|

|

The Wilsco 79 diesel

Before proceeding with this review, it’s both my duty and my pleasure to extend my very sincere thanks to my valued friend and colleague Kevin Richards. It would be foolhardy in the extreme to write about any of the early British model diesel ranges without consulting Kevin, who must surely rank as one of the world’s leading experts on this subject. As always, in this instance Kevin was most generous in sharing his time and his knowledge. I could not have written on this very obscure topic without his assistance. Thanks, mate!!

As far as can be determined, the Wilsco 79 was never nationally advertised, presumably being marketed primarily in its area of manufacture through direct sales from the makers. Even so, a few examples did end up in the hands of the retail trade - Kevin Richards actually acquired a pair of unused New Old Stock examples from a model shop in Redcar, Yorkshire in the 1970’s. They had been in the shop’s stock since 1948, having failed to sell during all of that time! It has not proved possible to find any record of the engine’s selling price when new.

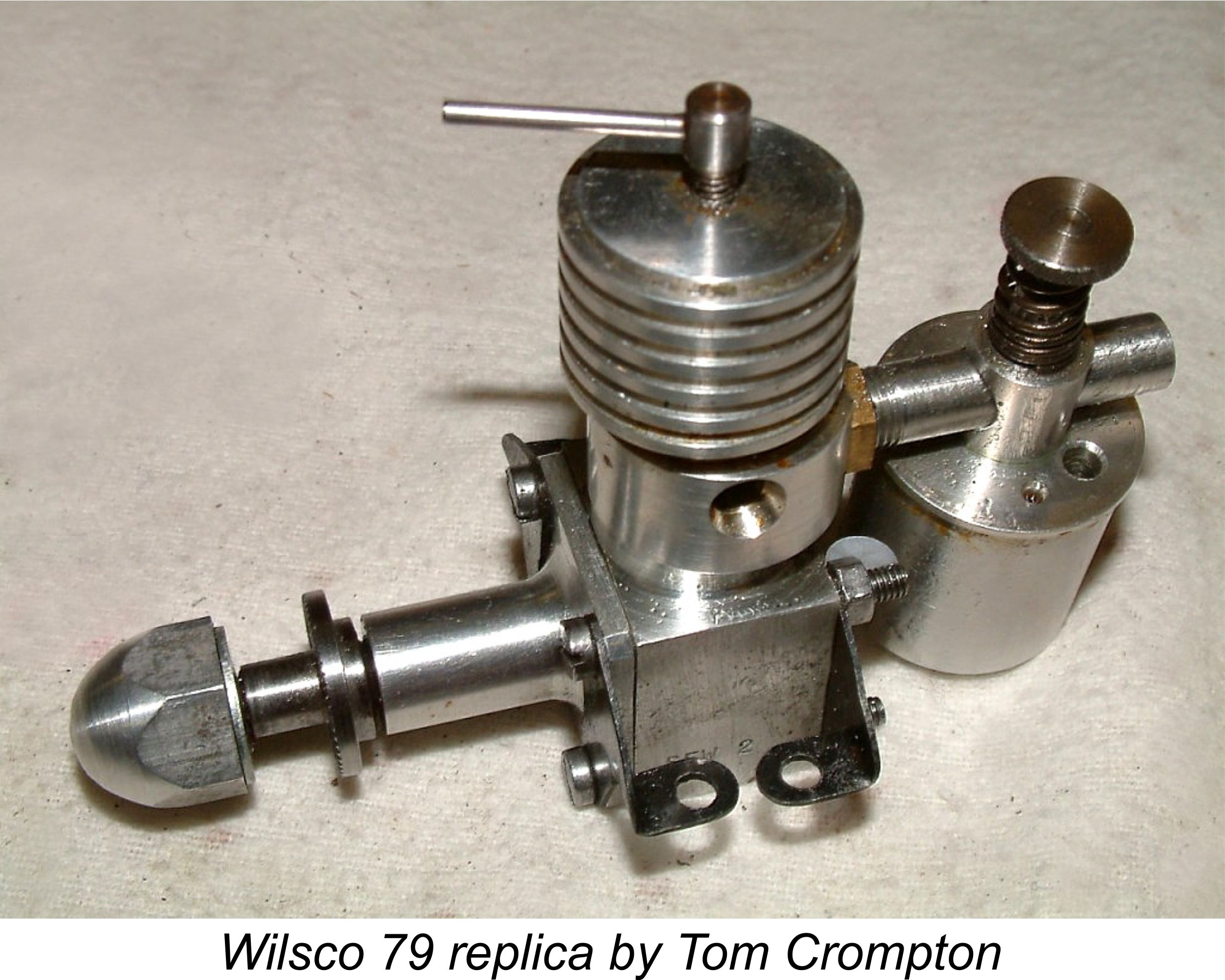

The marine example illustrated in Ted Sladden's 2014 book "British Model Aero Engines - 1946-2011" bears the clearly-visible serial number 70. This is the highest serial number yet encountered, semingly confirming that the numbering started at 1 and that at least 70 examples were made. However, the extreme rarity of surviving examples today makes it appear highly doubtful that the total number manufactured reached three figures. Indeed, the Wilsco made so little impression upon the contemporary marketplace that it does not seem to have come to the attention of any of the model engine commentators of its day. No mention of it is to be found in contemporary modelling periodicals, nor was it included in any of the various early post-war books on model engines by such individuals as D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson, Col. C. E. Bowden and Ron Warring. The Wilsco even managed to escape the attention of Peter Chinn, the individual who probably followed the classic British model engine scene more closely than anyone else. In his "Power Topics" article which Even O. F. W. Fisher failed to note the existence of the Wilsco in his 1977 "Collector's Guide to Model Aero Engines". It was left to Mike Clanford and Ted Sladden to create the sole media records of the engine in Clanford's frequently unreliable 1986 "Pictorial A to Z of Vintage and Classic Model Airplane Engines" and Sladden's "British Model Aero Engines - 1946-2011", both of which included images of the engine. The quality of construction of the Wilsco was very high - up to the very best “model engineering” standards, in fact. The engine could easily be mistaken for a model engineering “one-off” if it wasn’t for the model identification stampings. No present-day model engineer would have any reason to feel ashamed of his efforts if they resulted in an engine as well-constructed as the Wilsco. Indeed, the engine would make an excellent subject for a release in plan form to guide present-day model engineers who might wish to try making their own replica. Description Like most of its sideport contemporaries, the Wilsco was a long-stroke design. It featured checked bore and stroke measurements of 9.53 mm (0.375 inches) and 11.10 mm (0.437 inches) respectively for a displacement of 0.79 cc (0.0483 cubic inches). The engine was rather heavy for its displacement, weighing in at a checked bare weight (in radial mount configuration) of 87 gm (3.07 ounces) with tank. Design-wise, the Wilsco was a more or less completely conventional sideport diesel of its era. It was constructed entirely from the solid without the use of castings at any point. The central component was a combined crankcase and cylinder barrel unit which incorporated both the exhaust ports and provision for the rear-mounted induction tube. This component involved a great deal of careful machining, both milling and turning, at a range of workpiece settings. The backplate was machined integrally with the rest of the component, leaving the working crankcase volume open only at the front. The upper part of the crankcase unit above the twin exhaust ports was externally threaded to accommodate a screw-on aluminium alloy cooling jacket having relatively shallow cooling grooves - no expectations of high operating temperatures here! The steel cylinder liner was a drop-in affair which was secured in position by the cooling jacket. A cast iron piston was employed along with a hardened steel con-rod operating through a conventional gudgeon pin.

The beautifully-machined one-piece hardened steel crankshaft was a truly superb fit in a plain bearing formed directly in the material of the main bearing, with no sleeve. The crankweb was a plain un-counterbalanced disc, implying that high operating speeds were not envisioned for this engine. The steel prop driver was mounted on a shallow taper formed immediately in front of the main journal, with a spinner nut of aluminium alloy being used to secure the prop.

