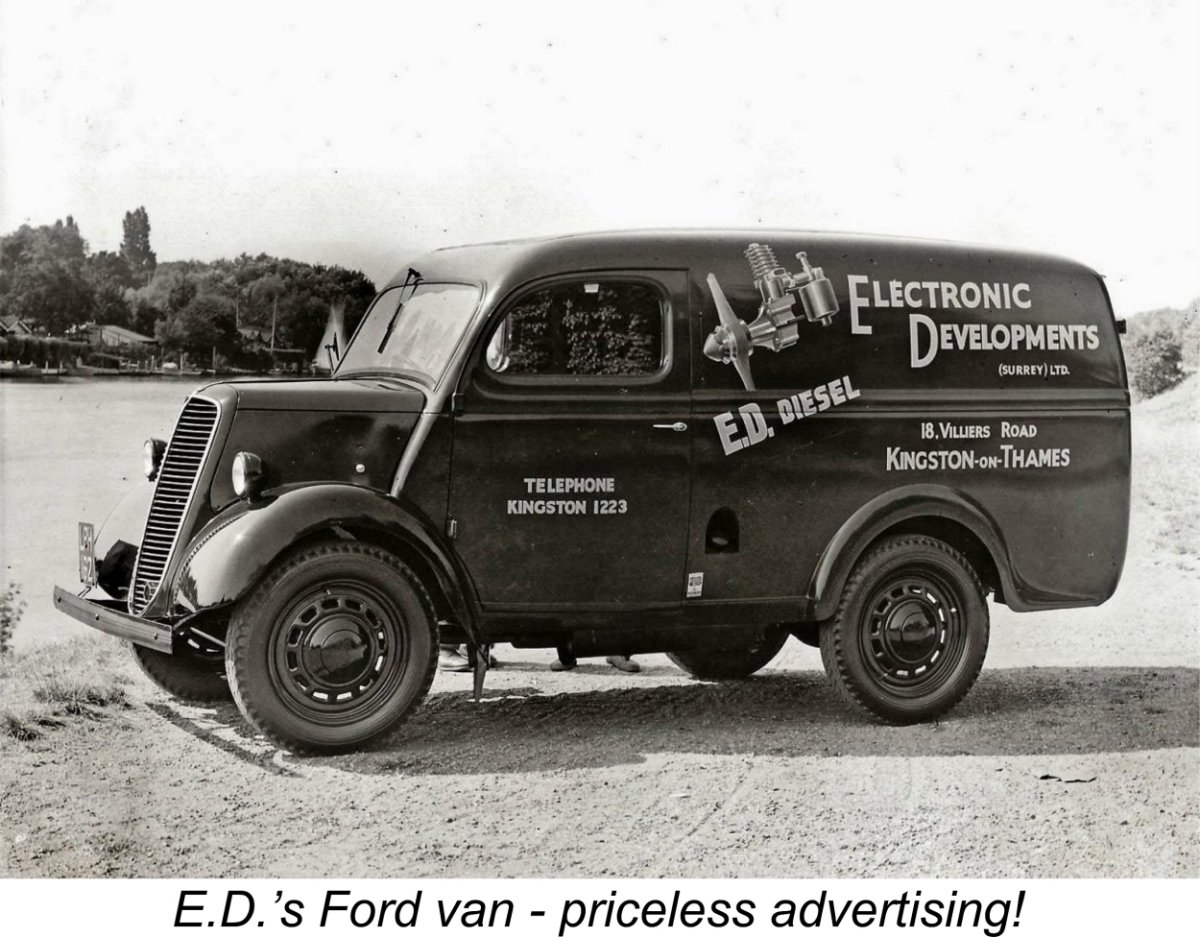

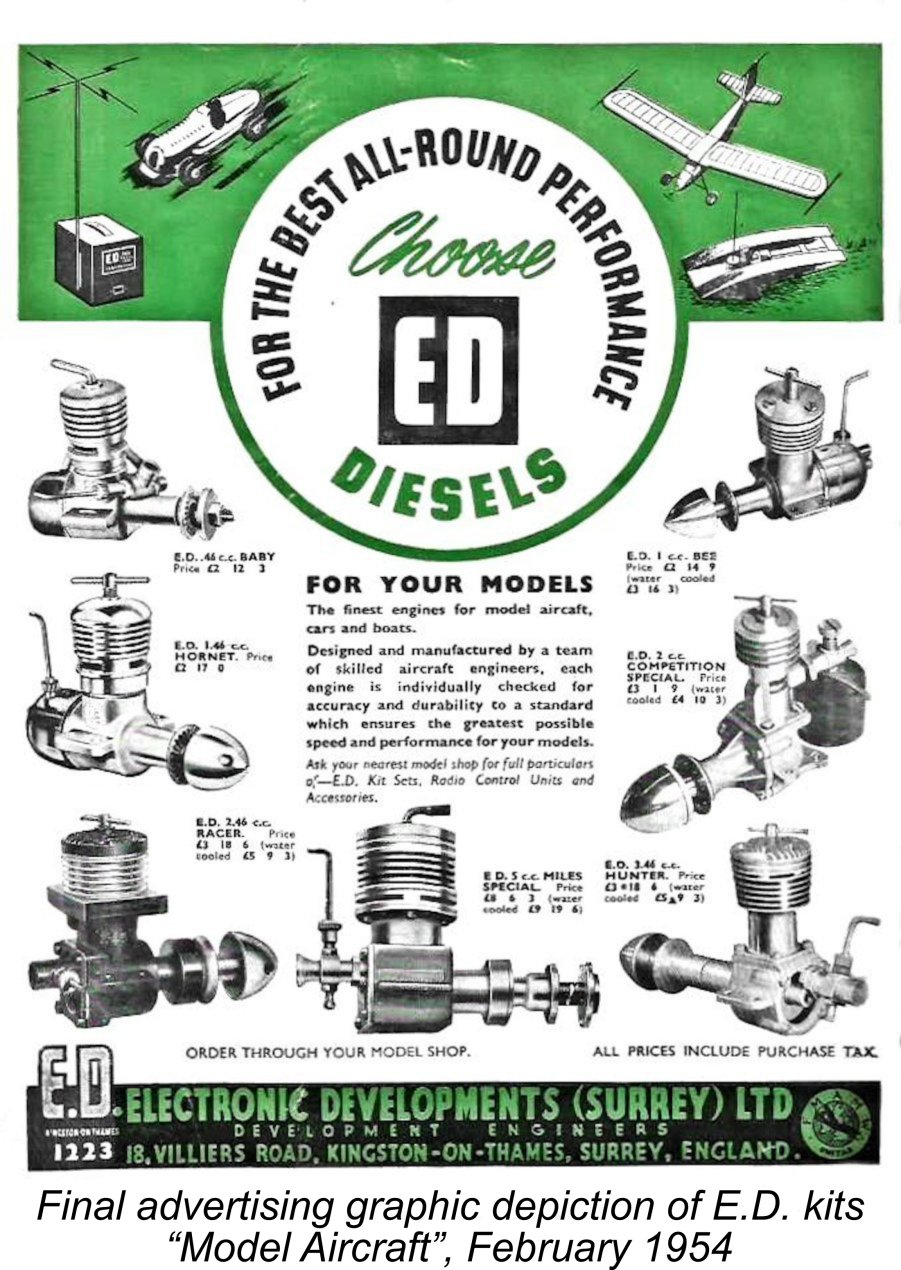

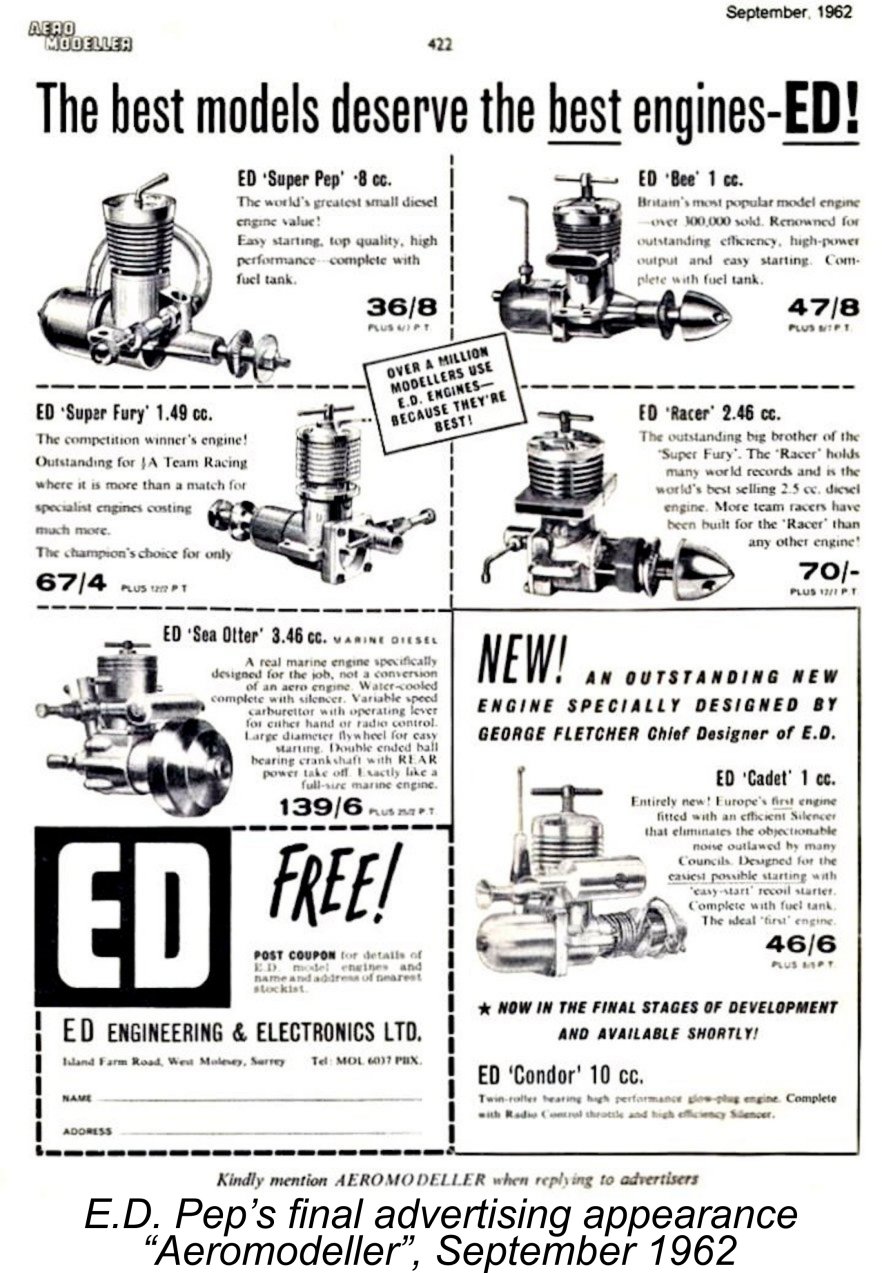

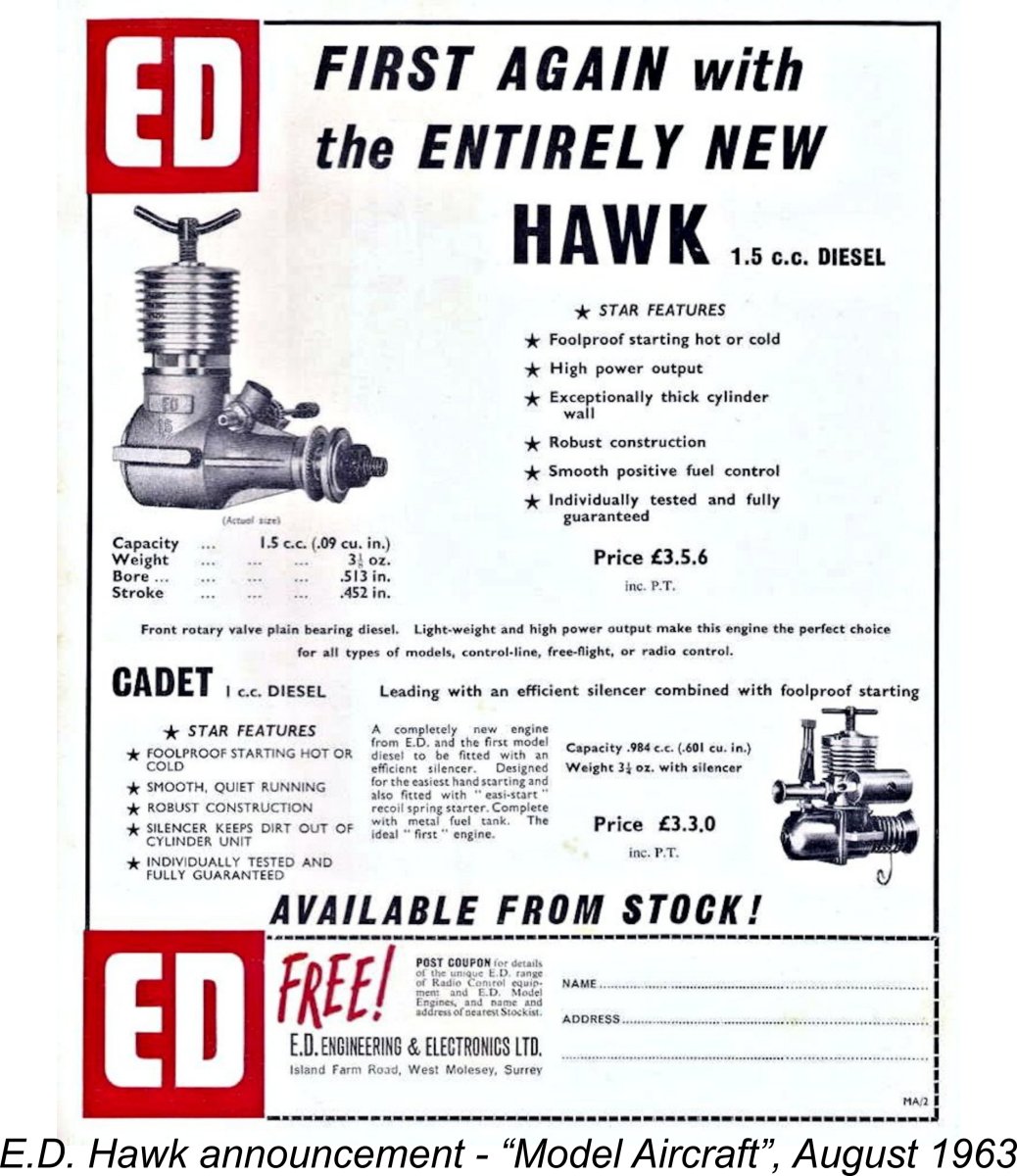

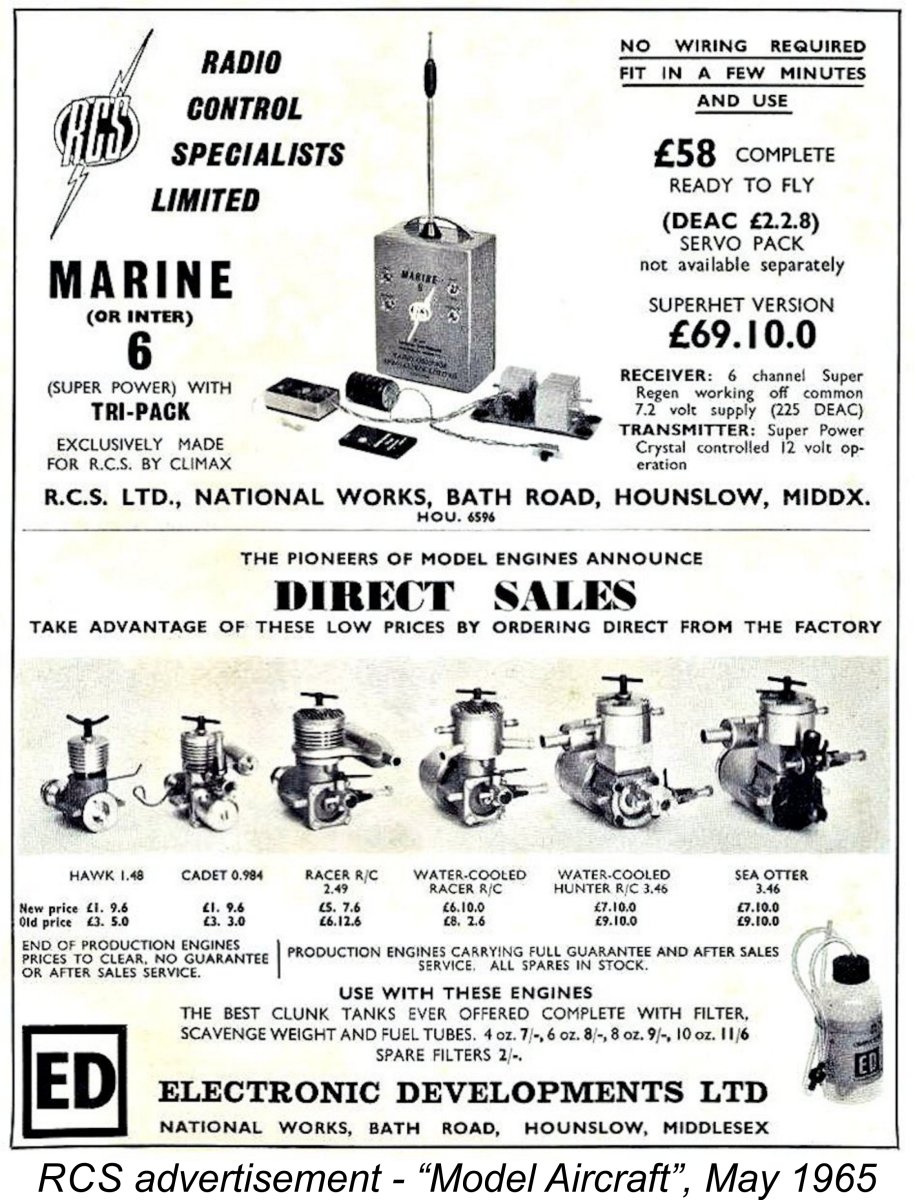

As a little-known example of the collaboration between Basil Miles and Charlie Cray, it's on record that in 1948 Cray designed a powerful 10 cc racing motor, the prototype of which was constructed by Miles. This prototype was installed in fellow Malden club member George Stone's record-holding "Lady Babs II" hydroplane. The first attempt to run the hydro with the new engine on December 28th, 1948 was thwarted by the club's pond being covered in ice! The second attempt was made at dawn on New Year's Eve after Miles had waded out waist deep in the freezing water to secure the tether to the pylon. The motor started easily and screamed around to something of a then-current record for a standing start lap at 60.3 mph. The weather precluded any more serious attempts but the performance of the motor right off the workbench convinced the three club-mates that it represented a serious challenge to the supremacy of the American motors. Through Cray's and Miles' connections with E.D., it was confidently hoped that the company would produce the motor commercially as the E.D. Fireball, with the later addition of a 5 cc version. However, as far as can be ascertained, the company never took any action with respect to this model. The issue of Charlie Cray's involvement is rather clouded by the fact that Alan Greenfield, who holds a number of surviving original E.D. design drawings, could only find one such drawing which bore Cray's signature. This at least confirms that he was an E.D. employee. Miles does not appear to have entered the E.D. picture on an "official" basis until mid 1949 at the earliest, and possibly later. Even then, his role appears to have been strictly confined throughout to the development of specific engine designs. In fact, much if not all of Miles’ association with E.D. may well have had a contractual basis, with Miles acting as an outside design consultant. Returning now to late 1946, once its focus shifted towards the modelling field, the newly-formed enterprise quickly identified a two-fold set of model-related goals - firstly, to develop and produce a range of commercial radio control equipment that would encourage increased modeller participation in this then-new field of model flying activity, thus supporting E.D.'s commercial interests in that field; and secondly, to develop and produce a range of model engines that would provide dependable power for models using E.D.’s radio control gear as well as for other modelling applications. At the outset, the manufacture of model engines was seen as a subsidiary activity, although this was to change as the years went by. On the production front, the company's machine shop was equipped initially with used wartime tooling which the cessation of hostilities had made redundant from Hawker Siddeley. The purchase of this equipment at auction for a particularly advantageous price was facilitated by the fact that a number of E.D. shareholders were still working there while under notice of redundancy. These individuals identified the best of the machines listed for auction, using their inside knowledge. Among these were several Harrison centre lathes which had large lockable tool cabinets built into them. The pot was sweetened by these lockable tool cabinets being surreptitiously filled to the brim with useful tooling and other small items, including metrology equipment, after which the cabinets were locked and the keys retained. These selected lathes with their valuable hidden cargo were then successfully bid upon by E.D. at auction, along with other pre-selected machine tools. Perhaps not strictly ethical, but those invoved were playing for their economic survival during tough times .................... However, there was a significant downside. The machinery acquired in this manner had already given its best to the war effort, hence becoming both increasingly well-worn and out-of-date as the 1950’s wore on. Some new equipment was added during the mid-1950's, as we shall see, but by the time that the need for wholesale replacement of machine tooling became really pressing for E.D., the company lacked the financial resources to undertake the necessary wholesale upgrades. A number of other post-war British One advantage enjoyed by the E.D. company was their location in close proximity to a number of scrap yards which at that time were unusually well stocked with redundant war-related materials suitable for small-scale engineering projects. In addition to high quality steel, there were non-ferrous materials such as aluminium alloy sheet from second-hand Heinkels along with a ready supply of used Rolls-Royce Merlin pistons, apparently perfect for the aluminium castings used in model engines. At a fairly early stage in their existence, the E.D. company invested in a custom-painted Ford van which was used for a wide range of business-related transportation requirements. With its prominent company markings, complete with an image of the E.D. Mk. II, the van must have served as an excellent ambassador at model shops, model meetings and trade events at which it appeared. My thanks to Mike Noakes for making this very rare image available! If you look closely at the air photo reproduced above, you'll see what appears to be this van parked in the forecourt of the E.D. building. Early Production History Perhaps the most informative way to follow the progression of the E.D. range is to check out their regular advertising placements in the two major British modelling magazines at the time - “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”. The company seldom missed an issue of either magazine with its advertising, thus providing us with very detailed evidence regarding the introductory dates of their various models. I will therefore present a number of these adverts as illustrations, interspersed with images of the engines themselves. When using published advertisements as a guide to introductory dates, it's important to remember that the development of advertising copy had to precede the actual appearance of the advertisement by some time. There would have been an advance editorial deadline by which material for the next issue would have to be submitted. Moreover, it would take time to develop and create the advertising copy itself. For this reason, it's probably safe to assume that the actual introduction of a given model likely preceded its initial advertising appearance by at least a month, and possibly more.

