|

|

The ETA 15 Glow-Plug Prototypes

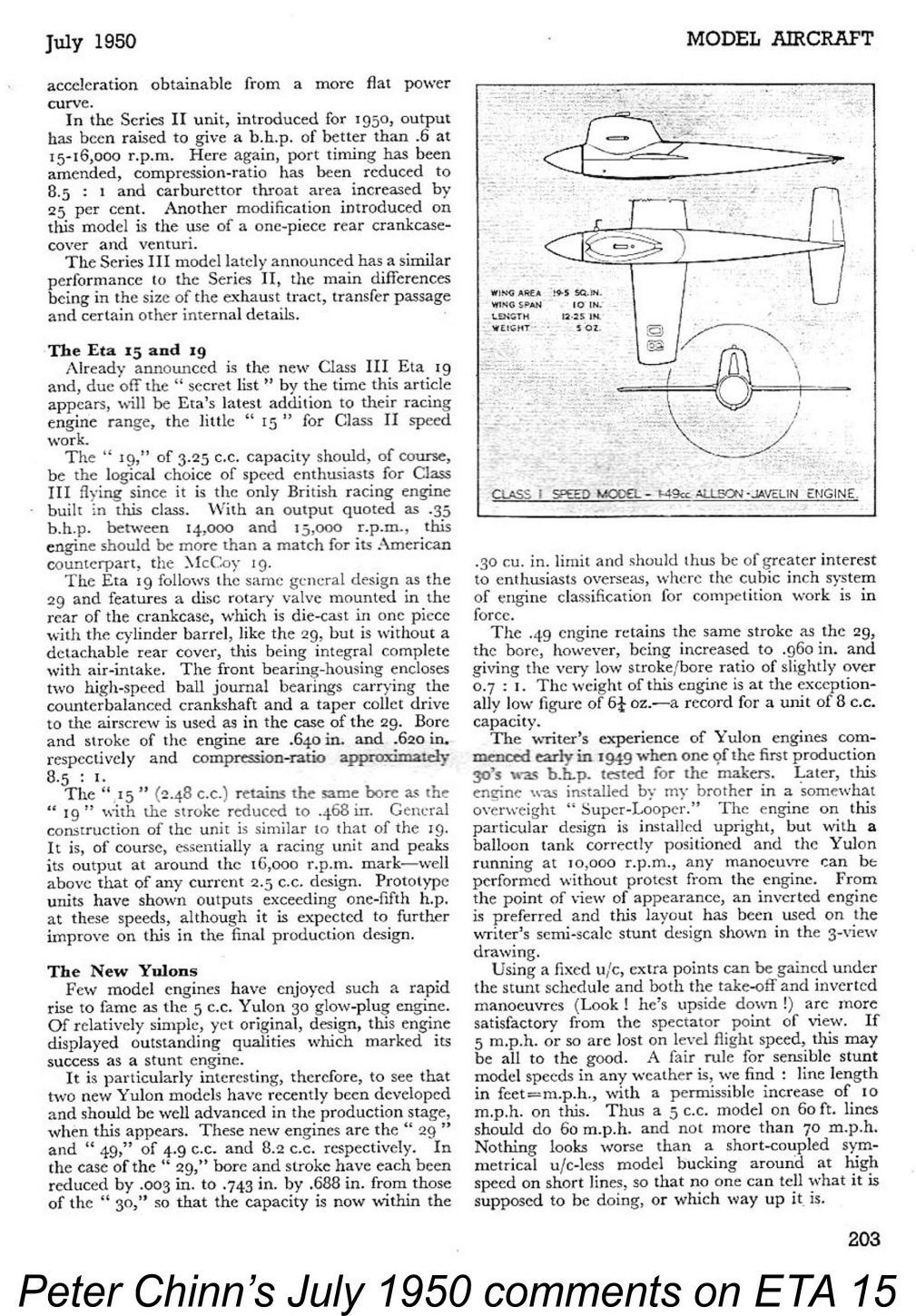

However, the same cannot be said of the central subject of the present article. Retentive readers will recall that near the end of my earlier article I made brief reference to a hitherto virtually unknown ETA glow-plug model, the ETA 15 of 1950. This extremely rare engine is not to be confused with the famous ETA 15D diesel of a decade later. It only ever appeared in prototype form, although it’s clear from the evidence that designer Ken Bedford must have entertained serious thoughts about putting it into production at some point in time. I’d actually put this unit into the category of an “engine that nearly was” as opposed to “never was”. The sole contemporary media reference to the existence of this model that I can find appeared in Peter Chinn's "Accent on Power" column in the July 1950 issue of "Model Aircraft" magazine which is reproduced below in a later section of this article. In his column for that month, Chinn made reference to the previously-announced release of the ETA 19 (May 1950), but also mentioned the anticipated appearance of In the event, nothing more was heard of the ETA 15 glow-plug model - it was dropped by the company later in 1950 while still in the development stage. The reasons for this have been a bit of a mystery up to now. The initial key to providing a degree of clarity on this issue came from the fact that before his untimely death in March 2016, my late and much missed friend David Owen mentioned to my friend and colleague Miles Patience that quite a few years previously he had discussed the ETA 15 glow-plug project and the reasons for its abandonment directly with Ken Bedford. Apparently Ken told David at that time that the ETA 15 glow-plug project was abandoned because tests showed that the design offered no significant performance advantages over its contemporary 2.5 cc competition. In addition, Ken reportedly claimed that it turned out to be "heavy for its displacement". Shortly before he passed away in January 2015 at age 91, Ken was asked once more about the 15 glow-plug project. However, by then he had no recollection of it - the passage of 65 years had dimmed his memories.

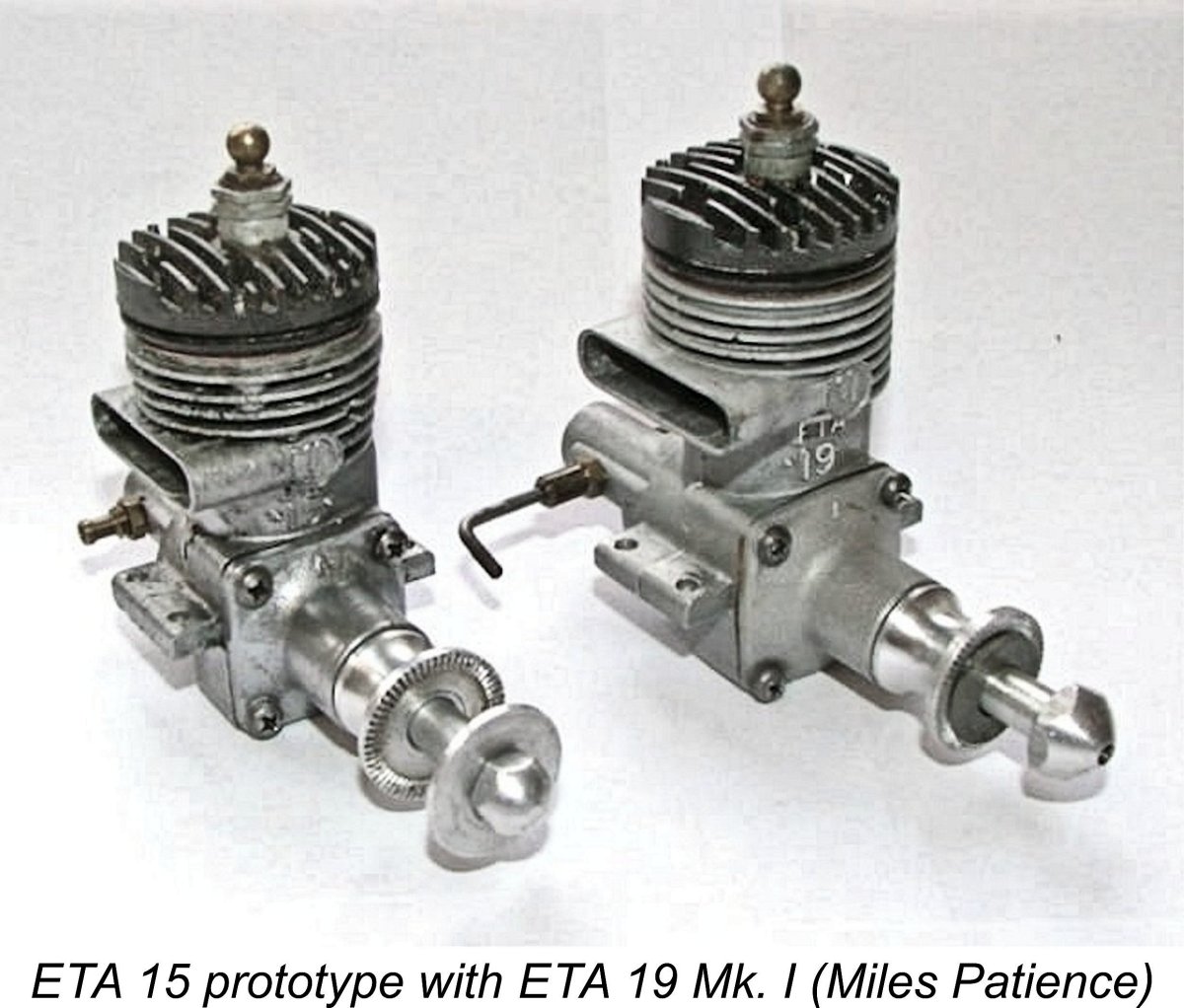

Following its late 1950 abandonment, the engine vanished from sight and memory, not to reappear until October 2013. At that point, Miles Patience initiated the process of bringing this long-forgotten engine back to life through his discovery and acquisition of a collection of components for this variant. These presumably came from the estate of Ken Bedford’s then recently-deceased older brother Eric. There were enough components to build one complete engine and to serve as patterns for the missing items required to complete other examples. Since there were five crankcase castings (two of which were un-machined), the potential was there for the completion of five as-new examples. Miles therefore set about arranging for the precise duplication of missing parts in sufficient numbers to assemble an additional four units. This required a considerable amount of research and coordination on his part. A remarkable number of individuals participated in this exercise. John Alcott made a pattern for the front housing, after which the castings were produced by Bullett & Co., who are suppliers of castings to the British Royal Household. Gavin Carter carried out some crankshaft work, made the disc valve rotors and finished the two un-machined crankcases. Jon Fletcher produced the prop nuts and washers, which differ from those used on the ETA 19. My good friend Peter Valicek machined the front housing castings and lapped the crankshafts to the correct fit. Miles' father Mike Patience worked out all the required corrections and adjustments, established the final fits and carried out much of the final assembly work. Miles himself did the balance of the assembly work as well as conducting the testing of the completed engines. Even yours truly made a small contribution by establishing the final form of the cylinder head through experimentation. More on that later ............. I was fortunate enough to be one of the individuals who was privileged to be entrusted with one of the five examples of this engine which are presently known to exist. As a result, I’m in a position to add a review of this motor to my growing portfolio of tests of classic 2.5 cc racing engines from the 1950’s and early 1960’s.

