|

|

Those Perplexing Pierce 29 Engines

In a detailed article which appeared in January 2010 in issue no. 197 of Tim Dannel’s now sadly discontinued “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ), Tim presented an exhaustive structural comparison between the Pierce and Forster .29 cuin. disc rear rotary valve (RRV) models. I have no intention of simply repeating Tim’s detailed observations here - interested readers must seek out a copy of that article for themselves. However, I have referred to it extensively during the preparation of my own article, also being greatly indebted to Tim for his generous provision of a wealth of images from the ECJ files. Suffice it for present purposes to say that the similarities between the Pierce and Forster 29 RRV models are far too marked to be entirely coincidental. In the present article, I’ll focus on the provision of a description and chronological summary of the Pierce range. In doing so, I will necessarily include some general notes regarding the comparison between the Pierce and Forster models. Those requiring more detail are referred to Tim’s article in ECJ, from which most of that information was extracted. I’ll also include some test results extracted from a couple of examples in my possession. Having established the scope of this article, I’ll begin with a discussion of the various competing rumours surrounding the Pierce/Forster relationship. These being no more than unsubstatiated rumours, a certain amount of speculation will inevitably enter into what follows! Readers are of course quite free to form their own opinions .................. The Pierce/Forster Relationship

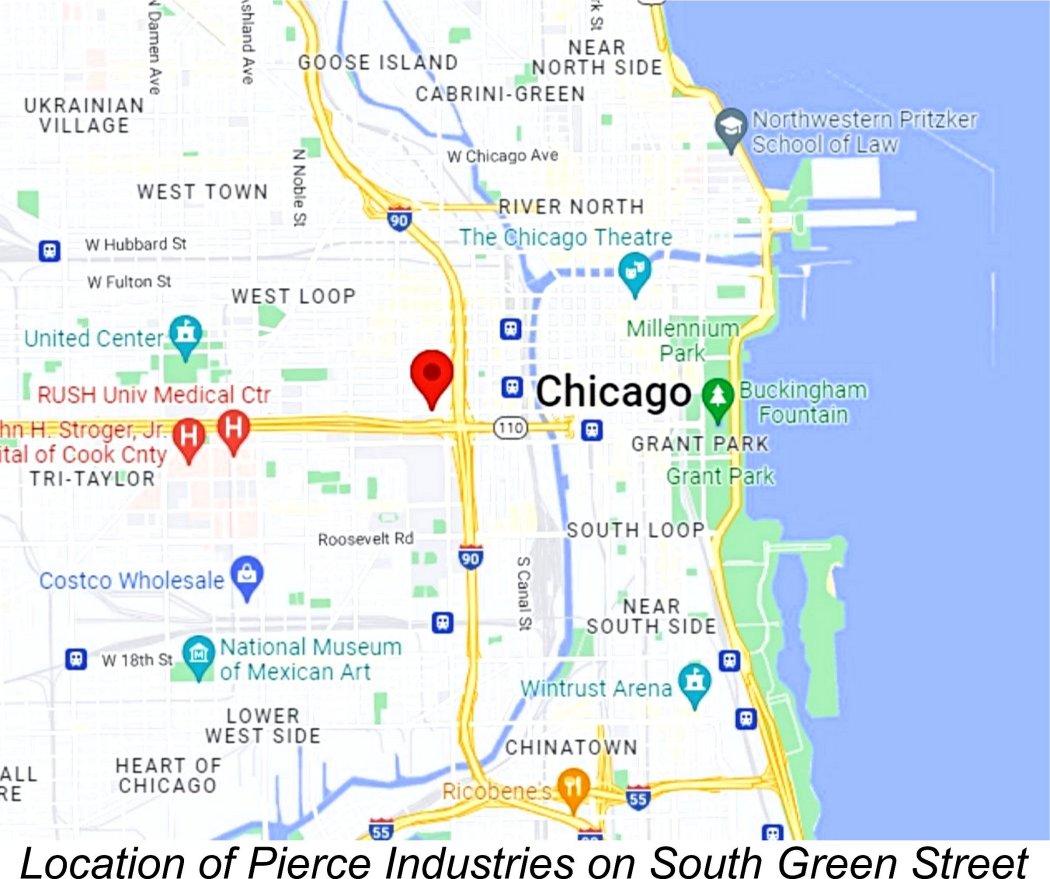

During the same period, the Forster brothers Henry and Bob were continuing to manufacture their famous and even then long-established line of model engines which had first appeared eleven years previously in 1935. During our period of interest, they were doing so from premises located at 8537 N. Kenton Avenue, Chicago 41, Illinois. They remained at that address until March 1949, when they relocated to Lanark, Illinois, a relatively small community lying some distance to the west of Chicago. By that time, the Pierce engines had already come and gone.

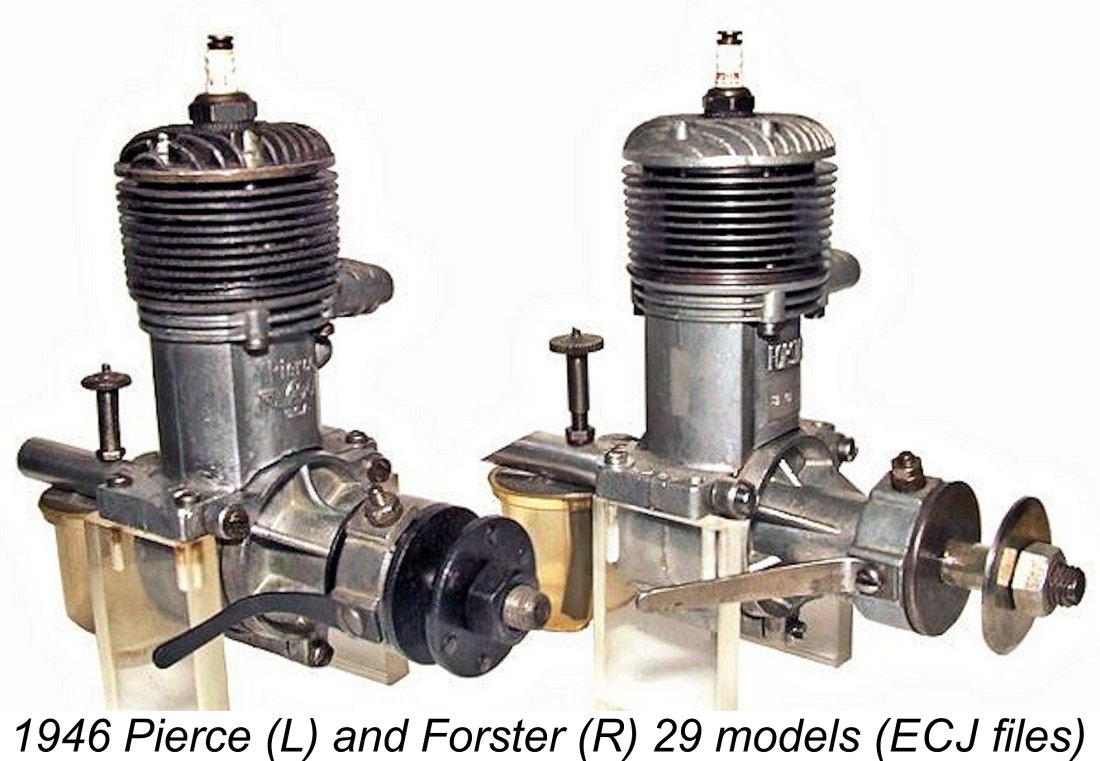

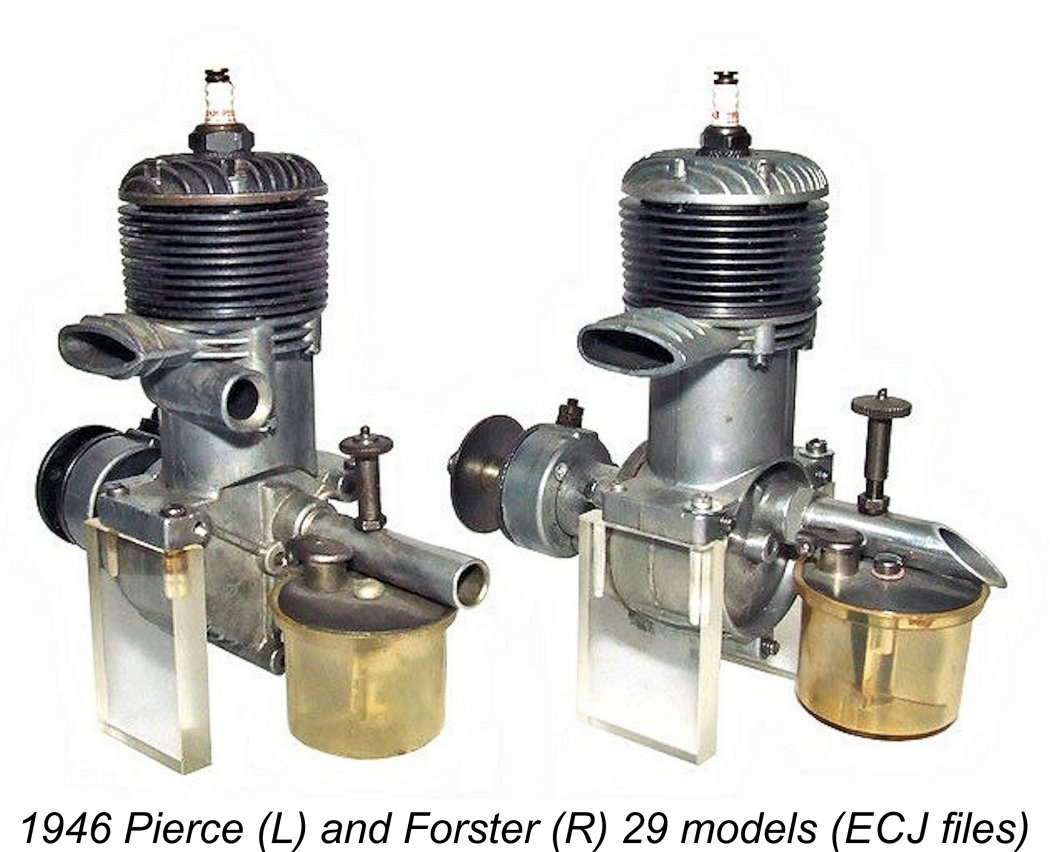

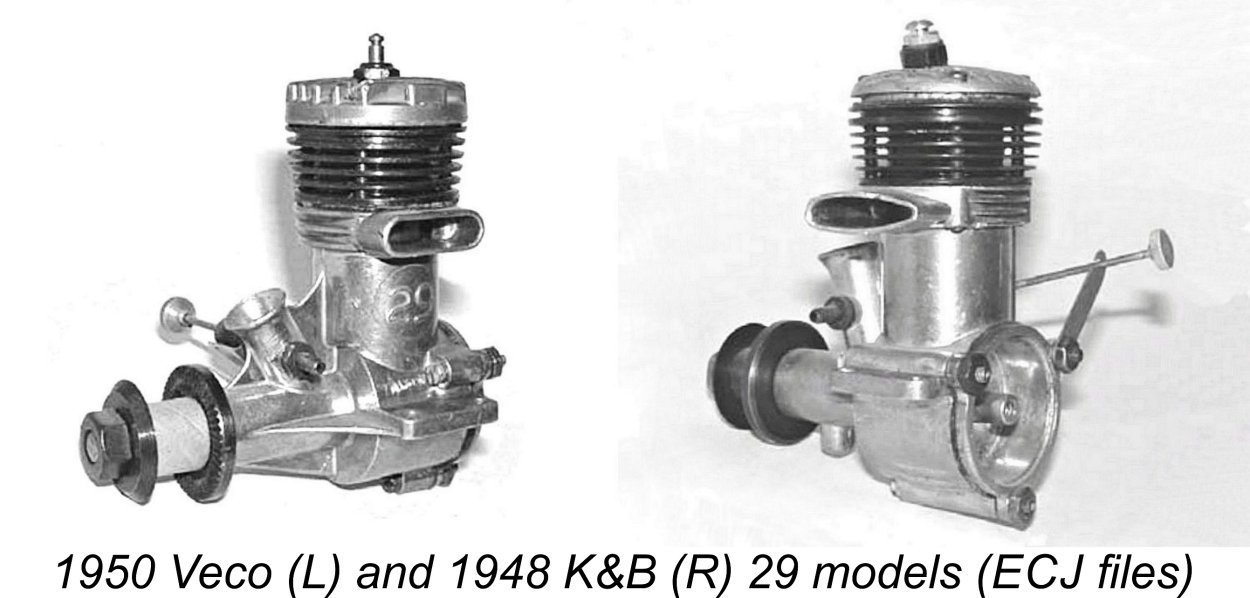

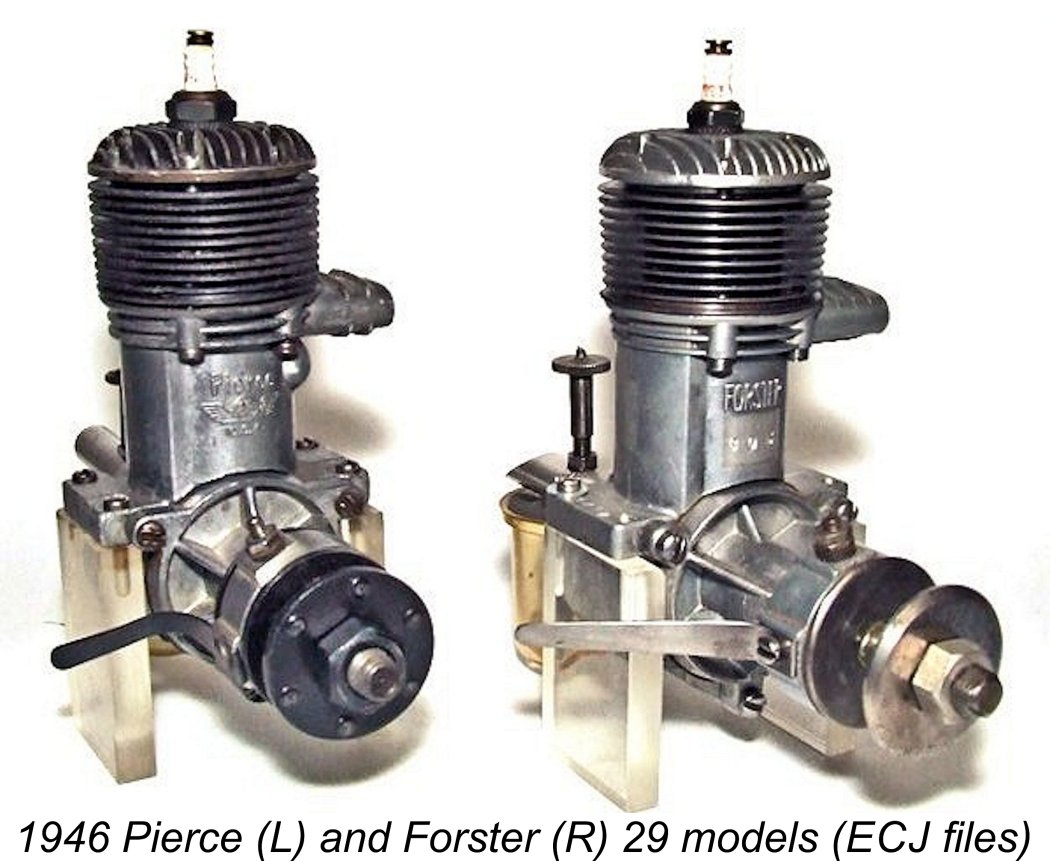

And yet some kind of relationship is clearly implied when one looks at the 1946 Pierce and Forster 29 RRV models side by side. If nothing else, it’s unarguably evident that whoever drew up the plans for the Pierce dies and components must certainly have had an early post-WW2 Forster 29 RRV unit sitting right next to the drawing board! This raises the possibility that the Pierce venture may have been initiated by a former Forster employee who wished to engage in the model engine business on his own account. However, it must be stressed that I'm aware of absolutely no hard evidence to support this possibility.

