|

|

The Thorning 3.5 cc Diesel

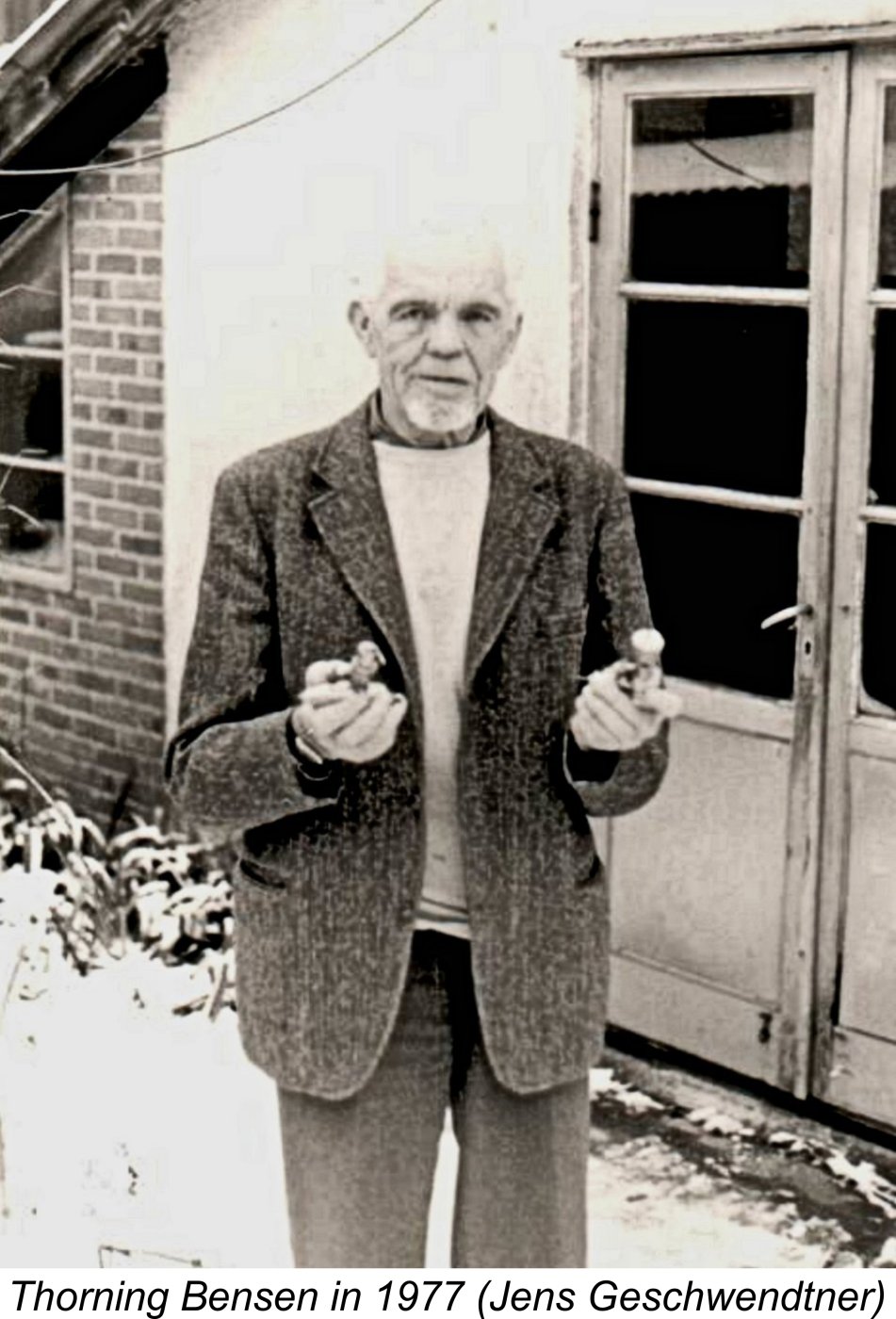

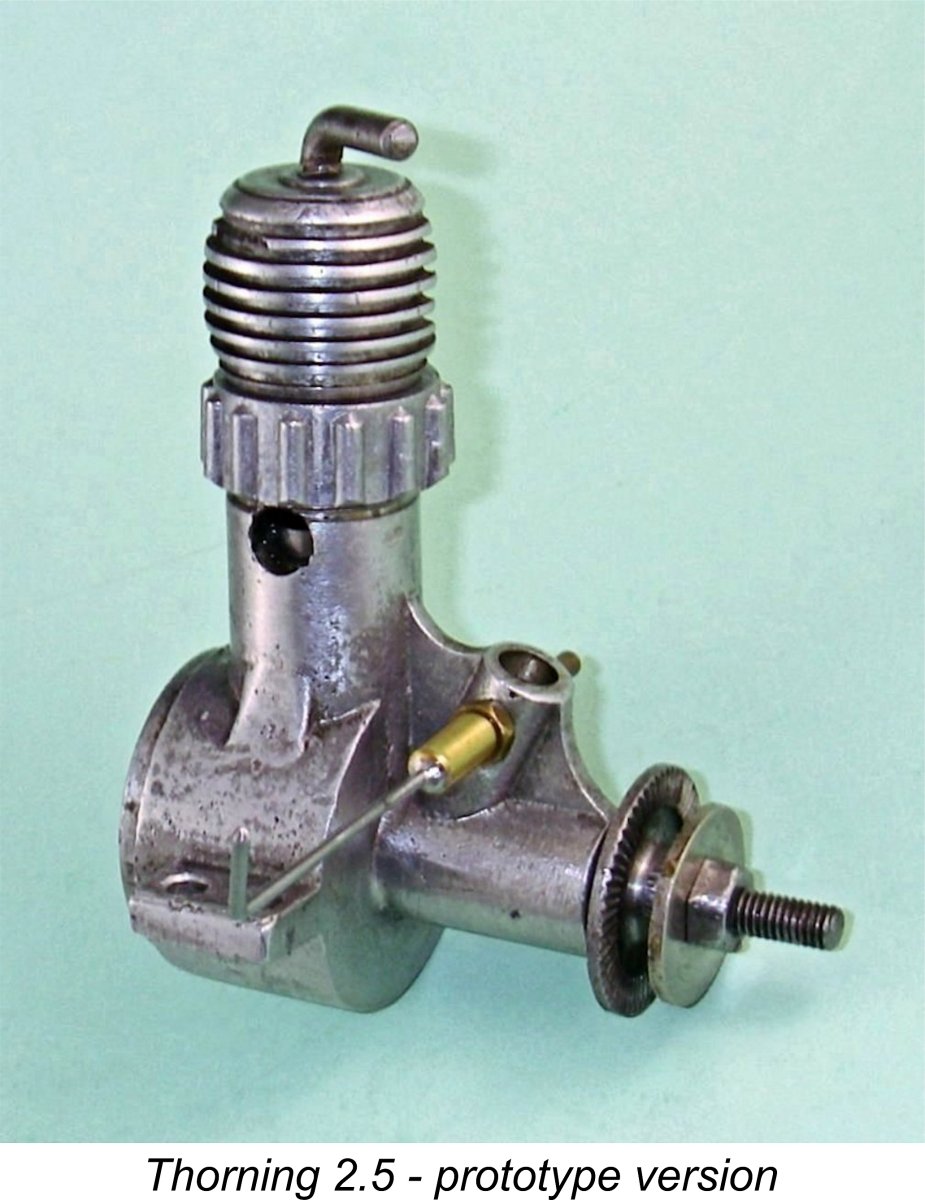

A full account of Bensen’s activities during the 1940’s has already been published here in my in-depth review of the 2.41 cc Thorning III sideport model, which was perhaps the manufacturer’s best-known model engine product. I will not repeat that material here. A detailed review of the Thorning III’s ill-fated successor, the Thorning 2.5 FRV model, appears elsewhere on this web-site. Introduced in late 1946, the Thorning III was an excellent if rather odd-looking engine which was Denmark’s most popular model power unit for most of the latter half of the 1940’s. However, the Thorning III Having acquired two fine examples of this very rare engine through the kindness of my friend Jens Geschwendtner, I felt that I had a responsibility to share them as widely as possible. This article represents my attempt to do so. But before getting started, I must also take note of the unstinting assistance and support for my research which was provided both by Jens and by my other valued Danish friend Luis Petersen during the preparation of this article. Without such support from colleagues who are "on the spot"and speak the language, no article of this sort could be written by an "outsider". My very sincere thanks to both Jens and Luis! As always, I’ll begin by summarizing the background events which led to the appearance of this excellent engine. Background In my separate article on the Thorning III, I covered the activities of Thorning Bensen during the 1940’s in Readers of that article will recall that as 1949 drew towards its close, Bensen became aware of the incipient emergence of a serious domestic competitor for the Thorning III. Word got around that Christian Tommerup Clausen was consulting with members of the Odense Model Flying Club regarding the design of a 2.5 cc diesel that would represent very stiff domestic competition for