|

|

Forgotten Masterpieces – the Webra “Blaukopf” Diesels

Having been a very satisfied user of these units in the past, I developed an interest in learning more about them. However, an intensive search of the Internet failed to turn up any significant information about these fine powerplants. Even the very informative website maintained by M.E.C.A. Region 16 (Germany) has no information beyond a single image of the smaller Sport 10 model. It appears that these units came and went without making much impression on the power modelling scene. As time went by, I noticed that I almost never encountered fellow users of these models, although those who saw my examples in action were very impressed. This seeming lack of appreciation is a great pity, because these were excellent model diesels with the capability of serving their owners very well. I’ve never personally encountered an example of the .40 cuin. Bluehead diesel, but I can confirm from extensive personal experience that the Speed 28 in particular was a fine, trouble-free unit. The smaller Sport 10 did have a few quirks which needed some knowing, but once those quirks were recognized and accommodated it too was an outstanding performer. The very low level of available documentation on these fine engines convinced me that the preservation of a little of their history and their operational qualities would be well worthwhile. After all, these engines had the distinction of being the last factory-produced diesels to bear the iconic Webra name. As such, they are certainly not without their historical significance.

A considerable amount of misinformation on the history of the Webra marque has appeared in the past in the English-language modelling media. We are therefore greatly indebted to Jochen Schneider of M.E.C.A. Region 16 for the presentation on that website of a comprehensive German-language history of the company from its beginnings down to 1984, when the Berlin-based Fein und Modelltechnik company which had previously manufactured the Webra range was finally dissolved, leaving the ongoing manufacture in the hands of others. Schneider was personally acquainted with Webra founder Werner Martin Bragenitz, hence having access to a very authoritative source of information. He also made frequent reference to source information which appeared in the contemporary German modelling media. I’m happy to acknowledge his immense contribution to my coverage of this subject. Vielen Dank, mein Freund!! Webra Corporate History The name of Webra goes way back to the early years of model engine manufacture in post-WW2 Germany. The history of German modelling during this period is greatly obscured by the fact that for some years following the conclusion of that conflict, model flying activities in Germany were severely restricted by the occupying powers. This undoubtedly applied the brakes to the development of German modelling technology as well as minimizing the visibility of German modelling activities to the rest of the world. Of course, the enthusiasm of German modellers was by no means diminished by these restrictions – you can regulate peoples’ activities, but not their enthusiasm! Consequently, modelling activity become re-established relatively quickly in Germany following the conclusion of the war, albeit at a somewhat constrained level. For instance, the flying of power model aircraft was banned for some years following the conclusion of the war.

