|

|

OK Oddity – the OK Cub .149 Diesel

A number of diesels, some of them having considerable merit, had appeared in America prior to Ray Arden’s late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug. From that point in time onwards, American power modelling had been dominated by that form of ignition.

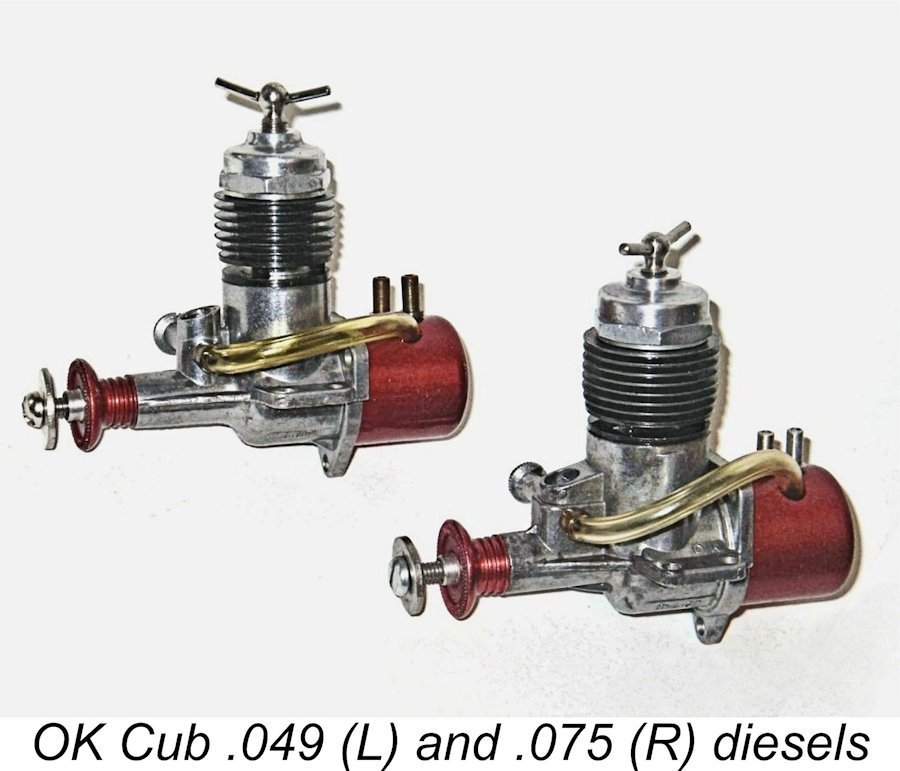

The first design decision to be taken was - in which displacement categories should diesel versions of the Cub series be developed for the mass market? This is actually one It appears that Brebeck himself was unsure of the answer to the displacement question at the outset, hence deciding to hedge his bets by simultaneously trying out diesel versions of the basic Cub design in two fairly divergent displacement categories. Accordingly, the Herkimer company entered the diesel market in April 1953 with a pair of diesel models, neither of which was either an .049 or an .075!!