the increasingly-venerable Thorning III. This model was destined to appear in early 1950 as the very successful Viking 2.5 cc diesel, a model which I've covered in detail elsewhere. The Viking engines were manufactured by Clausen in Lundbyvej in the northern part of the south-central Danish island of Fyn, on which the city of Odense is also located. This news served as a salutary reminder of the fact that no model engine manufacturer who wished to remain in business could afford to stand pat for too long! Accordingly, in the latter part of 1949 Thorning Bensen began to plan for the replacement of the Thorning III with a far more up-to-date design featuring However, the domestic competition for Bensen did not come solely from Viking. The oldest-established model engine marque in Denmark was the CEROS range which had been inaugurated in 1938 by Carl Rose and was manufactured from 1946 onwards in Brønshøj, a suburb of Copenhagen. Until 1950, Rose did not compete directly with Bensen, manufacturing a series of early post-WW2 spark ignition engines followed by a 4.9 cc glowplug motor. However, in early 1950 Bensen became aware that Rose was in the process of developing a 3.5 cc diesel model of quite up-to-the-minute design. This triggered an immediate response from Bensen, who promptly shelved work on his 2.5 cc FRV model and got to work on a 3.5 cc diesel design of his own. It is this engine which is the central subject of the present article. Bensen appears to have spent much of 1950 developing his new 3.5 cc offering and tooling up for its series production. The engine appeared in late 1950, prior to the initial appearance of the 2.5 cc FRV model. It was released in time to offer direct competition to the very similar CEROS 3.5 cc model which made its market debut at around the same time. More of the latter model in a separate article on the CEROS range which will appear on this website in due course. The Thorning 3.5 cc Diesel Described

