|

|

Frank Ellis, Elfin Manufacturer by Adrian Duncan, in collaboration with Jim Woodside

Jim subsequently passed several of the tapes on to the late former “Aeromodeller” editor Ron Moulton, who was planning to write up a history of the Elfin range at the time. Jim also kept a cassette tape of another interview, which he most generously passed on to me for study purposes. Ron Moulton never did write up his Elfin history, but he subsequently copied the tapes in his possession onto disc and provided me with an audio record of those discussions also. Big thanks to Jim and Ron for their generous gesture in making this priceless first-hand record available to me! It is solely thanks to their splendid and unselfish co-operation that I’m able to share this material. The recorded interviews occupy several hours in total. As might be expected, they cover a considerable amount of common ground, and it has to be admitted that Frank's recollections on a given topic are somewhat hazy in certain instances - not surprising at age 81 after the passage of almost half a century! However, the main thread of the Elfin story runs strongly and clearly throughout the interviews - it just takes a little sorting out in spots.

In addition, it's often hard to determine exactly which engine Jim and Frank were talking about at a given point, since they were looking at actual engines and images as they talked and generally didn't name the model under discussion other than to refer to it as "this one" or "that one"! It was usually possible to come to a fairly definite conclusion based on the context of the discussion, but this was not always the case.

For the most part I have not attempted to reproduce Frank's exact words, instead summarizing the content of the discussion. I have also taken the liberty of inserting a few additional details which were not mentioned during the interviews, purely for clarity, context and completeness. Finally, I have omitted a number of matters having little or no bearing upon the story as well as some general sidebar discussion about aeromodelling in general and present-day engine technology. Where Frank contradicted himself, I have adopted what appears to be the most probable version based on repetition, independent evidence and other factors. I retain the interview recordings for further reference if required. With these caveats in mind, off we go on a fascinating walk down Memory Lane - the Elfin story as related by the man who started it all! Frank Ellis’s Recollections as Recorded by Jim Woodside

Frank was an electrician by trade, although he was to prove as time went by that he was well able to turn his hand to almost anything! He worked before WW2 for the Rootes Group - exactly where and how was not made clear. In his spare time, he was an active participant in the Liverpool modelling scene, focusing on self-designed rubber-powered models. He was one of the founders of Liverpool's pioneering model aero club, the Liverpool & District Model Club which was destined to survive into the modern era as an R/C organization. He was also keen on fishing, and it was through this mutual interest that he became a friend of Jim Woodside's Uncle Jim, thus establishing the family connection which ultimately led to these interviews taking place. Frank was of course too young to become involved in WW1, but was in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) at the outbreak of WW2, at which time he was 30 years old. For reasons which he didn't clarify during the interviews, he was not called up to active service, working instead during the war for Dunlop as an electrician in the maintenance section at their various Liverpool-area plants. In all probability, his employment with Dunlop met the criteria applicable to a “reserved occupation” given the critical importance of rubber tire production to the war effort.