Beam mounting lugs milled in unit with the crankcase would have been far more sturdy as well as providing a firmer mounting which was less prone to vibration. However, the system used did have the advantage of allowing for easy angle-plate replacement in the event of breakage - significantly less problematic than fixing a broken lug! Moreover, damage due to a hard crash impact would likely be confined to the angle-plates rather than the rest of the engine. I suspect that angle-plate replacement would have been a fairly regular requirement for one of these engines in service……….

Like many of its contemporaries, the engine used a surface jet arrangement for fuel metering. A neat aluminium alloy hang tank consisting of a top with a separate “last drop” bowl was attached to the fuel pickup side of the carburettor. The tank bowl was retained by a thin wire clip. The screw-in venturi assembly was secured in place at the rear of the cylinder barrel by a neat internally-threaded brass locking ring. This allowed the secure positioning of the fuel supply system in any desired orientation relative to the rest of the engine.

At first glance, this mechanism might be taken to be some kind of rather complex cut-out device. However, a detailed examination reveals that it is in fact an The intent of this device is very clear. The user could adjust the venturi throat area to provide a varying amount of power when the engine was adjusted for best running. This means that the engine would run smoothly and hence predictably on any given prop at a fairly wide range of speeds. The usual manner in which this is achieved for trimming purposes is to reduce compression and enrich the mixture to give the classic diesel “burp-burp” slow-speed running. However, power delivery in this model is inherently inconsistent. With the device fitted to the Wilsco, the engine can be leaned out and the compression optimized for smooth running and steady, predictable power delivery at whatever speed is desired using a given prop.

