|

|

The Early Years at Enya

In itself, this would be sufficient to establish the Enya range as one demanding our respect. However, the quality and performance of the company’s products throughout have consistently met the very highest standards achieved by major commercial manufacturers anywhere in the world. The range is thus doubly worthy of our attention. The serviceable and durable engines produced over the years by Enya have always been among my personal favorites. In this article, I’ll attempt to provide a broad overview of the early evolution of the Japanese model engine manufacturing industry in general, leading up to a primary focus upon the appearance of the early “classic” Enya engines beginning in 1949 and going up to the mid 1950’s when the range was beginning to gain traction in the international model engine market. I’ll also provide some overarching information about the Enya range in general, thus setting the stage for future technical reviews of the engines themselves throughout the entire “classic” era.

Hopefully this will lay the groundwork for a series of more technically-oriented articles about specific models covering the entire “classic” era. In a very real sense, this article will be a preamble to a future series of reviews of Enya classics. I’ll get to those as and when time permits - I'm not working to a schedule here! The products of the Enya company during the decade or so following the conclusion of WW2 are widely seen today as desirable collector’s items. It’s high time that a serious attempt was made to establish an accessible record of the company’s early history. But before starting along this road, it’s both a duty and a pleasure to acknowledge the assistance which I’ve received from a number of individuals. First off, I wish to pay tribute to Bob Allan of Australia and Pat King of the USA, both of whom are dyed-in-the-wool Enya enthusiasts (aka Enya-philes!) with a vast store of knowledge and experience in connection with this range. They were both extremely generous in providing a great deal of the background material upon which this article is based, also reviewing and commenting upon the draft texts of these articles. Their contributions will often be cited in what follows. Secondly, I must acknowledge the considerable assistance rendered to me by Alan Strutt of England, whose insights into the history of Japanese engines from the pioneering and early classic eras have immense value. Alan made many pertinent suggestions and provided a number of key images as well as running a critical eye over what I’ve written here. With those richly deserved acknowledgements having been recorded, it’s time to begin our tale by setting the stage ………beginning with an overview of the main challenge with which the long-suffering Enya reviewer is faced! The Documentation Issue It’s an odd fact that despite Japan’s long and proud history of producing model engines to very high standards since well before WW2, the Japanese model engine industry has tended to be less careful than it might have been when it comes to preserving its own heritage in a readily accessible form. This is odd in some ways given the fact that almost all of the companies concerned (including Enya) began as small family workshop operations which developed over a considerable period of time into the significant international commercial enterprises that a number of them became. One would think that pride in family accomplishments would have dictated a more careful approach to the preservation and dissemination of company history.

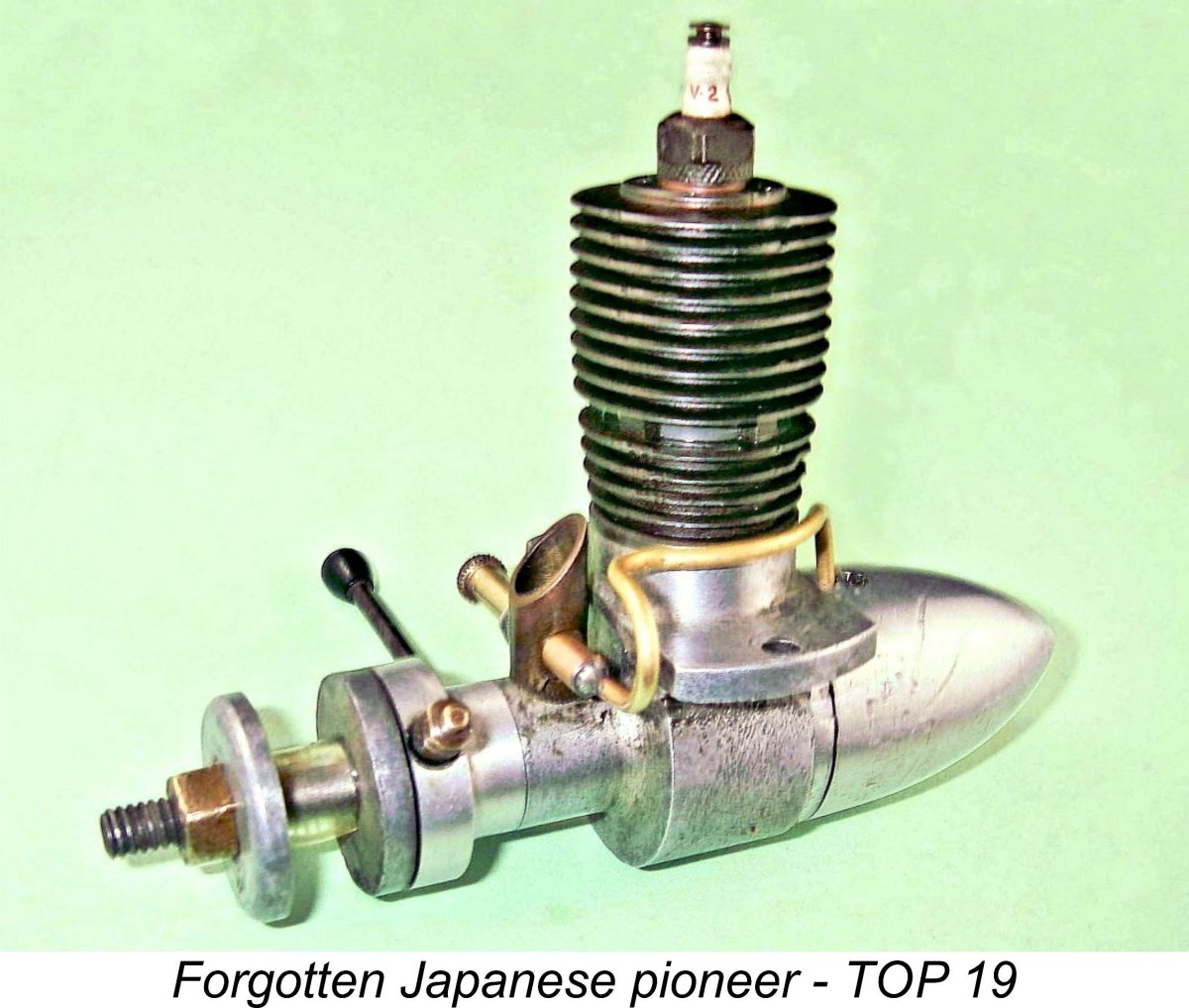

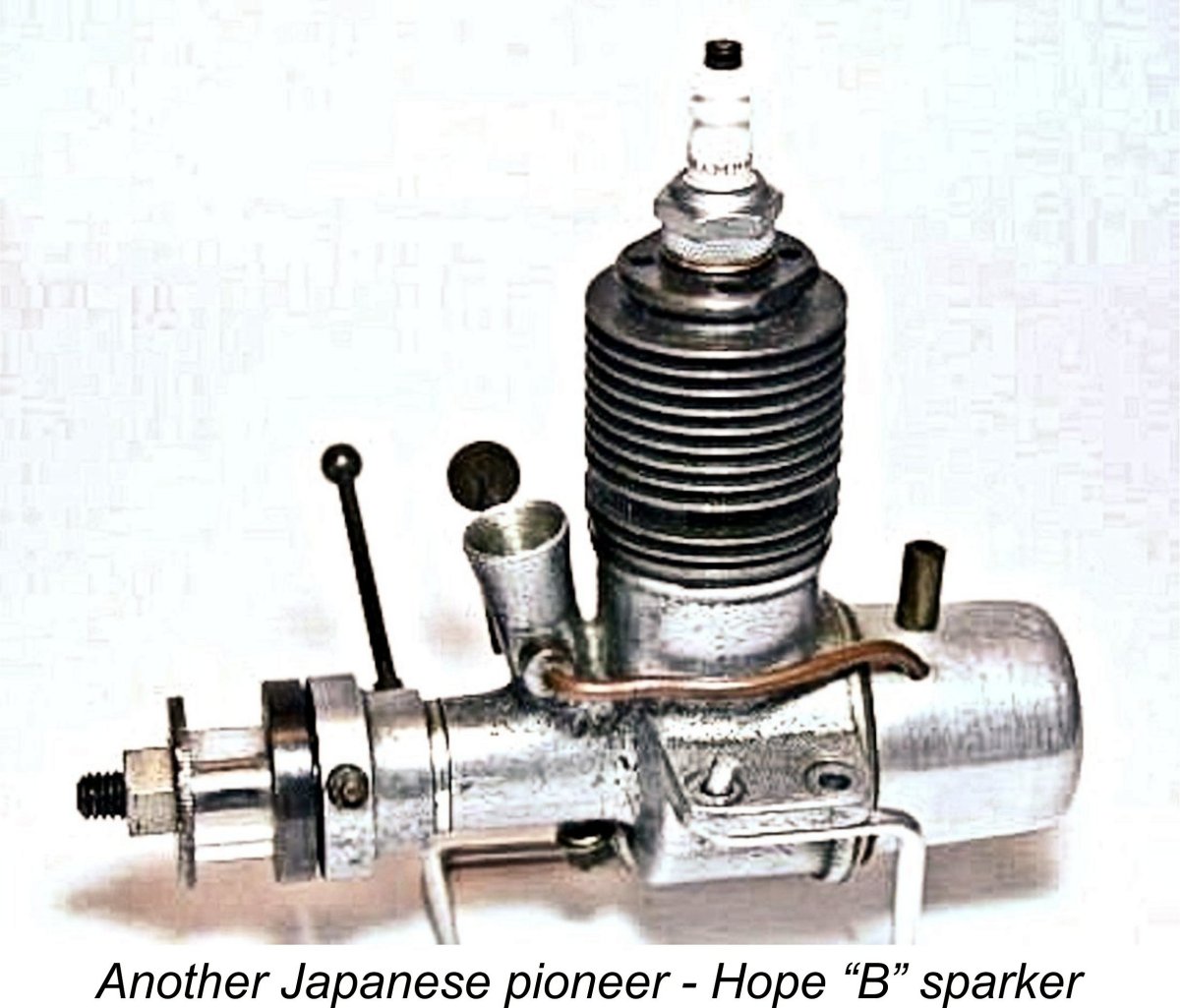

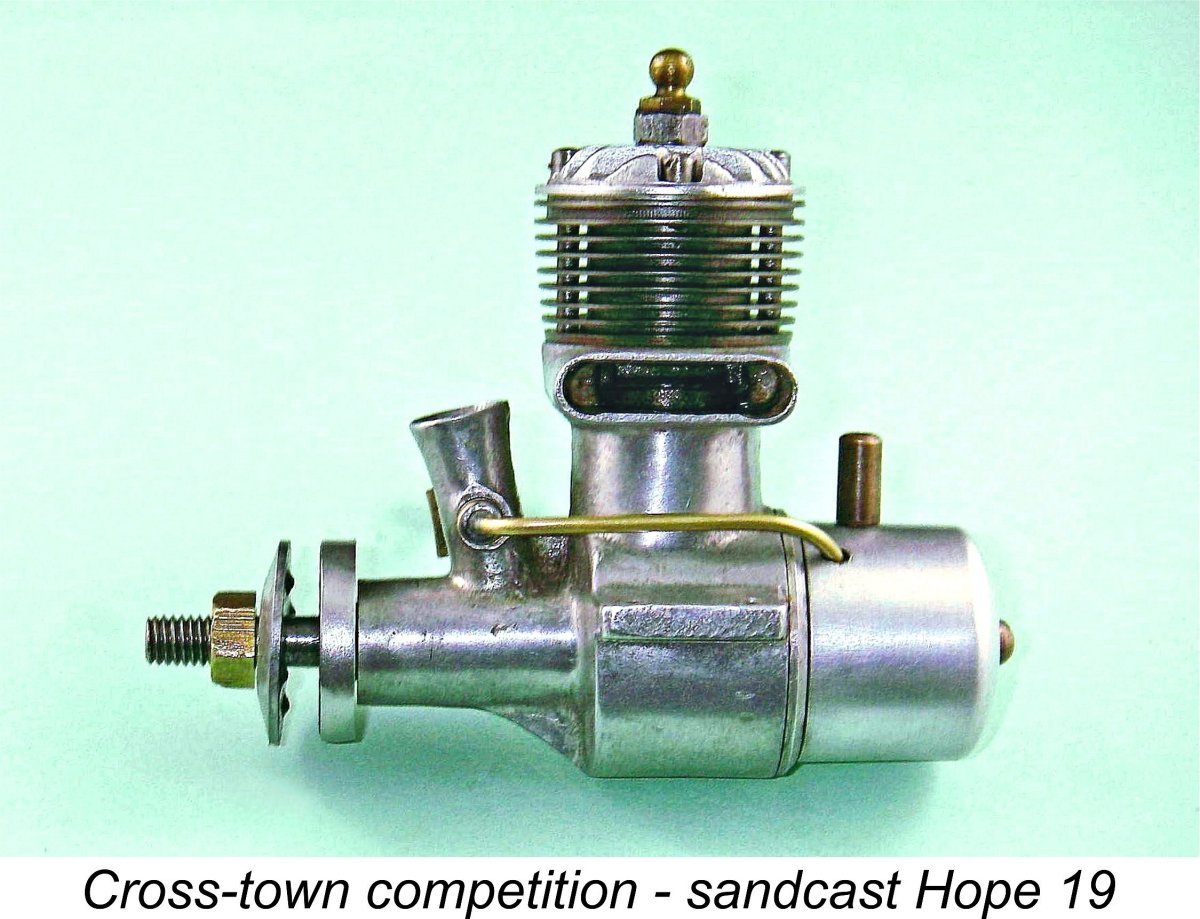

Even this reference is incomplete and in a few instances inaccurate - several known O.S. products are omitted. Still, the O.S. company is perhaps the sole exception to the general truth that the pre-war and early post-war history of this dynamic Japanese industrial sector has been largely lost or at best mislaid, at least as far as enthusiasts outside Japan are concerned. O.S. are to be commended for their standout efforts. Hence, with the notable exception of O.S., accessible information in the English language on most pre-WW2 and early post-war Japanese model engine manufacturers appears to be well-nigh non-existent. Indeed, many Japanese manufacturers of the first few post-WW2 decades up to the early 1960’s are not even so much as memories for most people today - once-proud names like TOP, Haru, Hope, Mamiya, K.O., Boxer, Atsuta, Strong, Ueda and Kyowa have faded out of mind for all but a few older enthusiasts (like yours truly!) who recall using these motors and/or retain an interest in early post-WW2 Japanese model engines. The above-named companies appear to have flourished and died (or remained active in other areas, like Mamiya, Ueda and the manufacturers of the TOP range) without any focused effort being made to record their history as model engine producers, at least in accessible English-language form. Through the publication of the previously-linked articles both here and on the late Ron Chernich’s now-frozen ”Model Engine News” (MEN) website, I’ve done what I can to recover the histories of some of these manufacturers, but much remains undocumented.

