|

|

The Vivell Diesels

Somewhat surprisingly given the attachment of his name to these products, Earl Vivell was not a manufacturer per se – rather, he was a hobby shop owner, an avid hands-on modeller and a business promoter. All of his offerings were manufactured for him by others. Vivell operated the engine marketing side of his business from his home at 2470 - 27th Avenue, San Francisco, California. From the standpoint of the model engine enthusiast, a point of particular interest in the Vivell story is the fact that he was the promoter of one of the ranges of model diesel engines developed in America during the early classic period. Moreover, the diesels marketed under the Vivell name were both very well made and endowed with some highly original features. I’ve mentioned the Vivell diesels in several previous articles on this website. However, I thought that it might be helpful to add a focused article on these engines to complement my other articles on American diesels. The following represents my attempt to do so. Background

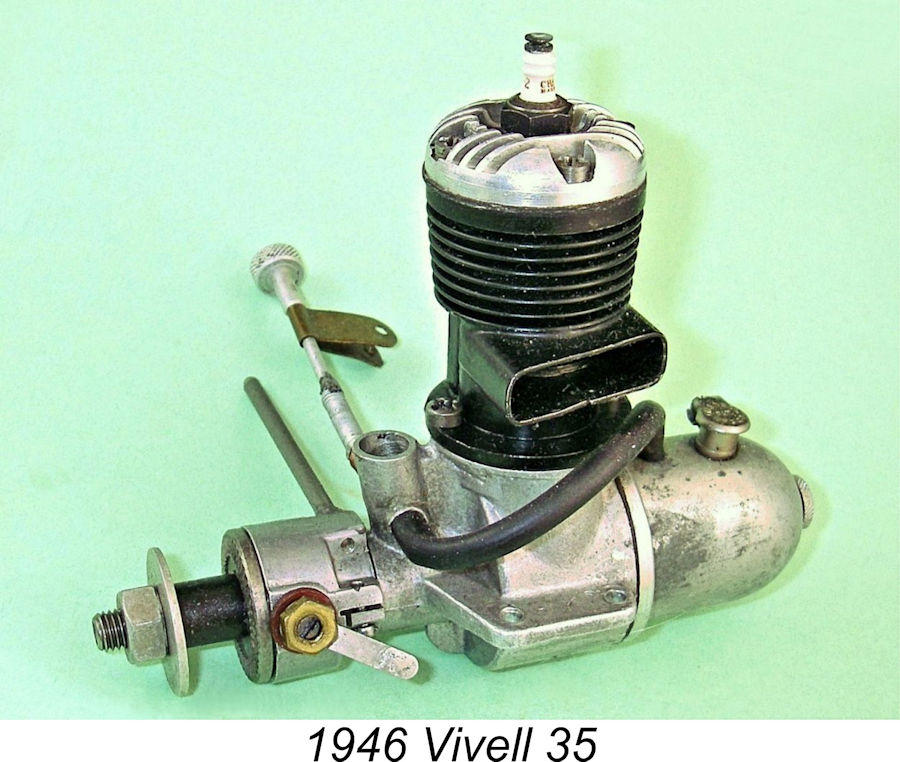

Earl proceeded to advertise “A Few Small Class C Engines Left”. These were the so-called Vivell “Class C” engines which were actually the left-over Comet 35 units with a few very minor changes to distinguish them from their Comet ancestors. In this way, the Vivell line of engines was born. The “real” Vivell 35 engines appeared in 1945, continuing to be manufactured by Jack Keener with help from Jim Brown, another well-known West Coast engine man resident in Oakland. These two individuals were among the most prolific The Vivell 35 went through numerous design changes and in late 1946 was joined by the Vivell “Forty Niner”, this time a direct successor to the earlier Thermite and Little Dynamite designs of Jim Brown. This model was manufactured jointly by Jim Brown and Jack Keener. Earl Vivell was on a roll! His engine line was expanding and his hobby business was still doing very well, riding the crest of the post-war modelling boom. A Twin was added to the range and was produced in several variants. Beginning in 1948 Vivell added a line of small engines under the “Precision” heading. The first Vivell diesel, the Vivell Precision 10, was introduced locally in October 1947 and first advertised nationally in the April 1948 issue of “Air Trails”.

While researching the Vivell range for “Model Builder” magazine, the late John Pond gained the impression that although Earl clearly had national marketing ambitions, his ambitions out-ran his financial capacity. His venture was always under-capitalized, hence being unable to fund the production of the Vivell-branded engines in the kind of quantities which would be required to support a national marketing program. Moreover, while the Vivell engines were perfectly serviceable powerplants, they really didn’t offer sufficient stand-out inducement to prospective buyers to choose them over the available alternatives from the likes of Ohlsson, Atwood, Forster, Herkimer and others.

The various Vivell diesel models are covered in some detail in Volume 2 of Tim Dannels’ indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE). In addition, the engines received some additional coverage in the late John Pond’s “Plug Sparks” column which was a feature of “Model Builder” magazine during the 1980’s. John’s comments on the Vivell .102 and .035 diesel models appeared in the August 1984 and January 1986 issues respectively. Finally, my good mate Maris Dislers wrote up a review of the Vivell 10 some years ago which was never published. Maris very generously shared this with me, allowing me to roll his comments into this article. Now, having summarized the background and acknowledged my principal sources, I’ll share what I’ve been able to learn about these unexpectedly excellent model diesels from America. The Vivell .10 diesel

