The Mills Diesels – A Production History

An analysis by Adrian Duncan in collaboration with David Owen

I suppose that no model engine web-site having any pretensions to credibility can afford to be without at least one article on the famous Mills model diesel engines from England! The following represents my belated attempt to make good this hitherto glaring deficiency on my own site!

I suppose that no model engine web-site having any pretensions to credibility can afford to be without at least one article on the famous Mills model diesel engines from England! The following represents my belated attempt to make good this hitherto glaring deficiency on my own site!

Some years ago now I collaborated with my late and greatly-missed friend and colleague David Owen of Woolongong, Australia on the assembly of a significant database of recorded serial numbers for these engines. It had been our shared intention to analyze these data and present the findings on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) web-site, but Ron’s untimely passing and the subsequent freezing of that wonderful site prevented us from carrying this project through to completion at that time.

The assembly of this database drew on the generous input provided by a sizeable number of our friends and colleagues, all of whom put time and effort into the project. Moreover, the subsequent analysis both of our data and that generated by others yielded some very useful information and insights. I felt that all this collaborative effort should not be allowed to go to waste, hence my decision to present the material here. Ron would have been the first to encourage me to do so. Sadly, David also passed away before we got around to preparing this article for publication. However, he too would have wanted me to press on regardless.

Right off the top, some readers may already be wondering why I’m bothering! The Mills diesels are surely one of the most comprehensively-documented model engine ranges of them all, with numerous well-informed articles having been written about them in the past by others. Why add yet another article to the pile - what more is there to say?!?

Right off the top, some readers may already be wondering why I’m bothering! The Mills diesels are surely one of the most comprehensively-documented model engine ranges of them all, with numerous well-informed articles having been written about them in the past by others. Why add yet another article to the pile - what more is there to say?!?

Indeed, such an addition can only be defended in terms of the extent to which it contributes anything new to the documentation of these engines and/or helps to bring existing information together into an accessible form. In my view, this study can readily be defended on both of those grounds.

Admittedly, the Mills engines have been described in great technical detail by others, leaving us with nothing to do there. You will not find any detailed technical descriptions of the Mills engines in what follows, nor will we report any test results. However, what has not been done is a focused, credible and above all online-accessible in-depth analysis of a statistically significant sampling of Mills serial numbers with the objective of establishing some reasonable estimates of production figures and providing rational explanations for some of the anomalies. That’s what we intend to present here.

Before doing so, however, I believe that it will be useful to summarize the most noteworthy available sources of information on these engines to facilitate the efforts of interested readers to make themselves better informed if they desire to do so.

Available Sources of Information on Mills Engines

A great deal of information on the Mills range has appeared in the past in the pages of various publications relating to model engines in general. The late Roger J. Schroeder presented a four-part history of the Mills range in his “Engine-uity” column in the pages of the “Engine Collectors Journal” (ECJ) spaced out between 1991 and 1992.

A great deal of information on the Mills range has appeared in the past in the pages of various publications relating to model engines in general. The late Roger J. Schroeder presented a four-part history of the Mills range in his “Engine-uity” column in the pages of the “Engine Collectors Journal” (ECJ) spaced out between 1991 and 1992.

Mike Noakes subsequently authored a most informative and highly authoritative five-part history of Mills in the pages of the now-defunct “Model Engine World” (MEW) magazine from October 1995 through to February 1996 (Volume 2, issues six through ten). This latter article remains the most authoritative hard-copy history of the Mills model engine venture to date in my personal opinion. I freely acknowledge having consulted it frequently during the preparation of the present article, with my very sincere thanks to Mike Noakes.

Indeed, my indebtedness to Mike Noakes goes far deeper than that! When he became aware of my intention to publish this article, Mike was good enough to contact me and offer full access to the data which he had collected in support of his earlier article. My gratitude to Mike for making this generous gesture knows no bounds. A colleague after my own heart!!

That said, both of the sources noted above are hard-copy paper references. You have to possess (or be able to borrow) hard copies or scans of the publications in question to refer to these sources. In today’s high-speed inter-connected world, most people seem to be looking for information that is readily available on-line. Indeed, the extent to which people today rely upon on-line sources is such that hard-copy material is in danger of becoming marginalized or even of disappearing completely over time through neglect. Sad but true ……………. historians of the future face a daunting challenge as electronic data becomes corrupted or lost.

Fortunately,  thanks in large part to the efforts of my late and much-missed mate Ron Chernich, a number of sources of information on the Mills engines remain available online at MEN. All of these are plentifully provided with pointers towards other reference material. Here’s a summary:

thanks in large part to the efforts of my late and much-missed mate Ron Chernich, a number of sources of information on the Mills engines remain available online at MEN. All of these are plentifully provided with pointers towards other reference material. Here’s a summary:

Mills 1.3 Mk. I - a brief summary of the history and technical features of the Mills 1.3 model that started it all. This page was still under construction when Ron passed away, but it remains a very useful online reference.

Mills P75 and S75 - covers the story of the smallest Mills engines, the .75 cc models, including technical details.

Mills 2.4 - covers the story of the ill-fated Mills 2.4 model which failed to compete successfully in the early post-war British marketplace.

The Original Mills History - presents the history of the Mills enterprise as recalled by Mike Harding (b. 1944), son of the instigator of the Mills model engine range, Arnold Lewis Hardinge.

Readers interested in the technical details of the engines are referred to the sources listed above – we will not reprise that information here. That said, in order for the following analysis to make any sense it will be necessary to take note of the major design milestones in the history of the Mills range. We’ll do so as we go along. As a preamble to set this review in context, I’ll now attempt to summarize the history of the company which made the Mills engines.

Corporate History of Mills Brothers (Model Engineers) Ltd.

The original Mills Brothers (Model Engineers) company was based in Sheffield, South Yorkshire (my home town from 1957 though 1966), operating from premises at 129 St. Mary’s Road. This was less than 2 miles from my Sheffield home, and St. Mary's Road was a commonly-travelled route – young Adrian must have passed the site countless times!

The firm was established by the three Mills brothers Bert, Frank and a third whose first name is not recorded. The company actually had its origins as far back as 1913, the objective being to enter the model railway manufacturing business. However, the onset of WW1 put a premature stop to any such ambitions, at least in the short term. The Mills brothers reportedly all volunteered for military service, setting their commercial ambitions to one side.

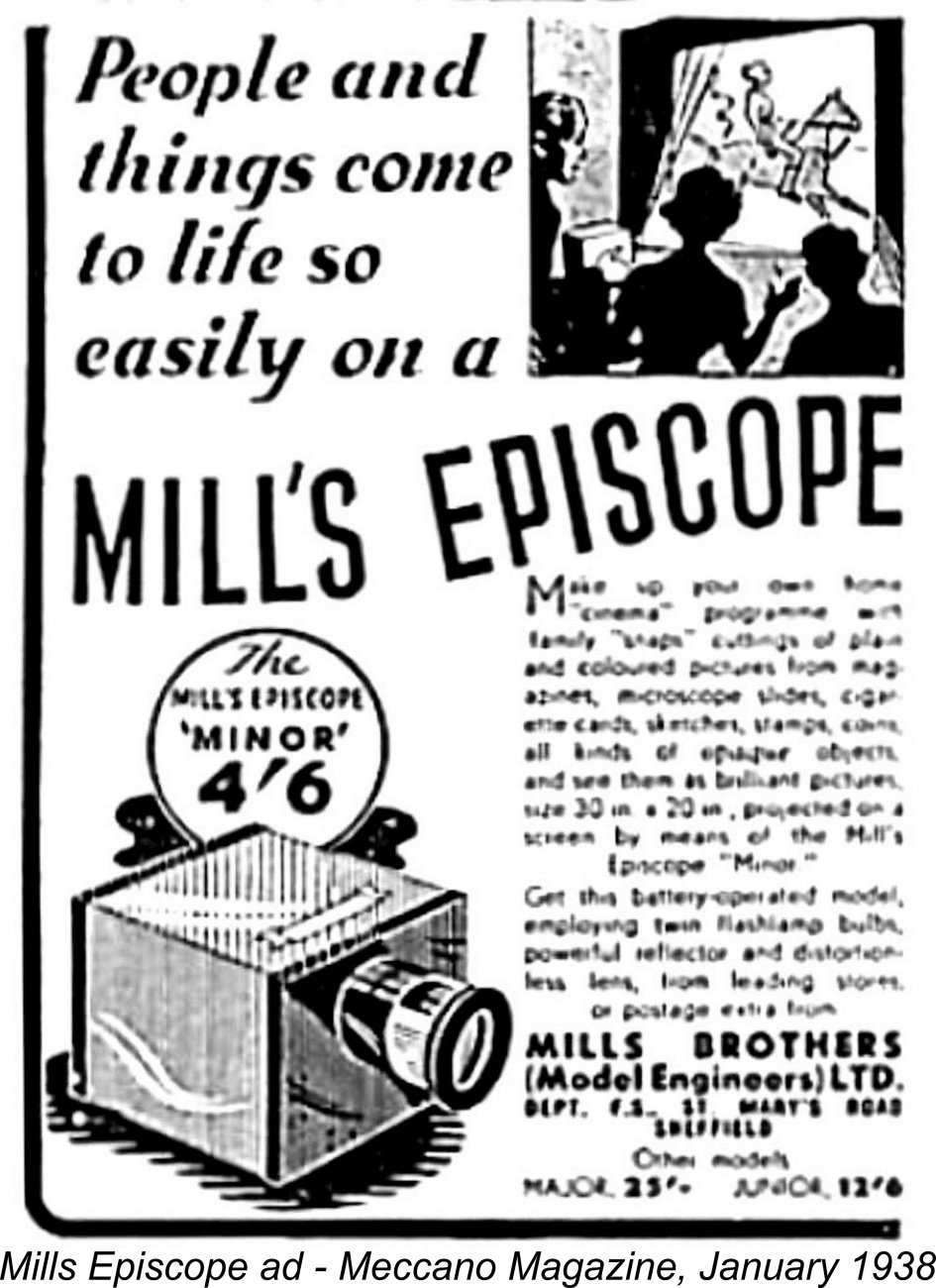

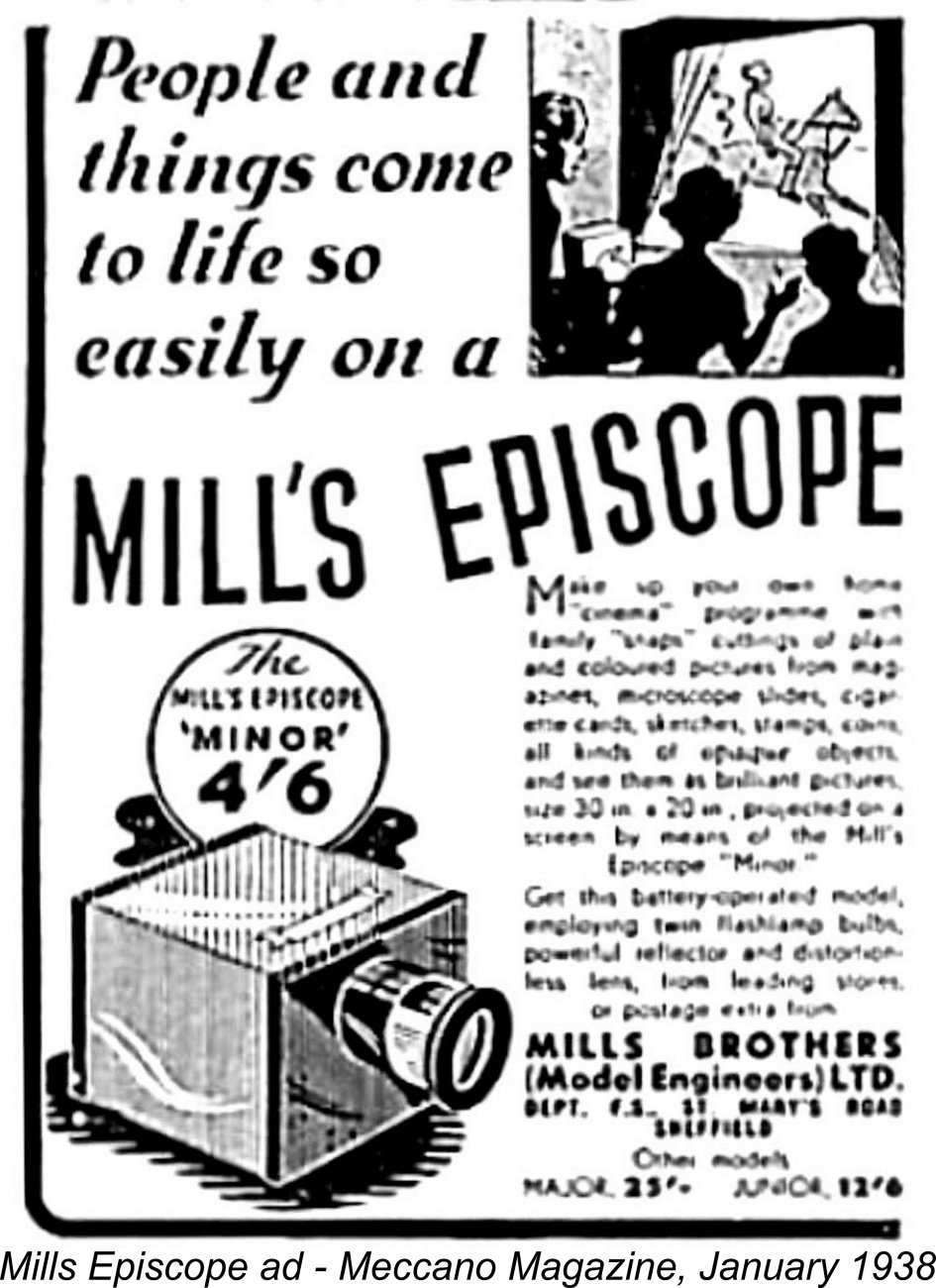

Following the conclusion of WW1, which all three survived, the Mills brothers resumed their efforts to develop their model railway business. At the outset (and for many years thereafter) the firm had nothing to do with model engines, instead manufacturing O-gauge tinplate model railway equipment including locomotives, track and accessories at their St. Mary's Road location in Sheffield. These products were marketed under the “Milbro” trade-name. The company also manufactured such diverse items as “Episcopes” (optical devices for projecting photographs onto walls), pumps for the brewing industry and even military buttons! They advertised some of their products in popiular publications such as the “Meccano Magazine”. Sincere thanks go to Mike Noakes for the provision of the above details.

Following the conclusion of WW1, which all three survived, the Mills brothers resumed their efforts to develop their model railway business. At the outset (and for many years thereafter) the firm had nothing to do with model engines, instead manufacturing O-gauge tinplate model railway equipment including locomotives, track and accessories at their St. Mary's Road location in Sheffield. These products were marketed under the “Milbro” trade-name. The company also manufactured such diverse items as “Episcopes” (optical devices for projecting photographs onto walls), pumps for the brewing industry and even military buttons! They advertised some of their products in popiular publications such as the “Meccano Magazine”. Sincere thanks go to Mike Noakes for the provision of the above details.

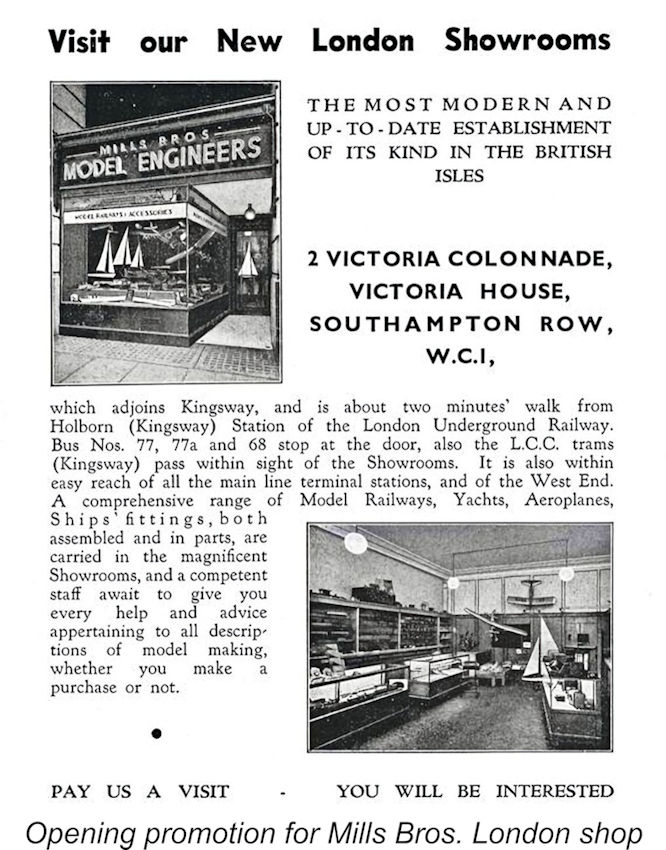

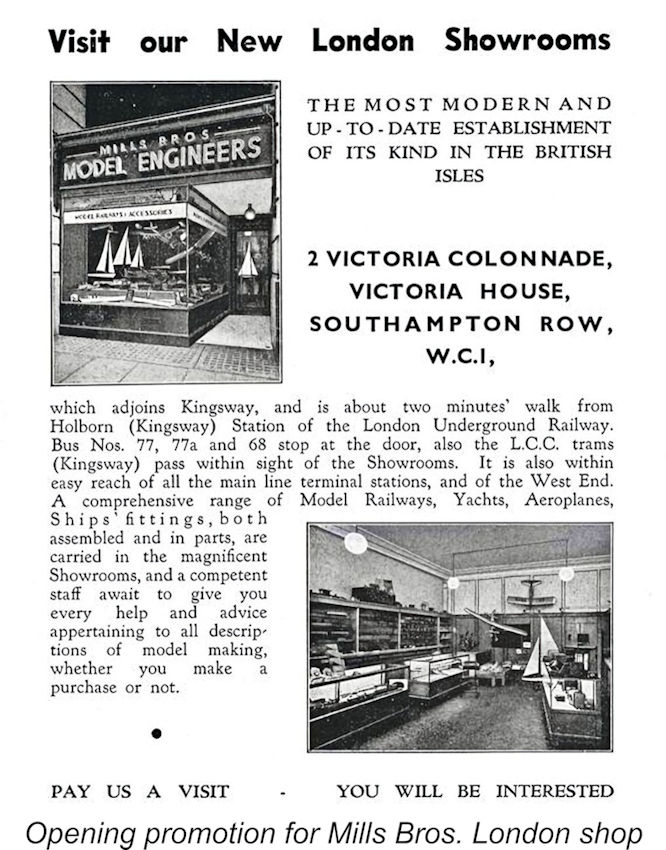

In 1938 Mills Brothers secured premises at 2 Victoria Colonnade, Southampton Row  in Holborn, London to serve as a showroom and retail outlet for their model railway products in the major market area of London. Model boats and model airplanes were very quickly added to the range of goods on offer.

in Holborn, London to serve as a showroom and retail outlet for their model railway products in the major market area of London. Model boats and model airplanes were very quickly added to the range of goods on offer.

This shop was to play a central role in the Mills model aero engine story, as we shall see. It was managed by two presumably related associates of the Mills brothers named R. M. and E. R. Spofforth. The actual manufacturing continued to take place in Sheffield.

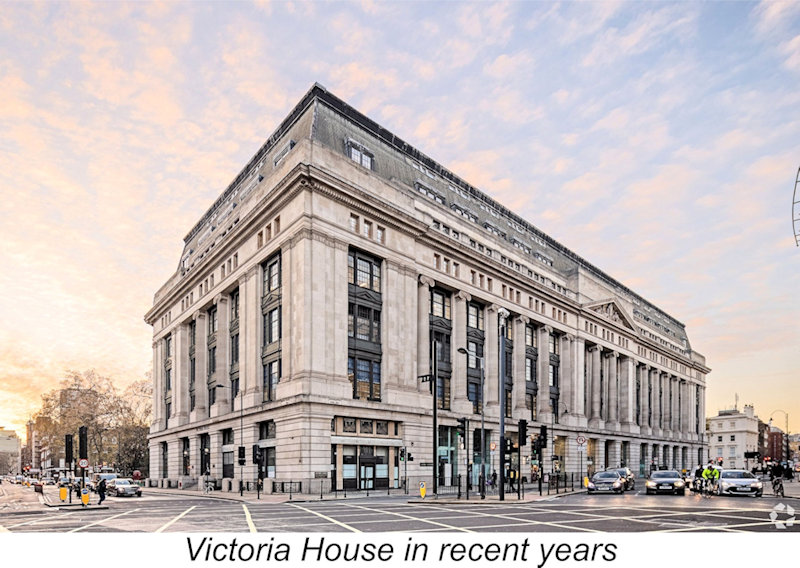

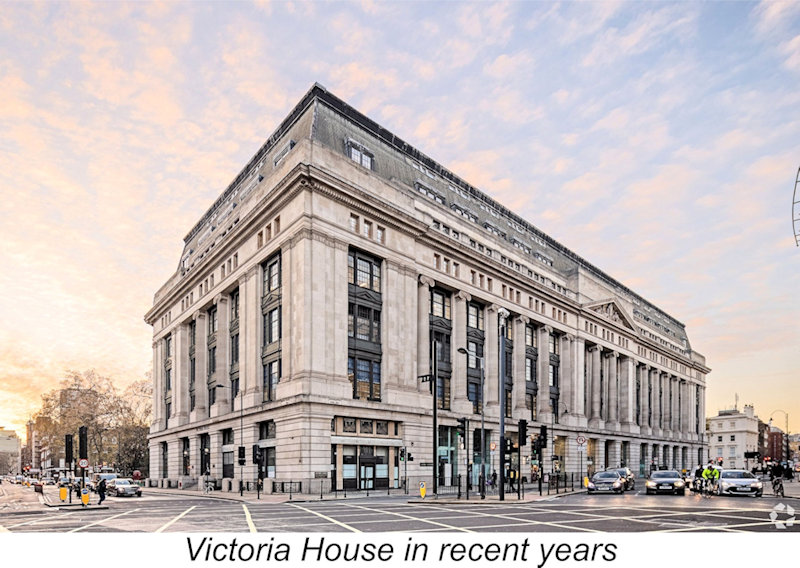

The new London outlet was located in surprisingly upmarket premises, being housed in the ground floor of a large neoclassical building known as Victoria House which had been completed in 1932. Victoria House occupied an island of land lying between Bloomsbury Square and Southampton Row. The Mills Brothers shop occupied one of a number of retail bays located on the ground floor of the side facing Southampton Row. It was this line-up of retail premises that was collectively known as Victoria  Colonnade. The company promoted their new business outlet quite actively, as reflected in the attached promotional sheet seen at the left. This must date from shortly after the opening of the new premises.