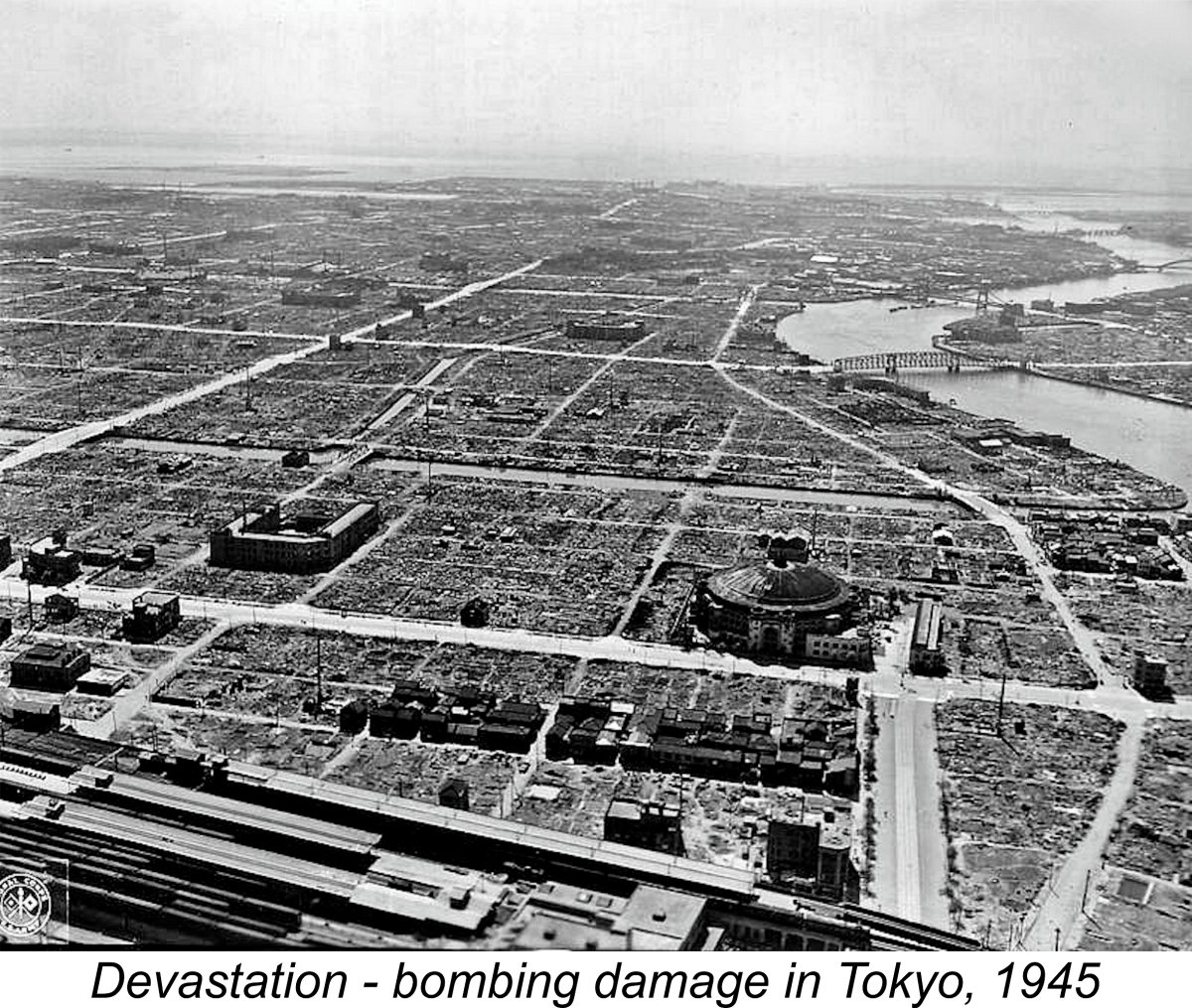

The one reference of which I'm aware which sheds some light on the pre-war and wartime status of aeromodelling in Japan is an article which was published in the July 1946 issue of "Air Trails". This article was written by Frank Nekimken, an American military troop carrier pilot who arrived in Japan with US forces a few days after VJ Day (September 2nd, 1945). The article included the substance of an interview with Mr. K. Shimozin, owner of Tokyo's largest model shop (which had somehow resumed business following the wartime bombing) and then-President of the Japanese Model Industry Association. Apart from his retail activities, Mr. Shimozin had been a major kit manufacturer for some thirty-four years at the time of the interview. Before the B-29's wiped out his factory, he had been Japan's largest kit producer, employing 12 men who produced approximately 12,000 kits per month. This included both flying and static models. Mr. Shimozin reported that there had been as many as three hundred kit manufacturers in Japan prior to the war. Their products were marketed through some seventy wholesale jobbers and 600 retail outlets nationwide. Clearly a thriving industry! The article pointed out that the building and flying of kites and model aircraft had been part of every child's education both before and during the war. Aircraft recognition had been an integral part of the wartime school curriculum. As a result, Nekimken went so far as to state his view that there were almost certainly more model airplane builders in Japan than there were in the USA despite the discrepancies in terms of population! Of particular relevance to the present discussion, Mr. Shimozin advised that some ten percent of Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. This level of interest supported the activities of some 10 model engine manufacturers, who produced around 500 engines monthly between them. Most notable among these was the previously-cited O.S. marque which had become well established in Osaka following its initial market entry in 1936 and had even succeeded in penetrating the pre-war US market to a small extent. But O.S. was far from being alone - Mr. Shimozin confirmed that there were quite a few other pre-war Japanese model engine makers. In large part, the obscurity of this phase of the history of Japanese model engine manufacture is a readily comprehensible reflection of the times in which all of this activity took place. Even before WW2, Japan was under considerable economic stress. The intervention of the war did nothing to improve this situation. Many Japanese model engine manufacturers (including our main subject, Enya) started out or in some cases resumed operation in the early post-war period in a situation in which economic survival in a war-ravaged economy was the primary objective.

Compounding this situation, people from elsewhere weren’t interested - quite apart from the language difficulties, there was enough residual anti-Japanese feeling after WW2 that scant outside interest was taken in such “trivial” matters as post-war Japanese efforts in model engine manufacture. That only came later after firms like Enya, O.S. and Fuji had begun to make their presence felt in the world marketplace to the extent that they could be ignored no longer. Finally, there was a widespread perception that Japanese goods were greatly inferior in quality. The term “Made in Japan” was widely viewed with scorn and derision, largely prompted by the cheap tinplate Japanese-made toys which flooded Asian and other markets during the early post-WW2 period. It was assumed that such products accurately reflected Japanese precision engineering capabilities, a very poor assumption indeed. It took some time for the realization to sink in that Japanese industry was fully capable of matching or even exceeding accepted precision engineering standards elsewhere. In the interim, Japanese engines were assumed to be vastly inferior to their offshore counterparts, hence not being seen as worthy of notice.

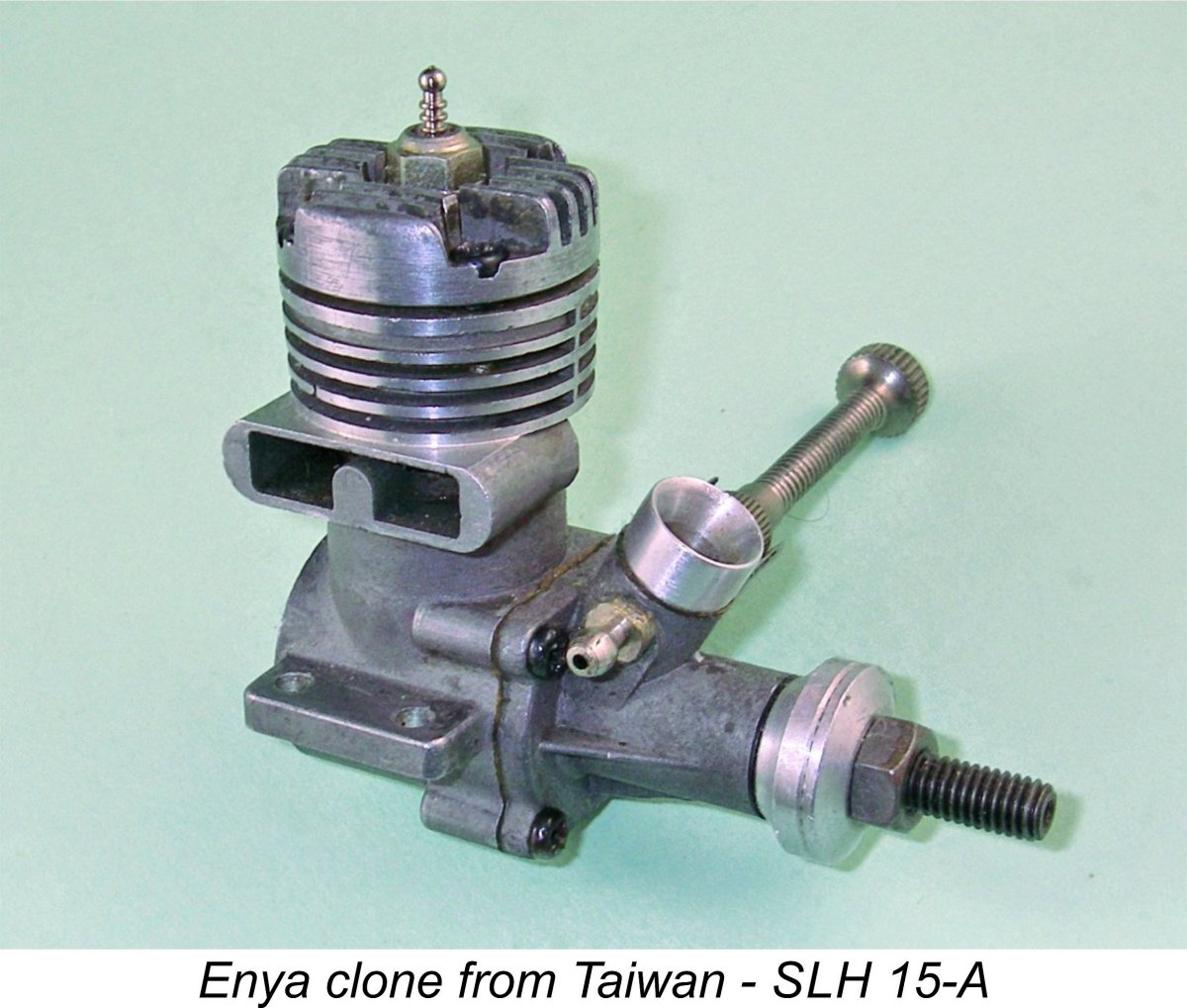

The result was that from that time onwards the ongoing history of Japanese model engine manufacture is very well documented. During the late 1950’s and through the 1960’s into the '70's, Enya and O.S. (and to a lesser extent, Fuji) reaped the benefits of a massive world-wide demand for their products, no doubt helped by the relatively low wage scales then prevalent in Japan and the consequent manufacturing cost advantages which they enjoyed. However, times change, and not always for the better. Today, factors such as the ever-dwindling number of “real” hands-on modellers in our increasingly recreationally-passive world (as witness the push-button all-electric ARF and drone phenomena), environmental concerns (noisy, oily and polluting I/C engines being replaced by electrics) and the flooding of world markets with cheap clones of “name” designs from China or Taiwan have combined to erode the market for newly-manufactured quality model I/C engines to the point at which it has become more or less a specialist niche market.

Recovering that history at this relatively late stage is a daunting task, even in the case of those companies such as Enya which remain in business at the time of writing (2019). Inevitably, these survivor companies are very different from what they were over half a century ago, and are run on far more “corporate” lines than the artisan operations as which they started out. They also operate in a vastly changed economic environment. It’s a sad fact of life that the continued success of any company requires a constant ongoing effort to design and produce saleable products to meet the demands of an ever-evolving marketplace. This inevitably leaves little room for attention to such matters as the preservation of company history. Certainly, my own inquiries directed to the few surviving major model engine manufacturers regarding their products in the “classic” era have invariably drawn a blank - quite apart from the language difficulties, the present-day company personnel themselves no longer appear even to be aware of some of the models that their companies produced in earlier decades! So the recovery and preservation of the history of these companies is essentially down to those of us who retain a sufficient interest in such matters to do some serious digging. In the case of the Enya engines, for the most part my colleagues and I have had to rely on our own personal experience of these engines together with information gleaned from the Web; from the contemporary modelling media; and from the comments of knowledgeable “classic-era” observers from outside Japan such as Peter Chinn, Ron Moulton, Ron Warring and a few others. At the outset, it’s worth making it very clear indeed that the dates which will appear in this and subsequent articles are in many cases simply the best estimates that can be made based on comments published in the contemporary modelling media; advertisements placed in said media; and model associations derived from promotional literature generated by the Enya company and its distributors at various times. By cross-referencing these various sources, it is generally possible to get fairly close to the date at which a given model was introduced, at least to customers in the English-speaking world. However, there is nothing to say that a given model couldn't have been introduced beforehand in Japan. Nor is it even possible to say with certainty that there wasn’t a degree of production (or at least marketing) overlap between successive models in the same displacement category. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that successive models of a number of Enya engines did remain available concurrently at certain times, as we shall see in future articles. Accordingly, all dates given for the introduction of new models should be accepted as “best estimates” rather than as hard-and-fast benchmarks. If more definite information comes to light in the future, I will of course update the findings presented here accordingly. And if someone out there can provide me with greater certainty on any given topic, please don’t be shy about speaking up!! When it comes to the technical information presented in connection with the Enya range, I’m on far more secure ground. This is because my colleague Pat King has kindly undertaken the monumental task of examining, measuring, testing and recording examples of practically every classic Enya engine ever made! Moreover, Alan Strutt has perhaps the world’s largest assemblage of the original 63 models with which the Enya venture was started. So considerable reliance may be placed upon the technical information presented in this series of articles, although I admit that hitherto unrecognized variations may exist. As a final note before I begin, I wish to make it clear that all of the conclusions and interpretations presented in what follows are my own, and I assume full responsibility for them. I further acknowledge that some of these conclusions are necessarily somewhat speculative, hence undoubtedly incorporating errors in some cases. In my view, presenting a credible scenario which at least fits the known facts is far better than saying nothing at all! It’s true that there are almost certainly errors in what follows, but as a wise man once said, “The man who never made a mistake never made anything at all!”. Accordingly, if others more knowledgeable than I or my colleagues come forward with more credible interpretations and set us straight, no-one will be better pleased than I! Gaining knowledge is what it’s all about! Now let’s take a look at how it all got started…………… The Pre-War Japanese Model Engine Industry

The situation in Japan was analogous to that in 1930’s Britain, where similar restrictions on participation in power modelling were very much based on discretionary spending power in the aftermath of the Great Depression. Things may have been different in the USA, where many younger people could evidently afford to buy their own engines instead of waiting for an indulgent auntie to put one under the Christmas tree! Elsewhere, power modelling was restricted to the more affluent and generally older members of society. The activities of pre-WW2 Japanese manufacturers were undoubtedly affected by the economic situation facing Japan as the 1930’s drew on. For some years before Japan attacked America in December 1941, the country was hurting economically. This was caused primarily by sanctions imposed on Japan by the US and other Western countries (League of Nations) as a reaction to Japanese expansionism in SE Asia, particularly in relation to its activities in China. Obviously, a major build-up of Japan’s military capability was required to support this expansion and (later) Japan’s WW2 involvement. This required the assembly and consumption of huge quantities of strategic materials by the Japanese military, leaving raw materials in far shorter supply for other sectors of the economy. In the end, it was a desire to alleviate the consequent economic pain that precipitated Japan’s fateful decision to secure access to additional resources by attacking the US in late 1941.