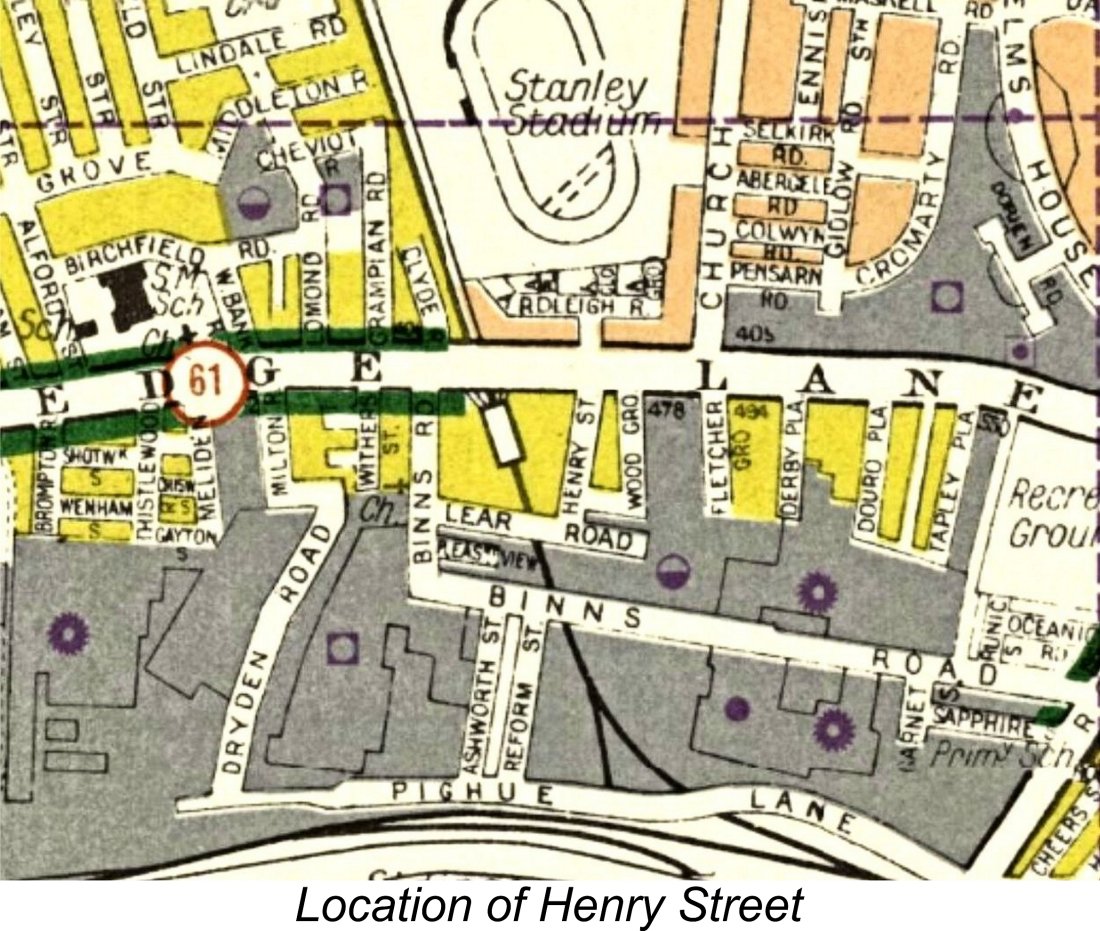

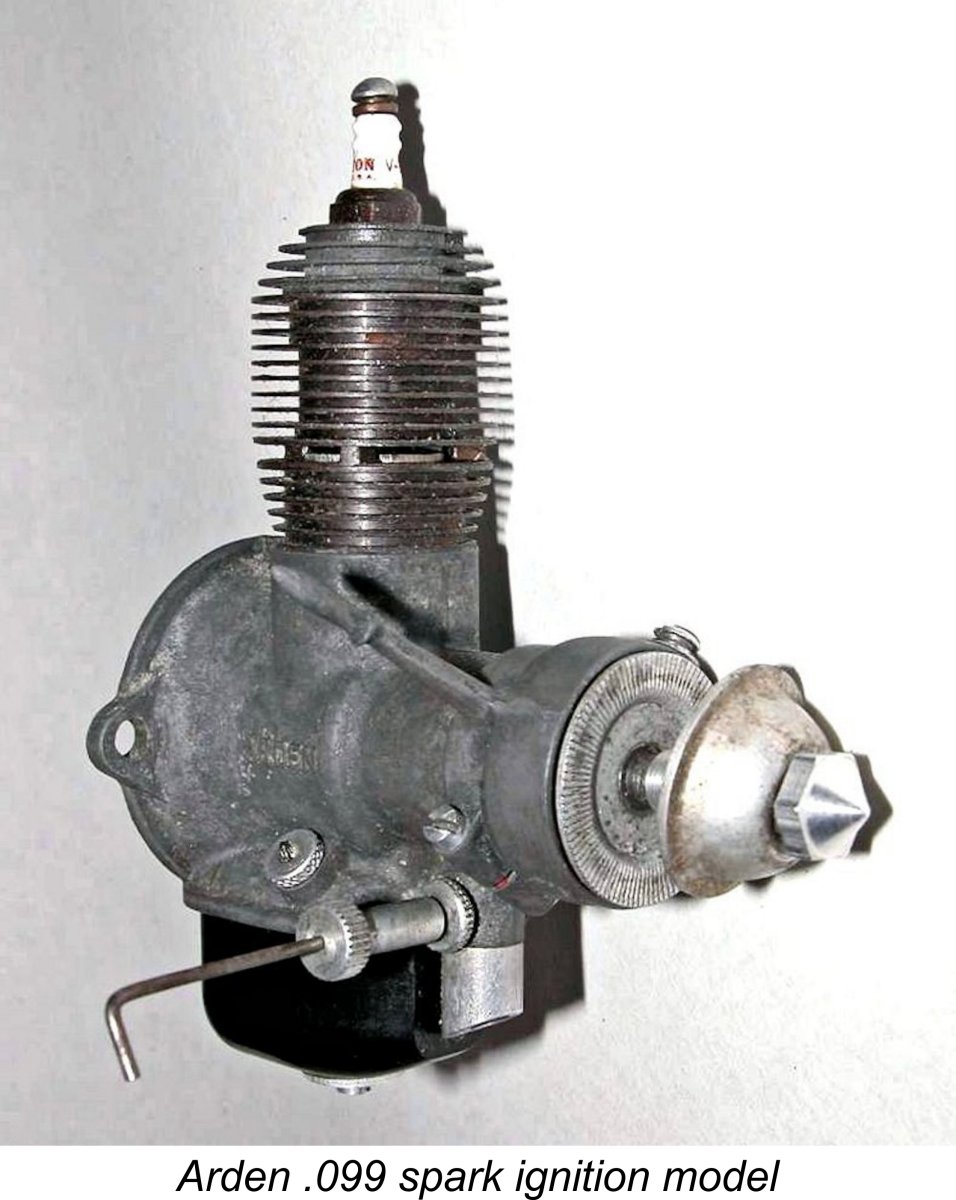

The war ended in mid-1945, leaving the 36-year-old Frank searching for other work opportunities. By 1946, he had become involved with a scrap metal business located at the top end of Henry Street off Edge Lane in Liverpool 13 (not the "other" Henry Street in Liverpool City Centre). The factory where Meccano erector sets were made (under the direction of a then well-known aeromodeller, the late Doug McHard) was located very nearby on Binns Road. The scrap metal business was established in association with (among others) a chap named Finn, providing the inspiration for the later name El-Fin! The establishment of this business didn't stop Frank from continuing to experiment with model engines on the side, and his first workshop was a lean-to in a corner of the scrap-yard! Although he didn’t mention it specifically, he must have owned a lathe by this time.

