|

|

The Baab-Fox .604

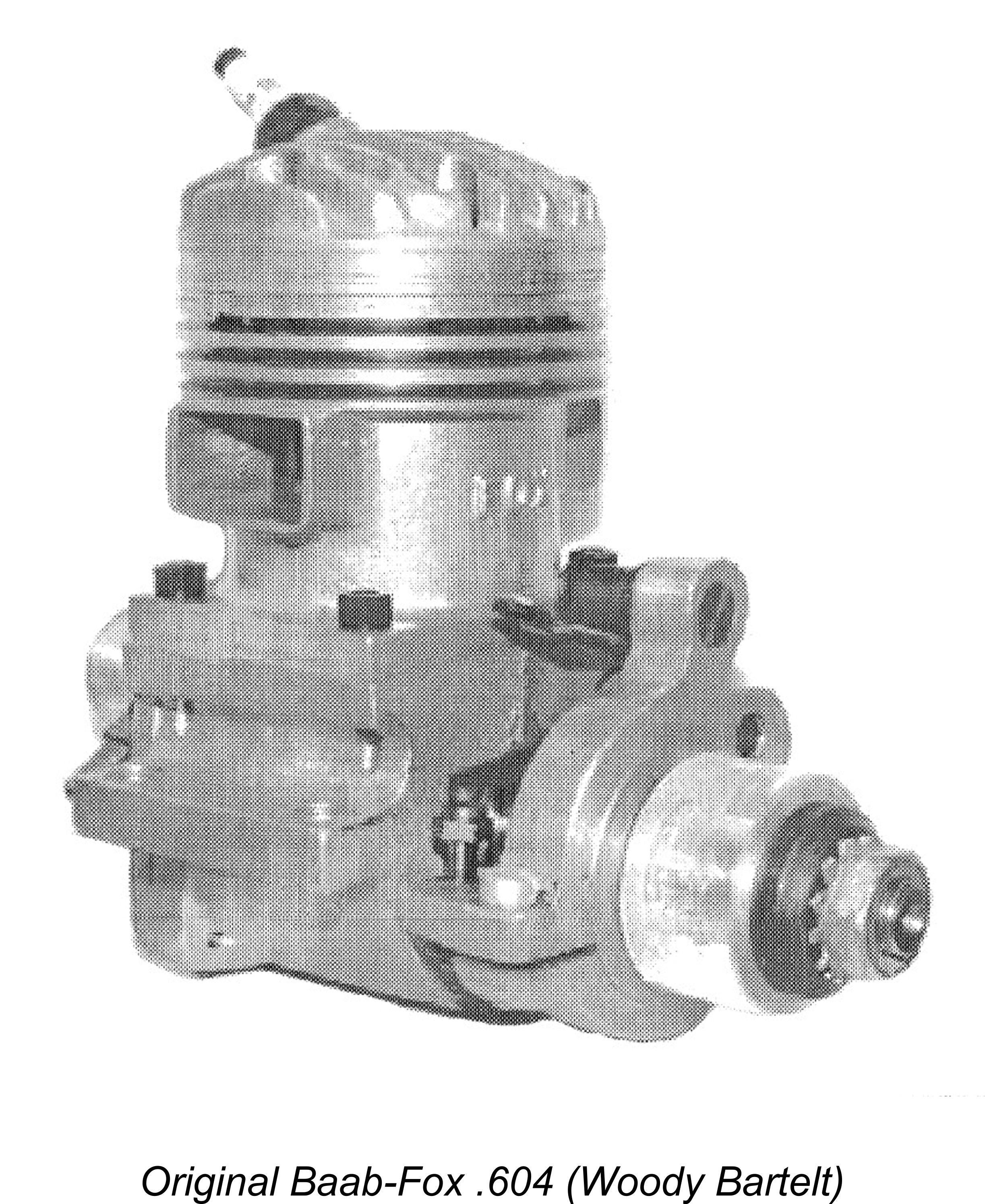

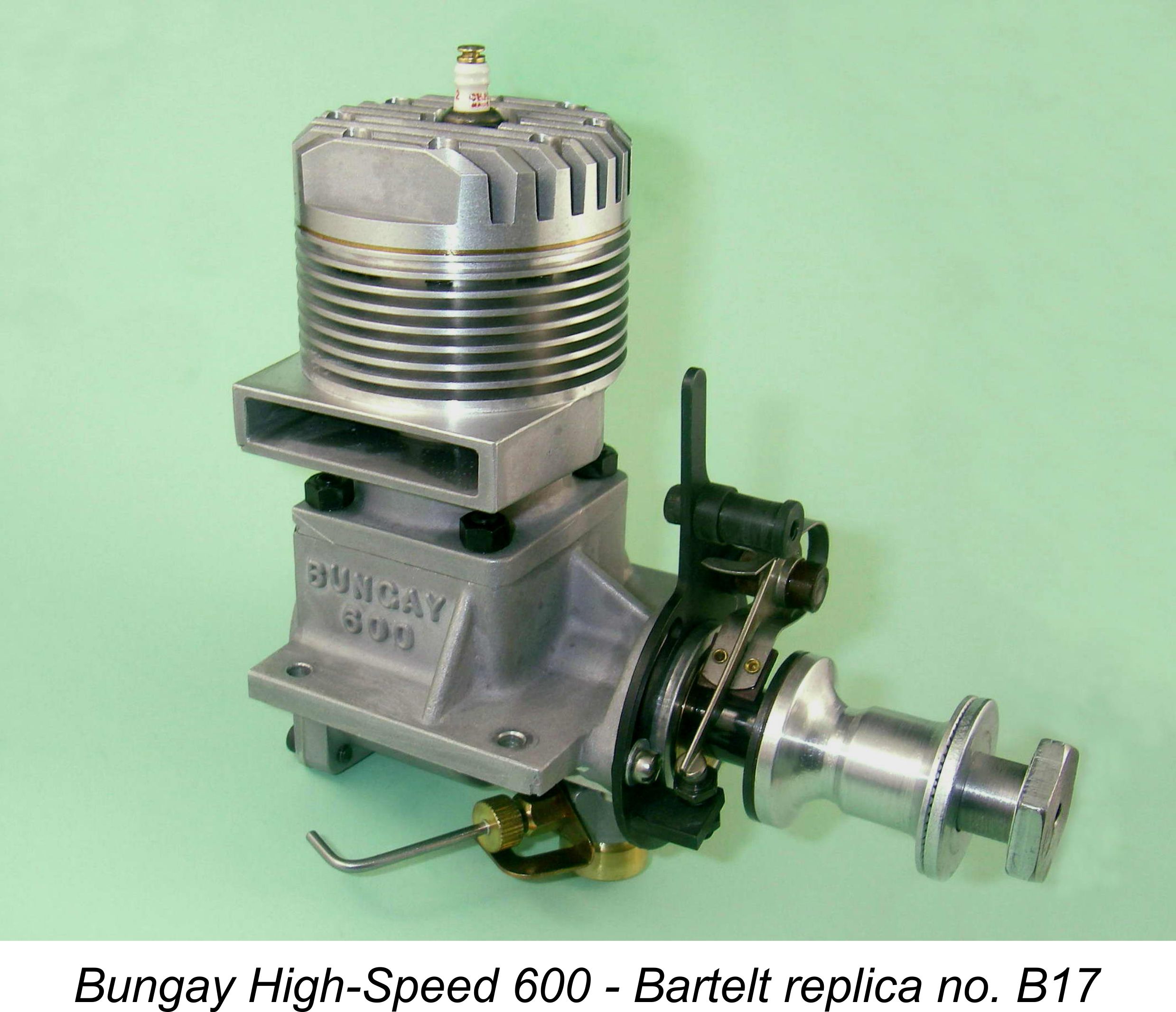

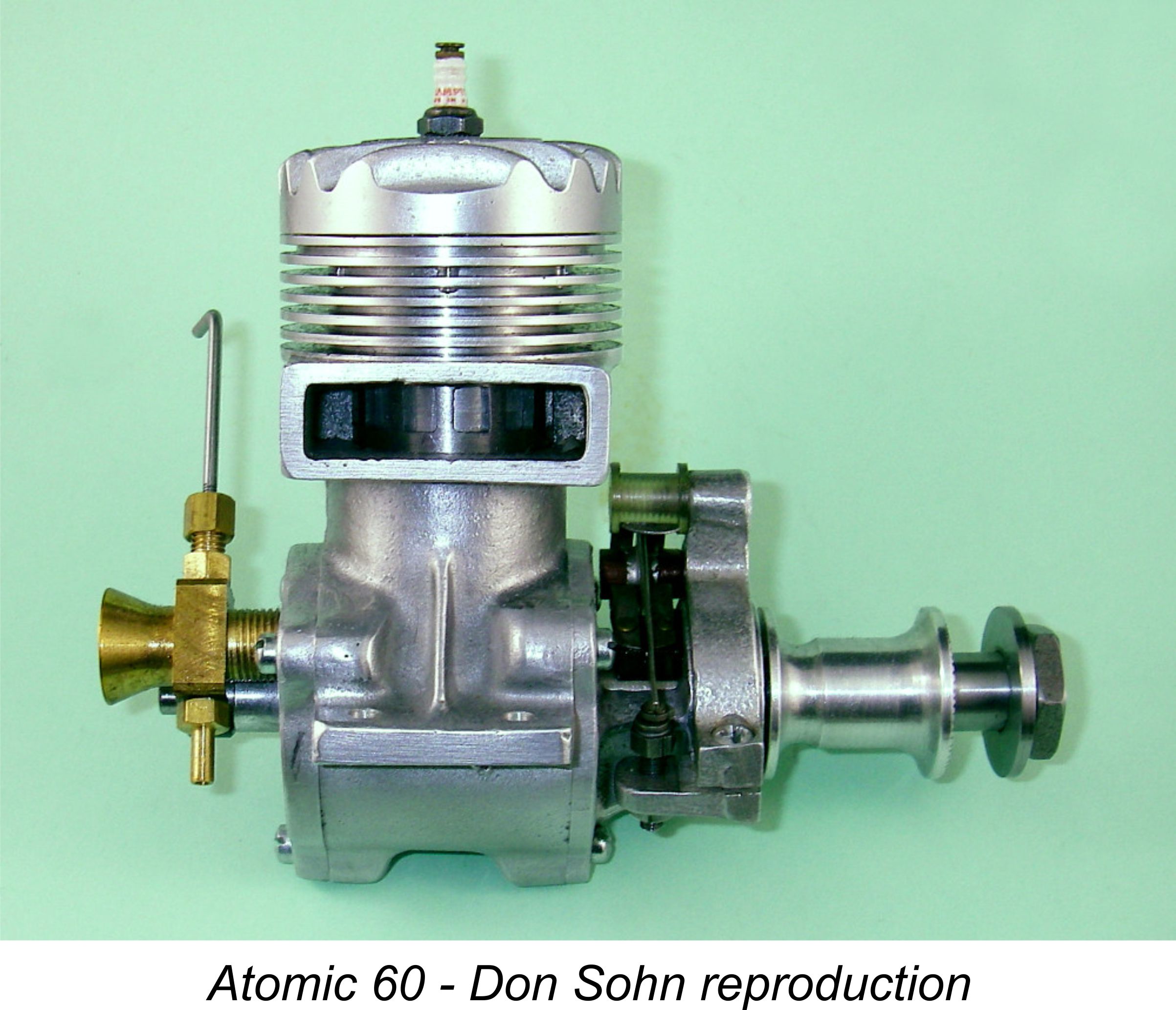

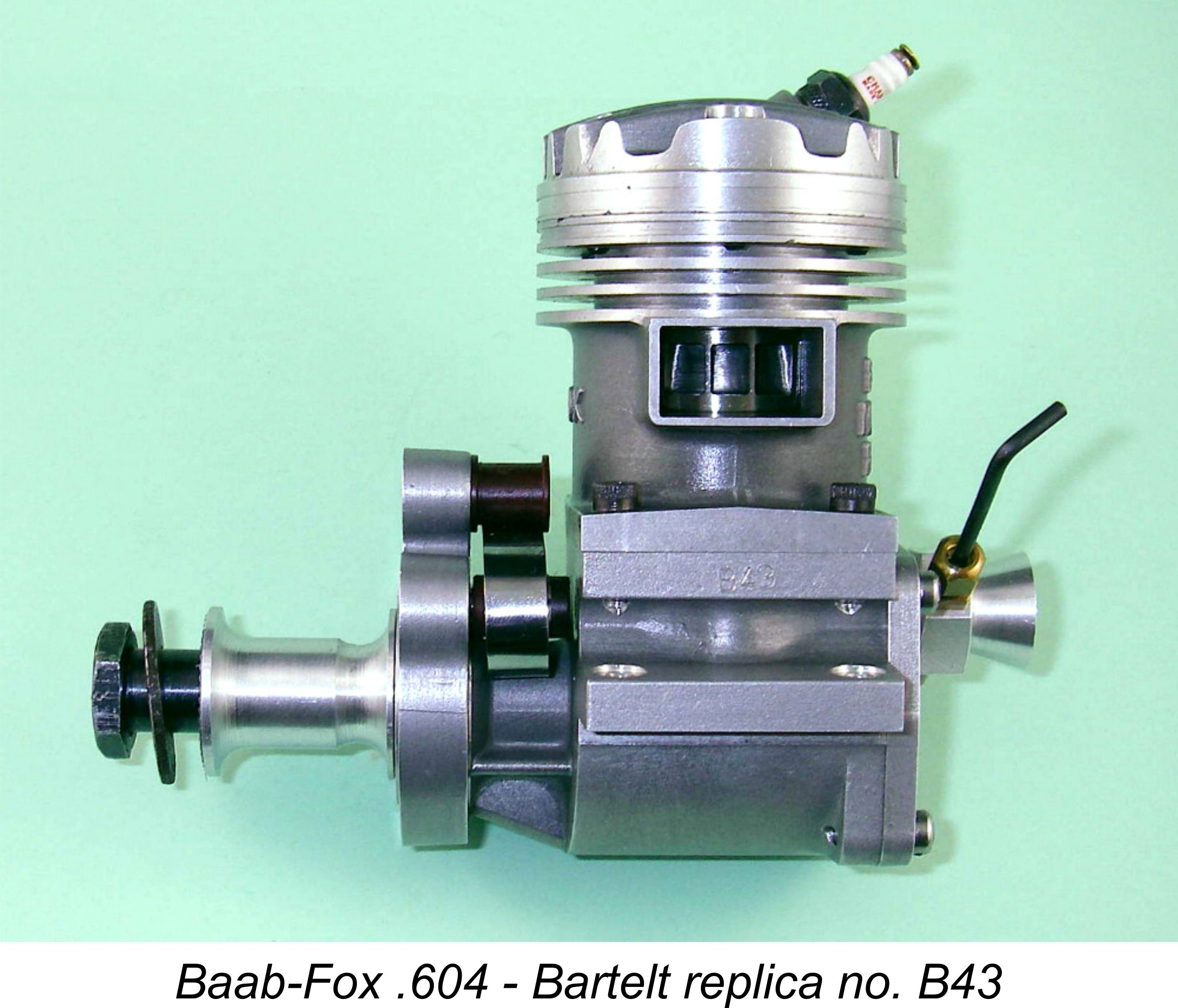

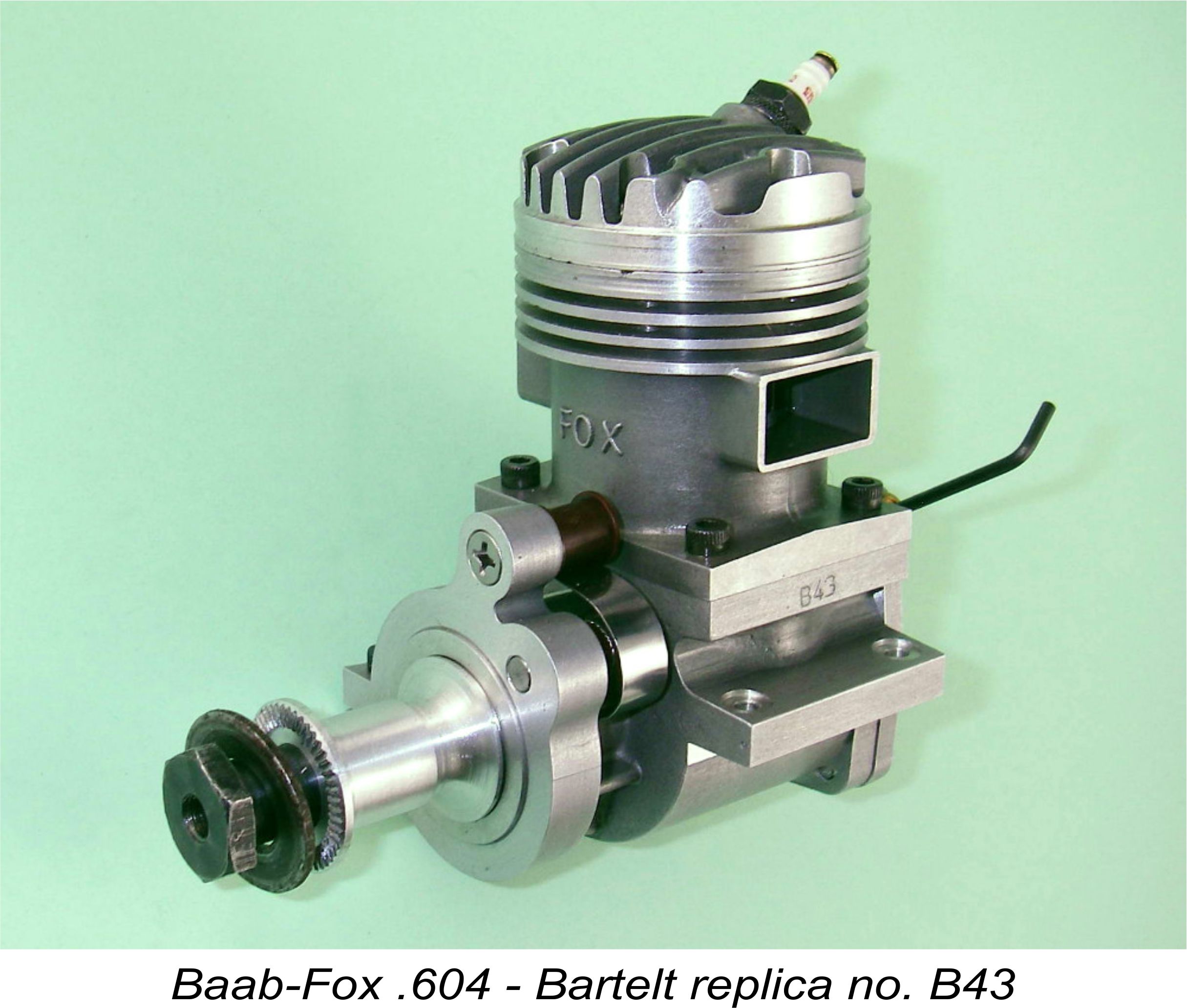

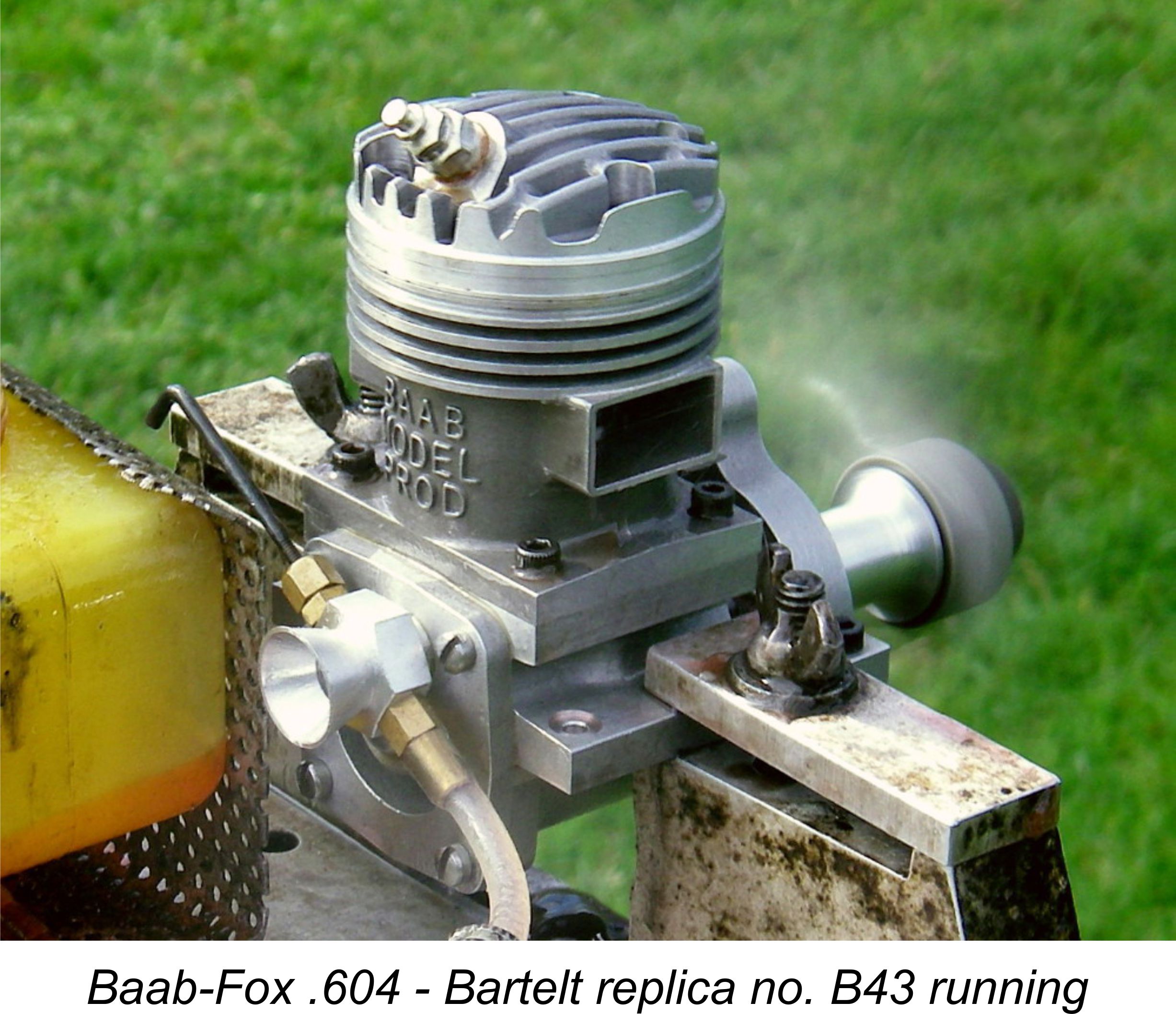

Many of the Hornet’s competitors paid it the highest- However, there were those who were convinced that the basic Hornet design could be improved upon, particularly in the bypass/transfer department. As we have seen in our separate article on the tuned Hornets, the major factor limiting the performance of that engine was an unduly constricted bypass/transfer In the present article, I'll take a look at one designer’s attempt to redress this deficiency. The engine with which we are concerned here is the Baab-Fox .604 cubic inch racing engine of 1946. I may as well state right up front that the rarity of this engine is such that there was never any realistic hope of my orchestrating an opportunity to examine an original example. I am only able to present much of the information in this article along with the accompanying images thanks to my acquisition of one of a limited series of fine replicas produced in Ukraine by the well-known Profi firm for the late and much missed Woody Bartelt of Aero Electric, one of the world’s leading suppliers of replica engines and parts. Woody’s Profi replicas were copied directly from an original example in Woody’s possession, thus being extremely faithful to the originals. They were also constructed to Profi's usual high standard.