OK, back to our main story.........E.D. began to develop their range of commercial compression ignition engines in the latter half of 1946, quite soon after the formation of the company. Their initial effort was a somewhat primitive sideport model known simply as the E.D. 2 cc diesel. Reports in the contemporary modelling media indicate that examples of this engine began to appear on flying fields in southern England in December 1946 with little or no commercial fanfare. Kevin Richards believes that this original model was never offered for public sale and that the engines seen in action in late 1946 were development prototypes in the hands of E.D. employees. This seems entirely plausible to me in the current absence of any convincing evidence to the contrary. I noted earlier that although it has been widely assumed in the past that Basil Miles was the E.D. engine designer from the outset, this assumption appears to be only partially correct. In his April 1955 announcement of the then-forthcoming J.B. model engine range (see below), Jack Ballard claimed that J.B. designer Charlie Cray had been “primarily responsible for all the engines manufactured by me (Ballard) during the past ten years”. While this was clearly a gross misrepresentation of the facts since it completely ignored the very significant contributions of Basil Miles, Dennis Allen and Ted Martin to the E.D. and AMCO engines produced earlier under Ballard's management, it may nonetheless harbour a kernel of truth. It appears that Charlie Cray was involved with the early E.D. models, since his signature appears on at least one surviving design drawing. Miles may well have had at least an advisory role, although he appears to have taken over centre stage only when the new disc rear rotary valve models began to appear. More of those models below in their place .............

In keeping with my earlier comment about actual introductory dates generally preceding the initial advertising placement, E.D.'s first advertisement announcing the release of the Mk. II appeared one month later in the March 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. This advertisement is reproduced below. Thereafter, a variety of full-page advertisements for this engine appeared in “Aeromodeller” throughout the remainder of 1947, conveying the image of an enthusiastic, rapidly developing company that was very much “on the move”. H In taking this approach, E.D. was anticipating the pattern employed by many present-day computer software companies - get a relatively under-developed product into the field as soon as possible and use the cash flow from sales to fund the ongoing development program. Your customers will perform your field testing for you (provided the product is not too awful!), and you can respond to any identified issues by releasing updates as required, thus appearing to be responsive to customer feedback. The production volumes extrapolated from the serial numbers for engines produced during this period suggest that this strategy almost certainly paid off in a financial sense - sales were clearly quite brisk despite the initial shortcomings of the design. However, there was a downside—the engine’s under-developed state necessitated the implementation of a whole series of improvements in rapid succession during 1947, none of which were highlighted in the advertising since they were mostly responses to or Traditionally, the annual Christmas issue of “Aeromodeller” was a double size "bumper" issue which was eagerly awaited by the modelling public. E.D. took full advantage of this in 1947 by announcing the “Competition Special” refinement of the Mk. II (always colloquially known then and now as the Comp Special) in the December 1947 Christmas issue. This model featured an enlarged bypass passage along with sub-piston induction which was made possible by extending the exhaust ports downwards while omitting the exhaust stacks of the Mk. II. It also featured a conventional compression screw in place of the Mk. II’s somewhat awkward penny-slot arrangement. Some elements of the Comp Special design (notably the enlarged bypass) were concurrently transferred directly to what was to become the final design of the Mk. II. The

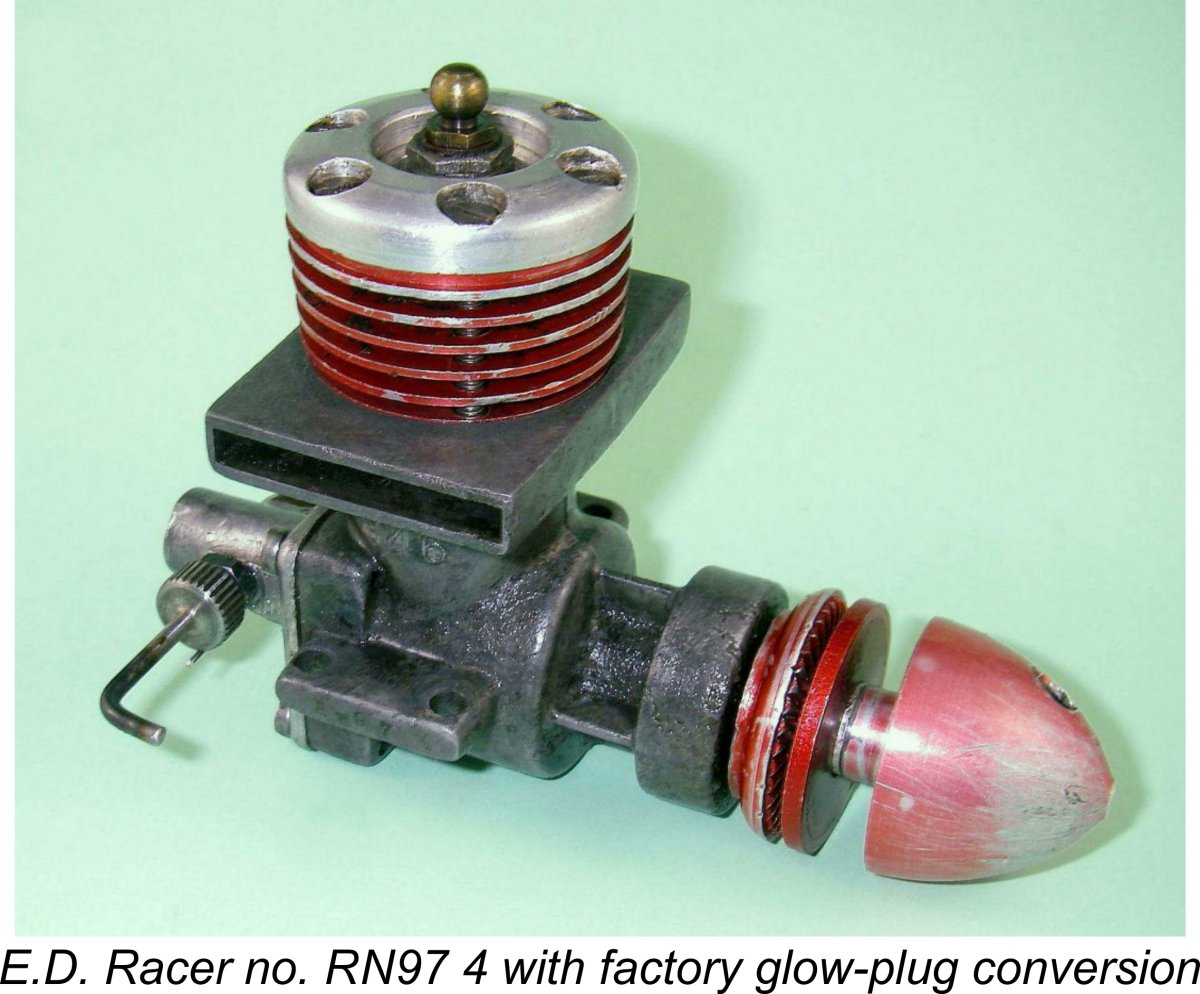

The Mk. III established a number of early speed records in both aircraft and car service, but was quickly overshadowed by improved designs from other manufacturers. Consequently, it actually proved to be one of E.D.’s least successful models, with only perhaps 6,000 units at most being manufactured durin The E.D. Mk. III was highly significant in one respect - it was the first E.D. model to be specifically designed for glow-plug operation at the owner’s discretion. In fact, it was the first commercial model engine to be offered to the British public for either diesel or glow-plug operation. Very quick work by E.D. considering the fact that the commercial glow-plug as perfected by Ray Arden had only arrived on the scene in America in late 1947.

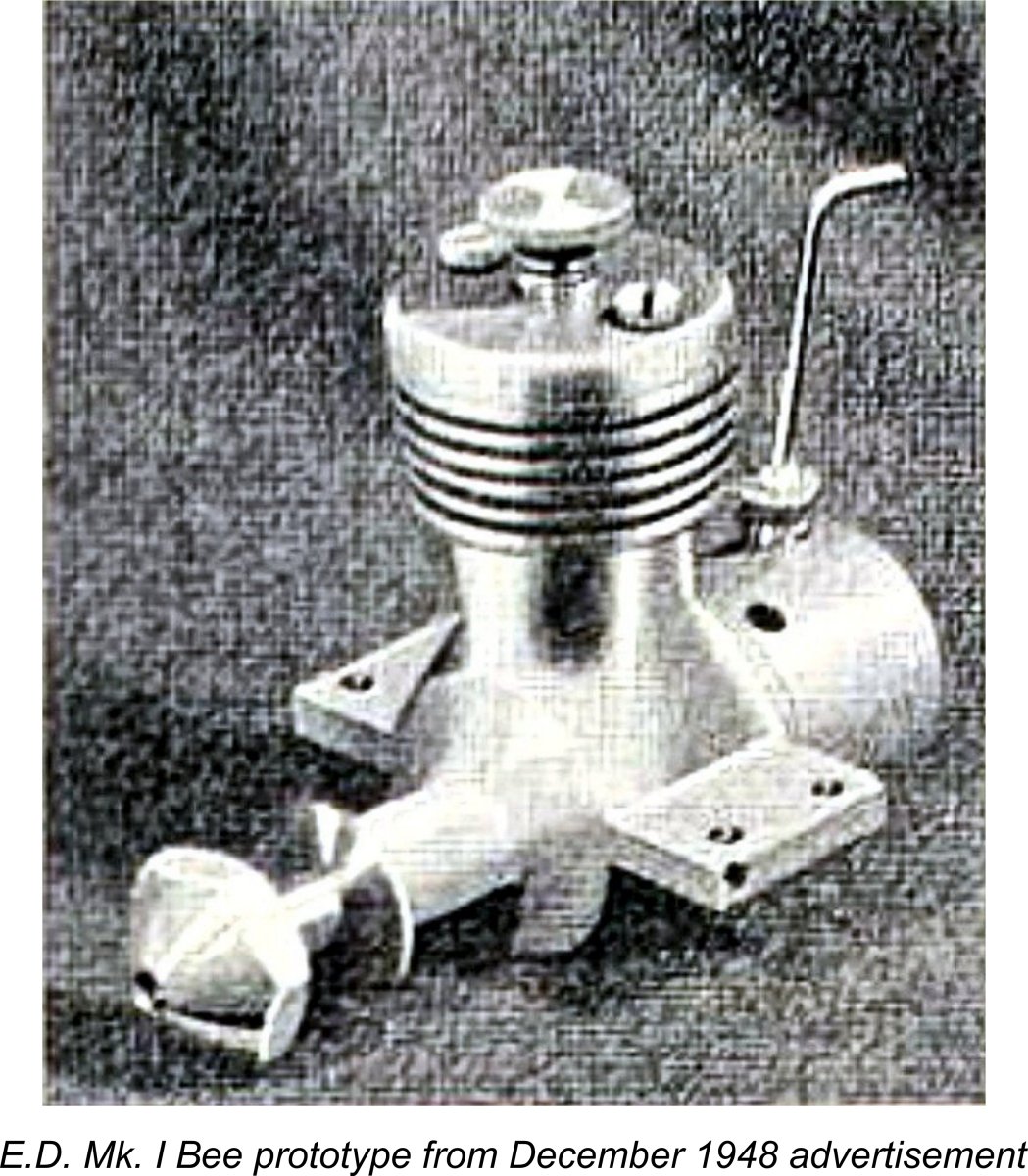

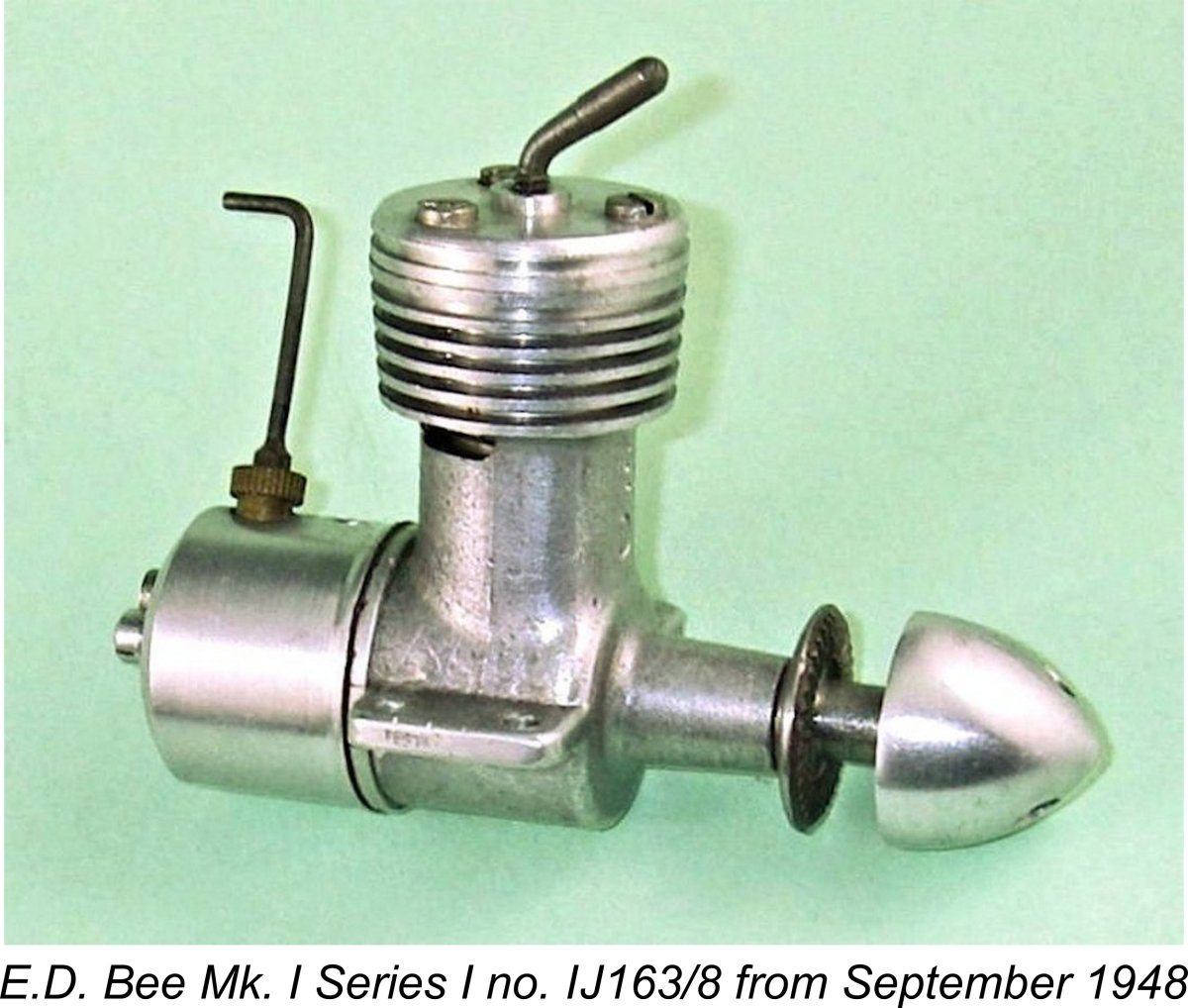

One of the things which set E.D. apart from most other manufacturers was their tendency to produce unadvertised variants of a few of their more familiar models. A case in point was the aforementioned FRV 2.49cc Mk. III, which was also produced to special order in an unadvertised sideport version for some time. This engine looked for all the world like a slightly overbored Comp Special, which was in fact exactly what it was. Most modellers proba The nomenclature used by E.D. during this period was rather confusing at first sight. For example, E.D.'s next new design, the E.D. Mk. I Bee (“The Engine with a Sting”) did not enter series production until August 1948, and this was well after the appearance of both the Mk. II in March 1947 and the Mk. III in March 1948! And it might have been even more confusing if cooler heads had not prevailed - Kevin Richards has irrefutable evidence in the form of a boxed example that the Comp Special of December 1947 was originally intended to be known as the Mk. III 2 cc model!! The label on the box clearly shows both the model designation as Mk. III and the size as 2.00 cc.