We’ll never know the degree to which Bensen and Rose became aware of the design approaches being taken by each other. All that can be said with certainty is that the two competing Danish 3.5 cc models ended up looking very similar indeed, both clearly being strongly influenced by the design of the very successful AMCO 3.5 PB. It might be thought that one was guilty of copying the other, but in fact it’s most probable that both designers independently got the very logical idea of sidestepping much of the normal development work by drawing upon the same very successful established design. All model engines are derivative from others to some extent, and the creation of what amounted to a “clone” was simply the ultimate expression of this. Besides, if you’re going to copy anyway, it makes sense to copy from the best!

One fairly marked difference was the engine’s weight. The illustrated example of the Thorning has a checked weight of 155 gm (5.47 ounces) against the AMCO’s checked figure of 119 gm (4.20 ounces). As far as I can tell, the difference is due to the Thorning’s use of a bushed main bearing installed in a somewhat bulkier gravity die-cast crankcase casting, along with a heavy steel prop washer and a somewhat heavier cylinder. Even so, the weight was still well within acceptable limits for an engine of this displacement.

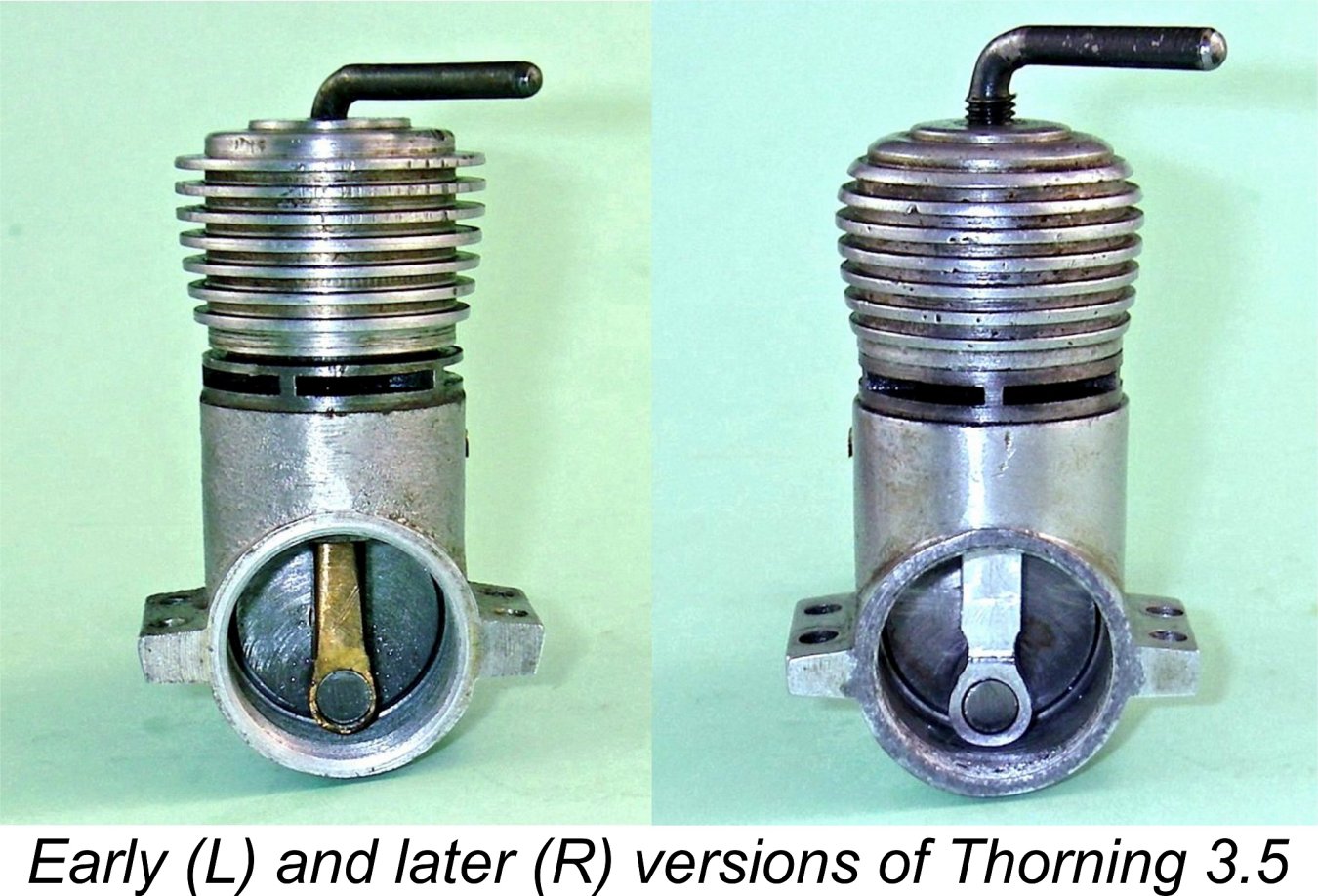

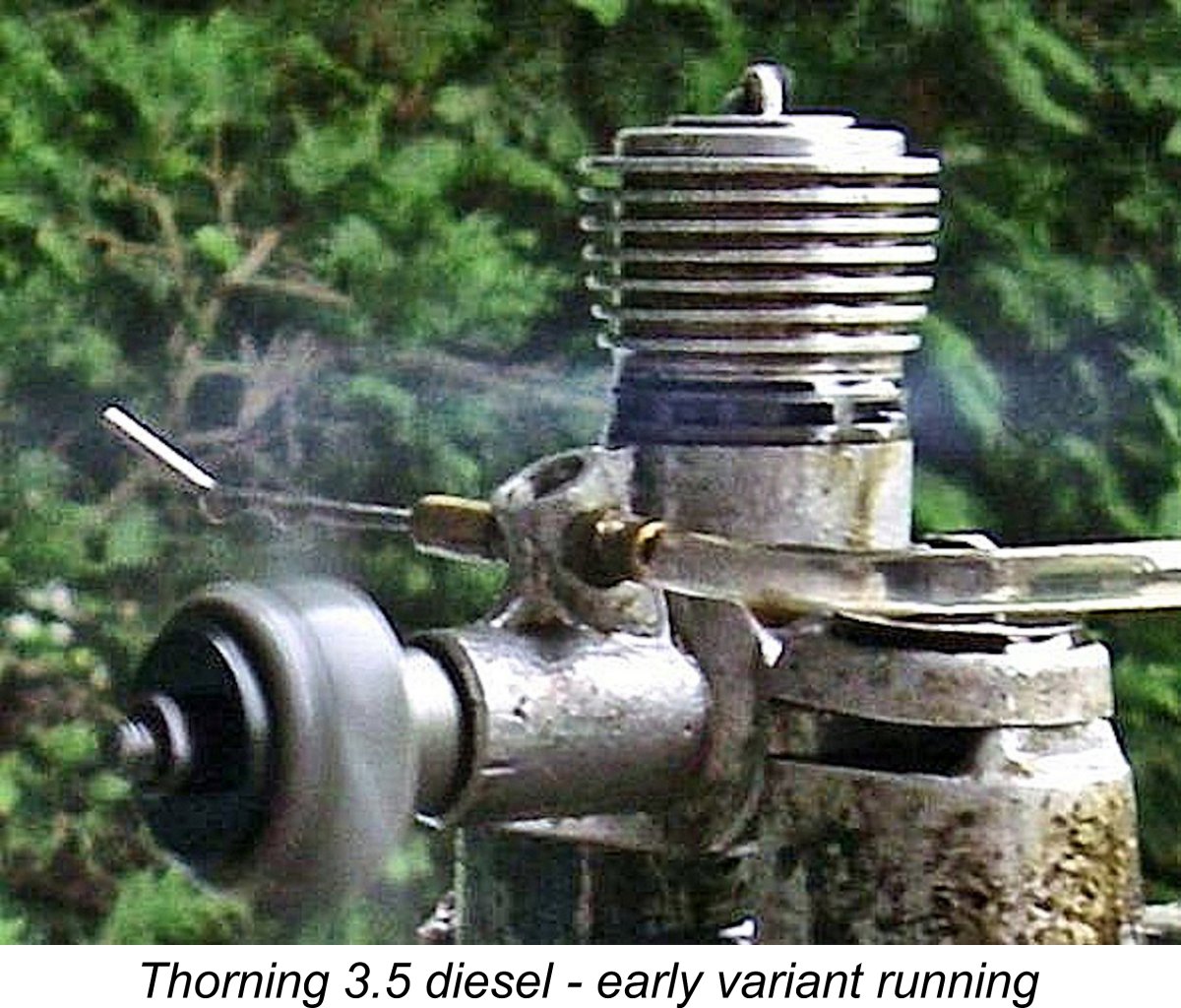

The earlier example was also distinguished from its successor in having a con-rod which was machined from a solid bronze billet. The later models used a rod which was milled from high-strength aluminium alloy barstock. In addition, the main casting of the earlier variant had a far rougher surface finish, in contrast to the later version which had a case which was cleaned up and brushed to finish. The main differences between the two variants are all clearly visible in the accompanying images.