Finally, as always when writing about an American model engine, it’s both a duty and a pleasure to acknowledge the immense contribution made over the years by my valued friend and colleague Tim Dannels. Tim was both the publisher of the sadly now-discontinued “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ) and the equally indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE), both of which are required references for anyone writing on the subject of American model engines. This material remains readily available from Tim through direct contact via this link. Having acknowledged our sources, let’s look at the background to the manufacture of this very interesting and unusual engine. Background

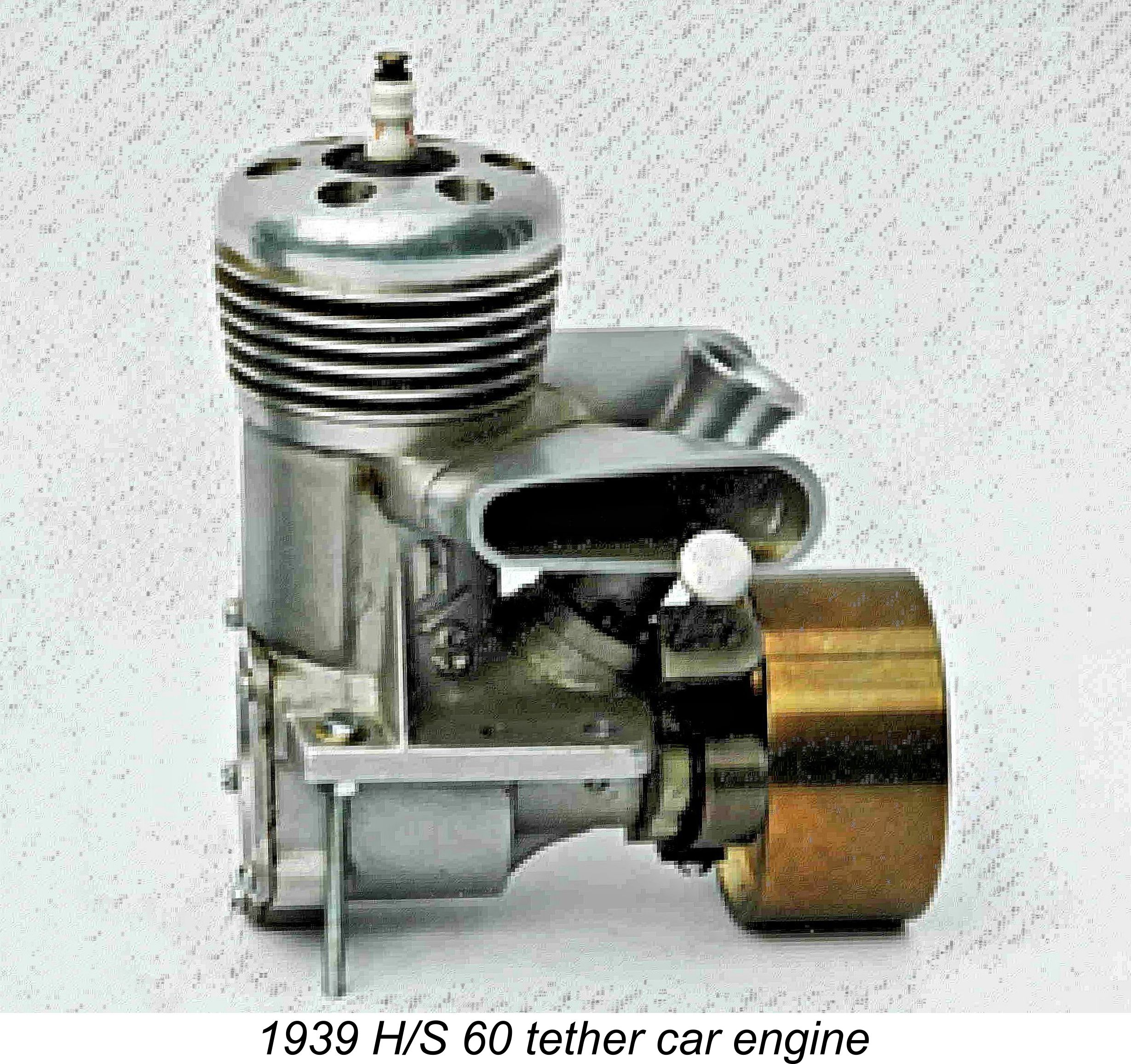

The primary application which inspired the successive development of these two designs was the then-new activity of model car racing which had been pioneered by the Dooling brothers beginning in 1937. We have recounted the history of the Dooling brothers’ pioneering activities in a separate article which may still be accessed on the MEN web-site.

During the pre-war period, the Hornet reigned supreme in the big-bore racing engine field. It was challenged by a few others, notably the FRV designs of Ira Hassad as well as one-off specials produced by the likes of Dick McCoy, but there was little other meaningful competition.