In this scenario, the Mk. II was released as soon as possible in order to generate some doubtless-needed cash flow, leaving the Mk. I designation available for the future 1 cc design whenever it was ready. As matters turned out, even the Mk. III beat the Mk. I into the field, as noted earlier. On the surface this looks reasonable enough, but Kevin Richards has presented a persuasive argument to the effect that matters were almost certainly more convoluted than this! It’s actually more probable that the decision to re-designate the original 2 cc model as the Mk. II was nothing more than a marketing ploy to convince the public that considerable development of the original 2 cc model had already taken place. The original plan to designate the Comp Special as the Mk. III 2 cc is completely consistent with this notion since it clearly implies the prior existence of Mk. I and Mk. II versions of the 2 cc model. If this scenario is correct, as seems highly likely to me, then the fact that there was a gap in the Mark sequence to accommodate the far later Bee was entirely fortuitous. Since it certainly doesn’t take 18 months to develop a simple engine like the Bee from scratch, it appears highly likely that the decision to develop the Bee was made long after the Mk. II was well and truly launched. The fact that the Bee first appeared in prototype form in April/May 1948 strongly suggests that the decision to develop that model was most likely taken in late 1947 or early 1948, more or less concurrently with the release of the Comp Special. It was probably at that stage (after a few Comp Specials had been manufactured and packaged as Mk. III’s) that the company belatedly realized the neatness of going up the displacement categories in step with the mark numbers. Having come to this realization, they quickly removed the Mk. III designation from the Comp Special, thus leaving that designation free to be applied to the forthcoming Mk. III 2.49 cc model. The fact that the improved 2 cc engine was never advertised as anything other than the Competition Special suggests that the boxed Mk. III 2 cc models were part of the stock build-up run which preceded the announcement of any new engine for which brisk sales were anticipated. Inter E.D. were well aware of the ongoing need to develop their engines in order to remain abreast of the competition. In common with other manufacturers at the time, they had a continuous development programme, driven for the most part by the need to keep pace with new designs from other manufacturers or to implement their own improvements to existing models. In a very interesting conversation many years ago, Basil Miles told Kevin Richards that E.D. actually made a practise of regularly buying the opposition’s latest engines, testing them, stripping them down and generally finding out what made them tick. Any design concepts that were found to have merit on the basis of this evaluation were quickly adopted by E.D.! An example of this process at work in the initial phase was the deflector piston introduced early on in the career of the Mk. II and also applied to the later Comp Special and Mk. III. This was a direct response to E.D.’s realisation on the basis of their own evaluation that the Mills 1.3 was a superior design to the original Mk. II largely because of the directional control of transfer gas provided by this feature. The later improvements in the bypass passage design on the Mk. II and Comp Special were similarly influenced. In The fact that this worked both ways was confirmed only a few years ago in a conversation between Kevin Richards and Trevor Woodason, who was responsible for the development of the Mills 2.4 cc model of 1949. Trevor stated that it was only when Mills Bros. bought and evaluated an E.D. Comp Special that they realised the significance of sub piston induction. Not that it did them much good - the Mills 2.4 was even less successful than the earlier E.D. Mk. III had been.

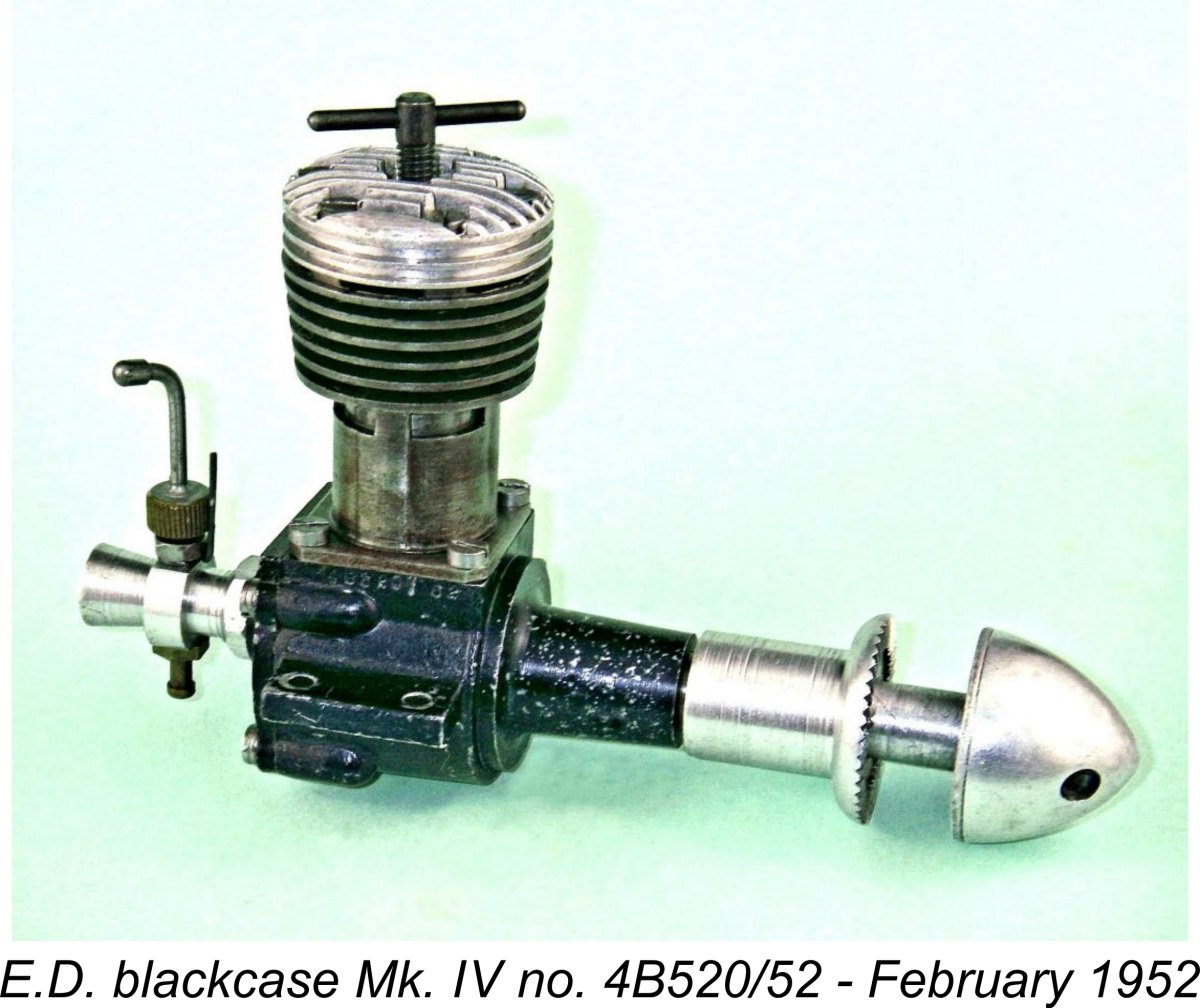

Due to teething problems with the production of the die-cast cases for this model, the initial production batches used barstock cases. A close look at one of these barstock cases confirms that each individual component required a great deal of careful and painstaking hand-work. The use of this seemingly costly component rather than simply delaying the engine's release to the public pending resolution of the die-casting issue makes it appear that E.D. was very anxious to get the engine onto the market as quickly as possible to counter the sales success of the competing AMCO 3.5 PB unit. As soon as supplies of the originally-intended die-cast cases became available, a change was made to the use of that component, doubtless reducing manufacturing costs considerably. However, resolution of that issue appears to have taken some time, during which a fair number of engines had been made with barstock cases. Even so, the barstock variant of the E.D. Mk. IV remains the rarest form in which the engine is encountered today.

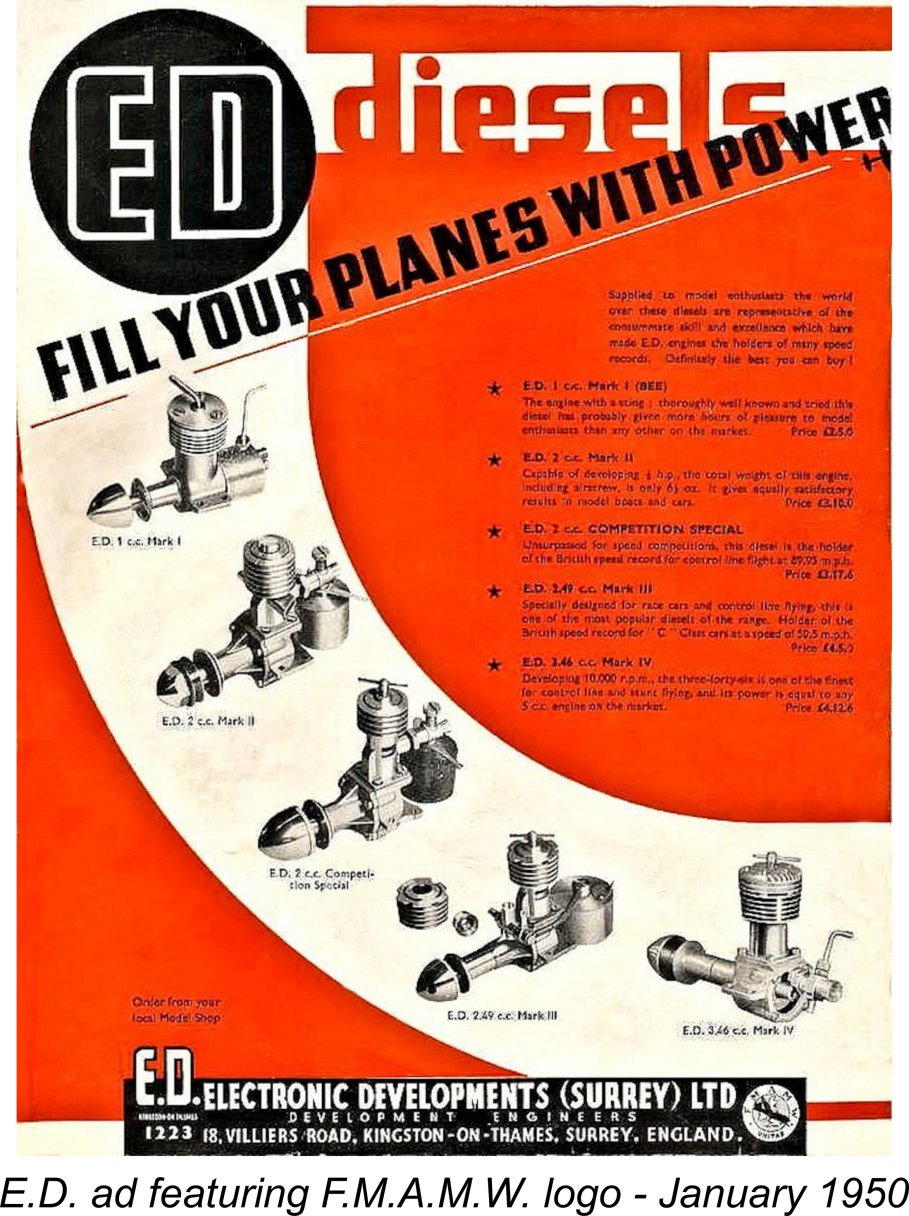

At the end of 1949, the engines were priced between £2 5s 0d for the smallest model, the Mk. I Bee, to £4 12s 6d for the largest model, the Mk. IV 3.46. To place this in context, during 1950 “Aeromodeller” magazine advertised a vacancy at their Eaton Bray office "...for a "solid scale" model builder. Must be skilled in detail work. Age 20-25. Salary about £5 a week". Presumably this was a competitive before-tax wage for a skilled young man. Hence, at this time the cost of a pretty basic model engine was in the order of a week’s take-home wages for a skilled individual. Puts a bit of context into latter-day model engine prices, doesn’t it?!? The E.D. Serial Numbering System

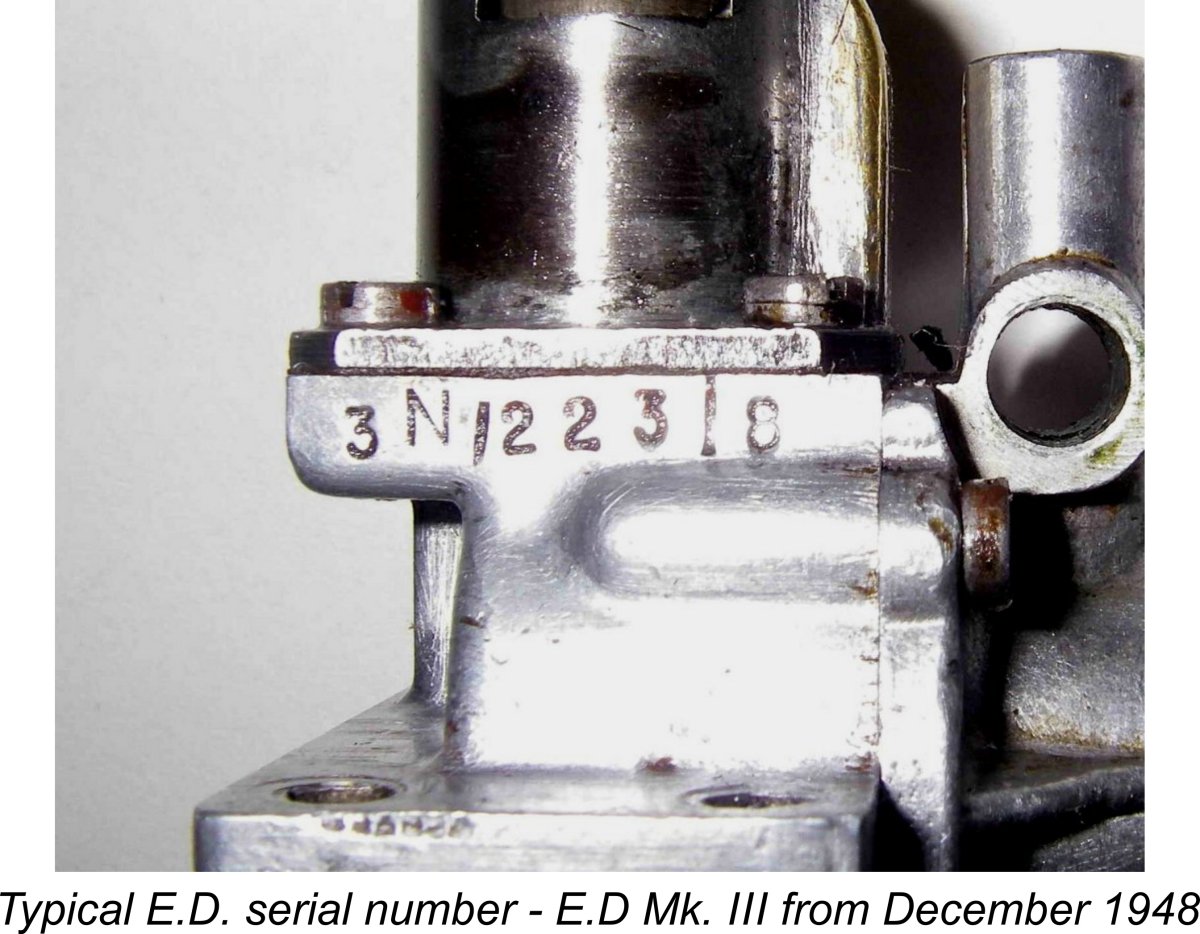

Since this system so completely defines the engines to which it was applied, it’s well worth taking a little time at this point to provide a clear understanding of the manner in which it was used. Basically, the number applied to each engine contained the following elements:

In summary, the serial number shown in the above example defines an E.D. Mk. III 2.49 cc model made in December 1948. Moreover, it was the 223rd example of that model made during that month. Narrows things down nicely! It's an interesting observation that batch numbers in the M and N categories tend to be substantially larger than those in other batches. This doubtless reflects the approach of the Christmas season during the months of November and December, during which a significant sales spike might be anticipated and provided for. By contrast, the January A batches tend to be on the low side, no doubt due to the need to sell off any surplus engines from the previous year's M and N batches. The following table lists the various model identification codes applied to the E.D. engines manufactured by the “original” E.D. company.

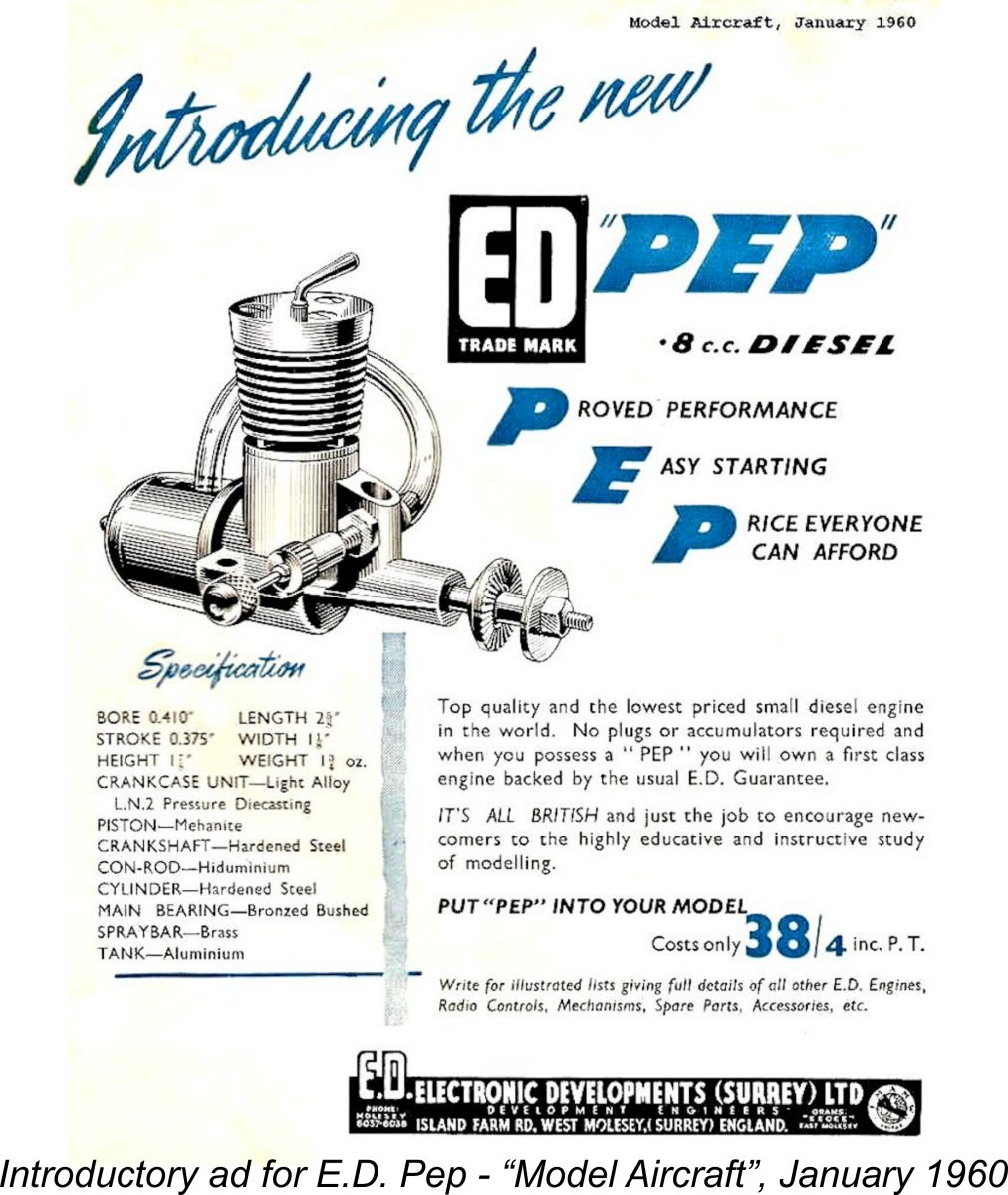

So for example, E.D. engine number E23/7 is a Mk. II made in May 1947 which was the 23rd such engine to have been produced in that month’s batch. Engine number E3/166/8 is a Mk. III made in May 1948 which was the 166th such engine made that month. Engine number XN2227 is an E.D. Bee Series 2, second variant, made in the December year-end batch in 1957 as the 222nd engine completed in that batch. And so it goes................... This system allows owners to identify and date their individual engines to a level of precision not possible with other makes from the same era. It also allows the easy identification of engines which have been restored through the grafting-on of parts from a different variant - very common with the early sideport models, for example. It would have been really great for us historians and restorers if others had followed suit! There are a few ambiguities. Although they were both marketed by the E.D. company, the E.D. Pep and the Miles Special (see below) were actually made in whole or in part by others. Both of these models used different serial number sequences which do not conform to the system described above and are not completely clear at the present time. A full discussion of the system applied to the Pep may be found in my separate article on the E.D. Pep which appears on MEN. First Stumbling Block - the Purchase Tax Case One of the first and biggest administrative problems which E.D. had to face in these early years was the 1948 Government decision to bring model aircraft parts and accessories, including "power units of all kinds" under Group 20 ("amusements") of the Purchase Tax Schedules. Prior to September 1948, kits and accessories of a constructional nature, while classified under "toys and games", had been exempt from this tax. The 1948 change in policy had the immediate effect of imposing a whopping 331/3% increase in over-the-counter domestic prices of modelling goods. In the context of the cash-starved post-war British economy, this was bad news indeed. Arguments presented by representatives of the Model Aircraft Trade Association (MATA) were successful in reversing this decision on kits, but the Commissioners of Taxation continued to insist that all parts and accessories, including engines, propellers, spinners, wheels, and in fact every identifiable accessory that could be used in conjunction with a model should be subject to tax. The tax was calculated not on the To fight this Government decision, MATA formed a sub-committee comprising Eddie Keil (KeilKraft), Jack Ballard (E.D.), Arnold L. Hardinge (Mills Bros.) and Henry J. Nicholls (Mercury Models Ltd.). Primarily at the instigation of Eddie Keil (1902 - 1968), participation in the effort to reverse the tax decision was soon greatly expanded through the formation of a new organization called the “Federation of Model Aeronautical Manufacturers and Wholesalers” (F.M.A.M.W.), the membership of which was open to any and all firms involved in any way in the model trade in a manufacturing, distribution or retail capacity. This made sense because it was the manufacturers who were most directly affected by the changed policy, although everyone's interests were of course affected in some way. The F.M.A.M.W. was in effect a campaigning and lobby group which provided individual companies with a voice to add to the joint efforts of all parties to get the 1948 purchase tax decision reversed for all classes of modelling goods, not just kits. According to Kevin Richards, a lot of firms involved in the model trade became members of this group, KeilKraft, Yulon and E.D. being just three of them. The logo of the F.M.A.M.W. appears in the lower right-hand corner of both E.D. and Yulon advertisements from early 1950 onwards. It appeared at the right-hand end of E.D.’s address block in their advertising from January 1950 right through to August 1961, after which it disappeared from the advertising.

