|

|

The AMCO 3.5 cc Engines

First appearing in May 1949, these engines immediately set new standards in Britain, particularly in the control-line stunt field. Their power-to-weight ratio was approached by few if any of their competitors, and most power modellers who were active in the 1950’s encountered them at some point. Their qualities were such that they remained in use in quite large numbers long after production had ceased. I recall seeing a few of them still flying regularly when I started power modelling in Britain in 1959 at the age of 12 years. This article is a reworking of my original April 2011 piece on the AMCO 3.5 cc engines which may still be found on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Unfortunately, Ron left us in 2014 without sharing the access codes for his heavily-encrypted site. Consequently, no maintenance has since been possible, the result being that the site is now showing unmistakable signs of deterioration as time passes. It is for this reason that I’ve been transferring many of my earlier MEN articles over to my own site. In the present instance, I’ve It appears that interest in these engines remains strong today, since I couldn't recall receiving so much “fan mail” and additional information following the initial publication of any article prior to 2011! The expressions of appreciation which followed the initial appearance of this article on MEN meant a lot to me, and my thanks were due to one and all who sent them in – encouragement of this kind still keeps me going today!! But equally important was the additional information which readers so kindly provided. The preservation of model engine history is a shared responsibility, and it’s extremely gratifying to find that this view is becoming increasingly espoused by my readers. The revised text which follows now incorporates a significant amount of additional detail supplied by friends like Kevin Richards, Chris Murphy, Bernard Smith and Jon Fletcher. My very sincere thanks to these valued friends and colleagues! Having acknowledged my indebtedness to the above-named individuals, it’s now time to begin our in-depth look at the AMCO 3.5 cc series. Because they were so highly regarded, people tended to hang onto them, and this has had the happy result of ensuring that a significant proportion of those that were produced still survive today. Let’s review the history of these trend-setting engines on the basis of my own and others’ considerable experience with them! But first, some background ................ Background

The company had been founded in the 1930’s as a firm of automotive engineers, thus having much in common with the contemporary North Downs Engineering Co. of Whyteleaf in Surrey, makers of the 10 cc Nordec racing engines, in that their primary business related to full-sized automobiles. In both instances the model engine manufacturing was a sideline, evidently added because of an interest in modelling at the management level.

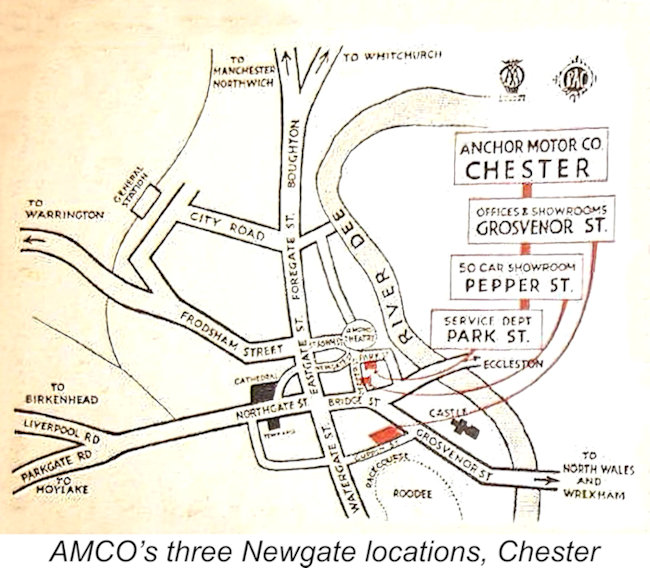

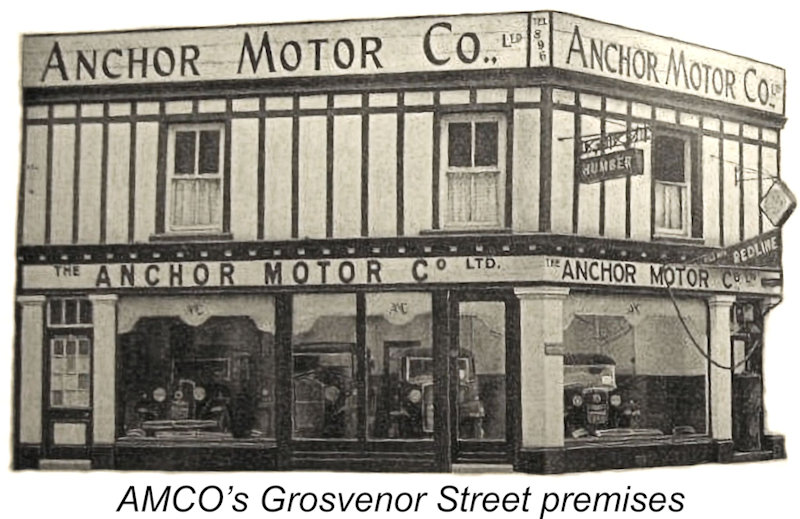

A pre-war Anchor Motor Co. promotional booklet discovered by my friend Jim Woodside yielded further details regarding the company’s operations during the 1930’s. As shown on the attached map from the booklet, the company had premises at three different locations. The offices were located on Grosvenor Street, with a small showroom on the ground floor. There was a far larger showroom having space for 50 cars on nearby Pepper Street, while the service department was It’s worth noting at this point that the machine shop itself did not share accommodation with the rest of the operation at The Newgate, but was separately located on Victoria Road in the outskirts of Chester to the north. It was presumably at that location that the model engines were subsequently made. During WW2 the company engaged in the renovation of lorry (aka truck) and car engine parts, limited during that period to vehicles in essential national service use. They did re-bores and re-sleeving, reground camshafts and crankshafts, re-ground heads and restored brake-drums and clutches (skimming and re-lining), among other things. They also applied their expertise to the production of components for Wellington and Lancaster bomber gun turrets as well as tail units and wiring harnesses for the legendary Spitfire fighter. They must have been busy!

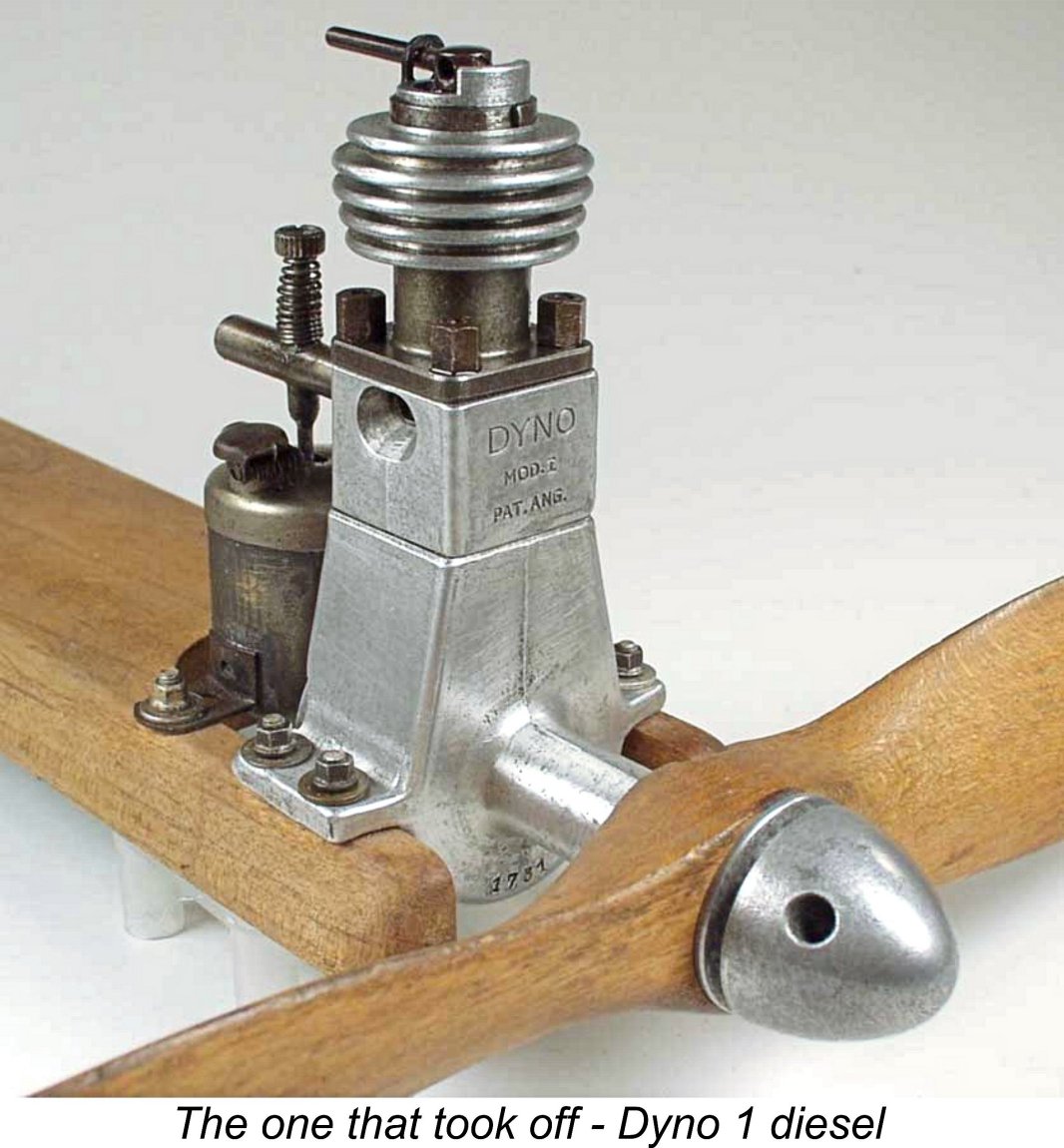

According to the recollections of the late Ted Martin as related to Jim Woodside, the AMCO model engine range had its genesis in the fact that following the end of WW2 the Managing Director of Anchor Motor Co., Bill Leeman, bought a Swiss Dyno model diesel for his son. Leeman took a good look at this engine and realized that the excellent machine tooling which the company had at its disposal could well be turned to commercial advantage in manufacturing a similar product. Once they had decided to enter the model engine manufacturing business, a decision which they evidently took in 1946, the company had to come up with an appropriate design for their first commercial offering. They had no design or manufacturing experience of their own with model diesels, which were in any case very much in their evolutionary stage at the time in question – the first British-made commercial model diesels didn’t begin to appear until mid-1946. Accordingly, the idea of adopting someone else's established design would have had considerable attraction for them at the outset.

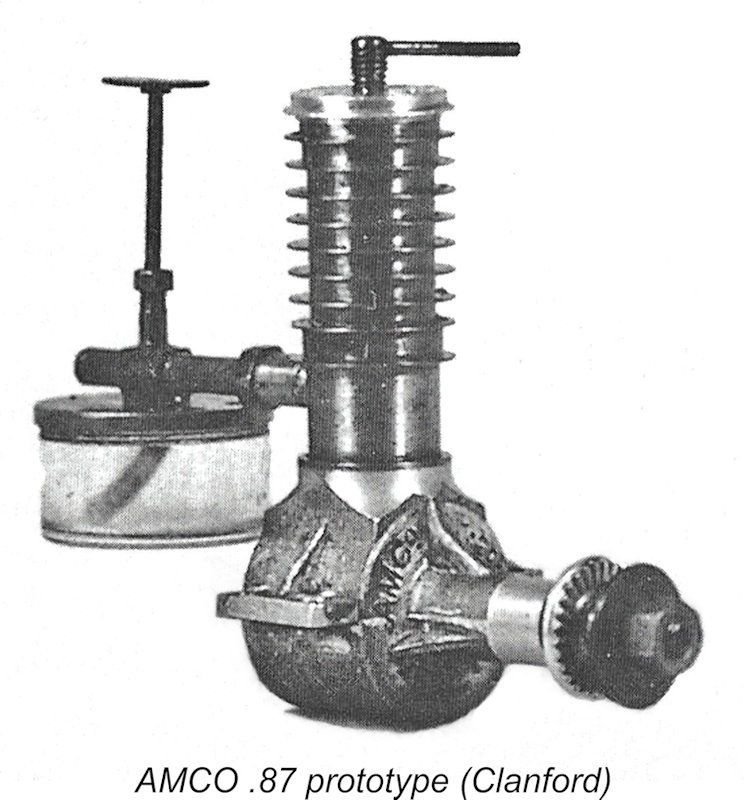

The initial prototypes of the AMCO .87 were very similar indeed to the Healy Midge from which the engine was derived. The “Healy 1.2 cc” diesel shown on page 93 of Mike Clanford’s well-known but often misleading “A-Z” book is actually an AMCO prototype - the case says as much. The resemblance to the original Healy design is quite striking.

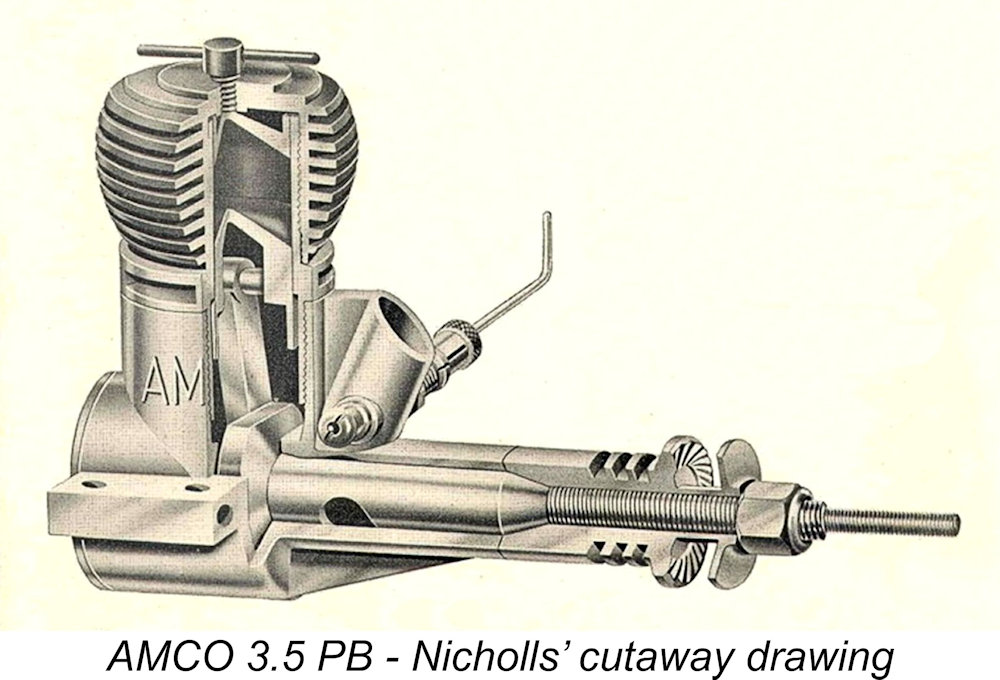

This advertisement was brought to the attention of 25-year-old E. C. “Ted” Martin, who immediately jumped at the chance, becoming the Anchor Motor Co.’s resident model engine design and production expert. Ted had plenty of The Stentor was quite successful, appearing in two successive variants and being sold primarily through the Bournemouth Model Shop, where the late Phil Smith achieved so much in terms of model design work under the Veron banner, including the "Stentorian" design which was created especially for the Stentor. The engine was also used quite extensively in model car racing, then very popular. Following Ted Martin’s arrival, the initial production difficulties were progressively sorted, the end result being the company’s first commercial product, the AMCO .87 Mk. I. The initial advertisement for this model appeared in the August 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The market prospects for this engine doubtless appeared to be very good, because For reasons which must forever remain unclear, the Anchor Motor Co. used their own company name in connection with this initial offering only. Thereafter, they always identified their engines as products of Anchor Motors rather than the Anchor Motor Co. My good friend Marcus Tidmarsh was unable to find any evidence to suggest that Anchor Motors was ever a formally registered company. It may simply have been a “flag of convenience” used solely in connection with the company’s model engines. It certainly slides off the tongue more easily than Anchor Motor Company! Appearance of the AMCO 3.5 PB Diesel The success of the AMCO .87 was such that by 1949 the AMCO name stood high in the affections of British and Commonwealth modellers. This set the stage for a favourable market response to the company’s first venture into a larger displacement category, which came in May 1949 with the The new model was promoted by the makers as “the first engine ever to be designed and built specifically for modern C/L stunt and speed”. A few American manufacturers might have taken issue with this unqualified statement, as might the British makers of the Yulon engines, the Nordec series and the ETA 29, but the AMCO 3.5 PB was certainly the first mid-sized diesel to be designed specifically for such service. The AMCO engines were distributed by Mercury Models, which was operated by Henry J. Nicholls from his well-known shop at 308 Holloway Road, London. Mercury Models also acted as the service centre for the AMCO range, with the well-known modeller and later engine manufacturer Dennis Allen in charge. This arrangement relieved Anchor Motors of the need to undertake repairs at the Chester factory - all they had to do was turn out the engines and supply the spare parts! Despite a few early failings, including a rash of broken crankshafts and a tendency towards rapid con-rod wear, the AMCO 3.5 plain bearing diesel remained a popular engine for a number of years. It was particularly favoured by control-line stunt fliers on account of its high power and light weight, although the same characteristics made it a free flight standout as well. The AMCO 3.5 PB on Test Some idea of the impact which the AMCO 3.5 PB made on the British model engine scene may be gauged from the fact that it became one of the the most-tested engines of the early post-WW2 period in Britain. The model engine commentators for the British and Commonwealth aeromodelling publications were quick to spot the potential of the new design, resulting in the speedy appearance of no fewer than four published tests of the diesel model and one test of its glow-plug version. The first test of the engine followed its introduction very closely. This test was conducted by AMCO distributor Henry J. Nicholls and was published in the 1949 issue of the annual Ian Allan periodical “Model Aviation Planbook”.