Tensions between Forster and Pierce would have been significantly exacerbated if the Pierce venture had in fact been established by a “rogue” Forster employee, perhaps sufficiently so to tip the level of animosity into the realm of actual legal intervention or the threat thereof. The joint Chicago-area location of the two companies makes this possibility appear at least credible, if completely unsubstantiated. That having been said, no-one has ever presented any hard evidence to either confirm or disprove the legal action rumour. Having discussed the unsubstantiated rumour of legal action having been taken, it’s necessary to address the equally unsubstantiated opposite rumour to the effect that Forster actually made some or all of the components of the Pierce engines. Three factors appear to me to argue quite persuasively against this possibility. The first is the inherent improbability of Forster Brothers facilitating the marketing of what amounted to their own engine by a rival company located in the same general area. Why cooperate with a neighboring copy-cat competitor to this extent? The second and perhaps more significant objection is Tim Dannels’ conclusive demonstration in his 2010 ECJ article that although the designs of the 1946 Forster and Pierce 29 RRV models were indeed very similar, to the point that most of the key components are interchangeable, those components display sufficient differences in detail to confirm Consider the example of the early K&B/Veco .29 engines, since we do know the history of the relationship between these units. The first two Veco models were manufactured for Henry Engineering of Burbank, California by K&B at their Bell Gardens, California factory. While the various castings are certainly different between the 1948 Glo-Torp 29 and the 1950 Veco .29, the cylinder/piston/rod units and crankshafts are identical, and for one simple reason - they didn’t need to make them different, so why re-tool in order to do so?!? The same would have been true if Forster had manufactured the components for the Pierce. Even though the parts remain practically interchangeable, why make slightly different crankshafts, pistons, heads, front housings, timers and needle valve assemblies, among other components? It seems highly unlikely that Forster would manufacture two distinct sets of almost (but not quite) identical components.

To me, the most probable (albeit completely unsubstantiated) scenario is that the Pierce venture was established independently by a former Forster Brothers employee who was either fired or left voluntarily, taking a detailed knowledge of the Forster 29 design with him. In the former case, the establishment of the Pierce venture might represent a desire to “get back” at the individual’s former employers by beating them at their own game with what amounted to their own product! Once again, there’s absolutely no hard evidence to support this entirely circumstantial possibility. However, it would have injected an element of animosity into the situation which might have led to legal action having been pursued or at least contemplated. It seems highly unlikely that we’ll ever know the truth behind the Pierce/Forster relationship. All that we can say is that there’s definitely an untold story there! Now that we’ve examined the background to the establishment of the Pierce venture and its relationship (or otherwise) to the Forster marque, it’s time to undertake a chronological survey of the various models which were marketed under the Pierce identity. I’ll begin by discussing the original 1946 Pierce 29 model in some detail, since the subsequent engines in the series were all modifications of this design. The First Pierce 29 Model

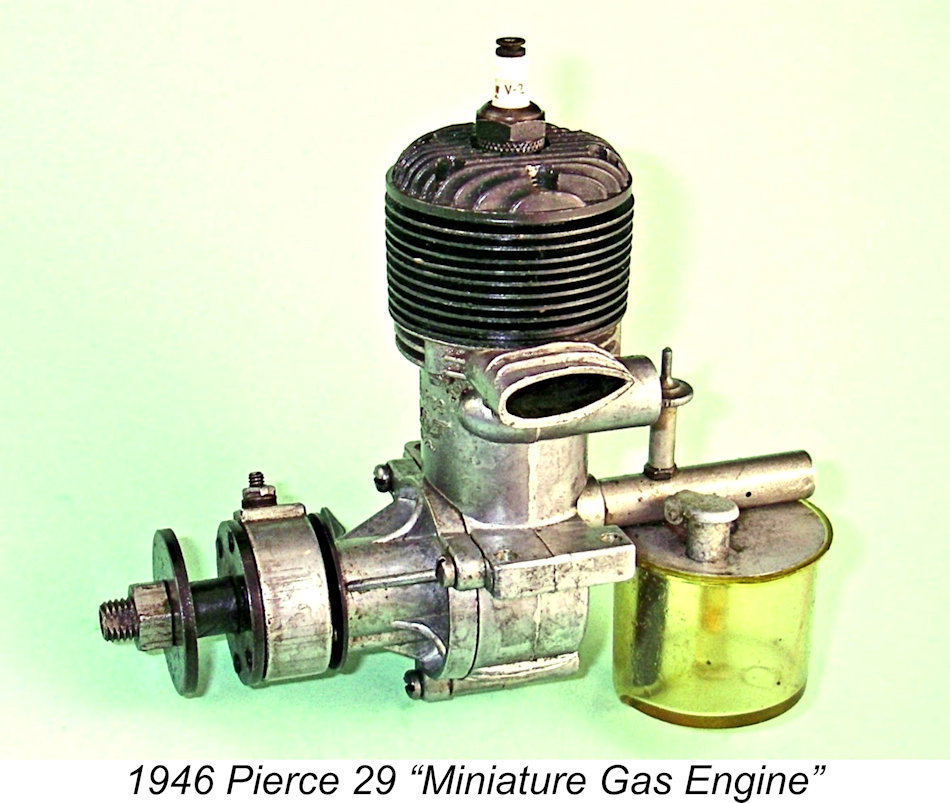

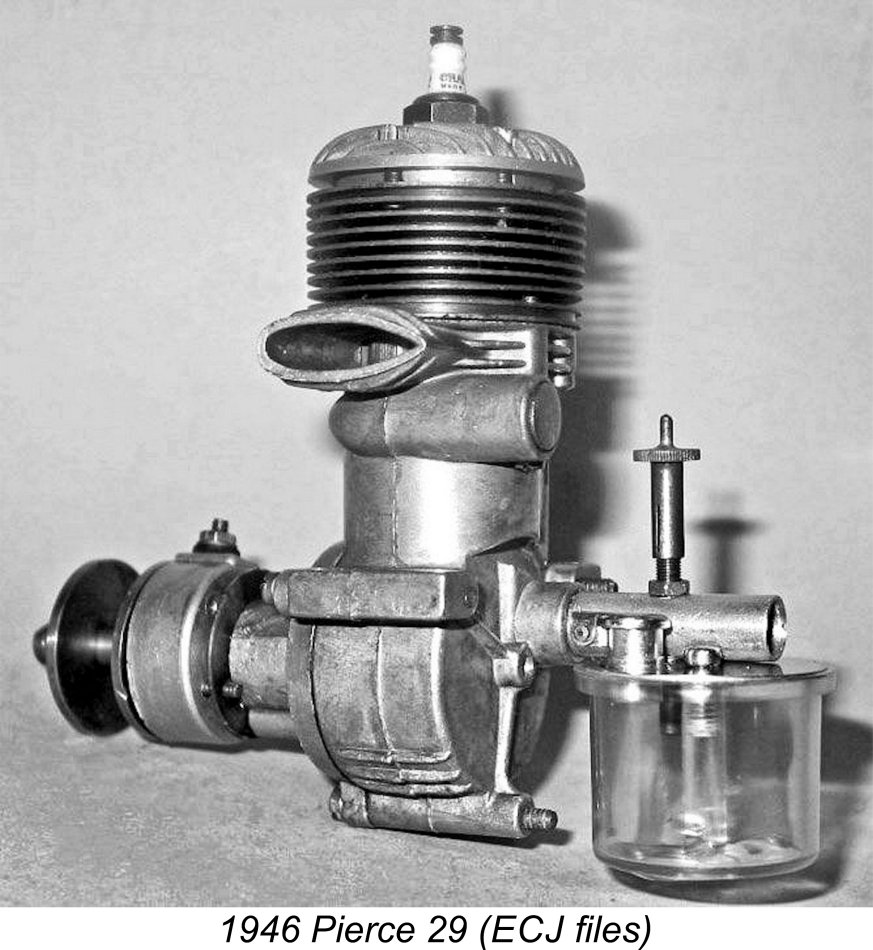

As can be seen from the accompanying images, the original Pierce 29 RV was a visual near-replica of the contemporary Forster 29 RRV model. However, there were enough detail differences between various components to suggest quite strongly that the Pierce rendition was a separate production. Bore and stroke dimensions of the Pierce 29 were 0.750 in. (19.05 mm) and 0.6718 in. (17.06 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.297 cuin. (4.86 cc). These figures are identical to those of the contemporary Forster 29, undeniably emphasizing the evident design relationship between the two.