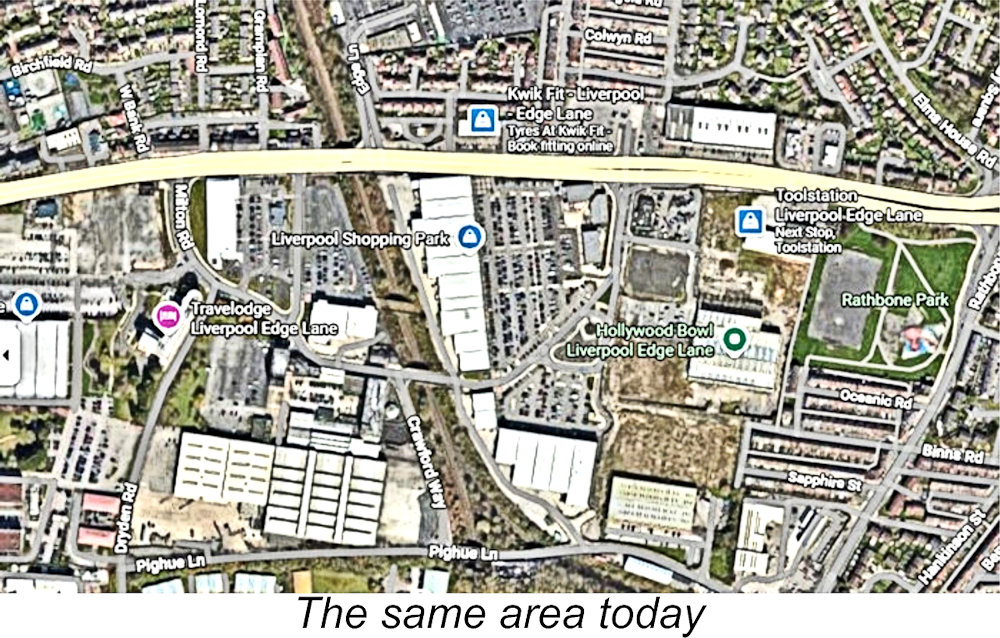

By late 1946 Frank had made several successful model diesel engines from the solid, including one of only 0.5 cc - an early effort at this small size. He showed these around as evidence of his capabilities, eventually using them to lever a £300 float (a lot of money in 1946!) from a certain Colonel Thomas E. H. Davies of the old-established Liverpool cotton brokerage firm of Davies, Benachi & Co., who were then located at 75 Oxford Street in Liverpool. This money was used to build and equip the first "purpose-built factory", which Frank described as a metal shed with a tin roof in a corner of the scrap-yard, replacing the former lean-to. They later expanded into a far larger two-storey brick building on the same site, assuming a considerable debt load in order to do so. The name Aerol Engineering was adopted to keep the model engine production separate from the scrap metal business, which provided much of the material required to produce the engines. Frank stated quite clearly that the well-used equipment with which production began was obtained from "Pratt's in Manchester". I’ve been unable to find any record of any engineering company or machine tool dealer called Pratt’s operating in Manchester during or immediately after WW2. Can any reader identify such a firm? It’s possible that Frank was somehow mistaken in either the city or the company name. However, this is only a minor detail which really doesn’t matter much anyway! Frank recalled that the model engine manufacturing venture started with a Herbert capstan lathe, a centre lathe, a drill press and a Delapena honing machine, plus a bench grinder for sharpening tools. Later, when they built the new brick factory, they added a second capstan lathe, a milling machine and a precision grinding machine. This equipment too was well-used and rather "tired", but it was all that they could afford. It's apparent that Colonel Davies must have been a dyed-in-the-wool enthusiast when it came to model aero engines! In particular, he showed himself to be an enthusiastic and loyal supporter of the Aerol and later Elfin engines, because his firm not only backed the venture but also stepped aside from its mainstream cotton brokerage business to become Elfin's primary distributor as well. Henry J. Nicholls later became a major UK sales agent, as did Eddie Keil. Aerol Engineering was very much an "in-house" operation. Although by his own admission he was no engineer, Frank did all of the design work himself throughout the life of the Aerol and Elfin ranges. The drawings were produced as blueprints by a fellow who worked full time for English Electric at their factory on the East Lancashire Road in Liverpool and did the Aerol drawings on the side. Very little of the actual manufacturing was ever contracted out - the castings, the When considering his first commercial design, Frank naturally took note of the FROG, E.D. and Mills diesels, which had already appeared as of early 1947, thus representing much of the competition which he would have to meet. But he was also aware of the Arden engines from America, having seen a picture of an example, although he never saw any of the internal details of that design. Very much liking the look of the Arden, Frank got the idea of making a diesel along Arden lines as opposed to simply repeating the FROG, Mills or E.D. pattern. At the time, America was recognized as the world leader in model engine design and production. Frank recognized from the outset that the American manufacturers could do far better work on a mass production basis, but decided that he could design a simple diesel engine along Arden lines that could be made to a sufficiently high standard with the available equipment. The result was Frank’s first commercial model engine, the very futuristic-looking 2 cc Aerol Gremlin diesel, which appeared in mid-1947 and was followed in early 1948 by the 2 cc Aerol Incidentally, Frank made no mention at all of any connection between the Aerol engines and the Clan engines from Scotland. Such a connection has been suggested in the past, but Frank claimed in these interviews that the Gremlin and all subsequent Aerol products The Gremlin caught on immediately despite its somewhat steep asking price of 5 guineas (£5 5s 0d - £5.25). The appearance of the attached article about Frank and his engines in the Liverpool Evening Express newspaper of October 30th, 1947 doubtless helped the cause along! At the time, model engines were undeniably expensive, but people would save up and pay for them because they were still something of a novelty in Britain at the time. The article included the information that Aerol production was then running at around 20 engines weekly, with the manufacturing being carried out by Frank himself in company with three other men, one of whom was named Harold Leahy. Most of the engines were said to be going for export. Frank reckoned that the Gremlin was a "terrific engine"! They reportedly ran one for a week straight (some 180 hours) on a big tank at 8,000 rpm, and Frank claimed that when dismantled after the test it was found to be as good as it had been when first assembled. Frank referred to the steel that they used for cylinders and crankshafts as "drift steel". This was probably something along the lines of H13 steel, a tough high-hardenability tool steel which retains its hardness right up to orange heat. The cylinders were water quench-hardened after machining, and the cast-iron pistons were individually lapped into the Delapena-honed bores. They found that the first few heat cycles actually caused the bore to contract by about one-tenth of a thou. This was why the bores of these engines lasted so long - if they started with a good fit and finish, the initial running-in wear was taken up by the shrinkage.