Apart from the previously-noted differences, the general design layout of the Thorning was otherwise so close to that of the AMCO that to describe one is to describe the other. The engine employed a screw-in steel cylinder having identical cylinder porting arrangements to the AMCO, with five milled exhaust slots and five internally-formed bypass/transfer flutes which necessarily terminated just below the lower edge of the exhaust ports. The screw-on cooling jacket was machined from a light alloy casting. In both variants of the Thorning model, its The cast iron piston was a relatively heavy component having a conical crown. The one unusual design feature of the piston/cylinder assembly was the use of hardened steel in place of cast iron for the contra-piston. This can be a problematic material choice, since a steel contra piston operating in a steel bore has a well-documented tendency to stick in the bore when hot. The piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a con-rod which was nicely machined from bronze in the earlier examples and light alloy in the later models. A plain disc crankweb having no counterbalance was featured. The main journal diameter was 9.5 mm, virtually identical to the 0.375 in. dimension featured in the AMCO. The shaft in both variants ran in a closely-fitted steel bushing.

Both of my examples of the engine are very well made, with excellent fits despite the considerable amount of running that both examples have clearly done in the past. The manufacturer hasn't devoted a great deal of effort to the engine's external appearance, but the fits and finishes which really matter are beyond reproach. Overall, the similarities between the Thorning 3.5 and the AMCO 3.5 PB are so marked as to label the Thorning as virtually a “clone” in functional terms. This being the case, we might expect very comparable levels of performance. However, expectations are not always fulfilled, so it’s time to put this matter to the test! The Thorning 3.5 on Test My example of the later variant of the Thorning 3.5, one of the pair which I obtained through the kindness of my friend Jens Geschwendtner, is timed for normal anti-clockwise rotation viewed from the front. I was thus in a position to undertake a full test of the engine using my usual range of calibrated test props. I was particularly