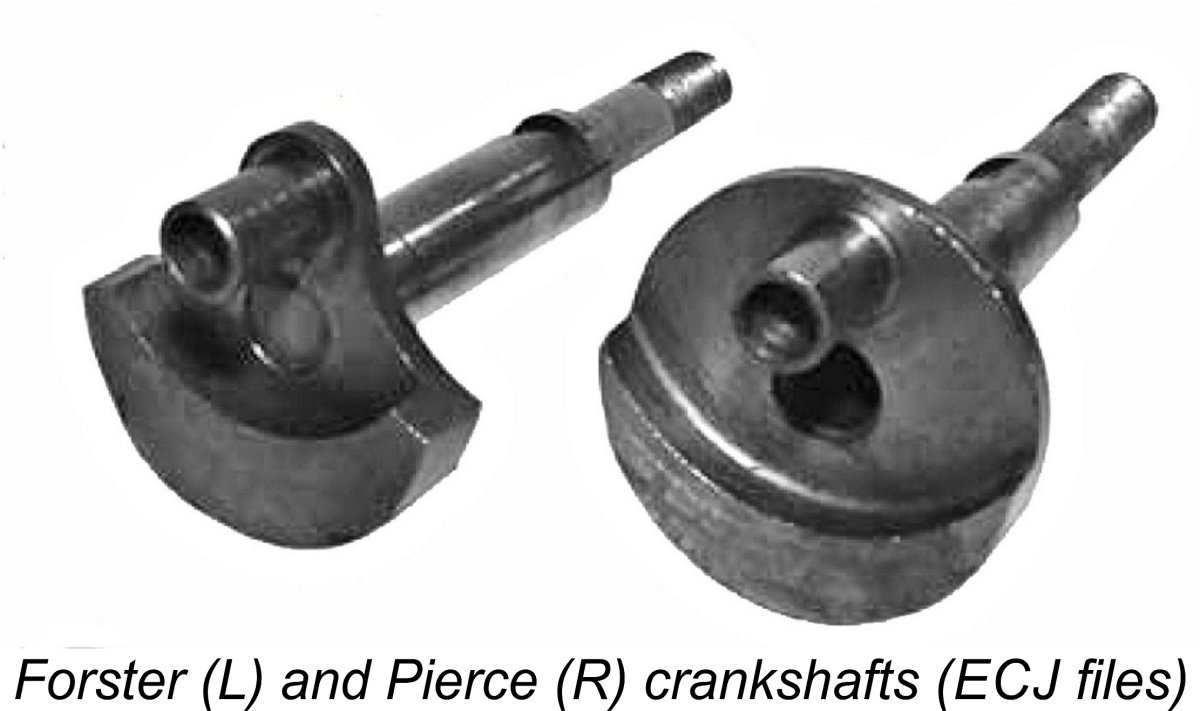

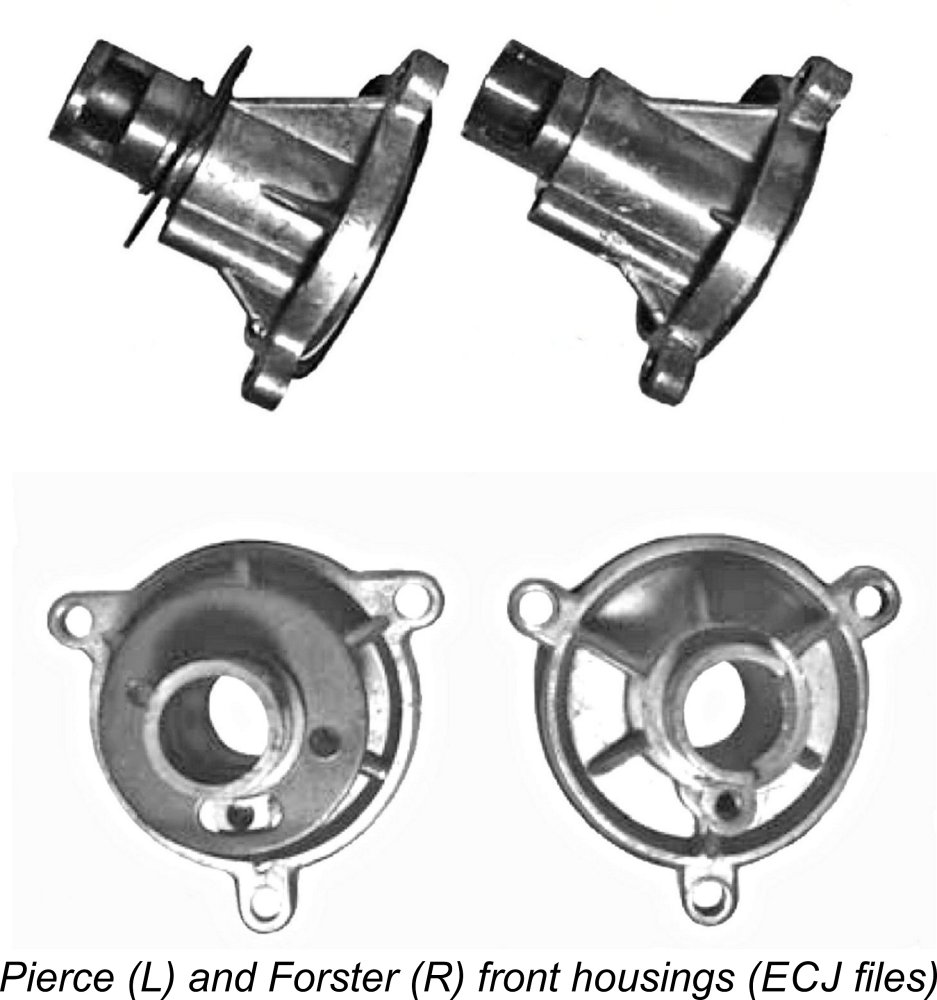

The most distinctive feature of the Pierce main casting is the fact that it incorporates induction bosses for both disc rear rotary valve (RRV) and side-port induction, with the unused side-port boss being left either un-machined internally or plugged on the original model. Even so, this feature proves conclusively that the production of a side-port Pierce model was envisioned from the outset. By contrast, the Forster case was not provided with a side-port boss, nor did Forster ever produce a side-port version of their 29. Tim Dannels has provided photographic confirmation that both the front housings and bolt-on cylinder heads were also distinct casings. An interesting observation may be made at this point. The presence of the unused side-port boss created the possibility of placing a suitably-located aperture in the lower cylinder wall on the exhaust side to allow this boss to serve as a sub-piston induction port. The makers never appear to have taken advantage of this possibility, apparently feeling that the disc valve induction system alone was well up to the task. Given the engine's relatively modest operating speed (see test data below), they were probably right. Starting at the top, the Pierce and Forster heads appear externally to be identical apart from the black paint used on the early Pierce engines - indeed, they will both fit onto The differing provisions for the baffle in the respective heads reflect the very distinctive crown configurations of the cast iron pistons used in the two models. The Forster features a curved baffle raised above the crown of the piston, while the Pierce has a wide dome with a flat top. Two short “wings” towards the transfer side combine with the dome to constitute an effective piston baffle configuration. The Pierce combustion chamber is specifically configured to accommodate these protrusions at top dead centre. It must be said that the resulting combustion chamber configuration is very far from efficient. The cylinders of the two models are seemingly identical. Both are secured somewhat unusually by retaining screws which are installed from below to engage with tapped holes in the lower cylinder installation flange. While a little awkward in terms of access, this arrangement has the great benefit of freeing the working bore from any potentially distorting installation stresses. The presence of the side-port boss on the Pierce prevents the use of the same cylinder installation hole arrangement used in the Forster - the rear exhaust-side hole has to be located laterally closer to its transfer-side neighbour in order to clear the side-port induction passage. However, an odd feature of the Pierce is the fact that at least some examples retain the seemingly redundant installation hole to permit the installation of the Moving on downwards, the diecast alloy connecting rod appears to be more or less identical in both the Forster and Pierce models. However, we have to remind ourselves once again that a common design does not necessarily prove a common origin. The rod drove a one-piece steel crankshaft having a heavily counterbalanced web. The shafts in the Pierce and Forster 29 models are very similar, to the point that they are interchangeable between the two models. However, they are clearly different productions - the Pierce crankshaft features a full-disc crankweb, while The front housings on the Pierce and Forster models are also very similar, although there are sufficient differences in detail to confirm that they were produced from different dies. The spacing of the securing holes is identical, although the Pierce uses three 4-40 screws for retention, while those on the Forster are 4-36 items. Don't lose those 4-36 screws - replacements are hard to come by! When it comes to the timer, we are once again confronted with the now-familiar fact that while the Pierce and Forster timers are very similar, they are sufficiently different to confirm that they are not from the same production line. Their diecast bodies are very close in almost all dimensions, but there are enough differences to confirm that they were not produced from the same die. The Pierce employed a rather unique method of securing the timer, another point which distinguishes it from the Forster. It featured a steel retainer ring which was trapped by a short expansion of the bronze main bearing bushing at the time when that bushing was pressed into the main bearing housing. This of course makes the ring impossible to remove once installed. The ring has two tapped holes to accommodate the timer tensioning screws, along with an annular slot which aligns with a stop pin installed in a boss at the bottom of the main bearing housing. The purpose of this latter arrangement is to limit the extent of potential annular timing adjustment. The Pierce .29 also featured a black timer arm along with black-finished prop washers and prop nuts. This sets these components well apart from the natural steel Forster parts. The Pierce timer arm also had a different curve to it as well as a different outline. Once again, distinct manufacturing programs are implied.

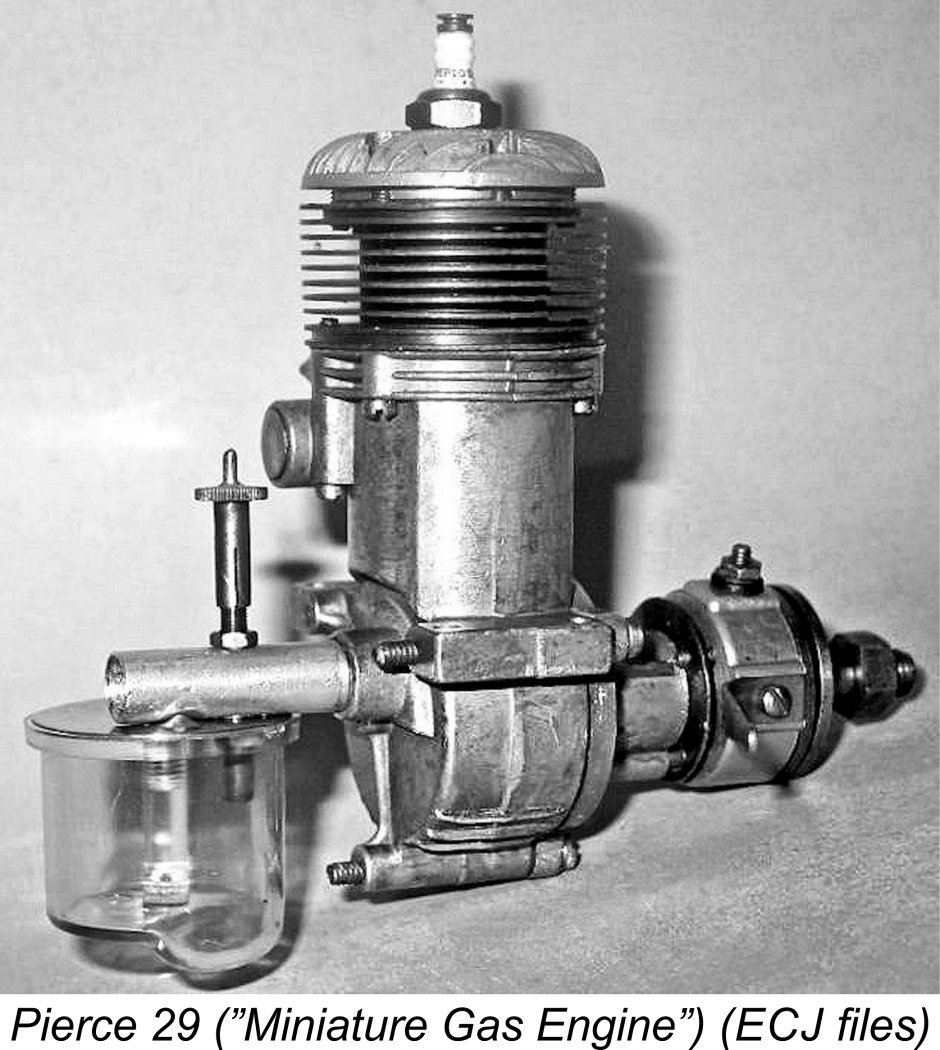

The engines were presumably supplied in boxes of some sort, but I have yet to encounter or even see an image of an original Pierce box. The question of whether it was a printed box, as was the norm in the late 1940’s, or alternatively a plain brown box with a label of some sort affixed therefore remains unresolved. Can any reader help? Initial sales of the Pierce 29 appear to have been confined to the Chicago area, presumably being promoted by word of mouth or through local hobby shops. The engine's first national media appearance was its inclusion in a listing of then-current model engines which appeared in the April 1947 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN), some time after the engine's initial market entry. The first national advertisement that Tim Dannels was able to find appeared in the May 1947 issue of MAN. This took the form of a full page placement by Pierce Industries in which the advertised price of their "Miniature Gas Engine" was cited as $12.95. This pretty much concludes my description of the original 1946 Pierce 29 RV based on the sources noted earlier. We’re now in a position to consider the further development of the range. Further Development of the Pierce Range