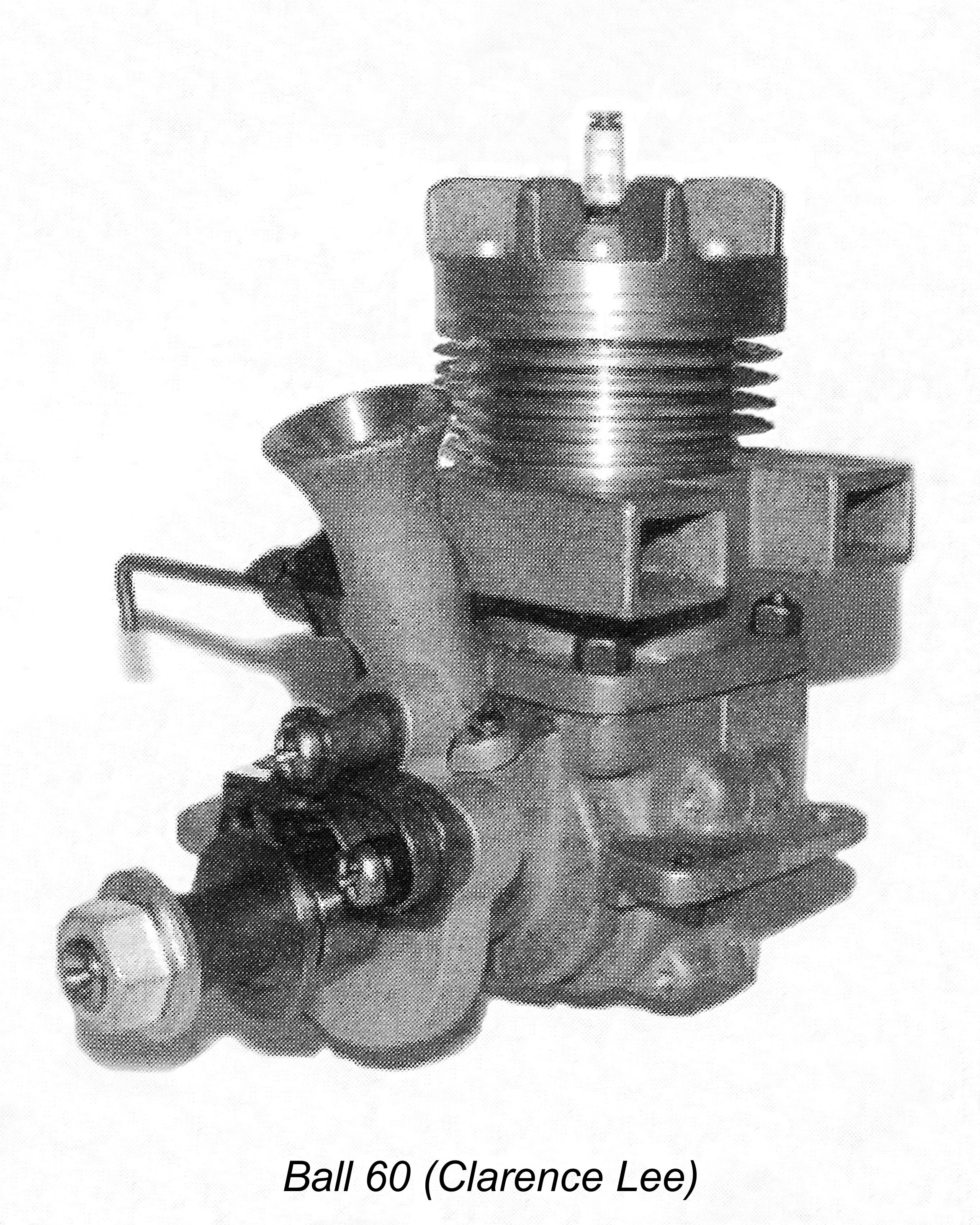

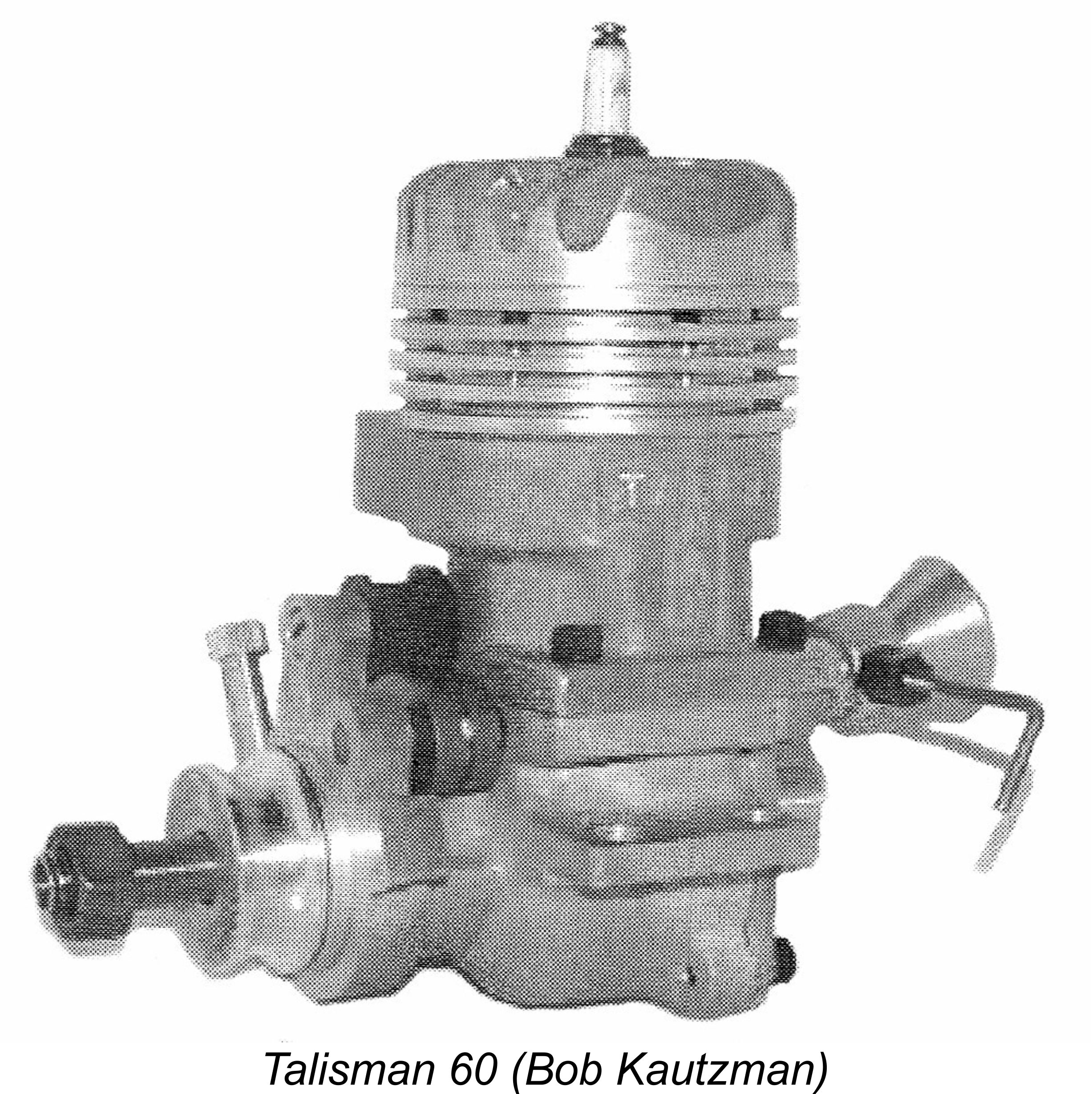

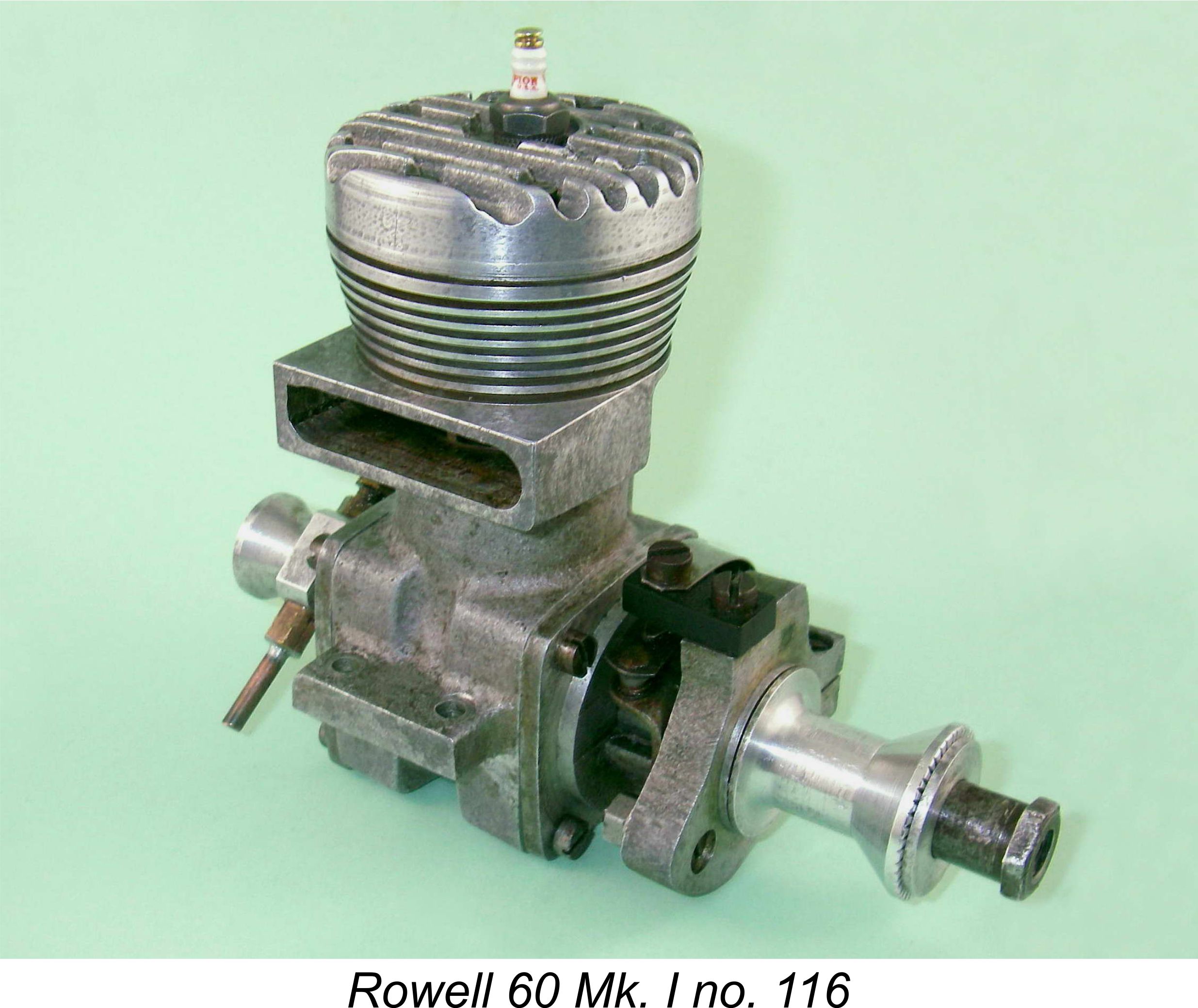

Others watched the emerging competition between the Hornet and the McCoy with great interest. Several of them decided that while the basic design of the Hornet was sound enough, there was still room for improvement. This led More relevant in the context of this article, there were also experiments with changes to the porting system. An example of this approach was the 1946 Ball 60 designed and manufactured by a fellow named Henry "Hank" Ball, who had established a facility known as the B&D Racing Engine Laboratory in Drayton Plains, Michigan. A detailed study of the Ball 60 may be found elsewhere on this web-site. The Ball 60 featured FRV induction, a twin ball-race shaft and a ringed aluminium piston. More to the point, it also featured dual exhausts with dual bypasses between them - shades of Cox in years to come. The exhausts exited at both front and rear, with bypass passages on both sides of the case. This allowed the use of six transfer ports (three to a side) along with the six exhaust openings, which were of course split between the two As of 1946, the use of large racing engines in model aircraft was just beginning its rise to market dominance as a result of the post-war emergence of control-line flying, which allowed the operation of high-speed model aircraft under full control and restraint. However, at this time the majority of such engines continued to be used for model car racing, with some finding application in tethered hydroplane service. In the case of the Ball 60, the exhaust stack arrangements were evidently tailored towards the engine being transversely mounted in a spur-geared tether car such as the Dooling Frog - the layout appeared less than ideal for aircraft service. That said, the manufacturers claimed in their literature that the engine had set an official AMA speed record for model aircraft in 1946. The model car racing fraternity was very close-knit, the result being that developments in various parts of the country quickly became known to those elsewhere. In addition to Henry Ball, another individual who soon began to put his mind towards the improvement of the basic Hornet design was hobby shop owner and keen race car competitor Cliff Fox (as far as I can tell, no relation to Duke!) of Fox was obviously well aware of the Hornet 60, since it was still the leading model car racing engine as of 1946. He had undoubtedly also taken note of the Hornet-influenced Talisman 60 and Atomic 60 models produced in very small This is not to say that the Ball influenced the design of what was to become our subject Be that as it may, Cliff Fox, Henry Ball and Walt Cave (independently or otherwise) all clearly recognised the limitation on performance represented by the Hornet’s rather constricted bypass/transfer system. All three designers evidently reasoned that twinning the bypass/transfer system would improve top end performance by increasing the engine’s pumping efficiency. However, Fox and Cave appear to have considered the balance of the RRV Hornet design approach to be perfectly satisfactory, while Ball elected to throw FRV induction into the mix when finalizing his own design.

Having described the background to the development of the Baab-Fox .604, let’s take a look at the main design features of this very individualistic engine. Description

There can be no question that the Baab-Fox .604 owed much to the design of the Hornet 60. In fact, the two designs were very similar indeed below the exhaust stacks. There were some detail differences, but it would have been useless for Cliff Fox to deny the influence of the Hornet upon his new model. I’d almost bet that the prototype Baab-Fox was a Hornet with Cliff Fox’s upper cylinder assembly attached!