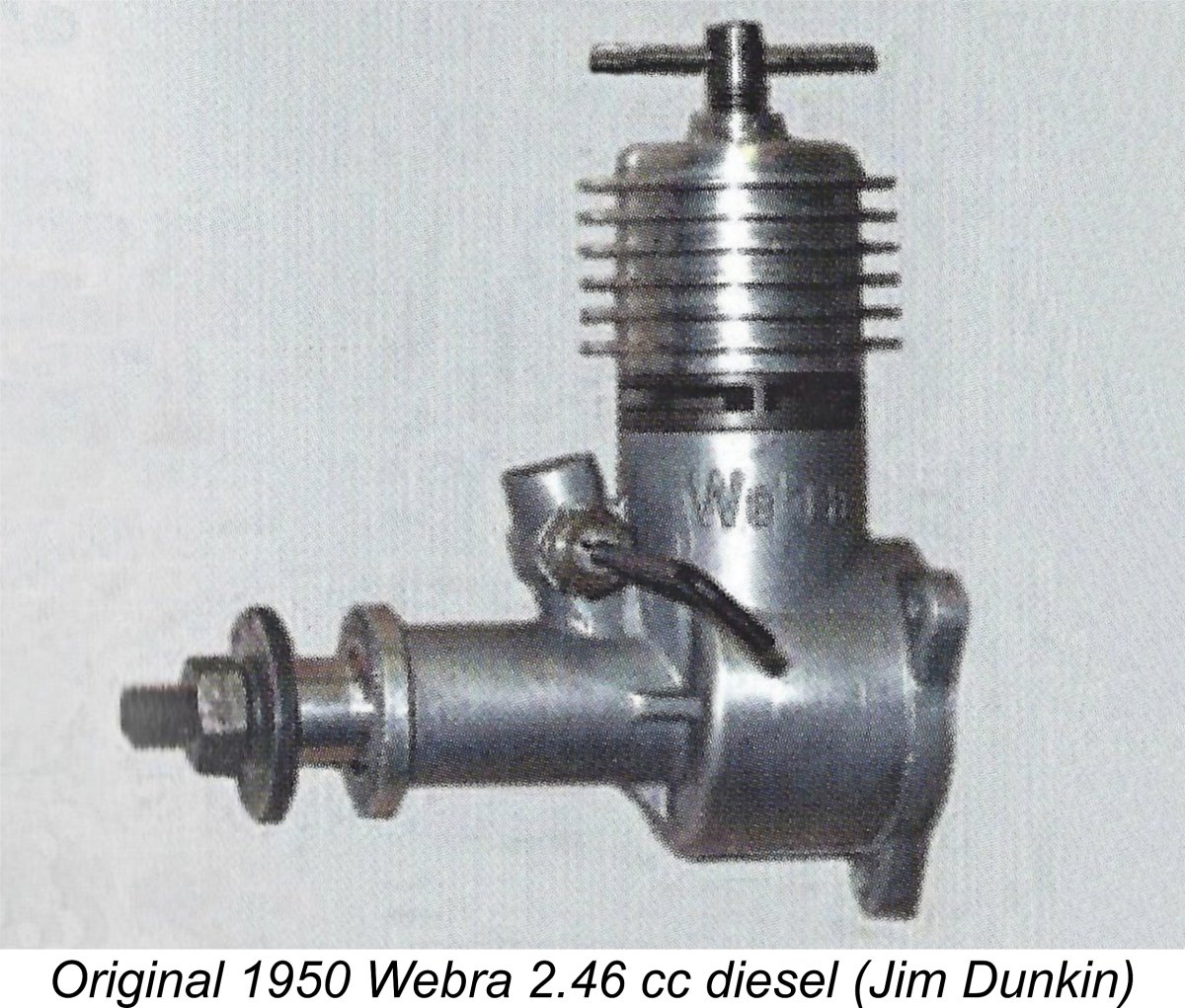

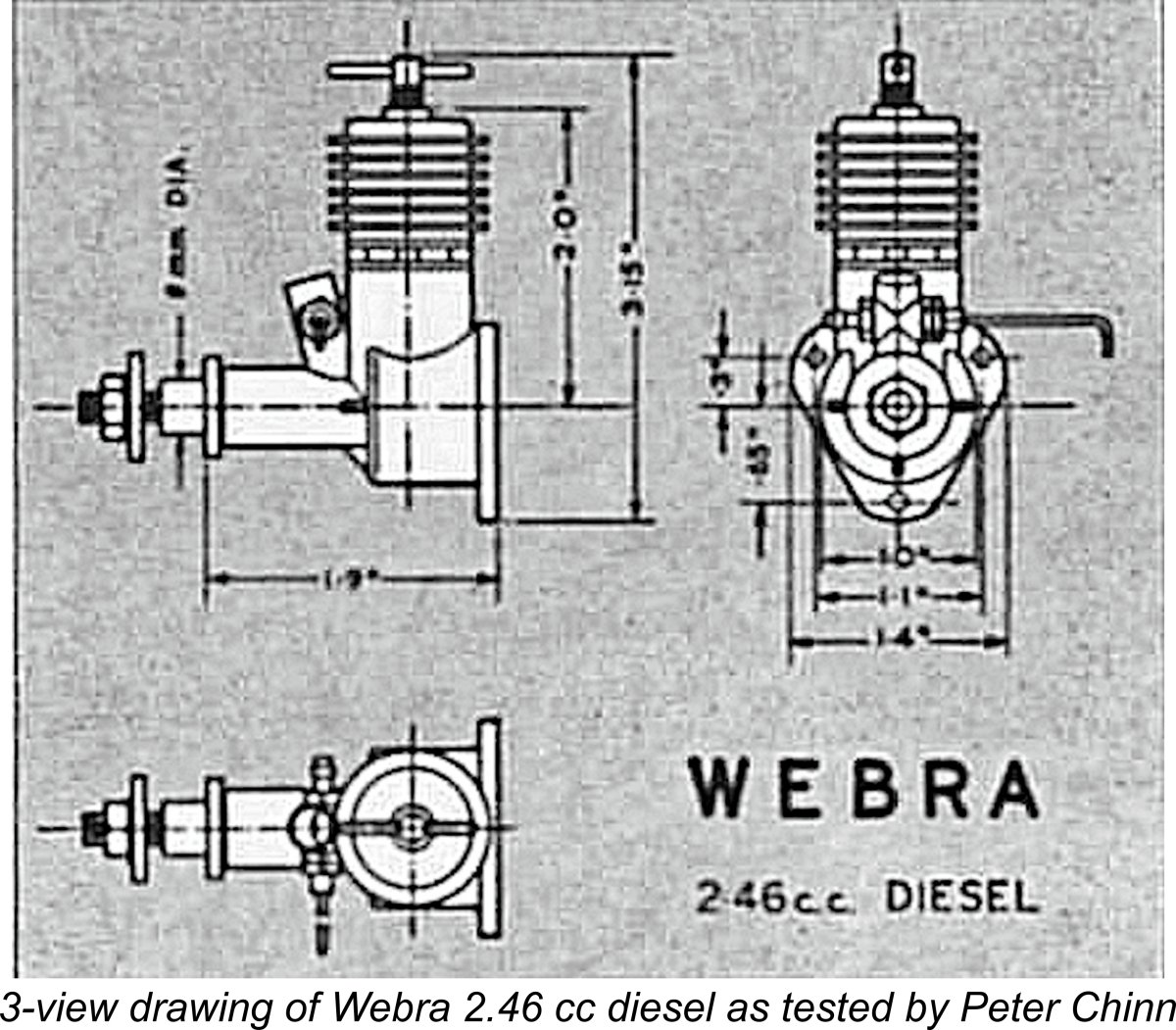

Indeed, it’s likely that many of the German model engines produced during this period were used in model boats and cars, the operation of which was not restricted. There were also a number of stationary “table top” units such as the Rauch 3.2 cc model which has been reviewed elsewhere on this website. One of the individuals wishing to become involved with model engine production in early post-WW2 Germany was an engineer named Werner Martin Bragenitz (b. 1914), often referred to by his middle name of Martin. Before and during WW2, Bragenitz had worked as a master mechanic and operations engineer for the major Siemens company. This company was fragmented in the turmoil of the post-war period, leaving Bragenitz living at Falkensee near Berlin and seeking fresh opportunities to re-establish himself. In 1946, Bragenitz founded a company called “Feintechnik, Zahnradfräserei und Feinmaschinen” with its facilities located in Berlin-Spandau at Päwesiner Weg 19. The company specialized in the manufacture of precision mechanical components, principally gears, under contract to other companies. Bragenitz was therefore dependent on his clients for business, which was not without risk for the company's ongoing existence in those uncertain times. His aim therefore became to have his precision engineering company develop and manufacture its own products to be marketed independently. As a first step, Bragenitz took on his former Siemens colleague Senninger as a partner, intending to produce and sell model diesel engines with him. These planned engines ranged in displacement from 0.5 to 10 cc, to be manufactured by a re-named company called “Bragenitz & Senninger”, still in Berlin-Spandau at Päwesiner Weg 19. This information was confirmed in a one-page brochure in which all the data for the “BSG small diesel engines” was summarized. However, since nothing more was ever heard of these engines, it would appear that the project was not a success. The partnership with Senninger evidently didn’t last long.

From the outset, distribution of the Webra 2.46 was managed by “Walter Weichler oHG”, Berlin W 15, Uhlandstrasse 46. In German corporate terminology. oHG signifies a partnership in which no partner's liability towards the partnership's creditors is limited. This marketing company had initially specialized in the distribution of English engines, construction kits and radio control equipment in Germany. It now added the Webra 2.46 to its portfolio. Weichler promoted his offerings particularly through attendance at model aircraft, boat and car racing events. A certain spectator appeared more and more frequently at these events – he was a very capable mechanic named Günther Bodemann (b. 1921). Bodemann soon began working for Bragenitz in the production field. At the same time, he also took on responsibility for the design and construction of new Webra model engines, quickly demonstrating an extremely high level of ability.

Walter Weichler left the marketing company in mid-1951 and Werner Martin Bragenitz took his place as Spivey’s partner. At the beginning of 1952, the company was re-named “Modelltechnik, Spivey & Bragenitz”. A move to a new location took place at this time. The address was still in Berlin W 15, but now at Wielandstrasse 23. During the transition phase, the engines continued to be manufactured by Bragenitz at his workshop in Berlin-Spandau at Päwesiner Weg 19. Günther Bodemann continued to assist Bragenitz in this activity. However, production was soon focused at the Wielandstrasse location. At this time, other Berlin companies were developing and producing model engines. Among them was a recently-established company named “Feintechnik Martin Eberth” of Geneststrasse 5 in Berlin-Schöneberg. The owner, Martin Eberth (b. 1913) came originally from the Erzgebirge and arrived in Berlin in 1949. At the age of 22 he had already co-founded a precision engineering company in Glashütte. Later, after separating from his original partner, he established another similar operation in Lauenburg, near Hamburg, which he ran from 1942 throughout the war and on up to 1949, when his move to Berlin took place. Eberth’s new company survived initially with orders from the Berlin waterworks, producing precision mechanical parts, gears, worms, etc. However, he soon began planning to enter the model engine field, although his plans were still in their early stages as of mid-1950. It was therefore a lucky coincidence that Martin Eberth and Werner M. Bragenitz became acquainted during the course of 1950. Both quickly saw a great opportunity potentially arising from a merger of their two precision engineering companies into one. The advantages would include a larger customer base as well as more efficient utilization of the machinery and staff. Both parties soon came to a mutual agreement on a merger. At the same time, one of Eberth's brothers-in-law, Rudolf Brauer, joined the new company. All of this was put into a contract and signed on July 24th, 1951. The newly founded company bore the name “Feintechnik Bragenitz, Eberth, Brauer oHG”, operating from Eberth’s established facilities in Berlin-Schöneberg at Geneststrasse 5. Bragenitz’s workshop at Wielandstrasse 23 in Berlin W 15 was now abandoned. As with the previous individual companies, the stated purpose of the new combination was to produce precision mechanical products.

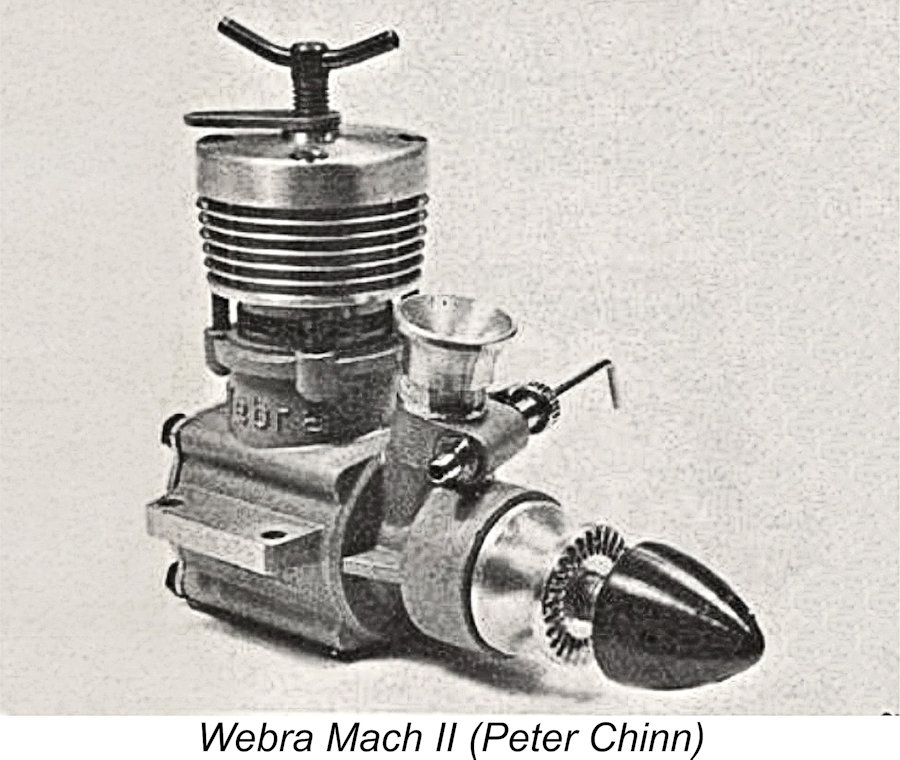

Günther Bodemann was also brought into the new venture by Bragenitz – a wise move. Bodemann now had the opportunity to carry out experiments in the field of model engine technology on a firmer and better-funded basis than before. The improved work environment quickly bore fruit. The first result of Bodemann's development work, the original radial-mount Webra 1.5 cc diesel, was announced in the hobby magazines in November 1952. This engine was in essence a downscaled version of the original Webra 2.46 model. It quickly emerged as the most powerful diesel engine in the 1.5 cc class at the time. 1952 was a pivotal year for Webra in more ways than one. It was in that year that that the remaining restrictions relating to model aircraft operation in Germany were finally relaxed. At the same time, Germany was re-admitted to the international competition arena, leading to the country’s progressive re-emergence as a force to be reckoned with in such competitions. Several German competitors showed up at the 1952 World Free Flight Power Championship meeting held in September at Dubendorf Aerodrome in Switzerland. Using then-current Webra 2.46 cc plain bearing diesels, they finished 6th and 7th respectively, thus making a very respectable come-back showing for Germany. Webra engines also powered around half the entries in the 1952 German national free flight power championships, including the winner. At the beginning of 1953 there was a change in the company management - Eric Spivey joined as co-owner. Spivey and Bragenitz dissolved their sales company “Modelltechnik, Spivey & Bragenitz”, allowing that company's assets and liabilities to flow into the “Feintechnik” company, whose name was changed again to Fortunately, these rather significant management changes within a year had no noticeable impact on engine production. By this time, around 10,000 Webra engines had been sold in Germany alone. The engines that had been developed so far continued to be refined. The Webra 1.5 and Webra 2.46 were made available with provision for both beam and radial mounting. And in June 1953 Günther Bodemann’s Webra Mach 1 twin ball-race disc valve racing diesel was introduced. With this motor, Webra finally achieved its long-sought global marketing breakthrough. The Mach 1 quickly became recognized as a virtual guarantee of competition success in all areas of modelling competition. The quality and reliability of Webra engines was on very clear display at the 1953 Free Flight World Championships held at Cranfield (England), where out of 100 participants, 31 entrants used Webra engines.

During 1955, the management team changed again – Eric Spivey left the company after only two years of direct involvement. As a result, the company name also changed, becoming “Fein und Modelltechnik Bragenitz & Eberth”. The centre of operations was unchanged, remaining in Berlin-Schöneberg at Geneststrasse 5. In this corporate form, the company would stabilize and operate for the next seven years.