Colonnade. The company promoted their new business outlet quite actively, as reflected in the attached promotional sheet seen at the left. This must date from shortly after the opening of the new premises.

Naturally, the onset of WW2 in September 1939 had a profound impact upon small engineering firms such as Mills Brothers. British industrial resources were firmly re-directed towards war-related production, to the extent that the manufacture of model railway equipment was actually banned in 1941 and even its retail sale was banned in 1942! Presumably Mills Brothers engaged thereafter in war production, although no details are presently available. All that is known is that once the war ended they quickly resumed their former model railway manufacturing activities, competing with the likes of Bassett-Lowke and Hornby.

Victoria House survived the WW2 Blitz, although it was a near thing - the buildings on the opposite side of Southampton Row were all destroyed by the bombing. The Mills Brothers shop continued in operation after the war, adding the Mills model engines to the model railways, aircraft and boats in 1946. Reportedly, all Mills engines sold at this location were tested on the premises, doubtless to the great annoyance of the occupants of the adjacent business spaces!

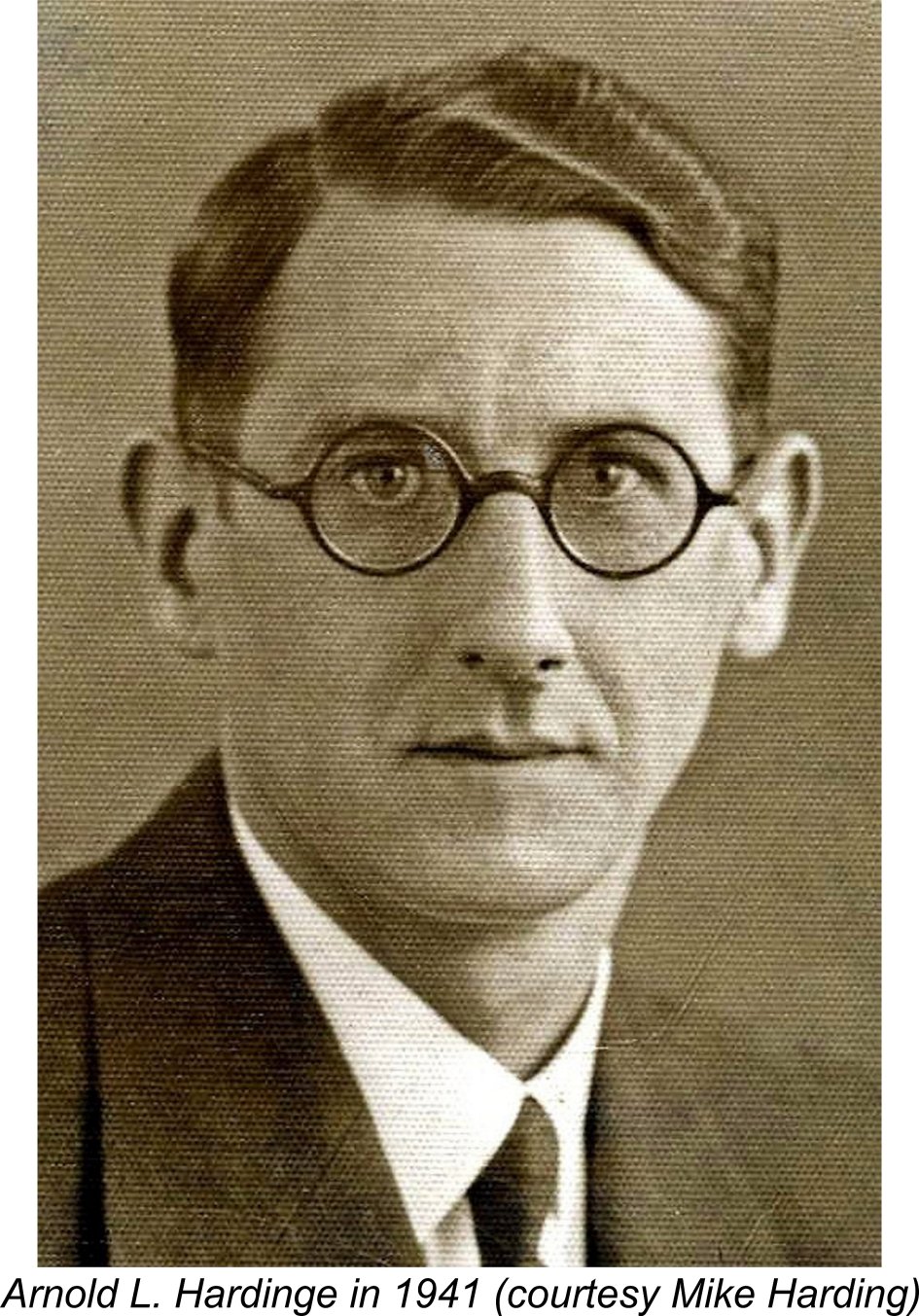

The individual who diverted the attention of Mills Brothers away from model railway manufacturing into the model aero engine field was Arnold Lewis Hardinge (b. 1906), a London-born son of a German father named Walter Neumeister and an English mother. Mike Noakes has reviewed some relevant census records which confirm that Arnold's mother was one Louisa Batho, to whom Arnold's father Walter was married in 1902. For some reason (probably to cover up some kind of "family issue", both Louisa and her mother had assumed the name of Hardinge for census purposes in 1891, although this name-change was never legally confirmed - she remained Louisa Batho in a legal sense. In any case, Louisa became a Neumeister after her marriage. Her son Arnold was thus born in 1906 as Arnold Neumeister.

The individual who diverted the attention of Mills Brothers away from model railway manufacturing into the model aero engine field was Arnold Lewis Hardinge (b. 1906), a London-born son of a German father named Walter Neumeister and an English mother. Mike Noakes has reviewed some relevant census records which confirm that Arnold's mother was one Louisa Batho, to whom Arnold's father Walter was married in 1902. For some reason (probably to cover up some kind of "family issue", both Louisa and her mother had assumed the name of Hardinge for census purposes in 1891, although this name-change was never legally confirmed - she remained Louisa Batho in a legal sense. In any case, Louisa became a Neumeister after her marriage. Her son Arnold was thus born in 1906 as Arnold Neumeister.

As a resident German alien, Arnold's father Walter Neumeister was interned on the Isle of Man following the outbreak of WW1 in 1914. In the face of difficulties arising from British-German hostility during WW1, the rest of the family relocated to Germany in 1914, where they were joined by Walter Neumeister after his release from internment following the war.

Arnold remained in Germany, living there as Arnold Neumeister from 1914 until 1937 when he ran afoul of the Nazi authorities and promptly relocated to the land of his birth, understandably taking his mother's informally-adopted surname of Hardinge from that point onwards. He spent the war years working on the Allied side in the highly technical and extremely hazardous field of bomb disposal. His survival against the odds was a fortunate thing for aficionados of classic model diesels - without him, there would probably have been no Mills model engine range.

Immediately following the conclusion of the war, Hardinge entered into an association with Mills Brothers, who were once again engaged in the manufacture of model railway equipment at the time. However, Hardinge’s attention had already become fixed upon the emerging field of model diesel engines, to the extent that he soon persuaded Mills Brothers to support his plans to add this line of products to their range.

After making a number of experimental prototypes, Hardinge took out his first Patent with respect to model diesel transfer systems in May 1946. A scan of this Patent is included in Ron Chernich's article on the Mills 2.4.

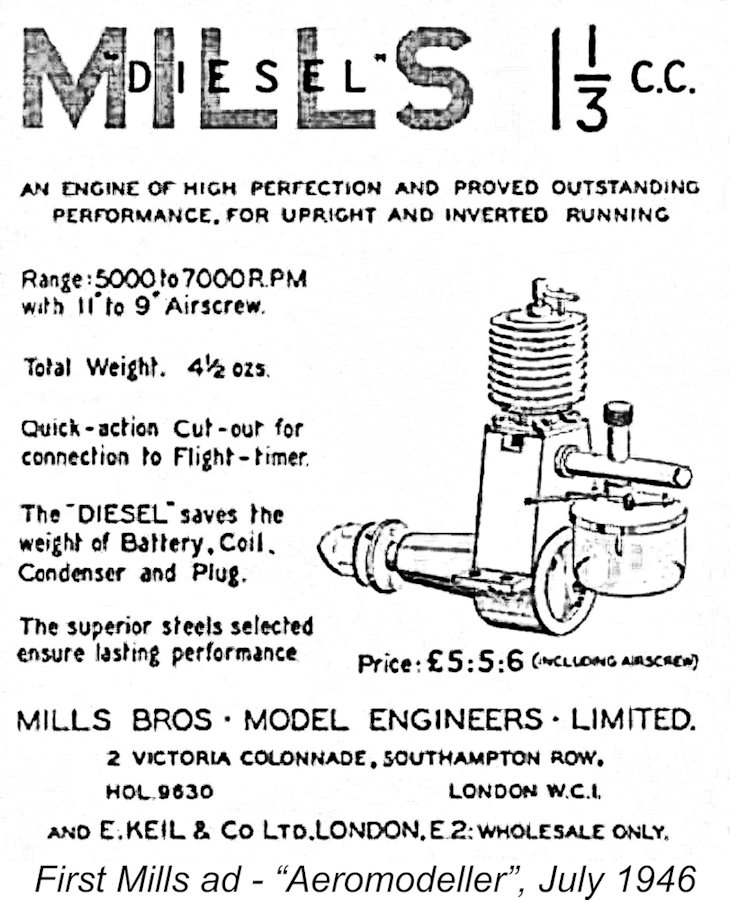

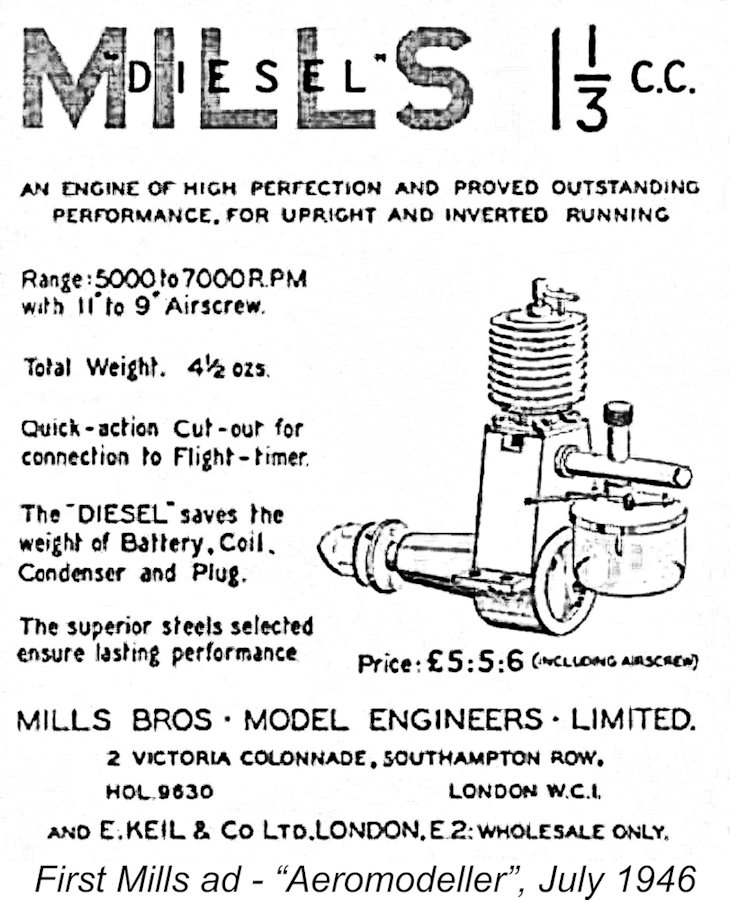

Shortly thereafter, the initial examples of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 1 diesel appeared on the market, being first advertised in July 1946. At this stage, Mills Bros. were citing the Southampton Row location in London as their business address. E. Keil & Co. Ltd. were appointed as the trade distributors for the Mills model engine range, an arrangement which continued up to late 1949.

Shortly thereafter, the initial examples of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 1 diesel appeared on the market, being first advertised in July 1946. At this stage, Mills Bros. were citing the Southampton Row location in London as their business address. E. Keil & Co. Ltd. were appointed as the trade distributors for the Mills model engine range, an arrangement which continued up to late 1949.

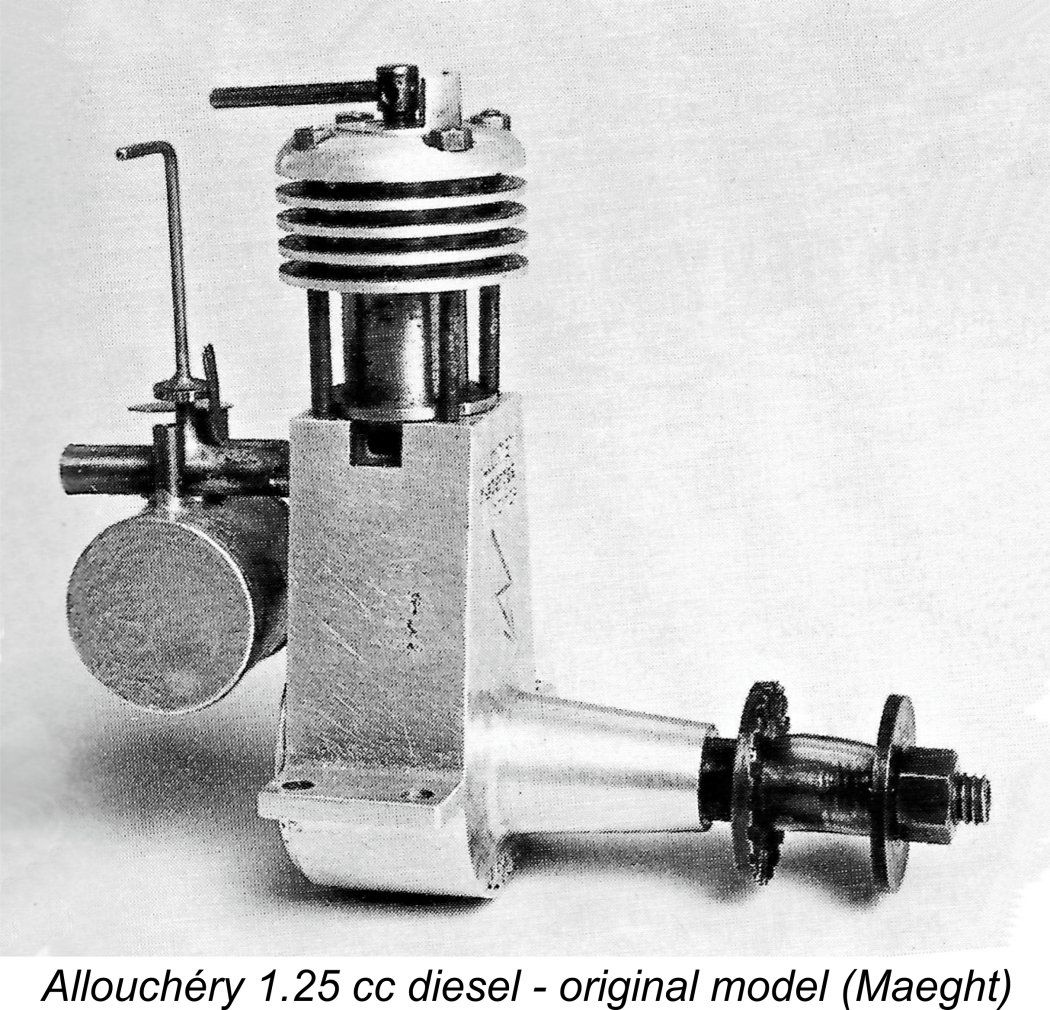

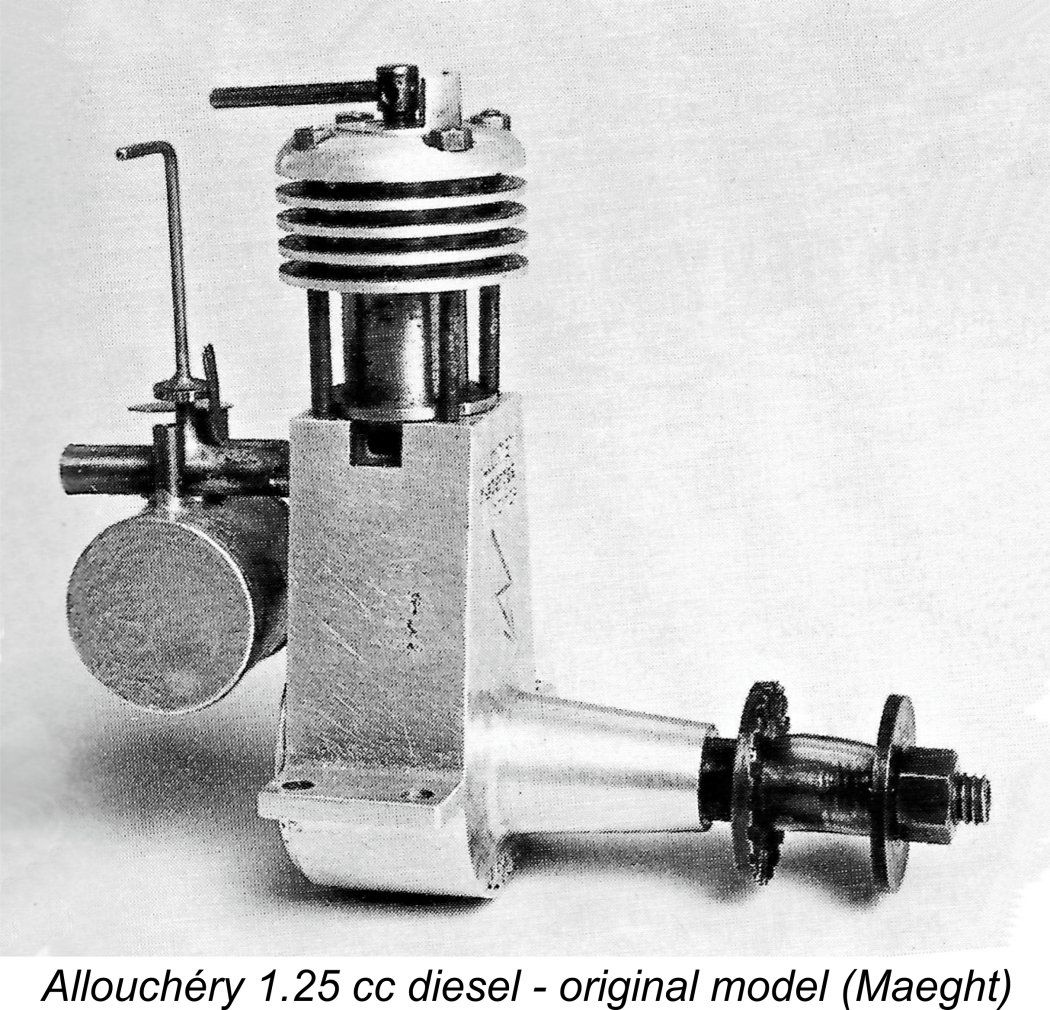

This appears to be an appropriate point at which to interject a hitherto largely ignored and perhaps controversial matter in relation to the design origins of the Mills 1.3. This is the very strong likelihood that Arnold Hardinge's design was based to a certain extent upon that of the earlier Allouchéry 1.25 cc sideport diesel from France.

The Allouchéry 1.25 cc sideport diesel appeared in late 1943 or early 1944. It was a fine little engine which quickly acquired a very high reputation. There's no doubt at all that the original Mills 1.3 bore what appears to be a far more than coincidental resemblance to the earlier Allouchéry model, even down to the displacement.

It appears that this resemblance didn't escape Prosper Allouchéry's notice! In a late 1946 article by one "R.F." which appeared in the French modelling media, Allouchéry was directly quoted as follows:

"Generally speaking, small craftsmen should be protected against all manner of sharks who without being technicians themselves  loot them without scruple, copy their best models and artificially raise the selling prices. I was recently the victim of this kind of despoilation, but a legal action would take too much time and too much money, with probably an unsatisfactory result ......... .."

loot them without scruple, copy their best models and artificially raise the selling prices. I was recently the victim of this kind of despoilation, but a legal action would take too much time and too much money, with probably an unsatisfactory result ......... .."

The late 1946 timing of Allouchéry's statement makes it appear almost certain that he was referring to the July 1946 appearance of the Mills 1.3 diesel in England. There's no doubt at all that the Mills conveys a distinct impression of having been influenced by the Allouchéry 1.25 cc design. It's also an indisputable fact that the Allouchéry 1.25 cc model had been seen in England, since it won a major contest at Eaton Bray in the same year of 1946. The range also received quite comprehensive coverage in D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson's late 1946 book "Model Diesels".