interested in finding out how the engine compared with the AMCO 3.5 PB which seems to have served as its design inspiration. Although the engine had clearly had a fair bit of use, all fits remained excellent with very good compression. It was accordingly obvious that no break-in was required. This being the case, I set it up in the test stand with a 9x6 airscrew fitted. This would have been a pretty standard flight prop for an engine I have to say that this engine proved to be one of the more challenging units to start that I’d experienced for some time. Initially, I couldn’t even get it to fire, no matter what I tried with the comp screw. After all these years, I can usually tell pretty accurately by “feel” where the compression of a given engine needs to be for starting, and even at obviously higher settings than this there was no reaction. Feeling rather discouraged, I wondered if the fuel had gone “off”. I therefore went to the trouble of checking that the fuel was OK by replacing the Thorning in the test stand with my trusty well-used 1 cc FROG 100 Mk. II and firing it up on the same fuel using an APC 7x5 airscrew. The little FROG started up right away and ran extremely well, recording a cool 11,000 RPM on the APC 7x5 prop (around 0.105 BHP – a very good performance indeed). Clearly the fuel was A-OK! So back into the stand went the recalcitrant Thorning. This time, after a great deal of sweating and cursing, I finally got the thing to commence firing, after which a start was soon obtained.

I also found that hot restarts were a bit problematic. Thanks no doubt to its minimal cooling fin area, the engine got extremely hot when running, to the point that the ether in the cylinder boiled away before it could participate in the ignition process during a hot restart. It was far better to allow at least partial cooling between runs. Overall, I’d have to classify the Thorning 3.5 as a somewhat “difficult” starter, requiring just the right approach to get it going. While an experience diesel handler would quickly get on top of it as I did, I would have hesitated to recommend this engine to a beginner.