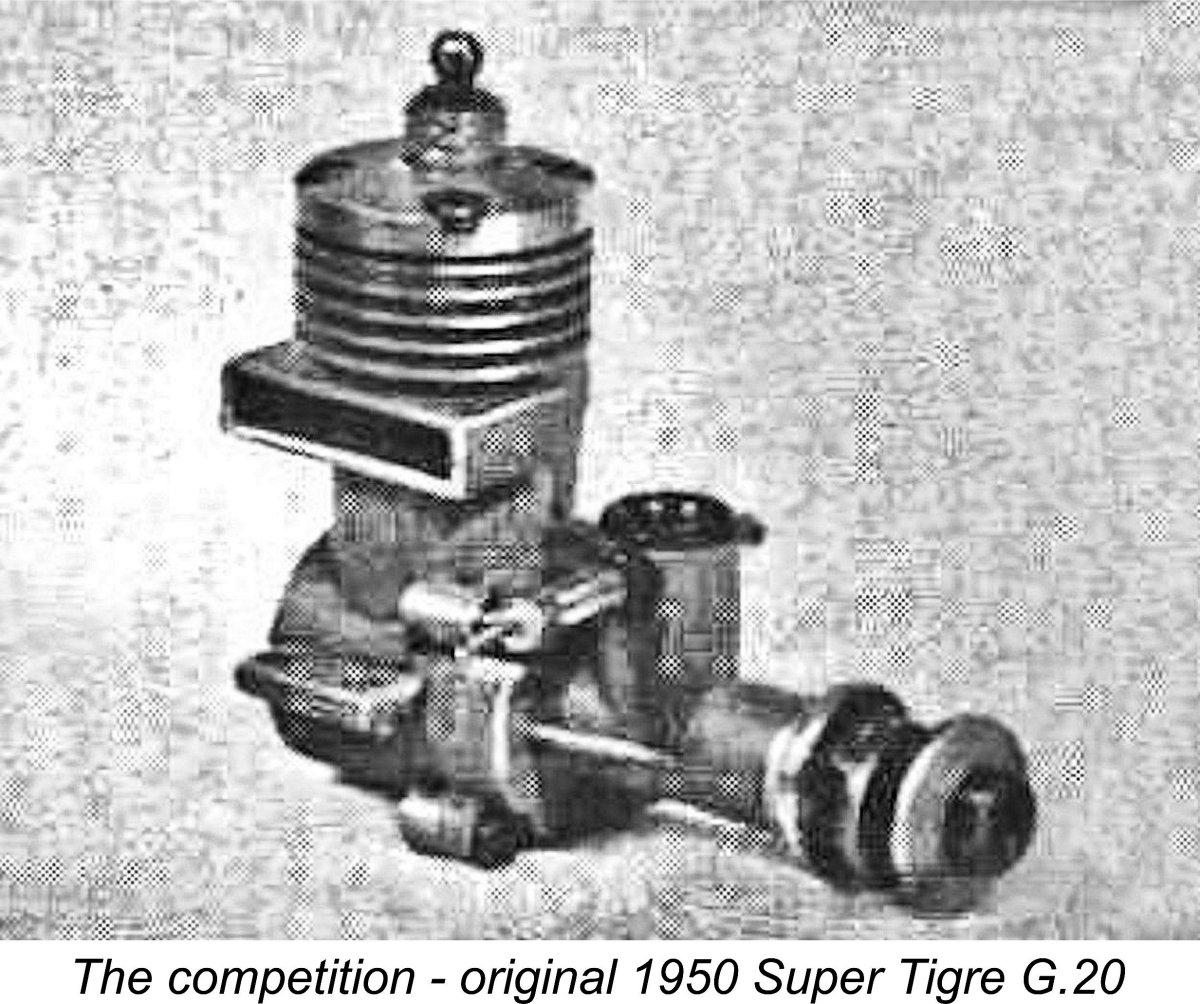

This immediately raises the question – how would the ETA 15 glow-plug model have stacked up against the Super Tigre and the diesels if ETA Instruments had gone ahead and released it in 1950 or 1951? Put another way, what kind of an engine did the British modelling community miss out on?? The answer to this question could possibly clarify the basis for its non-release, and the only way to come to that answer was to second-guess Ken Bedford by testing the engine. Before doing so, I’ll spend a little time summarizing the circumstances surrounding the creation of this almost unknown motor. Progenitor – the ETA 19