The design was thus available in England to serve as a source of design inspiration, and perhaps it did exert some influence........but really, so what?!? All model engines reflect the designs of their predecessors to some degree - look at all the Dyno clones from a number of countries. In my personal view, a more positive reaction on Allouchéry's part to any perception of imitation would have been to take it as a compliment - imitation is surely the most sincere form of flattery!

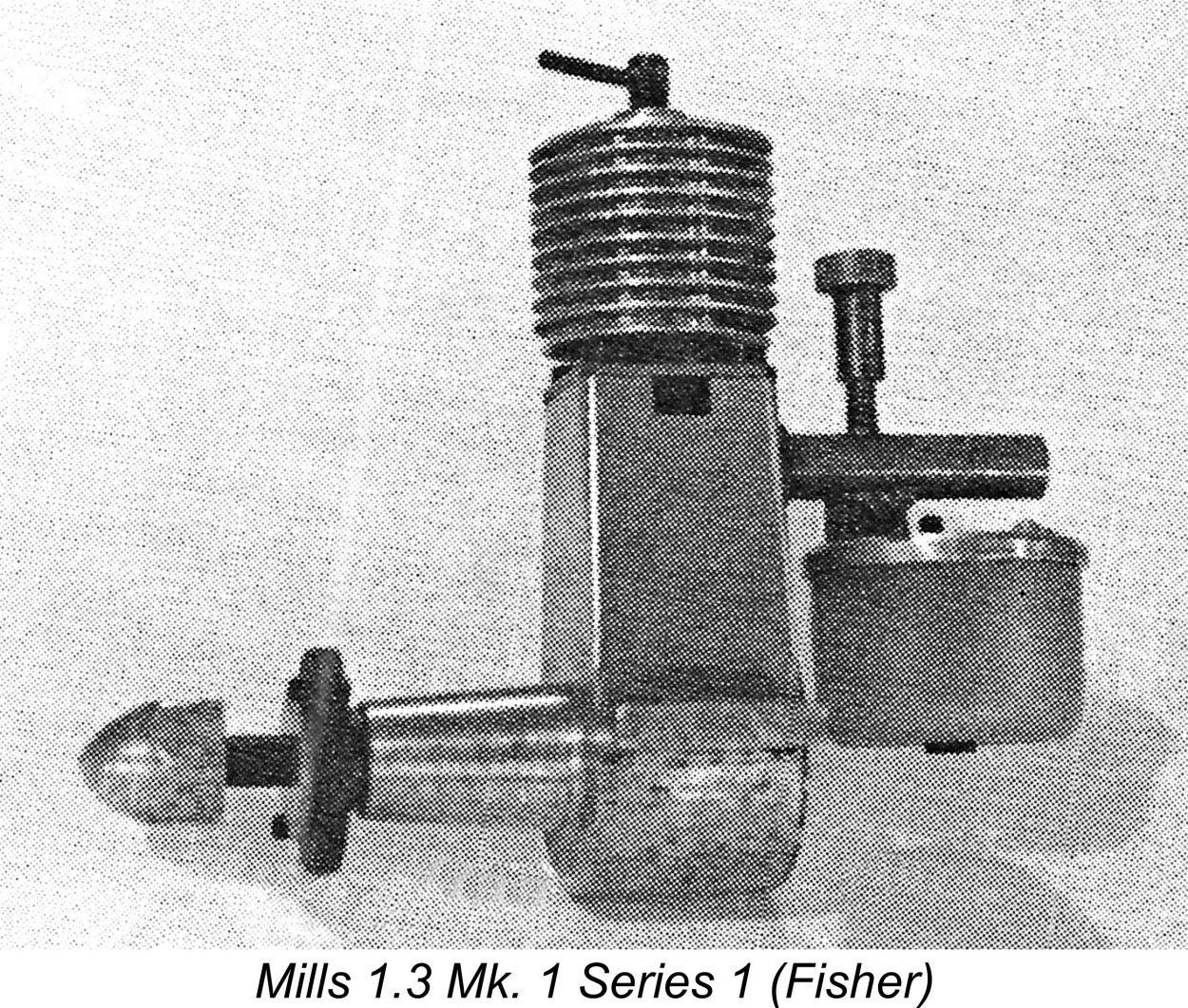

Stepping back now from this controversy, the Mills engines were initially marketed from the Mills Bros. retail outlet on Southampton Row in Holborn. However, those premises were quite small – certainly far too small to house a model engine manufacturing operation in addition to the retail business. In his 1977 “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines”, the late O.F.W. Fisher recalled visiting the Holborn shop in 1946 to buy one of the first Mills 1.3 engines after seeing it run on the premises (diesel aroma drifting down High Holborn?!? Mmmmmm............those were the days!). However, it seems almost certain that those early Mills engines originated in Sheffield.

Stepping back now from this controversy, the Mills engines were initially marketed from the Mills Bros. retail outlet on Southampton Row in Holborn. However, those premises were quite small – certainly far too small to house a model engine manufacturing operation in addition to the retail business. In his 1977 “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines”, the late O.F.W. Fisher recalled visiting the Holborn shop in 1946 to buy one of the first Mills 1.3 engines after seeing it run on the premises (diesel aroma drifting down High Holborn?!? Mmmmmm............those were the days!). However, it seems almost certain that those early Mills engines originated in Sheffield.

In the accompanying 1951 image at the left, the Mills Bros. premises on Southampton Row occupy the leftmost complete bay in the photo, which was the second bay from the left as the number suggests. Interestingly enough, their immediate neighbours to the right were a company called Clements which sold Sheffield cutlery! Two adjacent Sheffield companies...... coincidence?!? Note also the unrepaired bomb damage on the nearside of Southampton Row. Such bombed-out sites were still commonplace when I was growing up in England during the fifties - we used to play in them! Different days .................

The response of the modelling community to the release of the Mills 1.3 was immediate and overwhelming. Quite apart from its inherently excellent handling and running characteristics as well as the quality of its construction, it had virtually no domestic competition as of mid 1946. Consequently, demand far outstripped supply right from the outset.

In response to the immediate sales success of the new model, steps were quickly taken to enhance the company’s model engine production capacity – the Sheffield facilities evidently lacked the capacity to maintain the simultaneous production of both the ongoing "Milbro" model railway range and the new Mills model diesel. This almost certainly explains the fact that relatively few of the original Mills Mk. 1 Series 1 models appear to have been manufactured - the Sheffield factory in which they were most likely produced simply didn't have the surplus capacity. Supply doubtless fell behind demand to an ever-increasing degree.

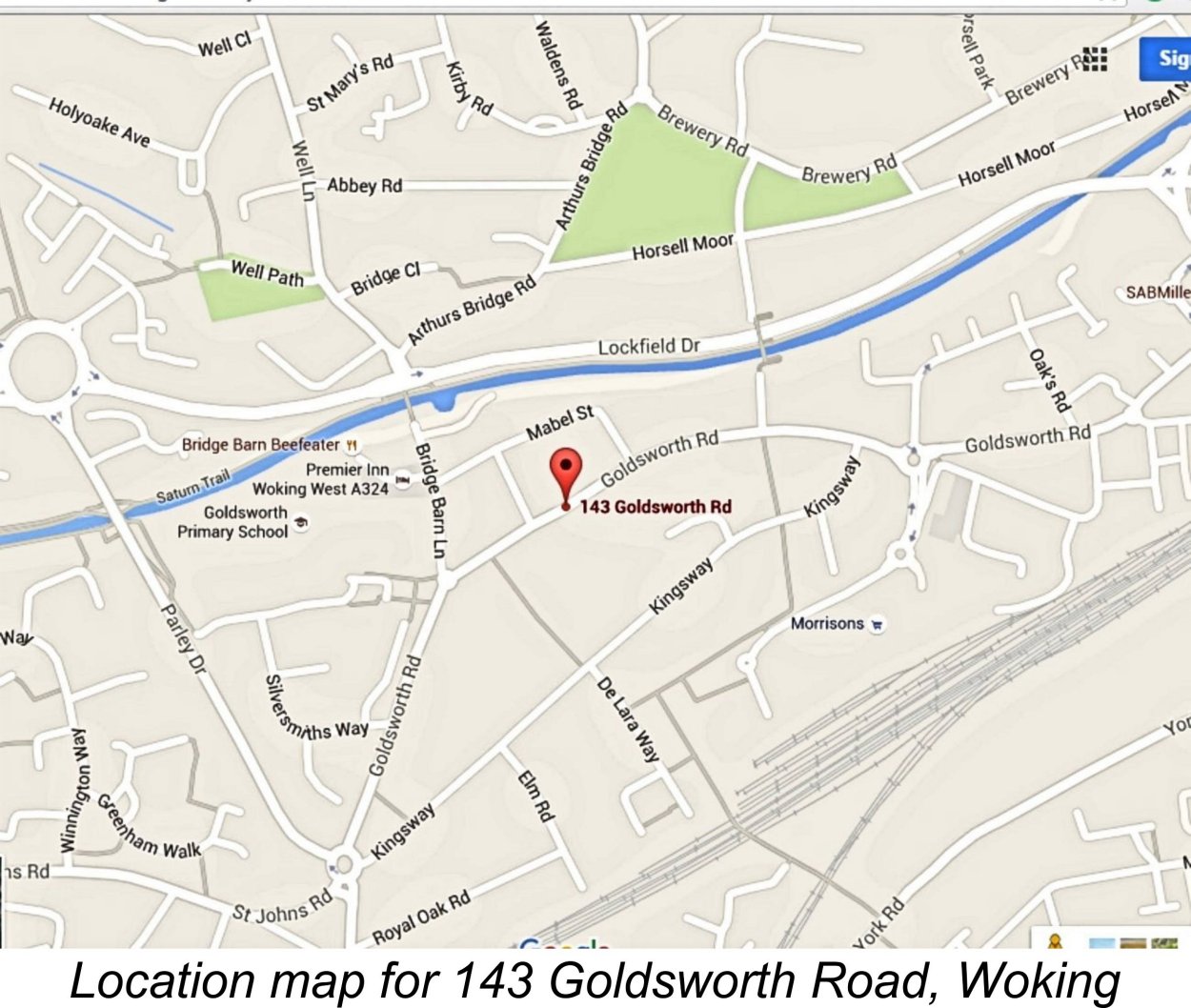

This unsatisfactory situation was relieved in late 1946 with the establishment of a new manufacturing operation at 143 Goldsworth Road in Woking, Surrey, in premises which had formerly housed a builder, plumber and decorator. As Mills Brothers’ resident model diesel expert, Arnold Hardinge was quite logically appointed as manager of this facility.

This unsatisfactory situation was relieved in late 1946 with the establishment of a new manufacturing operation at 143 Goldsworth Road in Woking, Surrey, in premises which had formerly housed a builder, plumber and decorator. As Mills Brothers’ resident model diesel expert, Arnold Hardinge was quite logically appointed as manager of this facility.

According to Reg Elton, an early employee at the Woking location, this facility produced the crankcases and cooling jackets in addition to some of the other less demanding components. The assembly and testing of the engines also took place at this location, a fact which subsequently led to noise-related conflicts with the neighbours given the inconvenient fact that the premises backed onto a residential area!

However, many key components continued to be manufactured elsewhere, with crankshafts apparently being sent down from Sheffield and the cylinders being produced by the Precision Reed Company of Crawley in Sussex. The business affairs of the company continued to be handled through the Southampton Row location in Holborn, while KeilKraft retained their role as trade distributors.

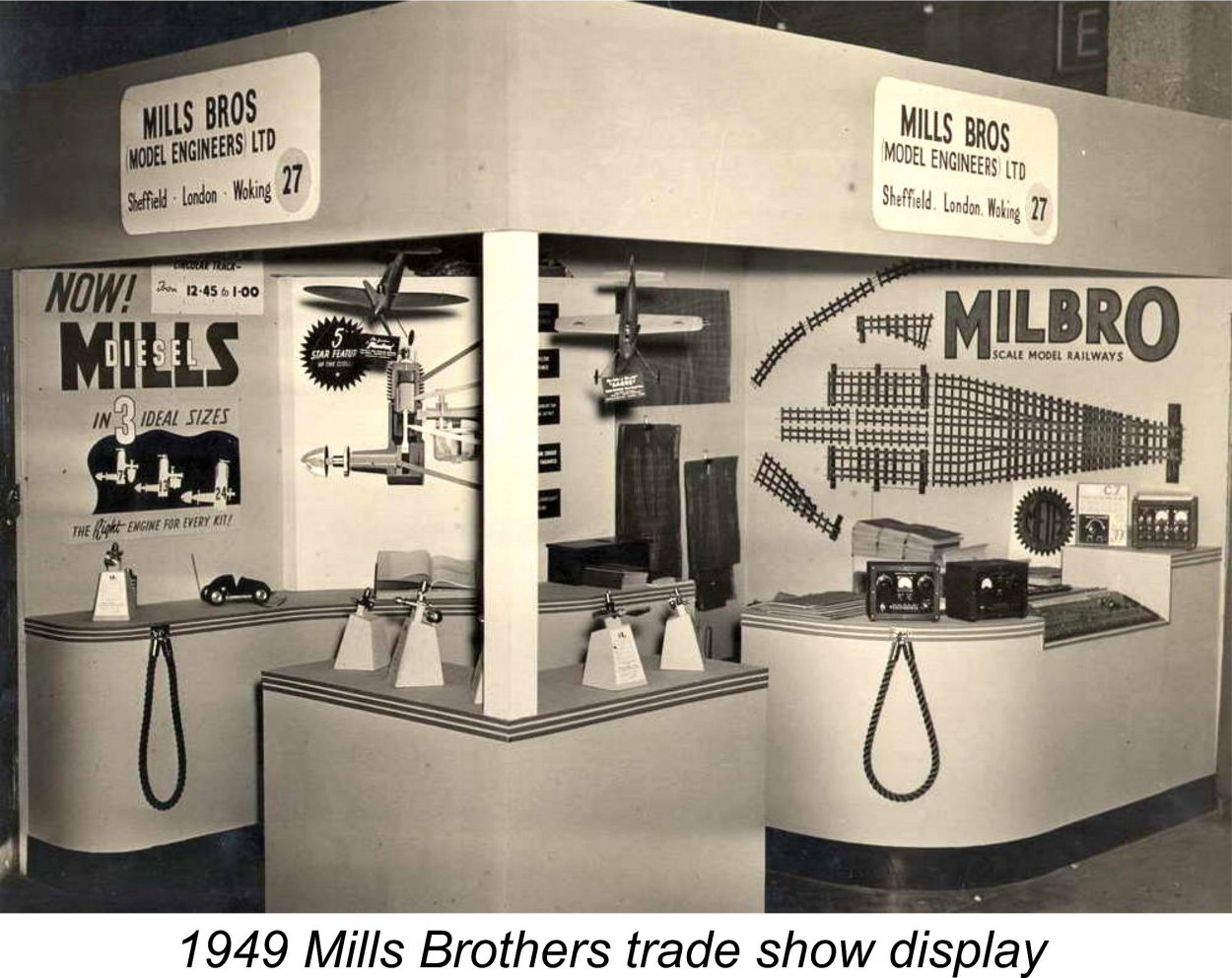

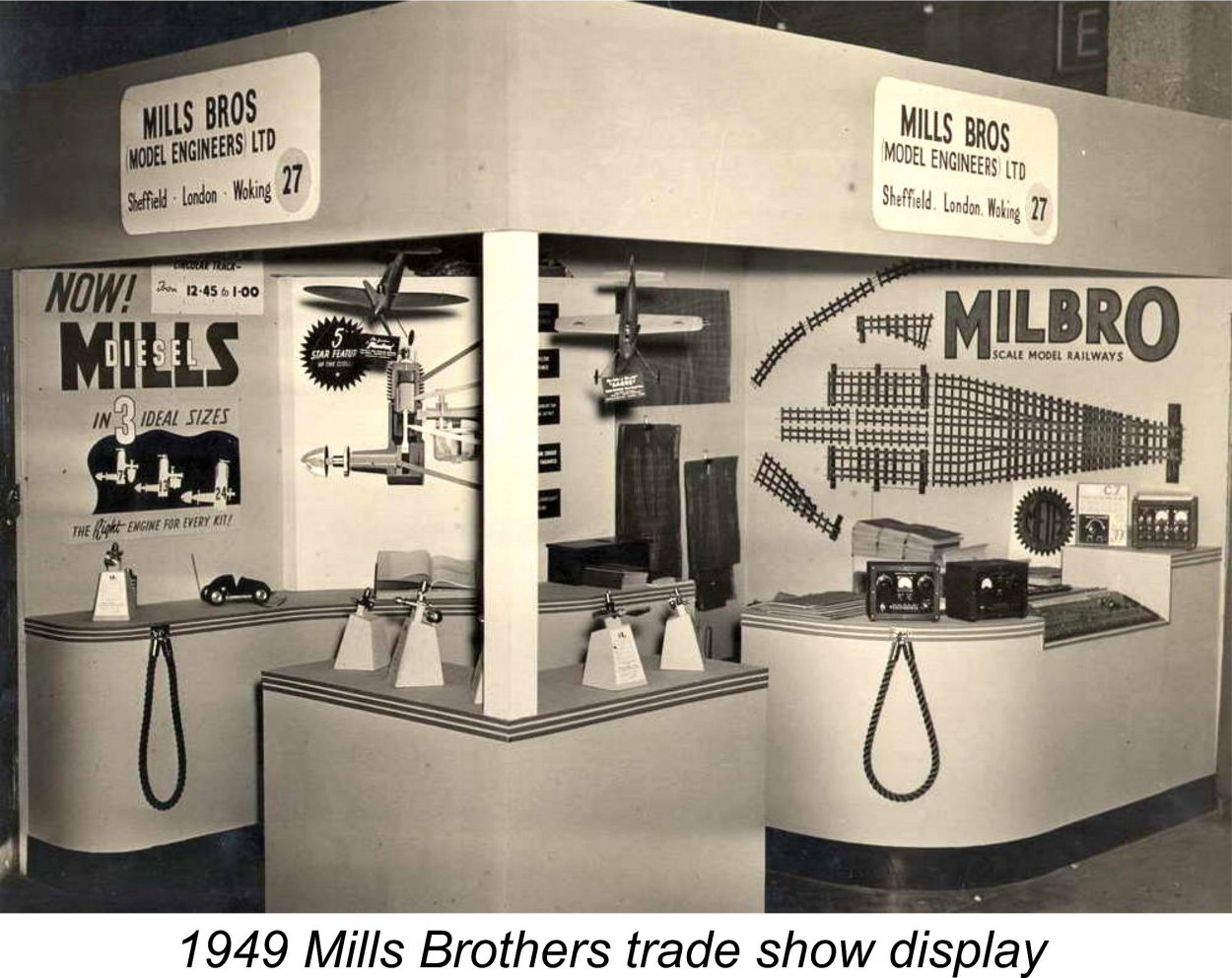

For some years after their entry into the model engine field, Mills Bros. hedged their bets by continuing to manufacture their “Milbro” line of model railway track and accessories in Sheffield alongside the Woking-based production and expansion of their very successful model engine range. The attached image of a 1949 Mills Brothers trade show stand proves that both model diesel engines and model railway material were still being manufactured and promoted at that time. The model railway manufacturing was still taking place at the Sheffield factory - the illustrated display confirms that the company retained its Sheffield and Holborn braches alongside the Woking facilities, since all three are mentioned.

For some years after their entry into the model engine field, Mills Bros. hedged their bets by continuing to manufacture their “Milbro” line of model railway track and accessories in Sheffield alongside the Woking-based production and expansion of their very successful model engine range. The attached image of a 1949 Mills Brothers trade show stand proves that both model diesel engines and model railway material were still being manufactured and promoted at that time. The model railway manufacturing was still taking place at the Sheffield factory - the illustrated display confirms that the company retained its Sheffield and Holborn braches alongside the Woking facilities, since all three are mentioned.

However, things changed radically in late 1949 when Arnold Hardinge bought the Mills Brothers business (or a portion of it) outright. From that point onwards, his focus switched decisively to model diesel engine production.

However, that was by no means the end of the Milbro model railway range! Following the initial publication of this article, I was delighted to hear from model railway historian Malcolm Harrison of England, who is developing a most interesting website devoted to the history of the Milbro model railway range. Malcolm advises that the manufacture of the Milbro model railway range at the St. Mary's Road address in Sheffield actually continued until the late 1950's at least. However, the name of the company which manufactured these products was changed to Mills Brothers (Sheffield) Ltd., as confirmed by the address on a catalogue in Malcolm's possession dated 1957-58. A fragmentation of the Mills Brothers company in 1949 is clearly implied here.

It's interesting to note at this point that the Mills Brothers shop on Southampton Row in Holborn remained in operation until at least 1955 - possibly longer. Mike Noakes located a dated photo showing the premises in 1955, still occupying the same retail bay in the ground-floor frontage of Victoria House. It's not known when Mills Brothers finally abandoned these premises.What is known is the remarkable fact that these premises are still in existence today! Victoria House became a Grade II listed building in 1990 and has since been extensively modernised internally, although its external appearance has been left largely unchanged. The retail bay on the Southampton Row side of the building which once housed the Mills Brothers showroom is still there, although it has been internally reconfigured to suit other purposes. In the accompanying image, the former Mills Bros. shop occupied the second narrow bay from the left (behind the lamp standard).

