|

|

The Hurricane Engines

The Hurricane engines have received a fair amount of previous attention, albeit in the now distant past. They were featured as the Engine of the Month (EOM) in issue no. 9 of the late Tim Dannels’ outstanding “Engine Collectors’ Journal” (ECJ), way back in November 1964, when I was still at school and the range’s introduction lay only 20 years in the past. The author was the late Mike Cook, a native of Toronto, Ontario where the Hurricane engines had their origin. Time marches on, and the readership of ECJ expanded considerably during the 1960’s. In view of this, Tim felt that the engines deserved another airing for a wider audience some 6 years later in issue no. 34 of ECJ for March-April 1970. Once again, the Hurricanes were EOM for that issue, only this time the author was Mike Thomas, another Toronto resident who was a well-known and very talented model engine restorer and constructor. Mike Thomas was able to add considerably to the information provided earlier by Mike Cook. Now here comes Duncan writing about the Hurricanes yet Still, while my website is up and running, it seems to me that there’s value in making information of this kind available online to those interested. Hence the preparation of this article. I won’t be sharing anything new here other than a few of my own test results - rather, I’ll be making information painstakingly gathered by others many decades ago freely available online to present-day enthusiasts. In doing so, I openly acknowledge my indebtedness to my predecessors, who had the immense advantage of writing when the trail was still relatively fresh. The only thing that I can add to the work of those individuals is some test data on a few variants of the Hurricane 24 in my possession. It’s important to see the Hurricane engines in context if one is to fully appreciate their significance. I’ve presented the background to the early production of model engines in Canada in several previous articles. To save readers of the present text from having to go hopping about between articles, I’ve repeated the relevant portions of that information here. Those who are already familiar with this material are invited to skip straight to the following section of the present article. Background

The first of these two factors tended to restrict model engine manufacturing in Canada to small-scale ventures producing limited numbers of engines intended primarily for the local Canadian market in the immediate area of production. The second factor - the competition from the USA - made it difficult or impossible for Canadian manufacturers to compete price-wise in the broader marketplace. Those who tried certainly deserve our respect!

These engines were marketed through the St. John Model Shop in Winnipeg. The associated brochures specifically cited this engine as “the first motor to be manufactured in Canada”, seemingly confirming its priority. It was produced in very small numbers - no surviving examples are known today. Only a few fuzzy photograhs like that seen here remain to confirm that the engine did exist!

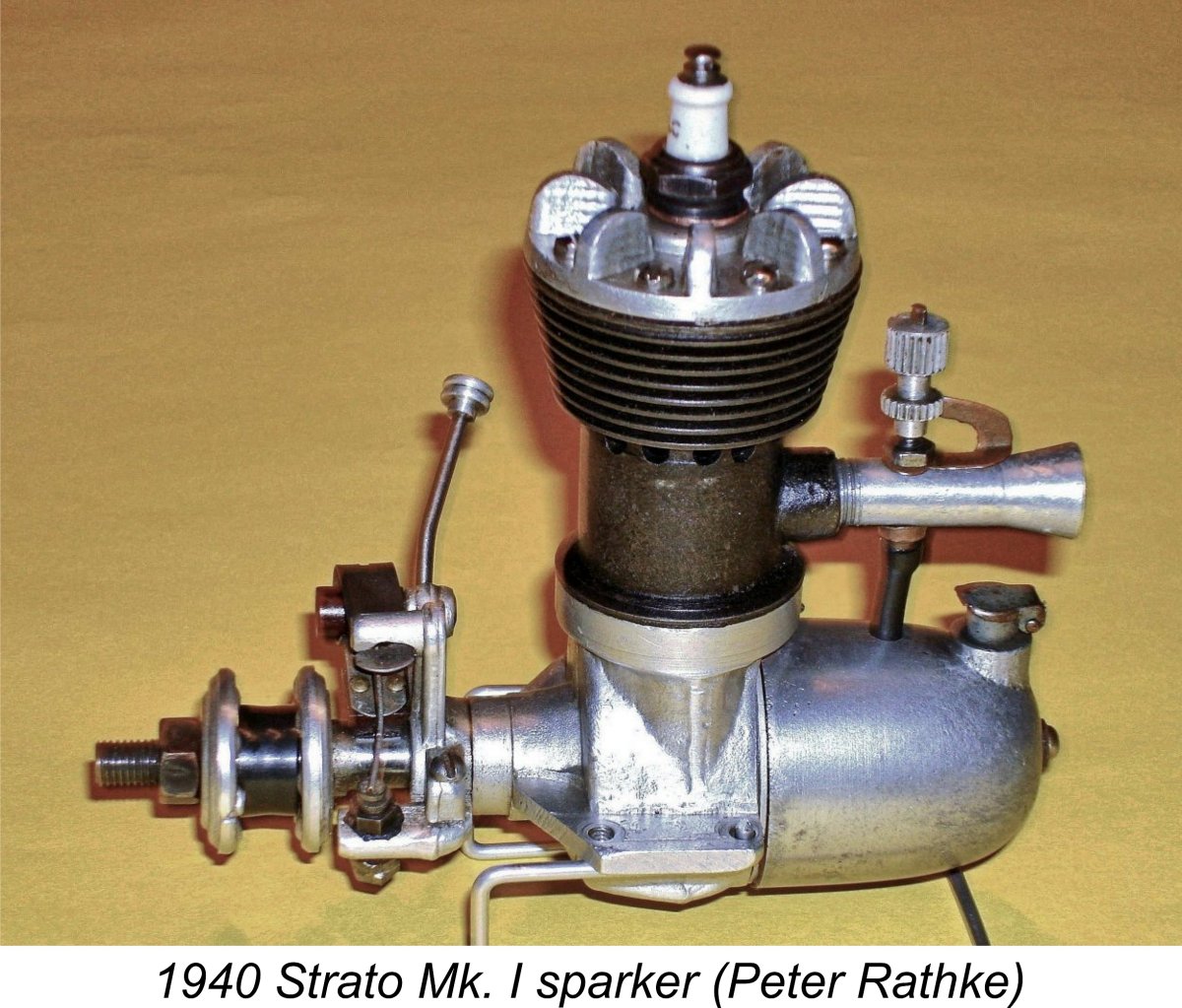

An individual who managed to stay the course for considerably longer than Paul Drimmie was Randall Bainbridge of Montreal, Quebec. According to the genealogical information very kindly tracked down by Tim Dannels' son-in-law Sheldon Jones, Bainbridge had been born in northern England on January 1st, 1913 at Tynemouth, Northumberland but emigrated with his family to Quebec, Canada in 1925 at the age of 12. He lived the rest of his life there, passing away in Montreal on March 7th, 2006 at the grand old age of 94. Beginning at the age of 27, Bainbridge somehow managed to construct a small Given the ongoing Canadian involvement in WW2, it’s unclear who Bainbridge’s customers may have been. Perhaps some of the engines were used by the Canadian military to power target drones?!? As WW2 drew closer to its increasingly-predictable end, model engine production in the USA resumed in September 1944 when the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen. Up in Canada, Randall Bainbridge Sadly, Bainbridge found that with his very limited production capacity based upon individual construction to very high standards he couldn’t compete in price terms with mass-produced American-built .60 cuin. alternatives such as the Ohlsson & Rice, Atwood, Herkimer (OK) and Super Cyclone units which became increasingly available in Canada following WW2. Not enough people were willing to meet the extra cost of the Strato engines’ hand-built tool-room quality. After some 40 examples of the “Super” Mk. IV sparker had been manufactured, Bainbridge finally abandoned the model engine field. A detailed review of the various Strato models appears elsewhere on this website.

Among these new manufacturers was a firm called Canadian Hobbycraft of Toronto, Ontario, which was owned by a gentleman going by the name of Sammy Crystal (not his birth name). This company’s flagship product was the 0.232 cuin. (3.80 cc) Merlin Super “B” sideport spark ignition unit which first appeared in 1944 and survived until 1948. The address given on the advertisements for the engine was 716 Bathurst Street, Toronto 4. That model too is covered in a focused article to be found elsewhere on this website. Now at last we come to the central subject of this article - the Hurricane 24 series which was manufactured between 1944 and 1949 in Toronto. The Hurricane engines carry the best-known and longest-lasting name in Canadian model engine manufacturing history. Let’s review the production record which this range accumulated. The Hurricane Series - Production History

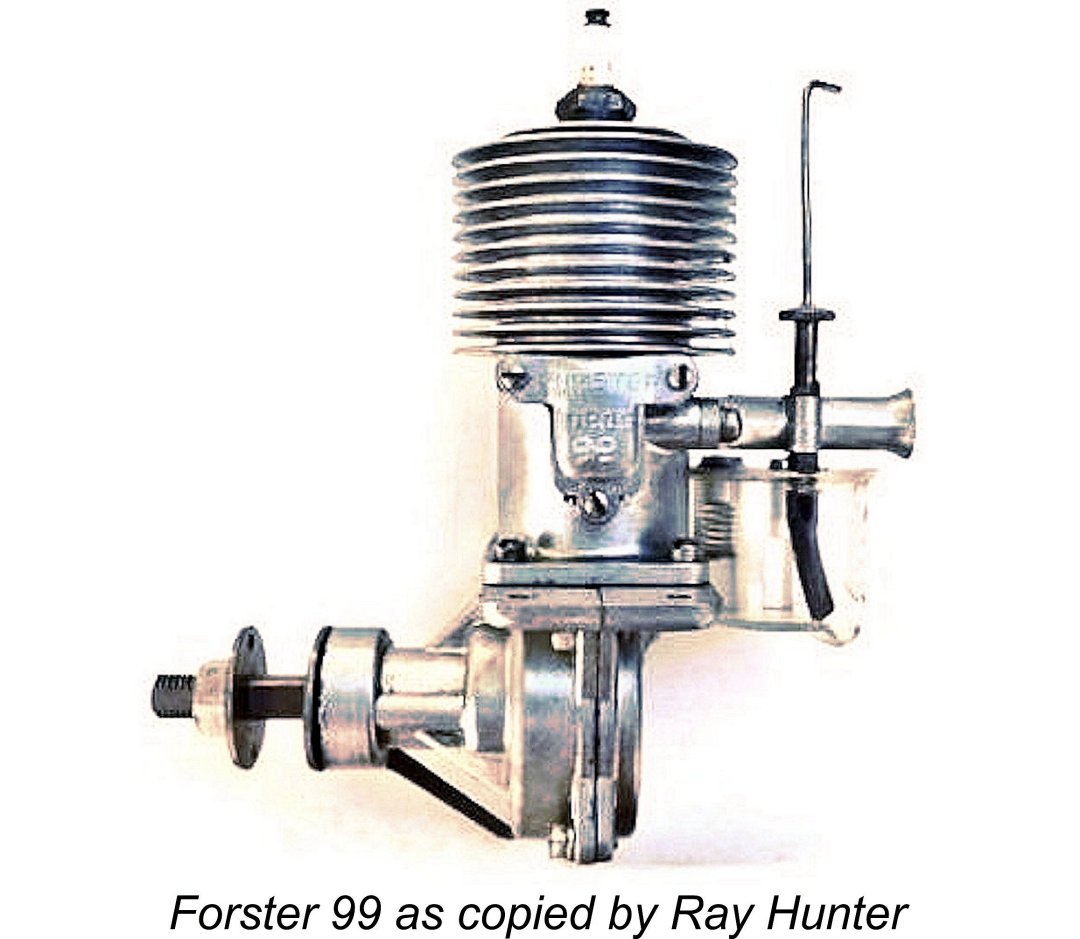

Ray Hunter was a well-known member of the Toronto-area modelling community who was also a skilled machinist. He had acquired those skills as a teenager working in the machine shop attached to his father's automotive garage, eventually becoming a licensed mechanic. He has left us with a fairly comprehensive memoir of his life which may be read here beginning on page 9. There are a few inconsistencies, but Ray was past 90 years old when he wrote this account, making a little blurring of the details quite understandable!! My very sincere thanks go out to Sheldon Jones for unearthing this invaluable reference for us. Beginning in the 1930’s when in his early to mid twenties, Ray had constructed a number of one-off motors for his own use, including a fine copy of a Forster 99 which he made from scratch, including the patterns for the castings. Mike Thomas reported that this engine was still running well in 1970!! Ray was a pioneer in the pre-war R/C field, designing and constructing his own transmitters and receivers which were used to control boats as well as aircraft. He had thus amassed a considerable amount of model engine construction and operational experience prior to the outbreak of WW2, much of which he spent working as an inspector at the A. V. Roe plant at Malton, Ontario. A major focus was the inspection of the Hawker Hurricane wings being made in Canada, and it may have been this experience that suggested the name of Ray's later model engine series. Mike Cook was 12 years old in 1944 when he first met Ray Hunter, who was then 35 years old. Mike remembered Ray as a friendly man, always ready to help a fellow modeller who was having engine trouble. He once gave Mike a new Hurricane to replace one which had been stolen. Apparently by 1944 he had ended his hands-on involvement with model building, focusing his energies entirely upon the creation of his Hurricane model engines. I was surprised to learn that the first Hurricane engines appeared in early 1944 while WW2 was still very much ongoing, some time prior to the official relaxation of material supply constraints for non-military purposes. Ray explained this in his memoirs by reporting that at some previous point in time he and his partners had somehow secured an ”Education Priority” materials supply rating, enabling them to assemble enough material to commence production in early 1944. He also noted that the USA was a major marketing area at the time because US model engine manufacturers were not permitted to resume production until later in 1944 and didn't get fully back up to speed until mid 1945. The early Hurricane engines therefore had a clear field! They were apparently brought into the USA through a distributor located in nearby Buffalo. Apparently Ray Hunter’s original intention was to call his offering the “Whirlwind”, but this choice of name was amended to “Hurricane” just as production was getting underway. Hunter’s intention is indisputably confirmed by the fact that a few boxes were actually produced bearing the “Whirlwind” name. Some of the early Hurricane engines were sold in these boxes with the “Whirlwind” name taped over.

