|

|

The Vltavan 5

The Vltavan 5 was the subject of an earlier article which may still be accessed on the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful “Model Engine News” (MEN) web site. The re-publication of this article on my own website was made necessary by the fact that my mate Ron unfortunately left us in 2014 without sharing the required access codes for his heavily encrypted site. This has resulted in that site becoming frozen, with no maintenance being possible. I was unwilling to risk the loss of this material as Ron’s unavoidably-neglected site deteriorates, hence its re-publication here. In my earlier article on the classic MVVS glow-plug models, I described the circumstances which led to the 1953 creation of a state-sponsored model development centre at Brno, Czechoslovakia. This facility was known as the Modelárského Výzkumného a Vývojového Strediska (Modelling Research & Development Centre), better recognized by its initials of MVVS. The creation of this Centre resulted from a belief on the part of the Czechoslovakian State authorities that there was international prestige to be gained through Communist success in the field of model aircraft competition at the World Championship level. Back then, aeromodelling was a far more mainstream hobby than it is today, attracting large numbers of enthusiasts of all ages and from all walks of life. Accordingly, international events were widely reported in the Western modelling media and were avidly read by many young and potentially impressionable people, adding to the perceived propaganda value of this concept.

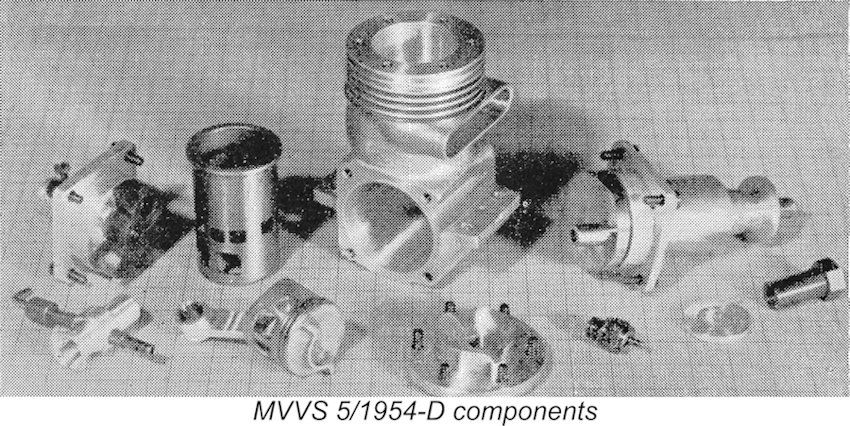

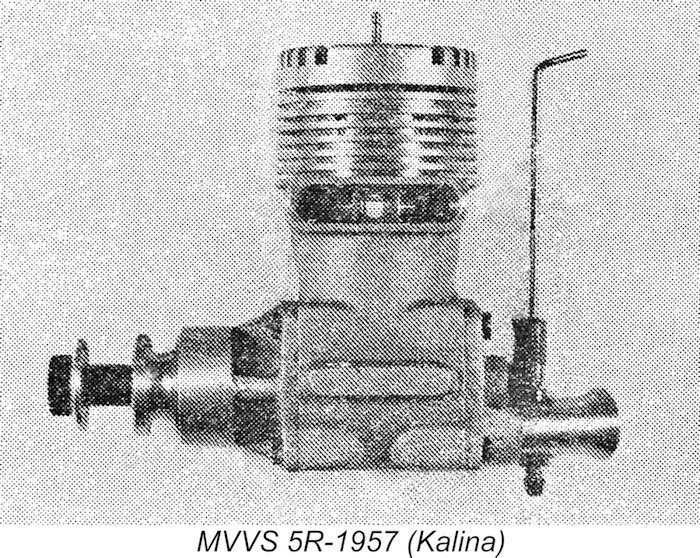

The resulting design was based very closely upon the then all-conquering Dooling 29 model with its "bulge bypass" transfer system. The MVVS version was known as the MVVS 5/1954-D. Like all MVVS engines during the first 5 years of the Centre's operation, this model was individually constructed to very high standards in extremely small numbers. Using this engine, Mir Zatocil achieved the first honours for MVVS in international competition when he won the 5 cc class at the International Competition for People's Democratic States held in 1954 at Moscow. This was not actually a true international event, since the entries were of course confined to those from the various Iron Curtain states of the day. Zatocil's winning speed of 200.03 km/hr (124.3 mph) placed him ahead of the Hungarian Impressive though this was in the context of that particular competition, Zatocil's winning speed still fell well short of the highest then-current international standards. As a result, the Czechs decided that they were not yet ready to take on the rest of the world, a decision which was fully justified by the results of the World Championship contest held at The Hague, Holland in August 1954. Zatocil's performance at Moscow would only have placed him equal 6th at that contest, well short of the winning speed of 221.9 km/hr (137.9 mph) set by the American Bob Lutker using a modified Dooling 29. Such a result was not at all what the Czechs had in mind!