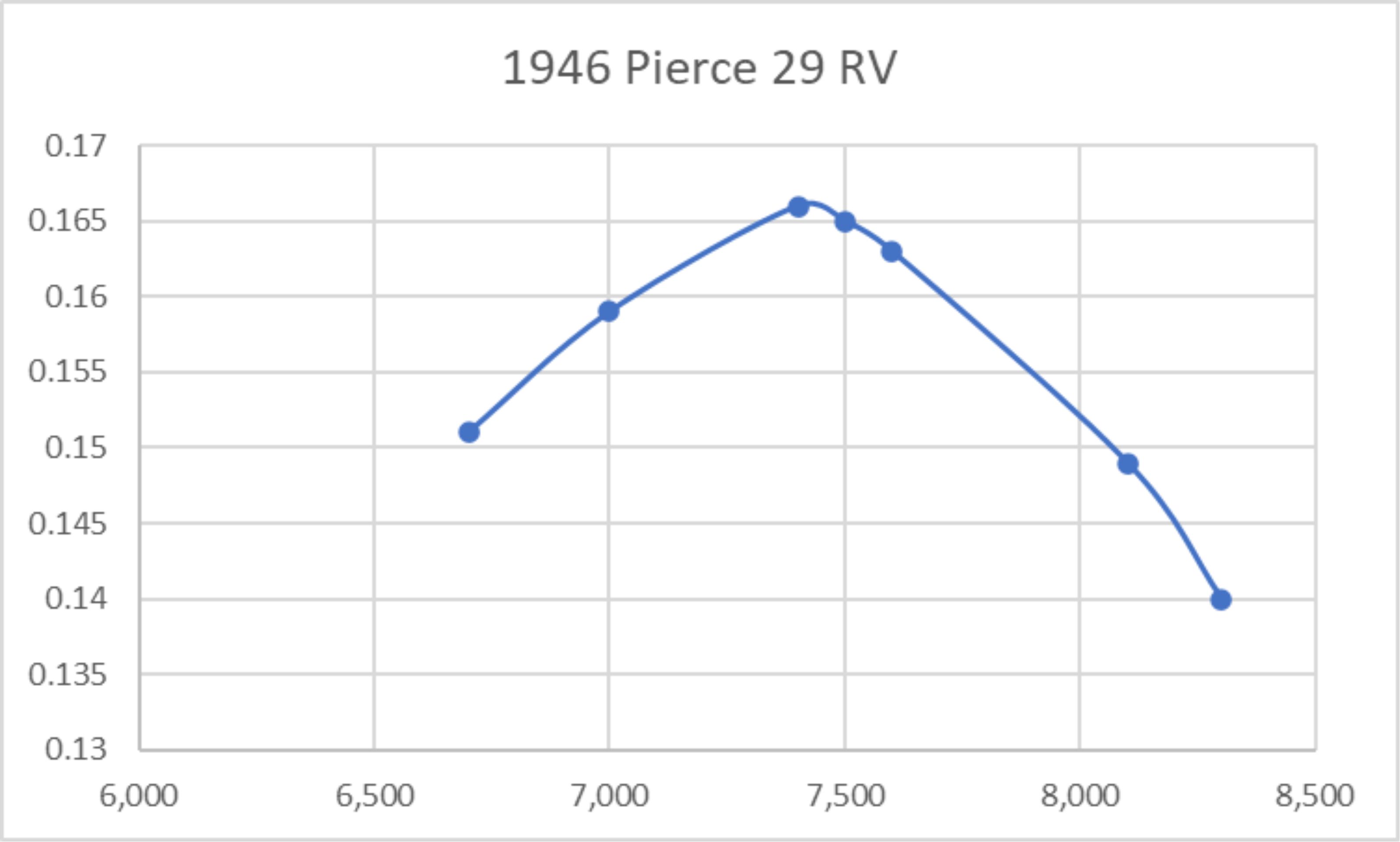

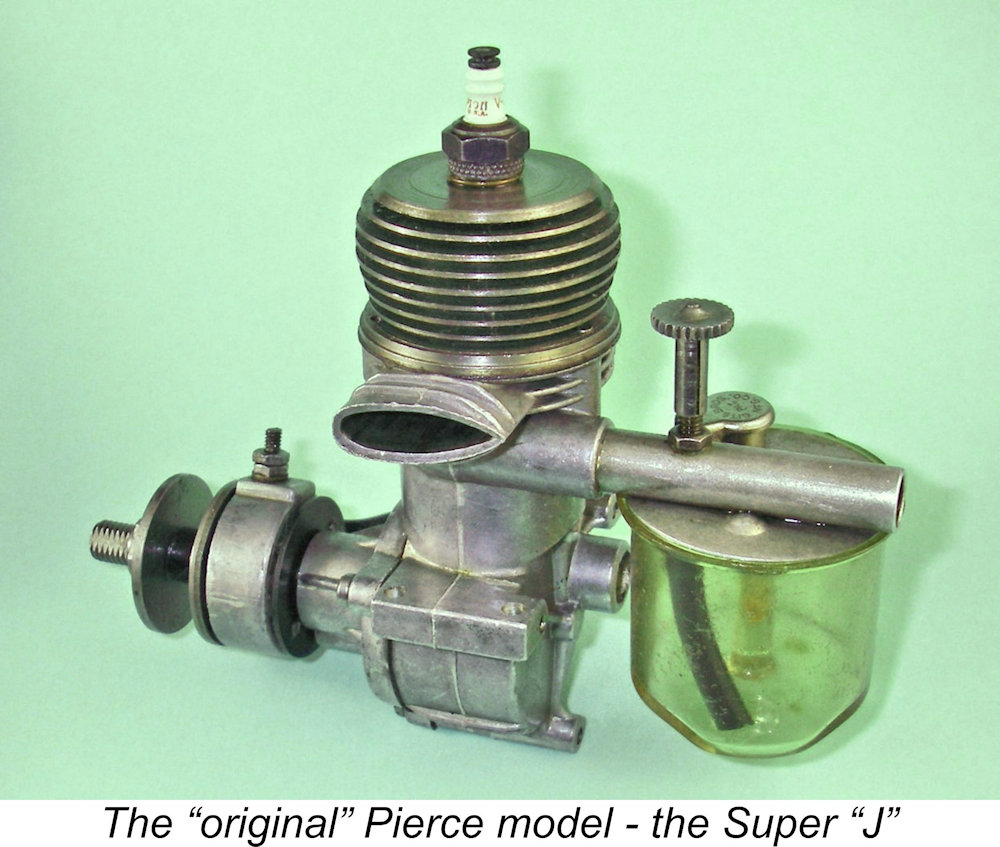

A number of fairly significant changes were introduced on this model. The most immediately obvious of these was the switch to side-port induction, with the still-present RRV induction boss being either left undrilled or plugged. Equally obvious was a switch to a blind-bored steel cylinder with integral head. A revised piston machined from steel bar and having an upstanding baffle was used in place of the former iron casting. Along with these changes came a somewhat inexplicable amendment to the engine’s internal dimensions. The bore remained unchanged at 0.75 in. (19.03 mm), but the stroke was reduced to 0.656 in. (16.66 mm) for a very slightly reduced displacement of 0.290 cuin. (4.75 cc). The volumetrically checked compression ratio was a somewhat uninspiring 6 to 1. With a blind-bored cylinder, the presence of the upstanding piston baffle placed a significant constraint upon the designer's ability to provide a higher ratio, or indeed to create an efficient combustion chamber. The final change was not to the engine itself but to its price. The Super “J” was first advertised in the September 1947 issue of MAN at a price of $9.95. This was a significant reduction from the $12.95 price of the original RRV model.

However, it seems more likely that a desire to develop a lower-cost alternative product was a major driving force behind the institution of these changes. A sideport model had clearly been envisioned from the outset - the Super "J" merely represented the implementation of that intention. Where did the cost savings come from to get the price of the new model down to $9.95? Well, for starters the one-piece blind-bored cylinder was simpler and cheaper to make. In addition, a separate diecast head was no longer needed. It was no longer necessary to make and fit the rear disc valve. The use of a simple machined piston would also represent a cost saving over the former cast iron component. Otherwise the two engines were basically the same. The entire front assembly remained unchanged, including the crankshaft and timer, while the same fuel supply components continued to be used.

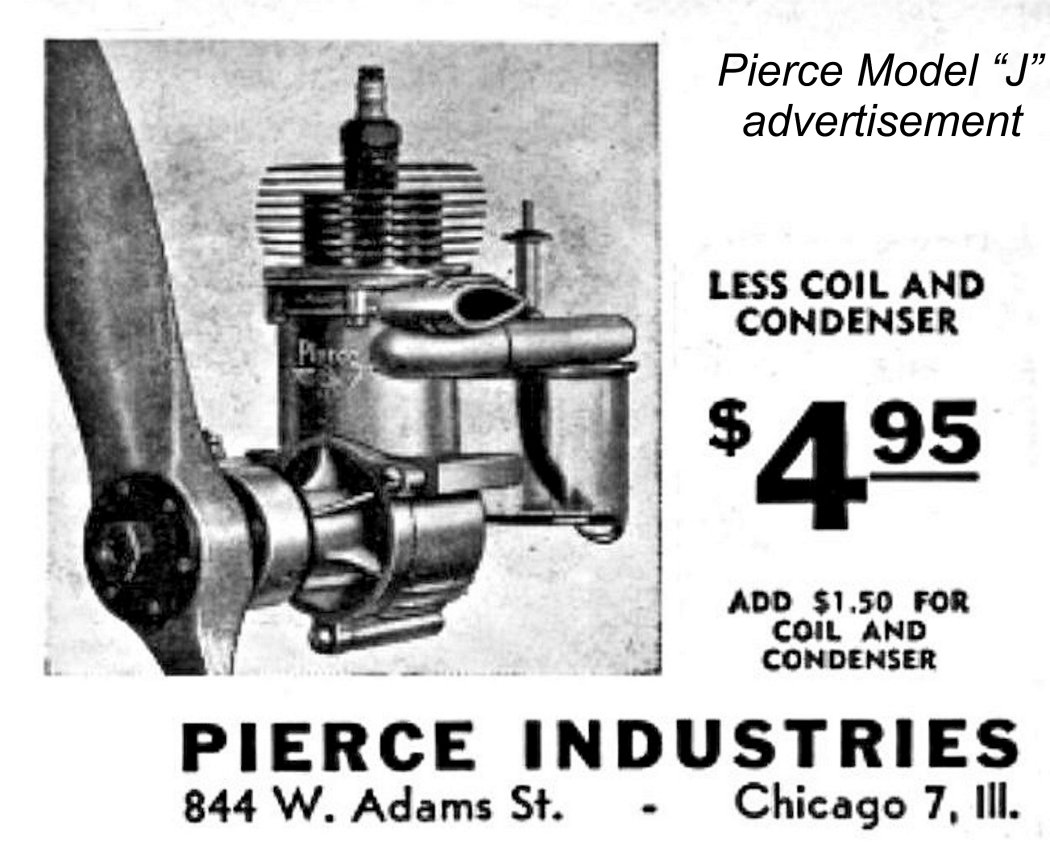

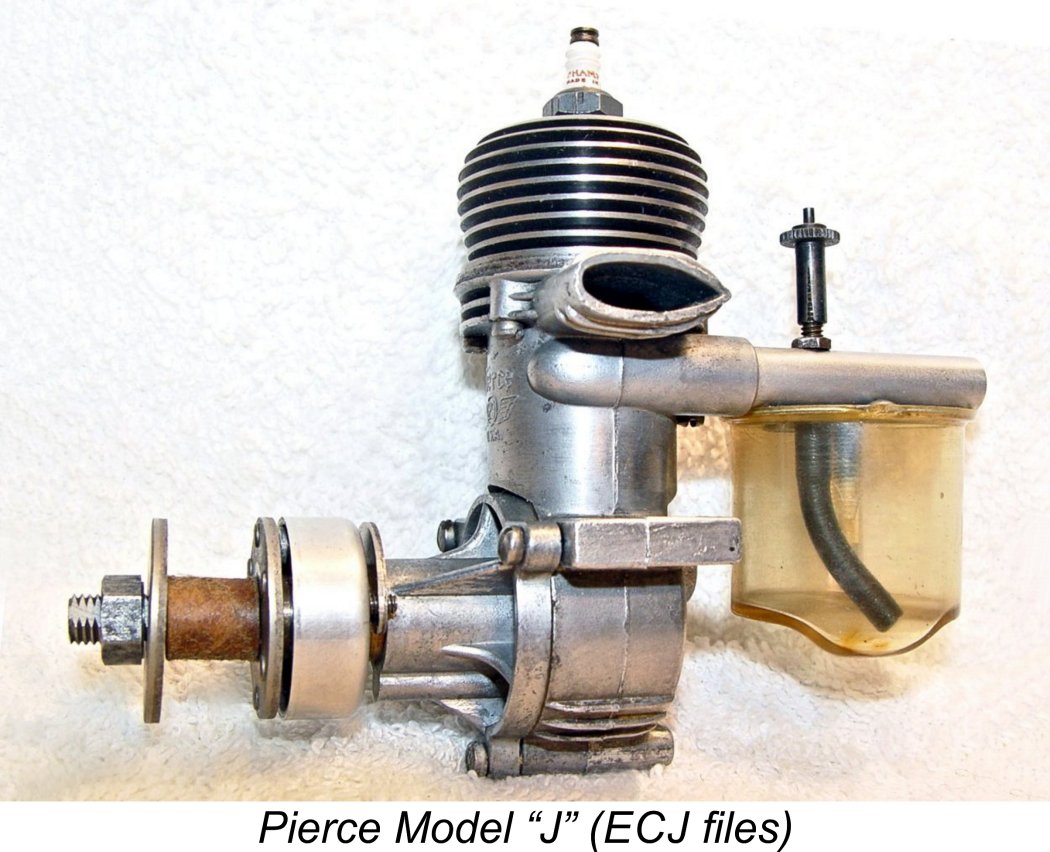

Pierce were also continuing their efforts to market their products at prices which undercut the competition. In late 1947 they introduced a kit version of the Super “J” which they designated as the Pierce Model “J” (no Super). By December of 1947 this was the only product being advertised, the price tag being set at a remarkably low $4.95. For an additional $1.50 a coil and condenser could be supplied with the engine.

It appears that a considerable number of Ohlsson-type timers and matching timer arms were Speaking of which, it’s apparent that the company had built up a considerable over-stock of components for the original 1946 Pierce 29 RRV model. It was probably a reduction in demand for that model that had led to the introduction of the lower-priced ready-to-run Super “J” and kit “J” models. The challenge of liquidating unsold stocks of unused components was greatly exacerbated by the fact that Ray Arden’s November 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug had unmistakably signalled the impending end of the spark ignition era.

The price of the Model "R" kit was set at $6.95. Following the introduction of both Pierce models in kit form, complete ready-to-run units were no longer advertised, strongly suggesting that actual manufacture had ceased. In the promotion of these kit offerings, only photos of the two engines were shown, with none of their features being spelled out. You had to base your purchasing decisions solely on the basis of what you could see in the advertising images. Perhaps a little short of being fully persuasive ..........!? Reading between the lines, it’s tempting to infer that the late 1947 relocation from 430 South Green St. to 844 W. Adams St. reflected the cessation of actual production of the Pierce engines. The timing of the move may suggest that Pierce Industries were quick to recognise Ray Arden’s November 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug (which was clearly seen coming several months earlier) as spelling the imminent doom of the spark ignition model engine - others certainly did so. Pierce’s focus may have shifted immediately from production of their engines to disposal of their existing inventory in order to free up the capital that it represented. Such a decision would eliminate the need for the maintenance of production facilities, quite likely opening the door to a relocation to smaller and less expensive premises nearby which would be involved solely with the marketing of existing pre-manufactured assets. Viewed from another angle, a relocation motivated by such a situation would offer further support for the idea that Pierce had in fact been manufacturing their own engines.

The Glo-Champ engines were marketed exclusively by the Mercury Model Airplane Co., with the Pierce name never being mentioned at any time in connection with this model. The Glo-Champ was possibly unique in that it was supplied with both a stamped Ohlsson-style timer for spark ignition operation and a stamped steel press-on cap to replace the timer for glow-plug operation. In recognition of the adverse effects of glow fuel upon plastic tanks, it was equipped with a large metal tank in place of the former plastic bowl. If all of this wasn’t enough, Pierce Industries had one more trick up their sleeves, just to confuse things! The late Woody Bartelt added more fuel to the fire when he provided Tim Dannels with copies of a “29” instruction sheet having yet another address rubber-stamped onto it - Pierce Industries, 1942 Palm Grove Ave., Los Angeles 16, California. There was no indication of date or anything else. Apparently the last Pierce engines were shipped from California. Tim could find no later ads with the California address on them, leaving this situation unresolved. This brings us to the end of the saga of the original Pierce engines. However, it wasn’t over - enthusiasts of a later generation were set to add their own contributions to the story! A Later Experiment - the Samson 30

