|

|

The ZSTKAM Engines

In other articles on this website, I’ve covered the history of a number of the better-known model engines originating in the former USSR. These have included the early K-16 diesel, the MK-12S diesel, the MK-16 and MK-17 diesels, the MD-2.5 “Moscow” and MD-5 “Kometa” racing glow-plug engines, the RITM team race diesel, the Kharkov MK-25 diesel and the MARZ 2.5 cc design. Anyone who follows the model engine offerings on eBay will be well aware that many of these engines make frequent appearances on that platform, generally selling for quite reasonable prices. In addition to the above focused articles, I’ve also presented a summary of the overall history of Russian model engine production. That article recounted the story of the development and manufacture of model engines in Russia from its beginnings in the 1930’s down to the closing years of the pre-Schnürle “classic” era which ended in the late 1970's as far as I’m concerned. Readers wanting the full story of Russian model engine development and manufacture up to that point are recommended to that article - I do not intend to repeat the majority of it here. The telling of the ҴCTKAM story provides an opportunity to carry the history of Russian model engine manufacture onward into the post-classic Schnürle era and into the period of re-adjustment which followed the 1991 break-up of the Soviet Union. The various members of the ҴCTKAM (ZSTKAM) series continue to make frequent appearances on eBay and similar forums today. The degree to which these engines appear to remain in circulation seems to me to make it desirable that some basic information regarding the series should be available to today’s engine aficionados.

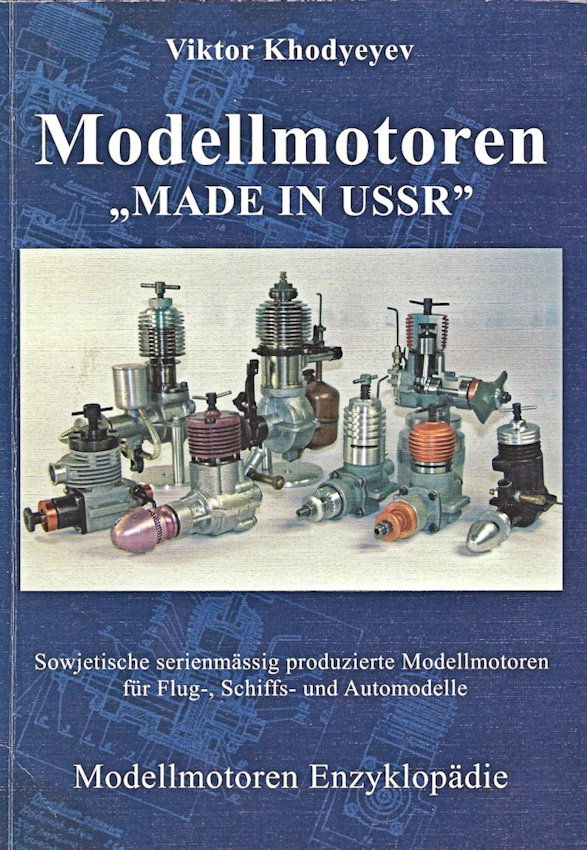

In order to place the ZSTKAM engines in context, it’s necessary to summarize the development of Soviet aeromodelling technology to the point at which the Central Sports Technical Model Flying Club (ZSTKAM) became the focal point for model engine development in the USSR. In meeting this requirement, I have drawn quite heavily upon the information contained in the highly instructive 2014 German-language book “Modellmotoren Made in USSR” by Ukrainian commentator Viktor Khodyeyev. I freely acknowledge my indebtedness to Viktor for making this information available – I could not have completed this article without the information contained in his book. Perhaps the best sorce of information on the engines themselves came from the 1991 Russian-language book "Engines of the ZSTKAM Series" by V. E. Merzlykin. Although only available in Russian, the book nonetheless provides a very useful guide to the engines which bore the ҴCTKAM name up to 1990. I also wish to acknowledge the contribution to this history made by my late valued friend and colleague Jim Dunkin. Jim’s outstanding book “Reference Book of .15 ci / 2.5 cc Model Airplane Engines” included information on a number of 2.5 cc ҴCTKAM (ZSTKAM) engines, providing some very useful data plus a few images which were otherwise lacking. Without further preamble, let’s share a condensed look at the development of the Soviet model engine manufacturing industry up to the point at which the ZSTKAM organization came to the forefront of Russian model engine design. The Development of Russian Model Engine Manufacture

As recorded in my earlier article, the series production of model engines in the USSR dates back to the mid-1930's. At that time, the entire sports modelling activity was under the auspices of the military-patriotic organization OSOAVIAKHIM (ОСОАВИАХИМ in Russian script). Roughly translated, the name stands for “Union of Societies of Assistance to Defense and Aviation-Chemical Construction of the USSR”. Quite a mouthful - I’ll stick to OSOAVIAKHIM! OSOAVIAKHIM had been created on January 27th, 1927 by merging three earlier Societies having narrower individual mandates. The underlying goal of the combined Society was the creation and maintenance of a reserve and recruiting capacity for the armed forces. The development of aeromodelling as a means of OSOAVIAKHIM soon developed into a powerful militarized organization with its own airfields, radio clubs, parachuting towers, firing ranges and aeromodelling clubs among other assets. Although OSOAVIAKHIM technically had the status of a non-governmental organization, it was completely controlled by the Communist State political system in reality. The State went so far as to issue stamps to promote the organization. The 1 ruble stamp pictured at the right is an example.

