|

|

The Origins of Diesel Model Aero Engines and Richard Gron’s Etha 1 Replica By Maris Dislers With thanks to Peter Scott, Darrel Peugh, Tim Dannels, Anthony Williams and Holger Menrad.

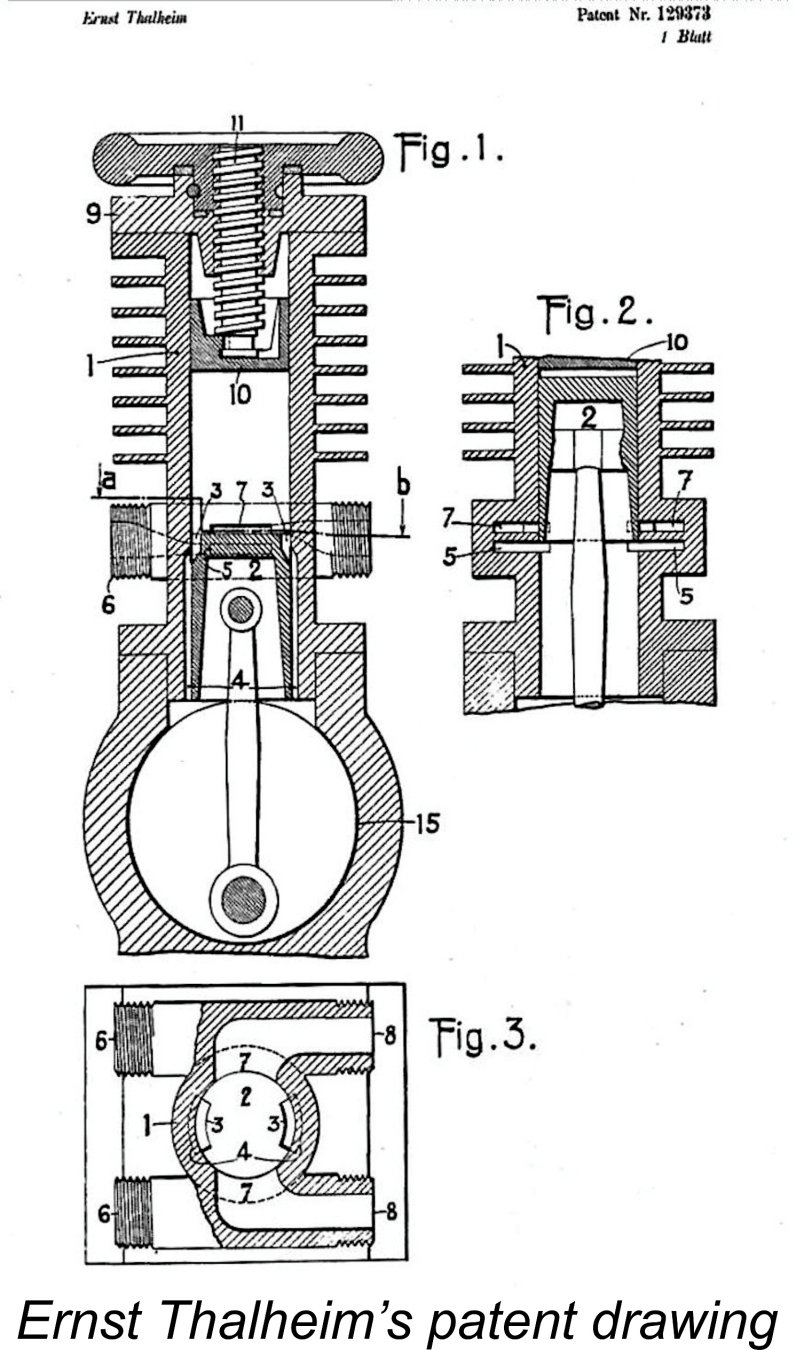

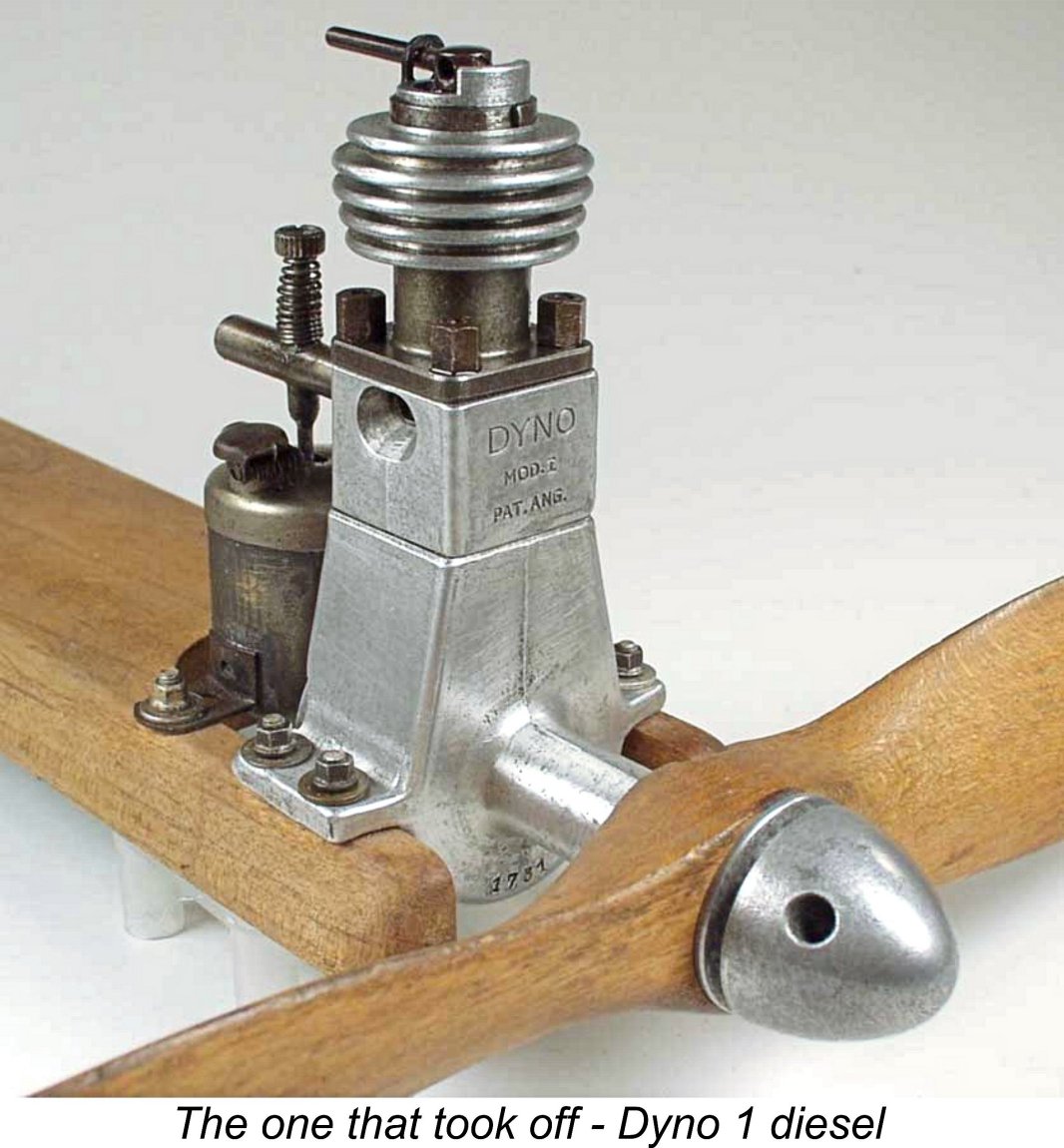

The popular "short history" of model diesel engines is that the Klemenz-Schenk Dyno 1 engine from Switzerland popped up in 1941 in such miraculously well-developed form that, despite a raging world war, it became the template for a host of first-generation model “diesels” which just about wiped out spark ignition types in Europe and the U.K. by the end of the decade. Fair enough, except for the fact that Jakob Klemenz and others were actually drawing on the earlier ideas of fellow countryman Ernst Thalheim, who had been granted a Swiss patent for his invention way back in 1928. What is of particular interest to us is the little-known fact that Thalheim made engines of model size at that time. These were the very first "model diesels". The abiding question is why they didn’t immediately “take off”, while the Dyno most emphatically did so in 1941 and beyond. In the search for answers, we test-ran a replica of Thalheim’s Etha 1 model diesel engine. But let’s first go over the known history, taken from the available published references which are listed at the end of this article. Ernst Thalheim (born October 12, 1907) was a precision engineer/mechanic from Lausen in north-west Switzerland – current population around 5,000. This community is located 15 km southeast of Basel, close to the border with Germany. Asked by a customer to extract more power from his motorcycle engine, young Ernst increased its compression ratio. The engine was a vintage hot-bulb “semi-diesel” type, with an external gas flame needed to keep a metal bulb sufficiently hot to initiate ignition - a very distant ancestor of the latter-day glow plug. It’s hard to believe that anyone would use such a slow-revving and potentially hazardous engine in a motorcycle. Be that as it may, the elevated compression ratio released more power, and Thalheim also noticed that it would then keep running even with the gas flame extinguished. Watch a few Youtube videos of people starting stationary, marine and tractor hot-bulb engines and you’ll see that it’s normal practice to remove the external heat source once the engine is running. Back then, the external flame probably came from a kerosene blowtorch.