However, the use of cast alloy conrods and the like may not have been entirely due to the shortage of higher-quality materials. Japan had a centuries-long history of casting metals, and it’s possible that they were simply perpetuating the way in which things had always been done. During the course of WW2, the sale of engines to the public was of course stopped. However, a number of Japanese engines continued to appear during the war years. The explanation for this lies in the fact that the Japanese military authorities encouraged (or perhaps required) trainee pilots to construct and fly powered model aircraft as part of their training. The required engines had to come from somewhere. As a result, power modelling in Japan was sustained at some level throughout WW2. Many pre-war and wartime participants survived the conflict, resulting in a strong post-war domestic interest in resuming participation in this activity. However, the Japanese economy more or less lay in ruins at this time, severely limiting the number of Japanese residents who were in an economic position to participate. Moreover, all Japanese aeromodelling activity was stopped by the occupation authorities immediately following the 1945 conclusion of the war. However, a 1946 appeal to the American occupation leadership by a famed Japanese writer and keen model aircraft enthusiast named Komatsu Kitamura was successful in lifting the ban. It was of course at this juncture that the Japanese economy received a significant post-war boost - the Americans had arrived! After the lifting of the ban on aeromodelling, the first Japanese-American model club was established in 1946 by an American GI, and the hobby immediately took flight once more. More of that development in the following section ……….. The Early days at Enya

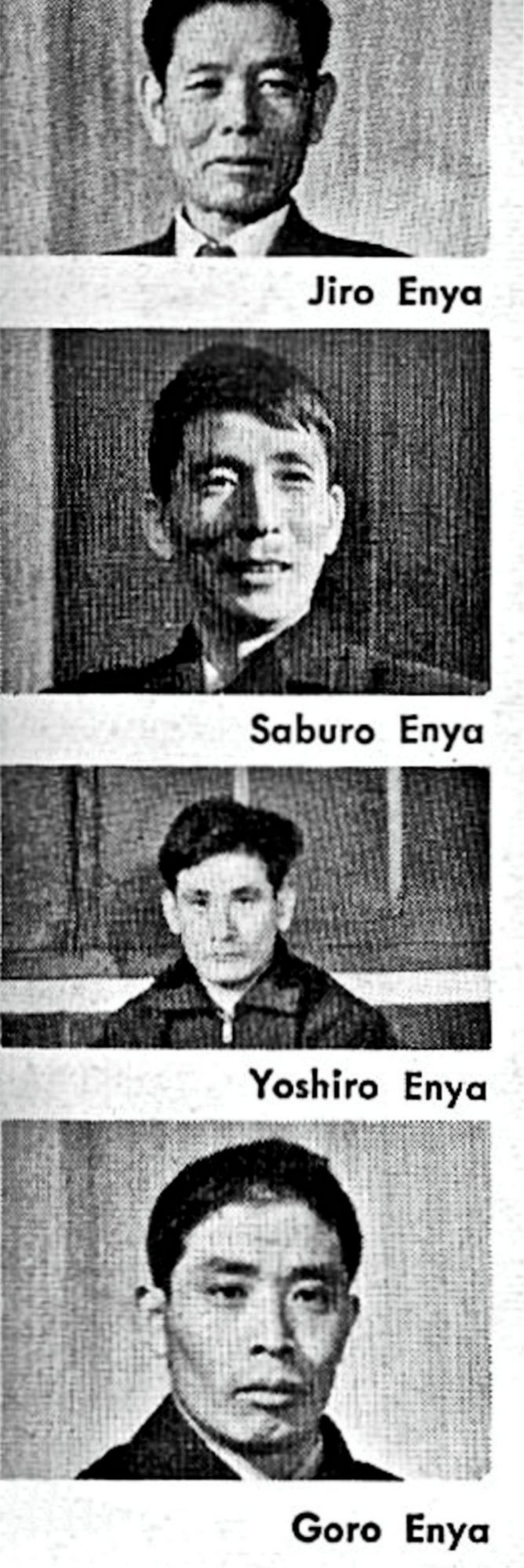

The Enya enterprise began in post-WW1 Japan as a family business. The patriarch of the Enya family was Hachiro Enya, who owned a small machine shop in Tokyo in which he produced medical instruments. He had no fewer than five sons, named Ichiro (birth-date unknown, but he was the eldest), Jiro (b. 1917), Saburo (1923 - 2008), Yoshiro (b. 1927), and Goro (b. 1933). All but Ichiro are seen in later years at the right. The elder two sons Ichiro and Jiro became active as model aircraft enthusiasts as far back as 1930, when they started building rubber-powered model aircraft with the enthusiastic encouragement of their father. Sadly, Ichiro Enya was killed in a motor vehicle accident in 1937, hence not being destined to share in the family’s post-war success as major model engine manufacturers. However, his younger brothers Saburo and Yoshiro had by now become actively involved with aeromodelling as well, and this shared interest was to carry them to great things in the years to come. Japan’s December 1941 entry into WW2 naturally put a stop to such recreational activities as aeromodelling, at least as far as the Japanese public was concerned. Jiro was drafted into the Japanese army, while Yoshiro ended up undergoing pilot training with the Japanese Army Air Force while still in his teens. Doubtless his pre-war aeromodelling experience stood him in good stead at this time! Saburo was exempted from military service by virtue of his enrollment in engineering studies at Tokyo University, from which institution he eventually graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. He had been intending to make a career as an aeronautical engineer, but this ambition was rather overwhelmed by the Enya company's success in the model engine field! Regardless, Saburo's engineering qualifications were to stand the Enya company in very good stead in the years to come. It was not until after the war had ended that the next steps were taken towards the establishment of the Enya family’s model engine manufacturing business. Apart from Ichiro, all the previously-mentioned members of the Enya family miraculously survived the war, and Hachiro Enya’s small machine shop soon resumed its former peace-time operations, with the surviving sons (excluding Goro, who was then only 12 years old and still at school) helping their father.

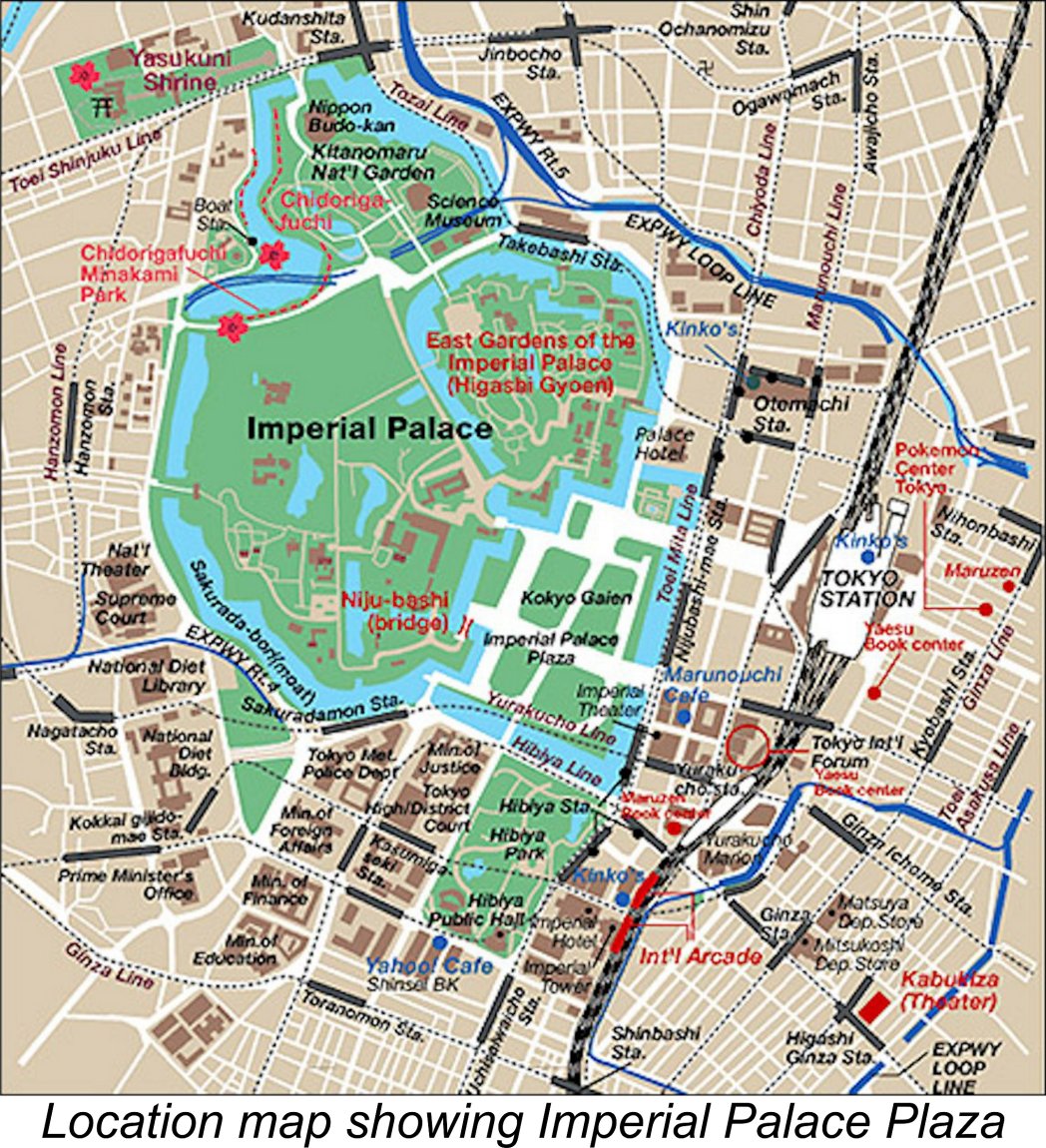

During the immediate post-war period, the sport of aeromodelling in Japan received a huge boost through the presence of the predominantly US forces of occupation, a good few of whom were modellers in their free time. More or less coincidentally with the end of the war, the power modelling movement had really taken off in the USA, largely fuelled by the rapidly increasing availability of good low-cost model engines which flooded the US market during the early post-war period. These resulted from the need for US industry to find other product lines in place of previous military production programs. Obviously, American model enthusiasts serving in Japan would have wanted a piece of the burgeoning power modelling action, thus being ready customers for whatever the Japanese could offer them. These individuals represented a large and well-organized group of keen modellers having both leisure and discretionary spending power far beyond that of the average citizen in war-ravaged Japan. Their influence on the growth of the modelling hobby in general and power modelling in particular in Japan cannot be over-stated. All of the US bases in Japan had their own on-site hobby shops, from which the marketing of the products of local suppliers was evidently encouraged as part of the officially-sanctioned effort to help rebuild the Japanese economy. We already saw that enthusiasm for model engines had undoubtedly survived the war among the Japanese themselves. It was inevitable that the combination of indigenous enthusiasm and alien demand would spark the beginnings of a vibrant model engine manufacturing industry in post-war Japan. This new source of inspiration and potential custom was Being based in Tokyo, the Enya brothers benefited from a unique opportunity during these early post-war years. The sport of control-line flying caught on as rapidly in post-war Japan as it did everywhere else, and it’s an interesting commentary on the levels of tolerance displayed towards the rather noisy business of early post-war power modelling that one of the leading venues for control-line flying in Japan in the late 1940’s was an open square in the centre of Tokyo right in front of the Emperor’s palace! The raucous sound of control-line models powered by the un-silenced large-displacement engines then in fashion must often have reached the Imperial ears! I’ve been in that square myself (it still exists as the Imperial Palace Plaza), and I can assure readers that anyone trying to fly their McCoy 60-powered speed model there today would doubtless get short shrift!

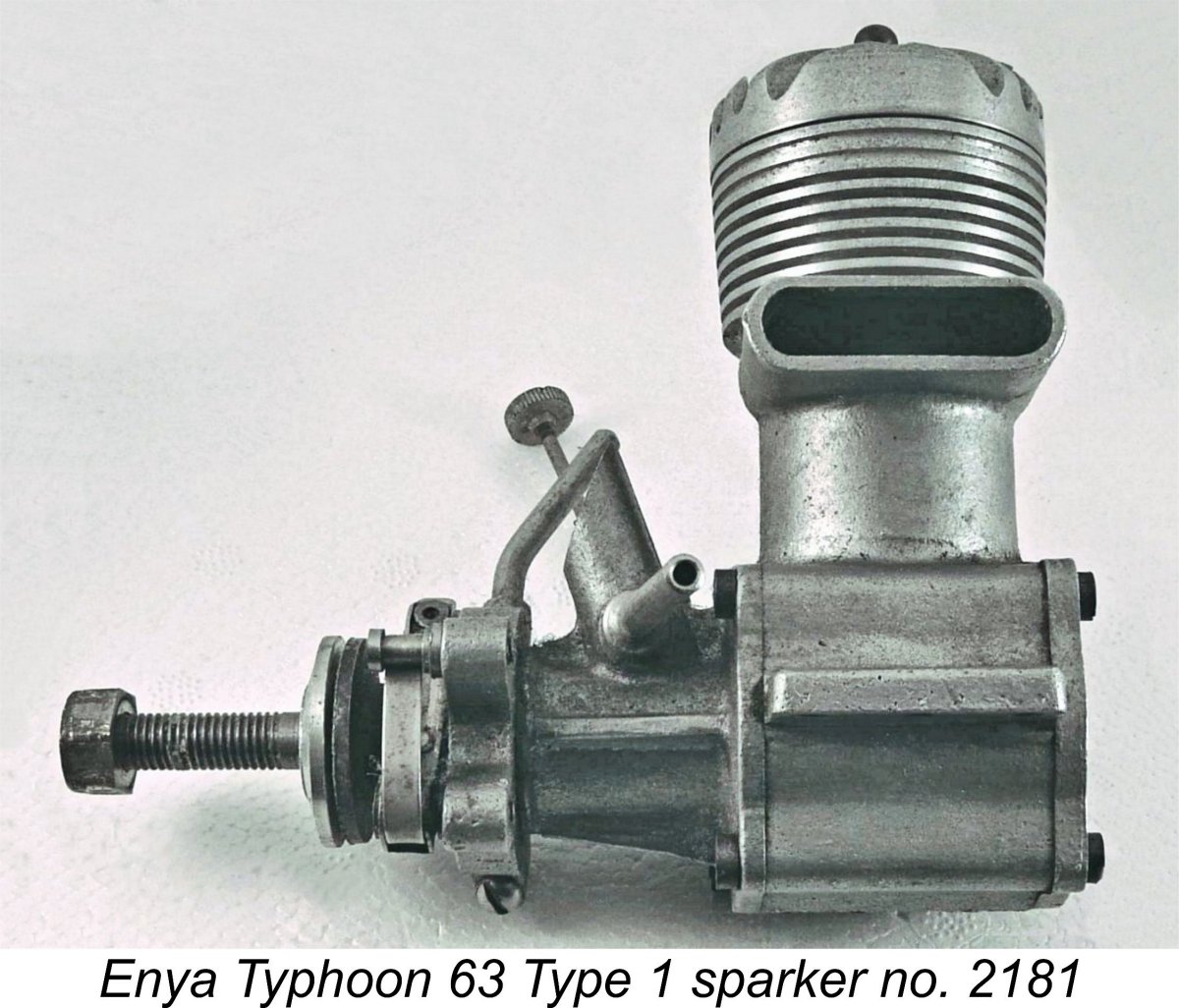

The peer response to this doubtless noisy demonstration was sufficiently encouraging that the brothers initiated efforts to persuade their father Hachiro that their design should be put into production in the family workshop. At the very least, they argued that their model engine would be a worthwhile addition to the workshop’s existing product line. Hachiro Enya doubtless took some persuading! It seems almost certain that the workshop did not switch overnight to full-time model engine production. On the contrary, it’s likely that the model engines were produced initially as a sideline when time could be spared from the family’s established production program relating to other items for which a market had already been developed. Equally, they could have been an “after hours” venture on the brothers’ own time. Either way, the engines were most likely constructed individually on the basis of prior orders. Hachiro Enya would have to be convinced through ongoing sales interest that there was a viable future in model engine manufacture. By this time, of course, the glow-plug era had well and truly arrived. Unlike their Osaka-based rival Japanese manufacturer Shigeo Ogawa, who had founded the O.S. line from equally small beginnings well prior to WW2, the Enya family did not become active as commercial manufacturers until after the spark ignition era had effectively come to a close. Hence their involvement in the series manufacture of spark ignition engines was quite limited. That said, the two original 63 models were both produced in spark ignition form as well as in glow-plug configuration. This reflects the fact that even in 1949 a certain proportion of competition modellers continued to view spark ignition as being superior to glow-plug ignition on account of the far more precise control of ignition timing which it afforded. The relative numbers of the two ignition formats are unknown, but the numbers of each type encountered today appear to be quite comparable, suggesting a fairly even distribution of production between the two ignition systems. Enya Production Commences - the Early .63 cuin. Models