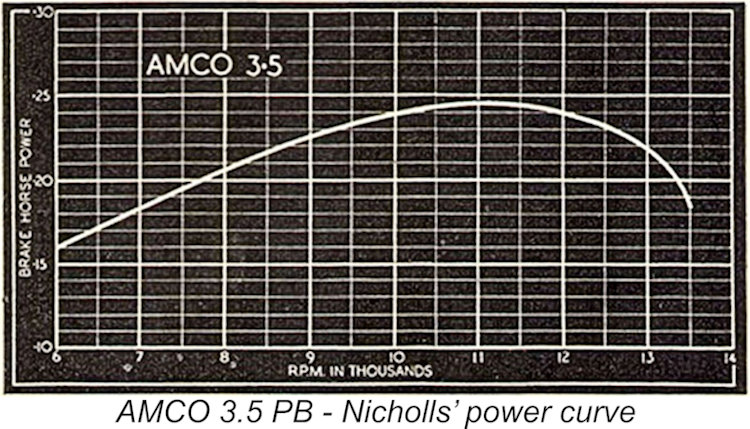

Nicholls praised the engine’s handling and running qualities as well as its light and compact construction. He found a peak output of 0.247 BHP @ 11,200 rpm for the best of his three examples, but reported that it appeared to require further running-in since the performance was continuing to improve with running time. Nonetheless, when coupled with the very light weight of only just over 4 ounces this gave the AMCO the highest power-to-weight ratio yet recorded in any model engine test published up to that time. Nicholls reported that one of the test engines showed excessive conrod big end wear at the conclusion of the tests - apparently a not-uncommon failing with the early examples of this engine. He also experienced some difficulty keeping the cylinder of one example sufficiently tight to prevent unscrewing during running. But he recorded no other problems, and his assessment was extremely favourable in all other respects.

This statement underscores the strong influence that progress in engine design was exerting upon model design during this very dynamic evolutionary period in modelling history. In today's "bought in a box" push-button scene, I find myself envying the experiences of modellers then engaged in what must have been a very exciting period of rapid and inter-related hands-on development in so many facets of the modelling hobby. I was fortunate enough to become active in the hobby at a time (late 1950's) when this intense development phase was still ongoing to some extent.

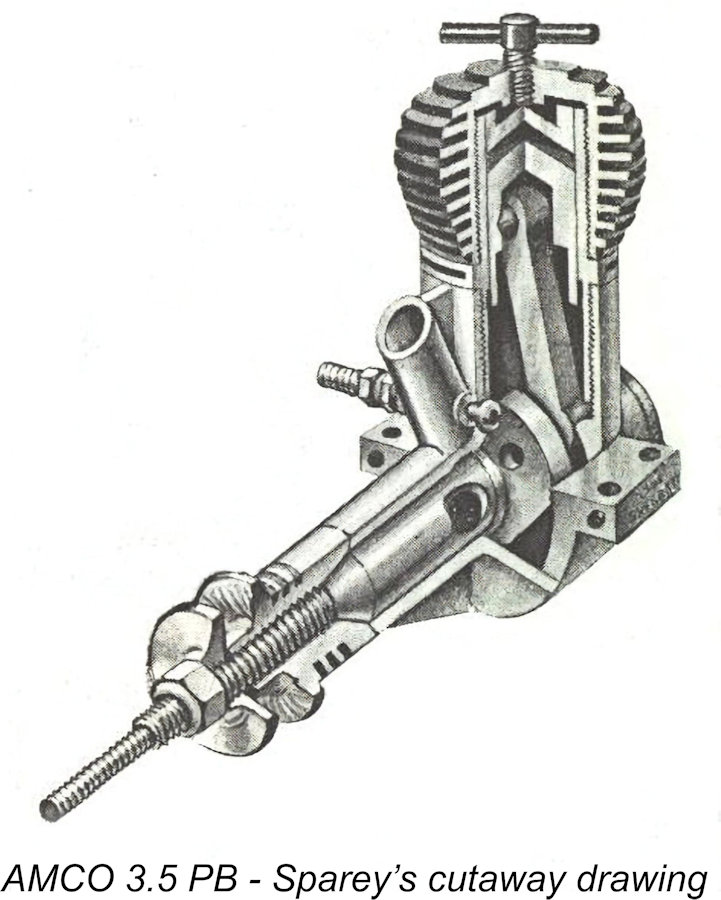

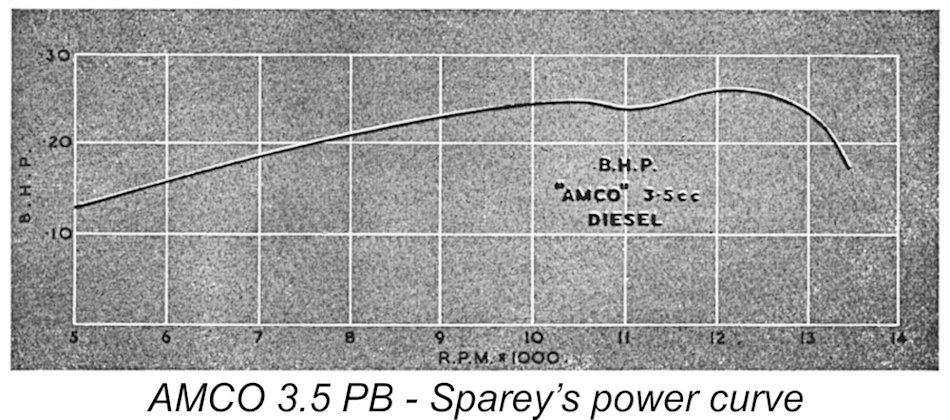

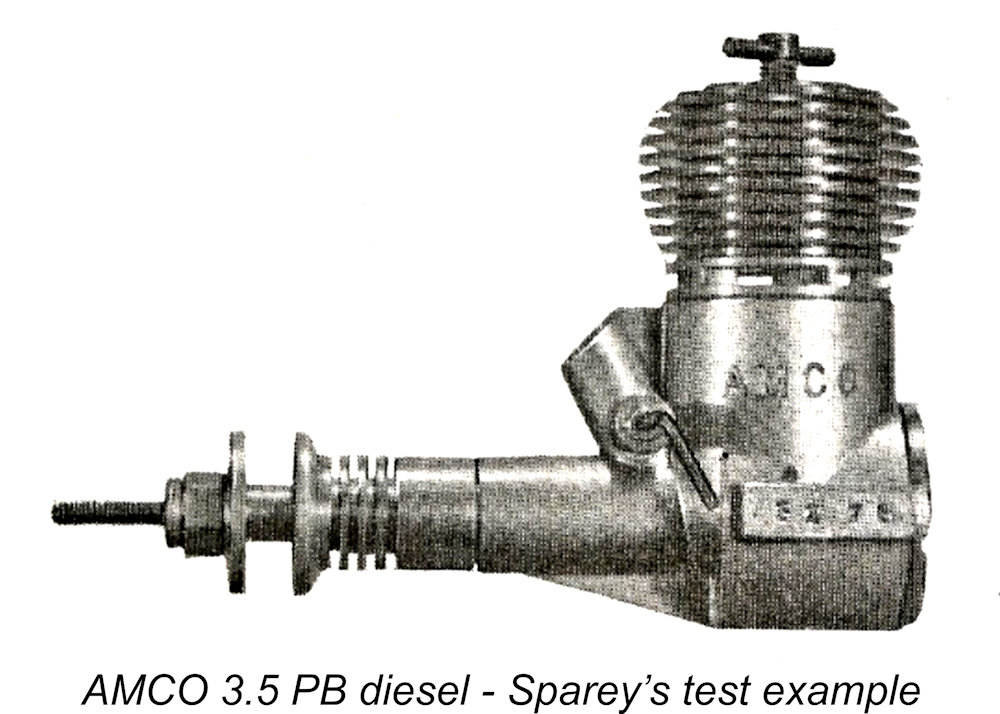

Sparey noted a tendency towards inconsistency at speeds below 5,000 RPM, leaving one wondering what on earth he was doing testing an ultra-short stroke engine of this specification and performance at such speeds! Clearly old Lawrence was a member of the “old school” who had some difficulty adapting to the performance characteristics of the then-evolving breed of (to use Sparey’s own term) “hot stuff” diesels! This behavior was almost certainly related to what can be seen in hindsight as an excessively large intake choke area. Sparey obtained a peak output of 0.260 BHP @ 11,600 RPM, thus slightly bettering Nicholls’ figures. For context, it’s worth noting that in January of 1949 the same tester had obtained just 0.246 BHP @ 8,900 RPM from the Mk. I version of the far bulkier and heavier 5 cc “K” Vulture!

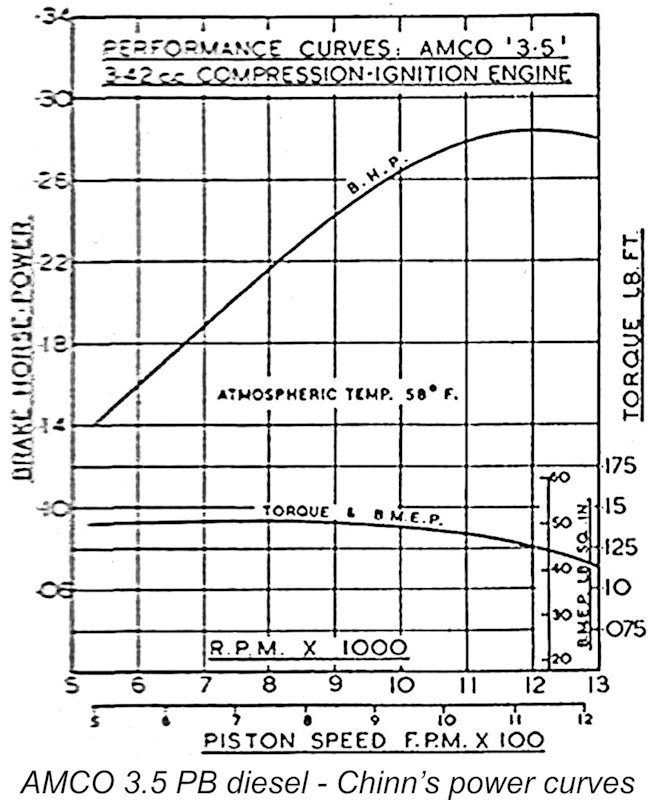

Sparey’s power curve for the engine displayed an odd “dip” just below the peak, a feature which was also reflected in the curve published by the manufacturers. This actually prompted Sparey to test a second example of the engine, with the same result. It’s hard today to account for this anomaly, but there it is ……………It’s also worth noting that Nicholls’ results had not displayed this characteristic.

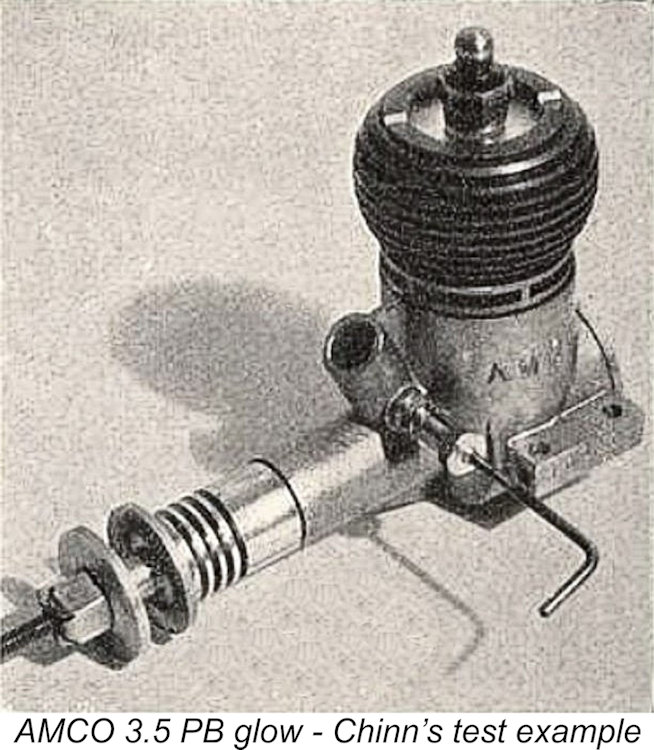

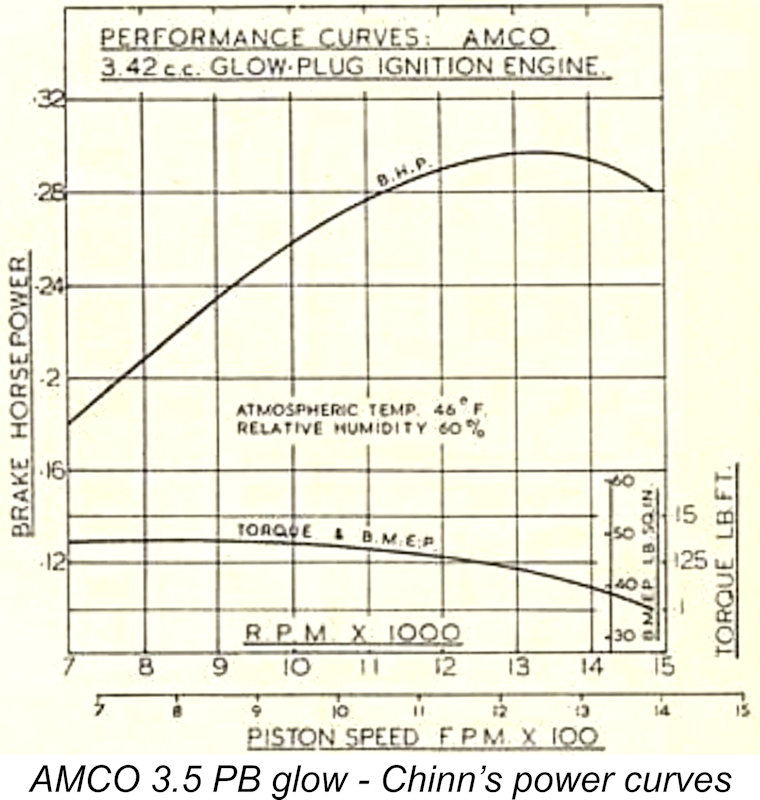

Overall, Chinn was quite favourably impressed with the AMCO 3.5 PB glow-plug model, stating that in its optimum speed range of between 10,000 and 15,000 RPM “the engine ran with a good crisp (exhaust) note and held fairly even torque readings”. He also praised its handling qualities, stating that it was “better, in this respect, than the diesel model”. His sole criticism related to the split-thimble needle valve, which reportedly failed to maintain settings in the face of the engine’s operational vibration.

