|

|

Polish Pearls - The Classic Model Engines of Stanislaw Górski

The main obstacle facing anyone tackling this subject, particularly an English speaker like me, is an almost complete absence of any comprehensive and readily accessible source material. Information in the English language regarding the early history of model engine development in Poland is fragmentary at best. The Górski engines were never the subject of any published tests in the English-language modelling media, probably in large part because they were never imported in commercial quantities into Britain or the USA. Indeed, the range was only mentioned occasionally, with most of the material focusing upon a particular model rather than presenting anything like a comprehensive picture. Naturally, the Polish language represents a significant barrier to the acquisition of information from Polish sources. Even if this was not the case, I’m advised by my Polish contacts that there’s actually not all that much documentary information available in Poland itself. There is a paragraph on Górski in the Polish modelling encyclopedia entitled "1000 Słow o Modelarstwie" (1000 Words on Modelling) compiled by Stefan Smolis, but this provides only a few relevant details about Górski's career, with no information regarding his engines beyond their names. The most productive Polish source that I have so far located is the very interesting thread on the subject of Polish model engines which is to be found on a very comprehensive Polish modelling forum to which my attention was drawn by my valued mate Maris Dislers. A good sampling of the collective knowledge of numerous Polish model engine enthusiasts may be found on that thread. The use of Google’s translation feature renders this material readily accessible to an English speaker like me. The information gleaned from this source was still relatively limited, but I’d nonetheless like to express my very sincere appreciation to all of the participants on that thread who provided useful snippets of information as well as a number of the images used to illustrate this article. Of course, an outsider like me couldn't get to first base on a project like this without the active assistance of residents of the country of interest. In that context, I'd like to acknowledge the very considerable assistance rendered to me by my Polish friends and colleagues Paul Praus and Grzegorz Zesiek, whom I "met" through the afore-mentioned forum. They filled in many of the undocumented details which were not available from any documentary source. In addition, Paul Praus supplied me with a superb replica of an original Jaskółka needle valve assembly to complete one of my own engines. My very sincere thanks to both!

Jim was also incredibly generous in providing me with a number of the original images which were used to illustrate the section of his book which covers Polish engines. I could have gained access to quality images of some of the models covered here in no other way. It’s hard for me to express my sense of gratitude to Jim. He is greatly missed. Apart from the sources mentioned above, I’ll just have to do the best that I can using the limited source material available. In doing so, I’d like to make it very clear indeed that I consider this to be a work in progress even after its publication. I have no doubt at all that there will be significant errors and omissions in what follows, but someone has to get the ball rolling! I will of course welcome corrections or suggestions from knowledgeable readers at any time. Any and all authoritative input received will be gratefully added and fully credited. In the interests of providing some context to this story, it makes sense to begin by summarizing the history of model engine development and manufacture in Poland leading up to the mid 1950’s introduction of the series of model engines designed and manufactured by Stanislaw Górski. Background

The opportunity for Poland to regain its independence came at the end of WW1, when the three partitioning powers were all fatally weakened by a combination of war losses and revolution. In 1918 the Second Polish Republic was established, surviving as an independent state until September 1939, when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union combined to destroy it in their shameful joint invasion of Poland which triggered the onset of WW2. The WW2 years were a national tragedy for Poland. Millions of Polish citizens perished in the course of the Nazi occupation between 1939 and 1945 as Nazi Germany classified ethnic Poles and other Slavs, Jews and Romani (gypsies) as sub-human. Nazi authorities targeted the last two groups for short-term extermination, deferring the extermination and/or enslavement of the Slavs as part of the "Generalplan Ost" (General Plan for the East) conceived by the Nazi régime. Poland never formally surrendered either to Germany or to the Soviets, and a Polish government-in-exile functioned throughout the war and afterwards, initially in France and later in London, England. Virtually the entire Polish navy escaped to Britain, while tens of thousands of Polish soldiers and airmen escaped via various routes to France and later Britain. These free Polish forces contributed significantly to the eventual Allied victory through participation in military campaigns on both the eastern and western fronts. The westward advances of the Soviet Red Army in 1944 and 1945 compelled Nazi Germany's forces to retreat from Poland, ultimately leading to Soviet domination of the country after the war. Poland thus became a communist satellite state of the Soviet Union, known from 1952 onwards as the Polish People's Republic. This was to survive until 1989, at which point the efforts of the Solidarity movement brought about a peaceful transition from a communist state to a capitalist democracy, the Third Polish Republic. With the above political background in mind, it’s easier to appreciate the conditions under which pioneering Polish model engine designers and manufacturers were working, particularly those who were already active during the war years. It was not the easiest of times in which to pursue an interest in model engine design and construction!

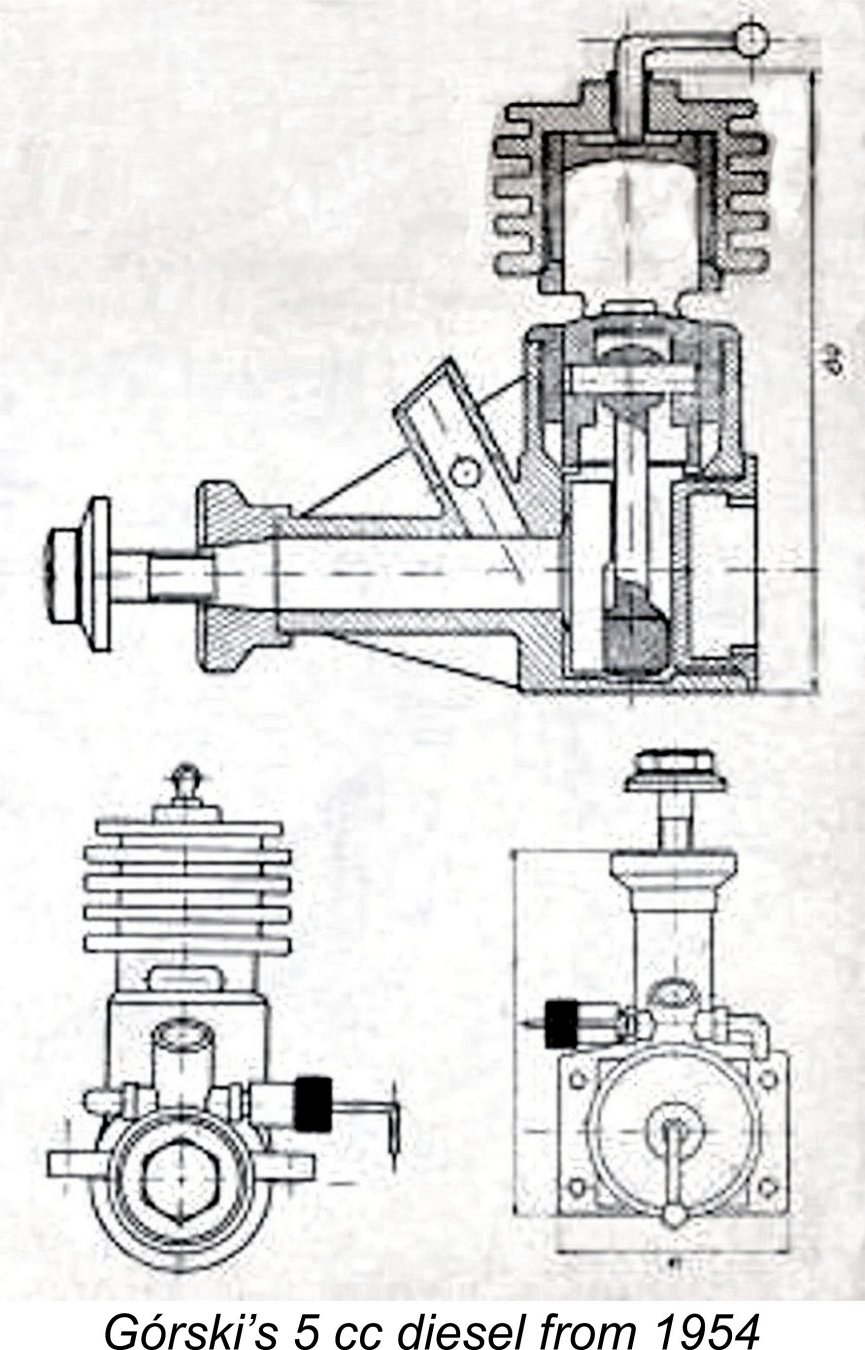

This particular unit displayed a number of interesting design features. Perhaps most notably, it was a short-stroke unit - very unusual indeed for the time! Bore and stroke were 20.5 mm and 18.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 5.94 cc. Both exhaust and transfer ports consisted of 16 radially-disposed holes drilled through the liner, much like the later Yulon engines from England. The engine weighed a healthy 290 gm (10.23 ounces). These units reportedly developed around 0.17 BHP @ 4,500 rpm. They apparently sold for a price of 180 zloty, which represented an average month’s salary at the time – not cheap!! As far as I can ascertain, the first named designer and manufacturer of model engines in Poland was Felicjan Gadomski of Warsaw, who reportedly began building model engines in 1942 during the period of Nazi occupation. Gadomski’s first effort was a spark ignition motor, but he subsequently developed a number of From 1942 onwards, Gadomski somehow managed to construct a very small number of model engines in his home workshop. During the war he produced four diesels, but increased his level of production following the conclusion of hostilities. By November of 1946 he had reportedly produced some two hundred units. This information is of great interest in that it clearly implies some level of continuing interest in aeromodelling in Poland during the harsh political environment of the war years and the early post-war period. Over the years, Gadomski went on to produce a number of additional models, including the Lilliput, Gado and Fegad designs. He also built Poland's first pulse-jet unit, the Gado 300. He was still active in the 1980’s and early 1990’s, producing a series of very up-to-date 2.5 cc racing engines, both diesel and glow, under the Fegad label. All of his engines were produced to very high standards in relatively small numbers in his own home workshop.

Returning to the early post-war period, the construction of model engines in Poland soon began to expand following the war’s conclusion. Among the earliest post-war constructors was Stanislaw Albrecht, an employee of the National Aviation Engine Factory no. 2 at Rzeszów. In 1945 Albrecht constructed a 9.55 cc spark ignition sideport engine designated the A. S-7. The engine weighed a healthy 400 gm (14.11 ounces) all complete and developed a claimed 0.40 BHP @ 6,000 rpm. A matching 3-blade 370 mm dia. x 200 mm pitch propeller was also developed, along with a suitable ignition coil. The engine apparently performed very dependably during testing.

The ongoing shortfall in the supply of model engines to Polish aeromodelling enthusiasts led certain talented individuals to make efforts to redress the supply situation, at least in their own communities. One such individual was Wladyslaw Kulik of the Baltic seaport of Szczecin near the German-Polish border. Kulik Wladyslaw Kulik deserves special mention because he was one of the first Polish designers to conduct serious experiments with glow-plug ignition. Since the operating parameters for this form of ignition were poorly understood at the outset, Kulik constructed a very interesting experimental glow-plug model which featured a variable compression head arrangement to allow him to experiment with different compression ratios. Kulik went on to construct several very good diesels, albeit in relatively small numbers. During the early to mid 1950’s, members of his model club in Szczecin reportedly won quite a few contests using his engines.