It's interesting to note at this point that the Mills Brothers shop on Southampton Row in Holborn remained in operation until at least 1955 - possibly longer. Mike Noakes located a dated photo showing the premises in 1955, still occupying the same retail bay in the ground-floor frontage of Victoria House. It's not known when Mills Brothers finally abandoned these premises.What is known is the remarkable fact that these premises are still in existence today! Victoria House became a Grade II listed building in 1990 and has since been extensively modernised internally, although its external appearance has been left largely unchanged. The retail bay on the Southampton Row side of the building which once housed the Mills Brothers showroom is still there, although it has been internally reconfigured to suit other purposes. In the accompanying image, the former Mills Bros. shop occupied the second narrow bay from the left (behind the lamp standard).

It would appear from this information that what actually happened in late 1949 was that Arnold Hardinge bought the Mills Brothers (Model Engineers) name from whoever owned the company at the time (probably one or more of the original Mills brothers) along with the exclusive manufacturing rights to the Mills model aero engines by that name. He also acquired the Woking premises at which the engines were made. This is completely consistent with the previously-noted fact that the Mills brothers had started the company on the specific basis of an interest in model railways, hence likely viewing the model aero engine side as being somewhat peripheral to their interests in addition to being carried on at an inconveniently remote location (Woking). They were probably happy to let that side of the business go so that they could devote themselves full-time to model railway manufacture in their native Sheffield uunder a slightly changed company name.

Regardless of what actually transpired, from late 1949 onwards Hardinge focused exclusively upon model diesel engine production at the Woking facility which he now owned. From this point onwards the business affairs of the company were also handled from the Woking address. This included the wholesale distribution of the engines to the model trade, thus ending the former association with KeilKraft. No more was heard of the Holborn retail outlet in connection with the Mills diesels, although it remained in business as an outlet for the ongoing products of the Sheffield company and may have continued to sell the Mills engines on a retail basis.

Regardless of what actually transpired, from late 1949 onwards Hardinge focused exclusively upon model diesel engine production at the Woking facility which he now owned. From this point onwards the business affairs of the company were also handled from the Woking address. This included the wholesale distribution of the engines to the model trade, thus ending the former association with KeilKraft. No more was heard of the Holborn retail outlet in connection with the Mills diesels, although it remained in business as an outlet for the ongoing products of the Sheffield company and may have continued to sell the Mills engines on a retail basis.

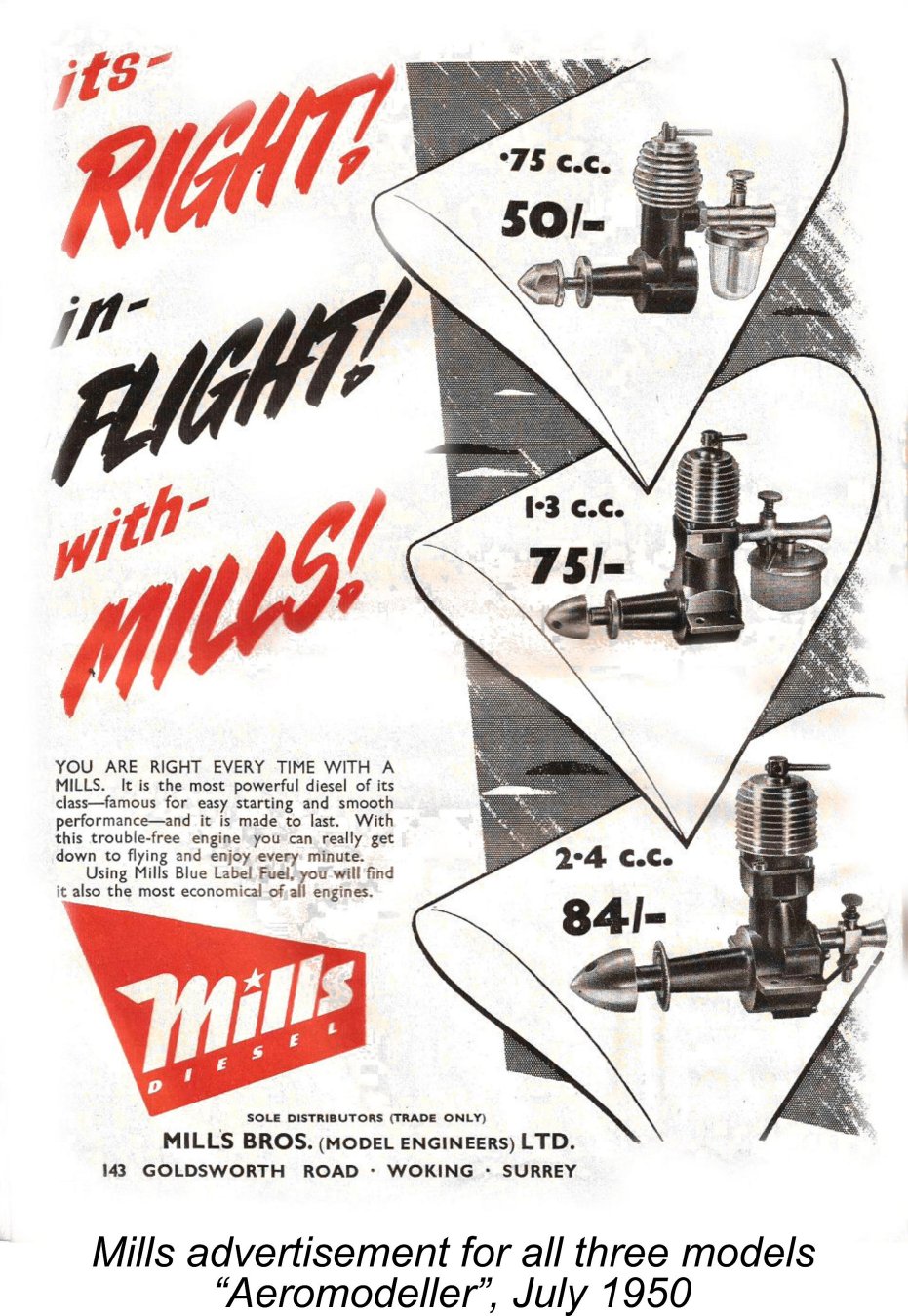

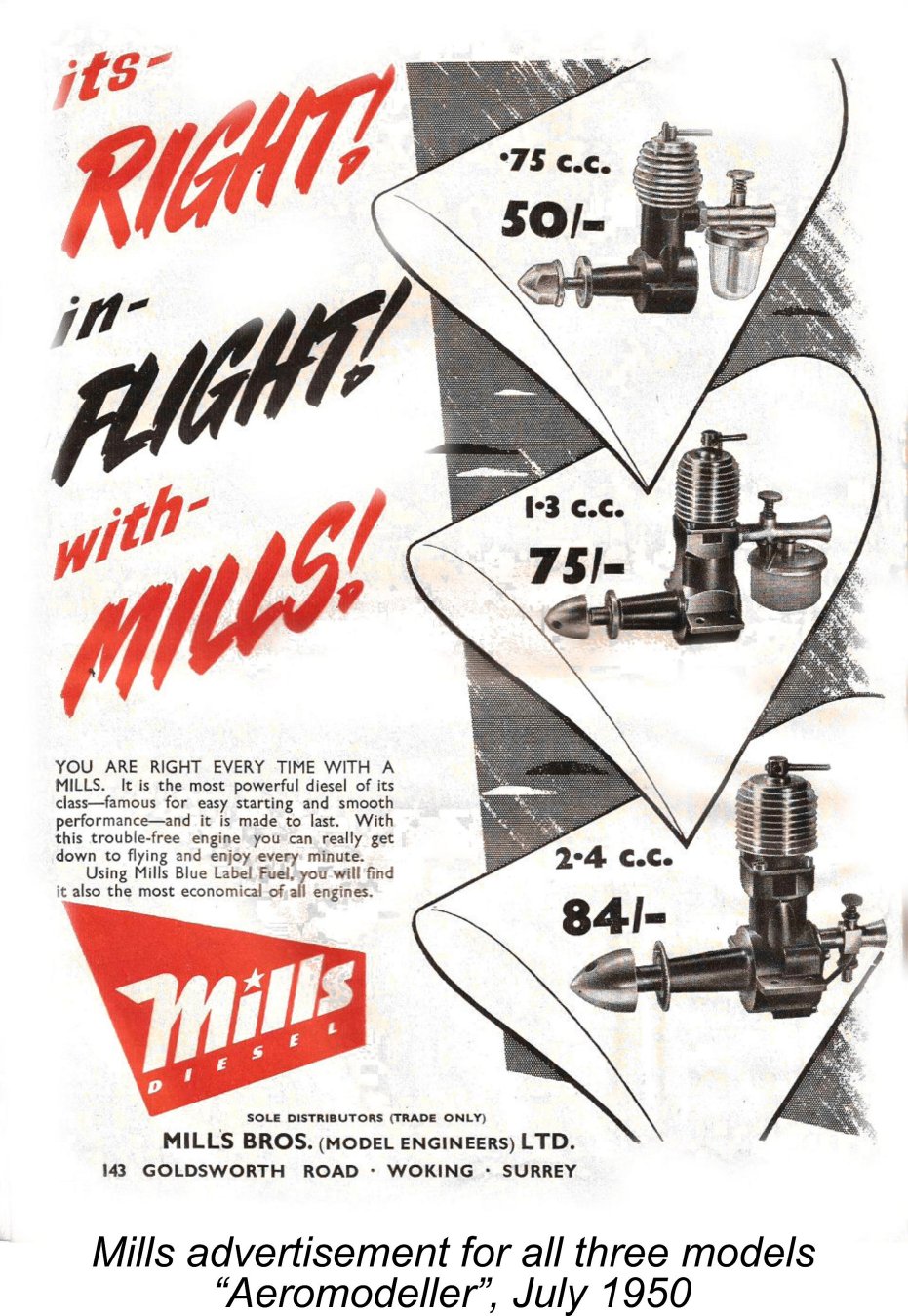

The Mills diesels ended up being manufactured and advertised in three displacement categories – 0.75 cc, 1.3 cc and 2.4 cc. The 2.4 cc model was not a success, being outclassed by a number of more powerful and less expensive competing models. It only remained on offer until mid 1951. However, the flagship .75 and 1.3 models continued in production for many years thereafter in their fully developed forms.

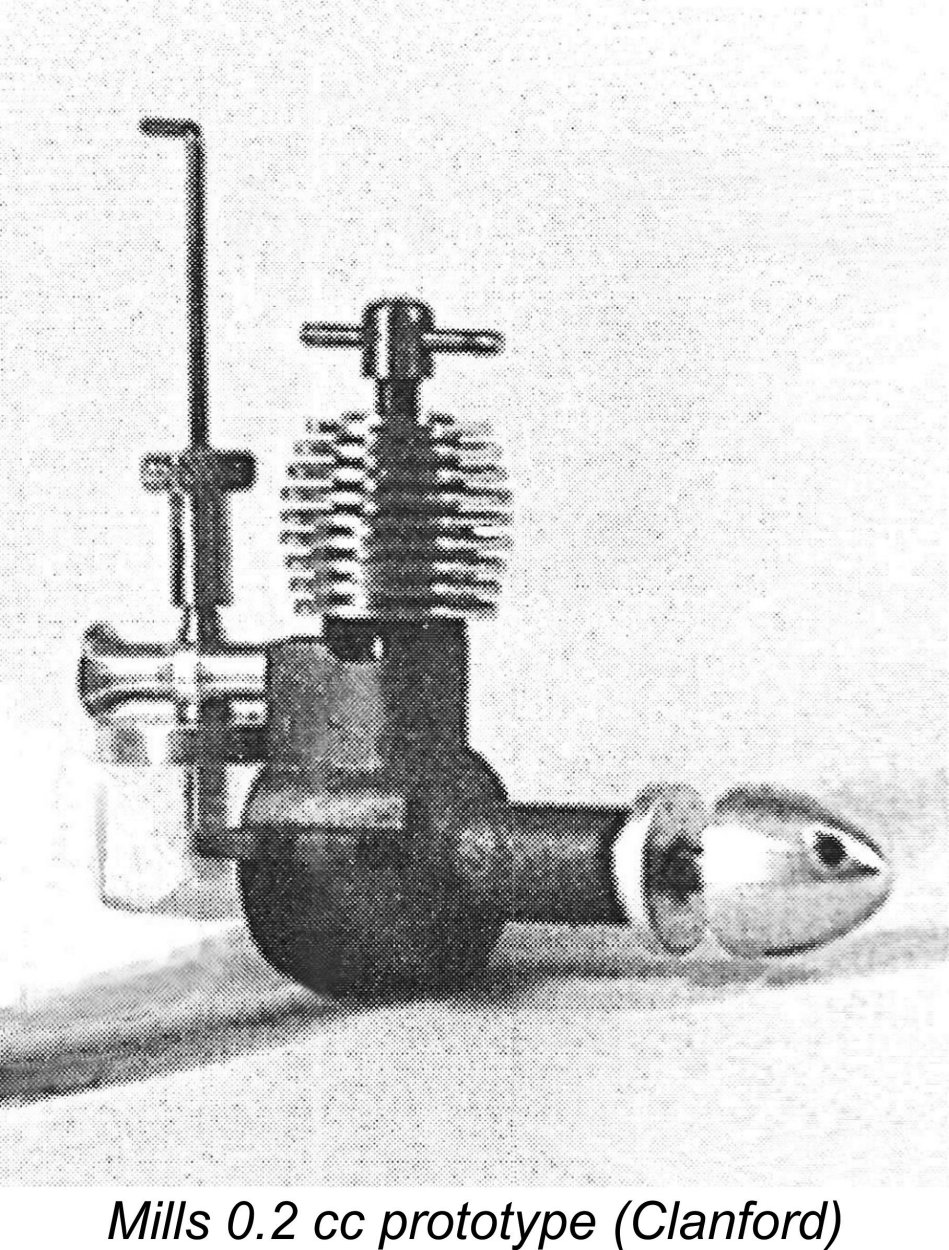

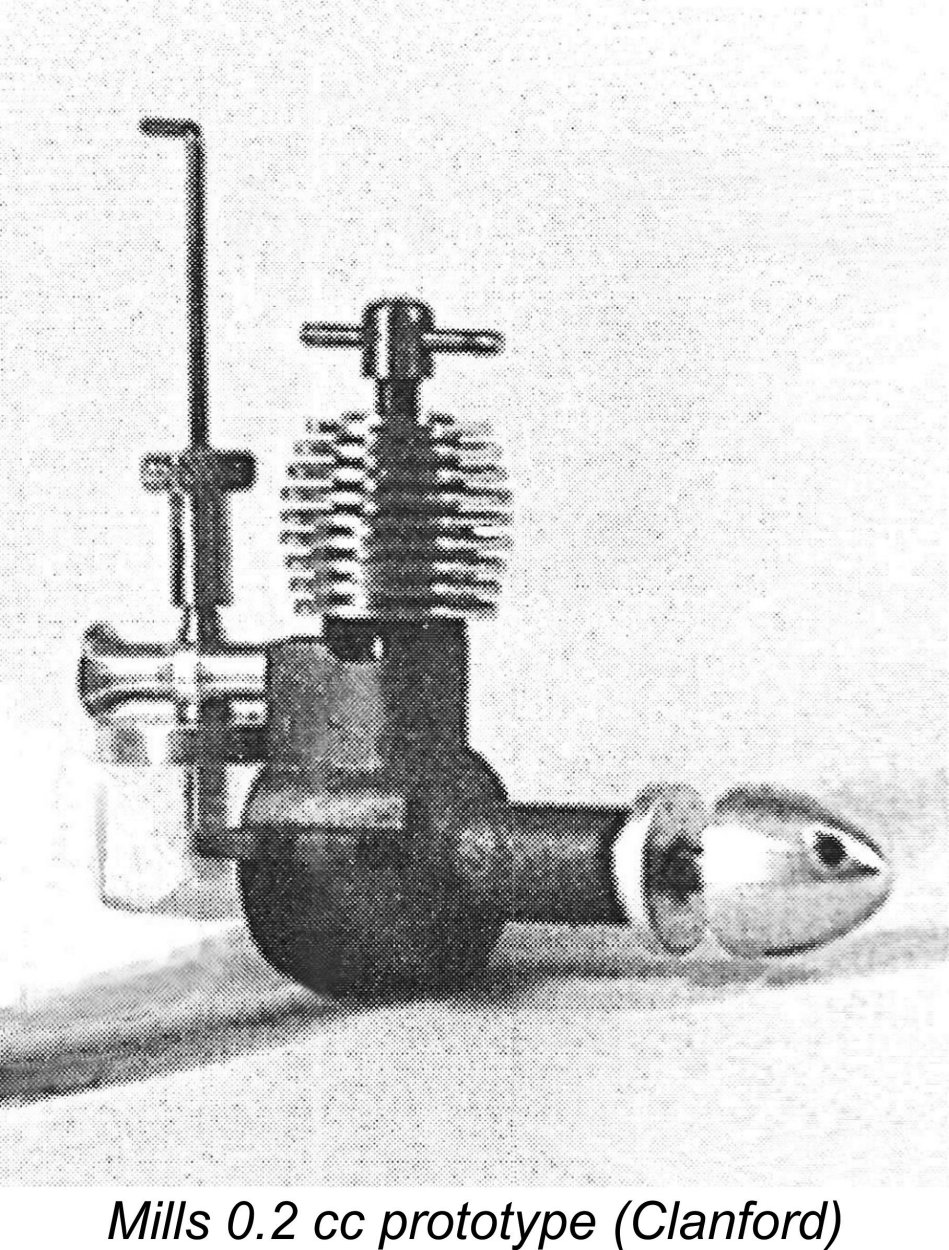

Arnold Hardinge's son Mike Harding recalled that at one point his father considered adding a fourth model to the range - a real sub-miniature of only 0.2 cc. This was apparently at least in part a reaction to the neighbourhood noise issue to which reference was made earlier. According to Mike Clanford, two examples of this little gem were constructed at Woking. One was lost on its first test flight near Woking, as recalled by Mike Harding who was present to watch this unfortunate occurrence. The other survived to be illustrated by Mike Clanford in his well-known "A-Z" book. What a pity that this model never became a commercial reality!

Arnold Hardinge's son Mike Harding recalled that at one point his father considered adding a fourth model to the range - a real sub-miniature of only 0.2 cc. This was apparently at least in part a reaction to the neighbourhood noise issue to which reference was made earlier. According to Mike Clanford, two examples of this little gem were constructed at Woking. One was lost on its first test flight near Woking, as recalled by Mike Harding who was present to watch this unfortunate occurrence. The other survived to be illustrated by Mike Clanford in his well-known "A-Z" book. What a pity that this model never became a commercial reality!