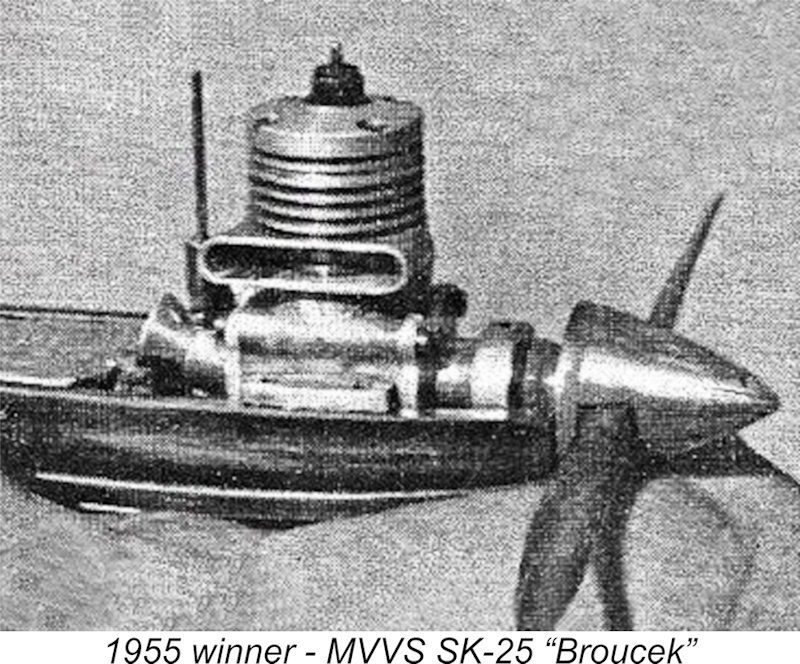

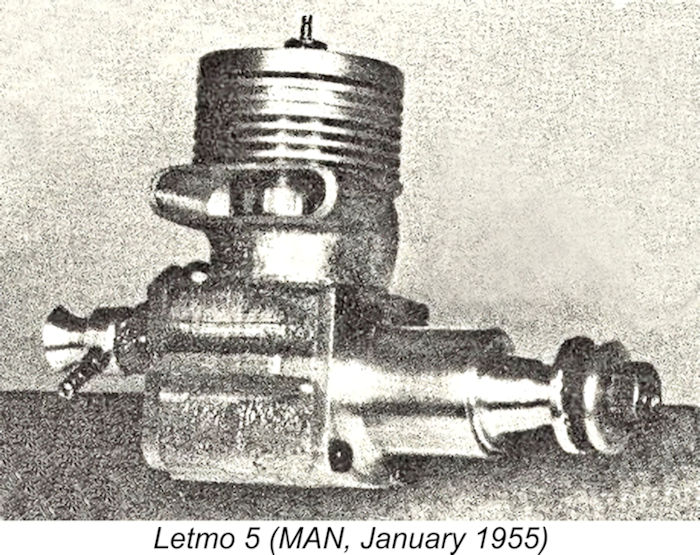

This situation made the MVVS 5/1954-D something of an orphan - no further development work was undertaken on this model for several years thereafter. However, it had shown itself to be a fine performer in the context of regional competition, if not necessarily at the world level. Not wishing to see his design team's efforts go to waste, MVVS Director Zdenek Husicka used his earlier connections with the Letmo range to arrange for Having taken the individual title at the 1955 control line speed World Championships, MVVS never looked back. However, their designs continued to be individually constructed in extremely small numbers for the exclusive use of Czech national team members. It would clearly have been impossible to produce equivalent engines commercially at anything like a reasonable price, and no attempt was made at this time to do so, at least at the MVVS facility. However, a need was perceived for the production of more affordable engines of similar design for the use of a larger spectrum of aspiring flyers in order for them to gain the experience necessary to challenge for positions on the Czech team.