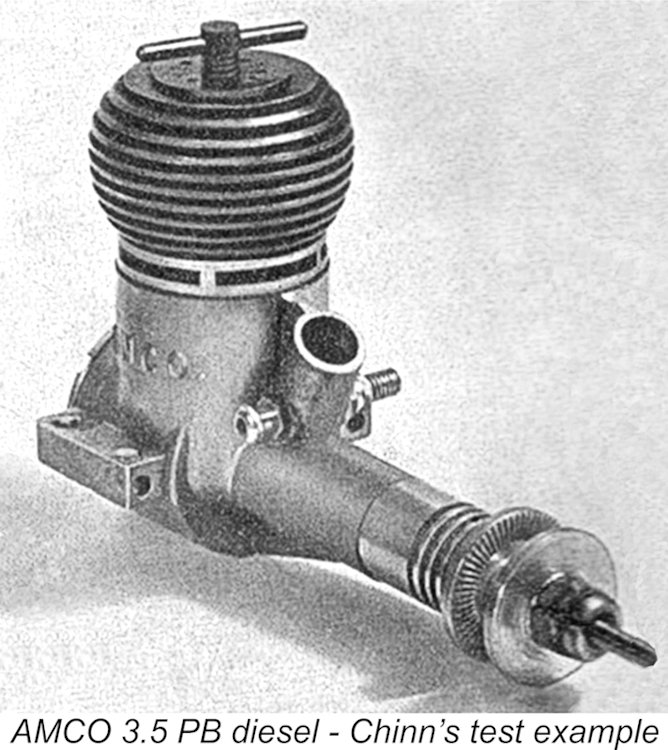

The article referred to improvements having been made in the form of a revised conrod (as referred to earlier by Sparey) as well as upgraded heat treatment specifications for the steel components. Oddly, no reference was made to changes in the shaft design which are known from surviving examples to have been introduced in addition by this time. The report went on to recall the earlier test of the AMCO 3.5 PB glow-plug model, which had come through its test with flying colours. This test was of course published during the period when the AMCO 3.5 PB was temporarily out of production, the design having been sold to the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. of Alperton, Middlesex (near Ealing) who had yet to resume production (see below). According to the report, new examples were still occasionally to be found in the odd model shop, and used examples were widely available. The report made much of the fact that the AMCO 3.5 PB had apparently acquired a reputation as being difficult to start. Chinn (assuming it was he) refuted this claim most decisively, stating that he had handled half-a-dozen examples apart from the one under test and had found them all to be perfectly straightforward to start provided the correct technique was used. The main requirement was reportedly to use some means of introducing fuel directly into the upper cylinder - choking alone would not suffice. The very large transfer port area doubtless had much to do with this.

Chinn repeated his earlier criticism of the split thimble needle valve set-up, which failed to retain needle settings sufficiently dependably on the bench, also mentioning the need for a lengthy break-in period. Otherwise, he had little but praise for the engine. He found a peak output of 0.285 BHP at just over 12,000 RPM, which he noted was bettered among contemporary diesel designs only by the companion AMCO 3.5 BB model (see below). He also commented on the outstanding power-to-weight ratio of the engine. It’s interesting to note that the diesel version of the engine fell slightly short of matching the performance of the glow-plug model measured by the same tester in May 1951. However, since the diesel developed greater torque at lower revs, it would be expected to swing a larger and hence more efficient airscrew. Moreover, there’s no doubt at all that a well freed-up example of the diesel would handily beat the published figure. My own very "experienced" example certainly does so (see below). Another test of the AMCO 3.5 PB appeared in the Australian modelling magazine “Australian Model Hobbies”. I don’t have the date of the specific issue, but the report remains accessible through the above link. It doesn’t really add anything to what was reported by the other testers cited earlier. Subsequent Production History of the AMCO range During the three years following its introduction, the AMCO 3.5 PB came to occupy a very high place in the affections of performance-oriented power modellers in Britain and elsewhere, especially after its initial teething troubles were addressed by the manufacturer. Although the rigors of actual use in the field had quickly revealed a number of areas in which the design required improvement (as noted by Chinn in the above-referenced test report), the company was quick to learn from these experiences and make the required modifications, replacing any failed components with their upgraded equivalents. For those interested, I'll go through the various changes in detail in a following section.

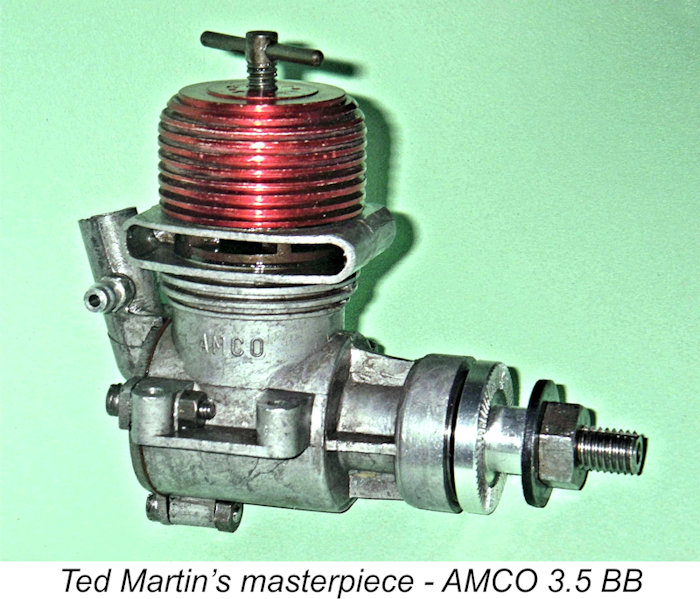

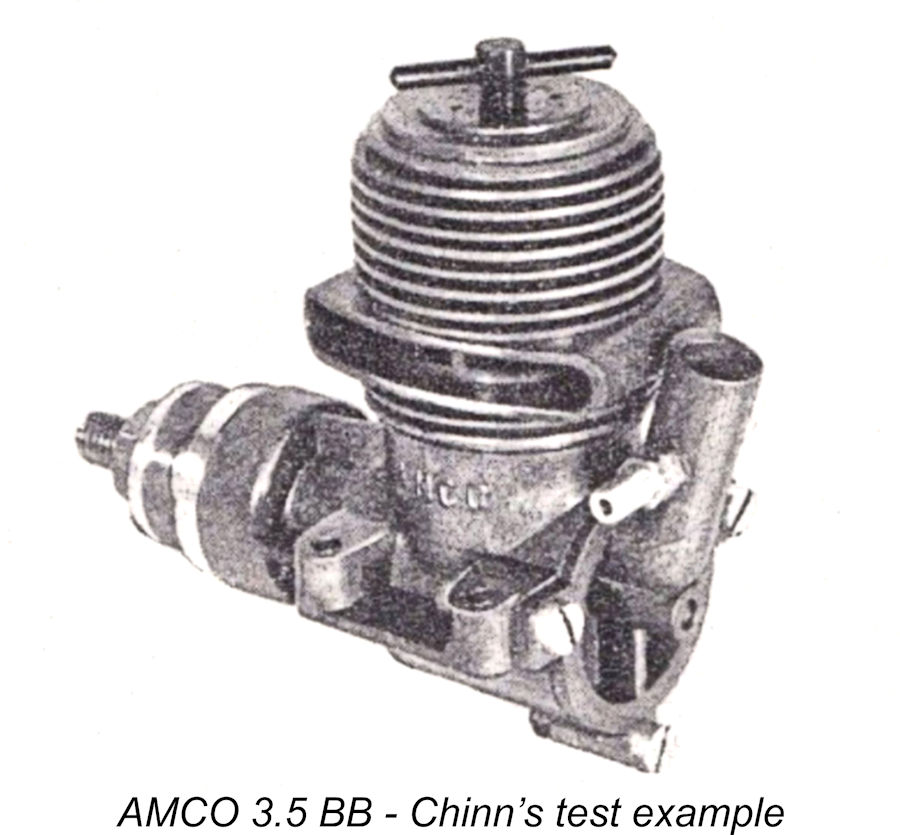

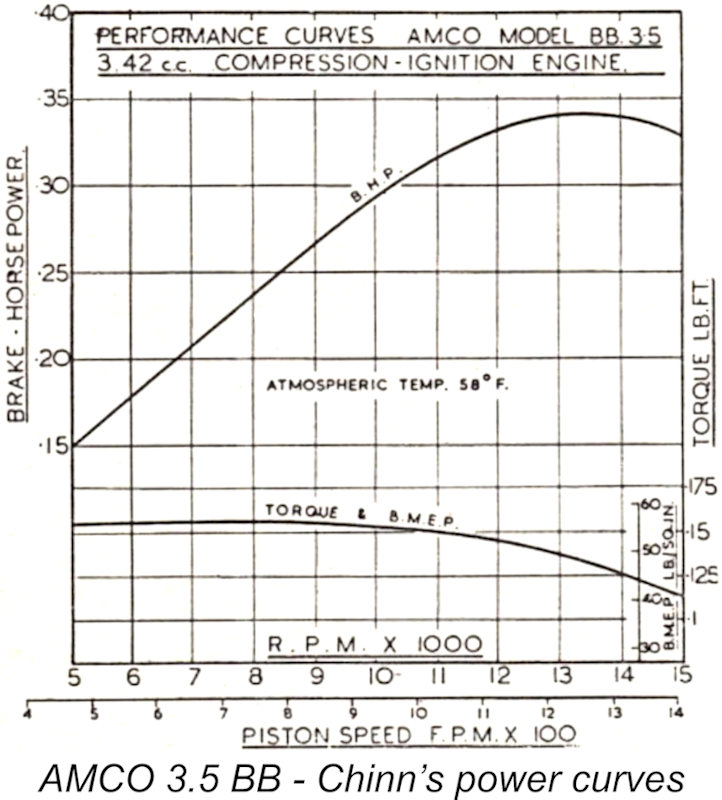

The new model was the subject of a test which appeared in the August 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Although the report was unattributed, it’s all but certain that its author was Peter Chinn. The tone of the report was entirely positive in terms of both handling and performance. The recorded peak output of 0.34 BHP @ 13,500 RPM was rightly characterized as “exceptional”, which it certainly was by the standards of 1951. Despite this, shortly after designing the AMCO 3.5 BB for the Anchor Motor Co. and seeing it through the early stages of series production, Ted Martin not only left the company but also left England! On January 5th, 1952 (a date noted by Peter Chinn in his April 1952 “Accent on Power” column in “Model Aircraft”), Martin sailed for Canada, where he had accepted an engine development job with General Motors Canada in the automotive industry. However, he retained ambitions of starting his own model engine manufacturing company, beginning with an ultra high-performance twin BB .049 diesel with which to compete in the huge US ½A market. Chinn probably remembered this matter very well indeed because Martin had apparently invited Chinn to join him in this venture. Perhaps wisely as things turned out, Chinn declined ………….. Although his planned .049 diesel project unfortunately never got off the ground, likely due to funding difficulties, Ted Martin’s association with model engines continued through his position as the resident engine tester for “Model Airplane News” for some years in the mid to late 1950’s. For more information on Ted Martin’s remarkable career, see my companion article on his life and work.

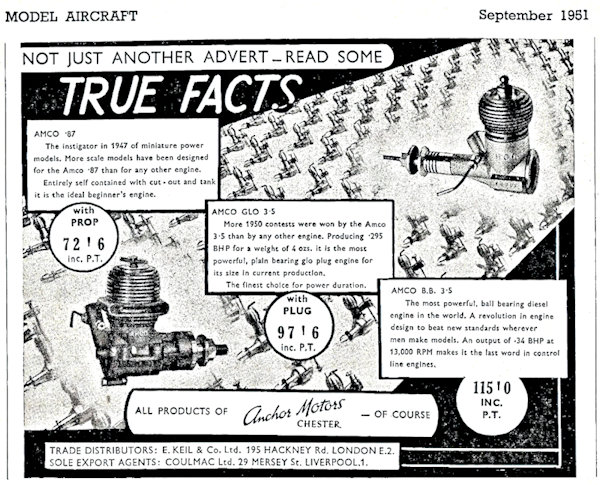

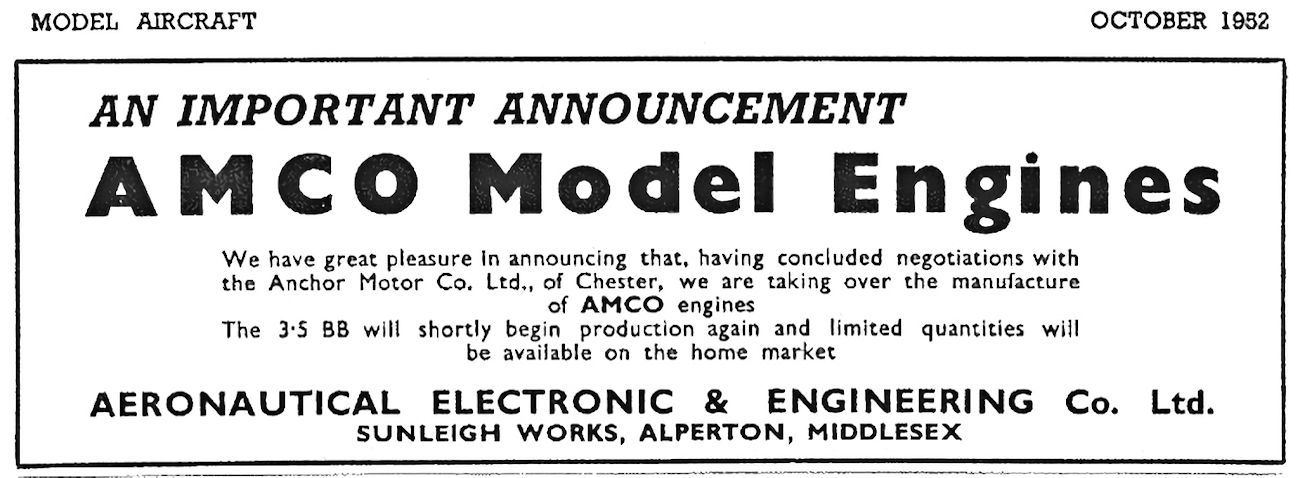

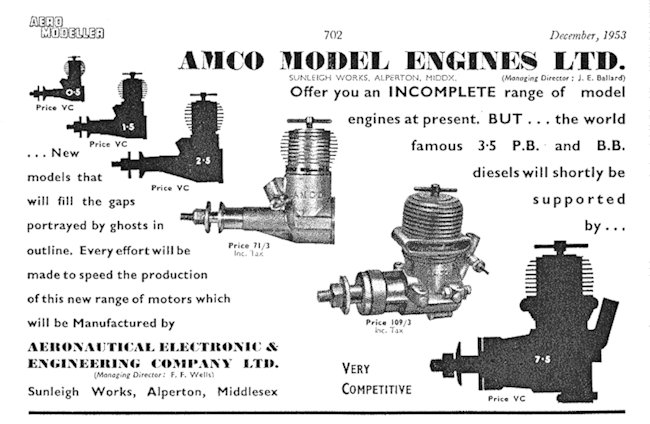

Some insight into the domino effect which may have resulted from this situation may be gleaned from the fact that the AMCO 3.5 PB diesel was omitted from the company’s advertisement in the September 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The advertisement (right) included the AMCO .87 along with the AMCO 3.5 PB glow-plug model and the AMCO 3.5 BB diesel as being part of the company’s then-current range. The AMCO 3.5 PB diesel was conspicuous by its absence. This creates the impression that the pressure of other work that eventually caused Anchor Motors to sell off the AMCO range had already forced a cessation of 3.5 PB production as of September 1951 – they were evidently out of stock of the 3.5 PB diesel and weren’t making any more. This left them selling off residual stocks of the 3.5 glow, the 3.5 BB diesel and the .87 Mk. II. If any manufacturing was continuing at this point, it must have been focused upon the 3.5 BB, for which a considerable pent-up demand existed. In May 1952, all model engine production by Anchor Motors ceased. The AMCO name, designs, parts, tooling and dies were offered for sale, eventually being purchased by a newly-formed London-based company, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. of Alperton, Middlesex (near Ealing). The managing director of this company was a certain F. F. Wells, about whom I have been unable to uncover any specific information.