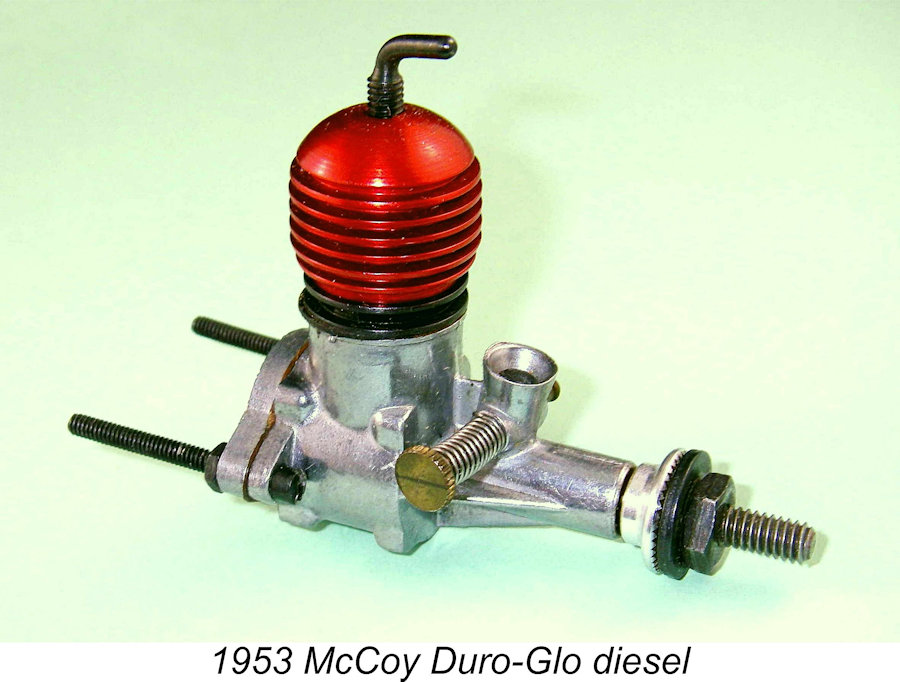

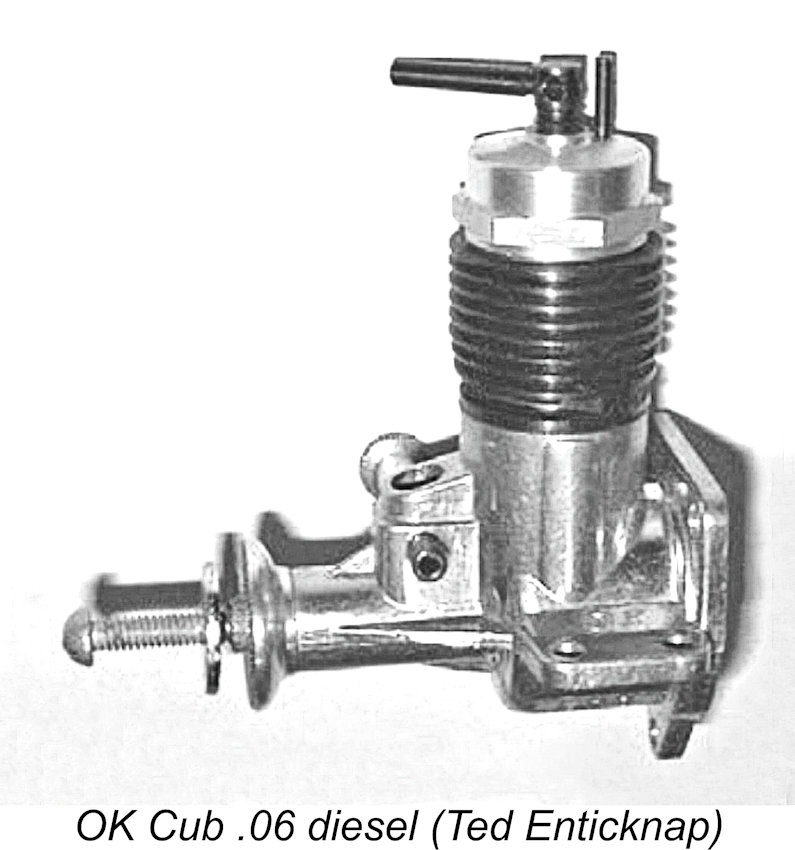

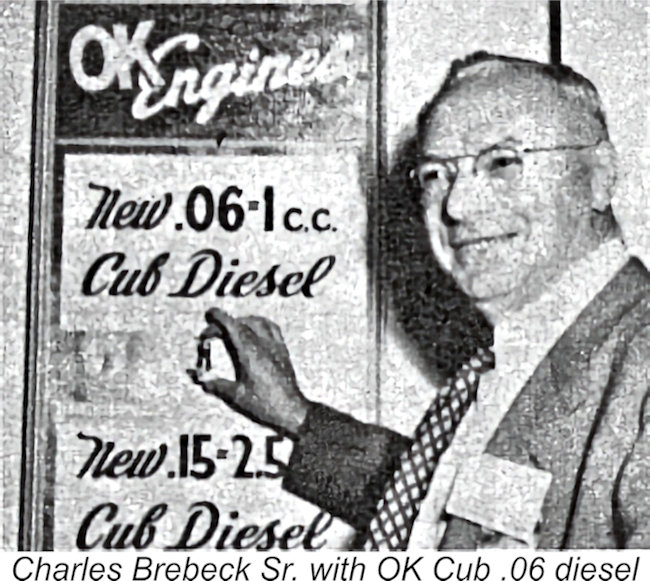

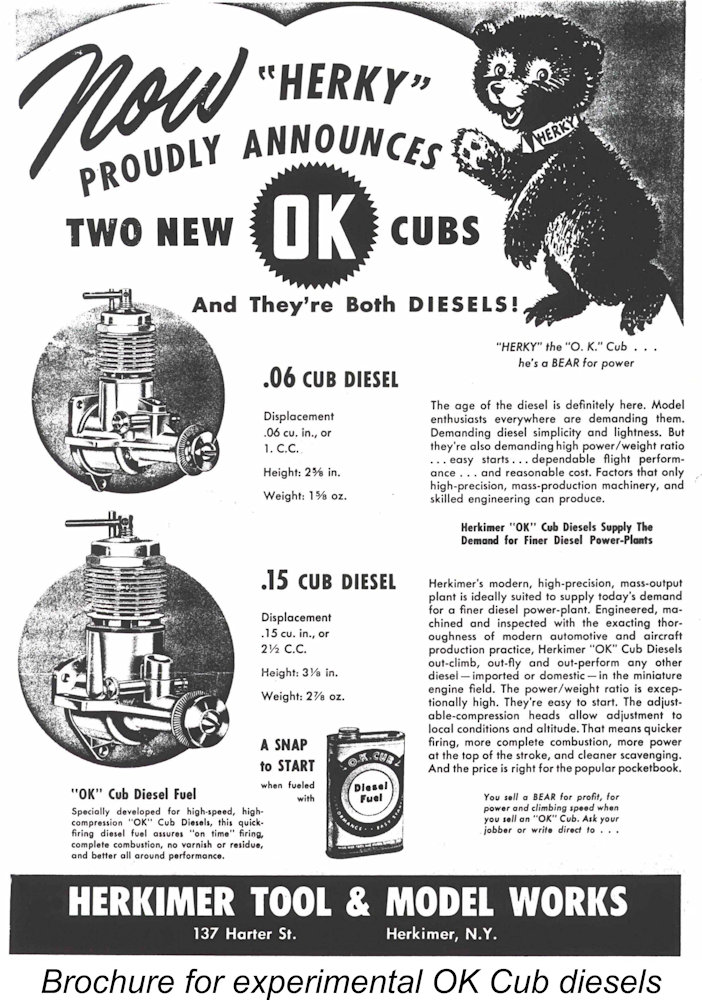

One of these models was essentially a diesel conversion of the company's previously-established .149 cuin. (2.46 cc) glow-plug model of 1952, while the other was built to an entirely new displacement for OK, that of .06 cuin. (1 cc). The latter model was based on the original long-stroke case and shaft used in the early .049 Cub glow model, with the piston/cylinder combination almost certainly being that of the short-stroke .049X which had then recently been introduced. Contrary to a seemingly widespread impression, these diesel models were actually introduced with some fanfare. The May 1953 issue of "Air Trails" included an article entitled "Showcase - Model Men" which consisted of photographs of prominent model manufacturers with some of their products. The "Air Trails" assemblage included an image of Charles Brebeck Sr. beside a poster promoting both the OK Cub .06 and .15 diesels. He is shown holding an example of the .06 model. Herkimer also produced a promotional brochure covering the engines, as reproduced here below at the left. This can scarcely be viewed as a low key introduction! Given the seeming level of effort put into the launch of these engines into the American market, it's rather surprising that Brebeck seems to have made little or no subsequent effort thereafter to attract attention to the new models.They weren't picked up by the contemporary US modelling media, in which neither tests nor descriptive articles appeared. Brebeck evidently made no Despite this lack of promotional fervor, some distribution within the USA undoubtedly did take place. The OK Cub .06 and .15 diesels both appeared in America's Hobby Center (AHC) advertisements in "Model Airplane News" (MAN) between May and December 1953. Indeed, the Cub .15 diesel continued to appear in AHC's advertising right through to April 1954, although the Cub .06 diesel disappeared after December 1953. Domestic marketing of the engines was not confined to AHC. In the October 1953 issue of "Air Trails", an Ohio company called "Fast Engine Exchange" advertised the OK Cub .06 and .15 diesels. However, this was the sole advertisement by this company that included those two models - their December 1953 and January 1954 placements included only the Cub .075 diesel. The January 1954 advertisement was their final placement - they ceased advertising thereafter. The June 1953 issue of "Flying Models" included an advertising listing of the Cub .06 and .15 diesel models from LANSCO Model Aircraft of South Haven, Kansas. This turned out to be that company's only listing of these engines. Nonetheless, it's clear that the new models did receive some level of distribution to multiple sales outlets across the country. There were almost certainly other such locations. It appears that the AHC, Fast Engine Exchange and LANSCO listings probably related to a single relatively small trial batch of the .06 and .15 diesel models, with the .06 model selling out first. This impression is heightened by the fact that the Cub .075 diesel which evidently supplanted the .06 model was first advertised in an OK advertisement in the October 1953 issue of MAN (see below). It seems highly unlikely that any further examples of the two pioneering models would have been manufactured thereafter. My sincere thanks to my good mate Gordon Beeby for ferreting out the above information!