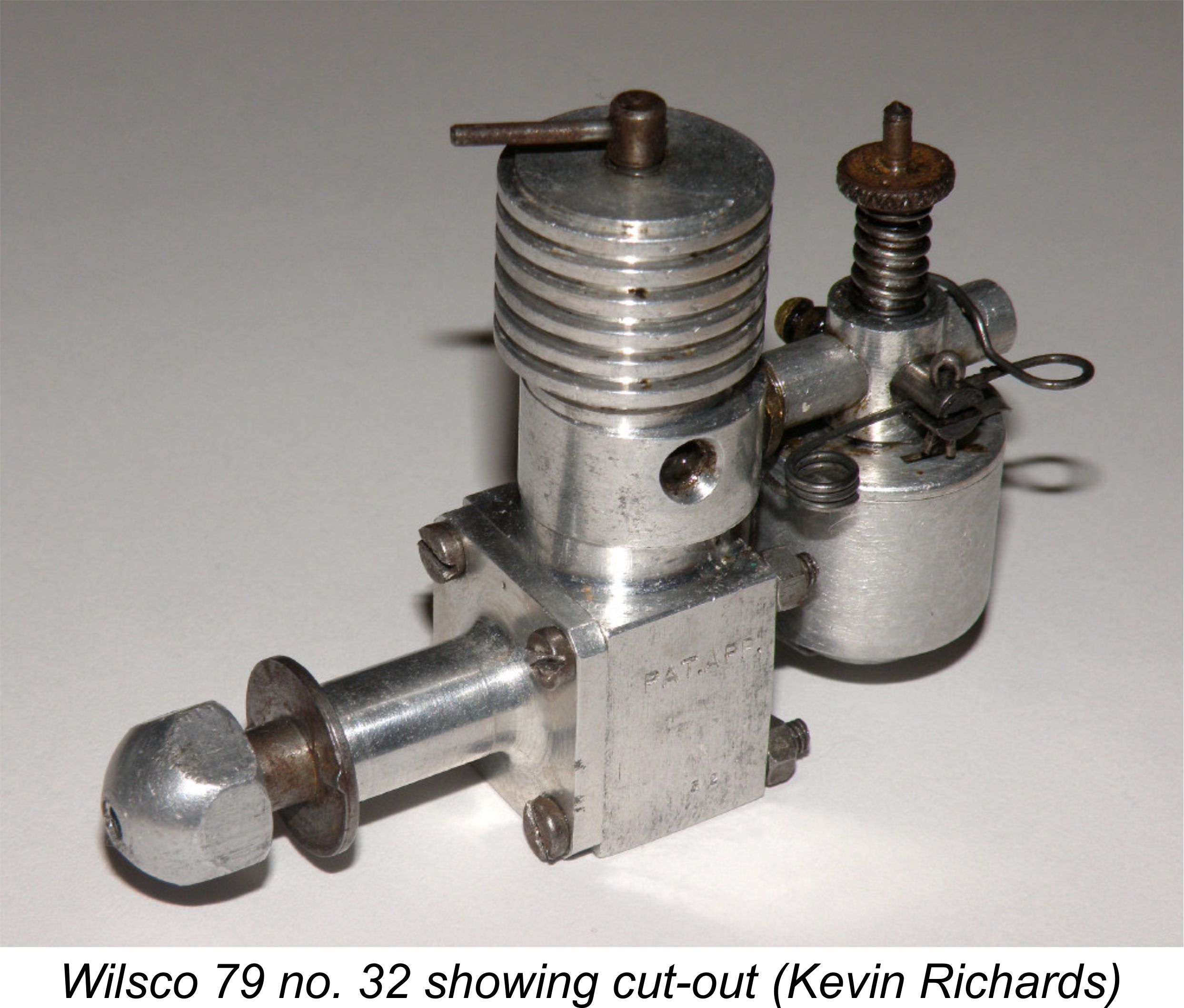

As noted previously, engine numbers 19 and 32 both featured this device, as did engine number 43 acquired in late 2015 by Miles Patience. They also both feature the inscription “Pat App” stamped on the side with the serial number. Since my

A very few examples of the Wilsco were produced as marine models. These featured brass water-cooled jackets and heavy brass flywheels. Since boat modellers might be expected to favour long runs, hence using separate tanks which held a lot more fuel, the marine models don't seem to have been supplied with tanks. They do however appear to have been supplied with the unique throttle arrangement described earlier. The Wilsco 79 on Test As noted at the outset, the Wilsco 79 appears to have come and gone completely undocumented during its original production period. Fortunately, we can do a little better than this - we have a very nice example on hand to test! Let’s get right to it ……….

I elected to test the Wilsco in radial mount configuration, which in my view would provide a far sturdier mounting than the use of the thin steel angle-brackets with which the engines were supplied. I thus saved myself the immediate trouble of having to make up a set of these plates, although I will probably tackle that later just to get the engine back to fully original condition.

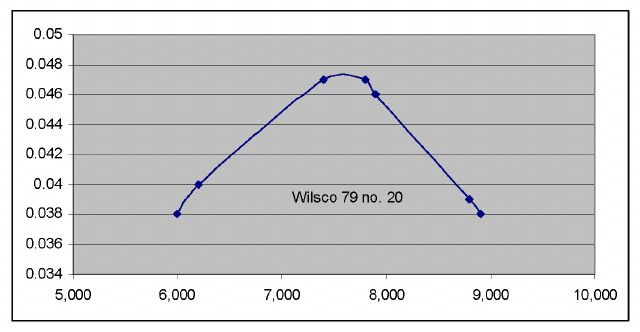

Once running, the engine performed very well indeed, although it soon became clear that it was no match for the Mills. Both needle and compression were perfectly straightforward to set, and the engine would run the tank out very dependably. It did however exhibit a marked This problem may have been due at least in part to the fact that I was using my regular nitrated diesel fuel for this test. As I noted in my separate article on fuels for variable-compression model diesels, the use of an ignition improver may actually be detrimental at the lower speeds at which sideport diesels of the pioneering era typically operate. The use of organic nitrates in model diesel fuel is intended primarily to reduce ignition lag - that is, the time it takes for ignition to commence once the fuel's auto-ignition temperature is reached. At speeds of up to (say) around 8,000 rpm, the issue of ignition lag is far less of a problem than it is at higher speeds because everything is happening at a reduced rate anyway. The avoidance of sag following warm-up becomes paramount in such a case. Consequently, it will often be found that a straight fuel without ignition improver will yield superior results with a low-speed vintage sideport diesel than a more potent blend with some improver. I suspect that the Wilsco may be an example of just such an engine. Setting this issue aside, the following figures were obtained using the same props and fuel blend which had been used for the earlier Mills test:

These figures resolve themselves nicely into a power curve showing a well-defined peak output of some 0.048 BHP at around 7,600 rpm. Somewhat less on both counts than the peak achieved by the Mills, but not altogether dismal for an engine of this era and displacement. The Wilsco would certainly have done a creditable job of flying a typical small power model of its era. It is also extremely well-made and would doubtless give excellent service over an extended working life. That said, if a prospective purchaser were offered the option of either the Mills or the Wilsco, there’s no question that the Mills would be the first choice of most modellers, Apart from its superior power output, it also weighs considerably less than the Wilsco - 55 gm (1.94 ounces) as opposed to the Wilsco’s somewhat excessive 87 gm (3.07 ounces). One suspects that the mid 1948 introduction of the Mills may have had as much to do with the Wilsco’s apparent marketplace failure as anything else. Conclusion

As one might expect from the very small number evidently produced, the Wilsco is extremely elusive these days. However, examples do turn up occasionally. Anyone fortunate enough to acquire one cannot fail to be pleased with the engine’s quality and steady running characteristics. Keep your eyes open! As always, if anyone out there can extend my list of known serial numbers or provide any additional information, I’d love to hear from you! __________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, first published April 2014 |

||||

| |

In this necessarily short article we focus upon one of the almost forgotten products of the early post-war British model engine manufacturing industry - the Wilsco 79 diesel. We say “necessarily short” because there’s so little record of the circumstances surrounding this engine’s origins that we’re pretty much confined to reporting what can be learned through a direct examination of one or two of the very few surviving examples. We use the term “forgotten” because the same sparse record has understandably left the majority of today’s model engine aficionados in blissful ignorance even of this engine’s existence!

In this necessarily short article we focus upon one of the almost forgotten products of the early post-war British model engine manufacturing industry - the Wilsco 79 diesel. We say “necessarily short” because there’s so little record of the circumstances surrounding this engine’s origins that we’re pretty much confined to reporting what can be learned through a direct examination of one or two of the very few surviving examples. We use the term “forgotten” because the same sparse record has understandably left the majority of today’s model engine aficionados in blissful ignorance even of this engine’s existence!  The Wilsco 79 was a neat little 0.79 cc barstock sideport diesel made in extremely small numbers in 1948 by a firm called Williams & Scott of Balsall Common, a small rural community lying to the SE of Birmingham about midway between Birmingham and Coventry, England. This was almost certainly one of the small-scale “garden shed” operations which were quite common in England during the early post-war period. It’s likely that Messrs. Williams and Scott were model engineers who carried out all of the manufacturing between the two of them, without any outside assistance.

The Wilsco 79 was a neat little 0.79 cc barstock sideport diesel made in extremely small numbers in 1948 by a firm called Williams & Scott of Balsall Common, a small rural community lying to the SE of Birmingham about midway between Birmingham and Coventry, England. This was almost certainly one of the small-scale “garden shed” operations which were quite common in England during the early post-war period. It’s likely that Messrs. Williams and Scott were model engineers who carried out all of the manufacturing between the two of them, without any outside assistance. In terms of production figures, my own illustrated example bears the serial number 20, while Kevin Richards formerly owned engine number 19 and still owns engine number 32 at the time of writing (2013). In addition, Miles Patience subsequently reported that he acquired engine number 43 in late 2015.

In terms of production figures, my own illustrated example bears the serial number 20, while Kevin Richards formerly owned engine number 19 and still owns engine number 32 at the time of writing (2013). In addition, Miles Patience subsequently reported that he acquired engine number 43 in late 2015.