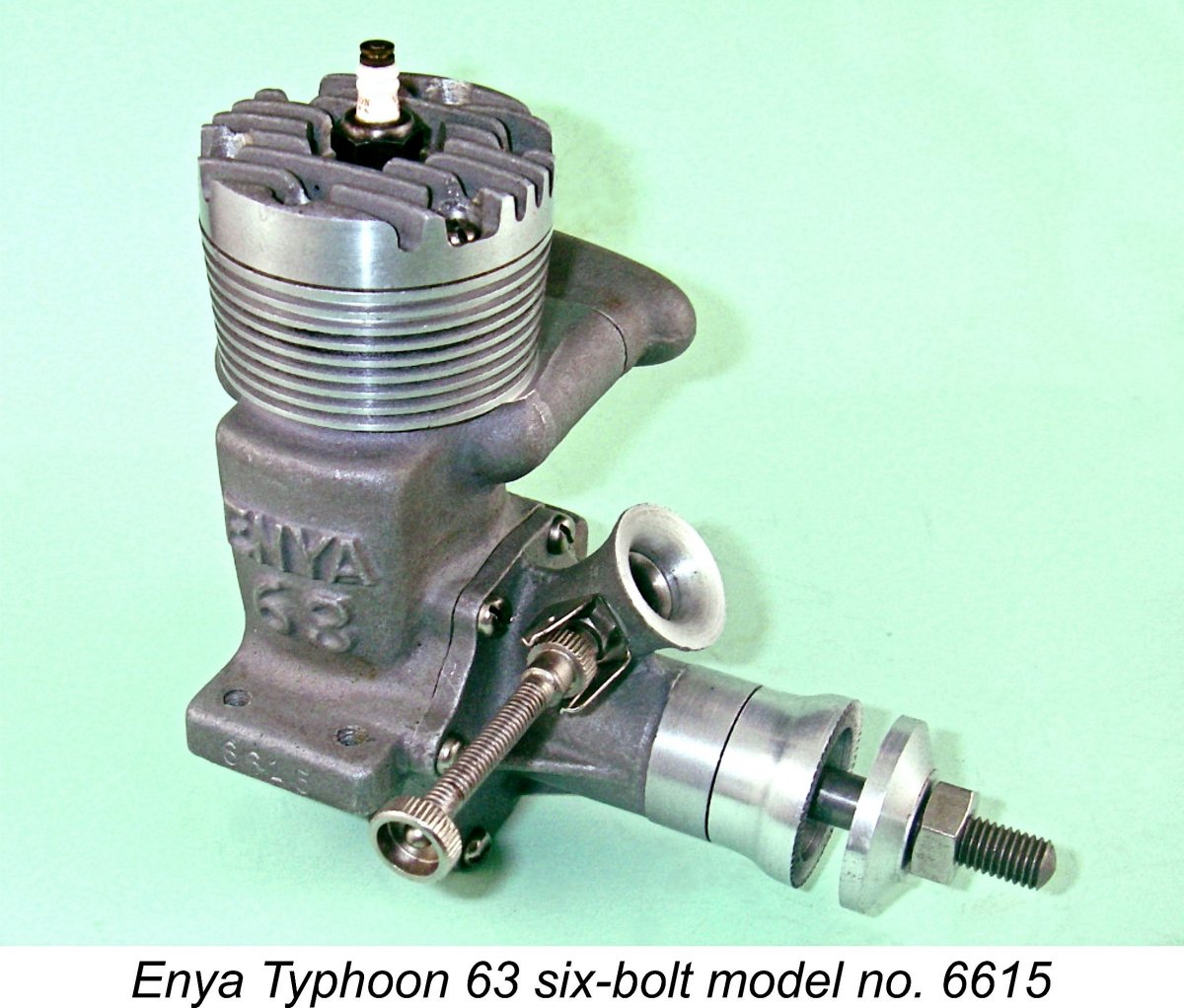

The “Typhoon” name was to become something of an Enya trade-mark during their first decade in business, being applied to a number of engines of various displacements during that period. However, the use of the term appears to have died out during the first part of the 1960’s. More of that elsewhere …………. Mention of the "Typhoon" name warrants a comment at this point regarding the issue of the naming of Japanese engines in general during this period. Prior to the conclusion of WW2, the use of non-Japanese ciphers on Japanese products was forbidden by the Japanese government. But as soon as that prohibition ended, Japanese manufacturers began to fall over themselves using Anglicised names for their products. In doing so, they tended to name their engines from a completely different perspective from that of their Western counterparts, who frequently just used their company names and the displacement. The Japanese makers tended to apply names to their products which reflected the related concepts of excellence, power and progress, as exemplified by evocative names such as Top Class, TOP, PEAK, Great Leap Forward, Super Devil, Cherry and Hope. The name Jin Puu (or Gin Fuu, both meaning Great Wind or Returning to 1949, the two original “Typhoon 63” models were produced in rather limited quantities by Enya’s later standards, consequently ranking today as the rarest Enya’s of them all. Type 1 was a plain bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) engine, while Type 2 was a twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) “racing” model. At this early stage, both models were based upon a common central block with detachable front and rear covers secured by four screws apiece. Both models used lapped cast iron pistons for the most part, although a few examples have been reported with ringed aluminium pistons. According to the timelines page on the factory website, the company considered the Type 1 FRV version of the Enya 63 to have been their first quantity-produced model. It was certainly a survivor in the range! In the latter part of 1952 this model was updated into the more familiar six-bolt front housing version with integrally-cast backplate, finally being replaced in 1956 by the first of the Enya 60 series, of which more elsewhere.

My English informant Alan Strutt has kindly provided some interesting information regarding the various versions of the “Typhoon” 63. Alan is fortunate enough to own a total of seven examples of these very rare models, covering both RRV and FRV variants. Although at first glance the respective RRV and FRV engines in Alan’s possession look very similar to each other, on closer examination some startling differences become evident. This confirms the previously-stated impression that at this early stage of development each individual engine was basically a handmade “model engineer’s special", perhaps made to custom order, with model standardization still some way off. Further details will be provided in due course in a more closely focused technical article on these models.

Jerry retained a recollection of Saburo Enya’s mode of personal transportation. Apparently he travelled to work each day riding a bicycle which was fitted with a flywheel-equipped Enya 63 engine driving the front wheel through a spring-loaded friction roller. No need for a bell with this set-up - you’d have had to be deaf or dead not to hear him coming!! At the outset, sales were reportedly far from brisk - it has been reliably stated (and confirmed by reference to surviving serial numbers) that combined sales figures in the order of 20 to 30 units per month were the best that the Enya family could achieve with their new big-bore products. This should have come as no surprise given the fact that these were large and somewhat specialized engines which were doubtless beyond the financial means of most Japanese citizens at the time. No doubt many purchasers of these engines were American servicemen, but even that market would have been limited. There was also stiff competition from other Japanese manufacturers. Accordingly, it must have been clear right from the start that in order to establish their fledgling model engine business upon a more financially-sustainable basis, the Enya brothers would have to diversify their product line very rapidly to embrace a more “popular” displacement category than the rather specialized and high-priced “big bore” .63 size, which could not reasonably be expected to attract mass sales over the long term. Their first move in this direction was to enter the .19 cu. in. category, which at that time was one of the recognized “economy” classes, hence being widely used in Japan. The Range Expands - the Early .19 and .29 cuin. Models

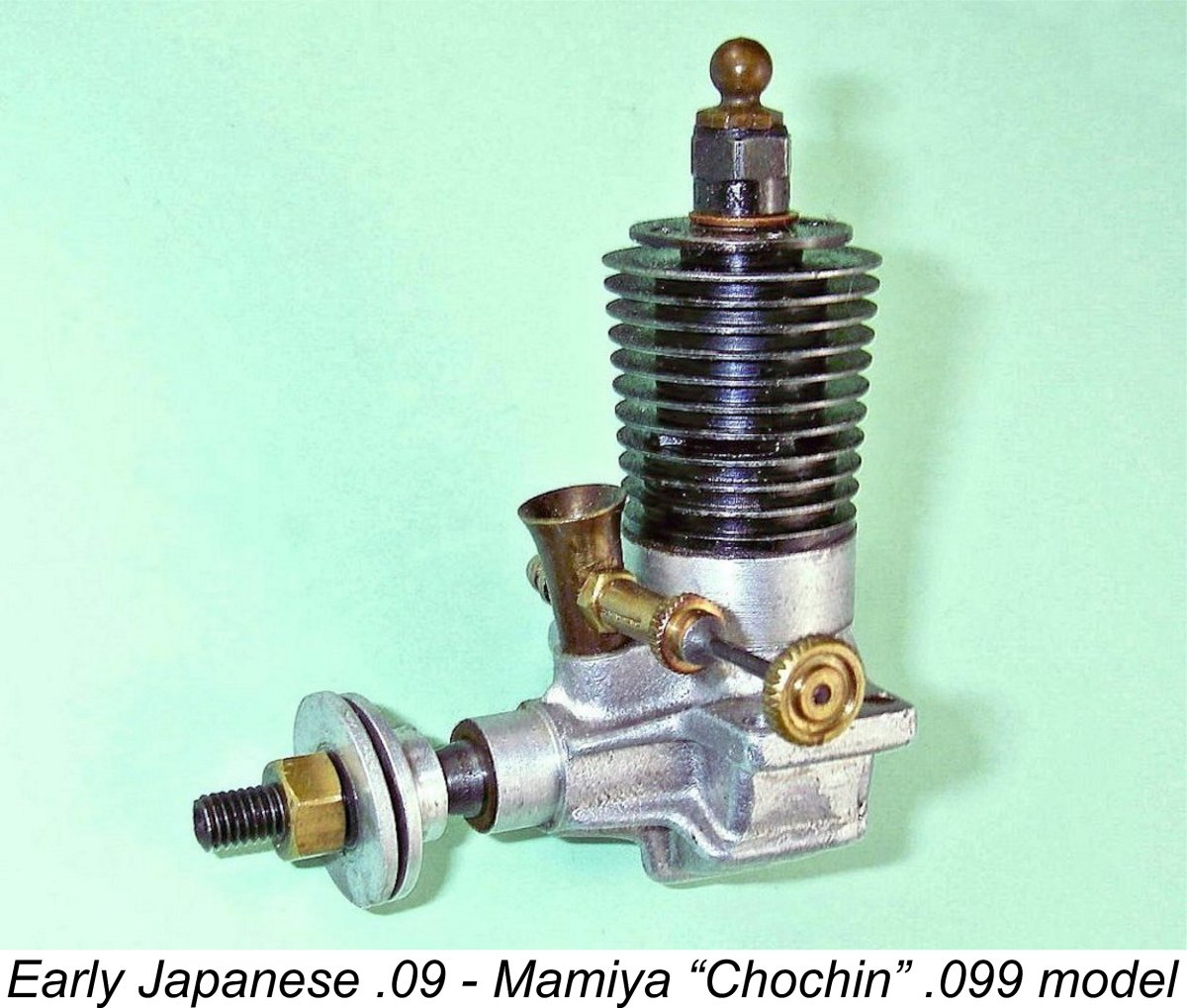

This is underscored by the fact that Boxer, Mamiya, O.S., Fuji and KO all jumped on the .099 bandwagon very quickly beginning in 1949. So why not Enya in 1950 (when they would have been ahead of KO and O.S. and pretty much on pace with Fuji, Mamiya and Boxer)?? As matters transpired, they didn’t enter the .099 cuin. sweepstakes with their excellent Model 3001 until May 1954, making them very much the Johnny-come-lately among Japanese manufacturers in this category. A number of factors appear to have influenced Enya’s decision to ignore the .099 displacement for the moment in favor of the 0.199 cuin. category. Firstly, the pre-war Japanese Class I encompassed engines up to a size of 3.2 cc rather than the American Class A standard of 0.199 cuin. (3.27 cc). However, there does not appear to be any evidence to suggest that pre-war Japanese model engine manufacturers had offered engines built strictly to the pre-war limit. Japanese power modellers of that era seem to have focused on the larger-displacement categories, with manufacturers understandably following along.

Enya was a latecomer in this displacement category too, being preceded by Hope and KO and more or less dead-heating with Mamiya. Enya thus joined a number of others in competing for sales of powerplants to suit a competition class which had long been in existence but had been relatively sparsely served by Japanese manufacturers prior to the arrival of the Americans. The fact that it was a competition class as opposed to a sport-flying category almost certainly added to the incentive given the potential for status-enhancing competition success. Another major factor was doubtless the fact that as of 1950 the .09 market was already well served by domestic Japanese manufacturers, with Mamiya and Fuji already having popular .09 models on the market and O.S., KO and Boxer on the point of adding to the competition. This most likely led to a perception by Enya that as of 1950 they were too late and that the .09 field was in danger of becoming over-crowded.

We’ve already seen that there was competition for Enya in the .19 field as well. This was not a case of Enya entering a field in which there was little competition - rather, it must surely have been a case of Saburo Enya believing that he could do better than the others and that in any case the domestic market as it then existed could absorb the 300 or so examples of the Enya 19 that he and his family members could produce annually at this time. This is an impressive testament to the positive and confident spirit in which Saburo Enya approached his task, especially given the obvious fact that the entire future economic welfare of the family depended upon him coming up with a winner. Regardless of the reason for the choice of its displacement, the first Enya 19 was introduced in February 1950, only some four months after the commencement of series production of the company’s original two Typhoon 63 models. This represents remarkably quick work on Saburo Enya’s part!

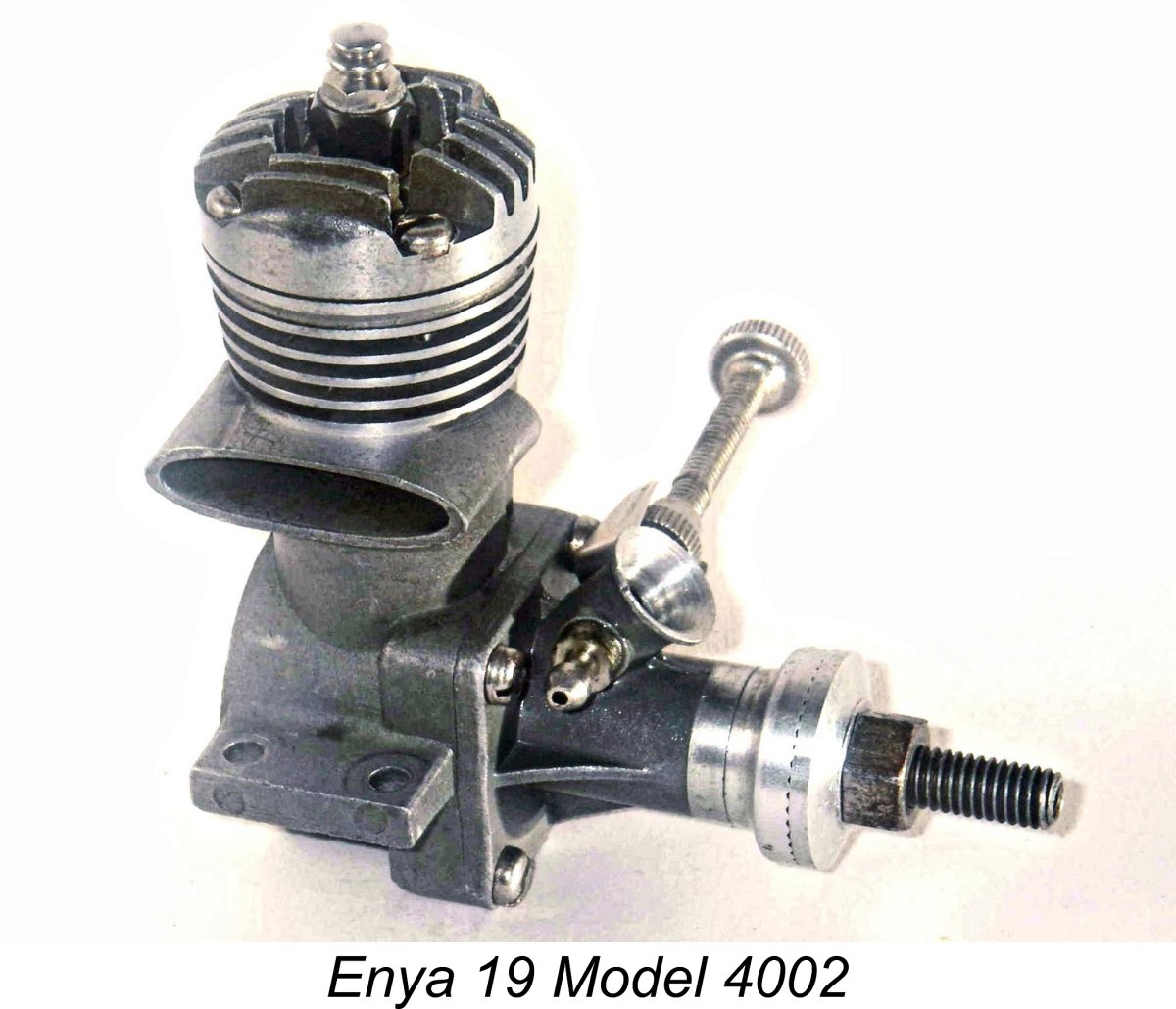

The fact that the Enya brothers were making all of the components in-house at this time is underscored by the fact that the plain steel screws used on the first version of the 3-bolt 19 were not the plated items used for subsequent models - rather, they had machined heads which were not headed or upset but were turned from stock. It seems likely that these screws were made in-house. This would be a relatively simple production job using a turret lathe. Both the head and prop driver of most examples of this model were anodized red. However, the color achieved through the anodizing process used by Enya at this time did not stand the tests of time and usage well, fading rapidly with heat and exposure to sunlight and fuel. The majority of surviving examples (of which there are relatively few) tend to have rather faded anodized components. The Enya 19 series bears the distinction of being the one displacement category which was represented in the Enya range almost throughout its long history. The original sandcast Red Head model just described survived in production with minor variations until late 1953, when the construction of a new factory at Nerima in Tokyo coincided with the introduction of a die-cast version of the Enya 19 designated the Model 4002. A few early examples of that model retained the red anodized head of the earlier variant. More of that model and its successors in a future article.