Enter Stanislaw Górski

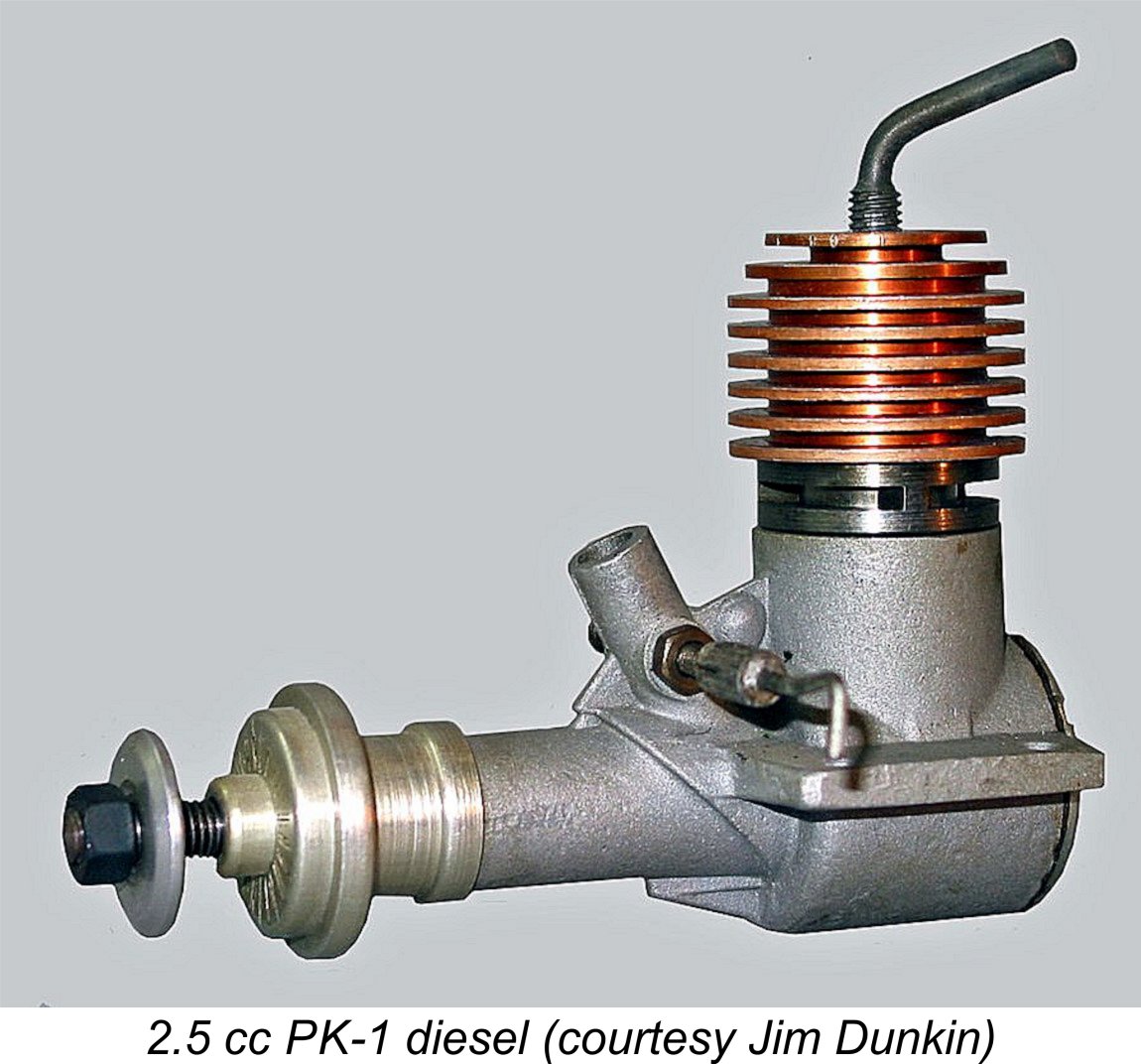

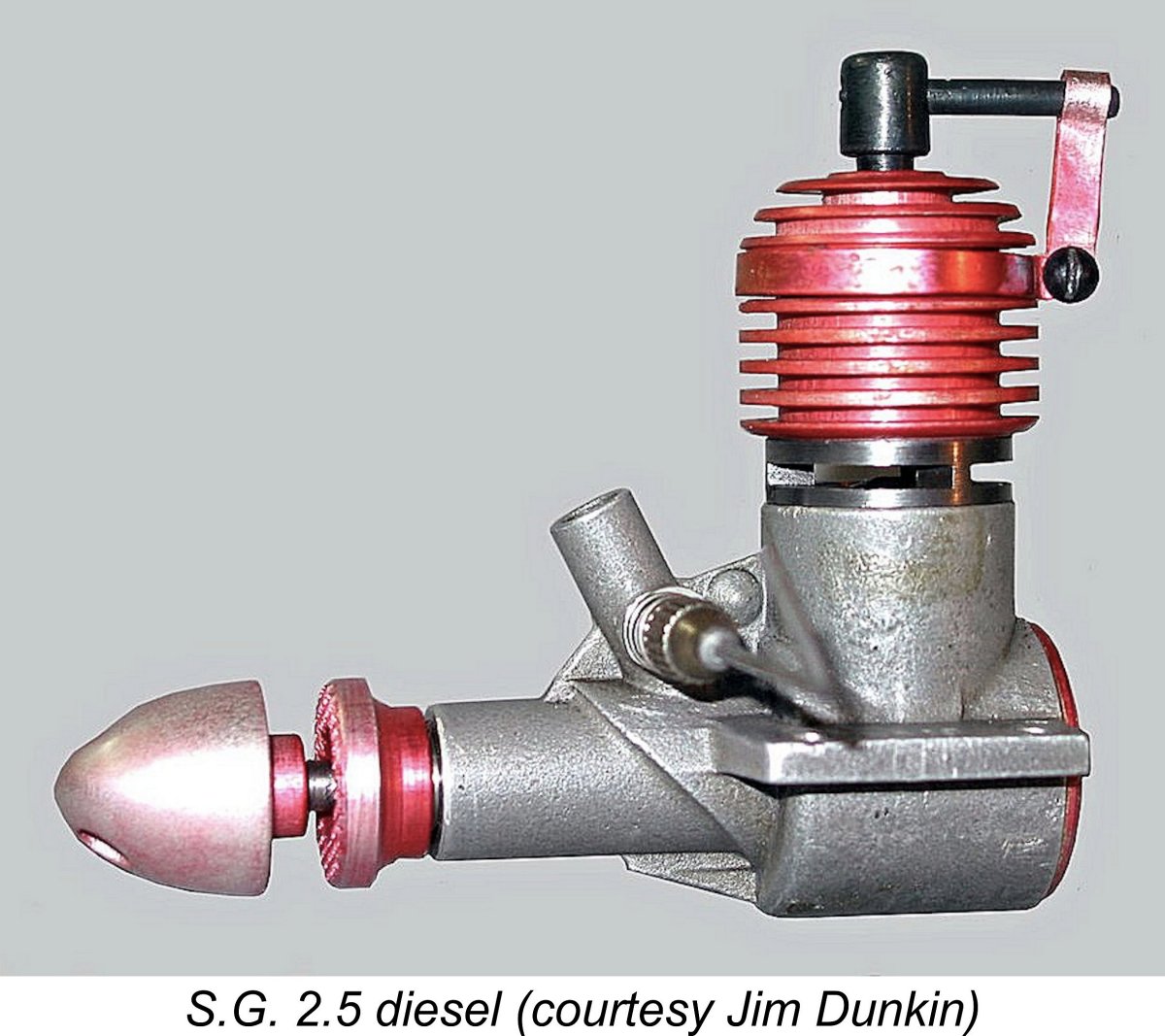

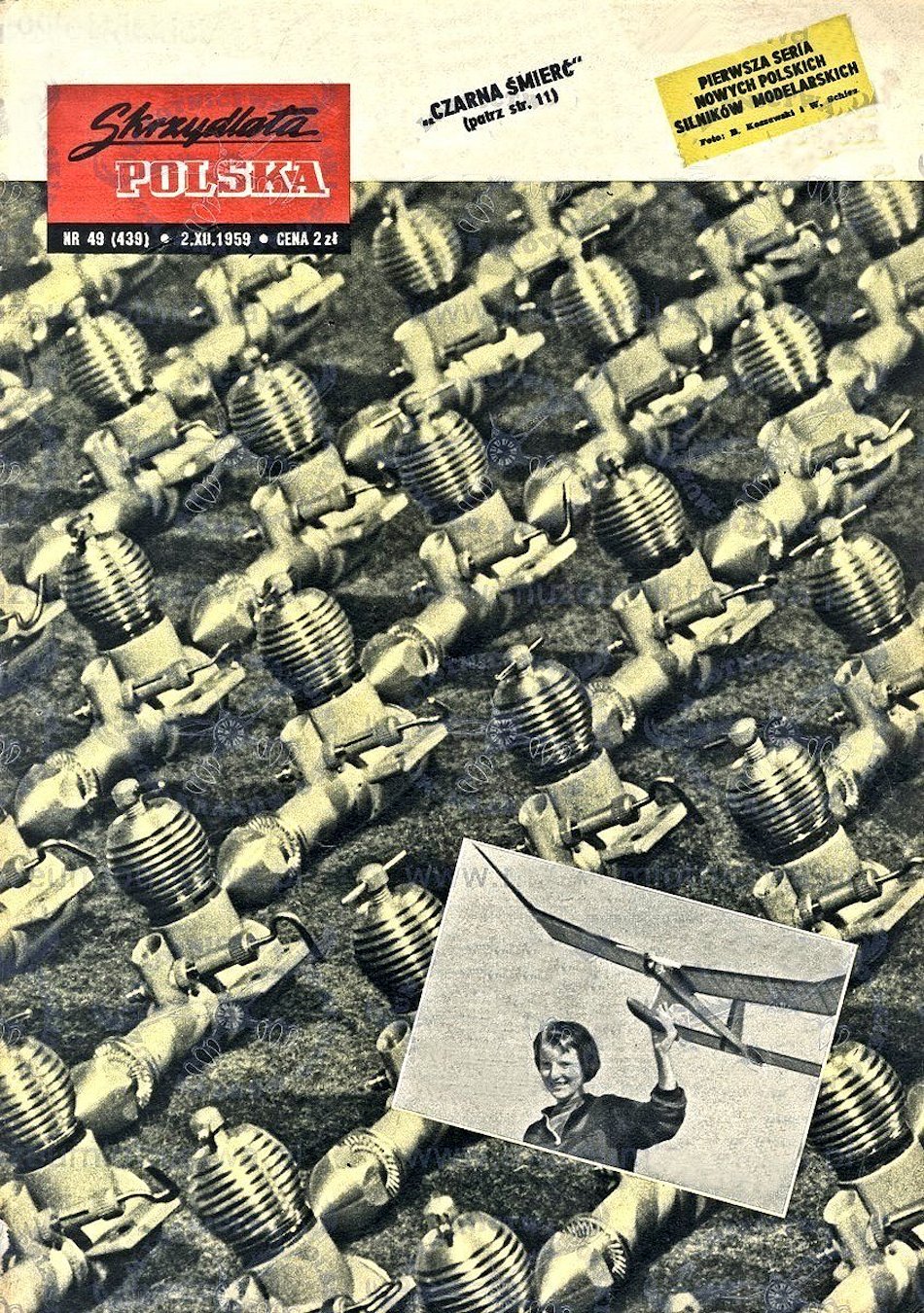

According to information contained in Jiri Kalina’s Czech-language book entitled “Modelářské Motory” (Model Engines), which was published in Prague in 1980, the first record of a model engine made by Stanislaw Górski dates to 1947. This design was reportedly a diesel of 3.6 cc displacement. The engine in the image which is reproduced below may or may not be an example of this model, but it has been authoritatively identified as an early Górski design. It is inscribed 01 SG, which may (or may not) indicate that it is Górski’s first engine. Jim Dunkin’s previously-cited reference book of 2.5 cc engines tells us that in 1949 Stanislaw Górski started working at the Centrali Zaopatrzenia Szkol (Cezas – Central School Supply) in Rzeszów. There he became one of a group of model engine enthusiasts who designed and constructed their own model engine designs in very small numbers while working at Cezas. This group also included Jan Staszek, Wladyslawa Niestoja and the aforementioned Włodzimierz Bretsznajdera. While he was working at Cezas, Górski became active in the development of radio control for model aircraft, actually being a pioneer in this field in Poland. By 1953 he had developed and constructed his own radio control equipment, which he used in a large model of his own design having a wingspan of 3.33 m and weighing some 6 kg. This huge model was powered by a 20 cc engine of unspecified origin, likely made by Górski. Stanislaw Górski’s first recorded commercial model engine design during his time at Cezas was a 2.5 cc plain bearing (FRV) diesel known as the PK-1. This engine seems to have appeared in late Attentive model engine enthusuaiasts may have noticed that a surprising number of Eastern European model engines of this era, such as the PK-1, used screw-in construction. This form of construction was largely driven by the fact that miniature machine screws suitable for model engine assembly were almost unobtainable in the Eastern Bloc during this period. A few constructors such as Hans Drenkhahn of East Germany got around this by making their own fasteners, but the majority simply side-stepped the problem by using screw-in construction. The PK-1 was provided with a red-anodized cooling jacket having 8 fins and an extended prop driver which was also anodized. A layer of extra metal was incorporated into the crankcase casting around the intake At some point during 1954 a few additional changes were made. A form of cooling jacket clamp was now provided which could be adjusted to guard against the compression setting running back during operation. The comp screw was revised to accommodate this clamp. A shorter red-anodized alloy prop driver was used, while a matching spinner replaced the former sleeve nut and washer. These latter two components were to be features of Górski’s later Jaskółka 2.5 cc diesels. It is with this model that we see the first appearance of the S.G. model identification based upon the designer's initials (see below), since this variant was widely referred to as the S.G. 2.5 diesel. The December 1954 issue of the Polish aviation magazine “Skrzydlata Polska” (Winged Poland) It was also during this period that Stanislaw Górski began his experiments with larger-displacement model diesels. The same previously-mentioned December 1954 article announcing the new 2.48 cc design from The published three-view drawing shows this prototype engine's main features very clearly. In several respects it differed significantly from later Górski designs. It featured a screw-in cylinder which had only two exhaust ports (shown fore and aft on the drawing) and a pair of overlapping transfer ports located between them. Given the screw-in cylinder attachment, the transfer ports were presumably of the internal flute variety. The cooling jacket was provided with only 5 cooling fins, and the main bearing housing seemingly lacked the extra thickness of metal around the intake venturi which was a feature of the smaller 2.5 cc models. The comp screw was ball-ended on this design. The prop was secured using a steel sleeve nut and washer. The accompanying article tells us that this prototype unit was a long-stroke design, reportedly featuring bore and stroke measurements of 18.0 mm and 19.0 mm respectively. The article stated that the engine weighed 250 gm (8.8 ounces) and could operate at up to 12,000 RPM. The article also gave the fuel formula then being used by Górski and his colleagues. This consisted of 50% ether, 25% road diesel oil and 25% lubricating oil.

By 1955 Stanislaw Górski had left Cezas to go to work for the Wytwornia Sprzetu Komunikacyjnego (WSK – Transportation Equipment Manufacturing Centre) in Mielec, a town of modest size in south-east Poland. This aviation-oriented facility had its beginnings in 1938-1939 when Poland’s largest aviation company, the previously mentioned Państwowe Zakłady Lotnicze (PZL - State Aviation Works) of Warsaw built a satellite factory in Mielec, designated as PZL After the German/Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939 signaled the end of Polish independence and the outbreak of World War II, the city of Mielec and the PZL aircraft company both ended up in the hands of the German invaders. The period of German occupation in Mielec lasted from September 9th, 1939 to August 6th, 1944. During the intervening years, the factory was operated as part of the Heinkel organization, producing components for German bombers as well as carrying out repair work. The Nazis staffed much of the factory with slave labour, with the workforce reaching a total of 5500 workers as of 1944 prior to the German pull-out.