Mike Cook’s first engine was a 1944 Hurricane 24, engine no. 250, purchased in the spring of 1944. This seemingly dates the commencement of Hurricane production quite unambiguously to early 1944. Mike took it back to Ray Hunter to have a minor construction error attended to and was given a tour of the Production & Tool workshops where the engines were then being made. The machine shop was apparently very well equipped and equally well staffed - Ray later recalled as many as 65 toolmakers being employed there. However, Mike saw no evidence of any castings being produced at that location - that rather specialist process was almost certainly contracted out at that time. It was apparent to Mike that The Production & Tool Company didn't confine its involvement in the model trade to the manufacture of the Hurricane engines. A surviving box in my possession confirms that they also made flight timers and presumably other accessories. The company is clearly identified on the box as the manufacturer of this device. I don't have an actual example of the device which this box once contained, but the instructions printed on the box exterior imply that it was a pneumatic device of the kind then in common use.

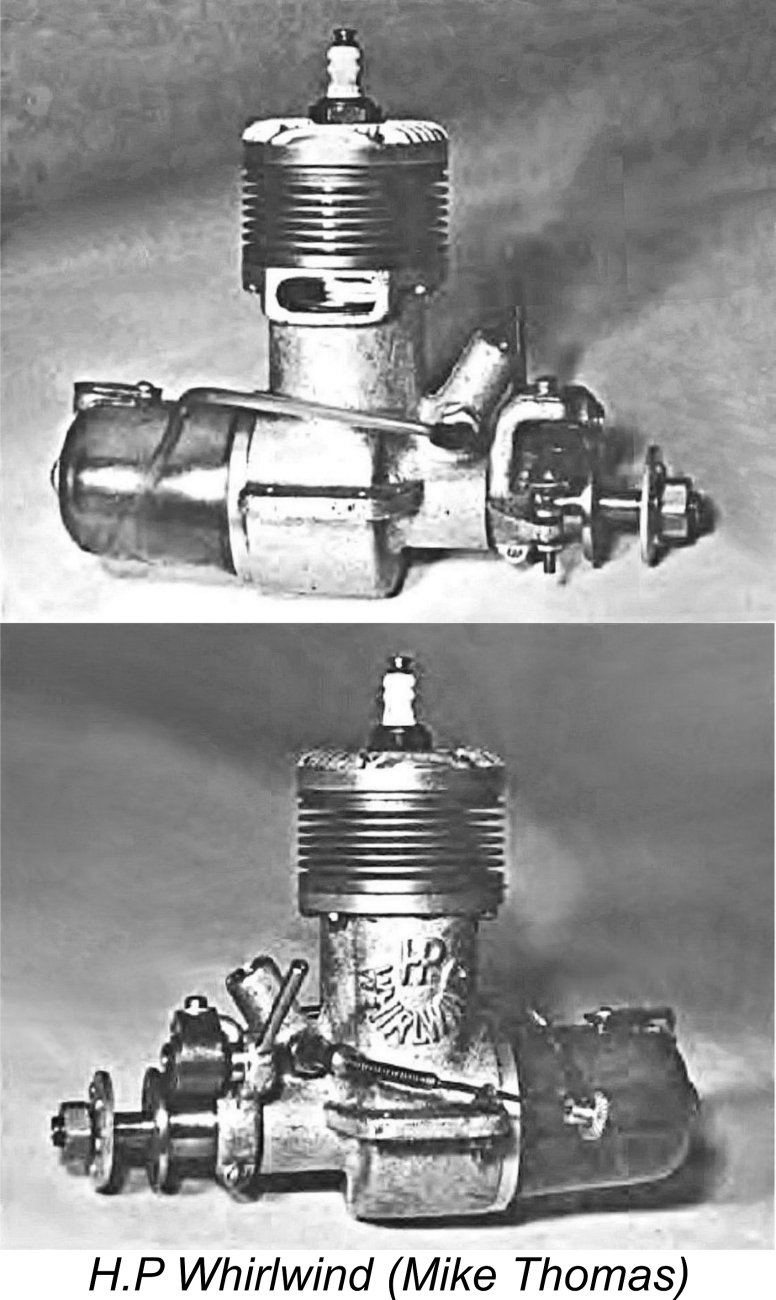

The partnership between Hunter and Patch continued into 1946. Work was actually started on a .60 cuin. unit of quite up-to-date design called the “H.P. Whirlwind”, with the H.P. standing for Hunter & Patch and the unused Whirlwind name being revived. The intent was apparently to sell these engines to the Canadian military to power target drones. Six examples were constructed, but with the end of the war in sight the military did not buy, causing the abandonment of the project. In any case, the Hunter/Patch partnership was not destined to last. At some indeterminate point in the first half of 1946, the partners came to a falling-out over a manufacturing issue. The cylinder liners in the Hurricane were vertically Under the terms of the split, Patch retained most of the machine tool inventory, while Hunter assumed ownership of the model engine parts, tooling and designs along with the right to continue to manufacture them on his own account and a sufficient number of machine tools to do so. He set up his share of the equipment in the basement of his home and continued to produce the engines himself, now trading as Hurricane Engines of 28½ Adelaide Street East in Toronto. Mike Cook visited Ray’s basement premises in the summer of 1946, soon after the split. The final advertisement naming Production & Tool as the manufacturers appeared in the June 1946 issue of “Air Trails”. As of August 1946 the adverts gave only a distributor’s address. Ray Hunter continued to produce the Hurricanes in his basement workshop for some years after Production & Tool ceased manufacturing the engines. The castings were evidently still supplied as required by the At some point in 1948 Ray ended production of the spark ignition Super Hurricane, replacing it with a modified "Hot Top" version lacking the timer and fitted with a higher-compression head to permit operation on glow-plug ignition. This was a very good runner indeed but couldn’t compete with the best of the competing American products. It appears that Ray Hunter recognized this, consequently ending all Hurricane production in the latter part of 1949. He subsequently moved into the retail hobby business, including the evolving field of jewellery handicrafts. He also became an enthusiastic participant in the "ham" radio movement, in which field his handle was "Uncle Ray". He died in 2003 at Orillia, Ontario. Having traced the production history of the Hurricane engines, let’s take a closer look at the engines themselves. In doing so, I’ll attempt to define the different versions in which the engine appeared, doing so in chronological order. The First Versions of the Hurricane 24 - Description