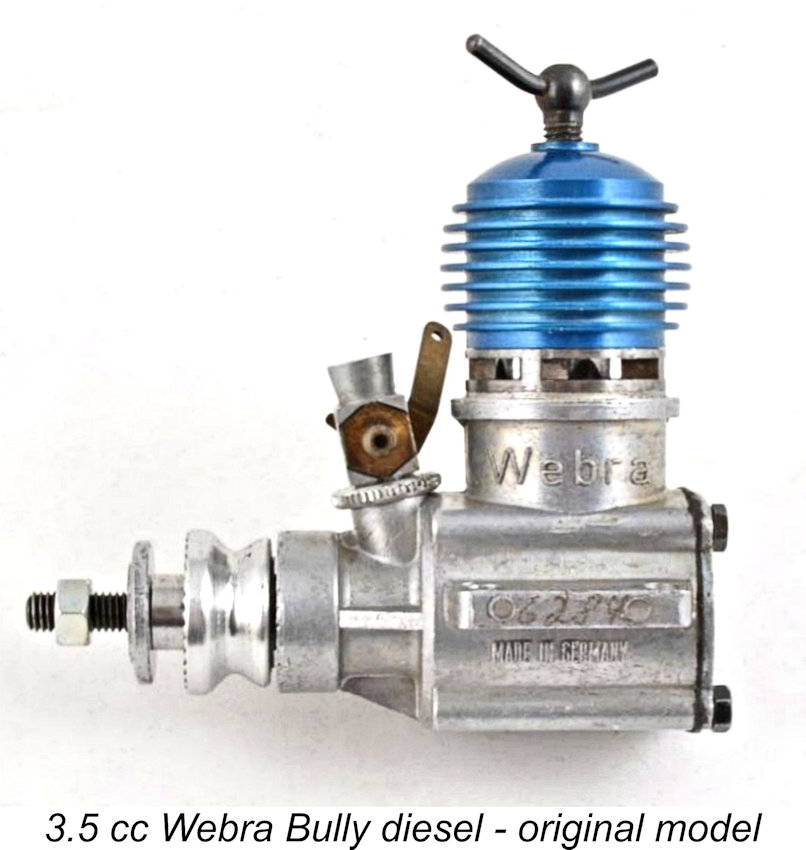

A significant event occurred in 1958 when Günther Bodemann moved to Hans Hörnlein’s company at Vöhringen near Ulm, where the competing Taifun engines were manufactured. Fein und Modelltechnik carried on regardless, presenting three new Webra diesel engines at the 1958 Nuremberg Toy Fair. The new models The company carried on into the 1960’s, with the rate of introduction of new models slowing down somewhat. In Bodemann's absence, the company was not free from the consequences of design errors - in fact, a series of crankshaft failures forced the 1960 introduction of a revised version of the 3.5 cc FRV Bully diesel, a switch being made to disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction to permit the use of a stronger crankshaft. The new design was designated the Bully 2.

During 1962, the 48-year old Werner Martin Bragenitz left the company after almost 12 years of co-ownership. From 1955 onwards, after Brauer and Spivey left, he had successfully managed the company in co-operation with Martin Eberth. He now accepted an offer from his pre-war employer, the now-reconstituted major corporation Siemens. The product name “Webra”, which had originated with him, remained with the model engine company, of which Martin Eberth now became the sole owner.

In 1967, company owner Martin Eberth converted Fein und Modelltechnik into a limited company (GmbH) and three months later into a limited partnership (KG). The corresponding entries in the commercial register of companies were made on November 24th, 1967 and March 6th, 1968. At the end of the 1960’s, life took a very sad turn for Günther Bodemann. He developed an incurable cancer and died tragically prematurely on October 21st, 1971 at the age of only 50. This was a great loss both for the hobby and the company, since the worldwide success of Webra engines could be attributed almost entirely to Bodemann’s design and production work. During the 1960’s, the political situation in West Berlin had become increasingly uncertain, to the point that many Berlin-based entrepreneurs became worried about the future of their businesses. Martin Eberth was no exception. In search of a possible comfort zone, he initiated contact with one of his competitors, Hirtenberger Patronen und Zündhütchen AG of Hirtenberg in Austria, makers of the respected HP model engine range.

In 1968, Johann Kaineder was hired as a technician, subsequently becoming plant manager when Paul Bugl left the company. From this point onwards, the company's model engine focus switched to glow-plug units. The very talented Peter Billes joined the company to serve as chief designer. Martin Eberth first established contact with Johann Kaineder at the 1971 Nuremberg Toy Fair, subsequently meeting at length with Peter Billes at the 1972 event. They quickly came to an agreement, and in 1972 a new Webra/HP factory was established in Austria at Enzesfeld (not far from Hirtenberg), about 35 km south of Vienna. Manufacturing operations commenced immediately, with Johann Kaineder served as the managing director of the new enterprise and Peter Billes being the chief designer.

Enzesfeld now became the centre for technical development of the Webra range. In 1976/1977, probably for economic reasons, Martin Eberth established another facility in Weidenberg, near Bayreuth in Upper Franconia on the outskirts of the Federal Republic of Germany, with the aim of gradually dismantling the Berlin plant, which was suffering from a lack of space. Initially, Weidenberg took over the distribution function, but engine production was also increasingly relocated from Berlin to Weidenberg, where limited production of a few of the classic “Berlin” designs was maintained for a time.

All of the new model engine designs from 1972 onwards were developed at Enzesfeld, primarily by Peter Billes. Indeed, Webra Enzesfeld eventually became an independent Austrian company when the parent German company Fein und Modelltechnik was finally dissolved in 1984. Manufacture of the Webra engines was now concentrated at the Enzesfeld facility. In 1985 there was a change in the management at Webra Enzesfeld when Johann Kaineder retired for reasons of age and his son Gerhard Kaineder took over his duties. Gerhard Kaineder and his designer Peter Billes were the driving forces in the further development of the company’s engines.

At this point, Webra Enzesfeld stepped into the breach created by HP’s departure, immediately joining the proliferating competition circuit to focus upon the development of engines meeting the requirements of competition fliers. Both the Austrian Hanno Prettner, seven-time world R/C Aerobatics champion, and the Liechtensteiner Wolfgang Matt of R/C Pattern fame achieved their successes with engines bearing the Webra trade-name, as did many others.

Although the refinement and production of internal combustion engines remained at the core of Webra’s interests, changing market conditions forced them to diversify into peripheral areas such as electric powerplants, servos and R/C transmitters and receivers. Webra also entered the four-stroke engine field with their T4 series, while continuing to believe that there was a lot of development potential left in the two-stroke type.

The results were apparently decisive - although there undoubtedly were (and still are!) some individuals to whom the use of diesels to power their models was an attraction, it soon became evident that their numbers were insufficient to justify any further commercial consideration of that type of engine, at least on Webra's part. The Blueheads thus became the final diesel models to bear the Webra name. Although Webra remained committed to supporting the model flying hobby, other products also became established areas of interest, particularly those having an electronic basis. The company developed into a much-respected specialist in the field of industrial electronics. This new market segment became another mainstay for Webra, easily compensating for the sometimes-fluctuating demand for leisure products, including those related to model flying. During the 1990’s, a new factor emerged which created difficult conditions for European manufacturers of quality model goods. This was the ever-increasing penetration of world markets by a number of Chinese and Taiwanese manufacturers. Initially, these products lacked the quality of their European equivalents but were sold at extremely low prices which consumers were unable or unwilling to resist. Given the high production costs The final straw was the world financial crisis of 2008. This impacted the Webra Enzesfeld plant to the point that by 2010 the company was forced to file for bankruptcy. The revival of the company was not considered by the shareholders to be possible, so the Webra model engine initiative which had begun in 1950 finally came to an end after 60 years. A sad ending to a great story ………….. Ownership of the WEBRA trade-name passed into the hands of MECOA, from whom a range of spare parts for the later Webra engines may still be obtained. The Webra Bluehead Diesels Unveiled Now that I’ve reviewed the start-to-finish history of the Webra enterprise, it’s time to go back to the early 1990’s to review what turned out to be the last of a long line of model diesels to bear the Webra name. In 1993 Webra Enzesfeld ended a long disengagement with diesels by releasing three diesel models having displacements of .10, .28 and .40 cuin.