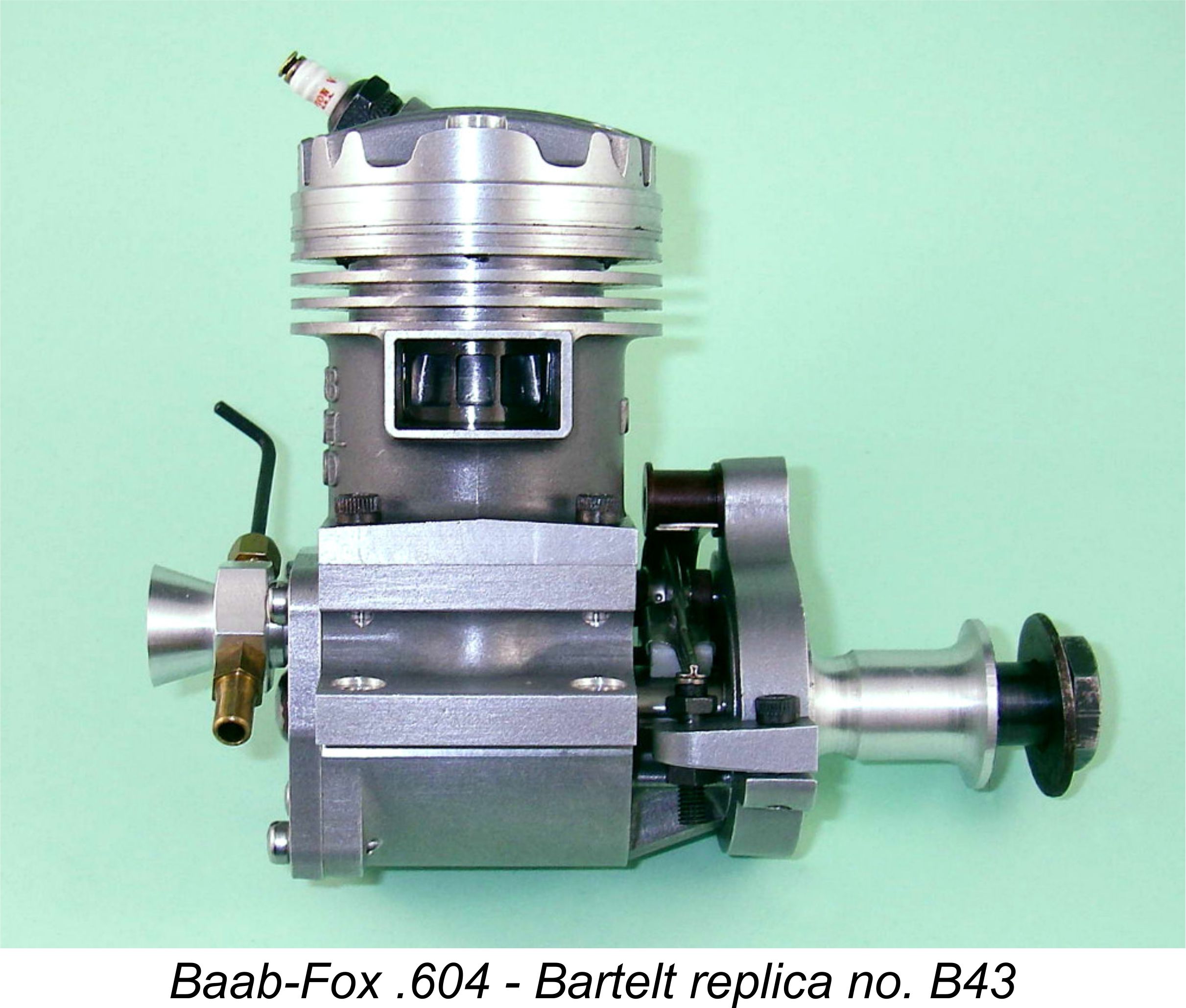

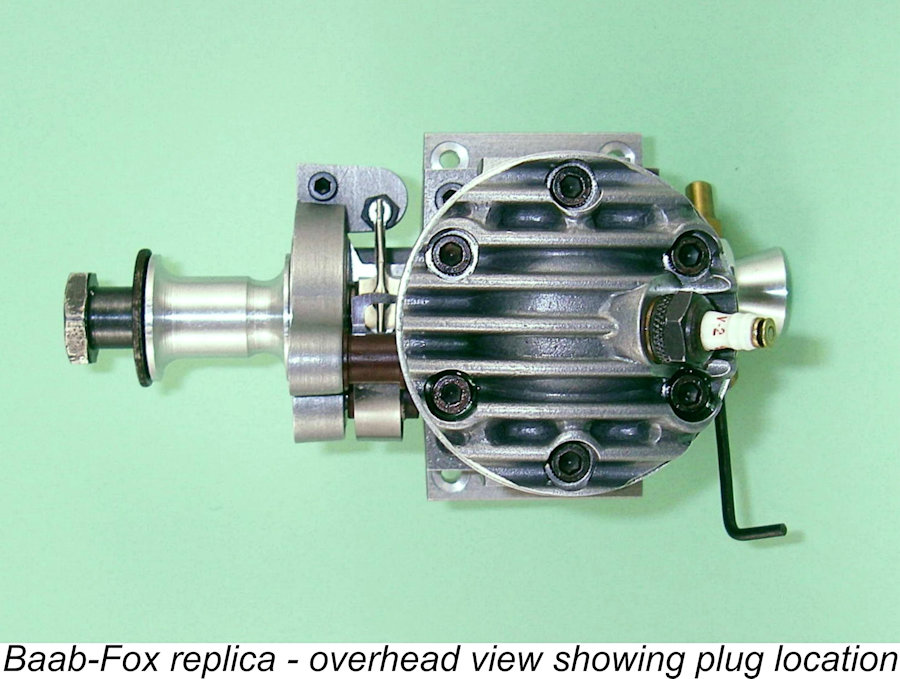

At the front of the engine, the heavily-counterbalanced one-piece steel crankshafts of both the Hornet and Baab-Fox were carried in two ball bearings. The timers of the two engines were also extremely similar in design terms. In fact, the only real difference to be found here was the method of securing the flywheel or prop driver to the shaft. In the Hornet, the race car version used a plain shaft which relied either upon friction or a split collar to secure the flywheel, while the aero version with its steel prop driver used the standard square-on-shaft keying system to lock the driver. By contrast, the Baab-Fox followed the McCoy pattern by using a Woodruff key at this point, regardless of the type of fitting to be mounted. The length of the Baab-Fox shaft was adequate to permit the use of a McCoy style bobbin prop driver with sleeve nut for aircraft service - the illustrated replica example has been so equipped, mainly to facilitate testing but also because I’m an aero guy at heart! However, Woody’s replicas were supplied with a flywheel.