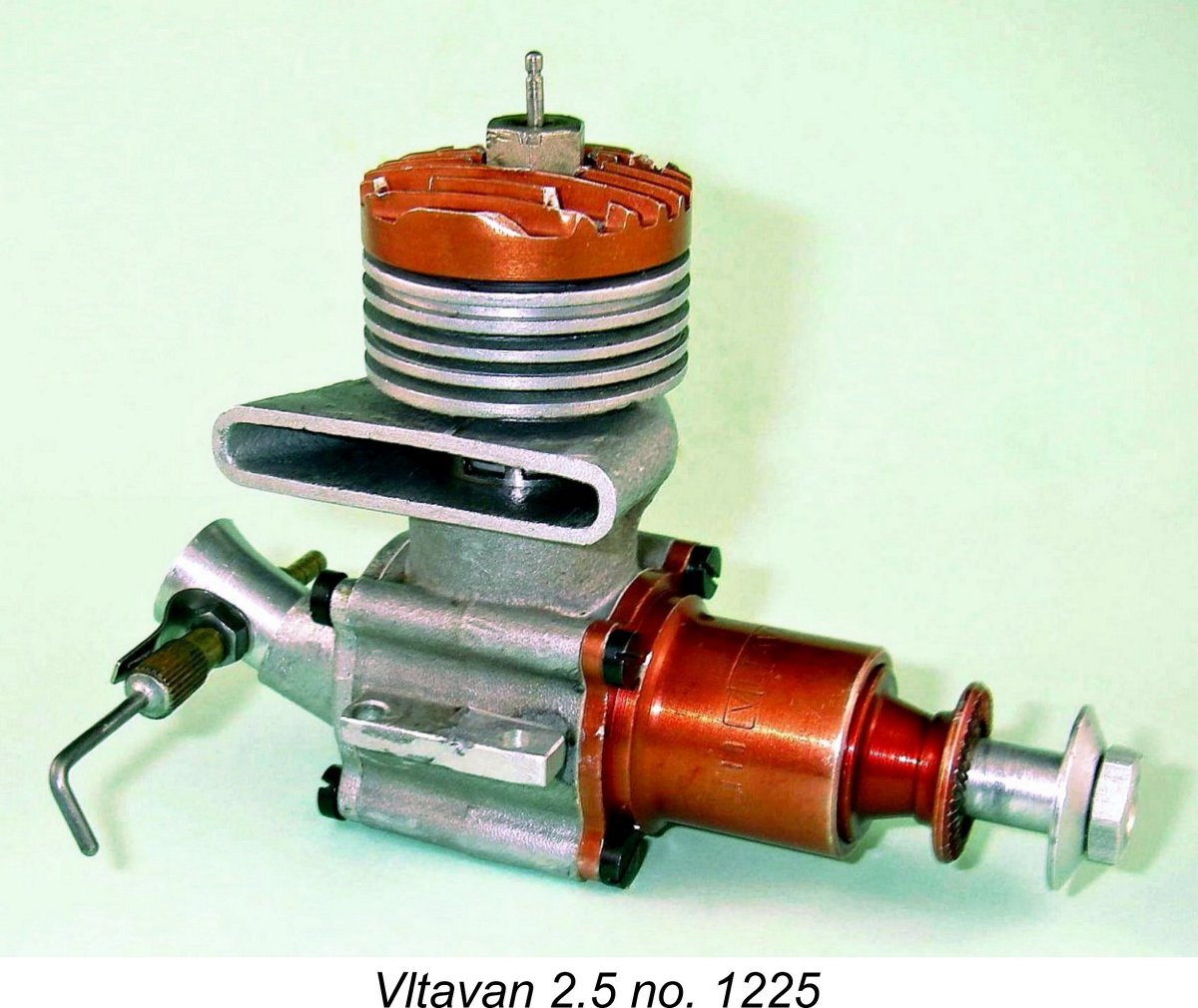

Series production of both the 2.5 cc and 5 cc Vltavan models seems to have commenced in early 1957. I’ve described the Vltavan 2.5 cc model in detail elsewhere. The Vltavan 5 cc model was in effect a clone of the former MVVS 5/1954-D unit. Consequently, it displayed a very definite Dooling 29 influence, although it did incorporate a number of original features presumably taken from its MVVS prototype.

Chinn praised the engine's starting and running characteristics, also including a number of positive comments about the engineering design. He was guardedly optimistic regarding the engine's further potential if properly set up. However, his overall conclusion was exactly the same as my own - this was a well-engineered design that was imperfectly executed in some respects.

That having been said, it's only fair to report that in his May 1954 test of the ETA 29 Mk. III, Chinn had reported a slightly higher peak output of 0.62 BHP @ 15,700 RPM. Even so, this didn't completely outclass the Vltavan by any means. Chinn mentioned that he had tried the 35% nitro mix for which the engine was reportedly designed, but experienced difficulty getting the Vltavan to run consistently on this brew. In retrospect, it appears that this was probably due to pre-ignition caused by a problem with the heat range of the plug used for the test (which was the Czech original). Had a plug of the correct heat range been fitted to allow the effective use of the intended fuel, it seems likely that the Vltavan might well have more closely approached the performance of the Carter Special and ETA 29.

The most immediately apparent of these is the fact that the exhaust stack is not swept back in the manner employed on the 2.5 cc model. Moreover, the stack is located on the left-hand side of the engine (looking forward in the direction of flight). Many examples encountered today have their stacks conventionally located on the right, but there is considerable evidence to the effect that this was not the orientation in which the engines were originally supplied. The MVVS "bulge bypass" series on which the Vltavan 5 was based certainly featured a left-hand orientation, an arrangement for which there were a number of persuasive arguments. I’ve reviewed these arguments in depth in my companion articles on the MVVS glow models, and will not repeat that discussion here.