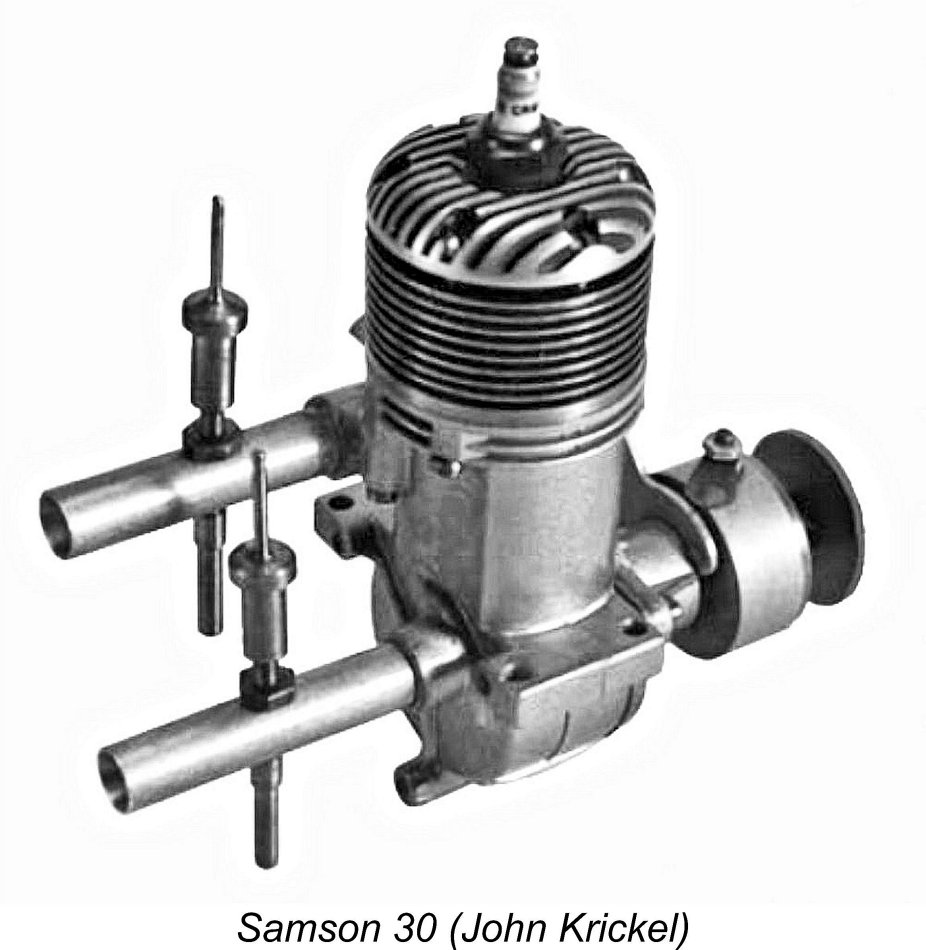

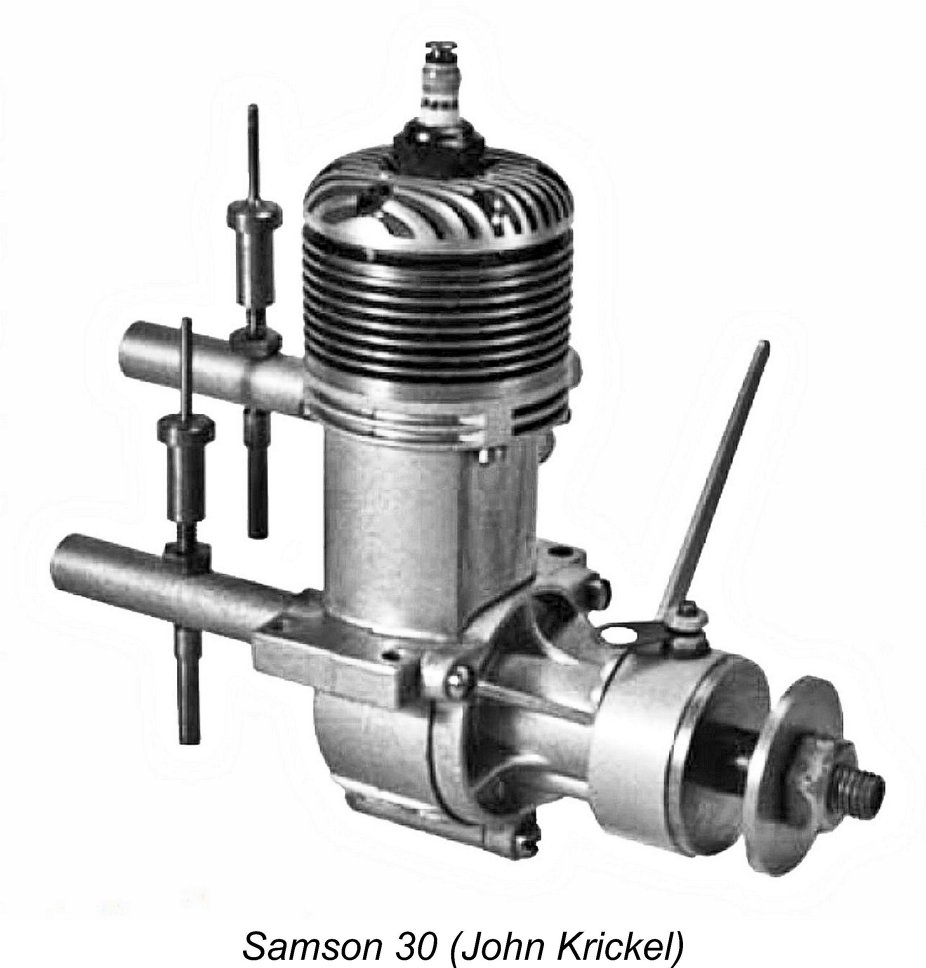

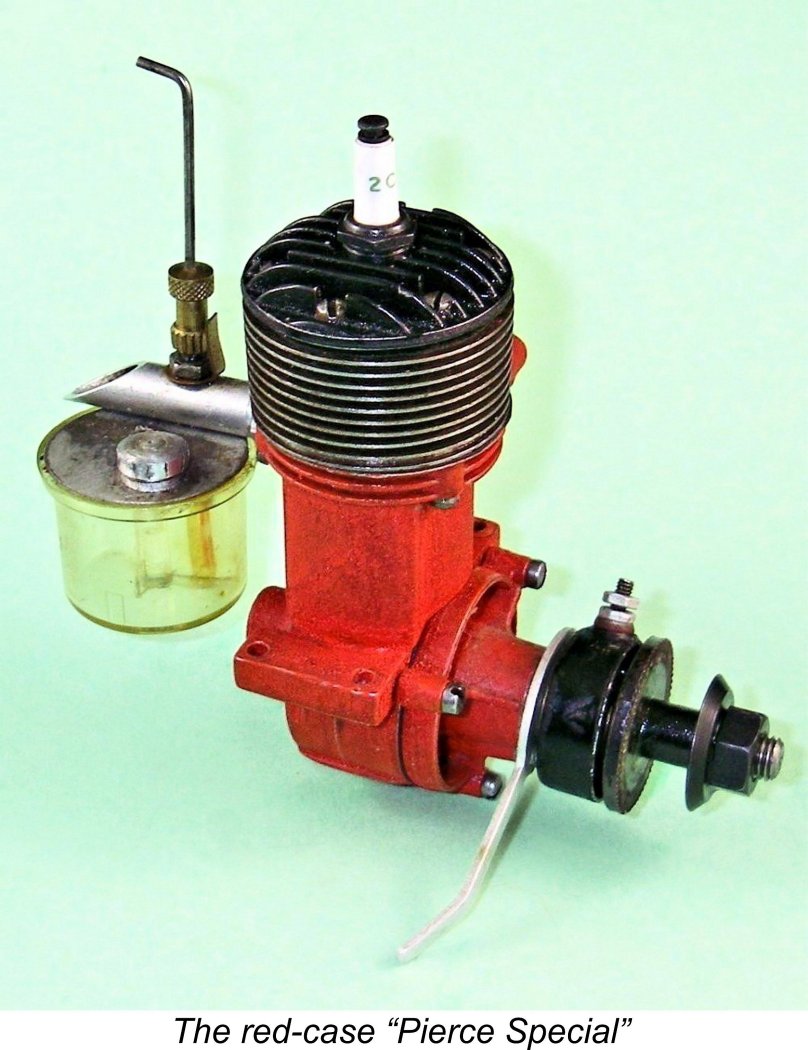

It was clear from these images that the Samson was based at least in part upon Pierce components. The remarkable feature was its use of both the RRV and sideport induction systems, something which Pierce Industries are not known to have tried. Such an arrangement raises obvious questions regarding the engine’s ability to suck fuel from the tank through both intakes, but someone clearly thought the idea worth trying! Since nothing was known (or revealed) about its origin at that time apart from the obvious use of at least some Pierce components in its construction, the Samson was relegated to Tim Dannels’ “curiosity” file. There it rested for some years until Tim had an opportunity to visit with the late Don Belote during Don informed Tim that the Samson was a joint project between him and Steve Ditta, motivated solely by a shared desire to come up with something “different”. Steve apparently had a number of Pierce castings, while Don had both a fully equipped machine shop and the desire to do something original. The Samson was the result. The only original Pierce components were the castings. Everything else was made by Don in his shop - the new cylinder, which followed neither the Pierce nor Forster patterns, the machined timer housing, custom needle valve assemblies, etc. The engine was finished off in a hammer-tone gray paint job on the case and front shaft housing, while most of the rest retained the as-machined finish. At the time, Tim thought that Don had made just the one engine, but he learned later that several examples were actually constructed. Since Don is sadly no longer with us, verification of the actual number built is no longer possible. The Mysterious Red-Case Engine It’s apparent that Don Belote and Steve Ditta were not the only ones to experiment with the creation of “specials” based in part on Pierce components. In late 2022 I acquired an intriguing-looking red-painted side-port spark ignition engine which was Upon receipt, it turned out that the seller had been completely honest in categorizing the engine as “little used”. It showed little evidence of having been run previously and was certainly unmounted. A brief examination was enough to confirm that this engine was a composite of components from several Pierce and Forster 29 models, underscoring the general interchangeability of the components of these units. The crankcase was clearly a Pierce component, while the casting for the front housing appeared to have a Forster origin. The engine sports a Forster 29 cylinder and upstanding curved baffle piston with a Forster head which has been painted black like the original Pierce 29 models - it may even be such a head. Bore and stroke are 0.75 in. and 0.672 in. respectively for a displacement of 0.297 cuin. - identical figures to the original Pierce and Forster models. The engine’s weight is 7.2 ounces (204 gm) complete with spark plug. The boss for the RRV induction system has been left undrilled. The cylinder has necessarily been modified by the creation of an extra induction port below the exhaust aperture to align with the The Pierce identification markings have been neatly removed from the front of the main casting, making it appear likely that this is one of the later Glo-Champ cases. Both this casting and that for the front end have received a very cleanly-applied and seemingly durable matte red paint finish. This had obviously been done prior to assembly - there’s no sign of any paint bleed onto adjoining components or gasket edges. Based on the cam placement, the crankshaft appears to be a Forster component. The engine has a black-painted original O&R timer as opposed to the look-alike used on the later Pierce kit engines without the black paint. This timer functions perfectly. A brand new un-run ¼-32 AC spark plug is fitted. Measured compression ratio is a somewhat uninspiring 6 to 1. The chamfered screw-in induction tube appears to be a Forster 29 RRV component with chamfered entry mated to a non-standard universal needle valve assembly. The intake tube is secured with a lock-nut identical to that used on the Forster models. There’s no serial number. The above description will have confirmed that in terms of the components used in its construction, this engine is far more "Forster" than it is "Pierce". I get a strong impression that this engine was an experimental side-port conversion of a Forster 29 to see how well the design would have worked out in that form. The use of a Pierce crankcase with its built-in sideport intake stub would have greatly facilitated such an experiment. The standard of fitting in this example is beyond reproach. It has clearly not been the subject of repeated rebuilds, since the assembly screw slot heads show no signs of repeat use. It gives the impression of being a well thought-out hybrid created by someone who had access to a good stash of unused Pierce and Forster parts and knew exactly what he was doing. Whoever it was, he deserves our respect - this is an extremely competently-executed unit! The Pierce 29 Engines on test