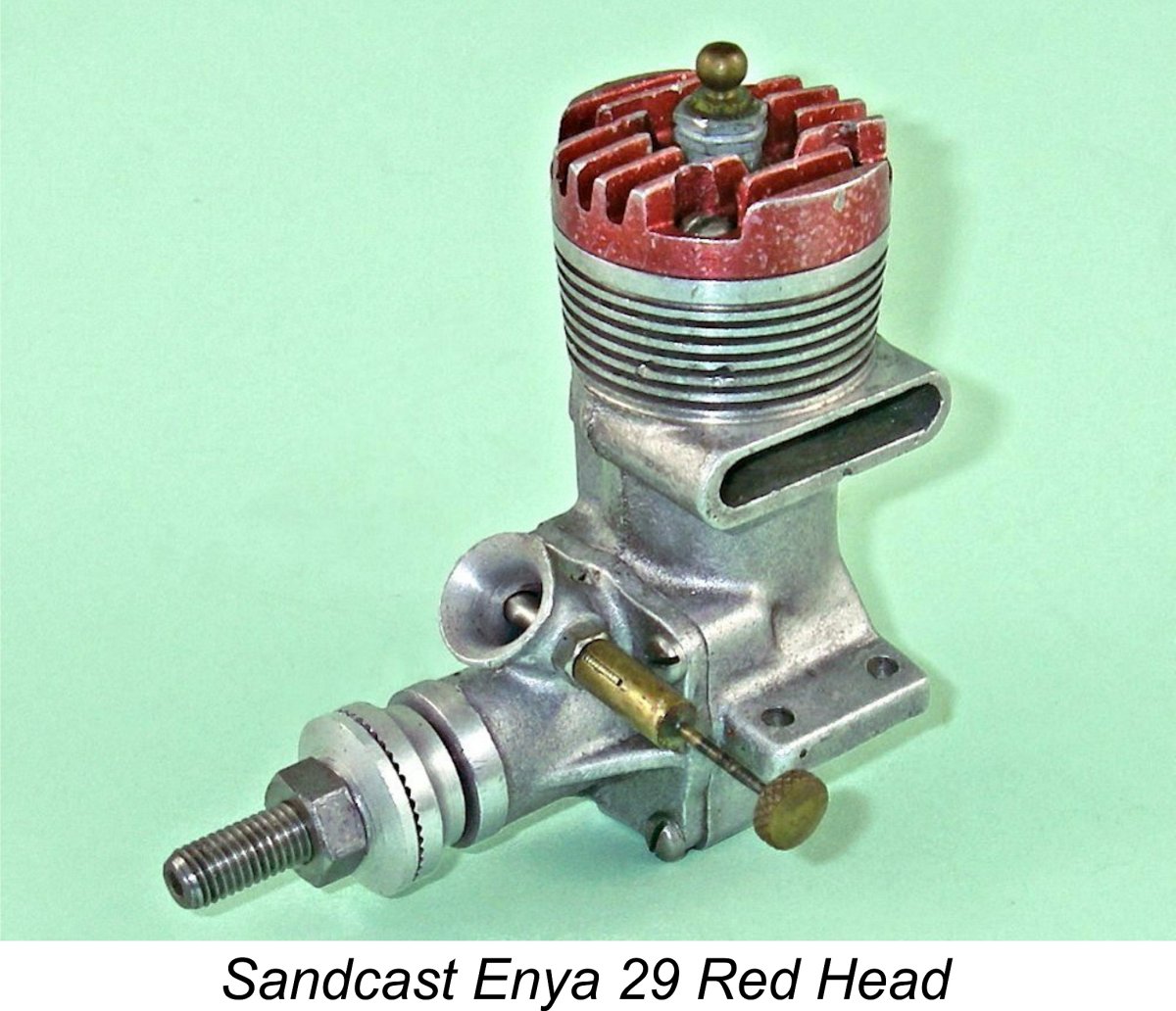

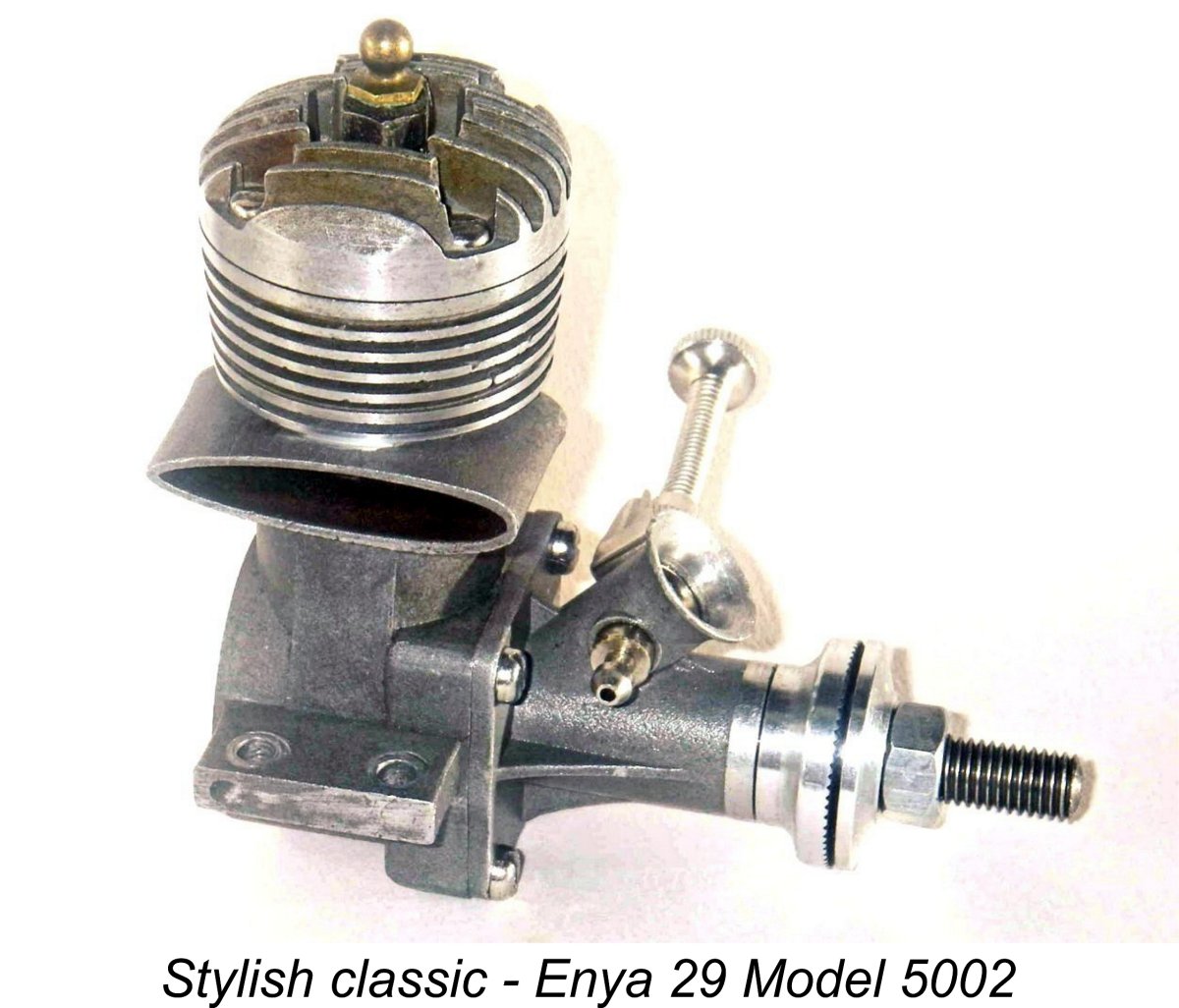

The first Enya .29 was the Red Head model which made its initial appearance in April 1952, some two years after the initial appearance of its 19 sibling. Like the companion .19 and .63 models, the new 29 had a sandcast case with left-hand exhaust stack and integrally-cast backplate. However, it departed from both of its siblings by having a four-bolt front housing (the 63 featured a 6 bolt front housing by this time). The head fins had a flat-topped contour and the head was anodized red, as the name suggests. A few of the later examples also had red-anodized prop drivers of a different more cylindrical design. There is The Enya 29 Red Head remained in production until late 1953, when a die-cast replacement appeared in the shape of the Model 5002 with its striking "airfoil" section exhaust stack on the right-hand side. That particular model is among my personal favorites - it runs as well as it looks! Throughout the period just described, Hachiro Enya had served as President of the company, a position that he was to hold until his death in 1963. He was succeeded by his eldest surviving son Jiro Enya. Saburo continued throughout to serve as Managing Director in charge of engine design and production scheduling. We have now brought the story up to late 1953, at which time Enya had been in business for some 4 years and was steadily increasing its market share on the basis of its established models in the .19, .29 and .63 cuin. displacement categories. The company was also now operating out of a greatly-expanded factory and was moving into die-casting for most of its products. In addition, Saburo Enya was finally contemplating the long-delayed addition of an .09 model to the range, which eventually appeared in May 1954. Additional details of all the models mentioned above will be provided in future more technically focused articles covering the classic range in general. For now, it seems to be worth pausing at this point to lay the groundwork for those future articles by dealing with a few general comments regarding the company’s evolving approach to the business of designing, manufacturing and marketing model engines. For a start, let’s consider the company’s approach to the identification of their products. The Enya Model Identification System The only “classic” Enya models which bore serial numbers were the original Type 1 and Type 2 “Typhoon” 63 engines discussed above and the subsequent 60 model based on the six-bolt 63 Type 1 which was introduced at some point prior to 1956 and produced sporadically until 1965. All of these models were manufactured in substantially smaller quantities than the other engines in the Enya range, always using sand-castings rather than the die-casting process applied to all the other models from late 1953 onwards. With the exception of the original sand-cast 19 and 29 red-head models mentioned above (which were un-numbered apart from the displacement), the company’s mass-produced products dispensed with serial numbers in favor of a generic numerical system under which models, rather than individual engines, were identified. However, for most subsequent models an additional Model number appeared which broadly identified both the displacement and the design series to which the particular engine belonged. This approach appears to have been initiated in late 1953 with the previously-mentioned 19 Model 4002 and its companion 29 Model 5002 which were Enya’s first die-cast designs. In very broad terms, the first two digits in the Model number sequence indicated the displacement of the engine in question, although there were a few departures from this system for reasons which are unclear - the anomalies in the numbering applied to the 15 and 35 series constitute examples of such departures, as we shall see in future articles. The digits 30 identified an .09, 33 a .15, 40 a .19, 50 a .29, and so on, although there were departures from this system. The fourth and final digit generally corresponded to the position of the engine in the design sequence for that displacement. The third digit in the sequence is less easy to decipher - it seems to have served as a “tie-breaker” in certain cases. The fact that it is most often a zero may indicate simply that the Enya brothers anticipated the possibility that their design evolutions in some cases might reach double figures!

At the outset, it appears that some attempt was made to maintain a degree of consistency between the various Model numbering sequences applied to the different displacement categories. However, this attempt was doomed to fail in the long run as the company continued to introduce a rapid succession of new models in an ever-widening range of displacements. There was no way that these models could logically be brought into step with the numbers applied to earlier models which were into their second or third design evolutions. Consequently, as the 1950’s progressed the company abandoned their drive towards uniformity and became a great deal more haphazard in assigning Model numbers. In fact, the only displacement category in which a completely rational numbering sequence was followed from start to finish during the “classic” era was the .19 category, which progressed logically during this era through 5 evolutions from 4002 to 4006 inclusive. The company clearly considered the original red-headed sandcast 19 to have been the 4001 model, although it was never idenified as such. There was some degree of convergence between engines of basically identical design but slightly differing displacements. For example, the mid-1960’s versions of the 29 and 35 models, which were essentially identical apart from their displacements, were both identified by the same Model number, and there were other similar convergences. Presumably the company saw the engines concerned as merely being slightly different versions of the same model. The .15 diesels departed from this sequence, being identified only by a D to indicate their ignition system along with the digits 15 for the displacement and a final Roman numeral to indicate the design evolution, of which there were only two in the “classic” era. They do not appear to have been assigned Model numbers. The D letters appeared only in the backplates of these engines. In all subsequent articles in this series I will make use of the above numbering system to identify the model(s) being discussed. Production figures An unfortunate consequence of the fact that Enya did not use serial numbers for the most part is the fact that it robs us of perhaps the most reliable means of estimating production rates and totals for a given model. This is compounded by the fact that reliable production figures for the Enya range are hard to come by from other sources.

It must be appreciated at this point that the world model engine market has by no means remained static over time. The aeromodelling hobby has undergone constant and radical change over the years, beginning with the post-WW2 emergence of control line as well as the advent of the glow-plug in 1947. This paved the way for smaller and lighter engines and led directly to the ½A revolution in the USA, for example. The 1950’s saw control-line enjoy its day in the sun as the predominant form of aeromodelling, while the ‘60’s saw the rapid expansion and eventual complete dominance of the R/C market. This latter development raised the cost and complexity of participation considerably, hence replacing many of the former buyers-on-a-budget (sadly including many younger enthusiasts) with a less numerous but older and more affluent class of buyer who was willing and able to pay for the larger and more complex engines and related equipment required to complement the changing face of the hobby. In a very real sense, the hobby reverted to its 1930’s state, with spending power increasingly controlling the ability of individuals to participate.

This cost stands in stark contrast to the fact that in that same year of 1960 a teenage modeller like myself could buy a used Enya or equivalent control line engine for something in the $7-10 range and then spend a further $5 or so on the materials for a suitable control line or free flight model. Result - hours of low-budget fun and a highly satisfying and skill-developing creative experience!! Basically, the emerging emphasis on the application of pay-as-you-go technology as opposed to basic modelling skills using raw materials transformed the hobby from the low-cost and widely-accessible activity of the 1950's into a high-cost luxury pastime restricted to those with the means to participate. In my possibly biased view, the model trade and indeed the entire hobby have been paying for this change ever since………aeromodelling is among the few leisure activities that has successfully killed off its own entry-level participant category. Naturally, the high cost of participation in the new modelling era meant that the numbers of engines that could be sold en masse were significantly less than they had been in the simple low-cost worlds of control line and free flight with their far more numerous participants. Hence the business of model engine production became necessarily focused on the manufacture of a smaller number of more complex engines that could be sold at a higher unit profit. This trend has continued to the present day, with the added impact of the progressive inroads being made by electric power, which have accelerated a massive decline in sales of conventional model I/C engines. The point to be made here is that the 1950’s saw a huge world-wide boom in demand for model engines which most likely peaked in the late 1950’s and then leveled out for a time before entering a steady decline as the hobby became progressively more sophisticated and hence costly, squeezing out the entry level. There’s no doubt that Enya was well placed to benefit from that boom throughout its peak period.