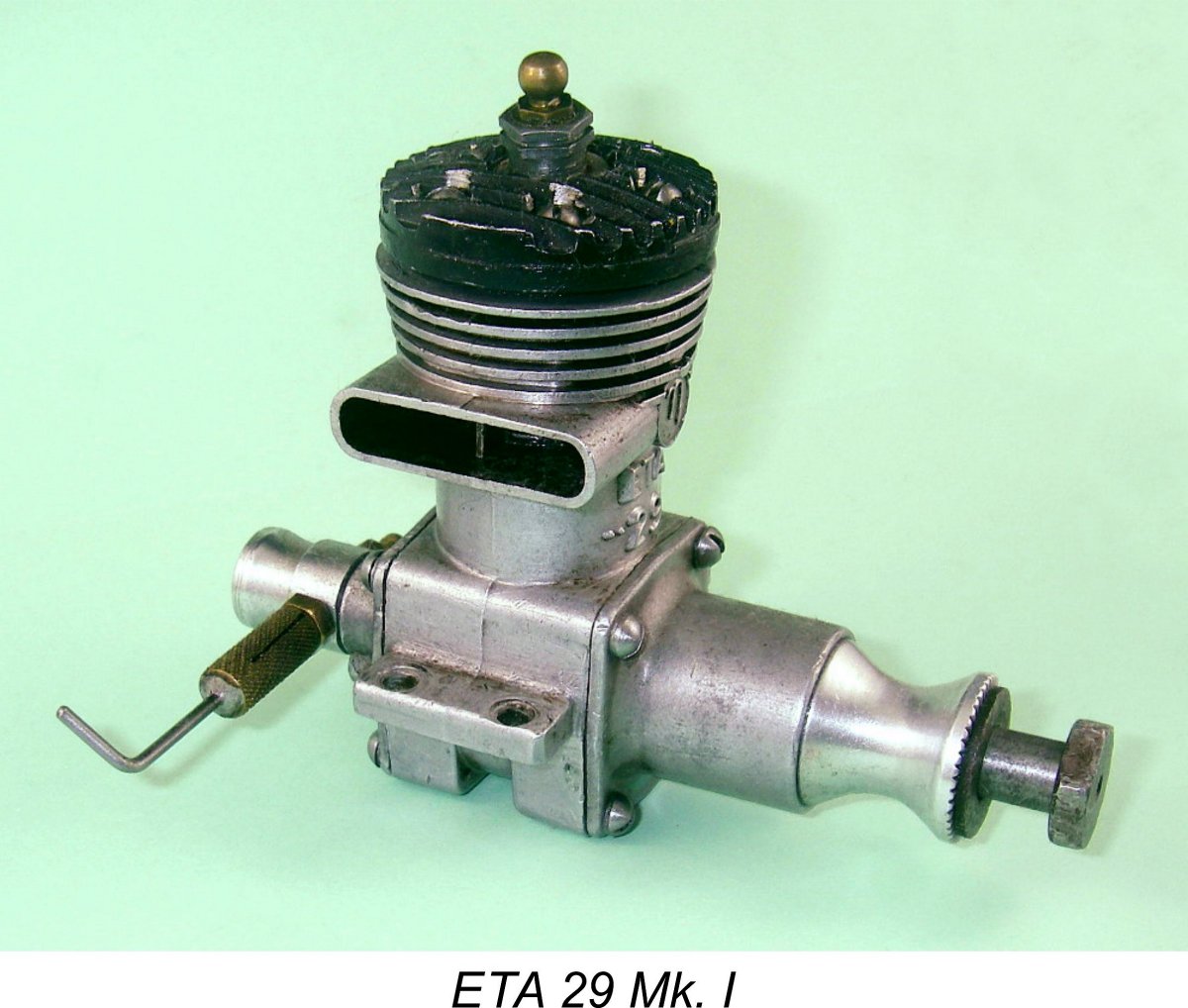

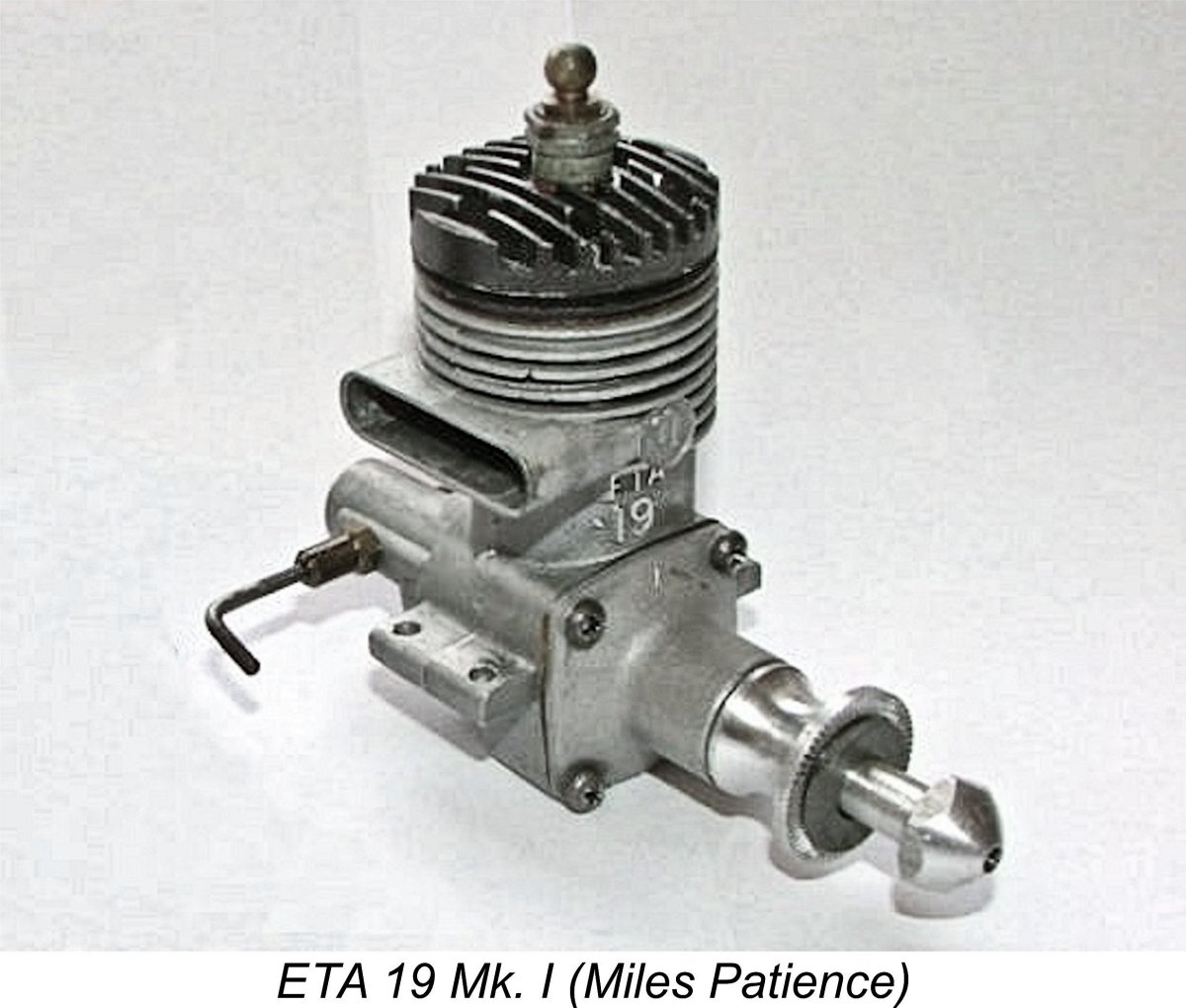

However, it seems likely that Ken also entertained hopes of making some inroads into the US market. Prevailing AMA rules allowed engines of up to .199 cuin. displacement in their Class A competitions. This is probably the explanation for the new model's displacement of .199 cuin. (3.27 cc) rather than the full .21 cuin. (3.5 cc). The ETA 19 first appeared in May 1950, well over a year after the ETA 29 – clearly Ken Bedford had not begun work on this model until the ETA 29 was well and truly launched. Like its big brother, the ETA 19 was a cross-flow loop-scavenged disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction twin ball-race design with a The ETA 29 had been designed following Ken Bedford’s examination of a McCoy 29. The design of the ETA 19 also clearly paid tribute to Dick McCoy’s efforts, bearing a strong resemblance to the then-current version of the McCoy 19. Ken undoubtedly got his hands on an actual example of the McCoy 19 for direct examination and test, since he took the trouble to develop his own performance curves for that model. These have been preserved thanks once again to the diligence of Miles Patience. Like the McCoy, the ETA 19 featured a backplate and intake venturi which were cast in unit with the main crankcase/exhaust stack/bypass/cylinder jacket casting. Only the front housing was detachable on this model. A significant departure from the design of the then-current McCoy 19 was the use from the outset of a twin ball race crankshaft as opposed to the single inboard ball-race used by the McCoy prior to the appearance of the twin ball-race Red Head version in early 1950.

Oddly enough, the ETA 19 then disappeared immediately from ETA’s advertising, not to reappear until the early 1959 appearance of the Mk. II version which featured a lapped piston in place of the original ringed component. However, it undoubtedly remained available for some time after May 1950 - just how long and in what quantities is currently impossible to state with any certainty. The engine may have retained the status of a “special order” item all along. It’s also likely that it became a temporary casualty of the well-documented 1955 diversion of ETA’s entire model engine manufacturing resources into other product lines.

However, it’s apparent from reading between the lines that the seal provided by the rings when new was less than perfect, since Chinn commented on the need for a period of 1 - 2 hours running to bed in the rings. He recommended that in the interim a castor oil prime be administered to create a sufficient seal for starting. Other than that, he characterized the engine as being easy to start by hand using standard procedures. Vibration levels were said to be very low. This of course represented a very positive endorsement of the ETA 19 by one of the world’s most respected model engine authorities. Despite this, the engine never seems to have featured prominently in the ETA range during the mid 1950's – the focus was almost entirely upon the larger ETA 29 model until early 1959. Still, the ETA 19 was an excellent engine in all respects, and a very worthy companion to its far better-known 29 big brother in the ETA range. I for one rate it very highly. The ETA 15 Glow-Plug Prototypes