The name of the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. suggests a concern with electronics in addition to model engines. As it happens, this was far from coincidental! The management of the new venture was soon to be reinforced by none other than 49-year-old Jack E. Ballard (1904 - 1990), who was a former Managing Director of the competing Electronic Developments (E.D.) company. E.D. had always been as much involved in electronics as they had with engines, and Ballard understandably brought this perspective to the new venture as well. The new company did indeed enter the radio control field with their Avionic line during their rather short lifetime. Ballard had apparently come to a parting of the ways with E.D. because he had ideas about future design and marketing trends which differed radically from those of his rather conservative fellow E.D. Directors. This made a split inevitable. It appears that Ballard saw the change of ownership of the AMCO range as his opportunity to make the break from E.D. while remaining involved with the model trade which by then he knew so well.

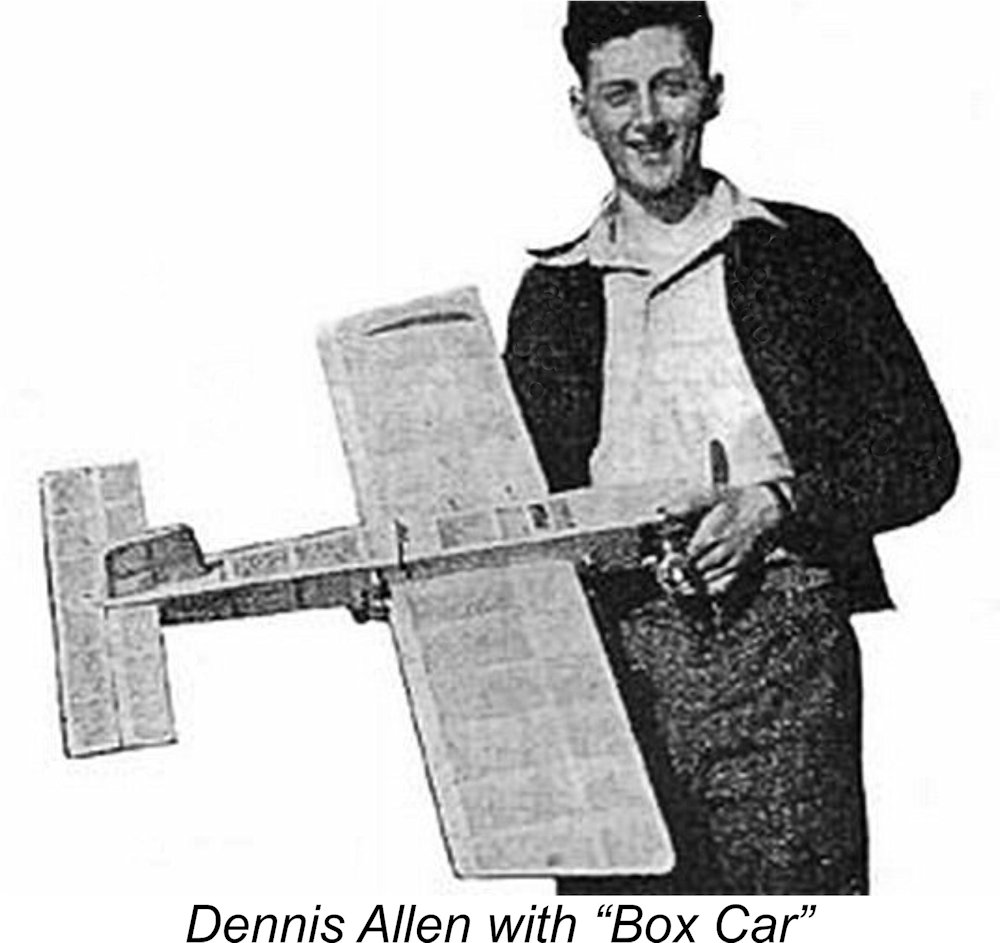

There could have been no better choice than Allen to step into the shoes of Ted Martin. Allen was a highly competent aeromodeller who had been among the pioneers of control-line stunt flying in Britain with his famous “Box Car” model, with which he won the stunt competition at the 1948 West Essex Gala and finished second to Peter Cock in the 1948 Gold Trophy. He thus understood the practical challenges of model engine operation in the field. In addition, he had worked as one of the engine repair wizards at Henry J. Nicholls’ famous shop at “308” during the time when Nicholls’ Mercury Models division was acting as the trade distributor and service centre for the AMCO engines. He therefore had the opportunity to get to know the AMCO engines very well indeed, especially with all those broken crankshafts and worn-out rods!!

Kevin Richards reminded me of the fact that there is evidence to suggest that Allen was not the only “name” model engineering type to work at Alperton - it seems that Arthur Weaver, designer of the well-known Weaver 1 cc home-built engine, was also employed by the new company. In addition, Allen’s long-time friend and fellow West Essex clubmate Len “Stoo” Steward, former owner of the “K” Model Engineering Company, also joined Allen in the new venture. It would appear that Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. had an engineering staff with an unusually strong model engine background!

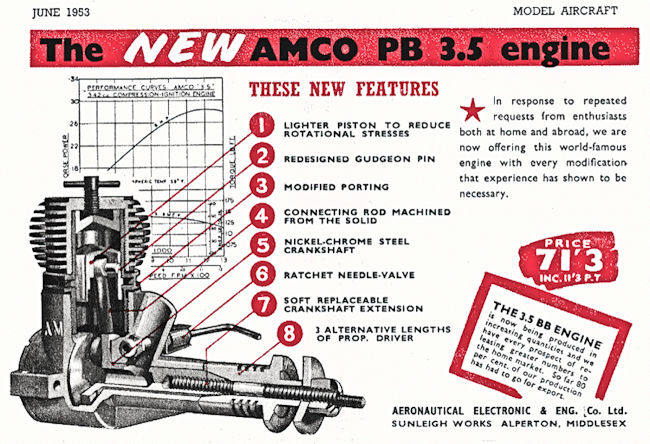

Warring’s test report was extremely positive, just as Chinn’s earlier effort had been, with a similar level of performance being reported. It’s worth noting here in passing that Warring gave the name of the new makers as “Aeronautical & Electronic Engineering Co.”. This is incorrect – the “&” is where I’ve consistently placed it elsewhere in this article, as confirmed on the boxes and in the advertisements. It took a little longer for the AMCO 3.5 PB to re-enter production - as far as I’m presently aware, the initial advertisements for this re-introduced model appeared in June 1953, as reproduced below at the right. As we shall see, it incorporated a few well-considered modifications from the original Anchor Motors design, but remained basically the same engine.

Under the new arrangement, the engines continued to be manufactured by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., which was still led by F. F. Wells as Managing Director. However, a separate entity known as AMCO Model Engines Ltd. was established to market the engines, with Ballard in the position of Managing Director. At this stage, Dennis Allen was still involved with the company’s technical side, hence presumably reporting to Wells rather than Ballard.

The design improvements which are reflected in the later models of the 3.5 PB (to be described below) must surely be credited to Dennis Allen. However, Allen had not confined his attention to the AMCO 3.5 cc models - in his spare time he had been working with Len Steward on the design of a new lightweight 2.5 cc model which he believed to have considerable commercial potential. According to an article which appeared in the June 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, he offered this design to his new employers, who were not interested. This rejection had far-reaching consequences for all concerned, since Allen’s unswerving belief in his new design led him to seek other avenues for getting it into production.

It’s clear from this that Allen’s association with Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. must have ended at some point in the first half of 1954. To make matters worse for the company, Len Steward also left to join Allen in his new venture. Their joint departure seems to have left a major void in the company’s engineering department, because it appears that AMCO production sputtered thereafter and ended in early 1955 - the last advertisement for the AMCO engines of which I’m presently aware appeared in February of that year.

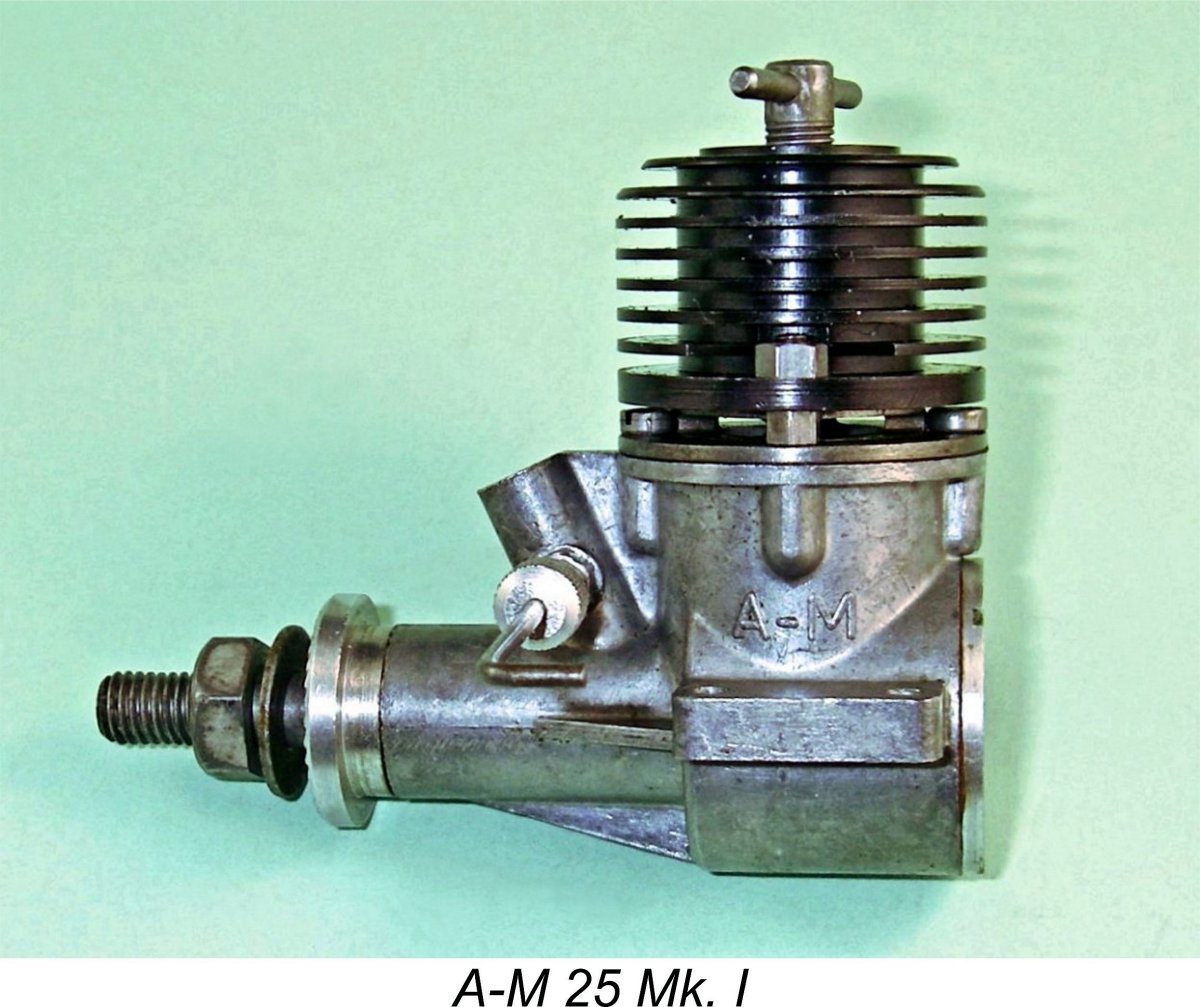

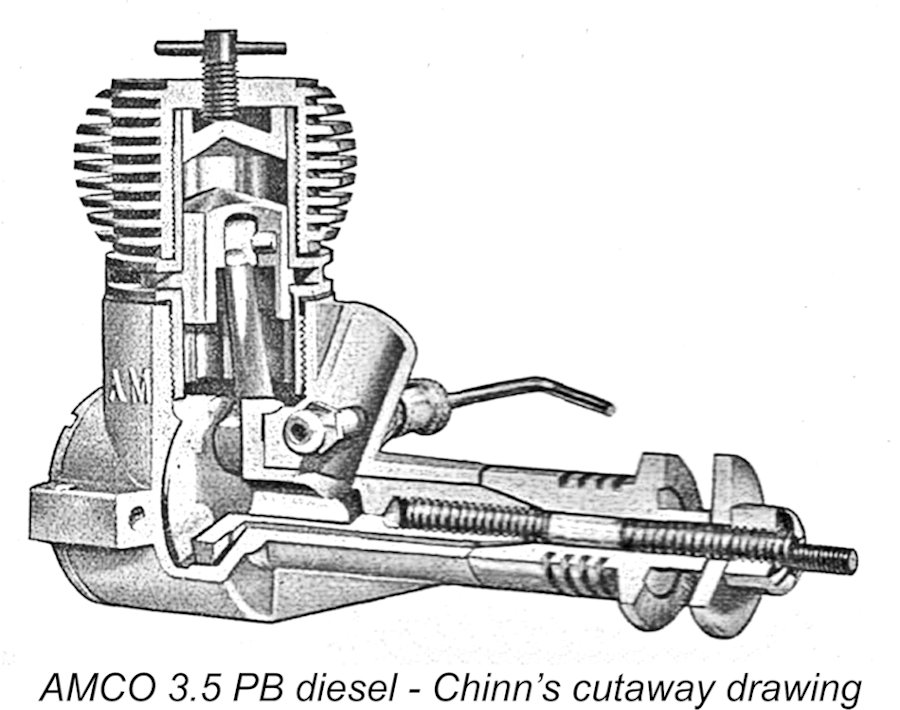

The very over-square bore and stroke of the AMCO 3.5 must surely have influenced Allen when designing the later A-M 35 (released in April 1955), since he adopted exactly the same bore and stroke dimensions for that engine. But he was careful to use a very sturdy shaft for the A-M 35 …………!! So despite its different porting system, the AMCO 3.5 PB may thus be seen quite legitimately as being very much the “parent” or prototype of the A-M 35. I love connections ………. Having looked at the fate of the AMCO line and seen Dennis Allen safely on his way to prominence as a British engine manufacturer, let’s now begin our detailed technical review of the various models which together made up the AMCO 3.5 cc series. Since it was the first AMCO 3.5 cc model to appear, it seems appropriate that we should begin by returning to May 1949 to trace the development of the AMCO 3.5 PB that started it all. The AMCO 3.5 PB - the Anchor Motors Variants The history of the AMCO 3.5 PB is complicated by the fact that it underwent a greater-than-usual number of detail modifications over its production life and was also manufactured by two distinct companies, each of which put their own design stamp upon the engine. It’s instructive to attempt to tie the various changes into the serial number sequence, beginning with the examples which were manufactured by the original makers, the Anchor Motor Co. of Chester, or Anchor Motors as they styled themselves on the 3.5 cc boxes and in the literature supplied with the engines. But before doing so, it’s worth summarizing the common points shared by all variants. Bore and stroke remained constant throughout at 17.46 mm (0.687 in.) and 14.29 mm (0.562 in.) respectively for a displacement of 3.42 cc (0.209 cuin.). These were unusually over-square dimensions by contemporary diesel standards – a bore/stroke ratio of 1.22 to 1. Weight also remained essentially constant at around 114 gm (just over 4 ounces).