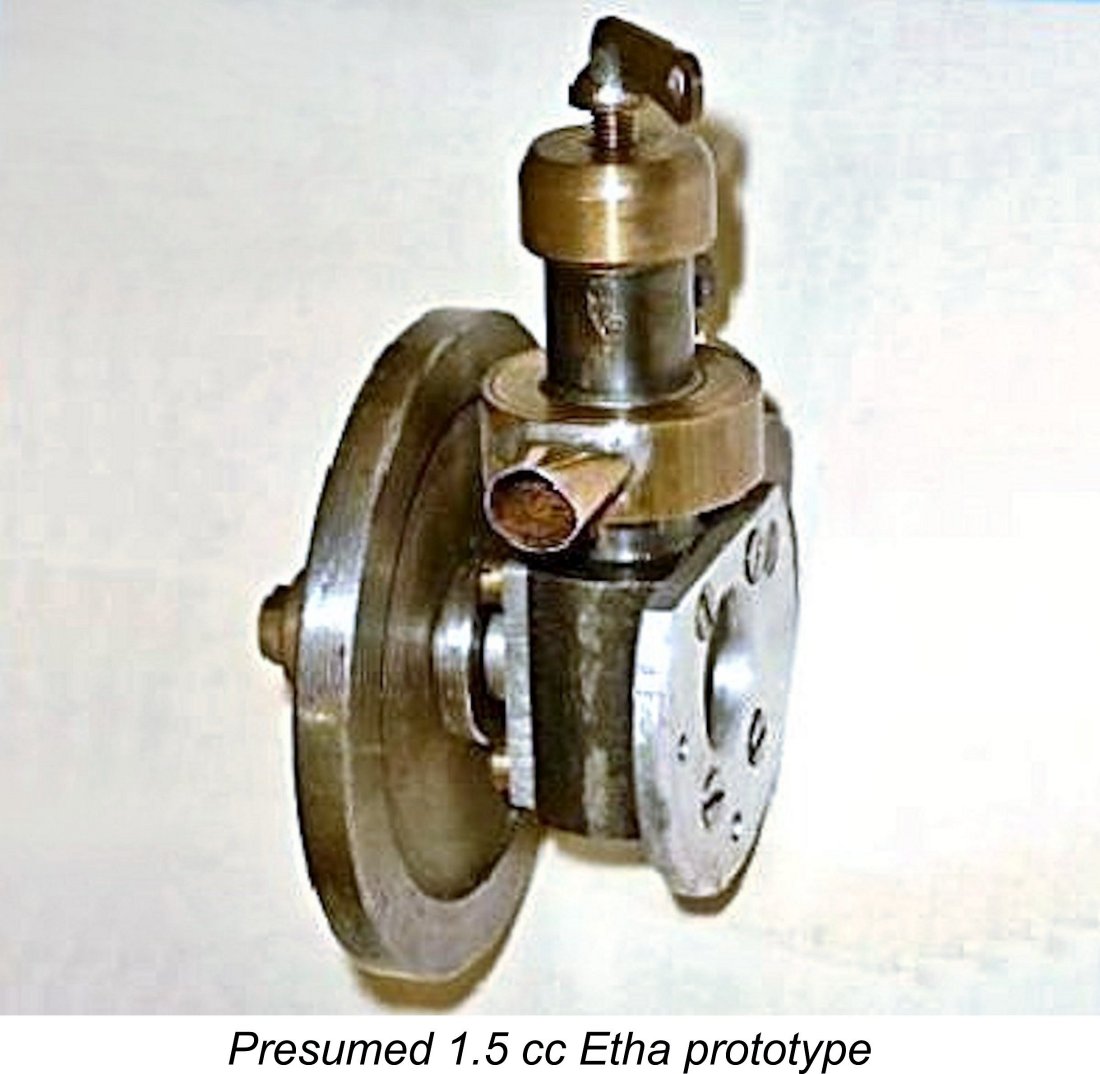

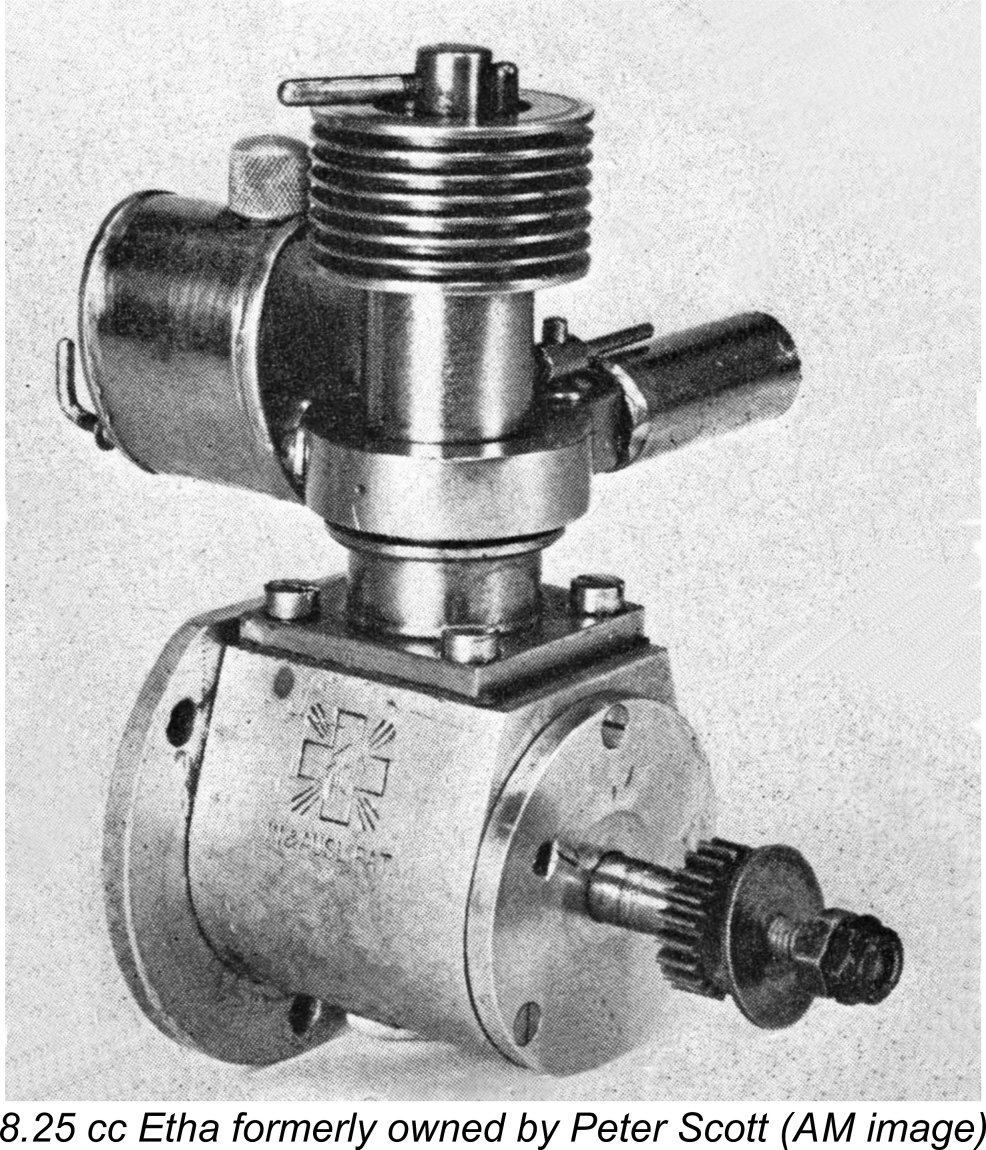

Thalheim obtained his patent and demonstrated one of these engines at an inventors’ fair in Basel in 1928. It seems that the demonstration did not elicit offers of instant riches, but Thalheim did produce “full size” Etha (Ernst Thalheim) two-stroke stationary engines, according to the customer’s particular requirements. These included single cylinder farm engines, an inline 500 cc (30 in3) boat engine rated at 20 HP and a 106 Peter Scott’s experience with the illustrated 8.25 cc (0.50 in3) Etha which he once owned is interesting. When run, this chunky 1.16 kg (41 oz) beast shook mightily. Peter had carved a suitable propeller and used a sturdy clock gear that happened to fit on the crankshaft end as an impromptu driver plate. But judging by its weight and the long unsupported exposed crankshaft portion, this one was intended to accommodate a sensible flywheel and was not meant to leave the ground. Note the gravity feed tank and rotary throttle on the exhaust outlet. Thanks to AeroModeller magazine for preserving this image! The availability of proven spark ignition engines from America and the German Kratmo company in the late 1930’s ignited Swiss interest in powered models. Perhaps some saw the potential in Thalheim’s unusual little engines, if their power to weight ratios could be improved. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when this happened! Jakob Klemenz is reported to have been experimenting along that line, in cooperation with others. His firstfixed-compression engine was unsuccessful, so he turned to Thalheim’s variable compression method, presumably having come to some arrangement regarding the patented contra- Thalheim’s involvement is not known, but perhaps his creativity was reinvigorated, leading him to refine his own engine design concept at this late stage for model aero application. Assumptions by some that his Etha 1 and 2 engines date back as far as 1928 are unsubstantiated, but they were certainly there by the time that the Dyno arrived. There appears to be solid evidence to suggest that they were on sale to the general public by 1938. After only a handful of powered models appeared at the 1940 Swiss National Championships, the 1941 meet saw a healthy entry. Around half the models were diesel powered – 11 with Dyno 1’s and 5 with Ethas. Dyno-powered models performed very well, while the Ethas started and ran OK, but it was said that they failed to excel because of “incorrect porting”. The report of the 1941 Swiss Nationals makes a comparison between the Etha 1 and the Dyno 1 inevitable. There's no The 1941 Swiss Nationals results must have filtered through to Germany, Czechoslovakia, France and Italy, setting in motion model 2-stroke diesel developments there. It is not clear to what extent Thalheim’s patent rights extended beyond Switzerland. Perhaps assuming that they did and that Thalheim would extend his patent beyond December 31st, 1942, the designers of some of the earliest foreign engines used fixed compression (which worked well enough for larger engines) or variable compression via an eccentric crankshaft bush. Either approach would neatly circumvent the Thalheim patent. As events were to prove, Thalheim allowed his patent to lapse. Perhaps he was making his real living from other precision engineering work or was inclined towards a fairly widespread Swiss notion that inventors should not selfishly deny their invention to others. Different days ............ It’s not known what Klemenz-Schenk’s particular patent for the Dyno 1 contained, but it didn’t stop many of those dipping a toe into the waters of this new technology from copying Thalheim’s variable contra piston and Klemenz-Schenk’s cylinder porting for many of the better first-generation model diesel engine designs. We owe those Swiss pioneers a real debt of gratitude. Editor's note - no summary of early model diesel development would be complete without making mention of the remarkable achievements of the talented machine tool manufacturer and model engineer Gustav Eisfeld of Gera, Germany. Eisfeld chose a different and far more challenging development path by working on “true” diesels equipped with fixed compression, miniature injectors and high-pressure fuel pumps. This approach may have been directed at getting around Thalheim's patent, which specified the use of conventional carburetion along with variable compression. Be that as it may, by the end of 1937 Eisfeld had built a successful prototype having a displacement of 15 cc (0.915 cuin.). This engine ran on a fixed 22:1 compression ratio and was equipped with a high-pressure injection pump and a needle injector. When properly adjusted, it apparently ran very well on regular full-sized diesel fuel. A promising start, but further development of this remarkable engine was halted in view of the far greater ease of manufacture and superior dependability of the conventional spark ignition engines of that time. Even so, following the onset of war in 1939 and working in collaboration with A. Thusius (who went on to produce model diesels under his own name), Eisfeld did resume his model diesel experiments, citing his reasons for doing so as the unreliability of the miniature accumulators then available as well as the problematic availability of dry batteries under wartime conditions. Eventually in 1942 he produced an amazing and successful 3.7 cc (0.225 cuin.) injector-equipped true diesel prototype suitable for model aircraft. Reportedly this unit weighed no more than a comparable spark ignition model with its ignition support equipment. Its compression ratio was a daunting 23:1 - starting must have been fun! However, the manufacture of the tiny fuel pump and injector required a level of precision which could only be achieved on a series production basis through the application of the most exacting industrial methods and equipment. Such facilities were not available to Eisfeld due to the ongoing war. Since Ernst Thalheim's 1928 patent was set to expire in December 1942 in any case, Eisfeld concentrated thereafter on the development and production of his excellent conventional “diesel” models which were designed in collaboration with A. Thusius. He did however take the trouble to record his earlier experiments in an article which appeared in November 1943 in the wartime German publication “Luftwacht-Modellflug” (pp. 107-109). It is this article which provided much of the above information - A.D. Ernst Thalheim’s Etha 1 and Etha 2 Models In his 1946 book “Model Diesels”, D.J. Laidlaw-Dixon lists both the 2.5 cc (.15 in3) Etha 1 and 6 cc (.36 in3) Etha 2 along with Klemenz-Schenk’s 2 cc (.12 in3) Dyno 1 and the .6 cc (.037 in3) Buchmann as the Swiss diesels in production at that time. The table provides engine weight, power, rpm and propeller sizes. Original examples of these two Ethas exist in the collections of both the Thalheim family and Darrel Peugh of the USA. The present-day scarcity of Ethas is such that almost all photos in model publications are of the Peugh engines, purchased in the 1970’s in Spain by Darrel Peugh Sr. To assist in the assembly of this report, Darrel kindly provided photographs of his engines and checked their respective weights.