The aluminium alloy front cover was again machined from the solid. It was secured to the main crankcase unit by four 6 BA machine screws which passed right through both components and protruded at the rear, being fastened by matching nuts. With the nuts removed, these machine screws could of course be used to attach the engine to a model using a radial mounting.

The aluminium alloy front cover was again machined from the solid. It was secured to the main crankcase unit by four 6 BA machine screws which passed right through both components and protruded at the rear, being fastened by matching nuts. With the nuts removed, these machine screws could of course be used to attach the engine to a model using a radial mounting. In addition to the radial mounting option noted above, the engines were supplied with an unusual alternative mounting system consisting of four thin and somewhat flimsy steel angle-plates which were secured to the case by the 6 BA front cover retaining bolts and nuts. It must be admitted that this arrangement is perhaps the sole questionable design feature of this otherwise extremely well-designed engine. The thin steel from which the angle-plates were formed would undoubtedly flex due to operational vibration, hence being subject to fatigue stresses at the bend locations. Quite apart from the adverse effect upon power output due to uncontrolled vibration, I would objectively expect these angle-plates to suffer fatigue failure at a relatively early stage in the engine’s working life. Even if this did not occur, a reasonably hard impact with the big green thing would probably see them off. In my view, this engine is far better suited to operation in radial mount mode as well as being more aesthetically pleasing in that configuration.

In addition to the radial mounting option noted above, the engines were supplied with an unusual alternative mounting system consisting of four thin and somewhat flimsy steel angle-plates which were secured to the case by the 6 BA front cover retaining bolts and nuts. It must be admitted that this arrangement is perhaps the sole questionable design feature of this otherwise extremely well-designed engine. The thin steel from which the angle-plates were formed would undoubtedly flex due to operational vibration, hence being subject to fatigue stresses at the bend locations. Quite apart from the adverse effect upon power output due to uncontrolled vibration, I would objectively expect these angle-plates to suffer fatigue failure at a relatively early stage in the engine’s working life. Even if this did not occur, a reasonably hard impact with the big green thing would probably see them off. In my view, this engine is far better suited to operation in radial mount mode as well as being more aesthetically pleasing in that configuration.  At the rear, the fuel supply requirements were met through the use of a well-machined light alloy carburettor unit consisting of a screw-in venturi tube which was a tight push-fit in a cross-mounted barrel of larger diameter. This cross-barrel incorporated the mounting for the spring-tensioned externally-threaded needle at one end and the aluminium alloy fuel pickup tube at the other.

At the rear, the fuel supply requirements were met through the use of a well-machined light alloy carburettor unit consisting of a screw-in venturi tube which was a tight push-fit in a cross-mounted barrel of larger diameter. This cross-barrel incorporated the mounting for the spring-tensioned externally-threaded needle at one end and the aluminium alloy fuel pickup tube at the other. Somewhat unusually for the period, no form of fuel cut-out was provided. However, engine number 32 in the possession of Kevin Richards features a somewhat strange “throttling” device which is clearly original. Engine number 19 which Kevin formerly owned was also equipped with this device, as was the one illustrated by Clanford. It thus appears that the engine was supplied either with or without this device at the buyer’s discretion, presumably with some effect upon the selling price.

Somewhat unusually for the period, no form of fuel cut-out was provided. However, engine number 32 in the possession of Kevin Richards features a somewhat strange “throttling” device which is clearly original. Engine number 19 which Kevin formerly owned was also equipped with this device, as was the one illustrated by Clanford. It thus appears that the engine was supplied either with or without this device at the buyer’s discretion, presumably with some effect upon the selling price. adjustable venturi throat area restrictor, hence being perhaps more correctly termed a throttle. The main plunger visible on the left side is pressed inwards by the spring and is so formed on the inside that it progressively restricts the intake throat area as it moves further inward. The extent of its inward movement is adjustable using the screw which is visible on the right-hand side of the carburettor.