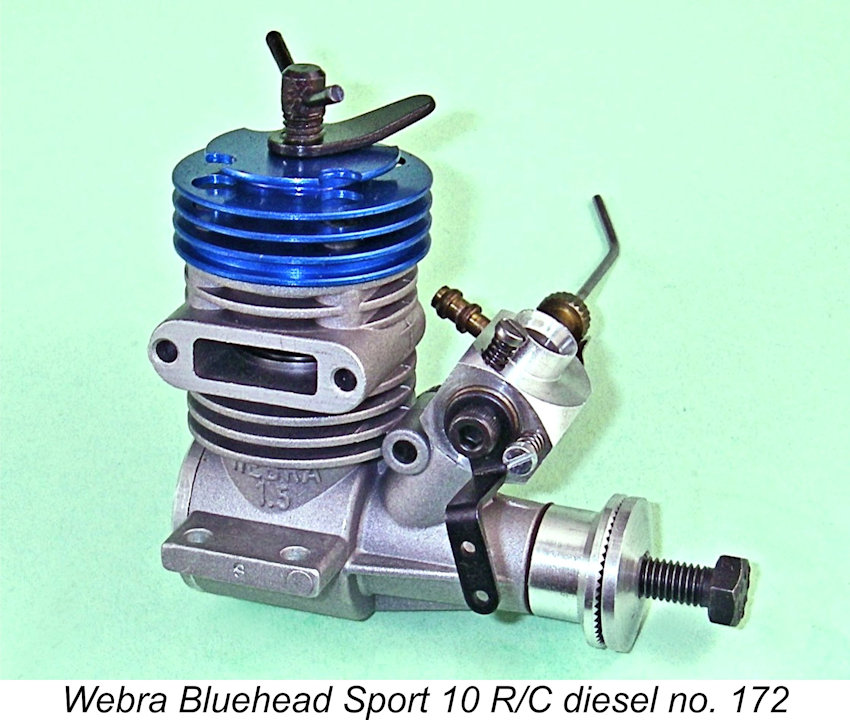

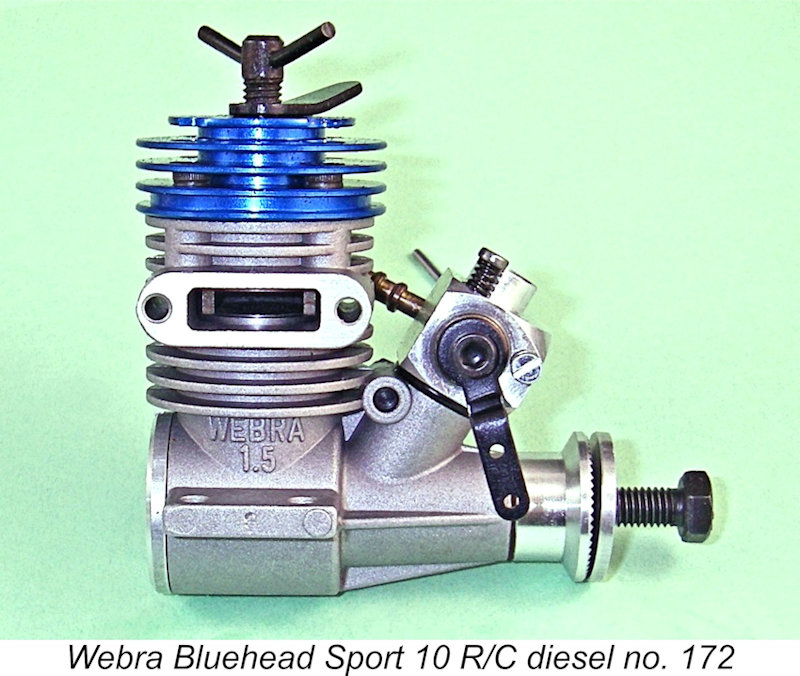

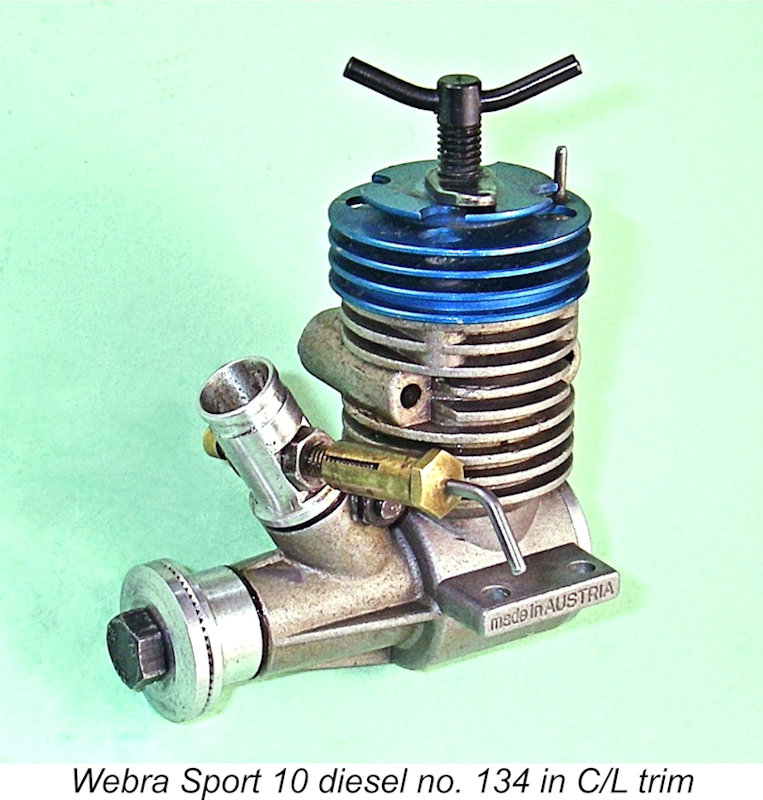

I learned that the Webra Sport 10 and Speed 28 Bluehead diesels had been imported into Canada by a company called Swift Electronics of Winnipeg, Manitoba. I have no information regarding whether or not they also imported the .40 diesel model – all I can say is that I never saw one. One of Vern’s fellow club members, a guy named Bryce Patterson, had been acting as Swift’s British Columbia agent, having both the 10 and the 28 in stock. I purchased examples of both models from Bryce. Both engines were R/C models equipped with throttles. Being a control line guy myself, I made simple straight-through venturis for the two engines, subsequently using them both in aerobatic C/L models. I found them to be excellent performers in every respect – in fact, I liked them so much that I purchased extra examples of both models from Bryce. This positive experience gave me both the motivation and the means to write up their story. Too bad that it's taken this long to get around to it! Since the two examples of this series with which I’ll be concerned here are very distinct designs having very divergent displacements, I’ll deal with the two of them in separate sections of this article. I’ll begin with the smaller Webra Sport 10 model. The Webra Sport 10 Diesel One matter needs to be settled at the outset of this discussion. This is the fact that the 1993 Webra Bluehead diesels were not purpose-built diesels designed as such from the ground up. Rather, they were very competently-executed diesel conversions of existing glow-plug models in the then-current Webra range. At this time, the engines on offer from Webra Enzesfeld were basically divided into two categories. The “Sport” series consisted of conventional plain bearing cross-flow loop scavenged designs having conventional iron-and-steel piston/cylinder sets, while the “Speed” series featured far more up-to-date twin ball race Schnuerle-ported ABC units.

The head was constructed to a design which was quite familiar by the time in question, being basically similar to the diesel conversion heads then available for a number of glow-plug units. It consisted of a turned outer casing with a cylindrical cavity machined into its underside. This cavity accommodated an aluminium alloy contra-piston which sealed to the outer casing using a non-metallic O-ring. Compression was varied using a conventional Y-shaped comp screw. The visible surfaces of the head were anodized blue.

On the downside, the use of a head of this configuration prevented the inclusion of a piston baffle. We might expect some attenuation of the incoming fuel mixture as a result of short-circuiting losses across the piston crown and out through the exhaust. A further issue arises from the fact that the O-ring contra piston provides essentially zero resistance to run-back during operation. For this reason, the comp screw was provided with a steel locking lever to retain the compression setting once established. Experience shows that this is a very necessary feature. The rest of the engine followed conventional lines, hence requiring no detailed description for most readers. Bore and stroke are 13 mm and 12 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 1.59 cc (0.097 cuin.). The engine as supplied with R/C throttle weighed in at 110 gm (3.88 ounces).

Looking at this matter with an engineer’s eye (my former life!), it’s pretty easy to see how this engine might be susceptible to such failures. The crankpin diameter is only 3.5 mm – pretty skimpy for a diesel of this displacement. This is clearly a reflection of the previously-mentioned fact that we’re dealing with a simple bolt-on head conversion of an engine which was originally designed as a glow-plug unit. If the engine had been designed from the outset as a diesel, a more substantial crankpin would undoubtedly have been used. In all likelihood, the diameter of the internal gas passage would also have been decreased somewhat to create an increase in crankshaft wall thickness. Even so, there may have been contributing factors surrounding these failures. For one thing, many of the engines appear to have been assembled with extremely tight piston/cylinder fits – the dreaded “Continental Squeak” of legend in all its ugliness. Both of my examples suffered from this issue, which greatly increases levels of stress on the wrist pin/rod/crankpin assembly until enough running time has been accumulated to ease the fit. This might draw heavily upon the fatigue life of the components, particularly if they’re marginally dimensioned to begin with.

Recognizing the above issues right away, I relieved the piston/cylinder fits in my two engines by lapping before even attempting to start them. I also refrained from even thinking about using an electric starter – easy to do, since I don’t even own such an accessory! Once properly fitted, the engines proved to be perfectly straightforward hand starters, so running them in was easily accomplished. Thereafter they both saw service in control line models, giving a very good account of themselves. The more experienced of the two engines now has some 4 hours of running time, much of it at relatively high speed in the air in addition to going through the present test (see below). Although I bought a spare crankshaft from Bryce “just in case”, I have yet to use it.

These engines all appear to have borne serial numbers stamped beneath the left-hand mounting lug. The highest serial number of my present acquaintance is 172. I’m sure that the numbers went considerably higher than this, but I doubt that they went notably high – these engines do not appear to have been made in large numbers. If any reader is able to extend the known serial number sequence, I’d love to hear from you! OK, so how does the Webra Sport 10 Bluehead diesel actually perform? Let’s find out! The Webra Sport 10 Bluehead Diesel on Test

The manufacturers recommended that this engine be used in its intended R/C form with 8x4 or 8x5 props. I had always used it in control line service with a 7x6 prop fitted – a roughly equivalent load to an 8x4. Using this prop, the engine performed very well in the air. The fuel mixture recommended by the manufacturers was 40% kerosene, 35% ether and 25% castor oil. This is basically my standard mixture for latter-day diesels, except that I add 1½% ignition improve to the overall mix. I used such a fuel for the present tests. Set up in the test stand, the engine felt really good when flicked over. I began with an APC 8x6 prop fitted and put on a couple of shake-down runs to blow out the cobwebs after a long layoff. I was quickly reminded that this engine cannot honestly be classified as an “easy” starter. It seems to be rather sensitive to the amount of fuel in the case – easily flooded, in fact. The trick was to choke to fill the fuel line, give it one choked flick to get a little fuel into the case, administer a small prime and then go for a start. If this procedure was followed, starting was usually quite prompt, although a few flicks were generally required.