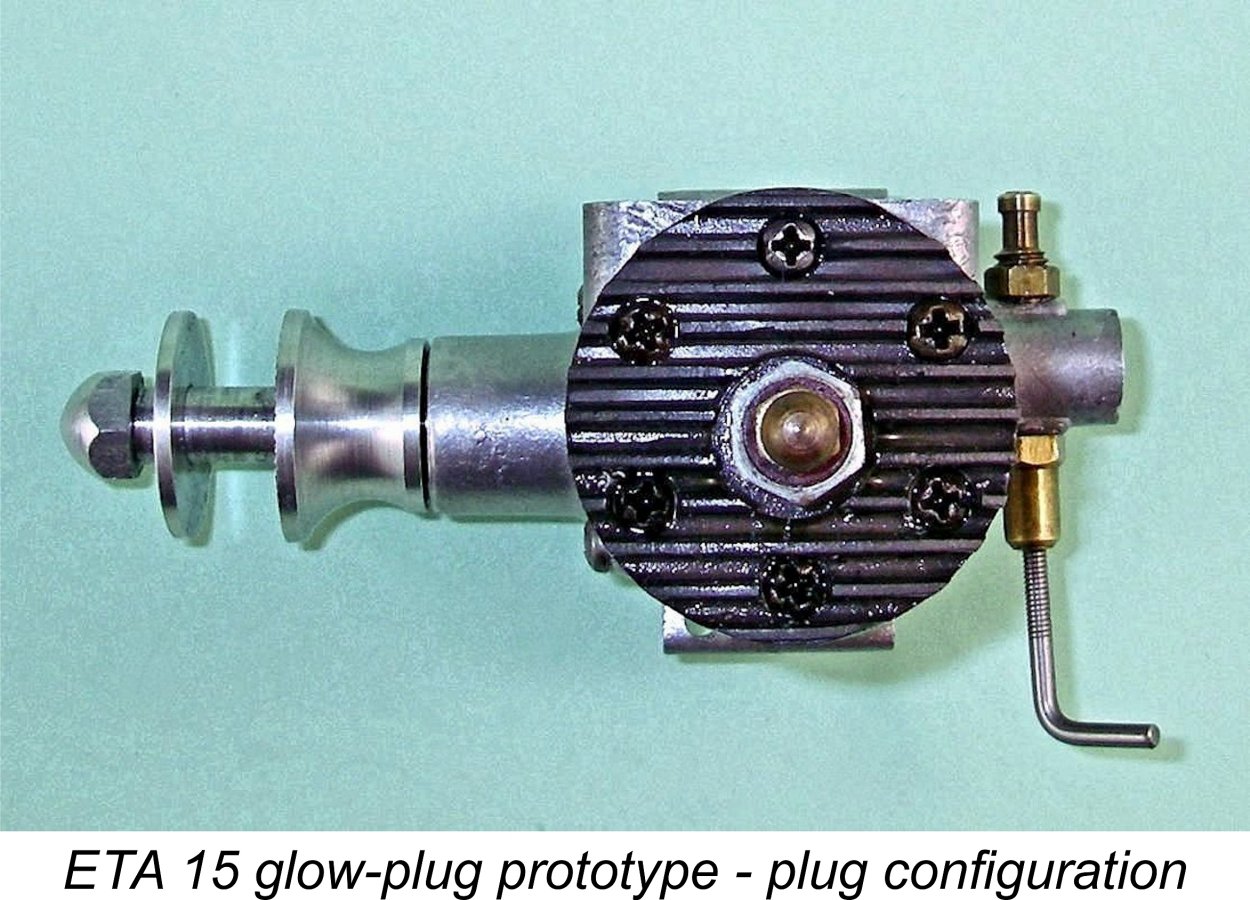

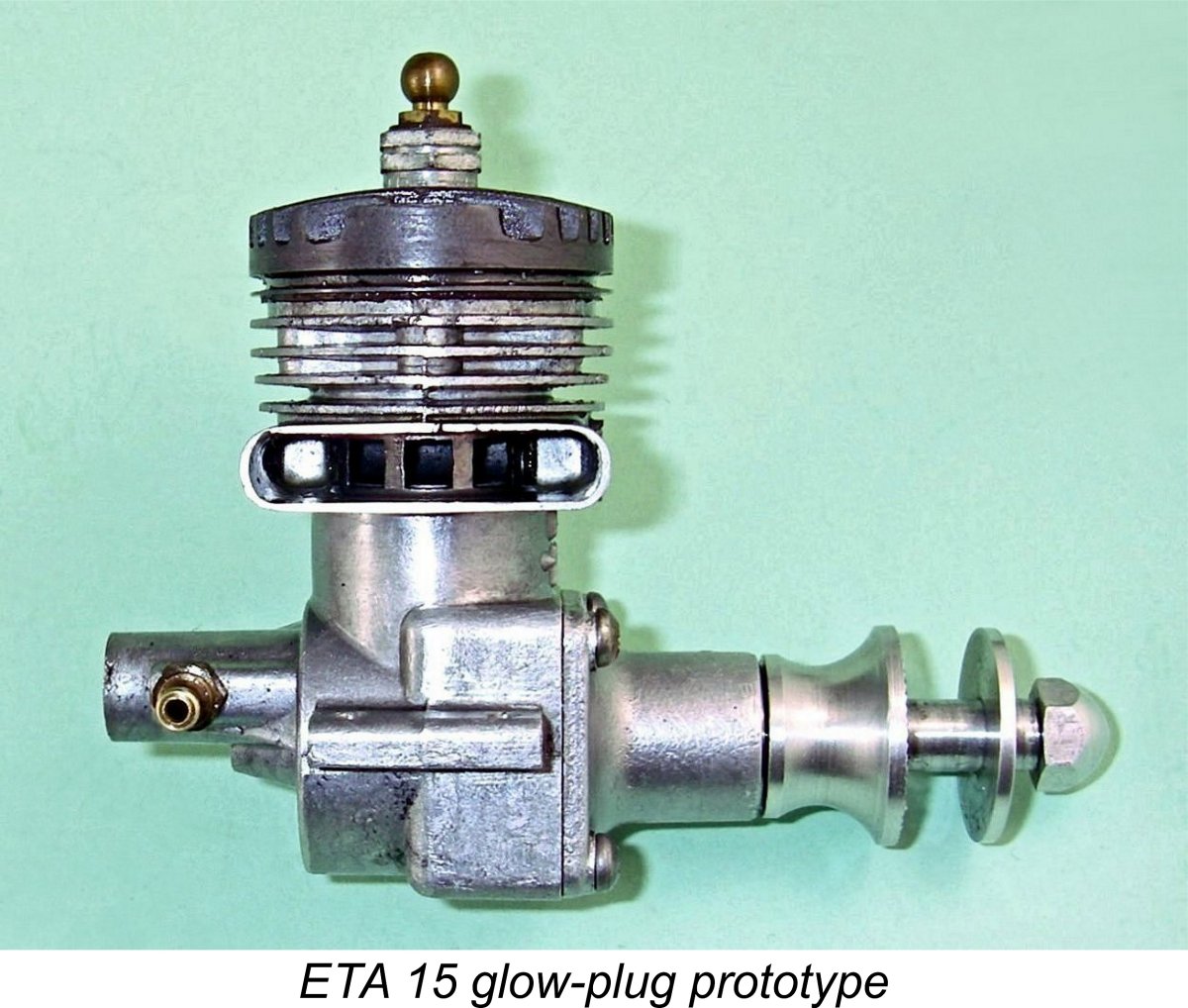

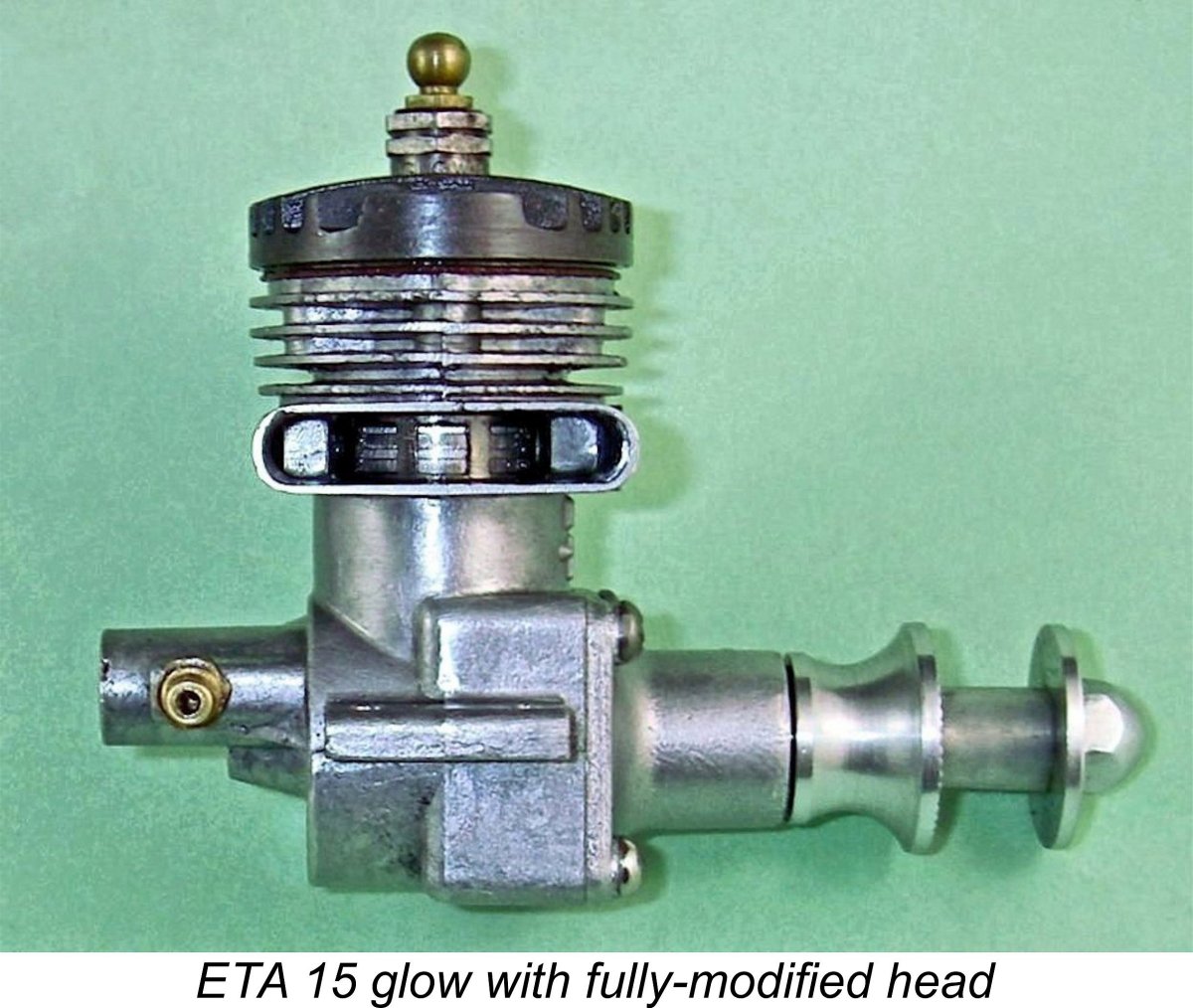

The broad objective of the exercise seems clear enough. The FAI 2.5 cc displacement limit for International competition did not come into effect until 1955, but as of 1950 there was a British Class II control line speed category which catered to 2.5 cc engines. Peter Chinn stated specifically that this was the engine's intended application. Several other countries had similar classes, to the point that a number of International competitions of the early 1950’s included a 2.5 cc control line speed category. A fully developed ETA 15 glow-plug model doubtless had the potential to fare well in this class. Moreover, the ETA 29 had quickly become a dominant powerplant in British Class B team racing, which would naturally have led Ken Bedford to wonder how what amounted to a 2.5 cc version of the same engine would fare in the emerging field of S.M.A.E. Class A team racing, which placed an upper limit of 2.5 cc on engine displacement. The established reputation of the ETA 29 would doubtless have stirred considerable interest in the ETA 15 glow among practitioners of the smaller-displacement class. As mentioned earlier, a number of drawings of the ETA 15 survive thanks to the efforts of Miles Patience. Interestingly enough, the cylinder head is not among them. It appears that the test prototypes must have used ETA 19 heads, which were actually incorporated into the surviving restored examples of the engine. However, they required considerable modification to function correctly with the 15, as we shall see in due As can be seen from the photos, the ETA 15 glow-plug model was basically a downsized version of the original 1950 ringed-piston variant of the ETA 19. Interestingly, it was not an under-bored ETA 19 as we might expect - rather, it was under-stroked! In fact, everything apart from the bore was downsized, including the castings. The 15 was noticeably shorter and less bulky than its 19 companion, although the relatively large bore gave it a rather squat appearance. It was clearly identified on the front of the main casting as the ETA 15, confirming the individuality of its castings. The prototype status of this and other examples of the 15 is reflected in the fact that although they are structurally sound, the castings show somewhat more cosmetic imperfections than those of typical ETA production models. In particular, Ken Bedford seems to have had trouble getting the molten casting alloy to flow cleanly into the grooves in the die for the cooling fins on the main casting. All five surviving cases show evidence of this. However, since these test prototypes were not destined for sale, such imperfections could be ignored – they had no effect upon performance.