The test case dragged on for almost two years, ending in late 1950 with the court unexpectedly upholding the Government position. To add insult to injury, the court also re-instated the tax on model kits which had previously been rescinded. Ouch …….take that, Eddie!! It does seem possible that this latter finding was a direct swipe at Eddie Keil by the court, who may have wished to "punish" the well-known kit maker and trade distributor for his temerity in bringing the case in the first place. Be that as it may, this outcome meant that British model engine and kit manufacturers entered 1951 facing not only a whopping bite out of future profits but also a very substantial bill for two years’ worth of unpaid taxes. It appears that E.D. had not made adequate provision for the payment of back taxes in the event of this outcome. While they managed to weather the storm, it seems certain that their R&D and equipment upgrading programs suffered as a consequence of having to divert precious capital towards the servicing of the substantial overdraft needed to settle their tax bill. Others were even harder hit than E.D. - Yulon ceased trading soon thereafter, while Alan Allbon barely weathered the storm. E.D.’s Golden Decade - the 1950’s

On the strength of a number of early competition successes, their 2 cc Competition Special also achieved excellent sales during the early years, continuing in production into the 1950’s and even beyond, long after most other manufacturers had abandoned their side-port designs. It was particularly (and deservedly) popular as a marine unit. Following its introduction in October 1949, the 3.46cc Mk. IV (soon to become known as the Hunter) also

In early 1952, following E.D.'s successful September 1951 model boat crossing of the English Channel (see below), E.D. entered the model boat kit business. Their flagship offering in this category was a reduced-scale pre-built version of the "Miss EeDee" model which had actually achieved the Channel crossing. This was marketed as the "Miss E.D. 2" model. However, they also included an even smaller offering known as the "E.D. Junior Cruiser". The latter model featured a pre-built hull but otherwise required completion by the purchaser. It appears however that the outcome of the Purchase Tax case discussed earlier had somewhat dampened E.D.s enthusiasm for long-term pursuit The question of the origin of these kits is an interesting one. The E.D. workshops were very much set up as precision engineering and electronic facilities, with no provision seemingly being made for precision woodworking activities. Indeed, woodworking and metalworking can scarcely be viewed as compatible activities under the same roof given the inevitable dust issues arising from the woodworking. Dust and oil make an unholy mixture! It seems very likely that the kits were produced elsewhere by others under contract. In E.D.s case, an entirely logical contract kit producer would have been International Model Aircraft (IMA), who were located only a few miles away in nearby Merton. We'll probably never know for sure ............

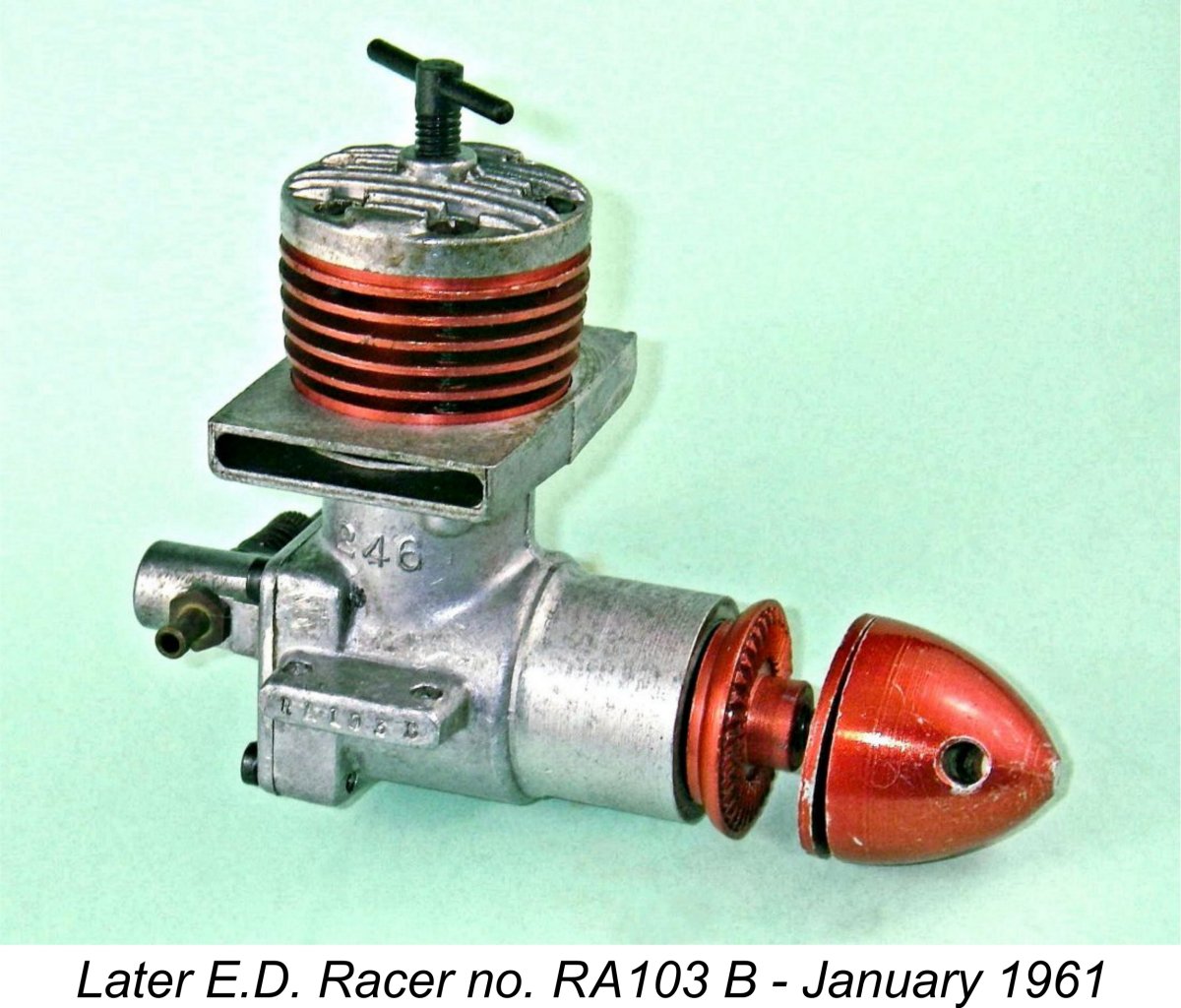

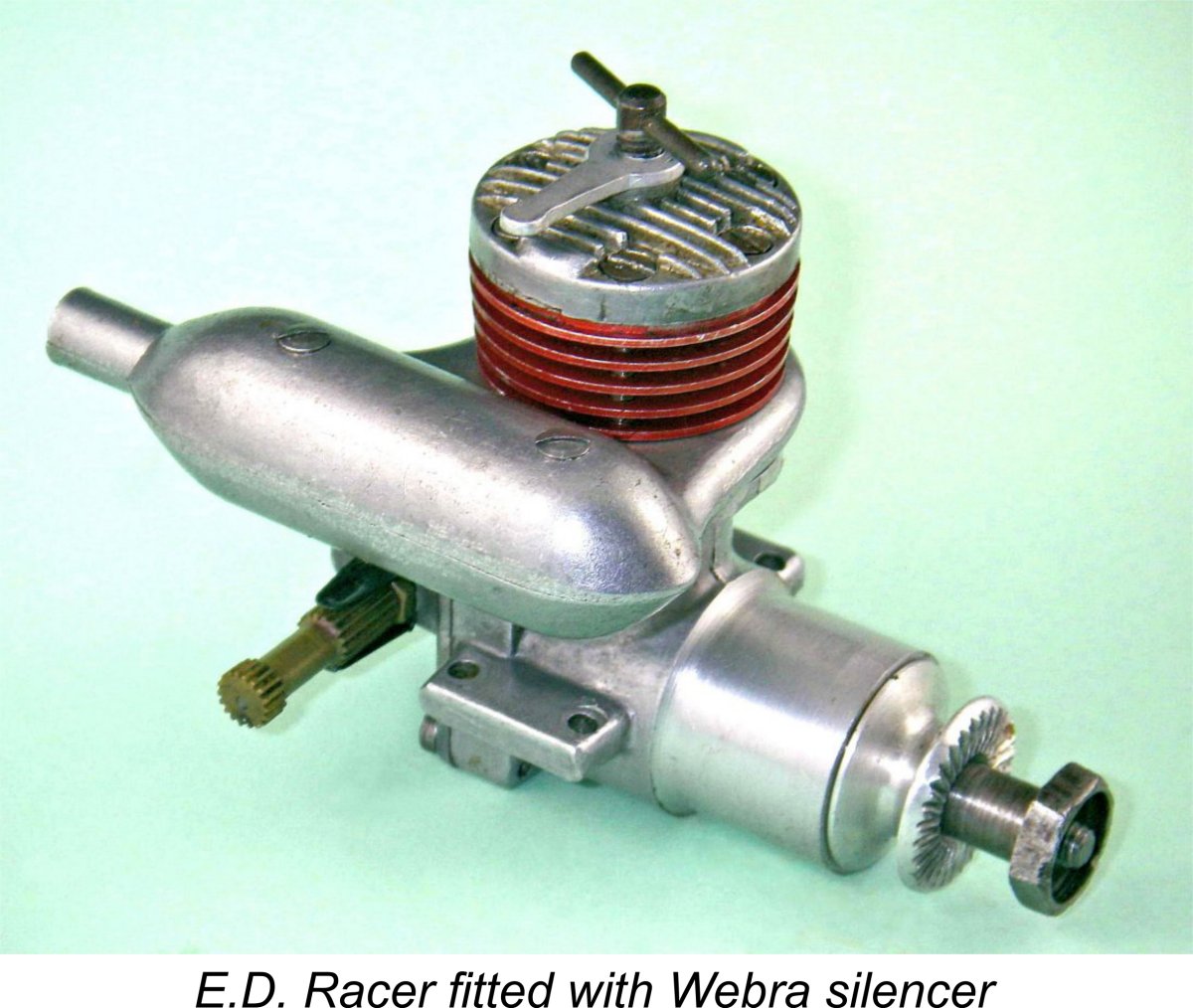

Along the way the Racer accumulated an outstanding contest record, both at the National and International levels. This was particularly true in the control line stunt event, which was then dominated in Europe by small-displacement diesels as opposed to the larger glow-plug motors which ruled the roost in the USA. The Racer powered the Gold Trophy winners at the British National Championships in every year from 1953 to 1957 inclusive, also picking up wins at the World Control-Line Stunt Championships in 1954 and 1956 just for good measure. Quite a run of success! In the hands of Pete Buskell, the engine also proved to be a formidable competitor in the International free flight contest arena. Glow-plug v Wright topped even this performance later in 1954, further raising the British record to 113.30 mph (182.33 km/hr). Some going for a 1951 radially-ported engine! However, things did not go so well for him a year later at the 1955 World Control Line Speed Championships. Still using his E.D. Racer glow-plug motor, Wright could only manage a speed of 99.4 mph (159.96 km/hr) at that meeting, good for tenth place. Even so, the Racer was unquestionably E.D.'s all-time most successful contest engine. I have This engine came to me many years ago out of the blue in a multi-engine trade. I haven't run any extensive tests on it, although I should probably do so at some point. I only recall that on a fuel containing 15% nitro, it would up very impressively on a 7x4 prop when I last ran it some years ago. I'd love to know who reworked it so competently - could it have been a test "special" made up by Basil Miles, or could it even perhaps be an ex-Pete Wright motor? At this remove in time, there's probably no way of knowing......... unless some kind reader can offer a clue?!? The Racer was always sold as a diesel, but both glow-plug and spark ignition conversion kits were made available. In diesel form, it quickly became the engine of choice for British Class A team racing competitors until challenged by the Oliver Tiger Mk. III in mid 1954. Even then, it continued to have success. Many examples used for team racing were converted by their owners into reed valve units due to the improved fuel economy which resulted. This led to the 1957 introduction of an unadvertised factory-built green-headed reed valve version of the Racer. It appears to have been this version which inspired the later 1.49 cc reed valve E.D. Fury, of which more below in its place.

Even the Bee and the 3.46 cc Mk. IV with their rotary disc valves bear only a superficial imprint of Basil Miles’ design style, although the fact that we have the obviously posed image reproduced earlier showing Basil testing an early Mk. IV engine appears to suggest some involvement on his part with that design. It’s actually possible that the Racer was the first E.D. design for which Miles was solely responsible - certainly, it is the first design to which his name was openly and consistently attached by the manufacturers. Unfortunately, the strong sales figures achieved by these engines and E.D.’s other product lines did not fully offset the financial hangover resulting from the late 1950 failure of the previously-mentioned Purchase Tax case. The unfavourable financial situation which resulted from this outcome together with the relatively weak domestic market due to continuing restricted discretionary spending levels among the hard-pressed post-war British public led E.D. to view foreign markets, in particular North America, as the principal areas in which to attempt to re-make their fortunes.