At first, the factory produced Soviet-designed aircraft under license. In this way it became the primary production site for the widely used Antonov An-2 light transport biplane. The factory also manufactured Polish versions of the MiG-15 and MiG-17 fighters as well as building Polish designs such as the TS-11 Iskra jet trainer which was used by both Poland and India. Over time, it produced over 16,000 aircraft, most of which were licensed for export to the USSR. It was during this expansionist post-war period that Stanislaw Górski entered the employ of WSK, no doubt motivated at least in part by his personal interest in aviation. It would appear that his new employer saw the manufacture of model aero engines as a logical add-on to its full-scale aircraft business lines. After all, involvement with model aeronautics might be expected to increase the number of young Poles having both the interest and capacity for participation in full-sized aviation. Regardless of the reason, this allowed Górski’s future designs to be manufactured in significantly larger quantities than had formerly been possible. The Jaskółka Engines Appear Górski immediately set to work to commence the development of a series of ever-improving 2.5 cc model diesels to be manufactured by WSK. The resulting engines were thenceforth generally referred to as the Jaskółka (Swallow) line.

As noted earlier, the S.G. identification had already appeared prior to the appearance of the Jaskółka series. A number of the later models actually displayed this identification cast onto their cases. The Jaskółka name is simply a series identifier which was applied to all of Górski’s 2.5 cc designs. The manufacturer was always clearly identified as WSK Mielec on the boxes in which the engines were supplied, as seen in the accompanying illustration kindly supplied by Paul Praus.

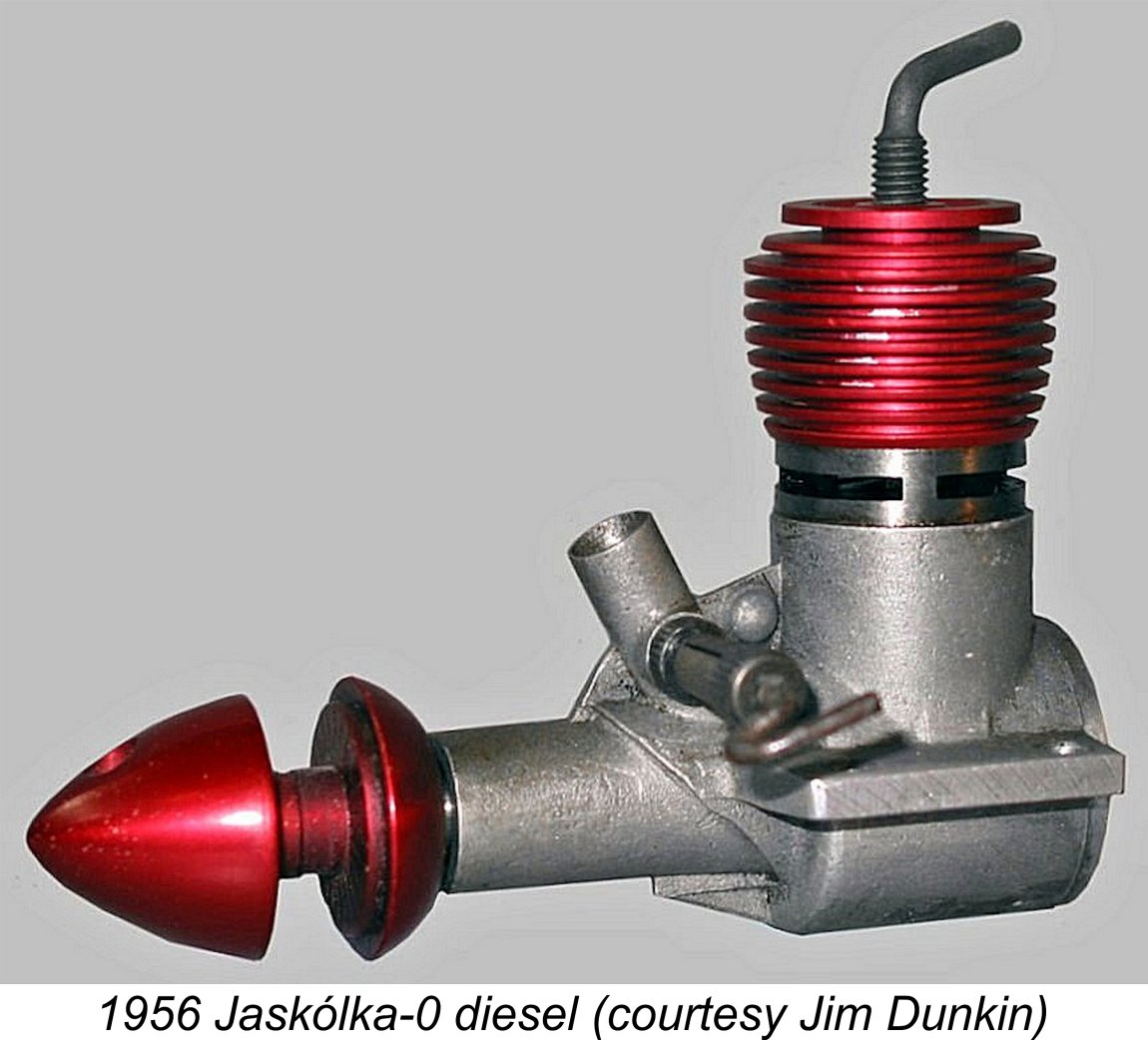

This model was a more or less conventional crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model diesel having bore and stroke measurements of 14.5 and 15.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.48 cc (0.151 cuin.). The crankcase of this model was seemingly identical to that of Górski’s original PK-1 model, retaining the additional thickness of metal around the venturi intake and in the stiffening web behind the intake. The case also continued to feature the parallel-profile main bearing housing. The alloy components (cooling jacket, prop driver, spinner) were profiled slightly differently but continued to be anodized red. The illustrated example does not display a serial number.