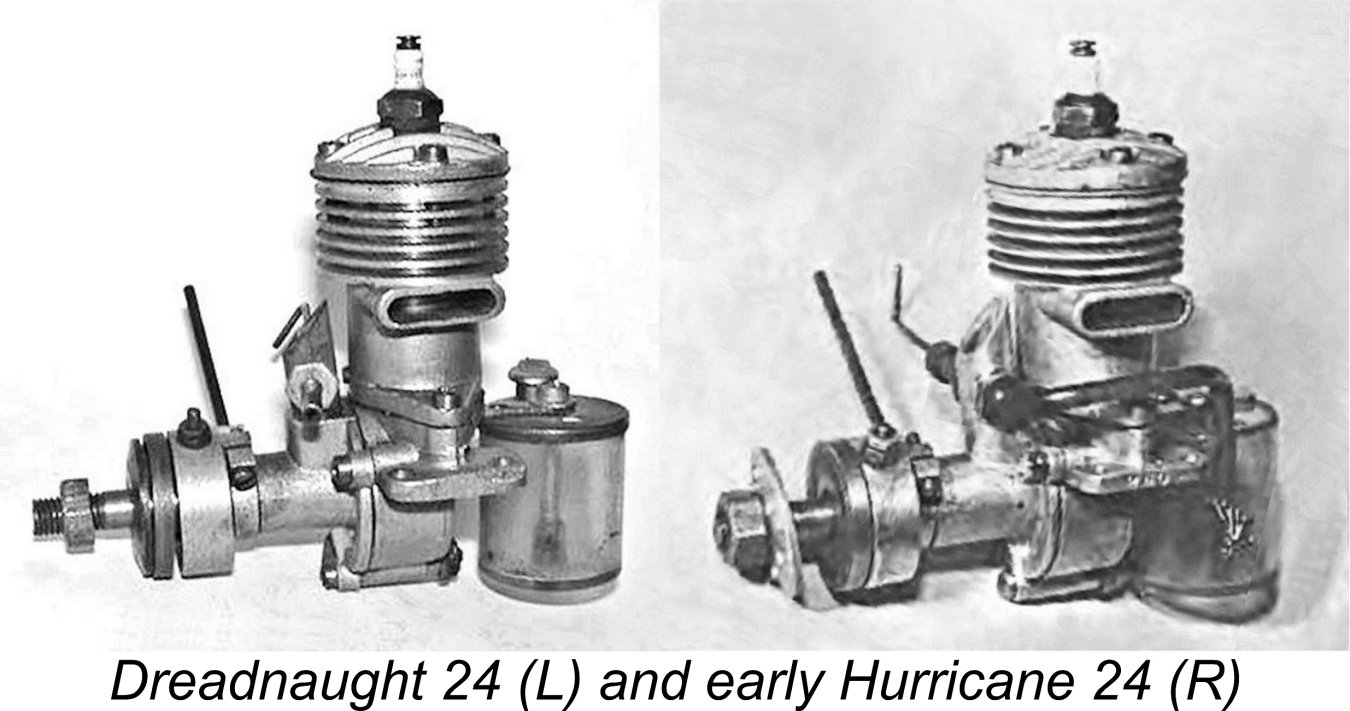

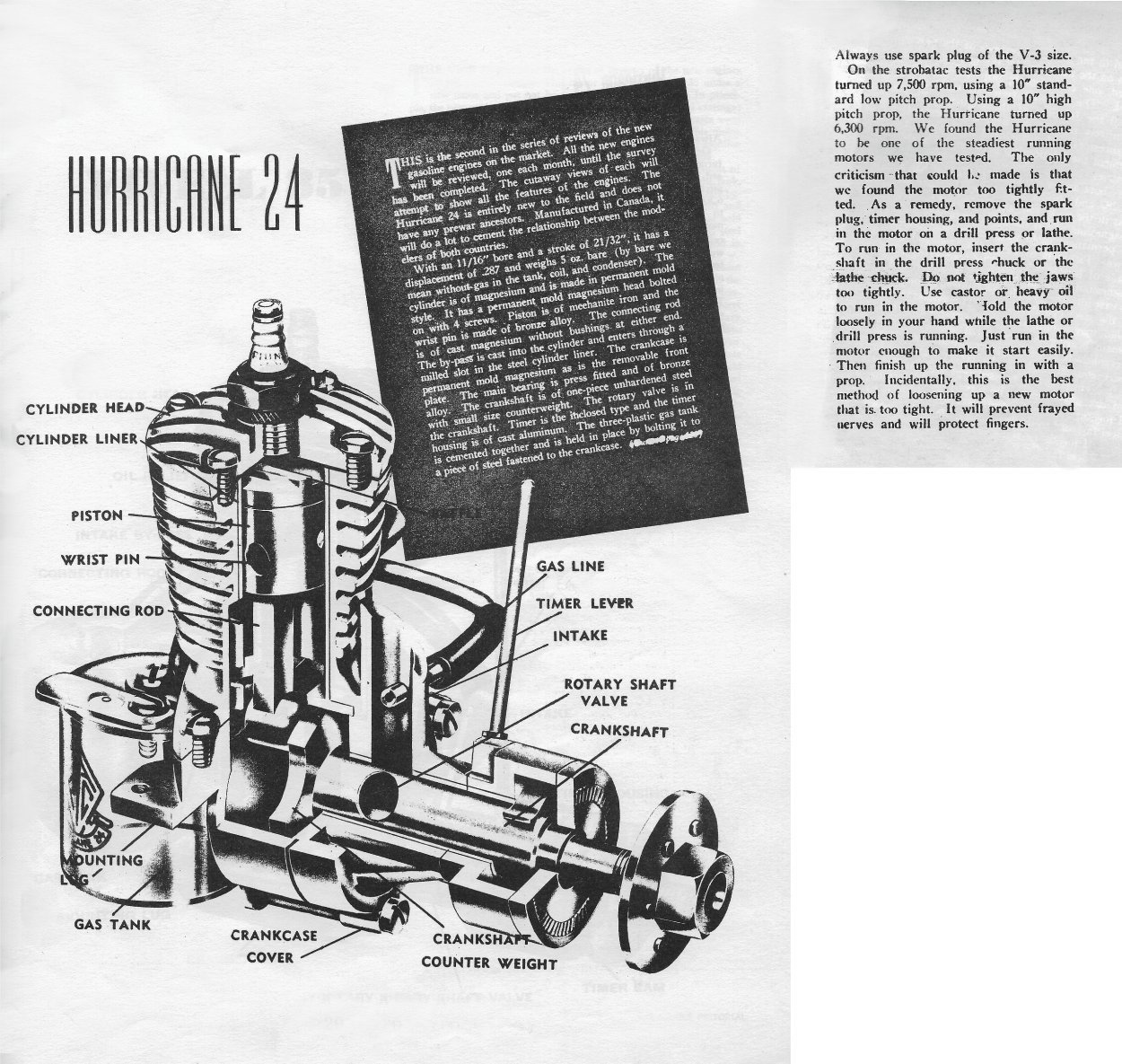

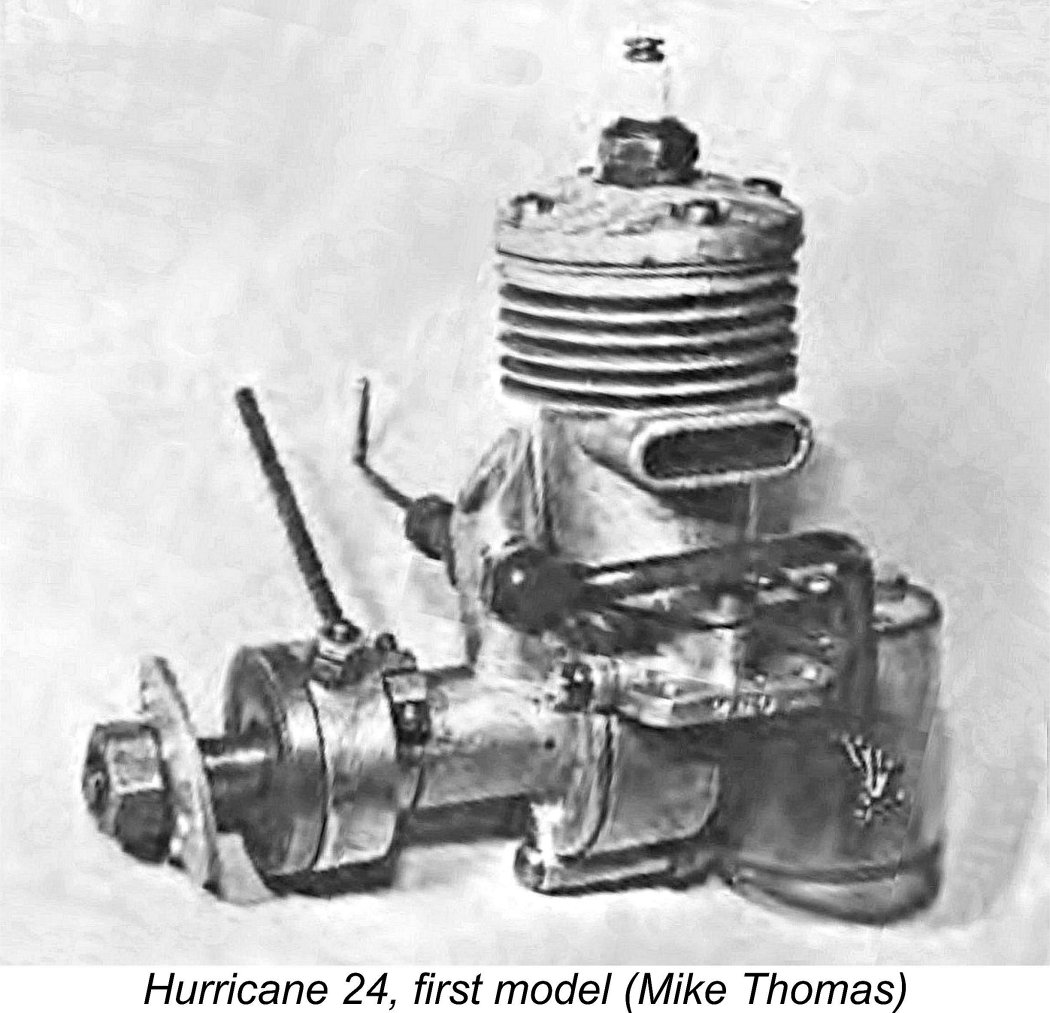

Production of the Dreadnaught had doubtless been stopped pretty much as soon as it began as the USA focused its material supplies and manufacturing capabilities on the production of war materiel. The design itself clearly survived the war, but when model engine production in the USA resumed in September 1944 following the US War Production Board decision to release sufficient material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen, Dreadnaught Motors did not resume their involvement in the industry. Evidently Ray Hunter had already somehow acquired the rights to the design. Or had he ………........?!? In reality, there may have been a few skeletons rattling about in this particular closet! My late good mate Tim Dannels shared a recollection of a meeting which he had years later with Ray Hunter at a MECA Grando in Muncie, Indiana. Tim found Ray to be a most pleasant gentleman with whom he enjoyed a very amicable chat. This ended abruptly when Tim made the mistake of mentioning the name Dreadnaught. Ray immediately walked away and never spoke to Tim again! What’s that rattling sound that I hear emanating from that cupboard?!? All of the engines in the Hurricane series shared a number of common features. They were all crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) designs featuring cross-flow loop scavenging, downdraft induction, cast iron cylinder liners, lapped cast iron baffle pistons and separate upper cylinder assemblies attached to the lower crankcase by two machine screws. All models in the Hurricane 24 series from first to last retained bore and stroke dimensions of 11/16 in. (0.6875 in./17.46 mm) and 21/32 in. (0.6562 in./16.67 mm) for a calculated displacement of 0.244 cuin. (3.99 cc). The original Dreadnaught-based Huricanes of early 1944 featured a crankcase having an integrally-cast backplate and a separate front housing secured by three machine screws. The downdraft intake venturi was cast integrally with the main bearing housing, unlike the Dreadnaught’s screw-in brass component. In addition, the main bearing housing itself was unbraced. The cases were investment-cast, almost certainly by an outside contractor. The cast cylinder jacket with its integral cooling fins was perfectly cylindrical in plan view, while the fins themselves were of uniform diameter from top to bottom. The unusually thin drop-in cast iron cylinder liner was vertically located by a bronze rivet at the front near the base, as previously illustrated.

The Meehanite cast iron piston had a conventional baffle on the transfer side of the otherwise flat crown. It was originally provided with a narrow oil retention groove near the top in an effort to improve The piston was relatively light, thanks mainly to having rather thin walls with no attempt to provide it with elongated bosses for the bronze gudgeon (wrist) pin. This left the gudgeon pin supported by two extremely short bearings at the ends, with a relatively long unsupported length between them. This might be expected to result in elevated levels of bending stress during operation, although the fact that this was a relatively low-compression spark ignition motor might have prevented this from becoming a major dependability issue. Mike Cook recalled that a more serious consequence of the minimal piston boss length was a certain tendency towards premature wear of the gudgeon pin at its outer ends, eventually to the extent that the pin would slip out of one of its bosses to jam inside the piston at an angle. The inevitable consequence was a broken or bent rod to go along with a useless gudgeon pin.

As the accompanying image shows, the lower bypass entry was of very modest proportions. Access was somewhat improved by the provision in the lower casting of a channel to improve gas access (see earlier crankcase illustration), but the supply of fresh mixture to the bypass was greatly facilitated by the inclusion of two drilled skirt ports in the lower piston wall on the transfer side. These aligned at bottom dead centre with a large rectangular port in the cylinder wall, very much like the arrangement seen in many racing engines of the period. Later examples featured a rectangular skirt port in place of the two drilled holes.

The crankweb was quite heavily counterbalanced. Main journal diameter was 3/8 in. (0.375 in./9.53 mm) - fair enough, but the internal gas passage in the shaft had a heroic diameter of 0.280 in (7.11 mm), which left a rather marginal wall thickness of only 0.0475 in. (1.206 mm) - pretty skimpy by normal standards! What probably saved the engine was once again the fact that it was a low-compression low-speed sparkie which would impose relatively minimal loads on its working components if properly handled.

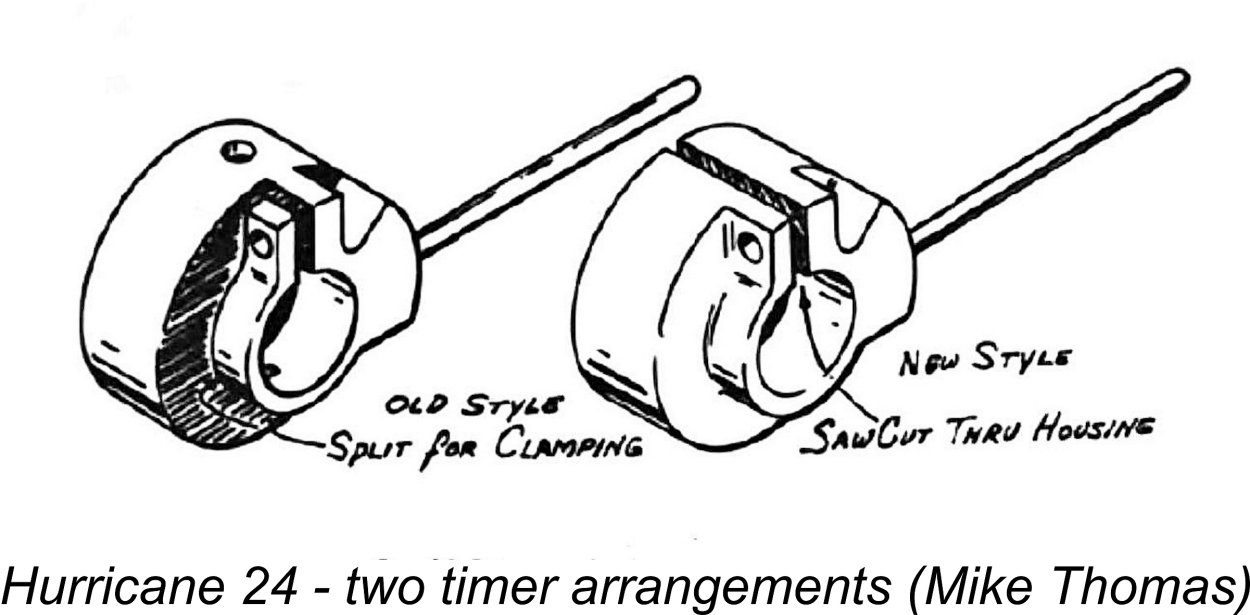

Whichever timer was used, the points were activated by a flat formed in the crankshaft journal at the front which served as a cam. The steel prop driver had a D-shaped hole formed at its centre which engaged with a flat formed at the front of the shaft. Prop drivers keyed to the shaft in this way have an annoying tendency to develop a “wobble” fairly quickly in service - splines, a "square-in-socket" arrangement or a conoidal split-collar mounting are all very much superior.

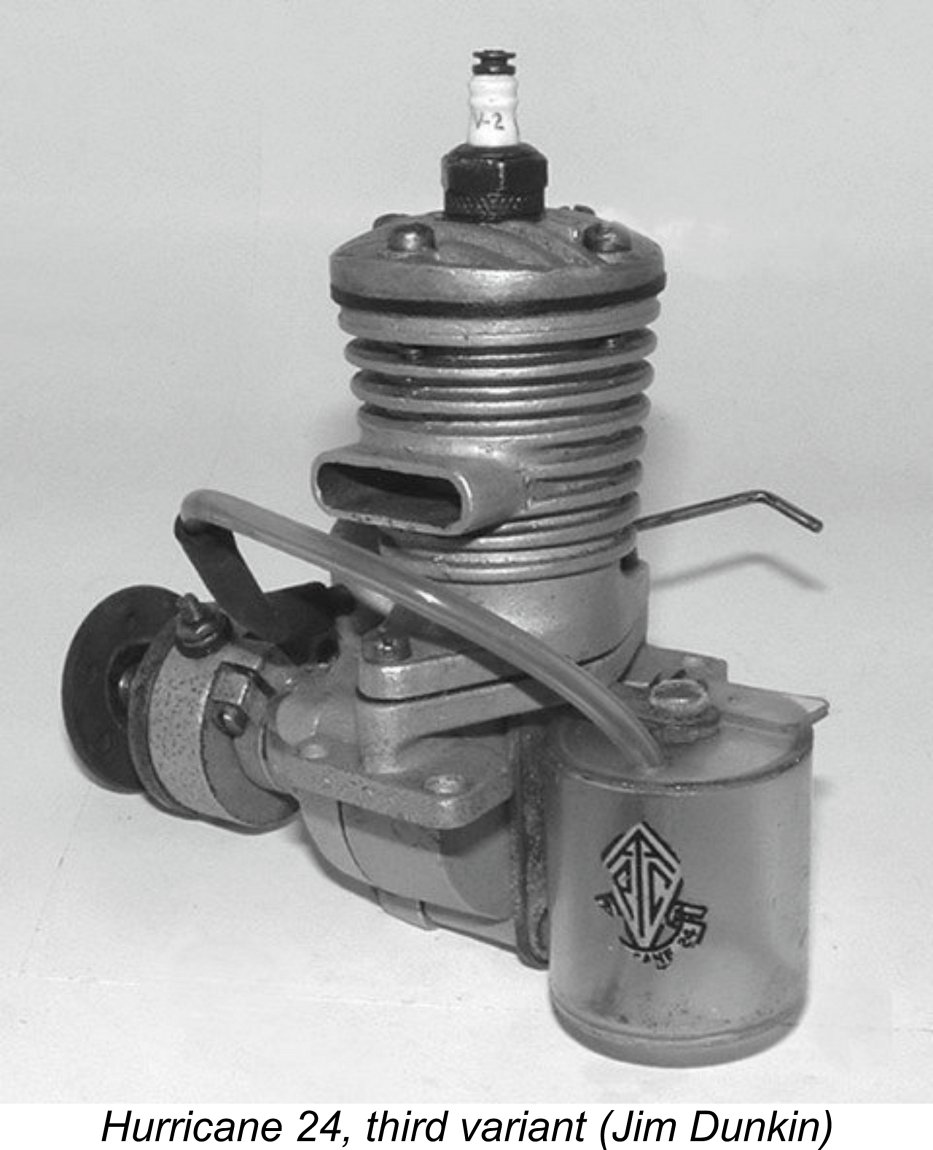

The engine was completed by a plastic hang tank attached to the rear by a metal bracket. This bracket was secured to the engine by a single screw which engaged with a tapped hole at the rear base of the crankcase. The tanks for the first three models featured a decal showing the logo of the Production & Tool Co., along with the Hurricane 24 title below it in a half-circle. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached incomplete rendition of the decal, but it's the sole image that I was able to come up with. At least it shows the clever way in which the PTC initials of the company name were incorporated into the logo.