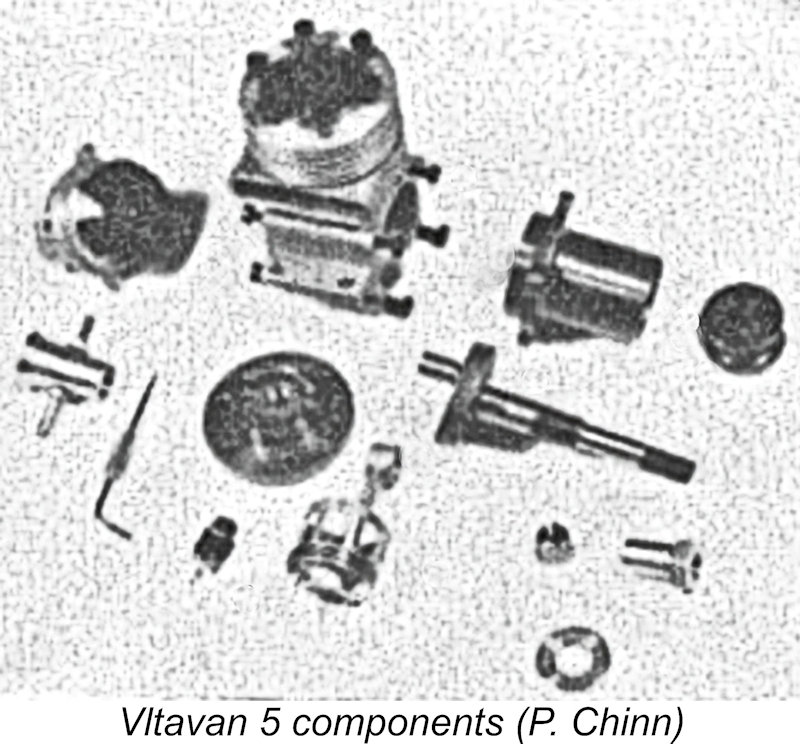

The other major difference is found in the transfer arrangements. The give-away is the familiar "bulge" bypass beloved of all Dooling fans. The 2.5 cc engine used a normal transfer passage which was open at the bottom but was supplemented by two large piston ports and matching cylinder ports. On the 5 cc model, there is no lower opening - the entire transfer takes place through three enormous rectangular ports in the piston skirt which register with similar openings in the cylinder liner at and near bottom dead center. These ports are even larger than those used in the Dooling 29, taking up almost the entire piston skirt on the transfer side. They feed a "bulge" bypass chamber which in turn feeds the cylinder transfer ports.

In most other respects, the engine mirrors the construction of the 2.5 cc model. The same high standard of casting and fitting is evident on the piston and rod assembly, and the reciprocating weight is once again extremely low. A notable feature of the piston is the rings, which are extremely thin for an engine of this size and are also very lightly tensioned radially. However, they seal very well indeed under gas pressure - better than those used on the 2.5 cc model. The cylinder head on the 5 cc model is plain rather than finned, but the combustion chamber is generally very similar to that of the smaller unit, as is the offset plug location. The example tested by Peter Chinn exhibited one extremely interesting feature which is absent on both of my own examples - the crankweb in his test unit featured a semi-circular counterbalance weight of lead which was keyed in place using holes drilled in the steel crankweb disc. Chinn reported that the degree of counterbalance was sufficient not only to balance all of the rotating mass but much of the reciprocating weight as well! This level of counterbalance is highly unusual, leading Chinn to speculate that the intent may have been to allow owners to fine-tune the balance factor by drilling out portions of lead as necessary.

A highly aggravating similarity between the two models is the absence of any attempt to true up the underside of the mounting lugs. In the case of the 5 cc model, the as-cast lugs actually bulge out in the centre, making a true mount impossible to achieve. As with the smaller engine, an owner wishing to obtain the best possible performance and avoid distortion issues would have to take action to true up the mounting surfaces. In the case of the 5 cc model, there is plenty of metal to allow for this. The illustrated example (engine no. 3736) appears to have received little or no use - it even retains its original Czech glow-plug which has a M6x0.75 installation thread. The present-day standard for glow-plugs is ¼-32, which in metric terms is 6.38 mm x 0.79 mm pitch, so don't expect a standard glow-plug to screw in! Of course, the hole can easily and successfully be tapped out to take a standard Western plug - with the correct ¼-32 tap mind you, not a glow plug and brute force! Alternatively, you can re-cut the thread of a standard glow-plug to the required metric standard. From a conservation standpoint, the latter approach is far preferable.

I have little doubt that a good example of the Vltavan could have been tweaked to Dooling standards of performance by an expert tuner. Remember, this is basically the same design with which Mir Zatocil beat Geza Egerváry's Dooling-powered model way back in 1954 ................. Overall, I would summarize the Vltavan engines as being classic examples of first-class engineering that were somewhat less than perfectly executed. The basic designs are top-notch by the standards of their time, as you would expect from the MVVS design crew - it's the details of the execution of those designs by the manufacturers of the Vltavan engines that let them down here and there. That said, there's no doubt that they ran quite well enough to fulfill their intended purpose of providing opportunities for aspiring Czech modellers to gain invaluable competition experience.