The rather heavy cast iron piston had a conical crown, with the contra-piston being contoured to match. The working piston of the Anchor Motors variants was not internally machined in any way to lighten, which was a pity since direct latter-day experience confirms that these engines run far better and more dependably if the piston is internally lightened by milling, leaving plenty of material at the boss locations. No doubt cost considerations were a factor here, but it’s still a bit odd that the makers didn’t carry their obvious quest for overall lightness of the engine into the area of the piston where reciprocating weight reduction would confer a definite benefit upon performance and reliability. It was left to their successors to take this step. Another problematic design feature was the fact that the gudgeon pin did not pass completely through the piston. Only one end of the transverse gudgeon pin hole in the piston was left open. The pin passed though the open hole in the piston to engage with a blind hole in the other piston boss using a press fit. The intent was clearly to discourage lateral movement of the pin and possible fouling of the transfer ports. Rather oddly, the open end of the pin was not machined in any way to facilitate its removal. This made rod replacement a bit of a pain - I have heard of people drilling these pins out from the blind side as their only recourse!

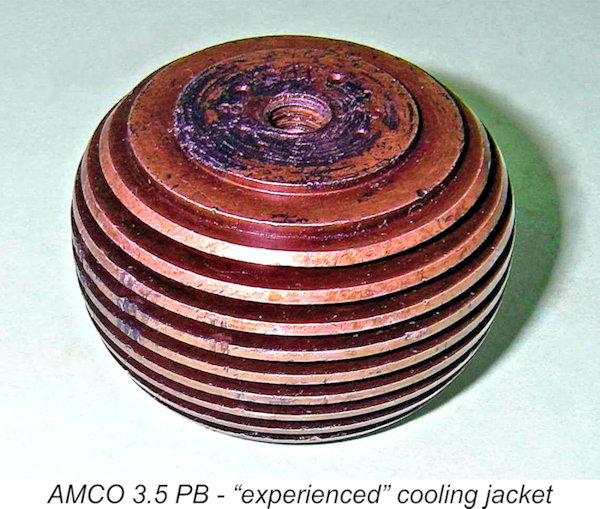

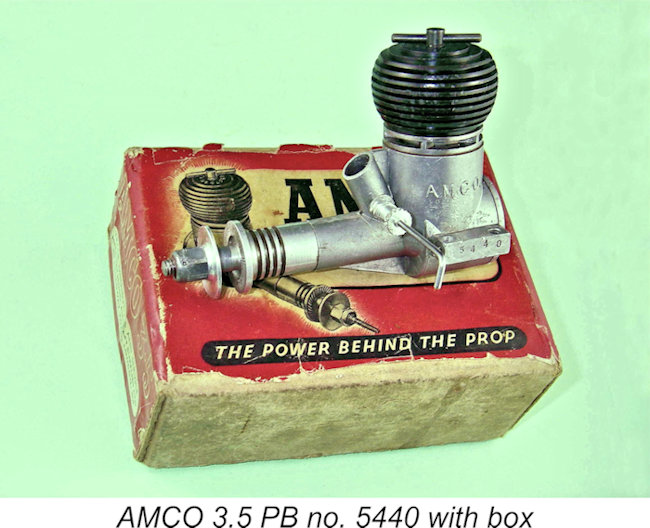

The cylinder, cooling jacket and backplate were all screw-in items, allowing for extremely compact and lightweight construction - no screws were used anywhere in the engine. It has been reported from time to time that some of the early AMCO 3.5 PB engines had brown-anodized cooling jackets. This is incorrect - in fact, the cooling jackets of all of these early engines started out life as black-anodized components. However, the black dye used in the anodizing process quickly developed a pronounced brownish hue under the influence of repeated heat cycles. I know - I’ve watched this happen as formerly-black engines turned brown!! You can see in the attached image that traces of the black color have survived in the centre of the head at the coolest point during operation. A few batches of the AMCO 3.5 PB were sold with red-anodized jackets, although they appear to be very much in the minority. I’ve never encountered one of these myself, but they undoubtedly exist - Kevin Richards had seen a few of them, and a few more have shown up on eBay. Presumably they date from after the introduction of the red-headed glow-plug version of the engine in mid 1950. It’s likely that some of the PB diesel heads went into the same anodizing batches used for the glow and BB diesel heads. This change was not made wholesale - some of the highest-numbered 3.5 PB examples have black heads. The red coloration was presumably confined to certain specific batches. A somewhat more puzzling occurrence is the occasional appearance of one of these engines with a green-anodized jacket. Again, I have personally yet to encounter a green-jacketed example in the Anchor Motor Co. serial number sequence, but they do exist - engine numbers 2962 and 11412 are both indisputable Anchor Motor Co. products having green jackets. It seems that advantage was taken of a few batches of green anodizing being applied to the company's automotive components. Either that, or some enthusiastic if misguided owners re-anodized that component just to confuse us!

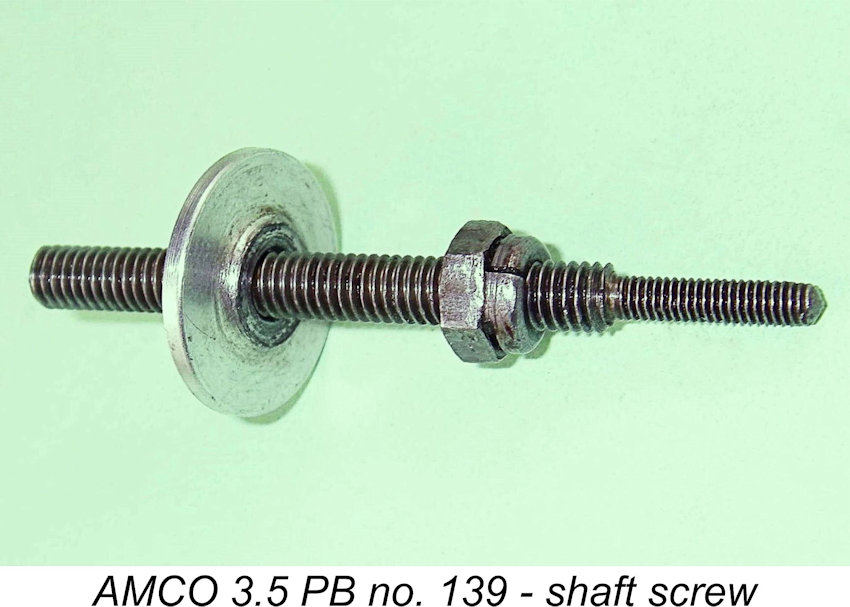

A bad feature of all of the Anchor Motors engines was the compression screw – this was far too short and way too close to the top of the cylinder jacket. Peter Chinn quite legitimately criticised the engine on these grounds. The top of the jacket was numbered circumferentially in the same manner as on the earlier AMCO .87 models, presumably to allow the recording of compression settings. The engines were sold in sturdy cardboard boxes which were heavily decorated. The package included a well-written and quite comprehensive instruction sheet. So much for the constant features. Let’s now take a look at the changes which become apparent as we work our way up the serial number sequence of the 3.5 PB engines produced by the Anchor Motor Co. 139 – a very early example from my own collection which is LNIB and has had only a few bench runs. Bought new in 1949 by my late Canadian friend Sqd. Ldr. Laurie Ellis, RCAF, who was then still stationed in England. It has a black-anodized head which is un-faded from hot running. The very low serial number indicates that it is one of the very earliest models dating from 1949, and it has the original and notoriously weak “big hole” shaft with large centre hole and induction port as well as a rather “primitive” lightweight rectangular crankweb. I probably have the fact that this engine appears to be more or less unrun to thank for its structural integrity!

But the main reason for these breakages was almost certainly the inherent structural weakness of the shaft itself. You only have to look at one of them to see that the boring of the very large central gas passage leaves far too little wall thickness for adequate strength, particularly with an unbalanced 3.5 cc big-bore short stroke plain bearing diesel and an ultra-lightweight crankweb. The round induction port in the shaft journal surface is also far too large for comfort, structurally speaking. This example also has the original rod, which appears to be of cast “pot-metal” and wore very rapidly – both Henry J. Nicholls and Lawrence Sparey commented on this in their respective 1949 tests, as did Peter Chinn in retrospect in his November 1952 test. The rod in this example is very well fitted, almost certainly due to its virtually un-run state.

The previously-reproduced cut-away drawing which accompanied Sparey’s test of this engine shows the rectangular crankweb and other structural details clearly but is misleading in one respect. The shaft is correctly depicted as having an internally threaded portion at the front to accommodate the separate screw-in prop mounting stud. The main shaft ends at the front of the taper upon which the prop driver mounts. The shaft is centrally drilled and tapped 2 BA back from that point almost (but not quite) to the induction passage, and a separate 2 BA prop fixing stud called a “shaft screw” by the manufacturers threads into this hole. So far, so good!

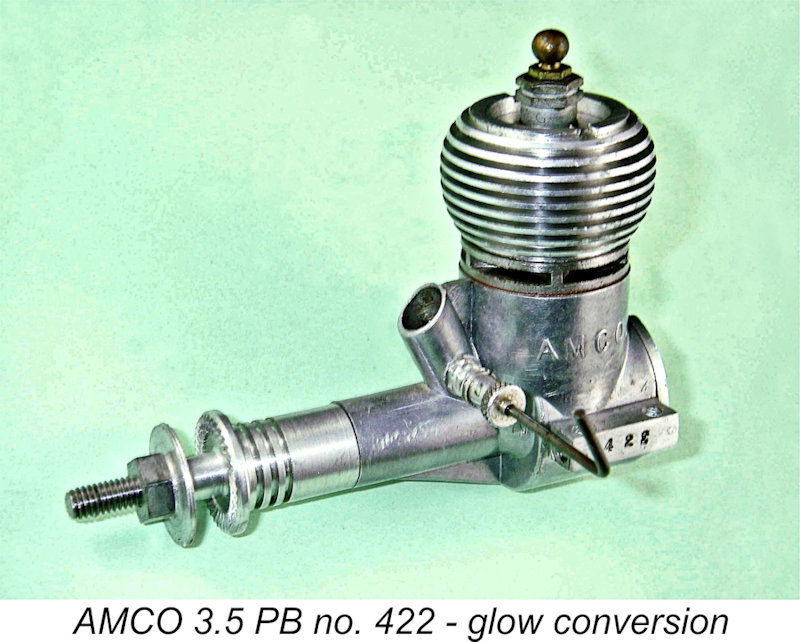

The use of this separate prop mounting stud was doubtless a good idea in terms of protecting the shaft from crash damage – a replacement shaft screw was no big deal by comparison with a replacement shaft. A nice touch was the use of a 2 BA prop nut which featured a fibre insert for a measure of self-locking. This was carried through the entire production life of the engine. All but two of my examples have such a nut, as does the engine depicted in Sparey’s cut-away drawing – the others are presumably replacements for lost prop nuts. 422 – also from my own collection. Another early example, with the big-hole shaft and cast pot-metal rod. This one has been converted from diesel to glow operation using the factory glow conversion kit, which was available as an accessory more or less from the outset. It had a standard black diesel head originally, although it had done enough running in diesel form to fade the black colour to brown. This head (illustrated earlier) was still with the engine when I acquired it and remains with it today, as do the original contra-piston and comp screw - a careful owner, obviously! These components clearly did some running before they were removed for the installation of the glow conversion.

Although the engine is in very nice (EXC) condition, it has clearly been mounted and run a fair bit by a careful owner, and I think the fact that the shaft and rod are still with us is simply a reflection of the fact that glow-plug operation is far easier on these components than diesel operation! I’ve actually run this one myself, and it starts and runs well (and very noisily!) but seems to produce less torque than its diesel equivalent. By “feel”, compression ratio seems a bit marginal to my very experienced hand – probably good for the shaft, though! A bit of nitro really helps to smooth put the running because of the low compression ratio. I’ve never rev-tested it on a series of props – I should do so sometime. I bet the diesel would beat it handily on the big ‘uns ………… The glow conversion kit is in two parts – a head button with the tapped hole for the short-reach plug, and a screw-on cooling jacket which clamps the button in place on the top of the cylinder. This jacket has a large hole in the centre to provide clearance for the plug. There’s also a sealing gasket of some kind of fibre-based material that supposedly seals the unit properly. Seems to work well on my own operational example.

The main point of interest here is that the glow head was promoted as a means of prolonging the useful life of the engine rather than as a legitimate alternative to the diesel. All I can say is that number 422 is very far from being worn out for diesel operation – the piston fit is superb! So the original owner of that engine clearly ignored these instructions – he probably ran the thing in as a diesel and then switched right away to the glow conversion.

In addition, a number of prop drivers of differing lengths were available as extras, to allow for locating the prop at different distances from the main engine body to aid cowling. The standard driver supplied with the engine was ¾ in. long, but alternative drivers of ½ in. and 5/16 in. could be purchased. In mid-1950, the makers released an over-the-counter glow-plug version of the 3.5 PB. This was simply a 3.5 PB diesel which was works-fitted with a standard factory glow conversion and had a more loosely-fitted piston. However, the cooling jackets of the factory-assembled glow-plug models were anodized red to distinguish them at a distance from their black-topped diesel counterparts. It was one of these units which was tested by (presumably) Peter Chinn in the previously-mentioned test which appeared in the May 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. I don’t have access to an example myself.

Although the black coloration of the head suggests that this example actually had relatively little use, Bernard reported that the rod was well and truly shot - clearly it didn't take much running to produce this result! However, the most interesting point brought out by this particular engine is that it exemplifies yet another failure mode for this design. As received, the piston was found to be cracked starting from the open end of the gudgeon pin hole. This may be an example of the “gudgeon pin failures” mentioned by Peter Chinn in the November 1952 “Model Aircraft” test to which reference was made earlier. 2798 – this is the cited serial number of the example illustrated by Fisher in his well-known book. It clearly has the wrong needle valve assembly. This example reportedly had a black head, which is not obvious in Fisher’s photo (# 72, page 101). No information regarding its internal structure.

4792 - owned by Jon Fletcher. This one is a black-head diesel model with the usual brownish coloration due to heat. This one originally had the early big-hole shaft with rectangular web, but Jon noticed that this shaft had a hairline crack starting opposite the induction port in the usual failure mode for these shafts. A replacement was made with a full-disc crankweb. Nonetheless, this example shows that the big-hole shaft with rectangular crankweb stayed around for a surprisingly long time despite its demonstrated inadequacies. This engine also had a turned alloy con-rod in place of the earlier cast one. Thanks to Jon for this very useful bit of information.