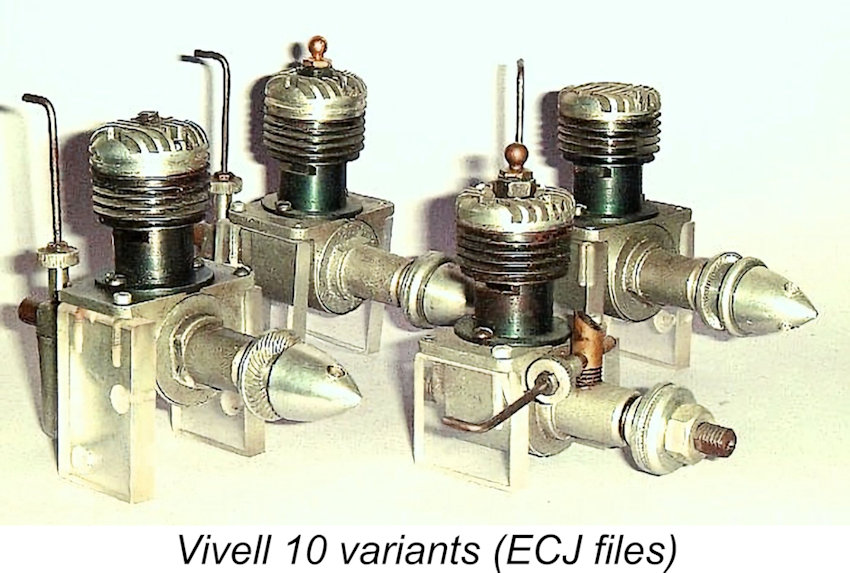

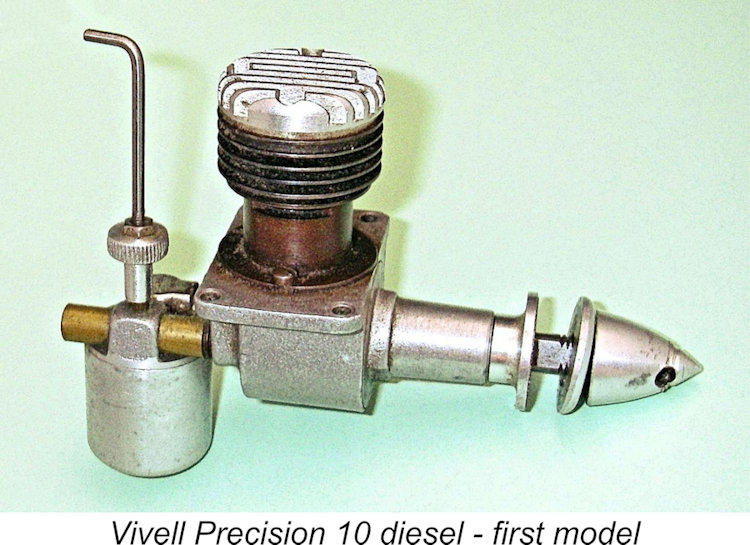

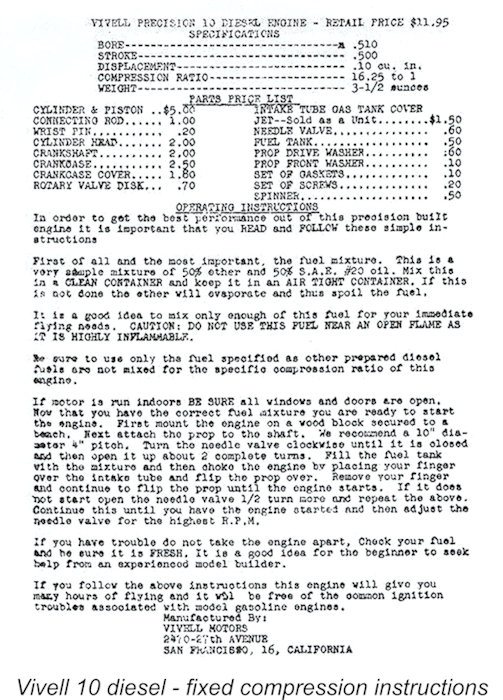

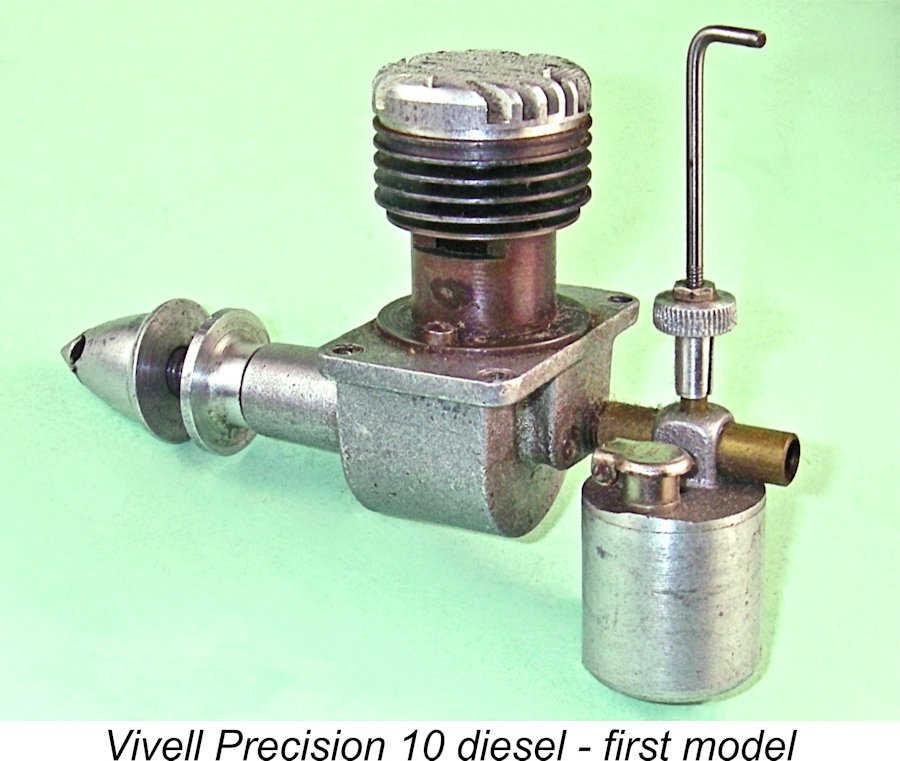

The Vivell 10 diesel was marketed as the Vivell Precision 10 model. Bore and stroke of this plain bearing unit were 0.510 in. (12.95 mm) and 0.500 in. (12.70 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.102 cuin. (1.674 cc). The original version of The engine featured a hardened steel piston operating in a steel cylinder. The instruction leaflet cited a design compression ratio of 16.25 to 1, a figure which appears to be quite compatible with the recommended fuel mixture of equal parts ether and S.A.E. 20 mineral oil. However, it appears that this compression ratio was not built into a number of examples of this model. More of this below. The cylinder port timing was relatively mild. Exhaust and transfer durations were 110 degrees and 100 degrees respectively. The disc rear rotary valve opened at around 60 degrees ABDC and closed at 20 degrees ATDC for a total induction period of 140 degrees. The one-piece steel crankshaft had a counterbalanced web. It ran in a brass-bushed main bearing. An important feature worth noting was the screwed-in front plate which used left-hand threads to keep the plate from unscrewing while the engine was running. Owners of these engines should be mindful of this thread orientation if their engines ever require dismantling for servicing.