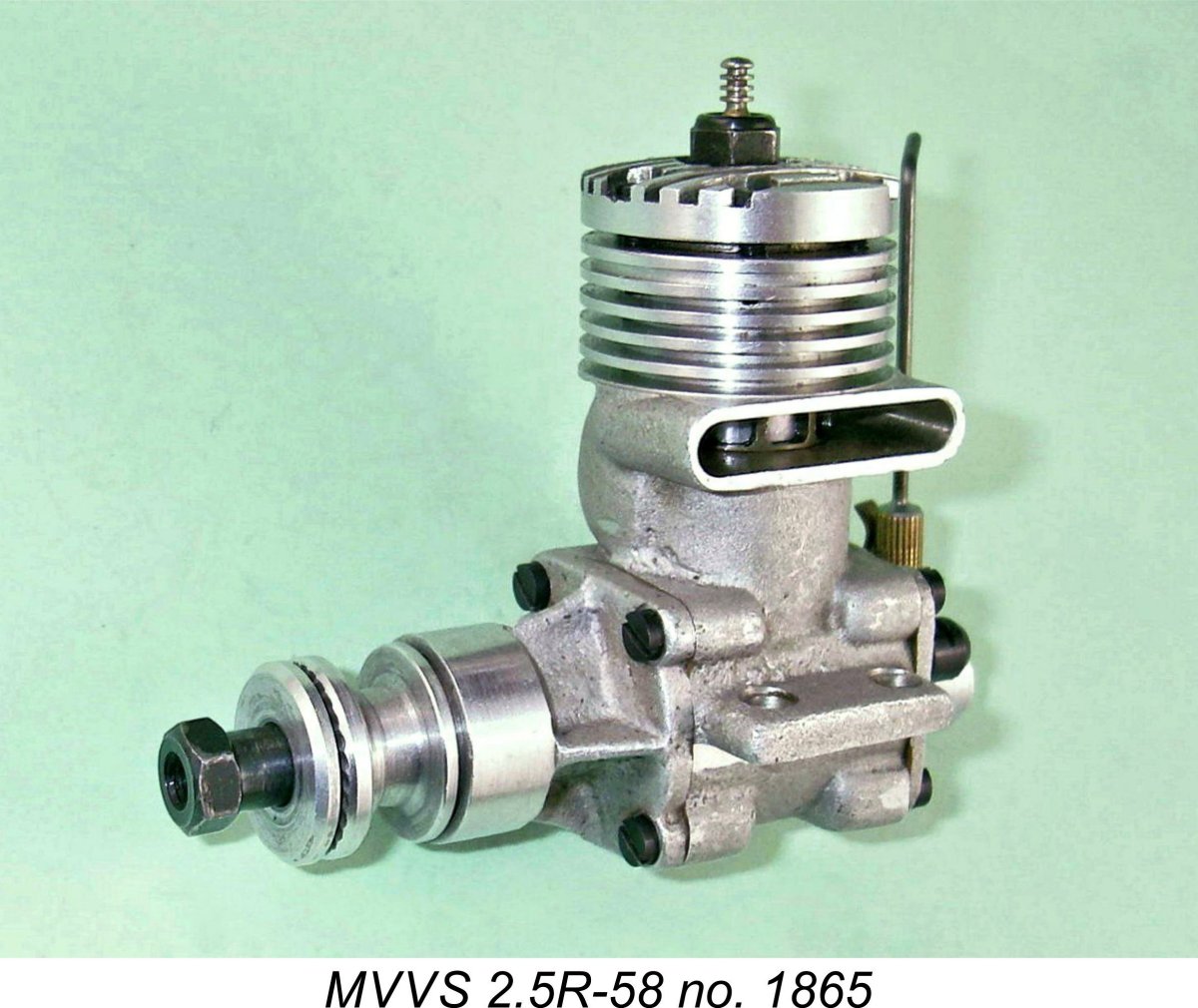

By 1959 this policy had taken full effect, with the very well-made and powerful MVVS 2.5R/1958 racing glow-plug engine being manufactured in sufficient numbers that there was no It's impossible now to state with any certainty how many of the 5 cc engines were made. All I can say can is that the highest 5 cc serial number which has come to my attention in years of looking is 5019. This number appears on an original case used to create one of the Vltavan-based in-line twins produced in very small numbers by František Ježdík, M. Herber and perhaps a few others beginning in 1960. Ježdík later (in 1965) also created an opposed twin made from two Vltavan cases. Following these efforts, he went on to design and produce the well-known FIT engines.

If we may assume that the Vltavan engines were sequentially numbered, we know that at least 5019 Vltavan 5 cases were produced. Some of these cases ended up being incorporated into special projects such as those of Ježdík, Herber and Vašek. Clearly, there may have been a few more such projects. However, at least three thousand examples of both 2.5 cc and 5 cc racing models in their original form had undoubtedly found their way into the hands of modellers here and there, and there's no doubt that an aspiring speed flyer could have used these engines to gain valuable experience in building, trimming, tuning and flying the control-line speed models of the day. Perhaps a few of these users went on to greater things, who knows? _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN December 2007 This revised edition published March 2024

|

| |

In this article I’ll be taking a look at an unexpectedly capable "consumer grade" 5 cc racing engine from Czechoslovakia (as Czechia was at the time). This is the 1957 Vltavan 5 from Prague.

In this article I’ll be taking a look at an unexpectedly capable "consumer grade" 5 cc racing engine from Czechoslovakia (as Czechia was at the time). This is the 1957 Vltavan 5 from Prague. At the time when the MVVS centre was established, the FAI had already announced that the 1954 control line speed World Championship would be contested using 5 cc engines. Accordingly, the first priority of the new MVVS Centre was the development of a 5 cc design with which Czech modellers might challenge the rest of the world.