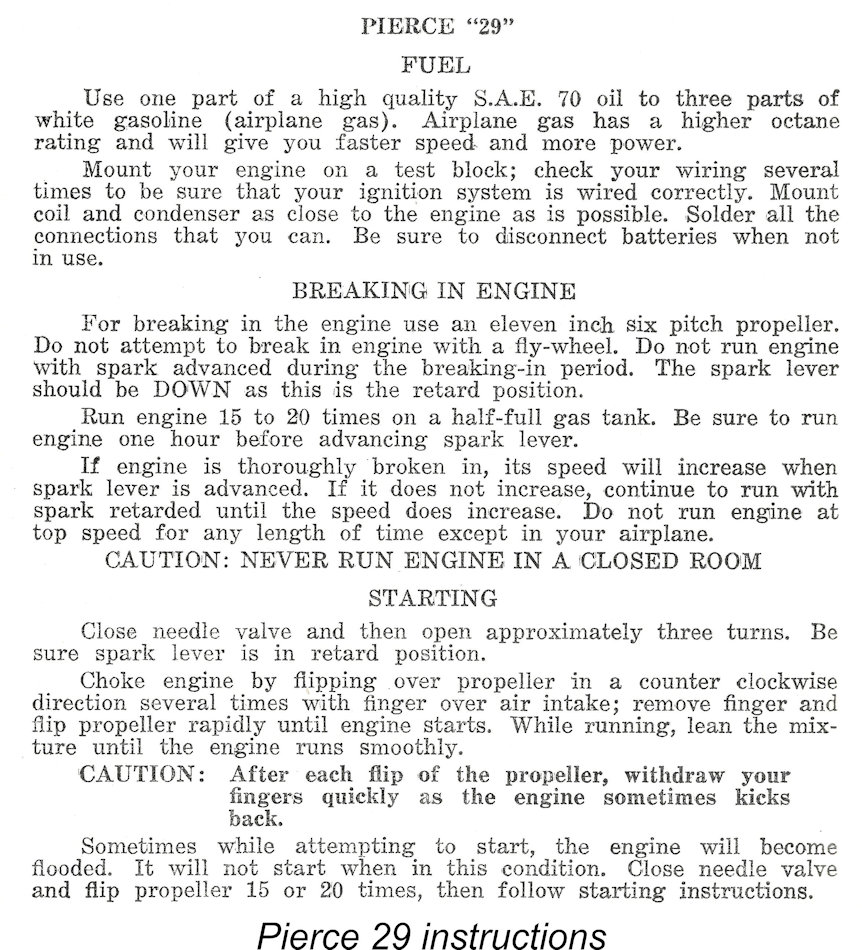

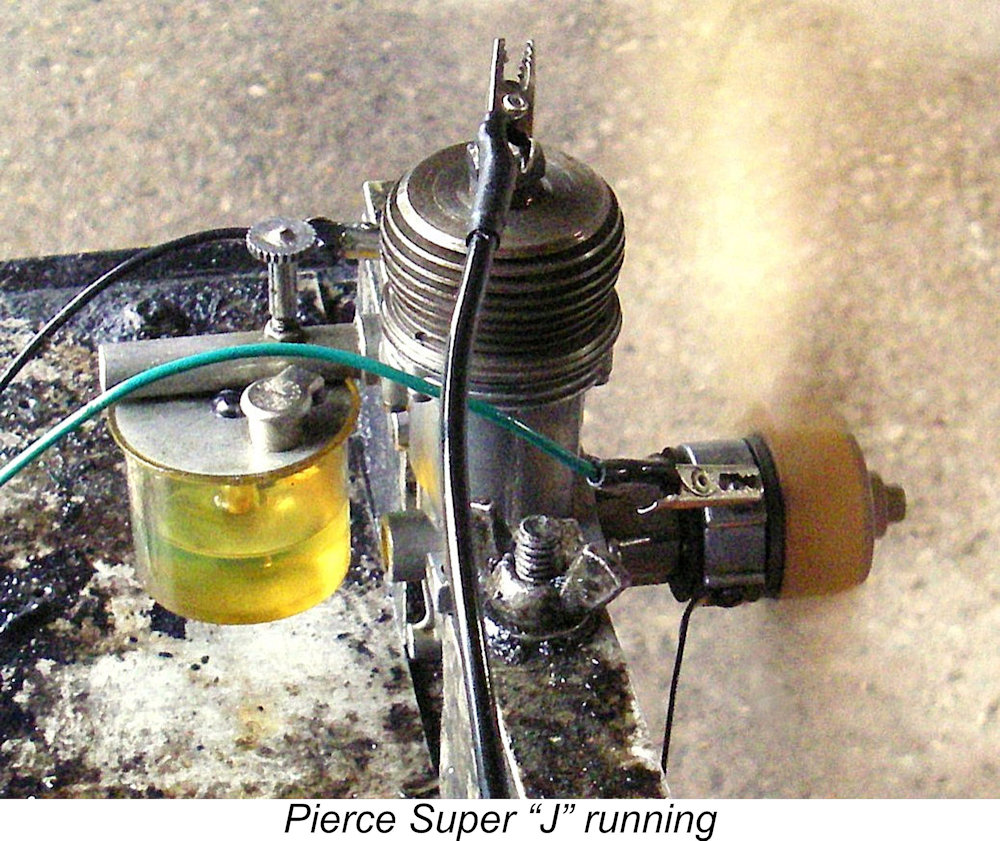

First up was the original 1946 disc-valve Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine". I set it up in the test stand and connected one of my very dependable Larry Davidson spark ignition support systems. The manufacturers recommended an 11x6 prop for running in, but I chose to begin with a Top Flite 10x7 Power Point wood prop which I felt would be a reasonable equivalent. For some reason, I just find it more satisfying to test sparkies using wooden props as far as possible - don't ask me why! The use of a methanol-based fuel was of course precluded by the plastic gas tank, which would have responded poorly to such a fuel. Accordingly, I used my usual mixture of 75/25 Coleman Camp Fuel (white gas/naptha) and S.A.E. 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120). This was the proportion of ingredients recommended in the manufacturer's instruction sheet - most contemporary modellers as of 1946 would have used such a fuel. The attached reproduction of those instructions was extracted from the post-WW2 edition of Bernie Winston's very useful little reference book entitled "Model Gas Engine Handbook". Checked using a continuity tester, the timer was found to be working perfectly. The previously-mentioned combination of the annular slot in the steel retainer ring and the stop pin set into the front housing was found to limit the available movement of the timer to around 30 degrees of rotation. In the fully retarded position, the points opened a few degrees prior to top dead centre - perfect for starting. Once running, the ignition timing could be advanced by up to 30 degrees, but no more. The range of available timing adjustment was thus entirely appropriate for an engine of this type. The timer's dwell period (points closed) was found to be of the order of 55 degrees - a seemingly reasonable figure.

Beginning with the needle set at three turns as recommended by the manufacturers and the timer in the retarded position, I administered a small prime, switched on the ignition and got stuck in. The engine started firing immediately, but did so in short high-speed bursts before stopping. The needle setting was clearly too lean. I actually had to open the needle out to over 5 turns before the engine would pick up on the fuel in the tank and keep going. Once the first start was achieved, I had no further trouble. The repeated starts of the Pierce required during the testing demonstrated that the engine did not like to be too wet for starting. A couple of choked flicks and a small "dry" prime (exhaust port closed) were all that was required. If this procedure was followed, starting was almost immediate. The engine responded well to both controls, making an optimal setting quite easy to establish. Running was smooth and steady, with no tendecy to sag when really hot. Despite the slightly "soft" compression when cold, compression when hot appeared to be quite adequate when checked by hand immediately after stopping - the thermal expansions of the piston and cylinder appeared to be well matched, while the heavy S.A.E. 60 oil doubtless helped. The Pierce proved to be an excellent performer by 1946 standards. Running on the straight white gas/mineral oil mix, the following data were obtained.

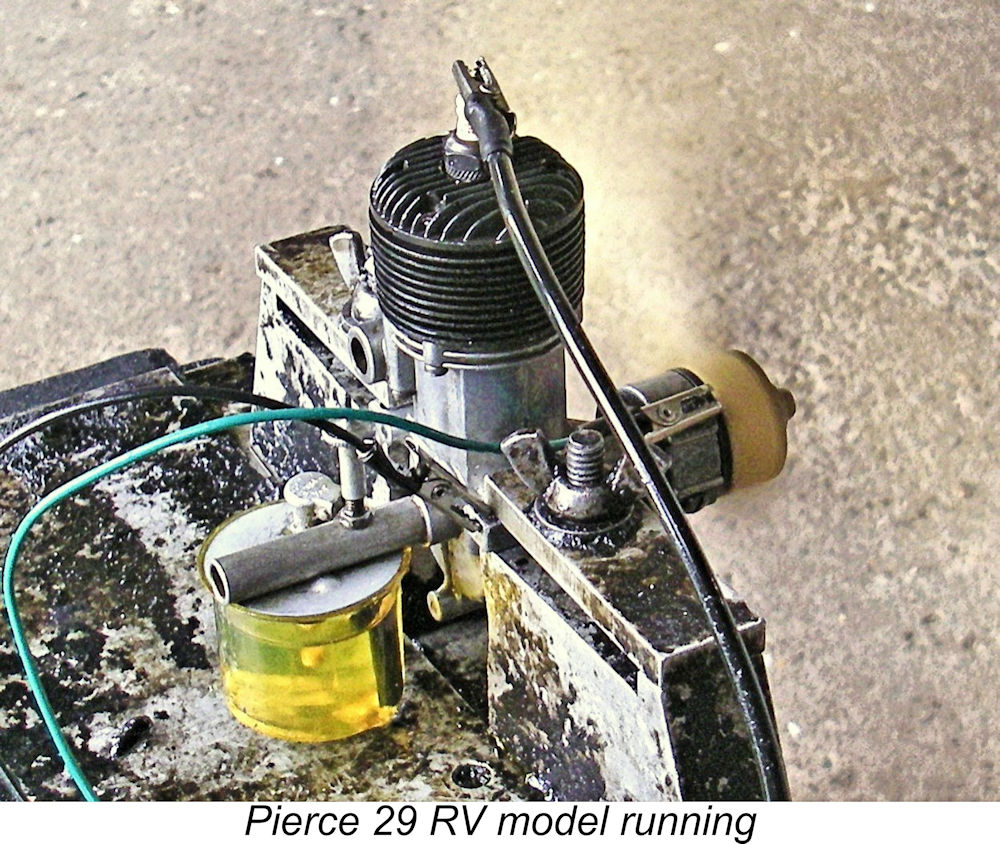

As can be seen, the disc-valve Pierce 29 developed a peak output of around 0.166 BHP @ 7,400 RPM on this fuel. The power curve was relatively flat across the peak, with 0.15 BHP (90% of peak) being delivered at all speeds between 6,700 and 8,100 RPM, implying considerable flexibility in terms of prop selection. This performance compares quite favorably with figures measured earlier for such competing 1946 models as the side-port Melcraft 29 (0.117 BHP @ 6,400 RPM), the front rotary valve Cannon 300 (0.188 BHP @ 7,500 RPM) and the Super Hurricane 24 (0.140 BHP @ 7,200 RPM). I have to say that I was quite impressed with the Pierce! Then it was the turn of the Pierce Super "J". By both appearance and feel, this example seemed to be new and unrun - it had certainly never been mounted. I judged that a full break-in would be required to free it up to the point at which it would deliver its best performance. The manufacturers evidently agreed with this assessment of their product - they recommended a minimum 1 hour break-in using the suggested 11x6 prop with short runs on a retarded ignition setting, while admitting that even this might not be enough. Considerations of time and anticipated noise levels led to a decision that I would not undertake a full break-in, particularly since I had no intention of actually flying the engine. Rather, I would give it a few shake-down runs and then take some quick spot readings without stressing it unduly.

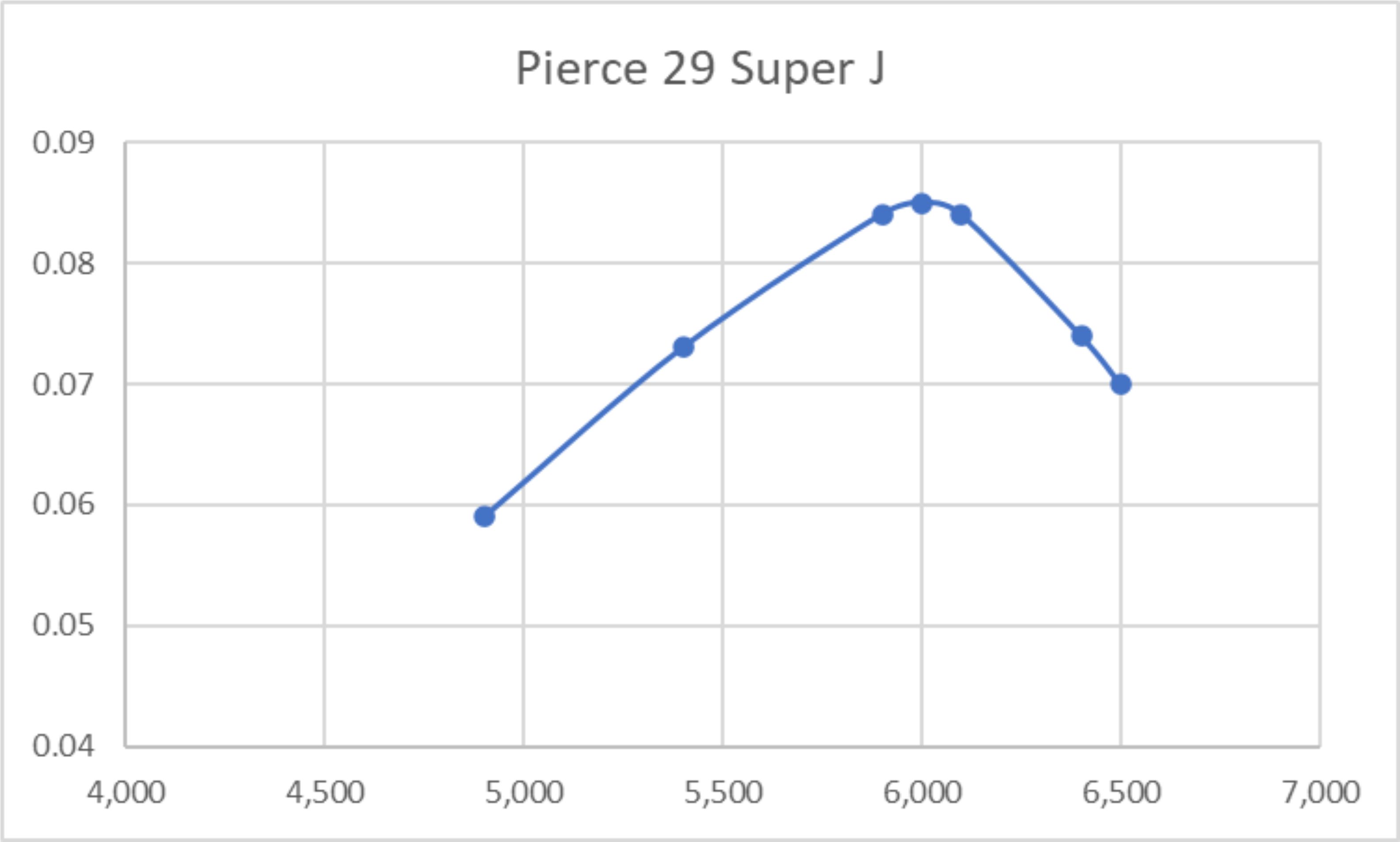

It took a while to achieve the first start for two reasons. First, the needle setting with which I began turned out to be way too rich, quickly flooding the engine to a halt; and second, this proved to be one of those units which is unusually sensitive to the amount of fuel in the cylinder during starting. The very inefficient combustion chamber configuration probably has a lot to do with this characteristic. Like its previously-tested stablemate, the Pierce Super "J" did not like to be too "wet" for starting. In fact, the dry port prime proved to be unnecessary - experimentation showed that a few choked flicks generally sufficed to achieve a start, while the starting needle setting was found to be around 1½ turns as opposed to the recommended 3. Once these lessons had been learned, the Pierce proved to be a dependable enough starter, although it generally took a few flicks to get it going. After achieving the first start, I left the timer in the retarded position and adjusted the needle to smooth out the running, keeping the engine in four-stroke mode. The I put on some 15 minutes in 3 minute runs on this prop, allowing complete cooling between runs, then began to take a few spot readings. My approach was to start the engine, allow it to run rich and retarded for a minute or so and then lean it out and advance the ignition timing to reach the best speed on the prop being tested. I kept the leaned-out running to the minimum necessary to obtain a reading, after which I stopped the engine and allowed it to cool completely before switching props and trying again. The engine ran very well when leaned out but showed signs of sagging as it approached maximum temperature during the brief leaned-out portions of the run. I put this down to the unmistakable fact that it was still definitely tight, hence being in need of the additional break-in time which I was reluctant to give it. While recognising the limitations which this imposed upon my testing, I went ahead and took spot readings using the same series of calibrated test props on which I had tested the RV model, with the following results:

As can be seen, the Super "J" exhibited a somewhat lacklustre level of performance on this showing, topping out at around 6,000 rpm with an output of some 0.085 BHP. I have absolutely no doubt at all that it would beat these figures by some margin if fully freed up through a lengthy break-in process, which I had no intention of giving it for the reasons outlined earlier. Even so, I would expect any improvement to be relatively modest, leaving this model still well short of its disc-valve predecessor in the performance department. On the plus side, I demonstrated that the Pierce Super "J" was an easy-starting, well-made and sturdy unit which had the potential to give excellent service to its owners over the long term in a sport-flying context. Unfortunately, the "long term" was confined to a few months thanks to the appearance of Ray Arden's commercial miniature glow-plug in November 1947, only a couple of months after the initial appearance of the Super "J". In all probability it is actually this circumstance which is responsible for this example's pristine condition - it was rendered obselete more or less as soon as it was sold, hence being set aside essentially unrun and certainly unflown. Even if this circumstance hadn't arisen, the engine was undeniably saddled with a rather modest performance by the standards of its day. This would have sidelined it in relatively short order even without the intervention of the glow-plug. This actually raises one of the more obscure points in connection with the Pierce range - why did the manufacturer switch from a very sturdy performer (the disc-valve Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine") to a basically uncompetitive model (the side-port Pierce Super "J")? Reading between the lines, it would seem that the reason(s) for doing so must have been quite compelling. Such a move would have been a logical response to a threat of legal action from Forster Brothers based upon the near-clone design of the original Pierce 29, but a desire to come up with a lower-priced offering may also have been responsible. I suspect that we'll never know .............