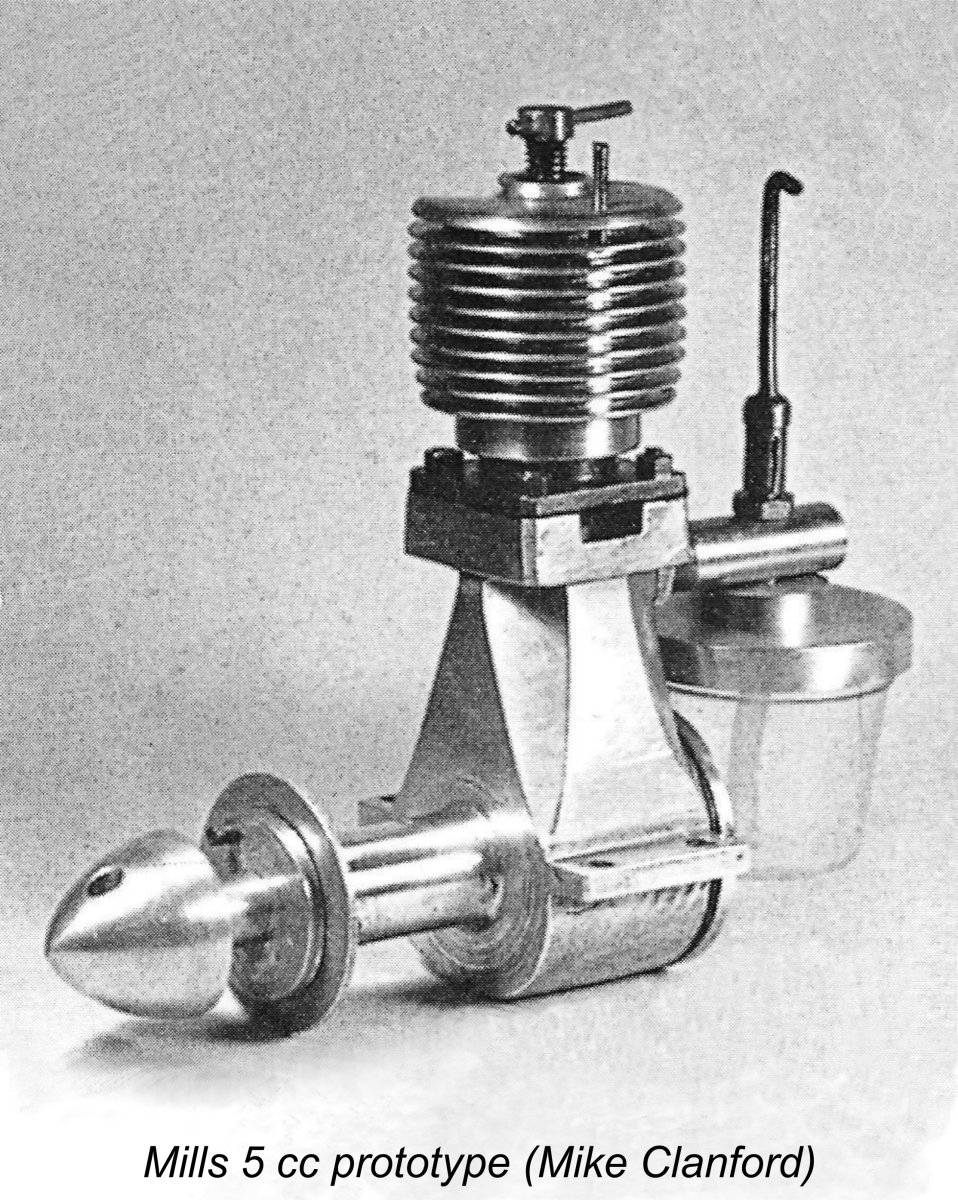

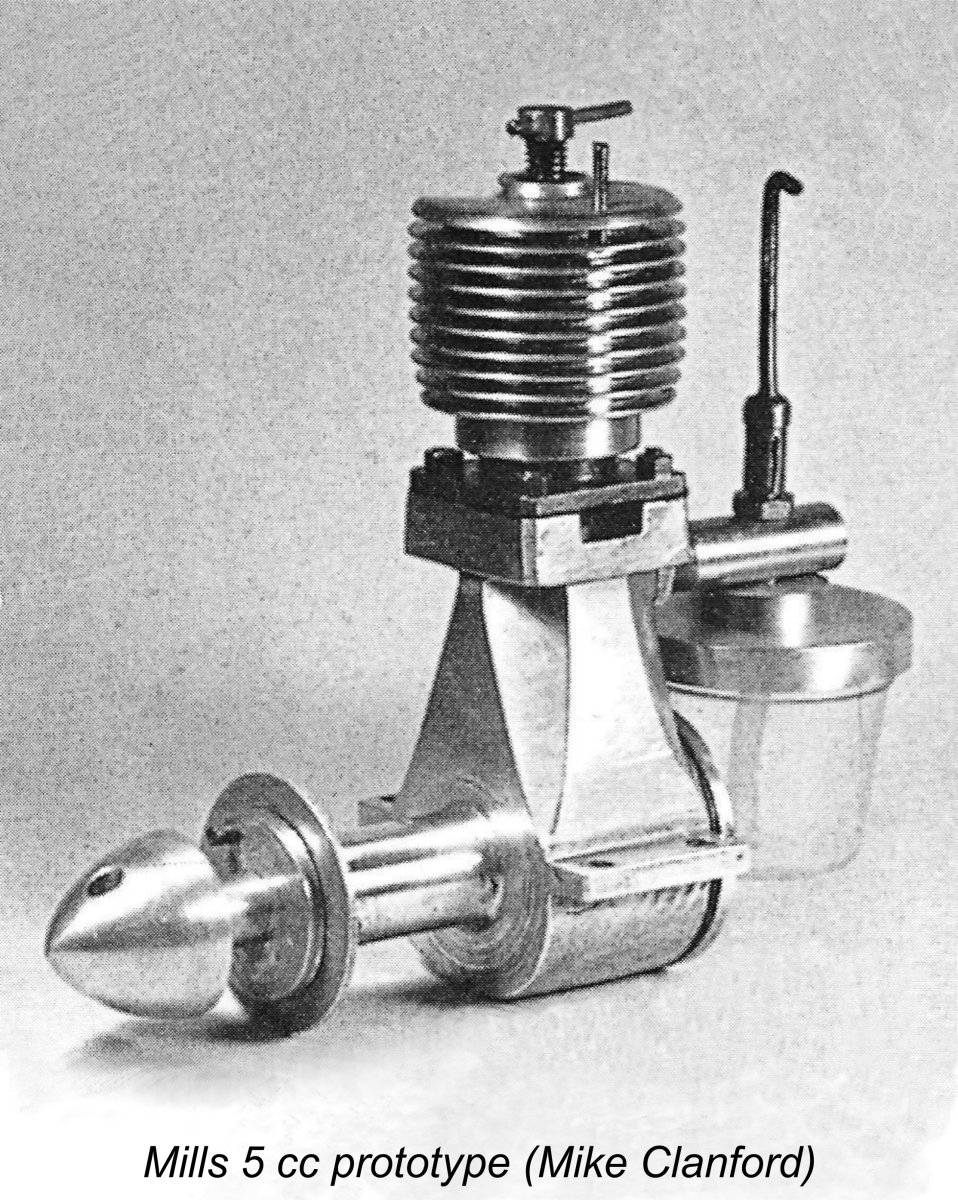

There was also talk of a potential 5 cc offering from Mills Brothers. It turns out that there was substance to this rumor - at least one eample of a 5 cc Mills prototype was in fact produced. This engine was also featured in Mike Clanford's "A-Z" book. It was a nice-looking unit, but as a large sideport diesel it was well behind the times in design terms. This doubtless explains why it never achieved production  status.

status.

A very few replicas of this engine were produced in later years by the Aurora Model Manufacturing Co. Pvt. Ltd. of Calcutta, India after they acquired the name, designs and tooling of the original Mills Brothers enterprise in the mid 1960's (see below). In addition, a few examples of a Mills 5 cc model were produced by the very talented engine maker Derek Giles. Any example of this engine which may be encountered today is almost certainly one of these replicas. My own test of an example of the Aurora version owned by Derek Butler has demonstrated that it runs very well.

In addition to maintaining production of their two very successful “bread-and-butter” .75 cc and 1.3 cc models, the company also undertook the experimental development and prototype manufacture of high-precision components for clients such as Vickers-Armstong, the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough and the Ministry of Defence. Many of these projects were one-off experimental prototypes which had to be manufactured to very exacting specifications, often using metals presenting inherent machining problems. According to his son Mike, Hardinge delighted in facing such challenges, particularly if very small components were involved.

This would doubtless have led to some very lucrative larger-scale production contracts if Hardinge’s company had possessed the capacity to undertake them. However, although the company was very successful in the development of precision prototypes, it did not have the capacity to undertake the series manufacture of any of the projects that subsequently went into full scale production. As a result, those long-term production contracts went elsewhere after Mills Bros. had done all the hard work by completing the exacting prototype development phase. Model engine manufacturing continued to be the company’s mainstream ongoing manufacturing activity.

Even so, it may have been the income derived from outside contract work of this nature which enabled Mills Bros. to weather the storm created by the unfavourable outcome of the infamous Purchase Tax case in late 1950. I've covered that matter in detail in my separate article about the career of Alan Allbon. Suffice it to say here that this decision confirmed the applicability of Purchase Tax to all modelling goods, including engines, which had previously been exempt. It created significant economic challenges for model engine manufacturers in Britain, driving Yulon out of the business altogether and almost ending Alan Allbon's career as a model engine designer and manufacturer. It also appears to have seriously eroded the ability of the E.D. company to maintain adequate levels of funding for their reaseach and development programs. However, there's no compelling evidence to suggest that Mills Bros. were seriously compromised by this unhappy situation - they simply carried on as before, although doubtless at reduced profit margins thanks to the imposition of Purchase Tax.

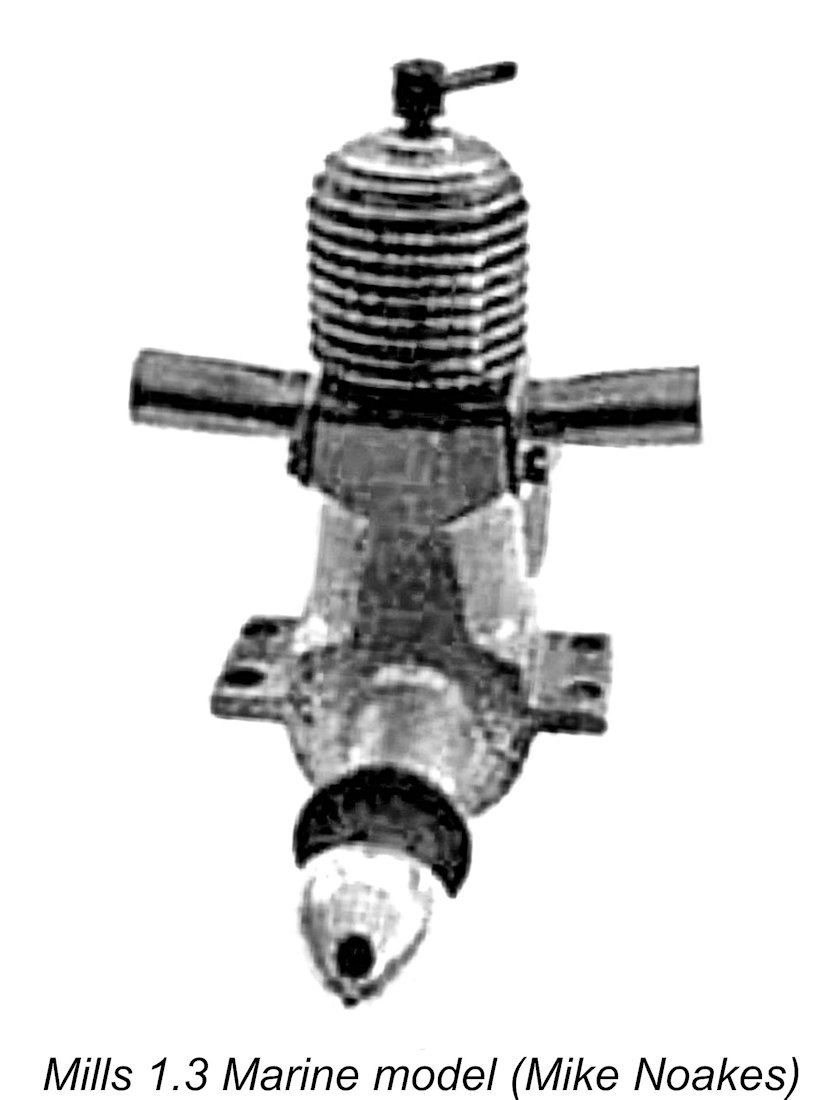

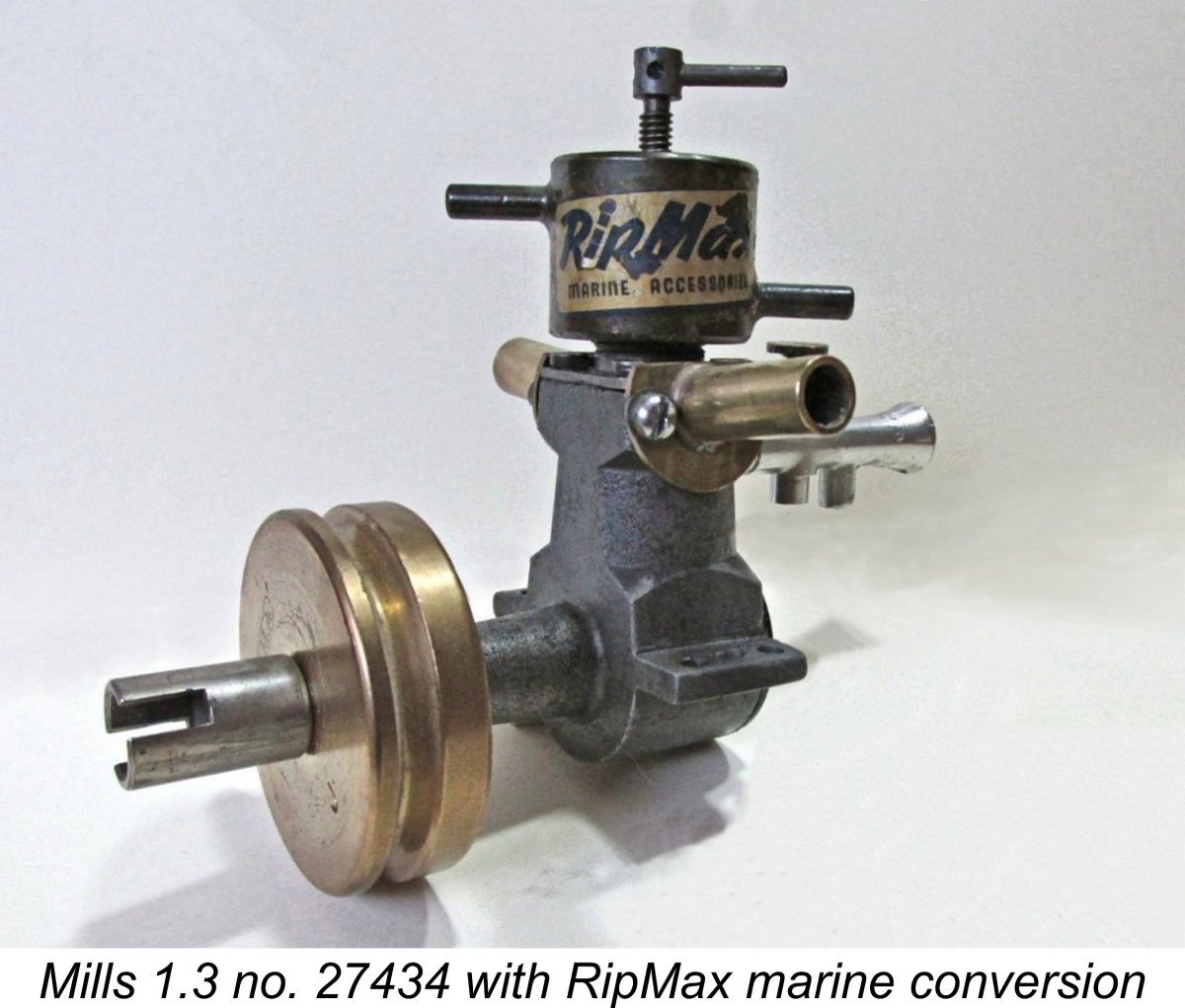

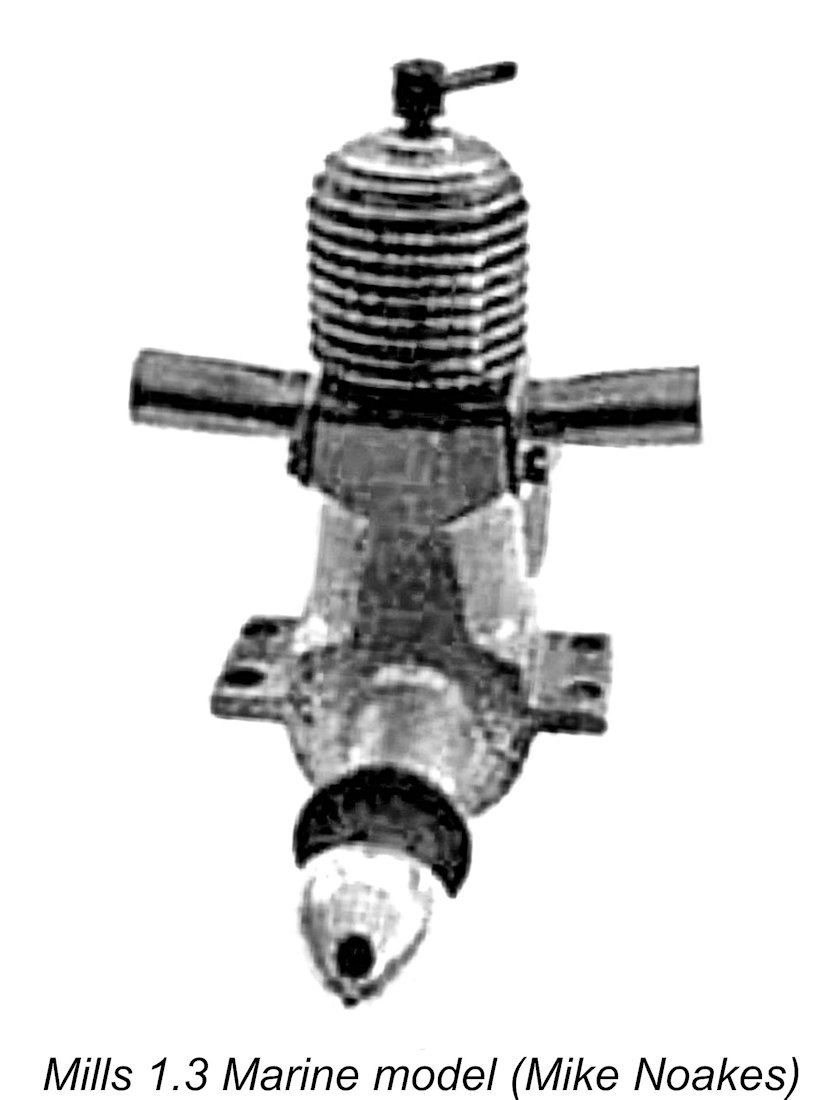

One noteworthy aspect of Mills Brothers model engine production (in the context of the British marketplace) was the fact that they never produced any marine versions of their engines apart from a very few examples of an aluminium-case 1.3 cc model in 1948, of which more below in its place. It's true that the market for marine engines was significantly smaller than that for aero units. It's also an inescapable fact of life that the use of magnesium castings would have made the Mills engines unusually susceptible to corrosion in marine applications. These factors may well have discouraged the company from entering the marine engine field in a big way.

One noteworthy aspect of Mills Brothers model engine production (in the context of the British marketplace) was the fact that they never produced any marine versions of their engines apart from a very few examples of an aluminium-case 1.3 cc model in 1948, of which more below in its place. It's true that the market for marine engines was significantly smaller than that for aero units. It's also an inescapable fact of life that the use of magnesium castings would have made the Mills engines unusually susceptible to corrosion in marine applications. These factors may well have discouraged the company from entering the marine engine field in a big way.

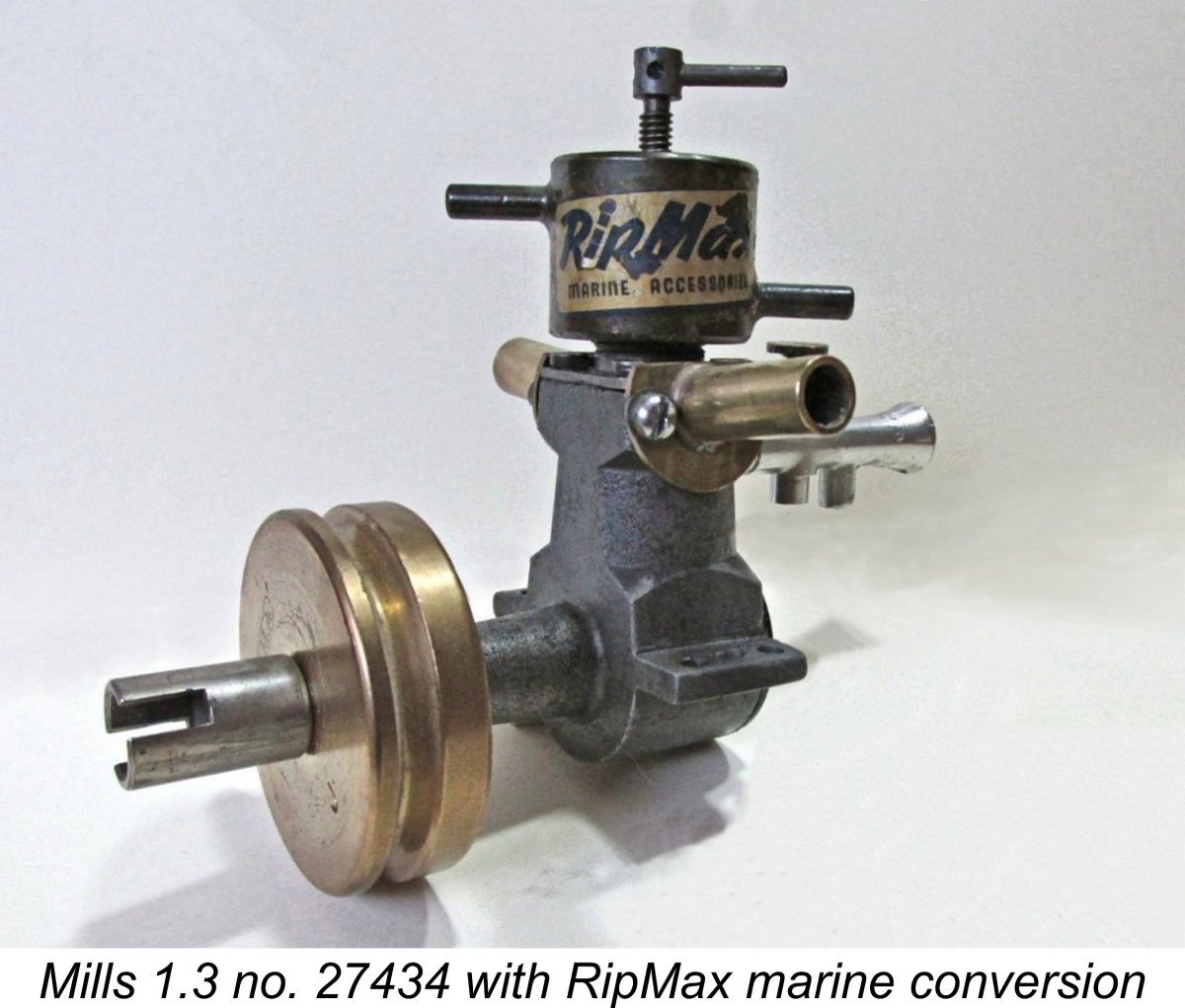

However, others took note of the fact that in terms of their performance characteristics the Mills engines would doubtless make excellent marine engines in an operational sense. My valued French friend and colleague Christian Farcy, who specializes in marine engines, has confirmed that RipMax included marine conversion kits for both the Mills .75 and 1.3 models in their extensive range of such kits for a wide variety of British model engines. Chris's illustrated example of the Mills 1.3 (no. 27434) is fitted with one of these conversions. Note that this example is also fitted with a nice pair of exhaust stacks along the lines of the earlier Mills 1.3 aluminium-case model (see below), although the serial number and the case material both confirm that it is not in fact one of those models. It's unclear whether or not the fitting of exhausts stacks was a service which was offered by RipMax to purchasers of its marine conversions.