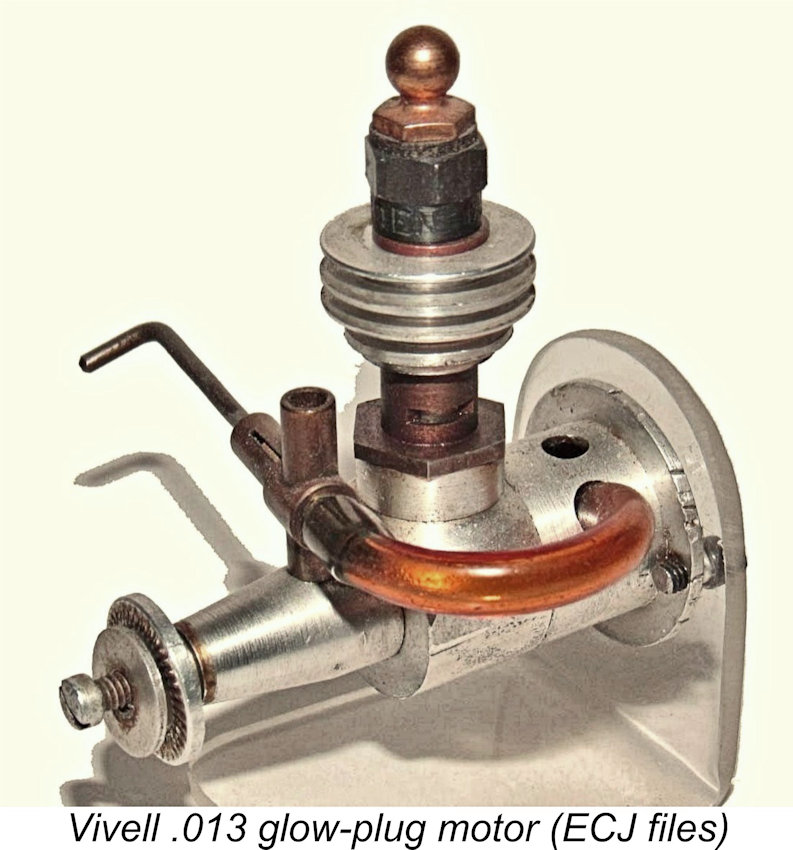

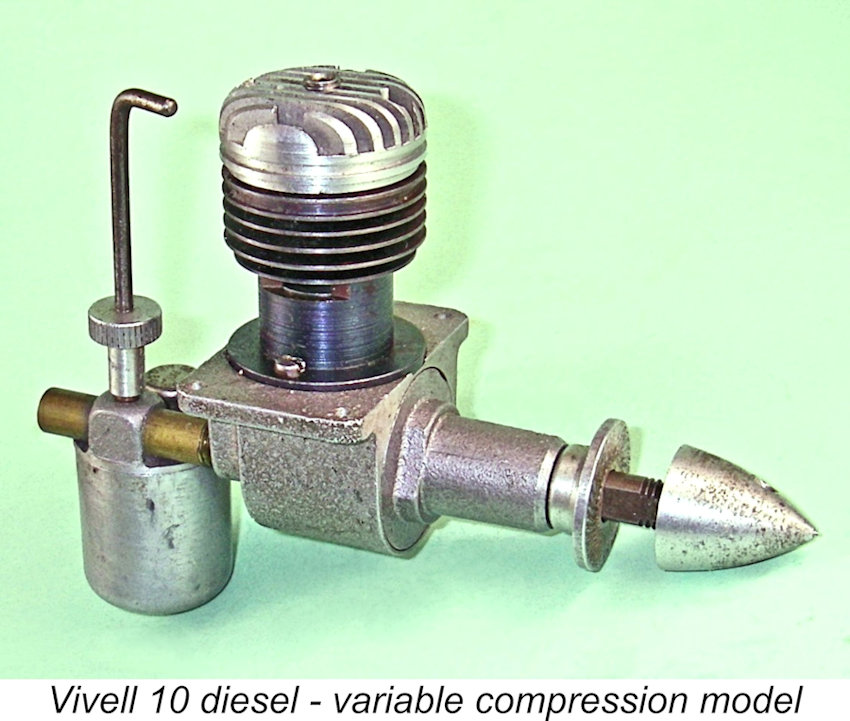

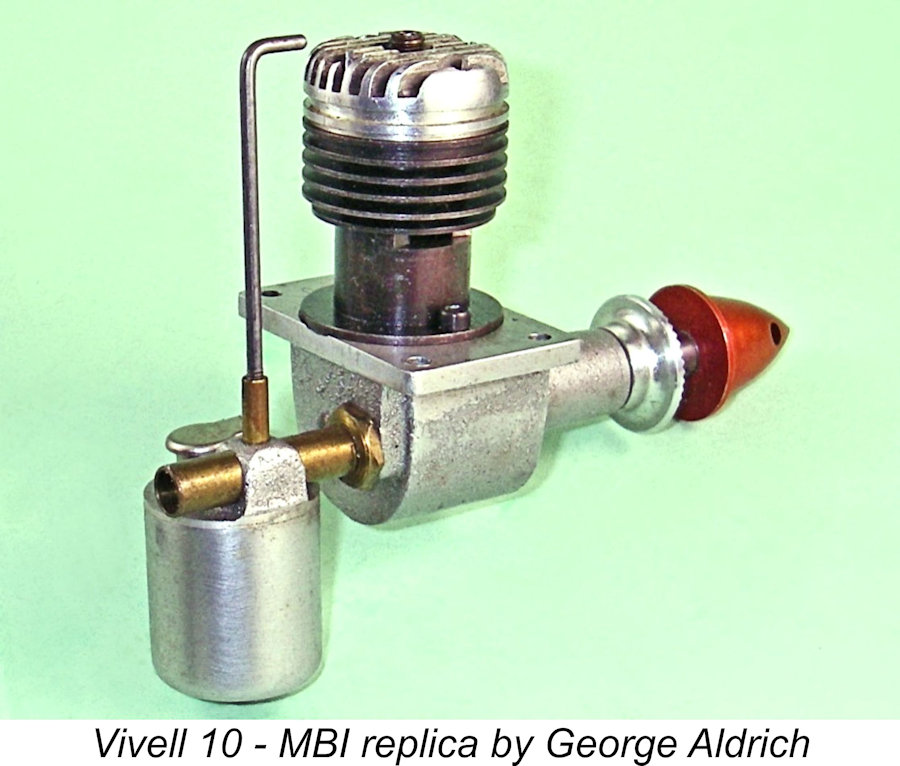

The fixed-compression Vivell 10 diesels appear to have been somewhat undependable runners. Maris Dislers attempted to test two distinct examples, failing to extract more than a few pops from them regardless of the fuel used. This issue appeared to be down to the fact that the tested examples appeared to have fixed compression ratios that were far too low - around 10 to 1 in Maris's estimate, very much lower than the claimed 16.25 to 1 figure. At Difficulties of this kind prompted the appearance of a variable compression version of the engine soon thereafter in 1948. The contra piston was located in the head rather than in the top of the cylinder bore. The use of an Allen screw to adjust the compression was a bit problematic – a conventional tommy bar would have been greatly preferable. Bore and stroke were unchanged, but the bulkier and more complex head caused an increase in the weight to 4.23 ounces (120 gm). In order to attempt to move with the times, a glow-plug variant of this engine was also developed. However, this was not a sales success, being produced in very small numbers. A few examples of the glow-plug variant were produced with crankshaft front rotary valve induction, but these fared no better. The Motor Boys Replicas In the year 2000, the members of Motor Boys International (MBI) got together to create a number of superb replicas of the second model of the Vivell Precision 10 diesel. A detailed article describing the project was written up by the late Ron Chernich and published on his “Model Engine News” (MEN) website, where it may still be found.

The MBI version of the Vivell Precision .09 diesel followed the original very closely indeed. Sand cast case, front housing and tank top, bar stock head with internal contra piston, rear disc rotary valve induction and machined tank were all featured. The major change was the use of two transfer ports rather than the single port