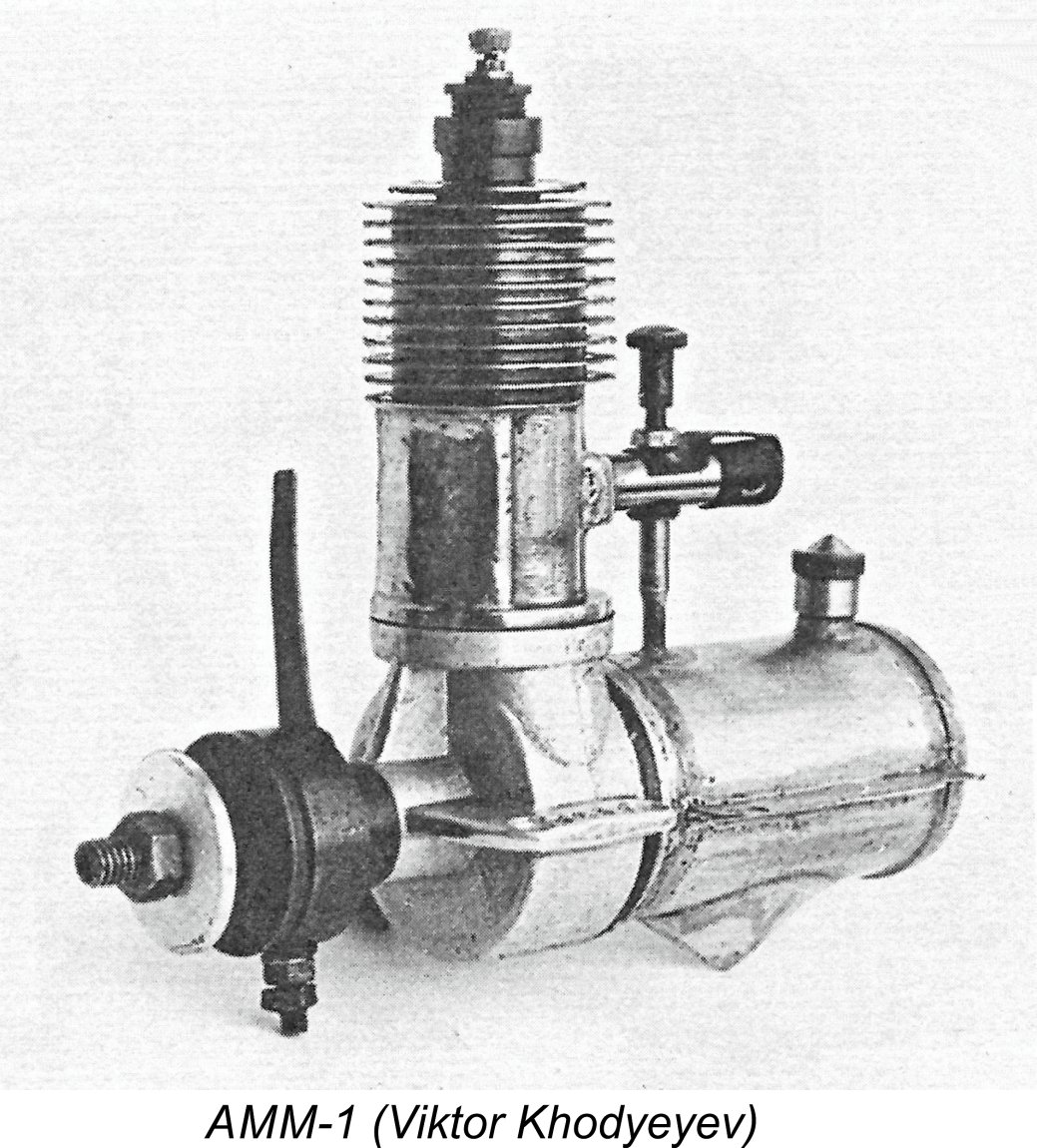

During the mid 1930's, the USSR purchased a number of examples of the then world-famous American Brown Junior gasoline engine in order to inspire the younger generation to build and fly power model aircraft. Using this iconic design as a guide, the manufacture of the first Russian model aircraft engine to enter series production, the AMM-1 sparker, was commenced in the Moscow aircraft repair workshops of OSOAVIAKHIM. The engine was produced in quite large numbers.

There were no private companies in the USSR, so no other avenues were open for alternative model engine production to be pursued. Despite the lack of series production alternatives, a number of creative and technically gifted modelling enthusiasts working independently did construct successful one-off examples of small model engines during the pre-WW2 period. However, these were isolated cases and the resulting designs were never put into series production, although plans and even castings were made available for some of them to facilitate their individual construction by skilled enthusiasts. One very far-reaching pre-WW2 action taken by OSOAVIAKHIM was the 1937 establishment of the Central Aircraft Modelling Laboratory (ZAML / Russian ҴAMӅ) in Moscow. In English texts, the name of this facility is generally rendered as CAML, a convention which I will follow in this text. Staffed by the most experienced available aeromodelling specialists, this facility was Following the upheaval of WW2, development of model engines by CAML and others soon resumed. By the late 1940’s, a few additional designs had entered series production, including the CAML-50 and K-16 diesels. These designs and several others were developed at the CAML headquarters in Moscow.

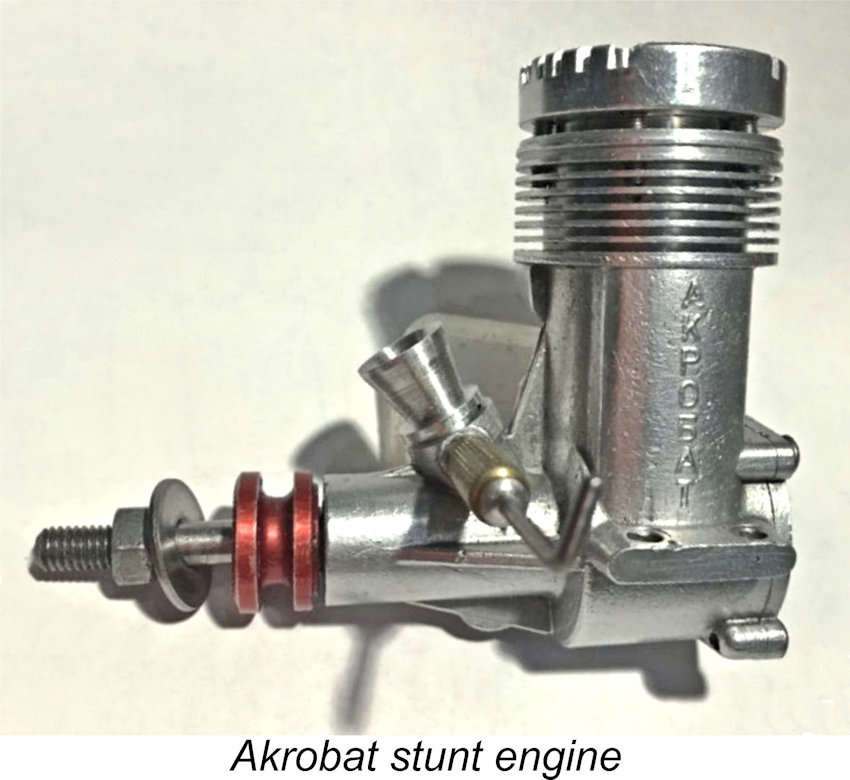

Like its predecessor, DOSAAF was in essence a paramilitary sport organization concerned with the promotion of sporting activities which encouraged the development of skills which could be of service to the State in military capacities. The new organization wasted little time in picking up the reins of the aeromodelling movement from its predecessor. Despite theover-arching organizational change, new engine designs continued to be designed for the most part in the development Both DOSAAF and CAML continued their combined efforts to develop the technical aspects of aeromodelling throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s. The result was a steady succession of new model engine designs, a number of which have been covered elsewhere on this website, with more to follow in due course. Since it was the practice of DOSAAF to assign the manufacture of these engines to various facilities over which they had some level of control, the quality of these engines tended to be highly variable. My own experiences with the illustrated MK-12V amply bear this out. As the 1970’s approached, DOSAAF became increasingly aware of the quality issue, viewing it quite logically as a potential barrier to the export sales One of the premier model flying clubs in the USSR was a Moscow-based group named the Central Sports Model Flying Club (ZSKAM / Russian ҴCKAM). This group boasted some of the country’s most talented power modelling competitors among its members, including the well-known speed flier Valentin Natalenko and a number of his colleagues. One of the earliest designs to result from this collaboration was the 1965 Veterok 1.48 cc diesel. The ZSKAM name was not attached to this design, but this was to change as time went on. The club members continued to develop additional model engine designs, some of which which were deemed worthy of being put into series production. The well-known Akrobat stunt engine was an example of a design which benefited from their work. The success of the members of ZSKAM in developing model engines of real merit soon convinced DOSAAF that the clearly-productive efforts of ZSKAM should be placed on a more formal basis. The Emergence of ZSTKAM At the end of the 1960’s, the activities of CAML were rolled into those of ZSKAM, with the reorganized group continuing its operations under the ZSKAM designation. In this way, the former responsibilities of CAML were now transferred to ZSKAM. Despite its continuing “club” pretensions, the reality was that ZSKAM had now become a State-sponsored research and development organization staffed by experts whose participation was solely by Government appointment. DOSAAF continued to have full oversight of the group's activities. In around 1974 the name of the club was amended very slightly to ZSTKAM (Russian ҴCTKAM), standing roughly for “Central Sport Technical Club for Aircraft Models”. The addition of the “technical” term reflected the fact that the group was now focused primarily upon engine development rather than aeromodelling in general. A lengthy series of generally serviceable engines bearing that name continued to emerge well into the 1990’s after the break-up of the USSR.