At the time when the MVVS centre was established, the FAI had already announced that the 1954 control line speed World Championship would be contested using 5 cc engines. Accordingly, the first priority of the new MVVS Centre was the development of a 5 cc design with which Czech modellers might challenge the rest of the world. representative Geza Egerváry, who used an American Dooling .29 in his model. Although the design of the MVVS 5/1954-D owed much to that of the Dooling, this was still a notable achievement less than twelve months after the establishment of the MVVS Centre.

representative Geza Egerváry, who used an American Dooling .29 in his model. Although the design of the MVVS 5/1954-D owed much to that of the Dooling, this was still a notable achievement less than twelve months after the establishment of the MVVS Centre. In any event, the engine development spotlight quickly shifted to the 2.5 cc category with the announcement by the FAI that future World Championship control line speed events would be restricted to engines of the smaller displacement. This immediately diverted the attention of the MVVS design team away from their 5 cc model towards the creation of a competitive 2.5 cc design. How well they succeeded in meeting this objective is fully described in my

In any event, the engine development spotlight quickly shifted to the 2.5 cc category with the announcement by the FAI that future World Championship control line speed events would be restricted to engines of the smaller displacement. This immediately diverted the attention of the MVVS design team away from their 5 cc model towards the creation of a competitive 2.5 cc design. How well they succeeded in meeting this objective is fully described in my  limited production of this design outside the mainstream MVVS work program. This effort was apparently led by Josef Sladký. The engines produced under this arrangement were regionally distributed under the Letmo 5 designation. This was the first of a number of initiatives involving the manufacture of MVVS "clones" by other names.

limited production of this design outside the mainstream MVVS work program. This effort was apparently led by Josef Sladký. The engines produced under this arrangement were regionally distributed under the Letmo 5 designation. This was the first of a number of initiatives involving the manufacture of MVVS "clones" by other names.  Accordingly, a decision was taken to establish a separate factory in Prague (very distant from Brno) for the purpose of manufacturing "consumer" versions of the 2.5 cc and 5 cc MVVS racing engines in sufficient numbers to make them readily and economically available to modellers in the Iron Curtain countries. This decision was acted upon in late 1956, and the Vltavan engines were born. The facility at which these units were manufactured was known as the Praha-Modrany factory. The engines were named for the river Vltava, which flows northward through Prague. In effect, the Vltavan engines were "the engines from the banks of the Vltava"! Sort of like calling a line of engines made in Newcastle the "Tyne" range...............

Accordingly, a decision was taken to establish a separate factory in Prague (very distant from Brno) for the purpose of manufacturing "consumer" versions of the 2.5 cc and 5 cc MVVS racing engines in sufficient numbers to make them readily and economically available to modellers in the Iron Curtain countries. This decision was acted upon in late 1956, and the Vltavan engines were born. The facility at which these units were manufactured was known as the Praha-Modrany factory. The engines were named for the river Vltava, which flows northward through Prague. In effect, the Vltavan engines were "the engines from the banks of the Vltava"! Sort of like calling a line of engines made in Newcastle the "Tyne" range............... The first example of this engine known to have reached Britain was obtained by the well-known free-flight competitor Ron Draper, who somehow managed to get hold of an example through a friend of his in Prague - no mean feat in that era! Ron loaned the engine to

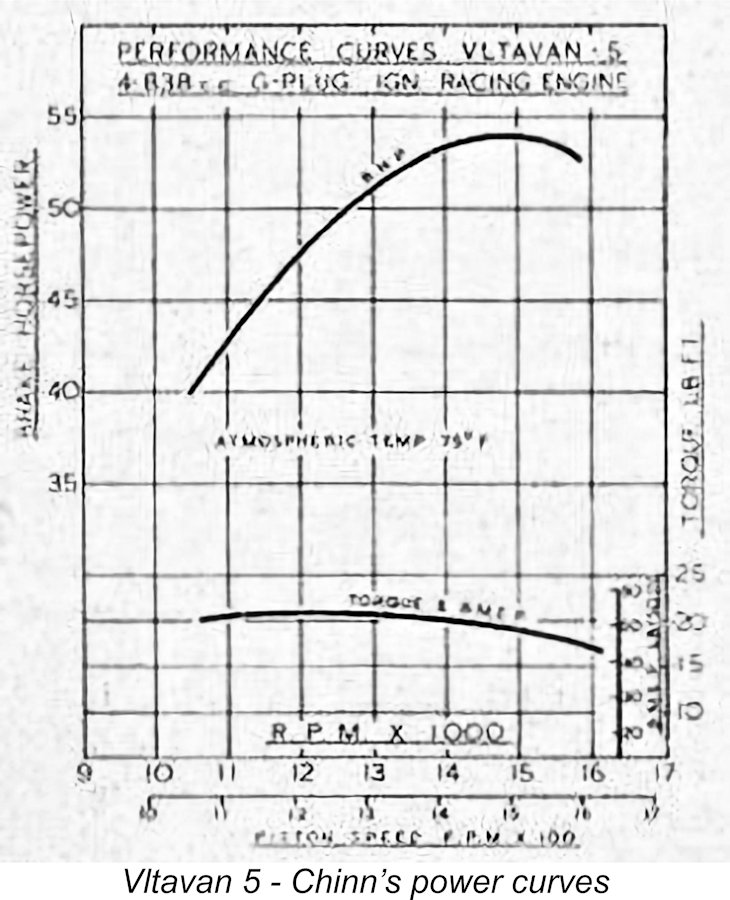

The first example of this engine known to have reached Britain was obtained by the well-known free-flight competitor Ron Draper, who somehow managed to get hold of an example through a friend of his in Prague - no mean feat in that era! Ron loaned the engine to  Chinn measured an output of 0.540 BHP at 15,000 RPM on 25% nitro for the Vltavan 5. This may be compared with