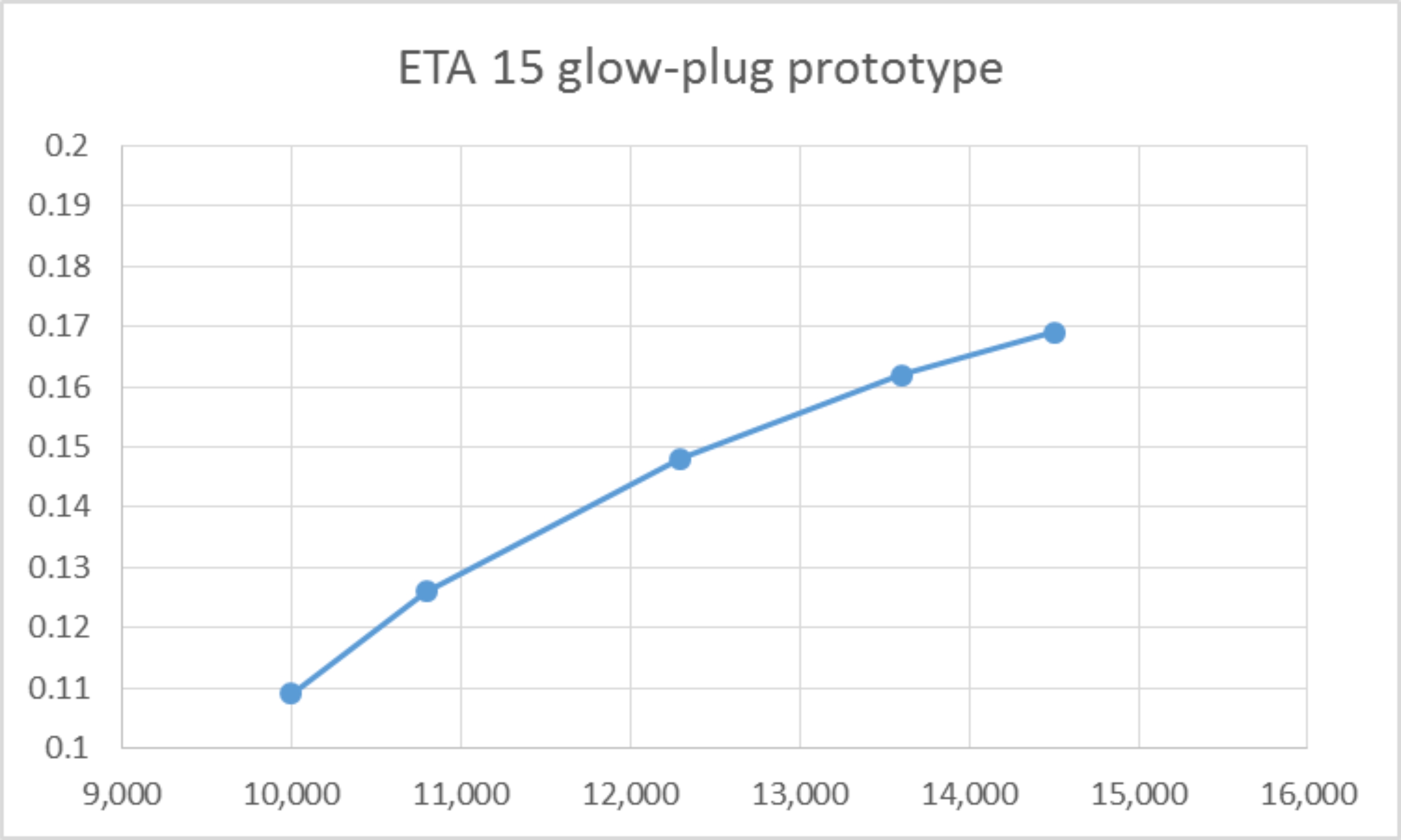

Because it retains the same bore as the 19 but has a considerably shorter stroke, the ETA 15 glow-plug model is an exaggeratedly short-stroke engine, especially for its time and place. Nominal bore and stroke of the 15 turn out to be 0.640 in. (16.26 mm, same as the 19) and 0.468 in. (11.89 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.) and a bore/stroke ratio of 1.37 to 1 – shades of Dooling influence! The illustrated example weighs a commendably light 108 gm (3.81 ounces). Because of its short stroke and shortened conrod, the engine is also notably compact. The ETA 15 glow-plug model followed the structural arrangement of the 19 in essentially every respect. It featured a backplate and intake venturi which were cast in unit with the main crankcase/exhauststack/bypass/cylinder jacket casting. The front housing was detachable, being secured by four machine screws. A twin The lightweight twin-ringed alloy baffle piston operated in a steel cylinder liner. The two cast iron rings were apparently standard ETA 19 components. The long-reach glow-plug was very slightly offset towards the transfer side. For those not familiar with this very common design feature of the baffle-piston era, it was related to the fact that at top dead centre the piston baffle effectively isolated a portion of the fresh fuel mixture from the main combustion chanber where actual ignition took place. The offsetting of the plug towards the baffle (transfer) side was intended to hasten the involvement of this The very short and extremely sturdy un-bushed conrod was fully machined from light alloy barstock. It's likely that if the engine had reached the production stage this rod would have been equipped with bronze bushings in its bearings. But again, why bother with this refinement in a test prototype? The gudgeon (wrist) pin was fitted with brass end pads to protect the bore. The piston itself had an unusually short skirt and a notably high baffle. Despite the very sturdy rod, the entire piston/ring/wrist pin/rod assembly as illustrated weighed only 7 gm - good for vibration reduction. Like that of the original 19, the well-counterbalanced rotary valve disc was made of aluminium alloy, a material which proved to be unsatisfactory in service in the larger 29 model. On this example at least, it seals very well. However, its longevity in service might be another matter .......... The timing of this particular example is a somewhat odd mixture of aggression and relative conservatism. The exhaust opens notably early at only 105 degrees after top dead centre for a very lengthy exhaust period of 150 degrees. The opening of the transfer ports is delayed for some 10 degrees. providing a generous transfer period of 130 degrees. It seems to me that the opening of both ports could have been delayed by up to 8 degrees or so with some The disc valve gives an induction period extending from 55 degrees after bottom dead centre to 45 degrees after top dead centre for a total 170 degree induction period - perhaps opening some ten degrees later than it could have done. The intake venturi has a measured internal throat diameter of 0.240 in. (6.10 mm) at the spraybar location - perhaps a bit on the skinny side for a spraybar-equipped 2.5 cc racing engine. The externally threaded spraybar passes transversely through the venturi using a 2 BA thread. Like that featured in the early 19 models, it is made in one piece, including the split thimble at the needle end for security of settings. The thread was turned off and the spraybar waisted to a measured diameter of 0.110 in. (2.79 mm) along the length which crosses the venturi throat. The spraybar is locked in position using a nut on the fuel pick-up side. Reference to Maris Dislers’ extremely useful Choke Area Calculator confirms that this combination provides an effective choke area of 12.819 square mm with a stable minimum operating speed on suction of 10,639 The above induction arrangements are supplemented by a short period of sub-piston induction extending around 15 degrees either side of top dead centre. I’ve never been a big fan of sub-piston induction on side-stack engines since any gas drawn in is likely to be spent exhaust gas rather than cool fresh air. However, Ken Bedford used the concept with great success on the later versions of the ETA 29, so it must confer some benefit. The fact that Ken went to the considerable trouble and expense of producing dies for the ETA 15 glow-plug model indicates that at some point there must have been a serious intention of putting this engine into series production. The reason for its ultimate failure to appear on the market at any time certainly warrants investigation. To start that particular ball rolling, it seems best to begin by evaluating the engine’s performance. No sooner said than done ………… The ETA 15 Glow-Plug Model on Test The only previously-published information on the performance of the ETA 15 glow-plug model came once again from Peter Chinn's previously-reproduced July 1950 article in "Model Aircraft". In that article, Chinn reported that the ETA 15 prototypes peaked at "around the 16,000 rpm mark - well above that of any other 2.5 cc design". Somewhat strangely in view of that statement, he then added the comment that "prototype units have shown outputs exceeding one-fifth h.p. at these speeds, although it is expected to further improve on this in the final production design". One would certainly hope so - even by the standards of 1950, a peak output of only just above 0.200 BHP could scarcely be viewed as a competitive racing performance for a 2.5 cc engine. Fortunately, the diligence and kindness of my good mate Miles Patience have combined to place me in a position to see for myself just how representative of the design Chinn's comments actually were. If I couldn't improve on the output cited by Chinn, this would constitute an adequate explanation for the engine's failure to appear on the market. Miles had warned me that this example of the ETA 15 glow-plug model had rather poor compression when forwarded to me. Shades of Peter Chinn’s test example of the ETA 19, in fact! Miles had run the engine for some 15 minutes, finding that it started easily enough but would not keep running with the plug leads disconnected. He put this down to the relatively poor ring seal, although he also noted that his use of a vintage KLG Miniglow plug of relatively cold heat rating and some very old fuel which might have absorbed water could well have contributed to this characteristic.

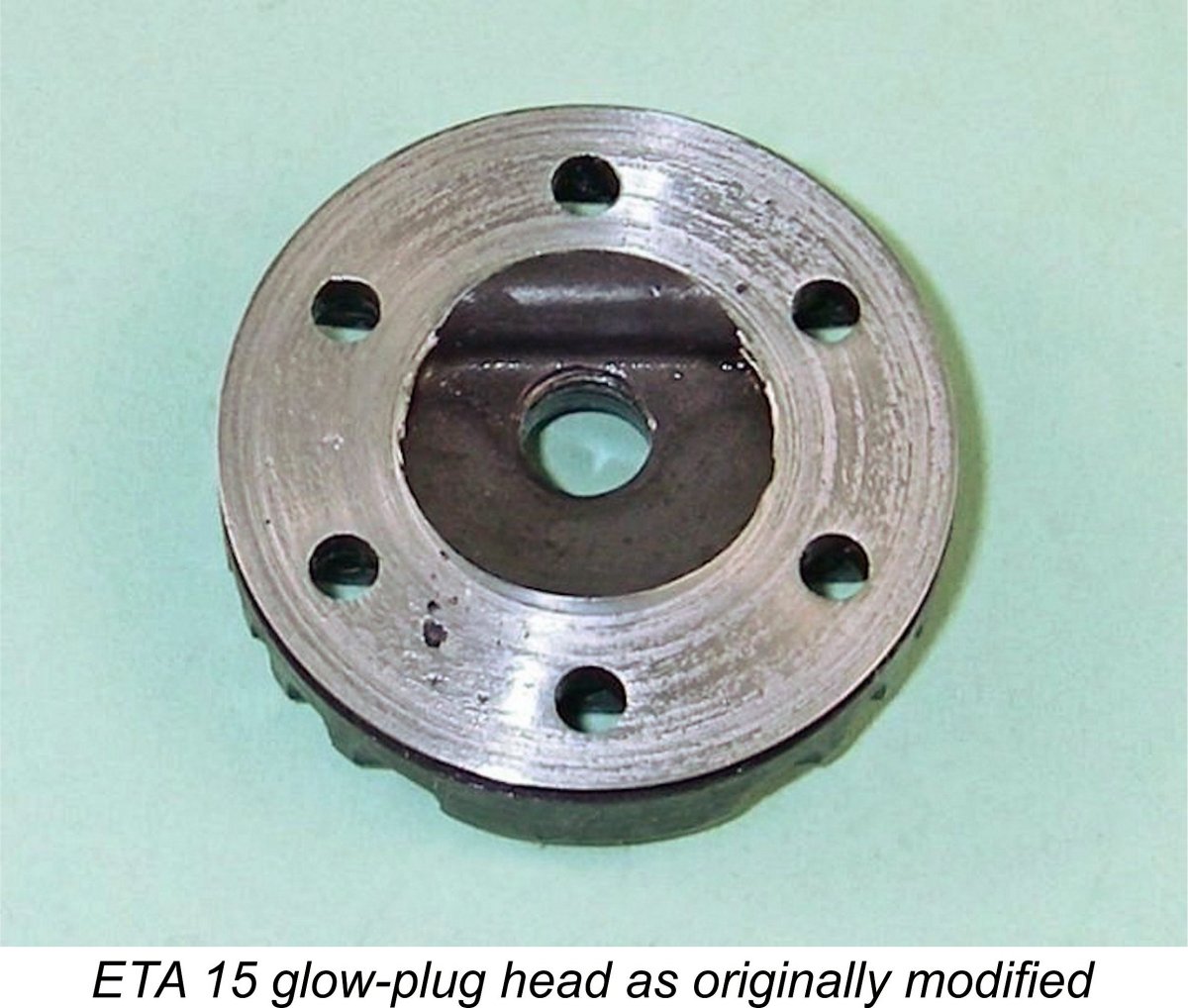

I removed the head and turned 0.060 in. (1.5 mm) off its sealing face, retaining the combustion chamber contours as they were. This had the effect of placing the combustion chamber lower in the bore by that amount, thus reducing the 0.75 cc combustion chamber volume at top dead centre by 0.31 cc to only 0.44 cc and raising the compression ratio to a far more reasonable 6.6:1 – still very much on the low side for a racing engine, but certainly enough to ensure running with the plug disconnected. I would have gone a little further had it not been for the fact that the piston was showing symptoms of contacting the head at top dead centre. So this was as far as I went at this point in time. A poor decision, as event were to prove ………… It now appeared to me that the head with which this example was received was a standard 19 item which required some modification to suit the lesser stroke of the 15 model. Presumably the factory test prototypes were modified in this fashion. Upon reassembly, the engine felt just fine. The rings were a touch leaky, as Miles had warned me, but in my judgement they were sealing quite well enough for good starting. With some more running, they would doubtless bed in nicely. Accordingly, I headed out to the flying field to give the ETA 15 some running time. I began with an 8x4 APC prop and some fuel containing 15% nitro. In deference to the very low compression ratio, I used a “hot” Fox glow plug.

