|

|

A Forgotten British Manufacturer - Rogers & Geary

The importance of getting to grips with these topics sooner rather than later is emphasized by the fact that pretty much all of the individuals who might have had some first-hand knowledge of them through actual use back in the day have now left us. High time to do what can be done to preserve the stories of these pioneering engines before they sink irretrievably and without trace into the engulfing quicksands of time!

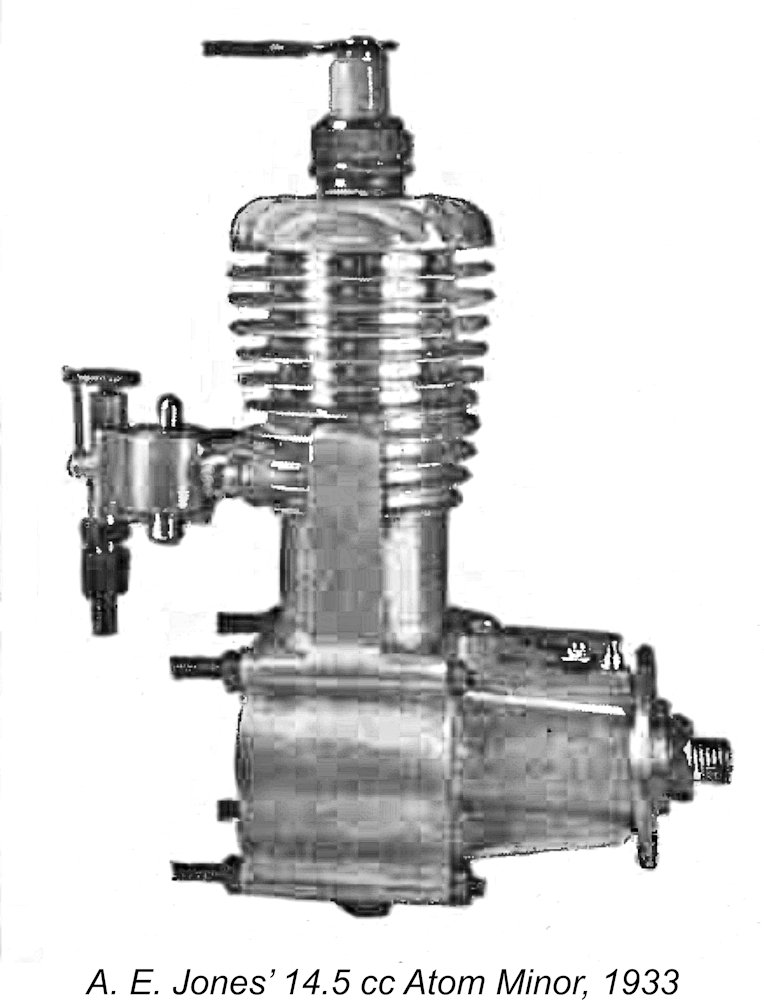

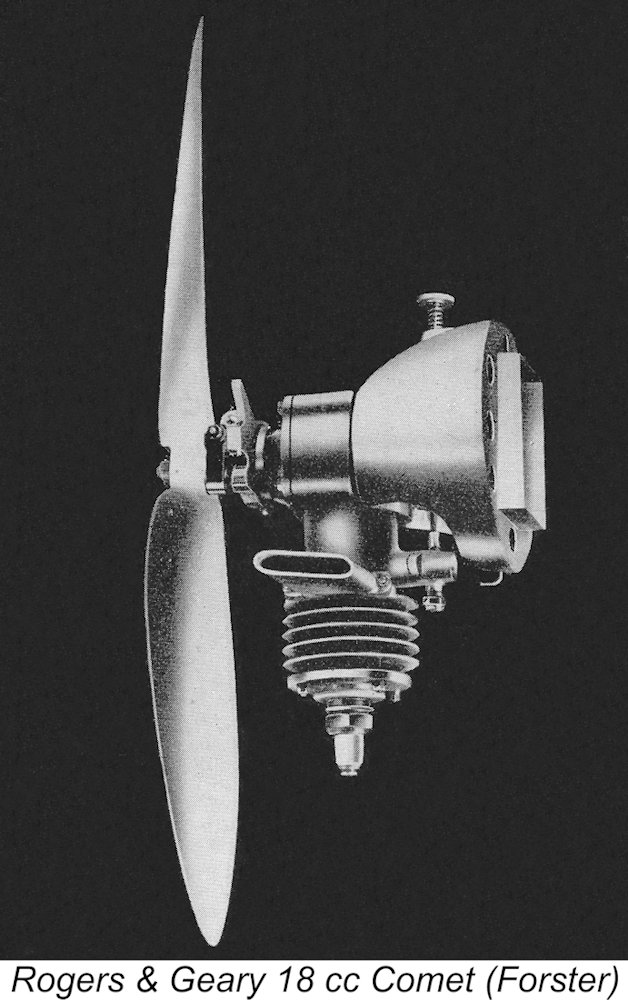

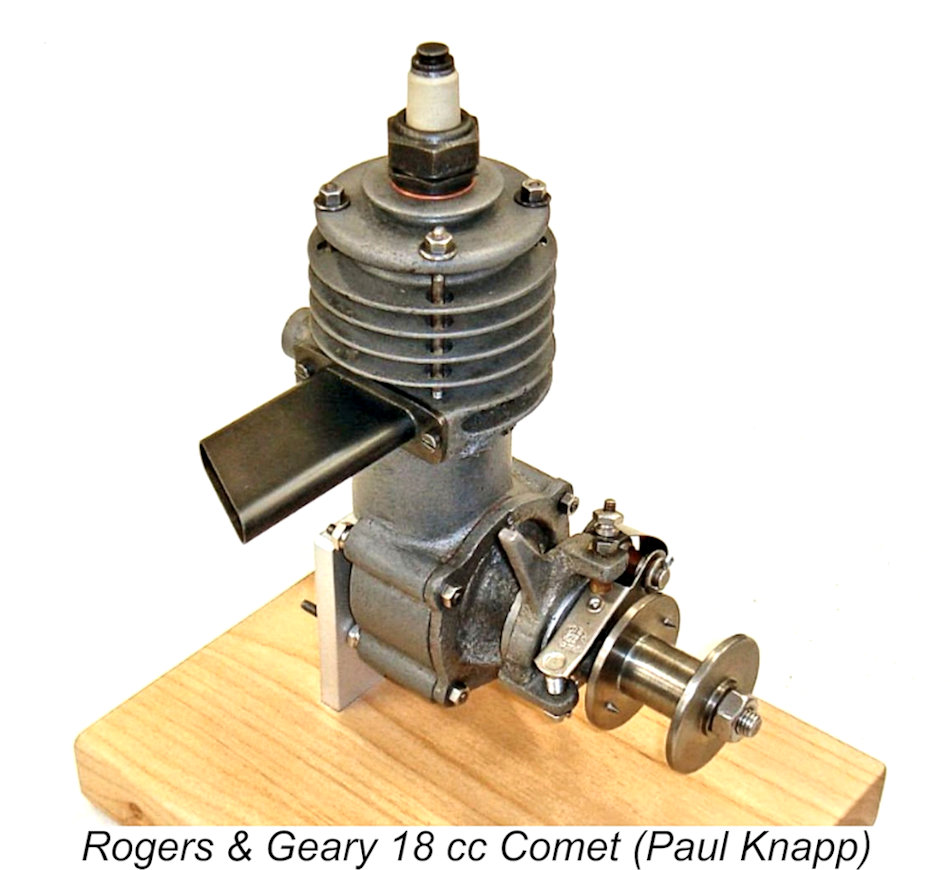

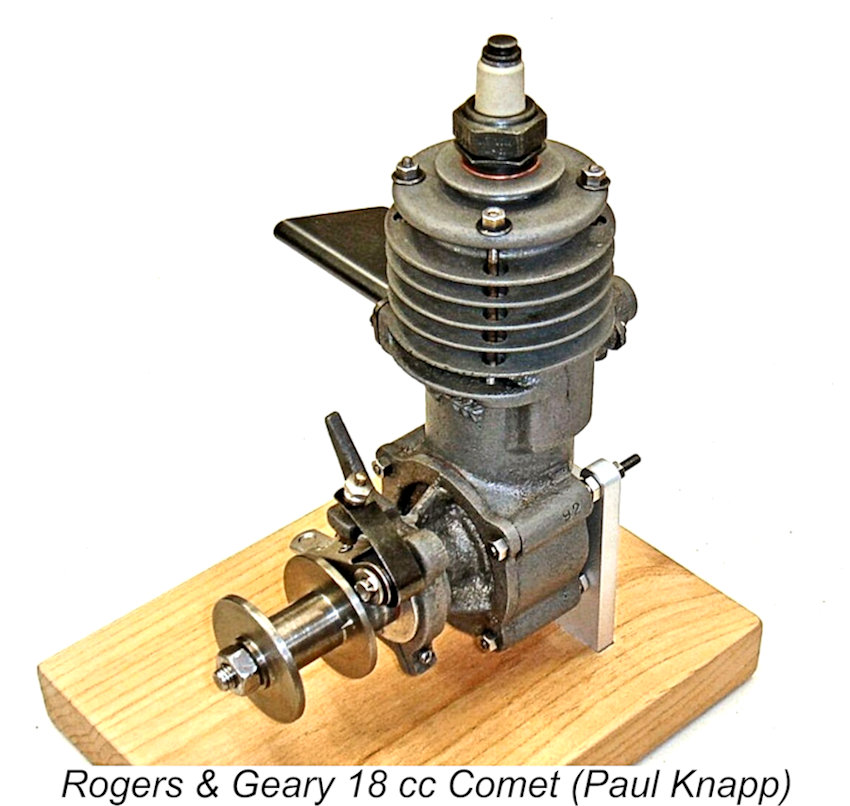

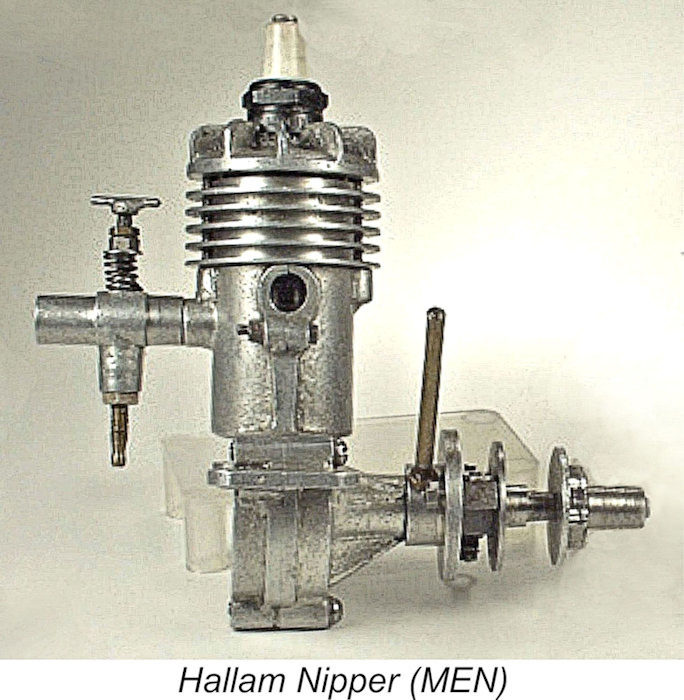

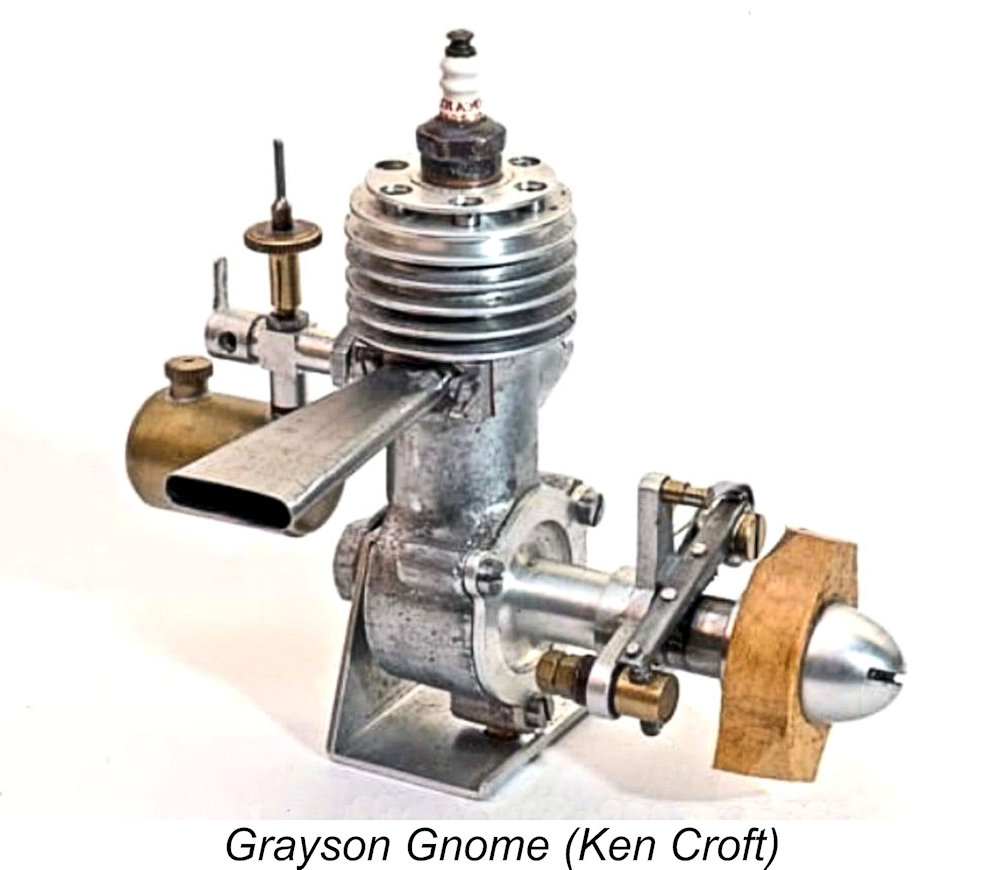

At around the same time, the prominent London model supply firm of A. E. Jones introduced their own aero model in the form of the 14.5 cc Atom Minor. Like the Gray and Hallam offerings, this was made available both ready-to-run and in casting kit form. It was quite an advanced design for its era. I’ve been unable to learn anything about A. E. Jones apart from his firm’s involvement with the Atom Minor. All that I can say is that the introduction of that model did not translate into the establishment of a true range of engines – as far as I’ve Thus, as 1935 rolled around there were three notable manufacturers of model aero engines in Britain – Gray & Son, Hallam & Son and A. E. Jones, all producing spark ignition aero engines of around 15 cc displacement. Although their engines were very much pioneering designs, lacking the design refinements which were developed later, their positive reception was sufficient to make it clear to all that a market for model aero engines was developing in Britain despite the difficult economic circumstances arising from the Great Depression. This encouraged others to enter the market themselves. Several established firms did so by making arrangements to import a few notable engines from America. Prices were high thanks to import surcharges, but their reputation preceded them. These