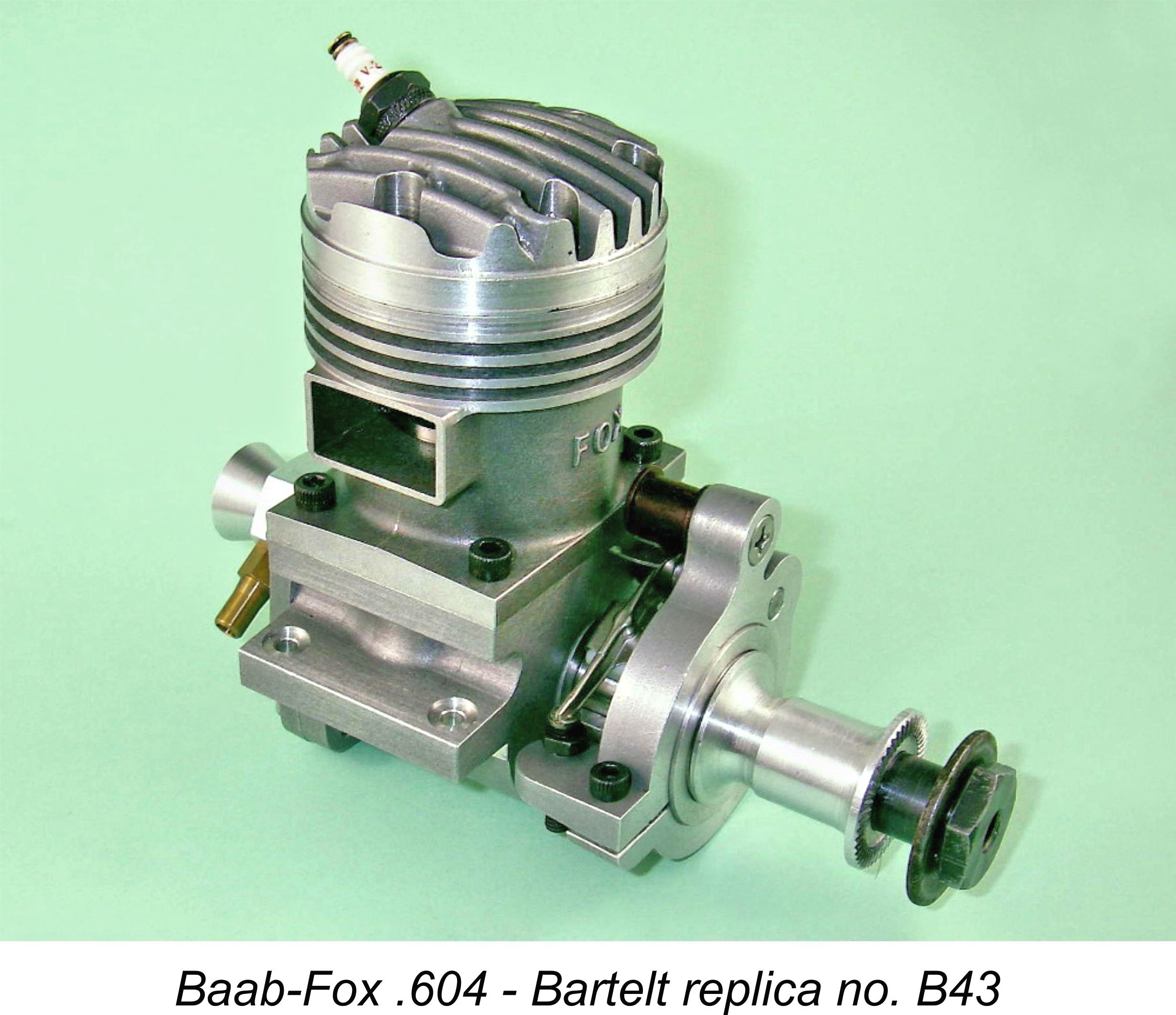

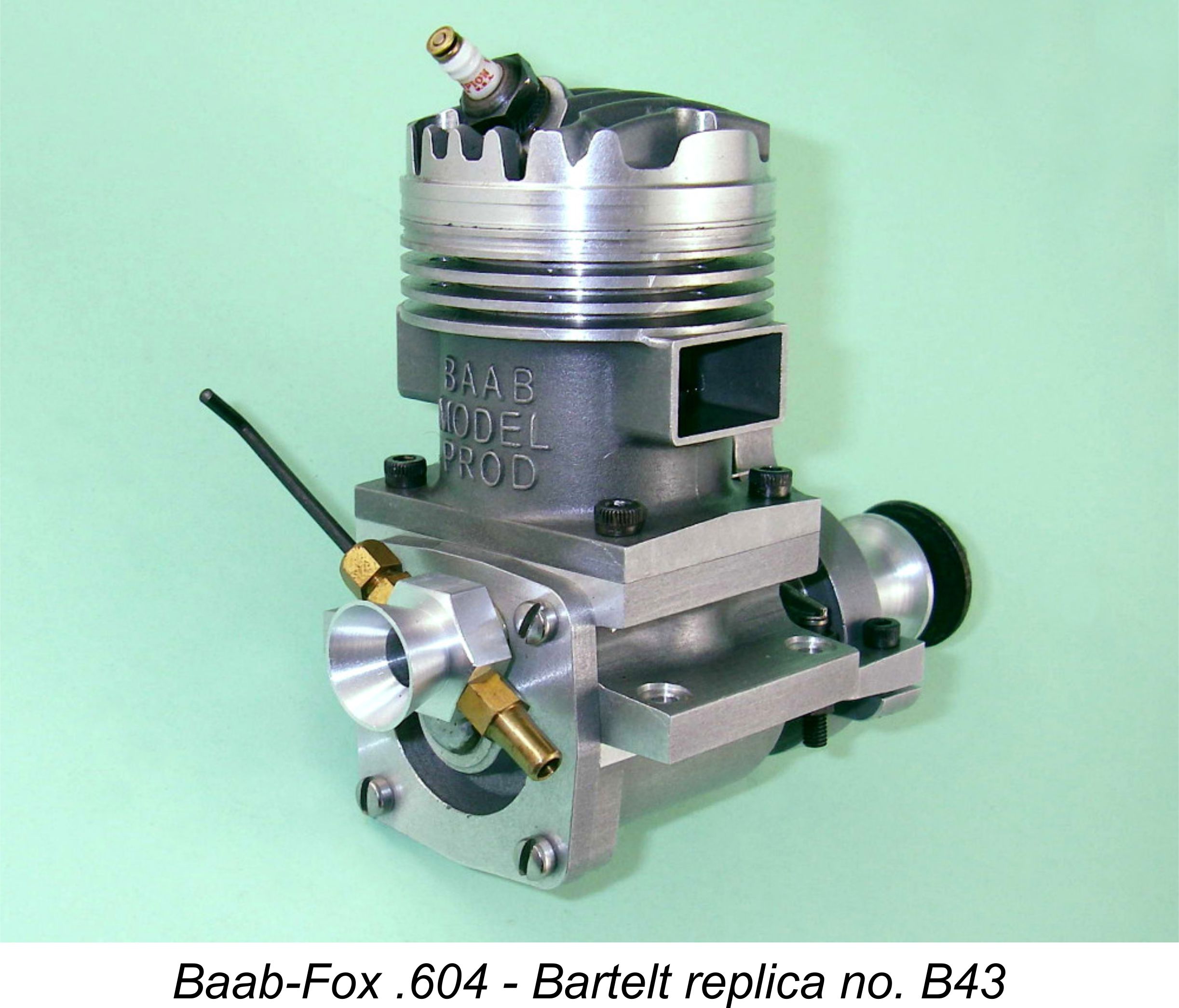

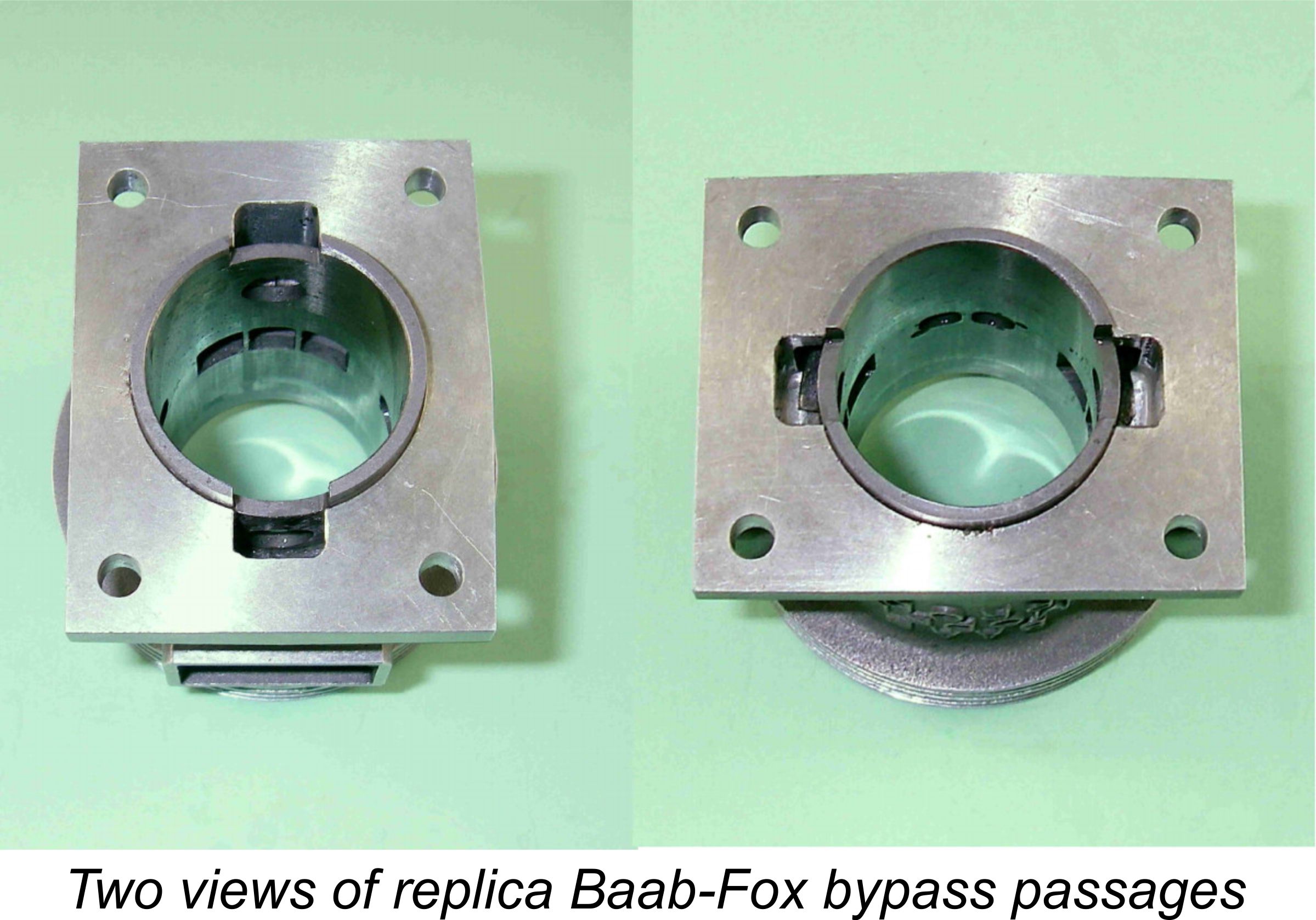

The one substantial design change in this assembly was the Baab-Fox’s use of a single ball bearing to support the disc valve spindle - a rather deluxe feature which we encountered in our examination of the tuned Hornet engines discussed elsewhere. Apart from this, the disc valve followed the Hornet pattern in being retained in its bearing by a soldered-on washer at the rear of the rotary valve spindle. The needle valves too were more or less identical, both being of the standard surface jet type with gland nut for needle tension. So far, we could almost be talking about minor variants of the same engine! However, when we look above the split between the lower and upper castings, we find that things are very different indeed! As mentioned earlier, Cliff Fox’s chief goal in designing the Baab-Fox .604 seems to have been to increase the engine’s pumping efficiency by freeing up the bypass system. To do this, Fox elected to use two pairs of transfer openings in place of the Hornet’s single group of three openings, placing these paired openings at the front and rear of the cylinder. The two groups of three exhaust openings each were placed at the sides between the two sets of transfer ports, each group discharging through a stubby exhaust stack.

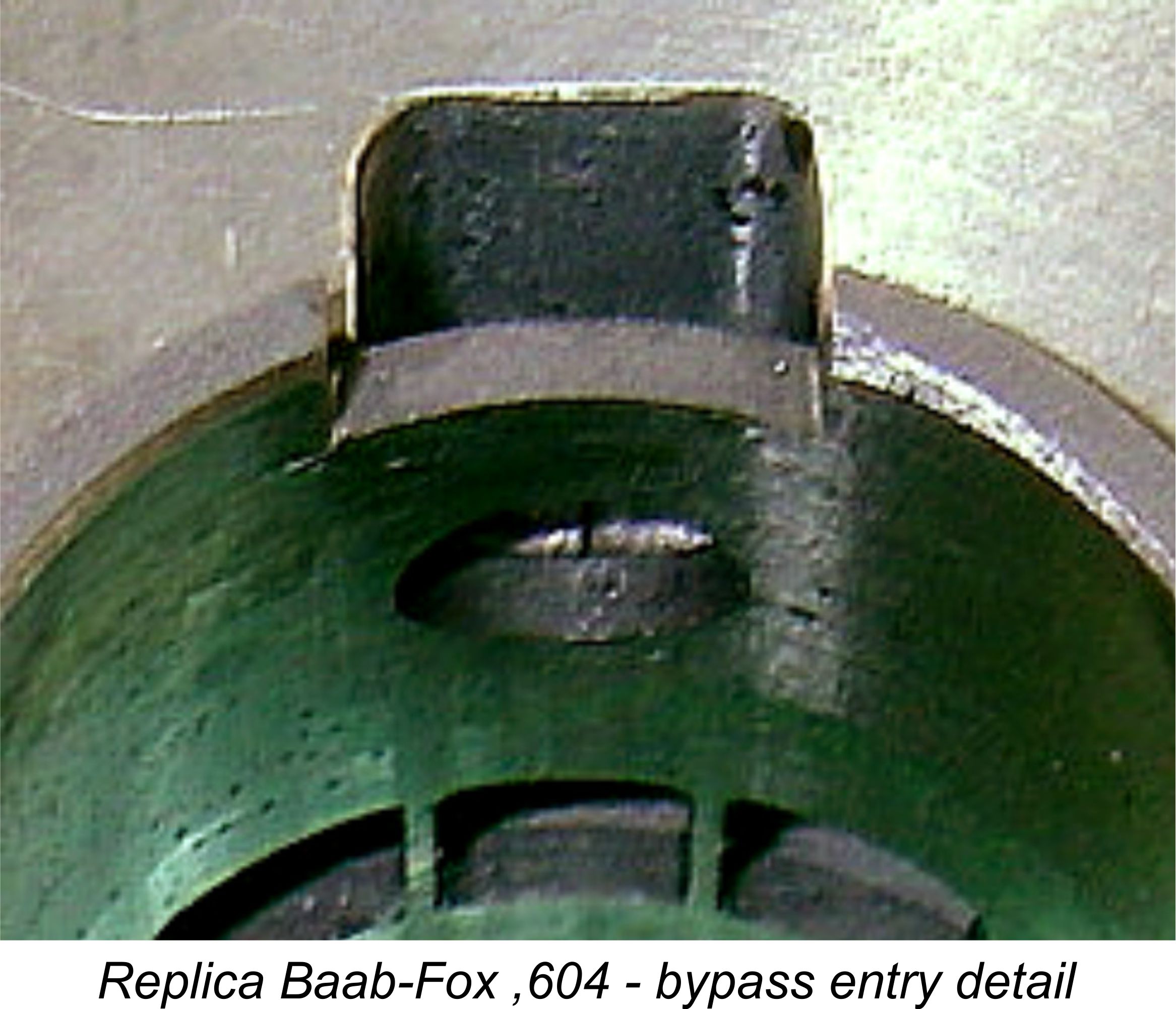

The bypass passages were fed from the lower crankcase by a pair of relatively small openings, one on each side directly beneath the exhaust ports. Since these entry points were radially located at 90 degrees from the transfer ports, incoming mixture had to spiral up from the lower bypass entry ports to the transfers, following a somewhat tortuous path in doing so. The resulting bypass system was undeniably rather convoluted, also increasing crankcase volume somewhat. I would guess that the rather small bypass entry openings (which were unassisted by any piston porting), the increased crankcase volume and the more convoluted gas pathway would together have more than offset any potential advantage gained with the extra transfer opening. Objectively speaking, it has to be said that it’s difficult to see any real advantage for this arrangement over the standard Hornet setup with its piston ports and more direct gas pathway. However, Cliff Fox clearly felt otherwise.

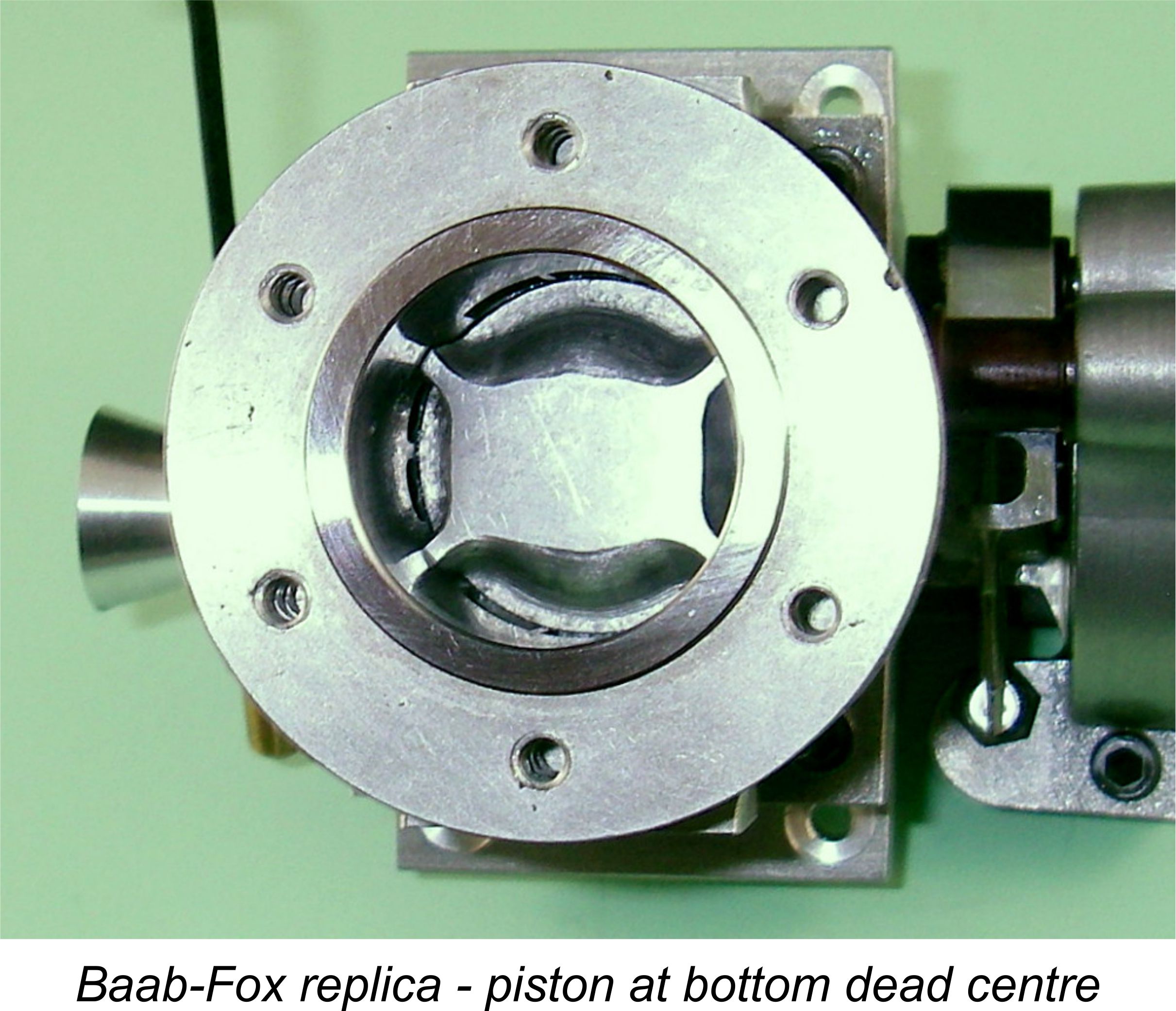

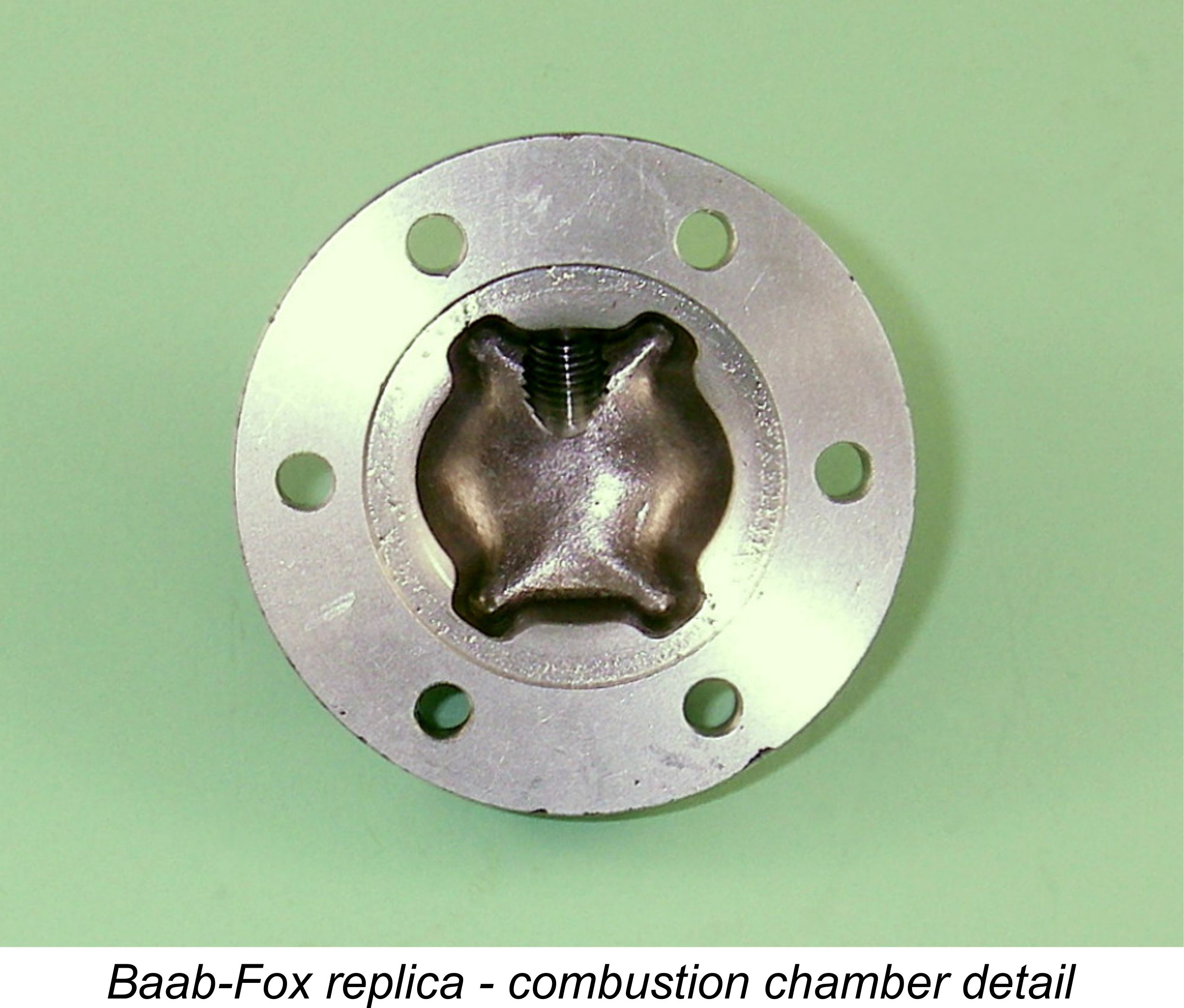

It will be appreciated that the system of porting employed rendered the use of a Hornet-style domed piston with a single baffle no longer practicable. Both engines employed a cast alloy piston having two rings. However, the Baab-Fox used what was in effect an X-baffled piston having a basically rectangular crown. The intent of this design was clearly to keep the exhaust and transfer gas flows as separate as possible - always an appropriate goal when designing a two-stroke engine which does not feature a resonant exhaust system. The attached illustration of the situation at bottom dead centre will hopefully show the very high degree of directional channelling of gas flows into and out of the cylinder which this arrangement promoted.