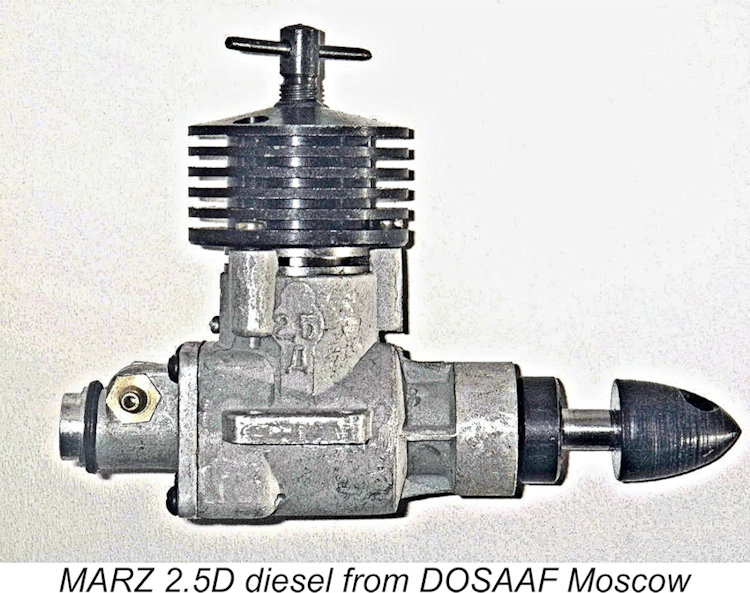

Moreover, ZSTKAM was not the sole developer of new Russian model engine designs at this time. For example, the MARZ 2.5D diesel of c. 1978 was reportedly designed as a class exercise by students at the Engineering Department of the University of Moscow. DOSAAF had access to a number of aircraft repair shops where full-sized sports aircraft were maintained, as well as a variety of smaller specialized workshops. A number of model engines, such as the MK-12V, MARZ 2.5D and ZSTKAM 2.5 D, were produced in bulk at DOSAAF’s long-established “MARZ” (Russian MAP3) In most of the production facilities which were directly controlled by DOSAAF, manufacturing standards were not particularly high - on the one hand, there was a shortage of appropriately-skilled personnel; and on the other hand, high-quality materials were not always available (light casting alloy, high-strength alloy steel, etc.). Overall, the quality of manufactured products was not a top priority in the USSR's planned economy. The most important production criterion was quantity.

As a result, although engines developed at the Central Sports Technical Model Flight Club bore the designation ZSKAM (subsequently amended to ZSTKAM - see below), they were actually manufactured in different workshops. Accordingly, they differed from each other in terms of their quality and functionality. The term ZSTKAM denoted a marque, not a manufacturer. The engines manufactured in military and aerospace workshops displayed significantly better quality than the others. Since the engines developed by ZSTKAM were specifically designed by experts for high-performance applications, they were among the models whose manufacture was assigned for the most part to such workshops. Consequently, the best of them are among the higher-quality Russian model engines. Almost all engines produced in the USSR were marked with a serial number. This was done in various ways (stamped, engraved, etc.), generally appearing on the engine mounting lugs. Different manufacturers often had their own system of serial numbers and letters. To add to the confusion, excessively long numerical sequences were not infrequently “re-set to zero” and a new series started with a shorter number. It is frequently impossible to determine the production date of the engine from these numbers, or even the number produced.

As a rule, one could only obtain the full range of model building items via the DOSAAF distribution network organized around its model clubs. The Ministry of Education also established such clubs specifically for students. These were run by experienced model fliers, many of whom took part in high-level competitions. Although there were exceptions, few of the model engines produced in the USSR were really suitable for achieving winning performances at the international level due to their technical characteristics as delivered. They tended to lack precision, hence having to be individually rebuilt, often using components “borrowed” from other engines. Some modellers used machine tools and equipment owned by the various model clubs to build powerful one-off engines of their own design. The most successful of these were sometimes produced in small series. Having now summarized the manner in which ZSTKAM came into existence as well as the basis on which it functioned, we’re now ready to take a look at a representative sample of the engines which were designed by that organization and manufactured in series at various locations. ZSKAM 1-2.5

This cross-flow loop-scavenged 2.5 cc glow-plug engine was a derivative of the earlier Meteor MD-2.5 model, with which it is often confused. It continued the use of Super Tigre porting with an iron-and-steel piston/cylinder combination, also retaining the familiar 15 mm and 14 mm bore and stroke dimensions which had become more or less standardized in Europe by the time in question. The shaft continued to be supported by two ball-races. However, the ZSKAM rendition differed from the Meteor in featuring a separate bolt-on front housing instead of the integrally-cast main bearing housing used on the Meteor. The castings were gravity die-cast as opposed to the former use of pressure die-casting, implying a somewhat lower rate of production. The engine also featured a more forward-raked induction venturi. There were almost certainly some internal modifications as well, although I don't have any authoritative information on what these might have been since I don't have an example available for inspection. The ZSKAM 1-2.5 was actually designed by the well-known speed flier Valentin Natalenko, being his final normally-aspirated design before he turned his attention to piped Schnürle-ported units. It was produced as a general-purpose powerplant of relatively high performance, intended primarily for club-level use in control-line models. Like their Meteor predecessors, the engines were manufactured at DOSAAF’s MARZ aircraft maintenance plant in Moscow.

The diesel variant of this design was intended primarily for team racing at the club level. It used modified porting in which the bridge separating the two transfer ports was omitted, leaving a single enormous upwardly-angled aperture. The induction port in the crankshaft journal was given an oval shape as opposed to a sharp-edged rectangular form in order to provide increased strength to the diesel version, while the diameter of the internal gas passage in the 10 mm diameter shaft was reduced to 6.5 mm to increase the wall strength of the shaft. In addition, a conventional transverse spraybar was used in place of the offset tangential control employed on the glow-plug variant. My illustrated example is a very strong runner. Claimed peak output of this diesel model was a possibly optimistic 0.35 BHP @ 15,000 RPM. According to Viktor Khodyeyev, a 5 cc version was also produced in modest numbers. This latter unit featured a displacement of 4.82 cc derived from bore and stroke dimensions of 19 mm and 17 mm respectively. It weighed in at 225 gm (7.94 ounces). Claimed output was 0.368 Kw (0.493 BHP) @ 12,000 RPM. This engine was intended primarily for control line service. At present, I don't know for certain how long these models continued in production. I can only report that the ZSKAM 1-2.5 diesel variant was still featured among then-current Soviet products in a 1973 Russian book on model engines. The 1975 appearance of the next model to be discussed, the ZSTKAM-2.5 D, implies that it was a replacement for the ZSKAM 1-2.5 diesel, of which production was presumably ended in 1974 concurrently with the name change of the designing organization. ZSTKAM 2.5 D