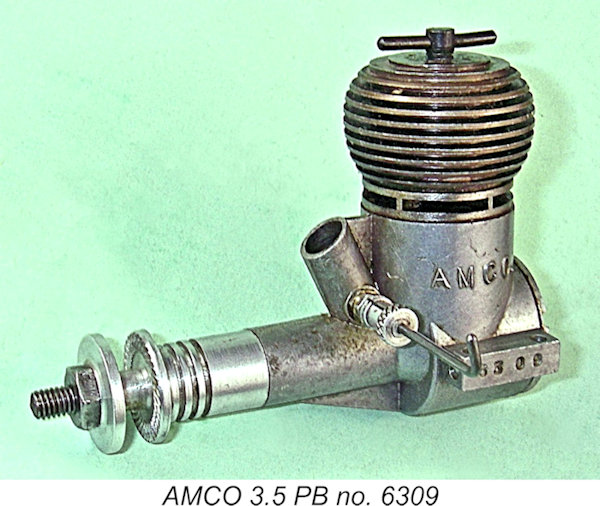

It’s worth noting in passing that the revised crankshaft appears to have been in use by early 1951 at the latest, since the previously-reproduced cutaway drawing of the AMCO 3.5 PB glow model which appeared with the May 1951 “Model Aircraft” test of that model clearly shows the revised crankshaft. Of course, it could well have been introduced some time before that date. The design represented by number 5440 appears to have remained fixed from there on until the end of production by the Anchor Motors Co. in early 1952. However, there is evidence to suggest that the company used up some of the earlier cast rods which remained on hand in their spares inventory by installing them in some of the later examples of this model (see below). 6309 – my usual “flyer” from my own collection. In EXC condition, although obviously used quite a bit and has had considerably more use from me. Very little wear, though – all fits remain excellent, and the engine has a positively “silky” feel when turned over slowly, with no “stiction” at any point. Black head, which as usual has faded to brown from the effects of heat. Small-hole shaft with full-disc crankweb, but unaccountably reverts to the earlier cast rod. This may be a case of the makers using up a left-over component from their spares inventory - indeed, a few such rods 9334 - owned by Jon Fletcher. This one arrived in very abused condition, although it retained a quite well-preserved black head. Its primary significance was the fact that for a while it enjoyed the distinction of having the highest serial number then reported for one of these engines - that is, until red-headed engine no. 10616 and green-headed unit no. 11412 showed up on eBay a few years ago. It is of course possible that the series extended further than this, and I’d be most grateful for any authoritative information which would allow me to extend the known range of serial numbers. As matters stand, it appears that some 12,000 examples of the AMCO 3.5 PB may have been made by the original manufacturers over an approximately 2½-year period. A Latter-Day Test

The engine started immediately if a small prime was given, and ran flawlessly. The sole hint of the starting problems reported by others was an undeniable tendency towards finger-biting on the 8 in. dia. props. Even so, it’s no wonder that people liked them so much – plenty of power for not much weight. I chose not to push the engine above 12,000 rpm in deference to its age (60 years and counting at the time!). In any case, both Sparey’s and Chinn’s tests as well as the power curves supplied in the instruction leaflet show peak power occurring at just over 12,000 rpm, so there’s no point in pushing things any higher. My own very limited test resullted in the following excellent figures being obtained: 10x4 Taipan grey G/F nylon – 10,000 RPM (0.266 BHP) 9x6 Taipan grey G/F nylon – 10,300 RPM (0.283 BHP) 8x6 Tornado nylon – 11,500 RPM (0.309 BHP) 8x6 Taipan grey G/F nylon – 11,900 RPM (0.305 BHP) The BHP figures in brackets are approximate only, being derived from estimated airscrew power absorption factors for the airscrews in question. They cannot be taken as precise, but they do imply a peak output of around 0.310 BHP in the vicinity of 11,700 RPM - a little higher than the figure reported by Chinn and considerably higher than the numbers reported by Nicholls and Sparey. Indeed, the implied performance is considerably in excess of the manufacturer’s own claims. This well-used example is evidently a “good ‘un” and is doubtless far better run-in than any of the originally-tested units thanks to the air-time which it has received. This probably explains the considerably higher performance. Clearly there’s plenty of lovely torque on hand! Overall, these figures reflect a very handy performance indeed for a classic 1950 diesel weighing only 4.1 ounces. I found that for control-line flying a wide-blade 9x6 seemed to be a perfect match – I used a trimmed 10x6 myself. In control line service with such a prop, the motor hits peak RPM (in the vicinity of 12,000 RPM) in the air and pulls a model very well indeed while remaining well within safe rev limits. In flying trim, the engine won’t quite match the performance indicated by the above figures - suction with the stock spraybar is minimal because the intake is far too large for the diameter of spraybar used, so you have to restrict things a bit. I used my own needle valve assembly for flying to preserve the original, and even then I had to use a venturi insert to get the thing to suck consistently in an aerobatic model! Good pulling power regardless …… The Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering AMCO 3.5 PB Models With the previously-documented resumption of AMCO 3.5 PB production in mid 1953 by the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., a few more consequential changes made their appearance. In conjunction with the change of ownership, the serial number sequence appears to have been re-started from engine number 1. Let’s look at a few of these revised designs.

Kevin Richards kindly drew attention to a very subtle change which had escaped my previous notice. As we shall see when we come to discuss that model, the cylinder of the AMCO 3.5 BB differed in length very slightly from that of the Anchor Motors version of the AMCO 3.5 PB and the gudgeon pin hole in the piston was differently dimensioned and located. Hence the piston/cylinder/rod components were not interchangeable between the two models. Since the new manufacturers very sensibly wished to use the same piston, cylinder and rod for both models, the case of the revised 3.5 PB model was made fractionally higher to accommodate the BB components. An internal modification that was long overdue was the reduction of reciprocating mass through the internal milling of the piston. The component used by Anchor Motors had always been far too heavy, and the revised model with its lighter piston must have benefited considerably in terms of performance and reliability. The extended ¾ in. prop driver is gone as a standard item, the new driver being the shorter ½ in. item, reducing prop overhang to a substantial degree. The new driver has no grooves cut in it either. However, the maker’s advertising claimed that prop drivers of varying lengths remained available as accessories. The needle valve is now a simple plain un-split and lightly corrugated thimble which is tensioned by a conventional double-sided spring clip. It is definitely more positive in action than the old split thimble. The compression screw is higher and hence far more convenient to handle, and the numbers on top of the cylinder are gone. They were never really of much practical use. The extended front element of the shaft screw is history – there’s no sign that such an extension was cut off from the shaft screw fitted to this engine.

Another subtle change pointed out by Kevin Richards is the fact that the mounting lugs of the later examples of the Alperton-built AMCO 3.5 PB models such as this one were not drilled through horizontally like those made by Anchor Motors - presumably it had finally been recognized that few if any owners would consider mounting one of these engines radially. The elimination of these holes cut out one manufacturing step and also strengthened the lugs. I’ve never run this one, but I’d guess that it would be a very fine performer, and quite dependable too.

1346 - owned by Chris Murphy. This one reverts to the green head seen on engine number 940. It also features the horizontally undrilled lugs and the turned alloy rod of the earlier Alperton engines. Somewhat oddly, however, it also reverts to the plain-disc crankweb seen in engine number 522 which had been supplanted in engine number 940 by a seemingly superior counterbalanced component. This may be another case of the manufacturers using up component stocks on hand, and may indicate that this engine dates from the latter stages of production at Alperton. Certainly, this engine bears the highest serial number yet brought to my attention for a plain bearing engine from that source. Again, any serial numbers which extend the known range of the Alperton-produced AMCO models will be most sincerely appreciated and fully acknowledged. A Few Deductions regarding the AMCO 3.5 PB What to make of the above litany?? First of all, it seems clear that the engines produced by the Anchor Motor Co. were numbered sequentially starting at number 1. However, the numbering seems to have gone back to 1 again when the green-head models appeared after the take-over by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering. This event appears to have taken place after perhaps 12,000 examples had been produced by Anchor Motors over a period of around 2½ years - an average of some 400 engines monthly, give or take. This is well below the known production figures for such major producers as the rival E.D. company, for example. The relatively low production figures implied by the presently-known serial numbers suggest that model engine production remained very much a sideline with the Anchor Motor Co. This is scarcely surprising when we reflect upon the scope of their automotive activities. Most likely the model engines were made in batches during periods when the machine shop was under-utilised. A production figure of 400 engines monthly is consistent with the fact that Lawrence Sparey was able to publish a test of engine number 3276 in December 1949. In terms of design features, the original rod was made of a material which wore rapidly in diesel service, as noted by Sparey. The material of this rod was evidently changed, although the rod remained of the same general design at this point. This must have occurred fairly early on in the production life of the engine – Sparey implies in his test published in December 1949 that the rod material had been changed, and he was speaking about engine number 3276 when saying this. The change probably occurred rather earlier than that. The improved rod seems to have been replaced by a turned alloy item at some point around engine number 4000 or so, although left-over cast rods were evidently fitted to some later examples, presumably to use up stock on hand. The original big-hole shaft with rectangular crankweb seems to have lasted a surprisingly long time before the manufacturers finally yielded to sorry experience and began using the far stronger small-hole shaft with full-disc crankweb. Sparey's engine no. 3276 still featured the original shaft, and we know of engine number 4792 which originally had such a shaft. However, by the time we get to 5440 we find the redesigned shaft being used. It thus seems likely that the change was made at around engine number 5000, although examples with lower serial numbers having the later shaft will doubtless be encountered as a consequence of the replacement of broken shafts with the updated components. The change probably took place in early 1950. The original shaft was woefully inadequate for diesel operation, although it was probably OK for glow service. The problems were two-fold – it had both an oversized induction port which created a major stress-raiser at that point; and an oversized central hole which left far too little wall thickness to resist shear and bending stresses. The web was also extremely skimpy for a diesel engine of this size. As a result, these shafts didn’t last long in service! Sparey’s example survived his testing somehow, but many didn’t last all that far past the break-in if my old-timer colleagues from my early modelling days were to be believed. The crack in the original shaft of Jon Fletcher’s number 4792 is, alas, all too typical. This must have become apparent to the manufacturers very quickly based on the requests for spares which they doubtless received, and it’s really odd that they persisted for as long as they seem to have done with this shaft design. Presumably they tried changing either the material or the heat treatment specifications (or perhaps both) before bowing to the inevitable and re-designing the shaft. When it did finally appear at around engine number 5000, the redesigned shaft proved to be a far stronger unit having a smaller induction port and a smaller centre hole. They also went to a full disc crank-web – a good move for the reasons stated earlier. Performance probably suffered a little from this change and weight went up a fraction, but the engines no doubt became far more dependable. And as my number 6309 proves, they still ran pretty strongly! It was apparently Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering who introduced the un-numbered green head and later the counterbalanced shaft. Indeed, the previously-reproduced advertisement placed by them in the June 1953 issue of “Model Aircraft” focused on the re-introduced AMCO 3.5 PB design, drawing attention to its turned alloy conrod, lighter piston and revised needle valve among other features. They also shortened the front end of the motor to a significant degree. Doubtless Dennis Allen can be credited with these improvements. The fact that number 522 uses the old plain-disc small hole shaft and cast rod suggests that they likely acquired a batch of those components in the sale from Anchor Motors, which they elected to use up before switching to the superior components seen on number 940. The presence of a full-disc web in engine number 1346 may be another case of using up parts on hand. Having now reviewed the AMCO 3.5 PB in some detail, it’s time to return to mid-1951 and take a look at its top-of-the-range companion - the AMCO 3.5 BB. The AMCO 3.5 BB

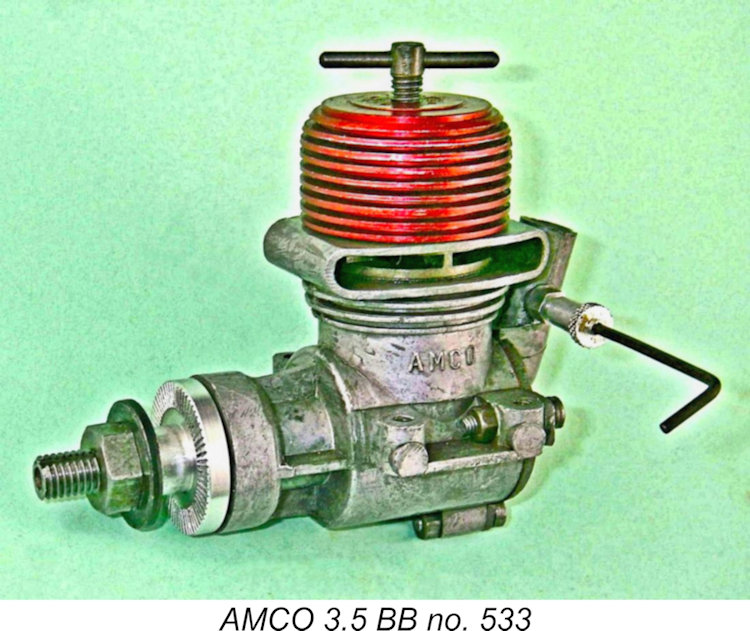

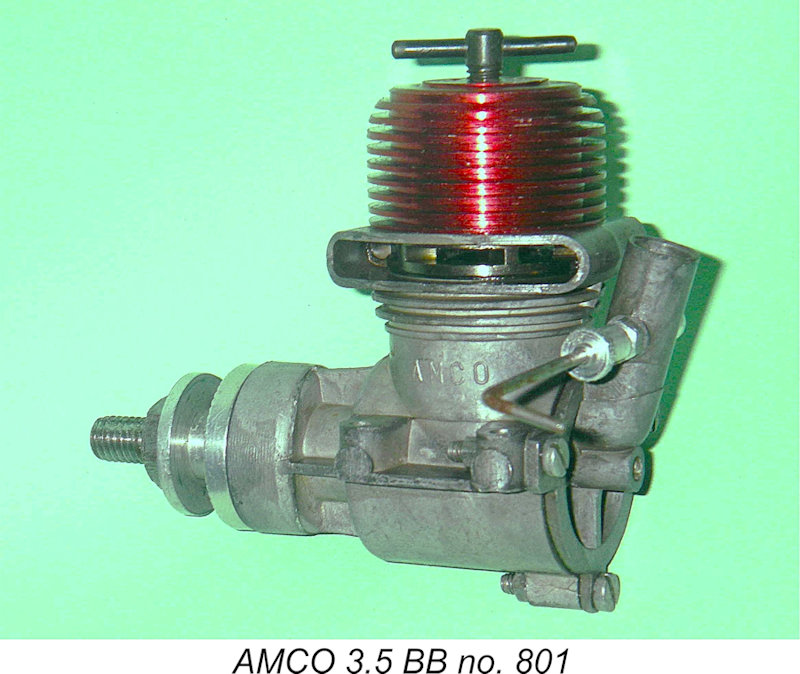

Given this background, it was only to be expected that the new AMCO 3.5 BB model would incorporate a number of “racing” features. These included a twin ball-race crankshaft and a rear rotary disc valve. In fact, this was an entirely different design, with almost no components being interchangeable between the PB and BB models. The new BB model used the same bore and stroke figures of 17.46 mm (0.687 in.) and 14.29 mm (0.562 in.) respectively for a displacement of 3.42 cc (0.209 cu. in.) - still unusually short-stroke geometry by then-current diesel standards. The cylinder porting too was identical. However, for reasons which are unclear, the cylinder of the BB model was very slightly different from that of its PB companion. The threads for the screw-on cooling jacket were made slightly shorter than they had been in the earlier PB model. My thanks to Kevin Richards for pointing this out.

The one-piece aluminium alloy crankcase was among the most impressive and complex pressure die-castings produced by the early post-war British model engine manufacturing industry. Apart from the necessary accommodation for the two ball races in the front housing, it also included a pair of exhaust stacks, one on each side, as well as unusually complex mounting lugs having expansions at the mounting hole locations. There were also lugs for the rear cover retaining screws. One area in which this casting proved over time to be a little lacking was the main bearing. A number of users have reported cracking problems both with the main bearing itself and with the front ball race housing. I’ve never experienced this myself, but it's definitely a point to watch when considering the purchase of one of these engines. There has been considerable confusion regarding the material used for the AMCO 3.5 BB cases. The fact that they generally have a dark grey hue has led many people to the conclusion that they were cast in magnesium alloy. Fortunately, Peter Chinn set this matter straight in his August 1951 test of this model. He stated quite categorically that the cases and backplates were cast in LAC 112A aluminium alloy which was chromate-treated (or anodized, according to Chinn) to produced the characteristic dark grey hue. The engines treated in this way are often referred to as the “dark case” engines. Cylinder porting was identical to that of the PB model, with 5 exhaust slots and 5 internally-milled transfer flutes which terminated just below the exhaust ports - basically the same system that was soon to be adopted by Webra for their famous Mach I diesel and by many others thereafter. The cylinder screwed into the case exactly as in the 3.5 PB. The cooling jacket was of slightly different profile to blend with the two exhaust stacks and was anodized red. It retained the numbers on the top for recording compression settings, and the same very short compression screw was also used.