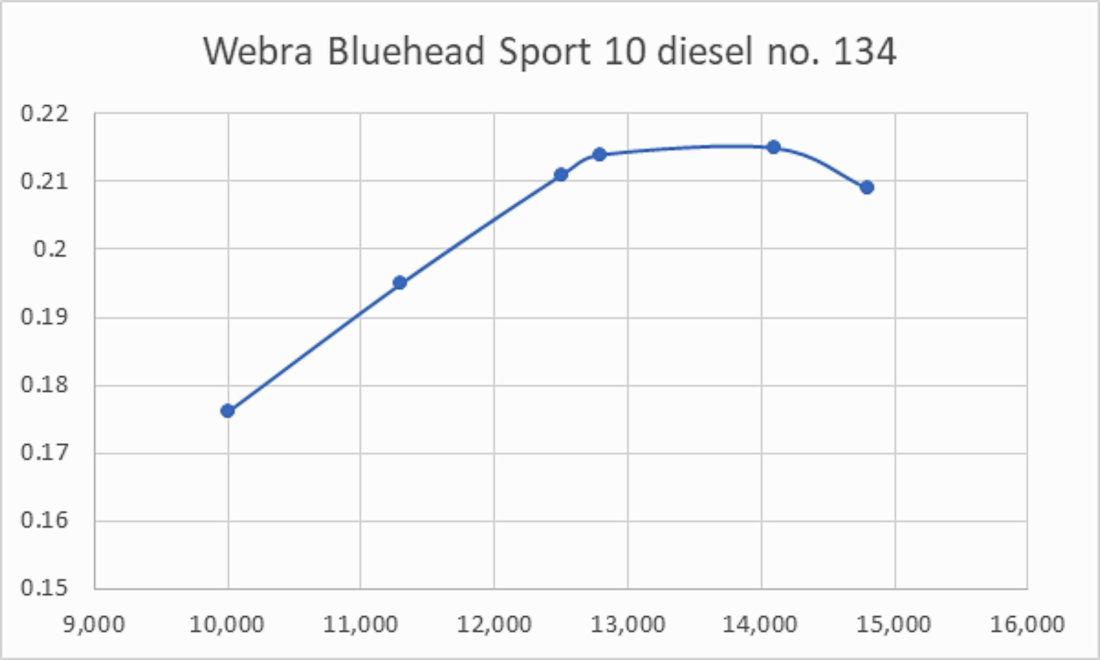

If the case did become flooded, it was necessary to back off compression and flick for quite a while to clear the excess fuel. This could take some time …….better not to go there! Still, even in the worst case the engine never failed to start, although it occasionally took a while! It’s simply one of those engines that takes a bit of “knowing”. My notes from years past confirm that the issue of crankcase flooding was far less pronounced with the engine mounted in sidewinder mode, as it was in my control line models. In that mode, gravity tends to cause excess fuel to run out of the exhaust rather than down the bypass. I actually found the engine to be considerably easier to start in that orientation. Once running, things become far more satisfactory! The Sport 10 showed itself to be a superb runner, responding perfectly to the controls and never missing a beat. Vibration levels were relatively modest – I couldn’t honestly fault the engine in that respect. The various test props seemed to be spun with authority, an impression which was confirmed by the prop/RPM figures obtained, as follows.

These are excellent figures for a basically conventional “classic” iron and steel plain bearing diesel of this displacement. I clearly missed the peak, but the shape of the curve implies a peak output of somewhere in the region of 0.218 BHP @ 13,700 RPM with a relatively flat peak - output exceeded 0.210 BHP at all speeds between 12,400 RPM and 14,700 RPM. The manufacturer’s prop recommendations appear to be entirely appropriate. The 7x6 that I used for control-line applications probably allowed the engine to over-speed a little in the air, but not by much. I didn’t try the engine with an R/C throttle as supplied (I’m a control line guy!), but I very much doubt that it would have performed at this level with a throttle fitted. The few guys of my acquaintance who did use a throttled example told me that it throttled surprisingly well for a diesel, especially when equipped with the accessory muffler and fitted with an 8-inch diameter prop. That’s about all that I can say on this subject, since I never had an opportunity to see one of these engines actually being used in R/C service. The Webra Speed 28 Bluehead Diesel

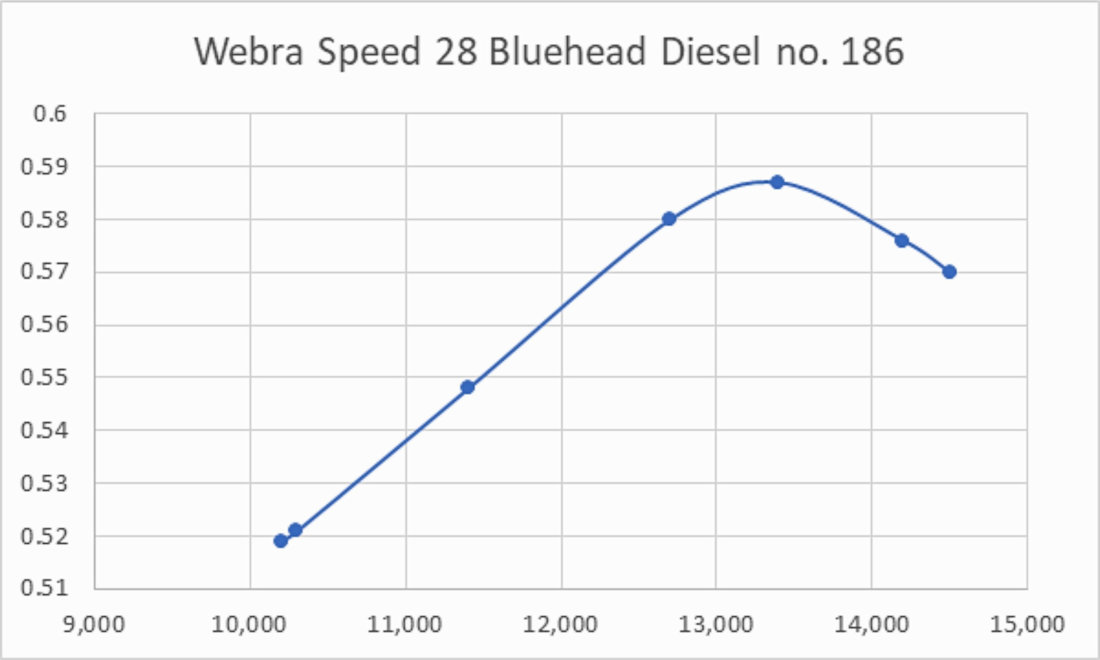

The Speed 28 is a thoroughly up-to-date twin ball-race FRV Schnuerle-ported unit of basically conventional design which is equipped with a quite sophisticated R/C throttle. It features an ABC piston/cylinder combination using a plain un-ringed aluminium alloy piston operating in a chrome-plated brass liner. Fit and finish are both superb, with outstanding compression. Bore and stroke dimensions are 18.5 mm and 17 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 4.57 cc (0.279 cuin.). The engine turns the scales at 255 gm (9.0 ounces) complete with R/C throttle.

Like the smaller Sport 10 model, the Speed 28 diesels carried serial numbers. The highest such number of my present acquaintance is illustrated engine number 225. No doubt the sequence went somewhat higher than this, but once again the number manufactured doesn’t appear to have been large. If any reader is able to extend the serial number sequence, please get in touch! Having commented a little on the engine’s structural attributes, it’s time to answer the question – how does it perform? Let’s head for the test bench to find out! The Webra Bluehead Speed 28 Diesel on Test

The props recommended by the manufacturer for this engine were 10x6 and 10x7 airscrews. For control line flying, I had always found a 10x6 to be a very dependable load for the motor, giving an excellent airborne performance. The fuel mixture recommended by the manufacturers was the same as that suggested for the smaller model - 40% kerosene, 35% ether and 25% castor oil. I used such a fuel for the present tests, with the addition of 1½% ignition improver.

The technique was to give the engine a couple of choked flicks, administer a small prime and then get flicking! It generally took a few flicks to get the fuel mixture to the point where the engine was happy, after which it just started right up with no warning at all in the way of any preliminary pops or firing strokes. Once running, things went very well indeed. Control function was exceptional – the engine was very responsive to both controls without being in the least bit critical. The optimum setting for a given prop was very easy to establish. Once set, running was outstandingly smooth and completely mis-free, with no tendency to sag as things became hot. Despite its relatively high-tech specification, the Webra is not a particularly high-speed engine. This might be deduced from the manufacturer’s airscrew recommendations, which the test results bear out completely. The following data were measured on test.