This plain bearing Schnürle-ported 2.5 cc diesel engine was produced as a general-purpose powerplant of relatively high performance, evidently replacing the ZSKAM 1-2.5 in that role. Its primary intended application seems to have been to power control-line models. The engine had a displacement of 2.47 cc, derived from the customary bore and stroke measurements of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. It weighed in at a commendably light 140 gm (4.94 ounces). The peak output was claimed as being 0.25 Kw (0.335 BHP) @15,500 RPM. Based on consideration of its design features, this claim appears perfectly credible for a good example. I actually get the impression The engine featured a monobloc crankcase with the main bearing cast in unit, while the main crankshaft journal ran in a plain bearing. Crankshaft front rotary valve induction was employed. The cylinder featured three-channel Schnürle porting. The piston was machined from gray cast iron and ran in a steel liner. The connecting rod was made of aluminum alloy. The backplate was a screw-in component machined from aluminium alloy bar stock. The designation “ҴCTKAM-2.5 Д” (ZSTKAM-2.5 D) was cast onto the motor housing. The ZSTKAM-2.5 D was manufactured in large quantities at DOSAAF’s MARZ aviation repair plant in Moscow. The standard of manufacture was not perfect, but was better than that exhibited by some other contemporary Russian models – DOSAAF were learning! Examples in good condition are offered regularly on eBay and similar venues today, selling for prices which make them excellent value for money. ZSTKAM 3.2 D

Merzlykin tells us that this engine was designed by ZSTKAM in 1979. Series production commenced in 1980, being carried out at DOSAAF’s Ivanovo facility where the TALKA model engines were manufactured. This explains the fact that the same “flaming torch” logo that appears on the TALKA engines also appears cast in relief onto the front ball-race housing of the ZSTKAM 3.2 cc diesel. Like other engines manufactured at this facility, the engine was built to quite high standards.

The cylinder cooling fins were formed as part of the main casting and left as cast, rather than being machined into the casting as applied to the smaller models. The steel cylinder featured three-channel Schnürle porting, with a cast iron piston being employed. The engine’s use of a side-stack exhaust gave it a more “traditional” appearance than that of its smaller 2.5 cc companion. It also differed from the 2.5 D in featuring a twin ball-race crankshaft.

Another rather odd observation is the fact that my example of this engine does not display a serial number of any kind. As stated earlier, the absence of a serial number is rare among engines of Russian manufacture. Most of the other ZSTKAM models bore such numbers. The implication may be that this engine was manufactured in lesser quantities than the other ZSTKAM designs. The only markings on the case are “ҴCTKAM” on the transfer side and “3.2” beneath the exhaust stack. Both sets of characters are cast in relief as opposed to being stamped or engraved. According to Merzlykin, the ZSTKAM 3.2 D delivered a peak output of 0.26 kW (~ 0.35 BHP) @ 16,000 RPM. I've never run my example, but its design features and its evident quality of construction combine to suggest that this claim has a good deal of credibility. ZSTKAM 2.5 K

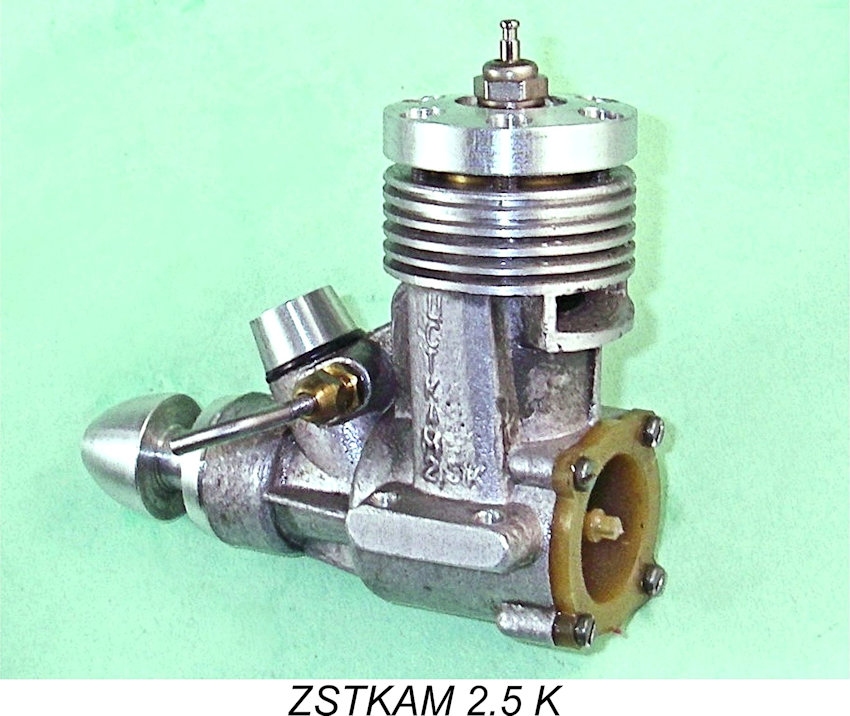

Some examples of the ZSTKAM-2.5 K engines were also produced at the DOSAAF plant in Ivanovo. These engines differed slightly in their external appearance. However, the main difference was the replacement of the ABC piston/cylinder set-up with a piston made of gray cast iron running in a steel liner. ZSTKAM 2.5 KR-AS

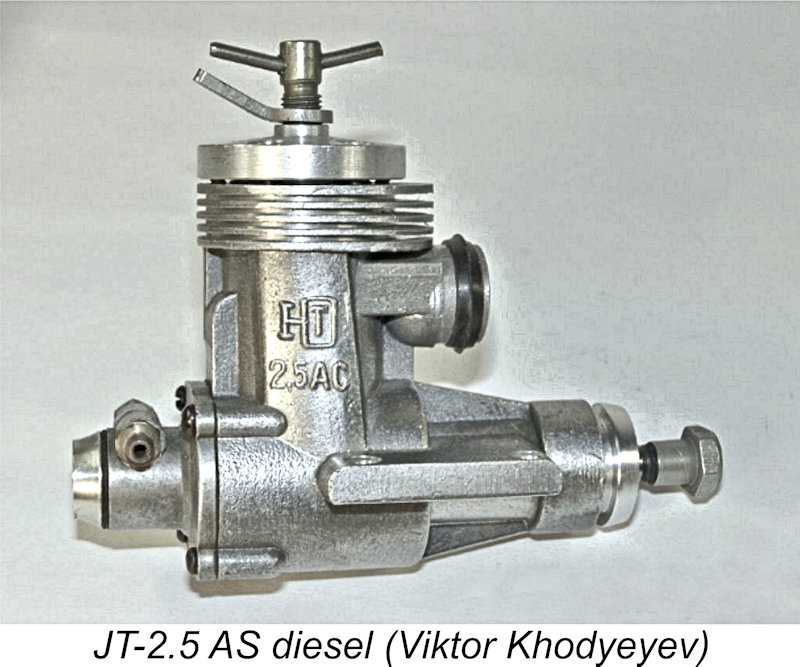

The initial focus on car and boat applications was reflected in the engine’s rather unusual monobloc design layout, which rendered its use with an airscrew impossible if the pipe was to be employed. Since the engine had obvious potential for use in high-speed aircraft applications, a revised version was developed which featured both detachable front and rear housings. This allowed the case to be reversed, bringing the exhaust to the rear above the induction system in an orientation suitable for piped aircraft applications. The engine thus became a dual-purpose unit. The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS featured the usual bore and stroke dimensions of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. It weighed in at a healthy 200 gm (7.06 ounces) complete with tuned pipe. The substantial aluminum main casting was fitted with a bolt-on backplate which incorporated a steel rotary drum valve. The crankshaft was supported in twin ball bearings. The engine was equipped with three-channel Schnüerle scavenging timed for tuned pipe operation. An ABC piston/cylinder combination was featured. Either glow buttons or conventional glow plugs could be used optionally. The inscription "ҴCTKAM-2.5 KP-AC" (ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS) was cast onto the main casting. Since operating engines fuelled with methanol was prohibited in competitions with young participants in the USSR at the time (perhaps due to fears regarding substance abuse), a diesel version of the ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS designated as the JT-2.5 AS (Russian ЮT-2.5 AC) was developed especially for teenagers and young model builders. However, this was produced in relatively small quantities. ZSTKAM 1.5 KR-AS