Chinn measured an output of 0.540 BHP at 15,000 RPM on 25% nitro for the Vltavan 5. This may be compared with  The illustrated Like New example is from my own collection, bearing the serial number 3736. Bore and stroke are 20.0 mm x 15.4 mm respectively, giving a displacement of 4.84 cc. The engine is thus very much over-square, a characteristic which it shares with the Dooling 29. Weight is 7.25 ounces (206 gm). Visually, the engine bears some similarity to its smaller

The illustrated Like New example is from my own collection, bearing the serial number 3736. Bore and stroke are 20.0 mm x 15.4 mm respectively, giving a displacement of 4.84 cc. The engine is thus very much over-square, a characteristic which it shares with the Dooling 29. Weight is 7.25 ounces (206 gm). Visually, the engine bears some similarity to its smaller  The next significant difference is the rotary disc itself. On the 5 cc model it is made of some form of extremely tough molded plastic. This material would doubtless stand up far better than aluminum alloy to the stresses of high-speed running. It seems a pity that the same molded plastic was not used on the 2.5 cc Vltavan - if they could use it for one model, why not for the other? Regardless, the disc mounting system is identical to that employed on the 2.5 cc model, with a long steel shaft secured by a collar and drilled for bearing lubrication. The carburettor arrangements are identical too, a standard spraybar set-up being employed.

The next significant difference is the rotary disc itself. On the 5 cc model it is made of some form of extremely tough molded plastic. This material would doubtless stand up far better than aluminum alloy to the stresses of high-speed running. It seems a pity that the same molded plastic was not used on the 2.5 cc Vltavan - if they could use it for one model, why not for the other? Regardless, the disc mounting system is identical to that employed on the 2.5 cc model, with a long steel shaft secured by a collar and drilled for bearing lubrication. The carburettor arrangements are identical too, a standard spraybar set-up being employed. The result of this set-up is that there simply isn't a lot of piston left on the transfer side, and that of course is the side which absorbs the side-thrust loads when the engine is running. This is one of the previously-mentioned arguments in favor of placing the exhaust on the left so that the unbroken surface of the piston wall takes the far greater side thrust generated during the power stroke.

The result of this set-up is that there simply isn't a lot of piston left on the transfer side, and that of course is the side which absorbs the side-thrust loads when the engine is running. This is one of the previously-mentioned arguments in favor of placing the exhaust on the left so that the unbroken surface of the piston wall takes the far greater side thrust generated during the power stroke. It appears that for whatever reason, this set-up didn't work out well - perhaps the keying failed at high speeds? After all, lead is not a strong or stable material in a mechanical sense. Or perhaps it was found to be unnecessary. Regardless, later models reverted to a standard one-piece steel crankshaft with a normal integrally-machined counterbalance, exactly like that used on the 2.5 cc version. Both of my examples are of this type.

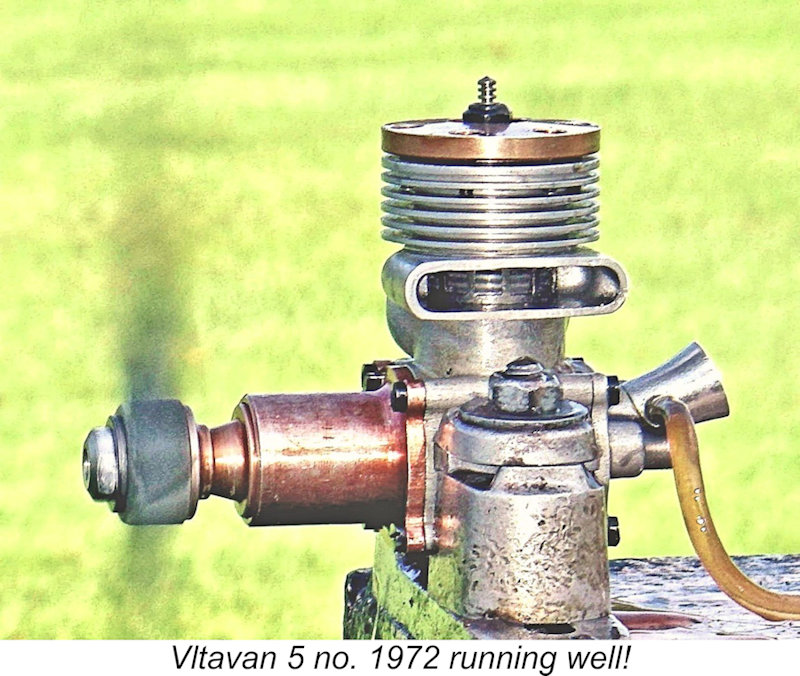

It appears that for whatever reason, this set-up didn't work out well - perhaps the keying failed at high speeds? After all, lead is not a strong or stable material in a mechanical sense. Or perhaps it was found to be unnecessary. Regardless, later models reverted to a standard one-piece steel crankshaft with a normal integrally-machined counterbalance, exactly like that used on the 2.5 cc version. Both of my examples are of this type. I also have a used example (serial number 1972) with trued-up mounting lugs, which I have run. I have to say that this engine seems well able to give a pretty good account of itself - it starts very easily, runs extremely smoothly and needles very well indeed. Spot checks show that it gets to within 200-300 RPM of my best unmodified Dooling when both motors are identically propped for speeds in the 18,000 RPM range on the same 30% nitro fuel. At that speed, the Vltavan 5 ran absolutely smoothly with no sign of sagging and no evidence of mechanical distress.