OK themselves added to the confusion by stating in their own October 1953 advertisement (right) that they were "announcing a new OK Cub series of diesel engines" and that the Cub .075 was "the first" of these. This was manifestly untrue. The company actually appears to have made a conscious effort to "bury" the earlier .06 and .15 diesel models. The very clear and presumably intentional implication of this ad is that the .09 and 15 models never existed! There has been a widely-held impression that most of these pioneering OK Cub diesels were fed with little or no fanfare into the diesel-friendly European and South American markets, in which these two displacements were quite popular. However, this has always appeared to be rather improbable - during this period, many European and South American countries either restricted or prohibited the import of American model engines, classifying them as "Luxury Imports". Moreover, there's no evidence in the form of advertisements, media commentaries or surviving examples to support this idea. It actually appears far more likely that production of these models was confined to a single relatively small batch of each model, all of which were sold in North America. I suspect that the engines were announced with some fanfare and were distributed to certain American sales outlets, most notably AHC. The fact that they were withdrawn so quickly, being replaced by the Cub .075 diesel, implies that they failed to live up to the claims asserted by the manufacturer. It seems likely that they exhibited a tendency to fail in service, consequently being consigned to the waste bin. Such a tendency would completely explain both the lack of promotional effort and the extreme scarcity of surviving examples. Whatever the reason, few of these engines seem to have been sold in North America, and neither of the two models appears individually to have reached the 500-unit mark in terms of total production. Indeed, if they even got that far one has to wonder where they all are now ...........perhaps still in service in melted-down recycled form in classic Buicks! As a result, these are undoubtedly the rarest and least-known members of the OK Cub series - I was Original examples of the 1953 OK Cub .06 diesel are somewhat rarer than rocking horse droppings. However, my good mate Maris Dislers didn't allow this to deter him - he created a Cub .059 cuin. diesel using a combination of components from several different models together with a modified Cox .049 RJL diesel conversion head. This didn't exactly duplicate the original 1953 prototype but was essentially identical apart from the upper cylinder assembly. If its performance is anything to go by, those 1953 Cub .06 prototypes were very stout performers! They certainly made a good enough showing to encourage the development of the Cub .075 diesel which did reach production status. Maris's test report may be found elsewhere on this website. From an overall design standpoint, these two pioneering diesel models were essentially identical to the more familiar diesel units which were subsequently to appear in commercial form. The main visual difference was the fact that the promotional images showed them equipped with a single-arm compression lever with a stop pin in the cylinder head, rather along the lines of the Mills Bros. and Davies-Charlton diesels. They also lacked fuel tanks. It seems likely that Brebeck saw these engines more or less as "test beds" for his ideas regarding the conversion of the basic Cub design to diesel operation. The OK Cub .149 Diesel – Design Features