Things continued in this manner throughout the nineteen-fifties. In 1960, Mills Brothers (Model Engineers) Ltd. was acquired by the Ayling Industries Group. At the outset the new owners stated their intention to continue production and even pursue the expansion of the Mills model engine range.

Things continued in this manner throughout the nineteen-fifties. In 1960, Mills Brothers (Model Engineers) Ltd. was acquired by the Ayling Industries Group. At the outset the new owners stated their intention to continue production and even pursue the expansion of the Mills model engine range.

For a time, it appeared that this intention might actually be fulfilled, at least in terms of continued production. Arnold Hardinge remained as plant manager to oversee the ongoing manufacture of the .75 and 1.3 models which he knew so well. However, model engine production was finally terminated in 1964 in order to free the company to apply its resources to the more lucrative aviation market which had been exploited earlier by Hardinge. As far as can now be determined, Arnold Hardinge retired from the company at this point.

In fairness to Ayling, it must be admitted that production figures for the Mills range had almost certainly fallen off considerably by this time. The engines were undoubtedly well into their transition from mainstream status to the “cult” category at this point. Even so, they continued to be widely (and justifiably) regarded as the ideal beginner and sports engines.

A significant factor in reducing demand was doubtless the fact that the Mills engines were unusually durable, tending to last forever in service. Consequently, many of the tens of thousands of engines that had been manufactured remained in service or readily available in good condition on the second-hand market at the time in question (just as they still do today, albeit at somewhat higher prices!). Those who wanted one could readily fill their needs by looking to that market rather than buying new. I have to confess my own guilt in this regard - I never purchased a new Mills because good used ones were readily available at a lower price. In that sense, the range may have fallen victim to its own excellence!

Even so, the psychological void left by the demise of the Mills engines was considerable. For most active British aeromodellers in 1964, diesels still ruled and the Mills engines had “always been there”! Peter Chinn went so far as to characterize the termination of the range as being viewed as “……..nothing short of a national disaster by those who had come to regard the .75 as almost indispensable to the survival of the hobby". Although I never bought a new Mills engine during the time when they were still being produced, I well recall my own feelings of shock and loss arising from the news of their departure from the scene.

Thankfully, this unhappy event was very far from being the end of the Mills story - in fact, in many ways it was only the end of the beginning! When Ayling ended all Mills production, the remaining factory spare parts inventory was taken over in whole or in part by an entity called Woking Models, who continued to supply new original parts for some time thereafter. However, there's no evidence that Woking Models assembled any complete engines. Indeed, they may have been acting merely as a retail outlet to help Ayling to dispose of a redundant asset.

Thankfully, this unhappy event was very far from being the end of the Mills story - in fact, in many ways it was only the end of the beginning! When Ayling ended all Mills production, the remaining factory spare parts inventory was taken over in whole or in part by an entity called Woking Models, who continued to supply new original parts for some time thereafter. However, there's no evidence that Woking Models assembled any complete engines. Indeed, they may have been acting merely as a retail outlet to help Ayling to dispose of a redundant asset.

Even before production at their Mills Brothers subsidiary ended, Ayling had already been looking for a buyer for their model engine manufacturing interests. In April 1963 an expression of interest was received from Mr. Suresh Kumar, a businessman, manufacturer and keen modelling enthusiast from Calcutta, India. Following a fairly lengthy period of negotiation, the surviving dies, designs, drawings, production fixtures, tooling and parts inventory were finally acquired by Mr. Kumar in early 1965. Mr. Kumar also acquired the exclusive worldwide right to the use of the Mills name. At around the same time he also acquired rights, production equipment and parts inventory for the defunct Allen-Mercury (A-M) series as well as certain FROG models. He went on in 1969 to add the rights to the Taplin Twin to his list of acquisitions. His products were marketed under the Aurora name. Flying model kits were produced in addition to the engines.

At the outset, the Aurora Mills reproductions fell well short of matching the quality and durability of the Mills Bros. originals, although the better examples performed quite well, also retaining the easy starting and flexible operating characteristics of the originals thanks to their generally excellent piston/cylinder fits. Mr. Kumar worked diligently to address many of the problems with those early engines, the result being that the later examples were significantly improved. They served as a much appreciated stop-gap pending the many subsequent revivals which followed from numerous other manufacturers.

However, that’s another story in itself, which I have summarized in a separate article to be found on this website ……………… suffice it to say here that the Mills engines are almost certainly the most-replicated model engines of them all. If that sound like a compliment to the design, that's because it is!

Now, having briefly summarized the origins and subsequent manufacturing history of the Mills model engine range, we need to say something about the main focus of this article – the Mills serial number system.

The Mills Serial Numbering System

It has been claimed by a number of previous commentators that the Mills serial numbering system is somewhat “disjointed” and hence of little use in the estimation of production figures. While we agree with the comment about the system displaying a number of anomalies, we believe that there are rational explanations for both the numbering sequences and most of the associated anomalies. Consequently, we believe that the system is generally quite intelligible and that some fairly reliable production estimates can be derived. Let’s see if we can convince you!!

The serial numbers applied to the Mills engines are interesting in that for the most part they were applied in two elements which were stamped in two separate locations. A two or three-digit number appears on one lug with another two or three-digit number generally (but not invariably) appearing on the other lug. The total number of digits reported to date varies from two to five. If more than two digits are involved (as they usually are), they are generally (but not always) split between the two lugs. The numbers for the rare two-digit examples all appear on one lug. The number of digits on the left-hand lug varies between two and three.

The fact that the numbers were split in this way would appear at first glance to imply that the makers saw the two elements of the overall number as somehow distinct. It has been suggested that one element (generally the one appearing on the left-hand lug) was in effect a “batch number” and that the other element indicated the engine’s sequential location within that batch.

However, this view of the matter is seriously undemined by the fact that the two-digit "batch numbers" on the left-hand lug are in fact duplicated for the same model in some cases. The lower-numbered examples of the Mills 1.3 Mk. I (for example) display two-digit numbers on the left-hand lug which are duplicated on later examples of the Mills 1.3 in its Mk. II form. For example, engine numbers 1995 and 2075 reported by Mike Noakes display the numbers 19 and 20 on the left-hand lug, as do many examples of the later Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 in the 19000 - 20999 range. No exclusivity, hence these can't be batch numbers.

Furthermore, engine numbers on both lugs of the later chromate-blackened magnesium case models were clearly stamped prior to the chromate blackening process being applied, and hence prior to final assembly. The inescapable conclusion is that all of the numbers on each case were applied at the same time, since the chromate treatment necessarily had to be applied prior to assembly.

It thus appears to be the case that the unassembled cases were sequentially numbered in full prior to being sent to the assembly line. The result would be nothing more than a simple sequential numbering system for each model - the only variable would be the starting point of the sequence for each model. The number was likely split between the two lugs for no better reason than the fact that the Mills mounting lugs would not have accommodated a four or five-digit sequence on one lug using the available numerical dies (have a look for yourself!).

In summary, it appears that the Mills engines of a given type were simply numbered sequentially from a specific starting point for that model, the numbers being applied to the cases prior to assembly. The anomalies to which we have referred will be discussed as we look though the data for each specific model. However, those anomalies are very much the exceptions.

The most noteworthy conclusion arising out of the above discussion is the complete absence of any evidence whatsoever for any “hidden” indication of the date of manufacture in the above numbers. As far as I’m presently aware, the only British model engine ranges for which dates can be accurately derived from serial numbers are the original E.D. engines up to 1963, the later E.D. models from the Surbiton era (dated by year and month only) and the early ETA models.

The key objective of the present project was to collect as many Mills serial numbers as possible for the purpose of establishing a statistically dependable database upon which to base our conclusions regarding production figures for these engines. This has been done before, most notably by Mike Noakes in the context of his excellent 5-part series on the Mills engine in the pages of MEW. However, that information is not available on line. Moreover, there’s always value in testing the reported results from a single previous survey using independently-collected evidence. There’s also always more to be learned.

To accomplish our objective, David Owen and I needed help! In addition to the examples in our own possession, a number of other Mills owners contributed to this study, and we’d like to acknowledge their assistance. Like David, some of them are no longer with us, but their assistance merits acknowledgement all the same.

So big thanks go out to Roger Schroeder, Ivor F, Bert Streigler, Nick Brooks, Dave Campling, Paul Rossitter, Peter Scott, Peter Coleman, Stan Pilgrim, Maris Dislers, Vic Johnson, Mike Noakes (both through his MEW articles and through direct contact), Alf Maslin and Bob Allison. Sincere apologies to anyone whom we’ve inadvertently missed. Without the many additional serial numbers provided by these gentlemen, David and I could never have assembled anything approaching a statistically reliable sample.

I should mention that following the initial appearance of this article, both Alan Strutt and Chris Murphy provided additional serial numbers which contributed greatly to the enhancement of our knowledge. Much appreciated, guys!

OK, time now to commence our review of the serial numbers associated with each of the Mills models and attempt to draw what conclusions we can from those data. Since they came first, we’ll start by looking at the 1.3 cc models in sequence. Those who are interested in a specific Mills model of any particular displacement are invited to skim though the following sections to find the paragraphs relating to that model.

Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 1 (July 1946 – c. October 1946)

This is the original 1.3 cc engine which was introduced in June of 1946. It was in fact one of the very first commercial model diesels to appear in Britain. The Leesil from Bradford in Yorkshire may possibly have preceded it by a month or two, but that is not certain. The Owat 5 cc fixed compression diesel (also from Bradford) seems to have come onto the market at about the same time as the Mills.

This is the original 1.3 cc engine which was introduced in June of 1946. It was in fact one of the very first commercial model diesels to appear in Britain. The Leesil from Bradford in Yorkshire may possibly have preceded it by a month or two, but that is not certain. The Owat 5 cc fixed compression diesel (also from Bradford) seems to have come onto the market at about the same time as the Mills.

However, neither of these other models represented a serious competitor to the Mills, which thus had the field more or less to itself during the balance of 1946. This allowed the manufacturers to sell the engine at a premium retail price of £5 5s 6d (£5.28) complete with airscrew. Although this was a rather high price at the time, representing at least a week’s take-home wages for an average individual in early post-WW2 Britain, the attractions of the engine were such that the company quickly found that it could sell all that it could bring to the market, and more. In fact, demand rapidly outstripped supply, forcing the company to make alternative arrangements for the engine's manufacture, as recounted earlier.

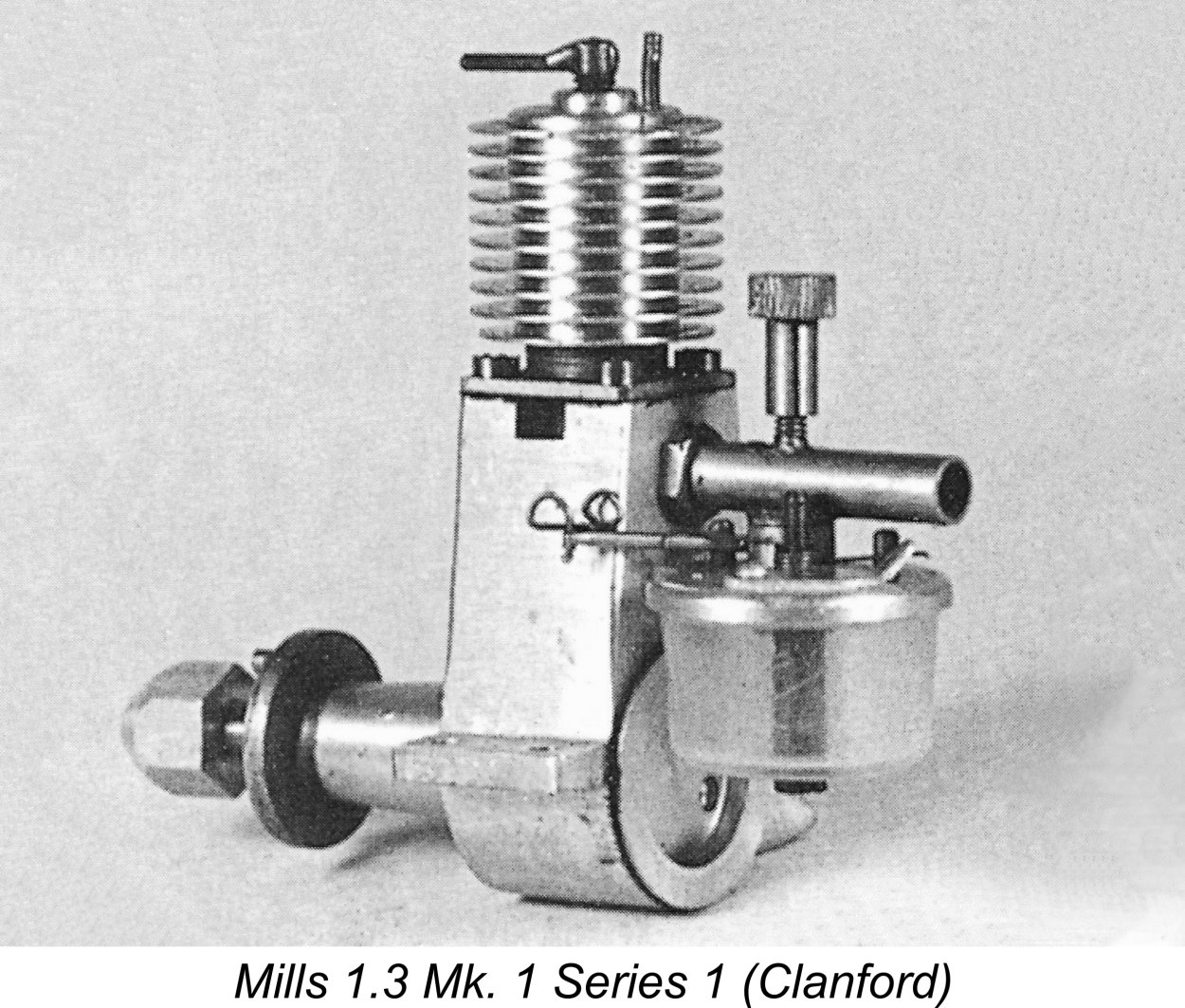

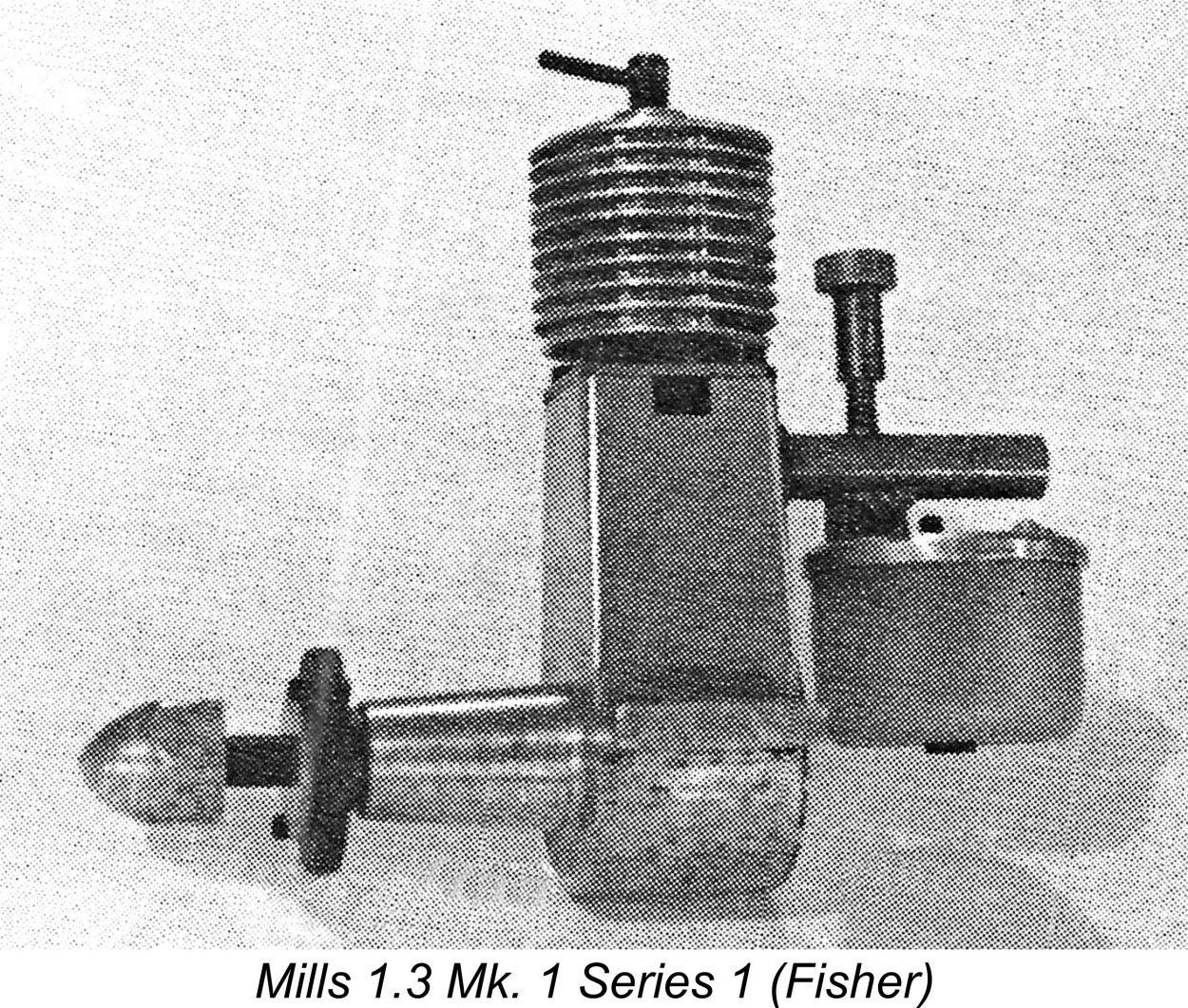

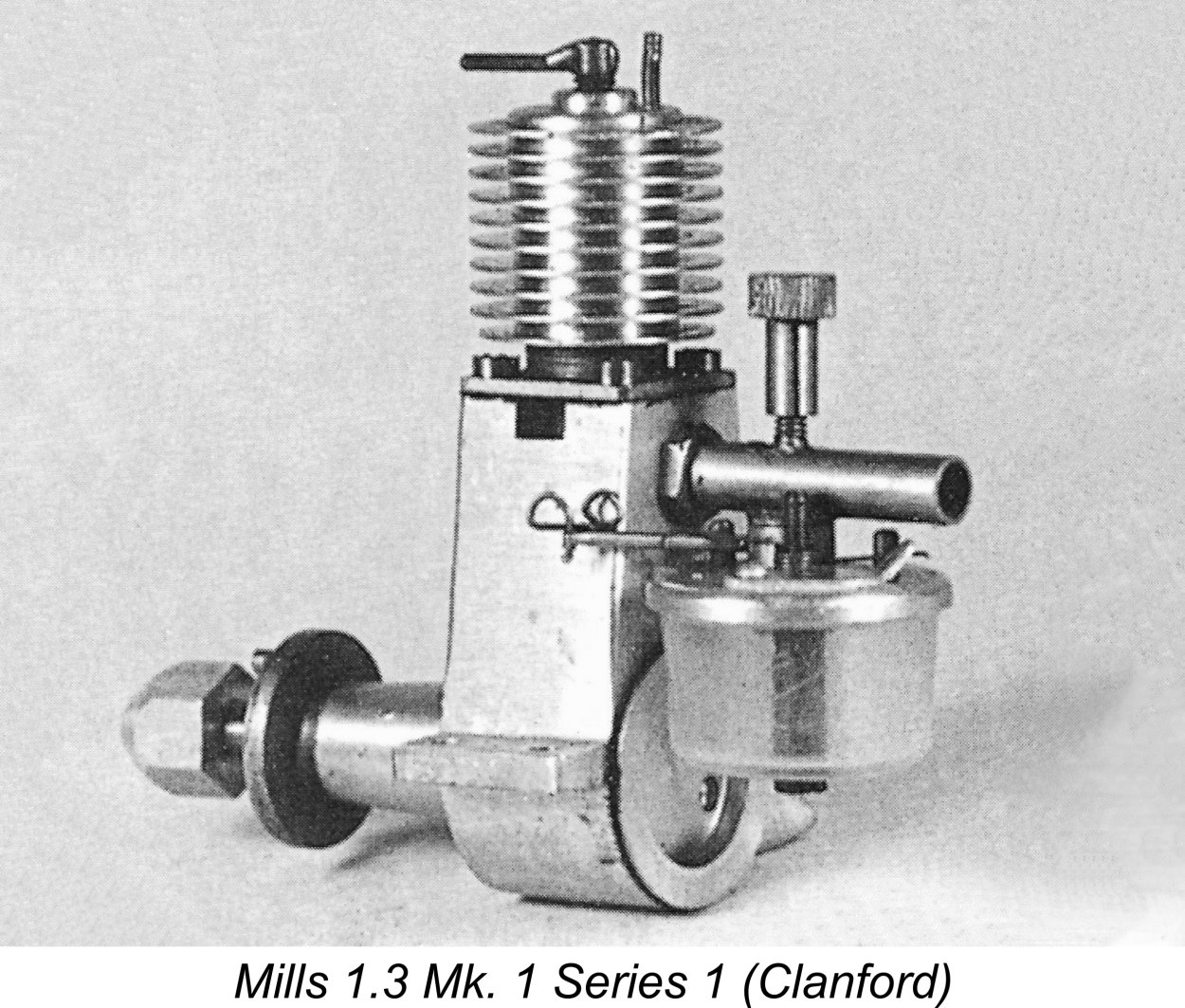

This introductory model featured a slab-sided aluminium crankcase with a plain brushed finish. The intake venturi was a straight parallel-sided screw-in tube which was secured by a lock-nut. A spring-loaded cut-out arm was provided.