used in the originals. The exhaust period was also extended slightly, as was the induction period. Original engines used the previously-mentioned Allen head set screw compression adjustment arrangement, but the MB plans show either the Allen head screw or a standard tommy bar adjuster. It must be said that the tommy bar system is far more convenient to use. Larry Jenno of Las Vegas also produced a few replica Vivell 10 diesels. Like all of Larry’s work, they were produced to very high standards. Since they featured a tommy bar comp screw and a rather different carburettor/needle valve assembly, they are readily distinguishable from the originals. The Vivell 10 Diesel on Test My decision to pull together a stand-alone article on the Vivell diesels triggered a somewhat foggy memory that my good mate Maris Dislers had undertaken some testing of the Vivell 10 diesel a few years ago. My inquiry to Maris resulted in him supplying not only his test results but also the text of an unpublished article which he had written up on the engines. Treasure trove indeed! With Maris's kind permission, I was able to roll his comments into this article. I mentioned earlier that Maris had no luck at all with the original fixed-compression version of the engine despite having access to two examples to test. The recommended fuel for this variant was a standard fixed-compression mix of equal parts ether and mineral oil, but the engine simply didn't want to know, regardless of the fuel used. The problem appeared to be the result of a fixed compression ratio that was far too low - around 10 to 1 according to Maris's estimate. The best that Maris could extract was a few pops and bangs. No such problems were encountered with the variable compression model! Maris tried the engine using a more conventional fuel consisting of equal parts castor oil, ether and kerosene, with .8% EHN ignition improver added. Using this blend, the engine started easily, adjusted nicely and ran with low vibration at all speeds. The following data were recorded.