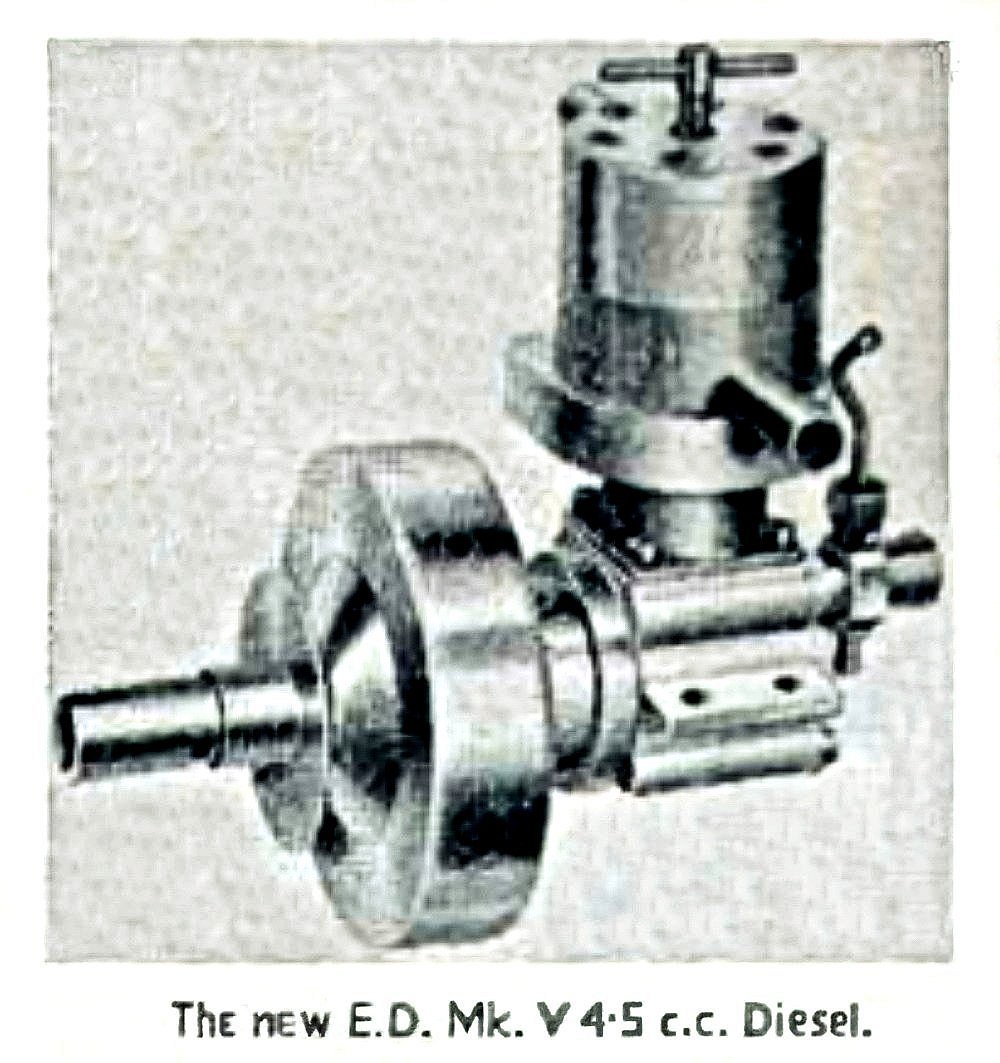

As far as the engines were concerned, American modellers were not particularly interested in diesels, preferring the glow-plug form of ignition. The US model engine manufacturing industry was years ahead in design, development and manufacturing techniques as applied to powerplants of that type. American manufacturers also had a far larger and wealthier consumer base upon which to base their revenue picture, allowing them to take full advantage of the economies of large-scale mass production. On top of this, E.D. got very little return for any export success that they did achieve in the US, since wholesaler discounts in America were far higher than those in the UK. Hence the only people who really made money were the wholesalers. Despite all the problems with the American market, E.D. did manage to achieve some export success. Finances in many European countries remained as tight as they were in Britain due to the fallout from World War II, which limited E.D.’s market potential on the Continent. However, the fact that British purchase taxes did not apply to export sales helped to make this market somewhat remunerative, with sales and competition successes being notched up in such diverse Another major challenge for E.D. during the early 1950’s was self-inflicted, since it arose from internal competition between their separate product lines. In some respects, having competing product lines doubtless made sense - accountants love the clear separation of distinct profit centres within a company. However, in the case of E.D. it compounded decision-making problems due to each product line competing within the company for financial support from the Directors in circumstances under which the level of available funding was severely limited. The significantly increased domestic competition from the likes of International Model Aircraft (IMA - FROG), Aerol Engineering (Elfin), Allbon and D-C Ltd. among others combined with these competing demands for internal resources to place the E.D. management team under considerable pressure. The ongoing financial fallout from the purchase tax decision together with the company’s limited export performance did nothing to relieve this situation. Whatever company management decided, some elements of their various programs would inevitably be under-funded. In view of these obvious problems, it was decided that the company would benefit from the development of face-to-face contacts at the decision-making level in potential market areas, both at home and abroad. A major focus of such initiatives was the development of sales to scientific, educational and military organizations. Coupled with demonstrations of the technical and educational potential of its products, the company hoped to convince governments that E.D. products had scientific and educational value and should not attract the same sales tax ra Despite this, E.D. continued to make innovative and aggressive moves to promote their products. On the 6th of September 1951, the year of the Festival of Britain, E.D. achieved a genuine modelling publicity coup. A 5 foot long model boat named "Miss EeDee" had been designed and built by George Honnest-Redlich and fitted with E.D. radio gear along with a prototype E.D. 4.5 cc water cooled diesel engine designed by Basil Miles. Using this combination, an English Channel crossing was successfully undertaken - the first such feat by a model boat. The non-stop crossing was made from the port of Dover to the port of Calais in just under 9½ hours, passing outbound through the entrance of Dover harbour at 11:30 and arriving at the entrance to the port of Calais at 20:55. The model boat was followed by a small cabin cruiser carrying the radio control operator and a mechanic as well as necessary crew. Coming hot on the heels of the Festival of Britain, the news of this event was worth much more than any conventional advertising campaign. Such a trip would have been considered heavy going for a small full-scale boat, let alone an even smaller model boat. The feat remains a testament to the designers and builders of the model, the engine and the radio equipment - in fact, to all co Interestingly enough, the 4.5 cc engine used in this venture appeared to be an enlarged marine version of the 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter. It was featured in the E.D. promotional spread reproduced above which appeared in the December 1951 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In that placement, it was specifically referred to as a prototype of the "new E.D. Mk. V 4.5 cc diesel", implying that E.D. had ideas at the time about putting it into production as the next upward step in their displacement range, maintaining their established displacement-related “Mark” series in doing so. However, for reasons which are now unclear this model never actually achieved production status. Instead, Basil Miles carried on to develop his famous 5 cc Miles Special model, manufacturing it in relatively small numbers (by E.D. standards) in his own independent workshop for marketing by E.D. as part of their range. The Miles Special began appearing in E.D.'s advertising in mid 1953. While all this was going on, work was in hand to further expand the range by adding several new models in the smaller displacement categories. The immediate and overwhelming success of the 0.55 cc Allbon Dart beginning in late 1950 had attracted the attention of a number of British model engine manufacturers, E.D. among them. This prompted a rush to get competing ½ cc models onto the market, with E.D. joining the parade by introducing the popular 0.46 cc Baby FRV engine in March 1952. This was followed in November 1952 by the 1.46 cc RRV Hornet, introduced to fill a gap in the range with respect to the British ½A contest class for engines having a displacement not exceeding 1.5 cc. As an RRV engine, the Hornet was a design derivative of the Bee, but utilize This seems to be an appropriate point at which to note a potentially serious but easily correctible design flaw in both the Hornet and its direct relatives in the 1 cc Bee series. This is the issue of crankshaft end-float (the degree to which the shaft is free to move fore and aft in its bearing when the engine is assembled). The steel prop drivers used in these models were secured using a 7 degree included angle taper formed on the shaft forward of the main journal. As delivered, almost all of them displayed a considerable gap between the rear of the prop driver and the front of the main bearing when the shaft was pushed all the way back. This was very bad news indeed - by rights the rearward movement of the shaft should be limited by contact with the front of the main bearing housing. As it was, the appearance of that tell-tale gap meant that the rearward movement in those engines was being limited by pressure applied by the crankpin to the rotary disc valve! Flicking the prop for starting inevitably pushed the shaft back against the disc, resulting in accelerated (and uneven) wear of the alloy disc and generation of harmful particulates. Even worse, if the engines were used in pusher applications or started in reverse (as sometimes happens), the rear disc became the thrust bearing, greatly increasing the wear rate as well as adding a ton of friction. Finally, a nose-on crash would "punch" the crankpin into the rear disc, potentially damaging either or both of the respective components. One can of course fix this problem very easily by removing the prop driver using a suitable puller and installing a steel spacer of the required thickness between the prop driver and the front of the main bearing. However, a far more elegant and less obtrusive fix is to mount the prop driver in a lathe and use a 7 degree tapered reamer to deepen the tapered recess in the rear of the prop driver to the amount required to eliminate all but 5 to 10 thou of the end float. This eliminates any possibility of pressure being applied to the rear disc by the crankpin, since the rearward movement of the shaft will now be limited by the front of the main bearing. As a side benefit, this approach also adds to the available prop mounting thread length by setting the prop driver a little further back, something which the use of a spacer would not do. The prop mounting thread length on these engines was marginal as supplied, particularly given the use of a light alloy spinner nut to secure the prop, so this alone is a valuable improvement. This step can add many hours to the working life of one of these engines. All of my own E.D. Bee and Hornet models have been modified in this way. I assume that it was cost which precluded the more precise fitting of these components at the E.D. factory.

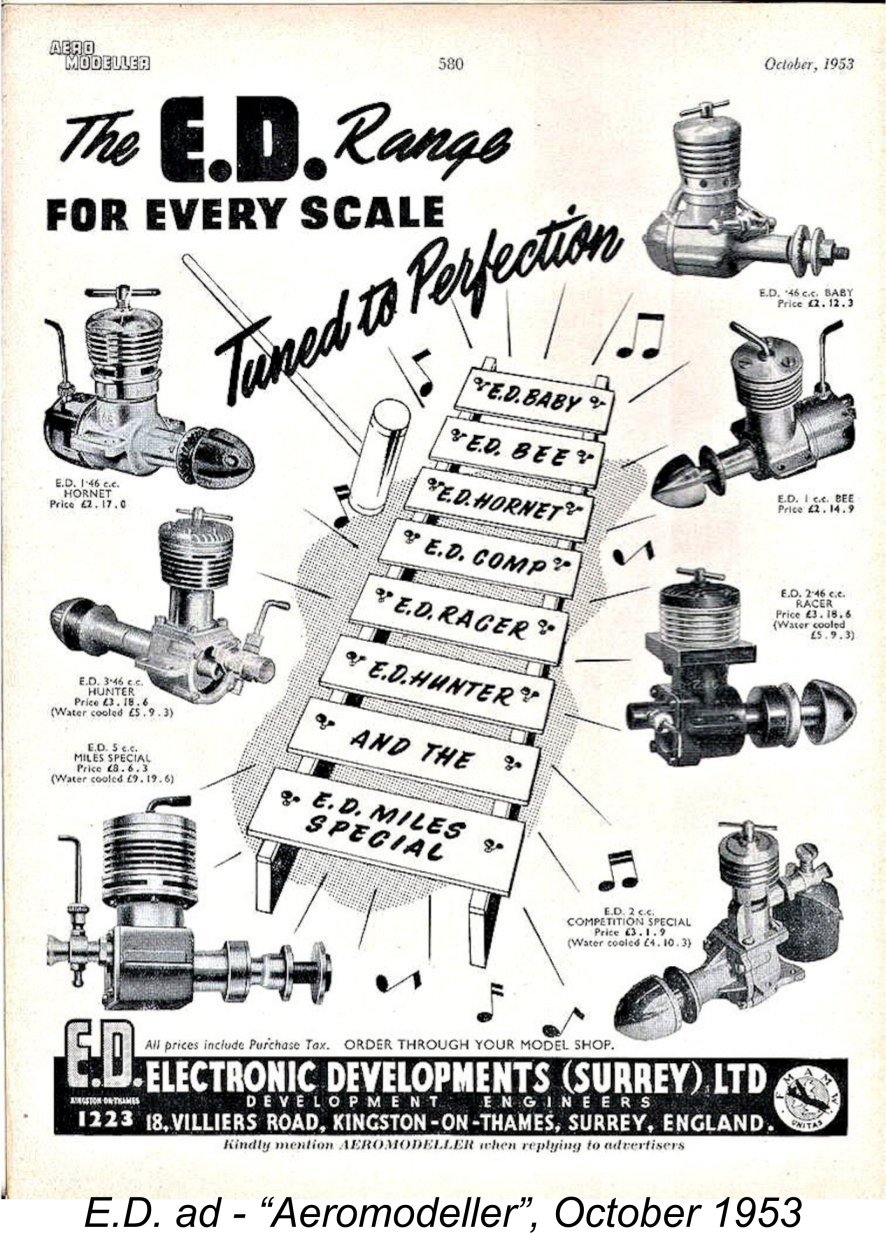

According to later reports, E.D. had also planned to phase out the increasingly venerable Comp Special at the end of 1952, more or less concurrently with the introduction of the Hornet, which they clearly saw as being in effect a updated replacement for the Comp Special. However, orders for the dependable and user-friendly old Comp Special continued to be received in such numbers that this decision was reversed. The engine was destined to remain in production for another 9 years, largely on account of the great and well-deserved popularity of its marine version. As noted earlier, the high end of the displacement scale was augmented in mid 1953 by the addition to the range of the Miles Special 5 cc RRV diesel engine. Although marketed by E.D. along with their other models, the Miles Special was in fact independently manufactured by Basil Miles in his own workshop. The engine was also available in glow-plug form direct from Miles - it was never specifically advertised by E.D. in this guise. The above advertisement placed in the October 1953 issu At around this time, Basil Miles had some personal problems which forced him to sever his open association with E.D. which had commenced in early 1951 with the announcement of the E.D. Mk. III Racer. However this did not stop Miles from continuing to design and build engines at home for distribution by E.D., the Miles Special being the best-known example. He also retained some form of arms-length design consultancy with the firm. Also in 1953 there was a change in leadership, with founding Managing Director Jack Ballard leaving E.D. to become involved with an entirely separate manufacturing operation which was in direct competition with the E.D. firm which Ballard had helped to found and had led for seven years. There has been a fair bit of speculation in the past regarding the basis for this split. According to the late Ron Moulton (as related to Kevin Richards), it was falling sales figures and disagreements among E.D.'s Board of Directors regarding appropriate responses on E.D.’s part which led to the parting of the ways between Ballard and the rest of the Board. Evidently Ballard had some very strong ideas in this regard but was unable to obtain the necessary support of the Board as a whole. In the end, a compromise could not be reached and Ballard departed to run his own show in his own style.

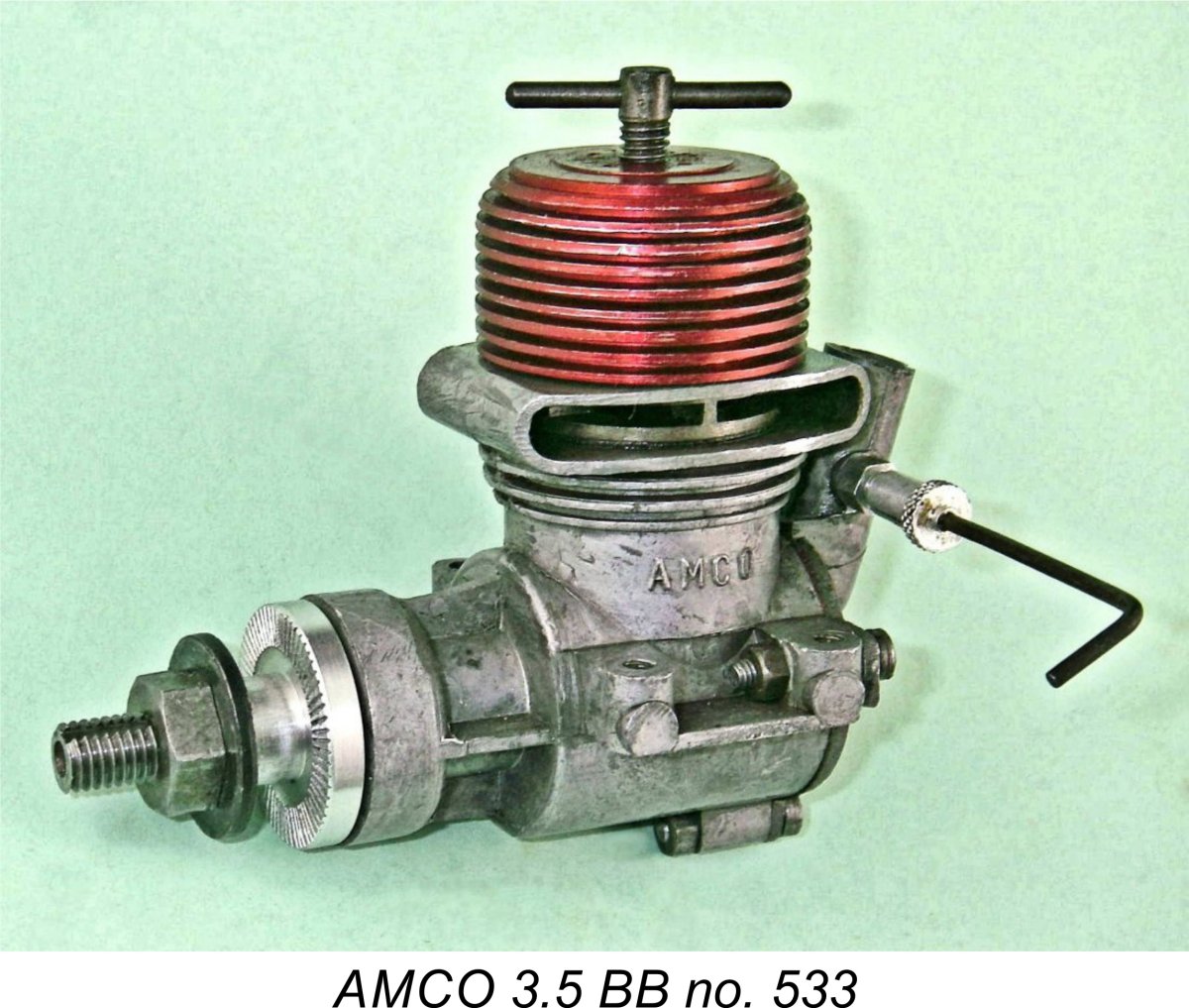

After joining forces with Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., Ballard established a sister company called AMCO Model Engines Ltd. to market the engines. Dennis Allen was brought on board to assist on the engine production side. The re-introduced AMCO 3.5 BB was soon joined by an improved version of the AMCO 3.5 PB design along with a range of radio control equipment marketed as the Avionic line. However, the results fell well short of meeting Ballard’s expectations in commercial terms. I The strong American marketing influence may provide some clues as to the kind of advice that Ballard was offering to the E.D. Board of Directors prior to his departure - update the appearance of their products and package them more along American lines. Ballard clearly believed in the selling power of “eye appeal”, which the J.B. range undeniably had in buckets!