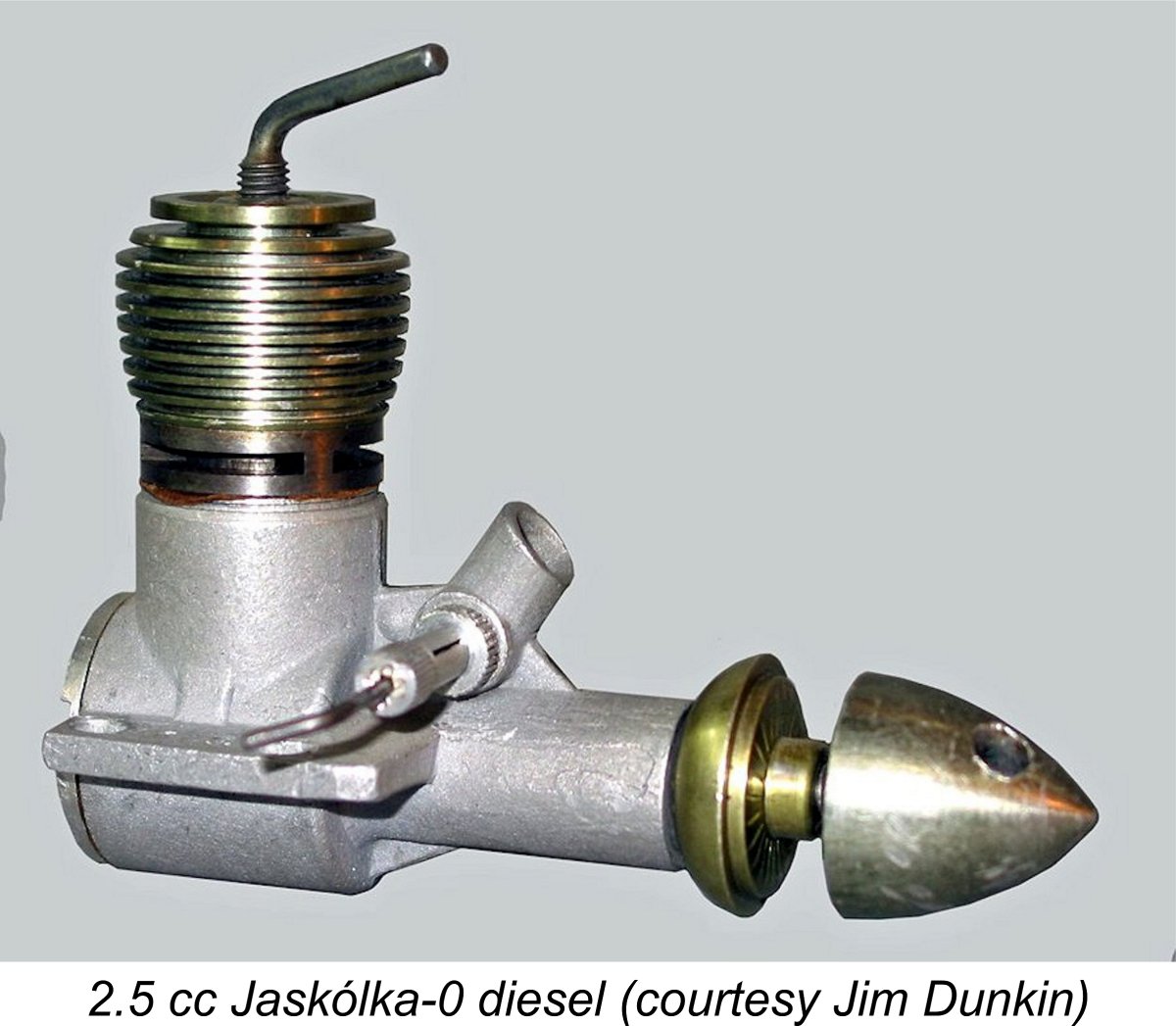

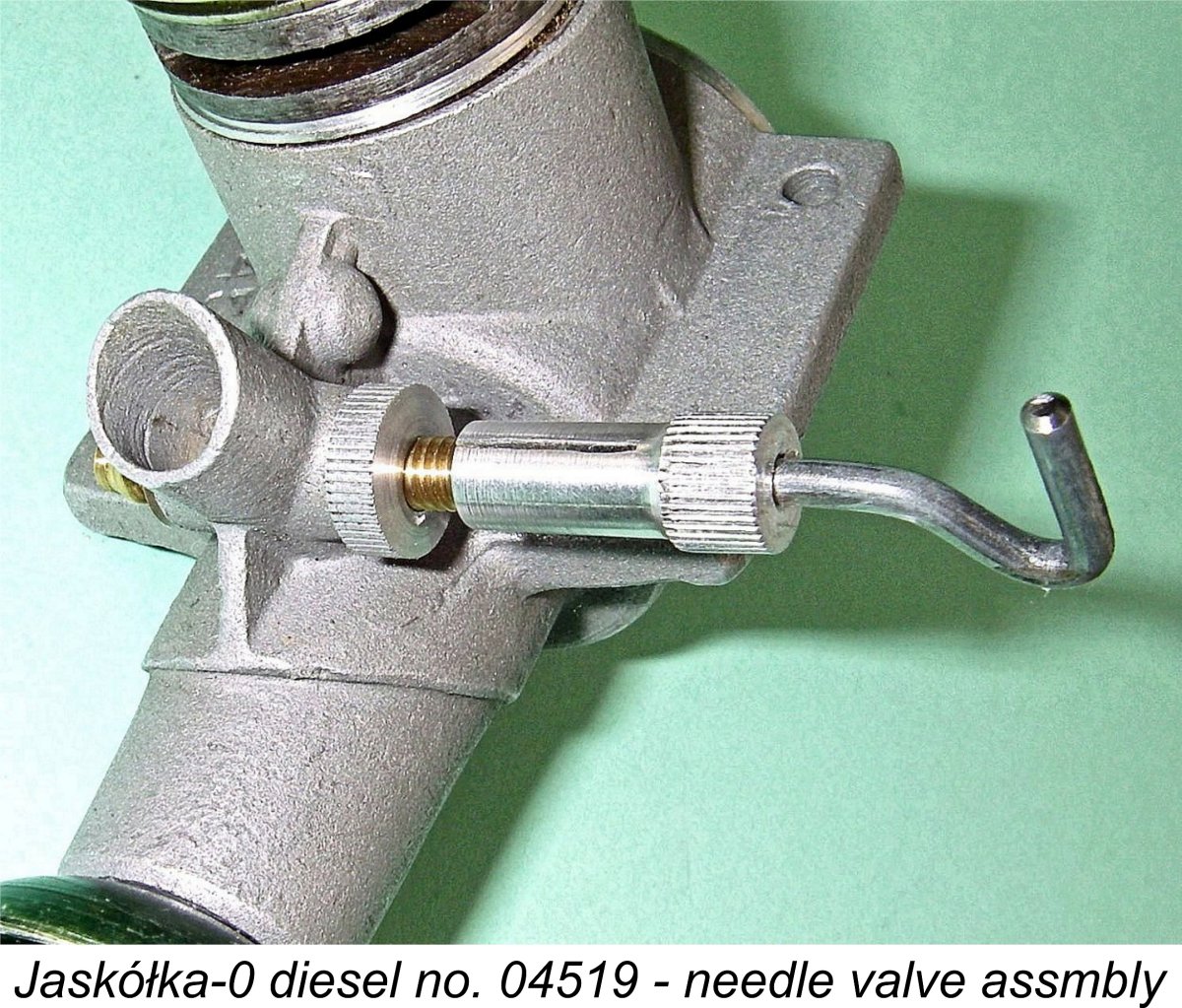

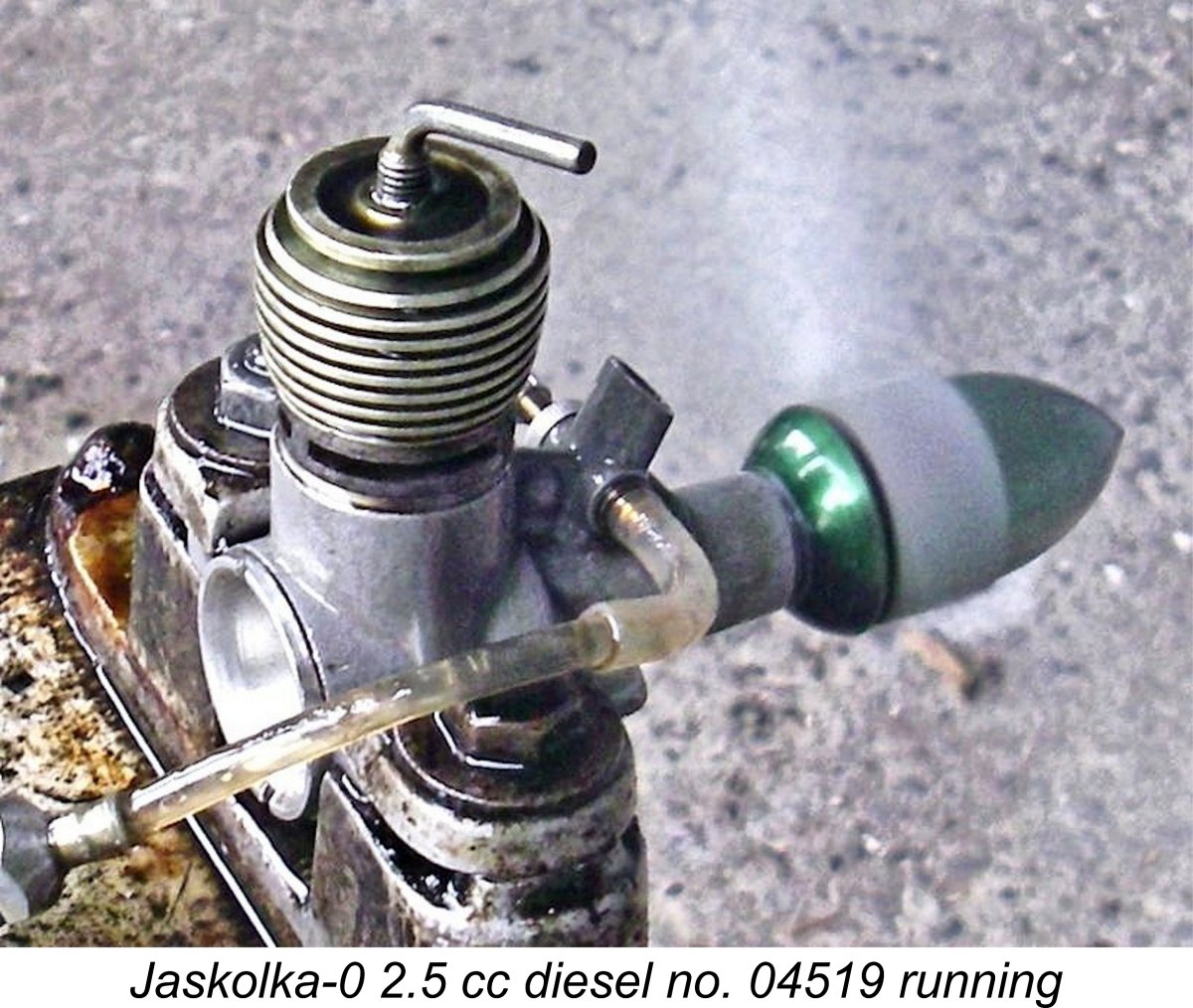

Jim Dunkin illustrated Jaskółka-0 engine number 1123 of this type, as seen at the left. I have no information regarding the starting point for the serial number sequence. Many of these engines featured a dark pea-green anodizing on the spinner, prop driver and cooling jacket in place of the red anodizing used previously. The year 1958 also saw the appearance of two more The other new addition to the range was the S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-II which was produced in both diesel and glow-plug versions. It featured a twin ball race crankshaft to go along with its reed valve induction. Again, the S.G. 2.5 identification was cast in relief onto the right-hand side of the crankcase, with the Jaskólka-II name appearing on the opposite side. Interestingly enough, since the engine was based upon the same crankcase casting as used on the Jaskółka-I, the extra I of the Later in 1958 the design of the S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-0 was slightly changed, with the main bearing now having a tapered profile to provide extra metal in the vicinity of the intake and the bearing-crankcase interface. The extra metal around and behind the intake venturi also reappeared with this model. This is the variant that I have. My illustrated engine is numbered 04519, while Jim Dunkin included an illustration of engine no. 03207 of this type. I was greatly intrigued by the fact that my illustrated example of this engine turned out to be timed for reverse rotation (clockwise viewed from the front). Hearing this, my good mate Maris Dislers checked his example and found that it was similarly timed. Upon checking with Paul Praus, I was advised that this was in fact the standard direction of rotation for these engines. By way of confirmation, Paul sent me a scan of the instruction sheet for the Jaskolka-0, which reads in part: "Kierunek obrotów - lewe (patrząc w kierunku lotu)". This translates more or less into “Running direction – left (looking in the flight direction)”. This provides a complete explanation of the failure of the Jaskolka-0 (which is what it was officially called, apparently) to penetrate the Western market – who in the West would buy an engine that needed a pusher prop to work in tractor mode?!? That having been said, clockwise rotation was actually a widely-followed convention among Continental and German manufacturers during the early post-WW2 years. I have encountered several classic Danish engines which are set up for operation in this manner. Maris determined by "eyeball" that the timing on his example had the induction port open at around 90 degrees after bottom dead centre and close at approximately 30 degrees after top dead centre for an extremely conservative 120 degree induction period. Coupled with a relatively small gas passage in the crankshaft and an absence of any sub-piston induction, this would lead us to expect a rather modest performance from this unit.

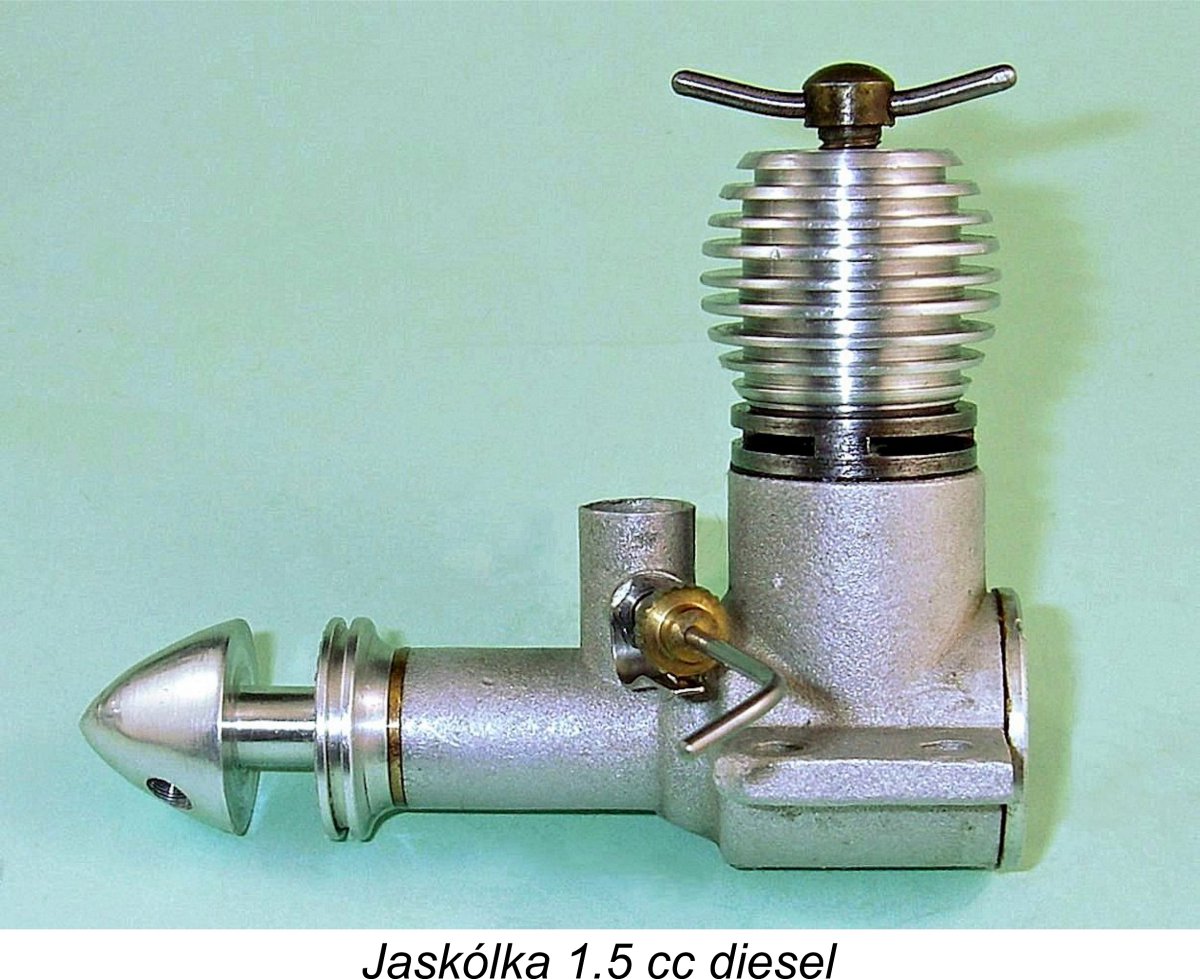

The new 1.5 cc model was basically a scaled-down version of the plain bearing FRV 2.5 cc Jaskółka-0, although there were a few detail changes. The intake venturi was vertical rather than being slanted forward, while the main bearing housing reverted to a parallel side profile. An annular expansion was incorporated into the crankcase casting at the point where the main bearing housing met the crankcase, presumably to strengthen this always-vulnerable area. Bore and stroke of this model were 12.3 mm and 12.5 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.49 cc (0.091 cuin.). The engine weighed in at 83 gm (2.93 ounces). Some of these engines had red-anodized alloy components, while others were left in their as-machined state. The presumably early units depicted on the previously-mentioned magazine cover were of the latter type, as is my own illustrated example, perhaps implying that the red anodizing was applied to later examples. The magazine cover illustration confirms that the needle valve was of the standard Jaskółka pattern, confirming the connection. My example has a Webra assembly, the original having been lost. The engines carry no identification whatsoever. At present it is not known if the 1.5 cc units retained the Jaskółka series identification or whether a new name was applied. Unless or until clarification becomes Although there is agreement that, like the other Górski designs of the period, these engines were produced under the auspices of PZL, there seems to be some question regarding the actual location at which they were manufactured. A contributor to the Polish model engine forum which was linked earlier in this article stated his understanding that these 1.5 cc units were produced independently from the Mielec plant at a separate PZL facility in Warsaw, namely the Wola Engineering Works, whose main business was the production of full-sized aero engines. If this is the case, then we must remain open to the possibility that the engine was marketed under a different name. The original source of this information was cited as Antoni Sulis, a well-known Polish model flier who was living in Warsaw at the time. According to Sulis, those responsible for the construction of these 1.5 cc units were Jan Rosiński, Waldemar Salach, Zdzisław Piatkowski and Stanisław Grabowski. Sulis was Jan One interesting feature of the Jaskółka series which deserves mention was the needle valve assembly used on most of the mainstream models. This was basically a fairly conventional assembly using a brass spraybar with a single jet hole in combination with an aluminium split thimble for tension. The unusual feature was the fact that the sparybar was secured using a knurled internally-threaded disc rather than the more conventional hexagonal nut. This meant that it was finger-tightened only, thus protecting the spaybar from the common problem of breakage due to over-tightening. My very sincere thanks to Paul Praus for supplying the accurate replica assemble which is fitted to my own illustrated example of the Jaskółka-0 diesel. Maris Dislers has suggested that the reason for this rather unusual arrangement may well have been that like the miniature machine screws mentioned earlier, model-sized hex nuts were in short supply in Poland at During the period just covered, Górski reportedly continued to participate in aeromodelling competitions. He was best known as a free flight expert, but according to the encyclopedia entry quoted earier he also achieved success in speed and aerobatic competitions as well as continuing his personal involvement with model engineering. The attached photograph of Górski in his natural habitat appeared in the April 1960 issue of "Model Aircraft". It shows him admiring the FAI free flight power model of K. Ginalski. One wonders who the young fellow with Górski might be - a son, perhaps?!? English-Language Media Coverage

The highly laudatory text of the “Motor Mart” article read as follows: "This column rarely reaches for superlatives in describing a new motor, but we must make an exception for the Polish Jaskólka-II (Swallow), being made by Stanislaw Górski at the Transportation Equipment Factory (sic) in Mielec. No 2.5 c.c. diesel has ever attracted such ooh’s and aah’s at the editorial offices. The exhaust flanges shine like stainless steel, the rear cover and induction stub are mirror polished alloy, and the matt grey crankcase is a clean blend from the close-fitted red prop driver to the neat red anodized cylinder fins. The designer claims 0.26 BHP at 14,500 rpm, and our prop-rpm checks give 9,000 on Frog 9x6, 10,900 on 9x3, 12,200 on 8x4, and 14,850 on 8x3.5. This is exactly parallel to the best of the Carl Zeiss engines, and in fact the Jaskólka is as close a relative to the Zeiss as one could get, except that the intake is given a curved and opposite proportion venturi on the Jaskólka when compared with that of the Zeiss, for which 0.36 BHP is optimistically claimed. Cost is 325 zloty, or about one week’s earnings, so it is very much an export item for the Continental market. Incidentally, pronunciation of its name is close to "Yes—Cool car". Sadly, despite this ringing endorsement, it appears that the article failed to stimulate any interest in pursuing the commercial importation of the Jaskółka engines into Britain. Indeed, there followed a long period of silence regarding the Jaskółka series as far as the British modelling media was concerned.