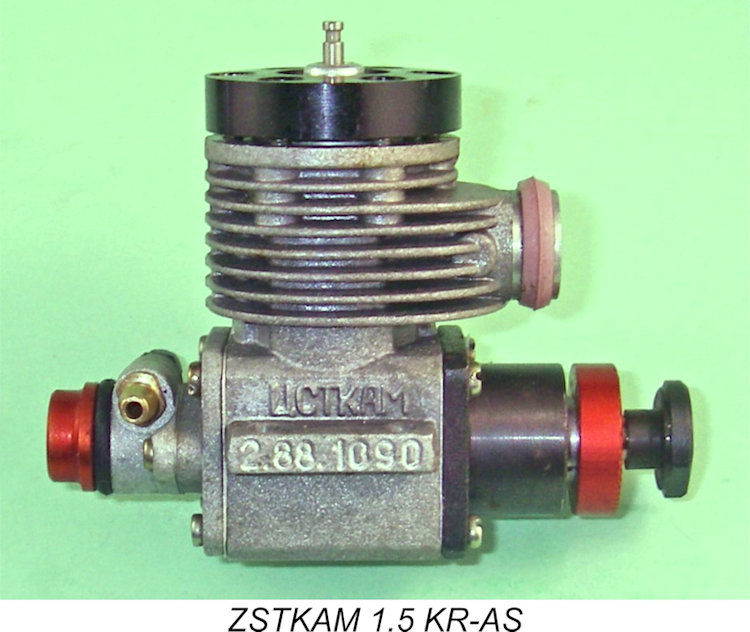

The engine had a displacement of 1.49 cc derived from bore and stroke dimensions of 13.15 mm and 11.00 mm respectively. Without the tuned pipe, it weighed a hefty 150 gm (5.29 ounces), which went up to 180 gm (6.35 ounces) complete with pipe. Claimed output was 0.40 Kw (0.536 BHP) @ 28,000 RPM with the pipe. All components were designed for severe operating conditions under heavy loads. The main engine casing was fitted with a bolt-on backplate which incorporated a steel drum induction valve. The bolt-on front housing was of steel. This latter choice of materials was adopted in order to match the coefficients of thermal expansion of the ball races and their housing. This innovation had been introduced by multiple World Champion Boris Krasnoroutski of Ukraine in 1973 in his self-constructed team race “specials”. It was very effective, being widely copied by other designers.

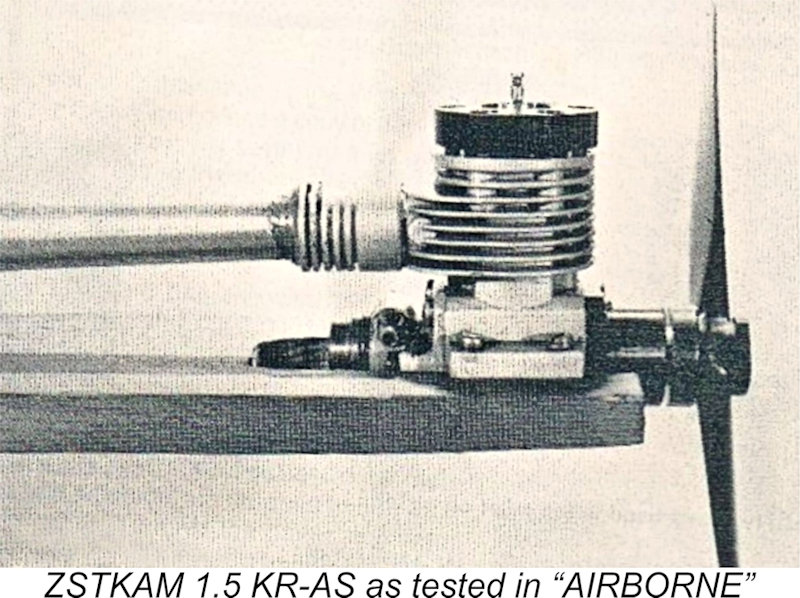

The engine featured a three-channel Schnüerle bypass system designed for operation with the tuned pipe which was supplied with the engine. An ABC piston/cylinder set was also featured. The head was arranged to accommodate a Rossi glow-plug button. The inscription on the motor housing read: "ҴCTKAM -1.5 KP-AC" (ZSTKAM-1.5 KR-AS). The ZSTKAM 1.5 KR-AS glow-plug unit appears to be the sole member of the ZSTKAM family to have been featured in a published operational test in the modelling media. The engine was reviewed in issue no. 111 of the Australian publication “Airborne” in mid 1992. Although uncredited, the author was almost certainly the late Brian Winch. The report in question may be viewed here on the invaluable Sceptre Flight website, which is devoted to the preservation and sharing of model engine tests. The engines were reportedly being imported to Australia by Ilya Leydmann, trading under the name Eastcam from an address in Bondi, New South Wales. Ilya provided the example which was The tester had mostly good things to say about this engine. It was the first Russian engine of his experience, and he confessed to having been pleasantly surprised. He commented on the engine’s previously-mentioned use of a steel front housing to accommodate the twin ball races, a feature with which he was unfamiliar. The tester found that the tuned pipe with which the engines were supplied had a very broad operating bandwidth, coming on song quite readily during bench testing and creating a major increase in engine speed along with a worthwhile reduction in the intensity of the exhaust note. With the pipe fitted and using a fuel containing only methanol and castor oil at a 4:1 ratio, the engine turned a 6x3 Zingali prop at 25,000 RPM and a Power Prop wood airscrew of unspecified size at 25,500 RPM. Such figures imply that the manufacturer’s performance claims were quite credible for a good example. Since operating engines on methanol fuel was My good mate Maris Dislers had an example of the MDS-1.5D diesel on hand. Years ago he had modified this engine to render it more suitable for control-line service. It was originally fitted with a venturi insert having a 4.5 mm throat diameter - clearly unsuitable for use with a 1.5 cc diesel. My example of the same engine has a far more appropriate 3 mm throat diameter - perhaps they ran out of those components and substituted the more open fitting from the piped glow-plug version?!? Maris fitted a replacement venturi insert having a far more practical 2.7 mm throat diameter, also making a replacement head and removing material where possible to lighten the engine. The modfied unit ran well enough on the bench, but never actually entered control-line service due to other matters claiming Maris's attention. At my request, he dug it out of storage and tried it on a few test props, with the following results.