Laidlaw-Dixon lists the Etha 2’s weight as 500 gm - perhaps a different variant, of which a number appear to exist. By comparison, the contemporary Kratmo 10 sparker with ignition gear and propeller but no batteries weighed 430 gm. Nevertheless, if the Etha 2’s listed 0.3 BHP power output is not too exaggerated, it could certainly fly the “Moskito” 1.7 metre (67 inch) span free flight monoplane. A 1942 advertisement photograph appears to show an Etha 2 engine in this model. An all up weight of 1.2 kg (42 oz) is cited.

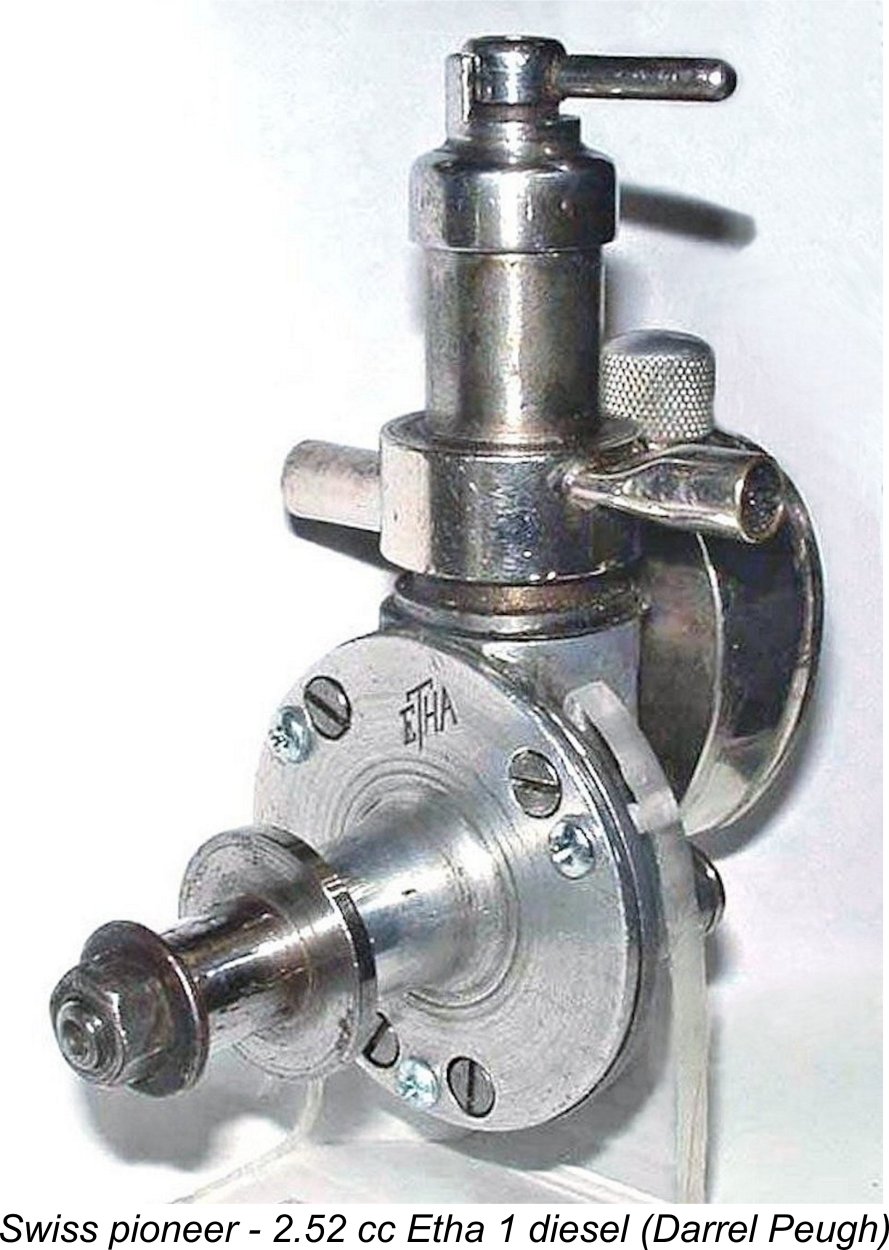

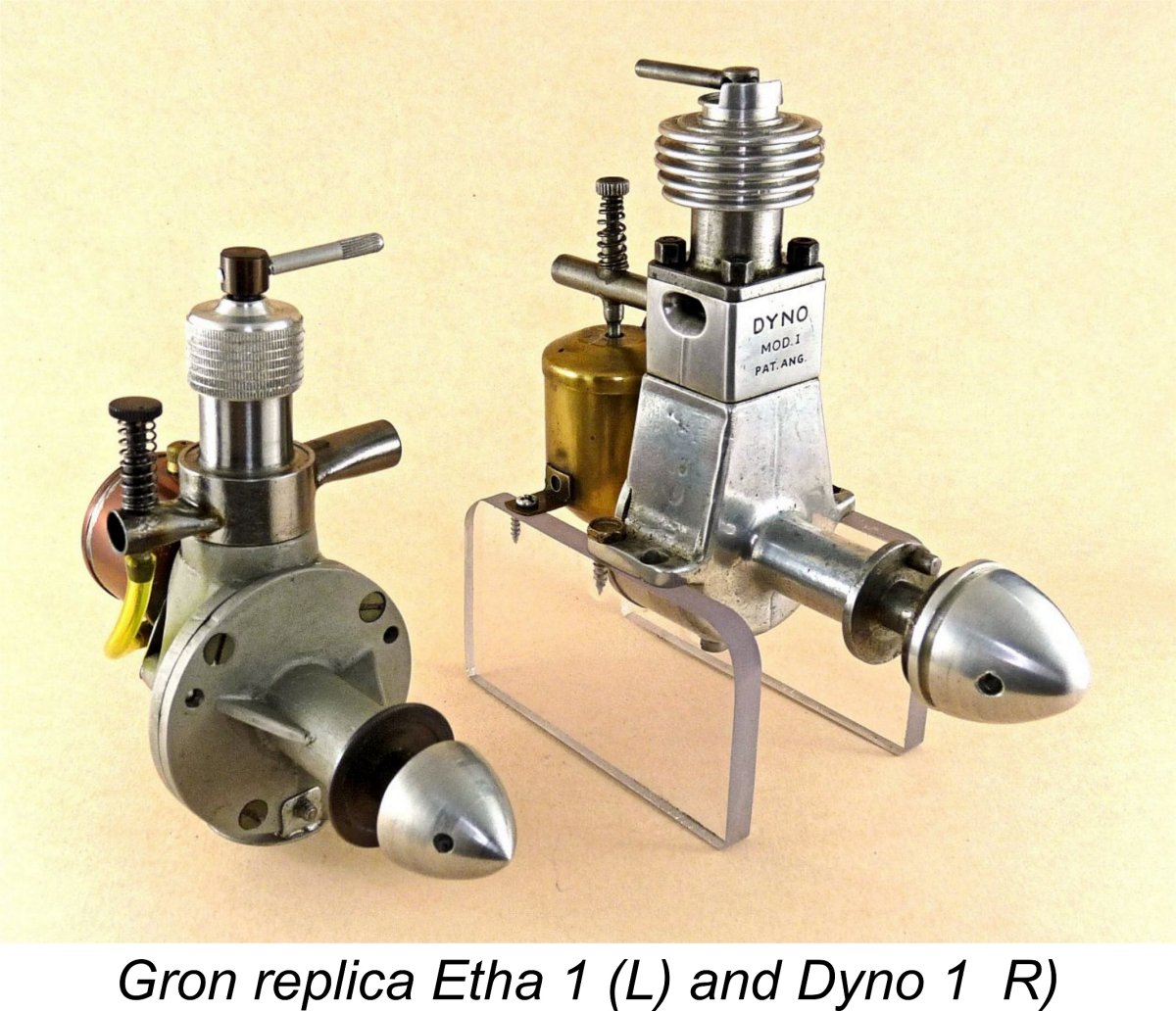

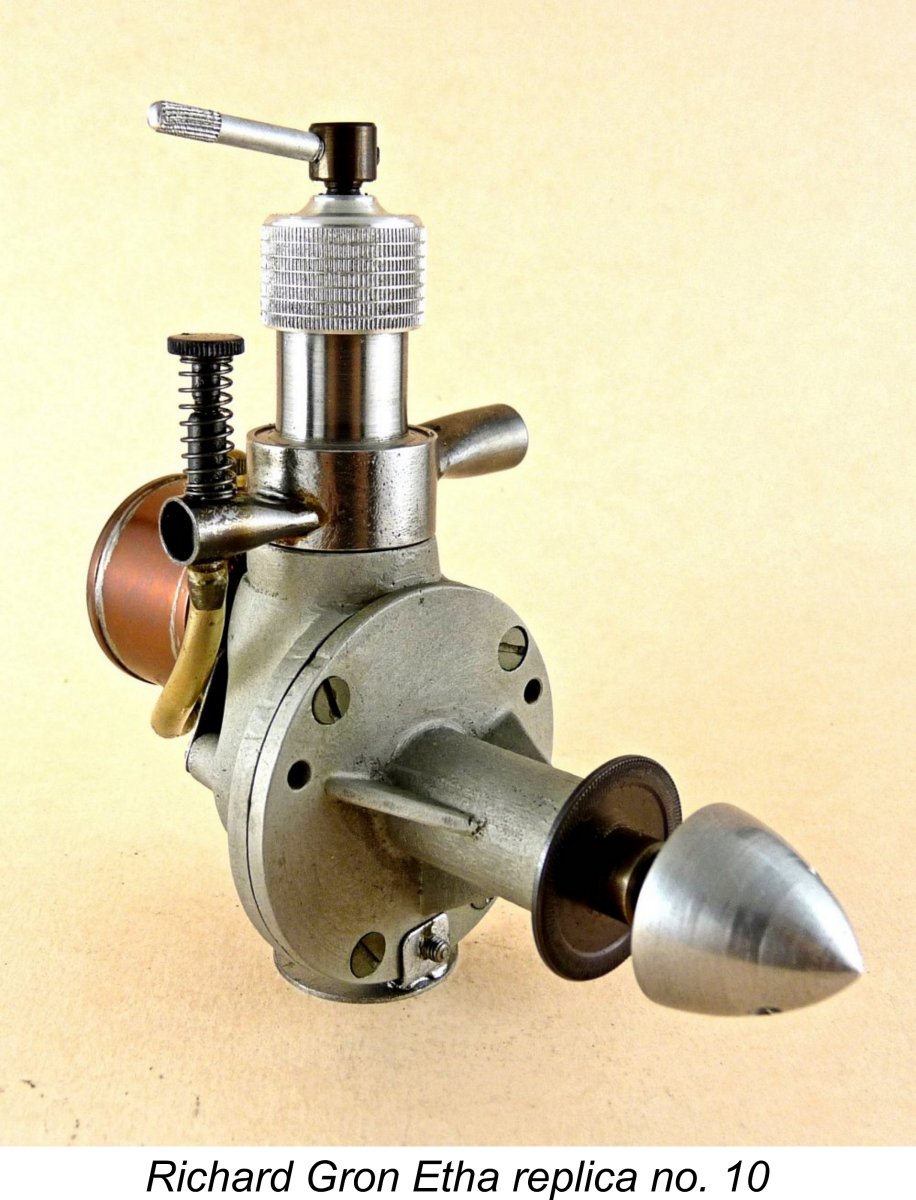

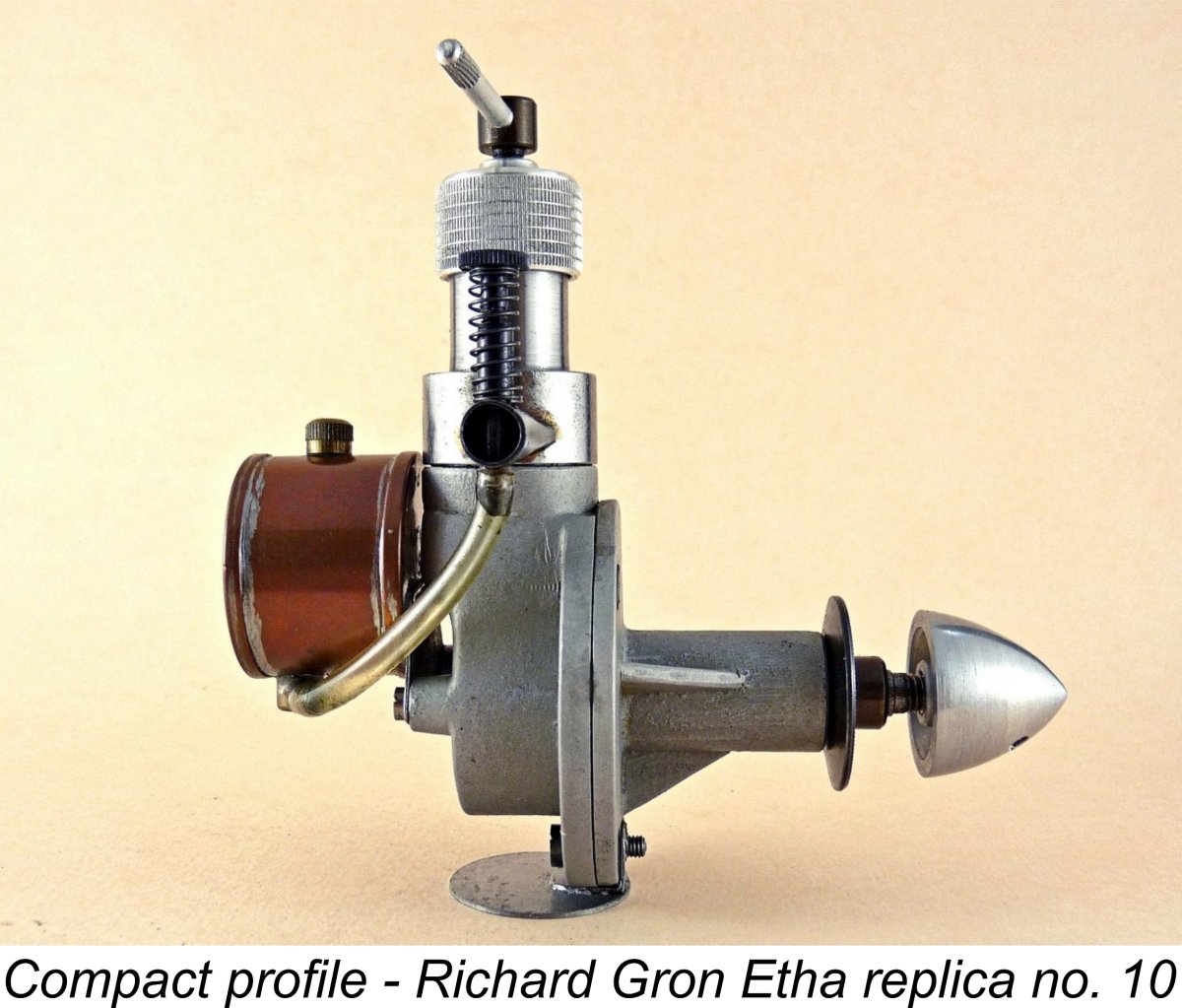

Despite the lack of cylinder cooling fins, the far more compact Etha 1 seen at the right looks much more like a model aero engine, with