I also have a used example (serial number 1972) with trued-up mounting lugs, which I have run. I have to say that this engine seems well able to give a pretty good account of itself - it starts very easily, runs extremely smoothly and needles very well indeed. Spot checks show that it gets to within 200-300 RPM of my best unmodified Dooling when both motors are identically propped for speeds in the 18,000 RPM range on the same 30% nitro fuel. At that speed, the Vltavan 5 ran absolutely smoothly with no sign of sagging and no evidence of mechanical distress.  However, few human endeavors are as dynamic as technological advancement. By 1958 the MVVS Centre had developed updated versions of both their 2.5 cc and 5 cc models which far exceeded the performances of both their own progenitor designs and the Vltavan clones. Consequently, the Czechs quickly came to the logical conclusion that circulating increasingly uncompetitive clones to aspiring contestants was perhaps not the best way to instill enthusiasm and generate a larger pool of capable flyers. It was this conclusion that led in 1958 to the MVVS Centre beginning to take on additional workers and equipment, subsequently putting several of their then-current designs into limited production.

However, few human endeavors are as dynamic as technological advancement. By 1958 the MVVS Centre had developed updated versions of both their 2.5 cc and 5 cc models which far exceeded the performances of both their own progenitor designs and the Vltavan clones. Consequently, the Czechs quickly came to the logical conclusion that circulating increasingly uncompetitive clones to aspiring contestants was perhaps not the best way to instill enthusiasm and generate a larger pool of capable flyers. It was this conclusion that led in 1958 to the MVVS Centre beginning to take on additional workers and equipment, subsequently putting several of their then-current designs into limited production. longer any need for the consumer-grade Vltavan 2.5 models. Moreover, the 5 cc category had remained something of a side-show given the fact that the 2.5 cc displacement limit was now firmly established as the official international competition category, consequently drawing much of the attention from aspiring competitors. As a result, demand for 5 cc racing engines was relatively low. By early 1959, manufacture of both Vltavan models in their aircraft configuration appears to have ceased. The factory continued to make car versions of both models for some time, but all production seems to have ended at some point in 1960.

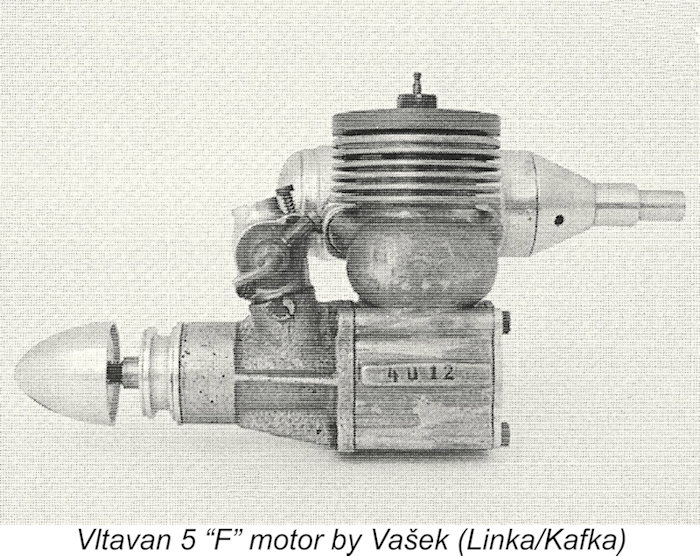

longer any need for the consumer-grade Vltavan 2.5 models. Moreover, the 5 cc category had remained something of a side-show given the fact that the 2.5 cc displacement limit was now firmly established as the official international competition category, consequently drawing much of the attention from aspiring competitors. As a result, demand for 5 cc racing engines was relatively low. By early 1959, manufacture of both Vltavan models in their aircraft configuration appears to have ceased. The factory continued to make car versions of both models for some time, but all production seems to have ended at some point in 1960. Ježdík’s in-line twin was not the only project which involved the conversion of the Vltavan 5 from its original configuration. Also in 1960, an individual named Vašek constructed a few front-rotary valve conversions of the Vltavan 5. Designated the Vltavan 5 “F”, these were assembled in R/C configuration, complete with muffler. An example is illustrated in the excellent book "

Ježdík’s in-line twin was not the only project which involved the conversion of the Vltavan 5 from its original configuration. Also in 1960, an individual named Vašek constructed a few front-rotary valve conversions of the Vltavan 5. Designated the Vltavan 5 “F”, these were assembled in R/C configuration, complete with muffler. An example is illustrated in the excellent book "