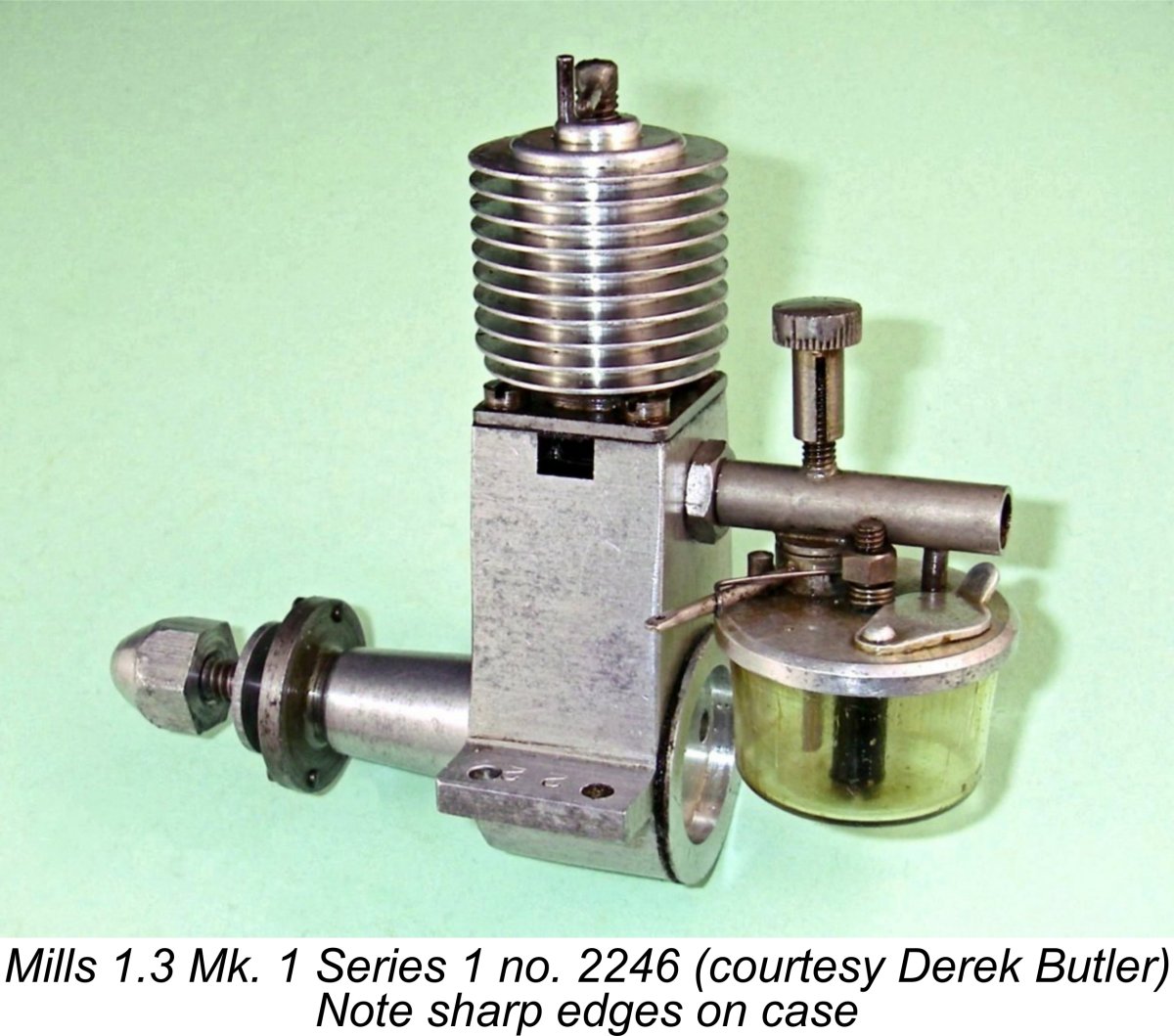

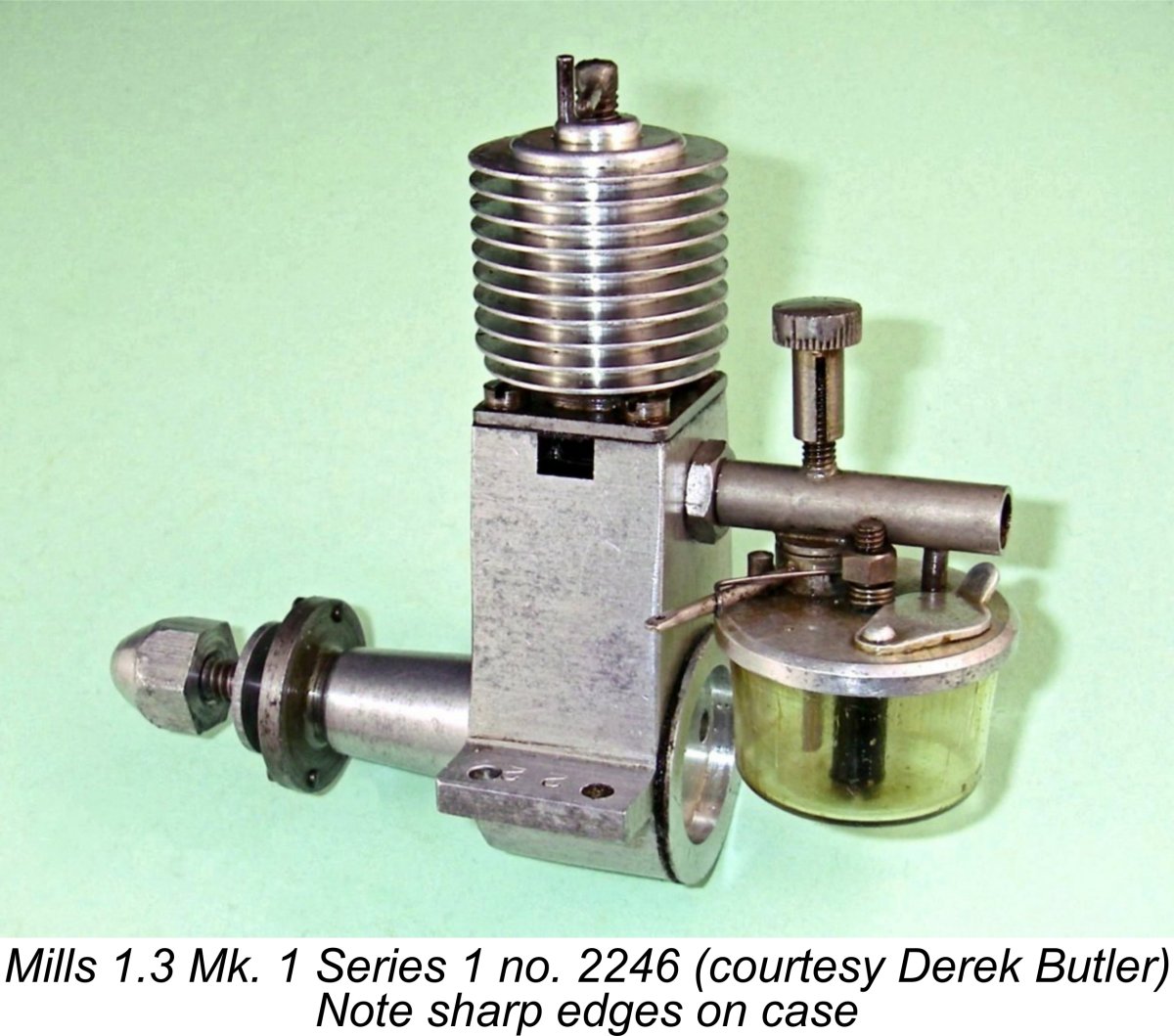

This variant was distinguished from the later Mk. 1 Series 2 variant by its straight-finned cooling jacket, which actually widened very slightly towards the top. Another distinguishing feature is the fact that the edges of the vertical portion of the crakcase were left "sharp" as machined. The edges on later models were generally rounded off by filing. Finally, the Series 1 engine also had a one-piece main bearing bushing as opposed to the two-piece bushing which was used in the following Series 2 variant (see below).

Unquestionably original engines having the straight-finned head and one-piece main bearing bushing are quite rare. The lowest reliably-reported serial numbers for examples of this variant which we accept as genuine originals are 17 and 40, both of which appear on one lug only. Seemingly the first batch of 1000 engines was the “zero” batch, which started at engine number 1 and was not represented by a number on the opposite lug since there was room for a two or three-digit number on one lug only.

Unquestionably original engines having the straight-finned head and one-piece main bearing bushing are quite rare. The lowest reliably-reported serial numbers for examples of this variant which we accept as genuine originals are 17 and 40, both of which appear on one lug only. Seemingly the first batch of 1000 engines was the “zero” batch, which started at engine number 1 and was not represented by a number on the opposite lug since there was room for a two or three-digit number on one lug only.

We are also aware of straight-finned engine number 2246, which was reported by my friend and colleague Derek Butler. Since Derek is only the second owner of this near-pristine and little-used example, its provenance as original seems pretty secure. The results of a test of this example appear in a separate article on this site.

Based on the presently-available evidence, we appear to be pretty secure in stating that the production figures for the Mk. I Series 1 variant of the Mills 1.3 undoubtedly got up at least into the middle of the 3000 range. Initial confirmation of this came from my English informant Alan Strutt, who read the article as originally published and was subsequently kind enough to contact me to advise that he has apparently-original Mk. 1 Series 1 engine number 2873. The notion was further reinforced by my subsequent encounter with what appeared to be a little-used and all-original example bearing the number 3777.

In support of these numbers, Mike Noakes found some rather tenuous evidence to suggest that the Mk. 1 Series 1 variant may have continued all the way up to serial number 4500. While this is certainly possible, none of the engines reported by our correspondents in connection with the present independent study having serial numbers above 4000 displayed the signature features of this early model.

In support of these numbers, Mike Noakes found some rather tenuous evidence to suggest that the Mk. 1 Series 1 variant may have continued all the way up to serial number 4500. While this is certainly possible, none of the engines reported by our correspondents in connection with the present independent study having serial numbers above 4000 displayed the signature features of this early model.

It seems not impossible that some higher-numbered engines of the later Series 2 configuration may have been retro-fitted by previous owners with replica straight-finned Series 1 cooling jackets (easily made), presumably to enhance their perceived value as collectibles. A probable example of this is found in the shape of Chris Murphy's 1.3 Mk. 1 engine number 11135 which has a straight-finned head but is clearly numbered deep in the Mk. 1 Series 2 range (see below).

Of course, one can't discount the alternative possibility that engines having numbers below 4500 which sport the contoured jacket (such as engine number 1746 in our survey, which unquestionably lies within the confirmed Series 1 serial number range) may have been retro-fitted with later cooling jackets to replace original straight-finned components which had been damaged in some way. We'll probably never know for sure.

Overall, it appears to me to be probable that relatively few examples of the Mk. 1 Mills 1.3 were produced with the straight head fin profile, sharp case edges and one-piece main bearing bushing which distinguish the Series 1 variant. It’s quite possible that fewer than four thousand examples were produced with these features. The majority of these may in fact be the original engines produced at Mills Brothers’ Sheffield manufacturing facility prior to production being transferred to Woking in late 1946.

Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 (c. November 1946 – May 1948)

The timing of this variant's introduction seems to coincide very closely with the establishment of the Mills Bros. model engine manufacturing operation at Woking. In terms of its external appearance, the sole distinguishing features of this variant from its predecessor are the use of a revised cooling jacket having the top two fins turned to reduced diameters to give a “beehive” effect and the filing of the vertical edges of the crankcase. Both revisions were probably just a matter of “prettying-up” the otherwise rather utilitarian engine.

The timing of this variant's introduction seems to coincide very closely with the establishment of the Mills Bros. model engine manufacturing operation at Woking. In terms of its external appearance, the sole distinguishing features of this variant from its predecessor are the use of a revised cooling jacket having the top two fins turned to reduced diameters to give a “beehive” effect and the filing of the vertical edges of the crankcase. Both revisions were probably just a matter of “prettying-up” the otherwise rather utilitarian engine.

The only other change of which I’m aware was a switch from a one-piece main bearing bushing inserted from the rear to a two piece design whose two components were pressed in from opposite ends. It’s unclear whether or not there were any other internal changes, but it actually seems rather unlikely.

Reported serial numbers for a sample of 26 examples of this variant go from a low figure of 1746 (perhaps one of the previously-noted Series 1 examples which may have replacement heads) all the way up to 15838, split between the two lugs as usual with Mills engines. It’s tempting to assume that the serial numbering for this variant started at 2500 (or perhaps 4500), but this is completely unsubstantiated at the present time. This model was replaced by the comprehensively revised magnesium-case Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model (see below) in June 1948.

Reported serial numbers for a sample of 26 examples of this variant go from a low figure of 1746 (perhaps one of the previously-noted Series 1 examples which may have replacement heads) all the way up to 15838, split between the two lugs as usual with Mills engines. It’s tempting to assume that the serial numbering for this variant started at 2500 (or perhaps 4500), but this is completely unsubstantiated at the present time. This model was replaced by the comprehensively revised magnesium-case Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model (see below) in June 1948.

Mike Noakes reported that the aluminium crankcase of engine number 15682 had been turned down below the exhaust ports to resemble the revised magnesium crankcase of the Mk. 2 Series I model. This brings up a significant point which seems to warrant a mention at this juncture. Mike also noted the existence of a very limited number of  additional examples of the Mills 1.3 featuring similarly-machined aluminium cases but bearing serial numbers in the 30000 - 30300 range. These engines also featured tapped holes below their exhaust openings to facilitate the fitting of bolt-on exhaust stubs. Most examples have lost their stubs, but a few do survive to attest to their existence. Mike Noakes' illustrated example is one of these rare survivors, as is the example photographed by Ken Campbell.

additional examples of the Mills 1.3 featuring similarly-machined aluminium cases but bearing serial numbers in the 30000 - 30300 range. These engines also featured tapped holes below their exhaust openings to facilitate the fitting of bolt-on exhaust stubs. Most examples have lost their stubs, but a few do survive to attest to their existence. Mike Noakes' illustrated example is one of these rare survivors, as is the example photographed by Ken Campbell.

In hs 1991 survey of the Mills engines for the late Tim Dannels' “Engine Collectors’ Journal” (ECJ), the late Roger Schroeder designated this variant as the “Anniversary Model”, seemingly on the basis of anecdotal information received from England without supporting evidence. In fact, the name appears to have originated with one of Roger's 1991 contacts, who gave Roger the name without providing any supporting evidence for its legitimacy.

As far as I'm aware, no such evidence exists! Accordingly, unless someone can provide compelling evidence to prove otherwise, I'm personally satisfied that no designated Mills "Anniversary Model" ever existed! Maris  Dislers and I have collaborated in a detailed analysis of this matter in a separate article to be found on this website. The reality appears to be that these twin-stack aluminium-case units are actually examples of the short-lived Mills 1.3 Marine Model, which is discussed more fully in Maris's separate article on the Mills marine engines.

Dislers and I have collaborated in a detailed analysis of this matter in a separate article to be found on this website. The reality appears to be that these twin-stack aluminium-case units are actually examples of the short-lived Mills 1.3 Marine Model, which is discussed more fully in Maris's separate article on the Mills marine engines.

Returning now to the Mk. 1 Mills 1.3, the reported serial numbers suggest that some 16,000 examples of that variant (including both Series) were manufactured over an approximately twenty-two month production period – a rate of around 725 units monthly. Given the fact that this was the only model being manufactured by Mills Bros during this period, this appears to be a perfectly credible figure, although it does imply the mobilization of a significant workforce. However, it pales beside the figures achieved by the far larger E.D. manufacturing venture in nearby Kingston-on-Thames, which showed itself to be capable of producing over 2,000 examples of a single model (among several others) in a given month.

Oddly enough, the above figures suggest that this variant was the Mills 1.3 model which was actually manufactured in the largest numbers. Speaking personally, I find this to be intuitively surprising …… but there it is!

Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 (June 1948 – November 1949)

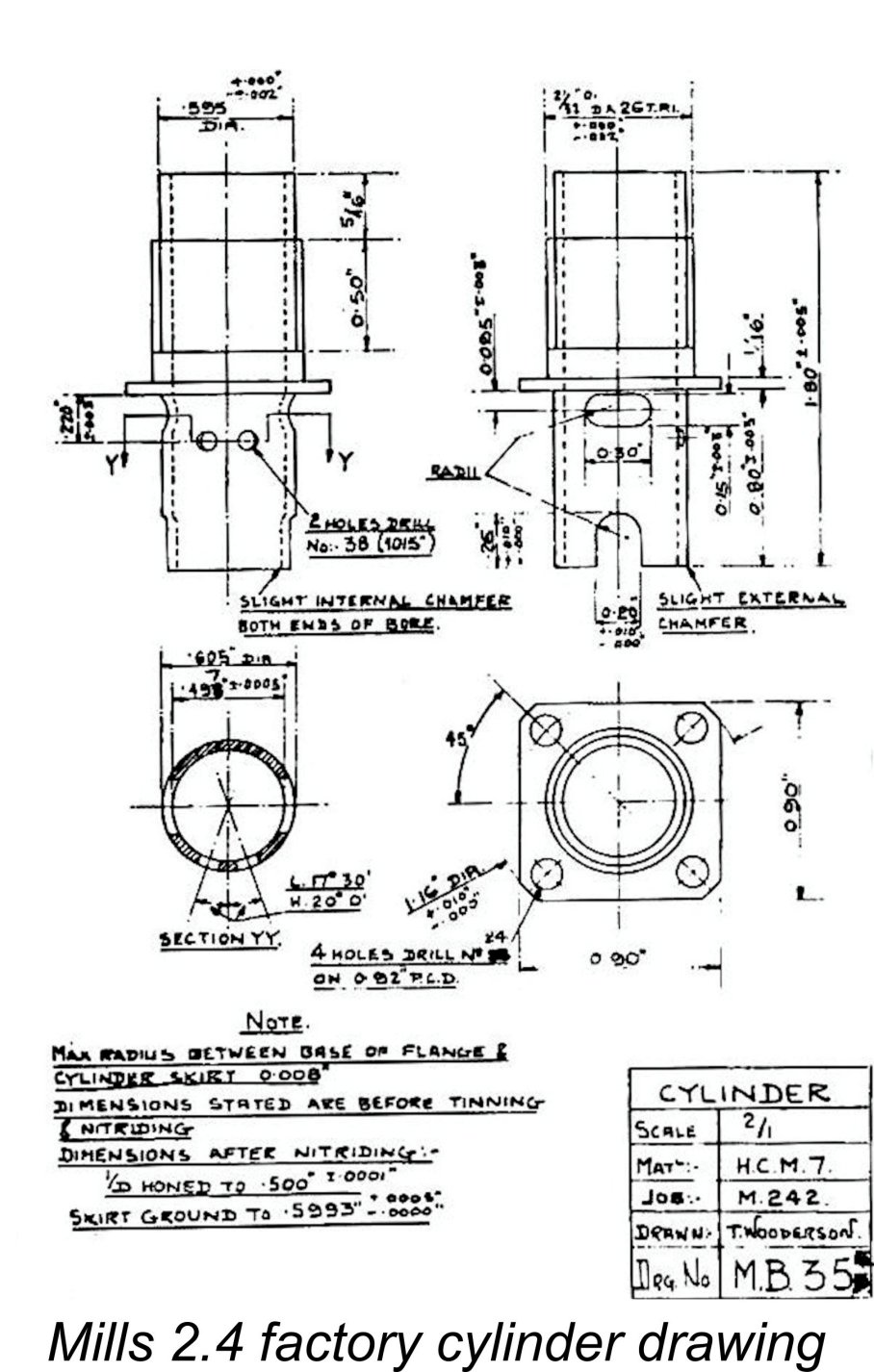

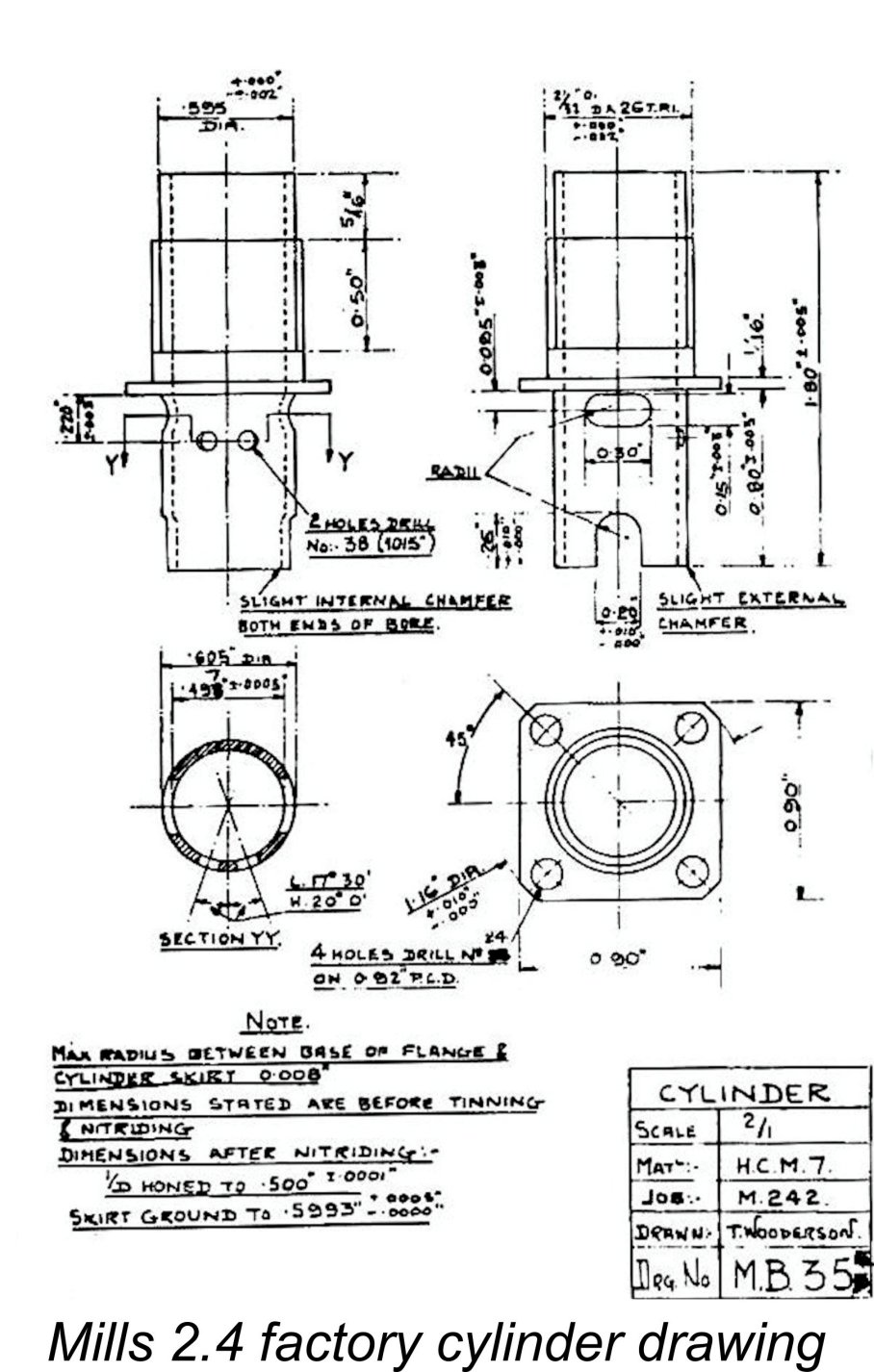

This variant appeared in June 1948 to replace the previously described Mk. 1 Series 2 model. The design revisions which it embodied were principally developed by Trevor Wooderson, who also designed the companion 0.75 cc and 2.4 cc models (see below).