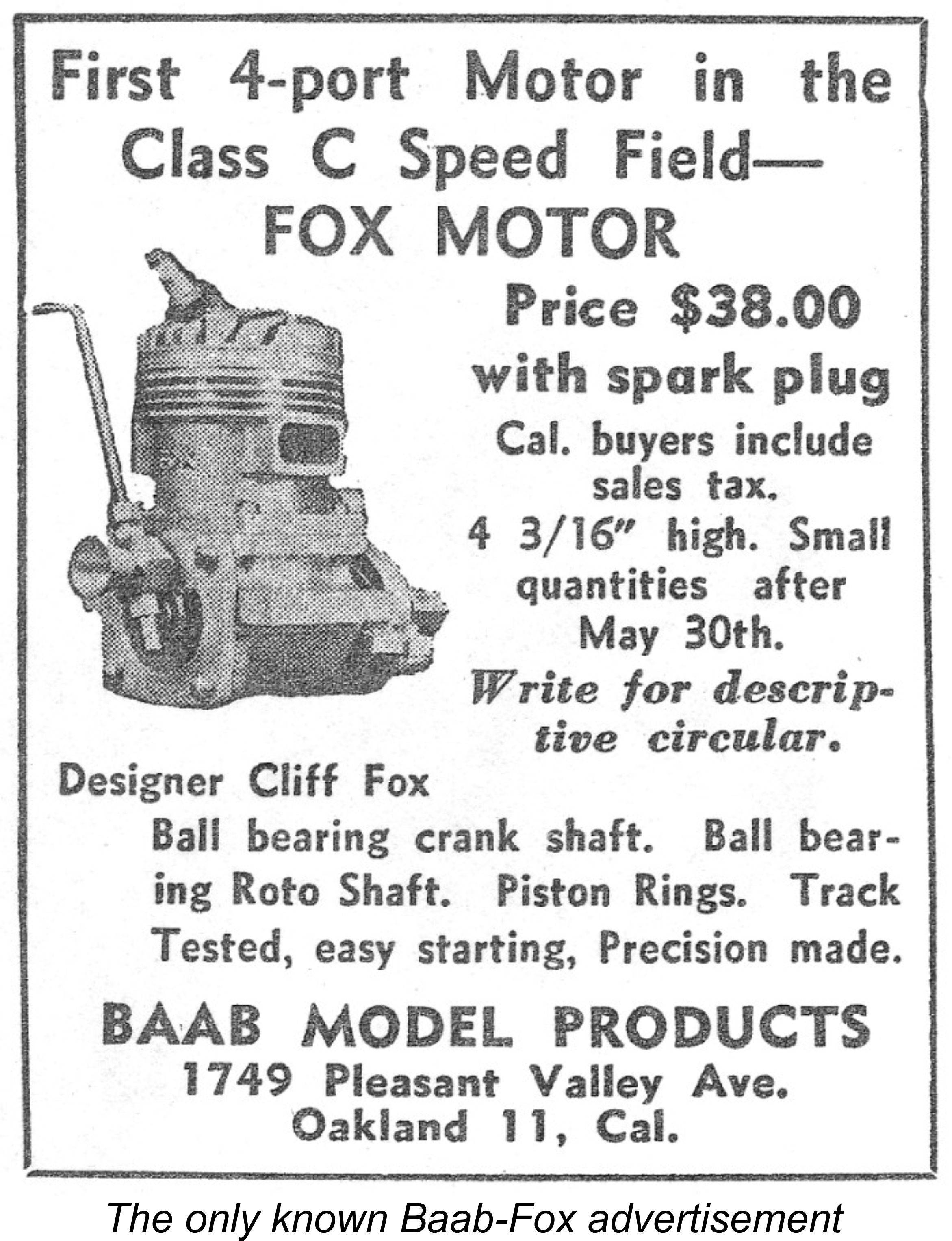

The length of the piston skirt in the Baab-Fox was such as to create a sub-piston The final feature which distinguished the Baab-Fox from its better-known Hornet competitor was the use of a plug which was steeply angled towards the rear of the unit. The adoption of this In summary, the Baab-Fox .604 was basically a Hornet 60 with extensively-revised cylinder porting, a modified piston/combustion chamber combination and a ball-bearing disc valve spindle. Clearly Cliff Fox believed that these modifications would give his design a competitive edge. It’s actually rather sad to have to reflect upon how wrong events quickly proved him to be. Let’s now turn to the engine’s production history. Production History As with my earlier article on the equally-rare Bungay High-Speed 600 from New York, still to be found on MEN, this section won’t take long! Having developed a design which he clearly felt would offer a performance advantage over the Hornet and McCoy opposition of the day, the next problem facing Fox was arranging for the engine’s manufacture. This challenge was greatly simplified by the fact that Fox was already collaborating on the manufacturing side with W. Lloyd Baab, a very well-known figure in the model car racing world who was then serving as the Managing Editor of “Rail & Cable News” magazine located at 8215 Outlook Avenue in Oakland.

The first (and seemingly the only) national advertisement for the Baab-Fox .604 appeared in the June 1946 issue of “Model Craftsman” magazine. It’s probable that the engine was marketed An interesting observation relating to this advertisement was the fact that the illustration of the engine showed the name “FOX” cast in relief onto the rear of the upper cylinder casting. All of the surviving examples which have been reported have carried this name at the front of the casting, with the name “BAAB MODEL PROD” appearing in relief on the rear surface of the casting. Woody Bartelt’s replicas follow the pattern displayed by the actual engines rather than that implied in the advertisement. Having said this, there’s actually no structural impediment to the mounting of the upper cylinder block in either orientation. The Baab-Fox was promoted as “the first four-port motor in the Class C speed field”. At first glance, this characterization of the engine appears to imply either that Baab and Fox were unaware of the similarly-ported Ball 60 and Cave Cobra models, or that their design did indeed predate both of these units. Either way, the fact remains that the four-port arrangement had in reality been pioneered in 1941 by Ira Hassad’s H.R.E. Special mentioned earlier, although admittedly that design never reached series production.

Despite this, the engine appears to have made very little impression upon the market, either in the burgeoning control-line speed category or in the hotbed of model car racing activity that flourished at the time in Southern California. It was likely a combination of high price and a failure to match the performance of the Hornet and McCoy opposition that led to the engine being withdrawn very soon following the placement of that one national advertisement. It actually seems likely that the “small quantity” advertised as being available by May 30th, 1946 was the only batch ever manufactured. There’s no way of estimating production figures, but the number actually completed must have been extremely small. When researching his indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE), Tim Dannels uncovered only three surviving original examples (of which Woody Bartelt’s example was one), although there may well be a few more hiding out there. Interestingly enough, all of these examples reportedly displayed machining differences of one sort or another, implying that the engines were individually constructed rather than being cranked out on a production line. Woody’s replicas are of course based upon his own example - others may have exhibited minor variations. The Replica Baab-Fox .604 on Test Given the foregoing comments on the rarity of this engine, it will come as no surprise to learn that I don’t have an original example to test - in fact, I have never seen an original Baab-Fox .604 in the metal, nor do I expect to do so. However, the fact that I’m fortunate enough to have one of Woody Bartelt’s fine replicas on hand places me in a position to at least report on the performance of the replica. The fact that Woody’s replica was copied directly from an original example in Woody’s possession (the actual example illustrated on page 21 of AMEE, in fact) should result in performance figures which at least approximate those of the original. In the interest of simplicity, I elected to test the engine on glow-plug ignition. I used my usual test fuel containing 10% nitromethane along with a good helping of castor oil. Experience with other 10 cc racing engines of similar vintage gave me a pretty good idea of the range of airscrews that might yield useful information.

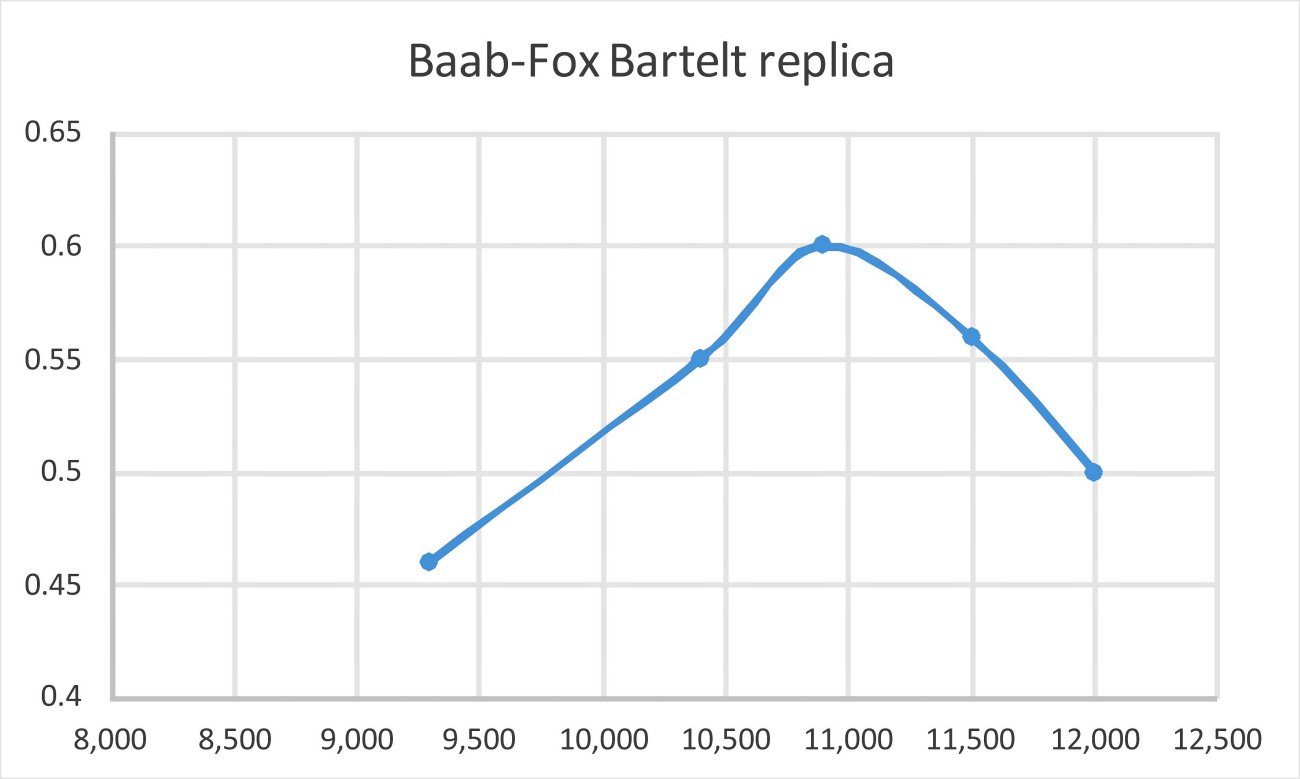

As things turned out, I need not have worried at all about limiting the speeds! The Baab-Fox replica never got anywhere near 15,000 rpm on any of the props tested. It proved to be a very easy starter as long as a good prime was administered. The challenge here was keeping the prime in the cylinder. The very steep sides of the piston crown The engine was completely happy running on suction feed. Response to the needle was excellent, making the establishment of settings very straightforward. Running was very smooth at all times, with no tendency towards misfiring or sagging. I put on 25 minutes in slightly rich 5 minute runs to give the rings a chance to bed in and then took some brief leaned-out spot readings. I have to say that the results were somewhat less than I had expected. The

Obviously there’s insufficient data here to allow the development of a truly representative power curve. However, the above figures seem to imply that the engine is more or less done by around 11,100 rpm, at which speed it probably develops around 0.61 BHP. I was frankly hoping for somewhat more than this! It’s probable that more running would yield some improvement, but not to any major extent. It’s also quite likely that a slightly higher output could be achieved using spark ignition. Finally, a higher nitro fuel would undoubtedly improve performance substantially. It must also be recognized that we are dealing with a design dating from early 1946 which was specifically intended for spark ignition operation on straight fuel. This was the time before glow-plugs or nitromethane, remember! When we reflect that manufacturer Ray Snow’s claimed performance for the original pre-war Hornet 60 was only 0.55 BHP @ 15,500 rpm (less power, and obviously far less torque), it’s clear that the Baab-Fox was at least in the general ball-park if we go by that standard (as Cliff Fox may have done). Perhaps more significantly in a tether car context where torque is important, the Baab-Fox peaked at a relatively low speed, seemingly as a result of developing considerably greater low-end torque than the pre-war Hornet. However, the performance of the Hornet was quickly improved once production re-commenced in the post-war period. By mid 1946 the factory claim for the post-war Hornet (which remained the performance standard at the time) had risen to 0.82 BHP at 13,800 rpm. Present-day testing amply supports this claim. This of course left the contemporary Baab-Fox in its wake if the above test is anything to go by. Even allowing for the possibility that the original engines may have performed somewhat better than the replica, there seems to be little doubt on the basis of this test that the Baab-Fox failed to match the performance standard which had been established by the 1946 Hornet and was even then being challenged by Dick McCoy with his popular 60 model. It’s probable that this performance shortfall became immediately obvious to the modelling fraternity, which would completely explain the engine’s extremely short market tenure.

In this manner, Tom acquired a batch of some 30 cars and even more engines. In his own words, he was “young enough and dumb enough” to think that there might be a gem among those engines that was better than the Series 20 McCoy or Dooling 61 which were the standard speed engines at the time.