The original Elfin 1.8 which replaced the Aerol Hurricane in June 1948 was the first model to be sold under the Elfin banner. This was the engine that really put control-line stunt flying on the map in Britain, although it was also offered in free-flight guise with provision for a tubular plastic free-flight tank, as illustrated below. Frank was once again very pleased with this design. He repeated the earlier experiment with the Gremlin by running one of the new 1.8 models for 48 hours straight using a large tank. At the end of this, the engine remained in top condition.

One matter that Frank clarified in this interview was the often-repeated story that the somewhat odd 1.8 cc displacement arose simply because Frank found some steel tubing that was easily machined into cylinders for an engine of that displacement. When asked about this by Jim, Frank confirmed that the 1.8 cylinders were indeed made from tubular steel, although it was the sole model built in this way - all the others were machined from solid bar stock. However, Frank stated very firmly that the choice of the 1.8 cc displacement was a design decision based upon his view that an engine of that displacement made to Frank's design struck the perfect balance between high power, compact size and light weight. The tubular steel was used simply because it just happened to be suitable for making these cylinders - it didn't dictate the bore. The cases for the original radial-mounted engines (Aerol Gremlin and Hurricane, Elfin 1.8 cc and 2.49 cc) were gravity die-cast. Frank made these dies himself, but the actual castings were produced from piston alloy by a local engineering firm in Liverpool. Frank was very pleased with those cases because they were both strong and extremely resistant to distortion. In order to maximize cleanliness, the engines were assembled and tested in a room which was quite separate from the actual manufacturing. After testing, they were cleaned in trichlorethylene (Frank shuddered in retrospect at the thought of the health implications!) and then packed. The week's production was delivered every Friday to Davies-Benachi's nearby Oxford Street office, and a cheque would come straight back to cover the agreed wholesale value of the engines received. Davies-Benachi then distributed them to the various suppliers both at home and abroad.

Frank recalled having far more trouble with crankcase distortion when they switched to the less substantial pressure die-cast cases used on these later beam-mount engines. He put some of this down to the fact that they never quite settled on the right casting alloy for the job. Contrary to popular belief, the fins on the later 249 PB cases were not put there to provide extra cooling but to increase the distortion resistance of the castings.

Notwithstanding Frank's reservations, a series of notable competition successes soon followed, with beam-mount Elfin engines powering the winning models at the 1951 European Stunt Championship, the 1952 World Free Flight Championship and both the 1951 and 1952 Gold Trophy stunt contests. As a result of the attendant publicity, the Elfin engines became increasingly popular during the first half of the 1950's, taxing the company's production capacity. Frank recalled production during their hey-day reaching 200 engines per week at times – a very far cry from the 1947 Aerol Gremlin days! During this period, they had a workforce of as many as 7 employees, who were on straight wages as opposed to piece-work rates. The 149 PB was their biggest seller. Their production program was not "scheduled" but fluctuated according to the state of the order book. They made the engines in batches of a given type, stopping only to change tooling when switching to a different model for the next batch. Frank stated that he was very much in the model engine business because he enjoyed it, not because he harboured any delusions that it would make him rich! This enthusiasm led him to make a fair number of experimental prototypes along the way, including a 5 cc in-line twin which was unfortunately stolen from the factory. Frank had his own ideas about who was responsible, but named no names! Where is it now …….?!? He kept his eye on the quality issue, thus being well aware of the company's equipment limitations and their effect upon quality control. He would have liked to slow down, take more time over each engine and make them better, but the economics and practical considerations dictated otherwise.