adjustable venturi throat area restrictor, hence being perhaps more correctly termed a throttle. The main plunger visible on the left side is pressed inwards by the spring and is so formed on the inside that it progressively restricts the intake throat area as it moves further inward. The extent of its inward movement is adjustable using the screw which is visible on the right-hand side of the carburettor. In effect, the device was a pre-set throttle which allowed precise adjustment of steady in-flight power delivery characteristics - a potentially useful aid to trimming at lower power levels. The downside was that no in-flight adjustment was possible. Hence the device cannot be considered a “true” throttle as generally understood in the context of today’s R/C flying. It is simply a device for pre-setting the engine at a desired output for trimming purposes. A basically similar device was offered for the famous

In effect, the device was a pre-set throttle which allowed precise adjustment of steady in-flight power delivery characteristics - a potentially useful aid to trimming at lower power levels. The downside was that no in-flight adjustment was possible. Hence the device cannot be considered a “true” throttle as generally understood in the context of today’s R/C flying. It is simply a device for pre-setting the engine at a desired output for trimming purposes. A basically similar device was offered for the famous  example which is not fitted with the “throttle” does not feature this inscription, and given the fact that there appear to be no novel (and hence patentable) features in the engine’s basic design, it seems logical to assume that the patent which had been applied for most likely related to the “throttle” device which was evidently an optional extra. This would explain why only those engines with the “throttle” seemingly bore the patent inscription.