The red-case engine showed itself to be an easy starter, although unlike its predecessor in the test stand it seemed to appreciate a small "dry" prime (administered with the exhaust port closed). Once the needle valve setting had been established at 4½ turns, it usually started within a few flicks. Once running, it performed very smoothly indeed, showing no evidence of sagging when leaned out. Although apparently unmounted, it actually appeared to be well run in or at least very well fitted. The red-case side-port Special turned the APC 10x6 prop at a smooth 7,300 rpm, showing an implied output of around 0.144 BHP at that speed. This represented a massive improvement over the 6,100 rpm managed by the side-port Super "J" - in fact, it's not all that far behind the RRV Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine" tested earlier. It certainly seems to be a significantly stronger performer than its Super "J" progenitor. I suspect that the more efficient combustion chamber may have contributed to this result, or perhaps the unknown builder hit upon the sweet spot in terms of induction timing and port size. The red-case Special is clearly a well thought-out and competently executed hybrid that would have given excellent service in the field. Although I could personally do without the red paint, I have no intention of removing it - that finish is a legacy of the engine's creator, hence being part of the engine's heritage!

The Forster proved to be the nicest-handling engine tested on this particular day, perhaps because it was the best run in. It seemed to like a dry prime in addition to a couple of choked flicks, but started immediately once these preliminaries were applied. It ran flawlessly, turning the APC 10x6 prop at a smooth and steady 7,700 rpm - around 0.169 BHP at that speed. This was some 100 RPM faster than the speed achieved by the Pierce 29 RV "clone". Moreover, it's entirely possible that the Forster peaks at a somewhat higher speed than this, while the Pierce is actually just past its peak at 7,600 RPM on this prop. The use of a methanol-based fuel which this example's metal tank would have permitted would enhance its performance still further. The main lesson to be gleaned from this sampling of the Forster is just how far behind the prevailing levels of performance the Pierce Super "J" had slipped as of 1947. Looking objectively at this situation, it's not hard to see why the Pierce range failed to stay the course in the increasingly competitive model engine market of the latter half of the 1940's. Conclusion

In my view, the most probable scenario has a former Forster employee leaving the company voluntarily or otherwise and making an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to take Forster on at their own game. If so, the strategy was woefully ill-considered - the initial Pierce 29 was more or less a straight Forster copy, while the following Super "J" model represented a significant technological step backwards from the earlier model at a time when Forster Brothers and others were pressing ahead towards the future. At no time did Pierce ever come up with an original design which offered any threat to the Forster range. Still, if my example is anything to go by, the unknown designer did come up with one more or less completely original design - the Pierce Super "J" - which, while offering nothing remarkable in design or performance terms, was constructed to a very good standard and handled very well. Its maker(s) were clearly more than capable - it's too bad that they were unable to come up with a product that allowed them to continue to exercise those capabilities! ________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia Canada First published June 2023

|

||

| |

In this article I’ll attempt to unravel the somewhat clouded history of the Pierce 29 series from early post-WW2 Chicago, Illinois, USA. This range has received relatively little attention in the past, perhaps due to the significant degree of uncertainty surrounding its origins and later history. Chief among these uncertainties is the relationship of the Pierce engines to the far better-known Forster models, which were also manufactured in the Chicago area during the period in question.

In this article I’ll attempt to unravel the somewhat clouded history of the Pierce 29 series from early post-WW2 Chicago, Illinois, USA. This range has received relatively little attention in the past, perhaps due to the significant degree of uncertainty surrounding its origins and later history. Chief among these uncertainties is the relationship of the Pierce engines to the far better-known Forster models, which were also manufactured in the Chicago area during the period in question.  The Pierce engines were introduced in 1946 by a firm calling itself Pierce Industries of 430 South Green St., Chicago 7, Illinois. They evidently remained at this address until November 1947, after which the advertisements from December 1947 onwards place them at 844 West Adams St., still in the Chicago 7 area. This actually wasn’t much of a move - the West Adams Street location is only two blocks or so north of the original South Green Street premises.

The Pierce engines were introduced in 1946 by a firm calling itself Pierce Industries of 430 South Green St., Chicago 7, Illinois. They evidently remained at this address until November 1947, after which the advertisements from December 1947 onwards place them at 844 West Adams St., still in the Chicago 7 area. This actually wasn’t much of a move - the West Adams Street location is only two blocks or so north of the original South Green Street premises.  A glance at the accompanying maps will confirm that the respective locations of the two firms as of 1946 were quite distant from one another. The location of Forster Brothers lay some 20 km north of the Chicago city center, while that of Pierce Industries was very close to the downtown core. Geographic proximity could thus have played little part in promoting any relationship between the two marques. Moreover, absolutely no business connection between the two companies has ever been established.

A glance at the accompanying maps will confirm that the respective locations of the two firms as of 1946 were quite distant from one another. The location of Forster Brothers lay some 20 km north of the Chicago city center, while that of Pierce Industries was very close to the downtown core. Geographic proximity could thus have played little part in promoting any relationship between the two marques. Moreover, absolutely no business connection between the two companies has ever been established.  That said, a straw in the wind in this regard may be the long-established rumour that the Forster brothers actually sued the principal(s) of the Pierce venture for “stealing” their design. Given the fundamentally derivative nature of almost all model engine designs, many manufacturers other than Forster could have levelled such charges against their competitors! The fact that very few did so demonstrates the essentially moot character of such disputes given that they were all designing their products based on similar design precedents and identical underlying operating principles. This being the case, a certain uniformity of design was inevitable, although the Pierce/Forster RRV designs admittedly do seem more “uniform” than most!

That said, a straw in the wind in this regard may be the long-established rumour that the Forster brothers actually sued the principal(s) of the Pierce venture for “stealing” their design. Given the fundamentally derivative nature of almost all model engine designs, many manufacturers other than Forster could have levelled such charges against their competitors! The fact that very few did so demonstrates the essentially moot character of such disputes given that they were all designing their products based on similar design precedents and identical underlying operating principles. This being the case, a certain uniformity of design was inevitable, although the Pierce/Forster RRV designs admittedly do seem more “uniform” than most!  All that can be said is that if legal action was in fact pursued, it had little or no immediate effect - as we shall see, marketing of the Pierce engines appears to have continued for some time into the glow-plug era which began in late 1947.

All that can be said is that if legal action was in fact pursued, it had little or no immediate effect - as we shall see, marketing of the Pierce engines appears to have continued for some time into the glow-plug era which began in late 1947.  that they were distinct productions. The only components that were sufficiently identical to imply the possibility of joint production were the cylinder and the conrod, and those seem insufficient to support the notion of a shared production source - a common design specification does not confirm a common source. If Forster Brothers were engaging in joint production with Pierce, why stop at the cylinder and rod? In particular, why produce a different piston for the same cylinder?

that they were distinct productions. The only components that were sufficiently identical to imply the possibility of joint production were the cylinder and the conrod, and those seem insufficient to support the notion of a shared production source - a common design specification does not confirm a common source. If Forster Brothers were engaging in joint production with Pierce, why stop at the cylinder and rod? In particular, why produce a different piston for the same cylinder? The final point supporting the independence of Pierce production is the fact that their later designs display significantly less Forster influence than the original 1946 RRV model. Among other things, they soon developed a side-port version of their 29, which Forster never did. They also adopted a blind bored cylinder with integral head, a somewhat retrograde feature which Forster never applied to their 29 models. A little later, they also adopted an Ohlsson-style stamped timer in place of the diecast component used originally. This all supports the idea that Pierce were in fact following their own design and production path, taking the basic Forster design as their starting point.

The final point supporting the independence of Pierce production is the fact that their later designs display significantly less Forster influence than the original 1946 RRV model. Among other things, they soon developed a side-port version of their 29, which Forster never did. They also adopted a blind bored cylinder with integral head, a somewhat retrograde feature which Forster never applied to their 29 models. A little later, they also adopted an Ohlsson-style stamped timer in place of the diecast component used originally. This all supports the idea that Pierce were in fact following their own design and production path, taking the basic Forster design as their starting point.  The first model to appear under the Pierce trade-name was the .297 cuin. spark ignition RRV "Pierce Miniature Gas Engine" of 1946. It’s perhaps worth noting at the outset that the early advertisements referred to the Pierce 29 only as the “Pierce Miniature Gas Engine” - no other designation was applied. Collectors have been calling this model the Pierce “R” for years, but that was not the factory name, at least at this stage. More on this topic below in its place…...meanwhile, perhaps it's best just to call the engine the 1946 Pierce 29 RV. I'll do so from this point onwards.

The first model to appear under the Pierce trade-name was the .297 cuin. spark ignition RRV "Pierce Miniature Gas Engine" of 1946. It’s perhaps worth noting at the outset that the early advertisements referred to the Pierce 29 only as the “Pierce Miniature Gas Engine” - no other designation was applied. Collectors have been calling this model the Pierce “R” for years, but that was not the factory name, at least at this stage. More on this topic below in its place…...meanwhile, perhaps it's best just to call the engine the 1946 Pierce 29 RV. I'll do so from this point onwards.  Beginning with the castings, those used for the Pierce undoubtedly came from different dies. The component featured on the Pierce bore the name PIERCE plus a "winged 29" logo cast in relief onto the front of the case along with a "USA" designation. The exhaust stack on the Pierce was shorter and angled back at its outer end by comparison with that of the Forster. In addition, the stack fins were more pronounced on the Pierce.

Beginning with the castings, those used for the Pierce undoubtedly came from different dies. The component featured on the Pierce bore the name PIERCE plus a "winged 29" logo cast in relief onto the front of the case along with a "USA" designation. The exhaust stack on the Pierce was shorter and angled back at its outer end by comparison with that of the Forster. In addition, the stack fins were more pronounced on the Pierce.  either case. However, the combustion chamber configurations are significantly different. The Forster head has a simple hemispherical form which incorporates a broad transverse groove for the curved piston baffle. It also has an X cast opposite the groove to designate the exhaust position. By contrast, the Pierce head has a wide U-shaped combustion chamber which is sufficiently relieved on the transfer side to accommodate the small wings on the piston crown which form the baffle, while retaining the X to designate the exhaust side. These heads were clearly produced from different casting dies.

either case. However, the combustion chamber configurations are significantly different. The Forster head has a simple hemispherical form which incorporates a broad transverse groove for the curved piston baffle. It also has an X cast opposite the groove to designate the exhaust position. By contrast, the Pierce head has a wide U-shaped combustion chamber which is sufficiently relieved on the transfer side to accommodate the small wings on the piston crown which form the baffle, while retaining the X to designate the exhaust side. These heads were clearly produced from different casting dies.  Pierce cylinder in a Forster case. This has been taken by some to represent confirmation that the cylinders were made by Forster. However, this can by no means be taken as certain. Such cylinders may simply represent later replacement of a broken or worn Pierce cylinder with a Forster component, with the additional hole being added as a preliminary by whoever did the repair.

Pierce cylinder in a Forster case. This has been taken by some to represent confirmation that the cylinders were made by Forster. However, this can by no means be taken as certain. Such cylinders may simply represent later replacement of a broken or worn Pierce cylinder with a Forster component, with the additional hole being added as a preliminary by whoever did the repair.  that in the Forster has large cutaways on either side of the crankpin. In addition, the cam placement is slightly different on the Pierce and Forster shafts. The main journal runs in a plain bronze bushing inserted into the diecast front housing.

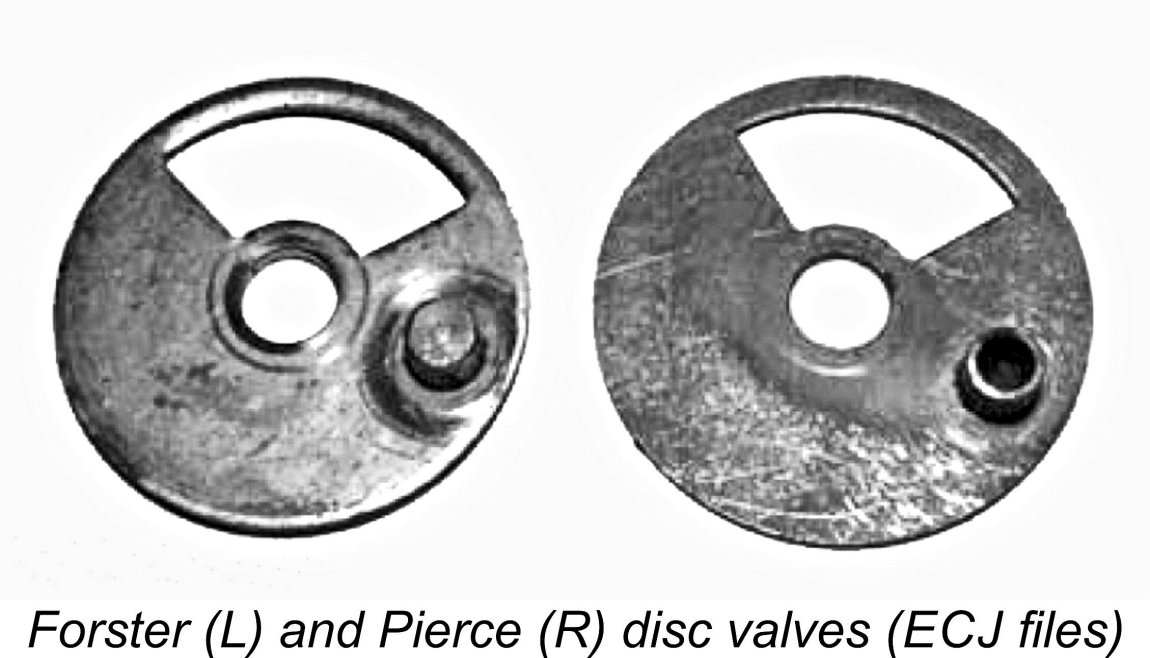

that in the Forster has large cutaways on either side of the crankpin. In addition, the cam placement is slightly different on the Pierce and Forster shafts. The main journal runs in a plain bronze bushing inserted into the diecast front housing.  Moving now to the rear of the engine, both the Pierce and Forster 29 models feature thin steel disc valves running in contact with the cast aluminium alloy of the main casting's integral backplate. These discs are mounted on steel pins which are pressed into the centre of the backplates. While very similar, the discs have different thicknesses, that in the Pierce being only 0.031 in. thick, while the Forster disc has a thickness of 0.061 in. The pressed-in disc drive pin on the Forster is solid, while that in the Pierce is hollow. Timing appears to be identical. However, the differences represent yet another indication of independent production.