By the summer of 1944, enough examples of the Hurricane had entered service that a design issue urgently requiring correction had become apparent. This was the tendency of the unbraced front housing to crack even under relatively modest impact stresses. To address this issue, the installation flange on the front housing was made much thicker, while substantial reinforcing webs were added to stabilize the main bearing in the housing. The resulting front housing was far less susceptible to breakage. In other respects, this second variant was essentially unchanged from the original model. The changes had however sent the weight up to a checked 163 gm (5.75 ounces) complete with plug and tank.

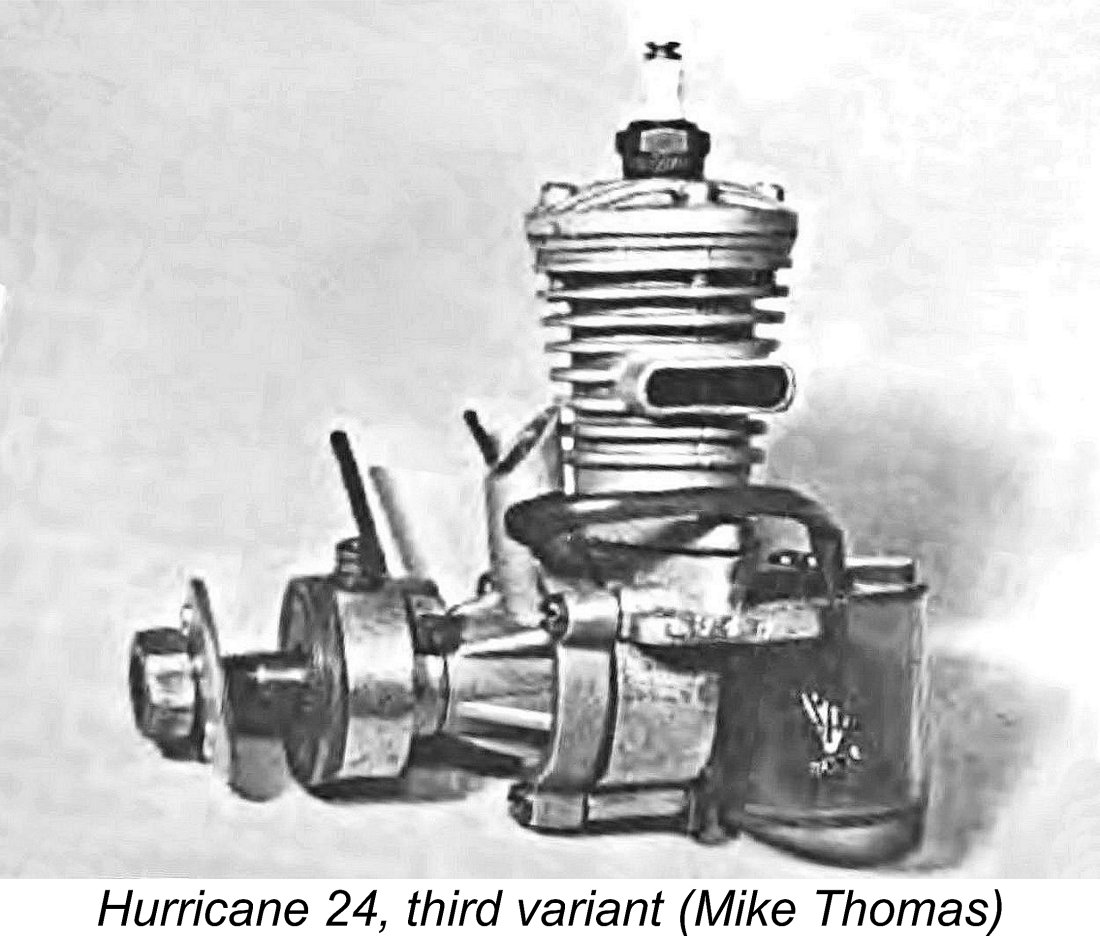

This third variant was the subject of the second installment in the series of model engine reviews published in the pages of “Air Trails” magazine. Unfortunately I don’t have the date of this publication - can any reader advise? It must have been in 1945, but that's as close as I can come.

The article included a fairly detailed description of the engine, the main anomaly being that the castings were said to have been formed in magnesium alloy. I’ve never encountered a magnesium-cast example of the Hurricane 24 - has anyone else? Another incompatibility is the statement that a V-3 plug should be used - all of the heads that I’ve ever seen have been dimensioned to take a long reach V-2 plug. Indeed, the magazine's own cutaway drawing clearly showed a V-2 plug. In performance terms, the only test figures given were a claimed speed of 7,500 rpm on a “standard” 10 in. dia. low-pitch prop, while a “standard” 10 in. dia. high-pitch prop was turned at 6,300 rpm. The Hurricane was said to be “one of the steadiest running motors” of the tester’s experience. His only criticism was the fact that his example was set up extremely tight as received - he had to do some running-in on a lathe to free it up sufficiently for easy starting. Still, better too tight than too loose! Serial Numbers and Production Figures

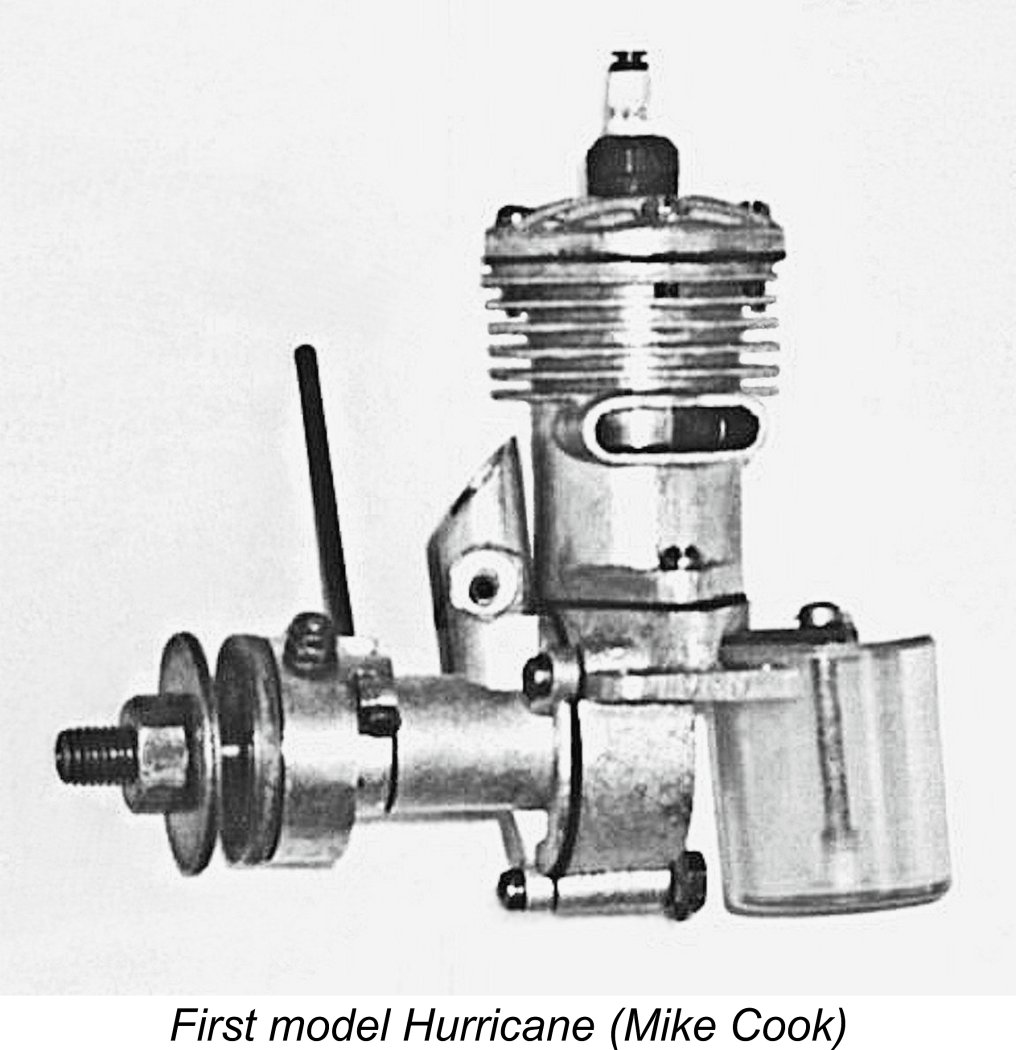

I can only comment that the example of this first model pictured by Mike Thomas as reproduced at the right unquestionably bore a three-digit serial number. To me, the number looks like 200, although this could easily be a misreading - the half-century old image is far from perfectly clear. However, the first digit definitely isn’t a 1. It thus seems possible that as many as 200 examples of this variant may have been manufactured in reality. When it comes to the second “thick-web” model with the straight fin profile, we have a little more to go on. Mike Cook owned second variant engine number 250, while my own example bears the number 731. I also have engine number The situation regarding the third “thick-fin” model is rather unclear. Mike Cook reported the existence of engine no. 2366, while reader Peter Wakefield owns engine number 2800. However, a problem with this variant is the fact that at some indeterminate point during its production life the application of serial numbers was discontinued. This has resulted in the survival of a number of examples which do not bear serial numbers at all. The true number produced will therefore never be known - all that can be said is that over 1500 examples appear to have been manufactured. What can be stated with some certainty is that over 3,000 examples of the lost wax investment-cast engines may well have been produced during the 20 months or so that these models were manufactured. This represents an average of around 150 units per month - not bad going for a small Canadian company! That said, I've seen production figures in excess of 200,000 units being bandied about for all models of the Hurricane 24. If true, the majority of these would have had to be produced during the approximately 30 month period during which the Production & Tool Company was manufacturing the engines - Ray Hunter couldn't have come near the implied production rate working alone in his basement. All I can say is that neither the number of surviving examples nor the production figures implied for the first two variants by their serial numbers offer any support whatsoever for such figures having been achieved. The Super Hurricane 24

The design of the crankcase was altered considerably. The front housing and intake venturi were now cast in unit with the main crankcase, and a screw-in backplate now sealed the case. The beam mounting lugs were beefed up considerably. The upper cylinder casting was further revised to create an elongation of the cooling fins to the rear, where their extra length and associated cooling area should theoretically help to cool the rear of the cylinder which was less exposed to the cooling slipstream. As a bonus, the resulting “teardrop” vertical profile added greatly to the engine's stylistic appeal. In adopting this configuration, Ray Hunter may have been influenced by the similar form seen earlier on the Merlin Super “B” .23 cuin. model also from Toronto and dating from 1944.

Another improvement was the use of a thicker cylinder liner. The earlier liners had been made very thin and were somewhat prone to distortion. The revised thicker liner did much to reduce the incidence of such problems.

It’s impossible to develop any authoritative estimate of total production figures, because neither this model nor its successors ever carried serial numbers at any time. All that can be said is that the various Super Hurricane models and derivatives survive today in far larger numbers than the earlier investment-cast models prior to December 1945. The implication is that Ray Hunter somehow managed to produce them in quite large numbers.