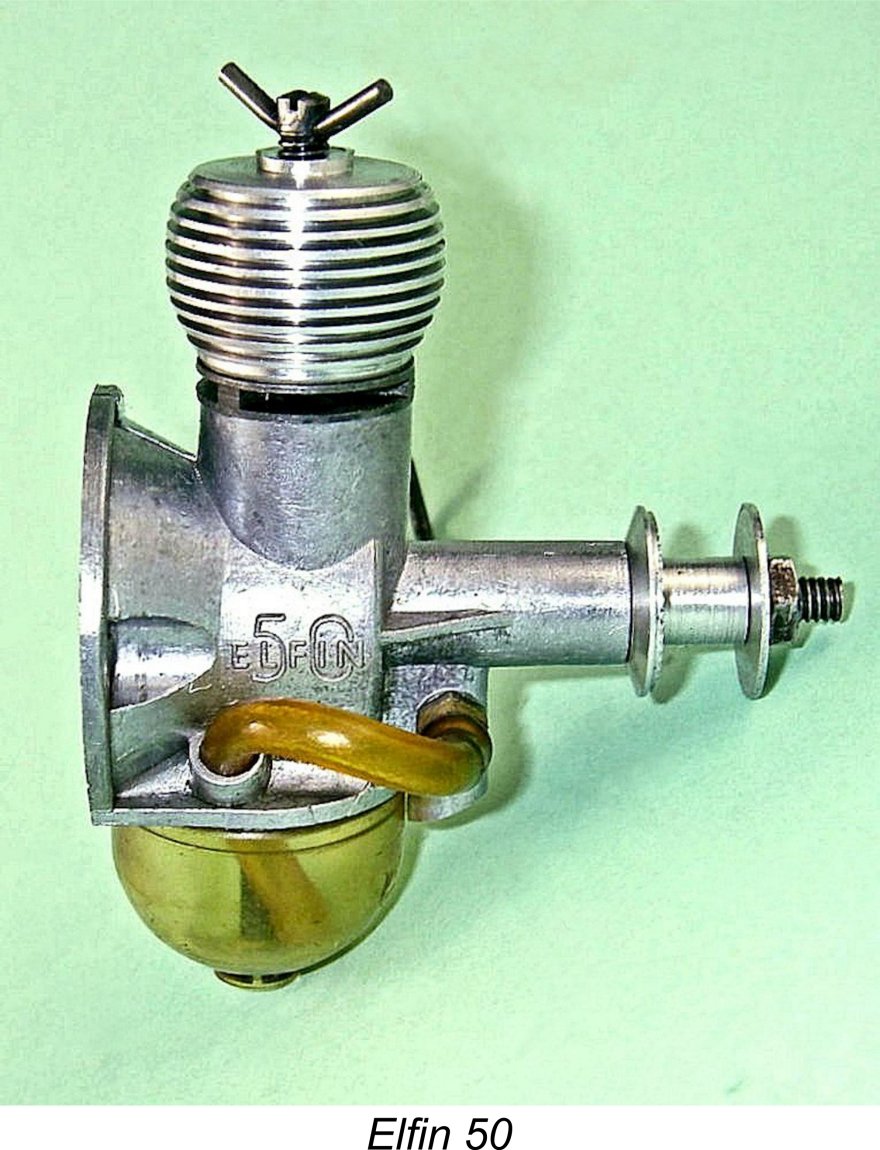

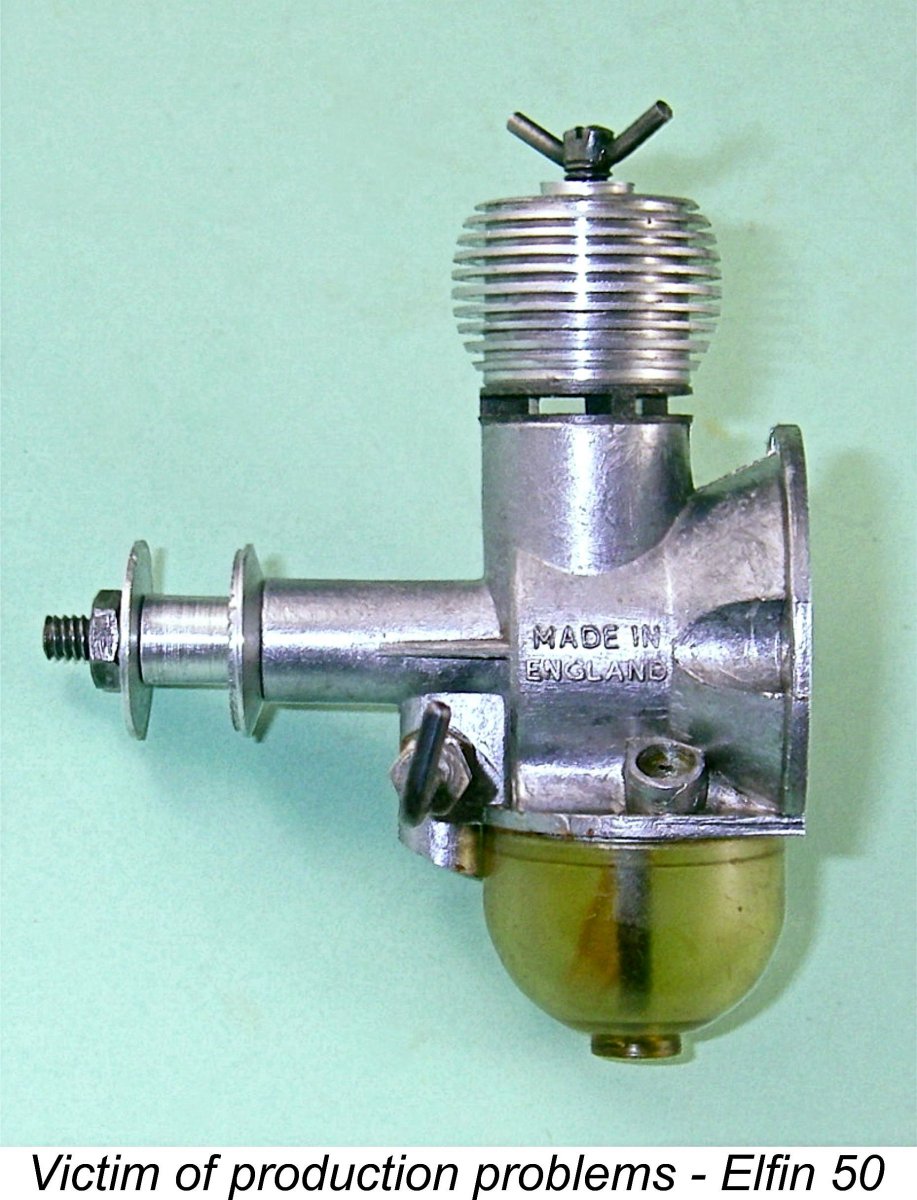

Nowhere was the aging equipment issue brought more starkly into relief than with the Elfin 50, Frank's smallest commercial design. This model was developed during 1951 at the suggestion of Frank's backer Colonel Davies of Davies-Benachi, who perhaps recalled Frank's earlier effort with his original 0.5 cc promotional model of 1946. Frank was really high on the Elfin 50 (his most Arden-like effort), recalling that he was extremely happy with its performance on test in prototype form. The engine was introduced in early 1952, but they quickly found that they couldn't make them in quantity to the required quality standards - smaller engines require more exact tolerances, which their tired equipment simply couldn't maintain. An unacceptably high proportion of the completed engines proved to have flaws which made them un-saleable. It was clear that if the 50 was to be saved, new equipment would have to be procured. Aerol Engineering was still in debt for their earlier factory expansion and the additional equipment which they had bought at the same time, so they were in no position themselves to finance the acquisition of new equipment. Frank therefore approached Davies-Benachi once more. Since the Elfin 50 had been developed at Colonel Davies' suggestion, he was naturally keen for its production to go ahead. Accordingly, he agreed to back the financing of new equipment, which was duly ordered. However, in one of those cruel twists of fate by which people's futures can be so greatly influenced, Colonel Davies unexpectedly died on May 5th, 1952 - the very day on which the new machinery arrived at Henry Street! Colonel Davies' partner in Davies-Benachi had no interest whatsoever in backing the Elfin venture, so Aerol Engineering found themselves at one fell swoop without a financial guarantor, leaving them with no recourse other than to send the new equipment straight back on the same truck. Frank's quote: "If Colonel Davies hadn't died when he did, that business (Aerol Engineering) would still be going today!"

After this set-back, Frank saw no alternative other than to suspend production of the Elfin 50. He made it extremely clear in the interviews that this action was taken very reluctantly for no other reason than the fact that their equipment was obviously too knackered to make it - an unacceptable proportion of the completed engines turned out to be too deeply flawed to sell! They only sold a few hundred of them in total, and even some of those that they did sell proved to have quality control issues. This explains the extreme rarity of original examples today. Frank genuinely regretted not having made more - he reckoned that the engine would have sold really well if they could have kept making it. As it was, they never came close to recovering their investment in this engine.

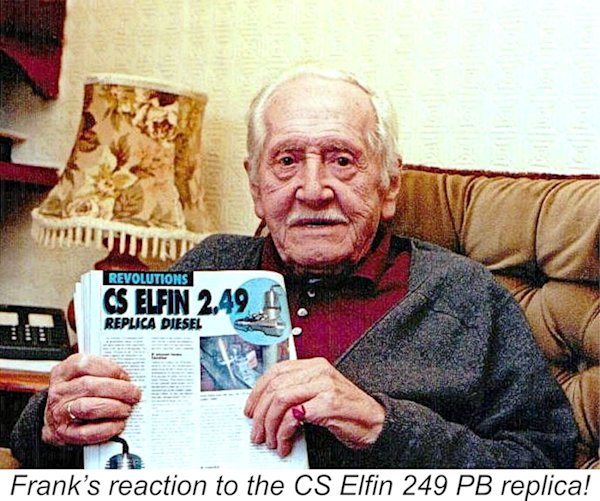