engines included the Brown Junior, One of these individuals was a certain Mr. Brooks from Leicester in the English Midlands. In early 1935 he came up with a design for an 18 cc engine which he called the Comet. This engine evidently performed sufficiently well that he came to see it as a viable design for series production. Unfortunately, Brooks was not in a position himself to manufacture the engine – he needed help! The subsequent sequence of events is obscure in the extreme. It’s not known who approached whom or in which order the contacts were made. All that is certain is that Brooks managed to persuade a Leicester precision engineering firm to produce the engine in series. This firm was none other than our subject model engine manufacturer Rogers & Geary. Now manufacturing an engine is one thing – marketing it is quite another! It’s hard to know how it came about, but either Brooks or Rogers & Geary somehow reached an agreement with the prominent model supply firm “Model Aircraft Stores” (MAS), then located at 133 Richmond Park Road in distant Bournemouth on England’s south coast, to market the engine. Before going any further, I may as well admit right at the outset that I know almost nothing about Rogers & Geary, and relatively little about the engines that they produced. I don't even know the address of their Leicester factory. In part, this is because Rogers & Geary were never openly credited in the media with the manufacture of these engines, which were marketed predominantly by MAS as their "house range" all along. We only know that Rogers & Geary were the actual manufacturers from little snippets of information dropped here and there along the way. If any reader knows more, please get in touch! The Rogers & Geary engines are extremely rare today – I’ve never so much as seen one myself. Accordingly, the best that I can do is give the reader some idea of the general form of the engines and their dates of manufacture. It’s not much, but it’s surely better than nothing! The First Rogers & Geary Model – the 18 cc Comet