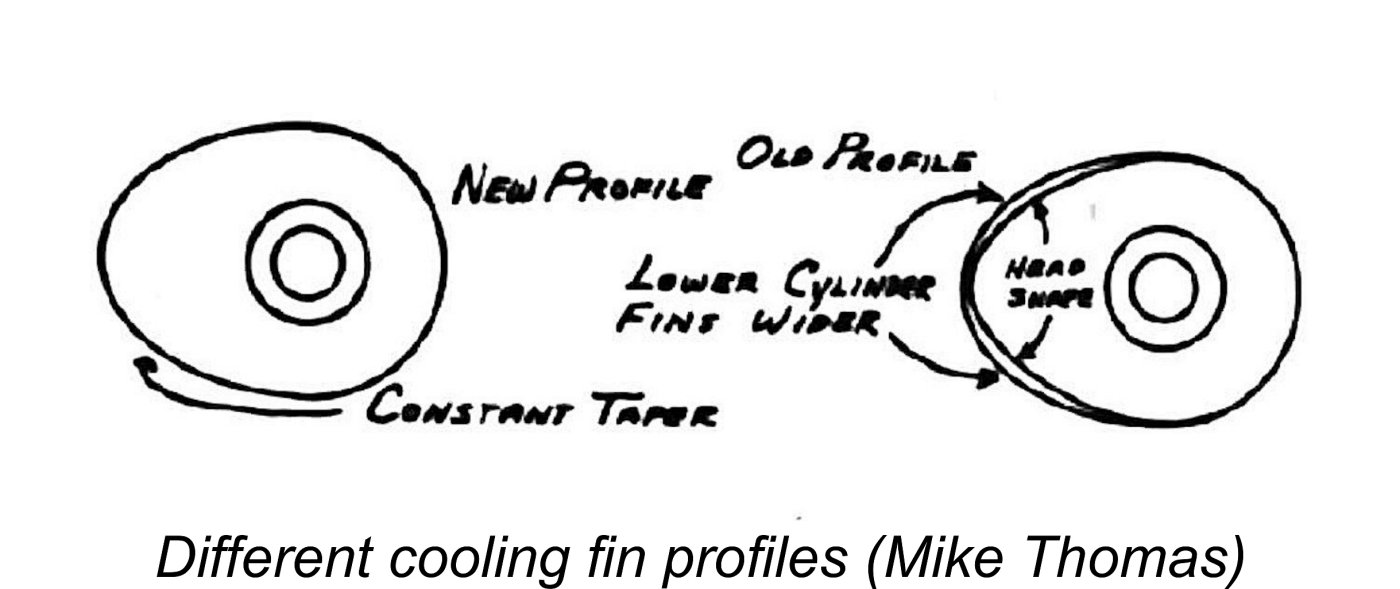

The interesting feature of this tank was that it was sealed at the front by a plastic disc rather than by a gasket around the perimeter in the more conventional manner. This of course meant that the interior cavity of the backplate was not available to contribute to the engine’s fuel capacity in the more typical fashion. By this time, the oil retention groove in the piston had been eliminated for the reasons stated earlier. Some of these engines The only other minor change which was implemented at around this time was the creation of a slightly modified die (presumably to replace a worn-out original) which narrowed the relatively broad curve of the lower cooling fins in plan view. You wouldn’t notice this very slight change unless someone told you! Hopefully Mike Thomas’s attached sketch will make this change clear. It can help to define whether you have an early or late example. The Hurricane Spark Ignition Series - Contemporary User Impressions All of the engines described so far were of course spark ignition models. Mike Cook has left us with some very informative comments on the various spark ignition Hurricanes from his viewpoint as a long-time user. He characterized the first three investment-cast designs as being “of average workmanship, started easily, ran reliably and had a long working life”. He mentioned the issue of the poorly-supported gudgeon pin, also noting that some examples were set up extremely tight, causing handling problems at the outset. The reader may recall that the “Air Trails” tester mentioned the same issue - he initiated the running-in of his third variant example on a lathe! Mike’s major criticism was the apparent fact that the engines had a tendency to lose compression when brought up to full operating temperature during extended runs on the ground. This was likely due at least in part to the very thin cylinder liners used in these models, which were doubtless susceptible to thermal distortion. I also suspect that the rather thin cylinder heads secured by only four screws may have had a tendency to warp, making their own contribution to this problem. Mike stated that the die-cast Super Hurricane units were superior to the earlier investment-cast units in every way. The revisions to the gudgeon pin design completely cured the former wear problems with that component. The problem of compression loss when hot persisted but was far less evident - evidently the thicker cylinder liner did much to alleviate this issue. Mike stated that vibration levels were well within acceptable limits and that the engine started very easily, also developing noticeably more power than the earlier variants. He claimed that the Super Hurricane would out-perform an Ohlsson 23 in the same airframe. Into the Glow-Plug Era - the Hurricane “Hot Top”

The Hurricane “Hot Top” was a well thought-out glow-plug conversion of the final spark ignition variant described earlier. It weighed 176 gm (6.2 ounces) complete with tank, plug and fuel tubing. Ray Hunter had clearly recognized the fact that operation on glow-plug ignition required a higher compression ratio than that available with the piston and cylinder head combination used up to that point. To address this issue, a revised head was produced having a spigot which extended the lower surface down somewhat into the cylinder bore. This created an interference issue with the piston baffle, requiring that a slot be machined into the underside to the revised head to accommodate the baffle at top dead centre. The revised head provided a volumetrically-checked compression ratio of 7 to 1 as compared to the 5.5 to 1 figure measured for the Super Hurricane sparker. This is still a bit on the low side but should be adequate for glow-plug operation at the relatively low speeds of which these engines were capable.

The “Hot Top” was a fine performer, but was not able to compete with the best of the competing models from American producers. Its manufacture appears to have ended in late 1949. This did not prevent Lawrence H. Sparey from publishing a rather belated test report in the December 1951 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, long after production had ceased. His example must have been obtained from New Old Stock. Sparey was clearly quite impressed with the engine. He commented on its “easy starting and flexibility” as well as its relatively insensitive needle valve, which made optimum settings easy to establish. He characterised its running qualities as “good at all tested speeds”.

Interestingly enough, Sparey commented upon the fact that while currency restrictions had severely limited the number of examples of the Hurricane “Hot Top” reaching Britain, those that had done so seemed to have acquitted themselves well. Sparey made particular mention of one Johnny Jones, who had achieved excellent results in Class B team racing with his “Scramble” design powered by a Hurricane “Hot Top”. Although the Hurricane gave away a full 20% displacement to other competing engines built to the full 5 cc displacement limit, such as the favoured ETA and McCoy 29's, the engine’s fine handling and excellent fuel economy evidently allowed Jones to get away quickly and complete the full five mile heat distance non-stop on a single 30 cc tank of fuel while maintaining an airspeed of around 75 mph. In the interests of conservation, I should take this opportunity to point out that many examples of the Hurricane “Hot Top” have unfortunately been damaged by ill-informed attempts to remove what appears to be a slip-on bronze cam cover at the front of the main bearing, the intent being to retro-fit a timer. In reality, this seeming "cover" is machined in one piece with the bronze main bearing bushing. Any attempt to remove it on the assumption that it is a slip-on component can only result in serious damage. Let's have no more of that!! The Hurricane “Specials”

I already mentioned the H.P. Whirlwind 10 cc model which was constructed during Ray’s partnership with Mr. Patch. Both before and after the break-up of the partnership, Ray continued to try a number of different concepts. One of these was a 0.19 cuin rendition of the basic Hurricane design. Ray produced three distinct variants of this model. The first two were constructed as single-copy prototypes, but six examples of the third and final variant ended up being completed. Mike Thomas recalled that these engines were very compact and had a good deal of power for their displacement. The idea was presumably to create a model that would be eligible for Class A competition, but by the time that the final design was complete Ray was working alone in his basement, hence lacking the time to produce both the 19 and his well-established bread-and-butter 24.

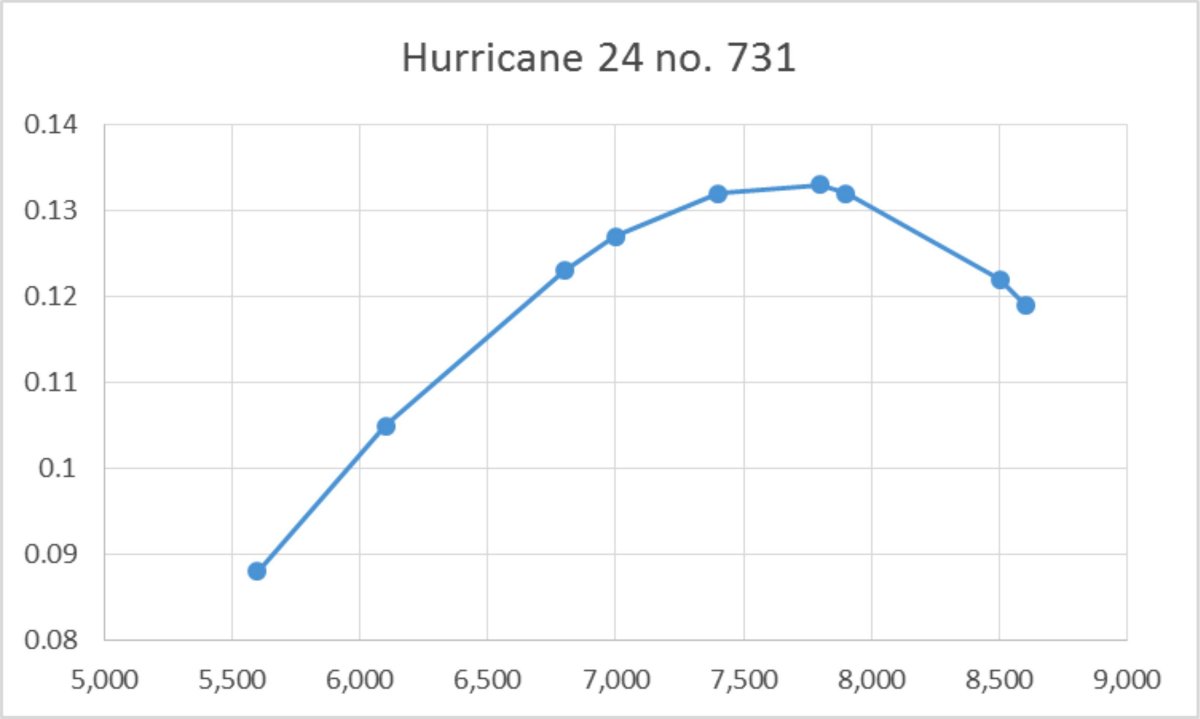

Towards the end of his model engine manufacturing career, Ray Hunter’s interests switched back to radio control and model power boats. In support of the latter interest, he produced around ten examples of a modified version of the Hurricane “Hot Top” glow-plug model which had its cooling fins machined off to allow the fitting of a tightly-wrapped copper coil for water cooling. Some of these engines featured twin needle valve installations to allow two-speed operation with radio control. The Hurricane 24 Series Reappraised When assessing the qualities of a given model engine range, there’s no substitute for a hands-on encounter as opposed to reliance on the comments of others. Having complete and original examples of four of the Hurricane 24 variants in excellent condition on hand, I felt that the quest for knowledge obliged me to put them on the test stand to see how they performed. First up was my example of the second investment-cast variant bearing the serial number 731. For this test, I elected to try the same series of calibrated airscrews that I had used previously to test the competing Merlin Super “B” 0.23 cuin. sparkie from just up the road in Toronto. The sparks were supplied by one of my ever-dependable Larry Davidson solid state trigger systems, while the fuel was my standard sparkie brew of 75% Coleman camp fuel (white gas) and 25% SAE 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120). The vintage Champion V-2 spark plug with which the engine was fitted as received was used for this test.

Since I was using white gas as my base fuel, it was possible to use the standard plastic hang tank throughout these tests. The 77-year-old Hurricane started up right away following a few choked turns and a small exhaust prime. Once the engine had a run under its belt, the prime proved to be unnnecessary - a few finger chokes sufficed to get enough fuel into the engine for starting. The engine was an unfailing one-or-two flick starter - extremely user-friendly!! Once running, response to the needle was excellent, making it easy to bring the engine to a fast 4-stroke just on the rich side of 2-stroking - a perfect setting for running in. During its brief lean-out period at the end of the run, I saw 7,200 RPM on the 10x4 test prop, although I had little doubt that the engine would beat this figure if fully run in and carefully adjusted for best performance. After some 30 minutes of this treatment, allowing complete cooling between runs, I judged that the engine was ready to yield a few test figures. Accordingly, I ran more or less the same series of airscrews that I had used earlier for the Merlin Super "B", in each case running rich for 1 minute and then leaning out and adjusting the timer for maximum speed. Once this was done, I stopped the engine and allowed complete cooling before changing props and repeating the process. In this way, the break-in continued. The results obtained are reported below.

On this showing, the Hurricane 24 outperformed its rival Toronto offering, the Merlin Super "B", by some margin. We might expect this given the Hurricane's used of FRV induction as opposed to the Merlin's sideport configuration. The Hurricane 24 appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.134 BHP @ 7,700 RPM - a quite respectable performance by 1944 standards for an engine of this displacement running on white gas. With its excellent handling qualities, it would have been a completely satisfactory engine to use by the standards of its day.