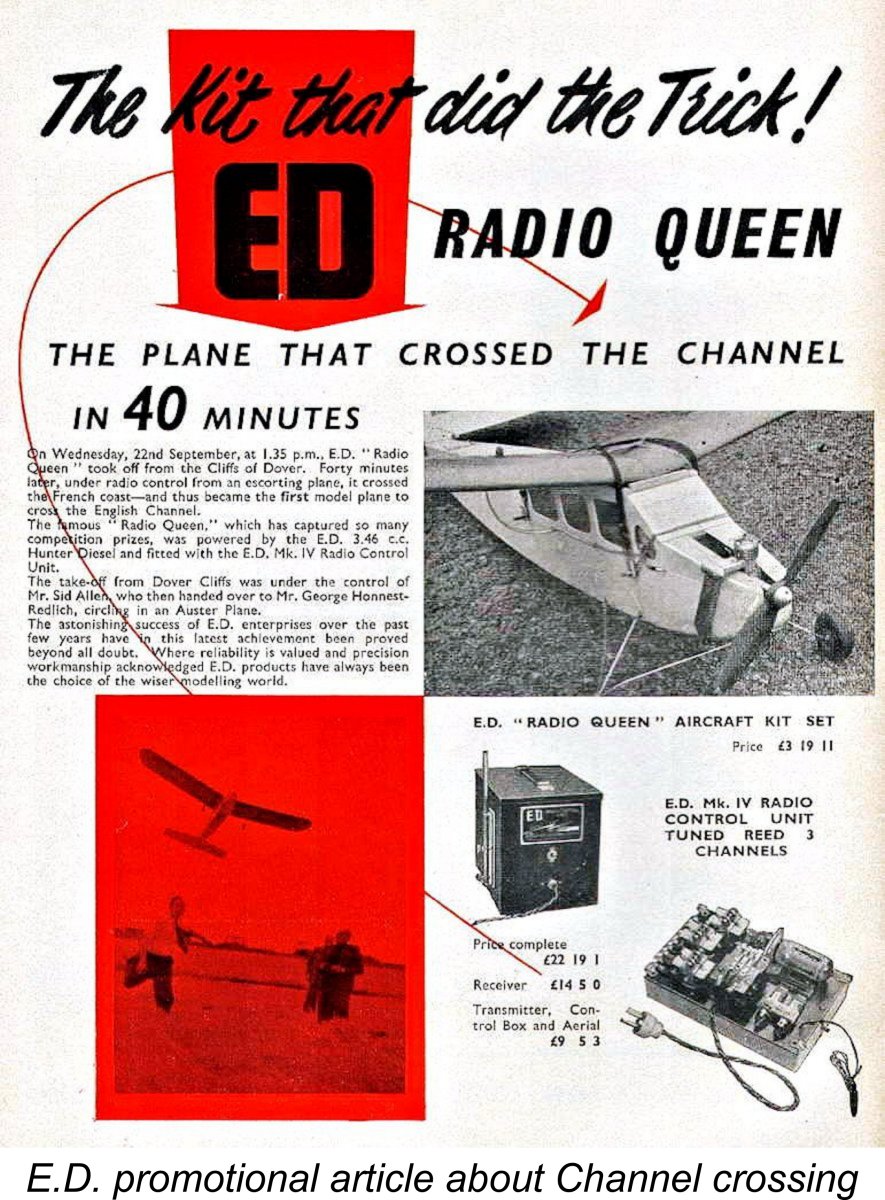

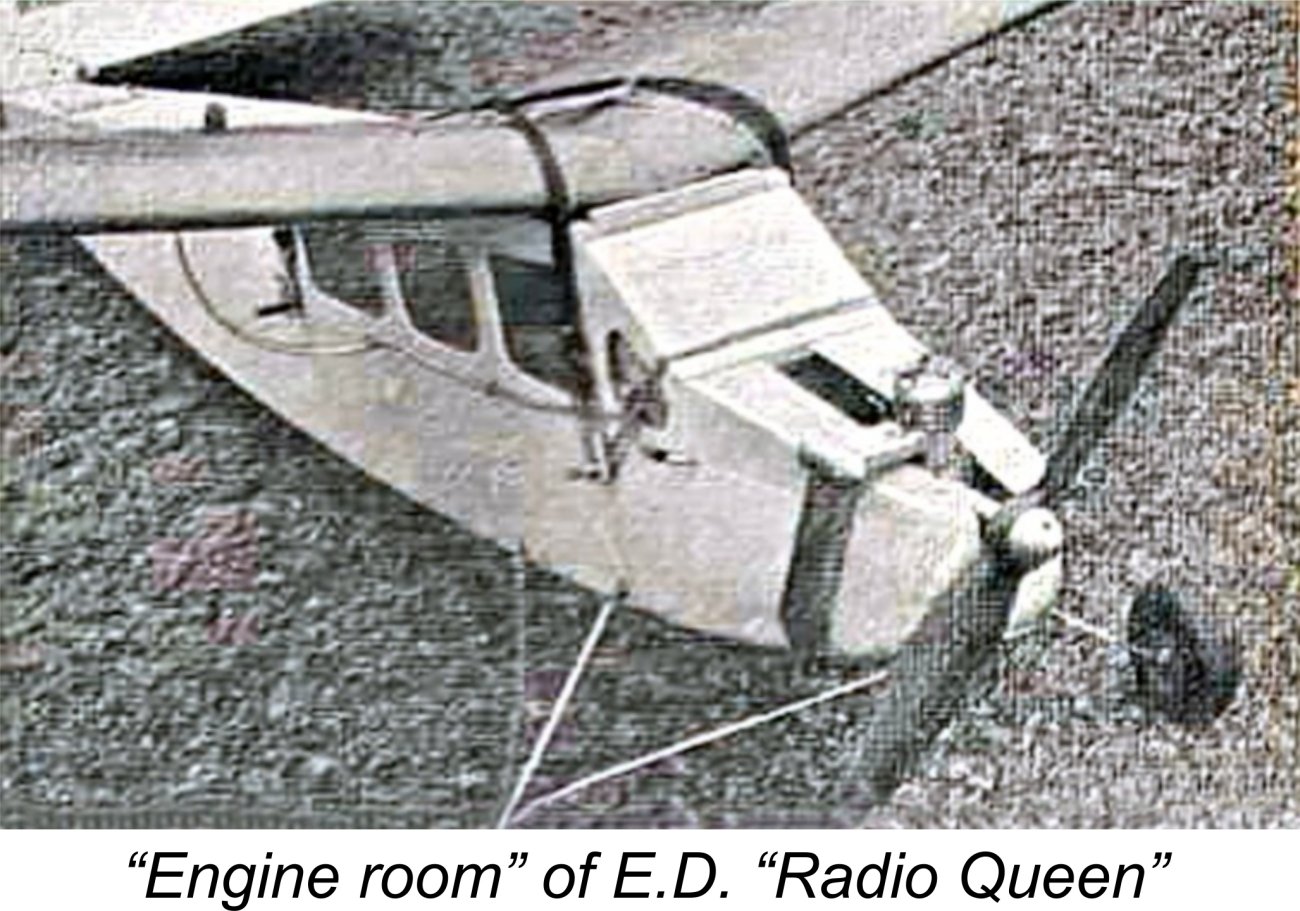

Following Ballard’s departure, the job of Managing Director at E.D. was taken over by Jim Donald, one of the original Directors. One of Donald’s early achievements was yet another major publicity tour de force. On September 21, 1954, doubtless inspired by the success and publicity derived from the earlier Channel crossing by a model boat, E.D. successfully undertook the first non-stop crossing of the English Channel from England to France by a model aeroplane, thus reprising the 1909 achievement of the French aviation pioneer Louis Blériot in miniature (and in reverse!) 45 years later. The aircraft used for this very impressive achievement was a "Radio Queen", E.D.'s one and only model aircraft kit which had been designed by Lt. Col. H. J. Taplin. It was powered (or perhaps more precisely, underpowered!) by an E.D. 3.46 cc Hunter, as it was now known. Th At 13:35, following an athletic but successful launch from a field appropriately named Blériot’s Meadow, climb-out was controlled by one of the famous names of the day, Sid Allen. Control of the heavily-laden model was then handed over to E.D.’s George Honnest-Redlich in the circling Auster which would follow the Radio Queen during its journey. The flight itself was uneventful, and after crossing the French coast at 14:15 the model had achieved its maximum altitude of 3,100 feet and was turned on course for Calais Marck airfield. On arriving over the field at 15:17 after a flight of 102 minutes (as compared to Blériot’s time of 37 minutes between the same two points), the model was spiraled down to 800 ft and the Auster rapidly landed to regain control from the ground. Unfortunately, by the time the Auster had It should be borne in mind that this feat was accomplished using the vacuum-tube radio equipment of the day in an overweight model inadequately powered by a 3.46 cc (.21 cuin.) diesel engine of basically 1949 vintage. The poor old E.D. Mk. IV looks positively overwhelmed by the size (and the doubtless considerable take-off weight) of the model! In this day and age, power would probably have been a 0.61 cuin. (10 cc) glow-plug engine at the very least. Quite an achievement and From this point onwards the engine side of the business assumed an ever-greater importance in the affairs of the company, perhaps due in large part to the continued lack of trans-Atlantic success in selling E.D.’s radio gear in North America. This may have had something to do with a further parting of the ways, when E.D.’s original radio control guru George Honnest-Redlich left to form his own company called Radio & Electronic Products located in nearby Mortlake. He reportedly became a pioneer in the development of remote-controlled garage door openers! One by one, the Old Guard was moving on ........... by this time, only around half of the original working shareholders remained with the company. This raises an intriguing question - how was the departure of the original shareholders managed from a fiscal standpoint? It would be interesting to know if their stakes in the company were bought out or whether they simply continued to be E.D. shareholders despite now being retired or working elsewhere. I suspect that the latter approach was the most likely one to have been taken, but it would be good to know.

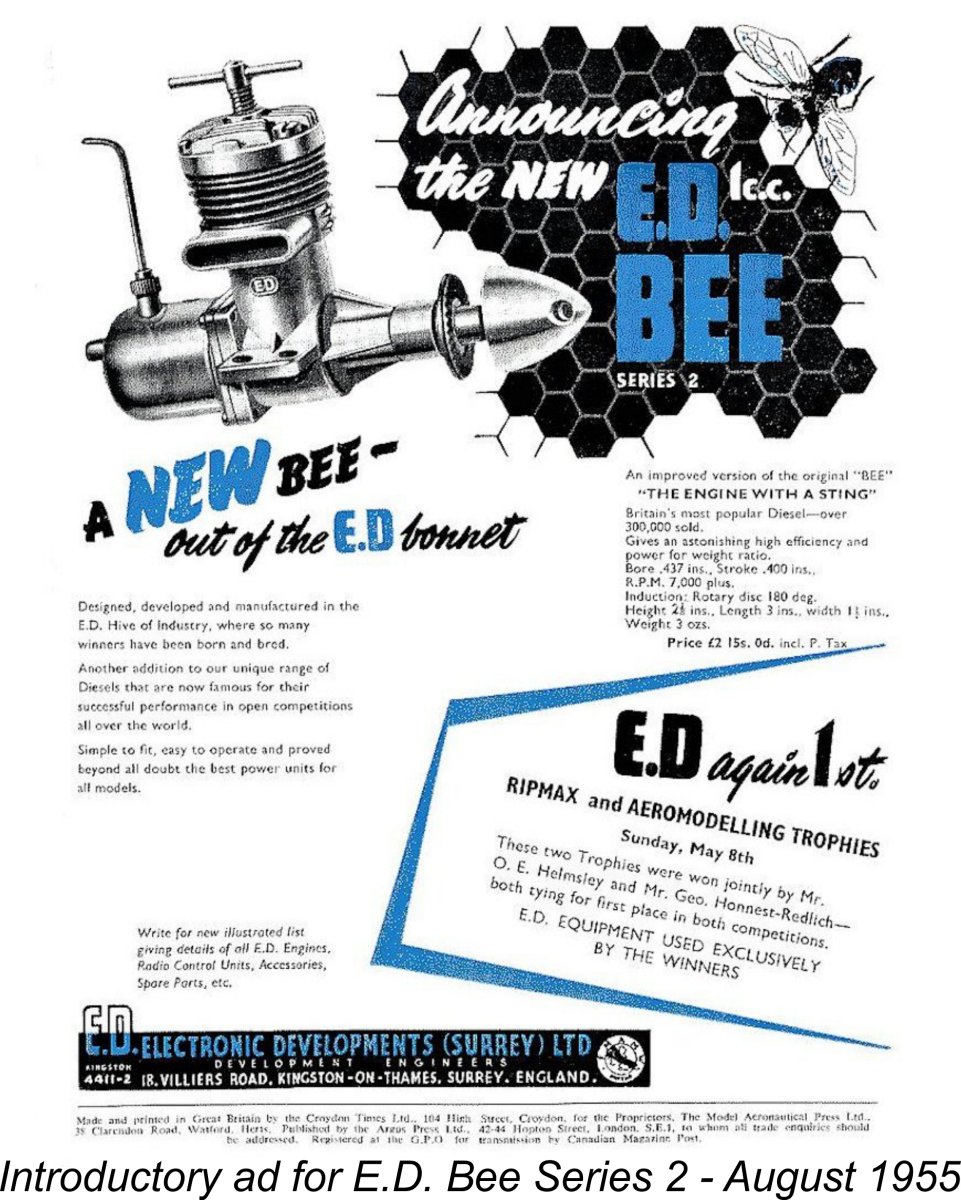

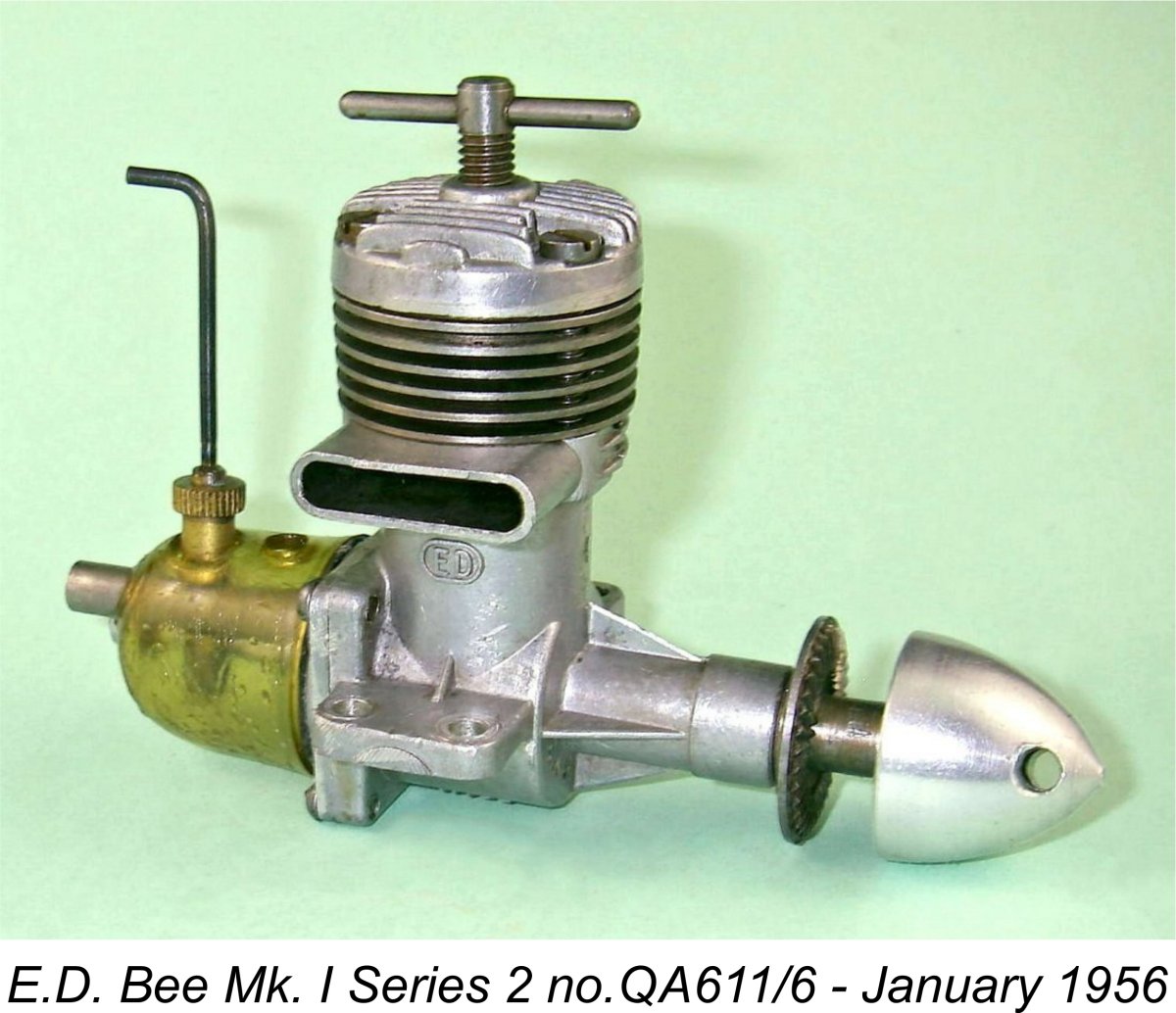

There was no great improvement in performance, but the engine certainly presented a striking appearance and proved to be both reliable and easy to handle. Its Achilles heel was the continued use of an aluminium alloy valve disc, which wore relatively rapidly in service. This was exacerbated by the fact that the engines also continued to incorporate the excessive shaft end-float to which reference was made earlier. The Series 2 Bee went through several more design evolutions, most notably with respect to the transfer porting. The first such revision was a change from the original system using two internally-formed bypass flutes in the cylinder wall (carried over from the Mk. IV Hunter) to a revised arrangement using external bypass passages which fed three upwardly-angled transfer ports. The final evolution, of which more below in its place, increased the number of transfer ports from three to four. It also featured a valve disc made of more suitable material. The Bee maintained its position as one of Britain’s top-selling engines for the balance of the 1950's largely due to its wide acceptance among beginners and sport fliers. My own first new diesel (in 1959) was one of these units, and I was far from being alone. The sales figures achieved by the Bee and a number of its stablemates in the E.D. model engine line-up seem to have had the effect of reinforcing the Director’s growing perception of the ever-increasing importance of the model engine range in E.D.’ However, the rate at which the engines were now being manufactured was taking its toll upon the aging wartime machine tooling which the company was still using at this point. This machinery was in urgent need of upgrading by this time. If E.D. wished to maintain and if possible enhance full production of both engine and R/C lines, some form of action was clearly required to redress both the imbalance in designated production space and the need for upgraded equipment. Fortunately, the revenues generated from engine sales at this point in time were apparently sufficient to enable the company to lever the financial support necessary to fund the required improvements in their production facilities. This did however impose a significant additional debt servicing load upon the company's finances, which was to haunt them in future years.