For a number of reasons, sales of the BR models fell below expectations. Frank recalled that with the exception of the original 149 BR (which was an outstanding performer, albeit with a bit of a vibration problem), the BR models failed to achieve the anticipated levels of performance - he had been expecting more, especially from the 249's. They were also unavoidably heavy and expensive by the standards of their day due to the twin ball races. However, the real sticking point continued to be the quality issue. Despite their best efforts, Frank and his colleagues found that they were unable to maintain production at an acceptable level of quality with their worn-out equipment. This had already led to the abandonment of the Elfin 50 as noted above, and as time went on it resulted in an increasing level of customer dissatisfaction in relation to their other products. The warranty returns began to pile up…………. In the end, they found themselves with no option other than to wind up the business, which they did in early 1957, placing their final "Aeromodeller" advertisement in January of that year. They managed to liquidate the company without going into receivership, but had to sell everything to get clear. Frank made no mention of any residual involvement with Auto-Vaporizers of Lymm, Cheshire, who took over the Elfin range for a relatively short time before themselves disappearing from the scene in mid-1958. Sadly, Frank dropped out of aeromodelling entirely for a while after the wind-up of Aerol Engineering - that event really gutted him, and he felt that an important part of his life had ended. He went to work for Otis Elevator in a totally unrelated field, staying there for 13 years, 6 months of which were spent in America. He had in fact At the time of the 1990 interviews, Frank was disarmingly unaware of the renewed interest in the Aerol and Elfin engines being shown at that time - he had assumed that they would have been long forgotten! He was particularly amazed at being subsequently shown one of the Chinese-made CS replicas of the original Elfin 249 radial model! He reckoned that they owed him royalties!! Reportedly, he later became quite scathing regarding what he saw as the opportunism of those making capital out of his designs, having difficulty seeing it as the very sincere compliment that it really was. Frank Ellis died on February 18th, 2003, a month after his 94th birthday. We may all be grateful for the legacy that he left us in the form of the fine Elfin engines, many of which still survive. Long may the famous "crackle" continue to be heard! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First version published on MEN This revised and expanded edition published here February 2026

|

| |

In this article, I’m privileged to be able to present the story of Frank Newton Ellis and the Elfin model engine range from Liverpool, England at a level of detail never previously attempted. What follows is based primarily on the first-hand evidence of several taped interviews with Frank himself which were conducted by family friend Jim Woodside around 1990, when Frank was approximately 81 years old.