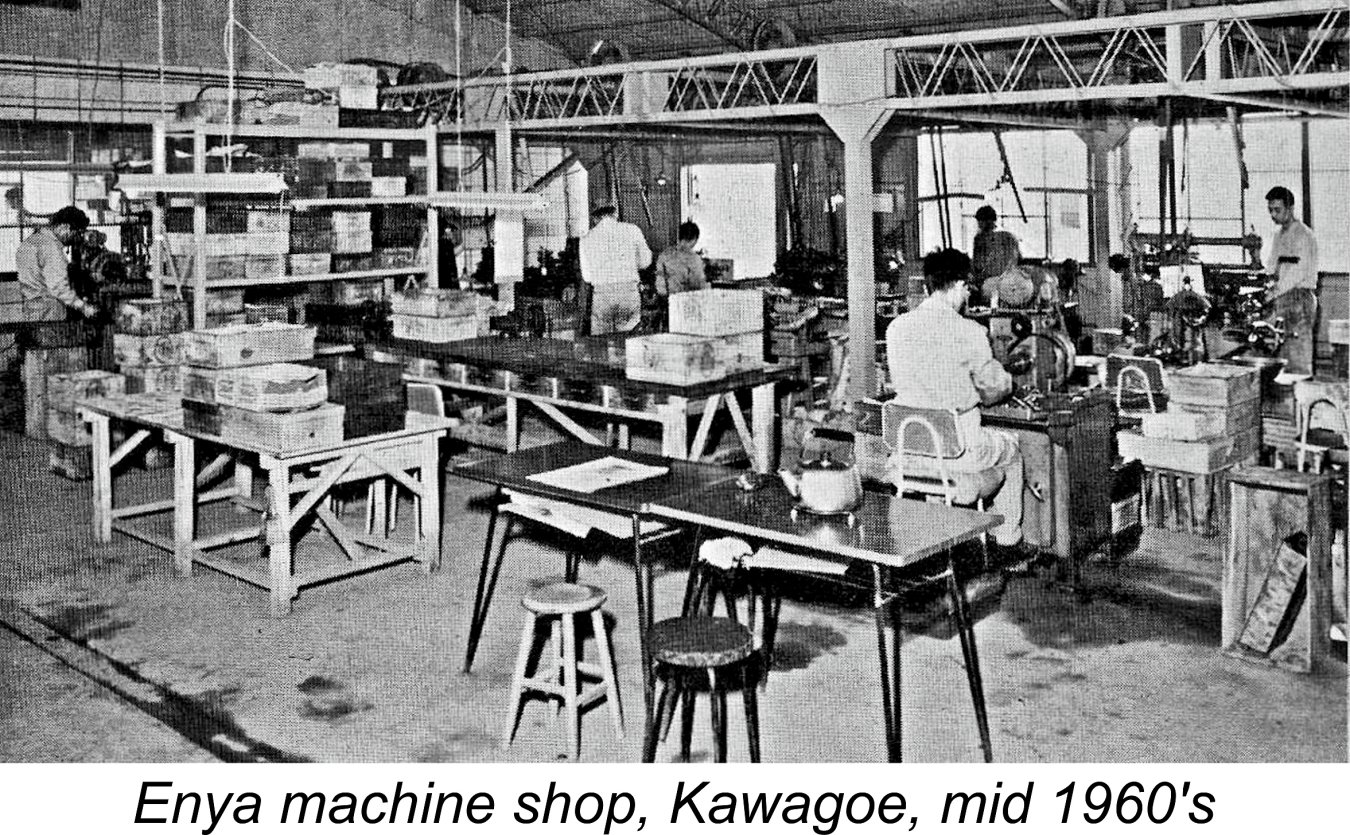

The .09 series was one of the more popular Enya product lines, being eminently suitable for beginner and sport-flying uses as well as being very economical both to run and to keep supplied with suitable models. It seems unlikely that other models in the range would have greatly exceeded this production figure, and some of the larger models would undoubtedly have been produced in far smaller numbers given their higher costs and more specialized utility. If we were to assume an average annual production figure across the range of, say, 12,000 units of each different model, we would probably not be too far wrong. During the years in question, Enya had models in the .06 (glow and diesel), .09, 15 (glow and diesel) .19, .29., .35, .45 and .60 cuin. displacement categories - a total of 10 distinct productions, setting aside the fact that there were both R/C and control line models on offer as well as marine versions. The .06 glow and diesel models were so nearly identical that we might count them as a single product, and the 60 was a limited production item which was still based on a sand-cast case at this time. Ignoring the .06 and .60 models for the moment, we see that the application of our 12,000 figure for annual production to the other seven categories yields an average annual production figure of around 85,000 units in total, not including the .06 and .60 models. The .60 model remained a low-volume sand-cast item during this period, probably adding relatively little to the total. Moreover, since they seem to have been targeted primarily at the domestic market we have no way of estimating how many of the .06 tiddlers were made. However, the .06 and .60 categories might possibly have increased the total annual production to around 100,000 units, give or take - equivalent to some 8,400 units monthly in total. An impressive figure, and a long way from those early days in the family workshop!! The above figures appear quite believable to me and constitute an impressive achievement as they stand. However, we then have to deal with a statement which appeared in a 1965 Enya catalogue issued by the Model Rectifier Corporation (MRC) in which the claim is made that "The machinists in the ENYA factory turn out more than 50,000 engines a month to satisfy a world wide demand." If we were to accept this figure, we would have to believe that Enya were making no fewer than 600,000 engines per year during the same period as that encompassed by Chinn’s comment discussed above! Clearly the two figures are in no way compatible. Frankly, I find the MRC figure to be completely lacking in credibility - it implies a level of demand that doesn’t appear to have existed. The MRC statement in question was primarily dedicated to extolling the virtues of Enya’s vaunted hand-lapping process. I think it likely that the 50,000 figure was some kind of reference to the rate at which Enya was able to produce their hand-lapped piston/cylinder sets. Alternatively, it could be nothing more than a figure pulled out of the air by MRC as a sales pitch .................... So for now I’m inclined to go with Peter Chinn’s information and state my view that from their early beginnings in the family workshop when they could turn out perhaps 500 units annually, the company’s production rose steadily throughout the 1950’s, eventually peaking in the early 1960’s at an annual production figure of somewhere near 100,000 units. It then stayed fairly level for some years and then entered the decline which has attended the overall shrinkage of the model engine market worldwide. The implication is that the total production of the company over the years must surely by now be approaching the 2 million mark. Quite an achievement!! The highest-production Enya models of them all were probably the very popular 5224 “twins” in .29 and .35 cuin. displacements. It seems likely that combined production figures for those units ran into the hundreds of thousands. The Enya Hand-Lapping Process One of the features of Enya engines which was always promoted by the company and its distributors was the claim that all of their iron-and-steel piston/cylinder sets were individually hand-lapped. While this was normal procedure among diesel manufacturers, it represented a commitment to the maintenance of close piston/cylinder fits which was by no means universal among high-volume manufacturers of predominantly glow-plug engines. After taking over the Enya distributorship in the USA from International Models Inc. in 1963, MRC was never backward in citing this feature as part of their advertising, promoting the Enya range as “the hand-lapped engine”. And it is certainly true that the piston/cylinder fits of these engines generally meet the highest standards achieved anywhere in the world. In a 1968 “Model Airplane News” (MAN) article about the Enya factory, the hand lapping was said to be done by a single person. But how credible was this claim, given the production figures cited above? My fellow Enya-phile Bob Allan has researched this matter in some depth, and his comments are quite revealing! It appears that while all of Enya’s iron-and-steel models were indeed hand-lapped, an eye-witness report of which Bob was aware suggested that this process was in fact rather a cursory one undertaken purely with a view to legitimizing the manufacturer’s advertising claim. The excellence of the fits obtained had far more to do with careful initial machining than with the final hand-lapping process. Bob first dug out his calculator to try and figure out how many piston/liner sets that one poor overworked employee would need to hand-lap to supply 50,000 engines a month, as the MRC literature claimed he could. The Industrial Rules & Conditions (if any) which applied to the Japanese workplace at that point in time were unknown to Bob, but they appear to have been far less stringent than those which applied elsewhere. Bob elected to use a benchmark of 9 hours a day, 6 days per week, over a 30 day monthly period. To hand-lap 50,000 units in that period would require our heroic hand-lapper (assuming that he was working alone as the article suggested) to turn out around 3 sets a minute or about 1 lapped piston/cylinder every 20 seconds (and that's not including meal or smoke breaks, although these could have been covered by a substitute or secondary hand-lapper). Bob’s conclusion was that there simply had to have been more than one person doing the hand-lapping, so he contacted the eye-witness mentioned above to try to learn more. Here is the response as recorded by Bob with non-relevant parts edited: "I probably visited the factory in 1961. I went to see the Enya brothers in their office in Tokyo. There were four Enya brothers, and I met three of them. Saburo was the eldest (not correct) and did the designing and worked in the factory. The second brother (Jiro??) spoke very good English and ran the office in Tokyo. The third brother (either Yoshiro or Goro??) worked in the factory, and it was this one who was doing the hand lapping. I remember watching him do this - he rubbed on some lapping paste and sent it up and down the cylinder about TWICE! I did make a comment at the time about how little lapping was actually done, and they just laughed and said it covered their advertising claims! Sorry I cannot give you any more specific information, but you are correct when you suggest that they were lapping about 3 cylinders a minute". It thus appears that the hand-lapping process was maintained at a minimal level of effort as much to substantiate Enya’s advertising claims as anything else and that extremely high initial machining standards were largely responsible for the uniformly excellent piston/cylinder fits on almost all Enya iron-and-steel engines. Now the idea of spending of day after day doing nothing more than smearing on some lapping compound and pushing pistons up and down cylinders does not appeal, and it’s hard to envision anyone being willing to put up with this on an on-going basis. Fortunately, in light of the above re-interpretation of the evidence on production figures, there’s no need to do so! Based on the above eye-witness report, it appears certain that the individual responsible for the hand-lapping process was capable of lapping 50,000 piston/cylinder sets monthly. However, it seems to me to be highly unlikely than he had to achieve anywhere near such a figure. In my considered opinion, the reality was that our long-suffering hand-lapper actually only had to keep pace with a monthly production of some 8,400 units rather than 50,000! This being the case, he could meet demand by working on hand-lapping at the above-described rate for perhaps one day per week (or equivalent spread over a working week), spending the rest of his time performing other and perhaps less tedious tasks. Alternatively, he could relax a bit and work at a far more leisurely pace of perhaps 1 set every 2 minutes or so! And if he did indeed have a fellow hand-lapper working with him, his load would be halved. This is a completely believable scenario for the long term.

By contrast, the Enya approach continued to place considerable reliance upon good old-fashioned craftsmanship, which makes their achievements all the more impressive. It must also be recalled that the Cox models didn’t encompass anything like the displacement range of their Enya counterparts. In the long run too, Cox’s undeniably world-beating precision was somewhat offset by a simple, fatal flaw - the economics-based decision to use a cheaper-to-manufacture ball & socket "little" end, rather than the much more robust gudgeon pin. Why else would it be necessary to purchase a special rod resetting tool to "fix" your Cox engine, maybe only the running equivalent of a season after it was brand new! The problem of material availability Any discussion of model engine production in Japan during the early post-war years requires at least some consideration of the question of availability of materials. It’s an indisputable fact that early post-war Japanese engines acquired a certain reputation for “fragility”. While the Japanese designers of this period undeniably adopted a functionally-based and hence minimalist design philosophy quite distinct from that of their Western counterparts, it’s my considered opinion that the “fragility” reputation had far more to do with the relative difficulty of gaining access to materials of consistently suitable quality than with any deficiencies in design and construction of the engines themselves. This situation was in fact by no means a post-war development. As noted earlier, it appears that the issue of non-availability of premium materials to Japanese heavy industry had made its effect felt much earlier in connection with the Japanese war effort. In a letter published in the September 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”, one of Peter Chinn’s Japanese correspondents recalled that the pre-war decision by Kawasaki to build what amounted to copies of the German Daimler-Benz 601 aero engine instead of copies of the Rolls Royce Merlin unit was based largely upon the fact that the Merlin was more delicately dimensioned and hence required higher-quality materials for its successful construction and dependable operation. He was commenting on the use of a ¼ in. diameter crankshaft in the ETA 15 diesel, implying that earlier Japanese model engine manufacturers could never have used such small sizes successfully, even with a solid shaft like that on the ETA. If the leading Japanese manufacturers of war materiel could not obtain premium-class materials before WW2, it appears logical to suppose that Enya (and others like them) had little hope of obtaining such materials during the early post-war years, particularly when said materials would have been destined for use in products which would have been seen at the time as little more than frivolous “toys” and hence of low priority. Any high-quality steel which might have been available would undoubtedly have been earmarked as a first priority for use in the rebuilding of the shattered national infrastructure. “Fringe” users like model engine manufacturers would have had to be content with such scraps as fell from the table. It would thus seem abundantly clear that early post-war Japanese manufacturers such as Enya (and others) would have had to deal with the simple fact of life that the average quality of metal (and steel in particular) that was available in post-war Japan was not up to the highest standards that had been achieved elsewhere in the world, for example in my old hometown of Sheffield, England. Furthermore, the consequent need to use whatever was available at a given time posed clear problems in terms of material consistency. This being the case, the indisputable quality, dependability and longevity of the early Enya engines become even more remarkable, showing that considerable attention was paid to the materials issue by Saburo Enya and his colleagues. It was almost certainly this factor that led to Saburo Enya’s well-known adherence to the use of crankshafts having unusually large diameters for the displacement of the engine(s) to which they were fitted. He has occasionally been criticized for this, but it’s likely that he had very good reasons for following this design philosophy. I’m not aware of any scientific metallurgical analysis of metal used in the manufacture of Enya engines, but over half a century of use (and countless engines sold to other satisfied users) has proven to my own satisfaction that right from the start whatever grade of iron & steel was used, particularly in the crankshafts, pistons and liners of Enya engines, was well matched to the requirements of the designs. Enya's have an un-surpassed reputation for longevity, and it’s enormously to the company’s credit that their 70-year commitment to excellence has never wavered. Count the 40 or 50 year-old Enya's around, still running perfectly after a lifetime of use. I and my colleagues know - we have some!! That an engine this dependable could be built out of mixed-grade post-war scrap materials is a noteworthy achievement. Despite their obvious attention to this issue, there is evidence to suggest that the Enya family did encounter problems arising from the use of sub-par post-war materials in some of their designs. Future articles on specific Enya models will present some further discussion of this issue. General Notes To conclude this general discussion regarding the inception and early development of the Enya marque, it may be convenient at this point to summarize a few general notes regarding the various products of the company.

Conclusion

This is a huge task, and I have no intention of committing myself to a timetable here - future articles will appear as and when I find the time to write them. As usual, I will make every effort to tell the tale as completely and accurately as possible. I will also include tests of a few models for which published tests are not available. However, despite my best efforts I’m certain that my articles will contain errors and omissions. If any reader knows something that I don’t, let’s hear from you! _____________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2019 |

| |

This article will serve as the preamble to what I hope will end up as a succession of articles on the long-running series of model engines produced to very high standards by the

This article will serve as the preamble to what I hope will end up as a succession of articles on the long-running series of model engines produced to very high standards by the  In this introductory article, I have no intention of describing the engines mentioned in any technical detail, nor will any test results be reported. Rather, my goal is to present a summary of the genesis of the Enya company as well as the early years of the marque’s history. I will also provide a range of general information about the company's operations and the engines that it produced.

In this introductory article, I have no intention of describing the engines mentioned in any technical detail, nor will any test results be reported. Rather, my goal is to present a summary of the genesis of the Enya company as well as the early years of the marque’s history. I will also provide a range of general information about the company's operations and the engines that it produced.  The O.S. company made a very worthy effort with their famous 40

The O.S. company made a very worthy effort with their famous 40

Once the realization hit in the mid-1950’s that this assumption was very far from accurate, people really began to sit up and take notice. The late Ron Draper's victory in the 1956 World Free Flight Championship using an O.S. Max-I 15 certainly underscored the point.

Once the realization hit in the mid-1950’s that this assumption was very far from accurate, people really began to sit up and take notice. The late Ron Draper's victory in the 1956 World Free Flight Championship using an O.S. Max-I 15 certainly underscored the point.  It thus appears timely that an effort should be made to record the history of these fine companies while they remain active as model engine manufacturers and are still well-remembered by many modellers and former modellers worldwide. The present article represents my own first step towards just such an effort in connection with the Enya range.