Nonetheless, I persisted in giving the engine a series of 5 minute runs on the 8x4, mainly to allow the rings to bed in a little. This seemed to be effective – compression seal did improve quite noticeably. However, when I switched to a 30% nitro fuel after some 45 minutes of running time, I quickly found that the ETA simply didn’t want to run into the 11,000 rpm bracket – in fact, it only managed 10,600 rpm on an APC 7x4, which is nowhere, especially on a “hot” fuel! The symptoms were all of under-compression – above 9,000 rpm on the smaller props, the engine would not lean out and two-stroke smoothly, regardless of the needle setting.

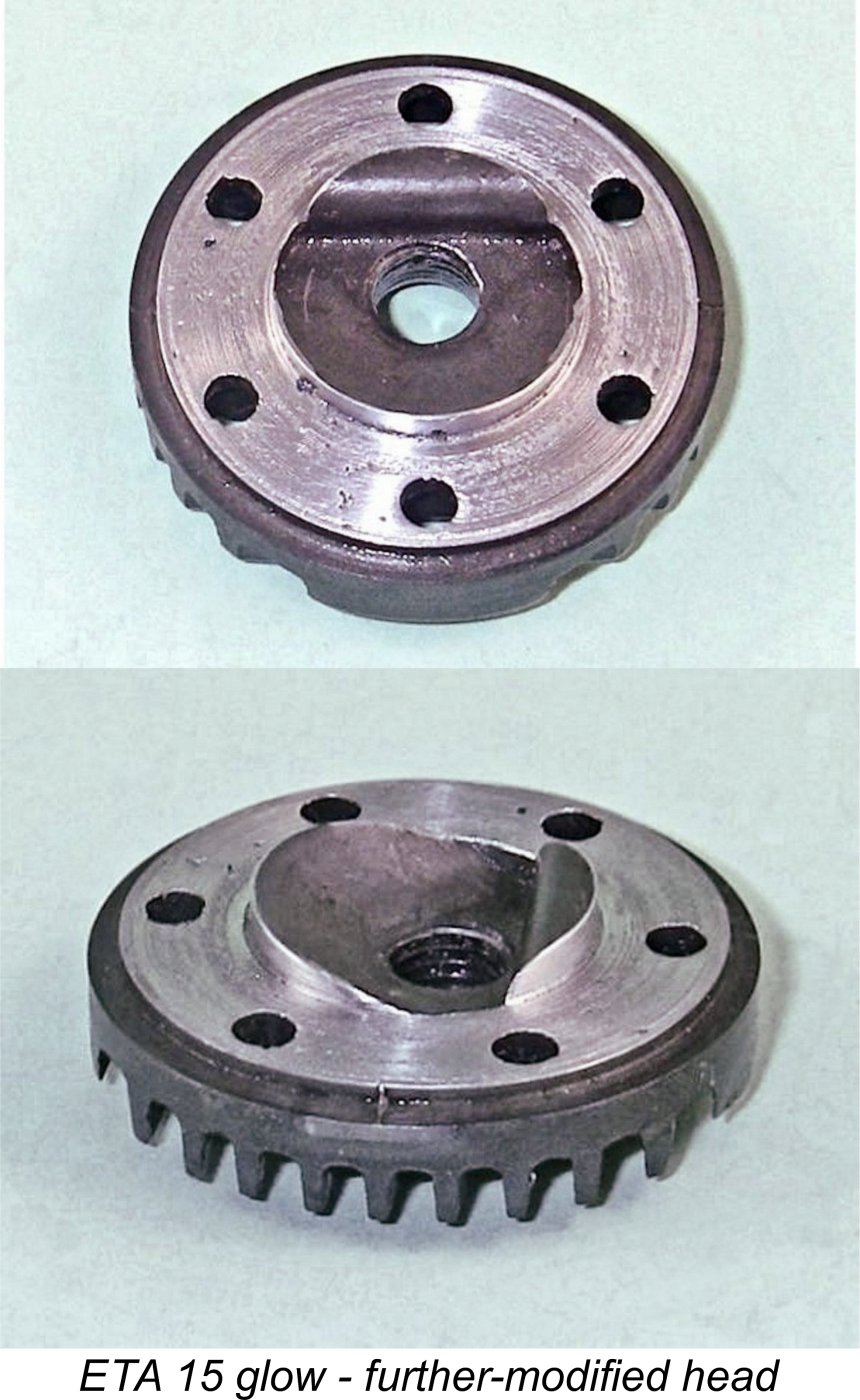

Since it was clear that there was nothing more to be learned from any further running as matters stood, I took the engine back home to sort the problem once and for all. I removed the head once more and turned an additional 0.025 in. (0.063 mm) off its sealing face, having first checked the available piston/head clearances. This actually eliminated the head’s lowest circumferential cooling fin, giving the engine an even more squat appearance when reassembled. The view included below at the left should make this very apparent - compare it with the side view presented above, a few images earlier. I had to do a little hand-trimming of the edges of the combustion chamber to deal with the problem of piston contact, but this was easily accomplished using a modelling knife. I also had to run a 6 BA finishing tap down the threaded holes for the cylinder head hold-down screws, since the thinner head allowed them to penetrate beyond the originally threaded length as received. The underside of the cylinder head was now located .085 in. (2.16 mm) lower in the cylinder than it had been originally. This reduced the original combustion chamber volume of 0.75 cc at top dead centre to only 0.31 cc, cranking the compression ratio up to a far more acceptable 9.0 to 1, exactly where it needed to be in my opinion. Moreover, the piston-to-head clearances were now sufficiently close to promote the intended displacement-induced swirl effect at top dead centre, theoretically resulting in more rapid combustion. I anticipated that the engine would now perform up to its full potential.

This time, things went a lot better. Using the 30% nitro fuel, the engine was dead easy to start, requiring only one or two flicks every time. A real ETA in that respect! It would now two-stroke smoothly on all props tested, with minimal vibration. However, another bugbear reared its ugly head at this point. Since it would now go into two-stroke mode without difficulty, the engine naturally ran considerably hotter. Presumably as a result of this, it now displayed a tendency to sag after a relatively short period of two-stroking. It would come up to speed in two-stroke mode, stay there for a short time and then sag. This simply had to be somehow related to the fit of the piston and/or rings in the bore. Naturally, I responded instantly with the needle to prevent the sagging condition from developing into a seizure, so no harm appeared to have been done. However, I had very little time to establish the optimum needle setting and measure the top speed for each prop. Because of this problem, the figures set out below are almost certainly the least that the engine could achieve if it was assembled with the ideal clearances all round. It could well take some hours of running to deal with this issue, a treatment to which I was not eager to subject this very rare engine. After all, it's never going to be used in a model (by me at least), so what would be the point?!?

As can be seen, I never got to the peak on this test. The engine appeared to be heading for a peak output of around 0.175 BHP @ 15,700 rpm, or perhaps a little more at a higher speed. Even by 1950 standards, this wasn't exactly a stellar performance! However, in my view these numbers mean very little - a well run-in example which was capable of continuous two-stroking for extended periods while leaned out would undoubtedly be capable of more than this.