In this article, I’m privileged to be able to present the story of Frank Newton Ellis and the Elfin model engine range from Liverpool, England at a level of detail never previously attempted. What follows is based primarily on the first-hand evidence of several taped interviews with Frank himself which were conducted by family friend Jim Woodside around 1990, when Frank was approximately 81 years old. Despite Frank's age at the time, he sounded hale and hearty on the recordings, still retaining many very clear memories of his Elfin years, although he did contradict himself at times, also tending to wander off topic fairly readily! In fact, the discussions were far more in the nature of conversations between friends than true interviews - the thread wandered all over the place and often touched on matters having little or no connection with the Elfin engines. Apart from the occasional contradiction, there are also gaps in the recording due to technical glitches as well as the odd word here and there that was unintelligible on the recording.

Despite Frank's age at the time, he sounded hale and hearty on the recordings, still retaining many very clear memories of his Elfin years, although he did contradict himself at times, also tending to wander off topic fairly readily! In fact, the discussions were far more in the nature of conversations between friends than true interviews - the thread wandered all over the place and often touched on matters having little or no connection with the Elfin engines. Apart from the occasional contradiction, there are also gaps in the recording due to technical glitches as well as the odd word here and there that was unintelligible on the recording.

Frank Newton Ellis was born on January 17

Frank Newton Ellis was born on January 17 Since he retained his early interest in small engines, Frank started tinkering with a lathe at work in his free time, trying to make his own model internal combustion engine. With a machinist friend named Jimmy Smith, Frank finally finished a model petrol engine, which didn't run until they tried adding some ether to the fuel. When they did so, they found that the thing would sometimes fire without the spark ignition system being connected! This triggered Frank's interest in compression ignition engines (aka "diesels", which they aren't!).

Since he retained his early interest in small engines, Frank started tinkering with a lathe at work in his free time, trying to make his own model internal combustion engine. With a machinist friend named Jimmy Smith, Frank finally finished a model petrol engine, which didn't run until they tried adding some ether to the fuel. When they did so, they found that the thing would sometimes fire without the spark ignition system being connected! This triggered Frank's interest in compression ignition engines (aka "diesels", which they aren't!).

pressure dies and the stamped reed valves for the later BR models were the only out-sourced items as far as Frank could recall. Even the end caps for the Elfin 1.8 plastic tube free-flight fuel tanks were made in-house, as were the taps used to form the threads in the crankcase castings.

pressure dies and the stamped reed valves for the later BR models were the only out-sourced items as far as Frank could recall. Even the end caps for the Elfin 1.8 plastic tube free-flight fuel tanks were made in-house, as were the taps used to form the threads in the crankcase castings. Hurricane. The radial mounting was of course a direct consequence of Frank's decision to follow the Arden layout. Frank put the FRV intake beneath the shaft because that's where it was on the Arden and also because inverted engine mounting was quite fashionable at the time. However, the Arden's underslung tank was omitted due to its unsuitability for inverted mounting or control line flying, which was then becoming increasingly popular in Britain. The needles of this and all subsequent Elfin engines were standard darning needles!

Hurricane. The radial mounting was of course a direct consequence of Frank's decision to follow the Arden layout. Frank put the FRV intake beneath the shaft because that's where it was on the Arden and also because inverted engine mounting was quite fashionable at the time. However, the Arden's underslung tank was omitted due to its unsuitability for inverted mounting or control line flying, which was then becoming increasingly popular in Britain. The needles of this and all subsequent Elfin engines were standard darning needles! were designed entirely by him. In these interviews, he specifically cited the Arden engines as his primary design influence at the outset - no mention of any influence from north of the border! Oddly, in later years he reportedly tended to downplay even the Arden influence, claiming the Aerol/Elfin design as all his own!

were designed entirely by him. In these interviews, he specifically cited the Arden engines as his primary design influence at the outset - no mention of any influence from north of the border! Oddly, in later years he reportedly tended to downplay even the Arden influence, claiming the Aerol/Elfin design as all his own! In early 1948 the Gremlin was replaced in turn by the Hurricane, also of 2 cc displacement. This model was very similar to the Gremlin but featured revised cylinder porting. Like the Gremlin, the Hurricane was sold under the Aerol banner. The full story of the

In early 1948 the Gremlin was replaced in turn by the Hurricane, also of 2 cc displacement. This model was very similar to the Gremlin but featured revised cylinder porting. Like the Gremlin, the Hurricane was sold under the Aerol banner. The full story of the  After the 1.8 was introduced, Frank built a model for one and took it to a major contest at Leighton Buzzard, strictly to promote the engine. He recalled starting the engine up and immediately attracting a large crowd - that Elfin "crackle", no doubt!! One of the individuals in the crowd was none other than Henry J. Nicholls, who told Frank on the spot that he would take as many as Frank could make! Nicholls' famous shop at 308 Holloway Road thus became a major UK sales outlet for the Elfin range.

After the 1.8 was introduced, Frank built a model for one and took it to a major contest at Leighton Buzzard, strictly to promote the engine. He recalled starting the engine up and immediately attracting a large crowd - that Elfin "crackle", no doubt!! One of the individuals in the crowd was none other than Henry J. Nicholls, who told Frank on the spot that he would take as many as Frank could make! Nicholls' famous shop at 308 Holloway Road thus became a major UK sales outlet for the Elfin range. During this period, Frank remained active in the aeromodelling field. He made several examples of the Elfin 1.8 with their displacements reduced to 1.5 cc for his own use and that of his friend Roland Scott in Class 1 control line contests which were restricted to engines of the lesser displacement. He must have been a very capable competitor, because the record shows that he won the control-line speed competition at the 1949 Isle of Man Rally with a handicap speed of 66.5 MPH, also winning the control line stunt category by a handsome margin at the same meeting. Roland Scott won the Class 1 speed category at the 1949 British National Championships with an impressive speed of 70.87 MPH. However, Frank made no mention of these noteworthy successes in the interviews.