The results of these test were most interesting! In Tom’s very clear recollection, the best engine using that prop was the McCoy 60 Series 20. The Dooling needed to rev out more to give of its best, hence requiring a smaller prop. The “best of the rest” were the Hornet 60 models, which pushed the McCoy fairly hard. None of the other engines tested could match the original Hornet, which was itself only beaten by a relatively small margin by the later “bulge bypass” Hornet kit conversion. However, a modified example of the Ball 60 also showed a great deal of promise, pushing the best of the Hornets very hard. The batch of engines that had been given to Tom included such mouth-watering gems as the Ball, Bungay, Cave Cobra, Orr, EDCO Sky Devil, Bluestreak, Hassad (prewar), Ancil 60, Atomic, Thunderbird, Baab-Fox, Batzloff, Blakely, Thermite, Talisman and probably some other racing classics which Tom cannot now recall. There were also some other cars and engines (O&R, Dennymite, Super Cyclone, Atwood Red Crown, OK Tornado etc.) which Tom did not include in his tests since they were undoubtedly obsolete in a 1950's speed-flying context. Tom clearly recalled his finding that the Baab-Fox was dead at the starting line in competition terms, comng nowhere near matching any of the other tested units. He put this down to the engine's undersized, convoluted and hence highly restrictive bypass set-up, which was clearly far less efficient than the more conventional arrangements seen in the other models tested. Tom's impression is amply borne out by my own results reported above. It's very difficult to believe that Cliff Fox and Lloyd Baab would not have undertaken their own comparative tests prior to announcing their new design. It they did so, they could scarcely have failed to realize that in performance terms the engine was an also-ran which stood no chance of competition success. The fact that they went so far as to actually advertise the engine regardless will always remain a mystery ............. In Conclusion - the Baab-Fox .604 Today

Even if by some miracle an original example did cross your path, you’d better have your line of credit well cleared before commencing negotiations! Woody Bartelt told me that the original example which was used in the creation of his replicas was later sold for no less than US$5,000! This being the case, a far more realistic and doubtless cost-effective option is to try to locate an example of Woody Bartelt’s replica. All of Woody's replicas had been sold by early 2014, but examples will doubtless resurface from time to time on eBay and elsewhere. In summary, the Baab-Fox .604 was a very interesting example of one designer’s attempt to take an existing and highly successful model racing engine (the Hornet 60) and rework the design to deal with a few aspects of that model which appeared amenable to improvement. A very worthy effort by Messrs. Baab and Fox - too bad that it was not rewarded by greater technical and marketplace success. Still, thanks to Woody Bartelt’s initiative in making his fine replicas available, a few of us can still enjoy contemplating this very creditable if unsuccessful effort to create an improved model racing engine. It’s a story well worth preserving - I hope that you’ve enjoyed my attempt to prevent yet another “ship that passed in the night” from disappearing completely from the consciousness of model engine enthusiasts worldwide!! ______________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada First published December 2014 Updated September 2018 |

||

| |

In an earlier article on the late Ron Chernich’s “

In an earlier article on the late Ron Chernich’s “ possible compliment by following its design in almost all respects. For example, although the iconic McCoy 60 of 1946 exhibited a number of architectural differences from the Hornet, that original version of the McCoy was functionally almost identical, to the extent that a number of parts were interchangeable between the two models.

possible compliment by following its design in almost all respects. For example, although the iconic McCoy 60 of 1946 exhibited a number of architectural differences from the Hornet, that original version of the McCoy was functionally almost identical, to the extent that a number of parts were interchangeable between the two models. combination. Our

combination. Our

As recorded

As recorded  At the time in question, the use of large racing engines in model aircraft was impracticable since no technique then existed which allowed the safe operation and timing of high-speed model aircraft under full control. This situation only changed following the wartime advent of Jim Walker’s U-control system (far better known today as control-line). In the interim, tethered operation of model cars and hydroplanes, as well as rail-guided model car racing, remained the only practicable applications for large full-blown racing engines.

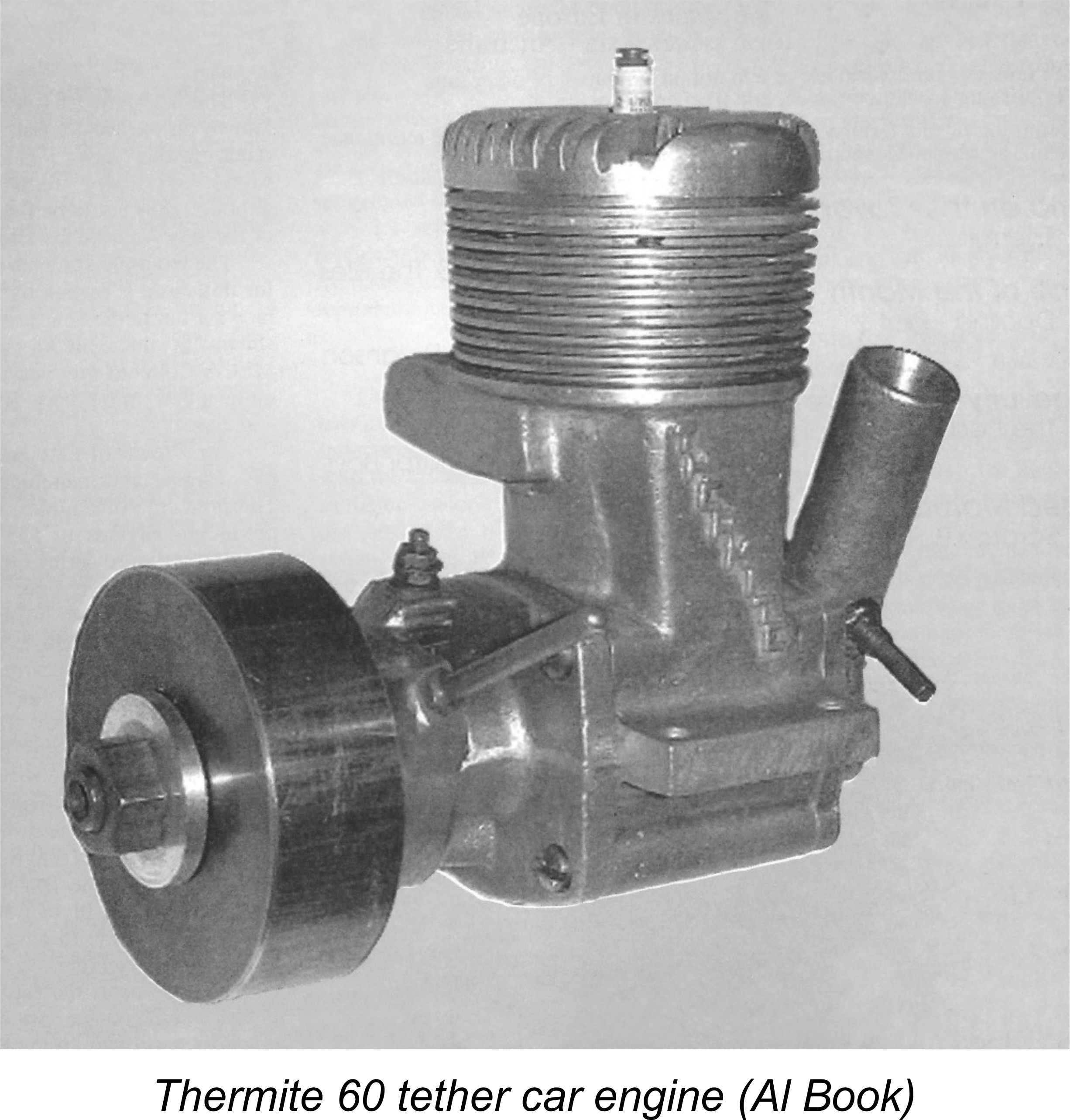

At the time in question, the use of large racing engines in model aircraft was impracticable since no technique then existed which allowed the safe operation and timing of high-speed model aircraft under full control. This situation only changed following the wartime advent of Jim Walker’s U-control system (far better known today as control-line). In the interim, tethered operation of model cars and hydroplanes, as well as rail-guided model car racing, remained the only practicable applications for large full-blown racing engines. The onset of WW2 in December 1941 (as far as the USA was concerned) put an end to model racing engine development as a mainstream activity, at least for the time being. A few limited-production models such as Jim Brown’s 1944 Thermite 60 from Oakland, California, did appear sporadically in very small numbers, but that was about all. Consequently, little further development occurred during the war years, the result being that the Hornet re-entered production during the early post-war period as still the engine to beat.

The onset of WW2 in December 1941 (as far as the USA was concerned) put an end to model racing engine development as a mainstream activity, at least for the time being. A few limited-production models such as Jim Brown’s 1944 Thermite 60 from Oakland, California, did appear sporadically in very small numbers, but that was about all. Consequently, little further development occurred during the war years, the result being that the Hornet re-entered production during the early post-war period as still the engine to beat. However, this didn’t last long! Under an agreement signed during the war years between Dick McCoy and the Duromatic Products Co. of Los Angeles, quantity production of the McCoy 60 was soon underway. Since this engine was very closely based upon the Hornet in purely functional terms, it was only to be expected that it would offer stiff competition to Ray Snow and his Hornet design.

However, this didn’t last long! Under an agreement signed during the war years between Dick McCoy and the Duromatic Products Co. of Los Angeles, quantity production of the McCoy 60 was soon underway. Since this engine was very closely based upon the Hornet in purely functional terms, it was only to be expected that it would offer stiff competition to Ray Snow and his Hornet design. to ongoing experiments with FRV induction as opposed to the rear rotary disc valve (RRV) induction of the Hornet - the

to ongoing experiments with FRV induction as opposed to the rear rotary disc valve (RRV) induction of the Hornet - the  exhaust stacks. A considerable improvement on the three transfer ports used by the Hornet and McCoy models at the time! By all contemporary accounts, the Ball was a very stout performer.

exhaust stacks. A considerable improvement on the three transfer ports used by the Hornet and McCoy models at the time! By all contemporary accounts, the Ball was a very stout performer.

numbers in the San Francisco Bay area by William P. “Bill” Cubitt, a marine operating engineer by profession and a model car racer by inclination. Finally, there’s little doubt that he would very quickly have become aware of the twin-transfer approach taken by Henry Ball when designing his Ball 60 model mentioned earlier.

numbers in the San Francisco Bay area by William P. “Bill” Cubitt, a marine operating engineer by profession and a model car racer by inclination. Finally, there’s little doubt that he would very quickly have become aware of the twin-transfer approach taken by Henry Ball when designing his Ball 60 model mentioned earlier.

In accordance with his own ideas, Fox drew up a design for an engine which was basically a Hornet bottom end grafted onto a cylinder unit having twin bypass passages together with twin exhausts. In addition to retaining the RRV induction of the Hornet design, Fox placed his exhausts to the sides of the engine with the transfer ports fore and aft, in contrast to Henry Ball’s placement of the exhausts at front and rear with the bypass passages to the sides. Otherwise, the porting of the Ball and Fox designs was basically similar.

In accordance with his own ideas, Fox drew up a design for an engine which was basically a Hornet bottom end grafted onto a cylinder unit having twin bypass passages together with twin exhausts. In addition to retaining the RRV induction of the Hornet design, Fox placed his exhausts to the sides of the engine with the transfer ports fore and aft, in contrast to Henry Ball’s placement of the exhausts at front and rear with the bypass passages to the sides. Otherwise, the porting of the Ball and Fox designs was basically similar. It seems best to begin with a few vital statistics. The Baab-Fox .604 featured the “racing standard” bore and stroke measurements established by the Hornet 60 of 0.937 inch (23.80 mm) and 0.875 inch (22.22 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.604 cubic inches (9.89 cc). It was of course designed strictly for spark ignition - the emergence of the commercial miniature glow-plug still lay several years in the future at the time when it was produced. The volumetrically-measured compression ratio of my own replica Baab-Fox is a fairly healthy 10 to 1.

It seems best to begin with a few vital statistics. The Baab-Fox .604 featured the “racing standard” bore and stroke measurements established by the Hornet 60 of 0.937 inch (23.80 mm) and 0.875 inch (22.22 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.604 cubic inches (9.89 cc). It was of course designed strictly for spark ignition - the emergence of the commercial miniature glow-plug still lay several years in the future at the time when it was produced. The volumetrically-measured compression ratio of my own replica Baab-Fox is a fairly healthy 10 to 1. I have no way of knowing what the original examples weighed - all that I can report is that the Bartelt replica in my possession weighs all of 18.0 ounces (510 gm) complete with plug, timer and bobbin-style prop driver but minus any ignition support equipment. This is some 1.75 ounces heavier than the Hornet 60, being only exceeded among 10 cc racing engines of my acquaintance by the 1948

I have no way of knowing what the original examples weighed - all that I can report is that the Bartelt replica in my possession weighs all of 18.0 ounces (510 gm) complete with plug, timer and bobbin-style prop driver but minus any ignition support equipment. This is some 1.75 ounces heavier than the Hornet 60, being only exceeded among 10 cc racing engines of my acquaintance by the 1948  This being the case, let’s begin by dealing with a few of the major similarities between the Baab-Fox and the Hornet. Both models were based upon a set of four major castings having parallel functions - the main crankcase unit, the backplate with disc valve bearing, the cylinder barrel with exhaust stacks and bypass passage(s) and the cylinder head. In both cases, the main crankcase casting incorporated the main bearing housing cast in unit rather than being bolted on as in the cases of engines such as the McCoy and Atomic models. Both designs also featured crankcase castings which were truncated just above crankdisc level, with a sturdy rectangular flange being incorporated at that point to serve as the seat for the upper cylinder barrel casting. In both cases, the latter unit terminated at its lower end in a matching rectangular-section flange, being attached to the lower casting by four screws placed at the corners of the flange.

This being the case, let’s begin by dealing with a few of the major similarities between the Baab-Fox and the Hornet. Both models were based upon a set of four major castings having parallel functions - the main crankcase unit, the backplate with disc valve bearing, the cylinder barrel with exhaust stacks and bypass passage(s) and the cylinder head. In both cases, the main crankcase casting incorporated the main bearing housing cast in unit rather than being bolted on as in the cases of engines such as the McCoy and Atomic models. Both designs also featured crankcase castings which were truncated just above crankdisc level, with a sturdy rectangular flange being incorporated at that point to serve as the seat for the upper cylinder barrel casting. In both cases, the latter unit terminated at its lower end in a matching rectangular-section flange, being attached to the lower casting by four screws placed at the corners of the flange. The backplates too were basically very similar, being attached to the main crankcase with four machine screws. The main difference was that the Baab-Fox’s backplate did not incorporate part of the cylinder location flange as in the Hornet. Consequently, it was possible to remove the backplate of the Baab-Fox without disturbing the two rear cylinder attachment screws, something which was not possible with the Hornet. However, that was the main architectural difference - both models used a cast alloy rotary disc valve controlling induction through a screw-in venturi of basically similar design in both cases. The rotary disc valve in both engines was mounted on a steel spindle and driven in the usual manner from the end of the crankpin.

The backplates too were basically very similar, being attached to the main crankcase with four machine screws. The main difference was that the Baab-Fox’s backplate did not incorporate part of the cylinder location flange as in the Hornet. Consequently, it was possible to remove the backplate of the Baab-Fox without disturbing the two rear cylinder attachment screws, something which was not possible with the Hornet. However, that was the main architectural difference - both models used a cast alloy rotary disc valve controlling induction through a screw-in venturi of basically similar design in both cases. The rotary disc valve in both engines was mounted on a steel spindle and driven in the usual manner from the end of the crankpin. The manner in which the fore-and-aft transfer ports were supplied with mixture from the crankcase was both interesting and ingenious, if perhaps excessively convoluted. The presence of the disc valve at the rear and the crankweb and rear main ball race at the front precluded the creation of straight bypass passages which were fed from directly beneath the transfer ports. Instead, the upper cylinder casting incorporated what amounted to a set of annular passages running in spiral fashion around the cylinder liner from the lower gas entry point to connect to the transfer ports through suitably-positioned risers. Careful routing of these passages was required to prevent any overlap with the exhausts.