Moving now to the rear of the engine, both the Pierce and Forster 29 models feature thin steel disc valves running in contact with the cast aluminium alloy of the main casting's integral backplate. These discs are mounted on steel pins which are pressed into the centre of the backplates. While very similar, the discs have different thicknesses, that in the Pierce being only 0.031 in. thick, while the Forster disc has a thickness of 0.061 in. The pressed-in disc drive pin on the Forster is solid, while that in the Pierce is hollow. Timing appears to be identical. However, the differences represent yet another indication of independent production.

In mid 1947 the Pierce range was expanded through the introduction of a side-port version of the Pierce 29, for which provision had been made at the outset by the inclusion of the unoccupied side-port induction boss on the original model. This variant was designated the Pierce Super “J” for some obscure reason. It was built up around the same castings as its predecessor.

In mid 1947 the Pierce range was expanded through the introduction of a side-port version of the Pierce 29, for which provision had been made at the outset by the inclusion of the unoccupied side-port induction boss on the original model. This variant was designated the Pierce Super “J” for some obscure reason. It was built up around the same castings as its predecessor.  Returning for a moment to the previously-discussed possibility that Pierce Industries were sued by Forster Brothers or perhaps threatened with such action, one possible motivation for making these changes could have been to distance the Pierce design from that of the Forster. Certainly, the Pierce Super "J" was an original Pierce design (as far as any model engine design is truly original), owing little to the Forster 29 which had inspired the initial Pierce 29 "Miniature Gas Engine".

Returning for a moment to the previously-discussed possibility that Pierce Industries were sued by Forster Brothers or perhaps threatened with such action, one possible motivation for making these changes could have been to distance the Pierce design from that of the Forster. Certainly, the Pierce Super "J" was an original Pierce design (as far as any model engine design is truly original), owing little to the Forster 29 which had inspired the initial Pierce 29 "Miniature Gas Engine".  Pierce Industries were undergoing considerable change at this time. Their advertisements prior to December 1947 placed them at 430 South Green St. in Chicago. As of December 1947 they had begun to advertise from a new location at 844 W. Adams St., Chicago. This didn’t represent much of a move, since the two locations are only a matter of two blocks distant from each other.

Pierce Industries were undergoing considerable change at this time. Their advertisements prior to December 1947 placed them at 430 South Green St. in Chicago. As of December 1947 they had begun to advertise from a new location at 844 W. Adams St., Chicago. This didn’t represent much of a move, since the two locations are only a matter of two blocks distant from each other.  In part, this price was achieved through further cost-cutting changes to the engines. Quite apart from no longer having to pay someone to assemble the engines, what other corners could be cut to lower the price? How about doing away with that extra timer attachment ring on the front bearing? How about going even further by using a stamped-out Ohlsson-style timer housing rather than the diecast component? The groove in the shaft bearing that previously accommodated the steel timer locking ring would serve perfectly well as the groove for the Ohlsson-type timer arm. While we’re at it, might as well omit the blackening process for the timer arm, prop washer and propnut.

In part, this price was achieved through further cost-cutting changes to the engines. Quite apart from no longer having to pay someone to assemble the engines, what other corners could be cut to lower the price? How about doing away with that extra timer attachment ring on the front bearing? How about going even further by using a stamped-out Ohlsson-style timer housing rather than the diecast component? The groove in the shaft bearing that previously accommodated the steel timer locking ring would serve perfectly well as the groove for the Ohlsson-type timer arm. While we’re at it, might as well omit the blackening process for the timer arm, prop washer and propnut.

It was almost certainly these circumstances that led to the February 1948 introduction of a kit version of the 1946 RV sparkie. It was this kit offering that was designated the Pierce 29 Model “R” by the manufacturer. The kit version was essentially identical to the original $12.95 ready-to-run “Pierce Miniature Gas Engine”, retaining that model’s bore and stroke dimensions of 0.750 in. (19.05 mm) and 0.6718 in. (17.06 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.297 cuin. (4.86 cc). The only real defining differences were the use of a J-type stamped Ohlsson-style timer and the omission of the black paint on the diecast cylinder head. Both of these features make distinguishing between this variant and the original "Pierce Miniature Gas Engine" very easy.

It was almost certainly these circumstances that led to the February 1948 introduction of a kit version of the 1946 RV sparkie. It was this kit offering that was designated the Pierce 29 Model “R” by the manufacturer. The kit version was essentially identical to the original $12.95 ready-to-run “Pierce Miniature Gas Engine”, retaining that model’s bore and stroke dimensions of 0.750 in. (19.05 mm) and 0.6718 in. (17.06 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.297 cuin. (4.86 cc). The only real defining differences were the use of a J-type stamped Ohlsson-style timer and the omission of the black paint on the diecast cylinder head. Both of these features make distinguishing between this variant and the original "Pierce Miniature Gas Engine" very easy.  As far as the advertising trail takes us, we’ve now reached the end of the Pierce series - no other models were ever advertised under the Pierce trade-name. However, the Pierce story doesn’t end here by any means! As mentioned earlier, the glow-plug era had now well and truly arrived. This evidently led Pierce to try a different approach to the liquidation of remaining stocks of their Model “J” components. They appear to have reached an agreement with the Mercury Model Airplane Co. of Brooklyn, New York to supply glow-plug versions of the Model “J” under the designation “Glo-Champ”.

As far as the advertising trail takes us, we’ve now reached the end of the Pierce series - no other models were ever advertised under the Pierce trade-name. However, the Pierce story doesn’t end here by any means! As mentioned earlier, the glow-plug era had now well and truly arrived. This evidently led Pierce to try a different approach to the liquidation of remaining stocks of their Model “J” components. They appear to have reached an agreement with the Mercury Model Airplane Co. of Brooklyn, New York to supply glow-plug versions of the Model “J” under the designation “Glo-Champ”.

Issue 45 of ECJ for January/April 1973 featured a photo of an unusual engine called the Samson 30 on the cover. Three photos of this easily identifiable hybrid were sent in by John Krickel, apparently showing an engine then in the Steve Ditta collection.

Issue 45 of ECJ for January/April 1973 featured a photo of an unusual engine called the Samson 30 on the cover. Three photos of this easily identifiable hybrid were sent in by John Krickel, apparently showing an engine then in the Steve Ditta collection.

As far as I'm aware, none of the various Pierce offerings was ever the subject of a published test in the contemporary modelling media. This left it down to me! Having fine examples of both the original Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine" and the Pierce Super "J" sideport model on hand, I thought that a bench test would constitute an appropriate finale to this review.

As far as I'm aware, none of the various Pierce offerings was ever the subject of a published test in the contemporary modelling media. This left it down to me! Having fine examples of both the original Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine" and the Pierce Super "J" sideport model on hand, I thought that a bench test would constitute an appropriate finale to this review.  Although it was complete and in cosmetically-perfect original condition, this example had either done a fair bit of running or had been fitted rather loosely initially - it had slightly "soft" compression as a result. Nonetheless, there was plenty of compression for starting and running, while all bearings seemed to be in first-class condition.

Although it was complete and in cosmetically-perfect original condition, this example had either done a fair bit of running or had been fitted rather loosely initially - it had slightly "soft" compression as a result. Nonetheless, there was plenty of compression for starting and running, while all bearings seemed to be in first-class condition.

As with the 1946 disc-valve Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine" tested previously, I began with a Top Flite 10x7 Power Point wood prop fitted. After making sure that the timer was in the retarded position, I filled the tank and opened the needle valve by the three turns recommended by the manufacturer. I then applied a couple of choked flicks, administered a small exhaust port prime, switched on the ignition and got stuck in.

As with the 1946 disc-valve Pierce "Miniature Gas Engine" tested previously, I began with a Top Flite 10x7 Power Point wood prop fitted. After making sure that the timer was in the retarded position, I filled the tank and opened the needle valve by the three turns recommended by the manufacturer. I then applied a couple of choked flicks, administered a small exhaust port prime, switched on the ignition and got stuck in.  engine seemed happy enough on the 10x7 prop, turning it at around 4,700 RPM during the brief leaned-out but still retarded period with which the run ended as the tank ran dry. Indications were that a somewhat lighter load would be more appropriate! Even so, it was already clear that the performance of the Super "J" would fall well short of that achieved by its disc-valve relative.

engine seemed happy enough on the 10x7 prop, turning it at around 4,700 RPM during the brief leaned-out but still retarded period with which the run ended as the tank ran dry. Indications were that a somewhat lighter load would be more appropriate! Even so, it was already clear that the performance of the Super "J" would fall well short of that achieved by its disc-valve relative.

Returning to my test session and seeking some more fun, I set up the previously-described red-case "Special" in the test stand just to experience its qualities. Given the fact that this is an undocumented one-off owner creation, I saw little reason to subject it to a full test, confining myself to trying it with the APC 10x6 prop that the Super "J" had turned at 6,100 RPM, right around what proved to be its peaking speed of 6,000 rpm. I used the same Coleman/AeroShell fuel for these test runs.

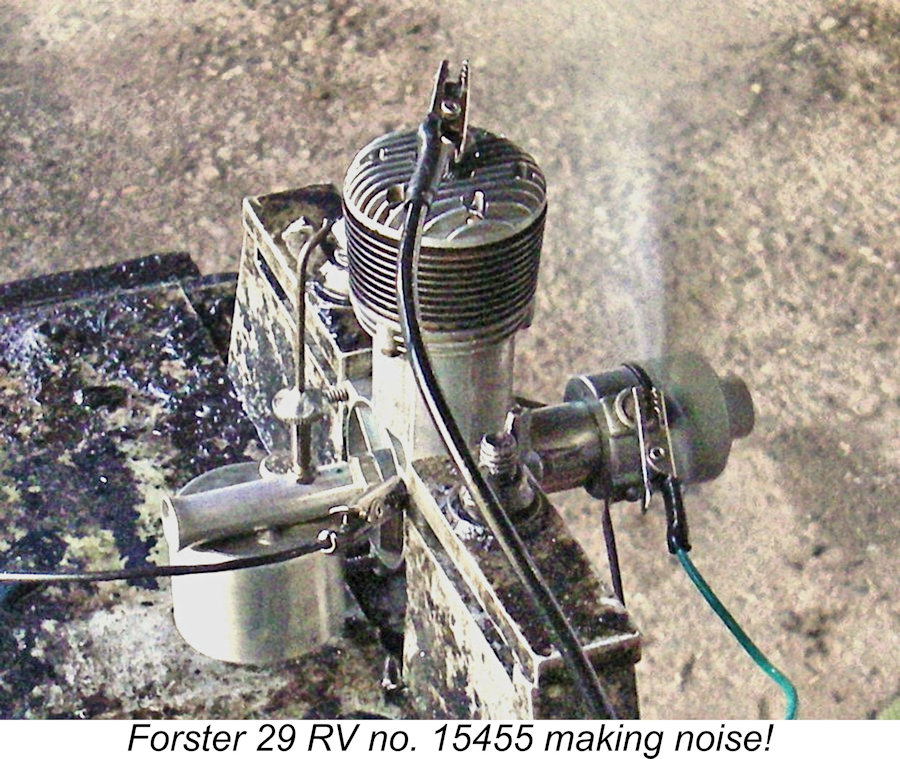

Returning to my test session and seeking some more fun, I set up the previously-described red-case "Special" in the test stand just to experience its qualities. Given the fact that this is an undocumented one-off owner creation, I saw little reason to subject it to a full test, confining myself to trying it with the APC 10x6 prop that the Super "J" had turned at 6,100 RPM, right around what proved to be its peaking speed of 6,000 rpm. I used the same Coleman/AeroShell fuel for these test runs.  Finding that I still hadn't had enough fun for the day, I decided to give my Forster 29 RV sparkie an airing. By 1947 Forster Brothers had enhanced the design of their 29 RV model through the addition of a single ball-race at the rear of the crankshaft. My engine is one of those 1947 ball-race units bearing the serial number 15455. It has been mounted and used a little, hence being fully run in. However, it remains complete and original.

Finding that I still hadn't had enough fun for the day, I decided to give my Forster 29 RV sparkie an airing. By 1947 Forster Brothers had enhanced the design of their 29 RV model through the addition of a single ball-race at the rear of the crankshaft. My engine is one of those 1947 ball-race units bearing the serial number 15455. It has been mounted and used a little, hence being fully run in. However, it remains complete and original.  The Pierce engines undoubtedly constitute the material evidence of an interesting untold story. At the outset there simply had to be some kind of connection between the Pierce and Forster marques - considerations of both design and geographical relationships appear to make this indisputable. Sadly we have no direct evidence which might clarify the nature of this connection - it's all circumstantial.

The Pierce engines undoubtedly constitute the material evidence of an interesting untold story. At the outset there simply had to be some kind of connection between the Pierce and Forster marques - considerations of both design and geographical relationships appear to make this indisputable. Sadly we have no direct evidence which might clarify the nature of this connection - it's all circumstantial.