The engine was provided with a neat spun aluminium alloy conical radial mount and backplate, giving it the appearance of a massively-oversized Cox Babe Bee! However, it could be used without this accessory, also being amenable to either upright or inverted mounting. It was intended for use with an 18x12 airscrew, which it reportedly swung at over 3,000 RPM. Claimed output was 0.5 BHP at an undisclosed speed. This information was extracted from the book by the well-known pioneering British power modeller Dr. J. F. P. Forster entitled “Petrol Engines for Model Aircraft”, from which the accompanying illustration at the left was also extracted. The advertised price was £5 10s (£5.50) ready to run, a fairly steep price at a time when a typical British working man would count himself fortunate to be pulling down £4 per week, or indeed to be working at all. Somewhat oddly, the Comet seems to have been offered only in ready-to-run form – most British model aero engines of this era, like the Grayson, Jones and Hallam offerings, were also offered as casting kits to cater to the many model engineering practitioners who wished to construct their engines themselves both to save money and for the enjoyment of the process. Model engineering was a very popular hobby at the time in question, particularly since ready-to-run engines were extremely expensive by the standards of the day. Brooks wasted no time in establishing a positive reputation for his engine by making an attempt on the British record for petrol-driven model aircraft using his own-design “Sky Rocket” model powered by an 18 cc Comet engine – whether a prototype or a production model is not recorded. This attempt took place on July 21st, 1935 at Cranborne, some twenty miles north of Bournemouth, presumably with the cooperation of MAS. It was duly if somewhat belatedly reported in Frederick J. Camm’s “Model Aero Topics” column in the January 1936 issue of “Newnes Practical Mechanics” (NPM) magazine.

The participants sadly headed homeward, believing that the model was lost. However, it transpired that the “Sky Rocket” had actually made it all the way to the coast, where it eventually splashed down in the sea just off Cowes in the Isle of Wight and was fortuitously retrieved by the crew of a coastal vessel, subsequently being returned to its owner somewhat the worse for wear. The distance covered was over 35 miles (56 km) as the crow flies! Sadly, although the model and engine had undoubtedly achieved this feat, it could not be claimed as an official S.M.A.E. record since the flight had not been observed in its entirety as required by the rules for record claims. This was not the Comet’s only notable achievement during 1935. Models powered by the engine took first places at both the 1935 Bournemouth Model Aero Society power competition and the same society’s “Hallam” competition (presumably sponsored by the competing Hallam company, who didn't win!), both held at Cranbourne. A Comet-powered model also took second place at the S.M.A.E.’s prestigious 1935 Sir John Shelley national competition held at Fairey’s Aerodrome at Heathrow near London (eventually to develop into today’s Heathrow International Airport).

MAS continued to advertise the Comet in NPM throughout 1936, making much of the engine’s 1935 track record. Mr. Brooks cooperated with W. J. Forster (presumably a relative of Dr. J. F. P. Forster) in designing a model intended expressly for use with this engine. MAS offered this model either in kit or plan form. Fittingly enough, this 6-foot wingspan model was called the Comet – how original! An improved version called the Comet II appeared in early 1937, subsequently becoming the British record-holder.

Whatever the truth of that matter, someone associated with the Rogers & Geary manufacturing effort clearly took a very good look at the Baby Cyclone, deriving a considerable degree of design influence in doing so. The result was the appearance of the next Rogers & Geary model to appear – the Spitfire. Let’s look at that model next. The Second Rogers & Geary Model – the Spitfire

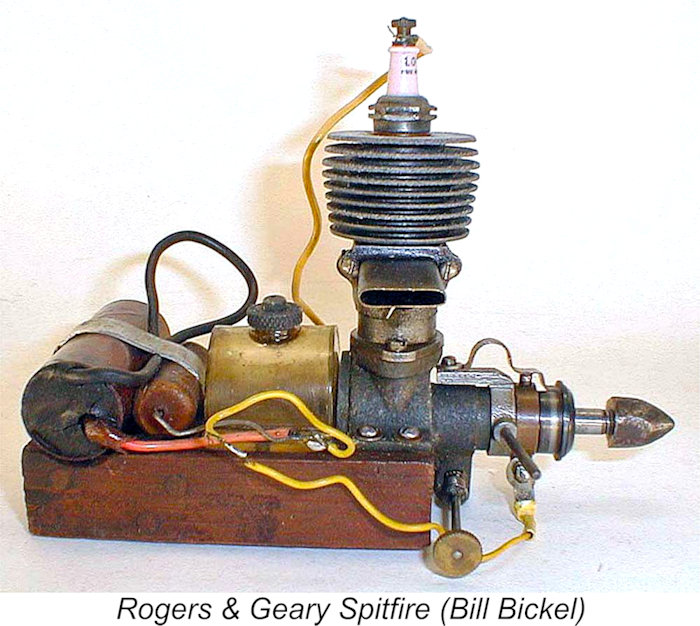

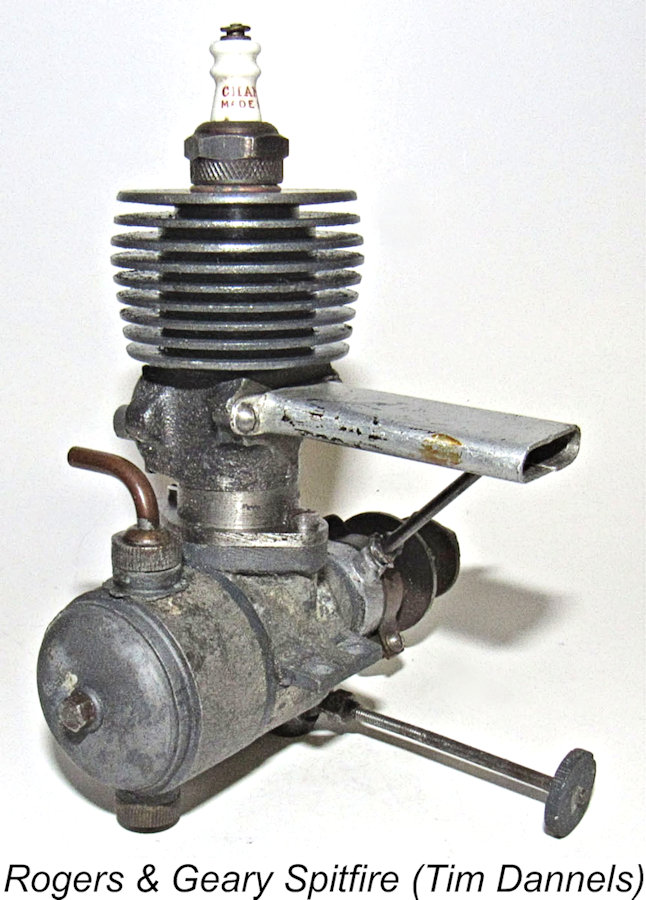

It’s not known who actually designed the Spitfire for Rogers & Geary. All that can be said with certainty is that he was very strongly influenced by the design of the Baby Cyclone which was then being distributed by Comet Aero Supplies, also of Leicester. The notion of a connection between the two firms is almost irresistible! The MAS advertisement in the December 1936 issue of NPM included the statement that “the Spitfire, our new BRITISH BABY ENGINE, will be ready soon”. However, it wasn’t until April 1937 that MAS began to advertise the engine as being available. Interestingly, it seems that MAS didn’t have the exclusive right to market the engine, since the Spitfire was advertised in the same month as being available from Kanga Aeromodels of Birmingham, far closer to Leicester. The introductory price of the engine was £4 4s 0d (£4.20) complete with 1½ ounce coil, condenser and prop.