During this period, Frank remained active in the aeromodelling field. He made several examples of the Elfin 1.8 with their displacements reduced to 1.5 cc for his own use and that of his friend Roland Scott in Class 1 control line contests which were restricted to engines of the lesser displacement. He must have been a very capable competitor, because the record shows that he won the control-line speed competition at the 1949 Isle of Man Rally with a handicap speed of 66.5 MPH, also winning the control line stunt category by a handsome margin at the same meeting. Roland Scott won the Class 1 speed category at the 1949 British National Championships with an impressive speed of 70.87 MPH. However, Frank made no mention of these noteworthy successes in the interviews.  In 1949 the range was expanded with the introduction of the radial-mount Elfin 249 PB. This was an excellent performer which achieved instant popularity. However, the radial-mount Elfin 1.8 and 249 models didn't remain long in production, both being replaced in 1950 with beam-mounted versions featuring pressure die-cast crankcases. The 1.8 was replaced with the beam-mounted pressure die-cast Elfin 149 PB, while the 249 was replaced by a new beam-mounted model of unchanged displacement.

In 1949 the range was expanded with the introduction of the radial-mount Elfin 249 PB. This was an excellent performer which achieved instant popularity. However, the radial-mount Elfin 1.8 and 249 models didn't remain long in production, both being replaced in 1950 with beam-mounted versions featuring pressure die-cast crankcases. The 1.8 was replaced with the beam-mounted pressure die-cast Elfin 149 PB, while the 249 was replaced by a new beam-mounted model of unchanged displacement.  So why did Frank switch in 1950 from the powerful and highly-regarded gravity die-cast radial-mount 1.8 and 249 PB models to their slightly less powerful and more problematic pressure die-cast beam mount replacements? Basically, because demand was rising and they could make the revised models faster! Frank would have liked to take his time and get things right, but production and financial pressures didn't allow him that luxury. They contracted out the pressure die-castings, including the making of the dies, to a firm in Blackpool - when asked, Frank couldn't recall the name. Each new set of outsourced dies cost them around £500 before they ever saw a single casting. In retrospect, Frank reckoned that he should have stuck with the earlier designs and developments thereof based upon his own gravity dies, accepting lower production rates as a trade-off for higher quality.

So why did Frank switch in 1950 from the powerful and highly-regarded gravity die-cast radial-mount 1.8 and 249 PB models to their slightly less powerful and more problematic pressure die-cast beam mount replacements? Basically, because demand was rising and they could make the revised models faster! Frank would have liked to take his time and get things right, but production and financial pressures didn't allow him that luxury. They contracted out the pressure die-castings, including the making of the dies, to a firm in Blackpool - when asked, Frank couldn't recall the name. Each new set of outsourced dies cost them around £500 before they ever saw a single casting. In retrospect, Frank reckoned that he should have stuck with the earlier designs and developments thereof based upon his own gravity dies, accepting lower production rates as a trade-off for higher quality. What they really needed was new machinery. Frank reckoned that if they'd got it, they would have survived far longer. At one point, Frank actually had a serious offer from New Zealand to move his entire operation to that country - they were even prepared to build him a new factory there! This move might have solved the equipment problem as well as providing Gordon Burford with some local competition, but it never came about because Frank's wife Queenie flatly refused to relocate!

What they really needed was new machinery. Frank reckoned that if they'd got it, they would have survived far longer. At one point, Frank actually had a serious offer from New Zealand to move his entire operation to that country - they were even prepared to build him a new factory there! This move might have solved the equipment problem as well as providing Gordon Burford with some local competition, but it never came about because Frank's wife Queenie flatly refused to relocate! The impact of Colonel Davies' death went even further than the loss of his financial backing - with Colonel Davies no longer in control, Davies-Benachi had no interest in continuing as Elfin distributors either. In fact, according to the records held today by the International Cotton Association in Liverpool, the firm itself was quickly wound up after Colonel Davies' death. Fortunately, Frank was able to make alternative arrangements. The overseas distribution of the Elfin engines was taken up by Lang Overseas Ltd. of 33 George Street, Liverpool, while E. Keil & Co. became the Elfin distributors to the home market.

The impact of Colonel Davies' death went even further than the loss of his financial backing - with Colonel Davies no longer in control, Davies-Benachi had no interest in continuing as Elfin distributors either. In fact, according to the records held today by the International Cotton Association in Liverpool, the firm itself was quickly wound up after Colonel Davies' death. Fortunately, Frank was able to make alternative arrangements. The overseas distribution of the Elfin engines was taken up by Lang Overseas Ltd. of 33 George Street, Liverpool, while E. Keil & Co. became the Elfin distributors to the home market. Colonel Davies' death left them still in debt for the factory and for their existing equipment, which they had no alternative other than to keep using. They carried on for a while, developing the famous BR series of reed-valve engines in 1.49 cc, 1.8 cc and 2.49 cc displacements. The full history of the

Colonel Davies' death left them still in debt for the factory and for their existing equipment, which they had no alternative other than to keep using. They carried on for a while, developing the famous BR series of reed-valve engines in 1.49 cc, 1.8 cc and 2.49 cc displacements. The full history of the