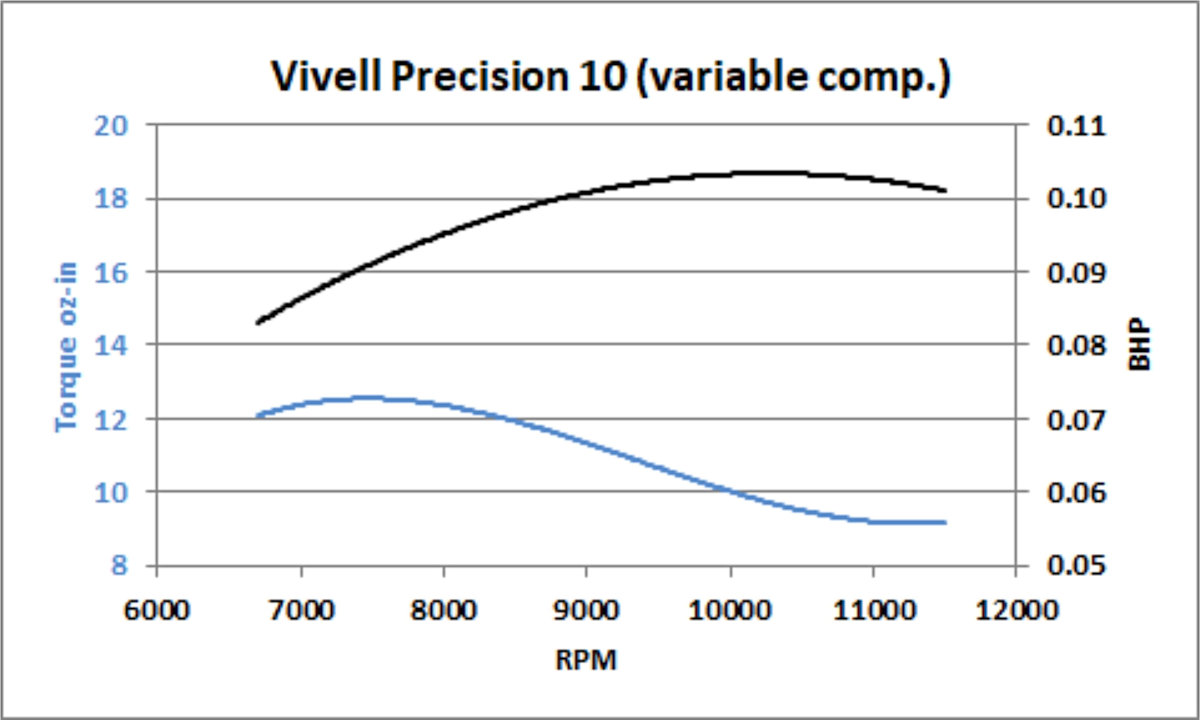

The performance curves show power topping the .1 BHP mark right across the 8,500 – 11,500 RPM range, with an indicated peak of .103 BHP at 10,300 RPM, where torque remained at almost 10 oz-in. Maximum torque of 12.6 oz-in occurred at 7,500 RPM. This is an excellent performance for a 1.6 cc diesel of 1948 vintage - it matched the measured performance of the slightly larger-displacement FROG 180 diesel of 1948, for example. It would be several years before British manufacturers developed 1.5 cc diesels which beat these figures.

The Vivell Precision 10’s performance shows the advantage of applying “next generation” design principles when compared against other contemporary American diesels. Power equalled the bulkier and heavier Micro and C.I.E. 10 models, despite those engines' 30% and 50% greater swept volumes respectively. Torque of the Vivell falls a little short of the levels developed by those two units, but peak power comes in at significantly higher RPM, which would be desirable in certain applications. Maris also sent along some notes supplied by Stan Pilgrim, one of the talented builders of a Motor Boys replica. Stan tried his Motor Boys replica using a fuel consisting of 24% castor oil, 4% Castrol A747 (a semi-synthetic 2-stroke racing oil), 35% ether and 35.5% Jet A1 (refined kerosene) plus 1.5% IPN. A 7x6 APC prop was used for initial testing. Tested on a relatively cool day, the engine was found to be capable of around 11,200 RPM on this prop with a flash to 11,400 before the main bearing seized! The engine was cleaned out and the top of the piston face was relieved slightly along with the piston skirt below the gudgeon pin bosses. The piston seal was now not as good when the engine was hot, but still more than adequate for starting and running.