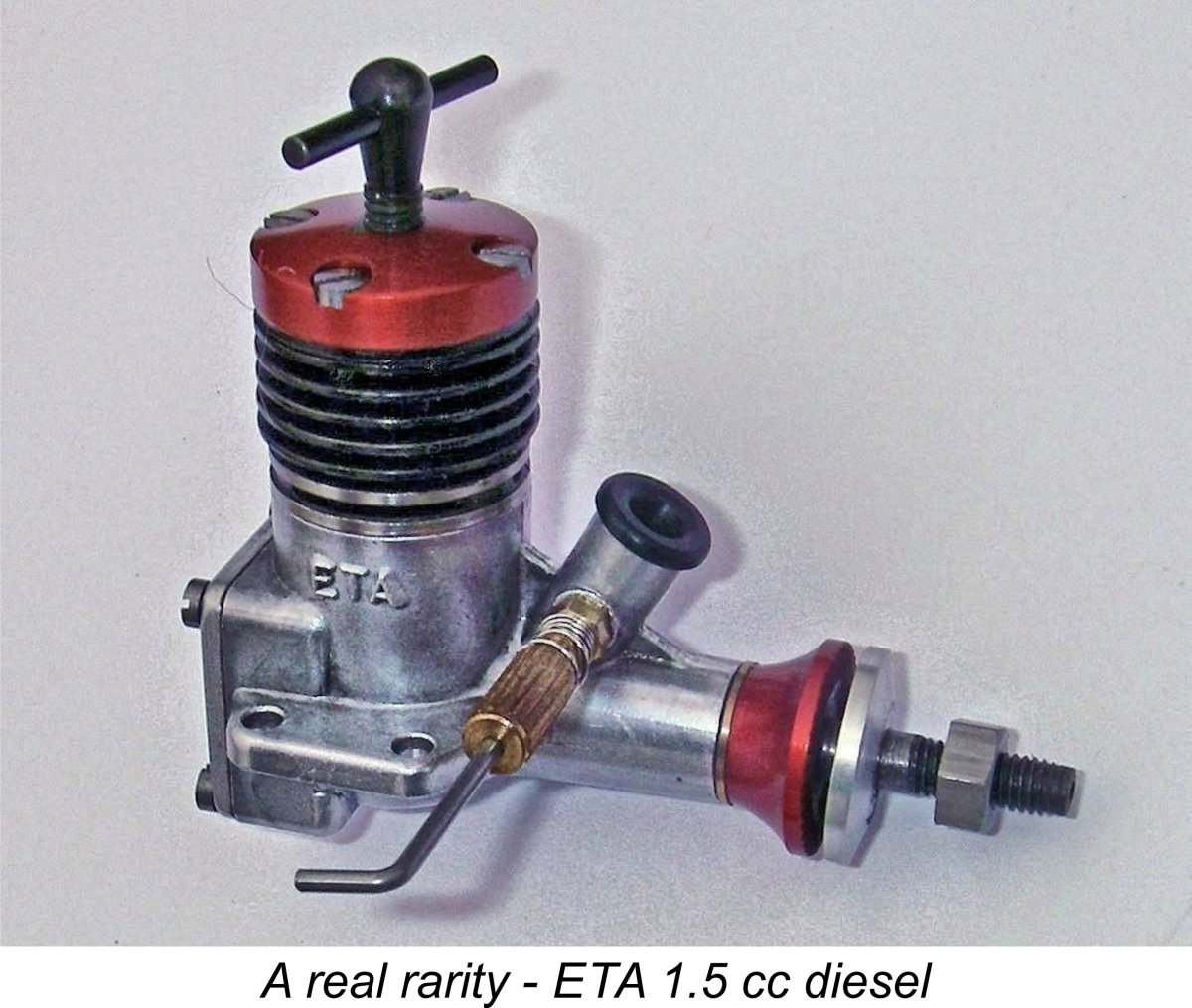

Since there was nothing to be done about this (you can't replace missing metal), I reassembled the long-suffering little ETA, hopefully for the last time!! Following this reassembly, I put a further 30 minutes of running time on the engine, purely to bed the rings in a little better. This was effective - compression seal continued to improve. However, a few spot checks showed that the improved ring seal had not resulted in any significant improvement in performance, although the engine would now two-stroke smoothly for quite extended periods on all props tried. Seemingly the sagging tendency had been down to leaky rings, which were definitely improving with running time. No doubt more running time would result in a further improvement. Regardless, I have to admit to seeing little indication here that the engine as it stood was capable of a world-beating performance, even by 1950 standards. I can well believe that if appropriately fitted and well run in it could readily top the 0.200 BHP mark in the vicinity of 16,000 rpm, as cited by Peter Chinn. However, in all honesty I don't see the engine doing a lot better than that without considerable further development. I can see plenty of development potential in the design, but I can also understand why Ken Bedford eventually decided that the company was better off concentrating on improvements to the successful 29 and 19 models rather than spending more time and effort developing the 15. In my personal opinion, the pathway towards further development of the ETA 15 glow-plug model would more than likely have included a significant reduction in the bore/stroke ratio. The figures reported above all imply relatively poor torque development in what we might expect to be the normal operating range for this engine. It seems highly likely that the ultra-short stroke is a major factor here. The very early opening of the exhaust and transfer ports almost certainly contributes as well. The ETA 29 featured a bore/stroke ratio of 1.12 to 1, while the companion 19 had a ratio of only 1.03 to 1. The previously-cited figure of 1.37 to 1 for the ETA 15 as tested seems highly excessive to me. It was probably the result of a desire to reduce development costs somewhat by sticking with the same bore as the 19 and achieving the reduced displacement solely through a reduction in the stroke. If development had continued, I'd almost put money on the notion that the next development configuration would have featured a far lower bore/stroke ratio along with revised cylinder port timing. However, this would have involved the production of an entire new set of dies, including one for the cylinder head. Expensive .............. As it was, the very short stroke of the ETA 15 glow coupled with the early opening of its exhaust and transfer ports clearly had the effect of compromising the engine's ability to develop useable torque in the speed range over which it might reasonably be expected to operate. I have little doubt that a longer-stroke variant of the same basic design with somewhat more conservative cylinder port timing would have come close to matching the specific outputs of the 19 and 29. In the context of 1951, a further-developed variant along these lines would likely have been a quite competitive powerplant. Conclusion It’s interesting to note the fact that the ETA 15 glow-plug model was not the only ETA design that was brought all the way up to the pre-production stage in 1950 but never released. In my earlier article on the ETA 29, I also mentioned the fine 1.5 cc diesel developed by Eric Bedford in late 1950. Having designed the ETA 5 diesel which got the company started in the model engine field, Eric was very keen to continue the development of updated diesel models. In this, he stood apart from Ken Bedford and their father, C. J. Bedford, both of whom saw competition glow-plug motors as the more promising field to pursue.

However, for reasons which will forever remain unclear the design was not pursued, although Peter Chinn somehow obtained an example much later, publishing a thumbnail retrospective review in the May 1968 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine. Once again, it was Miles Patience who rescued this engine from obscurity by acquiring the entire ETA 1.5 diesel project from Eric Bedford's estate. This facilitated the completion of a further nine engines using a mixture of original and replica parts. Miles and I got together in February 2017 to test Miles' own example of this engine, finding it to be a very good runner having a performance which was well above average for a 1.5 cc diesel of its era. We measured a peak output of around 0.170 BHP @ 13,200 RPM, implying significantly better-than-average torque development for an early 1950's diesel of this displacement. However, we also found the engine to be somewhat temperamental to start. Perhaps this was why the ETA 1.5 diesel never saw production…………

Once that was done, the engine certainly showed promise, undoubtedly being potentially capable of matching or beating the manufacturer's unofficially-quoted figures reported by Peter Chinn. However, I was unable to extract a genuine "racing" performance from this example, even by 1950 standards. I was however able to confirm the improbability of the ETA 15 glow-plug model constituting a world-beater as it stood. In particular, its exaggeratedly short stroke and over-aggressive cylinder port timing seem to have represented major impediments, particularly in a team-race context due to their adverse effect upon torque development.

So what's the answer to our original question - what kind of an engine did the British modelling community miss out on? In a nutshell, a 2.5 cc racing engine with considerable potential built to ETA's usual high standards, but one which was never developed to the point at which it could show its true paces. A pity - I have no doubt that a designer of Ken Bedford's calibre could have developed this unit as we find it today into a really useful 2.5 cc glow-plug motor by early 1950's standards, which would have upheld the ETA reputation very capably and carried the ETA name proudly! Oh well ......at least he tried! _____________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2019

|

||

| |

Regular readers of my long-running series of articles on model engine history will doubtless recall my review of the fine

Regular readers of my long-running series of articles on model engine history will doubtless recall my review of the fine

The first of Ken's earlier claims may or may not be true - that's one of the matters that will be investigated in a later section of this article. However, the engine's checked weight as illustrated of only 108 gm (3.81 ounces) actually makes it one of the lightest 2.5 cc competition units of its time (or any other time, for that matter). Ken's reported comment that it was "heavy for its displacement" therefore remains a real puzzle, for which no rational explanation is apparent other than the possibility that Ken never actually made that statement - this could be an example of the "

The first of Ken's earlier claims may or may not be true - that's one of the matters that will be investigated in a later section of this article. However, the engine's checked weight as illustrated of only 108 gm (3.81 ounces) actually makes it one of the lightest 2.5 cc competition units of its time (or any other time, for that matter). Ken's reported comment that it was "heavy for its displacement" therefore remains a real puzzle, for which no rational explanation is apparent other than the possibility that Ken never actually made that statement - this could be an example of the " At this point, I hear a few of you wondering why I would bother doing this given the fact that this is an engine that never saw production! Indeed, very few people will ever see one of these units, let alone own one! The reason is quite simple – curiousity, which I'm sure a few of you share! At the time when Ken Bedford was working on this design, the only other 2.5 cc racing glow-plug motor of any real stature was the then-recently released early ringed-piston version of the

At this point, I hear a few of you wondering why I would bother doing this given the fact that this is an engine that never saw production! Indeed, very few people will ever see one of these units, let alone own one! The reason is quite simple – curiousity, which I'm sure a few of you share! At the time when Ken Bedford was working on this design, the only other 2.5 cc racing glow-plug motor of any real stature was the then-recently released early ringed-piston version of the  Following the February 1949 introduction of the ETA 29 Mk. I which has been fully described

Following the February 1949 introduction of the ETA 29 Mk. I which has been fully described

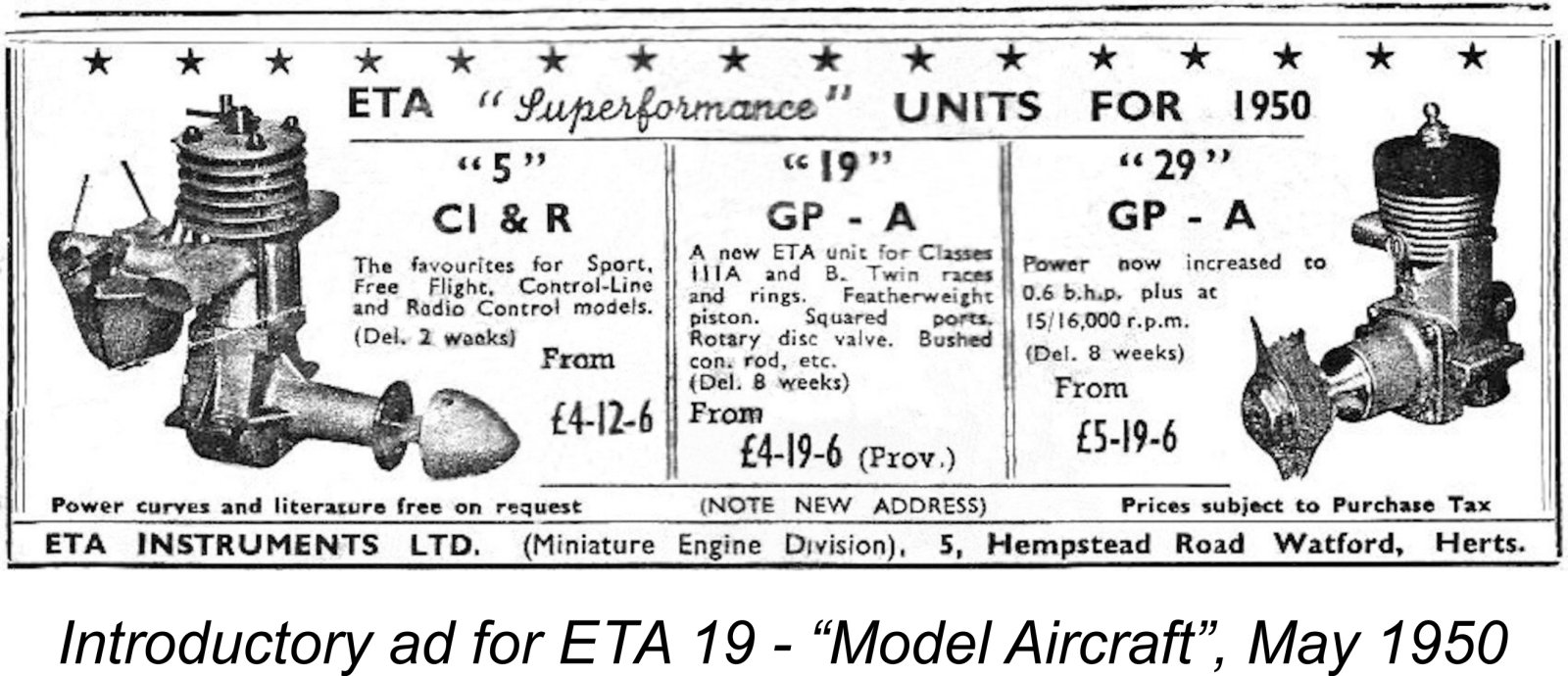

The earliest advertisement for the ETA 19 in my present possession is the ETA placement which appeared in the May 1950 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The engine must still have been in the introductory process as of that date, because the quoted price of £4 19s 6d (£4.97) was qualified as being “provisional”. A delivery time of 8 weeks following receipt of order was cited, implying that production was just then getting underway, perhaps strictly on an individual order basis. There was no mention of a forthcoming 15 model. Incidentally, this was also the final advertising appearance of the