its well-supported single-ended crankshaft with overhanging crankpin. Laidlaw-Dixon lists it at 270 gm (9.52 oz), but Darrel Peugh’s example weighs 235 gm (8.30 oz) and the Gron replica is lighter still at 173 gm (6.1 oz). Darrel Peugh's illustrated original example features a horizontal needle valve which is integral with the fuel tank and pick-up tube. The Etha 1’s bright plated parts add distinction to its appearance. The absence of cylinder fins is unusual, being reminiscent of the later Thorning models from Denmark. The crankcase mounting arrangement might have been influenced by the design of the Kratmo 10 & 4 engines – or it could be purely coincidental. Our replica Etha 1 (serial No. 10) was made in 2007 by Czech machinist Richard Gron. Externally, it differs somewhat from the genuine examples in the Thalheim and Darrel Peugh collections, perhaps more closely

The steel cylinder screws into the upper crankcase against a base seat. An internal bypass flute is milled into the bore on each side. Exhaust slots are formed over the intake slots at front and rear. These are cut in the two gaps between three fins on the lower cylinder portion. An annular ring with side intake and exhaust tubes completes the intake/exhaust manifolds. A knurled screw-on finless cylinder cap is threaded for the compression screw, which adjusts the contra piston in the usual manner. I was not prepared to unscrew the cylinder, so the shape of the intake/exhaust ports and port timing is not known. Nor can I comment on the shape of the piston crown, but the arrangement probably follows the diagram in Thalheim’s Patent. On the Test Bench