Stan also tried the 7x6 APC on this fuel. The engine behaved much the same as it had done on the other fuel but achieved a slightly higher best speed of 11,200 RPM - around 0.143 BHP at this speed. It actually seemed happier when set slightly rich to run at 11,000 RPM. It appears from the results recorded by both Maris and Stan that the Motor Boys replica out-performed the original by a substantial margin. We might expect this given the replica's use of two transfer ports along with extended exhaust and induction periods. Regardless, the performance of the replica proves beyond argument that with further development, the Vivell 10 had the potential to set a standard of diesel performance in its displacement category that would not be matched for some years. The Vivell .035 diesel

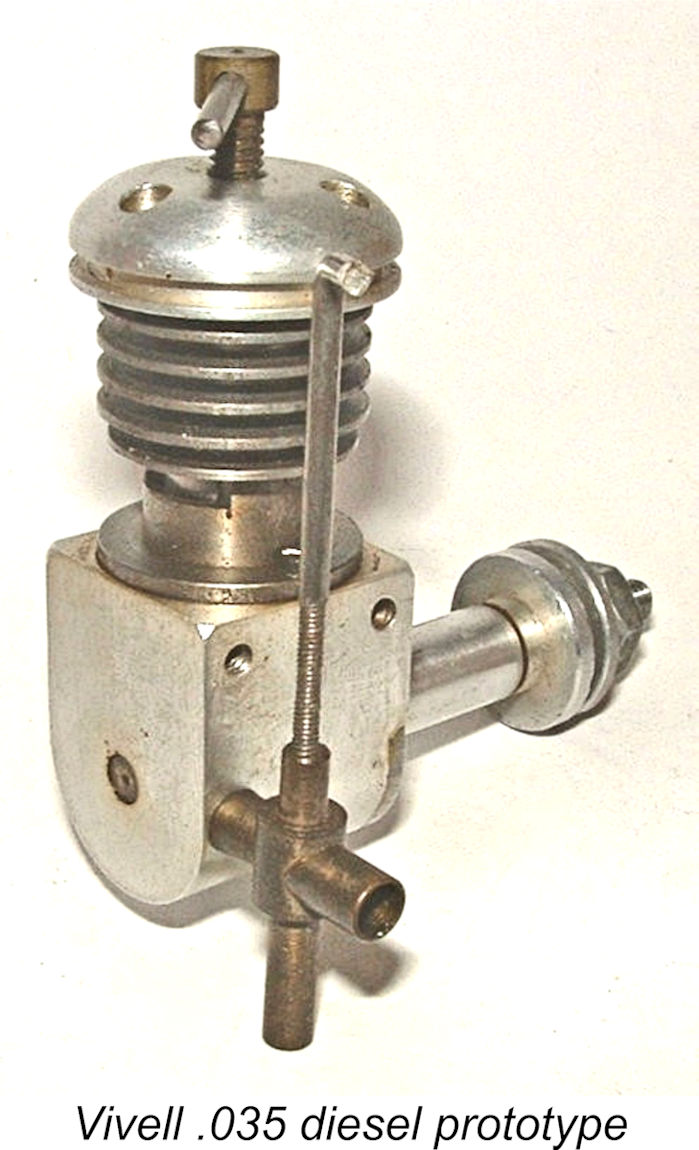

A number of prototypes of this engine were tried, including examples with one and two exhaust ports respectively as well as the rather strange variant seen at the right, which featured an intake tube mounted on the side of the crankcase and timed by an induction port located peripherally on the circumference of the rotary disc. However, the design eventually adopted for production featured a conventional disc valve induction system along with conventional radial porting having three exhaust ports and three transfer ports located between them.

The mounting system was somewhat problematic – the crankcase was not provided with mounting lugs of any kind. It would have been necessary to create some kind of radial mounting ring to be secured to the rear of the case using the three machine screws provided. A clearance hole would have to be included to accommodate the rear induction tube.

Of course, by this time the American market for diesels had largely evaporated. According to John Pond, the majority of these engines ended up being exported to Europe, where sales prospects for diesels were significantly better. However, if this is so, one wonders how such an initiative escaped the attention of the Eurpopean modelling media so completely and why no advertising appears to have taken place. Moreover, where are those engines now? Almost all surviving examples show up in America rather than Europe. Personally, I'm far from convinced .......... The probable reality is that several other factors conspired to erode the engine’s sales prospects. For one thing, the somewhat awkward mounting system can’t have helped – it would have put off many prospective buyers. The absence of any advertising also wouldn't have helped. But a more serious issue was the fact that for some unexplained reason (probably cost), the engines used an unhardened Another issue reported by John Pond was the fact that the engine apparently used an aluminium alloy contra-piston which sometimes seized in the head when hot, driving the engine into over-compression mode with no ability to make a correcting adjustment. If this happened and the engine was not stopped immediately, failure of the bronze conrod due to pre-ignition could result.

The smallest Vivell glow-plug design as illustrated here has generally been cited as an .020 model, although there have been seemingly reliable reports that its actual displacement was 0.013 cuin. (0.213 cc). The cylinder diameter is certainly consistent with this figure - the engine was almost dwarfed by its standard ¼-32 Arden glow-plug! The former owner of the illustrated engine, my good mate Tim Dannels, recalled that the glow-plug threaded directly into the cylinder bore, thus forming the actual cylinder head! Since the base diameter of a ¼-32 thread is 0.2128 in. (5.405 mm), the bore couldn't have been larger than 0.2125 in. (5.35 mm). If we assume that this engine used a modified .035 diesel shaft having a stroke of 0.365 in. (9.27 mm), we get a calculated displacement of 0.0129 cuin. (0.212 cc). I'm certain that this is how the illustrated engine was constructed, confirming the cited .013 cuin. nominal displacement. I have no knowledge of any confirmed .020 cuin. examples. At the time when I prepared this article, I hadn't found an opportunity to make up a test mount for the Vivell .035 diesel. If and when I do so, I will run a series of bench tests and report the findings in an addendum to this article. Summary and Conclusion

It's undeniably true that the original fixed compression rendition of the Vivell 10 represented something of a false start. However, the addition of variable compression pretty much sorted the problems. Although the revised model ran very well as it stood, there was clearly still plenty of development potential in the design, as demonstrated by the Motor Boys renditions. If that potential had been pursued, there's little doubt that the Vivell 10 would be remembered today as one of the most remarkable diesels of its era, regardless of origin. The smaller .035 cuin. Vivell diesel had a few warts, pricipally centering upon its cylinder material and its mounting idiosyncracies. However, it too clearly had the potential to be developed into one of the better diesels of its era and displacement. So hats off to Jack Keener, Jim Brown and their mentor Earl Vivell! Between them, their efforts resulted in the manufacture of a couple of diesels of real quality and distinction. These engines and their creators are well worthy of our respectful remembrance! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2024 |

|

| |

During the early post-WW2 period in America, one of the more prominent names in modelling, especially on the West Coast of the United States, was Vivell. From 1944 through to 1952, Vivell engines and products were very popular.