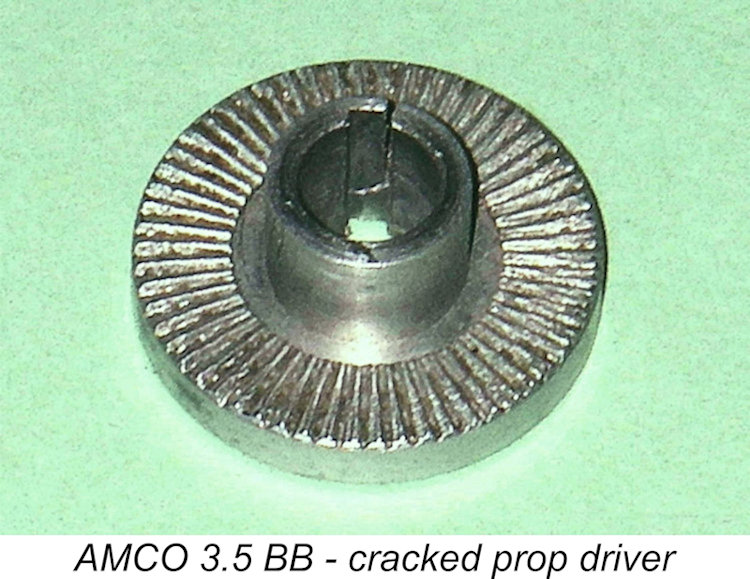

The crankshaft had a heavily counterbalanced web, resulting in significantly lower levels of vibration for this model. A potential weakness of this shaft was the use of a Woodruff key to secure the alloy prop driver. This was doubtless another instance of the engine’s racing influence, but it created a significant stress-raiser in the shaft and could also lead to cracking of the prop driver - I have encountered two examples which were damaged in this way. A split collar would have been far better.

The rotary disc which controlled the induction was of Tufnol, a non-metallic reinforced plastic material which was becoming increasingly popular in Britain at the time. Experience had shown that discs made of this material wore very well indeed, generally outlasting the rest of the engine. As we saw earlier, this model was probably manufactured by the Anchor Motor Co. for only some 8 months or so following its July 1951 introduction. Production was suspended during early 1952 pending the sale of the AMCO range to the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., but resumed under the auspices of the new owners in January 1953. The re-issued model was essentially identical to the original version apart from having a slightly longer comp screw. Accordingly, there is no need to describe it separately here. The sole other change of which I’m aware was the use of the revised (and it must be said, superior) needle valve assembly introduced on the Alperton-produced AMCO 3.5 PB model in mid-1953.

This version of the AMCO 3.5 BB dispensed with the chromate treatment of the main castings, being left in its natural finish. Apart from the removable stacks, it had a completely new crankcase which was much stronger and heavier than the old one, being beefed up around the main bearing area which had proved somewhat vulnerable to failure in the earlier version. It also had a slightly revised cooling jacket profile. Finally, it used the later spring-tensioned needle valve assembly which had first appeared on the companion PB greenhead models. Although this variant is considerably rarer than the dark case version, Kevin stated that about a dozen examples had passed through his hands over the previous 20 year period. This certainly seems to prove that that this variant did make it past the prototype stage into production. Kevin rated this as probably the most useable of all the AMCO 3.5’s. The AMCO 3.5 BB on Test

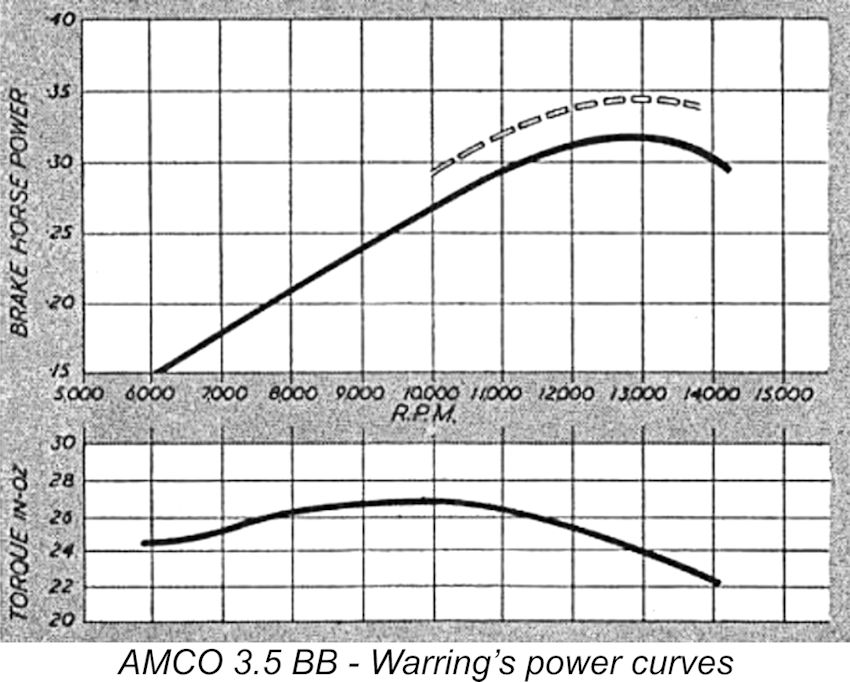

Chinn stated that the new model was considerably “more robustly constructed” than its plain bearing predecessor. He noted the various design features described earlier and commented upon the considerable improvement in performance over the plain bearing model, noting that the specific power output of the BB engine had “not been bettered by any model compression ignition engine so far tested”. He also stated that in Chinn criticised the very short length of the compression screw, but was otherwise uniformly complimentary. He characterised the measured output of 0.34 BHP @ 13,500 RPM as “exceptional”, which it certainly was by the standards of the day, also praising the very flat peak exhibited by the engine’s power curve. He noted that the performance available exceeded that of many American .19 cu. in. glow-plug motors, and summed up the engine as one from which “beginners and experts alike should get good results”. The rival “Aeromodeller” magazine never got around to testing the AMCO 3.5 BB while it was still being produced by Anchor Motors. However, they did publish a Ron Warring test of one of the later examples produced by the successor company, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. This test appeared in the May 1953 issue of the magazine.

On the basis of these tests, Warring expressed the opinion that the output could possibly be raised to as much as 0.345 BHP @ 14,200 rpm by using a tailored fuel, as reflected in the dashed curve included in his power diagram. This estimate almost exactly mirrored the actual results obtained earlier by Chinn. However one looks at it, these were very creditable figures indeed in 1953 for a compact 3.5 cc diesel weighing only 5½ ounces. The AMCO 3.5 cc Engines in Hindsight In September 1995, the very informative “Model Engine World” publication carried a double test by Dick Roberts which covered both the plain bearing and ball bearing versions of the AMCO 3.5 cc diesel models. The PB example was fitted with the later small-hole shaft with plain disc crankweb. This test was perhaps unfortunate in that the borrowed examples of the engines which were tested both appear to have been flawed in some way. Dick reported having considerable difficulty getting the 3.5 PB to start. He eventually reached a point where starting became fairly consistent, but it never became easy in his view. Once running, the engine ran dependably enough although the power output implied by the readings obtained from the series of calibrated test props was only of the order of 0.21 BHP @ 10,000 rpm - well down on other reported figures and indeed far below the implied performance of my own well-used tested example. By contrast, Dick’s example of the AMCO 3.5 BB reportedly started on the third flick following two choked turns. However, the testing of this engine was drastically curtailed when it was noticed that the front bearing housing had cracked. In the view of MEW editor John Goodall, this was due to over-enthusiastic removal of casting flash from an already too thin area of the casting. As noted earlier, it is apparently a point to watch with any AMCO 3.5 BB, although I have never experienced such a failure myself. Regardless, this put an end to testing and no performance figures were reported apart from two prop/rpm figures which showed a marked edge in performance over the PB model. It seems that Dick was unfortunate in the choice of examples made available for testing! A Latter-day Clone from Far, Far Away

The quality of the CS replicas varied widely, but definitely improved on average as time went by. I purchased one of the AMCO replicas from Carlson Engine Imports in 2006. I have to say that I’ve never had cause to regret this purchase! All of the CS engines tended to be “engine guy’s specials” - that is, they invariably required some careful individual attention before being run. I would never have recommended a CS replica to anyone who simply wanted an engine to mount on the test bench or bolt into a model unless they were both willing and able to sort any issues beforehand. My example was supplied rather tight (at my request to Ed Carlson) and needed the usual internal clean-up that seemed to be a fact of life with CS products. While I had it apart to do this work, I also matched the crankshaft induction port to the venturi base by grinding (it was a little out of register in an axial direction) and then tempered the crankshaft given the fact that CS tended to make their shafts rather on the brittle side. This process involved placing the clean shaft in a cold domestic over, heating the oven to 550 degrees Fahrenheit with the shaft inside, holding it there for around 2 hours and then switching the oven off without opening it and allowing slow but complete cooling of the shaft in the unopened oven. After the engine was reassembled and carefully run in, it proved to be a more than acceptable substitute for the real thing. The CS replica blended many (but not all) of the better features of the later Alperton-produced AMCO 3.5 PB engines - it had the turned rod, the plain-disc small-hole crankshaft, the internally-milled piston, the horizontally undrilled mounting lugs, the extended comp screw and the shorter prop driver along with an absence of numerals on the head. It also featured a prop mounting bolt in place of the former shaft screw and nut - a far more convenient system.

Unlike the AMCO originals, the anodizing on these heads appeared to be relatively impervious to heat-induced fading - the cooling jacket of my original acquisition is still as black as the Ace of Spades despite having had some hours of running on the bench and in the air. Having been well run-in and seen some airborne service, my illustrated black-head example of this engine is now well freed up and handles just as well as the original. It turns a given prop at within 100 rpm of the figures given above for my better-than-average original example. All fits remain excellent, with first-class compression and no trace of play in the bearings. Having said this, fairness compels me to balance the rose-tinted view presented above by stating clearly that not all purchasers were as fortunate as I was! Chris Murphy owned two of these CS replicas, both of the red-headed variety. The first one sheared off the crankpin after about an hour's bench running. Chris suspected that this was largely due to poor workmanship - the crankpin hole was drilled well off centre. He returned it to the suppliers under guarantee and they replaced it, but the replacement one was just as bad and had a chewed-up rod as well. Chris intended to try his examples again at some point, but not until he had tempered the shafts in the manner noted above. By contrast, my example ran just great in the air and provided the “AMCO experience” without the need to risk an original in flight. Overall, I’d rate this as one of CS’s better efforts, although I am admittedly speaking about just one example, which may be better than the average. That said, my red-headed example appears to be every bit as well-made. I haven't run that one, although I have cleaned it up and tempered the shaft "just in case". Mind you, I’m quite willing to fly an original later-model AMCO myself - for me, knowing that I have the real thing out there on the end of my lines still means something! But for anyone who understandably wants to preserve their originals, the CS replica can offer a perfectly valid alternative provided you clean it up, temper the shaft and give it a careful break-in. The J.B. Connection

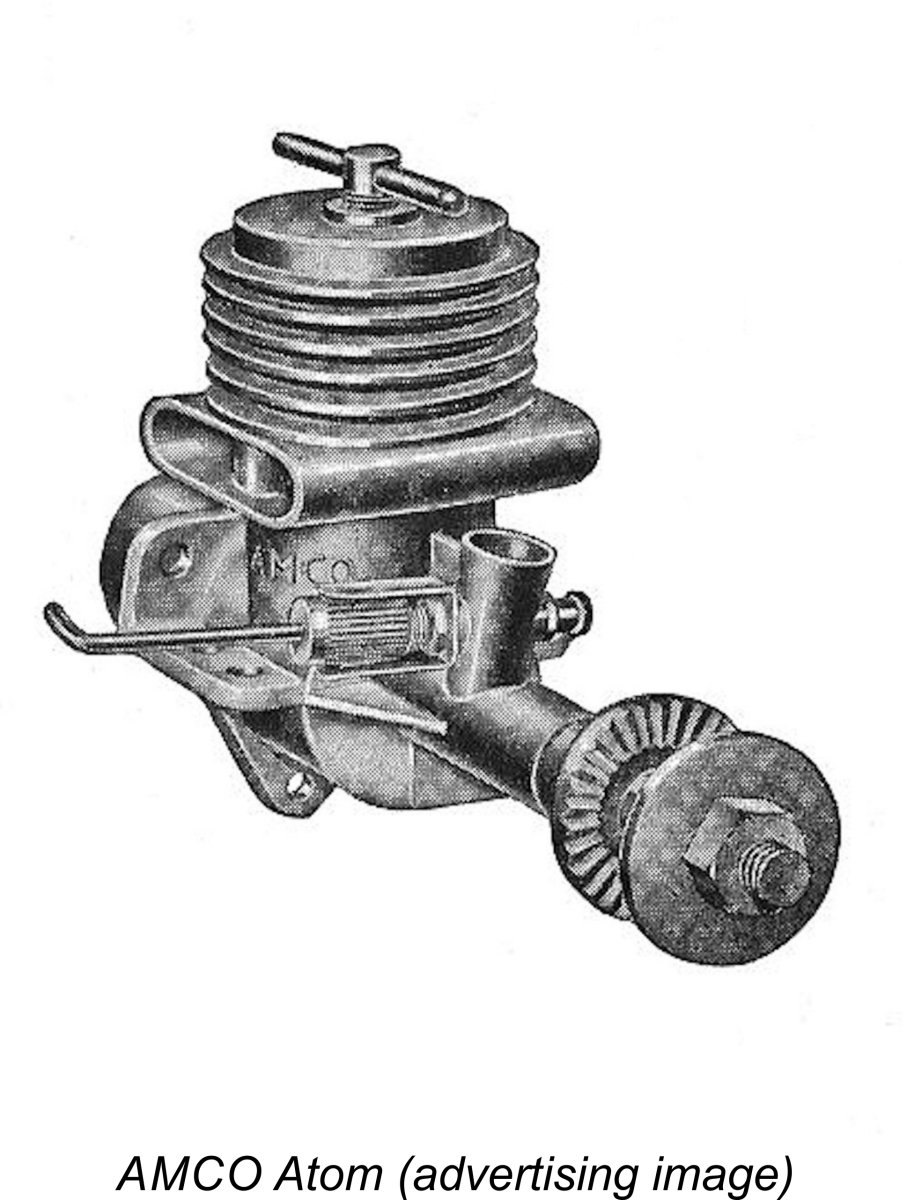

In mid 1954, soon after the departure of Dennis Allen and Len Steward, AMCO Model Engines Ltd. announced a new 1.5 cc AMCO engine called the Atom. Jack Ballard seems to have made a practise of issuing premature announcements, and this one was no exception - as of October 1954 we find him apologising for the delay in getting the Atom out to the model shops! This apology was repeated in December of 1954. It seems highly likely that the departures of Dennis Allen and Len Steward had something to do with this ………. A few examples of the AMCO Atom were made before AMCO production ceased in March of 1955, since one or two are known to exist today in private collections. Still, this remains the rarest AMCO model. However, the 1.5 cc Atom design did not die as a result of the cessation of AMCO production - it resurfaced in October 1955 in the form of the J.B. Atom 1.5 cc diesel. Peter Chinn confirmed this connection in a comment made in his “Accent on Power” column which appeared in the February 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. In this article, Chinn mentioned the earlier still-born AMCO Atom model announced in 1954 by AMCO Model Engines Ltd. and then stated that the then newly-introduced J.B. Atom appeared to be essentially the same engine in a slightly revised form and under a new name. It’s evident from all of this that at some point following the placement of that final AMCO advertisement in February 1955, Jack Ballard decided that the time was right to make a further move by forming yet another new company, this time under his own name. This decision may have been prompted by the ongoing production problems with the other AMCO models prematurely announced by AMCO Model Engines Ltd. over a year earlier in late 1953. Ballard may have felt (with some justification) that the existing companies had squandered too much of their credibility by that time.