Maris considered these results to be OK, although they fell short of those expected from Fora 09 or Parra Wasp diesels with similar choke areas. Experience shows that an APC 7x3 typically allows an engine of this type to run at or near its peaking speed. We might therefore expect a The engine's torque was well sustained, although the figures start from a relatively low point. This may be a reflection of the fact that the cylinder porting design is intended primarily for operation on glow-plug ignition using a pipe. As a final note, it's worth recording the fact that there was another variant of the MDS 1.5 cc diesel. This model used a revised crankcase having a side-stack exhaust. The machined steel front housing was replaced with a more conventional integrally-cast aluminium alloy housing. This version of the engine was designated the MDS 09. I have no definite knowledge regarding whether it preceded or followed the MDS-1.5D, although I strongly suspect the latter. ZSTKAM 2.5 KR

The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR had a monoblock main casting from aluminum alloy incorporating the housing for a double ball-race crankshaft. The engine was equipped with a chrome-plated brass liner and a ringless aluminum piston. Glow-plug buttons were used. In conjunction with a The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR was equipped with a three-channel Schnürle scavenging system and was completed with an aluminum propeller spinner. The carburettor venturi insert was anodized red and the cylinder head was anodized black. The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR was characterized by a high standard of workmanship. It was delivered in a robust package made of hard foam, together with a tuned pipe, 0-rings, glow head and operating instructions. The engine was produced in large quantities. Some examples of the ZSTKAM-2.5 KR were also manufactured at the DOSAAF plant in Ivanovo, where the TALKA engines were produced. These engines differed both externally and internally from the others. The main casting was configured somewhat differently, while the liner was made of steel and the piston was made of gray cast iron, replacing the ABC set-up used in the other examples. ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2

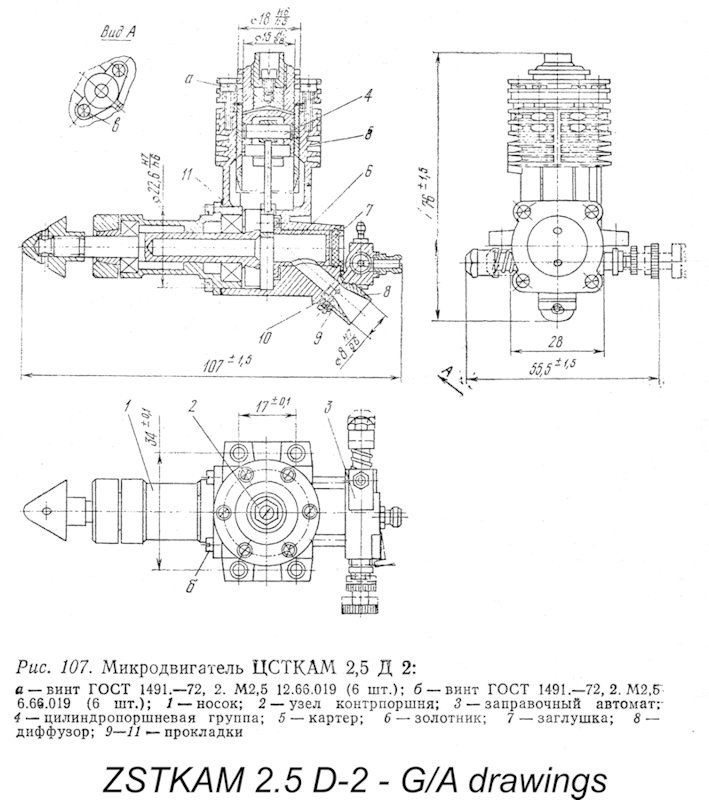

The ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2 was developed beginning in 1983. As the attached image extracted from Merzlykin's book shows, it was a state-of-the-art Schnürle-ported FAI team race diesel employing updraft rear drum induction with a remote needle valve assembly incorporating a cut-out. Claimed peak output was 0.37 Kw (~ 0.50 BHP) @ 20,000 RPM. The ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2 appears to have been made in extremely small numbers - Merzlykin was unable to find an example to photograph for his 1991 book. I've never seen another reference to this engine, nor am I aware of any surviving examples. It would seem that the ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2 fell into the category of an "experts only" model which never entered full-scale series production. The needs of the far more numerous club-level competitors were met quite adequately by the excellent KMD-2.5 diesel, which first appeared in around 1973. The very well-made KMD was found on test by Maris Dislers to develop 0.48 BHP @ 19,500 RPM. Conclusion The 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union changed the political picture in Russia completely. It now became possible for State production facilities such as those formerly utilized by DOSAAF to re-organize themselves into private companies operating very much along Western lines.

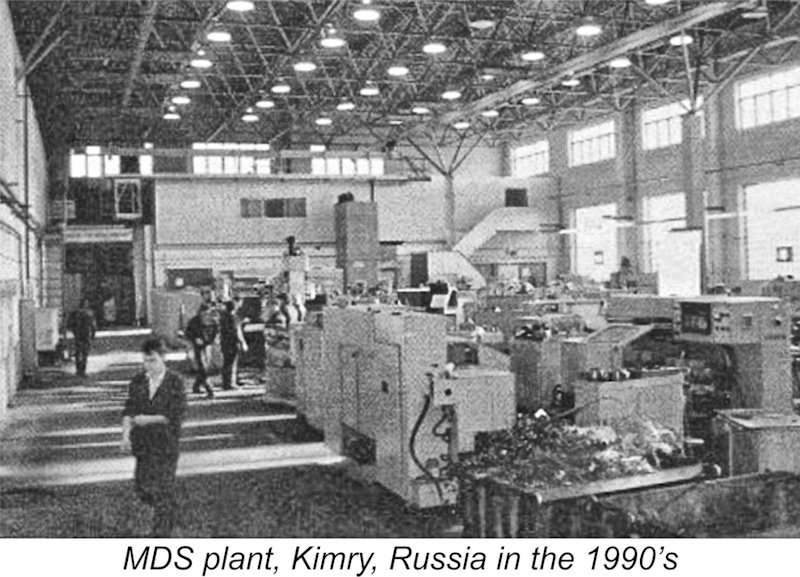

According to the late Jim Dunkin, writing in his invaluable book “Reference Book of .15 ci / 2.5 cc Model Airplane Engines”, the manufacture of engines bearing the ҴCTKAM trade-name was continued for a time at the Kimry plant. However, the engines were eventually absorbed into the MDS range, which was imported into Britain by Ripmax. The previously-mentioned MDS-1.5D appears to be an example of this transition. The above summary covers the Russian-made model engines bearing the ҴCTKAM trade-name of which I’ve become aware to date. I have little doubt that there are other members of the series of which I remain in ignorance. If any reader is able to add to our shared knowledge, let’s hear from you!! _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2024 |

|||

| |

In this relatively brief overview, I’ll attempt to summarize the history of the various model engines which appeared in the former USSR between 1967 and 1991 under the designation ҴCTKAM (in Russian script). This name is phonetically pronounced in English more or less as “Ts – s – t – k – ah – m”, which comes out sounding very much like “Zsstkahm”. It is generally rendered as ZSTKAM when written in English-language texts. Pronounced as written, it’s pretty close!