During the early post-WW2 period in America, one of the more prominent names in modelling, especially on the West Coast of the United States, was Vivell. From 1944 through to 1952, Vivell engines and products were very popular. As WW2 was approaching its final stages beginning in 1943, Earl Vivell’s hobby shop in San Franciso was doing well. However, this wasn’t enough for Earl – his entrepreneurial leanings had prompted him to begin looking for a product line that he could call his own. Of course, he knew most of the manufacturers of model goods in the area, particularly the engine producers. He discovered that the Comet Company of Chicago was planning to drop the Comet 35 engine that Jack Keener of Oakland, California had been making for them. After discussing the situation, Earl got Jack to make some changes to the design and continue production, albeit now under the Vivell name.

As WW2 was approaching its final stages beginning in 1943, Earl Vivell’s hobby shop in San Franciso was doing well. However, this wasn’t enough for Earl – his entrepreneurial leanings had prompted him to begin looking for a product line that he could call his own. Of course, he knew most of the manufacturers of model goods in the area, particularly the engine producers. He discovered that the Comet Company of Chicago was planning to drop the Comet 35 engine that Jack Keener of Oakland, California had been making for them. After discussing the situation, Earl got Jack to make some changes to the design and continue production, albeit now under the Vivell name.

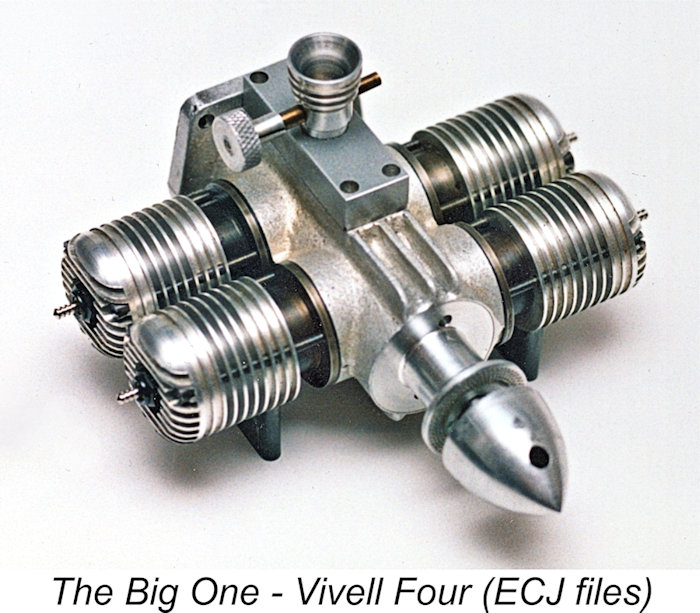

This developed into a series of .102 cuin. diesels, both fixed and variable compression, along with a small number of .102 glow-plug units, a few of which featured front rotary valve induction. A small run of .035 glow and diesel engines was added in 1950, and there was even a little .013 cuin. glow-plug unit. The piece de resistance was a .599 cuin. four cylinder unit, of which only a very few were made.

This developed into a series of .102 cuin. diesels, both fixed and variable compression, along with a small number of .102 glow-plug units, a few of which featured front rotary valve induction. A small run of .035 glow and diesel engines was added in 1950, and there was even a little .013 cuin. glow-plug unit. The piece de resistance was a .599 cuin. four cylinder unit, of which only a very few were made.  The Twins and the little .102 and .035 engines were reportedly designed and built by Jack Keener, as were the fours. Jim Brown may have had input to the diesel designs given his earlier experiments with the

The Twins and the little .102 and .035 engines were reportedly designed and built by Jack Keener, as were the fours. Jim Brown may have had input to the diesel designs given his earlier experiments with the  By 1952 the Vivell range had fallen more or less off the radar as far as most modellers were concerned. In any event, it all came to a sad end later in that year when Earl came home after a particularly gruelling day at the office and sat down in the living room to read the paper while awaiting dinner. He never answered his wife’s call to the table – a fatal heart attack claimed him right there at home.

By 1952 the Vivell range had fallen more or less off the radar as far as most modellers were concerned. In any event, it all came to a sad end later in that year when Earl came home after a particularly gruelling day at the office and sat down in the living room to read the paper while awaiting dinner. He never answered his wife’s call to the table – a fatal heart attack claimed him right there at home. The Vivell Precision 10 diesel was reportedly designed primarily by Jack Keener, although Jim Brown may well have had input to the design given his previous experience with the

The Vivell Precision 10 diesel was reportedly designed primarily by Jack Keener, although Jim Brown may well have had input to the design given his previous experience with the  the engine with its fixed compression head weighed in at 3.95 ounces (112 gm) complete with tank. The engine used disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with a cylinder featuring two opposing exhaust ports and a single interposing transfer port which overlapped the exhaust to a considerable extent.

the engine with its fixed compression head weighed in at 3.95 ounces (112 gm) complete with tank. The engine used disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with a cylinder featuring two opposing exhaust ports and a single interposing transfer port which overlapped the exhaust to a considerable extent.  The original fixed compression version of the Vivell Precision 10 was first announced rather quietly in late 1947, being sold initially through Earl Vivell's hobby shop. The first national advertisement didn’t appear until the April 1948 issue of “Air Trails”, complete with picture. Oddly enough, the picture advertisements didn’t last long, ceasing to appear within six months or so.