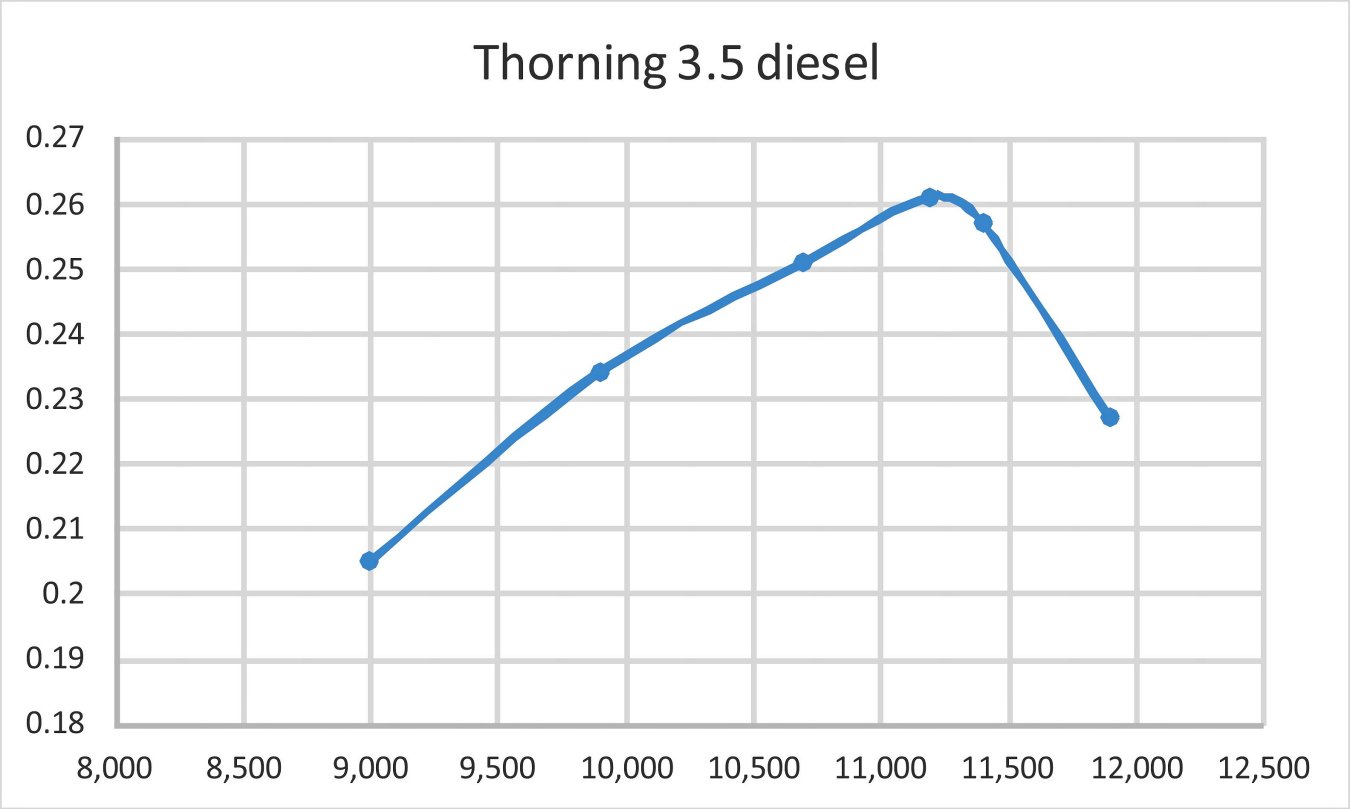

Running was very smooth at all speeds tested. As mentioned earlier, the engine got extremely hot, which probably accounts for the fact that it sagged by some 200 RPM as it warmed up. Once stabilized, it ran very steadily indeed for as long as required with no trace of a misfire. It's actually possible that this is one engine which would do better on a straight fuel with no ignition improver. The engine turned the APC 9x6 prop with which I started at a steady 9,900 RPM. This was pretty much in line with my expectations. Wishing to find out which side of the peak I was on, I tried an APC 9x5, which the engine turned at 10,700 RPM for a higher implied output. Evidently the peak had not been reached. I continued with APC 9x4 and 8x6 props, finding that the engine was pretty much operating at its peak output on the 9x4. Smaller props than this indicated rapidly dropping power outputs. The steady-state prop-RPM figures obtained for the full range of props tested are shown in the table below along with the derived power curve. The APC 7½x4 WB is a cut-down APC 9x4 which I calibrated to fill a gap in my test set.