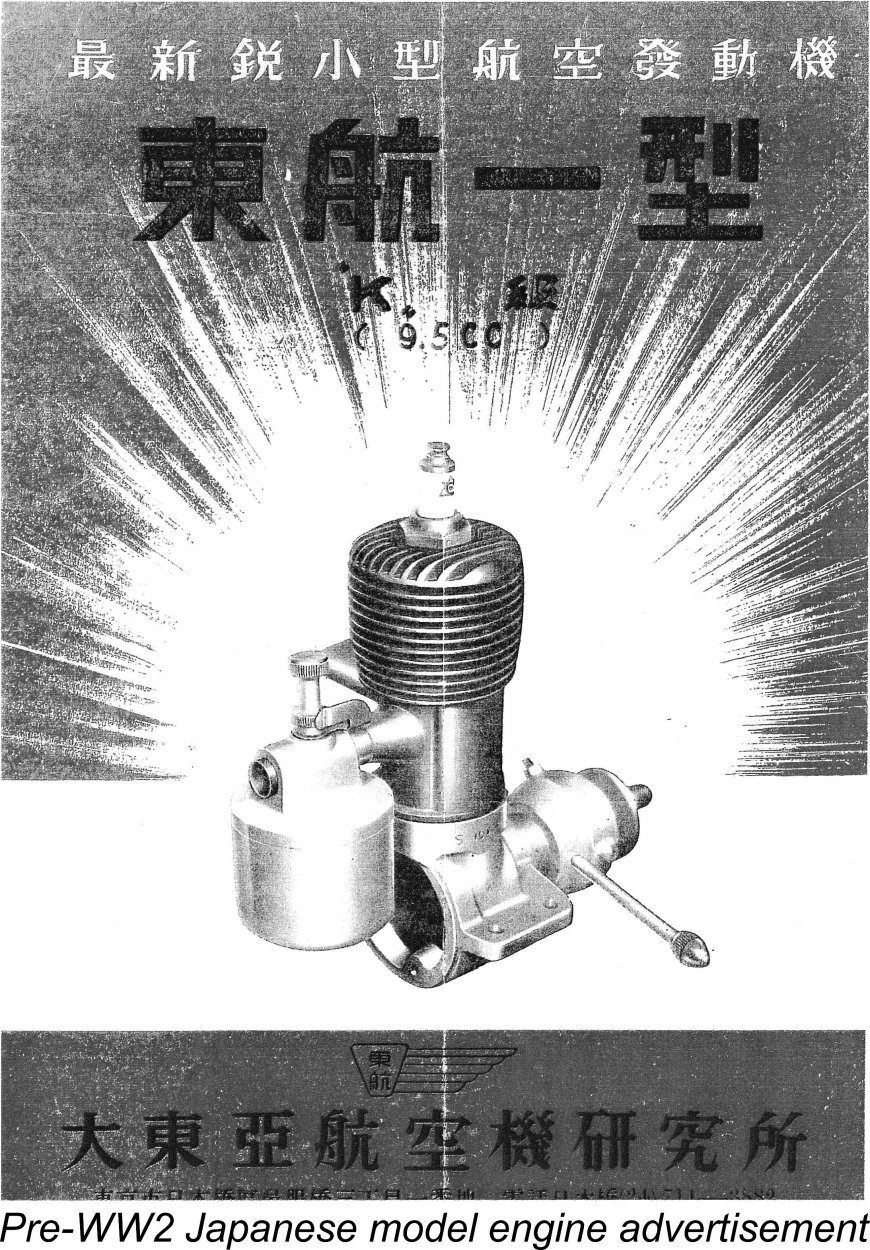

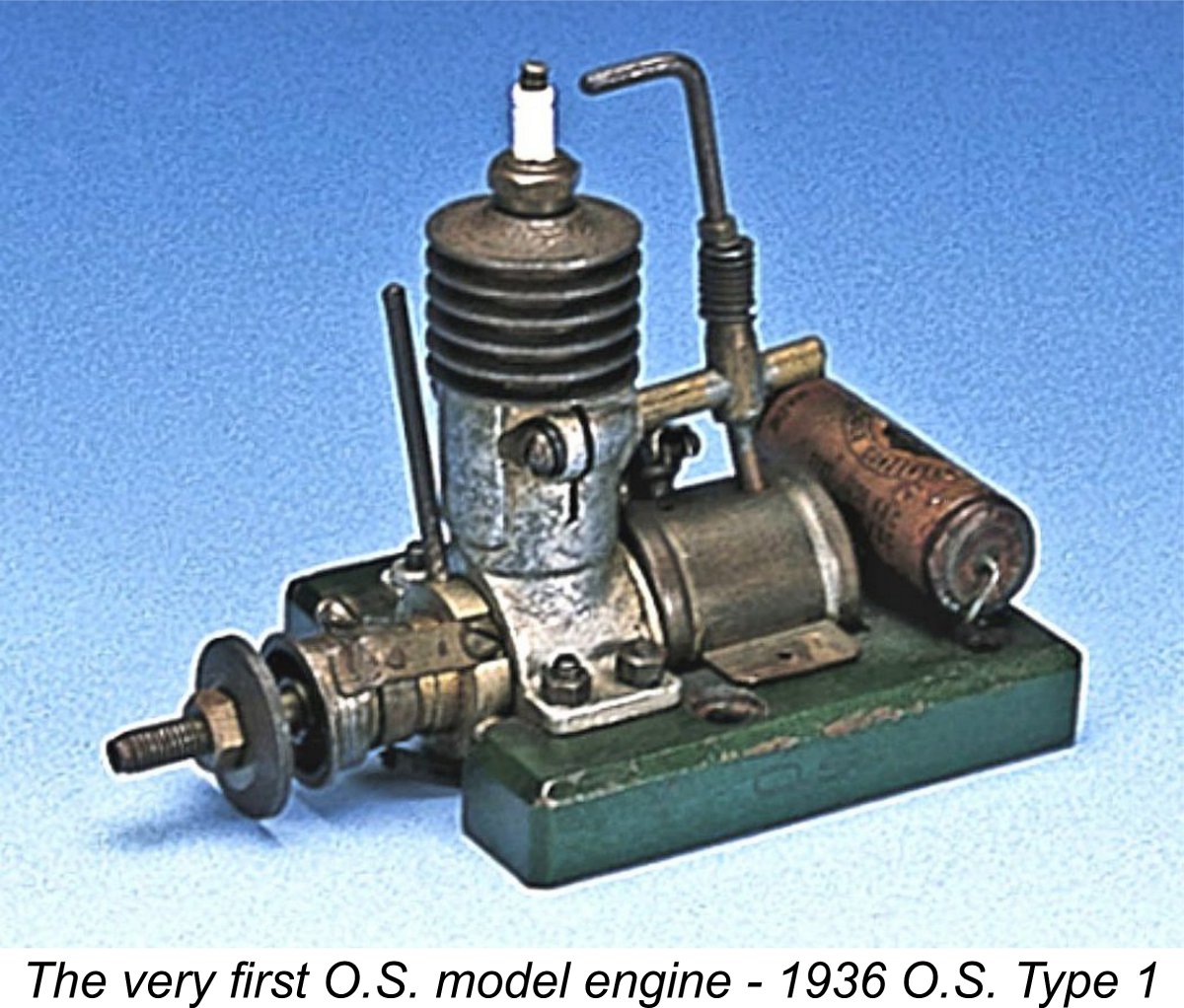

It thus appears timely that an effort should be made to record the history of these fine companies while they remain active as model engine manufacturers and are still well-remembered by many modellers and former modellers worldwide. The present article represents my own first step towards just such an effort in connection with the Enya range. It’s a widely under-appreciated fact that power modelling was a thriving activity in Japan well prior to the country’s entry into WW2. The cost of model engines was indisputably high, restricting participation in power modelling to the wealthier (and hence generally older) male members of Japanese society. However, there were enough such individuals that those model engines which were available found a ready market - in the previously-cited July 1946 "Air Trails" article, Mr. K. Shimozin estimated that around 10% of Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. It was to serve that market that Shigeo Ogawa was able to establish the O.S. company in 1936.

It’s a widely under-appreciated fact that power modelling was a thriving activity in Japan well prior to the country’s entry into WW2. The cost of model engines was indisputably high, restricting participation in power modelling to the wealthier (and hence generally older) male members of Japanese society. However, there were enough such individuals that those model engines which were available found a ready market - in the previously-cited July 1946 "Air Trails" article, Mr. K. Shimozin estimated that around 10% of Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. It was to serve that market that Shigeo Ogawa was able to establish the O.S. company in 1936. It would seem that although companies like O.S. had a ready market for such engines as they could produce during the mid to late 1930’s, Japanese model engine manufacturers at this time found it hard to obtain access to the better-quality materials which were doubtless reserved for military applications. This situation is manifested by many Japanese model engines of the period having cast pot metal (or poor grade aluminium alloy) conrods, back plates and fuel tanks. A few of the more expensive pre-war engines used higher-grade cast bronze con-rods, but these were the exceptions.

It would seem that although companies like O.S. had a ready market for such engines as they could produce during the mid to late 1930’s, Japanese model engine manufacturers at this time found it hard to obtain access to the better-quality materials which were doubtless reserved for military applications. This situation is manifested by many Japanese model engines of the period having cast pot metal (or poor grade aluminium alloy) conrods, back plates and fuel tanks. A few of the more expensive pre-war engines used higher-grade cast bronze con-rods, but these were the exceptions. Although the Enya family had not participated in the pre-war Japanese model engine manufacturing industry, the business that was to develop into the post-war Enya Metal Products Company had its roots in the years immediately following the conclusion of WW1. It is often forgotten that Japan was an active ally of Britain, the USA and other participating countries against Germany during that earlier conflict. Their navy played an important role in securing the principle sea-lanes in the Pacific and Indian Oceans against the Imperial German Navy. From their assigned base on the island of Malta, they made numerous vital escort sorties in the Mediterranean, saving many Allied lives. They also sent highly-regarded Japanese Red Cross teams to Europe.

Although the Enya family had not participated in the pre-war Japanese model engine manufacturing industry, the business that was to develop into the post-war Enya Metal Products Company had its roots in the years immediately following the conclusion of WW1. It is often forgotten that Japan was an active ally of Britain, the USA and other participating countries against Germany during that earlier conflict. Their navy played an important role in securing the principle sea-lanes in the Pacific and Indian Oceans against the Imperial German Navy. From their assigned base on the island of Malta, they made numerous vital escort sorties in the Mediterranean, saving many Allied lives. They also sent highly-regarded Japanese Red Cross teams to Europe.  During these early post-war years during which large areas of Tokyo still lay in ruins, the imperative was economic survival. The family turned their hands to making whatever products they felt they could sell, including such items as a cigarette lighter and a rifle cartridge re-sizing die (thus emulating the Forster company of America!). Interestingly enough, the original family workshop in which it all began was preserved as part of the Enya office complex in Tokyo for many years.

During these early post-war years during which large areas of Tokyo still lay in ruins, the imperative was economic survival. The family turned their hands to making whatever products they felt they could sell, including such items as a cigarette lighter and a rifle cartridge re-sizing die (thus emulating the Forster company of America!). Interestingly enough, the original family workshop in which it all began was preserved as part of the Enya office complex in Tokyo for many years.

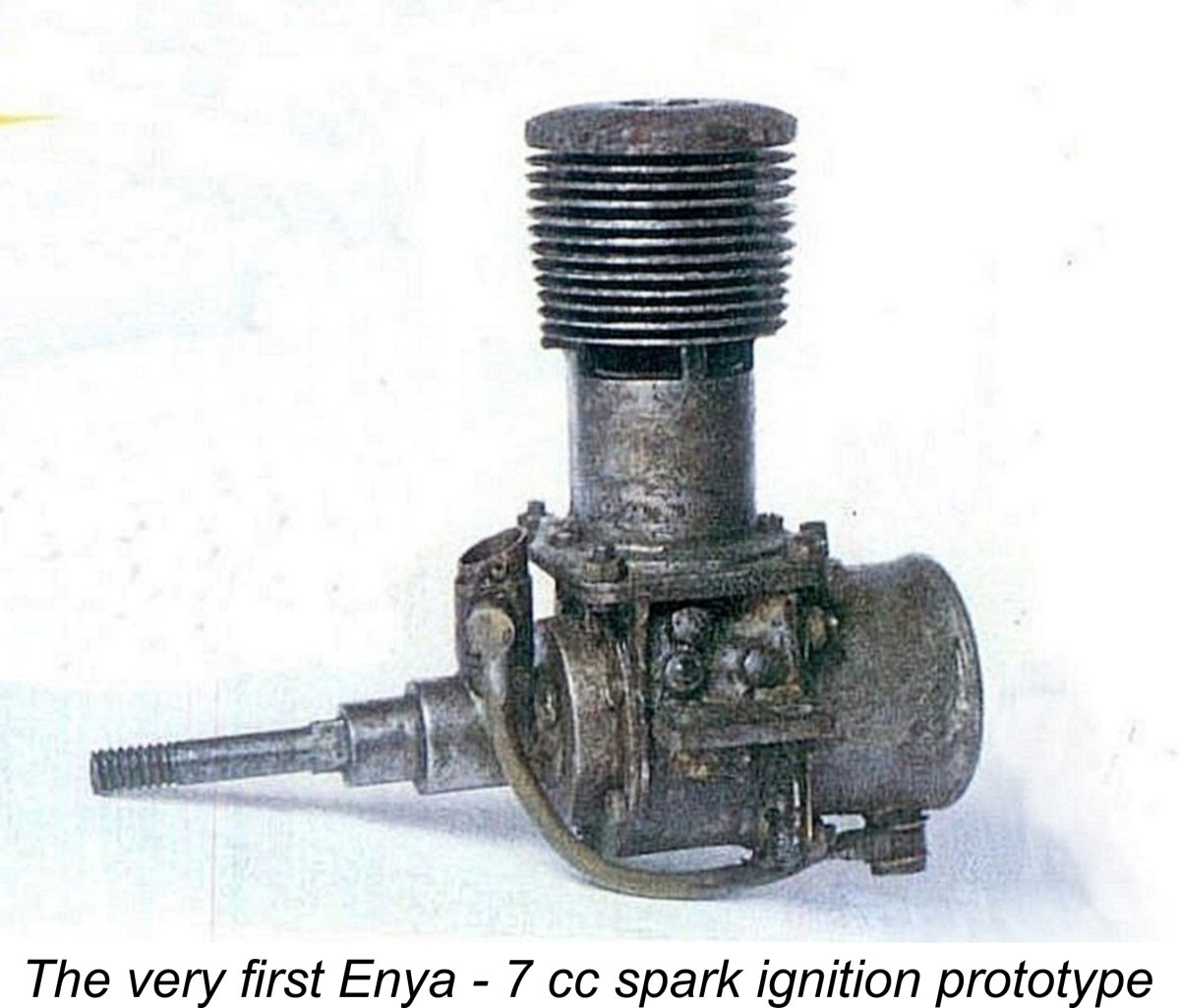

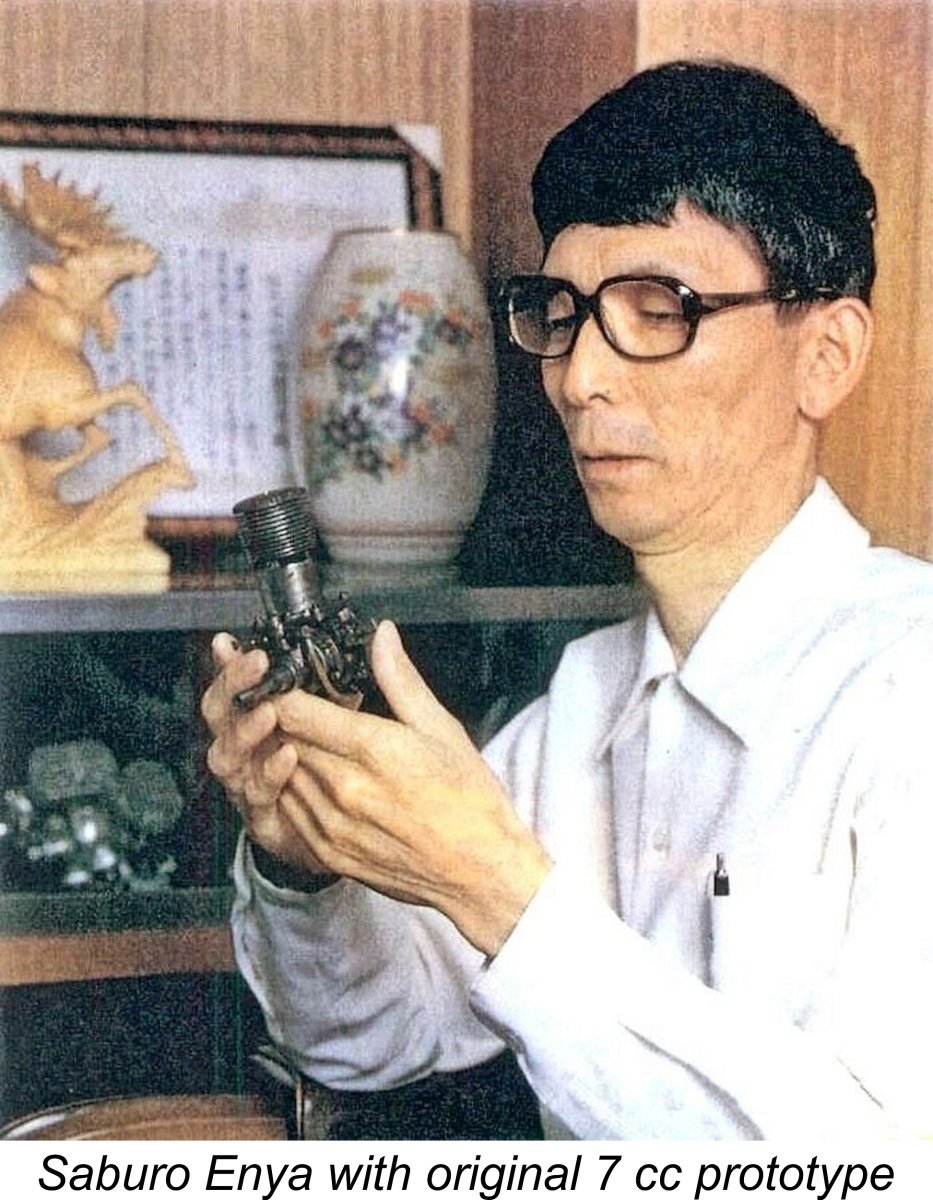

By 1948 the Enya brothers had produced a prototype which they believed could be developed into a commercially-viable product. Their first engine was a 7 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model, but they soon began to focus on a rather massive .63 cuin. job, of which Saburo Enya reportedly made 7 prototypes before finally unveiling his design in public at a major 1949 Japanese flying meet held in the aforementioned Tokyo square.