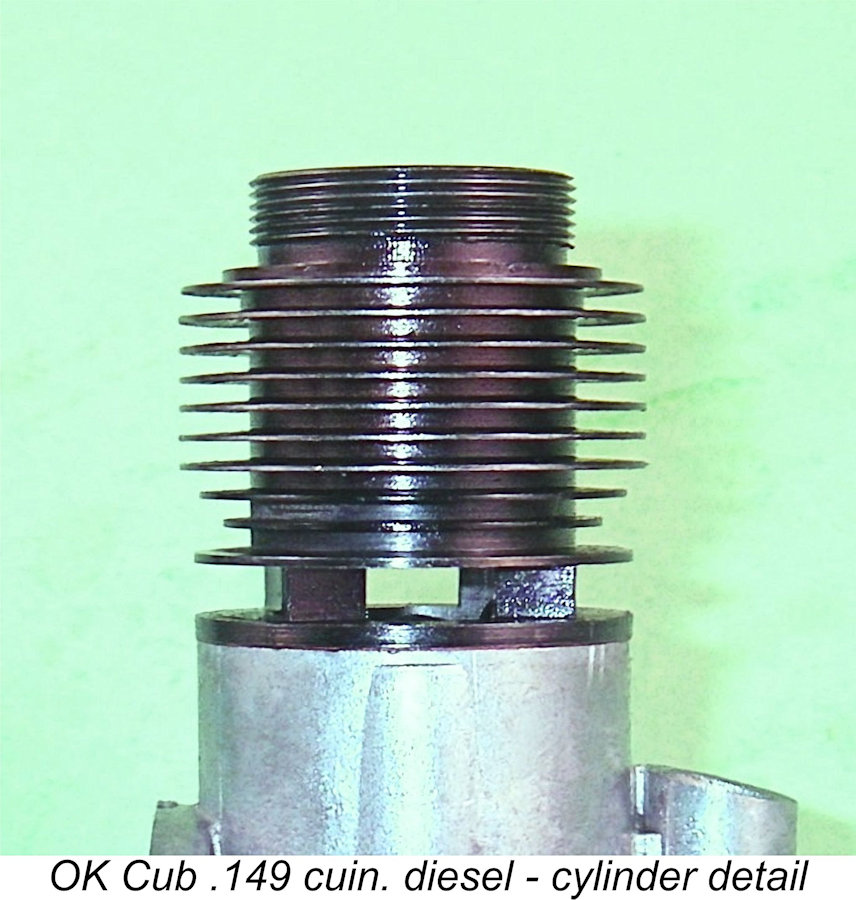

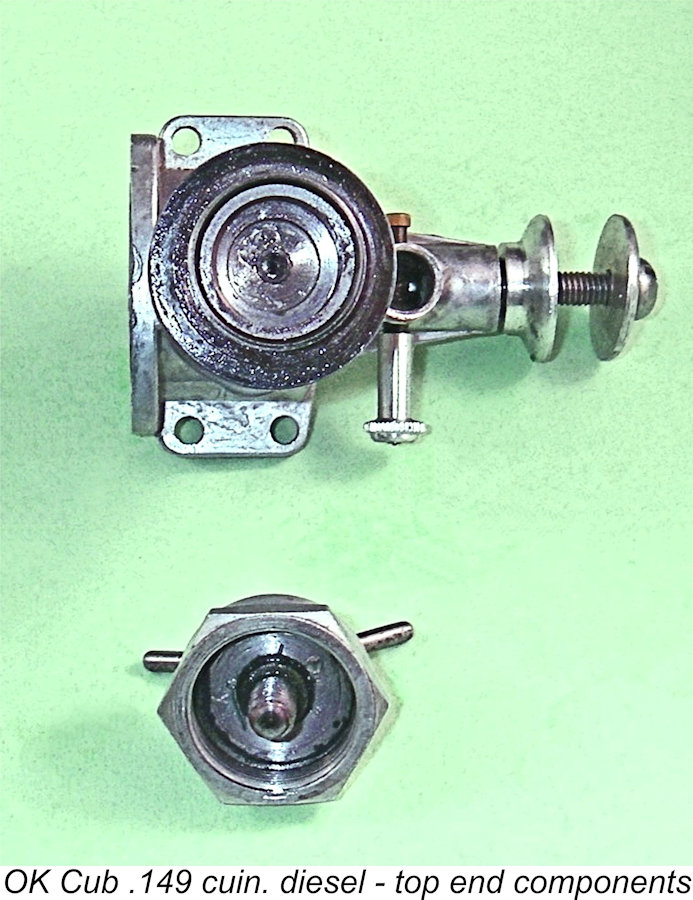

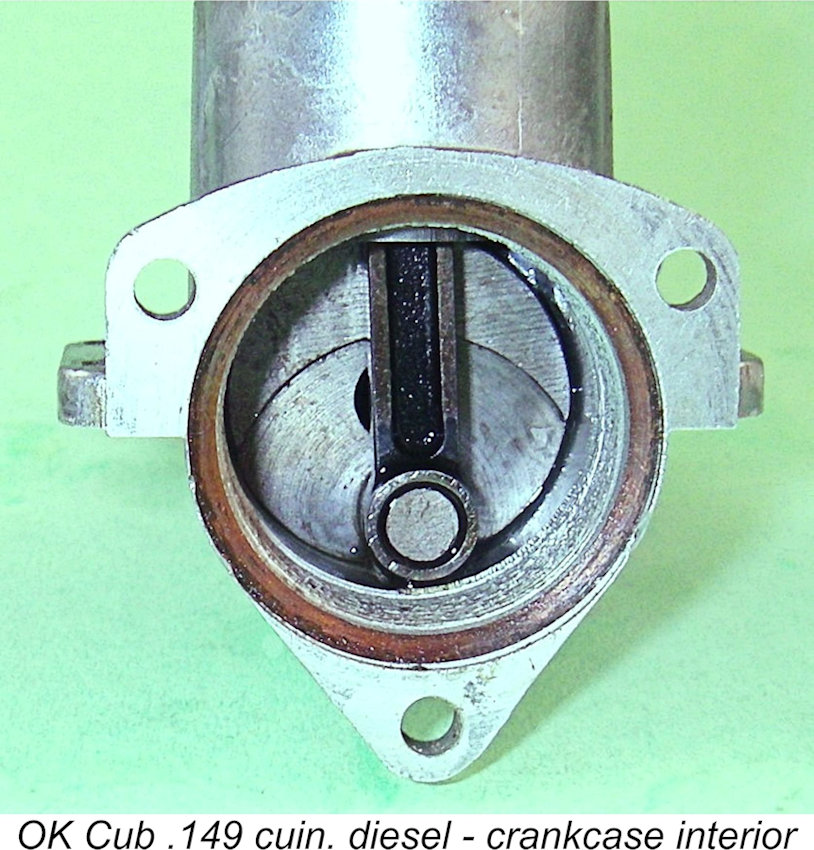

The diesel features the same bore and stroke as the glow version – 0.600 in. (15.24 mm) and 0.530 in. (13.46 mm) for a displacement of 0.1499 cuin. (2.46 cc). Checked weight is 3.10 ounces (88 gm) – pretty light for a 2.5 cc diesel! This is actually only some 7 gm greater than the parent glow-plug model’s checked 2.86 ounces (81 gm). However, there are some very significant structural differences which relate to the switch from glow-plug to compression ignition. One very obvious difference is the presence of a comp screw in place of the glow-plug. Interestingly enough, my illustrated example

Like all of the OK Cub diesels, the steel contra-piston utilizes a non-metallic O-ring to provide the necessary seal. However, the stamped steel triple-armed “shock absorber” used in the later diesel models is missing from the .149 diesel’s top end. The purpose of that component was to introduce some “give” into the engine’s structure to hopefully reduce shock loadings to the working components arising from the use of compression ignition. This feature is fully discussed in my companion article on the overall OK Cub diesel series.

Another feature of the later Cub diesels which is missing from the .149 model is the flange at the top of the contra piston to limit the depth to which the contra-piston could be screwed down into the cylinder. The later OK Cub diesels all exhibited this feature, which was intended to guard against the application of excessive compression by operators unfamiliar with diesels. It was the addition of The crankcase of the diesel appears to be the exact same component as that used in the earlier glow-plug model. The diesel’s case is identified in precisely the same fashion as the .149 glow model, bearing the following cast-on ciphers: OK Cub PAT’D .149 2179683 (US Patent number)