As can be seen, the engine delivered a peak output of 0.261 BHP @ 11,200 RPM with a sharp drop-off beyond the peak. This is very much in line with the previously-cited published test figures for the AMCO 3.5 PB which clearly served as the Thorning 3.5’s design inspiration. We might expect such consistency given the design similarities. The above figures make it clear that the Thorning 3.5 will deliver its best performance if propped for around 11,000 RPM in the air. It would be a great mistake to under-prop this unit. A 9x6 or 8x8 would work well for control-line, while a 9x5 looks like a good bet for free flight.

Due to its being timed for reverse rotation, I was unable to fully test the earlier variant in my possession. I did give it a few runs using standard props mounted in reverse and hence functioning in pusher mode. Thanks to my previous experience with the later variant, I was spared the starting problems that had initially bedevilled my earlier test. Using the same techniques developed for the later model, the earlier unit was very straightforward to start. However, I was reminded that I hate flicking in reverse! Since the cylinder gets very hot quite quickly, I had to keep the runs down to short durations given the far less effective cooling airflow in pusher mode. Even so, I was able to confirm through spot checks that the performance of this unit was more or less identical to that of its later sibling. It managed 10,600 on an APC 9x5 and 11,100 RPM on an APC 9x4 - very comparable to the figures obtained for my other example. It also ran every bit as smoothly as its later companion. Conclusion

This makes it a bit of a puzzle why Bensen elected to omit the bushing with the smaller model. He evidently designed the 2.5 cc model with a plain unbushed bearing in imitation of the English diesel designs which had used a similar approach very effectively. Presumably cost considerations were a factor in this decision. What Bensen overlooked was the fact that the English engines used crankcases which were cast from a very hard-wearing high-silicon die-casting alloy, whereas the Thorning cases were gravity die-cast in plain aluminium. A forgivable mistake, but one which ultimately had the effect of forcing Bensen out of the model engine business. An article covering the Thorning 2.5 cc diesel story appears elsewhere on this website.

This outcome was a great pity, because there was nothing fundamentally wrong with either model. In particular, the 3.5 cc unit was an excellent engine which deserved a better fate. After abandoning the model engine field, Thorning Bensen went into the business of making printing equipment for newspapers and magazines. It's worth recording to his great credit that Bensen continued to offer repair and spare parts services for the Thorning engines for as long as the supply of spare parts held up. All parts were apparently gone by 1959, after which Bensen had no further involvement with model engines. He later took up painting and sculpture, becoming one of Denmark's more highly regarded artists. He died in 1987 at the age of 81. Given Thorning Bensen’s demonstrated abilities and personal integrity, his departure from the model engine manufacturing scene as a result of the failure of the Thorning 2.5 and 3.5 in the marketplace was a great loss to the Danish modelling community. The 3.5 in particular richly deserved a better fate than it was accorded. If the 2.5 and 3.5 diesels had met with better success, Bensen might well have gone on for some time to challenge the likes of Viking and CEROS on the Danish market. But that's all in the realm of what might have been .......!! For now, I hope that you’ve enjoyed this in-depth look at a little-known but very serviceable product of the Danish model engine manufacturing industry! _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published August 2018 |

||

| |

In

In

As of early 1950 when both Bensen and Carl Rose began work on their respective 3.5 cc models, one of the leading 3.5 cc diesels on the market was the

As of early 1950 when both Bensen and Carl Rose began work on their respective 3.5 cc models, one of the leading 3.5 cc diesels on the market was the  Looking at the Thorning 3.5 and the AMCO 3.5 PB side by side, the derivative relationship is obvious. Further evidence of this is found in the Thorning’s internal design. Like the AMCO, the Thorning is significantly over-square in terms of its internal geometry, having checked bore and stroke dimensions of 17.6 mm (measured 0.694 in.) and 14.0 mm (measured 0.551 in.) respectively for a displacement of 3.41 cc (0.208 cuin.). This made it very slightly more over-square than the AMCO, which checked out at 17.46 mm (0.687 in.) and 14.29 mm (0.562 in.) respectively for an almost identical displacement of 3.42 cc (0.209 cuin.).

Looking at the Thorning 3.5 and the AMCO 3.5 PB side by side, the derivative relationship is obvious. Further evidence of this is found in the Thorning’s internal design. Like the AMCO, the Thorning is significantly over-square in terms of its internal geometry, having checked bore and stroke dimensions of 17.6 mm (measured 0.694 in.) and 14.0 mm (measured 0.551 in.) respectively for a displacement of 3.41 cc (0.208 cuin.). This made it very slightly more over-square than the AMCO, which checked out at 17.46 mm (0.687 in.) and 14.29 mm (0.562 in.) respectively for an almost identical displacement of 3.42 cc (0.209 cuin.). The Thorning 3.5 cc diesel appeared in two very similar but nonetheless quite distinct variants. What appears to be the earlier of the two had a screw-on cooling jacket which was finned at full diameter right up to the topmost fin. At a later date in 1951, the diameter of the two top fins was progresively reduced to create a more rounded jacket profile at the expense of some cooling area.