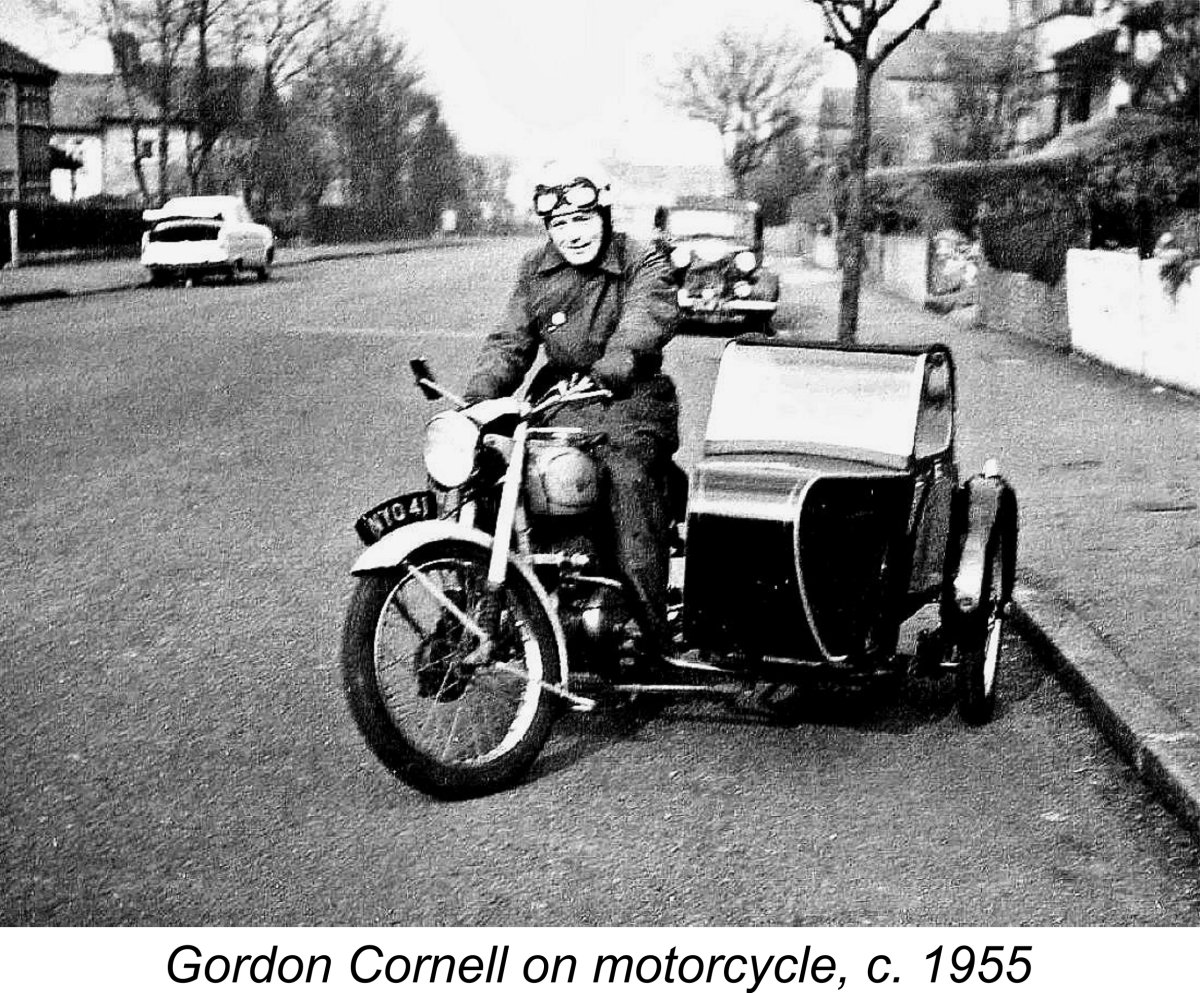

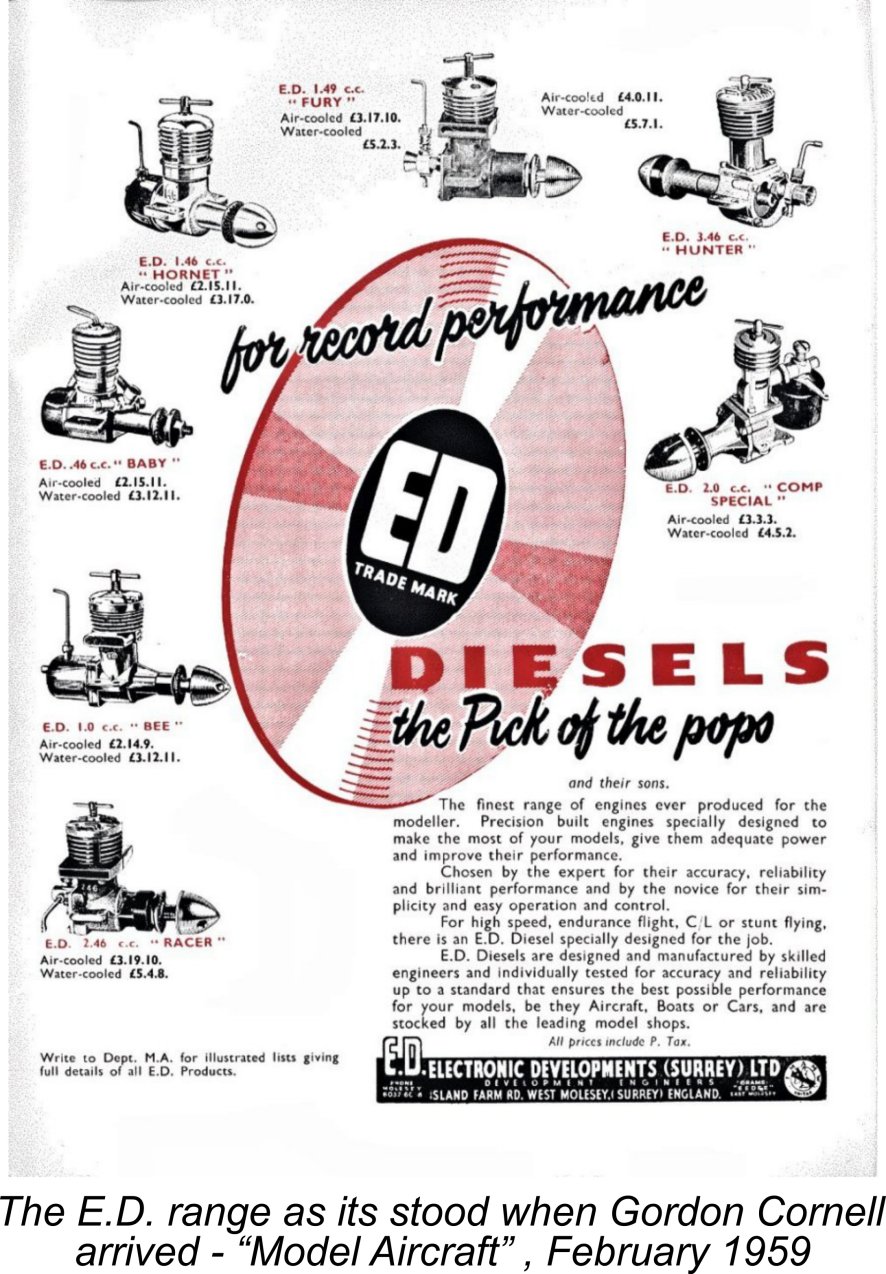

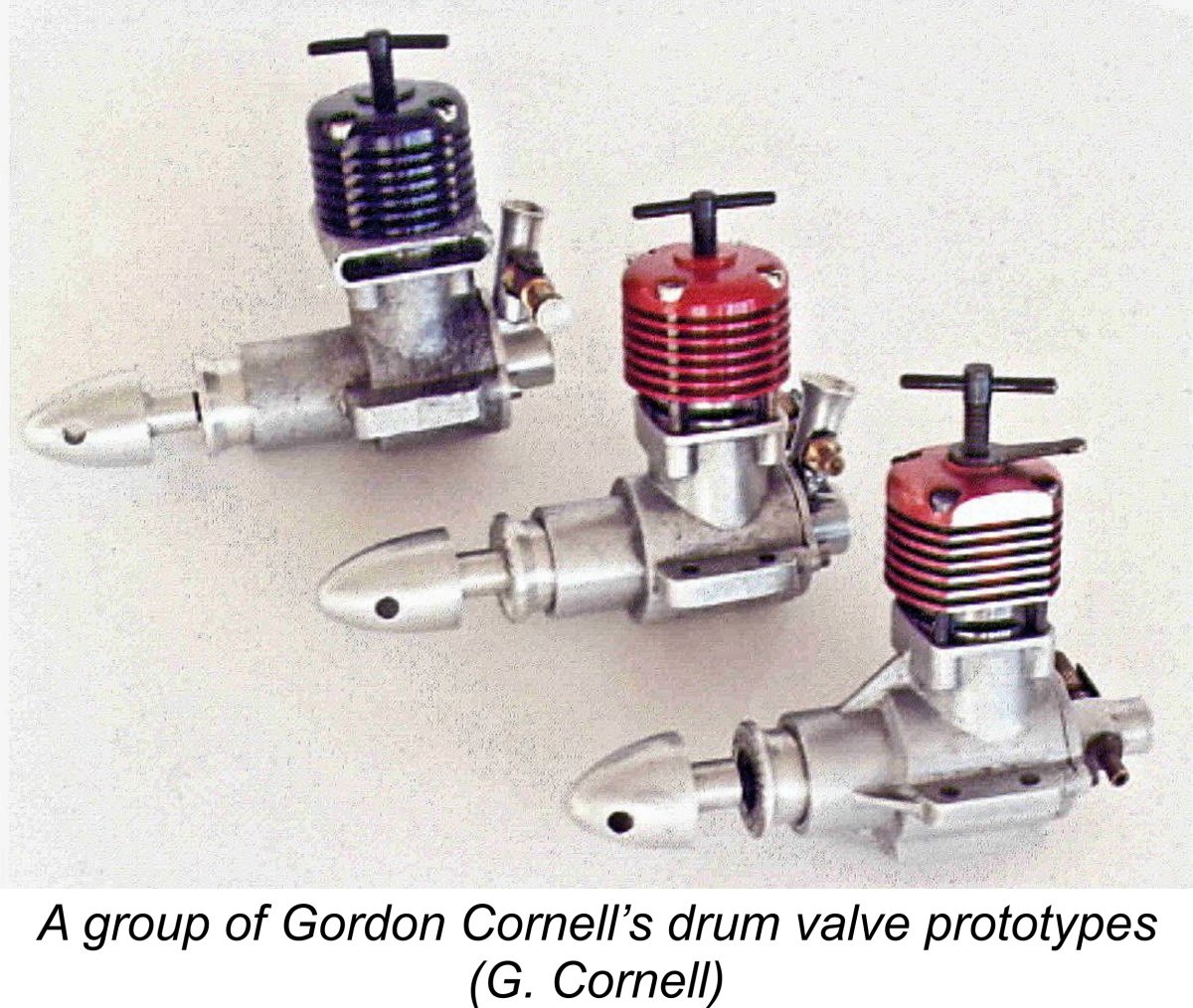

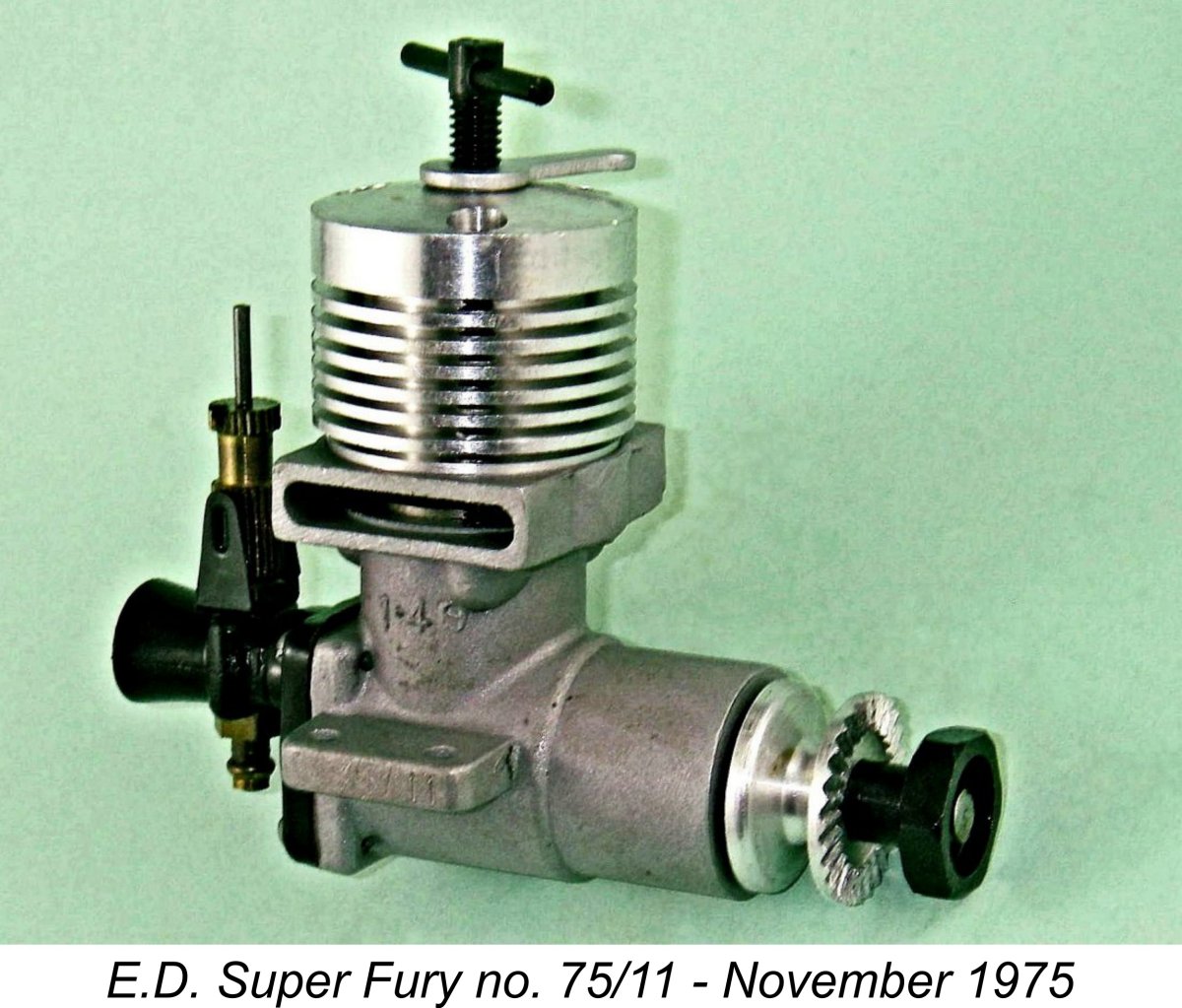

The investment required to accomplish this move must have taxed E.D.’s financial resources in the short term at least, since the financial return resulting from their enhanced production capacity would of course take some time to accrue. In the meantime, they had to service the debt which the upgrades had imposed upon them. It would seem that E.D.’s R&D programs suffered to a degree from this situation, since after settling into their new premises E.D. stood pat for the next two years, introducing no new models but rather re-evaluating and making minor modifications to their existing designs and production programs while maintaining their sales performance with their loyal customer base. At this stage the com However, no company in a competitive field such as this can afford to stand pat for too long. By 1958 it was clear that new models were urgently required to meet the evolving competition from other manufacturers. In May 1958, E.D. finally announced their first all-new model for two years, the 1.46 cc reed-valve Fury. This was the final E.D. design with which Basil Miles was associated, albeit on an unattributed basis. The Fury looked like a scaled-down version of the Racer but was equipped with reed valve induction. Most of them had green-anodized heads, although a few were left plain as machined. As previously-mentioned, an unadvertised but very similar 2.46 cc green-headed reed valve version of the Racer The Fury was released with high expectations but sadly proved to be uncompetitive both in terms of price and performance. It was by no means the success that it was hoped to be, hence doing nothing to pull E.D. out of the doldrums into which they were then just beginning to sink. It seems to have been at around this time that Basil Miles’ arms-length connection with E.D. was finally severed for good, although he remained active in model engine development into the An interesting sideline to the E.D. story which had its origins during this period was the development of the 7 cc Taplin Twin which made its commercial debut in Mk. I form in December 1958. This unit was designed by Radio Queen designer Col. H. J. Taplin following a series of experiments beginning in the mid 1950’s. The Twin was manufactured by Col. Taplin’s Birchington Engineering Company of Albion Road, Birchington in Kent. Earlier 4 cc and 5 cc prototypes had respectively used cylinder assemblies from the E.D. Despite this successful collaboration, the failure of the Fury as well as a number of on-going production problems still left E.D. in the latter part of 1958 facing a situation in which development of their range had gone sideways and their production program was in a very shaky state, with a rising incidence of quality control problems due in large part to their continued partial dependence upon aging equipment which they could not afford to fully replace. Moreover, they had now lost the services of Basil Miles and had little in-house engineering expertise of their own. Clearly they needed help, and needed it quickly! As matters transpired, such help was available in close Accordingly, in late 1958 Gordon Cornell moved over from IMA to become the chief engineer for E.D. It quickly became apparent to Gordon that there were many problems at E.D., the shaky state of their finances being merely one of a number of challenging issues facing the company. He found that although all of the key players were very nice people to work with, there did not Gordon’s brief from the E.D. Board of Directors was, in his own words, “to create a development plan to bring all designs up to a satisfactory production standard in order to satisfy both the bank and the Directors”. It would appear from this that E.D.’s financial backers were now putting serious pressure on the company to improve its financial performance. In a subsequent conversation with Kevin Richards, Gordon shared some of his impressions upon his initial familiarization with the E.D. operation. He particularly recalled his astonishment at finding that the somewhat unique job of soldering the transfer port and inlet boss on the venerable Comp Special, then in its 11th year of production, was still being carried out in the same manner by the same personnel as it had been in 1948!! Gordon wanted to carry out a time-and-motion study of the entire E.D. machining and assembly process, including this archaic operation. However, management did not support his recommendation. This was just one of a number of factors which led to Gordon becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the state of affairs at E.D. as time went by. In the company’s defense with respect to the Comp Special at least, it’s only fair to point out that production levels for that old warhorse had probably fallen to the point at which money spent on the recommended study would probably have generated little if any return. Into the Swinging ‘60’s

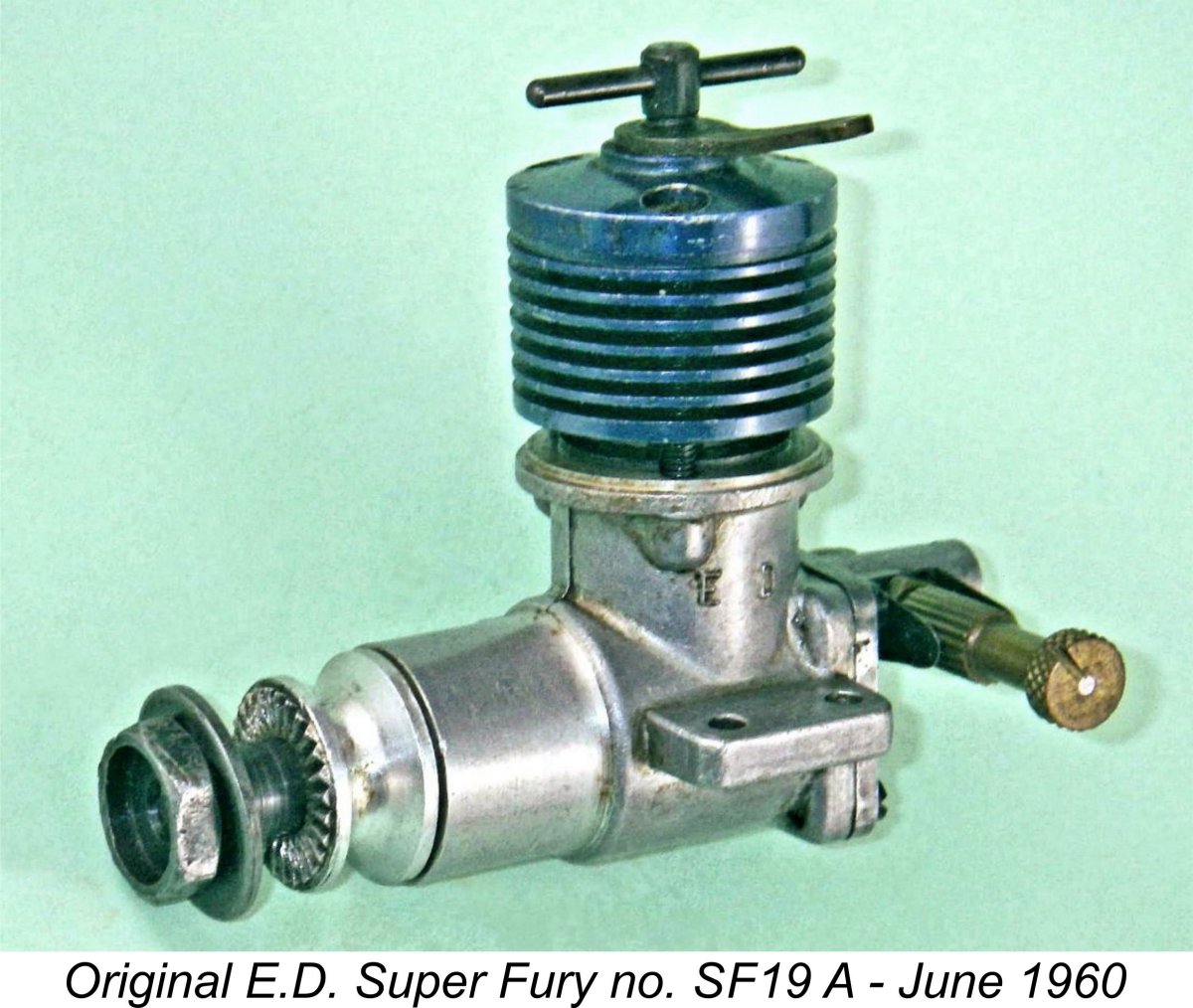

Upon joining E.D., Gordon showed his TR 148 prototype to E.D. management, who were duly impressed. They went so far as to ask Gordon to assess the feasibility of putting this model into production. However, Gordon took note of the company's financial condition and decided that the resources required to develop this prototype into a production model simply weren't there. Instead, he recommended that the best way forward would be to focus upon the further development of E.D.'s existing models. This plan was duly adopted. Once he had settled in and assessed the many problems requiring attention, Gordon initially tackled the task of completely redesigning the lacklustre Fury to deal with its performance shortcomings. The result was the first in the long-lived series of Super Fury 1.46 cc engines that were to come. In addition to other internal modifications, Gordon returned to the RRV induction system of Basil Miles’ original Racer design and did away with the opposing exhaust ducts in the crankcase casting, allowing the 360° porting of the cylinder to vent freely—a logical modification applied not infrequently and often less expertly by many earlier Racer owners.

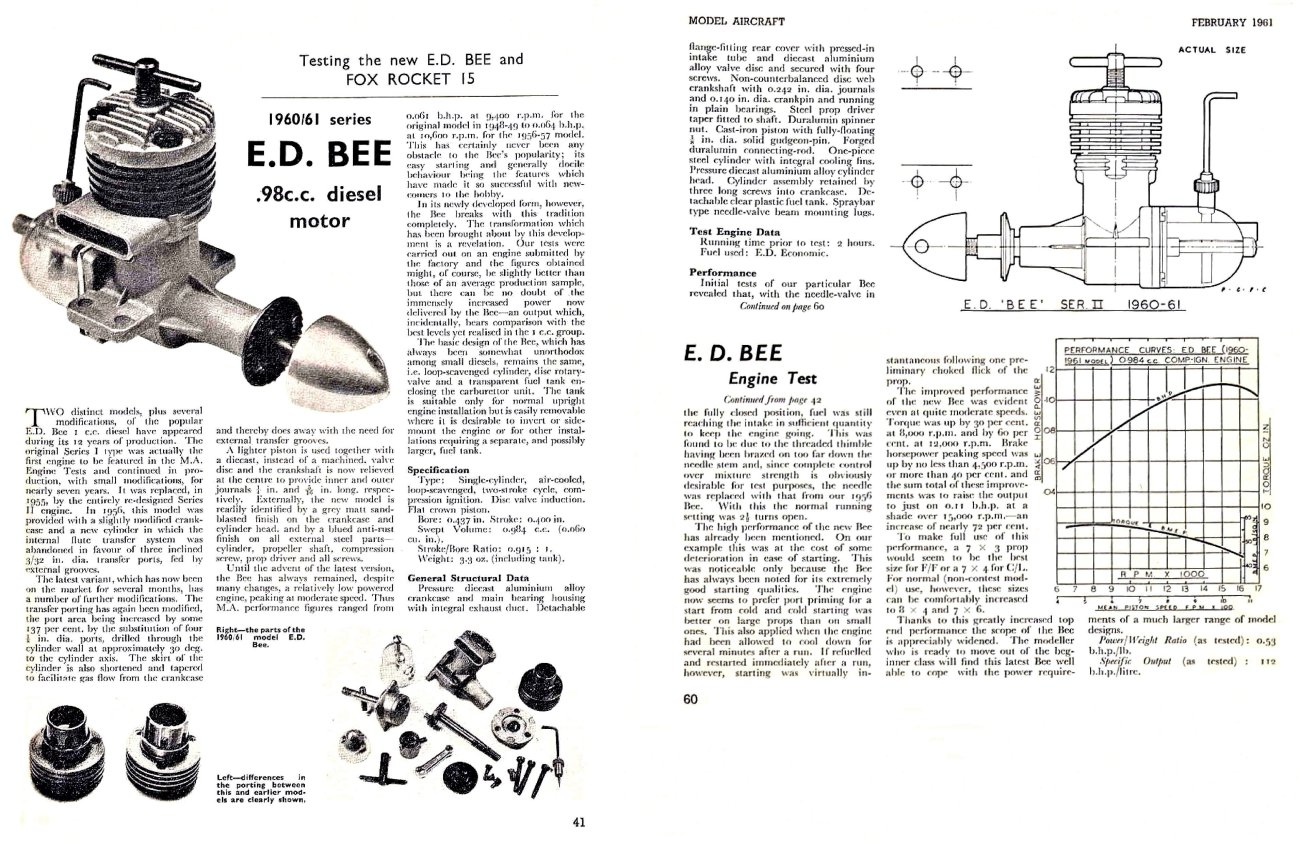

Thankfully, Gordon has taken the trouble to set out a very comprehensive record of the development program which led to the creation of the Super Fury. This account may still be found on Ron Chernich's "Model Engine News" (MEN) website. Well worth reading! The Super Fury was a top performer by the standards of its day, surviving for some years in its original form before finally disappearing at least for a while in mid 1964, subsequently making a comeback in 1970 under new ownership (see below). The first 200 or so examples of the new model were produced with magnesium alloy cases which were most likely left-over Fury components. However, these were to be the last engines produced by E.D. using cases cast from this material - all subsequent castings were produced in aluminium alloy. There have been tales to the effect that this change was prompted by the risk of fire arising from the use of the potentially inflammable magnesium alloy, but Gordon Cornell later told Kevin Richards that the real reason was the poor quality of the magnesium alloy cases. In Gordon’s recollection, something like 50% of the cases had proved to be unusable, a clearly unacceptable ratio. Having got the Super Fury off to a good start, next on Gordon’s upgrade list was the old E.D. Bee, now in its fifth year of production in Series 2 form with loop scavenging and side-stack exhaust. Apart from its first year or so of production in Series I form beginning way back in mid 1948, the Bee had never been noted as a “performance” model, although it had proved extremely popular with beginners and sport fliers. However, its performance disadvantage over a number of competing models had now widened to the point where sales were definitely beginning to flag even among its target purchasers.