In this relatively brief overview, I’ll attempt to summarize the history of the various model engines which appeared in the former USSR between 1967 and 1991 under the designation ҴCTKAM (in Russian script). This name is phonetically pronounced in English more or less as “Ts – s – t – k – ah – m”, which comes out sounding very much like “Zsstkahm”. It is generally rendered as ZSTKAM when written in English-language texts. Pronounced as written, it’s pretty close!  All engines in the ZSTKAM series (as I will henceforth call it) were developed by a group called the Central Sports Technical Model Flying Club (ZSTKAM) in Moscow. The engines in this series were developed for operation in high-speed aircraft, boat and car models, generally delivering quite respectable levels of performance. They were manufactured to somewhat “flexible” standards at various manufacturing facilities in the USSR.

All engines in the ZSTKAM series (as I will henceforth call it) were developed by a group called the Central Sports Technical Model Flying Club (ZSTKAM) in Moscow. The engines in this series were developed for operation in high-speed aircraft, boat and car models, generally delivering quite respectable levels of performance. They were manufactured to somewhat “flexible” standards at various manufacturing facilities in the USSR.  I’ve covered this subject in considerable detail in my earlier article on the history of

I’ve covered this subject in considerable detail in my earlier article on the history of  preparation for later participation in the Soviet air defense system was clearly captured by the Society’s mandate.

preparation for later participation in the Soviet air defense system was clearly captured by the Society’s mandate. The organization became prestigious and romanticized among Russian youth, who were extremely keen to earn the elaborate badges which were issued by the Society to recognize outstanding accomplishments in the various fields with which it was involved. Aeromodelling was among these recognized activities. A typical badge is seen at the left.

The organization became prestigious and romanticized among Russian youth, who were extremely keen to earn the elaborate badges which were issued by the Society to recognize outstanding accomplishments in the various fields with which it was involved. Aeromodelling was among these recognized activities. A typical badge is seen at the left. The AMM-1 was the first of a long line of Russian “clones” of successful designs from beyond the Iron Curtain. It was a great success, becoming the most widely-used model engine in Russia for the better part of a decade and remaining in production until the intervention of World War II in Russian affairs in 1941, returning for several years after the war. However, the engine never went on general sale, instead being distributed exclusively through the OSOAVIAKHIM aeromodelling club system.

The AMM-1 was the first of a long line of Russian “clones” of successful designs from beyond the Iron Curtain. It was a great success, becoming the most widely-used model engine in Russia for the better part of a decade and remaining in production until the intervention of World War II in Russian affairs in 1941, returning for several years after the war. However, the engine never went on general sale, instead being distributed exclusively through the OSOAVIAKHIM aeromodelling club system.  destined to oversee the development of many of the Russian model engine designs which were to appear during the following three decades.

destined to oversee the development of many of the Russian model engine designs which were to appear during the following three decades. A further organizational change took place on August 20

A further organizational change took place on August 20

It’s important to understand that ZSTKAM had no production facilities of their own. They merely developed and tested prototypes of various model engines. The production of the designs which were judged to be worthy remained under the control of DOSAAF, being carried out elsewhere by others. ZSTKAM was strictly a design organization, not a manufacturer.

It’s important to understand that ZSTKAM had no production facilities of their own. They merely developed and tested prototypes of various model engines. The production of the designs which were judged to be worthy remained under the control of DOSAAF, being carried out elsewhere by others. ZSTKAM was strictly a design organization, not a manufacturer.

To address the quality issue, DOSAAF arranged for the production of some of the more promising engines, or those intended primarily for export, in military workshops. For example, the “ZNAR” (Russian 3HAP) Aircraft Fuel Systems plant in Moscow produced such internationally-popular engines as the 1.5 cc

To address the quality issue, DOSAAF arranged for the production of some of the more promising engines, or those intended primarily for export, in military workshops. For example, the “ZNAR” (Russian 3HAP) Aircraft Fuel Systems plant in Moscow produced such internationally-popular engines as the 1.5 cc

There were very few specialty model shops in the USSR. Only in a few large cities were there so-called “Youth Technology” model shops where one could buy model engines and aircraft kits. However, these items were very rarely offered for sale. In addition to Soviet engines, it was sometimes possible to find Zeiss “JENA” model engines from East Germany, which was after all still within the sphere of Russian control. The USSR also purchased more exotic foreign competition engines from beyond the Iron Curtain in smaller quantities, including Super Tigre, MVVS, OPS and Webra products. However, the DOSAAF organization restricted the distribution of these engines to the most promising competition fliers. They were not available for free sale.

There were very few specialty model shops in the USSR. Only in a few large cities were there so-called “Youth Technology” model shops where one could buy model engines and aircraft kits. However, these items were very rarely offered for sale. In addition to Soviet engines, it was sometimes possible to find Zeiss “JENA” model engines from East Germany, which was after all still within the sphere of Russian control. The USSR also purchased more exotic foreign competition engines from beyond the Iron Curtain in smaller quantities, including Super Tigre, MVVS, OPS and Webra products. However, the DOSAAF organization restricted the distribution of these engines to the most promising competition fliers. They were not available for free sale.  The ZSKAM 1-2.5 G (Russian ҴCKAM 1-2.5 G) glow-plug motor appeared in 1967, before the official State transfer of design responsibilities from CAML to ZSKAM. As far as I’m aware, it was the first engine to bear the ҴCKAM name. The date 1967 appeared cast in relief onto the right-hand side of the crankcase below the exhaust stack. At this time, the name of the organization had not yet been expanded to ҴCTKAM.

The ZSKAM 1-2.5 G (Russian ҴCKAM 1-2.5 G) glow-plug motor appeared in 1967, before the official State transfer of design responsibilities from CAML to ZSKAM. As far as I’m aware, it was the first engine to bear the ҴCKAM name. The date 1967 appeared cast in relief onto the right-hand side of the crankcase below the exhaust stack. At this time, the name of the organization had not yet been expanded to ҴCTKAM. Again like its MD-2.5 Meteor predecessor, this engine was also produced in diesel form with a red-anodized head, venturi, prop driver and prop washer. This version was the subject of a qualitative

Again like its MD-2.5 Meteor predecessor, this engine was also produced in diesel form with a red-anodized head, venturi, prop driver and prop washer. This version was the subject of a qualitative  The ZSTKAM 2.5 D (Russian ҴCTKAM 2.5 Д) appeared in 1975, evidently being the first model to bear the expanded name. It was the subject of a qualitative

The ZSTKAM 2.5 D (Russian ҴCTKAM 2.5 Д) appeared in 1975, evidently being the first model to bear the expanded name. It was the subject of a qualitative

By contrast with the 2.5 cc diesel just described, the ZSTKAM 3.2 D appears to be one of the least frequently-encountered members of the ZSTKAM series - very few of them seem to have escaped to Western countries. I’ve never found so much as a reference to this engine in the English-language modelling media – indeed, I only became aware of its existence as a result of my good fortune in acquiring a pristine example some years ago, quite by happenstance. I subsequently acquired a copy of V. E. Merzlykin's previously-cited 1991 Russian-language book entitled "Engines of the ZSTKAM Series", from which much of the following information was extracted.