The original fixed compression version of the Vivell Precision 10 was first announced rather quietly in late 1947, being sold initially through Earl Vivell's hobby shop. The first national advertisement didn’t appear until the April 1948 issue of “Air Trails”, complete with picture. Oddly enough, the picture advertisements didn’t last long, ceasing to appear within six months or so.

Examples of the engine were completed by Motor Boys Ron Chernich, Stan Pilgrim, Bert Streigler, Roger Schroeder and George Aldrich, some of whom may have constructed more than a single example. A few engines may have been constructed by others. I was subsequently fortunate enough to acquire one of the examples made by the late Motor Boy George Aldrich.

Examples of the engine were completed by Motor Boys Ron Chernich, Stan Pilgrim, Bert Streigler, Roger Schroeder and George Aldrich, some of whom may have constructed more than a single example. A few engines may have been constructed by others. I was subsequently fortunate enough to acquire one of the examples made by the late Motor Boy George Aldrich.

We do not know the specified fuel for this version of the engine, but it likely had a mineral oil base, ether and perhaps kerosene. Ignition improvers were unknown before 1948. Tested using a fuel containing equal parts SAE 50 mineral oil, ether and kerosene, the engine continued to start and run well, with no power loss up to 10,000 RPM. Performance at higher speeds might be affected by detonation, but maximum power had already been reached.

We do not know the specified fuel for this version of the engine, but it likely had a mineral oil base, ether and perhaps kerosene. Ignition improvers were unknown before 1948. Tested using a fuel containing equal parts SAE 50 mineral oil, ether and kerosene, the engine continued to start and run well, with no power loss up to 10,000 RPM. Performance at higher speeds might be affected by detonation, but maximum power had already been reached. Tried again on a far hotter day (around 33ºC), the engine started easily once runnable settings were established, but tended to run hot when pushed towards its limit on this prop, which was around the 10,800 RPM mark. Stan then changed fuels to a brew with only 1% IPN and probably 20% Castrol A747 with 5% castor oil. The test prop was also changed to an 8x4 APC. As before, the engine started easily and loved this prop! It was less critical to tune and ran at a steady 11,060 RPM flat out - around 0.146 BHP at that speed. This would be a good choice as a flying propeller with the 1% IPN.

Tried again on a far hotter day (around 33ºC), the engine started easily once runnable settings were established, but tended to run hot when pushed towards its limit on this prop, which was around the 10,800 RPM mark. Stan then changed fuels to a brew with only 1% IPN and probably 20% Castrol A747 with 5% castor oil. The test prop was also changed to an 8x4 APC. As before, the engine started easily and loved this prop! It was less critical to tune and ran at a steady 11,060 RPM flat out - around 0.146 BHP at that speed. This would be a good choice as a flying propeller with the 1% IPN. The Vivell .035 diesel was developed during 1949, apparently with the intention of cashing in on the small-engine craze which began in late 1948 with the appearance of the K&B Infant .020 glow-plug model. The engine was again designed primarily by Jack Keener.

The Vivell .035 diesel was developed during 1949, apparently with the intention of cashing in on the small-engine craze which began in late 1948 with the appearance of the K&B Infant .020 glow-plug model. The engine was again designed primarily by Jack Keener. Bore and stroke of this model were 0.345 in. (8.76 mm) and 0.365 in. (9.27 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.3412 cuin. (0.559 cc). The production engines weighed in at 1.27 ounces (36 gm). A few early examples featured contra-pistons operating within the upper cylinder bore, as illustrated at the left, but the majority sported more bulky heads which contained the contra-piston, exactly like the heads of the larger 10 models.

Bore and stroke of this model were 0.345 in. (8.76 mm) and 0.365 in. (9.27 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.3412 cuin. (0.559 cc). The production engines weighed in at 1.27 ounces (36 gm). A few early examples featured contra-pistons operating within the upper cylinder bore, as illustrated at the left, but the majority sported more bulky heads which contained the contra-piston, exactly like the heads of the larger 10 models. The engine seems to have appeared in production form in early 1950. However, it was never advertised, apparently being entirely dependent upon Earl Vivell’s ability to market it directly through his hobby shop. Since they did not display serial numbers, the estimation of production figures is somewhat problematic. John Pond reported that the best available estimates suggested that perhaps 500 examples ended up being manufactured in total. Even this figure seems a bit high to me.

The engine seems to have appeared in production form in early 1950. However, it was never advertised, apparently being entirely dependent upon Earl Vivell’s ability to market it directly through his hobby shop. Since they did not display serial numbers, the estimation of production figures is somewhat problematic. John Pond reported that the best available estimates suggested that perhaps 500 examples ended up being manufactured in total. Even this figure seems a bit high to me.  steel cylinder. Those owners who actually put their examples into service reportedly found that the piston/cylinder fit wore out very rapidly, an even more serious problem for a small-bore small-displacement engine that it would be with a design having a larger bore and displacement. Word of this problem soon got around, dooming the engine in sales terms.

steel cylinder. Those owners who actually put their examples into service reportedly found that the piston/cylinder fit wore out very rapidly, an even more serious problem for a small-bore small-displacement engine that it would be with a design having a larger bore and displacement. Word of this problem soon got around, dooming the engine in sales terms.