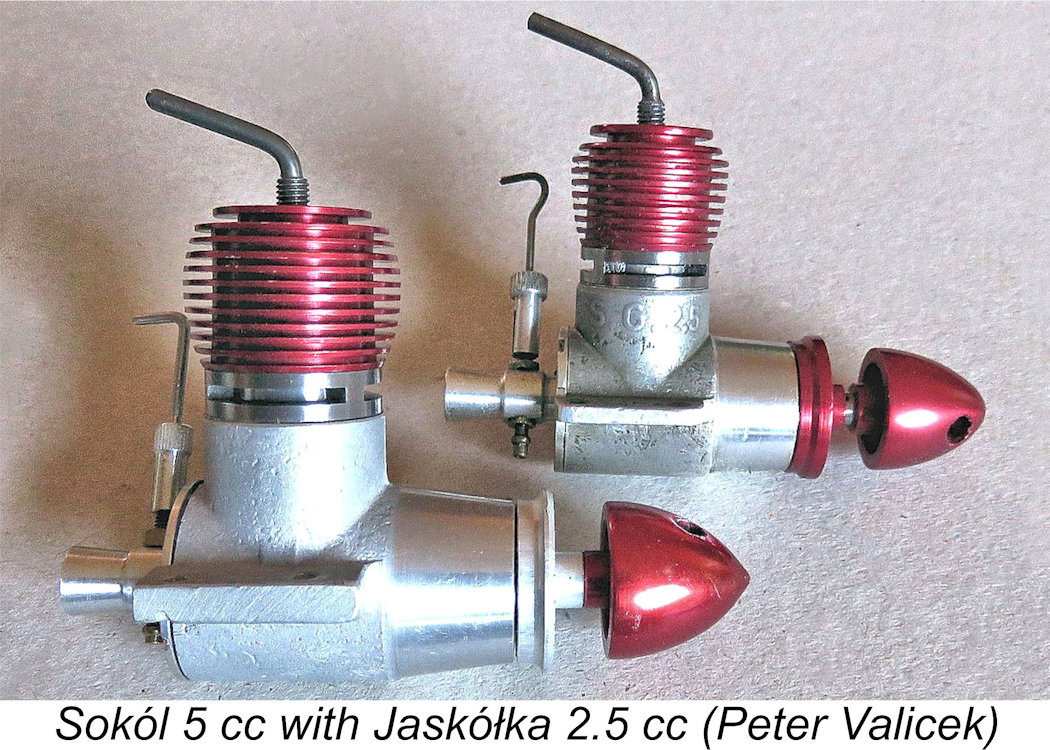

As can be seen from the accompanying image, the original Sokól 5 cc model was pretty much an enlarged clone of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka model. It was made in the same three variants as the 2.5 cc units - plain bearing reed valve; twin ball bearing reed valve; and plain bearing FRV model. Bore and stroke dimensions were 19.0 mm and 16.40 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 4.65 cc. Weight averaged around 190 gm (6.7 ounces).

In 1961 Górski introduced a new feature to both the Jaskółka 2.5 cc and Sokól 5 cc series. This was the addition of disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction to both models. The new disc-valve 2.5 cc variant was designated the S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-III model. It retained the twin ball-races of the reed valve Jaskółka-II design, being essentially identical apart from the induction system. Once again it used the same crankcase casting as the Jaskółka-I model, necessitating the addition of two additional hand-scribed numerals. The Jaskółka-III was intended as a competition powerplant, being produced in relatively small numbers. It reportedly developed some 0.300 BHP @ 15,000 RPM. It is a relatively rare engine today. The new 5 cc model was named the Super Sokól. It A glow-plug version of the Super Sokól was assembled at a separate facility known (in English) as the Polish Model Test Centre in Warsaw. This version of the engine was rated at 0.50 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. It was primarily intended for C/L stunt work, although the Test Centre did assemble a limited number of throttle-equipped versions for R/C and scale U-control models. The conversion consisted of a simple butterfly valve in the intake which was linked to a pivoted blade type exhaust restrictor. This combination reportedly provided a low-speed setting of 3,000 – 4,000 rpm depending upon the prop being used.

The Górski designs received some further coverage in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the July 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Like its “Aeromodeller” predecessor, this article focused upon a description of the twin ball-race Jaskółka-II reed valve design. It read as follows: “We have recently had the opportunity of examining one of the Mk. II reed valve model Jaskólka S.G. 2.5 diesels from Poland. The Jaskólka (“Swallow”), designed by Stanislaw Górski, has been made in several models, both rotary-valve and reed-valve, with and without ball bearings.

The reed valve and carburettor unit is a little different from usual practise. The screwed-in backplate has a 17/32 in. dia. opening in its front wall, forming an annular seating for the rim of the valve reed. The reed is of 0.005 in. spring steel. The carburettor has a venturi section and is turned in one piece with a flange of similar diameter to the reed at the front end. A collar, threaded on its periphery to screw into an internal thread in the backplate, secures the carburettor, and the reed is thereby clamped between the annular seating in the backplate and the flange of the carburettor. The arrangement allows the carburettor to be rotated a full 360 degrees to bring the needle valve to any convenient position. Performance of the Jaskólka is not up to the high levels now being reached with 2.5 cc contest diesels, but it appears to be a sound design, well produced. The complete motor weighs 4¾ ounces”. This was the last mention of the Górski engines that I can find in the two major British modelling magazines. As far as I can discover, no test of a Jaskółka or Super Sokól engine was ever published in the English-language modelling media. However, the range did not drop out of sight completely. The reed valve Jaskółka-II diesel was next mentioned in the article “Iron Curtain Engines – Da? Nyet?” which appeared in the August 1962 issue of “American Modeller”. Although unattributed, there are compelling indications that this article was almost certainly written by Peter Chinn some time prior to its publication. The text read as follows: “The Jaskólka SG-2.5 Mk. 2 diesel is one of a series of model motors designed by one of Poland’s best-known model engineers and free flight modellers, Stanislaw Górski. It is built at the P.Z.L. aircraft plant (Chinn is of course referring here to WSN in Mielec – Ed.). The model featured is the Series 2 version with reed valve induction and twin ball bearing shaft. The Jaskólka has also been built in plain bearing and rotary valve models. Cylinder porting is again of the Webra type just described and the major components, crankcase, cylinder, backplate and head, are threaded assemblies, no separate screws being used. The carburettor screws into the backplate, clamping a 0.005“ spring steel reed and can be rotated through 360 degrees to bring the needle valve to any convenient position. Performance is about average for engines of this type – around 0.25 BHP – and the motor weighs 4.75 ounces”. The Jaskółka 2.5 cc models were also included along with the Super Sokól in Peter Chinn’s unattributed “Global Engine Review” which appeared in the 1962 “American Modeller Annual”. Chin did not include the Jaskółka 1.5 cc model (by that name or any other), either because he was unaware of it or because its production had already been terminated as of mid to late 1962 when the article was written. The text read as follows:

This engine is an entirely new design. The standard production version is a diesel manufactured by Ryszard Szmidtke of Mielec (a name that does not appear elsewhere – Ed.). Unlike the older Sokól’s, it is loop scavenged (the first Polish engine of this type) with ball bearing shaft and disc intake. Unique among diesels, it has a curved baffle on the piston, the contra piston being recessed to take this. A glow version is assembled by the Polish Model Test Centre in Warsaw. Rated 0.50 BHP at 14,000 rpm, it is for C/L stunt work. In addition, the Test Centre is making a limited number of throttle-equipped versions for R/C and scale U-control models. The conversion consists of a simple butterfly valve in the intake which, linked to a pivoted blade type exhaust restrictor, drops rpm to 3 or 4,000 rpm according to prop used”. The final English-language mention of the Górski engines that I can find appeared in Peter Chinn’s unattributed “1965 Global Engine Review” which was published in the 1965 “American Modeller Annual”. It was clearly written in mid to late 1964. The comment read as follows: “Jaskólka and Sokól engines are no longer being manufactured, but some stocks of the Jaskólka-2 and Super Sokól diesels remain”. It thus appears that production of the Górski series of model engines had ceased by early 1964 at the latest. The Super Sokól was briefly mentioned in O. F. W. Fisher’s 1977 book “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines”, in which it was characterized as “a lovely BR stunt engine” which was “probably the last 5 cc diesel to remain in production”. This was well prior to the advent of the PAW .29 and the diesel version of the MD-5 Kometa! Fisher’s example reportedly had a black-anodized cooling jacket to go with its red-anodized prop driver and spinner, as seen in the above image. Workmanship was said to be “of a high order”. The 2.5 cc Jaskółka-0 Model on Test