The one-piece steel crankshaft has a counterbalanced full-disc crankweb. It is almost identical to the component used in the glow-plug model. Main journal diameter is 0.282 in. (7.15 mm) with a 0.195 in. dia. (4.95 mm) internal gas passage, leaving a somewhat marginal wall thickness of only 1.1 mm. The sole concession to the need to accommodate additional stress levels when operating on compression ignition is the fact that the crankshaft induction port for the diesel's front rotary valve (FRV) induction system is a simple round hole with no sharp stress-raising edges, as opposed to the sharp-cornered cross-milled aperture used in the glow-plug model. Even so, the shaft The needle valve assembly used on the diesel is exactly the same as that featured on the glow-plug unit. The spraybar is pressed into the transverse hole through the intake rather than being secured using a nut. The aluminium alloy thimble is split to provide stability for the needle setting. Finally, the screw-in backplate is made of magnesium alloy as opposed to the aluminium alloy component used in the glow-plug version. This was presumably a weight-saving measure, although the saving would have been miniscule. Like other Herkimer products, the .149 diesel was produced to very high “consumer-grade” standards, with a very attractive external finish. As long experience with OK diesels leads one to expect, the .149 features a relatively slack piston/cylinder fit by diesel standards, although there seems to be plenty of compression for starting with an oily fuel. Speaking of which, it appears to be time to get our hands oily by giving this very rare diesel a run or two! Let’s get to it …………… The OK Cub .149 cuin. Diesel on Test

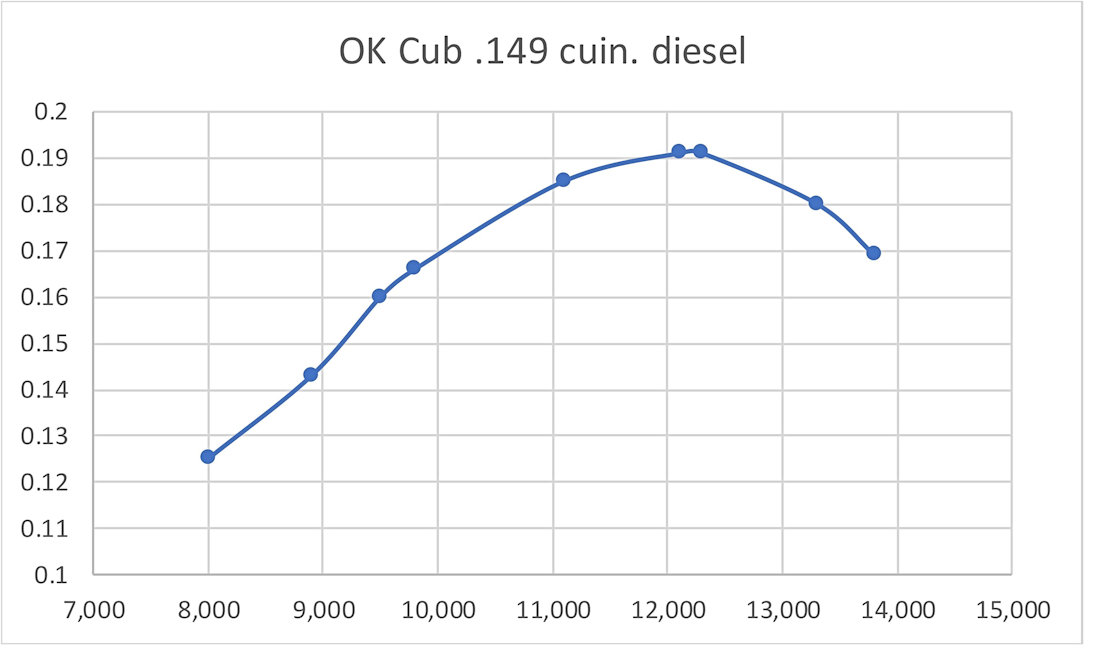

In his test report on the Cub .149 glow-plug motor which appeared in the April 1953 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Peter Chinn reported an output of 0.21 BHP @ 13,500 RPM, but had to use a fuel containing 30% nitromethane to achieve this figure. One suspects that on a more rational low-nitro sport-flying mix, the results would have been considerably less impressive. Ron Warring’s test report which was published in the July 1953 issue of “Aeromodeller” recorded data obtained using a fuel containing only 20% nitro - still a healthy proportion. The reported power peak was 0.195 BHP @ 12,500 RPM. Making allowance for the different fuels used, these two results seem to be quite compatible. One interesting observation based upon a reading of Warring’s report is the fact that he clearly didn’t understand the very significant influence of glow-plug heat range on the performance of a glow-plug engine. He reported having replaced the original OK glow-plug with a K.L.G. Miniglow component for no better reason than the fact that the K.L.G. would stand up to the 2v accumulator that Warring was using to light the plug for starting, evidently without a voltage-control resistor. He then complained that the Cub wouldn't keep going with the plug disconnected following starting - the classic symptom of a too-cold plug! Of course, Warring was failing completely to take account of the fact that the contemporary OK plugs for which the engine was designed were relatively “hot”, while the K.L.G. Miniglow was notably “cold”. The Cub .149 glow-plug model has a comparatively modest measured compression ratio of around 7 to 1, clearly being tailored to the use of the “hot” OK glow-plug fitted as standard. This compression ratio was clearly insufficient to keep the K.L.G. plug sufficiently hot once disconnected – an element requiring 2 volts to heat it for starting may be expected to be a lot colder than its 1.5v counterpart. By contrast, Peter Chinn used the standard OK plug with a resistor in the line to keep the voltage applied to the plug within acceptable limits. He reported no difficulties of the kind evidently experienced by Warring. Be that as it may, it would appear logical to assume that the Cub .149 glow-plug model might be expected to develop around 0.190 BHP @ 12,500 RPM using a standard low-nitro sport-flying fuel along with a suitably-matched glow-plug. Not bad by 1953 standards for an engine weighing only 81 gm!! How does the diesel version compare?