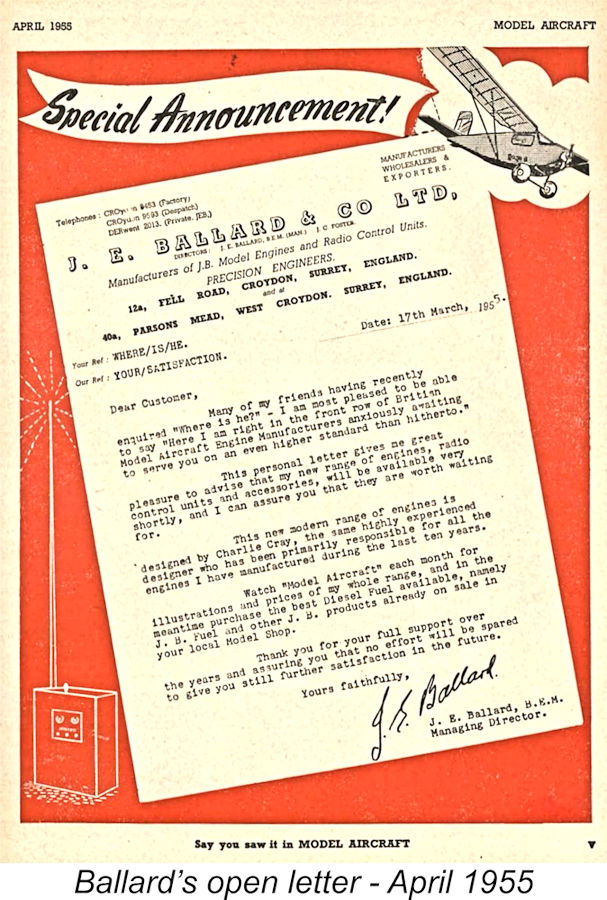

As an aside, it’s interesting to note Ballard’s comment in his April 1955 open letter that the designer of his new line of engines was Charlie Cray, “the same highly experienced designer primarily responsible for all the engines manufactured by me (Ballard) during the past ten years”. I’m sure that Basil Miles (of E.D. fame), Ted Martin and Dennis Allen would all have been surprised to read this …………. A close perusal of this letter raises a few other interesting points. In the signature block, Ballard styled himself as "J. E. Ballard, B.E.M.". The term "B.E.M." apparently refers to the British Empire Medal, of which Ballard was evidently a recipient. The date of this award and its basis are unknown at the time of writing. All that is clear is that Ballard was very proud of this honor.

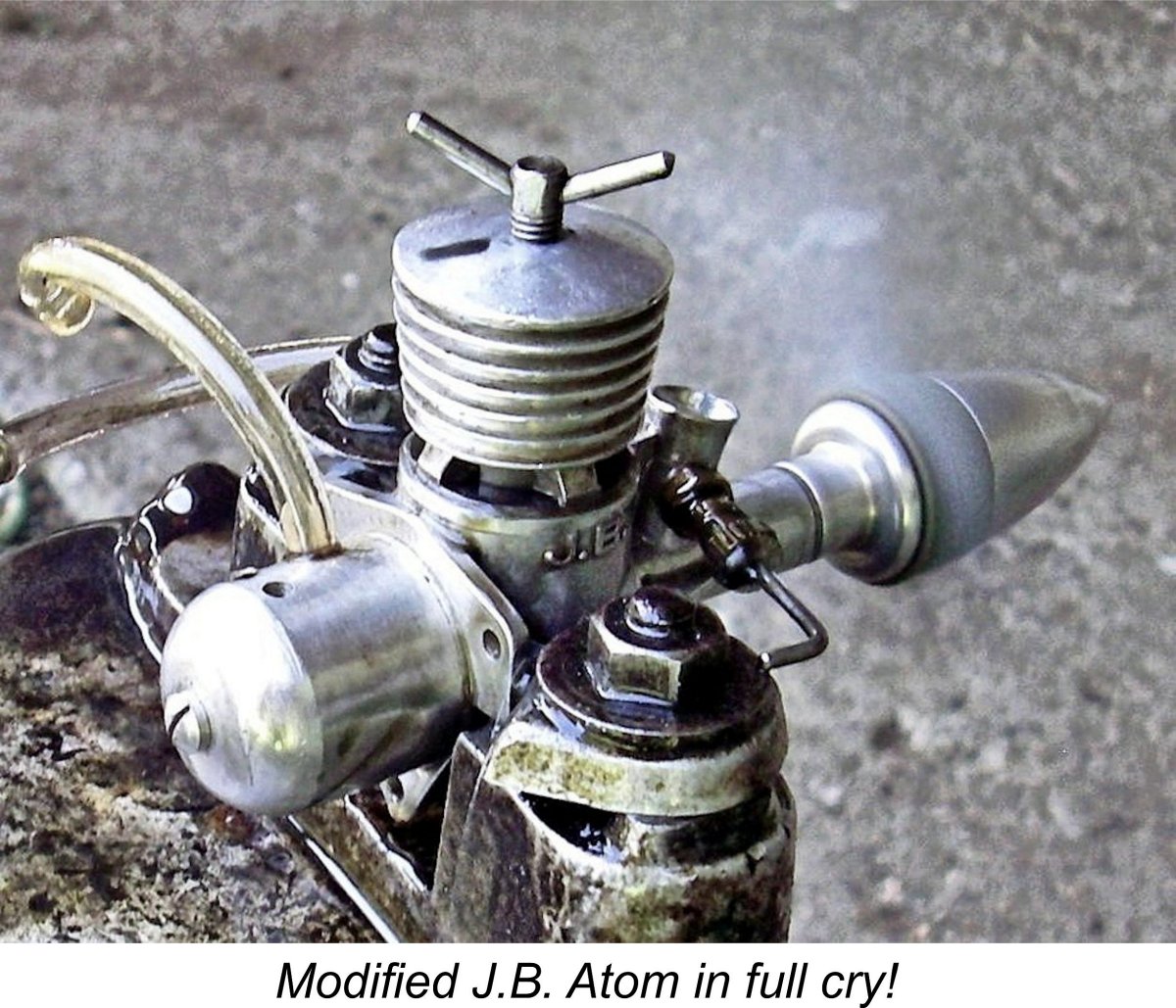

Regardless, the first product of the new company was a model diesel fuel blend sold under the J.B. banner. This was being advertised by July 1955. At this time, the new company had yet to release an engine under its own name, but this changed in October 1955 with the initial announcement of the company’s first model engine, the aforementioned J.B. Atom diesel of 1.5 cc. Ballard subsequently went on to produce both a glow version of the J.B. Atom and a smaller 1 cc version called the J.B. Bomb in both diesel and glow configuration. These three additional models were announced in April of 1956. The J.B. engines were very well made, also being competently designed in a purely functional sense. Unfortunately, they suffered from several flaws in their production specifications and metallurgy which prevented them from realizing their potential in terms of both performance and working life. Consequently, they failed to make any real impression upon This is all a bit sad, because my own research has demonstrated that the Atom (and presumably the others) could have been pretty good engines. Some years ago I acquired a rather sad example of the Atom which had suffered greatly at the hands of a previous owner who attempted unsuccessfully to modify it. The engine also sported a totally clapped-out rod and wrist pin, a typical consequence of the use of a poorly-designed hardened steel rod.

The company continued its promotional efforts throughout the balance of 1956, but seemingly without sufficient sales success to justify continued production. The actual manufacture of the J.B engines appears to have ended in late 1956 - the last J.B. advertisement that I’ve been able to find appeared in the January 1957 issue of “Aeromodeller”. This did not prevent Peter Chinn from featuring a very positive test of the 1 cc J.B. Bomb in the June 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, at which time the engines were evidently still available from the stocks of a number of dealers. By this time, however, it’s almost certain that the company was simply liquidating their unsold inventory. Kevin Richards recalled that some years ago he was in contact with a former distributor of the J.B. engines. This indiviual retained a tea-chest full of boxed J.B. engines along with many spares, all of which were acquired by Kevin. Some of the spares constituted evidence that there had been some ongoing development of the J.B. engines to try and iron out the various faults. However, these efforts proved to be too little and too late to save the range. Still, it’s worth remembering that despite the name, the J.B. engines were in reality the final representatives of the AMCO line which had begun with so much success back in 1947 in Chester! Many people have wondered what became of Jack Ballard after the failure or the J.B. enterprise. Virtually nothing was known of his subsequent activities until 2025, when I was delighted to hear from his grandson, John Foster, who had just read my articles on his grandfather's various companies. John commented that all that I'd written about Jack Ballard appeared to fit the man that John remembered. It appears that after the failure of the J.B. enterprise, Ballard left the model business, going on to own a sweet shop. However, that too eventually failed. He then worked for Decca radar for some years, ending up living in somewhat reduced circumstances in a council flat in Surbiton. His financial situation worsened to the point that John Foster's mother (Jack Ballard's daughter) would often have to provide food to keep him going in his later years. Despite these various vicissitudes, Ballard retained his interest in model airplanes, continuing to fly them for some years on Epsom Downs. We may legitimately conclude that he was a genuine enthusiast whose career in the model trade was stunted to a significant degree by certain personality traits to which I've alluded. Jack Ballard died in October 1990 at Kingston-upon-Thames, thus making it well into his eighties. He died of a heart attack after collecting a £500 winning horse racing bet at a local bookmaker. John Foster was never quite sure if his passing on such a high was good or unlucky, as he finally won but did not get to enjoy the proceeds! Conclusion The Anchor Motor Co. remained in business for many years following the end of their involvement with model engines, finally closing their doors in 1983. Today the location at which they produced the AMCO engines has been extensively redeveloped, much of it being absorbed by the Grosvenor Shopping Centre, although The Newgate still exists. I have no information regarding the eventual fate of Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. or their Alperton facilities.

If you run across an original blackhead (or brownhead!) model and are tempted to buy it for the purpose of actually using it for vintage flying, I’d suggest checking that its serial number lies in the higher range for that version - say, above 5000. That way you stand a good chance of getting one with the stronger shaft and improved rod, although I’d still recommend removing the backplate to check. I would strongly recommend against using any AMCO 3.5 PB with the early big-hole shaft with rectangular crankweb - it will fail at some point. The later (and rarer) examples with green heads made by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering all seem sturdy enough to take a fair bit of use.

The other potential issue with this model is the tendency of the Woodruff key mounting of the prop driver to cause cracks in that item. But a replica replacement using a split collet is easily made. My usual “runner” AMCO 3.5 BB has been very successfully repaired in this manner. Overall, my recommendation is - go for it! Anyone who likes classic model diesels can’t fail to enjoy the experience of running and/or flying one of these fine engines! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN April 2011 This revised edition published here February 2025 Updated June 2025 - more info on Jack Ballard |

| |

In this article, I’ll take a comprehensive look at a series of British-made model engines which were real trend-setters in their day and remain highly respected by today’s collectors and vintage modellers. These are the AMCO 3.5 cc models, which were offered in both plain bearing and ball-race versions as well as diesel and glow-plug variants.

In this article, I’ll take a comprehensive look at a series of British-made model engines which were real trend-setters in their day and remain highly respected by today’s collectors and vintage modellers. These are the AMCO 3.5 cc models, which were offered in both plain bearing and ball-race versions as well as diesel and glow-plug variants.

The AMCO range of model engines was the creation of the Model Engineering Division of the Anchor Motor Company, who gave their address as The Newgate, Chester, Cheshire, England. Before going any further, I should point out that the company’s trade-name is correctly rendered as “AMCO”, not “Amco”, since it represents the initials of the company. Such names are conventionally rendered entirely in capital letters (ABC, BBC, BMW, BSA, IBM, etc.). The Anchor Motor Co. themselves always rendered their trade-name in this manner – we should pay them the respect of doing the same.

The AMCO range of model engines was the creation of the Model Engineering Division of the Anchor Motor Company, who gave their address as The Newgate, Chester, Cheshire, England. Before going any further, I should point out that the company’s trade-name is correctly rendered as “AMCO”, not “Amco”, since it represents the initials of the company. Such names are conventionally rendered entirely in capital letters (ABC, BBC, BMW, BSA, IBM, etc.). The Anchor Motor Co. themselves always rendered their trade-name in this manner – we should pay them the respect of doing the same.  The Anchor Motor Company grew into quite a large organization, employing up to 80 staff during its heyday. They were engaged in car sales (Hillman, Riley, Humber, Thames and Rootes in later years) as well as operating a major vehicle servicing facility which included both a spray shop and a very extensive machine shop. They were deeply involved in motor engineering, including servicing, rebuilding and re-boring a variety of engines, both automotive and commercial (Perkins diesels, etc.). They also made custom vehicles for specialized transportation applications in the agricultural and other fields. The machine shop thus lay at the core of the company's business.

The Anchor Motor Company grew into quite a large organization, employing up to 80 staff during its heyday. They were engaged in car sales (Hillman, Riley, Humber, Thames and Rootes in later years) as well as operating a major vehicle servicing facility which included both a spray shop and a very extensive machine shop. They were deeply involved in motor engineering, including servicing, rebuilding and re-boring a variety of engines, both automotive and commercial (Perkins diesels, etc.). They also made custom vehicles for specialized transportation applications in the agricultural and other fields. The machine shop thus lay at the core of the company's business. located round the corner on Park Street (in effect, a continuation of The Newgate opposite). It may appear odd that the address of the company was given as The Newgate, since none of its premises actually appear to have been located on that street! However, The Newgate has long been identified with a general area within the city of Chester rather than with a mere street.

located round the corner on Park Street (in effect, a continuation of The Newgate opposite). It may appear odd that the address of the company was given as The Newgate, since none of its premises actually appear to have been located on that street! However, The Newgate has long been identified with a general area within the city of Chester rather than with a mere street. The importance of this war-related work allowed the company to keep its machine tool inventory well up to spec, replacing worn equipment as necessary. As a result, the company entered the post-war period with an extensive machine tool inventory that was of excellent quality and in fine condition, a luxury enjoyed by few other early post-war British model engine manufacturers.

The importance of this war-related work allowed the company to keep its machine tool inventory well up to spec, replacing worn equipment as necessary. As a result, the company entered the post-war period with an extensive machine tool inventory that was of excellent quality and in fine condition, a luxury enjoyed by few other early post-war British model engine manufacturers. At about the same time, a certain Basil Healy of Ilford in Essex was developing his own design for a small model diesel engine called the Midge and manufacturing it in very small numbers in his home workshop for sale locally. The stereotypical one-man "garden shed" operation, in fact! The Healy Midge engine was made in several displacements from 0.5 cc through 0.99 cc to 1.2 cc. Healy's location has often been reported as Rayleigh, Essex, but the late

At about the same time, a certain Basil Healy of Ilford in Essex was developing his own design for a small model diesel engine called the Midge and manufacturing it in very small numbers in his home workshop for sale locally. The stereotypical one-man "garden shed" operation, in fact! The Healy Midge engine was made in several displacements from 0.5 cc through 0.99 cc to 1.2 cc. Healy's location has often been reported as Rayleigh, Essex, but the late

Probably because they still lacked the appropriate in-house expertise, the company encountered some production challenges in preparing to put this engine into series production. Their response to this problem was to place an advertisement in a trade magazine seeking an individual with an engineering background who was knowledgeable about model engines.