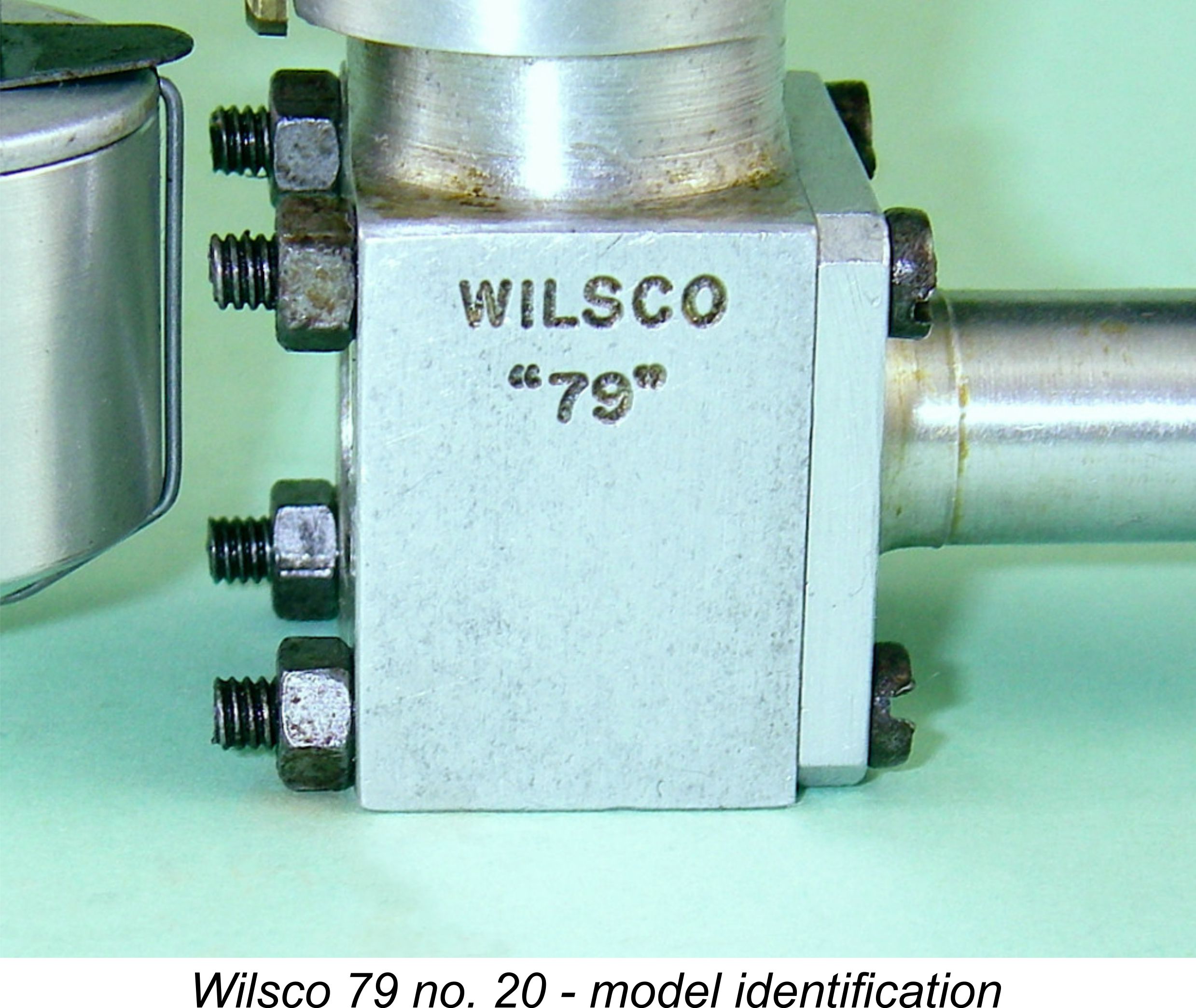

example which is not fitted with the “throttle” does not feature this inscription, and given the fact that there appear to be no novel (and hence patentable) features in the engine’s basic design, it seems logical to assume that the patent which had been applied for most likely related to the “throttle” device which was evidently an optional extra. This would explain why only those engines with the “throttle” seemingly bore the patent inscription. All of the engines were identified by the neatly-stamped inscription WILSCO “79” on the right-hand side of the crankcase. This appears to have been created with a single strike of a stamp which incorporated the entire inscription. The original engines also bore serial numbers which were stamped in very small font on the left-hand side of the crankcase. This can be clearly seen in several of the attached images.

All of the engines were identified by the neatly-stamped inscription WILSCO “79” on the right-hand side of the crankcase. This appears to have been created with a single strike of a stamp which incorporated the entire inscription. The original engines also bore serial numbers which were stamped in very small font on the left-hand side of the crankcase. This can be clearly seen in several of the attached images.

I had recently had occasion to test one of the Wilsco’s direct 1948 contemporaries - the

I had recently had occasion to test one of the Wilsco’s direct 1948 contemporaries - the  The little Wilsco proved to be every bit the equal of the Mills when it came to starting. Compression seal was outstanding, with a single choked flick being all that was required - any more, and the engine became flooded. If this occurred (as it did to me several times) all that was necessary was to back off the compression and flick until a rich start was achieved, then increase compression as the engine picked up. However, starting was more or less instantaneous if the correct starting mixture was provided.

The little Wilsco proved to be every bit the equal of the Mills when it came to starting. Compression seal was outstanding, with a single choked flick being all that was required - any more, and the engine became flooded. If this occurred (as it did to me several times) all that was necessary was to back off the compression and flick until a rich start was achieved, then increase compression as the engine picked up. However, starting was more or less instantaneous if the correct starting mixture was provided.

It’s impossible not to feel a strong sense of kinship with the makers of the Wilsco 79. They were clearly skilled model engineers who took pride in their work and produced an engine which could stand comparison with all comers in terms of quality. At the time when they were developing the engine, it would probably have been a top performer in its displacement category. As much as anything, it was probably the simultaneous emergence of the overwhelming competition from Mills that sealed the Wilsco’s fate.

It’s impossible not to feel a strong sense of kinship with the makers of the Wilsco 79. They were clearly skilled model engineers who took pride in their work and produced an engine which could stand comparison with all comers in terms of quality. At the time when they were developing the engine, it would probably have been a top performer in its displacement category. As much as anything, it was probably the simultaneous emergence of the overwhelming competition from Mills that sealed the Wilsco’s fate.