The Spitfire incorporated the Baby Cyclone’s signature features of crankshaft front rotary valve induction, an updraft intake, an external bypass with bolt-on cover and an integrally-finned iron cylinder. The MAS advertising cited its “all-on” weight as 7½ ounces, but it wasn’t made clear whether or not “all-on” meant complete with airscrew and/or ignition components.

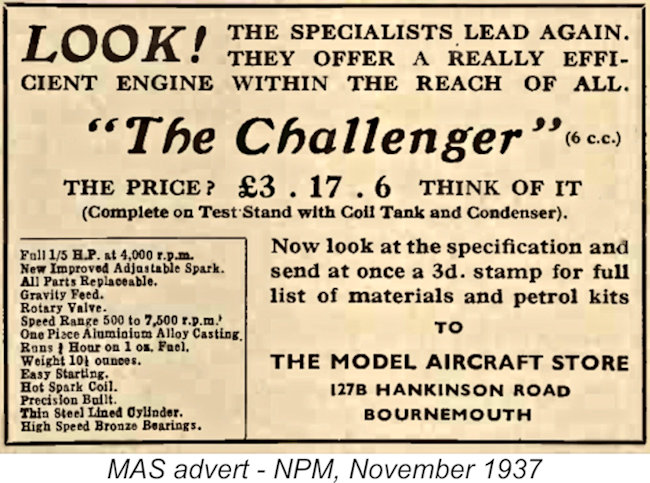

Some slackening in demand, doubtless driven by the ever-increasing competition at the time, had resulted in the price of the engine being reduced to £4 even by May 1939. This price was maintained right up to the end of promotion of the engine. The Super Spitfire remained on offer from MAS right up to the onset of WW2, making its final advertising appearance in October 1939 following the commencement of hostilities. At this point, we have to take a brief detour to look at what I consider to be one of the most fascinating unsolved mysteries of the pre-war British model engine manufacturing scene. This is the story (such as it is) of the mysterious Challenger 6 cc unit. The Challenger 6 cc Engine – What Was It?!?

All that can be deduced from the advertising is that this was a 6 cc unit which was built up around a one-piece aluminium alloy casting and featured rotary valve induction. The cylinder was apparently provided with a thin steel liner, presumably installed in a finned aluminium alloy shell. The engine reportedly weighed 10½ ounces and developed a claimed output of 0.20 BHP @ 4,000 RPM. It seems reasonable to suppose that the Challenger did indeed exist, since it was advertised by MAS on a regular basis from November 1937 to June 1938 at a bargain price of only £3 17s 6d (£3.88), thus undercutting even the smaller Rogers & Geary Spitfire offering which was offered concurrently. No indication of its actual manufacturer was ever provided – it may or may not have been a Rogers & Geary product. I’d be no end grateful to any reader who is able to shed some light on this otherwise unattested engine! Speaking of Rogers & Geary, they had not been idle on the development front during this period. In their May 1939 “Aeromodeller” advertisement, MAS announced the arrival of what they termed two “New British Super Engines” - the 6 cc Wasp and the 3.5 cc Hornet. Time to take a look at those models! The Final Pre-War Rogers & Geary engines – the Wasp and Hornet

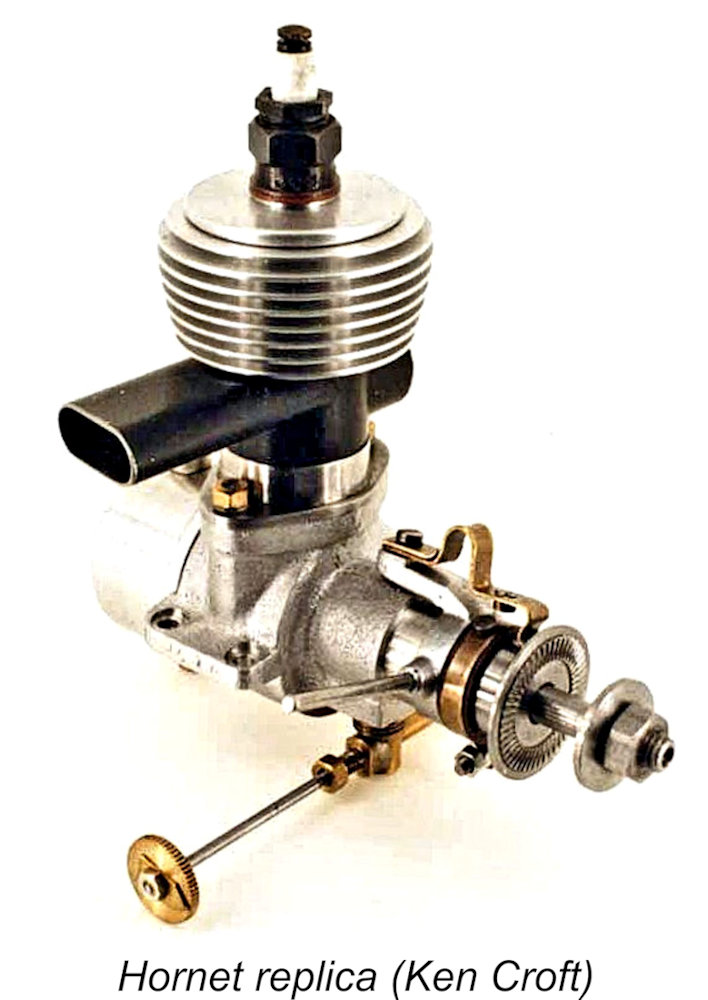

Starting with the larger Wasp, this engine was configured very much along the lines of the earlier Spitfire, featuring crankshaft front rotary valve induction, an updraft intake and cross-flow loop scavenging. It's not impossible that it was actually a development of the earlier 6 cc Challenger discussed above, but we have no evidence one way or the other. The Wasp was a long-stroke design having bore and stroke Unlike the Spitfire (and the Hornet for that matter), the Wasp was provided with lugs for radial rather than beam mounting. One fascinating accessory associated with the Wasp was the provision of a matching spun streamlined nose cone and backplate into which the engine would fit neatly. Totally impractical, but surely imparting an impressive dose of charm and character! Since the use of this accessory was not required for the engine’s installation in a model, many owners doubtless set it aside when mounting the engine. The Wasp was the subject of a brief commentary which appeared in the August 1939 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Although this reference adds nothing to the preceding description of the engine, Turning now to the Hornet, this was essentially a scaled-down version of the Wasp, its main visible departure being the use of beam mounting as opposed to the Wasp’s radial arrangement. In addition, there’s no evidence that the streamlined spun nose-cone accessory was ever created for the Hornet. Internally, the Hornet abandoned the Wasp’s long-stroke geometry in favour of a short-stroke configuration. Bore and stroke were 17 mm and 15 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 3.41 cc, more or less as advertised. Unlike the Wasp, the Hornet was never the subject of any commentary in the contemporary modelling media. Accordingly, I’m unable to provide any further information. All that I can say is that both engines continued to be promoted by MAS right up to their final pre-war advertisement for engines in the October 1939 issue of “Aeromodeller”. At that point, the pressures of war put an end to model engine manufacturing in Britain for the duration. The Final Rogers & Geary Product - the Stentor 6 cc Model

Along the way they had acquired the services of a young engineer by the name of Ted Martin, who was a keen aeromodelling enthusiast. Once free to do so, Martin turned his hand to model engine design, coming up with what proved to be the final model to be produced by Rogers & Geary – the 6 cc Stentor unit. The relationship between Rogers & Geary and MAS had survived the war, with the result that MAS resumed their former role as marketing agents for the new model. They had however changed their company name to Model Aircraft (Bournemouth) Ltd. and had begun using the soon-to-be-famous Veron trade-name.