The manner in which the fore-and-aft transfer ports were supplied with mixture from the crankcase was both interesting and ingenious, if perhaps excessively convoluted. The presence of the disc valve at the rear and the crankweb and rear main ball race at the front precluded the creation of straight bypass passages which were fed from directly beneath the transfer ports. Instead, the upper cylinder casting incorporated what amounted to a set of annular passages running in spiral fashion around the cylinder liner from the lower gas entry point to connect to the transfer ports through suitably-positioned risers. Careful routing of these passages was required to prevent any overlap with the exhausts. An interesting observation is the presence of a single round hole in the cylinder wall immediately above each of the two entry points to the bypass system. Each of these holes communicates with its respective bypass passage. At first glance, these holes look very like part of a piston port system intended to ease gas entry into the bypass passages, but there are no corresponding piston ports, nor indeed could these be provided without destroying the engine’s crankcase compression seal since they would be open to the exhaust

An interesting observation is the presence of a single round hole in the cylinder wall immediately above each of the two entry points to the bypass system. Each of these holes communicates with its respective bypass passage. At first glance, these holes look very like part of a piston port system intended to ease gas entry into the bypass passages, but there are no corresponding piston ports, nor indeed could these be provided without destroying the engine’s crankcase compression seal since they would be open to the exhaust

The resulting piston was unusually high-domed, requiring that the underside of the cylinder head be contoured to match. If the engine had followed the usual pattern of having the piston crown remain below the top of the liner at top dead centre, the overall height of the engine would have become somewhat unwieldy. Indeed, one of the designer’s goals was clearly to keep the engine as compact as possible.

The resulting piston was unusually high-domed, requiring that the underside of the cylinder head be contoured to match. If the engine had followed the usual pattern of having the piston crown remain below the top of the liner at top dead centre, the overall height of the engine would have become somewhat unwieldy. Indeed, one of the designer’s goals was clearly to keep the engine as compact as possible.

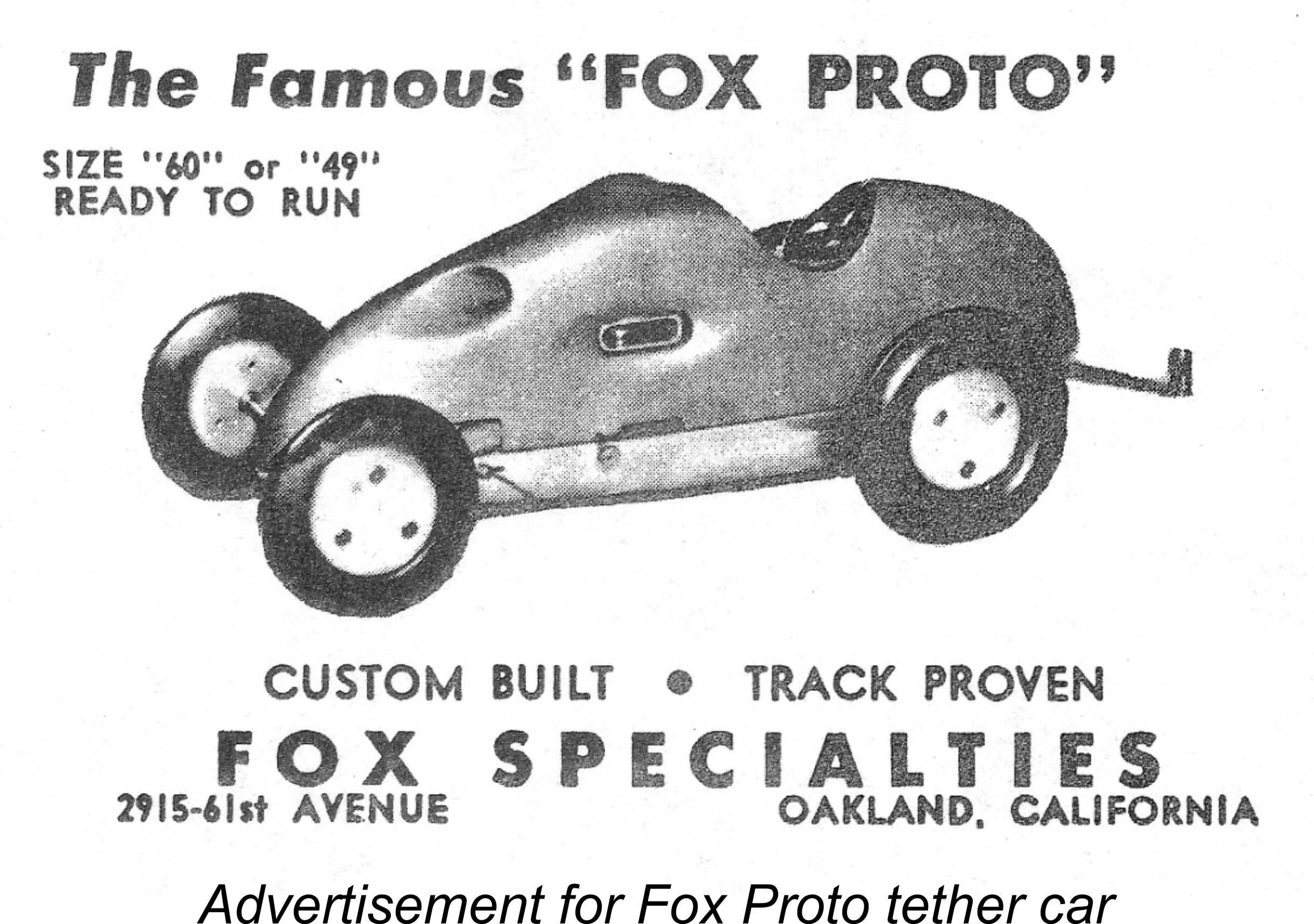

Apart from his journalistic activities, Baab operated a manufacturing facility under the name Baab Model Products at 1749 Pleasant Valley Avenue in Oakland. One of his more popular products was the Fox Proto model car design which was marketed by Cliff Fox through his Fox Specialities hobby shop on 61st Avenue in Oakland. We’ll never know the terms of the arrangement, but Fox was successful in obtaining Baab’s agreement to add what was to become known as the Baab-Fox .604 racing engine to his existing manufacturing program.

Apart from his journalistic activities, Baab operated a manufacturing facility under the name Baab Model Products at 1749 Pleasant Valley Avenue in Oakland. One of his more popular products was the Fox Proto model car design which was marketed by Cliff Fox through his Fox Specialities hobby shop on 61st Avenue in Oakland. We’ll never know the terms of the arrangement, but Fox was successful in obtaining Baab’s agreement to add what was to become known as the Baab-Fox .604 racing engine to his existing manufacturing program.

Although the Baab-Fox was clearly aimed directly at the model race car market, it’s noteworthy that the shaft was dimensioned to accept a conventional bobbin-type prop driver of the kind typically used in the Class C control-line speed category which was then rapidly gaining popularity. The promoters of the engine were evidently keeping their marketing options open. In this context, the promotion of the engine as a “Class C” unit clearly referred to its use in control-line speed applications, since Class C as such did not exist in the model car racing category. Like the earlier H.R.E. Special, both the Ball 60 and the Cave Cobra were specifically designed as car units, both having layouts which were somewhat inconvenient for aircraft use. Viewed in this light, the Baab-Fox advertising claim may well have been literally true in a Class C context ……..

Although the Baab-Fox was clearly aimed directly at the model race car market, it’s noteworthy that the shaft was dimensioned to accept a conventional bobbin-type prop driver of the kind typically used in the Class C control-line speed category which was then rapidly gaining popularity. The promoters of the engine were evidently keeping their marketing options open. In this context, the promotion of the engine as a “Class C” unit clearly referred to its use in control-line speed applications, since Class C as such did not exist in the model car racing category. Like the earlier H.R.E. Special, both the Ball 60 and the Cave Cobra were specifically designed as car units, both having layouts which were somewhat inconvenient for aircraft use. Viewed in this light, the Baab-Fox advertising claim may well have been literally true in a Class C context …….. As far as I’m aware, no performance claims were ever published for the Baab-Fox .604. However, beating the Hornet 60 was clearly the engine’s performance target. Accordingly, we might look to see peak power developed in the vicinity of 15,000 rpm or so - a little higher than the official post-war Hornet claim of 0.85 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. This expectation influenced my decision to set 15,000 rpm as the upper speed limit to which I was prepared to push the engine.

As far as I’m aware, no performance claims were ever published for the Baab-Fox .604. However, beating the Hornet 60 was clearly the engine’s performance target. Accordingly, we might look to see peak power developed in the vicinity of 15,000 rpm or so - a little higher than the official post-war Hornet claim of 0.85 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. This expectation influenced my decision to set 15,000 rpm as the upper speed limit to which I was prepared to push the engine. encourage the prime to run straight back out of the exhausts or down through the bypass passages into the case. The best approach was to prime through an open exhaust and then immediately close the exhaust with the piston. Then connect the plug, hit the prop backwards from the BDC position against compression to induce a backfire which sets the prop spinning in the correct direction (the only safe way to hand-start a classic racing 60) and away you go.

encourage the prime to run straight back out of the exhausts or down through the bypass passages into the case. The best approach was to prime through an open exhaust and then immediately close the exhaust with the piston. Then connect the plug, hit the prop backwards from the BDC position against compression to induce a backfire which sets the prop spinning in the correct direction (the only safe way to hand-start a classic racing 60) and away you go. following table tells the story:

following table tells the story: The impression that the Baab-Fox was a chronic under-performer is confirmed by the latter-day (2014) recollections of former American Miniature Racing Car Association (AMRCA) President Tom Pearson, who was kind enough to share some of his personal recollections of the early big-bore racing engines, including the Baab-Fox. As a teenage member of the Chicago U-Liners model flying club in the early 1950’s, Tom was flying control-line speed, which was then the most popular form of power model racing given the plummeting interest in model car racing at the time. It was indeed this very plummeting of interest along with the closure of their local track which led to a number of car racers from the Harvey, Illinois tether car club abandoning the sport at this time. A number of them gave their now-redundant cars and engines to young Tom. Some guys have all the luck ………!

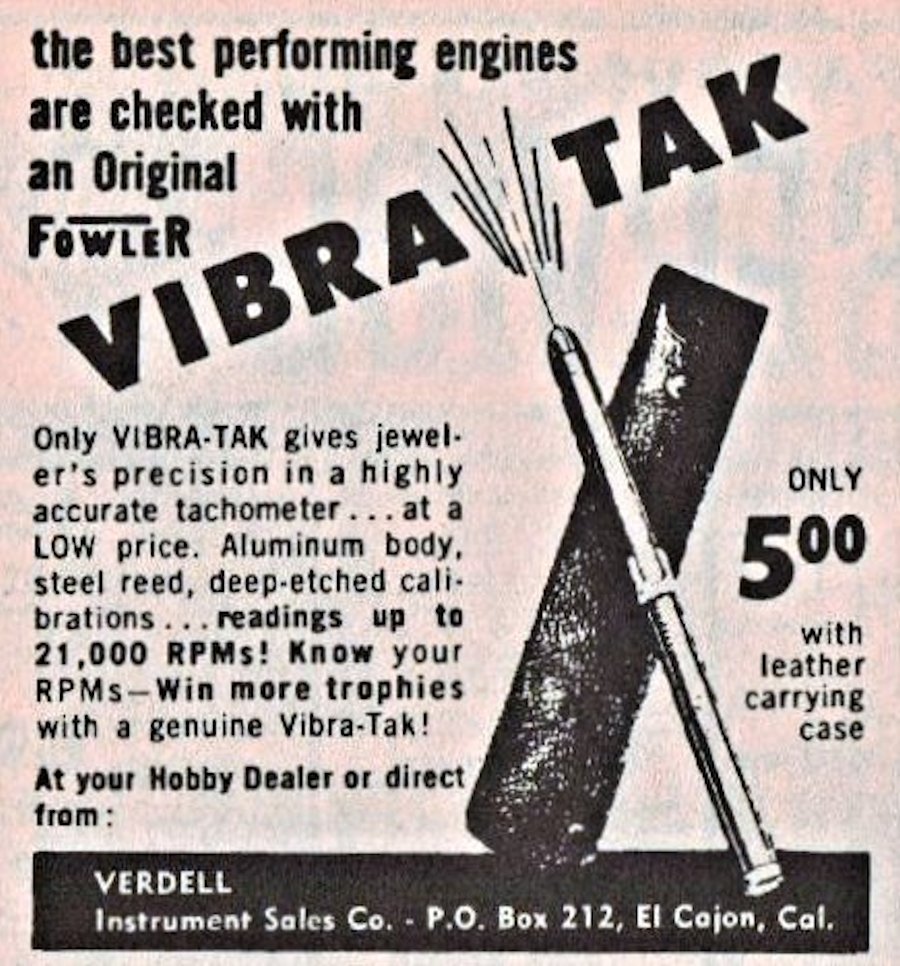

The impression that the Baab-Fox was a chronic under-performer is confirmed by the latter-day (2014) recollections of former American Miniature Racing Car Association (AMRCA) President Tom Pearson, who was kind enough to share some of his personal recollections of the early big-bore racing engines, including the Baab-Fox. As a teenage member of the Chicago U-Liners model flying club in the early 1950’s, Tom was flying control-line speed, which was then the most popular form of power model racing given the plummeting interest in model car racing at the time. It was indeed this very plummeting of interest along with the closure of their local track which led to a number of car racers from the Harvey, Illinois tether car club abandoning the sport at this time. A number of them gave their now-redundant cars and engines to young Tom. Some guys have all the luck ………! To evaluate this possibility, Tom proceeded to test all of his new acquisitions on a 9x12 Tornado speed prop, which was pretty much a standard for .60-class control-line speed at the time. The fuel used was his model flying club’s usual competition brew of 37.5% nitro, 37.5% methanol and 25% castor oil. A Fowler Vibra-Tach was used to measure rpm, since that was all that was available back then.

To evaluate this possibility, Tom proceeded to test all of his new acquisitions on a 9x12 Tornado speed prop, which was pretty much a standard for .60-class control-line speed at the time. The fuel used was his model flying club’s usual competition brew of 37.5% nitro, 37.5% methanol and 25% castor oil. A Fowler Vibra-Tach was used to measure rpm, since that was all that was available back then.