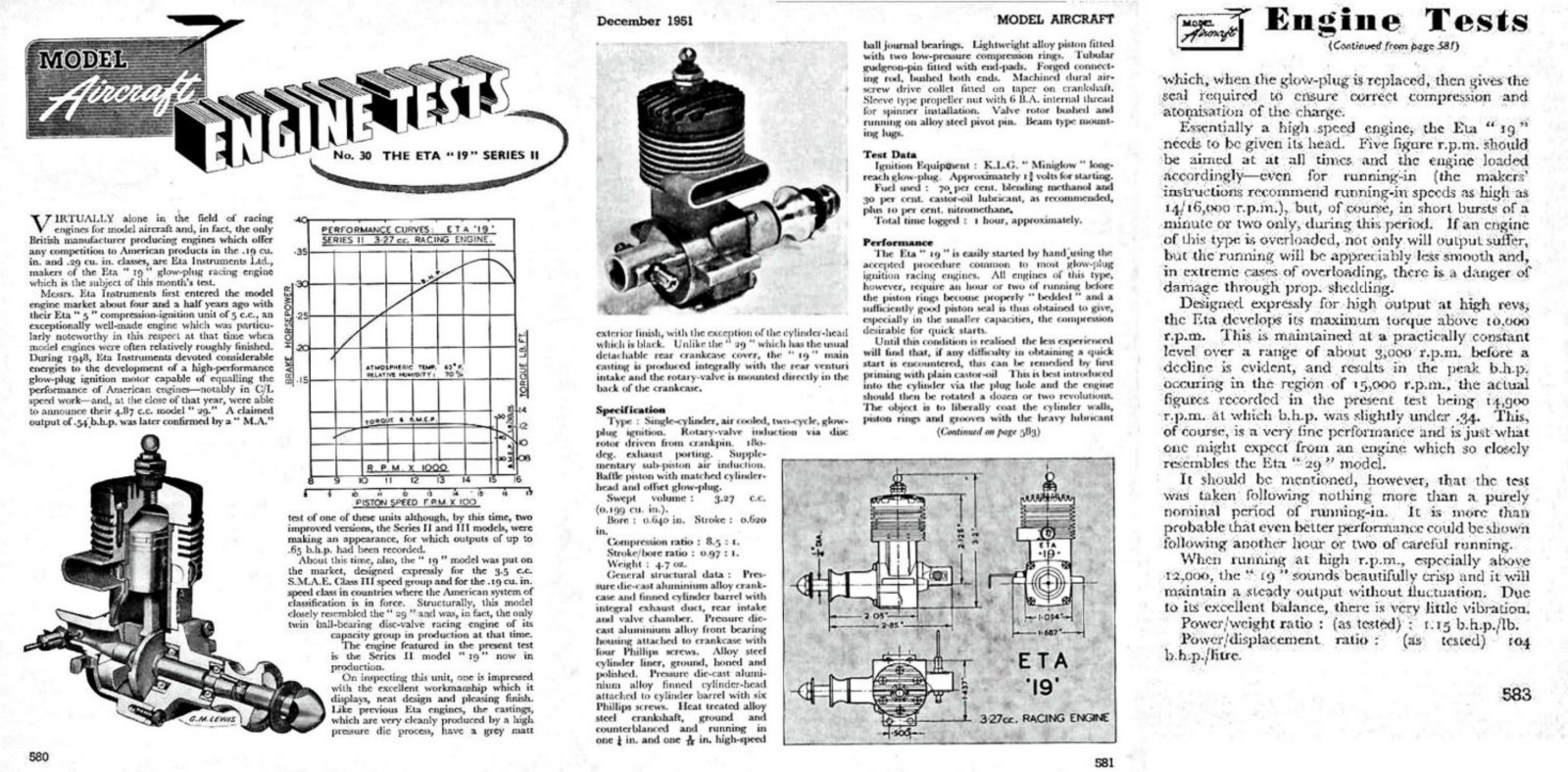

The earliest advertisement for the ETA 19 in my present possession is the ETA placement which appeared in the May 1950 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The engine must still have been in the introductory process as of that date, because the quoted price of £4 19s 6d (£4.97) was qualified as being “provisional”. A delivery time of 8 weeks following receipt of order was cited, implying that production was just then getting underway, perhaps strictly on an individual order basis. There was no mention of a forthcoming 15 model. Incidentally, this was also the final advertising appearance of the  The ETA 19 Mk. I was certainly still available as of late 1951, because Peter Chinn published the above test of the engine in the December 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Interestingly enough, Chinn referred to the tested engine as the “Series II” version of the ETA 19 Mk. I, clearly implying that there must have been an earlier variant. Unfortunately I have been unable to uncover any information regarding changes to the original version which may have resulted in the variant tested by Chinn.

The ETA 19 Mk. I was certainly still available as of late 1951, because Peter Chinn published the above test of the engine in the December 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Interestingly enough, Chinn referred to the tested engine as the “Series II” version of the ETA 19 Mk. I, clearly implying that there must have been an earlier variant. Unfortunately I have been unable to uncover any information regarding changes to the original version which may have resulted in the variant tested by Chinn. The engine fared extremely well in Chinn’s hands. Using a fuel containing 15% nitromethane, he measured a peak output of 0.338 BHP @ 14,800 RPM, a very good figure indeed for a glow-plug motor of this era and displacement running on a relatively modest nitromethane content. He praised the engine’s construction very highly, citing the “excellent workmanship which it displays, neat design and pleasing finish”.

The engine fared extremely well in Chinn’s hands. Using a fuel containing 15% nitromethane, he measured a peak output of 0.338 BHP @ 14,800 RPM, a very good figure indeed for a glow-plug motor of this era and displacement running on a relatively modest nitromethane content. He praised the engine’s construction very highly, citing the “excellent workmanship which it displays, neat design and pleasing finish”. We have Peter Chinn's previously-cited evidence in his July 1950 article in "Model Aircraft" (reproduced at the left) to confirm the fact that at the same time as he was working on the development of the ETA 19, Ken Bedford had also been investigating the possibility of producing an even smaller 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.) version of the same design. A number of the surviving drawings in the possession of Miles Patience confirm this - they are variously dated from August 23

We have Peter Chinn's previously-cited evidence in his July 1950 article in "Model Aircraft" (reproduced at the left) to confirm the fact that at the same time as he was working on the development of the ETA 19, Ken Bedford had also been investigating the possibility of producing an even smaller 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.) version of the same design. A number of the surviving drawings in the possession of Miles Patience confirm this - they are variously dated from August 23

Upon receiving the engine, my first step was naturally to explore all possible causes for this behaviour. This investigation didn’t take long! As usual in such cases, I began by checking the compression ratio, which immediately identified itself as the culprit. The

Upon receiving the engine, my first step was naturally to explore all possible causes for this behaviour. This investigation didn’t take long! As usual in such cases, I began by checking the compression ratio, which immediately identified itself as the culprit. The  The testing began well enough – the engine started instantly without an oil prime and would run just fine with the plug lead disconnected. However, speed on the 8x4 was a good deal below expectations – I only saw 8,700 rpm on that prop. Even for a 1950 design, this was well below par. The engine ran smoothly enough on this prop, but there was very little “urge” on display.

The testing began well enough – the engine started instantly without an oil prime and would run just fine with the plug lead disconnected. However, speed on the 8x4 was a good deal below expectations – I only saw 8,700 rpm on that prop. Even for a 1950 design, this was well below par. The engine ran smoothly enough on this prop, but there was very little “urge” on display.

Eric persisted nonetheless, producing his 1.5 cc diesel design in late 1950. This engine displayed a certain degree of stylistic influence from the OK Cub models from America. ETA Instruments completed a few prototypes, one of which was later submitted to Dennis Allen to assess as a possible subject for licensed larger-scale mass production than ETA were then able to contemplate.

Eric persisted nonetheless, producing his 1.5 cc diesel design in late 1950. This engine displayed a certain degree of stylistic influence from the OK Cub models from America. ETA Instruments completed a few prototypes, one of which was later submitted to Dennis Allen to assess as a possible subject for licensed larger-scale mass production than ETA were then able to contemplate.  Returning to our main subject, the ETA 15 glow-plug prototype, it’s readily apparent that the cylinder head which was fitted to my example as received was not in its intended configuration. Indeed, it appeared to be a standard ETA 19 Mk. I component. Getting it to work properly on this engine required some careful machining to make it compatible with the shorter stroke and reduced displacement of the 15 prototype. No doubt any examples which may have been completed and tested by Ken Bedford would have been modified in this way.

Returning to our main subject, the ETA 15 glow-plug prototype, it’s readily apparent that the cylinder head which was fitted to my example as received was not in its intended configuration. Indeed, it appeared to be a standard ETA 19 Mk. I component. Getting it to work properly on this engine required some careful machining to make it compatible with the shorter stroke and reduced displacement of the 15 prototype. No doubt any examples which may have been completed and tested by Ken Bedford would have been modified in this way.