In view of the engine’s slightly “soft” compression seal (a typical characteristic of OK Cub diesels), it appeared that the use of a fuel containing more than the usual proportion of oil might be in order. In that regard, it’s interesting to note that during the course of his July 1954 “Model Aircraft” test of the later OK Cub .075 diesel, Peter Chinn consulted Herkimer directly to inquire about the best fuel on which to test their product. The specially-formulated OK Cub diesel fuel was not available in England – instead, the company recommended a fuel consisting of 40% kerosene equivalent, 28½ % ether, 30% SAE 70 mineral oil and 1½ % amyl nitrate or equivalent. It‘s clear that Herkimer recognized the benefits of using an oily fuel in their diesels. As it happens, this is pretty much the exact same conservation-oriented formula of the home-brewed fuel which I use for general-purpose testing of classic diesels apart from my normal use of castor oil as opposed to mineral oil. I therefore felt comfortable in using this fuel in the present instance. As far as props went, it seemed reasonable to expect the Cub diesel to swing a larger prop than its glow-plug equivalent, mainly due to the fact that the ignition timing could be optimized at any speed through appropriate use of the compression control. This is a major advantage of variable-compression diesels over glow-plug motors – they can accommodate a far wider range of speeds from an ignition timing standpoint. Bearing this in mind, I decided to begin with a 9x6 APC prop fitted. Ron Warring’s test example of the glow-plug version had turned a 9x6 wood airscrew at 7,700 RPM, suggesting that this might be a good size to try at the outset. My intention was to keep the running time down to the minimum necessary to obtain some reasonably representative prop/RPM readings on an appropriate range of prop sizes. The Cub .149 diesel felt pretty good when flicked over while mounted in the test stand with its 9x6 airscrew. The somewhat “soft” compression seal was certainly apparent, but the introduction of my “oily” fuel mixture into the cylinder was sufficient to seal things to a fully satisfactory level. I set the compression by “feel” based on long experience and set the needle at 3 turns open, at which setting the fuel jumped along the fuel line in a satisfactory manner when the engine was choked. After administering a small ”dry” prime (exhaust ports closed), I got down to the serious flicking.

I quickly found that the requirement for a certain specific amount of fuel in the cylinder – no more and no less – was a prerequisite to a quick start. I ended up using a single choked turn to fill the fuel line and get a little fuel into the case, followed by a dry prime. A few flicks then sufficed to establish the perfect conditions for starting, at which point the engine fired up very strongly. I wouldn’t classify the Cub .149 diesel as an “easy” starter, but it could legitimately be characterized as a “dependable” starter – although a few preliminary flicks continued to be required before a response could be elicited, it never took long to get the engine running. It’s just one of those units that needs a bit of “knowing”. Once running, response to the controls was all that could be desired – very positive but by no means excessively sensitive. Getting to the optimum setting for each prop was a completely straightforward process. Once set, running was completely smooth, with no trace of a misfire and no tendency to sag. While there was some vibration, it didn't appear to me to be excessive. Both controls held their settings perfectly. Overall, I was quite impressed with the engine’s running qualities. The following data were recorded with no problems at any time.

We must also remember that the OK Cub .149 cuin. diesel dates from 1953. The performance measured during my test is quite comparable with reported figures for other contemporary lightweight plain-bearing diesels. For example, Peter Chinn found only 0.220 BHP @ 12,750 RPM for the A-M 25 Mk. I which was introduced a year later in 1954. The contemporary BWM 250D could only manage 0.190 BHP @ 11,500 RPM when tested by Chinn in 1955. Moreover, both of those engines outweighed the Cub by a significant amount. One outcome of this fairly lengthy test that really pleased me was the simple fact that the engine survived all of the running that it received, some of which was done at relatively high speeds. I still think that the shaft is a little under-nourished for a 2.5 cc diesel, but it seems to be good for a certain amount of running. I have no intention of conducting a “test to destruction” to explore the limits – the fact that the engine remains in perfect running order following the above test is good enough for me! Conclusion It’s clear from the above review that Charles Brebeck’s initial foray into the world of model diesel engine design was by no means unsuccessful. If his .149 cuin. (2.46 cc) diesel had entered full-scale series production in 1953, it would have set a new standard for power-to-weight ratio in the 2.5 cc sports diesel category Brebeck must have had some cogent reasons for electing not to pursue the development of this model. I suspect that experience in the field with the early examples may have revealed some underlying weakness in the 2.5 cc design, the most likely culprit being the crankshaft. For reasons of manufacturing economy, the design had to be based in large part on the existing glow-plug model, in particular the crankcase and crankshaft. Perhaps experience showed that the components of the glow-plug model weren’t quite up to the task, even with the modifications applied. The accommodation of a significantly stronger crankshaft would have required the development of a different crankcase die, something which the economic constraints applied to the project evidently rendered impracticable. Accordingly, this engine stands as a reminder that even relatively successful experiments by model engine manufacturers didn’t always result in the introduction of production versions of the experimental models. I hope that you’ve enjoyed this look at one such experiment which, although it represented a dead end in commercial terms, nevertheless stands as a worthy attempt to develop something new in the context of the North American market! ________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published November 2023 |