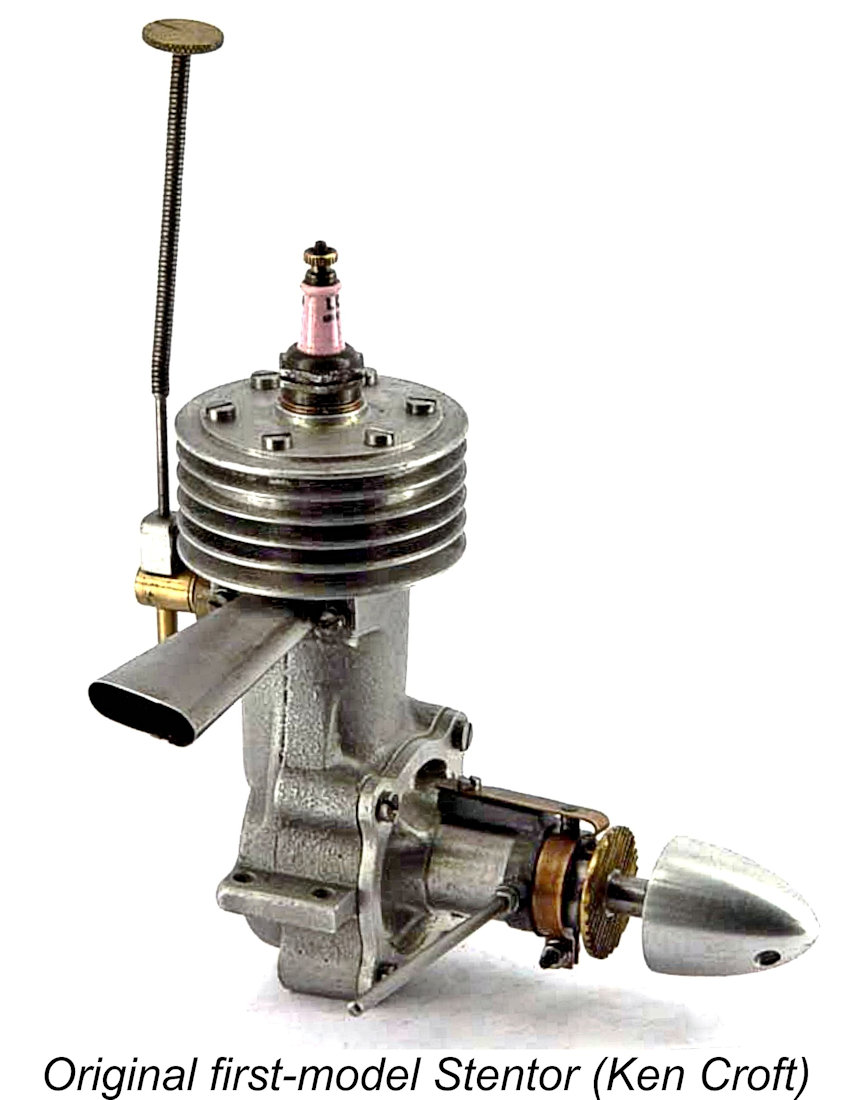

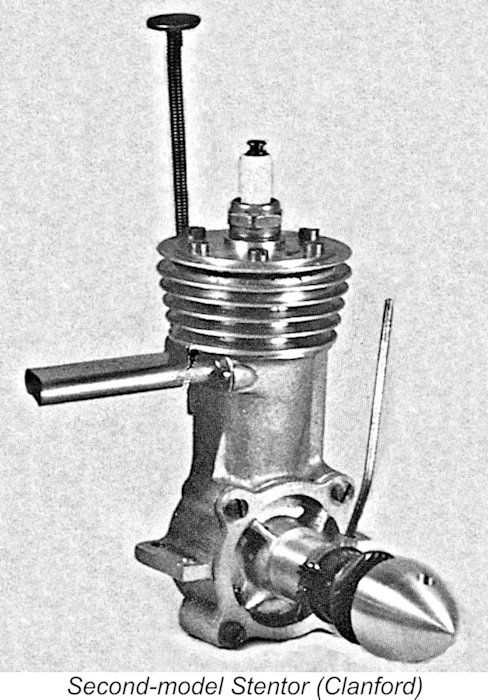

Bore and stroke of the Stentor were 19 mm and 21 mm respectively for a displacement of 5.95 cc, more or less as advertised. The engine weighed in at a somewhat porky 11.25 ounces bare. According to Ron Warring, writing in his early 1949 book “Miniature Aero Motors”, the recommended airscrews were 13x8 for free flight and 10x8 for control line. I must say that I find these recommendations extremely difficult to reconcile with one another!

What I can confirm is that the most focused advertisement for the Stentor appeared very late in its production life. This was a placement by Veron in the November 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller” (reproduced here at the right). By this time the writing was clearly on the wall for the spark ignition engine – the British “diesel revolution” initiated by the mid-1946 release of the excellent Mills 1.3 Mk. I diesel had begun the process of driving the sparkies from the field, and Ray Arden’s November 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug had driven the last nail into the coffin lid. The November 1947 Veron advertisement for the Stentor thus appears to have been a somewhat desperate last-ditch attempt to sell off remaining stocks of the engine. It evidently didn’t change the engine’s fate – after November 1947, no more was heard of the Stentor apart from a few residual listings in various model shop adverts. So ended the saga of the Rogers & Geary engines from Leicester. It had been a productive 13-year run, but all things come to an end………… there’s no evidence that the company made any effort at all to become involved in diesel or glow-motor production. Summary and Conclusion Several of the protagonists in the Rogers & Geary story went on to far greater things. Under the guidance of the late Phil Smith, Veron went from strength to strength, becoming one of the leading kit and accessory producers in the country. Ted Martin joined the Anchor Motor Co. of Chester as their chief model engine designer, developing the iconic AMCO 3.5 cc engines before moving to Canada and becoming involved very successfully in the full-sized auto industry, combining this with a period spent as the resident engine tester for the American “Model Engine News” (MAN) magazine. Sadly, there’s no record of the further activities or the ultimate fate of Rogers & Geary. Nor are there all that many surviving examples of their work. In an article which is still to be found on the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful “Model Engine News” (MEN) website, my late and much-missed mate Ken Croft expressed his assessment of the relative rarity of these engines, starting with the rarest. He considered the old Comet 18 cc model which started it all to be the rarest Rogers & Geary offering – original examples are apparently The 3.5 cc Hornet is equally rare – Ken stated that he had never seen an original example, although he and a few others had made replicas. The illustrated example is a fine replica made by John Maddaford. There are apparently a few original examples of the Wasp floating around in addition to a handful of replicas made by Ken and others. The Spitfire is apparently the Rogers & Geary model which survives in the largest numbers, but even so Ken reckoned that less than a dozen original examples probably still existed. Ken thought at one time that there were plenty of original examples of the Stentor in circulation, because he had a few of them himself. However, he had noticed that they were showing up increasingly seldom in later years. Apparently, John Goodall made castings available for the Stentor, from which quite a few replicas were made by various constructors. Ken considered the Stentor to be a good flying engine once the user sorted out its reluctance to maintain a steady two-stroke mode of operation. The very low numbers of surviving examples seem to imply that production figures weren’t all that large. Moreover, the pre-war models doubtless suffered significant losses due to being destroyed by enemy action, recycled for their metal or simply being set aside and lost in the face of more pressing concerns. They also had more time than most to wear out! Whatever the reason, they rank among the least commonly-encountered British model engines today. Most of us (like me) will never so much as see one! There appear to be somewhat more examples of the post-war Stentor floating around. However, if Ken Croft is to be believed, the majority of those that show up periodically will turn out to be latter-day replicas. In my book, that does not detract in any way from their interest! Whichever way you slice it, the Rogers & Geary model engine series is a range that richly deserves our respectful remembrance! If you’re ever lucky enough to acquire one, whether original or replica, treasure it! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2026 |

| |

In earlier articles on this website, I’ve presented as much information as I can find on several of the pioneering British commercial manufacturers of model aero engines of the pre-WW2 era. I’ve assigned some priority to this effort, because the earliest pioneering model engines are the most distant from us in time and tend to be the least well-documented. Paradoxically, they're also among the most important designs of them all, since they represent the first steps which laid the groundwork for the remarkable model engine developments of later decades.