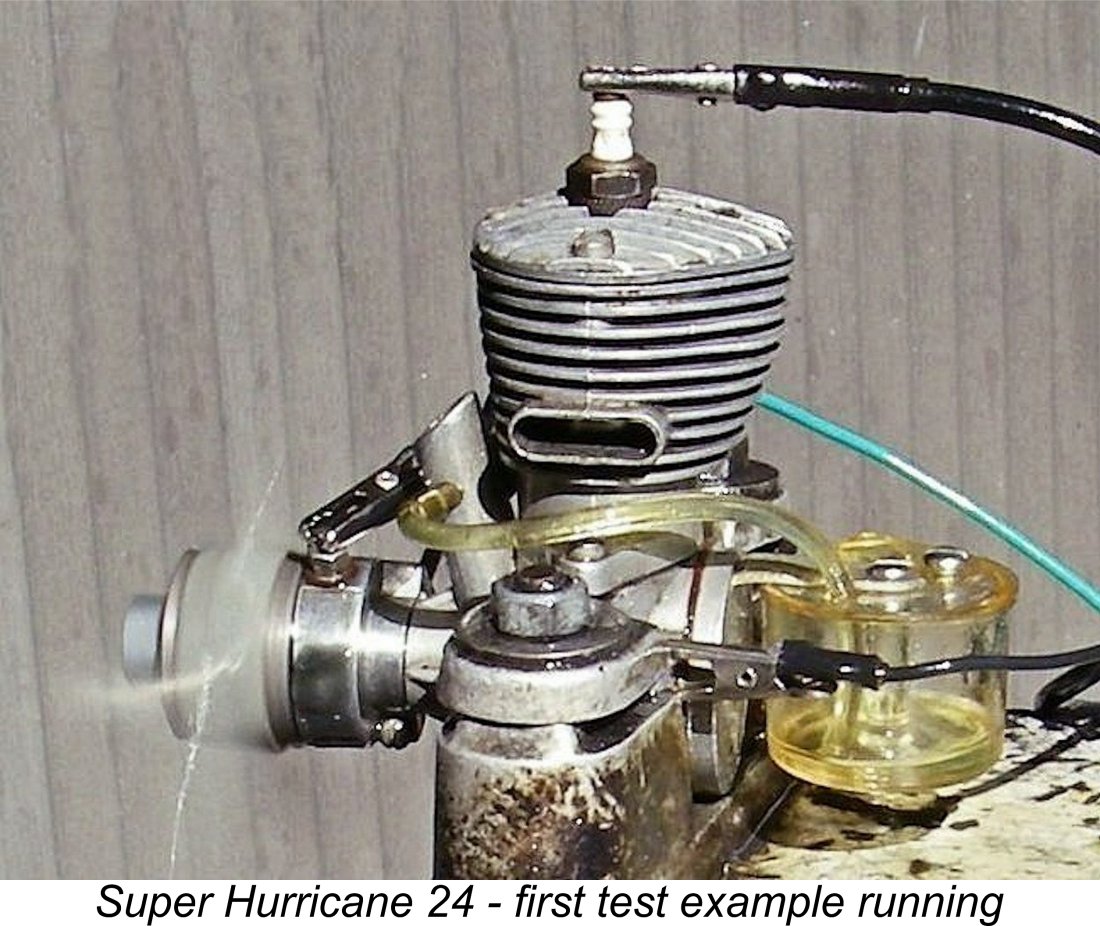

I had run the hang-tank example previously but had not taken any prop/RPM figures. However, I already knew that it started and ran very well, so I wasn't anticipating any problems. I decided to run the full suite of test props on that engine and then spot-check a few props around the peak with the second example, just to check on consistency of performance. If the second example showed itself to be significantly faster than its stablemate, I would run the full suite of test props on that example as well. The hang-tank engine proved to be just as easy a starter as its predecessor, engine no. 731. As before, no prime was necessary - just a few choked flicks on a full fuel line. The engine was also just as easy to set - response to the needle was very positive without being over-sensitive. Running qualities were all that could be desired - no trace of a misfire and no tendency to sag. The Super Hurricane turned out to develop considerably more low-end torque than its investment-cast predecessor no. 731. I had to add a Top Flite 10x8 wood prop to the test suite to get a reasonable power curve below what turned out to be the peak. In fact, the tested Super Hurricane peaked at a slightly lower speed than its earlier relative, albeit at a substantially higher level of torque development with a consequently greater peak output despite the lower peaking speed. The following data tell the story.

The above data suggest a peak output for this example of around 0.140 BHP @ 7,200 RPM. A little more power than the previous model, but at a lower speed. The Super Hurricane could swing a larger and presumably more efficient prop than its predecessor. It would do very well on the PP 10x6, which would over-prop the earlier model. An 11x5 would probably be an excellent free flight airscrew.

The second example started just as promptly as its predecessor, also running equally smoothly once set. However, it could only manage 6,900 RPM on the 11x4 prop, which its companion had swung at 7,100 RPM. The Rev-Up 10x4 was turned at 7,600 RPM, again a little behind the other test model. It was clear that the example tested first was a slightly better performer, although the difference wasn't all that great. Even so, I saw no reason to run the full suite of test props on the second example. The figures obtained from the hang-tank engine therefore stand as the measured performance of the Super Hurricane 24 sparkie. As a general observation, I must acknowledge the fact that all three tested examples of the spark ignition Hurricane 24 exhibited the tendency reported by Mike Cook to lose some of their compression seal when hot. This didn't appear to affect running unduly, but it did make instant hot re-starts a little more challenging than they might otherwise have been. Upon allowing the engines to cool down, full compression was restored, preparing the engine for an instant re-start. Finally, it was the turn of the glow-plug "Hot Top" model. I chose a complete and original example of this model that was in excellent mechanical and cosmetic condition, seemingly having had little previous running. For this reason, I decided that I would run four or five tankfuls of fuel through it on a slightly rich setting, just to be sure.

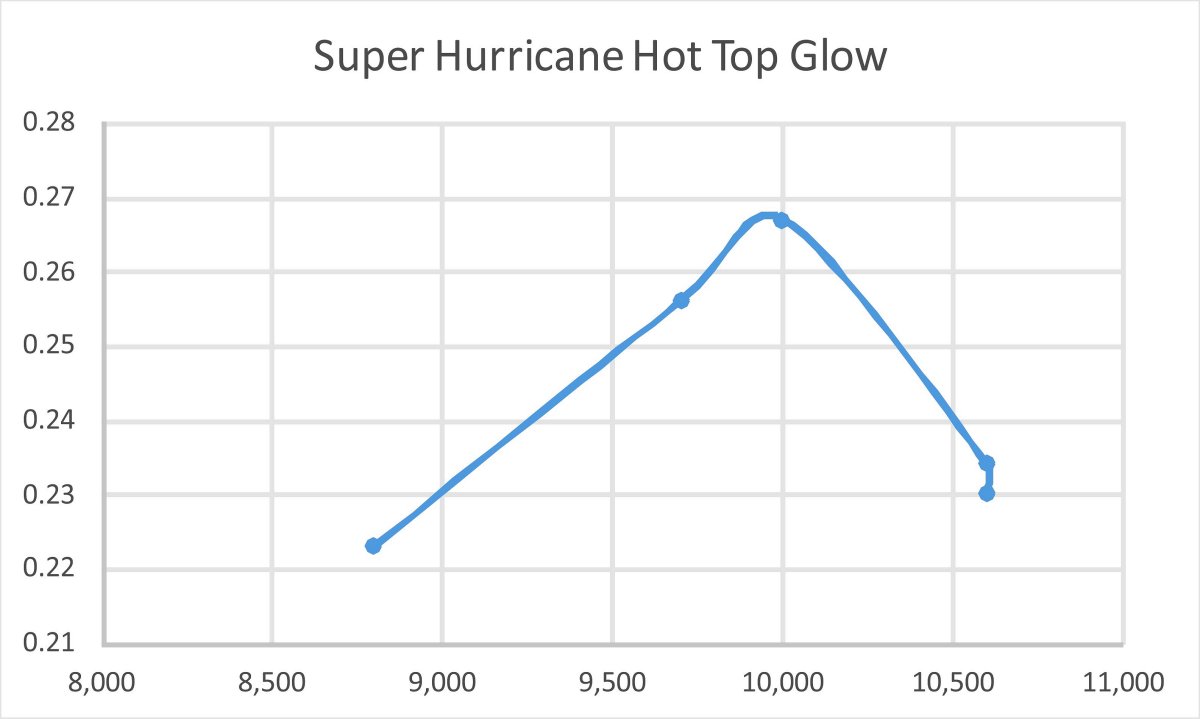

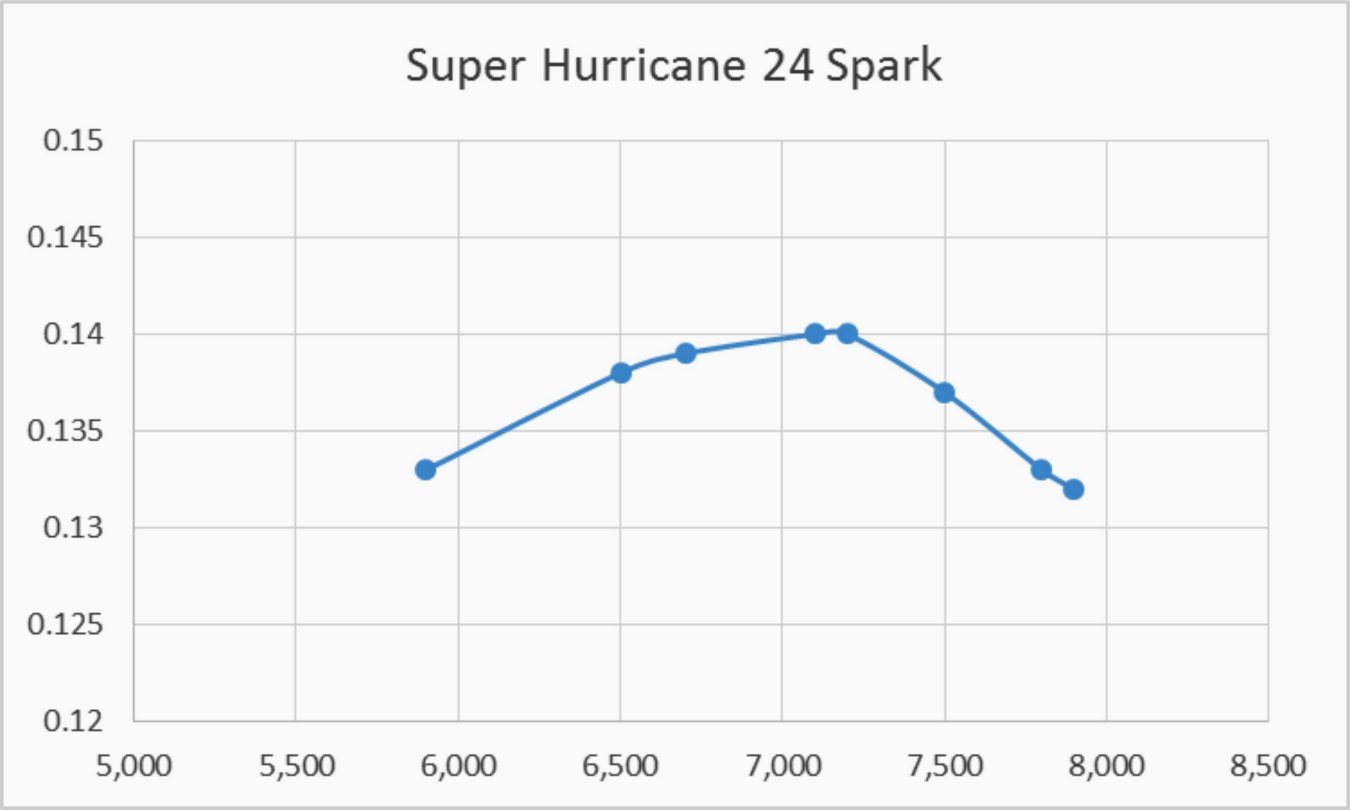

The Hurricane Hot Top proved to be just as nice an engine to handle as its spark-ignition relatives. It didn't like to be particularly wet for starting - a few choked turns on a full fuel line generally sufficed. Starts were generally achieved with only one or two flicks. I could see why Johnny Jones found it to be a useful team race motor! Response to the needle valve was very well defined without being unduly critical. By feel, this example appeared to be a bit on the tight side - it had evidently done little previous running and had never been mounted. Accordingly, I ran half-a-dozen tankfuls through it on a rich mixture just to settle it down, tightening the head bolts and allowing complete cooling between runs. Even then it still felt a little tight, but I judged that it could now be leaned out without damage. I kept the leaned-out runs down to the minimum necessary to obtain a steady maximum speed reading, stopping the engine immediately thereafter by pinching off the fuel line. It was immediately obvious that using its 15% nitro fuel along with its higher-compression head, the Hot Top was going to outperform the white gas-fuelled Super Hurricane sparkie by a considerable margin. Frankly, this was not unexpected. The 10x4 prop was turned at 9,700 RPM, a full 1,900 RPM up on the sparkie. A similar performance edge was apparent for all of the other props tested using both engines. The data measured in the Hot Top test were as follows.

As can be seen, the tested example of the Hot Top turned out to peak at around 0.267 BHP @ 10,100 RPM with a sharp falloff thereafter. The output is only a little lower than that found by Sparey, albeit at considerably lower RPM. I put this down to the fact that even after all this testing the engine showed unmistakable signs of being tighter That having been said, I consider that my test more or less confirmed Sparey's findings. The engine's recorded success as a team race powerplant is amply explained by its truly excellent primeless starting and its apparent fuel economy - a full tank seemed to run forever! I think that it would also have done well in a control line stunt capacity - the break from four-stroking to two-stroking is unsually well defined, while suction seems excellent. Finally, with its relatively light weight for its displacement it would have made a very useful free flight sport motor. Despite these observations, it has to be admitted that the Hot Top's output was not really competitive by evolving 1949 standards. If Ray Hunter had really wanted to remain active in the model engine field, there's no doubt at all that a complete redesign of the engine would have been necessary. Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this close-up look at perhaps the most successful model engine range to originate in my adopted country of Canada. Ray Hunter provided modellers from Canada and elsewhere with a series of very useable powerplants which would have served them well. For that, he deserves our respectful recognition! These engines seem to appear on eBay and elsewhere on a fairly regular basis, often selling for quite reasonable prices. Anyone taking the plunge will acquire the opportunity to enjoy an engine of considerable merit. This is a motor that can be run with confidence! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published November 2022 |

||

| |

In this article, I’ll present a detailed look at perhaps Canada’s best-remembered model engine range - the Hurricane 24 series from Toronto, Ontario. This succession of very competently-designed and well-produced engines survived in a highly competitive marketplace for almost 6 years - longer than any other Canadian model engine range. As such, it commands a high level of respect, especially from a long-time Canadian resident like me!