As can be seen, the Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel peaked in the vicinity of 13,400 RPM, at which speed it was developing around 0.587 BHP. This is actually a very useable sports performance for a 4.58 cc diesel weighing only 8 ounces. The manufacturer’s airscrew recommendations appear to be completely appropriate, as was my former use of a 10x6 prop in control line service. Once again, I didn’t try the engine with an R/C throttle as supplied (as I said, I’m a control line guy!), but I very much doubt that it would have quite matched this level of performance with a throttle fitted. The few guys of my personal acquaintance who did use a throttled example told me that it throttled surprisingly well for a diesel, especially when fitted with the accessory muffler. Back in the day, I actually witnessed Vern Kienas’s R/C example being flown in a model, and it appeared to perform very well in that application. Summary and Conclusion

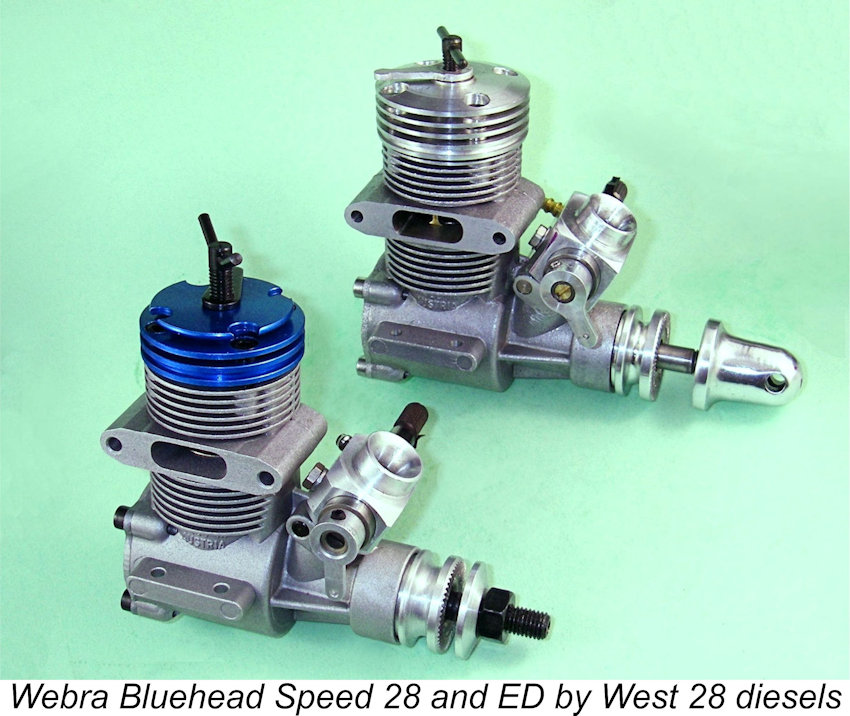

This is a pity, because the Webra Bluehead diesels were actually very good engines which would have given full satisfaction to any individual who preferred to use diesels for his power modelling fun. The Speed 28 in particular was an outstanding engine, creating an expectation that the .40 variant would have been just as good. Finding an example of one of these units might be somewhat challenging today – they seem to show up rather infrequently. However, in the case of the two larger models there was still a latter-day alternative as of the time of writing in 2024. These were the "ED by West" diesels designed by Alan Greenfield of Weston UK. Alan was the chief designer at the E.D. company during the early 1970's, subsequently acquiring the rights to the E.D. name and designs.

After Webra ceased model engine production, Alan acquired the crankcase dies and tooling from Webra and continued production of the West glow-plug motors using castings produced in Hungary from the original Webra dies, everything else being made in the UK apart from some CNC machining which was done by a friend of Alan's in Italy. The engines were assembled and individually tested by Weston in the UK. When the decision was taken to develop a range of diesels based upon the West designs, these units were designated by the "ED by West" name to distinguish them from their glow-plug counterparts while also paying homage to their diesel heritage. As of 2024, the ED by West diesels were offered in displacements of .25, .28, .32, .36 and .52 cuin. The ED by West .28 diesel appears at first sight to be pretty much a reproduction of the Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel. It lacks the blue head of course, but in most other respects seems to be a more or less identical powerplant to its Webra predecessor. However, there are some observable differences in the cylinder porting, which appears to be more aggressively developed. In addition, the carburettor throat area is considerably larger. It seems likely that there are other changes which are not visible externally. Based on these observations, I would expect the ED by Anyone wanting the experience of running or even flying one of these fine motors would be well served through the acquisition of one of Alan’s excellent units. They are available in both R/C and control line renditions. In a recent telephone conversation with Alan, I learned that they are not available from stock but are assembled individually from components on hand in prompt response to specific orders. Prior to my unfortunate then-recent encounter with the medical profession, about which I informed my readers elsewhere, I had ordered a .28 diesel of my own, which arrived promptly during my initial hospital stay. It met my expectations in every way, although I hadn't yet had a chance to give it a test at the time of writing. Webra did us diesel die-hards a great service by reminding us that the compression ignition principle was completely amenable to being translated seamlessly into the “modern” Schnuerle/ABC era with excellent results. It’s too bad that their efforts weren’t more widely appreciated. They certainly went out on a high note as far as diesel production was concerned! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2024

|

||

| |

I can think of a few model engines of outstanding quality which somehow never caught on, subsequently becoming almost forgotten. High on my personal list of such undeservedly-forgotten engines are the Webra “Blaukopf” (Bluehead) diesels which were produced in modest numbers at Webra’s Austrian plant at Enzesfeld, about 35 km south of Vienna, beginning in 1993. These engines were offered in .10, .28 and .40 cuin. displacements. They are particularly significant in that they were the very last diesels to proudly bear the Webra name.

I can think of a few model engines of outstanding quality which somehow never caught on, subsequently becoming almost forgotten. High on my personal list of such undeservedly-forgotten engines are the Webra “Blaukopf” (Bluehead) diesels which were produced in modest numbers at Webra’s Austrian plant at Enzesfeld, about 35 km south of Vienna, beginning in 1993. These engines were offered in .10, .28 and .40 cuin. displacements. They are particularly significant in that they were the very last diesels to proudly bear the Webra name.  Accordingly, I may as well get on with it! As usual, I’ll begin by setting out the background to the production of these engines. The Blueheads’ Austrian origins while still bearing the name of an iconic German brand certainly requires an explanation! The need to fulfill this requirement provides a perfect opportunity to present a summary of the surprisingly convoluted history of the Webra enterprise. It’s a story that is well worth preserving!

Accordingly, I may as well get on with it! As usual, I’ll begin by setting out the background to the production of these engines. The Blueheads’ Austrian origins while still bearing the name of an iconic German brand certainly requires an explanation! The need to fulfill this requirement provides a perfect opportunity to present a summary of the surprisingly convoluted history of the Webra enterprise. It’s a story that is well worth preserving! A number of new German model engine manufacturers soon emerged regardless, although at the outset they were small-scale operations which were limited to serving only the German domestic market as well as the odd member of the occupying forces. Their early products escaped notice elsewhere, due in significant part to the ongoing restrictions against the participation of German model fliers in international competition.

A number of new German model engine manufacturers soon emerged regardless, although at the outset they were small-scale operations which were limited to serving only the German domestic market as well as the odd member of the occupying forces. Their early products escaped notice elsewhere, due in significant part to the ongoing restrictions against the participation of German model fliers in international competition. Despite the almost insurmountable difficulties caused by the

Despite the almost insurmountable difficulties caused by the  At the beginning of 1951, the Englishman Eric Tom Spivey joined Weichler in his marketing venture. Spivey had good business connections with his home country, from which much of the material marketed in Germany by Weichler originated. Naturally, Spivey’s influence worked both ways. His involvement marked the first step towards the marketing of the Webra 2.46 beyond the borders of Germany. Arthur Mullett of Brighton in Sussex soon became the British distributor for the Webra engines.

At the beginning of 1951, the Englishman Eric Tom Spivey joined Weichler in his marketing venture. Spivey had good business connections with his home country, from which much of the material marketed in Germany by Weichler originated. Naturally, Spivey’s influence worked both ways. His involvement marked the first step towards the marketing of the Webra 2.46 beyond the borders of Germany. Arthur Mullett of Brighton in Sussex soon became the British distributor for the Webra engines.  In that context, Bragenitz added his small diesel production to the new company’s portfolio. This activity would have a broader, safer foundation in the new company than before. For the development work that he had completed up to that point, Bragenitz received a contractually-agreed sum of money as compensation, which was paid out to him in royalty installments of DM 0.50 for each engine sold.

In that context, Bragenitz added his small diesel production to the new company’s portfolio. This activity would have a broader, safer foundation in the new company than before. For the development work that he had completed up to that point, Bragenitz received a contractually-agreed sum of money as compensation, which was paid out to him in royalty installments of DM 0.50 for each engine sold. “Fein und Modelltechnik Bragenitz & Co”. The headquarters were still in Berlin-Schöneberg at Geneststrasse 5. Shortly afterwards, the company management change yet again - Eberth's brother-in-law, Rudolf Brauer, terminated his share in the company on May 7, 1953 and left the company after only a two-year tenure.

“Fein und Modelltechnik Bragenitz & Co”. The headquarters were still in Berlin-Schöneberg at Geneststrasse 5. Shortly afterwards, the company management change yet again - Eberth's brother-in-law, Rudolf Brauer, terminated his share in the company on May 7, 1953 and left the company after only a two-year tenure.  The following year of 1954 saw the introduction of the 0.78 cc

The following year of 1954 saw the introduction of the 0.78 cc  In the first half of 1956, the entire “Fein und Modelltechnik” company, both administration and production, was relocated to Bessemerstrasse 76a in Berlin-Tempelhof. The engine range was being expanded, with an emerging emphasis on new glow-plug models - the company had recognized the constantly growing number of glow-plug enthusiasts. Their interest in such powerplants was spurred by an agreement with the major Schuco toy company,

In the first half of 1956, the entire “Fein und Modelltechnik” company, both administration and production, was relocated to Bessemerstrasse 76a in Berlin-Tempelhof. The engine range was being expanded, with an emerging emphasis on new glow-plug models - the company had recognized the constantly growing number of glow-plug enthusiasts. Their interest in such powerplants was spurred by an agreement with the major Schuco toy company,  which was then just entering the model aircraft market with their Hegi-10 and Hegi-20 ARF control line trainers. Webra’s newly-developed

which was then just entering the model aircraft market with their Hegi-10 and Hegi-20 ARF control line trainers. Webra’s newly-developed

1961 saw the introduction of a glow-plug version of the Bully 2 called the Bully 2 Glo. This was very definitely aimed at the ever-growing R/C market. The 5 cc Big Ben glow-plug model was also added to the range during the year as the company's focus on glow-plug ignition continued to expand. Also in 1961 the company's headquarters were relocated again to Berlin SO 36, Oranienstrasse 6. This represented the company's third location since its establishment.