In earlier articles on this website, I’ve presented as much information as I can find on several of the pioneering British commercial manufacturers of model aero engines of the pre-WW2 era. I’ve assigned some priority to this effort, because the earliest pioneering model engines are the most distant from us in time and tend to be the least well-documented. Paradoxically, they're also among the most important designs of them all, since they represent the first steps which laid the groundwork for the remarkable model engine developments of later decades.

The first model manufactured by Rogers & Geary beginning in 1935 was a production rendition of Mr. Brooks’ original 18 cc Comet design. It was a bulky radially-mounted side-port unit having nominal bore and stroke measurements of 1.125 in. (28.57 mm) apiece for a nominal displacement of 1.18 cuin. (18.33 cc). The engine was based upon castings formed in lightweight magnesium alloy. Even so, it weighed a ponderable 19 ounces (538 gm) without the essential airborne ignition support system (typically around 4 ounces at the time).

The first model manufactured by Rogers & Geary beginning in 1935 was a production rendition of Mr. Brooks’ original 18 cc Comet design. It was a bulky radially-mounted side-port unit having nominal bore and stroke measurements of 1.125 in. (28.57 mm) apiece for a nominal displacement of 1.18 cuin. (18.33 cc). The engine was based upon castings formed in lightweight magnesium alloy. Even so, it weighed a ponderable 19 ounces (538 gm) without the essential airborne ignition support system (typically around 4 ounces at the time). Unfortunately, this attempt did not go as smoothly as planned. The model took off with no problems but flew in a far straighter line than anticipated. Consequently, it flew away happily from the field - the duly-accredited S.M.A.E. timekeepers were only able to keep it in sight for some ten minutes. An attempt to follow it by car proved unavailing.

Unfortunately, this attempt did not go as smoothly as planned. The model took off with no problems but flew in a far straighter line than anticipated. Consequently, it flew away happily from the field - the duly-accredited S.M.A.E. timekeepers were only able to keep it in sight for some ten minutes. An attempt to follow it by car proved unavailing. The success of the Comet during 1935 encouraged the engine’s MAS distributors to initiate a national advertising campaign, which they did in December 1935 through the placement of an advertisement for the Comet in the December 1935 issue of NPM. It must be recalled that “Aeromodeller” magazine had only just commenced publication, having done so in November 1935. Prior to that date, NPM had been established as the only British magazine featuring regular in-depth coverage of aeromodelling in general, although its coverage went well beyond that hobby to encompass many facets of the do-it-yourself movement, very much including model engineering. MAS were to remain loyal NPM advertisers until late 1938, when they finally transferred their advertising allegiance to “Aeromodeller”.

The success of the Comet during 1935 encouraged the engine’s MAS distributors to initiate a national advertising campaign, which they did in December 1935 through the placement of an advertisement for the Comet in the December 1935 issue of NPM. It must be recalled that “Aeromodeller” magazine had only just commenced publication, having done so in November 1935. Prior to that date, NPM had been established as the only British magazine featuring regular in-depth coverage of aeromodelling in general, although its coverage went well beyond that hobby to encompass many facets of the do-it-yourself movement, very much including model engineering. MAS were to remain loyal NPM advertisers until late 1938, when they finally transferred their advertising allegiance to “Aeromodeller”. Although other models took centre stage after 1936 (see below), the Comet 18 cc engine remained on offer from the company right up to its final advertising appearance in August 1938. However, things had been moving behind the scenes. In the September 1936 issue of NPM, it was announced that a Leicester company called Comet Aero Supplies had become the British distributors of the

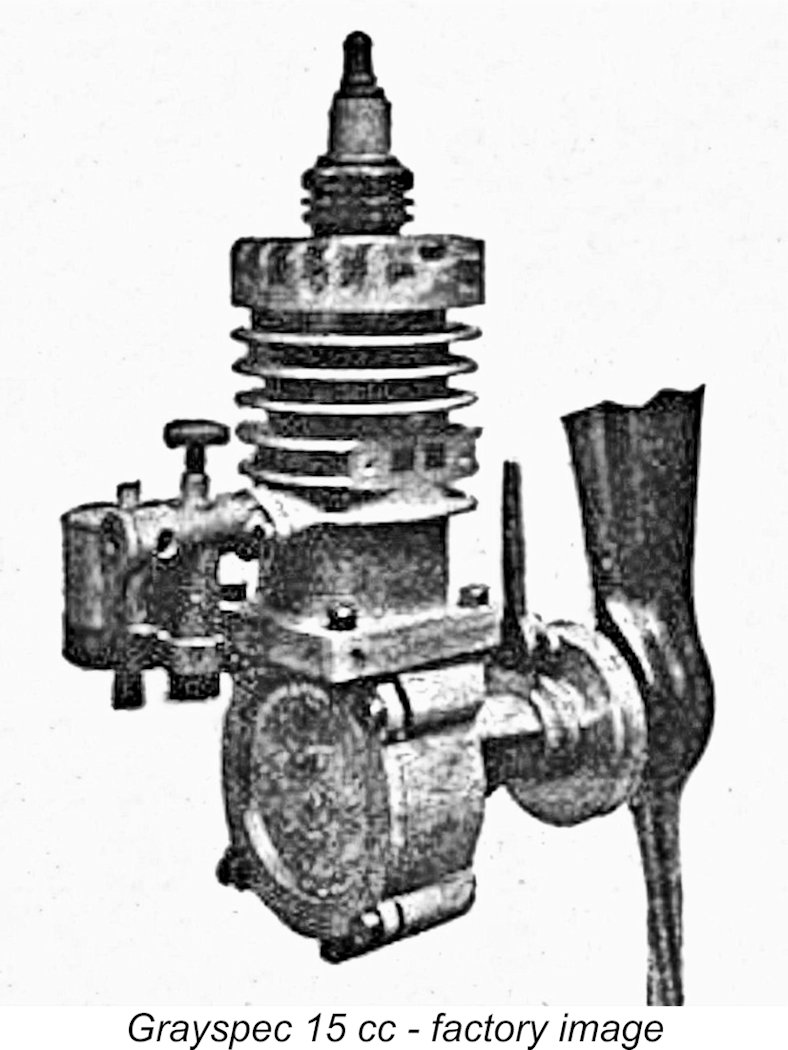

Although other models took centre stage after 1936 (see below), the Comet 18 cc engine remained on offer from the company right up to its final advertising appearance in August 1938. However, things had been moving behind the scenes. In the September 1936 issue of NPM, it was announced that a Leicester company called Comet Aero Supplies had become the British distributors of the  By 1936 the concept of smaller models was exerting a considerable attraction for British aeromodellers. The 6-7 foot span behemoths required to match larger engines such as the Comet 18 cc, Grayspec 15 cc, Atom Minor 14.5 cc and Hallam 13.5 cc units had the significant disadvantages that they required a large building space, consumed a lot of expensive building materials, occupied a large space during storage at home and were a major headache to transport to and from the flying site. The power modelling movement was more than ready for the introduction of smaller engines which would match models of considerably smaller size.