By 1948 the Enya brothers had produced a prototype which they believed could be developed into a commercially-viable product. Their first engine was a 7 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model, but they soon began to focus on a rather massive .63 cuin. job, of which Saburo Enya reportedly made 7 prototypes before finally unveiling his design in public at a major 1949 Japanese flying meet held in the aforementioned Tokyo square. In October 1949 (according to information obtained from knowledgeable Japanese sources), the Enya family began small-scale production of two variants of their newly-refined .63 cuin. engine, Types 1 and 2. These were both offered with either glowplug or spark ignition under the name Enya "Typhoon" 63. It appears that at this stage both types were in simultaneous production, although the Type 2 “racing” model may well have remained a special order item throughout.

In October 1949 (according to information obtained from knowledgeable Japanese sources), the Enya family began small-scale production of two variants of their newly-refined .63 cuin. engine, Types 1 and 2. These were both offered with either glowplug or spark ignition under the name Enya "Typhoon" 63. It appears that at this stage both types were in simultaneous production, although the Type 2 “racing” model may well have remained a special order item throughout. Typhoon) had been a commonly-used name for pre-war and wartime Japanese model engines. After WW2 it required only a short step for this to evolve into the Anglicized Typhoon name which was used extensively in the 1950’s by Enya. So in using this name the Enya family were carrying on a long-standing Japanese tradition.

Typhoon) had been a commonly-used name for pre-war and wartime Japanese model engines. After WW2 it required only a short step for this to evolve into the Anglicized Typhoon name which was used extensively in the 1950’s by Enya. So in using this name the Enya family were carrying on a long-standing Japanese tradition. The Enya brothers almost certainly saw the Type 2 variant as a “racing special” which had the potential to underscore their technical capabilities through strong showings in the contest arena against racing engines from elsewhere. It was doubtless never seen as a long-term quantity production unit, probably being sold strictly on a “special order” basis. Production of the Type 2 appears to have ended in 1951. Other Japanese makers of the day were similarly motivated, with limited numbers of “showcase” .60 cuin. racing models appearing under the Hope, O.S., Mamiya, Super Devil, TOP, Wasp and KO banners during this period.

The Enya brothers almost certainly saw the Type 2 variant as a “racing special” which had the potential to underscore their technical capabilities through strong showings in the contest arena against racing engines from elsewhere. It was doubtless never seen as a long-term quantity production unit, probably being sold strictly on a “special order” basis. Production of the Type 2 appears to have ended in 1951. Other Japanese makers of the day were similarly motivated, with limited numbers of “showcase” .60 cuin. racing models appearing under the Hope, O.S., Mamiya, Super Devil, TOP, Wasp and KO banners during this period. An interesting sideline may be injected at this point. During the early stages of the glow-plug era when Enya was looking to get into the manufacture of such plugs, the necessary platinum-iridium wire was unobtainable in Japan. Enya formed a relationship with US serviceman Jerry Asner, who supplied them with such wire. Jerry also established a company called Eureka Importing Co. to market the Enya engines in America, but was defeated by the tendency of prospective customers to buy them in Japan and import them personally to the USA. When his stock of engines and kits was wiped out in a storm, Jerry terminated the business.

An interesting sideline may be injected at this point. During the early stages of the glow-plug era when Enya was looking to get into the manufacture of such plugs, the necessary platinum-iridium wire was unobtainable in Japan. Enya formed a relationship with US serviceman Jerry Asner, who supplied them with such wire. Jerry also established a company called Eureka Importing Co. to market the Enya engines in America, but was defeated by the tendency of prospective customers to buy them in Japan and import them personally to the USA. When his stock of engines and kits was wiped out in a storm, Jerry terminated the business. One question that deserves consideration at the outset is - why did Saburo Enya in effect tie the future of his family’s evolving model engine business to the series production of a .19 cuin. model?? If it failed, the future of the company would look bleak indeed! So why not an .09, for example?? The .099 cuin. category was at least as viable in Japan as the .19 category, and indeed appears to have occupied the same “mass” market niche in Japan that the .049’s did in the USA at around the same time.

One question that deserves consideration at the outset is - why did Saburo Enya in effect tie the future of his family’s evolving model engine business to the series production of a .19 cuin. model?? If it failed, the future of the company would look bleak indeed! So why not an .09, for example?? The .099 cuin. category was at least as viable in Japan as the .19 category, and indeed appears to have occupied the same “mass” market niche in Japan that the .049’s did in the USA at around the same time.  This changed after the war, when a number of Japanese manufacturers developed models to suit the increasingly popular 3.2 cc class. A major driving force behind this change was doubtless the fact that Class A (0.199 cuin.) was a very popular category among the many American modellers then resident in Japan as part of the occupation forces. The potential combined sales to these individuals and interested Japanese residents must have been seen by Enya as an added incentive to participate.

This changed after the war, when a number of Japanese manufacturers developed models to suit the increasingly popular 3.2 cc class. A major driving force behind this change was doubtless the fact that Class A (0.199 cuin.) was a very popular category among the many American modellers then resident in Japan as part of the occupation forces. The potential combined sales to these individuals and interested Japanese residents must have been seen by Enya as an added incentive to participate. Finally, there may have been the added attraction that while the actual manufacturing costs of a .19 would not be significantly greater than those for an .09, the selling price could be set higher. This would of course generate a greater unit profit for the new company.

Finally, there may have been the added attraction that while the actual manufacturing costs of a .19 would not be significantly greater than those for an .09, the selling price could be set higher. This would of course generate a greater unit profit for the new company. The new 19 featured a sandcast crankcase with an integrally-cast exhaust stack discharging to the left. The detachable front housing was secured by three bolts, while the backplate was cast integrally with the main crankcase. The very short vertical FRV intake was cast integrally with the front housing.

The new 19 featured a sandcast crankcase with an integrally-cast exhaust stack discharging to the left. The detachable front housing was secured by three bolts, while the backplate was cast integrally with the main crankcase. The very short vertical FRV intake was cast integrally with the front housing.  Well prior to that point in time, Saburo Enya had already moved energetically to develop a larger companion model of generally similar design in the .29 cuin. class. This was a momentous addition to the range, because if one had to pick a single displacement category in which the Enya company was destined to finally earn the respect of modellers worldwide, it would probably be their .29 cuin. (5 cc) models. The company’s achievements in this category during the “classic” era were nothing short of outstanding, as I hope to show in a later article.

Well prior to that point in time, Saburo Enya had already moved energetically to develop a larger companion model of generally similar design in the .29 cuin. class. This was a momentous addition to the range, because if one had to pick a single displacement category in which the Enya company was destined to finally earn the respect of modellers worldwide, it would probably be their .29 cuin. (5 cc) models. The company’s achievements in this category during the “classic” era were nothing short of outstanding, as I hope to show in a later article.  evidence in the form of an example in my own possession that Enya experimented with an over-bored .33 cuin. version of this model to allow the same airframe to compete in different classes simply by switching engines. This was a common practise among US manufacturers, making it quite logical for Enya to follow suit.

evidence in the form of an example in my own possession that Enya experimented with an over-bored .33 cuin. version of this model to allow the same airframe to compete in different classes simply by switching engines. This was a common practise among US manufacturers, making it quite logical for Enya to follow suit.  In accordance with this approach, each Enya engine bore the name “Enya” cast in relief onto the crankcase along with the displacement figure in cubic inches (implying a close concern with the American market). This was as far as the identification went with the original sandcast 19 and 29 models.

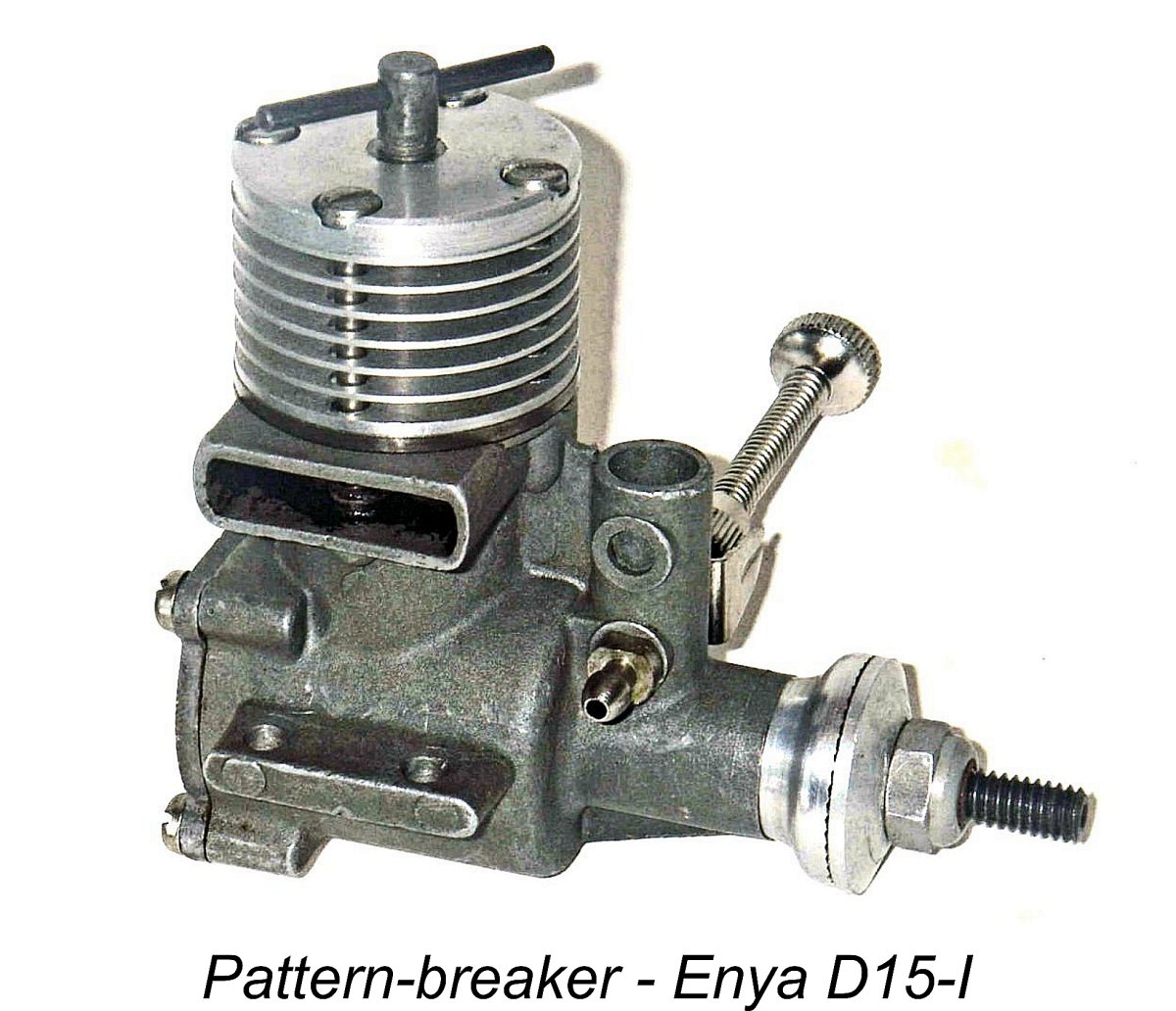

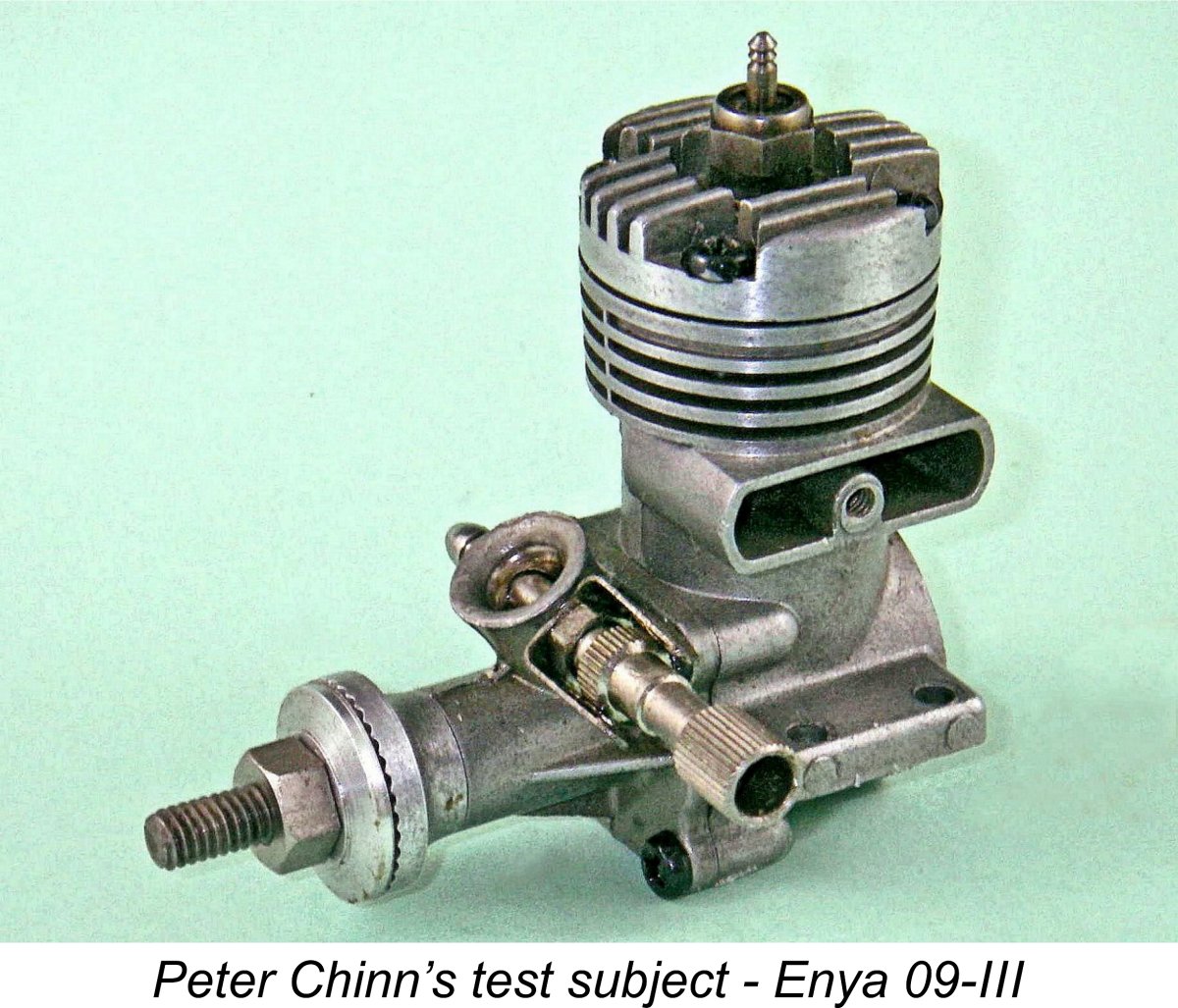

In accordance with this approach, each Enya engine bore the name “Enya” cast in relief onto the crankcase along with the displacement figure in cubic inches (implying a close concern with the American market). This was as far as the identification went with the original sandcast 19 and 29 models. As time progressed, a further figure in Roman numerals was added. This followed the displacement figure and indicated the position in the design sequence for the displacement category to which the particular engine belonged. This additional means of model identification appears to have been initiated with the Enya D15-I diesel released in late 1956, and it was applied to most (but not all) subsequent models during the “classic” era under discussion here. Thus for example the Enya 09-II was the second design evolution of Enya’s .09 glow model.

As time progressed, a further figure in Roman numerals was added. This followed the displacement figure and indicated the position in the design sequence for the displacement category to which the particular engine belonged. This additional means of model identification appears to have been initiated with the Enya D15-I diesel released in late 1956, and it was applied to most (but not all) subsequent models during the “classic” era under discussion here. Thus for example the Enya 09-II was the second design evolution of Enya’s .09 glow model. We have the evidence of at least one contemporary Japanese source that initial production in the 1949/50 start-up period was limited to figures in the order of 20-30 units per month for the 63 model with which the company got off the ground. Following its introduction, the original .19 model was said to have been manufactured at a rate of around 25 units per month. However, those figures date from a period when the engines were being more or less individually produced in the family workshop. Once the range had expanded into the world market and production capacity had been increased to match through the construction of a new factory at Nerima in 1953, followed by a second factory at Kawagoe in 1964, these figures were of course totally eclipsed.