In this article, I’ll present a detailed look at perhaps Canada’s best-remembered model engine range - the Hurricane 24 series from Toronto, Ontario. This succession of very competently-designed and well-produced engines survived in a highly competitive marketplace for almost 6 years - longer than any other Canadian model engine range. As such, it commands a high level of respect, especially from a long-time Canadian resident like me!

Canada is definitely not the first country that comes to mind when the subject of commercial model engine manufacturing is brought up. In large part this is doubtless due to the combination of two factors – one, a huge geographic area which created a very widespread distribution of a relatively small population and hence a highly fragmented domestic marketplace of no great size; and two, the presence of a ready source of competitively-priced engines which were produced to a high standard immediately south of the border in the USA.

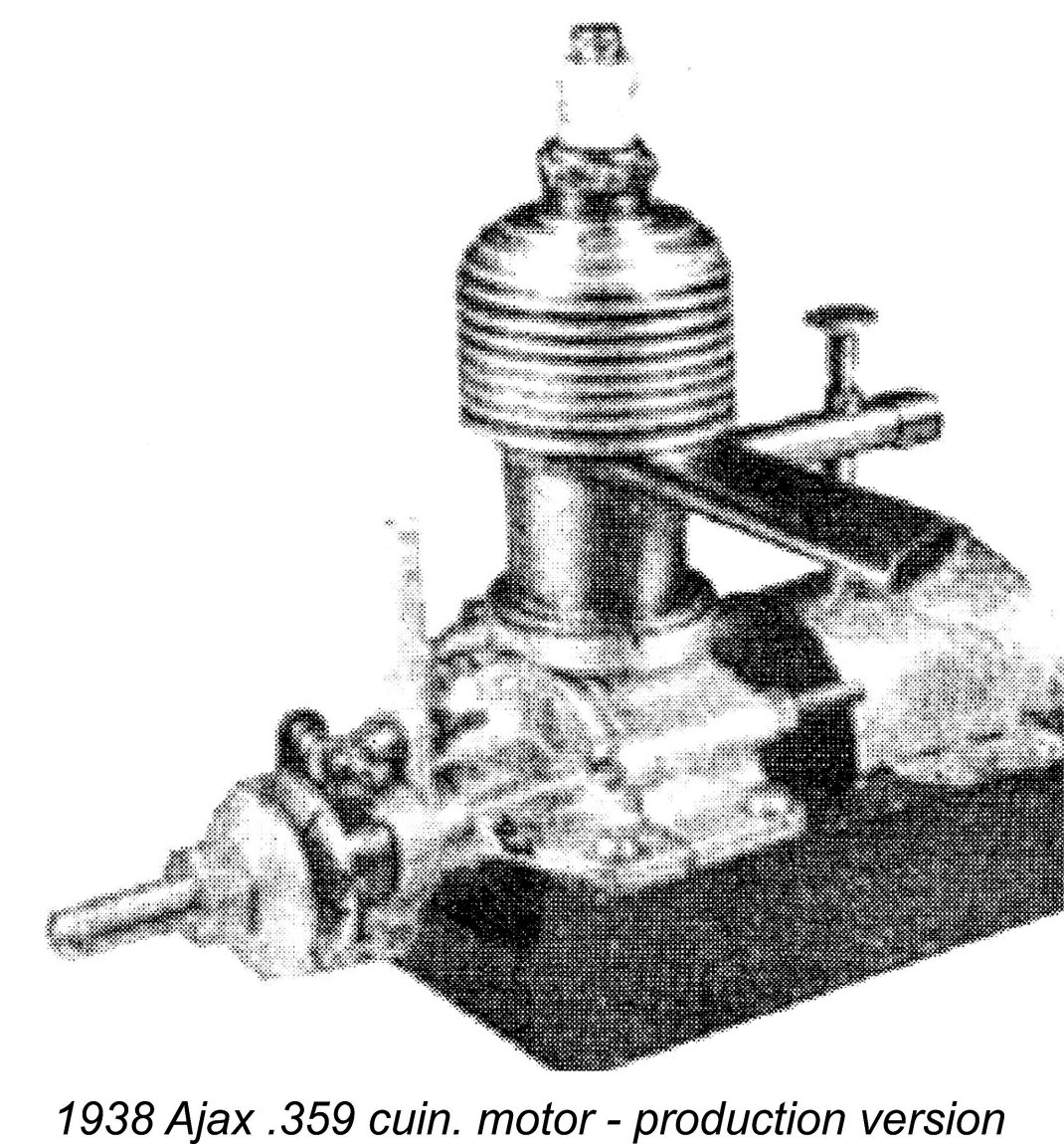

Canada is definitely not the first country that comes to mind when the subject of commercial model engine manufacturing is brought up. In large part this is doubtless due to the combination of two factors – one, a huge geographic area which created a very widespread distribution of a relatively small population and hence a highly fragmented domestic marketplace of no great size; and two, the presence of a ready source of competitively-priced engines which were produced to a high standard immediately south of the border in the USA. Although a few individual model engines were undoubtedly constructed in Canada by talented home machinists during the pre-WW2 period, there seems to be only one record of any commercial-scale series production being undertaken in Canada during those years. This relates to the Ajax .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) spark ignition model which was manufactured in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1938 and 1939 by one Arthur Jaques following some successful prototype testing in 1937. No prizes for guessing the derivation of the Ajax name!

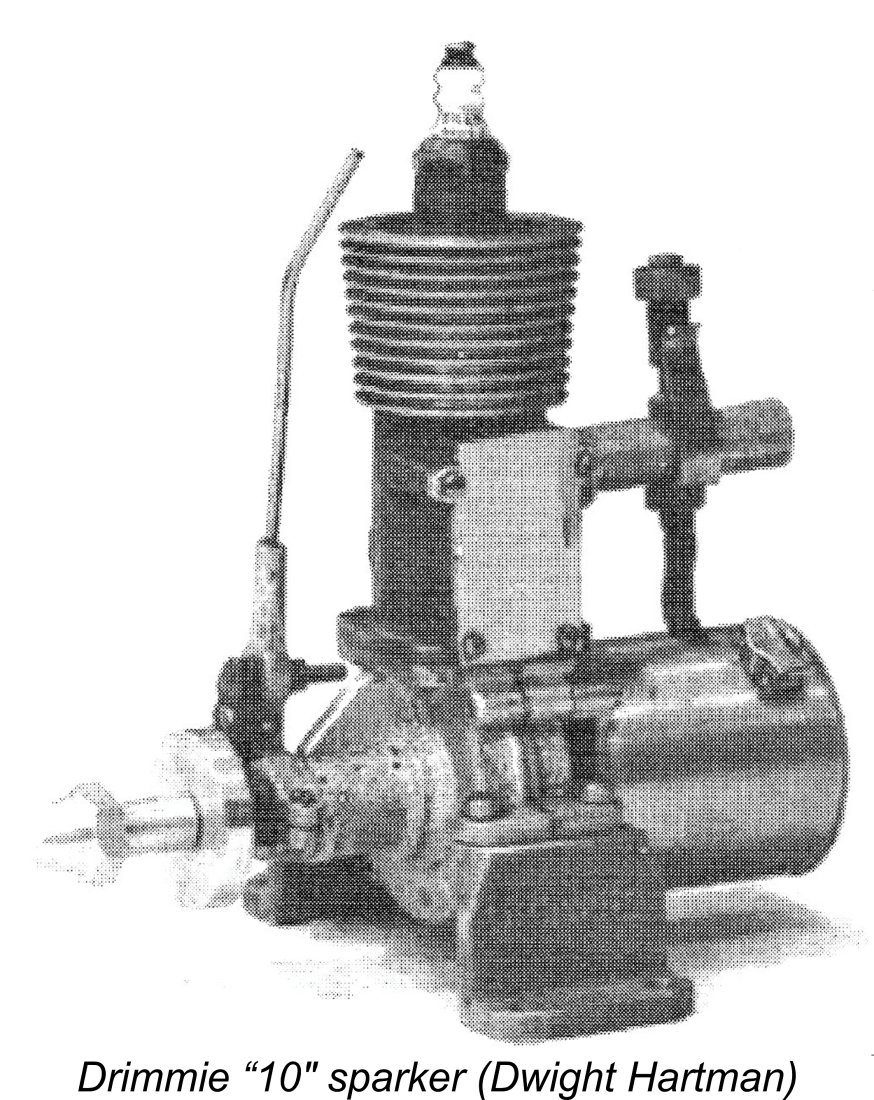

Although a few individual model engines were undoubtedly constructed in Canada by talented home machinists during the pre-WW2 period, there seems to be only one record of any commercial-scale series production being undertaken in Canada during those years. This relates to the Ajax .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) spark ignition model which was manufactured in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1938 and 1939 by one Arthur Jaques following some successful prototype testing in 1937. No prizes for guessing the derivation of the Ajax name! Although Canada was actively involved in WW2 from September 1939 onwards, an enthusiast named Paul Drimmie of Toronto, Ontario somehow managed in 1940 to produce a very small number of examples of a 0.607 cuin. (9.95 cc) sideport spark ignition engine called the Drimmie ”10”. However, this effort ended almost as soon as it began, doubtless due to the intrusion of other more pressing concerns. There's no evidence that Drimmie ever resumed model engine manufacture after the war.

Although Canada was actively involved in WW2 from September 1939 onwards, an enthusiast named Paul Drimmie of Toronto, Ontario somehow managed in 1940 to produce a very small number of examples of a 0.607 cuin. (9.95 cc) sideport spark ignition engine called the Drimmie ”10”. However, this effort ended almost as soon as it began, doubtless due to the intrusion of other more pressing concerns. There's no evidence that Drimmie ever resumed model engine manufacture after the war.

also took advantage of the relaxation of wartime restrictions to resume model engine production at this time with an updated Mk. III version of his Strato .604 model. In 1946 he produced his final Strato sideport design, which he designated the Strato “Super” Mk. IV. He also produced two crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) units and a single fixed compression diesel as experiments, but these never saw series production.

also took advantage of the relaxation of wartime restrictions to resume model engine production at this time with an updated Mk. III version of his Strato .604 model. In 1946 he produced his final Strato sideport design, which he designated the Strato “Super” Mk. IV. He also produced two crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) units and a single fixed compression diesel as experiments, but these never saw series production. Bainbridge's efforts had not gone unnoticed! Several other Canadian manufacturers were inspired by his example to enter the model engine field in 1944 as the war drew towards its conclusion. I’ve covered that story in broad terms in my separate article on the somewhat later Canadian-built

Bainbridge's efforts had not gone unnoticed! Several other Canadian manufacturers were inspired by his example to enter the model engine field in 1944 as the war drew towards its conclusion. I’ve covered that story in broad terms in my separate article on the somewhat later Canadian-built  The man behind the Hurricane engines was a gentleman named Murray Eugene Hunter (1909 - 2003), always known to his friends and associates as "Ray". The series was initially manufactured by the Production & Tool Company located on Pape Avenue in Toronto. According to Mike Thomas, this company was owned by Hunter in partnership with an individual named Patch.

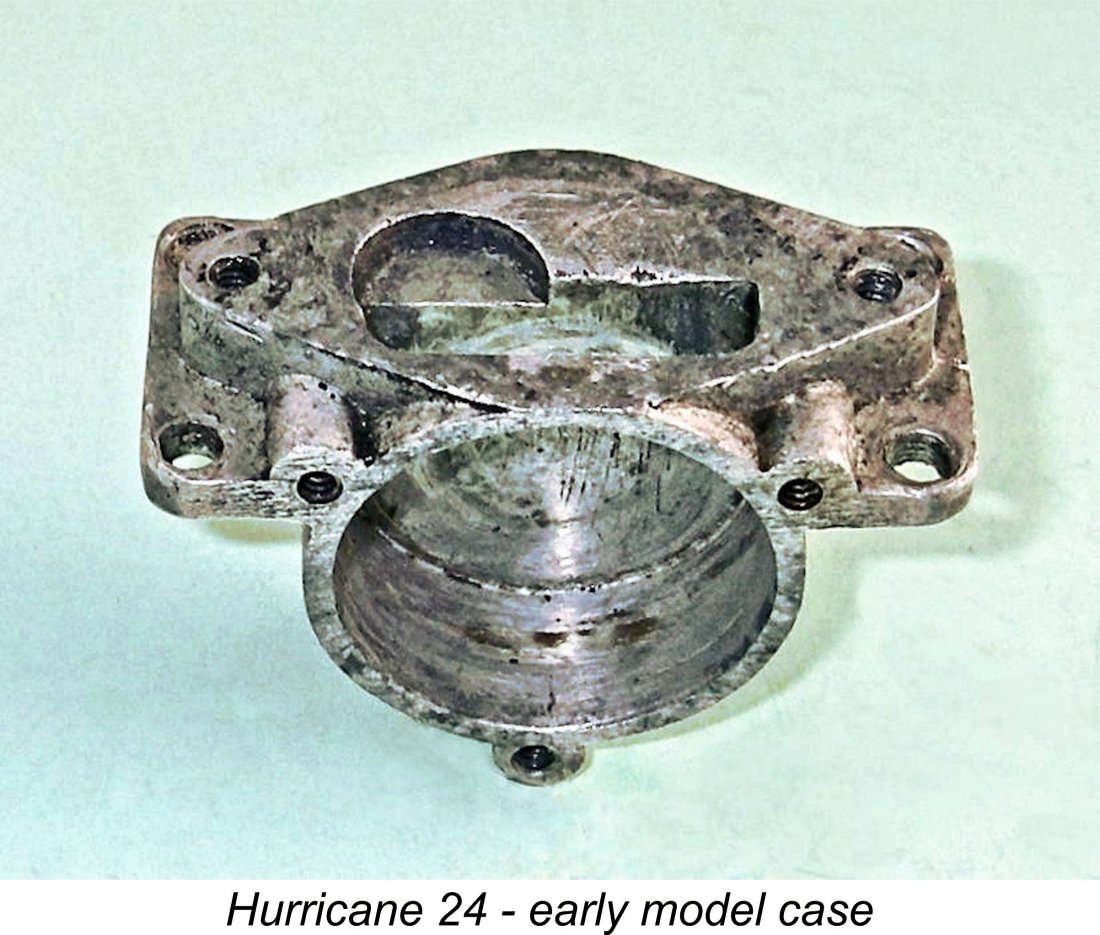

The man behind the Hurricane engines was a gentleman named Murray Eugene Hunter (1909 - 2003), always known to his friends and associates as "Ray". The series was initially manufactured by the Production & Tool Company located on Pape Avenue in Toronto. According to Mike Thomas, this company was owned by Hunter in partnership with an individual named Patch.  The castings for the first three variants of the Hurricane 24 (see below) were produced by the “lost wax” investment casting process. This technique facilitates the production of quite intricate components having a far better surface finish than conventional sand-casting - the crankcase casting seen at the right would have been very challenging to produce as a sand-casting. The downside was cost - the lost wax technique pushed the cost of a set of castings (crankcase, upper cylinder, cylinder head, front housing, timer housing) up to around $4.50 for a single engine.