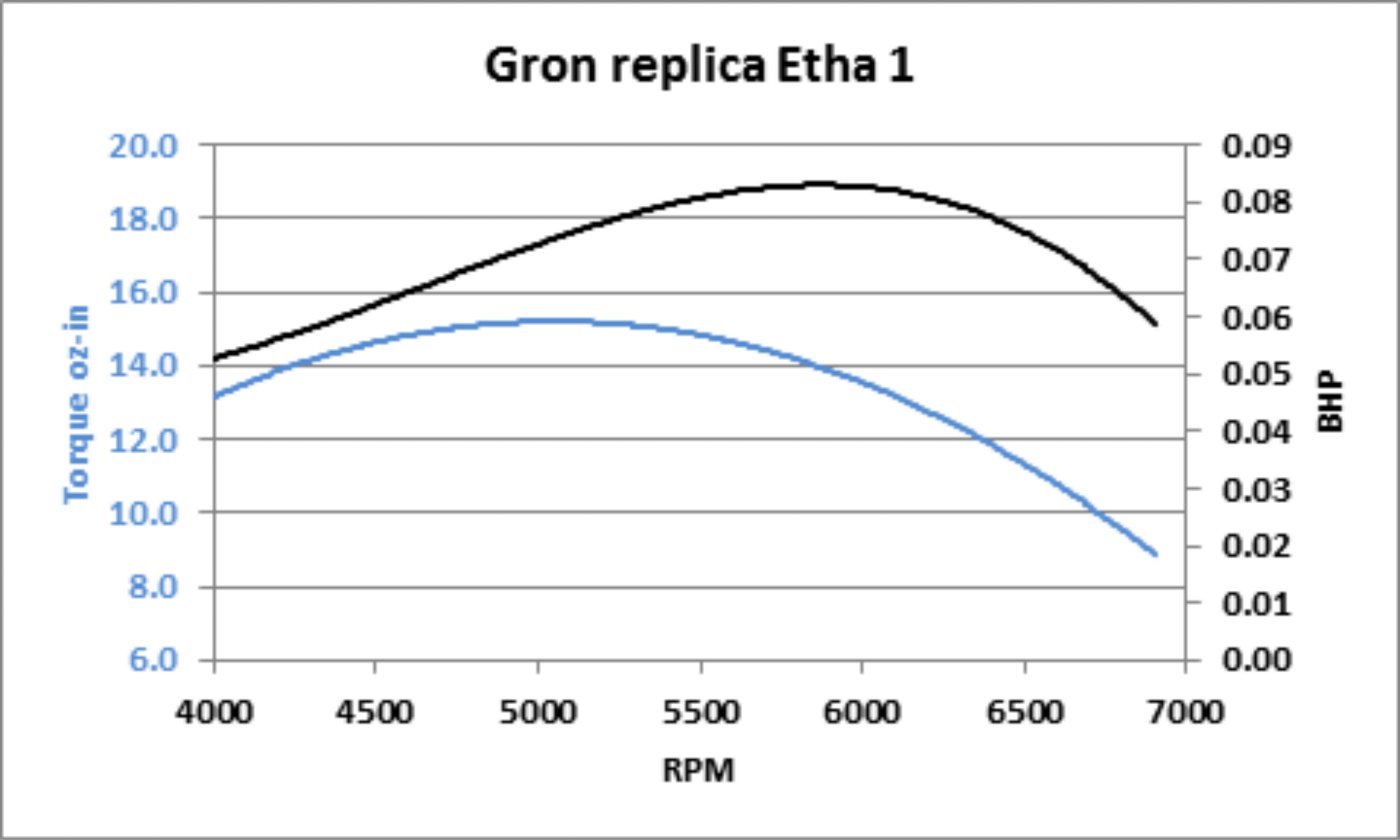

Needle adjustment became increasingly vague as speed fell off with larger propellers. As my intake Choke Area Calculator indicates, a 2.52 cc engine having an 8.5 mm2 effective choke size really needs 7,000+ rpm for good suction at the needle valve. The lack of cooling fins was no problem and cylinder operating temperature remained moderate. We used our usual old-style diesel fuel containing equal parts ether/kerosene/castor oil with 0.8% added Amsoil Cetane Boost (ethyl hexyl nitrate). As expected from a first generation long-stroke sideport diesel, the Etha's useful operating range is quite narrow. It struggled with the 12x6 propeller and could not build adequate rpm with the light 9x4 prop to sustain peak power. Our performance curves show a maximum output of a little over 0.08 BHP somewhere between 5,500 and 6000 rpm. This precisely matches the 0.08 BHP mark given by Laidlaw-Dixon, making the engine quite capable of flying the same size model as the Dyno 1 (rated at 0.09 BHP, weight 7 oz with tank).

Further Experimentation with Fuels Laidlaw-Dixon lists the recommended Etha fuel mix of 40% ether, 25% turpentine, 10% motor oil and 25% paraffin oil. For authenticity, we ran a spot check with the Gron Etha using a 10x6 prop and a batch of fuel mixed to that formula. Starting was easy enough, but the compression setting required to approach peak rpm was higher than we dared go. A notably sooty exhaust residue and rough running were clear signs of detonation and excessive ignition lag. We assumed that the Swiss probably used traditional turpentine distilled from pine resin. Thinking that our pure gum turpentine down here in Oz was possibly at fault, we switched to fuel with equal parts ether, kerosene and SAE 50 mineral motor oil. There was little improvement and the Etha continued to run with a gravelly exhaust note. The extra weight of Darrel Peugh’s genuine Etha 1 and the hefty Etha 2 comes almost entirely from very robust internals. Those were probably necessary to squeeze the most from un-nitrated fuel. Our earlier results overstate the Etha’s likely actual performance back in the day. With the maker’s recommended fuel mix, it probably developed closer to 0.06 BHP. This would still have been enough to fly a model, but not up to the Dyno 1 in competition. Our test might explain the recommended 12 x 71/8 prop in Laidlaw-Dixon’s book. Ignition lag at lower speeds would not have been such a problem. As a comparative test, we tried the original Etha fuel mixture in Anthony Williams’ genuine Dyno 1. It coped much better, running reasonably smoothly once carefully adjusted. The speed with the same 10x6 propeller was only 200 rpm less than the Gron Etha with our nitrated ether/kero/castor oil mix. To complete our tests, adding 0.8% Amsoil Diesel Cetane Boost to the original Etha fuel mix gave a big improvement and the Gron Etha then ran happily, matching the Dyno’s rpm from the previous test. These results might be the reason for the “incorrect porting” observation way back in 1941. Etha porting works fine, but importantly, not with the then-known fuels before ignition improvers came onto the scene. The Dyno’s ability to perform well with un-nitrated fuel is probably due to its particular cylinder porting. That ability was doubtless a major reason for its success. Even with a competitive US$15 (equivalent) selling price, the Etha 1’s lower power and extra weight compared with the US$18 (equivalent) Dyno 1 would have hurt sales. And for competitions where specific power output counts, the Dyno 1 wins hands down. 5000-6000 Dyno 1’s were made, but the Etha engines soon faded from the market. Postscript

Tim Dannels provided the photo reproduced at the right of an engine of quite different design, which was also believed to be an Etha replica. Comparing the Some confusion has been injected into the Etha story by Laidlaw-Dickson's publication on page 27 of his previously-cited book of an image which he identified as an example of the Etha 1. While sharing the Etha's lack of any cooling fins, this one also sports a rectangular side-stack exhaust, a feature shared by no confirmed Etha model. It appears that this engine was actually constructed by an individual named X. M. Wuest rather than Ernst Thalheim. This was not Laidlaw-Dickson's only error - on page 68, he also incorrectly identified a photo of the 2.5 cc Etha 1 as the 6 cc Etha 2. These errors are understandable given the strong likelihood that Laidlaw-Dickson never actually handled an Etha engine. Even so, it would appear that Ernst Thalheim was by no means content to rest on his laurels with his original designs. He evidently continued to experiment, producing a somewhat unexpected array of variants as a result. It would seem that there's no such thing as a "standard" design for the Etha 1! References "Aero Modeller", September 1977, Peter Chinn "Aero Modeller", August 1981, Alex Imrie "Aero Modeller", August 1997, Alex Imrie "Model Engine News" (MEN), September 1997, Holger Menrad "Engine Collectors Journal" (ECJ), Issue 206 – October 2011, Holger Menrad "Aero Modeller", November 2014, Peter Scott https://modellflugsport.ch/modellflugtechnik/schweizer-motor-etha ______________________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia First published October 2019

|

|

| |

Where would we be without inventors and their great ideas? Like Romain and Anijah’s ”improved electropathic socks for boots and shoes”, or Kreussler’s “improved combination folding bath and bedstead”. About where we are now. But imagine life without the ”Wright brothers’ improved aeronautical machine”, or Thalheim’s “high speed combustion engine without ignition equipment”.

Where would we be without inventors and their great ideas? Like Romain and Anijah’s ”improved electropathic socks for boots and shoes”, or Kreussler’s “improved combination folding bath and bedstead”. About where we are now. But imagine life without the ”Wright brothers’ improved aeronautical machine”, or Thalheim’s “high speed combustion engine without ignition equipment”.