By 1936 the concept of smaller models was exerting a considerable attraction for British aeromodellers. The 6-7 foot span behemoths required to match larger engines such as the Comet 18 cc, Grayspec 15 cc, Atom Minor 14.5 cc and Hallam 13.5 cc units had the significant disadvantages that they required a large building space, consumed a lot of expensive building materials, occupied a large space during storage at home and were a major headache to transport to and from the flying site. The power modelling movement was more than ready for the introduction of smaller engines which would match models of considerably smaller size. Naturally, this was obvious to manufacturers other than Rogers & Geary.

Naturally, this was obvious to manufacturers other than Rogers & Geary.  To all intents and purposes, the Spitfire was a reduced-scale rendition of the Baby Cyclone. It was built up around a main casting in magnesium alloy, which was admittedly an improvement over the near-pot metal used for the Baby Cyclone cases, which tended to deteriorate rapidly in storage. Unfortunately, since the Spitfire was never the subject of a detailed technical commentary in the contemporary hobby media, details such as its material specification and working dimensions were never reported. All that is known is that the original variant of the engine had a displacement of 2.31 cc and was equipped with a ringed light alloy piston.

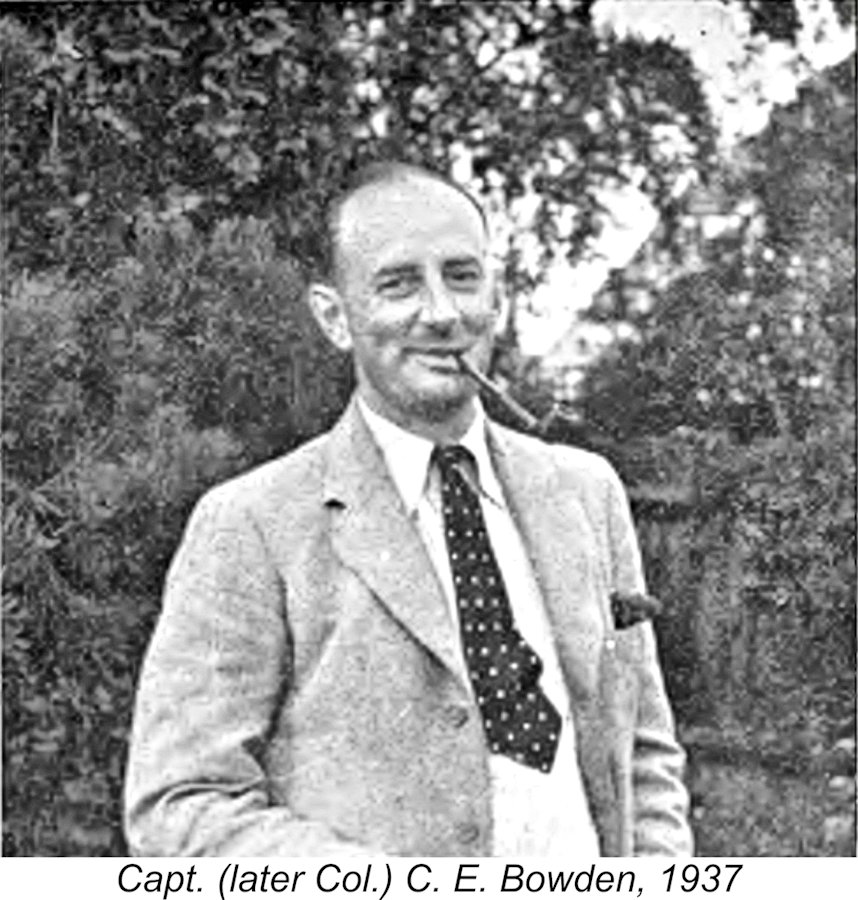

To all intents and purposes, the Spitfire was a reduced-scale rendition of the Baby Cyclone. It was built up around a main casting in magnesium alloy, which was admittedly an improvement over the near-pot metal used for the Baby Cyclone cases, which tended to deteriorate rapidly in storage. Unfortunately, since the Spitfire was never the subject of a detailed technical commentary in the contemporary hobby media, details such as its material specification and working dimensions were never reported. All that is known is that the original variant of the engine had a displacement of 2.31 cc and was equipped with a ringed light alloy piston. The closest approaches to any contemporary commentaries on the engine of which I’m currently aware came from then-Captain C. E. Bowden, another notable pioneering British power modelling advocate. The first of these took the form of a few paragraphs in Bowden’s “Petrol Planes” article in the August 1937 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Bowden stated that some problems had been experienced with the original rendition of the Spitfire, which had been fitted with a ringed light alloy piston. The manufacturers had switched to a lapped ferrous piston, which apparently cured the problems. Bowden’s snapshot assessment of the improved engine was very positive.

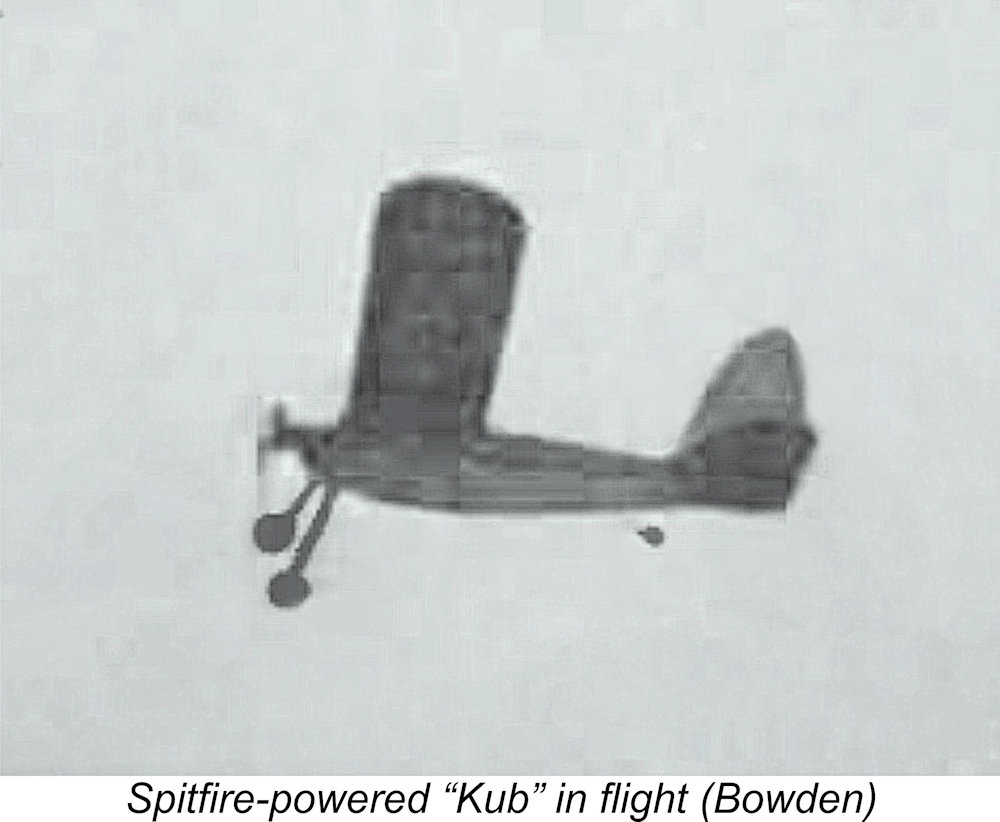

The closest approaches to any contemporary commentaries on the engine of which I’m currently aware came from then-Captain C. E. Bowden, another notable pioneering British power modelling advocate. The first of these took the form of a few paragraphs in Bowden’s “Petrol Planes” article in the August 1937 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Bowden stated that some problems had been experienced with the original rendition of the Spitfire, which had been fitted with a ringed light alloy piston. The manufacturers had switched to a lapped ferrous piston, which apparently cured the problems. Bowden’s snapshot assessment of the improved engine was very positive. Bowden repeated this assessment in a separate article which constituted the first installment of his new “Notes on Petrol-Driven Model Aeroplanes” feature in the September 1937 issue of NPM. In this article, he more or less repeated his comments from the previous month’s “Aeromodeller”. He stated that he had run his re-configured Spitfire for “some time” and its performance was if anything better than it had been initially. Sounds like breaking-in to me! He commented that it developed a “fierce thrust”, predicting an “excellent future” for the engine if it wore as well as it ran. He included an in-flight image of a Spitfire-powered 5-foot span model called the “Kub” which apparently performed well. The Kub was later kitted by Kanga Aeromodels of Birmingham.