1961 saw the introduction of a glow-plug version of the Bully 2 called the Bully 2 Glo. This was very definitely aimed at the ever-growing R/C market. The 5 cc Big Ben glow-plug model was also added to the range during the year as the company's focus on glow-plug ignition continued to expand. Also in 1961 the company's headquarters were relocated again to Berlin SO 36, Oranienstrasse 6. This represented the company's third location since its establishment.  The same year of 1962 saw another significant personnel change - Günther Bodemann left the Taifun engine manufacturer Hans Hörnlein at Vöhringen and returned to work at Fein und Modelltechnik in Berlin after a 4-year absence. Bodemann's influence soon became apparent. He quickly developed a new high-performance 2.5 cc diesel called the

The same year of 1962 saw another significant personnel change - Günther Bodemann left the Taifun engine manufacturer Hans Hörnlein at Vöhringen and returned to work at Fein und Modelltechnik in Berlin after a 4-year absence. Bodemann's influence soon became apparent. He quickly developed a new high-performance 2.5 cc diesel called the  During the early 1960’s, the company continued to expand its involvement with glow-plug motors, producing such models as the 5 cc Big Ben and the 3.5 cc Bully 2 Glo. These were followed by the

During the early 1960’s, the company continued to expand its involvement with glow-plug motors, producing such models as the 5 cc Big Ben and the 3.5 cc Bully 2 Glo. These were followed by the  The main business of the long-established Hirtenberg company was the production of munitions - model engines only entered the picture in the 1960’s, with munitions production continuing to be the company’s primary focus. In the mid-1960’s, the Hirtenberg company established a model engine production facility under the management of

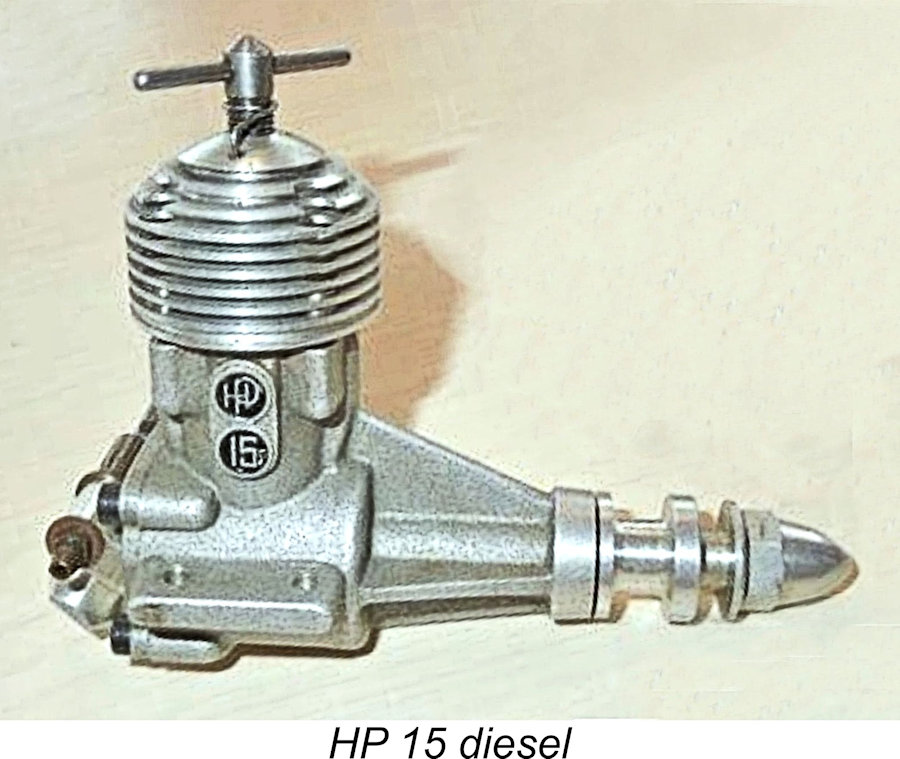

The main business of the long-established Hirtenberg company was the production of munitions - model engines only entered the picture in the 1960’s, with munitions production continuing to be the company’s primary focus. In the mid-1960’s, the Hirtenberg company established a model engine production facility under the management of  Kaineder quickly initiated series production, getting things started with the Webra 3.5 cc Glo-Star, which was fully adopted from Berlin without modification, being the first unit coming off the production line before the Enzesfeld operation switched exclusively to in-house designs. The second-generation Webra and HP engines were quickly developed by Kaineder and Billes. These included the successful glow-plug units of the HP 40 and HP 60 “Silverline” generation. These were more powerful engines than their Webra “Blackhead” predecessors thanks to their use of Schnuerle porting. They were developed with particular emphasis on the increasingly-dominant R/C market. Peter Billes was chiefly responsible for these designs.

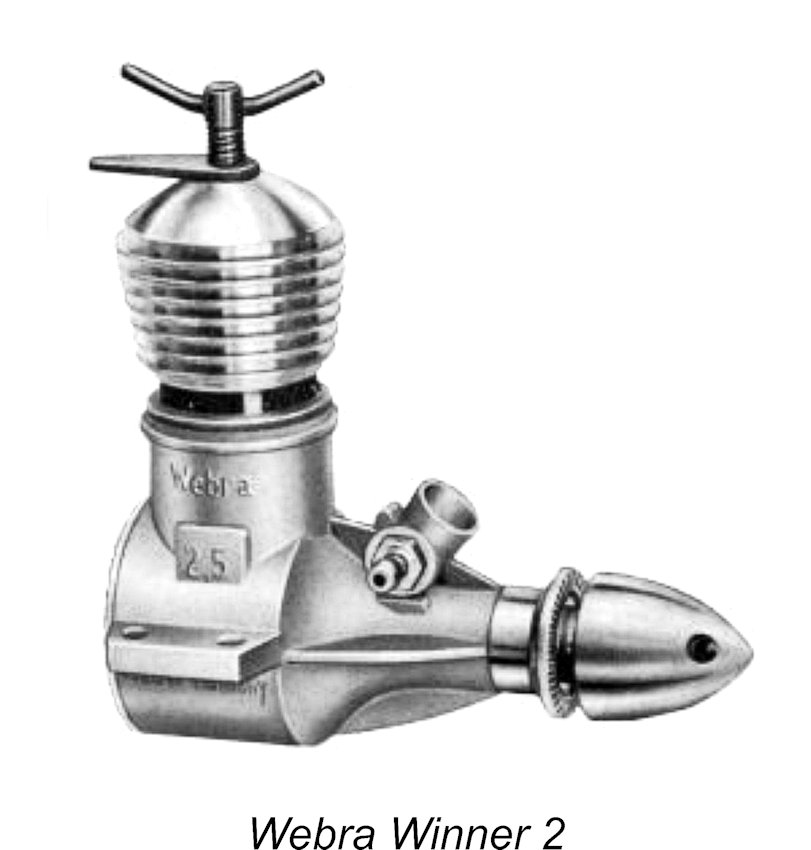

Kaineder quickly initiated series production, getting things started with the Webra 3.5 cc Glo-Star, which was fully adopted from Berlin without modification, being the first unit coming off the production line before the Enzesfeld operation switched exclusively to in-house designs. The second-generation Webra and HP engines were quickly developed by Kaineder and Billes. These included the successful glow-plug units of the HP 40 and HP 60 “Silverline” generation. These were more powerful engines than their Webra “Blackhead” predecessors thanks to their use of Schnuerle porting. They were developed with particular emphasis on the increasingly-dominant R/C market. Peter Billes was chiefly responsible for these designs. The demand for diesel engines was steadily shrinking by this time. Webra diesels were now only produced in small numbers, with their manufacture remaining in Berlin. Of the previously extensive range of diesels that satisfied all needs, only the 1.5 cc Record 2 and the 2.5 cc Winner 2 were still being manufactured as remaining demand dictated. The end of the Webra diesel era was approaching, with the emphasis shifting decisively to the production of glow-plug models. Fein und Modelltechnik manufactured their last diesel engines in 1975.

The demand for diesel engines was steadily shrinking by this time. Webra diesels were now only produced in small numbers, with their manufacture remaining in Berlin. Of the previously extensive range of diesels that satisfied all needs, only the 1.5 cc Record 2 and the 2.5 cc Winner 2 were still being manufactured as remaining demand dictated. The end of the Webra diesel era was approaching, with the emphasis shifting decisively to the production of glow-plug models. Fein und Modelltechnik manufactured their last diesel engines in 1975.

Hirtenberger Patronen und Zündhütchen AG carried on with the HP range for a while, but model engines formed an increasingly minor component of their business portfolio. They eventually ceased model engine production altogether in 1986, returning to their munitions roots. They subsequently divested themselves of this business line too in 2019, focusing today on car safety equipment and agricultural machinery. The rights to the HP model engine range were acquired by

Hirtenberger Patronen und Zündhütchen AG carried on with the HP range for a while, but model engines formed an increasingly minor component of their business portfolio. They eventually ceased model engine production altogether in 1986, returning to their munitions roots. They subsequently divested themselves of this business line too in 2019, focusing today on car safety equipment and agricultural machinery. The rights to the HP model engine range were acquired by  Model helicopter enthusiasts also benefited from the development work undertaken by Webra Enzesfeld. The company created engines that were especially adapted to the operation of rotary wing aircraft, having higher power, improved efficiency, more effective cooling and, above all, reduced noise levels. These developments were the result of close cooperation with model helicopter manufacturers and proficient helicopter pilots like former World Champion Sepp Brennsteiner, seen at the right.