This being the case, it's a completely inexplicable fact that E.D.’s advertising failed to so much as mention the vastly improved performance of the revised design, continuing to present the Bee exactly as before. Consequently, the modelling public remained for the most part in blissful ignorance of said improvements unless they happened to either read Chinn’s test report or see one of the new models in operation. Unfortunately, in the absence of any promotional effort by the manufacturers, the Bee’s reputation as a dependable but less-than-stellar performer was too well entrenched by this time for the performance of the relatively few examples of the revised model which reached the flying field to restore the engine’s former popularity. Hence the vastly improved design really didn’t have much impact upon the waning fortunes of the E.D. enterprise - another clear and totally inexplicable case of lost opportunity. Examples of the Bee in this form are relatively rare, hence being prized collector’s items today.

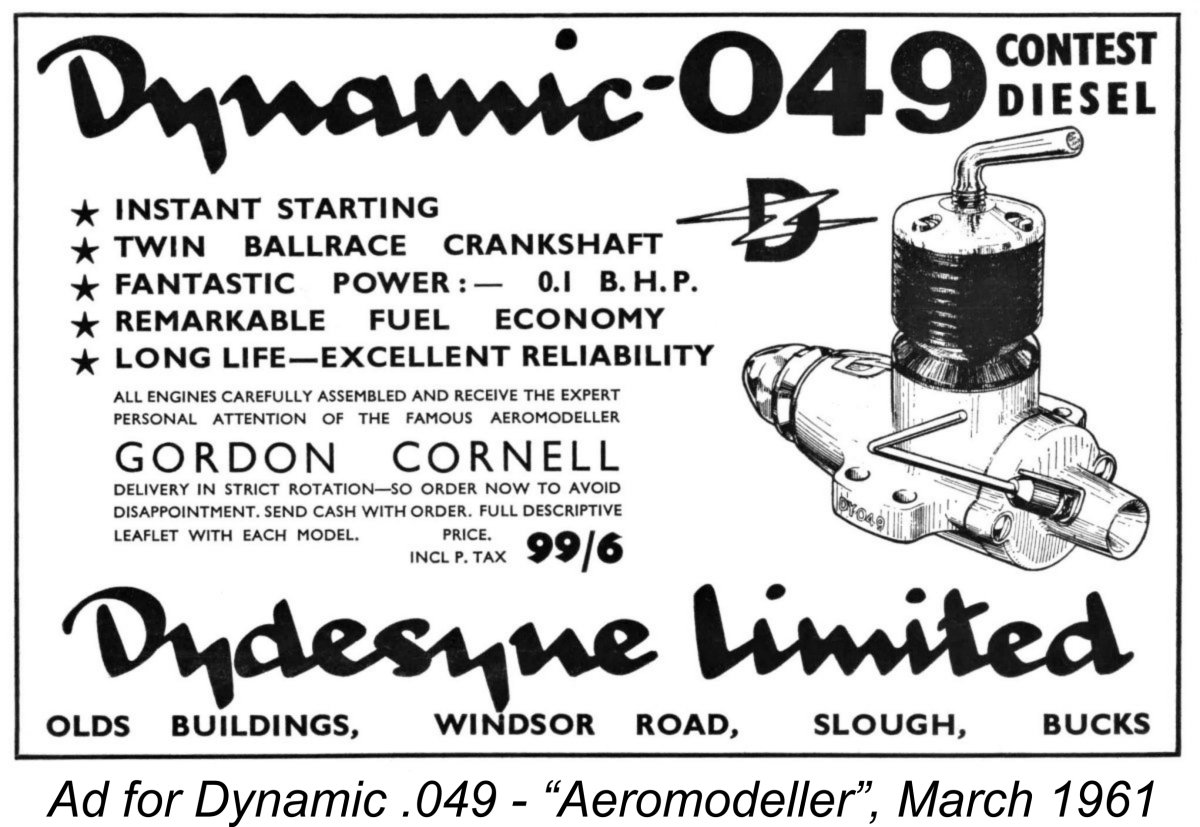

However, events had been unfolding at E.D. that were to have a decisive influence on Gordon’s future relations with the company. While Gordon was sorting out the various production issues and finalizing the design of the Super Fury in 1959, the company management had been looking at expanding into the .049 cuin. 1/2A field which was then becoming a preoccupation of a number of British manufacturers. This was prompted by the success of the American .049 glow-plug models which had begun to reach the British market in quantity in the late 1950’s. A British “.049 revolution” of sorts had been started in mid 1959, with D-C Ltd., Allen-Mercury and IMA (FROG) all adding .049 glow models to their respective ranges and KeilKraft joining in the fun later in 1960 with their excellent Cox-influenced Cobra .049 glow-plug model. Shades of the earlier 1/2 cc diesel stampede of 1951-52............ Quite understandably, E.D. wanted to be a part of this movement. However, in deciding to participate they made the first of a whole series of critical errors of judgment which were ultimately to have a profound influence upon the future of the company. For reasons which defy rational analysis, they failed to recognize the fact that the "British 1/2A revolution" of 1959 had been triggered specifically by a rising interest in small glow-plug engines as opposed to diesels. The model diesel market in this displacement category was already well served by such domestic products as the FROG 80, the D-C Merlin and the Mills .75, and had been for years. Indeed, there was almost certainly an over-supply of small diesels in this displacement category. It was small glow-plug motors that now appealed to the British modelling public.

It was at this point that they made their next critical error of judgment with respect to this project. They appear to have wanted to keep Gordon Cornell hard at work on the various other projects on which he was engaged at this time. It was presumably for this reason that they decided not to involve Gordon in their 1/2A diesel development program. In making this decision, they eliminated their own chief engineer from the design process! Not a step that most companies would choose to take .............

To further muddy the waters, E.D. also broke precedent by contracting out at least part of the development and production work to an outside company named Bardsley’s located in Brentwood, Middlesex. The details of the agreement with Bardsley's remain unclear, but it appears from the evidence that the agreement was largely confined to the assembly, testing, packaging and servicing of the engines, using parts mostly manufactured by E.D. Since Gordon Cornell was not consulted beforehand regarding the criteria to be applied to either the design or production of the new model, the project was pursued entirely without his input and in collaboration at some level with others outside the E.D. company. The project was not subjected to an internal technical evaluation by qualified E.D. staff until a considerable investment had already been made in design and tooling. As events proved, the prototype engines fell well short of meeting expectations despite the considerable funds that had been invested by E.D. up to the prototype stage. It was only when E.D. management woke up to the fact that they had invested heavily in an uncompetitive new model that panic appears to have set in. Gordon was finally deflected from the other work upon which he was then engaged and was tasked with the job of sorting out the dog's breakfast into which the 1/2A diesel program had evolved. Management were clearly hoping that Gordon could somehow salvage their investment in the new model.

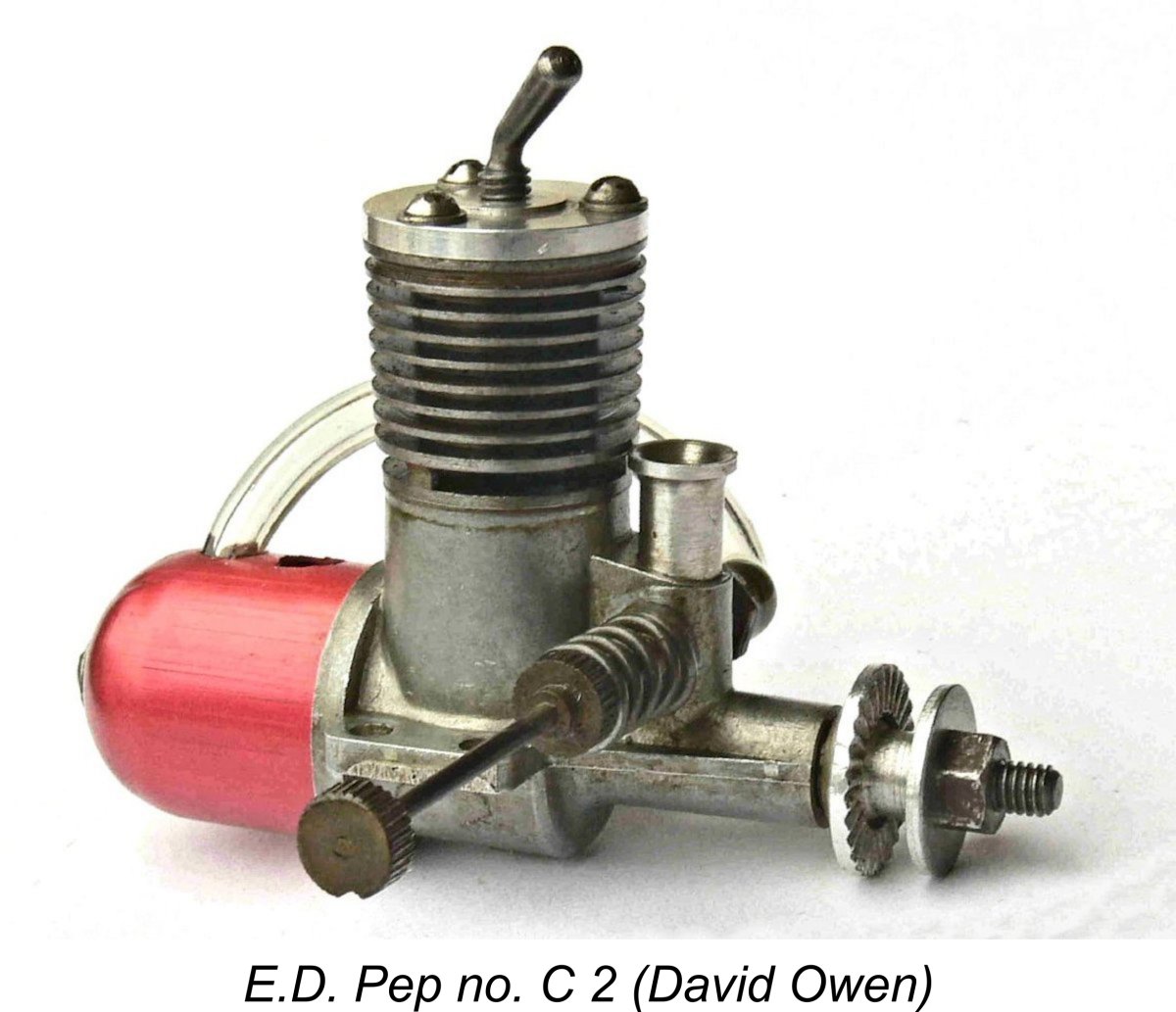

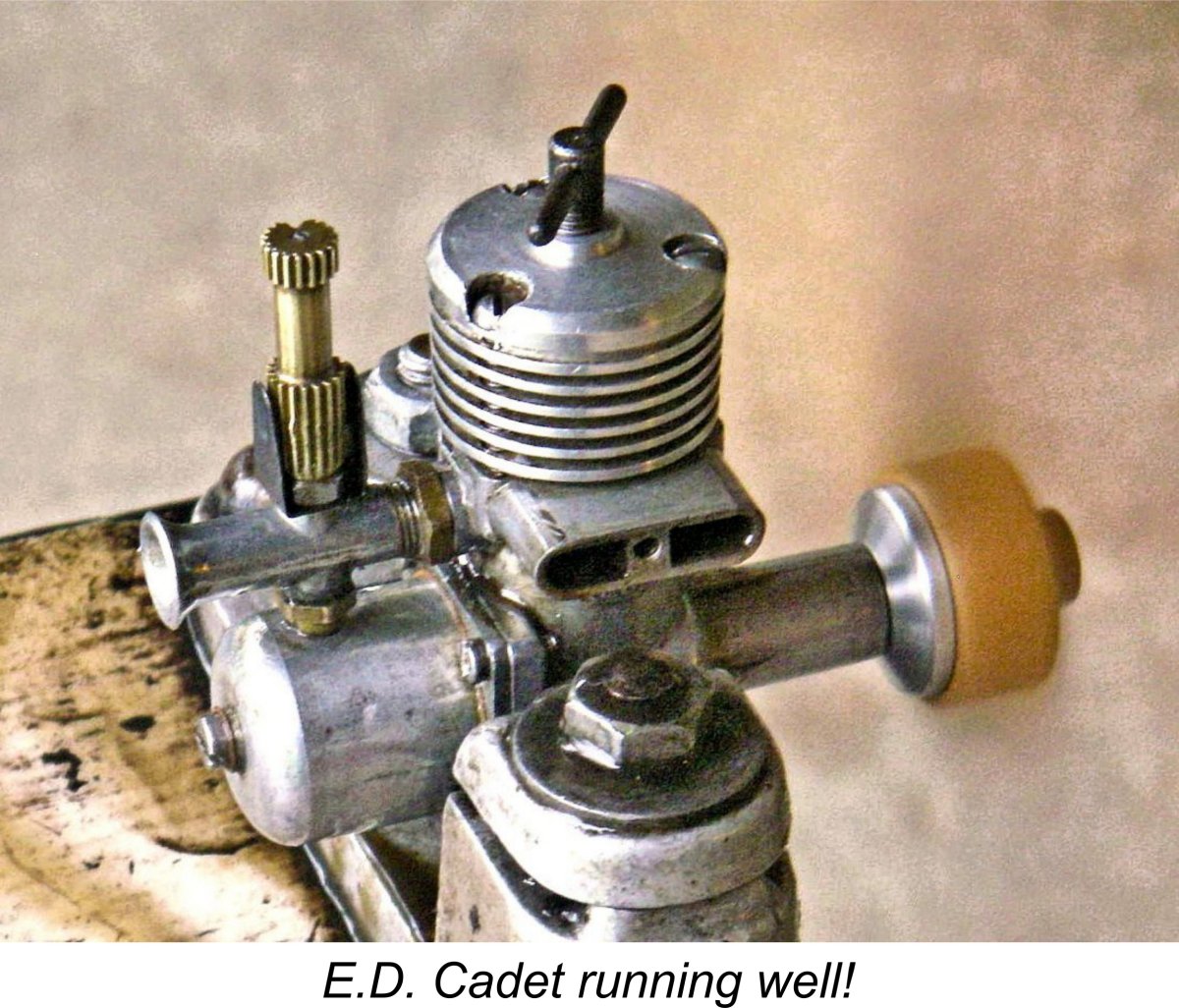

The most critical issue with the engine as it then existed was the fact that the venturi bore was too large for the development of adequate suction, hence giving rise to inconsistent running. This was easily fixed through the use of a venturi insert, but that was as far as the major modifications could be taken. A significant number of examples have been seen with an aluminium spacer under the cylinder, which may have been used to modify the port timing by raising the cylinder (as with illustrated engine no. C 2 and my own example no. H 2.69B pictured below), but it’s not clear whether or not Gordon had anything to do with this. Gordon also considered the existing con-rods to be inadequate for use in a diesel, but management were not prepared to write off the investment which those components represented, so they had to be used. Gordon did Despite this unsatisfactory outcome, it’s an undeniable fact that the production version of the Pep which finally appeared at the end of 1959 was a good looking little engine which performed quite well by the standards of its day. Although most of them featured blue-anodized heads and tanks, the engine appeared in a number of color schemes including red, green and even plain un-anodized alloy. I’m able to speak with some authority on the running qualities of the Pep since I’m a past user and present owner of several of these engines. I always found them to be perfectly satisfactory if unspectacular performers. A present-day ex-Brit club-mate of mine also had one “way back then”, and he too recalls it with great affection. It’s perfectly true that the Pep offered no particular threat to the US imports and possessed no real It would appear that things were becoming a bit desperate at E.D. by this time, since they were now beginning to cast about for entirely new product lines unrelated to model engines. As an example, Gordon recalled that they were approached by the Ministry of Defence to develop and manufacture small diesel-powered generators for lifeboats – Ministry staff evidently did not appreciate that E.D. “diesel” engines were not true diesels at all! Given the fact that E.D. did not have the financial capacity to undertake such a project, Gordon judged it to be not feasible at that time. As 1960 drew on, Gordon became increasingly frustrated at management inaction with respect both to his recommended production improvements and his proposed upgrade programme for the Racer. His one real success was the development of his proposed new 3.5 cc aero model (which management also did not support) into the outstanding "front flywheel" Sea Otter marine diesel which was deservedly to remain very popular for many years to come. However, this success did not alter the fact that Gordon's frustration was reaching critical levels. The handling of the Pep situation had done nothing to improve his outlook, and presumably the failure of management to promote his vastly improved version of the Bee was the final straw which caused Gordon to decide that enough was enough and resign from E.D. around the end of 1960. His departure was very much E.D.’s loss.

Gordon may understandably have taken some rather ghoulish satisfaction from the fact that the Pep failed to make much of an impression in the marketplace despite a somewhat frenzied effort by E.D. to promote the engine in an attempt to recover their considerable investment in the design. This was in stark contrast to their total lack of attention to the promotion of the much-improved Bee which As mentioned earlier, the Pep was actually far better than its subsequent reputation might suggest, and it’s my impression that to a certain extent its failure was due to the public perception of E.D. by this time as one of “yesterday’s brands”. It's interesting to contemplate the effect upon this perception which might have resulted from the 1960 release of Gordon's updated E.D. Racer together with his proposed twin ball-race .049 and the active promotion of his vastly improved version of the E.D. Bee. Together with the outstanding E.D. Super Fury and the ground-breaking Sea Otter, the result of a combination of such moves would have been the return of E.D. to the top of the performance heap ........ As it was, it soon became apparent that the British small-engine craze of 1959/60 had already peaked and was beginning to lose steam, the result being that the British market was becoming over-saturated with small engines. There also appear to have been quality problems with Bardsley’s assembly and servicing activities, since there is evidence in the form of some later Pep instruction leaflets to the effect that towards the end of the Pep’s production life E.D. cancelled the contract with Bardsley’s and took over the assembly and servicing themselves. As a result of these factors, not that many Peps were actually made and sold. There's little doubt that the engine failed to repay its development costs, thus further deepening the financial swamp into which E.D was now steadily sinking. Examples of the Pep in good condition are now relatively few and far between, changing hands on the collector's market for surprisingly high prices. It's worth noting in passing that after E.D. cancelled their contract for the Pep with Bardsley’s, a new company was formed in Brentwood under the name of De-Za-Lux Developments Ltd. There’s presently no evidence apart from the location to suggest that this company had anything to do with Bardsley’s - the street address was certainly different. In fact, the new venture may have been funded by RipMax, who undoubtedly became their exclusive distributors. Be that as it may, De-Za-Lux took over the Pep project after E.D. abandoned it and undertook some more development work, including an increase in the displacement to 0.92 cc. This was achieved through a modest increase in the bore, the stroke being unchanged.