Bowden repeated this assessment in a separate article which constituted the first installment of his new “Notes on Petrol-Driven Model Aeroplanes” feature in the September 1937 issue of NPM. In this article, he more or less repeated his comments from the previous month’s “Aeromodeller”. He stated that he had run his re-configured Spitfire for “some time” and its performance was if anything better than it had been initially. Sounds like breaking-in to me! He commented that it developed a “fierce thrust”, predicting an “excellent future” for the engine if it wore as well as it ran. He included an in-flight image of a Spitfire-powered 5-foot span model called the “Kub” which apparently performed well. The Kub was later kitted by Kanga Aeromodels of Birmingham. Bowden’s comments were made with specific reference to the 2.3 cc variant of the engine. At some point along the way, probably in early 1938, the design of the engine was revised further to produce the “Super Spitfire”. This model had its displacement increased to a full 2.5 cc. The Spitfire was first advertised as a 2.5 cc engine in June 1938 at an increased price of £4 17s 6d (£4.88) and was promoted as the Super Spitfire from July 1938 onwards. Unfortunately, I’m currently not in possession of any technical details of this model provided either by the distributors or the contemporary modelling media, so I’m unable to document the changes made to produce it.

Bowden’s comments were made with specific reference to the 2.3 cc variant of the engine. At some point along the way, probably in early 1938, the design of the engine was revised further to produce the “Super Spitfire”. This model had its displacement increased to a full 2.5 cc. The Spitfire was first advertised as a 2.5 cc engine in June 1938 at an increased price of £4 17s 6d (£4.88) and was promoted as the Super Spitfire from July 1938 onwards. Unfortunately, I’m currently not in possession of any technical details of this model provided either by the distributors or the contemporary modelling media, so I’m unable to document the changes made to produce it. That said, a paragraph in the “At the Sign of the Windsock” feature in the December 1938 issue of “Aeromodeller” made favourable reference to the upgraded 2.5 cc rendition of the Spitfire, also recalling an “On Test” article which had appeared in the same magazine a few months earlier. This appears to refer to some kind of practical test of the Spitfire, from which the engine evidently emerged with flying colours. I don’t have access to any 1938 issues of “Aeromodeller” prior to the December 1938 issue, but a look at that test might be of considerable assistance in describing the engine in more detail. Does any reader have access to this test? If so, I’d be no end grateful for a copy!

That said, a paragraph in the “At the Sign of the Windsock” feature in the December 1938 issue of “Aeromodeller” made favourable reference to the upgraded 2.5 cc rendition of the Spitfire, also recalling an “On Test” article which had appeared in the same magazine a few months earlier. This appears to refer to some kind of practical test of the Spitfire, from which the engine evidently emerged with flying colours. I don’t have access to any 1938 issues of “Aeromodeller” prior to the December 1938 issue, but a look at that test might be of considerable assistance in describing the engine in more detail. Does any reader have access to this test? If so, I’d be no end grateful for a copy! In October 1937 the MAS advertising placement in NPM for that month featured an entirely new engine – something called the Challenger 6 cc unit. I have to admit that, try as I may, I have been unable to find any references at all to this engine apart from its successive appearances in the MAS advertising. I have no idea whether or not it was a “lost” Rogers & Geary product, but include it here “just in case”! It may have appeared in "Aeromodeller" at some point, but if so I don't have access to the relevant issue.

In October 1937 the MAS advertising placement in NPM for that month featured an entirely new engine – something called the Challenger 6 cc unit. I have to admit that, try as I may, I have been unable to find any references at all to this engine apart from its successive appearances in the MAS advertising. I have no idea whether or not it was a “lost” Rogers & Geary product, but include it here “just in case”! It may have appeared in "Aeromodeller" at some point, but if so I don't have access to the relevant issue.  It’s convenient to deal with these two models together for two reasons. One, they both shared the same all-too brief production history; and two, they were built to a basically common design in two different displacements, with a few minor detail differences. Indeed, their shared design owed much to that of the Baby Cyclone-influenced Spitfire, albeit with a few structural alterations such as the use of a screw-on alloy cooling jacket in place of the Spitfire’s integrally-turned cooling fins; a permanently-attached exhaust pipe; and a bypass formed integrally with the crankcase, hence dispensing with the bolt-on bypass cover.

It’s convenient to deal with these two models together for two reasons. One, they both shared the same all-too brief production history; and two, they were built to a basically common design in two different displacements, with a few minor detail differences. Indeed, their shared design owed much to that of the Baby Cyclone-influenced Spitfire, albeit with a few structural alterations such as the use of a screw-on alloy cooling jacket in place of the Spitfire’s integrally-turned cooling fins; a permanently-attached exhaust pipe; and a bypass formed integrally with the crankcase, hence dispensing with the bolt-on bypass cover.  measurements of 19.5 mm and 21 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 6.27 cc. Despite this, the engine was always promoted as a 6 cc unit. This was not an uncommon practice at the time – many British manufacturers tended to “round off” the displacements of their offerings.

measurements of 19.5 mm and 21 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 6.27 cc. Despite this, the engine was always promoted as a 6 cc unit. This was not an uncommon practice at the time – many British manufacturers tended to “round off” the displacements of their offerings. the writer claimed to have run an example and found it to be of “robust construction” and capable of developing “good power”. He also recalled having seen an example in action powering one of the competing models at the then-recent Hamley Trophy competition.

the writer claimed to have run an example and found it to be of “robust construction” and capable of developing “good power”. He also recalled having seen an example in action powering one of the competing models at the then-recent Hamley Trophy competition. Although I can present no supporting evidence, it may be assumed that the precision engineering capabilities of Rogers & Geary were soon diverted away from model engine production into manufacturing programs relating to the war effort. The company certainly survived throughout the war, at the conclusion of which they were free once more to resume their former pre-war activities.

Although I can present no supporting evidence, it may be assumed that the precision engineering capabilities of Rogers & Geary were soon diverted away from model engine production into manufacturing programs relating to the war effort. The company certainly survived throughout the war, at the conclusion of which they were free once more to resume their former pre-war activities. The design of the Stentor owed little to that of the pre-war 6 cc Wasp and 3.5 cc Hornet. It abandoned the crankshaft front rotary valve induction of those models in favour of a return to the old tried-and-tested sideport arrangement. Unlike the Wasp, it featured a detachable exhaust stack and a separate front housing secured by four machine screws. It was manufactured in two distinct series which were mainly distinguishable by their different cooling fin side-profiles.

The design of the Stentor owed little to that of the pre-war 6 cc Wasp and 3.5 cc Hornet. It abandoned the crankshaft front rotary valve induction of those models in favour of a return to the old tried-and-tested sideport arrangement. Unlike the Wasp, it featured a detachable exhaust stack and a separate front housing secured by four machine screws. It was manufactured in two distinct series which were mainly distinguishable by their different cooling fin side-profiles.

pretty much in the “unobtanium” category, although a small handful do exist. He recalled that Gordon Williams made about a dozen repro castings and John Maddaford made up and sold about 11 fine replicas using these castings. Paul Knapp's previously-illustrated example of the Comet is almost certainly one of these Maddaford replicas.

pretty much in the “unobtanium” category, although a small handful do exist. He recalled that Gordon Williams made about a dozen repro castings and John Maddaford made up and sold about 11 fine replicas using these castings. Paul Knapp's previously-illustrated example of the Comet is almost certainly one of these Maddaford replicas.