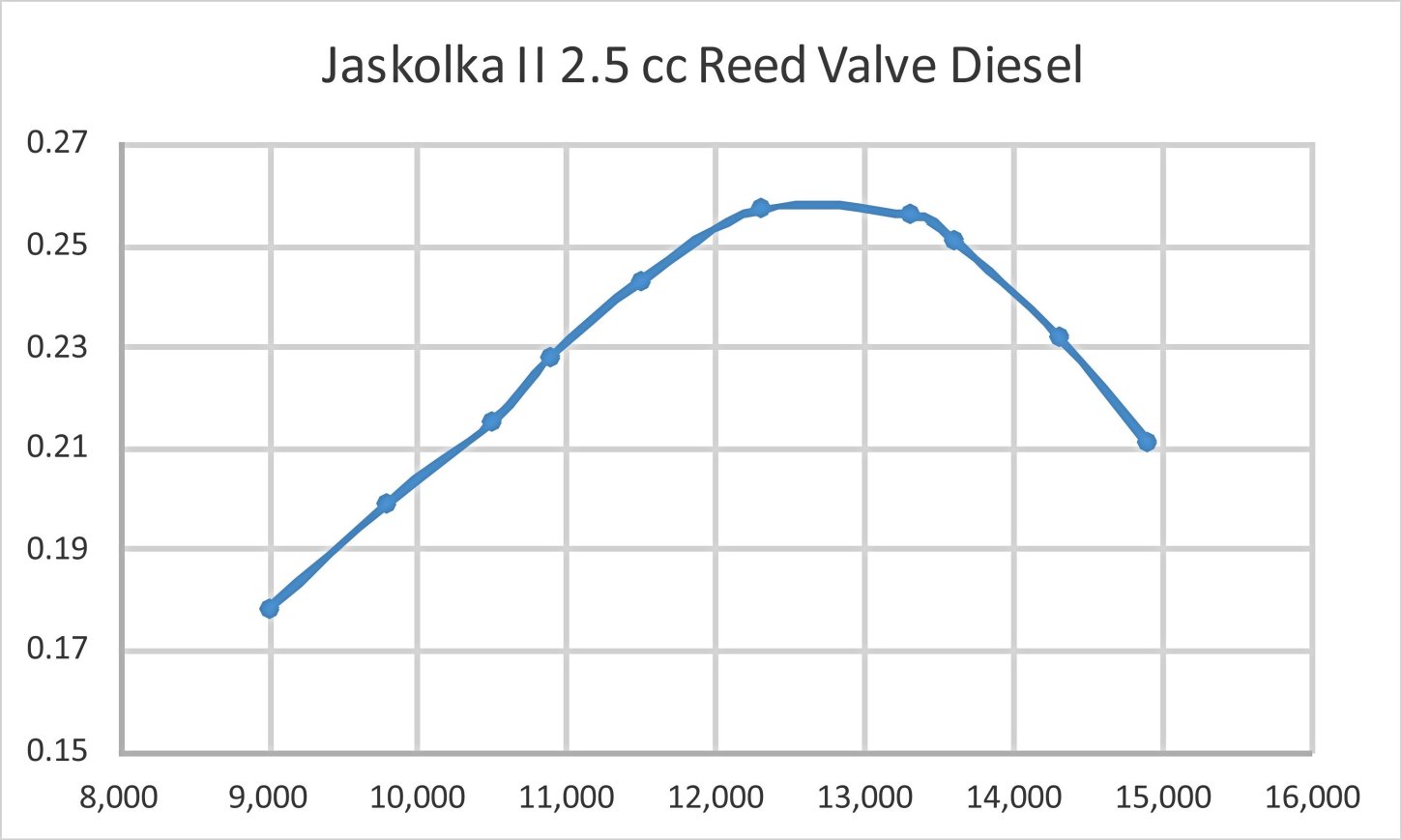

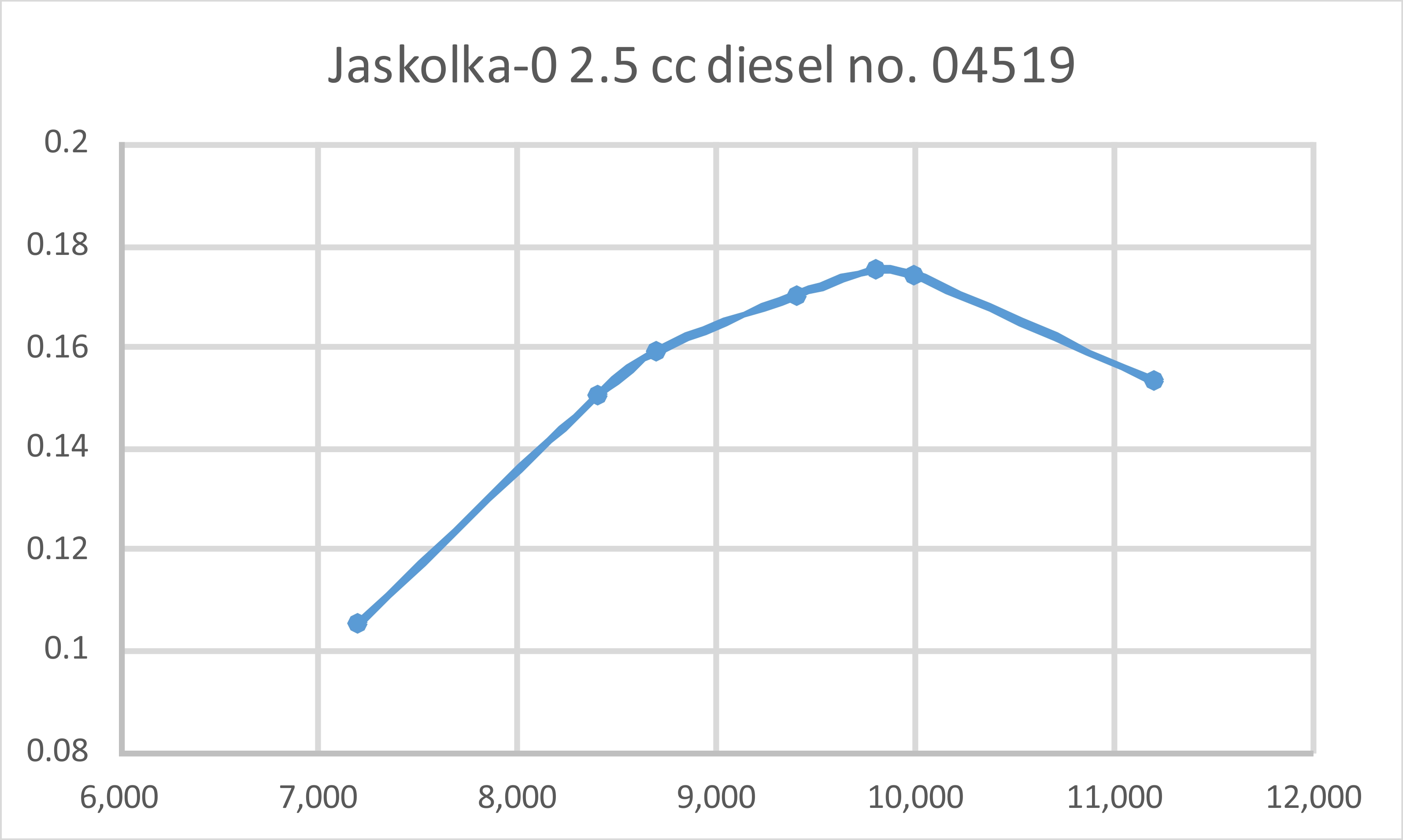

Although it appears to be unmounted, the engine has had a fair bit of use, presumably on the bench, as witness the faded green anodizing on the cooling jacket, which presumably once matched the spinner and prop driver. However, it remains in excellent condition apart from missing its original needle valve assembly. The faithful replica assembly now fitted was kindly supplied by Paul Praus, as mentioned earlier. All fits throughout are absolutely first-class. Assuming that this example somehow reached the West relatively early on, its apparent lack of active service in an airframe is almost certainly down to the previously-noted fact that it is timed for reverse The actual test runs were conducted with my standard calibrated test props mounted backwards and necessarily running in reverse. Given the greatly reduced cooling slipstream, I kept these runs down to very short durations – just enough to get a steady reading on each prop. I find flicking in the reverse direction to be quite awkward, so it was just as well that the Jaskółka proved to be an almost absurdly easy starter. A few choked turns and a small prime followed by a few relatively lazy flicks was all that it took. One of the easiest-starting engines of my latter-day acquaintance! Once running, the engine was very responsive to the controls, making the establishment of the optimum settings for each prop very straightforward indeed. Both controls held their settings perfectly while never being stiff. Running qualities were outstanding - dead smooth with relatively little vibration. The data collected during the test is shown in the following table and graph.

As the figures show, this engine cannot be viewed in any sense as a powerhouse! The implied peak output is around 0.175 BHP @ 9,900 RPM. Given the unusually restrictive induction arrangements noted earlier, this doesn't come as much of a surprise. However, quite a few very highly regarded 2.5 cc plain bearing diesels of the era didn't produce that kind of power at that speed - they had to run quite a bit faster to pull ahead. Torque development at moderate speeds is clearly the Jaskółka's forte. Propped for operation at or near its peak using something like a 9x5, the Jaskółka could pull a sport model aloft with the best of them. It was also a very easy engine to manage, being built to last in addition. Polish modellers were well served by these engines! The 2.5 cc Jaskółka-II Model on Test

Naturally enough, I was very keen to get this finely refurbished engine into the test stand. Being a reed valve engine, it didn't suffer from being restricted to reverse operation, allowing my usual set of tractor test props to be fitted as required. I elected to begin my test-running with a 9x6 APC prop, which is generally a good running-in airscrew for classic iron-and-steel 2.5 cc diesels. However, this particular engine had been extremely well fitted by my mate Peter, who had also given it some initial test running. As a result, it felt absolutely superb right from the outset. I nevertheless decided to give it a few shake-down runs prior to undertaking any actual power testing. The engine endeared itself to me right away by proving to be an extremely easy starter once the best technique had been established. I found that anything more than minimal choking tended to flood the crankcase. The best approach was to choke just enough to fill the fuel line and then administer a small Once running, response to the controls proved to be extremely good, with no sign of the delayed needle response which is so often encountered with reed valve engines. This allowed optimal settings to be established very easily. Although the engine felt absolutely superb right from the start, I gave it three 5 minute runs at slightly reduced compression and a slightly rich needle. In accordance with my own article on iron-and-steel diesel break-in, I leaned it out fully and optimized the compression setting for the final 30 seconds or so, just to put the working parts through the full heat cycles which are absolutely essential for a good break-in. At the end of this shake-down running, the engine felt so good that I judged any further break-in operation to be a waste of time and fuel. I therefore began to take speed readings for my range of calibrated test airscrews, going from slowest to fastest and continuing to allow complete cooling between runs. The WB props are cut-down examples of formerly larger props which have been created and calibrated to fill power absorption gaps in my range of test airscrews. The following data were obtained during the course of this testing:

As can be seen, the Jaskółka-II showed itself to be quite a bit more powerful than the Jaskółka-0 model tested earlier. It appeared to develop around 0.258 BHP @ 12,700 RPM. This is of course very close indeed to Peter Chinn's previously-cited August 1962 power output figure of 0.25 BHP. As Chinn pointed out, this is not a particularly impressive figure by 1962 competition diesel standards, but it is more than adequate for sport flying. When taken together with the engine's outstanding handling, ultra-smooth running, attractive appearance and very sturdy construction, it's clear that this is a very useable engine indeed with a wide range of potential applications. A fine effort by Stan Górski! Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this summary of the immense contribution made by Stanislaw Górski and his colleagues to the development of aeromodelling in Poland during the Iron Curtain era when engines from elsewhere were essentially unavailable. Without their efforts, the aeromodelling movement in Poland would have lagged very badly for many years following WW2. So hats off to all of them - they did their compatriots proud! ______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2018

|

||

| |

This article will summarize the outcome of one of my more challenging self-imposed research projects! I’ll be attempting to throw a little light upon the history of the series of model engines developed during the classic era by one of Poland’s best-known model engine designers, Stanislaw Górski (1923-1978). This designer is perhaps best remembered for his development of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka (Swallow) series of model diesels, although he has other very considerable claims to fame in addition.

This article will summarize the outcome of one of my more challenging self-imposed research projects! I’ll be attempting to throw a little light upon the history of the series of model engines developed during the classic era by one of Poland’s best-known model engine designers, Stanislaw Górski (1923-1978). This designer is perhaps best remembered for his development of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka (Swallow) series of model diesels, although he has other very considerable claims to fame in addition.

Prior to World War 1, the country that we know today as Poland did not exist as an independent sovereign state, its territory having been carved up in 1795 between the Russian Empire (as it was then), the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy. A strong Polish resistance movement existed, resulting among other things in the January uprising of 1863 which was brutally put down by the Russians. Despite their lengthy domination by foreign powers, the people of Poland managed to retain a sense of national identity through education programs and collaborative Praca Organiczna (Organic Works) efforts to modernize both their economic and social situations.

Prior to World War 1, the country that we know today as Poland did not exist as an independent sovereign state, its territory having been carved up in 1795 between the Russian Empire (as it was then), the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy. A strong Polish resistance movement existed, resulting among other things in the January uprising of 1863 which was brutally put down by the Russians. Despite their lengthy domination by foreign powers, the people of Poland managed to retain a sense of national identity through education programs and collaborative Praca Organiczna (Organic Works) efforts to modernize both their economic and social situations.  Model engine manufacture had actually commenced in Poland before the war, albeit on a very small scale. Piotr Zawada tells us that a few examples of a 6 cc two-stroke spark ignition engine designated the IZ-5 were produced in Cracow during 1938-39 by a maker whose name seems to be lost in the mists of time. These appear to have been the first commercially-manufactured Polish model engines. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image, but we're lucky to have any image at all!

Model engine manufacture had actually commenced in Poland before the war, albeit on a very small scale. Piotr Zawada tells us that a few examples of a 6 cc two-stroke spark ignition engine designated the IZ-5 were produced in Cracow during 1938-39 by a maker whose name seems to be lost in the mists of time. These appear to have been the first commercially-manufactured Polish model engines. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image, but we're lucky to have any image at all!

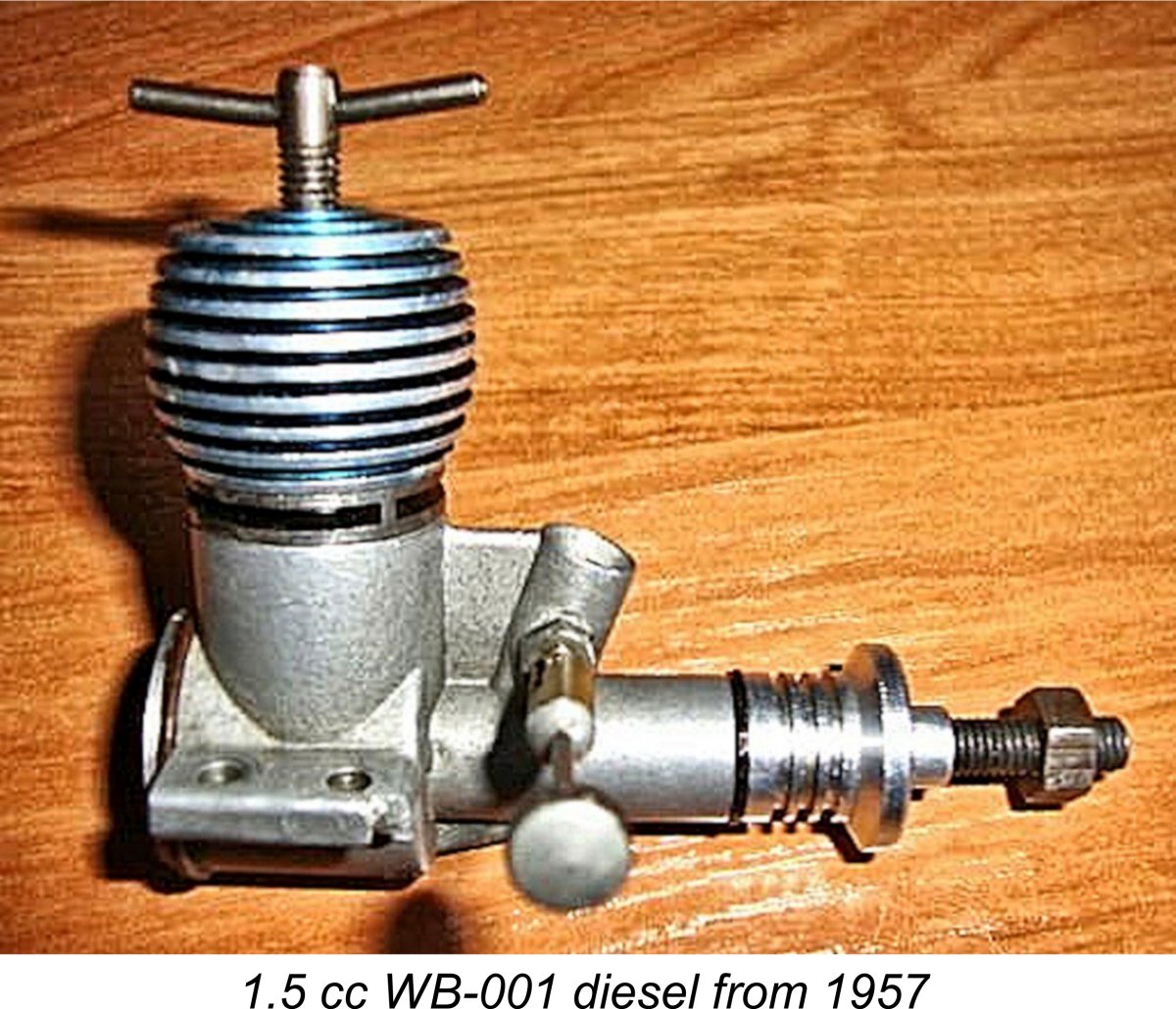

Another very early producer of model engines in Poland was Włodzimierz Bretsznajdera of Poznan, who also allegedly commenced production during the wartime occupation. At present I have no information regarding his original designs, but he later became a colleague of our main subject, Stanislaw Górski. He was still active in 1957, at which time he had developed a neat little 1.5 cc diesel model called the WB-001. A series of 500 examples of this engine was reportedly produced.