Model helicopter enthusiasts also benefited from the development work undertaken by Webra Enzesfeld. The company created engines that were especially adapted to the operation of rotary wing aircraft, having higher power, improved efficiency, more effective cooling and, above all, reduced noise levels. These developments were the result of close cooperation with model helicopter manufacturers and proficient helicopter pilots like former World Champion Sepp Brennsteiner, seen at the right.

The Webra Bluehead diesels (as they seem to have been colloquially known) were a very well-kept secret in Western Canada, where I was living as of the mid 1990’s. I never saw one in a Vancouver-area model shop. In fact, I only became aware of their existence in 1996 when I went over to Parksville on Vancouver Island to take part in an inter-club competition. At that event I encountered a fellow modeller named Vern Kienas who had been flying a Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel in an R/C model, finding it to be completely satisfactory. He recommended the engine to me very highly.

The Webra Bluehead diesels (as they seem to have been colloquially known) were a very well-kept secret in Western Canada, where I was living as of the mid 1990’s. I never saw one in a Vancouver-area model shop. In fact, I only became aware of their existence in 1996 when I went over to Parksville on Vancouver Island to take part in an inter-club competition. At that event I encountered a fellow modeller named Vern Kienas who had been flying a Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel in an R/C model, finding it to be completely satisfactory. He recommended the engine to me very highly. The Webra Bluehead Sport 10 diesel with which we are concerned here fell into the former category. It was a basically conventional old-tech design, clearly being developed with the objective of minimizing production costs. The sole departure from the glow-plug version was the use of a diesel conversion head in place of the glow-plug equivalent.

The Webra Bluehead Sport 10 diesel with which we are concerned here fell into the former category. It was a basically conventional old-tech design, clearly being developed with the objective of minimizing production costs. The sole departure from the glow-plug version was the use of a diesel conversion head in place of the glow-plug equivalent. Since the diameter of the contra-piston was considerably less than that of the bore, the assembled head presented a central combustion cavity surrounded by a fixed squish band to the flat-topped piston. This might be expected to constitute a relatively efficient combustion chamber.

Since the diameter of the contra-piston was considerably less than that of the bore, the assembled head presented a central combustion cavity surrounded by a fixed squish band to the flat-topped piston. This might be expected to constitute a relatively efficient combustion chamber.

Another issue which is perhaps even more likely is the fact that by Bryce’s admission, the owners of the affected engines were electric starter users. I don’t know how many times I have to say it, but in the long term the use of electric starters on diesels is a death sentence. In their instructions, Webra went to great pains to discourage such a practice, actually mentioning it twice in very strong terms in two separate locations. You may get away with it for quite a while, but eventually you’ll apply the starter with too much fuel in the head or case, forcing the engine past a hydraulic lock. Under that condition, something has to break! In the present case, the somewhat undersized crankpin is the weak link in the power train, so it’s that component that fails.

Another issue which is perhaps even more likely is the fact that by Bryce’s admission, the owners of the affected engines were electric starter users. I don’t know how many times I have to say it, but in the long term the use of electric starters on diesels is a death sentence. In their instructions, Webra went to great pains to discourage such a practice, actually mentioning it twice in very strong terms in two separate locations. You may get away with it for quite a while, but eventually you’ll apply the starter with too much fuel in the head or case, forcing the engine past a hydraulic lock. Under that condition, something has to break! In the present case, the somewhat undersized crankpin is the weak link in the power train, so it’s that component that fails. My conclusion is that the Webra Sport 10 Bluehead diesel undoubtedly suffered somewhat from being a simple diesel conversion of a glow-plug model as opposed to a purpose-built diesel designed as such from the ground up. The strength of certain components appears to have been a bit on the marginal side for diesel operation – I reckon that the conrod could also do with some beefing up. However, if prepared properly and handled intelligently, there appears to have been no reason why this engine shouldn’t have given good service to its owners. Mine have certainly served me well so far!

My conclusion is that the Webra Sport 10 Bluehead diesel undoubtedly suffered somewhat from being a simple diesel conversion of a glow-plug model as opposed to a purpose-built diesel designed as such from the ground up. The strength of certain components appears to have been a bit on the marginal side for diesel operation – I reckon that the conrod could also do with some beefing up. However, if prepared properly and handled intelligently, there appears to have been no reason why this engine shouldn’t have given good service to its owners. Mine have certainly served me well so far!  For this test, I elected to use my most “experienced” example, engine no. 134, in control line mode. The engine is fitted with a P.A.W.-style intake venturi complete with P.A.W. needle valve assembly. The stop pin visible in the head was added to prevent the compression locking lever from rotating out of reach during starting in a model. In this form, the unit had survived over three hours of hard running in the air following its 45-minute break-in. It was about as well freed-up as one could wish!

For this test, I elected to use my most “experienced” example, engine no. 134, in control line mode. The engine is fitted with a P.A.W.-style intake venturi complete with P.A.W. needle valve assembly. The stop pin visible in the head was added to prevent the compression locking lever from rotating out of reach during starting in a model. In this form, the unit had survived over three hours of hard running in the air following its 45-minute break-in. It was about as well freed-up as one could wish! However, getting even just a little too much fuel into the case created difficulties – the first firing stroke caused excess fuel to be thrown up from the case into the cylinder, drowning the engine and causing it to die immediately. This condition generally arose as a result of over-enthusiastic priming. The fact that there’s no baffle encourages a prime to shoot straight across the piston crown and down the bypass into the case. For that reason, a “dry” prime (exhaust port closed) generally seemed to produce better results.

However, getting even just a little too much fuel into the case created difficulties – the first firing stroke caused excess fuel to be thrown up from the case into the cylinder, drowning the engine and causing it to die immediately. This condition generally arose as a result of over-enthusiastic priming. The fact that there’s no baffle encourages a prime to shoot straight across the piston crown and down the bypass into the case. For that reason, a “dry” prime (exhaust port closed) generally seemed to produce better results.

This engine is a complete contrast to the Sport 10 reviewed earlier. Like the smaller engine, it is a straightforward diesel conversion of a unit originally designed as a glow-plug motor. However, the design of the engine upon which it is based is completely different.

This engine is a complete contrast to the Sport 10 reviewed earlier. Like the smaller engine, it is a straightforward diesel conversion of a unit originally designed as a glow-plug motor. However, the design of the engine upon which it is based is completely different.

In all other respects, the engine is a completely conventional sports unit of its 1990’s era, warranting no detailed description here. Both Bryce Patterson and Vern Kienas had been using their examples in R/C service for some time, as had several others on Vancouver Island, while my own engine performed very well indeed in a control line model, giving no trouble over several hours of airborne operation following its break-in. It would appear that the working components of the Speed 28 were well up to the challenge of being operated on compression ignition.

In all other respects, the engine is a completely conventional sports unit of its 1990’s era, warranting no detailed description here. Both Bryce Patterson and Vern Kienas had been using their examples in R/C service for some time, as had several others on Vancouver Island, while my own engine performed very well indeed in a control line model, giving no trouble over several hours of airborne operation following its break-in. It would appear that the working components of the Speed 28 were well up to the challenge of being operated on compression ignition. The example of the Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel that I chose to test was my fully run-in example that had seen several hours of airborne operation in a control-line model. This unit is fitted with a plain unthrottled intake venturi of my own making. I used a Super Tigre needle valve assembly with this venturi, since I have always found these assemblies to offer the best combination of control and stability. The engine is otherwise in completely stock unmodified condition. As tested, the U/C variant of the Webra weighed in at 227 gm (8 ounces). It bears the serial number 186.

The example of the Webra Speed 28 Bluehead diesel that I chose to test was my fully run-in example that had seen several hours of airborne operation in a control-line model. This unit is fitted with a plain unthrottled intake venturi of my own making. I used a Super Tigre needle valve assembly with this venturi, since I have always found these assemblies to offer the best combination of control and stability. The engine is otherwise in completely stock unmodified condition. As tested, the U/C variant of the Webra weighed in at 227 gm (8 ounces). It bears the serial number 186. Set up in the stand, the Speed 28 felt superb, all ready to go. Given its previous use, there was clearly no requirement to put on any break-in runs, so I just got straight down to it. The initial start proved to be a bit of a challenge, probably due to the presence of storage oil in the engine. Subsequent starts were considerably less challenging, although the engine did exhibit what I often think of as a “goldilocks” response to the amount of fuel in the cylinder – that amount had to be “just right” for a start to be achieved.

Set up in the stand, the Speed 28 felt superb, all ready to go. Given its previous use, there was clearly no requirement to put on any break-in runs, so I just got straight down to it. The initial start proved to be a bit of a challenge, probably due to the presence of storage oil in the engine. Subsequent starts were considerably less challenging, although the engine did exhibit what I often think of as a “goldilocks” response to the amount of fuel in the cylinder – that amount had to be “just right” for a start to be achieved.

The Webra Bluehead diesels don’t appear to have been particularly strong sellers. They were evidently produced in relatively small numbers, hence being somewhat rarely encountered these days, over 30 years on. Their fate was probably a reflection of the fact that model diesel enthusiasts were in a growing minority by the time of their appearance in 1993, particularly in an R/C context.

The Webra Bluehead diesels don’t appear to have been particularly strong sellers. They were evidently produced in relatively small numbers, hence being somewhat rarely encountered these days, over 30 years on. Their fate was probably a reflection of the fact that model diesel enthusiasts were in a growing minority by the time of their appearance in 1993, particularly in an R/C context.