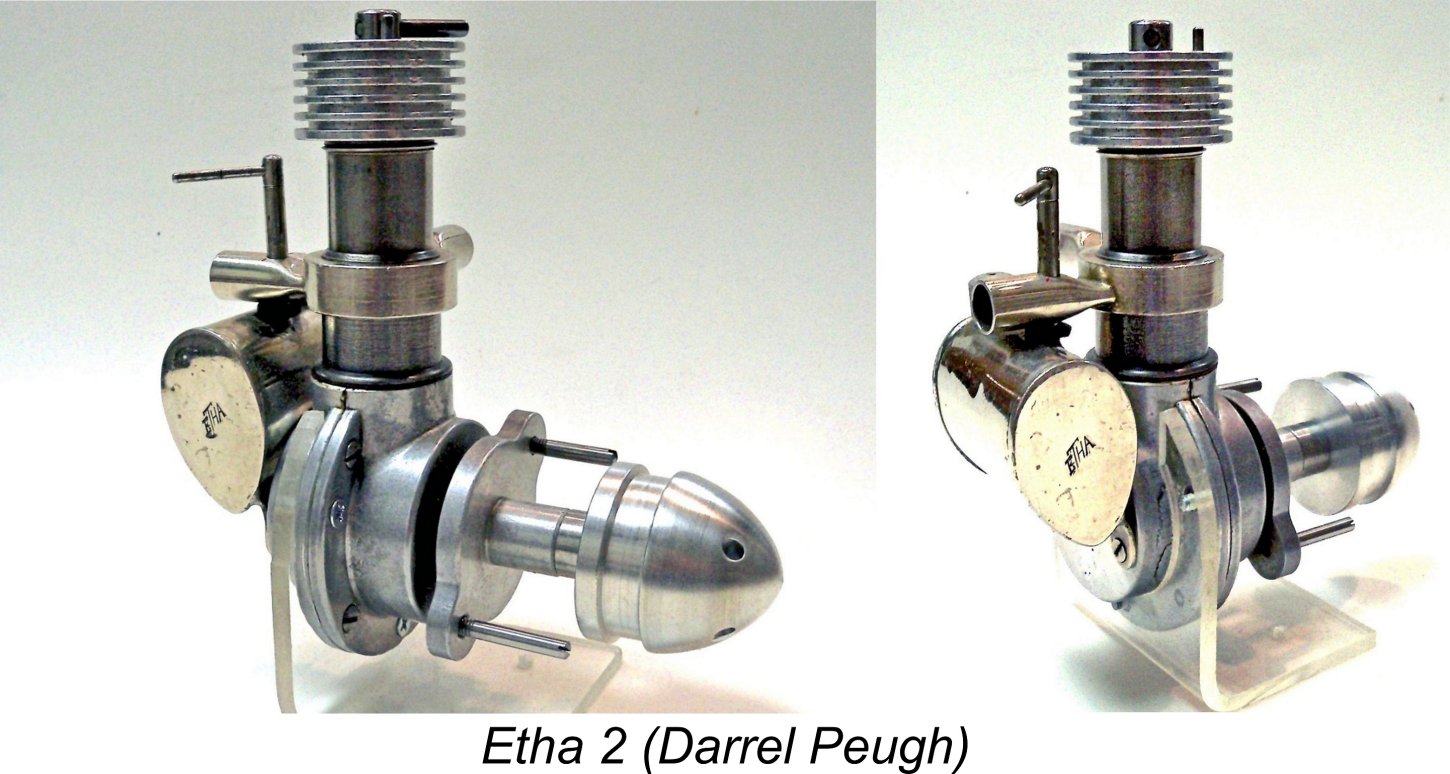

In overall layout, the larger Etha 2 is much closer to an early motorcycle engine than an aero engine, suggesting that Thalheim was not familiar with full-size or model aero engine designs. It might have been his first attempt at “lightening up”. If so, the exercise was only marginally successful, the final weight being all of 21.8 oz (618 gm).

In overall layout, the larger Etha 2 is much closer to an early motorcycle engine than an aero engine, suggesting that Thalheim was not familiar with full-size or model aero engine designs. It might have been his first attempt at “lightening up”. If so, the exercise was only marginally successful, the final weight being all of 21.8 oz (618 gm).

The engine is constructed around a die cast aluminium crankcase, joining vertically at the bulkhead-mounting flange. The composite steel crankshaft has a 6 mm (0.236 in.) main journal diameter with a generously counterbalanced pressed-on crankweb (keyed against rotation with a round pin at the joint). A pressed-in hardened 4 mm (

The engine is constructed around a die cast aluminium crankcase, joining vertically at the bulkhead-mounting flange. The composite steel crankshaft has a 6 mm (0.236 in.) main journal diameter with a generously counterbalanced pressed-on crankweb (keyed against rotation with a round pin at the joint). A pressed-in hardened 4 mm ( As a direct exhaust prime cannot be administered, cold starts were a bit slow – there was little response until enough cranking pumped sufficient combustible mixture up from the crankcase. Warm/hot restarts were quite good with a light finger choke after filling the fuel line. If the finger choking was well judged, the Etha would restart in a few flips. Vibration at all speeds was quite acceptable and the response to compression adjustment was good, allowing good control down to tick-over.

As a direct exhaust prime cannot be administered, cold starts were a bit slow – there was little response until enough cranking pumped sufficient combustible mixture up from the crankcase. Warm/hot restarts were quite good with a light finger choke after filling the fuel line. If the finger choking was well judged, the Etha would restart in a few flips. Vibration at all speeds was quite acceptable and the response to compression adjustment was good, allowing good control down to tick-over.

It appears that Ernst Thalheim continued for a while to develop his design concept beyond the generally-known Etha 1 and Etha 2 models. Les Stone made a replica of what appears to be a later Etha 1, copied from Graham A. Pod’s genuine example that came from Miguel Devezeaux De Rancougne’s collection. It has a longitudinally-oriented cylindrical fuel tank and a knurled aluminium cylinder cap more like the Gron replica. It also features a repositioned intake and revised crankcase with screw-in front crankcase portion. This measure was presumably intended to reduce weight and improve mounting in a slim-nosed model. Thalheim’s trademark cylinder porting remains unchanged. Les reported that his engine turned a Top-Flite nylon 11x7 prop at a respectable speed.

It appears that Ernst Thalheim continued for a while to develop his design concept beyond the generally-known Etha 1 and Etha 2 models. Les Stone made a replica of what appears to be a later Etha 1, copied from Graham A. Pod’s genuine example that came from Miguel Devezeaux De Rancougne’s collection. It has a longitudinally-oriented cylindrical fuel tank and a knurled aluminium cylinder cap more like the Gron replica. It also features a repositioned intake and revised crankcase with screw-in front crankcase portion. This measure was presumably intended to reduce weight and improve mounting in a slim-nosed model. Thalheim’s trademark cylinder porting remains unchanged. Les reported that his engine turned a Top-Flite nylon 11x7 prop at a respectable speed.