Another very early producer of model engines in Poland was Włodzimierz Bretsznajdera of Poznan, who also allegedly commenced production during the wartime occupation. At present I have no information regarding his original designs, but he later became a colleague of our main subject, Stanislaw Górski. He was still active in 1957, at which time he had developed a neat little 1.5 cc diesel model called the WB-001. A series of 500 examples of this engine was reportedly produced.  According to a contemporary Polish-language article (from which the above data as well as the attached unavoidably fuzzy image were extracted), it was hoped that the Rzeszów factory’s parent company, the Państwowe Zakłady Lotnicze (PZL - State Aviation Works) of Warsaw, might be persuaded to put this unit into production, since the writer felt that the advancement of aeromodelling in Poland required that inexpensive model engines be made generally available. At present I have no information regarding the actual fate of this engine in production terms. However, it appears to have been the first new post-war model engine design to appear in Poland.

According to a contemporary Polish-language article (from which the above data as well as the attached unavoidably fuzzy image were extracted), it was hoped that the Rzeszów factory’s parent company, the Państwowe Zakłady Lotnicze (PZL - State Aviation Works) of Warsaw, might be persuaded to put this unit into production, since the writer felt that the advancement of aeromodelling in Poland required that inexpensive model engines be made generally available. At present I have no information regarding the actual fate of this engine in production terms. However, it appears to have been the first new post-war model engine design to appear in Poland.

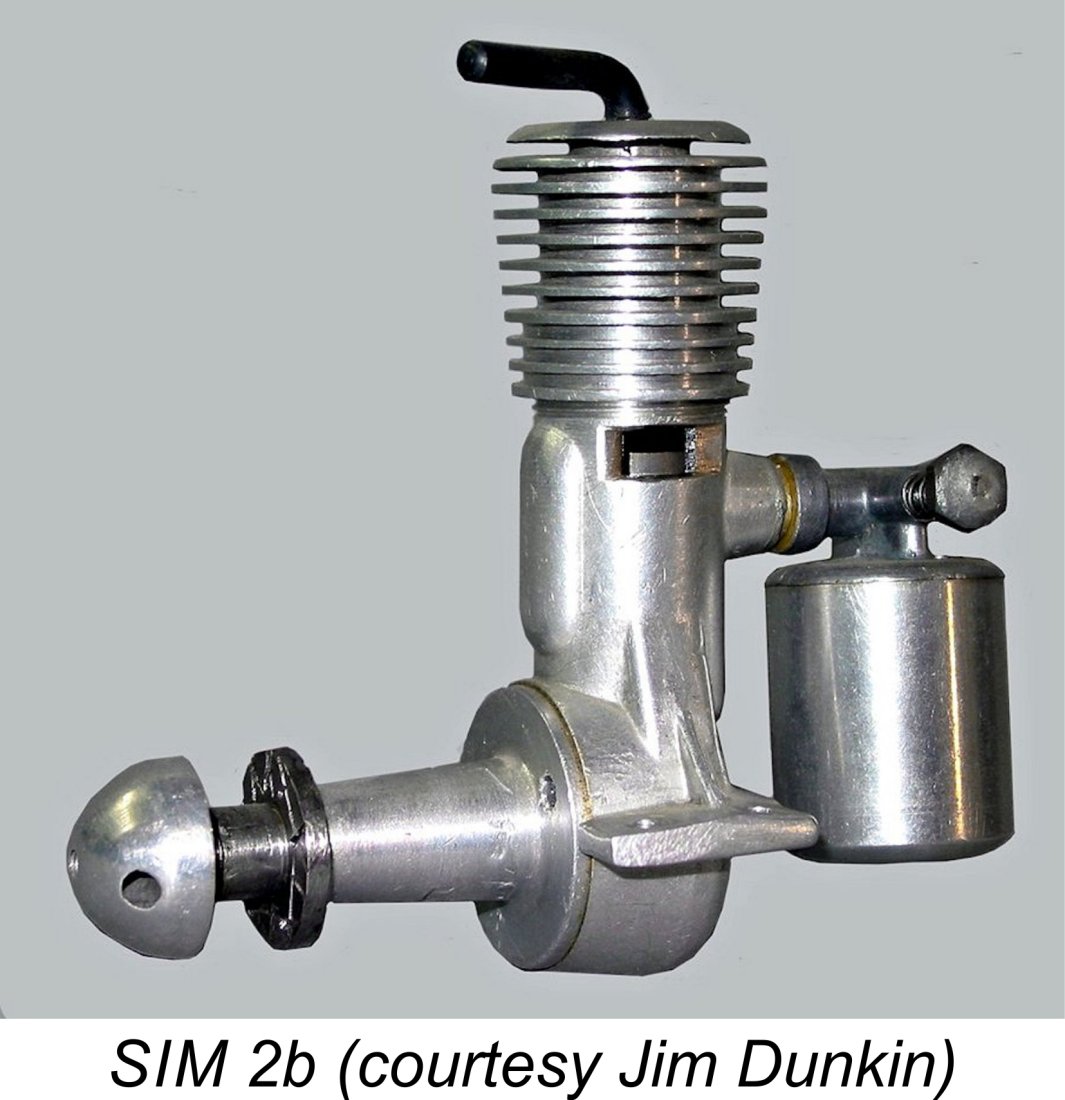

The larger-scale commercial production of model engines in early post-war Poland seems to have been initiated by Michal Oldachowski of Warsaw. In 1948 he began to manufacture a series of nice-looking sideport diesel engines, all of which were known by the designation SIM, standing for a combination of the word Silink (meaning “engine” in Polish) and the designer’s initial. There was a SIM-1 of 5 cc displacement along with a SIM-2 and a SIM-2b, the latter two being of 2.5 cc displacement. Several thousand examples of these units were reportedly manufactured between 1948 and 1954. Oldachowski also manufactured a 0.8 cc diesel of generally similar design layout designated the SIM-3. The SIM engines were apparently the most widely used model powerplants in Poland during their period of manufacture.

The larger-scale commercial production of model engines in early post-war Poland seems to have been initiated by Michal Oldachowski of Warsaw. In 1948 he began to manufacture a series of nice-looking sideport diesel engines, all of which were known by the designation SIM, standing for a combination of the word Silink (meaning “engine” in Polish) and the designer’s initial. There was a SIM-1 of 5 cc displacement along with a SIM-2 and a SIM-2b, the latter two being of 2.5 cc displacement. Several thousand examples of these units were reportedly manufactured between 1948 and 1954. Oldachowski also manufactured a 0.8 cc diesel of generally similar design layout designated the SIM-3. The SIM engines were apparently the most widely used model powerplants in Poland during their period of manufacture.  Stanislaw Górski was born in 1923. At present I have no information regarding his birthplace, upbringing or education. Nor do I know how he passed the war years. I would welcome the receipt of any information on those topics, since I firmly believe that the story of the model engines that we love is just as much the story of the talented individuals who designed and built them.

Stanislaw Górski was born in 1923. At present I have no information regarding his birthplace, upbringing or education. Nor do I know how he passed the war years. I would welcome the receipt of any information on those topics, since I firmly believe that the story of the model engines that we love is just as much the story of the talented individuals who designed and built them.

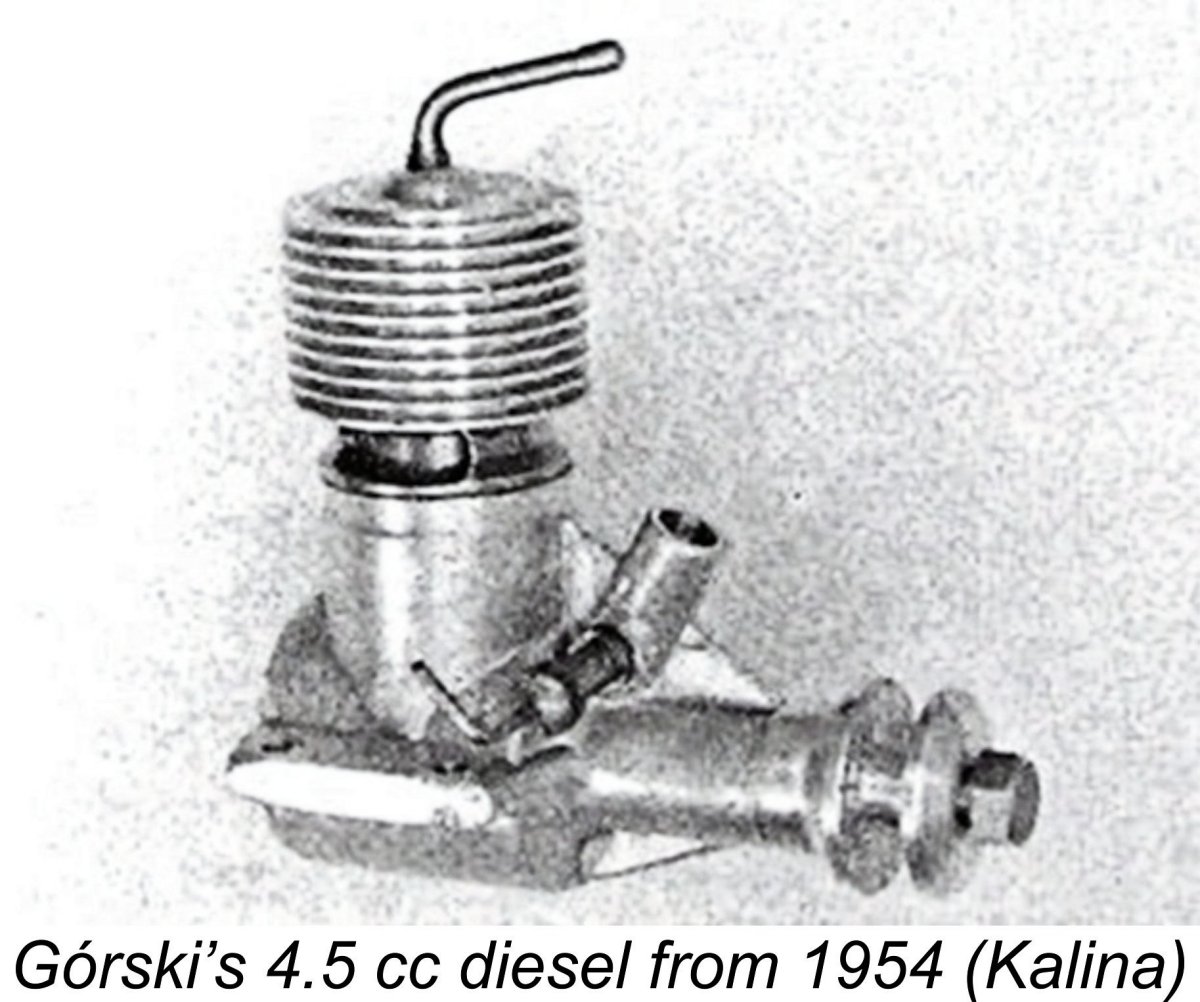

Although information on this engine is somewhat sketchy, it does appear that a slightly revised version did enter small-scale production, albeit at a reduced displacement of only 4.5 cc. An image of this engine was included in the second edition of Jiri Kalina's previously-cited book “Modelářské Motory” (Model Engines). Aplologies yet again for the poor quality of this image, but any image is surely better than none at all!!

Although information on this engine is somewhat sketchy, it does appear that a slightly revised version did enter small-scale production, albeit at a reduced displacement of only 4.5 cc. An image of this engine was included in the second edition of Jiri Kalina's previously-cited book “Modelářské Motory” (Model Engines). Aplologies yet again for the poor quality of this image, but any image is surely better than none at all!!

After 1945, the Mielec plant was returned by the Soviets to Polish administration, subsequently becoming the largest aviation factory in Poland. Operating under the WSK name as part of the PZL organization, it served as the main source of employment for people living in Mielec and the surrounding communities.

After 1945, the Mielec plant was returned by the Soviets to Polish administration, subsequently becoming the largest aviation factory in Poland. Operating under the WSK name as part of the PZL organization, it served as the main source of employment for people living in Mielec and the surrounding communities.

The first design to be assigned to the S.G. 2.5 cc Jaskólka series made its appearance in 1956. It was called the Jaskółka-0 for some now-obscure reason. Being the first member of this series, why not the Jaskółka-I?!? Only Stanislaw Górski knows, and he’s not telling, since he passed away in 1978!

The first design to be assigned to the S.G. 2.5 cc Jaskólka series made its appearance in 1956. It was called the Jaskółka-0 for some now-obscure reason. Being the first member of this series, why not the Jaskółka-I?!? Only Stanislaw Górski knows, and he’s not telling, since he passed away in 1978!

engine’s name was created by hand-scribing. This was the model which came most prominently to the attention of modellers outside Poland, evidently due to the manufacturer making fairly serious but minimally successful efforts to market it outside of Poland. I'll have more to say about this model below in its place.

engine’s name was created by hand-scribing. This was the model which came most prominently to the attention of modellers outside Poland, evidently due to the manufacturer making fairly serious but minimally successful efforts to market it outside of Poland. I'll have more to say about this model below in its place.

The first mention of the Jaskółka series which I can find in the English language media appeared in the September 1958 “Motor Mart” feature in “Aeromodeller”, which focused very much upon the then-new S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-II reed valve diesel, an example of which had somehow come into the hands of the magazine staff. This may well have been a result of the manufacturer sending a sample to “Aeromodeller” in the hope that this might stimulated some export business from Britain. If so, the initiative failed – as far as I can discover, the Górski engines were never imported into Britain in commercial quantities.