||

| |

In a

In a

of the more interesting pieces of information which an in-depth study of the OK diesels throws up! Most people immediately think of the familiar OK Cub .049 and .075 diesel models whenever the subject of the OK diesels is raised. However, these were actually not the initial diesel offerings by the company!

of the more interesting pieces of information which an in-depth study of the OK diesels throws up! Most people immediately think of the familiar OK Cub .049 and .075 diesel models whenever the subject of the OK diesels is raised. However, these were actually not the initial diesel offerings by the company!

In general, the design of the Cub .149 diesel follows that of the 1952 Cub .149 glow-plug model to a large extent. This was clearly the intention of the exercise - the objective was to test a straightforward diesel conversion of the existing glow-plug model with as few changes as possible.

In general, the design of the Cub .149 diesel follows that of the 1952 Cub .149 glow-plug model to a large extent. This was clearly the intention of the exercise - the objective was to test a straightforward diesel conversion of the existing glow-plug model with as few changes as possible.

Both the witness marks in the centre of the contra piston and the length of the comp screw pretty much confirm that the “shock absorber” was never there in the .149 diesel model. As mentioned earlier, the .149 diesel was one of Herkimer’s first experimental diesel models in mid-1953, hence pre-dating the smaller units which followed. Presumably the “shock absorber” idea post-dated those initial experiments.

Both the witness marks in the centre of the contra piston and the length of the comp screw pretty much confirm that the “shock absorber” was never there in the .149 diesel model. As mentioned earlier, the .149 diesel was one of Herkimer’s first experimental diesel models in mid-1953, hence pre-dating the smaller units which followed. Presumably the “shock absorber” idea post-dated those initial experiments.

A major concession to the need to beef things up for diesel operation is the use of a very sturdy forged I-section bronze conrod in the .149 diesel as opposed to the smaller-section drop-forged light alloy component used in the glow-plug unit. This represented a trade off between reciprocating weight reduction and strength. The later .049 and .075 diesels used a fully machined rod turned from steel and then hardened.

A major concession to the need to beef things up for diesel operation is the use of a very sturdy forged I-section bronze conrod in the .149 diesel as opposed to the smaller-section drop-forged light alloy component used in the glow-plug unit. This represented a trade off between reciprocating weight reduction and strength. The later .049 and .075 diesels used a fully machined rod turned from steel and then hardened.

In deciding whether or not to pursue the concept of a .149 cuin. diesel, it would have been entirely natural for Herkimer to compare the performance of their experimental diesel model with that of the well-established glow-plug version of the .149 on which this diesel was based. The latter model had been extensively tested in the contemporary modelling media.

In deciding whether or not to pursue the concept of a .149 cuin. diesel, it would have been entirely natural for Herkimer to compare the performance of their experimental diesel model with that of the well-established glow-plug version of the .149 on which this diesel was based. The latter model had been extensively tested in the contemporary modelling media.  In contemplating an attempt to answer this question, I will admit to being a bit nervous regarding the ability of the Cub .149 crankshaft to stand up to diesel operation, even with its modified induction port. Indeed, it may well have been problems with this component that led to the abandonment of the Cub .149 diesel experiment. However, I felt that if I didn’t have a go, no-one else would! I therefore decided to proceed, resolving to keep both compression settings and running time to a minimum.

In contemplating an attempt to answer this question, I will admit to being a bit nervous regarding the ability of the Cub .149 crankshaft to stand up to diesel operation, even with its modified induction port. Indeed, it may well have been problems with this component that led to the abandonment of the Cub .149 diesel experiment. However, I felt that if I didn’t have a go, no-one else would! I therefore decided to proceed, resolving to keep both compression settings and running time to a minimum. It turned out that the Cub .149 was very particular regarding the amount of fuel in the cylinder for starting. It also didn't like too much fuel in the crankcase. I flicked for quite a while with absolutely no response, and then suddenly the conditions in the cylinder became perfect and the engine started right up! It turned out that I had set the needle a little rich, but the required correction was quickly made.

It turned out that the Cub .149 was very particular regarding the amount of fuel in the cylinder for starting. It also didn't like too much fuel in the crankcase. I flicked for quite a while with absolutely no response, and then suddenly the conditions in the cylinder became perfect and the engine started right up! It turned out that I had set the needle a little rich, but the required correction was quickly made.