By contrast with the 2.5 cc diesel just described, the ZSTKAM 3.2 D appears to be one of the least frequently-encountered members of the ZSTKAM series - very few of them seem to have escaped to Western countries. I’ve never found so much as a reference to this engine in the English-language modelling media – indeed, I only became aware of its existence as a result of my good fortune in acquiring a pristine example some years ago, quite by happenstance. I subsequently acquired a copy of V. E. Merzlykin's previously-cited 1991 Russian-language book entitled "Engines of the ZSTKAM Series", from which much of the following information was extracted.

The ZSTKAM-2.5 K (Russian ҴCTKAM-2.5 K) glow-plug motor was specifically designed for use in control line combat models (category F-2D) and competition free flight models (F-1C). It was mass-produced at the DOSAAF factory in Kiev beginning in 1978. As usual, this engine’s displacement of 2.47 cc was derived from bore and stroke measurements of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The engine weighed in at 170 gm (6.00 ounces) – the weight was creeping up! To compensate for this, a peak output of 0.55 Kw (0.737 BHP) was claimed, with a peak operating speed of 22,000 RPM.

The ZSTKAM-2.5 K (Russian ҴCTKAM-2.5 K) glow-plug motor was specifically designed for use in control line combat models (category F-2D) and competition free flight models (F-1C). It was mass-produced at the DOSAAF factory in Kiev beginning in 1978. As usual, this engine’s displacement of 2.47 cc was derived from bore and stroke measurements of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The engine weighed in at 170 gm (6.00 ounces) – the weight was creeping up! To compensate for this, a peak output of 0.55 Kw (0.737 BHP) was claimed, with a peak operating speed of 22,000 RPM.  The engine featured a monobloc main casting which included both the cylinder cooling fins and the housing for the main bearing, including accommodation for the two ball races which supported the shaft. This casting incorporated a rectangular rear exhaust, albeit not configured for use with a tuned pipe. Crankshaft front rotary valve induction continued to be employed. Both glow heads and cylinder heads with inserts for standard glow-plugs were available. The engine featured three-channel Schnürle scavenging and an ABC piston/cylinder set. The connecting rod was machined from aluminum alloy. The backplate was molded from plastic. The characters “ҴCTKAM 2.5 K” (ZSTKAM-2.5 K) were cast onto the crankcase.

The engine featured a monobloc main casting which included both the cylinder cooling fins and the housing for the main bearing, including accommodation for the two ball races which supported the shaft. This casting incorporated a rectangular rear exhaust, albeit not configured for use with a tuned pipe. Crankshaft front rotary valve induction continued to be employed. Both glow heads and cylinder heads with inserts for standard glow-plugs were available. The engine featured three-channel Schnürle scavenging and an ABC piston/cylinder set. The connecting rod was machined from aluminum alloy. The backplate was molded from plastic. The characters “ҴCTKAM 2.5 K” (ZSTKAM-2.5 K) were cast onto the crankcase.  The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS (Russian ҴCTKAM-2.5 KP-AC) glow-plug engine was developed in the year 1978 specifically for use in competition tethered car and boat models. The engine was produced in large quantities at DOSAAF's Kiev plant in Ukraine.

The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS (Russian ҴCTKAM-2.5 KP-AC) glow-plug engine was developed in the year 1978 specifically for use in competition tethered car and boat models. The engine was produced in large quantities at DOSAAF's Kiev plant in Ukraine.

The ZSTKAM 1.5 KR-AS (Russian ҴCTKAM-1.5 KP-AC) was developed specifically for use in high-speed tethered car and boat models in the 1.5 cc category. Development commenced in 1978, with series production following in 1980. In essence, the engine was a down-scaled rendition of the ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS dual-purpose model described earlier. It was produced in substantial numbers alongside its 2.5 cc sibling at the DOSAAF plant in Kiev, Ukraine.

The ZSTKAM 1.5 KR-AS (Russian ҴCTKAM-1.5 KP-AC) was developed specifically for use in high-speed tethered car and boat models in the 1.5 cc category. Development commenced in 1978, with series production following in 1980. In essence, the engine was a down-scaled rendition of the ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS dual-purpose model described earlier. It was produced in substantial numbers alongside its 2.5 cc sibling at the DOSAAF plant in Kiev, Ukraine.  The crankshaft with its short nose was supported in twin ball bearings. A significant departure from the design of the larger ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS as originally released was the used of bolt-on front and rear housings. The design of the crankcase made it possible to swap the backplate and the crankshaft housing to place the exhaust at either end, allowing the engine to be used with either a flywheel or an airscrew. If this was done, however, it was necessary to modify the crankcase internally to prevent the entry to the crankcase from the intake from becoming partially obscured.

The crankshaft with its short nose was supported in twin ball bearings. A significant departure from the design of the larger ZSTKAM-2.5 KR-AS as originally released was the used of bolt-on front and rear housings. The design of the crankcase made it possible to swap the backplate and the crankshaft housing to place the exhaust at either end, allowing the engine to be used with either a flywheel or an airscrew. If this was done, however, it was necessary to modify the crankcase internally to prevent the entry to the crankcase from the intake from becoming partially obscured.

The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR (Russian ҴCTKAM 2.5 KP) glow-plug motor was specially designed for control-line speed models in the F2A category and for free flight models in the F1C category. This engine represented a return to the earlier “cloning” era in Russian model engine manufacture, since it was actually a 100% copy of the Italian record-breaking Rossi R-15 engine. It was developed beginning in 1976 and was produced in series from 1983 at the Savma "PROGRES" aviation engineering plant in Savyolovo, Kimry.

The ZSTKAM-2.5 KR (Russian ҴCTKAM 2.5 KP) glow-plug motor was specially designed for control-line speed models in the F2A category and for free flight models in the F1C category. This engine represented a return to the earlier “cloning” era in Russian model engine manufacture, since it was actually a 100% copy of the Italian record-breaking Rossi R-15 engine. It was developed beginning in 1976 and was produced in series from 1983 at the Savma "PROGRES" aviation engineering plant in Savyolovo, Kimry.

There were doubtless other designs developed by ZSTKAM which never made it into full-scale production. An apparent example which is included in Merzlykin's previously-cited 1991 Russian-language book was the ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2 diesel. Despite its name association with the earlier ZSTKAM 2.5 D, it was actually a completely different design from the ground up, sharing little other than the same bore/stroke dimensions of 15/14 mm.

There were doubtless other designs developed by ZSTKAM which never made it into full-scale production. An apparent example which is included in Merzlykin's previously-cited 1991 Russian-language book was the ZSTKAM 2.5 D-2 diesel. Despite its name association with the earlier ZSTKAM 2.5 D, it was actually a completely different design from the ground up, sharing little other than the same bore/stroke dimensions of 15/14 mm. Some elements of the former DOSAAF operation undoubtedly made such changes successfully, thereby weathering the storm – for example, the Savma "PROGRES" aviation engineering plant in Savyolovo, Kimry was definitely still in operation in 1996, producing the MDS range of engines. There’s also some evidence to suggest that the DOSAAF plant in Ivanovo continued to produce the TALKA engines, at least for a while.

Some elements of the former DOSAAF operation undoubtedly made such changes successfully, thereby weathering the storm – for example, the Savma "PROGRES" aviation engineering plant in Savyolovo, Kimry was definitely still in operation in 1996, producing the MDS range of engines. There’s also some evidence to suggest that the DOSAAF plant in Ivanovo continued to produce the TALKA engines, at least for a while.