The first mention of the Jaskółka series which I can find in the English language media appeared in the September 1958 “Motor Mart” feature in “Aeromodeller”, which focused very much upon the then-new S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-II reed valve diesel, an example of which had somehow come into the hands of the magazine staff. This may well have been a result of the manufacturer sending a sample to “Aeromodeller” in the hope that this might stimulated some export business from Britain. If so, the initiative failed – as far as I can discover, the Górski engines were never imported into Britain in commercial quantities. However, Stanislaw Górski was by no means idle during this “dark” period. It will be recalled that he had been experimenting with 5 cc diesels as early as 1954. Apart from the appearance of the 1.5 cc model (which may not have been manufactured by Górski), production of a 5 cc design which was in effect a scaled-up version of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka engines had also been ongoing. These 5 cc units were given the series identification S.G. “Sokól” (Kestrel) to distinguish them from their smaller relatives.

However, Stanislaw Górski was by no means idle during this “dark” period. It will be recalled that he had been experimenting with 5 cc diesels as early as 1954. Apart from the appearance of the 1.5 cc model (which may not have been manufactured by Górski), production of a 5 cc design which was in effect a scaled-up version of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka engines had also been ongoing. These 5 cc units were given the series identification S.G. “Sokól” (Kestrel) to distinguish them from their smaller relatives.

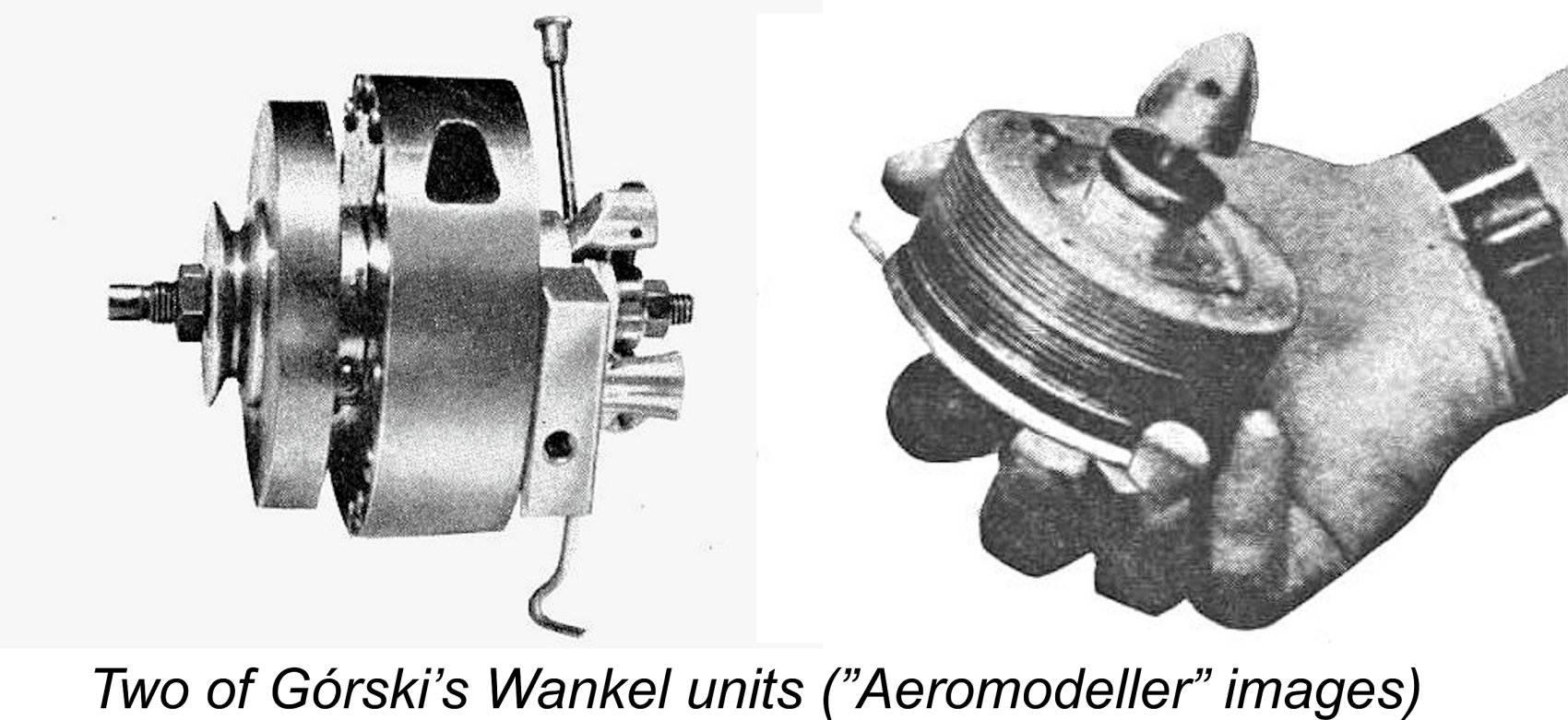

The lengthy English-language media silence surrounding the Górski designs was finally broken in April 1961 with the inclusion of a recent Górski production in the “Motor Mart” feature in that month’s issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. The featured engine was one of a remarkable series of individually-created Wankel rotary piston models made by Stanislaw Górski personally. This was a major achievement in model engineering terms – by producing this unit, Górski became the first model engineer to produce a successful model-sized Wankel engine. A further development of this remarkable unit was featured in the September 1961 “Motor Mart” feature in the same magazine.

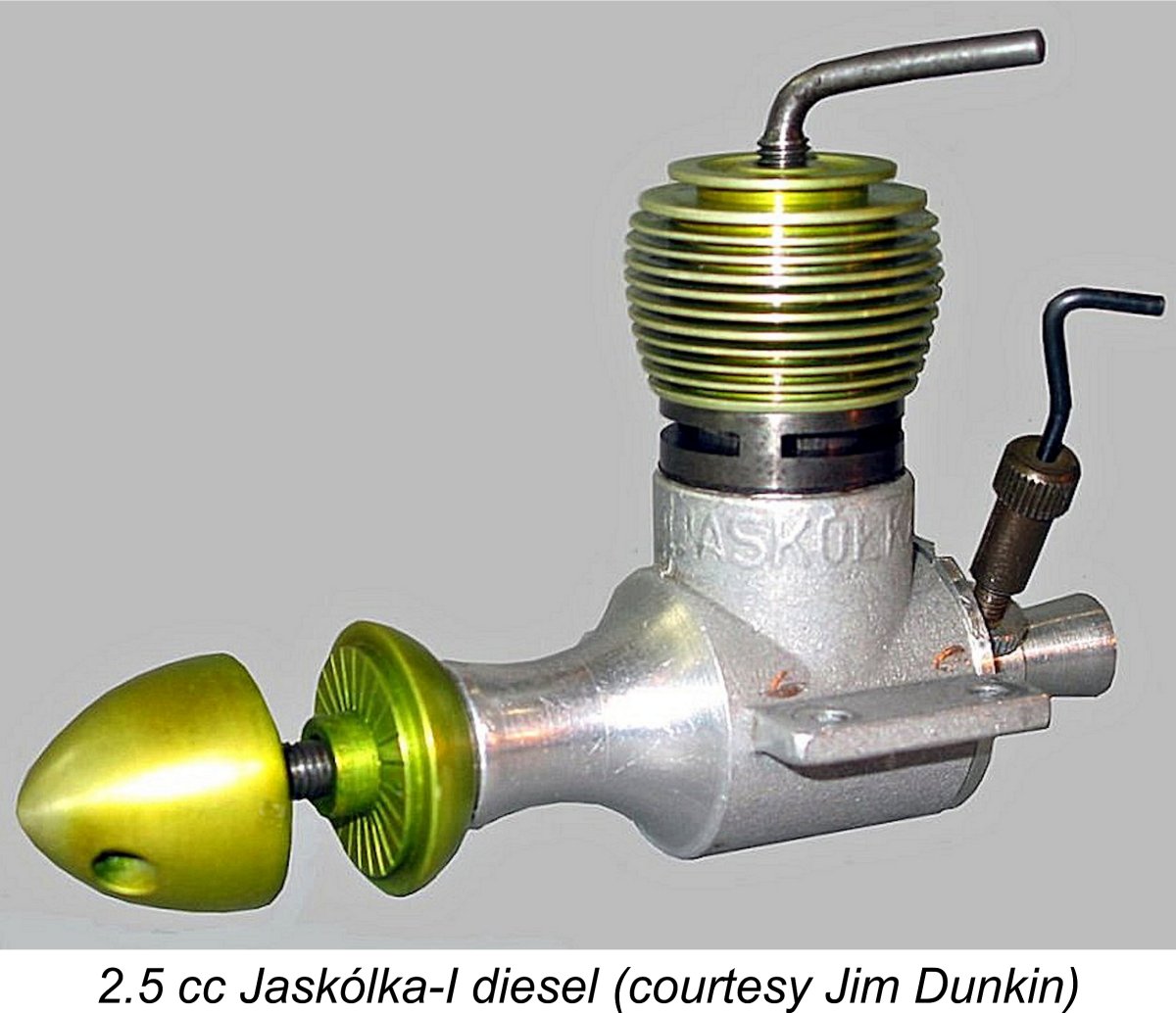

The lengthy English-language media silence surrounding the Górski designs was finally broken in April 1961 with the inclusion of a recent Górski production in the “Motor Mart” feature in that month’s issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. The featured engine was one of a remarkable series of individually-created Wankel rotary piston models made by Stanislaw Górski personally. This was a major achievement in model engineering terms – by producing this unit, Górski became the first model engineer to produce a successful model-sized Wankel engine. A further development of this remarkable unit was featured in the September 1961 “Motor Mart” feature in the same magazine.  General layout is orthodox, with circumferential exhaust porting and multiple deep internal transfer flutes spaced at 60 degree intervals below the exhausts. This arrangement, attention to which was first drawn by its use in the Webra Mach I in 1953, is popular with Eastern European designers and can also be seen in the East German Schlosser 2.5 and Hungarian Rekord 2.5 diesels. The cylinder, which is hardened, screws into the crankcase and is topped by a screwed-on alloy cooling barrel, anodized red. The crankshaft, supported in two ball bearings, is of the plain non-counterbalanced disc web type. A substantial turned alloy connecting-rod couples a conical-crown piston to the shaft by means of a small-diameter fully-floating gudgeon pin. There is a substantial degree of sub-piston supplementary air induction at the top of the stroke.

General layout is orthodox, with circumferential exhaust porting and multiple deep internal transfer flutes spaced at 60 degree intervals below the exhausts. This arrangement, attention to which was first drawn by its use in the Webra Mach I in 1953, is popular with Eastern European designers and can also be seen in the East German Schlosser 2.5 and Hungarian Rekord 2.5 diesels. The cylinder, which is hardened, screws into the crankcase and is topped by a screwed-on alloy cooling barrel, anodized red. The crankshaft, supported in two ball bearings, is of the plain non-counterbalanced disc web type. A substantial turned alloy connecting-rod couples a conical-crown piston to the shaft by means of a small-diameter fully-floating gudgeon pin. There is a substantial degree of sub-piston supplementary air induction at the top of the stroke.  “Poland’s leading designer (of model engines) is Stanislaw Górski, an accomplished modeller and engineer who built the first successful Wankel rotary-piston type miniature in Europe. Poland’s most widely-used powerplants, the Jaskólka (Swallow) .15 and Sokól (Kestrel) .29 diesels, were both by Górski. The Jaskólka has progressed through four models – shaft valve and reed valve plain bearing, reed valve and disc valve ball bearing types. The last two, known as the Jaskólka-II and Jaskólka-III, are included on our list. Similar variations of the larger Sokól have also been produced, but a successor to these, the Super Sokól, also by Górski, is being turned out.

“Poland’s leading designer (of model engines) is Stanislaw Górski, an accomplished modeller and engineer who built the first successful Wankel rotary-piston type miniature in Europe. Poland’s most widely-used powerplants, the Jaskólka (Swallow) .15 and Sokól (Kestrel) .29 diesels, were both by Górski. The Jaskólka has progressed through four models – shaft valve and reed valve plain bearing, reed valve and disc valve ball bearing types. The last two, known as the Jaskólka-II and Jaskólka-III, are included on our list. Similar variations of the larger Sokól have also been produced, but a successor to these, the Super Sokól, also by Górski, is being turned out. Given the complete absence of any published performance data measurements on the Jaskółka engines, I felt duty-bound to put my own example of the S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-0 diesel into the test stand. This is one of the later serial-numbered examples (no. 04519) with the tapered main bearing housing and added metal around the intake. In addition to the serial number, the numeral 8 appears beneath the right-hand mounting lug – I have no idea of the significance of this number.

Given the complete absence of any published performance data measurements on the Jaskółka engines, I felt duty-bound to put my own example of the S.G. 2.5 Jaskółka-0 diesel into the test stand. This is one of the later serial-numbered examples (no. 04519) with the tapered main bearing housing and added metal around the intake. In addition to the serial number, the numeral 8 appears beneath the right-hand mounting lug – I have no idea of the significance of this number.

Following the initial publication of this article, I was fortunate enough to acquire a fine example of the twin ball-race reed valve Jaskółka-II model. This came about solely through the kindness of my valued friend and colleague Peter Valicek of the Netherlands. Peter acquire the well-used engine on my behalf, subsequently restoring it to almost as-new condition. It's hard for me to adequately express my thanks to Peter.

Following the initial publication of this article, I was fortunate enough to acquire a fine example of the twin ball-race reed valve Jaskółka-II model. This came about solely through the kindness of my valued friend and colleague Peter Valicek of the Netherlands. Peter acquire the well-used engine on my behalf, subsequently restoring it to almost as-new condition. It's hard for me to adequately express my thanks to Peter.