This variant appeared in June 1948 to replace the previously described Mk. 1 Series 2 model. The design revisions which it embodied were principally developed by Trevor Wooderson, who also designed the companion 0.75 cc and 2.4 cc models (see below).

The revised model exhibited several significant changes from the Mk. 1 designs described earlier. The most obvious of these was the cast and machined magnesium alloy crankcase with relieved sides and chromate blackening (often incorrectly referred to as black anodizing) to guard against corrosion. The use of a tapered intake venturi made of cast alloy was also a distinguishing feature.

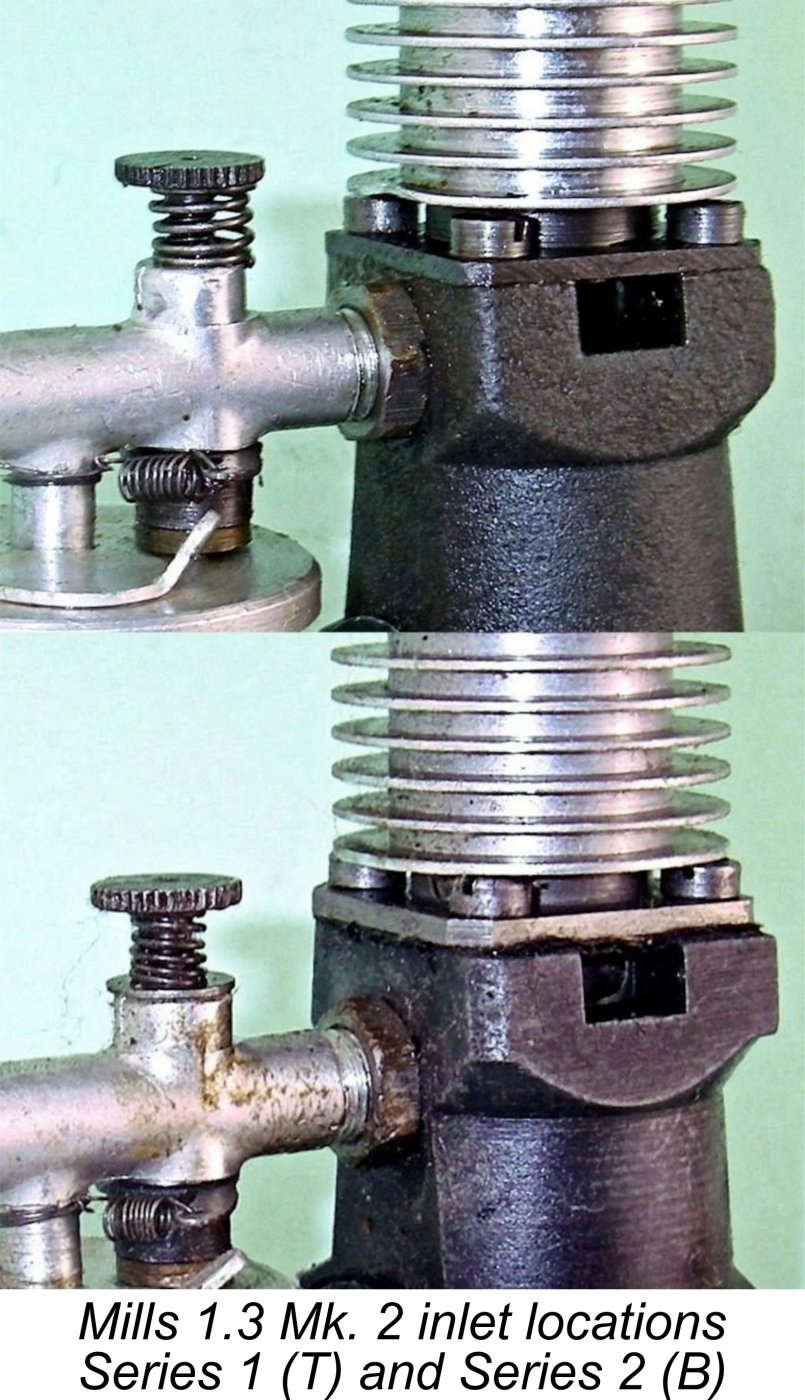

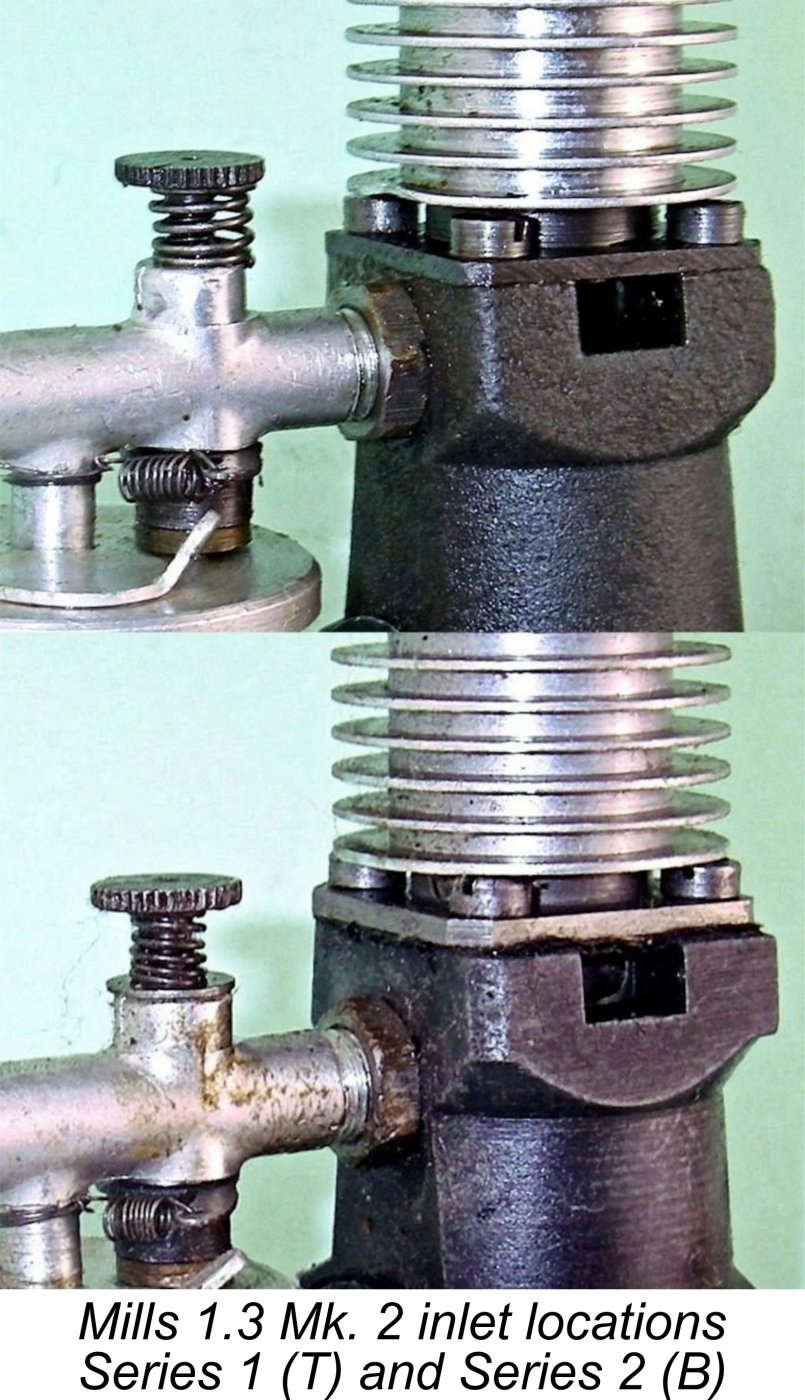

What set this variant apart from its Series 2 successor (see below) was the induction timing. The Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 variant had its induction port set comparatively high in the cylinder wall, resulting in a relatively restricted induction period.

By the time that this model appeared, the model engine market had become far more diversified, with a wide range of competing models on offer. As a result, selling price was beginning to exert a considerable influence upon sales figures. The new Mills 1.3 variant sold at a price of £4 15s 0d (£4.75), down from the £5 5s 6d (£5.28) figure which had been maintained throughout for the Mk. 1 Series 2 model discussed earlier. This was still a relatively high figure which was presumably made possible by the outstanding reputation which the Mills 1.3 had built up over its first two years on the market.

Reported serial numbers for this variant in our survey range over 14 samples from a low of 18500 up to 26459, which was specifically noted by Peter Chinn as having been the final example of this variant to come off the production line. This implies a total production figure for this model of around 8,000 units over the roughly 17 month period during which it was produced.

If this figure is accurate, it would confirm that the average production rate for the Mills 1.3 over this period had fallen to around 470 units monthly. This was almost certainly due to the diversion of manufacturing resources necessitated by the almost simultaneous introduction of the companion .75 cc Series 1 and 2.4 cc models, of which more in their place below. Even so, its relatively short production life makes this the third rarest variant of the Mills 1.3 diesel behind the original Mk. 1 Series 1 and “Anniversary” models.

If this figure is accurate, it would confirm that the average production rate for the Mills 1.3 over this period had fallen to around 470 units monthly. This was almost certainly due to the diversion of manufacturing resources necessitated by the almost simultaneous introduction of the companion .75 cc Series 1 and 2.4 cc models, of which more in their place below. Even so, its relatively short production life makes this the third rarest variant of the Mills 1.3 diesel behind the original Mk. 1 Series 1 and “Anniversary” models.

There’s an obvious gap in the sequence between the highest reported Mk. 1 Series 2 serial number (15838) and the lowest reported Mk. 2 Series 1 serial number (18500). This is one of the anomalies mentioned at the outset. Between the present survey and that conducted earlier by Mike Noakes, the number of reported examples of both models is sufficient that there’s a very low statistical probability of this gap being the result of unreported intervening serial numbers. It thus appears likely that the numbering system for the Mk. 2 Series 1 model was intentionally started at 18000 or perhaps 18500, leaving a gap of some 2000 numbers which were left available for some other product to take up.

The only rational explanation that I can come up with is the idea that the introduction of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 was preceded by the build-up of a good inventory of the new magnesium alloy crankcases which were numbered in advance of assembly, as seems to have been the usual practise. Due to the independent schedules under which certain key components may have been supplied by outside contractors, the company may have been uncertain at the time exactly when the new model would be ready, hence being uncertain how many of the original aluminium case Mk. 1 variants they would end up making. When stamping the inventory stock of the new cases, they may have left a gap in the serial numbering sequence to accommodate this uncertainty.

Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 (December 1949 – mid 1964)

This was the second and more common variant of the Mk. 2 magnesium case 1.3 cc engine. It appeared in around December 1949. It was little changed from the Mk. 2 Series 1 variant, the main distinguishing feature being a lower induction port, a change which substantially extended the inlet duration. This change resulted in a 25% increase in power output according to Peter Chinn’s test results.

This was the second and more common variant of the Mk. 2 magnesium case 1.3 cc engine. It appeared in around December 1949. It was little changed from the Mk. 2 Series 1 variant, the main distinguishing feature being a lower induction port, a change which substantially extended the inlet duration. This change resulted in a 25% increase in power output according to Peter Chinn’s test results.

This being the case, it’s something of a mystery why it took Mills Bros. so long to come up with this very worthwhile modification. You’d think that they would have experimented with different induction periods during the development phase.

This is by no means a trivial matter if you're considering acquiring a Mills 1.3 to use in a vintage model. The Series 2 variant is very noticeably more powerful than the Series 1. That said, I hasten to emphasise that both variants of the engine start and run extremely well. It's just that the Series 2 version provides a noticeable amount of extra "urge". If I had purchased a Series 1 variant just prior to the release of the Series 2, I'd have been a bit cheesed off!

Fortunately, there's no possibility of mistaking one variant for the other if you know these engines. Naturally, the serial number is the clincher - if it's lower than 26460, it's a Series 1. Quite apart from that, the lower position of the inlet on the Series 2 model is very obvious when you take a careful look. The accompanying comparative photos should make this clear.

Fortunately, there's no possibility of mistaking one variant for the other if you know these engines. Naturally, the serial number is the clincher - if it's lower than 26460, it's a Series 1. Quite apart from that, the lower position of the inlet on the Series 2 model is very obvious when you take a careful look. The accompanying comparative photos should make this clear.

By the time that this variant appeared, cost had become an even more significant factor in terms of a given engine’s sales performance as competing offerings from other manufacturers continued to proliferate. Although the manufacturing processes and associated costs required to construct the new Mills 1.3 variant were essentially unchanged from those applicable to its predecessor, the manufacturers felt compelled to reduce the retail price to £3 15s 0d (£3.75) in order to remain competitive. It must be assumed that they absorbed the price reduction through the acceptance of a reduced profit margin. The blow was doubtless cushioned by the fact that the major development costs of the Mk. 2 must surely have been fully absorbed by this time through sales of the Series 1 variant at the higher price.

The serial numbering sequence clearly continued uninterrupted when this variant was introduced. If we accept Peter Chinn’s evidence, the first of these variants off the line bore the number 26460. Our sample of 53 reported examples extends the numbering sequence from 26749 (seemingly consistent with Chinn’s evidence) all the way up to engine number 38537. These figures imply the manufacture of a total of perhaps 12,500 examples in total.

This was the final variant of the Mills 1.3, remaining in production right up to the end of the line in 1964, at which time it was selling at a modestly increased price of £4 15s 9d (£4.79), an increase which more or less reflected the degree of inflation over the same period. If our estimate of the total production figure is anywhere near correct, the average production rate for this unit over its 14½ year production life was only some 70 units monthly. Of course it was presumably far larger than this at the outset.

However, it’s necessary to recall the fact that by the time this model appeared Mills Bros. had introduced the Mills .75 Series 2 (see below), which became an instant best-seller, hence absorbing a high proportion of Mills Bros.' manufacturing capacity. The ill-fated 2.4 model also remained in limited production at this time. Both of these factors would inevitably have diverted production resources away from the established 1.3 model. Furthermore, all the evidence suggests that the Series 2 variant of the Mills .75 (see below) quickly assumed a dominant position in the production and sales picture at Mills Bros.

So much for the production history of the Mills 1.3 variants. Time now to turn our attention to the smallest and perhaps best-loved member of the Mills stable – the .75 cc model.

Mills .75 Series 1 (August 1948 - November 1949)

This is the first variant of the Mills .75. It appeared in August 1948 only a month or two after the companion Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model. Like its larger companion, it was designed by Trevor Wooderson.

This is the first variant of the Mills .75. It appeared in August 1948 only a month or two after the companion Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model. Like its larger companion, it was designed by Trevor Wooderson.

I have designated this variant as the Mills .75 Series 1 rather than as the Mills .75 Mk. 1 to respect the fact that the manufacturers themselves never used different Mark numbers in connection with the Mills .75 models. Nonetheless, some means of distinguishing the two is absolutely necessary given the very significant differences between the respective designs. I have chosen to use the Series designation for this purpose.

The initial version of the Mills .75 was basically a scaled-down rendition of the companion 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model which appeared at essentially the same time. It had a chromate-blackened magnesium alloy crankcase of similar shape to the larger model, using fours screws to hold down the cylinder. The fuel tank was retained by a spring clip and had a “tear-drop” shape. Like many others, the illustrated example has lost its original tank, which has been replaced with a component from a later model.

This model was relatively expensive to manufacture, hence surviving in production for only some 16 months. The range of reported serial numbers from a sample of 19 examples extends from a low of 33503 up to a high of 36844. We thus appear to have confirmation of the manufacture of perhaps as many as 3,500 examples of this model.

This implies that production figures for this model were relatively low. The derived monthly average of 220 examples is well below the comparable figure of 470 units for the companion 1.3 model during the same period. Presumably the 1.3 remained the Mills “flagship” model at this time.

That said, the total monthly average production figures for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 and the .75 Series 1 add up to 690 units monthly. This is very comparable with the figure of 725 units estimated earlier for the Mk. 1 Series 2 variant of the Mills 1.3. Allowing for the relatively low production figures for the 2.4 cc model which appeared at about the same time (see below), it would appear that the full production capacity at Woking had remained unchanged at perhaps some 750 total units monthly but had been re-distributed among the various models as they appeared.

That said, the total monthly average production figures for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 and the .75 Series 1 add up to 690 units monthly. This is very comparable with the figure of 725 units estimated earlier for the Mk. 1 Series 2 variant of the Mills 1.3. Allowing for the relatively low production figures for the 2.4 cc model which appeared at about the same time (see below), it would appear that the full production capacity at Woking had remained unchanged at perhaps some 750 total units monthly but had been re-distributed among the various models as they appeared.

An anomaly with which we have to deal is the fact that the numbers for the .75 Series 1 engines fall within the same range as those for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 reported earlier. Specifically, examples of both models have been reported as bearing numbers in the 33000 to 35000 bocks.

The key to resolving this anomaly almost certainly lies in the timing. All of the .75 Series 1 engines were produced prior to the introduction of the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2, at a time when the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model was its sole 1.3 cc companion in the range. We see no numbers for the .75 Series 1 below 33000, making it appear likely that they were simply leaving headroom for the continued production of the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 beyond the 26459 limit that was actually reached.

In the event, both the .75 Series 1 and the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 were replaced more or less concurrently with improved models in December 1949. The numbering sequence for the new .75 Series 2 was apparently started at 41,000 (see below) while the numbering sequence for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 was simply continued without a break from its Series 1 predecessor.

In the event, both the .75 Series 1 and the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 were replaced more or less concurrently with improved models in December 1949. The numbering sequence for the new .75 Series 2 was apparently started at 41,000 (see below) while the numbering sequence for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 was simply continued without a break from its Series 1 predecessor.

Now here’s the key point – beginning in December 1949 it would have taken quite a while (several years at least) for the 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 to get from 26460 up to the 33,000 range occupied previously by the now-discontinued .75 Series 1. By the time that it did so, the smaller model was long gone and its replacement was well established in a separate numbering sequence. Consequently, the duplication of serial numbers no longer had any significance and could be ignored.

The comparatively low production figures for the Mills .75 Series 1 model most likely had a great deal to do with the relatively high price which Mills Bros. were compelled by economics to charge for that model. The engine retailed at a price of £3 5s 0d (£3.25) at a time when the larger and more powerful E.D. Bee was selling for £2 5s 0d (£2.25) and the FROG 100 diesel could be purchased for £2 8s 0d (£2.40) fully equipped. This being the case, it was inevitable that Mills Bros. would take steps to reduce the manufacturing costs of this model. The result was the next variant to be considered here.

Mills .75 Series 2

This is the second and by far the most common variant of the Mills .75. It was introduced in November 1949 more or less concurrently with the companion 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 model described earlier. The introduction of both these models coincided very closely with Arnold Hardinge's assumption of ownership of the Mills model engine range.

This is the second and by far the most common variant of the Mills .75. It was introduced in November 1949 more or less concurrently with the companion 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 model described earlier. The introduction of both these models coincided very closely with Arnold Hardinge's assumption of ownership of the Mills model engine range.

The motivation for the development of the revised .75 model was almost certainly a desire to reduce manufacturing costs, since price was exerting an increasing influence upon sales competitiveness by this time. The new variant sold at a basic retail price of only £2 10s 0d (£2.50) - a very significant price reduction.