The castings for the first three variants of the Hurricane 24 (see below) were produced by the “lost wax” investment casting process. This technique facilitates the production of quite intricate components having a far better surface finish than conventional sand-casting - the crankcase casting seen at the right would have been very challenging to produce as a sand-casting. The downside was cost - the lost wax technique pushed the cost of a set of castings (crankcase, upper cylinder, cylinder head, front housing, timer housing) up to around $4.50 for a single engine.

One look at the original Hurricane 24 spark ignition unit of early 1944 will convince any objective observer that this model was actually a Canadian-made rendition of the 1942 Dreadnaught 24 from Oakland, California with a few very minor detail alterations. At this distance in time we’ll probably never know how the transfer of the Dreadnaught design from Oakland to Toronto came about.

One look at the original Hurricane 24 spark ignition unit of early 1944 will convince any objective observer that this model was actually a Canadian-made rendition of the 1942 Dreadnaught 24 from Oakland, California with a few very minor detail alterations. At this distance in time we’ll probably never know how the transfer of the Dreadnaught design from Oakland to Toronto came about.  There’s a story there, but we’ll never learn the details …………….

There’s a story there, but we’ll never learn the details ……………. The cylinder head was another casting which was secured to the cylinder jacket by four machine screws. Its underside was perfectly flat, with no attempt at contouring, no location spigot and no provision for the accommodation of the piston baffle at top dead centre. This limited the degree to which the piston crown could approach the head, thus confining the engine’s compression ratio to a relatively low figure with a very inefficient combustion chamber. The centrally-located plug installation hole was sized for a ¼-32 long reach Champion V-2 spark plug.

The cylinder head was another casting which was secured to the cylinder jacket by four machine screws. Its underside was perfectly flat, with no attempt at contouring, no location spigot and no provision for the accommodation of the piston baffle at top dead centre. This limited the degree to which the piston crown could approach the head, thus confining the engine’s compression ratio to a relatively low figure with a very inefficient combustion chamber. The centrally-located plug installation hole was sized for a ¼-32 long reach Champion V-2 spark plug.

The cylinder porting was quite conventional, with large rectangular openings serving as both transfer and exhaust ports. The transfer port overlapped the exhaust to a considerable extent. It was fed by a bypass passage of modest dimensions which was incorporated into a conventional cast “bulge” on the transfer side of the upper cylinder casting.

The cylinder porting was quite conventional, with large rectangular openings serving as both transfer and exhaust ports. The transfer port overlapped the exhaust to a considerable extent. It was fed by a bypass passage of modest dimensions which was incorporated into a conventional cast “bulge” on the transfer side of the upper cylinder casting. The piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a conrod which was cast in light alloy. Neither of the conrod bearings was bushed, although the shaft itself ran in a well-fitted bronze bushing.

The piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a conrod which was cast in light alloy. Neither of the conrod bearings was bushed, although the shaft itself ran in a well-fitted bronze bushing.

This version of the engine reportedly had a bare weight (presumably minus tank and perhaps without a plug) of 5 ounces (142 gm). It appears that a few performance-related changes from the Dreadnaught design may have been made by Ray Hunter. In Mike Cook’s recollection, the original Hurricane 24 outperformed the Dreadnaught 24 on which it was based by a considerable margin.

This version of the engine reportedly had a bare weight (presumably minus tank and perhaps without a plug) of 5 ounces (142 gm). It appears that a few performance-related changes from the Dreadnaught design may have been made by Ray Hunter. In Mike Cook’s recollection, the original Hurricane 24 outperformed the Dreadnaught 24 on which it was based by a considerable margin. In early 1945 a third variant appeared. Once again, this was little changed from its predecessor. It still utilized investment castings, but the form of the upper cylinder jacket was now changed to create thicker fins which were progressively reduced in diameter going down the cylinder. In addition, the fins now continued for some distance below the exhaust stack instead of terminating there as on the first two versions. Otherwise, the design continued unchanged.

In early 1945 a third variant appeared. Once again, this was little changed from its predecessor. It still utilized investment castings, but the form of the upper cylinder jacket was now changed to create thicker fins which were progressively reduced in diameter going down the cylinder. In addition, the fins now continued for some distance below the exhaust stack instead of terminating there as on the first two versions. Otherwise, the design continued unchanged.

There's a very high degree of uncertainty in connection with the production figures associated with these three investment-cast models. The original thin-web versions all carried serial numbers which were stamped onto the outer edge of the left-hand mounting lug (looking forward in the direction of flight). The highest such number that Mike Cook reported ever having seen was 85. He estimated that perhaps 100 examples of this first model were made in total.

There's a very high degree of uncertainty in connection with the production figures associated with these three investment-cast models. The original thin-web versions all carried serial numbers which were stamped onto the outer edge of the left-hand mounting lug (looking forward in the direction of flight). The highest such number that Mike Cook reported ever having seen was 85. He estimated that perhaps 100 examples of this first model were made in total.

The next variant to appear introduced a number of very significant changes. The most significant of these in production terms was a switch to die-castings in the construction of the Hurricane series. This apparently reduced the cost of a set of castings for a single engine from around $4.50 using the lost wax process to somewhere in the vicinity of 90 cents! The changes were deemed sufficient that the engine’s name was changed from Hurricane 24 to Super Hurricane 24. The engine's weight had gone up to a checked 180 gm (6.35 ounces) complete with plug, tank and fuel tubing.

The next variant to appear introduced a number of very significant changes. The most significant of these in production terms was a switch to die-castings in the construction of the Hurricane series. This apparently reduced the cost of a set of castings for a single engine from around $4.50 using the lost wax process to somewhere in the vicinity of 90 cents! The changes were deemed sufficient that the engine’s name was changed from Hurricane 24 to Super Hurricane 24. The engine's weight had gone up to a checked 180 gm (6.35 ounces) complete with plug, tank and fuel tubing.  The problems with the gudgeon pin were largely overcome through the use of a new tubular component of larger diameter made from drill rod. This was allied to a piston having slightly thicker walls and hence longer bosses. The con-rod too was beefed up considerably, now being a forging instead of a casting. It had a far longer small end bearing to better distribute loads along the gudgeon pin. According to Mike Cook, the former problems with the gudgeon pin wearing prematurely were largely eliminated by these changes.

The problems with the gudgeon pin were largely overcome through the use of a new tubular component of larger diameter made from drill rod. This was allied to a piston having slightly thicker walls and hence longer bosses. The con-rod too was beefed up considerably, now being a forging instead of a casting. It had a far longer small end bearing to better distribute loads along the gudgeon pin. According to Mike Cook, the former problems with the gudgeon pin wearing prematurely were largely eliminated by these changes. The tank used on this model was still made of plastic, but had a larger diameter along with a lesser depth. It was suspended from a bracket which extended horizontally rearward from the top of a vertical stamped steel disc. This disc in turn was secured to the screw-in backplate by a screw which engaged with a tapped boss at the centre of the backplate. In all other respects, this engine continued to follow the design pattern of its predecessors.

The tank used on this model was still made of plastic, but had a larger diameter along with a lesser depth. It was suspended from a bracket which extended horizontally rearward from the top of a vertical stamped steel disc. This disc in turn was secured to the screw-in backplate by a screw which engaged with a tapped boss at the centre of the backplate. In all other respects, this engine continued to follow the design pattern of its predecessors. In early 1948 a further variant of the Super Hurricane appeared. It may not be entirely appropriate to call this a distinct variant, because the only change was the style of the fuel tank supplied with the engine, which was otherwise little if at all changed. The new tank took the form of a streamlined plastic component which was secured by a long screw running axially through its centre to engage with the tapped central boss used previously to retain the metal bracket supporting the former hang tank.

In early 1948 a further variant of the Super Hurricane appeared. It may not be entirely appropriate to call this a distinct variant, because the only change was the style of the fuel tank supplied with the engine, which was otherwise little if at all changed. The new tank took the form of a streamlined plastic component which was secured by a long screw running axially through its centre to engage with the tapped central boss used previously to retain the metal bracket supporting the former hang tank.

The four-year production run of the spark ignition Hurricane 24 came to an end in early 1948 when the advent of the commercial miniature glow-plug and the consequent general switch by North American modellers to the new form of ignition effectively sealed the doom of the spark ignition motor. Ray Hunter recognized this immediately, ending production of the Hurricane 24 sparker and introducing the Hurricane “Hot Top” glow-plug model. This was the final commercial model produced by Ray Hunter.

The four-year production run of the spark ignition Hurricane 24 came to an end in early 1948 when the advent of the commercial miniature glow-plug and the consequent general switch by North American modellers to the new form of ignition effectively sealed the doom of the spark ignition motor. Ray Hunter recognized this immediately, ending production of the Hurricane 24 sparker and introducing the Hurricane “Hot Top” glow-plug model. This was the final commercial model produced by Ray Hunter. Because glow fuel would have attacked the plastic fuel tank, a revised component made of plated brass was used. This had the same streamlined profile as its plastic predecessor and was attached in the same way. Because it was no longer sealed at the front by a disc, the metal tank was sealed in the conventional manner using a gasket around its perimeter. The internal cavity of the backplate now formed part of the tank, increasing its capacity somewhat.

Because glow fuel would have attacked the plastic fuel tank, a revised component made of plated brass was used. This had the same streamlined profile as its plastic predecessor and was attached in the same way. Because it was no longer sealed at the front by a disc, the metal tank was sealed in the conventional manner using a gasket around its perimeter. The internal cavity of the backplate now formed part of the tank, increasing its capacity somewhat.

This mint-condition all-original example appeared to be more or less unused, actually feeling a bit stiff when turned over by hand. This was apparently typical for these engines when new. Accordingly, I decided to give it a little running-in time prior to taking any test figures. I used a 10x4 Rev-Up wooden airscrew for this purpose.

This mint-condition all-original example appeared to be more or less unused, actually feeling a bit stiff when turned over by hand. This was apparently typical for these engines when new. Accordingly, I decided to give it a little running-in time prior to taking any test figures. I used a 10x4 Rev-Up wooden airscrew for this purpose.

In accordance with my original plan, I removed the tested hang-tank Super Hurricane and replaced it in the test stand with the bullet-tank example. Since it had allowed the first example to approach its peak, I fitted the Zinger 11x4 prop to see how closely the two examples compared in performance terms at or near the peak.

In accordance with my original plan, I removed the tested hang-tank Super Hurricane and replaced it in the test stand with the bullet-tank example. Since it had allowed the first example to approach its peak, I fitted the Zinger 11x4 prop to see how closely the two examples compared in performance terms at or near the peak.  For my test of this engine I used a 15% nitro fuel with plenty of castor oil. The engine had an Arden plug fitted, but for conservation reasons I elected to use a Fox plug for all testing. Based on Sparey's findings, I anticipated a peaking speed in the vicinity of 11,000 RPM or thereabouts. If this expectation proved accurate, subjecting the engine to speeds below 8,000 RPM or so on glow-plug ignition would not be a good idea. Accordingly, I fitted a 10x4 Rev-Up wood prop for the shakedown runs, just to ensure that the engine would not be subject to pre-ignition as a result of being over-loaded. We have to look after these 80-year-old engines!

For my test of this engine I used a 15% nitro fuel with plenty of castor oil. The engine had an Arden plug fitted, but for conservation reasons I elected to use a Fox plug for all testing. Based on Sparey's findings, I anticipated a peaking speed in the vicinity of 11,000 RPM or thereabouts. If this expectation proved accurate, subjecting the engine to speeds below 8,000 RPM or so on glow-plug ignition would not be a good idea. Accordingly, I fitted a 10x4 Rev-Up wood prop for the shakedown runs, just to ensure that the engine would not be subject to pre-ignition as a result of being over-loaded. We have to look after these 80-year-old engines!