The Thorning 3.5 cc diesel appeared in two very similar but nonetheless quite distinct variants. What appears to be the earlier of the two had a screw-on cooling jacket which was finned at full diameter right up to the topmost fin. At a later date in 1951, the diameter of the two top fins was progresively reduced to create a more rounded jacket profile at the expense of some cooling area.  A peculiarity of my example of the earlier version of the Thorning 3.5 is the fact that its crankshaft rotary valve is timed for reverse operation! I'm quite sure that it was intentionally manufactured this way, presumably to special order. It seems that some Danish modellers preferred this direction of operation, since my example of the CEROS 4.9 cc glow-plug model is similarly timed, as is one of my Thorning 2.5 cc examples. Indeed, engines featuring this running direction are not confined to Denmark - I have a

A peculiarity of my example of the earlier version of the Thorning 3.5 is the fact that its crankshaft rotary valve is timed for reverse operation! I'm quite sure that it was intentionally manufactured this way, presumably to special order. It seems that some Danish modellers preferred this direction of operation, since my example of the CEROS 4.9 cc glow-plug model is similarly timed, as is one of my Thorning 2.5 cc examples. Indeed, engines featuring this running direction are not confined to Denmark - I have a

Again like the AMCO, the Thorning used a light alloy prop driver which engaged with a self-releasing taper at the front of the main journal. The end of the shaft was internally threaded to accept an externally-threaded stud which accommodated the nut-and-washer combination used to secure the prop. The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate and a needle valve assembly of standard split-thimble configuration.

Again like the AMCO, the Thorning used a light alloy prop driver which engaged with a self-releasing taper at the front of the main journal. The end of the shaft was internally threaded to accept an externally-threaded stud which accommodated the nut-and-washer combination used to secure the prop. The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate and a needle valve assembly of standard split-thimble configuration.

I quickly learned that this engine has the somewhat unusual characteristic of refusing to start or even fire if there’s even a little too much fuel hanging about in the system. After some experimentation with subsequent restarts, during which I experienced a few more “difficult” periods, I found that the correct approach was to choke to just fill the fuel line (and no more!), administer a small prime (a few drops only) down the intake venturi to get just a little fuel into the crankcase and then administer a “dry” exhaust prime (ports closed by the piston). Once I worked out this routine, starting became perfectly straightforward. My previous difficulties had been down to my responding to a refusal to fire by adding even more fuel. With this engine, that’s a guaranteed non-start!

I quickly learned that this engine has the somewhat unusual characteristic of refusing to start or even fire if there’s even a little too much fuel hanging about in the system. After some experimentation with subsequent restarts, during which I experienced a few more “difficult” periods, I found that the correct approach was to choke to just fill the fuel line (and no more!), administer a small prime (a few drops only) down the intake venturi to get just a little fuel into the crankcase and then administer a “dry” exhaust prime (ports closed by the piston). Once I worked out this routine, starting became perfectly straightforward. My previous difficulties had been down to my responding to a refusal to fire by adding even more fuel. With this engine, that’s a guaranteed non-start! Once running, the engine performed very well. The needle has a very sharp taper, making the optimum needle setting rather touchy. However, that optimum setting was pretty clearly indicated thanks to the engine’s very definite response to the controls. The one problem encountered was the fact that the contra-piston stuck in the bore when hot – a common characteristic of steel contra-pistons in steel bores. However, the engine would start at running settings for the most part, so this was not really an issue.

Once running, the engine performed very well. The needle has a very sharp taper, making the optimum needle setting rather touchy. However, that optimum setting was pretty clearly indicated thanks to the engine’s very definite response to the controls. The one problem encountered was the fact that the contra-piston stuck in the bore when hot – a common characteristic of steel contra-pistons in steel bores. However, the engine would start at running settings for the most part, so this was not really an issue.

As related elsewhere, the reputation of the Thorning range suffered a serious set-back in 1951 due to the premature release of the 2.5 cc FRV model with a plain unbushed main bearing which wore out very rapidly. Bensen hadn't made the same mistake with the earlier 3.5 cc model, which featured a bushed main bearing from the outset.

As related elsewhere, the reputation of the Thorning range suffered a serious set-back in 1951 due to the premature release of the 2.5 cc FRV model with a plain unbushed main bearing which wore out very rapidly. Bensen hadn't made the same mistake with the earlier 3.5 cc model, which featured a bushed main bearing from the outset.